Список голландских изобретений и инноваций

| История Нидерландов |

|---|

|

Нидерланды . и их народ внесли огромный вклад в мировую цивилизацию в области искусства, науки, технологий и техники, экономики и финансов, картографии и географии, исследований и навигации, права и юриспруденции, мысли и философии, медицины и сельского хозяйства Следующий список состоит из объектов, идей, явлений, процессов, методов, техник и стилей, которые были открыты или изобретены выходцами из Нидерландов и говорящими по-голландски людьми из бывших Южных Нидерландов ( Zuid-Nederlanders по-голландски). До падения Антверпена (1585 г.) голландцы и фламандцы обычно считались одним народом. [номер 1]

Изобретения и инновации

[ редактировать ]Искусство и архитектура

[ редактировать ]Движения и стили

[ редактировать ]Де Стиль (неопластицизм) (1917)

[ редактировать ]Школа Де Стиджа предлагала простоту и абстракцию как в архитектуре, так и в живописи, используя только прямые горизонтальные и вертикальные линии и прямоугольные формы. Более того, их формальный словарь был ограничен основными цветами: красным, желтым и синим, а также тремя основными значениями: черным, белым и серым. Основными членами Де Стейла были художники Тео ван Дусбург (1883–1931), Пит Мондриан (1872–1944), Вильмош Хусар (1884–1960) и Барт ван дер Лек (1876–1958) и архитекторы Геррит Ритвельд (1888–1964). , Роберт ван 'т Хофф (1888–1979) и Дж. Дж. П. Уд (1890–1963).

Архитектура

[ редактировать ]Брабантская готическая архитектура (14 век)

[ редактировать ]Брабантская готика , иногда называемая Брабантской готикой , представляет собой значительный вариант готической архитектуры , типичный для Нидерландов . Он появился в первой половине 14 века в соборе Святого Румбольда в городе Мехелене . Брабантский готический стиль зародился с появлением герцогства Брабант и распространился по Бургундским Нидерландам .

Нидерландская остроконечная архитектура (15–17 вв.)

[ редактировать ]

Голландский фронтон был примечательной особенностью голландско-фламандской архитектуры эпохи Возрождения (или северного маньеризма архитектуры ), которая распространилась в северную Европу из Нидерландов и прибыла в Великобританию во второй половине 16 века. Известные замки/здания, в том числе замок Фредериксборг , замок Русенборг , замок Кронборг , Борсен , Рижский Дом Черноголовых и Зеленые ворота Гданьска , были построены в стиле голландско-фламандского ренессанса с широкими фронтонами , украшениями из песчаника и покрытыми медью крышами. Позже голландские фронтоны с плавными изгибами стали частью архитектуры барокко . Примеры голландских остроконечных зданий можно найти в исторических городах Европы, таких как Потсдам ( Голландский квартал ), Фридрихштадт , Гданьск и Гетеборг . Этот стиль распространился за пределы Европы, например, Барбадос хорошо известен голландскими фронтонами своих исторических зданий. Голландские поселенцы в Южной Африке привезли с собой стили строительства из Нидерландов : голландские фронтоны, затем адаптированные к региону Западного Кейпа , где этот стиль стал известен как Мыс-голландская архитектура . В Америке и Северной Европе - Соборная церковь Вест-Энда (Нью-Йорк, 1892 г.), здание компании Chicago Varnish Company (Чикаго, 1895 г.), здания в голландском стиле на Понт-стрит (Лондон, 1800-е гг.), Станция Хельсингёр ( Хельсингёр , 1891 г.) и Гданьского технологического университета главное здание ( Гданьск , 1904 г.) являются типичными примерами архитектуры голландского возрождения ( неоренессанса ) конца 19 века.

Нидерландская маньеристская архитектура (Антверпенский маньеризм) (16 век)

[ редактировать ]Антверпенский маньеризм — это название стиля анонимной группы художников из Антверпена начала 16 века. Стиль не имел прямого отношения к Ренессансу или итальянскому маньеризму , но название предполагает особенность, которая была реакцией на классический стиль ранней нидерландской живописи . Антверпенский маньеризм также можно использовать для описания стиля архитектуры, который в общих чертах является маньеристским , разработанным в Антверпене примерно к 1540 году и который тогда имел влияние во всей Северной Европе. Зеленые ворота (Brama Zielona) в Гданьске , Польша , — это здание, вдохновленное мэрией Антверпена . Он был построен между 1568 и 1571 годами Ренье ван Амстердамом и Гансом Крамером и служил официальной резиденцией польских монархов во время посещения Гданьска.

Мыс-голландская архитектура (1650-е гг.)

[ редактировать ]Капская голландская архитектура — это архитектурный стиль, встречающийся в Западно-Капской провинции Южной Африки. Этот стиль был заметен в первые дни (17 век) Капской колонии , а название происходит от того факта, что первые поселенцы Капской провинции были в основном голландцами. Стиль имеет корни в средневековых Нидерландах, Германии, Франции и Индонезии. Дома в этом стиле имеют характерный и узнаваемый дизайн, отличительной чертой которого являются большие, богато закругленные фронтоны , напоминающие черты таунхаусов Амстердама, построенных в голландском стиле .

Амстердамская школа (голландская экспрессионистская архитектура) (1910-е годы)

[ редактировать ]Амстердамская школа (голландский: Amsterdamse School ) процветала с 1910 по 1930 год в Нидерландах. Движение Амстердамской школы является частью международной экспрессионистской архитектуры , иногда связанной с немецким кирпичным экспрессионизмом .

Дом Ритвельда Шредера (архитектура Де Стиль) (1924 г.)

[ редактировать ]Дом Ритвельда Шредера или Дом Шредера (Rietveld Schröderhuis по- голландски ) в Утрехте был построен в 1924 году голландским архитектором Герритом Ритвельдом . В 1976 году он стал памятником архитектуры, а в 2000 году — объектом Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО. Дом Ритвельда Шредера как внутри, так и снаружи представляет собой радикальный разрыв с традицией, практически не делая различий между внутренним и внешним пространством. Прямолинейные линии и плоскости перетекают снаружи внутрь, сохраняя ту же цветовую палитру и поверхности. Внутри — динамичная, изменчивая открытая зона, а не статичное скопление комнат. Этот дом является одним из самых известных примеров архитектуры Де Стиджа и, возможно, единственным настоящим зданием Де Стиджа . [1] [2] [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10] [11] [12]

Фабрика Ван Нелле (1925–1931)

[ редактировать ]Фабрика Ван Нелле была построена между 1925 и 1931 годами. Ее самой яркой особенностью являются огромные стеклянные фасады. Завод был спроектирован с учетом того, что современная, прозрачная и здоровая рабочая среда в зеленой зоне будет полезна как для производства, так и для благосостояния работников. Фабрика Ван Нелле является национальным памятником Нидерландов ( Rijksmonument ) и с 2014 года имеет статус объекта Всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО . «Обоснование выдающейся универсальной ценности» было представлено в 2013 году Комитету всемирного наследия ЮНЕСКО.

Супер голландский (1990 – настоящее время)

[ редактировать ]Архитектурное движение, начатое поколением новых архитекторов в 1990 году, среди этого поколения архитекторов были OMA, MVRDV, UNStudio, Mecanoo, Meyer en Van Schooten и многие другие. Они начали со зданий, которые стали известны во всем мире благодаря своему новому и свежему стилю.

Мебель

[ редактировать ]Голландская дверь (17 век)

[ редактировать ]

The Dutch door (also known as stable door or half door) is a type of door divided horizontally in such a fashion that the bottom half may remain shut while the top half opens. The initial purpose of this door was to keep animals out of farmhouses, while keeping children inside, yet allowing light and air to filter through the open top. This type of door was common in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century and appears in Dutch paintings of the period. They were commonly found in Dutch areas of New York and New Jersey (before the American Revolution) and in South Africa.[13]

Red and Blue Chair (1917)

[edit]

The Red and Blue Chair was designed in 1917 by Gerrit Rietveld. It represents one of the first explorations by the De Stijl art movement in three dimensions. It features several Rietveld joints.

Zig-Zag Chair (1934)

[edit]The Zig-Zag Chair was designed by Rietveld in 1934. It is a minimalist design without legs, made by 4 flat wooden tiles that are merged in a Z-shape using Dovetail joints. It was designed for the Rietveld Schröder House in Utrecht.

Visual arts

[edit]Glaze (painting technique) (15th century)

[edit]Glazing is a technique employed by painters since the invention of modern oil painting. Early Netherlandish painters in the 15th century were the first to make oil the usual painting medium, and explore the use of layers and glazes, followed by the rest of Northern Europe, and only then Italy.[14]

Proto-Realism (15th–17th centuries)

[edit]Two aspects of realism were rooted in at least two centuries of Dutch tradition: conspicuous textural imitation and a penchant for ordinary and exaggeratedly comic scenes. Two hundred years before the rise of literary realism, Dutch painters had already made an art of the everyday – pictures that served as a compelling model for the later novelists. By the mid-1800s, 17th-century Dutch painting figured virtually everywhere in the British and French fiction we esteem today as the vanguard of realism.

Proto-Surrealism (1470s–1510s)

[edit]Hieronymus Bosch is considered one of the prime examples of Pre-Surrealism. The surrealists relied most on his insights. In the 20th century, Bosch's paintings (e.g. The Garden of Earthly Delights, The Haywain, The Temptation of St. Anthony and The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things) were cited by the Surrealists as precursors to their own visions.

Modern still-life painting (16th–17th century)

[edit]Still-life painting as an independent genre or specialty first flourished in the Netherlands in the last quarter of the 16th century, and the English term derives from stilleven: still life, which is a calque, while Romance languages (as well as Greek, Polish, Russian and Turkish) tend to use terms meaning dead nature.

Naturalistic landscape painting (16th–17th century)

[edit]The term "landscape" derives from the Dutch word landschap (and the German Landschaft), which originally meant "region, tract of land" but acquired the artistic connotation, "a picture depicting scenery on land" in the early 16th century. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the tradition of depicting pure landscapes declined and the landscape was seen only as a setting for religious and figural scenes. This tradition continued until the 16th century when artists began to view the landscape as a subject in its own right. The Dutch Golden Age painting of the 17th century saw the dramatic growth of landscape painting, in which many artists specialized, and the development of extremely subtle realist techniques for depicting light and weather.

Genre painting (15th century)

[edit]The Flemish Renaissance painter Pieter Brueghel the Elder chose peasants and their activities as the subject of many paintings. Genre painting flourished in Northern Europe in his wake. Adriaen van Ostade, David Teniers, Aelbert Cuyp, Jan Steen, Johannes Vermeer and Pieter de Hooch were among many painters specializing in genre subjects in the Netherlands during the 17th century. The generally small scale of these artists' paintings was appropriate for their display in the homes of middle class purchasers.

Marine painting (17th century)

[edit]

Marine painting began in keeping with medieval Christian art tradition. Such works portrayed the sea only from a bird's eye view, and everything, even the waves, was organized and symmetrical. The viewpoint, symmetry and overall order of these early paintings underlined the organization of the heavenly cosmos from which the earth was viewed. Later Dutch artists such as Hendrick Cornelisz Vroom, Cornelius Claesz, Abraham Storck, Jan Porcellis, Simon de Vlieger, Willem van de Velde the Elder, Willem van de Velde the Younger and Ludolf Bakhuizen developed new methods for painting, often from a horizontal point of view, with a lower horizon and more focus on realism than symmetry.[15][16]

Vanitas (17th century)

[edit]The term vanitas is most often associated with still life paintings that were popular in seventeenth-century Dutch art, produced by the artists such as Pieter Claesz. Common vanitas symbols included skulls (a reminder of the certainty of death); rotten fruit (decay); bubbles, (brevity of life and suddenness of death); smoke, watches, and hourglasses, (the brevity of life); and musical instruments (the brevity and ephemeral nature of life). Fruit, flowers and butterflies can be interpreted in the same way, while a peeled lemon, as well as the typical accompanying seafood was, like life, visually attractive but with a bitter flavor.

Civil group portraiture (17th century)

[edit]Group portraits were produced in great numbers during the Baroque period, particularly in the Netherlands. Unlike in the rest of Europe, Dutch artists received no commissions from the Calvinist Church which had forbidden such images or from the aristocracy which was virtually non-existent. Instead, commissions came from civic and businesses associations. Dutch painter Frans Hals used fluid brush strokes of vivid color to enliven his group portraits, including those of the civil guard to which he belonged. Rembrandt benefitted greatly from such commissions and from the general appreciation of art by bourgeois clients, who supported portraiture as well as still-life and landscape painting. Notably, the world's first significant art and dealer markets flourished in Holland at that time.

Tronie (17th century)

[edit]

In the 17th century, Dutch painters (especially Frans Hals, Rembrandt, Jan Lievens and Johannes Vermeer) began to create uncommissioned paintings called tronies that focused on the features and/or expressions of people who were not intended to be identifiable. They were conceived more for art's sake than to satisfy conventions. The tronie was a distinctive type of painting, combining elements of the portrait, history, and genre painting. This was usually a half-length of a single figure which concentrated on capturing an unusual mood or expression. The actual identity of the model was not supposed to be important, but they might represent a historical figure and be in exotic or historic costume. In contrast to portraits, "tronies" were painted for the open market. They differ from figurative paintings and religious figures in that they are not restricted to a moral or narrative context. It is, rather, much more an exploration of the spectrum of human physiognomy and expression and the reflection of conceptions of character that are intrinsic to psychology's pre-history.

Rembrandt lighting (17th century)

[edit]

Rembrandt lighting is a lighting technique that is used in studio portrait photography.It can be achieved using one light and a reflector, or two lights, and is popular becauseit is capable of producing images which appear both natural and compelling with a minimumof equipment. Rembrandt lighting is characterized by an illuminated triangle under the eyeof the subject, on the less illuminated side of the face. It is named for the Dutch painterRembrandt, who often used this type of lighting in his portrait paintings.

Mezzotint (1642)

[edit]The first known mezzotint was done in Amsterdam in 1642 by Utrecht-born German artist Ludwig von Siegen. He lived in Amsterdam from 1641 to about 1644, when he was supposedly influenced by Rembrandt.[17][18]

Aquatint (1650s)

[edit]The painter and printmaker Jan van de Velde is often credited to be the inventor of the aquatint technique, in Amsterdam around 1650.[18]

Pronkstilleven (1650s)

[edit]Pronkstilleven (pronk still life or ostentatious still life) is a type of banquet piece whose distinguishing feature is a quality of ostentation and splendor. These still lifes usually depict one or more especially precious objects. Although the term is a post-17th century invention, this type is characteristic of the second half of the seventeenth century. It was developed in the 1640s in Antwerp from where it spread quickly to the Dutch Republic. Flemish artists such as Frans Snyders and Adriaen van Utrecht started to paint still lifes that emphasized abundance by depicting a diversity of objects, fruits, flowers and dead game, often together with living people and animals. The style was soon adopted by artists from the Dutch Republic.[19] A leading Dutch representative was Jan Davidsz. de Heem, who spent a long period of his active career in Antwerp and was one of the founders of the style in Holland.[20][21] Other leading representatives in the Dutch Republic were Abraham van Beyeren, Willem Claeszoon Heda and Willem Kalf.[19]

Proto-Expressionism (1880s)

[edit]Vincent van Gogh's work is most often associated with Post-Impressionism, but his innovative style had a vast influence on 20th-century art and established what would later be known as Expressionism, also greatly influencing fauvism and early abstractionism. His impact on German and Austrian Expressionists was especially profound. "Van Gogh was father to us all," the German Expressionist painter Max Pechstein proclaimed in 1901, when Van Gogh's vibrant oils were first shown in Germany and triggered the artistic reformation, a decade after his suicide in obscurity in France. In his final letter to Theo, Van Gogh stated that, as he had no children, he viewed his paintings as his progeny. Reflecting on this, the British art historian Simon Schama concluded that he "did have a child of course, Expressionism, and many, many heirs."

M. C. Escher's graphic arts (1920s–1960s)

[edit]Dutch graphic artist Maurits Cornelis Escher, usually referred to as M. C. Escher, is known for his often mathematically inspired woodcuts, lithographs, and mezzotints. These feature impossible constructions, explorations of infinity, architecture and tessellations. His special way of thinking and rich graphic work has had a continuous influence in science and art, as well as permeating popular culture. His ideas have been used in fields as diverse as psychology, philosophy, logic, crystallography and topology. His art is based on mathematical principles like tessellations, spherical geometry, the Möbius strip, unusual perspectives, visual paradoxes and illusions, different kinds of symmetries and impossible objects. Gödel, Escher, Bach by Douglas Hofstadter discusses the ideas of self-reference and strange loops, drawing on a wide range of artistic and scientific work, including Escher's art and the music of J. S. Bach, to illustrate ideas behind Gödel's incompleteness theorems.

Miffy (Nijntje) (1955)

[edit]Miffy (Nijntje) is a small female rabbit in a series of picture books drawn and written by Dutch artist Dick Bruna.

Music

[edit]Franco-Flemish School (Netherlandish School) (15th–16th century)

[edit]In music, the Franco-Flemish School or more precisely the Netherlandish school refers to the style of polyphonic vocal music composition in the Burgundian Netherlands in the 15th and early 16th centuries, and to the composers who wrote it.

Venetian School (Venetian polychoral style) (16th century)

[edit]The Venetian School of polychoral music was founded by the Netherlandish composer Adrian Willaert.

Hardcore (electronic dance music genre) (1990s)

[edit]Hardcore or hardcore techno is a subgenre of electronic dance music originating in Europe from the emergent raves in the 1990s. It was initially designed at Rotterdam in Netherlands, derived from techno.[22]

Hardstyle (electronic dance music genre) (1990s–2000s)

[edit]Hardstyle is an electronic dance genre mixing influences from hardtechno and hardcore. Hardstyle was influenced by gabber. Hardstyle has its origins in the Netherlands where artists like DJ Zany, Lady Dana, DJ Isaac, DJ Pavo, DJ Luna and The Prophet, who produced hardcore, started experimenting while playing their hardcore records.

Agriculture

[edit]Brussels sprout (13th century)

[edit]Forerunners to modern Brussels sprouts were likely cultivated in ancient Rome. Brussels sprouts as we now know them were grown possibly as early as the 13th century in the Low Countries (may have originated in Brussels). The first written reference dates to 1587. During the 16th century, they enjoyed a popularity in the Southern Netherlands that eventually spread throughout the cooler parts of Northern Europe.

Orange-coloured carrot (16th century)

[edit]

Through history, carrots weren't always orange. They were black, purple, white, brown, red and yellow. Probably orange too, but this was not the dominant colour. Orange-coloured carrots appeared in the Netherlands in the 16th century.[23] Dutch farmers in Hoorn bred the color. They succeeded by cross-breeding pale yellow with red carrots. It is more likely that Dutch horticulturists actually found an orange rooted mutant variety and then worked on its development through selective breeding to make the plant consistent. Through successive hybridisation the orange colour intensified. This was developed to become the dominant species across the world, a sweet orange.

Belle de Boskoop (apple) (1856)

[edit]Belle de Boskoop is an apple cultivar which, as its name suggests, originated in Boskoop, where it began as a chance seedling in 1856. There are many variants: Boskoop red, yellow or green. This rustic apple is firm, tart and fragrant. Greenish-gray tinged with red, the apple stands up well to cooking. Generally Boskoop varieties are very high in acid content and can contain more than four times the vitamin C of 'Granny Smith' or 'Golden Delicious'.[24]

Karmijn de Sonnaville (apple) (1949)

[edit]Karmijn de Sonnaville is a variety of apple bred by Piet de Sonnaville, working in Wageningen in 1949. It is a cross of Cox's Orange Pippin and Jonathan, and was first grown commercially beginning in 1971. It is high both in sugars (including some sucrose) and acidity. It is a triploid, and hence needs good pollination, and can be difficult to grow. It also suffers from fruit russet, which can be severe. In Manhart's book, "apples for the 21st century", Karmijn de Sonnaville is tipped as a possible success for the future. Karmijn de Sonnaville is not widely grown in large quantities, but in Ireland, at The Apple Farm, 8 acres (3.2 ha) it is grown for fresh sale and juice-making, for which the variety is well suited.

Elstar (apple) (1950s)

[edit]Elstar apple is an apple cultivar that was first developed in the Netherlands in the 1950s by crossing Golden Delicious and Ingrid Marie apples. It quickly became popular, especially in Europe and was first introduced to America in 1972.[25] It remains popular in Continental Europe. The Elstar is a medium-sized apple whose skin is mostly red with yellow showing. The flesh is white, and has a soft, crispy texture. It may be used for cooking and is especially good for making apple sauce. In general, however, it is used in desserts due to its sweet flavour.

Groasis Waterboxx (2010)

[edit]The Groasis Waterboxx is a device designed to help grow trees in dry areas. It was developed by former flower exporter Pieter Hoff, and won Popular Science's "Green Tech Best of What's New" Innovation of the year award for 2010.

Cartography and geography

[edit]Method for determining longitude using a clock (1530)

[edit]The Dutch-Frisian geographer Gemma Frisius was the first to propose the use of a chronometer to determine longitude in 1530. In his book On the Principles of Astronomy and Cosmography (1530), Frisius explains for the first time how to use a very accurate clock to determine longitude.[26] The problem was that in Frisius’ day, no clock was sufficiently precise to use his method. In 1761, the British clock-builder John Harrison constructed the first marine chronometer, which allowed the method developed by Frisius.

Triangulation and the systematic use of triangulation networks (1533 and 1615)

[edit]Triangulation had first emerged as a map-making method in the mid-sixteenth century when the Dutch-Frisian mathematician Gemma Frisius set out the idea in his Libellus de locorum describendorum ratione (Booklet concerning a way of describing places).[27][28][29][30][31][32] Dutch cartographer Jacob van Deventer was among the first to make systematic use of triangulation, the technique whose theory was described by Gemma Frisius in his 1533 book.

The modern systematic use of triangulation networks stems from the work of the Dutch mathematician Willebrord Snell (born Willebrord Snel van Royen), who in 1615 surveyed the distance from Alkmaar to Bergen op Zoom, approximately 70 miles (110 kilometres), using a chain of quadrangles containing 33 triangles in all[33][34][35] – a feat celebrated in the title of his book Eratosthenes Batavus (The Dutch Eratosthenes), published in 1617.

Mercator projection (1569)

[edit]

The Mercator projection is a cylindrical map projection presented by the Flemish geographer and cartographer Gerardus Mercator in 1569. It became the standard map projection for nautical purposes because of its ability to represent lines of constant course, known as rhumb lines or loxodromes, as straight segments which conserve the angles with the meridians.[36]

First modern world atlas (1570)

[edit]

Flemish geographer and cartographer Abraham Ortelius generally recognized as the creator of the world's first modern atlas, the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (Theatre of the World). Ortelius's Theatrum Orbis Terrarum is considered the first true atlas in the modern sense: a collection of uniform map sheets and sustaining text bound to form a book for which copper printing plates were specifically engraved. It is sometimes referred to as the summary of sixteenth-century cartography.[37][38][39][40]

First printed atlas of nautical charts (1584)

[edit]The first printed atlas of nautical charts (De Spieghel der Zeevaerdt or The Mirror of Navigation / The Mariner's Mirror) was produced by Lucas Janszoon Waghenaer in Leiden. This atlas was the first attempt to systematically codify nautical maps. This chart-book combined an atlas of nautical charts and sailing directions with instructions for navigation on the western and north-western coastal waters of Europe. It was the first of its kind in the history of maritime cartography, and was an immediate success. The English translation of Waghenaer's work was published in 1588 and became so popular that any volume of sea charts soon became known as a "waggoner", the Anglicized form of Waghenaer's surname.[41][42][43][44][45][46][47]

Concept of atlas (1595)

[edit]

Gerardus Mercator was the first to coin the word atlas to describe a bound collection of maps through his own collection entitled "Atlas sive Cosmographicae meditationes de fabrica mvndi et fabricati figvra". He coined this name after the Greek god who held The Sky up, later changed to holding up The Earth.[40][48]

Charting of the far southern skies (southern constellations) (1595–97)

[edit]The constellations around the South Pole were not observable from north of the equator, by Babylonians, Greeks, Chinese or Arabs. The modern constellations in this region were defined during the Age of Exploration, notably by Dutch navigators Pieter Dirkszoon Keyser and Frederick de Houtman at the end of sixteenth century. These twelve Dutch-created southern constellations represented flora and fauna of the East Indies and Madagascar. They were depicted by Johann Bayer in his star atlas Uranometria of 1603.[49] Several more were created by Nicolas Louis de Lacaille in his star catalogue, published in 1756.[50] By the end of the Ming dynasty, Xu Guangqi introduced 23 asterisms of the southern sky based on the knowledge of western star charts.[51] These asterisms have since been incorporated into the traditional Chinese star maps. Among the IAU's 88 modern constellations, there are 15 Dutch-created constellations (including Apus, Camelopardalis, Chamaeleon, Columba, Dorado, Grus, Hydrus, Indus, Monoceros, Musca, Pavo, Phoenix, Triangulum Australe, Tucana and Volans).

Continental drift hypothesis (1596)

[edit]The speculation that continents might have 'drifted' was first put forward by Abraham Ortelius in 1596. The concept was independently and more fully developed by Alfred Wegener in 1912. Because Wegener's publications were widely available in German and English and because he adduced geological support for the idea, he is credited by most geologists as the first to recognize the possibility of continental drift. During the 1960s geophysical and geological evidence for seafloor spreading at mid-oceanic ridges established continental drift as the standard theory or continental origin and an ongoing global mechanism.

Chemicals and materials

[edit]Bow dye (1630)

[edit]While making a coloured liquid for a thermometer, Cornelis Drebbel dropped a flask of Aqua regia on a tin window sill, and discovered that stannous chloride makes the color of carmine much brighter and more durable. Though Drebbel himself never made much from his work, his daughters Anna and Catharina and his sons-in-law Abraham and Johannes Sibertus Kuffler set up a successful dye works. One was set up in 1643 in Bow, London, and the resulting color was called bow dye.

Dyneema (1979)

[edit]Dutch chemical company DSM invented and patented the Dyneema in 1979. Dyneema fibres have been in commercial production since 1990 at their plant at Heerlen. These fibers are manufactured by means of a gel-spinning process that combines extreme strength with incredible softness. Dyneema fibres, based on ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene (UHMWPE), is used in many applications in markets such as life protection, shipping, fishing, offshore, sailing, medical and textiles.

Communication and multimedia

[edit]Compact cassette (1962)

[edit]

In 1962 Philips invented the compact audio cassette medium for audio storage, introducing it in Europe in August 1963 (at the Berlin Radio Show) and in the United States (under the Norelco brand) in November 1964, with the trademark name Compact Cassette.[52][53][54][55][56]

Laserdisc (1969)

[edit]Laserdisc technology, using a transparent disc,[57] was invented by David Paul Gregg in 1958 (and patented in 1961 and 1990).[58] By 1969, Philips developed a videodisc in reflective mode, which has great advantages over the transparent mode. MCA and Philips decided to join forces. They first publicly demonstrated the videodisc in 1972. Laserdisc entered the market in Atlanta, on 15 December 1978, two years after the VHS VCR and four years before the CD, which is based on Laserdisc technology. Philips produced the players and MCA made the discs.

Compact disc (1979)

[edit]

The compact disc was jointly developed by Philips (Joop Sinjou) and Sony (Toshitada Doi). In the early 1970s, Philips' researchers started experiments with "audio-only" optical discs, and at the end of the 1970s, Philips, Sony, and other companies presented prototypes of digital audio discs.

Bluetooth (1990s)

[edit]Bluetooth, a low-energy, peer-to-peer wireless technology was originally developed by Dutch electrical engineer Jaap Haartsen and Swedish engineer Sven Mattisson in the 1990s, working at Ericsson in Lund, Sweden. It became a global standard of short distance wireless connection.

Wi-fi (1990s)

[edit]In 1991, NCR Corporation/AT&T Corporation invented the precursor to 802.11 in Nieuwegein. Dutch electrical engineer Vic Hayes chaired IEEE 802.11 committee for 10 years, which was set up in 1990 to establish a wireless networking standard. He has been called the father of Wi-Fi (the brand name for products using IEEE 802.11 standards) for his work on IEEE 802.11 (802.11a & 802.11b) standard in 1997.

DVD (1995)

[edit]The DVD optical disc storage format was invented and developed by Philips and Sony in 1995.

Ambilight (2002)

[edit]Ambilight, short for "ambient lighting", is a lighting system for televisions developed by Philips in 2002.

Blu-ray (2006)

[edit]Philips and Sony in 1997 and 2006 respectively, launched the Blu-ray video recording/playback standard.

Computer science and information technology

[edit]Dijkstra's algorithm (1956)

[edit]Dijkstra's algorithm, conceived by Dutch computer scientist Edsger Dijkstra in 1956 and published in 1959, is a graph search algorithm that solves the single-source shortest path problem for a graph with non-negative edge path costs, producing a shortest path tree. Dijkstra's algorithm is so powerful that it not only finds the shortest path from a chosen source to a given destination, it finds all of the shortest paths from the source to all destinations. This algorithm is often used in routing and as a subroutine in other graph algorithms.

Dijkstra's algorithm is considered as one of the most popular algorithms in computer science. It is also widely used in the fields of artificial intelligence, operational research/operations research, network routing, network analysis, and transportation engineering.

Foundations of concurrent programming (1960s)

[edit]The academic study of concurrent programming (concurrent algorithms in particular) started in the 1960s, with Edsger Dijkstra (1965) credited with being the first paper in this field, identifying and solving mutual exclusion.[59] A pioneer in the field of concurrent computing, Per Brinch Hansen considers Dijkstra's Cooperating Sequential Processes (1965) to be the first classic paper in concurrent programming. As Brinch Hansen notes: ‘Here Dijkstra lays the conceptual foundation for abstract concurrent programming.’[60]

Shunting-yard algorithm (1960)

[edit]In computer science, the shunting-yard algorithm is a method for parsing mathematical expressions specified in infix notation. It can be used to produce output in Reverse Polish notation (RPN) or as an abstract syntax tree (AST). The algorithm was invented by Edsger Dijkstra and named the "shunting yard" algorithm because its operation resembles that of a railroad shunting yard. Dijkstra first described the Shunting Yard Algorithm in the Mathematisch Centrum report.

Schoonschip (early computer algebra system) (1963)

[edit]In 1963/64, during an extended stay at SLAC, Dutch theoretical physicist Martinus Veltman designed the computer program Schoonschip for symbolic manipulation of mathematical equations, which is now considered the very first computer algebra system.

Mutual exclusion (mutex) (1965)

[edit]In computer science, mutual exclusion refers to the requirement of ensuring that no two concurrent processes are in their critical section at the same time; it is a basic requirement in concurrency control, to prevent race conditions. The requirement of mutual exclusion was first identified and solved by Edsger W. Dijkstra in his seminal 1965 paper titled Solution of a problem in concurrent programming control,[61][62] and is credited as the first topic in the study of concurrent algorithms.[59]

Semaphore (programming) (1965)

[edit]The semaphore concept was invented by Dijkstra in 1965 and the concept has found widespread use in a variety of operating systems.[63]

Sleeping barber problem (1965)

[edit]In computer science, the sleeping barber problem is a classic inter-process communication and synchronization problem between multiple operating system processes. The problem is analogous to that of keeping a barber working when there are customers, resting when there are none and doing so in an orderly manner. The sleeping barber problem was introduced by Edsger Dijkstra in 1965.[63]

Banker's algorithm (deadlock prevention algorithm) (1965)

[edit]The Banker's algorithm is a resource allocation and deadlock avoidance algorithm developed by Edsger Dijkstra that tests for safety by simulating the allocation of predetermined maximum possible amounts of all resources, and then makes an "s-state" check to test for possible deadlock conditions for all other pending activities, before deciding whether allocation should be allowed to continue. The algorithm was developed in the design process for the THE multiprogramming system and originally described (in Dutch) in EWD108.[64] The name is by analogy with the way that bankers account for liquidity constraints.

Dining philosophers problem (1965)

[edit]In computer science, the dining philosophers problem is an example problem often used in concurrent algorithm design to illustrate synchronization issues and techniques for resolving them. It was originally formulated in 1965 by Edsger Dijkstra as a student exam exercise, presented in terms of computers competing for access to tape drive peripherals.Soon after, Tony Hoare gave the problem its present formulation.[65][66]

Dekker's algorithm (1965)

[edit]Dekker's algorithm is the first known correct solution to the mutual exclusion problem in concurrent programming. Dijkstra attributed the solution to Dutch mathematician Theodorus Dekker in his manuscript on cooperating sequential processes. It allows two threads to share a single-use resource without conflict, using only shared memory for communication. It is also the first published software-only, two-process mutual exclusion algorithm.

THE multiprogramming system (1968)

[edit]The THE multiprogramming system was a computer operating system designed by a team led by Edsger W. Dijkstra, described in monographs in 1965–66[67] and published in 1968.[68]

Van Wijngaarden grammar (1968)

[edit]Van Wijngaarden grammar (also vW-grammar or W-grammar) is a two-level grammar that provides a technique to define potentially infinite context-free grammars in a finite number of rules. The formalism was invented by Adriaan van Wijngaarden to rigorously define some syntactic restrictions that previously had to be formulated in natural language, despite their formal content. Typical applications are the treatment of gender and number in natural language syntax and the well-definedness of identifiers in programming languages. The technique was used and developed in the definition of the programming language ALGOL 68. It is an example of the larger class of affix grammars.

Structured programming (1968)

[edit]In 1968, computer programming was in a state of crisis. Dijkstra was one of a small group of academics and industrial programmers who advocated a new programming style to improve the quality of programs. Dijkstra coined the phrase "structured programming" and during the 1970s this became the new programming orthodoxy. Structured programming is often regarded as "goto-less programming".

EPROM (1971)

[edit]An EPROM or erasable programmable read only memory, is a type of memory chip that retains its data when its power supply is switched off. Development of the EPROM memory cell started with investigation of faulty integrated circuits where the gate connections of transistors had broken. Stored charge on these isolated gates changed their properties. The EPROM was invented by the Amsterdam-born Israeli electrical engineer Dov Frohman in 1971, who was awarded US patent 3660819[69] in 1972.

Self-stabilization (1974)

[edit]Self-stabilization is a concept of fault-tolerance in distributed computing. A distributed system that is self-stabilizing will end up in a correct state no matter what state it is initialized with. That correct state is reached after a finite number of execution steps.[70]

Predicate transformer semantics (1975)

[edit]Predicate transformer semantics were introduced by Dijkstra in his seminal paper "Guarded commands, nondeterminacy and formal derivation of programs".

Guarded Command Language (1975)

[edit]The Guarded Command Language (GCL) is a language defined by Edsger Dijkstra for predicate transformer semantics.[71] It combines programming concepts in a compact way, before the program is written in some practical programming language.

Van Emde Boas tree (VEB tree) (1975)

[edit]A Van Emde Boas tree (or Van Emde Boas priority queue, also known as a vEB tree, is a tree data structure which implements an associative array with m-bit integer keys. The vEB tree was invented by a team led by Dutch computer scientist Peter van Emde Boas in 1975.[72]

ABC (programming language) (1980s)

[edit]ABC is an imperative general-purpose programming language and programming environment developed at CWI, Netherlands by Leo Geurts, Lambert Meertens, and Steven Pemberton. It is interactive, structured, high-level, and intended to be used instead of BASIC, Pascal, or AWK. It is not meant to be a systems-programming language but is intended for teaching or prototyping.

The language had a major influence on the design of the Python programming language (as a counterexample); Guido van Rossum, who developed Python, previously worked for several years on the ABC system in the early 1980s.[73][74]

Dijkstra-Scholten algorithm (1980)

[edit]The Dijkstra–Scholten algorithm (named after Edsger W. Dijkstra and Carel S. Scholten) is an algorithm for detecting termination in a distributed system.[75][76] The algorithm was proposed by Dijkstra and Scholten in 1980.[77]

Smoothsort (1981)

[edit]Smoothsort[78] is a comparison-based sorting algorithm. It is a variation of heapsort developed by Edsger Dijkstra in 1981. Like heapsort, smoothsort's upper bound is O(n log n). The advantage of smoothsort is that it comes closer to O(n) time if the input is already sorted to some degree, whereas heapsort averages O(n log n) regardless of the initial sorted state.

Amsterdam Compiler Kit (1983)

[edit]The Amsterdam Compiler Kit (ACK) is a fast, lightweight and retargetable compiler suite and toolchain developed by Andrew Tanenbaum and Ceriel Jacobs at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. It is MINIX's native toolchain. The ACK was originally closed-source software (that allowed binaries to be distributed for MINIX as a special case), but in April 2003 it was released under an open-source BSD license. It has frontends for programming languages C, Pascal, Modula-2, Occam, and BASIC. The ACK's notability stems from the fact that in the early 1980s it was one of the first portable compilation systems designed to support multiple source languages and target platforms.[79]

Eight-to-fourteen modulation (1985)

[edit]EFM (Eight-to-Fourteen Modulation) was invented by Dutch electrical engineer Kees A. Schouhamer Immink in 1985. EFM is a data encoding technique – formally, a channel code – used by CDs, laserdiscs and pre-Hi-MD MiniDiscs.

MINIX (1987)

[edit]MINIX (from "mini-Unix") is a Unix-like computer operating system based on a microkernel architecture. Early versions of MINIX were created by Andrew S. Tanenbaum for educational purposes. Starting with MINIX 3, the primary aim of development shifted from education to the creation of a highly reliable and self-healing microkernel OS. MINIX is now developed as open-source software. MINIX was first released in 1987, with its complete source code made available to universities for study in courses and research. It has been free and open-source software since it was re-licensed under the BSD license in April 2000. Tanenbaum created MINIX at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam to exemplify the principles conveyed in his textbook, Operating Systems: Design and Implementation (1987), that Linus Torvalds described as "the book that launched me to new heights".

Amoeba (operating system) (1989)

[edit]Amoeba is a distributed operating system developed by Andrew S. Tanenbaum and others at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. The aim of the Amoeba project was to build a timesharing system that makes an entire network of computers appear to the user as a single machine. The Python programming language was originally developed for this platform.[80]

Python (programming language) (1989)

[edit]Python is a widely used general-purpose, high-level programming language.[81][82] Its design philosophy emphasizes code readability, and its syntax allows programmers to express concepts in fewer lines of code than would be possible in languages such as C++ or Java.[83][84] The language provides constructs intended to enable clear programs on both a small and large scale. Python supports multiple programming paradigms, including object-oriented, imperative and functional programming or procedural styles. It features a dynamic type system and automatic memory management and has a large and comprehensive standard library.

Python was conceived in the late 1980s and its implementation was started in December 1989 by Guido van Rossum at CWI in the Netherlands as a successor to the ABC language (itself inspired by SETL) capable of exception handling and interfacing with the Amoeba operating system. Van Rossum is Python's principal author, and his continuing central role in deciding the direction of Python is reflected in the title given to him by the Python community, benevolent dictator for life (BDFL).

Vim (text editor) (1991)

[edit]Vim is a text editor written by the Dutch free software programmer Bram Moolenaar and first released publicly in 1991. Based on the Vi editor common to Unix-like systems, Vim carefully separated the user interface from editing functions.[citation needed] This allowed it to be used both from a command line interface and as a standalone application in a graphical user interface.[citation needed]

Blender (1995)

[edit]

Blender is a professional free and open-source 3D computer graphics software product used for creating animated films, visual effects, art, 3D printed models, interactive 3D applications and video games. Blender's features include 3D modeling, UV unwrapping, texturing, raster graphics editing, rigging and skinning, fluid and smoke simulation, particle simulation, soft body simulation, digital sculpting, computer animation, match moving, camera tracking, rendering, video editing and compositing. Alongside the modelling features it also has an integrated game engine. Blender has been successfully used in the media industry in several parts of the world including Argentina, Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Russia, Sweden, and the United States.

The Dutch animation studio Neo Geo and Not a Number Technologies (NaN) developed Blender as an in-house application, with the primary author being Ton Roosendaal. The name Blender was inspired by a song by Yello, from the album Baby.[85]

EFMPlus (1995)

[edit]EFMPlus is the channel code used in DVDs and SACDs, a more efficient successor to EFM used in CDs. It was created by Dutch electrical engineer Kees A. Schouhamer Immink, who also designed EFM. It is 6% less efficient than Toshiba's SD code, which resulted in a capacity of 4.7 gigabytes instead of SD's original 5 GB. The advantage of EFMPlus is its superior resilience against disc damage such as scratches and fingerprints.

Economics

[edit]

First megacorporation (1602)

[edit]

The Dutch East India Company was arguably the first megacorporation, possessing quasi-governmental powers, including the ability to wage war, imprison and execute convicts, negotiate treaties, coin money and establish colonies. Many economic and political historians consider the Dutch East India Company as the most valuable and powerful corporation in the world history.

The VOC existed for almost 200 years from its founding in 1602, when the States-General of the Netherlands granted it a 21-year monopoly over Dutch operations in Asia until its demise in 1796. During those two centuries (between 1602 and 1796), the VOC sent almost a million Europeans to work in the Asia trade on 4,785 ships, and netted for their efforts more than 2.5 million tons of Asian trade goods. By contrast, the rest of Europe combined sent only 882,412 people from 1500 to 1795, and the fleet of the English (later British) East India Company, the VOC's nearest competitor, was a distant second to its total traffic with 2,690 ships and a mere one-fifth the tonnage of goods carried by the VOC. The VOC enjoyed huge profits from its spice monopoly through most of the 17th century.[86]

Dutch auction (17th century)

[edit]A Dutch auction is also known as an open descending price auction. Named after the famous auctions of Dutch tulip bulbs in the 17th century, it is based on a pricing system devised by Nobel Prize–winning economist William Vickrey. In the traditional Dutch auction, the auctioneer begins with a high asking price which is lowered until some participant is willing to accept the auctioneer's price. The winning participant pays the last announced price. Dutch auction is also sometimes used to describe online auctions where several identical goods are sold simultaneously to an equal number of high bidders. In addition to cut flower sales in the Netherlands, Dutch auctions have also been used for perishable commodities such as fish and tobacco.

Concept of corporate governance (17th century)

[edit]Isaac Le Maire, an Amsterdam businessman and a sizeable shareholder of the VOC, became the first recorded investor to actually consider the corporate governance's problems. In 1609, he complained of the VOC's shoddy corporate governance. On 24 January 1609, Le Maire filed a petition against the VOC, marking the first recorded expression of shareholder activism. In what is the first recorded corporate governance dispute, Le Maire formally charged that the directors (the VOC's board of directors – the Heeren XVII) sought to "retain another's money for longer or use it ways other than the latter wishes" and petitioned for the liquidation of the VOC in accordance with standard business practice.[87][88][89]

The first shareholder revolt happened in 1622, among Dutch East India Company (VOC) investors who complained that the company account books had been "smeared with bacon" so that they might be "eaten by dogs." The investors demanded a "reeckeninge," a proper financial audit.[90] The 1622 campaign by the shareholders of the VOC is a testimony of genesis of CSR (Corporate Social Responsibility) in which shareholders staged protests by distributing pamphlets and complaining about management self enrichment and secrecy.[91]

Modern concept of foreign direct investment (17th century)

[edit]The construction in 1619 of a train-oil factory on Smeerenburg in the Spitsbergen islands by the Noordsche Compagnie, and the acquisition in 1626 of Manhattan Island by the Dutch West India Company are referred to as the earliest cases of outward foreign direct investment (FDI) in Dutch and world history. Throughout the seventeenth century, the Dutch East India Company (VOC) and the Dutch West India Company (GWIC/WIC) also began to create trading settlements around the globe. Their trading activities generated enormous wealth, making the Dutch Republic one of the most prosperous countries of that time. The Dutch Republic's extensive arms trade occasioned an episode in the industrial development of early-modern Sweden, where arms merchants like Louis de Geer and the Trip brothers, invested in iron mines and iron works, another early example of outward foreign direct investment.

First capitalist nation-state (17th century)

[edit]

Some economic historians consider the Netherlands as the first predominantly capitalist nation.[92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101] The development of European capitalism began among the city-states of Italy, Flanders, and the Baltic. It spread to the European interstate system, eventually resulting in the world's first capitalist nation-state, the Dutch Republic of the seventeenth century.[102] The Dutch were the first to develop capitalism on a nationwide scale (as opposed to earlier city states).

First modern economic miracle (1585–1714)

[edit]The Dutch economic transition from a possession of the Holy Roman Empire in the 1590s to the foremost maritime and economic power in the world has been called the "Dutch Miracle" (or "Dutch Tiger") by many economic historians, including K. W. Swart.[103] During their Golden Age, the provinces of the Northern Netherlands rose from almost total obscurity as the poor cousins of the industrious and heavily urbanised southern regions (Southern Netherlands) to become the world leader in economic success.[104][105][106][107] Its manufacturing towns grew so quickly that by the middle of the century the Netherlands had supplanted France as the leading industrial nation of the world.[108][109]

Dynamic macroeconomic model (1936)

[edit]Dutch economist Jan Tinbergen developed the first national comprehensive macroeconomic model, which he first built for the Netherlands and after World War II later applied to the United States and the United Kingdom.

Fairtrade certification (1988)

[edit]The concept of fair trade has been around for over 40 years, but a formal labelling scheme emerged only in the 1980s. At the initiative of Mexican coffee farmers, the world's first Fairtrade labeling organisation, Stichting Max Havelaar, was launched in the Netherlands on 15 November 1988 by Nico Roozen, Frans van der Hoff and Dutch ecumenical development agency Solidaridad. It was branded "Max Havelaar" after a fictional Dutch character who opposed the exploitation of coffee pickers in Dutch colonies.

Finance

[edit]Concept of bourse (13th century)

[edit]An exchange, or bourse, is a highly organized market where (especially) tradable securities, commodities, foreign exchange, futures, and options contracts are sold and bought. The term bourse is derived from the 13th-century inn named Huis ter Beurze in Bruges, Low Countries, where traders and foreign merchants from across Europe conducted business in the late medieval period.[110] The building, which was established by Robert van der Buerze as a hostelry, had operated from 1285. Its managers became famous for offering judicious financial advice to the traders and merchants who frequented the building. This service became known as the "Beurze Purse" which is the basis of bourse, meaning an organised place of exchange.

Foundations of stock market (1602)

[edit]

The seventeenth-century Dutch merchants laid the foundations for modern stock market.[112] The Dutch merchants were also the pioneers in developing the basic techniques of stock trading. Although bond sales by municipalities and states can be traced to the thirteenth century, the origin of modern stock exchanges that specialize in creating and sustaining secondary markets in corporate securities goes back to the formation of the Dutch East India Company in the year 1602.[113][114][115][116]

Foundations of corporate finance (17th century)

[edit]What is now known as corporate finance has its modern roots in financial management policies of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in the 17th century and some basic aspects of modern corporate finance began to appear in financial activities of Dutch businessmen in the early 17th century.

Foundations of investment banking (17th century)

[edit]The Dutch were the pioneers in laying the basis for investment banking, allowing the risk of loans to be distributed among thousands of investors in the early seventeenth century.[117]

Foundations of central banking (1609)

[edit]

Prior to the 17th century most money was commodity money, typically gold or silver. However, promises to pay were widely circulated and accepted as value at least five hundred years earlier in both Europe and Asia. The Song dynasty was the first to issue generally circulating paper currency, while the Yuan dynasty was the first to use notes as the predominant circulating medium. In 1455, in an effort to control inflation, the succeeding Ming dynasty ended the use of paper money and closed much of Chinese trade. The medieval European Knights Templar ran an early prototype of a central banking system, as their promises to pay were widely respected, and many regard their activities as having laid the basis for the modern banking system. The Bank of Amsterdam (Amsterdamsche Wisselbank or literally Amsterdam Exchange Bank) established in 1609 is considered to be the precursor to modern central banks, if not the first true central bank.[118][119][120][121][122][123][124][125]

Short selling (1609)

[edit]Financial innovation in Amsterdam took many forms. In 1609, investors led by Isaac Le Maire formed history's first bear syndicate to engage in short selling, but their coordinated trading had only a modest impact in driving down share prices, which tended to be robust throughout the 17th century.

Concept of dividend policy (1610)

[edit]In the first decades of the 17th century, the VOC was the first recorded company ever to pay regular dividends. To encourage investors to buy shares, a promise of an annual payment (called a dividend) was made. An investor would receive dividends instead of interest and the investment was permanent in the form of shares in the company. Between 1600 and 1800 the Dutch East India Company (VOC) paid annual dividends worth around 18 percent of the value of the shares.

First European banknote (1661)

[edit]In 1656, King Charles X Gustav of Sweden signed two charters creating two private banks under the directorship of Johan Palmstruch (though before having been ennobled he was called Johan Wittmacher or Hans Wittmacher), a Riga-born merchant of Dutch origin. Palmstruch modeled the banks on those of Amsterdam where he had become a burgher. The first real European banknote was issued in 1661 by the Stockholms Banco of Johan Palmstruch, a private bank under state charter (precursor to the Sveriges Riksbank, the central bank of Sweden).

First book on stock trading (1688)

[edit]Joseph de la Vega, also known as Joseph Penso de la Vega, was an Amsterdam trader from a Spanish Jewish family and a prolific writer as well as a successful businessman. His 1688 book Confusion de Confusiones (Confusion of Confusions) explained the workings of the city's stock market. It was the earliest book about stock trading, taking the form of a dialogue between a merchant, a shareholder and a philosopher. The book described a market that was sophisticated but also prone to excesses, and de la Vega offered advice to his readers on such topics as the unpredictability of market shifts and the importance of patience in investment.[126]

Concept of technical analysis (1688)

[edit]The principles of technical analysis are derived from hundreds of years of financial market data. These principles in a raw form have been studied since the seventeenth century.[127] Some aspects of technical analysis began to appear in Joseph de la Vega's accounts of the Dutch markets in the late 17th century. In Asia, technical analysis is said to be a method developed by Homma Munehisa during the early 18th century which evolved into the use of candlestick techniques, and is today a technical analysis charting tool.[128][129]

Concept of behavioral finance (1688)

[edit]Josseph de la Vega was in 1688 the first person to give an account of irrational behaviour in financial markets. His 1688 book Confusion of Confusions, has been described as the first precursor of modern behavioural finance, with its descriptions of investor decision-making still reflected in the way some investors operate today.

Concept of investment fund (1774)

[edit]The first investment fund has its roots back in 1774. A Dutch merchant named Adriaan van Ketwich formed a trust named Eendragt Maakt Magt. The name of Ketwich's fund translates to "unity creates strength". In response to the financial crisis of 1772–1773, Ketwich's aim was to provide small investors an opportunity to diversify (Rouwenhorst & Goetzman, 2005). This investment scheme can be seen as the first near-mutual fund. In the years following, near-mutual funds evolved and become more diverse and complex.

Mutual fund (1774)

[edit]The first mutual funds were established in 1774 in the Netherlands. Amsterdam-based businessman Abraham van Ketwich (a.k.a. Adriaan van Ketwich) is often credited as the originator of the world's first mutual fund.[130] The first mutual fund outside the Netherlands was the Foreign & Colonial Government Trust, which was established in London in 1868.

Foods and drinks

[edit]Gibbing (14th century)

[edit]Gibbing is the process of preparing salt herring (or soused herring), in which the gills and part of the gullet are removed from the fish, eliminating any bitter taste. The liver and pancreas are left in the fish during the salt-curing process because they release enzymes essential for flavor. The fish is then cured in a barrel with one part salt to 20 herring. Today many variations and local preferences exist on this process. The process of gibbing was invented by Willem Beuckelszoon[131] (aka Willem Beuckelsz, William Buckels[132] or William Buckelsson), a 14th-century Zealand Fisherman. The invention of this fish preservation technique led to the Dutch becoming a seafaring power.[133] This invention created an export industry for salt herring that was monopolized by the Dutch.

Doughnut (17th century)

[edit]Some people believe it was the Dutch who invented doughnuts. A Dutch snack made from potatoes had a round shape like a ball, but, like Gregory's dough balls, needed a little longer time when fried to cook the inside thoroughly. These potato-balls developed into doughnuts when the Dutch finally made them into ring-shapes reduce frying time.[citation needed]

Gin (jenever) (1650)

[edit]

Gin is a spirit which derives its predominant flavour from juniper berries (Juniperus communis). From its earliest origins in the Middle Ages, gin has evolved over the course of a millennium from a herbal medicine to an object of commerce in the spirits industry. Gin was developed on the basis of the older Jenever, and become widely popular in Great Britain when William III of Orange, leader of the Dutch Republic, occupied the British throne with his wife Mary. Today, the gin category is one of the most popular and widely distributed range of spirits, and is represented by products of various origins, styles, and flavour profiles that all revolve around juniper as a common ingredient.

The Dutch physician Franciscus Sylvius is often credited with the invention of gin in the mid-17th century,[134][135] although the existence of genever is confirmed in Massinger's play The Duke of Milan (1623), when Dr. Sylvius would have been but nine years of age. It is further claimed that British soldiers who provided support in Antwerp against the Spanish in 1585, during the Eighty Years' War, were already drinking genever (jenever) for its calming effects before battle, from which the term Dutch Courage is believed to have originated.[136] The earliest known written reference to genever appears in the 13th century encyclopaedic work Der Naturen Bloeme (Bruges), and the earliest printed genever recipe from 16th century work Een Constelijck Distileerboec (Antwerp).[137]

Stroopwafel (1780s)

[edit]A stroopwafel (also known as syrup waffle, treacle waffle or caramel waffle) is a waffle made from two thin layers of baked batter with a caramel-like syrup filling the middle. They were first made in Gouda in the 1780s. The traditional way to eat the stroopwafel is to place it atop of a drinking vessel with a hot beverage (coffee, tea or chocolate) inside that fits the diameter of the waffle. The heat from the rising steam warms the waffle and slightly softens the inside and makes the waffle soft on one side while still crispy on the other.

Cocoa powder (1828)

[edit]In 1815, Dutch chemist Coenraad van Houten introduced alkaline salts to chocolate, which reduced its bitterness. In the 1820s, Casparus van Houten, Sr. patented an inexpensive method for pressing the fat from roasted cocoa beans.[138][139][140] He created a press to remove about half the natural fat (cacao butter) from chocolate liquor, which made chocolate both cheaper to produce and more consistent in quality.

Dutch-process chocolate (1828)

[edit]Dutch-processed chocolate or Dutched chocolate is chocolate that has been treated with an alkalizing agent to modify its color and give it a milder taste compared to "natural cocoa" extracted with the Broma process. It forms the basis for much of modern chocolate, and is used in ice cream, hot cocoa, and baking. The Dutch process was developed in the early 19th century by Dutch chocolate maker Coenraad Johannes van Houten, whose father Casparus is responsible for the development of the method of removing fat from cacao beans by hydraulic press around 1828, forming the basis for cocoa powder.[139][140]

Law and jurisprudence

[edit]Doctrine of the Freedom of the Seas (foundations of the Law of the Sea/UNCLOS) (1609)

[edit]In 1609, Hugo Grotius, the Dutch jurist who is generally known as the father of modern international law, published his book Mare Liberum (The Free Sea), which first formulated the notion of freedom of the seas. He developed this idea into a legal principle.[141] It is said to be 'the first, and classic, exposition of the doctrine of the freedom of the seas' which has been the essence and backbone of the modern law of the sea.[142][143] It is generally assumed that Grotius first propounded the principle of freedom of the seas, although all countries in the Indian Ocean and other Asian seas accepted the right of unobstructed navigation long before Grotius wrote his De Jure Praedae (On the Law of Spoils) in the year of 1604. His work sparked a debate in the seventeenth century over whether states could exclude the vessels of other states from certain waters. Grotius won this debate, as freedom of the seas became a universally recognized legal principle, associated with concepts such as communication, trade and peace. Grotius's notion of the freedom of the seas would persist until the mid-twentieth century, and it continues to be applied even to this day for much of the high seas, though the application of the concept and the scope of its reach is changing.

Secularized natural law (foundations of modern international law) (1625)

[edit]The publication of De jure belli ac pacis (On the Laws of War and Peace) by Hugo Grotius in 1625 had marked the emergence of international law as an 'autonomous legal science'.[144][145][146] Grotius's On the Law of War and Peace, published in 1625, is best known as the first systematic treatise on international law, but to thinkers of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it seemed to set a new agenda in moral and political philosophy across the board. Grotius developed pivotal treatises on freedom of the seas, the law of spoils, the laws of war and peace and he created an autonomous place for international law as its own discipline. Jean Barbeyrac's Historical and Critical Account of the Science of Morality, attached to his translation of Samuel von Pufendorf's Law of Nature and Nations in 1706, praised Grotius as "the first who broke the ice" of "the Scholastic Philosophy; which [had] spread itself all over Europe" (1749: 67, 66).[147] Grotius' truly distinctive contribution to jurisprudence and philosophy of law (public international law or law of nations in particular) was that he secularized natural law.[148][149][150][151][152][153][154] Grotius had divorced natural law from theology and religion by grounding it solely in the social nature and natural reason of man.[142][143] When Grotius, considered by many to be the founder of modern natural law theory (or secular natural law), said that natural law would retain its validity 'even if God did not exist' (etiamsi daremus non-esse Deum), he was making a clear break with the classical tradition of natural law.[155][156][157][158]

Cannon shot rule (1702)

[edit]By the end of the seventeenth century, support was growing for some limitation to the seaward extent of territorial waters. What emerged was the so-called "cannon shot rule", which acknowledged the idea that property rights could be acquired by physical occupation and in practice to the effective range of shore-based cannon: about three nautical miles. The rule was long associated with Cornelis van Bijnkershoek, a Dutch jurist who, especially in his De Dominio Maris Dissertatio (1702), advocated a middle ground between the extremes of Mare Liberum and John Selden's Mare Clausum, accepting both the freedom of states to navigate and exploit the resources of the high seas and a right of coastal states to assert wide-ranging rights in a limited marine territory.

Permanent Court of Arbitration (1899)

[edit]The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) is an international organization based in The Hague in the Netherlands. The court was established in 1899 as one of the acts of the first Hague Peace Conference, which makes it the oldest global institution for international dispute resolution.[159] Its creation is set out under Articles 20 to 29 of the 1899 Hague Convention for the pacific settlement of international disputes, which was a result of the first Hague Peace Conference. The most concrete achievement of the Conference was the establishment of the PCA as the first institutionalized global mechanism for the settlement of disputes between states. The PCA encourages the resolution of disputes that involve states, state entities, intergovernmental organizations, and private parties by assisting in the establishment of arbitration tribunals and facilitating their work. The court offers a wide range of services for the resolution of international disputes which the parties concerned have expressly agreed to submit for resolution under its auspices. Dutch-Jew legal scholar Tobias Asser's role in the creation of the PCA at the first Hague Peace Conference (1899) earned him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1911.

International Opium Convention (1912)

[edit]The International Opium Convention, sometimes referred to as the Hague Convention of 1912, signed on 23 January 1912 at The Hague, was the first international drug control treaty and is the core of the international drug control system. The adoption of the convention was a turning point in multilateralism, based on the recognition of the transnational nature of the drug problem and the principle of shared responsibility.[160]

Marriage equality (legalization of same-sex marriage) (2001)

[edit]Denmark was the first state to recognize a legal relationship for same-sex couples, establishing "registered partnerships" very much like marriage in 1989. In 2001, the Netherlands became the first nation in the world to grant same-sex marriages. The first laws enabling same-sex marriage in modern times were enacted during the first decade of the 21st century. As of 29 March 2014[update], sixteen countries (Argentina, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Denmark,[nb 2] France, Iceland, Netherlands,[nb 3] New Zealand,[nb 4] Norway, Portugal, Spain, South Africa, Sweden, United Kingdom,[nb 5] Uruguay) and several sub-national jurisdictions (parts of Mexico and the United States) allow same-sex couples to marry. Polls in various countries show that there is rising support for legally recognizing same-sex marriage across race, ethnicity, age, religion, political affiliation, and socioeconomic status.

Measurement

[edit]Pendulum clock (first high-precision clock) (1656)

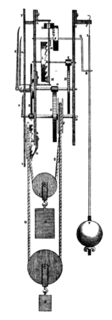

[edit]

The first mechanical clocks, employing the verge escapement mechanism with a foliot or balance wheel timekeeper, were invented in Europe at around the start of the 14th century, and became the standard timekeeping device until the pendulum clock was invented in 1656. The pendulum clock remained the most accurate timekeeper until the 1930s, when quartz oscillators were invented, followed by atomic clocks after World War 2.[161]

A pendulum clock uses a pendulum's arc to mark intervals of time. From their invention until about 1930, the most accurate clocks were pendulum clocks. Pendulum clocks cannot operate on vehicles or ships at sea, because the accelerations disrupt the pendulum's motion, causing inaccuracies. The pendulum clock was invented by Christiaan Huygens, based on the pendulum introduced by Galileo Galilei. Although Galileo studied the pendulum as early as 1582, he never actually constructed a clock based on that design. Christiaan Huygens invented pendulum clock in 1656 and patented the following year. He contracted the construction of his clock designs to clockmaker Salomon Coster, who actually built the clock.

Concept of the standardization of the temperature scale (1665)

[edit]Various authors have credited the invention of the thermometer to Cornelis Drebbel, Robert Fludd, Galileo Galilei or Santorio Santorio. The thermometer was not a single invention, however, but a development. However, each inventor and each thermometer was unique – there was no standard scale. In 1665 Christiaan Huygens suggested using the melting and boiling points of water as standards.[162][163] The Fahrenheit scale is now usually defined by two fixed points: the temperature at which water freezes into ice is defined as 32 degrees Fahrenheit (°F), and the boiling point of water is defined to be 212 °F (100 °C), a 180-degree separation, as defined at sea level and standard atmospheric pressure. In 1742, Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius created a temperature scale which was the reverse of the scale now known by the name "Celsius": 0 represented the boiling point of water, while 100 represented the freezing point of water. From 1744 until 1954, 0 °C was defined as the freezing point of water and 100 °C was defined as the boiling point of water, both at a pressure of one standard atmosphere with mercury being the working material.

Spiral-hairspring watch (1675)

[edit]

The invention of the mainspring in the early 15th century allowed portable clocks to be built, evolving into the first pocketwatches by the 17th century, but these were not very accurate until the balance spring was added to the balance wheel in the mid-17th century. Some dispute remains as to whether British scientist Robert Hooke (his was a straight spring) or Dutch scientist Christiaan Huygens was the actual inventor of the balance spring. This innovation increased watches' accuracy enormously, reducing error from perhaps several hours per day[164] to perhaps 10 minutes per day,[165] resulting in the addition of the minute hand to the face from around 1680 in Britain and 1700 in France.

Mercury thermometer (1714)

[edit]

Various authors have credited the invention of the thermometer to Cornelis Drebbel, Robert Fludd, Galileo Galilei or Santorio Santorio. The thermometer was not a single invention, however, but a development. Though Galileo is often said to be the inventor of the thermometer, what he produced were thermoscopes. The difference between a thermoscope and a thermometer is that the latter has a scale.[166] The first person to put a scale on a thermoscope is variously said to be Francesco Sagredo[167] or Santorio Santorio[168] in about 1611 to 1613. Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit began constructing his own thermometers in 1714, and it was in these that he used mercury for the first time.

Fahrenheit scale (1724)

[edit]

Various authors have credited the invention of the thermometer to Cornelis Drebbel, Robert Fludd, Galileo Galilei or Santorio Santorio. The thermometer was not a single invention, however, but a development. However, each inventor and each thermometer was unique – there was no standard scale. In 1665 Christiaan Huygens suggested using the melting and boiling points of water as standards, and in 1694 Carlo Renaldini proposed using them as fixed points on a universal scale. In 1701 Isaac Newton proposed a scale of 12 degrees between the melting point of ice and body temperature. Finally in 1724 Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit produced a temperature scale which now (slightly adjusted) bears his name. He could do this because he manufactured thermometers, using mercury (which has a high coefficient of expansion) for the first time and the quality of his production could provide a finer scale and greater reproducibility, leading to its general adoption. By the end of the 20th century, most countries used the Celsius scale rather than the Fahrenheit scale, though Canada retained it as a supplementary scale used alongside Celsius. Fahrenheit remains the official scale for Jamaica, the Cayman Islands, Belize, the Bahamas, Palau and the United States and associated territories.

Snellen chart (1862)

[edit]The Snellen chart is an eye chart used by eye care professionals and others to measure visual acuity. Snellen charts are named after Dutch ophthalmologist Hermann Snellen who developed the chart in 1862. Vision scientists now use a variation of this chart, designed by Ian Bailey and Jan Lovie.

String galvanometer (1902)

[edit]Previous to the string galvanometer, scientists used a machine called the capillary electrometer to measure the heart's electrical activity, but this device was unable to produce results at a diagnostic level. Dutch physiologist Willem Einthoven developed the string galvanometer in the early 20th century, publishing the first registration of its use to record an electrocardiogram in a Festschrift book in 1902. The first human electrocardiogram was recorded in 1887, however only in 1901 was a quantifiable result obtained from the string galvanometer.

Schilt photometer (1922)

[edit]In 1922, Dutch astronomer Jan Schilt invented the Schilt photometer, a device that measures the light output of stars and, indirectly, their distances.

Medicine

[edit]Clinical electrocardiography (first diagnostic electrocardiogram) (1902)

[edit]

In the 19th century it became clear that the heart generated electric currents. The first to systematically approach the heart from an electrical point-of-view was Augustus Waller, working in St Mary's Hospital in Paddington, London. In 1911 he saw little clinical application for his work. The breakthrough came when Willem Einthoven, working in Leiden, used his more sensitive string galvanometer, than the capillary electrometer that Waller used. Einthoven assigned the letters P, Q, R, S and T to the various deflections that it measured and described the electrocardiographic features of a number of cardiovascular disorders. He was awarded the 1924 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine for his discovery.[169][170][171][172][173][174][175][176]

Einthoven's triangle (1902)