Оружейная политика в США

Политика в отношении оружия определяется в Соединенных Штатах двумя основными противоположными идеологиями, касающимися частной собственности на огнестрельное оружие. Те, кто выступает за контроль над оружием, поддерживают все более ограничительное регулирование владения оружием; те, кто выступает за права на оружие, выступают против усиления ограничений или поддерживают либерализацию владения оружием. Эти группы обычно расходятся во мнениях относительно интерпретации текста, истории и традиций законов и судебных заключений, касающихся владения оружием в Соединенных Штатах, а также значения Второй поправки к Конституции Соединенных Штатов . Американская политика в отношении оружия включает в себя дальнейшие разногласия этих групп относительно роли огнестрельного оружия в общественной безопасности, изученного влияния владения огнестрельным оружием на здоровье и безопасность населения, а также роли оружия в национальной и государственной преступности. [ 2 ] [ 3 ] [ 4 ] : 1–3 [ 5 ]

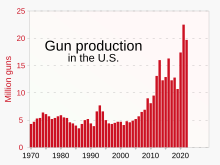

Private firearm ownership has experienced a steady increase in the United States since the turn of the 21st century, and accelerated rapidly during and following the year of 2020.[6] The National Firearms Survey of 2021, currently the nation's largest and most comprehensive study into American firearm ownership, found that privately-owned firearms are used in roughly 1.7 million defensive usage cases (self-defense from an attacker/attackers inside and outside the home) per year across the nation.[7] The study also found an increase in diversity amongst firearm owner demographics, reporting that rates of firearm ownership amongst females and ethnic minorities had risen sharply since the last national survey had been conducted.[8][9]

American gun politics is increasingly a question of demography and political party affiliation, and is influenced by well-known gender, age and income differences according to major social surveys.[10][11]

History

[edit]

Firearms in American life begin with the earliest attempts to settle and colonize the United States. Firearms were made, imported and provided for agrarian, hunting, defense and diplomatic purposes. A connection between shooting skills and survival among American men in the colonial expanses was often a necessity, and could serve as a 'rite of passage' for those entering manhood.[11]: 9 Today, the figures of the settler colonist, hunter and outdoorsman survive as central to American gun culture, regardless of modern trends away from hunting and rural life.[5]

Prior to the American Revolution, there was neither the ability nor political desire to maintain a standing army in the American colonies. Since at least the time of the Glorious Revolution, English political ideology was strongly opposed to the idea of a standing army. Therefore, the armed citizen-soldier carried responsibility. Service in colonial militia, including providing one's own ammunition and weapons, was mandatory for all men. Yet, as early as the 1790s, the mandatory universal militia duty evolved gradually to voluntary militia units and a reliance on a regular army. Throughout the 19th century the institution of the organized civilian militia gradually declined.[11]: 10 The unorganized civilian militia under current U.S. law consists of all able-bodied males at least seventeen years of age and under the age of 45—with some exceptions—who are not members of the National Guard or Naval Militia, as codified in 10 U.S.C. § 246.

Closely related to the militia tradition is the frontier tradition, with the need for self-protection pursuant to westward expansion and the extension of the American frontier.[11]: 10–11 Though it has not been a necessary part of daily survival for over a century, "generations of Americans continued to embrace and glorify it as a living inheritance – as a permanent ingredient of this nation's style and culture".[12]: 21 Since the founding-era of American Federalist politics, debates regarding firearm availability and gun violence in the United States have been characterized by concerns about the right to bear arms, as found in the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and the responsibility of the United States government to serve the needs of its citizens and to prevent crime and deaths. Firearms regulation supporters say that indiscriminate or unrestricted gun rights inhibit the government from fulfilling that responsibility, and causes a safety concern. Gun rights supporters promote firearms for self-defense – including security against tyranny, as well as hunting and sporting activities.[13]: 96 [14] Gun control advocates state that restricting and tracking gun access would result in safer communities, while gun rights advocates state that increased firearm ownership by law-abiding citizens reduces crime and assert that criminals have always had easy access to firearms.[15][16] Gun legislation in the United States has become increasingly subject to federal judicial interpretation of the Constitution. The Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution reads: "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed."[17] In 1791, the United States adopted the Second Amendment, and in 1868 adopted the Fourteenth Amendment. The historical tradition bounded by these two amendments has been the subject of U.S. Supreme Court decisions in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008), where the Court affirmed for the first time that the Second Amendment guarantees an individual right to possess firearms for traditionally lawful purposes (such as self-defense within the home), independent of service in a state militia, in McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010), where the Court ruled that the Second Amendment's restrictions are incorporated by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment and thereby apply to state as well as federal law, and most recently in the NYSRPA v. Bruen (2022). As emphasized in Bruen, the Second Amendment makes an "unqualified command" that the "individual-right" of firearms ownership, as opposed to the collective or militia-based theory of the right, is protected from all restriction unless a government authority can demonstrate their law is with the Nation's historical tradition of firearms regulation.[18]

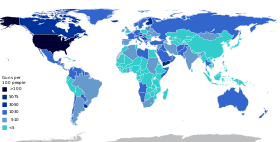

In 2018 it was estimated that U.S. civilians own 393 million firearms,[19] and that 40% to 42% of the households in the country have at least one gun. However, record gun sales followed in the following years.[20][21][22] The U.S. has by far the highest estimated number of guns per capita in the world, at 120.5 guns for every 100 people.[23]

Colonial era through the Civil War

[edit]In the summer of 1619 in Jamestown, Virginia, leaders of the settlement came together to pass the first gun law:[24]

That no man do sell or give any Indians any piece, shot, or powder, or any other arms offensive or defensive, upon pain of being held a traitor to the colony and of being hanged as soon as the fact is proved, without all redemption.

In the years prior to the American Revolution, the British, in response to the colonists' unhappiness over increasingly direct control and taxation of the colonies, imposed a gunpowder embargo on the colonies in an attempt to lessen the ability of the colonists to resist British encroachments into what the colonies regarded as local matters. Two direct attempts to disarm the colonial militias fanned what had been a smoldering resentment of British interference into the fires of war.[25]

These two incidents were the attempt to confiscate the cannon of the Concord and Lexington militias, leading to the Battles of Lexington and Concord of April 19, 1775, and the attempt, on April 20, to confiscate militia powder stores in the armory of Williamsburg, Virginia, which led to the Gunpowder Incident and a face-off between Patrick Henry and hundreds of militia members on one side and the Royal Governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, and British seamen on the other. The Gunpowder Incident was eventually settled by paying the colonists for the powder.[25]

According to historian Saul Cornell, states passed some of the first gun control laws, beginning with Kentucky's law to "curb the practice of carrying concealed weapons in 1813." There was opposition and, as a result, the individual right interpretation of the Second Amendment began and grew in direct response to these early gun control laws, in keeping with this new "pervasive spirit of individualism." As noted by Cornell, "Ironically, the first gun control movement helped give birth to the first self-conscious gun rights ideology built around a constitutional right of individual self-defense."[26]: 140–141

The individual right interpretation of the Second Amendment first arose in Bliss v. Commonwealth (1822),[27] which evaluated the right to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state pursuant to Section 28 of the Second Constitution of Kentucky (1799). The right to bear arms in defense of themselves and the state was interpreted as an individual right, for the case of a concealed sword cane. This case has been described as about "a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons [that] was violative of the Second Amendment".[28]

The first state court decision relevant to the "right to bear arms" issue was Bliss v. Commonwealth. The Kentucky court held that "the right of citizens to bear arms in defense of themselves and the State must be preserved entire,..."[29]: 161 [30]

Also during the Jacksonian Era, the first collective right (or group right) interpretation of the Second Amendment arose. In State v. Buzzard (1842), the Arkansas high court adopted a militia-based, political right, reading of the right to bear arms under state law, and upheld the 21st section of the second article of the Arkansas Constitution that declared, "that the free white men of this State shall have a right to keep and bear arms for their common defense",[31] while rejecting a challenge to a statute prohibiting the carrying of concealed weapons.

The Arkansas high court declared "That the words 'a well-regulated militia being necessary for the security of a free State', and the words 'common defense' clearly show the true intent and meaning of these Constitutions [i.e., Arkansas and the U.S.] and prove that it is a political and not an individual right, and, of course, that the State, in her legislative capacity, has the right to regulate and control it: This being the case, then the people, neither individually nor collectively, have the right to keep and bear arms." Joel Prentiss Bishop's influential Commentaries on the Law of Statutory Crimes (1873) took Buzzard's militia-based interpretation, a view that Bishop characterized as the "Arkansas doctrine," as the orthodox view of the right to bear arms in American law.[31][32]

The two early state court cases, Bliss and Buzzard, set the fundamental dichotomy in interpreting the Second Amendment, i.e., whether it secured an individual right versus a collective right.[citation needed]

Post Civil War

[edit]

In the years immediately following the Civil War, the question of the rights of freed slaves to carry arms and to belong to the militia came to the attention of the federal courts. In response to the problems freed slaves faced in the Southern states, the Fourteenth Amendment was drafted.

When the Fourteenth Amendment was drafted, Representative John A. Bingham of Ohio used the Court's own phrase "privileges and immunities of citizens" to include the first Eight Amendments of the Bill of Rights under its protection and guard these rights against state legislation.[33]

The debate in Congress on the Fourteenth Amendment after the Civil War also concentrated on what the Southern States were doing to harm the newly freed slaves. One particular concern was the disarming of former slaves.

The Second Amendment attracted serious judicial attention with the Reconstruction era case of United States v. Cruikshank which ruled that the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment did not cause the Bill of Rights, including the Second Amendment, to limit the powers of the State governments, stating that the Second Amendment "has no other effect than to restrict the powers of the national government."

Akhil Reed Amar notes in The Yale Law Journal, the basis of common law for the first ten amendments of the U.S. Constitution, which would include the Second Amendment, "following John Randolph Tucker's famous oral argument in the 1887 Chicago anarchist Haymarket affair case, Spies v. Illinois":

Though originally the first ten Amendments were adopted as limitations on Federal power, yet in so far as they secure and recognize fundamental rights – common law rights – of the man, they make them privileges and immunities of the man as citizen of the United States...[34]: 1270

20th century

[edit]First half of 20th century

[edit]Since the late 19th century, with three key cases from the pre-incorporation era, the U.S. Supreme Court consistently ruled that the Second Amendment (and the Bill of Rights) restricted only Congress, and not the States, in the regulation of guns.[35] Scholars predicted that the Court's incorporation of other rights suggested that they may incorporate the Second, should a suitable case come before them.[36]

National Firearms Act

[edit]The first major federal firearms law passed in the 20th century was the National Firearms Act (NFA) of 1934. It was passed after Prohibition-era gangsterism peaked with the Saint Valentine's Day massacre of 1929. The era was famous for criminal use of firearms such as the Thompson submachine gun (Tommy gun) and sawed-off shotgun. Under the NFA, machine guns, short-barreled rifles and shotguns, and other weapons fall under the regulation and jurisdiction of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF) as described by Title II.[37]

United States v. Miller

[edit]In United States v. Miller[38] (1939) the Court did not address incorporation, but whether a sawn-off shotgun "has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well-regulated militia."[36] In overturning the indictment against Miller, the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Arkansas stated that the National Firearms Act of 1934, "offend[ed] the inhibition of the Second Amendment to the Constitution." The federal government then appealed directly to the Supreme Court. On appeal the federal government did not object to Miller's release since he had died by then, seeking only to have the trial judge's ruling on the unconstitutionality of the federal law overturned. Under these circumstances, neither Miller nor his attorney appeared before the Court to argue the case. The Court only heard argument from the federal prosecutor. In its ruling, the Court overturned the trial court and upheld the NFA.[39]

Second half of 20th century

[edit]

The Gun Control Act of 1968 (GCA) was passed after the assassinations of President John F. Kennedy, Senator Robert Kennedy, and African-American activists Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. in the 1960s.[11] The GCA focuses on regulating interstate commerce in firearms by generally prohibiting interstate firearms transfers except among licensed manufacturers, dealers, and importers. It also prohibits selling firearms to certain categories of individuals defined as "prohibited persons."

In 1986, Congress passed the Firearm Owners Protection Act.[40] It was supported by the National Rifle Association because it reversed many of the provisions of the GCA. It also banned ownership of unregistered fully automatic rifles and civilian purchase or sale of any such firearm made from that date forward.[41][42]

The assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan in 1981 led to enactment of the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act (Brady Law) in 1993 which established the national background check system to prevent certain restricted individuals from owning, purchasing, or transporting firearms.[43] In an article supporting passage of such a law, retired chief justice Warren E. Burger wrote:

Americans also have a right to defend their homes, and we need not challenge that. Nor does anyone seriously question that the Constitution protects the right of hunters to own and keep sporting guns for hunting game any more than anyone would challenge the right to own and keep fishing rods and other equipment for fishing – or to own automobiles. To 'keep and bear arms' for hunting today is essentially a recreational activity and not an imperative of survival, as it was 200 years ago. 'Saturday night specials' and machine guns are not recreational weapons and surely are as much in need of regulation as motor vehicles.[44]

A Stockton, California, schoolyard shooting in 1989 led to passage of the Federal Assault Weapons Ban of 1994 (AWB or AWB 1994), which defined and banned the manufacture and transfer of "semiautomatic assault weapons" and "large capacity ammunition feeding devices."[45]

According to journalist Chip Berlet, concerns about gun control laws along with outrage over two high-profile incidents involving the ATF (Ruby Ridge in 1992 and the Waco siege in 1993) mobilized the militia movement of citizens who feared that the federal government would begin to confiscate firearms.[46][47]

Though gun control is not strictly a partisan issue, there is generally more support for gun control legislation in the Democratic Party than in the Republican Party.[48] The Libertarian Party, whose campaign platforms favor limited government regulation, is outspokenly against gun control.[49]

Advocacy groups

[edit]The National Rifle Association (NRA) was founded to promote firearm competency and natural conservation in 1871. The NRA supported the NFA and, ultimately, the GCA.[50] After the GCA, more strident groups, such as the Gun Owners of America (GOA), began to advocate for gun rights.[51] According to the GOA, it was founded in 1975 when "the radical left introduced legislation to ban all handguns in California."[52] The GOA and other national groups like the Second Amendment Foundation (SAF) and its offshoot the Firearms Policy Coalition (FPC), Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership (JPFO), and the Second Amendment Sisters (SAS), often take stronger stances than the NRA and criticize its history of support for some firearms legislation, such as GCA. The National Association for Gun Rights (NAGR) has been an outspoken critic of the NRA for a number of years. According to the Huffington Post, "NAGR is the much leaner, more pugnacious version of the NRA. Where the NRA has looked to find some common ground with gun reform advocates and at least appear to be reasonable, NAGR has been the unapologetic champion of opening up gun laws even more."[53] These groups believe any compromise leads to greater restrictions.[54]: 368 [55]: 172

According to the authors of The Changing Politics of Gun Control (1998), in the late 1970s, the NRA changed its activities to incorporate political advocacy.[56] Despite the impact on the volatility of membership, the politicization of the NRA has been consistent and the NRA-Political Victory Fund ranked as "one of the biggest spenders in congressional elections" as of 1998.[56] According to the authors of The Gun Debate (2014), the NRA taking the lead on politics serves the gun industry's profitability. In particular when gun owners respond to fears of gun confiscation with increased purchases and by helping to isolate the industry from the misuse of its products used in shooting incidents.[57]

The Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence began in 1974 as Handgun Control Inc. (HCI). Soon after, it formed a partnership with another fledgling group called the National Coalition to Ban Handguns (NCBH) – later known as the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence (CSGV). The partnership did not last, as NCBH generally took a tougher stand on gun regulation than HCI.[58]: 186 In the wake of the 1980 murder of John Lennon, HCI saw an increase of interest and fundraising and contributed $75,000 to congressional campaigns. Following the Reagan assassination attempt and the resultant injury of James Brady, Sarah Brady joined the board of HCI in 1985. HCI was renamed in 2001 to Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence.[59]

Centers for Disease Control (CDC) restriction

[edit]In 1996, Congress added language to the relevant appropriations bill which required "none of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control."[60] This language was added to prevent the funding of research by the CDC that gun rights supporters considered politically motivated and intended to bring about further gun control legislation. In particular, the NRA and other gun rights proponents objected to work supported by the National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, then run by Mark L. Rosenberg, including research authored by Arthur Kellermann.[61][62][63]

21st century

[edit]

In October 2003, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published a report on the effectiveness of gun violence prevention strategies that concluded "Evidence was insufficient to determine the effectiveness of any of these laws."[65]: 14 A similar survey of firearms research by the National Academy of Sciences arrived at nearly identical conclusions in 2004.[66] In September of that year, the Assault Weapons Ban expired due to a sunset provision. Efforts by gun control advocates to renew the ban failed, as did attempts to replace it after it became defunct.

The NRA opposed bans on handguns in Chicago, Washington D.C., and San Francisco while supporting the NICS Improvement Amendments Act of 2007 (also known as the School Safety And Law Enforcement Improvement Act), which strengthened requirements for background checks for firearm purchases.[67] The GOA took issue with a portion of the bill, which they termed the "Veterans' Disarmament Act."[68]

Besides the GOA, other national gun rights groups continue to take a stronger stance than the NRA. These groups include the Second Amendment Sisters, Second Amendment Foundation, Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership, and the Pink Pistols. New groups have also arisen, such as the Students for Concealed Carry, which grew largely out of safety-issues resulting from the creation of gun-free zones that were legislatively mandated amidst a response to widely publicized school shootings.

In 2001, in United States v. Emerson, the Fifth Circuit became the first federal appeals court to recognize an individual's right to own guns. In 2007, in Parker v. District of Columbia, the D.C. Circuit became the first federal appeals court to strike down a gun control law on Second Amendment grounds.[69]

Smart guns

[edit]Smart guns only fire when in the hands of the owner, a feature gun control advocates say eliminates accidental firings by children, and the risk of hostile persons (such as prisoners, criminal suspects, an opponent in a fight, or an enemy soldier) grabbing the gun and using it against the owner. Gun rights advocates fear mandatory smart gun technology will make it more difficult to fire a gun when needed.

Smith & Wesson reached a settlement in 2000 with the administration of President Bill Clinton, which included a provision for the company to develop a smart gun. A consumer boycott organized by the NRA and NSSF nearly drove the company out of business and forced it to drop its smart gun plans.[70][71]

The New Jersey Childproof Handgun Law of 2002 requires that 30 months after "personalized handguns are available" anywhere in the United States, only smart guns may be sold in the state.[72]

Some gun safety advocates worry that by raising the stakes of introducing the technology, this law contributes to the opposition that has prevented smart guns from being sold anywhere in the United States despite availability in other countries.

In 2014, a Maryland gun dealer dropped plans to sell the first smart gun in the United States after receiving complaints.[73]

District of Columbia v. Heller

[edit]In June 2008, in District of Columbia v. Heller, the Supreme Court upheld by a 5–4 vote the Parker decision striking down the D.C. gun law. Heller ruled that Americans have an individual right to possess firearms, irrespective of membership in a militia, "for traditionally lawful purposes, such as self-defense within the home."[74] However, in delivering the majority opinion, Justice Antonin Scalia argued that the operative clause of the amendment, "the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed," codifies an individual right derived from English common law and codified in the English Bill of Rights (1689). The majority held that the Second Amendment's preamble, "A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State," is consistent with this interpretation when understood in light of the framers' belief that the most effective way to destroy a citizens' militia was to disarm the citizens. The majority also found that United States v. Miller supported an individual-right rather than a collective-right view, contrary to the dominant 20th-century interpretation of that decision. (In Miller, the Supreme Court unanimously held that a federal law requiring the registration of sawed-off shotguns did not violate the Second Amendment because such weapons did not have a "reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia.") Finally, the court held that, because the framers understood the right of self-defense to be "the central component" of the right to keep and bear arms, the Second Amendment implicitly protects the right "to use arms in defense of hearth and home."[75][76]

The four dissenting justices said that the majority had broken established precedent on the Second Amendment,[77] and took the position that the Amendment refers to an individual right, but in the context of militia service.[78][79][80][81]

McDonald v. City of Chicago

[edit]In June 2010, a Chicago law that banned handguns was struck down. The 5–4 ruling incorporated the Second Amendment, stating that "The Fourteenth Amendment makes the Second Amendment right to keep and bear arms fully applicable to the States." Justice Samuel Alito's plurality opinion attributed incorporation to the Amendment's Due Process Clause.

New York State Rifle & Pistol Association, Inc. v. Bruen

[edit]In June 2022, the Supreme Court struck down the Sullivan Act's requirement for New York residents to show proper cause to obtain a license for concealed carry of handguns. The Supreme Court's 6-3 majority opinion authored by Justice Clarence Thomas rejected a two-part test previously used by federal courts to review challenges to gun-control measures. It found that carrying a handgun in public for self-defense is protected under the Second Amendment, while still allowing for restrictions on carrying handguns in certain "sensitive places." The opinion however only allows for "sensitive place" restrictions where historical analogues may be present (such as schools, courthouses, and polling places), using the island of Manhattan as an example of one such sensitive place that would be considered unconstitutional.[82]

Advocacy groups, PACs, and lobbying

[edit]One way advocacy groups influence politics is through "outside spending," using political action committees (PACs) and 501(c)(4) organizations.[83] PACs and 501(c)(4)s raise and spend money to affect elections.[84][85] PACs pool campaign contributions from members and donate those funds to candidates for political office.[86] Super PACs, created in 2010, are prohibited from making direct contributions to candidates or parties, but influence races by running ads for or against specific candidates.[87] Both gun control and gun rights advocates use these types of organizations.

The NRA's Political Victory Fund super PAC spent $11.2 million in the 2012 election cycle,[88] and as of April 2014, it had raised $13.7 million for 2014 elections.[89] Michael Bloomberg's gun-control super PAC, Independence USA, spent $8.3 million in 2012[90][91] and $6.3 million in 2013.[92] Americans for Responsible Solutions, another gun-control super PAC started by retired Congresswoman Gabby Giffords, raised $12 million in 2013,[93] and planned to raise $16 to $20 million by the 2014 elections.[94] The group's treasurer said that the funds would be enough to compete with the NRA "on an even-keel basis."[94]

Another way advocacy groups influence politics is through lobbying; some groups use lobbying firms, while others employ in-house lobbyists. According to OpenSecrets, gun politics groups with the most lobbyists in 2013 were: the NRA's Institute for Legislative Action (NRA-ILA); Mayors Against Illegal Guns (MAIG); the National Shooting Sports Foundation (NSSF); and the Brady Campaign.[95] Gun rights groups spent over $15.1 million lobbying in Washington D.C. in 2013, with the National Association for Gun Rights (NAGR) spending $6.7 million, and the NRA spending $3.4 million.[96] Gun control groups spent $2.2 million, with MAIG spending $1.7 million, and the Brady Campaign spending $250,000 in the same period.[97]

3D printed firearms

[edit]In August 2012, an open source group called Defense Distributed launched a project to design and release a blueprint for a handgun that could be downloaded from the Internet and manufactured using a 3D printer.[98][99] In May 2013, the group made public the STL files for the world's first fully 3D printable gun, the Liberator .380 single shot pistol.[100][101][102] Since 2018, 3D printed gun files have exponentially multiplied and been freely published on the Internet for anyone in the world to access, on websites like DEFCAD and Odysee.[103]

Proposals made by the Obama administration

[edit]On January 16, 2013, in response to the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting and other mass shootings, President Barack Obama announced a plan for reducing gun violence in four parts: closing background check loopholes; banning so-called "assault weapons" and "large capacity magazines"; making schools safer; and increasing access to mental health services.[104][105]: 2 The plan included proposals for new laws to be passed by Congress, and a series of executive actions not requiring Congressional approval.[104][106][107] No new federal gun control legislation was passed as a result of these proposals.[108] President Obama later stated in a 2015 interview with the BBC that gun control:

has been the one area where I feel that I've been most frustrated and most stymied, it is the fact that the United States of America is the one advanced nation on earth in which we do not have sufficient common-sense, gun-safety laws. Even in the face of repeated mass killings. And you know, if you look at the number of Americans killed since 9/11 by terrorism, it's less than 100. If you look at the number that have been killed by gun violence, it's in the tens of thousands. And for us not to be able to resolve that issue has been something that is distressing. But it is not something that I intend to stop working on in the remaining 18 months.[109]

2013 United Nations Arms Treaty

[edit]The Arms Trade Treaty (ATT) is a multilateral treaty that regulates the international trade in conventional weapons, which entered into force on December 24, 2014.[110] Work on the treaty commenced in 2006 with negotiations for its content conducted at a global conference under the auspices of the United Nations from July 2–27, 2012, in New York.[111] As it was not possible to reach an agreement on a final text at that time, a new meeting for the conference was scheduled for March 18–28, 2013.[112] On April 2, 2013, the UN General Assembly adopted the ATT.[113][114] The treaty was opened for signing on June 3, 2013, and by August 15, 2015, it had been signed by 130 states and ratified or acceded to by 72. It entered into force on December 24, 2014, after it was ratified and acceded to by 50 states.[115]

On September 25, 2013, Secretary of State John Kerry signed the ATT on behalf of the Obama administration. This was a reversal of the position of the Bush administration which had chosen not to participate in the treaty negotiations. Then in October a bipartisan group of 50 senators and 181 representatives released concurrent letters to President Barack Obama pledging their opposition to ratification of the ATT. The group was led by Senator Jerry Moran (R-Kansas) and Representatives Mike Kelly (R-Pennsylvania) and Collin Peterson (D-Minnesota). Following these two letters, four Democratic senators sent a separate letter to the President stating that "because of unaddressed concerns that this Treaty's obligations could undermine our nation's sovereignty and the Second Amendment rights of law-abiding Americans [they] would oppose the Treaty if it were to come before the U.S. Senate." The four Senators are Jon Tester (D-Montana), Max Baucus (D-Montana), Heidi Heitkamp (D-North Dakota), and Joe Donnelly (D-Indiana).[116][117]

Supporters of the treaty claim that the treaty is needed to help protect millions around the globe in danger of human rights abuses. Frank Jannuzi of Amnesty International USA states, "This treaty says that nations must not export arms and ammunition where there is an 'overriding risk' that they will be used to commit serious human rights violations. It will help keep arms out of the hands of the wrong people: those responsible for upwards of 1,500 deaths worldwide every day."[118] Secretary Kerry was quoted as saying that his signature would "help deter the transfer of conventional weapons used to carry out the world's worst crimes."[119] As of December 2013, the U.S. has not ratified or acceded to the treaty.

Proposals made by the Trump administration

[edit]Following the Las Vegas shooting in October 2017 and the Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in February 2018, President Donald Trump and the Department of Justice (DOJ) sought ways to ban bump stocks, devices that can be used to make semi-automatic weapons fire as fully automatic ones as used in both shootings. Initially, the DOJ believed it had to wait for Congress to pass the appropriate legislation to ban the sale and possession of bump stocks.[120] However, by March 2018, the DOJ introduced proposed revised regulations on gun control that incorporated bump stocks under the definition of machine guns, which would make them banned devices, as Congress had not yet taken any action.[121] After a period of public review, the DOJ implemented the proposed ban starting on December 18, 2018, giving owners of bump stocks the option to either destroy them or turn them into authorities within 90 days, after which the ban would be in full effect (on March 26, 2019).[122] Pro-gun groups immediately sought to challenge the order, but could not get the Supreme Court to put the ban on hold while the litigation was ongoing.[123] In the following week, the Supreme Court refused to exempt the litigants in the legal challenge from the DOJ's order after this was raised as a separate challenge.[124]

Proposals made by the Biden administration

[edit]Since his election, President Joe Biden urged Congress to pass a ban on assault rifles and other measures.

In April 2022, the President announced plans to crack down on privately made firearms, saying that they have become "weapons of choice for many criminals."[125] From 2016 to 2021, the number of suspected privately made firearms recovered in criminal investigations increased tenfold, with about 20,000 suspected privately made firearms reported to ATF in 2021.[126] The 2022 Justice Department decision restricted the sale of weapons parts kits (determining the kits, which can be assembled into firearms in a little as 20 minutes, to qualify as "firearms" within the definition of the federal Gun Control Act, thus requiring serial numbers and licensure of manufacturers and commercial sellers).[126] U.S. district judge in Texas, Reed O'Connor, blocked the rule, finding that it exceeded the department's authority and issuing a nationwide injunction.[126] The U.S. has appealed to the Fifth Circuit.[126]

On June 25, 2022, President Biden signed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act into law, which included strengthened background checks for firearm purchasers under the age of 21, $15 billion in funding for mental health programs and school security upgrades, federal funding to encourage states to implement red flag laws, and gun ownership bans for individuals convicted of domestic abuse charges.[127][128]

Public opinion

[edit]

Polls

[edit]Huffington Post reported in September 2013 that 48% of Americans said gun laws should be made more strict, while 16% said they should be made less strict and 29% said there should be no change.[129] Similarly, a Gallup poll found that support for stricter gun laws has fallen from 58% after the Newtown shooting, to 49% in September 2013.[129] Both the Huffington Post poll and the Gallup poll were conducted after the Washington Navy Yard shooting.[129] Meanwhile, the Huffington Post poll found that 40% of Americans believe stricter gun laws would prevent future mass shootings, while 52% said changing things would not make a difference.[129] The same poll also found that 57% of Americans think better mental health care is more likely to prevent future mass shootings than stricter gun laws, while 29% said the opposite.[129] 74% of those who incorrectly believed that the USA has universal background checks supported stricter gun laws, but 89% of those who thought that such checks were not universally required supported stricter laws.[130]

In a 2015 study conducted by the Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, state gun laws were examined based on various policy approaches, and were scored on grade-based and ranked scales.[131] States were rated positively for having passed stricter measures and stronger gun laws. Positive points were also given for states that required background checks on all sales of firearms and that limited bulk firearms purchases, and that prohibited sales of assault weapons and large-capacity magazines, and that carried out stricter evaluations of applications for handgun concealed-carry licenses, especially in the context of prohibited domestic-violence offenders. Meanwhile, points were deducted from states with laws that expanded access to guns, or that allowed concealed carry in public areas (particularly schools and bars) without a permit, or that passed "Stand Your Ground Laws" – which remove the duty to retreat and instead allow people to shoot potential assailants. Eventually, states were graded indicating the overall strengths or weakness of their gun laws. The ten states with the strongest gun laws ranked from strongest starting with California, then New Jersey, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Hawaii, New York, Maryland, Illinois, Rhode Island and finally Michigan. The states with weakest gun laws were ranked as follows: South Dakota, Arizona, Mississippi, Vermont, Louisiana, Montana, Wyoming, Kentucky, Kansas, and Oklahoma. A comparable study of state laws was also conducted in 2016.[132] Based on these findings, The Law Center concluded that comprehensive gun laws reduce gun violence deaths, whereas weaker guns laws increase gun-related deaths. Furthermore, among different kinds of legislation, universal background checks were the most effective at reducing gun-related deaths.[133]

Gallup poll

[edit]The Gallup organization regularly polls Americans on their views on guns. On December 22, 2012:[134]

- 44% supported a ban on "semi-automatic guns known as assault weapons."

- 92% supported background checks on all gun-show gun sales.

- 62% supported a ban on "high-capacity ammunition magazines that can contain more than 10 rounds."

On April 25, 2013:[136]

- 56% supported reinstating and strengthening the assault weapons ban of 1994.

- 83% supported requiring background checks for all gun purchases.

- 51% supported limiting the sale of ammunition magazines to those with 10 rounds or less.

On October 6, 2013:[137]

- 49% felt that gun laws should be more strict.

- 74% opposed civilian handgun bans.

- 37% said they had a gun in their home.

- 27% said they personally owned a gun.

- 60% of gun owners have guns for personal safety/protection, 36% for hunting, 13% for recreation/sport, 8% for target shooting, 5% as a Second Amendment right.

In January 2014:[138]

- 40% are satisfied with the current state of gun laws, 55% are dissatisfied

- 31% want stricter control, 16% want less strict laws

On October 19, 2015:[139]

- 55% said the law on sales of firearms should be more strict, 33% kept as they are, 11% less strict

- this was sharply polarised by party, with 77% of Democratic Party supporters wanting stricter laws, against 27% of Republican Party supporters

- 72% continued to oppose civilian handgun bans.

On October 16, 2017:[140]

- 58% of Americans believing that new gun laws would have little or no effect on mass shootings.

- 60% said the law on sales of firearms should be more strict.

- 48% "would support a law making it illegal to manufacture, sell or possess" semi-automatic firearms

- The following day, a survey was published stating:[141]

- 96% supported "requiring background checks for all gun purchases"

- this includes 95% of gun owners and 96% of non-gun owners

- 75% supported "enacting a 30-day waiting period for all gun sales"

- this includes 57% of gun owners and 84% of non-gun owners

- 70% supported "requiring all privately owned guns to be registered with the police"

- this includes 48% of gun owners and 82% of non-gun owners

- 96% supported "requiring background checks for all gun purchases"

According to a 2023 Fox News poll found registered voters overwhelmingly supported a wide variety of gun restrictions:

- 87% said they support requiring criminal background checks for all gun buyers;

- 81% support raising the age requirement to buy guns to 21;

- 80% support requiring mental health checks for all gun purchasers;

- 80% said police should be allowed take guns away from people considered a danger to themselves or others;

- 61% supported banning assault rifles and semi-automatic weapons.[142][143]

National Rifle Association

[edit]A member poll conducted for the NRA between January 13 and 14, 2013 found:[144]

- 90.7% of members favor "Reforming our mental health laws to help keep firearms out of the hands of people with mental illness." (A majority of 86.4% believe that strengthening laws this way would be more effective at preventing mass murders than banning semi-automatic rifles.)

- 92.2% of NRA members oppose gun confiscation via mandatory buy-back laws.

- 88.5% oppose banning semi-automatic firearms, firearms that chamber a new round automatically when discharged.

- 92.6% oppose a law requiring gun owners to register with the federal government.

- 92.0% oppose a federal law banning the sale of firearms between private citizens.

- 82.3% of members are in favor of a program that would place armed security professionals in every school.

- 72.5% agreed that President Obama's ultimate goal is the confiscation of many firearms that are currently legal.

Place of living of respondents:

- 35.4% A rural area

- 26.4% A small town

- 22.9% A suburban area

- 14.7% An urban area or city

Regional Break:

- 36.1% South

- 24.1% Mid-West

- 21.5% West

- 18.3% North-East / Mid-Atlantic

Media depictions and public opinion

[edit]A study conducted by Berryessa et al. in 2020 with 3410 qualifying respondents investigated how characteristics of victims and types of incidents described in a media report would affect respondents' support towards gun regulations. They found that mentions of victim race, particularly those of Black victims, was a strong predictor of lowered support for all categories of firearm regulation. Furthermore, regulations designed to address gun deaths from suicide and accidents were less likely to garner support compared to those addressing mass shootings or street-level gun homicide. Descriptions of age, mental illness, prior incarceration, and victim gender were less salient predictors of public support than those of race or incident type.[145]

Political arguments

[edit]Rights-based arguments

[edit]Rights-based arguments involve the most fundamental question about gun control: to what degree the government has the authority to regulate guns.

Proponents of gun rights include but are not limited to the following:[146]

- National Rifle Association

- Second Amendment Foundation

- Gun Owners of America

- American Rifle & Pistol Association

- National Association for Gun Rights

- Firearms Policy Coalition (FPC)

- Pink Pistols

- The Well-Armed Woman

- Evolve USA

- Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership

- National African American Gun Association

- California Rifle & Pistol Association

- Socialist Rifle Association[147]

- Redneck Revolt[148]

Fundamental right

[edit]

The primary author of the United States Bill of Rights, James Madison, considered the rights contained within– including a right to keep and bear arms – to be fundamental. In 1788, he wrote: "The political truths declared in that solemn manner acquire by degrees the character of fundamental maxims of free Government, and as they become incorporated with the national sentiment, counteract the impulses of interest and passion."[149][150]

The view that gun ownership is a fundamental right was affirmed by the U.S. Supreme Court in District of Columbia v. Heller (2008). The Court stated: "By the time of the founding, the right to have arms had become fundamental for English subjects."[151] The Court observed that the English Bill of Rights of 1689 had listed a right to arms as one of the fundamental rights of Englishmen.

When the Court interpreted the Fourteenth Amendment in McDonald v. City of Chicago (2010), it looked to the year 1868, when the amendment was ratified and said that most states had provisions in their constitutions explicitly protecting this right. The Court concluded: "It is clear that the Framers and ratifiers of the Fourteenth Amendment counted the right to keep and bear arms among those fundamental rights necessary to our system of ordered liberty."[152][153]

Second Amendment rights

[edit]

The Second Amendment to the United States Constitution, adopted on December 15, 1791, states:

A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free state, the right of the people to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.[155]

Prior to District of Columbia v. Heller, in the absence of a clear court ruling, there was a debate about whether or not the Second Amendment included an individual right.[156] In Heller, the Court concluded that there is indeed such a right, but not an unlimited one.[156] Although the decision was not unanimous, all justices endorsed an individual right viewpoint but differed on the scope of that right.[78][79]

Before Heller gun rights advocates argued that the Second Amendment protects an individual right to own guns. They stated that the phrase "the people" in that amendment applies to individuals rather than an organized collective and that the phrase "the people" means the same thing in the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 9th, and 10th Amendments.[157]: 55–87 [158][159] They also said the Second's placement in the Bill of Rights defines it as an individual right.[160][161] As part of the Heller decision, the majority endorsed the view that the Second Amendment protects an individual, though not unlimited, right to own guns. Political scientist Robert Spitzer and Supreme Court law clerk Gregory P. Magarian argued that this final decision by the Supreme Court was a misinterpretation of the U.S. Constitution.[162][163][164]

After the Heller decision there was an increased amount of attention on whether or not the Second Amendment applies to the states. In 2010 in the case of McDonald v. City Chicago, the Supreme Court ruled that the Second Amendment's provisions do apply to the states as a result of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Defense of self and state

[edit]

The eighteenth-century English jurist William Blackstone (b. 1723), whose writings influenced the drafters of the U.S. Constitution,[165] called self-defense "the primary law of nature" which (he said) man-made law cannot take away.[166] Following Blackstone, the American jurist St. George Tucker (b. 1752) wrote that "the right of self-defense is the first law of nature; in most governments, it has been the study of rulers to confine this right within the narrowest limits possible."[167]

In both Heller (2008) and McDonald (2010) the Supreme Court deemed that the right of self-defense is at least partly protected by the United States Constitution. The court left details of that protection to be worked out in future court cases.[168]

The two primary interest groups regarding this issue are the Brady Campaign and the National Rifle Association.[169] They have clashed, for example, regarding stand-your-ground laws which give individuals a legal right to use guns for defending themselves without any duty to retreat from a dangerous situation.[170] After the Supreme Court's 2008 decision in Heller, the Brady Campaign indicated that it would seek gun laws "without infringing on the right of law-abiding persons to possess guns for self-defense."[171]

Protection of marginalized people

[edit]Left-wing and far-left advocates for gun rights argue that gun ownership is necessary for protecting marginalized communities, such as African Americans and the working class, from state repression.[172][173] Far-left advocates argue that gun control laws mostly benefit white people and harm people of color.[173]

Security against tyranny

[edit]Another fundamental political argument associated with the right to keep and bear arms is that banning or even regulating gun ownership makes government tyranny more likely.[174] A January 2013 Rasmussen Reports poll indicated that 65 percent of Americans believe the purpose of the Second Amendment is to "ensure that people are able to protect themselves from tyranny."[175] A Gallup poll in October 2013 showed that 60 percent of American gun owners mention "personal safety/protection" as a reason for owning them, and 5 percent mention a "Second Amendment right," among other reasons.[176] Another poll, published by the Pew Research Center in August 2023, confirms these results: 72% of polled gun owners state that self-protection is a major reason for their gun ownership.[177] The anti-tyranny argument extends back to the days of colonial America and earlier in Great Britain.[178]

Various gun rights advocates and organizations, such as former governor Mike Huckabee,[179] former Congressman Ron Paul,[180] and Gun Owners of America,[14] say that an armed citizenry is the population's last line of defense against tyranny by their own government. This belief was also familiar at the time the Constitution was written.[181][182] The Declaration of Independence mentions "the Right of the People to alter or to abolish" the government, and Abraham Lincoln's first inaugural address reiterated the "revolutionary right" of the people.[183] A right of revolution was not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution; instead, the Constitution was designed to ensure a government deriving its power from the consent of the governed.[184] Historian Don Higginbotham wrote that the well-regulated militia protected by the Second Amendment was more likely to put down rebellions than participate in them.[185]

Gun rights advocates such as Stephen Halbrook and Wayne LaPierre support the "Nazi gun control" theory. The theory states that gun regulations enforced by the Third Reich rendered victims of the Holocaust weak, and that more effective resistance to oppression would have been possible if they had been better armed.[186]: 484 [187]: 87–8, 167–168 Other gun laws of authoritarian regimes have also been brought up such as gun control in the Soviet Union and in China. This counterfactual history theory is not supported by mainstream scholarship,[188]: 412, 414 [189]: 671, 677 [190]: 728 though it is an element of a "security against tyranny" argument in U.S. politics.[191]

American gun rights activist Larry Pratt says that the anti-tyranny argument for gun rights is supported by successful efforts in Guatemala and the Philippines to arm ordinary citizens against communist insurgency in the 1980s.[192][193] Gun-rights advocacy groups argue that the only way to enforce democracy is through having the means of resistance.[157]: 55–87 [158][159] Militia-movement groups cite the Battle of Athens (Tennessee, 1946) as an example of citizens who "[used] armed force to support the Rule of Law" in what they said was a rigged county election.[194] Then-senator John F. Kennedy wrote in 1960 that, "it is extremely unlikely that the fears of governmental tyranny which gave rise to the Second Amendment will ever be a major danger to our nation...."[195]

In 1957, the legal scholar Roscoe Pound expressed a different view:[196][197] He stated, "A legal right of the citizen to wage war on the government is something that cannot be admitted. ... In the urban industrial society of today, a general right to bear efficient arms so as to be enabled to resist oppression by the government would mean that gangs could exercise an extra-legal rule which would defeat the whole Bill of Rights."

Public policy arguments

[edit]

Public policy arguments are based on the idea that the central purpose of government is to establish and maintain order. This is done through public policy, which Blackstone defined as "the due regulation and domestic order of the kingdom, whereby the inhabitants of the State, like members of a well-governed family, are bound to conform their general behavior to the rules of propriety, good neighborhood, and good manners, and to be decent, industrious, and inoffensive in their respective stations."[11]: 2–3

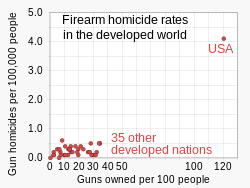

Gun violence debate

[edit]The public policy debates about gun violence include discussions about firearms deaths – including homicide, suicide, and unintentional deaths – as well as the impact of gun ownership, criminal and legal, on gun violence outcomes. After the Sandy Hook shooting, the majority of people, including gun owners and non-gun owners, wanted the government to spend more money in order to improve mental health screening and treatment, to deter gun violence in America. In the United States in 2009 there were 3.0 recorded intentional homicides committed with a firearm per 100,000 inhabitants. The U.S. ranks 28 in the world for gun homicides per capita.[199] A U.S. male aged 15–24 is 70 times more likely to be killed with a gun than their counterpart in the eight (G-8) largest industrialized nations in the world (United Kingdom, France, Germany, Japan, Canada, Italy, Russia).[200] In 2013, there were 33,636 gun-related deaths, in the United States. Meanwhile, in the same year of Japan, there were only 13 deaths that were involved with guns. In incidents concerning gun homicide or accidents, a person in America is about 300 times more likely to die than a Japanese person.[201] In 2015, there were 36,252 deaths due to firearms, and some claim as many as 372 mass shootings, in the U.S., while guns were used to kill about 50 people in the U.K.[200] More people are typically killed with guns in the U.S. in a day (about 85) than in the U.K. in a year.[200][better source needed][circular reporting?]

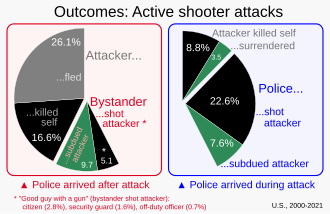

Within the gun politics debate, gun control and gun rights advocates disagree over the role that guns play in crime. Gun control advocates concerned about high levels of gun violence in the United States look to restrictions on gun ownership as a way to stem the violence and say that increased gun ownership leads to higher levels of crime, suicide and other negative outcomes.[202][203] Gun rights groups say that a well-armed civilian populace prevents crime and that making civilian ownership of firearms illegal would increase the crime rate by making civilians vulnerable to criminal activity.[204][205] They say that more civilians defend themselves with a gun every year than the law enforcement arrest for violent crimes and burglary[206] and that civilians legally shoot almost as many criminals as law enforcement officers do.[207]

Studies using FBI data and Police Reports of the incidents, have found that there are approximately 1,500 verified instances of firearms used in self-defense annually in the United States.[208] Survey-based research derived from data gathered by the National Crime Victimization Survey has generated estimates that, out of roughly 5.5 million violent crime victims in the U.S. annually approximately 1.1 percent, or 55,000 used a firearm in self-defense (175,000 for the 3-year period.)[209] When including property crimes, of the 15.5 million victims of property crimes annually found in the survey (46.5 million for 2013–2015), the NCV survey data yielded estimates that around 0.2 percent of property crime victims, or 36,000 annually (109,000 for the 3-year period) used a firearm in self-defense from the loss of property.[209] Researchers working from the most recent NCVS data sets have found approximately 95,000 uses of a firearm in self-defense in the U.S. each year (284,000 for the years 2013–2015).[209] In addition, the United States has a higher rate of firearm ownership than any other nation. The United States' gun homicide rate, while high compared to other developed nations, has been declining since the 1990s.[210]

Gun Control has limited the availability of firearms to many individuals. Some of the limitations include any persons who have been dishonorably discharged from the military, any person that has renounced their United States citizenship, has been declared mentally ill or committed to a mental institution, is a fugitive, is a user or addicted to a controlled substance, and anyone illegally in the country.[211] Still, in 2016, according to the Center for Disease Control, there were 19,362 homicides in the United States. Firearms were used in 14,415 or a little over 74% of all homicides. There were also 22,938 suicides that were performed with the assistance of a firearm.[212] In total, in 2016, firearms were involved in the deaths of 38,658 Americans. According to Rifat Darina Kamal and Charles Burton, in 2016, study data, presented by Priedt (2016), showed that just the homicide rate, by itself, was 18 times greater than the rates of Australia, Sweden, and France.[213] Due to the increase in mass shootings, in the United States, new laws are being passed. Recently, Colorado became the fifteenth state to pass the "Red Flag" bill which gives judges the authority to remove firearms from those believed to be a high risk of harming others or themselves.[214] This "Red Flag" law has now been proposed in twenty-three states.[215]

Criminal violence

[edit]There is an open debate regarding a causal connection (or the lack of one) between gun control and its effect on gun violence and other crimes. The numbers of lives saved or lost by gun ownership are debated by criminologists. Research difficulties include the difficulty of accounting accurately for confrontations in which no shots are fired and jurisdictional differences in the definition of "crime."

Such research is also subject to a more fundamental difficulty affecting all research in this field: the effectiveness of the Criminal Law in preventing crime in general or in specific cases is inherently and notoriously difficult to prove and measure, and thus issues in establishing a causal link between gun control or particular gun control policies and violent crime must be understood to be an aspect of a more general empirical difficulty, which pervades the fields of Criminology and Law at large. It is not simple, for example, to prove a causal connection between the laws against murder and the prevailing murder rates, either. Consequently, this general background must be appreciated when discussing the causal and empirical issues here.

A study published in The American Journal of Economics and Sociology in 1997 concluded that the amount of gun-related crime and deaths is affected more by the state of the area in terms of unemployment, alcohol problems and drug problems instead of the laws and regulations.[216] This study analyzed statistics gathered on the amount of gun crime in states with strict and lenient gun policies and determined that the amount of gun crime is related to how impoverished an area is.

A 2003 CDC study determined "The Task Force found insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of any of the firearms laws or combinations of laws reviewed on violent outcomes."[65] They go on to state "a finding of insufficient evidence to determine effectiveness should not be interpreted as evidence of ineffectiveness but rather as an indicator that additional research is needed before an intervention can be evaluated for its effectiveness."

Homicide

[edit]

With 5% of the world's population, U.S. residents own roughly 50% of the world's civilian-owned firearms. In addition, up to 48% of households within America have guns.[220] According to the UNODC, 60% of U.S. homicides in 2009 were perpetrated using a firearm.[221] U.S. homicide rates vary widely from state to state. In 2014, the lowest homicide rates were in New Hampshire, North Dakota, and Vermont (each 0.0 per 100,000 people), and the highest were in Louisiana (11.7) and Mississippi (11.4).[222]

Gary Kleck, a criminologist at Florida State University, and his colleague Marc Gertz, published a study in 1995 estimating that approximately 2.5 million American adults used their gun in self-defense annually. The incidents that Kleck extrapolated based on his questionnaire results generally did not involve the firing of the gun, and he estimates that as many as 1.9 million of those instances involved a handgun.[223]: 164 These studies have been subject to criticism on a number of methodological and logical grounds [224] and Kleck has responded with a rebuttal.[225][226]

Another study from the same period, the National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS), estimated 65,000 DGUs (Defensive gun use) annually. The NCVS survey differed from Kleck's study in that it only interviewed those who reported a threatened, attempted, or completed victimization for one of six crimes: rape, robbery, assault, burglary, non-business larceny, and motor vehicle theft. The NCVS, however, does not actually directly ask about defensive gun use, so estimates of this set of events are not very meaningful. A National Research Council report said that Kleck's estimates appeared to be exaggerated and that it was almost certain that "some of what respondents designate[d] as their own self-defense would be construed as aggression by others".[227]

In a review of research of the effects of gun rates on crime rates, Kleck determined that of studies addressing homicide rate, half of them found a connection between gun ownership and homicide, but these were usually the least rigorous studies. Only six studies controlled at least six statistically significant confound variables, and none of them showed a significant positive effect. Eleven macro-level studies showed that crime rates increase gun levels (not vice versa). The reason that there is no opposite effect may be that most owners are noncriminals and that they may use guns to prevent violence.[228]

Commenting on the external validity of Kleck's report, David Hemenway, director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center, said: "Given the number of victims allegedly being saved with guns, it would seem natural to conclude that owning a gun substantially reduces your chances of being murdered. Yet a careful case-control study of homicide in the home found that a gun in the home was associated with an increased rather than a reduced risk of homicide. Virtually all of this risk involved homicide by a family member or intimate acquaintance."[229]: 1443 Kleck however pointed out that most of the firearms used in the Kellermann study were not the same ones kept in the household by the victim.[230] Similarly in 2007 when the Permit-To-Purchase law was repealed in Missouri, 2008 saw a 34% increase in the rate of firearm homicides in that year alone, and the figure continues to be higher than the figure pre-2007.[231]

One study found that homicide rates as a whole, especially those as a result of firearms use, are not always significantly lower in many other developed countries. Kleck wrote, "...cross-national comparisons do not provide a sound basis for assessing the impact of gun ownership levels on crime rates."[232] One study published in the International Journal of Epidemiology found that for the year of 1998: "During the one-year study period (1998), 88,649 firearm deaths were reported. Overall firearm mortality rates are five to six times higher in high-income (HI) and upper-middle-income (UMI) countries in the Americas (12.72) than in Europe (2.17) or Oceania (2.57) and 95 times higher than in Asia (0.13). The rate of firearm deaths in the United States (14.24 per 100,000) exceeds that of its economic counterparts (1.76) eightfold and that of UMI countries (9.69) by a factor of 1.5. Suicide and homicide contribute equally to total firearm deaths in the U.S., but most firearm deaths are suicides (71%) in HI countries and homicides (72%) in UMI countries."[233]

Suicide

[edit]Firearms accounted for 51.5% of U.S. suicides in 2013, and suicides account for 63% of all firearm-related deaths.[236] A 2012 review by researchers at the Harvard School of Public Health found that in the United States, the percent of suicide attempts that prove fatal is "strongly related to the availability of household firearms."[237] Prior to this, one book written by criminologist Gary Kleck in the 1990s stated that they found no relationship between gun availability and suicide rates.[238]

Public health crisis

[edit]Though the CDC does not prescribe firearm legislation measures, due to limited policy-related research findings, a CDC Vital Signs report identifies firearm-related death as "a significant and growing public health problem in the United States."[239] The same report states that firearm related violence in the U.S. is linked to widening racial and ethnic inequalities.[239]

A 2022 correspondence between researchers at the University of Michigan and the New England Journal of Medicine states that "generational investments are being made in the prevention of firearm violence, including new funding opportunities from the CDC and the National Institutes of Health."[240] The correspondence refers to "funding for the prevention of community violence (that) has been proposed in federal infrastructure legislation."[240] The researchers emphasize the significance of such policy measures as a preventative public health solution, in light of data indicating rising child mortality as a result of firearm related incidents, citing statistical evidence of firearm-related deaths replacing motor vehicle accidents as the leading cause of child mortality in 2020.[240]

In 2009, the Public Health Law Research program,[241] an independent organization, published several evidence briefs summarizing the research assessing the effect of a specific law or policy on public health, that concern the effectiveness of various laws related to gun safety. Among their findings:

- There is not enough evidence to establish the effectiveness of "shall issue" laws, as distinct from "may issue" laws, as a public health intervention to reduce violent crime.[242]

- There is insufficient evidence to determine the effectiveness of waiting period laws as public health interventions aimed at preventing gun-related violence and suicide.[243]

- Although child access prevention laws may represent a promising intervention for reducing gun-related morbidity and mortality among children, there is currently insufficient evidence to validate their effectiveness as a public health intervention aimed at reducing gun-related harms.[244]

- There is insufficient evidence to establish the effectiveness of such bans as public health interventions aimed at reducing gun-related harms.[245]

- There is insufficient evidence to validate the effectiveness of firearm licensing and registration requirements as legal interventions aimed to reduce firearm related harms.[246]

Federal and state laws

[edit]The number of federal and state gun laws is unknown. A 2005 American Journal of Preventive Medicine study says 300,[247] and the NRA says 20,000, though the Washington Post fact checker says of that decades-old figure: "This 20,000 figure appears to be an ancient guesstimate that has hardened over the decades into a constantly repeated, never-questioned talking point. It could be lower, or higher, depending on who's counting what."[248]

Federal laws

[edit]Federal gun laws are enforced by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF). Most federal gun laws were enacted through:[249][250]

- National Firearms Act (1934)

- Omnibus Crime Control and Safe Streets Act of 1968 (1968)

- Gun Control Act of 1968 (1968)

- Firearm Owners Protection Act (1986)

- Undetectable Firearms Act (1988)

- Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990 (1990) (ruled unconstitutional as originally written; upheld after minor edits were made by Congress)

- Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act (1993)

- Federal Assault Weapons Ban (1994) (expired 2004)

State laws and constitutions

[edit]

In addition to federal gun laws, all U.S. states and some local jurisdictions have imposed their own firearms restrictions. Each of the fifty states has its own laws regarding guns.

Provisions in State constitutions vary.[251] For example, Hawaii's constitution simply copies the text of the Second Amendment verbatim,[252] while North Carolina and South Carolina begin with the same but continue with an injunction against maintaining standing armies.[253][254] Alaska also begins with the full text of the Second Amendment, but adds that the right "shall not be denied or infringed by the State or a political subdivision of the State".[255] Rhode Island subtracts the first half of the Second Amendment, leaving only, "[t]he right of the people to keep and bear arms shall not be infringed".[256]

The majority of the remaining states' constitutions differ from the text of the U.S. Constitution primarily in their clarification of exactly to whom the right belongs or by the inclusion of additional, specific protections or restrictions. Seventeen states refer to the right to keep and bear arms as being an individual right, with Utah and Alaska referring to it explicitly as "[t]he individual right to keep and bear arms",[255][257] while the other fifteen refer to the right as belonging to "every citizen",[258] "all individuals",[259] "all persons",[260] or another, very similar phrase.[nb 1] In contrast are four states which make no mention whatever of an individual right or of defense of one's self as a valid basis for the right to arms. Arkansas, Massachusetts, and Tennessee all state that the right is "for the common defense",[273][274][275] while Virginia's constitution explicitly indicates that the right is derived from the need for a militia to defend the state.[276]

Most state constitutions enumerate one or more reasons for the keeping of arms. Twenty-four states include self-defense as a valid, protected use of arms;[nb 2] twenty-eight cite defense of the state as a proper purpose.[nb 3] Ten states extend the right to defense of home and/or property,[nb 4] five include the defense of family,[nb 5] and six add hunting and recreation.[nb 6] Idaho is uniquely specific in its provision that "[n]o law shall impose licensure, registration, or special taxation on the ownership or possession of firearms or ammunition. Nor shall any law permit the confiscation of firearms, except those actually used in the commission of a felony".[277] Fifteen state constitutions include specific restrictions on the right to keep and bear arms. Florida's constitution calls for a three-day waiting period for all modern cartridge handgun purchases, with exceptions for handgun purchases by those holding a CCW license, or for anyone who purchases a black-powder handgun.[278] Illinois prefaces the right by indicating that it is "[s]ubject ... to the police power".[268] Florida and the remaining thirteen states with specific restrictions all carry a provision to the effect that the state legislature may enact laws regulating the carrying, concealing, and/or wearing of arms.[nb 7] Forty states preempt some or all local gun laws, due in part to campaigning by the NRA for such legislation.[279]

See also

[edit]- 2018 United States gun violence protests

- Concealed carry in the United States

- Gun culture in the United States

- Gun ownership

- Gun show loophole

- High-capacity magazine ban

- One handgun a month law

Organizations

[edit]Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ↑ Согласно конституциям Алабамы право хранить и носить оружие принадлежит «каждому гражданину». [ 258 ] Коннектикут, [ 261 ] Мэн, [ 262 ] Миссисипи, [ 263 ] Миссури, [ 264 ] Невада, [ 265 ] и Техас; [ 266 ] «отдельному гражданину» от Аризоны, [ 267 ] Иллинойс, [ 268 ] и Вашингтон; [ 269 ] и уникальному, но очень похожему варианту Луизианы («каждый гражданин», [ 270 ] ) Мичиган («каждый человек», [ 271 ] ) Монтана («любой человек», [ 272 ] ) Нью-Гэмпшир («все люди», [ 260 ] ) и Северная Дакота («все люди». [ 259 ] )

- ^ Защита себя указана в качестве действительной цели хранения и ношения оружия конституциями штатов Алабама, Аризона, Колорадо, Коннектикут, Делавэр, Флорида, Индиана, Кентукки, Мичиган, Миссисипи, Миссури, Монтана, Нью-Йорк. Хэмпшир, Северная Дакота, Огайо, Орегон, Пенсильвания, Южная Дакота, Техас, Юта, Вермонт, Вашингтон, Запад Вирджиния и Вайоминг.

- ^ Защита штата или просто общая оборона указана как надлежащая цель хранения и ношения оружия в конституциях штатов Алабама, Арканзас, Аризона, Колорадо, Коннектикут, Делавэр, Флорида, Индиана, Кентукки, Массачусетс, Мичиган, Миссисипи, Миссури, Монтана, Нью-Гэмпшир, Северная Дакота, Оклахома, Орегон, Пенсильвания, Юг Дакота, Теннесси, Техас, Юта, Вермонт, Вирджиния, Вашингтон, Западная Вирджиния и Вайоминг.

- ^ Защита дома и/или собственности включена в качестве охраняемой цели хранения и ношения оружия конституциями штатов Колорадо, Делавэр, Миссисипи, Миссури, Монтана, Нью-Гэмпшир, Северная Дакота, Оклахома, Юта и Западная Вирджиния.

- ^ Защита своей семьи указана в качестве уважительной причины для хранения и ношения оружия конституциями штатов Делавэр, Нью-Гэмпшир, Северная Дакота, Юта (включая как семью, так и «других лиц»). [ 257 ] ) и Западная Вирджиния.

- ^ Охота и отдых включены в конституционное положение штата о праве на хранение и ношение оружия в штатах Делавэр, Невада, Нью-Мексико, Северная Дакота, Западная Вирджиния и Висконсин.

- ^ Объем конституционного права штата на хранение и ношение оружия ограничен штатами Колорадо, Айдахо, Кентукки, Луизиана, Миссисипи, Миссури, Монтана, Нью-Мексико и Северная Каролина, что позволяет регулировать или запрещать ношение оружия. скрытое оружие; конституции Флориды, Джорджии, Оклахомы, Теннесси и Техаса допускают правила ношения или ношения оружия в целом.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «На фоне серии массовых расстрелов в США политика в отношении оружия по-прежнему вызывает глубокие разногласия» . PewResearch.org . 20 апреля 2021 г. Архивировано из оригинала 30 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Ингрэм, Кристофер (24 ноября 2021 г.). «Анализ | Пришло время вернуть запрет на боевое оружие, говорят эксперты по вопросам насилия с применением огнестрельного оружия» . Вашингтон Пост . ISSN 0190-8286 . Проверено 7 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Уизерс, Рэйчел (16 февраля 2018 г.). «Джимми Киммел снова плакал, рассказывая о стрельбе в Паркленде, отчаянно призывая к «здравому смыслу» » . Сланец . ISSN 1091-2339 . Проверено 7 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Брюс, Джон М.; Уилкокс, Клайд (1998). "Введение" . В Брюсе, Джон М.; Уилкокс, Клайд (ред.). Меняющаяся политика контроля над огнестрельным оружием . Лэнхэм, Мэриленд: Роуман и Литтлфилд. ISBN 978-0847686155 . OCLC 833118449 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Спитцер, Роберт Дж. (1995). Политика контроля над оружием . Чатем Хаус. ISBN 978-1566430227 .

- ^ Хелмор, Эдвард (20 декабря 2021 г.). «Как показывает исследование, в период с 2020 по 2021 год в США ускорились закупки оружия» . Хранитель . ISSN 0261-3077 . Проверено 25 января 2024 г.

- ^ Инглиш, Уильям (18 мая 2022 г.). «Национальное исследование огнестрельного оружия 2021 года: обновленный анализ, включая типы имеющегося в собственности огнестрельного оружия» . дои : 10.2139/ssrn.4109494 . S2CID 249165467 . ССНР 4109494 .

- ^ Саллум, Джейкоб (9 сентября 2022 г.). «Крупнейшее в истории исследование владельцев оружия в США показало, что использование огнестрельного оружия в целях защиты является обычным явлением» . Причина.com . Проверено 25 января 2024 г.

- ^ «Крупнейший за всю историю опрос владельцев оружия выявил увеличение разнообразия, общее ношение оружия и более 1,6 миллиона защитных применений в год» . Перезагрузка . 8 сентября 2022 г. . Проверено 25 января 2024 г.

- ^ Лизотт, Мэри-Кейт (3 июля 2019 г.). «Авторитарная личность и гендерные различия в отношении к контролю над оружием». Журнал женщин, политики и политики . 40 (3): 385–408. дои : 10.1080/1554477X.2019.1586045 . S2CID 150628197 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж Спитцер, Роберт Дж. (2012). «Определение политики и контроль над оружием» . Политика контроля над оружием . Боулдер, Колорадо: Парадигма. ISBN 978-1594519871 . OCLC 714715262 .

- ^ Андерсон, Джервис (1984). Оружие в американской жизни . Случайный дом. ISBN 978-0394535982 .

ингредиент.

- ^ Леван, Кристина (2013). «Четыре оружия и преступность: содействие преступности и предупреждение преступности» . В Макки, Дэвид А.; Леван, Кристина (ред.). Предупреждение преступности . Джонс и Бартлетт. п. 438. ИСБН 978-1449615932 .