Южная Азия

| |

| Область | 5 222 321 км 2 (2 016 349 квадратных миль) |

|---|---|

| Население | 2,04 миллиарда (2024 г.) [ 1 ] |

| Population density | 362.3/km2 (938/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | $18.05 trillion (2024)[2] |

| GDP (nominal) | $5.04 trillion (2024)[3] |

| GDP per capita | $2,650 (nominal) (2024) $9,470 (PPP) (2024)[4] |

| HDI | |

| Ethnic groups | Indo-Aryan, Iranian, Dravidian, Sino-Tibetan, Austroasiatic, Turkic etc. |

| Religions | Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, Irreligion |

| Demonym | |

| Countries | |

| Dependencies | External (1) |

| Languages | Official languages (national level) Other official languages (provincial/regional level) |

| Time zones | 5 time zones |

| Internet TLD | .af, .bd, .bt, .in, .io, .lk, .mv, .np, .pk |

| Calling code | Zone 8 & 9 |

| Largest cities | |

| UN M49 code | 034 – Southern Asia142 – Asia001 – World |

Южная Азия — южный субрегион Азии и , который определяется как в географическом, так этнокультурном в плане . Согласно общепринятому мнению, современные государства Южной Азии включают Бангладеш , Бутан , Индию , Мальдивы , Непал , Пакистан и Шри-Ланку , а также часто включаемый Афганистан , который в противном случае можно было бы классифицировать как часть Центральной Азии . [ 6 ] [ 7 ] Южная Азия граничит с Восточной Азией на северо-востоке, Центральной Азией на северо-западе, Западной Азией на западе и Юго-Восточной Азией на востоке. Помимо Юго-Восточной Азии, Приморская Южная Азия является единственным субрегионом Азии, частично лежащим в Южном полушарии . Британская территория в Индийском океане и два из 26 атоллов Мальдивских островов в Южной Азии полностью расположены в Южном полушарии . Топографически он находится во власти Индийского субконтинента и ограничен Индийским океаном на юге и Гималаями , Каракорумом и Памирскими горами на севере. [8]

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) is an economic cooperation organization in the region which was established in 1985 and includes all eight nations comprising South Asia.[9] South Asia has a total area of 5.2 million sq.km (2 million sq.mi), which is 10% of the Asian continent.[10] The population of South Asia is estimated to be 1.94 billion or about one-fourth of the world's population, making it both the most populous and the most densely populated geographical region in the world.[11]

In 2022, South Asia had the world's largest populations of Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, Jains, and Zoroastrians.[12] South Asia alone accounts for 90.47% of Hindus, 95.5% of Sikhs, and 31% of Muslims worldwide, as well as 35 million Christians and 25 million Buddhists.[13][14][15][16]

Definition

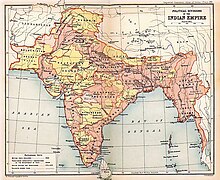

The geographical extent is not clear cut as systemic and foreign policy orientations of its constituents are quite asymmetrical.[18] Beyond the core territories of the Indian Empire (territories of the British Empire which were under the system of British Raj), there is a high degree of variation as to which other countries are included in South Asia.[19][20][21][22] There is no clear boundary – geographical, geopolitical, socio-cultural, economical, or historical – between South Asia and other parts of Asia, especially Southeast Asia and West Asia.[23]

The common definition of South Asia is largely inherited from the administrative boundaries of the Indian Empire,[24] with several exceptions. The current territories of Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan which were the core territories of the British Empire from 1857 to 1947 also form the core territories of South Asia.[25][26] The mountain countries of Nepal and Bhutan, two independent countries that were not under the British Raj but were protectorates of the Empire,[27] and the island countries of Sri Lanka and the Maldives are generally included.[28] By various definitions based on substantially different reasons, the British Indian Ocean Territory and the Tibet Autonomous Region may be included as well.[29][30][31][32][33][34] Myanmar (Burma), a former British colony and now largely considered a part of Southeast Asia, is also sometimes included.[18][20][35] Afghanistan is also included by some sources.[18][20][36][6]

The South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), a contiguous block of countries, started in 1985 with seven countries – Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, the Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka – and admitted Afghanistan as an eighth member in 2007.[38][39] China and Myanmar have also applied for the status of full members of SAARC.[40][41] The South Asia Free Trade Agreement admitted Afghanistan in 2011.[42]

The World Bank and United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) recognizes the eight SAARC countries as South Asia,[43][44][45][46] The Hirschman–Herfindahl index of the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific for the region excludes Afghanistan from South Asia.[47] Population Information Network (POPIN) excludes Maldives which is included as a member Pacific POPIN subregional network.[48] The United Nations Statistics Division's scheme of subregions, for statistical purpose,[17] includes Iran along with all eight members of the SAARC as part of Southern Asia.[49]

The boundaries of South Asia vary based on how the region is defined. South Asia's northern, eastern, and western boundaries vary based on definitions used, while the Indian Ocean is the southern periphery. Most of this region rests on the Indian Plate and is isolated from the rest of Asia by mountain barriers.[50][51] Much of the region consists of a peninsula in south-central Asia, rather resembling a diamond which is delineated by the Himalayas on the north, the Hindu Kush in the west, and the Arakanese in the east,[52] and which extends southward into the Indian Ocean with the Arabian Sea to the southwest and the Bay of Bengal to the southeast.[53][54]

The terms "Indian subcontinent" and "South Asia" are sometimes used interchangeably.[28][53][55][56][57] The Indian subcontinent is largely a geological term referring to the land mass that drifted northeastwards from ancient Gondwana, colliding with the Eurasian plate nearly 55 million years ago, towards the end of Palaeocene. This geological region largely includes Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.[58] Historians Catherine Asher and Cynthia Talbot state that the term "Indian subcontinent" describes a natural physical landmass in South Asia that has been relatively isolated from the rest of Eurasia.[59]

The use of the term Indian subcontinent began in the British Empire, and has been a term particularly common in its successors.[55] South Asia as the preferred term is particularly common when scholars or officials seek to differentiate this region from East Asia.[60] According to historians Sugata Bose and Ayesha Jalal, the Indian subcontinent has come to be known as South Asia "in more recent and neutral parlance."[56] This "neutral" notion refers to the concerns of Pakistan and Bangladesh, particularly given the recurring conflicts between India and Pakistan, wherein the dominant placement of "India" as a prefix before the subcontinent might offend some political sentiments.[35] However, in Pakistan, the term "South Asia" is considered too India-centric and was banned until 1989 after the death of Zia ul Haq.[61] This region has also been labelled as "India" (in its classical and pre-modern sense) and "Greater India".[35][52]

According to Robert M. Cutler – a scholar of political science at Carleton University,[62] the terms South Asia, Southwest Asia, and Central Asia are distinct, but the confusion and disagreements have arisen due to the geopolitical movement to enlarge these regions into Greater South Asia, Greater Southwest Asia, and Greater Central Asia. The frontier of Greater South Asia, states Cutler, between 2001 and 2006 has been geopolitically extended to eastern Iran and western Afghanistan in the west, and in the north to northeastern Iran, northern Afghanistan, and southern Uzbekistan.[62]

Identification with a South Asian identity was found to be significantly low among respondents in an older two-year survey across Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.[63]

History

Pre-history

The history of core South Asia begins with evidence of human activity of Homo sapiens, as long as 75,000 years ago, or with earlier hominids including Homo erectus from about 500,000 years ago.[64] The earliest prehistoric culture have roots in the mesolithic sites as evidenced by the rock paintings of Bhimbetka rock shelters dating to a period of 30,000 BCE or older,[note 3] as well as neolithic times.[note 4]

Ancient era

The Indus Valley civilization, which spread and flourished in the northwestern part of South Asia from c. 3300 to 1300 BCE in present-day Pakistan, Northern India and Afghanistan, was the first major civilization in South Asia.[65] A sophisticated and technologically advanced urban culture developed in the Mature Harappan period, from 2600 to 1900 BCE.[66] According to anthropologist Possehl, the Indus Valley civilization provides a logical, if somewhat arbitrary, starting point for South Asian religions, but these links from the Indus religion to later-day South Asian traditions are subject to scholarly dispute.[67]

The Vedic period, named after the Vedic religion of the Indo-Aryans,[note 5] lasted from c. 1900 to 500 BCE.[69][70] The Indo-Aryans were Indo-European-speaking pastoralists[71] who migrated into north-western India after the collapse of the Indus Valley Civilization.[68][72] Linguistic and archaeological data show a cultural change after 1500 BCE,[68] with the linguistic and religious data clearly showing links with Indo-European languages and religion.[73] By about 1200 BCE, the Vedic culture and agrarian lifestyle were established in the northwest and northern Gangetic plain of South Asia.[71][74][75] Rudimentary state-forms appeared, of which the Kuru-Pañcāla union was the most influential.[76][77] The first recorded state-level society in South Asia existed around 1000 BCE.[71] In this period, states Samuel, emerged the Brahmana and Aranyaka layers of Vedic texts, which merged into the earliest Upanishads.[78] These texts began to ask the meaning of a ritual, adding increasing levels of philosophical and metaphysical speculation,[78] or "Hindu synthesis".[79]

Increasing urbanisation of South Asia between 800 and 400 BCE, and possibly the spread of urban diseases, contributed to the rise of ascetic movements and of new ideas which challenged the orthodox Brahmanism.[80][failed verification] These ideas led to Sramana movements, of which Mahavira (c. 549–477 BCE), proponent of Jainism, and Buddha (c. 563 – c. 483), founder of Buddhism, was the most prominent icons.[81]

The Greek army led by Alexander the Great stayed in the Hindu Kush region of South Asia for several years and then later moved into the Indus valley region. Later, the Maurya Empire extended over much of South Asia in the 3rd century BCE. Buddhism spread beyond south Asia, through northwest into Central Asia. The Bamiyan Buddhas of Afghanistan and the edicts of Aśoka suggest that the Buddhist monks spread Buddhism (Dharma) in eastern provinces of the Seleucid Empire, and possibly even farther into West Asia.[82][83][84] The Theravada school spread south from India in the 3rd century BCE, to Sri Lanka, later to Southeast Asia.[85] Buddhism, by the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE, was prominent in the Himalayan region, Gandhara, Hindu Kush region and Bactria.[86][87][88]

From about 500 BCE through about 300 CE, the Vedic-Brahmanic synthesis or "Hindu synthesis" continued.[79] Classical Hindu and Sramanic (particularly Buddhist) ideas spread within South Asia, as well as outside South Asia.[89][90][91] The Gupta Empire ruled over a large part of the region between the 4th and 7th centuries, a period that saw the construction of major temples, monasteries and universities such as the Nalanda.[92][93][94] During this era, and through the 10th century, numerous cave monasteries and temples such as the Ajanta Caves, Badami cave temples and Ellora Caves were built in South Asia.[95][96][97]

Medieval era

Islam came as a political power in the fringe of South Asia in 8th century CE when the Arab general Muhammad bin Qasim conquered Sindh, and Multan in Southern Punjab, in modern-day Pakistan.[98] By 962 CE, Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms in South Asia were under a wave of raids from Muslim armies from Central Asia.[99] Among them was Mahmud of Ghazni, who raided and plundered kingdoms in north India from east of the Indus river to west of Yamuna river seventeen times between 997 and 1030.[100] Mahmud of Ghazni raided the treasuries but retracted each time, only extending Islamic rule into western Punjab.[101][102]

The wave of raids on north Indian and western Indian kingdoms by Muslim warlords continued after Mahmud of Ghazni, plundering and looting these kingdoms.[103] The raids did not establish or extend permanent boundaries of their Islamic kingdoms. The Ghurid Sultan Mu'izz al-Din Muhammad began a systematic war of expansion into North India in 1173.[104] He sought to carve out a principality for himself by expanding the Islamic world,[100][105] and thus laid the foundation for the Muslim kingdom that became the Delhi Sultanate.[100] Some historians chronicle the Delhi Sultanate from 1192 due to the presence and geographical claims of Mu'izz al-Din in South Asia by that time.[106]

The Delhi Sultanate covered varying parts of South Asia and was ruled by a series of dynasties: Mamluk, Khalji, Tughlaq, Sayyid and Lodi dynasties. Muhammad bin Tughlaq came to power in 1325, launched a war of expansion and the Delhi Sultanate reached it largest geographical reach over the South Asian region during his 26-year rule.[107] A Sunni Sultan, Muhammad bin Tughlaq persecuted non-Muslims such as Hindus, as well as non-Sunni Muslims such as Shia and Mahdi sects.[108][109][110]

Revolts against the Delhi Sultanate sprang up in many parts of South Asia during the 14th century.[citation needed] In the northeast, the Bengal Sultanate became independent in 1346 CE. It remained in power through the early 16th century. The state religion of the sultanate was Islam.[111][112] In South India, the Hindu Vijayanagara Empire came to power in 1336 and persisted until the middle of the 16th century. It was ultimately defeated and destroyed by an alliance of Muslim Deccan sultanates at the battle of Talikota.[113][114]

About 1526, the Punjab governor Dawlat Khan Lodī reached out to the Mughal Babur and invited him to attack the Delhi Sultanate. Babur defeated and killed Ibrahim Lodi in the Battle of Panipat in 1526. The death of Ibrahim Lodi ended the Delhi Sultanate, and the Mughal Empire replaced it.[115]

Modern era

The modern history period of South Asia, that is 16th-century onwards, witnessed the establishment of the Mughal empire, with Sunni Islam theology. The first ruler was Babur had Turco-Mongol roots and his realm included the northwestern and Indo-Gangetic Plain regions of South Asia. The southern and northeastern regions of South Asia were largely under Hindu kings such as those of Vijayanagara Empire and Ahom kingdom,[116] with some regions such as parts of modern Telangana and Andhra Pradesh under local Sultanates namely Deccan sultanates.[117][118]

The Mughal Empire continued its wars of expansion after Babur's death. With the fall of the Rajput kingdoms and Vijayanagara, its boundaries encompassed almost the entirety of the Indian subcontinent.[119] The Mughal Empire was marked by a period of artistic exchanges and a Central Asian and South Asian architecture synthesis, with remarkable buildings such as the Taj Mahal.[120][118][121]

However, this time also marked an extended period of religious persecution.[122] Two of the religious leaders of Sikhism, Guru Arjan and Guru Tegh Bahadur were arrested under orders of the Mughal emperors after their revolts and were executed when they refused to convert to Islam.[123][124][125] Religious taxes on non-Muslims called jizya were imposed. Buddhist, Hindu and Sikh temples were desecrated. However, not all Muslim rulers persecuted non-Muslims. Akbar, a Mughal ruler for example, sought religious tolerance and abolished jizya.[126][127][128][129]

After the death of Aurangzeb and the collapse of the Mughal Empire, which marks the beginning of modern India, in the early 18th century, it provided opportunities for the Marathas, Sikhs, Mysoreans and Nawabs of Bengal to exercise control over large regions of the Indian subcontinent.[130][131] By the mid-18th century, India was a major proto-industrializing region.[132][118]

Maritime trading between South Asia and European merchants began after the Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama returned to Europe. British, French, Portuguese colonial interests struck treaties with these rulers and established their trading ports. In northwestern South Asia, a large region was consolidated into the Sikh Empire by Ranjit Singh.[133][134] After the defeat of the Nawab of Bengal and Tipu Sultan and his French allies, British traders went on to dominate much of South Asia through divide-and-rule tactics by the early 19th century. The region experienced significant de-industrialisation in its first few decades of British rule.[135] Control over the subcontinent was then transferred to the British government after the Indian Rebellion of 1857, with the British cracking down to some extent afterwards.[136]

An increase of famines and extreme poverty characterised the colonial period, though railways built with British technology eventually provided crucial famine relief by increasing food distribution throughout India.[137][135] Millions of South Asians began to migrate throughout the world, impelled by the economic/labour needs and opportunities presented by the British Empire.[138][139][140] The introduction of Western political thought inspired a growing Indian intellectual movement, and so by the 20th century, British rule began to be challenged by the Indian National Congress, which sought full independence under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi.[141][142]

Britain, under pressure from Indian freedom fighters, increasingly gave self-rule to British India. By the 1940s, two rival camps emerged among independence activists: those who favored a separate nation for Indian Muslims, and those who wanted a united India. As World War II raged, over 2 million Indians fought for Britain;[143] by the end of the war, Britain was greatly weakened, and thus decided to grant independence to the vast majority of South Asians in 1947,[144][145] though this coincided with the partition of India into a Hindu-majority India and a Muslim-majority Pakistan, which resulted in significant displacement and violence and hardened religious divides in the region.[146]

Contemporary era

In 1947, the newly independent India and Pakistan had to decide how to deal with the hundreds of princely states that controlled much of the subcontinent, as well as what to do with the remaining European (non-British) colonies.[147] A combination of referendums, military action, and negotiated accessions took place in rapid succession, leading to the political integration of the vast majority of India and Pakistan within a few years.[148][149]

India and Pakistan clashed several times in the decades after Independence, with disputes over Kashmir playing a significant role.[150] In 1971, the eastern half of Pakistan seceded with help from India and became the People's Republic of Bangladesh after the traumatic Bangladesh Liberation War.[151] This, along with India and Pakistan gaining nuclear weapons soon afterwards, increased tensions between the two countries.[152] The Cold War decades also contributed to the divide, as Pakistan aligned with the West and India with the Soviet Union;[153][154] other factors include the time period after the 1962 India-China War, which saw India and China move apart while Pakistan and China built closer relations.[155]

Pakistan has been beset with terrorism, economic issues and military dominance of its government since Independence,[156] with none of its Prime Ministers having completed a full 5-year term in office.[157] India has grown significantly,[158] having slashed its rate of extreme poverty to below 20%.[159] Bangladesh, having struggled greatly for decades due to conflict with and economic exploitation by Pakistan,[160][161] is now one of the fastest-growing countries in the region, beating India in terms of GDP per capita.[162][163] Afghanistan has gone through several invasions and Islamist regimes, with many of its refugees having gone to Pakistan and other parts of South Asia and bringing back cultural influences such as cricket.[164][165] Religious nationalism has grown across the region,[166][167] with persecution causing millions of Hindus and Christians to flee Pakistan and Bangladesh,[168][169] and Hindu nationalism having grown in India with the election of the Bharatiya Janata Party in 2014.[170]

A recent phenomenon has been that of India and China fighting on their border, as well as vying for dominance of South Asia, with China partnering with Pakistan and using its superior economy to attract countries surrounding India, while America and other countries have strengthened ties with India to counter China in the broader Indo-Pacific.[171][172]

Geography

According to Saul Cohen, early colonial era strategists treated South Asia with East Asia, but in reality, the South Asia region excluding Afghanistan is a distinct geopolitical region separated from other nearby geostrategic realms, one that is geographically diverse.[173] The region is home to a variety of geographical features, such as glaciers, rainforests, valleys, deserts, and grasslands that are typical of much larger continents. It is surrounded by three water bodies – the Bay of Bengal, the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea – and has acutely varied climate zones. The tip of the Indian Peninsula had the highest quality pearls.[174]

Indian Plate

Most of this region is resting on the Indian Plate, the northerly portion of the Indo-Australian Plate, separated from the rest of the Eurasian Plate. The Indian Plate includes most of South Asia, forming a land mass which extends from the Himalayas into a portion of the basin under the Indian Ocean, including parts of South China and Eastern Indonesia, as well as Kunlun and Karakoram ranges,[175][176] and extending up to but not including Ladakh, Kohistan, the Hindu Kush range, and Balochistan.[177][178][179] It may be noted that geophysically the Yarlung Tsangpo River in Tibet is situated at the outside the border of the regional structure, while the Pamir Mountains in Tajikistan are situated inside that border.[180]

The Indian subcontinent formerly formed part of the supercontinent Gondwana, before rifting away during the Cretaceous period and colliding with the Eurasian Plate about 50–55 million years ago and giving birth to the Himalayan range and the Tibetan plateau. It is the peninsular region south of the Himalayas and Kuen Lun mountain ranges and east of the Indus River and the Iranian Plateau, extending southward into the Indian Ocean between the Arabian Sea (to the southwest) and the Bay of Bengal (to the southeast).

Climate

The climate of this vast region varies considerably from area to area from tropical monsoon in the south to temperate in the north. The variety is influenced by not only the altitude but also by factors such as proximity to the seacoast and the seasonal impact of the monsoons. Southern parts are mostly hot in summers and receive rain during monsoon periods. The northern belt of Indo-Gangetic plains also is hot in summer, but cooler in winter. The mountainous north is colder and receives snowfall at higher altitudes of Himalayan ranges.

As the Himalayas block the north-Asian bitter cold winds, the temperatures are considerably moderate in the plains down below. For the most part, the climate of the region is called the monsoon climate, which keeps the region humid during summer and dry during winter, and favours the cultivation of jute, tea, rice, and various vegetables in this region.

South Asia is largely divided into four broad climate zones:[182]

- The northern Indian edge and northern Pakistani uplands have a dry subtropical continental climate

- The far south of India and southwest Sri Lanka have an equatorial climate

- Most of the peninsula has a tropical climate with variations:

- Hot subtropical climate in northwest India

- Cool winter hot tropical climate in Bangladesh

- Tropical semi-arid climate in the center

- The Himalayas and most of the Hindu Kush have an Alpine climate

Maximum relative humidity of over 80% has been recorded in Khasi and Jaintia Hills and Sri Lanka, while the area adjustment to Pakistan and western India records lower than 20%–30%.[182] Climate of South Asia is largely characterized by monsoons. South Asia depends critically on monsoon rainfall.[183] Two monsoon systems exist in the region:[184]

- The summer monsoon: Wind blows from the southwest to most parts of the region. It accounts for 70%–90% of the annual precipitation.

- The winter monsoon: Wind blows from the northeast. Dominant in Sri Lanka and Maldives.

The warmest period of the year precedes the monsoon season (March to mid June). In the summer the low pressures are centered over the Indus-Gangetic Plain and high wind from the Indian Ocean blows towards the center. The monsoons are the second coolest season of the year because of high humidity and cloud covering. But, at the beginning of June, the jetstreams vanish above the Tibetan Plateau, low pressure over the Indus Valley deepens and the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ) moves in. The change is violent. Moderately vigorous monsoon depressions form in the Bay of Bengal and make landfall from June to September.[182]

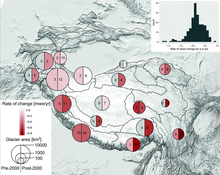

Climate change

South Asian countries are expected to experience more flooding in the future as the monsoon pattern intensifies.[186]: 1459 Across Asia as a whole, 100-year extremes in vapor transport (directly related to extreme precipitation) would become 2.6 times more frequent under 1.5 °C (2.7 °F) of global warming, yet 3.9 and 7.5 times more frequent under 2 °C (3.6 °F) and 3 °C (5.4 °F). In parts of South Asia, they could become up to 15 times more frequent.[185] At the same time, up to two-thirds of glacier ice in the Hindu Kush region may melt by 2100 under high warming, and these glaciers feed the water basin of over 220 million people.[186]: 1487 As glacier meltwater flow diminishes after 2050, Hydropower generation would become less predictable and reliable, while agriculture would become more reliant on the intensified monsoon than ever before.[187][188][189] Around 2050, people living in the Ganges and Indus river basins (where up to 60% of non-monsoon irrigation comes from the glaciers[190]) may be faced with severe water scarcity due to both climate and socioeconomic reasons.[186]: 1486

By 2030, major Indian cities such as Mumbai, Kolkata, Cuttack and Kochi are expected to end up with much of their territory below the tide level.[191] In Mumbai alone, failing to adapt to this would result in damages of US$112–162 billion by 2050, which would nearly triple by 2070.[186] Sea level rise in Bangladesh will displace 0.9–2.1 million people by 2050 and may force the relocation of up to one third of power plants by 2030.[186] Food security will become more uneven, and some South Asian countries could experience significant social impacts from global food price volatility.[186]: 1494 Infectious diarrhoea mortality and dengue fever incidence is also likely to increase across South Asia.[186]: 1508 Parts of South Asia would also reach "critical health thresholds" for heat stress under all but the lowest-emission climate change scenarios.[186]: 1465 Under the high-emission scenario, 40 million people (nearly 2% of the South Asian population) may be driven to internal migration by 2050 due to climate change.[186]: 1469

India is estimated to have the world's highest social cost of carbon - meaning that it experiences the greatest impact from greenhouse gas emissions.[192] Other estimates describe Bangladesh as the country most likely to be the worst-affected.[193][194][195] In the 2017 edition of Germanwatch's Climate Risk Index, Bangladesh and Pakistan ranked sixth and seventh respectively as the countries most affected by climate change in the period from 1996 to 2015, while India ranked fourth among the list of countries most affected by climate change in 2015.[196] Some research suggests that South Asia as a whole would lose 2% of its GDP to climate change by 2050, while these losses would approach 9% by the end of the century under the most intense climate change scenario.[186]: 1468

Regions

Land and water area

This list includes dependent territories within their sovereign states (including uninhabited territories), but does not include claims on Antarctica. EEZ+TIA is exclusive economic zone (EEZ) plus total internal area (TIA) which includes land and internal waters.

| Country | Area in km2 | EEZ | Shelf | EEZ+TIA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 652,864 | 0 | 0 | 652,864 | |

| 148,460 | 86,392 | 66,438 | 230,390 | |

| 38,394 | 0 | 0 | 38,394 | |

| 3,287,263 | 2,305,143 | 402,996 | 5,592,406 | |

| 147,181 | 0 | 0 | 147,181 | |

| 298 | 923,322 | 34,538 | 923,622 | |

| 881,913 | 290,000 | 51,383 | 1,117,911 | |

| 65,610 | 532,619 | 32,453 | 598,229 | |

| Total | 5,221,093 | 4,137,476 | 587,808 | 9,300,997 |

Society

Population

The population of South Asia is about 1.938 billion which makes it the most populated region in the world.[197] It is socially very mixed, consisting of many language groups and religions, and social practices in one region that are vastly different from those in another.[198]

| Country | Population in thousands | % of South Asia | % of world[200] | Density (per km2) | Population growth rate[201] | Population projection (in thousands)[199][1] | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005–10 | 2010–15 | 2015–20 | 1950 | 1975 | 2000 | 2025 | 2050 | 2075 | 2100 | |||||

| 42,240 | 2.17% | 0.525% | 61.8 | 2.78 | 3.16 | 2.41 | 7,752 | 12,689 | 20,779 | 44,516 | 74,075 | 98,732 | 110,855 | |

| 172,954 | 8.92% | 2.15% | 1301 | 1.18 | 1.16 | 1.04 | 37,895 | 70,066 | 127,658 | 170,937 | 203,905 | 201,891 | 176,366 | |

| 787 | 0.04% | 0.00978% | 20.3 | 2.05 | 1.58 | 1.18 | 177 | 348 | 591 | 797 | 874 | 803 | 654 | |

| 1,428,628 | 73.7% | 17.5% | 473.4 | 1.46 | 1.23 | 1.10 | 376,325 | 623,103 | 1,056,576 | 1,454,607 | 1,670,491 | 1,676,035 | 1,529,850 | |

| 521 | 0.03% | 0.00647% | 1738.2 | 2.68 | 2.76 | 1.85 | 74 | 136 | 279 | 515 | 570 | 543 | 469 | |

| 30,897 | 1.59% | 0.384% | 204.1 | 1.05 | 1.17 | 1.09 | 8,483 | 13,420 | 23,941 | 31,577 | 37,401 | 38,189 | 33,770 | |

| 240,486 | 12.4% | 2.98% | 300.2 | 2.05 | 2.09 | 1.91 | 37,542 | 66,817 | 142,344 | 249,949 | 367,808 | 453,262 | 487,017 | |

| 21,894 | 1.13% | 0.272% | 347.2 | 0.68 | 0.50 | 0.35 | 7,971 | 13,755 | 18,778 | 22,000 | 21,815 | 19,000 | 14,695 | |

| South Asia | 1,938,407 | 100% | 24.094% | 377.5 | - | - | - | 476,220 | 800,335 | 1,390,946 | 1,974,898 | 2,376,939 | 2,488,455 | 2,353,676 |

| Population of South Asian countries in 1950, 1975, 2000, 2025, 2050, 2075 and 2100 projection from the United Nations has been displayed in table. The given population projections are based on medium fertility index. With India and Bangladesh approaching replacement rates fast, population growth in South Asia is facing steep decline and may turn negative in mid 21st century.[199][1] | ||||||||||||||

Languages

There are numerous languages in South Asia. The spoken languages of the region are largely based on geography and shared across religious boundaries, but the written script is sharply divided by religious boundaries. In particular, Muslims of South Asia such as in Afghanistan and Pakistan use the Arabic alphabet and Persian Nastaliq. Till 1952, Muslim-majority Bangladesh (then known as East Pakistan) also mandated only the Nastaliq script, but after that adopted regional scripts and particularly Bengali, after the Language Movement for the adoption of Bengali as the official language of the then East Pakistan. Non-Muslims of South Asia, and some Muslims in India, on the other hand, use scripts such as those derived from Brahmi script for Indo-European languages and non-Brahmi scripts for Dravidian languages and others.[202][203]

The Nagari script has been the primus inter pares of the traditional South Asian scripts.[204] The Devanagari script is used for over 120 South Asian languages,[205] including Hindi,[206] Marathi, Nepali, Pali, Konkani, Bodo, Sindhi and Maithili among other languages and dialects, making it one of the most used and adopted writing systems in the world.[207] The Devanagari script is also used for classical Sanskrit texts.[205]

The largest spoken language in this region is Hindustani language, followed by Bengali, Telugu, Tamil, Marathi, Gujarati, Kannada, and Punjabi.[202][203] In the modern era, new syncretic languages developed in the region such as Urdu that are used by the Muslim community of northern South Asia (particularly Pakistan and northern states of India).[208] The Punjabi language spans three religions: Islam, Hinduism, and Sikhism. The spoken language is similar, but it is written in three scripts. The Sikh use Gurmukhi alphabet, Muslim Punjabis in Pakistan use the Nastaliq script, while Hindu Punjabis in India use the Gurmukhi or Nāgarī script. The Gurmukhi and Nagari scripts are distinct but close in their structure, but the Persian Nastaliq script is very different.[209]

Sino-Tibetan languages are spoken across northern belts of the region in the Himalayan areas, often using the Tibetan script.[210] These languages are predominantly spoken in Bhutan and Nepal as well as parts of Burma and northern India in the state of Sikkim and the Ladakh region.[211] The national language of Bhutan is Dzongkha, while Lepcha, Limbu, Gurung, Magar, Rai, Newari, Tamang, Tshangla, Thakali and Sikkimese are also spoken in Bhutan, Nepal and Sikkim, and Ladakhi is spoken in Ladakh.[211] Both Buddhism and Bon are often predominant in areas where these languages are present.[211][210] Some areas in Gilgit-Baltistan also speak Balti language, however speakers write with the Urdu script.[210] The Tibetan script fell out of use in Pakistani Baltistan hundreds of years ago upon the region's adoption of Islam[210]

English, with British spelling, is commonly used in urban areas and is a major economic lingua franca of South Asia.[212]

Religions

Religion in British India 1871–1872 Census (includes modern-day India, Bangladesh, most of Pakistan and coastal Myanmar)[213]

In 2010, South Asia had the world's largest population of Hindus,[15] about 510 million Muslims,[15] over 27 million Sikhs, 35 million Christians and over 25 million Buddhists.[13] Hindus make up about 68 percent or about 900 million and Muslims at 31 percent or 510 million of the overall South Asia population,[214] while Buddhists, Jains, Christians and Sikhs constitute most of the rest. The Hindus, Buddhists, Jains, Sikhs and Christians are concentrated in India, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Bhutan, while the Muslims are concentrated in Afghanistan (99%), Bangladesh (90%), Pakistan (96%) and Maldives (100%).[15] With all major religions practised in the subcontinent, South Asia is known for its religious diversity and one of the most religiously diverse regions on earth.

Indian religions are the religions that originated in the Indian subcontinent; namely Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism and Sikhism.[215] The Indian religions are distinct yet share terminology, concepts, goals and ideas, and from South Asia spread into East Asia and southeast Asia.[215] Early Christianity and Islam were introduced into coastal regions of South Asia by merchants who settled among the local populations. Later Sindh, Balochistan, and parts of the Punjab region saw conquest by the Arab caliphates along with an influx of Muslims from Persia and Central Asia, which resulted in spread of both Shia and Sunni Islam in parts of northwestern region of South Asia. Subsequently, under the influence of Muslim rulers of the Islamic sultanates and the Mughal Empire, Islam spread in South Asia.[216][217] About one-third of the world's Muslims are from South Asia.[14][16][12]

| Country | State religion | Religious population as a percentage of total population | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buddhism | Christianity | Hinduism | Islam | Kiratism | Sikhism | Others | Year reported | ||

| Islam | – | – | – | 99.7% | – | – | 0.3% | 2019[218] | |

| Islam | 0.6% | 0.4% | 9.5% | 90.4% | – | – | – | 2011[219] | |

| Vajrayana Buddhism | 74.8% | 0.5% | 22.6% | 0.1% | – | – | 2% | 2010[220][221] | |

| Secular | 0.7% | 2.3% | 79.8% | 14.2% | – | 1.7% | 1.3% | 2011[222][223] | |

| Islam | – | – | – | 100% | – | – | – | [224][225][226] | |

| Secular | 9% | 1.3% | 81.3% | 4.4% | 3% | – | 0.8% | 2013[227] | |

| Islam | – | 1.59% | 1.85% | 96.28% | – | – | 0.07% | 2010[228] | |

| Theravada Buddhism | 70.2% | 6.2% | 12.6% | 9.7% | – | – | 1.4% | 2011[229] | |

Largest urban areas

South Asia is home to some of the most populated urban areas in the world. According to the 2023 edition of Demographia World Urban Areas, the region contains 8 of the world's 35 megacities (urban areas over 10 million population):[230]

| Rank | Urban Area | State/Province | Country | Skyline | Population[230] | Area (km2)[230] | Density (/km2)[230] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Delhi | National Capital Region |  |

31,190,000 | 2,344 | 13,307 | |

| 2 | Mumbai | Maharashtra |  |

25,189,000 | 1,046 | 24,073 | |

| 3 | Kolkata | West Bengal |  |

21,747,000 | 1,352 | 16,085 | |

| 4 | Karachi | Sindh |  |

20,249,000 | 1,124 | 18,014 | |

| 5 | Dhaka | Dhaka Division |  |

19,134,000 | 619 | 30,911 | |

| 6 | Bangalore | Karnataka |  |

15,257,000 | 1,743 | 8,753 | |

| 7 | Lahore | Punjab |  |

13,504,000 | 945 | 14,285 | |

| 8 | Chennai | Tamil Nadu |  |

11,570,000 | 1,225 | 9,444 | |

| 9 | Hyderabad | Telangana |  |

9,797,000 | 1,689 | 5,802 | |

| 10 | Ahmedabad | Gujarat | 8,006,000 | 505 | 15,852 |

Diaspora

Culture

Sports

Cricket is the most popular sport in South Asia,[234] with 90% of the sport's worldwide fans being in the Indian subcontinent.[235] There are also some traditional games, such as kabaddi and kho-kho, which are played across the region and officially at the South Asian Games and Asian Games;[236][237][238] the leagues created for these traditional sports (such as Pro Kabaddi League and Ultimate Kho Kho) are some of the most-watched sports competitions in the region.[239][240]

Cinema

Music

Cuisine

Economy

India is the largest economy in the region (US$ 4.11 trillion) and makes up almost 80% of the South Asian economy; it is the world's 5th largest in nominal terms and 3rd largest by purchasing power adjusted exchange rates (US$ 14.26 trillion).[242] India is the member of G-20 major economies and BRICS from the region. It is the fastest-growing major economy in the world and one of the world's fastest registering a growth of 7.2% in FY 2022–23.[243]

India is followed by Bangladesh, which has a GDP of ($446 billion). It has the fastest GDP growth rate in Asia. It is one of the emerging and growth-leading economies of the world, and is also listed among the Next Eleven countries. It is also one of the fastest-growing middle-income countries. It has the world's 33rd largest GDP in nominal terms and is the 25th largest by purchasing power adjusted exchange rates ($1.476 trillion). Bangladesh's economic growth was 6.4% in 2022.[244] The next one is Pakistan, which has an economy of ($340 billion). Next is Sri Lanka, which has the 2nd highest GDP per capita and the 4th largest economy in the region. According to a World Bank report in 2015, driven by a strong expansion in India, coupled with favorable oil prices, from the last quarter of 2014 South Asia became the fastest-growing region in the world.[245]

Certain parts of South Asia are significantly wealthier than others; the four Indian states of Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat and Karnataka are projected to account for almost 50% of India's GDP by 2030, while the five South Indian states comprising 20% of India's population are expected to contribute 35% of India's GDP by 2030.[246]

| Country [247][248][249] |

GDP | Inflation

(2022)[250] |

HDI | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal GDP (in millions) (2022) (%Share)[251] |

GDP per capita

(2022)[252] |

GDP (PPP) (in millions) (2022) (%Share) |

GDP (PPP) per capita (2022) | GDP growth

(2022)[253] |

HDI (Rank)

(2022)[254] |

Inequality-adjusted HDI (Rank) (2022)[255] | ||

| $20,136 (2020) | $611 (2020) | $80,912 (2020) | $2,456 (2020) | -2.4% (2020) | 5.6% (2020) | |||

| $460,751 (10.41%) | $2,734 | $1,345,646 (8.97%) | $7,985 | 7.2% | 6.1% | |||

| $2,707 (0.06%) | $3,562 | $9,937 (0.07%) | $13,077 | 4.0% | 7.7% | |||

| $3,468,566 (78.35%) | $2,466 | $11,665,490 (77.74%) | $8,293 | 6.8% | 6.9% | |||

| $5,900 (0.13%) | $15,097 | $12,071 (0.08%) | $30,888 | 8.7% | 4.3% | |||

| $39,028 (0.88%) | $1,293 | $141,161 (0.94%) | $4,677 | 4.2% | 6.3% | |||

| $376,493 (8.50%) | $1,658 | $1,512,476 (10.08%) | $6,662 | 6.0% | 12.10% | |||

| $73,739 (1.67%) | $3,293 | $318,690 (2.12%) | $14,230 | -8.7% | 48.2% | |||

| South Asia[257] | $4,427,184 (100%) | $2,385 | $15,005,471 (100%) | $8,085 | 6.4% | 8.1% | - | |

According to the World Bank's 2011 report, based on 2005 ICP PPP, about 24.6% of the South Asian population was below the international poverty line of $1.25/day.[258] Bhutan, Maldives and Sri Lanka had the lowest number of people below the poverty line, with 2.4%, 1.5% and 4.1% respectively.

According to the 2023 MPI (multidimensional poverty index) report by the UN, around 20% of South Asians are poor.[259]

51.7% of Afghanistan's population was under the MPI poverty threshold in 2019,[260] while 24.1% of Bangladesh's population was under the threshold in 2021.[261] India lifted 415 million people from MPI-poverty from 2005/06 to 2019/21; 16.4% of India's population was MPI-poor in 2019/2021, compared to 55.1% in 2005/2006.[159] 10% of India's population was under the international poverty line of $2.15/day in 2021.[262]

| Country [247][248][249] |

Population below poverty line (at $1.9/day) | Global Hunger Index (2021)[263] | Population under-nourished (2015)[264] | Life expectancy (2019)[265] (global rank) | Global wealth report (2019)[266][267][268] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| World Bank[269] (year) | 2022 Multidimensional Poverty Index Report (MPI source year)[270] | Population in Extreme poverty (2022)[271] | CIA Factbook (2015)[272] | Total national wealth in billion USD (global rank) | Wealth per adult in USD | Median wealth per adult in USD (global rank) | ||||

| 54.5% (2016) | 55.91% (2015–16) | 18% | 36% | 28.3 (103rd) | 26.8% | 63.2 (160th) | 25 (116th) | 1,463 | 640 (156th) | |

| 24.3% (2016) | 24.64% (2019) | 4% | 31.5% | 19.1 (76th) | 16.4% | 74.3 (82nd) | 697 (44th) | 6,643 | 2,787 (117th) | |

| 8.2% (2017) | 37.34% (2010) | 4% | 12% | No data | No data | 73.1 (99th) | No Data | No Data | No Data | |

| 21.9% (2011) | 16.4% (2019–21) | 3% | 29.8% | 27.5 (101st) | 15.2% | 70.8 (117th) | 12,614 (7th) | 14,569 | 3,042 (115th) | |

| 8.2% (2016) | 0.77% (2016–17) | 4% | 16% | No data | 5.2% | 79.6 (33rd) | 7 (142nd) | 23,297 | 8,555 (74th) | |

| 25.2% (2010) | 17.50% (2019) | 8% | 25.2% | 19.1 (76th) | 7.8% | 70.9 (116th) | 68 (94th) | 3,870 | 1,510 (136th) | |

| 24.3% (2015) | 38.33% (2017–18) | 5% | 12.4% | 24.7 (94th) | 22% | 69.3 (144th) | 465 (49th) | 4,096 | 1,766 (128th) | |

| 4.1% (2016) | 2.92% (2016) | 5% | 8.9% | 16 (65th) | 22% | 76.9 (54th) | 297 (60th) | 20,628 | 8,283 (77th) | |

The major stock exchanges in the region are Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) with market Capitalization of $3.5 trillion (10th largest in the world), National Stock Exchange of India (NSE) with market capitalization of $3.55 trillion (9th largest in the world), Dhaka Stock Exchange (DSE), Colombo Stock Exchange (CSE), and Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) with market capitalization of $72 billion.[273] Economic data is sourced from the International Monetary Fund, current as of April 2017, and is given in US dollars.[274]

Education

One of the key challenges in assessing the quality of education in South Asia is the vast range of contextual difference across the region, complicating any attempt to compare between countries.[275] In 2018, 11.3 million children at the primary level and 20.6 million children at the lower secondary level were out-of-school in South Asia, while millions of children completed primary education without mastering the foundational skills of basic numeracy and literacy.[276]

According to UNESCO, 241 million children between six and fourteen years or 81 percent of the total were not learning in Southern and Central Asia in 2017. Only sub-Saharan Africa had a higher rate of children not learning. Two-thirds of these children were in school, sitting in classrooms. Only 19% of children attending primary and lower secondary schools attain a minimum proficiency level in reading and mathematics.[277][278] According to a citizen-led assessment, only 48% in Indian public schools and 46% of children in Pakistan public schools could read a class two level text by the time they reached class five.[279][278] This poor quality of education in turn has contributed to some of the highest drop-out rates in the world, while over half of the students complete secondary school with acquiring requisite skills.[278]

In South Asia, classrooms are teacher-centred and rote-based, while children are often subjected to corporal punishment and discrimination.[276] Different South Asian countries have different education structures. While by 2018 India and Pakistan has two of the most developed and increasingly decentralised education systems, Bangladesh still had a highly centralised system, and Nepal is in a state of transition from a centralized to a decentralized system.[275] In most South Asian countries children's education is theoretically free; the exceptions are the Maldives, where there is no constitutionally guaranteed free education, as well as Bhutan and Nepal, where fees are charged by primary schools. But parents are still faced with unmanageable secondary financial demands, including private tuition to make up for the inadequacies of the education system.[280]

The larger and poorer countries in the region, like India and Bangladesh, struggle financially to get sufficient resources to sustain an education system required for their vast populations, with an added challenge of getting large numbers of out-of-school children enrolled into schools.[275] Their capacity to deliver inclusive and equitable quality education is limited by low levels of public finance for education,[276] while the smaller emerging middle-income countries like Sri Lanka, Maldives and Bhutan have been able to achieve universal primary school completion, and are in a better position to focus on quality of education.[275]

Children's education in the region is also adversely affected by natural and human-made crises including natural hazards, political instability, rising extremism and civil strife that makes it difficult to deliver educational services.[276] Afghanistan and India are among the top ten countries with the highest number of reported disasters due to natural hazards and conflict. The precarious security situation in Afghanistan is a big barrier in rolling out education programmes on a national scale.[275]

According to UNICEF, girls face incredible hurdles to pursue their education in the region,[276] while UNESCO estimated in 2005 that 24 million girls of primary-school age in the region were not receiving any formal education.[281][282] Between 1900 and 2005, most of the countries in the region had shown progress in girls' education with Sri Lanka and the Maldives significantly ahead of the others, while the gender gap in education has widened in Pakistan and Afghanistan. Bangladesh made the greatest progress in the region in the period increasing girls' secondary school enrolment from 13 percent to 56 percent in ten years.[283][284]

With about 21 million students in 700 universities and 40 thousand colleges India had one of the largest higher education systems in the world in 2011, accounting for 86 percent of all higher-level students in South Asia. Bangladesh (two million) and Pakistan (1.8 million) stood at distant second and third positions in the region. In Nepal (390 thousand) and Sri Lanka (230 thousand) the numbers were much smaller. Bhutan with only one university and Maldives with none hardly had between them about 7000 students in higher education in 2011. The gross enrolment ratio in 2011 ranged from about 10 percent in Pakistan and Afghanistan to above 20 percent in India, much below the global average of 31 percent.[285]

| Parameters | Afghanistan | Bangladesh | Bhutan | India | Maldives | Nepal | Pakistan | Sri Lanka | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary School Enrollment[286] | 29% | 90% | 85% | 92% | 94% | 96% | 73% | 98% | |

| Secondary School Enrollment[287] | 49% | 54% | 78% | 68% | N/A | 72% | 45% | 96% | |

Health and nutrition

According to World Health Organization (WHO), South Asia is home to two out of the three countries in the world still affected by polio, Pakistan and Afghanistan, with 306 & 28 polio cases registered in 2014 respectively.[288] Attempts to eradicate polio have been badly hit by opposition from militants in both countries, who say the program is cover to spy on their operations. Their attacks on immunization teams have claimed 78 lives since December 2012.[289]

The World Bank estimates that India is one of the highest ranking countries in the world for the number of children suffering from malnutrition. The prevalence of underweight children in India is among the highest in the world and is nearly double that of Sub Saharan Africa with dire consequences for mobility, mortality, productivity, and economic growth.[290]

According to the World Bank, 64% of South Asians lived in rural areas in 2022.[291] In 2008, about 75% of South Asia's poor lived in rural areas and most relied on agriculture for their livelihood[292] according to the UN's Food and Agricultural Organisation.

In 2021, approximately 330 million people in the region were malnourished.[293] A 2015 report says that Nepal reached both the WFS target as well as MDG and is moving towards bringing down the number of undernourished people to less than 5% of the population.[264] Bangladesh reached the MDG target with the National Food Policy framework – with only 16.5% of the population undernourished. In India, the malnourished comprise just over 15 percent of the population. While the number of malnourished people in the neighborhood has shown a decline over the last 25 years, the number of under-nourished in Pakistan displays an upward trend. There were 28.7 million hungry in Pakistan in the 1990s – a number that has steadily increased to 41.3 million in 2015 with 22% of the population malnourished. Approximately 194.6 million people are undernourished in India, which accounts for the highest number of people suffering from hunger in any single country.[264][294]

The 2006 report stated, "the low status of women in South Asian countries and their lack of nutritional knowledge are important determinants of high prevalence of underweight children in the region." Corruption and the lack of initiative on the part of the government has been one of the major problems associated with nutrition in India. Illiteracy in villages has been found to be one of the major issues that need more government attention. The report mentioned that although there has been a reduction in malnutrition due to the Green Revolution in South Asia, there is concern that South Asia has "inadequate feeding and caring practices for young children."[295]

Governance and politics

Systems of government

India is a secular federative parliamentary republic with the prime minister as head of government. With the most populous functional democracy in world[297] and the world's longest written constitution,[298][299][300] India has been stably sustaining the political system it adopted in 1950 with no regime change except that by a democratic election. India's sustained democratic freedoms are unique among the world's newer establishments. Since the formation of its republic abolishing British law, it has remained a democracy with civil liberties, an active Supreme Court, and a largely independent press.[301] India leads region in Democracy Index. It has a multi-party system in its internal regional politics[302] whereas alternative transfer of powers to alliances of Indian left-wing and right-wing political parties in national government provide it with characteristics of a two-party state.[303] India has been facing notable internal religious conflicts and separatism however consistently becoming more and more stable with time.

The foundation of Pakistan lies in the Pakistan movement which began in colonial India based on Islamic nationalism. Pakistan is a federal parliamentary Islamic republic and was the world's first country to adopt Islamic republic system to modify its republican status under its otherwise secular constitution in 1956. Pakistan's governance is one of the most conflicted in the world. The military rule and the unstable governments in Pakistan have become a concern for the South Asian region. Out of 22 appointed Pakistani Prime ministers, none of them have ever been able to complete a full term in office.[304] The nature of Pakistani politics can be characterized as a multi-party system.

The unitary semi-presidential constitutional republic of Sri Lanka is the oldest sustained democracy in Asia. Tensions between the Sinhalese and the Tamils led to the emergence of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, a separatist Sri Lankan Tamil militant group and the outbreak of the Sri Lankan Civil War. The war, which ended in 2009, would undermine the country's stability for more than two and a half decades.[305] Sri Lanka, however, has been leading the region in HDI with per capita GDP well ahead of India, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Sri Lanka has a multi-party system, and the political situation in Sri Lanka has been dominated by an increasingly assertive ideology of Sinhalese nationalism.

Bangladesh is a unitary parliamentary republic. The law of Bangladesh defines it as Islamic[306] as well as secular.[307] The nature of Bangladeshi politics can be characterized as a multi-party system. Bangladesh is a unitary state and parliamentary democracy.[308] Bangladesh also stands out as one of the few Muslim-majority democracies. "It is a moderate and generally secular and tolerant — though sometimes this is getting stretched at the moment — alternative to violent extremism in a very troubled part of the world", said Dan Mozena, the U.S. ambassador to Bangladesh. Although Bangladesh's legal code is secular, more citizens are embracing a conservative version of Islam, with some pushing for sharia law, analysts say. Experts say that the rise in conservatism reflects the influence of foreign-financed Islamic charities and the more austere version of Islam brought home by migrant workers in Persian Gulf countries.[309]

By the 18th century, the Hindu Gorkha Kingdom achieved the unification of Nepal. Hinduism became the state religion and Hindu laws were formulated as national policies. A small oligarchic group of Gorkha region based Hindu Thakuri and Chhetri political families dominated the national politics, military and civic affairs until the abdication of the Rana dynasty regime and establishment of Parliamentary democratic system in 1951, which was twice suspended by Nepalese monarchs, in 1960 and 2005. It was the last Hindu state in world before becoming a secular democratic republic in 2008. The country's modern development suffered due to the various significant events like the 1990 Nepalese revolution, 1996–2006 Nepalese Civil War, April 2015 Nepal earthquake and the 2015 Nepal blockade by India leading to the grave 2015–2017 Nepal humanitarian crisis. There is also a huge turnover in the office of the Prime Minister of Nepal leading to serious concerns of political instability. The country has been ranked one of the poor countries in terms of GDP per capita but it has one of the lowest levels of hunger problem in South Asia.[263] When the stability of the country ensured as late as recent, it has also made considerable progress in development indicators outpacing many other South Asian states.

Afghanistan has been a unitary theocratic Islamic emirate since 2021. Afghanistan has been suffering from one of the most unstable regimes on earth as a result of multiple foreign invasions, civil wars, revolutions and terrorist groups. Persisting instability for decades have left the country's economy stagnated and torn and it remains one of the most poor and least developed countries on the planet, leading to the influx of Afghan refugees to neighboring countries like Iran.[218]

Bhutan is a Buddhist state with a constitutional monarchy. The country has been ranked as the least corrupt and most peaceful country in the region, with the most economic freedom, in 2016.

Maldives is a unitary presidential republic with Sunni Islam strictly as the state religion.

| Parameters | Afghanistan | Bangladesh | Bhutan | India | Maldives | Nepal | Pakistan | Sri Lanka | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fragile States Index[310] | 102.9 | 85.7 | 69.5 | 75.3 | 66.2 | 82.6 | 92.1 | 81.8 | |

| Corruption Perceptions Index (2019)[311] (Global rank out of 179 countries) | 16 (173rd) | 26 (146th) | 68 (25th) | 41 (80th) | 29 (130th) | 34 (113th) | 32 (120th) | 38 (93rd) | |

| The Worldwide Governance Indicators (2015)[312] |

Government Effectiveness | 8% | 24% | 68% | 56% | 41% | 13% | 27% | 53% |

| Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism |

1% | 11% | 89% | 17% | 61% | 16% | 1% | 47% | |

| Rule of law | 2% | 27% | 70% | 56% | 35% | 27% | 24% | 60% | |

| Voice and accountability | 16% | 31% | 46% | 61% | 30% | 33% | 27% | 36% | |

Regional politics

India has been the dominant geopolitical power in the region[313][314][315] and alone accounts for most part of the landmass, population, economy and military expenditure in the region.[316] India is a major economy, member of G4, has world's third highest military budget[317] and exerts strong cultural and political influence over the region.[318][319] Sometimes referred as a great power or emerging superpower primarily attributed to its large and expanding economic and military abilities, India acts as fulcrum of South Asia.[320][321]

Bangladesh, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka are middle powers with sizeable populations and economies with significant impact on regional politics.[322][323]

During the Partition of India in 1947, subsequent violence and territorial disputes left relations between India and Pakistan sour and very hostile[324] and various confrontations and wars which largely shaped the politics of the region and contributed to the emergence of Bangladesh as an independent country.[325] With Yugoslavia, India founded the Non-Aligned Movement but later entered an agreement with the former Soviet Union following Western support for Pakistan.[326] Amid the Indo-Pakistani War of 1971, US sent its USS Enterprise to the Indian Ocean in what was perceived as a nuclear threat by India.[327] India's nuclear test in 1974 pushed Pakistan's nuclear program[328] who conducted nuclear tests in Chagai-I in 1998, just 18 days after India's series of nuclear tests for thermonuclear weapons.[329]

The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979 accelerated efforts to form a union to restrengthen deteriorating regional security.[330] After agreements, the union, known as the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC), was finally established in Dhaka in December 1985.[331] However, deterioration of India-Pakistan ties have led India to emphasize more on sub-regional groups SASEC, BIMSTEC and BBIN.

While in East Asia, regional trade accounts for 50% of total trade, it accounts for only a little more than 5% in South Asia.[332]

Populism is a general characteristic of internal politics of India.[333]

Regional groups of countries

| Name | Area (km2) |

Population | Population density (per km2) |

Capital or Secretariat | Currency | Countries | Official language | Coat of arms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core definition of South Asia | 5,220,460 | 1,726,907,000 | 330.79 | — | — | Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka | — | — |

| UNSD definition of Southern Asia | 6,778,083 | 1,702,000,000 | 270.77 | — | — | Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Iran, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka | — | — |

| SAARC | 4,637,469 | 1,626,000,000 | 350.6 | Kathmandu | — | Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka | English | — |

| SASEC | 3,565,467 | 1,485,909,931 | 416.75 | — | — | Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka | — | — |

| BBIN | 3,499,559 | 1,465,236,000 | 418.69 | — | — | Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Nepal | — | — |

See also

- Genetics and archaeogenetics of South Asia

- List of tallest buildings and structures in the Indian subcontinent

- List of territorial disputes

- A Region in Turmoil: South Asian Conflicts since 1947 by Rob Johnson

- South Asia Olympic Council

- South Asian cuisine

- South Asian Football Federation

- South Asian Games

Broader regions

- Global Southeast, South Asia, and Southeast Asia

- India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor

Notes

- ^ Administered by the United Kingdom, claimed by Mauritius as the Chagos Archipelago.

- ^ According to the UN cartographic section website disclaimers, "DESIGNATIONS USED: The depiction and use of boundaries, geographic names and related data shown on maps and included in lists, tables, documents, and databases on this website are not warranted to be error free nor do they necessarily imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations."[37]

- ^ Doniger 2010, p. 66: "Much of what we now call Hinduism may have had roots in cultures that thrived in South Asia long before the creation of textual evidence that we can decipher with any confidence. Remarkable cave paintings have been preserved from Mesolithic sites dating from c. 30,000 BCE in Bhimbetka, near present-day Bhopal, in the Vindhya Mountains in the province of Madhya Pradesh."

- ^ Jones & Ryan 2006, p. xvii: "Some practices of Hinduism must have originated in Neolithic times (c. 4000 BCE). The worship of certain plants and animals as sacred, for instance, could very likely have very great antiquity. The worship of goddesses, too, a part of Hinduism today, maybe a feature that originated in the Neolithic."

- ^ Michaels: "They called themselves arya ("Aryans," literally "the hospitable," from the Vedic arya, "homey, the hospitable") but even in the Rgveda, arya denotes a cultural and linguistic boundary and not only a racial one."[68]

References

Citations

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Overall total population" (xlsx). United Nations. Retrieved 16 July 2019.

- ^ "GDP, current prices". International Monetary Fund.

- ^ "GDP, current prices, Purchasing power parity; billions of international dollars, Billions of U.S. dollars". International Monetary Fund.

- ^ "GDP per capita, current prices". International Monetary Fund.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2020 – "Human Development Indices and Indicators"" (PDF). HDRO (Human Development Report Office) United Nations Development Programme. p. 346. Retrieved 16 December 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Saez 2012, p. 58: "Afghanistan is considered to be part of Central Asia. It regards itself as a link between Central Asia and South Asia."

- ^ "South Asia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 1 April 2023.

- ^ Baker, Kathleen M.; Chapman, Graham P. (11 March 2002). The Changing Geography of Asia. Routledge. pp. 10–. ISBN 978-1-134-93384-6.

This greater India is well defined in terms of topography; it is the Indian sub-continent, hemmed in by the Himalayas on the north, the Hindu Khush in the west and the Arakanese in the east.

- ^ SAARC Summit. "SAARC". SAARC Summit. Archived from the original on 16 December 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- ^ "Indian Subcontinent Archived 21 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine" Encyclopedia of Modern Asia Macmillan Reference USA (Gale Group), 2006: "The area is divided between five major nation-states, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka, and includes as well the two small nations of Bhutan and the Maldives Republic... The total area can be estimated at 4.4 million square kilometres or exactly 10 percent of the land surface of Asia."

- ^ "South Asia Regional Overview". South Asian Regional Development Gateway. Archived from the original on 21 November 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Pillalamarri, Akhilesh (8 January 2016). "How South Asia Will Save Global Islam". The Diplomat. Archived from the original on 8 February 2017. Retrieved 7 February 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Religion population totals in 2010 by Country". Pew Research Center. 2012. Archived from the original on 9 December 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Ruffle 2013, p. 193.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Region: Asia-Pacific". Pew Research Center. 27 January 2011. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «10 стран с самым большим мусульманским населением, 2010 и 2050 годы» . Проект Pew Research Center «Религия и общественная жизнь» . 2 апреля 2015 г. Архивировано из оригинала 7 февраля 2017 г. Проверено 7 февраля 2017 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Стандартные коды стран или регионов для статистического использования» . Объединенные Нации. Архивировано из оригинала 11 июля 2017 года . Проверено 25 августа 2012 г. Цитата: «Отнесение стран или территорий к конкретным группам сделано для статистического удобства и не предполагает каких-либо предположений относительно политической или иной принадлежности стран или территорий со стороны Организации Объединенных Наций».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Гош, Парта Сарати (1989). Сотрудничество и конфликты в Южной Азии . Технические публикации. стр. 4–5. ISBN 978-81-85054-68-1 . Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2016 года . Проверено 12 августа 2015 г.

- ^ Бертрам Хьюз Фармер, Введение в Южную Азию , страницы 1, Routledge, 1993, ISBN 0-415-05695-0

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Раззак, Йона (2004). Судебные разбирательства по вопросам защиты общественных интересов в Индии, Пакистане и Бангладеш . Клювер Лоу Интернэшнл. стр. 3 со сносками 1 и 2. ISBN 978-90-411-2214-8 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 октября 2017 года . Проверено 11 декабря 2016 г.

- ^ Манн, Майкл (2014). Современная история Южной Азии: тематические перспективы . Тейлор и Фрэнсис. стр. 13–15. ISBN 978-1-317-62445-5 .

- ^ Андерсон, Юэн В.; Андерсон, Лиам Д. (2013). Атлас по делам Ближнего Востока . Рутледж. п. 5. ISBN 978-1-136-64862-5 . , Цитата: "На востоке Иран, как государство Персидского залива, предлагает общепринятую границу Ближнего Востока. Однако Афганистан, также мусульманское государство, при этом остается в изоляции. Он не воспринимается как часть Центральной Азии. и это явно не часть Индийского субконтинента».

- ^ Даллен Дж. Тимоти и Гьян П. Ньяупане, Культурное наследие и туризм в развивающемся мире: региональная перспектива , стр. 127, Routledge, 2009, ISBN 978-1-134-00228-3

- ^ Навнита Чадха Бехера, Международные отношения в Южной Азии: поиск альтернативной парадигмы , стр. 129, SAGE Publications India, 2008, ISBN 978-81-7829-870-2

- ^ «Всемирный банк» . Архивировано из оригинала 10 ноября 2015 года . Проверено 5 ноября 2015 г.

- ^ «Институт исследований развития: Афганистан» . Архивировано из оригинала 1 июня 2017 года . Проверено 28 февраля 2019 г.

- ^ Сол Бернард Коэн (2008). Геополитика: География международных отношений (2-е изд.). Издательство Rowman & Littlefield. п. 329. ИСБН 978-0-7425-8154-8 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маклеод, Джон (2002). История Индии . Гринвуд Пресс. п. 1. ISBN 978-0-313-31459-9 .

- ^ Кейт, Артур Берридейл (1936). Конституционная история Индии: 1600–1935 гг . Метуэн и Ко, стр. 440–444. OCLC 18526 .

- ^ Н.Д. Арора, Основной экзамен по политологии для государственной службы , стр. 42:1, Tata McGraw-Hill Education, 2010, 9780070090941

- ^ Стивен Адольф Вурм, Питер Мюльхойслер и Даррел Т. Трайон, Атлас языков межкультурного общения в Тихоокеанском регионе, Азии и Америке , страницы 787, Международный совет по философии и гуманистическим исследованиям, опубликовано Вальтером де Грюйтером, 1996, ISBN 3-11-013417-9

- ^ «Индийский субконтинент»> Геология и география. Архивировано 20 февраля 2012 года в Wayback Machine .

- ^ Хаггетт, Питер (2001). Энциклопедия мировой географии (Том 1) . Маршалл Кавендиш. п. 2710. ИСБН 978-0-7614-7289-6 .

- ^ Территории (Британская территория в Индийском океане) , Информационная группа Джейн

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д Сушил Миттал и Джин Терсби, Религии Южной Азии: Введение , стр. 3, Routledge, 2006, ISBN 978-1-134-59322-4

- ^ Роббинс, Кейт (2012). Преобразование мира: глобальная политическая история после Второй мировой войны . Пэлгрейв Макмиллан. п. 386. ИСБН 978-1-137-29656-6 . , Цитата: «Некоторые думали, что Афганистан является частью Ближнего Востока, а вовсе не Южной Азии».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Картографический центр Организации Объединенных Наций. Архивировано 30 июня 2017 года на Wayback Machine. Проверено 18 июня 2015 года.

- ^ Саркар, Судешна (16 мая 2007 г.). «СААРК: Афганистан оправляется от холода» . Текущие события – Служба безопасности . Швейцарский федеральный технологический институт, Цюрих. Архивировано из оригинала 14 июня 2011 года . Проверено 6 апреля 2011 г.

- ^ «Южноазиатская организация регионального сотрудничества (официальный сайт)» . Секретариат СААРК, Катманду, Непал. Архивировано из оригинала 16 декабря 2013 года . Проверено 6 апреля 2011 г.

- ^ Чаттерджи Аник, Международные отношения сегодня: концепции и приложения , стр. 166, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-81-317-3375-2

- ^ «Членство в СААРК: Индия пока блокирует вступление Китая» . Экономические времена . 2 декабря 2014 г. Архивировано из оригинала 18 декабря 2018 г. Проверено 17 марта 2015 г.

- ^ Проект Global Summitry. Архивировано 12 июля 2020 г. в Wayback Machine , СААРК.

- ^ Южная Азия: данные, проекты и исследования. Архивировано 14 апреля 2008 г. в Wayback Machine , Всемирный банк.

- ^ «Протокол САФТА» . Архивировано из оригинала 15 марта 2015 года . Проверено 20 марта 2015 г.

- ^ «Южная Азия» . ЮНИСЕФ.org . Архивировано из оригинала 20 декабря 2016 года . Проверено 16 декабря 2016 г. .

- ^ «ЮНИСЕФ РОЗА» . ЮНИСЕФ.org . Архивировано из оригинала 20 декабря 2016 года . Проверено 16 декабря 2016 г. .

- ^ Картирование и анализ либерализации торговли сельскохозяйственной продукцией в Южной Азии. Архивировано 19 марта 2009 г. в Wayback Machine , Отдел торговли и инвестиций (TID), Экономическая и социальная комиссия ООН для Азии и Тихого океана.

- ^ Отчет консультативного семинара POPIN в Азиатско-Тихоокеанском регионе. Архивировано 25 октября 2012 г. в Wayback Machine , Бюллетень POPIN в Азиатско-Тихоокеанском регионе, Том. 7, № 2 (1995), страницы 7–11.

- ^ Географический регион и состав. Архивировано 13 июля 2011 года в Wayback Machine , Состав макрогеографических (континентальных) регионов, географических субрегионов и отдельных экономических и других группировок, Организация Объединенных Наций.

- ^ «Азия»> Геология и география. Архивировано 23 февраля 2012 года в Wayback Machine . Электронная энциклопедия Колумбии , 6-е изд. Columbia University Press, 2003: «Азию можно разделить на шесть регионов, каждый из которых обладает отличительными физическими, культурными, экономическими и политическими характеристиками... Южная Азия (Афганистан и страны Индийского полуострова) изолирована от остальной Азии великие горные преграды».

- ^ «Азия»> Геологическая история – Тектоническая структура. Архивировано 1 мая 2011 года в Wayback Machine . Британская энциклопедия . Британская энциклопедия Online, 2009: «Палеотектоническая эволюция Азии завершилась около 50 миллионов лет назад в результате столкновения Индийской плиты с Евразией. Последующее неотектоническое развитие Азии в значительной степени разрушило существовавшую ранее ткань континента. Неотектонические единицы первого порядка Азия – Стабильная Азия, Аравийский и Индийский кратоны, пограничная зона Альпийских плит (вдоль которой расположены Аравийская и Индийская платформы). столкнулась с Евразийской континентальной плитой), а также островными дугами и окраинными бассейнами».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Бейкер, Кэтлин М.; Чепмен, Грэм П. (2002) [Впервые опубликовано в 1992 году]. Меняющаяся география Азии . Тейлор и Фрэнсис. п. 10. ISBN 978-1-134-93384-6 . : «Эта большая Индия хорошо определена с точки зрения топографии; это Индийский полуостров, окруженный Гималаями на севере, Гиндукушем на западе и Араканским полуостровом на востоке».

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Индийский субконтинент». Новый Оксфордский словарь английского языка ( ISBN 0-19-860441-6 ) Нью-Йорк: Oxford University Press, 2001; п. 929: «часть Азии к югу от Гималаев, которая образует полуостров, простирающийся до Индийского океана, между Аравийским морем и Бенгальским заливом. Исторически образуя всю территорию Большой Индии, этот регион теперь разделен между Индией, Пакистаном и Бенгальским заливом. и Бангладеш».

- ^ Маклеод, Джон (2002). История Индии . Гринвуд Пресс. п. 2. ISBN 978-0-313-31459-9 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Милтон Уолтер Мейер, Южная Азия: Краткая история субконтинента , страницы 1, Адамс Литтлфилд, 1976, ISBN 0-8226-0034-X

Джим Норвин и Альфонсо Гонсалес, Третий мир: состояния разума и бытия , стр. 209, Тейлор и Фрэнсис, 1988, ISBN 0-04-910121-8

Бонифаций, Брайан Г.; Купер, Кристофер П. (2005). Мировые направления: география путешествий и туризма . Баттерворт-Хайнеманн. ISBN 978-0-7506-5997-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 19 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 19 июля 2015 г.

Джудит Шотт и Аликс Хенли, Культура, религия и деторождение в многорасовом обществе , стр. 274, Elsevier Health Sciences, 1996, ISBN 0-7506-2050-1

Радж С. Бхопал, Этническая принадлежность, раса и здоровье в мультикультурных обществах , стр. 33, Oxford University Press, 2007 г., ISBN 0-19-856817-7

Люциан В. Пай и Мэри В. Пай, Азиатская власть и политика , страницы 133, издательство Гарвардского университета, 1985, ISBN 0-674-04979-9

Марк Юргенсмайер, Оксфордский справочник мировых религий , страницы 465, Oxford University Press, США, 2006 г., ISBN 0-19-513798-1 - ^ Перейти обратно: а б Босе, Сугата ; Джалал, Аиша (2004) [Впервые опубликовано в 1998 году]. Современная Южная Азия (2-е изд.). Рутледж. п. 3. ISBN 0-415-30787-2 .

Индийский субконтинент – или Южная Азия – как его стали называть на более современном и нейтральном языке.

- ^ Электронная энциклопедия Колумбии , 6-е изд. Columbia University Press, 2003: «регион Южной Центральной Азии, включающий страны Пакистан, Индию и Бангладеш, а также гималайские штаты Непал и Бутан. Шри-Ланку, остров у юго-восточной оконечности Индийского полуострова, часто считают часть субконтинента».

- ^ Роберт Винн Джонс (2011). Применение палеонтологии: методы и тематические исследования . Издательство Кембриджского университета. стр. 267–271. ISBN 978-1-139-49920-0 .

- ^ Ашер, Кэтрин Б.; Талбот, Синтия (16 марта 2006 г.), Индия до Европы , Cambridge University Press, стр. 5–8, 12–14, 51, 78–80, ISBN 978-0-521-80904-7 , архивировано из оригинала 24 апреля 2016 года , получено 9 декабря 2016 года.

- ^ Рональд Б. Инден, Воображая Индию , стр. 51, C. Hurst & Co. Publishers, 2000, ISBN 1-85065-520-0 , Цитата: «Сегодня в академических и официальных кругах очень распространено говорить об Индийском субконтиненте как о «Южной Азии», тем самым отличая его от «Восточной Азии».

- ^ Теория международных отношений и Южная Азия (OIP): Том II: Безопасность, политическая экономия, внутренняя политика, идентичности и образы . Издательство Оксфордского университета. 13 ноября 2014 г. ISBN 978-0-19-908940-6 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Катлер, Роберт М. (2007). Амина, Мехди (ред.). Большой Ближний Восток в глобальной политике: взгляды социальных наук на меняющуюся географию мировой политики . БРИЛЛ. стр. xv, 112. ISBN. 978-90-474-2209-9 .

- ^ Кишор К. Дэш, Регионализм в Южной Азии , страницы 172–175, Routledge, 2008, ISBN 0-415-43117-4

- ^ Бонгард-Левин, генеральный менеджер (1979). «История Индии . Москва: Издательство Прогресс. п. 11. ISBN 0-7147-1336-8 .

- ^ Тапар 1966 , с. 23.

- ^ Тапар 1966 , с. 24.

- ^ Поссель 2002 , с. 141–156.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Майклс 2004 , с. 33.

- ^ Майклс 2004 , с. 32.

- ^ Витцель 1995 , с. 3-4.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Витцель 1995 .

- ^ Наводнение 1996 , с. 30-35.

- ^ Наводнение 1996 , с. 33.

- ^ Самуэль 2010 , с. 41-48.

- ^ Штейн 2010 , с. 48-49.

- ^ Витцель 1995 , с. 6.

- ^ Самуэль 2010 , с. 51-53.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Самуэль 2010 , с. 25.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Хилтебейтель 2007 , с. 12.

- ^ Наводнение 1996 , стр. 81–82.