Бактерии

| Бактерии | |

|---|---|

| |

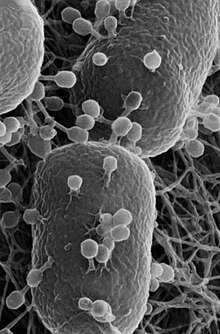

| Сканирующая электронная микрофотография Escherichia coli стержней | |

| Научная классификация | |

| Domain: | Bacteria Woese et al. 1990 |

| Phyla | |

|

See § Phyla | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Бактерии ( / b æ K T ɪəriəɪɪ ; подготовительный : Бактерия) вездесущи, в основном свободноживущие организмы, часто состоящие из одной биологической клетки . большую область прокариотических микроорганизмов . Они составляют Как правило, несколько микрометра в длину, бактерии были одними из первых форм жизни, которые появлялись на Земле , и присутствуют в большинстве его среда обитания . Бактерии населяют почву, воду, кислотные горячие источники , радиоактивные отходы и глубокую биосферу земной коры . Бактерии играют жизненно важную роль во многих стадиях цикла питательных веществ путем переработки питательных веществ и фиксации азота из атмосферы . Цикл питательных веществ включает в разложение трупов себя ; Бактерии несут ответственность за стадию гниения в этом процессе. В биологических сообществах, окружающих гидротермальные вентиляционные отверстия и холодные просачивания , экстремофильные бактерии обеспечивают питательные вещества, необходимые для поддержания жизни путем преобразования растворенных соединений, таких как сероводород и метатан , в энергию. Бактерии также живут в взаимных , комменсальных и паразитных отношениях с растениями и животными. Большинство бактерий не были охарактеризованы, и есть много видов, которые не могут быть выращивается в лаборатории. Изучение бактерий известно как бактериология , ветвь микробиологии .

Like all animals, humans carry vast numbers (approximately 1013 to 1014) of bacteria.[2] Most are in the gut, though there are many on the skin. Most of the bacteria in and on the body are harmless or rendered so by the protective effects of the immune system, and many are beneficial,[3] particularly the ones in the gut. However, several species of bacteria are pathogenic and cause infectious diseases, including cholera, syphilis, anthrax, leprosy, tuberculosis, tetanus and bubonic plague. The most common fatal bacterial diseases are respiratory infections. Antibiotics are used to treat bacterial infections and are also used in farming, making antibiotic resistance a growing problem. Bacteria are important in sewage treatment and the breakdown of oil spills, the production of cheese and yogurt through fermentation, the recovery of gold, palladium, copper and other metals in the mining sector (biomining, bioleaching), as well as in biotechnology, and the manufacture of antibiotics and other chemicals.

Once regarded as plants constituting the class Schizomycetes ("fission fungi"), bacteria are now classified as prokaryotes. Unlike cells of animals and other eukaryotes, bacterial cells do not contain a nucleus and rarely harbour membrane-bound organelles. Although the term bacteria traditionally included all prokaryotes, the scientific classification changed after the discovery in the 1990s that prokaryotes consist of two very different groups of organisms that evolved from an ancient common ancestor. These evolutionary domains are called Bacteria and Archaea.[4]

Etymology

The word bacteria is the plural of the Neo-Latin bacterium, which is the Latinisation of the Ancient Greek βακτήριον (baktḗrion),[5] the diminutive of βακτηρία (baktēría), meaning "staff, cane",[6] because the first ones to be discovered were rod-shaped.[7][8]

Origin and early evolution

The ancestors of bacteria were unicellular microorganisms that were the first forms of life to appear on Earth, about 4 billion years ago.[10] For about 3 billion years, most organisms were microscopic, and bacteria and archaea were the dominant forms of life.[11][12][13] Although bacterial fossils exist, such as stromatolites, their lack of distinctive morphology prevents them from being used to examine the history of bacterial evolution, or to date the time of origin of a particular bacterial species. However, gene sequences can be used to reconstruct the bacterial phylogeny, and these studies indicate that bacteria diverged first from the archaeal/eukaryotic lineage.[14] The most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of bacteria and archaea was probably a hyperthermophile that lived about 2.5 billion–3.2 billion years ago.[15][16][17] The earliest life on land may have been bacteria some 3.22 billion years ago.[18]

Bacteria were also involved in the second great evolutionary divergence, that of the archaea and eukaryotes.[19][20] Here, eukaryotes resulted from the entering of ancient bacteria into endosymbiotic associations with the ancestors of eukaryotic cells, which were themselves possibly related to the Archaea.[21][22] This involved the engulfment by proto-eukaryotic cells of alphaproteobacterial symbionts to form either mitochondria or hydrogenosomes, which are still found in all known Eukarya (sometimes in highly reduced form, e.g. in ancient "amitochondrial" protozoa). Later, some eukaryotes that already contained mitochondria also engulfed cyanobacteria-like organisms, leading to the formation of chloroplasts in algae and plants. This is known as primary endosymbiosis.[23]

Habitat

Bacteria are ubiquitous, living in every possible habitat on the planet including soil, underwater, deep in Earth's crust and even such extreme environments as acidic hot springs and radioactive waste.[24][25] There are thought to be approximately 2×1030 bacteria on Earth,[26] forming a biomass that is only exceeded by plants.[27] They are abundant in lakes and oceans, in arctic ice, and geothermal springs[28] where they provide the nutrients needed to sustain life by converting dissolved compounds, such as hydrogen sulphide and methane, to energy.[29] They live on and in plants and animals. Most do not cause diseases, are beneficial to their environments, and are essential for life.[3][30] The soil is a rich source of bacteria and a few grams contain around a thousand million of them. They are all essential to soil ecology, breaking down toxic waste and recycling nutrients. They are even found in the atmosphere and one cubic metre of air holds around one hundred million bacterial cells. The oceans and seas harbour around 3 x 1026 bacteria which provide up to 50% of the oxygen humans breathe.[31] Only around 2% of bacterial species have been fully studied.[32]

| Habitat | Species | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Cold (minus 15 °C Antarctica) | Cryptoendoliths | [33] |

| Hot (70–100 °C geysers) | Thermus aquaticus | [32] |

| Radiation, 5MRad | Deinococcus radiodurans | [33] |

| Saline, 47% salt (Dead Sea, Great Salt Lake) | several species | [32][33] |

| Acid pH 3 | several species | [24] |

| Alkaline pH 12.8 | betaproteobacteria | [33] |

| Space (6 years on a NASA satellite) | Bacillus subtilis | [33] |

| 3.2 km underground | several species | [33] |

| High pressure (Mariana Trench – 1200 atm) | Moritella, Shewanella and others | [33] |

Morphology

Size. Bacteria display a wide diversity of shapes and sizes. Bacterial cells are about one-tenth the size of eukaryotic cells and are typically 0.5–5.0 micrometres in length. However, a few species are visible to the unaided eye—for example, Thiomargarita namibiensis is up to half a millimetre long,[34] Epulopiscium fishelsoni reaches 0.7 mm,[35] and Thiomargarita magnifica can reach even 2 cm in length, which is 50 times larger than other known bacteria.[36][37] Among the smallest bacteria are members of the genus Mycoplasma, which measure only 0.3 micrometres, as small as the largest viruses.[38] Some bacteria may be even smaller, but these ultramicrobacteria are not well-studied.[39]

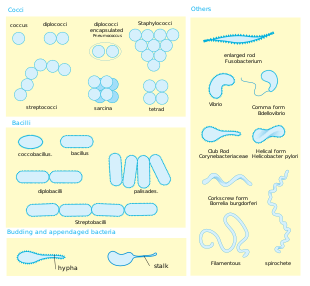

Shape. Most bacterial species are either spherical, called cocci (singular coccus, from Greek kókkos, grain, seed), or rod-shaped, called bacilli (sing. bacillus, from Latin baculus, stick).[40] Some bacteria, called vibrio, are shaped like slightly curved rods or comma-shaped; others can be spiral-shaped, called spirilla, or tightly coiled, called spirochaetes. A small number of other unusual shapes have been described, such as star-shaped bacteria.[41] This wide variety of shapes is determined by the bacterial cell wall and cytoskeleton and is important because it can influence the ability of bacteria to acquire nutrients, attach to surfaces, swim through liquids and escape predators.[42][43]

Multicellularity. Most bacterial species exist as single cells; others associate in characteristic patterns: Neisseria forms diploids (pairs), streptococci form chains, and staphylococci group together in "bunch of grapes" clusters. Bacteria can also group to form larger multicellular structures, such as the elongated filaments of Actinomycetota species, the aggregates of Myxobacteria species, and the complex hyphae of Streptomyces species.[45] These multicellular structures are often only seen in certain conditions. For example, when starved of amino acids, myxobacteria detect surrounding cells in a process known as quorum sensing, migrate towards each other, and aggregate to form fruiting bodies up to 500 micrometres long and containing approximately 100,000 bacterial cells.[46] In these fruiting bodies, the bacteria perform separate tasks; for example, about one in ten cells migrate to the top of a fruiting body and differentiate into a specialised dormant state called a myxospore, which is more resistant to drying and other adverse environmental conditions.[47]

Biofilms. Bacteria often attach to surfaces and form dense aggregations called biofilms[48] and larger formations known as microbial mats.[49] These biofilms and mats can range from a few micrometres in thickness to up to half a metre in depth, and may contain multiple species of bacteria, protists and archaea. Bacteria living in biofilms display a complex arrangement of cells and extracellular components, forming secondary structures, such as microcolonies, through which there are networks of channels to enable better diffusion of nutrients.[50][51] In natural environments, such as soil or the surfaces of plants, the majority of bacteria are bound to surfaces in biofilms.[52] Biofilms are also important in medicine, as these structures are often present during chronic bacterial infections or in infections of implanted medical devices, and bacteria protected within biofilms are much harder to kill than individual isolated bacteria.[53]

Cellular structure

Intracellular structures

The bacterial cell is surrounded by a cell membrane, which is made primarily of phospholipids. This membrane encloses the contents of the cell and acts as a barrier to hold nutrients, proteins and other essential components of the cytoplasm within the cell.[54] Unlike eukaryotic cells, bacteria usually lack large membrane-bound structures in their cytoplasm such as a nucleus, mitochondria, chloroplasts and the other organelles present in eukaryotic cells.[55] However, some bacteria have protein-bound organelles in the cytoplasm which compartmentalise aspects of bacterial metabolism,[56][57] such as the carboxysome.[58] Additionally, bacteria have a multi-component cytoskeleton to control the localisation of proteins and nucleic acids within the cell, and to manage the process of cell division.[59][60][61]

Many important biochemical reactions, such as energy generation, occur due to concentration gradients across membranes, creating a potential difference analogous to a battery. The general lack of internal membranes in bacteria means these reactions, such as electron transport, occur across the cell membrane between the cytoplasm and the outside of the cell or periplasm.[62] However, in many photosynthetic bacteria, the plasma membrane is highly folded and fills most of the cell with layers of light-gathering membrane.[63] These light-gathering complexes may even form lipid-enclosed structures called chlorosomes in green sulfur bacteria.[64]

Bacteria do not have a membrane-bound nucleus, and their genetic material is typically a single circular bacterial chromosome of DNA located in the cytoplasm in an irregularly shaped body called the nucleoid.[65] The nucleoid contains the chromosome with its associated proteins and RNA. Like all other organisms, bacteria contain ribosomes for the production of proteins, but the structure of the bacterial ribosome is different from that of eukaryotes and archaea.[66]

Some bacteria produce intracellular nutrient storage granules, such as glycogen,[67] polyphosphate,[68] sulfur[69] or polyhydroxyalkanoates.[70] Bacteria such as the photosynthetic cyanobacteria, produce internal gas vacuoles, which they use to regulate their buoyancy, allowing them to move up or down into water layers with different light intensities and nutrient levels.[71]

Extracellular structures

Around the outside of the cell membrane is the cell wall. Bacterial cell walls are made of peptidoglycan (also called murein), which is made from polysaccharide chains cross-linked by peptides containing D-amino acids.[72] Bacterial cell walls are different from the cell walls of plants and fungi, which are made of cellulose and chitin, respectively.[73] The cell wall of bacteria is also distinct from that of achaea, which do not contain peptidoglycan. The cell wall is essential to the survival of many bacteria, and the antibiotic penicillin (produced by a fungus called Penicillium) is able to kill bacteria by inhibiting a step in the synthesis of peptidoglycan.[73]

There are broadly speaking two different types of cell wall in bacteria, that classify bacteria into Gram-positive bacteria and Gram-negative bacteria. The names originate from the reaction of cells to the Gram stain, a long-standing test for the classification of bacterial species.[74]

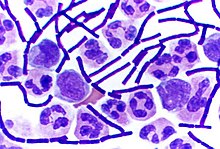

Gram-positive bacteria possess a thick cell wall containing many layers of peptidoglycan and teichoic acids. In contrast, Gram-negative bacteria have a relatively thin cell wall consisting of a few layers of peptidoglycan surrounded by a second lipid membrane containing lipopolysaccharides and lipoproteins. Most bacteria have the Gram-negative cell wall, and only members of the Bacillota group and actinomycetota (previously known as the low G+C and high G+C Gram-positive bacteria, respectively) have the alternative Gram-positive arrangement.[75] These differences in structure can produce differences in antibiotic susceptibility; for instance, vancomycin can kill only Gram-positive bacteria and is ineffective against Gram-negative pathogens, such as Haemophilus influenzae or Pseudomonas aeruginosa.[76] Some bacteria have cell wall structures that are neither classically Gram-positive or Gram-negative. This includes clinically important bacteria such as mycobacteria which have a thick peptidoglycan cell wall like a Gram-positive bacterium, but also a second outer layer of lipids.[77]

In many bacteria, an S-layer of rigidly arrayed protein molecules covers the outside of the cell.[78] This layer provides chemical and physical protection for the cell surface and can act as a macromolecular diffusion barrier. S-layers have diverse functions and are known to act as virulence factors in Campylobacter species and contain surface enzymes in Bacillus stearothermophilus.[79][80]

Flagella are rigid protein structures, about 20 nanometres in diameter and up to 20 micrometres in length, that are used for motility. Flagella are driven by the energy released by the transfer of ions down an electrochemical gradient across the cell membrane.[81]

Fimbriae (sometimes called "attachment pili") are fine filaments of protein, usually 2–10 nanometres in diameter and up to several micrometres in length. They are distributed over the surface of the cell, and resemble fine hairs when seen under the electron microscope.[82] Fimbriae are believed to be involved in attachment to solid surfaces or to other cells, and are essential for the virulence of some bacterial pathogens.[83] Pili (sing. pilus) are cellular appendages, slightly larger than fimbriae, that can transfer genetic material between bacterial cells in a process called conjugation where they are called conjugation pili or sex pili (see bacterial genetics, below).[84] They can also generate movement where they are called type IV pili.[85]

Glycocalyx is produced by many bacteria to surround their cells,[86] and varies in structural complexity: ranging from a disorganised slime layer of extracellular polymeric substances to a highly structured capsule. These structures can protect cells from engulfment by eukaryotic cells such as macrophages (part of the human immune system).[87] They can also act as antigens and be involved in cell recognition, as well as aiding attachment to surfaces and the formation of biofilms.[88]

The assembly of these extracellular structures is dependent on bacterial secretion systems. These transfer proteins from the cytoplasm into the periplasm or into the environment around the cell. Many types of secretion systems are known and these structures are often essential for the virulence of pathogens, so are intensively studied.[88]

Endospores

Some genera of Gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus, Clostridium, Sporohalobacter, Anaerobacter, and Heliobacterium, can form highly resistant, dormant structures called endospores.[90] Endospores develop within the cytoplasm of the cell; generally, a single endospore develops in each cell.[91] Each endospore contains a core of DNA and ribosomes surrounded by a cortex layer and protected by a multilayer rigid coat composed of peptidoglycan and a variety of proteins.[91]

Endospores show no detectable metabolism and can survive extreme physical and chemical stresses, such as high levels of UV light, gamma radiation, detergents, disinfectants, heat, freezing, pressure, and desiccation.[92] In this dormant state, these organisms may remain viable for millions of years.[93][94][95] Endospores even allow bacteria to survive exposure to the vacuum and radiation of outer space, leading to the possibility that bacteria could be distributed throughout the Universe by space dust, meteoroids, asteroids, comets, planetoids, or directed panspermia.[96][97]

Endospore-forming bacteria can cause disease; for example, anthrax can be contracted by the inhalation of Bacillus anthracis endospores, and contamination of deep puncture wounds with Clostridium tetani endospores causes tetanus, which, like botulism, is caused by a toxin released by the bacteria that grow from the spores.[98] Clostridioides difficile infection, a common problem in healthcare settings, is caused by spore-forming bacteria.[99]

Metabolism

Bacteria exhibit an extremely wide variety of metabolic types.[100] The distribution of metabolic traits within a group of bacteria has traditionally been used to define their taxonomy, but these traits often do not correspond with modern genetic classifications.[101] Bacterial metabolism is classified into nutritional groups on the basis of three major criteria: the source of energy, the electron donors used, and the source of carbon used for growth.[102]

Phototrophic bacteria derive energy from light using photosynthesis, while chemotrophic bacteria breaking down chemical compounds through oxidation,[103] driving metabolism by transferring electrons from a given electron donor to a terminal electron acceptor in a redox reaction. Chemotrophs are further divided by the types of compounds they use to transfer electrons. Bacteria that derive electrons from inorganic compounds such as hydrogen, carbon monoxide, or ammonia are called lithotrophs, while those that use organic compounds are called organotrophs.[103] Still, more specifically, aerobic organisms use oxygen as the terminal electron acceptor, while anaerobic organisms use other compounds such as nitrate, sulfate, or carbon dioxide.[103]

Many bacteria, called heterotrophs, derive their carbon from other organic carbon. Others, such as cyanobacteria and some purple bacteria, are autotrophic, meaning they obtain cellular carbon by fixing carbon dioxide.[104] In unusual circumstances, the gas methane can be used by methanotrophic bacteria as both a source of electrons and a substrate for carbon anabolism.[105]

| Nutritional type | Source of energy | Source of carbon | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phototrophs | Sunlight | Organic compounds (photoheterotrophs) or carbon fixation (photoautotrophs) | Cyanobacteria, Green sulfur bacteria, Chloroflexota, or Purple bacteria |

| Lithotrophs | Inorganic compounds | Organic compounds (lithoheterotrophs) or carbon fixation (lithoautotrophs) | Thermodesulfobacteriota, Hydrogenophilaceae, or Nitrospirota |

| Organotrophs | Organic compounds | Organic compounds (chemoheterotrophs) or carbon fixation (chemoautotrophs) | Bacillus, Clostridium, or Enterobacteriaceae |

In many ways, bacterial metabolism provides traits that are useful for ecological stability and for human society. For example, diazotrophs have the ability to fix nitrogen gas using the enzyme nitrogenase.[106] This trait, which can be found in bacteria of most metabolic types listed above,[107] leads to the ecologically important processes of denitrification, sulfate reduction, and acetogenesis, respectively.[108] Bacterial metabolic processes are important drivers in biological responses to pollution; for example, sulfate-reducing bacteria are largely responsible for the production of the highly toxic forms of mercury (methyl- and dimethylmercury) in the environment.[109] Nonrespiratory anaerobes use fermentation to generate energy and reducing power, secreting metabolic by-products (such as ethanol in brewing) as waste. Facultative anaerobes can switch between fermentation and different terminal electron acceptors depending on the environmental conditions in which they find themselves.[110]

Growth and reproduction

Unlike in multicellular organisms, increases in cell size (cell growth) and reproduction by cell division are tightly linked in unicellular organisms. Bacteria grow to a fixed size and then reproduce through binary fission, a form of asexual reproduction.[112] Under optimal conditions, bacteria can grow and divide extremely rapidly, and some bacterial populations can double as quickly as every 17 minutes.[113] In cell division, two identical clone daughter cells are produced. Some bacteria, while still reproducing asexually, form more complex reproductive structures that help disperse the newly formed daughter cells. Examples include fruiting body formation by myxobacteria and aerial hyphae formation by Streptomyces species, or budding. Budding involves a cell forming a protrusion that breaks away and produces a daughter cell.[114]

In the laboratory, bacteria are usually grown using solid or liquid media.[115] Solid growth media, such as agar plates, are used to isolate pure cultures of a bacterial strain. However, liquid growth media are used when the measurement of growth or large volumes of cells are required. Growth in stirred liquid media occurs as an even cell suspension, making the cultures easy to divide and transfer, although isolating single bacteria from liquid media is difficult. The use of selective media (media with specific nutrients added or deficient, or with antibiotics added) can help identify specific organisms.[116]

Most laboratory techniques for growing bacteria use high levels of nutrients to produce large amounts of cells cheaply and quickly.[115] However, in natural environments, nutrients are limited, meaning that bacteria cannot continue to reproduce indefinitely. This nutrient limitation has led the evolution of different growth strategies (see r/K selection theory). Some organisms can grow extremely rapidly when nutrients become available, such as the formation of algal and cyanobacterial blooms that often occur in lakes during the summer.[117] Other organisms have adaptations to harsh environments, such as the production of multiple antibiotics by Streptomyces that inhibit the growth of competing microorganisms.[118] In nature, many organisms live in communities (e.g., biofilms) that may allow for increased supply of nutrients and protection from environmental stresses.[52] These relationships can be essential for growth of a particular organism or group of organisms (syntrophy).[119]

Bacterial growth follows four phases. When a population of bacteria first enter a high-nutrient environment that allows growth, the cells need to adapt to their new environment. The first phase of growth is the lag phase, a period of slow growth when the cells are adapting to the high-nutrient environment and preparing for fast growth. The lag phase has high biosynthesis rates, as proteins necessary for rapid growth are produced.[120][121] The second phase of growth is the logarithmic phase, also known as the exponential phase. The log phase is marked by rapid exponential growth. The rate at which cells grow during this phase is known as the growth rate (k), and the time it takes the cells to double is known as the generation time (g). During log phase, nutrients are metabolised at maximum speed until one of the nutrients is depleted and starts limiting growth. The third phase of growth is the stationary phase and is caused by depleted nutrients. The cells reduce their metabolic activity and consume non-essential cellular proteins. The stationary phase is a transition from rapid growth to a stress response state and there is increased expression of genes involved in DNA repair, antioxidant metabolism and nutrient transport.[122] The final phase is the death phase where the bacteria run out of nutrients and die.[123]

Genetics

Most bacteria have a single circular chromosome that can range in size from only 160,000 base pairs in the endosymbiotic bacteria Carsonella ruddii,[125] to 12,200,000 base pairs (12.2 Mbp) in the soil-dwelling bacteria Sorangium cellulosum.[126] There are many exceptions to this; for example, some Streptomyces and Borrelia species contain a single linear chromosome,[127][128] while some Vibrio species contain more than one chromosome.[129] Some bacteria contain plasmids, small extra-chromosomal molecules of DNA that may contain genes for various useful functions such as antibiotic resistance, metabolic capabilities, or various virulence factors.[130]

Bacteria genomes usually encode a few hundred to a few thousand genes. The genes in bacterial genomes are usually a single continuous stretch of DNA. Although several different types of introns do exist in bacteria, these are much rarer than in eukaryotes.[131]

Bacteria, as asexual organisms, inherit an identical copy of the parent's genome and are clonal. However, all bacteria can evolve by selection on changes to their genetic material DNA caused by genetic recombination or mutations. Mutations arise from errors made during the replication of DNA or from exposure to mutagens. Mutation rates vary widely among different species of bacteria and even among different clones of a single species of bacteria.[132] Genetic changes in bacterial genomes emerge from either random mutation during replication or "stress-directed mutation", where genes involved in a particular growth-limiting process have an increased mutation rate.[133]

Some bacteria transfer genetic material between cells. This can occur in three main ways. First, bacteria can take up exogenous DNA from their environment in a process called transformation.[134] Many bacteria can naturally take up DNA from the environment, while others must be chemically altered in order to induce them to take up DNA.[135] The development of competence in nature is usually associated with stressful environmental conditions and seems to be an adaptation for facilitating repair of DNA damage in recipient cells.[136] Second, bacteriophages can integrate into the bacterial chromosome, introducing foreign DNA in a process known as transduction. Many types of bacteriophage exist; some infect and lyse their host bacteria, while others insert into the bacterial chromosome.[137] Bacteria resist phage infection through restriction modification systems that degrade foreign DNA[138] and a system that uses CRISPR sequences to retain fragments of the genomes of phage that the bacteria have come into contact with in the past, which allows them to block virus replication through a form of RNA interference.[139][140] Third, bacteria can transfer genetic material through direct cell contact via conjugation.[141]

In ordinary circumstances, transduction, conjugation, and transformation involve transfer of DNA between individual bacteria of the same species, but occasionally transfer may occur between individuals of different bacterial species, and this may have significant consequences, such as the transfer of antibiotic resistance.[142][143] In such cases, gene acquisition from other bacteria or the environment is called horizontal gene transfer and may be common under natural conditions.[144]

Behaviour

Movement

Many bacteria are motile (able to move themselves) and do so using a variety of mechanisms. The best studied of these are flagella, long filaments that are turned by a motor at the base to generate propeller-like movement.[145] The bacterial flagellum is made of about 20 proteins, with approximately another 30 proteins required for its regulation and assembly.[145] The flagellum is a rotating structure driven by a reversible motor at the base that uses the electrochemical gradient across the membrane for power.[146]

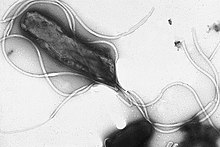

Bacteria can use flagella in different ways to generate different kinds of movement. Many bacteria (such as E. coli) have two distinct modes of movement: forward movement (swimming) and tumbling. The tumbling allows them to reorient and makes their movement a three-dimensional random walk.[147] Bacterial species differ in the number and arrangement of flagella on their surface; some have a single flagellum (monotrichous), a flagellum at each end (amphitrichous), clusters of flagella at the poles of the cell (lophotrichous), while others have flagella distributed over the entire surface of the cell (peritrichous). The flagella of a group of bacteria, the spirochaetes, are found between two membranes in the periplasmic space. They have a distinctive helical body that twists about as it moves.[145]

Two other types of bacterial motion are called twitching motility that relies on a structure called the type IV pilus,[148] and gliding motility, that uses other mechanisms. In twitching motility, the rod-like pilus extends out from the cell, binds some substrate, and then retracts, pulling the cell forward.[149]

Motile bacteria are attracted or repelled by certain stimuli in behaviours called taxes: these include chemotaxis, phototaxis, energy taxis, and magnetotaxis.[150][151][152] In one peculiar group, the myxobacteria, individual bacteria move together to form waves of cells that then differentiate to form fruiting bodies containing spores.[47] The myxobacteria move only when on solid surfaces, unlike E. coli, which is motile in liquid or solid media.[153]

Several Listeria and Shigella species move inside host cells by usurping the cytoskeleton, which is normally used to move organelles inside the cell. By promoting actin polymerisation at one pole of their cells, they can form a kind of tail that pushes them through the host cell's cytoplasm.[154]

Communication

A few bacteria have chemical systems that generate light. This bioluminescence often occurs in bacteria that live in association with fish, and the light probably serves to attract fish or other large animals.[155]

Bacteria often function as multicellular aggregates known as biofilms, exchanging a variety of molecular signals for intercell communication and engaging in coordinated multicellular behaviour.[156][157]

The communal benefits of multicellular cooperation include a cellular division of labour, accessing resources that cannot effectively be used by single cells, collectively defending against antagonists, and optimising population survival by differentiating into distinct cell types.[156] For example, bacteria in biofilms can have more than five hundred times increased resistance to antibacterial agents than individual "planktonic" bacteria of the same species.[157]

One type of intercellular communication by a molecular signal is called quorum sensing, which serves the purpose of determining whether the local population density is sufficient to support investment in processes that are only successful if large numbers of similar organisms behave similarly, such as excreting digestive enzymes or emitting light.[158][159] Quorum sensing enables bacteria to coordinate gene expression and to produce, release, and detect autoinducers or pheromones that accumulate with the growth in cell population.[160]

Classification and identification

Classification seeks to describe the diversity of bacterial species by naming and grouping organisms based on similarities. Bacteria can be classified on the basis of cell structure, cellular metabolism or on differences in cell components, such as DNA, fatty acids, pigments, antigens and quinones.[116] While these schemes allowed the identification and classification of bacterial strains, it was unclear whether these differences represented variation between distinct species or between strains of the same species. This uncertainty was due to the lack of distinctive structures in most bacteria, as well as lateral gene transfer between unrelated species.[162] Due to lateral gene transfer, some closely related bacteria can have very different morphologies and metabolisms. To overcome this uncertainty, modern bacterial classification emphasises molecular systematics, using genetic techniques such as guanine cytosine ratio determination, genome-genome hybridisation, as well as sequencing genes that have not undergone extensive lateral gene transfer, such as the rRNA gene.[163] Classification of bacteria is determined by publication in the International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology,[164] and Bergey's Manual of Systematic Bacteriology.[165] The International Committee on Systematic Bacteriology (ICSB) maintains international rules for the naming of bacteria and taxonomic categories and for the ranking of them in the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria.[166]

Historically, bacteria were considered a part of the Plantae, the Plant kingdom, and were called "Schizomycetes" (fission-fungi).[167] For this reason, collective bacteria and other microorganisms in a host are often called "flora".[168] The term "bacteria" was traditionally applied to all microscopic, single-cell prokaryotes. However, molecular systematics showed prokaryotic life to consist of two separate domains, originally called Eubacteria and Archaebacteria, but now called Bacteria and Archaea that evolved independently from an ancient common ancestor.[4] The archaea and eukaryotes are more closely related to each other than either is to the bacteria. These two domains, along with Eukarya, are the basis of the three-domain system, which is currently the most widely used classification system in microbiology.[169] However, due to the relatively recent introduction of molecular systematics and a rapid increase in the number of genome sequences that are available, bacterial classification remains a changing and expanding field.[170][171] For example, Cavalier-Smith argued that the Archaea and Eukaryotes evolved from Gram-positive bacteria.[172]

The identification of bacteria in the laboratory is particularly relevant in medicine, where the correct treatment is determined by the bacterial species causing an infection. Consequently, the need to identify human pathogens was a major impetus for the development of techniques to identify bacteria.[173]

The Gram stain, developed in 1884 by Hans Christian Gram, characterises bacteria based on the structural characteristics of their cell walls.[174][74] The thick layers of peptidoglycan in the "Gram-positive" cell wall stain purple, while the thin "Gram-negative" cell wall appears pink.[174] By combining morphology and Gram-staining, most bacteria can be classified as belonging to one of four groups (Gram-positive cocci, Gram-positive bacilli, Gram-negative cocci and Gram-negative bacilli). Some organisms are best identified by stains other than the Gram stain, particularly mycobacteria or Nocardia, which show acid fastness on Ziehl–Neelsen or similar stains.[175] Other organisms may need to be identified by their growth in special media, or by other techniques, such as serology.[176]

Culture techniques are designed to promote the growth and identify particular bacteria while restricting the growth of the other bacteria in the sample.[177] Often these techniques are designed for specific specimens; for example, a sputum sample will be treated to identify organisms that cause pneumonia, while stool specimens are cultured on selective media to identify organisms that cause diarrhea while preventing growth of non-pathogenic bacteria. Specimens that are normally sterile, such as blood, urine or spinal fluid, are cultured under conditions designed to grow all possible organisms.[116][178] Once a pathogenic organism has been isolated, it can be further characterised by its morphology, growth patterns (such as aerobic or anaerobic growth), patterns of hemolysis, and staining.[179]

As with bacterial classification, identification of bacteria is increasingly using molecular methods,[180] and mass spectroscopy.[181] Most bacteria have not been characterised and there are many species that cannot be grown in the laboratory.[182] Diagnostics using DNA-based tools, such as polymerase chain reaction, are increasingly popular due to their specificity and speed, compared to culture-based methods.[183] These methods also allow the detection and identification of "viable but nonculturable" cells that are metabolically active but non-dividing.[184] However, even using these improved methods, the total number of bacterial species is not known and cannot even be estimated with any certainty. Following present classification, there are a little less than 9,300 known species of prokaryotes, which includes bacteria and archaea;[185] but attempts to estimate the true number of bacterial diversity have ranged from 107 to 109 total species—and even these diverse estimates may be off by many orders of magnitude.[186][187]

Phyla

The following phyla have been validly published according to the Bacteriological Code:[188]

- Acidobacteriota

- Actinomycetota

- Aquificota

- Armatimonadota

- Atribacterota

- Bacillota

- Bacteroidota

- Balneolota

- Bdellovibrionota

- Caldisericota

- Calditrichota

- Campylobacterota

- Chlamydiota

- Chlorobiota

- Chloroflexota

- Chrysiogenota

- Coprothermobacterota

- Cyanobacteria

- Deferribacterota

- Deinococcota

- Dictyoglomota

- Elusimicrobiota

- Fibrobacterota

- Fusobacteriota

- Gemmatimonadota

- Ignavibacteriota

- Lentisphaerota

- Mycoplasmatota

- Myxococcota

- Nitrospinota

- Nitrospirota

- Planctomycetota

- Pseudomonadota

- Rhodothermota

- Spirochaetota

- Synergistota

- Thermodesulfobacteriota

- Thermomicrobiota

- Thermotogota

- Verrucomicrobiota

Interactions with other organisms

Despite their apparent simplicity, bacteria can form complex associations with other organisms. These symbiotic associations can be divided into parasitism, mutualism and commensalism.[190]

Commensals

The word "commensalism" is derived from the word "commensal", meaning "eating at the same table"[191] and all plants and animals are colonised by commensal bacteria. In humans and other animals, millions of them live on the skin, the airways, the gut and other orifices.[192][193] Referred to as "normal flora",[194] or "commensals",[195] these bacteria usually cause no harm but may occasionally invade other sites of the body and cause infection. Escherichia coli is a commensal in the human gut but can cause urinary tract infections.[196] Similarly, streptococci, which are part of the normal flora of the human mouth, can cause heart disease.[197]

Predators

Some species of bacteria kill and then consume other microorganisms; these species are called predatory bacteria.[198] These include organisms such as Myxococcus xanthus, which forms swarms of cells that kill and digest any bacteria they encounter.[199] Other bacterial predators either attach to their prey in order to digest them and absorb nutrients or invade another cell and multiply inside the cytosol.[200] These predatory bacteria are thought to have evolved from saprophages that consumed dead microorganisms, through adaptations that allowed them to entrap and kill other organisms.[201]

Mutualists

Certain bacteria form close spatial associations that are essential for their survival. One such mutualistic association, called interspecies hydrogen transfer, occurs between clusters of anaerobic bacteria that consume organic acids, such as butyric acid or propionic acid, and produce hydrogen, and methanogenic archaea that consume hydrogen.[202] The bacteria in this association are unable to consume the organic acids as this reaction produces hydrogen that accumulates in their surroundings. Only the intimate association with the hydrogen-consuming archaea keeps the hydrogen concentration low enough to allow the bacteria to grow.[203]

In soil, microorganisms that reside in the rhizosphere (a zone that includes the root surface and the soil that adheres to the root after gentle shaking) carry out nitrogen fixation, converting nitrogen gas to nitrogenous compounds.[204] This serves to provide an easily absorbable form of nitrogen for many plants, which cannot fix nitrogen themselves. Many other bacteria are found as symbionts in humans and other organisms. For example, the presence of over 1,000 bacterial species in the normal human gut flora of the intestines can contribute to gut immunity, synthesise vitamins, such as folic acid, vitamin K and biotin, convert sugars to lactic acid (see Lactobacillus), as well as fermenting complex undigestible carbohydrates.[205][206][207] The presence of this gut flora also inhibits the growth of potentially pathogenic bacteria (usually through competitive exclusion) and these beneficial bacteria are consequently sold as probiotic dietary supplements.[208]

Nearly all animal life is dependent on bacteria for survival as only bacteria and some archaea possess the genes and enzymes necessary to synthesise vitamin B12, also known as cobalamin, and provide it through the food chain. Vitamin B12 is a water-soluble vitamin that is involved in the metabolism of every cell of the human body. It is a cofactor in DNA synthesis and in both fatty acid and amino acid metabolism. It is particularly important in the normal functioning of the nervous system via its role in the synthesis of myelin.[209]

Pathogens

The body is continually exposed to many species of bacteria, including beneficial commensals, which grow on the skin and mucous membranes, and saprophytes, which grow mainly in the soil and in decaying matter. The blood and tissue fluids contain nutrients sufficient to sustain the growth of many bacteria. The body has defence mechanisms that enable it to resist microbial invasion of its tissues and give it a natural immunity or innate resistance against many microorganisms.[210] Unlike some viruses, bacteria evolve relatively slowly so many bacterial diseases also occur in other animals.[211]

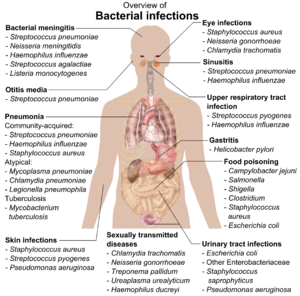

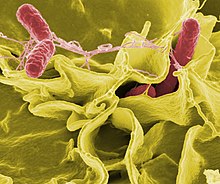

If bacteria form a parasitic association with other organisms, they are classed as pathogens.[212] Pathogenic bacteria are a major cause of human death and disease and cause infections such as tetanus (caused by Clostridium tetani), typhoid fever, diphtheria, syphilis, cholera, foodborne illness, leprosy (caused by Mycobacterium leprae) and tuberculosis (caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis).[213] A pathogenic cause for a known medical disease may only be discovered many years later, as was the case with Helicobacter pylori and peptic ulcer disease.[214] Bacterial diseases are also important in agriculture, and bacteria cause leaf spot, fire blight and wilts in plants, as well as Johne's disease, mastitis, salmonella and anthrax in farm animals.[215]

Each species of pathogen has a characteristic spectrum of interactions with its human hosts. Some organisms, such as Staphylococcus or Streptococcus, can cause skin infections, pneumonia, meningitis and sepsis, a systemic inflammatory response producing shock, massive vasodilation and death.[216] Yet these organisms are also part of the normal human flora and usually exist on the skin or in the nose without causing any disease at all. Other organisms invariably cause disease in humans, such as Rickettsia, which are obligate intracellular parasites able to grow and reproduce only within the cells of other organisms. One species of Rickettsia causes typhus, while another causes Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Chlamydia, another phylum of obligate intracellular parasites, contains species that can cause pneumonia or urinary tract infection and may be involved in coronary heart disease.[217] Some species, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Burkholderia cenocepacia, and Mycobacterium avium, are opportunistic pathogens and cause disease mainly in people who are immunosuppressed or have cystic fibrosis.[218][219] Some bacteria produce toxins, which cause diseases.[220] These are endotoxins, which come from broken bacterial cells, and exotoxins, which are produced by bacteria and released into the environment.[ 221 ] бактерий Clostridium botulinum Например, производит мощный экзотоксин, который вызывает респираторный паралич, а сальмонеллы продуцируют эндотоксин, который вызывает гастроэнтерит. [ 221 ] Некоторые экзотоксины могут быть преобразованы в токсоиды , которые используются в качестве вакцин для предотвращения заболевания. [ 222 ]

Бактериальные инфекции могут рассматриваться антибиотиками , которые классифицируются как бактериоцидные, если они убивают бактерии или бактериостатические , если они просто предотвращают рост бактерий. Существует много типов антибиотиков, и каждый класс ингибирует процесс, который отличается в патогене от того, который обнаружен у хозяина. Примером того, как антибиотики производят селективную токсичность, являются хлорамфеникол и пуромицин , которые ингибируют бактериальную рибосому , но не структурно различную эукариотическую рибосому. [ 223 ] Антибиотики используются как при лечении заболеваний человека, так и при интенсивном сельском хозяйстве , чтобы способствовать росту животных, где они могут способствовать быстрому развитию устойчивости к антибиотикам в бактериальных популяциях. [ 224 ] Инфекции могут быть предотвращены антисептическими показателями, такими как стерилизация кожи до прокалывания ее иглой шприца и надлежащим уходом за постоянными катетерами. Хирургические и стоматологические инструменты также стерилизованы для предотвращения загрязнения бактериями. Дезинфицирующие средства, такие как отбеливатель, используются для убийства бактерий или других патогенов на поверхностях, чтобы предотвратить загрязнение и еще больше снизить риск заражения. [ 225 ]

Значение в технологиях и промышленности

Бактерии, часто молочных кислотных бактерий , такие как виды лактобациллуса и виды лактококка , в сочетании с дрожжами и плесенью , в течение тысячелетий использовались в приготовлении ферментированных продуктов, таких как сыр , соленые огурцы , соевый соус , квадрат, винегар , вина , вино и йогурт . [ 226 ] [ 227 ]

Способность бактерий деградировать различные органические соединения примечательна и использовалась при обработке и биоремедиации отходов . Бактерии, способные переваривать углеводороды в нефтью, часто используются для очистки разливов нефти . [ 228 ] Условие было добавлено к некоторым пляжам в Принсе Уильяме Саунд в попытке стимулировать рост этих естественных бактерий после Exxon Valdez разлива нефти 1989 года . Эти усилия были эффективны на пляжах, которые не были слишком густыми в масле. Бактерии также используются для биоремедиации промышленных токсичных отходов . [ 229 ] В химической промышленности бактерии наиболее важны в производстве энантиометрически чистых химических веществ для использования в качестве фармацевтических препаратов или агрихемических веществ . [ 230 ]

Бактерии также могут использоваться вместо пестицидов в биологическом борьбе с вредителями . Это обычно включает в себя Bacillus thuringiensis (также называемый Bt), граммаположительная бактерия для почвы. Подвиды этих бактерий используются в качестве лепидоптерана специфических для инсектицидами в рамках таких торговых наименований, как Dipel и Thuricide. [ 231 ] Из -за их специфики эти пестициды считаются экологически чистыми , практически не влияя на людей, диких животных , опылителей и большинства других полезных насекомых . [ 232 ] [ 233 ]

Из -за их способности быстро расти и относительной легкость, с которой они могут манипулировать, бактерии являются рабочими лошадями для областей молекулярной биологии , генетики и биохимии . Создавая мутации в бактериальной ДНК и изучая полученные фенотипы, ученые могут определить функцию генов, ферментов и метаболических путей в бактериях, а затем применить эти знания к более сложным организмам. [ 234 ] Эта цель понимания биохимии клетки достигает своей наиболее сложной экспрессии в синтезе огромных количества данных фермента кинетических и экспрессии генов в математические модели целых организмов. Это достижимо у некоторых хорошо изученных бактерий, причем модели метаболизма Escherichia coli в настоящее время продуцируется и испытывается. [ 235 ] [ 236 ] Это понимание бактериального метаболизма и генетики позволяет использовать биотехнологию для биоинженерных бактерий для производства терапевтических белков, таких как инсулин , факторы роста или антитела . [ 237 ] [ 238 ]

Из -за их важности для исследований в целом образцы бактериальных штаммов выделяются и сохраняются в биологических ресурсных центрах . Это обеспечивает доступность напряжения ученых по всему миру. [ 239 ]

История бактериологии

Бактерии впервые наблюдали голландский микроскопист Антони Ван Леувенхук с одной линзой в 1676 году, используя микроскоп своего собственного дизайна. Затем он опубликовал свои наблюдения в серии писем Королевскому обществу Лондона . [ 240 ] Бактериями были самым замечательным микроскопическим открытием Леувенхука. Их размер был только на пределе того, что его простые линзы могли разрешить, и в одном из самых ярких перерывов в истории науки никто больше не увидит их снова более века. [ 241 ] Его наблюдения также включали простейшие, которые он назвал Animalcules , и его выводы были снова рассмотрены в свете более поздних результатов теории клеток . [ 242 ]

Кристиан Готфрид Эренберг представил слово «бактерия» в 1828 году. [ 243 ] Фактически, его бактерия была родом, который содержал необразующие бактерии в форме штата, [ 244 ] В отличие от Bacillus , рода спортивных бактерий в форме споры, определяемых Эренбергом в 1835 году. [ 245 ]

Луи Пастер продемонстрировал в 1859 году, что рост микроорганизмов вызывает процесс ферментации и что этот рост связан не с спонтанной генерацией ( дрожжи и плесени , обычно связанные с ферментацией, не являются бактериями, а скорее грибами ). Наряду со своим современником Робертом Кохом , Пастер был ранним сторонником теории болезней зародышей . [ 246 ] Перед ними Игназ Семмелвейс и Джозеф Листер осознали важность дезинфицированных рук в медицинской работе. Семмельвейс, который в 1840 -х годах сформулировал свои правила для мытья рук в больнице, до появления теории зародышей приписывает болезнь «разлагающемуся органическому веществу животных». Его идеи были отвергнуты, а его книга по этой теме осуждена медицинским сообществом. Однако после Листера врачи начали продезинфицировать руки в 1870 -х годах. [ 247 ]

Роберт Кох, пионер в области медицинской микробиологии, работал над холерой , сибирской и туберкулезом . В своем исследовании туберкулеза Кох, наконец, доказал теорию зародышей, за которую он получил Нобелевскую премию в 1905 году. [ 248 ] В постулатах Коха он установил критерии, чтобы проверить, является ли организм причиной болезни , и эти постулаты все еще используются сегодня. [ 249 ]

Говорят, что Фердинанд Кон является основателем бактериологии , изучая бактерии с 1870 года. Кон был первым, кто классифицировал бактерии на основе их морфологии. [ 250 ] [ 251 ]

Хотя в девятнадцатом веке было известно, что бактерии являются причиной многих заболеваний, никаких эффективных антибактериальных методов лечения не было. [ 252 ] В 1910 году Пол Эрлих разработал первый антибиотик, изменяя красители, которые избирательно окрашивали Treponema pallidum - спирочет , который вызывает сифилис - соединения, которые избирательно убивали патоген. [ 253 ] Эрлих, который был удостоен Нобелевской премии 1908 года за свою работу по иммунологии , впервые использовал пятна для обнаружения и выявления бактерий, а его работа была основой пятно грамма и пятна Зиля -Нилсена . [ 254 ]

Основной шаг вперед в изучении бактерий произошел в 1977 году, когда Карл Воиз признал, что у археи есть отдельная линия эволюционного происхождения от бактерий. [ 255 ] Эта новая филогенетическая таксономия зависела от секвенирования рибосомной РНК 16S и разделенных прокариот на два эволюционных домена, как часть трехдоменной системы . [ 4 ]

Смотрите также

Ссылки

- ^ «31. Древняя жизнь: апекс Черт Микрофоссил» . www.lpi.usra.edu . Получено 12 марта 2022 года .

- ^ Sender R, Fuchs S, Milo R (19 августа 2016 г.). «Пересмотренные оценки количества клеток человека и бактерий в организме» . PLOS Биология . 14 (8): E1002533. doi : 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002533 . ISSN 1545-7885 . PMC 4991899 . PMID 27541692 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный McCutcheon JP (октябрь 2021 г.). «Геномика и клеточная биология увлеченных внутриклеточных инфекций» . Ежегодный обзор биологии клеток и развития . 37 (1): 115–142. doi : 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-120219-024122 . PMID 34242059 . S2CID 235786110 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Зал 2008 , с. 145.

- Бактерии . Лидделл, Генри Джордж ? Скотт, Роберт ? Греческий английский лексикон в проекте Персея .

- ^ Бактерии в Лидделле и Скотте .

- ^ Харпер Д. "Бактерии" . Онлайн этимологический словарь .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Krasner 2014 , p. 74

- ^ Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML (июнь 1990 г.). «На пути к естественной системе организмов: предложение о доменах археи, бактерий и эурья» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 87 (12): 4576–79. Bibcode : 1990pnas ... 87.4576w . doi : 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 . PMC 54159 . PMID 2112744 .

- ^ Холл 2008 , с. 84

- ^ Godoy-Vitorino F (июль 2019). «Человеческая микробная экология и растущая новая медицина» . Анналы трансляционной медицины . 7 (14): 342. doi : 10.21037/atm.2019.06.56 . PMC 6694241 . PMID 31475212 .

- ^ Schopf JW (июль 1994 г.). «Разрозненные скорости, разные судьбы: темп и режим эволюции изменяются от докембрийца к фанерозойму» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 91 (15): 6735–42. Bibcode : 1994pnas ... 91.6735s . doi : 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6735 . PMC 44277 . PMID 8041691 .

- ^ Делонг Эф, Пейс Н.Р. (август 2001 г.). «Разнообразие окружающей среды бактерий и археи». Систематическая биология . 50 (4): 470–78. Citeseerx 10.1.1.321.8828 . doi : 10.1080/106351501750435040 . PMID 12116647 .

- ^ Браун -младший, Дулиттл В.Ф. (декабрь 1997 г.). «Археа и переход прокариот-эукариот» . Микробиология и молекулярная биология обзоры . 61 (4): 456–502. doi : 10.1128/mmbr.61.4.456-502.1997 . PMC 232621 . PMID 9409149 .

- ^ Daum B, Gold V (июнь 2018 г.). «Твитка или плавание: к пониманию прокариотического движения на основе плана Pilus типа IV». Биологическая химия . 399 (7): 799–808. doi : 10.1515/hsz-2018-0157 . HDL : 10871/33366 . PMID 29894297 . S2CID 48352675 .

- ^ Di Jiulio M (декабрь 2003 г.). «Универсальный предок и предок бактерий были гипертермофилами». Журнал молекулярной эволюции . 57 (6): 721–30. Bibcode : 2003jmole..57..721d . doi : 10.1007/s00239-003-2522-6 . PMID 14745541 . S2CID 7041325 .

- ^ Battistuzzi Fu, Feijao A, Hedges SB (ноябрь 2004 г.). «Геномный шкала времени эволюции прокариота: понимание происхождения метаногенеза, фототрофии и колонизации земли» . BMC Эволюционная биология . 4 : 44. DOI : 10.1186/1471-2148-4-44 . PMC 533871 . PMID 15535883 .

- ^ Homann M, Sansjofre P, Van Zuilen M, Heubeck C, Gong J, Killingsworth B, et al. (23 июля 2018 г.). «Микробная жизнь и биогеохимическая езда на земле 3220 миллионов лет назад» (PDF) . Природа Геонаука . 11 (9): 665–671. Bibcode : 2018natge..11..665h . doi : 10.1038/s41561-018-0190-9 . S2CID 134935568 .

- ^ Габальдон Т (октябрь 2021 г.). «Происхождение и ранняя эволюция эукариотической клетки» . Ежегодный обзор микробиологии . 75 (1): 631–647. doi : 10.1146/annurev-micro-090817-062213 . PMID 34343017 . S2CID 236916203 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 августа 2022 года . Получено 19 августа 2022 года .

- ^ Callier V (8 июня 2022 года). «Митохондрии и происхождение эукариот» . Познаваемый журнал . doi : 10.1146/Познание-060822-2 . Получено 19 августа 2022 года .

- ^ Пул А.М., Пенни Д (январь 2007 г.). «Оценка гипотез для происхождения эукариот». Биологии . 29 (1): 74–84. doi : 10.1002/bies.20516 . PMID 17187354 .

- ^ Dyall SD, Brown Mt, Johnson PJ (апрель 2004 г.). «Древние вторжения: от эндосимбионтов до органелл». Наука . 304 (5668): 253–257. Bibcode : 2004sci ... 304..253d . doi : 10.1126/science.1094884 . PMID 15073369 . S2CID 19424594 .

- ^ Стивенс Т.Г., Габр А., Калатрава В., Гроссман А.Р., Бхаттачарья Д (сентябрь 2021 г.). «Почему первичный эндосимбиоз так редко?» Полем Новый фитолог . 231 (5): 1693–1699. doi : 10.1111/nph.17478 . PMC 8711089 . PMID 34018613 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Бейкер-Остин С., Допсон М (апрель 2007 г.). «Жизнь в кислоте: рН гомеостаз у ацидофилов». Тенденции в микробиологии . 15 (4): 165–171. doi : 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.005 . PMID 17331729 .

- ^ Jeong Sw, Choi YJ (октябрь 2020 г.). «Экстремофильные микроорганизмы для лечения токсичных загрязняющих веществ в окружающей среде» . Молекулы . 25 (21): 4916. DOI : 10.3390/Molecules25214916 . PMC 7660605 . PMID 33114255 .

- ^ Flemming HC, Wuertz S (апрель 2019 г.). «Бактерии и архаи на земле и их изобилие в биопленках». Природные обзоры. Микробиология . 17 (4): 247–260. doi : 10.1038/s41579-019-0158-9 . PMID 30760902 . S2CID 61155774 .

- ^ Bar-On YM, Phillips R, Milo R (июнь 2018 г.). «Распределение биомассы на Земле» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 115 (25): 6506–6511. BIBCODE : 2018PNAS..115.6506B . doi : 10.1073/pnas.1711842115 . PMC 6016768 . PMID 29784790 .

- ^ Wheelis 2008 , p. 362

- ^ Kushkevych I, Procházka J, Gajdács M, Rittmann SK, Vítězová M (июнь 2021 г.). «Молекулярная физиология анаэробных фототрофических фиолетовых и зеленых серных бактерий» . Международный журнал молекулярных наук . 22 (12): 6398. DOI : 10.3390/IJMS22126398 . PMC 8232776 . PMID 34203823 .

- ^ Wheelis 2008 , p. 6

- ^ Pommerville 2014 , p. 3–6.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Krasner 2014 , p. 38

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и фон глин Pommerville 2014 , с. 134.

- ^ Schulz HN, Jorgensen BB (2001). «Большие бактерии». Ежегодный обзор микробиологии . 55 : 105–137. doi : 10.1146/annurev.micro.55.1.105 . PMID 11544351 . S2CID 18168018 .

- ^ Уильямс С. (2011). "Кого ты называешь простым?". Новый ученый . 211 (2821): 38–41. doi : 10.1016/s0262-4079 (11) 61709-0 .

- ^ Волланд Дж. М., Гонсалес-Риццо С., Грос О., Тимл Т., Иванова Н., Шульц Ф., Гоуду Д., Элизабет Н.Х., Натх Н., Удвари Д., Мальмстрем Р.Р. (18 февраля 2022 г.). «Бактерия длиной сантиметра с ДНК-компартментализированной в мембрановых органеллах» . Biorxiv (препринт). doi : 10.1101/2022.02.16.480423 . S2CID 246975579 .

- ^ Сандерсон К (июнь 2022 г.). «Самая большая бактерия, когда -либо обнаруженная, на удивление сложна». Природа . doi : 10.1038/d41586-022-01757-1 . PMID 35750919 . S2CID 250022076 .

- ^ Робертсон Дж., Гомерслл М., Гилл П (ноябрь 1975 г.). «Mycoplasma hominis: рост, размножение и выделение мелких жизнеспособных клеток» . Журнал бактериологии . 124 (2): 1007–1018. doi : 10.1128/jb.124.2.1007-1018.1975 . PMC 235991 . PMID 1102522 .

- ^ Велимиров Б. (2001). «Нанобактерии, ультрамикробактерии и формы голода: поиск самой маленькой метаболизирующей бактерии» . Микробы и среды . 16 (2): 67–77. doi : 10.1264/jsme2.2001.67 .

- ^ Dusenbery DB (2009). Жизнь в микромасштабе . Кембридж, Массачусетс: издательство Гарвардского университета . С. 20–25. ISBN 978-0-674-03116-6 .

- ^ Ян Д.К., Блэр К.М., Салама Н.Р. (март 2016 г.). «Оставаться в форме: влияние формы клеток на выживаемость бактерий в разнообразных средах» . Микробиология и молекулярная биология обзоры . 80 (1): 187–203. doi : 10.1128/mmbr.00031-15 . PMC 4771367 . PMID 26864431 .

- ^ Cabeen Mt, Jacobs-Wagner C (август 2005 г.). «Форма бактериальной клеток». Природные обзоры. Микробиология . 3 (8): 601–10. doi : 10.1038/nrmicro1205 . PMID 16012516 . S2CID 23938989 .

- ^ Young KD (сентябрь 2006 г.). «Селективная ценность бактериальной формы» . Микробиология и молекулярная биология обзоры . 70 (3): 660–703. doi : 10.1128/mmbr.00001-06 . PMC 1594593 . PMID 16959965 .

- ^ Кроуфорд 2007 , с. xi.

- ^ Claessen D, Rozen DE, Kuipers OP, Søgaard-Andersen L, Van Wezel GP (февраль 2014 г.). «Бактериальные решения для многоклеточности: рассказ о биопленках, филаментах и плодоносящих телах» . Природные обзоры. Микробиология . 12 (2): 115–24. doi : 10.1038/nrmicro3178 . HDL : 11370/0DB66A9C-72EF-4E11-A75D-9D1E5827573D . PMID 24384602 . S2CID 20154495 .

- ^ Shimkets LJ (1999). «Межклеточная передача сигналов во время развития плодоношения тела Myxococcus xanthus». Ежегодный обзор микробиологии . 53 : 525–49. doi : 10.1146/annurev.micro.53.1.525 . PMID 10547700 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Кайзер Д. (2004). «Сигнализация в миксобактерии». Ежегодный обзор микробиологии . 58 : 75–98. doi : 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123620 . PMID 15487930 .

- ^ Wheelis 2008 , p. 75

- ^ Мандал А., Датта А., Дас Р., Мукерджи Дж (июнь 2021 г.). «Роль литовых микробных сообществ в секвестрации углекислого газа и удалении загрязняющих веществ: обзор». Бюллетень загрязнения морской пехоты . 170 : 112626. Bibcode : 2021marpb.17012626M . doi : 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112626 . PMID 34153859 .

- ^ Донлан Р.М. (сентябрь 2002 г.). «Биопленки: микробная жизнь на поверхностях» . Возникающие инфекционные заболевания . 8 (9): 881–90. doi : 10.3201/eid0809.020063 . PMC 2732559 . PMID 12194761 .

- ^ Бранда С.С., Вик С., Фридман Л., Колтер Р (январь 2005 г.). «Биопленки: пересмотренная матрица». Тенденции в микробиологии . 13 (1): 20–26. doi : 10.1016/j.tim.2004.11.006 . PMID 15639628 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Дэйви меня, О'Тул Г.А. (декабрь 2000 г.). «Микробные биопленки: от экологии к молекулярной генетике» . Микробиология и молекулярная биология обзоры . 64 (4): 847–67. doi : 10.1128/mmbr.64.4.847-867.2000 . PMC 99016 . PMID 11104821 .

- ^ Donlan RM, Costerton JW (апрель 2002 г.). «Биопленки: механизмы выживания клинически значимых микроорганизмов» . Клинические обзоры микробиологии . 15 (2): 167–93. doi : 10.1128/cmr.15.2.167-193.2002 . PMC 118068 . PMID 11932229 .

- ^ Slonczewski JL, Foster JW (2013). Микробиология: развивающаяся наука (третье изд.). Нью -Йорк: WW Norton. п. 82. ISBN 978-0-393-12367-8 .

- ^ Feijoo-Siota L, Rama JL, Sánchez-Pérez A, Villa TG (июль 2017 г.). «Соображения по бактериальным нуклеоидам». Прикладная микробиология и биотехнология . 101 (14): 5591–602. doi : 10.1007/s00253-017-8381-7 . PMID 28664324 . S2CID 10173266 .

- ^ Бобик Та (май 2006 г.). «Полигранные органеллевые бактериальные метаболические процессы». Прикладная микробиология и биотехнология . 70 (5): 517–25. doi : 10.1007/s00253-005-0295-0 . PMID 16525780 . S2CID 8202321 .

- ^ Yeates to, Kerfeld CA, Heinhorst S, Cannon GC, Shively JM (сентябрь 2008 г.). «Белковые органеллы у бактерий: карбоксизомы и связанные с ними микрокомплекторы». Природные обзоры. Микробиология . 6 (9): 681–91. doi : 10.1038/nrmicro1913 . PMID 18679172 . S2CID 22666203 .

- ^ Kerfeld CA, Sawaya MR, Tanaka S, Nguyen CV, Phillips M, Beeby M, Yeates to (август 2005 г.). «Протеиновые структуры, образующие оболочку примитивных бактериальных органеллов». Наука . 309 (5736): 936–38. Bibcode : 2005sci ... 309..936K . Citeseerx 10.1.1.1026.896 . doi : 10.1126/science.1113397 . PMID 16081736 . S2CID 24561197 .

- ^ Gitai Z (март 2005 г.). «Новая биология бактериальных клеток: движущиеся части и субклеточная архитектура» . Клетка . 120 (5): 577–86. doi : 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.026 . PMID 15766522 . S2CID 8894304 .

- ^ Shih YL, Rothfield L (сентябрь 2006 г.). «Бактериальный цитоскелет» . Микробиология и молекулярная биология обзоры . 70 (3): 729–54. doi : 10.1128/mmbr.00017-06 . PMC 1594594 . PMID 16959967 .

- ^ Норрис В., Ден Блаувен Т., Кабанка Фламана А., Дой Р.Х., Харши Р., Янсьер Л., Хименес-Санчес А., Джин Д., Левин П.А., Майлейковская Е., Мински А., Сайер М., Скарстад К (март 2007 г.). «Функциональная таксономия бактериальных гиперструктур» . Микробиология и молекулярная биология обзоры . 71 (1): 230–53. doi : 10.1128/mmbr.00035-06 . PMC 1847379 . PMID 17347523 .

- ^ Pommerville 2014 , с. 120–121.

- ^ Брайант Д.А., Фригаард Ню (ноябрь 2006 г.). «Прокариотический фотосинтез и фототрофия освещены». Тенденции в микробиологии . 14 (11): 488–96. doi : 10.1016/j.tim.2006.09.001 . PMID 16997562 .

- ^ Psencík J, Ikonen TP, Laurinmäki P, Merckel MC, Butcher SJ, Serimaa RE, Tuma R (август 2004 г.). «Пластичная организация пигментов в хлорсомах, комплексы сбора света зеленых фотосинтетических бактерий» . Биофизический журнал . 87 (2): 1165–72. Bibcode : 2004bpj .... 87.1165p . doi : 10.1529/biophysj.104.040956 . PMC 1304455 . PMID 15298919 .

- ^ Thanbichler M, Wang SC, Shapiro L (октябрь 2005 г.). «Бактериальный нуклеоид: высокоорганизованная и динамическая структура» . Журнал сотовой биохимии . 96 (3): 506–21. doi : 10.1002/jcb.20519 . PMID 15988757 . S2CID 25355087 .

- ^ Poehlsgaard J, Douthwaite S (ноябрь 2005 г.). «Бактериальная рибосома как мишень для антибиотиков». Природные обзоры. Микробиология . 3 (11): 870–81. doi : 10.1038/nrmicro1265 . PMID 16261170 . S2CID 7521924 .

- ^ Yeo M, Chater K (март 2005 г.). «Взаимодействие метаболизма и дифференцировки гликогена дает представление о биологии развития Streptomyces coelicolor» . Микробиология . 151 (Pt 3): 855–61. doi : 10.1099/mic.0.27428-0 . PMID 15758231 . Архивировано из оригинала 29 сентября 2007 года.

- ^ Shiba T, Tsutsumi K, Ishige K, Noguchi T (март 2000 г.). «Неорганическая полифосфатная и полифосфатная киназа: их новые биологические функции и применения» . Биохимия. Biohhimiia . 65 (3): 315–23. PMID 10739474 . Архивировано из оригинала 25 сентября 2006 года.

- ^ Брун, округ Колумбия (июнь 1995 г.). «Выделение и характеристика белков с серой глобулы из хроматического виносума и тиокапса розоперсицины». Архив микробиологии . 163 (6): 391–99. Bibcode : 1995Armic.163..391b . doi : 10.1007/bf00272127 . PMID 7575095 . S2CID 22279133 .

- ^ Кадури Д., Юркевич Е., Окон Й., Кастро-Совински С. (2005). «Экологическая и сельскохозяйственная значимость бактериальных полигидроксиалканоатов». Критические обзоры в микробиологии . 31 (2): 55–67. doi : 10.1080/10408410590899228 . PMID 15986831 . S2CID 4098268 .

- ^ Walsby AE (март 1994 г.). "Газовые везикулы" . Микробиологические обзоры . 58 (1): 94–144. doi : 10.1128/mmbr.58.1.94-144.1994 . PMC 372955 . PMID 8177173 .

- ^ Van Heijenoort J (март 2001 г.). «Образование цепей гликана в синтезе бактериального пептидогликана» . Гликобиология . 11 (3): 25R - 36R. doi : 10.1093/glycob/11.3.25r . PMID 11320055 . S2CID 46066256 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Кох Ал (октябрь 2003 г.). «Бактериальная стена как цель для атаки: прошлое, настоящее и будущие исследования» . Клинические обзоры микробиологии . 16 (4): 673–87. doi : 10.1128/cmr.16.4.673-687.2003 . PMC 207114 . PMID 14557293 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Грэм HC (1884). «С помощью изолированной окраски шизомицетов при резке и сухой препаратах». Прогик Медик 2 : 185–89.

- ^ Hugenholtz P (2002). «Изучение прокариотического разнообразия в эпоху генома» . Биология генома . 3 (2): отзывы0003. doi : 10.1186/gb-2002-3-2-reviews0003 . PMC 139013 . PMID 11864374 .

- ^ Уолш Ф.М., Эмис С.Г. (октябрь 2004 г.). «Микробиология и механизмы лекарственной устойчивости полностью устойчивых патогенов» (PDF) . Текущее мнение о микробиологии . 7 (5): 439–44. doi : 10.1016/j.mib.2004.08.007 . PMID 15451497 .

- ^ Alderwick LJ, Harrison J, Lloyd GS, Birch HL (март 2015 г.). «Микобактериальная клеточная стенка - пептидогликан и арабиногалактан» . Перспективы Cold Spring Harbor в медицине . 5 (8): A021113. doi : 10.1101/cshperspect.a021113 . PMC 4526729 . PMID 25818664 .

- ^ Fagan RP, Fairweather NF (март 2014 г.). «Биогенез и функции бактериальных S-слоев» (PDF) . Природные обзоры. Микробиология . 12 (3): 211–22. doi : 10.1038/nrmicro3213 . PMID 24509785 . S2CID 24112697 .

- ^ Томпсон С.А. (декабрь 2002 г.). «Поверхностные слои Campylobacter (S-слои) и иммунное уклонение» . Анналы пародонтологии . 7 (1): 43–53. doi : 10.1902/annals.2002.7.1.43 . PMC 2763180 . PMID 16013216 .

- ^ Bevering TJ, Книги PH, Salt M, Costant A, Lounatmaa K, Carrier K, Cross E, Haapasalo M, EM, Skyer I, Weath SF Coval (июнь 1997 г.). "S-Layers" Обзоры микробиологии FEMS . 20 (1–2): 99–149. doi : 10.1111/j . PMID 9276929 .

- ^ Кодзима С., Блэр Д.Ф. (2004). Бактериальный жгутиковый двигатель: структура и функция сложной молекулярной машины . Международный обзор цитологии. Тол. 233. С. 93–134. doi : 10.1016/s0074-7696 (04) 33003-2 . ISBN 978-0-12-364637-8 Полем PMID 15037363 .

- ^ Wheelis 2008 , p. 76

- ^ Ченг Р.А., Видманн М (2020). «Недавние достижения в нашем понимании разнообразия и роли шаперона-ошера Fimbriae в облегчении хозяина сальмонеллы и тканевого тропизма» . Границы в клеточной и инфекционной микробиологии . 10 : 628043. DOI : 10.3389/fcimb.2020.628043 . PMC 7886704 . PMID 33614531 .

- ^ Silverman PM (февраль 1997 г.). «На пути к структурной биологии бактериального сопряжения» . Молекулярная микробиология . 23 (3): 423–29. doi : 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2411604.x . PMID 9044277 . S2CID 24126399 .

- ^ Costa TR, Felisberto-Rodrigues C, Meir A, Prevost MS, Redzej A, Trokter M, Waksman G (июнь 2015 г.). «Системы секреции в грамотрицательных бактериях: структурное и механистическое понимание». Природные обзоры. Микробиология . 13 (6): 343–59. doi : 10.1038/nrmicro3456 . PMID 25978706 . S2CID 8664247 .

- ^ Luong P, Dube DH (июль 2021 г.). «Развитие бактериального гликокаликс: химические инструменты для зонда, возмущения и изображений бактериальных гликанов» . Биоорганическая и лекарственная химия . 42 : 116268. DOI : 10.1016/j.bmc.2021.116268 . ISSN 0968-0896 . PMC 8276522 . PMID 34130219 .

- ^ Стоукс Р.В., Норрис-Джонс Р., Брукс Д.Е., Беверидж Т.Дж., Доксзе Д., Торсон Л.М. (октябрь 2004 г.). «Богатый гликаном внешний слой клеточной стенки микобактерии туберкулеза действует как антифагогоцитарная капсула, ограничивающая связь бактерии с макрофагами» . Инфекция и иммунитет . 72 (10): 5676–86. doi : 10.1128/iai.72.10.5676-5686.2004 . PMC 517526 . PMID 15385466 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Kalscheuer R, Palacios A, Anso I, Cifuente J, Anguita J, Jacobs WR, Guerin ME, Prados-Rosales R (июль 2019). «Капсула Mycobacterium tuberculosis: клеточная структура с ключевыми последствиями для патогенеза» . Биохимический журнал . 476 (14): 1995–2016. doi : 10.1042/bcj20190324 . PMC 6698057 . PMID 31320388 .

- ^ Джерниган Дж.А., Стивенс Д.С., Эшфорд Д.А., Оменака С., Топиэль М.С., Гэлбрейт М., Таппер М., Фиск Т.Л., Заки С., Попович Т., Мейер Р.Ф., Куинн С.П., Харпер С.А., Фридкин С.К., Сейвар Дж.Дж., Шепард С.В., Макконнелл М. , Guarner J, Shieh WJ, Malecki JM, Gerberding JL, Hughes JM, Perkins BA (2001). «Связанная с биотерроризмом ингаляционную сибирскую сибирс: первые 10 случаев, о которых сообщалось в Соединенных Штатах» . Возникающие инфекционные заболевания . 7 (6): 933–44. doi : 10.3201/eid0706.010604 . PMC 2631903 . PMID 11747719 .

- ^ Николсон В.Л., Мунаката Н., Хорнек Г., Мелош Х.Дж., Setlow P (сентябрь 2000 г.). «Сопротивление эндоспоров Bacillus к чрезвычайной наземной и внеземной среде» . Микробиология и молекулярная биология обзоры . 64 (3): 548–72. doi : 10.1128/mmbr.64.3.548-572.2000 . PMC 99004 . PMID 10974126 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный McKenney PT, Driks A, Eichenberger P (январь 2013 г.). «Bacillus subtilis endospore: сборка и функции многослойного пальто» . Природные обзоры. Микробиология . 11 (1): 33–44. doi : 10.1038/nrmicro2921 . PMC 9910062 . PMID 23202530 . S2CID 205498395 .

- ^ Николсон В.Л., Фаджардо-Кавазос П., Ребейл Р., Слман Т.А., Ризенман П.Дж., Лоу Дж. Ф., Сюэ Y (август 2002 г.). «Бактериальные эндоспоры и их значение в стрессовой устойчивости». Антони Ван Леувенхук . 81 (1–4): 27–32. Doi : 10.1023/a: 1020561122764 . PMID 12448702 . S2CID 30639022 .

- ^ Vreeland RH, Rosenzweig WD, Powers DW (октябрь 2000 г.). «Выделение 250-миллионной галотолерантной бактерии от первичного солевого кристалла». Природа . 407 (6806): 897–900. Bibcode : 2000natur.407..897V . doi : 10.1038/35038060 . PMID 11057666 . S2CID 9879073 .

- ^ Cano RJ, Borucki Mk (май 1995). «Возрождение и идентификация бактериальных споров у Доминиканского янтаря от 25 до 40 миллионов лет». Наука . 268 (5213): 1060–64. Bibcode : 1995sci ... 268.1060c . doi : 10.1126/science.7538699 . PMID 7538699 .

- ^ «Строка над древними бактериями» . BBC News . 7 июня 2001 года . Получено 26 апреля 2020 года .

- ^ Николсон WL, Schuerger AC, Setlow P (апрель 2005 г.). «Солнечная ультрафиолетовая среда и устойчивость к ультрафиолету бактерий: соображения для транспортировки от земли в марки естественными процессами и человеческим космическим полетом». Мутационные исследования . 571 (1–2): 249–64. Bibcode : 2005mrfmm.571..249n . doi : 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.10.012 . PMID 15748651 .

- ^ «Колонизация галактики тяжелая. Почему бы не послать бактерии вместо этого?» Полем Экономист . 12 апреля 2018 года. ISSN 0013-0613 . Получено 26 апреля 2020 года .

- ^ Revitt-Mills SA, Vidor CJ, Watts TD, Lyras D, Rood Ji, Adams V (май 2019). «Плазмиды вирулентности патогенных клостридий» . Микробиологический спектр . 7 (3). doi : 10.1128/microbiolspec.gpp3-0034-2018 . PMID 31111816 . S2CID 160013108 .

- ^ Reigadas E, Van Prehn J, Falcone M, Fitzpatrick F, Vehreschild MJ, Kuijper EJ, Bouza E (июль 2021 г.). «Как: профилактические вмешательства для профилактики инфекции Clostridioides инфекции» . Клиническая микробиология и инфекция . 27 (12): 1777–1783. doi : 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.06.037 . HDL : 1887/3249077 . PMID 34245901 .

- ^ Нилсон К.Х. (январь 1999). «Микробиология после Viking: новые подходы, новые данные, новые идеи». Происхождение жизни и эволюции биосферы . 29 (1): 73–93. Bibcode : 1999oleb ... 29 ... 73n . doi : 10.1023/a: 1006515817767 . PMID 11536899 . S2CID 12289639 .

- ^ Сюй Дж (июнь 2006 г.). «Микробная экология в эпоху геномики и метагеномики: концепции, инструменты и последние достижения» . Молекулярная экология . 15 (7): 1713–31. doi : 10.1111/j.1365-294x.2006.02882.x . PMID 16689892 . S2CID 16374800 .

- ^ Zillig W (декабрь 1991 г.). «Сравнительная биохимия археи и бактерий». Текущее мнение в области генетики и развития . 1 (4): 544–51. doi : 10.1016/s0959-437x (05) 80206-0 . PMID 1822288 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Slonczewski JL, Foster JW. Микробиология: развивающаяся наука (3 изд.). WW Norton & Company. С. 491–44.

- ^ Hellingwerf KJ, Crielaard W, Hoff WD, Matthijs HC, Mur Lr, из Rotterdam BJ (1994). «Фотобиология бактерий» . Антони Ван Леувенхук (представленная рукопись). 65 (4): 331–47. Doi : 10,1007/bf00872217 . PMID 7832590 . S2CID 23438926 .

- ^ Далтон Х (июнь 2005 г.). «Лекция Leeuwenhoek 2000 Натуральная и неестественная история метана-окисляющих бактерий» . Философские транзакции Королевского общества Лондона. Серия B, биологические науки . 360 (1458): 1207–22. doi : 10.1098/rstb.2005.1657 . PMC 1569495 . PMID 16147517 .

- ^ Имран А., Хаким С., Тарик М., Наваз М.С., Ларайб И., Гульзар У, Ханиф М.К., Сиддик М.Дж., Хаят М., Фрэз А., Ахмад М. (2021). «Диазотрофы для снижения кризисов загрязнения азота: глядя глубоко в корни» . Границы в микробиологии . 12 : 637815. DOI : 10.3389/fmicb.2021.637815 . PMC 8180554 . PMID 34108945 .

- ^ Zehr JP, Jenkins BD, Short SM, Steward GF (июль 2003 г.). «Разнообразие генов нитрогеназы и структура микробного сообщества: сравнение межсистемы» . Экологическая микробиология . 5 (7): 539–54. Bibcode : 2003envmi ... 5..539Z . doi : 10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00451.x . PMID 12823187 .

- ^ Kosugi Y, Matsuura N, Liang Q, Yamamoto-ikemoto R (октябрь 2020 г.). «Обработка сточных вод с использованием процесса« восстановление сульфата, денитрификация и частичная нитрификация (SRDAPN) ». Хемосфера . 256 : 127092. BIBCODE : 2020CHMSP.25627092K . doi : 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2020.127092 . PMID 32559887 . S2CID 219476361 .

- ^ Морель Ф.М., Краэпиэль А.М., Амит М. (1998). «Химический цикл и биоаккумуляция ртути». Ежегодный обзор экологии и систематики . 29 : 543–66. doi : 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.29.1.543 . S2CID 86336987 .

- ^ Ślesak I, Kula M, ślesak H, Miszalski Z, Strzałka K (август 2019). определить обязательный анаэробоз? « Как Свободная радикальная биология и медицина . 140 : 61–73. doi : 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.03.004 . PMID 30862543 .

- ^ Стюарт Э.Дж., Мэдден Р., Пол Г., Таддеи Ф (февраль 2005 г.). «Старение и смерть в организме, который воспроизводит морфологически симметричное разделение» . PLOS Биология . 3 (2): E45. doi : 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030045 . PMC 546039 . PMID 15685293 .

- ^ Кох А.Л. (2002). «Контроль бактериального клеточного цикла путем цитоплазматического роста». Критические обзоры в микробиологии . 28 (1): 61–77. doi : 10.1080/1040-840291046696 . PMID 12003041 . S2CID 11624182 .

- ^ Pommerville 2014 , p. 138.

- ^ Pommerville 2014 , p. 557.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Wheelis 2008 , p. 42

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Томсон Р.Б., Бертрам Х (декабрь 2001 г.). «Лабораторная диагностика инфекций центральной нервной системы». Инфекционные болезни Клиники Северной Америки . 15 (4): 1047–71. doi : 10.1016/s0891-5520 (05) 70186-0 . PMID 11780267 .