Генная терапия

| Часть серии о |

| Генная инженерия |

|---|

|

| Генетически модифицированные организмы |

| История и регулирование |

| Процесс |

| Applications |

| Controversies |

Генная терапия — это медицинская технология , целью которой является достижение терапевтического эффекта посредством манипулирования экспрессией генов или изменения биологических свойств живых клеток. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ]

Первая попытка модификации человеческой ДНК была предпринята в 1980 году Мартином Клайном , но первый успешный перенос ядерных генов у человека, одобренный Национальными институтами здравоохранения , был осуществлен в мае 1989 года. [ 4 ] Первое терапевтическое использование переноса генов, а также первое прямое встраивание ДНК человека в ядерный геном было осуществлено Френчем Андерсоном в ходе исследования, начавшегося в сентябре 1990 года. В период с 1989 по декабрь 2018 года было проведено более 2900 клинических испытаний, в которых участвовало более половина из них в фазе I. [ 5 ] В 2003 году Гендицин стал первой генной терапией, получившей одобрение регулирующих органов. С этого времени были одобрены и другие препараты генной терапии, такие как Glybera (2012), Стримвелис (2016), Kymriah (2017), Luxturna (2017), Onpattro (2018), Zolgensma (2019), Abecma (2021), Адстиладрин , Роктавиан и Хемгеникс (весь 2022 год). Большинство этих подходов используют аденоассоциированные вирусы (AAV) и лентивирусы для выполнения вставок генов in vivo и ex vivo соответственно. AAV характеризуются стабилизацией вирусного капсида , более низкой иммуногенностью, способностью трансдуцировать как делящиеся, так и неделящиеся клетки, способностью специфически интегрировать сайт и достигать долгосрочной экспрессии при лечении in vivo. [6] Подходы ASO / siRNA , подобные тем, которые применяются Alnylam и Ionis Pharmaceuticals , требуют невирусных систем доставки и используют альтернативные механизмы доставки в клетки печени посредством транспортеров GalNAc .

Not all medical procedures that introduce alterations to a patient's genetic makeup can be considered gene therapy. Bone marrow transplantation and organ transplants in general have been found to introduce foreign DNA into patients.[7]

Background

[edit]Gene therapy was first conceptualized in the 1960s, when the feasibility of adding new genetic functions to mammalian cells began to be researched. Several methods to do so were tested, including injecting genes with a micropipette directly into a living mammalian cell, and exposing cells to a precipitate of DNA that contained the desired genes. Scientists theorized that a virus could also be used as a vehicle, or vector, to deliver new genes into cells.

One of the first scientists to report the successful direct incorporation of functional DNA into a mammalian cell was biochemist Dr. Lorraine Marquardt Kraus (6 September 1922 – 1 July 2016)[8] at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center in Memphis, Tennessee, United States. In 1961, she managed to genetically alter the hemoglobin of cells from bone marrow taken from a patient with sickle cell anaemia. She did this by incubating the patient’s cells in tissue culture with DNA extracted from a donor with normal hemoglobin. In 1968, researchers Theodore Friedmann, Jay Seegmiller, and John Subak-Sharpe at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Bethesda, in the United States successfully corrected genetic defects associated with Lesch-Nyhan syndrome, a debilitating neurological disease, by adding foreign DNA to cultured cells collected from patients suffering from the disease.[9]

The first attempt, an unsuccessful one, at gene therapy (as well as the first case of medical transfer of foreign genes into humans not counting organ transplantation) was performed by geneticist Martin Cline of the University of California, Los Angeles in California, United States on 10 July 1980.[10][11] Cline claimed that one of the genes in his patients was active six months later, though he never published this data or had it verified.[12]

After extensive research on animals throughout the 1980s and a 1989 bacterial gene tagging trial on humans, the first gene therapy widely accepted as a success was demonstrated in a trial that started on 14 September 1990, when Ashanthi DeSilva was treated for ADA-SCID.[13]

The first somatic treatment that produced a permanent genetic change was initiated in 1993.[14] The goal was to cure malignant brain tumors by using recombinant DNA to transfer a gene making the tumor cells sensitive to a drug that in turn would cause the tumor cells to die.[15]

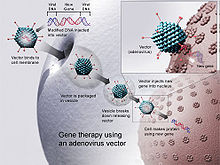

The polymers are either translated into proteins, interfere with target gene expression, or possibly correct genetic mutations. The most common form uses DNA that encodes a functional, therapeutic gene to replace a mutated gene. The polymer molecule is packaged within a "vector", which carries the molecule inside cells.[medical citation needed]

Early clinical failures led to dismissals of gene therapy. Clinical successes since 2006 regained researchers' attention, although as of 2014[update], it was still largely an experimental technique.[16] These include treatment of retinal diseases Leber's congenital amaurosis[17][18][19][20] and choroideremia,[21] X-linked SCID,[22] ADA-SCID,[23][24] adrenoleukodystrophy,[25] chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL),[26] acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL),[27] multiple myeloma,[28] haemophilia,[24] and Parkinson's disease.[29] Between 2013 and April 2014, US companies invested over $600 million in the field.[30]

The first commercial gene therapy, Gendicine, was approved in China in 2003, for the treatment of certain cancers.[31] In 2011, Neovasculgen was registered in Russia as the first-in-class gene-therapy drug for treatment of peripheral artery disease, including critical limb ischemia.[32] In 2012, Glybera, a treatment for a rare inherited disorder, lipoprotein lipase deficiency, became the first treatment to be approved for clinical use in either Europe or the United States after its endorsement by the European Commission.[16][33]

Following early advances in genetic engineering of bacteria, cells, and small animals, scientists started considering how to apply it to medicine. Two main approaches were considered – replacing or disrupting defective genes.[34] Scientists focused on diseases caused by single-gene defects, such as cystic fibrosis, haemophilia, muscular dystrophy, thalassemia, and sickle cell anemia. Glybera treats one such disease, caused by a defect in lipoprotein lipase.[33]

DNA must be administered, reach the damaged cells, enter the cell and either express or disrupt a protein.[35] Multiple delivery techniques have been explored. The initial approach incorporated DNA into an engineered virus to deliver the DNA into a chromosome.[36][37] Naked DNA approaches have also been explored, especially in the context of vaccine development.[38]

Generally, efforts focused on administering a gene that causes a needed protein to be expressed. More recently, increased understanding of nuclease function has led to more direct DNA editing, using techniques such as zinc finger nucleases and CRISPR. The vector incorporates genes into chromosomes. The expressed nucleases then knock out and replace genes in the chromosome. As of 2014[update] these approaches involve removing cells from patients, editing a chromosome and returning the transformed cells to patients.[39]

Gene editing is a potential approach to alter the human genome to treat genetic diseases,[40] viral diseases,[41] and cancer.[42][43] As of 2020[update] these approaches are being studied in clinical trials.[44][45]

Classification

[edit]Breadth of definition

[edit]

In 1986, a meeting at the Institute Of Medicine defined gene therapy as the addition or replacement of a gene in a targeted cell type. In the same year, the FDA announced that it had jurisdiction over approving "gene therapy" without defining the term. The FDA added a very broad definition in 1993 of any treatment that would ‘modify or manipulate the expression of genetic material or to alter the biological properties of living cells’. In 2018 this was narrowed to ‘products that mediate their effects by transcription or translation of transferred genetic material or by specifically altering host (human) genetic sequences’.[46]

Writing in 2018, in the Journal of Law and the Biosciences, Sherkow et al. argued for a narrower definition of gene therapy than the FDA's in light of new technology that would consist of any treatment that intentionally and permanently modified a cell's genome, with the definition of genome including episomes outside the nucleus but excluding changes due to episomes that are lost over time. This definition would also exclude introducing cells that did not derive from a patient themselves, but include ex vivo approaches, and would not depend on the vector used.[46]

During the COVID-19 pandemic, some academics insisted that the mRNA vaccines for COVID were not gene therapy to prevent the spread of incorrect information that the vaccine could alter DNA, other academics maintained that the vaccines were a gene therapy because they introduced genetic material into a cell.[47] Fact-checkers, such as Full Fact,[48] Reuters,[49] PolitiFact,[50] and FactCheck.org[51] said that calling the vaccines a gene therapy was incorrect. Podcast host Joe Rogan was criticized for calling mRNA vaccines gene therapy as was British politician Andrew Bridgen, with fact checker Full Fact calling for Bridgen to be removed from the conservative party for this and other statements.[52][53]

Genes present or added

[edit]Gene therapy encapsulates many forms of adding different nucleic acids to a cell. Gene augmentation adds a new protein coding gene to a cell. One form of gene augmentiation is gene replacement therapy, a treatment for monogenic recessive disorders where a single gene is not functional an additional functional gene is added. For diseases caused by multiple genes or a dominant gene, gene silencing or gene editing approaches are more appropriate but gene addition, a form of gene augmentation where new gene is added, may improve a cells function without modifying the genes that cause a disorder.[54]: 117

Cell types

[edit]Gene therapy may be classified into two types by the type of cell it affects: somatic cell and germline gene therapy.

In somatic cell gene therapy (SCGT), the therapeutic genes are transferred into any cell other than a gamete, germ cell, gametocyte, or undifferentiated stem cell. Any such modifications affect the individual patient only, and are not inherited by offspring. Somatic gene therapy represents mainstream basic and clinical research, in which therapeutic DNA (either integrated in the genome or as an external episome or plasmid) is used to treat disease.[55] Over 600 clinical trials utilizing SCGT are underway[when?] in the US. Most focus on severe genetic disorders, including immunodeficiencies, haemophilia, thalassaemia, and cystic fibrosis. Such single gene disorders are good candidates for somatic cell therapy. The complete correction of a genetic disorder or the replacement of multiple genes is not yet possible. Only a few of the trials are in the advanced stages.[56][needs update]

In germline gene therapy (GGT), germ cells (sperm or egg cells) are modified by the introduction of functional genes into their genomes. Modifying a germ cell causes all the organism's cells to contain the modified gene. The change is therefore heritable and passed on to later generations. Australia, Canada, Germany, Israel, Switzerland, and the Netherlands[57] prohibit GGT for application in human beings, for technical and ethical reasons, including insufficient knowledge about possible risks to future generations[57] and higher risks versus SCGT.[58] The US has no federal controls specifically addressing human genetic modification (beyond FDA regulations for therapies in general).[57][59][60][61]

In vivo versus ex vivo therapies

[edit]

In in vivo gene therapy, a vector (typically, a virus) is introduced to the patient, which then achieves the desired biological effect by passing the genetic material (e.g. for a missing protein) into the patient's cells. In ex vivo gene therapies, such as CAR-T therapeutics, the patient's own cells (autologous) or healthy donor cells (allogeneic) are modified outside the body (hence, ex vivo) using a vector to express a particular protein, such as a chimeric antigen receptor.[62]

In vivo gene therapy is seen as simpler, since it does not require the harvesting of mitotic cells. However, ex vivo gene therapies are better tolerated and less associated with severe immune responses.[63] The death of Jesse Gelsinger in a trial of an adenovirus-vectored treatment for ornithine transcarbamylase deficiency due to a systemic inflammatory reaction led to a temporary halt on gene therapy trials across the United States.[64] As of 2021[update], in vivo and ex vivo therapeutics are both seen as safe.[65]

Gene editing

[edit]

The concept of gene therapy is to fix a genetic problem at its source. If, for instance, a mutation in a certain gene causes the production of a dysfunctional protein resulting (usually recessively) in an inherited disease, gene therapy could be used to deliver a copy of this gene that does not contain the deleterious mutation and thereby produces a functional protein. This strategy is referred to as gene replacement therapy and could be employed to treat inherited retinal diseases.[17][66]

While the concept of gene replacement therapy is mostly suitable for recessive diseases, novel strategies have been suggested that are capable of also treating conditions with a dominant pattern of inheritance.

- The introduction of CRISPR gene editing has opened new doors for its application and utilization in gene therapy, as instead of pure replacement of a gene, it enables correction of the particular genetic defect.[40] Solutions to medical hurdles, such as the eradication of latent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) reservoirs and correction of the mutation that causes sickle cell disease, may be available as a therapeutic option in the future.[67][68][69]

- Prosthetic gene therapy aims to enable cells of the body to take over functions they physiologically do not carry out. One example is the so-called vision restoration gene therapy, that aims to restore vision in patients with end-stage retinal diseases.[70][71] In end-stage retinal diseases, the photoreceptors, as the primary light sensitive cells of the retina are irreversibly lost. By the means of prosthetic gene therapy light sensitive proteins are delivered into the remaining cells of the retina, to render them light sensitive and thereby enable them to signal visual information towards the brain.

In vivo, gene editing systems using CRISPR have been used in studies with mice to treat cancer and have been effective at reducing tumors.[72]: 18 In vitro, the CRISPR system has been used to treat HPV cancer tumors. Adeno-associated virus, Lentivirus based vectors have been to introduce the genome for the CRISPR system.[72]: 6

Vectors

[edit]The delivery of DNA into cells can be accomplished by multiple methods. The two major classes are recombinant viruses (sometimes called biological nanoparticles or viral vectors) and naked DNA or DNA complexes (non-viral methods).[73]

Viruses

[edit]

In order to replicate, viruses introduce their genetic material into the host cell, tricking the host's cellular machinery into using it as blueprints for viral proteins.[54]: 39 Retroviruses go a stage further by having their genetic material copied into the nuclear genome of the host cell. Scientists exploit this by substituting part of a virus's genetic material with therapeutic DNA or RNA.[54]: 40 [74] Like the genetic material (DNA or RNA) in viruses, therapeutic genetic material can be designed to simply serve as a temporary blueprint that degrades naturally, as in a non-integrative vectors, or to enter the host's nucleus becoming a permanent part of the host's nuclear DNA in infected cells.[54]: 50

A number of viruses have been used for human gene therapy, including viruses such as lentivirus, adenoviruses, herpes simplex, vaccinia, and adeno-associated virus.[5]

Adenovirus viral vectors (Ad) temporarily modify a cell's genetic expression with genetic material that is not integrated into the host cell's DNA.[75]: 5 As of 2017, such vectors were used in 20% of trials for gene therapy.[74]: 10 Adenovirus vectors are mostly used in cancer treatments and novel genetic vaccines such as the Ebola vaccine, vaccines used in clinical trials for HIV and SARS-CoV-2, or cancer vaccines.[75]: 5

Lentiviral vectors based on lentivirus, a retrovirus, can modify a cell's nuclear genome to permanently express a gene, although vectors can be modified to prevent integration.[54]: 40,50 Retroviruses were used in 18% of trials before 2018.[74]: 10 Libmeldy is an ex vivo stem cell treatment for metachromatic leukodystrophy which uses a lentiviral vector and was approved by the european medical agency in 2020.[76]

Adeno-associated virus (AAV) is a virus that is incapable of transmission between cells unless the cell is infected by another virus, a helper virus. Adenovirus and the herpes viruses act as helper viruses for AAV. AAV persists within the cell outside of the cell's nuclear genome for an extended period of time through the formation of concatemers mostly organized as episomes.[77]: 4 Genetic material from AAV vectors is integrated into the host cell's nuclear genome at a low frequency and likely mediated by the DNA-modifying enzymes of the host cell.[78]: 2647 Animal models suggest that integration of AAV genetic material into the host cell's nuclear genome may cause hepatocellular carcinoma, a form of liver cancer.[78] Several AAV investigational agents have been explored in treatment of wet age related macular degeneration by both intravitreal and subretinal approaches as a potential application of AAV gene therapy for human disease. [79] [80]

Non-viral

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2021) |

Non-viral vectors for gene therapy[81] present certain advantages over viral methods, such as large scale production and low host immunogenicity. However, non-viral methods initially produced lower levels of transfection and gene expression, and thus lower therapeutic efficacy. Newer technologies offer promise of solving these problems, with the advent of increased cell-specific targeting and subcellular trafficking control.

Methods for non-viral gene therapy include the injection of naked DNA, electroporation, the gene gun, sonoporation, magnetofection, the use of oligonucleotides, lipoplexes, dendrimers, and inorganic nanoparticles. These therapeutics can be administered directly or through scaffold enrichment.[82][83]

More recent approaches, such as those performed by companies such as Ligandal, offer the possibility of creating cell-specific targeting technologies for a variety of gene therapy modalities, including RNA, DNA and gene editing tools such as CRISPR. Other companies, such as Arbutus Biopharma and Arcturus Therapeutics, offer non-viral, non-cell-targeted approaches that mainly exhibit liver trophism. In more recent years, startups such as Sixfold Bio, GenEdit, and Spotlight Therapeutics have begun to solve the non-viral gene delivery problem. Non-viral techniques offer the possibility of repeat dosing and greater tailorability of genetic payloads, which in the future will be more likely to take over viral-based delivery systems.

Companies such as Editas Medicine, Intellia Therapeutics, CRISPR Therapeutics, Casebia, Cellectis, Precision Biosciences, bluebird bio, Excision BioTherapeutics, and Sangamo have developed non-viral gene editing techniques, however frequently still use viruses for delivering gene insertion material following genomic cleavage by guided nucleases. These companies focus on gene editing, and still face major delivery hurdles.

BioNTech, Moderna Therapeutics and CureVac focus on delivery of mRNA payloads, which are necessarily non-viral delivery problems.

Alnylam, Dicerna Pharmaceuticals, and Ionis Pharmaceuticals focus on delivery of siRNA (antisense oligonucleotides) for gene suppression, which also necessitate non-viral delivery systems.

In academic contexts, a number of laboratories are working on delivery of PEGylated particles, which form serum protein coronas and chiefly exhibit LDL receptor mediated uptake in cells in vivo.[84]

Treatment

[edit]Cancer

[edit]

There have been attempts to treat cancer using gene therapy. As of 2017, 65% of gene therapy trials were for cancer treatment.[74]: 7

Adenovirus vectors are useful for some cancer gene therapies because adenovirus can transiently insert genetic material into a cell without permanently altering the cell's nuclear genome. These vectors can be used to cause antigens to be added to cancers causing an immune response, or hinder angiogenesis by expressing certain proteins.[85]: 5 An Adenovirus vector is used in the commercial products Gendicine and Oncorine.[85]: 10 Another commercial product, Rexin G, uses a retrovirus-based vector and selectively binds to receptors that are more expressed in tumors.[85]: 10

One approach, suicide gene therapy, works by introducing genes encoding enzymes that will cause a cancer cell to die. Another approach is the use oncolytic viruses, such as Oncorine,[86]: 165 which are viruses that selectively reproduce in cancerous cells leaving other cells unaffected.[87]: 6 [88]: 280

mRNA has been suggested as a non-viral vector for cancer gene therapy that would temporarily change a cancerous cell's function to create antigens or kill the cancerous cells and there have been several trials.[89]

Genetic diseases

[edit]Gene therapy approaches to replace a faulty gene with a healthy gene have been proposed and are being studied for treating some genetic diseases. As of 2017, 11.1% of gene therapy clinical trials targeted monogenic diseases.[74]: 9

Diseases such as sickle cell disease that are caused by autosomal recessive disorders for which a person's normal phenotype or cell function may be restored in cells that have the disease by a normal copy of the gene that is mutated, may be a good candidate for gene therapy treatment.[90][91] The risks and benefits related to gene therapy for sickle cell disease are not known.[91]

Gene therapy has been used in the eye. The eye is especially suitable for adeno-associated virus vectors. Luxturna is an approved gene therapy to treat Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy.[92]: 1354 Glybera, a treatment for pancreatitis caused by a genetic condition, and Zolgensma for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy both use an adeno-associated virus vector.[78]: 2647

Infectious diseases

[edit]As of 2017, 7% of genetic therapy trials targeted infectious diseases. 69.2% of trials targeted HIV, 11% hepatitis B or C, and 7.1% malaria.[74]

List of gene therapies for treatment of disease

[edit]Some genetic therapies have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the European Medicines Agency (EMA), and for use in Russia and China.

| INN | Brand name | Type | Manufacturer | Target | US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved | European Medicines Agency (EMA) authorized |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| alipogene tiparvovec | Glybera | In vivo | Chiesi Farmaceutici | lipoprotein lipase deficiency | No | Withdrawn |

| atidarsagene autotemcel | Libmeldy, Lenmeldy

(Arylsulfatase A gene encoding autologous CD34+ cells) |

Ex vitro | Orchard Therapeutics | metachromatic leukodystrophy | 18 March 2024[93] | 17 December 2020[94] |

| autologous CD34+ | Strimvelis | adenosine deaminase deficiency (ADA-SCID) | 26 May 2016 | |||

| axicabtagene ciloleucel | Yescarta | Ex vitro | Kite pharma | large B-cell lymphoma | 18 October 2017 | 23 August 2018 |

| beremagene geperpavec | Vyjuvek | In vivo | Krystal Biotech | Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) | 19 May 2023[95] | No |

| betibeglogene autotemcel | Zynteglo | beta thalassemia | 17 August 2022[96] | 29 May 2019 | ||

| brexucabtagene autoleucel | Tecartus | Ex vitro | Kite Pharma | mantle cell lymphoma and acute lymphoblastic leukemia | 24 July 2020[97][98] | 14 December 2020[99] |

| cambiogenplasmid | Neovasculgen | vascular endothelial growth factor peripheral artery disease | ||||

| delandistrogene moxeparvovec | Elevidys | In vivo | Catalent | Duchenne muscular dystrophy | 22 June 2023[100] | No |

| elivaldogene autotemcel | Skysona | cerebral adrenoleukodystrophy | 16 July 2021 | |||

| exagamglogene autotemcel | Casgevy | Ex vivo | Vertex Pharmaceuticals | sickle cell disease | December 2023[101] | |

| gendicine | head and neck squamous cell carcinoma | |||||

| idecabtagene vicleucel | Abecma | Ex vivo | Celgene | multiple myeloma | 26 March 2021[102] | No |

| lisocabtagene maraleucel | Breyanzi | Ex vivo | Juno Therapeutics | B-cell lymphoma | 5 February 2021[103] | No |

| lovotibeglogene autotemcel | Lyfgenia | Ex vivo | Bluebird Bio | sickle cell disease | December 2023[104] | |

| nadofaragene firadenovec | Adstiladrin | Ferring Pharmaceuticals | high-risk Bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG)-unresponsive non-muscle-invasive bladder cancer (NMIBC) with carcinoma in situ (CIS) | Yes[105] | No | |

| onasemnogene abeparvovec | Zolgensma | In vivo | Novartis Gene Therapies | Spinal muscular atrophy Type I | 24 May 2019[106] | 26 March 2020[107] |

| talimogene laherparepvec | Imlygic | In vivo | Amgen | melanoma | 27 October 2015[108] | 16 December 2015[109] |

| tisagenlecleucel | Kymriah | B cell lymphoblastic leukemia | 22 August 2018 | |||

| valoctocogene roxaparvovec | Roctavian | BioMarin International Limited | hemophilia A | August 2022[110][111][112] | ||

| voretigene neparvovec | Luxturna | In vivo | Spark Therapeutics | biallelic RPE65 mutation associated Leber congenital amaurosis | 18 December 2017[113] | 22 November 2018[114] |

Adverse effects, contraindications and hurdles for use

[edit]Some of the unsolved problems include:

- Off-target effects – The possibility of unwanted, likely harmful, changes to the genome present a large barrier to the widespread implementation of this technology.[115] Improvements to the specificity of gRNAs and Cas enzymes present viable solutions to this issue as well as the refinement of the delivery method of CRISPR.[116] It is likely that different diseases will benefit from different delivery methods.

- Short-lived nature – Before gene therapy can become a permanent cure for a condition, the therapeutic DNA introduced into target cells must remain functional and the cells containing the therapeutic DNA must be stable. Problems with integrating therapeutic DNA into the nuclear genome and the rapidly dividing nature of many cells prevent it from achieving long-term benefits. Patients require multiple treatments.

- Immune response – Any time a foreign object is introduced into human tissues, the immune system is stimulated to attack the invader. Stimulating the immune system in a way that reduces gene therapy effectiveness is possible. The immune system's enhanced response to viruses that it has seen before reduces the effectiveness to repeated treatments.

- Problems with viral vectors – Viral vectors carry the risks of toxicity, inflammatory responses, and gene control and targeting issues.

- Multigene disorders – Some commonly occurring disorders, such as heart disease, high blood pressure, Alzheimer's disease, arthritis, and diabetes, are affected by variations in multiple genes, which complicate gene therapy.

- Some therapies may breach the Weismann barrier (between soma and germ-line) protecting the testes, potentially modifying the germline, falling afoul of regulations in countries that prohibit the latter practice.[117]

- Insertional mutagenesis – If the DNA is integrated in a sensitive spot in the genome, for example in a tumor suppressor gene, the therapy could induce a tumor. This has occurred in clinical trials for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (X-SCID) patients, in which hematopoietic stem cells were transduced with a corrective transgene using a retrovirus, and this led to the development of T cell leukemia in 3 of 20 patients.[118][119] One possible solution is to add a functional tumor suppressor gene to the DNA to be integrated. This may be problematic since the longer the DNA is, the harder it is to integrate into cell genomes.[120] CRISPR technology allows researchers to make much more precise genome changes at exact locations.[121]

- Cost – Alipogene tiparvovec or Glybera, for example, at a cost of $1.6 million per patient, was reported in 2013, to be the world's most expensive drug.[122][123]

Deaths

[edit]Three patients' deaths have been reported in gene therapy trials, putting the field under close scrutiny. The first was that of Jesse Gelsinger, who died in 1999, because of immune rejection response.[124][125] One X-SCID patient died of leukemia in 2003.[13] In 2007, a rheumatoid arthritis patient died from an infection; the subsequent investigation concluded that the death was not related to gene therapy.[126]

Regulations

[edit]Regulations covering genetic modification are part of general guidelines about human-involved biomedical research.[citation needed] There are no international treaties which are legally binding in this area, but there are recommendations for national laws from various bodies.[citation needed]

The Helsinki Declaration (Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects) was amended by the World Medical Association's General Assembly in 2008. This document provides principles physicians and researchers must consider when involving humans as research subjects. The Statement on Gene Therapy Research initiated by the Human Genome Organization (HUGO) in 2001, provides a legal baseline for all countries. HUGO's document emphasizes human freedom and adherence to human rights, and offers recommendations for somatic gene therapy, including the importance of recognizing public concerns about such research.[127]

United States

[edit]No federal legislation lays out protocols or restrictions about human genetic engineering. This subject is governed by overlapping regulations from local and federal agencies, including the Department of Health and Human Services, the FDA and NIH's Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee. Researchers seeking federal funds for an investigational new drug application, (commonly the case for somatic human genetic engineering,) must obey international and federal guidelines for the protection of human subjects.[128]

NIH serves as the main gene therapy regulator for federally funded research. Privately funded research is advised to follow these regulations. NIH provides funding for research that develops or enhances genetic engineering techniques and to evaluate the ethics and quality in current research. The NIH maintains a mandatory registry of human genetic engineering research protocols that includes all federally funded projects.[129]

An NIH advisory committee published a set of guidelines on gene manipulation.[130] The guidelines discuss lab safety as well as human test subjects and various experimental types that involve genetic changes. Several sections specifically pertain to human genetic engineering, including Section III-C-1. This section describes required review processes and other aspects when seeking approval to begin clinical research involving genetic transfer into a human patient.[131] The protocol for a gene therapy clinical trial must be approved by the NIH's Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee prior to any clinical trial beginning; this is different from any other kind of clinical trial.[130]

As with other kinds of drugs, the FDA regulates the quality and safety of gene therapy products and supervises how these products are used clinically. Therapeutic alteration of the human genome falls under the same regulatory requirements as any other medical treatment. Research involving human subjects, such as clinical trials, must be reviewed and approved by the FDA and an Institutional Review Board.[132][133]

Gene doping

[edit]Athletes may adopt gene therapy technologies to improve their performance.[134] Gene doping is not known to occur, but multiple gene therapies may have such effects. Kayser et al. argue that gene doping could level the playing field if all athletes receive equal access. Critics claim that any therapeutic intervention for non-therapeutic/enhancement purposes compromises the ethical foundations of medicine and sports.[135]

Genetic enhancement

[edit]Genetic engineering could be used to cure diseases, but also to change physical appearance, metabolism, and even improve physical capabilities and mental faculties such as memory and intelligence. Ethical claims about germline engineering include beliefs that every fetus has a right to remain genetically unmodified, that parents hold the right to genetically modify their offspring, and that every child has the right to be born free of preventable diseases.[136][137][138] For parents, genetic engineering could be seen as another child enhancement technique to add to diet, exercise, education, training, cosmetics, and plastic surgery.[139][140] Another theorist claims that moral concerns limit but do not prohibit germline engineering.[141]

A 2020 issue of the journal Bioethics was devoted to moral issues surrounding germline genetic engineering in people.[142]

Possible regulatory schemes include a complete ban, provision to everyone, or professional self-regulation. The American Medical Association's Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs stated that "genetic interventions to enhance traits should be considered permissible only in severely restricted situations: (1) clear and meaningful benefits to the fetus or child; (2) no trade-off with other characteristics or traits; and (3) equal access to the genetic technology, irrespective of income or other socioeconomic characteristics."[143]

As early in the history of biotechnology as 1990, there have been scientists opposed to attempts to modify the human germline using these new tools,[144] and such concerns have continued as technology progressed.[145][146] With the advent of new techniques like CRISPR, in March 2015 a group of scientists urged a worldwide moratorium on clinical use of gene editing technologies to edit the human genome in a way that can be inherited.[147][148][149][150] In April 2015, researchers sparked controversy when they reported results of basic research to edit the DNA of non-viable human embryos using CRISPR.[151][152] A committee of the American National Academy of Sciences and National Academy of Medicine gave qualified support to human genome editing in 2017[153][154] once answers have been found to safety and efficiency problems "but only for serious conditions under stringent oversight."[155]

History

[edit]This section may be too long and excessively detailed. (November 2018) |

1970s and earlier

[edit]In 1972, Friedmann and Roblin authored a paper in Science titled "Gene therapy for human genetic disease?".[156] Rogers (1970) was cited for proposing that exogenous good DNA be used to replace the defective DNA in those with genetic defects.[157]

1980s

[edit]In 1984, a retrovirus vector system was designed that could efficiently insert foreign genes into mammalian chromosomes.[158]

1990s

[edit]The first approved gene therapy clinical research in the US took place on 14 September 1990, at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), under the direction of William French Anderson.[159] Four-year-old Ashanti DeSilva received treatment for a genetic defect that left her with adenosine deaminase deficiency (ADA-SCID), a severe immune system deficiency. The defective gene of the patient's blood cells was replaced by the functional variant. Ashanti's immune system was partially restored by the therapy. Production of the missing enzyme was temporarily stimulated, but the new cells with functional genes were not generated. She led a normal life only with the regular injections performed every two months. The effects were successful, but temporary.[160]

Cancer gene therapy was introduced in 1992/93 (Trojan et al. 1993).[161] The treatment of glioblastoma multiforme, the malignant brain tumor whose outcome is always fatal, was done using a vector expressing antisense IGF-I RNA (clinical trial approved by NIH protocol no.1602 24 November 1993,[162] and by the FDA in 1994). This therapy also represents the beginning of cancer immunogene therapy, a treatment which proves to be effective due to the anti-tumor mechanism of IGF-I antisense, which is related to strong immune and apoptotic phenomena.

In 1992, Claudio Bordignon, working at the Vita-Salute San Raffaele University, performed the first gene therapy procedure using hematopoietic stem cells as vectors to deliver genes intended to correct hereditary diseases.[163] In 2002, this work led to the publication of the first successful gene therapy treatment for ADA-SCID. The success of a multi-center trial for treating children with SCID (severe combined immune deficiency or "bubble boy" disease) from 2000 and 2002, was questioned when two of the ten children treated at the trial's Paris center developed a leukemia-like condition. Clinical trials were halted temporarily in 2002, but resumed after regulatory review of the protocol in the US, the United Kingdom, France, Italy, and Germany.[164]

In 1993, Andrew Gobea was born with SCID following prenatal genetic screening. Blood was removed from his mother's placenta and umbilical cord immediately after birth, to acquire stem cells. The allele that codes for adenosine deaminase (ADA) was obtained and inserted into a retrovirus. Retroviruses and stem cells were mixed, after which the viruses inserted the gene into the stem cell chromosomes. Stem cells containing the working ADA gene were injected into Andrew's blood. Injections of the ADA enzyme were also given weekly. For four years T cells (white blood cells), produced by stem cells, made ADA enzymes using the ADA gene. After four years more treatment was needed.[165]

In 1996, Luigi Naldini and Didier Trono developed a new class of gene therapy vectors based on HIV capable of infecting non-dividing cells that have since then been widely used in clinical and research settings, pioneering lentivirals vector in gene therapy.[166]

Jesse Gelsinger's death in 1999 impeded gene therapy research in the US.[167][168] As a result, the FDA suspended several clinical trials pending the reevaluation of ethical and procedural practices.[169]

2000s

[edit]The modified gene therapy strategy of antisense IGF-I RNA (NIH n˚ 1602)[162] using antisense / triple helix anti-IGF-I approach was registered in 2002, by Wiley gene therapy clinical trial - n˚ 635 and 636. The approach has shown promising results in the treatment of six different malignant tumors: glioblastoma, cancers of liver, colon, prostate, uterus, and ovary (Collaborative NATO Science Programme on Gene Therapy USA, France, Poland n˚ LST 980517 conducted by J. Trojan) (Trojan et al., 2012). This anti-gene antisense/triple helix therapy has proven to be efficient, due to the mechanism stopping simultaneously IGF-I expression on translation and transcription levels, strengthening anti-tumor immune and apoptotic phenomena.

2002

[edit]Sickle cell disease can be treated in mice.[170] The mice – which have essentially the same defect that causes human cases – used a viral vector to induce production of fetal hemoglobin (HbF), which normally ceases to be produced shortly after birth. In humans, the use of hydroxyurea to stimulate the production of HbF temporarily alleviates sickle cell symptoms. The researchers demonstrated this treatment to be a more permanent means to increase therapeutic HbF production.[171]

A new gene therapy approach repaired errors in messenger RNA derived from defective genes. This technique has the potential to treat thalassaemia, cystic fibrosis and some cancers.[172]

Researchers created liposomes 25 nanometers across that can carry therapeutic DNA through pores in the nuclear membrane.[173]

2003

[edit]In 2003, a research team inserted genes into the brain for the first time. They used liposomes coated in a polymer called polyethylene glycol, which unlike viral vectors, are small enough to cross the blood–brain barrier.[174]

Short pieces of double-stranded RNA (short, interfering RNAs or siRNAs) are used by cells to degrade RNA of a particular sequence. If a siRNA is designed to match the RNA copied from a faulty gene, then the abnormal protein product of that gene will not be produced.[175]

Gendicine is a cancer gene therapy that delivers the tumor suppressor gene p53 using an engineered adenovirus. In 2003, it was approved in China for the treatment of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.[31]

2006

[edit]In March, researchers announced the successful use of gene therapy to treat two adult patients for X-linked chronic granulomatous disease, a disease which affects myeloid cells and damages the immune system. The study is the first to show that gene therapy can treat the myeloid system.[176]

In May, a team reported a way to prevent the immune system from rejecting a newly delivered gene.[177] Similar to organ transplantation, gene therapy has been plagued by this problem. The immune system normally recognizes the new gene as foreign and rejects the cells carrying it. The research utilized a newly uncovered network of genes regulated by molecules known as microRNAs. This natural function selectively obscured their therapeutic gene in immune system cells and protected it from discovery. Mice infected with the gene containing an immune-cell microRNA target sequence did not reject the gene.

In August, scientists successfully treated metastatic melanoma in two patients using killer T cells genetically retargeted to attack the cancer cells.[178]

In November, researchers reported on the use of VRX496, a gene-based immunotherapy for the treatment of HIV that uses a lentiviral vector to deliver an antisense gene against the HIV envelope. In a phase I clinical trial, five subjects with chronic HIV infection who had failed to respond to at least two antiretroviral regimens were treated. A single intravenous infusion of autologous CD4 T cells genetically modified with VRX496 was well tolerated. All patients had stable or decreased viral load; four of the five patients had stable or increased CD4 T cell counts. All five patients had stable or increased immune response to HIV antigens and other pathogens. This was the first evaluation of a lentiviral vector administered in a US human clinical trial.[179][180]

2007

[edit]In May, researchers announced the first gene therapy trial for inherited retinal disease. The first operation was carried out on a 23-year-old British male, Robert Johnson, in early 2007.[181]

2008

[edit]Leber's congenital amaurosis is an inherited blinding disease caused by mutations in the RPE65 gene. The results of a small clinical trial in children were published in April.[17] Delivery of recombinant adeno-associated virus (AAV) carrying RPE65 yielded positive results. In May, two more groups reported positive results in independent clinical trials using gene therapy to treat the condition. In all three clinical trials, patients recovered functional vision without apparent side-effects.[17][18][19][20]

2009

[edit]In September researchers were able to give trichromatic vision to squirrel monkeys.[182] In November 2009, researchers halted a fatal genetic disorder called adrenoleukodystrophy in two children using a lentivirus vector to deliver a functioning version of ABCD1, the gene that is mutated in the disorder.[183]

2010s

[edit]2010

[edit]An April paper reported that gene therapy addressed achromatopsia (color blindness) in dogs by targeting cone photoreceptors. Cone function and day vision were restored for at least 33 months in two young specimens. The therapy was less efficient for older dogs.[184]

In September it was announced that an 18-year-old male patient in France with beta thalassemia major had been successfully treated.[185] Beta thalassemia major is an inherited blood disease in which beta haemoglobin is missing and patients are dependent on regular lifelong blood transfusions.[186] The technique used a lentiviral vector to transduce the human β-globin gene into purified blood and marrow cells obtained from the patient in June 2007.[187] The patient's haemoglobin levels were stable at 9 to 10 g/dL. About a third of the hemoglobin contained the form introduced by the viral vector and blood transfusions were not needed.[187][188] Further clinical trials were planned.[189] Bone marrow transplants are the only cure for thalassemia, but 75% of patients do not find a matching donor.[188]

Cancer immunogene therapy using modified antigene, antisense/triple helix approach was introduced in South America in 2010/11 in La Sabana University, Bogota (Ethical Committee 14 December 2010, no P-004-10). Considering the ethical aspect of gene diagnostic and gene therapy targeting IGF-I, the IGF-I expressing tumors i.e. lung and epidermis cancers were treated (Trojan et al. 2016).[190][191]

2011

[edit]In 2007 and 2008, a man (Timothy Ray Brown) was cured of HIV by repeated hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (see also allogeneic stem cell transplantation, allogeneic bone marrow transplantation, allotransplantation) with double-delta-32 mutation which disables the CCR5 receptor. This cure was accepted by the medical community in 2011.[192] It required complete ablation of existing bone marrow, which is very debilitating.[193]

In August two of three subjects of a pilot study were confirmed to have been cured from chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The therapy used genetically modified T cells to attack cells that expressed the CD19 protein to fight the disease.[26] In 2013, the researchers announced that 26 of 59 patients had achieved complete remission and the original patient had remained tumor-free.[194]

Human HGF plasmid DNA therapy of cardiomyocytes is being examined as a potential treatment for coronary artery disease as well as treatment for the damage that occurs to the heart after myocardial infarction.[195][196]

In 2011, Neovasculgen was registered in Russia as the first-in-class gene-therapy drug for treatment of peripheral artery disease, including critical limb ischemia; it delivers the gene encoding for VEGF.[32] Neovasculogen is a plasmid encoding the CMV promoter and the 165 amino acid form of VEGF.[197][198]

2012

[edit]The FDA approved Phase I clinical trials on thalassemia major patients in the US for 10 participants in July.[199] The study was expected to continue until 2015.[189]

In July 2012, the European Medicines Agency recommended approval of a gene therapy treatment for the first time in either Europe or the United States. The treatment used Alipogene tiparvovec (Glybera) to compensate for lipoprotein lipase deficiency, which can cause severe pancreatitis.[200] The recommendation was endorsed by the European Commission in November 2012,[16][33][201][202] and commercial rollout began in late 2014.[203] Alipogene tiparvovec was expected to cost around $1.6 million per treatment in 2012,[204] revised to $1 million in 2015,[205] making it the most expensive medicine in the world at the time.[206] As of 2016[update], only the patients treated in clinical trials and a patient who paid the full price for treatment have received the drug.[207]

In December 2012, it was reported that 10 of 13 patients with multiple myeloma were in remission "or very close to it" three months after being injected with a treatment involving genetically engineered T cells to target proteins NY-ESO-1 and LAGE-1, which exist only on cancerous myeloma cells.[28]

2013

[edit]In March researchers reported that three of five adult subjects who had acute lymphocytic leukemia (ALL) had been in remission for five months to two years after being treated with genetically modified T cells which attacked cells with CD19 genes on their surface, i.e. all B cells, cancerous or not. The researchers believed that the patients' immune systems would make normal T cells and B cells after a couple of months. They were also given bone marrow. One patient relapsed and died and one died of a blood clot unrelated to the disease.[27]

Following encouraging Phase I trials, in April, researchers announced they were starting Phase II clinical trials (called CUPID2 and SERCA-LVAD) on 250 patients[208] at several hospitals to combat heart disease. The therapy was designed to increase the levels of SERCA2, a protein in heart muscles, improving muscle function.[209] The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted this a breakthrough therapy designation to accelerate the trial and approval process.[210] In 2016, it was reported that no improvement was found from the CUPID 2 trial.[211]

In July researchers reported promising results for six children with two severe hereditary diseases had been treated with a partially deactivated lentivirus to replace a faulty gene and after 7–32 months. Three of the children had metachromatic leukodystrophy, which causes children to lose cognitive and motor skills.[212] The other children had Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, which leaves them to open to infection, autoimmune diseases, and cancer.[213] Follow up trials with gene therapy on another six children with Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome were also reported as promising.[214][215]

In October researchers reported that two children born with adenosine deaminase severe combined immunodeficiency disease (ADA-SCID) had been treated with genetically engineered stem cells 18 months previously and that their immune systems were showing signs of full recovery. Another three children were making progress.[24] In 2014, a further 18 children with ADA-SCID were cured by gene therapy.[216] ADA-SCID children have no functioning immune system and are sometimes known as "bubble children".[24]

Also in October researchers reported that they had treated six people with haemophilia in early 2011 using an adeno-associated virus. Over two years later all six were producing clotting factor.[24][217]

2014

[edit]In January researchers reported that six choroideremia patients had been treated with adeno-associated virus with a copy of REP1. Over a six-month to two-year period all had improved their sight.[66][218] By 2016, 32 patients had been treated with positive results and researchers were hopeful the treatment would be long-lasting.[21] Choroideremia is an inherited genetic eye disease with no approved treatment, leading to loss of sight.

In March researchers reported that 12 HIV patients had been treated since 2009 in a trial with a genetically engineered virus with a rare mutation (CCR5 deficiency) known to protect against HIV with promising results.[219][220]

Clinical trials of gene therapy for sickle cell disease were started in 2014.[221][222]

In February LentiGlobin BB305, a gene therapy treatment undergoing clinical trials for treatment of beta thalassemia gained FDA "breakthrough" status after several patients were able to forgo the frequent blood transfusions usually required to treat the disease.[223]

In March researchers delivered a recombinant gene encoding a broadly neutralizing antibody into monkeys infected with simian HIV; the monkeys' cells produced the antibody, which cleared them of HIV. The technique is named immunoprophylaxis by gene transfer (IGT). Animal tests for antibodies to ebola, malaria, influenza, and hepatitis were underway.[224][225]

In March, scientists, including an inventor of CRISPR, Jennifer Doudna, urged a worldwide moratorium on germline gene therapy, writing "scientists should avoid even attempting, in lax jurisdictions, germline genome modification for clinical application in humans" until the full implications "are discussed among scientific and governmental organizations".[147][148][149][150]

In December, scientists of major world academies called for a moratorium on inheritable human genome edits, including those related to CRISPR-Cas9 technologies[226] but that basic research including embryo gene editing should continue.[227]

2015

[edit]Researchers successfully treated a boy with epidermolysis bullosa using skin grafts grown from his own skin cells, genetically altered to repair the mutation that caused his disease.[228]

In November, researchers announced that they had treated a baby girl, Layla Richards, with an experimental treatment using donor T cells genetically engineered using TALEN to attack cancer cells. One year after the treatment she was still free of her cancer (a highly aggressive form of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia [ALL]).[229] Children with highly aggressive ALL normally have a very poor prognosis and Layla's disease had been regarded as terminal before the treatment.[230][231]

2016

[edit]In April the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use of the European Medicines Agency endorsed a gene therapy treatment called Strimvelis[232][233] and the European Commission approved it in June.[234] This treats children born with adenosine deaminase deficiency and who have no functioning immune system. This was the second gene therapy treatment to be approved in Europe.[235]

In October, Chinese scientists reported they had started a trial to genetically modify T cells from 10 adult patients with lung cancer and reinject the modified T cells back into their bodies to attack the cancer cells. The T cells had the PD-1 protein (which stops or slows the immune response) removed using CRISPR-Cas9.[236][237]

A 2016 Cochrane systematic review looking at data from four trials on topical cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene therapy does not support its clinical use as a mist inhaled into the lungs to treat cystic fibrosis patients with lung infections. One of the four trials did find weak evidence that liposome-based CFTR gene transfer therapy may lead to a small respiratory improvement for people with CF. This weak evidence is not enough to make a clinical recommendation for routine CFTR gene therapy.[238]

2017

[edit]In February Kite Pharma announced results from a clinical trial of CAR-T cells in around a hundred people with advanced non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[239]

In March, French scientists reported on clinical research of gene therapy to treat sickle cell disease.[240]

In August, the FDA approved tisagenlecleucel for acute lymphoblastic leukemia.[241] Tisagenlecleucel is an adoptive cell transfer therapy for B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia; T cells from a person with cancer are removed, genetically engineered to make a specific T-cell receptor (a chimeric T cell receptor, or "CAR-T") that reacts to the cancer, and are administered back to the person. The T cells are engineered to target a protein called CD19 that is common on B cells. This is the first form of gene therapy to be approved in the United States. In October, a similar therapy called axicabtagene ciloleucel was approved for non-Hodgkin lymphoma.[242]

In October, biophysicist and biohacker Josiah Zayner claimed to have performed the very first in-vivo human genome editing in the form of a self-administered therapy.[243][244]

On 13 November, medical scientists working with Sangamo Therapeutics, headquartered in Richmond, California, announced the first ever in-body human gene editing therapy.[245][246] The treatment, designed to permanently insert a healthy version of the flawed gene that causes Hunter syndrome, was given to 44-year-old Brian Madeux and is part of the world's first study to permanently edit DNA inside the human body.[247] The success of the gene insertion was later confirmed.[248][249] Clinical trials by Sangamo involving gene editing using zinc finger nuclease (ZFN) are ongoing.[250]

In December the results of using an adeno-associated virus with blood clotting factor VIII to treat nine haemophilia A patients were published. Six of the seven patients on the high dose regime increased the level of the blood clotting VIII to normal levels. The low and medium dose regimes had no effect on the patient's blood clotting levels.[251][252]

In December, the FDA approved Luxturna, the first in vivo gene therapy, for the treatment of blindness due to Leber's congenital amaurosis.[253] The price of this treatment is US$850,000 for both eyes.[254][255]

2019

[edit]In May, the FDA approved onasemnogene abeparvovec (Zolgensma) for treating spinal muscular atrophy in children under two years of age. The list price of Zolgensma was set at US$2.125 million per dose, making it the most expensive drug ever.[256]

In May, the EMA approved betibeglogene autotemcel (Zynteglo) for treating beta thalassemia for people twelve years of age and older.[257][258]

In July, Allergan and Editas Medicine announced phase I/II clinical trial of AGN-151587 for the treatment of Leber congenital amaurosis 10.[259] This is the first study of a CRISPR-based in vivo human gene editing therapy, where the editing takes place inside the human body.[260] The first injection of the CRISPR-Cas System was confirmed in March 2020.[261]

2020s

[edit]2020

[edit]In May, onasemnogene abeparvovec (Zolgensma) was approved by the European Union for the treatment of spinal muscular atrophy in people who either have clinical symptoms of SMA type 1 or who have no more than three copies of the SMN2 gene, irrespective of body weight or age.[262]

In August, Audentes Therapeutics reported that three out of 17 children with X-linked myotubular myopathy participating the clinical trial of a AAV8-based gene therapy treatment AT132 have died. It was suggested that the treatment, whose dosage is based on body weight, exerts a disproportionately toxic effect on heavier patients, since the three patients who died were heavier than the others.[263][264] The trial has been put on clinical hold.[265]

On 15 October, the Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) adopted a positive opinion, recommending the granting of a marketing authorisation for the medicinal product Libmeldy (autologous CD34+ cell enriched population that contains hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells transduced ex vivo using a lentiviral vector encoding the human arylsulfatase A gene), a gene therapy for the treatment of children with the "late infantile" (LI) or "early juvenile" (EJ) forms of metachromatic leukodystrophy (MLD).[266] The active substance of Libmeldy consists of the child's own stem cells which have been modified to contain working copies of the ARSA gene.[266] When the modified cells are injected back into the patient as a one-time infusion, the cells are expected to start producing the ARSA enzyme that breaks down the build-up of sulfatides in the nerve cells and other cells of the patient's body.[267] Libmeldy was approved for medical use in the EU in December 2020.[268]

On 15 October, Lysogene, a French biotechnological company, reported the death of a patient in who has received LYS-SAF302, an experimental gene therapy treatment for mucopolysaccharidosis type IIIA (Sanfilippo syndrome type A).[269]

2021

[edit]In May, a new method using an altered version of HIV as a lentivirus vector was reported in the treatment of 50 children with ADA-SCID obtaining positive results in 48 of them,[270][271][272] this method is expected to be safer than retroviruses vectors commonly used in previous studies of SCID where the development of leukemia was usually observed[273] and had already been used in 2019, but in a smaller group with X-SCID.[274][275][276][277]

In June a clinical trial on six patients affected with transthyretin amyloidosis reported a reduction the concentration of missfolded transthretin (TTR) protein in serum through CRISPR-based inactivation of the TTR gene in liver cells observing mean reductions of 52% and 87% among the lower and higher dose groups.This was done in vivo without taking cells out of the patient to edit them and reinfuse them later.[278][279][280]

In July results of a small gene therapy phase I study was published reporting observation of dopamine restoration on seven patients between 4 and 9 years old affected by aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency (AADC deficiency).[281][282][283]

2022

[edit]In February, the first ever gene therapy for Tay–Sachs disease was announced, it uses an adeno-associated virus to deliver the correct instruction for the HEXA gene on brain cells which causes the disease. Only two children were part of a compassionate trial presenting improvements over the natural course of the disease and no vector-related adverse events.[284][285][286]

In May, eladocagene exuparvovec is recommended for approval by the European Commission.[287][288]

In July results of a gene therapy candidate for haemophilia B called FLT180 were announced, it works using an adeno-associated virus (AAV) to restore the clotting factor IX (FIX) protein, normal levels of the protein were observed with low doses of the therapy but immunosuppression was necessitated to decrease the risk of vector-related immune responses.[289][290][291]

In December, a 13-year girl that had been diagnosed with T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia was successfully treated at Great Ormond Street Hospital (GOSH) in the first documented use of therapeutic gene editing for this purpose, after undergoing six months of an experimental treatment, where all attempts of other treatments failed. The procedure included reprogramming a healthy T-cell to destroy the cancerous T-cells to first rid her of leukaemia, and then rebuilding her immune system using healthy immune cells.[292] The GOSH team used BASE editing and had previously treated a case of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in 2015 using TALENs.[231]

2023

[edit]In May the FDA approved Vyjuvek for the treatment of wounds in patients with dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa (DEB) which is applied as a topical gel that delivers a herpes-simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) vector encoding the collagen type VII alpha 1 chain (COL7A1) gene that is dysfunctional on those affected by DEB . One trial found 65% of the Vyjuvek-treated wounds completely closed while only 26% of the placebo-treated at 24 weeks.[95] It has been also reported its use as a eyedrops for a patient with DEB that had vision loss due to the widespread blistering with good results.[293]

In June the FDA gave an accelerated approval to Elevidys for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) only for boys 4 to 5 years old as they are more likely to benefit from the therapy which consists of one-time intravenous infusion of a virus (AAV rh74 vector) that delivers a functioning “microdystrophin” gene (138 kDa) into the muscle cells to act in place of the normal dystrophin (427 kDa) that is found mutated in this disease.[100]

In July it was reported that it had been developed a new method to affect genetic expressions through direct current.[294]

List of gene therapies

[edit]- Gene therapy for color blindness

- Gene therapy for epilepsy

- Gene therapy for osteoarthritis

- Gene therapy in Parkinson's disease

- Gene therapy of the human retina

Gene therapies are under development for:

- Usher syndrome deafness

- Otoferlin mutation deafness

References

[edit]- ^ Kaji EH, Leiden JM (February 2001). "Gene and stem cell therapies". JAMA. 285 (5): 545–550. doi:10.1001/jama.285.5.545. PMID 11176856.

- ^ Ermak G (2015). Emerging Medical Technologies. World Scientific. ISBN 978-981-4675-81-9.

- ^ Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and (9 December 2020). "What is Gene Therapy?". FDA.

- ^ Розенберг С.А., Эберсолд П., Корнетта К., Касид А., Морган Р.А., Моен Р. и др. (август 1990 г.). «Перенос генов человеку - иммунотерапия пациентов с прогрессирующей меланомой с использованием проникающих в опухоль лимфоцитов, модифицированных трансдукцией ретровирусных генов» . Медицинский журнал Новой Англии . 323 (9): 570–578. дои : 10.1056/NEJM199008303230904 . ПМИД 2381442 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Всемирная база данных клинических испытаний генной терапии» . Журнал генной медицины . Уайли. Июнь 2016. Архивировано из оригинала 31 июля 2020 года.

- ^ Горелл Э., Нгуен Н., Лейн А., Сипрашвили З. (апрель 2014 г.). «Генная терапия заболеваний кожи» . Перспективы Колд-Спринг-Харбора в медицине . 4 (4): а015149. doi : 10.1101/cshperspect.a015149 . ПМЦ 3968787 . ПМИД 24692191 .

- ^ Циммер С (16 сентября 2013 г.). «Двойной дубль ДНК» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Архивировано из оригинала 2 января 2022 года.

- ^ «Некролог Лоррейн Краус» . Коммерческий призыв . Проверено 7 июля 2023 г.

- ^ «Генная терапия» . WhatIsBiotechnology.org . Фонд образования в области биотехнологии и медицины (Биотехмет) . Проверено 7 июля 2023 г.

- ^ Конгресс США, Управление по оценке технологий (декабрь 1984 г.). Генная терапия человека – Справочный документ . Издательство ДИАНА. ISBN 978-1-4289-2371-3 .

- ^ Сунь М (октябрь 1982 г.). «Мартин Клайн проигрывает апелляцию по гранту НИЗ». Наука . 218 (4567): 37. Бибкод : 1982Sci...218...37S . дои : 10.1126/science.7123214 . ПМИД 7123214 .

- ^ Ловенштейн PR (2008). «Генная терапия неврологических расстройств: новые методы лечения или эксперименты на людях?» . В Берли Дж., Харрис Дж. (ред.). Компаньон генетики . Джон Уайли и сыновья. ISBN 978-0-470-75637-9 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шеридан С. (февраль 2011 г.). «Генная терапия находит свою нишу». Природная биотехнология . 29 (2): 121–128. дои : 10.1038/nbt.1769 . ПМИД 21301435 . S2CID 5063701 .

- ^ О'Мэлли BW, Ледли FD (октябрь 1993 г.). «Соматическая генная терапия. Методы настоящего и будущего». Арка Отоларингол Хирургия головы и шеи . 119 (10): 1100–7. дои : 10.1001/archotol.1993.01880220044007 . ПМИД 8398061 .

- ^ Олдфилд Э.Х., Рэм З., Калвер К.В., Блез Р.М., ДеВрум Х.Л., Андерсон В.Ф. (февраль 1993 г.). «Генная терапия для лечения опухолей головного мозга с использованием внутриопухолевой трансдукции геном тимидинкиназы и внутривенного введения ганцикловира». Генная терапия человека . 4 (1): 39–69. дои : 10.1089/hum.1993.4.1-39 . ПМИД 8384892 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Ричардс С. (6 ноября 2012 г.). «Генная терапия приходит в Европу» . Ученый .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Магуайр А.М., Симонелли Ф., Пирс Э.А., Пью Э.Н., Мингоцци Ф., Бенничелли Дж. и др. (май 2008 г.). «Безопасность и эффективность переноса генов при врожденном амаврозе Лебера» . Медицинский журнал Новой Англии . 358 (21): 2240–2248. doi : 10.1056/NEJMoa0802315 . ПМЦ 2829748 . ПМИД 18441370 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Симонелли Ф., Магуайр А.М., Теста Ф., Пирс Э.А., Мингоцци Ф., Бенничелли Дж.Л. и др. (март 2010 г.). «Генная терапия врожденного амавроза Лебера безопасна и эффективна в течение 1,5 лет после введения вектора» . Молекулярная терапия . 18 (3): 643–650. дои : 10.1038/mt.2009.277 . ПМЦ 2839440 . ПМИД 19953081 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сидециан А.В., Хаусвирт В.В., Алеман Т.С., Каушал С., Шварц С.Б., Бойе С.Л., Виндзор Э.А., Конлон Т.Дж., Сумарока А., Роман А.Дж., Бирн Б.Дж., Джейкобсон С.Г. (август 2009 г.). «Зрение через 1 год после генной терапии врожденного амавроза Лебера» . Медицинский журнал Новой Англии . 361 (7): 725–727. дои : 10.1056/NEJMc0903652 . ПМЦ 2847775 . ПМИД 19675341 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бейнбридж Дж.В., Смит А.Дж., Баркер С.С., Робби С., Хендерсон Р., Балагган К. и др. (май 2008 г.). «Влияние генной терапии на зрительную функцию при врожденном амаврозе Лебера». Медицинский журнал Новой Англии . 358 (21): 2231–2239. doi : 10.1056/NEJMoa0802268 . hdl : 10261/271174 . ПМИД 18441371 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гош П. (28 апреля 2016 г.). «Генная терапия обращает вспять потерю зрения и действует надолго» . Новости BBC онлайн . Проверено 29 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ Фишер А., Хасейн-Бей-Абина С., Каваццана-Кальво М. (июнь 2010 г.). «20 лет генной терапии ТКИН». Природная иммунология . 11 (6): 457–460. дои : 10.1038/ni0610-457 . ПМИД 20485269 . S2CID 11300348 .

- ^ Ферруа Ф, Бригида I, Аюти А (декабрь 2010 г.). «Обновленная информация о генной терапии тяжелого комбинированного иммунодефицита с дефицитом аденозиндезаминазы». Современное мнение в области аллергии и клинической иммунологии . 10 (6): 551–556. doi : 10.1097/ACI.0b013e32833fea85 . ПМИД 20966749 . S2CID 205435278 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Геддес Л. (30 октября 2013 г.). « Успех «ребенка-пузыря» возвращает генную терапию в нужное русло» . Новый учёный . Проверено 2 января 2022 г.

- ^ Картье Н., Обур П. (июль 2010 г.). «Трансплантация гемопоэтических стволовых клеток и генная терапия гемопоэтическими стволовыми клетками при Х-сцепленной адренолейкодистрофии» . Патология головного мозга . 20 (4): 857–862. дои : 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2010.00394.x . ПМЦ 8094635 . ПМИД 20626747 . S2CID 24182017 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Ледфорд Х (2011). «Клеточная терапия борется с лейкемией». Природа . дои : 10.1038/news.2011.472 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Коглан А. (26 марта 2013 г.). «Генная терапия лечит лейкемию за восемь дней» . Новый учёный . Проверено 15 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Коглан А. (11 декабря 2013 г.). «Усиленные иммунные клетки приводят к ремиссии лейкемии» . Новый учёный . Проверено 15 апреля 2013 г.

- ^ Левитт П.А., Резай А.Р., Лихи М.А., Оджеманн С.Г., Флаэрти А.В., Эскандар Э.Н. и др. (апрель 2011 г.). «Генная терапия AAV2-GAD при прогрессирующей болезни Паркинсона: двойное слепое рандомизированное исследование, контролируемое ложной хирургической операцией». «Ланцет». Неврология . 10 (4): 309–319. дои : 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70039-4 . ПМИД 21419704 . S2CID 37154043 .

- ^ Герпер М. (26 марта 2014 г.). «Большое возвращение генной терапии» . Форбс . Проверено 28 апреля 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Пирсон С., Цзя Х., Кандачи К. (январь 2004 г.). «Китай одобряет первую генную терапию» . Природная биотехнология . 22 (1): 3–4. дои : 10.1038/nbt0104-3 . ПМК 7097065 . ПМИД 14704685 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Одобрена генная терапия при ЗПА» . 6 декабря 2011 года . Проверено 5 августа 2015 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Галлахер Дж. (2 ноября 2012 г.). «Генная терапия: Glybera одобрена Европейской Комиссией» . Новости Би-би-си . Проверено 15 декабря 2012 г.

- ^ «Что такое генная терапия?» . Домашний справочник по генетике . 28 марта 2016 г. Архивировано из оригинала 6 апреля 2016 г. Проверено 2 января 2022 г.

- ^ «Как работает генная терапия?» . Домашний справочник по геномике . Национальная медицинская библиотека США.

- ^ Пеццоли Д., Кьеза Р., Де Нардо Л., Кандиани Дж. (сентябрь 2012 г.). «Нам еще предстоит пройти долгий путь до эффективной доставки генов!». Журнал прикладных биоматериалов и функциональных материалов . 10 (2): 82–91. дои : 10.5301/JABFM.2012.9707 . ПМИД 23015375 . S2CID 6283455 .

- ^ Ваннуччи Л., Лай М., Кьюппези Ф., Чеккерини-Нелли Л., Пистелло М. (январь 2013 г.). «Вирусные векторы: взгляд назад и вперед на технологию переноса генов». Новая микробиология . 36 (1): 1–22. ПМИД 23435812 .

- ^ Готелф А., Гейл Дж. (ноябрь 2012 г.). «Что вам всегда нужно было знать о ДНК-вакцинах на основе электропорации» . Человеческие вакцины и иммунотерапия . 8 (11): 1694–1702. дои : 10.4161/hv.22062 . ПМК 3601144 . ПМИД 23111168 .

- ^ Урнов Ф.Д., Ребар Э.Дж., Холмс М.К., Чжан Х.С., Грегори П.Д. (сентябрь 2010 г.). «Редактирование генома с помощью модифицированных нуклеаз с цинковыми пальцами». Обзоры природы Генетика . 11 (9): 636–646. дои : 10.1038/nrg2842 . ПМИД 20717154 . S2CID 205484701 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бак Р.О., Гомес-Оспина Н., Портеус М.Х. (август 2018 г.). «Редактирование генов в центре внимания». Тенденции в генетике . 34 (8): 600–611. дои : 10.1016/j.tig.2018.05.004 . ПМИД 29908711 . S2CID 49269023 .

- ^ Стоун Д., Нийонзима Н., Джером КР (сентябрь 2016 г.). «Редактирование генома и противовирусная терапия нового поколения» . Генетика человека . 135 (9): 1071–82. дои : 10.1007/s00439-016-1686-2 . ПМЦ 5002242 . ПМИД 27272125 .

- ^ Кросс Д., Бурместер Дж.К. (сентябрь 2006 г.). «Генная терапия для лечения рака: прошлое, настоящее и будущее» . Клиническая медицина и исследования . 4 (3): 218–27. дои : 10.3121/cmr.4.3.218 . ПМК 1570487 . ПМИД 16988102 .

- ^ Медер М.Л., Герсбах, Калифорния (март 2016 г.). «Технологии редактирования генома для генной и клеточной терапии» . Молекулярная терапия . 24 (3): 430–46. дои : 10.1038/mt.2016.10 . ПМЦ 4786923 . ПМИД 26755333 .

- ^ «Испытания показывают, что ученые впервые осуществили редактирование генов «в организме» . АП НОВОСТИ . 7 февраля 2019 года . Проверено 17 ноября 2020 г.

- ^ «Первая дозировка CRISPR-терапии» . Природная биотехнология . 38 (4): 382. 1 апреля 2020 г. doi : 10.1038/s41587-020-0493-4 . ISSN 1546-1696 . PMID 32265555 . S2CID 215406440 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шерков Дж.С., Зеттлер П.Дж., Грили Х.Т. (декабрь 2018 г.). «Это «генная терапия»?» . Журнал права и биологических наук . 5 (3): 786–793. дои : 10.1093/jlb/lsy020 . ПМК 6534757 . ПМИД 31143463 .

- ^ Асале А., Чжоу Дж., Рахманян Н. (ноябрь 2022 г.). « Письмо в редакцию: урок на будущее — Как семантическая неоднозначность привела к распространению антинаучных взглядов на мРНК-вакцины от COVID-19» . Генная терапия человека . 33 (21–22): 1213–1216. doi : 10.1089/hum.2022.29223.aas (неактивен 31 января 2024 г.). ПМИД 36375123 .

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI неактивен по состоянию на январь 2024 г. ( ссылка ) - ^ «Эндрю Бриджен неправильно называл мРНК-вакцины генной терапией» . Полный факт . 12 января 2023 г. Проверено 19 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Вакцины Fact Check-mRNA отличаются от генной терапии, которая изменяет гены реципиента» . Рейтер . 10 августа 2021 г. Проверено 19 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Джо Роган ложно утверждает, что мРНК-вакцины — это «генная терапия» » . ПолитиФакт . Проверено 19 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Спенсер С.Х. (28 июня 2022 г.). «Веб-сайт торгует старой, опровергнутой ложью о мРНК-вакцинах против COVID-19» . FactCheck.org . Проверено 19 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Эти эксперты говорят, что Джо Роган «чрезвычайно опасен» для общества – и вот почему» . Независимый . 2 февраля 2022 г. Проверено 19 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ «Ложные заявления депутата Эндрю Бриджена ставят под угрозу жизни людей» . Полный факт . 11 января 2023 г. Проверено 19 февраля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Нобрега К., Мендонса Л., Матос К.А. (2020). Справочник по генной и клеточной терапии . Чам: Спрингер. ISBN 978-3-030-41333-0 . OCLC 1163431307 .

- ^ Уильямс Д.А., Оркин С.Х. (апрель 1986 г.). «Соматическая генная терапия. Современное состояние и перспективы» . Журнал клинических исследований . 77 (4): 1053–6. дои : 10.1172/JCI112403 . ПМЦ 424438 . ПМИД 3514670 .

- ^ Мавилио Ф, Феррари G (июль 2008 г.). «Генетическая модификация соматических стволовых клеток. Развитие, проблемы и перспективы новой терапевтической технологии» . Отчеты ЭМБО . 9 (Приложение 1): S64–69. дои : 10.1038/embor.2008.81 . ПМЦ 3327547 . ПМИД 18578029 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Международное право» . Центр генетики и государственной политики Берманского института биоэтики при Университете Джонса Хопкинса. Архивировано 2010. 2 сентября 2014 года.

- ^ Страчнан Т., Рид AP (2004). Молекулярная генетика человека (3-е изд.). Издательство «Гирлянда». п. 616 . ISBN 978-0-8153-4184-0 .

- ^ Ханна К. (2006). «Перенос генов зародышевой линии» . Национальный институт исследования генома человека.

- ^ «Клонирование человека и генетическая модификация» . Ассоциация представителей репродуктивного здоровья. 2013. Архивировано из оригинала 18 июня 2013 года.

- ^ «Генная терапия» . ama-assn.org . 4 апреля 2014 г. Архивировано из оригинала 15 марта 2015 г. Проверено 22 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «Часто задаваемые вопросы по генной и клеточной терапии | ASGCT — Американское общество генной и клеточной терапии | ASGCT — Американское общество генной и клеточной терапии» . asgct.org . Проверено 23 июля 2021 г.

- ^ «Оценка клинического успеха генной терапии ex vivo и in vivo» . Журнал юных исследователей . Январь 2009 года . Проверено 23 июля 2021 г.

- ^ «Проблемы генной терапии» . Learn.genetics.utah.edu . Проверено 23 июля 2021 г.

- ^ Маллард А. (июнь 2020 г.). «Конвейер редактирования генов набирает обороты». Обзоры природы. Открытие наркотиков . 19 (6): 367–372. дои : 10.1038/d41573-020-00096-y . ПМИД 32415249 . S2CID 218657910 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Макларен Р.Э., Гропп М., Барнард А.Р., Коттриалл С.Л., Толмачева Т., Сеймур Л., Кларк К.Р., Во время MJ, Кремерс Ф.П., Блэк GC, Лотери А.Дж., Даунс С.М., Вебстер А.Р., Сибра MC (март 2014 г.). «Генная терапия сетчатки у пациентов с хоридеремией: первые результаты клинического исследования фазы 1/2» . Ланцет . 383 (9923): 1129–1137. дои : 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62117-0 . ПМК 4171740 . ПМИД 24439297 .

- ^ Девер Д.П., Бак Р.О., Рейниш А., Камарена Дж., Вашингтон Дж., Николас С.Э. и др. (ноябрь 2016 г.). «Нацеливание на ген CRISPR/Cas9 β-глобина в гемопоэтических стволовых клетках человека» . Природа . 539 (7629): 384–389. Бибкод : 2016Natur.539..384D . дои : 10.1038/nature20134 . ПМЦ 5898607 . ПМИД 27820943 .

- ^ Гупта Р.М., Мусунуру К. (октябрь 2014 г.). «Расширение набора инструментов генетического редактирования: ZFN, TALEN и CRISPR-Cas9» . Журнал клинических исследований . 124 (10): 4154–61. дои : 10.1172/JCI72992 . ПМК 4191047 . ПМИД 25271723 .

- ^ Санчес-да-Сильва Г.Н., Медейрос Л.Ф., Лима FM (21 августа 2019 г.). «Потенциальное использование системы CRISPR-Cas для генной терапии ВИЧ-1» . Международный журнал геномики . 2019 : 8458263. doi : 10.1155/2019/8458263 . ПМК 6721108 . ПМИД 31531340 .

- ^ Патент: US7824869B2.

- ^ Би А, Цуй Дж, Ма Ю.П., Ольшевская Е, Пу М, Дижоор А.М., Пан Ж. (апрель 2006 г.). «Эктопическая экспрессия родопсина микробного типа восстанавливает зрительные реакции у мышей с дегенерацией фоторецепторов» . Нейрон . 50 (1): 23–33. дои : 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.026 . ПМК 1459045 . ПМИД 16600853 .