Советско-афганская война

Эта статья может оказаться слишком длинной для удобного чтения и навигации . Когда этот тег был добавлен, его читаемый размер составлял 19 000 слов. ( март 2022 г. ) |

| Советско-афганская война | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Часть холодной войны и афганского конфликта | |||||||

| |||||||

| |||||||

| Воюющие стороны | |||||||

| Командиры и лидеры | |||||||

Суннитские моджахеды :

Шиитские моджахеды :

Маоисты : Другой :

| |||||||

| Задействованные подразделения | |||||||

Военизированные формирования: | Суннитские моджахеды Фракции: Фракции: Фракции: Фракции: Единицы: | ||||||

| Сила | |||||||

| |||||||

| Жертвы и потери | |||||||

| Итого: 242 000–253 000 | Итого: 162 579–192 579+

| ||||||

| Потери среди гражданского населения (афганцы): 1) 1 000 000 погибших [27] 2) 1 500 000 погибших [28] 3) 2 000 000 погибших [29] Всего смертей: Примерно 1–3 миллиона убитых [30] 3 000 000 раненых [31] 5 000 000 вынужденных переселенцев 2 000 000 внутренне перемещенных лиц | |||||||

Советско -афганская война — затяжной вооруженный конфликт, который велся на территории контролируемой Советским Союзом Демократической Республики Афганистан (ДРА) с 1979 по 1989 год. Война была крупным конфликтом «холодной войны», поскольку она стала свидетелем масштабных боевых действий между Советским Союзом, ДРА и союзные военизированные группировки против афганских моджахедов и союзных им иностранных боевиков . Хотя моджахедов поддерживали различные страны и организации, большая часть их поддержки исходила из Пакистана , США (в рамках операции «Циклон »), Великобритании , Китая , Ирана и арабских государств Персидского залива . Участие иностранных держав сделало войну прокси-войной между Соединенными Штатами и Советским Союзом. Бои происходили на протяжении 1980-х годов, в основном в сельской местности Афганистана. Война привела к гибели около 3 000 000 афганцев, а еще миллионы бежали из страны в качестве беженцев; большинство вынужденных переселенцев из Афганистана искали убежища в Пакистане и Иране . По оценкам, примерно от 6,5% до 11,5% бывшего населения Афганистана, составлявшего 13,5 миллионов человек (по переписи 1979 года), были убиты в ходе конфликта. Советско-афганская война вызвала серьезные разрушения по всему Афганистану и также была названа учеными важным фактором, способствовавшим распад Советского Союза , формально положивший конец Холодной войне . Его также часто называют « Вьетнамом Советского Союза ».

В марте 1979 года в Герате произошло жестокое восстание, в ходе которого были казнены несколько советских военных советников. НДПА , которая решила , что не сможет подавить восстание в одиночку, обратилась за срочной советской военной помощью; в 1979 г. было отправлено более 20 запросов. Советский премьер Алексей Косыгин , отказавшись послать войска, в одном из звонков премьер-министру Афганистана Нуру Мухаммаду Тараки посоветовал использовать местных промышленных рабочих в провинции Герат. Очевидно, это было сделано из расчета, что эти рабочие будут сторонниками афганского советского правительства. Далее это обсуждалось в Советском Союзе с широким спектром взглядов, как желающих гарантировать, что Афганистан останется коммунистическим, так и тех, кто был обеспокоен эскалацией войны. В конце концов был достигнут компромисс: отправить военную помощь, но не войска.

Война началась после того, как Советы под командованием Леонида Брежнева начали вторжение в Афганистан, чтобы поддержать местное просоветское правительство, которое было установлено во время операции «Шторм-333» . [номер 1] В ответ международное сообщество ввело в отношении Советского Союза многочисленные санкции и эмбарго. Советские войска оккупировали крупные города Афганистана и все основные транспортные артерии, в то время как моджахеды вели партизанскую войну небольшими группами на 80% территории страны, которая не находилась под неоспоримым советским контролем, и почти исключительно охватывала пересеченную гористую местность сельской местности. Помимо установки миллионов наземных мин по всему Афганистану, Советы использовали свою воздушную мощь для жесткой борьбы как с афганским сопротивлением, так и с гражданским населением, уничтожая деревни, чтобы лишить моджахедов убежища, разрушая жизненно важные оросительные канавы и применяя другие тактики выжженной земли.

Первоначально советское правительство планировало быстро обеспечить безопасность городов и дорожных сетей Афганистана, стабилизировать правительство Народно-демократической партии Афганистана (НДПА) и вывести все ее вооруженные силы в течение периода от шести месяцев до одного года. Однако они встретили ожесточенное сопротивление афганских партизан и испытали большие оперативные трудности на пересеченной горной местности. К середине 1980-х годов советское военное присутствие в Афганистане увеличилось примерно до 115 000 военнослужащих, и боевые действия по всей стране усилились; осложнение военных действий постепенно дорого обошлось Советскому Союзу, поскольку военные, экономические и политические ресурсы все больше истощались. К середине 1987 года советский лидер-реформатор Михаил Горбачев объявил, что советские военные начнут полный вывод войск из Афганистана . Последняя волна разъединения началась 15 мая 1988 года, а 15 февраля 1989 года последняя советская военная колонна, оккупировавшая Афганистан, перешла границу. Узбекская ССР . При продолжающейся внешней советской поддержке правительство НДПА предприняло одиночную военную операцию против моджахедов, и конфликт перерос в гражданскую войну в Афганистане . Однако после распада Советского Союза в декабре 1991 года вся поддержка республики была прекращена, что привело к свержению Партии Родины изолированной республики руками моджахедов в 1992 году и началу новой гражданской войны в Афганистане .

Мы

В Афганистане войну обычно называют Советской войной в Афганистане ( пушту : په افغانستان کې شوروی جګړه , латинизировано: Пах Афганистан ке Шурави Джагера ; дари : جنگ شوروی در افغانس تان , латинизировано: Джанг-э Шурави дар Афганистан ). В России и других странах бывшего Советского Союза ее обычно называют афганской войной ( русский : Афганская война ; украинский : Війна в Афганистани ; белорусский : Афганская вайна ; узбекский : Afgʻon urushi ); иногда ее называют просто « Афган » (русский: Афган ), понимая, что имеется в виду война (точно так же, как Вьетнамскую войну часто называют «Вьетнамом» или просто « Намом» в США ). [35] Он также известен как афганский джихад , особенно среди неафганских добровольцев моджахедов.

Фон

| История Афганистана |

|---|

|

| Хронология |

Этот раздел может содержать чрезмерное количество сложных деталей, которые могут заинтересовать только определенную аудиторию . ( июнь 2024 г. ) |

Интерес России к Центральной Азии

В 19 веке Британская империя опасалась, что Российская империя вторгнется в Афганистан и будет использовать его для угрозы крупным британским колониям в Индии . Это региональное соперничество получило название « Большая игра ». спорный оазис к югу от реки Оксус В 1885 году русские войска захватили у афганских войск , что стало известно как Пандждехский инцидент . Граница была согласована совместной англо-российской афганской пограничной комиссией 1885–1887 годов. Интерес России к Афганистану сохранялся на протяжении всей советской эпохи: в период с 1955 по 1978 год в Афганистан была отправлена экономическая и военная помощь на миллиарды долларов. [36]

После Амануллы-хана восхождения на престол в 1919 году и последующей Третьей англо-афганской войны британцы признали полную независимость Афганистана. Впоследствии король Аманулла написал в Россию (теперь находящуюся под контролем большевиков ), желая установить постоянные дружеские отношения. В ответ Владимир Ленин поздравил афганцев с их защитой от британцев, и в 1921 году был заключен договор о дружбе между Афганистаном и Россией. Советы видели возможности в союзе с Афганистаном против Соединенного Королевства, например, в использовании его в качестве базы для революционное наступление на контролируемую Британией Индию . [37] [38]

Красная Армия вторглась в Афганистан для подавления исламского движения басмачей в 1929 и 1930 годах , поддерживая свергнутого короля Амануллу, в рамках Гражданской войны в Афганистане (1928–1929) . [39] [40] Движение басмачей зародилось в 1916 году в результате восстания против призыва русских на военную службу во время Первой мировой войны , поддержанного турецким генералом Энвер-пашой во время Кавказской кампании . После этого Советская Армия разместила в Средней Азии около 120 000–160 000 военнослужащих, что по размеру соответствовало пиковой численности советской интервенции в Афганистане. [39] К 1926–1928 годам басмачи были в основном разгромлены Советским Союзом, и Средняя Азия вошла в состав Советского Союза. [39] [41] В 1929 году вновь вспыхнуло восстание басмачей, связанное с бунтами против насильственной коллективизации . [39] Басмачи перешли в Афганистан при Ибрагим-беке , что дало повод для интервенций Красной Армии в 1929 и 1930 годах. [39] [40]

Советско-афганские отношения после 1920-х годов

Советский Союз (СССР) был крупным влиятельным посредником и влиятельным наставником в афганской политике , его участие варьировалось от гражданской и военной инфраструктуры до афганского общества. [42] С 1947 года Афганистан находился под влиянием советского правительства и получал большие объемы помощи, экономической помощи, обучения военной технике и военной техники из Советского Союза. Экономическая помощь и помощь были предоставлены Афганистану еще в 1919 году, вскоре после русской революции и когда режим столкнулся с гражданской войной в России . Продовольствие было предоставлено в виде стрелкового оружия , боеприпасов, нескольких самолетов и (согласно обсуждаемым советским источникам) миллиона золотых рублей для поддержки сопротивления во время Третьей англо-афганской войны в 1919 году. В 1942 году СССР снова перешел на укрепить Вооруженные Силы Афганистана путем предоставления стрелкового оружия и авиации и создания учебных центров в Узбекской Ташкенте ССР . Советско-афганское военное сотрудничество началось на регулярной основе в 1956 году, а в 1970-е годы были заключены дальнейшие соглашения, в рамках которых СССР направлял советников и специалистов. Советский Союз также имел интересы в энергетических ресурсах Афганистана, включая разведку нефти и природного газа в 1950-х и 1960-х годах. [43] СССР начал импортировать афганский газ с 1968 года. [44] В период с 1954 по 1977 год Советский Союз предоставил Афганистану экономическую помощь на сумму около 1 миллиарда рублей. [45]

Граница Афганистана и Пакистана

В 19 веке, когда войска царской России приближались к горам Памира , недалеко от границы с Британской Индией, государственный служащий Мортимер Дюран был послан очертить границу, вероятно, для того, чтобы контролировать Хайберский перевал . Результатом демаркации горного региона стало соглашение, подписанное с афганским эмиром Абдур Рахман-ханом в 1893 году. Оно стало известно как « линия Дюранда» . [46]

В 1947 году премьер-министр Королевства Афганистан Мохаммад Дауд Хан отверг линию Дюранда, которая принималась в качестве международной границы сменявшими друг друга афганскими правительствами на протяжении более полувека. [47]

Британское владычество также подошло к концу, и Доминион Пакистан получил независимость от Британской Индии и унаследовал линию Дюрана в качестве границы с Афганистаном.

При режиме Дауда Хана Афганистан имел враждебные отношения как с Пакистаном, так и с Ираном. [48] [49] Как и все предыдущие афганские правители с 1901 года, Дауд Хан также хотел подражать эмиру Абдур Рахман-хану и объединить свою разделенную страну.

Для этого ему нужно было народное дело, объединяющее афганский народ, разделенный по племенному признаку, а также современную, хорошо оснащенную афганскую армию, которая будет использоваться для подавления любого, кто будет выступать против афганского правительства. Его политика в отношении Пуштунистана заключалась в аннексии пуштунских территорий Пакистана, и он использовал эту политику в своих интересах. [49]

Дауда Хана, Ирредентистская внешняя политика направленная на воссоединение родины пуштунов, вызвала большую напряженность в отношениях с Пакистаном, государством, которое вступило в союз с Соединенными Штатами. [49] Эта политика также вызвала возмущение непуштунского населения Афганистана. [50] Точно так же пуштуны в Пакистане также не были заинтересованы в аннексии их территорий Афганистаном. [51] В 1951 году Госдепартамент США призвал Афганистан отказаться от претензий к Пакистану и принять «линию Дюрана». [52]

1960–1970-е: Прокси-война

В 1954 году Соединенные Штаты начали продавать оружие своему союзнику Пакистану, одновременно отклонив просьбу Афганистана о покупке оружия из-за опасений, что афганцы будут использовать это оружие против Пакистана. [52] Как следствие, Афганистан, хотя официально был нейтральным в холодной войне, сблизился с Индией и Советским Союзом, которые были готовы продавать ему оружие. [52] В 1962 году Китай победил Индию в приграничной войне , и в результате Китай сформировал союз с Пакистаном против их общего врага, Индии, подталкивая Афганистан еще ближе к Индии и Советскому Союзу.

В 1960 и 1961 годах афганская армия по приказу Дауда Хана, следуя его политике пуштунского ирредентизма , совершила два безуспешных вторжения в пакистанский округ Баджаур . В обоих случаях афганская армия была разгромлена , понеся тяжелые потери. [53] В ответ Пакистан закрыл свое консульство в Афганистане и заблокировал все торговые пути через пакистано-афганскую границу. Это нанесло ущерб экономике Афганистана, и режим Дауда был вынужден стремиться к более тесному торговому союзу с Советским Союзом. Однако этих временных мер оказалось недостаточно, чтобы компенсировать потери, понесенные экономикой Афганистана из-за закрытия границы. В результате продолжающегося недовольства автократическим правлением Дауда, тесных связей с Советским Союзом и экономического спада Дауд Хан был вынужден уйти в отставку король Афганистана Мохаммед Захир Шах . После его отставки кризис между Пакистаном и Афганистаном был разрешен, и Пакистан вновь открыл торговые пути. [53] После смещения Дауда Хана король назначил нового премьер-министра и начал создавать баланс в отношениях Афганистана с Западом и Советским Союзом. [53] что возмутило Советский Союз. [51]

Государственный переворот 1973 года

В 1973 году Дауд Хан при поддержке обученных в Советском Союзе офицеров афганской армии отобрал власть у короля в результате бескровного переворота и основал первую афганскую республику . [53] После своего возвращения к власти Дауд возобновил свою политику в отношении Пуштунистана и впервые начал опосредованную войну против Пакистана. [54] поддерживая антипакистанские группировки и предоставляя им оружие, обучение и убежища. [51] Правительство Пакистана во главе с премьер-министром Зульфикаром Али Бхутто было встревожено этим. [55] Советский Союз также поддержал воинственность Дауда Хана против Пакистана. [51] поскольку они хотели ослабить Пакистан, который был союзником как США, так и Китая. Однако он не пытался открыто создать проблемы для Пакистана, поскольку это нанесло бы ущерб отношениям Советского Союза с другими исламскими странами, поэтому он полагался на Дауда Хана, чтобы ослабить Пакистан. То же самое они думали и относительно Ирана, еще одного крупного союзника США. Советский Союз также считал, что враждебное поведение Афганистана по отношению к Пакистану и Ирану может оттолкнуть Афганистан от Запада, и Афганистан будет вынужден вступить в более тесные отношения с Советским Союзом. [56] Просоветские афганцы (такие как Народно-демократическая партия Афганистана (НДПА)) также поддерживали враждебность Дауда Хана по отношению к Пакистану, поскольку они считали, что конфликт с Пакистаном побудит Афганистан обратиться за помощью к Советскому Союзу. В результате просоветские афганцы смогут установить свое влияние в Афганистане. [57]

В ответ на опосредованную войну в Афганистане Пакистан начал поддерживать афганцев, критиковавших политику Дауда Хана. Бхутто санкционировал тайную операцию под командованием Насируллы МИ генерал-майора Бабара . [58] В 1974 году Бхутто санкционировал еще одну секретную операцию в Кабуле , в ходе которой Межведомственная разведка (ISI) и Воздушная разведка Пакистана (AI) экстрадировали Бурхануддина Раббани , Гульбеддина Хекматияра и Ахмад Шаха Масуда в Пешавар на фоне опасений, что Раббани, Хекматияр и Масуд могут быть убит Даудом. [58] По словам Бабера, операция Бхутто была отличной идеей и оказала сильное влияние на Дауда и его правительство, что заставило Дауда усилить свое желание заключить мир с Бхутто. [58] Целью Пакистана было свержение режима Дауда и установление на его месте исламистской теократии. [59] Первая операция ISI в Афганистане состоялась в 1975 году. [60] поддержка боевиков партии «Джамиат-и Ислами» во главе с Ахмад Шахом Масудом, пытающихся свергнуть правительство. Они начали свое восстание в долине Панджшера , но отсутствие поддержки, а также правительственные силы, легко разгромившие их, привели к тому, что оно потерпело неудачу, и значительная часть повстанцев нашла убежище в Пакистане, где они пользовались поддержкой правительства Бхутто. [55] [57]

Восстание 1975 года, хотя и безуспешное, потрясло президента Дауда Хана и заставило его осознать, что дружественный Пакистан отвечает его интересам. [60] [57] Он начал улучшать отношения с Пакистаном и совершил государственные визиты туда в 1976 и 1978 годах. Во время визита 1978 года он согласился прекратить поддержку антипакистанских боевиков и изгнать всех оставшихся боевиков в Афганистане. В 1975 году Дауд Хан основал свою собственную партию – Национально-революционную партию Афганистана – и объявил вне закона все остальные партии. Затем он начал отстранять членов крыла Парчама от правительственных постов, в том числе тех, кто поддержал его переворот, и начал заменять их знакомыми лицами из традиционной правительственной элиты Кабула. Дауд также начал снижать свою зависимость от Советского Союза. В результате действий Дауда отношения Афганистана с Советским Союзом ухудшились. [51] В 1978 году, став свидетелем ядерного испытания Индии « Улыбающийся Будда» Пакистана , Дауд Хан инициировал наращивание военной мощи, чтобы противостоять вооруженным силам и военному влиянию Ирана в афганской политике.

Саурская революция 1978 года.

ее . основания Сила Марксистской Народно-Демократической партии Афганистана значительно возросла после В 1967 году НДПА раскололась на две конкурирующие фракции: фракцию «Хальк» («Массы»), возглавляемую Нур Мухаммадом Тараки , и фракцию «Парчам» («Флаг»), возглавляемую Бабраком Кармалем . [61] [62] Символическим разным происхождением двух фракций был тот факт, что отец Тараки был бедным пуштуном-пастухом, а отец Кармаля был таджикским генералом Королевской афганской армии. [62] Что еще более важно, радикальная фракция Хальк верила в быстрое преобразование Афганистана, при необходимости даже с применением насилия, из феодальной системы в коммунистическое общество, в то время как умеренная фракция Парчама выступала за более постепенный и мягкий подход, утверждая, что Афганистан просто не готов к коммунизму. и не будет в течение некоторого времени. [62] Фракция Парчама выступала за создание НДПА как массовой партии в поддержку правительства Дауда Хана, в то время как фракция Хальк была организована в ленинском стиле как небольшая, хорошо организованная элитная группа, что позволяло последней иметь превосходство над первой. [62] В 1971 году посольство США в Кабуле сообщило, что в стране растет активность левых сил, что объясняется разочарованием в социальных и экономических условиях и плохой реакцией со стороны руководства Королевства. Он добавил, что НДПА была «пожалуй, самой недовольной и организованной из левых групп страны». [63]

Острая оппозиция со стороны фракций НДПА была вызвана репрессиями, наложенными на них режимом Дауда, и смертью ведущего члена НДПА Мира Акбара Хайбера . [64] Загадочные обстоятельства смерти Хайбера спровоцировали массовые демонстрации против Дауда в Кабуле , в результате которых были арестованы несколько видных лидеров НДПА. [65] 27 апреля 1978 года афганская армия , симпатизировавшая делу НДПА, свергла и казнила Дауда вместе с членами его семьи. [66] Финский ученый Раймо Вяйринен писал о так называемой «Саурской революции»: «Существует множество предположений относительно истинной природы этого переворота. Реальность такова, что он был вызван, прежде всего, внутренними экономическими и политическими проблемами и что Советский Союз не сыграл никакой роли в Саурской революции». [59] После этого была образована Демократическая Республика Афганистан (ДРА). Нур Мухаммад Тараки, генеральный секретарь Народно-демократической партии Афганистана, стал председателем Революционного совета и председателем Совета министров недавно созданной Демократической Республики Афганистан. 5 декабря 1978 года был подписан договор о дружбе между Советским Союзом и Афганистаном. [67]

«Красный террор» революционного правительства

«Нам нужен только один миллион человек, чтобы совершить революцию. Неважно, что произойдет с остальными. Нам нужна земля, а не люди».

- Объявление из Халкиста радиопередачи после апрельского переворота 1978 года в Афганистане. [68]

После революции Тараки взял на себя руководство, пост премьер-министра и генерального секретаря НДПА. Как и раньше в партии, правительство никогда не называло себя « коммунистическим ». [69] Правительство было разделено по фракционному принципу: Тараки и заместитель премьер-министра Хафизулла Амин из фракции Хальк противостояли лидерам Парчама, таким как Бабрак Кармаль. Хотя новый режим сразу же вступил в союз с Советским Союзом, многие советские дипломаты полагали, что планы Халки по преобразованию Афганистана спровоцируют восстание широких слоев населения, которое было социально и религиозно консервативным. [62] Сразу после прихода к власти Халкис начали преследовать Парчами, не в последнюю очередь потому, что Советский Союз отдавал предпочтение фракции Парчами, чьи планы «действовать медленно» считались более подходящими для Афганистана, тем самым вынуждая Халкис устранять своих соперников, поэтому У Советов не было бы другого выбора, кроме как поддержать их. [70] Внутри НДПА конфликты привели к изгнанию , чисткам и казням членов Парчама. [71] в штате Хальк было казнено от 10 000 до 27 000 человек, в основном в тюрьме Пули-Чархи . До советской интервенции [72] [73] По оценкам политолога Оливье Роя , в период Тараки-Амина пропало от 50 000 до 100 000 человек: [74]

В стране есть только одна ведущая сила – Хафизулла Амин. В Политбюро все боятся Амина.

В течение первых 18 месяцев своего правления НДПА применяла программу модернизации реформ в советском стиле, многие из которых консерваторы считали противоречащими исламу. [76] Указы, устанавливающие изменения в брачных обычаях и земельной реформе, не были хорошо приняты населением, глубоко погруженным в традиции и ислам, особенно влиятельными землевладельцами, которым был нанесен экономический ущерб в результате отмены ростовщичества (хотя ростовщичество запрещено в исламе) и отмены фермерских долги. Новое правительство также расширило права женщин, стремилось к быстрой ликвидации неграмотности и способствовало развитию этнических меньшинств Афганистана, хотя эти программы, похоже, возымели эффект только в городских районах. [77] К середине 1978 года началось восстание, когда повстанцы атаковали местный военный гарнизон в районе Нуристан на востоке Афганистана, и вскоре гражданская война распространилась по всей стране. В сентябре 1979 года заместитель премьер-министра Хафизулла Амин захватил власть, арестовав и убив Тараки. Более двух месяцев нестабильности охватили режим Амина, когда он выступил против своих оппонентов в НДПА и растущего восстания.

Дела с СССР после революции

Еще до прихода революционеров к власти Афганистан был «военно и политически нейтральной страной, фактически зависимой от Советского Союза». [63] Договор, подписанный в декабре 1978 года, позволял Демократической Республике обращаться к Советскому Союзу за военной поддержкой. [78]

Мы считаем, что ввод наземных войск был бы фатальной ошибкой. [...] Если бы наши войска вошли, ситуация в вашей стране не улучшится. Наоборот, будет еще хуже. Нашим войскам пришлось бы бороться не только с внешним агрессором, но и со значительной частью собственного народа. И народ никогда бы такого не простил.

- Алексей Косыгин, Председатель Совета Министров СССР, в ответ на просьбу Тараки о советском присутствии в Афганистане. [79]

После восстания в Герате , ставшего первым серьезным признаком сопротивления режиму, генеральный секретарь Тараки [80] связался с Алексеем Косыгиным и председателем Совета Министров СССР попросил «практической и технической помощи людьми и вооружением». Косыгин не поддержал это предложение из-за негативных политических последствий, которые такое действие могло бы иметь для его страны, и отверг все дальнейшие попытки Тараки заручиться советской военной помощью в Афганистане. [81] После отказа Косыгина Тараки обратился за помощью к Леониду Брежневу , генеральному секретарю Коммунистической партии Советского Союза и главе советского государства , который предупредил Тараки, что полное советское вмешательство «только сыграет на руку нашим врагам – как вашим, так и нашим». ". Брежнев также посоветовал Тараки смягчить радикальные социальные реформы и искать более широкую поддержку своего режима. [82]

В 1979 году Тараки присутствовал на конференции Движения неприсоединения в Гаване , Куба. На обратном пути он 20 марта остановился в Москве и встретился с Брежневым, министром иностранных дел СССР Андреем Громыко и другими советскими официальными лицами. Ходили слухи, что Кармаль присутствовал на встрече в попытке примирить фракцию Тараки Хальк и Парчам против Амина и его последователей. На встрече Тараки удалось договориться о некоторой советской поддержке, включая передислокацию двух советских вооруженных дивизий на советско-афганской границе, отправку 500 военных и гражданских советников и специалистов, а также немедленную поставку советской вооруженной техники, проданной по 25-процентной цене. ниже первоначальной цены; однако Советы были недовольны развитием событий в Афганистане, и Брежнев внушил Тараки необходимость партийного единства. Несмотря на достижение этого соглашения с Тараки, Советы по-прежнему не хотели продолжать дальнейшее вмешательство в Афганистане и неоднократно отказывались от советского военного вмешательства в пределах афганских границ во время правления Тараки, а также позже во время недолгого правления Амина. [83]

Ленин учил нас быть беспощадными к врагам революции, и необходимо было уничтожить чтобы обеспечить победу Октябрьской революции, миллионы людей .

- Ответ Тараки советскому послу Александру Пузанову, который просил Тараки пощадить двух паршамитов, приговоренных к смертной казни. [84]

Режим Тараки и Амина даже пытался устранить лидера Парчама Бабрака Кармаля. После освобождения от обязанностей посла он остался в Чехословакии в изгнании, опасаясь за свою жизнь, если он вернется по требованию режима. Он и его семья находились под защитой Чехословацкой СтБ ; В файлах за январь 1979 года содержится информация о том, что Афганистан отправил шпионов AGSA в Чехословакию, чтобы найти и убить Кармаля. [85]

Начало восстания

В 1978 году правительство Тараки инициировало ряд реформ, включая радикальную модернизацию традиционного исламского гражданского права, особенно закона о браке, направленного на «искоренение феодализма » в афганском обществе. [86] [ нужна страница ] Правительство не терпело сопротивления реформам. [71] и ответил насилием на беспорядки. В период с апреля 1978 года до советской интервенции в декабре 1979 года тысячи заключенных, возможно, около 27 000, были казнены в печально известной тюрьме. [73] Pul-e-Charkhi prison, including many village mullahs and headmen.[72] Other members of the traditional elite, the religious establishment and intelligentsia fled the country.[72]

Large parts of the country went into open rebellion. The Parcham Government claimed that 11,000 were executed during the Amin/Taraki period in response to the revolts.[87] The revolt began in October among the Nuristani tribes of the Kunar Valley in the northeastern part of the country near the border with Pakistan, and rapidly spread among the other ethnic groups. By the spring of 1979, 24 of the 28 provinces had suffered outbreaks of violence.[88][89] The rebellion began to take hold in the cities: in March 1979 in Herat, rebels led by Ismail Khan revolted. Between 3,000 and 5,000 people were killed and wounded during the Herat revolt. Some 100 Soviet citizens and their families were killed.[90][91] By August 1979, up to 165,000 Afghans had fled across the border to Pakistan.[92] The main reason the revolt spread so widely was the disintegration of the Afghan army in a series of insurrections.[93] The numbers of the Afghan army fell from 110,000 men in 1978 to 25,000 by 1980.[94] The U.S. embassy in Kabul cabled to Washington the army was melting away "like an ice floe in a tropical sea".[95] According to scholar Gilles Dorronsoro, it was the violence of the state rather than its reforms that caused the uprisings.[96]

Pakistan–U.S. relations and rebel aid

Pakistani intelligence officials began privately lobbying the U.S. and its allies to send materiel assistance to the Islamist rebels. Pakistani President Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq's ties with the U.S. had been strained during Jimmy Carter's presidency due to Pakistan's nuclear program and the execution of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in April 1979, but Carter told National Security Adviser Zbigniew Brzezinski and Secretary of State Cyrus Vance as early as January 1979 that it was vital to "repair our relationships with Pakistan" in light of the unrest in Iran.[97] According to former Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) official Robert Gates, "the Carter administration turned to CIA ... to counter Soviet and Cuban aggression in the Third World, particularly beginning in mid-1979." In March 1979, "CIA sent several covert action options relating to Afghanistan to the SCC [Special Coordination Committee]" of the United States National Security Council. At a 30 March meeting, U.S. Department of Defense representative Walter B. Slocombe "asked if there was value in keeping the Afghan insurgency going, 'sucking the Soviets into a Vietnamese quagmire?'"[98] When asked to clarify this remark, Slocombe explained: "Well, the whole idea was that if the Soviets decided to strike at this tar baby [Afghanistan] we had every interest in making sure that they got stuck."[99] Yet a 5 April memo from National Intelligence Officer Arnold Horelick warned: "Covert action would raise the costs to the Soviets and inflame Moslem opinion against them in many countries. The risk was that a substantial U.S. covert aid program could raise the stakes and induce the Soviets to intervene more directly and vigorously than otherwise intended."[98]

In May 1979, U.S. officials secretly began meeting with rebel leaders through Pakistani government contacts.[63] After additional meetings Carter signed two presidential findings in July 1979 permitting the CIA to spend $695,000 on non-military assistance (e.g., "cash, medical equipment, and radio transmitters") and on a propaganda campaign targeting the Soviet-backed leadership of the DRA, which (in the words of Steve Coll) "seemed at the time a small beginning."[100][101]

Soviet deployment, 1979

The Amin government, having secured a treaty in December 1978 that allowed them to call on Soviet forces, repeatedly requested the introduction of troops in Afghanistan in the spring and summer of 1979. They requested Soviet troops to provide security and to assist in the fight against the mujahideen ("Those engaged in jihad") rebels. After the killing of Soviet technicians in Herat by rioting mobs, the Soviet government sold several Mi-24 helicopters to the Afghan military. On 14 April 1979, the Afghan government requested that the USSR send 15 to 20 helicopters with their crews to Afghanistan, and on 16 June, the Soviet government responded and sent a detachment of tanks, BMPs, and crews to guard the government in Kabul and to secure the Bagram and Shindand air bases. In response to this request, an airborne battalion, commanded by Lieutenant Colonel A. Lomakin, arrived at Bagram on 7 July. They arrived without their combat gear, disguised as technical specialists. They were the personal bodyguards for General Secretary Taraki. The paratroopers were directly subordinate to the senior Soviet military advisor and did not interfere in Afghan politics. Several leading politicians at the time such as Alexei Kosygin and Andrei Gromyko were against intervention.

After a month, the Afghan requests were no longer for individual crews and subunits, but for regiments and larger units. In July, the Afghan government requested that two motorized rifle divisions be sent to Afghanistan. The following day, they requested an airborne division in addition to the earlier requests. They repeated these requests and variants to these requests over the following months right up to December 1979. However, the Soviet government was in no hurry to grant them.

We should tell Taraki and Amin to change their tactics. They still continue to execute those people who disagree with them. They are killing nearly all of the Parcham leaders, not only the highest rank, but of the middle rank, too.

– Kosygin speaking at a Politburo session.[102]

Based on information from the KGB, Soviet leaders felt that Prime Minister Hafizullah Amin's actions had destabilized the situation in Afghanistan. Following his initial coup against and killing of Taraki, the KGB station in Kabul warned Moscow that Amin's leadership would lead to "harsh repressions, and as a result, the activation and consolidation of the opposition."[103]

The Soviets established a special commission on Afghanistan, comprising the KGB chairman Yuri Andropov, Boris Ponomarev from the Central Committee and Dmitry Ustinov, the Minister of Defence. In late April 1979, the committee reported that Amin was purging his opponents, including Soviet loyalists, that his loyalty to Moscow was in question and that he was seeking diplomatic links with Pakistan and possibly the People's Republic of China (which at the time had poor relations with the Soviet Union). Of specific concern were Amin's supposed meetings with the U.S. chargé d'affaires, J. Bruce Amstutz, which were used as a justification for the invasion by the Kremlin.[104][105][106]

Information forged by the KGB from its agents in Kabul provided the last arguments to eliminate Amin. Supposedly, two of Amin's guards killed the former General Secretary Nur Muhammad Taraki with a pillow, and Amin himself was portrayed as a CIA agent. The latter is widely discredited, with Amin repeatedly demonstrating friendliness toward the various delegates of the Soviet Union in Afghanistan and maintaining the pro-Soviet line.[107] Soviet General Vasily Zaplatin, a political advisor of Premier Brezhnev at the time, claimed that four of General Secretary Taraki's ministers were responsible for the destabilization. However, Zaplatin failed to emphasize this in discussions and was not heard.[108]

During meetings between General Secretary Taraki and Soviet leaders in March 1979, the Soviets promised political support and to send military equipment and technical specialists, but upon repeated requests by Taraki for direct Soviet intervention, the leadership adamantly opposed him; reasons included that they would be met with "bitter resentment" from the Afghan people, that intervening in another country's civil war would hand a propaganda victory to their opponents, and Afghanistan's overall inconsequential weight in international affairs, in essence realizing they had little to gain by taking over a country with a poor economy, unstable government, and population hostile to outsiders. However, as the situation continued to deteriorate from May–December 1979, Moscow changed its mind on dispatching Soviet troops. The reasons for this complete turnabout are not entirely clear, and several speculative arguments include: the grave internal situation and inability for the Afghan government to retain power much longer; the effects of the Iranian Revolution that brought an Islamic theocracy into power, leading to fears that religious fanaticism would spread through Afghanistan and into Soviet Muslim Central Asian republics; Taraki's murder and replacement by Amin, who the Soviet leadership believed had secret contacts within the American embassy in Kabul and "was capable of reaching an agreement with the United States";[109] however, allegations of Amin colluding with the Americans have been widely discredited and it was revealed in the 1990s that the KGB actually planted the story;[107][105][106] and the deteriorating ties with the United States after NATO's two-track missile deployment decision in response to Soviet nuclear presence in Eastern Europe and the failure of Congress to ratify the SALT II treaty, creating the impression that détente was "already effectively dead."[110]

The British journalist Patrick Brogan wrote in 1989: "The simplest explanation is probably the best. They got sucked into Afghanistan much as the United States got sucked into Vietnam, without clearly thinking through the consequences, and wildly underestimating the hostility they would arouse".[111] By the fall of 1979, the Amin regime was collapsing with morale in the Afghan Army having fallen to rock-bottom levels, while the mujahideen had taken control of much of the countryside. The general consensus amongst Afghan experts at the time was that it was not a question of if, but when the mujahideen would take Kabul.[111]

In October 1979, a KGB Spetsnaz force Zenith covertly dispatched a group of specialists to determine the potential reaction from local Afghans to a presence of Soviet troops there. They concluded that deploying troops would be unwise and could lead to war, but this was reportedly ignored by the KGB chairman Yuri Andropov. A Spetsnaz battalion of Central Asian troops, dressed in Afghan Army uniforms, was covertly deployed to Kabul between 9 and 12 November 1979. They moved a few days later to the Tajbeg Palace, where Amin was moving to.[75]

In Moscow, Leonid Brezhnev was indecisive and waffled as he usually did when faced with a difficult decision.[112] The three decision-makers in Moscow who pressed the hardest for an invasion in the fall of 1979 were the troika consisting of Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko; the Chairman of KGB, Yuri Andropov, and the Defense Minister Marshal Dmitry Ustinov.[112] The principal reasons for the invasion were the belief in Moscow that Amin was a leader both incompetent and fanatical who had lost control of the situation, together with the belief that it was the United States via Pakistan who was sponsoring the Islamist insurgency in Afghanistan.[112] Andropov, Gromyko and Ustinov all argued that if a radical Islamist regime came to power in Kabul, it would attempt to sponsor radical Islam in Soviet Central Asia, thereby requiring a preemptive strike.[112] What was envisioned in the fall of 1979 was a short intervention under which Moscow would replace radical Khalqi Communist Amin with the moderate Parchami Communist Babrak Karmal to stabilize the situation.[112] Contrary to the contemporary view of Brzezinski and the regional powers, access to the Persian Gulf played no role in the decision to intervene on the Soviet side.[113][114]

The concerns raised by the Chief of the Soviet Army General Staff, Marshal Nikolai Ogarkov who warned about the possibility of a protracted guerrilla war, were dismissed by the troika who insisted that any occupation of Afghanistan would be short and relatively painless.[112] Most notably, though the diplomats of the Narkomindel at the Embassy in Kabul and the KGB officers stationed in Afghanistan were well informed about the developments in that country, such information rarely filtered through to the decision-makers in Moscow who viewed Afghanistan more in the context of the Cold War rather than understanding Afghanistan as a subject in its own right.[115] The viewpoint that it was the United States that was fomenting the Islamic insurgency in Afghanistan with the aim of destabilizing Soviet-dominated Central Asia tended to downplay the effects of an unpopular Communist government pursuing policies that the majority of Afghans violently disliked as a generator of the insurgency and strengthened those who argued some sort of Soviet response was required to a supposed "outrageous American provocation."[115] It was assumed in Moscow that because Pakistan (an ally of both the United States and China) was supporting the mujahideen that therefore it was ultimately the United States and China who were behind the rebellion in Afghanistan.

Amin's revolutionary government had lost credibility with virtually all of the Afghan population. A combination of chaotic administration, excessive brutality from the secret police, unpopular domestic reforms, and a deteriorating economy, along with public perceptions that the state was atheistic and anti-Islamic, all added to the government's unpopularity. After 20 months of Khalqist rule, the country deteriorated in almost every facet of life. The Soviet Union believed that without intervention, Amin's government would have been disintegrated by the resistance and the country would have been "lost" to a regime most likely hostile to the USSR.[116]

Soviet invasion and palace coup

On 31 October 1979, Soviet informants under orders from the inner circle of advisors around Soviet General Secretary Leonid Brezhnev relayed information to the Afghan Armed Forces for them to undergo maintenance cycles for their tanks and other crucial equipment. Meanwhile, telecommunications links to areas outside of Kabul were severed, isolating the capital.

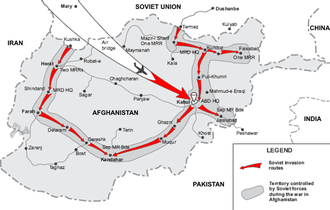

The Soviet 40th Army launched its initial incursion into Afghanistan on 25 December under the pretext of extending "international aid" to its puppet Democratic Republic of Afghanistan. On 25 December, Soviet Defence Minister Dmitry Ustinov issued an official order, stating that "[t]he state frontier of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan is to be crossed on the ground and in the air by forces of the 40th Army and the Air Force at 15:00 hrs on 25 December". This was the formal beginning of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan.[117] Subsequently, on December 27, Soviet troops arrived at Kabul International Airport, causing a stir among the city's residents.[118]

Simultaneously, Amin moved the offices of the General Secretary to the Tajbeg Palace, believing this location to be more secure from possible threats. According to Colonel General Tukharinov and Merimsky, Amin was fully informed of the military movements, having requested Soviet military assistance to northern Afghanistan on 17 December.[119][120] His brother and General Dmitry Chiangov met with the commander of the 40th Army before Soviet troops entered the country, to work out initial routes and locations for Soviet troops.[119]

On 27 December 1979, 700 Soviet troops dressed in Afghan uniforms, including KGB and GRU special forces officers from the Alpha Group and Zenith Group, occupied major governmental, military and media buildings in Kabul, including their primary target, the Tajbeg Palace. The operation began at 19:00, when the KGB-led Soviet Zenith Group destroyed Kabul's communications hub, paralyzing Afghan military command. At 19:15, the assault on Tajbeg Palace began; as planned, General Secretary Hafizullah Amin was assassinated. Simultaneously, other key buildings were occupied (e.g., the Ministry of Interior Affairs at 19:15). The operation was fully complete by the morning of 28 December 1979.

The Soviet military command at Termez, Uzbek SSR, announced on Radio Kabul that Afghanistan had been "liberated" from Amin's rule. According to the Soviet Politburo, they were complying with the 1978 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation and Good Neighborliness, and Amin had been "executed by a tribunal for his crimes" by the Afghan Revolutionary Central Committee. That committee then installed former Deputy Prime Minister Babrak Karmal as head of government, who had been demoted to the relatively insignificant post of ambassador to Czechoslovakia following the Khalq takeover and announced that it had requested Soviet military assistance.[121]

Soviet ground forces, under the command of Marshal Sergey Sokolov, entered Afghanistan from the north on 27 December. In the morning, the 103rd Guards 'Vitebsk' Airborne Division landed at the airport at Bagram and the deployment of Soviet troops in Afghanistan was underway. The force that entered Afghanistan, in addition to the 103rd Guards Airborne Division, was under command of the 40th Army and consisted of the 108th and 5th Guards Motor Rifle Divisions, the 860th Separate Motor Rifle Regiment, the 56th Separate Airborne Assault Brigade, and the 36th Mixed Air Corps. Later on, the 201st and 68th Motor Rifle Divisions also entered the country, along with other smaller units.[122] In all, the initial Soviet force was around 1,800 tanks, 80,000 soldiers and 2,000 AFVs. In the second week alone, Soviet aircraft had made a total of 4,000 flights into Kabul.[123] With the arrival of the two later divisions, the total Soviet force rose to over 100,000 personnel.

As part of Baikal-79, a larger operation aimed at taking 20 key strongholds in and around Kabul, the Soviet 105th Airborne Division secured the city and disarmed Afghan Army units without facing opposition. On 1 January 1980, Soviet paratroopers ordered the 26th Airborne Regiment in Bala Hissar to disarm, only for them to refuse and fire upon the Soviets as a firefight ensued.[124] The Soviet paratroopers annihilated most of the regiment, with 700 Afghan paratroopers being killed or captured. In the aftermath of the battle, 26th Airborne Regiment was disbanded and later reorganized into the 37th Commando Brigade, led by Col. Shahnawaz Tanai, being the largest commando formation at a strength of three battalions.[125] As a result of the battle with the 26th Airborne Regiment, the Soviet 357th Guards Airborne Regiment were permanently stationed in Bala Hissar fortress, meaning this new brigade was stationed as Rishkhor Garrison In the same year, the 81st Artillery Brigade was given airborne training and converted into the 38th Commando Brigade, stationed in Mahtab Qala (lit. Moonlit Fortress) garrison southwest of Kabul under the command of Brig. Tawab Khan.[124]

International positions on Soviet invasion

The invasion of a practically defenseless country was shocking for the international community, and caused a sense of alarm for its neighbor Pakistan.[126] Foreign ministers from 34 Muslim-majority countries adopted a resolution which condemned the Soviet intervention and demanded "the immediate, urgent and unconditional withdrawal of Soviet troops" from the Muslim nation of Afghanistan.[127] Soviet military activities were met with strong criticism internationally, including some of its allied states at the UN General Assembly.[128] The UN General Assembly passed a resolution protesting the Soviet intervention in Afghanistan by a vote of 104–18.[129] According to political scientist Gilles Kepel, the Soviet intervention or invasion was viewed with "horror" in the West, considered to be a fresh twist on the geo-political "Great Game" of the 19th century in which Britain feared that Russia sought access to the Indian Ocean, and posed a threat to Western security, explicitly violating the world balance of power agreed upon at Yalta in 1945.[130]

The general feeling in the United States was that inaction against the Soviet Union could encourage Moscow to go further in its international ambitions.[126] President Jimmy Carter placed a trade embargo against the Soviet Union on shipments of commodities such as grain, while also leading a 66-nation boycott of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow. The invasion, along with other concurrent events such as the Iranian Revolution and the hostage stand-off that accompanied it showed the volatility of the wider region for U.S. foreign policy:

Massive Soviet military forces have invaded the small, nonaligned, sovereign nation of Afghanistan, which had hitherto not been an occupied satellite of the Soviet Union. [...] This is a callous violation of international law and the United Nations Charter. [...] If the Soviets are encouraged in this invasion by eventual success, and if they maintain their dominance over Afghanistan and then extend their control to adjacent countries, the stable, strategic, and peaceful balance of the entire world will be changed. This would threaten the security of all nations including, of course, the United States, our allies, and our friends.

— U.S. President Jimmy Carter during the Address to the Nation, January 4, 1980[131]

Carter also withdrew the SALT-II treaty from consideration before the Senate,[132] recalled the US Ambassador Thomas J. Watson from Moscow,[133] and suspended high-technology exports to the Soviet Union.[134][135]

China condemned the Soviet coup and its military buildup, calling it a threat to Chinese security (both the Soviet Union and Afghanistan shared borders with China), that it marked the worst escalation of Soviet expansionism in over a decade, and that it was a warning to other Third World leaders with close relations to the Soviet Union. Vice Premier Deng Xiaoping warmly praised the "heroic resistance" of the Afghan people. Beijing also stated that the lacklustre worldwide reaction against Vietnam (in the Sino-Vietnamese War earlier in 1979) encouraged the Soviets to feel free invading Afghanistan.[136]

Ba'athist Syria, led by Hafez al-Assad, was one of the few states outside the Warsaw Pact that publicly favoured the invasion. Soviet Union expanded its military support to the Syrian government in return.[137] The Warsaw Pact Soviet satellites (excluding Romania) publicly supported the intervention; however, a press account in June 1980 showed that Poland, Hungary and Romania privately informed the Soviet Union that the invasion was a damaging mistake.[75]

Military aid

Weapons supplies were made available through numerous countries. Before the Soviet intervention, the insurgents received support from the United States, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, Libya and Kuwait, albeit on a limited scale.[138][139] After the intervention, aid was substantially increased. The United States purchased all of Israel's captured Soviet weapons clandestinely, and then funnelled the weapons to the Mujahideen, while Egypt upgraded its army's weapons and sent the older weapons to the militants. Turkey sold their World War II stockpiles to the warlords, and the British and Swiss provided Blowpipe missiles and Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns respectively, after they were found to be poor models for their own forces.[140] China provided the most relevant weapons, likely due to their own experience with guerrilla warfare, and kept meticulous record of all the shipments.[140] The US, Saudi and Chinese aid combined totaled between $6 billion and $12 billion.[141]

State of the Cold War

In the wider Cold War, drastic changes were taking place in Southwestern Asia concurrent with the 1978–1979 upheavals in Afghanistan that changed the nature of the two superpowers. In February 1979, the Iranian Revolution ousted the American-backed Shah from Iran, losing the United States as one of its most powerful allies.[142] The United States then deployed twenty ships in the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea including two aircraft carriers, and there were constant threats of war between the U.S. and Iran.[143]

American observers argued that the global balance of power had shifted to the Soviet Union following the emergence of several pro-Soviet regimes in the Third World in the latter half of the 1970s (such as in Nicaragua and Ethiopia), and the action in Afghanistan demonstrated the Soviet Union's expansionism.[63]

March 1979 marked the signing of the U.S.-backed peace agreement between Israel and Egypt. The Soviet leadership saw the agreement as giving a major advantage to the United States. A Soviet newspaper stated that Egypt and Israel were now "gendarmes of the Pentagon". The Soviets viewed the treaty not only as a peace agreement between their erstwhile allies in Egypt and the US-supported Israelis but also as a military pact.[144] In addition, the US sold more than 5,000 missiles to Saudi Arabia, and the USSR's previously strong relations with Iraq had recently soured, as in June 1978 it began entering into friendlier relations with the Western world and buying French and Italian-made weapons, though the vast majority still came from the Soviet Union, its Warsaw Pact satellites, and China.

The Soviet invasion has also been analyzed with the model of the resource curse. The 1979 Islamic Revolution in Iran saw a massive increase in the scarcity and price of oil, adding tens of billions of dollars to the Soviet economy, as it was the major source of revenue for the USSR that spent 40–60% of its entire federal budget (15% of the GDP) on the military.[145] The oil boom may have overinflated national confidence, serving as a catalyst for the invasion. The Politburo was temporarily relieved of financial constraints and sought to fulfill a long-term geopolitical goal of seizing the lead in the region between Central Asia and the Gulf.[135]

December 1979 – February 1980: Occupation and national unrest

The first phase of the war began with the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and first battles with various opposition groups.[127] Soviet troops entered Afghanistan along two ground routes and one air corridor, quickly taking control of the major urban centers, military bases and strategic installations. However, the presence of Soviet troops did not have the desired effect of pacifying the country. On the contrary, it exacerbated nationalistic sentiment, causing the rebellion to spread further.[146] Babrak Karmal, Afghanistan's new leadership, charged the Soviets with causing an increase in the unrest, and demanded that the 40th Army step in and quell the rebellion, as his own army had proved untrustworthy.[147] Thus, Soviet troops found themselves drawn into fighting against urban uprisings, tribal armies (called lashkar), and sometimes against mutinying Afghan Army units. These forces mostly fought in the open, and Soviet airpower and artillery made short work of them.[148]

The Soviet occupation provoked a great deal of fear and unrest amongst a wide spectrum of the Afghan populace. The Soviets held the view that their presence would be accepted after having rid Afghanistan of the "tyrannical" Khalq regime, but this was not to be. In the first week of January 1980, attacks against Soviet soldiers in Kabul became common, with roaming soldiers often assassinated in the city in broad daylight by civilians. In the summer of that year, numerous members of the ruling party would be assassinated in individual attacks. The Soviet Army quit patrolling Kabul in January 1981 after their losses due to terrorism, handing the responsibility over to the Afghan army. Tensions in Kabul peaked during the 3 Hoot uprising on 22 February 1980, when the Soviet soldiers murdered hundreds of protesters.[149][150] The city uprising took a dangerous turn once again during the student demonstrations of April and May 1980, in which scores of students were killed by soldiers and PDPA sympathizers.[151]

The opposition to the Soviet presence was great nationally, crossing regional, ethnic, and linguistic lines. Never before in Afghan history had this many people been united in opposition against an invading foreign power. In Kandahar a few days after the invasion, civilians rose up against Soviet soldiers, killing a number of them, causing the soldiers to withdraw to their garrison. In this city, 130 Khalqists were murdered between January and February 1980.[150]

According to the Mitrokhin Archive, the Soviet Union deployed numerous active measures at the beginning of the intervention, spreading disinformation relating to both diplomatic status and military intelligence. These efforts focused on most countries bordering Afghanistan, on several international powers, the Soviet's main adversary, the United States, and neutral countries.[152] The disinformation was deployed primarily by "leaking" forged documents, distributing leaflets, publishing nominally independent articles in Soviet-aligned press, and conveying reports to embassies through KGB residencies.[152] Among the active measures pursued in 1980–1982 were both pro- and anti-separatist documents disseminated in Pakistan, a forged letter implying a Pakistani-Iranian alliance, alleged reports of U.S. bases on the Iranian border, information regarding Pakistan's military intentions filtered through the Pakistan embassy in Bangkok to the Carter Administration, and various disinformation about armed interference by India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Nepal, Indonesia, Jordan, Italy, and France, among others.[152]

Soviet occupation, 1980–1985

Soviet military operations against Afghan guerrillas

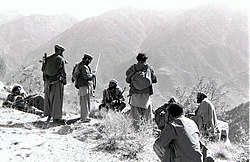

The war now developed into a new pattern: the Soviets occupied the cities and main axis of communication, while the Afghan mujahideen, which the Soviet Army soldiers called 'Dushman,' meaning 'enemy',[153] divided into small groups and waged a guerrilla war in the mountains. Almost 80 percent of the country was outside government control.[154] Soviet troops were deployed in strategic areas in the northeast, especially along the road from Termez to Kabul. In the west, a strong Soviet presence was maintained to counter Iranian influence. Incidentally, special Soviet units would have[clarification needed] also performed secret attacks on Iranian territory to destroy suspected Mujahideen bases, and their helicopters then got engaged in shootings with Iranian jets.[155] Conversely, some regions such as Nuristan, in the northeast, and Hazarajat, in the central mountains of Afghanistan, were virtually untouched by the fighting, and lived in almost complete independence.

Periodically the Soviet Army undertook multi-divisional offensives into Mujahideen-controlled areas. Between 1980 and 1985, nine offensives were launched into the strategically important Panjshir Valley, but government control in the area did not improve.[156] Heavy fighting also occurred in the provinces neighbouring Pakistan, where cities and government outposts were constantly besieged by the Mujahideen. Massive Soviet operations would regularly break these sieges, but the Mujahideen would return as soon as the Soviets left.[157] In the west and south, fighting was more sporadic, except in the cities of Herat and Kandahar, which were always partly controlled by the resistance.[158]

The Soviets did not initially foresee taking on such an active role in fighting the rebels and attempted to play down their role there as giving light assistance to the Afghan army. However, the arrival of the Soviets had the opposite effect as it incensed instead of pacified the people, causing the Mujahideen to gain in strength and numbers.[159] Originally the Soviets thought that their forces would strengthen the backbone of the Afghan army and provide assistance by securing major cities, lines of communication and transportation.[160] The Afghan army forces had a high desertion rate and were loath to fight, especially since the Soviet forces pushed them into infantry roles while they manned the armored vehicles and artillery. The main reason that the Afghan soldiers were so ineffective, though, was their lack of morale, as many of them were not truly loyal to the communist government but simply wanting a paycheck.[citation needed]Once it became apparent that the Soviets would have to get their hands dirty, they followed three main strategies aimed at quelling the uprising.[161] Intimidation was the first strategy, in which the Soviets would use airborne attacks and armored ground attacks to destroy villages, livestock and crops in trouble areas. The Soviets would bomb villages that were near sites of guerrilla attacks on Soviet convoys or known to support resistance groups. Local peoples were forced to either flee their homes or die as daily Soviet attacks made it impossible to live in these areas. By forcing the people of Afghanistan to flee their homes, the Soviets hoped to deprive the guerrillas of resources and safe havens. The second strategy consisted of subversion, which entailed sending spies to join resistance groups and report information, as well as bribing local tribes or guerrilla leaders into ceasing operations. Finally, the Soviets used military forays into contested territories in an effort to root out the guerrillas and limit their options. Classic search and destroy operations were implemented using Mil Mi-24 helicopter gunships that would provide cover for ground forces in armored vehicles. Once the villages were occupied by Soviet forces, inhabitants who remained were frequently interrogated and tortured for information or killed.[162]

Afghanistan is our Vietnam. Look at what has happened. We began by simply backing a friendly regime; slowly we got more deeply involved; then we started manipulating the regime – sometimes using desperate measures – and now? Now we are bogged down in a war we cannot win and cannot abandon. [.,.] but for Brezhnev and company we would never have got into it in the first place. – Vladimir Kuzichkin, a KGB defector, 1982[163]

To complement their brute force approach to weeding out the insurgency, the Soviets used KHAD (Afghan secret police) to gather intelligence, infiltrate the Mujahideen, spread false information, bribe tribal militias into fighting and organize a government militia. While it is impossible to know exactly how successful KHAD was in infiltrating Mujahideen groups, it is thought that they succeeded in penetrating a good many resistance groups based in Afghanistan, Pakistan and Iran.[164] KHAD is thought to have had particular success in igniting internal rivalries and political divisions amongst the resistance groups, rendering some of them completely useless because of infighting.[165] KHAD had some success in securing tribal loyalties but many of these relationships were fickle and temporary. Often KHAD secured neutrality agreements rather than committed political alignment.[166]

The Sarandoy were a centrally-commanded government paramilitary group placed under the control of the Ministry of Interior Affairs, before being placed under the control of the unified Ministry of State Security (WAD) in 1986.[167] They had mixed success in the war, as Osama bin Laden and the Arab mujahideen fought the Sarandoy's 7th Operative Regiment, only to fail and sustain massive casualties. The label “Sarandoy” additionally included traffic police, provincial officers and corrections/labor facility officers.[168][169] Large salaries and proper weapons attracted a good number of recruits to the cause, even if they were not necessarily "pro-communist". The problem was that many of the recruits they attracted were in fact Mujahideen who would join up to procure arms, ammunition and money while also gathering information about forthcoming military operations.[165] By the end of 1981, there were reports of Bulgarian Armed Forces present in Mazar-i-Sharif, the Warsaw Pact and the Cuban Revolutionary Armed Forces all operating in Afghanistan. A fighter of the Mujahideen, describing the Cubans in combat, said they were "big and black and shout very loudly when they fight. Unlike the Russians they were not afraid to attack us in the open".[170]

In 1985, the size of the LCOSF (Limited Contingent of Soviet Forces) was increased to 108,800 and fighting increased throughout the country, making 1985 the bloodiest year of the war. However, despite suffering heavily, the Mujahideen were able to remain in the field, mostly because they received thousands of new volunteers daily, and continued resisting the Soviets.

Reforms of the Karmal administration

Babrak Karmal, after the invasion, promised reforms to win support from the population alienated by his ousted predecessors. A temporary constitution, the Fundamental Principles of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan, was adopted in April 1980. On paper, it was a democratic constitution including "right of free expression" and disallowing "torture, persecution, and punishment, contrary to human dignity". Karmal's government was formed of his fellow Parchamites along with (pro-Taraki) Khalqists, and a number of known non-communists/leftists in various ministries.[150]

Karmal called his regime "a new evolutionary phase of the glorious April Revolution", but he failed at uniting the PDPA. In the eyes of many Afghans, he was still seen as a "puppet" of the Soviet Union.[150][171][172][154]

Mujahideen insurrection

In the mid-1980s, the Afghan resistance movement, assisted by the United States, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, the United Kingdom, Egypt, the People's Republic of China and others, contributed to Moscow's high military costs and strained international relations. The U.S. viewed the conflict in Afghanistan as an integral Cold War struggle, and the CIA provided assistance to anti-Soviet forces through the Pakistani intelligence services, in a program called Operation Cyclone.[173]

Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province became a base for the Afghan resistance fighters and the Deobandi ulama of that province played a significant role in the Afghan 'jihad', with Darul Uloom Haqqania becoming a prominent organisational and networking base for the anti-Soviet Afghan fighters.[174] As well as money, Muslim countries provided thousands of volunteer fighters known as "Afghan Arabs", who wished to wage jihad against the atheist communists. Notable among them was a young Saudi named Osama bin Laden, whose Arab group eventually evolved into al-Qaeda.[175]: 5–8 [176][177] Despite their numbers,[178][179][180] the contribution has been called a "curious sideshow to the real fighting,"[181] with only an estimated 2000 of them fighting "at any one time", compared with about 250,000 Afghan fighters and 125,000 Soviet troops.[182]

Their efforts were also sometimes counterproductive, as in the March 1989 battle for Jalalabad, when they showed the enemy the fate awaiting infidels in the form of a truck filled with dismembered bodies of their comrades chopped to pieces after surrendering to radical non-Afghan salafists.[183] Though demoralized by the abandonment of them by the Soviets, the Afghan Communist government forces rallied to break the siege of Jalalabad and to win the first major government victory in years. "This success reversed the government's demoralization from the withdrawal of Soviet forces, renewed its determination to fight on, and allowed it to survive three more years."[175]: 58–59

Maoist guerrilla groups were also active, to a lesser extent compared to the religious Mujahideen. A notable Maoist group was the Liberation Organization of the People of Afghanistan (SAMA), whose founder and leader Abdul Majid Kalakani was reportedly arrested in 1980.[184]

Afghanistan's resistance movement was born in chaos, spread and triumphed chaotically, and did not find a way to govern differently. Virtually all of its war was waged locally by regional warlords. As warfare became more sophisticated, outside support and regional coordination grew. Even so, the basic units of Mujahideen organization and action continued to reflect the highly segmented nature of Afghan society.[185]

Olivier Roy estimates that after four years of war, there were at least 4,000 bases from which Mujahideen units operated. Most of these were affiliated with the seven expatriate parties headquartered in Pakistan, which served as sources of supply and varying degrees of supervision. Significant commanders typically led 300 or more men, controlled several bases and dominated a district or a sub-division of a province. Hierarchies of organization above the bases were attempted. Their operations varied greatly in scope, the most ambitious being achieved by Ahmad Shah Massoud of the Panjshir valley north of Kabul. He led at least 10,000 trained troopers at the end of the Soviet war and had expanded his political control of Tajik-dominated areas to Afghanistan's northeastern provinces under the Supervisory Council of the North.[185]

Roy also describes regional, ethnic and sectarian variations in Mujahideen organization. In the Pashtun areas of the east, south and southwest, tribal structure, with its many rival sub-divisions, provided the basis for military organization and leadership. Mobilization could be readily linked to traditional fighting allegiances of the tribal lashkar (fighting force). In favorable circumstances such formations could quickly reach more than 10,000, as happened when large Soviet assaults were launched in the eastern provinces, or when the Mujahideen besieged towns, such as Khost in Paktia province in July 1983.[186] But in campaigns of the latter type the traditional explosions of manpower—customarily common immediately after the completion of harvest—proved obsolete when confronted by well dug-in defenders with modern weapons. Lashkar durability was notoriously short; few sieges succeeded.[185]

Mujahideen mobilization in non-Pashtun regions faced very different obstacles. Prior to the intervention, few non-Pashtuns possessed firearms. Early in the war they were most readily available from army troops or gendarmerie who defected or were ambushed. The international arms market and foreign military support tended to reach the minority areas last. In the northern regions, little military tradition had survived upon which to build an armed resistance. Mobilization mostly came from political leadership closely tied to Islam. Roy contrasts the social leadership of religious figures in the Persian- and Turkic-speaking regions of Afghanistan with that of the Pashtuns. Lacking a strong political representation in a state dominated by Pashtuns, minority communities commonly looked to pious learned or charismatically revered pirs (saints) for leadership. Extensive Sufi and maraboutic networks were spread through the minority communities, readily available as foundations for leadership, organization, communication and indoctrination. These networks also provided for political mobilization, which led to some of the most effective of the resistance operations during the war.[185]

The Mujahideen favoured sabotage operations. The more common types of sabotage included damaging power lines, knocking out pipelines and radio stations, blowing up government office buildings, air terminals, hotels, cinemas, and so on. In the border region with Pakistan, the Mujahideen would often launch 800 rockets per day. Between April 1985 and January 1987, they carried out over 23,500 shelling attacks on government targets. The Mujahideen surveyed firing positions that they normally located near villages within the range of Soviet artillery posts, putting the villagers in danger of death from Soviet retaliation. The Mujahideen used land mines heavily. Often, they would enlist the services of the local inhabitants, even children.

They concentrated on both civilian and military targets, knocking out bridges, closing major roads, attacking convoys, disrupting the electric power system and industrial production, and attacking police stations and Soviet military installations and air bases. They assassinated government officials and PDPA members, and laid siege to small rural outposts. In March 1982, a bomb exploded at the Ministry of Education, damaging several buildings. In the same month, a widespread power failure darkened Kabul when a pylon on the transmission line from the Naghlu power station was blown up. In June 1982 a column of about 1,000 young communist party members sent out to work in the Panjshir valley were ambushed within 30 km of Kabul, with heavy loss of life. On 4 September 1985, insurgents shot down a domestic Bakhtar Airlines plane as it took off from Kandahar airport, killing all 52 people aboard.

Mujahideen groups used for assassination had three to five men in each. After they received their mission to kill certain government officials, they busied themselves with studying his pattern of life and its details and then selecting the method of fulfilling their established mission. They practiced shooting at automobiles, shooting out of automobiles, laying mines in government accommodation or houses, using poison, and rigging explosive charges in transport.

In May 1985, the seven principal rebel organizations formed the Seven Party Mujahideen Alliance to coordinate their military operations against the Soviet Army. Late in 1985, the groups were active in and around Kabul, unleashing rocket attacks and conducting operations against the communist government.

Raids inside Soviet territory

In an effort to foment unrest and rebellion by the Islamic populations of the Soviet Union, starting in late 1984 Director of CIA William Casey encouraged Mujahideen militants to mount sabotage raids inside the Soviet Union, according to Robert Gates, Casey's executive assistant and Mohammed Yousef, the Pakistani ISI brigadier general who was the chief for Afghan operations. The rebels began cross-border raids into the Soviet Union in spring 1985.[187][188][189] In April 1987, three separate teams of Afghan rebels were directed by the ISI to launch coordinated raids on multiple targets across the Soviet border and extending, in the case of an attack on an Uzbek factory, as deep as over 16 kilometres (10 mi) into Soviet territory. In response, the Soviets issued a thinly-veiled threat to invade Pakistan to stop the cross-border attacks, and no further attacks were reported.[190]

Media reaction

Those hopelessly brave warriors I walked with, and their families, who suffered so much for faith and freedom and who are still not free, they were truly the people of God. – Journalist Rob Schultheis, 1992[191][192]

International journalistic perception of the war varied. Major American television journalists were sympathetic to the Mujahideen. Most visible was CBS News correspondent Dan Rather, who in 1982 accused the Soviet Union of genocide, comparing them to Hitler.[193] Rather was embedded with the Mujahideen for a 60 Minutes report.[194] In 1987, CBS produced a full documentary special on the war.[195][196][197]

Reader's Digest took a highly positive view of the Mujahideen, a reversal of their usual view of Islamic fighters. The publication praised their martyrdom and their role in entrapping the Soviets in a Vietnam War-style disaster.[198]

Leftist journalist Alexander Cockburn was unsympathetic, criticizing Afghanistan as "an unspeakable country filled with unspeakable people, sheepshaggers and smugglers, who have furnished in their leisure hours some of the worst arts and crafts ever to penetrate the occidental world. I yield to none in my sympathy to those prostrate beneath the Russian jackboot, but if ever a country deserved rape it's Afghanistan."[199] Robert D. Kaplan on the other hand, thought any perception of Mujahideen as "barbaric" was unfair: "Documented accounts of mujahidin savagery were relatively rare and involved enemy troops only. Their cruelty toward civilians was unheard of during the war, while Soviet cruelty toward civilians was common."[200] Lack of interest in the Mujahideen cause, Kaplan believed, was not the lack of intrinsic interest to be found in a war between a small, poor country and a superpower where a million civilians were killed, but the result of the great difficulty and unprofitability of media coverage. Kaplan noted that "none of the American TV networks had a bureau for a war",[201] and television cameramen venturing to follow the Mujahideen "trekked for weeks on little food, only to return ill and half starved".[202] In October 1984, the Soviet ambassador to Pakistan, Vitaly Smirnov, told Agence France Presse "that journalists traveling with the mujahidin 'will be killed. And our units in Afghanistan will help the Afghan forces to do it.'"[201] Unlike Vietnam and Lebanon, Afghanistan had "absolutely no clash between the strange and the familiar", no "rock-video quality" of "zonked-out GIs in headbands" or "rifle-wielding Shiite terrorists wearing Michael Jackson T-shirts" that provided interesting "visual materials" for newscasts.[203]

Soviet exit and change of Afghan leadership, 1985–1989

Foreign diplomatic efforts

As early as 1983, Pakistan's Foreign Ministry began working with the Soviet Union to provide them an exit from Afghanistan, initiatives led by Foreign Minister Yaqub Ali Khan and Khurshid Kasuri. Despite an active support for insurgent groups, Pakistanis remained sympathetic to the challenges faced by the Soviets in restoring the peace, eventually exploring the possibility of setting up an interim system of government under former monarch Zahir Shah, but this was not authorized by President Zia-ul-Haq due to his stance on the issue of the Durand Line.: 247–248 [204] In 1984–85, Foreign Minister Yaqub Ali Khan paid state visits to China, Saudi Arabia, Soviet Union, France, United States and the United Kingdom in order to develop a framework. On 20 July 1987, the withdrawal of Soviet troops from the country was announced.

April 1985 – January 1987: Exit strategy

The first step of the Soviet Union's exit strategy was to transfer the burden of fighting the Mujahideen to the Afghan armed forces, with the aim of preparing them to operate without Soviet help. During this phase, the Soviet contingent was restricted to supporting the DRA forces by providing artillery, air support and technical assistance, though some large-scale operations were still carried out by Soviet troops.

Under Soviet guidance, the DRA armed forces were built up to an official strength of 302,000 in 1986. To minimize the risk of a coup d'état, they were divided into different branches, each modeled on its Soviet counterpart. The ministry of defence forces numbered 132,000, the ministry of interior 70,000 and the ministry of state security (KHAD) 80,000. However, these were theoretical figures: in reality each service was plagued with desertions, the army alone suffering over 10% annual losses, or 32,000 per year.