Династия Сун

Песня Песня | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 960–1279 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

Династия Сун в расцвете сил в 1111 году. | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Капитал | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Common languages | Middle Chinese | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | Chinese Buddhism, Taoism, Confucianism, Chinese folk religion, Islam, Nestorian Christianity | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Emperor | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 960–976 | Emperor Taizu (founder of Northern Song) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1127–1162 | Emperor Gaozong (founder of Southern Song) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1278–1279 | Zhao Bing (last) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Historical era | Postclassical | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Established | 4 February 960[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Signing of the Chanyuan Treaty with Liao | 1005 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1115–1125 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1127 | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• Beginning of Mongol invasion | 1235 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Fall of Lin'an | 1276 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Battle of Yamen (end of dynasty) | 19 March 1279 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| 958 est.[2] | 800,000 km2 (310,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 980 est.[2] | 3,100,000 km2 (1,200,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1127 est.[2] | 2,100,000 km2 (810,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1204 est.[2] | 1,800,000 km2 (690,000 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||||||

• 1120s | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | estimate | ||||||||||||||||||||||

• Per capita | |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | Jiaozi, Guanzi, Huizi, Chinese cash | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||

| Song dynasty | |||

|---|---|---|---|

"Song dynasty" in Chinese characters | |||

| Chinese | 宋朝 | ||

| |||

| Part of a series on the |

| History of China |

|---|

Династия Сун ( / s ʊ ŋ / ) — императорская династия Китая , правившая с 960 по 1279 год. Династия была основана императором Тайцзу Сун , который узурпировал трон династии Поздняя Чжоу и продолжил завоевание остальной территории Китая. Десять Королевств , завершающие период Пяти династий и Десяти королевств . Сун часто вступала в конфликт с современными династиями Ляо , Западная Ся и Цзинь в северном Китае. После отступления в южный Китай после нападений династии Цзинь, Сун в конечном итоге была завоевана возглавляемой монголами династией Юань .

The dynasty's history is divided into two periods: during the Northern Song (北宋; 960–1127), the capital was in the northern city of Bianjing (now Kaifeng) and the dynasty controlled most of what is now Eastern China. The Southern Song (南宋; 1127–1279) comprise the period following the loss of control over the northern half of Song territory to the Jurchen-led Jin dynasty in the Jin–Song Wars. At that time, the Song court retreated south of the Yangtze and established its capital at Lin'an (now Hangzhou). Although the Song dynasty had lost control of the traditional Chinese heartlands around the Yellow River, the Southern Song Empire contained a large population and productive agricultural land, sustaining a robust economy. In 1234, the Jin dynasty was conquered by the Mongols, who took control of northern China, maintaining uneasy relations with the Southern Song. Möngke Khan, the fourth Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, died in 1259 while besieging the mountain castle Diaoyucheng in Chongqing. His younger brother Kublai Khan was proclaimed the new Great Khan and in 1271 founded the Yuan dynasty.[6] After two decades of sporadic warfare, Kublai Khan's armies conquered the Song dynasty in 1279 after defeating the Southern Song in the Battle of Yamen, and reunited China under the Yuan dynasty.[7]

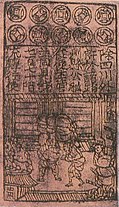

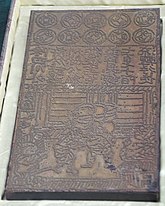

Technology, science, philosophy, mathematics, and engineering flourished during the Song era. The Song dynasty was the first in world history to issue banknotes or true paper money and the first Chinese government to establish a permanent standing navy. This dynasty saw the first surviving records of the chemical formula for gunpowder, the invention of gunpowder weapons such as fire arrows, bombs, and the fire lance. It also saw the first discernment of true north using a compass, first recorded description of the pound lock, and improved designs of astronomical clocks. Economically, the Song dynasty was unparalleled with a gross domestic product three times larger than that of Europe during the 12th century.[8][9] China's population doubled in size between the 10th and 11th centuries. This growth was made possible by expanded rice cultivation, use of early-ripening rice from Southeast and South Asia, and production of widespread food surpluses.[10][11] The Northern Song census recorded 20 million households, double that of the Han and Tang dynasties. It is estimated that the Northern Song had a population of 90 million people,[12] and 200 million by the time of the Ming dynasty.[13] This dramatic increase of population fomented an economic revolution in pre-modern China.

The expansion of the population, growth of cities, and emergence of a national economy led to the gradual withdrawal of the central government from direct involvement in economic affairs. The lower gentry assumed a larger role in local administration and affairs. Social life during the Song was vibrant. Citizens gathered to view and trade precious artworks, the populace intermingled at public festivals and private clubs, and cities had lively entertainment quarters. The spread of literature and knowledge was enhanced by the rapid expansion of woodblock printing and the 11th-century invention of movable type printing. Philosophers such as Cheng Yi and Zhu Xi reinvigorated Confucianism with new commentary, infused with Buddhist ideals, and emphasized a new organization of classic texts that established the doctrine of Neo-Confucianism. Although civil service examinations had existed since the Sui dynasty, they became much more prominent in the Song period. Officials gaining power through imperial examination led to a shift from a military-aristocratic elite to a scholar-bureaucratic elite.

History

[edit]Northern Song, 960–1127

[edit]

After usurping the throne of the Later Zhou dynasty, Emperor Taizu of Song (r. 960–976) spent sixteen years conquering the rest of China proper, reuniting much of the territory that had once belonged to the Han and Tang empires and ending the upheaval of the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period.[1] In Kaifeng, he established a strong central government over the empire. The establishment of this capital marked the start of the Northern Song period. He ensured administrative stability by promoting the civil service examination system of drafting state bureaucrats by skill and merit (instead of aristocratic or military position) and promoted projects that ensured efficiency in communication throughout the empire. In one such project, cartographers created detailed maps of each province and city that were then collected in a large atlas.[14] Emperor Taizu also promoted groundbreaking scientific and technological innovations by supporting works like the astronomical clock tower designed and built by the engineer Zhang Sixun.[15]

The Song court maintained diplomatic relations with Chola India, the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt, Srivijaya, the Kara-Khanid Khanate in Central Asia, the Goryeo Kingdom in Korea, and other countries that were also trade partners with Japan.[16][17][18][19][20] Chinese records even mention an embassy from the ruler of "Fu lin" (拂菻, i.e. the Byzantine Empire), Michael VII Doukas, and its arrival in 1081.[21] However, China's closest neighbouring states had the greatest impact on its domestic and foreign policy. From its inception under Taizu, the Song dynasty alternated between warfare and diplomacy with the ethnic Khitans of the Liao dynasty in the northeast and with the Tanguts of the Western Xia in the northwest. The Song dynasty used military force in an attempt to quell the Liao dynasty and to recapture the Sixteen Prefectures, a territory under Khitan control since 938 that was traditionally considered to be part of China proper (Most parts of today's Beijing and Tianjin).[22] Song forces were repulsed by the Liao forces, who engaged in aggressive yearly campaigns into Northern Song territory until 1005, when the signing of the Shanyuan Treaty ended these northern border clashes. The Song were forced to provide tribute to the Khitans, although this did little damage to the Song economy since the Khitans were economically dependent upon importing massive amounts of goods from the Song.[23] More significantly, the Song state recognized the Liao state as its diplomatic equal.[24] The Song created an extensive defensive forest along the Song-Liao border to thwart potential Khitan cavalry attacks.[25]

The Song dynasty managed to win several military victories over the Tanguts in the early 11th century, culminating in a campaign led by the polymath scientist, general, and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095).[26] However, this campaign was ultimately a failure due to a rival military officer of Shen disobeying direct orders, and the territory gained from the Western Xia was eventually lost.[27] The Song fought against the Vietnamese kingdom of Đại Việt twice, the first conflict in 981 and later a significant war from 1075 to 1077 over a border dispute and the Song's severing of commercial relations with Đại Việt.[28] After the Vietnamese forces inflicted heavy damages in a raid on Guangxi, the Song commander Guo Kui (1022–1088) penetrated as far as Thăng Long (modern Hanoi).[29] Heavy losses on both sides prompted the Vietnamese commander Thường Kiệt (1019–1105) to make peace overtures, allowing both sides to withdraw from the war effort; captured territories held by both Song and Vietnamese were mutually exchanged in 1082, along with prisoners of war.[30]

During the 11th century, political rivalries divided members of the court due to the ministers' differing approaches, opinions, and policies regarding the handling of the Song's complex society and thriving economy. The idealist Chancellor, Fan Zhongyan (989–1052), was the first to receive a heated political backlash when he attempted to institute the Qingli Reforms, which included measures such as improving the recruitment system of officials, increasing the salaries for minor officials, and establishing sponsorship programs to allow a wider range of people to be well educated and eligible for state service.[31]

After Fan was forced to step down from his office, Wang Anshi (1021–1086) became Chancellor of the imperial court. With the backing of Emperor Shenzong (1067–1085), Wang Anshi severely criticized the educational system and state bureaucracy. Seeking to resolve what he saw as state corruption and negligence, Wang implemented a series of reforms called the New Policies. These involved land value tax reform, the establishment of several government monopolies, the support of local militias, and the creation of higher standards for the Imperial examination to make it more practical for men skilled in statecraft to pass.[32]

The reforms created political factions in the court. Wang Anshi's "New Policies Group" (Xin Fa), also known as the "Reformers", were opposed by the ministers in the "Conservative" faction led by the historian and Chancellor Sima Guang (1019–1086).[33] As one faction supplanted another in the majority position of the court ministers, it would demote rival officials and exile them to govern remote frontier regions of the empire.[32] One of the prominent victims of the political rivalry, the famous poet and statesman Su Shi (1037–1101), was jailed and eventually exiled for criticizing Wang's reforms.[32]

The continual alternation between reform and conservatism had effectively weakened the dynasty. This decline can also be attributed to Cai Jing (1047–1126), who was appointed by Emperor Zhezong (1085–1100) and who remained in power until 1125. He revived the New Policies and pursued political opponents, tolerated corruption and encouraged Emperor Huizong (1100–1126) to neglect his duties to focus on artistic pursuits. Later, a peasant rebellion broke out in Zhejiang and Fujian, headed by Fang La in 1120. The rebellion may have been caused by an increasing tax burden, the concentration of landownership and oppressive government measures.[34]

While the central Song court remained politically divided and focused upon its internal affairs, alarming new events to the north in the Liao state finally came to its attention. The Jurchen, a subject tribe of the Liao, rebelled against them and formed their own state, the Jin dynasty (1115–1234).[35] The Song official Tong Guan (1054–1126) advised Emperor Huizong to form an alliance with the Jurchens, and the joint military campaign under this Alliance Conducted at Sea toppled and completely conquered the Liao dynasty by 1125. During the joint attack, the Song's northern expedition army removed the defensive forest along the Song-Liao border.[25]

However, the poor performance and military weakness of the Song army was observed by the Jurchens, who immediately broke the alliance, beginning the Jin–Song Wars of 1125 and 1127. Because of the removal of the previous defensive forest, the Jin army marched quickly across the North China Plain to Kaifeng.[25] In the Jingkang Incident during the latter invasion, the Jurchens captured not only the capital, but the retired Emperor Huizong, his successor Emperor Qinzong, and most of the Imperial court.[35]

The remaining Song forces regrouped under the self-proclaimed Emperor Gaozong of Song (1127–1162) and withdrew south of the Yangtze to establish a new capital at Lin'an (modern Hangzhou). The Jurchen conquest of North China and shift of capitals from Kaifeng to Lin'an was the dividing line between the Northern and Southern Song dynasties.

After their fall to the Jin, the Song lost control of North China. Now occupying what has been traditionally known as "China Proper", the Jin regarded themselves the rightful rulers of China. The Jin later chose earth as their dynastic element and yellow as their royal color. According to the theory of the Five Elements (wuxing), the earth element follows the fire, the dynastic element of the Song, in the sequence of elemental creation. Therefore, their ideological move showed that the Jin considered Song reign in China complete, with the Jin replacing the Song as the rightful rulers of China Proper.[36]

Southern Song, 1127–1279

[edit]

Although weakened and pushed south beyond the Huai River, the Southern Song found new ways to bolster its strong economy and defend itself against the Jin dynasty. It had able military officers such as Yue Fei and Han Shizhong. The government sponsored massive shipbuilding and harbor improvement projects, and the construction of beacons and seaport warehouses to support maritime trade abroad, including at the major international seaports, such as Quanzhou, Guangzhou, and Xiamen, that were sustaining China's commerce.[37][38][39]

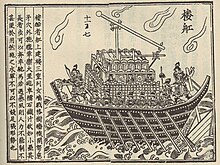

To protect and support the multitude of ships sailing for maritime interests into the waters of the East China Sea and Yellow Sea (to Korea and Japan), Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, and the Red Sea, it was necessary to establish an official standing navy.[40] The Song dynasty therefore established China's first permanent navy in 1132,[39] with a headquarters at Dinghai.[41] With a permanent navy, the Song were prepared to face the naval forces of the Jin on the Yangtze River in 1161, in the Battle of Tangdao and the Battle of Caishi. During these battles the Song navy employed swift paddle wheel driven naval vessels armed with traction trebuchet catapults aboard the decks that launched gunpowder bombs.[41] Although the Jin forces commanded by Wanyan Liang (the Prince of Hailing) boasted 70,000 men on 600 warships, and the Song forces only 3,000 men on 120 warships,[42] the Song dynasty forces were victorious in both battles due to the destructive power of the bombs and the rapid assaults by paddlewheel ships.[43] The strength of the navy was heavily emphasized following these victories. A century after the navy was founded it had grown in size to 52,000 fighting marines.[41]

The Song government confiscated portions of land owned by the landed gentry in order to raise revenue for these projects, an act which caused dissension and loss of loyalty amongst leading members of Song society but did not stop the Song's defensive preparations.[44][45][46] Financial matters were made worse by the fact that many wealthy, land-owning families—some of which had officials working for the government—used their social connections with those in office in order to obtain tax-exempt status.[47]

Although the Song dynasty was able to hold back the Jin, a new foe came to power over the steppe, deserts, and plains north of the Jin dynasty. The Mongols, led by Genghis Khan (r. 1206–1227), initially invaded the Jin dynasty in 1205 and 1209, engaging in large raids across its borders, and in 1211 an enormous Mongol army was assembled to invade the Jin.[48] The Jin dynasty was forced to submit and pay tribute to the Mongols as vassals; when the Jin suddenly moved their capital city from Beijing to Kaifeng, the Mongols saw this as a revolt.[49] Under the leadership of Ögedei Khan (r.1229–1241), both the Jin dynasty and Western Xia dynasty were conquered by Mongol forces in 1233/34.[49][50]

The Mongols were allied with the Song, but this alliance was broken when the Song recaptured the former imperial capitals of Kaifeng, Luoyang, and Chang'an at the collapse of the Jin dynasty. After the first Mongol invasion of Vietnam in 1258, Mongol general Uriyangkhadai attacked Guangxi from Hanoi as part of a coordinated Mongol attack in 1259 with armies attacking in Sichuan under Mongol leader Möngke Khan and other Mongol armies attacking in modern-day Shandong and Henan.[51][52] On August 11, 1259, Möngke Khan died during the siege of Diaoyu Castle in Chongqing.[53]

His successor Kublai Khan continued the assault against the Song, gaining a temporary foothold on the southern banks of the Yangtze.[54] By the winter of 1259, Uriyangkhadai's army fought its way north to meet Kublai's army, which was besieging Ezhou in Hubei.[51] Kublai made preparations to take Ezhou, but a pending civil war with his brother Ariq Böke—a rival claimant to the Mongol Khaganate—forced Kublai to move back north with the bulk of his forces.[55] In Kublai's absence, the Song forces were ordered by Chancellor Jia Sidao to make an immediate assault and succeeded in pushing the Mongol forces back to the northern banks of the Yangtze.[56] There were minor border skirmishes until 1265, when Kublai won a significant battle in Sichuan.[57]

From 1268 to 1273, Kublai blockaded the Yangtze River with his navy and besieged Xiangyang, the last obstacle in his way to invading the rich Yangtze River basin.[57] Kublai officially declared the creation of the Yuan dynasty in 1271. In 1275, a Song force of 130,000 troops under Chancellor Jia Sidao was defeated by Kublai's newly appointed commander-in-chief, general Bayan.[58] By 1276, most of the Song territory had been captured by Yuan forces, including the capital Lin'an.[50]

In the Battle of Yamen on the Pearl River Delta in 1279, the Yuan army, led by the general Zhang Hongfan, finally crushed the Song resistance. The last remaining ruler, the 13-year-old emperor Zhao Bing, committed suicide, along with Prime Minister Lu Xiufu[59] and 1300 members of the royal clan. On Kublai's orders, carried out by his commander Bayan, the rest of the former imperial family of Song were unharmed; the deposed Emperor Gong was demoted, being given the title 'Duke of Ying', but was eventually exiled to Tibet where he took up a monastic life. The former emperor would eventually be forced to commit suicide under the orders of Kublai's great-great-grandson, Gegeen Khan, out of fear that Emperor Gong would stage a coup to restore his reign.[60] Other members of the Song imperial family continued to live in the Yuan dynasty, including Zhao Mengfu and Zhao Yong.

Culture and society

[edit]

The Song dynasty[61] was an era of administrative sophistication and complex social organization. Some of the largest cities in the world were found in China during this period (Kaifeng and Hangzhou had populations of over a million).[62][63] People enjoyed various social clubs and entertainment in the cities, and there were many schools and temples to provide the people with education and religious services.[62] The Song government supported social welfare programs including the establishment of retirement homes, public clinics, and paupers' graveyards.[62] The Song dynasty supported a widespread postal service that was modeled on the earlier Han dynasty (202 BCE – CE 220) postal system to provide swift communication throughout the empire.[64] The central government employed thousands of postal workers of various ranks to provide service for post offices and larger postal stations.[65] In rural areas, farming peasants either owned their own plots of land, paid rents as tenant farmers, or were serfs on large estates.[66]

Although women were on a lower social tier than men according to Confucian ethics, they enjoyed many social and legal privileges and wielded considerable power at home and in their own small businesses. As Song society became more and more prosperous and parents on the bride's side of the family provided larger dowries for her marriage, women naturally gained many new legal rights in ownership of property.[67] Under certain circumstances, an unmarried daughter without brothers, or a surviving mother without sons, could inherit one-half of her father's share of undivided family property.[68][69][70] There were many notable and well-educated women, and it was a common practice for women to educate their sons during their earliest youth.[71][72] The mother of the scientist, general, diplomat, and statesman Shen Kuo taught him essentials of military strategy.[72] There were also exceptional women writers and poets, such as Li Qingzhao (1084–1151), who became famous even in her lifetime.[67]

Religion in China during this period had a great effect on people's lives, beliefs, and daily activities, and Chinese literature on spirituality was popular.[73] The major deities of Daoism and Buddhism, ancestral spirits, and the many deities of Chinese folk religion were worshipped with sacrificial offerings. Tansen Sen asserts that more Buddhist monks from India traveled to China during the Song than in the previous Tang dynasty (618–907).[74] With many ethnic foreigners travelling to China to conduct trade or live permanently, there came many foreign religions; religious minorities in China included Middle Eastern Muslims, the Kaifeng Jews, and Persian Manichaeans.[75][76]

The populace engaged in a vibrant social and domestic life, enjoying such public festivals as the Lantern Festival and the Qingming Festival. There were entertainment quarters in the cities providing a constant array of amusements. There were puppeteers, acrobats, theatre actors, sword swallowers, snake charmers, storytellers, singers and musicians, prostitutes, and places to relax, including tea houses, restaurants, and organized banquets.[62][77][78] People attended social clubs in large numbers; there were tea clubs, exotic food clubs, antiquarian and art collectors' clubs, horse-loving clubs, poetry clubs, and music clubs.[62] Like regional cooking and cuisines in the Song, the era was known for its regional varieties of performing arts styles as well.[79] Theatrical drama was very popular amongst the elite and general populace, although Classical Chinese—not the vernacular language—was spoken by actors on stage.[80][81] The four largest drama theatres in Kaifeng could hold audiences of several thousand each.[82] There were also notable domestic pastimes, as people at home enjoyed activities such as the go and xiangqi board games.

Civil service examinations and the gentry

[edit]During this period greater emphasis was laid upon the civil service system of recruiting officials; this was based upon degrees acquired through competitive examinations, in an effort to select the most capable individuals for governance. Selecting men for office through proven merit was an ancient idea in China. The civil service system became institutionalized on a small scale during the Sui and Tang dynasties, but by the Song period, it became virtually the only means for drafting officials into the government.[83] The advent of widespread printing helped to widely circulate Confucian teachings and to educate more and more eligible candidates for the exams.[84] This can be seen in the number of exam takers for the low-level prefectural exams rising from 30,000 annual candidates in the early 11th century to 400,000 candidates by the late 13th century.[84] The civil service and examination system allowed for greater meritocracy, social mobility, and equality in competition for those wishing to attain an official seat in government.[85] Using statistics gathered by the Song state, Edward A. Kracke, Sudō Yoshiyuki, and Ho Ping-ti supported the hypothesis that simply having a father, grandfather, or great-grandfather who had served as an official of state did not guarantee one would obtain the same level of authority.[85][86][87] Robert Hartwell and Robert P. Hymes criticized this model, stating that it places too much emphasis on the role of the nuclear family and considers only three paternal ascendants of exam candidates while ignoring the demographic reality of Song China, the significant proportion of males in each generation that had no surviving sons, and the role of the extended family.[86][87] Many felt disenfranchised by what they saw as a bureaucratic system that favored the land-holding class able to afford the best education.[85] One of the greatest literary critics of this was the official and famous poet Su Shi. Yet Su was a product of his times, as the identity, habits, and attitudes of the scholar-official had become less aristocratic and more bureaucratic with the transition of the periods from Tang to Song.[88] At the beginning of the dynasty, government posts were disproportionately held by two elite social groups: a founding elite who had ties with the founding emperor and a semi-hereditary professional elite who used long-held clan status, family connections, and marriage alliances to secure appointments.[89] By the late 11th century, the founding elite became obsolete, while political partisanship and factionalism at court undermined the marriage strategies of the professional elite, which dissolved as a distinguishable social group and was replaced by a multitude of gentry families.[90]

Due to Song's enormous population growth and the body of its appointed scholar-officials being accepted in limited numbers (about 20,000 active officials during the Song period), the larger scholarly gentry class would now take over grassroots affairs on the vast local level.[91] Excluding the scholar-officials in office, this elite social class consisted of exam candidates, examination degree-holders not yet assigned to an official post, local tutors, and retired officials.[92] These learned men, degree-holders, and local elites supervised local affairs and sponsored necessary facilities of local communities; any local magistrate appointed to his office by the government relied upon the cooperation of the few or many local gentry in the area.[91] For example, the Song government—excluding the educational-reformist government under Emperor Huizong—spared little amount of state revenue to maintain prefectural and county schools; instead, the bulk of the funds for schools was drawn from private financing.[93] This limited role of government officials was a departure from the earlier Tang dynasty (618–907), when the government strictly regulated commercial markets and local affairs; now the government withdrew heavily from regulating commerce and relied upon a mass of local gentry to perform necessary duties in their communities.[91]

The gentry distinguished themselves in society through their intellectual and antiquarian pursuits,[94][95][96] while the homes of prominent landholders attracted a variety of courtiers, including artisans, artists, educational tutors, and entertainers.[97] Despite the disdain for trade, commerce, and the merchant class exhibited by the highly cultured and elite exam-drafted scholar-officials, commercialism played a prominent role in Song culture and society.[77] A scholar-official would be frowned upon by his peers if he pursued means of profiteering outside of his official salary; however, this did not stop many scholar-officials from managing business relations through the use of intermediary agents.[98]

Law, justice, and forensic science

[edit]The Song judicial system retained most of the legal code of the earlier Tang dynasty, the basis of traditional Chinese law up until the modern era.[99] Roving sheriffs maintained law and order in the municipal jurisdictions and occasionally ventured into the countryside.[100] Official magistrates overseeing court cases were not only expected to be well-versed in written law but also to promote morality in society.[99] Magistrates such as the famed Bao Zheng (999–1062) embodied the upright, moral judge who upheld justice and never failed to live up to his principles. Song judges specified the guilty person or party in a criminal act and meted out punishments accordingly, often in the form of caning.[99][101] A guilty individual or parties brought to court for a criminal or civil offense were not viewed as wholly innocent until proven otherwise, while even accusers were viewed with a high level of suspicion by the judge.[101] Due to costly court expenses and immediate jailing of those accused of criminal offenses, people in the Song preferred to settle disputes and quarrels privately, without the court's interference.[101]

Shen Kuo's Dream Pool Essays argued against traditional Chinese beliefs in anatomy (such as his argument for two throat valves instead of three); this perhaps spurred the interest in the performance of post-mortem autopsies in China during the 12th century.[102][103] The physician and judge known as Song Ci (1186–1249) wrote a pioneering work of forensic science on the examination of corpses in order to determine cause of death (strangulation, poisoning, drowning, blows, etc.) and to prove whether death resulted from murder, suicide, or accidental death.[104] Song Ci stressed the importance of proper coroner's conduct during autopsies and the accurate recording of the inquest of each autopsy by official clerks.[105]

Military and methods of warfare

[edit]

The Song military was chiefly organized to ensure that the army could not threaten Imperial control, often at the expense of effectiveness in war. Northern Song's Military Council operated under a Chancellor, who had no control over the imperial army. The imperial army was divided among three marshals, each independently responsible to the Emperor. Since the Emperor rarely led campaigns personally, Song forces lacked unity of command.[106] The imperial court often believed that successful generals endangered royal authority, and relieved or even executed them (notably Li Gang,[107] Yue Fei, and Han Shizhong[108]).

Although the scholar-officials viewed military soldiers as lower members in the hierarchic social order,[109] a person could gain status and prestige in society by becoming a high-ranking military officer with a record of victorious battles.[110] At its height, the Song military had one million soldiers[32] divided into platoons of 50 troops, companies made of two platoons, battalions composed of 500 soldiers.[111][112] Crossbowmen were separated from the regular infantry and placed in their own units as they were prized combatants, providing effective missile fire against cavalry charges.[112] The government was eager to sponsor new crossbow designs that could shoot at longer ranges, while crossbowmen were also valuable when employed as long-range snipers.[113] Song cavalry employed a slew of different weapons, including halberds, swords, bows, spears, and 'fire lances' that discharged a gunpowder blast of flame and shrapnel.[114]

Military strategy and military training were treated as sciences that could be studied and perfected; soldiers were tested in their skills of using weaponry and in their athletic ability.[116] The troops were trained to follow signal standards to advance at the waving of banners and to halt at the sound of bells and drums.[112]

The Song navy was of great importance during the consolidation of the empire in the 10th century; during the war against the Southern Tang state, the Song navy employed tactics such as defending large floating pontoon bridges across the Yangtze River in order to secure movements of troops and supplies.[117] There were large ships in the Song navy that could carry 1,000 soldiers aboard their decks,[118] while the swift-moving paddle-wheel craft were viewed as essential fighting ships in any successful naval battle.[118][119]

In a battle on January 23, 971, massive arrow fire from Song dynasty crossbowmen decimated the war elephant corps of the Southern Han army.[120] This defeat not only marked the eventual submission of the Southern Han to the Song dynasty, but also the last instance where a war elephant corps was employed as a regular division within a Chinese army.[120]

There was a total of 347 military treatises written during the Song period, as listed by the history text of the Song Shi (compiled in 1345).[121] However, only a handful of these military treatises have survived, which includes the Wujing Zongyao written in 1044. It was the first known book to have listed formulas for gunpowder;[122] it gave appropriate formulas for use in several different kinds of gunpowder bombs.[123] It also provided detailed descriptions and illustrations of double-piston pump flamethrowers, as well as instructions for the maintenance and repair of the components and equipment used in the device.[124]

Arts, literature, philosophy, and religion

[edit]The visual arts during the Song dynasty were heightened by new developments such as advances in landscape and portrait painting. The gentry elite engaged in the arts as accepted pastimes of the cultured scholar-official, including painting, composing poetry, and writing calligraphy.[125] The poet and statesman Su Shi and his associate Mi Fu (1051–1107) enjoyed antiquarian affairs, often borrowing or buying art pieces to study and copy.[31] Poetry and literature profited from the rising popularity and development of the ci poetry form. Enormous encyclopedic volumes were compiled, such as works of historiography and dozens of treatises on technical subjects. This included the universal history text of the Zizhi Tongjian, compiled into 1000 volumes of 9.4 million written Chinese characters. The genre of Chinese travel literature also became popular with the writings of the geographer Fan Chengda (1126–1193) and Su Shi, the latter of whom wrote the 'daytrip essay' known as Record of Stone Bell Mountain that used persuasive writing to argue for a philosophical point.[126] Although an early form of the local geographic gazetteer existed in China since the 1st century, the matured form known as "treatise on a place", or fangzhi, replaced the old "map guide", or transl. zho – transl. tujing, during the Song dynasty.[127]

The imperial courts of the emperor's palace were filled with his entourage of court painters, calligraphers, poets, and storytellers. Emperor Huizong was the eighth emperor of the Song dynasty and he was a renowned artist as well as a patron of the art and the catalogue of his collection listed over 6,000 known paintings.[128] A prime example of a highly venerated court painter was Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145) who painted an enormous panoramic painting, Along the River During the Qingming Festival. Emperor Gaozong of Song initiated a massive art project during his reign, known as the Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute from the life story of Cai Wenji (b. 177). This art project was a diplomatic gesture to the Jin dynasty while he negotiated for the release of his mother from Jurchen captivity in the north.[129]

In philosophy, Chinese Buddhism had waned in influence but it retained its hold on the arts and on the charities of monasteries. Buddhism had a profound influence upon the budding movement of Neo-Confucianism, led by Cheng Yi (1033–1107) and Zhu Xi (1130–1200).[130] Mahayana Buddhism influenced Fan Zhongyan and Wang Anshi through its concept of ethical universalism,[131] while Buddhist metaphysics deeply affected the pre–Neo-Confucian doctrine of Cheng Yi.[130] The philosophical work of Cheng Yi in turn influenced Zhu Xi. Although his writings were not accepted by his contemporary peers, Zhu's commentary and emphasis upon the Confucian classics of the Four Books as an introductory corpus to Confucian learning formed the basis of the Neo-Confucian doctrine. By the year 1241, under the sponsorship of Emperor Lizong, Zhu Xi's Four Books and his commentary on them became standard requirements of study for students attempting to pass the civil service examinations.[132] The neighbouring countries of Japan and Korea also adopted Zhu Xi's teaching, known as the Shushigaku (朱子學, School of Zhu Xi) of Japan, and in Korea the Jujahak (주자학). Buddhism's continuing influence can be seen in painted artwork such as Lin Tinggui's Luohan Laundering. However, the ideology was highly criticized and even scorned by some. The statesman and historian Ouyang Xiu (1007–1072) called the religion a "curse" that could only be remedied by uprooting it from Chinese culture and replacing it with Confucian discourse.[133] The Chan sect experienced a literary flourishing in the Song period, which saw the publication of several major classical koan collections which remain influential in Zen philosophy and practice to the present day. A true revival of Buddhism in Chinese society would not occur until the Mongol rule of the Yuan dynasty, with Kublai Khan's sponsorship of Tibetan Buddhism and Drogön Chögyal Phagpa as the leading lama. The Christian sect of Nestorianism, which had entered China in the Tang era, would also be revived in China under Mongol rule.[134]

Cuisine and clothing

[edit]Sumptuary laws regulated the food that one consumed and the clothes that one wore according to status and social class. Clothing was made of hemp or cotton cloths, restricted to a color standard of black and white. Trousers were the acceptable attire for peasants, soldiers, artisans, and merchants, although wealthy merchants might choose to wear more ornate clothing and male blouses that came down below the waist. Acceptable apparel for scholar-officials was rigidly defined by the social ranking system. However, as time went on this rule of rank-graded apparel for officials was not as strictly enforced. Each official was able to display his awarded status by wearing different-colored traditional silken robes that hung to the ground around his feet, specific types of headgear, and even specific styles of girdles that displayed his graded-rank of officialdom.[135]

Women wore long dresses, blouses that came down to the knee, skirts, and jackets with long or short sleeves, while women from wealthy families could wear purple scarves around their shoulders. The main difference in women's apparel from that of men was that it was fastened on the left, not on the right.[136]

The main food staples in the diet of the lower classes remained rice, pork, and salted fish.[138] In 1011, Emperor Zhenzong of Song introduced Champa rice to China from Vietnam's Kingdom of Champa, which sent 30,000 bushels as a tribute to Song. Champa rice was drought-resistant and able to grow fast enough to offer two harvests a year instead of one.[139]

Song restaurant and tavern menus are recorded. They list entrees for feasts, banquets, festivals, and carnivals. They reveal a diverse and lavish diet for those of the upper class. They could choose from a wide variety of meats and seafood, including shrimp, geese, duck, mussel, shellfish, fallow deer, hare, partridge, pheasant, francolin, quail, fox, badger, clam, crab, and many others.[138][140][141] Dairy products were rare in Chinese cuisine at this time. Beef was rarely consumed since the bull was a valuable draft animal, and dog meat was absent from the diet of the wealthy, although the poor could choose to eat dog meat if necessary (yet it was not part of their regular diet).[142] People also consumed dates, raisins, jujubes, pears, plums, apricots, pear juice, lychee-fruit juice, honey and ginger drinks, spices and seasonings of Sichuan pepper, ginger, soy sauce, vegetable oil, sesame oil, salt, and vinegar.[140][143]

Economy

[edit]The Song dynasty had one of the most prosperous and advanced economies in the medieval world. Song Chinese invested their funds in joint stock companies and in multiple sailing vessels at a time when monetary gain was assured from the vigorous overseas trade and domestic trade along the Grand Canal and Yangtze River.[144] Both private and government-controlled industries met the needs of a growing Chinese population in the Song; prominent merchant families and private businesses were allowed to occupy industries that were not already government-operated monopolies.[32][145] Economic historians emphasize this toleration of market mechanisms over population growth or new farming technologies as the major cause of Song economic prosperity.[146][page needed] Artisans and merchants formed guilds that the state had to deal with when assessing taxes, requisitioning goods, and setting standard workers' wages and prices on goods.[144][147]

The iron industry was pursued by both private entrepreneurs who owned their own smelters as well as government-supervised smelting facilities.[148] The Song economy was stable enough to produce over 100,000,000 kg (220,000,000 lb) of iron products per year.[149] Large-scale Deforestation in China would have continued if not for the 11th-century innovation of the use of coal instead of charcoal in blast furnaces for smelting cast iron.[149] Much of this iron was reserved for military use in crafting weapons and armouring troops, but some was used to fashion the many iron products needed to fill the demands of the growing domestic market. The iron trade within China was advanced by the construction of new canals, facilitating the flow of iron products from production centres to the large market in the capital city.[150]

The annual output of minted copper currency in 1085 reached roughly six billion coins.[10] The most notable advancement in the Song economy was the establishment of the world's first government issued paper-printed money, known as Jiaozi (see also Huizi).[10] For the printing of paper money, the Song court established several government-run factories in the cities of Huizhou, Chengdu, Hangzhou, and Anqi.[151] The size of the workforce employed in paper money factories was large; it was recorded in 1175 that the factory at Hangzhou employed more than a thousand workers a day.[151]

The economic power of Song China can be attested by the growth of the urban population of its capital city Hangzhou. The population was 200,000 at the start of the 12th century and increased to 500,000 around 1170 and doubled to over a million a century later.[152] This economic power also heavily influenced foreign economies abroad. In 1120 alone, the Song government collected 18,000,000 ounces (510,000 kg) of silver in taxes.[153] The Moroccan geographer al-Idrisi wrote in 1154 of the prowess of Chinese merchant ships in the Indian Ocean and of their annual voyages that brought iron, swords, silk, velvet, porcelain, and various textiles to places such as Aden (Yemen), the Indus River, and the Euphrates.[40] Foreigners, in turn, affected the Chinese economy. For example, many West and Central Asian Muslims went to China to trade, becoming a preeminent force in the import and export industry, while some were even appointed as officers supervising economic affairs.[76][154] Sea trade with the South-west Pacific, the Hindu world, the Islamic world, and East Africa brought merchants great fortune and spurred an enormous growth in the shipbuilding industry of Song-era Fujian.[155] However, there was risk involved in such long overseas ventures. In order to reduce the risk of losing money on maritime trade missions abroad, wrote historians Ebrey, Walthall, and Palais:

[Song era] investors usually divided their investment among many ships, and each ship had many investors behind it. One observer thought eagerness to invest in overseas trade was leading to an outflow of copper cash. He wrote, "People along the coast are on intimate terms with the merchants who engage in overseas trade, either because they are fellow-countrymen or personal acquaintances. ... [They give the merchants] money to take with them on their ships for purchase and return conveyance of foreign goods. They invest from ten to a hundred strings of cash, and regularly make profits of several hundred percent".[88]

Science and technology

[edit]Gunpowder warfare

[edit]

Advancements in weapons technology enhanced by gunpowder, including the evolution of the early flamethrower, explosive grenades, firearms, cannons, and land mines, enabled the Song Chinese to ward off their militant enemies until the Song's ultimate collapse in the late 13th century.[156][157][158][159][160] The Wujing Zongyao manuscript of 1044 was the first book in history to provide formulas for gunpowder and their specified use in different types of bombs.[161] While engaged in a war with the Mongols, in 1259 the official Li Zengbo wrote in his Kezhai Zagao, Xugaohou that the city of Qingzhou was manufacturing one to two thousand strong iron-cased bombshells a month, dispatching to Xiangyang and Yingzhou about ten to twenty thousand such bombs at a time.[162] In turn, the invading Mongols employed northern Chinese soldiers and used these same types of gunpowder weapons against the Song.[163] By the 14th century the firearm and cannon could also be found in Europe, India, and the Middle East, during the early age of gunpowder warfare.

Measuring distance and mechanical navigation

[edit]As early as the Han dynasty, when the state needed to accurately measure distances traveled throughout the empire, the Chinese relied on a mechanical odometer.[164] The Chinese odometer was a wheeled carriage, its gearwork being driven by the rotation of the carriage's wheels; specific units of distance—the Chinese li—were marked by the mechanical striking of a drum or bell as an auditory signal.[165] The specifications for the 11th-century odometer were written by Chief Chamberlain Lu Daolong, who is quoted extensively in the historical text of the Song Shi (compiled by 1345).[166] In the Song period, the odometer vehicle was also combined with another old complex mechanical device known as the south-pointing chariot.[167] This device, originally crafted by Ma Jun in the 3rd century, incorporated a differential gear that allowed a figure mounted on the vehicle to always point in the southern direction, no matter how the vehicle's wheels turned about.[168] The concept of the differential gear that was used in this navigational vehicle is now found in modern automobiles in order to apply an equal amount of torque to a car's wheels even when they are rotating at different speeds.

Полиматематика, изобретения и астрономия

[ редактировать ]Такие эрудиты, как ученые и государственные деятели Шэнь Го (1031–1095) и Су Сун (1020–1101), олицетворяли достижения во всех областях науки, включая ботанику , зоологию , геологию , минералогию , металлургию , механику , магнетизм , метеорологию , часовое дело , астрономию. , фармацевтическая медицина , археология , математика , картография , оптика , искусствоведение , гидравлика и многие другие области. [ 95 ] [ 172 ] [ 173 ]

Шэнь Го был первым, кто различил магнитное склонение истинного севера , экспериментируя с компасом. [ 174 ] [ 175 ] Шен предположил, что географический климат постепенно меняется с течением времени. [ 176 ] [ 177 ] Он создал теорию землеустройства, основанную на представлениях, принятых в современной геоморфологии . [ 178 ] Он проводил оптические эксперименты с камерой-обскурой всего через несколько десятилетий после того, как Ибн аль-Хайсам сделал это первым. [ 179 ] Он также усовершенствовал конструкции астрономических инструментов, таких как расширенная астрономическая смотровая труба , которая позволяла Шэнь Го фиксировать положение полярной звезды (которая смещалась за столетия). [ 180 ] Шэнь Куо также был известен своими гидравлическими часовыми механизмами, поскольку он изобрел новую клепсидру высшего порядка с переливным резервуаром, которая имела более эффективную интерполяцию вместо линейной интерполяции при калибровке меры времени. [ 180 ]

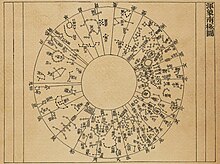

Су Сун был наиболее известен своим трактатом по часовому искусству, написанным в 1092 году, в котором очень подробно описывалась и иллюстрировалась его с гидравлическим с астрономическими часами высотой 12 м (39 футов) башня приводом, построенная в Кайфэне. На башне с часами были установлены большие астрономические инструменты армиллярной сферы и небесного глобуса , оба приводились в движение ранним периодически работающим спусковым механизмом (аналогично спусковому механизму западного края настоящих механических часов , появившемуся в средневековых часовых механизмах, заимствованным из древних часовых механизмов классических времен). [ 181 ] [ 182 ] В башне Су было вращающееся зубчатое колесо со 133 манекенами с часовыми механизмами , которые должны были вращаться мимо окон с ставнями, звоня в гонги и колокола, барабаня и демонстрируя таблички с объявлениями. [ 183 ] В своей печатной книге Су опубликовал небесный атлас пяти звездных карт . Эти звездные карты имеют цилиндрическую проекцию, похожую на проекцию Меркатора , причем последняя является картографическим нововведением Герарда Меркатора в 1569 году. [ 169 ] [ 170 ]

Китайцы Сун наблюдали сверхновые , в том числе SN 1054 , остатки которой образовали Крабовидную туманность . Более того, Сучжоуская астрономическая карта китайских планисфер была подготовлена в 1193 году для обучения наследного принца астрономическим открытиям. Планисферы были выгравированы на камне несколько десятилетий спустя. [ 184 ] [ 185 ]

Математика и картография

[ редактировать ]

произошло много заметных улучшений в китайской математике В эпоху Сун . Книга математика Ян Хуэя 1261 года предоставила самую раннюю китайскую иллюстрацию треугольника Паскаля , хотя ранее он был описан Цзя Сянем примерно в 1100 году. [ 186 ] Ян Хуэй также предоставил правила построения комбинаторных расположений в магических квадратах , предоставил теоретическое доказательство параллелограммах сорок третьего предложения Евклида о и был первым, кто использовал отрицательные коэффициенты при 'x' в квадратных уравнениях . [ 187 ] Современник Яна Цинь Цзюшао ( ок. 1202–1261 ) был первым, кто ввел символ нуля в китайскую математику; [ 188 ] вместо нулей использовались пробелы До этого в системе счетных палочек . [ 189 ] Он также известен своей работой с китайской теоремой об остатках , формулой Герона и астрономическими данными, используемыми при определении зимнего солнцестояния . Основной работой Цинь был « Математический трактат в девяти разделах», опубликованный в 1247 году.

Геометрия имела важное значение для геодезии и картографии . Самые ранние дошедшие до нас китайские карты датируются IV веком до нашей эры. [ 190 ] тем не менее, только во времена Пэй Сю (224–271) топографическая высота , формальная система прямоугольной сетки и использование стандартной градуированной шкалы расстояний были применены к картам местности. [ 191 ] [ 192 ] Следуя давней традиции , Шэнь Го создал карту с рельефом , в то время как другие его карты имели единый градуированный масштаб 1:900 000. [ 193 ] [ 194 ] Квадратная карта 1137 года площадью 3 фута (0,91 м), высеченная на каменном блоке, имела единый масштаб сетки 100 ли для каждого квадрата с сеткой и точно отображала очертания побережий и речных систем Китая, простирающихся до Индия. [ 195 ] Более того, самая старая известная в мире карта местности в печатном виде взята из отредактированной энциклопедии Ян Цзя 1155 года, на которой западный Китай изображен без формальной системы координат, которая была характерна для более профессионально созданных китайских карт. [ 196 ] Хотя географические справочники существовали с 52 г. н.э. во времена династии Хань, а географические справочники, сопровождаемые иллюстративными картами (китайский: туцзин ), со времен династии Суй, иллюстрированные географические справочники стали гораздо более распространенными во время династии Сун, когда главной заботой было то, чтобы иллюстративные географические справочники служили политическим источникам. , административных и военных целях. [ 197 ]

Печать подвижным шрифтом

[ редактировать ]Инновацию печати подвижным шрифтом придумал ремесленник Би Шэн (990–1051), впервые описанную ученым и государственным деятелем Шэнь Го в его «Очерках бассейна снов» 1088 года. [ 198 ] [ 199 ] Коллекция оригинального глиняного шрифта Би Шэна была передана одному из племянников Шэнь Го и бережно хранилась. [ 199 ] [ 200 ] Подвижный шрифт способствовал и без того широкому использованию методов гравюры для печати тысяч документов и томов письменной литературы, охотно потребляемой все более грамотной публикой. Развитие книгопечатания глубоко повлияло на образование и класс ученых и чиновников, поскольку больше книг можно было изготовить быстрее, а печатные книги массового производства были дешевле по сравнению с трудоемкими рукописными копиями. [ 84 ] [ 88 ] Таким образом, развитие широко распространенной печати и печатной культуры в период Сун стало прямым катализатором роста социальной мобильности и расширения образованного класса научной элиты, размер последней резко увеличился с 11 по 13 века. [ 84 ] [ 201 ]

Подвижный шрифт, изобретенный Би Шэном, в конечном итоге был вытеснен использованием гравюры из-за ограничений китайских иероглифов , однако печать подвижным шрифтом продолжала использоваться и была улучшена в более поздние периоды. Ученый-чиновник Юань Ван Чжэнь ( эт. 1290–1333 ) реализовал более быстрый процесс набора текста, улучшил набор символов подвижного шрифта Би из обожженной глины с помощью деревянного и экспериментировал с подвижным шрифтом из олова и металла. [ 202 ] Богатый покровитель книгопечатания Хуа Суй (1439–1513) из династии Мин в 1490 году создал первый в Китае металлический подвижный шрифт (с использованием бронзы). [ 203 ] В 1638 году « Пекинская газета» перешла с печати на дереве на печать подвижным шрифтом. [ 204 ] Тем не менее, именно во времена династии Цин в крупных полиграфических проектах начали использовать печать с использованием подвижных шрифтов. Это включает в себя печать шестидесяти шести экземпляров энциклопедии объемом 5020 томов в 1725 году « Полное собрание классиков Древнего Китая» , что потребовало изготовления 250 000 подвижных шрифтовых знаков, отлитых из бронзы. [ 205 ] К 19 веку печатный станок европейского типа заменил старые китайские методы подвижного шрифта, в то время как традиционная гравюра на дереве в современной Восточной Азии используется редко и по эстетическим соображениям.

Гидравлическое и морское машиностроение

[ редактировать ]Самым важным морским нововведением периода Сун, по-видимому, стало появление магнитного морского компаса , который позволял точно ориентироваться в открытом море независимо от погоды. [ 193 ] Намагниченная стрелка компаса, известная по-китайски как «стрелка, указывающая на юг», была впервые описана Шэнь Куо в его «Очерках бассейна снов » 1088 года и впервые упомянута в активном использовании моряками в Чжу Юя 1119 года «Застольных беседах в Пинчжоу» .

были и другие значительные достижения в области гидротехники Во времена династии Сун и морских технологий. Изобретение в X веке шлюза для систем каналов позволило поднимать и понижать разные уровни воды на отдельных участках канала, что значительно способствовало безопасности движения по каналу и позволяло использовать баржи большего размера. [ 207 ] В эпоху Сун появилась инновация в виде водонепроницаемых переборочных отсеков , которые позволяли повреждать корпуса, не затопляя корабли. [ 88 ] [ 208 ] Если корабли были повреждены, китайцы XI века использовали сухие доки для их ремонта, пока они находились в подвешенном состоянии над водой. [ 209 ] Песня использовала перекладины для крепления ребер кораблей, чтобы укрепить их в скелетоподобную структуру. [ 210 ] Кормовые рули . устанавливались на китайских кораблях с I века, о чем свидетельствует сохранившаяся модель корабля из гробницы Хань В период Сун китайцы разработали способ механического подъема и опускания рулей, чтобы корабли могли путешествовать в более широком диапазоне глубин воды. [ 210 ] Песня расположила выступающие зубцы якорей по кругу, а не в одном направлении. [ 210 ] Дэвид Графф и Робин Хайэм заявляют, что такое расположение «[сделало] их более надежными» для постановки на якорь кораблей. [ 210 ]

Структурное проектирование и архитектура

[ редактировать ]Архитектура периода Сун достигла новых высот сложности. Такие авторы, как Ю Хао и Шэнь Куо, написали книги, в которых описываются области архитектурной планировки, мастерства и строительного проектирования в 10 и 11 веках соответственно. Шэнь Го сохранил письменные диалоги Юй Хао при описании технических вопросов, таких как наклонные стойки, встроенные в башни пагоды для диагональной защиты от ветра. [ 211 ] Шэнь Го также сохранил указанные Юем размеры и единицы измерения для различных типов зданий. [ 212 ] Архитектор Ли Цзе (1065–1110), опубликовавший « Инцзао Фаши» («Трактат об архитектурных методах») в 1103 году, значительно расширил работы Юй Хао и собрал стандартные строительные нормы, используемые центральными правительственными учреждениями и мастерами повсюду. империя. [ 213 ] Он рассмотрел стандартные методы строительства, проектирования и применения рвов и укреплений, каменную кладку, большую работу по дереву, меньшую работу по дереву, резьбу по дереву, токарную обработку и сверление, распиловку, работу с бамбуком, облицовку плиткой, строительство стен, покраску и отделку, кирпичную кладку, глазурование. изготовление плитки и предоставил пропорции для раствора рецептур для кладки . [ 214 ] [ 215 ] В своей книге Ли представил подробные и яркие иллюстрации архитектурных компонентов и поперечных сечений зданий. На этих иллюстрациях показаны различные варианты применения консольных кронштейнов, консольных рычагов, пазов и шипов для связующих балок и поперечных балок, а также диаграммы, показывающие различные типы зданий залов ступенчатых размеров. [ 216 ] Он также изложил стандартные единицы измерения и стандартные размеры всех компонентов здания, описанных и проиллюстрированных в его книге. [ 217 ]

Правительство поддерживало грандиозные строительные проекты, включая возведение высоких буддийских китайских пагод и строительство огромных мостов (деревянных или каменных, эстакадных или сегментных арочных мостов ). Многие из башен-пагод, построенных в период Сун, были возведены на высоте более десяти этажей. Одними из самых известных являются Железная пагода, построенная в 1049 году во времена Северной Сун, и пагода Люхэ, построенная в 1165 году во времена Южной Сун, хотя были и другие. Самая высокая — пагода Ляоди, построенная в 1055 году в Хэбэе , общая высота которой составляет 84 м (276 футов). Некоторые из мостов достигали длины 1220 м (4000 футов), причем многие из них были достаточно широкими, чтобы обеспечить одновременное движение двух полос движения телег по водному пути или ущелью. [ 218 ] Правительство также курировало строительство собственных административных учреждений, дворцовых апартаментов, городских укреплений, храмов предков и буддийских храмов. [ 219 ]

Профессии архитектора, мастера, плотника и инженера-строителя не считались профессионально равными профессиям конфуцианского ученого-чиновника. Архитектурные знания передавались в Китае на протяжении тысячелетий устно, во многих случаях от отца-ремесленника к сыну. Известно, что в период Сун существовали школы строительной инженерии и архитектуры; возглавлял известный мостостроитель Цай Сян (1012–1067) одну престижную инженерную школу в средневековой провинции Фуцзянь . [ 220 ]

Помимо существующих зданий и технической литературы с руководствами по строительству, произведения искусства династии Сун, изображающие городские пейзажи и другие здания, помогают современным ученым в их попытках реконструировать и реализовать нюансы архитектуры Сун. Художники династии Сун, такие как Ли Чэн , Фань Куань , Го Си , Чжан Цзэдуань , император Сун Хуэйцзун и Ма Линь, рисовали крупным планом изображения зданий, а также большие пространства городских пейзажей с арочными мостами , залами и павильонами , башнями-пагодами , и отчетливые китайские городские стены . Ученый и государственный деятель Шэнь Го был известен своей критикой архитектуры, заявляя, что для художника важнее передать целостный взгляд на пейзаж, чем сосредоточиться на углах и углах зданий. [ 221 ] Например, Шэнь раскритиковал работу художника Ли Чэна за несоблюдение принципа «видеть малое с точки зрения большого» при изображении зданий. [ 221 ]

В эпоху Сун также существовали пирамидальные гробницы, такие как императорские гробницы Сун, расположенные в Гунсяне, Хэнань . [ 222 ] Примерно в 100 км (62 милях) от Гунсяня находится еще одна гробница династии Сун в Байша, в которой представлены «тщательно продуманные кирпичные копии китайского деревянного каркаса, от дверных перемычек до колонн и пьедесталов и комплектов кронштейнов, украшающих внутренние стены». [ 222 ] Две большие камеры гробницы Байша также имеют крыши конической формы. [ 223 ] По бокам аллей, ведущих к этим гробницам, расположены ряды каменных статуй чиновников, хранителей гробниц, животных и легендарных существ времен династии Сун .

Археология

[ редактировать ]

В дополнение к антикварным занятиям дворян Сун коллекционированием произведений искусства, ученые-чиновники во время Сун проявили большой интерес к извлечению древних реликвий из археологических памятников, чтобы возродить использование древних сосудов в церемониях государственного ритуала. [ 224 ] Ученые-чиновники периода Сун утверждали, что обнаружили древние бронзовые сосуды, созданные еще во времена династии Шан (1600–1046 гг. До н.э.), на которых была надпись на костях оракула эпохи Шан. [ 225 ] Некоторые пытались воссоздать эти бронзовые сосуды, используя только воображение, а не наблюдая осязаемые свидетельства существования реликвий; эта практика подверглась критике со стороны Шэнь Го в его работе 1088 года. [ 224 ] И все же Шэнь Го мог критиковать гораздо больше, чем одну только эту практику. Шен возражал против идеи своих коллег о том, что древние реликвии были продуктами, созданными известными «мудрецами» в знаниях или древним аристократическим классом ; Шэнь справедливо относил обнаруженные ремесленные изделия и сосуды древнейших времен к работам ремесленников и простолюдинов предыдущих эпох. [ 224 ] Он также не одобрял занятия своих коллег археологией просто для усиления государственных ритуалов, поскольку Шэнь не только использовал междисциплинарный подход к изучению археологии, но также делал упор на изучение функциональности и изучение первоначальных процессов изготовления древних реликвий. . [ 224 ] Шен использовал древние тексты и существующие модели армиллярных сфер , чтобы создать модель, основанную на древних стандартах; Шен описал древнее вооружение, такое как использование масштабного прицела на арбалетах; Экспериментируя с древними музыкальными тактами , Шен предложил повесить древний колокол с помощью полой ручки. [ 224 ]

Несмотря на преобладающий интерес дворянства к археологии просто ради возрождения древних государственных ритуалов, некоторые из сверстников Шена придерживались аналогичного подхода к изучению археологии. Его современник Оуян Сю (1007–1072) составил аналитический каталог древних гравюр на камне и бронзе, который положил начало идеям ранней эпиграфики и археологии. [ 95 ] В XI веке ученые Сун обнаружили древнее святилище У Ляна (78–151 гг. Н. Э.), Ученого династии Хань; они сделали оттиски резьбы и барельефов, украшавших стены его гробницы, чтобы их можно было проанализировать в другом месте. [ 226 ] О недостоверности исторических сочинений, написанных постфактум, эпиграфист и поэт Чжао Минчэн (1081–1129) констатировал: «...надписи на камне и бронзе сделаны в то время, когда происходили события, и им можно безоговорочно доверять, и таким образом, могут быть обнаружены несоответствия». [ 227 ] Историк Р. К. Рудольф утверждает, что упор Чжао на обращение к современным источникам для точной датировки параллелен озабоченности немецкого историка Леопольда фон Ранке (1795–1886). [ 227 ] и на самом деле это подчеркивалось многими учеными эпохи Сун. [ 228 ] Ученый Сун Хун Май (1123–1202) резко раскритиковал то, что он назвал «нелепым» придворным археологическим каталогом Богуту, составленным в периоды правления Хуэйцзун Чжэн Хэ и Сюань Хэ (1111–1125). [ 229 ] Хун Май получил старые сосуды времен династии Хань и сравнил их с описаниями, предложенными в каталоге, которые он нашел настолько неточными, что ему пришлось «держаться от смеха». [ 230 ] Хун Май отметил, что ошибочный материал был виной канцлера Цай Цзина , который запретил ученым читать и консультироваться с письменными историческими книгами . [ 230 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Лорге 2015 , стр. 4–5.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Таагепера 1997 , с. 493.

- ^ Чаффи 2015 , стр. 29, 327.

- ^ Чаффи 2015 , с. 625.

- ^ Бродберри, Стивен. «Китай, Европа и великое расхождение: исследование исторических национальных счетов, 980–1850 гг.» (PDF) . Ассоциация экономической истории. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 9 января 2021 года . Проверено 15 августа 2020 г. .

- ^ Россаби 1988 , с. 115.

- ^ Россаби 1988 , с. 76.

- ^ Чаффи 2015 , с. 435.

- ^ Лю 2015 , с. 294.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 156.

- ^ Брук 1998 , с. 96.

- ^ Дюран, Джон (1960). «Статистика населения Китая, 2–1953 гг. н.э.». Исследования народонаселения . 13 (3): 209–256. дои : 10.2307/2172247 . JSTOR 2172247 .

- ^ Вик и др. 2007 , стр. 103–104.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986b , с. 518.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , стр. 469–471.

- ^ Эбри 1999 , с. 138.

- ^ Холл 1985 , с. 23.

- ^ Шастри 1984 , стр. 173, 316.

- ^ Шен 1996 , с. 158.

- ^ Брозе 2008 , с. 258.

- ^ Пол Холсолл (2000) [1998]. Джером С. Аркенберг (ред.). «Справочник по истории Восточной Азии: китайские отчеты о Риме, Византии и Ближнем Востоке, ок. 91 г. до н.э. – 1643 г. н.э.» Fordham.edu . Фордэмский университет . Проверено 14 сентября 2016 г.

- ^ Мода 1999 , стр. 69.

- ^ Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 , с. 154.

- ^ Мода 1999 , стр. 70–71.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Чен 2018 .

- ^ Сивин 1995 , с. 8.

- ^ Сивин 1995 , с. 9.

- ^ Андерсон 2008 , с. 207.

- ^ Андерсон 2008 , с. 208.

- ^ Андерсон 2008 , стр. 208–209.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 163.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 164.

- ^ Сивин 1995 , стр. 3-4.

- ^ Робертс, JAG (1996). История Китая . Нью-Йорк: Пресса Святого Мартина. п. 148. ИСБН 9780312163341 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 165.

- ^ Чен 2014 .

- ^ Деньги 2000 , с. 14.

- ^ Сивин 1995 , с. 5.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Палудан 1998 , стр. 136.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шен 1996 , стр. 159–161.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Нидхэм 1986d , с. 476.

- ^ Леватес 1994 , стр. 43–47.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986a , с. 134.

- ^ Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 , с. 239.

- ^ Эмбри и Глюк 1997 , с. 385.

- ^ Adshead 2004 , стр. 90–91.

- ^ Россаби 1988 , с. 80.

- ^ Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 , с. 235.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 236.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нидэм 1986а , с. 139.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хау, Стивен Г. (2013). «Смерть двух каганов: сравнение событий 1242 и 1260 годов». Бюллетень Школы восточных и африканских исследований Лондонского университета . 76 (3): 361–371. дои : 10.1017/S0041977X13000475 . JSTOR 24692275 .

- ^ Россаби, Моррис (2009). Хубилай-хан: его жизнь и времена . Издательство Калифорнийского университета. п. 45. ИСБН 978-0520261327 .

- ^ Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 , с. 240.

- ^ Россаби 1988 , с. 49.

- ^ Россаби 1988 , стр. 50–51.

- ^ Россаби 1988 , с. 56.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Россаби 1988 , с. 82.

- ^ Россаби 1988 , с. 88.

- ^ Россаби 1988 , с. 94.

- ^ Россаби 1988 , с. 90.

- ^ Китай в 1000 году н.э.: самое развитое общество в мире , Эбри, Патрисия и Конрад Широкауэр, консультанты, Династия Сун в Китае (960–1279): Жизнь в Сун, увиденная через свиток 12-го века ([§ ] Asian Topics on Asia for Educators (Азия для преподавателей, Колумбийский университет) , дата доступа: 6 и 9 октября, 2012.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 167.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman 2006 , с. 89.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 35.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 36.

- ^ Эбри 1999 , с. 155.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эбри 1999 , с. 158.

- ^ «Фэньцзя: разделение домохозяйств и наследование в Цин и республиканском Китае», Дэвид Уэйкфилд [1]

- ^ Ли, Лилиан М. (2001). «Женщины и собственность в Китае, 960-1949 (обзор)» (PDF) . Журнал междисциплинарной истории . 32 (1): 160–162. дои : 10.1162/jinh.2001.32.1.160 . S2CID 142559461 . Проект МУЗА 16192 .

- ^ Исследование прав дочерей на владение и распоряжение имуществом своих родителей в период от Тан до династии Сун http://en.cnki.com.cn/Article_en/CJFDTOTAL-TSSF201003024.htm. Архивировано 7 марта 2014 г. на машина обратного пути

- ^ Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 , с. 71.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сивин 1995 , с. 1.

- ^ Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 , с. 172.

- ^ Сен 2003 , с. 13.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , стр. 82–83.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нидхэм 1986d , с. 465.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Китай» , Британская энциклопедия , 2007 г. , получено 28 июня 2007 г.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , стр. 222–225.

- ^ Вест 1997 , стр. 69–70.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , с. 223.

- ^ Россаби 1988 , с. 162.

- ^ Запад 1997 , с. 76.

- ^ Эбри 1999 , стр. 145–146.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Эбри 1999 , с. 147.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 162.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хартвелл 1982 , стр. 417–418.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хаймс 1986 , стр. 35–36.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 159.

- ^ Хартвелл 1982 , стр. 405–413.

- ^ Хартвелл 1982 , стр. 416–420.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Фэрбанк и Голдман 2006 , с. 106.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman 2006 , стр. 101–106.

- ^ Юань 1994 , стр. 196–199.

- ^ Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 , стр. 162–163.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Эбри 1999 , с. 148.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman 2006 , с. 104.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , стр. 92–93.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , стр. 60–61, 68–69.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 161.

- ^ Макнайт 1992 , стр. 155–157.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Гернет 1962 , с. 107.

- ^ Сивин 1995 , стр. 30-31.

- ^ Сивин 1995 , стр. 30–31, сноска 27.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , с. 170.

- ^ Сунг 1981 , стр. 12, 72.

- ^ Бай 2002 , стр. 239.

- ^ Бай 2002 , стр. 250.

- ^ Бай 2002 , с. 254.

- ^ Графф и Хайэм 2002 , стр. 25–26.

- ^ Лорге 2005 , с. 43.

- ^ Лорге 2005 , с. 45.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Пирс 2006 , с. 130.

- ^ Пирс 2006 , стр. 130–131.

- ^ Пирс 2006 , с. 131.

- ^ Цай 2011 , стр. 81–82.

- ^ Пирс 2006 , с. 129.

- ^ Графф и Хайэм 2002 , с. 87.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Графф и Хайэм, 2002 , стр. 86–87.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 422.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шафер 1957 , с. 291.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 19.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 119.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 122–124.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 82–84.

- ^ Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 , стр. 81–83.

- ^ Харгетт 1985 , стр. 74–76.

- ^ Bol 2001 , p. 44.

- ^ Эбри, Кембридж, 149.

- ^ Эбри 1999 , с. 151.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 168.

- ^ Райт 1959 , с. 93.

- ^ Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 , с. 169.

- ^ Райт 1959 , стр. 88–89.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , с. 215.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , стр. 127–30.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , с. 129.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , с. 134.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гернет 1962 , стр. 134–137.

- ^ Йен-Ма 2008 , с. 102.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Россаби 1988 , с. 78.

- ^ Запад 1997 , с. 73.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , стр. 135–136.

- ^ Запад 1997 , с. 86.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 157.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , с. 23.

- ^ Лю 2015 .

- ^ Гернет 1962 , стр. 88, 94.

- ^ Вагнер 2001 , стр. 178–179, 181–183.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 г. , с. 158.

- ^ Эмбри и Глюк 1997 , с. 339.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нидэм 1986e , с. 48.

- ^ Гернет 1962 , с. 38.

- ^ Эбри, Кембриджская иллюстрированная история Китая , 142.

- ^ «Ислам в Китае (с 650 г. по настоящее время): Истоки» , «Религия и этика - Ислам» , BBC, заархивировано из оригинала 8 февраля 2007 г. , получено 1 августа 2007 г.

- ^ Голас 1980 .

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 80.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 82.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 220–221.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 192.

- ^ Россаби 1988 , с. 79.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 117.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 173–174.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 174–175.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , с. 283.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , стр. 281–282.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , стр. 283–284.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , с. 291.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , с. 287.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нидхэм 1986d , с. 569.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нидэм 1986b , с. 208.

- ^ Сивин 1995 , с. 32.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986a , с. 136.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , с. 446.

- ^ Мон 2003 , стр. 1.

- ^ Эмбри и Глюк 1997 , с. 843.

- ^ Чан, Кланси и Лой 2002 , стр. 15.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986b , с. 614.

- ^ Сивин 1995 , стр. 23-24.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , с. 98.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сивин 1995 , с. 17.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , с. 445.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , с. 448.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , стр. 165, 445.

- ^ «Рецензия на книгу: Астрономическая карта Сучжоу» . Природа . 160 (4061): 279. 30 августа 1947 г. doi : 10.1038/160279b0 . hdl : 2027/mdp.39015071688480 . ISSN 0028-0836 . S2CID 9218319 .

- ^ Нидхэм 1986b , стр. 278, 280, 428.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986b , стр. 134–137.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986b , стр. 46, 59–60, 104.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986b , с. 43.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986b , стр. 62–63.

- ^ Сюй 1993 , стр. 90–93.

- ^ Сюй 1993 , стр. 96–97.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986b , стр. 538–540.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сивин 1995 , с. 22.

- ^ Темпл 1986 , с. 179.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986b , стр. 547–549, фото 81.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986b , с. 549, Табличка 82

- ^ Харгетт 1996 , стр. 406, 409–412.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 201–203.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Сивин 1995 , с. 27.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986c , с. 33.

- ^ Эбри, Уолтхолл и Пале, 2006 , стр. 159–160.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 206–208, 217.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 212–213.

- ^ Брук 1998 , с. XXI.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986e , стр. 215–216.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 350.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 350–351.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 463.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 660.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Графф и Хайэм, 2002 , с. 86.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 141.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 82–84.

- ^ Го 1998 , стр. 4–6.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 85.

- ^ Го 1998 , стр. 5.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 96–100, 108–109.

- ^ Го 1998 , стр. 1–6.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 151–153.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 84.

- ^ Нидхэм 1986d , стр. 153.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нидхэм 1986d , с. 115.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Стейнхардт 1993 , с. 375.

- ^ Стейнхардт 1993 , с. 376.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и Фрейзер и Хабер 1986 , с. 227.

- ^ Fairbank & Goldman 2006 , с. 33.

- ^ Хансен 2000 , стр. 142.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рудольф 1963 , с. 170.

- ^ Рудольф 1963 , с. 172.

- ^ Рудольф 1963 , стр. 170–171.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рудольф 1963 , с. 171.

Источники

[ редактировать ]- Адсхед, СЭМ (2004), Танский Китай: Возвышение Востока в мировой истории , Нью-Йорк: Пэлгрейв Макмиллан, ISBN 978-1-4039-3456-7 (в твердом переплете).

- Андерсон, Джеймс А. (2008), « « Коварные фракции »: изменение приграничных альянсов в результате распада китайско-вьетнамских отношений накануне пограничной войны 1075 года», в Вятте, Дон Дж. (ред.), Battlefronts Real и Воображаемый: война, граница и идентичность в средний период Китая , Нью-Йорк: Пэлгрейв Макмиллан, стр. 191–226, ISBN. 978-1-4039-6084-9

- Бай, Шоуи (2002), Очерк истории Китая (пересмотренная редакция), Пекин: Foreign Languages Press, ISBN 978-7-119-02347-2

- Бол, Питер К. (2001), «Расцвет местной истории: история, география и культура в Южной Сун и Юань Учжоу», Гарвардский журнал азиатских исследований , 61 (1): 37–76, doi : 10.2307/3558587 , JSTOR 3558587

- Брук, Тимоти (1998), Путаница удовольствий: торговля и культура в Минском Китае , Беркли, Калифорния: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-22154-3

- Броуз, Майкл К. (2008), «Люди в середине: уйгуры в северо-западной пограничной зоне», в Вятте, Дон Дж. (редактор), « Фронты сражений реальные и воображаемые: война, граница и идентичность в средний период Китая». , Нью-Йорк: Пэлгрейв Макмиллан, стр. 253–289, ISBN. 978-1-4039-6084-9