Квебек

Эта статья может оказаться слишком длинной для удобного чтения и навигации . Когда этот тег был добавлен, его читаемый размер составлял 14 769 слов. ( июнь 2024 г. ) |

Квебек

Квебек ( французский ) | |

|---|---|

| Девиз(ы): | |

| Координаты: 52 ° с.ш. 72 ° з.д. / 52 ° с.ш. 72 ° з.д. [ 1 ] | |

| Страна | Канада |

| До конфедерации | Канада Восток |

| Конфедерация | 1 июля 1867 г. (1-е место вместе с Нью-Брансуиком , Новая Шотландия , Онтарио ) |

| Капитал | Квебек Сити |

| Крупнейший город | Монреаль |

| Крупнейшее метро | Большой Монреаль |

| Правительство | |

| • Тип | Парламентская конституционная монархия |

| • Вице-губернатор | Манон Жаннот |

| • Премьер | Франсуа Лего |

| Законодательная власть | Национальное собрание Квебека |

| Федеральное представительство | Парламент Канады |

| Сиденья для дома | 78 из 338 (23,1%) |

| Места в Сенате | 24 из 105 (22,9%) |

| Область | |

| • Общий | 1 542 056 км 2 (595 391 квадратных миль) |

| • Земля | 1 365 128 км 2 (527 079 квадратных миль) |

| • Вода | 176 928 км 2 (68 312 квадратных миль) 11,5% |

| • Классифицировать | 2-й |

| 15,4% Канады | |

| Население ( 2021 ) | |

| • Общий | 8,501,833 [ 2 ] |

| • Оценивать (2 квартал 2024 г.) | 9,030,684 [ 3 ] |

| • Классифицировать | 2-й |

| • Плотность | 6,23/км 2 (16,1/кв. миль) |

| Демон(ы) | на английском языке: Квебекер, Квебекер, Квебекуа на французском языке: Québécois ( м ), [ 4 ] Квебекуа ( ж ) [ 4 ] |

| Официальные языки | Французский [ 5 ] |

| ВВП | |

| • Классифицировать | 2-й |

| • Всего (2022 г.) | 552,737 миллиарда канадских долларов [ 6 ] |

| • На душу населения | 63 651 канадский доллар (9-е место) |

| ИЧР | |

| • ИЧР (2019 г.) | 0.916 [ 7 ] — Очень высокий ( 9 место ) |

| Часовой пояс | UTC−05:00 ( восточный часовой пояс для большей части провинции). [ 8 ] ) |

| • Лето ( летнее время ) | UTC-04:00 |

| Канадская почтовая аббревиатура. | КК [ 9 ] |

| Рейтинги включают все провинции и территории. | |

Квебек [ а ] ( Французский : Квебек [kebɛk] ) [ 12 ] — одна из тринадцати провинций и территорий Канады . Это самая большая по площади провинция. [ б ] и второй по величине по численности населения .

Имея площадь 1,5 миллиона квадратных километров (0,58 миллиона квадратных миль) и более 12 000 км (7500 миль) границ, [ 13 ] [ 14 ] В Северной Америке Квебек расположен в Центральной Канаде . Провинция граничит по суше с провинциями Онтарио на западе, Ньюфаундлендом и Лабрадором на северо-востоке, Нью-Брансуиком на юго-востоке и прибрежной границей с территорией Нунавута . На севере он омывается заливом Джеймса , Гудзонова залива , Гудзонова пролива , залива Унгава , Северным Ледовитым и Атлантическим океанами, а на юге граничит с Соединенными Штатами . [ с ]

Большая часть населения Квебека проживает в долине реки Святого Лаврентия . [ 15 ] между его самым густонаселенным городом Монреалем , Труа-Ривьером и столицей провинции Квебеком .

1763 годами территория нынешнего Квебека была французской колонией Канады Между 1534 и и самой развитой колонией в Новой Франции . После Семилетней войны Канада стала британской колонией , сначала как провинция Квебек (1763–1791), затем Нижняя Канада (1791–1841) и, наконец, как часть провинции Канада (1841–1867). в восстания Нижней Канаде . В 1867 году он был объединен с Онтарио, Новой Шотландией и Нью-Брансуиком. До начала 1960-х годов католическая церковь играла большую роль в социальных и культурных учреждениях Квебека. Однако Тихая революция 1960-1980-х годов увеличила роль правительства Квебека в l'État Québécois (государственной власти Квебека).

Правительство Квебека функционирует в рамках Вестминстерской системы и является одновременно либеральной демократией и конституционной монархией . Премьер Квебека исполняет обязанности главы правительства . Дебаты о независимости сыграли большую роль в политике Квебека . общества Квебека Сплоченность и специфика основаны на трех его уникальных уставных документах: Квебекской Хартии прав и свобод человека , Хартии французского языка и Гражданском кодексе Квебека . Кроме того, в отличие от других регионов Канады, право в Квебеке является смешанным: частное право осуществляется в рамках системы гражданского права , а публичное право осуществляется в рамках системы общего права .

Квебека Официальным языком является французский; Квебекский французский — региональный сорт . Квебек — единственная провинция с франкоязычным большинством населения. Экономика Квебека в основном поддерживается крупным сектором услуг и разнообразным промышленным сектором. Что касается экспорта, то он опирается на ключевые отрасли авиационной промышленности , где он занимает 6-е место по величине продаж в мире. [ 16 ] гидроэлектроэнергия , горнодобывающая промышленность, фармацевтика , алюминий, древесина и бумага. Квебек хорошо известен производством кленового сиропа , своей комедией и тем, что сделал хоккей одним из самых популярных видов спорта в Канаде . Он также известен своей культурой ; В провинции производят литературу , музыку , фильмы , телешоу , фестивали и многое другое.

Этимология

Название Квебек происходит от алгонкинского слова, означающего «узкий проход» или «пролив». [ 17 ] Первоначально это название относилось к территории вокруг Квебека , где река Святого Лаврентия сужается до ущелья, окруженного скалами. Ранние варианты написания включали Québecq и Kébec . [ 18 ] Французский исследователь Самюэль де Шамплен в 1608 году выбрал название Квебек для колониального форпоста, который он будет использовать в качестве административного центра Новой Франции . [ 19 ]

История

Коренные народы и европейские экспедиции (до 1608 г.)

Палеоиндейцы , предположительно мигрировавшие из Азии в Америку между 20 000 и 14 000 лет назад, были первыми людьми , обосновавшимися на землях Квебека, прибывшими после того, как Лаврентидский ледниковый щит растаял примерно 11 000 лет назад. [ 20 ] [ 21 ] Из них многие этнокультурные группы возникли . К моменту европейских исследований 1500-х годов существовало одиннадцать коренных народов : инуиты и десять коренных народов — абенаки , алгонкины (или аничинабе), атикамекв , кри , гурон-виандот , малисит , микмакс , ирокезы , инну и наскаписы . [ 22 ] Алгонкины объединились в семь политических образований и вели кочевой образ жизни, основанный на охоте, собирательстве и рыболовстве. [ 23 ] Инуиты ловили рыбу и охотились на китов и тюленей вдоль побережий Гудзонова и Унгавского заливов. [ 24 ]

В 15 веке пала Византийская империя , что побудило западных европейцев искать новые морские пути на Дальний Восток . [ 25 ] Около 1522–1523 годов Джованни да Верраццано убедил короля Франции Франциска I организовать экспедицию для поиска западного пути в Китай (Китай) через Северо-Западный проход . Хотя эта экспедиция не увенчалась успехом, она установила название Новая Франция для северо-востока Северной Америки. [ 26 ] В своей первой экспедиции, заказанной из Королевства Франции, Жак Картье стал первым европейским исследователем, открывшим и нанесшим на карту Квебек, когда он высадился в Гаспе 24 июля 1534 года. [ 27 ] Во второй экспедиции, в 1535 году, Картье исследовал земли Стадаконы и назвал деревню и прилегающие к ней территории Канадой (от kanata , «деревня» на ирокезском языке ). Картье вернулся во Францию с примерно 10 ирокезами Святого Лаврентия , включая вождя Доннакону . легенду о королевстве Сагеней В 1540 году Доннакона рассказал королю , вдохновив его заказать третью экспедицию, на этот раз под руководством Жана-Франсуа де Ла Рок де Роберваля ; ему не удалось достичь своей цели - найти королевство. [ 28 ]

После этих экспедиций Франция на 50 лет в основном покинула Северную Америку из-за финансового кризиса; Франция участвовала в итальянских войнах и религиозных войнах. [ 29 ] Примерно в 1580 году рост торговли мехом возобновил интерес Франции; Новая Франция стала колониальным торговым постом . [ 30 ] В 1603 году Самюэль де Шамплен отправился к реке Святого Лаврентия и на Пуэнт-Сен-Матье заключил оборонительный пакт с инну, малиситами и микмаками, который стал «решающим фактором в сохранении французского колониального предприятия в Америке, несмотря на огромное численное преимущество по сравнению с британцами». [ 31 ] Так началась военная поддержка французами алгонкинских и гуронских народов против нападений ирокезов; они стали известны как Ирокезские войны и продолжались с начала 1600-х до начала 1700-х годов. [ 32 ]

Новая Франция (1608–1763)

Самуэль де Шамплен в 1608 году. [ 33 ] вернулся в регион в качестве руководителя разведочной партии. 3 июля 1608 года при поддержке короля Генриха IV он основал Жилище Квебека (ныне Квебек-Сити) и сделал его столицей Новой Франции и ее регионов. [ 30 ] Поселение было построено как постоянный форпост по торговле мехом, где коренные народы обменивали меха на французские товары, такие как металлические предметы, оружие, алкоголь и одежду. [ 34 ] Миссионерские группы прибыли в Новую Францию после основания Квебека. Coureurs des Bois и католические миссионеры использовали речные каноэ , чтобы исследовать внутренние районы и основать форты для торговли мехом. [ 35 ] [ 36 ]

Компания Compagnie des Cent-Associés , которой в 1627 году был предоставлен королевский мандат на управление Новой Францией, ввела Парижский обычай и сеньорическую систему и запретила поселение кому-либо, кроме католиков. [ 37 ] В 1629 году Квебек без боя сдался английским каперам во время англо-французской войны ; в 1632 году английский король согласился вернуть его по Сен-Жермен-ан-Ле . Труа-Ривьер был основан по просьбе де Шамплена в 1634 году. [ 38 ] Поль де Шомедей де Мезоннев основал Виль-Мари (ныне Монреаль) в 1642 году.

В 1663 году Компания Новой Франции уступила Канаду королю Людовику XIV , который превратил Новую Францию в королевскую провинцию Франции. [ 39 ] Новая Франция теперь была настоящей колонией , управляемой Суверенным советом Новой Франции из Квебека. Генерал -губернатор , управлял Канадой и ее административными зависимостями: Акадией, Луизианой и Плезансом. [ 40 ] Французские поселенцы были в основном фермерами и известны как « Канадиенс » или « Жители ». Хотя иммиграции было мало, [ 41 ] колония росла из-за высокой рождаемости среди жителей. [ 42 ] [ 43 ] В 1665 году полк Кариньян-Сальер построил линию укреплений, известную как «Долина фортов», для защиты от вторжений ирокезов, и привел с собой 1200 новых солдат. [ 44 ] около 800 молодых француженок (« дочерей короля »). Чтобы исправить гендерный дисбаланс и ускорить рост населения, король Людовик XIV спонсировал переезд в колонию [ 39 ] В 1666 году интендант Жан Талон организовал первую перепись и насчитал 3215 жителей. Тэлон принял политику диверсификации сельского хозяйства и поощрения рождаемости, в результате чего в 1672 году население увеличилось до 6700 человек. [ 45 ]

Территория Новой Франции расширилась от Гудзонова залива до Мексиканского залива и охватила Великие озера . [ 46 ] В начале 1700-х годов губернатор Кальер заключил Великий Монреальский мир , который не только подтвердил союз между алгонкинами и Новой Францией, но и окончательно положил конец ирокезским войнам. [ 47 ] Начиная с 1688 года, ожесточенная конкуренция между французами и британцами за контроль над внутренними районами Северной Америки и монополизацию торговли мехом столкнула Новую Францию и ее союзников из числа коренных народов с ирокезами и англичанами в четырех последовательных войнах, названных американцами Французской и Индийской войнами , и Межколониальных войнах. в Квебеке. [ 48 ] Первыми тремя были война короля Вильгельма (1688–1697), война королевы Анны (1702–1713) и война короля Георга (1744–1748). В 1713 году, после Утрехтского мира , герцог Орлеанский уступил Акадию и залив Плезанс Великобритании, но сохранил за собой Иль-Сен-Жан и Иль-Рояль , где крепость Луисбург впоследствии была возведена . Эти потери были значительными, поскольку залив Плезанс был основным маршрутом сообщения между Новой Францией и Францией, а в Акадии проживало 5000 академиков . [ 49 ] [ 50 ] При осаде Луисбурга (1745 г.) британцы одержали победу, но после военных уступок вернули город Франции. [ 51 ]

Последней из четырех французско-индийских войн была Семилетняя война война (« Завоевательная » в Квебеке) и продолжалась с 1754 по 1763 год. [ 52 ] [ 53 ] В 1754 году напряженность в борьбе за контроль над долиной Огайо обострилась , поскольку власти Новой Франции стали более агрессивными в попытках изгнать британских торговцев и колонистов. [ 54 ] В 1754 году Джордж Вашингтон предпринял внезапную атаку на группу спящих канадских солдат, известную как битва при Джумонвилл-Глен , первое сражение войны. В 1755 году губернатор Чарльз Лоуренс и офицер Роберт Монктон приказали насильственно изгнать академиков . В 1758 году на острове Иль-Рояль британский генерал Джеймс Вулф осадил и захватил крепость Луисбург. [ 55 ] Это позволило ему контролировать доступ к заливу Св. Лаврентия через пролив Кэбота . В 1759 году он в течение трех месяцев осадил Квебек со стороны острова Орлеан . [ 56 ] Затем Вулф штурмовал Квебек и сражался против Монкальма за контроль над городом в битве на равнинах Авраама . После британской победы наместник короля и лорд Рамезей заключил статьи о капитуляции Квебека . Весной 1760 года шевалье де Леви осадил Квебек и вынудил британцев закрепиться во время битвы при Сент-Фуа . Однако потеря французских судов, отправленных для пополнения запасов Новой Франции после падения Квебека во время битвы при Рестигуше, ознаменовала конец усилий Франции по возвращению колонии. Губернатор Пьер де Риго, маркиз де Водрей-Каваньяль подписали Акты о капитуляции Монреаля 8 сентября 1760 года.

В ожидании результатов Семилетней войны в Европе Новая Франция оказалась под британским военным режимом во главе с губернатором Джеймсом Мюрреем . [ 57 ] В 1762 году командующий Джеффри Амхерст положил конец французскому присутствию на Ньюфаундленде в битве при Сигнал-Хилл . Франция тайно уступила западную часть Луизианы и дельту реки Миссисипи Испании по договору в Фонтенбло . 10 февраля 1763 года Парижский договор завершил войну. Франция уступила свои североамериканские владения Великобритании. [ 58 ] Таким образом, Франция положила конец Новой Франции и отказалась от оставшихся 60 000 канадиенс, которые встали на сторону католического духовенства в отказе принести присягу британской короне . [ 59 ] Отрыв от Франции спровоцировал бы трансформацию среди потомков Канадиенс , которая в конечном итоге привела бы к рождению новой нации . [ 60 ]

Британская Северная Америка (1763–1867)

После того, как британцы приобрели Канаду в 1763 году, британское правительство установило конституцию для вновь приобретенной территории в соответствии с Королевской прокламацией . [ 61 ] Канадиенс были подчинены правительству Британской империи и ограничены областью долины Святого Лаврентия и острова Антикости, называемой провинцией Квебек . В связи с ростом волнений в южных колониях британцы были обеспокоены тем, что «Канадиенс» могут поддержать то, что впоследствии стало американской революцией . Чтобы обеспечить верность британской короне, губернатор Джеймс Мюррей , а затем губернатор Гай Карлтон настаивали на необходимости приспособления, что привело к принятию Закона о Квебеке. [ 62 ] 1774 года. Этот акт позволил канадиенсам восстановить свои гражданские обычаи , вернуться к сеньоральной системе, восстановить определенные права, включая использование французского языка, и повторно присвоить свои старые территории: Лабрадор, Великие озера, долину Огайо, страну Иллинойс и территорию Индии . [ 63 ]

Еще в 1774 году Континентальный конгресс сепаратистских Тринадцати колоний попытался сплотить Канадиенс на свою сторону. Однако его вооруженным войскам не удалось отразить британское контрнаступление во время вторжения в Квебек в 1775 году. Большинство канадиенс оставались нейтральными, хотя некоторые полки объединились с американцами в кампании Саратоги 1777 года. Когда британцы признали независимость повстанческих колоний в После подписания Парижского договора 1783 года он уступил Иллинойс и долину Огайо недавно образованным Соединенным Штатам и обозначил 45-ю параллель в качестве своей границы, резко уменьшив размер Квебека.

Некоторые лоялисты Объединенной Империи из США мигрировали в Квебек и заселили различные регионы. [ 64 ] Неудовлетворенные законными правами, предусмотренными французским сеньорическим режимом, действовавшим в Квебеке, и желая использовать британскую правовую систему, к которой они привыкли, лоялисты протестовали британским властям до тех пор, пока не был принят Конституционный акт 1791 года, разделивший провинцию Квебек на две отдельные колонии, начинающиеся от реки Оттава : Верхняя Канада на западе (преимущественно англо-протестантская) и Нижняя Канада на востоке. (франко-католик). Земли Нижней Канады включали побережья реки Святого Лаврентия, Лабрадора и острова Антикости, причем территория простиралась на север до Земли Руперта , а также на юг, восток и запад до границ с США, Нью-Брансуиком и Верхней Канадой. Создание Верхней и Нижней Канады позволило лоялистам жить в соответствии с британскими законами и институтами, в то время как канадиенсы могли сохранить свое французское гражданское право и католическую религию. Губернатор Халдиманд отвлек лоялистов из Квебека и Монреаля, предложив бесплатную землю на северном берегу озера Онтарио всем, кто готов присягнуть на верность Георгу III. Во время года В войне 1812 Шарль-Мишель де Салаберри стал героем, приведя канадские войска к победе в битве при Шатоге . Эта потеря заставила американцев отказаться от кампании Святого Лаврентия, их главного стратегического усилия по завоеванию Канады.

Постепенно Законодательное собрание Нижней Канады , представлявшее народ, вступило в конфликт с высшей властью Короны и назначенными ею представителями . Начиная с 1791 года правительство Нижней Канады подвергалось критике и оспариванию со стороны Канадской партии . В 1834 году Канадская партия представила 92 резолюции , политические требования, в которых выражалась утрата доверия к британской монархии . Недовольство усиливалось на публичных собраниях 1837 года, и в 1837 году началось восстание в Нижней Канаде . [ 66 ] В 1837 году Луи-Жозеф Папино и Роберт Нельсон возглавили жителей Нижней Канады, чтобы сформировать вооруженную группу под названием « Патриоты» . В 1838 году они приняли Декларацию независимости , гарантирующую права и равенство всем гражданам без дискриминации. [ 67 ] Их действия привели к восстаниям как в Нижней, так и в Верхней Канаде . Патриоты одержали победу в своей первой битве, битве при Сен-Дени . Однако они были неорганизованы и плохо оснащены, что привело к их поражению от британской армии в битве при Сен-Шарле и поражению в битве при Сен-Эсташ . [ 65 ]

В ответ на восстания лорда Дарема попросили провести исследование и подготовить отчет, предлагающий решение британскому парламенту. [ 68 ] Дарем рекомендовал культурно ассимилировать канадиенс , сделав английский единственным официальным языком. Для этого британцы приняли Акт о Союзе 1840 года , который объединил Верхнюю Канаду и Нижнюю Канаду в единую колонию: Провинцию Канада . Нижняя Канада стала франкоязычной и густонаселенной Восточной Канадой , а Верхняя Канада стала англоязычной и малонаселенной Западной Канадой . Неудивительно, что этот союз был основным источником политической нестабильности до 1867 года. Несмотря на разницу в численности населения, Восточная и Западная Канада получили одинаковое количество мест в Законодательном собрании провинции Канада , что создало проблемы с представительством. Вначале Восточная Канада была недостаточно представлена из-за большей численности населения. Однако со временем произошла массовая иммиграция с Британских островов на запад Канады. Поскольку оба региона по-прежнему имели равное представительство, это означало, что теперь Западная Канада была недостаточно представлена. Вопросы представительства были поставлены под сомнение в ходе дебатов по «Представительство населения» . Британское население стало использовать термин « канадец », имея в виду Канаду, место своего проживания. Французское население, которое до сих пор идентифицировалось как «канадцы», стало отождествляться со своей этнической общиной под названием « французские канадцы », поскольку они были «французами Канады». [ 69 ]

Поскольку доступ к новым землям оставался проблематичным, поскольку они все еще были монополизированы кликой замка , начался исход канадиенс в Новую Англию , который продолжался в течение следующих ста лет. Это явление известно как Большая геморрагия и угрожает выживанию канадской нации. Массовая британская иммиграция из Лондона, последовавшая за неудавшимся восстанием, усугубила ситуацию. Чтобы бороться с этим, Церковь приняла политику мести колыбели . В 1844 году столица провинции Канада была перенесена из Кингстона в Монреаль. [ 70 ]

Политические волнения достигли апогея в 1849 году, когда англо-канадские бунтовщики подожгли здание парламента в Монреале после принятия Закона о потерях от восстания — закона, который компенсировал французским канадцам, чья собственность была разрушена во время восстаний 1837–1838 годов. [ 71 ] Этот законопроект, ставший результатом коалиции Болдуина - Лафонтена и совета лорда Элджина, был важен, поскольку он установил понятие ответственного правительства . [ 72 ] В 1854 году сеньорская система была упразднена, Большая магистральная железная дорога была построена и вступил в силу Канадско-американский договор о взаимности . В 1866 году Гражданский кодекс Нижней Канады . был принят [ 73 ] [ 74 ] [ 75 ]

Канадская провинция (1867 – настоящее время)

В 1864 году начались переговоры о создании Канадской Конфедерации между провинцией Канады, Нью-Брансуиком и Новой Шотландией на Шарлоттаунской конференции и Квебекской конференции .

После борьбы в качестве патриота Жорж-Этьен Картье занялся политикой в провинции Канада, став одним из сопремьеров и сторонником объединения британских североамериканских провинций. Он стал ведущей фигурой на Квебекской конференции, на которой были приняты Квебекские резолюции , ставшие основой Канадской Конфедерации. [ 76 ] Признанный отцом Конфедерации , он успешно выступал за создание провинции Квебек, первоначально состоящей из исторического центра территории франко-канадской нации и где французские канадцы, скорее всего, сохранят статус большинства.

После Лондонской конференции 1866 года Квебекские резолюции были реализованы в виде Закона о Британской Северной Америке 1867 года и вступили в силу 1 июля 1867 года, в результате чего была создана Канада. Канада состояла из четырех провинций-основателей: Нью-Брансуика, Новой Шотландии, Онтарио и Квебека. Последние два произошли в результате разделения провинции Канада и использовали старые границы Нижней Канады для Квебека и Верхней Канады для Онтарио. 15 июля 1867 года Пьер-Жозеф-Оливье Шово Квебека стал первым премьер-министром .

От Конфедерации до Первой мировой войны Католическая церковь находилась на пике своего развития. Целью клерико-националистов было продвижение ценностей традиционного общества: семьи, французского языка, католической церкви и сельской жизни. Такие события, как восстание на Северо-Западе , вопрос о школах Манитобы Онтарио, и Постановление 17 превратили продвижение и защиту прав французских канадцев в важную проблему. [ 77 ] Под эгидой католической церкви и политической деятельностью Анри Бурасса были разработаны символы национальной гордости, такие как Флаг Карильона и « О Канада » — патриотическая песня, написанная ко Дню Сен-Жан-Батиста . Многие организации продолжали освящать утверждение франко-канадского народа, в том числе Caisses populaires Desjardins в 1900 году, Канадский хоккейный клуб в 1909 году, Le Devoir в 1910 году, Конгресс по французскому языку в Канаде в 1912 году и L' Национальное действие в 1917 году. В 1885 году либеральные и консервативные депутаты сформировали Национальную партию из-за гнева на предыдущее правительство за то, что оно не вмешалось в казнь Луи Риэля . [ 78 ]

В 1898 году канадский парламент принял Закон о расширении границ Квебека 1898 года , который дал Квебеку часть Земли Руперта, которую Канада купила у компании Гудзонова залива в 1870 году. [ 79 ] Этот акт расширил границы Квебека на север. В 1909 году правительство приняло закон, обязывающий перерабатывать древесину и целлюлозу в Квебеке, что помогло замедлить Великую геморрагию , позволив Квебеку экспортировать готовую продукцию в США вместо своей рабочей силы. [ 80 ] В 1910 году Арман Лавернь принял Закон Лаверни — первый языковой закон в Квебеке. Он требовал использования французского языка наряду с английским в билетах, документах, счетах и контрактах, выдаваемых транспортными и коммунальными компаниями. В то время компании редко признавали основной язык Квебека. [ 81 ] Клерико-националисты в конце концов начали терять популярность на федеральных выборах 1911 года . В 1912 году канадский парламент принял Закон о расширении границ Квебека 1912 года , который дал Квебеку еще одну часть Земли Руперта: округ Унгава . [ 82 ] Это расширило границы Квебека на север до Гудзонова пролива .

Когда разразилась Первая мировая война, Канада была автоматически вовлечена в нее, и многие английские канадцы вызвались добровольцами. Однако, поскольку они не чувствовали такой же связи с Британской империей и не было прямой угрозы Канаде, французские канадцы не видели причин для борьбы. К концу 1916 года потери начали вызывать проблемы с подкреплением. После огромных трудностей в федеральном правительстве, поскольку почти каждый франкоговорящий член парламента выступал против призыва на военную службу, в то время как почти все англоговорящие члены парламента поддерживали его, Закон о военной службе стал законом. 29 августа 1917 года [ 83 ] Французские канадцы протестовали в ходе так называемого призывного кризиса 1917 года , который привел к бунту в Квебеке . [ 84 ]

В 1919 году запрет на спиртные напитки был принят по итогам провинциального референдума . [ 85 ] Но запрет был отменен в 1921 году в связи с принятием Закона об алкогольных напитках, согласно которому была создана Комиссия по ликерам Квебека . [ 86 ] В 1927 году Британский юридический комитет Тайного совета провел четкую границу между северо-востоком Квебека и южным Лабрадором . Однако правительство Квебека не признало решение Судебного комитета, что привело к пограничному спору , который продолжается до сих пор . был Вестминстерский статут 1931 года принят и подтвердил автономию доминионов – включая Канаду и ее провинции – от Великобритании, а также их свободную ассоциацию в Содружестве . [ 87 ] В 1930-х годах экономика Квебека пострадала от Великой депрессии , поскольку она значительно снизила спрос США на экспорт Квебека. В период с 1929 по 1932 год уровень безработицы увеличился с 8% до 26%. Пытаясь исправить это, правительство Квебека реализовало инфраструктурные проекты, кампании по колонизации отдаленных регионов, финансовую помощь фермерам и управление службами безопасности – предшественником канадского страхования занятости . [ 88 ]

Французские канадцы оставались против призыва на военную службу во время Второй мировой войны. Когда Канада объявила войну в сентябре 1939 года, федеральное правительство обязалось не призывать солдат на службу за границу. По мере того как война продолжалась, все больше и больше английских канадцев выражали поддержку призыву на военную службу, несмотря на твердое сопротивление со стороны Французской Канады. После опроса 1942 года, который показал, что 73% жителей Квебека были против призыва на военную службу, в то время как 80% или более были за призыв в любой другой провинции, федеральное правительство приняло законопроект 80 о службе за границей. Протесты вспыхнули , и Народный блок выступил против призыва на военную службу. [ 83 ] Резкие различия между ценностями французской и английской Канады способствовали популяризации выражения « Два одиночества ».

После кризиса призыва к власти пришел Морис Дюплесси из Национального союза и провел консервативную политику, известную как Grande Noirceur . Он сосредоточился на защите автономии провинций , католического и франкоязычного наследия Квебека, а также либерализма laissez-faire вместо развивающегося государства всеобщего благосостояния . [ 89 ] Однако уже в 1948 году франко-канадское общество начало развивать новые идеологии и желания в ответ на социальные изменения, такие как телевидение, бэби-бум , рабочие конфликты , электрификация сельской местности, появление среднего класса , исход из сельской местности и урбанизация , расширение университетов и бюрократии, создание автомагистралей , ренессанс литературы и поэзии и другие.

Современный Квебек (1960 – настоящее время)

Тихая революция была периодом модернизации, секуляризации и социальных реформ, когда французские канадцы выразили свою обеспокоенность и недовольство своим худшим социально-экономическим положением , а также культурной ассимиляцией франкоязычных меньшинств в провинциях с англоязычным большинством. Это привело к формированию современной квебекской идентичности и квебекского национализма . [ 90 ] [ 91 ] В 1960 году Либеральная партия Квебека пришла к власти с большинством в два места, проводя кампанию под лозунгом «Пришло время все изменить». Это правительство провело реформы в социальной политике, образовании, здравоохранении и экономическом развитии. Он создал Caisse de dépôt et Placement du Québec , Трудовой кодекс, Министерство социальных дел , Министерство образования , Québécois de la langue française , Régie des rentes и Société Générale de Finance . В 1962 году правительство Квебека ликвидировало финансовые синдикаты улицы Сен-Жак . Квебек начал национализировать электричество . Чтобы выкупить все частные электрические компании и построить новые плотины Гидро-Квебека , в 1962 году США предоставили Квебеку кредит в размере 300 миллионов долларов. [ 92 ] и 100 миллионов долларов от Британской Колумбии в 1964 году. [ 93 ]

Тихая революция особенно характеризовалась лозунгом Либеральной партии 1962 года «Хозяева в нашем собственном доме», который для англо-американских конгломератов, доминировавших в экономике и природных ресурсах, провозглашал коллективную волю франко-канадского народа к свободе. [ 94 ] В результате противостояния низшего духовенства и мирян государственные учреждения стали оказывать услуги без помощи церкви, а многие части гражданского общества стали носить более светский характер. В 1965 году Королевская комиссия по двуязычию и бикультурализму [ 95 ] написал предварительный отчет, подчеркивающий особый характер Квебека, и продвигал открытый федерализм - политическую позицию, гарантирующую Квебеку минимальное внимание. [ 96 ] [ 97 ] Чтобы отдать предпочтение Квебеку во время его «Тихой революции», Лестер Б. Пирсон принял политику открытого федерализма. [ 98 ] [ 99 ] В 1966 году Национальный союз был переизбран и продолжил крупные реформы. [ 100 ]

В 1967 году президент Франции Шарль де Голль посетил Квебек для участия в выставке Expo 67 . Там он обратился к более чем 100-тысячной толпе, произнеся речь, закончившуюся восклицанием: «Да здравствует свободный Квебек!» Эта декларация оказала глубокое влияние на Квебек, поддержав растущее современное движение за суверенитет Квебека и приведя к политическому кризису между Францией и Канадой. После этого возникли различные гражданские группы, иногда противостоящие государственной власти, например, во время октябрьского кризиса 1970 года. [ 101 ] Заседания Генеральных штатов Французской Канады в 1967 году стали переломным моментом, когда отношения между франкоязычными странами Америки , и особенно франкоязычными странами Канады, разорвались. Этот распад повлиял на эволюцию общества Квебека. [ 102 ]

В 1968 году усилились классовые конфликты и изменения в менталитетах. [ 103 ] Вариант «Квебек» вызвал конституционные дебаты о политическом будущем провинции, противопоставив федералистскую и суверенистскую друг другу доктрины. В 1969 году был принят федеральный Закон об официальных языках, призванный создать лингвистический контекст, способствующий развитию Квебека. [ 104 ] [ 105 ] В 1973 году либеральное правительство Роберта Бурасса инициировало проект залива Джеймс на реке Ла-Гранд . В 1974 году был принят Закон об официальном языке , который сделал французский официальным языком Квебека. В 1975 году была принята Хартия прав и свобод человека и Соглашение Джеймс-Бей и Северного Квебека .

Первое современное суверенное правительство Квебека во главе с Рене Левеском материализовалось, когда Партия Квебека пришла к власти на всеобщих выборах в Квебеке 1976 года . [ 106 ] В следующем году вступила в силу Хартия французского языка , что расширило использование французского языка. В период с 1966 по 1969 годы Генеральные штаты Французской Канады подтвердили, что штат Квебек является основной политической средой нации и что он имеет право на самоопределение . [ 107 ] [ 108 ] На референдуме 1980 года о суверенитете 60% были против. [ 109 ] После референдума Левеск вернулся в Оттаву, чтобы начать переговоры по внесению изменений в конституцию. 4 ноября 1981 года Кухонное соглашение состоялось . Делегации остальных девяти провинций и федерального правительства достигли соглашения в отсутствие уехавшей на ночь делегации Квебека. [ 110 ] Из-за этого Национальное собрание отказалось признать новый Закон о Конституции 1982 года , который закрепил за собой канадскую конституцию и внес в нее изменения. [ 111 ] Поправки 1982 года применяются к Квебеку, несмотря на то, что Квебек никогда не давал на это согласия. [ 112 ]

В период с 1982 по 1992 годы позиция правительства Квебека изменилась и теперь стала уделять приоритетное внимание реформированию федерации. Попытки внести поправки в конституцию со стороны правительств Малруни и Бурасса закончились неудачей с подписанием Соглашения Мич-Лейк 1987 года и Шарлоттаунского соглашения 1992 года, в результате которых был создан Блок Квебека . [ 113 ] [ 114 ] В 1995 году Жак Паризо созвал референдум о независимости Квебека от Канады. Эта консультация закончилась неудачей для суверенистов, хотя результат был очень близким: 50,6% «нет» и 49,4% «да». [ 115 ] [ 116 ] [ 117 ]

В 1998 году, после Верховного суда Канады решения по вопросу об отделении Квебека , парламенты Канады и Квебека определили правовые рамки , в которых их соответствующие правительства будут действовать на другом референдуме. 30 октября 2003 года Национальное собрание единогласно проголосовало за подтверждение того, «что народ Квебека образует нацию». [ 118 ] 27 ноября 2006 года Палата общин приняла символическое предложение, заявившее, что «эта Палата признает, что квебекцы образуют нацию в рамках единой Канады». [ 119 ] В 2007 году Квебекская партия была отброшена в официальную оппозицию в Национальном собрании во главе с Либеральной партией. Во время канадских федеральных выборов 2011 года избиратели Квебека отвергли Блок Квебека в пользу ранее второстепенной Новой демократической партии (НДП). Поскольку логотип НДП оранжевый, это назвали «оранжевой волной». [ 120 ] После трех последующих либеральных правительств Квебекская партия вернула себе власть в 2012 году, и ее лидер Полина Маруа стала первой женщиной-премьером Квебека. [ 121 ] Либеральная партия Квебека затем вернулась к власти в 2014 году. [ 122 ] В 2018 году коалиция Avenir Québec выиграла всеобщие выборы в провинции . [ 123 ] В период с 2020 по 2021 год Квебек принял меры против пандемии COVID-19 . [ 124 ] В 2022 году коалиция Avenir Québec, возглавляемая премьер-министром Квебека Франсуа Лего , увеличила свое парламентское большинство на всеобщих выборах в провинции. [ 125 ]

- Территориальная эволюция Квебека

-

Канада в 18 веке.

-

Провинция Квебек с 1763 по 1783 год.

-

Квебек с 1867 по 1927 год.

-

Квебек сегодня. Квебек (синий) имеет пограничный спор с Лабрадором (красный).

География

Расположенный в восточной части Канады, Квебек занимает территорию, почти в три раза превышающую площадь Франции или Техаса . Большая часть Квебека очень малонаселена. [ 126 ] Самый густонаселенный физико-географический регион — Великие озера – Св. Лоуренс Лоулендс . Сочетание богатых почв и относительно теплого климата низменностей делает эту долину самым плодородным сельскохозяйственным районом Квебека. Сельская часть ландшафта разделена на узкие прямоугольные участки земли, простирающиеся от реки и относящиеся к сеньорической системе.

Квебека Топография сильно отличается от одного региона к другому из-за различного состава почвы, климата и близости к воде. Более 95% территории Квебека, включая полуостров Лабрадор , находится в пределах Канадского щита . [ 127 ] Как правило, это довольно плоская и открытая гористая местность с вкраплениями более высоких точек, таких как Лаврентийские горы на юге Квебека, горы Отиш в центральном Квебеке и горы Торнгат возле залива Унгава . В то время как низкие и средние вершины простираются от западного Квебека до крайнего севера, высокогорные горы возникают в регионе Капитал-Национале на крайнем востоке. Самая высокая точка Квебека высотой 1652 метра (5420 футов) — гора д'Ибервиль, известная на английском языке как гора Кобвик . [ 128 ] В части Щита, расположенной на полуострове Лабрадор, крайний северный регион Нунавик включает полуостров Унгава и представляет собой плоскую арктическую тундру , населенную в основном инуитами. Дальше на юг находится таежный экорегион Восточно-Канадского щита и леса Центрально-Канадского щита . Регион Аппалачей представляет собой узкую полосу древних гор вдоль юго-восточной границы Квебека. [ 129 ]

Квебек обладает одним из крупнейших в мире запасов пресной воды . [ 130 ] занимающий 12% его поверхности [ 131 ] и составляет 3% мировых возобновляемых запасов пресной воды . [ 132 ] Более полумиллиона озер и 4500 рек. [ 130 ] впадает в Атлантический океан , через залив Святого Лаврентия и Северный Ледовитый океан через заливы Джеймса , Гудзона и Унгавы. Самый крупный внутренний водоем — водохранилище Каниапискау ; Озеро Мистассини — самое большое природное озеро. [ 133 ] На реке Святого Лаврентия расположены одни из крупнейших в мире устойчивых внутренних портов Атлантического океана. С 1959 года морской путь Святого Лаврентия обеспечивает судоходное сообщение между Атлантическим океаном и Великими озерами.

Государственные земли Квебека занимают примерно 92% его территории, включая почти все водоемы. Охраняемые территории можно разделить примерно на двадцать различных юридических обозначений (например, исключительная лесная экосистема, охраняемая морская среда, национальный парк , заповедник биоразнообразия , заповедник дикой природы, зона контроля эксплуатации (ZEC) и т. д.). [ 134 ] Сегодня более 2500 объектов в Квебеке являются охраняемыми территориями. [ 135 ] По состоянию на 2013 год охраняемые территории составляют 9,14% территории Квебека. [ 136 ]

Климат

В целом климат Квебека холодный и влажный, вариации которого зависят от широты, моря и высоты. [ 137 ] Из-за влияния обеих штормовых систем из ядра Северной Америки и Атлантического океана осадки выпадают в изобилии в течение всего года, при этом в большинстве районов выпадает более 1000 мм (39 дюймов) осадков, в том числе более 300 см (120 дюймов) осадков. снег во многих районах. [ 138 ] Летом время от времени случаются суровые погодные условия (например, торнадо и сильные грозы ). [ 139 ]

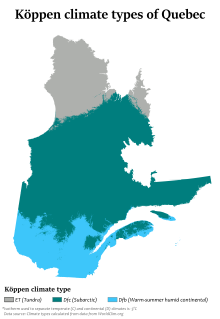

Квебек разделен на четыре климатические зоны: арктическую, субарктическую, влажную континентальную и восточно-морскую. С юга на север средняя температура летом колеблется от 25 до 5 ° C (от 77 до 41 ° F), а зимой от -10 до -25 ° C (от 14 до -13 ° F). [ 140 ] [ 141 ] В периоды сильной жары и холода летом температура может достигать 35 ° C (95 ° F). [ 142 ] и -40 ° C (-40 ° F) зимой в Квебеке, [ 142 ] Большая часть центрального Квебека, от 51 до 58 градусов северной широты, имеет субарктический климат (Köppen Dfc ). [ 137 ] Зимы длинные, очень холодные и снежные, одни из самых холодных на востоке Канады, а лето теплое, но очень короткое из-за более высокой широты и большего влияния арктических воздушных масс. Осадков также несколько меньше, чем южнее, за исключением некоторых возвышенностей. В северных регионах Квебека арктический климат (Köppen ET ) с очень холодной зимой и коротким, гораздо более прохладным летом. [ 137 ] Основное влияние в этом регионе оказывают течения Северного Ледовитого океана (такие как Лабрадорское течение ) и континентальные воздушные массы из высоких широт Арктики .

Рекордно высокая температура за всю историю составила 40,0 ° C (104,0 ° F), а самая низкая за всю историю - -51,0 ° C (-59,8 ° F). [ 143 ] Рекорд максимального количества осадков зимой был установлен зимой 2007–2008 гг.: более пяти метров. [ 144 ] снега в районе Квебека. [ 145 ] Однако в марте 1971 года произошла « Метель века от 40 см (16 дюймов) в Монреале до 80 см (31 дюйм) в Монт-Апике », когда во многих регионах южного Квебека за 24 часа выпало снега . Зима 2010 года была самой теплой и сухой за последние более чем 60 лет. [ 146 ]

Флора и фауна

Учитывая геологию провинции и ее различные климатические условия, в Квебеке есть несколько крупных площадей растительности. Эти территории перечислены в порядке от самого северного к самому южному: тундра , тайга , канадский бореальный лес (хвойный), смешанный лес и лиственный лес. [ 127 ] На границе залива Унгава и Гудзонова пролива находится тундра, флора которой ограничена лишайником , вегетация которого составляет менее 50 дней в году. Южнее климат благоприятствует росту канадского бореального леса , ограниченного с севера тайгой. Не такая засушливая, как тундра, тайга связана с субарктическими районами Канадского щита. [ 147 ] и характеризуется большим количеством как растений (600), так и животных (206) видов. Тайга занимает около 20% общей площади Квебека. [ 127 ] Канадский бореальный лес — самый северный и самый богатый из трех лесных массивов Квебека, расположенных между Канадским щитом и верхними низменностями провинции. В условиях более теплого климата выше и разнообразие организмов: насчитывается около 850 видов растений и 280 видов позвоночных. Смешанный лес представляет собой переходную зону между канадским бореальным лесом и лиственным лесом . Несмотря на относительно низкие температуры , на этой территории обитает множество видов растений (1000) и позвоночных (350). Экозона смешанного леса характерна для Лаврентийских гор , Аппалачей и восточных равнинных лесов. [ 147 ] Третий по северу лесной массив характеризуется широколиственными лесами . Благодаря своему климату эта территория отличается наибольшим разнообразием видов, включая более 1600 сосудистых растений и 440 позвоночных.

Общая площадь лесов Квебека оценивается в 750 300 км2. 2 (289 700 квадратных миль). [ 148 ] От Абитиби-Темискаминге до Северного берега лес состоит в основном из хвойных пород, таких как пихта бальзамея , сосна обыкновенная , ель белая , ель черная и тамарак . Лиственный лес Великих озер – Св. Лоуренса Лоулендс в основном состоит из лиственных пород, таких как сахарный клен , красный клен , ясень белый , бук американский , орех орех (белый орех) , вяз американский , липа , гикори горький , а северный красный дуб. также как некоторые хвойные породы, такие как восточная белая сосна и северный белый кедр . Ареалы берёзы бумажной , осины дрожащей и рябины покрывают более половины территории Квебека. [ 149 ]

Биоразнообразие устья и залива реки Святого Лаврентия [ 150 ] включает диких водных млекопитающих, таких как синий кит , белуха , малый полосатик и гренландский тюлень (безухий тюлень). К морским животным Северной Европы относятся морж и нарвал . [ 151 ] Внутренние воды населены мелкой и крупной пресноводной рыбой, такой как большеротый окунь , американская щука , судак , Acipenser oxyrinchus , мускусная треска , атлантическая треска , арктический голец , ручьевая форель , томкод Microgadus (томкод), атлантический лосось и радужная форель . [ 152 ]

Среди птиц, обычно встречающихся в южной части Квебека, — американская малиновка , домашний воробей , краснокрылый дрозд , кряква , обыкновенный гракль , голубая сойка , американская ворона , черношапочная синица , некоторые славки и ласточки , скворец и сизый голубь . [ 153 ] Птичья фауна включает хищных птиц, таких как беркут , сапсан , полярная сова и белоголовый орлан . Морские и полуводные птицы, встречающиеся в Квебеке, - это в основном канадский гусь , двухохлатый баклан , северная олуша , европейская серебристая чайка , большая голубая цапля , песчаный журавль , атлантический тупик и обыкновенная гагара . [ 154 ]

Крупная наземная дикая природа включает белохвостого оленя , лося , овцебыка , карибу (северного оленя) , американского черного медведя и белого медведя . Наземная дикая природа среднего размера включает пуму , койота , восточного волка , рыси , песца , лису и т. д. Из мелких животных чаще всего встречаются восточная серая белка , заяц-беляк , сурок , скунс . , енот , бурундук и канадский бобр .

Правительство и политика

Квебек основан на Вестминстерской системе и является одновременно либеральной демократией и конституционной монархией с парламентским режимом . Главой правительства Квебека является премьер-министр ( по-французски «премьер-министр» ), который возглавляет крупнейшую партию в однопалатном Национальном собрании ( Assemblée Nationale ), из которого Исполнительный совет Квебека назначается . Совет трезора поддерживает министров Исполнительного совета в их функции по управлению государством. Вице -губернатор представляет короля Канады и действует как глава государства . [ 155 ] [ 156 ]

Квебек имеет 78 членов парламента (депутатов) в Палате общин Канады . [ 157 ] Они избираются на федеральных выборах. На уровне Сената Канады Квебек представлен 24 сенаторами, которые назначаются по рекомендации премьер-министра Канады . [ 158 ]

Правительство Квебека обладает административной и полицейской властью в районах своей исключительной юрисдикции . Парламент 43-го законодательного собрания состоит из следующих партий: Коалиция Avenir Québec (CAQ), Либеральная партия Квебека (PLQ), Солидарная партия Квебека (QS) и Партия Квебека (PQ), а также независимый член . действуют В Квебеке 25 официальных политических партий . [ 159 ]

Квебек имеет сеть из трех офисов для представления себя и защиты своих интересов в Канаде: один в Монктоне для всех восточных провинций, один в Торонто для всех западных провинций и один в Оттаве для федерального правительства. Мандат этих офисов заключается в обеспечении институционального присутствия правительства Квебека рядом с другими правительствами Канады. [ 160 ] [ 161 ]

Подразделения

Экологическая классификация территории Квебека, установленная Министерством лесов, дикой природы и парков 2021 года, представлена на 9 уровнях, она включает разнообразие наземных экосистем по всему Квебеку с учетом как особенностей растительности ( физиономии, структуры и состава). и физическая среда (рельеф, геология , геоморфология , гидрография ). [ 129 ]

- Зона растительности

- Подзона растительности

- Биоклиматическая область

- Биоклиматический поддомен

- Экологический регион

- Экологический субрегион

- Региональный ландшафтный отдел

- Экологический район

- Стадия вегетации

Территория Квебека разделена на 17 административных регионов следующим образом: [ 162 ] [ 163 ]

В провинции также есть следующие подразделения:

- 4 территории ( Абитиби , Ашуанипи , Мистассини и Нунавик ), которые группируют вместе земли, которые когда-то образовывали округ Унгава.

- 36 judicial districts

- 73 circonscriptions foncières

- 125 electoral districts[164]

For municipal purposes, Quebec is composed of:

- 1,117 local municipalities of various types:

- 11 agglomerations (agglomérations) grouping 42 of these local municipalities

- 45 boroughs (arrondissements) within 8 of these local municipalities

- 89 regional county municipalities or RCMs (municipalités régionales de comté, MRC)

- 2 metropolitan communities (communautés métropolitaines)

- the regional Kativik administration

- the unorganised territories[165]

Ministries and policies

Quebec's constitution is enshrined in a series of social and cultural traditions that are defined in a set of judicial judgments and legislative documents, including the Loi sur l'Assemblée Nationale ("Law on the National Assembly"), the Loi sur l'éxecutif ("Law on the Executive"), and the Loi électorale du Québec ("Electoral Law of Quebec").[166] Other notable examples include the Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, the Charter of the French language, and the Civil Code of Quebec.[167]

Quebec's international policy is founded upon the Gérin-Lajoie doctrine,[168] formulated in 1965. While Quebec's Ministry of International Relations coordinates international policy, Quebec's general delegations are the main interlocutors in foreign countries. Quebec is the only Canadian province that has set up a ministry to exclusively embody the state's powers for international relations.[169]

Since 2006, Quebec has adopted a green plan to meet the objectives of the Kyoto Protocol regarding climate change.[170] The Ministry of Sustainable Development, Environment, and Fight Against Climate Change (MELCC) is the primary entity responsible for the application of environmental policy. The Société des établissements de plein air du Québec (SEPAQ) is the main body responsible for the management of national parks and wildlife reserves.[171] Nearly 500,000 people took part in a climate protest on the streets of Montreal in 2019.[172]

Agriculture in Quebec has been subject to agricultural zoning regulations since 1978.[173] Faced with the problem of expanding urban sprawl, agricultural zones were created to ensure the protection of fertile land, which make up 2% of Quebec's total area. Quebec's forests are essentially public property. The calculation of annual cutting possibilities is the responsibility of the Bureau du forestier en chef.[174] The Union des producteurs agricoles (UPA) seeks to protect the interests of its members, including forestry workers, and works jointly with the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (MAPAQ) and the Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources.

The Ministère de l'Emploi et de la Solidarité sociale du Québec has the mandate to oversee social and workforce developments through Emploi-Québec and its local employment centres (CLE).[175] This ministry is also responsible for managing the Régime québécois d'assurance parentale (QPIP) as well as last-resort financial support for people in need. The Commission des normes, de l'équité, de la santé et de la sécurité du travail (CNESST) is the main body responsible for labour laws in Quebec[176] and for enforcing agreements concluded between unions of employees and their employers.[177]

Revenu Québec is the body responsible for collecting taxes. It takes its revenue through a progressive income tax, a 9.975% sales tax,[178] various other provincial taxes (ex. carbon, corporate and capital gains taxes), equalization payments, transfer payments from other provinces, and direct payments.[179] By some measures Quebec residents are the most taxed;[180] a 2012 study indicated that "Quebec companies pay 26 per cent more in taxes than the Canadian average".[181]

Quebec's immigration philosophy is based on the principles of pluralism and interculturalism.The Ministère de l'Immigration et des Communautés culturelles du Québec is responsible for the selection and integration of immigrants.[182] Programs favour immigrants who know French, have a low risk of becoming criminals and have in-demand skills.

Quebec's health and social services network is administered by the Ministry of Health and Social Services. It is composed of 95 réseaux locaux de services (RLS; 'local service networks') and 18 agences de la santé et des services sociaux (ASSS; 'health and social services agencies'). Quebec's health system is supported by the Régie de l'assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ) which works to maintain the accessibility of services for all citizens of Quebec.[183]

The Ministère de la Famille et des Aînés du Québec operate centres de la petite enfance (CPEs; 'centres for young children'). Quebec's education system is administered by the Ministry of Education and Higher Education (primary and secondary schools), the Ministère de l'Enseignement supérieur (CEGEP) and the Conseil supérieure de l'Education du Québec (universities and colleges).[184] In 2012, the annual cost for postsecondary tuition was CA$2,168 (€1,700)—less than half of Canada's average tuition. Part of the reason for this is that tuition fees were frozen to a relatively low level when CEGEPS were created during the Quiet Revolution. When Jean Charest's government decided in 2012 to sharply increase university fees, students protests erupted.[185] Because of these protests, Quebec's tuition fees remain relatively low.

External relationships

Quebec's closest international partner is the United States, with which it shares a long and positive history. Products of American culture like songs, movies, fashion and food strongly affect Québécois culture.

Quebec has a historied relationship with France, as Quebec was a part of the French Empire and both regions share a language. The Fédération France-Québec and the Francophonie are a few of the tools used for relations between Quebec and France. In Paris, a place du Québec was inaugurated in 1980.[186] Quebec also has a historied relationship with the United Kingdom, having been a part of the British Empire. Quebec and the UK share the same head of state, King Charles III.

Quebec has a network of 32 offices in 18 countries. These offices serve the purpose of representing Quebec in foreign countries and are overseen by Quebec's Ministry of International Relations. Quebec, like other Canadian provinces, also maintains representatives in some Canadian embassies and consulates general. As of 2019[update], the Government of Quebec had delegates-general (agents-general) in Brussels, London, Mexico City, Munich, New York City, Paris and Tokyo; delegates to Atlanta, Boston, Chicago, Houston, Los Angeles, and Rome; and offices headed by directors offering more limited services in Barcelona, Beijing, Dakar, Hong Kong, Mumbai, São Paulo, Shanghai, Stockholm, and Washington. In addition, there are the equivalent of honorary consuls, titled antennes, in Berlin, Philadelphia, Qingdao, Seoul, and Silicon Valley.

Quebec also has a representative to UNESCO and participates in the Organization of American States.[187] Quebec is a member of the Assemblée parlementaire de la Francophonie and of the Organisation internationale de la francophonie.

Law

Quebec law is the shared responsibility of the federal and provincial government. The federal government is responsible for criminal law, foreign affairs and laws relating to the regulation of Canadian commerce, interprovincial transportation, and telecommunications.[188] The provincial government is responsible for private law, the administration of justice, and several social domains, such as social assistance, healthcare, education, and natural resources.[188]

Quebec law is influenced by two judicial traditions (civil law and common law) and four classic sources of law (legislation, case law, doctrine and customary law).[189] Private law in Quebec affects all relationships between individuals (natural or juridical persons) and is largely under the jurisdiction of the Parliament of Quebec. The Parliament of Canada also influences Quebec private law, in particular through its power over banks, bankruptcy, marriage, divorce and maritime law.[190] The Droit civil du Québec is the primary component of Quebec's private law and is codified in the Civil Code of Quebec.[191] Public law in Quebec is largely derived from the common law tradition.[192] Quebec constitutional law governs the rules surrounding the Quebec government, the Parliament of Quebec and Quebec's courts. Quebec administrative law governs relations between individuals and the Quebec public administration. Quebec also has some limited jurisdiction over criminal law. Finally, Quebec, like the federal government, has tax law power.[193] Certain portions of Quebec law are considered mixed. This is the case, for example, with human rights and freedoms which are governed by the Quebec Charter of Human Rights and Freedoms, a Charter which applies to both government and citizens.[194][195]

English is not an official language in Quebec law.[196] However, both English and French are required by the Constitution Act, 1867 for the enactment of laws and regulations, and any person may use English or French in the National Assembly and the courts. The books and records of the National Assembly must also be kept in both languages.[197][198]

Courts

Although Quebec is a civil law jurisdiction, it does not follow the pattern of other civil law systems which have court systems divided by subject matter. Instead, the court system follows the English model of unitary courts of general jurisdiction. The provincial courts have jurisdiction to decide matters under provincial law as well as federal law, including civil, criminal and constitutional matters.[199] The major exception to the principle of general jurisdiction is that the Federal Court and Federal Court of Appeal have exclusive jurisdiction over some areas of federal law, such as review of federal administrative bodies, federal taxes, and matters relating to national security.[200]

The Quebec courts are organized in a pyramid. At the bottom, there are the municipal courts, the Professions Tribunal, the Human Rights Tribunal, and administrative tribunals. Decisions of those bodies can be reviewed by the two trial courts, the Court of Quebec the Superior Court of Quebec. The Court of Quebec is the main criminal trial court, and also a court for small civil claims. The Superior Court is a trial court of general jurisdiction, in both criminal and civil matters. The decisions of those courts can be appealed to the Quebec Court of Appeal. Finally, if the case is of great importance, it may be appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada.

The Court of Appeal serves two purposes. First, it is the general court of appeal for all legal issues from the lower courts. It hears appeals from the trial decisions of the Superior Court and the Quebec Court. It also can hear appeals from decisions rendered by those two courts on appeals or judicial review matters relating to the municipal courts and administrative tribunals.[201] Second, but much more rarely, the Court of Appeal possesses the power to respond to reference questions posed to it by the Quebec Cabinet. The Court of Appeal renders more than 1,500 judgments per year.[202]

Law enforcement

The Sûreté du Québec is the main police force of Quebec. The Sûreté du Québec can also serve a support and coordination role with other police forces, such as with municipal police forces or with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).[203][204] The RCMP has the power to enforce certain federal laws in Quebec. However, given the existence of the Sûreté du Québec, its role is more limited than in the other provinces.[205]

Municipal police, such as the Service de police de la Ville de Montréal and the Service de police de la Ville de Québec, are responsible for law enforcement in their municipalities. The Sûreté du Québec fulfils the role of municipal police in the 1038 municipalities that do not have a municipal police force.[206] The Indigenous communities of Quebec have their own police forces.[207]

For offences against provincial or federal laws in Quebec (including the Criminal Code), the Director of Criminal and Penal Prosecutions is responsible for prosecuting offenders in court through Crown attorneys. The Department of Justice of Canada also has the power to prosecute offenders, but only for offences against specific federal laws (ex. selling narcotics). Quebec is responsible for operating the prison system for sentences of less than two years, and the federal government operates penitentiaries for sentences of two years or more.[208]

Demographics

In the 2016 census, Quebec had a population of 8,164,361, a 3.3% increase from its 2011 population of 7,903,001. With a land area of 1,356,625.27 km2 (523,795.95 sq mi), it had a population density of 6.0/km2 (15.6/sq mi) in 2016. Quebec accounts for a little under 23% of the Canadian population. The most populated cities in Quebec are Montreal (1,762,976), Quebec City (538,738), Laval (431,208), and Gatineau (281,501).[209]

In 2016, Quebec's median age was 41.2 years. As of 2020, 20.8% of the population were younger than 20, 59.5% were aged between 20 and 64, and 19.7% were 65 or older. In 2019, Quebec witnessed an increase in the number of births compared to the year before (84,200 vs 83,840) and had a total fertility rate of about 1.6 children born per woman. As of 2020, the average life expectancy was 82.3 years. Quebec in 2019 registered the highest rate of population growth since 1972, with an increase of 110,000 people, mostly because of the arrival of a high number of immigrants. As of 2019, most international immigrants came from China, India or France.[210] In 2016, 30% of the population possessed a postsecondary degree or diploma. Most residents, particularly couples, are property owners. In 2016, 80% of both property owners and renters considered their housing to be "unaffordable".[211] In the 2021 Canadian census, 29.3% of Quebec's population stated their ancestry was of Canadian origin and 21.1% stated their ancestry was of French origin.[212] As of 2021, 18% of Quebec's population were visible minorities.[213]

Religion

According to the 2021 census, the most commonly cited religions in Quebec were:[214]

- Christianity (5,385,240 residents, or 64.8%)

- Irreligion (2,267,720 or 27.3%)

- Islam (421,710 or 5.1%)

- Judaism (84,530 or 1.0%)

- Buddhism (48,365 or 0.6%)

- Hinduism (47,390 or 0.6%)

- Sikhism (23,345 or 0.3%)

- Indigenous spirituality (3,790 or <0.1%)

- Other (26,385 or 0.3%)

The Roman Catholic Church has long occupied a central and integral place in Quebec society since the foundation of Quebec City in 1608. However, since the Quiet Revolution, which secularized Quebec, irreligion has been growing significantly.[215]

The oldest parish church in North America is the Cathedral-Basilica of Notre-Dame de Québec. Its construction began in 1647, when it was known under the name Notre-Dame-de-la-Paix, and it was finished in 1664.[216] The most frequented place of worship in Quebec is the Basilica of Sainte-Anne-de-Beaupré. This basilica welcomes millions of visitors each year. Saint Joseph's Oratory is the largest place of worship in the world dedicated to Saint Joseph. Many pilgrimages include places such as Saint Benedict Abbey, Sanctuaire Notre-Dame-du-Cap, Notre-Dame de Montréal Basilica, Marie-Reine-du-Monde de Montréal Basilica-Cathedral, Saint-Michel Basilica-Cathedral, and Saint-Patrick's Basilica. Another important place of worship in Quebec is the Anglican Holy Trinity Cathedral, which was erected between 1800 and 1804. It was the first Anglican cathedral built outside the British Isles.[217]

Language

Linguistic map of the province of Quebec (source: Statistics Canada, 2006 census) Francophone majority, less than 33% Anglophone Francophone majority, more than 33% Anglophone Anglophone majority, more than 33% Francophone Anglophone majority, less than 33% Francophone Data not available |

Quebec differs from other Canadian provinces in that French is the only official and preponderant language, while English predominates in the rest of Canada.[218] French is the common language, understood and spoken by 94.4% of the population.[219][220] Québécois French is the local variant of the language. Canada is estimated to be home to roughly 30 regional French accents,[221][222] 17 of which can be found in Quebec.[223] The Office québécois de la langue française oversees the application of linguistic policies respecting French on the territory, jointly with the Superior Council of the French Language and the Commission de toponymie du Québec. The foundation for these linguistic policies was created in 1968 by the Gendron Commission and they have been accompanied the Charter of the French language ("Bill 101") since 1977. The policies are in effect to protect Quebec from being assimilated by its English-speaking neighbours (the rest of Canada and the United States)[224][225] and were also created to rectify historical injustice between the Francophone majority and Anglophone minority, the latter of which were favoured since Quebec was a colony of the British Empire.[226]

Quebec is the only Canadian province whose population is mainly Francophone, meaning that French is their native language. In the 2011 Census, 6,102,210 people (78.1% of the population) recorded French as their sole native language and 6,249,085 (80.0%) recorded that they spoke French most often at home.[227]

People with English as their native language, called Anglo-Quebecers, constitute the second largest linguistic group in Quebec. In 2011, English was the mother tongue of nearly 650,000 Quebecers (8% of the population).[228] Anglo-Quebecers reside mainly in the west of the island of Montreal (West Island), downtown Montreal and the Pontiac.

Three families of Indigenous languages encompassing eleven languages exist in Quebec: the Algonquian language family (Abenaki, Algonquin, Maliseet-passamaquoddy, Mi'kmaq, and the linguistic continuum of Atikamekw, Cree, Innu-aimun, and Naskapi), the Inuit–Aleut language family (Nunavimmiutitut, an Inuktitut dialect spoken by the Inuit of Nord-du-Québec), and the Iroquoian language family (Mohawk and Wendat). In the 2016 census, 50,895 people said they knew at least one Indigenous language[229] and 45,570 people declared having an Indigenous language as their mother tongue.[230] In Quebec, most Indigenous languages are transmitted quite well from one generation to the next with a mother tongue retention rate of 92%.[231]

As of the 2016 census, the most common immigrant languages claimed as a native language were Arabic (2.5% of the total population), Spanish (1.9%), Italian (1.4%), Creole languages (mainly Haitian Creole) (0.8%), and Mandarin (0.6%).[232]

As of the 2021 Canadian Census, the ten most spoken languages in the province were French (spoken by 7,786,735 people, or 93.72% of the population), English (4,317,180 or 51.96%), Spanish (453,905 or 5.46%), Arabic (343,675 or 4.14%), Italian (168,040 or 2.02%), Haitian Creole (118,010 or 1.42%), Mandarin (80,520 or 0.97%), Portuguese (65,605 or 0.8%), Russian (55,485 or 0.7%), and Greek (50,375 or 0.6%).[233] The question on knowledge of languages allows for multiple responses.

Indigenous peoples

In 2021, the Indigenous population of Quebec numbered 205,010 (2.5% of the population), including 15,800 Inuit, 116,550 First Nations people, and 61,010 Métis.[234] There is an undercount, as some Indian bands regularly refuse to participate in Canadian censuses. In 2016, the Mohawk reserves of Kahnawake and Doncaster 17 along with the Indian settlement of Kanesatake and Lac-Rapide, a reserve of the Algonquins of Barriere Lake, were not counted.[235]

The Inuit of Quebec live mainly in Nunavik in Nord-du-Québec. They make up the majority of the population living north of the 55th parallel. There are ten First Nations ethnic groups in Quebec: the Abenaki, the Algonquin, the Attikamek, the Cree, the Wolastoqiyik, the Mi'kmaq, the Innu, the Naskapis, the Huron-Wendat and the Mohawks. The Mohawks were once part of the Iroquois Confederacy. Aboriginal rights were enunciated in the Indian Act and adopted at the end of the 19th century. This act confines First Nations within the reserves created for them. The Indian Act is still in effect today.[236] In 1975, the Cree, Inuit and the Quebec government agreed to an agreement called the James Bay and Northern Quebec Agreement that would extended indigenous rights beyond reserves, and to over two-thirds of Quebec's territory. Because this extension was enacted without the participation of the federal government, the extended indigenous rights only exist in Quebec. In 1978, the Naskapis joined the agreement when the Northeastern Quebec Agreement was signed. Discussions have been underway with the Montagnais of the Côte-Nord and Saguenay–Lac-Saint-Jean for the potential creation of a similar autonomy in two new distinct territories that would be called Innu Assi and Nitassinan.[237]

A few political institutions have also been created over time:

- The Assembly of First Nations Quebec-Labrador[238]

- The Grand Council of the Crees[239]

- The Makivik Corporation[240]

Acadians

The subject of Acadians in Quebec is an important one as more than a million people in Quebec are of Acadian descent, with roughly 4.8 million people possessing one or multiple Acadian ancestors in their genealogy tree, because a large number of Acadians had fled Acadia to take refuge in Quebec during the Great Upheaval. Furthermore, more than a million people have a patronym of Acadian origin.[241][242][243][244]

Quebec houses Acadian communities. Acadians mainly live on the Magdalen Islands and in Gaspesia, but about thirty other communities are present elsewhere in Quebec, mostly in the Côte-Nord and Centre-du-Québec regions. An Acadian community in Quebec can be called a "Cadie", "Petite Cadie" or "Cadien".[245]

Economy

This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: Economic data is out-of-date, most is from 2011. (June 2019) |

Quebec has an advanced, market-based, and open economy. In 2022, its gross domestic product (GDP) was US$50,000 per person at purchasing power parity.[246] The economy of Quebec is the 46th largest in the world behind Chile and 29th for GDP per person.[247][248] Quebec represents 19% of the GDP of Canada. The provincial debt-to-GDP ratio peaked at 51% in 2012–2013, and declined to 43% in 2021.[249]

Like most industrialized countries, the economy is based mainly on the services sector. Quebec's economy has traditionally been fuelled by abundant natural resources and a well-developed infrastructure, but has undergone significant change over the past decade.[250] Firmly grounded in the knowledge economy, Quebec has one of the highest growth rates of GDP in Canada. The knowledge sector represents about 31% of Quebec's GDP.[251] In 2011, Quebec experienced faster growth of its research-and-development (R&D) spending than other Canadian provinces.[252] Quebec's spending in R&D in 2011 was equal to 2.63% of GDP, above the European Union average of 1.8%.[253] The percentage spent on research and technology is the highest in Canada and higher than the averages for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and the G7 countries.[254]

Some of the most important companies from Quebec are: Bombardier, Desjardins, the National Bank of Canada, the Jean Coutu Group, Transcontinental média, Quebecor, the Métro Inc. food retailers, Hydro-Québec, the Société des alcools du Québec, the Bank of Montreal, Saputo, the Cirque du Soleil, the Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, the Normandin restaurants, and Vidéotron.

Exports and imports

Thanks to the World Trade Organization (WTO) and the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), Quebec had, as of 2009[update], experienced an increase in its exports and in its ability to compete on the international market. International exchanges contribute to the strength of the Quebec economy.[255] NAFTA is especially advantageous as it gives Quebec, among other things, access to a market of 130 million consumers within a radius of 1,000 kilometres.

In 2008, Quebec's exports to other provinces in Canada and abroad totalled 157.3 billion CND$, or 51.8% of Quebec's gross domestic product (GDP). Of this total, 60.4% were international exports, and 39.6% were interprovincial exports. The breakdown by destination of international merchandise exports is: United States (72.2%), Europe (14.4%), Asia (5.1%), Middle East (2.7%), Central America (2.3%), South America (1.9%), Africa (0.8%) and Oceania (0.7%).[255]

In 2008, Quebec imported $178 billion worth of goods and services, or 58.6% of its GDP. Of this total, 62.9% of goods were imported from international markets, while 37.1% of goods were interprovincial imports. The breakdown by origin of international merchandise imports is as follows: United States (31.1%), Europe (28.7%), Asia (17.1%), Africa (11.7%), South America (4.5%), Central America (3.7%), Middle East (1.3%) and Oceania (0.7%).[255]

Primary sector

Quebec produces most of Canada's hydroelectricity and is the second biggest hydroelectricity producer in the world (2019).[256] Because of this, Quebec has been described as a potential clean energy superpower.[257] In 2019, Quebec's electricity production amounted to 214 terawatt-hours (TWh), 95% of which comes from hydroelectric power stations, and 4.7% of which come from wind energy. The public company Hydro-Québec occupies a dominant position in the production, transmission and distribution of electricity in Quebec. Hydro-Québec operates 63 hydroelectric power stations and 28 large reservoirs.[258] Because of the remoteness of Hydro-Québec's TransÉnergie division, it operates the largest electricity transmission network in North America. Quebec stands out for its use of renewable energy. In 2008, electricity ranked as the main form of energy used in Quebec (41.6%), followed by oil (38.2%) and natural gas (10.7%).[259] In 2017, 47% of all energy came from renewable sources.[260] The Quebec government's energy policy seeks to build, by 2030, a low carbon economy.

Quebec ranks among the top ten areas to do business in mining in the world.[261] In 2011, the mining industry accounted for 6.3% of Quebec's GDP[262] and it employed about 50,000 people in 158 companies.[263] It has around 30 mines, 158 exploration companies and 15 primary processing industries. While many metallic and industrial minerals are exploited, the main ones are gold, iron, copper and zinc. Others include: titanium, asbestos, silver, magnesium and nickel, among many others.[264] Quebec is also as a major source of diamonds.[265] Since 2002, Quebec has seen an increase in its mineral explorations. In 2003, the value of mineral exploitation reached $3.7 billion.[266]

The agri-food industry plays an important role in the economy of Quebec, with meat and dairy products being the two main sectors. It accounts for 8% of the Quebec's GDP and generate $19.2 billion. In 2010, this industry generated 487,000 jobs in agriculture, fisheries, manufacturing of food, beverages and tobacco and food distribution.[267]

Secondary sector

In 2021, Quebec's aerospace industry employed 35,000 people and its sales totalled C$15.2 billion. Many aerospace companies are active here, including CMC Electronics, Bombardier, Pratt & Whitney Canada, Héroux-Devtek, Rolls-Royce, General Electric, Bell Textron, L3Harris, Safran, SONACA, CAE Inc., and Airbus, among others. Montreal is globally considered one of the aerospace industry's great centres, and several international aviation organisations seat here.[268] Both Aéro Montréal and the CRIAQ were created to assist aerospace companies.[269][270]

The pulp and paper industry accounted for 3.1% of Quebec's GDP in 2007 [271] and generated annual shipments valued at more than $14 billion.[272] This industry employs 68,000 people in several regions of Quebec.[273] It is also the main -and in some circumstances only- source of manufacturing activity in more than 250 municipalities in the province. The forest industry has slowed in recent years because of the softwood lumber dispute.[274] In 2020, this industry represented 8% of Quebec's exports.[275]

As Quebec has few significant deposits of fossil fuels,[276] all hydrocarbons are imported. Refiners' sourcing strategies have varied over time and have depended on market conditions. In the 1990s, Quebec purchased much of its oil from the North Sea. Since 2015, it now consumes almost exclusively the crude produced in western Canada and the United States.[277] Quebec's two active refineries have a total capacity of 402,000 barrels per day, greater than local needs which stood at 365,000 barrels per day in 2018.[276]

Thanks to hydroelectricity, Quebec is the world's fourth largest aluminum producer and creates 90% of Canadian aluminum. Three companies make aluminum here: Rio Tinto, Alcoa and Aluminium Alouette. Their 9 alumineries produce 2,9 million tons of aluminum annually and employ 30,000 workers.[278]

Tertiary sector

The finance and insurance sector employs more than 168,000 people. Of this number, 78,000 are employed by the banking sector, 53,000 by the insurance sector and 20,000 by the securities and investment sector.[279] The Bank of Montreal, founded in 1817 in Montreal, was Quebec's first bank but, like many other large banks, its central branch is now in Toronto. Several banks remain based in Quebec National Bank of Canada, the Desjardins Group and the Laurentian Bank.

The tourism industry is a major sector in Quebec. The Ministry of Tourism ensures the development of this industry under the commercial name "Bonjour Québec".[280] Quebec is the second most important province for tourism in Canada, receiving 21.5% of tourists' spending (2021).[281] The industry provides employment to over 400,000 people.[282] These employees work in the more than 29,000 tourism-related businesses in Quebec, most of which are restaurants or hotels. 70% of tourism-related businesses are located in or close to Montreal or Quebec City. It is estimated that, in 2010, Quebec welcomed 25.8 million tourists. Of these, 76.1% came from Quebec, 12.2% from the rest of Canada, 7.7% from the United States and 4.1% from other countries. Annually, tourists spend more than $6.7 billion in Quebec's tourism industry.[283]