Международное право

Международное право (также известное как международное публичное право и право наций ) — это набор правил , норм и стандартов, которым государства и другие субъекты чувствуют себя обязанными подчиняться в своих взаимных отношениях и в целом подчиняются. В международных отношениях акторами являются просто отдельные лица и коллективные образования, такие как государства, международные организации и негосударственные группы, которые могут делать поведенческий выбор, законный или незаконный. Правила — это формальные, часто записанные ожидания относительно поведения, а нормы — это менее формальные, общепринятые ожидания относительно соответствующего поведения, которые часто не записаны. [ 1 ] Он устанавливает нормы для государств в широком спектре областей, включая войну и дипломатию , экономические отношения и права человека .

основанных на государствах, Международное право отличается от внутренних правовых систем, тем, что оно действует в основном посредством согласия , поскольку не существует общепризнанного органа, обеспечивающего его соблюдение суверенными государствами . Государства и негосударственные субъекты могут решить не соблюдать международное право и даже нарушить договор, но такие нарушения, особенно императивных норм , могут быть встречены неодобрением со стороны других, а в некоторых случаях и принудительными действиями, начиная от дипломатических и экономических санкций до война.

Источниками международного права являются международный обычай (общая государственная практика, принятая в качестве закона), договоры и общие принципы права, признанные большинством национальных правовых систем. Хотя международное право может также отражаться в международной вежливости – практике, принятой государствами для поддержания хороших отношений и взаимного признания – такие традиции не являются юридически обязательными . Отношения и взаимодействие между национальной правовой системой и международным правом сложны и изменчивы. Национальное право может стать международным правом, если договоры допускают национальную юрисдикцию наднациональных трибуналов, таких как Европейский суд по правам человека или Международный уголовный суд . Такие договоры, как Женевские конвенции, требуют, чтобы национальное законодательство соответствовало положениям договора. Национальные законы или конституции могут также предусматривать выполнение или интеграцию международно-правовых обязательств во внутреннее право.

Terminology

[edit]The modern term "international law" was originally coined by Jeremy Bentham in his 1789 book Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation to replace the older law of nations, a direct translation of the late medieval concepts of ius gentium, used by Hugo Grotius, and droits des gens, used by Emer de Vattel.[2][3] The definition of international law has been debated; Bentham referred specifically to relationships between states which has been criticised for its narrow scope.[4] Lassa Oppenheim defined it in his treatise as "a law between sovereign and equal states based on the common consent of these states" and this definition has been largely adopted by international legal scholars.[5]

There is a distinction between public and private international law; the latter is concerned with whether national courts can claim jurisdiction over cases with a foreign element and the application of foreign judgments in domestic law, whereas public international law covers rules with an international origin.[6] The difference between the two areas of law has been debated as scholars disagree about the nature of their relationship. Joseph Story, who originated the term "private international law", emphasised that it must be governed by the principles of public international law but other academics view them as separate bodies of law.[7][8] Another term, transnational law, is sometimes used to refer to a body of both national and international rules that transcend the nation state, although some academics emphasise that it is distinct from either type of law. It was defined by Philip Jessup as "all law which regulates actions or events that transcend national frontiers".[9]

A more recent concept is supranational law, which was described in a 1969 paper as "[a] relatively new word in the vocabulary of politics".[10] Systems of supranational law arise when nations explicitly cede their right to make decisions to this system's judiciary and legislature, which then have the right to make laws that are directly effective in each member state.[10][11] This has been described as "a level of international integration beyond mere intergovernmentalism yet still short of a federal system".[10] The most common example of a supranational system is the European Union.[11]

History

[edit]

The origins of international law can be traced back to antiquity.[13] With origins tracing back to antiquity, states have a long history of negotiating interstate agreements. An initial framework was conceptualised by the Ancient Romans and this idea of ius gentium has been used by various academics to establish the modern concept of international law. Among the earliest recorded examples are peace treaties between the Mesopotamian city-states of Lagash and Umma (approximately 3100 BCE), and an agreement between the Egyptian pharaoh, Ramesses II, and the Hittite king, Ḫattušili III, concluded in 1279 BCE.[12] Interstate pacts and agreements were negotiated and agreed upon by polities across the world, from the eastern Mediterranean to East Asia.[14] In Ancient Greece, many early peace treaties were negotiated between its city-states and, occasionally, with neighbouring states.[15] The Roman Empire established an early conceptual framework for international law, jus gentium, which governed the status of foreigners living in Rome and relations between foreigners and Roman citizens.[16][17] Adopting the Greek concept of natural law, the Romans conceived of jus gentium as being universal.[18] However, in contrast to modern international law, the Roman law of nations applied to relations with and between foreign individuals rather than among political units such as states.[19]

Beginning with the Spring and Autumn period of the eighth century BCE, China was divided into numerous states that were often at war with each other. Rules for diplomacy and treaty-making emerged, including notions regarding just grounds for war, the rights of neutral parties, and the consolidation and partition of states; these concepts were sometimes applied to relations with barbarians along China's western periphery beyond the Central Plains.[20][21] The subsequent Warring States period saw the development of two major schools of thought, Confucianism and Legalism, both of which held that the domestic and international legal spheres were closely interlinked, and sought to establish competing normative principles to guide foreign relations.[21][22] Similarly, the Indian subcontinent was divided into various states, which over time developed rules of neutrality, treaty law, and international conduct, and established both temporary and permanent embassies.[23][24]

Following the collapse of the western Roman Empire in the fifth century CE, Europe fragmented into numerous often-warring states for much of the next five centuries. Political power was dispersed across a range of entities, including the Church, mercantile city-states, and kingdoms, most of which had overlapping and ever-changing jurisdictions. As in China and India, these divisions prompted the development of rules aimed at providing stable and predictable relations. Early examples include canon law, which governed ecclesiastical institutions and clergy throughout Europe; the lex mercatoria ("merchant law"), which concerned trade and commerce; and various codes of maritime law, such as the Rolls of Oléron— aimed at regulating shipping in North-western Europe — and the later Laws of Wisby, enacted among the commercial Hanseatic League of northern Europe and the Baltic region.[25]

In the Islamic world, Muhammad al-Shaybani published Al-Siyar Al-Kabīr in the eighth century, which served as a fundamental reference work for siyar, a subset of Sharia law, which governed foreign relations.[26][27] This was based on the division of the world into three categories: the dar al-Islam, where Islamic law prevailed; the dar al-sulh, non-Islamic realms that concluded an armistice with a Muslim government; and the dar al-harb, non-Islamic lands which were contested through jihad.[28][29] Islamic legal principles concerning military conduct served as precursors to modern international humanitarian law and institutionalised limitations on military conduct, including guidelines for commencing war, distinguishing between civilians and combatants and caring for the sick and wounded.[30][31]

During the European Middle Ages, international law was concerned primarily with the purpose and legitimacy of war, seeking to determine what constituted "just war".[32] The Greco-Roman concept of natural law was combined with religious principles by Jewish philosopher Maimonides (1135–1204) and Christian theologian Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) to create the new discipline of the "law of nations", which unlike its eponymous Roman predecessor, applied natural law to relations between states.[33][34] In Islam, a similar framework was developed wherein the law of nations was derived, in part, from the principles and rules set forth in treaties with non-Muslims.[35]

Emergence of modern international law

[edit]The 15th century witnessed a confluence of factors that contributed to an accelerated development of international law. Italian jurist Bartolus de Saxoferrato (1313–1357) was considered the founder of private international law. Another Italian jurist, Baldus de Ubaldis (1327–1400), provided commentaries and compilations of Roman, ecclesiastical, and feudal law, creating an organised source of law that could be referenced by different nations.[citation needed] Alberico Gentili (1552–1608) took a secular view to international law, authoring various books on issues in international law, notably Law of War, which provided comprehensive commentary on the laws of war and treaties.[36] Francisco de Vitoria (1486–1546), who was concerned with the treatment of indigenous peoples by Spain, invoked the law of nations as a basis for their innate dignity and rights, articulating an early version of sovereign equality between peoples.[37] Francisco Suárez (1548–1617) emphasised that international law was founded upon natural law and human positive law.[38][39]

Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) is widely regarded as the father of international law,[40] being one of the first scholars to articulate an international order that consists of a "society of states" governed not by force or warfare but by actual laws, mutual agreements, and customs.[41] Grotius secularised international law;[42] his 1625 work, De Jure Belli ac Pacis, laid down a system of principles of natural law that bind all nations regardless of local custom or law.[40] He inspired two nascent schools of international law, the naturalists and the positivists.[43] In the former camp was German jurist Samuel von Pufendorf (1632–1694), who stressed the supremacy of the law of nature over states.[44][45] His 1672 work, Of the Law of Nature and Nations, expanded on the theories of Grotius and grounded natural law to reason and the secular world, asserting that it regulated only external acts of states.[44] Pufendorf challenged the Hobbesian notion that the state of nature was one of war and conflict, arguing that the natural state of the world is actually peaceful but weak and uncertain without adherence to the law of nations.[46] The actions of a state consist of nothing more than the sum of the individuals within that state, thereby requiring the state to apply a fundamental law of reason, which is the basis of natural law. He was among the earliest scholars to expand international law beyond European Christian nations, advocating for its application and recognition among all peoples on the basis of shared humanity.[47]

In contrast, positivist writers, such as Richard Zouche (1590–1661) in England and Cornelis van Bynkershoek (1673–1743) in the Netherlands, argued that international law should derive from the actual practice of states rather than Christian or Greco-Roman sources. The study of international law shifted away from its core concern on the law of war and towards the domains such as the law of the sea and commercial treaties.[48] The positivist school grew more popular as it reflected accepted views of state sovereignty and was consistent with the empiricist approach to philosophy that was then gaining acceptance in Europe.[49]

Establishment of Westphalian system

[edit]The developments of the 17th century culminated at the conclusion of the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, which is considered the seminal event in international law.[50] The resulting Westphalian sovereignty is said to have established the current international legal order characterised by independent nation states, which have equal sovereignty regardless of their size and power, defined primarily by non-interference in the domestic affairs of sovereign states, although historians have challenged this narrative.[51] The idea of nationalism further solidified the concept and formation of nation-states.[52] Elements of the naturalist and positivist schools were synthesised, notably by German philosopher Christian Wolff (1679–1754) and Swiss jurist Emer de Vattel (1714–1767), both of whom sought a middle-ground approach.[53][54] During the 18th century, the positivist tradition gained broader acceptance, although the concept of natural rights remained influential in international politics, particularly through the republican revolutions of the United States and France.[citation needed]

Until the mid-19th century, relations between states were dictated mostly by treaties, agreements between states to behave in a certain way, unenforceable except by force, and nonbinding except as matters of honour and faithfulness.[citation needed] One of the first instruments of modern armed conflict law was the Lieber Code of 1863, which governed the conduct of warfare during the American Civil War, and is noted for codifying rules and articles of war adhered to by nations across the world, including the United Kingdom, Prussia, Serbia and Argentina.[55] In the years that followed, numerous other treaties and bodies were created to regulate the conduct of states towards one another, including the Permanent Court of Arbitration in 1899, and the Hague and Geneva Conventions, the first of which was passed in 1864.[56][57]

20th and 21st century developments

[edit]

Colonial expansion by European powers reached its peak in the late 19th century and its influence began to wane following the unprecedented bloodshed of World War I, which spurred the creation of international organisations. Right of conquest was generally recognized as international law before World War II.[58] The League of Nations was founded to safeguard peace and security.[59][60] International law began to incorporate notions such as self-determination and human rights.[61] The United Nations (UN) was established in 1945 to replace the League, with an aim of maintaining collective security.[62] A more robust international legal order followed, buttressed by institutions such as the International Court of Justice (ICJ) and the UN Security Council (UNSC).[63] The International Law Commission (ILC) was established in 1947 to develop and codify international law.[62]

In the 1940s through the 1970s, the dissolution of the Soviet bloc and decolonisation across the world resulted in the establishment of scores of newly independent states.[64] As these former colonies became their own states, they adopted European views of international law.[65] A flurry of institutions, ranging from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (World Bank) to the World Health Organization furthered the development of a multilateralist approach as states chose to compromise on sovereignty to benefit from international cooperation.[66] Since the 1980s, there has been an increasing focus on the phenomenon of globalisation and on protecting human rights on the global scale, particularly when minorities or indigenous communities are involved, as concerns are raised that globalisation may be increasing inequality in the international legal system.[67]

Sources of international law

[edit]The sources of international law applied by the community of nations are listed in Article 38(1) of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, which is considered authoritative in this regard. These categories are, in order, international treaties, customary international law, general legal principles and judicial decisions and the teachings of prominent legal scholars as "a subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law".[68] It was originally considered that the arrangement of the sources sequentially would suggest an implicit hierarchy of sources; however, the statute does not provide for a hierarchy and other academics have argued that therefore the sources must be equivalent.[69][70]

General principles of law have been defined in the Statute as "general principles of law recognized by civilized nations" but there is no academic consensus about what is included within this scope.[71][72] They are considered to be derived from both national and international legal systems, although including the latter category has led to debate about potential cross-over with international customary law.[73][74] The relationship of general principles to treaties or custom has generally been considered to be "fill[ing] the gaps" although there is still no conclusion about their exact relationship in the absence of a hierarchy.[75]

Treaties

[edit]

A treaty is defined in Article 2 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) as "an international agreement concluded between States in written form and governed by international law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments and whatever its particular designation".[76] The definition specifies that the parties must be states, however international organisations are also considered to have the capacity to enter treaties.[76][77] Treaties are binding through the principle of pacta sunt servanda, which allows states to create legal obligations on themselves through consent.[78][79] The treaty must be governed by international law; however it will likely be interpreted by national courts.[80] The VCLT, which codifies several bedrock principles of treaty interpretation, holds that a treaty "shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose".[81] This represents a compromise between three theories of interpretation: the textual approach which looks to the ordinary meaning of the text, the subjective approach which considers factors such as the drafters' intention, and the teleological approach which interprets a treaty according to its objective and purpose.[81][82]

A state must express its consent to be bound by a treaty through signature, exchange of instruments, ratification, acceptance, approval or accession. Accession refers to a state choosing to become party to a treaty that it is unable to sign, such as when establishing a regional body. Where a treaty states that it will be enacted through ratification, acceptance or approval, the parties must sign to indicate acceptance of the wording but there is no requirement on a state to later ratify the treaty, although they may still be subject to certain obligations.[83] When signing or ratifying a treaty, a state can make a unilateral statement to negate or amend certain legal provisions which can have one of three effects: the reserving state is bound by the treaty but the effects of the relevant provisions are precluded or changes, the reserving state is bound by the treaty but not the relevant provisions, or the reserving state is not bound by the treaty.[84][85] An interpretive declaration is a separate process, where a state issues a unilateral statement to specify or clarify a treaty provision. This can affect the interpretation of the treaty but it is generally not legally binding.[86][87] A state is also able to issue a conditional declaration stating that it will consent to a given treaty only on the condition of a particular provision or interpretation.[88]

Article 54 of the VCLT provides that either party may terminate or withdraw from a treaty in accordance with its terms or at any time with the consent of the other party, with 'termination' applying to a bilateral treaty and 'withdrawal' applying to a multilateral treaty.[89] Where a treaty does not have provisions allowing for termination or withdrawal, such as the Genocide Convention, it is prohibited unless the right was implied into the treaty or the parties had intended to allow for it.[90] A treaty can also be held invalid, including where parties act ultra vires or negligently, where execution has been obtained through fraudulent, corrupt or forceful means, or where the treaty contradicts peremptory norms.[91]

International custom

[edit]Customary international law requires two elements: a consistent practice of states and the conviction of those states that the consistent practice is required by a legal obligation, referred to as opinio juris.[92][93] Custom distinguishes itself from treaty law as it is binding on all states, regardless of whether they have participated in the practice, with the exception of states who have been persistent objectors during the process of the custom being formed and special or local forms of customary law.[94] The requirement for state practice relates to the practice, either through action or failure to act, of states in relation to other states or international organisations.[95] There is no legal requirement for state practice to be uniform or for the practice to be long-running, although the ICJ has set a high bar for enforcement in the cases of Anglo-Norwegian Fisheries and North Sea Continental Shelf.[96] There has been legal debate on this topic with the only prominent view on the length of time necessary to establish custom explained by Humphrey Waldock as varying "according to the nature of the case".[97] The practice is not required to be followed universally by states, but there must be a "general recognition" by states "whose interests are specially affected".[98]

The second element of the test, opinio juris, the belief of a party that a particular action is required by the law is referred to as the subjective element.[99] The ICJ has stated in dictum in North Sea Continental Shelf that, "Not only must the acts concerned amount to a settled practice, but they must also be such, or be carried out in such a way, as to be evidence of a belief that this practice is rendered obligatory by the existence of a rule of law requiring it".[100] A committee of the International Law Association has argued that there is a general presumption of an opinio juris where state practice is proven but it may be necessary if the practice suggests that the states did not believe it was creating a precedent.[100] The test in these circumstances is whether opinio juris can be proven by the states' failure to protest.[101] Other academics believe that intention to create customary law can be shown by states including the principle in multiple bilateral and multilateral treaties, so that treaty law is necessary to form customs.[102]

The adoption of the VCLT in 1969 established the concept of jus cogens, or peremptory norms, which are "a norm accepted and recognized by the international community of States as a whole as a norm from which no derogation is permitted and which can be modified only by a subsequent norm of general international law having the same character".[103] Where customary or treaty law conflicts with a peremptory norm, it will be considered invalid, but there is no agreed definition of jus cogens.[104] Academics have debated what principles are considered peremptory norms but the mostly widely agreed is the principle of non-use of force.[105] The next year, the ICJ defined erga omnes obligations as those owed to "the international community as a whole", which included the illegality of genocide and human rights.[103]

Monism and dualism

[edit]There are generally two approaches to the relationship between international and national law, namely monism and dualism.[106] Monism assumes that international and national law are part of the same legal order.[107] Therefore, a treaty can directly become part of national law without the need for enacting legislation, although they will generally need to be approved by the legislature. Once approved, the content of the treaty is considered as a law that has a higher status than national laws. Examples of countries with a monism approach are France and the Netherlands.[108] The dualism approach considers that national and international law are two separate legal orders, so treaties are not granted a special status.[106][109] The rules in a treaty can only be considered national law if the contents of the treaty have been enacted first.[109] An example is the United Kingdom; after the country ratified the European Convention on Human Rights, the convention was only considered to have the force of law in national law after Parliament passed the Human Rights Act 1998.[110]

In practice, the division of countries between monism and dualism is often more complicated; countries following both approaches may accept peremptory norms as being automatically binding and they may approach treaties, particularly later amendments or clarifications, differently than they would approach customary law.[111] Many countries with older or unwritten constitutions do not have explicit provision for international law in their domestic system and there has been an upswing in support for monism principles in relation to human rights and humanitarian law, as most principles governing these concepts can be found in international law.[112]

International actors

[edit]States

[edit]A state is defined under Article 1 of the Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States as a legal person with a permanent population, a defined territory, government and capacity to enter relations with other states. There is no requirement on population size, allowing micro-states such as San Marino and Monaco to be admitted to the UN, and no requirement of fully defined boundaries, allowing Israel to be admitted despite border disputes. There was originally an intention that a state must have self-determination, but now the requirement is for a stable political environment. The final requirement of being able to enter relations is commonly evidenced by independence and sovereignty.[113]

Under the principle of par in parem non habet imperium, all states are sovereign and equal,[114] but state recognition often plays a significant role in political conceptions. A country may recognise another nation as a state and, separately, it may recognise that nation's government as being legitimate and capable of representing the state on the international stage.[115][116] There are two theories on recognition; the declaratory theory sees recognition as commenting on a current state of law which has been separately satisfied whereas the constitutive theory states that recognition by other states determines whether a state can be considered to have legal personality.[117] States can be recognised explicitly through a released statement or tacitly through conducting official relations, although some countries have formally interacted without conferring recognition.[118]

Throughout the 19th century and the majority of the 20th century, states were protected by absolute immunity, so they could not face criminal prosecution for any actions. However a number of countries began to distinguish between acta jure gestionis, commercial actions, and acta jure imperii, government actions; the restrictive theory of immunity said states were immune where they were acting in a governmental capacity but not a commercial one. The European Convention on State Immunity in 1972 and the UN Convention on Jurisdictional Immunities of States and their Property attempt to restrict immunity in accordance with customary law.[119]

Individuals

[edit]Historically individuals have not been seen as entities in international law, as the focus was on the relationship between states.[120][121] As human rights have become more important on the global stage, being codified by the UN General Assembly (UNGA) in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948, individuals have been given the power to defend their rights to judicial bodies.[122] International law is largely silent on the issue of nationality law with the exception of cases of dual nationality or where someone is claiming rights under refugee law but as, argued by the political theorist Hannah Arendt, human rights are often tied to someone's nationality.[123] The European Court of Human Rights allows individuals to petition the court where their rights have been violated and national courts have not intervened and the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights have similar powers.[122]

International organisations

[edit]Traditionally, sovereign states and the Holy See were the sole subjects of international law. With the proliferation of international organisations over the last century, they have also been recognised as relevant parties.[124] One definition of international organisations comes from the ILC's 2011 Draft Articles on the Responsibility of International Organizations which in Article 2(a) states that it is "an organization established by treaty or other instrument governed by international law and possessing its own international legal personality".[125] This definition functions as a starting point but does not recognise that organisations can have no separate personality but nevertheless function as an international organisation.[125] The UN Economic and Social Council has emphasised a split between inter-government organisations (IGOs), which are created by inter-governmental agreements, and international non-governmental organisations (INGOs).[126] All international organisations have members; generally this is restricted to states, although it can include other international organisations.[127] Sometimes non-members will be allowed to participate in meetings as observers.[128]

The Yearbook of International Organizations sets out a list of international organisations, which include the UN, the WTO, the World Bank and the IMF.[129][130] Generally organisations consist of a plenary organ, where member states can be represented and heard; an executive organ, to decide matters within the competence of the organisation; and an administrative organ, to execute the decisions of the other organs and handle secretarial duties.[131] International organisations will typically provide for their privileges and immunity in relation to its member states in their constitutional documents or in multilateral agreements, such as the Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations.[132] These organisations also have the power to enter treaties, using the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties between States and International Organizations or between International Organizations as a basis although it is not yet in force.[77] They may also have the right to bring legal claims against states depending, as set out in Reparation for Injuries, where they have legal personality and the right to do so in their constitution.[133]

United Nations

[edit]The UNSC has the power under Chapter VII of the UN Charter to take decisive and binding actions against states committing "a threat to the peace, breach of the peace, or an act of aggression" for collective security although prior to 1990, it has only intervened once, in the case of Korea in 1950.[134][135] This power can only be exercised, however, where a majority of member states vote for it, as well as receiving the support of the permanent five members of the UNSC.[136] This can be followed up with economic sanctions, military action, and similar uses of force.[137] The UNSC also has a wide discretion under Article 24, which grants "primary responsibility" for issues of international peace and security.[134] The UNGA, concerned during the Cold War with the requirement that the USSR would have to authorise any UNSC action, adopted the "Uniting for Peace" resolution of 3 November 1950, which allowed the organ to pass recommendations to authorize the use of force. This resolution also led to the practice of UN peacekeeping, which has been notably been used in East Timor and Kosovo.[138]

International courts

[edit]

There are more than one hundred international courts in the global community, although states have generally been reluctant to allow their sovereignty to be limited in this way.[139] The first known international court was the Central American Court of Justice, prior to World War I, when the Permanent Court of International Justice (PCIJ) was established. The PCIJ was replaced by the ICJ, which is the best known international court due to its universal scope in relation to geographical jurisdiction and subject matter.[140] There are additionally a number of regional courts, including the Court of Justice of the European Union, the EFTA Court and the Court of Justice of the Andean Community.[141] Interstate arbitration can also be used to resolve disputes between states, leading in 1899 to the creation of the Permanent Court of Arbitration which facilitates the process by maintaining a list of arbitrators. This process was used in the Island of Palmas case and to resolve disputes during the Eritrean-Ethiopian war.[142]

The ICJ operates as one of the six organs of the UN, based out of the Hague with a panel of fifteen permanent judges.[143] It has jurisdiction to hear cases involving states but cannot get involved in disputes involving individuals or international organizations. The states that can bring cases must be party to the Statute of the ICJ, although in practice most states are UN members and would therefore be eligible. The court has jurisdiction over all cases that are referred to it and all matters specifically referred to in the UN Charter or international treaties, although in practice there are no relevant matters in the UN Charter.[144] The ICJ may also be asked by an international organisation to provide an advisory opinion on a legal question, which are generally considered non-binding but authoritative.[145]

Social and economic policy

[edit]Conflict of laws

[edit]Conflict of laws, also known as private international law, was originally concerned with choice of law, determining which nation's laws should govern a particular legal circumstance.[146][147] Historically the comity theory has been used although the definition is unclear, sometimes referring to reciprocity and sometimes being used as a synonym for private international law.[148][149] Story distinguished it from "any absolute paramount obligation, superseding all discretion on the subject".[149] There are three aspects to conflict of laws – determining which domestic court has jurisdiction over a dispute, determining if a domestic court has jurisdiction and determining whether foreign judgments can be enforced. The first question relates to whether the domestic court or a foreign court is best placed to decide the case.[150] When determining the national law that should apply, the lex causae is the law that has been chosen to govern the case, which is generally foreign, and the lexi fori is the national law of the court making the determination. Some examples are lex domicilii, the law of the domicile, and les patriae, the law of the nationality.[151]

The rules which are applied to conflict of laws will vary depending on the national system determining the question. There have been attempts to codify an international standard to unify the rules so differences in national law cannot lead to inconsistencies, such as through the Hague Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Judgments in Civil and Commercial Matters and the Brussels Regulations.[152][153][154] These treaties codified practice on the enforcement of international judgments, stating that a foreign judgment would be automatically recognised and enforceable where required in the jurisdiction where the party resides, unless the judgement was contrary to public order or conflicted with a local judgment between the same parties. On a global level, the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards was introduced in 1958 to internationalise the enforcement of arbitral awards, although it does not have jurisdiction over court judgments.[155]

A state must prove that it has jurisdiction before it can exercise its legal authority.[156] This concept can be divided between prescriptive jurisdiction, which is the authority of a legislature to enact legislation on a particular issue, and adjudicative jurisdiction, which is the authority of a court to hear a particular case.[157] This aspect of private international law should first be resolved by reference to domestic law, which may incorporate international treaties or other supranational legal concepts, although there are consistent international norms.[158] There are five forms of jurisdiction which are consistently recognised in international law; an individual or act can be subject to multiple forms of jurisdiction.[159][160] The first is the territorial principle, which states that a nation has jurisdiction over actions which occur within its territorial boundaries.[161] The second is the nationality principle, also known as the active personality principle, whereby a nation has jurisdiction over actions committed by its nationals regardless of where they occur. The third is the passive personality principle, which gives a country jurisdiction over any actions which harm its nationals.[162] The fourth is the protective principle, where a nation has jurisdiction in relation to threats to its "fundamental national interests". The final form is universal jurisdiction, where a country has jurisdiction over certain acts based on the nature of the crime itself.[162][163]

Human rights

[edit]

Following World War II, the modern system for international human rights was developed to make states responsible for their human rights violations.[164] The UN Economic and Security Council established the UN Commission on Human Rights in 1946, which developed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), which established non-binding international human rights standards, for work, standards of living, housing and education, non-discrimination, a fair trial and prohibition of torture. Two further human rights treaties were adopted by the UN in 1966, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR). These two documents along with the UDHR are considered the International Bill of Human Rights.[165]

Non-domestic human rights enforcement operates at both the international and regional levels. Established in 1993, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights supervises Charter-based and treaty-based procedures.[165] The former are based on the UN Charter and operate under the UN Human Rights Council, where each global region is represented by elected member states. The Council is responsible for Universal Periodic Review, which requires each UN member state to review its human rights compliance every four years, and for special procedures, including the appointment of special rapporteurs, independent experts and working groups.[166] The treaty-based procedure allows individuals to rely on the nine primary human rights treaties:

- International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination

- ICCPR

- ICESCR

- Convention on the Elimination of All forms of Discrimination against Women

- Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment

- Convention on the Rights of the Child

- International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families

- Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities

- International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance – to enforce their rights.[167]

The regional human rights enforcement systems operate in Europe, Africa and the Americas through the European Court of Human Rights, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights.[168] International human rights has faced criticism for its Western focus, as many countries were subject to colonial rule at the time that the UDHR was drafted, although many countries in the Global South have led the development of human rights on the global stage in the intervening decades.[169]

Labour law

[edit]International labour law is generally defined as "the substantive rules of law established at the international level and the procedural rules relating to their adoption and implementation". It operates primarily through the International Labor Organization (ILO), a UN agency with the mission of protecting employment rights which was established in 1919.[170][171] The ILO has a constitution setting out a number of aims, including regulating work hours and labour supply, protecting workers and children and recognising equal pay and the right to free association, as well as the Declaration of Philadelphia of 1944, which re-defined the purpose of the ILO.[171][172] The 1998 Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work further binds ILO member states to recognise fundamental labour rights including free association, collective bargaining and eliminating forced labour, child labour and employment discrimination.[172]

МОТ также разработала трудовые стандарты, изложенные в ее конвенциях и рекомендациях. Тогда у государств-членов будет выбор: ратифицировать и внедрить эти стандарты или нет. [172] Секретариатом МОТ является Международное бюро труда, с которым государства могут консультироваться для определения значения конвенции, которая формирует прецедентное право МОТ. Хотя Конвенция о праве на организацию не предусматривает явного права на забастовку, это было истолковано в договоре через прецедентное право. [ 173 ] [ 174 ] ООН не уделяет особого внимания международному трудовому праву, хотя некоторые из ее договоров затрагивают те же темы. Многие из основных конвенций по правам человека также являются частью международного трудового права, обеспечивая защиту в сфере занятости и от дискриминации по признаку пола и расы. [ 175 ]

Экологическое право

[ редактировать ]Утверждалось, что не существует концепции отдельного международного экологического права , вместо этого к этим вопросам применяются общие принципы международного права. [ 176 ] С 1960-х годов был ратифицирован ряд договоров, посвященных охране окружающей среды, в том числе Декларация Конференции Организации Объединенных Наций по окружающей среде человека 1972 года, Всемирная хартия природы 1982 года и Венская конвенция об охране озонового слоя Земли. 1985. Государства в целом согласились сотрудничать друг с другом в вопросах экологического права, как это закреплено в принципе 24 Декларации Рио-де-Жанейро 1972 года. [ 177 ] Несмотря на эти и другие многосторонние экологические соглашения , охватывающие конкретные вопросы, не существует всеобъемлющей политики в области международной охраны окружающей среды или какой-либо одной конкретной международной организации, за исключением Экологической программы ООН . Вместо этого общий договор, устанавливающий рамки для решения проблемы, затем был дополнен более конкретными протоколами. [ 178 ]

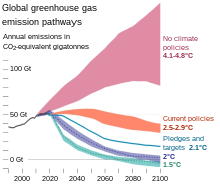

Изменение климата стало одной из самых важных и широко обсуждаемых тем в современном экологическом законодательстве. Рамочная конвенция Организации Объединенных Наций об изменении климата , призванная установить основу для смягчения последствий выбросов парниковых газов и реагирования на возникающие в результате изменения окружающей среды, была принята в 1992 году и вступила в силу два года спустя. По состоянию на 2023 год участниками были 198 штатов. [ 179 ] [ 180 ] Отдельные протоколы были приняты на конференциях сторон , в том числе Киотский протокол , который был принят в 1997 году для установления конкретных целей по сокращению выбросов парниковых газов, и Парижское соглашение 2015 года , которое поставило цель удержать глобальное потепление как минимум на уровне ниже 2 °C (3,6 °C). F) выше доиндустриального уровня. [ 181 ]

Отдельные лица и организации имеют некоторые права в соответствии с международным экологическим правом, поскольку Орхусская конвенция 1998 года установила обязательства государств предоставлять информацию и разрешать участие общественности по этим вопросам. [ 182 ] Однако лишь немногие споры в соответствии с режимами, установленными в природоохранных соглашениях, передаются в Международный суд, поскольку в соглашениях, как правило, указываются процедуры их соблюдения. Эти процедуры, как правило, направлены на то, чтобы побудить государство снова соблюдать требования посредством рекомендаций, но все еще существует неопределенность в отношении того, как должны работать эти процедуры, и были предприняты усилия по регулированию этих процессов, хотя некоторые опасаются, что это снизит эффективность самих процедур. [ 183 ]

Территория и море

[ редактировать ]Правовую территорию можно разделить на четыре категории. Существует территориальный суверенитет , который охватывает сушу и территориальное море, включая воздушное пространство над ним и недра под ним, территорию за пределами суверенитета любого государства, res nullius , которая еще не находится в пределах территориального суверенитета, но является территорией, которая по закону может быть приобретена государство и res communis — это территория, которая не может быть приобретена государством. [ 184 ] Исторически существовало пять методов приобретения территориального суверенитета , отражающих римское право собственности: оккупация, приращение, уступка , завоевание и давность . [ 185 ]

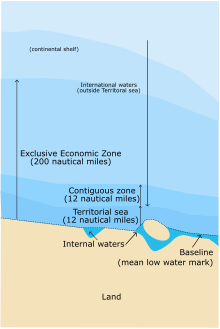

— Морское право это область международного права, касающаяся принципов и правил, согласно которым государства и другие субъекты взаимодействуют в морских вопросах. Он охватывает такие области и вопросы, как права судоходства, права на морские полезные ископаемые и юрисдикция прибрежных вод. [ 186 ] Морское право в основном состояло из обычного права до 20 века, начиная с Конференции по кодификации Лиги Наций в 1930 году, Конференции ООН по морскому праву и принятия ЮНКЛОС в 1982 году. [ 187 ] ЮНКЛОС особенно примечательна тем, что возложила на международные суды и трибуналы ответственность за морское право. [ 188 ]

страны будут составлять три мили. границы территориального моря Первоначально в конце 18 века предполагалось, что [ 189 ] Вместо этого UNCLOS определила его как находящееся на расстоянии не более 12 морских миль от базовой линии (обычно прибрежной отметки отлива) государства; как военным, так и гражданским иностранным кораблям разрешен мирный проход через эти воды, несмотря на то, что море находится под суверенитетом государства. [ 190 ] [ 191 ] Государство может иметь юрисдикцию за пределами своих территориальных вод, если оно претендует на прилежащую зону длиной до 24 морских миль от своей исходной линии с целью предотвращения нарушения своих «таможенных, налоговых, иммиграционных и санитарных правил». [ 192 ] Государства также могут претендовать на исключительную экономическую зону (ИЭЗ) после принятия ЮНКЛОС, которая может простираться на расстояние до 200 морских миль от базовой линии и дает суверенному государству права на природные ресурсы. Вместо этого некоторые штаты предпочли сохранить свои исключительные рыболовные зоны, которые охватывают одну и ту же территорию. [ 193 ] Существуют особые правила в отношении континентального шельфа, поскольку он может простираться дальше, чем на 200 морских миль. Международный трибунал по морскому праву уточнил, что государство имеет суверенные права на ресурсы всего континентального шельфа , независимо от его расстояния от базовой линии, но к континентальному шельфу и водной толще над ним, где оно находится, применяются разные права. находится дальше чем в 200 морских милях от берега. [ 194 ]

UNCLOS определяет открытое море как все части моря, которые не находятся в пределах ИЭЗ, территориального моря или внутренних вод государства. [ 195 ] В открытом море существует шесть свобод — мореплавание, полеты над землей, прокладка подводных кабелей и трубопроводов, строительство искусственных островов, рыбная ловля и научные исследования — некоторые из которых подлежат юридическим ограничениям. [ 196 ] Считается, что корабли в открытом море имеют национальность того флага, под которым они имеют право плавать, и ни одно другое государство не может осуществлять над ними юрисдикцию; Исключением являются суда, используемые для пиратства, на которые распространяется универсальная юрисдикция. [ 197 ]

Финансовое и торговое право

[ редактировать ]В 1944 году Бреттон-Вудская конференция учредила Международный банк реконструкции и развития (позже Всемирный банк ) и МВФ. На конференции было предложено создать Международную торговую организацию , но создать ее не удалось из-за отказа США ратифицировать ее устав. Три года спустя Часть IV статута была принята для создания Генерального соглашения по тарифам и торговле , которое действовало с 1948 по 1994 год, когда была создана ВТО. ОПЕК . , которая объединилась для контроля над мировыми поставками нефти и ценами, привела к отказу от прежней опоры на фиксированные обменные курсы валют в пользу плавающих обменных курсов в 1971 году Во время этой рецессии премьер-министр Великобритании Маргарет Тэтчер и президент США Рональд Рейган настаивали на за свободную торговлю и дерегулирование в рамках неолиберальной программы, известной как Вашингтонский консенсус . [ 198 ]

Конфликт и сила

[ редактировать ]Война и вооруженный конфликт

[ редактировать ]Закон, касающийся начала вооруженного конфликта, является jus ad bellum . [ 199 ] Это было закреплено в 1928 году в Пакте Келлога-Бриана , в котором говорилось, что конфликты должны разрешаться путем мирных переговоров, за исключением, посредством оговорок, составленных некоторыми государствами-участниками, самообороны . [ 200 ] Эти основополагающие принципы были вновь подтверждены в Уставе ООН , который предусматривал «почти абсолютный запрет на применение силы», за лишь тремя исключениями. [ 201 ] [ 202 ] Первый предполагает применение силы, санкционированной СБ ООН, поскольку организация несет ответственность в первую очередь за реагирование на нарушения или угрозы миру и акты агрессии, включая применение силы или миротворческие миссии . [ 203 ] Второе исключение – случаи, когда государство действует в целях индивидуальной или коллективной самообороны. Государству разрешено действовать в порядке самообороны в случае «вооруженного нападения», но намерение, лежащее в основе этого исключения, было поставлено под сомнение, особенно в связи с тем, что ядерное оружие стало более распространенным, и многие государства вместо этого полагаются на обычное право на самооборону. защита, как указано в Кэролайн тесте . [ 204 ] [ 205 ] Международный суд рассмотрел вопрос о коллективной самообороне в деле Никарагуа против Соединенных Штатов , где США безуспешно утверждали, что они заминировали гавани в Никарагуа в целях упреждения нападения сандинистского правительства на другого члена Организации американских государств . [ 206 ] Последним исключением являются случаи, когда СБ ООН делегирует свою ответственность за коллективную безопасность региональной организации , такой как НАТО . [ 207 ]

По гуманитарным соображениям использование наземных мин ( Оттавский договор ) и кассетных боеприпасов ( ККМ ) запрещено международным правом.

Гуманитарное право

[ редактировать ]

Международное гуманитарное право (МГП) – это попытка «смягчить человеческие страдания, вызванные войной», и оно часто дополняет право вооруженных конфликтов и международное право прав человека. [ 208 ] Понятие jus in bello (право войны) охватывает МГП, которое отличается от jus ad bellum . [ 199 ] Его сфера действия простирается от начала конфликта до достижения мирного урегулирования. [ 209 ] В МГП есть два основных принципа; принцип различия требует, чтобы с комбатантами и некомбатантами обращались по-разному, а также принцип не причинения непропорциональных страданий комбатантам. В своей работе «Законность угрозы или применения ядерного оружия » Международный суд назвал эти концепции «непреложными принципами международного обычного права». [ 210 ]

Две Гаагские конвенции 1899 и 1907 годов рассматривали ограничения на ведение войны, а Женевские конвенции 1949 года, организованные Международным комитетом Красного Креста , рассматривали защиту невиновных сторон в зонах конфликтов. [ 211 ] Первая Женевская конвенция распространяется на раненых и больных комбатантов , Вторая Женевская конвенция распространяется на комбатантов на море, которые ранены, больны или потерпели кораблекрушение, Третья Женевская конвенция распространяется на военнопленных , а Четвертая Женевская конвенция распространяется на гражданских лиц. [ 210 ] Эти конвенции были дополнены дополнительными Протоколами I и Протоколами II , которые были кодифицированы в 1977 году. [ 211 ] Первоначально считалось, что конвенции МГП применяются к конфликту только в том случае, если все стороны ратифицировали соответствующую конвенцию в соответствии с оговоркой si omnes , но это вызвало обеспокоенность, и оговорка Мартенса начала применяться, при условии, что закон в целом будет считаться применимым. [ 212 ]

Существовали различные соглашения, запрещающие определенные виды оружия, такие как Конвенция о химическом оружии и Конвенция о биологическом оружии . Международный Суд в 1995 году установил, что применение ядерного оружия противоречит принципам МГП, хотя суд также постановил, что он «не может сделать окончательный вывод о том, будет ли угроза или применение ядерного оружия законными или незаконными в чрезвычайных обстоятельствах самооборона». [ 213 ] Использование этого оружия пытались регулировать многочисленные договоры, в том числе Договор о нераспространении и Совместный всеобъемлющий план действий , но ключевые государства не подписали его или вышли из него. ведутся Подобные дебаты по поводу использования дронов и киберпрограмм и на международной арене. [ 214 ]

Международное уголовное право

[ редактировать ]Международное уголовное право дает определение международных преступлений и обязывает государства осуществлять судебное преследование за эти преступления. [ 215 ] Хотя военные преступления преследовались на протяжении всей истории, исторически это делалось национальными судами. [ 216 ] Международный военный трибунал в Нюрнберге и Международный военный трибунал для Дальнего Востока в Токио были созданы в конце Второй мировой войны для преследования ключевых игроков в Германии и Японии. [ 217 ] Юрисдикция трибуналов ограничивалась преступлениями против мира (на основе Пакта Келлога-Бриана), военными преступлениями (на основе Гаагских конвенций) и преступлениями против человечности , устанавливая новые категории международных преступлений. [ 218 ] [ 219 ] На протяжении двадцатого века отдельные преступления геноцида , пыток и терроризма . также признавались [ 219 ]

Первоначально предполагалось, что эти преступления будут расследоваться национальными судами в соответствии с их внутренними процедурами. [ 220 ] Женевские конвенции 1949 года, Дополнительные протоколы 1977 года и Конвенция ООН против пыток 1984 года предписывали национальным судам договаривающихся стран привлекать к ответственности за эти преступления, если преступник находится на их территории, или выдавать их любому другому заинтересованному государству. [ 221 ] В 1990-е годы два специальных трибунала — Международный уголовный трибунал по бывшей Югославии (МТБЮ) и Международный уголовный трибунал по Руанде (МУТР) для рассмотрения конкретных злодеяний. СБ ООН создал [ 222 ] [ 223 ] МТБЮ имел полномочия преследовать по суду военные преступления, преступления против человечности и геноцид, произошедшие в Югославии после 1991 года , а МУТР имел полномочия преследовать по суду геноцид, преступления против человечности и серьезные нарушения Женевских конвенций 1949 года во время геноцида в Руанде в 1994 году . [ 224 ] [ 225 ]

Международный уголовный суд (МУС), учрежденный Римским статутом 1998 года , является первым и единственным постоянным международным судом, который занимается судебным преследованием за геноцид, военные преступления, преступления против человечности и преступления агрессии . [ 226 ] Участниками МУС являются 123 государства, хотя ряд государств заявили о своем несогласии с судом; его критиковали африканские страны, включая Гамбию и Кению, за «империалистические» преследования. [ 227 ] [ 228 ] Одним из конкретных аспектов суда, который подвергся тщательному изучению, является принцип взаимодополняемости, в соответствии с которым МУС обладает юрисдикцией только в том случае, если национальные суды государства, обладающего юрисдикцией, «не желают или не могут осуществлять судебное преследование» или когда государство провело расследование, но решило не возбуждать уголовное преследование. случай. [ 229 ] [ 230 ] У Соединенных Штатов особенно сложные отношения с МУС ; Первоначально подписав договор в 2000 году, США в 2002 году заявили, что не намерены становиться его стороной, поскольку считают, что МУС угрожает их национальному суверенитету, а страна не признает юрисдикцию суда. [ 231 ] [ 232 ]

Гибридные суды являются новейшим типом международных уголовных судов; они стремятся объединить как национальный, так и международный компоненты, действуя в юрисдикции, где произошли рассматриваемые преступления. [ 233 ] [ 234 ] Международные суды подвергались критике за недостаточную легитимность, поскольку может показаться, что они не связаны с произошедшими преступлениями, но гибридные суды способны предоставить ресурсы, которых может не хватать в странах, переживающих последствия серьезного конфликта. [ 233 ] Были споры о том, какие суды могут быть включены в это определение, но в основном это Специальные комиссии по тяжким преступлениям в Восточном Тиморе , Специализированные палаты Косово , Специальный суд по Сьерра-Леоне , Специальный трибунал по Ливану и Чрезвычайные палаты судов. Камбоджи были включены в список. [ 235 ] [ 226 ] [ 234 ]

Международно-правовая теория

[ редактировать ]Теория международного права включает в себя множество теоретических и методологических подходов, используемых для объяснения и анализа содержания, формирования и эффективности международного права и институтов, а также для предложения улучшений. Некоторые подходы сосредоточены на вопросе соблюдения: почему государства следуют международным нормам при отсутствии силы принуждения, обеспечивающей соблюдение. [ 236 ] [ 237 ] Некоторые ученые рассматривают несоблюдение требований как проблему правоприменения, в результате которой государства могут быть заинтересованы в соблюдении международного права из-за международных стимулов, взаимности, опасений по поводу репутации или внутриполитических факторов. [ 238 ] Другие ученые считают, что несоблюдение требований коренится в недостатке государственного потенциала , когда желающее государство неспособно полностью следовать международно-правовым обязательствам. [ 238 ]

Другие точки зрения ориентированы на политику: они разрабатывают теоретические основы и инструменты для критики существующих норм и внесения предложений о том, как их улучшить. Некоторые из этих подходов основаны на отечественной правовой теории , некоторые являются междисциплинарными , а третьи были разработаны специально для анализа международного права. Классическими подходами к теории международного права являются школы естественного права, эклектики и юридического позитивизма. [ 239 ] [ нужна страница ]

Подход естественного права утверждает, что международные нормы должны основываться на аксиоматических истинах. Писатель естественного права XVI века де Витория исследовал вопросы справедливой войны , испанской власти в Америке и прав коренных американских народов. В 1625 году Гроций утверждал, что нации, как и люди, должны управляться универсальными принципами, основанными на морали и божественной справедливости, в то время как отношения между государствами должны регулироваться законом народов, jus gentium , установленным с согласия сообщества. наций на основе принципа pacta sunt servanda , то есть на основе соблюдения обязательств. Со своей стороны, де Ваттель вместо этого выступал за равенство государств, сформулированное в естественном праве XVIII века, и предполагал, что право наций состоит из обычаев и закона, с одной стороны, и естественного права, с другой. В 17 веке основные положения Гротианской или эклектической школы, особенно доктрины юридического равенства, территориального суверенитета и независимости государств, стали фундаментальными принципами европейской политической и правовой системы и были закреплены в Вестфальском мире 1648 года. . [ нужна ссылка ]

Ранняя позитивистская школа подчеркивала важность обычаев и договоров как источников международного права. В 16 веке Джентили использовал исторические примеры, чтобы утверждать, что позитивное право ( jus voluntarium ) определяется всеобщим согласием. ван Бинкершук утверждал, что основой международного права являются обычаи и договоры, на которые обычно соглашаются различные государства, а Джон Джейкоб Мозер подчеркивал важность государственной практики в международном праве. Школа позитивизма сузила диапазон международной практики, которая могла бы квалифицироваться как право, отдав рациональности морали предпочтение и этике . 1815 года Венский конгресс ознаменовал официальное признание политической и международной правовой системы, основанной на условиях Европы. [ нужна ссылка ] Современные юридические позитивисты рассматривают международное право как единую систему правил, исходящую из воли государств. Международное право, как оно есть, представляет собой « объективную » реальность, которую необходимо отличать от права, «каким оно должно быть». Классический позитивизм требует строгих проверок на юридическую обоснованность и считает неуместными все внеправовые аргументы. [ 240 ]

Альтернативные взгляды

[ редактировать ]Джон Остин утверждал, что из-за принципа par in parem non habet imperium «так называемое» международное право, лишенное суверенной силы и поэтому не имеющее исковой силы, на самом деле было вообще не законом, а «позитивной моралью», состоящей из «мнений и чувства... более этические, чем юридические по своей природе». [ 241 ] Поскольку государства немногочисленны, разнообразны и нетипичны по своему характеру, не поддаются ответственности, не имеют централизованной суверенной власти, а их соглашения не контролируются и децентрализованы, Мартин Уайт утверждал, что международное общество лучше описывать как анархию. [ 242 ]

Ганс Моргентау считал международное право самой слабой и примитивной системой обеспечения правопорядка; он сравнил ее децентрализованную природу с законом, который преобладает в дописьменных племенных обществах. Монополия на насилие – это то, что делает внутреннее законодательство осуществимым; но между странами существует множество конкурирующих источников силы. Путаница, создаваемая договорными законами, которые напоминают частные контракты между людьми, смягчается лишь относительно небольшим числом государств. [ 243 ] Он заявил, что ни одно государство не может быть принуждено передать спор в международный трибунал, что делает законы неисполнимыми и добровольными. Международное право также не контролируется, и у него нет органов, обеспечивающих его соблюдение. Он цитирует опрос общественного мнения в США 1947 года, в котором 75% респондентов хотели, чтобы «международная полиция поддерживала мир во всем мире», но только 13% хотели, чтобы эта сила превосходила вооруженные силы США. Более поздние исследования дали аналогичные противоречивые результаты. [ 244 ]

Проблемы и противоречия

[ редактировать ]Международное право в настоящее время сталкивается со сложным комплексом проблем и противоречий, которые подчеркивают динамичный характер международных отношений в 21 веке. Некоторые из этих проблем включают трудности с правоприменением, влияние технологических достижений, изменение климата и мировые пандемии. [ 245 ] Возможное возрождение права завоевания в качестве международного права является спорным. [ 246 ]

Среди наиболее острых проблем — трудности с правоприменением, когда отсутствие централизованной глобальной власти часто приводит к несоблюдению международных норм, что особенно проявляется в нарушениях международного гуманитарного права (МГП). Споры о суверенитете еще больше усложняют международно-правовую среду, поскольку возникают конфликты по поводу территориальных претензий и границ юрисдикции, бросающие вызов принципам невмешательства и мирного разрешения. Более того, появление новых глобальных держав привносит дополнительные уровни сложности, поскольку эти страны отстаивают свои интересы и бросают вызов устоявшимся нормам, что требует переоценки глобального правового порядка, чтобы приспособиться к меняющейся динамике сил. [ 247 ]

Кибербезопасность также стала серьезной проблемой, поскольку международное право стремится устранить угрозы, создаваемые кибератаками для национальной безопасности, инфраструктуры и личной жизни. Изменение климата требует беспрецедентного международного сотрудничества, о чем свидетельствуют такие соглашения, как Парижское соглашение, хотя неравенство в ответственности между странами создает серьезные проблемы для коллективных действий. [ 248 ]

Пандемия COVID-19 еще раз подчеркнула взаимосвязанность мирового сообщества, подчеркнув необходимость скоординированных усилий по управлению кризисами в области здравоохранения, распространению вакцин и восстановлению экономики. [ 249 ]

Эти современные проблемы подчеркивают необходимость постоянной адаптации и сотрудничества в рамках международного права для решения многогранных проблем современного мира, обеспечения справедливого, мирного и устойчивого глобального порядка.

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Список дел Международного Суда

- Список тем международного публичного права

- Список договоров

- Закон

- Справедливость

- Консульское право

- Авиационное право и космическое право

- Центр международного права (CIL)

- Сравнительное правоведение

- Дипломатическое право и дипломатическое признание

- Глобальное административное право

- Глобальный полицейский

- Международные судебные разбирательства

- Международное сообщество

- Международное конституционное право

- Международное регулирование

- Международные отношения

- Интерпол

- Закон о премиях

- Закон о беженцах

- Подходы третьего мира к международному праву (TWAIL)

- УНИДРУА

- Проект «Верховенство закона в вооруженных конфликтах» (RULAC)

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Хендерсон, Конвей В. (2010). Понимание международного права . Уайли. п. 5. ISBN 978-1-4051-9764-9 .

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 3.

- ^ Янис 1984 , с. 408.

- ^ Янис 1996 , с. 333.

- ^ Онума 2000 , стр. 3–4.

- ^ Стивенсон 1952 , стр. 561–562.

- ^ Стивенсон 1952 , стр. 564–567.

- ^ Стейнхардт 1991 , с. 523.

- ^ Коттеррелл 2012 , с. 501.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Глава 1994 , с. 622.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Деган 1997 , с. 126.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нуссбаум 1954 , стр. 1–2.

- ^ Бедерман 2001 , с. 267.

- ^ Бедерман 2001 , стр. 3–4.

- ^ Нуссбаум 1954 , стр. 5–6.

- ^ Нуссбаум 1954 , стр. 13–15.

- ^ Бедерман 2001 , с. 84.

- ^ Нуссбаум 1954 , стр. 15–16.

- ^ Нуссбаум 1954 , с. 14.

- ^ Нефф 2014 , стр. 17–18.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б деЛисл 2000 , стр. 268–269.

- ^ Нефф 2014 , с. 21.

- ^ Александр 1952 , с. 289.

- ^ Патель 2016 , стр. 35–38.

- ^ Франкот, Прошлое (2007). Средневековое морское право от Олерона до Висби: юрисдикции морского права (PDF) . Plus Edition – Издательство Пизанского университета. ISBN 978-88-8492-462-9 .

- ^ Орахелашвили 2020 , стр. 315–316.

- ^ Башир 2018 , с. 5.

- ^ Хаддури 1956 , с. 359.

- ^ Парвин и Соммер 1980 , стр. 3–4.

- ^ Саид 2018 , с. 299.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2020 , с. 322.

- ^ Нуссбаум 1954 , с. 35.

- ^ Нуссбаум 1954 , стр. 36–39.

- ^ Роден и Сорабджи 2006 , стр. 14, 24–25.

- ^ Хаддури 1956 , стр. 360–361.

- ^ Нуссбаум 1954 , стр. 94–101.

- ^ фон Глан 1992 , стр. 27–28.

- ^ Глава 1994 , с. 614.

- ^ Нуссбаум 1954 , стр. 84–91.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Глава 1994 , стр. 607–608.

- ^ Епремян 2022 , с. 197–200.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2020 , с. 90.

- ^ Глава 1994 , стр. 616–617.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нуссбаум 1954 , с. 147.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2020 , с. 342.

- ^ Саастамойнен 1995 , стр. 14, 36.

- ^ Саастамойнен 1995 , стр. 168.

- ^ Нуссбаум 1954 , стр. 164–172.

- ^ Глава 1994 , с. 617.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2020 , стр. 331–332.

- ^ Осиандер 2001 , с. 260–261.

- ^ Осиандер 2001 , с. 283.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2020 , стр. 343.

- ^ Нуссбаум 1954 , стр. 150–164.

- ^ Вс 2016 , с. 45.

- ^ Нортедж 1986 , стр. 10–11.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2020 , стр. 396–398.

- ^ [Корман, Шэрон. Право завоевания: приобретение территории силой в международном праве и практике. Кларендон Пресс, 1996.]

- ^ Нортедж 1986 , с. 1.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2011 , стр. 482–484.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2011 , стр. 487–489.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Орахелашвили 2011 , стр. 493–494.

- ^ Эванс 2014 , с. 22.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2011 , стр. 498–499.

- ^ Глава 1994 , стр. 620–621.

- ^ Глава 1994 , с. 606.

- ^ Эванс 2014 , стр. 23–24.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 6.

- ^ Прост 2017 , стр. 288–289.

- ^ Шелтон 2006 , с. 291.

- ^ Шао 2021 , стр. 219–220.

- ^ Бассиуни 1990 , с. 768.

- ^ Шао 2021 , стр. 221.

- ^ Бассиуни 1990 , с. 772.

- ^ Шао 2021 , стр. 246–247.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Гардинер 2008 , стр. 20.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Браунли и Кроуфорд, 2012 , с. 179.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 9.

- ^ Клабберс 1996 , с. 38–40.

- ^ Гардинер 2008 , с. 21.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дотан 2019 , с. 766–767.

- ^ Джейкобс 1969 , с. 319.

- ^ Эванс 2014 , стр. 171–175.

- ^ Август 2007 г. , с. 131.

- ^ Гардинер 2008 , стр. 84–85.

- ^ Гардинер 2008 , стр. 86–87.

- ^ Эванс 2014 , с. 191.

- ^ Гардинер 2008 , с. 90.

- ↑ Август 2007 г. , стр. 277–278, 288.

- ^ Август 2007 г. , с. 289–290.

- ^ Август 2007 г. , стр. 312–319.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , стр. 23–24.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2022 , раздел 3.3.1.

- ^ Thirlway 2014 , стр. 54–56.

- ^ Thirlway 2014 , с. 63.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд, 2012 , стр. 24–25.

- ^ Д'Амато 1971 , стр. 57–58.

- ^ Thirlway 2014 , с. 65.

- ^ Харрисон 2011 , с. 13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Тривей 2014 , стр. 74–76.

- ^ Д'Амато 1971 , стр. 68–70.

- ^ Д'Амато 1971 , стр. 70–71.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Орахелашвили 2011 , стр. 508–509.

- ^ Линдерфальк 2007 , с. 854.

- ^ Линдерфальк 2007 , с. 859.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Шелтон 2011 , с. 2.

- ^ Бьёргвинссон 2015 , стр. 19–20.

- ^ Август 2007 г. , стр. 183–185.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Август 2007 , с. 187.

- ^ Август 2007 г. , стр. 189–192.

- ^ Шелтон 2011 , стр. 2–3.

- ^ Шелтон 2011 , стр. 4–5.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , стр. 128–135.

- ^ Бейкер 1923 , стр. 11–12.

- ^ фон Глан 1992 , с. 85.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 144.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд, 2012 , стр. 144–146.

- ^ фон Глан 1992 , с. 86.

- ^ Коллинз и Харрис 2022 , стр. 340–341.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 121.

- ^ Клабберс 2013 , с. 107.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клабберс 2013 , стр. 109–112.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , стр. 132–133.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 73.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Браунли и Кроуфорд, 2012 , стр. 166–167.

- ^ Арчер 2014 , стр. 32–33.

- ^ Шермерс и Блоккер 2011 , с. 61.

- ^ Шермерс и Блоккер 2011 , с. 63.

- ^ Мюллер 1997 , с. 106.

- ^ Клабберс 2013 , стр. 84–85.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , стр. 93–94.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , стр. 171–172.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 180.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Орахелашвили 2011 , с. 493.

- ^ Глава 1994 , стр. 624–625.

- ^ Слагтер, ван Дорн и Сломансон, 2022 , стр. 456.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 188.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , стр. 194–195.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 155.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 159.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 160.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 158.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 161.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , стр. 163–165.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 178.

- ^ Бриггс 2013 , с. 2.

- ^ Коллинз и Харрис 2022 , с. 4.

- ^ Бомонт, Антон и МакЭливи 2011 , с. 374.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Коллинз и Харрис 2022 , с. 272.

- ^ Норт 1979 , стр. 7–8.

- ^ Коллинз и Харрис 2022 , стр. 15–16.

- ^ Норт 1979 , стр. 9–11.

- ^ Бомонт, Антон и МакЭливи 2011 , с. 403.

- ^ Ван Лун 2020 , стр. 6–7.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 301.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2015 , с. 1.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2015 , стр. 54–58.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2015 , стр. 13–14.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2015 , с. 15.

- ^ Слагтер, ван Дорн и Сломансон, 2022 , стр. 267.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2015 , с. 23.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Орахелашвили 2015 , с. 57.

- ^ Мэй и Хоскинс 2009 , с. 17.

- ^ Дугард и др. 2020 , с. 2.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Дугард и др. 2020 , с. 3.

- ^ Дугард и др. 2020 , стр. 5–7.

- ^ Дугард и др. 2020 , с. 8.

- ^ Дугард и др. 2020 , с. 4.

- ^ Дугард и др. 2020 , стр. 4–5.

- ^ Финкин и Мундлак 2015 , стр. 47.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Валтикос 2013 , стр. 4.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Финкин и Мундлак, 2015 , стр. 48–49.

- ^ Валтикос 2013 , стр. 37.

- ^ Финкин и Мундлак 2015 , стр. 51.

- ^ Финкин и Мундлак, 2015 , стр. 53–54.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 282.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2011 , с. 506.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 287.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , стр. 288–289.

- ^ «Статус ратификации Конвенции» . Изменение климата ООН . Проверено 10 мая 2023 г.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , стр. 289–290.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 294.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , стр. 296–297.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 203.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 220.

- ^ Харрисон 2011 , с. 1.

- ^ Ротвелл и др. 2015 , с. 2.

- ^ Дженсен 2020 , стр. 4–5.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 256.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд, 2012 , стр. 257, 260.

- ^ Фроман 1984 , стр. 644–645.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , стр. 265–266.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд, 2012 , стр. 274–277.

- ^ Моссоп 2016 , стр. 2–3.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 296.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд, 2012 , стр. 299–300.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , стр. 301–302, 311.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2011 , с. 505.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кроу и Уэстон-Шойбер, 2013 , с. 7.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 745.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , стр. 746–748.

- ^ Батчер, ван Дорн и Сломансон, 2022 , стр. 456–466.

- ^ Браунли и Кроуфорд 2012 , с. 757.

- ^ Слагтер, ван Дорн и Сломансон, 2022 , стр. 458.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 211.

- ^ Слагтер, ван Дорн и Сломансон, 2022 , стр. 461.

- ^ Слагтер, ван Дорн и Сломансон, 2022 , стр. 466.

- ^ Вс 2016 , с. 24

- ^ Crowe & Weston-Scheuber 2013 , стр. 14–15.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клабберс 2020 , с. 224.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Клабберс 2020 , с. 223.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , стр. 224–225.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 230.

- ^ Клабберс 2020 , с. 231.

- ^ Кассезе 2003 , с. 15.

- ^ Шабас 2020 , с. 1.

- ^ Орахелашвили 2011 , стр. 494–495.

- ^ Шабас 2020 , с. 6.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кассезе 2003 , с. 16.

- ^ Кассезе 2003 , с. 17.

- ^ Кассезе 2003 , с. 9.

- ^ Шабас 2020 , стр. 11–13.

- ^ Кассезе 2003 , с. 11.

- ^ Уолд 2002 , с. 1119.

- ^ Боед 2001 , стр. 60–61.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Орахелашвили 2011 , с. 518.

- ^ «Государства-участники Римского статута» . Международный уголовный суд . Проверено 28 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Коуэлл 2017 , с. 2.

- ^ Берк-Уайт 2002 , с. 8.

- ^ Коуэлл 2017 , с. 8.

- ^ Ральф 2003 , стр. 198–199.

- ^ Тооси, Нахаль (2 апреля 2021 г.). «Байден снимает санкции с чиновников Международного уголовного суда» . Политик . Проверено 28 апреля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Нувен 2006 , стр. 190–191.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Крайер, Робинсон и Васильев, 2019 , стр. 173–175.

- ^ Нувен 2006 , с. 192.

- ^ фон Штайн, Яна (2012), Дунофф, Джеффри Л.; Поллак, Марк А. (ред.), «Двигатели соблюдения требований» , Междисциплинарные перспективы международного права и международных отношений: современное состояние дел , Cambridge University Press, стр. 477–501, ISBN 978-1-107-02074-0

- ^ Симмонс, Бет А. (1998). «Соблюдение международных соглашений» . Ежегодный обзор политической науки . 1 (1): 75–93. дои : 10.1146/annurev.polisci.1.1.75 . ISSN 1094-2939 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Штейн, Яна фон (2010), «Соблюдение международного права» , Оксфордская исследовательская энциклопедия международных исследований , doi : 10.1093/acrefore/9780190846626.013.55 , ISBN 978-0-19-084662-6

- ^ Орахелашвили 2020 .

- ^ Симма и Паулюс 1999 , с. 304.

- ^ Скотт 1905 , стр. 128–130.

- ^ Уайт 1986 , с. 101.

- ^ Моргентау 1972 , стр. 273–275.

- ^ Моргентау 1972 , стр. 281, 289, 323–234.

- ^ Джерия, Мишель Бачелет (2016). «Вызовы международному праву в XXI веке» . Материалы ежегодного собрания ASIL . 110 : 3–11. дои : 10.1017/S0272503700102435 . ISSN 0272-5037 .