Народная освободительная армия

| Chinese People's Liberation Army | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 中国人民解放军 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 中國人民解放軍 | ||

| Literal meaning | "China People Liberation Army" | ||

| |||

| People's Liberation Army |

|---|

|

| Executive departments |

| Staff |

| Services |

| Arms |

| Domestic troops |

| Special operations force |

| Military districts |

| History of the Chinese military |

| Military ranks of China |

|

|---|

|

|

Народная освободительная армия ( PLA ) является военным Китайской коммунистической партии (CCP) и Китайской Народной Республики . Он состоит из четырех служб - наземных сил , военно -морского флота , военно -воздушных сил и ракетных сил - и четырех рук - аэрокосмических сил , силы киберпространства , силы поддержки информации и силы поддержки совместной логистики . Его возглавляет Центральная военная комиссия (CMC) с его председателем в качестве главнокомандующего .

PLA может проследить свое происхождение в республиканскую эпоху до левых подразделений Национальной революционной армии (NRA) Куминтанга ( КМТ), когда они оторвались в 1927 году в восстании против националистического правительства в качестве китайской Красной армии , перед реинтегрируется в NRA как подразделения новой четвертой армии и восьмой маршрут во время второй китайско-японской войны . Два коммунистических подразделения NRA были восстановлены как PLA в 1947 году. [ 9 ] Since 1949, the PLA has used nine different military strategies, which it calls "strategic guidelines". The most important came in 1956, 1980, and 1993.[10] Политически, ПЛА и вооруженные люди вооруженной полиции (PAP) имеют самую большую делегацию в Национальном народном конгрессе (NPC); В настоящее время в совместной делегации 281 депутата - в течение 9% от общего числа - все из которых являются членами КПК.

The PLA is not a traditional nation-state military. It is a part, and the armed wing, of the CCP and controlled by the party, not by the state. The PLA's primary mission is the defense of the party and its interests. The PLA is the guarantor of the party's survival and rule, and the party prioritizes maintaining control and the loyalty of the PLA. According to Chinese law, the party has leadership over the armed forces and the CMC exercises supreme military command; the party and state CMCs are practically a single body by membership. Since 1989, the CCP general secretary has also held been the CMC Chairman; this grants significant political power as the only member of the Politburo Standing Committee with direct responsibilities for the armed forces. The Ministry of National Defense has no command authority; it is the PLA's interface with state and foreign entities and insulates the PLA from external influence.

Today, the majority of military units around the country are assigned to one of five theatre commands by geographical location. The PLA is the world's largest military force (not including paramilitary or reserve forces) and has the second largest defence budget in the world. China's military expenditure was US$296 billion in 2023, accounting for 12 percent of the world's defence expenditures. It is also one of the fastest modernizing militaries in the world, and has been termed as a potential military superpower, with significant regional defence and rising global power projection capabilities.[11][12]: 259

In addition to wartime arrangements, the PLA is also involved in the peacetime operations of other components of the armed forces. This is particularly visible in maritime territorial disputes where the navy is heavily involved in the planning, coordination and execution of operations by the PAP's China Coast Guard.[13]

Mission

The PLA's primary mission is the defense of the CCP and its interests.[14] It is the guarantor of the party's survival and rule,[14][15] and the party prioritizes maintaining control and the loyalty of the PLA.[15]

In 2004, paramount leader Hu Jintao stated the mission of the PLA as:[16]

- The insurance of CCP leadership

- The protection of the sovereignty, territorial integrity, internal security and national development of the People's Republic of China

- Safeguarding the country's interests

- Maintaining and safeguarding world peace.

China describes its military posture as active defense, defined in a 2015 state white paper as "We will not attack unless we are attacked, but we will surely counterattack if attacked."[17]: 41

History

Early history

The CCP founded its military wing on 1 August 1927 during the Nanchang uprising, beginning the Chinese Civil War. Communist elements of the National Revolutionary Army rebelled under the leadership of Zhu De, He Long, Ye Jianying, Zhou Enlai, and other leftist elements of the Kuomintang (KMT), after the Shanghai massacre in 1927.[18] They were then known as the Chinese Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, or simply the Red Army.[19]

In 1934 and 1935, the Red Army survived several campaigns led against it by Chiang Kai-Shek's KMT and engaged in the Long March.[20]

During the Second Sino-Japanese War from 1937 to 1945, the CCP's military forces were nominally integrated into the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China forming two main units, the Eighth Route Army and the New Fourth Army.[9] During this time, these two military groups primarily employed guerrilla tactics, generally avoiding large-scale battles with the Japanese, at the same time consolidating by recruiting KMT troops and paramilitary forces behind Japanese lines into their forces.[21]

After the Japanese surrender in 1945, the CCP continued to use the National Revolutionary Army unit structures until the decision was made in February 1947 to merge the Eighth Route Army and New Fourth Army, renaming the new million-strong force the People's Liberation Army (PLA).[9] The reorganization was completed by late 1948. The PLA eventually won the Chinese Civil War, establishing the People's Republic of China in 1949.[22] It then underwent a drastic reorganization, with the establishment of the Air Force leadership structure in November 1949, followed by the Navy leadership structure the following April.[23][24]

In 1950, the leadership structures of the artillery, armored troops, air defence troops, public security forces, and worker–soldier militias were also established. The chemical warfare defence forces, the railroad forces, the communications forces, and the strategic forces, as well as other separate forces (like engineering and construction, logistics and medical services), were established later on.

In this early period, the People's Liberation Army overwhelmingly consisted of peasants.[25] Its treatment of soldiers and officers was egalitarian[25] and formal ranks were not adopted until 1955.[26] As a result of its egalitarian organization, the early PLA overturned strict traditional hierarchies that governed the lives of peasants.[25] As sociologist Alessandro Russo summarizes, the peasant composition of the PLA hierarchy was a radical break with Chinese societal norms and "overturned the strict traditional hierarchies in unprecedented forms of egalitarianism[.]"[25]

In the PRC's early years, the PLA was a dominant foreign policy institution in the country.[27]: 17

Modernization and conflicts

During the 1950s, the PLA with Soviet assistance began to transform itself from a peasant army into a modern one.[28] Since 1949, China has used nine different military strategies, which the PLA calls "strategic guidelines". The most important came in 1956, 1980, and 1993.[10] Part of this process was the reorganization that created thirteen military regions in 1955.[citation needed]

In November 1950, some units of the PLA under the name of the People's Volunteer Army intervened in the Korean War as United Nations forces under General Douglas MacArthur approached the Yalu River.[29] Under the weight of this offensive, Chinese forces drove MacArthur's forces out of North Korea and captured Seoul, but were subsequently pushed back south of Pyongyang north of the 38th Parallel.[29] The war also catalyzed the rapid modernization of the PLAAF.[30]

In 1962, the PLA ground force also fought India in the Sino-Indian War.[31][32] In a series of border clashes in 1967 with Indian troops, the PLA suffered heavy numerical and tactical losses.[33][34][35]

Before the Cultural Revolution, military region commanders tended to remain in their posts for long periods. The longest-serving military region commanders were Xu Shiyou in the Nanjing Military Region (1954–74), Yang Dezhi in the Jinan Military Region (1958–74), Chen Xilian in the Shenyang Military Region (1959–73), and Han Xianchu in the Fuzhou Military Region (1960–74).[36]

In the early days of the Cultural Revolution, the PLA abandoned the use of the military ranks that it had adopted in 1955.[26]

The establishment of a professional military force equipped with modern weapons and doctrine was the last of the Four Modernizations announced by Zhou Enlai and supported by Deng Xiaoping.[37][38] In keeping with Deng's mandate to reform, the PLA has demobilized millions of men and women since 1978 and has introduced modern methods in such areas as recruitment and manpower, strategy, and education and training.[39] In 1979, the PLA fought Vietnam over a border skirmish in the Sino-Vietnamese War where both sides claimed victory.[40] However, western analysts agree that Vietnam handily outperformed the PLA.[36]

During the Sino-Soviet split, strained relations between China and the Soviet Union resulted in bloody border clashes and mutual backing of each other's adversaries.[41] China and Afghanistan had neutral relations with each other during the King's rule.[42] When the pro-Soviet Afghan Communists seized power in Afghanistan in 1978, relations between China and the Afghan communists quickly turned hostile.[43] The Afghan pro-Soviet communists supported China's enemies in Vietnam and blamed China for supporting Afghan anticommunist militants.[43] China responded to the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan by supporting the Afghan mujahidin and ramping up their military presence near Afghanistan in Xinjiang.[43] China acquired military equipment from the United States to defend itself from Soviet attacks.[44]

The PLA Ground Force trained and supported the Afghan Mujahideen during the Soviet-Afghan War, moving its training camps for the mujahideen from Pakistan into China itself.[45] Hundreds of millions of dollars worth of anti-aircraft missiles, rocket launchers, and machine guns were given to the Mujahideen by the Chinese.[46] Chinese military advisors and army troops were also present with the Mujahideen during training.[44]

Since 1980

In 1981, the PLA conducted its largest military exercise in North China since the founding of the People's Republic.[10][47]

In the 1980s, the PLA gained more autonomy and permission to engage in commercial activities in exchange for a reduced role in political affairs and limited budgets;[48] the military was downsized to free resources for economic development.[49] The lack of oversight, ineffective self-regulation, and Jiang Zemin's and Hu Jintao's lack of close personal ties to the PLA,[48] led to systemic corruption that persisted through the late-2010s.[50] Jiang's attempt to divest the PLA of its commercial interests was only partly successful as many were still run by close associates of PLA officers.[48] Corruption lowered readiness and proficiency,[51] was a barrier to modernization and professionalization,[52] and eroded party control.[15] The 2010s anti-corruption campaigns and military reforms under Xi Jinping from the early-2010s were in part executed to address these problems.[53][54]

Following the PLA's suppression of the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre, ideological correctness was temporarily revived as the dominant theme in Chinese military affairs.[55] Reform and modernization have today resumed their position as the PLA's primary objectives, although the armed forces' political loyalty to the CCP has remained a leading concern.[56][57]

Beginning in the 1980s, the PLA tried to transform itself from a land-based power centered on a vast ground force to a smaller, more mobile, high-tech one capable of mounting operations beyond its borders.[10] The motivation for this was that a massive land invasion by Russia was no longer seen as a major threat, and the new threats to China are seen to be a declaration of independence by Taiwan, possibly with assistance from the United States, or a confrontation over the Spratly Islands.[58]

In 1985, under the leadership of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party and the CMC, the PLA changed from being constantly prepared to "hit early, strike hard and to fight a nuclear war" to developing the military in an era of peace.[10] The PLA reoriented itself to modernization, improving its fighting ability, and becoming a world-class force. Deng Xiaoping stressed that the PLA needed to focus more on quality rather than on quantity.[58]

The decision of the Chinese government in 1985 to reduce the size of the military by one million was completed by 1987. Staffing in military leadership was cut by about 50 percent. During the Ninth Five Year Plan (1996–2000) the PLA was reduced by a further 500,000. The PLA had also been expected to be reduced by another 200,000 by 2005. The PLA has focused on increasing mechanization and informatization to be able to fight a high-intensity war.[58]

Former CMC chairman Jiang in 1990 called on the military to "meet political standards, be militarily competent, have a good working style, adhere strictly to discipline, and provide vigorous logistic support" (Chinese: 政治合格、军事过硬、作风优良、纪律严明、保障有力; pinyin: zhèngzhì hégé, jūnshì guòyìng, zuòfēng yōuliáng, jìlǜ yánmíng, bǎozhàng yǒulì).[59] The 1991 Gulf War provided the Chinese leadership with a stark realization that the PLA was an oversized, almost-obsolete force.[60][61] The USA's sending of two aircraft carrier groups to the vicinity of Taiwan during the Third Taiwan Strait Crisis prompted Jiang to order a ten-year PLA modernization program.[62]

The possibility of a militarized Japan has also been a continuous concern to the Chinese leadership since the late 1990s.[63] In addition, China's military leadership has been reacting to and learning from the successes and failures of the United States Armed Forces during the Kosovo War,[64] the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan,[65] the 2003 invasion of Iraq,[66] and the Iraqi insurgency.[66] All these lessons inspired China to transform the PLA from a military based on quantity to one based on quality. Chairman Jiang Zemin officially made a "revolution in military affairs" (RMA) part of the official national military strategy in 1993 to modernize the Chinese armed forces.[67]

A goal of the RMA is to transform the PLA into a force capable of winning what it calls "local wars under high-tech conditions" rather than a massive, numbers-dominated ground-type war.[67] Chinese military planners call for short decisive campaigns, limited in both their geographic scope and their political goals. In contrast to the past, more attention is given to reconnaissance, mobility, and deep reach. This new vision has shifted resources towards the navy and air force. The PLA is also actively preparing for space warfare and cyber-warfare.[68][69][70]

In 2002, the PLA began holding military exercises with militaries from other countries.[71]: 242 From 2018 to 2023, more than half of these exercises have focused on military training other than war, generally antipiracy or antiterrorism exercises involving combatting non-state actors.[71]: 242 In 2009, the PLA held its first military exercise in Africa, a humanitarian and medical training practice conducted in Gabon.[71]: 242

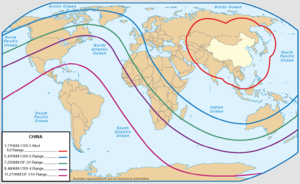

For the past 10 to 20 years, the PLA has acquired some advanced weapons systems from Russia, including Sovremenny class destroyers,[72] Sukhoi Su-27[73] and Sukhoi Su-30 aircraft,[74] and Kilo-class diesel-electric submarines.[75] It has also started to produce several new classes of destroyers and frigates including the Type 052D class guided-missile destroyer.[76][77] In addition, the PLAAF has designed its very own Chengdu J-10 fighter aircraft[78] and a new stealth fighter, the Chengdu J-20.[79] The PLA launched the new Jin class nuclear submarines on 3 December 2004 capable of launching nuclear warheads that could strike targets across the Pacific Ocean[80] and have three aircraft carriers, with the latest, the Fujian, launched in 2022.[81][82][83]

From 2014 to 2015, the PLA deployed 524 medical staff on a rotational basis to combat the Ebola virus outbreak in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and Guinea-Bissau.[71]: 245 As of 2023, this was the PLA's largest medical assistance mission in another country.[71]: 245

China re-organized its military from 2015 to 2016. In 2015, the PLA formed new units including the PLA Ground Force, the PLA Rocket Force and the PLA Strategic Support Force.[84] In 2016, the CMC replaced the four traditional military departments with a number of new bodies.[85]: 288–289 China replaced its system of seven military regions with newly established Theater Commands: Northern, Southern, Western, Eastern, and Central.[85]: 289 In the prior system, operations were segmented by military branch and region.[85]: 289 In contrast, each Theater Command is intended to function as a unified entity with joint operations across different military branches.[85]: 289

The PLA on 1 August 2017 marked its 90th anniversary.[86] Before the big anniversary it mounted its biggest parade yet and the first outside of Beijing, held in the Zhurihe Training Base in the Northern Theater Command (within the Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region).[87]

In December 2023, Reuters reported a military leadership purge after high-ranking generals were ousted from the National People's Congress.[88] Prior to 2017, over sixty generals were investigated and sacked.[89]

Overseas deployments and peacekeeping operations

In addition to its Support Base in Djibouti, the PLA operates a base in Tajikistan and a listening station in Cuba.[90][91] The Espacio Lejano Station in Argentina is operated by a unit of a PLA.[92][93] The PLAN has also undertaken rotational deployments of its warships at the Ream Naval Base in Cambodia.[94][95]

The People's Republic of China has sent the PLA to various hotspots as part of China's role as a prominent member of the United Nations.[96] Such units usually include engineers and logistical units and members of the paramilitary People's Armed Police and have been deployed as part of peacekeeping operations in Lebanon,[97][98] the Republic of the Congo,[97] Sudan,[99] Ivory Coast,[100] Haiti,[101][102] and more recently, Mali and South Sudan.[97][103]

Engagements

- 1927–1950: Chinese Civil War[104]

- 1937–1945: Second Sino-Japanese War[105]

- 1949: Yangtze incident against British warships on the Yangtze River[106]

- 1949: Incorporation of Xinjiang into the People's Republic of China[107]

- 1950: Annexation of Tibet by the People's Republic of China[108]

- 1950–1953: Korean War under the banner of the Chinese People's Volunteer Army[109]

- 1954–1955: First Taiwan Strait Crisis[110]

- 1955–1970: Vietnam War[111]

- 1958: Second Taiwan Strait Crisis at Quemoy and Matsu[112]

- 1962: Sino-Indian War[113]

- 1967: Border skirmishes with India[33]

- 1969: Sino-Soviet border conflict[114]

- 1974: Battle of the Paracel Islands with South Vietnam[115]

- 1979: Sino-Vietnamese War[116]

- 1979–1990: Sino-Vietnamese conflicts[117]

- 1988: Johnson South Reef Skirmish with Vietnam[118]

- 1989: Enforcement of martial law in Beijing during the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and massacre[119]

- 1990: Barin uprising[120]

- 1995–1996: Third Taiwan Strait Crisis[121]

- 1997: PLA establishes Hong Kong Garrison

- 1999: PLA establishes Macao Garrison

- 2007–present: UNIFIL peacekeeping operations in Lebanon[97]

- 2009–present: Anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden[122]

- 2014: Search and rescue efforts for Malaysia Airlines Flight 370[123]

- 2014: UN peacekeeping operations in Mali[124]

- 2015: UNMISS peacekeeping operations in South Sudan[125]

- 2020–2021: China–India skirmishes[126]

As of at least early 2024, China has not fought a war since 1979 and has only fought relatively minor conflicts since.[17]: 72

Organization

The PLA is a component of the armed forces of China, which also includes the PAP, the reserves, and the militia.[127] The armed forces are controlled by the CCP under the doctrine of "the Party must always control the gun".(Chinese: 党指挥枪; pinyin: Dǎng zhǐhuī qiāng)[15] The PLA and the PAP have the largest delegation in the National People's Congress (NPC), which are elected by servicemember election committees of top-level military subdivisions, including the PLA's theater commands and service branches.[128] At the 14th National People's Congress; the joint delegation has 281 deputies—over 9% of the total—all of whom are CCP members.[129]

Central Military Commission

The PLA is governed by the Central Military Commission (CMC); under the arrangement of "one institution with two names", there exists a state CMC and a Party CMC, although both commissions have identical personnel, organization and function, and effectively work as a single body.[130] The only difference in membership between the two occurs for a few months every five years, during the period between a Party National Congress, when Party CMC membership changes, and the next ensuing National People's Congress, when the state CMC changes.[131]

The CMC is composed of a chairman, vice chairpersons and regular members. The chairman of the CMC is the commander-in-chief of the PLA, with the post generally held by the paramount leader of China; since 1989, the post has generally been held together with the CCP general secretary.[15][130][132] Unlike in other countries, the Ministry of National Defense and its Minister do not have command authority, largely acting as diplomatic liaisons of the CMC, insulating the PLA from external influence.[133] However, the Minister has always been a member of the CMC.[130]

- Chairman

- Xi Jinping (also General Secretary, President and Commander-in-chief of Joint Battle Command)

- Vice Chairmen

- General Zhang Youxia

- General He Weidong

- Members

- Chief of the Joint Staff Department (JSD) – General Liu Zhenli

- Director of the Political Work Department – Admiral Miao Hua

- Secretary of the Commission for Discipline Inspection – General Zhang Shengmin

Previously, the PLA was governed by four general departments; the General Political, the General Logistics, the General Armament, and the General Staff Departments. These were abolished in 2016 under the military reforms undertaken by Xi Jinping, replaced with 15 new functional departments directly reporting to the CMC:[134]

- General Office

- Joint Staff Department

- Political Work Department

- Logistic Support Department

- Equipment Development Department

- Training and Administration Department

- National Defense Mobilization Department

- Discipline Inspection Commission

- Politics and Legal Affairs Commission

- Science and Technology Commission

- Office for Strategic Planning

- Office for Reform and Organizational Structure

- Office for International Military Cooperation

- Audit Office

- Agency for Offices Administration

Included among the 15 departments are three commissions. The CMC Discipline Inspection Commission is charged with rooting out corruption.

Political leadership

The CCP maintains absolute control over the PLA.[135] It requires the PLA to undergo political education, instilling CCP ideology in its members.[136] Additionally, China maintains a political commissar system.[137] Regiment-level and higher units maintain CCP committees and political commissars (Chinese: 政治委员 or 政委).[137][138] Additionally, battalion-level and company-level units respectively maintain political directors and political instructors.[139] The political workers are officially equal to commanders in status.[136] The political workers are officially responsible for the implementation of party committee decisions, instilling and maintaining party discipline, providing political education, and working with other components of the political work system.[139]

As a rule, the political worker serves as the party committee secretary while the commander serves as the deputy secretary.[139] Key decisions in the PLA are generally made in the CCP committees throughout the military.[136] Due to the CCP's absolute leadership, non-CCP political parties, groups and organizations except the Communist Youth League of China are not allowed to establish organizations or have members in the PLA. Additionally, only the CCP is allowed to appoint the leading cadres at all levels of the PLA.[138]

Grades

Grades determine the command hierarchy from the CMC to the platoon level. Entities command lower-graded entities, and coordinate with like-graded entities.[140] Since 1988, all organizations, billets, and officers in the PLA have a grade.[141]

Civil–military relations within the wider state bureaucracy is also influenced by grades. The grading systems used by the armed forces and the government are parallel, making it easier for military entities to identify the civilian entities they should coordinate with.[140]

An officer's authority, eligibility for billets, pay, and retirement age is determined by grade.[142][140] Career progression includes lateral transfers between billets of the same grade, but which are not considered promotions.[143][144] An officer retiring to the civil service has their grade translated to the civil grade system;[140] their grade continues to progress and draw retirement benefits through the civil system rather than the armed forces.[145]

Historically, an officer's grade — or position (Chinese: 职务等级; pinyin: zhiwu dengji[146]) — was more important than their rank (Chinese: 军衔; pinyin: junxian[146]).[140] Historically, time-in-grade and time-in-rank requirements[147] and promotions were not synchronized;[143] multiple ranks were present in each grade[148] with all having the same authority.[145] Rank was mainly a visual aid to roughly determine relative position when interacting with Chinese and foreign personnel.[140] PLA etiquette preferred addressing personnel by position rather than by rank.[149] Reforms to a more rank-centric system began in 2021.[146] In 2023, a revised grade structure associated one rank per grade, with some ranks spanning multiple grades.[150]

Operational control

Operational control of combat units is divided between the service headquarters and domestic geographically based theatre commands.

Theatre commands are multi-service ("joint") organizations that are broadly responsible for strategy, plans, tactics, and policy specific to their assigned area of responsibility. In wartime, they will likely have full control of subordinate units; in peacetime, units also report to their service headquarters.[152] Force-building is the responsibility of the services and the CMC.[153] The five theatre commands, in order of stated significance are:[154]

- Eastern Theater Command

- Southern Theater Command

- Western Theater Command

- Northern Theater Command

- Central Theater Command

The service headquarters retain operational control in some areas within China and outside of China. For example, army headquarters controls or is responsible for the Beijing Garrison, the Tibet Military District, the Xinjiang Military District,[155] and border and coastal defences. The counterpiracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden are controlled by navy headquarters.[156] The JSD nominally controls operations beyond China's periphery,[157] but in practice this seems to apply only to army operations.[158]

Services and theater commands have the same grade. The overlap of areas or units of responsibility may create disputes requiring CMC arbitration.[158]

As part of the 2015 reforms, military regions were replaced by theatre commands in 2016.[159] Military regions were − uinlike the theatre commands − army-centric[160] peacetime administrative organizations,[161] and joint wartime commands were created on-demand by the army-dominated General Staff Department.[161]

Organization table

State-owned enterprises

Multiple state-owned enterprises have established internal People's Armed Forces Departments run by the People's Liberation Army.[163][164][165] The internal units are expected "to work together with grassroots organizations to collect intelligence and information, dissolve and/or eliminate security concerns at the budding stage," according to the People's Liberation Army Daily.[164]

Academic Institutions

There are two academic institutions directly subordinate to the CMC, the National Defense University and the National University of Defense Technology, and they are considered the two top military education institutions in China. There are also 35 institutions affiliated to the PLA's branches and arms, and 7 institutions affiliated to the People's Armed Police.[166]

Service branches

The PLA consists of four services (Ground Force, Navy, Air Force, and Rocket Force) and four arms (Aerospace Force, Cyberspace Force, Information Support Force, and Joint Logistics Support Force).[167]

Services

The PLA maintains four services (Chinese: 军种; pinyin: jūnzhǒng): the Ground Force, the Navy, the Air Force, and the Rocket Force. Following the 200,000 and 300,000 personnel reduction announced in 2003 and 2005 respectively, the total strength of the PLA has been reduced from 2.5 million to around 2 million.[168] The reductions came mainly from non-combat ground forces, which would allow more funds to be diverted to naval, air, and strategic missile forces. This shows China's shift from ground force prioritization to emphasizing air and naval power with high-tech equipment for offensive roles over disputed territories, particularly in the South China Sea.[169]

Ground Force

The PLA Ground Force (PLAGF) is the largest of the PLA's five services with 975,000 active duty personnel, approximately half of the PLA's total manpower of around 2 million personnel.[12]: 260 The PLAGF is organized into twelve active duty group armies sequentially numbered from the 71st Group Army to the 83rd Group Army which are distributed to each of the PRC's five theatre commands, receiving two to three group armies per command. In wartime, numerous PLAGF reserve and paramilitary units may be mobilized to augment these active group armies. The PLAGF reserve component comprises approximately 510,000 personnel divided into thirty infantry and twelve anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) divisions. The PLAGF is led by Commander Liu Zhenli and Political Commissar Qin Shutong.[170]

Navy

Until the early 1990s, the PLA Navy (PLAN) performed a subordinate role to the PLA Ground Force (PLAGF). Since then it has undergone rapid modernisation. The 300,000 strong PLAN is organized into three major fleets: the North Sea Fleet headquartered at Qingdao, the East Sea Fleet headquartered at Ningbo, and the South Sea Fleet headquartered in Zhanjiang.[171] Each fleet consists of a number of surface ship, submarine, naval air force, coastal defence, and marine units.[172][12]: 261

The navy includes a 25,000 strong Marine Corps (organised into seven brigades), a 26,000 strong Naval Aviation Force operating several hundred attack helicopters and fixed-wing aircraft.[12]: 263–264 As part of its overall programme of naval modernisation, the PLAN is in the stage of developing a blue water navy.[173] In November 2012, then Party General Secretary Hu Jintao reported to the CCP's 18th National Congress his desire to "enhance our capacity for exploiting marine resource and build China into a strong maritime power".[174] According to the United States Department of Defense, the PLAN has numerically the largest navy in the world.[175] The PLAN is led by Commander Dong Jun and Political Commissar Yuan Huazhi.[176]

Air Force

The 395,000 strong People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) was organized into five Theatre Command Air Forces (TCAF) and 24 air divisions.[177]: 249–259 As of 2024[update], the system has been changed into 11 Corps Deputy-grade "Bases" controlling air brigades.[178] Divisions have been mostly converted to brigades,[178] although some (specifically the Bomber divisions, and some of the special mission units)[179] remain operational as divisions. The largest operational units within the Aviation Corps is the air division, which has 2 to 3 aviation regiments, each with 20 to 36 aircraft. An Air Brigade has from 24 to 50 aircraft.[180]

The surface-to-air missile (SAM) Corps is organized into SAM divisions and brigades. There are also three airborne divisions manned by the PLAAF. J-XX and XXJ are names applied by Western intelligence agencies to describe programs by the People's Republic of China to develop one or more fifth-generation fighter aircraft.[181][182] The PLAAF is led by Commander Chang Dingqiu and Political Commissar Guo Puxiao.[183][184]

Rocket Force

The People's Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) is the main strategic missile force of the PLA and consists of at least 120,000 personnel.[12]: 259 It controls China's nuclear and conventional strategic missiles.[185] China's total nuclear arsenal size is estimated to be between 100 and 400 thermonuclear warheads. The PLARF is organized into bases sequentially numbered from 61 through 67, wherein the first six are operational and allocated to the nation's theatre commands while Base 67 serves as the PRC's central nuclear weapons storage facility.[186] The PLARF is led by Command Li Yuchao and Political Commissar Xu Zhongbo.[187]

Arms

The PLA maintains four arms (Chinese: 兵种): the Aerospace Force, the Cyberspace Force, the Information Support Force, and the Joint Logistics Support Force. The four-arm system was established on 19 April 2024.[167]

Personnel

Recruitment and terms of service

The PLA began as an all-volunteer force. In 1955, as part of an effort to modernize the PLA, the first Military Service Law created a system of compulsory military service.[4] Since the late 1970s, the PLA has been a hybrid force that combines conscripts and volunteers.[4][188][189] Conscripts who fulfilled their service obligation can stay in the military as volunteer soldiers for a total of 16 years.[4][189] De jure, military service with the PLA is obligatory for all Chinese citizens. However, mandatory military service has not been enacted in China since 1949.[190][191]

Women and ethnic minorities

Women participated extensively in unconventional warfare, including in combat positions, in the Chinese Red Army during the revolutionary period, Chinese Civil War (1927–1949) and the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945).[192][193] After the establishment of the People's Republic of China, along with the People's Liberation Army (PLA)'s transition toward the conventional military organization, the role of women in the armed forces gradually reduced to support, medical, and logistics roles.[192] It was considered a prestigious choice for women to join the military. Serving in the military opens up opportunities for education, training, higher status, and relocation to cities after completing the service. During the Cultural Revolution, military service was regarded as a privilege and a method to avoid political campaign and coresion.[192]

In the 1980s, the PLA underwent large-scale demobilization amid the Chinese economic reform, and women were discharged back to civilian society for economic development while the exclusion of women in the military expanded.[192] In the 1990s, the PLA revived the recruitment of female personnel in regular military formations but primarily focused on non-combat roles at specialized positions.[192] Most women were trained in areas such as academic/engineering, medics, communications, intelligence, cultural work, and administrative work, as these positions conform to the traditional gender roles. Women in the PLA were more likely to be cadets and officers instead of enlisted soldiers because of their specializations.[192] The military organization still preserved some female combat units as public exemplars of social equality.[192][193]

Both enlisted and cadet women personnel underwent the same basic training as their male counterparts in the PLA, but many of them serve in predominantly female organizations. Due to ideological reasons, the regulation governing the segregation of sex in the PLA is prohibited, but a quasi-segregated arrangement for women's organizations is still applied through considerations of convenience.[192] Women were likelier to hold commanding positions in female-heavy organizations such as medical, logistic, research, and political work units, but sometimes in combat units during peacetime.[192] In PLAAF, women traditionally pilot transport aircraft or serve as crew members.[194] There had been a small number of high-ranking female officials in the PLA since 1949, but the advancement of position had remained relatively uncommon.[192][193] In the 2010s, women were increasingly serving in combat roles, in mixed-gender organizations alongside their male counterparts, and to the same physical standard.[193]

The military actively promotes opportunities for women in the military, such as celebrating International Women's Day for the members of the armed forces, publicizing the number of firsts for female officers and enlisted personnel, including deployments with peacekeeping forces or serving on PLA Navy's first aircraft carrier, announcing female military achievements in state media, and promoting female special forces through news reports or popular media.[193] PLA does not publish detailed gender composition of its armed forces, but the Jamestown Foundation estimated approximately 5% of the active military force in China is female.[195]

National unity and territorial integrity are central themes of the Chinese Communist Revolution. The Chinese Red Army and the succeeding PLA actively recruited ethnic minorities. During the Chinese Civil War, Mongol cavalry units were formed. During the Korean War, as many as 50,000 ethnic Koreans in China volunteered to join the PLA. PLA's recruitment of minorities generally correlates to state policies. During the early years, minorities were given preferential treatment, with special attention given to recruitment and training. In the 1950s, ethnic Mongols accounted for 52% of all officers in Inner Mongolia military region. During the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution, armed forces emphasized "socialist culture", assimilation policies, and the construction of common identities between soldiers of different ethnicities.[196]

For ethnic minority cadets and officials, overall development follows national policies. Typically, minority officers hold officer positions in their home regions. Examples included over 34% of the battalion and regimental cadres in Yi autonomous region militia were of the Yi ethnicity, and 45% of the militia cadres in Tibetan local militia were of Tibetan ethnicity. Ethnical minorities achieved high-ranking positions in the PLA, and the percentage of appointments appears to follow the ratio of the Chinese population composition.[196] Prominent figures included ethnic Mongol general Ulanhu, who served in high-ranking roles in the Inner Mongolian region and as vice president of China, and ethnic Uyghur Saifuddin Azizi, a Lieutenant General who served in the CCP Central Committee.[196] There were a few instances of ethnic distrust within the PLA, with one prominent example being the defection of Margub Iskhakov, an ethnic Muslim Tatar PLA general, to the Soviet Union in the 1960s. However, his defection largely contributed to his disillusion with the failed Great Leap Forward policies, instead of his ethnic background.[197] In modern times, ethnic representation is most visible among junior-ranking officers. Only a few minorities reach the highest-ranking positions.[197]

Rank structure

Officers

Other ranks

| Rank group | Senior NCOs | Junior NCOs | Enlisted | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 一级军士长 Yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

二级军士长 Èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

三级军士长 Sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

四级军士长 Sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

上士 Shàngshì |

中士 Zhōngshì |

下士 Xiàshì |

上等兵 Shàngděngbīng |

列兵 Lièbīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 海军一级军士长 Hǎijūn yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军二级军士长 Hǎijūn èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军三级军士长 Hǎijūn sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军四级军士长 Hǎijūn sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

海军上士 Hǎijūn shàngshì |

海军中士 Hǎijūn zhōngshì |

海军下士 Hǎijūn xiàshì |

海军上等兵 Hǎijūn shàngděngbīng |

海军列兵 Hǎijūn lièbīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 空军一级军士长 Kōngjūn yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军二级军士长 Kōngjūn èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军三级军士长 Kōngjūn sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军四级军士长 Kōngjūn sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

空军上士 Kōngjūn shàngshì |

空军中士 Kōngjūn zhōngshì |

空军下士 Kōngjūn xiàshì |

空军上等兵 Kōngjūn shàngděngbīng |

空军列兵 Kōngjūn lièbīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

No equivalent |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Master sergeant class one 一级军士长 yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

Master sergeant class two 二级军士长 èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

Master sergeant class three 三级军士长 sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

Master sergeant class four 四级军士长 sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

Sergeant first class 上士 shàngshì |

Sergeant 中士 zhōngshì |

Corporal 下士 xiàshì |

Private first class 上等兵 shàngděngbīng |

Private 列兵 lièbīng

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 一级军士长 Yījí jūnshìzhǎng |

二级军士长 Èrjí jūnshìzhǎng |

三级军士长 Sānjí jūnshìzhǎng |

四级军士长 Sìjí jūnshìzhǎng |

上士 Shàngshì |

中士 Zhōngshì |

下士 Xiàshì |

上等兵 Shàngděngbīng |

列兵 Lièbīng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Weapons and equipment

According to the United States Department of Defense, China is developing kinetic-energy weapons, high-powered lasers, high-powered microwave weapons, particle-beam weapons, and electromagnetic pulse weapons with its increase of military fundings.[199]

The PLA has said of reports that its modernisation is dependent on sales of advanced technology from American allies, senior leadership have stated "Some have politicized China's normal commercial cooperation with foreign countries, damaging our reputation." These contributions include advanced European diesel engines for Chinese warships, military helicopter designs from Eurocopter, French anti-submarine sonars and helicopters,[200] Australian technology for the Houbei class missile boat,[201] and Israeli supplied American missile, laser and aircraft technology.[202]

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute's data, China became the world's third largest exporter of major arms in 2010–14, an increase of 143 percent from the period 2005–2009.[203] SIPRI also calculated that China surpassed Russia to become the world's second largest arms exporter by 2020.[204]

China's share of global arms exports hence increased from 3 to 5 percent. China supplied major arms to 35 states in 2010–14. A significant percentage (just over 68 percent) of Chinese exports went to three countries: Pakistan, Bangladesh and Myanmar. China also exported major arms to 18 African states. Examples of China's increasing global presence as an arms supplier in 2010–14 included deals with Venezuela for armoured vehicles and transport and trainer aircraft, with Algeria for three frigates, with Indonesia for the supply of hundreds of anti-ship missiles and with Nigeria for the supply of several unmanned combat aerial vehicles.[205]

Following rapid advances in its arms industry, China has become less dependent on arms imports, which decreased by 42 percent between 2005–09 and 2010–14. Russia accounted for 61 percent of Chinese arms imports, followed by France with 16 percent and Ukraine with 13 per cent. Helicopters formed a major part of Russian and French deliveries, with the French designs produced under licence in China.[205]

Over the years, China has struggled to design and produce effective engines for combat and transport vehicles. It continued to import large numbers of engines from Russia and Ukraine in 2010–14 for indigenously designed combat, advanced trainer and transport aircraft, and naval ships. It also produced British-, French- and German-designed engines for combat aircraft, naval ships and armoured vehicles, mostly as part of agreements that have been in place for decades.[205]

In August 2021, China tested a nuclear-capable hypersonic missile that circled the globe before speeding towards its target.[206] The Financial Times reported that "the test showed that China had made astounding progress on hypersonic weapons and was far more advanced than U.S. officials realized."[207] During the Exercise Zapad-81 in 2021 with Russian forces, most of the gear were novel Chinese arms such as the KJ-500 airborne early warning and control aircraft, J-20 and J-16 fighters, Y-20 transport planes, and surveillance and combat drones.[208] Another joint forces exercise took place in August 2023 near Alaska.[209]

Cyberwarfare

There is a belief in the Western military doctrines that the PLA have already begun engaging countries using cyber-warfare.[210] There has been a significant increase in the number of presumed Chinese military initiated cyber events from 1999 to the present day.[211]

Cyberwarfare has gained recognition as a valuable technique because it is an asymmetric technique that is a part of information operations and information warfare. As is written by two PLAGF Colonels, Qiao Liang and Wang Xiangsui in the book Unrestricted Warfare, "Methods that are not characterized by the use of the force of arms, nor by the use of military power, nor even by the presence of casualties and bloodshed, are just as likely to facilitate the successful realization of the war's goals, if not more so.[212]

While China has long been suspected of cyber spying, on 24 May 2011 the PLA announced the existence of having 'cyber capabilities'.[213]

In February 2013, the media named "Comment Crew" as a hacker military faction for China's People's Liberation Army.[214] In May 2014, a Federal Grand Jury in the United States indicted five Unit 61398 officers on criminal charges related to cyber attacks on private companies based in the United States after alleged investigations by the Federal Bureau of Investigation who exposed their identities in collaboration with US intelligence agencies such as the CIA.[215][216]

In February 2020, the United States government indicted members of China's People's Liberation Army for the 2017 Equifax data breach, which involved hacking into Equifax and plundering sensitive data as part of a massive heist that also included stealing trade secrets, though the CCP denied these claims.[217][218]

Nuclear capabilities

The first of China's nuclear weapons tests took place in 1964, and its first hydrogen bomb test occurred in 1967 at Lop Nur. Tests continued until 1996, when the country signed the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), but did not ratify it.[219]

The number of nuclear warheads in China's arsenal remains a state secret.[220] There are varying estimates of the size of China's arsenal. The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists and Federation of American Scientists estimated in 2024 that China has a stockpile of approximately 438 nuclear warheads,[220][221] while the United States Department of Defense put the estimate at more than 500 operational nuclear warheads,[222] making it the third-largest in the world.

China's policy has traditionally been one of no first use while maintaining a deterrent retaliatory force targeted for countervalue targets.[223] According to a 2023 study by the National Defense University, China's nuclear doctrine has historically leaned toward maintaining a secure second-strike capability.[224]

Space

Having witnessed the crucial role of space to United States military success in the Gulf War, China continues to view space as a critical domain in both conflict and international strategic competition.[225][226] The PLA operates a various satellite constellations performing reconnaissance, navigation, communication, and counterspace functions.[227][228][229][230] Planners at PLA's National Defense University project China's space actions as retaliatory or preventative, following conditions like an attack on a Chinese satellite, an attack on China, or the interruption of a PLA amphibious landing.[231] According to this approach, PLA planners assume that the country must have the capacity for retaliation and second-strike capability against a powerful opponent.[231] PLA planners envision a limited space war and therefore seek to identify weak but critical nodes in other space systems.[231]

Significant components of the PLA's space-based reconnaissance include Jianbing (vanguard) satellites with cover names Yaogan (遥感; 'remote sensing') and Gaofen (高分; 'high resolution').[227][232] These satellites collect electro-optical (EO) imagery to collect a literal representation of a target, synthetic aperture radar (SAR) imagery to penetrate the cloudy climates of southern China,[233] and electronic intelligence (ELINT) to provide targeting intelligence on adversarial ships.[234][235] The PLA also leverages a restricted, high-performance service of the country's BeiDou positioning, navigation, and timing (PNT) satellites for its forces and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) platforms.[236][237] For secure communications, the PLA uses the Zhongxing and Fenghuo series of satellites which enable secure data and voice transmission over C-band, Ku-band, and UHF.[229] PLA deployment of anti-satellite and counterspace satellites including those of the Shijian and Shiyan series have also brought significant concern from western nations.[238][230][239]

The PLA also plays a significant role in the Chinese space program.[225] To date, all the participants have been selected from members of the PLA Air Force.[225] China became the third country in the world to have sent a man into space by its own means with the flight of Yang Liwei aboard the Shenzhou 5 spacecraft on 15 October 2003,[240] the flight of Fei Junlong and Nie Haisheng aboard Shenzhou 6 on 12 October 2005,[241] and Zhai Zhigang, Liu Boming, and Jing Haipeng aboard Shenzhou 7 on 25 September 2008.[242]

The PLA started the development of an anti-ballistic and anti-satellite system in the 1960s, code named Project 640, including ground-based lasers and anti-satellite missiles.[243] On 11 January 2007, China conducted a successful test of an anti-satellite missile, with an SC-19 class KKV.[244]

The PLA has tested two types of hypersonic space vehicles, the Shenglong Spaceplane and a new one built by Chengdu Aircraft Corporation. Only a few pictures have appeared since it was revealed in late 2007. Earlier, images of the High-enthalpy Shock Waves Laboratory wind tunnel of the CAS Key Laboratory of high-temperature gas dynamics (LHD) were published in the Chinese media. Tests with speeds up to Mach 20 were reached around 2001.[245][246]

Бюджет

| Публикация дата |

Ценить (миллиарды долларов США ) |

|---|---|

| Март 2000 | 14.6 [ Цитация необходима ] |

| Март 2001 г. | 17.0 [ Цитация необходима ] |

| Март 2002 г. | 20.0 [ Цитация необходима ] |

| Март 2003 г. | 22.0 [ Цитация необходима ] |

| Март 2004 г. | 24.6 [ Цитация необходима ] |

| Март 2005 г. | 29.9 [ Цитация необходима ] |

| Март 2006 г. | 35.0 [ Цитация необходима ] |

| Март 2007 г. | 44.9 [ Цитация необходима ] |

| Март 2008 г. | 58.8 [ 247 ] |

| Март 2009 г. | 70.0 [ Цитация необходима ] |

| Март 2010 г. | 76.5 [ 248 ] |

| Март 2011 г. | 90.2 [ 248 ] |

| Март 2012 года | 103.1 [ 248 ] |

| Март 2013 года | 116.2 [ 248 ] |

| Март 2014 года | 131.2 [ 248 ] |

| Март 2015 | 142.4 [ 248 ] |

| Март 2016 года | 143.7 [ 248 ] |

| Март 2017 года | 151.4 [ 248 ] |

| Март 2018 года | 165.5 [ 249 ] |

| Март 2019 года | 177.6 [ 250 ] |

| Май 2020 года | 183.5 [ 251 ] |

| Март 2021 г. | 209.4 [ 252 ] |

| Март 2022 года | 229.4 [ 253 ] |

| Март 2023 г. | 235.8 [ Цитация необходима ] |

Стокгольмский международный институт исследований мира (SIPRI) подсчитал, что военные расходы Китая в 2023 году составляли 296 миллиардов долларов США, что было вторым по величине в мире после Соединенных Штатов и составило 12 процентов расходов на оборону мира . [ 254 ]

Символы

Гимн

Марш китайской народной Армии освобождения был принят в качестве военного гимна Центральной военной комиссией 25 июля 1988 года. [ 255 ] Лирика гимна была написана композитором Гонг Му (настоящее имя: Чжан Юнньян; Китайский : 张永年), а музыка была написана китайским композитором Кореи Чжэн Люхенг . [ 256 ] [ 257 ]

Флаг и знаки отличия

Знакейки PLA состоит из Roundel с красной звездой с двумя китайскими иеханными « 八一 » (буквально «восемь-один»), ссылаясь на восстание Нанчанга , которое началось 1 августа 1927 года (первый день восьмого месяца) и символического как основание КПК ПЛА. [ 258 ] Включение двух персонажей (« 八一 ») является символом революционной истории партии, несущей сильные эмоциональные коннотации политической власти, которую она проливает кровь, чтобы получить. Флаг китайской народной Армии освобождения - это военный флаг Народной освободительной армии; Уставка флага имеет золотую звезду в верхнем левом углу и « 八一 » справа от звезды, расположенной на красном поле. У каждого филиала обслуживания также есть свои флаги: вершина 5 ~ 8 флагов такой же, как и флаг PLA; дно 3 ⁄ 8 заняты цветами ветвей. [ 259 ]

Флаг наземных войск имеет лесной зеленый бар на дне. Военно -морской прапорщик имеет полосы синего и белого внизу. Военно -воздушные силы используют голубую бар. Ракетная сила использует желтую полосу внизу. Лесной зеленый представляет землю, синие и белые полосы представляют моря, небо синий представляет воздух, а желтый представляет вспышку запуска ракет. [ 260 ] [ 261 ]

-

Плата

Смотрите также

- Схема гражданской войны Китая

- Схема военной истории Китая Народной Республики

- Китайская Республика вооруженные силы

Ссылки

- ^ « Китайская армия освобождения » . » « Память о Янане] Название начинается этого с

- ^ народной армии . » была 1947 года Китая выпущена« Декларация на «10 октября

- ^ «Фон и адаптация Красной Армии возглавляют Коммунистическую партию Китая в восьмом . героев Тайханга - сеть маршруте »

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Аллен, Кеннет (14 января 2022 года). «Эволюция зачисленной в PLA силы: призыв и набор (часть первая)» . Фонд Джеймстауна . Архивировано из оригинала 16 апреля 2023 года . Получено 11 февраля 2024 года .

После неудачи культурной революции, в конце 1970 -х годов, ПЛА приступила к амбициозной программе для модернизации многих аспектов военных, включая образование, обучение и набор персонала. Призывники и добровольцы были объединены в одну систему, которая разрешила призывцам, которые выполняли свое обязательство по обслуживанию оставаться в армии в качестве добровольных солдат в общей сложности 16 лет.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Международный институт стратегических исследований 2022 , с. 255

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Тянь, Нэн; Флерант, Ауд; Куймова, Александра; Wezeman, Pieter D.; Wezeman, Siemon T. (24 апреля 2022 г.). «Тенденции мировых военных расходов, 2021 год» (PDF) . Стокгольмский Международный институт исследования мира . Архивировано из оригинала 25 апреля 2022 года . Получено 25 апреля 2022 года .

- ^ Сюэ, Мэринн (4 июля 2021 года). «Торговля оружием Китая: в каких странах он покупает и продает?» Полем Южно -Китайский утренний пост . Архивировано из оригинала 26 мая 2022 года . Получено 26 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный «Импорт/экспорт оружия из Китая, 2010–2021» . Стокгольмский Международный институт исследования мира . 7 февраля 2022 года. Архивировано из оригинала 21 июня 2023 года . Получено 26 января 2023 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Бентон, Грегор (1999). Новая четвертая армия: коммунистическое сопротивление вдоль Янцзы и Хуай, 1938–1941 . Калифорнийский университет. п. 396. ISBN 978-0-520-21992-2 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 15 января 2023 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и Fravel, M. Taylor (2019). Активная защита: военная стратегия Китая с 1949 года . Тол. 2. Princeton University Press . doi : 10.2307/j.ctv941tzj . ISBN 978-0-691-18559-0 Полем JSTOR J.CTV941TZJ . S2CID 159282413 .

- ^ «Глобальные военные расходы остаются высокими в 1,7 триллиона долларов» . Стокгольмский Международный институт исследования мира . 2 мая 2018 года. Архивировано с оригинала 27 мая 2018 года . Получено 13 октября 2018 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и Международный институт стратегических исследований (2020). Военный баланс . Лондон: Routledge . doi : 10.1080/045972222.2020.1707967 . ISBN 978-0367466398 .

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019 , с. 148.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Saunders et al. 2019 , стр. 13–14.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и Saunders et al. 2019 , с. 521.

- ^ военно-морского флота PLA « Новые исторические миссии : расширение возможностей для восстановления морской власти» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 28 апреля 2011 года . Получено 1 апреля 2011 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Гарлик, Джереми (2024). Преимущество Китая: агент изменений в эпоху глобальных сбоев . Bloomsbury Academic . ISBN 978-1-350-25231-8 .

- ^ Картер, Джеймс (4 августа 2021 г.). «Начневое восстание и рождение ПЛА» . Китай проект . Архивировано из оригинала 7 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «История Организационной структуры и военных регионов Грузовой силы ПЛА» . Королевский институт Объединенных служб . 17 июня 2004 года. Архивировано с оригинала 11 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Bianco, Lucien (1971). Происхождение китайской революции, 1915–1949 гг . Издательство Стэнфордского университета . п. 68. ISBN 978-0-8047-0827-2 .

- ^ Zedong, Mao (2017). На партизанской войне: Мао Це-Тун на партизанской войне . Martino Fine Books. ISBN 978-1-68422-164-6 .

- ^ «Китайская революция 1949 года» . Государственный департамент Соединенных Штатов , Управление историка . Архивировано из оригинала 19 мая 2017 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Кен Аллен, Глава 9, «Организация ВВС PLA», архивировав 2007-09-29 на The Wayback Machine , PLA As Ascory, Ed. Джеймс С. Малвенон и Эндрю Н.Д. Ян (Санта -Моника, Калифорния: Рэнд, 2002), 349.

- ^ основания военно -морского флота Армии Народной армии » «Пресс -конференция по многонациональной военно -морской деятельности для Циндао состоялась в 70 -й годовщины из оригинала 1 O Ctober 2022. Получено 18 мая 2020 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Руссо, Алессандро (2020). Культурная революция и революционная культура . Дарем: издательство Duke University Press . С. 36–37. ISBN 978-1-4780-1218-4 Полем OCLC 1156439609 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный «Народная народная армия освобождения, вторая по величине обычная в мире ...» UPI . Архивировано из оригинала 4 декабря 2022 года . Получено 4 декабря 2022 года .

- ^ Ло, Дилан М.Х. (2024). Растущее министерство иностранных дел Китая: практика и представления о настойчивой дипломатии . Издательство Стэнфордского университета . ISBN 9781503638204 .

- ^ Брошюра № 30-51, Справочник по коммунистической армии Китая (PDF) , Департамент армии, 7 декабря 1960 года, архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 29 апреля 2011 года , полученное 1 апреля 2011 г.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Стюарт, Ричард (2015). Корейская война: китайское вмешательство . CreateSpace Независимая издательская платформа. ISBN 978-1-5192-3611-1 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Клифф, Роджер; Фэй, Джон; Хаген, Джефф; Гаага, Элизабет; Хегинботам, Эрик; Шилляон, Джон (2011), «Эволюция доктрины китайских ВВС», встряхивая небеса и разделяя землю , концепции занятости ВВС Китая в 21 -м веке, Rand Corporation , с. 33–46, ISBN 978-0-8330-4932-2 , JSTOR 10.7249/MG915AF.10

- ^ Хоффман, Стивен А. (1990). Индия и Китайский кризис . Беркли: Университет Калифорнийской прессы. С. 101–104. ISBN 978-0-520-30172-6 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 9 октября 2021 года . Получено 1 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Ван Трондер, Джерри (2018). Сино-индийская война: пограничная столкновения: октябрь-ноябрь 1962 года . Ручка и меч военный. ISBN 978-1-5267-2838-8 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 25 июня 2021 года . Получено 1 октября 2020 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Брахма Челлани (2006). Азиатский джаггернаут: рост Китая, Индии и Японии . HarperCollins . п. 195. ISBN 978-8172236502 Полем

Действительно, признание Пекина в индийском контроле над Сиккимом, кажется, ограничено целью облегчения торговли через головокружительный перевал Нату-ла, сцену кровавых артиллерийских разунов в сентябре 1967 года, когда индийские войска обрывают атаку, атакующие китайские силы.

- ^ Ван Прааг, Дэвид (2003). Большая игра: Гонка Индии с судьбой и Китаем . McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP. п. 301. ISBN 978-0773525887 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 25 декабря 2018 года . Получено 6 августа 2021 года .

(Индийский) Jawans, обученные и оснащенные для высокогорного боя, использовали американскую артиллерию, развернутую на возвышенности, чем у их противников, для решительного тактического преимущества в Нату Ла и Чо Ла возле границы Сикким-Тибета.

- ^ Hoontrakul, Ponesak (2014), «Развивающаяся экономическая динамизм и политическое давление Азии» , в P. Hoontrakul; C. лысеть; R. Marwah (Eds.), Глобальный рост азиатской трансформации: тенденции и события в динамике экономического роста , Palgrave Macmillan US, p. 37, ISBN 978-1-137-41236-2 , архивировано из оригинала 25 декабря 2018 года , получено 6 августа 2021 года ,

инцидент Чо Ла (1967) - Победитель: Индия / Победил: Китай

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Ли, Сяобинг (2007). История современной китайской армии . Университетская пресса Кентукки . doi : 10.2307/j.ctt2jcq4k . ISBN 978-0-8131-2438-4 Полем JSTOR J.CTT2JCQ4K .

- ^ Эбри, Патриция Бакли. «Четыре модернизации эпоха» . Визуальный сборник китайской цивилизации . Университет Вашингтона. Архивировано из оригинала 7 октября 2010 года . Получено 20 октября 2012 года .

- ^ Народные ежедневные (31 января 1963 г.). В прошлом году Чжоу Энлай объяснил значение модернизации науки и техники в Шанхае [Наука и техника в Шанхае на конференции на Чжоу Энлай объяснили значение современной науки и техники]. Люди ежедневно (на китайском языке). Центральный комитет Коммунистической партии Китая. п. 1. Архивировано из оригинала 14 февраля 2016 года . Получено 21 октября 2011 года .

- ^ Мейсон, Дэвид (1984). «Четыре модернизации Китая: план развития или прелюдия к суматохам?». Азиатские дела . 11 (3): 47–70. doi : 10.1080/00927678.1984.10553699 . ISSN 0092-7678 . JSTOR 30171968 .

- ^ Винсент, Трэвилс (9 февраля 2022 г.). «Почему Вьетнам не преподает историю китайско-вьетнамской войны?» Полем Дипломат . Архивировано из оригинала 18 февраля 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Fravel, M. Taylor (2007). «Сдвиг власти и эскалация: объяснение применения силы Китая в территориальных спорах». Международная безопасность . 32 (3): 44–83. doi : 10.1162/isec.2008.32.3.44 . ISSN 0162-2889 . JSTOR 30130518 . S2CID 57559936 .

- ^ Китай и Афганистан , Джеральд Сегал, Азиатское обследование, вып. 21, № 11 (ноябрь 1981 г.), издательство Калифорнийского университета

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Хилали, Аризона (сентябрь 2001 г.). «Реакция Китая на советское вторжение в Афганистан». Опрос Центральной Азии . 20 (3): 323–351. doi : 10.1080/02634930120095349 . ISSN 0263-4937 . S2CID 143657643 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Starri, S. Frederick (2004). Синьцзян: мусульманская граница Китая . Я Шарп. С. 157–158. ISBN 0765613182 .

- ^ Zczudlik-Tatar, Justyna (октябрь 2014 г.). «Развивающаяся позиция Китая в Афганистане: к более надежной дипломатии с« китайскими характеристиками » ( PDF) . Стратегический файл . 58 (22). Польский институт международных дел. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 29 августа 2023 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Галстер, Стив (9 октября 2001 г.). «Том II: Афганистан: уроки из последней войны» . Архив национальной безопасности, Университет Джорджа Вашингтона . Архивировано из оригинала 6 сентября 2021 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Годвин, Павел Х.Б. (2019). Заведение Китая: преемственность и изменения в 1980 -х годах . Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-31540-0 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 11 февраля 2024 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Saunders et al. 2019 , с. 523.

- ^ Зиссис, Карин (5 декабря 2006 г.). «Модернизация Народной Армии освобождения Китая» . Совет по иностранным отношениям . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019 , с. 51

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019 , с. 520.

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019 , с. 526.

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019 , стр. 51–52.

- ^ Saunders et al. 2019 , с. 531.

- ^ «Абсолютная лояльность PLA» к партии сомневается » . Фонд Джеймстауна . 30 апреля 2009 года. Архивировано с оригинала 13 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «Си Цзиньпин настаивает на абсолютной верности PLA к коммунистической партии» . Экономические времена . 20 августа 2018 года. Архивировано с оригинала 15 марта 2023 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Чан, Минни (23 сентября 2022 г.). «Военные Китая сказали« решительно делать то, что партия просит ее сделать » . Южно -Китайский утренний пост . Архивировано из оригинала 19 октября 2023 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в Политическая система Китайской Народной Республики. Главный редактор Пу Синзу, Шанхай, 2005, Шанхайский народный издательство. ISBN 7-208-05566-1 , Глава 11 Государственная военная система.

- ^ Новости о коммунистической партии Китая, гиперссылка архивировала 13 октября 2006 года на машине Wayback . Получено 28 марта 2007 года.

- ^ Фарли, Роберт (1 сентября 2021 года). «Китай не забыл уроки войны в Персидском заливе» . Национальный интерес . Архивировано с оригинала 11 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Скобелл, Эндрю (2011). Китайские уроки из войн других людей (PDF) . Институт стратегических исследований, военный колледж армии США. ISBN 978-1-58487-511-6 Полем Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Лэмптон, Дэвид М. (2024). Жизнь связей с американскими и китайцами: от холодной войны до холодной войны . Ланхэм, доктор медицины: Роуман и Литтлфилд . п. 225. ISBN 978-1-5381-8725-8 .

- ^ Сасаки, Томонори (23 сентября 2010 г.). «Китай смотрит на японские военные: восприятие угрозы Китая в Японии с 1980 -х годов» . Китай ежеквартально . 203 : 560–580. doi : 10.1017/s0305741010000597 . ISSN 1468-2648 . S2CID 153828298 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Сагагучи, Йошаки; Mayama, Katsuhiko (1999). «Значение войны в Косово для Китая и России» (PDF ) Отчеты о безопасности NIDS (3): 1–2 Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 14 августа Получено 12 ноября

- ^ Солнце, Юнь (8 апреля 2020 года). «Стратегическая оценка Китая Афганистана» . Война на скалах . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Чейз, Майкл С. (19 сентября 2007 г.). «Оценка войны Китая в Ираке:« Самый глубокий капитан Америки »и последствия для китайской национальной безопасности» . Китай Бриф . 7 (17). Фонд Джеймстауна . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Джи, ты (1999). «Революция в военных делах и эволюция стратегического мышления Китая» . Современная Юго -Восточная Азия . 21 (3): 344–364. doi : 10.1355/cs21-3b . ISSN 0129-797X . JSTOR 25798464 . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Ворцель, Ларри М. (2007). «Китайская народная освободительная армия и космическая война». Космическая политика . Американский институт предприятия . JSTOR RESREP03013 .

- ^ Hjortdal, Magnus (2011). «Использование Китая кибер -войны: шпионаж отвечает стратегическому сдерживанию» . Журнал стратегической безопасности . 4 (2): 1–24. doi : 10.5038/1944-0472.4.2.1 . ISSN 1944-0464 . JSTOR 26463924 . S2CID 145083379 .

- ^ Джингхуа, Лю. "Каковы кибер -возможности Китая и намерения?" Полем Карнеги -фонд для международного мира . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и Шинн, Дэвид Х .; Эйзенман, Джошуа (2023). Отношения Китая с Африкой: новая эра стратегического участия . Нью -Йорк: издательство Колумбийского университета . ISBN 978-0-231-21001-0 .

- ^ Осборн, Крис (21 марта 2022 г.). «Китай модернизирует своих российских эсминцев новым оружием» . Национальный интерес . Архивировано из оригинала 4 февраля 2023 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Гао, Чарли (1 января 2021 года). «Как Китай получил свой собственный русский производство Su-27« Flanker "Jets" . Национальный интерес . Архивировано из оригинала 5 декабря 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Кадам, Танмай (26 сентября 2022 г.). «2 Русские бойцы Су-30, костяк ВВС и китайских военно-воздушных сил, нокаутированные Украиной-утверждает Киева» . Евразийские времена . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Ларсон, Калеб (11 мая 2021 г.). «Смертельные подводные лодки в Китае из Китая из России с любовью» . Национальный интерес . Архивировано из оригинала 4 февраля 2023 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Вавассер, Ксавье (21 августа 2022 г.). «Пять типа 052D эсминцев, строящихся в Китае» . Военно -морские новости . Архивировано из оригинала 25 августа 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Вертхейм, Эрик (январь 2020 г.). «Китайский эсминчик Luyang III/Type 052D - мощный противник» . Военно -морской институт Соединенных Штатов . Архивировано из оригинала 10 июня 2023 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Rogoway, Тайлер; Хелфрих, Эмма (18 июля 2022 года). «Китайский боец J-10, обнаруженный в новой конфигурации« Большой позвоночник »(обновлен)» . Военная зона . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Осборн, Крис (4 октября 2022 г.). «Китай повышает производство истребителей J-20, чтобы противостоять американским стелс-бойцам» . Национальный интерес . Архивировано из оригинала 1 декабря 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Funaiole, Matthew P. (4 августа 2021 г.). «Проблема китайских баллистических подводных лодок» . Центр стратегических и международных исследований . Архивировано из оригинала 7 октября 2023 года.

- ^ Лендон, Брэд (25 июня 2022 года). «Не берите в голову новый авианосец Китая, это те корабли, о которых должны беспокоиться США» . CNN . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «Fujian Aircraint Raturer еще не имеет радаров, вооруженных систем, фото показывают» . Южно -Китайский утренний пост . 19 июля 2022 года. Архивировано с оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Хендрикс, Джерри (6 июля 2022 года). «Зловещий предзнаменование нового носителя Китая» . Национальный обзор . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ «Китай устанавливает ракетные силы и стратегическую силу поддержки - Китайский военный онлайн» . Архивировано с оригинала 10 апреля 2016 года . Получено 2 января 2016 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Дуан, Лей (2024). «На пути к более совместной стратегии: оценка китайских военных реформ и реконструкции милиции». В клыке, Цянь; Ли, Сяобинг (ред.). Китай при Си Цзиньпин: новая оценка . Leiden University Press . ISBN 9789087284411 Полем JSTOR JJ.15136086 .

- ^ «Эксклюзив: массовый парад, проведенный на 90 -летие PLA» . Южно -Китайский утренний пост . 15 марта 2017 года. Архивировано с оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Бакли, Крис (30 июля 2017 г.). «Китай демонстрирует военную мощь, когда Си Цзиньпин пытается закрепить власть» . New York Times . ISSN 0362-4331 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 октября 2021 года . Получено 12 октября 2021 года .

- ^ «Китайская военная чистка раскрывает слабость, может расширить» . Рейтер . 31 декабря 2023 года . Получено 22 июля 2024 года .

- ^ «График« Великая чистка »Китая под XI» . BBC News . 22 октября 2017 года. Архивировано с оригинала 6 июня 2021 года . Получено 1 января 2024 года .

- ^ Ян, София (10 июля 2024 г.). «Китай строит секретную военную базу в Таджикистане, чтобы сокрушить угрозу со стороны талибов» . Ежедневный телеграф . ISSN 0307-1235 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 июля 2024 года . Получено 10 июля 2024 года .

- ^ «Секретные сигналы: декодирование разведывательной деятельности Китая на Кубе» . Центр стратегических и международных исследований . 1 июля 2024 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2 июля 2024 года . Получено 2 июля 2024 года .

- ^ Гаррисон, Кассандра (31 января 2019 г.). «Военная космическая станция Китая в Аргентине-« черный ящик » » . Рейтер . Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2022 года . Получено 25 января 2022 года .

- ^ «Глаза на небо: растущий космический след в Южной Америке» . Центр стратегических и международных исследований . 4 октября 2022 года. Архивировано с оригинала 5 октября 2022 года . Получено 4 октября 2022 года .

- ^ Чеанг, Софенг; Дэвид, Восстание (8 мая 2024 г.). «Китайские военные корабли были пристыкованы в Камбодже в течение 5 месяцев, но правительство говорит, что это не постоянно» . Ассошиэйтед Пресс . Архивировано из оригинала 9 июля 2024 года . Получено 10 июля 2024 года .

- ^ «Китайские военные корабли вращаются на военно -морской базе Камбоджи» . Радио Свободная Азия . 4 июля 2024 года . Получено 10 июля 2024 года .

- ^ Гован, Ричард (14 сентября 2020 г.). «Прагматический подход Китая к миротворческому поддержанию ООН» . Брукингс институт . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Роуленд, Даниэль Т. (сентябрь 2022 г.). Китайская деятельность по вопросам сотрудничества в области безопасности: тенденции и последствия для политики США (PDF) (отчет). Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 10 декабря 2022 года . Получено 10 декабря 2022 года .

- ^ Роль Китая в миротворчестве ООН (PDF) (отчет). Институт политики безопасности и развития. Март 2018 года. Архивировал (PDF) из оригинала 5 октября 2022 года . Получено 10 декабря 2022 года .

- ^ Даниэль М. Хартнет, 2012-03-13, первое внедрение в Китае боевых сил в ООН. Миссия по поддержанию мира-Южный Судан Архивировал 14 октября 2012 года. В The Wayback Machine , Комиссия по экономическому и безопасности США и Кита

- ^ Бернард Юдкин Geoxavier, 2012-09-18, Китай как миротворца: обновленная перспектива на гуманитарное вмешательство архивировало 31 января 2013 года на машине Wayback , Йельский журнал международных дел

- ^ «Китайские миротворцы на Гаити: много внимания, больше путаницы» . Королевский институт Объединенных служб . 1 февраля 2005 года. Архивировано из оригинала 11 февраля 2024 года . Получено 10 декабря 2022 года .

- ^ Николс, Мишель (14 июля 2022 года). «Китай стремится к эмбарго ООН на преступных бандах Гаити» . Рейтер . Архивировано из оригинала 10 декабря 2022 года . Получено 10 декабря 2022 года .

- ^ Dyrenforth, Томас (19 августа 2021 г.). «Голубые шлемы Пекина: что делать с роли Китая в миротворчестве ООН в Африке» . Современный институт войны . Архивировано из оригинала 12 ноября 2022 года . Получено 12 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Лью, Кристофер Р.; Leung, Pak-Wah, eds. (2013). Исторический словарь гражданской войны Китая . Ланхэм, Мэриленд: Theckrow Press, Inc. p. 3. ISBN 978-0810878730 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 11 апреля 2023 года . Получено 10 декабря 2022 года .

- ^ Пейн, SCM (2012). Войны за Азию, 1911–1949 . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 123. ISBN 978-1-139-56087-0 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 12 октября 2022 года . Получено 28 ноября 2017 года .

- ^ «Требуется проверка безопасности» . Архивировано из оригинала 14 апреля 2015 года . Получено 1 мая 2016 года .

- ^ «Синьян и китайско-советские отношения» (PDF) . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 5 июня 2011 года . Получено 14 марта 2017 года .

- ^ Шакья 1999 с. 32 (6 октября); Гольдштейн (1997) , с. 45 (7 октября).

- ^ Райан, Марк А.; Финкельштейн, Дэвид М.; Макдевитт, Майкл А. (2003). Китайская боевая борьба: опыт PLA с 1949 года . Армонк, Нью -Йорк: Я Шарп. п. 125. ISBN 0-7656-1087-6 .

- ^ Rushkoff, Bennett C. (1981). «Эйзенхауэр, Даллес и Кризис Кемоя-Мацу, 1954–1955». Политология ежеквартально . 96 (3): 465–480. doi : 10.2307/2150556 . ISSN 0032-3195 . JSTOR 2150556 .

- ^ Zhai, Qiang (2000). Китай и Вьетнамские войны, 1950–1975 . Чапел Хилл: Университет Северной Каролины Пресс. ISBN 978-0807825327 Полем OCLC 41564973 .