Гладить

| Гладить | |

|---|---|

| Другие имена | Инсульт головного мозга (ЦВА), цереброваскулярный инсульт (ЦВН), приступ головного мозга |

| |

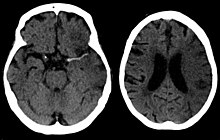

| CT scan of the brain showing a prior right-sided ischemic stroke from blockage of an artery. Changes on a CT may not be visible early on.[1] | |

| Specialty | Neurology, stroke medicine |

| Symptoms | Inability to move or feel on one side of the body, problems understanding or speaking, dizziness, loss of vision to one side[2][3] |

| Complications | Persistent vegetative state[4] |

| Causes | Ischemic (blockage) and hemorrhagic (bleeding)[5] |

| Risk factors | Age,[6] high blood pressure, tobacco smoking, obesity, high blood cholesterol, diabetes mellitus, previous TIA, end-stage kidney disease, atrial fibrillation[2][7][8] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms with medical imaging typically used to rule out bleeding[9][10] |

| Differential diagnosis | Low blood sugar[9] |

| Treatment | Based on the type[2] |

| Prognosis | Average life expectancy 1 year[2] |

| Frequency | 42.4 million (2015)[11] |

| Deaths | 6.3 million (2015)[12] |

Инсульт (также известный как нарушение мозгового кровообращения ( ЦВА ) или приступ головного мозга ) – это заболевание, при котором плохой приток крови к мозгу вызывает гибель клеток . [ 5 ] Существует два основных типа инсульта:

- ишемический , обусловленный отсутствием кровотока, и

- геморрагический , вследствие кровотечения . [ 5 ]

Оба приводят к тому, что части мозга перестают функционировать должным образом. [ 5 ]

Признаки и симптомы инсульта могут включать неспособность двигаться или чувствовать одну сторону тела, проблемы с пониманием или речью , головокружение или потерю зрения на одну сторону . [ 2 ] [ 3 ] Признаки и симптомы часто появляются вскоре после того, как произошел инсульт. [ 3 ] Если симптомы длятся менее одного или двух часов, инсульт представляет собой транзиторную ишемическую атаку (ТИА), также называемую мини-инсультом. [ 3 ] Геморрагический инсульт также может сопровождаться сильной головной болью . [ 3 ] Симптомы инсульта могут быть постоянными. [ 5 ] Долгосрочные осложнения могут включать пневмонию и потерю контроля над мочевым пузырем . [ 3 ]

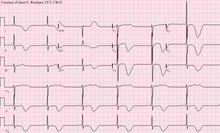

The biggest risk factor for stroke is high blood pressure.[7] Other risk factors include high blood cholesterol, tobacco smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, a previous TIA, end-stage kidney disease, and atrial fibrillation.[2][7][8] Ischemic stroke is typically caused by blockage of a blood vessel, though there are also less common causes.[13][14][15] Hemorrhagic stroke is caused by either bleeding directly into the brain or into the space between the brain's membranes.[13][16] Bleeding may occur due to a ruptured brain aneurysm.[13] Diagnosis is typically based on a physical exam and supported by medical imaging such as a CT scan or MRI scan.[9] A CT scan can rule out bleeding, but may not necessarily rule out ischemia, which early on typically does not show up on a CT scan.[10] Other tests such as an electrocardiogram (ECG) and blood tests are done to determine risk factors and rule out other possible causes.[9] Low blood sugar may cause similar symptoms.[9]

Prevention includes decreasing risk factors, surgery to open up the arteries to the brain in those with problematic carotid narrowing, and warfarin in people with atrial fibrillation.[2] Aspirin or statins may be recommended by physicians for prevention.[2] Stroke is a medical emergency.[5] Ischemic strokes, if detected within three to four-and-a-half hours, may be treatable with medication that can break down the clot,[2] while hemorrhagic strokes sometimes benefit from surgery.[2] Treatment to attempt recovery of lost function is called stroke rehabilitation, and ideally takes place in a stroke unit; however, these are not available in much of the world.[2]

In 2023, 15 million people worldwide had a stroke.[17] In 2021, stroke was the third biggest cause of death, responsible for approximately 10% of total deaths.[18] In 2015, there were about 42.4 million people who had previously had stroke and were still alive.[11] Between 1990 and 2010 the annual incidence of stroke decreased by approximately 10% in the developed world, but increased by 10% in the developing world.[19] In 2015, stroke was the second most frequent cause of death after coronary artery disease, accounting for 6.3 million deaths (11% of the total).[12] About 3.0 million deaths resulted from ischemic stroke while 3.3 million deaths resulted from hemorrhagic stroke.[12] About half of people who have had stroke live less than one year.[2] Overall, two thirds of cases of stroke occurred in those over 65 years old.[19]

Classification

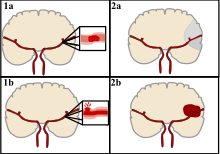

Stroke can be classified into two major categories: ischemic and hemorrhagic.[20] Ischemic stroke is caused by interruption of the blood supply to the brain, while hemorrhagic stroke results from the rupture of a blood vessel or an abnormal vascular structure.

About 87% of stroke is ischemic, with the rest being hemorrhagic. Bleeding can develop inside areas of ischemia, a condition known as "hemorrhagic transformation." It is unknown how many cases of hemorrhagic stroke actually start as ischemic stroke.[2]

Definition

In the 1970s the World Health Organization defined "stroke" as a "neurological deficit of cerebrovascular cause that persists beyond 24 hours or is interrupted by death within 24 hours",[21] although the word "stroke" is centuries old. This definition was supposed to reflect the reversibility of tissue damage and was devised for the purpose, with the time frame of 24 hours being chosen arbitrarily. The 24-hour limit divides stroke from transient ischemic attack, which is a related syndrome of stroke symptoms that resolve completely within 24 hours.[2] With the availability of treatments that can reduce stroke severity when given early, many now prefer alternative terminology, such as "brain attack" and "acute ischemic cerebrovascular syndrome" (modeled after heart attack and acute coronary syndrome, respectively), to reflect the urgency of stroke symptoms and the need to act swiftly.[22]

Ischemic

During ischemic stroke, blood supply to part of the brain is decreased, leading to dysfunction of the brain tissue in that area. There are four reasons why this might happen:

- Thrombosis (obstruction of a blood vessel by a blood clot forming locally)

- Embolism (obstruction due to an embolus from elsewhere in the body),[2]

- Systemic hypoperfusion (general decrease in blood supply, e.g., in shock)[23]

- Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis.[24]

Stroke without an obvious explanation is termed cryptogenic stroke (idiopathic); this constitutes 30–40% of all cases of ischemic stroke.[2][25]

There are classification systems for acute ischemic stroke. The Oxford Community Stroke Project classification (OCSP, also known as the Bamford or Oxford classification) relies primarily on the initial symptoms; based on the extent of the symptoms, the stroke episode is classified as total anterior circulation infarct (TACI), partial anterior circulation infarct (PACI), lacunar infarct (LACI) or posterior circulation infarct (POCI). These four entities predict the extent of the stroke, the area of the brain that is affected, the underlying cause, and the prognosis.[26][27]

The TOAST (Trial of Org 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment) classification is based on clinical symptoms as well as results of further investigations; on this basis, stroke is classified as being due to

(1) thrombosis or embolism due to atherosclerosis of a large artery,

(2) an embolism originating in the heart,

(3) complete blockage of a small blood vessel,

(4) other determined cause,

(5) undetermined cause (two possible causes, no cause identified, or incomplete investigation).[28]

Users of stimulants such as cocaine and methamphetamine are at a high risk for ischemic stroke.[29]

Hemorrhagic

There are two main types of hemorrhagic stroke:[30][31]

- Intracerebral hemorrhage, which is bleeding within the brain itself (when an artery in the brain bursts, flooding the surrounding tissue with blood), due to either intraparenchymal hemorrhage (bleeding within the brain tissue) or intraventricular hemorrhage (bleeding within the brain's ventricular system).

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage, which is bleeding that occurs outside of the brain tissue but still within the skull, and precisely between the arachnoid mater and pia mater (the delicate innermost layer of the three layers of the meninges that surround the brain).

The above two main types of hemorrhagic stroke are also two different forms of intracranial hemorrhage, which is the accumulation of blood anywhere within the cranial vault; but the other forms of intracranial hemorrhage, such as epidural hematoma (bleeding between the skull and the dura mater, which is the thick outermost layer of the meninges that surround the brain) and subdural hematoma (bleeding in the subdural space), are not considered "hemorrhagic stroke".[32]

Hemorrhagic stroke may occur on the background of alterations to the blood vessels in the brain, such as cerebral amyloid angiopathy, cerebral arteriovenous malformation and an intracranial aneurysm, which can cause intraparenchymal or subarachnoid hemorrhage.[33]

In addition to neurological impairment, hemorrhagic stroke usually causes specific symptoms (for instance, subarachnoid hemorrhage classically causes a severe headache known as a thunderclap headache) or reveal evidence of a previous head injury.

Signs and symptoms

Stroke symptoms typically start suddenly, over seconds to minutes, and in most cases do not progress further. The symptoms depend on the area of the brain affected. The more extensive the area of the brain affected, the more functions that are likely to be lost. Some forms of stroke can cause additional symptoms. For example, in intracranial hemorrhage, the affected area may compress other structures. Most forms of stroke are not associated with a headache, apart from subarachnoid hemorrhage and cerebral venous thrombosis and occasionally intracerebral hemorrhage.[33]

Early recognition

Systems have been proposed to increase recognition of stroke. Sudden-onset face weakness, arm drift (i.e., if a person, when asked to raise both arms, involuntarily lets one arm drift downward) and abnormal speech are the findings most likely to lead to the correct identification of a case of stroke, increasing the likelihood by 5.5 when at least one of these is present. Similarly, when all three of these are absent, the likelihood of stroke is decreased (– likelihood ratio of 0.39).[34] While these findings are not perfect for diagnosing stroke, the fact that they can be evaluated relatively rapidly and easily make them very valuable in the acute setting.

A mnemonic to remember the warning signs of stroke is FAST (facial droop, arm weakness, speech difficulty, and time to call emergency services),[35] as advocated by the Department of Health (United Kingdom) and the Stroke Association, the American Stroke Association, and the National Stroke Association (US). FAST is less reliable in the recognition of posterior circulation stroke.[36] The revised mnemonic BE FAST, which adds balance (sudden trouble keeping balance while walking or standing) and eyesight (new onset of blurry or double vision or sudden, painless loss of sight) to the assessment, has been proposed to address this shortcoming and improve early detection of stroke even further.[37][38] Other scales for prehospital detection of stroke include the Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS)[39] and the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS),[40] on which the FAST method was based.[41] Use of these scales is recommended by professional guidelines.[42]

For people referred to the emergency room, early recognition of stroke is deemed important as this can expedite diagnostic tests and treatments. A scoring system called ROSIER (recognition of stroke in the emergency room) is recommended for this purpose; it is based on features from the medical history and physical examination.[42][43]

Associated symptoms

Loss of consciousness, headache, and vomiting usually occur more often in hemorrhagic stroke than in thrombosis because of the increased intracranial pressure from the leaking blood compressing the brain.

If symptoms are maximal at onset, the cause is more likely to be a subarachnoid hemorrhage or an embolic stroke.

Subtypes

If the area of the brain affected includes one of the three prominent central nervous system pathways—the spinothalamic tract, corticospinal tract, and the dorsal column–medial lemniscus pathway, symptoms may include:

- hemiplegia and muscle weakness of the face

- numbness

- reduction in sensory or vibratory sensation

- initial flaccidity (reduced muscle tone), replaced by spasticity (increased muscle tone), excessive reflexes, and obligatory synergies.[44]

In most cases, the symptoms affect only one side of the body (unilateral). The defect in the brain is usually on the opposite side of the body. However, since these pathways also travel in the spinal cord and any lesion there can also produce these symptoms, the presence of any one of these symptoms does not necessarily indicate stroke. In addition to the above central nervous system pathways, the brainstem gives rise to most of the twelve cranial nerves. A brainstem stroke affecting the brainstem and brain, therefore, can produce symptoms relating to deficits in these cranial nerves:[citation needed]

- altered smell, taste, hearing, or vision (total or partial)

- drooping of eyelid (ptosis) and weakness of ocular muscles

- decreased reflexes: gag, swallow, pupil reactivity to light

- decreased sensation and muscle weakness of the face

- balance problems and nystagmus

- altered breathing and heart rate

- weakness in sternocleidomastoid muscle with inability to turn head to one side

- weakness in tongue (inability to stick out the tongue or move it from side to side)

If the cerebral cortex is involved, the central nervous system pathways can again be affected, but can also produce the following symptoms:

- aphasia (difficulty with verbal expression, auditory comprehension, reading and writing; Broca's or Wernicke's area typically involved)

- dysarthria (motor speech disorder resulting from neurological injury)

- apraxia (altered voluntary movements)

- visual field defect

- memory deficits (involvement of temporal lobe)

- hemineglect (involvement of parietal lobe)

- disorganized thinking, confusion, hypersexual gestures (with involvement of frontal lobe)

- lack of insight of his or her, usually stroke-related, disability

If the cerebellum is involved, ataxia might be present and this includes:

- altered walking gait

- altered movement coordination

- vertigo and or disequilibrium

Preceding signs and symptoms

In the days before a stroke (generally in the previous 7 days, even the previous one), a considerable proportion of patients have a "sentinel headache": a severe and unusual headache that indicates a problem.[45] Its appearance makes it advisable to seek medical review and to consider prevention against stroke.

Causes

Thrombotic stroke

In thrombotic stroke, a thrombus[46] (blood clot) usually forms around atherosclerotic plaques. Since blockage of the artery is gradual, onset of symptomatic thrombotic stroke is slower than that of hemorrhagic stroke. A thrombus itself (even if it does not completely block the blood vessel) can lead to an embolic stroke (see below) if the thrombus breaks off and travels in the bloodstream, at which point it is called an embolus. Two types of thrombosis can cause stroke:

- Large vessel disease involves the common and internal carotid arteries, the vertebral artery, and the Circle of Willis.[47] Diseases that may form thrombi in the large vessels include (in descending incidence): atherosclerosis, vasoconstriction (tightening of the artery), aortic, carotid or vertebral artery dissection, inflammatory diseases of the blood vessel wall (Takayasu arteritis, giant cell arteritis, vasculitis), noninflammatory vasculopathy, Moyamoya disease and fibromuscular dysplasia. Strokes caused by artery dissections are in the strictest sense not always caused by a 'defined disease state', such events can occur in very young people and can be caused by physical injury such as hyperextension of the neck area or often by other forms of trauma.[48]

- Small vessel disease involves the smaller arteries inside the brain: branches of the circle of Willis, middle cerebral artery, stem, and arteries arising from the distal vertebral and basilar artery.[49] Diseases that may form thrombi in the small vessels include (in descending incidence): lipohyalinosis (build-up of fatty hyaline matter in the blood vessel as a result of high blood pressure and aging) and fibrinoid degeneration (stroke involving these vessels is known as a lacunar stroke) and microatheroma (small atherosclerotic plaques).[50]

Anemia causes increase blood flow in the blood circulatory system. This causes the endothelial cells of the blood vessels to express adhesion factors which encourages the clotting of blood and formation of thrombus.[51] Sickle-cell anemia, which can cause blood cells to clump up and block blood vessels, can also lead to stroke. Stroke is the second leading cause of death in people under 20 with sickle-cell anemia.[52] Air pollution may also increase stroke risk.[53]

Embolic stroke

An embolic stroke refers to an arterial embolism (a blockage of an artery) by an embolus, a traveling particle or debris in the arterial bloodstream originating from elsewhere. An embolus is most frequently a thrombus, but it can also be a number of other substances including fat (e.g., from bone marrow in a broken bone), air, cancer cells or clumps of bacteria (usually from infectious endocarditis).[54]

Because an embolus arises from elsewhere, local therapy solves the problem only temporarily. Thus, the source of the embolus must be identified. Because the embolic blockage is sudden in onset, symptoms are usually maximal at the start. Also, symptoms may be transient as the embolus is partially resorbed and moves to a different location or dissipates altogether.

Emboli most commonly arise from the heart (especially in atrial fibrillation) but may originate from elsewhere in the arterial tree. In paradoxical embolism, a deep vein thrombosis embolizes through an atrial or ventricular septal defect in the heart into the brain.[54]

Causes of stroke related to the heart can be distinguished between high- and low-risk:[55]

- High risk: atrial fibrillation and paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, rheumatic disease of the mitral or aortic valve disease, artificial heart valves, known cardiac thrombus of the atrium or ventricle, sick sinus syndrome, sustained atrial flutter, recent myocardial infarction, chronic myocardial infarction together with ejection fraction <28 percent, symptomatic congestive heart failure with ejection fraction <30 percent, dilated cardiomyopathy, Libman-Sacks endocarditis, Marantic endocarditis, infective endocarditis, papillary fibroelastoma, left atrial myxoma, and coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery.

- Low risk/potential: calcification of the annulus (ring) of the mitral valve, patent foramen ovale (PFO), atrial septal aneurysm, atrial septal aneurysm with patent foramen ovale, left ventricular aneurysm without thrombus, isolated left atrial "smoke" on echocardiography (no mitral stenosis or atrial fibrillation), and complex atheroma in the ascending aorta or proximal arch

Among those who have a complete blockage of one of the carotid arteries, the risk of stroke on that side is about one percent per year.[56]

A special form of embolic stroke is the embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS). This subset of cryptogenic stroke is defined as a non-lacunar brain infarct without proximal arterial stenosis or cardioembolic sources. About one out of six cases of ischemic stroke could be classified as ESUS.[57]

Cerebral hypoperfusion

Cerebral hypoperfusion is the reduction of blood flow to all parts of the brain. The reduction could be to a particular part of the brain depending on the cause. It is most commonly due to heart failure from cardiac arrest or arrhythmias, or from reduced cardiac output as a result of myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism, pericardial effusion, or bleeding.[citation needed] Hypoxemia (low blood oxygen content) may precipitate the hypoperfusion. Because the reduction in blood flow is global, all parts of the brain may be affected, especially vulnerable "watershed" areas—border zone regions supplied by the major cerebral arteries. A watershed stroke refers to the condition when the blood supply to these areas is compromised. Blood flow to these areas does not necessarily stop, but instead it may lessen to the point where brain damage can occur.

Venous thrombosis

Cerebral venous sinus thrombosis leads to stroke due to locally increased venous pressure, which exceeds the pressure generated by the arteries. Infarcts are more likely to undergo hemorrhagic transformation (leaking of blood into the damaged area) than other types of ischemic stroke.[24]

Intracerebral hemorrhage

It generally occurs in small arteries or arterioles and is commonly due to hypertension,[58] intracranial vascular malformations (including cavernous angiomas or arteriovenous malformations), cerebral amyloid angiopathy, or infarcts into which secondary hemorrhage has occurred.[2] Other potential causes are trauma, bleeding disorders, amyloid angiopathy, illicit drug use (e.g., amphetamines or cocaine). The hematoma enlarges until pressure from surrounding tissue limits its growth, or until it decompresses by emptying into the ventricular system, CSF or the pial surface. A third of intracerebral bleed is into the brain's ventricles. ICH has a mortality rate of 44 percent after 30 days, higher than ischemic stroke or subarachnoid hemorrhage (which technically may also be classified as a type of stroke[2]).

Other

Other causes may include spasm of an artery. This may occur due to cocaine.[59] Cancer is also another well recognized potential cause of stroke. Although, malignancy in general can increase the risk of stroke, certain types of cancer such as pancreatic, lung and gastric are typically associated with a higher thromboembolism risk. The mechanism with which cancer increases stroke risk is thought to be secondary to an acquired hypercoagulability.[60]

Silent stroke

Silent stroke is stroke that does not have any outward symptoms, and people are typically unaware they had experienced stroke. Despite not causing identifiable symptoms, silent stroke still damages the brain and places the person at increased risk for both transient ischemic attack and major stroke in the future. Conversely, those who have had major stroke are also at risk of having silent stroke.[61] In a broad study in 1998, more than 11 million people were estimated to have experienced stroke in the United States. Approximately 770,000 of these were symptomatic and 11 million were first-ever silent MRI infarcts or hemorrhages. Silent stroke typically causes lesions which are detected via the use of neuroimaging such as MRI. Silent stroke is estimated to occur at five times the rate of symptomatic stroke.[62][63] The risk of silent stroke increases with age, but they may also affect younger adults and children, especially those with acute anemia.[62][64]

Pathophysiology

Ischemic

This section needs more reliable medical references for verification or relies too heavily on primary sources. (June 2022) |  |

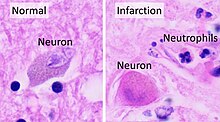

Ischemic stroke occurs because of a loss of blood supply to part of the brain, initiating the ischemic cascade.[65] Atherosclerosis may disrupt the blood supply by narrowing the lumen of blood vessels leading to a reduction of blood flow by causing the formation of blood clots within the vessel or by releasing showers of small emboli through the disintegration of atherosclerotic plaques.[66] Embolic infarction occurs when emboli formed elsewhere in the circulatory system, typically in the heart as a consequence of atrial fibrillation, or in the carotid arteries, break off, enter the cerebral circulation, then lodge in and block brain blood vessels. Since blood vessels in the brain are now blocked, the brain becomes low in energy, and thus it resorts to using anaerobic metabolism within the region of brain tissue affected by ischemia. Anaerobic metabolism produces less adenosine triphosphate (ATP) but releases a by-product called lactic acid. Lactic acid is an irritant which could potentially destroy cells since it is an acid and disrupts the normal acid-base balance in the brain. The ischemia area is referred to as the "ischemic penumbra".[67] After the initial ischemic event the penumbra transitions from a tissue remodeling characterized by damage to a remodeling characterized by repair.[68]

As oxygen or glucose becomes depleted in ischemic brain tissue, the production of high energy phosphate compounds such as adenosine triphosphate (ATP) fails, leading to failure of energy-dependent processes (such as ion pumping) necessary for tissue cell survival. This sets off a series of interrelated events that result in cellular injury and death. A major cause of neuronal injury is the release of the excitatory neurotransmitter glutamate. The concentration of glutamate outside the cells of the nervous system is normally kept low by so-called uptake carriers, which are powered by the concentration gradients of ions (mainly Na+) across the cell membrane. However, stroke cuts off the supply of oxygen and glucose which powers the ion pumps maintaining these gradients. As a result, the transmembrane ion gradients run down, and glutamate transporters reverse their direction, releasing glutamate into the extracellular space. Glutamate acts on receptors in nerve cells (especially NMDA receptors), producing an influx of calcium which activates enzymes that digest the cells' proteins, lipids, and nuclear material. Calcium influx can also lead to the failure of mitochondria, which can lead further toward energy depletion and may trigger cell death due to programmed cell death.[69]

Ischemia also induces production of oxygen free radicals and other reactive oxygen species. These react with and damage a number of cellular and extracellular elements. Damage to the blood vessel lining or endothelium may occur. These processes are the same for any type of ischemic tissue and are referred to collectively as the ischemic cascade. However, brain tissue is especially vulnerable to ischemia since it has little respiratory reserve and is completely dependent on aerobic metabolism, unlike most other organs.

Collateral flow

The brain can compensate inadequate blood flow in a single artery by the collateral system. This system relies on the efficient connection between the carotid and vertebral arteries through the circle of Willis and, to a lesser extent, the major arteries supplying the cerebral hemispheres. However, variations in the circle of Willis, caliber of collateral vessels, and acquired arterial lesions such as atherosclerosis can disrupt this compensatory mechanism, increasing the risk of brain ischemia resulting from artery blockage.[70]

The extent of damage depends on the duration and severity of the ischemia. If ischemia persists for more than 5 minutes with perfusion below 5% of normal, some neurons will die. However, if ischemia is mild, the damage will occur slowly and may take up to 6 hours to completely destroy the brain tissue. In case of severe ischemia lasting more than 15 to 30 minutes, all of the affected tissue will die, leading to infarction. The rate of damage is affected by temperature, with hyperthermia accelerating damage and hypothermia slowing it down and other factors. Prompt restoration of blood flow to ischemic tissues can reduce or reverse injury, especially if the tissues are not yet irreversibly damaged. This is particularly important for the moderately ischemic areas (penumbras) surrounding areas of severe ischemia, which may still be salvageable due to collateral flow.[70][71][72]

Hemorrhagic

Hemorrhagic stroke is classified based on their underlying pathology. Some causes of hemorrhagic stroke are hypertensive hemorrhage, ruptured aneurysm, ruptured AV fistula, transformation of prior ischemic infarction, and drug-induced bleeding.[73] They result in tissue injury by causing compression of tissue from an expanding hematoma or hematomas. In addition, the pressure may lead to a loss of blood supply to affected tissue with resulting infarction, and the blood released by brain hemorrhage appears to have direct toxic effects on brain tissue and vasculature.[52][74] Inflammation contributes to the secondary brain injury after hemorrhage.[74]

Diagnosis

Stroke is diagnosed through several techniques: a neurological examination (such as the NIHSS), CT scans (most often without contrast enhancements) or MRI scans, Doppler ultrasound, and arteriography. The diagnosis of stroke itself is clinical, with assistance from the imaging techniques. Imaging techniques also assist in determining the subtypes and cause of stroke. There is yet no commonly used blood test for the stroke diagnosis itself, though blood tests may be of help in finding out the likely cause of stroke.[75] In deceased people, an autopsy of stroke may help establishing the time between stroke onset and death.

Physical examination

A physical examination, including taking a medical history of the symptoms and a neurological status, helps giving an evaluation of the location and severity of stroke. It can give a standard score on e.g., the NIH stroke scale.

Imaging

For diagnosing ischemic (blockage) stroke in the emergency setting:[76]

- CT scans (without contrast enhancements)

- sensitivity= 16% (less than 10% within first 3 hours of symptom onset)

- specificity= 96%

- MRI scan

- sensitivity= 83%

- specificity= 98%

For diagnosing hemorrhagic stroke in the emergency setting:

- CT scans (without contrast enhancements)

- sensitivity= 89%

- specificity= 100%

- MRI scan

- sensitivity= 81%

- specificity= 100%

For detecting chronic hemorrhages, an MRI scan is more sensitive.[77]

For the assessment of stable stroke, nuclear medicine scans such as single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography–computed tomography (PET/CT) may be helpful. SPECT documents cerebral blood flow, whereas PET with an FDG isotope shows cerebral glucose metabolism.

CT scans may not detect ischemic stroke, especially if it is small, of recent onset,[10] or in the brainstem or cerebellum areas (posterior circulation infarct). MRI is better at detecting a posterior circulation infarct with diffusion-weighted imaging.[78] A CT scan is used more to rule out certain stroke mimics and detect bleeding.[10] The presence of leptomeningeal collateral circulation in the brain is associated with better clinical outcomes after recanalization treatment.[79] Cerebrovascular reserve capacity is another factor that affects stroke outcome – it is the amount of increase in cerebral blood flow after a purposeful stimulation of blood flow by the physician, such as by giving inhaled carbon dioxide or intravenous acetazolamide. The increase in blood flow can be measured by PET scan or transcranial doppler sonography.[80] However, in people with obstruction of the internal carotid artery of one side, the presence of leptomeningeal collateral circulation is associated with reduced cerebral reserve capacity.[81]

Underlying cause

When stroke has been diagnosed, other studies may be performed to determine the underlying cause. With the treatment and diagnosis options available, it is of particular importance to determine whether there is a peripheral source of emboli. Test selection may vary since the cause of stroke varies with age, comorbidity and the clinical presentation. The following are commonly used techniques:

- an ultrasound/doppler study of the carotid arteries (to detect carotid stenosis) or dissection of the precerebral arteries;

- an electrocardiogram (ECG) and echocardiogram (to identify arrhythmias and resultant clots in the heart which may spread to the brain vessels through the bloodstream);

- a Holter monitor study to identify intermittent abnormal heart rhythms;

- an angiogram of the cerebral vasculature (if a bleed is thought to have originated from an aneurysm or arteriovenous malformation);

- blood tests to determine if blood cholesterol is high, if there is an abnormal tendency to bleed, and if some rarer processes such as homocystinuria might be involved.

For hemorrhagic stroke, a CT or MRI scan with intravascular contrast may be able to identify abnormalities in the brain arteries (such as aneurysms) or other sources of bleeding, and structural MRI if this shows no cause. If this too does not identify an underlying reason for the bleeding, invasive cerebral angiography could be performed but this requires access to the bloodstream with an intravascular catheter and can cause further stroke as well as complications at the insertion site and this investigation is therefore reserved for specific situations.[82] If there are symptoms suggesting that the hemorrhage might have occurred as a result of venous thrombosis, CT or MRI venography can be used to examine the cerebral veins.[82]

Misdiagnosis

Among people with ischemic stroke, misdiagnosis occurs 2 to 26% of the time.[83] A "stroke chameleon" (SC) is stroke which is diagnosed as something else.[83][84]

People not having stroke may also be misdiagnosed with the condition. Giving thrombolytics (clot-busting) in such cases causes intracerebral bleeding 1 to 2% of the time, which is less than that of people with stroke. This unnecessary treatment adds to health care costs. Even so, the AHA/ASA guidelines state that starting intravenous tPA in possible mimics is preferred to delaying treatment for additional testing.[83]

Women, African-Americans, Hispanic-Americans, Asian and Pacific Islanders are more often misdiagnosed for a condition other than stroke when in fact having stroke. In addition, adults under 44 years of age are seven times more likely to have stroke missed than are adults over 75 years of age. This is especially the case for younger people with posterior circulation infarcts.[83] Some medical centers have used hyperacute MRI in experimental studies for people initially thought to have a low likelihood of stroke, and in some of these people, stroke has been found which were then treated with thrombolytic medication.[83]

Prevention

Given the disease burden of stroke, prevention is an important public health concern.[85] Primary prevention is less effective than secondary prevention (as judged by the number needed to treat to prevent one stroke per year).[85] Recent guidelines detail the evidence for primary prevention in stroke.[86] About the use of aspirin as a preventive medication for stroke, in healthy people aspirin does not appear beneficial and thus is not recommended,[87] but in people with high cardiovascular risk, or those who have had a myocardial infarction, it provides some protection against a first stroke.[88][89] In those who have previously had stroke, treatment with medications such as aspirin, clopidogrel, and dipyridamole may be beneficial.[88] The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends against screening for carotid artery stenosis in those without symptoms.[90]

Risk factors

The most important modifiable risk factors for stroke are high blood pressure and atrial fibrillation, although the size of the effect is small; 833 people have to be treated for 1 year to prevent one stroke.[91][92] Other modifiable risk factors include high blood cholesterol levels, diabetes mellitus, end-stage kidney disease,[8] cigarette smoking[93][94] (active and passive), heavy alcohol use,[95] drug use,[96] lack of physical activity, obesity, processed red meat consumption,[97] and unhealthy diet.[98] Smoking just one cigarette per day increases the risk more than 30%.[99] Alcohol use could predispose to ischemic stroke, as well as intracerebral and subarachnoid hemorrhage via multiple mechanisms (for example, via hypertension, atrial fibrillation, rebound thrombocytosis and platelet aggregation and clotting disturbances).[100] Drugs, most commonly amphetamines and cocaine, can induce stroke through damage to the blood vessels in the brain and acute hypertension.[73][101] Migraine with aura doubles a person's risk for ischemic stroke.[102][103] Untreated, celiac disease regardless of the presence of symptoms can be an underlying cause of stroke, both in children and adults.[104] According to a 2021 WHO study, working 55+ hours a week raises the risk of stroke by 35% and the risk of dying from heart conditions by 17%, when compared to a 35-40-hour week.[105]

High levels of physical activity reduce the risk of stroke by about 26%.[106] There is a lack of high quality studies looking at promotional efforts to improve lifestyle factors.[107] Nonetheless, given the large body of circumstantial evidence, best medical management for stroke includes advice on diet, exercise, smoking and alcohol use.[108] Medication is the most common method of stroke prevention; carotid endarterectomy can be a useful surgical method of preventing stroke.

Blood pressure

High blood pressure accounts for 35–50% of stroke risk.[109] Blood pressure reduction of 10 mmHg systolic or 5 mmHg diastolic reduces the risk of stroke by ~40%.[110] Lowering blood pressure has been conclusively shown to prevent both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.[111][112] It is equally important in secondary prevention.[113] Even people older than 80 years and those with isolated systolic hypertension benefit from antihypertensive therapy.[114][115][116] The available evidence does not show large differences in stroke prevention between antihypertensive drugs—therefore, other factors such as protection against other forms of cardiovascular disease and cost should be considered.[117][118] The routine use of beta-blockers following stroke or TIA has not been shown to result in benefits.[119]

Blood lipids

High cholesterol levels have been inconsistently associated with (ischemic) stroke.[112][120] Statins have been shown to reduce the risk of stroke by about 15%.[121] Since earlier meta-analyses of other lipid-lowering drugs did not show a decreased risk,[122] statins might exert their effect through mechanisms other than their lipid-lowering effects.[121]

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus increases the risk of stroke by 2 to 3 times.[clarification needed][citation needed] While intensive blood sugar control has been shown to reduce small blood vessel complications such as kidney damage and damage to the retina of the eye it has not been shown to reduce large blood vessel complications such as stroke.[123][124]

Anticoagulant drugs

Oral anticoagulants such as warfarin have been the mainstay of stroke prevention for over 50 years. However, several studies have shown that aspirin and other antiplatelets are highly effective in secondary prevention after stroke or transient ischemic attack.[88] Low doses of aspirin (for example 75–150 mg) are as effective as high doses but have fewer side effects; the lowest effective dose remains unknown.[125] Thienopyridines (clopidogrel, ticlopidine) might be slightly more effective than aspirin and have a decreased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding but are more expensive.[126] Both aspirin and clopidogrel may be useful in the first few weeks after a minor stroke or high-risk TIA.[127] Clopidogrel has less side effects than ticlopidine.[126] Dipyridamole can be added to aspirin therapy to provide a small additional benefit, even though headache is a common side effect.[128] Low-dose aspirin is also effective for stroke prevention after having a myocardial infarction.[89]

Those with atrial fibrillation have a 5% a year risk of stroke, and those with valvular atrial fibrillation have an even higher risk.[129] Depending on the stroke risk, anticoagulation with medications such as warfarin or aspirin is useful for prevention with various levels of comparative effectiveness depending on the type of treatment used.[130][131]

Oral anticoagulants, especially Xa (apixaban) and thrombin (dabigatran) inhibitors, have been shown to be superior to warfarin in stroke reduction and have a lower or similar bleeding risk in patients with atrial fibrillation.[131] Except in people with atrial fibrillation, oral anticoagulants are not advised for stroke prevention—any benefit is offset by bleeding risk.[132]

In primary prevention, however, antiplatelet drugs did not reduce the risk of ischemic stroke but increased the risk of major bleeding.[133][134] Further studies are needed to investigate a possible protective effect of aspirin against ischemic stroke in women.[135][136]

Surgery

Carotid endarterectomy or carotid angioplasty can be used to remove atherosclerotic narrowing of the carotid artery. There is evidence supporting this procedure in selected cases.[108] Endarterectomy for a significant stenosis has been shown to be useful in preventing further stroke in those who have already had the condition.[137] Carotid artery stenting has not been shown to be equally useful.[138][139] People are selected for surgery based on age, gender, degree of stenosis, time since symptoms and the person's preferences.[108] Surgery is most efficient when not delayed too long—the risk of recurrent stroke in a person who has a 50% or greater stenosis is up to 20% after 5 years, but endarterectomy reduces this risk to around 5%. The number of procedures needed to cure one person was 5 for early surgery (within two weeks after the initial stroke), but 125 if delayed longer than 12 weeks.[140][141]

Screening for carotid artery narrowing has not been shown to be a useful test in the general population.[142] Studies of surgical intervention for carotid artery stenosis without symptoms have shown only a small decrease in the risk of stroke.[143][144] To be beneficial, the complication rate of the surgery should be kept below 4%. Even then, for 100 surgeries, 5 people will benefit by avoiding stroke, 3 will develop stroke despite surgery, 3 will develop stroke or die due to the surgery itself, and 89 will remain stroke-free but would also have done so without intervention.[108]

Diet

Nutrition, specifically the Mediterranean-style diet, has the potential to decrease the risk of having a stroke by more than half.[145] It does not appear that lowering levels of homocysteine with folic acid affects the risk of stroke.[146][147]

Women

A number of specific recommendations have been made for women including taking aspirin after the 11th week of pregnancy if there is a history of previous chronic high blood pressure and taking blood pressure medications during pregnancy if the blood pressure is greater than 150 mmHg systolic or greater than 100 mmHg diastolic. In those who have previously had preeclampsia, other risk factors should be treated more aggressively.[148]

Previous stroke or TIA

Keeping blood pressure below 140/90 mmHg is recommended.[149] Anticoagulation can prevent recurrent ischemic stroke. Among people with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation, anticoagulation can reduce stroke by 60% while antiplatelet agents can reduce stroke by 20%.[150] However, a recent meta-analysis suggests harm from anticoagulation started early after an embolic stroke.[151][152] Stroke prevention treatment for atrial fibrillation is determined according to the CHA2DS2–VASc score. The most widely used anticoagulant to prevent thromboembolic stroke in people with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation is the oral agent warfarin while a number of newer agents including dabigatran are alternatives which do not require prothrombin time monitoring.[149]

Anticoagulants, when used following stroke, should not be stopped for dental procedures.[153]

If studies show carotid artery stenosis, and the person has a degree of residual function on the affected side, carotid endarterectomy (surgical removal of the stenosis) may decrease the risk of recurrence if performed rapidly after stroke.

Management

Stroke, whether ischemic or hemorrhagic, is an emergency that warrants immediate medical attention.[5][154] The specific treatment will depend on the type of stroke, the time elapsed since the onset of symptoms, and the underlying cause or presence of comorbidities.[154]

Ischemic stroke

Aspirin reduces the overall risk of recurrence by 13% with greater benefit early on.[155] Definitive therapy within the first few hours is aimed at removing the blockage by breaking the clot down (thrombolysis), or by removing it mechanically (thrombectomy). The philosophical premise underlying the importance of rapid stroke intervention was summed up as Time is Brain! in the early 1990s.[156] Years later, that same idea, that rapid cerebral blood flow restoration results in fewer brain cells dying, has been proved and quantified.[157]

Tight blood sugar control in the first few hours does not improve outcomes and may cause harm.[158] High blood pressure is also not typically lowered as this has not been found to be helpful.[159][160] Cerebrolysin, a mixture of pig brain-derived neurotrophic factors used widely to treat acute ischemic stroke in China, Eastern Europe, Russia, post-Soviet countries, and other Asian countries, does not improve outcomes or prevent death and may increase the risk of severe adverse events.[161] There is also no evidence that cerebrolysin‐like peptide mixtures which are extracted from cattle brain is helpful in treating acute ischemic stroke.[161]

Thrombolysis

Thrombolysis, such as with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rtPA), in acute ischemic stroke, when given within three hours of symptom onset, results in an overall benefit of 10% with respect to living without disability.[162][163] It does not, however, improve chances of survival.[162] Benefit is greater the earlier it is used.[162] Between three and four and a half hours the effects are less clear.[164][165][166] The AHA/ASA recommend it for certain people in this time frame.[167] A 2014 review found a 5% increase in the number of people living without disability at three to six months; however, there was a 2% increased risk of death in the short term.[163] After four and a half hours thrombolysis worsens outcomes.[164] These benefits or lack of benefits occurred regardless of the age of the person treated.[168] There is no reliable way to determine who will have an intracranial bleed post-treatment versus who will not.[169] In those with findings of savable tissue on medical imaging between 4.5 hours and 9 hours or who wake up with stroke, alteplase results in some benefit.[170]

Its use is endorsed by the American Heart Association, the American College of Emergency Physicians and the American Academy of Neurology as the recommended treatment for acute stroke within three hours of onset of symptoms as long as there are no other contraindications (such as abnormal lab values, high blood pressure, or recent surgery). This position for tPA is based upon the findings of two studies by one group of investigators[171] which showed that tPA improves the chances for a good neurological outcome. When administered within the first three hours thrombolysis improves functional outcome without affecting mortality.[172] 6.4% of people with large stroke developed substantial brain bleeding as a complication from being given tPA thus part of the reason for increased short term mortality.[173] The American Academy of Emergency Medicine had previously stated that objective evidence regarding the applicability of tPA for acute ischemic stroke was insufficient.[174] In 2013 the American College of Emergency Medicine refuted this position,[175] acknowledging the body of evidence for the use of tPA in ischemic stroke;[176] but debate continues.[177][178] Intra-arterial fibrinolysis, where a catheter is passed up an artery into the brain and the medication is injected at the site of thrombosis, has been found to improve outcomes in people with acute ischemic stroke.[179]

Endovascular treatment

Mechanical removal of the blood clot causing the ischemic stroke, called mechanical thrombectomy, is a potential treatment for occlusion of a large artery, such as the middle cerebral artery. In 2015, one review demonstrated the safety and efficacy of this procedure if performed within 12 hours of the onset of symptoms.[180][181] It did not change the risk of death but did reduce disability compared to the use of intravenous thrombolysis, which is generally used in people evaluated for mechanical thrombectomy.[182][183] Certain cases may benefit from thrombectomy up to 24 hours after the onset of symptoms.[184]

Craniectomy

Stroke affecting large portions of the brain can cause significant brain swelling with secondary brain injury in surrounding tissue. This phenomenon is mainly encountered in stroke affecting brain tissue dependent upon the middle cerebral artery for blood supply and is also called "malignant cerebral infarction" because it carries a dismal prognosis. Relief of the pressure may be attempted with medication, but some require hemicraniectomy, the temporary surgical removal of the skull on one side of the head. This decreases the risk of death, although some people – who would otherwise have died – survive with disability.[185][186]

Hemorrhagic stroke

People with intracerebral hemorrhage require supportive care, including blood pressure control if required. People are monitored for changes in the level of consciousness, and their blood sugar and oxygenation are kept at optimum levels. Anticoagulants and antithrombotics can make bleeding worse and are generally discontinued (and reversed if possible).[citation needed] A proportion may benefit from neurosurgical intervention to remove the blood and treat the underlying cause, but this depends on the location and the size of the hemorrhage as well as patient-related factors, and ongoing research is being conducted into the question as to which people with intracerebral hemorrhage may benefit.[187]

In subarachnoid hemorrhage, early treatment for underlying cerebral aneurysms may reduce the risk of further hemorrhages. Depending on the site of the aneurysm this may be by surgery that involves opening the skull or endovascularly (through the blood vessels).[188]

Stroke unit

Ideally, people who have had stroke are admitted to a "stroke unit", a ward or dedicated area in a hospital staffed by nurses and therapists with experience in stroke treatment. It has been shown that people admitted to stroke units have a higher chance of surviving than those admitted elsewhere in hospital, even if they are being cared for by doctors without experience in stroke.[2][189] Nursing care is fundamental in maintaining skin care, feeding, hydration, positioning, and monitoring vital signs such as temperature, pulse, and blood pressure.[190]

Rehabilitation

Stroke rehabilitation is the process by which those with disabling stroke undergo treatment to help them return to normal life as much as possible by regaining and relearning the skills of everyday living. It also aims to help the survivor understand and adapt to difficulties, prevent secondary complications, and educate family members to play a supporting role. Stroke rehabilitation should begin almost immediately with a multidisciplinary approach. The rehabilitation team may involve physicians trained in rehabilitation medicine, neurologists, clinical pharmacists, nursing staff, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, speech-language pathologists, and orthotists. Some teams may also include psychologists and social workers, since at least one-third of affected people manifests post stroke depression. Validated instruments such as the Barthel scale may be used to assess the likelihood of a person who has had stroke being able to manage at home with or without support subsequent to discharge from a hospital.[191]

Stroke rehabilitation should be started as quickly as possible and can last anywhere from a few days to over a year. Most return of function is seen in the first few months, and then improvement falls off with the "window" considered officially by U.S. state rehabilitation units and others to be closed after six months, with little chance of further improvement.[medical citation needed] However, some people have reported that they continue to improve for years, regaining and strengthening abilities like writing, walking, running, and talking.[medical citation needed] Daily rehabilitation exercises should continue to be part of the daily routine for people who have had stroke. Complete recovery is unusual but not impossible and most people will improve to some extent: proper diet and exercise are known to help the brain to recover.

Spatial neglect

The body of evidence is uncertain on the efficacy of cognitive rehabilitation for reducing the disabling effects of neglect and increasing independence remains unproven.[192] However, there is limited evidence that cognitive rehabilitation may have an immediate beneficial effect on tests of neglect.[192] Overall, no rehabilitation approach can be supported by evidence for spatial neglect.

Automobile driving

The body of evidence is uncertain whether the use of rehabilitation can improve on-road driving skills following stroke.[193] There is limited evidence that training on a driving simulator will improve performance on recognizing road signs after training.[193] The findings are based on low-quality evidence as further research is needed involving large numbers of participants.

Yoga

Based on low quality evidence, it is uncertain whether yoga has a significant benefit for stroke rehabilitation on measures of quality of life, balance, strength, endurance, pain, and disability scores.[194] Yoga may reduce anxiety and could be included as part of patient-centred stroke rehabilitation.[194] Further research is needed assessing the benefits and safety of yoga in stroke rehabilitation.

Action observation physical therapy for upper limbs

Low-quality evidence suggests that action observation (a type of physiotherapy that is meant to improve neural plasticity through the mirror-neuronal system) may be of some benefit and has no significant adverse effects, however this benefit may not be clinically significant and further research is suggested.[195]

Cognitive rehabilitation for attention deficits

The body of scientific evidence is uncertain on the effectiveness of cognitive rehabilitation for attention deficits in patients following stroke.[196] While there may be an immediate effect after treatment on attention, the findings are based on low to moderate quality and small number of studies.[196] Further research is needed to assess whether the effect can be sustained in day-to-day tasks requiring attention.

Motor imagery for gait rehabilitation

The latest evidence supports the short-term benefits of motor imagery (MI) on walking speed in individuals who have had stroke, in comparison to other therapies.[197] MI does not improve motor function after stroke and does not seem to cause significant adverse events.[197] The findings are based on low-quality evidence as further research is needed to estimate the effect of MI on walking endurance and the dependence on personal assistance.

Physical and occupational therapy

Physical and occupational therapy have overlapping areas of expertise; however, physical therapy focuses on joint range of motion and strength by performing exercises and relearning functional tasks such as bed mobility, transferring, walking and other gross motor functions. Physiotherapists can also work with people who have had stroke to improve awareness and use of the hemiplegic side. Rehabilitation involves working on the ability to produce strong movements or the ability to perform tasks using normal patterns. Emphasis is often concentrated on functional tasks and people's goals. One example physiotherapists employ to promote motor learning involves constraint-induced movement therapy. Through continuous practice the person relearns to use and adapt the hemiplegic limb during functional activities to create lasting permanent changes.[198] Physical therapy is effective for recovery of function and mobility after stroke.[199] Occupational therapy is involved in training to help relearn everyday activities known as the activities of daily living (ADLs) such as eating, drinking, dressing, bathing, cooking, reading and writing, and toileting. Approaches to helping people with urinary incontinence include physical therapy, cognitive therapy, and specialized interventions with experienced medical professionals, however, it is not clear how effective these approaches are at improving urinary incontinence following stroke.[200]

Treatment of spasticity related to stroke often involves early mobilizations, commonly performed by a physiotherapist, combined with elongation of spastic muscles and sustained stretching through different positions.[44] Gaining initial improvement in range of motion is often achieved through rhythmic rotational patterns associated with the affected limb.[44] After full range has been achieved by the therapist, the limb should be positioned in the lengthened positions to prevent against further contractures, skin breakdown, and disuse of the limb with the use of splints or other tools to stabilize the joint.[44] Cold ice wraps or ice packs may briefly relieve spasticity by temporarily reducing neural firing rates.[44] Electrical stimulation to the antagonist muscles or vibrations has also been used with some success.[44] Physical therapy is sometimes suggested for people who experience sexual dysfunction following stroke.[201]

Interventions for age-related visual problems in patients with stroke

With the prevalence of vision problems increasing with age in stroke patients, the overall effect of interventions for age-related visual problems is uncertain. It is also not sure whether people with stroke respond differently from the general population when treating eye problems.[202] Further research in this area is needed as the body of evidence is very low quality.

Speech and language therapy

Speech and language therapy is appropriate for people with the speech production disorders: dysarthria[203] and apraxia of speech,[204] aphasia,[205] cognitive-communication impairments, and problems with swallowing.

Speech and language therapy for aphasia following stroke improves functional communication, reading, writing and expressive language. Speech and language therapy that is higher intensity, higher dose or provided over a long duration of time leads to significantly better functional communication but people might be more likely to drop out of high intensity treatment (up to 15 hours per week).[206] A total of 20-50 hours of speech and language therapy is necessary for the best recovery. The most improvement happens when 2-5 hours of therapy is provided each week over 4-5 days. Recovery is further improved when besides the therapy people practice tasks at home.[207][208] Speech and language therapy is also effective if it is delivered online through video or by a family member who has been trained by a professional therapist.[207][208]

Recovery with therapy for aphasia is also dependent on the recency of stroke and the age of the person. Receiving therapy within a month after the stroke leads to the greatest improvements. 3 or 6 months after the stroke more therapy will be needed but symptoms can still be improved. People with aphasia who are younger than 55 years are the most likely to improve but people older than 75 years can still get better with therapy.[209][210]

People who have had stroke may have particular problems, such as dysphagia, which can cause swallowed material to pass into the lungs and cause aspiration pneumonia. The condition may improve with time, but in the interim, a nasogastric tube may be inserted, enabling liquid food to be given directly into the stomach. If swallowing is still deemed unsafe, then a percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube is passed and this can remain indefinitely. Swallowing therapy has mixed results as of 2018.[211]

Devices

Often, assistive technology such as wheelchairs, walkers and canes may be beneficial. Many mobility problems can be improved by the use of ankle foot orthoses.[212]

Physical fitness

Stroke can also reduce people's general fitness.[213] Reduced fitness can reduce capacity for rehabilitation as well as general health.[214] Physical exercises as part of a rehabilitation program following stroke appear safe.[213] Cardiorespiratory fitness training that involves walking in rehabilitation can improve speed, tolerance and independence during walking, and may improve balance.[213] There are inadequate long-term data about the effects of exercise and training on death, dependence and disability after stroke.[213] The future areas of research may concentrate on the optimal exercise prescription and long-term health benefits of exercise. The effect of physical training on cognition also may be studied further.

The ability to walk independently in their community, indoors or outdoors, is important following stroke. Although no negative effects have been reported, it is unclear if outcomes can improve with these walking programs when compared to usual treatment.[215]

Other therapy methods

Some current and future therapy methods include the use of virtual reality and video games for rehabilitation. These forms of rehabilitation offer potential for motivating people to perform specific therapy tasks that many other forms do not.[216] While virtual reality and interactive video gaming are not more effective than conventional therapy for improving upper limb function, when used in conjunction with usual care these approaches may improve upper limb function and ADL function.[217] There are inadequate data on the effect of virtual reality and interactive video gaming on gait speed, balance, participation and quality of life.[217] Many clinics and hospitals are adopting the use of these off-the-shelf devices for exercise, social interaction, and rehabilitation because they are affordable, accessible and can be used within the clinic and home.[216]

Mirror therapy is associated with improved motor function of the upper extremity in people who have had stroke.[218]

Other non-invasive rehabilitation methods used to augment physical therapy of motor function in people recovering from stroke include transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation.[219] and robotic therapies.[220] Constraint‐induced movement therapy (CIMT), mental practice, mirror therapy, interventions for sensory impairment, virtual reality and a relatively high dose of repetitive task practice may be effective in improving upper limb function. However, further primary research, specifically of CIMT, mental practice, mirror therapy and virtual reality is needed.[221]

Orthotics

Clinical studies confirm the importance of orthoses in stroke rehabilitation.[222][223][224] The orthosis supports the therapeutic applications and also helps to mobilize the patient at an early stage. With the help of an orthosis, physiological standing and walking can be learned again, and late health consequences caused by a wrong gait pattern can be prevented. A treatment with an orthosis can therefore be used to support the therapy.

Self-management

Stroke can affect the ability to live independently and with quality. Self-management programs are a special training that educates stroke survivors about stroke and its consequences, helps them acquire skills to cope with their challenges, and helps them set and meet their own goals during their recovery process. These programs are tailored to the target audience, and led by someone trained and expert in stroke and its consequences (most commonly professionals, but also stroke survivors and peers). A 2016 review reported that these programs improve the quality of life after stroke, without negative effects. People with stroke felt more empowered, happy and satisfied with life after participating in this training.[225]

Prognosis

Disability affects 75% of stroke survivors enough to decrease their ability to work.[226] Stroke can affect people physically, mentally, emotionally, or a combination of the three. The results of stroke vary widely depending on size and location of the lesion.[227]

Physical effects

Some of the physical disabilities that can result from stroke include muscle weakness, numbness, pressure sores, pneumonia, incontinence, apraxia (inability to perform learned movements), difficulties carrying out daily activities, appetite loss, speech loss, vision loss and pain. If the stroke is severe enough, or in a certain location such as parts of the brainstem, coma or death can result. Up to 10% of people following stroke develop seizures, most commonly in the week subsequent to the event; the severity of the stroke increases the likelihood of a seizure.[228][229] An estimated 15% of people experience urinary incontinence for more than a year following stroke.[200] 50% of people have a decline in sexual function (sexual dysfunction) following stroke.[201]

Emotional and mental effects

Emotional and mental dysfunctions correspond to areas in the brain that have been damaged. Emotional problems following stroke can be due to direct damage to emotional centers in the brain or from frustration and difficulty adapting to new limitations. Post-stroke emotional difficulties include anxiety, panic attacks, flat affect (failure to express emotions), mania, apathy and psychosis. Other difficulties may include a decreased ability to communicate emotions through facial expression, body language and voice.[230]

Disruption in self-identity, relationships with others, and emotional well-being can lead to social consequences after stroke due to the lack of ability to communicate. Many people who experience communication impairments after stroke find it more difficult to cope with the social issues rather than physical impairments. Broader aspects of care must address the emotional impact speech impairment has on those who experience difficulties with speech after stroke.[203] Those who experience a stroke are at risk of paralysis, which could result in a self-disturbed body image, which may also lead to other social issues.[231]

30 to 50% of stroke survivors develop post-stroke depression, which is characterized by lethargy, irritability, sleep disturbances, lowered self-esteem and withdrawal.[232] Depression can reduce motivation and worsen outcome, but can be treated with social and family support, psychotherapy and, in severe cases, antidepressants. Psychotherapy sessions may have a small effect on improving mood and preventing depression after stroke.[233] Antidepressant medications may be useful for treating depression after stroke but are associated with central nervous system and gastrointestinal adverse events.[233]

Emotional lability, another consequence of stroke, causes the person to switch quickly between emotional highs and lows and to express emotions inappropriately, for instance with an excess of laughing or crying with little or no provocation. While these expressions of emotion usually correspond to the person's actual emotions, a more severe form of emotional lability causes the affected person to laugh and cry pathologically, without regard to context or emotion.[226] Some people show the opposite of what they feel, for example crying when they are happy.[234] Emotional lability occurs in about 20% of those who have had stroke. Those with a right hemisphere stroke are more likely to have empathy problems which can make communication harder.[235]

Cognitive deficits resulting from stroke include perceptual disorders, aphasia,[236] dementia,[237][238] and problems with attention[239] and memory.[240] Stroke survivors may be unaware of their own disabilities, a condition called anosognosia. In a condition called hemispatial neglect, the affected person is unable to attend to anything on the side of space opposite to the damaged hemisphere. Cognitive and psychological outcome after stroke can be affected by the age at which the stroke happened, pre-stroke baseline intellectual functioning, psychiatric history and whether there is pre-existing brain pathology.[241]

Epidemiology

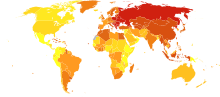

| no data <250 250–425 425–600 600–775 775–950 950–1125 | 1125–1300 1300–1475 1475–1650 1650–1825 1825–2000 >2000 |

Stroke was the second most frequent cause of death worldwide in 2011, accounting for 6.2 million deaths (~11% of the total).[243] Approximately 17 million people had stroke in 2010 and 33 million people have previously had stroke and were still alive.[19] Between 1990 and 2010 the incidence of stroke decreased by approximately 10% in the developed world and increased by 10% in the developing world.[19] Overall, two-thirds of stroke occurred in those over 65 years old.[19] South Asians are at particularly high risk of stroke, accounting for 40% of global stroke deaths.[244] Incidence of ischemic stroke is ten times more frequent than haemorrhagic stroke.[245]

It is ranked after heart disease and before cancer.[2] In the United States stroke is a leading cause of disability, and recently declined from the third leading to the fourth leading cause of death.[246] Geographic disparities in stroke incidence have been observed, including the existence of a "stroke belt" in the southeastern United States, but causes of these disparities have not been explained.

The risk of stroke increases exponentially from 30 years of age, and the cause varies by age.[247] Advanced age is one of the most significant stroke risk factors. 95% of stroke occurs in people age 45 and older, and two-thirds of stroke occurs in those over the age of 65.[52][232]

A person's risk of dying if he or she does have stroke also increases with age. However, stroke can occur at any age, including in childhood.[citation needed]

Family members may have a genetic tendency for stroke or share a lifestyle that contributes to stroke. Higher levels of Von Willebrand factor are more common amongst people who have had ischemic stroke for the first time.[248] The results of this study found that the only significant genetic factor was the person's blood type. Having stroke in the past greatly increases one's risk of future stroke.

Men are 25% more likely to develop stroke than women,[52] yet 60% of deaths from stroke occur in women.[234] Since women live longer, they are older on average when they have stroke and thus more often killed.[52] Some risk factors for stroke apply only to women. Primary among these are pregnancy, childbirth, menopause, and the treatment thereof (HRT).

History

Episodes of stroke and familial stroke have been reported from the 2nd millennium BC onward in ancient Mesopotamia and Persia.[249] Hippocrates (460 to 370 BC) was first to describe the phenomenon of sudden paralysis that is often associated with ischemia. Apoplexy, from the Greek word meaning "struck down with violence", first appeared in Hippocratic writings to describe this phenomenon.[250][251] The word stroke was used as a synonym for apoplectic seizure as early as 1599,[252] and is a fairly literal translation of the Greek term. The term apoplectic stroke is an archaic, nonspecific term, for a cerebrovascular accident accompanied by haemorrhage or haemorrhagic stroke.[253] Martin Luther was described as having an apoplectic stroke that deprived him of his speech shortly before his death in 1546.[254]

In 1658, in his Apoplexia, Johann Jacob Wepfer (1620–1695) identified the cause of hemorrhagic stroke when he suggested that people who had died of apoplexy had bleeding in their brains.[52][250] Wepfer also identified the main arteries supplying the brain, the vertebral and carotid arteries, and identified the cause of a type of ischemic stroke known as a cerebral infarction when he suggested that apoplexy might be caused by a blockage to those vessels.[52] Rudolf Virchow first described the mechanism of thromboembolism as a major factor.[255]

The term cerebrovascular accident was introduced in 1927, reflecting a "growing awareness and acceptance of vascular theories and (...) recognition of the consequences of a sudden disruption in the vascular supply of the brain".[256] Its use is now discouraged by a number of neurology textbooks, reasoning that the connotation of fortuitousness carried by the word accident insufficiently highlights the modifiability of the underlying risk factors.[257][258][259] Cerebrovascular insult may be used interchangeably.[260]

The term brain attack was introduced for use to underline the acute nature of stroke according to the American Stroke Association,[260] which has used the term since 1990,[261] and is used colloquially to refer to both ischemic as well as hemorrhagic stroke.[262]

Research

As of 2017, angioplasty and stents were under preliminary clinical research to determine the possible therapeutic advantages of these procedures in comparison to therapy with statins, antithrombotics, or antihypertensive drugs.[263]

See also

References

- ^ Gaillard F. "Ischaemic stroke". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t Donnan GA, Fisher M, Macleod M, Davis SM (May 2008). "Stroke". Lancet. 371 (9624): 1612–23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60694-7. PMID 18468545. S2CID 208787942.(subscription required)

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "What Are the Signs and Symptoms of a Stroke?". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. March 26, 2014. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Martin G (2009). Palliative Care Nursing: Quality Care to the End of Life, Third Edition. Springer Publishing Company. p. 290. ISBN 978-0-8261-5792-8. Archived from the original on 2017-08-03.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g "What Is a Stroke?". www.nhlbi.nih.gov/. March 26, 2014. Archived from the original on 18 February 2015. Retrieved 26 February 2015.

- ^ "Stroke - Causes". 24 October 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Who Is at Risk for a Stroke?". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. March 26, 2014. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Hu A, Niu J, Winkelmayer WC (November 2018). "Oral Anticoagulation in Patients With End-Stage Kidney Disease on Dialysis and Atrial Fibrillation". Seminars in Nephrology. 38 (6): 618–628. doi:10.1016/j.semnephrol.2018.08.006. PMC 6233322. PMID 30413255.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e "How Is a Stroke Diagnosed?". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. March 26, 2014. Archived from the original on 27 February 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Yew KS, Cheng E (July 2009). "Acute stroke diagnosis". American Family Physician. 80 (1): 33–40. PMC 2722757. PMID 19621844.

- ^ Jump up to: a b GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMC 5055577. PMID 27733282.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death Collaborators (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet. 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMC 5388903. PMID 27733281.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Types of Stroke". www.nhlbi.nih.gov. March 26, 2014. Archived from the original on 19 March 2015. Retrieved 27 February 2015.

- ^ Roos KL (2012). Emergency Neurology. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-387-88584-1. Archived from the original on 2017-01-08.

- ^ Wityk RJ, Llinas RH (2007). Stroke. ACP Press. p. 296. ISBN 978-1-930513-70-9. Archived from the original on 2017-01-08.

- ^ Фейгин В.Л., Ринкель Г.Дж., Лоус СМ, Алгра А., Беннетт Д.А., ван Гейн Дж. и др. (декабрь 2005 г.). «Факторы риска субарахноидального кровоизлияния: обновленный систематический обзор эпидемиологических исследований» . Гладить . 36 (12): 2773–80. дои : 10.1161/01.STR.0000190838.02954.e8 . ПМИД 16282541 .

- ^ «Инсульт, нарушение мозгового кровообращения» . Всемирная организация здравоохранения. 2024 . Проверено 12 марта 2024 г.

- ^ «10 главных причин смерти» . www.who.int . Проверено 12 августа 2024 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Фейгин В.Л., Форузанфар М.Х., Кришнамурти Р., Менса Г.А., Коннор М., Беннетт Д.А. и др. (январь 2014 г.). «Глобальное и региональное бремя инсульта в 1990-2010 годах: результаты исследования глобального бремени болезней 2010 года» . Ланцет . 383 (9913): 245–54. дои : 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61953-4 . ПМК 4181600 . ПМИД 24449944 .

- ^ «Основы работы мозга: предотвращение инсульта» . Национальный институт неврологических расстройств и инсульта. Архивировано из оригинала 8 октября 2009 г. Проверено 24 октября 2009 г.

- ^ Всемирная организация здравоохранения (1978). Цереброваскулярные расстройства (офсетные публикации) . Женева: Всемирная организация здравоохранения . ISBN 978-92-4-170043-6 . OCLC 4757533 .

- ^ Кидвелл К.С., Варах С. (декабрь 2003 г.). «Острый ишемический цереброваскулярный синдром: критерии диагностики». Гладить . 34 (12): 2995–8. дои : 10.1161/01.STR.0000098902.69855.A9 . PMID 14605325 . S2CID 16083887 .

- ^ Шуайб А., Хачинский В.К. (сентябрь 1991 г.). «Механизмы и лечение инсульта у пожилых» . CMAJ . 145 (5): 433–43. ПМЦ 1335826 . ПМИД 1878825 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Стэм Дж. (апрель 2005 г.). «Тромбоз вен и синусов головного мозга» (PDF) . Медицинский журнал Новой Англии . 352 (17): 1791–8. дои : 10.1056/NEJMra042354 . ПМИД 15858188 . S2CID 42126852 .