Гриб

| Грибы | |

|---|---|

| |

Clockwise from top left:

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Clade: | Obazoa |

| (unranked): | Opisthokonta |

| Clade: | Holomycota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi R.T.Moore (1980)[1][2] |

| Subkingdoms/phyla | |

Грибок Грибы ( пл .: [ 3 ] или грибки [ 4 ] ) является любым членом группы эукариотических организмов, которая включает в себя микроорганизмы, такие как дрожжи и плесени , а также более знакомые грибы . Эти организмы классифицируются как одно из традиционных эукариотических королевств , наряду с животными , платья и либо профиста [ 5 ] или простейшие и хромиста . [ 6 ]

A characteristic that places fungi in a different kingdom from plants, bacteria, and some protists is chitin in their cell walls. Fungi, like animals, are heterotrophs; they acquire their food by absorbing dissolved molecules, typically by secreting digestive enzymes into their environment. Fungi do not photosynthesize. Growth is their means of mobility, except for spores (a few of which are flagellated), which may travel through the air or water. Fungi are the principal decomposers in ecological systems. These and other differences place fungi in a single group of related organisms, named the Eumycota (true fungi or Eumycetes), that share a common ancestor (i.e. they form a monophyletic group), an interpretation that is also strongly supported by molecular phylogenetics. This fungal group is distinct from the structurally similar myxomycetes (slime molds) and oomycetes (water molds). The discipline of biology devoted to the study of fungi is known as mycology (from the Greek μύκης mykes, mushroom). In the past, mycology was regarded as a branch of Ботаника , хотя теперь известно, что грибы генетически более тесно связаны с животными, чем с растениями.

Abundant worldwide, most fungi are inconspicuous because of the small size of their structures, and their cryptic lifestyles in soil or on dead matter. Fungi include symbionts of plants, animals, or other fungi and also parasites. They may become noticeable when fruiting, either as mushrooms or as molds. Fungi perform an essential role in the decomposition of organic matter and have fundamental roles in nutrient cycling and exchange in the environment. They have long been used as a direct source of human food, in the form of mushrooms and truffles; as a leavening agent for bread; and in the fermentation of various food products, such as wine, beer, and soy sauce. Since the 1940s, fungi have been used for the production of antibiotics, and, more recently, various enzymes produced by fungi are used industrially and in detergents. Fungi are also used as biological pesticides to control weeds, plant diseases, and insect pests. Many species produce bioactive compounds called mycotoxins, such as alkaloids and polyketides, that are toxic to animals, including humans. The fruiting structures of a few species contain psychotropic compounds and are consumed recreationally or in traditional spiritual ceremonies. Fungi can break down manufactured materials and buildings, and become significant pathogens of humans and other animals. Losses of crops due to fungal diseases (e.g., rice blast disease) or food spoilage can have a large impact on human food supplies and local economies.

The fungus kingdom encompasses an enormous diversity of taxa with varied ecologies, life cycle strategies, and morphologies ranging from unicellular aquatic chytrids to large mushrooms. However, little is known of the true biodiversity of the fungus kingdom, which has been estimated at 2.2 million to 3.8 million species.[7] Of these, only about 148,000 have been described,[8] with over 8,000 species known to be detrimental to plants and at least 300 that can be pathogenic to humans.[9] Ever since the pioneering 18th and 19th century taxonomical works of Carl Linnaeus, Christiaan Hendrik Persoon, and Elias Magnus Fries, fungi have been classified according to their morphology (e.g., characteristics such as spore color or microscopic features) or physiology. Advances in molecular genetics have opened the way for DNA analysis to be incorporated into taxonomy, which has sometimes challenged the historical groupings based on morphology and other traits. Phylogenetic studies published in the first decade of the 21st century have helped reshape the classification within the fungi kingdom, which is divided into one subkingdom, seven phyla, and ten subphyla.

Etymology

The English word fungus is directly adopted from the Latin fungus (mushroom), used in the writings of Horace and Pliny.[10] This in turn is derived from the Greek word sphongos (σφόγγος 'sponge'), which refers to the macroscopic structures and morphology of mushrooms and molds;[11] the root is also used in other languages, such as the German Schwamm ('sponge') and Schimmel ('mold').[12]

The word mycology is derived from the Greek mykes (μύκης 'mushroom') and logos (λόγος 'discourse').[13] It denotes the scientific study of fungi. The Latin adjectival form of "mycology" (mycologicæ) appeared as early as 1796 in a book on the subject by Christiaan Hendrik Persoon.[14] The word appeared in English as early as 1824 in a book by Robert Kaye Greville.[15] In 1836 the English naturalist Miles Joseph Berkeley's publication The English Flora of Sir James Edward Smith, Vol. 5. also refers to mycology as the study of fungi.[11][16]

A group of all the fungi present in a particular region is known as mycobiota (plural noun, no singular).[17] The term mycota is often used for this purpose, but many authors use it as a synonym of Fungi. The word funga has been proposed as a less ambiguous term morphologically similar to fauna and flora.[18] The Species Survival Commission (SSC) of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in August 2021 asked that the phrase fauna and flora be replaced by fauna, flora, and funga.[19]

Characteristics

Before the introduction of molecular methods for phylogenetic analysis, taxonomists considered fungi to be members of the plant kingdom because of similarities in lifestyle: both fungi and plants are mainly immobile, and have similarities in general morphology and growth habitat. Although inaccurate, the common misconception that fungi are plants persists among the general public due to their historical classification, as well as several similarities.[20][21] Like plants, fungi often grow in soil and, in the case of mushrooms, form conspicuous fruit bodies, which sometimes resemble plants such as mosses. The fungi are now considered a separate kingdom, distinct from both plants and animals, from which they appear to have diverged around one billion years ago (around the start of the Neoproterozoic Era).[22][23] Some morphological, biochemical, and genetic features are shared with other organisms, while others are unique to the fungi, clearly separating them from the other kingdoms:

Shared features:

- With other eukaryotes: Fungal cells contain membrane-bound nuclei with chromosomes that contain DNA with noncoding regions called introns and coding regions called exons. Fungi have membrane-bound cytoplasmic organelles such as mitochondria, sterol-containing membranes, and ribosomes of the 80S type.[24] They have a characteristic range of soluble carbohydrates and storage compounds, including sugar alcohols (e.g., mannitol), disaccharides, (e.g., trehalose), and polysaccharides (e.g., glycogen, which is also found in animals[25]).

- With animals: Fungi lack chloroplasts and are heterotrophic organisms and so require preformed organic compounds as energy sources.[26]

- With plants: Fungi have a cell wall[27] and vacuoles.[28] They reproduce by both sexual and asexual means, and like basal plant groups (such as ferns and mosses) produce spores. Similar to mosses and algae, fungi typically have haploid nuclei.[29]

- With euglenoids and bacteria: Higher fungi, euglenoids, and some bacteria produce the amino acid L-lysine in specific biosynthesis steps, called the α-aminoadipate pathway.[30][31]

- The cells of most fungi grow as tubular, elongated, and thread-like (filamentous) structures called hyphae, which may contain multiple nuclei and extend by growing at their tips. Each tip contains a set of aggregated vesicles—cellular structures consisting of proteins, lipids, and other organic molecules—called the Spitzenkörper.[32] Both fungi and oomycetes grow as filamentous hyphal cells.[33] In contrast, similar-looking organisms, such as filamentous green algae, grow by repeated cell division within a chain of cells.[25] There are also single-celled fungi (yeasts) that do not form hyphae, and some fungi have both hyphal and yeast forms.[34]

- In common with some plant and animal species, more than one hundred fungal species display bioluminescence.[35]

Unique features:

- Some species grow as unicellular yeasts that reproduce by budding or fission. Dimorphic fungi can switch between a yeast phase and a hyphal phase in response to environmental conditions.[34]

- The fungal cell wall is made of a chitin-glucan complex; while glucans are also found in plants and chitin in the exoskeleton of arthropods,[36] fungi are the only organisms that combine these two structural molecules in their cell wall. Unlike those of plants and oomycetes, fungal cell walls do not contain cellulose.[37][38]

Most fungi lack an efficient system for the long-distance transport of water and nutrients, such as the xylem and phloem in many plants. To overcome this limitation, some fungi, such as Armillaria, form rhizomorphs,[39] which resemble and perform functions similar to the roots of plants. As eukaryotes, fungi possess a biosynthetic pathway for producing terpenes that uses mevalonic acid and pyrophosphate as chemical building blocks.[40] Plants and some other organisms have an additional terpene biosynthesis pathway in their chloroplasts, a structure that fungi and animals do not have.[41] Fungi produce several secondary metabolites that are similar or identical in structure to those made by plants.[40] Many of the plant and fungal enzymes that make these compounds differ from each other in sequence and other characteristics, which indicates separate origins and convergent evolution of these enzymes in the fungi and plants.[40][42]

Diversity

Fungi have a worldwide distribution, and grow in a wide range of habitats, including extreme environments such as deserts or areas with high salt concentrations[43] or ionizing radiation,[44] as well as in deep sea sediments.[45] Some can survive the intense UV and cosmic radiation encountered during space travel.[46] Most grow in terrestrial environments, though several species live partly or solely in aquatic habitats, such as the chytrid fungi Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis and B. salamandrivorans, parasites that have been responsible for a worldwide decline in amphibian populations. These organisms spend part of their life cycle as a motile zoospore, enabling them to propel themselves through water and enter their amphibian host.[47] Other examples of aquatic fungi include those living in hydrothermal areas of the ocean.[48]

As of 2020,[update] around 148,000 species of fungi have been described by taxonomists,[8] but the global biodiversity of the fungus kingdom is not fully understood.[50] A 2017 estimate suggests there may be between 2.2 and 3.8 million species.[7] The number of new fungi species discovered yearly has increased from 1,000 to 1,500 per year about 10 years ago, to about 2,000 with a peak of more than 2,500 species in 2016. In the year 2019, 1,882 new species of fungi were described, and it was estimated that more than 90% of fungi remain unknown.[8] The following year, 2,905 new species were described—the highest annual record of new fungus names.[51] In mycology, species have historically been distinguished by a variety of methods and concepts. Classification based on morphological characteristics, such as the size and shape of spores or fruiting structures, has traditionally dominated fungal taxonomy.[52] Species may also be distinguished by their biochemical and physiological characteristics, such as their ability to metabolize certain biochemicals, or their reaction to chemical tests. The biological species concept discriminates species based on their ability to mate. The application of molecular tools, such as DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis, to study diversity has greatly enhanced the resolution and added robustness to estimates of genetic diversity within various taxonomic groups.[53]

Mycology

Mycology is the branch of biology concerned with the systematic study of fungi, including their genetic and biochemical properties, their taxonomy, and their use to humans as a source of medicine, food, and psychotropic substances consumed for religious purposes, as well as their dangers, such as poisoning or infection. The field of phytopathology, the study of plant diseases, is closely related because many plant pathogens are fungi.[54]

The use of fungi by humans dates back to prehistory; Ötzi the Iceman, a well-preserved mummy of a 5,300-year-old Neolithic man found frozen in the Austrian Alps, carried two species of polypore mushrooms that may have been used as tinder (Fomes fomentarius), or for medicinal purposes (Piptoporus betulinus).[55] Ancient peoples have used fungi as food sources—often unknowingly—for millennia, in the preparation of leavened bread and fermented juices. Some of the oldest written records contain references to the destruction of crops that were probably caused by pathogenic fungi.[56]

History

Mycology became a systematic science after the development of the microscope in the 17th century. Although fungal spores were first observed by Giambattista della Porta in 1588, the seminal work in the development of mycology is considered to be the publication of Pier Antonio Micheli's 1729 work Nova plantarum genera.[57] Micheli not only observed spores but also showed that, under the proper conditions, they could be induced into growing into the same species of fungi from which they originated.[58] Extending the use of the binomial system of nomenclature introduced by Carl Linnaeus in his Species plantarum (1753), the Dutch Christiaan Hendrik Persoon (1761–1836) established the first classification of mushrooms with such skill as to be considered a founder of modern mycology. Later, Elias Magnus Fries (1794–1878) further elaborated the classification of fungi, using spore color and microscopic characteristics, methods still used by taxonomists today. Other notable early contributors to mycology in the 17th–19th and early 20th centuries include Miles Joseph Berkeley, August Carl Joseph Corda, Anton de Bary, the brothers Louis René and Charles Tulasne, Arthur H. R. Buller, Curtis G. Lloyd, and Pier Andrea Saccardo. In the 20th and 21st centuries, advances in biochemistry, genetics, molecular biology, biotechnology, DNA sequencing and phylogenetic analysis has provided new insights into fungal relationships and biodiversity, and has challenged traditional morphology-based groupings in fungal taxonomy.[59]

Morphology

Microscopic structures

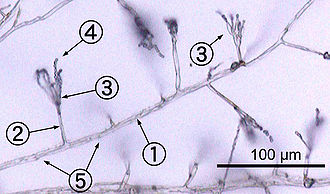

Most fungi grow as hyphae, which are cylindrical, thread-like structures 2–10 μm in diameter and up to several centimeters in length. Hyphae grow at their tips (apices); new hyphae are typically formed by emergence of new tips along existing hyphae by a process called branching, or occasionally growing hyphal tips fork, giving rise to two parallel-growing hyphae.[60] Hyphae also sometimes fuse when they come into contact, a process called hyphal fusion (or anastomosis). These growth processes lead to the development of a mycelium, an interconnected network of hyphae.[34] Hyphae can be either septate or coenocytic. Septate hyphae are divided into compartments separated by cross walls (internal cell walls, called septa, that are formed at right angles to the cell wall giving the hypha its shape), with each compartment containing one or more nuclei; coenocytic hyphae are not compartmentalized.[61] Septa have pores that allow cytoplasm, organelles, and sometimes nuclei to pass through; an example is the dolipore septum in fungi of the phylum Basidiomycota.[62] Coenocytic hyphae are in essence multinucleate supercells.[63]

Many species have developed specialized hyphal structures for nutrient uptake from living hosts; examples include haustoria in plant-parasitic species of most fungal phyla,[64] and arbuscules of several mycorrhizal fungi, which penetrate into the host cells to consume nutrients.[65]

Although fungi are opisthokonts—a grouping of evolutionarily related organisms broadly characterized by a single posterior flagellum—all phyla except for the chytrids have lost their posterior flagella.[66] Fungi are unusual among the eukaryotes in having a cell wall that, in addition to glucans (e.g., β-1,3-glucan) and other typical components, also contains the biopolymer chitin.[38]

Macroscopic structures

Fungal mycelia can become visible to the naked eye, for example, on various surfaces and substrates, such as damp walls and spoiled food, where they are commonly called molds. Mycelia grown on solid agar media in laboratory petri dishes are usually referred to as colonies. These colonies can exhibit growth shapes and colors (due to spores or pigmentation) that can be used as diagnostic features in the identification of species or groups.[67] Some individual fungal colonies can reach extraordinary dimensions and ages as in the case of a clonal colony of Armillaria solidipes, which extends over an area of more than 900 ha (3.5 square miles), with an estimated age of nearly 9,000 years.[68]

The apothecium—a specialized structure important in sexual reproduction in the ascomycetes—is a cup-shaped fruit body that is often macroscopic and holds the hymenium, a layer of tissue containing the spore-bearing cells.[69] The fruit bodies of the basidiomycetes (basidiocarps) and some ascomycetes can sometimes grow very large, and many are well known as mushrooms.

Growth and physiology

The growth of fungi as hyphae on or in solid substrates or as single cells in aquatic environments is adapted for the efficient extraction of nutrients, because these growth forms have high surface area to volume ratios.[70] Hyphae are specifically adapted for growth on solid surfaces, and to invade substrates and tissues.[71] They can exert large penetrative mechanical forces; for example, many plant pathogens, including Magnaporthe grisea, form a structure called an appressorium that evolved to puncture plant tissues.[72] The pressure generated by the appressorium, directed against the plant epidermis, can exceed 8 megapascals (1,200 psi).[72] The filamentous fungus Paecilomyces lilacinus uses a similar structure to penetrate the eggs of nematodes.[73]

The mechanical pressure exerted by the appressorium is generated from physiological processes that increase intracellular turgor by producing osmolytes such as glycerol.[74] Adaptations such as these are complemented by hydrolytic enzymes secreted into the environment to digest large organic molecules—such as polysaccharides, proteins, and lipids—into smaller molecules that may then be absorbed as nutrients.[75][76][77] The vast majority of filamentous fungi grow in a polar fashion (extending in one direction) by elongation at the tip (apex) of the hypha.[78] Other forms of fungal growth include intercalary extension (longitudinal expansion of hyphal compartments that are below the apex) as in the case of some endophytic fungi,[79] or growth by volume expansion during the development of mushroom stipes and other large organs.[80] Growth of fungi as multicellular structures consisting of somatic and reproductive cells—a feature independently evolved in animals and plants[81]—has several functions, including the development of fruit bodies for dissemination of sexual spores (see above) and biofilms for substrate colonization and intercellular communication.[82]

Fungi are traditionally considered heterotrophs, organisms that rely solely on carbon fixed by other organisms for metabolism. Fungi have evolved a high degree of metabolic versatility that allows them to use a diverse range of organic substrates for growth, including simple compounds such as nitrate, ammonia, acetate, or ethanol.[83][84] In some species the pigment melanin may play a role in extracting energy from ionizing radiation, such as gamma radiation. This form of "radiotrophic" growth has been described for only a few species, the effects on growth rates are small, and the underlying biophysical and biochemical processes are not well known.[44] This process might bear similarity to CO2 fixation via visible light, but instead uses ionizing radiation as a source of energy.[85]

Reproduction

Fungal reproduction is complex, reflecting the differences in lifestyles and genetic makeup within this diverse kingdom of organisms.[86] It is estimated that a third of all fungi reproduce using more than one method of propagation; for example, reproduction may occur in two well-differentiated stages within the life cycle of a species, the teleomorph (sexual reproduction) and the anamorph (asexual reproduction).[87] Environmental conditions trigger genetically determined developmental states that lead to the creation of specialized structures for sexual or asexual reproduction. These structures aid reproduction by efficiently dispersing spores or spore-containing propagules.

Asexual reproduction

Asexual reproduction occurs via vegetative spores (conidia) or through mycelial fragmentation. Mycelial fragmentation occurs when a fungal mycelium separates into pieces, and each component grows into a separate mycelium. Mycelial fragmentation and vegetative spores maintain clonal populations adapted to a specific niche, and allow more rapid dispersal than sexual reproduction.[88] The "Fungi imperfecti" (fungi lacking the perfect or sexual stage) or Deuteromycota comprise all the species that lack an observable sexual cycle.[89] Deuteromycota (alternatively known as Deuteromycetes, conidial fungi, or mitosporic fungi) is not an accepted taxonomic clade and is now taken to mean simply fungi that lack a known sexual stage.[90]

Sexual reproduction

Sexual reproduction with meiosis has been directly observed in all fungal phyla except Glomeromycota[91] (genetic analysis suggests meiosis in Glomeromycota as well). It differs in many aspects from sexual reproduction in animals or plants. Differences also exist between fungal groups and can be used to discriminate species by morphological differences in sexual structures and reproductive strategies.[92][93] Mating experiments between fungal isolates may identify species on the basis of biological species concepts.[93] The major fungal groupings have initially been delineated based on the morphology of their sexual structures and spores; for example, the spore-containing structures, asci and basidia, can be used in the identification of ascomycetes and basidiomycetes, respectively. Fungi employ two mating systems: heterothallic species allow mating only between individuals of the opposite mating type, whereas homothallic species can mate, and sexually reproduce, with any other individual or itself.[94]

Most fungi have both a haploid and a diploid stage in their life cycles. In sexually reproducing fungi, compatible individuals may combine by fusing their hyphae together into an interconnected network; this process, anastomosis, is required for the initiation of the sexual cycle. Many ascomycetes and basidiomycetes go through a dikaryotic stage, in which the nuclei inherited from the two parents do not combine immediately after cell fusion, but remain separate in the hyphal cells (see heterokaryosis).[95]

In ascomycetes, dikaryotic hyphae of the hymenium (the spore-bearing tissue layer) form a characteristic hook (crozier) at the hyphal septum. During cell division, the formation of the hook ensures proper distribution of the newly divided nuclei into the apical and basal hyphal compartments. An ascus (plural asci) is then formed, in which karyogamy (nuclear fusion) occurs. Asci are embedded in an ascocarp, or fruiting body. Karyogamy in the asci is followed immediately by meiosis and the production of ascospores. After dispersal, the ascospores may germinate and form a new haploid mycelium.[96]

Sexual reproduction in basidiomycetes is similar to that of the ascomycetes. Compatible haploid hyphae fuse to produce a dikaryotic mycelium. However, the dikaryotic phase is more extensive in the basidiomycetes, often also present in the vegetatively growing mycelium. A specialized anatomical structure, called a clamp connection, is formed at each hyphal septum. As with the structurally similar hook in the ascomycetes, the clamp connection in the basidiomycetes is required for controlled transfer of nuclei during cell division, to maintain the dikaryotic stage with two genetically different nuclei in each hyphal compartment.[97] A basidiocarp is formed in which club-like structures known as basidia generate haploid basidiospores after karyogamy and meiosis.[98] The most commonly known basidiocarps are mushrooms, but they may also take other forms (see Morphology section).

In fungi formerly classified as Zygomycota, haploid hyphae of two individuals fuse, forming a gametangium, a specialized cell structure that becomes a fertile gamete-producing cell. The gametangium develops into a zygospore, a thick-walled spore formed by the union of gametes. When the zygospore germinates, it undergoes meiosis, generating new haploid hyphae, which may then form asexual sporangiospores. These sporangiospores allow the fungus to rapidly disperse and germinate into new genetically identical haploid fungal mycelia.[99]

Spore dispersal

The spores of most of the researched species of fungi are transported by wind.[100][101] Such species often produce dry or hydrophobic spores that do not absorb water and are readily scattered by raindrops, for example.[100][102][103] In other species, both asexual and sexual spores or sporangiospores are often actively dispersed by forcible ejection from their reproductive structures. This ejection ensures exit of the spores from the reproductive structures as well as traveling through the air over long distances.

Specialized mechanical and physiological mechanisms, as well as spore surface structures (such as hydrophobins), enable efficient spore ejection.[104] For example, the structure of the spore-bearing cells in some ascomycete species is such that the buildup of substances affecting cell volume and fluid balance enables the explosive discharge of spores into the air.[105] The forcible discharge of single spores termed ballistospores involves formation of a small drop of water (Buller's drop), which upon contact with the spore leads to its projectile release with an initial acceleration of more than 10,000 g;[106] the net result is that the spore is ejected 0.01–0.02 cm, sufficient distance for it to fall through the gills or pores into the air below.[107] Other fungi, like the puffballs, rely on alternative mechanisms for spore release, such as external mechanical forces. The hydnoid fungi (tooth fungi) produce spores on pendant, tooth-like or spine-like projections.[108] The bird's nest fungi use the force of falling water drops to liberate the spores from cup-shaped fruiting bodies.[109] Another strategy is seen in the stinkhorns, a group of fungi with lively colors and putrid odor that attract insects to disperse their spores.[110]

Homothallism

In homothallic sexual reproduction, two haploid nuclei derived from the same individual fuse to form a zygote that can then undergo meiosis. Homothallic fungi include species with an Aspergillus-like asexual stage (anamorphs) occurring in numerous different genera,[111] several species of the ascomycete genus Cochliobolus,[112] and the ascomycete Pneumocystis jirovecii.[113] The earliest mode of sexual reproduction among eukaryotes was likely homothallism, that is, self-fertile unisexual reproduction.[114]

Other sexual processes

Besides regular sexual reproduction with meiosis, certain fungi, such as those in the genera Penicillium and Aspergillus, may exchange genetic material via parasexual processes, initiated by anastomosis between hyphae and plasmogamy of fungal cells.[115] The frequency and relative importance of parasexual events is unclear and may be lower than other sexual processes. It is known to play a role in intraspecific hybridization[116] and is likely required for hybridization between species, which has been associated with major events in fungal evolution.[117]

Evolution

In contrast to plants and animals, the early fossil record of the fungi is meager. Factors that likely contribute to the under-representation of fungal species among fossils include the nature of fungal fruiting bodies, which are soft, fleshy, and easily degradable tissues, and the microscopic dimensions of most fungal structures, which therefore are not readily evident. Fungal fossils are difficult to distinguish from those of other microbes, and are most easily identified when they resemble extant fungi.[118] Often recovered from a permineralized plant or animal host, these samples are typically studied by making thin-section preparations that can be examined with light microscopy or transmission electron microscopy.[119] Researchers study compression fossils by dissolving the surrounding matrix with acid and then using light or scanning electron microscopy to examine surface details.[120]

The earliest fossils possessing features typical of fungi date to the Paleoproterozoic era, some 2,400 million years ago (Ma); these multicellular benthic organisms had filamentous structures capable of anastomosis.[121] Other studies (2009) estimate the arrival of fungal organisms at about 760–1060 Ma on the basis of comparisons of the rate of evolution in closely related groups.[122] The oldest fossilizied mycelium to be identified from its molecular composition is between 715 and 810 million years old.[123] For much of the Paleozoic Era (542–251 Ma), the fungi appear to have been aquatic and consisted of organisms similar to the extant chytrids in having flagellum-bearing spores.[124] The evolutionary adaptation from an aquatic to a terrestrial lifestyle necessitated a diversification of ecological strategies for obtaining nutrients, including parasitism, saprobism, and the development of mutualistic relationships such as mycorrhiza and lichenization.[125] Studies suggest that the ancestral ecological state of the Ascomycota was saprobism, and that independent lichenization events have occurred multiple times.[126]

In May 2019, scientists reported the discovery of a fossilized fungus, named Ourasphaira giraldae, in the Canadian Arctic, that may have grown on land a billion years ago, well before plants were living on land.[127][128][129] Pyritized fungus-like microfossils preserved in the basal Ediacaran Doushantuo Formation (~635 Ma) have been reported in South China.[130] Earlier, it had been presumed that the fungi colonized the land during the Cambrian (542–488.3 Ma), also long before land plants.[131] Fossilized hyphae and spores recovered from the Ordovician of Wisconsin (460 Ma) resemble modern-day Glomerales, and existed at a time when the land flora likely consisted of only non-vascular bryophyte-like plants.[132] Prototaxites, which was probably a fungus or lichen, would have been the tallest organism of the late Silurian and early Devonian. Fungal fossils do not become common and uncontroversial until the early Devonian (416–359.2 Ma), when they occur abundantly in the Rhynie chert, mostly as Zygomycota and Chytridiomycota.[131][133][134] At about this same time, approximately 400 Ma, the Ascomycota and Basidiomycota diverged,[135] and all modern classes of fungi were present by the Late Carboniferous (Pennsylvanian, 318.1–299 Ma).[136]

Lichens formed a component of the early terrestrial ecosystems, and the estimated age of the oldest terrestrial lichen fossil is 415 Ma;[137] this date roughly corresponds to the age of the oldest known sporocarp fossil, a Paleopyrenomycites species found in the Rhynie Chert.[138] The oldest fossil with microscopic features resembling modern-day basidiomycetes is Palaeoancistrus, found permineralized with a fern from the Pennsylvanian.[139] Rare in the fossil record are the Homobasidiomycetes (a taxon roughly equivalent to the mushroom-producing species of the Agaricomycetes). Two amber-preserved specimens provide evidence that the earliest known mushroom-forming fungi (the extinct species Archaeomarasmius leggetti) appeared during the late Cretaceous, 90 Ma.[140][141]

Some time after the Permian–Triassic extinction event (251.4 Ma), a fungal spike (originally thought to be an extraordinary abundance of fungal spores in sediments) formed, suggesting that fungi were the dominant life form at this time, representing nearly 100% of the available fossil record for this period.[142] However, the relative proportion of fungal spores relative to spores formed by algal species is difficult to assess,[143] the spike did not appear worldwide,[144][145] and in many places it did not fall on the Permian–Triassic boundary.[146]

Sixty-five million years ago, immediately after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event that famously killed off most dinosaurs, there was a dramatic increase in evidence of fungi; apparently the death of most plant and animal species led to a huge fungal bloom like "a massive compost heap".[147]

Taxonomy

Although commonly included in botany curricula and textbooks, fungi are more closely related to animals than to plants and are placed with the animals in the monophyletic group of opisthokonts.[148] Analyses using molecular phylogenetics support a monophyletic origin of fungi.[53][149] The taxonomy of fungi is in a state of constant flux, especially due to research based on DNA comparisons. These current phylogenetic analyses often overturn classifications based on older and sometimes less discriminative methods based on morphological features and biological species concepts obtained from experimental matings.[150]

There is no unique generally accepted system at the higher taxonomic levels and there are frequent name changes at every level, from species upwards. Efforts among researchers are now underway to establish and encourage usage of a unified and more consistent nomenclature.[53][151] Until relatively recent (2012) changes to the International Code of Nomenclature for algae, fungi and plants, fungal species could also have multiple scientific names depending on their life cycle and mode (sexual or asexual) of reproduction.[152] Web sites such as Index Fungorum and MycoBank are officially recognized nomenclatural repositories and list current names of fungal species (with cross-references to older synonyms).[153]

The 2007 classification of Kingdom Fungi is the result of a large-scale collaborative research effort involving dozens of mycologists and other scientists working on fungal taxonomy.[53] It recognizes seven phyla, two of which—the Ascomycota and the Basidiomycota—are contained within a branch representing subkingdom Dikarya, the most species rich and familiar group, including all the mushrooms, most food-spoilage molds, most plant pathogenic fungi, and the beer, wine, and bread yeasts. The accompanying cladogram depicts the major fungal taxa and their relationship to opisthokont and unikont organisms, based on the work of Philippe Silar,[154] "The Mycota: A Comprehensive Treatise on Fungi as Experimental Systems for Basic and Applied Research"[155] and Tedersoo et al. 2018.[156] The lengths of the branches are not proportional to evolutionary distances.

| Zoosporia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Taxonomic groups

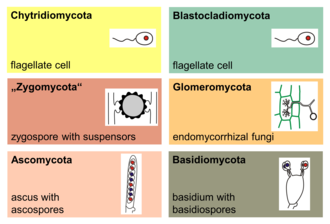

The major phyla (sometimes called divisions) of fungi have been classified mainly on the basis of characteristics of their sexual reproductive structures. As of 2019[update], nine major lineages have been identified: Opisthosporidia, Chytridiomycota, Neocallimastigomycota, Blastocladiomycota, Zoopagomycotina, Mucoromycota, Glomeromycota, Ascomycota and Basidiomycota.[157]

Phylogenetic analysis has demonstrated that the Microsporidia, unicellular parasites of animals and protists, are fairly recent and highly derived endobiotic fungi (living within the tissue of another species).[124] Previously considered to be "primitive" protozoa, they are now thought to be either a basal branch of the Fungi, or a sister group–each other's closest evolutionary relative.[158]

The Chytridiomycota are commonly known as chytrids. These fungi are distributed worldwide. Chytrids and their close relatives Neocallimastigomycota and Blastocladiomycota (below) are the only fungi with active motility, producing zoospores that are capable of active movement through aqueous phases with a single flagellum, leading early taxonomists to classify them as protists. Molecular phylogenies, inferred from rRNA sequences in ribosomes, suggest that the Chytrids are a basal group divergent from the other fungal phyla, consisting of four major clades with suggestive evidence for paraphyly or possibly polyphyly.[159]

The Blastocladiomycota were previously considered a taxonomic clade within the Chytridiomycota. Molecular data and ultrastructural characteristics, however, place the Blastocladiomycota as a sister clade to the Zygomycota, Glomeromycota, and Dikarya (Ascomycota and Basidiomycota). The blastocladiomycetes are saprotrophs, feeding on decomposing organic matter, and they are parasites of all eukaryotic groups. Unlike their close relatives, the chytrids, most of which exhibit zygotic meiosis, the blastocladiomycetes undergo sporic meiosis.[124]

The Neocallimastigomycota were earlier placed in the phylum Chytridiomycota. Members of this small phylum are anaerobic organisms, living in the digestive system of larger herbivorous mammals and in other terrestrial and aquatic environments enriched in cellulose (e.g., domestic waste landfill sites).[160] They lack mitochondria but contain hydrogenosomes of mitochondrial origin. As in the related chrytrids, neocallimastigomycetes form zoospores that are posteriorly uniflagellate or polyflagellate.[53]

Members of the Glomeromycota form arbuscular mycorrhizae, a form of mutualist symbiosis wherein fungal hyphae invade plant root cells and both species benefit from the resulting increased supply of nutrients. All known Glomeromycota species reproduce asexually.[91] The symbiotic association between the Glomeromycota and plants is ancient, with evidence dating to 400 million years ago.[161] Formerly part of the Zygomycota (commonly known as 'sugar' and 'pin' molds), the Glomeromycota were elevated to phylum status in 2001 and now replace the older phylum Zygomycota.[162] Fungi that were placed in the Zygomycota are now being reassigned to the Glomeromycota, or the subphyla incertae sedis Mucoromycotina, Kickxellomycotina, the Zoopagomycotina and the Entomophthoromycotina.[53] Some well-known examples of fungi formerly in the Zygomycota include black bread mold (Rhizopus stolonifer), and Pilobolus species, capable of ejecting spores several meters through the air.[163] Medically relevant genera include Mucor, Rhizomucor, and Rhizopus.[164]

The Ascomycota, commonly known as sac fungi or ascomycetes, constitute the largest taxonomic group within the Eumycota.[52] These fungi form meiotic spores called ascospores, which are enclosed in a special sac-like structure called an ascus. This phylum includes morels, a few mushrooms and truffles, unicellular yeasts (e.g., of the genera Saccharomyces, Kluyveromyces, Pichia, and Candida), and many filamentous fungi living as saprotrophs, parasites, and mutualistic symbionts (e.g. lichens). Prominent and important genera of filamentous ascomycetes include Aspergillus, Penicillium, Fusarium, and Claviceps. Many ascomycete species have only been observed undergoing asexual reproduction (called anamorphic species), but analysis of molecular data has often been able to identify their closest teleomorphs in the Ascomycota.[165] Because the products of meiosis are retained within the sac-like ascus, ascomycetes have been used for elucidating principles of genetics and heredity (e.g., Neurospora crassa).[166]

Members of the Basidiomycota, commonly known as the club fungi or basidiomycetes, produce meiospores called basidiospores on club-like stalks called basidia. Most common mushrooms belong to this group, as well as rust and smut fungi, which are major pathogens of grains. Other important basidiomycetes include the maize pathogen Ustilago maydis,[167] human commensal species of the genus Malassezia,[168] and the opportunistic human pathogen, Cryptococcus neoformans.[169]

Fungus-like organisms

Because of similarities in morphology and lifestyle, the slime molds (mycetozoans, plasmodiophorids, acrasids, Fonticula and labyrinthulids, now in Amoebozoa, Rhizaria, Excavata, Cristidiscoidea and Stramenopiles, respectively), water molds (oomycetes) and hyphochytrids (both Stramenopiles) were formerly classified in the kingdom Fungi, in groups like Mastigomycotina, Gymnomycota and Phycomycetes. The slime molds were studied also as protozoans, leading to an ambiregnal, duplicated taxonomy.[170]

Unlike true fungi, the cell walls of oomycetes contain cellulose and lack chitin. Hyphochytrids have both chitin and cellulose. Slime molds lack a cell wall during the assimilative phase (except labyrinthulids, which have a wall of scales), and take in nutrients by ingestion (phagocytosis, except labyrinthulids) rather than absorption (osmotrophy, as fungi, labyrinthulids, oomycetes and hyphochytrids). Neither water molds nor slime molds are closely related to the true fungi, and, therefore, taxonomists no longer group them in the kingdom Fungi. Nonetheless, studies of the oomycetes and myxomycetes are still often included in mycology textbooks and primary research literature.[171]

The Eccrinales and Amoebidiales are opisthokont protists, previously thought to be zygomycete fungi. Other groups now in Opisthokonta (e.g., Corallochytrium, Ichthyosporea) were also at given time classified as fungi. The genus Blastocystis, now in Stramenopiles, was originally classified as a yeast. Ellobiopsis, now in Alveolata, was considered a chytrid. The bacteria were also included in fungi in some classifications, as the group Schizomycetes.

The Rozellida clade, including the "ex-chytrid" Rozella, is a genetically disparate group known mostly from environmental DNA sequences that is a sister group to fungi.[157] Members of the group that have been isolated lack the chitinous cell wall that is characteristic of fungi. Alternatively, Rozella can be classified as a basal fungal group.[149]

The nucleariids may be the next sister group to the eumycete clade, and as such could be included in an expanded fungal kingdom.[148] Many Actinomycetales (Actinomycetota), a group with many filamentous bacteria, were also long believed to be fungi.[172][173]

Ecology

Although often inconspicuous, fungi occur in every environment on Earth and play very important roles in most ecosystems. Along with bacteria, fungi are the major decomposers in most terrestrial (and some aquatic) ecosystems, and therefore play a critical role in biogeochemical cycles[174] and in many food webs. As decomposers, they play an essential role in nutrient cycling, especially as saprotrophs and symbionts, degrading organic matter to inorganic molecules, which can then re-enter anabolic metabolic pathways in plants or other organisms.[175][176]

Symbiosis

Many fungi have important symbiotic relationships with organisms from most if not all kingdoms.[177][178][179] These interactions can be mutualistic or antagonistic in nature, or in the case of commensal fungi are of no apparent benefit or detriment to the host.[180][181][182]

With plants

Mycorrhizal symbiosis between plants and fungi is one of the most well-known plant–fungus associations and is of significant importance for plant growth and persistence in many ecosystems; over 90% of all plant species engage in mycorrhizal relationships with fungi and are dependent upon this relationship for survival.[183]

The mycorrhizal symbiosis is ancient, dating back to at least 400 million years.[161] It often increases the plant's uptake of inorganic compounds, such as nitrate and phosphate from soils having low concentrations of these key plant nutrients.[175][184] The fungal partners may also mediate plant-to-plant transfer of carbohydrates and other nutrients.[185] Such mycorrhizal communities are called "common mycorrhizal networks".[186][187] A special case of mycorrhiza is myco-heterotrophy, whereby the plant parasitizes the fungus, obtaining all of its nutrients from its fungal symbiont.[188] Some fungal species inhabit the tissues inside roots, stems, and leaves, in which case they are called endophytes.[189] Similar to mycorrhiza, endophytic colonization by fungi may benefit both symbionts; for example, endophytes of grasses impart to their host increased resistance to herbivores and other environmental stresses and receive food and shelter from the plant in return.[190]

With algae and cyanobacteria

Lichens are a symbiotic relationship between fungi and photosynthetic algae or cyanobacteria. The photosynthetic partner in the relationship is referred to in lichen terminology as a "photobiont". The fungal part of the relationship is composed mostly of various species of ascomycetes and a few basidiomycetes.[191] Lichens occur in every ecosystem on all continents, play a key role in soil formation and the initiation of biological succession,[192] and are prominent in some extreme environments, including polar, alpine, and semiarid desert regions.[193] They are able to grow on inhospitable surfaces, including bare soil, rocks, tree bark, wood, shells, barnacles and leaves.[194] As in mycorrhizas, the photobiont provides sugars and other carbohydrates via photosynthesis to the fungus, while the fungus provides minerals and water to the photobiont. The functions of both symbiotic organisms are so closely intertwined that they function almost as a single organism; in most cases the resulting organism differs greatly from the individual components.[195] Lichenization is a common mode of nutrition for fungi; around 27% of known fungi—more than 19,400 species—are lichenized.[196] Characteristics common to most lichens include obtaining organic carbon by photosynthesis, slow growth, small size, long life, long-lasting (seasonal) vegetative reproductive structures, mineral nutrition obtained largely from airborne sources, and greater tolerance of desiccation than most other photosynthetic organisms in the same habitat.[197]

With insects

Many insects also engage in mutualistic relationships with fungi. Several groups of ants cultivate fungi in the order Chaetothyriales for several purposes: as a food source, as a structural component of their nests, and as a part of an ant/plant symbiosis in the domatia (tiny chambers in plants that house arthropods).[198] Ambrosia beetles cultivate various species of fungi in the bark of trees that they infest.[199] Likewise, females of several wood wasp species (genus Sirex) inject their eggs together with spores of the wood-rotting fungus Amylostereum areolatum into the sapwood of pine trees; the growth of the fungus provides ideal nutritional conditions for the development of the wasp larvae.[200] At least one species of stingless bee has a relationship with a fungus in the genus Monascus, where the larvae consume and depend on fungus transferred from old to new nests.[201] Termites on the African savannah are also known to cultivate fungi,[177] and yeasts of the genera Candida and Lachancea inhabit the gut of a wide range of insects, including neuropterans, beetles, and cockroaches; it is not known whether these fungi benefit their hosts.[202] Fungi growing in dead wood are essential for xylophagous insects (e.g. woodboring beetles).[203][204][205] They deliver nutrients needed by xylophages to nutritionally scarce dead wood.[206][204][205] Thanks to this nutritional enrichment the larvae of the woodboring insect is able to grow and develop to adulthood.[203] The larvae of many families of fungicolous flies, particularly those within the superfamily Sciaroidea such as the Mycetophilidae and some Keroplatidae feed on fungal fruiting bodies and sterile mycorrhizae.[207]

As pathogens and parasites

Many fungi are parasites on plants, animals (including humans), and other fungi. Serious pathogens of many cultivated plants causing extensive damage and losses to agriculture and forestry include the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe oryzae,[208] tree pathogens such as Ophiostoma ulmi and Ophiostoma novo-ulmi causing Dutch elm disease,[209] Cryphonectria parasitica responsible for chestnut blight,[210] and Phymatotrichopsis omnivora causing Texas Root Rot, and plant pathogens in the genera Fusarium, Ustilago, Alternaria, and Cochliobolus.[181] Some carnivorous fungi, like Paecilomyces lilacinus, are predators of nematodes, which they capture using an array of specialized structures such as constricting rings or adhesive nets.[211] Many fungi that are plant pathogens, such as Magnaporthe oryzae, can switch from being biotrophic (parasitic on living plants) to being necrotrophic (feeding on the dead tissues of plants they have killed).[212] This same principle is applied to fungi-feeding parasites, including Asterotremella albida, which feeds on the fruit bodies of other fungi both while they are living and after they are dead.[213]

Some fungi can cause serious diseases in humans, several of which may be fatal if untreated. These include aspergillosis, candidiasis, coccidioidomycosis, cryptococcosis, histoplasmosis, mycetomas, and paracoccidioidomycosis. Furthermore, a person with immunodeficiency is more susceptible to disease by genera such as Aspergillus, Candida, Cryptoccocus,[182][214][215] Histoplasma,[216] and Pneumocystis.[217] Other fungi can attack eyes, nails, hair, and especially skin, the so-called dermatophytic and keratinophilic fungi, and cause local infections such as ringworm and athlete's foot.[218] Fungal spores are also a cause of allergies, and fungi from different taxonomic groups can evoke allergic reactions.[219]

As targets of mycoparasites

Organisms that parasitize fungi are known as mycoparasitic organisms. About 300 species of fungi and fungus-like organisms, belonging to 13 classes and 113 genera, are used as biocontrol agents against plant fungal diseases.[220] Fungi can also act as mycoparasites or antagonists of other fungi, such as Hypomyces chrysospermus, which grows on bolete mushrooms. Fungi can also become the target of infection by mycoviruses.[221][222]

Communication

There appears to be electrical communication between fungi in word-like components according to spiking characteristics.[223]

Possible impact on climate

According to a study published in the academic journal Current Biology, fungi can soak from the atmosphere around 36% of global fossil fuel greenhouse gas emissions.[224][225]

Mycotoxins

![(6aR,9R)-N-((2R,5S,10aS,10bS)-5-benzyl-10b-hydroxy-2-methyl-3,6-dioxooctahydro-2H-oxazolo[3,2-a] pyrrolo[2,1-c]pyrazin-2-yl)-7-methyl-4,6,6a,7,8,9-hexahydroindolo[4,3-fg] quinoline-9-carboxamide](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/9/94/Ergotamine3.png/220px-Ergotamine3.png)

Many fungi produce biologically active compounds, several of which are toxic to animals or plants and are therefore called mycotoxins. Of particular relevance to humans are mycotoxins produced by molds causing food spoilage, and poisonous mushrooms (see above). Particularly infamous are the lethal amatoxins in some Amanita mushrooms, and ergot alkaloids, which have a long history of causing serious epidemics of ergotism (St Anthony's Fire) in people consuming rye or related cereals contaminated with sclerotia of the ergot fungus, Claviceps purpurea.[226] Other notable mycotoxins include the aflatoxins, which are insidious liver toxins and highly carcinogenic metabolites produced by certain Aspergillus species often growing in or on grains and nuts consumed by humans, ochratoxins, patulin, and trichothecenes (e.g., T-2 mycotoxin) and fumonisins, which have significant impact on human food supplies or animal livestock.[227]

Mycotoxins are secondary metabolites (or natural products), and research has established the existence of biochemical pathways solely for the purpose of producing mycotoxins and other natural products in fungi.[40] Mycotoxins may provide fitness benefits in terms of physiological adaptation, competition with other microbes and fungi, and protection from consumption (fungivory).[228][229] Many fungal secondary metabolites (or derivatives) are used medically, as described under Human use below.

Pathogenic mechanisms

Ustilago maydis is a pathogenic plant fungus that causes smut disease in maize and teosinte. Plants have evolved efficient defense systems against pathogenic microbes such as U. maydis. A rapid defense reaction after pathogen attack is the oxidative burst where the plant produces reactive oxygen species at the site of the attempted invasion. U. maydis can respond to the oxidative burst with an oxidative stress response, regulated by the gene YAP1. The response protects U. maydis from the host defense, and is necessary for the pathogen's virulence.[230] Furthermore, U. maydis has a well-established recombinational DNA repair system which acts during mitosis and meiosis.[231] The system may assist the pathogen in surviving DNA damage arising from the host plant's oxidative defensive response to infection.[232]

Cryptococcus neoformans is an encapsulated yeast that can live in both plants and animals. C. neoformans usually infects the lungs, where it is phagocytosed by alveolar macrophages.[233] Some C. neoformans can survive inside macrophages, which appears to be the basis for latency, disseminated disease, and resistance to antifungal agents. One mechanism by which C. neoformans survives the hostile macrophage environment is by up-regulating the expression of genes involved in the oxidative stress response.[233] Another mechanism involves meiosis. The majority of C. neoformans are mating "type a". Filaments of mating "type a" ordinarily have haploid nuclei, but they can become diploid (perhaps by endoduplication or by stimulated nuclear fusion) to form blastospores. The diploid nuclei of blastospores can undergo meiosis, including recombination, to form haploid basidiospores that can be dispersed.[234] This process is referred to as monokaryotic fruiting. This process requires a gene called DMC1, which is a conserved homologue of genes recA in bacteria and RAD51 in eukaryotes, that mediates homologous chromosome pairing during meiosis and repair of DNA double-strand breaks. Thus, C. neoformans can undergo a meiosis, monokaryotic fruiting, that promotes recombinational repair in the oxidative, DNA damaging environment of the host macrophage, and the repair capability may contribute to its virulence.[232][234]

Human use

The human use of fungi for food preparation or preservation and other purposes is extensive and has a long history. Mushroom farming and mushroom gathering are large industries in many countries. The study of the historical uses and sociological impact of fungi is known as ethnomycology. Because of the capacity of this group to produce an enormous range of natural products with antimicrobial or other biological activities, many species have long been used or are being developed for industrial production of antibiotics, vitamins, and anti-cancer and cholesterol-lowering drugs. Methods have been developed for genetic engineering of fungi,[235] enabling metabolic engineering of fungal species. For example, genetic modification of yeast species[236]—which are easy to grow at fast rates in large fermentation vessels—has opened up ways of pharmaceutical production that are potentially more efficient than production by the original source organisms.[237] Fungi-based industries are sometimes considered to be a major part of a growing bioeconomy, with applications under research and development including use for textiles, meat substitution and general fungal biotechnology.[238][239][240][241][242]

Therapeutic uses

Modern chemotherapeutics

Many species produce metabolites that are major sources of pharmacologically active drugs.

Antibiotics

Particularly important are the antibiotics, including the penicillins, a structurally related group of β-lactam antibiotics that are synthesized from small peptides. Although naturally occurring penicillins such as penicillin G (produced by Penicillium chrysogenum) have a relatively narrow spectrum of biological activity, a wide range of other penicillins can be produced by chemical modification of the natural penicillins. Modern penicillins are semisynthetic compounds, obtained initially from fermentation cultures, but then structurally altered for specific desirable properties.[244] Other antibiotics produced by fungi include: ciclosporin, commonly used as an immunosuppressant during transplant surgery; and fusidic acid, used to help control infection from methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus bacteria.[245] Widespread use of antibiotics for the treatment of bacterial diseases, such as tuberculosis, syphilis, leprosy, and others began in the early 20th century and continues to date. In nature, antibiotics of fungal or bacterial origin appear to play a dual role: at high concentrations they act as chemical defense against competition with other microorganisms in species-rich environments, such as the rhizosphere, and at low concentrations as quorum-sensing molecules for intra- or interspecies signaling.[246]

Other

Other drugs produced by fungi include griseofulvin isolated from Penicillium griseofulvum, used to treat fungal infections,[247] and statins (HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors), used to inhibit cholesterol synthesis. Examples of statins found in fungi include mevastatin from Penicillium citrinum and lovastatin from Aspergillus terreus and the oyster mushroom.[248] Psilocybin from fungi is investigated for therapeutic use and appears to cause global increases in brain network integration.[249] Fungi produce compounds that inhibit viruses[250][251] and cancer cells.[252] Specific metabolites, such as polysaccharide-K, ergotamine, and β-lactam antibiotics, are routinely used in clinical medicine. The shiitake mushroom is a source of lentinan, a clinical drug approved for use in cancer treatments in several countries, including Japan.[253][254] In Europe and Japan, polysaccharide-K (brand name Krestin), a chemical derived from Trametes versicolor, is an approved adjuvant for cancer therapy.[255]

Traditional medicine

Certain mushrooms are used as supposed therapeutics in folk medicine practices, such as traditional Chinese medicine. Mushrooms with a history of such use include Agaricus subrufescens,[252][256] Ganoderma lucidum,[257] and Ophiocordyceps sinensis.[258]

Cultured foods

Baker's yeast or Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a unicellular fungus, is used to make bread and other wheat-based products, such as pizza dough and dumplings.[259] Yeast species of the genus Saccharomyces are also used to produce alcoholic beverages through fermentation.[260] Shoyu koji mold (Aspergillus oryzae) is an essential ingredient in brewing Shoyu (soy sauce) and sake, and the preparation of miso,[261] while Rhizopus species are used for making tempeh.[262] Several of these fungi are domesticated species that were bred or selected according to their capacity to ferment food without producing harmful mycotoxins (see below), which are produced by very closely related Aspergilli.[263] Quorn, a meat substitute, is made from Fusarium venenatum.[264]

In food

Edible mushrooms include commercially raised and wild-harvested fungi. Agaricus bisporus, sold as button mushrooms when small or Portobello mushrooms when larger, is the most widely cultivated species in the West, used in salads, soups, and many other dishes. Many Asian fungi are commercially grown and have increased in popularity in the West. They are often available fresh in grocery stores and markets, including straw mushrooms (Volvariella volvacea), oyster mushrooms (Pleurotus ostreatus), shiitakes (Lentinula edodes), and enokitake (Flammulina spp.).[265]

Many other mushroom species are harvested from the wild for personal consumption or commercial sale. Milk mushrooms, morels, chanterelles, truffles, black trumpets, and porcini mushrooms (Boletus edulis) (also known as king boletes) demand a high price on the market. They are often used in gourmet dishes.[266]

Certain types of cheeses require inoculation of milk curds with fungal species that impart a unique flavor and texture to the cheese. Examples include the blue color in cheeses such as Stilton or Roquefort, which are made by inoculation with Penicillium roqueforti.[267] Molds used in cheese production are non-toxic and are thus safe for human consumption; however, mycotoxins (e.g., aflatoxins, roquefortine C, patulin, or others) may accumulate because of growth of other fungi during cheese ripening or storage.[268]

Poisonous fungi

Many mushroom species are poisonous to humans and cause a range of reactions including slight digestive problems, allergic reactions, hallucinations, severe organ failure, and death. Genera with mushrooms containing deadly toxins include Conocybe, Galerina, Lepiota and the most infamous, Amanita.[269] The latter genus includes the destroying angel (A. virosa) and the death cap (A. phalloides), the most common cause of deadly mushroom poisoning.[270] The false morel (Gyromitra esculenta) is occasionally considered a delicacy when cooked, yet can be highly toxic when eaten raw.[271] Tricholoma equestre was considered edible until it was implicated in serious poisonings causing rhabdomyolysis.[272] Fly agaric mushrooms (Amanita muscaria) also cause occasional non-fatal poisonings, mostly as a result of ingestion for its hallucinogenic properties. Historically, fly agaric was used by different peoples in Europe and Asia and its present usage for religious or shamanic purposes is reported from some ethnic groups such as the Koryak people of northeastern Siberia.[273]

As it is difficult to accurately identify a safe mushroom without proper training and knowledge, it is often advised to assume that a wild mushroom is poisonous and not to consume it.[274][275]

Pest control

In agriculture, fungi may be useful if they actively compete for nutrients and space with pathogenic microorganisms such as bacteria or other fungi via the competitive exclusion principle,[276] or if they are parasites of these pathogens. For example, certain species eliminate or suppress the growth of harmful plant pathogens, such as insects, mites, weeds, nematodes, and other fungi that cause diseases of important crop plants.[277] This has generated strong interest in practical applications that use these fungi in the biological control of these agricultural pests. Entomopathogenic fungi can be used as biopesticides, as they actively kill insects.[278] Examples that have been used as biological insecticides are Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium spp., Hirsutella spp., Paecilomyces (Isaria) spp., and Lecanicillium lecanii.[279][280] Endophytic fungi of grasses of the genus Epichloë, such as E. coenophiala, produce alkaloids that are toxic to a range of invertebrate and vertebrate herbivores. These alkaloids protect grass plants from herbivory, but several endophyte alkaloids can poison grazing animals, such as cattle and sheep.[281] Infecting cultivars of pasture or forage grasses with Epichloë endophytes is one approach being used in grass breeding programs; the fungal strains are selected for producing only alkaloids that increase resistance to herbivores such as insects, while being non-toxic to livestock.[282][283]

Bioremediation

Certain fungi, in particular white-rot fungi, can degrade insecticides, herbicides, pentachlorophenol, creosote, coal tars, and heavy fuels and turn them into carbon dioxide, water, and basic elements.[284] Fungi have been shown to biomineralize uranium oxides, suggesting they may have application in the bioremediation of radioactively polluted sites.[285][286][287]

Model organisms

Several pivotal discoveries in biology were made by researchers using fungi as model organisms, that is, fungi that grow and sexually reproduce rapidly in the laboratory. For example, the one gene-one enzyme hypothesis was formulated by scientists using the bread mold Neurospora crassa to test their biochemical theories.[288] Other important model fungi are Aspergillus nidulans and the yeasts Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Schizosaccharomyces pombe, each of which with a long history of use to investigate issues in eukaryotic cell biology and genetics, such as cell cycle regulation, chromatin structure, and gene regulation. Other fungal models have emerged that address specific biological questions relevant to medicine, plant pathology, and industrial uses; examples include Candida albicans, a dimorphic, opportunistic human pathogen,[289] Magnaporthe grisea, a plant pathogen,[290] and Pichia pastoris, a yeast widely used for eukaryotic protein production.[291]

Others

Fungi are used extensively to produce industrial chemicals like citric, gluconic, lactic, and malic acids,[292] and industrial enzymes, such as lipases used in biological detergents,[293] cellulases used in making cellulosic ethanol[294] and stonewashed jeans,[295] and amylases,[296] invertases, proteases and xylanases.[297]

See also

References

Citations

- ^ Moore RT (1980). "Taxonomic proposals for the classification of marine yeasts and other yeast-like fungi including the smuts". Botanica Marina. 23 (6): 361–373. doi:10.1515/bot-1980-230605.

- ^ "Record Details: Fungi R.T. Moore, Bot. Mar. 23(6): 371 (1980)". Index Fungorum. Retrieved 18 June 2024.

- ^ /ˈfʌndʒaɪ/ , /ˈfʌŋɡaɪ/ , /ˈfʌŋɡi/ or /ˈfʌndʒi/ . The first two pronunciations are favored more in the US and the others in the UK, however all pronunciations can be heard in any English-speaking country.

- ^ "Fungus". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- ^ Whittaker R (January 1969). "New concepts of kingdoms or organisms. Evolutionary relations are better represented by new classifications than by the traditional two kingdoms". Science. 163 (3863): 150–60. Bibcode:1969Sci...163..150W. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.403.5430. doi:10.1126/science.163.3863.150. PMID 5762760.

- ^ Cavalier-Smith T (1998). "A revised six-kingdom system of life". Biological Reviews. 73 (3): 203–66. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.1998.tb00030.x. PMID 9809012. S2CID 6557779.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hawksworth DL, Lücking R (July 2017). "Fungal Diversity Revisited: 2.2 to 3.8 Million Species". Microbiology Spectrum. 5 (4): 79–95. doi:10.1128/microbiolspec.FUNK-0052-2016. ISBN 978-1-55581-957-6. PMID 28752818.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Cheek M, Nic Lughadha E, Kirk P, Lindon H, Carretero J, Looney B, et al. (2020). "New scientific discoveries: Plants and fungi". Plants, People, Planet. 2 (5): 371–388. doi:10.1002/ppp3.10148. hdl:1854/LU-8705210.

- ^ "Stop neglecting fungi". Nature Microbiology. 2 (8): 17120. 25 July 2017. doi:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.120. PMID 28741610.

- ^ Simpson DP (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5 ed.). London, UK: Cassell Ltd. p. 883. ISBN 978-0-304-52257-6.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ainsworth 1976, p. 2.

- ^ Mitzka W, ed. (1960). Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache [Etymological dictionary of the German language] (in German). Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, p. 1.

- ^ Persoon CH (1796). Observationes Mycologicae: Part 1 (in Latin). Leipzig, (Germany): Peter Philipp Wolf. Archived from the original on 19 December 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ Greville RK (1824). Scottish Cryptogamie Flora: Or Coloured Figures and Descriptions of Cryptogamic Plants, Belonging Chiefly to the Order Fungi. Vol. 2. Edinburgh, Scotland: Maclachland and Stewart. p. 65. From p. 65: "This little plant will probably not prove rare in Great Britain, when mycology shall be more studied."

- ^ Smith JE (1836). Hooker WJ, Berkeley MJ (eds.). The English Flora of Sir James Edward Smith. Vol. 5, part II: "Class XXIV. Cryptogamia". London, England: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, Green & Longman. p. 7. From p. 7: "This has arisen, I conceive, partly from the practical difficulty of preserving specimens for the herbarium, partly from the absence of any general work, adapted to the immense advances which have of late years been made in the study of Mycology."

- ^ "LIAS Glossary". Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 14 August 2013.

- ^ Kuhar F, Furci G, Drechsler-Santos ER, Pfister DH (2018). "Delimitation of Funga as a valid term for the diversity of fungal communities: the Fauna, Flora & Funga proposal (FF&F)". IMA Fungus. 9 (2): A71–A74. doi:10.1007/BF03449441. hdl:11336/88035.

- ^ "IUCN SSC acceptance of Fauna Flora Funga" (PDF). Fungal Conservation Committee, IUCN SSC. 2021. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 November 2021. Retrieved 11 November 2021.

The IUCN Species Survival Commission calls for the due recognition of fungi as major components of biodiversity in legislation and policy. It fully endorses the Fauna Flora Funga Initiative and asks that the phrases animals and plants and fauna and flora be replaced with animals, fungi, and plants and fauna, flora, and funga.

- ^ "Fifth-Grade Elementary School Students' Conceptions and Misconceptions about the Fungus Kingdom". Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ "Common Student Ideas about Plants and Animals" (PDF). Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ Bruns T (October 2006). "Evolutionary biology: a kingdom revised". Nature. 443 (7113): 758–61. Bibcode:2006Natur.443..758B. doi:10.1038/443758a. PMID 17051197. S2CID 648881.

- ^ Baldauf SL, Palmer JD (December 1993). "Animals and fungi are each other's closest relatives: congruent evidence from multiple proteins". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 90 (24): 11558–62. Bibcode:1993PNAS...9011558B. doi:10.1073/pnas.90.24.11558. PMC 48023. PMID 8265589.

- ^ Deacon 2005, p. 4.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Deacon 2005, pp. 128–129.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 28–33.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Shoji JY, Arioka M, Kitamoto K (2006). "Possible involvement of pleiomorphic vacuolar networks in nutrient recycling in filamentous fungi". Autophagy. 2 (3): 226–7. doi:10.4161/auto.2695. PMID 16874107.

- ^ Deacon 2005, p. 58.

- ^ Zabriskie TM, Jackson MD (February 2000). "Lysine biosynthesis and metabolism in fungi". Natural Product Reports. 17 (1): 85–97. doi:10.1039/a801345d. PMID 10714900.

- ^ Xu H, Andi B, Qian J, West AH, Cook PF (2006). "The alpha-aminoadipate pathway for lysine biosynthesis in fungi". Cell Biochemistry and Biophysics. 46 (1): 43–64. doi:10.1385/CBB:46:1:43. PMID 16943623. S2CID 22370361.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 27–28.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, p. 685.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, p. 30.

- ^ Desjardin DE, Perry BA, Lodge DJ, Stevani CV, Nagasawa E (2010). "Luminescent Mycena: new and noteworthy species". Mycologia. 102 (2): 459–77. doi:10.3852/09-197. PMID 20361513. S2CID 25377671. Archived from the original on 11 November 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2018.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996, p. 33.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: a b Gow NA, Latge JP, Munro CA, Heitman J (2017). «Грибковая клеточная стенка: структура, биосинтез и функция». Микробиологический спектр . 5 (3). doi : 10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0035-2016 . HDL : 2164/8941 . PMID 28513415 . S2CID 5026076 .

- ^ Mihail JD, Bruhn JN (ноябрь 2005 г.). «Формативное поведение систем ризоморфы Armillaria ». Микологические исследования . 109 (Pt 11): 1195–207. doi : 10.1017/s0953756205003606 . PMID 16279413 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый Келлер Н.П., Тернер Г., Беннетт Дж.В. (декабрь 2005 г.). «Вторичный метаболизм грибов - от биохимии до геномики». Природные обзоры. Микробиология . 3 (12): 937–47. doi : 10.1038/nrmicro1286 . PMID 16322742 . S2CID 23537608 .

- ^ Wu S, Schalk M, Clark A, Miles RB, Coates R, Chappell J (ноябрь 2006 г.). «Пере перенаправление цитозольных или пластидных изопреноидных предшественников повышает выработку терпена у растений». Nature Biotechnology . 24 (11): 1441–7. doi : 10.1038/nbt1251 . PMID 17057703 . S2CID 23358348 .

- ^ Tudzynski B (март 2005 г.). «Биосинтез Gibberellin в грибах: гены, ферменты, эволюция и влияние на биотехнологию». Прикладная микробиология и биотехнология . 66 (6): 597–611. doi : 10.1007/s00253-004-1805-1 . PMID 15578178 . S2CID 11191347 .

- ^ Vaupotic T, Veranic P, Jenoe P, Plemenitas A (июнь 2008 г.). «Митохондриальное посредничество осмолитов окружающей среды при дискриминации во время осмоадаптации в чрезвычайно галатолерантных черных дрожжевых hortaea werneckii». Грибная генетика и биология . 45 (6): 994–1007. doi : 10.1016/j.fgb.2008.01.006 . PMID 18343697 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Дадачва Е., Брайан Р.А., Хуан Х, Моадль Т., Швейцер А.Д., Айзен П. и др. (2007). «Ионизирующее излучение меняет электронные свойства меланина и усиливает рост меланизированных грибов» . Plos один . 2 (5): E457. Bibcode : 2007ploso ... 2..457d . doi : 10.1371/journal.pone.0000457 . PMC 1866175 . PMID 17520016 .

- ^ Рагхукумар С., Рагхукумар С. (1998). «Баротолерантность грибов, изолированных из глубоководных отложений Индийского океана» . Водная микробная экология . 15 (2): 153–163. doi : 10.3354/ame015153 .

- ^ Sancho LG, De La Torre R, Horneck G, Ascase C, De Los Rios A, Pintodo A, et al. (Июнь 2007 г.). «Лишайники выживают в космосе: результаты эксперимента лишайника 2005 года». Астробиология . 7 (3): 443–54. Bibcode : 2007asbio ... 7..443s . Doi : 10.1089/ast2006.0046 . PMID 17630840 . S2CID 4121180 .

- ^ Fisher MC, Garner TW (2020). «Хитридные грибы и глобальные амфибии снижаются» . Nature Reviews Microbiology . 18 (6): 332–343. doi : 10.1038/s41579-020-0335-x . HDL : 10044/1/78596 . PMID 32099078 . S2CID 211266075 .

- ^ Варгас-Гастелум Л, Рикельм М (2020). «Микобиота глубокого моря: что может предложить OMICS» . Жизнь . 10 (11): 292. Bibcode : 2020life ... 10..292V . doi : 10.3390/life10110292 . PMC 7699357 . PMID 33228036 .

- ^ «Грибы в мульчах и компостах» . Университет Массачусетса Амхерст . 6 марта 2015 года . Получено 15 декабря 2022 года .

- ^ Mueller GM, Schmit JP (2006). «Грибковое биоразнообразие: что мы знаем? Что мы можем предсказать?». Биоразнообразие и сохранение . 16 (1): 1–5. doi : 10.1007/s10531-006-9117-7 . S2CID 23827807 .

- ^ Wang K, Cai L, Yao Y (2021). «Обзор новичков новинок грибов в мире и Китае (2020)» . Биоразнообразие науки . 29 (8): 1064–1072. doi : 10.17520/biods.2021202 . S2CID 240568551 .

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный Kirk et al. 2008 , с.

- ^ Подпрыгнуть до: а беременный в дюймовый и фон Хиббетт Д.С., Биндер М., Бишофф Дж. Ф., Блэквелл М., Кэннон П.Ф., Эрикссон О.Е. и др. (Май 2007). «Филогенетическая классификация грибов более высокого уровня» (PDF) . Микологические исследования . 111 (Pt 5): 509–47. Citeseerx 10.1.1.626.9582 . doi : 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.03.004 . PMID 17572334 . S2CID 4686378 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 26 марта 2009 года . Получено 8 марта 2007 года .

- ^ Согласно одной оценке 2001 года, известно около 10 000 грибковых заболеваний. Удар С (2006). «Стратегии инфекции растений паразитических грибов». В Куке Б.М., Джонс Д.Г., Кэй Б. (ред.). Эпидемиология заболеваний растений . Берлин, Германия: Спрингер. п. 117. ISBN 978-1-4020-4580-6 .

- ^ Peintner U, Pöder R, Pümpel T (1998). «Грибы Айдмана». Микологические исследования . 102 (10): 1153–1162. doi : 10.1017/s0953756298006546 .

- ^ Ainsworth 1976 , p. 1

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996 , с. 1–2.

- ^ Ainsworth 1976 , p. 18

- ^ Hawksworth DL (сентябрь 2006 г.). «Микологическая коробка Пандоры: молекулярные последовательности против морфологии в понимании грибковых отношений и биоразнообразия». Revista Iberoamericana de Micología . 23 (3): 127–33. doi : 10.1016/s1130-1406 (06) 70031-6 . PMID 17196017 .

- ^ Харрис С.Д. (2008). «Разветвление грибковых гиф: регуляция, механизмы и сравнение с другими ветвящими системами» . Микология . 100 (6): 823–32. doi : 10.3852/08-177 . PMID 19202837 . S2CID 2147525 . Архивировано с оригинала 12 апреля 2016 года . Получено 5 июля 2011 года .

- ^ Дикон 2005 , с. 51

- ^ Дикон 2005 , с. 57

- ^ Чанг -стрит, Майлз П.Г. (2004). Грибы: выращивание, питательная ценность, лекарственное действие и воздействие на окружающую среду . Бока Ратон, Флорида: CRC Press . ISBN 978-0-8493-1043-0 .

- ^ Bozkurt to, Kamoun S, Lennon-Duménil Am (2020). «Растение -патогеновый разейный интерфейс с первого взгляда» . Журнал сотовой науки . 133 (5). doi : 10.1242/jcs.237958 . PMC 7075074 . PMID 32132107 .

- ^ Парнике М (октябрь 2008 г.). «Арбускулярная микориза: мать эндосимбиозов корня растений». Природные обзоры. Микробиология . 6 (10): 763–75. doi : 10.1038/nrmicro1987 . PMID 18794914 . S2CID 5432120 .

- ^ Standy ET, Wright J, Baldaaf SL (январь 2006 г.). «Протесты происхождение животных и веселья » Молекулярная биология и эволюция 23 (1): 93–1 Doi : 10.1093/ molbev/ msj0 16151185PMID

- ^ Hanson 2008 , с. 127–141.

- ^ Фергюсон Б.А., Дрейсбах Т.А., Паркс К.Г., Филип Г.М., Шмитт К.Л. (2003). «Грубая популяционная структура патогенных видов Armillaria в смешанном лесу в Голубых горах северо-восточного Орегона» . Канадский журнал лесных исследований . 33 (4): 612–623. doi : 10.1139/x03-065 . Архивировано с оригинала 3 июля 2019 года . Получено 3 июля 2019 года .

- ^ Alexopoulos, Mims & Blackwell 1996 , с. 204–205.

- ^ Мосс -стрит (1986). Биология морских грибов . Кембридж, Великобритания: издательство Кембриджского университета . п. 76. ISBN 978-0-521-30899-1 .

- ^ Peñalva MA, Arst HN (сентябрь 2002 г.). «Регуляция экспрессии генов путем окружающего рН в нитевидных грибах и дрожжах» . Микробиология и молекулярная биология обзоры . 66 (3): 426–46, содержимое. doi : 10.1128/mmbr.66.3.426-446.2002 . PMC 120796 . PMID 12208998 .