Barack Obama

Barack Obama | |

|---|---|

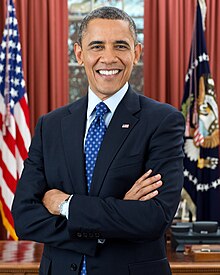

Официальный портрет, 2012 г. | |

| 44-й президент США | |

| In office 20 января 2009 г. – 20 января 2017 г. | |

| Vice President | Joe Biden |

| Preceded by | George W. Bush |

| Succeeded by | Donald Trump |

| United States Senator from Illinois | |

| In office January 3, 2005 – November 16, 2008 | |

| Preceded by | Peter Fitzgerald |

| Succeeded by | Roland Burris |

| Member of the Illinois Senate from the 13th district | |

| In office January 8, 1997 – November 4, 2004 | |

| Preceded by | Alice Palmer |

| Succeeded by | Kwame Raoul |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Barack Hussein Obama II August 4, 1961 Honolulu, Hawaii, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouse | |

| Children | |

| Parents | |

| Relatives | Obama family |

| Education | |

| Occupation |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Signature | |

| Website | |

| ||

|---|---|---|

Pre-presidency 44th President of the United States Appointments First term Second term Post-presidency Publications Personal Others  | ||

Барак Хусейн Обама II [а] (родился 4 августа 1961 года) — американский политик, занимавший пост 44-го президента США с 2009 по 2017 год. Будучи членом Демократической партии , он был первым афроамериканским президентом в Соединённых Штатов истории . Ранее Обама был сенатором США, представляющим Иллинойс с 2005 по 2008 год, сенатором штата Иллинойс с 1997 по 2004 год, а также организатором общественных работ, юристом по гражданским правам и преподавателем университета.

Обама родился в Гонолулу , Гавайи . Он окончил Колумбийский университет в 1983 году со степенью бакалавра гуманитарных наук в области политологии, а затем работал общественным организатором в Чикаго. В 1988 году Обама поступил на юридический факультет Гарвардского университета , где стал первым чернокожим президентом журнала Harvard Law Review . Он стал адвокатом по гражданским правам и академиком, преподавая конституционное право на юридическом факультете Чикагского университета с 1992 по 2004 год. Он также занимался выборной политикой; Обама представлял 13-й округ в Сенате Иллинойса с 1997 по 2004 год, когда он успешно баллотировался в Сенат США . В 2008 году, после напряженной первичной кампании против Хиллари Клинтон , он был выдвинут Демократической партией на пост президента и выбрал сенатора от Делавэра Джо Байдена своим кандидатом на пост вице-президента. Обама был избран президентом, победив от Республиканской партии кандидата Джона Маккейна на президентских выборах , и вступил в должность 20 января 2009 года. Девять месяцев спустя он был назван лауреатом Нобелевской премии мира 2009 года , и это решение вызвало смесь критики и похвалы.

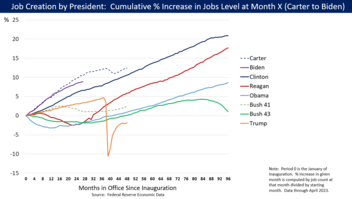

Obama's first-term actions addressed the global financial crisis and included a major stimulus package to guide the economy in recovering from the Great Recession, a partial extension of George W. Bush's tax cuts, legislation to reform health care, a major financial regulation reform bill, and the end of a major U.S. military presence in Iraq. Obama also appointed Supreme Court justices Sonia Sotomayor and Elena Kagan, the former being the first Hispanic American on the Supreme Court. He ordered the counterterrorism raid which killed Osama bin Laden and downplayed Bush's counterinsurgency model, expanding air strikes and making extensive use of special forces, while encouraging greater reliance on host-government militaries. Obama also ordered military involvement in Libya in order to implement UN Security Council Resolution 1973, contributing to the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi.

After winning re-election by defeating Republican opponent Mitt Romney, Obama was sworn in for a second term on January 20, 2013. In his second term, Obama took steps to combat climate change, signing a major international climate agreement and an executive order to limit carbon emissions. Obama also presided over the implementation of the Affordable Care Act and other legislation passed in his first term. He negotiated a nuclear agreement with Iran and normalized relations with Cuba. The number of American soldiers in Afghanistan fell dramatically during Obama's second term, though U.S. soldiers remained in the country throughout Obama's presidency. Obama promoted inclusion for LGBT Americans, becoming the first sitting U.S. president to publicly support same-sex marriage.

Obama left office on January 20, 2017, and continues to reside in Washington, D.C. His presidential library in Chicago began construction in 2021. Since leaving office, Obama has remained politically active, campaigning for candidates in various American elections, including Biden's successful bid for president in 2020. Outside of politics, Obama has published three books: Dreams from My Father (1995), The Audacity of Hope (2006), and A Promised Land (2020). Historians and political scientists rank him among the upper tier in historical rankings of American presidents.

Early life and career

Obama was born on August 4, 1961,[1] at Kapiolani Medical Center for Women and Children in Honolulu, Hawaii.[2][3][4][5] He is the only president born outside the contiguous 48 states.[6] He was born to an American mother and a Kenyan father. His mother, Ann Dunham (1942–1995), was born in Wichita, Kansas and was of English, Welsh, German, Swiss, and Irish descent. In 2007 it was discovered her great-great-grandfather Falmouth Kearney emigrated from the village of Moneygall, Ireland to the US in 1850.[7] In July 2012, Ancestry.com found a strong likelihood that Dunham was descended from John Punch, an enslaved African man who lived in the Colony of Virginia during the seventeenth century.[8][9] Obama's father, Barack Obama Sr. (1934–1982),[10][11] was a married[12][13][14] Luo Kenyan from Nyang'oma Kogelo.[12][15] His last name, Obama, was derived from his Luo descent.[16] Obama's parents met in 1960 in a Russian language class at the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa, where his father was a foreign student on a scholarship.[17][18] The couple married in Wailuku, Hawaii, on February 2, 1961, six months before Obama was born.[19][20]

In late August 1961, a few weeks after he was born, Barack and his mother moved to the University of Washington in Seattle, where they lived for a year. During that time, Barack's father completed his undergraduate degree in economics in Hawaii, graduating in June 1962. He left to attend graduate school on a scholarship at Harvard University, where he earned an M.A. in economics. Obama's parents divorced in March 1964.[21] Obama Sr. returned to Kenya in 1964, where he married for a third time and worked for the Kenyan government as the Senior Economic Analyst in the Ministry of Finance.[22] He visited his son in Hawaii only once, at Christmas 1971,[23] before he was killed in an automobile accident in 1982, when Obama was 21 years old.[24] Recalling his early childhood, Obama said: "That my father looked nothing like the people around me—that he was black as pitch, my mother white as milk—barely registered in my mind."[18] He described his struggles as a young adult to reconcile social perceptions of his multiracial heritage.[25]

In 1963, Dunham met Lolo Soetoro at the University of Hawaii; he was an Indonesian East–West Center graduate student in geography. The couple married on Molokai on March 15, 1965.[26] After two one-year extensions of his J-1 visa, Lolo returned to Indonesia in 1966. His wife and stepson followed sixteen months later in 1967. The family initially lived in the Menteng Dalam neighborhood in the Tebet district of South Jakarta. From 1970, they lived in a wealthier neighborhood in the Menteng district of Central Jakarta.[27]

Education

At the age of six, Obama and his mother had moved to Indonesia to join his stepfather. From age six to ten, he was registered in school as "Barry"[28] and attended local Indonesian-language schools: Sekolah Dasar Katolik Santo Fransiskus Asisi (St. Francis of Assisi Catholic Elementary School) for two years and Sekolah Dasar Negeri Menteng 01 (State Elementary School Menteng 01) for one and a half years, supplemented by English-language Calvert School homeschooling by his mother.[29][30] As a result of his four years in Jakarta, he was able to speak Indonesian fluently as a child.[31] During his time in Indonesia, Obama's stepfather taught him to be resilient and gave him "a pretty hardheaded assessment of how the world works".[32]

In 1971, Obama returned to Honolulu to live with his maternal grandparents, Madelyn and Stanley Dunham. He attended Punahou School—a private college preparatory school—with the aid of a scholarship from fifth grade until he graduated from high school in 1979.[33] In high school, Obama continued to use the nickname "Barry" which he kept until making a visit to Kenya in 1980.[34] Obama lived with his mother and half-sister, Maya Soetoro, in Hawaii for three years from 1972 to 1975 while his mother was a graduate student in anthropology at the University of Hawaii.[35] Obama chose to stay in Hawaii when his mother and half-sister returned to Indonesia in 1975, so his mother could begin anthropology field work.[36] His mother spent most of the next two decades in Indonesia, divorcing Lolo Soetoro in 1980 and earning a PhD degree in 1992, before dying in 1995 in Hawaii following unsuccessful treatment for ovarian and uterine cancer.[37]

Of his years in Honolulu, Obama wrote: "The opportunity that Hawaii offered — to experience a variety of cultures in a climate of mutual respect — became an integral part of my world view, and a basis for the values that I hold most dear."[38] Obama has also written and talked about using alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine during his teenage years to "push questions of who I was out of my mind".[39] Obama was also a member of the "Choom Gang" (the slang term for smoking marijuana), a self-named group of friends who spent time together and smoked marijuana.[40][41]

College and research jobs

After graduating from high school in 1979, Obama moved to Los Angeles to attend Occidental College on a full scholarship. In February 1981, Obama made his first public speech, calling for Occidental to participate in the disinvestment from South Africa in response to that nation's policy of apartheid.[42] In mid-1981, Obama traveled to Indonesia to visit his mother and half-sister Maya, and visited the families of college friends in Pakistan for three weeks.[42] Later in 1981, he transferred to Columbia University in New York City as a junior, where he majored in political science with a specialty in international relations[43] and in English literature[44] and lived off-campus on West 109th Street.[45] He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1983 and a 3.7 GPA. After graduating, Obama worked for about a year at the Business International Corporation, where he was a financial researcher and writer,[46][47] then as a project coordinator for the New York Public Interest Research Group on the City College of New York campus for three months in 1985.[48][49][50]

Community organizer and Harvard Law School

Two years after graduating from Columbia, Obama moved from New York to Chicago when he was hired as director of the Developing Communities Project, a faith-based community organization originally comprising eight Catholic parishes in Roseland, West Pullman, and Riverdale on Chicago's South Side. He worked there as a community organizer from June 1985 to May 1988.[49][51] He helped set up a job training program, a college preparatory tutoring program, and a tenants' rights organization in Altgeld Gardens.[52] Obama also worked as a consultant and instructor for the Gamaliel Foundation, a community organizing institute.[53] In mid-1988, he traveled for the first time in Europe for three weeks and then for five weeks in Kenya, where he met many of his paternal relatives for the first time.[54][55]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Despite being offered a full scholarship to Northwestern University School of Law, Obama enrolled at Harvard Law School in the fall of 1988, living in nearby Somerville, Massachusetts.[57] He was selected as an editor of the Harvard Law Review at the end of his first year,[58] president of the journal in his second year,[52][59] and research assistant to the constitutional scholar Laurence Tribe while at Harvard.[60] During his summers, he returned to Chicago, where he worked as a summer associate at the law firms of Sidley Austin in 1989 and Hopkins & Sutter in 1990.[61] Obama's election as the first black president of the Harvard Law Review gained national media attention[52][59] and led to a publishing contract and advance for a book about race relations,[62] which evolved into a personal memoir. The manuscript was published in mid-1995 as Dreams from My Father.[62] Obama graduated from Harvard Law in 1991 with a Juris Doctor magna cum laude.[63][58]

University of Chicago Law School

In 1991, Obama accepted a two-year position as Visiting Law and Government Fellow at the University of Chicago Law School to work on his first book.[62][64] He then taught constitutional law at the University of Chicago Law School for twelve years, first as a lecturer from 1992 to 1996, and then as a senior lecturer from 1996 to 2004.[65]

From April to October 1992, Obama directed Illinois's Project Vote, a voter registration campaign with ten staffers and seven hundred volunteer registrars; it achieved its goal of registering 150,000 of 400,000 unregistered African Americans in the state, leading Crain's Chicago Business to name Obama to its 1993 list of "40 under Forty" powers to be.[66]

Family and personal life

In a 2006 interview, Obama highlighted the diversity of his extended family: "It's like a little mini-United Nations," he said. "I've got relatives who look like Bernie Mac, and I've got relatives who look like Margaret Thatcher."[67] Obama has a half-sister with whom he was raised (Maya Soetoro-Ng) and seven other half-siblings from his Kenyan father's family, six of them living.[68] Obama's mother was survived by her Kansas-born mother, Madelyn Dunham,[69] until her death on November 2, 2008,[70] two days before his election to the presidency. Obama also has roots in Ireland; he met with his Irish cousins in Moneygall in May 2011.[71] In Dreams from My Father, Obama ties his mother's family history to possible Native American ancestors and distant relatives of Jefferson Davis, President of the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. He also shares distant ancestors in common with George W. Bush and Dick Cheney, among others.[72][73][74]

Obama lived with anthropologist Sheila Miyoshi Jager while he was a community organizer in Chicago in the 1980s.[75] He proposed to her twice, but both Jager and her parents turned him down.[75][76] The relationship was not made public until May 2017, several months after his presidency had ended.[76]

In June 1989, Obama met Michelle Robinson when he was employed at Sidley Austin.[77] Robinson was assigned for three months as Obama's adviser at the firm, and she joined him at several group social functions but declined his initial requests to date.[78] They began dating later that summer, became engaged in 1991, and were married on October 3, 1992.[79] After suffering a miscarriage, Michelle underwent in vitro fertilization to conceive their children.[80] The couple's first daughter, Malia Ann, was born in 1998,[81] followed by a second daughter, Natasha ("Sasha"), in 2001.[82] The Obama daughters attended the University of Chicago Laboratory Schools. When they moved to Washington, D.C., in January 2009, the girls started at the Sidwell Friends School.[83] The Obamas had two Portuguese Water Dogs; the first, a male named Bo, was a gift from Senator Ted Kennedy.[84] In 2013, Bo was joined by Sunny, a female.[85] Bo died of cancer on May 8, 2021.[86]

Obama is a supporter of the Chicago White Sox, and he threw out the first pitch at the 2005 ALCS when he was still a senator.[87] In 2009, he threw out the ceremonial first pitch at the All-Star Game while wearing a White Sox jacket.[88] He is also primarily a Chicago Bears football fan in the NFL, but in his childhood and adolescence was a fan of the Pittsburgh Steelers, and rooted for them ahead of their victory in Super Bowl XLIII 12 days after he took office as president.[89] In 2011, Obama invited the 1985 Chicago Bears to the White House; the team had not visited the White House after their Super Bowl win in 1986 due to the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster.[90] He plays basketball, a sport he participated in as a member of his high school's varsity team,[91] and he is left-handed.[92]

In 2005, the Obama family applied the proceeds of a book deal and moved from a Hyde Park, Chicago condominium to a $1.6 million house (equivalent to $2.5 million in 2023) in neighboring Kenwood, Chicago.[93] The purchase of an adjacent lot—and sale of part of it to Obama by the wife of developer, campaign donor and friend Tony Rezko—attracted media attention because of Rezko's subsequent indictment and conviction on political corruption charges that were unrelated to Obama.[94]

In December 2007, Money Magazine estimated Obama's net worth at $1.3 million (equivalent to $1.9 million in 2023).[95] Their 2009 tax return showed a household income of $5.5 million—up from about $4.2 million in 2007 and $1.6 million in 2005—mostly from sales of his books.[96][97] On his 2010 income of $1.7 million, he gave 14 percent to non-profit organizations, including $131,000 to Fisher House Foundation, a charity assisting wounded veterans' families, allowing them to reside near where the veteran is receiving medical treatments.[98][99] Per his 2012 financial disclosure, Obama may be worth as much as $10 million.[100]

Religious views

Obama is a Protestant Christian whose religious views developed in his adult life.[101] He wrote in The Audacity of Hope that he "was not raised in a religious household." He described his mother, raised by non-religious parents, as being detached from religion, yet "in many ways the most spiritually awakened person ... I have ever known", and "a lonely witness for secular humanism." He described his father as a "confirmed atheist" by the time his parents met, and his stepfather as "a man who saw religion as not particularly useful." Obama explained how, through working with black churches as a community organizer while in his twenties, he came to understand "the power of the African-American religious tradition to spur social change."[102]

In January 2008, Obama told Christianity Today: "I am a Christian, and I am a devout Christian. I believe in the redemptive death and resurrection of Jesus Christ. I believe that faith gives me a path to be cleansed of sin and have eternal life."[103] On September 27, 2010, Obama released a statement commenting on his religious views, saying:

I'm a Christian by choice. My family didn't—frankly, they weren't folks who went to church every week. And my mother was one of the most spiritual people I knew, but she didn't raise me in the church. So I came to my Christian faith later in life, and it was because the precepts of Jesus Christ spoke to me in terms of the kind of life that I would want to lead—being my brothers' and sisters' keeper, treating others as they would treat me.[104][105]

Obama met Trinity United Church of Christ pastor Jeremiah Wright in October 1987 and became a member of Trinity in 1992.[106] During Obama's first presidential campaign in May 2008, he resigned from Trinity after some of Wright's statements were criticized.[107] Since moving to Washington, D.C., in 2009, the Obama family has attended several Protestant churches, including Shiloh Baptist Church and St. John's Episcopal Church, as well as Evergreen Chapel at Camp David, but the members of the family do not attend church on a regular basis.[108][109][110]

In 2016, he said that he gets inspiration from a few items that remind him "of all the different people I've met along the way", adding: "I carry these around all the time. I'm not that superstitious, so it's not like I think I necessarily have to have them on me at all times." The items, "a whole bowl full", include rosary beads given to him by Pope Francis, a figurine of the Hindu deity Hanuman, a Coptic cross from Ethiopia, a small Buddha statue given by a monk, and a metal poker chip that used to be the lucky charm of a motorcyclist in Iowa.[111][112]

Legal career

Civil rights attorney

He joined Davis, Miner, Barnhill & Galland, a 13-attorney law firm specializing in civil rights litigation and neighborhood economic development, where he was an associate for three years from 1993 to 1996, then of counsel from 1996 to 2004. In 1994, he was listed as one of the lawyers in Buycks-Roberson v. Citibank Fed. Sav. Bank, 94 C 4094 (N.D. Ill.). This class action lawsuit was filed in 1994 with Selma Buycks-Roberson as lead plaintiff and alleged that Citibank Federal Savings Bank had engaged in practices forbidden under the Equal Credit Opportunity Act and the Fair Housing Act. The case was settled out of court.

From 1994 to 2002, Obama served on the boards of directors of the Woods Fund of Chicago—which in 1985 had been the first foundation to fund the Developing Communities Project—and of the Joyce Foundation.[49] He served on the board of directors of the Chicago Annenberg Challenge from 1995 to 2002, as founding president and chairman of the board of directors from 1995 to 1999.[49] Obama's law license became inactive in 2007.[113][114]

Legislative career

Illinois Senate (1997–2004)

Obama was elected to the Illinois Senate in 1996, succeeding Democratic State Senator Alice Palmer from Illinois's 13th District, which, at that time, spanned Chicago South Side neighborhoods from Hyde Park–Kenwood south to South Shore and west to Chicago Lawn.[115] Once elected, Obama gained bipartisan support for legislation that reformed ethics and health care laws.[116][117] He sponsored a law that increased tax credits for low-income workers, negotiated welfare reform, and promoted increased subsidies for childcare.[118] In 2001, as co-chairman of the bipartisan Joint Committee on Administrative Rules, Obama supported Republican Governor George Ryan's payday loan regulations and predatory mortgage lending regulations aimed at averting home foreclosures.[119][120]

He was reelected to the Illinois Senate in 1998, defeating Republican Yesse Yehudah in the general election, and was re-elected again in 2002.[121][122] In 2000, he lost a Democratic primary race for Illinois's 1st congressional district in the United States House of Representatives to four-term incumbent Bobby Rush by a margin of two to one.[123]

In January 2003, Obama became chairman of the Illinois Senate's Health and Human Services Committee when Democrats, after a decade in the minority, regained a majority.[124] He sponsored and led unanimous, bipartisan passage of legislation to monitor racial profiling by requiring police to record the race of drivers they detained, and legislation making Illinois the first state to mandate videotaping of homicide interrogations.[118][125][126][127] During his 2004 general election campaign for the U.S. Senate, police representatives credited Obama for his active engagement with police organizations in enacting death penalty reforms.[128] Obama resigned from the Illinois Senate in November 2004 following his election to the U.S. Senate.[129]

2004 U.S. Senate campaign

In May 2002, Obama commissioned a poll to assess his prospects in a 2004 U.S. Senate race. He created a campaign committee, began raising funds, and lined up political media consultant David Axelrod by August 2002. Obama formally announced his candidacy in January 2003.[130]

Obama was an early opponent of the George W. Bush administration's 2003 invasion of Iraq.[131] On October 2, 2002, the day President Bush and Congress agreed on the joint resolution authorizing the Iraq War,[132] Obama addressed the first high-profile Chicago anti-Iraq War rally,[133] and spoke out against the war.[134] He addressed another anti-war rally in March 2003 and told the crowd "it's not too late" to stop the war.[135]

Decisions by Republican incumbent Peter Fitzgerald and his Democratic predecessor Carol Moseley Braun not to participate in the election resulted in wide-open Democratic and Republican primary contests involving 15 candidates.[136] In the March 2004 primary election, Obama won in an unexpected landslide—which overnight made him a rising star within the national Democratic Party, started speculation about a presidential future, and led to the reissue of his memoir, Dreams from My Father.[137] In July 2004, Obama delivered the keynote address at the 2004 Democratic National Convention,[138] seen by nine million viewers. His speech was well received and elevated his status within the Democratic Party.[139]

Obama's expected opponent in the general election, Republican primary winner Jack Ryan, withdrew from the race in June 2004.[140] Six weeks later, Alan Keyes accepted the Republican nomination to replace Ryan.[141] In the November 2004 general election, Obama won with 70 percent of the vote, the largest margin of victory for a Senate candidate in Illinois history.[142] He took 92 of the state's 102 counties, including several where Democrats traditionally do not do well.

U.S. Senate (2005–2008)

Obama was sworn in as a senator on January 3, 2005,[143] becoming the only Senate member of the Congressional Black Caucus.[144] He introduced two initiatives that bore his name: Lugar–Obama, which expanded the Nunn–Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction concept to conventional weapons;[145] and the Federal Funding Accountability and Transparency Act of 2006, which authorized the establishment of USAspending.gov, a web search engine on federal spending.[146] On June 3, 2008, Senator Obama—along with Senators Tom Carper, Tom Coburn, and John McCain—introduced follow-up legislation: Strengthening Transparency and Accountability in Federal Spending Act of 2008.[147] He also cosponsored the Secure America and Orderly Immigration Act.[148]

In December 2006, President Bush signed into law the Democratic Republic of the Congo Relief, Security, and Democracy Promotion Act, marking the first federal legislation to be enacted with Obama as its primary sponsor.[149][150] In January 2007, Obama and Senator Feingold introduced a corporate jet provision to the Honest Leadership and Open Government Act, which was signed into law in September 2007.[151][152]

Later in 2007, Obama sponsored an amendment to the Defense Authorization Act to add safeguards for personality-disorder military discharges.[153] This amendment passed the full Senate in the spring of 2008.[154] He sponsored the Iran Sanctions Enabling Act supporting divestment of state pension funds from Iran's oil and gas industry, which was never enacted but later incorporated in the Comprehensive Iran Sanctions, Accountability, and Divestment Act of 2010;[155] and co-sponsored legislation to reduce risks of nuclear terrorism.[156] Obama also sponsored a Senate amendment to the State Children's Health Insurance Program, providing one year of job protection for family members caring for soldiers with combat-related injuries.[157]

Obama held assignments on the Senate Committees for Foreign Relations, Environment and Public Works and Veterans' Affairs through December 2006.[158] In January 2007, he left the Environment and Public Works committee and took additional assignments with Health, Education, Labor and Pensions and Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs.[159] He also became Chairman of the Senate's subcommittee on European Affairs.[160] As a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Obama made official trips to Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Central Asia and Africa. He met with Mahmoud Abbas before Abbas became President of the Palestinian National Authority, and gave a speech at the University of Nairobi in which he condemned corruption within the Kenyan government.[161]

Obama resigned his Senate seat on November 16, 2008, to focus on his transition period for the presidency.[162]

Presidential campaigns

2008

On February 10, 2007, Obama announced his candidacy for President of the United States in front of the Old State Capitol building in Springfield, Illinois.[163][164] The choice of the announcement site was viewed as symbolic, as it was also where Abraham Lincoln delivered his "House Divided" speech in 1858.[163][165] Obama emphasized issues of rapidly ending the Iraq War, increasing energy independence, and reforming the health care system.[166]

Numerous candidates entered the Democratic Party presidential primaries. The field narrowed to Obama and Senator Hillary Clinton after early contests, with the race remaining close throughout the primary process, but with Obama gaining a steady lead in pledged delegates due to better long-range planning, superior fundraising, dominant organizing in caucus states, and better exploitation of delegate allocation rules.[167] On June 2, 2008, Obama had received enough votes to clinch his nomination. After an initial hesitation to concede, on June 7, Clinton ended her campaign and endorsed Obama.[168] On August 23, 2008, Obama announced his selection of Delaware Senator Joe Biden as his vice presidential running mate.[169] Obama selected Biden from a field speculated to include former Indiana Governor and Senator Evan Bayh and Virginia Governor Tim Kaine.[169] At the Democratic National Convention in Denver, Colorado, Hillary Clinton called for her supporters to endorse Obama, and she and Bill Clinton gave convention speeches in his support.[170][171] Obama delivered his acceptance speech at Invesco Field at Mile High stadium to a crowd of about eighty-four thousand; the speech was viewed by over three million people worldwide.[172][173][174] During both the primary process and the general election, Obama's campaign set numerous fundraising records, particularly in the quantity of small donations.[175] On June 19, 2008, Obama became the first major-party presidential candidate to turn down public financing in the general election since the system was created in 1976.[176]

John McCain was nominated as the Republican candidate, and he selected Sarah Palin as his running mate. Obama and McCain engaged in three presidential debates in September and October 2008.[177] On November 4, Obama won the presidency with 365 electoral votes to 173 received by McCain.[178] Obama won 52.9 percent of the popular vote to McCain's 45.7 percent.[179] He became the first African-American to be elected president.[180] Obama delivered his victory speech before hundreds of thousands of supporters in Chicago's Grant Park.[181][182] He is one of the three United States senators moved directly from the U.S. Senate to the White House, the others being Warren G. Harding and John F. Kennedy.[183]

2012

On April 4, 2011, Obama filed election papers with the Federal Election Commission and then announced his reelection campaign for 2012 in a video titled "It Begins with Us" that he posted on his website.[184][185][186] As the incumbent president, he ran virtually unopposed in the Democratic Party presidential primaries,[187] and on April 3, 2012, Obama secured the 2778 convention delegates needed to win the Democratic nomination.[188] At the Democratic National Convention in Charlotte, North Carolina, Obama and Joe Biden were formally nominated by former President Bill Clinton as the Democratic Party candidates for president and vice president in the general election. Their main opponents were Republicans Mitt Romney, the former governor of Massachusetts, and Representative Paul Ryan of Wisconsin.[189]

On November 6, 2012, Obama won 332 electoral votes, exceeding the 270 required for him to be reelected as president.[190][191][192] With 51.1 percent of the popular vote,[193] Obama became the first Democratic president since Franklin D. Roosevelt to win the majority of the popular vote twice.[194][195] Obama addressed supporters and volunteers at Chicago's McCormick Place after his reelection and said: "Tonight you voted for action, not politics as usual. You elected us to focus on your jobs, not ours. And in the coming weeks and months, I am looking forward to reaching out and working with leaders of both parties."[196][197]

Presidency (2009–2017)

First 100 days

The inauguration of Barack Obama as the 44th president took place on January 20, 2009. In his first few days in office, Obama issued executive orders and presidential memoranda directing the U.S. military to develop plans to withdraw troops from Iraq.[198] He ordered the closing of the Guantanamo Bay detention camp,[199] but Congress prevented the closure by refusing to appropriate the required funds[200][201] and preventing moving any Guantanamo detainee.[202] Obama reduced the secrecy given to presidential records.[203] He also revoked President George W. Bush's restoration of President Ronald Reagan's Mexico City policy which prohibited federal aid to international family planning organizations that perform or provide counseling about abortion.[204]

Domestic policy

The first bill signed into law by Obama was the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act of 2009, relaxing the statute of limitations for equal-pay lawsuits.[205] Five days later, he signed the reauthorization of the State Children's Health Insurance Program to cover an additional four million uninsured children.[206] In March 2009, Obama reversed a Bush-era policy that had limited funding of embryonic stem cell research and pledged to develop "strict guidelines" on the research.[207]

Obama appointed two women to serve on the Supreme Court in the first two years of his presidency. He nominated Sonia Sotomayor on May 26, 2009, to replace retiring Associate Justice David Souter. She was confirmed on August 6, 2009,[208] becoming the first Supreme Court Justice of Hispanic descent.[209] Obama nominated Elena Kagan on May 10, 2010, to replace retiring Associate Justice John Paul Stevens. She was confirmed on August 5, 2010, bringing the number of women sitting simultaneously on the Court to three for the first time in American history.[210]

On March 11, 2009, Obama created the White House Council on Women and Girls, which formed part of the Office of Intergovernmental Affairs, having been established by Executive Order 13506 with a broad mandate to advise him on issues relating to the welfare of American women and girls. The council was chaired by Senior Advisor to the President Valerie Jarrett. Obama also established the White House Task Force to Protect Students from Sexual Assault through a government memorandum on January 22, 2014, with a broad mandate to advise him on issues relating to sexual assault on college and university campuses throughout the United States. The co-chairs of the Task Force were Vice President Joe Biden and Jarrett. The Task Force was a development out of the White House Council on Women and Girls and Office of the Vice President of the United States, and prior to that the 1994 Violence Against Women Act first drafted by Biden.

In July 2009, Obama launched the Priority Enforcement Program, an immigration enforcement program that had been pioneered by George W. Bush, and the Secure Communities fingerprinting and immigration status data-sharing program.[211]

In a major space policy speech in April 2010, Obama announced a planned change in direction at NASA, the U.S. space agency. He ended plans for a return of human spaceflight to the moon and development of the Ares I rocket, Ares V rocket and Constellation program, in favor of funding earth science projects, a new rocket type, research and development for an eventual crewed mission to Mars, and ongoing missions to the International Space Station.[212]

On January 16, 2013, one month after the Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, Obama signed 23 executive orders and outlined a series of sweeping proposals regarding gun control.[213] He urged Congress to reintroduce an expired ban on military-style assault weapons, such as those used in several recent mass shootings, impose limits on ammunition magazines to 10 rounds, introduce background checks on all gun sales, pass a ban on possession and sale of armor-piercing bullets, introduce harsher penalties for gun-traffickers, especially unlicensed dealers who buy arms for criminals and approving the appointment of the head of the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives for the first time since 2006.[214] On January 5, 2016, Obama announced new executive actions extending background check requirements to more gun sellers.[215] In a 2016 editorial in The New York Times, Obama compared the struggle for what he termed "common-sense gun reform" to women's suffrage and other civil rights movements in American history.

In 2011, Obama signed a four-year renewal of the Patriot Act.[216] Following the 2013 global surveillance disclosures by whistleblower Edward Snowden, Obama condemned the leak as unpatriotic,[217] but called for increased restrictions on the National Security Agency (NSA) to address violations of privacy.[218][219] Obama continued and expanded surveillance programs set up by George W. Bush, while implementing some reforms.[220] He supported legislation that would have limited the NSA's ability to collect phone records in bulk under a single program and supported bringing more transparency to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC).[220]

Racial issues

In his speeches as president, Obama did not make more overt references to race relations than his predecessors,[221][222] but according to one study, he implemented stronger policy action on behalf of African-Americans than any president since the Nixon era.[223]

Following Obama's election, many pondered the existence of a "postracial America".[224][225] However, lingering racial tensions quickly became apparent,[224][226] and many African-Americans expressed outrage over what they saw as an intense racial animosity directed at Obama.[227] The acquittal of George Zimmerman following the killing of Trayvon Martin sparked national outrage, leading to Obama giving a speech in which he noted that "Trayvon Martin could have been me 35 years ago."[228] The shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri sparked a wave of protests.[229] These and other events led to the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement, which campaigns against violence and systemic racism toward black people.[229] Though Obama entered office reluctant to talk about race, by 2014 he began openly discussing the disadvantages faced by many members of minority groups.[230]

Several incidents during Obama's presidency generated disapproval from the African-American community and with law enforcement, and Obama sought to build trust between law enforcement officials and civil rights activists, with mixed results. Some in law enforcement criticized Obama's condemnation of racial bias after incidents in which police action led to the death of African-American men, while some racial justice activists criticized Obama's expressions of empathy for the police.[231] In a March 2016 Gallup poll, nearly one third of Americans said they worried "a great deal" about race relations, a higher figure than in any previous Gallup poll since 2001.[232]

LGBT rights

On October 8, 2009, Obama signed the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, a measure that expanded the 1969 United States federal hate-crime law to include crimes motivated by a victim's actual or perceived gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, or disability.[233] On October 30, 2009, Obama lifted the ban on travel to the United States by those infected with HIV. The lifting of the ban was celebrated by Immigration Equality.[234] On December 22, 2010, Obama signed the Don't Ask, Don't Tell Repeal Act of 2010, which fulfilled a promise made in the 2008 presidential campaign[235][236] to end the don't ask, don't tell policy of 1993 that had prevented gay and lesbian people from serving openly in the United States Armed Forces. In 2016, the Pentagon ended the policy that barred transgender people from serving openly in the military.[237]

Same-sex marriage

As a candidate for the Illinois state senate in 1996, Obama stated he favored legalizing same-sex marriage.[238] During his Senate run in 2004, he said he supported civil unions and domestic partnerships for same-sex partners but opposed same-sex marriages.[239] In 2008, he reaffirmed this position by stating "I believe marriage is between a man and a woman. I am not in favor of gay marriage."[240] On May 9, 2012, shortly after the official launch of his campaign for re-election as president, Obama said his views had evolved, and he publicly affirmed his personal support for the legalization of same-sex marriage, becoming the first sitting U.S. president to do so.[241][242] During his second inaugural address on January 21, 2013,[197] Obama became the first U.S. president in office to call for full equality for gay Americans, and the first to mention gay rights or the word "gay" in an inaugural address.[243][244] In 2013, the Obama administration filed briefs that urged the Supreme Court to rule in favor of same-sex couples in the cases of Hollingsworth v. Perry (regarding same-sex marriage)[245] and United States v. Windsor (regarding the Defense of Marriage Act).[246]

Economic policy

On February 17, 2009, Obama signed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009, a $787 billion (equivalent to $1118 billion in 2023) economic stimulus package aimed at helping the economy recover from the deepening worldwide recession.[247] The act includes increased federal spending for health care, infrastructure, education, various tax breaks and incentives, and direct assistance to individuals.[248] In March 2009, Obama's Treasury Secretary, Timothy Geithner, took further steps to manage the financial crisis, including introducing the Public–Private Investment Program for Legacy Assets, which contains provisions for buying up to $2 trillion in depreciated real estate assets.[249]

Obama intervened in the troubled automotive industry[250] in March 2009, renewing loans for General Motors (GM) and Chrysler to continue operations while reorganizing. Over the following months the White House set terms for both firms' bankruptcies, including the sale of Chrysler to Italian automaker Fiat[251] and a reorganization of GM giving the U.S. government a temporary 60 percent equity stake in the company.[252] In June 2009, dissatisfied with the pace of economic stimulus, Obama called on his cabinet to accelerate the investment.[253] He signed into law the Car Allowance Rebate System, known colloquially as "Cash for Clunkers", which temporarily boosted the economy.[254][255][256]

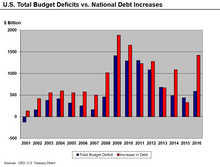

The Bush and Obama administrations authorized spending and loan guarantees from the Federal Reserve and the Department of the Treasury. These guarantees totaled about $11.5 trillion, but only $3 trillion had been spent by the end of November 2009.[257] On August 2, 2011, after a lengthy congressional debate over whether to raise the nation's debt limit, Obama signed the bipartisan Budget Control Act of 2011. The legislation enforced limits on discretionary spending until 2021, established a procedure to increase the debt limit, created a Congressional Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction to propose further deficit reduction with a stated goal of achieving at least $1.5 trillion in budgetary savings over 10 years, and established automatic procedures for reducing spending by as much as $1.2 trillion if legislation originating with the new joint select committee did not achieve such savings.[258] By passing the legislation, Congress was able to prevent a U.S. government default on its obligations.[259]

The unemployment rate rose in 2009, reaching a peak in October at 10.0 percent and averaging 10.0 percent in the fourth quarter. Following a decrease to 9.7 percent in the first quarter of 2010, the unemployment rate fell to 9.6 percent in the second quarter, where it remained for the rest of the year.[260] Between February and December 2010, employment rose by 0.8 percent, which was less than the average of 1.9 percent experienced during comparable periods in the past four employment recoveries.[261] By November 2012, the unemployment rate fell to 7.7 percent,[262] decreasing to 6.7 percent in the last month of 2013.[263] During 2014, the unemployment rate continued to decline, falling to 6.3 percent in the first quarter.[264] GDP growth returned in the third quarter of 2009, expanding at a rate of 1.6 percent, followed by a 5.0 percent increase in the fourth quarter.[265] Growth continued in 2010, posting an increase of 3.7 percent in the first quarter, with lesser gains throughout the rest of the year.[265] In July 2010, the Federal Reserve noted that economic activity continued to increase, but its pace had slowed, and chairman Ben Bernanke said the economic outlook was "unusually uncertain".[266] Overall, the economy expanded at a rate of 2.9 percent in 2010.[267]

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and a broad range of economists credit Obama's stimulus plan for economic growth.[270][271] The CBO released a report stating that the stimulus bill increased employment by 1–2.1 million,[271][272][273] while conceding that "it is impossible to determine how many of the reported jobs would have existed in the absence of the stimulus package."[270] Although an April 2010, survey of members of the National Association for Business Economics showed an increase in job creation (over a similar January survey) for the first time in two years, 73 percent of 68 respondents believed the stimulus bill has had no impact on employment.[274] The economy of the United States has grown faster than the other original NATO members by a wider margin under President Obama than it has anytime since the end of World War II.[275] The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development credits the much faster growth in the United States to the stimulus plan of the U.S. and the austerity measures in the European Union.[276]

Within a month of the 2010 midterm elections, Obama announced a compromise deal with the Congressional Republican leadership that included a temporary, two-year extension of the 2001 and 2003 income tax rates, a one-year payroll tax reduction, continuation of unemployment benefits, and a new rate and exemption amount for estate taxes.[277] The compromise overcame opposition from some in both parties, and the resulting $858 billion (equivalent to $1.2 trillion in 2023) Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 passed with bipartisan majorities in both houses of Congress before Obama signed it on December 17, 2010.[278]

In December 2013, Obama declared that growing income inequality is a "defining challenge of our time" and called on Congress to bolster the safety net and raise wages. This came on the heels of the nationwide strikes of fast-food workers and Pope Francis' criticism of inequality and trickle-down economics.[279] Obama urged Congress to ratify a 12-nation free trade pact called the Trans-Pacific Partnership.[280]

Environmental policy

On April 20, 2010, an explosion destroyed an offshore drilling rig at the Macondo Prospect in the Gulf of Mexico, causing a major sustained oil leak. Obama visited the Gulf, announced a federal investigation, and formed a bipartisan commission to recommend new safety standards, after a review by Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar and concurrent Congressional hearings. He then announced a six-month moratorium on new deepwater drilling permits and leases, pending regulatory review.[281] As multiple efforts by BP failed, some in the media and public expressed confusion and criticism over various aspects of the incident, and stated a desire for more involvement by Obama and the federal government.[282] Prior to the oil spill, on March 31, 2010, Obama ended a ban on oil and gas drilling along the majority of the East Coast of the United States and along the coast of northern Alaska in an effort to win support for an energy and climate bill and to reduce foreign imports of oil and gas.[283]

In July 2013, Obama expressed reservations and said he "would reject the Keystone XL pipeline if it increased carbon pollution [or] greenhouse emissions."[284][285] On February 24, 2015, Obama vetoed a bill that would have authorized the pipeline.[286] It was the third veto of Obama's presidency and his first major veto.[287]

In December 2016, Obama permanently banned new offshore oil and gas drilling in most United States-owned waters in the Atlantic and Arctic Oceans using the 1953 Outer Continental Shelf Act.[288][289][290]

Obama emphasized the conservation of federal lands during his term in office. He used his power under the Antiquities Act to create 25 new national monuments during his presidency and expand four others, protecting a total of 553,000,000 acres (224,000,000 ha) of federal lands and waters, more than any other U.S. president.[291][292][293]

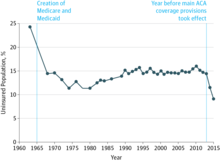

Health care reform

Obama called for Congress to pass legislation reforming health care in the United States, a key campaign promise and a top legislative goal.[294] He proposed an expansion of health insurance coverage to cover the uninsured, cap premium increases, and allow people to retain their coverage when they leave or change jobs. His proposal was to spend $900 billion over ten years and include a government insurance plan, also known as the public option, to compete with the corporate insurance sector as a main component to lowering costs and improving quality of health care. It would also make it illegal for insurers to drop sick people or deny them coverage for pre-existing conditions, and require every American to carry health coverage. The plan also includes medical spending cuts and taxes on insurance companies that offer expensive plans.[295][296]

On July 14, 2009, House Democratic leaders introduced a 1,017-page plan for overhauling the U.S. health care system, which Obama wanted Congress to approve by the end of 2009.[294] After public debate during the Congressional summer recess of 2009, Obama delivered a speech to a joint session of Congress on September 9 where he addressed concerns over the proposals.[298] In March 2009, Obama lifted a ban on using federal funds for stem cell research.[299]

On November 7, 2009, a health care bill featuring the public option was passed in the House.[300][301] On December 24, 2009, the Senate passed its own bill—without a public option—on a party-line vote of 60–39.[302] On March 21, 2010, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA, colloquially "Obamacare") passed by the Senate in December was passed in the House by a vote of 219 to 212. Obama signed the bill into law on March 23, 2010.[303]

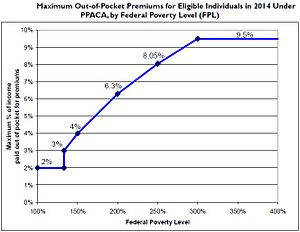

The ACA includes health-related provisions, most of which took effect in 2014, including expanding Medicaid eligibility for people making up to 133 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL) starting in 2014,[304] subsidizing insurance premiums for people making up to 400 percent of the FPL ($88,000 for family of four in 2010) so their maximum "out-of-pocket" payment for annual premiums will be from 2 percent to 9.5 percent of income,[305] providing incentives for businesses to provide health care benefits, prohibiting denial of coverage and denial of claims based on pre-existing conditions, establishing health insurance exchanges, prohibiting annual coverage caps, and support for medical research. According to White House and CBO figures, the maximum share of income that enrollees would have to pay would vary depending on their income relative to the federal poverty level.[306]

The costs of these provisions are offset by taxes, fees, and cost-saving measures, such as new Medicare taxes for those in high-income brackets, taxes on indoor tanning, cuts to the Medicare Advantage program in favor of traditional Medicare, and fees on medical devices and pharmaceutical companies;[308] there is also a tax penalty for those who do not obtain health insurance, unless they are exempt due to low income or other reasons.[309] In March 2010, the CBO estimated that the net effect of both laws will be a reduction in the federal deficit by $143 billion over the first decade.[310]

The law faced several legal challenges, primarily based on the argument that an individual mandate requiring Americans to buy health insurance was unconstitutional. On June 28, 2012, the Supreme Court ruled by a 5–4 vote in National Federation of Independent Business v. Sebelius that the mandate was constitutional under the U.S. Congress's taxing authority.[311] In Burwell v. Hobby Lobby the Court ruled that "closely-held" for-profit corporations could be exempt on religious grounds under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act from regulations adopted under the ACA that would have required them to pay for insurance that covered certain contraceptives. In June 2015, the Court ruled 6–3 in King v. Burwell that subsidies to help individuals and families purchase health insurance were authorized for those doing so on both the federal exchange and state exchanges, not only those purchasing plans "established by the State", as the statute reads.[312]

Foreign policy

In February and March 2009, Vice President Joe Biden and Secretary of State Hillary Clinton made separate overseas trips to announce a "new era" in U.S. foreign relations with Russia and Europe, using the terms "break" and "reset" to signal major changes from the policies of the preceding administration.[313] Obama attempted to reach out to Arab leaders by granting his first interview to an Arab satellite TV network, Al Arabiya.[314] On March 19, Obama continued his outreach to the Muslim world, releasing a New Year's video message to the people and government of Iran.[315][316] On June 4, 2009, Obama delivered a speech at Cairo University in Egypt calling for "A New Beginning" in relations between the Islamic world and the United States and promoting Middle East peace.[317] On June 26, 2009, Obama condemned the Iranian government's actions towards protesters following Iran's 2009 presidential election.[318]

In 2011, Obama ordered a drone strike in Yemen which targeted and killed Anwar al-Awlaki, an American imam suspected of being a leading Al-Qaeda organizer. al-Awlaki became the first U.S. citizen to be targeted and killed by a U.S. drone strike. The Department of Justice released a memo justifying al-Awlaki's death as a lawful act of war,[319] while civil liberties advocates described it as a violation of al-Awlaki's constitutional right to due process. The killing led to significant controversy.[320] His teenage son and young daughter, also Americans, were later killed in separate US military actions, although they were not targeted specifically.[321][322]

In March 2015, Obama declared that he had authorized U.S. forces to provide logistical and intelligence support to the Saudis in their military intervention in Yemen, establishing a "Joint Planning Cell" with Saudi Arabia.[323][324] In 2016, the Obama administration proposed a series of arms deals with Saudi Arabia worth $115 billion.[325] Obama halted the sale of guided munition technology to Saudi Arabia after Saudi warplanes targeted a funeral in Yemen's capital Sanaa, killing more than 140 people.[326]

In September 2016 Obama was snubbed by Xi Jinping and the Chinese Communist Party as he descended from Air Force One to the tarmac of Hangzhou International Airport for the 2016 G20 Hangzhou summit without the usual red carpet welcome.[327]

War in Iraq

On February 27, 2009, Obama announced that combat operations in Iraq would end within 18 months.[328] The Obama administration scheduled the withdrawal of combat troops to be completed by August 2010, decreasing troop's levels from 142,000 while leaving a transitional force of about 50,000 in Iraq until the end of 2011. On August 19, 2010, the last U.S. combat brigade exited Iraq. Remaining troops transitioned from combat operations to counter-terrorism and the training, equipping, and advising of Iraqi security forces.[329][330] On August 31, 2010, Obama announced that the United States combat mission in Iraq was over.[331] On October 21, 2011, President Obama announced that all U.S. troops would leave Iraq in time to be "home for the holidays."[332]

In June 2014, following the capture of Mosul by ISIL, Obama sent 275 troops to provide support and security for U.S. personnel and the U.S. Embassy in Baghdad. ISIS continued to gain ground and to commit widespread massacres and ethnic cleansing.[333][334] In August 2014, during the Sinjar massacre, Obama ordered a campaign of U.S. airstrikes against ISIL.[335] By the end of 2014, 3,100 American ground troops were committed to the conflict[336] and 16,000 sorties were flown over the battlefield, primarily by U.S. Air Force and Navy pilots.[337] In early 2015, with the addition of the "Panther Brigade" of the 82nd Airborne Division the number of U.S. ground troops in Iraq increased to 4,400,[338] and by July American-led coalition air forces counted 44,000 sorties over the battlefield.[339]

Afghanistan and Pakistan

In his election campaign, Obama called the war in Iraq a "dangerous distraction" and that emphasis should instead be put on the war in Afghanistan,[340] the region he cites as being most likely where an attack against the United States could be launched again.[341] Early in his presidency, Obama moved to bolster U.S. troop strength in Afghanistan. He announced an increase in U.S. troop levels to 17,000 military personnel in February 2009 to "stabilize a deteriorating situation in Afghanistan", an area he said had not received the "strategic attention, direction and resources it urgently requires."[342] He replaced the military commander in Afghanistan, General David D. McKiernan, with former Special Forces commander Lt. Gen. Stanley A. McChrystal in May 2009, indicating that McChrystal's Special Forces experience would facilitate the use of counterinsurgency tactics in the war.[343] On December 1, 2009, Obama announced the deployment of an additional 30,000 military personnel to Afghanistan and proposed to begin troop withdrawals 18 months from that date;[344] this took place in July 2011. David Petraeus replaced McChrystal in June 2010, after McChrystal's staff criticized White House personnel in a magazine article.[345] In February 2013, Obama said the U.S. military would reduce the troop level in Afghanistan from 68,000 to 34,000 U.S. troops by February 2014.[346] In October 2015, the White House announced a plan to keep U.S. Forces in Afghanistan indefinitely in light of the deteriorating security situation.[347]

Regarding neighboring Pakistan, Obama called its tribal border region the "greatest threat" to the security of Afghanistan and Americans, saying that he "cannot tolerate a terrorist sanctuary." In the same speech, Obama claimed that the U.S. "cannot succeed in Afghanistan or secure our homeland unless we change our Pakistan policy."[348]

Death of Osama bin Laden

Starting with information received from Central Intelligence Agency operatives in July 2010, the CIA developed intelligence over the next several months that determined what they believed to be the hideout of Osama bin Laden. He was living in seclusion in a large compound in Abbottabad, Pakistan, a suburban area 35 miles (56 km) from Islamabad.[349] CIA head Leon Panetta reported this intelligence to President Obama in March 2011.[349] Meeting with his national security advisers over the course of the next six weeks, Obama rejected a plan to bomb the compound, and authorized a "surgical raid" to be conducted by United States Navy SEALs.[349] The operation took place on May 1, 2011, and resulted in the shooting death of bin Laden and the seizure of papers, computer drives and disks from the compound.[350][351] DNA testing was one of five methods used to positively identify bin Laden's corpse,[352] which was buried at sea several hours later.[353] Within minutes of the President's announcement from Washington, DC, late in the evening on May 1, there were spontaneous celebrations around the country as crowds gathered outside the White House, and at New York City's Ground Zero and Times Square.[350][354] Reaction to the announcement was positive across party lines, including from former presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush.[355]

Relations with Cuba

Since the spring of 2013, secret meetings were conducted between the United States and Cuba in the neutral locations of Canada and Vatican City.[356] The Vatican first became involved in 2013 when Pope Francis advised the U.S. and Cuba to exchange prisoners as a gesture of goodwill.[357] On December 10, 2013, Cuban President Raúl Castro, in a significant public moment, greeted and shook hands with Obama at the Nelson Mandela memorial service in Johannesburg.[358]

In December 2014, after the secret meetings, it was announced that Obama, with Pope Francis as an intermediary, had negotiated a restoration of relations with Cuba, after nearly sixty years of détente.[359] Popularly dubbed the Cuban Thaw, The New Republic deemed the Cuban Thaw to be "Obama's finest foreign policy achievement."[360] On July 1, 2015, President Obama announced that formal diplomatic relations between Cuba and the United States would resume, and embassies would be opened in Washington and Havana.[361] The countries' respective "interests sections" in one another's capitals were upgraded to embassies on July 20 and August 13, 2015, respectively.[362] Obama visited Havana, Cuba for two days in March 2016, becoming the first sitting U.S. president to arrive since Calvin Coolidge in 1928.[363]

Israel

During the initial years of the Obama administration, the U.S. increased military cooperation with Israel, including increased military aid, re-establishment of the U.S.-Israeli Joint Political Military Group and the Defense Policy Advisory Group, and an increase in visits among high-level military officials of both countries.[364] The Obama administration asked Congress to allocate money toward funding the Iron Dome program in response to the waves of Palestinian rocket attacks on Israel.[365] In March 2010, Obama took a public stance against plans by the government of Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu to continue building Jewish housing projects in predominantly Arab neighborhoods of East Jerusalem.[366][367] In 2011, the United States vetoed a Security Council resolution condemning Israeli settlements, with the United States being the only nation to do so.[368] Obama supports the two-state solution to the Arab–Israeli conflict based on the 1967 borders with land swaps.[369]

In 2013, Jeffrey Goldberg reported that, in Obama's view, "with each new settlement announcement, Netanyahu is moving his country down a path toward near-total isolation."[370] In 2014, Obama likened the Zionist movement to the civil rights movement in the United States. He said both movements seek to bring justice and equal rights to historically persecuted peoples, explaining: "To me, being pro-Israel and pro-Jewish is part and parcel with the values that I've been fighting for since I was politically conscious and started getting involved in politics."[371] Obama expressed support for Israel's right to defend itself during the 2014 Israel–Gaza conflict.[372] In 2015, Obama was harshly criticized by Israel for advocating and signing the Iran Nuclear Deal; Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, who had advocated the U.S. congress to oppose it, said the deal was "dangerous" and "bad."[373]

On December 23, 2016, under the Obama Administration, the United States abstained from United Nations Security Council Resolution 2334, which condemned Israeli settlement building in the occupied Palestinian territories as a violation of international law, effectively allowing it to pass.[374] Netanyahu strongly criticized the Obama administration's actions,[375][376] and the Israeli government withdrew its annual dues from the organization, which totaled $6 million, on January 6, 2017.[377] On January 5, 2017, the United States House of Representatives voted 342–80 to condemn the UN Resolution.[378][379]

Libya

In February 2011, protests in Libya began against long-time dictator Muammar Gaddafi as part of the Arab Spring. They soon turned violent. In March, as forces loyal to Gaddafi advanced on rebels across Libya, calls for a no-fly zone came from around the world, including Europe, the Arab League, and a resolution[380] passed unanimously by the U.S. Senate.[381] In response to the passage of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1973 on March 17, the Foreign Minister of Libya Moussa Koussa announced a ceasefire. However Gaddafi's forces continued to attack the rebels.[382]

On March 19 a multinational coalition lead by France and the United Kingdom with Italian and U.S. support, approved by Obama, took part in air strikes to destroy the Libyan government's air defense capabilities to protect civilians and enforce a no-fly-zone,[383] including the use of Tomahawk missiles, B-2 Spirits, and fighter jets.[384][385][386] Six days later, on March 25, by unanimous vote of all its 28 members, NATO took over leadership of the effort, dubbed Operation Unified Protector.[387] Some members of Congress[388] questioned whether Obama had the constitutional authority to order military action in addition to questioning its cost, structure and aftermath.[389][390] In 2016 Obama said “Our coalition could have and should have done more to fill a vacuum left behind” and that it was "a mess".[391] He has stated that the lack of preparation surrounding the days following the government's overthrow was the "worst mistake" of his presidency.[392]

Syrian civil war

On August 18, 2011, several months after the start of the Syrian civil war, Obama issued a written statement that said: "The time has come for President Assad to step aside."[393] This stance was reaffirmed in November 2015.[394] In 2012, Obama authorized multiple programs run by the CIA and the Pentagon to train anti-Assad rebels.[395] The Pentagon-run program was later found to have failed and was formally abandoned in October 2015.[396][397]

In the wake of a chemical weapons attack in Syria, formally blamed by the Obama administration on the Assad government, Obama chose not to enforce the "red line" he had pledged[398] and, rather than authorize the promised military action against Assad, went along with the Russia-brokered deal that led to Assad giving up chemical weapons; however attacks with chlorine gas continued.[399][400] In 2014, Obama authorized an air campaign aimed primarily at ISIL.[401]

Iran nuclear talks

On October 1, 2009, the Obama administration went ahead with a Bush administration program, increasing nuclear weapons production. The "Complex Modernization" initiative expanded two existing nuclear sites to produce new bomb parts. In November 2013, the Obama administration opened negotiations with Iran to prevent it from acquiring nuclear weapons, which included an interim agreement. Negotiations took two years with numerous delays, with a deal being announced on July 14, 2015. The deal titled the "Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action" saw sanctions removed in exchange for measures that would prevent Iran from producing nuclear weapons. While Obama hailed the agreement as being a step towards a more hopeful world, the deal drew strong criticism from Republican and conservative quarters, and from Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.[402][403][404] In addition, the transfer of $1.7 billion in cash to Iran shortly after the deal was announced was criticized by the Republican party. The Obama administration said that the payment in cash was because of the "effectiveness of U.S. and international sanctions."[405] In order to advance the deal, the Obama administration shielded Hezbollah from the Drug Enforcement Administration's Project Cassandra investigation regarding drug smuggling and from the Central Intelligence Agency.[406][407]On a side note, the very same year, in December 2015, Obama started a $348 billion worth program to back the biggest U.S. buildup of nuclear arms since Ronald Reagan left the White House.[408]

Russia

In March 2010, an agreement was reached with the administration of Russian President Dmitry Medvedev to replace the 1991 Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty with a new pact reducing the number of long-range nuclear weapons in the arsenals of both countries by about a third.[409] Obama and Medvedev signed the New START treaty in April 2010, and the U.S. Senate ratified it in December 2010.[410] In December 2011, Obama instructed agencies to consider LGBT rights when issuing financial aid to foreign countries.[411] In August 2013, he criticized Russia's law that discriminates against gays,[412] but he stopped short of advocating a boycott of the upcoming 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi, Russia.[413]

After Russia's invasion of Crimea in 2014, military intervention in Syria in 2015, and the interference in the 2016 U.S. presidential election,[414] George Robertson, a former UK defense secretary and NATO secretary-general, said Obama had "allowed Putin to jump back on the world stage and test the resolve of the West", adding that the legacy of this disaster would last.[415]

Cultural and political image

Obama's family history, upbringing, and Ivy League education differ markedly from those of African-American politicians who launched their careers in the 1960s through participation in the civil rights movement.[416] Expressing puzzlement over questions about whether he is "black enough", Obama told an August 2007 meeting of the National Association of Black Journalists that "we're still locked in this notion that if you appeal to white folks then there must be something wrong."[417] Obama acknowledged his youthful image in an October 2007 campaign speech, saying: "I wouldn't be here if, time and again, the torch had not been passed to a new generation."[418] Additionally, Obama has frequently been referred to as an exceptional orator.[419] During his pre-inauguration transition period and continuing into his presidency, Obama delivered a series of weekly Internet video addresses.[420]

Job approval

According to the Gallup Organization, Obama began his presidency with a 68 percent approval rating,[421] the fifth highest for a president following their swearing in.[422] His ratings remained above the majority level until November 2009[423] and by August 2010 his approval was in the low 40s,[424] a trend similar to Ronald Reagan's and Bill Clinton's first years in office.[425] Following the death of Osama bin Laden on May 2, 2011, Obama experienced a small poll bounce and steadily maintained 50–53 percent approval for about a month, until his approval numbers dropped back to the low 40s.[426][427][428]

His approval rating fell to 38 percent on several occasions in late 2011[429] before recovering in mid-2012 with polls showing an average approval of 50 percent.[430] After his second inauguration in 2013, Obama's approval ratings remained stable around 52 percent[431] before declining for the rest of the year and eventually bottoming out at 39 percent in December.[426] In polling conducted before the 2014 midterm elections, Obama's approval ratings were at their lowest[432][433] with his disapproval rating reaching a high of 57 percent.[426][434][435] His approval rating continued to lag throughout most of 2015 but began to reach the high 40s by the end of the year.[426][436] According to Gallup, Obama's approval rating reached 50 percent in March 2016, a level unseen since May 2013.[426][437] In polling conducted January 16–19, 2017, Obama's final approval rating was 59 percent, which placed him on par with George H. W. Bush and Dwight D. Eisenhower, whose final Gallup ratings also measured in the high 50s.[438]

Obama has maintained relatively positive public perceptions after his presidency.[439] In Gallup's retrospective approval polls of former presidents, Obama garnered a 63 percent approval rating in 2018 and again in 2023, ranking him the fourth most popular president since World War II.[440][441]

Foreign perceptions

Polls showed strong support for Obama in other countries both before and during his presidency.[442][443][444] In a February 2009 poll conducted in Western Europe and the U.S. by Harris Interactive for France 24 and the International Herald Tribune, Obama was rated as the most respected world leader, as well as the most powerful.[445] In a similar poll conducted by Harris in May 2009, Obama was rated as the most popular world leader, as well as the one figure most people would pin their hopes on for pulling the world out of the economic downturn.[446][447]

On October 9, 2009—only nine months into his first term—the Norwegian Nobel Committee announced that Obama had won the 2009 Nobel Peace Prize "for his extraordinary efforts to strengthen international diplomacy and cooperation between peoples",[448] which drew a mixture of praise and criticism from world leaders and media figures.[449][450][451][452] He became the fourth U.S. president to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, and the third to become a Nobel laureate while in office.[453] He himself called it a "call to action" and remarked: "I do not view it as a recognition of my own accomplishments but rather an affirmation of American leadership on behalf of aspirations held by people in all nations".[454]

Thanks, Obama

In 2009 the saying "thanks, Obama" first appeared in a Twitter hashtag "#thanks Obama" and was later used in a demotivational poster. It was later adopted satirically to blame Obama for any socio-economic ills. Obama himself used the phrase in video in 2015 and 2016. In 2017 the phrase was used by Stephen Colbert to express gratitude to Obama on his last day in office.

Post-presidency (2017–present)

Obama's presidency ended on January 20, 2017, upon the inauguration of his successor, Donald Trump.[455][456] The family moved to a house they rented in Kalorama, Washington, D.C.[457] On March 2, the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum awarded the Profile in Courage Award to Obama "for his enduring commitment to democratic ideals and elevating the standard of political courage."[458] His first public appearance since leaving the office was a seminar at the University of Chicago on April 24, where he appealed for a new generation to participate in politics.[459] On September 7, Obama partnered with former presidents Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush to work with One America Appeal to help the victims of Hurricane Harvey and Hurricane Irma in the Gulf Coast and Texas communities.[460] From October 31 to November 1, Obama hosted the inaugural summit of the Obama Foundation,[461] which he intended to be the central focus of his post-presidency and part of his ambitions for his subsequent activities following his presidency to be more consequential than his time in office.[462]

Barack and Michelle Obama signed a deal on May 22, 2018, to produce docu-series, documentaries and features for Netflix under the Obamas' newly formed production company, Higher Ground Productions.[463][464] Higher Ground's first film, American Factory, won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 2020.[465] On October 24, a pipe bomb addressed to Obama was intercepted by the Secret Service. It was one of several pipe-bombs that had been mailed out to Democratic lawmakers and officials.[466] In 2019, Barack and Michelle Obama bought a home on Martha's Vineyard from Wyc Grousbeck.[467] On October 29, Obama criticized "wokeness" and call-out culture at the Obama Foundation's annual summit.[468][469]

Obama was reluctant to make an endorsement in the 2020 Democratic presidential primaries because he wanted to position himself to unify the party, regardless of the nominee.[470] On April 14, 2020, Obama endorsed Biden, the presumptive nominee, for president in the presidential election, stating that he has "all the qualities we need in a president right now."[471][472] In May, Obama criticized President Trump for his handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, calling his response to the crisis "an absolute chaotic disaster", and stating that the consequences of the Trump presidency have been "our worst impulses unleashed, our proud reputation around the world badly diminished, and our democratic institutions threatened like never before."[473] On November 17, Obama's presidential memoir, A Promised Land, was released.[474][475][476]

In February 2021, Obama and musician Bruce Springsteen started a podcast called Renegades: Born in the USA where the two talk about "their backgrounds, music and their 'enduring love of America.'"[477][478] Later that year, Regina Hicks had signed a deal with Netflix, in a venture with his and Michelle's Higher Ground to develop comedy projects.[479]

On March 4, 2022, Obama won an Audio Publishers Association (APA) Award in the best narration by the author category for the narration of his memoir A Promised Land.[480] On April 5, Obama visited the White House for the first time since leaving office, in an event celebrating the 12th annual anniversary of the signing of the Affordable Care Act.[481][482][483] In June, it was announced that the Obamas and their podcast production company, Higher Ground, signed a multi-year deal with Audible.[484][485] In September, Obama visited the White House to unveil his and Michelle's official White House portraits.[486] Around the same time, he won a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Narrator[487] for his narration in the Netflix documentary series Our Great National Parks.[488]

In 2022, Obama opposed expanding the Supreme Court beyond the present nine Justices.[489]

In March 2023, Obama traveled to Australia as a part of his speaking tour of the country. During the trip, Obama met with Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese and visited Melbourne for the first time.[490] Obama was reportedly paid more than $1 million for two speeches.[491][492]

In October 2023, during the Israel–Hamas war, Obama declared that Israel must dismantle Hamas in the wake of the October 7 massacre.[493] Weeks later, Obama warned Israel that its actions could "harden Palestinian attitudes for generations" and weaken international support for Israel; any military strategy that ignored the war's human costs "could ultimately backfire."[494]