Stonewall riots

| Stonewall riots | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Part of events leading to gay liberation | |||

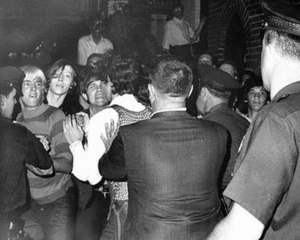

The only known photograph taken during the first night of the riots, by freelance photographer Joseph Ambrosini, shows gay youth scuffling with police.[1] | |||

| Date | June 28 – July 3, 1969[2] | ||

| Location | 40°44′02″N 74°00′08″W / 40.7338°N 74.0021°W | ||

| Caused by | Police raid on the Stonewall Inn (specifically) General repression of LGBT rights (more broadly) | ||

| Goals | Gay liberation and LGBT rights in the United States | ||

| Methods | Rioting, street protests | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Number | |||

| |||

The Stonewall riots, also known as the Stonewall uprising, Stonewall rebellion, Stonewall revolution[3], or simply Stonewall, were a series of spontaneous, violent demonstrations against a police raid that took place in the early morning hours of June 28, 1969, at the Stonewall Inn, in the Greenwich Village neighborhood of New York City. Although the demonstrations were not the first time American homosexuals fought back against government-sponsored persecution of sexual minorities, the Stonewall riots marked a new beginning for the gay rights movement in the United States and around the world.[note 1]

American gays and lesbians in the 1950s and 1960s faced a legal system more anti-homosexual than those of some Warsaw Pact countries.[note 2] Early homophile groups in the U.S. sought to prove that gay people could be assimilated into society, and they favored non-confrontational education for homosexuals and heterosexuals alike. The last years of the 1960s, however, were very contentious, as many social movements were active, including the African American Civil Rights Movement, the Counterculture of the 1960s, and antiwar demonstrations. These influences, along with the liberal environment of Greenwich Village, served as catalysts for the Stonewall riots.

Very few establishments welcomed openly gay people in the 1950s and 1960s. Those that did were often bars, although bar owners and managers were rarely gay. The Stonewall Inn was owned by the Mafia[4][5] and catered to an assortment of patrons, popular among the poorest and most marginalized people in the gay community: drag queens, representatives of a newly self-aware transgender community, effeminate young men, hustlers, and homeless youth. Police raids on gay bars were routine in the 1960s, but officers quickly lost control of the situation at the Stonewall Inn and attracted a crowd that was incited to riot. Tensions between New York City police and gay residents of Greenwich Village erupted into more protests the next evening and again several nights later. Within weeks, Village residents quickly organized into activist groups to concentrate efforts on establishing places for gays and lesbians to be open about their sexual orientation without fear of being arrested.

Following the Stonewall riots, sexual minorities in New York City faced gender, class, and generational obstacles to becoming a cohesive community. In the weeks and months after, they initiated politically active social organizations and launched publications that spoke openly about rights for gay people. The first anniversary of the riots was marked by peaceful demonstrations in several American cities that have since grown to become pride parades. The Stonewall National Monument was established at the site in 2016. Today, pride events are held annually throughout the world toward the end of June to mark the Stonewall riots.

Background

[edit]Homosexuality in 20th-century United States

[edit]| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

|

|

Following the social upheaval of World War II, many people in the United States felt a fervent desire to "restore the prewar social order and hold off the forces of change", according to historian Barry Adam.[6] Spurred by the national emphasis on anti-communism, Senator Joseph McCarthy conducted hearings searching for communists in the U.S. government, the U.S. Army, and other government-funded agencies and institutions, leading to a national paranoia. Anarchists, communists, and other people deemed un-American and subversive were considered security risks. Gay men and lesbians were included in this list by the U.S. State Department on the theory that they were susceptible to blackmail. In 1950, a Senate investigation chaired by Clyde R. Hoey noted in a report, "It is generally believed that those who engage in overt acts of perversion lack the emotional stability of normal persons",[7] and said all of the government's intelligence agencies "are in complete agreement that sex perverts in Government constitute security risks".[8] Between 1947 and 1950, 1,700 federal job applications were denied, 4,380 people were discharged from the military, and 420 were fired from their government jobs for being suspected homosexuals.[9]

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and police departments kept lists of known homosexuals and their favored establishments and friends; the U.S. Post Office kept track of addresses where material pertaining to homosexuality was mailed.[10] State and local governments followed suit: bars catering to gay men and lesbians were shut down and their customers were arrested and exposed in newspapers. Cities performed "sweeps" to rid neighborhoods, parks, bars, and beaches of gay people. They outlawed the wearing of opposite-gender clothes and universities expelled instructors suspected of being homosexual.[11]

In 1952, the American Psychiatric Association listed homosexuality in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) as a mental disorder. A large-scale study of homosexuality in 1962 was used to justify the inclusion of the "disorder" as a supposed pathological hidden fear of the opposite sex caused by traumatic parent–child relationships. This view was widely influential in the medical profession.[12] In 1956, the psychologist Evelyn Hooker performed a study that compared the happiness and well-adjusted nature of self-identified homosexual men with heterosexual men and found no difference.[13] Her study stunned the medical community and made her a hero to many gay men and lesbians,[14] but homosexuality remained in the DSM until 1974.[15]

Homophile activism

[edit]In response to this trend, two organizations formed independently of each other to advance the cause of gay men and lesbians and provide opportunities where they could socialize without fear of being arrested. Los Angeles area homosexuals created the Mattachine Society in 1950, in the home of communist activist Harry Hay.[16] Their objectives were to unify homosexuals, educate them, provide leadership, and assist "sexual deviants" with legal troubles.[17] Facing enormous opposition to their radical approach, in 1953 the Mattachine shifted their focus to assimilation and respectability. They reasoned that they would change more minds about homosexuality by proving that gay men and lesbians were normal people, no different from heterosexuals.[18][19] Soon after, several women in San Francisco met in their living rooms to form the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) for lesbians.[20] Although the eight women who created the DOB initially came together to be able to have a safe place to dance, as the DOB grew they developed similar goals to the Mattachine and urged their members to assimilate into general society.[21]

One of the first challenges to government repression came in 1953. An organization named ONE, Inc. published a magazine called ONE. The U.S. Postal Service refused to mail its August issue, which concerned homosexual people in heterosexual marriages, on the grounds that the material was obscene despite it being covered in brown paper wrapping. The case eventually went to the Supreme Court, which in 1958 ruled that ONE, Inc. could mail its materials through the Postal Service.[22]

Homophile organizations—as homosexual groups self-identified in this era—grew in number and spread to the East Coast. Gradually, members of these organizations grew bolder. Frank Kameny founded the Mattachine of Washington, D.C. He had been fired from the U.S. Army Map Service for being a homosexual and sued unsuccessfully to be reinstated. Kameny wrote that homosexuals were no different from heterosexuals, often aiming his efforts at mental health professionals, some of whom attended Mattachine and DOB meetings telling members they were abnormal.[23]

In 1965, news on Cuban prison work camps for homosexuals inspired Mattachine New York and D.C. to organize protests at the United Nations and the White House. Similar demonstrations were then held also at other government buildings. The purpose was to protest the treatment of gay people in Cuba[24][25] and U.S. employment discrimination. These pickets shocked many gay people and upset some of the leadership of Mattachine and the DOB.[26][27] At the same time, demonstrations in the civil rights movement and opposition to the Vietnam War all grew in prominence, frequency, and severity throughout the 1960s, as did their confrontations with police forces.[28]

Earlier resistance and riots

[edit]On the outer fringes of the few small gay communities were people who challenged gender expectations. They were effeminate men and masculine women, or people who dressed and lived in contrast to their sex assigned at birth, either part or full-time. Contemporaneous nomenclature classified them as transvestites and they were the most visible representatives of sexual minorities. They belied the carefully crafted image portrayed by the Mattachine Society and DOB asserted homosexuals were respectable, normal people.[29] The Mattachine and DOB considered the trials of being arrested for wearing clothing of the opposite gender as a parallel to the struggles of homophile organizations: similar but distinctly separate.

Gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people staged a small riot at the Cooper Do-nuts café in Los Angeles in 1959 in response to police harassment.[30] In a larger 1966 event in San Francisco, drag queens, hustlers, and trans women[31] were sitting in Compton's Cafeteria when the police arrived to arrest people appearing to be physically male who were presenting as women. A riot ensued, with the cafeteria patrons slinging cups, plates, and saucers and breaking the plexiglass windows in the front of the restaurant and returning several days later to smash the windows again after they were replaced.[32] Professor Susan Stryker classifies the Compton's Cafeteria riot as an "act of anti-transgender discrimination, rather than an act of discrimination against sexual orientation" and connects the uprising to the issues of gender, race, and class that were being downplayed by homophile organizations.[29] It marked the beginning of transgender activism in San Francisco.[32]

Greenwich Village

[edit]

The Manhattan neighborhoods of Greenwich Village and Harlem were home to sizable gay and lesbian populations after World War I, when people who had served in the military took advantage of the opportunity to settle in larger cities. The enclaves of gay men and lesbians, described by a newspaper story as "short-haired women and long-haired men", developed a distinct subculture through the following two decades.[33] Prohibition inadvertently benefited gay establishments, as drinking alcohol was pushed underground along with other behaviors considered immoral. New York City passed laws against homosexuality in public and private businesses, but because alcohol was in high demand, speakeasies and impromptu drinking establishments were so numerous and temporary that authorities were unable to police them all.[34] However, police raids continued, resulting in the closure of iconic establishments such as Eve's Hangout in 1926.[35]

The social repression of the 1950s resulted in a cultural revolution in Greenwich Village. A cohort of poets, later named the Beat poets, wrote about the evils of the social organization at the time, glorifying anarchy, drugs, and hedonistic pleasures over unquestioning social compliance, consumerism, and closed-mindedness. Of them, Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs—both Greenwich Village residents—also wrote bluntly and honestly about homosexuality. Their writings attracted sympathetic liberal-minded people, as well as homosexuals looking for a community.[36]

By the early 1960s, a campaign to rid New York City of gay bars was in full effect by order of Mayor Robert F. Wagner Jr., who was concerned about the image of the city in preparation for the 1964 World's Fair. The city revoked the liquor licenses of the bars and undercover police officers worked to entrap as many homosexual men as possible.[37] Entrapment usually consisted of an undercover officer who found a man in a bar or public park, engaged him in conversation; if the conversation headed toward the possibility that they might leave together—or the officer bought the man a drink—he was arrested for solicitation. One story in the New York Post described an arrest in a gym locker room, where the officer grabbed his crotch, moaning, and a man who asked him if he was all right was arrested.[38] Few lawyers would defend cases as undesirable as these and some of those lawyers kicked back their fees to the arresting officer.[39]

The Mattachine Society succeeded in getting newly elected mayor John Lindsay to end the campaign of police entrapment in New York City. They had a more difficult time with the New York State Liquor Authority (SLA). While no laws prohibited serving homosexuals, courts allowed the SLA discretion in approving and revoking liquor licenses for businesses that might become "disorderly".[4][40] Despite the high population of gay men and lesbians who called Greenwich Village home, very few places existed, other than bars, where they were able to congregate openly without being harassed or arrested. In 1966 the New York Mattachine held a "sip-in" at a Greenwich Village bar named Julius, which was frequented by gay men, to illustrate the discrimination homosexuals faced.[41]

None of the bars frequented by gay men and lesbians were owned by gay people. Almost all of them were owned and controlled by organized crime, who treated the regulars poorly, watered down the liquor, and overcharged for drinks. However, they also paid off police to prevent frequent raids.[42]

Stonewall Inn

[edit]The Stonewall Inn, located at 51 and 53 Christopher Street, along with several other establishments in the city, was owned by the Genovese crime family.[43] In 1966, three members of the Mafia invested $3,500 to turn the Stonewall Inn into a gay bar, after it had been a restaurant and a nightclub for heterosexuals. Once a week a police officer would collect envelopes of cash as a payoff known as a gayola, as the Stonewall Inn had no liquor license.[44][45] It had no running water behind the bar—dirty glasses were run through tubs of water and immediately reused.[42] There were no fire exits, and the toilets overran consistently.[46] Though the bar was not used for prostitution, drug sales and other black market activities took place. It was the only bar for gay men in New York City where dancing was allowed;[47] dancing was its main draw since its re-opening as a gay club.[48]

Visitors to the Stonewall Inn in 1969 were greeted by a bouncer who inspected them through a peephole in the door. The legal drinking age was 18 and to avoid unwittingly letting in undercover police (who were called "Lily Law", "Alice Blue Gown", or "Betty Badge"[49]), visitors would have to be known by the doorman or 'look gay'. Patrons were required to sign their names in a book to prove that the bar was a private "bottle club", but they rarely signed their real names. There were two dance floors in the Stonewall. The interior was painted black, making it very dark inside, with pulsing gel lights or black lights. If police were spotted, regular white lights were turned on, signaling that everyone should stop dancing or touching.[49] In the rear of the bar was a smaller room frequented by "queens"; it was one of two bars where effeminate men who wore makeup and teased their hair (though dressed in men's clothing) could go.[50] Only a few people in full drag were allowed in by the bouncers. The customers were "98 percent male" but a few lesbians sometimes came to the bar. Younger homeless adolescent males, who slept in nearby Christopher Park, would often try to get in so customers would buy them drinks.[51] The age of the clientele ranged between the upper teens and early thirties and the racial mix was distributed among mainly white, with Black, and Hispanic patrons.[50][52] Because of its mix of people, its location, and the attraction of dancing, the Stonewall Inn was known by many as "the gay bar in the city".[53]

Police raids on gay bars were frequent, occurring on average once a month for each bar. Many bars kept extra liquor in a secret panel behind the bar, or in a car down the block, to facilitate resuming business as quickly as possible if alcohol was seized.[43] Bar management usually knew about raids beforehand due to police tip-offs, and raids occurred early enough in the evening that business could commence after the police had finished.[54] During a typical raid, the lights were turned on and customers were lined up and their identification cards checked. Those without identification or dressed in full drag were arrested; others were allowed to leave. Some of the men, including those in drag, used their draft cards as identification. Women were required to wear three pieces of feminine clothing and would be arrested if found not wearing them. Typically, employees and management of the bars were also arrested.[54] The period immediately before June 28, 1969, was marked by frequent raids of local bars—including a raid at the Stonewall Inn on the Tuesday before the riots[55]—and the closing of the Checkerboard, the Tele-Star, and two other clubs in Greenwich Village.[56][57]

Riots

[edit]Police raid

[edit]

At 1:20 a.m. on Saturday, June 28, 1969, four plainclothes policemen in dark suits, two patrol officers in uniform, Detective Charles Smythe, and Deputy Inspector Seymour Pine arrived at the Stonewall Inn's double doors and announced "Police! We're taking the place!"[59] Two undercover policewomen and two undercover policemen entered the bar early that evening to gather visual evidence, as the Public Morals Squad waited outside for the signal. Once ready, the undercover officers called for backup from the Sixth Precinct using the bar's pay telephone. Stonewall employees do not recall being tipped off that a raid was to occur that night, as was the custom.[note 3] The music was turned off and the main lights were turned on. Approximately 200 people were in the bar that night. Patrons who had never experienced a police raid were confused. A few who realized what was happening began to run for doors and windows in the bathrooms, but police barred the doors. Michael Fader remembered, "Things happened so fast you kind of got caught not knowing. All of a sudden there were police there and we were told to all get in lines and to have our identification ready to be led out of the bar."[59]

The raid did not go as planned. Standard procedure was to line up the patrons, check their identification and have female police officers take customers dressed as women to the bathroom to verify their sex, upon which any people appearing to be physically male and dressed as women would be arrested. Those dressed as women that night refused to go with the officers. Men in line began to refuse to produce their identification. The police decided to take everyone present to the police station, after separating those suspected of cross-dressing in a room in the back of the bar. All parties involved recall that a sense of discomfort spread very quickly, started by police who assaulted some of the lesbians by "feeling some of them up inappropriately" while frisking them.[60]

When did you ever see a fag fight back? ... Now, times were a-changin'. Tuesday night was the last night for bullshit ... Predominantly, the theme [w]as, "this shit has got to stop!"

—anonymous Stonewall riots participant[61]

The police were to transport the bar's alcohol in patrol wagons. Twenty-eight cases of beer and nineteen bottles of hard liquor were seized, but the patrol wagons had not yet arrived, so patrons were required to wait in line for about 15 minutes.[62] Those who were not arrested were released from the front door, but they did not leave quickly as usual. Instead, they stopped outside and a crowd began to grow and watch. Within minutes, between 100 and 150 people had congregated outside, some after they were released from inside the Stonewall and some after noticing the police cars and the crowd. Although the police forcefully pushed or kicked some patrons out of the bar, some customers released by the police performed for the crowd by posing and saluting the police in an exaggerated fashion. The crowd's applause encouraged them further.[63]

When the first patrol wagon arrived, Inspector Pine recalled that the crowd—most of whom were homosexual—had grown to at least ten times the number of people who were arrested and they all became very quiet.[64] Confusion over radio communication delayed the arrival of a second wagon. The police began escorting Mafia members into the first wagon, to the cheers of the bystanders. Next, regular employees were loaded into the wagon. A bystander shouted, "Gay power!", someone began singing "We Shall Overcome" and the crowd reacted with amusement and general good humor mixed with "growing and intensive hostility".[65] An officer shoved a person in drag, who responded by hitting him on the head with her purse. The cop clubbed her over the head, as the crowd began to boo. Author Edmund White, who had been passing by, recalled, "Everyone's restless, angry, and high-spirited. No one has a slogan, no one even has an attitude, but something's brewing."[66] Pennies, then beer bottles, were thrown at the wagon as a rumor spread through the crowd that patrons still inside the bar were being beaten.

A scuffle broke out when a woman in handcuffs was escorted from the door of the bar to the waiting police wagon several times. She escaped repeatedly and fought with four of the police, swearing and shouting, for about ten minutes. Described as "a typical New York butch" and "a dyke–stone butch", she had been hit on the head by an officer with a baton for, as one witness claimed, complaining that her handcuffs were too tight.[67] Bystanders recalled that the woman, whose identity remains unknown (Stormé DeLarverie has been identified by some, including herself, as the woman, but accounts vary[68][note 4]), sparked the crowd to fight when she looked at bystanders and shouted, "Why don't you guys do something?" After an officer picked her up and heaved her into the back of the wagon,[71] the crowd became a mob and became violent.[72][73]

Violence breaks out

[edit]The police tried to restrain some of the crowd, knocking a few people down, which incited bystanders even more. Some of those handcuffed in the wagon escaped when police left them unattended (deliberately, according to some witnesses).[note 5][75] As the crowd tried to overturn the police wagon, two police cars and the wagon—with a few slashed tires—left immediately, with Inspector Pine urging them to return as soon as possible. The commotion attracted more people who learned what was happening. Someone in the crowd declared that the bar had been raided because "they didn't pay off the cops", to which someone else yelled, "Let's pay them off!"[76] Coins sailed through the air towards the police as the crowd shouted "Pigs!" and "Faggot cops!" Beer cans were thrown and the police lashed out, dispersing some of the crowd who found a construction site nearby with stacks of bricks. The police, outnumbered by between 500 and 600 people, grabbed several people, including activist folk singer (and mentor of Bob Dylan) Dave Van Ronk—who had been attracted to the revolt from a bar two doors away from the Stonewall. Though Van Ronk was not gay, he had experienced police violence when he participated in antiwar demonstrations: "As far as I was concerned, anybody who'd stand against the cops was all right with me and that's why I stayed in ... Every time you turned around the cops were pulling some outrage or another."[76] Van Ronk was the first of thirteen arrested that night.[77] Ten police officers—including two policewomen—barricaded themselves, Van Ronk, Howard Smith (a column writer for The Village Voice), and several handcuffed detainees inside the Stonewall Inn for their own safety.

Multiple accounts of the riot assert that there was no pre-existing organization or apparent cause for the demonstration; what ensued was spontaneous.[note 6] Michael Fader explained:[80]

We all had a collective feeling like we'd had enough of this kind of shit. It wasn't anything tangible anybody said to anyone else, it was just kind of like everything over the years had come to a head on that one particular night in the one particular place and it was not an organized demonstration ... Everyone in the crowd felt that we were never going to go back. It was like the last straw. It was time to reclaim something that had always been taken from us ... All kinds of people, all different reasons, but mostly it was total outrage, anger, sorrow, everything combined, and everything just kind of ran its course. It was the police who were doing most of the destruction. We were really trying to get back in and break free. And we felt that we had freedom at last, or freedom to at least show that we demanded freedom. We weren't going to be walking meekly in the night and letting them shove us around—it's like standing your ground for the first time and in a really strong way and that's what caught the police by surprise. There was something in the air, freedom a long time overdue and we're going to fight for it. It took different forms, but the bottom line was, we weren't going to go away. And we didn't.

The only known photograph from the first night of the riots, taken by freelance photographer Joseph Ambrosini, shows the homeless gay youth who slept in nearby Christopher Park, scuffling with police. Jackie Hormona and Tommy Lanigan-Schmidt are on the far left.[1][81]

The Mattachine Society newsletter a month later offered its explanation of why the riots occurred: "It catered largely to a group of people who are not welcome in, or cannot afford, other places of homosexual social gathering ... The Stonewall became home to these kids. When it was raided, they fought for it. That and the fact that they had nothing to lose other than the most tolerant and broadminded gay place in town, explains why."[82]

Garbage cans, garbage, bottles, rocks, and bricks were hurled at the building, breaking the windows. Witnesses attest that "flame queens", hustlers, and gay "street kids"—the most outcast people in the gay community—were responsible for the first volley of projectiles, as well as the uprooting of a parking meter used as a battering ram on the doors of the Stonewall Inn.[83]

The mob lit garbage on fire and stuffed it through the broken windows as the police grabbed a fire hose. Because it had no water pressure, the hose was ineffective in dispersing the crowd and seemed only to encourage them.[84] Marsha P. Johnson later said that it was the police that had started the fire in the bar.[85][note 7] When demonstrators broke through the windows—which had been covered by plywood by the bar owners to deter the police from raiding the bar—the police inside unholstered their pistols. The doors flew open and officers pointed their weapons at the angry crowd, threatening to shoot. Howard Smith, in the bar with the police, took a wrench from the bar and stuffed it in his pants, unsure if he might have to use it against the mob or the police. He watched someone squirt lighter fluid into the bar; as it was lit and the police took aim, sirens were heard and fire trucks arrived. The onslaught had lasted 45 minutes.[88]

When the violence broke out, the women and transmasculine people being held down the street at The Women's House of Detention joined in by chanting, setting fire to their belongings and tossing them into the street below. The historian Hugh Ryan says, "When I would talk to people about Stonewall, they would tell me, that night on Stonewall, we looked to the prison because we saw the women rioting and chanting, 'Gay rights, gay rights, gay rights.'"[89]

Escalation

[edit]The Tactical Patrol Force (TPF) of the New York City Police Department arrived to free the police trapped inside the Stonewall. One officer's eye was cut and a few others were bruised from being struck by flying debris. Bob Kohler, who was walking his dog by the Stonewall that night, saw the TPF arrive:

I had been in enough riots to know the fun was over ... The cops were totally humiliated. This never, ever happened. They were angrier than I guess they had ever been because everybody else had rioted ... but the fairies were not supposed to riot ... no group had ever forced cops to retreat before, so the anger was just enormous. I mean, they wanted to kill.[90]

With larger numbers, police detained anyone they could and put them in patrol wagons to go to jail, though Inspector Pine recalled, "Fights erupted with the transvestites, who wouldn't go into the patrol wagon." His recollection was corroborated by another witness across the street who said, "All I could see about who was fighting was that it was transvestites and they were fighting furiously."[91]

The TPF formed a phalanx and attempted to clear the streets by marching slowly and pushing the crowd back. The mob openly mocked the police. The crowd cheered, started impromptu kick lines and sang to the tune of "Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay": "We are the Stonewall girls/ We wear our hair in curls/ We don't wear underwear/ We show our pubic hair."[92][93][note 8] Lucian Truscott reported in The Village Voice: "A stagnant situation there brought on some gay tomfoolery in the form of a chorus line facing the line of helmeted and club-carrying cops. Just as the line got into a full kick routine, the TPF advanced again and cleared the crowd of screaming gay power[-]ites down Christopher to Seventh Avenue."[94] One participant who had been in the Stonewall during the raid recalled, "The police rushed us and that's when I realized this is not a good thing to do, because they got me in the back with a nightstick." Another account stated, "I just can't ever get that one sight out of my mind. The cops with the [nightsticks] and the kick line on the other side. It was the most amazing thing ... And all the sudden that kick line, which I guess was a spoof on the machismo ... I think that's when I felt rage. Because people were getting smashed with bats. And for what? A kick line."[95]

Marsha P. Johnson, an African-American street queen,[96][97][98] recalled arriving at the bar around "2:00 [am]", and that at that point the riots were well underway, with the building in flames.[85] As the riots went on into the early hours of the morning, Johnson, along with Zazu Nova and Jackie Hormona, were noted as "three individuals known to have been in the vanguard" of the pushback against the police.[99]

Craig Rodwell, owner of the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, reported watching police chase participants through the crooked streets, only to see them appear around the next corner behind the police. Members of the mob stopped cars, overturning one of them to block Christopher Street. Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke, in their column printed in Screw, declared that "massive crowds of angry protesters chased [the police] for blocks screaming, 'Catch them!'"[94]

By 4:00 am, the streets had nearly been cleared. Many people sat on stoops or gathered nearby in Christopher Park throughout the morning, dazed in disbelief at what had transpired. Many witnesses remembered the surreal and eerie quiet that descended upon Christopher Street, though there continued to be "electricity in the air".[101] One commented: "There was a certain beauty in the aftermath of the riot ... It was obvious, at least to me, that a lot of people really were gay and, you know, this was our street."[102] Thirteen people had been arrested. Some in the crowd were hospitalized,[note 9] and four police officers were injured. Almost everything in the Stonewall Inn was broken. Inspector Pine had intended to close and dismantle the Stonewall Inn that night. Pay phones, toilets, mirrors, jukeboxes, and cigarette machines were all smashed, possibly in the riot and possibly by the police.[88][104]

Second night of rioting

[edit]During the siege of the Stonewall, Craig Rodwell called The New York Times, the New York Post, and the Daily News to tell them what was happening. All three papers covered the riots; the Daily News placed coverage on the front page. News of the riot spread quickly throughout Greenwich Village, fueled by rumors that it had been organized by the Students for a Democratic Society, the Black Panthers, or triggered by "a homosexual police officer whose roommate went dancing at the Stonewall against the officer's wishes".[56] All day Saturday, June 28, people came to stare at the burned and blackened Stonewall Inn. Graffiti appeared on the walls of the bar, declaring "Drag power", "They invaded our rights", "Support gay power" and "Legalize gay bars", along with accusations of police looting and—regarding the status of the bar—"We are open."[56][105]

The next night, rioting again surrounded Christopher Street; participants remember differently which night was more frantic or violent. Many of the same people returned from the previous evening—hustlers, street youths, and "queens"—but they were joined by "police provocateurs", curious bystanders, and even tourists.[106] Remarkable to many was the sudden exhibition of homosexual affection in public, as described by one witness: "From going to places where you had to knock on a door and speak to someone through a peephole in order to get in. We were just out. We were in the streets."[107]

Thousands of people had gathered in front of the Stonewall, which had opened again, choking Christopher Street until the crowd spilled into adjoining blocks. The throng surrounded buses and cars, harassing the occupants unless they either admitted they were gay or indicated their support for the demonstrators.[108] Marsha P. Johnson was seen climbing a lamppost and dropping a heavy bag onto the hood of a police car, shattering the windshield.[109]

As on the previous evening, fires were started in garbage cans throughout the neighborhood. More than a hundred police were present from the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth and Ninth Precincts, but after 2:00 a.m. the TPF arrived again. Kick lines and police chases waxed and waned; when police captured demonstrators, whom the majority of witnesses described as "sissies" or "swishes", the crowd surged to recapture them.[110] Again, street battling ensued until 4:00 am.[109]

Beat poet and longtime Greenwich Village resident Allen Ginsberg lived on Christopher Street and happened upon the jubilant chaos. After he learned of the riot that had occurred the previous evening, he stated, "Gay power! Isn't that great! ... It's about time we did something to assert ourselves" and visited the open Stonewall Inn for the first time. While walking home, he declared to Lucian Truscott, "You know, the guys there were so beautiful—they've lost that wounded look that fags all had 10 years ago."[111]

Activist Mark Segal recounts that Martha Shelley and Marty Robinson stood and made speeches from the front door of the Stonewall on June 29, 1969, the second night of the riot.[112]

Leaflets, press coverage, and more violence

[edit]Activity in Greenwich Village was sporadic on Monday, June 30, and Tuesday, July 1, partly due to rain. Police and Village residents had a few altercations, as both groups antagonized each other. Craig Rodwell and his partner Fred Sargeant took the opportunity the morning after the first riot to print and distribute 5,000 leaflets, one of them reading: "Get the Mafia and the Cops out of Gay Bars." The leaflets called for gay people to own their own establishments, for a boycott of the Stonewall and other Mafia-owned bars, and for public pressure on the mayor's office to investigate the "intolerable situation".[113][114]

Not everyone in the gay community considered the revolt a positive development. To many older homosexuals and many members of the Mattachine Society who had worked throughout the 1960s to promote homosexuals as no different from heterosexuals, the display of violence and effeminate behavior was embarrassing. Randy Wicker, who had marched in the first gay picket lines before the White House in 1965, said the "screaming queens forming chorus lines and kicking went against everything that I wanted people to think about homosexuals ... that we were a bunch of drag queens in the Village acting disorderly and tacky and cheap."[115] Others found the closing of the Stonewall Inn, termed a "sleaze joint", as advantageous to the Village.[116]

On Wednesday, however, The Village Voice ran reports of the riots, written by Howard Smith and Lucian Truscott, that included unflattering descriptions of the events and its participants: "forces of faggotry", "limp wrists" and "Sunday fag follies".[117][note 10] A mob descended upon Christopher Street once again and threatened to burn down the offices of The Village Voice, which at the time was headquartered several buildings west of the Stonewall Inn on Christopher Street; that proximity gave Truscott and other writers for the newspaper first hand observations of the uprising. Also in the mob of between 500 and 1,000 were other groups that had had unsuccessful confrontations with the police and were curious how the police were defeated in this situation. Another explosive street battle took place, with injuries to demonstrators and police alike, local shops getting looted, and arrests of five people.[118][119] The incidents on Wednesday night lasted about an hour and were summarized by one witness: "The word is out. Christopher Street shall be liberated. The fags have had it with oppression."[120]

Aftermath

[edit]The feeling of urgency spread throughout Greenwich Village, even to people who had not witnessed the riots. Many who were moved by the rebellion attended organizational meetings, sensing an opportunity to take action. On July 4, 1969, the Mattachine Society performed its annual picket in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, called the Annual Reminder. Organizers Craig Rodwell, Frank Kameny, Randy Wicker, Barbara Gittings, and Kay Lahusen, who had all participated for several years, took a bus along with other picketers from New York City to Philadelphia. Since 1965, the pickets had been very controlled: women wore skirts and men wore suits and ties and all marched quietly in organized lines.[121] This year Rodwell remembered feeling restricted by the rules Kameny had set. When two women spontaneously held hands, Kameny broke them apart, saying, "None of that! None of that!" Rodwell, however, convinced about ten couples to hold hands. The hand-holding couples made Kameny furious, but they earned more press attention than all of the previous marches.[122][123] Participant Lilli Vincenz remembered, "It was clear that things were changing. People who had felt oppressed now felt empowered."[122] Rodwell returned to New York City determined to change the established quiet, meek ways of trying to get attention. One of his first priorities was planning Christopher Street Liberation Day.[124]

Gay Liberation Front

[edit]

Although the Mattachine Society had existed since the 1950s, many of their methods now seemed too mild for people who had witnessed or been inspired by the riots. Mattachine recognized the shift in attitudes in a story from their newsletter entitled, "The Hairpin Drop Heard Around the World."[125][note 11] When a Mattachine officer suggested an "amicable and sweet" candlelight vigil demonstration, a man in the audience fumed and shouted, "Sweet! Bullshit! That's the role society has been forcing these queens to play."[126] With a flyer announcing: "Do You Think Homosexuals Are Revolting? You Bet Your Sweet Ass We Are!",[126] the Gay Liberation Front (GLF) was soon formed, the first gay organization to use gay in its name. Previous organizations such as the Mattachine Society, the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB), and various homophile groups had masked their purpose by deliberately choosing obscure names.[127]

The rise of militancy became apparent to Frank Kameny and Barbara Gittings—who had worked in homophile organizations for years and were both very public about their roles—when they attended a GLF meeting to see the new group. A young GLF member demanded to know who they were and what their credentials were. Gittings, nonplussed, stammered, "I'm gay. That's why I'm here."[128] The GLF borrowed tactics from and aligned themselves with black and antiwar demonstrators with the ideal that they "could work to restructure American society".[129] They took on causes of the Black Panthers, marching to the Women's House of Detention in support of Afeni Shakur and other radical New Left causes. Four months after the group formed, however, it disbanded when members were unable to agree on operating procedure.[130]

Gay Activists Alliance

[edit]Within six months of the Stonewall riots, activists started a citywide newspaper called Gay; they considered it necessary because the most liberal publication in the city—The Village Voice—refused to print the word gay in GLF advertisements seeking new members and volunteers.[131] Two other newspapers were initiated within a six-week period: Come Out! and Gay Power; the readership of these three periodicals quickly climbed to between 20,000 and 25,000.[132][133]

GLF members organized several same-sex dances, but GLF meetings were chaotic. When Bob Kohler asked for clothes and money to help the homeless youth who had participated in the riots, many of whom slept in Christopher Park or Sheridan Square, the response was a discussion on the downfall of capitalism.[134] In late December 1969, several people who had visited GLF meetings and left out of frustration formed the Gay Activists Alliance (GAA). The GAA was to be more orderly and entirely focused on gay issues. Their constitution began, "We as liberated homosexual activists demand the freedom for expression of our dignity and value as human beings."[135] The GAA developed and perfected a confrontational tactic called a zap: they would catch a politician off guard during a public relations opportunity and force him or her to acknowledge gay and lesbian rights. City councilmen were zapped and mayor John Lindsay was zapped several times—once on television when GAA members made up the majority of the audience.[136]

Police raids on gay bars did not stop after the Stonewall riots. In March 1970, deputy inspector Seymour Pine raided the Zodiac and 17 Barrow Street. An after-hours gay club with no liquor or occupancy licenses called The Snake Pit was soon raided and 167 people were arrested. One of them was Diego Viñales, an Argentinian national so frightened that he might be deported as a homosexual that he tried to escape the police precinct by jumping out of a two-story window, impaling himself on a 14-inch (36 cm) spike fence.[137] The New York Daily News printed a graphic photo of the young man's impalement on the front page. GAA members organized a march from Christopher Park to the Sixth Precinct in which hundreds of gay men, lesbians, and liberal sympathizers peacefully confronted the TPF.[132] They also sponsored a letter-writing campaign to Mayor Lindsay in which the Greenwich Village Democratic Party and congressman Ed Koch sent pleas to end raids on gay bars in the city.[138]

The Stonewall Inn lasted only a few weeks after the riot. By October 1969 it was up for rent. Village residents surmised it was too notorious a location and Rodwell's boycott discouraged business.[139]

Gay Pride

[edit]Christopher Street Liberation Day, on June 28, 1970, marked the first anniversary of the Stonewall riots with an assembly on Christopher Street; with simultaneous Gay Pride marches in Los Angeles and Chicago, these were the first Gay Pride marches in US history.[140][141] The next year, Gay Pride marches took place in Boston, Dallas, Milwaukee, London, Paris, West Berlin and Stockholm.[142] The march in New York covered 51 blocks, from Christopher Street to Central Park. The march took less than half the scheduled time due to excitement, but also due to wariness about walking through the city with gay banners and signs. Although the parade permit was delivered only two hours before the start of the march, the marchers encountered little resistance from onlookers.[143] The New York Times reported (on the front page) that the marchers took up the entire street for about 15 city blocks.[144] Reporting by The Village Voice was positive, describing "the out-front resistance that grew out of the police raid on the Stonewall Inn one year ago".[142]

There was little open animosity and some bystanders applauded when a tall, pretty girl carrying a sign "I am a Lesbian" walked by.

—The New York Times coverage of Gay Liberation Day, 1970[144]

By 1972, the participating cities included Atlanta, Buffalo, Detroit, Washington, D.C., Miami, Minneapolis, and Philadelphia,[145] as well as San Francisco.

Frank Kameny soon realized the pivotal change brought by the Stonewall riots. An organizer of gay activism in the 1950s, he was used to persuasion, trying to convince heterosexuals that gay people were no different from them. When he and other people marched in front of the White House, the State Department, and Independence Hall only five years earlier, their objective was to look as if they could work for the US government.[146] Ten people marched with Kameny then and they alerted no press to their intentions. Although he was stunned by the upheaval by participants in the Annual Reminder in 1969, he later observed, "By the time of Stonewall, we had fifty to sixty gay groups in the country. A year later there were at least fifteen hundred. By two years later, to the extent that a count could be made, it was twenty-five hundred."[147]

Similar to Kameny's regret at his own reaction to the shift in attitudes after the riots, Randy Wicker came to describe his embarrassment as "one of the greatest mistakes of his life".[148] The image of gay people retaliating against police, after so many years of allowing such treatment to go unchallenged, "stirred an unexpected spirit among many homosexuals".[148] Kay Lahusen, who photographed the marches in 1965, stated, "Up to 1969, this movement was generally called the homosexual or homophile movement ... Many new activists consider the Stonewall uprising the birth of the gay liberation movement. Certainly, it was the birth of gay pride on a massive scale."[149] David Carter explained that even though there were several uprisings before Stonewall, the reason Stonewall was so significant was that thousands of people were involved, the riot lasted a long time (six days), it was the first to get major media coverage, and it sparked the formation of many gay rights groups.[150]

Trans organizations

[edit]According to Susan Stryker's book, Transgender History, the Stonewall riots had significant effects on trans rights activism. Sylvia Rivera and Marsha P. Johnson established the Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) organization, as they believed that trans people weren't being adequately represented in the Gay Activists Alliance and Gay Liberation Front. They established politicized versions of "houses", which came from Black and Latino queer communities, and were places that marginalized trans youth could seek shelter.[151]

Besides STAR, organizations such as Transvestites and Transsexuals (TAT) and Queens' Liberation Front (QLF) were also established. QLF, which was established by drag queen Lee Brewster and heterosexual transvestite Bunny Eisenhower, marched on Christopher Street Liberation Day and fought against drag erasure and for trans visibility.[151]

Legacy

[edit]The Stonewall riots are often considered to be the origin or impetus of the gay liberation movement, and many studies of LGBT history in the U.S. are divided into pre- and post-Stonewall analyses.[145] This has been criticized by historians of sexuality. Calls for the rights of gender and sexual minorities predate the Stonewall riots. The first homosexual movement began one hundred years earlier, in Germany. West Germany had abolished criminal liability for homosexual acts among adults over 21 years of age through a change of Section 175 of the German Criminal Code on June 25, 1969 − just three days before the Stonewall riots began.[152] There was already the emergence of a gay liberation movement in New York at the time of the riots. The Stonewall riots were not the only time LGBT people organized politically amid attacks on LGBT establishments. The event has been said to occupy a unique place in the collective memory of many LGBT people,[145] including those outside of the United States,[153] as it "is marked by an international commemorative ritual – an annual gay pride parade", according to sociologist Elizabeth A. Armstrong.[145]

Community

[edit]

Within two years of the Stonewall riots, there were gay rights groups in every major American city, as well as in Canada, Australia, and Western Europe.[154] People who joined activist organizations after the riots had very little in common other than their same-sex attraction. Many who arrived at GLF or GAA meetings were taken aback by the number of gay people in one place.[155] Race, class, ideology, and gender became frequent obstacles in the years after the riots. This was illustrated during the 1973 Stonewall rally when, moments after Barbara Gittings exuberantly praised the diversity of the crowd, feminist activist Jean O'Leary protested what she perceived as the mocking of women by cross-dressers and drag queens in attendance. During a speech by O'Leary, in which she claimed that drag queens made fun of women for entertainment value and profit, Sylvia Rivera and Lee Brewster jumped on the stage and shouted "You go to bars because of what drag queens did for you and these bitches tell us to quit being ourselves!"[156] Both the drag queens and lesbian feminists in attendance left in disgust.[157]

O'Leary also worked in the early 1970s to exclude transgender people from gay rights issues because she felt that rights for transgender people would be too difficult to attain.[157] Sylvia Rivera left New York City in the mid-1970s, relocating to upstate New York.[158] She later returned to the city in the mid-1990s, after the 1992 death of friend Marsha P. Johnson. Rivera lived on the "gay pier" at the end of Christopher street and advocated for homeless members of the gay community.[158][159] The initial disagreements among participants in the movements often evolved after further reflection. O'Leary later regretted her stance against the drag queens attending in 1973: "Looking back, I find this so embarrassing because my views have changed so much since then. I would never pick on a transvestite now."[157] "It was horrible. How could I work to exclude transvestites and at the same time criticize the feminists who were doing their best back in those days to exclude lesbians?"[160]

O'Leary was referring to the Lavender Menace, an appellation by second-wave feminist Betty Friedan based on attempts by members of the National Organization for Women (NOW) to distance themselves from the perception of NOW as a haven for lesbians. As part of this process, Rita Mae Brown and other lesbians who had been active in NOW were forced out. They staged a protest in 1970 at the Second Congress to Unite Women and earned the support of many NOW members, finally gaining full acceptance in 1971.[161]

The growth of lesbian feminism in the 1970s at times so conflicted with the gay liberation movement that some lesbians refused to work with gay men. Many lesbians found men's attitudes patriarchal and chauvinistic and saw in gay men the same misguided notions about women that they saw in heterosexual men.[162] The issues most important to gay men—entrapment and public solicitation—were not shared by lesbians. In 1977, a Lesbian Pride Rally was organized as an alternative to sharing gay men's issues, especially what Adrienne Rich termed "the violent, self-destructive world of the gay bars".[162] Veteran gay activist Barbara Gittings chose to work in the gay rights movement, explaining, "It's a matter of where does it hurt the most? For me it hurts the most not in the female arena, but the gay arena."[162]

На протяжении 1970-х годов гей-активизм имел значительные успехи. Одним из первых и наиболее важных стал «затык» в мае 1970 года, организованный GLF в Лос-Анджелесе на съезде Американской психиатрической ассоциации (АПА). На конференции по модификации поведения , во время показа фильма, демонстрирующего использование электрошоковой терапии для уменьшения однополого влечения, Моррис Кайт и члены GLF в зале прервали фильм криками «Пытка!» и «Варварство!» [ 163 ] Они взяли микрофон и заявили, что медицинские работники, прописывающие такую терапию своим пациентам-гомосексуалистам, были соучастниками их пыток. Хотя 20 присутствовавших психиатров ушли, GLF целый час следил за оставшимися, пытаясь убедить их, что гомосексуалисты не являются психически больными. [ 163 ] Когда в 1972 году АПА пригласила гей-активистов выступить перед группой, активисты привели Джона Э. Фрайера , психиатра-гея, который носил маску, потому что он чувствовал, что его практика находится в опасности. В декабре 1973 года — во многом благодаря усилиям гей-активистов — АПА единогласно проголосовала за исключение гомосексуализма из Диагностического и статистического руководства . [ 164 ] [ 165 ]

Геи и лесбиянки объединились, чтобы работать в низовых политических организациях в ответ на организованное сопротивление в 1977 году. Коалиция консерваторов под названием « Спасите наших детей» организовала кампанию по отмене постановления о гражданских правах в округе Майами-Дейд . «Спасите наших детей» оказалась достаточно успешной, чтобы повлиять на аналогичные отмены в нескольких американских городах в 1978 году. Однако в том же году кампания в Калифорнии под названием « Инициатива Бриггса» , направленная на принуждение к увольнению гомосексуальных сотрудников государственных школ, потерпела поражение. [ 166 ] Реакция на влияние «Спасите наших детей» и «Инициативы Бриггса» в гей-сообществе была настолько значительной, что для многих активистов ее назвали второй «каменной стеной», ознаменовав их начало политического участия. [ 167 ] Последующий Национальный марш 1979 года в Вашингтоне за права лесбиянок и геев был приурочен к десятой годовщине беспорядков в Стоунволле. [ 168 ]

Неприятие прежней гей-субкультуры

[ редактировать ]Беспорядки в Стоунволле стали настолько важным поворотным моментом, что многие аспекты предшествующей культуры геев и лесбиянок , такие как культура баров, сформировавшаяся в результате десятилетий стыда и секретности, были решительно проигнорированы и отвергнуты. Историк Мартин Дуберман пишет: «Десятилетия, предшествовавшие Стоунволлу ... по-прежнему рассматриваются большинством геев и лесбиянок как некая обширная неолитическая пустошь». [ 169 ] Социолог Барри Адам отмечает: «Каждое общественное движение в какой-то момент должно выбрать, что сохранить, а что отвергнуть из своего прошлого. Какие черты являются результатом угнетения, а какие являются здоровыми и подлинными?» [ 170 ] В связи с растущим феминистским движением начала 1970-х годов роли буча и женщины , возникшие в лесбийских барах в 1950-х и 1960-х годах, были отвергнуты, потому что, как выразился один писатель: «любые ролевые игры - это болезнь». [ 171 ] Лесбийские феминистки считали роли бучей архаичной имитацией мужского поведения. [ 172 ] Некоторые женщины, по словам Лилиан Фадерман , стремились отказаться от ролей, которые они чувствовали себя вынужденными играть. Роли вернулись к некоторым женщинам в 1980-х годах, хотя они допускали большую гибкость, чем до «Стоунволла». [ 173 ]

Автор Майкл Бронски подчеркивает «нападки на культуру до Стоунволла», особенно на гей-криминальное чтиво для мужчин, темы которого часто отражают ненависть к себе или двойственное отношение к тому, чтобы быть геем. Многие книги заканчивались неудовлетворительно и резко, часто самоубийством, а своих героев-геев писатели изображали алкоголиками или глубоко несчастными. Эти книги, которые он описывает как «огромную и связную литературу, написанную и для геев», [ 174 ] не переиздавались и потеряны для последующих поколений. Отвергая идею о том, что отказ был мотивирован политической корректностью, Бронски пишет: «Освобождение геев было молодежным движением, чье чувство истории в значительной степени определялось неприятием прошлого». [ 175 ]

Влияние и признание

[ редактировать ]

Беспорядки, возникшие в результате рейда в баре, стали буквальным примером сопротивления геев и лесбиянок и символическим призывом к оружию для многих людей. Историк Дэвид Картер в своей книге о беспорядках в Стоунволле отмечает, что бар сам по себе представлял собой сложный бизнес, который представлял собой общественный центр, возможность для мафии шантажировать своих клиентов, дом и место «эксплуатации и деградации». [ 176 ] Истинное наследие беспорядков в Стоунволле, настаивает Картер, - это "продолжающаяся борьба за равенство лесбиянок, геев, бисексуалов и трансгендеров". [ 177 ] Историк Николас Эдсолл пишет: [ 178 ]

Стоунволл сравнивают со многими актами радикального протеста и неповиновения в американской истории, начиная с Бостонского чаепития. Но лучшая и, безусловно, более современная аналогия — это отказ Розы Паркс сесть в заднюю часть автобуса в Монтгомери, штат Алабама, в декабре 1955 года, что положило начало современному движению за гражданские права. Через несколько месяцев после Стоунволла радикальные группы освобождения геев и информационные бюллетени возникли в городах и студенческих городках по всей Америке, а затем и по всей Северной Европе.

До восстания в гостинице «Стоунволл Инн» гомосексуалисты были, как историки Дадли Клендинен и Адам Нагурни : пишут [ 179 ]

тайный легион людей, о которых знают, но игнорируют, игнорируют, смеются или презирают. И, как и у обладателей секрета, у них было преимущество, которое одновременно было и недостатком, которого не было ни у одной другой группы меньшинств в Соединенных Штатах. Они были невидимы. В отличие от афроамериканцев, женщин, коренных американцев, евреев, ирландцев, итальянцев, азиатов, выходцев из Латинской Америки или любой другой культурной группы, которая боролась за уважение и равные права, гомосексуалисты не имели никаких физических или культурных признаков, никакого языка или диалекта, которые могли бы идентифицировать их. друг другу или кому-либо другому ... Но в ту ночь обычное молчаливое согласие впервые переросло в яростное сопротивление ... С этой ночи жизнь миллионов геев и лесбиянок и отношение к ним со стороны более широкой культуры в котором они жили, стали быстро меняться. Люди стали появляться на публике как гомосексуалы, требуя уважения.

Историк Лилиан Фадерман называет беспорядки «выстрелом, слышимым во всем мире», объясняя: «Восстание в Стоунволле имело решающее значение, потому что оно стало сплоченным для этого движения. Оно стало символом власти геев и лесбиянок. протеста, который использовался другими угнетенными группами, события в Стоунволле подразумевали, что у гомосексуалистов было столько же причин для недовольства, как и у них самих». [ 180 ]

Джоан Нестле стала соучредителем « Архивов истории лесбиянок» в 1974 году и приписывает «его создание той ночи и мужеству, нашедшему свой голос на улицах». [ 125 ] Однако, остерегаясь приписать начало гей-активизма беспорядкам в Стоунволле, Nestle пишет:

Я определенно не вижу, чтобы история геев и лесбиянок начиналась со Стоунволла ... и я не вижу, чтобы сопротивление началось со Стоунволла. Что я действительно вижу, так это историческое объединение сил, и шестидесятые годы изменили то, как люди терпели вещи в этом обществе и что они отказывались терпеть ... Конечно, в ту ночь 1969 года произошло что-то особенное, и мы сделали это еще более особенным в нашей потребности иметь то, что я называю точкой происхождения ... это сложнее, чем сказать, что все началось со Стоунволла. [ 181 ]

События раннего утра 28 июня 1969 года были не первыми случаями сопротивления геев и лесбиянок полиции в Нью-Йорке и других местах. Мало того, что Общество Маттачин действовало в крупных городах, таких как Лос-Анджелес и Чикаго, но также маргинализированные люди начали бунт в кафетерии Комптона в 1966 году, а еще один бунт стал ответом на рейд на таверну Black Cat в Лос-Анджелесе в 1967 году. [ 182 ] Однако имелось несколько обстоятельств, которые сделали беспорядки в Стоунволле незабываемыми. Место проведения рейда в Нижнем Манхэттене сыграло решающую роль: оно находилось через дорогу от офиса The Village Voice , а узкие кривые улочки давали бунтовщикам преимущество перед полицией. [ 145 ] Многие участники и жители Гринвич-Виллидж были вовлечены в политические организации, которые смогли эффективно мобилизовать большое и сплоченное гей-сообщество в течение недель и месяцев после восстания. Однако самым значительным аспектом беспорядков в Стоунволле было чествование их в День освобождения Кристофер-стрит, который перерос в ежегодные гей-прайды по всему миру. [ 145 ]

Stonewall (официальное название Stonewall Equality Limited) — благотворительная организация по защите прав ЛГБТ в Великобритании, основанная в 1989 году и названная в честь гостиницы Stonewall Inn из-за беспорядков в Стоунволле. Премия Stonewall Awards — это ежегодное мероприятие, которое благотворительная организация проводит с 2006 года для признания людей, которые повлияли на жизнь британских лесбиянок, геев и бисексуалов.

Середина 1990-х годов ознаменовалась включением бисексуалов в качестве представленной группы в гей-сообщество, когда они успешно попытались быть включенными в платформу Марша 1993 года в Вашингтоне за равные права и освобождение лесбиянок, геев и бисексуалов . Трансгендеры также просили, чтобы их включили, но не были, хотя транс-инклюзивный язык был добавлен в список требований марша. [ 183 ] Сообщество трансгендеров продолжало чувствовать себя одновременно желанным и враждебным по отношению к гей-сообществу, поскольку отношение к небинарной гендерной дискриминации и пансексуальной ориентации развивалось и все чаще вступало в конфликт. [ 29 ] [ 184 ] В 1994 году Нью-Йорк отпраздновал «Каменную стену 25» маршем, который прошел мимо штаб-квартиры Организации Объединенных Наций в Центральный парк . По оценкам, посещаемость составит 1,1 миллиона человек. [ 185 ] Сильвия Ривера возглавила альтернативный марш в Нью-Йорке в 1994 году в знак протеста против исключения трансгендеров из этих мероприятий. [ 186 ]

Посещаемость мероприятий ЛГБТ-прайдов существенно выросла за последние десятилетия. В большинстве крупных городов мира сейчас проводятся своего рода демонстрации гордости; Прайды в некоторых городах являются крупнейшими ежегодными праздниками любого рода. [ 186 ] Растущая тенденция к коммерциализации маршей в парады (когда мероприятия получают корпоративную спонсорскую поддержку) вызвала обеспокоенность по поводу лишения автономии первоначальных массовых демонстраций. [ 186 ]

Президент Барак Обама объявил июнь 2009 года Месяцем гордости лесбиянок, геев, бисексуалов и трансгендеров, назвав беспорядки поводом «обязаться добиться равного правосудия перед законом для американцев ЛГБТ». [ 187 ] В этом году исполнилось 40 лет со дня беспорядков. В редакционной статье Washington Blade сравнили неряшливую и жестокую активность во время и после беспорядков в Стоунволле с вялой реакцией на невыполненные обещания, данные президентом Обамой; на то, что их проигнорировали, богатые ЛГБТ-активисты отреагировали обещанием выделять меньше денег на демократические цели. [ 188 ] Два года спустя гостиница Stonewall Inn стала местом сбора для празднований после того, как Сенат штата Нью-Йорк проголосовал за принятие однополых браков . Закон был подписан губернатором Эндрю Куомо 24 июня 2011 года. [ 189 ]

Обама также упомянул беспорядки в Стоунволле, призывая к полному равенству во время своей второй инаугурационной речи 21 января 2013 года:

Мы, люди, заявляем сегодня, что самая очевидная из истин – что все мы созданы равными – это звезда, которая по-прежнему ведет нас; точно так же, как он вел наших предков через Сенека-Фолс, Сельму и Стоунволл ... Наше путешествие не завершится до тех пор, пока с нашими братьями и сестрами-геями не будут обращаться по закону так же, как и со всеми остальными, - ибо если мы действительно созданы равными, то, несомненно, любовь, которую мы совершаем, друг другу также должны быть равны. [ 190 ]

Это был исторический момент: президент впервые упомянул права геев или слово «гей» в инаугурационной речи. [ 190 ] [ 191 ]

В течение июня 2019 года в Нью-Йорке проходило мероприятие Stonewall 50 – WorldPride NYC 2019 , организованное Heritage of Pride в сотрудничестве с ЛГБТ-подразделением программы I Love New York , в ознаменование 50-летия восстания в Стоунволле. По окончательной официальной оценке, только на Манхэттене присутствовало 5 миллионов посетителей, что сделало это крупнейшее ЛГБТ-празднование в истории. [ 192 ] Июнь традиционно является месяцем прайдов в Нью-Йорке и во всем мире, и мероприятия проводились под эгидой ежегодного Марша прайдов в Нью-Йорке . 6 июня 2019 года, одновременно с WorldPride празднованием в Нью-Йорке, комиссар полиции Джеймс П. О'Нил извинился от имени полиции Нью-Йорка за действия ее офицеров во время восстания в Стоунволле. [ 193 ] [ 194 ]

Официальное празднование 50-летия Стоунволлского восстания произошло 28 июня на Кристофер-стрит перед гостиницей Stonewall Inn . Официальное празднование было оформлено в виде митинга, отсылающего к первоначальным митингам перед отелем Stonewall Inn в 1969 году. На этом мероприятии выступали мэр Билл Де Блазио , сенатор Кирстен Гиллибранд , конгрессмен Джерри Надлер , американский активист X Гонсалес и глобальный активист Реми. Бонни . [ 195 ] [ 196 ]

В 2019 году Париж, Франция, официально назвал площадь в Марэ районе Place des Émeutes-de-Stonewall. [ 197 ] (Площадь Стоунволлских беспорядков).

День Стоунволла

[ редактировать ]

В 2018 году, через 49 лет после восстания, День Стоунволла был объявлен днем памяти организацией Pride Live , занимающейся социальной защитой и взаимодействием с общественностью. [ 198 ] [ 199 ] Второй День Стоунволла прошел в пятницу, 28 июня 2019 года, возле гостиницы Stonewall Inn. [ 200 ] Во время этого мероприятия Pride Live представила свою программу «Послы Стоунволла», направленную на повышение осведомленности о 50-летии беспорядков в Стоунволле. [ 201 ]

Историческая достопримечательность и памятник

[ редактировать ]

В июне 1999 года Министерство внутренних дел США включило улицы Кристофер-стрит, 51 и 53 , а также прилегающую территорию в Гринвич-Виллидж в Национальный реестр исторических мест , первый объект, имеющий значение для ЛГБТ-сообщества. [ 202 ] [ 203 ] На церемонии открытия помощник министра внутренних дел Джон Берри заявил: «Пусть всегда будут помнить, что здесь — на этом месте — мужчины и женщины стояли гордо, они стояли стойко, чтобы мы могли быть теми, кто мы есть, мы можем работать, где захотим, жить там, где захотим, и любить тех, кого желает наше сердце». [ 204 ] В феврале 2000 года гостиница Stonewall Inn была также названа национальной исторической достопримечательностью . [ 205 ]

23 июня 2015 года Комиссия по сохранению достопримечательностей Нью-Йорка объявила Стоунволл городской достопримечательностью, первой, которая была определена только на основании его культурного значения для ЛГБТ. [ 206 ] 24 июня 2016 года президент Барак Обама объявил о создании Национального памятника Стоунволл , находящегося в ведении Службы национальных парков . [ 207 ] Обозначение защищает парк Кристофера и прилегающие территории общей площадью более семи акров; Гостиница Stonewall Inn находится в пределах памятника, но остается в частной собственности. [ 208 ] Фонд национальных парков сформировал новую некоммерческую организацию для сбора средств на станцию рейнджеров и экспонаты, поясняющие памятник. [ 209 ] включая первый официальный национальный центр для посетителей, посвященный ЛГБТКИА+, который был открыт 28 июня 2024 года. [ 210 ] [ 211 ] станция нью -йоркского метрополитена «Кристофер-стрит – Шеридан-сквер» была переименована в станцию «Кристофер-стрит – национальный памятник Стоунволл» . В тот же день [ 210 ] [ 212 ]

Представления в СМИ

[ редактировать ]О беспорядках не было снято ни кинохроники, ни телевизионных кадров, сохранилось мало домашних фильмов и фотографий, но те, что есть, были использованы в документальных фильмах. [ 213 ]

Фильм

[ редактировать ]- До Стоунволла: Создание сообщества геев и лесбиянок (1984), документальный фильм о десятилетиях, предшествовавших восстанию Стоунволла.

- Стоунволл (1995), драматическое представление событий, приведших к беспорядкам.

- После Стоунволла (1999), документальный фильм о годах от Стоунволла до конца века.

- Стоунволлское восстание (2010), документальный фильм, в котором использованы архивные кадры, фотографии, документы и показания свидетелей.

- «Стоунволл» (2015), драма о вымышленном главном герое, который взаимодействует с вымышленными версиями некоторых людей, участвовавших в беспорядках и вокруг них.

- С Днём Рождения, Маша! (2016), короткая экспериментальная драма, вдохновленная некоторыми легендами, окружающими активистов за права геев и трансгендеров Маршу П. Джонсон и Сильвию Риверу , действие которой происходит в ночь беспорядков.

Музыка

[ редактировать ]- Активистка Мэдлин Дэвис написала народную песню «Stonewall Nation» в 1971 году после своего первого марша за гражданские права геев. Выпущенный на Mark Custom Recording Service , он широко известен как первая пластинка, выступающая за освобождение геев, с текстами, которые «прославляют устойчивость и потенциальную силу радикального гей-активизма». [ 214 ]

- Песня « '69: Judy Garland», написанная Стефином Мерриттом и вошедшая в 50 Song Memoir группы The Magnetic Fields , сосредоточена на Стоунволлских беспорядках и идее. [ примечание 6 ] что они были вызваны смертью Джуди Гарланд шестью днями ранее, 22 июня 1969 года.

- В 2018 году Нью-Йоркская городская опера поручила английскому композитору Иэну Беллу и американскому либреттисту Марку Кэмпбеллу написать оперу «Каменная стена» в ознаменование 50-летия беспорядков, премьера которой состоится 19 июня 2019 года, режиссер Леонард Фолья . [ 215 ]

- The Stonewall Celebration Concert — дебютный студийный альбом Ренато Руссо , выпущенный в 1994 году. Альбом стал данью двадцатипятилетию беспорядков в Стоунволле в Нью-Йорке. Часть гонорара была пожертвована на кампанию Ação da Cidadania Contra a Fome, Miséria e Pela Vida (Гражданские действия против голода и бедности и за жизнь).

Театр

[ редактировать ]- Уличный театр (1982) Дорика Уилсона [ 216 ] [ 217 ]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Кристофер Стрит Дэй

- ЛГБТ-культура в Нью-Йорке

- История ЛГБТ в Нью-Йорке

- Права ЛГБТ в Нью-Йорке

- Квир-марш освобождения

Аналогичные события

- Танец сорока одного (1901), Мексика

- Рейд в баню Аристон (1903 г.), первый полицейский рейд против геев в Нью-Йорке.

- Уличный скандал Уанчака (15 июня 1969 г.), Чили

- Операция Мыло (1981), Торонто, Канада

- Рейд на секс-гараж (1990), Монреаль, Канада

- Вкусный рейд в ночном клубе (1994), получивший название «Каменная стена Австралии».

- Полицейский рейд Бар-Абаникоса (1997 г.), Эквадор

- Радужная ночь (2020), получившая название «Польская каменная стена».

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Дескрипторы в этой статье отражают терминологию, которая использовалась в то время. В 1950-х - начале 1980-х годов объединяющим термином для людей, состоящих в однополых отношениях или не соответствующих гендерным нормам, было «гомосексуалист» или «гей» (см. « Освобождение геев »). Позже (70-80-е годы) многие группы расширили это понятие до лесбиянок и геев , а затем, в 90-х и 00-х годах, до лесбиянок, геев, бисексуалов и трансгендеров (ЛГБТ).

- ↑ За исключением штата Иллинойс, который декриминализовал содомию в 1961 году, гомосексуальные действия, даже между взрослыми людьми по обоюдному согласию, действовавшими в частных домах, были уголовным преступлением во всех штатах США во время беспорядков в Стоунволле: «Взрослый человек, осужденный за совершение преступления, связанного с сексом с другой взрослый, давший согласие в уединении своего дома, мог получить от небольшого штрафа до пяти, десяти или двадцати лет – или даже пожизненного – тюремного заключения. В 1971 году в двадцати штатах действовали законы о «сексуальных психопатах», разрешавшие содержание под стражей. гомосексуалистов только по этой причине. В Пенсильвании и Калифорнии лица, совершившие сексуальные преступления, могут быть помещены в психиатрическое учреждение на всю жизнь, а в семи штатах их могут кастрировать». (Картер, стр. 15) Кастрация, рвота , гипноз, электрошоковая терапия и лоботомия использовались психиатрами в попытках вылечить гомосексуалистов в 1950-х и 1960-х годах. (Кац, стр. 181–197.) (Адам, стр. 60.)

- ^ По словам Дубермана (стр. 194), ходили слухи, что такое могло произойти, но, поскольку это было намного позже, чем обычно проводились рейды, руководство Stonewall сочло эту информацию неточной. Через несколько дней после рейда один из владельцев бара пожаловался, что предупреждение так и не поступило и что рейд был заказан Бюро по контролю за алкоголем, табаком и огнестрельным оружием не было штампов , который возразил, что на бутылках со спиртными напитками , указывающих на содержание алкоголя. был контрабандным . Дэвид Картер представляет информацию (стр. 96–103), указывающую на то, что мафиозные владельцы «Стоунволла» и менеджер шантажировали более богатых клиентов, особенно тех, кто работал на Уолл-стрит . Похоже, они зарабатывали больше денег на вымогательстве, чем на продаже спиртных напитков в баре. Картер приходит к выводу, что, когда полиция не смогла получить откаты от шантажа и кражи обращающихся облигаций (чему способствовало давление на клиентов-геев с Уолл-стрит), они решили навсегда закрыть Stonewall Inn.

- ↑ Сообщения людей, ставших свидетелями этой сцены, включая письма и новостные репортажи о женщине, дравшейся с полицией, противоречивы. Хотя свидетели утверждают, что одна женщина, которая боролась с обращением с ней со стороны полиции, вызвала гнев толпы, некоторые также вспомнили, что несколько «лесбиянок-мясников» начали сопротивляться, еще находясь в баре. По крайней мере, один из них уже истекал кровью, когда его вынесли из бара. [ 69 ] Крейг Родвелл [ 70 ] утверждает, что арест женщины был не основным событием, вызвавшим насилие, а одним из нескольких одновременных событий: «просто ... произошла вспышка группового — массового — гнева».

- ↑ Свидетель Морти Мэнфорд заявил: «Я не сомневаюсь, что этих людей намеренно оставили без охраны. Я предполагаю, что между руководством бара и местной полицией существовали какие-то отношения, поэтому они действительно не хотели арестовывать этих людей. Но они должны были хотя бы выглядеть так, будто выполняют свою работу». [ 74 ]

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б За годы, прошедшие с тех пор, как произошли беспорядки, смерть иконы гея Джуди Гарланд ранее на этой неделе, 22 июня 1969 года, считалась важным фактором беспорядков, но никто из участников субботних утренних демонстраций не помнит, как обсуждалось имя Гарланд. Ни в одном печатном отчете о беспорядках из надежных источников Гарланд не упоминается как причина беспорядков. Только один современный отчет предполагает это, рассказ гетеросексуального человека, высмеивающего беспорядки. [ 78 ] Боб Колер разговаривал с бездомной молодежью на Шеридан-сквер и говорил: «Когда люди говорят о том, что смерть Джуди Гарланд имеет какое-то отношение к беспорядкам, это сводит меня с ума. Беспризорные дети сталкивались со смертью каждый день. Им нечего было терять. ...И они не могли меньше заботиться о Джуди. Мы говорим о детях, которым было четырнадцать, пятнадцать, шестнадцать лет. Джуди Гарланд была любимицей геев среднего класса. Меня это расстраивает, потому что это упрощает ситуацию. целое дело». [ 79 ]

- ↑ Сильвия Ривера сообщила, что ей вручили коктейль Молотова и бросили его (свидетельств очевидцев о коктейлях Молотова в первую ночь не было, хотя было подожжено много пожаров). [ 84 ] В 2019 году Дэвид Картер признал, что этот отчет о действиях Риверы был сфабрикован и что многочисленные свидетели на протяжении многих лет, в том числе Марша П. Джонсон , согласились с тем, что Ривера не присутствовал при восстании. [ 86 ] [ 87 ] Боб Колер сказал Картеру, что, хотя Ривера не участвовала в восстании, он надеется, что Картер все равно изобразит ее присутствовавшей там. Другой ветеран «Стоунволла», Томас Ланиган-Шмидт , заявил, что он хотел, чтобы Картер включил Риверу, «чтобы у молодых пуэрториканских трансгендеров на улице был образец для подражания». [ 86 ] Когда Колер и Ривера обсуждали, поддержит ли Колер претензии Риверы к Картеру в отношении книги, Ривера попросил Колера сказать, что Ривера бросил коктейль Молотова. Колер ответил: «Сильвия, ты не бросала коктейль Молотова!» Ривера продолжал с ним торговаться, спрашивая, скажет ли он, что она бросила первый кирпич. Он ответил: «Сильвия, ты не бросала кирпич». Первая бутылка? Он все равно отказался. В конце концов Колер согласился солгать и сказать, что Ривера был там и в какой-то момент бросил бутылку . [ 86 ]

- ^ В некоторых ссылках последняя строка звучит как «... лобковые волосы».

- ↑ Одному протестующему понадобились швы, чтобы восстановить колено, сломанное дубинкой; другой потерял два пальца в двери машины. Свидетели вспоминают, что некоторых из самых «женственных мальчиков» сильно избили. [ 103 ]

- ↑ Картер (стр. 201) объясняет гнев по поводу репортажей The Village Voice тем, что они сосредоточены на женоподобном поведении участников, исключая какой-либо вид храбрости. Автор Эдмунд Уайт настаивает на том, что Смит и Траскотт пытались утвердить свою гетеросексуальность, называя события и людей в уничижительных терминах.