Анархизм в Соединенных Штатах

| Эта статья является частью серии, посвящённой |

| Анархизм в Соединенных Штатах |

|---|

| Часть серии о |

| Анархизм |

|---|

|

Анархизм в Соединенных Штатах зародился в середине 19-го века и начал расти в своем влиянии по мере того, как он проникал в американские рабочие движения , развивая анархо-коммунистическое течение, а также приобретая известность благодаря жестокой пропаганде этого дела и проведению кампаний за различные социальные реформы в Соединенных Штатах. начало 20 века. Примерно к началу 20-го века период расцвета индивидуалистического анархизма прошел. [ 1 ] и анархо-коммунизм и другие социальные анархистские течения стали доминирующей анархической тенденцией. [ 2 ]

In the post-World War II era, anarchism regained influence through new developments such as anarcho-pacifism, the American New Left and the counterculture of the 1960s. Contemporary anarchism in the United States influenced and became influenced and renewed by developments both inside and outside the worldwide anarchist movement such as platformism, insurrectionary anarchism, the new social movements (anarcha-feminism, queer anarchism and green anarchism) and the alter-globalization movements. Within contemporary anarchism, the anti-capitalism of classical anarchism has remained prominent.[3][4]

Around the turn of the 21st century, anarchism grew in popularity and influence as part of the anti-war, anti-capitalist and anti-globalization movements.[5] Anarchists became known for their involvement in protests against the meetings of the WTO, G8 and the World Economic Forum. Some anarchist factions at these protests engaged in rioting, property destruction and violent confrontations with the police. These actions were precipitated by ad hoc, leaderless and anonymous cadres known as black blocs, although other peaceful organizational tactics pioneered in this time include affinity groups, security culture and the use of decentralized technologies such as the Internet.[5] A significant event of this period was the 1999 Seattle WTO protests.[5]

History

[edit]Early anarchism

[edit]

For anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, American individualist anarchism "stresses the isolation of the individual—his right to his own tools, his mind, his body, and to the products of his labor. To the artist who embraces this philosophy it is 'aesthetic' anarchism, to the reformer, ethical anarchism, to the independent mechanic, economic anarchism. The former is concerned with philosophy, the latter with practical demonstration. The economic anarchist is concerned with constructing a society on the basis of anarchism. Economically he sees no harm whatever in the private possession of what the individual produces by his own labor, but only so much and no more. The aesthetic and ethical type found expression in the transcendentalism, humanitarianism, and romanticism of the first part of the nineteenth century, the economic type in the pioneer life of the West during the same period, but more favorably after the Civil War".[6] It is for this reason that it has been suggested that in order to understand American individualist anarchism one must take into account "the social context of their ideas, namely the transformation of America from a pre-capitalist to a capitalist society, [...] the non-capitalist nature of the early U.S. can be seen from the early dominance of self-employment (artisan and peasant production). At the beginning of the 19th century, around 80% of the working (non-slave) male population were self-employed. The great majority of Americans during this time were farmers working their own land, primarily for their own needs" and so "individualist anarchism is clearly a form of artisanal socialism [...] while communist anarchism and anarcho-syndicalism are forms of industrial (or proletarian) socialism".[7]

Historian Wendy McElroy reports that American individualist anarchism received an important influence of three European thinkers. According to McElroy, "[o]ne of the most important of these influences was the French political philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, whose words "Liberty is not the Daughter But the Mother of Order" appeared as a motto on Liberty's masthead",[8] an influential individualist anarchist publication of Benjamin Tucker. McElroy further stated that "[a]nother major foreign influence was the German philosopher Max Stirner. The third foreign thinker with great impact was the British philosopher Herbert Spencer".[8] Other influences to consider include William Godwin's anarchism which "exerted an ideological influence on some of this, but more so the socialism of Robert Owen and Charles Fourier.[9] After success of his British venture, Owen himself established a cooperative community within the United States at New Harmony, Indiana during 1825. One member of this commune was Josiah Warren, considered to be the first individualist anarchist.[10] The Peaceful Revolutionist, the four-page weekly paper Warren edited during 1833, was the first anarchist periodical published,[11] an enterprise for which he built his own printing press, cast his own type and made his own printing plates.[11] After New Harmony failed, Warren shifted his ideological loyalties from socialism to anarchism which anarchist Peter Sabatini described as "no great leap, given that Owen's socialism had been predicated on Godwin's anarchism".

The emergence and growth of anarchism in the United States in the 1820s and 1830s has a close parallel in the simultaneous emergence and growth of abolitionism as no one needed anarchy more than a slave. Warren termed the phrase "cost the limit of price", with "cost" here referring not to monetary price paid but the labor one exerted to produce an item.[12] Therefore, "[h]e proposed a system to pay people with certificates indicating how many hours of work they did. They could exchange the notes at local time stores for goods that took the same amount of time to produce".[10] He put his theories to the test by establishing an experimental "labor for labor store" called the Cincinnati Time Store, where trade was facilitated by notes backed by a promise to perform labor. The store proved successful and operated for three years after which it was closed so that Warren could pursue establishing colonies based on mutualism. These included Utopia and Modern Times. Warren said that Stephen Pearl Andrews' The Science of Society, published in 1852, was the most lucid and complete exposition of Warren's own theories.[13] Catalan historian Xavier Diez report that the intentional communal experiments pioneered by Warren were influential in European individualist anarchists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries such as Émile Armand and the intentional communities started by them.[14]

Henry David Thoreau was an important early influence in individualist anarchist thought in the United States and Europe. Thoreau was an American author, poet, naturalist, tax resister, development critic, surveyor, historian, philosopher and leading transcendentalist. Civil Disobedience is an essay by Thoreau that was first published in 1849. It argues that people should not permit governments to overrule or atrophy their consciences, and that people have a duty to avoid allowing such acquiescence to enable the government to make them the agents of injustice. Thoreau was motivated in part by his disgust with slavery and the Mexican–American War. It would influence Mohandas Gandhi, Martin Luther King Jr., Martin Buber and Leo Tolstoy through its advocacy of nonviolent resistance.[15] It is also the main precedent for anarcho-pacifism.[15] Anarchism started to have an ecological view mainly in the writings of American individualist anarchist and transcendentalist Thoreau. In his book Walden, he advocates simple living and self-sufficiency among natural surroundings in resistance to the advancement of industrial civilization:[16] "Many have seen in Thoreau one of the precursors of ecologism and anarcho-primitivism represented today in John Zerzan. For George Woodcock, this attitude can be also motivated by certain idea of resistance to progress and of rejection of the growing materialism which is the nature of American society in the mid-19th century".[16] Zerzan himself included the text "Excursions" (1863) by Thoreau in his edited compilation of anti-civilization writings called Against Civilization: Readings and Reflections from 1999.[17] Walden made Thoreau influential in the European individualist anarchist green current of anarcho-naturism.[16]

For American anarchist historian Eunice Minette Schuster, "[i]t is apparent [...] that Proudhonian Anarchism was to be found in the United States at least as early as 1848 and that it was not conscious of its affinity to the Individualist Anarchism of Josiah Warren and Stephen Pearl Andrews. [...] William B. Greene presented this Proudhonian Mutualism in its purest and most systematic form".[18] William Batchelder Greene was a 19th-century mutualist, individualist anarchist, Unitarian minister, soldier and promoter of free banking in the United States. Greene is best known for the works Mutual Banking (1850) which proposed an interest-free banking system and Transcendentalism, a critique of the New England philosophical school.

After 1850, Greene became active in labor reform[18] and was "elected vice president of the New England Labor Reform League, the majority of the members holding to Proudhon's scheme of mutual banking, and in 1869 president of the Massachusetts Labor Union".[18] He then published Socialistic, Mutualistic, and Financial Fragments (1875).[18] He saw mutualism as the synthesis of "liberty and order".[18] His "associationism [...] is checked by individualism. [...] 'Mind your own business,' 'Judge not that ye be not judged.' Over matters which are purely personal, as for example, moral conduct, the individual is sovereign, as well as over that which he himself produces. For this reason he demands 'mutuality' in marriage—the equal right of a woman to her own personal freedom and property".[18]

Stephen Pearl Andrews was an individualist anarchist and close associate of Josiah Warren. Andrews was formerly associated with the Fourierist movement, but converted to radical individualism after becoming acquainted with the work of Warren. Like Warren, he held the principle of "individual sovereignty" as being of paramount importance. Contemporary American anarchist Hakim Bey reports that "Steven Pearl Andrews [...] was not a fourierist, but he lived through the brief craze for phalansteries in America and adopted a lot of fourierist principles and practices [...], a maker of worlds out of words. He syncretized abolitionism, Free Love, spiritual universalism, Warren, and Fourier into a grand utopian scheme he called the Universal Pantarchy. [...] He was instrumental in founding several 'intentional communities,' including the 'Brownstone Utopia' on 14th Street in New York and 'Modern Times' in Brentwood, Long Island. The latter became as famous as the best-known fourierist communes (Brook Farm in Massachusetts and the North American Phalanx in New Jersey)—in fact, Modern Times became downright notorious for "Free Love" and finally foundered under a wave of scandalous publicity. Andrews (and Victoria Woodhull) were members of the infamous Section 12 of the 1st International, expelled by Marx for its anarchist, feminist, and spiritualist tendencies".[19]

19th-century individualist anarchism

[edit]

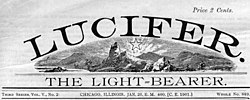

An important current within American individualist anarchism was free love.[20] Free love advocates sometimes traced their roots back to Josiah Warren and to experimental communities, and viewed sexual freedom as a clear, direct expression of an individual's self-ownership. Free love particularly stressed women's rights since most sexual laws discriminated against women: for example, marriage laws and anti-birth control measures.[20] The most important American free love journal was Lucifer the Lightbearer (1883–1907) edited by Moses Harman and Lois Waisbrooker[21] but also there existed Ezra Heywood and Angela Heywood's The Word (1872–1890, 1892–1893).[20] M. E. Lazarus was an important American individualist anarchist who promoted free love.[20]

Hutchins Hapgood was an American journalist, author, individualist anarchist and philosophical anarchist who was well known within the Bohemian environment of around the start of 20th-century New York City. He advocated free love and committed adultery frequently. Hapgood was a follower of the German philosophers Max Stirner and Friedrich Nietzsche.[22]

The mission of Lucifer the Lightbearer was, according to Harman, "to help woman to break the chains that for ages have bound her to the rack of man-made law, spiritual, economic, industrial, social and especially sexual, believing that until woman is roused to a sense of her own responsibility on all lines of human endeavor, and especially on lines of her special field, that of reproduction of the race, there will be little if any real advancement toward a higher and truer civilization." The name was chosen because "Lucifer, the ancient name of the Morning Star, now called Venus, seems to us unsurpassed as a cognomen for a journal whose mission is to bring light to the dwellers in darkness." In February 1887, the editors and publishers of Lucifer were arrested after the journal ran afoul of the Comstock Act for the publication of three letters, one in particular condemning forced sex within marriage, which the author identified as rape. In the letter, the author described the plight of a woman who had been raped by her husband, tearing stitches from a recent operation after a difficult childbirth and causing severe hemorrhaging. The letter lamented the woman's lack of legal recourse. The Comstock Act specifically prohibited the public, printed discussion of any topics that were considered "obscene, lewd, or lascivious," and discussing rape, although a criminal matter, was deemed obscene. A Topeka district attorney eventually handed down 216 indictments. Moses Harman spent two years in jail. Ezra Heywood, who had already been prosecuted under the Comstock Law for a pamphlet attacking marriage, reprinted the letter in solidarity with Harman and was also arrested and sentenced to two years in prison. In February 1890, Harman, now the sole producer of Lucifer, was again arrested on charges resulting from a similar article written by a New York physician. As a result of the original charges, Harman would spend large portions of the next six years in prison. In 1896, Lucifer was moved to Chicago; however, legal harassment continued. The United States Postal Service seized and destroyed numerous issues of the journal and, in May 1905, Harman was again arrested and convicted for the distribution of two articles, namely "The Fatherhood Question" and "More Thoughts on Sexology" by Sara Crist Campbell. Sentenced to a year of hard labor, the 75-year-old editor's health deteriorated greatly. After 24 years in production, Lucifer ceased publication in 1907 and became the more scholarly American Journal of Eugenics.

Heywood's philosophy was instrumental in furthering individualist anarchist ideas through his extensive pamphleteering and reprinting of works of Josiah Warren, author of True Civilization (1869), and William B. Greene. At a 1872 convention of the New England Labor Reform League in Boston, Heywood introduced Greene and Warren to eventual Liberty publisher Benjamin Tucker. Heywood saw what he believed to be a disproportionate concentration of capital in the hands of a few as the result of a selective extension of government-backed privileges to certain individuals and organizations. The Word was an individualist anarchist free love magazine edited by Ezra Heywood and Angela Heywood, issued first from Princeton, Massachusetts; and then from Cambridge, Massachusetts.[20] The Word was subtitled "A Monthly Journal of Reform", and it included contributions from Josiah Warren, Benjamin Tucker, and J.K. Ingalls. Initially, The Word presented free love as a minor theme which was expressed within a labor reform format. But the publication later evolved into an explicitly free love periodical.[20] At some point Tucker became an important contributor but later became dissatisfied with the journal's focus on free love since he desired a concentration on economics. In contrast, Tucker's relationship with Heywood grew more distant. Yet, when Heywood was imprisoned for his pro-birth control stand from August to December 1878 under the Comstock laws, Tucker abandoned the Radical Review in order to assume editorship of Heywood's The Word. After Heywood's release from prison, The Word openly became a free love journal; it flouted the law by printing birth control material and openly discussing sexual matters. Tucker's disapproval of this policy stemmed from his conviction that "Liberty, to be effective, must find its first application in the realm of economics".[20]

M. E. Lazarus was an American individualist anarchist from Guntersville, Alabama. He is the author of several essays and anarchist pamphlettes including Land Tenure: Anarchist View (1889). A famous quote from Lazarus is "Every vote for a governing office is an instrument for enslaving me." Lazarus was also an intellectual contributor to Fourierism and the Free Love movement of the 1850s, a social reform group that called for, in its extreme form, the abolition of institutionalized marriage.

Freethought as a philosophical position and as activism was important in North American individualist anarchism. In the United States "freethought was a basically anti-Christian, anti-clerical movement, whose purpose was to make the individual politically and spiritually free to decide for himself on religious matters. A number of contributors to Liberty were prominent figures in both freethought and anarchism. The individualist anarchist George MacDonald was a co-editor of Freethought and, for a time, The Truth Seeker. E.C. Walker was co-editor of the free-thought/free love journal Lucifer, the Light-Bearer".[8] "Many of the anarchists were ardent freethinkers; reprints from freethought papers such as Lucifer, the Light-Bearer, Freethought and The Truth Seeker appeared in Liberty...The church was viewed as a common ally of the state and as a repressive force in and of itself".[8]

Voltairine de Cleyre was an American anarchist writer and feminist. She was a prolific writer and speaker, opposing the state, marriage, and the domination of religion in sexuality and women's lives. She began her activist career in the freethought movement. De Cleyre was initially drawn to individualist anarchism but evolved through mutualism to an "anarchism without adjectives." She believed that any system was acceptable as long as it did not involve force. However, according to anarchist author Iain McKay, she embraced the ideals of stateless communism.[23] In her 1895 lecture entitled Sex Slavery, de Cleyre condemns ideals of beauty that encourage women to distort their bodies and child socialization practices that create unnatural gender roles. The title of the essay refers not to traffic in women for purposes of prostitution, although that is also mentioned, but rather to marriage laws that allow men to rape their wives without consequences. Such laws make "every married woman what she is, a bonded slave, who takes her master's name, her master's bread, her master's commands, and serves her master's passions."[24]

Individualist anarchism found in the United States an important space of discussion and development within what is known as the Boston anarchists.[25] Even among the 19th-century American individualists, there was not a monolithic doctrine, as they disagreed amongst each other on various issues including intellectual property rights and possession versus property in land.[26][27][28] A major schism occurred later in the 19th century when Tucker and some others abandoned their traditional support of natural rights as espoused by Lysander Spooner and converted to an egoism modeled upon Stirner's philosophy.[27] Besides his individualist anarchist activism, Spooner was also an important anti-slavery activist and became a member of the First International.[29] Some Boston anarchists, including Tucker, identified themselves as socialists which in the 19th century was often used in the sense of a commitment to improving conditions of the working class (i.e. "the labor problem").[30] The Boston anarchists such as Tucker and his followers are considered socialists to this day due to their opposition to usury.[31][32][33]

Liberty was a 19th-century anarchist market socialist[34] and libertarian socialist[35] periodical published in the United States by Benjamin Tucker from August 1881 to April 1908. The periodical was instrumental in developing and formalizing the individualist anarchist philosophy through publishing essays and serving as a format for debate. Contributors included Benjamin Tucker, Lysander Spooner, Auberon Herbert, Dyer Lum, Joshua K. Ingalls, John Henry Mackay, Victor Yarros, Wordsworth Donisthorpe, James L. Walker, J. William Lloyd, Florence Finch Kelly, Voltairine de Cleyre, Steven T. Byington, John Beverley Robinson, Jo Labadie, Lillian Harman, and Henry Appleton. Included in its masthead is a quote from Pierre Proudhon saying that liberty is "Not the Daughter But the Mother of Order."

Some of the American individualist anarchists later in this era such as Benjamin Tucker abandoned natural rights positions and converted to Max Stirner's egoist anarchism. Rejecting the idea of moral rights, Tucker said that there were only two rights, "the right of might" and "the right of contract." He also said, after converting to Egoist individualism, "In times past ... it was my habit to talk glibly of the right of man to land. It was a bad habit, and I long ago sloughed it off ... Man's only right to land is his might over it."[36] In adopting Stirnerite egoism (1886), Tucker rejected natural rights which had long been considered the foundation of libertarianism. This rejection galvanized the movement into fierce debates, with the natural rights proponents accusing the egoists of destroying libertarianism itself. So bitter was the conflict that a number of natural rights proponents withdrew from the pages of Liberty in protest even though they had hitherto been among its frequent contributors. Thereafter, Liberty championed egoism although its general content did not change significantly."[37]

Several publications "were undoubtedly influenced by Liberty's presentation of egoism. They included: I published by C.L. Swartz, edited by W.E. Gordak and J.William Lloyd (all associates of Liberty); The Ego and The Egoist, both of which were edited by Edward H. Fulton. Among the egoist papers that Tucker followed were the German Der Eigene, edited by Adolf Brand, and The Eagle and The Serpent, issued from London. The latter, the most prominent English-language egoist journal, was published from 1898 to 1900 with the subtitle 'A Journal of Egoistic Philosophy and Sociology'".[37] Among those American anarchists who adhered to egoism include Benjamin Tucker, John Beverley Robinson, Steven T. Byington, Hutchins Hapgood, James L. Walker, Victor Yarros and Edward H. Fulton.[37] Robinson wrote an essay called "Egoism" in which he states that "Modern egoism, as propounded by Stirner and Nietzsche, and expounded by Ibsen, Shaw and others, is all these; but it is more. It is the realization by the individual that they are an individual; that, as far as they are concerned, they are the only individual."[38] Steven T. Byington was a one-time proponent of Georgism who later converted to egoist stirnerist positions after associating with Benjamin Tucker. He is known for translating two important anarchist works into English from German: Max Stirner's The Ego and Its Own and Paul Eltzbacher's Anarchism: Exponents of the Anarchist Philosophy (also published by Dover with the title The Great Anarchists: Ideas and Teachings of Seven Major Thinkers). James L. Walker (sometimes known by the pen name "Tak Kak") was one of the main contributors to Benjamin Tucker's Liberty. He published his major philosophical work called Philosophy of Egoism in the May 1890 to September 1891 in issues of the publication Egoism.[39]

Early anarcho-communism

[edit]

By the 1880s anarcho-communism was already present in the United States as can be seen in the publication of the journal Freedom: A Revolutionary Anarchist-Communist Monthly by Lucy Parsons and Lizzy Holmes.[40] Lucy Parsons debated in her time in the US with fellow anarcha-communist Emma Goldman over issues of free love and feminism.[40] Included in their debates over questions of gender, patriarchy, and free love were questions of homosexuality. Part of Goldman’s specific brand of anarchism was a belief that the state should be removed from interpersonal and sexual relationships. Freedom from state sexual control included, in Goldman’s view, the freedom to choose a sexual or romantic partner regardless of their gender. It was free-love anarchists like Goldman who, during this period, introduced the beginnings of a homosexual rights movement to the United States.[41] Anarchists on this issue, however, were not united and many disagreed with Goldman’s inclusion of homosexuality and free love in an anarchist belief system.

Described by the Chicago Police Department as "more dangerous than a thousand rioters" in the 1920s, Parsons and her husband had become highly effective anarchist organizers primarily involved in the labor movement in the late 19th century, but also participating in revolutionary activism on behalf of political prisoners, people of color, the homeless and women. She began writing for The Socialist and The Alarm, the journal of the International Working People's Association (IWPA) that she and Parsons, among others, founded in 1883. In 1886 her husband, who had been heavily involved in campaigning for the eight-hour day, was arrested, tried and executed on November 11, 1887, by the state of Illinois on charges that he had conspired in the Haymarket Riot, an event which was widely regarded as a political frame-up and which marked the beginning of May Day labor rallies in protest.[42][43]

Another anarcho-communist journal called The Firebrand later appeared in the United States. Most anarchist publications in the United States were in Yiddish, German, or Russian, but Free Society was published in English, permitting the dissemination of anarchist communist thought to English-speaking populations in the United States.[44] Around that time these American anarcho-communist sectors entered in debate with the individualist anarchist group around Benjamin Tucker.[45] Encouraged by news of labor struggles and industrial disputes in the United States, the German anarchist Johann Most emigrated to the USA upon his release from prison in 1882. He promptly began agitating in his adopted land among other German émigrés. Among his associates was August Spies, one of the anarchists hanged for conspiracy in the Haymarket Square bombing, whose desk police found to contain an 1884 letter from Most promising a shipment of "medicine," his code word for dynamite.[46] Most was famous for stating the concept of the propaganda of the deed, namely that "[t]he existing system will be quickest and most radically overthrown by the annihilation of its exponents. Therefore, massacres of the enemies of the people must be set in motion."[47] Most is best known for a pamphlet published in 1885: The Science of Revolutionary Warfare, a how-to manual on the subject of bomb-making which earned the author the moniker "Dynamost". He acquired his knowledge of explosives while working at an explosives plant in New Jersey.[48] Most was described as "the most vilified social radical" of his time, a man whose profuse advocacy of social unrest and fascination with dramatic destruction eventually led Emma Goldman to denounce him as a recognized authoritarian.[49]

A gifted orator, Most propagated these ideas throughout Marxist and anarchist circles in the United States and attracted many adherents, most notably Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman. In February 1888 Berkman left for the United States from his native Russia.[50] Soon after his arrival in New York City, Berkman became an anarchist through his involvement with groups that had formed to campaign to free the men convicted of the 1886 Haymarket bombing.[51] He, as well as Goldman, soon came under the influence of Johann Most, the best-known anarchist in the United States, and an advocate of propaganda of the deed—attentat, or violence carried out to encourage the masses to revolt.[52][53][54] Berkman became a typesetter for Most's newspaper Freiheit.[51]

Inspired by Most's theories of Attentat, Goldman and Berkman, enraged by the deaths of workers during the Homestead strike, put words into action with Berkman's attempted assassination of Homestead factory manager Henry Clay Frick in 1892. Berkman and Goldman were soon disillusioned as Most became one of Berkman's most outspoken critics. In Freiheit, Most attacked both Goldman and Berkman, implying Berkman's act was designed to arouse sympathy for Frick.[55] Goldman's biographer Alice Wexler suggests that Most's criticisms may have been inspired by jealousy of Berkman.[56] Goldman was enraged and demanded that Most prove his insinuations. When he refused to respond, she confronted him at next lecture.[55] After he refused to speak to her, she lashed him across the face with a horsewhip, broke the whip over her knee, then threw the pieces at him.[55] She later regretted her assault, confiding to a friend, "At the age of twenty-three, one does not reason."

Emma Goldman was an anarchist known for her political activism, writing, and speeches. She played a pivotal role in the development of anarchist political philosophy in North America and Europe in the first half of the 20th century. Born in Kovno in the Russian Empire (present-day Kaunas, Lithuania), Goldman emigrated to the U.S. in 1885 and lived in New York City, where she joined the burgeoning anarchist movement in 1889.[57] Attracted to anarchism after the Haymarket affair, Goldman became a writer and a renowned lecturer on anarchist philosophy, women's rights, and social issues, attracting crowds of thousands.[57] She and anarchist writer Alexander Berkman, her lover and lifelong friend, planned to assassinate industrialist and financier Henry Clay Frick as an act of propaganda of the deed. Although Frick survived the attempt on his life, Berkman was sentenced to twenty-two years in prison. Goldman was imprisoned several times in the years that followed, for "inciting to riot" and illegally distributing information about birth control. In 1906, Goldman founded the anarchist journal Mother Earth. In 1917, Goldman and Berkman were sentenced to two years in jail for conspiring to "induce persons not to register" for the newly instated draft. After their release from prison, they were arrested—along with hundreds of others—and deported to Russia. Initially supportive of that country's Bolshevik revolution, Goldman quickly voiced her opposition to the Soviet use of violence and the repression of independent voices. In 1923, she wrote a book about her experiences, My Disillusionment in Russia. While living in England, Canada, and France, she wrote an autobiography called Living My Life. After the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War, she traveled to Spain to support the anarchist revolution there. She died in Toronto on May 14, 1940, aged 70. During her life, Goldman was lionized as a free-thinking "rebel woman" by admirers and denounced by critics as an advocate of politically motivated murder and violent revolution.[58]

Her writing and lectures spanned a wide variety of issues, including prisons, atheism, freedom of speech, militarism, capitalism, marriage, free love, and homosexuality. Although she distanced herself from first-wave feminism and its efforts toward women's suffrage, she developed new ways of incorporating gender politics into anarchism. After decades of obscurity, Goldman's iconic status was revived in the 1970s, when feminist and anarchist scholars rekindled popular interest in her life.

Anarchism and the labor movement

[edit]

The anti-authoritarian sections of the First International were the precursors of the anarcho-syndicalists, seeking to "replace the privilege and authority of the State" with the "free and spontaneous organization of labor."[59]

After embracing anarchism Albert Parsons, husband of Lucy Parsons, turned his activity to the growing movement to establish the 8-hour day. In January 1880, the Eight-Hour League of Chicago sent Parsons to a national conference in Washington, D.C., a gathering which launched a national lobbying movement aimed at coordinating efforts of labor organizations to win and enforce the 8-hour workday.[60] In the fall of 1884, Parsons launched a weekly anarchist newspaper in Chicago, The Alarm.[61] The first issue was dated October 4, 1884, and was produced in a press run of 15,000 copies.[62] The publication was a 4-page broadsheet with a cover price of 5 cents. The Alarm listed the IWPA as its publisher and touted itself as "A Socialistic Weekly" on its page 2 masthead.[63]

On May 1, 1886, Parsons, with his wife Lucy and their two children, led 80,000 people down Michigan Avenue, in what is regarded as the first-ever May Day Parade, in support of the eight-hour workday. Over the next few days 340,000 laborers joined the strike. Parsons, amidst the May Day Strike, found himself called to Cincinnati, where 300,000 workers had struck that Saturday afternoon. On that Sunday he addressed the rally in Cincinnati of the news from the "storm center" of the strike and participated in a second huge parade, led by 200 members of The Cincinnati Rifle Union, with certainty that victory was at hand. In 1886, the Federation of Organized Trades and Labor Unions (FOTLU) of the United States and Canada unanimously set 1 May 1886, as the date by which the eight-hour work day would become standard.[64] In response, unions across the United States prepared a general strike in support of the event.[64] On 3 May, in Chicago, a fight broke out when strikebreakers attempted to cross the picket line, and two workers died when police opened fire upon the crowd.[65] The next day, 4 May, anarchists staged a rally at Chicago's Haymarket Square.[66] A bomb was thrown by an unknown party near the conclusion of the rally, killing an officer.[67] In the ensuing panic, police opened fire on the crowd and each other.[68] Seven police officers and at least four workers were killed.[69]

Eight anarchists directly and indirectly related to the organisers of the rally were arrested and charged with the murder of the deceased officer. The men became international political celebrities among the labor movement. Four of the men were executed and a fifth committed suicide prior to his own execution. The incident became known as the Haymarket affair and was a setback for the labor movement and the struggle for the eight-hour day. In 1890 a second attempt, this time international in scope, to organise for the eight-hour day was made. The event also had the secondary purpose of memorializing workers killed as a result of the Haymarket affair.[70] Although it had initially been conceived as a once-off event, by the following year the celebration of International Workers' Day on May Day had become firmly established as an international worker's holiday.[64] Albert Parsons is best remembered as one of four Chicago radical leaders convicted of conspiracy and hanged following a bomb attack on police remembered as the Haymarket affair. Emma Goldman, the activist and political theorist, was attracted to anarchism after reading about the incident and the executions, which she later described as "the events that had inspired my spiritual birth and growth." She considered the Haymarket martyrs to be "the most decisive influence in my existence".[71] Her associate, Alexander Berkman also described the Haymarket anarchists as "a potent and vital inspiration."[72] Others whose commitment to anarchism crystallized as a result of the Haymarket affair included Voltairine de Cleyre and "Big Bill" Haywood, a founding member of the Industrial Workers of the World.[72] Goldman wrote to historian, Max Nettlau, that the Haymarket affair had awakened the social consciousness of "hundreds, perhaps thousands, of people".[73]

Two individualist anarchists who wrote in Benjamin Tucker's Liberty were also important labor organizers of the time. Jo Labadie was an American labor organizer, individualist anarchist, social activist, printer, publisher, essayist, and poet. Without the oppression of the state, Labadie believed, humans would choose to harmonize with "the great natural laws ... without robbing [their] fellows through interest, profit, rent and taxes." However, he supported community cooperation, as he supported community control of water utilities, streets, and railroads.[74] Although he did not support the militant anarchism of the Haymarket anarchists, he fought for the clemency of the accused because he did not believe they were the perpetrators. In 1888, Labadie organized the Michigan Federation of Labor, became its first president, and forged an alliance with Samuel Gompers.[74]

Dyer Lum was a 19th-century American individualist anarchist labor activist and poet.[75] A leading anarcho-syndicalist and a prominent left-wing intellectual of the 1880s,[76] he is remembered as the lover and mentor of early anarcha-feminist Voltairine de Cleyre.[77] Lum was a prolific writer who wrote a number of key anarchist texts, and contributed to publications including Mother Earth, Twentieth Century, Liberty (Benjamin Tucker's individualist anarchist journal), The Alarm (the journal of the IWPA) and The Open Court among others. He developed a "mutualist" theory of unions and as such was active within the Knights of Labor and later promoted anti-political strategies in the American Federation of Labor (AFL).[78] Frustration with abolitionism, spiritualism, and labor reform caused Lum to embrace anarchism and radicalize workers,[78] as he came to believe that revolution would inevitably involve a violent struggle between the working class and the employing class.[77] Convinced of the necessity of violence to enact social change he volunteered to fight in the American Civil War, hoping thereby to bring about the end of slavery.[77] The Freie Arbeiter Stimme was the longest-running anarchist periodical in the Yiddish language, founded initially as an American counterpart to Rudolf Rocker's London-based Arbeter Fraynd (Workers' Friend). Publication began in 1890 and continued under the editorial of Saul Yanovsky until 1923. Contributors have included David Edelstadt, Emma Goldman, Abba Gordin, Rudolf Rocker, Moishe Shtarkman, and Saul Yanovsky. The paper was also known for publishing poetry by Di Yunge, Yiddish poets of the 1910s and 1920s.[79]

The Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) was founded in Chicago in June 1905 at a convention of two hundred socialists, anarchists, and radical trade unionists from all over the United States (mainly the Western Federation of Miners) who were opposed to the policies of the AFL.

Red Scare, propaganda by the deed and World Wars period

[edit]

This was in an age when hundreds, if not thousands, of striking workers died at the hands of policemen and armed guards, and in which almost a hundred were killed each day in industrial accidents. While acts of anarchist terrorism were exceptional, however, they played a vital role in how Americans imagined the new world of industrial capitalism, providing early hints that the rise of Morganization would not come without violent resistance from below.

—Beverly Gage, 2009.[80]

Italian anti-organizationalist individualist anarchism was brought to the United States[81] by Italian born individualists such as Giuseppe Ciancabilla and others who advocated for violent propaganda by the deed there. Anarchist historian George Woodcock reports the incident in which the important Italian social anarchist Errico Malatesta became involved "in a dispute with the individualist anarchists of Paterson, who insisted that anarchism implied no organization at all, and that every man must act solely on his impulses. At last, in one noisy debate, the individual impulse of a certain Ciancabilla directed him to shoot Malatesta, who was badly wounded but obstinately refused to name his assailant."[82] Some anarchists, such as Johann Most, were already advocated publicizing violent acts of retaliation against counterrevolutionaries because "we preach not only action in and for itself, but also action as propaganda."[83]

By the 1880s, people inside and outside the anarchist movement began to use the slogan, "propaganda of the deed" to refer to individual bombings and targeted killings of members of the ruling class, including regicides, and tyrannicides, at times when such actions might garner sympathy from the population, such as during periods of heightened government repression or labor conflicts where workers were killed.[84] From 1905 onwards, the Russian counterparts of these anti-syndicalist anarchist-communists become partisans of economic terrorism and illegal 'expropriations'."[85] Illegalism as a practice emerged and within it "The acts of the anarchist bombers and assassins ("propaganda by the deed") and the anarchist burglars ("individual reappropriation") expressed their desperation and their personal, violent rejection of an intolerable society. Moreover, they were clearly meant to be exemplary invitations to revolt.".[86][87]

On September 6, 1901, the American anarchist Leon Czolgosz assassinated the President of the United States William McKinley. Emma Goldman was arrested on suspicion of being involved in the assassination but was released due to insufficient evidence. She later incurred a great deal of negative publicity when she published "The Tragedy at Buffalo". In the article, she compared Czolgosz to Marcus Junius Brutus, the killer of Julius Caesar, and called McKinley the "president of the money kings and trust magnates."[88] Other anarchists and radicals were unwilling to support Goldman's effort to aid Czolgosz, believing that he had harmed the movement.[89]

Luigi Galleani was an Italian anarchist active in the United States from 1901 to 1919, viewed by historians as an anarcho-communist and an insurrectionary anarchist. He is best known for his enthusiastic advocacy of "propaganda of the deed", i.e. the use of violence to eliminate "tyrants" and "oppressors" and to act as a catalyst to the overthrow of existing government institutions.[90][91][92] From 1914 to 1932, Galleani's followers in the United States (known as Galleanists), carried out a series of bombings and assassination attempts against institutions and persons they viewed as class enemies.[90] After Galleani was deported from the United States to Italy in June 1919, his followers are alleged to have executed the Wall Street bombing of 1920, which resulted in the deaths of 38 people. Galleani held forth at local anarchist meetings, assailed "timid" socialists, gave fire-breathing speeches, and continued to write essays and polemical treatises.The foremost proponent of "propaganda by the deed" in the United States, Galleani was the founder and editor of the anarchist newsletter Cronaca Sovversiva (Subversive Chronicle), which he published and mailed from offices in Barre.[91] Galleani published the anarchist newsletter for fifteen years until the United States government closed it down under the Sedition Act of 1918. Galleani attracted numerous radical friends and followers known as "Galleanists", including Frank Abarno, Gabriella Segata Antolini, Pietro Angelo, Luigi Bacchetti, Mario Buda also known as "Mike Boda", Carmine Carbone, Andrea Ciofalo, Ferrucio Coacci, Emilio Coda, Alfredo Conti, Nestor Dondoglioalso known as "Jean Crones", Roberto Elia, Luigi Falzini, Frank Mandese, Riccardo Orciani, Nicola Recchi, Giuseppe Sberna, Andrea Salsedo, Raffaele Schiavina, Carlo Valdinoci, and, most notably, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti.[90]

Sacco and Vanzetti were suspected anarchists who were convicted of murdering two men during the 1920 armed robbery of a shoe factory in South Braintree, Massachusetts. After a controversial trial and a series of appeals, the two Italian immigrants were executed on August 23, 1927.[93] Since their deaths, critical opinion has overwhelmingly felt that the two men were convicted largely on their anarchist political beliefs and unjustly executed.[94][95] In 1977, Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis issued a proclamation that Sacco and Vanzetti had been unfairly tried and convicted and that "any disgrace should be forever removed from their names." Many famous socialists and intellectuals campaigned for a retrial without success. John Dos Passos came to Boston to cover the case as a journalist, stayed to author a pamphlet called Facing the Chair,[96] and was arrested in a demonstration on August 10, 1927, along with Dorothy Parker.[97]

After being arrested while picketing the State House, Edna St. Vincent Millay pleaded her case to the governor in person and then wrote an appeal: "I cry to you with a million voices: answer our doubt ... There is need in Massachusetts of a great man tonight."[98] Others who wrote to Fuller or signed petitions included Albert Einstein, George Bernard Shaw and H. G. Wells.[99] The president of the American Federation of Labor cited "the long period of time intervening between the commission of the crime and the final decision of the Court" as well as "the mental and physical anguish which Sacco and Vanzetti must have undergone during the past seven years" in a telegram to the governor.[100] In August 1927, the IWW called for a three-day nationwide walkout to protest the pending executions.[101] The most notable response came in the Walsenburg coal district of Colorado, where 1,132 out of 1,167 miners participated, which led directly to the Colorado coal strike of 1927.[102] Italian anarchist Severino Di Giovanni, one of the most vocal supporters of Sacco and Vanzetti in Argentina, bombed the American embassy in Buenos Aires a few hours after Sacco and Vanzetti were condemned to death.[103] A few days after the executions, Sacco's widow thanked Di Giovanni by letter for his support and added that the director of the tobacco firm Combinados had offered to produce a cigarette brand named "Sacco & Vanzetti".[103] On November 26, 1927, Di Giovanni and others bombed a Combinados tobacco shop.[103]

The Modern Schools, also called Ferrer Schools, were American schools established in the early 20th century that were modeled after the Escuela Moderna of Francesc Ferrer i Guàrdia, the Catalan educator and anarchist. They were an important part of the anarchist, free schooling, socialist, and labor movements in the United States, intended to educate the working-classes from a secular, class-conscious perspective. The Modern Schools imparted day-time academic classes for children, and night-time continuing-education lectures for adults. The first and most notable of the Modern Schools was founded in New York City in 1911, two years after Guàrdia's execution for sedition in monarchist Spain on October 18, 1909. Commonly called the Ferrer Center, it was founded by notable anarchists, including Leonard Abbott, Alexander Berkman, Voltairine de Cleyre, and Emma Goldman, first meeting on St. Mark's Place, in Manhattan's Lower East Side, but twice moved elsewhere, first within lower Manhattan, then to Harlem. Besides Berkman and Goldman, the Ferrer Center faculty included the Ashcan School painters Robert Henri and George Bellows, and its guest lecturers included writers and political activists such as Margaret Sanger, Jack London, and Upton Sinclair.[104]

Student Magda Schoenwetter recalled that the school used Montessori methods and equipment, and emphasized academic freedom rather than fixed subjects, such as spelling and arithmetic.[105] The Modern School magazine originally began as a newsletter for parents, when the school was in New York City, printed with the manual printing press used in teaching printing as a profession. After moving to the Stelton Colony, New Jersey, the magazine's content expanded to poetry, prose, art, and libertarian education articles; the cover emblem and interior graphics were designed by Rockwell Kent. Acknowledging the urban danger to their school, the organizers bought 68 acres (275,000 m2) in Piscataway Township, New Jersey, and moved there in 1914, becoming the center of the Stelton Colony. Moreover, beyond New York City, the Ferrer Colony and Modern School was founded (c. 1910–1915) as a Modern School-based community, that endured some forty years. In 1933, James and Nellie Dick, who earlier had been principals of the Stelton Modern School,[106] founded the Modern School in Lakewood, New Jersey,[107] which survived the original Modern School, the Ferrer Center, becoming the final surviving such school, lasting until 1958.[108]

Ross Winn was an American anarchist writer and publisher from Texas who was mostly active within the Southern United States. Born in Dallas, Texas,[109] Winn wrote articles for The Firebrand, a short-lived, but renowned weekly out of Portland, Oregon; The Rebel, an anarchist journal published in Boston; and Emma Goldman's Mother Earth.[110] Winn began his first paper, known as Co-operative Commonwealth. He then edited and published Coming Era for a brief time in 1898 and then Winn's Freelance in 1899. In 1902, he announced a new paper called Winn's Firebrand. In 1901, Winn met Emma Goldman in Chicago, and found in her a lasting ally. As she wrote in his obituary, Emma "was deeply impressed with his fervor and complete abandonment to the cause, so unlike most American revolutionists, who love their ease and comfort too well to risk them for their ideals."[111] Winn kept up a correspondence with Goldman throughout his life, as he did with other prominent anarchist writers at the time. Joseph Labadie, a prominent writer and organizer in Michigan, was another friend to Winn, and contributed several pieces to Winn's Firebrand in its later years.[110] Enrico Arrigoni, pseudonym of Frank Brand, was an Italian American individualist anarchist Lathe operator, house painter, bricklayer, dramatist and political activist influenced by the work of Max Stirner.[112][113]

In the 1910s, he started becoming involved in anarchist and anti-war activism around Milan.[113] From the 1910s until the 1920s he participated in anarchist activities and popular uprisings in various countries including Switzerland, Germany, Hungary, Argentina and Cuba.[113] He lived from the 1920s onwards in New York City and there he edited the individualist anarchist eclectic journal Eresia in 1928. He also wrote for other American anarchist publications such as L' Adunata dei refrattari, Cultura Obrera, Controcorrente and Intessa Libertaria.[113] During the Spanish Civil War, he went to fight with the anarchists but was imprisoned and was helped on his release by Emma Goldman.[112][113] Afterwards Arrigoni became a longtime member of the Libertarian Book Club in New York City.[113] Vanguard: A Libertarian Communist Journal was a monthly anarchist political and theoretical journal, based in New York City, published between April 1932 and July 1939, and edited by Samuel Weiner, among others. Vanguard began as a project of the Vanguard Group, composed of members of the editorial collective of the Road to Freedom newspaper, as well as members of the Friends of Freedom group. Its initial subtitle was "An Anarchist Youth Publication" but changed to "A Libertarian Communist Journal " after Issue 1. Within several issues Vanguard would become a central sounding board for the international anarchist movement, including reports of developments during the Spanish Revolution as well as movement reports by Augustin Souchy and Emma Goldman.[113]

Attorney General Alexander Mitchell Palmer and J. Edgar Hoover, head of the United States Department of Justice's General Intelligence Division, were intent on using the Anarchist Exclusion Act of 1918 to deport any non-citizens they could identify as advocates of anarchy or revolution. "Emma Goldman and Alexander Berkman," Hoover wrote while they were in prison, "are, beyond doubt, two of the most dangerous anarchists in this country and return to the community will result in undue harm."[114] At her deportation hearing on October 27, she refused to answer questions about her beliefs on the grounds that her American citizenship invalidated any attempt to deport her under the Anarchist Exclusion Act, which could be enforced only against non-citizens of the U.S. She presented a written statement instead: "Today so-called aliens are deported. Tomorrow Native Americans will be banished. Already some patrioteers are suggesting that native American sons to whom democracy is a sacred ideal should be exiled."[115] The Labor Department included Goldman and Berkman among 249 aliens it deported en masse, mostly people with only vague associations with radical groups who had been swept up in government raids in November.[116]

Goldman and Berkman traveled around Russia during the time of the Russian civil War after the Russian revolution, and they found repression, mismanagement, and corruption instead of the equality and worker empowerment they had dreamed of. They met with Vladimir Lenin, who assured them that government suppression of press liberties was justified. He told them: "There can be no free speech in a revolutionary period."[117] Berkman was more willing to forgive the government's actions in the name of "historical necessity", but he eventually joined Goldman in opposing the Soviet state's authority.[118] After a short trip to Stockholm, they moved to Berlin for several years; during this time she agreed to write a series of articles about her time in Russia for Joseph Pulitzer's newspaper, the New York World. These were later collected and published in book form as My Disillusionment in Russia (1923) and My Further Disillusionment in Russia (1924). The titles of these books were added by the publishers to be scintillating and Goldman protested, albeit in vain.[119]

In July 1936, the Spanish Civil War started after an attempted coup d'état by parts of the Spanish Army against the government of the Second Spanish Republic. At the same time, the Spanish anarchists, fighting against the Nationalist forces, started an anarchist revolution. Goldman was invited to Barcelona and in an instant, as she wrote to her niece, "the crushing weight that was pressing down on my heart since Sasha's death left me as by magic".[120] She was welcomed by the Confederación Nacional del Trabajo (CNT) and Federación Anarquista Ibérica (FAI) organizations and for the first time in her life lived in a community run by and for anarchists, according to true anarchist principles. She would later write that "[i]n all my life I have not met with such warm hospitality, comradeship and solidarity."[121] After touring a series of collectives in the province of Huesca, she told a group of workers that "[y]our revolution will destroy forever [the notion] that anarchism stands for chaos."[122] She began editing the weekly CNT-FAI Information Bulletin and responded to English-language mail.[123]

The first prominent American to reveal his homosexuality was the poet Robert Duncan. This occurred when in 1944, using his own name in the anarchist magazine Politics, he wrote that homosexuals were an oppressed minority.[124]

Post-World War II period

[edit]

An American anarcho-pacifist current developed in this period as well as a related Christian anarchist one. For Andrew Cornell, "[m]any young anarchists of this period departed from previous generations both by embracing pacifism and by devoting more energy to promoting avant-garde culture, preparing the ground for the Beat Generation in the process. The editors of the anarchist journal Retort, for instance, produced a volume of writings by WWII draft resistors imprisoned at Danbury, Connecticut, while regularly publishing the poetry and prose of writers such as Kenneth Rexroth and Norman Mailer. From the 1940s to the 1960s, then, the radical pacifist movement in the United States harbored both social democrats and anarchists, at a time when the anarchist movement itself seemed on its last legs."[125] As such anarchism influenced writers associated with the Beat Generation such as Allen Ginsberg and Gary Snyder.[126]

Anarcho-pacifism is a tendency within the anarchist movement which rejects the use of violence in the struggle for social change.[15][82] The main early influences were the thought of Henry David Thoreau[15] and Leo Tolstoy while later the ideas of Mohandas Gandhi gained importance.[15][82] It developed "mostly in Holland, Britain, and the United States, before and during World War II.[127] Dorothy Day was an American journalist, social activist and devout Catholic convert who advocated the Catholic economic theory of distributism. She was also considered to be an anarchist[128][129][130] and did not hesitate to use the term.[131] In the 1930s, Day worked closely with fellow activist Peter Maurin to establish the Catholic Worker movement, a nonviolent, pacifist movement that continues to combine direct aid for the poor and homeless with nonviolent direct action on their behalf. The cause for Day's canonization is open in the Catholic Church. Ammon Hennacy was an American pacifist, Christian anarchist, vegetarian, social activist, member of the Catholic Worker Movement and a Wobbly. He practiced tax resistance and established the Joe Hill House of Hospitality in Salt Lake City, Utah.

Anarchism continued to influence important American literary and intellectual personalities of the time, such as Paul Goodman, Dwight Macdonald, Allen Ginsberg, Leopold Kohr,[132][133] Judith Malina, Julian Beck and John Cage.[134] Paul Goodman was an American sociologist, poet, writer, anarchist, and public intellectual. Goodman is now mainly remembered as the author of Growing Up Absurd (1960) and an activist on the pacifist left in the 1960s and an inspiration to that era's student movement. He is less remembered as a co-founder of Gestalt Therapy in the 1940s and 1950s. In the mid-1940s, together with C. Wright Mills, he contributed to politics, the journal edited during the 1940s by Dwight Macdonald.[135] In 1947, he published two books, Kafka's Prayer and Communitas, a classic study of urban design coauthored with his brother Percival Goodman.

Anarchism proved to be influential also in the early environmentalist movement in the United States. Leopold Kohr (1909–1994) was an economist, jurist and political scientist known both for his opposition to the "cult of bigness" in social organization and as one of those who inspired the Small Is Beautiful movement, mainly through his most influential work The Breakdown of Nations. Kohr was an important inspiration to the Green, bioregional, Fourth World, decentralist, and anarchist movements, Kohr contributed often to John Papworth's "journal for the Fourth World", Resurgence. One of Kohr's students was economist E. F. Schumacher, another prominent influence on these movements, whose best-selling book Small Is Beautiful took its title from one of Kohr's core principles.[132] Similarly, his ideas inspired Kirkpatrick Sale's books Human Scale (1980) and Dwellers in the Land: The Bioregional Vision (1985).[133] In 1958, Murray Bookchin defined himself as an anarchist,[136] seeing parallels between anarchism and ecology. His first book, Our Synthetic Environment, was published under the pseudonym Lewis Herber in 1962, a few months before Rachel Carson's Silent Spring.[137] The book described a broad range of environmental ills but received little attention because of its political radicalism. His groundbreaking essay "Ecology and Revolutionary Thought" introduced ecology as a concept in radical politics.[138]

In 1968, Bookchin founded another group that published the influential Anarchos magazine, which published that and other innovative essays on post-scarcity and on ecological technologies such as solar and wind energy, and on decentralization and miniaturization. Lecturing throughout the United States, he helped popularize the concept of ecology to the counterculture. Post-Scarcity Anarchism is a collection of essays written by Murray Bookchin and first published in 1971 by Ramparts Press. It outlines the possible form anarchism might take under conditions of post-scarcity. It is one of Bookchin's major works,[139] and its radical thesis provoked controversy for being utopian and messianic in its faith in the liberatory potential of technology.[140] Bookchin argues that post-industrial societies are also post-scarcity societies, and can thus imagine "the fulfillment of the social and cultural potentialities latent in a technology of abundance".[140] The self-administration of society is now made possible by technological advancement and, when technology is used in an ecologically sensitive manner, the revolutionary potential of society will be much changed.[141] In 1982, his book The Ecology of Freedom had a profound impact on the emerging ecology movement, both in the United States and abroad. He was a principal figure in the Burlington Greens in 1986 to 1990, an ecology group that ran candidates for city council on a program to create neighborhood democracy. In From Urbanization to Cities (originally published in 1987 as The Rise of Urbanization and the Decline of Citizenship), Bookchin traced the democratic traditions that influenced his political philosophy and defined the implementation of the libertarian municipalism concept. A few years later The Politics of Social Ecology, written by his partner of 20 years, Janet Biehl, briefly summarized these ideas.

The Libertarian League was founded in New York City in 1954 as a political organization building on the Libertarian Book Club.[142][143] Members included Sam Dolgoff,[144] Russell Blackwell, Dave Van Ronk, Enrico Arrigoni[113] and Murray Bookchin. Its central principle, stated in its journal Views and Comments, was "equal freedom for all in a free socialist society". Branches of the League opened in a number of other American cities, including Detroit and San Francisco. It was dissolved at the end of the 1960s. Sam Dolgoff (1902–1990) was a Russian American anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist. After being expelled from the Young People's Socialist League, Dolgoff joined the Industrial Workers of the World in the 1922 and remained an active member his entire life, playing an active role in the anarchist movement for much of the century.[145] He was a co-founder of the Libertarian Labor Review magazine, which was later renamed Anarcho-Syndicalist Review. In the 1930s, he was a member of the editorial board of Spanish Revolution, a monthly American publication reporting on the largest Spanish labor organization taking part in the Spanish Civil War. Among his books were Bakunin on Anarchy, The Anarchist Collectives: Workers' Self-Management in the Spanish Revolution, 1936–1939, and The Cuban Revolution (Black Rose Books, 1976), a denunciation of Cuban life under Fidel Castro.[146]

Анархизм оказал влияние на контркультуру 1960-х годов. [147][148][149] and anarchists actively participated in the late sixties students and workers revolts.[150] The New Left in the United States also included anarchist, countercultural and hippie-related radical groups such as the Yippies who were led by Abbie Hoffman and Black Mask/Up Against the Wall Motherfuckers. For David Graeber, "[a]s SDS splintered into squabbling Maoist factions, groups like the Diggers and Yippies (founded in '68) took the first option. Many were explicitly anarchist, and certainly, the late '60s turn towards the creation of autonomous collectives and institution building was squarely within the anarchist tradition, while the emphasis on free love, psychedelic drugs, and the creation of alternative forms of pleasure was squarely in the bohemian tradition with which Euro-American anarchism has always been at least tangentially aligned."[151][152] К концу 1966 года диггеры открыли бесплатные магазины , которые просто раздавали свои товары, предоставляли бесплатную еду, распространяли бесплатные лекарства, раздавали деньги, организовывали бесплатные музыкальные концерты и исполняли произведения политического искусства. [ 153 ] «Диггеры» получили свое название от первых английских диггеров под руководством Джеррарда Уинстенли. [ 154 ] и стремился создать мини-общество, свободное от денег и капитализма. [ 155 ] С другой стороны, йиппи использовали театральные жесты, такие как выдвижение свиньи (« Пигас Бессмертный») в качестве кандидата на пост президента в 1968 году, чтобы высмеять социальный статус-кво. [ 156 ] Их описывали как в высшей степени театральных, антиавторитарных и анархистских людей. [ 157 ] молодежное движение «символической политики». [ 158 ] «старой школы» Поскольку они были хорошо известны своими уличными театрами и розыгрышами на политическую тематику, многие представители левых политических сил либо игнорировали, либо осуждали их. По сообщению ABC News , «группа была известна своими розыгрышами в уличных театрах, и когда-то ее называли « Граучо марксистами ». [ 159 ] К 1960-м годам христианская анархистка Дороти Дэй заслужила похвалу таких лидеров контркультуры, как Эбби Хоффман, которая охарактеризовала ее как первую хиппи. [ 160 ] описание которого одобрил Дэй. [ 160 ]

Другой влиятельной личностью в американском анархизме является Ноам Хомский . Политическая идеология Хомского связана с анархо-синдикализмом и либертарианским социализмом . [ 161 ] [ 162 ] Он является членом Международного союза «Кампания за мир и демократию» и «Промышленные рабочие мира». [ 163 ] С 1960-х годов он стал более широко известен как политический диссидент , анархист, [ 164 ] и либертарианский социалистический интеллектуал. После публикации своих первых книг по лингвистике Хомский стал видным критиком войны во Вьетнаме и с тех пор продолжает публиковать книги политической критики. Он стал широко известен своей критикой внешней политики Соединенных Штатов . [ 165 ] государственный капитализм [ 166 ] [ 167 ] и основные средства массовой информации . Его критика СМИ включала книгу «Производственное согласие: политическая экономия средств массовой информации» (1988), написанную в соавторстве с Эдвардом С. Херманом , анализ, формулирующий теорию модели пропаганды для изучения средств массовой информации.

Конец 20 века и современность

[ редактировать ]

Эндрю Корнелл сообщает, что « Сэм Долгофф и другие работали над возрождением организации «Промышленные рабочие мира» (IWW) вместе с новыми синдикалистскими формированиями, такими как чикагская группа «Возрождение» и бостонская «Root & Branch». Коллектив «Анархос» Букчина углубил теоретические связи между экологическими и анархистскими мысли Пятое сословие в значительной степени опиралось на французское ультралевое мышление и к концу десятилетия начало проводить критику технологий; Анархическая Федерация объединяла отдельных людей и круги по всей стране посредством ежемесячного дискуссионного бюллетеня, печатаемого на мимеографе. Однако не менее влиятельными для анархистской среды, сформировавшейся в последующие десятилетия, были усилия Движения за новое общество (ДНС). национальная сеть феминистских радикальных пацифистских коллективов, существовавшая с 1971 по 1988 год». [ 168 ]

Дэвид Гребер сообщает, что в конце 1970-х годов на северо-востоке «главное вдохновение для антиядерных активистов — по крайней мере, главное организационное вдохновение — исходило от группы под названием «Движение за новое общество» (MNS), базирующейся в Филадельфии. MNS возглавлял активист за права геев по имени Джордж Лейки, который, как и несколько других членов группы, был одновременно анархистом и квакером ... Многие из того, что теперь стали стандартными чертами формальный процесс достижения консенсуса — например, принцип, согласно которому ведущий никогда не должен выступать в качестве заинтересованной стороны в дебатах, или идея «блока» — были впервые распространены на тренингах MNS в Филадельфии и Бостоне». [ 151 ] По мнению Эндрю Корнелла, «МНС популяризировало принятие решений на основе консенсуса, представило активистам в Соединенных Штатах метод организации «представительского совета» и было ведущим сторонником различных практик — общественной жизни, отказа от репрессивного поведения, создания предприятий, находящихся в совместной собственности — которые сейчас часто относят к категории « префигуративной политики ». [ 168 ]

Фреди Перлман был натурализованным американским писателем, издателем и активистом чешского происхождения. Его самая популярная работа — книга « Против его истории, против Левиафана !» описывает подъем государственного господства с пересказом истории через гоббсовскую метафору Левиафана , подробно . Книга остается основным источником вдохновения для антицивилизационных взглядов в современном анархизме , особенно на мысли философа Джона Зерзана. [ 169 ] Зерзан — американский анархист и философ-примитивист и писатель. Его пять основных книг: «Элементы отказа» (1988), «Будущие примитивы и другие эссе» (1994), «Бег по пустоте» (2002), «Против цивилизации: чтения и размышления» (2005) и «Сумерки машин » (2008). Зерзан был одним из редакторов «Зеленой анархии» , скандального журнала анархо-примитивистской и повстанческой анархистской мысли. Он также является ведущим программы Anarchy Radio в Юджине на Университета Орегона радиостанции KWVA . Он также работал редактором журнала Anarchy Magazine и публиковался в таких журналах, как AdBusters . Матч! — атеистический /анархистский журнал, издаваемый с 1969 года в Тусоне, штат Аризона . Матч! редактируется, публикуется и печатается Фредом Вудвортом. Матч! публикуется нерегулярно; новые выпуски обычно появляются один или два раза в год. На сегодняшний день опубликовано более 100 номеров. Green Anarchy — журнал, издаваемый коллективом из Юджина, штат Орегон . Его тираж составил 8000 экземпляров, частично в тюрьмах, причем тюремным подписчикам выдавались бесплатные экземпляры каждого номера, как указано в журнале. [ 170 ] Автор Джон Зерзан был одним из редакторов издания. [ 171 ]

Fifth Estate — американское периодическое издание, базирующееся в Детройте, основанное в 1965 году, но с удаленными сотрудниками по всей Северной Америке. Его редакционный коллектив иногда имеет разные взгляды на темы, рассматриваемые в журнале, но в целом разделяет анархистские, антиавторитарные взгляды и недогматический, ориентированный на действия подход к изменениям. Из названия следует, что издание является альтернативой четвертой власти (традиционной печатной журналистике). «Пятое сословие» часто называют старейшим англоязычным анархистским изданием в Северной Америке, хотя это иногда оспаривается, поскольку оно стало явно антиавторитарным только в 1975 году после десяти лет публикации в рамках движения Underground Press 1960-х годов. Anarchy: A Journal of Desire Armed — североамериканский анархистский журнал, одно из самых популярных анархистских изданий в Северной Америке в 1980-х и 1990-х годах. Его влияние можно охарактеризовать как совокупность пост-левого анархизма и различных разновидностей повстанческого анархизма. а иногда и анархо-примитивизм . Он был основан членами Колумбийской анархической лиги Колумбии, штат Миссури , и продолжал публиковаться там в течение почти пятнадцати лет, в конечном итоге под единоличным редакционным контролем Джейсона МакКуинна (который первоначально использовал псевдоним « Лев Черный »), прежде чем ненадолго переехать в в Нью-Йорк в 1995 году для публикации членами коллектива Autonomedia . Упадок независимого дистрибьютора Fine Print чуть не убил журнал, что потребовало его возвращения в коллектив Columbia после всего лишь двух выпусков. Он оставался в Колумбии с 1997 по 2006 год, после чего группа из Беркли, Калифорния, продолжала публиковаться два раза в год. [ 172 ] [ 173 ] Журнал известен тем, что возглавил критику пост-левой анархии («за пределами идеологии»), сформулированную такими авторами, как Хаким Бей , Лоуренс Джарах , Джон Зерзан , Боб Блэк и Вольфи Ландстрейхер (ранее Feral Faun/Feral Ranter). среди других псевдонимов ).

Анархисты стали более заметными в 1980-х годах в результате публикаций, протестов и съездов. В 1980 году в Портленде, штат Орегон, прошел Первый международный симпозиум по анархизму. [ 174 ] В 1986 году в Чикаго прошла конференция «Вспоминая Хеймаркет». [ 175 ] чтобы отметить столетие печально известного бунта на Хеймаркете . За этой конференцией последовали ежегодные континентальные съезды в Миннеаполисе (1987 г.), Торонто (1988 г.) и Сан-Франциско (1989 г.). В последнее время в Соединенных Штатах наблюдается возрождение анархистских идеалов. [ 176 ] В 1984 году был основан Альянс солидарности рабочих (WSA). [ 177 ] [ 178 ] Анархо -синдикалистская политическая организация, WSA публиковала «Идеи и действия» и входила в Международную ассоциацию рабочих (IWA-AIT), международную федерацию анархо-синдикалистских союзов и групп. [ 179 ]

В конце 1980-х годов «Любовь и ярость» начинала свою деятельность как газета, а в 1991 году расширилась до континентальной федерации. Это привнесло в основное русло движения новые идеи, такие как привилегии белых , и новых людей, включая антиимпериалистов и бывших членов Троцкистской Революционной Социалистической Лиги . организации Она распалась в 1998 году на фоне разногласий по поводу принципов расовой справедливости и жизнеспособности анархизма. [ 180 ] На пике популярности «Любовь и ярость» привлекла сотни активистов по всей стране. [ 181 ] и включал отделение Amor Y Rabia, базирующееся в Мехико, которое издавало одноименную газету. [ 182 ] Современный анархизм, с его смещением акцента с классового угнетения на все формы угнетения, начал всерьез заниматься проблемой расового угнетения в 1990-х годах вместе с черными анархистами Лоренцо Эрвином и Куваси Балагуном , журналом Race Traitor и организациями, создающими движение. включая Любовь и Ярость, Цветные анархисты , Черная автономия и Принесите Рукуса . [ 183 ]

В середине 1990-х годов в Соединенных Штатах также возникла повстанческая анархистская тенденция, поглощающая в основном южноевропейское влияние. [ 184 ] КриметИнк. , [ 185 ] представляет собой децентрализованный анархический коллектив автономных ячеек . [ 186 ] [ 187 ] [ 188 ] КриметИнк. возник в этот период первоначально как хардкор-панк -журнал Inside Front и начал работать как коллектив в 1996 году. [ 189 ] С тех пор он публиковал широко читаемые статьи и журналы анархистского движения, а также распространял плакаты и книги своего собственного издания. [ 190 ] КриметИнк. ячейки опубликовали книги, выпустили пластинки и организовали национальные кампании против глобализации и представительной демократии в пользу радикальной организации сообщества .

Американские анархисты все чаще становились заметными на протестах, особенно благодаря тактике, известной как Черный блок . Американские анархисты стали более заметными в результате протестов против ВТО в Сиэтле. [ 176 ] Общая борьба – Либертарианская коммунистическая федерация или Lucha Común – Federación Comunista Libertaria (ранее Северо-Восточная федерация коммунистов-анархистов (NEFAC) или Федерация коммунистов-либертариев Северного Востока) была платформистской / анархистско-коммунистической организацией, базирующейся в северо-восточном регионе США, которая была основана в 2000 году на конференции в Бостоне после протестов Всемирной торговой организации в Сиэтле в 1999 году. [ 191 ] [ 192 ] После нескольких месяцев дискуссий между бывшими членами Атлантического анархистского кружка и бывшими членами Love and Rage в Соединенных Штатах и бывшими членами газетного коллектива Demanarchie в Квебеке . Основанная как двуязычная французская и англоязычная федерация с группами членов и сторонников на северо-востоке Соединенных Штатов, на юге Онтарио и в провинции Квебек, организация позже распалась в 2008 году. Членство в Квебеке было преобразовано в Союз коммунистов-либертеров ( ЛЧ) [ 193 ] и американское членство сохранило название NEFAC, прежде чем в 2011 году изменило свое название на Common Struggle, а затем слилось с Анархистской Федерацией Черной Розы . Бывшие члены, базирующиеся в Торонто, впоследствии помогли основать платформистскую организацию в Онтарио, известную как Common Cause. [ 194 ] Коллектив анархистов Зеленой горы, который после Сиэтла стал местным филиалом NEFAC, поддерживал левые движения в Вермонте, такие как создание профсоюзов, кампания по прожиточному минимуму и доступ к социальным услугам. [ 195 ]

После урагана Катрина анархистские активисты стали членами-учредителями организации Common Ground Collective . [ 196 ] [ 197 ] Анархисты также сыграли раннюю роль в движении Occupy . [ 198 ] [ 199 ] В ноябре 2011 года журнал Rolling Stone выразил благодарность американскому анархисту и ученому Дэвиду Греберу за то, что он дал движению Occupy Wall Street тему: « Мы — 99 процентов ». Rolling Stone сообщил, что Гребер помог создать первую Генеральную ассамблею Нью-Йорка , в которой приняли участие всего 60 человек, 2 августа 2011 года. [ 200 ] Следующие шесть недель он провел, участвуя в растущем движении, включая содействие в проведении генеральных собраний, участие в собраниях рабочих групп, а также организацию юридических и медицинских тренингов и занятий по ненасильственному сопротивлению. [ 201 ] Вслед за движением «Захвати Уолл-стрит» автор Марк Брэй написал «Перевод анархии: анархизм захвати Уолл-стрит» , в котором из первых рук рассказал об участии анархистов. [ 202 ]