Глазго

Глазго

| |

|---|---|

Flag of Glasgow City Council[1] | |

| Nicknames: "The Dear Green Place", "Baile Mòr nan Gàidheal"[2] | |

| Motto(s): Let Glasgow Flourish Lord, let Glasgow flourish by the preaching of the word | |

Location of Glasgow | |

| Coordinates: 55°51′40″N 04°15′00″W / 55.86111°N 4.25000°W | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council Area | Glasgow City |

| Lieutenancy Area | Glasgow |

| Subdivisions | 23 Wards |

| Police | Police Scotland |

| Founded | Late-6th century |

| Burgh Charter | 1170s[4] |

| Government | |

| • Body | Glasgow City Council |

| • Lord Provost | Jacqueline McLaren (SNP) |

| • Council Leader | Susan Aitken (SNP) |

| • MSPs | |

| Area | |

| • Council area | 68 sq mi (175 km2) |

| • Urban | 142.3 sq mi (368.5 km2) |

| • Metro | 190 sq mi (492 km2) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • Council area | 622,820[3] |

| • Rank | 1st in Scotland 3rd in United Kingdom |

| • Density | 9,210/sq mi (3,555/km2) |

| • Urban | 632,350 (Locality)[5] 1,028,220 (Settlement)[5] |

| • Metro | 1,861,315[6] |

| • Language(s) | English Scots Gaelic |

| Demonym | Glaswegian |

| GDP | |

| • Council area | £28.439 billion (2022) |

| • Per head | £45,041 (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC±0 (Greenwich Mean Time) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+1 (British Summer Time) |

| Postcode areas | |

| Area code | 0141 |

| ISO 3166 code | GB-GLG |

| OS grid reference | NS590655 |

| International Airports | Glasgow Airport (GLA) Glasgow Prestwick Airport (PIK) |

| Main Railway Stations | Glasgow Central Glasgow Queen Street |

| Rapid transit | |

| Website | www |

Глазго ( Великобритания : / ˈ l ɑ z s ɡ ɡ ɡ ɡ , ˈ ɡ l æ z -, ˈ ɡ l ɑ æ -, ˈ ɡ l s - / GLA (h) z -goh, Gla (h) ss - [ А ] ; Шотландский гэльский : Глашу [ˈkl̪ˠas̪əxu] ) - самый густонаселенный город в Шотландии , расположенный на берегах реки Клайд в Западной Центральной Шотландии . [ 9 ] Город является третьим по численным городу в Великобритании [ 10 ] и 27-й самый полный город в Европе . [ 11 ] В 2022 году он имел предполагаемое население как определенную местность 632 350 и закрепил поселение городское 1 028,220.

Glasgow grew from a small rural settlement close to Glasgow Cathedral and descending to the River Clyde to become the largest seaport in Scotland, and tenth largest by tonnage in Britain. Expanding from the medieval bishopric and episcopal burgh (subsequently royal burgh), and the later establishment of the University of Glasgow in the 15th century, it became a major centre of the Scottish Enlightenment in the 18th century. From the 18th century onwards, the city also grew as one of Britain's main hubs of oceanic trade with North America and the West Indies; soon followed by the Orient, India, and China. With the onset of the Industrial Revolution, the population and economy of Glasgow and the surrounding region expanded rapidly to become one of the world's pre-eminent centres of chemicals, textiles and engineering; most notably in the shipbuilding and marine engineering industry, which produced many innovative and famous vessels. Glasgow was the "Second City of the British Empire" for much of the Victorian and Edwardian eras.[12][13][14][15]

Glasgow became a county in 1893, the city having previously been in the historic county of Lanarkshire, and later growing to also include settlements that were once part of Renfrewshire and Dunbartonshire. It now forms the Glasgow City Council area, one of the 32 council areas of Scotland, and is administered by Glasgow City Council. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Glasgow's population grew rapidly, reaching a peak of 1,127,825 people in 1938 (with a higher density and within a smaller territory than in subsequent decades).[16] The population was greatly reduced following comprehensive urban renewal projects in the 1960s which resulted in large-scale relocation of people to designated new towns, such as Cumbernauld, Livingston, East Kilbride and peripheral suburbs, followed by successive boundary changes. Over 1,000,000 people live in the Greater Glasgow contiguous urban area, while the wider Glasgow City Region is home to over 1,800,000 people (its defined functional urban area total was almost the same in 2020),[17] equating to around 33% of Scotland's population;[5] The city has one of the highest densities of any locality in Scotland at 4,023/km2.

Glasgow's major cultural institutions enjoy international reputations including The Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Burrell Collection, Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, Scottish Ballet and Scottish Opera. The city was the European Capital of Culture in 1990 and is notable for its architecture, culture, media, music scene, sports clubs and transport connections. It is the fifth-most-visited city in the United Kingdom.[18] The city is also well known in the sporting world for football, particularly for the Old Firm rivalry.

Etymology and heraldry

[edit]The name Glasgow is Brittonic in origin. The first element glas, meaning "grey-green, grey-blue" both in Brittonic, Scottish Gaelic and modern day Welsh and the second *cöü, "hollow" (cf. Welsh glas-cau),[19] giving a meaning of "green-hollow".[20] It is often said that the name means "dear green place" or that "dear green place" is a translation from Gaelic Glas Caomh.[21] "The dear green place" remains an affectionate way of referring to the city. The modern Gaelic is Glaschu and derived from the same roots as the Brittonic.

The settlement may have an earlier Brittonic name, Cathures; the modern name appears for the first time in the Gaelic period (1116), as Glasgu. It is also recorded that the King of Strathclyde, Rhydderch Hael, welcomed Saint Kentigern (also known as Saint Mungo), and procured his consecration as bishop about 540. For some thirteen years Kentigern laboured in the region, building his church at the Molendinar Burn where Glasgow Cathedral now stands, and making many converts. A large community developed around him and became known as Glasgu.

The coat of arms of the City of Glasgow was granted to the royal burgh by the Lord Lyon on 25 October 1866.[22] It incorporates a number of symbols and emblems associated with the life of Glasgow's patron saint, Mungo, which had been used on official seals prior to that date. The emblems represent miracles supposed to have been performed by Mungo[23] and are listed in the traditional rhyme:

- Here's the bird that never flew

- Here's the tree that never grew

- Here's the bell that never rang

- Here's the fish that never swam

St Mungo is also said to have preached a sermon containing the words Lord, Let Glasgow flourish by the preaching of the word and the praising of thy name. This was abbreviated to "Let Glasgow Flourish" and adopted as the city's motto.

In 1450, John Stewart, the first Lord Provost of Glasgow, left an endowment so that a "St Mungo's Bell" could be made and tolled throughout the city so that the citizens would pray for his soul. A new bell was purchased by the magistrates in 1641 and that bell is still on display in the People's Palace Museum, near Glasgow Green.

The supporters are two salmon bearing rings, and the crest is a half length figure of Saint Mungo. He wears a bishop's mitre and liturgical vestments and has his hand raised in "the act of benediction". The original 1866 grant placed the crest atop a helm, but this was removed in subsequent grants. The current version (1996) has a gold mural crown between the shield and the crest. This form of coronet, resembling an embattled city wall, was allowed to the four area councils with city status.

The arms were re-matriculated by the City of Glasgow District Council on 6 February 1975, and by the present area council on 25 March 1996. The only change made on each occasion was in the type of coronet over the arms.[24][25]

History

[edit]Early history

[edit]

The area around Glasgow has hosted communities for millennia,[specify] with the River Clyde providing a natural location for fishing. The Romans later built outposts in the area and, to protect Roman Britannia from the Brittonic speaking (Celtic) Caledonians, constructed the Antonine Wall. Items from the wall, such as altars from Roman forts like Balmuildy, can be found at the Hunterian Museum today.

Glasgow itself was reputed to have been founded by the Christian missionary Saint Mungo in the 6th century. He established a church on the Molendinar Burn, where the present Glasgow Cathedral stands, and in the following years Glasgow became a religious centre. Glasgow grew over the following centuries. The Glasgow Fair reportedly began in 1190.[26] A bridge over the River Clyde was recorded from around 1285, where Victoria Bridge now stands. As the lowest bridging point on the Clyde it was an important crossing. The area around the bridge became known as Briggait. The founding of the University of Glasgow adjoining the cathedral in 1451 and elevation of the bishopric to become the Archdiocese of Glasgow in 1492 increased the town's religious and educational status and landed wealth. Its early trade was in agriculture, brewing and fishing, with cured salmon and herring being exported to Europe and the Mediterranean.[27] By the fifteenth century the urban area stretched from the area around the cathedral and university in the north down to the bridge and the banks of the Clyde in the south along High Street, Saltmarket and Bridgegate, crossing an east–west route at Glasgow Cross which became the commercial centre of the city.[28]

Scottish Reformation

[edit]Following the European Protestant Reformation and with the encouragement of the Convention of Royal Burghs, the 14 incorporated trade crafts federated as the Trades House in 1605 to match the power and influence in the town council of the earlier Merchants' Guilds who established their Merchants House in the same year.[27] Glasgow was subsequently raised to the status of Royal Burgh in 1611.[29] Daniel Defoe visited the city in the early 18th century and famously opined in his book A tour thro' the whole island of Great Britain, that Glasgow was "the cleanest and beautifullest, and best built city in Britain, London excepted". At that time the city's population was about 12,000, and the city was yet to undergo the massive expansionary changes to its economy and urban fabric, brought about by the Scottish Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution.

The city prospered from its involvement in the triangular trade and the Atlantic slave trade that the former depended upon. Glasgow merchants dealt in slave-produced cash crops such as sugar, tobacco, cotton and linen.[30][31] From 1717 to 1766, Scottish slave ships operating out of Glasgow transported approximately 3,000 enslaved Africans to the Americas (out of a total number of 5,000 slaves carried by ships from Scotland). The majority of these slaving voyages left from Glasgow's satellite ports, Greenock and Port Glasgow.[32]

Economic growth

[edit]

After the Acts of Union in 1707, Scotland gained further access to the vast markets of the new British Empire, and Glasgow became prominent as a hub of international trade to and from the Americas, especially in sugar, tobacco, cotton, and manufactured goods. Starting in 1668, the city's Tobacco Lords created a deep water port at Port Glasgow about 20 mi (32 km) down the River Clyde, as the river from the city to that point was then too shallow for seagoing merchant ships.[33] By the late 18th century more than half of the British tobacco trade was concentrated on the River Clyde, with over 47,000,000 lb (21,000 t) of tobacco being imported each year at its peak.[34] At the time, Glasgow held a commercial importance as the city participated in the trade of sugar, tobacco and later cotton.[35] From the mid-eighteenth century the city began expanding westwards from its medieval core at Glasgow Cross, with a grid-iron street plan starting from the 1770s and eventually reaching George Square to accommodate much of the growth, with that expansion much later becoming known in the 1980s onwards as the Merchant City.[36] The largest growth in the city centre area, building on the wealth of trading internationally, was the next expansion being the grid-iron streets west of Buchanan Street riding up and over Blythswood Hill from 1800 onwards.[37]

The opening of the Monkland Canal and basin linking to the Forth and Clyde Canal at Port Dundas in 1795, facilitated access to the extensive iron-ore and coal mines in Lanarkshire. After extensive river engineering projects to dredge and deepen the River Clyde as far as Glasgow, shipbuilding became a major industry on the upper stretches of the river, pioneered by industrialists such as Robert Napier, John Elder, George Thomson, Sir William Pearce and Sir Alfred Yarrow. The River Clyde also became an important source of inspiration for artists, such as John Atkinson Grimshaw, John Knox, James Kay, Sir Muirhead Bone, Robert Eadie and L.S. Lowry, willing to depict the new industrial era and the modern world, as did Stanley Spencer downriver at Port Glasgow.

Population growth

[edit]

With the population growing, the first scheme to provide a public water supply was by the Glasgow Company in 1806. A second company was formed in 1812, and the two merged in 1838, but there was some dissatisfaction with the quality of the water supplied.[38] The Gorbals Gravitation Water Company began supplying water to residents living to the south of the River Clyde in 1846, obtained from reservoirs, which gave 75,000 people a constant water supply,[38] but others were not so fortunate, and some 4,000 died in an outbreak of cholera in 1848/1849.[39] This led to the development of the Glasgow Corporation Water Works, with a project to raise the level of Loch Katrine and to convey clean water by gravity along a 26 mi (42 km) aqueduct to a holding reservoir at Milngavie, and then by pipes into the city.[40] The project cost £980,000[39] and was opened by Queen Victoria in 1859.[41] In the early 19th century an eighth of the people lived in single-room accommodation.[42]

The engineer for the project was John Frederick Bateman, while James Morris Gale became the resident engineer for the city section of the project, and subsequently became Engineer in Chief for Glasgow Water Commissioners. He oversaw several improvements during his tenure, including a second aqueduct and further raising of water levels in Loch Katrine.[43] Additional supplies were provided by Loch Arklet in 1902, by impounding the water and creating a tunnel to allow water to flow into Loch Katrine. A similar scheme to create a reservoir in Glen Finglas was authorised in 1903, but was deferred, and was not completed until 1965.[39] Following the 2002 Glasgow floods, the waterborne parasite cryptosporidium was found in the reservoir at Milngavie, and so the new Milngavie water treatment works was built. It was opened by Queen Elizabeth in 2007, and won the 2007 Utility Industry Achievement Award, having been completed ahead of its time schedule and for £10 million below its budgeted cost.[44]

Good health requires both clean water and effective removal of sewage. The Caledonian Railway rebuilt many of the sewers, as part of a deal to allow them to tunnel under the city, and sewage treatment works were opened at Dalmarnoch in 1894, Dalmuir in 1904 and Shieldhall in 1910. The works experimented to find better ways to treat sewage, and a number of experimental filters were constructed, until a full activated sludge plant was built between 1962 and 1968 at a cost of £4 million.[45] Treated sludge was dumped at sea, and Glasgow Corporation owned six sludge ships between 1904 and 1998,[46] when the EU Urban Waste Water Treatment Directive ended the practice.[47] The sewerage infrastructure was improved significantly in 2017, with the completion of a tunnel 3.1 mi (5.0 km) long, which provides 20×106 imp gal (90 Ml) of storm water storage. It will reduce the risk of flooding and the likelihood that sewage will overflow into the Clyde during storms.[48] Since 2002, clean water provision and sewerage have been the responsibility of Scottish Water.[49]

Glasgow's population had surpassed that of Edinburgh by 1821. The development of civic institutions included the City of Glasgow Police in 1800, one of the first municipal police forces in the world. Despite the crisis caused by the City of Glasgow Bank's collapse in 1878, growth continued and by the end of the 19th century it was one of the cities known as the "Second City of the Empire" and was producing more than half Britain's tonnage of shipping[50] and a quarter of all locomotives in the world.[51] In addition to its pre-eminence in shipbuilding, engineering, industrial machinery, bridge building, chemicals, explosives, coal and oil industries it developed as a major centre in textiles, garment-making, carpet manufacturing, leather processing, furniture-making, pottery, food, drink and cigarette making; printing and publishing. Shipping, banking, insurance and professional services expanded at the same time.[27]

Glasgow became one of the first cities in Europe to reach a population of one million. The city's new trades and sciences attracted new residents from across the Lowlands and the Highlands of Scotland, from Ireland and other parts of Britain and from Continental Europe.[27] During this period, the construction of many of the city's greatest architectural masterpieces and most ambitious civil engineering projects, such as the Milngavie water treatment works, Glasgow Subway, Glasgow Corporation Tramways, City Chambers, Mitchell Library and Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum were being funded by its wealth. The city also held a series of International Exhibitions at Kelvingrove Park, in 1888, 1901 and 1911, with Britain's last major International Exhibition, the Empire Exhibition, being subsequently held in 1938 at Bellahouston Park, which drew 13 million visitors.[52]

20th century

[edit]

The 20th century witnessed both decline and renewal in the city. After World War I, the city suffered from the impact of the Post–World War I recession and from the later Great Depression, this also led to a rise of radical socialism and the "Red Clydeside" movement. The city had recovered by the outbreak of World War II. The city saw aerial bombardment by the Luftwaffe[53] during the Clydebank Blitz, during the war, then grew through the post-war boom that lasted through the 1950s. By the 1960s, growth of industry in countries like Japan and West Germany, weakened the once pre-eminent position of many of the city's industries. As a result of this, Glasgow entered a lengthy period of relative economic decline and rapid de-industrialisation, leading to high unemployment, urban decay, population decline, welfare dependency and poor health for the city's inhabitants. There were active attempts at regeneration of the city, when the Glasgow Corporation published its controversial Bruce Report, which set out a comprehensive series of initiatives aimed at turning round the decline of the city. The report led to a huge and radical programme of rebuilding and regeneration efforts that started in the mid-1950s and lasted into the late 1970s. This involved the mass demolition of the city's infamous slums and their replacement with large suburban housing estates and tower blocks.[54]

The city invested heavily in roads infrastructure, with an extensive system of arterial roads and motorways that bisected the central area. There are also accusations that the Scottish Office had deliberately attempted to undermine Glasgow's economic and political influence in post-war Scotland by diverting inward investment in new industries to other regions during the Silicon Glen boom and creating the new towns of Cumbernauld, Glenrothes, Irvine, Livingston and East Kilbride, dispersed across the Scottish Lowlands to halve the city's population base.[54] By the late 1980s, there had been a significant resurgence in Glasgow's economic fortunes. The "Glasgow's miles better" campaign, launched in 1983, and opening of the Burrell Collection in 1983 and Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre in 1985 facilitated Glasgow's new role as a European centre for business services and finance and promoted an increase in tourism and inward investment.[55] The latter continues to be bolstered by the legacy of the city's Glasgow Garden Festival in 1988, its status as European Capital of Culture in 1990,[56] and concerted attempts to diversify the city's economy.[57] However, it is the industrial heritage that serves as key tourism enabler.[58] Wider economic revival has persisted and the ongoing regeneration of inner-city areas, including the large-scale Clyde Waterfront Regeneration, has led to more affluent people moving back to live in the centre of Glasgow, fuelling allegations of gentrification.[59] In 2008, the city was listed by Lonely Planet as one of the world's top 10 tourist cities.[60]

Late 20th and early 21st centuries

[edit]

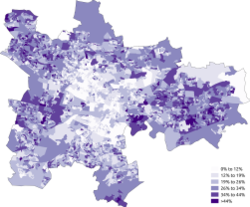

Despite Glasgow's economic renaissance, the East End of the city remains the focus of social deprivation.[61] A Glasgow Economic Audit report published in 2007 stated that the gap between prosperous and deprived areas of the city is widening.[62] In 2006, 47% of Glasgow's population lived in the most deprived 15% of areas in Scotland,[62] while the Centre for Social Justice reported 29.4% of the city's working-age residents to be "economically inactive".[61] Although marginally behind the UK average, Glasgow still has a higher employment rate than Birmingham, Liverpool and Manchester.[62]

In 2007, the city's primary airport was the target of a terrorist attack when a Jeep Cherokee filled with propane gas cylinders and petrol cans was driven at considerable speed into the entrance of the main terminal building. This was the first time that a terrorist attack had targeted Scotland specifically, and was the second terrorist attack to occur in Scotland following the explosion of Pan Am Flight 103 over the town of Lockerbie in the Scottish Borders in December 1988.[63] Immediately following the incident, a close link was established between the attack in Glasgow and an attack in London the previous day. One of the perpetrators of the attack, Kafeel Ahmed, was the only reported casualty, with a following five people sustaining injuries from the attack.[64]

In 2008 the city was ranked at 43 for Personal Safety in the Mercer index of top 50 safest cities in the world.[65] The Mercer report was specifically looking at Quality of Living, yet by 2011 within Glasgow, certain areas were (still) "failing to meet the Scottish Air Quality Objective levels for nitrogen dioxide (NO2) and particulate matter (PM10)".[66]

The city hosted the 2021 United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) at its main events venue, the SEC Centre. Glasgow hosted the 2014 Commonwealth Games, and will host the 2026 edition of the games. Glasgow also hosted the first European Championships in 2018, was one of the host cities for UEFA Euro 2020, and will be a host city of the UEFA Euro 2028. The UK's first official consumption room for illegal drugs including heroin and cocaine was established in Glasgow, which is set to open on 21 October 2024.[67]

Government and politics

[edit]Government

[edit]

Although Glasgow Corporation had been a pioneer in the municipal socialist movement from the late-nineteenth century, since the Representation of the People Act 1918, Glasgow increasingly supported left-wing ideas and politics at a national level. The city council was controlled by the Labour Party for over thirty years, since the decline of the Progressives. Since 2007, when local government elections in Scotland began to use the single transferable vote rather than the first-past-the-post system, the dominance of the Labour Party within the city started to decline. As a result of the 2017 United Kingdom local elections, the SNP was able to form a minority administration ending Labour's thirty-seven years of uninterrupted control.[68]

In the aftermath of the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the German Revolution of 1918–19, the city's frequent strikes and militant organisations caused serious alarm at Westminster, with one uprising in January 1919, the Battle of George Square, prompting Liberal Prime Minister David Lloyd George to deploy 10,000 soldiers and tanks on the city's streets. A huge demonstration in the city's George Square on 31 January ended in violence, known as the Battle of George Square, after the Riot Act was read.[69]

Industrial action at the shipyards gave rise to the "Red Clydeside" epithet. During the 1930s, Glasgow was the main base of the Independent Labour Party. Towards the end of the twentieth century, it became a centre of the struggle against the poll tax; which was introduced in Scotland a whole year before the rest of the United Kingdom and also served as the main base of the Scottish Socialist Party, another left-wing political party in Scotland. The city has not had a Conservative MP since the 1982 Hillhead by-election, when the SDP took the seat, which was in Glasgow's most affluent area. The fortunes of the Conservative Party continued to decline into the twenty-first century, winning only one of the 79 councillors on Glasgow City Council in 2012, despite having been the controlling party (as the Progressives) from 1969 to 1972 when Sir Donald Liddle was the last non-Labour Lord Provost.[70]

Politics

[edit]

Glasgow is represented in both the House of Commons in London, and the Scottish Parliament in Holyrood, Edinburgh. At Westminster, it is represented by seven Members of Parliament (MPs), all elected at least once every five years to represent individual constituencies, using the first-past-the-post system of voting. In Holyrood, Glasgow is represented by sixteen Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs), of whom nine are elected to represent individual constituencies once every four years using first-past-the-post, and seven are elected as additional regional members, by proportional representation. Since the 2016 Scottish Parliament election, Glasgow is represented at Holyrood by 9 Scottish National Party MSPs, 4 Labour MSPs, 2 Conservative MSPs and 1 Scottish Green MSP. In the European Parliament, the city formed part of the Scotland constituency, which elected six Members of the European Parliament (MEPs) prior to Brexit.[71]

Since Glasgow is covered and operates under two separate central governments, the devolved Scottish Parliament and UK Government, they determine various matters that Glasgow City Council is not responsible for. The Glasgow electoral region of the Scottish Parliament covers the Glasgow City council area, a north-western part of South Lanarkshire and a small eastern portion of Renfrewshire. It elects nine of the parliament's 73 first past the post constituency members and seven of the 56 additional members. Both kinds of member are known as Members of the Scottish Parliament (MSPs). The system of election is designed to produce a form of proportional representation.[72]

The first past the post seats were created in 1999 with the names and boundaries of then existing Westminster (House of Commons) constituencies. In 2005, the number of Westminster Members of Parliament (MPs) representing Scotland was cut to 59, with new constituencies being formed, while the existing number of MSPs was retained at Holyrood. In the 2011 Scottish Parliament election, the boundaries of the Glasgow region were redrawn.[73]

Currently, the nine Scottish Parliament constituencies in the Glasgow electoral region are:

- Glasgow Anniesland

- Glasgow Cathcart

- Glasgow Kelvin

- Glasgow Maryhill and Springburn

- Glasgow Pollok

- Glasgow Provan

- Glasgow Shettleston

- Glasgow Southside

- Rutherglen

At the 2021 Scottish Parliament election, all nine of these constituencies were won by Scottish National Party (SNP) candidates. On the regional vote, the Glasgow electoral region is represented by four Labour MSPs, two Conservative MSPs and one Green MSP.[74]

Following reform of constituencies of the House of Commons of the United Kingdom (Westminster) in 2005, which reduced the number of Scottish Members of Parliament (MPs), the current Westminster constituencies representing Glasgow are:

- Glasgow Central

- Glasgow East

- Glasgow North

- Glasgow North East

- Glasgow North West

- Glasgow South

- Glasgow South West

Following the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, in which 53.49% of the electorate of Glasgow voted in favour of Scottish independence; the SNP won every seat in the city at the 2015 general election, including a record-breaking 39.3% swing from Labour to SNP in the Glasgow North East constituency.[75]

At the 2017 snap general election, Glasgow was represented by 6 Scottish National Party MPs and 1 Labour MP; the Glasgow North East constituency which had a record 39.3% swing from Labour to SNP at the previous general election, was regained by Paul Sweeney of the Labour Party, who narrowly defeated sitting SNP MP Anne McLaughlin by 242 votes.[76][77]

Since the 2019 general election, Glasgow has been represented by 7 Scottish National Party MPs; the Glasgow North East constituency, was regained by Anne McLaughlin of the Scottish National Party, resulting in the same clean sweep like 4 years previously.[78]

In the Scottish independence referendum, Glasgow voted "Yes" by a margin of 53.5% to 46.5%.[79] In the Brexit referendum, results varied from constituency to constituency. Glasgow North recorded the biggest remain vote with 78% opting to stay in the EU whilst in Glasgow East this figure dropped to 56%.[80] The city as a whole voted to remain in the EU, by 66.6% to 33.3%.[81]

Voter turnout has often been lower in Glasgow than in the rest of the United Kingdom. In the Referendum of 2014 turnout was 75%, the lowest in Scotland;[82] in the Brexit referendum the city's voters, while joining the rest of Scotland in voting to remain part of the EU, again had a low turnout of 56.2%, although SNP MP Angus Robertson placed this in the historical context of traditional low turnout in Glasgow.[83]

In the 2015 general election, the six Scottish constituencies with the lowest turnout were all in Glasgow;[84] turnout further decreased in the 2017 election, when five of the city's seven seats reported a lowered turnout.[85]

Geography and climate

[edit]

Glasgow is located on the banks of the River Clyde, in West Central Scotland. Another important river is the Kelvin, a tributary of the River Clyde, whose name was used in creating the title of Baron Kelvin the renowned physicist for whom the SI unit of temperature, Kelvin, is named.

The burgh of Glasgow was historically in Lanarkshire, but close to the border with Renfrewshire. When elected county councils were established in 1890, Glasgow was deemed capable of running its own affairs and so was excluded from the administrative area of Lanarkshire County Council, whilst remaining part of Lanarkshire for lieutenancy and judicial purposes.[86][87] The burgh was substantially enlarged in 1891 to take in areas from both Lanarkshire and Renfrewshire where the urban area had grown beyond the old burgh boundary.[88] In 1893, the burgh became its own county for lieutenancy and judicial purposes too, being made a county of itself.[89] From 1975 to 1996 the city was part of Strathclyde Region, with the city's council becoming a lower-tier district council. Strathclyde was abolished in 1996, since when the city has again been responsible for all aspects of local government, being one of the 32 council areas in Scotland.[90]

Despite its northerly latitude, similar to that of Moscow, Glasgow's climate is classified as oceanic (Köppen Cfb). Data is available online for 3 official weather stations in the Glasgow area: Paisley, Abbotsinch and Bishopton. All are located to the west of the city, in neighbouring Renfrewshire. Owing to its westerly position and proximity to the Atlantic Ocean, Glasgow is one of Scotland's milder areas. Winter temperatures are usually higher than in most places of equal latitude away from the UK, due to the warming influence of the Gulf Stream. However, this results in less distinct seasons as compared to continental Western Europe. At Paisley, the annual precipitation averages 1,245 mm (49.0 in). Glasgow has been named as the rainiest city of the UK, having an average of 170 days of rain a year.[91][92]

Winters are cool and overcast, with a January mean of 5.0 °C (41.0 °F), though lows sometimes fall below freezing. Since 2000 Glasgow has experienced few very cold, snowy and harsh winters where temperatures have fallen much below freezing. The most extreme instances have however seen temperatures around −12 °C (10 °F) in the area. Snowfall accumulation is infrequent and short-lived. The spring months (March to May) are usually mild and often quite pleasant. Many of Glasgow's trees and plants begin to flower at this time of the year and parks and gardens are filled with spring colours. During the summer months (June to August) the weather can vary considerably from day to day, ranging from relatively cool and wet to quite warm with the odd sunny day. Long dry spells of warm weather are generally quite scarce. Overcast and humid conditions without rain are frequent. Generally the weather pattern is quite unsettled and erratic during these months, with only occasional heatwaves. The warmest month is usually July, with average highs above 20 °C (68 °F). Summer days can occasionally reach up to 27 °C (81 °F), and very rarely exceed 30 °C (86 °F). Autumns are generally cool to mild with increasing precipitation. During early autumn there can be some settled periods of weather and it can feel pleasant with mild temperatures and some sunny days.

The official Met Office data series goes back to 1959 and shows that there only have been a few warm and no hot summers in Glasgow, in stark contrast to areas further south in Great Britain and eastwards in Europe. The warmest month on record in the data series is July 2006, with an average high of 22.7 °C (72.9 °F) and low of 13.7 °C (56.7 °F).[93] Even this extreme event only matched a normal summer on similar parallels in continental Europe, underlining the maritime influences. The coldest month on record since the data series began is December 2010, during a severe cold wave affecting the British Isles. Even then, the December high was above freezing at 1.6 °C (34.9 °F) with the low of −4.4 °C (24.1 °F).[93] This still ensured Glasgow's coldest month of 2010 remained milder than the isotherm of −3 °C (27 °F) normally used to determine continental climate normals.

Temperature extremes have ranged from −19.9 °C (−4 °F), at Abbotsinch in December 1995 to[94] 31.9 °C (89 °F) at Bishopton in June 2018.[95]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.5 (56.3) |

14.4 (57.9) |

17.2 (63.0) |

24.4 (75.9) |

26.5 (79.7) |

29.6 (85.3) |

30.0 (86.0) |

31.0 (87.8) |

26.7 (80.1) |

22.8 (73.0) |

17.7 (63.9) |

14.1 (57.4) |

31.0 (87.8) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.2 (45.0) |

7.8 (46.0) |

9.8 (49.6) |

13.0 (55.4) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

19.8 (67.6) |

19.3 (66.7) |

16.7 (62.1) |

13.0 (55.4) |

9.6 (49.3) |

7.4 (45.3) |

13.2 (55.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

5.0 (41.0) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.0 (48.2) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.3 (57.7) |

15.9 (60.6) |

15.6 (60.1) |

13.3 (55.9) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.9 (44.4) |

4.7 (40.5) |

9.8 (49.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

2.2 (36.0) |

3.2 (37.8) |

5.1 (41.2) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

12.1 (53.8) |

11.9 (53.4) |

9.9 (49.8) |

6.8 (44.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

2.1 (35.8) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.8 (5.4) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−8.3 (17.1) |

−4.4 (24.1) |

−1.1 (30.0) |

1.5 (34.7) |

3.9 (39.0) |

2.2 (36.0) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−3.5 (25.7) |

−6.8 (19.8) |

−14.5 (5.9) |

−14.8 (5.4) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 146.4 (5.76) |

115.2 (4.54) |

97.4 (3.83) |

66.1 (2.60) |

68.8 (2.71) |

67.8 (2.67) |

82.9 (3.26) |

94.8 (3.73) |

98.4 (3.87) |

131.8 (5.19) |

131.8 (5.19) |

161.4 (6.35) |

1,262.8 (49.72) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 17.7 | 14.7 | 13.8 | 12.3 | 12.1 | 12.1 | 13.3 | 13.9 | 13.9 | 16.2 | 17.3 | 16.9 | 174.3 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 38.6 | 67.3 | 104.3 | 141.4 | 186.8 | 155.6 | 151.5 | 145.5 | 114.6 | 86.3 | 53.9 | 33.7 | 1,279.6 |

| Source 1: Met Office [96] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: KNMI/Royal Dutch Meteorological Institute[97] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

[edit]

In the 1950s, the population of the City of Glasgow area peaked at 1,089,000. Glasgow was then one of the most densely populated cities in the world. After the 1960s, clearances of poverty-stricken inner city areas like the Gorbals and relocation to "new towns" such as East Kilbride and Cumbernauld led to population decline. In addition, the boundaries of the city were changed twice during the late-twentieth century, making direct comparisons difficult.

The urban area continues to expand beyond the city council boundaries into surrounding suburban areas, encompassing around 400 sq mi (1,040 km2) of all adjoining suburbs, if commuter towns and villages are included.[99] There are two distinct definitions for the population of Glasgow: the Glasgow City Council Area which lost the districts of Rutherglen and Cambuslang to South Lanarkshire in 1996, and the Greater Glasgow Urban Area which includes the conurbation around the city (however in the 2016 definitions[100] the aforementioned Rutherglen and Cambuslang were included along with the likes of Paisley, Clydebank, Newton Mearns, Bearsden and Stepps but not others with no continuity of populated postcodes – although in some cases the gap is small – the excluded nearby settlements including Barrhead, Erskine and Kirkintilloch plus a large swathe of Lanarkshire which had been considered contiguous with Glasgow in previous definitions: the 'settlements' named Coatbridge & Airdrie, Hamilton and Motherwell & Wishaw, each containing a number of distinct smaller localities).[5]

Glasgow's population influx in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries was related to economic expansion as well as internally generated growth with the vast majority of newcomers to the city from outside Scotland being from Ireland, especially the north western counties of Donegal, Fermanagh, Tyrone and Londonderry. In the 1881 UK Census, 83% of the population was born in Scotland, 13% in Ireland, 3% in England and 1% elsewhere. By 1911, the city was no longer gaining population by migration. The demographic percentages in the 1951 UK census were: born in Scotland 93%, Ireland 3%, England 3% and elsewhere 1%.[27] In the early twentieth century, many Lithuanian refugees began to settle in Glasgow and at its height in the 1950s; there were around 10,000 in the Glasgow area.[103] Many Italian Scots also settled in Glasgow, originating from provinces like Frosinone in Lazio and Lucca in north-west Tuscany at this time, many originally working as "Hokey Pokey" men.[104]

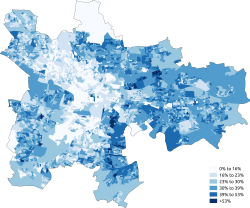

In the 1960s and 1970s, many Asians also settled in Glasgow, mainly in the Pollokshields area. These number 30,000 Pakistanis, 15,000 Indians and 3,000 Bangladeshis as well as Chinese people, many of whom settled in the Garnethill area of the city.[citation needed] The city is also home to some 8,406 (1.42%) Poles.[114] Since 2000, the UK government has pursued a policy of dispersal of asylum seekers to ease pressure on social housing in the London area. In 2023, 88% of the near 5,100 asylum seekers in the whole of Scotland were living in Glasgow.[115][116]

Since the United Kingdom Census 2001 the population decline has been reversed. The population was static for a time; but due to migration from other parts of Scotland as well as immigration from overseas, the population has begun to grow. The population of the city council area was 593,245 in 2011[117] and around 2,300,000 people live in the Glasgow travel to work area.[118] This area is defined as consisting of over 10% of residents travelling into Glasgow to work and is without fixed boundaries.[119]

The population density of London following the 2011 census was recorded as 5,200 people per square kilometre, while 3,395 people per square kilometre were registered in Glasgow.[120][121] In 1931, the population density was 16,166/sq mi (6,242/km2), highlighting the "clearances" into the suburbs and new towns that were built to reduce the size of one of Europe's most densely populated cities.[122]

In 2005, Glasgow had the lowest life expectancy of any UK city at 72.9 years.[123] Much was made of this during the 2008 Glasgow East by-election.[124] In 2008, a World Health Organization report about health inequalities, revealing that male life expectancy varied from 54 years in Calton to 82 years in nearby Lenzie, East Dunbartonshire.[125][126]

Areas and suburbs

[edit]

City centre

[edit]

The city centre is bounded by High Street at Glasgow Cross the historic centre of civic life, up to Glasgow Cathedral at Castle Street; Saltmarket including Glasgow Green and St Andrew's Square to the east; Clyde Street and Broomielaw (along the River Clyde) to the south; and Charing Cross and Elmbank Street, beyond Blythswood Square to the west. The northern boundary (from east to west) follows Cathedral Street to North Hanover Street and George Square. The city centre is based on a grid system of streets on the north bank of the River Clyde. The heart of the city is George Square, site of many of Glasgow's public statues and the elaborate Victorian Glasgow City Chambers, headquarters of Glasgow City Council.

Most offices, and the largest offices and international headquarters, are in the distinctive streets immediately west of Buchanan Street, starting around 1800 as townhouses, in the architecturally important streets embracing Blythswood Hill, Blythswood Holm further down and now including the Broomielaw next to the Clyde. To the south and west are the shopping precincts of Argyle Street, Sauchiehall Street and Buchanan Street, the last featuring more upmarket retailers and winner of the Academy of Urbanism "Great Street Award" 2008.[127] The collection of shops around these streets accumulate to become known as "The Style Mile".[128]

The main shopping areas include Buchanan Street, Buchanan Galleries, linking Buchanan Street and Sauchiehall Street, and the St. Enoch Centre linking Argyle Street and St Enoch Square), with the up-market Princes Square, which specifically features shops such as Ted Baker, Radley and Kurt Geiger.[129] Buchanan Galleries and other city centre locales were chosen as locations for the 2013 film Under the Skin directed by Jonathan Glazer.[130] Although the Glasgow scenes were shot with hidden cameras, star Scarlett Johansson was spotted around town.[131] The Italian Centre in Ingram Street also specialises in designer labels. Glasgow's retail portfolio forms the UK's second largest and most economically important retail sector after Central London.[132][133]

The city centre is home to most of Glasgow's main cultural venues: the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, Glasgow City Hall, Theatre Royal (performing home of Scottish Opera and Scottish Ballet), the Pavilion Theatre, the King's Theatre, Glasgow Film Theatre, Tron Theatre, Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA), Mitchell Library and Theatre, the Centre for Contemporary Arts, McLellan Galleries and the Lighthouse Museum of Architecture. The world's tallest cinema, the eighteen-screen Cineworld, is situated on Renfrew Street. The city centre is also home to four of Glasgow's higher education institutions: the University of Strathclyde, the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, Glasgow School of Art and Glasgow Caledonian University, and to the largest college in Britain – the City of Glasgow College in Cathedral Street.

Merchant City

[edit]

The Merchant City is the commercial and part-residential district of the Merchant City, a name coined by the historian Charles Oakley in the 1960s. This had started as a residential district of the wealthy city merchants involved in international trade and the textile industries in the 18th and early 19th centuries, with their warehouses nearby, including the Tobacco Lords from whom many of the streets take their name. With its mercantile wealth, and continuing growth even before the Industrial Revolution, the city expanded by creating the New Town around George Square, soon followed by the New Town of Blythswood on Blythswood Hill which includes Blythswood Square.[134] The original medieval centre around Glasgow Cross and the High Street was left behind.

Glasgow Cross, situated at the junction of High Street, leading up to Glasgow Cathedral, Gallowgate, Trongate and Saltmarket was the original centre of the city, symbolised by its Mercat cross. Glasgow Cross encompasses the Tolbooth Steeple, all that remains of the original Glasgow Tolbooth, which was demolished in 1921. Moving northward up High Street towards Rottenrow and Townhead lies the 15th century Glasgow Cathedral and the Provand's Lordship. Due to growing industrial pollution levels in the mid-to-late 19th century, the area fell out of favour with residents.[135]

From the 1980s onwards, the Merchant City has been rejuvenated with luxury city centre flats and warehouse conversions. This regeneration has supported an increasing number of cafés and restaurants.[136] The area is also home to a number of high end boutique style shops and some of Glasgow's most upmarket stores.[137]

The Merchant City is one centre of Glasgow's growing "cultural quarter", based on King Street, the Saltmarket and Trongate, and at the heart of the annual Merchant City Festival. The area has supported a growth in art galleries, the origins of which can be found in the late 1980s when it attracted artist-led organisations that could afford the cheap rents required to operate in vacant manufacturing or retail spaces.[138] The artistic and cultural potential of the Merchant City as a "cultural quarter" was harnessed by independent arts organisations and Glasgow City Council,[138] and the recent development of Trongate 103, which houses galleries, workshops, artist studios and production spaces, is considered a major outcome of the continued partnership between both.[139] The area also contains a number of theatres and concert venues, including the Tron Theatre, the Old Fruitmarket, the Trades Hall, St. Andrew's in the Square, Merchant Square, and the City Halls.[140]

West End

[edit]

Glasgow's West End grew firstly to and around Blythswood Square and Garnethill, extending then to Woodlands Hill and Great Western Road. It is a district of elegant townhouses and tenements with cafés, tea rooms, bars, boutiques, upmarket hotels, clubs and restaurants in the hinterland of Kelvingrove Park, the University of Glasgow, Glasgow Botanic Gardens and the Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre, focused especially on the area's main thoroughfares of Argyle Street (Finnieston), Great Western Road and Byres Road. The area is popular with tourists and students. The West End includes residential areas of Hillhead, Dowanhill, Kelvingrove, Kelvinside, Hyndland, Broomhill, Scotstoun, Jordanhill, Kelvindale, Anniesland and Partick. The name is also increasingly being used to refer to any area to the west of Charing Cross. The West End is bisected by the River Kelvin, which flows from the Campsie Fells in the north and confluences with the River Clyde at Yorkhill Quay.

The spire of Sir George Gilbert Scott's Glasgow University main building (the second largest Gothic Revival building in Great Britain) is a major landmark, and can be seen from miles around, sitting atop Gilmorehill. The university itself is the fourth oldest in the English-speaking world. Much of the city's student population is based in the West End, adding to its cultural vibrancy. The area is also home to the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, Kelvin Hall museums and research facilities, stores, and community sport. Adjacent to the Kelvin Hall was the Museum of Transport, which reopened in 2010 after moving to a new location on a former dockland site at Glasgow Harbour where the River Kelvin flows into the Clyde. The new building is built to a design by Zaha Hadid. The West End Festival, one of Glasgow's largest festivals, is held annually in June.

Glasgow is the home of the SEC Centre, Great Britain's largest exhibition and conference centre.[141][142][143] On 30 September 2013, a major expansion of the SECC facilities at the former Queen's Dock by Foster and Partners officially opened – the 13,000-seat Hydro arena. Adjacent to the SECC at Queen's Dock is the Clydeside distillery, a Scotch whisky distillery that opened in 2017 in the former dock pump house.[144]

East End

[edit]

The East End extends from Glasgow Cross in the City Centre to the boundary with North and South Lanarkshire. It is home to the Glasgow Barrowland market, popularly known as "The Barras",[145] Barrowland Ballroom, Glasgow Green, and Celtic Park, home of Celtic FC. Many of the original sandstone tenements remain in this district. The East End was once a major industrial centre, home to Sir William Arrol & Co., James Templeton & Co and William Beardmore and Company. A notable local employer continues to be the Wellpark Brewery, home of Tennent's Lager.

The Glasgow Necropolis Garden Cemetery was created by the Merchants House on a hill above the cathedral in 1831. Routes curve through the landscape uphill to the 21.3-metre-high (70 ft)[146] statue of John Knox at the summit. There are two late 18th century tenements in Gallowgate. Dating from 1771 and 1780, both have been well restored. The construction of Charlotte Street was financed by David Dale, whose former scale can be gauged by the one remaining house, now run by the National Trust for Scotland. Further along Charlotte Street there stands a modern Gillespie, Kidd & Coia building of some note. Once a school, it has been converted into offices. Surrounding these buildings are a series of innovative housing developments conceived as "Homes for the Future", part of a project during the city's year as UK City of Architecture and Design in 1999.[147]

East of Glasgow Cross is St Andrew's in the Square, the oldest post-Reformation church in Scotland, built in 1739–1757 and displaying a Presbyterian grandeur befitting the church of the city's wealthy tobacco merchants. Also close by is the more modest Episcopalian St Andrew's-by-the-Green, the oldest Episcopal church in Scotland. The Episcopalian St Andrew's was also known as the "Whistlin' Kirk" due to it being the first church after the Reformation to own an organ. Overlooking Glasgow Green is the façade of Templeton On The Green, featuring vibrant polychromatic brickwork intended to evoke the Doge's Palace in Venice.[148] The extensive Tollcross Park was originally developed from the estate of James Dunlop, the owner of a local steelworks. His large baronial mansion was built in 1848 by David Bryce, which later housed the city's Children's Museum until the 1980s. Today, the mansion is a sheltered housing complex. The new Scottish National Indoor Sports Arena, a modern replacement for the Kelvin Hall, is in Dalmarnock. The area was the site of the Athletes' Village for the 2014 Commonwealth Games, located adjacent to the new indoor sports arena.

The East End Healthy Living Centre (EEHLC) was established in mid-2005 at Crownpoint Road with Lottery Funding and City grants to serve community needs in the area. Now called the Glasgow Club Crownpoint Sports Complex, the centre provides service such as sports facilities, health advice, stress management, leisure and vocational classes.[149] To the north of the East End lie the two large gasometers of Provan Gas Works, which stand overlooking Alexandra Park and a major interchange between the M8 and M80 motorways.[150][151][152]

South Side

[edit]

Glasgow's South Side sprawls out south of the Clyde. The adjoining urban area includes some of Greater Glasgow's most affluent suburban towns, such as Newton Mearns, Clarkston, and Giffnock, all of which are in East Renfrewshire, as well as Thorntonhall in South Lanarkshire. Newlands and Dumbreck are examples of high-value residential districts within the city boundaries. There are many areas containing a high concentration of sandstone tenements like Shawlands, which is considered the "Heart of the Southside", with other examples being Battlefield, Govanhill and Mount Florida.[153] The large suburb of Pollokshields comprises both a quiet western part with undulating tree-lined boulevards lined with expensive villas, and a busier eastern part with a high-density grid of tenements and small shops. The south side also includes some post-war housing estates of various sizes such as Toryglen, Pollok, Castlemilk and Arden. The towns of Cambuslang and Rutherglen were included in the City of Glasgow district from 1975 to 1996, but are now in the South Lanarkshire council area.[154][155][156]

Although predominantly residential, the area does have several notable public buildings including, Charles Rennie Mackintosh's Scotland Street School Museum and House for an Art Lover; the Burrell Collection in Pollok Country Park; Alexander "Greek" Thomson's Holmwood House villa; the National Football Stadium Hampden Park in Mount Florida (home of Queens Park FC) and Ibrox Stadium (home of Rangers FC).

The former docklands site at Pacific Quay on the south bank of the River Clyde, opposite the SECC, is the site of the Glasgow Science Centre and the headquarters of BBC Scotland and STV Group (owner of STV), in a new purpose-built digital media campus.

In addition, several new bridges spanning the River Clyde have been built, including the Clyde Arc known by locals as the Squinty Bridge at Pacific Quay and others at Tradeston and Springfield Quay.

The South Side also includes many public parks, including Linn Park, Queen's Park, and Bellahouston Park and several golf clubs, including the championship course at Haggs Castle. The South Side is also home to the large Pollok Country Park, which was awarded the accolade of Europe's Best Park 2008.[157] The southside also directly borders Rouken Glen Park in neighbouring Giffnock. Pollok Park is Glasgow's largest park and until the early 2000s was the only country park in the city's boundary. In the early 2000s the Dams to Darnley Country Park was designated, although half of the park is in East Renfrewshire. As of 2021 the facilities at the still new park are quite lacking.

Govan is a district and former burgh in the south-western part of the city. It is situated on the south bank of the River Clyde, opposite Partick. It was an administratively independent Police Burgh from 1864 until it was incorporated into the expanding city of Glasgow in 1912. Govan has a legacy as an engineering and shipbuilding centre of international repute and is home to one of two BAE Systems Surface Ships shipyards on the River Clyde and the precision engineering firm, Thales Optronics. It is also home to the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital, one of the largest hospitals in the country, and the maintenance depot for the Glasgow Subway system. The wider Govan area includes the districts of Ibrox, Cessnock, Kinning Park and Kingston.

North Glasgow

[edit]

North Glasgow extends out from the north of the city centre towards the affluent suburbs of Bearsden, Milngavie and Bishopbriggs in East Dunbartonshire and Clydebank in West Dunbartonshire. The area also contains some of the city's poorest residential areas.

This has led to large-scale redevelopment of much of the poorer housing stock in north Glasgow, and the wider regeneration of many areas, such as Ruchill, which have been transformed; many run-down tenements have now been refurbished or replaced by modern housing estates. Much of the housing stock in north Glasgow is rented social housing, with a high proportion of high-rise tower blocks, managed by the North Glasgow Housing Association trading as NG Homes and Glasgow Housing Association.

Maryhill consists of well maintained traditional sandstone tenements. Although historically a working class area, its borders with the upmarket West End of the city mean that it is relatively wealthy compared to the rest of the north of the city, containing affluent areas such as Maryhill Park and North Kelvinside. Maryhill is also the location of Firhill Stadium, home of Partick Thistle F.C. since 1909. The junior team, Maryhill F.C. are also located in this part of north Glasgow.

The Forth and Clyde Canal passes through this part of the city, and at one stage formed a vital part of the local economy. It was for many years polluted and largely unused after the decline of heavy industry, but recent efforts to regenerate and re-open the canal to navigation have seen it rejuvenated, including art campuses at Port Dundas.

Sighthill was home to Scotland's largest asylum seeker community but the area is now regenerated as part of the Youth Olympic Games bid.[158]

A huge part of the economic life of Glasgow was once located in Springburn, where the Saracen Foundry, engineering works of firms like Charles Tennant and locomotive workshops employed many Glaswegians. Glasgow dominated this type of manufacturing, with 25% of all the world's locomotives being built in the area at one stage. It was home to the headquarters of the North British Locomotive Company. Today part of the Glasgow Works continues in use as a railway maintenance facility, all that is left of the industry in Springburn. It is proposed for closure in 2019.[159] Riddrie in the north east was intensively developed in the 1920s and retains several listed developments in the Art Deco style.

Culture

[edit]

The city has many amenities for a wide range of cultural activities, from curling to opera and ballet and from football to art appreciation; it also has a large selection of museums that include those devoted to transport, religion, and modern art. Many of the city's cultural sites were celebrated in 1990 when Glasgow was designated European Capital of Culture.[160]

The city's principal municipal library, the Mitchell Library, has grown into one of the largest public reference libraries in Europe, currently housing some 1.3 million books, an extensive collection of newspapers and thousands of photographs and maps.[161] Of academic libraries, Glasgow University Library started in the 15th century and is one of the oldest and largest libraries in Europe, with unique and distinctive collections of international status.[162]

Most of Scotland's national arts organisations are based in Glasgow, including Scottish Opera, Scottish Ballet, National Theatre of Scotland, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and Scottish Youth Theatre.

Glasgow has its own "Poet Laureate", a post created in 1999 for Edwin Morgan[163] and occupied by Liz Lochhead from 2005[164] until 2011, when she stood down to take up the position of Scots Makar.[165] Jim Carruth was appointed to the position of Poet Laureate for Glasgow in 2014 as part of the 2014 Commonwealth Games legacy.[166]

In 2013, PETA declared Glasgow to be the most vegan-friendly city in the UK.[167]

Recreation

[edit]Glasgow is home to major theatres including the Theatre Royal, the King's Theatre, Pavilion Theatre and the Citizens Theatre and home to many museums and art galleries, the largest and most famous being the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, the Hunterian Museum and Art Gallery, Burrell Collection, and the Gallery of Modern Art (GoMA). Most of the museums and galleries in Glasgow are publicly owned and free to enter.

The city has hosted many exhibitions over the years from the 1888 International Exhibition and 1901 International Exhibition to the Empire Exhibition 1938, including more recently The Glasgow Garden Festival in 1988, being the UK City of Architecture 1999, European Capital of Culture 1990, National City of Sport 1995–1999 and European Capital of Sport 2003. Glasgow has also hosted the National Mòd no less than twelve times since 1895.[168]

In addition, unlike the older and larger Edinburgh Festival (where all Edinburgh's main festivals occur in the last three weeks of August), Glasgow's festivals fill the calendar. Festivals include the Glasgow International Comedy Festival, Glasgow International Festival of Visual Art, Glasgow International Jazz Festival, Celtic Connections, Glasgow Fair, Glasgow Film Festival, West End Festival, Merchant City Festival, Glasgay, and the World Pipe Band Championships.

Music scene

[edit]

The city is home to numerous orchestras, ensembles and bands including those of Scottish Opera, Scottish Ballet, Royal Scottish National Orchestra, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra and related to the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland, the National Youth Orchestra of Scotland and the Universities and Colleges. Choirs of all type are well supported. Glasgow has many live music venues, pubs, and clubs. Some of the city's more well-known venues include the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, The OVO Hydro, the SECC, Glasgow Cathouse, The Art School, King Tut's Wah Wah Hut (where Oasis were spotted and signed by Glaswegian record mogul Alan McGee), the Queen Margaret Union (who have Kurt Cobain's footprint locked in a safe), the Barrowland, a ballroom converted into a live music venue as well as The Garage, which is the largest nightclub in Scotland. More recent mid-sized venues include ABC, destroyed in the art school fire of 15 June 2018, and the O2 Academy, which play host to a similar range of acts. There are also a large number of smaller venues and bars, which host many local and touring musicians, including Stereo, 13th Note and Nice N Sleazy. Most recent recipient of the SLTN Music Pub of the Year award was Bar Bloc, awarded in November 2011.[170] In 2010, Glasgow was named the UK's fourth "most musical" city by PRS for Music.[171] Glasgow is also the "most mentioned city in the UK" in song titles, outside London according, to a chart produced by PRS for music, with 119, ahead of closest rivals Edinburgh who received 95 mentions[172]

Since the 1980s, the success of bands such as The Blue Nile, Gun, Simple Minds, Del Amitri, Texas, Hipsway, Love & Money, Idlewild, Deacon Blue, Orange Juice, Lloyd Cole and the Commotions, Teenage Fanclub, Belle and Sebastian, Camera Obscura, Franz Ferdinand, Mogwai, Travis, and Primal Scream has significantly boosted the profile of the Glasgow music scene, prompting Time magazine to liken Glasgow to Detroit during its 1960s Motown heyday.[173] Artists to achieve successful from Glasgow during the 2000s and 2010s include The Fratellis, Chvrches, Rustie, Vukovi, Glasvegas and Twin Atlantic. The city of Glasgow was appointed a UNESCO City of Music on 20 August 2008 as part of the Creative Cities Network.

Glasgow's contemporary dance music scene has been spearheaded by Slam, and their record label Soma Quality Recordings,[174] with their Pressure club nights attracting DJs and clubbers from around the world; these nights were hosted by The Arches but moved to Sub Club after the closure of the former in 2015, also taking place at the SWG3 arts venue. The Sub Club has regularly been nominated as one of the best clubs in the world.[175][176]

The MOBO Awards were held at the SECC on 30 September 2009, making Glasgow the first city outside London to host the event since its launch in 1995. On 9 November 2014, Glasgow hosted the 2014 MTV Europe Music Awards at The OVO Hydro, it was the second time Scotland hosted the show since 2003 in Edinburgh and overall the fifth time that the United Kingdom has hosted the show since 2011 in Belfast, Northern Ireland. The event was hosted by Nicki Minaj and featured performances from Ariana Grande, Enrique Iglesias, Ed Sheeran, U2 and Slash.

Media

[edit]

There has been a considerable number of films made about Glasgow or in Glasgow.[177] Both BBC Scotland and STV have their headquarters in Glasgow. Television programs filmed in Glasgow include Rab C. Nesbitt, Taggart, Tutti Frutti, High Times, River City, City Lights, Chewin' the Fat, Still Game, Limmy's Show and Lovesick. Most recently,[when?] the long-running series Question Time and the early-evening quiz programme Eggheads moved its production base to the city. Most National Lottery game shows are also filmed in Glasgow. Children's game show Copycats is filmed there, and the Irish/UK programme Mrs. Brown's Boys is filmed at BBC Scotland.

The Scottish press publishes various newspapers in the city such as The Evening Times, The Herald, The Sunday Herald, the Sunday Mail and the Daily Record. Scottish editions of Trinity Mirror and News International titles are printed in the city. STV Group is a Glasgow-based media conglomerate with interests in television, and publishing advertising. STV Group owns and operates both Scottish ITV franchises (Central Scotland and Grampian), both branded STV. Glasgow also had its own television channel, STV Glasgow, which launched in June 2014, which also shows some of Glasgow's own programs filmed at the STV headquarters in Glasgow. Shows included The Riverside Show, Scottish Kitchen, City Safari, Football Show and Live at Five. STV Glasgow merged with STV Edinburgh to form STV2 in April 2017 which eventually closed in June 2018.

Various radio stations are also located in Glasgow. BBC Radio Scotland, the national radio broadcaster for Scotland, is located in the BBC's Glasgow headquarters alongside its Gaelic-language sister station, which is also based in Stornoway. Bauer Radio owns the principal commercial radio stations in Glasgow: Clyde 1 and Greatest Hits Radio Glasgow & The West, which can reach over 2.3 million listeners.[178] In 2004, STV Group plc (then known as SMG plc) sold its 27.8% stake in Scottish Radio Holdings to the broadcasting group EMAP for £90.5 million. Other stations broadcasting from Glasgow include Smooth Scotland, Heart Scotland, which are owned by Global. Global Radio's Central Scotland radio station Capital Scotland also broadcasts from studios in Glasgow. Nation Radio Scotland, owned by Nation Broadcasting, also broadcasts from the city. The city has a strong community radio sector, including Celtic Music Radio, Subcity Radio, Radio Magnetic, Sunny Govan Radio, AWAZ FM and Insight Radio.

Religion

[edit]Glasgow is a city of significant religious diversity. The Church of Scotland and the Roman Catholic Church are the two largest Christian denominations in the city. There are 147 congregations in the Church of Scotland's Presbytery of Glasgow (of which 104 are within the city boundaries, the other 43 being in adjacent areas).[179] Within the city boundaries there are 65 parishes of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Glasgow[180] and four parishes of the Diocese of Motherwell.[181] The city has four Christian cathedrals: Glasgow Cathedral, of the Church of Scotland; St Andrew's Cathedral, of the Roman Catholic Church; St Mary's Cathedral, of the Scottish Episcopal Church, and St Luke's Cathedral, of the Greek Orthodox Church. The Baptist Church and Salvation Army are well represented.

The Protestant churches are the largest in number, including Baptist, Episcopalian, Methodist and Presbyterian. 32% of the population follow the Protestant Church of Scotland whilst 29% following the Roman Catholic Church, according to the 2001 census (Christians overall form 65%).[182] Much of the city's Roman Catholic population are those of Irish ancestry. The divisions between the two denominations and their respective communities play a major part in sectarianism in Glasgow, in a similar nature to that of Northern Ireland, although not segregated territorially as in Belfast.[183][184]

Biblical unitarians are represented by three Christadelphian ecclesias, referred to geographically, as "South",[185] "Central"[186] and "Kelvin".[187]

The Sikh community is served by four Gurdwaras. Two are situated in the West End (Central Gurdwara Singh Sabha in Sandyford and Guru Nanak Sikh Temple in Kelvinbridge) and two in the Southside area of Pollokshields (Guru Granth Sahib Gurdwara and Sri Guru Tegh Bahadur Gurdwara). In 2013, Scotland's first purpose-built Gurdwara opened in a massive opening ceremony. Built at a cost of £3.8M, it can hold 1,500 worshippers.[188] Central Gurdwara is currently constructing a new building in the city. There are almost 10,000 Sikhs in Scotland and the majority live in Glasgow.[189]

Glasgow Central Mosque in the Gorbals district is the largest mosque in Scotland and, along with twelve other mosques in the city, caters for the city's Muslim population, estimated to number 33,000.[190] Glasgow also has a Hindu mandir.

Glasgow has seven synagogues, including the Romanesque-revival Garnethill Synagogue in the city centre. Glasgow currently has the seventh largest Jewish population in the United Kingdom after London, Manchester, Leeds, Gateshead, Brighton and Bournemouth but once had a Jewish population second only to London, estimated at 20,000 in the Gorbals alone.[191]

In 1993, the St Mungo Museum of Religious Life and Art opened in Glasgow. It is believed to be the only public museum to examine all the world's major religious faiths.[192][193]

Language

[edit]Glasgow is Scotland's main locus of Gaelic language use outside the Highlands and Islands. In 2011, 5,878 residents of the city over age 3 spoke Gaelic, amounting to 1.0% of the population. Of Scotland's 25 largest cities and towns, only Inverness, the unofficial capital of the Highlands, has a higher percentage of Gaelic speakers.[194] In the Greater Glasgow area there were 8,899 Gaelic-speakers, amounting to 0.8% of the population.[195] Both the Gaelic language television station BBC Alba and the Gaelic language radio station BBC Radio nan Gàidheal have studios in Glasgow, their only locations outside the Highlands and Islands.[196]

Architecture

[edit]

Very little of medieval Glasgow remains; the two main landmarks from this period being the 15th-century Provand's Lordship and 13th-century St. Mungo's Cathedral, although the original medieval street plan (along with many of the street names) on the eastern side of the city centre has largely survived intact. Also in the 15th century began the building of Cathcart Castle, completed c. 1450 with a view over the landscape in all directions. It was at this castle Mary Queen of Scots supposedly spent the night before her defeat at the Battle of Langside in May 1568. The castle was demolished in 1980 for safety reasons. The vast majority of the central city area as seen today dates from the 19th century. As a result, Glasgow has a heritage of Victorian architecture: the Glasgow City Chambers; the main building of the University of Glasgow, designed by Sir George Gilbert Scott; and the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, designed by Sir John W. Simpson, are notable examples.

The city is notable for architecture designed by the Glasgow School, the most notable exponent of that style being Charles Rennie Mackintosh. Mackintosh was an architect and designer in the Arts and Crafts Movement and the main exponent of Art Nouveau in the United Kingdom, designing numerous noted Glasgow buildings such as the Glasgow School of Art, Willow Tearooms and the Scotland Street School Museum. A hidden gem of Glasgow, also designed by Mackintosh, is the Queen's Cross Church, the only church by the renowned artist to be built.[198]

Another architect who has had an enduring impact on the city's appearance is Alexander Thomson, with notable examples including the Holmwood House villa, and likewise Sir John James Burnet, awarded the R.I.B.A.'s Royal Gold Medal for his lifetime's service to architecture. The buildings reflect the wealth and self-confidence of the residents of the "Second City of the Empire". Glasgow generated immense wealth from trade and the industries that developed from the Industrial Revolution. The shipyards, marine engineering, steel making, and heavy industry all contributed to the growth of the city.

Many of the city's buildings were built with red or blond sandstone, but during the industrial era those colours disappeared under a pervasive black layer of soot and pollutants from the furnaces, until the Clean Air Act was introduced in 1956. There are over 1,800 listed buildings in the city, of architectural and historical importance, and 23 Conservation Areas extending over 1,471 hectares (3,630 acres). Such areas include the Central Area, Dennistoun, the West End, Pollokshields – the first major planned garden suburb in Britain – Newlands and the village of Carmunnock.[199]

Modern buildings in Glasgow include the Glasgow Royal Concert Hall, and along the banks of the Clyde are the Glasgow Science Centre, The OVO Hydro and the Scottish Exhibition and Conference Centre, whose Clyde Auditorium was designed by Sir Norman Foster, and is colloquially known as the "Armadillo". In 2006 Zaha Hadid won a competition to design the new Museum of Transport.[200] Hadid's museum opened on the waterfront in 2011 and has been renamed the Riverside Museum to reflect the change in location and to celebrate Glasgow's rich industrial heritage stemming from the Clyde.[201]

Glasgow's historical and modern architectural traditions were celebrated in 1999 when the city was designated UK City of Architecture and Design,[202] winning the accolade over Liverpool and Edinburgh.[203]

Economy

[edit]

Glasgow has the largest economy in Scotland[204] and is at the hub of the metropolitan area of West Central Scotland. The city itself sustains more than 410,000 jobs in over 12,000 companies. Over 153,000 jobs were created in the city between 2000 and 2005 – a growth rate of 32%.[205] Glasgow's annual economic growth rate of 4.4% is now second only to that of London. In 2005, over 17,000 new jobs were created, and 2006 saw private-sector investment in the city reaching £4.2 billion, an increase of 22% in a single year.[206] 55% of the residents in the Greater Glasgow area commute to the city every day.

Once dominant export orientated manufacturing industries such as shipbuilding and other heavy engineering have been gradually replaced in importance by more diversified forms of economic activity, although major manufacturing firms continue to be headquartered in the city, such as Aggreko, Weir Group, Clyde Blowers, Howden, Linn Products, Firebrand Games, William Grant & Sons, Whyte and Mackay, The Edrington Group, British Polar Engines and Albion Motors.[207]

In 2023, major industries in the Glasgow City Region contributing to the economy of the city were public admin education & health, distribution, hotels & restaurants, banking, finance and insurance services and transport & communication.[208]

Transport

[edit]Public transport

[edit]Glasgow has a large urban transport system, mostly managed by the Strathclyde Partnership for Transport (SPT). The city has many bus services; since bus deregulation almost all are provided by private operators, though SPT part-funds some services. The principal bus operators within the city are: First Glasgow, McGill's Bus Services, Stagecoach West Scotland and Glasgow Citybus. The main bus terminal in the city is Buchanan bus station.

Glasgow has the most extensive urban rail network in the UK outside London, with rail services travelling to a large part of the West of Scotland. Most lines were electrified under British Rail. All trains running within Scotland, including the local Glasgow trains, are operated by ScotRail, which is owned by the Scottish Government. Central station and Queen Street station are the two main railway terminals. Glasgow Central is the terminus of the 642 km (399 mi) long West Coast Main Line[209] from London Euston, as well as TransPennine Express services from Manchester and CrossCountry services from Birmingham, Bristol, Plymouth and various other destinations in England. Glasgow Central is also the terminus for suburban services on the south side of Glasgow, Ayrshire and Inverclyde, as well as being served by the cross city link from Dalmuir to Motherwell. Most other services within Scotland – the main line to Edinburgh, plus services to Aberdeen, Dundee, Inverness and the Western Highlands – operate from Queen Street station.

The city's suburban network is currently divided by the River Clyde and the Crossrail Glasgow initiative has been proposed to link them; it is currently awaiting funding from the Scottish Government. The city is linked to Edinburgh by four direct railway links. In addition to the suburban rail network, SPT operates the Glasgow Subway. The Subway is the United Kingdom's only completely underground metro system and is generally recognised as the world's third oldest underground railway after the London Underground and the Budapest Metro.[211] Both railway and subway stations have a number of park and ride facilities.

As part of the wider regeneration along the banks of the River Clyde, a bus rapid transit system called Clyde Fastlink is operational between Glasgow City Centre to the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital.[212]

Shipping

[edit]Global-ship-management is carried out by maritime and logistics firms in Glasgow, in client companies employing over 100,000 seafarers. This reflects maritime skills over many decades and the training and education of deck officers and marine engineers from around the world at the City of Glasgow College, Nautical Campus, from which graduate around one third of all such graduates in the United Kingdom.[213]