Методистская церковь Великобритании

| Методистская церковь [ 1 ] | |

|---|---|

| Классификация | протестант |

| Ориентация | методист |

| Теология | Уэслианский |

| Управление | Коннексионализм |

| Президент | Хелен Кэмерон [ 2 ] |

| Вице-президент | Кэролин Годфри [ 2 ] |

| Ассоциации | Список |

| Область | Великобритания Нормандские острова · Остров Мэн · Гибралтар · Мальта |

| Штаб-квартира | Дом методистской церкви, , 25 Тависток Плейс , Лондон [ 3 ] |

| Источник | 1932 ( Методистский союз ) 1 Великобритания |

| Merger of | |

| Local churches | 4,110 (as of 2019[update])[4] |

| Members | 136,891 (as of 2022[update])[5] |

| Ministers | 3,459 |

| Aid organization | All We Can |

| Official website | methodist |

| 1. The Methodist movement originated in the 18th century | |

Методистская церковь Великобритании — протестантская христианская конфессия в Великобритании и материнская церковь для методистов во всем мире. [ 6 ] Он участвует во Всемирном методистском совете и Всемирном совете церквей, а также в других экуменических ассоциациях.

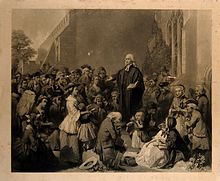

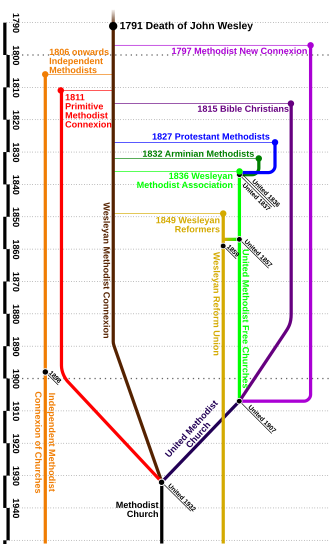

Methodism began primarily through the work of John Wesley, who led an evangelical revival in 18th-century Britain. An Anglican priest, Wesley adopted unconventional and controversial practices, such as open-air preaching, to reach factory labourers and newly urbanised masses uprooted from their traditional village culture at the start of the Industrial Revolution. His preaching centred upon the universality of God's grace for all, the transforming effect of faith on character, and the possibility of perfection in love during this life. He organised the new converts locally and in a "Connexion" across Britain. Following Wesley's death, the Methodist revival became a separate church and ordained its own ministers; it was called a Nonconformist church because it did not conform to the rules of the established Church of England. In the 19th century, the Wesleyan Methodist Church experienced many secessions, with the largest of the offshoots being the Primitive Methodists. The main streams of Methodism were воссоединились в 1932 году , образовав методистскую церковь в ее нынешнем виде.

Methodist circuits, containing several local churches, are grouped into thirty districts. The supreme governing body of the church is the annual Methodist Conference; it is headed by the president of Conference, a presbyteral minister, supported by a vice-president who can be a local preacher or deacon. The denomination ordains women and openly LGBT ministers.

The Methodist Church is Wesleyan in its theology and practice. It uses the historic creeds and bases its doctrinal standards on Wesley's Notes on the New Testament and his Forty-four Sermons.[7]: 213 Church services can be structured with liturgy taken from a service book—especially for the celebration of Holy Communion—but commonly include free forms of worship.

The 2009 British Social Attitudes Survey found that around 800,000 people, or 1.29 per cent of the British population, identified as Methodist.[8] As of 2022[update], active membership stood at approximately 137,000,[5] representing an 32 per cent decline from the 2014 figure.[9] Methodism is the fourth-largest Christian group in Britain.[10] Around 202,000 people attend a Methodist church service each week, while 490,000 to 500,000 take part in some other form of Methodist activity, such as youth work and community events organised by local churches.[11]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]

The movement that would become the Methodist Church originated in the early 18th century within the Church of England. A small group of students at Oxford University, including John Wesley (1703–1791) and his younger brother Charles (1707–1788), met together for the purpose of mutual improvement; they focused on studying the Bible and living a holy life. Other students mocked the group, saying they were the "Holy Club" and "the Methodists",[note 1] being methodical and exceptionally detailed in their Bible study, opinions and disciplined lifestyle.[13][14]

The first Methodist movement outside the Church of England was associated with Howell Harris (1714–1773),[15] who launched the Welsh Methodist revival in the 1730s.[16] This was to become the Calvinistic Methodist Church (today known as the Presbyterian Church of Wales).[17] Another branch of the Methodist revival was under the ministry of George Whitefield (1714–1770), a friend of the Wesleys from the Oxford Holy Club—resulting in the Countess of Huntingdon's Connexion.[18]

The largest branch of Methodism in England was organised by John Wesley. In May 1738 he claimed to have experienced a profound discovery of God in his heart, a pivotal event that has come to be called his evangelical conversion.[19] From 1739, Wesley took to open-air preaching, and converted people to his movement.[20] He formed small classes in which his followers would receive religious guidance and intensive accountability in their personal lives.[21] Wesley also appointed itinerant evangelists to travel and preach as he did and to care for these groups of people. It is a tribute to Wesley's powers of oratory and organisational skills that the term Methodism is today assumed to mean Wesleyan Methodism unless otherwise specified.[17] Theologically, Wesley held to the Arminian belief that salvation is available to all people,[22] in opposition to the Calvinist ideas of election and predestination that were accepted by the Calvinistic Methodists.[17]

Methodist preachers were famous for their impassioned sermons, though opponents accused them of "enthusiasm", i.e. fanaticism.[23] During Wesley's lifetime, many members of England's established church feared that new doctrines promulgated by the Methodists, such as the necessity of a new birth for salvation, and of the constant and sustained action of the Holy Spirit upon the believer's soul, would produce ill effects upon weak minds. Theophilus Evans, an early critic of the movement, even wrote that it was "the natural Tendency of their Behaviour, in Voice and Gesture and horrid Expressions, to make People mad."[24] In one of his prints, William Hogarth likewise attacked Methodists as enthusiasts full of "Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism".[25] Other attacks against the Methodists were physically violent—Wesley was nearly murdered by a mob at Wednesbury in 1743.[26] The Methodists responded vigorously to their critics and thrived despite the attacks against them.[27]

As Wesley and his assistants preached around the country they formed local societies, authorised and organised through Wesley's leadership and conferences of preachers. Wesley insisted that Methodists regularly attend their local parish church as well as Methodist meetings.[28] In 1784, Wesley made provision for the continuance as a corporate body after his death of the 'Yearly Conference of the People called Methodists'.[29] He nominated 100 people and declared them to be its members and laid down the method by which their successors were to be appointed. The Conference has remained the governing body of Methodism ever since.[29]

Separation from the Church of England

[edit]

As his societies multiplied, and elements of an ecclesiastical system were successively adopted, the breach between Wesley and the Church of England (Anglicanism) gradually widened. In 1784, Wesley responded to the shortage of priests in the American colonies due to the American Revolutionary War by ordaining preachers for America with power to administer the sacraments.[30] Wesley's actions precipitated the split between American Methodists and the Church of England (which holds that only bishops can ordain persons to ministry).[31]

With regard to the position of Methodism within Christendom, "John Wesley once noted that what God had achieved in the development of Methodism was no mere human endeavor but the work of God. As such it would be preserved by God so long as history remained."[32] Calling it "the grand depositum" of the Methodist faith, Wesley specifically taught that the propagation of the doctrine of entire sanctification was the reason that God raised up the Methodists in the world (see § Wesleyan theology).[33]

British Methodism separated from the Church of England soon after the death of Wesley. There were early contentions over the powers of preachers and the Conference, and the timing of chapel services.[34] At this point in time a majority of Methodist members were not attending Anglican church services.[34] The 1795 Plan of Pacification permitted Methodist chapels to celebrate Holy Communion where both a majority of trustees and a majority of the stewards and leaders allowed it.[35] (These services often used Wesley's abridgement of the Book of Common Prayer.[35]) This permission was later extended to the administration of baptism, burial and timing of services, bringing Methodist chapels into direct competition with the local parish church. Consequently, known Methodists were excluded from the Church of England.[34] Alexander Kilham and his 'radicals' denounced the Conference for giving too much power to the ministers of the church at the expense of the laity. In 1797, following the Plan of Pacification, Kilham was expelled from the church. The radicals formed the Methodist New Connexion, while the original body came to be known as the Wesleyan Methodist Church.[34]

1790 to 1900

[edit]

Early growth

[edit]Early Methodists were systematic in collecting statistics on membership.[36] Their growth was rapid, from 58,000 in 1790 to 302,000 in 1830 and 518,000 in 1850.[37] Those were the official members, but the national census of 1851 counted people with an informal connection to Methodism, and the total was 1,463,000.[37] Growth was steady in both rural and urban areas, despite disruption caused by numerous schisms; these resulted in separate denominations (or "connexions") such as the Wesleyan Methodist Church, the first and largest, followed by the New Connexion, the Bible Christian Church and the Primitive Methodist Church.[37] Some of the growth can be attributed to the failure of the established Church of England to provide church facilities.[38] In the later 19th century a programme of church building by the established church, in competition with the Nonconformists, increased the number of church-attending Anglicans.[39] This reduced the opportunities for the Nonconformists in general and the Methodists in particular to keep growing. Membership reached 602,000 in 1870 and peaked at 841,000 in 1910.[40][41]

Early Methodism was particularly prominent in Devon and Cornwall, which were key centres of activity by the Bible Christian faction.[42] The Bible Christians produced many preachers, and sent many missionaries to Australia.[43] Methodism as a whole grew rapidly in the old mill towns of Yorkshire and Lancashire, where the preachers stressed that the working classes were equal to the upper classes in the eyes of God.[44] In Wales, three elements separately welcomed Methodism: Welsh-speaking, English-speaking, and Calvinistic.[45]

The independent Methodist movement did not appeal to England's landed gentry; they favoured the developing evangelical movement inside the Church of England. However, Methodism became popular among ambitious middle class families.[46] For example, the Osborn family of Sheffield, whose steel company emerged in the mid-19th century in Sheffield's period of rapid industrialisation. Historian Clyde Binfield says their fervent Methodist faith strengthened their commitment to economic independence, spiritual certainty and civic responsibility.[46]

Methodism was especially popular among skilled workers and much less prevalent among labourers. Historians such as Élie Halévy, Eric J. Hobsbawm, E. P. Thompson, and Alan Gilbert have explored the role of Methodism in the early decades of the making of the British working class (1760–1820). On the one hand it provided a model of how to efficiently organise large numbers of people and sustain their connection over a long period of time, and on the other it diverted and discouraged political radicalism.[47] In explaining why Britain did not undergo a social revolution in the period 1790–1832, a time that appeared ripe for violent social upheaval, Halévy argued that Methodism forestalled revolution among the working class by redirecting its energies toward spiritual affairs rather than workplace concerns.[48] Thompson argues that overall it had a politically regressive effect.[49]

Leadership

[edit]

John Wesley was the longtime president of the Methodist Conference, but after his death it was agreed that in future, so much authority would not be placed in the hands of one man. Instead, the president would be elected for one year, to sit in Wesley's chair.[2] Successive Methodist schisms resulted in multiple presidents, before a united conference assembled in 1932.

Wesley wrote, edited or abridged some 400 publications. As well as theology he wrote about music, marriage, medicine, abolitionism and politics.[50] Wesley himself and the senior leadership were political conservatives. Although many trade union leaders were attracted to Methodism—the Tolpuddle Martyrs being an early example[51]—the church itself did not actively support the unions. Historians Patrick K. O'Brien and Roland Quinault argue:

John Wesley's own Tory sympathies and autocratic instincts had been strong and genuine, and as far as possible he had instilled into his followers deference toward established social and religious authorities. He emphasised political quietism. His mission he saw as strictly spiritual, and his own inherently conservative political instincts and social values reinforced a pragmatic concern to give as little offense as possible to a suspicious wider society. These same motives influenced the ministerial oligarchy...."Methodism" said Jabez Bunting...hates democracy as it hates sin."[52]

Jabez Bunting (1779–1858) was the most prominent leader of the Wesleyan Methodist movement after Wesley's death. He preached successful revivals until 1802, when he saw revivals leading to dissension and division. He then became dedicated to church order and discipline, and vehemently opposed revivalism.[53] He was a popular preacher in numerous cities. He was four times chosen to be president of the Conference and held numerous senior positions as administrator and watched budgets very closely. Bunting and his allies centralised power by making the Conference the final arbiter of Methodism, and giving it the power to reassign preachers and select superintendents. He was zealous in the cause of foreign missions. In English politics he was conservative. He had little tolerance for liberal elements or for Sunday schools and temperance crusades, which led to expulsion of his opponents, whereupon a third of the members broke away in 1849. Numerous alliances with other groups failed and weakened his control.[53][54]

William Bramwell (1759–1818) was a preacher who engendered controversy due to his intense revivalist preaching style, which spurred awakenings throughout the north of England—including the 1793–97 Yorkshire Revival—and his association with Alexander Kilham (1762–1798). Kilham was a revivalist who led the New Connexion secession from mainstream Wesleyan ministry.[55]

Hugh Price Hughes (1847–1902) was the first superintendent of the West London Methodist Mission, a key Methodist organisation. Recognised as one of the greatest orators of his era, he also founded and edited an influential newspaper, the Methodist Times in 1885. Hughes played a key role in leading Methodists into the Liberal Party coalition, away from the Conservative leanings of previous Methodist leaders.[56][57]

John Scott Lidgett (1854–1953) achieved prominence both as a theologian and reformer by stressing the importance of the church's engagement with the whole of society and human culture. He promoted the Social Gospel and founded the Bermondsey Settlement to reach the poor of London, as well as the Wesley Guild, a social organisation aimed at young people which reached 150,000 members by 1900.[58][59]

Women

[edit]Early Methodism experienced a radical and spiritual phase that allowed women authority in church leadership. In 1771, Mary Bosanquet (1739–1815) wrote to John Wesley to defend hers and Sarah Crosby's work preaching and leading classes at her orphanage, Cross Hall.[60] Her argument was that women should be able to preach when they experienced an "extraordinary call".[60][61] Wesley accepted Bosanquet's argument, and formally began to allow women to preach in Methodism in 1771.[61] In general, the role of the woman preacher emerged from the sense that the home should be a place of community care and should foster personal growth. Women gained self-esteem at this time when members were encouraged to testify about the nature of their faith. Methodist women formed a community that cared for the vulnerable, extending the role of mothering beyond physical care.[62] However the centrality of women's role sharply diminished after 1790 as the Methodist movement became more structured and more male dominated.[61]

In the 18th century Selina Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon, (1707–91) played a major role in financing and guiding early Methodism. Hastings was the first female principal of a men's college in Wales, Trevecca College, for the education of Methodist ministers.[63] She financed the building of 64 chapels in England and Wales, wrote often to George Whitefield and John Wesley, and funded mission work in colonial America. She is best remembered for her adversarial relationships with other Methodists who objected to a woman having power.[63][64]

Youth and education

[edit]Methodists placed a high priority on close guidance of their youth, as seen in the activities of Sunday schools and the Band of Hope (whose members signed a pledge to "abstain from all intoxicating liquors").[65][66]

Wesley himself opened schools at The Foundery in London, and Kingswood School. A Wesleyan report in 1832 said that for the church to prosper the system of Sunday schools should be augmented by day-schools with educated teachers. It was proposed in 1843 that 700 new day-schools be established within seven years. Though a steady increase was achieved, that ambitious target could not be reached, in part limited by the number of suitably qualified teachers. Most teachers came from one institution in Glasgow. The Wesleyan Education Report for 1844 called for a permanent Wesleyan teacher-training college. The result was the foundation of Westminster Training College at Horseferry Road, Westminster in 1851.[68]

19th-century England lacked a state school system; the major supplier was the Church of England. The Wesleyan Education Committee, which existed from 1838 to 1902, has documented Methodism's involvement in the education of children. At first most effort was placed in creating Sunday schools. In 1837 there were 3,339 Sunday schools with 59,297 teachers and 341,443 pupils.[69] In 1836 the Wesleyan Methodist Conference gave its blessing to the creation of 'Weekday schools'.[70][71] In 1902 the Methodists operated 738 schools, so their children would not have to learn from Anglican teachers. The Methodists, along with other Nonconformists, bitterly opposed the Education Act 1902, which funded Church of England schools and funded Methodists schools too but placed them under local education authorities that were usually controlled by Anglicans.[72] In the 20th century the number of Methodist Church-operated schools declined, as many became state-run schools, with only 28 still operating in 1996.[73]

Colonial missions

[edit]Through vigorous missionary work, Methodism spread throughout the British Empire. It was especially successful in the new United States, thanks to the Second Great Awakening of the early 19th century. English emigrants brought Methodism to Canada and Australia.[74] British and American missionaries reached out to India and some other imperial colonies.[75] In general the conversion efforts were only modestly successful, but reports back to Britain did have an influence in shaping how Methodists understood the wider world.[76]

Nonconformist conscience

[edit]Historians group Methodists together with other Protestant groups as "Nonconformists" or "Dissenters", standing in opposition to the established Church of England. In the 19th century the Dissenters who went to chapel comprised half the people who actually attended services on Sunday. The "Nonconformist conscience" was their moral sensibility which they tried to implement in British politics.[77][78] The two categories of Dissenters, or Nonconformists, were in addition to the evangelicals or "Low Church" element in the Church of England. "Old Dissenters", dating from the 16th and 17th centuries, included Baptists, Congregationalists, Quakers, Unitarians, and Presbyterians outside Scotland. "New Dissenters" emerged in the 18th century and were mainly Methodists, especially the Wesleyan Methodists.[77]

The "Nonconformist conscience" of the "Old" group emphasised religious freedom and equality, pursuit of justice, and opposition to discrimination, compulsion and coercion. The "New Dissenters" (and also the Anglican evangelicals) stressed personal morality issues, including sexuality, family values, temperance, and Sabbath-keeping. Both factions were politically active, but until the mid-19th century the Old group supported mostly Whigs and Liberals in politics, while the New generally supported Conservatives. However the Methodists changed and in the 1880s moved into the Liberal Party, drawn in large part by Gladstone's intense moralism. The result was a merging of the Old and New, strengthening their great weight as a political pressure group.[79][80] They joined on new issues especially supporting temperance and opposing the Education Act 1902, with the former of special interest to Methodists.[81][82] By 1914 the conscience was weakening and by the 1920s it was virtually dead politically.[83]

Architecture

[edit]

In the early days of Methodism chapels were sometimes built octagonal, largely to avoid conflict with the established Church of England. The first was in Norwich (1757); it was followed by Rotherham (1761), Whitby (1762), Yarm (1763), Heptonstall (1764) and nine others. John Wesley personally approved the design of the octagonal chapels, stating, "It is better for the voice and on many accounts more commodious than any other." He is also said to have added—"there are no corners for the devil to hide in".[84]

Methodist Heritage records the Yarm chapel as the oldest in England in continual use as a place of Methodist worship.[85] Its design and construction were overseen by Wesley, who preached at the chapel frequently and declared it as his "favourite".[85]

Nevertheless, the Heptonstall chapel has also contested for the title of oldest octagon chapel in continual use.[86] The building featured in the BBC television series Churches: How to Read Them. Presenter Richard Taylor named it as one of his ten favourite churches, saying: "If buildings have an aura, this one radiated friendship."[87]

Primitive Methodism

[edit]The Wesleyan Methodists' rejection of revivals and camp meetings led to the founding in 1820 of the Primitive Methodist Connexion in England and Scotland, which emphasised those practices. It was a democratic, lay-oriented movement. Its social base was among the poorer members of society; they appreciated both its content (damnation, salvation, sinners and saints) and style (direct, spontaneous, and passionate). It offered an alternative to the more middle class Wesleyan Methodists and the upper class controlled Anglican established church, and in turn sometimes led adherents to Pentecostalism.[88] The Primitive Methodists were poorly funded and had trouble building chapels or schools and supporting ministers.[89] Growth was strong in the middle 19th century. Membership declined after 1900 because of growing secularism in society, a resurgence of Anglicanism among the working classes, competition from other Nonconformist denominations (including former Methodist minister William Booth's Salvation Army), and competition among different Methodist branches.[90]

The leading theologian of the Primitive Methodists was Arthur Peake (1865–1929), professor of biblical criticism at the University of Manchester, 1904–29. He was active in numerous leadership roles and promoted Methodist Union that came about in 1932 after his death. He popularised modern biblical scholarship, including the new higher criticism. He approached the Bible not as the infallible word of God, but as the record of revelation written by fallible humans.[91]

1900 to present

[edit]Reunification

[edit]The second half of the 19th century saw many of the small schisms reunited to become the United Methodist Free Churches, and a further union in 1907 with the Methodist New Connexion and Bible Christian Church brought the United Methodist Church into being. In 1908 the major three branches were the Wesleyan Methodists, the Primitive Methodists, and the United Methodists. Membership of the various Methodist branches peaked at 841,000 in 1910, then fell steadily to 425,000 in 1990.[41]

After the late 19th century evangelical approaches to the unchurched were less effective and less used. Methodists paid more attention to their current membership, and less to outreach, while middle-class family size shrank steadily.[92] There were fewer famous preachers or outstanding leaders. The theological change that emphasised the conversion experience as being a one-time lifetime event rather than as a step on the road to perfection lessened the importance of class-meeting attendance and made revivals less meaningful.[93] The growth mechanisms that had worked so well in the expansion phase in the early 19th century were largely discarded, including revivals and the personal appeal in class meetings, as well as the love feast, the Sunday night prayer meeting, and the open-air meeting. The failure to grow was signalled by the flagging experience of the Sunday schools, whose enrolments fell steadily.[94][95]

With the Methodist Union of 1932 the three main Methodist connexions in Britain—the Wesleyans, Primitive Methodists, and United Methodists—came together to form the present Methodist Church.[96] Some offshoots of Methodism, such as the Independent Methodist Connexion, remain totally separate organisations.[97]

Attempts to reverse the decline

[edit]After the union of 1932 many towns and villages were left with rival Methodist churches and circuits that were slow to amalgamate.[98] Methodist historian Reginald Ward states that because unification was unevenly implemented until the 1950s, it distracted attention away from the urgent need to revive the fast-shrinking movement. The hoped-for financial gains proved to be illusory, and Methodist leaders spent the early post-war era vainly trying to achieve union with the Church of England.[99] Multiple approaches were used to turn around the membership decline and flagging zeal in the post-war era, but none worked well. For example, Methodist group tours were organised, but they ended when it was clear they made little impact.[100]

During the 20th century Methodists increasingly embraced Christian socialist ideas. Donald Soper (1903–1998) was perhaps the most widely recognised Methodist leader. An activist, he promoted pacifism and nuclear disarmament in cooperation with the Labour Party.[101] Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher was a moralistic Methodist; Soper denounced her policies as unchristian. However, in "the battle for Britain's soul" she was reelected over and over.[102] Methodist historian Martin Wellings says of Soper:

His combination of modernist theology, high sacramentalism, and Socialist politics, expressed with insouciant wit and unapologetic élan, thrilled audiences, delighted admirers, and reduced opponents to apoplectic fury.[101]

In 1967, Soper, then the only Methodist minister in the House of Lords, lamented that:

To-day we are living in what is the first genuinely pagan age—that is to say, there are so many people, particularly children, who never remember having heard hymns at their mother's knee, as I have, whose first tunes are from Radio One, and not from any hymn book; whose first acquaintance with their friends and relations and other people is not in the Sunday School or in the Church at all, as mine was.[103]

Scholars have suggested multiple possible reasons for the decline, but have not agreed on their relative importance. Wellings lays out the "classical model" of secularization, while noting that it has been challenged by some scholars.

The familiar starting-point, a classical model of secularization, argues that religious faith becomes less plausible and religious practice more difficult in advanced industrial and urbanized societies. The breakdown or disruption of traditional communities and norms of behavior; the spread of a scientific world-view diminishing the scope of the supernatural and the role of God; increasing material affluence promoting self-reliance and this-worldly optimism; and greater awareness and toleration of different creeds and ideas, encouraging religious pluralism and eviscerating commitment to a particular faith, all form components of the case for secularization. Applied to the British churches in general by Steve Bruce and to Methodism in particular by Robert Currie, this model traces decline back to the Victorian era and charts in the twentieth century a steady ebbing of the sea of faith.[101][104]

Over the ten-year period from 2006 to 2016 membership decreased from 262,972 to 188,398. This represents a decline at a rate of 3.5 per cent year-on-year.[11][105] There were 4,512 local churches in the denomination.[11] Over the following three years to 2019 the rate of decline slowed slightly, as membership reduced to under 170,000, and church numbers to 4,110.[4]

Worship and liturgy

[edit]

Methodism was endowed by the Wesley brothers with worship characterised by a twofold practice: the sacramental liturgy of the Anglican Book of Common Prayer on the one hand and the free form "service of the word", i.e. a Nonconformist preaching service, on the other.[106][107] Listening to the reading of Scripture and a sermon based upon the biblical text is virtually always included in Methodist worship.[106] The Methodist Church follows the Revised Common Lectionary, in common with other major denominations in Britain.[108] Similar to most historic Christian churches, the Methodist Church has official liturgies for services such as Holy Communion (the Lord's Supper), Baptism, Ordination, and Marriage. These and other patterns of worship are contained in the Methodist Worship Book, the most recent Methodist service book.[109] It states in its preface that worship is "a gracious encounter between God and the Church. God speaks to us, especially through scripture read and proclaimed and through symbols and sacraments. We respond chiefly through hymns and prayers and acts of dedication."[110] Methodism has typically allowed for freedom in how the liturgy is celebrated—the Worship Book serves as a guideline, but ministers, preachers and other worship leaders are not obligated to use it.[note 2]

The Methodist Church has used a succession of hymnals (hymn books) and service books. The Methodist Hymn-Book (1933) was the first hymnal published after the 1932 union.[109] In 1936 the church authorised the Book of Offices,[note 3] including an "Order for Morning Prayer", which followed the precedent of Wesleyan liturgies based on the Book of Common Prayer (1662).[112][113] Later, the Methodist Service Book (1975) modernised the language used in the Communion prayers; its widespread usage has been cited as a cause for more frequent celebration of Communion in the Methodist Church.[114] The publication of a new hymnal, Hymns and Psalms (1983), expanded the repertoire of 20th-century compositions.[109]

The Methodist Worship Book (1999) includes a wider range of services for every season; it continues the 1975 service book's intention of preserving Methodist traditions while taking into account the insights of the liturgical renewal movement.[113][114] News media took interest in its publication due to the utilisation of gender-neutral language and the inclusion of a prayer addressed to "God our Father and our Mother ".[114] This prayer was viewed by some traditionalists as a "challenging" departure from the masculine language which is traditionally used when referring to God.[115]

Hymnody is used to communicate doctrine, and is recognised as a central feature of Methodism's liturgical identity.[116] The church is known for its rich musical tradition, and Charles Wesley was instrumental in writing many of the popular hymns sung by Methodist congregations.[117][118][119] Singing the Faith is the current hymnal, published by the church in 2011.[120] It contains 748 hymns and songs and 42 liturgical settings (such as the Kyrie, the Sanctus and the Lord's Prayer, as well as material from the Taizé and Iona traditions).[120] There are also 50 canticles and psalms, selected on the basis of their use within liturgy.[120] The collection of 89 hymns by Charles Wesley[121] is a reduction from over 200 in the 1933 Hymn-Book.[109]

Holy Communion

[edit]Methodist congregations celebrate Holy Communion within a Sunday service generally at least once a month.[122] The practice of an open table is now widespread in the Methodist Church. Although the phrasing and exact requirements in a particular local church may vary, generally "all those who love the Lord Jesus Christ"[123]: 7 are invited to receive bread and wine, irrespective of age or denominational identity. However this is not historic Methodist practice. Guidelines about Children and Holy Communion, issued in 1987, affirmed that those receiving communion should, if not already baptised, be encouraged to be baptised—though acknowledging that this "theological principle" was not widely adhered to.[123]

Covenant Service

[edit]A distinctive liturgical feature of British Methodism is the Covenant Service. Methodists annually follow the call of John Wesley for a renewal of their covenant with God.[124] In 1755, Wesley crafted the original Covenant Service using material from the writings of eminent clerics Joseph and Richard Alleine. In 1780, Wesley printed an excerpt from Richard Alleine's Vindiciae Pietatis, which is prayer for renewal of a believer's covenant with God.[125] This excerpt, known in modified form as the Wesley Covenant Prayer, remained in use—linked with Holy Communion and observed on the first Sunday of the New Year—among Wesleyan Methodists until 1936.[125] In the 1920s, Wesleyan minister George B. Robson expanded the form of the Covenant Service by replacing most of the exhortation with prayers of adoration, thanksgiving and confession. Robson's Covenant Service was revised and officially authorised for use in the Book of Offices (1936). Further revisions, strengthening the link with Communion and intercession for the wider church and the world, appeared in the Service Book (1975) and Worship Book (1999).[125] This Covenant Prayer, which has been adopted by other Christian traditions, has been described as "a celebration of all that God has done and an affirmation that we give our lives and choices to God".[126]

Doctrine

[edit]Core beliefs

[edit]A summary of Methodist doctrine is contained in the Catechism for the Use of the People Called Methodists.[127] Some core beliefs that are affirmed by most Methodists include:

- The belief that God is all-knowing, possesses infinite love, is all-powerful, and the creator of all things.

- God has always existed and will always continue to exist.

- God is three persons in one: the Father, the Son (Jesus Christ), and the Holy Spirit.

- God is the master of all creation and humans are meant to live in a holy covenant with him. Humans have broken this covenant by their sins but all can be forgiven through the saving grace of Jesus Christ.

- Jesus was God in human form, who died by crucifixion as a sacrifice to achieve atonement for the sins of all people, and who was resurrected to bring them hope of eternal life.

- God's pardon for guilty sinners is granted to and received through faith alone.

- The grace of God is seen by people through the work of the Holy Spirit in their lives and in their world. (Scriptural holiness.)

- Scripture, comprising the Old and New Testaments, records divine revelation and is the primary source of authority for Christians.

- Baptism and the Lord's Supper (commonly called Holy Communion) are the two sacraments instituted by Jesus:

- Baptism involves being sprinkled with water or total immersion in it. This symbolises being brought into the community of faith; the sacrament requires a response of repentance and faith in Jesus Christ.[128] The church practices infant baptism in anticipation of a response to be made later in confirmation.[129]

- The Lord's Supper is a sacrament in which participants eat bread and drink wine in memory of the Last Supper. The Catechism states, "Jesus Christ is present with his worshipping people ... As they eat the bread and drink the wine, through the power of the Holy Spirit they receive him by faith and with thanksgiving."[130]

Wesleyan theology

[edit]Wesleyan tradition stands at a unique cross-roads between evangelical and sacramental, between liturgical and charismatic, and between Anglo-Catholic and Reformed theology and practice.[131] It has been characterised as Arminian theology with an emphasis on the work of the Holy Spirit to bring holiness into the life of the participating believer. The Methodist Church teaches the Arminian concepts of free will, conditional election, and sanctifying grace. John Wesley was perhaps the clearest English proponent of Arminianism.[132][133] Wesley taught that salvation is achieved through "divine/human cooperation" (which is referred to as synergism),[134][135] however, one cannot either turn to God nor believe unless God has first drawn a person and implanted the desire in their heart (the Wesleyan doctrine of prevenient grace).[136]

Wesley believed that certain aspects of the Christian faith required special emphasis.[137] Wesleyan Methodist minister William Fitzgerald (1856–1931) summarised the core emphases of Wesleyan doctrine by using four statements that collectively are called the 'Four Alls'.[138] These are expressed:

- All people need to be saved (total depravity)

- All people can be saved (unlimited atonement)

- All people can know they are saved (assurance of faith)

- All people can be saved to the uttermost (Christian perfection)[139]

Wesley described the mission of Methodism as being "to spread scriptural holiness over the land".[140] Methodists believe that inner holiness (sanctification) should be evidenced by external actions (that is, outward holiness), such as avoiding ostentation, dressing modestly, and acting honestly.[141] Wesley made much of the ongoing process or "journey" of sanctification, occasionally even seeming to claim that believers could to some degree attain perfection in this life.[142][note 4]

It is a traditional position of the Methodist Church that any disciplined theological work calls for the careful use of reason by which to understand God's action and will.[113] However, Methodists also look to Christian tradition as a source of doctrine. Wesley himself believed that the living core of the Christian faith was revealed in the Bible as the sole foundational source. The centrality of Scripture was so important for Wesley that he called himself "a man of one book".[144] Methodism has also emphasised a personal experience of faith; this is linked to the Methodist doctrine of assurance. These four elements taken together form the Wesleyan Quadrilateral.[145]

Scripture

[edit]According to a conference report, A Lamp to my Feet and a Light to my Path (1998),[note 5][146] there are different perspectives on biblical authority which are held within the Methodist Church. The report summarises a range of views, as follows:[147]

- The Bible is the Word of God and is therefore inerrant (free of all error and entirely trustworthy in everything which it records) and has complete authority in all matters of theology and behavior....

- The Bible's teaching about God, salvation and Christian living is entirely trustworthy. It cannot be expected, however, to provide entirely accurate scientific or historical information....

- The Bible is the essential foundation on which Christian faith and life are built. However, its teachings were formed in particular historical and cultural contexts and must therefore be read in that light....

- The Bible's teaching, while foundational and authoritative for Christians, needs to be interpreted by the church.... Church tradition is therefore high importance as a practical source of authority.

- The Bible is one of the main ways in which God speaks to the believer... Much stress is placed on spiritual experience itself, which conveys its own compelling authority.

- The Bible witnesses to God's revelation of himself through history and supremely through Jesus Christ. However, the Bible is not itself that revelation, but only the witness to it.... Reason, tradition and experience are as important as the biblical witnesses.

- The Bible comprises a diverse and often contradictory collection of documents which represent the experiences of various people in various times and places. The Christian's task is to follow, in some way, the example of Christ. And to the extent that the Bible records evidence of his character and teaching it offers a useful resource.

Doctrinal standards

[edit]The Methodist Church understands itself to be part of the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church.[148] It recognises the historic creeds—the Apostles' Creed and the Nicene Creed—as two statements of belief which have been in use since the earliest days of the Christian Church,[149] and which may be used in church services; alongside these a short "affirmation of faith" is also set out in the Methodist Worship Book.[150]

Although Methodist practices and interpretation of beliefs have evolved over time, these practices and beliefs can be traced to the writings, hymns and sermons of the church's founders,[151] especially John Wesley and Charles Wesley. The Methodist Church does not possess a strict set of doctrines comparable to that of the Westminster Confession, but it does specify general doctrinal standards, as follows:

The Methodist Church claims and cherishes its place in the Holy Catholic Church which is the Body of Christ. It rejoices in the inheritance of the apostolic faith and loyally accepts the fundamental principles of the historic creeds and of the Protestant Reformation. It ever remembers that in the providence of God Methodism was raised up to spread scriptural holiness through the land by the proclamation of the evangelical faith and declares its unfaltering resolve to be true to its divinely appointed mission.

The doctrines of the evangelical faith which Methodism has held from the beginning and still holds are based upon the divine revelation recorded in the Holy Scriptures. The Methodist Church acknowledges this revelation as the supreme rule of faith and practice. These evangelical doctrines to which the preachers of the Methodist Church are pledged are contained in Wesley's Notes on the New Testament and the first four volumes of his sermons.

The Notes on the New Testament and the 44 Sermons are not intended to impose a system of formal or speculative theology on Methodist preachers, but to set up standards of preaching and belief which should secure loyalty to the fundamental truths of the gospel of redemption and ensure the continued witness of the Church to the realities of the Christian experience of salvation.

— Deed of Union (1932)[7]: 213

Evangelism

[edit]The church is also evangelistic, i.e. concerned with spreading the Christian gospel. Being an evangelistic church is considered an integral part of the Methodist calling. The church offers a course called Everyone an evangelist, reflecting the church's evangelism and growth strategy and its focus on personal testimony.[152][153]

Positions on social and moral issues

[edit]Life issues

[edit]The Methodist Conference statement of 1976 says that the termination of any form of human life cannot be regarded superficially.[154] The church has also stated that the "unborn human" should be accorded rights progressively as it develops through the stages of gestation, from embryo to fetus, culminating with full respect as an individual at birth.[155] The 1976 statement gives examples of circumstances in which abortion may be permissible; these include situations where the life or health of the mother is at risk, in cases of serious abnormality where the child is incapable of survival, and in cases where the right of the unborn child to be healthy and wanted may not be met.[154] The Methodist Church believes that its members should work toward the elimination of the need for abortion by advocating for social support for mothers. The conference statement argues that "abortion must not be regarded as an alternative to contraception", and disagrees with complete legalisation, recommending that abortion "should remain subject to a legal framework and to responsible counselling and to medical judgement."[154] Within this legal framework, it advocates limiting elective abortions to 20 weeks of pregnancy.[156] The church generally approved of the Abortion Act 1967 which made abortion legal only under certain circumstances.[156][154] It also supports the use of "responsible contraception" and family planning as ways to prevent unwanted pregnancies.[157]

The Methodist Church strongly opposes assisted suicide and euthanasia. The conference statement of 1974 states: "The final stage of an illness is not one which need represent the ultimate defeat for the doctor or nurse, but a supreme opportunity to help the patient at many levels, including those relating to emotional and spiritual well-being ... Dedicated workers in this field of care, including specialised hospices, demonstrate that it is possible to deal with all the symptoms which cause problems to the patient ... Euthanasia, assisted dying – both are artificial precipitation of death. Many Christians believe this idea is wrong. An approach to death as outlined above makes euthanasia inappropriate and irrelevant."[158]

The Methodist Church supported the campaign to abolish capital punishment in the United Kingdom, and since then has totally opposed its reintroduction.[159]

Sexuality and marriage

[edit]Within the Methodist Church members have a broad range of views about sexual morality, relationships, and the purpose of marriage.[160] The church condemns all practices of sexuality "which are promiscuous, exploitative or demeaning in any way".[161] In his 1743 tract "Thoughts on Marriage and a Single Life", John Wesley taught that the ability to live a single life is given by God to all believers, although few people are able to accept this gift. He also taught that no one should forbid marriage.[162]

In 1993 the Methodist Conference met in Derby and passed six resolutions covering issues related with human sexuality (known as the "Derby Resolutions" or "1993 Resolutions"). Among these, the conference at the time reaffirmed the traditional Christian teaching of "chastity for all outside marriage and fidelity within it".[161] The Derby Resolutions also agreed that the church "recognises, affirms and celebrates the participation and ministry of lesbians and gay men" and allows the ordination of openly gay ministers.[161]

The Methodist Church historically has had a mixed position on the blessing of same-sex couples. In 2005 the Methodist Conference meeting in Torquay recommended that ministers be allowed to bless same-sex relationships, subject to local approval.[163][164] It affirmed that the church should be "welcoming and inclusive" and not turn people away because of their sexual orientation.[164] However, in 2006 the Methodist Conference decided not to authorise formal blessings in local churches, although ministers were allowed to offer informal private prayers.[165][166] The 2013 conference set up a working party to oversee a process of "deep reflection and discernment" before reporting back to the conference in 2016 with recommendations about whether the definition of marriage should be revised.[167] Subsequently, in 2016 the conference voted to "revisit" the church's position on same-sex marriage, with a mandate from members "expressing a desire to endorse same-sex relationships".[168]

On 3 July 2019 the Methodist Conference approved a report, God in Love Unites Us, and voted in principle to permit same-sex weddings in Methodist premises by Methodist ministers—the report was then sent to district synods for consultation.[169] A final decision was due to be made at the July 2020 conference,[170] however this was postponed until 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which prevented grassroots discussions of the proposals.[171] On 30 June 2021 the Conference, presided over by Sonia Hicks, overwhelmingly approved (254 votes in favour with 46 against) the recognition of same-sex marriage in the church. Ministers are not forced to conduct such weddings if they disagree.[172] The Conference also affirmed cohabitation.[173] The traditionalist caucus, Methodist Evangelicals Together, dissented with this recognition.[174]

Prior to this, the Methodist Church already permitted transgender individuals who had undergone a legal gender transition to marry in the church. This was because it allowed persons to be married based on their legal gender rather than their assigned sex at birth. The church has stated, "[t]here is no clear theological or Scriptural position on matters of gender reassignment."[175]

Dignity and Worth is a campaign group within the Methodist Church which aims to strengthen the Methodist Church's position as an LGBT-affirming denomination.[172][176] The chair of the group described the church's decision to recognise same-sex marriage as a "momentous step on the road to justice".[172]

Alcohol

[edit]In 1744, the directions the Wesleys gave to the Methodist societies required them "to taste no spirituous liquor ... unless prescribed by a physician."[177] Methodists, in particular the Primitives, later took a leading role in the British temperance movement of the 19th and early 20th centuries,[178] and Methodism remains closely associated with temperance in many people's minds.[179]: 3 Methodists saw social issues such as poverty and violence in the home as exacerbated by drunkenness and alcoholism, and sought to persuade people to abstain totally from alcoholic beverages.[66][180] Temperance appealed strongly to the Methodist doctrines of sanctification and perfection. At one time, ministers had to take a pledge not to drink, and encouraged their congregations to do the same.[181] To this day, alcohol remains banned in most Methodist premises.[note 6] The choice to consume alcohol outside of church is now a personal decision for any member: the 1974 conference recognised the "sincerity and integrity of those who take differing views on whether they should drink or abstain".[179]: 4 [183] The conference of 2000 later recommended that all Methodists should "consider seriously the claims of total abstinence", and "make a personal commitment either to total abstinence or to responsible drinking".[7]: 817

The Methodist Church uses non-alcoholic wine (grape juice) in the sacrament of Holy Communion.[184] In 1869, a Methodist dentist named Thomas Welch developed a method of pasteurising grape juice in order to produce an unfermented communion wine for his church.[185] He later founded Welch's grape juice company.[186] By the 1880s this non-alcoholic wine had become commonplace in Methodist churches worldwide.[187]

Poverty

[edit]From the start Methodism was sympathetic towards poor people. In 1753, John Wesley bemoaned, "So wickedly, devilishly false is that common objection, 'They are poor, only because they are idle'."[188] In a Joint Public Issues Team report issued with the Baptist Union of Great Britain, the Church of Scotland and United Reformed Church, the Methodist Church stated this misconception is also prevalent today.[189]

Daleep Mukarji, the former director of the charity Christian Aid,[190] who was vice-president of the Methodist Conference in 2013, stated economic inequality was more prevalent in 21st-century Britain than at any time since World War II. He highlighted the response of Methodists:

Working with others, people of faith or no faith, we need to work for justice, inclusion and development that benefits the poor and marginalised here in the UK and across the world. This requires that we be prepared for the education, organisation and equipping of our members so that we build the necessary energy and commitment to see changes in our society. (...) We must hold our leaders, the structures and systems accountable so that we see that the weak and vulnerable are given a better deal. (...) Many Methodists in our local churches and circuits have outstanding programmes that serve people in need. At this time when poverty, deprivation and neglect seem to have got worse we should do more. (...) Our Methodist church is known for our service, our commitment to social justice and our willingness to act to transform society.

— Daleep Mukarji[191]

Some Methodist churches host food banks, distributing food to those in need.[192][193]

Ministry

[edit]Presbyters and deacons

[edit]In 2016 there were 3,459 Methodist ministers, with 1,562 active in circuit ministry.[11] The church recognises two orders of ordained ministry—that of presbyter and deacon.[194][note 7] Church documents refer to both as "Minister", though common usage often limits this title to presbyters.[194][197]: 149 Presbyters are styled "The Reverend",[198] while "Deacon" is used as a title by members of the diaconate. Deacons (both women and men) also belong to a community of deacons in the Methodist Diaconal Order.[199] The Deed of Union (the key foundation document of the Methodist Church since union in 1932[1]) describes the roles of presbyters and deacons and the purpose of their ministries:

Christ's ministers in the church are stewards in the household of God and shepherds of his flock. Some are called and ordained to this occupation as presbyters or deacons. Presbyters have a principal and directing part in these great duties but they hold no priesthood differing in kind from that which is common to all the Lord's people and they have no exclusive title to the preaching of the gospel or the care of souls. These ministries are shared with them by others to whom also the Spirit divides his gifts severally as he wills.[7]: 213

Both the diaconal and presbyteral orders in the Methodist Church are considered equal, playing distinct yet complementary roles in the ministry.[197] Deacons are called to a ministry of service and witness: specifically to "assist God's people in worship and prayer" and "to visit and support the sick and the suffering".[199] Presbyters are called to a ministry of word and sacrament: "to preach by word and deed the Gospel of God's grace" and "to baptise, to confirm, and to preside at the celebration of the sacrament of Christ's body and blood."[199] Presbyters historically are itinerant preachers, and the current rules mandate that presbyters in active work are stationed in a circuit for typically five years before transferring to another circuit.[200]

Methodist presbyters are usually given pastoral charge of several local churches within the circuit. Ordinary presbyters are in turn overseen by a superintendent, who is the most senior minister in the circuit. Unlike many other Methodist denominations the British church does not have bishops. A report, What Sort of Bishops? to the conference of 2005, was accepted for study and report.[201] This report considered whether this should now be changed, and if so, what forms of episcopacy might be acceptable. Consultation at grassroots level during 2006 and 2007 revealed overwhelming opposition from those who responded. As a consequence, the 2007 conference decided not to move towards having bishops at present.[202]

Without bishops, the Methodist Church does not subscribe to the idea of an historical episcopate. It does, however, affirm the doctrine of apostolic succession.[203] In 1937 the Methodist Conference located the "true continuity" with the church of past ages in "the continuity of Christian experience, the fellowship in the gift of the one Spirit; in the continuity in the allegiance to one Lord, the continued proclamation of the message; the continued acceptance of the mission;..." [through a long chain which goes back to] "the first disciples in the company of the Lord Himself ... This is our doctrine of apostolic succession" [which neither depends on, nor is secured by,] "an official succession of ministers, whether bishops or presbyters, from apostolic times, but rather by fidelity to apostolic truth".[203]

Ordination of women

[edit]The Primitive Methodist Church always allowed female preachers and ministers, although there were never many of them.[204] The Wesleyan Methodist Church established an order of deaconesses in 1890. The Methodist Church has re-allowed ordination of women as presbyters since 2 July 1974, when 17 women were received into full connexion at the Methodist Conference in Bristol.[205][206] The Methodist Church, along with some other Protestant churches, holds that when the historical contexts involved are understood, a coherent biblical argument can be made in favour of women's ordination.[207]

Local preachers

[edit]A distinctive feature of British Methodism is its extensive use of "local preachers" ('local' because they stay in the same circuit, as opposed to 'itinerant' preachers who move to different circuits, in the case of presbyters).[208] They are laypeople who have been trained and accredited to preach and lead worship services in place of a presbyter; however, local preachers cannot ordinarily officiate at services of Holy Communion.[209] Local preachers are thus similar to lay readers in the Church of England.[210] It is estimated that local preachers conduct seven out of every ten Methodist services, either in their own circuit or in others where they are invited as "visiting preachers".[210]

Local preachers played an important role in English and Welsh social history, especially among the working class and labour movement.[211] Prominent 20th-century public figures who preached include George Thomas, Speaker of the House of Commons from 1976 to 1983;[212] David Frost, television broadcaster;[213][214] Len Murray, General Secretary of the Trades Union Congress from 1973 to 1983;[215] and David Blunkett, Home Secretary from 2001 to 2004.[213]

Other appointments

[edit]Other appointments may include pastoral and administrative roles. Church standing orders prohibit the appointment of anyone being appointed to undertake work with children, young people or vulnerable adults in the life of the church if they have a criminal conviction or caution under a number of laws, including the Sexual Offences Act 2003, or who is barred by the Disclosure and Barring Service from work with vulnerable people or who the Safeguarding Committee has concluded poses a risk to vulnerable groups.[7]: SO 010

Organisation

[edit]

Methodists belong to local churches or local ecumenical partnerships but also feel part of a larger connected community, known as 'The Connexion'. This sense of being connected makes a difference to how the Methodist Church as a whole is structured. From its inception under John Wesley, Methodism has always laid strong emphasis on the interdependence and mutual support of one local church for another.[216] The church community has never been seen in isolation either from its immediately neighbouring church communities or from the centralised national organisation. When ministers are ordained in the Methodist Church, they are also "received into full Connexion".[217]

A quarterly magazine entitled the connexion is published by the church.[218]

Local churches

[edit]

Membership of the Methodist Church is held in a particular local church, or in a local ecumenical partnership.[219] For people who wish to become members of the church there is a period of instruction and, once the local church council is satisfied with the person's sincere acceptance of the basis of membership of the Methodist Church, a service of confirmation and reception into membership is held; if they have not previously been baptised, the service will include baptism.[219] (Each member of a local church receives a membership ticket at least once a year; in early Methodism, tickets were issued by Wesley every three months as evidence of a member's good standing.[220][221]) As at October 2016[update], church members are dispersed over 4,512 local churches—unevenly distributed over a small number of large churches and a large number of small churches.[11]

Local church can refer to both the congregation and the building in which it meets (though the building may also be called a chapel).[222][223] It is the whole body of members of the Methodist Church linked with one particular place of worship. The concept of the local church is based on the original Methodist "societies" that existed within the Church of England during the time of John Wesley's ministry.[224] A local church is normally led by a presbyter, usually referred to as "the minister".

Some church members belong to a church council, either because they have been elected by the local church members, or because they hold one of a number of offices within the local church. The church council, with a minister, has responsibility for running the local church. Members of the church council are also trustees of the local church.[225] The church council appoints two or more church stewards, who exercise pastoral responsibility in conjunction with the minister and together provide a leadership role across "the whole range of the church's life and activity".[7]: 530

Circuits

[edit]Local churches are grouped into 368 circuits (as of 2016[update]) of various sizes.[11] The responsibilities of the circuit are exercised through the circuit meeting, led by the superintendent minister.[226] It is responsible for managing the finances, property and officeholders within the circuit. Most circuits have many fewer ministers than churches and the majority of services are led by local preachers, or by supernumerary ministers—retired ministers who are not officially counted in the number of ministers for the circuit in which they are listed.[227] The superintendent and other ministers are assisted in the leadership and administration of the circuit by lay circuit stewards, who together form the leadership team.[226][228]

Central halls

[edit]

Some large inner-city Methodist buildings, called 'central halls', are designated as circuits in themselves.[229] About a hundred such halls were built in Britain between 1886 and 1945, many in a Renaissance or Baroque style.[230] They were designated as multi-purpose venues; in their heyday they presented low-cost concerts and shows to entertain the working classes on Saturdays—encouraging them to avoid drinking establishments and thereby abstain from alcohol—as well as hosting church congregations on Sundays. However, many were bombed during the Second World War, and others declined as people moved out of the city centres; as of 2012[update] only sixteen remain in use as Methodist churches.[231] Others, such as the landmark Birmingham Central Hall, and Liverpool's Grand Central Hall, have been sold and adapted as retail or nightclub venues.[231] One of the remaining halls is Methodist Central Hall in Westminster (close to Parliament Square and Westminster Abbey), established in 1912 to serve as a church with additional use "for conferences on religious, educational, scientific, philanthropic and social questions".[232]

Districts

[edit]The Connexion is divided into thirty districts (as at 2018[update]) covering the whole of Great Britain, the Isle of Man, and the Channel Islands.[233] The district is a drawing together of a variable number of circuits in a geographic locality. Wales is covered by two districts: a Welsh-language synod and an English-language synod. Methodism has never been prevalent in Scotland, and there are only around 40 local churches gathered into one Scotland District.[234]

The governing body of a district is the twice-yearly synod.[235] Each district is presided over by a chair, except the large London District which has three chairs.[236] A chair was, at first, a superintendent of a circuit within the district, but now ministers are appointed exclusively to the separated role.[237] The prime function of the chair is pastoral—the care of ministers and lay workers, and their families, within the district; the appointment of ministers to circuits; candidates for the ministry and the oversight of probationer (trainee) ministers.[236] The district chair is also the person to whom other denominations relate ecumenically at regional or national level.[238]

Conference

[edit]The central governing body of the Connexion is the Methodist Conference which meets in June or July each year in a different part of the country.[7]: 216 [239] It represents both ministers and laypeople, and determines church policy.[239] The conference is a gathering of representatives from each district, along with some who have been elected by the conference and some ex officio members and representatives of the youth assembly. It is held in two sessions: a presbyteral session and a representative session including lay representatives.[7]: 216 The 2019 conference was held in Birmingham.[240] The 2020 conference took place as a virtual conference due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[241] The 2021 conference took place in Birmingham and online. The 2022 conference was held in Telford,[242] and the 2023 conference returned to Birmingham.[243]

The Methodist Conference is the formal authority on all matters of belief and practice.[244] Proposals for a change or development of Methodist teaching about personal, social or public Christian ethics can be initiated:

- by any two representatives to the annual conference proposing a resolution (known as a "notice of motion") at the conference itself;

- by local groupings of churches (circuit meetings) by regional groupings of churches (synods) proposing a resolution to the conference;

- by a resolution to conference from the Methodist Council (a smaller representative body which meets four times a year between conferences).

If, by methods 1 and 2 above, the proposed change or development is significant, the conference will usually direct the Methodist Council to look into the issues and to present a report at a subsequent Conference.[244]

In the course of preparing the report, staff who are appointed or employed by the council will be responsible for developing the church's thinking with the help of professional and theological expertise; and must undertake a wide range of consultations, both within the Methodist Church and with partner denominations. Then the report, with or without specific recommendations, will be presented to Conference for debate.

Examples of issues dealt with in this way are: abortion; civil disobedience; nuclear deterrence; the manufacture and sale of arms; disarmament; care of the environment; family and divorce law; gambling; housing; overseas development and fair trading; poverty; racial justice; asylum and immigration issues; human sexuality; political responsibility.[245]

Sometimes the conference will attempt a definitive judgement on an important theme which is intended to represent the Methodist Church's viewpoint for a decade or more. In such cases a final decision is made after two debates in conference, separated by at least a year, to allow for discussion in all parts of the church's life. Topics of personal, social or public Christian ethics dealt with in this way become official "Statements" or "Declarations" of the Methodist Church on the subject concerned, for example, Family Life, the Single Person and Marriage.[246]

The Methodist Conference is presided over by the president of conference, a presbyter. The president is supported by the vice-president, who is a layperson or deacon. The president and vice-president serve a one-year term, travelling across the Connexion—following the example of Wesley—and preaching in local churches.[247]

Constitutional Practice and Discipline

[edit]The Constitutional Practice and Discipline of the Methodist Church (CPD) is published annually by order of the conference. Its contents are prepared by the church's Law and Polity Committee and reviewed each year. Volume 1 contains a set of fixed texts, including acts of Parliament,[note 8] other legislation and historic documents; the 1988 preface has been retained in later revisions because, along with abridged versions of earlier forewords, its "value as a general introduction to Methodist constitutional practice and discipline remains unsurpassed".[248]: vi Volume 2 includes the Deed of Union and Model Trusts, along with the conference standing orders which are updated annually after amendments by the conference.[7]: 261

Children's and Youth Assembly

[edit]There is an annual assembly for children and youth, called 3Generate. It represents children and young adults aged 8 to 23.[249] There is also a youth president,[250] elected annually to serve a paid full-time role.[251]

Charities

[edit]The Methodist Church is closely associated with several charitable organisations: namely, Action for Children (formerly the National Children's Home),[252] Methodist Homes (MHA) and All We Can (the Methodist Relief and Development Fund).[253] The church also helps to run a number of faith schools, both state and independent. These include two leading private schools in East Anglia, Culford School and The Leys School.[254] It helps to promote an all round education with a strong Christian ethos.

Ecumenical and interfaith relations

[edit]| Christian denominations in the United Kingdom |

|---|

The Methodist Church participates in various ecumenical forums and associations with other denominations. The church is a founding member of Churches Together in Britain and Ireland (since 1990)[255] and the three national ecumenical bodies in Great Britain, namely Churches Together in England,[256] Cytûn in Wales,[257] and Action of Churches Together in Scotland.[258] Since 1975, the Methodist Church is one of the Covenanted Churches in Wales, along with the Church in Wales, the Presbyterian Church of Wales, the United Reformed Church and certain Baptist churches.[259] It participates in the Conference of European Churches and the World Council of Churches. The church has sent delegates to every Assembly of the World Council and has at various times been represented on its Central Committees and its Faith and Order Commission.[260]

The Methodist Church is officially committed to "seek opportunities to work in partnership with other denominations" and "seek opportunities to join with other Christians in sharing the Good News of the Gospel and to make more followers of Jesus Christ through together bearing witness to the unity of the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church."[148] From the 1970s onward, the Methodist Church has been involved in nearly 900 local ecumenical partnerships (LEPs) with neighbouring denominations,[10] such as the Church of England, the Baptist Union and the United Reformed Church. Christ Church in Nelson, Lancashire, is an unusual example of a joint Methodist–Catholic church in Britain.[261]

In April 2016 the World Methodist Council opened an Ecumenical Office in Rome, Italy. International Methodist leaders and Pope Francis met together to dedicate the new office.[262] It exists to offer a resource in the city of Rome for the global Methodist family and to help facilitate Methodist relationships with the wider Christian Church, especially the Roman Catholic Church.[263]

Proposals for merger with other denominations

[edit]In the 1960s, the Methodist Church made ecumenical overtures to the Church of England, aimed at church unity.[264] In February 1963, a report, Conversations between the Church of England and the Methodist Church, was published. This gave an outline of a scheme to unite the two churches. The scheme was not without opposition, for four Methodist representatives—Barrett, Meadley, Snaith and Jessop—issued a dissentient report.[265][266] Through much of the 1960s, controversy spread in the two churches. Central in the debate was the need for Methodist ministers to be ordained under the Anglican historic episcopate, which opponents characterised as "reordination" of Methodist ministers.[264] Discussions ultimately failed when the proposals for union were rejected by the Church of England's General Synod in 1972.[267]

In 1982, the Methodist Conference endorsed a covenant with the Church of England, the United Reformed Church and the Moravian Church, but the plan faltered after the House of Bishops in the General Synod vetoed it.[268][269] Bilateral discussions between the Anglicans and Methodists were renewed in the mid-1990s, with a series of Informal Conversations held in 1995 and 1996. These meetings concluded with the publication of a common statement in December 2000 which highlighted common beliefs and potential areas of cooperation between the two denominations.[264]

Anglican–Methodist Covenant

[edit]In 2002, the Methodist Conference voted on the proposals in An Anglican–Methodist Covenant, sending it to its districts for discussion. On 1 November 2003, in the presence of Queen Elizabeth II, the President and other leaders of the Methodist Conference and Archbishops of the Church of England signed the covenant at Methodist Central Hall in Westminster.[270] The covenant affirms the willingness of the two churches to work together at a diocesan/district level in matters of evangelism and joint worship.[271]

In 2021, the churches agreed to move ahead with the covenant and set up a new body to encourage cooperation between Anglicans and Methodists, despite opposition from the Church of England toward the Methodist Church's decision to allow same-sex weddings.[272]

Controversy over report on Zionism

[edit]Following the submission of a report entitled Justice for Palestine and Israel in June 2010,[273] the Methodist Conference was reported to have questioned whether "Zionism was compatible with Methodist beliefs".[274] Christian Zionism was broadly characterised as believing that Israel "must be held above criticism whatever policy is enacted", and Conference called for a boycott of selected goods from Israeli settlements.[275] The Chief Rabbi of Britain's Orthodox Jewish community described the report as "unbalanced, factually and historically flawed" and charged that it offered "no genuine understanding of one of the most complex conflicts in the world today. Many in both communities will be deeply disturbed."[274]

Worldwide Methodism

[edit]Methodism is a worldwide movement with around 80 million adherents (including members of united and uniting churches).[276] Its largest denomination is the United Methodist Church,[277] which has congregations on four continents, although the majority are in the United States.[278] Delegates from almost all Methodist denominations (and many uniting churches) meet together every five years in a conference of the World Methodist Council.[276]

St Andrew's Scots Church, Malta, is a joint congregation of the Methodist Church of Great Britain and the Church of Scotland situated in Valletta. It serves British expats.[279] There are also Methodist congregations in the Crown Dependencies of the Isle of Man and the Channel Islands (each forming a district).[229]

Methodist churches in Northern Ireland are part of the Methodist Church in Ireland,[280] a separate connexion which is historically associated with the British Methodist Church. John Wesley visited Ireland on twenty-one occasions between 1747 and 1789, establishing societies there.[281]

See also

[edit]- List of Methodist churches

- Saints in Methodism

- Independent Methodist Connexion

- History of Christianity in Britain

- Methodist Peace Fellowship

- Methodist Recorder – an independent Methodist newspaper

- Temperance movement in the United Kingdom – Methodists played a significant part in the movement

Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Pronounced as /ˈmɛθədɪst/. John Wesley would later reclaim the term Methodist when referring to the methodical pursuit of scriptural holiness.[12]

- ^ The preface to the Methodist Service Book (1975), in a discussion of the relationship between free and fixed (written) prayer in Methodist liturgy, argues that the forms presented in the book "are not intended, any more than those in earlier books, to curb creative freedom, but rather to provide for its guidance".[111] The preface to the Methodist Worship Book (1999) states that these words still apply.[110]

- ^ Offices refers to divine office or canonical hours. All Methodist service books contain evening and morning prayers for daily use.

- ^ Wesley insisted that the goal of Christian perfection was achievable and that he could name some of those who had "reached perfection's height". At the same time he admitted that he himself had not and that that was the case with most of the rest of us too.[143]

- ^ A reference to Psalm 119:105

- ^ Since 1977, this restriction no longer applies to domestic occasions in private homes on Methodist property, meaning that a minister may have a drink at home in the manse.[179]: 4 В 2004 году было сделано исключение из правила о запрете продажи алкоголя в помещениях методистов в отношении мероприятий, проводимых в помещениях, используемых в качестве конференц-центра; [ 66 ] Методистский центральный зал и получил ее подал заявку на лицензию на продажу алкоголя . [ 182 ]