История социалистического движения в США

| Эта статья является частью серии, посвященной |

| Социализм в Соединенных Штатах |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

История социалистического движения в Соединенных Штатах охватывает множество тенденций, включая анархистов , коммунистов , демократических социалистов , социал-демократов , марксистов , марксистов-ленинцев , троцкистов и социалистов-утопистов . Все началось с утопических сообществ начала 19-го века, таких как Шейкеры , активист-провидец Джозайя Уоррен , и интенциональных сообществ, вдохновленных Шарлем Фурье . Лейбористские активисты, обычно еврейские, немецкие или финские иммигранты, основали Социалистическую рабочую партию Америки в 1877 году. Социалистическая партия Америки была основана в 1901 году. К тому времени анархизм также приобрел известность по всей стране. Социалисты разных направлений были вовлечены в ранние американские рабочие организации и борьбу. Они достигли высшей точки во время резни на Хеймаркете в Чикаго, в результате которой Международный день трудящихся стал главным трудовым праздником во всем мире, Днем труда , а восьмичасовой рабочий день стал всемирной целью рабочих организаций и социалистических партий во всем мире. [ 1 ]

Under Socialist Party of America presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs, socialist opposition to World War I was widespread, leading to the governmental repression collectively known as the First Red Scare. The Socialist Party declined in the 1920s, but the party nonetheless often ran Norman Thomas for president. In the 1930s, the Communist Party USA took importance in labor and racial struggles while it suffered a split which converged in the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party. In the 1950s, socialism was affected by McCarthyism and in the 1960s it was revived by the general radicalization brought by the New Left and other social struggles and revolts. In the 1960s, Michael Harrington and other socialists were called to assist the Kennedy administration and then the Johnson administration's War on Poverty and Great Society[2] while socialists also played important roles in the civil rights movement.[3][4][5][6] Unlike in Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand, a major socialist party has never materialized in the United States[7] and the socialist movement in the United States was relatively weak in comparison.[8] In the United States, socialism can be stigmatized because it is commonly associated with authoritarian socialism, the Soviet Union and other authoritarian Marxist–Leninist regimes.[9] Writing for The Economist, Samuel Jackson argued that socialism has been used as a pejorative term, without any clear definition, by conservatives and right-libertarians to taint liberal and progressive policies, proposals and public figures.[10] The term socialization has been mistakenly used to refer to any state or government-operated industry or service (the proper term for such being either municipalization or nationalization). The term has also been used to mean any tax-funded programs, whether privately run or government run. The term socialism has been used to argue against economic interventionism, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, Medicare, the New Deal, Social Security and universal single-payer health care, among others.[11][12]

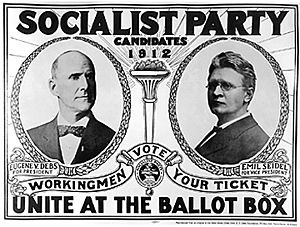

Milwaukee has had several socialist mayors such as Emil Seidel, Daniel Hoan and Frank Zeidler whilst Socialist Party presidential candidate Eugene V. Debs won nearly one million votes in the 1920 presidential election.[13][14] Self-declared democratic socialist Bernie Sanders won 13 million votes in the 2016 Democratic Party presidential primary, gaining considerable popular support, particularly among the younger generation and the working class.[15][16][17] A September 2022 poll reported 36% of American adults had a positive view of socialism and 57% had a positive view of capitalism.[18]

19th century

[edit]Utopian socialism and communities

[edit]

Utopian socialism was the first American socialist movement. Utopians attempted to develop model socialist societies to demonstrate the virtues of their brand of beliefs. Most utopian socialist ideas originated in Europe, but the United States was most often the site for the experiments themselves. Many utopian experiments occurred in the 19th century as part of this movement, including Brook Farm, the New Harmony, the Shakers, the Amana Colonies, the Oneida Community, The Icarians, Bishop Hill Commune, Aurora, Oregon and Bethel, Missouri.

Robert Owen, a wealthy Welsh industrialist, turned to social reform and socialism and in 1825 founded a communitarian colony called New Harmony in southwestern Indiana. The group fell apart in 1829, mostly due to conflict between utopian ideologues and non-ideological pioneers. In 1841, transcendentalist utopians founded Brook Farm, a community based on Frenchman Charles Fourier's brand of socialism. Nathaniel Hawthorne was a member of this short-lived community, and Ralph Waldo Emerson had declined invitations to join. The group had trouble reaching financial stability and many members left as their leader George Ripley turned more and more to Fourier's doctrine. All hope for its survival was lost when the expensive, Fourier-inspired main building burnt down while under construction. The community dissolved in 1847.

Fourierists also attempted to establish a community in Monmouth County, New Jersey. The North American Phalanx community built a Phalanstère—Fourier's concept of a communal-living structure—out of two farmhouses and an addition that linked the two. The community lasted from 1844 to 1856, when a fire destroyed the community's flour and saw-mills and several workshops. The community had already begun to decline after an ideological schism in 1853. French socialist Étienne Cabet, frustrated in Europe, sought to use his Icarian movement to replace capitalist production with workers cooperatives. He became the most popular socialist advocate of his day, with a special appeal to English artisans were being undercut by factories. In the 1840s, Cabet led groups of emigrants to found utopian communities in Texas and Illinois. However, his work was undercut by his many feuds with his own followers.[19]

Utopian socialism reached the national level fictionally in Edward Bellamy's 1888 novel Looking Backward, a utopian depiction of a socialist United States in the year 2000. The book sold millions of copies and became one of the best-selling American books of the nineteenth century. By one estimation, only Uncle Tom's Cabin surpassed it in sales.[20] The book sparked a following of Bellamy Clubs and influenced socialist and labor leaders, including Eugene V. Debs.[21] Likewise, Upton Sinclair's masterpiece The Jungle was first published in the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason, criticizing capitalism as being oppressive and exploitative to meatpacking workers in the industrial food system. The book is still widely referred to today as one of the most influential works of literature in modern history.

Josiah Warren is widely regarded as the first American anarchist[22] and the four-page weekly paper he edited during 1833, The Peaceful Revolutionist, was the first anarchist periodical published.[23] Warren, a follower of Robert Owen, joined Owen's community at New Harmony, Indiana. He coined the phrase "Cost the limit of price", with "cost" here referring not to monetary price paid but the labor one exerted to produce an item.[24] Therefore, "[h]e proposed a system to pay people with certificates indicating how many hours of work they did. They could exchange the notes at local time stores for goods that took the same amount of time to produce."[22] He put his theories to the test by establishing an experimental "labor for labor store" called the Cincinnati Time Store where trade was facilitated by notes backed by a promise to perform labor. The store proved successful and operated for three years, after which it was closed so that Warren could pursue establishing colonies based on mutualism. These included "Utopia" and "Modern Times." Warren said that Stephen Pearl Andrews' The Science of Society, published in 1852, was the most lucid and complete exposition of Warren's own theories.[25] For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster: "It is apparent ... that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews ... William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form."[26]

American anarchist Benjamin Tucker wrote in Individual Liberty:

The economic principles of Modern Socialism are a logical deduction from the principle laid down by Adam Smith in the early chapters of his Wealth of Nations,—namely, that labor is the true measure of price. ... Half a century or more after Smith enunciated the principle above stated, Socialism picked it up where he had dropped it, and in following it to its logical conclusions, made it the basis of a new economic philosophy ... This seems to have been done independently by three different men, of three different nationalities, in three different languages: Josiah Warren, an American; Pierre J. Proudhon, a Frenchman; Karl Marx, a German Jew ... That the work of this interesting trio should have been done so nearly simultaneously would seem to indicate that Socialism was in the air, and that the time was ripe and the conditions favorable for the appearance of this new school of thought. So far as priority of time is concerned, the credit seems to belong to Warren, the American,—a fact which should be noted by the stump orators who are so fond of declaiming against Socialism as an imported article.[27]

Early Marxism

[edit]German Marxist immigrants who arrived in the United States after the 1848 revolutions in Europe brought socialist ideas with them.[28] Joseph Weydemeyer, a German colleague of Karl Marx who sought refuge in New York in 1851 following the 1848 revolutions, established the first Marxist journal in the United States, Die Revolution, but It folded after two issues. In 1852, he established the Proletarierbund, which would become the American Workers' League, the first Marxist organization in the United States, but it too proved short-lived, having failed to attract a native English-speaking membership.[29] In 1866, William H. Sylvis formed the National Labor Union (NLU). Frederich Albert Sorge, a German who had found refuge in New York following the 1848 revolutions, took Local No. 5 of the NLU into the First International as Section One in the United States. By 1872, there were 22 sections, which held a convention in New York. The General Council of the International moved to New York with Sorge as General Secretary, but following internal conflict it dissolved in 1876.[30]

A larger wave of German immigrants followed in the 1870s and 1880s, including social democratic followers of Ferdinand Lasalle. Lasalle regarded state aid through political action as the road to revolution and opposed trade unionism, which he saw as futile, believing that according to the iron law of wages employers would only pay subsistence wages. The Lasalleans formed the Social Democratic Party of North America in 1874 and both Marxists and Lasalleans formed the Workingmen's Party of the United States in 1876. When the Lasalleans gained control in 1877, they changed the name to the Socialist Labor Party of America (SLP). However, many socialists abandoned political action altogether and moved to trade unionism. Two former socialists, Adolph Strasser and Samuel Gompers, formed the American Federation of Labor (AFL) in 1886.[28]

The Socialist Labor Party (SLP) was officially founded in 1876 at a convention in Newark, New Jersey. The party was made up overwhelmingly of German immigrants, who had brought Marxist ideals with them to North America. So strong was the heritage that the official party language was German for the first three years. In its nascent years, the party encompassed a broad range of various socialist philosophies, with differing concepts of how to achieve their goals. Nevertheless, there was a militia—the Lehr und Wehr Verein—affiliated to the party. When the SLP reorganised as a Marxist party in 1890, its philosophy solidified and its influence quickly grew and by around the start of the 20th century the SLP was the foremost American socialist party.

Bringing to light the resemblance of the American party's politics to those of Lassalle, Daniel De Leon emerged as an early leader of the Socialist Labor Party. He also adamantly supported unions, but criticized the collective bargaining movement within the United States at the time, favoring a slightly different approach.[a] The resulting disagreement between De Leon's supporters and detractors within the party led to an early schism. De Leon's opponents, led by Morris Hillquit, left the Socialist Labor Party in 1901 as they fused with Eugene V. Debs's Social Democratic Party and formed the Socialist Party of America.

As a leader within the socialist movement, Debs' movement quickly gained national recognition as a charismatic orator. He was often inflammatory and controversial, but also strikingly modest and inspiring. He once said: "I am not a Labor Leader; I do not want you to follow me or anyone else. [...] You must use your heads as well as your hands, and get yourself out of your present condition." Debs lent a great and powerful air to the revolution with his speaking: "There was almost a religious fervor to the movement, as in the eloquence of Debs."[31]

The Socialist movement became coherent and energized under Debs. It included "scores of former Populists, militant miners, and blacklisted railroad workers, who were ... inspired by occasional visits from national figures like Eugene V. Debs."[32]

The first socialist to hold public office in the United States was Fred C. Haack, the owner of a shoe store in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Haack was elected to the city council in 1897 as a member of the Populist Party, but soon became a socialist following the organization of Social Democrats in Sheboygan. He was re-elected alderman in 1898 on the Socialist ticket, along with August L. Mohr, a local baseball manager. Haack served on the city council for sixteen years, advocating for the building of schools and public ownership of utilities. He was recognized as the first socialist officeholder in the United States at the 1932 national Socialist Party convention held in Milwaukee.[33][34]

One of the first general strikes in the United States, the 1877 St. Louis general strike grew out of the Great Railroad Strike of 1877. The general strike was largely organized by the Knights of Labor and the Marxist-leaning Workingmen's Party, the main radical political party of the era. When the railroad strike reached East St. Louis, Illinois in July 1877, the St. Louis Workingman's Party led a group of approximately 500 people across the river in an act of solidarity with the nearly 1,000 workers on strike.[35]

Ties to labor

[edit]This article is missing information about the split between the IWW, SP, and SLP, with the IWW rejecting political means and the SP expelling IWW members. (March 2008) |

The Socialist Party formed strong alliances with a number of labor organizations because of their similar goals. In an attempt to rebel against the abuses of corporations, workers had found a solution—or so they thought—in a technique of collective bargaining. By banding together into "unions" and by refusing to work, or "striking", workers would halt production at a plant or in a mine, forcing management to meet their demands. From Daniel De Leon's early proposal to organize unions with a socialist purpose, the two movements became closely tied. They shared as one major ideal the spirit of collectivism—both in the socialist platform and in the idea of collective bargaining.

The most prominent American unions of the time included the American Federation of Labor, the Knights of Labor and the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW). In 1869, Uriah S. Stephens founded the Noble and Holy Order of the Knights of Labor, employing secrecy and fostering a semireligious aura to "create a sense of solidarity."[36] The Knights comprised in essence "one big union of all workers."[37] In 1886, a convention of delegates from twenty separate unions formed the American Federation of Labor, with Samuel Gompers as its head. It peaked[when?] at 4 million members. In 1905, the IWW (or "Wobblies") formed along the same lines as the Knights to become one big union. The IWW found early supporters in De Leon and in Debs.

The socialist movement was able to gain strength from its ties to labor. "The [economic] panic of 1907, as well as the growing strength of the Socialists, Wobblies, and trade unions, sped up the process of reform."[38] However, corporations sought to protect their profits and took steps against unions and strikers. They hired strikebreakers and pressured government to call in the state militias when workers refused to do their jobs. A number of strikes collapsed into violent confrontations.

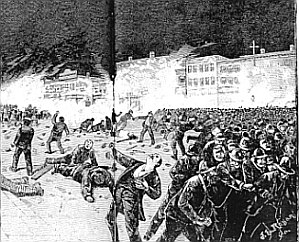

In May 1886, the Knights of Labor were demonstrating in the Haymarket Square in Chicago, demanding an eight-hour day in all trades. When police arrived, an unknown person threw a bomb into the crowd, killing one person and injuring several others. "In a trial marked by prejudice and hysteria," a court sentenced seven anarchists, six of them German-speaking, to death—with no evidence linking them to the bomb.[39]

Strikes also took place that same month (May 1886) in other cities, including in Milwaukee, where seven people died when Wisconsin Governor Jeremiah M. Rusk ordered state militia troops to fire upon thousands of striking workers who had marched to the Milwaukee Iron Works Rolling Mill in Bay View on Milwaukee's south side.

In early 1894, a dispute broke out between George Pullman and his employees. Debs, then leader of the American Railway Union, organized a strike. United States Attorney General Olney and President Grover Cleveland took the matter to court and were granted several injunctions preventing railroad workers from "interfering with interstate commerce and the mails."[40] The judiciary of the time denied the legitimacy of strikers. Said one judge, "[neither] the weapon of the insurrectionist, nor the inflamed tongue of him who incites fire and sword is the instrument to bring about reforms."[40] This was the first sign of a clash between the government and socialist ideals.

In 1914, one of the most bitter labor conflicts in American history took place at a mining colony in Colorado called Ludlow. After workers went on strike in September 1913 with grievances ranging from requests for an eight-hour day to allegations of subjugation, Colorado governor Elias Ammons called in the National Guard in October 1913. That winter, Guardsmen made 172 arrests.[b][41]

The strikers began to fight back, killing four mine guards and firing into a separate camp where strikebreakers lived. When the body of a strikebreaker was found nearby, the National Guard's General Chase ordered the tent colony destroyed in retaliation.[41]

"On Monday morning, April 20, two dynamite bombs were exploded, in the hills above Ludlow ... a signal for operations to begin. At 9 am a machine gun began firing into the tents [where strikers were living], and then others joined,"[41] one eyewitness reported as "[t]he soldiers and mine guards tried to kill everybody; anything they saw move."[41] That night, the National Guard rode down from the hills surrounding Ludlow and set fire to the tents. Twenty-six people, including two women and eleven children, were killed.[42]

Union members now feared to strike. The military, which saw strikers as dangerous insurgents, intimidated and threatened them. These attitudes were compounded by a public backlash against anarchists and radicals. As public opinion of strikes and of unions soured, the socialists often appeared guilty by association. They were lumped together with strikers and anarchists under a blanket of public distrust.

Early anarchism

[edit]

The American anarchist Benjamin Tucker (1844–1938) focused on economics, advocating "Anarchistic-Socialism"[43] and adhering to the mutualist economics of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and Josiah Warren while publishing his eclectic influential publication Liberty. Lysander Spooner (1808–1887), besides his individualist anarchist activism, was also an important anti-slavery activist and became a member of the First International.[44] Two individualist anarchists who wrote in Benjamin Tucker's Liberty were also important labor organizers of the time. Joseph Labadie was an American labor organizer, individualist anarchist, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist and poet. Without the oppression of the state, Labadie believed, humans would choose to harmonize with "the great natural laws ... without robbing [their] fellows through interest, profit, rent and taxes." However, he supported community cooperation as he supported community control of water utilities, streets and railroads.[45] Although he did not support the militant anarchism of the Haymarket anarchists, he fought for clemency for the accused because he did not believe they were the perpetrators. In 1888, Labadie organized the Michigan Federation of Labor, became its first president and forged an alliance with Samuel Gompers.[45] Dyer Lum was a 19th-century American individualist anarchist labor activist and poet.[46] A leading anarcho-syndicalist and a prominent left-wing intellectual of the 1880s,[47] he is remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarcha-feminist Voltairine de Cleyre.[48] Lum wrote prolifically, producing a number of key anarchist texts and contributed to publications including Mother Earth, Twentieth Century, Liberty (Tucker's individualist anarchist journal), The Alarm (the journal of the International Working People's Association) and The Open Court among others. He developed a "mutualist" theory of unions and as such was active within the Knights of Labor and later promoted anti-political strategies in the American Federation of Labor. Frustration with abolitionism, spiritualism and labor reform caused Lum to embrace anarchism and to radicalize workers, as he came to believe that revolution would inevitably involve a violent struggle between the working class and the employing class.[48] Convinced of the necessity of violence to enact social change, he volunteered to fight in the American Civil War of 1861–1865, hoping thereby to bring about the end of slavery.[48]

By the 1880s, anarcho-communism had reached the United States as can be seen in the publication of the journal Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly by Lucy Parsons and Lizzy Holmes.[49] Parsons debated in her time in the United States with fellow anarcha-communist Emma Goldman over issues of free love and feminism.[49] Another anarcho-communist journal, The Firebrand, later appeared in the United States. Most anarchist publications in the United States were in Yiddish, German, or Russian, but Free Society was published in English, permitting the dissemination of anarchist communist thought to English-speaking populations in the United States.[50] Around that time,[when?] these American anarcho-communist sectors entered into debate with the individualist anarchist faction led by Tucker.[51] In February 1888, Berkman left his native Russia for the United States.[52] Soon after his arrival in New York City, Berkman became an anarchist through his involvement with groups that had formed to campaign to free the men convicted of the 1886 Haymarket bombing.[53] Berkman and Goldman soon came under the influence of Johann Most, the best-known anarchist in the United States and an advocate of propaganda of the deed—attentat, or violence carried out to encourage the masses to revolt.[54][55][56] Berkman became a typesetter for Most's newspaper Freiheit.[53]

20th century

[edit]1900s–1920s: opposition to World War I and First Red Scare

[edit]

Victor L. Berger ran for Congress and lost in 1904 before winning Wisconsin's 5th congressional district seat in 1910 as the first Socialist to serve in the Congress. In Congress, he focused on issues related to the District of Columbia and also more radical proposals, including eliminating the president's veto, abolishing the Senate[57] and the socialization of major industries. Berger gained national publicity for his old-age pension bill, the first of its kind introduced into Congress. Less than two weeks after the Titanic passenger ship disaster of 1912, Berger introduced a bill in Congress providing for the nationalization of radio-wireless systems. A practical socialist, Berger argued that the wireless chaos which occurred during the Titanic disaster had demonstrated the need for a government-owned wireless system.[58] Outside of Congress, socialists were able to influence a number of progressive reforms (both directly and indirectly) on a local level.[59]

Socialists met harsh political opposition when they opposed American entry into World War I (1914–1918) and tried to interfere with the conscription laws that required all younger men to register for the draft. On April 7, 1917, the day after Congress declared war on Germany, an emergency convention of the Socialist Party took place in St. Louis. It declared the war "a crime against the people of the United States"[60] and began holding anti-war rallies. Socialist anti-draft demonstrations drew as many as 20,000 people.[61] In June 1917, President Woodrow Wilson signed into law the Espionage Act,[62] which included a clause providing prison sentences for up to twenty years for "[w]hoever, when the United States is at war, shall willfully cause or attempt to cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny, or refusal of duty ... or willfully obstruct the recruiting or enlistment of service of the United States."[61] With their talk of draft-dodging and war-opposition, the socialists found themselves the target of federal prosecutors as scores were convicted and jailed. Archibald E. Stevenson, a New York attorney with ties to the Justice Department, probably as a "volunteer spy",[63] testified on January 22, 1919, during the German phase of the subcommittee's work. He established that anti-war and anti-draft activism during World War I, which he described as "pro-German" activity, had now transformed itself into propaganda "developing sympathy for the Bolshevik movement."[64] The United States' wartime enemy, though defeated, had exported an ideology that now ruled Russia and threatened the United States anew: "The Bolsheviki movement is a branch of the revolutionary socialism of Germany. It had its origin in the philosophy of Marx and its leaders were Germans."[65]

After visiting three communists imprisoned in Canton, Ohio, Eugene V. Debs crossed the street and made a two-hour speech to a crowd in which he condemned the war. "Wars throughout history have been waged for conquest and plunder. [...] The master class has always declared the war and the subject class has always fought the battles," Debs told the crowd.[66] He was immediately arrested and soon convicted under the Espionage Act. During his trial, he did not take the stand, nor call a witness in his defense. However, before the trial began and after his sentencing, he made speeches to the jury: "I have been accused of obstructing the war. I admit it. Gentlemen, I abhor war. [...] I have sympathy with the suffering, struggling people everywhere ...." He also uttered what would become his most famous words: "While there is a lower class, I am in it; while there is a criminal element, I am of it; while there is a soul in prison, I am not free." Debs was sentenced to ten years in prison and served 32 months until President Warren G. Harding pardoned him.

During the war, about half the socialists supported the war, most famously Walter Lippmann. The other half were under attack for obstructing the draft and the Courts held they went beyond the bounds of free speech when they encouraged young men to break the law and not register for the draft. Howard Zinn, historian on the left, says: "The patriotic fervor of war [was] invoked. The courts and jails [were] used to reinforce the idea that certain ideas, certain kinds of resistance, could not be tolerated."[67] The government crackdown on dissenting radicalism paralleled public outrage towards opponents of the war. Several groups were formed on the local and national levels to stop the socialists from undermining the draft laws. The American Vigilante Patrol, a subdivision of the American Defense Society, was formed with the purpose "to put an end to seditious street oratory."[68] The American Protective League was a new private group that kept track of cases of "disloyalty". It eventually claimed it had found 3,000,000 such cases:[68] "Even if these figures are exaggerated, the very size and scope of the League gives a clue to the amount of 'disloyalty'."[68]

The press was also instrumental in spreading feelings of hatred against dissenters:

In April of 1917, the New York Times quoted (former Secretary of War) Elihu Root as saying: 'We must have no criticism now.' A few months later it quoted him again that 'there are men walking about the streets of this city tonight who ought to be taken out at sunrise tomorrow and shot for treason'. [...] The Minneapolis Journal carried an appeal by the [Minnesota Commission of Public Safety] 'for all patriots to join in the suppression of anti-draft and seditious acts and sentiment'.[68]

Meanwhile, corporations pressured the government to deal with strikes and other disruptions from disgruntled workers. The government felt especially pressured to keep war-related industries running: "As worker discontent and strikes [...] intensified in the summer of 1917, demands grew for prompt federal action. [...] The anti-labor forces concentrated their venom on the IWW."[69] Soon, "the halls of Congress rang with denunciations of the IWW" and the government sided with industry as "federal attorneys viewed strikes not as the behavior of discontented workers but as the outcome of subversive and even German influences."[69]

On September 5, 1917, at the request of President Wilson the Justice Department conducted a raid on the IWW. They stormed every one of the 48 IWW headquarters in the country as "[b]y month's end, a federal grand jury had indicted nearly two hundred IWW leaders on charges of sedition and espionage" under the Espionage Act.[70] Their sentences ranged from a few months to ten years in prison. An ally of the Socialist Party had been practically destroyed. However, Wilson did recognize a problem with the state of labor in the United States. In 1918, working closely with Samuel Gompers of the AFL, he created the National War Labor Board in an attempt to reform labor practices. The Board included an equal number of members from labor and business and included leaders of the AFL. The War Labor Board was able to "institute the eight-hour day in many industries, [...] to raise wages for transit workers [...] [and] to demand equal pay for women [...]."[71] It also required employers to bargain collectively, effectively making unions legal.

On January 21, 1919, 35,000 shipyard workers in Seattle went on strike seeking wage increases. They appealed to the Seattle Central Labor Council for support from other unions and found widespread enthusiasm. Within two weeks, more than 100 local unions joined in a call on February 3 for general strike to begin on the morning of February 6.[72] The 60,000 total strikers paralyzed the city's normal activities, like streetcar service, schools and ordinary commerce while their General Strike Committee maintained order and provided essential services, like trash collection and milk deliveries.[73] The national press called the general strike "Marxian" and "a revolutionary movement aimed at existing government."[74] "It is only a middling step," said the Chicago Tribune, "from Petrograd to Seattle."[74] Though the leadership of the American Federation of Labor (AFL) opposed a strike in the steel industry, 98% of their union members voted to strike beginning on September 22, 1919. It shut down half the steel industry, including almost all mills in Pueblo, Colorado; Chicago, Illinois; Wheeling, West Virginia; Johnstown, Pennsylvania; Cleveland, Ohio; Lackawanna, New York; and Youngstown, Ohio.[75] After strikebreakers and police clashed with unionists in Gary, Indiana, the United States Army took over the city on October 6 and martial law was declared. National guardsmen, leaving Gary after federal troops had taken over, turned their anger on strikers in nearby Indiana Harbor, Indiana.[76]

Internal strife caused a schism in the American left after Vladimir Lenin's successful revolution in Russia. Lenin invited the Socialist Party to join the Third International. The debate over whether to align with Lenin caused a major rift in the party. A referendum to join Lenin's Comintern passed with 90% approval, but the moderates who were in charge of the party expelled the extreme leftists before this could take place. The expelled members formed the Communist Labor Party and the Communist Party of America. The Socialist Party ended up, with only moderates left, at one third of its original size.[77] John Reed, Benjamin Gitlow and other socialists were among those who formed the Communist Labor Party while socialist foreign sections led by Charles Ruthenberg formed the Communist Party. These two groups would be combined as the Communist Party of the United States of America (CPUSA).[78] The Communists organized the Trade Union Unity League to compete with the AFL. By August 1919, only months after its founding, the Communist Party USA claimed 50,000 to 60,000 members.[79] Members also included anarchists and other radical leftists. In contrast, the more moderate Socialist Party of America had 40,000 members. The sections of the Communist Party's International Workers Order meanwhile organized for communism along linguistic and ethnic lines, providing mutual aid and tailored cultural activities to an IWO membership that peaked at 200,000 at its height.[80] (In 1928, following divisions inside the Soviet Union, Jay Lovestone, who had replaced Ruthenberg as general secretary of the CPUSA following his death, joined with William Z. Foster to expel Foster's former allies, James P. Cannon and Max Shachtman, who were followers of Leon Trotsky. Following another Soviet factional dispute, Lovestone and Gitlow were expelled and Earl Browder became party leader.[81])

On January 7, 1920, at the first session of the New York State Assembly, Assembly Speaker Thaddeus C. Sweet attacked the Assembly's five Socialist members, declaring they had been "elected on a platform that is absolutely inimical to the best interests of the state of New York and the United States." The Socialist Party, Sweet said, was "not truly a political party," but was rather "a membership organization admitting within its ranks aliens, enemy aliens, and minors." It had supported the revolutionaries in Germany, Austria and Hungary, he continued; and consorted with international Socialist parties close to the Communist International.[83] The Assembly suspended the five by a vote of 140 to 6, with just one Democrat supporting the Socialists. A trial in the Assembly, lasting from January 20 to March 11, resulted in a recommendation that the five be expelled and the Assembly voted overwhelmingly for expulsion on April 1, 1920.

Later in 1920, Anarchists bombed Wall Street and sent a number of mail-bombs to prominent businessmen and government leaders. The public lumped together the entire far left as terrorists. A wave of fear swept the country, giving support for the Justice Department to deport thousands of non-citizens active in the far-left. Emma Goldman was the most famous. This was known as the first Red Scare or the "Palmer Raids".[84]

Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, a Wilsonian Democrat, had a bomb explode outside his house. He set out to stop the "Communist conspiracy" that he believed was operating inside the United States. He created inside the Justice Department a new division the General Intelligence Division, led by young J. Edgar Hoover. Hoover soon amassed a card-catalogue system with information on 60,000 "radically inclined" individuals and many leftist groups and publications.[85] Palmer and Hoover both published press releases and circulated anti-Communist propaganda. Then on January 2, 1920, the Palmer Raids began, with Hoover in charge. On that single day in 1920, Hoover's agents rounded up 6,000 people. Many were deported but the Labor Department ended the raids with a ruling that the incarcerations and deportations were illegal.[86]

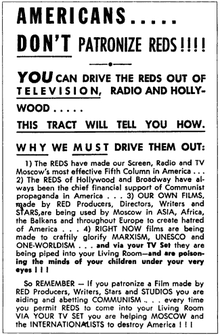

"Socialism" gradually came to be an American conservative attack-word aimed at merely liberal policies and politicians.[87] Since the late 19th century, conservatives had used the term "socialism" (or "creeping socialism") as a means of dismissing spending on public welfare programs which could potentially enlarge the role of the federal government, or lead to higher tax rates. This use of the word had little to do with government ownership of any means of production, or the various socialist parties, as when William Allen White attacked presidential candidate William Jennings Bryan in 1896 by warning that "[t]he election will sustain Americanism or it will plant Socialism."[88][89] Barry Goldwater in 1960 called for Republican unity against John F. Kennedy and the "blueprint for socialism presented by the Democrats."[90]

When the 1920s began, "the IWW was destroyed, the Socialist party falling apart. The strikes were beaten down by force, and the economy was doing just well enough for just enough people to prevent mass rebellion."[91] Thus, the decline of the socialist movement during the early 20th century was the result of a number of constrictions and attacks from several directions. The socialists had lost a major ally in the IWW Wobblies and their free speech had been restricted, if not denied. Immigrants, a major base of the socialist movement, were discriminated against and looked down upon. Eugene V. Debs—the charismatic leader of the socialists—was in prison, along with hundreds of fellow dissenters. Wilson's National War Labor Board and a number of legislative acts had ameliorated the plight of the workers.[92] The socialists were regarded as being "unnecessary", the "lunatic fringe" and a group of untrustworthy radicals. The press, courts and other establishment structures exhibited prejudice against them. After crippling schisms within the party and a change in public opinion due to the Palmer Raids, a general negative perception of the far-left and attribution to it of terrorist incidents such as the Wall Street Bombing, the Socialist Party found itself unable to gather popular support. At one time, it boasted 33 city mayors, many seats in state legislatures and two members of the House of Representatives.[93] The Socialist Party reached its peak in 1912 when Debs won 6% of the popular vote.[94]

Historian Eric Foner described the fundamental problem of those years in a 1984 article for the History Workshop Journal:

Where was the Socialist party at McKee's Rocks, Lawrence or the great steel strike of 1919? The Industrial Workers of the World demonstrated that it was possible to organize the new immigrant proletariat, but despite sympathy for the IWW on the part of Debs and other left-wing socialists, the two organizations went their separate ways. Here, indeed, was the underlying tragedy of those years: the militancy expressed in the IWW was never channeled for political purposes while socialist politics ignored the immigrant workers.[95]

However, despite this decline, a focus on specific local examples shows that within certain communities the socialist trends seen on a national scale continued to influence local socialist movements even after the decline of the mainstream Socialist Party. In specific parts of the USA, such as Ybor City, Tampa , immigrant populations played significant roles in helping translate national socialist efforts into local action. Fuelled by a rising and often radical Latin American immigrant population emerging in the early 1900s, Florida saw major socialist developments both politically for the Socialist Party with their successes in the 1904, 1908 and 1921 national elections and industrially through strike action such as the primarily Latin led February 1919 cigar factory strike in Ybor City, Tampa.[96]

Within Ybor City specifically, supported mainly by the predominantly immigrant workforce, radical socialist ideas spread rapidly, with these ideas continuing late into the 1920s and early 1930s even after the mainstream decline of socialism in the USA.[97] Within cigar factories the often-illiterate workforce would be educated by a 'lector'- a paid spokesperson who recited anarchist, communist and fictional material to workers.[97] Peter Kropotkin was a particular favourite of workers in Ybor City with his ideas of mutual aid inspiring community led projects and mutual aid societies.[98] These were almost always led by immigrant communities, such as Tampa’s significant Cuban, Spanish and Italian populations.[98] Women played major roles in these socialist projects, with a variety of women, predominantly Latin American, Italian and Spanish migrants expressing various degrees of leadership and taking up roles including teaching, volunteering and political organising.[99][100]

1930s–1940s: popular front and New Deal

[edit]The ideological rigidity of the Third Period (from c. 1928) began to crack with two events: the election of Franklin D. Roosevelt as President of the United States in 1932 and Adolf Hitler's rise to power in Nazi Germany in 1933. Roosevelt's election and the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1933 sparked a tremendous upsurge in union organizing in 1933 and 1934. Many conservatives equated the New Deal with socialism or with Communism as practiced in the Soviet Union and saw its policies as evidence that the government had been heavily influenced by Communist policy-makers in the Roosevelt administration.[101] Marxian economist Richard D. Wolff argues that socialist and communist parties, along with organized labor, played a collective role in pushing through New-Deal legislation, and that conservative opponents of the New Deal coordinated an effort to single out and destroy them as a result.[102] The United States Progressive Party of 1948 was a left-wing political party that served as a vehicle for former Vice President Henry A. Wallace's 1948 presidential campaign. The party sought desegregation, the establishment of a national health insurance system, an expansion of the welfare system, and the nationalization of the energy industry. The party also sought conciliation with the Soviet Union during the early stages of the Cold War. Accusations of Communist influences and Wallace's association with controversial Theosophist figure Nicholas Roerich undermined his campaign, and he received just 2.4 percent of the nationwide popular vote.

The Seventh Congress of the Comintern made a change in line official in 1935, when it declared the need for a popular front of all groups opposed to fascism. The CPUSA abandoned its opposition to the New Deal, provided many of the organizers for the Congress of Industrial Organizations and began supporting civil rights of African Americans. The party also sought unity with forces to its right. Earl Russell Browder offered to run as Norman Thomas' running mate on a joint Socialist Party–Communist Party ticket in the 1936 presidential election, but Thomas rejected this overture. The gesture did not mean that much in practical terms, since by 1936 the CPUSA was effectively supporting Roosevelt in much of his trade-union work. While continuing to run its own candidates for office, the CPUSA pursued a policy of representing the Democratic Party as the lesser evil in elections. Party members also rallied to the defense of the Spanish Republic of 1931-1939 during this period after a Nationalist military uprising moved to overthrow it, resulting in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939). The CPUSA, along with leftists throughout the world, raised funds for medical relief, while many of its members made their way to Spain with the aid of the party to join the Lincoln Brigade, one of the International Brigades. Among its other achievements, the Lincoln Brigade became the first American military force to include blacks and whites integrated on an equal basis.

Intellectually, the Popular-Front period saw the development of a strong communist influence in intellectual and artistic life. This often took place through various organizations influenced or controlled by the party, or—as they were pejoratively known—"fronts". The CPUSA under Browder supported Stalin's show trials in the Soviet Union, called the Moscow Trials.[103] Therein, between August 1936 and mid-1938, the Soviet government indicted, tried and shot virtually all of the remaining Old Bolsheviks.[103] Beyond the show trials lay a broader purge, the Great Purge, that killed millions.[103][need quotation to verify] Browder uncritically supported Stalin, likening Trotskyism to "cholera germs" and calling the purge "a signal service to the cause of progressive humanity."[104] He compared the show-trial defendants to domestic traitors (Benedict Arnold, Aaron Burr, disloyal War of 1812 Federalists and Confederate secessionists) while likening persons who "smeared" Stalin's name to those who had slandered Abraham Lincoln and Franklin D. Roosevelt.[104]

For the first half of the 20th century, the Communist Party was a highly influential force in various struggles for democratic rights. It played a prominent role in the United States labor-movement from the 1920s through the 1940s, having a major hand in mobilizing the unemployed during the worst of the Great Depression[105][106] in the early 1930s and founding most[quantify] of the country's first industrial unions (which would later use the 1950 McCarran Internal Security Act to expel their Communist members) while also becoming known for opposing racism and fighting for integration in workplaces and communities during the height of the Jim Crow period of racial segregation. Historian Ellen Schrecker concludes that decades of recent scholarship[107] offer "a more nuanced portrayal of the party as both a Stalinist sect tied to a vicious regime and the most dynamic organization within the American Left during the 1930s and '40s."[108] The Communist Party USA played a significant role in defending the rights of African Americans during its heyday in the 1930s and 1940s. Throughout its history, many of the party's leaders and political thinkers have been African Americans: James Ford, Charlene Mitchell, Angela Davis, and Jarvis Tyner (the current executive vice chair of the party) all ran as presidential or vice-presidential candidates on the party ticket. Others like Benjamin J. Davis, William L. Patterson, Harry Haywood, James Jackson, Henry Winston, Claude Lightfoot, Alphaeus Hunton, Doxey Wilkerson, Claudia Jones and John Pittman also contributed in important ways to the party's approaches to major issues from human and civil rights, peace, women's equality, the national question, working-class unity, socialist thought, cultural struggle and more. African-American thinkers, artists and writers such as Claude McKay, Richard Wright, Ann Petry, W. E. B. Du Bois, Shirley Graham Du Bois, Lloyd Brown, Charles White, Elizabeth Catlett, Paul Robeson, Gwendolyn Brooks and many more were one-time members or supporters of the party and the Communists also had a close alliance with Harlem Congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr.[109] A rivalry emerged in 1931 between the NAACP and the CPUSA, when the CPUSA responded quickly and effectively to support the Scottsboro Boys, nine African-American youth arrested in 1931 in Alabama for rape.[110] Du Bois and the NAACP felt that the case would not be beneficial to their cause, so they chose to let the CPUSA organize the defense efforts.[111]

In 1929 Reverend A. J. Muste attempted to organize radical unionists opposed to the passive policies of American Federation of Labor president William Green (in office: 1924–1952) under the banner of an organization called the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA).[112] In 1933 Muste's CPLA took the step of establishing itself as the core of a new political organization called the American Workers Party (AWP).[113] Contemporaries informally referred to this organization as "Musteite".[113] The AWP then merged with the Trotskyist Communist League of America in 1934 to establish a group called the Workers Party of the United States. Through it all Muste continued to work as a labor activist, leading the victorious Toledo Auto-Lite strike of 1934.[113] Throughout 1935 the Workers Party remained deeply divided over the "entryism" tactic called for by the "French Turn", and a bitter debate swept the organization. Ultimately, the majority faction of Jim Cannon, Max Shachtman and James Burnham won the day and the Workers Party determined to enter the Socialist Party of America (SPA), though a minority faction headed by Hugo Oehler refused to accept this result and split from the organization. The Trotskyists retained a common orientation with the radicalized SPA in their opposition to the European war,[which?] their preference for industrial unionism and the Congress of Industrial Organizations over the trade unionism of the AFL, a commitment to trade union activism, the defense of the Soviet Union as the first workers' state; while at the same time maintaining an antipathy toward the Stalin government and in their general aims in the 1936 election.[114] The Communist Party of the USA (Opposition) was a right oppositionist movement of the 1930s. The organization emerged from a factional fight in the CPUSA in 1929 and unsuccessfully sought to reintegrate with that organization for several years[115]

Norman Thomas attracted nearly 188,000 votes in his 1936 Socialist Party run for president, but performed poorly in historic strongholds of the party. Moreover, the Socialist Party of America's membership had begun to decline.[116] The organization was deeply factionalized, with the Militant faction split into right ("Altmanite"), center ("Clarity") and left ("Appeal") factions, in addition to the radical pacifists led by Thomas. A special convention was planned for the last week of March 1937 to set the party's future policy, initially intended as an unprecedented "secret" gathering.[117]

They fear, in a word, that Soviet America will become the counterpart of what they have been told Soviet Russia looks like. Actually American soviets will be as different from the Russian soviets as the United States of President Roosevelt differs from the Russian Empire of Czar Nicholas II. Yet communism can come in America only through revolution, just as independence and democracy came in America.

Trotsky on If American Should Go Communist in 1934.[118]

Constance Myers indicates that three factors led to the expulsion of the Trotskyists from the Socialist Party in 1937: the divergence between the official Socialists and the Trotskyist faction on the issues, the determination of Jack Altman's wing of the Militants to oust the Trotskyists and Trotsky's own decision to move towards a break with the party.[119] Recognizing that the Clarity faction had chosen to stand with the Altmanites and the Thomas group, Trotsky recommended that the Appeal group focus on disagreements over Spain to provoke a split. At the same time, Thomas, freshly returned from Spain, had come to the conclusion that the Trotskyists had joined the Socialist Party not to make it stronger, but to capture the organization for their own purposes.[120] The 1,000 or so Trotskyists who had entered the Socialist Party in 1936 exited in the summer of 1937 with their ranks swelled by another 1,000.[121] On December 31, 1937, representatives of this faction gathered in Chicago to establish a new political organization—the Socialist Workers Party (SWP).

1950s: Second Red Scare

[edit]

Monthly Review, established in 1949, is an independent socialist journal published monthly in New York City. As of 2013, the publication remains the longest continuously published socialist magazine in the United States. It was established by Christian socialist F. O. "Matty" Matthiessen and Marxist economist Paul Sweezy, who were former colleagues at Harvard University.[122] The world-famous physicist and resident in the United States Albert Einstein published a famous article in the first issue of Monthly Review (May 1949) arguing for socialism titled "Why Socialism?". It was subsequently published in May 1998 to commemorate the first issue of Monthly Review's fiftieth year.[123] Editors Huberman and Sweezy argued as early as 1952 that massive and expanding military spending was an integral part of the process of capitalist stabilization, driving corporate profits, bolstering levels of employment and absorbing surplus production. The illusion of an external military threat was required to sustain this system of priorities in government spending, they argued; consequently, the editors published material challenging the dominant Cold War paradigm of "Democracy versus Communism".[124] The Johnson–Forest tendency, sometimes called the Johnsonites, refers to a radical left tendency in the United States associated with Marxist theorists C. L. R. James and Raya Dunayevskaya, who used the pseudonyms J. R. Johnson and Freddie Forest respectively. They were joined by Grace Lee Boggs, a Chinese American woman who was considered the third founder. After leaving the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party, Johnson–Forest founded their own organization for the first time, called Correspondence. In 1956, James would see the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 as confirmation of this. Those who endorsed the politics of James took the name Facing Reality, after the 1958 book by James co-written with Grace Lee Boggs and Pierre Chaulieu, a pseudonym for Cornelius Castoriadis, on the Hungarian working class revolt of 1956.

Anarchism continued to influence important American literary and intellectual personalities of the time, such as Paul Goodman, Dwight Macdonald, Allen Ginsberg, Leopold Kohr,[125][126] Julian Beck and John Cage.[127] Goodman was an American sociologist, poet, writer, anarchist and public intellectual. Goodman is now mainly remembered as the author of Growing Up Absurd (1960) and an activist on the pacifist left in the 1960s and an inspiration to that era's student movement. He is less remembered as a co-founder of Gestalt Therapy in the 1940s and 1950s. In the mid-1940s, together with C. Wright Mills, he contributed to Politics, the journal edited during the 1940s by Dwight Macdonald.[128] An American anarcho-pacifist current developed in this period as well as a related Christian anarchist one. Anarcho-pacifism is a tendency within the anarchist movement which rejects the use of violence in the struggle for social change.[129][130] The main early influences were the thought of Henry David Thoreau[130] and Leo Tolstoy while later the ideas of Mohandas Gandhi gained importance.[129][130] It developed "mostly in Holland, Britain, and the United States, before and during the Second World War."[131] Dorothy Day was an American journalist, social activist and devout Catholic convert who advocated the Catholic economic theory of distributism. She was also considered to be an anarchist[132][133][134] and did not hesitate to use the term.[135] In the 1930s, Day worked closely with fellow activist Peter Maurin to establish the Catholic Worker Movement, a nonviolent, pacifist movement that continues to combine direct aid for the poor and homeless with nonviolent direct action on their behalf. The cause for Day's canonization is open in the Catholic Church. Ammon Hennacy was an American pacifist, Christian anarchist, vegetarian, social activist, member of the Catholic Worker Movement and a Wobbly. He established the Joe Hill House of Hospitality in Salt Lake City, Utah and practiced tax resistance.

Reunification with the Social Democratic Federation (SDF) was long a goal of Norman Thomas and his associates remaining in the Socialist Party. As early as 1938, Thomas had acknowledged that a number of issues had been involved in the split which led to the formation of the rival SDF, including "organizational policy, the effort to make the party inclusive of all socialist elements not bound by communist discipline; a feeling of dissatisfaction with social democratic tactics which had failed in Germany" as well as "the socialist estimate of Russia; and the possibility of cooperation with communists on certain specific matters." Still, he held that "those of us who believe that an inclusive socialist party is desirable, and ought to be possible, hope that the growing friendliness of socialist groups will bring about not only joint action but ultimately a satisfactory reunion on the basis of sufficient agreement for harmonious support of a socialist program."[136] Following directions from the Soviet Union, the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and its members were active in the Civil Rights Movement for African Americans.[137] Following Stalin's "theory of nationalism", the CPUSA once favored the creation of a separate "nation" for negroes to be located in the American Southeast.[138] In 1941, after Germany invaded the Soviet Union, Stalin ordered the CPUSA to abandon civil rights work and focus supporting American entry into World War II. Disillusioned, Bayard Rustin began working with members of the Socialist Party USA (SPUSA) of Norman Thomas, particularly A. Philip Randolph, the head of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. The Socialist Party and the SDF merged to form the Socialist Party–Social Democratic Federation (SP–SDF) in 1957. A small group of holdouts refused to reunify, establishing a new organization called the Democratic Socialist Federation (DSF). When the Soviet Union led an invasion of Hungary in 1956, half of the members of communist parties around the world quit and in the United States half did and many joined the Socialist Party. Frank Zeidler was an American socialist politician and mayor of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, serving three terms from April 20, 1948, to April 18, 1960. He was the most recent socialist mayor of any major American city. Zeidler was Milwaukee's third socialist mayor after Emil Seidel (1910–1912) and Daniel Hoan (1916–1940), making Milwaukee the largest American city to elect three socialists to its highest office.

In 1958, the SPUSA welcomed former members of the Independent Socialist League (ISL), which before its 1956 dissolution had been led by Max Shachtman. Shachtman had developed a Marxist critique of Soviet communism as "bureaucratic collectivism", a new form of class society that was more oppressive than any form of capitalism. Shachtman's theory was similar to that of many dissidents and refugees from Communism, such as the theory of the "new class" proposed by Yugoslavian dissident Milovan Djilas. Shachtman's ISL had attracted youth like Irving Howe, Michael Harrington,[139] Tom Kahn and Rachelle Horowitz.[140][141][142] The Young People's Socialist League was dissolved, but the party formed a new youth group under the same name.[143]

The Second Red Scare is a period lasting roughly from 1950 to 1956 and characterized by heightened fears of Communist influence on American institutions and espionage by Soviet agents. During the McCarthy era, thousands of Americans were accused of being communists or Communist sympathizers and became the subject of aggressive investigations and questioning before government or private-industry panels, committees and agencies. The primary targets of such suspicions were government employees, those in the entertainment industry, educators and union activists. Suspicions were often given credence despite inconclusive or questionable evidence and the level of threat posed by a person's real or supposed leftist associations or beliefs was often greatly exaggerated. Many people suffered loss of employment and/or destruction of their careers; and some even suffered imprisonment. Most of these punishments came about through trial verdicts later overturned,[144] laws that would be declared unconstitutional,[145] dismissals for reasons later declared illegal[146] or actionable,[147] or extra-legal procedures that would come into general disrepute. The most famous examples of McCarthyism include the speeches, investigations and hearings of Senator McCarthy himself; the Hollywood blacklist, associated with hearings conducted by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC); and the various anti-communist activities of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) under Director J. Edgar Hoover. It is difficult to estimate the number of victims of McCarthyism. The number imprisoned is in the hundreds and some ten or twelve thousand lost their jobs.[148] In many cases, simply being subpoenaed by HUAC or one of the other committees was sufficient cause to be fired.[149] Many of those who were imprisoned, lost their jobs or were questioned by committees did in fact have a past or present connection of some kind with the CPUSA. However, for the vast majority both the potential for them to do harm to the nation and the nature of their communist affiliation were tenuous.[150] The African American intellectual and activist W. E. B. Du Bois was affected by these policies and he became incensed in 1961 when the Supreme Court upheld the 1950 McCarran Act, a key piece of McCarthyism legislation which required communists to register with the government.[151] To demonstrate his outrage, he joined the CPUSA in October 1961 at the age of 93.[151] Around that time, he wrote: "I believe in communism. I mean by communism, a planned way of life in the production of wealth and work designed for building a state whose object is the highest welfare of its people and not merely the profit of a part."[152] In 1950, Du Bois had already run for senator from New York on the socialist American Labor Party ticket and received about 200,000 votes, or 4% of the statewide total.[153]

Harry Hay was an English-born American labor advocate, teacher and early leader in the American LGBT rights movement. He is known for his roles in helping to found several gay organizations, including the Mattachine Society, the first sustained gay rights group in the United States which in its early days had a strong Marxist influence. The Encyclopedia of Homosexuality reports: "As Marxists the founders of the group believed that the injustice and oppression which they suffered stemmed from relationships deeply embedded in the structure of American society."[154] A longtime member of the CPUSA, Hay's Marxist history led to his resignation from the Mattachine leadership in 1953. Hay's involvement in the gay movement became more informal after that, although he did co-found the Los Angeles chapter of the Gay Liberation Front in 1969. As Hay became more involved in his Mattachine work, he correspondingly became more concerned that his homosexuality would negatively affect the CPUSA, which did not allow gays to be members. Hay himself approached party leaders and recommended his own expulsion. The party refused to expel Hay as a homosexual, instead expelling him as a "security risk" at the same time declaring him to be a "Lifelong Friend of the People".[155] Homosexuality was classified as a psychiatric disorder in the 1950s.[156] However, in the context of the highly politicised Cold War environment homosexuality became framed as a dangerous, contagious social disease that posed a potential threat to state security.[156] This era also witnessed the establishment of widely spread FBI surveillance intended to identify homosexual government employees.[157]

1960s–1970s: New Left and social unrest

[edit]

The term New Left was popularised in the United States in an open letter written in 1960 by sociologist C. Wright Mills (1916–1962), entitled Letter to the New Left.[158] Mills argued for a new leftist ideology, moving away from the traditional focus on labor issues (Old Left), towards issues such as opposing alienation, anomie and authoritarianism. Mills argued for a shift from traditional leftism toward the values of the counterculture and emphasized an international perspective on the movement.[159] According to David Burner, C Wright Mills claimed that the proletariat were no longer the revolutionary force as the new agent of revolutionary change were young intellectuals around the world.[160]

In the wake of the downfall of Senator McCarthy (who never served in the House, nor HUAC), the prestige of HUAC began a gradual decline beginning in the late 1950s. By 1959, the committee was being denounced by former President Harry S. Truman as the "most un-American thing in the country today."[161] The committee lost considerable prestige as the 1960s progressed, increasingly becoming the target of political satirists and the defiance of a new generation of political activists. HUAC subpoenaed Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman of the Yippies in 1967 and again in the aftermath of the 1968 Democratic National Convention. The Yippies used the media attention to make a mockery of the proceedings. Rubin came to one session dressed as a United States Revolutionary War soldier and passed out copies of the United States Declaration of Independence to people in attendance. Rubin then "blew giant gum bubbles while his co-witnesses taunted the committee with Nazi salutes."[162]

The Progressive Labor Party (PLP) was formed in the fall of 1961 by members of the CPUSA who felt that the Soviet Union had betrayed communism and become revisionist amidst the Sino-Soviet Split. Progressive Labor Party founded the university campus-based May 2 Movement (M2M), which organized the first significant general march against the Vietnam War in New York City in 1964. However, once the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) came to the forefront of the American leftist activist political scene in 1965, PLP dissolved M2M and entered SDS, working vigorously to attract supporters and to form party clubs on campuses. On the other hand, the Trotskyist Socialist Workers Party (SWP) supported both the civil rights movement and the black nationalist movement which grew during the 1960s. It particularly praised the militancy of black nationalist leader Malcolm X, who in turn spoke at the SWP's public forums and gave an interview to the Young Socialist. Like all left wing groups, the SWP grew during the 1960s and experienced a particularly brisk growth in the first years of the 1970s. Much of this was due to its involvement in many of the campaigns and demonstrations against the war in Vietnam.

Kahn and Horowitz, along with Norman Hill, helped Bayard Rustin with the civil rights movement. Rustin had helped to spread pacificism and non-violence to leaders of the civil rights movement, like Martin Luther King Jr. Rustin's circle and A. Philip Randolph organized the 1963 March on Washington, where King delivered his "I Have a Dream" speech.[3][4][5][6] King began to speak of the need for fundamental changes in the political and economic life of the nation and more frequently expressed his opposition to the war and his desire to see a redistribution of resources to correct racial and economic injustice.[163] As such, he started his Poor People's Campaign in 1968 as an effort to gain economic justice for poor people in the United States. He guarded his language in public to avoid being linked to communism by his enemies, but in private he sometimes spoke of his support for democratic socialism. In a 1952 letter to Coretta Scott, he said: "I imagine you already know that I am much more socialistic in my economic theory than capitalistic."[164] In one speech, he stated that "something is wrong with capitalism" and claimed that "[t]here must be a better distribution of wealth, and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism."[165]

Dr. Martin Luther King was the leader of the Civil Rights Movement, which emphasized nonviolence in the struggle for social justice and to give Black Americans equal rights under the law. According to David J. Garrow, King in private conversation "made it clear to close friends that economically speaking he considered himself what he termed a Marxist, largely because he believed with increasing strength that American society needed a radical redistribution of wealth and economic power to achieve even a rough form of social justice."[166] King, in 1966, "rejected the idea of piecemeal reform within the existing socio-economic structure. Only at that time did he become persuaded that capitalism is the common determinant linking together racism, economic oppression, and militarism."[166] There is conflicting interpretation by scholars who view King's radicalization of thought as being a result of experience and pressure from the Black Power Movement or whether it was rooted in his formative experience at Morehouse College. It is speculated that King read Karl Marx as a college student. Nevertheless, King began to push for a more socialistic platform during his time as the leader of the Poor People's Campaign. He began pushing for policies such as a guaranteed annual income, constitutional amendments to secure social and economic equality, and greatly expanded public housing. In addition, he advocated for a jobs guarantee, a living wage and universal healthcare. King was transitioning from the leader who led campaigns for civil rights and racial justice, to a campaign that was more anti-Capitalistic, anti-War, and a full frontal attack on the war on poverty. In a 1961 speech to the Negro American Labor Council, King declared, "Call it democracy, or call it democratic socialism, but there must be a better distribution of wealth within this country for all God's children."

Michael Harrington soon became the most visible socialist in the United States when his The Other America became a best seller, following a long and laudatory New Yorker review by Dwight Macdonald.[167] Harrington and other socialists were called to Washington, D.C. to assist the Kennedy administration and then the Johnson administration's War on Poverty and Great Society.[2] Shachtman, Harrington, Kahn and Rustin argued advocated a political strategy called "realignment" that prioritized strengthening labor unions and other progressive organizations that were already active in the Democratic Party. Contributing to the day-to-day struggles of the Civil Rights Movement and labor unions had gained socialists credibility and influence, and had helped to push politicians in the Democratic Party towards social liberal or social democratic positions, at least on civil rights and the War on Poverty.[168][169] Harrington, Kahn and Horowitz were officers and staff-persons of the League for Industrial Democracy (LID), which helped to start the New Left Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).[170] The three LID officers clashed with the less experienced activists of SDS, like Tom Hayden, when the latter's Port Huron Statement criticized socialist and liberal opposition to communism and criticized the labor movement while promoting students as agents of social change.[171][172] LID and SDS split in 1965, when SDS voted to remove from its constitution the "exclusion clause" that prohibited membership by communists:[173] The SDS exclusion clause had barred "advocates of or apologists for totalitarianism."[174] The clause's removal effectively invited "disciplined cadre" to attempt to "take over or paralyze" SDS as had occurred to mass organizations in the thirties.[175] Afterwards, Marxism–Leninism, particularly the PLP, helped to write "the death sentence" for SDS,[176][175][177][178] which nonetheless had over 100 thousand members at its peak. Monopoly Capital: An Essay on the American Economic and Social Order is a book by Paul Sweezy and Paul A. Baran published in 1966 by Monthly Review Press. It made a major contribution to Marxian theory by shifting attention from the assumption of a competitive economy to the monopolistic economy associated with the giant corporations that dominate the modern accumulation process. Their work played a leading role in the intellectual development of the New Left in the 1960s and 1970s. As a review in the American Economic Review stated, it represented "the first serious attempt to extend Marx's model of competitive capitalism to the new conditions of monopoly capitalism."[179] It has recently attracted renewed attention following the Great Recession.[180][181][182]

In the 1960s, the hippie movement influenced a renewed interest in anarchism, and some anarchist and other left-wing groups developed out of the New Left[184][185][186] and anarchists actively participated in the late sixties students and workers revolts.[187] Anarchists began using direct action, organizing through affinity groups during anti-nuclear campaigns in the 1970s. The New Left in the United States also included anarchist, countercultural and hippie-related radical groups such as the Yippies who were led by Abbie Hoffman, the Diggers[188] and Black Mask/Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers. By late 1966, the Diggers opened free stores which simply gave away their stock, provided free food, distributed free drugs, gave away money, organized free music concerts and performed works of political art.[189] The Diggers took their name from the original English Diggers led by Gerrard Winstanley[190] and sought to create a mini-society free of money and capitalism.[191] On the other hand, the Yippies employed theatrical gestures, such as advancing a pig ("Pigasus the Immortal") as a candidate for president in 1968, to mock the social status quo.[192] They have been described as a highly theatrical, anti-authoritarian and anarchist[193] youth movement of "symbolic politics".[194] Since they were well known for street theater and politically themed pranks, many of the "old school" political left either ignored or denounced them. According to ABC News: "The group was known for street theater pranks and was once referred to as the 'Groucho Marxists'."[195] By the 1960s, Christian anarchist Dorothy Day earned the praise of counterculture leaders such as Abbie Hoffman, who characterized her as the first hippie,[196] a description of which Day approved.[196] Murray Bookchin[197] was an American anarchist and libertarian socialist author, orator and political theoretician.[197] A pioneer in the ecology movement[198] by publishing that and other innovative essays on post-scarcity and on ecological technologies such as solar and wind energy and on decentralization and miniaturization. Lecturing throughout the United States, he helped popularize the concept of ecology to the counterculture. The Black Panther Party was a black revolutionary socialist organization active in the United States from 1966 until 1982. The Black Panther Party achieved national and international notoriety through its involvement in the Black Power movement and American politics of the 1960s and 1970s.[199] Gaining national prominence, the Black Panther Party became an icon of the counterculture of the 1960s.[200] Ultimately, the Panthers condemned black nationalism as "black racism" and became more focused on socialism without racial exclusivity.[201] They instituted a variety of community social programs designed to alleviate poverty, improve health among inner city black communities and soften the Party's public image.[202]

Activists in the 1970s used Socialism and reinterpreted in order to encompass members of radical movements, whether it be the Black Panther Party or the Gay and Lesbian Left. The overlap between all of these different radical movements was that they were oppressed peoples who were subjugated by the ruling straight white male elite class. Similar themes between these different movements was the issue of capitalist violence that was used to preserve power for the ruling class. There was a prominent group of socialist activists in San Francisco who were combatting the issues of homophobia, American imperialism, and police brutality. The assassination of gay rights proponent Harvey Milk by an ex-cop resulted in police violence that "encouraged attacks on gay men, Lesbians, prostitutes, and Third World people."[203] Angela Davis, an ally of the Black Panther Party and a socialist, viewed capitalism as an inherently violent system. In response to a question regarding the violent nature of the Black Panthers, she says "If you are a black person who lives in a black community all your life and walk out on the street everyday seeing white policemen surrounding you… When you live under a situation like that constantly, and then you ask me whether I approve of violence, I mean, that just doesn't make sense at all." Davis speaks to how capitalism subjugates black people through violence and that the main purpose of police is to protect white supremacy. The Black Panther Party were prominent members of Black Power Movement and was fueled by what they saw as systemic racism perpetuated against black people. According to Douglas Sturm, Professor Emeritus of Religion and Political Science at Bucknell University: "Police brutality, lack of opportunity, and the realization that opportunity was not forthcoming in the near future led many Blacks to conclude that armed self-defense coupled with self-help was the only way to end the despair."[204] This armed-self defense made many white Americans fearful of the Black Panthers and contributed to the FBI's designation of the Black Panthers as a terrorist organization. Although the Black Panthers were labeled violent extremists and terrorists, they provided many resources to their communities, including free healthcare, breakfast, and education services.[205]