Теория заговора

Теория заговора – это объяснение события или ситуации, которое утверждает существование заговора могущественных и зловещих групп, часто политических по мотивам. [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] когда другие объяснения более вероятны. [ 3 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] Этот термин обычно имеет негативный оттенок , подразумевая, что привлекательность теории заговора основана на предрассудках, эмоциональной убежденности или недостаточности доказательств. [ 8 ] Теория заговора отличается от заговора ; это относится к гипотетическому заговору с конкретными характеристиками, включая, помимо прочего, противодействие общепринятому консенсусу среди тех, кто имеет право оценивать его точность, таких как ученые или историки . [ 9 ] [ 10 ] [ 11 ]

Теории заговора имеют тенденцию быть внутренне непротиворечивыми и коррелировать друг с другом; [ 12 ] они обычно предназначены для предотвращения фальсификации либо за счет доказательств против них, либо из-за отсутствия доказательств в их пользу. [ 13 ] Они подкрепляются круговыми рассуждениями : как доказательства против заговора , так и отсутствие доказательств в его пользу ошибочно интерпретируются как доказательства его истинности. [ 8 ] [ 14 ] Стефан Левандовски отмечает: «Эта интерпретация основана на том, что чем сильнее доказательства против заговора, тем больше заговорщики должны хотеть, чтобы люди поверили их версии событий». [ 15 ] As a consequence, the conspiracy becomes a matter of faith rather than something that can be proven or disproven.[1][16] Studies have linked belief in conspiracy theories to distrust of authority and political cynicism.[17][18][19] Some researchers suggest that conspiracist ideation—belief in conspiracy theories—may be psychologically harmful or pathological.[20][21] Such belief is correlated with psychological projection, paranoia, and Machiavellianism.[22]

Psychologists usually attribute belief in conspiracy theories to a number of psychopathological conditions such as paranoia, schizotypy, narcissism, and insecure attachment,[9] or to a form of cognitive bias called "illusory pattern perception".[23][24] It has also been linked with the so-called Dark triad personality types, whose common feature is lack of empathy.[25] However, a 2020 review article found that most cognitive scientists view conspiracy theorizing as typically nonpathological, given that unfounded belief in conspiracy is common across both historical and contemporary cultures, and may arise from innate human tendencies towards gossip, group cohesion, and religion.[9] One historical review of conspiracy theories concluded that "Evidence suggests that the aversive feelings that people experience when in crisis—fear, uncertainty, and the feeling of being out of control—stimulate a motivation to make sense of the situation, increasing the likelihood of perceiving conspiracies in social situations."[26]

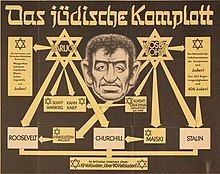

Historically, conspiracy theories have been closely linked to prejudice, propaganda, witch hunts, wars, and genocides.[12][27][28][29][30] They are often strongly believed by the perpetrators of terrorist attacks, and were used as justification by Timothy McVeigh and Anders Breivik, as well as by governments such as Nazi Germany, the Soviet Union,[27] and Turkey.[31] AIDS denialism by the government of South Africa, motivated by conspiracy theories, caused an estimated 330,000 deaths from AIDS.[32][33][34] QAnon and denialism about the 2020 United States presidential election results led to the January 6 United States Capitol attack,[35][36][37] and belief in conspiracy theories about genetically modified foods led the government of Zambia to reject food aid during a famine,[28] at a time when three million people in the country were suffering from hunger.[38] Conspiracy theories are a significant obstacle to improvements in public health,[28][39] encouraging opposition to such public health measures as vaccination and water fluoridation. They have been linked to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.[28][32][39][40] Other effects of conspiracy theories include reduced trust in scientific evidence,[12][28][41] radicalization and ideological reinforcement of extremist groups,[27][42] and negative consequences for the economy.[27]

Conspiracy theories once limited to fringe audiences have become commonplace in mass media, the internet, and social media,[9][12] emerging as a cultural phenomenon of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[43][44][45][46] They are widespread around the world and are often commonly believed, some even held by the majority of the population.[47][48][49] Interventions to reduce the occurrence of conspiracy beliefs include maintaining an open society, encouraging people to use analytical thinking, and reducing feelings of uncertainty, anxiety, or powerlessness.[41][47][48][50]

Origin and usage

The Oxford English Dictionary defines conspiracy theory as "the theory that an event or phenomenon occurs as a result of a conspiracy between interested parties; spec. a belief that some covert but influential agency (typically political in motivation and oppressive in intent) is responsible for an unexplained event". It cites a 1909 article in The American Historical Review as the earliest usage example,[51][52] although it also appeared in print for several decades before.[53]

The earliest known usage was by the American author Charles Astor Bristed, in a letter to the editor published in The New York Times on January 11, 1863.[54] He used it to refer to claims that British aristocrats were intentionally weakening the United States during the American Civil War in order to advance their financial interests.

England has had quite enough to do in Europe and Asia, without going out of her way to meddle with America. It was a physical and moral impossibility that she could be carrying on a gigantic conspiracy against us. But our masses, having only a rough general knowledge of foreign affairs, and not unnaturally somewhat exaggerating the space which we occupy in the world's eye, do not appreciate the complications which rendered such a conspiracy impossible. They only look at the sudden right-about-face movement of the English Press and public, which is most readily accounted for on the conspiracy theory.[54]

The term is also used as a way to discredit dissenting analyses.[55] Robert Blaskiewicz comments that examples of the term were used as early as the nineteenth century and states that its usage has always been derogatory.[56] According to a study by Andrew McKenzie-McHarg, in contrast, in the nineteenth century the term conspiracy theory simply "suggests a plausible postulate of a conspiracy" and "did not, at this stage, carry any connotations, either negative or positive", though sometimes a postulate so-labeled was criticized.[57] The author and activist George Monbiot argued that the terms "conspiracy theory" and "conspiracy theorist" are misleading, as conspiracies truly exist and theories are "rational explanations subject to disproof". Instead, he proposed the terms "conspiracy fiction" and "conspiracy fantasist".[58]

Alleged CIA origins

The term "conspiracy theory" is itself the subject of a conspiracy theory, which posits that the term was popularized by the CIA in order to discredit conspiratorial believers, particularly critics of the Warren Commission, by making them a target of ridicule.[59] In his 2013 book Conspiracy Theory in America, the political scientist Lance deHaven-Smith wrote that the term entered everyday language in the United States after 1964, the year in which the Warren Commission published its findings on the Kennedy assassination, with The New York Times running five stories that year using the term.[60]

Whether the CIA was responsible for popularising the term "conspiracy theory" was analyzed by Michael Butter, a Professor of American Literary and Cultural History at the University of Tübingen. Butter wrote in 2020 that the CIA document Concerning Criticism of the Warren Report, which proponents of the theory use as evidence of CIA motive and intention, does not contain the phrase "conspiracy theory" in the singular, and only uses the term "conspiracy theories" once, in the sentence: "Conspiracy theories have frequently thrown suspicion on our organisation [sic], for example, by falsely alleging that Lee Harvey Oswald worked for us."[61]

Difference from conspiracy

A conspiracy theory is not simply a conspiracy, which refers to any covert plan involving two or more people.[10] In contrast, the term "conspiracy theory" refers to hypothesized conspiracies that have specific characteristics. For example, conspiracist beliefs invariably oppose the mainstream consensus among those people who are qualified to evaluate their accuracy, such as scientists or historians.[11] Conspiracy theorists see themselves as having privileged access to socially persecuted knowledge or a stigmatized mode of thought that separates them from the masses who believe the official account.[10] Michael Barkun describes a conspiracy theory as a "template imposed upon the world to give the appearance of order to events".[10]

Real conspiracies, even very simple ones, are difficult to conceal and routinely experience unexpected problems.[62] In contrast, conspiracy theories suggest that conspiracies are unrealistically successful and that groups of conspirators, such as bureaucracies, can act with near-perfect competence and secrecy. The causes of events or situations are simplified to exclude complex or interacting factors, as well as the role of chance and unintended consequences. Nearly all observations are explained as having been deliberately planned by the alleged conspirators.[62]

In conspiracy theories, the conspirators are usually claimed to be acting with extreme malice.[62] As described by Robert Brotherton:

The malevolent intent assumed by most conspiracy theories goes far beyond everyday plots borne out of self-interest, corruption, cruelty, and criminality. The postulated conspirators are not merely people with selfish agendas or differing values. Rather, conspiracy theories postulate a black-and-white world in which good is struggling against evil. The general public is cast as the victim of organised persecution, and the motives of the alleged conspirators often verge on pure maniacal evil. At the very least, the conspirators are said to have an almost inhuman disregard for the basic liberty and well-being of the general population. More grandiose conspiracy theories portray the conspirators as being Evil Incarnate: of having caused all the ills from which we suffer, committing abominable acts of unthinkable cruelty on a routine basis, and striving ultimately to subvert or destroy everything we hold dear.[62]

Examples

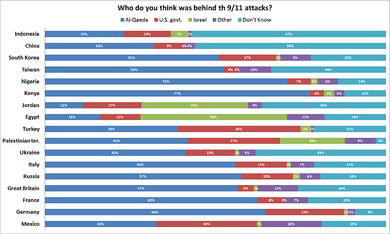

A conspiracy theory may take any matter as its subject, but certain subjects attract greater interest than others. Favored subjects include famous deaths and assassinations, morally dubious government activities, suppressed technologies, and "false flag" terrorism. Among the longest-standing and most widely recognized conspiracy theories are notions concerning the assassination of John F. Kennedy, the 1969 Apollo Moon landings, and the 9/11 terrorist attacks, as well as numerous theories pertaining to alleged plots for world domination by various groups, both real and imaginary.[63]

Popularity

Conspiracy beliefs are widespread around the world.[47] In rural Africa, common targets of conspiracy theorizing include societal elites, enemy tribes, and the Western world, with conspirators often alleged to enact their plans via sorcery or witchcraft; one common belief identifies modern technology as itself being a form of sorcery, created with the goal of harming or controlling the people.[47] In China, one widely published conspiracy theory claims that a number of events including the rise of Hitler, the 1997 Asian financial crisis, and climate change were planned by the Rothschild family, which may have led to effects on discussions about China's currency policy.[48][64]

Conspiracy theories once limited to fringe audiences have become commonplace in mass media, contributing to conspiracism emerging as a cultural phenomenon in the United States of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[43][44][45][46] The general predisposition to believe conspiracy theories cuts across partisan and ideological lines. Conspiratorial thinking is correlated with antigovernmental orientations and a low sense of political efficacy, with conspiracy believers perceiving a governmental threat to individual rights and displaying a deep skepticism that who one votes for really matters.[65]

Conspiracy theories are often commonly believed, some even being held by the majority of the population.[47][48][49] A broad cross-section of Americans today gives credence to at least some conspiracy theories.[66] For instance, a study conducted in 2016 found that 10% of Americans think the chemtrail conspiracy theory is "completely true" and 20–30% think it is "somewhat true".[67] This puts "the equivalent of 120 million Americans in the 'chemtrails are real' camp".[67] Belief in conspiracy theories has therefore become a topic of interest for sociologists, psychologists and experts in folklore.

Conspiracy theories are widely present on the Web in the form of blogs and YouTube videos, as well as on social media. Whether the Web has increased the prevalence of conspiracy theories or not is an open research question.[68] The presence and representation of conspiracy theories in search engine results has been monitored and studied, showing significant variation across different topics, and a general absence of reputable, high-quality links in the results.[69]

One conspiracy theory that propagated through former US President Barack Obama's time in office[70] claimed that he was born in Kenya, instead of Hawaii where he was actually born.[71] Former governor of Arkansas and political opponent of Obama Mike Huckabee made headlines in 2011[72] when he, among other members of Republican leadership, continued to question Obama's citizenship status.

| Conspiracy theory | Believe | Not sure |

|---|---|---|

| "A group of Satan-worshipping elites who run a child sex ring are trying to control our politics and media" (QAnon) | 17%

|

37%

|

| "Several mass shootings in recent years were staged hoaxes" (crisis actor theory) | 12%

|

27%

|

| Barack Obama was not born in the United States (birtherism) | 19%

|

22%

|

| Moon landing conspiracy theories | 8%

|

20%

|

| 9/11 conspiracy theories | 7%

|

20%

|

Types

A conspiracy theory can be local or international, focused on single events or covering multiple incidents and entire countries, regions and periods of history.[10] According to Russell Muirhead and Nancy Rosenblum, historically, traditional conspiracism has entailed a "theory", but over time, "conspiracy" and "theory" have become decoupled, as modern conspiracism is often without any kind of theory behind it.[74][75]

Walker's five kinds

Jesse Walker (2013) has identified five kinds of conspiracy theories:[76]

- The "Enemy Outside" refers to theories based on figures alleged to be scheming against a community from without.

- The "Enemy Within" finds the conspirators lurking inside the nation, indistinguishable from ordinary citizens.

- The "Enemy Above" involves powerful people manipulating events for their own gain.

- The "Enemy Below" features the lower classes working to overturn the social order.

- The "Benevolent Conspiracies" are angelic forces that work behind the scenes to improve the world and help people.

Barkun's three types

Michael Barkun has identified three classifications of conspiracy theory:[77]

- Event conspiracy theories. This refers to limited and well-defined events. Examples may include such conspiracies theories as those concerning the Kennedy assassination, 9/11, and the spread of AIDS.

- Systemic conspiracy theories. The conspiracy is believed to have broad goals, usually conceived as securing control of a country, a region, or even the entire world. The goals are sweeping, whilst the conspiratorial machinery is generally simple: a single, evil organization implements a plan to infiltrate and subvert existing institutions. This is a common scenario in conspiracy theories that focus on the alleged machinations of Jews, Freemasons, Communism, or the Catholic Church.

- Superconspiracy theories. For Barkun, such theories link multiple alleged conspiracies together hierarchically. At the summit is a distant but all-powerful evil force. His cited examples are the ideas of David Icke and Milton William Cooper.

Rothbard: shallow vs. deep

Murray Rothbard argues in favor of a model that contrasts "deep" conspiracy theories to "shallow" ones. According to Rothbard, a "shallow" theorist observes an event and asks Cui bono? ("Who benefits?"), jumping to the conclusion that a posited beneficiary is responsible for covertly influencing events. On the other hand, the "deep" conspiracy theorist begins with a hunch and then seeks out evidence. Rothbard describes this latter activity as a matter of confirming with certain facts one's initial paranoia.[78]

Lack of evidence

Belief in conspiracy theories is generally based not on evidence, but in the faith of the believer.[79] Noam Chomsky contrasts conspiracy theory to institutional analysis which focuses mostly on the public, long-term behavior of publicly known institutions, as recorded in, for example, scholarly documents or mainstream media reports.[80] Conspiracy theory conversely posits the existence of secretive coalitions of individuals and speculates on their alleged activities.[81][82] Belief in conspiracy theories is associated with biases in reasoning, such as the conjunction fallacy.[83]

Clare Birchall at King's College London describes conspiracy theory as a "form of popular knowledge or interpretation".[a] The use of the word 'knowledge' here suggests ways in which conspiracy theory may be considered in relation to legitimate modes of knowing.[b] The relationship between legitimate and illegitimate knowledge, Birchall claims, is closer than common dismissals of conspiracy theory contend.[85]

Theories involving multiple conspirators that are proven to be correct, such as the Watergate scandal, are usually referred to as investigative journalism or historical analysis rather than conspiracy theory.[86] Bjerg (2016) writes: "the way we normally use the term conspiracy theory excludes instances where the theory has been generally accepted as true. The Watergate scandal serves as the standard reference."[87] By contrast, the term "Watergate conspiracy theory" is used to refer to a variety of hypotheses in which those convicted in the conspiracy were in fact the victims of a deeper conspiracy.[88] There are also attempts to analyze the theory of conspiracy theories (conspiracy theory theory) to ensure that the term "conspiracy theory" is used to refer to narratives that have been debunked by experts, rather than as a generalized dismissal.[89]

Rhetoric

Conspiracy theory rhetoric exploits several important cognitive biases, including proportionality bias, attribution bias, and confirmation bias.[32] Their arguments often take the form of asking reasonable questions, but without providing an answer based on strong evidence.[90] Conspiracy theories are most successful when proponents can gather followers from the general public, such as in politics, religion and journalism. These proponents may not necessarily believe the conspiracy theory; instead, they may just use it in an attempt to gain public approval. Conspiratorial claims can act as a successful rhetorical strategy to convince a portion of the public via appeal to emotion.[28]

Conspiracy theories typically justify themselves by focusing on gaps or ambiguities in knowledge, and then arguing that the true explanation for this must be a conspiracy.[62] In contrast, any evidence that directly supports their claims is generally of low quality. For example, conspiracy theories are often dependent on eyewitness testimony, despite its unreliability, while disregarding objective analyses of the evidence.[62]

Conspiracy theories are not able to be falsified and are reinforced by fallacious arguments. In particular, the logical fallacy circular reasoning is used by conspiracy theorists: both evidence against the conspiracy and an absence of evidence for it are re-interpreted as evidence of its truth,[8][14] whereby the conspiracy becomes a matter of faith rather than something that can be proved or disproved.[1][16] The epistemic strategy of conspiracy theories has been called "cascade logic": each time new evidence becomes available, a conspiracy theory is able to dismiss it by claiming that even more people must be part of the cover-up.[28][62] Any information that contradicts the conspiracy theory is suggested to be disinformation by the alleged conspiracy.[41] Similarly, the continued lack of evidence directly supporting conspiracist claims is portrayed as confirming the existence of a conspiracy of silence; the fact that other people have not found or exposed any conspiracy is taken as evidence that those people are part of the plot, rather than considering that it may be because no conspiracy exists.[32][62] This strategy lets conspiracy theories insulate themselves from neutral analyses of the evidence, and makes them resistant to questioning or correction, which is called "epistemic self-insulation".[32][62]

Conspiracy theorists often take advantage of false balance in the media. They may claim to be presenting a legitimate alternative viewpoint that deserves equal time to argue its case; for example, this strategy has been used by the Teach the Controversy campaign to promote intelligent design, which often claims that there is a conspiracy of scientists suppressing their views. If they successfully find a platform to present their views in a debate format, they focus on using rhetorical ad hominems and attacking perceived flaws in the mainstream account, while avoiding any discussion of the shortcomings in their own position.[28]

The typical approach of conspiracy theories is to challenge any action or statement from authorities, using even the most tenuous justifications. Responses are then assessed using a double standard, where failing to provide an immediate response to the satisfaction of the conspiracy theorist will be claimed to prove a conspiracy. Any minor errors in the response are heavily emphasized, while deficiencies in the arguments of other proponents are generally excused.[28]

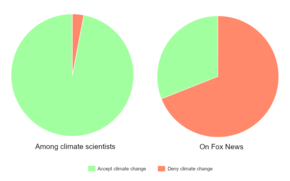

In science, conspiracists may suggest that a scientific theory can be disproven by a single perceived deficiency, even though such events are extremely rare. In addition, both disregarding the claims and attempting to address them will be interpreted as proof of a conspiracy.[28] Other conspiracist arguments may not be scientific; for example, in response to the IPCC Second Assessment Report in 1996, much of the opposition centered on promoting a procedural objection to the report's creation. Specifically, it was claimed that part of the procedure reflected a conspiracy to silence dissenters, which served as motivation for opponents of the report and successfully redirected a significant amount of the public discussion away from the science.[28]

Consequences

Historically, conspiracy theories have been closely linked to prejudice, witch hunts, wars, and genocides.[27][28] They are often strongly believed by the perpetrators of terrorist attacks, and were used as justification by Timothy McVeigh, Anders Breivik and Brenton Tarrant, as well as by governments such as Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union.[27] AIDS denialism by the government of South Africa, motivated by conspiracy theories, caused an estimated 330,000 deaths from AIDS,[32][33][34] while belief in conspiracy theories about genetically modified foods led the government of Zambia to reject food aid during a famine,[28] at a time when 3 million people in the country were suffering from hunger.[38]

Conspiracy theories are a significant obstacle to improvements in public health.[28][39] People who believe in health-related conspiracy theories are less likely to follow medical advice, and more likely to use alternative medicine instead.[27] Conspiratorial anti-vaccination beliefs, such as conspiracy theories about pharmaceutical companies, can result in reduced vaccination rates and have been linked to outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.[32][28][40][39] Health-related conspiracy theories often inspire resistance to water fluoridation, and contributed to the impact of the Lancet MMR autism fraud.[28][39]

Conspiracy theories are a fundamental component of a wide range of radicalized and extremist groups, where they may play an important role in reinforcing the ideology and psychology of their members as well as further radicalizing their beliefs.[27][42] These conspiracy theories often share common themes, even among groups that would otherwise be fundamentally opposed, such as the antisemitic conspiracy theories found among political extremists on both the far right and far left.[27] More generally, belief in conspiracy theories is associated with holding extreme and uncompromising viewpoints, and may help people in maintaining those viewpoints.[41] While conspiracy theories are not always present in extremist groups, and do not always lead to violence when they are, they can make the group more extreme, provide an enemy to direct hatred towards, and isolate members from the rest of society. Conspiracy theories are most likely to inspire violence when they call for urgent action, appeal to prejudices, or demonize and scapegoat enemies.[42]

Conspiracy theorizing in the workplace can also have economic consequences. For example, it leads to lower job satisfaction and lower commitment, resulting in workers being more likely to leave their jobs.[27] Comparisons have also been made with the effects of workplace rumors, which share some characteristics with conspiracy theories and result in both decreased productivity and increased stress. Subsequent effects on managers include reduced profits, reduced trust from employees, and damage to the company's image.[27][92]

Conspiracy theories can divert attention from important social, political, and scientific issues.[93][94] In addition, they have been used to discredit scientific evidence to the general public or in a legal context. Conspiratorial strategies also share characteristics with those used by lawyers who are attempting to discredit expert testimony, such as claiming that the experts have ulterior motives in testifying, or attempting to find someone who will provide statements to imply that expert opinion is more divided than it actually is.[28]

It is possible that conspiracy theories may also produce some compensatory benefits to society in certain situations. For example, they may help people identify governmental deceptions, particularly in repressive societies, and encourage government transparency.[48][93] However, real conspiracies are normally revealed by people working within the system, such as whistleblowers and journalists, and most of the effort spent by conspiracy theorists is inherently misdirected.[42] The most dangerous conspiracy theories are likely to be those that incite violence, scapegoat disadvantaged groups, or spread misinformation about important societal issues.[95]

Interventions

Target audience

Strategies to address conspiracy theories have been divided into two categories based on whether the target audience is the conspiracy theorists or the general public.[50][48] These strategies have been described as reducing either the supply or the demand for conspiracy theories.[48] Both approaches can be used at the same time, although there may be issues of limited resources, or if arguments are used which may appeal to one audience at the expense of the other.[48]

General public

People who feel empowered are more resistant to conspiracy theories. Methods to promote empowerment include encouraging people to use analytical thinking, priming people to think of situations where they are in control, and ensuring that decisions by society and government are seen to follow procedural fairness (the use of fair decision-making procedures).[50]

Methods of refutation which have shown effectiveness in various circumstances include: providing facts that demonstrate the conspiracy theory is false, attempting to discredit the source, explaining how the logic is invalid or misleading, and providing links to fact-checking websites.[50] It can also be effective to use these strategies in advance, informing people that they could encounter misleading information in the future, and why the information should be rejected (also called inoculation or prebunking).[50][96][97] While it has been suggested that discussing conspiracy theories can raise their profile and make them seem more legitimate to the public, the discussion can put people on guard instead as long as it is sufficiently persuasive.[9]

Other approaches to reduce the appeal of conspiracy theories in general among the public may be based in the emotional and social nature of conspiratorial beliefs. For example, interventions that promote analytical thinking in the general public are likely to be effective. Another approach is to intervene in ways that decrease negative emotions, and specifically to improve feelings of personal hope and empowerment.[47]

Conspiracy theorists

It is much more difficult to convince people who already believe in conspiracy theories.[48][50] Conspiracist belief systems are not based on external evidence, but instead use circular logic where every belief is supported by other conspiracist beliefs.[50] In addition, conspiracy theories have a "self-sealing" nature, in which the types of arguments used to support them make them resistant to questioning from others.[48]

Characteristics of successful strategies for reaching conspiracy theorists have been divided into several broad categories: 1) Arguments can be presented by "trusted messengers", such as people who were formerly members of an extremist group. 2) Since conspiracy theorists think of themselves as people who value critical thinking, this can be affirmed and then redirected to encourage being more critical when analyzing the conspiracy theory. 3) Approaches demonstrate empathy, and are based on building understanding together, which is supported by modeling open-mindedness in order to encourage the conspiracy theorists to do likewise. 4) The conspiracy theories are not attacked with ridicule or aggressive deconstruction, and interactions are not treated like an argument to be won; this approach can work with the general public, but among conspiracy theorists it may simply be rejected.[50]

Interventions that reduce feelings of uncertainty, anxiety, or powerlessness result in a reduction in conspiracy beliefs.[41] Other possible strategies to mitigate the effect of conspiracy theories include education, media literacy, and increasing governmental openness and transparency.[96] Due to the relationship between conspiracy theories and political extremism, the academic literature on deradicalization is also important.[50]

One approach describes conspiracy theories as resulting from a "crippled epistemology", in which a person encounters or accepts very few relevant sources of information.[48][98] A conspiracy theory is more likely to appear justified to people with a limited "informational environment" who only encounter misleading information. These people may be "epistemologically isolated" in self-enclosed networks. From the perspective of people within these networks, disconnected from the information available to the rest of society, believing in conspiracy theories may appear to be justified.[48][98] In these cases, the solution would be to break the group's informational isolation.[48]

Reducing transmission

Public exposure to conspiracy theories can be reduced by interventions that reduce their ability to spread, such as by encouraging people to reflect before sharing a news story.[50] Researchers Carlos Diaz Ruiz and Tomas Nilsson have proposed technical and rhetorical interventions to counter the spread of conspiracy theories on social media.[99]

| Type of intervention | Intervention |

|---|---|

| Technical | Expose sources that insert and circulate conspiracy theories on social media (flagging). |

| Diminish the source's capacity to monetize conspiracies (demonetization). | |

| Slow down the circulation of conspiracy theories (algorithm) | |

| Rhetorical | Issue authoritative corrections (fact-checking). |

| Authority-based corrections and fact-checking may backfire because personal worldviews cannot be proved wrong. | |

| Enlist spokespeople that can be perceived as allies and insiders. | |

| Rebuttals must spring from an epistemology that participants are already familiar with. | |

| Give believers of conspiracies an "exit ramp" to dis-invest themselves without facing ridicule. |

Government policies

The primary defense against conspiracy theories is to maintain an open society, in which many sources of reliable information are available, and government sources are known to be credible rather than propaganda. Additionally, independent nongovernmental organizations are able to correct misinformation without requiring people to trust the government.[48] The absence of civil rights and civil liberties reduces the number of information sources available to the population, which may lead people to support conspiracy theories.[48] Since the credibility of conspiracy theories can be increased if governments act dishonestly or otherwise engage in objectionable actions, avoiding such actions is also a relevant strategy.[96]

Joseph Pierre has said that mistrust in authoritative institutions is the core component underlying many conspiracy theories and that this mistrust creates an epistemic vacuum and makes individuals searching for answers vulnerable to misinformation. Therefore, one possible solution is offering consumers a seat at the table to mend their mistrust in institutions.[100] Regarding the challenges of this approach, Pierre has said, "The challenge with acknowledging areas of uncertainty within a public sphere is that doing so can be weaponized to reinforce a post-truth view of the world in which everything is debatable, and any counter-position is just as valid. Although I like to think of myself as a middle of the road kind of individual, it is important to keep in mind that the truth does not always lie in the middle of a debate, whether we are talking about climate change, vaccines, or antipsychotic medications."[101]

Researchers have recommended that public policies should take into account the possibility of conspiracy theories relating to any policy or policy area, and prepare to combat them in advance.[96][9] Conspiracy theories have suddenly arisen in the context of policy issues as disparate as land-use laws and bicycle-sharing programs.[96] In the case of public communications by government officials, factors that improve the effectiveness of communication include using clear and simple messages, and using messengers which are trusted by the target population. Government information about conspiracy theories is more likely to be believed if the messenger is perceived as being part of someone's in-group. Official representatives may be more effective if they share characteristics with the target groups, such as ethnicity.[96]

In addition, when the government communicates with citizens to combat conspiracy theories, online methods are more efficient compared to other methods such as print publications. This also promotes transparency, can improve a message's perceived trustworthiness, and is more effective at reaching underrepresented demographics. However, as of 2019[update], many governmental websites do not take full advantage of the available information-sharing opportunities. Similarly, social media accounts need to be used effectively in order to achieve meaningful communication with the public, such as by responding to requests that citizens send to those accounts. Other steps include adapting messages to the communication styles used on the social media platform in question, and promoting a culture of openness. Since mixed messaging can support conspiracy theories, it is also important to avoid conflicting accounts, such as by ensuring the accuracy of messages on the social media accounts of individual members of the organization.[96]

Public health campaigns

Successful methods for dispelling conspiracy theories have been studied in the context of public health campaigns. A key characteristic of communication strategies to address medical conspiracy theories is the use of techniques that rely less on emotional appeals. It is more effective to use methods that encourage people to process information rationally. The use of visual aids is also an essential part of these strategies. Since conspiracy theories are based on intuitive thinking, and visual information processing relies on intuition, visual aids are able to compete directly for the public's attention.[9]

In public health campaigns, information retention by the public is highest for loss-framed messages that include more extreme outcomes. However, excessively appealing to catastrophic scenarios (e.g. low vaccination rates causing an epidemic) may provoke anxiety, which is associated with conspiracism and could increase belief in conspiracy theories instead. Scare tactics have sometimes had mixed results, but are generally considered ineffective. An example of this is the use of images that showcase disturbing health outcomes, such as the impact of smoking on dental health. One possible explanation is that information processed via the fear response is typically not evaluated rationally, which may prevent the message from being linked to the desired behaviors.[9]

A particularly important technique is the use of focus groups to understand exactly what people believe, and the reasons they give for those beliefs. This allows messaging to focus on the specific concerns that people identify, and on topics that are easily misinterpreted by the public, since these are factors which conspiracy theories can take advantage of. In addition, discussions with focus groups and observations of the group dynamics can indicate which anti-conspiracist ideas are most likely to spread.[9]

Interventions that address medical conspiracy theories by reducing powerlessness include emphasizing the principle of informed consent, giving patients all the relevant information without imposing decisions on them, to ensure that they have a sense of control. Improving access to healthcare also reduces medical conspiracism. However, doing so by political efforts can also fuel additional conspiracy theories, which occurred with the Affordable Care Act (Obamacare) in the United States. Another successful strategy is to require people to watch a short video when they fulfil requirements such as registration for school or a drivers' license, which has been demonstrated to improve vaccination rates and signups for organ donation.[9]

Another approach is based on viewing conspiracy theories as narratives which express personal and cultural values, making them less susceptible to straightforward factual corrections, and more effectively addressed by counter-narratives.[97][102] Counter-narratives can be more engaging and memorable than simple corrections, and can be adapted to the specific values held by individuals and cultures. These narratives may depict personal experiences, or alternatively they can be cultural narratives. In the context of vaccination, examples of cultural narratives include stories about scientific breakthroughs, about the world before vaccinations, or about heroic and altruistic researchers. The themes to be addressed would be those that could be exploited by conspiracy theories to increase vaccine hesitancy, such as perceptions of vaccine risk, lack of patient empowerment, and lack of trust in medical authorities.[97]

Backfire effects

It has been suggested that directly countering misinformation can be counterproductive. For example, since conspiracy theories can reinterpret disconfirming information as part of their narrative, refuting a claim can result in accidentally reinforcing it,[62][103] which is referred to as a "backfire effect".[104] In addition, publishing criticism of conspiracy theories can result in legitimizing them.[93] In this context, possible interventions include carefully selecting which conspiracy theories to refute, requesting additional analyses from independent observers, and introducing cognitive diversity into conspiratorial communities by undermining their poor epistemology.[93] Any legitimization effect might also be reduced by responding to more conspiracy theories rather than fewer.[48]

There are psychological mechanisms by which backfire effects could potentially occur, but the evidence on this topic is mixed, and backfire effects are very rare in practice.[97][104][105] A 2020 review of the scientific literature on backfire effects found that there have been widespread failures to replicate their existence, even under conditions that would be theoretically favorable to observing them.[104] Due to the lack of reproducibility, as of 2020[update] most researchers believe that backfire effects are either unlikely to occur on the broader population level, or they only occur in very specific circumstances, or they do not exist.[104] Brendan Nyhan, one of the researchers who initially proposed the occurrence of backfire effects, wrote in 2021 that the persistence of misinformation is most likely due to other factors.[105]

In general, people do reject conspiracy theories when they learn about their contradictions and lack of evidence.[9] For most people, corrections and fact-checking are very unlikely to have a negative impact, and there is no specific group of people in which backfire effects have been consistently observed.[104] Presenting people with factual corrections, or highlighting the logical contradictions in conspiracy theories, has been demonstrated to have a positive effect in many circumstances.[47][103] For example, this has been studied in the case of informing believers in 9/11 conspiracy theories about statements by actual experts and witnesses.[47] One possibility is that criticism is most likely to backfire if it challenges someone's worldview or identity. This suggests that an effective approach may be to provide criticism while avoiding such challenges.[103]

Psychology

The widespread belief in conspiracy theories has become a topic of interest for sociologists, psychologists, and experts in folklore since at least the 1960s, when a number of conspiracy theories arose regarding the assassination of U.S. President John F. Kennedy. Sociologist Türkay Salim Nefes underlines the political nature of conspiracy theories. He suggests that one of the most important characteristics of these accounts is their attempt to unveil the "real but hidden" power relations in social groups.[106][107] The term "conspiracism" was popularized by academic Frank P. Mintz in the 1980s. According to Mintz, conspiracism denotes "belief in the primacy of conspiracies in the unfolding of history":[108]: 4

Conspiracism serves the needs of diverse political and social groups in America and elsewhere. It identifies elites, blames them for economic and social catastrophes, and assumes that things will be better once popular action can remove them from positions of power. As such, conspiracy theories do not typify a particular epoch or ideology.[108]: 199

Research suggests, on a psychological level, conspiracist ideation—belief in conspiracy theories—can be harmful or pathological,[20][21] and is highly correlated with psychological projection, as well as with paranoia, which is predicted by the degree of a person's Machiavellianism.[109] The propensity to believe in conspiracy theories is strongly associated with the mental health disorder of schizotypy.[110][111][112][113][114] Conspiracy theories once limited to fringe audiences have become commonplace in mass media, emerging as a cultural phenomenon of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[43][44][45][46] Exposure to conspiracy theories in news media and popular entertainment increases receptiveness to conspiratorial ideas, and has also increased the social acceptability of fringe beliefs.[27][115]

Conspiracy theories often make use of complicated and detailed arguments, including ones which appear to be analytical or scientific. However, belief in conspiracy theories is primarily driven by emotion.[47] One of the most widely confirmed facts about conspiracy theories is that belief in a single conspiracy theory tends be correlated with belief in other conspiracy theories.[32][116] This even applies when the conspiracy theories directly contradict each other, e.g. believing that Osama bin Laden was already dead before his compound in Pakistan was attacked makes the same person more likely to believe that he is still alive. One conclusion from this finding is that the content of a conspiracist belief is less important than the idea of a coverup by the authorities.[32][94][117] Analytical thinking aids in reducing belief in conspiracy theories, in part because it emphasizes rational and critical cognition.[41]

Some psychological scientists assert that explanations related to conspiracy theories can be, and often are "internally consistent" with strong beliefs that had previously been held prior to the event that sparked the conspiracy.[41] People who believe in conspiracy theories tend to believe in other unsubstantiated claims – including pseudoscience and paranormal phenomena.[118]

Attractions

Psychological motives for believing in conspiracy theories can be categorized as epistemic, existential, or social. These motives are particularly acute in vulnerable and disadvantaged populations. However, it does not appear that the beliefs help to address these motives; in fact, they may be self-defeating, acting to make the situation worse instead.[41][103] For example, while conspiratorial beliefs can result from a perceived sense of powerlessness, exposure to conspiracy theories immediately suppresses personal feelings of autonomy and control. Furthermore, they also make people less likely to take actions that could improve their circumstances.[41][103]

This is additionally supported by the fact that conspiracy theories have a number of disadvantageous attributes.[41] For example, they promote a negative and distrustful view of other people and groups, who are allegedly acting based on antisocial and cynical motivations. This is expected to lead to increased alienation and anomie, and reduced social capital. Similarly, they depict the public as ignorant and powerless against the alleged conspirators, with important aspects of society determined by malevolent forces, a viewpoint which is likely to be disempowering.[41]

Each person may endorse conspiracy theories for one of many different reasons.[119] The most consistently demonstrated characteristics of people who find conspiracy theories appealing are a feeling of alienation, unhappiness or dissatisfaction with their situation, an unconventional worldview, and a feeling of disempowerment.[119] While various aspects of personality affect susceptibility to conspiracy theories, none of the Big Five personality traits are associated with conspiracy beliefs.[119]

The political scientist Michael Barkun, discussing the usage of "conspiracy theory" in contemporary American culture, holds that this term is used for a belief that explains an event as the result of a secret plot by exceptionally powerful and cunning conspirators to achieve a malevolent end.[120][121] According to Barkun, the appeal of conspiracism is threefold:

- First, conspiracy theories claim to explain what institutional analysis cannot. They appear to make sense out of a world that is otherwise confusing.

- Second, they do so in an appealingly simple way, by dividing the world sharply between the forces of light, and the forces of darkness. They trace all evil back to a single source, the conspirators and their agents.

- Third, conspiracy theories are often presented as special, secret knowledge unknown or unappreciated by others. For conspiracy theorists, the masses are a brainwashed herd, while the conspiracy theorists in the know can congratulate themselves on penetrating the plotters' deceptions.[121]

This third point is supported by research of Roland Imhoff, professor of social psychology at the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. The research suggests that the smaller the minority believing in a specific theory, the more attractive it is to conspiracy theorists.[122] Humanistic psychologists argue that even if a posited cabal behind an alleged conspiracy is almost always perceived as hostile, there often remains an element of reassurance for theorists. This is because it is a consolation to imagine that difficulties in human affairs are created by humans, and remain within human control. If a cabal can be implicated, there may be a hope of breaking its power or of joining it. Belief in the power of a cabal is an implicit assertion of human dignity—an unconscious affirmation that man is responsible for his own destiny.[123]

People formulate conspiracy theories to explain, for example, power relations in social groups and the perceived existence of evil forces.[c][121][106][107] Proposed psychological origins of conspiracy theorising include projection; the personal need to explain "a significant event [with] a significant cause;" and the product of various kinds and stages of thought disorder, such as paranoid disposition, ranging in severity to diagnosable mental illnesses. Some people prefer socio-political explanations over the insecurity of encountering random, unpredictable, or otherwise inexplicable events.[124][125][126][127][128][129] According to Berlet and Lyons, "Conspiracism is a particular narrative form of scapegoating that frames demonized enemies as part of a vast insidious plot against the common good, while it valorizes the scapegoater as a hero for sounding the alarm".[130]

Causes

Some psychologists believe that a search for meaning is common in conspiracism. Once cognized, confirmation bias and avoidance of cognitive dissonance may reinforce the belief. In a context where a conspiracy theory has become embedded within a social group, communal reinforcement may also play a part.[131]

Inquiry into possible motives behind the accepting of irrational conspiracy theories has linked[132] these beliefs to distress resulting from an event that occurred, such as the events of 9/11. Additional research suggests that "delusional ideation" is the trait most likely to indicate a stronger belief in conspiracy theories.[133] Research also shows an increased attachment to these irrational beliefs leads to a decreased desire for civic engagement.[83] Belief in conspiracy theories is correlated with low intelligence, lower analytical thinking, anxiety disorders, paranoia, and authoritarian beliefs.[134][135][136]

Professor Quassim Cassam argues that conspiracy theorists hold their beliefs due to flaws in their thinking and more precisely, their intellectual character. He cites philosopher Linda Trinkaus Zagzebski and her book Virtues of the Mind in outlining intellectual virtues (such as humility, caution and carefulness) and intellectual vices (such as gullibility, carelessness and closed-mindedness). Whereas intellectual virtues help in reaching sound examination, intellectual vices "impede effective and responsible inquiry", meaning that those who are prone to believing in conspiracy theories possess certain vices while lacking necessary virtues.[137]

Some researchers have suggested that conspiracy theories could be partially caused by psychological mechanisms the human brain possesses for detecting dangerous coalitions. Such a mechanism could have been useful in the small-scale environment humanity evolved in but are mismatched in a modern, complex society and thus "misfire", perceiving conspiracies where none exist.[138]

Projection

Some historians have argued that psychological projection is prevalent amongst conspiracy theorists. This projection, according to the argument, is manifested in the form of attribution of undesirable characteristics of the self to the conspirators. Historian Richard Hofstadter stated that:

This enemy seems on many counts a projection of the self; both the ideal and the unacceptable aspects of the self are attributed to him. A fundamental paradox of the paranoid style is the imitation of the enemy. The enemy, for example, may be the cosmopolitan intellectual, but the paranoid will outdo him in the apparatus of scholarship, even of pedantry. ... The Ku Klux Klan imitated Catholicism to the point of donning priestly vestments, developing an elaborate ritual and an equally elaborate hierarchy. The John Birch Society emulates Communist cells and quasi-secret operation through "front" groups, and preaches a ruthless prosecution of the ideological war along lines very similar to those it finds in the Communist enemy. Spokesmen of the various fundamentalist anti-Communist "crusades" openly express their admiration for the dedication, discipline, and strategic ingenuity the Communist cause calls forth.[127]

Hofstadter also noted that "sexual freedom" is a vice frequently attributed to the conspiracist's target group, noting that "very often the fantasies of true believers reveal strong sadomasochistic outlets, vividly expressed, for example, in the delight of anti-Masons with the cruelty of Masonic punishments".[127]

Physiology

Marcel Danesi suggests that people who believe conspiracy theories have difficulty rethinking situations. Exposure to those theories has caused neural pathways which are more rigid and less subject to change. Initial susceptibility to believing the lies, dehumanizing language, and metaphors of these theories leads to the acceptance of larger and more extensive theories because the hardened neural pathways are already present. Repetition of the "facts" of conspiracy theories and their connected lies simply reinforces the rigidity of those pathways. Thus, conspiracy theories and dehumanizing lies are not mere hyperbole, they can actually change the way people think:

Unfortunately, research into this brain wiring also shows that once people begin to believe lies, they are unlikely to change their minds even when confronted with evidence that contradicts their beliefs. It is a form of brainwashing. Once the brain has carved out a well-worn path of believing deceit, it is even harder to step out of that path — which is how fanatics are born. Instead, these people will seek out information that confirms their beliefs, avoid anything that is in conflict with them, or even turn the contrasting information on its head, so as to make it fit their beliefs.

People with strong convictions will have a hard time changing their minds, given how embedded a lie becomes in the mind. In fact, there are scientists and scholars still studying the best tools and tricks to combat lies with some combination of brain training and linguistic awareness.[139]

Sociology

In addition to psychological factors such as conspiracist ideation, sociological factors also help account for who believes in which conspiracy theories. Such theories tend to get more traction among election losers in society, for example, and the emphasis of conspiracy theories by elites and leaders tends to increase belief among followers who have higher levels of conspiracy thinking.[140] Christopher Hitchens described conspiracy theories as the "exhaust fumes of democracy":[128] the unavoidable result of a large amount of information circulating among a large number of people.

Conspiracy theories may be emotionally satisfying, by assigning blame to a group to which the theorist does not belong and so absolving the theorist of moral or political responsibility in society.[141] Likewise, Roger Cohen writing for The New York Times has said that, "captive minds; ... resort to conspiracy theory because it is the ultimate refuge of the powerless. If you cannot change your own life, it must be that some greater force controls the world."[129]

Sociological historian Holger Herwig found in studying German explanations for the origins of World War I, "Those events that are most important are hardest to understand because they attract the greatest attention from myth makers and charlatans."[142] Justin Fox of Time magazine argues that Wall Street traders are among the most conspiracy-minded group of people, and ascribes this to the reality of some financial market conspiracies, and to the ability of conspiracy theories to provide necessary orientation in the market's day-to-day movements.[124]

Influence of critical theory

Bruno Latour notes that the language and intellectual tactics of critical theory have been appropriated by those he describes as conspiracy theorists, including climate-change denialists and the 9/11 Truth movement: "Maybe I am taking conspiracy theories too seriously, but I am worried to detect, in those mad mixtures of knee-jerk disbelief, punctilious demands for proofs, and free use of powerful explanation from the social neverland, many of the weapons of social critique."[143]

Fusion paranoia

Michael Kelly, a Washington Post journalist and critic of anti-war movements on both the left and right, coined the term "fusion paranoia" to refer to a political convergence of left-wing and right-wing activists around anti-war issues and civil liberties, which he said were motivated by a shared belief in conspiracism or shared anti-government views.[144]

Barkun has adopted this term to refer to how the synthesis of paranoid conspiracy theories, which were once limited to American fringe audiences, has given them mass appeal and enabled them to become commonplace in mass media,[145] thereby inaugurating an unrivaled period of people actively preparing for apocalyptic or millenarian scenarios in the United States of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.[146] Barkun notes the occurrence of lone-wolf conflicts with law enforcement acting as proxy for threatening the established political powers.[147]

Viability

As evidence that undermines an alleged conspiracy grows, the number of alleged conspirators also grows in the minds of conspiracy theorists. This is because of an assumption that the alleged conspirators often have competing interests. For example, if Republican President George W. Bush is allegedly responsible for the 9/11 terrorist attacks, and the Democratic party did not pursue exposing this alleged plot, that must mean that both the Democratic and Republican parties are conspirators in the alleged plot. It also assumes that the alleged conspirators are so competent that they can fool the entire world, but so incompetent that even the unskilled conspiracy theorists can find mistakes they make that prove the fraud. At some point, the number of alleged conspirators, combined with the contradictions within the alleged conspirators' interests and competence, becomes so great that maintaining the theory becomes an obvious exercise in absurdity.[148]

The physicist David Robert Grimes estimated the time it would take for a conspiracy to be exposed based on the number of people involved.[149][150] His calculations used data from the PRISM surveillance program, the Tuskegee syphilis experiment, and the FBI forensic scandal. Grimes estimated that:

- A Moon landing hoax would require the involvement of 411,000 people and would be exposed within 3.68 years;

- Climate-change fraud would require a minimum of 29,083 people (published climate scientists only) and would be exposed within 26.77 years, or up to 405,000 people, in which case it would be exposed within 3.70 years;

- A vaccination conspiracy would require a minimum of 22,000 people (without drug companies) and would be exposed within at least 3.15 years and at most 34.78 years depending on the number involved;

- A conspiracy to suppress a cure for cancer would require 714,000 people and would be exposed within 3.17 years.

Grimes's study did not consider exposure by sources outside of the alleged conspiracy. It only considered exposure from within the alleged conspiracy through whistleblowers or through incompetence.[151] Subsequent comments on the PubPeer website[152] point out that these calculations must exclude successful conspiracies since, by definition, we don't know about them, and are wrong by an order of magnitude about Bletchley Park, which remained a secret far longer than Grimes' calculations predicted.

Terminology

The term "truth seeker" is adopted by some conspiracy theorists when describing themselves on social media.[153] Conspiracy theorists are often referred to derogatorily as "cookers" in Australia.[154] The term "cooker" is also loosely associated with the far right.[155][156]

Politics

The philosopher Karl Popper described the central problem of conspiracy theories as a form of fundamental attribution error, where every event is generally perceived as being intentional and planned, greatly underestimating the effects of randomness and unintended consequences.[94] In his book The Open Society and Its Enemies, he used the term "the conspiracy theory of society" to denote the idea that social phenomena such as "war, unemployment, poverty, shortages ... [are] the result of direct design by some powerful individuals and groups".[158] Popper argued that totalitarianism was founded on conspiracy theories which drew on imaginary plots which were driven by paranoid scenarios predicated on tribalism, chauvinism, or racism. He also noted that conspirators very rarely achieved their goal.[159]

Historically, real conspiracies have usually had little effect on history and have had unforeseen consequences for the conspirators, in contrast to conspiracy theories which often posit grand, sinister organizations, or world-changing events, the evidence for which has been erased or obscured.[160][161] As described by Bruce Cumings, history is instead "moved by the broad forces and large structures of human collectivities".[160]

Arab world

Теории заговора являются распространенной чертой арабской культуры и политики. [ 162 ] Варианты включают в себя заговоры с участием колониализма, сионизма , сверхдержав, нефти и войны с терроризмом , которую в арабских СМИ часто называют « войной против ислама ». [ 162 ] Например, «Протоколы сионских мудрецов» , печально известный документ- мистификация , претендующий на то, чтобы быть еврейским планом мирового господства, широко читается и пропагандируется в мусульманском мире. [ 163 ] [ 164 ] [ 165 ] Роджер Коэн предположил, что популярность теорий заговора в арабском мире является «последним убежищем для бессильных». [ 129 ] Аль-Мумин Саид отметил опасность таких теорий, поскольку они «удерживают нас не только от истины, но и от противостояния нашим ошибкам и проблемам». [ 166 ] Усама бен Ладен и Айман аз-Завахири использовали теории заговора о Соединенных Штатах , чтобы заручиться поддержкой «Аль-Каиды» в арабском мире, а также в качестве риторики, чтобы отличиться от аналогичных групп, хотя они, возможно, сами не верили в заявления о заговоре. [ 167 ]

Турция

Теории заговора являются распространенной чертой культуры и политики Турции . Заговор – важный феномен в понимании турецкой политики. [ 168 ] Это объясняется желанием «восполнить утраченное османское величие». [ 168 ] унижение восприятия Турции как части «неблагополучной половины» мира, [ 169 ] и «низкий уровень медиаграмотности среди турецкого населения». [ 170 ]

Существует множество теорий заговора, включая иудео-масонскую теорию заговора . [ 171 ] [ 172 ] международная теория еврейского заговора и теория заговора войны против ислама . Например, исламисты , недовольные модернистскими и секуляристскими реформами, проходившими на протяжении всей истории Османской империи и Турецкой Республики, выдвинули множество теорий заговора с целью опорочить Лозаннский договор , важный мирный договор для страны, и основатель республики Кемаль Ататюрк . [ 173 ] [ 174 ] Другим примером является Севрский синдром , отсылка к Севрскому договору 1920 года, популярному в Турции убеждению, что опасные внутренние и внешние враги, особенно Запад , «сговариваются с целью ослабить и разделить Турецкую Республику». [ 175 ]

Соединенные Штаты

Историк Ричард Хофштадтер обратился к роли паранойи и заговора в истории США в своем эссе 1964 года « Параноидальный стиль в американской политике ». Бернарда Бейлина В классической книге «Идеологические истоки американской революции» (1967) отмечается, что аналогичный феномен можно было обнаружить в Северной Америке во время, предшествовавшее американской революции . Конспирализм обозначает взгляды людей, а также тип теорий заговора, которые в пропорциях более глобальны и исторически. [ 176 ]

Гарри Дж. Уэст и другие отметили, что, хотя теоретиков заговора часто можно отнести к маргинальному меньшинству, некоторые данные свидетельствуют о том, что широкий круг жителей США сохраняет веру в теории заговора. Уэст также сравнивает эти теории с гипернационализмом и религиозным фундаментализмом . [ 177 ] [ 178 ] Теолог Роберт Джуэтт и философ Джон Шелтон Лоуренс объясняют непреходящую популярность теорий заговора в США холодной войной , маккартизмом и контркультурным неприятием власти. Они заявляют, что как среди левых, так и среди правых сохраняется готовность использовать реальные события, такие как советские заговоры, несоответствия в отчете Уоррена и теракты 11 сентября , для поддержки существования непроверенных и продолжающихся крупных масштабные заговоры. [ 179 ]

В своих исследованиях «американской политической демонологии» историк Майкл Пол Рогин также проанализировал этот параноидальный стиль политики, который имел место на протяжении всей американской истории. Теории заговора часто идентифицируют воображаемую подрывную группу, которая якобы нападает на страну и требует от правительства и союзных сил проведения жестких внезаконных репрессий в отношении тех, кто угрожает подрывной деятельности. Рогин приводит примеры из «Красной паники» 1919 года, антикоммунистической кампании Маккарти в 1950-х годах и недавних опасений по поводу вторжения в США орд иммигрантов. В отличие от Хофштадтера, Рогин считал, что эти «контрподрывные» страхи часто исходят от тех, кто находится у власти и доминирующих групп, а не от обездоленных. В отличие от Роберта Джуэтта, Рогин обвинял не контркультуру, а доминирующую в Америке культуру либерального индивидуализма и страхи, которые она стимулировала, чтобы объяснить периодические вспышки иррациональных теорий заговора. [ 180 ] Уотергейтский скандал также использовался для придания легитимности другим теориям заговора, причем сам Ричард Никсон отмечал, что он послужил « чернильным пятном Роршаха », которое предложило другим заполнить основную схему. [ 86 ]

Историк Кэтрин С. Олмстед называет три причины, по которым американцы склонны верить в теории правительственного заговора:

- Подлинные правительственные злоупотребления и секретность во время холодной войны, такие как Уотергейт , эксперимент с сифилисом в Таскиги , проект MKUltra ЦРУ и покушения на Фиделя Кастро в сотрудничестве с бандитами.

- Прецедент создан официальными одобренными правительством теориями заговора для пропаганды, такими как утверждения о проникновении Германии в США во время Второй мировой войны или опровергнутое утверждение о том, что Саддам Хусейн сыграл роль в терактах 11 сентября .

- Недоверие, вызванное правительственным шпионажем и преследованием инакомыслящих, например, в соответствии с Законом о подстрекательстве к мятежу 1918 года , COINTELPRO , а также в рамках различных «красных угроз» . [ 181 ]

Алекс Джонс ссылался на многочисленные теории заговора, чтобы убедить своих сторонников поддержать Рона Пола , а не Митта Ромни на президентских праймериз Республиканской партии в 2012 году , и Дональда Трампа, а не Хиллари Клинтон на президентских выборах в США в 2016 году . [ 182 ] [ 183 ] В 2020-х годах теория заговора QAnon утверждает, что Трамп борется против глубокогосударственной клики занимающихся сексуальным насилием над детьми и поклоняющихся сатане демократов, . [ 35 ] [ 36 ] [ 184 ] [ 185 ] [ 186 ] [ 187 ]

См. также

- Большая ложь – Техника пропаганды

- Промывание мозгов - концепция, согласно которой человеческий разум можно изменить или контролировать.

- Сбор вишни – заблуждение неполных доказательств

- Заговорная фантастика - поджанр фантастических триллеров.

- Фейковые новости – ложная или вводящая в заблуждение информация, выдаваемая за реальную.

- Маргинальная теория - идея, которая отходит от общепринятых исследований в этой области.

- Скрытая ошибка – неформальная ошибка расстановки акцентов.

- Бритва Хэнлона – поговорка о том, что глупость важнее злого умысла

- Машина влияния - статья по психоанализу 1919 года.

- Список теорий заговора

- Список ошибок - Список ошибочных типов аргументов

- Список тем, характеризуемых как лженаука

- Бритва Оккама – философский принцип решения проблем

- Философия теорий заговора - Отрасль академических исследований.

- Пропаганда - коммуникация, используемая для влияния на мнение.

- Псевдоистория - псевдостипендия, пытающаяся исказить исторические записи.

- Лженаука – ненаучные утверждения, ошибочно представленные как научные.

- Суеверие – убеждение или поведение, которое считается иррациональным или сверхъестественным.

Ссылки

Информационные примечания

- ^ Бирчалл 2006: «[Мы] можем оценить теорию заговора как уникальную форму популярного знания или интерпретации и решить, что это может означать для любых знаний, которые мы получаем о ней, или как мы ее интерпретируем». [ 84 ] : 66

- ^ Бирчалл 2006: «Что мы быстро обнаруживаем... так это то, что становится невозможным сопоставить теорию заговора и академический дискурс с четким разделением на незаконное и законное». [ 84 ] : 72

- ^ Баркун 2003: «Суть верований в заговор заключается в попытках очертить и объяснить зло. В самом широком смысле теории заговора «рассматривают историю как контролируемую огромными демоническими силами». ... Для наших целей убеждение в заговоре — это убеждение в том, что организация, состоящая из отдельных лиц или групп, действовала или действует тайно для достижения злонамеренной цели». [ 120 ]

Цитаты

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Баркун, Майкл (2003). Культура заговора: апокалиптические видения в современной Америке . Беркли: Издательство Калифорнийского университета. стр. 3–4.

- ^ Исситт, Мика; Мэйн, Карлин (2014). Скрытая религия: величайшие тайны и символы мировых религиозных верований . АВС-КЛИО. ISBN 978-1-61069-478-0 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Харамбам, Джарон; Ауперс, Стеф (август 2021 г.). «От невероятного к неоспоримому: эпистемологический плюрализм, или как теоретики заговора оправдывают свои экстраординарные утверждения об истине» . Европейский журнал культурных исследований . 24 (4). Публикации SAGE : 990–1008. дои : 10.1177/1367549419886045 . hdl : 11245.1/7716b88d-4e3f-49ee-8093-253ccb344090 . ISSN 1460-3551 .

- ^ Герцель, Тед (декабрь 1994 г.). «Вера в теории заговора». Политическая психология . 15 (4). Уайли от имени Международного общества политической психологии : 731–742. дои : 10.2307/3791630 . ISSN 1467-9221 . JSTOR 3791630 .

объяснения важных событий, связанных с тайными заговорами могущественных и злонамеренных группировок

- ^ «теория заговора» . Оксфордский словарь английского языка (онлайн-изд.). Издательство Оксфордского университета . подписка или членство в участвующем учреждении ( Требуется .) «Теория о том, что событие или явление происходит в результате заговора между заинтересованными сторонами; конкретная вера в то, что ответственность несет некое тайное, но влиятельное агентство (обычно политическое по мотивам и репрессивное по намерениям). по необъяснимому событию»

- ^ Браттон, Роберт; Френч, Кристофер К.; Пикеринг, Алан Д. (2013). «Измерение веры в теории заговора: общая шкала убеждений конспирологов» . Границы в психологии . 4 : 279. дои : 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00279 . ISSN 1664-1078 . ПМЦ 3659314 . ПМИД 23734136 . S2CID 16685781 .

Веру в заговор можно охарактеризовать как «ненужное предположение о заговоре, когда другие объяснения более вероятны».

- ^ Дополнительные источники:

- Ааронович, Дэвид (2009). Истории вуду: роль теории заговора в формировании современной истории . Джонатан Кейп. п. 253. ИСБН 9780224074704 . Проверено 17 августа 2019 г.

В этой книге утверждается, что сторонники теории заговора не могут применить принцип бритвы Оккама к своим аргументам.

- Браттон, Роберт; Френч, Кристофер К. (2014). «Вера в теории заговора и подверженность ошибке конъюнкции» . Прикладная когнитивная психология . 28 (2): 238–248. дои : 10.1002/acp.2995 . ISSN 0888-4080 .

Теорию заговора можно определить как непроверенное и относительно неправдоподобное утверждение о заговоре, утверждающее, что важные события являются результатом тайного заговора, осуществленного сверхъестественно зловещей и могущественной группой людей.

- Джонасон, Питер Карл; Марш, Эвита; Спрингер, Джордан (2019). «Вера в теории заговора: прогностическая роль шизотипии, макиавеллизма и первичной психопатии» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 14 (12): e0225964. Бибкод : 2019PLoSO..1425964M . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0225964 . ISSN 1932-6203 . ПМК 6890261 . ПМИД 31794581 .

Теории заговора представляют собой разновидность ложных убеждений и обычно предполагают наличие злонамеренных сил (например, правительственного органа или тайного общества), вовлеченных в организацию крупных событий или предоставление дезинформации о деталях событий ничего не подозревающей публике в рамках заговора с целью достижения цели. зловещая цель.

- Трешер-Эндрюс, Кристофер (2013). «Введение в мир заговора» (PDF) . PsyPAG Ежеквартальный журнал . 1 (88): 5–8. дои : 10.53841/bpspag.2013.1.88.5 . ISSN 1746-6016 . S2CID 255932379 .

Теории заговора представляют собой необоснованную и менее правдоподобную альтернативу общепринятому объяснению события; они злонамеренно полагают, что все сделано намеренно. Важно отметить, что они также эпистемически самоизолированы в своих построениях и аргументах.

- Ааронович, Дэвид (2009). Истории вуду: роль теории заговора в формировании современной истории . Джонатан Кейп. п. 253. ИСБН 9780224074704 . Проверено 17 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Байфорд, Йован (2011). Теории заговора: критическое введение . Хаундмиллс, Бейзингсток, Хэмпшир: Пэлгрейв Макмиллан . ISBN 9780230349216 . OCLC 802867724 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж г час я дж к Андраде, Габриэль (апрель 2020 г.). «Теории медицинского заговора: когнитивная наука и значение этики» (PDF) . Медицина, здравоохранение и философия . 23 (3). Спрингер от имени Европейского общества философии медицины и здравоохранения : 505–518. дои : 10.1007/s11019-020-09951-6 . ISSN 1572-8633 . ПМЦ 7161434 . ПМИД 32301040 . S2CID 215787658 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 8 мая 2020 года . Проверено 7 октября 2021 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Баркун, Михаил (октябрь 2016 г.). Кэмпион-Винсент, Вероник; Ренар, Жан-Бруно (ред.). «Теории заговора как стигматизированное знание». Диоген . 62 (3–4: Теории заговора сегодня ). Публикации SAGE от имени Международного совета философии и гуманистических исследований : 114–120. дои : 10.1177/0392192116669288 . ISSN 0392-1921 . LCCN 55003452 . S2CID 152217672 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Браттон, Роберт (2013). «К определению« теории заговора » » (PDF) . PsyPAG Ежеквартальный журнал . 1 (88): 9–14. дои : 10.53841/bpspag.2013.1.88.9 . S2CID 141788005 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 7 октября 2013 года.

Теория заговора — это не просто одно из возможных объяснений среди других столь же правдоподобных альтернатив. Скорее, этот ярлык относится к утверждению, которое противоречит более правдоподобной и широко распространенной версии... [Конспирологические убеждения] неизменно противоречат общепринятому мнению среди ученых, историков или других законных судей относительно правдивости утверждения.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Дуглас, Карен М.; Саттон, Робби М. (январь 2023 г.). Фиске, Сьюзен Т. (ред.). «Что такое теории заговора? Определенный подход к их коррелятам, последствиям и коммуникации» . Ежегодный обзор психологии . 74 . Годовые обзоры : 271–298. doi : 10.1146/annurev-psych-032420-031329 . ISSN 1545-2085 . ОСЛК 909903176 . ПМИД 36170672 . S2CID 252597317 .

- ^ Дуглас, Карен М.; Саттон, Робби М. (12 апреля 2011 г.). «Нужно ли знать одно? На одобрение теорий заговора влияет личная готовность к заговору» (PDF) . Британский журнал социальной психологии . 10 (3). Уайли-Блэквелл от имени Британского психологического общества : 544–552. дои : 10.1111/j.2044-8309.2010.02018.x . ISSN 2044-8309 . LCCN 81642357 . OCLC 475047529 . ПМИД 21486312 . S2CID 7318352 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 ноября 2018 года . Проверено 8 мая 2024 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кили, Брайан Л. (март 1999 г.). «О теориях заговора». Журнал философии . 96 (3): 109–126. дои : 10.2307/2564659 . JSTOR 2564659 .

- ^ Левандовски, Стефан; Жиньяк, Жиль Э.; Оберауер, Клаус (2 октября 2013 г.). Денсон, Том (ред.). «Роль конспирологического мышления и мировоззрения в предсказании неприятия науки» . ПЛОС ОДИН . 8 (10): е75637. Бибкод : 2013PLoSO...875637L . дои : 10.1371/journal.pone.0075637 . ISSN 1932-6203 . ПМЦ 3788812 . ПМИД 24098391 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Баркун, Михаил (2011). В погоне за фантомами: реальность, воображение и национальная безопасность после 11 сентября . Чапел-Хилл: Издательство Университета Северной Каролины. п. 10.

- ^ Свами, Вирен (6 августа 2012 г.). «Социально-психологические истоки теорий заговора: случай еврейской теории заговора в Малайзии» . Границы в психологии . 3 . Лондон, Великобритания: 280. doi : 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00280 . ISSN 1664-1078 . ПМЦ 3412387 . ПМИД 22888323 .

- ^ Радниц, Скотт (2021), «Граждане-циники: как люди говорят и думают о заговоре», «Выявление схем » , Вашингтонский университет : Oxford University Press , стр. 153–172, doi : 10.1093/oso/9780197573532.003.0009 , ISBN 978-0-19-757353-2 , получено 17 мая 2022 г.