Клевета

| Часть серии о |

| Закон |

|---|

|

| Основы и философия |

| Правовая теория |

| Методологическая основа |

| Legal debate |

Клевета – это сообщение третьего лица , которое наносит ущерб репутации и причиняет ущерб, подлежащий возмещению по закону. Точное юридическое определение диффамации варьируется от страны к стране. Оно не обязательно ограничивается утверждениями , которые можно опровергнуть , и может распространяться на более абстрактные понятия, чем репутация, – например, достоинство и честь . В англоязычном мире закон о диффамации традиционно различает клевету (письменную, напечатанную, размещенную в Интернете, опубликованную в средствах массовой информации) и клевету (устную речь). Это рассматривается как гражданское правонарушение ( деликт , деликт ), как уголовное преступление или и то, и другое. [1] [2] [3] [4] [ необходимы дополнительные ссылки ]

Законы о диффамации и связанные с ней законы могут охватывать различные действия (от общей клеветы и оскорбления – применимых к каждому гражданину – до специализированных положений, охватывающих конкретные организации и социальные структуры): [5] [ необходимы дополнительные ссылки ]

- Defamation against a legal person in general

- Insult against a legal person in general

- Acts against public officials

- Acts against state institutions (government, ministries, government agencies, armed forces)

- Acts against state symbols

- Acts against the state itself

- Acts against heads of state

- Acts against religions (blasphemy)

- Acts against the judiciary or legislature (contempt of court)

History

[edit]Defamation law has a long history stretching back to classical antiquity. While defamation has been recognized as an actionable wrong in various forms across historical legal systems and in various moral and religious philosophies, defamation law in contemporary legal systems can primarily be traced back to Roman and early English law.[citation needed]

Roman law was aimed at giving sufficient scope for the discussion of a man's character, while it protected him from needless insult and pain. The remedy for verbal defamation was long confined to a civil action for a monetary penalty, which was estimated according to the significance of the case, and which, although punitive in its character, doubtless included practically the element of compensation. But a new remedy was introduced with the extension of the criminal law, under which many kinds of defamation were punished with great severity. At the same time increased importance attached to the publication of defamatory books and writings, the libri or libelli famosi, from which is derived the modern use of the word libel; and under the later emperors the latter term came to be specially applied to anonymous accusations or pasquils, the dissemination of which was regarded as particularly dangerous, and visited with very severe punishment, whether the matters contained in them were true or false.[citation needed]

The Praetorian Edict, codified circa AD 130, declared that an action could be brought up for shouting at someone contrary to good morals: "qui, adversus bonos mores convicium cui fecisse cuiusve opera factum esse dicitur, quo adversus bonos mores convicium fieret, in eum iudicium dabo."[6] In this case, the offence was constituted by the unnecessary act of shouting. According to Ulpian, not all shouting was actionable. Drawing on the argument of Labeo, he asserted that the offence consisted in shouting contrary to the morals of the city ("adversus bonos mores huius civitatis") something apt to bring in disrepute or contempt ("quae... ad infamiam vel invidiam alicuius spectaret") the person exposed thereto.[7] Any act apt to bring another person into disrepute gave rise to an actio injurarum.[8] In such a case the truth of the statements was no justification for the public and insulting manner in which they had been made, but, even in public matters, the accused had the opportunity to justify his actions by openly stating what he considered necessary for public safety to be denounced by the libel and proving his assertions to be true.[9] The second head included defamatory statements made in private, and in this case the offense lay in the content of the imputation, not in the manner of its publication. The truth was therefore a sufficient defense, for no man had a right to demand legal protection for a false reputation.[citation needed]

In Anglo-Saxon England, whose legal tradition is the predecessor of contemporary common law jurisdictions,[citation needed] slander was punished by cutting out the tongue.[10] Historically, while defamation of a commoner in England was known as libel or slander, the defamation of a member of the English aristocracy was called scandalum magnatum, literally "the scandal of magnates".[11]

Human rights

[edit]Following the Second World War and with the rise of contemporary international human rights law, the right to a legal remedy for defamation was included in Article 17 of the United Nations International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which states that:

- No one shall be subjected to arbitrary or unlawful interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to unlawful attacks on his honour and reputation.

- Everyone has the right to the protection of the law against such interference or attacks.

This implies a right to legal protection against defamation; however, this right co-exists with the right to freedom of opinion and expression under Article 19 of the ICCPR as well as Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.[12] Article 19 of the ICCPR expressly provides that the right to freedom of opinion and expression may be limited so far as it is necessary "for respect of the rights or reputations of others".[12] Consequently, international human rights law provides that while individuals should have the right to a legal remedy for defamation, this right must be balanced with the equally protected right to freedom of opinion and expression. In general, ensuring that domestic defamation law adequately balances individuals' right to protect their reputation with freedom of expression and of the press entails:[13]

- Providing for truth (i.e., demonstrating that the content of the defamatory statement is true) to be a valid defence,

- Recognising reasonable publication on matters of public concern as a valid defence, and

- Ensuring that defamation may only be addressed by the legal system as a tort.

In most of Europe, article 10 of the European Convention on Human Rights permits restrictions on freedom of speech when necessary to protect the reputation or rights of others.[14] Additionally, restrictions of freedom of expression and other rights guaranteed by international human rights laws (including the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)) and by the constitutions of a variety of countries are subject to some variation of the three-part test recognised by the United Nations Human Rights Committee which requires that limitations be: 1) "provided by law that is clear and accessible to everyone", 2) "proven to be necessary and legitimate to protect the rights or reputations of others", and 3) "proportionate and the least restrictive to achieve the purported aim".[15] This test is analogous to the Oakes Test applied domestically by the Supreme Court of Canada in assessing whether limitations on constitutional rights are "demonstrably justifiable in a free and democratic society" under Section 1 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the "necessary in a democratic society" test applied by the European Court of Human Rights in assessing limitations on rights under the ECHR, Section 36 of the post-Apartheid Constitution of South Africa,[16] and Section 24 of the 2010 Constitution of Kenya.[17] Nevertheless, the worldwide use of criminal[18] and civil defamation, to censor, intimidate or silence critics, has been increasing in recent years.[19]

General comment No. 34

[edit]In 2011, the United Nations Human Rights Committee published their General comment No. 34 (CCPR/C/GC/34) – regarding Article 19 of the ICCPR.[20]

Paragraph 47 states:

Defamation laws must be crafted with care to ensure that they comply with paragraph 3 [of Article 19 of the ICCPR], and that they do not serve, in practice, to stifle freedom of expression. All such laws, in particular penal defamation laws, should include such defences as the defence of truth and they should not be applied with regard to those forms of expression that are not, of their nature, subject to verification. At least with regard to comments about public figures, consideration should be given to avoiding penalizing or otherwise rendering unlawful untrue statements that have been published in error but without malice. In any event, a public interest in the subject matter of the criticism should be recognized as a defence. Care should be taken by States parties to avoid excessively punitive measures and penalties. Where relevant, States parties should place reasonable limits on the requirement for a defendant to reimburse the expenses of the successful party. States parties should consider the decriminalization of defamation and, in any case, the application of the criminal law should only be countenanced in the most serious of cases and imprisonment is never an appropriate penalty. It is impermissible for a State party to indict a person for criminal defamation but then not to proceed to trial expeditiously – such a practice has a chilling effect that may unduly restrict the exercise of freedom of expression of the person concerned and others.

Defamation as a tort

[edit]| Part of the common law series |

| Tort law |

|---|

| (Outline) |

| Trespass to the person |

| Property torts |

| Dignitary torts |

| Negligent torts |

| Principles of negligence |

| Strict and absolute liability |

| Nuisance |

| Economic torts |

| Defences |

| Liability |

| Remedies |

| Other topics in tort law |

|

| By jurisdiction |

| Other common law areas |

While each legal tradition approaches defamation differently, it is typically regarded as a tort[a] for which the offended party can take civil action. The range of remedies available to successful plaintiffs in defamation cases varies between jurisdictions and range from damages to court orders requiring the defendant to retract the offending statement or to publish a correction or an apology.

Common law

[edit]Background

[edit]Modern defamation in common law jurisdictions are historically derived from English defamation law. English law allows actions for libel to be brought in the High Court for any published statements alleged to defame a named or identifiable individual or individuals (under English law companies are legal persons, and allowed to bring suit for defamation[22][23][24]) in a manner that causes them loss in their trade or profession, or causes a reasonable person to think worse of them.

Overview

[edit]In contemporary common law jurisdictions, to constitute defamation, a claim must generally be false and must have been made to someone other than the person defamed.[25] Some common law jurisdictions distinguish between spoken defamation, called slander, and defamation in other media such as printed words or images, called libel.[26] The fundamental distinction between libel and slander lies solely in the form in which the defamatory matter is published. If the offending material is published in some fleeting form, such as spoken words or sounds, sign language, gestures or the like, then it is slander. In contrast, libel encompasses defamation by written or printed words, pictures, or in any form other than spoken words or gestures.[27][b] The law of libel originated in the 17th century in England. With the growth of publication came the growth of libel and development of the tort of libel.[28] The highest award in an American defamation case, at US$222.7 million was rendered in 1997 against Dow Jones in favour of MMAR Group Inc;[29] however, the verdict was dismissed in 1999 amid allegations that MMAR failed to disclose audiotapes made by its employees.[30]

In common law jurisdictions, civil lawsuits alleging defamation have frequently been used by both private businesses and governments to suppress and censor criticism. A notable example of such lawsuits being used to suppress political criticism of a government is the use of defamation claims by politicians in Singapore's ruling People's Action Party to harass and suppress opposition leaders such as J. B. Jeyaretnam.[31][32][33][34][35] Over the first few decades of the twenty first century, the phenomenon of strategic lawsuits against public participation has gained prominence in many common law jurisdictions outside Singapore as activists, journalists, and critics of corporations, political leaders, and public figures are increasingly targeted with vexatious defamation litigation.[36] As a result, tort reform measures have been enacted in various jurisdictions; the California Code of Civil Procedure and Ontario's Protection of Public Participation Act do so by enabling defendants to make a special motion to strike or dismiss during which discovery is suspended and which, if successful, would terminate the lawsuit and allow the party to recover its legal costs from the plaintiff.[37][38]

Defences

[edit]There are a variety of defences to defamation claims in common law jurisdictions.[39] The two most fundamental defences arise from the doctrine in common law jurisdictions that only a false statement of fact (as opposed to opinion) can be defamatory. This doctrine gives rise to two separate but related defences: opinion and truth. Statements of opinion cannot be regarded as defamatory as they are inherently non-falsifiable.[c] Where a statement has been shown to be one of fact rather than opinion, the most common defence in common law jurisdictions is that of truth. Proving the truth of an allegedly defamatory statement is always a valid defence.[41] Where a statement is partially true, certain jurisdictions in the Commonwealth have provided by statute that the defence "shall not fail by reason only that the truth of every charge is not proved if the words not proved to be true do not materially injure the claimant's reputation having regard to the truth of the remaining charges".[42] Similarly, the American doctrine of substantial truth provides that a statement is not defamatory if it has "slight inaccuracies of expression" but is otherwise true.[43] Since a statement can only be defamatory if it harms another person's reputation, another defence tied to the ability of a statement to be defamatory is to demonstrate that, regardless of whether the statement is true or is a statement of fact, it does not actually harm someone's reputation.

It is also necessary in these cases to show that there is a well-founded public interest in the specific information being widely known, and this may be the case even for public figures. Public interest is generally not "what the public is interested in", but rather "what is in the interest of the public".[44][45]

Other defences recognised in one or more common law jurisdictions include:[46][47]

- Privilege: A circumstance that justifies or excuses an act that would otherwise constitute a tort on the ground that it stemmed from a recognised interest of social importance, provides a complete bar and answer to a defamation suit, though conditions may have to be met before this protection is granted. While some privileges have long been recognised, courts may create a new privilege for particular circumstances – privilege as an affirmative defence is a potentially ever-evolving doctrine. Such newly created or circumstantially recognised privileges are referred to as residual justification privileges. There are two types of privilege in common law jurisdictions:

- Absolute privilege has the effect that a statement cannot be sued on as defamatory, even if it were made maliciously; a typical example is evidence given in court (although this may give rise to different claims, such as an action for malicious prosecution or perjury) or statements made in a session of the legislature by a member thereof (known as 'Parliamentary privilege' in Commonwealth countries).

- Qualified privilege: A more limited, or 'qualified', form of privilege may be available to journalists as a defence in circumstances where it is considered important that the facts be known in the public interest; an example would be public meetings, local government documents, and information relating to public bodies such as the police and fire departments. Another example would be that a professor – acting in good faith and honesty – may write an unsatisfactory letter of reference with unsatisfactory information.

- Mistake of fact: Statements made in a good faith and reasonable belief that they were true are generally treated the same as true statements; however, the court may inquire into the reasonableness of the belief. The degree of care expected will vary with the nature of the defendant: an ordinary person might safely rely on a single newspaper report, while the newspaper would be expected to carefully check multiple sources.

- Mere vulgar abuse: An insult that is not necessarily defamatory if it is not intended to be taken literally or believed, or likely to cause real damage to a reputation. Vituperative statements made in anger, such as calling someone "an arse" during a drunken argument, would likely be considered mere vulgar abuse and not defamatory.

- Fair comment: Statements made with an honest belief in their soundness on a matter of public interest (such as regarding official acts) are defendable against a defamation claim, even if such arguments are logically unsound; if a reasonable person could honestly entertain such an opinion, the statement is protected.

- Consent: In rare cases, a defendant can argue that the plaintiff consented to the dissemination of the statement.

- Innocent dissemination: A defendant is not liable if they had no actual knowledge of the defamatory statement or no reason to believe the statement was defamatory. Thus, a delivery service cannot be held liable for delivering a sealed defamatory letter. The defence can be defeated if the lack of knowledge was due to negligence.

- Incapability of further defamation: Historically, it was a defence at common law that the claimant's position in the community is so poor that defamation could not do further damage to the plaintiff. Such a claimant could be said to be "libel-proof", since in most jurisdictions, actual damage is an essential element for a libel claim. Essentially, the defence was that the person had such a bad reputation before the libel, that no further damage could possibly have been caused by the making of the statement.[48]

- Statute of limitations: Most jurisdictions require that a lawsuit be brought within a limited period of time. If the alleged libel occurs in a mass media publication such as a newspaper or the Internet, the statute of limitations begins to run at the time of publication, not when the plaintiff first learns of the communication.[49]

- No third-party communication: If an employer were to bring an employee into a sound-proof, isolated room, and accuse him of embezzling company money, the employee would have no defamation recourse, since no one other than the would-be plaintiff and would-be defendant heard the false statement.

- No actual injury: If there is third-party communication, but the third-party hearing the defamatory statement does not believe the statement, or does not care, then there is no injury, and therefore, no recourse.

Defamation per se

[edit]Many common law jurisdictions recognise that some categories of statements are considered to be defamatory per se, such that people making a defamation claim for these statements do not need to prove that the statement was defamatory.[50] In an action for defamation per se, the law recognises that certain false statements are so damaging that they create a presumption of injury to the plaintiff's reputation, allowing a defamation case to proceed to verdict with no actual proof of damages. Although laws vary by state, and not all jurisdictions recognise defamation per se, there are four general categories of false statement that typically support a per se action:[51]

- accusing someone of a crime;

- alleging that someone has a foul or loathsome disease;

- adversely reflecting on a person's fitness to conduct their business or trade; and

- imputing serious sexual misconduct.

If the plaintiff proves that such a statement was made and was false, to recover damages the plaintiff need only prove that someone had made the statement to any third party. No proof of special damages is required. However, to recover full compensation a plaintiff should be prepared to prove actual damages.[51]As with any defamation case, truth remains an absolute defence to defamation per se. This means that even if the statement would be considered defamatory per se if false, if the defendant establishes that it is in fact true, an action for defamation per se cannot survive.[52] The conception of what type of allegation may support an action for defamation per se can evolve with public policy. For example, in May 2012 an appeals court in New York, citing changes in public policy with regard to homosexuality, ruled that describing someone as gay is not defamation.[53]

Variations within common law jurisdictions

[edit]While defamation torts are broadly similar across common law jurisdictions; differences have arisen as a result of diverging case law, statutes and other legislative action, and constitutional concerns[d] specific to individual jurisdictions.

Some jurisdictions have a separate tort or delict of injury, intentional infliction of emotional distress, involving the making of a statement, even if truthful, intended to harm the claimant out of malice; some have a separate tort or delict of "invasion of privacy" in which the making of a true statement may give rise to liability: but neither of these comes under the general heading of "defamation". The tort of harassment created by Singapore's Protection from Harassment Act 2014 is an example of a tort of this type being created by statute.[42] There is also, in almost all jurisdictions, a tort or delict of "misrepresentation", involving the making of a statement that is untrue even though not defamatory. Thus a surveyor who states a house is free from risk of flooding has not defamed anyone, but may still be liable to someone who purchases the house relying on this statement. Other increasingly common claims similar to defamation in U.S. law are claims that a famous trademark has been diluted through tarnishment, see generally trademark dilution, "intentional interference with contract", and "negligent misrepresentation". In America, for example, the unique tort of false light protects plaintiffs against statements which are not technically false but are misleading.[54] Libel and slander both require publication.[55]

Although laws vary by state; in America, a defamation action typically requires that a plaintiff claiming defamation prove that the defendant:

- made a false and defamatory statement concerning the plaintiff;

- shared the statement with a third party (that is, somebody other than the person defamed by the statement);

- if the defamatory matter is of public concern, acted in a manner which amounted at least to negligence on the part of the defendant; and

- caused damages to the plaintiff.

Additionally, American courts apply special rules in the case of statements made in the press concerning public figures, which can be used as a defence. While plaintiff alleging defamation in an American court must usually prove that the statement caused harm, and was made without adequate research into the truthfulness of the statement; where the plaintiff is a celebrity or public official, they must additionally prove that the statement was made with actual malice (i.e. the intent to do harm or with reckless disregard for the truth).[56][57] A series of court rulings led by New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964) established that for a public official (or other legitimate public figure) to win a libel case in an American court, the statement must have been published knowing it to be false or with reckless disregard to its truth (i.e. actual malice).[58] The Associated Press estimates that 95% of libel cases involving news stories do not arise from high-profile news stories, but "run of the mill" local stories like news coverage of local criminal investigations or trials, or business profiles.[59] Media liability insurance is available to newspapers to cover potential damage awards from libel lawsuits. An early example of libel is the case of John Peter Zenger in 1735. Zenger was hired to publish the New York Weekly Journal. When he printed another man's article criticising William Cosby, the royal governor of Colonial New York, Zenger was accused of seditious libel.[28] The verdict was returned as not guilty on the charge of seditious libel, because it was proven that all the statements Zenger had published about Cosby had been true, so there was not an issue of defamation. Another example of libel is the case of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964). The Supreme Court of the United States overruled a state court in Alabama that had found The New York Times guilty of libel for printing an advertisement that criticised Alabama officials for mistreating student civil rights activists. Even though some of what The Times printed was false, the court ruled in its favour, saying that libel of a public official requires proof of actual malice, which was defined as a "knowing or reckless disregard for the truth".[60]

Many jurisdictions within the Commonwealth (e.g. Singapore,[61] Ontario,[62] and the United Kingdom[63]) have enacted legislation to:

- Codify the defences of fair comment and qualified privilege

- Provide that, while most instances of slander continue to require special damage to be proved (i.e. prove that pecuniary loss was caused by the defamatory statement), instances such as slander of title shall not

- Clarify that broadcast statements (including those that are only broadcast in spoken form) constitute libel rather than slander.

Libel law in England and Wales was overhauled even further by the Defamation Act 2013.

Defamation in Indian tort law largely resembles that of England and Wales. Indian courts have endorsed[64] the defences of absolute[65] and qualified privilege,[66] fair comment,[67] and justification.[68] While statutory law in the United Kingdom provides that, if the defendant is only successful in proving the truth of some of the several charges against him, the defence of justification might still be available if the charges not proved do not materially injure the reputation,[69] there is no corresponding provision in India, though it is likely that Indian courts would treat this principle as persuasive precedent.[70] Recently, incidents of defamation in relation to public figures have attracted public attention.[71]

The origins of U.S. defamation law pre-date the American Revolution.[e] Though the First Amendment of the American Constitution was designed to protect freedom of the press, it was primarily envisioned to prevent censorship by the state rather than defamation suits; thus, for most of American history, the Supreme Court did not interpret the First Amendment as applying to libel cases involving media defendants. This left libel laws, based upon the traditional common law of defamation inherited from the English legal system, mixed across the states. The 1964 case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan dramatically altered the nature of libel law in the country by elevating the fault element for public officials to actual malice – that is, public figures could win a libel suit only if they could demonstrate the publisher's "knowledge that the information was false" or that the information was published "with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not".[73] Later the Supreme Court held that statements that are so ridiculous to be clearly not true are protected from libel claims,[74] as are statements of opinion relating to matters of public concern that do not contain a provably false factual connotation.[75] Subsequent state and federal cases have addressed defamation law and the Internet.[76]

American defamation law is much less plaintiff-friendly than its counterparts in European and the Commonwealth countries. A comprehensive discussion of what is and is not libel or slander under American law is difficult, as the definition differs between different states and is further affected by federal law.[77] Some states codify what constitutes slander and libel together, merging the concepts into a single defamation law.[51]

New Zealand received English law with the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi in February 1840. The current Act is the Defamation Act 1992 which came into force on 1 February 1993 and repealed the Defamation Act 1954.[78] New Zealand law allows for the following remedies in an action for defamation: compensatory damages; an injunction to stop further publication; a correction or a retraction; and in certain cases, punitive damages. Section 28 of the Act allows for punitive damages only when a there is a flagrant disregard of the rights of the person defamed. As the law assumes that an individual suffers loss if a statement is defamatory, there is no need to prove that specific damage or loss has occurred. However, Section 6 of the Act allows for a defamation action brought by a corporate body to proceed only when the body corporate alleges and proves that the publication of the defamation has caused or is likely to cause pecuniary loss to that body corporate.

As is the case for most Commonwealth jurisdictions, Canada follows English law on defamation issues (except in Quebec where the private law is derived from French civil law). In common law provinces and territories, defamation covers any communication that tends to lower the esteem of the subject in the minds of ordinary members of the public.[79] Probably true statements are not excluded, nor are political opinions. Intent is always presumed, and it is not necessary to prove that the defendant intended to defame. In Hill v. Church of Scientology of Toronto (1995), the Supreme Court of Canada rejected the actual malice test adopted in the US case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan. Once a claim has been made, the defendant may avail themselves of a defence of justification (the truth), fair comment, responsible communication,[80] or privilege. Publishers of defamatory comments may also use the defence of innocent dissemination where they had no knowledge of the nature of the statement, it was not brought to their attention, and they were not negligent.[81][82]

Corporate defamation

[edit]Common law jurisdictions vary as to whether they permit corporate plaintiffs in defamation actions. Under contemporary Australian law, private corporations are denied the right to sue for defamation, with an exception for small businesses (corporations with less than 10 employees and no subsidiaries); this rule was introduced by the state of New South Wales in 2003, and then adopted nationwide in 2006.[83] By contrast, Canadian law grants private corporations substantially the same right to sue for defamation as individuals possess.[83] Since 2013, English law charts a middle course, allowing private corporations to sue for defamation, but requiring them to prove that the defamation caused both serious harm and serious financial loss, which individual plaintiffs are not required to demonstrate.[83]

Roman Dutch and Scots law

[edit]Defamation in jurisdictions applying Roman Dutch law (i.e. most of Southern Africa,[f] Indonesia, Suriname, and the Dutch Caribbean) gives rise to a claim by way of "actio iniuriarum". For liability under the actio iniuriarum, the general elements of delict must be present, but specific rules have been developed for each element. Causation, for example, is seldom in issue, and is assumed to be present. The elements of liability under the actio iniuriarum are as follows:

- harm, in the form of a violation of a personality interest (one's corpus, dignitas and fama);

- wrongful conduct;[g] and

- intention.

Under the actio iniuriarum, harm consists in the infringement of a personality right, either "corpus", "dignitas", or "fama". Dignitas is a generic term meaning 'worthiness, dignity, self-respect', and comprises related concerns like mental tranquillity and privacy. Because it is such a wide concept, its infringement must be serious. Not every insult is humiliating; one must prove contumelia. This includes insult (iniuria in the narrow sense), adultery, loss of consortium, alienation of affection, breach of promise (but only in a humiliating or degrading manner), et cetera. "Fama" is a generic term referring to reputation and actio iniuriarum pertaining to it encompasses defamation more broadly Beyond simply covering actions that fall within the broader concept of defamation, "actio iniuriarum" relating to infringements of a person's corpus provides civil remedies for assaults, acts of a sexual or indecent nature, and 'wrongful arrest and detention'.

In Scots law, which is closely related to Roman Dutch law, the remedy for defamation is similarly the actio iniuriarium and the most common defence is "veritas" (i.e. proving the truth of otherwise defamatory statement). Defamation falls within the realm of non-patrimonial (i.e. dignitary) interests. The Scots law pertaining to the protection of non-patrimonial interests is said to be 'a thing of shreds and patches'.[84] This notwithstanding, there is 'little historical basis in Scots law for the kind of structural difficulties that have restricted English law' in the development of mechanisms to protect so-called 'rights of personality'.[85] The actio iniuriarum heritage of Scots law gives the courts scope to recognise, and afford reparation in, cases in which no patrimonial (or 'quasi-patrimonial') 'loss' has occurred, but a recognised dignitary interest has nonetheless been invaded through the wrongful conduct of the defender. For such reparation to be offered, however, the non-patrimonial interest must be deliberately affronted: negligent interference with a non-patrimonial interest will not be sufficient to generate liability.[86] An actio iniuriarum requires that the conduct of the defender be 'contumelious'[87]—that is, it must show such hubristic disregard of the pursuer's recognised personality interest that an intention to affront (animus iniuriandi) might be imputed.[88]

Defamation as a crime

[edit]| Criminal law |

|---|

| Elements |

| Scope of criminal liability |

| Severity of offense |

|

| Inchoate offenses |

| Offense against the person |

| Sexual offenses |

| Crimes against property |

| Crimes against justice |

| Crimes against the public |

| Crimes against animals |

| Crimes against the state |

| Defenses to liability |

| Other common-law areas |

| Portals |

In addition to tort law, many jurisdictions treat defamation as a criminal offence and provide for penalties as such. Article 19, a British free expression advocacy group, has published global maps[89] charting the existence of criminal defamation law across the globe, as well as showing countries that have special protections for political leaders or functionaries of the state.[90]

There can be regional statutes that may differ from the national norm. For example, in the United States, criminal defamation is generally limited to the living. However, there are 7 states (Idaho, Kansas, Louisiana, Nevada, North Dakota, Oklahoma, Utah) that have criminal statutes regarding defamation of the dead.[91]

The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) has also published a detailed database on criminal and civil defamation provisions in 55 countries, including all European countries, all member countries of the Commonwealth of Independent States, America, and Canada.[4]

Questions of group libel have been appearing in common law for hundreds of years. One of the earliest known cases of a defendant being tried for defamation of a group was the case of R v Orme and Nutt (1700). In this case, the jury found that the defendant was guilty of libeling several subjects, though they did not specifically identify who these subjects were. A report of the case told that the jury believed that "where a writing ... inveighs against mankind in general, or against a particular order of men, as for instance, men of the gown, this is no libel, but it must descend to particulars and individuals to make it libel."[92] This jury believed that only individuals who believed they were specifically defamed had a claim to a libel case. Since the jury was unable to identify the exact people who were being defamed, there was no cause to identify the statements were a libel.

Another early English group libel which has been frequently cited is King v. Osborne (1732). In this case, the defendant was on trial "for printing a libel reflecting upon the Portuguese Jews". The printing in question claimed that Jews who had arrived in London from Portugal burned a Jewish woman to death when she had a child with a Christian man, and that this act was common. Following Osborne's anti-Semitic publication, several Jews were attacked. Initially, the judge seemed to believe the court could do nothing since no individual was singled out by Osborne's writings. However, the court concluded that "since the publication implied the act was one Jews frequently did, the whole community of Jews was defamed."[93] Though various reports of this case give differing accounts of the crime, this report clearly shows a ruling based on group libel. Since laws restricting libel were accepted at this time because of its tendency to lead to a breach of peace, group libel laws were justified because they showed potential for an equal or perhaps greater risk of violence.[94] For this reason, group libel cases are criminal even though most libel cases are civil torts.

In a variety of Common Law jurisdictions, criminal laws prohibiting protests at funerals, sedition, false statements in connection with elections, and the use of profanity in public, are also often used in contexts similar to criminal libel actions. The boundaries of a court's power to hold individuals in "contempt of court" for what amounts to alleged defamatory statements about judges or the court process by attorneys or other people involved in court cases is also not well established in many common law countries.

Criticism

[edit]While defamation torts are less controversial as they ostensibly involve plaintiffs seeking to protect their right to dignity and their reputation, criminal defamation is more controversial as it involves the state expressly seeking to restrict freedom of expression. Human rights organisations, and other organisations such as the Council of Europe and Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, have campaigned against strict defamation laws that criminalise defamation.[95][96] The freedom of expression advocacy group Article 19 opposes criminal defamation, arguing that civil defamation laws providing defences for statements on matters of public interest are better compliant with international human rights law.[13] The European Court of Human Rights has placed restrictions on criminal libel laws because of the freedom of expression provisions of the European Convention on Human Rights. One notable case was Lingens v. Austria (1986).

Laws by jurisdiction

[edit]This section needs to be updated. (April 2020) |

Summary table

[edit]| Country | General offences | Special offences | Custodial sentences |

|---|---|---|---|

| • | |||

| • | • | • | |

| Unclear | Unclear | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | ||

| • | • | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | ||

| Unclear | Unclear | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | ||

| • | • | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | |||

| • | • | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | ||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • | |

| • | |||

| Unclear | |||

| • | • | • | |

| • | • | • |

Albania

[edit]According to the Criminal Code of Albania, defamation is a crime. Slandering in the knowledge of falsity is subject to fines of from 40000 ALL (c. $350) to one million ALL (c. $8350).[102] If the slandering occurs in public or damages multiple people, the fine is 40,000 ALL to three million ALL (c. $25100).[103] In addition, defamation of authorities, public officials or foreign representatives (Articles 227, 239 to 241) are separate crimes with maximum penalties varying from one to three years of imprisonment.[104][105]

Argentina

[edit]In Argentina, the crimes of calumny and injury are foreseen in the chapter "Crimes Against Honor" (Articles 109 to 117-bis) of the Penal Code. Calumny is defined as "the false imputation to a determined person of a concrete crime that leads to a lawsuit" (Article 109). However, expressions referring to subjects of public interest or that are not assertive do not constitute calumny. Penalty is a fine from 3,000 to 30,000 pesos. He who intentionally dishonor or discredit a determined person is punished with a penalty from 1,500 to 20,000 pesos (Article 110).

He who publishes or reproduces, by any means, calumnies and injuries made by others, will be punished as responsible himself for the calumnies and injuries whenever its content is not correctly attributed to the corresponding source. Exceptions are expressions referring to subjects of public interest or that are not assertive (see Article 113). When calumny or injury are committed through the press, a possible extra penalty is the publication of the judicial decision at the expenses of the guilty (Article 114). He who passes to someone else information about a person that is included in a personal database and that one knows to be false, is punished with six months to three years in prison. When there is harm to somebody, penalties are aggravated by an extra half (Article 117 bis, §§ 2nd and 3rd).[106]

Australia

[edit]Defamation law in Australia developed primarily out of the English law of defamation and its cases, though now there are differences introduced by statute and by the implied constitutional limitation on governmental powers to limit speech of a political nature established in Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation (1997).[107]

In 2006, uniform defamation laws came into effect across Australia.[108] In addition to fixing the problematic inconsistencies in law between individual States and Territories, the laws made a number of changes to the common law position, including:

- Abolishing the distinction between libel and slander.[109]: §7 [110]

- Providing new defences including that of triviality, where it is a defence to the publication of a defamatory matter if the defendant proves that the circumstances of publication were such that the plaintiff was unlikely to sustain any harm.[110]

- The defences against defamation may be negated if there is proof the publication was actuated by malice.[109]: §24

- Greatly restricting the right of corporations to sue for defamation (see e.g. Defamation Act 2005 (Vic), s 9). Corporations may, however, still sue for the tort of injurious falsehood, where the burden of proof is greater than in defamation, because the plaintiff must show that the defamation was made with malice and resulted in economic loss.[111]

The 2006 reforms also established across all Australian states the availability of truth as an unqualified defence; previously a number of states only allowed a defence of truth with the condition that a public interest or benefit existed. The defendant however still needs to prove that the defamatory imputations are substantially true.[112]

The law as it currently stands in Australia was summarised in the 2015 case of Duffy v Google by Justice Blue in the Supreme Court of South Australia:[113]

The tort can be divided up into the following ingredients:

- the defendant participates in publication to a third party of a body of work;

- the body of work contains a passage alleged to be defamatory;

- the passage conveys an imputation;

- the imputation is about the plaintiff;

- the imputation is damaging to the plaintiff's reputation.

Defences available to defamation defendants include absolute privilege, qualified privilege, justification (truth), honest opinion, publication of public documents, fair report of proceedings of public concern and triviality.[46]

Online

[edit]On 10 December 2002, the High Court of Australia delivered judgment in the Internet defamation case of Dow Jones v Gutnick.[114] The judgment established that internet-published foreign publications that defamed an Australian in their Australian reputation could be held accountable under Australian defamation law. The case gained worldwide attention and is often said, inaccurately, to be the first of its kind. A similar case that predates Dow Jones v Gutnick is Berezovsky v Michaels in England.[115]

Australia's first Twitter defamation case to go to trial is believed to be Mickle v Farley. The defendant, former Orange High School student Andrew Farley was ordered to pay $105,000 to a teacher for writing defamatory remarks about her on the social media platform.[116]

A more recent case in defamation law was Hockey v Fairfax Media Publications Pty Limited [2015], heard in the Federal Court of Australia. This judgment was significant as it demonstrated that tweets, consisting of even as little as three words, can be defamatory, as was held in this case.[117]

Austria

[edit]In Austria, the crime of defamation is foreseen by Article 111 of the Criminal Code. Related criminal offences include "slander and assault" (Article 115), that happens "if a person insults, mocks, mistreats or threatens will ill-treatment another one in public", and yet "malicious falsehood" (Article 297), defined as a false accusation that exposes someone to the risk of prosecution.[118]

Azerbaijan

[edit]In Azerbaijan, the crime of defamation (Article 147) may result in a fine up to "500 times the amount of minimum salaries", public work for up to 240 hours, correctional work for up to one year, or imprisonment of up to six months. Penalties are aggravated to up to three years of prison if the victim is falsely accused of having committed a crime "of grave or very grave nature" (Article 147.2). The crime of insult (Article 148) can lead to a fine of up to 1,000 times the minimum wage, or to the same penalties of defamation for public work, correctional work or imprisonment.[119][120]

According to the OSCE report on defamation laws, "Azerbaijan intends to remove articles on defamation and insult from criminal legislation and preserve them in the Civil Code".[121]

Belgium

[edit]In Belgium, crimes against honor are foreseen in Chapter V of the Belgian Penal Code, Articles 443 to 453-bis. Someone is guilty of calumny "when law admits proof of the alleged fact" and of defamation "when law does not admit this evidence" (Article 443). The penalty is eight days to one year of imprisonment, plus a fine (Article 444). In addition, the crime of "calumnious denunciation" (Article 445) is punished with 15 days to six months in prison, plus a fine. In any of the crimes covered by Chapter V of the Penal Code, the minimum penalty may be doubled (Article 453-bis) "when one of the motivations of the crime is hatred, contempt or hostility of a person due to his or her intended race, colour of the skin, ancestry, national origin or ethnicity, nationality, gender, sexual orientation, marital status, place of birth, age, patrimony, philosophical or religious belief, present or future health condition, disability, native language, political belief, physical or genetical characteristic, or social origin".[122][123]

Brazil

[edit]In Brazil, defamation is a crime, which is prosecuted either as "defamation" (three months to a year in prison, plus fine; Article 139 of the Penal Code), "calumny" (six months to two years in prison, plus fine; Article 138 of the PC) or "injury" (one to six months in prison, or fine; Article 140), with aggravating penalties when the crime is practiced in public (Article 141, item III) or against a state employee because of his regular duties. Incitation to hatred and violence is also foreseen in the Penal Code (incitation to a crime, Article 286). Moreover, in situations like bullying or moral constraint, defamation acts are also covered by the crimes of "illegal constraint" (Article 146 of the Penal Code) and "arbitrary exercise of discretion" (Article 345 of PC), defined as breaking the law as a vigilante.[124]

Bulgaria

[edit]In Bulgaria, defamation is formally a criminal offence, but the penalty of imprisonment was abolished in 1999. Articles 146 (insult), 147 (criminal defamation) and 148 (public insult) of the Criminal Code prescribe a penalty of fine.[125]

Canada

[edit]Civil

[edit]Quebec

[edit]In Quebec, defamation was originally grounded in the law inherited from France and is presently established by Chapter III, Title 2 of Book One of the Civil Code of Quebec, which provides that "every person has a right to the respect of his reputation and privacy".[126]

To establish civil liability for defamation, the plaintiff must establish, on a balance of probabilities, the existence of an injury (fault), a wrongful act (damage), and of a causal connection (link of causality) between the two. A person who has made defamatory remarks will not necessarily be civilly liable for them. The plaintiff must further demonstrate that the person who made the remarks committed a wrongful act. Defamation in Quebec is governed by a reasonableness standard, as opposed to strict liability; a defendant who made a false statement would not be held liable if it was reasonable to believe the statement was true.[127]

Criminal

[edit]The Criminal Code of Canada specifies the following as criminal offences:

- Defamatory libel, defined as "matter published, without lawful justification or excuse, that is likely to injure the reputation of any person by exposing him to hatred, contempt or ridicule, or that is designed to insult the person of or concerning whom it is published",[128] receives the same penalty.[129]

- A "libel known to be false" is an indictable offence, for which the prison term is a maximum of five years.[130]

The criminal portion of the law has been rarely applied, but it has been observed that, when treated as an indictable offence, it often appears to arise from statements made against an agent of the Crown, such as a police officer, a corrections officer, or a Crown attorney.[131] In the most recent case, in 2012, an Ottawa restaurant owner was convicted of ongoing online harassment of a customer who had complained about the quality of food and service in her restaurant.[132]

According to the OSCE official report on defamation laws issued in 2005, 57 persons in Canada were accused of defamation, libel and insult, among which 23 were convicted – 9 to prison sentences, 19 to probation and one to a fine. The average period in prison was 270 days, and the maximum sentence was four years of imprisonment.[133]

Online

[edit]The rise of the internet as a medium for publication and the expression of ideas, including the emergence of social media platforms transcending national boundaries, has proven challenging to reconcile with traditional notions of defamation law. Questions of jurisdiction and conflicting limitation periods in trans-border online defamation cases, liability for hyperlinks to defamatory content, filing lawsuits against anonymous parties, and the liability of internet service providers and intermediaries make online defamation a uniquely complicated area of law.[134]

In 2011, the Supreme Court of Canada held that a person who posts hyperlinks on a website which lead to another site with defamatory content is not publishing that defamatory material for the purposes of libel and defamation law.[135][136]

Chile

[edit]In Chile, the crimes of calumny and slanderous allegation (injurias) are covered by Articles 412 to 431 of the Penal Code. Calumny is defined as "the false imputation of a determined crime and that can lead to a public prosecution" (Article 412). If the calumny is written and with publicity, penalty is "lower imprisonment" in its medium degree plus a fine of 11 to 20 "vital wages" when it refers to a crime, or "lower imprisonment" in its minimum degree plus a fine of six to ten "vital wages" when it refers to a misdemeanor (Article 413). If it is not written or with publicity, penalty is "lower imprisonment" in its minimum degree plus a fine of six to fifteen "vital wages" when it is about a crime, or plus a fine of six to ten "vital wages" when it is about a misdemeanor (Article 414).[137][138]

According to Article 25 of the Penal Code, "lower imprisonment" is defined as a prison term between 61 days and five years. According to Article 30, the penalty of "lower imprisonment" in its medium or minimum degrees carries with it also the suspension of the exercise of a public position during the prison term.[139]

Article 416 defines injuria as "all expression said or action performed that dishonors, discredits or causes contempt". Article 417 defines broadly injurias graves (grave slander), including the imputation of a crime or misdemeanor that cannot lead to public prosecution, and the imputation of a vice or lack of morality, which are capable of harming considerably the reputation, credit or interests of the offended person. "Grave slander" in written form or with publicity are punished with "lower imprisonment" in its minimum to medium degrees plus a fine of eleven to twenty "vital wages". Calumny or slander of a deceased person (Article 424) can be prosecuted by the spouse, children, grandchildren, parents, grandparents, siblings and heirs of the offended person. Finally, according to Article 425, in the case of calumnies and slander published in foreign newspapers, are considered liable all those who from Chilean territory sent articles or gave orders for publication abroad, or contributed to the introduction of such newspapers in Chile with the intention of propagating the calumny and slander.[140]

China

[edit]Civil

[edit]Based on text from Wikisource:[better source needed] Civil Code of the People's Republic of China, "Book Four" ("Personality Rights").

"Chapter I" ("General rules"):

- Personality rights: reputation, honour, privacy, dignity (Art. 990)

- Protection of personality rights (Arts. 991–993)

- Personality rights of the deceased (Art. 994)

- Liability for infringement; and requests to stop, restore reputation, offer apology (Arts. 995–1000)

"Chapter V" ("Rights to Reputation and Rights to Honor"):

- Right to reputation, protection from defamation and insults (Art. 1024)

- Reputation includes moral character, prestige, talent, credit

- Liability for fact fabrication, distortion, lack of verification, misrepresentation, insults (Art. 1025)

- Verification considerations, source credibility, controversial information, timeliness, public order and morals (Art. 1026)

- Depictions of real people and events, in literary and artistic works (Art. 1027)

- Right to request correction or deletion (Art. 1028)

- Right to request correction or deletion, for incorrect credit reports (Arts. 1029, 1030)

- Honorary titles and awards: protection, recording, correction (Art. 1031)

Criminal

[edit]Article 246 of the Criminal Law of the People's Republic of China (中华人民共和国刑法) makes serious defamation punishable by fixed-term imprisonment of not more than three years or criminal detention upon complaint, unless it is against the government.[141]

Croatia

[edit]In Croatia, the crime of insult prescribes a penalty of up to three months in prison, or a fine of "up to 100 daily incomes" (Criminal Code, Article 199). If the crime is committed in public, penalties are aggravated to up to six months of imprisonment, or a fine of "up to 150 daily incomes" (Article 199–2). Moreover, the crime of defamation occurs when someone affirms or disseminates false facts about other person that can damage his reputation. The maximum penalty is one year in prison, or a fine of up to 150 daily incomes (Article 200–1). If the crime is committed in public, the prison term can reach one year (Article 200–2). On the other hand, according to Article 203, there is an exemption for the application of the aforementioned articles (insult and defamation) when the specific context is that of a scientific work, literary work, work of art, public information conducted by a politician or a government official, journalistic work, or the defence of a right or the protection of justifiable interests, in all cases provided that the conduct was not aimed at damaging someone's reputation.[142]

Czech Republic

[edit]According to the Czech Criminal Code, Article 184, defamation is a crime. Penalties may reach a maximum prison term of one year (Article 184–1) or, if the crime is committed through the press, film, radio, TV, publicly accessible computer network, or by "similarly effective" methods, the offender may stay in prison for up to two years or be prohibited of exercising a specific activity.[143]However, only the most severe cases will be subject to criminal prosecution. The less severe cases can be solved by an action for apology, damages or injunctions.

Denmark

[edit]In Denmark, libel is a crime, as defined by Article 267 of the Danish Criminal Code, with a penalty of up to six months in prison or a fine, with proceedings initiated by the victim. In addition, Article 266-b prescribes a maximum prison term of two years in the case of public defamation aimed at a group of persons because of their race, colour, national or ethnic origin, religion or "sexual inclination".[144][145]

Finland

[edit]In Finland, defamation is a crime, according to the Criminal Code (Chapter 24, Sections 9 and 10), punishable with a fine, or, if aggravated, with up to two years' imprisonment or a fine. Defamation is defined as spreading a false report or insinuation apt to cause harm to a person, or otherwise disparaging someone. Defamation of the deceased may also constitute an offence if apt to cause harm to surviving loved ones. In addition, there is a crime called "dissemination of information violating personal privacy" (Chapter 24, Section 8), which consists in disseminating information, even accurate, in a way that is apt to harm someone's right to privacy. Information that may be relevant with regard to a person's conduct in public office, in business, or in a comparable position, or of information otherwise relevant to a matter of public interest, is not covered by this prohibition.[146][147] Finnish criminal law has no provisions penalizing the defamation of corporate entities, only of natural persons.

France

[edit]Civil

[edit]While defamation law in most jurisdictions centres on the protection of individuals' dignity or reputation, defamation law in France is particularly rooted in protecting the privacy of individuals.[148] While the broader scope of the rights protected make defamation cases easier to prove in France than, for example, in England; awards in defamation cases are significantly lower and it is common for courts to award symbolic damages as low as €1.[148] Controversially, damages in defamation cases brought by public officials are higher than those brought by ordinary citizens, which has a chilling effect on criticism of public policy[149] While the only statutory defence available under French defamation law is to demonstrate the truth of the defamatory statement in question, a defence that is unavailable in cases involving an individual's personal life; French courts have recognised three additional exceptions:[150]

- References to matters over ten years old

- References to a person's pardoned or expunged criminal record

- A plea of good faith, which may be made if the statement

- pursues a legitimate aim

- is not driven by animosity or malice

- is prudent and measured in presentation

- is backed by a serious investigation that dutifully sought to ascertain the truth of the statement.

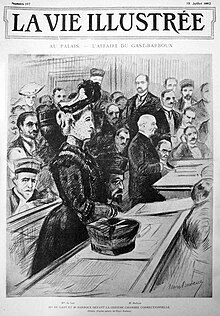

Criminal

[edit]

Defined as "the allegation or [the] allocation of a fact that damages the honor or reputation of the person or body to which the fact is imputed". A defamatory allegation is considered an insult if it does not include any facts or if the claimed facts cannot be verified.

Germany

[edit]In German law, there is no distinction between libel and slander. As of 2006[update], German defamation lawsuits are increasing.[151] The relevant offences of Germany's Criminal Code are §90 (denigration of the Federal President), §90a (denigration of the [federal] State and its symbols), §90b (unconstitutional denigration of the organs of the Constitution), §185 ("insult"), §186 (defamation of character), §187 (defamation with deliberate untruths), §188 (political defamation with increased penalties for offending against paras 186 and 187), §189 (denigration of a deceased person), §192 ("insult" with true statements). Other sections relevant to prosecution of these offences are §190 (criminal conviction as proof of truth), §193 (no defamation in the pursuit of rightful interests), §194 (application for a criminal prosecution under these paragraphs), §199 (mutual insult allowed to be left unpunished), and §200 (method of proclamation).

Greece

[edit]In Greece, the maximum prison term for defamation, libel or insult was five years, while the maximum fine was €15,000.[152]

The crime of insult (Article 361, § 1, of the Penal Code) may have led to up to one year of imprisonment or a fine, while unprovoked insult (Article361-A, § 1) was punished with at least three months in prison. In addition, defamation may have resulted in up to two months in prison or a fine, while aggravated defamation could have led to at least three months of prison, plus a possible fine (Article 363) and deprivation of the offender's civil rights. Finally, disparaging the memory of a deceased person is punished with imprisonment of up to six months (Penal Code, Article 365).[153]

India

[edit]In India, a defamation case can be filed under either criminal law or civil law or cyber crime law, together or in sequence.[154]

According to the Constitution of India,[155] the fundamental right to free speech (Article 19) is subject to "reasonable restrictions":

19. Protection of certain rights regarding freedom of speech, etc.

- (1) All citizens shall have the right—

- (a) to freedom of speech and expression;

- [(2) Nothing in sub-clause (a) of clause (1) shall affect the operation of any existing law, or prevent the State from making any law, in so far as such law imposes reasonable restrictions on the exercise of the right conferred by the said sub-clause in the interests of [the sovereignty and integrity of India], the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, decency or morality, or in relation to contempt of court, defamation or incitement to an offence.]

Accordingly, for the purpose of criminal defamation, "reasonable restrictions" are defined in Section 499 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860.[97][156] This section defines defamation and provides ten valid exceptions when a statement is not considered to be defamation. It says that defamation takes place, when someone "by words either spoken or intended to be read, or by signs or by visible representations, makes or publishes any imputation concerning any person intending to harm, or knowing or having reason to believe that such imputation will harm, the reputation of such person". The punishment is simple imprisonment for up to two years, or a fine, or both (Section 500).

Some other offences related to false allegations: false statements regarding elections (Section 171G), false information (Section 182), false claims in court (Section 209), false criminal charges (Section 211).

Some other offences related to insults: against public servants in judicial proceedings (Section 228), against religion or religious beliefs (Section 295A), against religious feelings (Section 298), against breach of peace (Section 504), against modesty of women (Section 509).

According to the Indian Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973[157] defamation is prosecuted only upon a complaint (within six months from the act) (Section 199), and is a bailable, non-cognisable and compoundable offence (See: The First Schedule, Classification of Offences).

Ireland

[edit]According to the (revised) Defamation Act 2009,[98] the last criminal offences (Sections 36–37, blasphemy) seem to have been repealed. The statute of limitations is one year from the time of first publication (may be extended to two years by the courts) (Section 38).

The 2009 Act repeals the Defamation Act 1961, which had, together with the underlying principles of the common law of tort, governed Irish defamation law for almost half a century. The 2009 Act represents significant changes in Irish law, as many believe that it previously attached insufficient importance to the media's freedom of expression and weighed too heavily in support of the individual's right to a good name.[158]

Israel

[edit]According to Defamation Prohibition Law[full citation needed] (1965), defamation can constitute either civil or criminal offence.

As a civil offence, defamation is considered a tort case and the court may award a compensation of up to NIS 50,000 to the person targeted by the defamation, while the plaintiff does not have to prove a material damage.

As a criminal offence, defamation is punishable by a year of imprisonment. In order to constitute a felony, defamation must be intentional and target at least two persons.

Italy

[edit]In Italy, there used to be different crimes against honor. The crime of injury (Article 594 of the Penal Code) referred to the act of offending someone's honor in their presence and was punishable with up to six months in prison or a fine of up to €516. The crime of defamation (Article 595, Penal Code) refers to any other situation involving offending one's reputation before many persons, and is punishable with a penalty of up to a year in prison or up to €1,032 in fine, doubled to up to two years in prison or a fine of €2,065 if the offence consists in the attribution of a determined fact. When the offence happens by the means of the press or by any other means of publicity, or in a public demonstration, the penalty is of imprisonment from six months to three years, or a fine of at least €516. Both of them were a querela di parte crimes, that is, the victim had the right of choosing, in any moment, to stop the criminal prosecution by withdrawing the querela (a formal complaint), or even prosecute the fact only with a civil action with no querela and therefore no criminal prosecution at all. Beginning from 15 January 2016, injury is no longer a crime but a tort, while defamation is still considered a crime like before.[159]

Article 31 of the Penal Code establishes that crimes committed with abuse of power or with abuse of a profession or art, or with the violation of a duty inherent to that profession or art, lead to the additional penalty of a temporary ban in the exercise of that profession or art. Therefore, journalists convicted of libel may be banned from exercising their profession.[160][161] Deliberately false accusations of defamation, as with any other crime, lead to the crime of calunnia ("calumny", Article 368, Penal Code), which, under the Italian legal system, is defined as the crime of falsely accusing, before the authorities, a person of a crime they did not commit. As to the trial, judgment on the legality of the evidence fades into its relevance.[162]

Japan

[edit]The Constitution of Japan[163] reads:

Article 21. Freedom of assembly and association as well as speech, press and all other forms of expression are guaranteed. No censorship shall be maintained, nor shall the secrecy of any means of communication be violated.

Civil

[edit]Under article 723 of the Japanese Civil Code, a court is empowered to order a tortfeasor in a defamation case to "take suitable measures for the restoration of the [plaintiff's] reputation either in lieu of or together with compensation for damages".[164] An example of a civil defamation case in Japan can be found at Japan civil court finds against ZNTIR President Yositoki (Mitsuo) Hataya and Yoshiaki.

Criminal

[edit]The Penal Code of Japan[99] (translation from government, but still not official text) seems to prescribe these related offences:

Article 92, "Damage to a Foreign National Flag". Seems relevant to the extent that the wording: "... defiles the national flag or other national emblem of a foreign state for the purpose of insulting the foreign state", can be construed to include more abstract defiling; translations of the Japanese term (汚損,[165] oson) include 'defacing'.

Article 172, "False Accusations". That is, false criminal charges (as in complaint, indictment, or information).

Article 188, "Desecrating Places of Worship; Interference with Religious Service". The Japanese term (不敬,[166] fukei) seems to include any act of 'disrespect' and 'blasphemy' – a standard term; as long as it is performed in a place of worship.

Articles 230 and 230-2, "Defamation" (名誉毀損, meiyokison). General defamation provision. Where the truth of the allegations is not a factor in determining guilt; but there is "Special Provision for Matters Concerning Public Interest", whereby proving the allegations is allowed as a defence. See also 232: "prosecuted only upon complaint".

Article 231, "Insults" (侮辱, bujoku). General insult provision. See also 232: "prosecuted only upon complaint".

Article 233, "Damage to Credibility; Obstruction of Business". Special provision for damaging the reputation of, or 'confidence' (信用,[167] shinnyou) in, the business of another.

For a sample penal defamation case, see President of the Yukan Wakayama Jiji v. States, Vol. 23 No. 7 Minshu 1966 (A) 2472, 975 (Supreme Court of Japan 25 June 1969) – also on Wikisource. The defence alleged, among other things, violation of Article 21 of the Constitution. The court found that none of the defence's grounds for appeal amounted to lawful grounds for a final appeal. Nevertheless, the court examined the case ex officio, and found procedural illegalities in the lower courts' judgments (regarding the exclusion of evidence from testimony, as hearsay). As a result, the court quashed the conviction on appeal, and remanded the case to a lower court for further proceedings.

Malaysia

[edit]In Malaysia, defamation is both a tort and a criminal offence meant to protect the reputation and good name of a person. The principal statutes relied upon are the Defamation Act 1957 (Revised 1983) and the Penal Code. Following the practice of other common law jurisdictions like the United Kingdom, Singapore, and India, Malaysia relies on case law. In fact, the Defamation Act 1957 is similar with the English Defamaiton Act 1952. The Malaysian Penal Code is pari materia with the Indian and Singaporean Penal Codes.

Mexico

[edit]In Mexico, crimes of calumny, defamation and slanderous allegation (injurias) have been abolished in the Federal Penal Code as well as in fifteen states. These crimes remain in the penal codes of seventeen states, where penalty is, in average, from 1.1 years (for ones convicted for slanderous allegation) to 3.8 years in jail (for those convicted for calumny).[168]

Netherlands

[edit]In the Netherlands, defamation is mostly dealt with by lodging a civil complaint at the District Court. Article 167 of book 6 of the Civil Code holds: "When someone is liable towards another person under this Section because of an incorrect or, by its incompleteness, misleading publication of information of factual nature, the court may, upon a right of action (legal claim) of this other person, order the tortfeasor to publish a correction in a way to be set by court." If the court grants an injunction, the defendant is usually ordered to delete the publication or to publish a rectification statement.

Norway

[edit]In Norway, defamation was a crime punished with imprisonment of up to six months or a fine (Penal Code, Chapter 23, § 246). When the offense is likely to harm one's "good name" and reputation, or exposes him to hatred, contempt or loss of confidence, the maximum prison term went up to one year, and if the defamation happens in print, in broadcasting or through an especially aggravating circumstance, imprisonment may have reached two years (§ 247). When the offender acts "against his better judgment", he was liable to a maximum prison term of three years (§ 248). According to § 251, defamation lawsuits must be initiated by the offended person, unless the defamatory act was directed to an indefinite group or a large number of persons, when it may also have been prosecuted by public authorities.[169][170]

Under the new Penal Code, decided upon by the Parliament in 2005, defamation would cease to exist as a crime. Rather, any person who believes he or she has been subject to defamation will have to press civil lawsuits. The Criminal Code took effect on 1 October 2015.

Philippines

[edit]Criminal

[edit]According to the Revised Penal Code of the Philippines ("Title Thirteen", "Crimes Against Honor"):[100]

ARTICLE 353. Definition of Libel. – A libel is a public and malicious imputation of a crime, or of a vice or defect, real or imaginary, or any act, omission, condition, status, or circumstance tending to cause the dishonor, discredit, or contempt of a natural or juridical person, or to blacken the memory of one who is dead.

- Malice presumed, even if true; exceptions: private communications in the course of duty, fair reports – without comments – on official proceedings (Art. 354)

- Punishment for libel in writing or similar medium (including radio, painting, theatre, cinema): imprisonment, fine, civil action (Art. 355)

- Threat to publish libel concerning one's family, for extracting money (Art. 356)

- Publication in the press of private-life facts – connected to official proceedings – offending virtue, honour, reputation (Art. 357)

- Slander – oral defamation (Art. 358)

- Slander by deed – "any act not included and punished in this title, which shall cast dishonor, discredit or contempt upon another person" (Art. 359)

- Responsibility for dissemination; same as for authorship (Art. 360)

- Conditions for defence of truth: good motives, justifiable ends; not available for allegations of non-criminal activities – unless related to official duties of government employees (Art. 361)

- Malicious comments cancel the exceptions of Art. 354 (Art. 362)

- Incriminating an innocent person (Art. 363)

- Intrigue against honour or reputation (Art. 364)

Related articles:

- Aggravating circumstances (Art. 14)

- Crime committed in contempt of, or with insult to, public authorities (¶ 2)

- Act committed with insult or disrespect, regarding rank, age, or sex (¶ 3)

- Intentionally causing ignominy, in addition to other effects of the act (¶ 17)

- Statute of limitations: Two years for libel, six months for slander, two months for light offences (Art. 90)

- Offending religious feelings – in places of worship, or during religious ceremonies (Art. 133)

- Disrespectful behaviour towards legislature or related bodies, during their proceedings (Art. 144)

- "Unlawful use of means of publication" (Art. 154)

- Publication of malicious fake news, endangering public order, or damaging state interests or credit (¶ 1)

- False testimony against defendant, in criminal cases (Art. 180)

- Spreading false rumours, when aiming to monopolize or restrain trade (Art. 186 ¶ 2)

- Lesser physical injury, when intended to insult, offend, cause ignominy (Art. 265 ¶ 2)

- Threats to harm honour – e.g. for extracting money (Art. 282)

In January 2012, The Manila Times published an article on a criminal defamation case. A broadcaster was jailed for more than two years, following conviction on libel charges, by the Regional Trial Court of Davao. The radio broadcast dramatized a newspaper report regarding former speaker Prospero Nograles, who subsequently filed a complaint. Questioned were the conviction's compatibility with freedom of expression, and the trial in absentia. The United Nations Human Rights Committee recalled its General comment No. 34, and ordered the Philippine government to provide remedy, including compensation for time served in prison, and to prevent similar violations in the future.[171]

Online