Испанская фонология

Эта статья о фонологии и фонетике испанского языка . Если не указано иное, заявления относятся к кастильскому испанскому языку , стандартному диалекту, используемому в Испании на радио и телевидении. [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] [ 4 ] Чтобы узнать об историческом развитии звуковой системы, см. «Историю испанского языка» . Подробную информацию о географических вариациях см. в разделе «Испанские диалекты и разновидности» .

Фонематические представления записываются внутри косых черт ( / / ), а фонетические — в скобках ( [ ] ).

Согласные

[ редактировать ]| губной | Стоматологический | Альвеолярный | Пост-альв. / Палатальный |

Велар | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| носовой | м | н | с | |||||||

| Останавливаться | п | б | т | д | тʃ | ʝ | к | ɡ | ||

| Continuant | f | θ* | s | (ʃ) | x | |||||

| Lateral | l | ʎ* | ||||||||

| Tap | ɾ | |||||||||

| Trill | r | |||||||||

The phonemes /b/, /d/, and /ɡ/ are pronounced as voiced stops only after a pause, after a nasal consonant, or—in the case of /d/—after a lateral consonant; in all other contexts, they are realized as approximants (namely [β̞, ð̞, ɣ˕], hereafter represented without the downtacks) or fricatives.[6][7]

The realization of the phoneme /ʝ/ varies greatly by dialect.[8] In Castilian Spanish, its allophones in word-initial position include the palatal approximant [j], the palatal fricative [ʝ], the palatal affricate [ɟʝ] and the palatal stop [ɟ].[8] After a pause, a nasal, or a lateral, it may be realized as an affricate ([ɟʝ]);[9][10] in other contexts, /ʝ/ is generally realized as an approximant [ʝ˕].

The phoneme /ʎ/ is distinguished from /ʝ/ in some areas in Spain (mostly northern and rural) and South America (mostly highland). Other accents of Spanish, comprising the majority of speakers, have lost the palatal lateral as a distinct phoneme and have merged historical /ʎ/ into /ʝ/: this is called yeísmo.

In addition, [ʒ] and [ʃ] occurs in Rioplatense Spanish as spoken across Argentina and Uruguay, where it is otherwise standard for the phonemes /ʝ/ or /ʎ/ to be realized as voiced palato-alveolar fricative [ʒ] instead of [ʝ] and /ʎ/, a feature called "zheísmo".[11] In the last few decades, it has further become popular, particularly among younger speakers in Argentina and Uruguay, to de-voice /ʒ/ to [ʃ] ("sheísmo").[12][13] In other dialects /ʃ/ is a marginal phoneme that occurs only in loanwords or certain dialects; many speakers have difficulty with this sound, tending to replace it with /tʃ/ or /s/. In a number of dialects (most notably, Northern Mexican Spanish, informal Chilean Spanish, and some Caribbean and Andalusian accents), [ʃ] occurs, as a deaffricated /tʃ/.[14]

Many young Argentinians have no distinct /ɲ/ phoneme and use the [nj] sequence instead, thus making no distinction between huraño and uranio (both [uˈɾanjo]).[15]

Most varieties spoken in Spain, including those prevalent on radio and television, have both /θ/ and /s/ (distinción). However, speakers in parts of southern Spain, the Canary Islands, and nearly all of Latin America have only /s/ (seseo). Some speakers in southernmost Spain (especially coastal Andalusia) have only [s̄] (a consonant similar to /θ/) and not /s/ (ceceo). This "ceceo" is not entirely unknown in the Americas, especially in coastal Peru. The word distinción itself is pronounced with /θ/ in varieties that have it.

The exact pronunciation of /s/ varies widely by dialect, with some realizing it as [h] or opting to omit it entirely [∅].[16]

The phonemes /t/ and /d/ are laminal denti-alveolar ([t̪, d̪]).[7] The phoneme /s/ becomes dental [s̪] before denti-alveolar consonants,[9] while /θ/ remains interdental [θ̟] in all contexts.[9]

Before front vowels /i, e/, the velar consonants /k, ɡ, x/ (including the lenited allophone of /ɡ/) are realized as post-palatal [k̟, ɡ˖, x̟, ɣ˕˖].[17]

According to some authors,[18] /x/ is post-velar or uvular in the Spanish of northern and central Spain.[19][20][21][22] Others[23] describe /x/ as velar in European Spanish, with a uvular allophone ([χ]) appearing before /o/ and /u/ (including when /u/ is in the syllable onset as [w]).[9]

A common pronunciation of /f/ in nonstandard speech is the voiceless bilabial fricative [ɸ], so that fuera is pronounced [ˈɸweɾa] rather than [ˈfweɾa].[24][14][25][26][27][28][29] In some Extremaduran, western Andalusian, and American varieties, this softened realization of /f/, when it occurs before the non-syllabic allophone of /u/ ([w]), is subject to merger with /x/; in some areas the homophony of fuego/juego is resolved by replacing fuego with lumbre or candela.[30][31]

Consonant neutralizations and assimilations

[edit]Some of the phonemic contrasts between consonants in Spanish are lost in certain phonological environments, especially in syllable-final position. In these cases, the phonemic contrast is said to be neutralized.

Sonorants

[edit]Nasals and laterals

[edit]In syllable-initial position, the nasal consonants show a three-way phonemic contrast between /m/, /n/, and /ɲ/ (e.g. cama 'bed', cana 'grey hair', caña 'sugar cane') but in syllable-final position, this contrast is generally neutralized, as nasals assimilate to the place of articulation of the following consonant[9]—even across a word boundary.[32]

Within a morpheme, a syllable-final nasal is obligatorily pronounced with the same place of articulation as a following stop consonant, as in banco [baŋ.ko].[33] An exception to coda nasal place assimilation is the sequence /mn/ that can be found in the middle of words such as alumno, columna, himno.[34][35]

At the end of a word, the only nasal consonant that occurs in native vocabulary is /n/.[34] When followed by a pause, it is realized for most speakers as alveolar [n] (though in Caribbean varieties, this may instead be [ŋ] or an omitted nasal with nasalization of the preceding vowel).[36][37] When followed by another consonant, morpheme-final /n/ shows variable place assimilation depending on speech rate and style.[33]

Word-final /m/ and /ɲ/ in stand-alone loanwords or proper nouns may be adapted to [n], e.g. álbum [ˈalβun] ('album').[38][dubious – discuss][39]

Similarly, /l/ assimilates to the place of articulation of a following coronal consonant, i.e. a consonant that is interdental, dental, alveolar, or palatal.[40][41][42] In dialects that maintain the use of /ʎ/, there is no contrast between /ʎ/ and /l/ in coda position, and syllable-final [ʎ] appears only as an allophone of /l/ in rapid speech.[43]

| nasal | lateral | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| word | IPA | gloss | word | IPA | gloss |

| invierno | 'winter' | ||||

| ánfora | 'amphora' | ||||

| encía | 'gum' | alzar | 'to raise' | ||

| antes | 'before' | alto | 'tall' | ||

| ancha | 'wide' | colcha | 'quilt' | ||

| cónyuge | 'spouse' | ||||

| rincón | 'corner' | ||||

| enjuto | 'thin' | ||||

Rhotics

[edit]The alveolar trill [r] and the alveolar tap [ɾ] are in phonemic contrast word-internally between vowels (as in carro 'car' vs. caro 'expensive'), but are otherwise in complementary distribution, as long as syllable division is taken into account: the tap occurs after any syllable-initial consonant, while the trill occurs after any syllable-final consonant.[44][45]

Only the trill can occur at the start of a morpheme (e.g. el rey 'the king', la reina 'the queen') or at the start of a syllable when the preceding syllable ends with a consonant, namely /l/, /n/, or /s/ (e.g. alrededor, enriquecer, desratizar), possibly as well as with /θ/ (e.g. lazrar).[46]

Only the tap can occur after a word-initial obstruent consonant (e.g. tres 'three', frío 'cold').

Either a trill or a tap can be found word-medially after /b/, /d/, /t/ depending on whether the rhotic consonant is pronounced in the same syllable as the preceding obstruent (forming a complex onset cluster) or in a separate syllable (with the obstruent forming the coda of the preceding syllable). The tap is found in words where no morpheme boundary separates the obstruent from the following rhotic consonant, such as sobre 'over', madre 'mother', ministro 'minister'. The trill is only found in words where the rhotic consonant is preceded by a morpheme boundary and thus a syllable boundary, such as subrayar, ciudadrealeño, postromántico;[47] compare the corresponding word-initial trills in raya 'line', Ciudad Real "Ciudad Real", and romántico "Romantic".

In syllable-final position inside a word, the tap is more frequent, but the trill can also occur (especially in emphatic[48] or oratorical[49] style) with no semantic difference—thus arma ('weapon') may be either [ˈaɾma] (tap) or [ˈarma] (trill).[50] In word-final position the rhotic is usually:

- either a tap or a trill when followed by a consonant or a pause, as in amo[ɾ ~ r] paterno ('paternal love'), the former being more common;[51]

- a tap when followed by a vowel-initial word, as in amo[ɾ] eterno ('eternal love').

Morphologically, a word-final rhotic always corresponds to the tapped [ɾ] in related words. Thus the word olor 'smell' is related to olores, oloroso 'smells, smelly' and not to *olorres, *olorroso.[8]

When two rhotics occur consecutively across a word or prefix boundary, they result in one trill, so that da rocas ('s/he gives rocks') and dar rocas ('to give rocks') are either neutralized or distinguished by a longer trill in the latter phrase.[52]

The tap/trill alternation has prompted a number of authors to postulate a single underlying rhotic; the intervocalic contrast then results from gemination (e.g. tierra /ˈtieɾɾa/ > [ˈtjera] 'earth').[53][54][55]

Obstruents

[edit]The phonemes /θ/, /s/,[9] and /f/[56][57] may be voiced before voiced consonants, as in jazmín ('Jasmine') [xaðˈmin], rasgo ('feature') [ˈrazɣo], and Afganistán ('Afghanistan') [avɣanisˈtan]. There is a certain amount of free variation in this, so jazmín can be pronounced [xaθˈmin] or [xaðˈmin].[58] Such voicing may occur across word boundaries, causing feliz navidad ('merry Christmas') /feˈliθ nabiˈdad/ to be pronounced [feˈlið naβ̞iˈð̞að̞].[16] In one region of Spain, the area around Madrid, word-final /d/ is sometimes pronounced [θ], especially in a colloquial pronunciation of the city's name, Madriz ().[59] More so, in some words now spelled with -z- before a voiced consonant, the phoneme /θ/ is in fact diachronically derived from original [ð] or /d/. For example, yezgo comes from Old Spanish yedgo, and juzgar comes from Old Spanish judgar, from Latin jūdicāre.[60]

Both in casual and formal speech, there is no phonemic contrast between voiced and voiceless consonants placed in syllable-final position. The merged phoneme is typically pronounced as a relaxed, voiced fricative or approximant,[61] although a variety of other realizations are also possible. So the clusters -bt- and -pt- in the words obtener and optimista are pronounced exactly the same way:

- obtener /obteˈner/ > [oβteˈneɾ]

- optimista /obtiˈmista/ > [oβtiˈmista]

Similarly, the spellings -dm- and -tm- are often merged in pronunciation, as well as -gd- and -cd-:

- adminículo

- atmosférico

- amígdala

- anécdota

Semivowels

[edit]Traditionally, the palatal consonant phoneme /ʝ/ is considered to occur only as a syllable onset,[62] whereas the palatal glide [j] that can be found after an onset consonant in words like bien is analyzed as a non-syllabic version of the vowel phoneme /i/[63] (which forms part of the syllable nucleus, being pronounced with the following vowel as a rising diphthong). The approximant allophone of /ʝ/, which can be transcribed as [ʝ˕], differs phonetically from [j] in the following respects: [ʝ˕] has a lower F2 amplitude, is longer, can be replaced by a palatal fricative [ʝ] in emphatic pronunciations, and is unspecified for rounding (e.g. viuda 'widow' vs. ayuda 'help').[62]

After a consonant, the surface contrast between [ʝ] and [j] depends on syllabification, which in turn is largely predictable from morphology: the syllable boundary before [ʝ] corresponds to the morphological boundary after a prefix.[8] A contrast is therefore possible after any consonant that can end a syllable, as illustrated by the following minimal or near-minimal pairs: after /l/ (italiano [itaˈljano] 'Italian' vs. y tal llano [italˈɟʝano] 'and such a plain'[8]), after /n/ (enyesar 'to plaster' vs. aniego 'flood'[10]) after /s/ (desierto /deˈsieɾto/ 'desert' vs. deshielo /desˈʝelo/ 'thawing'[8]), after /b/ (abierto /aˈbieɾto/ 'open' vs. abyecto /abˈʝeɡto/ 'abject'[8][64]).

Although there is dialectal and idiolectal variation, speakers may also exhibit a contrast in phrase-initial position.[65] In Argentine Spanish, the change of /ʝ/ to a fricative realized as [ʒ ~ ʃ] has resulted in clear contrast between this consonant and the glide [j]; the latter occurs as a result of spelling pronunciation in words spelled with ⟨hi⟩, such as hierba [ˈjeɾβa] 'grass' (which thus forms a minimal pair in Argentine Spanish with the doublet yerba [ˈʒeɾβa] 'maté leaves').[66]

There are some alternations between the two, prompting scholars like Alarcos Llorach (1950)[67] to postulate an archiphoneme /I/, so that ley would be transcribed phonemically as /ˈleI/ and leyes as /ˈleIes/.

In a number of varieties, including some American ones, there is a similar distinction between the non-syllabic version of the vowel /u/ and a rare consonantal /w̝/.[10][68] Near-minimal pairs include deshuesar ('to debone') vs. desuello ('skinning'), son huevos ('they are eggs') vs. son nuevos ('they are new'),[69] and huaca ('Indian grave') vs. u oca ('or goose').[63]

Vowels

[edit]

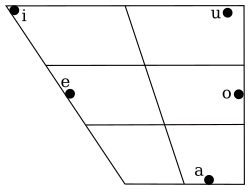

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | |

| Mid | e | o | |

| Open | a |

Spanish has five vowel phonemes, /i/, /u/, /e/, /o/ and /a/ (the same as Asturian-Leonese, Aragonese, and also Basque). Each of the five vowels occurs in both stressed and unstressed syllables:[70]

| stressed | unstressed | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| word | gloss | word | gloss | ||

| piso | 'I step' | pisó | 's/he stepped' | ||

| pujo | 'I bid' (present tense) | pujó | 's/he bid' | ||

| peso | 'I weigh' | pesó | 's/he weighed' | ||

| poso | 'I pose' | posó | 's/he posed' | ||

| paso | 'I pass' | pasó | 's/he passed' | ||

Nevertheless, there are some distributional gaps or rarities. For instance, an unstressed close vowel in the final syllable of a word is rare.[71]

There is no surface phonemic distinction between close-mid and open-mid vowels, unlike in Catalan, Galician, French, Italian and Portuguese. In the historical development of Spanish, former open-mid vowels /ɛ, ɔ/ were replaced with diphthongs /ie, ue/ in stressed syllables, and merged with the close-mid /e, o/ in unstressed syllables.[a] The diphthongs /ie, ue/ regularly correspond to open /ɛ, ɔ/ in Portuguese cognates; compare siete /ˈsiete/ 'seven' and fuerte /ˈfuerte/ 'strong' with the Portuguese cognates sete /ˈsɛtɨ/ and forte /ˈfɔɾtɨ/, meaning the same.[73]

There are some synchronic alternations between the diphthongs /ie, ue/ in stressed syllables and the monophthongs /e, o/ in unstressed syllables: compare heló /eˈlo/ 'it froze' and tostó /tosˈto/ 'he toasted' with hiela /ˈʝela/ 'it freezes' and tuesto /ˈtuesto/ 'I toast'.[74] It has thus been argued that the historically open-mid vowels remain underlyingly, giving Spanish seven vowel phonemes.[75]

Because of substratal Quechua, at least some speakers from southern Colombia down through Peru can be analyzed to have only three vowel phonemes /i, u, a/, as the close [i, u] are continually confused with the mid [e, o], resulting in pronunciations such as [dolˈsoɾa] for dulzura ('sweetness').[clarification needed] When Quechua-dominant bilinguals have /e, o/ in their phonemic inventory, they realize them as [ɪ, ʊ], which are heard by outsiders as variants of /i, u/.[76] Both of those features are viewed as strongly non-standard by other speakers.

Allophones

[edit]Phonetic nasalization occurs for vowels occurring between nasal consonants or when preceding a syllable-final nasal, e.g. cinco [ˈθĩŋko] ('five') and mano [ˈmãno] ('hand').[70]

Arguably, Eastern Andalusian and Murcian Spanish have ten phonemic vowels, with each of the above vowels paired by a lowered or fronted and lengthened version, e.g. la madre [la ˈmaðɾe] ('the mother') vs. las madres [læː ˈmæːðɾɛː] ('the mothers').[77] However, these are more commonly analyzed as allophones triggered by an underlying /s/ that is subsequently deleted.

Exact number of allophones

[edit]There is no agreement among scholars on how many vowel allophones Spanish has; an often[78] postulated number is five [i, u, e̞, o̞, a̠].

Some scholars,[79] however, state that Spanish has eleven allophones: the close and mid vowels have close [i, u, e, o] and open [ɪ, ʊ, ɛ, ɔ] allophones, whereas /a/ appears in front [a], central [a̠] and back [ɑ] variants. These symbols appear only in the narrowest variant of phonetic transcription; in broader variants, only the symbols ⟨i, u, e, o, a⟩ are used,[80] and that is the convention adopted in the rest of this article.

Tomás Navarro Tomás describes the distribution of said eleven allophones as follows:[81]

- Close vowels /i, u/

- The close allophones [i, u] appear in open syllables, e.g. in the words libre [ˈliβɾe] 'free' and subir [suˈβɪɾ] 'to raise'

- The open allophones are phonetically near-close [ɪ, ʊ], and appear:

- In closed syllables, e.g. in the word fin [fɪn] 'end'

- In both open and closed syllables when in contact with /r/, e.g. in the words rico [ˈrɪko] 'rich' and rubio [ˈrʊβjo] 'blond'

- In both open and closed syllables when before /x/, e.g. in the words hijo [ˈɪxo] 'son' and pujó [pʊˈxo] 's/he bid'

- Mid front vowel /e/

- The close allophone is phonetically close-mid [e], and appears:

- In open syllables, e.g. in the word dedo [ˈdeðo] 'finger'

- In closed syllables when before /m, n, t, θ, s/, e.g. in the word Valencia [ba̠ˈlenθja̠] 'Valencia'

- The open allophone is phonetically open-mid [ɛ], and appears:

- In open syllables when in contact with /r/, e.g. in the words guerra [ˈɡɛra̠] 'war' and reto [ˈrɛto] 'challenge'

- In closed syllables when not followed by /m, n, t, θ, s/, e.g. in the word belga [ˈbɛlɣa̠] 'Belgian'

- In the diphthong [ej], e.g. in the words peine [ˈpɛjne] 'comb' and rey [ˈrɛj] king

- The close allophone is phonetically close-mid [e], and appears:

- Mid back vowel /o/

- The close allophone is phonetically close-mid [o], and appears in open syllables, e.g. in the word como [ˈkomo] 'how'

- The open allophone is phonetically open-mid [ɔ], and appears:

- In closed syllables, e.g. in the word con [kɔn] 'with'

- In both open and closed syllables when in contact with /r/, e.g. in the words corro [ˈkɔrɔ] 'I run', barro [ˈba̠rɔ] 'mud', and roble [ˈrɔβle] 'oak'

- In both open and closed syllables when before /x/, e.g. in the word ojo [ˈɔxo] 'eye'

- In the diphthong [oj], e.g. in the word hoy [ɔj] 'today'

- In stressed position when preceded by /a/ and followed by either /ɾ/ or /l/, e.g. in the word ahora [ɑˈɔɾa̠] 'now'

- Open vowel /a/

- The front allophone [a] appears:

- Before palatal consonants, e.g. in the word despacho [desˈpatʃo] 'office'

- In the diphthong [aj], e.g. in the word aire [ˈajɾe] 'air'

- The back allophone [ɑ] appears:

- In the diphthong [aw], e.g. in the word flauta [ˈflɑwta̠] 'flute'

- Before /o/

- In closed syllables before /l/, e.g. in the word sal [sɑl] 'salt'

- In both open and closed syllables when before /x/, e.g. in the word tajada [tɑˈxa̠ða̠] 'chop'

- The central allophone [a̠] appears in all other cases, e.g. in the word casa [ˈka̠sa̠]

- The front allophone [a] appears:

According to Eugenio Martínez Celdrán, however, systematic classification of Spanish allophones is impossible due to the fact that their occurrence varies from speaker to speaker and from region to region. According to him, the exact degree of openness of Spanish vowels depends not so much on the phonetic environment, but rather on various external factors accompanying speech.[82]

Diphthongs and triphthongs

[edit]| IPA | Example | Meaning | IPA | Example | Meaning | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Falling | Rising | |||||

| a | [aj] | aire | air | [ja] | hacia | towards |

| [aw] | pausa | pause | [wa] | cuadro | picture | |

| e | [ej] | rey | king | [je] | tierra | earth |

| [ew] | neutro | neutral | [we] | fuego | fire | |

| o | [oj] | hoy | today | [jo] | radio | radio |

| [ow][83] | bou | seine fishing | [wo] | cuota | quota | |

| Falling | Rising | |||||

| i | — | [wi] | fuimos | we went | ||

| u | [uj][84] | muy | very | [ju] | viuda | widow |

Spanish has six falling diphthongs and eight rising diphthongs. While many diphthongs are historically the result of a recategorization of vowel sequences (hiatus) as diphthongs, there is still lexical contrast between diphthongs and hiatus.[85] Some lexical items vary amongst speakers and dialects between hiatus and diphthong: words like biólogo ('biologist') with a potential diphthong in the first syllable and words like diálogo with a stressed or pretonic sequence of /i/ and a vowel vary between a diphthong and hiatus.[86] Chițoran & Hualde (2007) hypothesize that this is because vocalic sequences are longer in these positions.

In addition to synalepha across word boundaries, sequences of vowels in hiatus become diphthongs in fast speech; when this happens, one vowel becomes non-syllabic (unless they are the same vowel, in which case they fuse together) as in poeta [ˈpo̯eta] ('poet') and maestro [ˈmae̯stɾo] ('teacher').[87] Similarly, the relatively rare diphthong /eu/ may be reduced to [u] in certain unstressed contexts, as in Eufemia, [uˈfemja].[88] In the case of verbs like aliviar ('relieve'), diphthongs result from the suffixation of normal verbal morphology onto a stem-final /j/ (that is, aliviar would be |alibj| + |ar|).[89] This contrasts with verbs like ampliar ('to extend') which, by their verbal morphology, seem to have stems ending in /i/.[90]

Non-syllabic /e/ and /o/ can be reduced to [j], [w], as in beatitud [bjatiˈtuð] ('beatitude') and poetisa [pweˈtisa] ('poetess'), respectively; similarly, non-syllabic /a/ can be completely elided, as in (e.g. ahorita [oˈɾita] 'right away'). The frequency (though not the presence) of this phenomenon differs amongst dialects, with a number having it occur rarely and others exhibiting it always.[91]

Spanish also possesses triphthongs like /uei/ and, in dialects that use a second person plural conjugation, /iai/, /iei/, and /uai/ (e.g. buey, 'ox'; cambiáis, 'you change'; cambiéis, '(that) you may change'; and averiguáis, 'you ascertain').[92]

Prosody

[edit]Spanish is usually considered a syllable-timed language. Even so, stressed syllables can be up to 50% longer in duration than non-stressed syllables.[93][94][95] Although pitch, duration, and loudness contribute to the perception of stress,[96] pitch is the most important in isolation.[97]

Primary stress occurs on the penultima (the next-to-last syllable) 80% of the time. The other 20% of the time, stress falls on the ultima (last syllable) or on the antepenultima (third-to-last syllable).[98]

Nonverbs are generally stressed on the penultimate syllable for vowel-final words and on the final syllable of consonant-final words. Exceptions are marked orthographically (see below), whereas regular words are underlyingly phonologically marked with a stress feature [+stress].[99]

In addition to exceptions to these tendencies, particularly learned words from Greek and Latin that feature antepenultimate stress, there are numerous minimal pairs which contrast solely on stress such as sábana ('sheet') and sabana ('savannah'), as well as límite ('boundary'), limite ('[that] he/she limit') and limité ('I limited').

Lexical stress may be marked orthographically with an acute accent (ácido, distinción, etc.). This is done according to the mandatory stress rules of Spanish orthography, which parallel the tendencies above (differing with words like distinción) and are defined so as to unequivocally indicate where the stress lies in a given written word. An acute accent may also be used to differentiate homophones, such as mi (my), and mí (me). In such cases, the accent is used on the homophone that normally receives greater stress when used in a sentence.

Lexical stress patterns are different between words carrying verbal and nominal inflection: in addition to the occurrence of verbal affixes with stress (something absent in nominal inflection), underlying stress also differs in that it falls on the last syllable of the inflectional stem in verbal words while those of nominal words may have ultimate or penultimate stress.[100] In addition, amongst sequences of clitics suffixed to a verb, the rightmost clitic may receive secondary stress, e.g. búscalo /ˈbuskaˌlo/ ('look for it').[101]

Phonotactics

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (April 2016) |

Syllable structure

[edit]Spanish syllable structure consists of an optional syllable onset, consisting of one or two consonants; an obligatory syllable nucleus, consisting of a vowel optionally preceded by and/or followed by a semivowel; and an optional syllable coda, consisting of one or two consonants.[102] This can be summarized as follows (parentheses enclose optional components):

- (C1 (C2)) (S1) V (S2) (C3 (C4))

The following restrictions apply:

- Onset

- First consonant (C1): Can be any consonant.[103] Either /ɾ/ or /r/ is possible as a word-internal onset after a vowel, but as discussed above, the contrast between the two rhotic consonants is neutralized at the start of a word or when the preceding syllable ends in a consonant: only /r/ is possible in those positions.

- Second consonant (C2): Can be /l/ or /ɾ/. Permitted only if the first consonant is a stop /p, t, k, b, d, ɡ/, a voiceless labiodental fricative /f/, or marginally the nonstandard /v/.[104][citation needed] /tl/ is prohibited as an onset cluster in most of Peninsular Spanish, while /tl/ sequences such as in atleta 'athlete' are usually treated as an onset cluster in Latin America and the Canaries.[102][105][106] The sequence /dl/ is also avoided as an onset,[102] seemingly to a greater degree than /tl/.[107]

- Nucleus

- Semivowel (S1): Can be [j] or [w], normally analyzed phonemically as allophones of non-syllabic /i, u/. Cannot be identical to the following vowel (*[ji] and *[wu] do not occur within a syllable).

- Vowel (V): Can be any of /a, e, i, o, u/.

- Semivowel (S2): Can be [j] or [w], normally analyzed phonemically as allophones of non-syllabic /i, u/. The sequences *[ij], *[iw] and *[uw] do not occur within a syllable. Some linguists consider postvocalic glides to be part of the coda rather than the nucleus.[108]

- Coda

- First consonant (C3): Can be any consonant except /ɲ/, /ʝ/ or /ʎ/.[102]

- Second consonant (C4): Always /s/ in native Spanish words.[102] Other consonants, except /ɲ/, /ʝ/ and /ʎ/, are tolerated as long as they are less sonorous than the first consonant in the coda, such as in York or the Catalan last name Brucart, though sometimes the final element is deleted in colloquial speech.[109] A coda of two consonants never appears in words inherited from Vulgar Latin.

- In many dialects, a coda cannot be more than one consonant (one of n, r, l or s) in informal speech. Realizations like /tɾasˈpoɾ.te/, /is.taˈlar/, /pes.peɡˈti.ba/ are very common, and in many cases, they are allowed even in formal speech.

Maximal onsets include transporte /tɾansˈpor.te/, flaco /ˈfla.ko/, clave /ˈkla.be/.

Maximal nuclei include buey /buei/, Uruguay /u.ɾuˈɡuai/.

Maximal codas include instalar /ins.taˈlar/, perspectiva /peɾs.peɡˈti.ba/.

Spanish syllable structure is phrasal, resulting in syllables consisting of phonemes from neighboring words in combination, sometimes even resulting in elision. The phenomenon is known in Spanish as enlace.[110] For a brief discussion contrasting Spanish and English syllable structure, see Whitley (2002:32–35).

Other phonotactic tendencies

[edit]- The palatal sonorants /ʎ, ɲ/ are rare in certain positions, although this may be a consequence of their diachronic origins (being derived often, though not exclusively, from Latin geminate consonants) rather than a matter of synchronic constraints.

- Per Baker 2004, the palatal sonorants /ʎ, ɲ/ are not found as word-internal onsets when the preceding syllable ends in a coda consonant or glide.[111][dubious – discuss] A number of exceptions to this generalization exist, however, including prefixed or compound words (such as conllevar, bienllegada, panllevar), borrowed words (such as huaiño,[112] aillu,[113] aclla,[114] from Quechua), and forms that originate from non-Castilian Romance varieties (such as Asturian piesllo[115]). The sequence [au̯ɲ] occurs in some proper names, such as the toponym Auñón (from Latin alneus[116]) and Auñamendi (a publishing house name taken from the Basque name of the Pic d'Anie); [au̯ʎ] occurs in some words, such as aullar and maullar.[117]

- Although word-initial /ɲ/ is not forbidden (for example, it occurs in borrowed words such as ñandú and ñu and in dialectal forms such as ñudo) it is relatively rare[34] and so may be described as having restricted distribution in this position.[107]

- In native Spanish words, the trill /r/ does not appear after a glide.[8] That said, it does appear after [w] in some Basque loans, such as Aurrerá, a grocery store, Abaurrea Alta and Abaurrea Baja, towns in Navarre, aurresku, a type of dance, and aurragado, an adjective referring to poorly tilled land.[8]

- When the final syllable of a word begins with any of /ʎ ɲ ʝ tʃ r/, the word typically does not display antepenultimate stress.[118]

Epenthesis

[edit]Because of the phonotactic constraints, an epenthetic /e/ is inserted before word-initial clusters beginning with /s/ (e.g. escribir 'to write') but not word-internally (transcribir 'to transcribe'),[119] thereby moving the initial /s/ to a separate syllable. The epenthetic /e/ is pronounced even when it is not reflected in spelling (e.g. the surname of Carlos Slim is pronounced /eˈslim/).[120] While Spanish words undergo word-initial epenthesis, cognates in Latin and Italian do not:

- Lat. status /ˈsta.tus/ ('state') ~ It. stato /ˈsta.to/ ~ Sp. estado /esˈta.do/

- Lat. splendidus /ˈsplen.di.dus/ ('splendid') ~ It. splendido /ˈsplen.di.do/ ~ Sp. espléndido /esˈplen.di.do/

- Fr. slave /slav/ ('Slav') ~ It. slavo /ˈzla.vo/ ~ Sp. eslavo /esˈla.bo/

In addition, Spanish adopts foreign words starting with pre-nasalized consonants with an epenthetic /e/. Nguema, a prominent last name from Equatorial Guinea, is pronounced as [eŋˈɡema].[121]

When adapting word-final complex codas that show rising sonority, an epenthetic /e/ is inserted between the two consonants. For example, al Sadr is typically pronounced [al.sa.ðeɾ].[122]

Occasionally Spanish speakers are faced with onset clusters containing elements of equal or near-equal sonority, such as Knoll (a German last name, common in parts of South America). Assimilated borrowings usually delete the first element in such clusters, for example (p)sicología 'psychology'. When attempting to pronounce such words for the first time without deleting the first consonant, Spanish speakers insert a short, often devoiced, schwa-like svarabhakti vowel between the two consonants.[123]

Alternations

[edit]Some alternations exist in Spanish that reflect diachronic changes in the language and arguably reflect morphophonological processes rather than strictly phonological ones. For instance, some words alternate between /k/ and /θ/ or /ɡ/ and /x/, with the latter in each pair appearing before a front vowel:[124]

| word | gloss | word | gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| opaco | /oˈpako/ | 'opaque' | opacidad | /opaθiˈdad/ | 'opacity' |

| подавать в суд ко на | /ˈсвеко/ | 'Шведский' | SuecШвеция | /ˈsweθja/ | ' Швеция ' |

| Бельгия | /ˈbelɡa/ | 'Бельгийский' | BélgБельгия | /ˈbelxika/ | ' Бельгия ' |

| análogаналог | /аналоɡо/ | 'аналогичный' | analogаналогия | /analoˈxi.a/ | 'аналогия' |

Обратите внимание, что при спряжении большинства глаголов с основой, оканчивающейся на /k/ или /ɡ/, ; такого чередования не наблюдается эти сегменты не превращаются в /θ/ или /x/ перед гласной переднего ряда:

| слово | блеск | слово | блеск | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| если c | /секо/ | «Я сохну» | сам, что е | /ˈсеке/ | '(что) я/он/она сухой (сослагательное наклонение)' |

| castigнаказание | /kasˈtiɡo/ | «Я наказываю» | наказать гу е | /kasˈtiɡe/ | '(что) я/он/она наказываю (сослагательное наклонение)' |

Есть также чередования между безударными /e/ и /o/ и ударными /ie/ (или /ʝe/ , если оно изначальное) и /ue/ соответственно: [ 125 ]

| слово | блеск | слово | блеск | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| он лошадь | /eˈlo/ | 'оно замерзло' | здравствуйте , эй ля | /ˈʝela/ | 'оно замерзает' |

| чтобы сто | /тосто/ | 'он тост' | вт сто | /ˈtuesto/ | «Я тост» |

Аналогичным образом, в очень небольшом количестве слов происходят чередования между небными сонорами /ʎ ɲ/ и соответствующими им альвеолярными сонорантами /l n/ ( doncella / doncel 'девица'/'юность', desdeñar / desdén 'презирать'/' презрение»). Это чередование не проявляется ни в глагольном, ни в номинальном изменении (то есть множественное число от doncel — donceles , а не * doncelles ). [ 126 ] Это результат дегеминации /ll/ и /nn/ народной латыни (происхождение /ʎ/ и /ɲ/ соответственно), а затем дегеминации в кодовой позиции. [ 127 ] Слова без небно-альвеолярной алломорфии являются результатом исторических заимствований. [ 127 ]

Другие чередования включают ɡs/ ~ /x/ ( ane xo vs. / ane j o ), [ 128 ] /ɡt/ ~ /tʃ/ ( no ct urno vs. no ch e ). [ 129 ] Здесь формы с /ɡs/ и /ɡt/ являются историческими заимствованиями, а формы с формами /x/ и /tʃ/ унаследованы из народной латыни.

Есть также пары, в которых присутствует предпоследнее ударение в существительных и прилагательных, но предпоследнее ударение в синонимических глаголах ( vómito «рвота» vs. vomito «меня рвет»). [ 130 ]

Приобретение как первый язык

[ редактировать ]Фонология

[ редактировать ]Фонологическое развитие сильно варьируется в зависимости от человека: как у тех, кто развивается регулярно, так и у тех, кто развивается с задержкой. Однако об общей закономерности усвоения фонем можно судить по уровню сложности их признаков, т. е. по классам звуков. [ 131 ] Можно построить иерархию, и если ребенок способен различать на одном уровне, он также будет способен различать на всех предыдущих уровнях. [ 132 ]

- Первый уровень состоит из стоп (без различия звонкости), носовых звуков, [l] и, необязательно, нелатерального аппроксиманта. Это включает в себя разницу мест на губах и коронках (например, [b] против [t] и [l] против [β] ).

- Второй уровень включает в себя голосовые различия оральных стоп и разницу мест в корональной / дорсальной зоне. Это позволяет различать [p] , [t] и [k] , а также их звонкие аналоги, а также различие между [l] и аппроксимантом [j] .

- Третий уровень включает фрикативные и/или аффрикаты.

- Четвертый уровень представляет жидкости, отличные от [l] , [ɹ] и [ɾ] . Он также вводит [θ] .

- Пятый уровень представляет трель [r] .

Эта иерархия основана только на производстве и представляет собой представление о способности ребенка производить звук, независимо от того, является ли этот звук правильной целью в речи взрослого или нет. Таким образом, он может содержать некоторые звуки, не вошедшие в фонологию взрослых, но образующиеся в результате ошибки.

Испаноязычные дети точно воспроизведут большинство сегментов в относительно раннем возрасте. Примерно к трем с половиной годам они перестанут продуктивно использовать фонологические процессы. [ нужны разъяснения ] большую часть времени. Некоторые распространенные шаблоны ошибок (обнаруживаются в 10% и более случаев) — это сокращение кластеров , жидкостное упрощение и остановка. Менее распространенные закономерности (проявляемые менее чем в 10% случаев) включают небное переднее положение , ассимиляцию и удаление конечного согласного . [ 133 ]

Типичный фонологический анализ испанского языка рассматривает согласные /b/ , /d/ и /ɡ/ и как основные фонемы их соответствующие аппроксиманты [β] , [ð] и [ɣ] аллофоническими и выводимыми по фонологическим правилам . Тем не менее, аппроксиманты могут быть более базовой формой, поскольку дети, изучающие испанский язык на одном языке, учатся производить непрерывный контраст между [pt k ] и [β ð ɣ] прежде, чем они начнут контрастировать по ведущему голосу между [p t k] и [b d ɡ] . [ 134 ] (Для сравнения, дети, изучающие английский язык, способны создавать контрасты голосов для этих остановок, как у взрослых, задолго до трехлетнего возраста.) [ 135 ] Аллофоническое распределение [b d ɡ] и [β ð ɣ], возникающее в речи взрослых, не усваивается до достижения двухлетнего возраста и полностью не осваивается даже в четыре года. [ 134 ]

Альвеолярная трель [r] — один из самых трудных для произнесения звуков в испанском языке, поэтому он усваивается на более позднем этапе развития. [ 136 ] Исследования показывают, что альвеолярная трель приобретается и развивается в возрасте от трех до шести лет. [ 137 ] Некоторые дети в этот период приобретают трель, подобную взрослой, а некоторым не удается усвоить трель должным образом. Звук трели у плохих триллеров часто воспринимается как серия постукиваний из-за гиперактивных движений языка во время производства. [ 138 ] Трель также часто очень сложна для тех, кто изучает испанский как второй язык, и иногда на ее правильное воспроизведение уходит больше года. [ 139 ]

Коды

[ редактировать ]Одно исследование показало, что дети усваивают средние коды раньше финальных кодов, а ударные коды раньше безударных кодов. [ 140 ] Поскольку медиальные коды часто подвергаются ударению и должны подвергаться пространственной ассимиляции, их усвоению придается большее значение. [ 141 ] Жидкие и носовые коды встречаются посередине слова и на концах часто используемых служебных слов, поэтому они часто усваиваются первыми. [ 142 ]

просодия

[ редактировать ]Исследования показывают, что дети чрезмерно обобщают правила ударения, когда воспроизводят новые испанские слова, и что они имеют тенденцию делать ударение на предпоследних слогах предпоследних слов с ударением, чтобы избежать нарушения правил неглагольного ударения, которые они усвоили. [ 143 ] Многие из наиболее часто встречающихся слов, которые слышат дети, имеют нерегулярную структуру ударения или являются глаголами, которые нарушают правила неглагольного ударения. [ 144 ] Это усложняет правила стресса до возраста трех-четырех лет, когда приобретение стресса практически завершено и дети начинают применять эти правила к новым нестандартным ситуациям.

Диалектный вариант

[ редактировать ]Некоторые особенности, такие как произношение глухих стоп /pt k / , не имеют диалектных вариаций. [ 145 ] Однако существует множество других особенностей произношения, которые различаются от диалекта к диалекту.

Йейсмо

[ редактировать ]диалектных особенностей является слияние звонкого небного аппроксиманта [ ʝ ] (как в y Одной из примечательных er ) с небным латеральным аппроксимантом [ ʎ ] в call ( как e ) в одну фонему ( yeísmo ), при этом /ʎ/ теряет свой латеральность. Хотя различие между этими двумя звуками традиционно было особенностью кастильского испанского языка, в последние поколения это слияние распространилось на большей части территории Испании, особенно за пределами регионов, находящихся в тесном лингвистическом контакте с каталонским и баскским языками. [ 146 ] В испанской Америке для большинства диалектов характерно это слияние, при этом различия сохраняются в основном в некоторых частях Перу, Боливии, Парагвая и северо-западной Аргентины. [ 147 ] В других частях Аргентины фонема, возникшая в результате слияния, реализуется как [ ʒ ] ; [ 9 ] а в Буэнос-Айресе этот звук недавно был посвящен [ ʃ ] среди молодого населения; изменения распространяются по всей Аргентине. [ 148 ]

Лисп , шепелявость и различие

[ редактировать ]

Говорящие в северной и центральной Испании, включая те, которые преобладают на радио и телевидении, имеют как /θ/, так и /s/ ( distinción , «различие»). Однако носители языка в Латинской Америке, на Канарских островах и в некоторых частях южной Испании говорят только /s/ ( seseo ), который на самом юге Испании произносится как [θ] , а не как [s] ( ceceo ). [ 9 ]

Реализация /с/

[ редактировать ]Фонема /s/ имеет три варианта произношения в зависимости от региона диалекта: [ 9 ] [ 41 ] [ 149 ]

- Апикальный , альвеолярный втянутый фрикативный звук (или « апико-альвеолярный » фрикативный звук) [s̺] , который звучит похоже на английский /ʃ/ и характерен для северной и центральной частей Испании Колумбии а также используется многими говорящими в департаменте Антиокия . [ 150 ] [ 151 ]

- Щелевой звук с пластинчатыми альвеолярными бороздками [s] , очень похожий на наиболее распространенное произношение английского языка /s/ , характерен для западной Андалусии (например, Малаги , Севилья и Кадис ), Канарских островов и Латинской Америки.

- Апикальный / с зубными бороздками фрикативный звук [s̄] (специальный символ), который имеет шепелявый характер и звучит как нечто среднее между английскими s/ и /θ/, но отличается от /θ/, встречающегося в диалектах, которые различают /s/. и /θ/ . Он встречается только в диалектах с ceceo , в основном в Гранаде , в некоторых частях Хаэна , в южной части Севильи и в горных районах, разделяемых между Кадисом и Малагой .

Обейд описывает апико-альвеолярный звук следующим образом: [ 152 ]

Существует кастильский s , который представляет собой глухой, вогнутый, верхушечный фрикативный звук: кончик языка, повернутый вверх, образует узкое отверстие напротив альвеол верхних резцов. Он напоминает слабый звук /ʃ/ и встречается на большей части северной половины Испании.

Далбор описывает апикально-дентальный звук следующим образом: [ 153 ]

[s̄] — глухой фрикативный короно-зубно-альвеолярный бороздок, так называемый s coronal или s plana из-за относительно плоской формы тела языка... Этому писателю следует, что корональный [s̄] , слышимый по всей Андалусии, должен характеризоваться такими терминами, как «мягкий», «нечеткий» или «неточный», что, как мы увидим, весьма приближает его к одной из разновидностей /θ/ ... Кэнфилд по нашему мнению, совершенно правильно назвал это [s̄] «шепелявым коронально-зубным », а Амадо Алонсо отмечает, насколько близко оно к постдентальному [θ̦] , предлагая комбинированный символ ⟨ θˢ̣ ⟩ для обозначения это.

В некоторых диалектах /s/ может стать аппроксимантом [ɹ] в коде слога (например, doscientos [doɹˈθjentos] «двести»). [ 154 ] В южных диалектах Испании, большинстве равнинных диалектов Северной и Южной Америки и на Канарских островах он дебуккализируется до [h] в конечной позиции (например, niños [ˈniɲoh] «дети») или перед другим согласным (например, fósforo [ˈfohfoɾo] ' match'), поэтому изменение происходит в позиции кода в слоге. В Испании изначально это был южный объект, но сейчас он быстро расширяется на север. [ 31 ]

С автосегментной точки зрения фонема /s/ в Мадриде определяется только своими глухими и фрикативными особенностями. Таким образом, точка артикуляции не определена и определяется по следующим за ней звукам в слове или предложении. В Мадриде встречаются следующие реализации: /pesˈkado/ > [pexˈkao] [ 155 ] и /ˈfosfoɾo/ > [ˈfofːoɾo] . В некоторых частях южной Испании единственная особенность, определенная для /s/, — это глухота ; он может полностью потерять свою оральную артикуляцию и стать [h] или даже близнецом со следующей согласной ( [ˈmihmo] или [ˈmimːo] от /ˈmismo/ 'тот же'). [ 156 ] В восточно-андалузском и мурсийском испанском языке конечные слова /s/ , /θ/ и /x/ регулярно ослабевают, а предыдущая гласная опускается и удлиняется: [ 157 ]

- /is/ > [ ɪː ] например, mis [mɪː] ('мой' pl)

- /es/ > [ εː ] например mes [mεː] («месяц»)

- /as/ > [ æː ] например más [mæː] («плюс»)

- /os/ > [ youː ] например, tos [toː] («кашель»)

- /us/ > [ ʊː ] например tus [tʊː] («ваш» pl)

последующий процесс гармонии гласных Происходит , поэтому lejos («далеко») — это [ˈlɛxɔ] , tenéis («у вас [множественное число] есть») — [tɛˈnɛj] , а tréboles («клевер») — это [ˈtɾɛβɔlɛ] или [ˈtɾɛβolɛ] . [ 158 ]

Упрощение кода

[ редактировать ]Южноевропейский испанский (андалузский испанский, мурсийский испанский и т. д.) и несколько равнинных диалектов Латинской Америки (например, диалекты Карибского бассейна, Панамы и атлантического побережья Колумбии) демонстрируют более крайние формы упрощения согласных коды:

- отбрасывание /s/ в конце слова (например, compás [komˈpa] «музыкальный ритм» или «компас»)

- опущение носовых звуков в конце слова с назализацией предыдущей гласной (например, ven [bẽ] «прийти»)

- опущение /r/ в инфинитивной морфеме (например, comer [kome] 'есть')

- случайное выпадение кодовых согласных внутри слова (например, доктор [doˈto(r)] 'доктор'). [ 159 ]

Выпадающие согласные появляются при появлении дополнительного суффикса (например, s es [ komˈpase] «бьет», ve n ían [beˈni.ã] «они шли», Come remos compas [komeˈɾemo] «мы будем есть»). Точно так же происходит ряд ассимиляций кодов:

- /l/ и /r/ могут нейтрализоваться на [j] (например, Cibaeño Dominican celda / cerda [ˈsejða] 'клетка'/'щетина'), на [l] (например, карибский испанский alma / Arma [ˈalma] 'душа'/ «оружие», андалузский испанский sartén [salˈtẽ] «пан»), до [r] (например, андалузский испанский alma / arma [ˈarma] ) или, путем полной регрессивной ассимиляции, на копию следующего согласного (например, pulga / purga [ˈpuɡːa] 'блоха'/'чистка', carne [ˈkanːe] 'мясо'). [ 159 ]

- /s/ , /x/ (и /θ/ на юге полуостровного испанского языка) и /f/ могут быть дебуккализованы или опущены в коде (например, los amigos [lo(h) aˈmiɣo(h)] «друзья»). [ 160 ]

- Стопы и носовые звуки могут быть реализованы как велярные (например, кубинское и венесуэльское étnico [ˈeɡniko] «этнический», hisno [ˈiŋno] «гимн»). [ 160 ]

Отбрасывание конечного /d/ (например, mitad [miˈta] «половина») является обычным явлением в большинстве диалектов испанского языка, даже в официальной речи. [ 161 ]

Нейтрализация /p/ , /t/ и /k/ в конце слога широко распространена в большинстве диалектов (например, Pepsi произносится как [ˈpeksi] ). Он не сталкивается с такой стигмой, как другие нейтрализации, и может остаться незамеченным. [ 162 ]

Пропуски и нейтрализации демонстрируют вариативность своего появления даже у одного и того же говорящего в одном и том же высказывании, поэтому в базовой структуре существуют неудаленные формы. [ 163 ] Диалекты, возможно, не находятся на пути к устранению кодовых согласных, поскольку процессы удаления существуют уже более четырех столетий. [ 164 ] Гитарт (1997) утверждает, что это результат того, что говорящие приобретают несколько фонологических систем с неравномерным контролем, как у изучающих второй язык.

В стандартном европейском испанском языке звонкие мешающие звуки /b, d, ɡ/ перед паузой приглушаются и ослабляются до [ β̥˕ , ð̥˕ , ɣ̊˕ ] , как в клубе b [kluβ̥˕] («[социальный] клуб»). , se d [seð̥] («жажда»), зигза г [θiɣˈθaɣ̊˕] . [ 165 ] Однако /b/ в конце слова встречается редко, а /ɡ/ тем более. В основном они ограничиваются заимствованиями и иностранными именами, такими как имя бывшего «Реала» спортивного директора Предрага Миятовича , которое произносится как [ˈpɾeð̞ɾaɣ̊˕] ; а после другой согласной звонкий шумный звук может быть даже удален, как в айсберге , произносимом [iθeˈβeɾ] . [ 166 ] В Мадриде и его окрестностях se d альтернативно произносится как [seθ] , где вышеупомянутое альтернативное произношение финала слова /d/ как [θ] сосуществует со стандартной реализацией, [ 167 ] но в остальном нестандартен. [ 59 ]

Звуки кредита

[ редактировать ]Фрикативный звук /ʃ/ может также появляться в заимствованиях из других языков, таких как науатль. [ 168 ] и английский . [ 169 ] Кроме того, аффрикаты / t͡s / и / t͡ɬ / также встречаются в заимствованиях на науатле. [ 168 ] Тем не менее, начальная группа /tl/ разрешена в большей части Латинской Америки, на Канарских островах и на северо-западе Испании, а также тот факт, что она произносится в то же время, что и другие глухие стопы + боковые группы /pl/. и /kl/ поддерживают анализ последовательности /tl/ как кластера, а не аффриката в мексиканском испанском языке. [ 105 ] [ 106 ]

Образец

[ редактировать ]Этот отрывок представляет собой адаптацию произведения Эзопа «El Viento del Norte y el Sol» ( «Северный ветер и солнце »), прочитанного мужчиной из Северной Мексики, родившимся в конце 1980-х годов. Как обычно в мексиканском испанском языке , /θ/ и /ʎ/ отсутствуют.

Орфографическая версия

[ редактировать ]Северный Ветер и Солнце поспорили, кто из двоих сильнее. Пока они спорили, подошел путник, закутанный в теплое пальто. Тогда решили, что сильнейшим будет тот, кто сумеет сорвать с путешественника пальто. Начался Северный Ветер, дующий изо всех сил, но чем сильнее он дул, тем сильнее укутывался путник. Тогда Ветер сдался. Настала очередь Солнца, которое начало ярко светить. От этого путешественнику стало жарко, и он снял пальто. Тогда Северному Ветру пришлось признать, что Солнце сильнее двоих.

Фонематическая транскрипция

[ редактировать ]/el ˈbiento del ˈnoɾte i el ˈsol diskuˈti.an poɾ saˈbeɾ ˈkien ˈeɾa el ˈmas ˈfueɾte de los ˈdos ‖ mientɾas diskuˈti.an se aseɾˈko un biaˈxeɾo kuˈbieɾto en un ˈkalido aˈbɾiɡo | enˈtonses desiˈdieɾon ke el ˈmas ˈfueɾte seˈɾi.a kien loˈɡɾase despoˈxaɾ al biaˈxeɾo de su aˈbɾiɡo ‖ el ˈbiento del ˈnoɾte empeˈso soˈplando tan ˈfueɾte komo poˈdi.a | peɾo entɾe ˈmas ˈfueɾte soˈplaba el biaˈxeɾo ˈmas se aroˈpaba | enˈtonses el ˈbiento desisˈtio | se ʝeˈɡo el ˈtuɾno del ˈsol kien komenˈso a bɾiˈʝaɾ kon ˈfueɾsa | ˈesto ˈiso ke el biaˈxeɾo sinˈtieɾa kaˈloɾ i poɾ ˈeʝo se kiˈto su aˈbɾiɡo ‖ enˈtonses el ˈbiento del ˈnoɾte ˈtubo ke rekonoˈseɾ ke el ˈsol ˈeɾa el ˈmas ˈfueɾte de los ˈdos/

Фонетическая транскрипция

[ редактировать ][el ˈβjento ðel ˈnoɾte j‿el ˈsol diskuˈti.am por saˈβeɾ ˈkjen eɾa‿e̯l ˈmas ˈfweɾte ð los ˈðos ‖ ˈmjentɾas ðiskuˈti.an ˌse̯‿aseɾˈko ‿wm bjaˈxeɾo kuˈβjeɾto̯‿en uŋ ˈkaliðo̯‿aˈβɾiɣo | enˈtonses ðesiˈðjeɾoŋ k‿el ˈmas ˈfweɾte seˈɾi.a kjen loˈɣɾase ðespoˈxaɾ al βjaˈxeɾo ðe swaˈβɾiɣo ‖ el ˈβjento ðel ˌnoɾt‿empe ˈso soˈplando taɱ ˈfweɾte ˌkomo poˈði.a | ˈpeɾo̯‿entɾe ˈmas ˈfweɾte soˈplaβa el βjaˈxeɾo ˈmas ˌse̯‿aroˈpaβa | enˈtonses el ˈβjento ðesisˈtjo | se ʝeˈɣo̯‿el ˈtuɾno ðel sol ˌkjeŋ komenˈso̯‿a βɾiˈʝar koɱ ˈfweɾsa | ˈesto‿jso k‿el βjaxeɾo sinˈtjeɾa kaˈloɾ i poɾ eʝo se kiˈto swaˈβɾiɣo ‖ enˈtonses el ˈβjento ðel ˈnoɾte ˈtuβo ke rekonoˈseɾ ˈkel ˈsol a‿e̯l ˈmas ˈfweɾte ð los ˈðos]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- История испанского языка

- Список тем фонетики

- Испанские диалекты и разновидности

- Ударение по-испански

- Фонетический алфавит RFE - система фонетической транскрипции иберийских языков, предложенная Томасом Наварро Томасом и принятая Центром исторических исследований для использования в его журнале «Журнал испанской

Примечания

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Полный словарь Random House , Random House Inc., 2006 г.

- ^ Словарь английского языка американского наследия (4-е изд.), Houghton Mifflin Company, 2006 г.

- ^ Пересмотренный полный словарь Вебстера , MICRA, Inc., 1998 г.

- ^ Всемирный словарь английского языка Encarta . Блумсбери Паблишинг Plc. 2007. Архивировано из оригинала 9 ноября 2009 г. Проверено 5 августа 2008 г.

- ^ Мартинес Селдран, Фернандес Планас и Каррера Сабате (2003 : 255)

- ^ Непрерывные аллофоны испанского языка / b, d, ɡ / традиционно описывались как звонкие фрикативные звуки. (например, Наварро Томас (1918) , который (в §100) описывает трение [ð] в воздухе как « tenue y suave » («слабый и плавный»); Харрис (1969) ; Далбор (1997) ; и Макферсон ( 1975 :62), который описывает [β] как «...со слышимым трением»). , их чаще называют аппроксимантами Однако в современной литературе, такой как D'Introno, Del Teso & Weston (1995) ; Мартинес Селдран, Фернандес Планас и Каррера Сабате (2003) ; и Хуальде (2005 :43). Разница зависит прежде всего от турбулентности воздуха, вызванной крайним сужением отверстия между артикуляторами , которое присутствует в фрикативных звуках и отсутствует в аппроксимантах. Мартинес Селдран (2004) демонстрирует звуковую спектрограмму испанского слова abogado, показывающую отсутствие турбулентности для всех трех согласных.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мартинес Селдран, Фернандес Планас и Каррера Сабате (2003 : 257)

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я Хуальде, Хосе Игнасио (2005). «Квазифонематические контрасты в испанском языке» . WCCFL 23: Материалы 23-й конференции Западного побережья по формальной лингвистике . Сомервилл, Массачусетс: Cascadilla Press. стр. 374–398.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г час я Мартинес Селдран, Фернандес Планас и Каррера Сабате (2003 : 258)

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Медленнее (1942 : 222)

- ^ Чанг (2008) , с. 54.

- ^ Чанг (2008) , с. 55.

- ^ Стэггс, Сесилия (2019). «Исследование восприятия риоплатенсского испанского языка» . Журнал исследований ученых Макнейра . 14 (1). Государственный университет Бойсе.

Многие исследования показали, что за последние 70–80 лет произошел сильный переход к глухому [ʃ] как в Аргентине, так и в Уругвае, причем Аргентина завершила этот переход к 2004 году, а Уругвай лишь недавно последовал [...]

- ^ Jump up to: а б Коттон и Шарп (1988 :15)

- ^ Колома (2018 : 245)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Нуньес-Мендес, Ева (июнь 2022 г.). «Вариация испанского языка / s /: обзор и новые перспективы» . Языки . 7 (2): 77. doi : 10.3390/languages7020077 . ISSN 2226-471X .

- ^ Канеллада и Мэдсен (1987 : 20–21)

- ^ Например , Чен (2007) , Хаммонд (2001) и Лайонс (1981).

- ^ Чен (2007 :13)

- ^ Хаммонд (2001 :?), цитируется по Scipione & Sayahi (2005 : 128).

- ^ Харрис и Винсент (1988 :83)

- ^ Лайонс (1981 :76)

- ^ такие как Мартинес Селдран, Фернандес Планас и Каррера Сабате (2003)

- ^ Бойд-Боуман (1953 :229)

- ^ Флорес (1951 :171)

- ^ Кани (1960 :236)

- ^ Ленц (1940 : 92 и далее)

- ^ Самора Висенте (1967 : 413)

- ^ Сапата Арельяно (1975)

- ^ Мотт (2011 : 110)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Пенни (2000 :122)

- ^ Кресси (1978 :61)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Моррис (1998 : 17–18)

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Хуальде (2022 :793)

- ^ Моррис (1998 :145)

- ^ Макдональд (1989 : 219)

- ^ Липски (1994 :?)

- ^ «5.3. Носовой (nasales)». Обучение испанскому произношению . OpenLearn Создать.

Однако распределение носовых звуков в испанском языке несколько недостаточное. В конце слова присутствует только альвеолярно-носовая часть. Таким образом, заимствования, оканчивающиеся на /ɲ/ или /m/, обычно передаются в испанский язык с конечной n, например, Adam -> Adán , шампанское -> champán .

- ^ «Álbum | 1384 произношения слова Álbum на испанском языке» .

- ^ Наварро Томас (1918 : §111, 113)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Далбор (1980)

- ^ Д'Интроно, Дель Тесо и Уэстон (1995 : 118–121)

- ^ Наварро Томас (1918 : §125)

- ^ Хупер (1972 :527)

- ^ Липски (1990 :155)

- ^ "лазрар | Определение | Словарь испанского языка | RAE - ASALE" .

- ^ Сорбет (2018 :73)

- ^ Д'Интроно, Дель Тесо и Уэстон (1995 : 294)

- ^ Кэнфилд (1981 :13)

- ^ Харрис (1969 :56)

- ^ Хуальде (2005 : 182–3)

- ^ Хуальде (2005 : 184).

- ^ Боуэн, Стоквелл и Сильва-Фуэнсалида (1956)

- ^ Харрис (1969)

- ^ Боне и Маскаро (1997)

- ^ Харрис (1969 : 37 н.)

- ^ Д'Интроно, Дель Тесо и Уэстон (1995 : 289)

- ^ Коттон и Шарп (1988 :19)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Сальгадо, Кристофер Гонсалес (2012). Eñe B1.2: курс испанского языка Издательство Хубер. п. 91. ИСБН 978-3-19-004294-4 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 августа 2020 года.

- ^ Дворкин, Стивен Н. (1978). «Деривационная прозрачность и изменение звука: двусторонний рост -ƏDU в испано-романском языке» . Романская филология . 31 (4): 613. JSTOR 44941944 . Проверено 4 октября 2023 г.

- ^ Наварро Томас (1918 , §98, §125)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Мартинес Селдран (2004 : 208)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Боуэн и Стоквелл (1955 :236)

- ^ Сапорта (1956 : 288)

- ^ Боуэн и Стоквелл (1955 :236) приводят минимальную пару ya visto [(ɟ)ʝa ˈβisto] («Я уже одеваюсь») и y ha visto [ja ˈβisto] («и он видел»)

- ^ Скарпас, Бири и Хуальде (2015 : 92)

- ^ цитируется в Сапорте (1956 : 289).

- ^ Обычно /w̝/ — это [ɣʷ] , хотя может быть и [βˠ] ( Охала и Лоренц (1977 :590), цитирующие Наварро Томаса (1961) и Харриса (1969) ).

- ^ Сапорта (1956 :289)

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Мартинес Селдран, Фернандес Планас и Каррера Сабате (2003 : 256)

- ^ Харрис (1969 : 78, 145). Примеры включают слова греческого происхождения, такие как énfasis /ˈenfasis/ («акцент»); клитики su /su/ , tu /tu/ , mi /mi/ ; три латинских слова espíritu /esˈpiɾitu/ («дух»), tribu /ˈtɾibu/ («племя») и ímpetu /ˈimpetu/ («стимул»); и эмоциональные слова, такие как мами /мами/ и папи /папи/ .

- ^ Пенни 1991 , с. 52.

- ^ Ульш (1971) , стр. 10, 12.

- ^ Харрис (1969) , стр. 26–27.

- ^ Харрис (1969) .

- ^ Коттон и Шарп (1988 : 182)

- ^ Самора Висенте (1967 :?). Первый /a/ в madres также подвергается этому фронтальному процессу как часть системы гармонии гласных. См . #Реализация /s/ ниже.

- ^ См., например, Мартинес Селдран, Фернандес Планас и Каррера Сабате (2003).

- ^ Такие, как Наварро Томас (1918)

- ^ Новиков (2012 : 16)

- ^ Наварро Томас (1918) , цитируется на сайте Хоакима Ллистерри.

- ^ Мартинес Селдран (1984 : 289, 294, 301)

- ^ /ou/ редко встречается в словах; другой пример — имя собственное Бусоньо ( Сапорта 1956 , с. 290). Однако это слово часто встречается за пределами слов, например, teng o u na casa («У меня есть дом»).

- ^ Харрис (1969 :89) указывает на muy («очень») как на единственный пример с [uj], а не с [wi] . Есть также несколько имен собственных с [uj] , эксклюзивных для Чуй (прозвище) и Руй . Минимальных пар не существует.

- ^ Чицоран и Хуальде (2007 :45)

- ^ Чицоран и Хуальде (2007 :46)

- ^ Мартинес Селдран, Фернандес Планас и Каррера Сабате (2003 : 256–257)

- ^ Коттон и Шарп (1988 :18)

- ^ Харрис (1969 : 99–101).

- ^ См. Harris (1969 : 147–148) для более обширного списка основ глаголов, оканчивающихся как на высокие гласные, так и на соответствующие им полугласные.

- ^ Боуэн и Стоквелл (1955 : 237)

- ^ Сапорта (1956 : 290)

- ^ Наварро Томас (1916)

- ^ Наварро Томас (1917)

- ^ Куилис (1971)

- ^ Коттон и Шарп (1988 : 19–20)

- ^ Гарсиа-Беллидо (1997 :492), цитируя Контрераса (1963) , Куилиса (1971) и Очерк новой грамматики испанского языка. (1973) Грамматики Королевской испанской академии .

- ^ Леон (2003 : 262)

- ^ Хохберг (1988 :684)

- ^ Гарсиа-Беллидо (1997 : 473–474)

- ^ Гарсия-Беллидо (1997 : 486), цитируя Наварро Томаса (1917 : 381–382, 385)

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Липский (2016 : 245)

- ^ Липски (2016 : 245), Моралес-Фронт (2018 : 196)

- ^ Владимир | 357 произношений слова Владимир — испанский (youglish.com) Кевлар | 20 произношений слова «кевлар» на испанском языке (youglish.com) Chevrón | 43 произношения слова Chevrón на испанском языке (youglish.com) Chevrolet | 84 произношения слова Chevrolet на испанском языке (youglish.com)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Хуальде, Джозеф Игнасио ; Карраско, Патрисио (2009). "/tl/ на мексиканском испанском. Сегмент или два?" (PDF) . Исследования экспериментальной фонетики (на испанском языке). XVIII : 175–191. ISSN 1575-5533 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Слоговое и орфографическое деление слов с «тл» » . Real Académia Española (на испанском языке) . Проверено 19 июля 2021 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Моралес-Фронт (2018 : 196)

- ^ Моралес-Фронт (2018 : 198)

- ^ Липски (2016 : 249–250)

- ^ «Enlace / Encadenamiento — испанское произношение беззакония» . 25 сентября 2020 г.

- ^ Бейкер (2004 :30)

- ^ Список девизов, содержащих «aiñ» | Словарь испанского языка | РАЭ - ПРОДАЖА

- ^ Список девизов, содержащих слово «аилл» | Словарь испанского языка | РАЭ - ПРОДАЖА

- ^ Список девизов, содержащих «cll» | Словарь испанского языка | РАЭ - ПРОДАЖА

- ^ Список девизов, содержащих «sll» | Словарь испанского языка | РАЭ - ПРОДАЖА

- ^ Менендес Пидаль, Рамон (1926). Происхождение испанского языка. Лингвистическое состояние Пиренейского полуострова до 11 века . Мадрид: Книжный магазин и издательство Эрнандо. п. 121.

- ^ Список девизов, содержащих слово «aull» | Словарь испанского языка | РАЭ - ПРОДАЖА

- ^ Бейкер (2004 : 4)

- ^ Кресси (1978 :86)

- ^ «Карлос Слим | 30 произношений Карлоса Слима на испанском языке» .

- ^ Липски (2016 : 252)

- ^ Липски (2016 : 250)

- ^ Липски (2016 : 254)

- ^ Харрис (1969 :79)

- ^ Харрис (1969 : 26–27)

- ^ Мысль (1997 : 595–597)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Пенсадо (1997 :608)

- ^ Харрис (1969 :188)

- ^ Харрис (1969 :189)

- ^ Харрис (1969 :97)

- ^ Катаньо, Барлоу и Мойна (2009 : 456)

- ^ Катаньо, Барлоу и Мойна (2009 : 448)

- ^ Гольдштейн и Иглесиас (1998 : 5–6)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Маккен и Бартон (1980b : 455)

- ^ Макен и Бартон (1980b : 73)

- ^ Карбальо и Мендоса (2000 : 588)

- ^ Карбальо и Мендоса (2000 : 589)

- ^ Карбальо и Мендоса (2000 : 596)

- ^ Лейбовиц, Брэндон (11 февраля 2015 г.). «Испанская фонология» . Беглость Фокс. Архивировано из оригинала 23 апреля 2016 года . Проверено 5 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ Леон (2003 : 271)

- ^ Леон (2003 : 278)

- ^ Леон (2003 : 279)

- ^ Хохберг (1988 :683)

- ^ Хохберг (1988 :685)

- ^ Коттон и Шарп (1988 :55)

- ^ Колома (2011 : 110–111)

- ^ Колома (2011 :95)

- ^ Липски (1994 :170)

- ^ Обейд (1973)

- ^ Флорес (1957 :41)

- ^ Кэнфилд (1981 :36)

- ^ Обейд (1973) .

- ^ Далбор (1980 :9).

- ^ Recasens (2004 : 436) со ссылкой на Fougeron (1999) и Browman & Goldstein (1995).

- ^ Райт, Робин (2017). Madrileño ejke: исследование восприятия и производства веляризованного / s / в Мадриде (доктор философии). Техасский университет в Остине. HDL : 2152/60470 . OCLC 993940787 .

- ^ Обейд (1973 :62)

- ^ Самора Висенте (1967 :?)

- ^ Льорет (2007 : 24–25)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Гитарт (1997 : 515)

- ^ Jump up to: а б Гитарт (1997 : 517)

- ^ Липски (1997 : 124)

- ^ Липски (1997 : 126)

- ^ Гитарт (1997 : 515, 517–518)

- ^ Guitart (1997 : 518, 527), цитируя Бойда-Боумана (1975) и Лабова (1994 : 595)

- ^ Wetzels & Mascaró (2001 :224) со ссылкой на Наварро Томаса (1961)

- ^ Оксфордский словарь испанского языка (Oxford University Press, 1994).

- ^ Молина Мартос, Изабель (2016). «Вариация последнего слова -/d/ в Мадриде: открытый или скрытый престиж?» . Филологический вестник . 51 (2): 347–367. дои : 10.4067/S0718-93032016000200013 . ISSN 0718-9303 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Лопе Бланш (2004 :29)

- ^ Авила (2003 :67)

Библиография

[ редактировать ]- Аберкромби, Дэвид (1967), Элементы общей фонетики , Эдинбург: Издательство Эдинбургского университета

- Аларкос Льорах, Эмилио (1950), Испанская фонология , Мадрид: Гредос

- Авила, Рауль (2003), «Произношение испанского языка: средства массовой информации и культурная норма» , Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica , 51 (1): 57–79, doi : 10.24201/nrfh.v51i1.2203

- Бейкер, Гэри Кеннет (2004), Палатальные явления в испанской фонологии (PDF) (доктор философии), Университет Флориды

- Боне, Эулалия; Маскаро, Хоан (1997), «О представлении контрастирующих ритмов», Мартинес-Хиль, Фернандо; Моралес-Фронт, Альфонсо (ред.), Проблемы фонологии и морфологии основных иберийских языков , издательство Джорджтаунского университета, стр. 103–126.

- Боуэн, Дж. Дональд; Стоквелл, Роберт П. (1955), «Фонематическая интерпретация полугласных в испанском языке», Language , 31 (2): 236–240, doi : 10.2307/411039 , JSTOR 411039

- Боуэн, Дж. Дональд; Стоквелл, Роберт П.; Сильва-Фуэнсалида, Исмаэль (1956), «Испанский стык и интонация», Language , 32 (4): 641–665, doi : 10.2307/411088 , JSTOR 411088

- Бойд-Боуман, Питер (1953), «О произношении испанского языка в Эквадоре», Nueva Revista de Filología Hispánica , 7 : 221–233, doi : 10.24201/nrfh.v7i1/2.310

- Бойд-Боуман, Питер (1975), «Образец испанской фонологии Карибского бассейна шестнадцатого века», в Милане, Уильям; Самора, Хуан К.; Стачек, Джон Дж. (ред.), Коллоквиум 1974 г. по испанской и португальской лингвистике , Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Издательство Джорджтаунского университета , стр. 1–11.

- Броуман, CP; Гольдштейн, Л. (1995), «Эффекты положения жестового слога в американском английском» (PDF) , в Белл-Берти, Ф.; Рафаэль, LJ (ред.), Создание речи: современные проблемы для К. Харриса , Нью-Йорк: AIP, стр. 19–33.

- Кэнфилд, Д. Линкольн (1981), Испанское произношение в Америке , Чикаго: University of Chicago Press

- Канельяда, Мария Хосефа; Мэдсен, Джон Кульманн (1987), испанское произношение: разговорный и литературный язык , Мадрид: Castalia, ISBN 978-8470394836

- Карбальо, Глория; Мендоса, Эльвира (2000), «Акустические характеристики произношения трелей группами испанских детей» (PDF) , Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics , 14 (8): 587–601, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.378.1561 , doi : 10.1080/026992000750048125 , S2CID 14574548

- Катаньо, Лорена; Барлоу, Джессика А.; Мойна, Мария Ирен (2009), «Ретроспективное исследование сложности фонетического инвентаря при освоении испанского языка: последствия для фонологических универсалий», Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics , 23 (6): 446–472, doi : 10.1080/02699200902839818 , PMC 4412371 , PMID 19504400

- Чанг, Чарльз Б. (2008), «Вариации небного образования в испанском Буэнос-Айресе» (PDF) , в Уэстморленде, Морис; Томас, Хуан Антонио (ред.), Избранные материалы 4-го семинара по испанской социолингвистике , Сомервилл, Массачусетс: Проект Cascadilla Proceedings, стр. 54–63.

- Чен, Юдонг (2007), Сравнение испанского языка, произведённого китайцами, изучающими L2, и носителями языка: подход к акустической фонетике , ISBN 9780549464037

- Чицоран, Джоанна; Хуальде, Хосе Игнасио (2007), «От перерыва до дифтонга: эволюция последовательностей гласных в романском языке» (PDF) , Фонология , 24 : 37–75, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.129.2403 , doi : 10.1017/ S095170X01770X0 S2CID 14947405

- Колома, Герман (2011), «Социально-экономические вариации диалектных фонетических особенностей испанского языка», Lexis , 35 (1): 91–118, doi : 10.18800/lexis.201101.003 , S2CID 170911379

- Колома, Херман (2018), «Аргентинский испанский» (PDF) , Журнал Международной фонетической ассоциации , 48 (2): 243–250, doi : 10.1017/S0025100317000275 , S2CID 232345835

- Контрерас, Хелес (1963), «Об акценте в испанском языке», Boletín de Filología , 15 , Университет Сантьяго де Чили : 223–237

- Коттон, Элеонора Грит; Шарп, Джон (1988), испанский язык в Америке , издательство Джорджтаунского университета, ISBN 978-0-87840-094-2

- Кресси, Уильям Уитни (1978), Испанская фонология и морфология: генеративный взгляд , издательство Джорджтаунского университета, ISBN 978-0-87840-045-4

- Далбор, Джон Б. (1997) [1969], Испанское произношение: теория и практика: вводное руководство по испанской фонологии и коррекционным упражнениям (3-е изд.), Форт-Уэрт: Холт, Райнхарт и Уинстон

- Далбор, Джон Б. (1980), «Наблюдения за современными Сесео и Чечео на юге Испании», Hispania , 63 (1): 5–19, doi : 10.2307/340806 , JSTOR 340806

- Д'Интроно, Франческо; Дель Тесо, Энрике; Уэстон, Розмари (1995), Современная фонетика и фонология испанского языка , Мадрид: Cátedra

- Эддингтон, Дэвид (2000), «Присвоение испанского ударения в рамках аналогового моделирования языка» (PDF) , Language , 76 (1): 92–109, doi : 10.2307/417394 , JSTOR 417394 , заархивировано из оригинала (PDF) на сайте 8 июля 2013 г. , получено 05 февраля 2008 г.

- Флорес, Луис (1951), Произношение испанского языка в Боготе , Богота: Публикации Института Каро-и-Куэрво

- Флорес, Луис (1957), Речь и популярная культура в Антиокии , Богота: Instituto Caro y Cuervo

- Фужерон, К. (1999), «Просодически обусловленная артикуляционная вариация: обзор» , Рабочие документы Калифорнийского университета в Лос-Анджелесе по фонетике , том. 97, стр. 1–73.

- Гарсиа-Беллидо, Палома (1997), «Взаимосвязь между присущим и структурным выдающимся положением в испанском языке», Мартинес-Хиль, Фернандо; Моралес-Фронт, Альфонсо (ред.), Проблемы фонологии и морфологии основных иберийских языков , издательство Джорджтаунского университета, стр. 469–511.

- Гольдштейн, Брайан А.; Иглесиас, Аквилес (1998), Фонологическое производство у испаноязычных дошкольников

- Гитарт, Хорхе М. (1997), «Изменчивость, мультилектализм и организация фонологии в карибских испанских диалектах» (PDF) , в Мартинес-Хил, Фернандо; Моралес-Фронт, Альфонсо (ред.), Проблемы фонологии и морфологии основных иберийских языков , издательство Джорджтаунского университета, стр. 515–536.

- Хаммонд, Роберт М. (2001), Звуки испанского языка: анализ и применение , Cascadilla Press, ISBN 978-1-57473-018-0

- Харрис, Джеймс (1969), испанская фонология , Кембридж: MIT Press

- Харрис, Мартин; Винсент, Найджел (1988), «Испанский» , Романские языки , Тейлор и Фрэнсис, стр. 79–130, ISBN 978-0-415-16417-7

- Хохберг, Джудит Г. (1988), «Изучение испанского стресса: перспективы развития и теории», Language , 64 (4): 683–706, doi : 10.2307/414564 , JSTOR 414564

- Хупер, Джоан Б. (1972), «Слог в фонологической теории», Language , 48 (3): 525–540, doi : 10.2307/412031 , JSTOR 412031

- Хуальде, Хосе Игнасио (2005), Звуки испанского языка , Издательство Кембриджского университета

- Уальде, Хосе Игнасио (2022), «24 года по-испански», Габриэль, Кристоф; Гесс, Рэндалл; Мейзенбург, Трудель (ред.), Руководство по романской фонетике и фонологии , Руководства по романской лингвистике, том 27, Берлин: Де Грюйтер, стр. 779–807, ISBN 978-3-11-054835-8

- Кани, Чарльз (1960), Американская испанская семантика , Калифорнийский университет Press

- Лабов, Уильям (1994), Принципы языковых изменений: Том I: Внутренние факторы , Кембридж, Массачусетс: Blackwell Publishers.

- Ладефогед, Питер ; Джонсон, Кейт (2010), Курс фонетики (6-е изд.), Бостон, Массачусетс: Wadsworth Publishing, ISBN 978-1-4282-3126-9

- Ленц, Родольфо (1940), «Фонетика чилийского кастильского языка» (PDF) , испанский язык в Чили , факультет философии и литературы Университета Буэнос-Айреса: Институт филологии, стр. 78–208

- Липски, Джон М. (1990), Испанские постукивания и трели: фонологическая структура изолированной позиции (PDF)

- Липски, Джон М. (1994), латиноамериканский испанский , Лондон: Longman

- Липски, Джон М. (1997). «В поисках фонетических норм испанского языка» (PDF) . В Коломби — М. Сесилия; Аларкони, Франсиско X. (ред.). Преподавание испанского языка испаноговорящим: практика и теория (на испанском языке). Бостон: Хоутон Миффлин. стр. 121–132. ISBN 9780669398441 .

- Липски, Джон М. (2016). «Испанская вокальная эпентеза: фонетика звучности и моры» (PDF) . В Нуньес-Седеньо, Рафаэль А. (ред.). Слог и ударение . Де Грюйтер Мутон. стр. 245–269. дои : 10.1515/9781614515975-010 . ISBN 9781614517368 .

- Ллео, Конксита (2003), «Просодическое лицензирование кодов при освоении испанского языка», Probus , 15 (2), De Gruyter: 257–281, doi : 10.1515/prbs.2003.010

- Льорет, Мария-Роза (2007), «О природе гармонии гласных: распространение с определенной целью» (PDF) , в Бисетто, Антониетта; Барбьери, Франческо (ред.), Труды XXXIII собрания по порождающей грамматике , стр. 15–35

- Лопе Бланш, Хуан М. (2004), Вопросы мексиканской филологии , Мексика: издательство Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México , ISBN 978-970-32-0976-7

- Лайонс, Джон (1981), Язык и лингвистика: введение , издательство Кембриджского университета, ISBN 978-0-521-54088-9

- Макдональд, Маргарита (1989), «Влияние испанской фонологии на английский язык, на котором говорят латиноамериканцы США», в Бьяркмане, Питере; Хаммонд, Роберт (ред.), Американское испанское произношение: теоретические и прикладные перспективы , Вашингтон, округ Колумбия: Издательство Джорджтаунского университета, стр. 215–236, ISBN 9780878400997

- Макен, Марлис А.; Бартон, Дэвид (1980a), «Приобретение голосового контраста в английском языке: исследование времени появления голоса в начальных стоповых согласных», Journal of Child Language , 7 (1): 41–74, doi : 10.1017/S0305000900007029 , PMID 7372738 , S2CID 252612

- Макен, Марлис А.; Бартон, Дэвид (1980b), «Приобретение голосового контраста в испанском языке: фонетическое и фонологическое исследование начальных стоп-согласных», Journal of Child Language , 7 (3): 433–458, doi : 10.1017/S0305000900002774 , ПМИД 6969264 , S2CID 29944336

- Макферсон, Ян Р. (1975), Испанская фонология: описательная и историческая. , Издательство Манчестерского университета , ISBN 978-0-7190-0788-0

- Мартинес Селдран, Эухенио (1984), Фонетика (с особым упором на испанский язык) , Барселона: Редакционный Тейде

- Мартинес Селдран, Эухенио; Фернандес Планас, Ана Ма; Каррера Сабате, Жозефина (2003), «Кастильский испанский» , Журнал Международной фонетической ассоциации , 33 (2): 255–259, doi : 10.1017/S0025100303001373

- Мартинес Селдран, Эухенио (2004), «Проблемы классификации аппроксимантов» , Журнал Международной фонетической ассоциации , 34 (2): 201–210, doi : 10.1017/S0025100304001732 , S2CID 144568679

- Моралес-Фронт, Альфонсо (2018). «9. Слог». В Джислине, Кимберли Л. (ред.). Кембриджский справочник по испанской лингвистике . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-1-107-17482-5 .

- Моррис, Ричард Э. (1998), Стилистические вариации в испанской фонологии (PDF) (доктор философии), Университет штата Огайо

- Мотт, Брайан Леонард (2011), Семантика и перевод для изучающих английский язык с испанского языка , Publicacions i Edicions de la Universitat de Barcelona, ISBN 978-84-475-3548-4

- Наварро Томас, Томас (1916), «Количество ударных гласных», Revista de Filología Española , 3 : 387–408

- Наварро Томас, Томас (1917), «Количество безударных гласных», Revista de Filologia Española , 4 : 371–388

- Наварро Томас, Томас (1918), Руководство по испанскому произношению (PDF) (21-е (1982 г.) изд.), Мадрид: CSIC, заархивировано из оригинала (PDF) 19 июня 2018 г.

- Наварро Томас, Томас (1961), «Руководство по испанскому произношению», публикации журнала испанской филологии (3), Мадрид

- Новиков, Вячеслав (2012) [Впервые опубликовано в 1992 г.], Fonetyka hiszpańska (3-е изд.), Варшава: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, ISBN 978-83-01-16856-8

- Обейд, Антонио Х. (1973), «Причуды испанской буквы S» , Hispania , 56 (1): 60–67, doi : 10.2307/339038 , JSTOR 339038

- Охала, Джон; Лоренц, Джеймс (1977), «История [w] : упражнение по фонетическому объяснению звуковых образов» (PDF) , в Уистлере, Кеннет; Кьярелло, Крис; ван Ван, Роберт младший (ред.), Труды 3-го ежегодного собрания Лингвистического общества Беркли , Беркли: Лингвистическое общество Беркли, стр. 577–599.

- Пенни, Ральф (1991), История испанского языка , Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета.

- Пенни, Ральф (2000), Вариации и изменения в испанском языке , издательство Кембриджского университета, ISBN 978-0-521-78045-2

- Пенсадо, Кармен (1997), «Об испанской депалатализации / Ҏ / и / ʎ / в рифмах», в Мартинес-Хил, Фернандо; Моралес-Фронт, Альфонсо (ред.), Проблемы фонологии и морфологии основных иберийских языков , издательство Джорджтаунского университета, стр. 595–618

- Куилис, Антонио (1971), «Фонетическая характеристика акцента в испанском языке», Travaux de Linguistique et de Littérature , 9 : 53–72.

- Реказенс, Дэниел (2004), «Влияние положения слога на сокращение согласных (данные по каталонским группам согласных)» (PDF) , Journal of Phonetics , 32 (3): 435–453, doi : 10.1016/j.wocn.2004.02 .001

- Сапорта, Сол (1956), «Заметка об испанских полугласных», Language , 32 (2): 287–290, doi : 10.2307/411006 , JSTOR 411006

- Скарпейс, Дэниел; Бири, Дэвид; Хуальде, Хосе Игнасио (2015), «Аллофония / ʝ / на полуостровном испанском языке», Phonetica , 72 (2–3): 76–97, doi : 10.1159/000381067 , PMID 26683214

- Сципион, Рут; Саяхи, Лотфи (2005), «Согласный вариант испанского языка в Северном Марокко» (PDF) , в Саяхи, Лотфи; Уэстморленд, Морис (ред.), Избранные материалы второго семинара по испанской социолингвистике , Сомервилл, Массачусетс: Проект Cascadilla Proceedings Project

- Сорбет, Петр (2018), «Соображения о ротических согласных», Люблинские исследования современных языков и литературы , 42 (1): 66–80, doi : 10.17951/lsmll.2018.42.1.66

- Трагер, Джордж (1942), «Фонематическая трактовка полугласных», Language , 18 (3): 220–223, doi : 10.2307/409556 , JSTOR 409556

- Улш, Джек Ли (1971), От испанского к португальскому , Институт дипломатической службы, заархивировано из оригинала 18 ноября 2022 г.

- Ветцелс, В. Лео; Маскаро, Жоан (2001), «Типология озвучивания и озвучивания» (PDF) , Language , 77 (2): 207–244, doi : 10.1353/lan.2001.0123 , S2CID 28948663

- Уитли, М. Стэнли (2002), Контрасты испанского и английского языков: курс испанской лингвистики (2-е изд.), Издательство Джорджтаунского университета, ISBN 978-0-87840-381-3

- Самора Висенте, Алонсо (1967), испанская диалектология (2-е изд.), Biblioteca Romanica Hispanica, Editorial Gredos, ISBN 9788424911157

- Сапата Арельяно, Родриго (1975), «Примечание об артикуляции фонемы / f / в чилийском испанском языке», Signos , 8 : 131–133.

Дальнейшее чтение

[ редактировать ]- Авелино, Эриберто (2018), «Испанский Мехико» (PDF) , Журнал Международной фонетической ассоциации , 48 (2): 223–230, doi : 10.1017/S0025100316000232