Египет

Арабская Республика Египет | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: « Билади, Билади, Билади ». «Моя страна, моя страна, моя страна» (Английский: «Моя страна, моя страна, моя страна» ) | |

| |

| Капитал и крупнейший город | Каир 30 ° 2' с.ш. 31 ° 13' в.д. / 30,033 ° с.ш. 31,217 ° в.д. |

| Официальные языки | арабский [1] |

| Национальный язык | Египетский арабский [а] |

| Религия | См. Религию в Египте. [б] |

| Demonym(s) | Египетский |

| Правительство | Унитарная полупрезидентская республика с авторитарным режимом [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] |

| Абдель Фаттах ас-Сиси | |

| Мостафа Мадбули | |

| Законодательная власть | Парламент |

| Сенат | |

| Палата представителей | |

| Учреждение | |

| в. 3150 г. до н.э. | |

• Падение Мемфиса | 343 г. до н.э. |

| 639–642 | |

| 1171/4–1517 | |

• династии Мухаммеда Али Провозглашение | 9 июля 1805 г. [13] |

| 28 февраля 1922 г. | |

| 23 июля 1952 г. | |

• Республика объявлена | 18 июня 1953 г. |

| 18 января 2014 г. | |

| Область | |

• Общий | 1,010,408 [14] [15] км 2 (390 121 квадратных миль) ( 30-е место ) |

• Вода (%) | 0.632 |

| Население | |

• 2024 [16] оценивать | |

• 2017 [17] перепись | |

• Плотность | 106,67/км 2 (276,3/кв. миль) ( 107-е место ) |

| ВВП ( ГЧП ) | оценка на 2024 год |

• Общий | |

• На душу населения | |

| ВВП (номинальный) | оценка на 2024 год |

• Общий | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2017) | medium |

| HDI (2022) | high (105th) |

| Currency | Egyptian pound (LE/E£/£E) (EGP) |

| Time zone | UTC+2[c] (EGY) |

• Summer (DST) | UTC+3 |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | +20 |

| ISO 3166 code | EG |

| Internet TLD | |

Египет ( арабский : مصر Миср [mesˁr] , Египетско-арабское произношение: [mɑsˤr] ), официально Арабская Республика Египет , — трансконтинентальная страна, охватывающая северо-восточный угол Африки и Синайский полуостров в юго-западном углу Азии . Она граничит со Средиземным морем на севере , сектором Газа Палестины Израилем и западе на северо-востоке Красным морем на востоке, Суданом на юге и Ливией на , . Залив Акаба на северо-востоке отделяет Египет от Иордании и Саудовской Аравии . Каир — столица и крупнейший город Египта , а Александрия , второй по величине город, — важный промышленный и туристический центр на побережье Средиземного моря . [20] Египет с населением около 100 миллионов человек является 14-й по численности населения страной в мире и третьей по численности населения в Африке.

Египет имеет одну из самых длинных историй среди всех стран: его наследие вдоль дельты Нила восходит к 6–4 тысячелетиям до нашей эры. Считающийся колыбелью цивилизации , Древний Египет стал свидетелем некоторых из самых ранних событий развития письменности, сельского хозяйства, урбанизации, организованной религии и центрального правительства. [21] Египет был ранним и важным центром христианства , позже принявшим ислам, начиная с седьмого века. Каир стал столицей Фатимидского халифата в десятом веке и мамлюкского султаната в 13 веке. Затем Египет стал частью Османской империи в 1517 году, прежде чем ее местный правитель Мухаммед Али основал современный Египет как автономный хедиват в 1867 году.

Затем страна была оккупирована Британской империей и обрела независимость в 1922 году как монархия . После революции 1952 года Египет провозгласил себя республикой . На короткий период между 1958 и 1961 годами Египет объединился с Сирией и образовал Объединенную Арабскую Республику . Египет участвовал в нескольких вооруженных конфликтах с Израилем в 1948 , 1956 , 1967 и 1973 годах и периодически оккупировал сектор Газа до 1967 года. В 1978 году Египет подписал Кэмп-Дэвидские соглашения , которые признали Израиль в обмен на его уход с оккупированного Синая. После Арабской весны , которая привела к египетской революции 2011 года и свержению Хосни Мубарака , страна столкнулась с длительным периодом политических волнений ; это включало в себя избрание в 2012 году кратковременного и недолговечного исламистского правительства, поддерживающего «Братьев-мусульман» , во главе с Мохамедом Мурси , и его последующее свержение после массовых протестов в 2013 году .

Нынешнее правительство Египта, полупрезидентская республика, которую возглавляет президент Абдель Фаттах ас-Сиси с момента его избрания в 2014 году, было описано рядом наблюдателей как авторитарное и ответственное за сохранение плохой ситуации с правами человека в стране . Ислам является официальной религией Египта, а арабский язык является его официальным языком. [1] Подавляющее большинство населения проживает недалеко от берегов реки Нил единственная пахотная земля , на площади около 40 000 квадратных километров (15 000 квадратных миль), где находится . Большие районы пустыни Сахара , составляющие большую часть территории Египта, малонаселены. Около 43% жителей Египта проживают в городских районах страны. [22] большая часть из них распространена в густонаселенных центрах Большого Каира, Александрии и других крупных городов дельты Нила. Египет считается региональной державой в Северной Африке , на Ближнем Востоке и в мусульманском мире , а также средней державой во всем мире. [23] Это развивающаяся страна с диверсифицированной экономикой, которая является крупнейшей в Африке , 38-й по величине экономикой по номинальному ВВП и 127-й по номинальному ВВП на душу населения. [24] Египет является одним из основателей Организации Объединенных Наций , Движения неприсоединения , Лиги арабских государств , Африканского союза , Организации исламского сотрудничества , Всемирного молодежного форума и членом БРИКС .

Имена

Английское название «Египет» происходит от древнегреческого « Aígyptos » (« Αἴγυπτος »), через среднефранцузское «Egypte» и латинское « Aegyptus ». это отражено В ранних греческих табличках с линейным письмом B как «а-ку-пи-ти-йо». [25] Прилагательное "aigýpti-"/"aigýptios" было заимствовано в коптский как " gyptios ", а оттуда в арабский как " qubṭī ", обратно образовавшееся в " قبط " (" qubṭ "), откуда английское " копт ". Выдающийся древнегреческий историк и Страбон географ представил народную этимологию , утверждающую, что « Αἴγυπτος » (Aigýptios) первоначально развилось как соединение из « Aἰγαίου ὑπτίως » Aegaeou huptiōs , что означает « ниже Эгейского моря ». [26]

"Miṣr" (Arabic pronunciation: [misˤɾ]; "مِصر") is the Classical Quranic Arabic and modern official name of Egypt, while "Maṣr" (Egyptian Arabic pronunciation: [mɑsˤɾ]; مَصر) is the local pronunciation in Egyptian Arabic.[27] The current name of Egypt, Misr/Misir/Misru, stems from the Ancient Semitic name for it. The term originally connoted "Civilization" or "Metropolis".[28] Classical Arabic Miṣr (Egyptian Arabic Maṣr) is directly cognate with the Biblical Hebrew Mitsráyīm (מִצְרַיִם / מִצְרָיִם), meaning "the two straits", a reference to the predynastic separation of Upper and Lower Egypt. Also mentioned in several Semitic languages as Mesru, Misir and Masar.[28] The oldest attestation of this name for Egypt is the Akkadian "mi-iṣ-ru" ("miṣru")[29][30] related to miṣru/miṣirru/miṣaru, meaning "border" or "frontier".[31] The Neo-Assyrian Empire used the derived term ![]() , Mu-ṣur.[32]

, Mu-ṣur.[32]

| |

History

This section may contain an excessive amount of intricate detail that may interest only a particular audience. (September 2023) |

Prehistory and Ancient Egypt

There is evidence of rock carvings along the Nile terraces and in desert oases. In the 10th millennium BCE, a culture of hunter-gatherers and fishers was replaced by a grain-grinding culture. Climate changes or overgrazing around 8000 BCE began to desiccate the pastoral lands of Egypt, forming the Sahara. Early tribal peoples migrated to the Nile River where they developed a settled agricultural economy and more centralised society.[39]

By about 6000 BCE, a Neolithic culture took root in the Nile Valley.[40] During the Neolithic era, several predynastic cultures developed independently in Upper and Lower Egypt. The Badarian culture and the successor Naqada series are generally regarded as precursors to dynastic Egypt. The earliest known Lower Egyptian site, Merimda, predates the Badarian by about seven hundred years. Contemporaneous Lower Egyptian communities coexisted with their southern counterparts for more than two thousand years, remaining culturally distinct, but maintaining frequent contact through trade. The earliest known evidence of Egyptian hieroglyphic inscriptions appeared during the predynastic period on Naqada III pottery vessels, dated to about 3200 BCE.[41]

A unified kingdom was founded c. 3150 BCE by King Menes, leading to a series of dynasties that ruled Egypt for the next three millennia. Egyptian culture flourished during this long period and remained distinctively Egyptian in its religion, arts, language and customs. The first two ruling dynasties of a unified Egypt set the stage for the Old Kingdom period, c. 2700–2200 BCE, which constructed many pyramids, most notably the Third Dynasty pyramid of Djoser and the Fourth Dynasty Giza pyramids.

The First Intermediate Period ushered in a time of political upheaval for about 150 years.[42] Stronger Nile floods and stabilisation of government, however, brought back renewed prosperity for the country in the Middle Kingdom c. 2040 BCE, reaching a peak during the reign of Pharaoh Amenemhat III. A second period of disunity heralded the arrival of the first foreign ruling dynasty in Egypt, that of the Semitic Hyksos. The Hyksos invaders took over much of Lower Egypt around 1650 BCE and founded a new capital at Avaris. They were driven out by an Upper Egyptian force led by Ahmose I, who founded the Eighteenth Dynasty and relocated the capital from Memphis to Thebes.

The New Kingdom c. 1550–1070 BCE began with the Eighteenth Dynasty, marking the rise of Egypt as an international power that expanded during its greatest extension to an empire as far south as Tombos in Nubia, and included parts of the Levant in the east. This period is noted for some of the most well known Pharaohs, including Hatshepsut, Thutmose III, Akhenaten and his wife Nefertiti, Tutankhamun and Ramesses II. The first historically attested expression of monotheism came during this period as Atenism. Frequent contacts with other nations brought new ideas to the New Kingdom. The country was later invaded and conquered by Libyans, Nubians and Assyrians, but native Egyptians eventually drove them out and regained control of their country.[43]

In 525 BCE, the Achaemenid Empire, led by Cambyses II, began their conquest of Egypt, eventually capturing the pharaoh Psamtik III at the battle of Pelusium. Cambyses II then assumed the formal title of pharaoh, but ruled Egypt from his home of Susa in Persia (modern Iran), leaving Egypt under the control of a satrapy. The entire Twenty-seventh Dynasty of Egypt, from 525 to 402 BCE, save for Petubastis III, was an entirely Achaemenid-ruled period, with the Achaemenid emperors all being granted the title of pharaoh. A few temporarily successful revolts against the Achaemenids marked the fifth century BCE, but Egypt was never able to permanently overthrow the Achaemenids.[44]

The Thirtieth Dynasty was the last native ruling dynasty during the Pharaonic epoch. It fell to the Achaemenids again in 343 BCE after the last native Pharaoh, King Nectanebo II, was defeated in battle. This Thirty-first Dynasty of Egypt, however, did not last long, as the Achaemenids were toppled several decades later by Alexander the Great. The Macedonian Greek general of Alexander, Ptolemy I Soter, founded the Ptolemaic dynasty.[45]

Ptolemaic and Roman Egypt

The Ptolemaic Kingdom was a powerful Hellenistic state, extending from southern Syria in the east, to Cyrene to the west, and south to the frontier with Nubia. Alexandria became the capital city and a centre of Greek culture and trade. To gain recognition by the native Egyptian populace, they named themselves as the successors to the Pharaohs. The later Ptolemies took on Egyptian traditions, had themselves portrayed on public monuments in Egyptian style and dress, and participated in Egyptian religious life.[46][47]

The last ruler from the Ptolemaic line was Cleopatra VII, who committed suicide following the burial of her lover Mark Antony, after Octavian had captured Alexandria and her mercenary forces had fled.The Ptolemies faced rebellions of native Egyptians and were involved in foreign and civil wars that led to the decline of the kingdom and its annexation by Rome.

Christianity was brought to Egypt by Saint Mark the Evangelist in the 1st century.[48] Diocletian's reign (284–305 CE) marked the transition from the Roman to the Byzantine era in Egypt, when a great number of Egyptian Christians were persecuted. The New Testament had by then been translated into Egyptian. After the Council of Chalcedon in CE 451, a distinct Egyptian Coptic Church was firmly established.[49]

Middle Ages (7th century – 1517)

The Byzantines were able to regain control of the country after a brief Sasanid Persian invasion early in the 7th century amidst the Byzantine–Sasanian War of 602–628 during which they established a new short-lived province for ten years known as Sasanian Egypt, until 639–42, when Egypt was invaded andconquered by the Islamic caliphate by the Muslim Arabs. When they defeated the Byzantine armies in Egypt, the Arabs brought Islam to the country. Some time during this period, Egyptians began to blend in their new faith with indigenous beliefs and practices, leading to various Sufi orders that have flourished to this day.[48] These earlier rites had survived the period of Coptic Christianity.[50]

In 639 an army were sent in Egypt by the second caliph, Umar, under the command of Amr ibn al-As. They defeated a Roman army at the battle of Heliopolis. Amr next proceeded in the direction of Alexandria, which surrendered to him by a treaty signed on 8 November 641. Alexandria was regained for the Byzantine Empire in 645 but was retaken by Amr in 646. In 654 an invasion fleet sent by Constans II was repulsed.

The Arabs founded the capital of Egypt called Fustat, which was later burned down during the Crusades. Cairo was later built in the year 986 to grow to become the largest and richest city in the Arab caliphate, second only to Baghdad.

The Abbasid period was marked by new taxations, and the Copts revolted again in the fourth year of Abbasid rule. At the beginning of the 9th century the practice of ruling Egypt through a governor was resumed under Abdallah ibn Tahir, who decided to reside at Baghdad, sending a deputy to Egypt to govern for him. In 828 another Egyptian revolt broke out, and in 831 the Copts joined with native Muslims against the government. Eventually the power loss of the Abbasids in Baghdad led for general upon general to take over rule of Egypt, yet being under Abbasid allegiance, the Tulunid dynasty (868–905) and Ikhshidid dynasty (935–969) were among the most successful to defy the Abbasid Caliph.

Muslim rulers remained in control of Egypt for the next six centuries, with Cairo as the seat of the Fatimid Caliphate. With the end of the Ayyubid dynasty, the Mamluks, a Turco-Circassian military caste, took control about 1250. By the late 13th century, Egypt linked the Red Sea, India, Malaya, and East Indies.[51] The mid-14th-century Black Death killed about 40% of the country's population.[52]

Early modern period: Ottoman Egypt (1517–1867)

Egypt was conquered by the Ottoman Turks in 1517, after which it became a province of the Ottoman Empire. The defensive militarisation damaged its civil society and economic institutions.[51] The weakening of the economic system combined with the effects of plague left Egypt vulnerable to foreign invasion. Portuguese traders took over their trade.[51] Between 1687 and 1731, Egypt experienced six famines.[53] The 1784 famine cost it roughly one-sixth of its population.[54] Egypt was always a difficult province for the Ottoman Sultans to control, due in part to the continuing power and influence of the Mamluks, the Egyptian military caste who had ruled the country for centuries. Egypt remained semi-autonomous under the Mamluks until it was invaded by the French forces of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798. After the French were defeated by the British, a three-way power struggle ensued between the Ottoman Turks, Egyptian Mamluks who had ruled Egypt for centuries, and Albanian mercenaries in the service of the Ottomans.

After the French were expelled, power was seized in 1805 by Muhammad Ali Pasha, an Albanian military commander of the Ottoman army in Egypt. Muhammad Ali massacred the Mamluks and established a dynasty that was to rule Egypt until the revolution of 1952. The introduction in 1820 of long-staple cotton transformed its agriculture into a cash-crop monoculture before the end of the century, concentrating land ownership and shifting production towards international markets.[55] Muhammad Ali annexed Northern Sudan (1820–1824), Syria (1833), and parts of Arabia and Anatolia; but in 1841 the European powers, fearful lest he topple the Ottoman Empire itself, forced him to return most of his conquests to the Ottomans. His military ambition required him to modernise the country: he built industries, a system of canals for irrigation and transport, and reformed the civil service.[55] He constructed a military state with around four percent of the populace serving the army to raise Egypt to a powerful positioning in the Ottoman Empire in a way showing various similarities to the Soviet strategies (without communism) conducted in the 20th century.[56]

Muhammad Ali Pasha evolved the military from one that convened under the tradition of the corvée to a great modernised army. He introduced conscription of the male peasantry in 19th century Egypt, and took a novel approach to create his great army, strengthening it with numbers and in skill. Education and training of the new soldiers became mandatory; the new concepts were furthermore enforced by isolation. The men were held in barracks to avoid distraction of their growth as a military unit to be reckoned with. The resentment for the military way of life eventually faded from the men and a new ideology took hold, one of nationalism and pride. It was with the help of this newly reborn martial unit that Muhammad Ali imposed his rule over Egypt.[57] The policy that Mohammad Ali Pasha followed during his reign explains partly why the numeracy in Egypt compared to other North-African and Middle-Eastern countries increased only at a remarkably small rate, as investment in further education only took place in the military and industrial sector.[58] Muhammad Ali was succeeded briefly by his son Ibrahim (in September 1848), then by a grandson Abbas I (in November 1848), then by Said (in 1854), and Isma'il (in 1863) who encouraged science and agriculture and banned slavery in Egypt.[56]

Egypt under the Muhammad Ali dynasty remained nominally an Ottoman province. It was granted the status of an autonomous vassal state or Khedivate (1867–1914) in 1867. The Suez Canal, built in partnership with the French, was completed in 1869. Its construction was financed by European banks. Large sums also went to patronage and corruption. New taxes caused popular discontent. In 1875 Isma'il avoided bankruptcy by selling all Egypt's shares in the canal to the British government. Within three years this led to the imposition of British and French controllers who sat in the Egyptian cabinet, and, "with the financial power of the bondholders behind them, were the real power in the Government."[59] Other circumstances like epidemic diseases (cattle disease in the 1880s), floods and wars drove the economic downturn and increased Egypt's dependency on foreign debt even further.[60]

Local dissatisfaction with the Khedive and with European intrusion led to the formation of the first nationalist groupings in 1879, with Ahmed ʻUrabi a prominent figure. After increasing tensions and nationalist revolts, the United Kingdom invaded Egypt in 1882, crushing the Egyptian army at the Battle of Tell El Kebir and militarily occupying the country.[61] Following this, the Khedivate became a de facto British protectorate under nominal Ottoman sovereignty.[62] In 1899 the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement was signed: the Agreement stated that Sudan would be jointly governed by the Khedivate of Egypt and the United Kingdom. However, actual control of Sudan was in British hands only. In 1906, the Denshawai incident prompted many neutral Egyptians to join the nationalist movement.

Sultanate and Kingdom of Egypt

In 1914 the Ottoman Empire entered World War I in alliance with the Central Empires; Khedive Abbas II (who had grown increasingly hostile to the British in preceding years) decided to support the motherland in war. Following such decision, the British forcibly removed him from power and replaced him with his brother Hussein Kamel.[63][64] Hussein Kamel declared Egypt's independence from the Ottoman Empire, assuming the title of Sultan of Egypt. Shortly following independence, Egypt was declared a protectorate of the United Kingdom.

After World War I, Saad Zaghlul and the Wafd Party led the Egyptian nationalist movement to a majority at the local Legislative Assembly. When the British exiled Zaghlul and his associates to Malta on 8 March 1919, the country arose in its first modern revolution. The revolt led the UK government to issue a unilateral declaration of Egypt's independence on 22 February 1922.[65] Following independence from the United Kingdom, Sultan Fuad I assumed the title of King of Egypt; despite being nominally independent, the Kingdom was still under British military occupation and the UK still had great influence over the state. The new government drafted and implemented a constitution in 1923 based on a parliamentary system. The nationalist Wafd Party won a landslide victory in the 1923–1924 election and Saad Zaghloul was appointed as the new Prime Minister. In 1936, the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty was concluded and British troops withdrew from Egypt, except for the Suez Canal. The treaty did not resolve the question of Sudan, which, under the terms of the existing Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement of 1899, stated that Sudan should be jointly governed by Egypt and Britain, but with real power remaining in British hands.[66]

Britain used Egypt as a base for Allied operations throughout the region, especially the battles in North Africa against Italy and Germany. Its highest priorities were control of the Eastern Mediterranean, and especially keeping the Suez Canal open for merchant ships and for military connections with India and Australia. When the war began in September 1939, Egypt declared martial law and broke off diplomatic relations with Germany. It broke diplomatic relations with Italy in 1940, but never declared war, even when the Italian army invaded Egypt. The Egyptian army did no fighting. In June 1940 the King dismissed Prime Minister Aly Maher, who got on poorly with the British. A new coalition Government was formed with the Independent Hassan Pasha Sabri as Prime Minister.

Following a ministerial crisis in February 1942, the ambassador Sir Miles Lampson, pressed Farouk to have a Wafd or Wafd-coalition government replace Hussein Sirri Pasha's government. On the night of 4 February 1942, British troops and tanks surrounded Abdeen Palace in Cairo and Lampson presented Farouk with an ultimatum. Farouk capitulated, and Nahhas formed a government shortly thereafter.

Most British troops were withdrawn to the Suez Canal area in 1947 (although the British army maintained a military base in the area), but nationalist, anti-British feelings continued to grow after the War. Anti-monarchy sentiments further increased following the disastrous performance of the Kingdom in the First Arab-Israeli War. The 1950 election saw a landslide victory of the nationalist Wafd Party and the King was forced to appoint Mostafa El-Nahas as new Prime Minister. In 1951 Egypt unilaterally withdrew from the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 and ordered all remaining British troops to leave the Suez Canal.

As the British refused to leave their base around the Suez Canal, the Egyptian government cut off the water and refused to allow food into the Suez Canal base, announced a boycott of British goods, forbade Egyptian workers from entering the base and sponsored guerrilla attacks. On 24 January 1952, Egyptian guerrillas staged a fierce attack on the British forces around the Suez Canal, during which the Egyptian Auxiliary Police were observed helping the guerrillas. In response, on 25 January, General George Erskine sent out British tanks and infantry to surround the auxiliary police station in Ismailia. The police commander called the Interior Minister, Fouad Serageddin, Nahas's right-hand man, to ask if he should surrender or fight. Serageddin ordered the police to fight "to the last man and the last bullet". The resulting battle saw the police station levelled and 43 Egyptian policemen killed together with 3 British soldiers. The Ismailia incident outraged Egypt. The next day, 26 January 1952 was "Black Saturday", as the anti-British riot was known, that saw much of downtown Cairo which the Khedive Ismail the Magnificent had rebuilt in the style of Paris, burned down. Farouk blamed the Wafd for the Black Saturday riot, and dismissed Nahas as prime minister the next day. He was replaced by Aly Maher Pasha.[67]

On 22–23 July 1952, the Free Officers Movement, led by Muhammad Naguib and Gamal Abdel Nasser, launched a coup d'état (Egyptian Revolution of 1952) against the king. Farouk I abdicated the throne to his son Fouad II, who was, at the time, a seven-month-old baby. The Royal Family left Egypt some days later and the Council of Regency, led by Prince Muhammad Abdel Moneim was formed. The council, however, held only nominal authority and the real power was actually in the hands of the Revolutionary Command Council, led by Naguib and Nasser. Popular expectations for immediate reforms led to the workers' riots in Kafr Dawar on 12 August 1952. Following a brief experiment with civilian rule, the Free Officers abrogated the monarchy and the 1923 constitution and declared Egypt a republic on 18 June 1953. Naguib was proclaimed as president, while Nasser was appointed as the new Prime Minister.

Republican Egypt under Nasser (1952–1970)

Following the 1952 Revolution by the Free Officers Movement, the rule of Egypt passed to military hands and all political parties were banned. On 18 June 1953, the Egyptian Republic was declared, with General Muhammad Naguib as the first President of the Republic, serving in that capacity for a little under one and a half years. Republic of Egypt (1953–1958) was declared.

Naguib was forced to resign in 1954 by Gamal Abdel Nasser – a Pan-Arabist and the real architect of the 1952 movement – and was later put under house arrest. After Naguib's resignation, the position of President was vacant until the election of Nasser in 1956.[68] In October 1954, Egypt and the United Kingdom agreed to abolish the Anglo-Egyptian Condominium Agreement of 1899 and grant Sudan independence; the agreement came into force on 1 January 1956. Nasser assumed power as president in June 1956 and began dominating the history of modern Egypt. British forces completed their withdrawal from the occupied Suez Canal Zone on 13 June 1956. He nationalised the Suez Canal on 26 July 1956; his hostile approach towards Israel and economic nationalism prompted the beginning of the Second Arab-Israeli War (Suez Crisis), in which Israel (with support from France and the United Kingdom) occupied the Sinai peninsula and the Canal. The war came to an end because of US and USSR diplomatic intervention and the status quo was restored.

In 1958, Egypt and Syria formed a sovereign union known as the United Arab Republic. The union was short-lived, ending in 1961 when Syria seceded, thus ending the union. During most of its existence, the United Arab Republic was also in a loose confederation with North Yemen (or the Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen), known as the United Arab States. In the early 1960s, Egypt became fully involved in the North Yemen Civil War. Despite several military moves and peace conferences, the war sank into a stalemate.[69] In mid May 1967, the Soviet Union issued warnings to Nasser of an impending Israeli attack on Syria. Although the chief of staff Mohamed Fawzi verified them as "baseless",[70][71] Nasser took three successive steps that made the war virtually inevitable: on 14 May he deployed his troops in Sinai near the border with Israel, on 19 May he expelled the UN peacekeepers stationed in the Sinai Peninsula border with Israel, and on 23 May he closed the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping.[72] On 26 May Nasser declared, "The battle will be a general one and our basic objective will be to destroy Israel".[73]

This prompted the beginning of the Third Arab Israeli War (Six-Day War) in which Israel attacked Egypt, and occupied Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip, which Egypt had occupied since the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. During the 1967 war, an Emergency Law was enacted, and remained in effect until 2012, with the exception of an 18-month break in 1980/81.[74] Under this law, police powers were extended, constitutional rights suspended and censorship legalised.[75] At the time of the fall of the Egyptian monarchy in the early 1950s, less than half a million Egyptians were considered upper class and rich, four million middle class and 17 million lower class and poor.[76] Fewer than half of all primary-school-age children attended school, most of them being boys. Nasser's policies changed this. Land reform and distribution, the dramatic growth in university education, and government support to national industries greatly improved social mobility and flattened the social curve. From academic year 1953–54 through 1965–66, overall public school enrolments more than doubled. Millions of previously poor Egyptians, through education and jobs in the public sector, joined the middle class. Doctors, engineers, teachers, lawyers, journalists, constituted the bulk of the swelling middle class in Egypt under Nasser.[76] During the 1960s, the Egyptian economy went from sluggish to the verge of collapse, the society became less free, and Nasser's appeal waned considerably.[77]

Egypt under Sadat and Mubarak (1971–2011)

In 1970, President Nasser died and was succeeded by Anwar Sadat. During his period, Sadat switched Egypt's Cold War allegiance from the Soviet Union to the United States, expelling the Soviet advisors in 1972. Egypt was renamed as Arab Republic of Egypt in 1971. Sadat launched the Infitah economic reform policy, while clamping down on religious and secular opposition. In 1973, Egypt, along with Syria, launched the Fourth Arab-Israeli War (Yom Kippur War), a surprise attack to regain part of the Sinai territory Israel had captured 6 years earlier. In 1975, Sadat shifted Nasser's economic policies and sought to use his popularity to reduce government regulations and encourage foreign investment through his programme of Infitah. Through this policy, incentives such as reduced taxes and import tariffs attracted some investors, but investments were mainly directed at low risk and profitable ventures like tourism and construction, abandoning Egypt's infant industries.[78] Because of the elimination of subsidies on basic foodstuffs, it led to the 1977 Egyptian Bread Riots. Sadat made a historic visit to Israel in 1977, which led to the 1979 Egypt-Israel peace treaty in exchange for Israeli withdrawal from Sinai. In return, Egypt recognised Israel as a legitimate sovereign state. Sadat's initiative sparked enormous controversy in the Arab world and led to Egypt's expulsion from the Arab League, but it was supported by most Egyptians.[79] Sadat was assassinated by an Islamic extremist in October 1981.

Hosni Mubarak came to power after the assassination of Sadat in a referendum in which he was the only candidate.[80] He became another leader to dominate the Egyptian history. Hosni Mubarak reaffirmed Egypt's relationship with Israel yet eased the tensions with Egypt's Arab neighbours. Domestically, Mubarak faced serious problems. Mass poverty and unemployment led rural families to stream into cities like Cairo where they ended up in crowded slums, barely managing to survive. On 25 February 1986, the Security Police started rioting, protesting against reports that their term of duty was to be extended from 3 to 4 years. Hotels, nightclubs, restaurants and casinos were attacked in Cairo and there were riots in other cities. A day time curfew was imposed. It took the army 3 days to restore order. 107 people were killed.[81]

In the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s, terrorist attacks in Egypt became numerous and severe, and began to target Christian Copts, foreign tourists and government officials.[82] In the 1990s an Islamist group, Al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, engaged in an extended campaign of violence, from the murders and attempted murders of prominent writers and intellectuals, to the repeated targeting of tourists and foreigners. Serious damage was done to the largest sector of Egypt's economy—tourism[83]—and in turn to the government, but it also devastated the livelihoods of many of the people on whom the group depended for support.[84] During Mubarak's reign, the political scene was dominated by the National Democratic Party, which was created by Sadat in 1978. It passed the 1993 Syndicates Law, 1995 Press Law, and 1999 Nongovernmental Associations Law which hampered freedoms of association and expression by imposing new regulations and draconian penalties on violations.[85] As a result, by the late 1990s parliamentary politics had become virtually irrelevant and alternative avenues for political expression were curtailed as well.[86] Cairo grew into a metropolitan area with a population of over 20 million.

On 17 November 1997, 62 people, mostly tourists, were massacred near Luxor. In late February 2005, Mubarak announced a reform of the presidential election law, paving the way for multi-candidate polls for the first time since the 1952 movement.[87] However, the new law placed restrictions on the candidates, and led to Mubarak's easy re-election victory.[88] Voter turnout was less than 25%.[89] Election observers also alleged government interference in the election process.[90] After the election, Mubarak imprisoned Ayman Nour, the runner-up.[91]

Human Rights Watch's 2006 report on Egypt detailed serious human rights violations under Mubarak's rule, including routine torture, arbitrary detentions and trials before military and state security courts.[92] In 2007, Amnesty International released a report alleging that Egypt had become an international centre for torture, where other nations send suspects for interrogation, often as part of the War on Terror.[93] Egypt's foreign ministry quickly issued a rebuttal to this report.[94] Constitutional changes voted on 19 March 2007 prohibited parties from using religion as a basis for political activity, allowed the drafting of a new anti-terrorism law, authorised broad police powers of arrest and surveillance, and gave the president power to dissolve parliament and end judicial election monitoring.[95] In 2009, Dr. Ali El Deen Hilal Dessouki, Media Secretary of the National Democratic Party (NDP), described Egypt as a "pharaonic" political system, and democracy as a "long-term goal". Dessouki also stated that "the real center of power in Egypt is the military".[citation needed]

Revolution, political crisis and transition (2011–Present)

Bottom: protests in Tahrir Square against President Morsi on 27 November 2012.

On 25 January 2011, widespread protests began against Mubarak's government. On 11 February 2011, Mubarak resigned and fled Cairo. Jubilant celebrations broke out in Cairo's Tahrir Square at the news.[96] The Egyptian military then assumed the power to govern.[97][98] Mohamed Hussein Tantawi, chairman of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, became the de facto interim head of state.[99][100] On 13 February 2011, the military dissolved the parliament and suspended the constitution.[101]

A constitutional referendum was held on 19 March 2011.[102] On 28 November 2011, Egypt held its first parliamentary election since the previous regime had been in power. Turnout was high and there were no reports of major irregularities or violence.[103]

Mohamed Morsi, who was affiliated with the Muslim Brotherhood, was elected president on 24 June 2012.[104] On 30 June 2012, Mohamed Morsi was sworn in as Egypt's president.[105] On 2 August 2012, Egypt's Prime Minister Hisham Qandil announced his 35-member cabinet comprising 28 newcomers, including four from the Muslim Brotherhood.[106] Liberal and secular groups walked out of the constituent assembly because they believed that it would impose strict Islamic practices, while Muslim Brotherhood backers threw their support behind Morsi.[107] On 22 November 2012, President Morsi issued a temporary declaration immunising his decrees from challenge and seeking to protect the work of the constituent assembly.[108]

The move led to massive protests and violent action throughout Egypt.[109] On 5 December 2012, tens of thousands of supporters and opponents of President Morsi clashed, in what was described as the largest violent battle between Islamists and their foes since the country's revolution.[110] Mohamed Morsi offered a "national dialogue" with opposition leaders but refused to cancel the December 2012 constitutional referendum.[111] On 3 July 2013, after a wave of public discontent with autocratic excesses of Morsi's Muslim Brotherhood government,[112] the military removed Morsi from office, dissolved the Shura Council and installed a temporary interim government.[113]

On 4 July 2013, 68-year-old Chief Justice of the Supreme Constitutional Court of Egypt Adly Mansour was sworn in as acting president over the new government following the removal of Morsi.[114] The new Egyptian authorities cracked down on the Muslim Brotherhood and its supporters, jailing thousands and forcefully dispersing pro-Morsi and pro-Brotherhood protests.[115][116] Many of the Muslim Brotherhood leaders and activists have either been sentenced to death or life imprisonment in a series of mass trials.[117][118][119] On 18 January 2014, the interim government instituted a new constitution following a referendum approved by an overwhelming majority of voters (98.1%). 38.6% of registered voters participated in the referendum[120] a higher number than the 33% who voted in a referendum during Morsi's tenure.[121]

In the elections of June 2014 El-Sisi won with a percentage of 96.1%.[122] On 8 June 2014, Abdel Fatah el-Sisi was officially sworn in as Egypt's new president.[123] Under President el-Sisi, Egypt has implemented a rigorous policy of controlling the border to the Gaza Strip, including the dismantling of tunnels between the Gaza strip and Sinai.[124] In April 2018, El-Sisi was re-elected by landslide in election with no real opposition.[125] In April 2019, Egypt's parliament extended presidential terms from four to six years. President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi was also allowed to run for third term in next election in 2024.[126]

Under El-Sisi Egypt is said to have returned to authoritarianism. New constitutional reforms have been implemented, meaning strengthening the role of military and limiting the political opposition.[127] The constitutional changes were accepted in a referendum in April 2019.[128] In December 2020, final results of the parliamentary election confirmed a clear majority of the seats for Egypt's Mostaqbal Watan (Nation's Future) Party, which strongly supports president El-Sisi. The party even increased its majority, partly because of new electoral rules.[129]

Geography

Egypt lies primarily between latitudes 22° and 32°N, and longitudes 25° and 35°E. At 1,001,450 square kilometres (386,660 sq mi), it is the world's 30th-largest country.[130] Due to the extreme aridity of Egypt's climate, population centres are concentrated along the narrow Nile Valley and Delta, meaning that about 99% of the population uses about 5.5% of the total land area.[131] 98% of Egyptians live on 3% of the territory.[132]

Egypt is bordered by Libya to the west, the Sudan to the south, and the Gaza Strip and Israel to the east. A transcontinental nation, it possesses a land bridge (the Isthmus of Suez) between Africa and Asia, traversed by a navigable waterway (the Suez Canal) that connects the Mediterranean Sea with the Indian Ocean by way of the Red Sea.

Apart from the Nile Valley, the majority of Egypt's landscape is desert, with a few oases scattered about. Winds create prolific sand dunes that peak at more than 30 metres (100 ft) high. Egypt includes parts of the Sahara desert and of the Libyan Desert.

Sinai peninsula hosts the highest mountain in Egypt, Mount Catherine at 2,642 metres. The Red Sea Riviera, on the east of the peninsula, is renowned for its wealth of coral reefs and marine life.

Towns and cities include Alexandria, the second largest city; Aswan; Asyut; Cairo, the modern Egyptian capital and largest city; El Mahalla El Kubra; Giza, the site of the Pyramid of Khufu; Hurghada; Luxor; Kom Ombo; Port Safaga; Port Said; Sharm El Sheikh; Suez, where the south end of the Suez Canal is located; Zagazig; and Minya. Oases include Bahariya, Dakhla, Farafra, Kharga and Siwa. Protectorates include Ras Mohamed National Park, Zaranik Protectorate and Siwa.

On 13 March 2015, plans for a proposed new capital of Egypt were announced.[133]

Climate

Most of Egypt's rain falls in the winter months.[134] South of Cairo, rainfall averages only around 2 to 5 mm (0.1 to 0.2 in) per year and at intervals of many years. On a very thin strip of the northern coast the rainfall can be as high as 410 mm (16.1 in),[135] mostly between October and March. Snow falls on Sinai's mountains and some of the north coastal cities such as Damietta, Baltim and Sidi Barrani, and rarely in Alexandria. A very small amount of snow fell on Cairo on 13 December 2013, the first time in many decades.[136] Frost is also known in mid-Sinai and mid-Egypt.

Egypt has an unusually hot, sunny and dry climate. Average high temperatures are high in the north but very to extremely high in the rest of the country during summer. The cooler Mediterranean winds consistently blow over the northern sea coast, which helps to get more moderated temperatures, especially at the height of the summertime. The Khamaseen is a hot, dry wind that originates from the vast deserts in the south and blows in the spring or in the early summer. It brings scorching sand and dust particles, and usually brings daytime temperatures over 40 °C (104 °F) and sometimes over 50 °C (122 °F) in the interior, while the relative humidity can drop to 5% or even less.

Prior to the construction of the Aswan Dam, the Nile flooded annually, replenishing Egypt's soil. This gave Egypt a consistent harvest throughout the years.

The potential rise in sea levels due to global warming could threaten Egypt's densely populated coastal strip and have grave consequences for the country's economy, agriculture and industry. Combined with growing demographic pressures, a significant rise in sea levels could turn millions of Egyptians into environmental refugees by the end of the 21st century, according to some climate experts.[137][138]

Biodiversity

Egypt signed the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 9 June 1992, and became a party to the convention on 2 June 1994.[139] It has subsequently produced a National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan, which was received by the convention on 31 July 1998.[140] Where many CBD National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plans neglect biological kingdoms apart from animals and plants,[141]

The plan stated that the following numbers of species of different groups had been recorded from Egypt: algae (1483 species), animals (about 15,000 species of which more than 10,000 were insects), fungi (more than 627 species), monera (319 species), plants (2426 species), protozoans (371 species). For some major groups, for example lichen-forming fungi and nematode worms, the number was not known. Apart from small and well-studied groups like amphibians, birds, fish, mammals and reptiles, the many of those numbers are likely to increase as further species are recorded from Egypt. For the fungi, including lichen-forming species, for example, subsequent work has shown that over 2200 species have been recorded from Egypt, and the final figure of all fungi actually occurring in the country is expected to be much higher.[142] For the grasses, 284 native and naturalised species have been identified and recorded in Egypt.[143]

Government

The House of Representatives, whose members are elected to serve five-year terms, specialises in legislation. Elections were held between November 2011 and January 2012, which were later dissolved. The next parliamentary election was announced to be held within 6 months of the constitution's ratification on 18 January 2014, and were held in two phases, from 17 October to 2 December 2015.[144] Originally, the parliament was to be formed before the president was elected, but interim president Adly Mansour pushed the date.[145] The 2014 Egyptian presidential election took place on 26–28 May. Official figures showed a turnout of 25,578,233 or 47.5%, with Abdel Fattah el-Sisi winning with 23.78 million votes, or 96.9% compared to 757,511 (3.1%) for Hamdeen Sabahi.[146]

After a wave of public discontent with the autocratic excesses[clarification needed] of the Muslim Brotherhood government of President Mohamed Morsi,[112] on 3 July 2013 then-General Abdel Fattah el-Sisi announced the removal of Morsi from office and the suspension of the constitution. A 50-member constitution committee was formed for modifying the constitution, which was later published for public voting and was adopted on 18 January 2014.[147]

In 2024, as part of its Freedom in the World report, Freedom House rated political rights in Egypt at 6 (with 40 representing the most free and 0 the least), and civil liberties at 12 (with 60 being the highest score and 0 the lowest), which gave it the freedom rating of "Not Free".[148] According to the 2023 V-Dem Democracy indices Egypt is the eighth least democratic country in Africa.[149] The 2023 edition of The Economist Democracy Index categorises Egypt as an "authoritarian regime", with a score of 2.93.[150]

Egyptian nationalism predates its Arab counterpart by many decades, having roots in the 19th century and becoming the dominant mode of expression of Egyptian anti-colonial activists and intellectuals until the early 20th century.[151] The ideology espoused by Islamists such as the Muslim Brotherhood is mostly supported by the lower-middle strata of Egyptian society.[152]

Egypt has the oldest continuous parliamentary tradition in the Arab world.[153] The first popular assembly was established in 1866. It was disbanded as a result of the British occupation of 1882, and the British allowed only a consultative body to sit. In 1923, however, after the country's independence was declared, a new constitution provided for a parliamentary monarchy.[153]

Military and foreign relations

The military is influential in the political and economic life of Egypt and exempts itself from laws that apply to other sectors. It enjoys considerable power, prestige and independence within the state and has been widely considered part of the Egyptian "deep state".[80][154][155]

Egypt is speculated by Israel to be the second country in the region with a spy satellite, EgyptSat 1[156] in addition to EgyptSat 2 launched on 16 April 2014.[157]

Bottom: President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and Russian President Vladimir Putin in Sochi, August 2014.

The United States provides Egypt with annual military assistance, which in 2015 amounted to US$1.3 billion.[158] In 1989, Egypt was designated as a major non-NATO ally of the United States.[159] Nevertheless, ties between the two countries have partially soured since the July 2013 overthrow of Islamist president Mohamed Morsi,[160] with the Obama administration denouncing Egypt over its crackdown on the Muslim Brotherhood, and cancelling future military exercises involving the two countries.[161] There have been recent attempts, however, to normalise relations between the two, with both governments frequently calling for mutual support in the fight against regional and international terrorism.[162][163][164] However, following the election of Republican Donald Trump as the President of the United States, the two countries were looking to improve the Egyptian-American relations. On 3 April 2017 al-Sisi met with Trump at the White House, marking the first visit of an Egyptian president to Washington in 8 years. Trump praised al-Sisi in what was reported as a public relations victory for the Egyptian president, and signaled it was time for a normalisation of the relations between Egypt and the US.[165]

Relations with Russia have improved significantly following Mohamed Morsi's removal[166] and both countries have worked since then to strengthen military[167] and trade ties[168] among other aspects of bilateral co-operation. Relations with China have also improved considerably. In 2014, Egypt and China established a bilateral "comprehensive strategic partnership".[169]

The permanent headquarters of the Arab League are located in Cairo and the body's secretary general has traditionally been Egyptian. This position is currently held by former foreign minister Ahmed Aboul Gheit. The Arab League briefly moved from Egypt to Tunis in 1978 to protest the Egypt–Israel peace treaty, but it later returned to Cairo in 1989. Gulf monarchies, including the United Arab Emirates[170] and Saudi Arabia,[171] have pledged billions of dollars to help Egypt overcome its economic difficulties since the overthrow of Morsi.[172]

Following the 1973 war and the subsequent peace treaty, Egypt became the first Arab nation to establish diplomatic relations with Israel. Despite that, Israel is still widely considered as a hostile state by the majority of Egyptians.[173] Egypt has played a historical role as a mediator in resolving various disputes in the Middle East, most notably its handling of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and the peace process.[174] Egypt's ceasefire and truce brokering efforts in Gaza have hardly been challenged following Israel's evacuation of its settlements from the strip in 2005, despite increasing animosity towards the Hamas government in Gaza following the ouster of Mohamed Morsi,[175] and despite recent attempts by countries like Turkey and Qatar to take over this role.[176]

Ties between Egypt and other non-Arab Middle Eastern nations, including Iran and Turkey, have often been strained. Tensions with Iran are mostly due to Egypt's peace treaty with Israel and Iran's rivalry with traditional Egyptian allies in the Gulf.[177] Turkey's recent support for the now-banned Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt and its alleged involvement in Libya also made both countries bitter regional rivals.[178]

Egypt is a founding member of the Non-Aligned Movement and the United Nations. It is also a member of the Organisation internationale de la francophonie, since 1983. Former Egyptian Deputy Prime Minister Boutros Boutros-Ghali served as Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1991 to 1996.

In 2008, Egypt was estimated to have two million African refugees, including over 20,000 Sudanese nationals registered with UNHCR as refugees fleeing armed conflict or asylum seekers. Egypt adopted "harsh, sometimes lethal" methods of border control.[179]

Law

The legal system is based on Islamic and civil law (particularly Napoleonic codes); and judicial review by a Supreme Court, which accepts compulsory International Court of Justice jurisdiction only with reservations.[67]

Islamic jurisprudence is the principal source of legislation. Sharia courts and qadis are run and licensed by the Ministry of Justice.[180] The personal status law that regulates matters such as marriage, divorce and child custody is governed by Sharia. In a family court, a woman's testimony is worth half of a man's testimony.[181]

On 26 December 2012, the Muslim Brotherhood attempted to institutionalise a controversial new constitution. It was approved by the public in a referendum held 15–22 December 2012 with 64% support, but with only 33% electorate participation.[182] It replaced the 2011 Provisional Constitution of Egypt, adopted following the revolution.

The Penal code was unique as it contains a "Blasphemy Law."[183] The present court system allows a death penalty including against an absent individual tried in absentia. Several Americans and Canadians were sentenced to death in 2012.[184]

On 18 January 2014, the interim government successfully institutionalised a more secular constitution.[185] The president is elected to a four-year term and may serve 2 terms.[185] The parliament may impeach the president.[185] Under the constitution, there is a guarantee of gender equality and absolute freedom of thought.[185] The military retains the ability to appoint the national Minister of Defence for the next two full presidential terms since the constitution took effect.[185] Under the constitution, political parties may not be based on "religion, race, gender or geography".[185]

Human rights

In 2003, the government established the National Council for Human Rights.[186] Shortly after its foundation, the council came under heavy criticism by local activists, who contend it was a propaganda tool for the government to excuse its own violations[187] and to give legitimacy to repressive laws such as the Emergency Law.[188]

The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life ranks Egypt as the fifth worst country in the world for religious freedom.[189][190] The United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, a bipartisan independent agency of the US government, has placed Egypt on its watch list of countries that require close monitoring due to the nature and extent of violations of religious freedom engaged in or tolerated by the government.[191] According to a 2010 Pew Global Attitudes survey, 84% of Egyptians polled supported the death penalty for those who leave Islam; 77% supported whippings and cutting off of hands for theft and robbery; and 82% support stoning a person who commits adultery.[192]

Coptic Christians face discrimination at multiple levels of the government, ranging from underrepresentation in government ministries to laws that limit their ability to build or repair churches.[193] Intolerance towards followers of the Baháʼí Faith, and those of the non-orthodox Muslim sects, such as Sufis, Shi'a and Ahmadis, also remains a problem.[92] When the government moved to computerise identification cards, members of religious minorities, such as Baháʼís, could not obtain identification documents.[194] An Egyptian court ruled in early 2008 that members of other faiths may obtain identity cards without listing their faiths, and without becoming officially recognised.[195]

Clashes continued between police and supporters of former President Mohamed Morsi. During violent clashes that ensued as part of the August 2013 sit-in dispersal, 595 protesters were killed[196] with 14 August 2013 becoming the single deadliest day in Egypt's modern history.[197]

Egypt actively practices capital punishment. Egypt's authorities do not release figures on death sentences and executions, despite repeated requests over the years by human rights organisations.[198] The United Nations human rights office[199] and various NGOs[198][200] expressed "deep alarm" after an Egyptian Minya Criminal Court sentenced 529 people to death in a single hearing on 25 March 2014. Sentenced supporters of former President Mohamed Morsi were to be executed for their alleged role in violence following his removal in July 2013. The judgement was condemned as a violation of international law.[201] By May 2014, approximately 16,000 people (and as high as more than 40,000 by one independent count, according to The Economist),[202] mostly Brotherhood members or supporters, have been imprisoned after Morsi's removal[203] after the Muslim Brotherhood was labelled as terrorist organisation by the post-Morsi interim Egyptian government.[204] According to human rights groups there are some 60,000 political prisoners in Egypt.[205][206]

Homosexuality is illegal in Egypt.[208] According to a 2013 survey by the Pew Research Center, 95% of Egyptians believe that homosexuality should not be accepted by society.[209]

In 2017, Cairo was voted the most dangerous megacity for women with more than 10 million inhabitants in a poll by Thomson Reuters Foundation. Sexual harassment was described as occurring on a daily basis.[210]

Freedom of the press

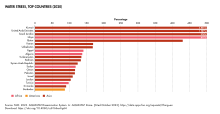

Reporters Without Borders ranked Egypt in their 2017 World Press Freedom Index at No. 160 out of 180 nations. At least 18 journalists were imprisoned in Egypt, as of August 2015[update]. A new anti-terror law was enacted in August 2015 that threatens members of the media with fines ranging from about US$25,000 to $60,000 for the distribution of wrong information on acts of terror inside the country "that differ from official declarations of the Egyptian Department of Defense".[211]

Some critics of the government have been arrested for allegedly spreading false information about the COVID-19 pandemic in Egypt.[212][213]

Administrative divisions

Egypt is divided into 27 governorates. The governorates are further divided into regions. The regions contain towns and villages. Each governorate has a capital, sometimes carrying the same name as the governorate.[214]

Economy

Egypt's economy depends mainly on agriculture, media, petroleum exports, natural gas, and tourism. There are also more than three million Egyptians working abroad, mainly in Libya, Saudi Arabia, the Persian Gulf and Europe. The completion of the Aswan High Dam in 1970 and the resultant Lake Nasser have altered the time-honoured place of the Nile River in the agriculture and ecology of Egypt. A rapidly growing population, limited arable land, and dependence on the Nile all continue to overtax resources and stress the economy.

In 2022, the Egyptian economy entered an ongoing crisis, the Egyptian pound was one of the worst performing currencies,[215] inflation. reached 32.6% and core inflation reached nearly 40% in March.[216]

The government has invested in communications and physical infrastructure. Egypt has received United States foreign aid since 1979 (an average of $2.2 billion per year) and is the third-largest recipient of such funds from the United States following the Iraq war. Egypt's economy mainly relies on these sources of income: tourism, remittances from Egyptians working abroad and revenues from the Suez Canal.[217]

In recent years, the Egyptian army has expanded its economic influence, dominating sectors such as petrol stations, fish-farming, car manufacturing, media, infrastructure including roads and bridges, and cement production. This hold on various industries has resulted in a suppression of competition, deterring private investment, and leading to adverse effects for ordinary Egyptians, including slower growth, higher prices, and limited opportunities.[218] The military-owned National Service Products Organization (NSPO) continues its expansion by establishing new factories dedicated to producing fertilisers, irrigation equipment, and veterinary vaccines. Businesses operated by the military, such as Wataniya and Safi, which manage petrol stations and bottled water, respectively, remain under government ownership.[219]

Economic conditions have started to improve considerably, after a period of stagnation, due to the adoption of more liberal economic policies by the government as well as increased revenues from tourism and a booming stock market. In its annual report, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) has rated Egypt as one of the top countries in the world undertaking economic reforms.[220] Some major economic reforms undertaken by the government since 2003 include a dramatic slashing of customs and tariffs. A new taxation law implemented in 2005 decreased corporate taxes from 40% to the current 20%, resulting in a stated 100% increase in tax revenue by 2006.

Although one of the main obstacles still facing the Egyptian economy is the limited trickle down of wealth to the average population, many Egyptians criticise their government for higher prices of basic goods while their standards of living or purchasing power remains relatively stagnant. Corruption is often cited by Egyptians as the main impediment to further economic growth.[221][222] The government promised major reconstruction of the country's infrastructure, using money paid for the newly acquired third mobile license ($3 billion) by Etisalat in 2006.[223] In the Corruption Perceptions Index 2013, Egypt was ranked 114 out of 177.[224]

An estimated 2.7 million Egyptians abroad contribute actively to the development of their country through remittances (US$7.8 billion in 2009), as well as circulation of human and social capital and investment.[225] Remittances, money earned by Egyptians living abroad and sent home, reached a record US$21 billion in 2012, according to the World Bank.[226]

Egyptian society is moderately unequal in terms of income distribution, with an estimated 35–40% of Egypt's population earning less than the equivalent of $2 a day, while only around 2–3% may be considered wealthy.[227]

Tourism

Tourism is one of the most important sectors in Egypt's economy. More than 12.8 million tourists visited Egypt in 2008, providing revenues of nearly $11 billion. The tourism sector employs about 12% of Egypt's workforce.[228] Tourism Minister Hisham Zaazou told industry professionals and reporters that tourism generated some $9.4 billion in 2012, a slight increase over the $9 billion seen in 2011.[229]

The Giza Necropolis is one of Egypt's best-known tourist attractions; it is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still in existence.

Egypt's beaches on the Mediterranean and the Red Sea, which extend to over 3,000 kilometres (1,900 miles), are also popular tourist destinations; the Gulf of Aqaba beaches, Safaga, Sharm el-Sheikh, Hurghada, Luxor, Dahab, Ras Sidr and Marsa Alam are popular sites.

Energy

Egypt has a developed energy market based on coal, oil, natural gas, and hydro power. Substantial coal deposits in the northeast Sinai are mined at the rate of about 600,000 tonnes (590,000 long tons; 660,000 short tons) per year. Oil and gas are produced in the western desert regions, the Gulf of Suez, and the Nile Delta. Egypt has huge reserves of gas, estimated at 2,180 cubic kilometres (520 cu mi),[230] and LNG up to 2012 exported to many countries. In 2013, the Egyptian General Petroleum Co (EGPC) said the country will cut exports of natural gas and tell major industries to slow output this summer to avoid an energy crisis and stave off political unrest, Reuters has reported. Egypt is counting on top liquid natural gas (LNG) exporter Qatar to obtain additional gas volumes in summer, while encouraging factories to plan their annual maintenance for those months of peak demand, said EGPC chairman, Tarek El Barkatawy. Egypt produces its own energy, but has been a net oil importer since 2008 and is rapidly becoming a net importer of natural gas.[231]

Egypt produced 691,000 bbl/d of oil and 2,141.05 Tcf of natural gas in 2013, making the country the largest non-OPEC producer of oil and the second-largest dry natural gas producer in Africa. In 2013, Egypt was the largest consumer of oil and natural gas in Africa, as more than 20% of total oil consumption and more than 40% of total dry natural gas consumption in Africa. Also, Egypt possesses the largest oil refinery capacity in Africa 726,000 bbl/d (in 2012).[230]

Egypt is currently building its first nuclear power plant in El Dabaa, in the northern part of the country, with $25 billion in Russian financing.[232]

Transport

Transport in Egypt is centred around Cairo and largely follows the pattern of settlement along the Nile. The main line of the nation's 40,800-kilometre (25,400 mi) railway network runs from Alexandria to Aswan and is operated by Egyptian National Railways. The vehicle road network has expanded rapidly to over 34,000 km (21,000 mi), consisting of 28 lines, 796 stations, 1800 trains covering the Nile Valley and Nile Delta, the Mediterranean and Red Sea coasts, the Sinai, and the Western oases.

The Cairo Metro consists of three operational lines with a fourth line expected in the future.

EgyptAir, which is now the country's flag carrier and largest airline, was founded in 1932 by Egyptian industrialist Talaat Harb, today owned by the Egyptian government. The airline is based at Cairo International Airport, its main hub, operating scheduled passenger and freight services to more than 75 destinations in the Middle East, Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The Current EgyptAir fleet includes 80 aeroplanes.

Suez Canal

The Suez Canal is an artificial sea-level waterway in Egypt, connecting the Mediterranean Sea and the Red Sea. Opened in November 1869 after 10 years of construction work, it allows ship transport between Europe and Asia without navigation around Africa. The northern terminus is Port Said and the southern terminus is Port Tawfiq at the city of Suez. Ismailia lies on its west bank, 3 kilometres (1+7⁄8 miles) from the half-way point.

The canal is 193.30 km (120+1⁄8 mi) long, 24 metres (79 feet) deep and 205 m (673 ft) wide as of 2010[update]. It consists of the northern access channel of 22 km (14 mi), the canal itself of 162.25 km (100+7⁄8 mi) and the southern access channel of 9 km (5+1⁄2 mi). The canal is a single lane with passing places in the Ballah By-Pass and the Great Bitter Lake. It contains no locks; seawater flows freely through the canal.

On 26 August 2014 a proposal was made for opening a New Suez Canal. Work on the New Suez Canal was completed in July 2015.[233][234] The channel was officially inaugurated with a ceremony attended by foreign leaders and featuring military flyovers on 6 August 2015, in accordance with the budgets laid out for the project.[235][236]

Water supply and sanitation

The piped water supply in Egypt increased between 1990 and 2010 from 89% to 100% in urban areas and from 39% to 93% in rural areas despite rapid population growth. Over that period, Egypt achieved the elimination of open defecation in rural areas and invested in infrastructure. Access to an improved water source in Egypt is now practically universal with a rate of 99%. About one half of the population is connected to sanitary sewers.[237]

Partly because of low sanitation coverage about 17,000 children die each year because of diarrhoea.[238] Another challenge is low cost recovery due to water tariffs that are among the lowest in the world. This in turn requires government subsidies even for operating costs, a situation that has been aggravated by salary increases without tariff increases after the Arab Spring. Poor operation of facilities, such as water and wastewater treatment plants, as well as limited government accountability and transparency, are also issues.

Due to the absence of appreciable rainfall, Egypt's agriculture depends entirely on irrigation. The main source of irrigation water is the river Nile of which the flow is controlled by the high dam at Aswan. It releases, on average, 55 cubic kilometres (45,000,000 acre·ft) water per year, of which some 46 cubic kilometres (37,000,000 acre·ft) are diverted into the irrigation canals.[239]

In the Nile valley and delta, almost 33,600 square kilometres (13,000 sq mi) of land benefit from these irrigation waters producing on average 1.8 crops per year.[239]

Demographics

Egypt is the most populated country in the Arab world and the third most populous on the African continent, with about 95 million inhabitants as of 2017[update].[240] Its population grew rapidly from 1970 to 2010 due to medical advances and increases in agricultural productivity[241] enabled by the Green Revolution.[242] Egypt's population was estimated at 3 million when Napoleon invaded the country in 1798.[243]

Egypt's people are highly urbanised, being concentrated along the Nile (notably Cairo and Alexandria), in the Delta and near the Suez Canal. Egyptians are divided demographically into those who live in the major urban centres and the fellahin, or farmers, that reside in rural villages. The total inhabited area constitutes only 77,041 km², putting the physiological density at over 1,200 people per km2, similar to Bangladesh.

While emigration was restricted under Nasser, thousands of Egyptian professionals were dispatched abroad in the context of the Arab Cold War.[244] Egyptian emigration was liberalised in 1971, under President Sadat, reaching record numbers after the 1973 oil crisis.[245] An estimated 2.7 million Egyptians live abroad. Approximately 70% of Egyptian migrants live in Arab countries (923,600 in Saudi Arabia, 332,600 in Libya, 226,850 in Jordan, 190,550 in Kuwait with the rest elsewhere in the region) and the remaining 30% reside mostly in Europe and North America (318,000 in the United States, 110,000 in Canada and 90,000 in Italy).[225] The process of emigrating to non-Arab states has been ongoing since the 1950s.[246]

Ethnic groups

Ethnic Egyptians are by far the largest ethnic group in the country, constituting 99.7% of the total population.[67] Ethnic minorities include the Abazas, Turks, Greeks, Bedouin Arab tribes living in the eastern deserts and the Sinai Peninsula, the Berber-speaking Siwis (Amazigh) of the Siwa Oasis, and the Nubian communities clustered along the Nile. There are also tribal Beja communities concentrated in the southeasternmost corner of the country, and a number of Dom clans mostly in the Nile Delta and Faiyum who are progressively becoming assimilated as urbanisation increases.

Some 5 million immigrants live in Egypt, mostly Sudanese, "some of whom have lived in Egypt for generations".[247] Smaller numbers of immigrants come from Iraq, Ethiopia, Somalia, South Sudan, and Eritrea.[247]

The Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees estimated that the total number of "people of concern" (refugees, asylum seekers, and stateless people) was about 250,000. In 2015, the number of registered Syrian refugees in Egypt was 117,000, a decrease from the previous year.[247] Egyptian government claims that a half-million Syrian refugees live in Egypt are thought to be exaggerated.[247] There are 28,000 registered Sudanese refugees in Egypt.[247]

Jewish communities in Egypt have almost disappeared. Several important Jewish archaeological and historical sites are found in Cairo, Alexandria and other cities.

Languages

The official language of the Republic is Literary Arabic.[248] The spoken languages are: Egyptian Arabic (68%), Sa'idi Arabic (29%), Eastern Egyptian Bedawi Arabic (1.6%), Sudanese Arabic (0.6%), Domari (0.3%), Nobiin (0.3%), Beja (0.1%), Siwi and others.[citation needed] Additionally, Greek, Armenian and Italian, and more recently, African languages like Amharic and Tigrigna are the main languages of immigrants.

The main foreign languages taught in schools, by order of popularity, are English, French, German and Italian.

Historically Egyptian was spoken, the latest stage of which is Coptic Egyptian. Spoken Coptic was mostly extinct by the 17th century but may have survived in isolated pockets in Upper Egypt as late as the 19th century. It remains in use as the liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria.[249][250] It forms a separate branch among the family of Afroasiatic languages.

Religion

Islam is the state religion of Egypt, and the country has the largest Muslim population in the Arab world and the world's sixth largest Muslim population, accounting for five percent of all Muslims worldwide.[251] Egypt also has the largest Christian population in the Middle East and North Africa.[252] Official data about religion is lacking due to social and political sensitivities.[253] An estimated 85–90% are identified as Muslim, 10–15% as Coptic Christians, and 1% as other Christian denominations; other estimates place the Christian population as high as 15–20%.[d]

Egypt was an early and leading center of Christianity into late antiquity; the Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria was founded in the first century and remains the largest church in the country. With the arrival of Islam in the seventh century, the country was gradually Islamised into a majority-Muslim country.[259][260] It is unknown when Muslims reached a majority, variously estimated from c. 1000 CE to as late as the 14th century. Egypt emerged as a centre of politics and culture in the Muslim world. Under Anwar Sadat, Islam became the official state religion and Sharia the main source of law.[261]

The majority of Egyptian Muslims adhere to the Sunni branch of Islam. Nondenominational Muslims form roughly 12% of the population.[4][262] There is also a Shi'a minority. The Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs estimates the Shia population at 1 to 2.2 million[263] and could measure as much as 3 million.[264] The Ahmadiyya population is estimated at less than 50,000,[265] whereas the Salafi (ultra-conservative Sunni) population is estimated at five to six million.[266] Cairo is famous for its numerous mosque minarets and has been dubbed "The City of 1,000 Minarets".[267] The city also hosts Al-Azhar University, which is considered the preeminent institution of Islamic higher learning and jurisprudence;[268] founded in the late tenth century, it is by some measures the second oldest continuously operating university in the world.[269] It is estimated that 15 million Egyptians follow native Sufi orders,[270][271][272] with Sufi leadership asserting that the numbers are much greater, as many Egyptian Sufis are not officially registered with a Sufi order.[271] At least 305 people were killed during a November 2017 attack on a Sufi mosque in Sinai.[273]

Of the Christian population in Egypt over 90% belong to the native Coptic Orthodox Church of Alexandria, an Oriental Orthodox Christian Church.[274] Other native Egyptian Christians are adherents of the Coptic Catholic Church, the Evangelical Church of Egypt and various other Protestant denominations. Non-native Christian communities are largely found in the urban regions of Cairo and Alexandria, such as the Syro-Lebanese, who belong to Greek Catholic, Greek Orthodox, and Maronite Catholic denominations.[275]

The Egyptian government recognises only three religions: Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. Other faiths and minority Muslim sects, such as the small Baháʼí Faith and Ahmadiyya communities, are not recognised by the state and face persecution by the government, which labels these groups a threat to Egypt's national security.[276][277] Individuals, particularly Baháʼís and atheists, wishing to include their religion (or lack thereof) on their mandatory state issued identification cards are denied this ability, and are put in the position of either not obtaining required identification or lying about their faith. A 2008 court ruling allowed members of unrecognised faiths to obtain identification and leave the religion field blank.[194][195]

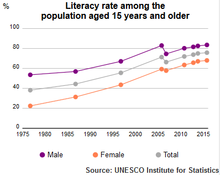

Education

In 2022, Egypt's adult literacy rate was 74.5%, compared to 71.1% in 2017.[278] Literacy is lowest among those over 60 years of age, at 35.1%, and highest among youth between 15 and 24 years of age, at 92.2%.[279]

A European-style education system was first introduced in Egypt by the Ottomans in the early 19th century to nurture a class of loyal bureaucrats and army officers.[280] Under British occupation, investment in education was curbed drastically, and secular public schools, which had previously been free, began to charge fees.[280]

In the 1950s, President Nasser phased in free education for all Egyptians.[280] The Egyptian curriculum influenced other Arab education systems, which often employed Egyptian-trained teachers.[280] Demand soon outstripped the level of available state resources, causing the quality of public education to deteriorate.[280] Today this trend has culminated in poor teacher–student ratios (often around one to fifty) and persistent gender inequality.[280]

Basic education, which includes six years of primary and three years of preparatory school, is a right for Egyptian children from the age of six.[281] After grade 9, students are tracked into one of two strands of secondary education: general or technical schools. General secondary education prepares students for further education, and graduates of this track normally join higher education institutes based on the results of the Thanaweya Amma, the leaving exam.[281]

Technical secondary education has two strands, one lasting three years and a more advanced education lasting five. Graduates of these schools may have access to higher education based on their results on the final exam, but this is generally uncommon.[281]

Cairo University is Egypt's premier public university. The country is currently opening new research institutes with the aim of modernising scientific research and development; the most recent example is Zewail City of Science and Technology. Egypt was ranked 86th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023, up from 92nd in 2019.[282][283]

Health

Egyptian life expectancy at birth was 73.20 years in 2011, or 71.30 years for males and 75.20 years for females. Egypt spends 3.7 percent of its gross domestic product on health including treatment costs 22 percent incurred by citizens and the rest by the state.[284] In 2010, spending on healthcare accounted for 4.66% of the country's GDP. In 2009, there were 16.04 physicians and 33.80 nurses per 10,000 inhabitants.[285]