Подводное плавание с аквалангом

Подводное плавание с аквалангом — это подводного вид плавания , при котором дайверы используют дыхательное оборудование , которое полностью независимо от подачи газа для дыхания на поверхности и, следовательно, имеет ограниченный, но переменный срок службы. [ 1 ] Название «акваланг» является анакронимом « автономного подводного дыхательного аппарата » и было придумано Кристианом Дж. Ламбертсеном в патенте, поданном в 1952 году. Аквалангисты имеют при себе собственный источник дыхательного газа , обычно сжатого воздуха . [ 2 ] давая им большую независимость и свободу передвижения, чем дайверам с поверхности , и больше времени под водой, чем фридайверам. [ 1 ] Хотя использование сжатого воздуха является обычным явлением, газовая смесь с более высоким содержанием кислорода, известная как обогащенный воздух или найтрокс , стала популярной из-за снижения потребления азота во время длительных или повторяющихся погружений. Кроме того, для уменьшения последствий азотного наркоза во время более глубоких погружений можно использовать дыхательный газ, разбавленный гелием.

Системы подводного плавания с открытым контуром выбрасывают дыхательный газ в окружающую среду при выдохе и состоят из одного или нескольких баллонов для дайвинга, содержащих дыхательный газ под высоким давлением, который подается дайверу под давлением окружающей среды через водолазный регулятор . Они могут включать дополнительные баллоны для увеличения дальности полета, декомпрессионного газа или газа для аварийного дыхания . [ 3 ] Closed-circuit or semi-closed circuit rebreather scuba systems allow recycling of exhaled gases. The volume of gas used is reduced compared to that of open-circuit, so a smaller cylinder or cylinders may be used for an equivalent dive duration. Rebreathers extend the time spent underwater compared to open-circuit for the same metabolic gas consumption; they produce fewer bubbles and less noise than open-circuit scuba, which makes them attractive to covert military divers to avoid detection, scientific divers to avoid disturbing marine animals, and media divers to avoid bubble interference.[1]

Scuba diving may be done recreationally or professionally in a number of applications, including scientific, military and public safety roles, but most commercial diving uses surface-supplied diving equipment when this is practicable. Scuba divers engaged in armed forces covert operations may be referred to as frogmen, combat divers or attack swimmers.[4]

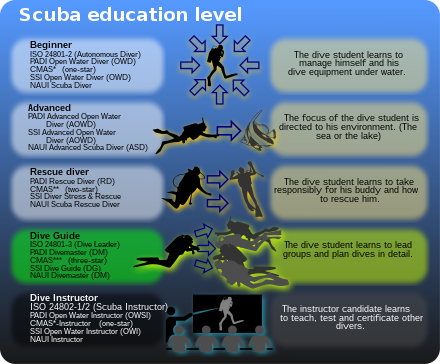

A scuba diver primarily moves underwater by using fins attached to the feet, but external propulsion can be provided by a diver propulsion vehicle, or a sled pulled from the surface.[5] Other equipment needed for scuba diving includes a mask to improve underwater vision, exposure protection by means of a diving suit, ballast weights to overcome excess buoyancy, equipment to control buoyancy, and equipment related to the specific circumstances and purpose of the dive, which may include a snorkel when swimming on the surface, a cutting tool to manage entanglement, lights, a dive computer to monitor decompression status, and signalling devices. Scuba divers are trained in the procedures and skills appropriate to their level of certification by diving instructors affiliated to the diver certification organisations which issue these certifications.[6] These include standard operating procedures for using the equipment and dealing with the general hazards of the underwater environment, and emergency procedures for self-help and assistance of a similarly equipped diver experiencing problems. A minimum level of fitness and health is required by most training organisations, but a higher level of fitness may be appropriate for some applications.[7]

History

[edit]

- 1. Breathing hose

- 2. Mouthpiece

- 3. Cylinder valve and regulator

- 4. Harness

- 5. Backplate

- 6. Cylinder

The history of scuba diving is closely linked with the history of scuba equipment. By the turn of the twentieth century, two basic architectures for underwater breathing apparatus had been pioneered; open-circuit surface supplied equipment where the diver's exhaled gas is vented directly into the water, and closed-circuit breathing apparatus where the diver's carbon dioxide is filtered from exhaled unused oxygen, which is then recirculated, and oxygen added to make up the volume when necessary. Closed circuit equipment was more easily adapted to scuba in the absence of reliable, portable, and economical high-pressure gas storage vessels.

By the mid-twentieth century, high pressure gas cylinders were available and two systems for scuba had emerged: open-circuit scuba where the diver's exhaled breath is vented directly into the water, and closed-circuit scuba where the carbon dioxide is removed from the diver's exhaled breath which has oxygen added and is recirculated. Oxygen rebreathers are severely depth-limited due to oxygen toxicity risk, which increases with depth, and the available systems for mixed gas rebreathers were fairly bulky and designed for use with diving helmets.[8] The first commercially practical scuba rebreather was designed and built by the diving engineer Henry Fleuss in 1878, while working for Siebe Gorman in London.[9] His self-contained breathing apparatus consisted of a rubber mask connected to a breathing bag, with an estimated 50–60% oxygen supplied from a copper tank and carbon dioxide scrubbed by passing it through a bundle of rope yarn soaked in a solution of caustic potash, the system giving a dive duration of up to about three hours. This apparatus had no way of measuring the gas composition during use.[9][10] During the 1930s and all through World War II, the British, Italians and Germans developed and extensively used oxygen rebreathers to equip the first frogmen. The British adapted the Davis Submerged Escape Apparatus and the Germans adapted the Dräger submarine escape rebreathers, for their frogmen during the war.[11] In the U.S. Major Christian J. Lambertsen invented an underwater free-swimming oxygen rebreather in 1939, which was accepted by the Office of Strategic Services.[12] In 1952 he patented a modification of his apparatus, this time named SCUBA (an acronym for "self-contained underwater breathing apparatus"),[13][2][14][15] which became the generic English word for autonomous breathing equipment for diving, and later for the activity using the equipment.[16] After World War II, military frogmen continued to use rebreathers since they do not make bubbles which would give away the presence of the divers. The high percentage of oxygen used by these early rebreather systems limited the depth at which they could be used due to the risk of convulsions caused by acute oxygen toxicity.[1]: 1–11

Although a working demand regulator system had been invented in 1864 by Auguste Denayrouze and Benoît Rouquayrol,[17] the first open-circuit scuba system developed in 1925 by Yves Le Prieur in France was a manually adjusted free-flow system with a low endurance, which limited its practical usefulness.[18] In 1942, during the German occupation of France, Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Émile Gagnan designed the first successful and safe open-circuit scuba, known as the Aqua-Lung. Their system combined an improved demand regulator with high-pressure air tanks.[19] This was patented in 1945. To sell his regulator in English-speaking countries Cousteau registered the Aqua-Lung trademark, which was first licensed to the U.S. Divers company,[20] and in 1948 to Siebe Gorman of England.[21] Siebe Gorman was allowed to sell in Commonwealth countries, but had difficulty in meeting the demand and the U.S. patent prevented others from making the product. The patent was circumvented by Ted Eldred of Melbourne, Australia, who developed the single-hose open-circuit scuba system, which separates the first stage and demand valve of the pressure regulator by a low-pressure hose, puts the demand valve at the diver's mouth, and releases exhaled gas through the demand valve casing. Eldred sold the first Porpoise Model CA single hose scuba early in 1952.[22]

Early scuba sets were usually provided with a plain harness of shoulder straps and waist belt. The waist belt buckles were usually quick-release, and shoulder straps sometimes had adjustable or quick-release buckles. Many harnesses did not have a backplate, and the cylinders rested directly against the diver's back.[23] Early scuba divers dived without a buoyancy aid.[note 1] In an emergency they had to jettison their weights. In the 1960s adjustable buoyancy life jackets (ABLJ) became available, which can be used to compensate for loss of buoyancy at depth due to compression of the neoprene wetsuit and as a lifejacket that will hold an unconscious diver face-upwards at the surface, and that can be quickly inflated. The first versions were inflated from a small disposable carbon dioxide cylinder, later with a small direct coupled air cylinder. A low-pressure feed from the regulator first-stage to an inflation/deflation valve unit an oral inflation valve and a dump valve lets the volume of the ABLJ be controlled as a buoyancy aid. In 1971 the stabilizer jacket was introduced by ScubaPro. This class of buoyancy aid is known as a buoyancy control device or buoyancy compensator.[24][25]

A backplate and wing is an alternative configuration of scuba harness with a buoyancy compensation bladder known as a "wing" mounted behind the diver, sandwiched between the backplate and the cylinder or cylinders. Unlike stabilizer jackets, the backplate and wing is a modular system, in that it consists of separable components. This arrangement became popular with cave divers making long or deep dives, who needed to carry several extra cylinders, as it clears the front and sides of the diver for other equipment to be attached in the region where it is easily accessible. This additional equipment is usually suspended from the harness or carried in pockets on the exposure suit.[5][26] Sidemount is a scuba diving equipment configuration which has basic scuba sets, each comprising a single cylinder with a dedicated regulator and pressure gauge, mounted alongside the diver, clipped to the harness below the shoulders and along the hips, instead of on the back of the diver. It originated as a configuration for advanced cave diving, as it facilitates penetration of tight sections of caves, since sets can be easily removed and remounted when necessary. The configuration allows easy access to cylinder valves, and provides easy and reliable gas redundancy. These benefits for operating in confined spaces were also recognized by divers who made wreck diving penetrations. Sidemount diving has grown in popularity within the technical diving community for general decompression diving,[27] and has become a popular specialty for recreational diving.[28][29][30]

In the 1950s the United States Navy (USN) documented enriched oxygen gas procedures for military use of what is today called nitrox,[1] and in 1970, Morgan Wells of NOAA began instituting diving procedures for oxygen-enriched air. In 1979 NOAA published procedures for the scientific use of nitrox in the NOAA Diving Manual.[3][31] In 1985 IAND (International Association of Nitrox Divers) began teaching nitrox use for recreational diving. This was considered dangerous by some, and met with heavy skepticism by the diving community.[32] Nevertheless, in 1992 NAUI became the first existing major recreational diver training agency to sanction nitrox,[33] and eventually, in 1996, the Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI) announced full educational support for nitrox.[34] The use of a single nitrox mixture has become part of recreational diving, and multiple gas mixtures are common in technical diving to reduce overall decompression time.[35]

Technical diving is recreational scuba diving that exceeds the generally accepted recreational limits, and may expose the diver to hazards beyond those normally associated with recreational diving, and to greater risks of serious injury or death. These risks may be reduced by appropriate skills, knowledge and experience, and by using suitable equipment and procedures. The concept and term are both relatively recent advents, although divers had already been engaging in what is now commonly referred to as technical diving for decades. One reasonably widely held definition is that any dive in which at some point of the planned profile it is not physically possible or physiologically acceptable to make a direct and uninterrupted vertical ascent to surface air is a technical dive.[36] The equipment often involves breathing gases other than air or standard nitrox mixtures, multiple gas sources, and different equipment configurations.[37] Over time, some equipment and techniques developed for technical diving have become more widely accepted for recreational diving.[36]

Oxygen toxicity limits the depth reachable by underwater divers when breathing nitrox mixtures. In 1924 the US Navy started to investigate the possibility of using helium and after animal experiments, human subjects breathing heliox 20/80 (20% oxygen, 80% helium) were successfully decompressed from deep dives,[38] In 1963 saturation dives using trimix were made during Project Genesis,[39] and in 1979 a research team at the Duke University Medical Center Hyperbaric Laboratory started work which identified the use of trimix to prevent the symptoms of high-pressure nervous syndrome.[40] Cave divers started using trimix to allow deeper dives and it was used extensively in the 1987 Wakulla Springs Project and spread to the north-east American wreck diving community.[41]

The challenges of deeper dives and longer penetrations and the large amounts of breathing gas necessary for these dive profiles and ready availability of oxygen sensing cells beginning in the late 1980s led to a resurgence of interest in rebreather diving. By accurately measuring the partial pressure of oxygen, it became possible to maintain and accurately monitor a breathable gas mixture in the loop at any depth.[36] In the mid-1990s semi-closed circuit rebreathers became available for the recreational scuba market, followed by closed circuit rebreathers around the turn of the millennium.[42] Rebreathers are currently manufactured for the military, technical and recreational scuba markets,[36] but remain less popular, less reliable, and more expensive than open-circuit equipment.

Equipment

[edit]

Scuba diving equipment, also known as scuba gear, is the equipment used by a scuba diver for the purpose of diving, and includes the breathing apparatus, diving suit, buoyancy control and weighting systems, fins for mobility, mask for improving underwater vision, and a variety of safety equipment and other accessories.

Breathing apparatus

[edit]The defining equipment used by a scuba diver is the eponymous scuba, the self-contained underwater breathing apparatus which allows the diver to breathe while diving, and is transported by the diver. It is also commonly referred to as the scuba set.

As one descends, in addition to the normal atmospheric pressure at the surface, the water exerts increasing hydrostatic pressure of approximately 1 bar (14.7 pounds per square inch) for every 10 m (33 feet) of depth. The pressure of the inhaled breath must balance the surrounding or ambient pressure to allow controlled inflation of the lungs. It becomes virtually impossible to breathe air at normal atmospheric pressure through a tube below 3 feet (0.9 m) under the water.[2]

Most recreational scuba diving is done using a half mask which covers the diver's eyes and nose, and a mouthpiece to supply the breathing gas from the demand valve or rebreather. Inhaling from a mouthpiece becomes second nature very quickly. The other common arrangement is a full-face mask which covers the eyes, nose and mouth, and often allows the diver to breathe through the nose. Professional scuba divers are more likely to use full-face masks, which protect the diver's airway if the diver loses consciousness.[43]

Open-circuit

[edit]

Open-circuit scuba has no provision for using the breathing gas more than once for respiration.[1] The gas inhaled from the scuba equipment is exhaled to the environment, or occasionally into another item of equipment for a special purpose, usually to increase the buoyancy of a lifting device such as a buoyancy compensator, inflatable surface marker buoy or small lifting bag. The breathing gas is generally provided from a high-pressure diving cylinder through a scuba regulator. By always providing the appropriate breathing gas at ambient pressure, demand valve regulators ensure the diver can inhale and exhale naturally and without excessive effort, regardless of depth, as and when needed.[23]

The most commonly used scuba set uses a "single-hose" open-circuit 2-stage demand regulator, connected to a single back-mounted high-pressure gas cylinder, with the first stage connected to the cylinder valve and the second stage at the mouthpiece.[1] This arrangement differs from Émile Gagnan's and Jacques Cousteau's original 1942 "twin-hose" design, known as the Aqua-lung, in which the cylinder pressure was reduced to ambient pressure in one or two stages which were all in the housing mounted to the cylinder valve or manifold.[23] The "single-hose" system has significant advantages over the original system for most applications.[44]

In the "single-hose" two-stage design, the first stage regulator reduces the cylinder pressure of up to about 300 bars (4,400 psi) to an intermediate pressure (IP) of about 8 to 10 bars (120 to 150 psi) above ambient pressure. The second stage demand valve regulator, supplied by a low-pressure hose from the first stage, delivers the breathing gas at ambient pressure to the diver's mouth. The exhaled gases are exhausted directly to the environment as waste through a non-return valve on the second stage housing. The first stage typically has at least one outlet port delivering gas at full tank pressure which is connected to the diver's submersible pressure gauge or dive computer, to show how much breathing gas remains in the cylinder.[44]

Rebreather

[edit]

Less common are closed circuit (CCR) and semi-closed (SCR) rebreathers which, unlike open-circuit sets that vent off all exhaled gases, process all or part of each exhaled breath for re-use by removing the carbon dioxide and replacing the oxygen used by the diver.[45] Rebreathers release few or no gas bubbles into the water, and use much less stored gas volume, for an equivalent depth and time because exhaled oxygen is recovered; this has advantages for research, military,[1] photography, and other applications. Rebreathers are more complex and more expensive than open-circuit scuba, and special training and correct maintenance are required for them to be safely used, due to the larger variety of potential failure modes.[45]

In a closed-circuit rebreather the oxygen partial pressure in the rebreather is controlled, so it can be maintained at a safe continuous maximum, which reduces the inert gas (nitrogen and/or helium) partial pressure in the breathing loop. Minimising the inert gas loading of the diver's tissues for a given dive profile reduces the decompression obligation. This requires continuous monitoring of actual partial pressures with time and for maximum effectiveness requires real-time computer processing by the diver's decompression computer. Decompression can be much reduced compared to fixed ratio gas mixes used in other scuba systems and, as a result, divers can stay down longer or require less time to decompress. A semi-closed circuit rebreather injects a constant mass flow of a fixed breathing gas mixture into the breathing loop, or replaces a specific percentage of the respired volume, so the partial pressure of oxygen at any time during the dive depends on the diver's oxygen consumption and/or breathing rate. Planning decompression requirements requires a more conservative approach for a SCR than for a CCR, but decompression computers with a real-time oxygen partial pressure input can optimise decompression for these systems. Because rebreathers produce very few bubbles, they do not disturb marine life or make a diver's presence known at the surface; this is useful for underwater photography, and for covert work.[36]

Gas mixtures

[edit]

For some diving, gas mixtures other than normal atmospheric air (21% oxygen, 78% nitrogen, 1% trace gases) can be used,[1][2] so long as the diver is competent in their use. The most commonly used mixture is nitrox, also referred to as Enriched Air Nitrox (EAN or EANx), which is air with extra oxygen, often with 32% or 36% oxygen, and thus less nitrogen, reducing the risk of decompression sickness or allowing longer exposure to the same pressure for equal risk. The reduced nitrogen may also allow for no stops or shorter decompression stop times or a shorter surface interval between dives.[46][2]: 304

The increased partial pressure of oxygen due to the higher oxygen content of nitrox increases the risk of oxygen toxicity, which becomes unacceptable below the maximum operating depth of the mixture. To displace nitrogen without the increased oxygen concentration, other diluent gases can be used, usually helium, when the resultant three gas mixture is called trimix, and when the nitrogen is fully substituted by helium, heliox.[3]

For dives requiring long decompression stops, divers may carry cylinders containing different gas mixtures for the various phases of the dive, typically designated as travel, bottom, and decompression gases. These different gas mixtures may be used to extend bottom time, reduce inert gas narcotic effects, and reduce decompression times. Back gas refers to any gas carried on the diver's back, usually bottom gas.[47]

Diver mobility

[edit]To take advantage of the freedom of movement afforded by scuba equipment, the diver needs to be mobile underwater. Personal mobility is enhanced by swimfins and optionally diver propulsion vehicles. Fins have a large blade area and use the more powerful leg muscles, so are much more efficient for propulsion and manoeuvering thrust than arm and hand movements, but require skill to provide fine control. Several types of fin are available, some of which may be more suited for maneuvering, alternative kick styles, speed, endurance, reduced effort or ruggedness.[3] Neutral buoyancy will allow propulsive effort to be directed in the direction of intended motion and will reduce induced drag. Streamlining dive gear will also reduce drag and improve mobility. Balanced trim which allows the diver to align in any desired direction also improves streamlining by presenting the smallest section area to the direction of movement and allowing propulsion thrust to be used more efficiently.[48]

Occasionally a diver may be towed using a "sled", an unpowered device towed behind a surface vessel that conserves the diver's energy and allows more distance to be covered for a given air consumption and bottom time. The depth is usually controlled by the diver by using diving planes or by tilting the whole sled.[49] Some sleds are faired to reduce drag on the diver.[50]

Buoyancy control and trim

[edit]

To dive safely, divers must control their rate of descent and ascent in the water[2] and be able to maintain a constant depth in midwater.[51] Ignoring other forces such as water currents and swimming, the diver's overall buoyancy determines whether they ascend or descend. Equipment such as diving weighting systems, diving suits (wet, dry or semi-dry suits are used depending on the water temperature) and buoyancy compensators(BC) or buoyancy control device(BCD) can be used to adjust the overall buoyancy.[1] When divers want to remain at constant depth, they try to achieve neutral buoyancy. This minimises the effort of swimming to maintain depth and therefore reduces gas consumption.[51]

The buoyancy force on the diver is the weight of the volume of the liquid that they and their equipment displace minus the weight of the diver and their equipment; if the result is positive, that force is upwards. The buoyancy of any object immersed in water is also affected by the density of the water. The density of fresh water is about 3% less than that of ocean water.[52] Therefore, divers who are neutrally buoyant at one dive destination (e.g. a freshwater lake) will predictably be positively or negatively buoyant when using the same equipment at destinations with different water densities (e.g. a tropical coral reef).[51] The removal ("ditching" or "shedding") of diver weighting systems can be used to reduce the diver's weight and cause a buoyant ascent in an emergency.[51]

Diving suits made of compressible materials decrease in volume as the diver descends, and expand again as the diver ascends, causing buoyancy changes. Diving in different environments also necessitates adjustments in the amount of weight carried to achieve neutral buoyancy. The diver can inject air into dry suits to counteract the compression effect and squeeze. Buoyancy compensators allow easy and fine adjustments in the diver's overall volume and therefore buoyancy.[51]

Neutral buoyancy in a diver is an unstable state. It is changed by small differences in ambient pressure caused by a change in depth, and the change has a positive feedback effect. A small descent will increase the pressure, which will compress the gas-filled spaces and reduce the total volume of diver and equipment. This will further reduce the buoyancy, and unless counteracted, will result in sinking more rapidly. The equivalent effect applies to a small ascent, which will trigger an increased buoyancy and will result in an accelerated ascent unless counteracted. The diver must continuously adjust buoyancy or depth in order to remain neutral. Fine control of buoyancy can be achieved by controlling the average lung volume in open-circuit scuba, but this feature is not available to the closed circuit rebreather diver, as exhaled gas remains in the breathing loop. This is a skill that improves with practice until it becomes second nature.[51]

Buoyancy changes with depth variation are proportional to the compressible part of the volume of the diver and equipment, and to the proportional change in pressure, which is greater per unit of depth near the surface. Minimising the volume of gas required in the buoyancy compensator will minimise the buoyancy fluctuations with changes in depth. This can be achieved by accurate selection of ballast weight, which should be the minimum to allow neutral buoyancy with depleted gas supplies at the end of the dive unless there is an operational requirement for greater negative buoyancy during the dive.[35] Buoyancy and trim can significantly affect drag of a diver. The effect of swimming with a head up angle of about 15°, as is quite common in poorly trimmed divers, can be an increase in drag in the order of 50%.[48]

The ability to ascend at a controlled rate and remain at a constant depth is important for correct decompression. Recreational divers who do not incur decompression obligations can get away with imperfect buoyancy control, but when long decompression stops at specific depths are required, the risk of decompression sickness is increased by depth variations while at a stop. Decompression stops are typically done when the breathing gas in the cylinders has been largely used up, and the reduction in weight of the cylinders increases the buoyancy of the diver. Enough weight must be carried to allow the diver to decompress at the end of the dive with nearly empty cylinders.[35]

Depth control during ascent is facilitated by ascending on a line with a buoy at the top. The diver can remain marginally negative and easily maintain depth by holding onto the line. A shotline or decompression buoy are commonly used for this purpose. Precise and reliable depth control are particularly valuable when the diver has a large decompression obligation, as it allows the theoretically most efficient decompression at the lowest reasonably practicable risk. Ideally the diver should practice precise buoyancy control when the risk of decompression sickness due to depth variation violating the decompression ceiling is low.

Underwater vision

[edit]

Water has a higher refractive index than air – similar to that of the cornea of the eye. Light entering the cornea from water is hardly refracted at all, leaving only the eye's crystalline lens to focus light. This leads to very severe hypermetropia. People with severe myopia, therefore, can see better underwater without a mask than normal-sighted people.[53] Diving masks and helmets solve this problem by providing an air space in front of the diver's eyes.[1] The refraction error created by the water is mostly corrected as the light travels from water to air through a flat lens, except that objects appear approximately 34% bigger and 25% closer in water than they actually are. The faceplate of the mask is supported by a frame and skirt, which are opaque or translucent, therefore the total field-of-view is significantly reduced and eye-hand coordination must be adjusted.[53]

Divers who need corrective lenses to see clearly outside the water would normally need the same prescription while wearing a mask. Generic corrective lenses are available off the shelf for some two-window masks, and custom lenses can be bonded onto masks that have a single front window or two windows.[54]

As a diver descends, they must periodically exhale through their nose to equalise the internal pressure of the mask with that of the surrounding water. Swimming goggles are not suitable for diving because they only cover the eyes and thus do not allow for equalisation. Failure to equalise the pressure inside the mask may lead to a form of barotrauma known as mask squeeze.[1][3]

Masks tend to fog when warm humid exhaled air condenses on the cold inside of the faceplate. To prevent fogging many divers spit into the dry mask before use, spread the saliva over the inside of the glass and rinse it out with a little water. The saliva residue allows condensation to wet the glass and form a continuous wet film, rather than tiny droplets. There are several commercial products that can be used as an alternative to saliva, some of which are more effective and last longer, but there is a risk of getting the anti-fog agent in the eyes.[55]

Dive lights

[edit]Water attenuates light by selective absorption.[53][56] Pure water preferentially absorbs red light, and to a lesser extent, yellow and green, so the colour that is least absorbed is blue light.[57] Dissolved materials may also selectively absorb colour in addition to the absorption by the water itself. In other words, as a diver goes deeper on a dive, more colour is absorbed by the water, and in clean water the colour becomes blue with depth. Colour vision is also affected by the turbidity of the water which tends to reduce contrast. Artificial light is useful to provide light in the darkness, to restore contrast at close range, and to restore natural colour lost to absorption.[53]

Dive lights can also attract fish and a variety of other sea creatures.

Exposure protection

[edit]

Protection from heat loss in cold water is usually provided by wetsuits or dry suits. These also provide protection from sunburn, abrasion and stings from some marine organisms. Where thermal insulation is not important, lycra suits/diving skins may be sufficient.[58]

A wetsuit is a garment, usually made of foamed neoprene, which provides thermal insulation, abrasion resistance and buoyancy. The insulation properties depend on bubbles of gas enclosed within the material, which reduce its ability to conduct heat. The bubbles also give the wetsuit a low density, providing buoyancy in water. Suits range from a thin (2 mm or less) "shortie", covering just the torso, to a full 8 mm semi-dry, usually complemented by neoprene boots, gloves and hood. A good close fit and few zips help the suit to remain waterproof and reduce flushing – the replacement of water trapped between suit and body by cold water from the outside. Improved seals at the neck, wrists and ankles and baffles under the entry zip produce a suit known as "semi-dry".[59][58]

A dry suit also provides thermal insulation to the wearer while immersed in water,[60][61][62][63] and normally protects the whole body except the head, hands, and sometimes the feet. In some configurations, these are also covered. Dry suits are usually used where the water temperature is below 15 °C (60 °F) or for extended immersion in water above 15 °C (60 °F), where a wetsuit user would get cold, and with an integral helmet, boots, and gloves for personal protection when diving in contaminated water.[64] Dry suits are designed to prevent water from entering. This generally allows better insulation making them more suitable for use in cold water. They can be uncomfortably hot in warm or hot air, and are typically more expensive and more complex to don. For divers, they add some degree of complexity as the suit must be inflated and deflated with changes in depth in order to avoid "squeeze" on descent or uncontrolled rapid ascent due to over-buoyancy.[64] Dry suit divers may also use the gas argon to inflate their suits via low pressure inflator hose. This is because the gas is inert and has a low thermal conductivity.[65]

Monitoring and navigation

[edit]

Unless the maximum depth of the water is known, and is quite shallow, a diver must monitor the depth and duration of a dive to avoid decompression sickness. Traditionally this was done by using a depth gauge and a diving watch, but electronic dive computers are now in general use, as they are programmed to do real-time modelling of decompression requirements for the dive, and automatically allow for surface interval. Many can be set for the gas mixture to be used on the dive, and some can accept changes in the gas mix during the dive. Most dive computers provide a fairly conservative decompression model, and the level of conservatism may be selected by the user within limits. Most decompression computers can also be set for altitude compensation to some degree,[35] and some will automatically take altitude into account by measuring actual atmospheric pressure and using it in the calculations.[66]

If the dive site and dive plan require the diver to navigate, a compass may be carried, and where retracing a route is critical, as in cave or wreck penetrations, a guide line is laid from a dive reel. In less critical conditions, many divers simply navigate by landmarks and memory, a procedure also known as pilotage or natural navigation. A scuba diver should always be aware of the remaining breathing gas supply, and the duration of diving time that this will safely support, taking into account the time required to surface safely and an allowance for foreseeable contingencies. This is usually monitored by using a submersible pressure gauge on each cylinder.[67]

Safety equipment

[edit]

Any scuba diver who will be diving below a depth from which they are competent to do a safe emergency swimming ascent should ensure that they have an alternative breathing gas supply available at all times in case of a failure of the equipment they are breathing from at the time. Several systems are in common use depending on the planned dive profile. Most common, but least reliable, is relying on the dive buddy for gas sharing using a secondary second stage, commonly called an octopus regulator connected to the primary first stage. This system relies entirely on the dive buddy being immediately available to provide emergency gas. More reliable systems require the diver to carry an alternative gas supply sufficient to allow the diver to safely reach a place where more breathing gas is available. For open water recreational divers this is the surface. A bailout cylinder provides emergency breathing gas sufficient for a safe emergency ascent. For technical divers on a penetration dive, it may be a stage cylinder positioned at a point on the exit path. An emergency gas supply must be sufficiently safe to breathe at any point on the planned dive profile at which it may be needed. This equipment may be a bailout cylinder, a bailout rebreather, a travel gas cylinder, or a decompression gas cylinder. When using a travel gas or decompression gas, the back gas (main gas supply) may be the designated emergency gas supply.

Cutting tools such as knives, line cutters or shears are often carried by divers to cut loose from entanglement in nets or lines. A surface marker buoy (SMB) on a line held by the diver indicates the position of the diver to the surface personnel. This may be an inflatable marker deployed by the diver at the end of the dive, or a sealed float, towed for the whole dive. A surface marker also allows easy and accurate control of ascent rate and stop depth for safer decompression.[68]

Various surface detection aids may be carried to help surface personnel spot the diver after ascent. In addition to the surface marker buoy, divers may carry mirrors, lights, strobes, whistles, flares or emergency locator beacons.[68]

Accessories and tools

[edit]Divers may carry underwater photographic or video equipment, or tools for a specific application in addition to diving equipment. Professional divers will routinely carry and use tools to facilitate their underwater work, while most recreational divers will not engage in underwater work.

Medicine

[edit]- Antihistamines[69]

- Scopolamine: Motion sickness, including sea sickness, leading the use of scopolamine use by scuba divers (where it is often applied as a transdermal patch behind the ear)[70][71][69]

- Promethazine[69]

Breathing from scuba

[edit]Breathing from scuba is mostly a straightforward matter. Under most circumstances, it differs very little from normal surface breathing. In the case of a full-face mask, the diver may usually breathe through the nose or mouth as preferred, and in the case of a mouth held demand valve, the diver will have to hold the mouthpiece between the teeth and maintain a seal around it with the lips. Over a long dive this can induce jaw fatigue, and for some people, a gag reflex. Various styles of mouthpiece are available off the shelf or as customised items, and one of them may work better if either of these problems occur.

The frequently quoted warning against holding one's breath on scuba is a gross oversimplification of the actual hazard. The purpose of the admonition is to ensure that inexperienced divers do not accidentally hold their breath while surfacing, as the expansion of gas in the lungs could over-expand the lung air spaces and rupture the alveoli and their capillaries, allowing lung gases to get into the pulmonary return circulation, the pleura, or the interstitial areas near the injury, where it could cause dangerous medical conditions. Holding the breath at constant depth for short periods with a normal lung volume is generally harmless, providing there is sufficient ventilation on average to prevent carbon dioxide buildup, and is done as a standard practice by underwater photographers to avoid startling their subjects. Holding the breath during descent can eventually cause lung squeeze, and may allow the diver to miss warning signs of a gas supply malfunction until it is too late to remedy.

Skilled open-circuit divers make small adjustments to buoyancy by adjusting their average lung volume during the breathing cycle. This adjustment is generally in the order of a kilogram (corresponding to a litre of gas), and can be maintained for a moderate period, but it is more comfortable to adjust the volume of the buoyancy compensator over the longer term.[72]

The practice of shallow breathing or skip breathing in an attempt to conserve breathing gas should be avoided as it is inefficient and tends to cause a carbon dioxide buildup, which can result in headaches and a reduced capacity to recover from a breathing gas supply emergency. The breathing apparatus will generally increase dead space by a small but significant amount, and cracking pressure and flow resistance in the demand valve will cause a net work of breathing increase, which will reduce the diver's capacity for other work. Work of breathing and the effect of dead space can be minimised by breathing relatively deeply and slowly. These effects increase with depth, as density and friction increase in proportion to the increase in pressure, with the limiting case where all the diver's available energy may be expended on simply breathing, with none left for other purposes. This would be followed by a buildup in carbon dioxide, causing an urgent feeling of a need to breathe, and if this cycle is not broken, panic and drowning are likely to follow. The use of a low-density inert gas, typically helium, in the breathing mixture can reduce this problem, as well as diluting the narcotic effects of the other gases.[73][74]

Breathing from a rebreather is much the same, except that the work of breathing is affected mainly by flow resistance in the breathing loop. This is partly due to the carbon dioxide absorbent in the scrubber, and is related to the distance the gas passes through the absorbent material, and the size of the gaps between the grains, as well as the gas composition and ambient pressure. Water in the loop can greatly increase the resistance to gas flow through the scrubber. There is even less point in shallow or skip breathing on a rebreather as this does not even conserve gas, and the effect on buoyancy is negligible when the sum of loop volume and lung volume remains constant.[74][75]

A breathing pattern of slow, deep breaths which limits gas velocity and thereby turbulent flow in the air passages will minimise the work of breathing for a given gas mixture composition and density, and respiratory minute volume.[74]

Procedures

[edit]

The underwater environment is unfamiliar and hazardous, and to ensure diver safety, simple, yet necessary procedures must be followed. A certain minimum level of attention to detail and acceptance of responsibility for one's own safety and survival are required. Most of the procedures are simple and straightforward, and become second nature to the experienced diver, but must be learned, and take some practice to become automatic and faultless, just like the ability to walk or talk. Most of the safety procedures are intended to reduce the risk of drowning, and many of the rest are to reduce the risk of barotrauma and decompression sickness. In some applications getting lost is a serious hazard, and specific procedures to minimise the risk are followed.[6]

Preparation for the dive

[edit]The purpose of dive planning is to ensure that divers do not exceed their comfort zone or skill level, or the safe capacity of their equipment, and includes gas planning to ensure that the amount of breathing gas to be carried is sufficient to allow for any reasonably foreseeable contingencies. Before starting a dive both the diver and their buddy[note 2] do equipment checks to ensure everything is in good working order and available. Recreational divers are responsible for planning their own dives, unless in training when the instructor is responsible.[76][77] Divemasters may provide useful information and suggestions to assist the divers, but are generally not responsible for the details unless specifically employed to do so. In professional diving teams, all team members are usually expected to contribute to planning and to check the equipment they will use, but the overall responsibility for the safety of the team lies with the supervisor as the appointed on-site representative of the employer.[43][78][79][80]

Standard diving procedures

[edit]

Some procedures are common to almost all scuba dives, or are used to manage very common contingencies. These are learned at entry level and may be highly standardised to allow efficient cooperation between divers trained at different schools.[81][82][6]

- Water entry procedures are intended to allow the diver to enter the water without injury, loss of equipment, or damage to equipment.[82][6]

- Descent procedures cover how to descend at the right place, time, and rate; with the correct breathing gas available; and without losing contact with the other divers in the group.[6][82]

- Equalisation of pressure in gas spaces to avoid barotraumas. The expansion or compression of enclosed air spaces may cause discomfort or injury while diving. Critically, the lungs are susceptible to over-expansion and subsequent collapse if a diver holds their breath while ascending: during training divers are taught not to hold their breath while diving. Ear clearing is another critical equalisation procedure, usually requiring conscious intervention by the diver.[6][83]

- Mask and regulator clearing may be needed to ensure the ability to see and breathe in case of flooding. This can easily happen, and while immediate correct response is necessary, the procedure is simple and routine and is not considered an emergency.[6][82]

- Buoyancy control and diver trim require frequent adjustment (particularly during depth changes) to ensure safe, effective, and convenient underwater mobility during the dive.

- Buddy checks, breathing gas monitoring, and decompression status monitoring are carried out to ensure that the dive plan is followed and that members of the group are safe and available to help each other in an emergency.[6][82]

- Ascent, decompression, and surfacing procedures are intended to ensure that dissolved inert gases are safely released, that barotraumas of ascent are avoided, and that it is safe to surface.[6][82]

- Water exit procedures are intended to let the diver leave the water without injury, loss of, or damage to equipment.[82][6]

- Underwater communication: Divers cannot talk underwater unless they are wearing a full-face mask and electronic communications equipment, but they can communicate basic and emergency information using hand signals, light signals, and rope signals, and more complex messages can be written on waterproof slates.[83][6][82]

Decompression

[edit]Inert gas components of the diver's breathing gas accumulate in the tissues during exposure to elevated pressure during a dive, and must be eliminated during the ascent to avoid the formation of symptomatic bubbles in tissues where the concentration is too high for the gas to remain in solution. This process is called decompression, and occurs on all scuba dives.[84] Decompression sickness is also known as the bends and can also include symptoms such as itching, rash, joint pain or nausea.[85] Most recreational and professional scuba divers avoid obligatory decompression stops by following a dive profile which only requires a limited rate of ascent for decompression, but will commonly also do an optional short, shallow, decompression stop known as a safety stop to further reduce risk before surfacing. In some cases, particularly in technical diving, more complex decompression procedures are necessary. Decompression may follow a pre-planned series of ascents interrupted by stops at specific depths, or may be monitored by a personal decompression computer.[86]

Post-dive procedures

[edit]These include debriefing where appropriate, and equipment maintenance, to ensure that the equipment is kept in good condition for later use.[83][6] It is also considered a best practice to log each dive upon completion. This is done for several reasons: If a diver is planning on doing multiple dives in a day, they need to know what the depth and duration of previous dives were in order to calculate residual inert gas levels in preparation for the next dive. It is helpful to note what equipment was used for each dive and what the conditions were like for reference when planning another similar dive. For example, the thickness and type of wetsuit used during a dive, and if it was in fresh or salt water, will influence the amount of weight needed. Knowing this information and taking note of whether the weight used was too heavy or too light can help when planning another dive in similar conditions. In order to achieve a level of certification the diver may be required to present evidence of a specified number of logged and verified dives.[87] Professional divers may be legally required to log specific information for every working dive.[43] When a personal dive computer is used, it will accurately record the details of the dive profile, and this data can usually be downloaded to an electronic logbook, in which the diver can add the other details manually.

Buddy, team or solo diving

[edit]Buddy and team diving procedures are intended to ensure that a recreational scuba diver who gets into difficulty underwater is in the presence of a similarly equipped person who will understand the problem and can render assistance. Divers are trained to assist in those emergencies specified in the training standards for their certification, and are required to demonstrate competence in a set of prescribed buddy assistance skills. The fundamentals of buddy and team safety are centred on diver communication, redundancy of gear and breathing gas by sharing with the buddy, and the added situational perspective of another diver.[88] There is general consensus that the presence of a buddy both willing and competent to assist can reduce the risk of certain classes of accidents, but much less agreement on how often this happens in practice.

Solo divers take responsibility for their own safety and compensate for the absence of a buddy with skill, vigilance and appropriate equipment. Like buddy or team divers, properly equipped solo divers rely on the redundancy of critical articles of dive gear which may include at least two independent supplies of breathing gas and ensuring that there is always enough available to safely terminate the dive if any one supply fails. The difference between the two practices is that this redundancy is carried and managed by the solo diver instead of a buddy. Agencies that certify for solo diving require candidates to have a relatively high level of dive experience – usually about 100 dives or more.[89][90]

Since the inception of scuba, there has been an ongoing debate regarding the wisdom of solo diving with strong opinions on both sides of the issue. This debate is complicated by the fact that the line which separates a solo diver from a buddy/team diver is not always clear.[91] For example, should a scuba instructor (who supports the buddy system) be considered a solo diver if their students do not have the knowledge or experience to assist the instructor through an unforeseen scuba emergency? Should the buddy of an underwater photographer consider themselves as effectively diving alone since their buddy (the photographer) is giving most or all of their attention to the subject of the photograph? This debate has motivated some prominent scuba agencies such as Global Underwater Explorers (GUE) to stress that its members only dive in teams and "remain aware of team member location and safety at all times."[92] Other agencies such as Scuba Diving International (SDI) and Professional Association of Diving Instructors (PADI) have taken the position that divers might find themselves alone (by choice or by accident) and have created certification courses such as the "SDI Solo Diver Course" and the "PADI Self-Reliant Diver Course" in order to train divers to handle such possibilities.[93][94]

Other organisations such as the International Diving Safety Standards Commission (IDSSC), do not accept recreational solo diving for unspecified "psychological, social and technical reasons", without providing logical arguments or evidence supporting their stance.[95][96] It is not clear that the IDSSC is formally recognised in the role they have claimed.

Emergency procedures

[edit]The most urgent underwater emergencies usually involve a compromised breathing gas supply. Divers are trained in procedures for donating and receiving breathing gas from each other in an emergency, and may carry an independent alternative air source if they do not choose to rely on a buddy.[83][6][82] Divers may need to make an emergency ascent in the event of a loss of breathing gas which cannot be managed at depth. Controlled emergency ascents are almost always a consequence of loss of breathing gas, while uncontrolled ascents are usually the result of a buoyancy control failure.[97] Other urgent emergencies may involve loss of control of depth and medical emergencies.

Divers may be trained in procedures that have been approved by the training agencies for recovery of an unresponsive diver to the surface, where it might be possible to administer first aid. Not all recreational divers have this training as some agencies do not include it in entry-level training. Professional divers may be required by legislation or code of practice to have a standby diver at any diving operation, who is both competent and available to attempt rescue of a distressed diver.[83][82]

Two basic types of entrapment are significant hazards for scuba divers: Inability to navigate out of an enclosed space, and physical entrapment which prevents the diver from leaving a location. The first case can usually be avoided by staying out of enclosed spaces, and when the objective of the dive includes penetration of enclosed spaces, taking precautions such as the use of lights and guidelines, for which specialised training is provided in the standard procedures.[98] The most common form of physical entrapment is getting snagged on ropes, lines or nets, and the use of a cutting implement is the standard method of dealing with the problem. The risk of entanglement can be reduced by careful configuration of equipment to minimise those parts which can easily be snagged, and allow easier disentanglement. Other forms of entrapment such as getting wedged into tight spaces can often be avoided, but must otherwise be dealt with as they happen. The assistance of a buddy may be helpful where possible.[5]

Scuba diving in relatively hazardous environments such as caves and wrecks, areas of strong water movement, relatively great depths, with decompression obligations, with equipment that has more complex failure modes, and with gases that are not safe to breathe at all depths of the dive require specialised safety and emergency procedures tailored to the specific hazards, and often specialised equipment. These conditions are generally associated with technical diving.[47]

Depth range

[edit]The depth range applicable to scuba diving depends on the application and training. Entry-level divers are expected to limit themselves to about 60 feet (18 m) to 20 metres (66 ft).[99] The major worldwide recreational diver certification agencies consider 130 feet (40 m) to be the limit for recreational diving. British and European agencies, including BSAC and SAA, recommend a maximum depth of 50 metres (160 ft)[100] Shallower limits are recommended for divers who are youthful, inexperienced, or who have not taken training for deep dives. Technical diving extends these depth limits through changes to training, equipment, and the gas mix used. The maximum depth considered safe is controversial and varies among agencies and instructors, however, there are programs that train divers for dives to 120 metres (390 ft).[101]

Professional diving usually limits the allowed planned decompression depending on the code of practice, operational directives, or statutory restrictions. Depth limits depend on the jurisdiction, and maximum depths allowed range from 30 metres (100 ft) to more than 50 metres (160 ft), depending on the breathing gas used and the availability of a decompression chamber nearby or on site.[79][43] Commercial diving using scuba is generally restricted for reasons of occupational health and safety. Surface supplied diving allows better control of the operation and eliminates or significantly reduces the risks of loss of breathing gas supply and losing the diver.[102] Scientific and media diving applications may be exempted from commercial diving constraints, based on acceptable codes of practice and a self-regulatory system.[103]

Applications

[edit]

Scuba diving may be performed for a number of reasons, both personal and professional. Recreational diving is done purely for enjoyment and has a number of technical disciplines to increase interest underwater, such as cave diving, wreck diving, ice diving and deep diving.[104][105][106] Underwater tourism is mostly done on scuba and the associated tour guiding must follow suit.[43]

Divers may be employed professionally to perform tasks underwater. Some of these tasks are suitable for scuba.[1][3][43]

There are divers who work, full or part-time, in the recreational diving community as instructors, assistant instructors, divemasters and dive guides. In some jurisdictions, the professional nature, with particular reference to responsibility for health and safety of the clients, of recreational diver instruction, dive leadership for reward and dive guiding is recognised and regulated by national legislation.[43]

Other specialist areas of scuba diving include military diving, with a long history of military frogmen in various roles. Their roles include direct combat, infiltration behind enemy lines, placing mines or using a manned torpedo, bomb disposal or engineering operations.[1] In civilian operations, many police forces operate police diving teams to perform "search and recovery" or "search and rescue" operations and to assist with the detection of crime which may involve bodies of water. In some cases diver rescue teams may also be part of a fire department, paramedical service or lifeguard unit, and may be classed as public safety diving.[43]

Underwater maintenance and research in large aquariums and fish farms, and harvesting of marine biological resources such as fish, abalones, crabs, lobsters, scallops, and sea crayfish may be done on scuba.[43][79] Boat and ship underwater hull inspection, cleaning and some aspects of maintenance (ships husbandry) may be done on scuba by commercial divers and boat owners or crew.[43][79][1]

Lastly, there are professional divers involved with underwater environments, such as underwater photographers or underwater videographers, who document the underwater world, or scientific diving, including marine biology, geology, hydrology, oceanography and underwater archaeology. This work is normally done on scuba as it provides the necessary mobility. Rebreathers may be used when the noise of open-circuit would alarm the subjects or the bubbles could interfere with the images.[3][43][79] Scientific diving under the OSHA (US) exemption has been defined as being diving work done by persons with, and using, scientific expertise to observe, or gather data on, natural phenomena or systems to generate non-proprietary information, data, knowledge or other products as a necessary part of a scientific, research or educational activity, following the direction of a diving safety manual and a diving control safety board.[103]

The choice between scuba and surface-supplied diving equipment is based on both legal and logistical constraints. Where the diver requires mobility and a large range of movement, scuba is usually the choice if safety and legal constraints allow. Higher risk work, particularly in commercial diving, may be restricted to surface-supplied equipment by legislation and codes of practice.[79][43]

Safety

[edit]The safety of underwater diving depends on four factors: the environment, the equipment, behaviour of the individual diver and performance of the dive team. The underwater environment can impose severe physical and psychological stress on a diver, and is mostly beyond the diver's control. Scuba equipment allows the diver to operate underwater for limited periods, and the reliable function of some of the equipment is critical to even short-term survival. Other equipment allows the diver to operate in relative comfort and efficiency. The performance of the individual diver depends on learned skills, many of which are not intuitive, and the performance of the team depends on competence, communication and common goals.[107]

There is a large range of hazards to which the diver may be exposed. These each have associated consequences and risks, which should be taken into account during dive planning. Where risks are marginally acceptable it may be possible to mitigate the consequences by setting contingency and emergency plans in place, so that damage can be minimised where reasonably practicable. The acceptable level of risk varies depending on legislation, codes of practice and personal choice, with recreational divers having a greater freedom of choice.[43]

Hazards

[edit]

Водолазы работают в среде, к которой человеческое тело не приспособлено. Они сталкиваются с особым физическим риском и риском для здоровья, когда погружаются под воду или используют дыхательный газ под высоким давлением. Последствия инцидентов с дайвингом варьируются от просто досадных до быстро фатальных, и результат часто зависит от снаряжения, навыков, реакции и физической подготовки дайвера и команды водолазов. Опасности включают водную среду , использование дыхательного оборудования в подводной среде , воздействие среды под давлением и изменения давления , особенно изменения давления во время спуска и подъема, а также дыхательные газы при высоком давлении окружающей среды. Снаряжение для дайвинга, кроме дыхательного аппарата, обычно надежно, но известно, что оно выходит из строя, а потеря контроля плавучести или тепловой защиты может стать серьезным бременем, которое может привести к более серьезным проблемам. Существуют также опасности, связанные с конкретной средой для дайвинга , а также опасности, связанные с доступом к воде и выходом из нее, которые варьируются от места к месту, а также могут меняться в зависимости от времени и прилива. Опасности, присущие дайверу, включают: ранее существовавшие физиологические и психологические условия , а также личное поведение и компетентность человека. Для тех, кто занимается другими видами деятельности во время дайвинга, существуют дополнительные опасности, связанные с нагрузкой, задачей погружения и специальным оборудованием, связанным с этой задачей. [ 108 ] [ 109 ]

Наличие комбинации нескольких опасностей одновременно является обычным явлением в дайвинге, и результатом этого обычно является повышенный риск для дайвера, особенно когда возникновение инцидента, вызванного одной опасностью, вызывает другие опасности с последующим каскадом инцидентов. Многие смертельные случаи при дайвинге являются результатом каскада инцидентов, которые подавляют дайвера, который должен быть в состоянии справиться с любым единичным разумно предсказуемым инцидентом. [ 110 ] Хотя подводное плавание сопряжено с множеством опасностей, дайверы могут снизить риски с помощью правильных процедур и соответствующего оборудования. Необходимые навыки приобретаются путем обучения и образования и оттачиваются на практике. Программы сертификации начального уровня освещают физиологию дайвинга, безопасные методы дайвинга и опасности при дайвинге, но не дают дайверу достаточной практики, чтобы стать по-настоящему искусным. [ 110 ]

Аквалангисты по определению носят с собой запас дыхательного газа во время погружения, и это ограниченное количество должно безопасно вернуть их на поверхность. перед погружением Планирование подходящей подачи газа для предполагаемого профиля погружения позволяет дайверу обеспечить достаточное количество дыхательного газа для запланированного погружения и на случай непредвиденных обстоятельств. [ 111 ] Они не соединены с наземной точкой управления с помощью шлангокабеля, как это используют дайверы с надводным подводным плаванием, и свобода передвижения, которую это дает, также позволяет дайверу проникать в надводную среду при подледном дайвинге , пещерном дайвинге и погружении на затонувшие объекты в той степени, в которой что дайвер может заблудиться и не сможет найти выход. Эта проблема усугубляется ограниченным запасом дыхательного газа, что дает ограниченное количество времени, прежде чем дайвер утонет, если не сможет всплыть. Стандартной процедурой управления этим риском является прокладка непрерывного ориентира из открытой воды, что позволяет дайверу быть уверенным в пути к поверхности. [ 98 ]

В большинстве случаев подводного плавания, особенно в любительском подводном плавании, используется мундштук для подачи дыхательного газа, который захватывается зубами дайвера и который относительно легко смещается при ударе. Обычно это легко исправить, если дайвер не является недееспособным, а соответствующие навыки являются частью обучения начального уровня. [ 6 ] Проблема становится серьезной и немедленно опасной для жизни, если дайвер теряет сознание и мундштук. Мундштуки ребризера, которые открываются при выходе изо рта, могут впустить воду, которая может затопить петлю, лишив их возможности подавать дыхательный газ, и потеряет плавучесть при выходе газа, таким образом ставя дайвера в ситуацию двух одновременных опасных для жизни проблемы. [ 112 ] Навыки управления такой ситуацией являются необходимой частью обучения конкретной конфигурации. Полнолицевые маски снижают эти риски и обычно предпочтительнее для профессионального подводного плавания, но могут затруднить совместное использование газа в экстренных ситуациях и менее популярны среди дайверов-любителей, которые часто полагаются на совместное использование газа с напарником в качестве варианта резервного дыхательного газа. [ 113 ]

Риск

[ редактировать ]Риск смерти во время любительского, научного или коммерческого дайвинга невелик, а при подводном плавании смертельные случаи обычно связаны с плохим обращением с газом , плохим контролем плавучести , неправильным использованием оборудования, попаданием в ловушки, бурными водными условиями и ранее существовавшими проблемами со здоровьем. Некоторые смертельные случаи неизбежны и вызваны непредвиденными ситуациями, выходящими из-под контроля, но большинство смертельных случаев при дайвинге можно объяснить человеческой ошибкой со стороны жертвы. Отказ оборудования случается редко в хорошо обслуживаемых аквалангах с открытым контуром , которые были правильно настроены и проверены перед погружением. [ 97 ]

Согласно свидетельствам о смерти, более 80% смертей в конечном итоге были связаны с утоплением, но другие факторы обычно в совокупности выводили дайвера из строя в последовательности событий, кульминацией которых было утопление, что является скорее следствием среды, в которой произошли несчастные случаи, чем самого факта. настоящая авария. Аквалангистам не следует тонуть, если нет других сопутствующих факторов, поскольку они имеют при себе запас дыхательного газа и оборудование, предназначенное для подачи газа по требованию. Утопление происходит в результате предшествующих проблем, таких как неконтролируемый стресс , сердечно-сосудистые заболевания, легочная баротравма, потеря сознания по любой причине, аспирация воды, травма , экологические опасности, трудности с оборудованием, ненадлежащая реакция на чрезвычайную ситуацию или неспособность контролировать подачу газа. [ 114 ] и часто скрывает истинную причину смерти. Воздушную эмболию также часто называют причиной смерти, и она также является следствием других факторов, ведущих к неконтролируемому и плохо управляемому всплытию , возможно, усугубленному медицинскими условиями. Около четверти смертельных случаев при дайвинге связаны с сердечно-сосудистыми заболеваниями, в основном у дайверов старшего возраста. Существует довольно большой объем данных о смертельных случаях при дайвинге, но во многих случаях эти данные недостаточны из-за стандартов расследования и отчетности. Это препятствует исследованиям, которые могли бы повысить безопасность дайверов. [ 97 ]

Уровень смертности сопоставим с бегом трусцой (13 смертей на 100 000 человек в год) и находится в пределах диапазона, в котором снижение желательно по критериям Управления здравоохранения и безопасности (HSE). [ 115 ] Наиболее частой причиной смертельных исходов при дайвинге является нехватка или нехватка газа. Другие упомянутые факторы включают отказ управления плавучестью, запутывание или застревание, бурную воду, неправильное использование или проблемы с оборудованием, а также аварийное всплытие . Наиболее распространенными травмами и причинами смерти были утопление или асфиксия вследствие вдыхания воды, воздушная эмболия и сердечные приступы. Риск остановки сердца выше у дайверов старшего возраста и выше у мужчин, чем у женщин, хотя к 65 годам риски одинаковы. [ 115 ]

Было высказано несколько правдоподобных мнений, но они еще не получили эмпирического подтверждения. Предполагаемые способствующие факторы включали неопытность, нечастые погружения, недостаточный контроль, недостаточный инструктаж перед погружением, разлуку с напарником и условия погружения, выходящие за рамки подготовки, опыта или физических возможностей дайвера. [ 115 ]

Декомпрессионная болезнь и артериальная газовая эмболия при любительском дайвинге связаны с конкретными демографическими, экологическими и поведенческими факторами. Статистическое исследование, опубликованное в 2005 году, проверило потенциальные факторы риска: возраст, астма, индекс массы тела, пол, курение, сердечно-сосудистые заболевания, диабет, предыдущая декомпрессионная болезнь, годы с момента сертификации, количество погружений в предыдущем году, количество последовательных дней погружений, количество погружений в повторяющейся серии, глубина предыдущего погружения, использование найтрокса в качестве дыхательного газа и использование сухого костюма. Никакой значимой связи с риском декомпрессионной болезни или артериальной газовой эмболии не было обнаружено для астмы, индекса массы тела, сердечно-сосудистых заболеваний, диабета или курения. Большая глубина погружения, предшествующая декомпрессионная болезнь, количество дней подряд погружений и мужской пол были связаны с более высоким риском декомпрессионной болезни и артериальной газовой эмболии. Использование сухих костюмов и дыхательного газа найтрокс, более высокая частота погружений в предыдущем году, более высокий возраст и большее количество лет с момента сертификации были связаны с меньшим риском, возможно, как показатели более обширной подготовки и опыта. [ нужна ссылка ]

Помимо оборудования и обучения, управление рисками имеет три основных аспекта: оценка риска , планирование действий в чрезвычайных ситуациях и страховое покрытие. Оценка риска для погружения - это, прежде всего, деятельность по планированию, и по формальности она может варьироваться от части проверки напарников перед погружением для дайверов-любителей до файла безопасности с профессиональной оценкой рисков и подробными планами действий в чрезвычайных ситуациях для профессиональных дайверских проектов. Некоторая форма инструктажа перед погружением является общепринятой при организованных развлекательных погружениях и обычно включает в себя изложение дайвмастером известных и прогнозируемых опасностей, рисков, связанных со значительными из них, и процедур, которым необходимо следовать в случае разумно предсказуемых опасностей. чрезвычайные ситуации, связанные с ними. Страхование от несчастных случаев при дайвинге может не быть включено в стандартные полисы. Есть несколько организаций, которые специализируются на безопасности дайверов и страховании, например, международная сеть Divers Alert Network. [ 116 ]

Чрезвычайные ситуации

[ редактировать ]Этот раздел нуждается в дополнении: Перечислите и объясните наиболее распространенные чрезвычайные ситуации, связанные с подводным плаванием, а также укажите навыки и процедуры для их устранения. Различайте аварийные ситуации и непредвиденные обстоятельства, какие из них могут быть смягчены напарником-дайвером, а какие, как правило, не могут быть смягчены напарником-дайвером. Вы можете помочь, добавив к нему . ( апрель 2023 г. ) |

Чрезвычайная ситуация при подводном плавании — это инцидент, при котором существует высокая вероятность смерти или серьезной травмы, если проблема не будет решена быстро.

Самая неотложная чрезвычайная ситуация при подводном плавании — это нехватка дыхательного газа под водой, что часто называют инцидентом с отсутствием воздуха . Это настоящая чрезвычайная ситуация, поскольку без доступа к дыхательному газу дайвер умрет в течение нескольких минут. В этой чрезвычайной ситуации можно справиться несколькими способами, включая помощь напарника по погружению, если напарник находится достаточно близко, чтобы помочь, путем совместного использования дыхательного газа. Другие варианты ответа заключаются в том, что дайвер предоставляет себе альтернативный (спасательный) источник для подводного плавания, который не зависит от напарника. Другая альтернатива, которая является жизнеспособной, если риск декомпрессии низок и нет тяжелых накладных расходов, - это аварийное всплытие , которое также не зависит от напарника.

Другие перебои в подаче дыхательного газа, такие как неисправность регулятора , смещение регулятора или полнолицевой маски, скатывание клапана баллона , могут стать аварийными, если их не устранить быстро и эффективно, хотя для компетентного дайвера большинство из них должны быть устранены. неудобства, а не чрезвычайные ситуации, если нет усугубляющих факторов.

Судороги, вызванные кислородным отравлением, сопровождаются временной потерей сознания, во время которой дайвер может потерять мундштук и, как следствие, утонуть. Наблюдательный приятель, возможно, сможет помочь .

Гипоксия, вызывающая потерю сознания, может быть следствием дыхания не из баллона, подходящего для текущей глубины, либо неисправности ребризера. Наблюдательный и компетентный друг может помочь.

Безвозвратная потеря контроля плавучести может стать чрезвычайной ситуацией в зависимости от того, когда она произошла, будь то потеря плавучести (например, выход из строя плавучести, катастрофическое затопление сухого костюма) или избыток плавучести (потеря веса, недостаточная утяжеленность в конце декомпрессионного погружения). ), достаточно ли в резерве дыхательного газа и есть ли необходимость декомпрессии. В некоторых обстоятельствах наблюдательный друг может помочь. (типы и причины, варианты лечения) Недостаточное взвешивание в конце погружения, когда грузы не были потеряны, обычно является признаком недостаточной подготовки и неспособности дайвера взять на себя ответственность за собственную безопасность и обычно вызвано тем, что дайвер не адекватная проверка того, что они правильно взвешены для погружения, и это часто происходит отчасти из-за плохих советов от поставщиков арендованного оборудования.

Симптоматическое отсутствие или недостаточная декомпрессия . Неотложность зависит от симптомов и времени их возникновения (боль, неврологические нарушения, внутреннее ухо/головокружение и тошнота). В некоторых случаях наблюдательный и компетентный приятель может помочь. (реакция на различные симптомы)

Токсичность углекислого газа из-за прорыва скруббера ребризера .

Переполняющая работа дыхания может быть вызвана высокой плотностью газа, неисправностью регулятора, затоплением контура ребризера или чрезмерным напряжением с гиперкапнией. Напарник с более низкой работой дыхания может оказаться в состоянии выполнить спасательную операцию, в зависимости от причины высокого уровня WoB.

Затопление сухого костюма в холодной воде представляет собой совокупный риск потери плавучести и переохлаждения. Напарник ничем не может помочь при переохлаждении и мало что может сделать при потере плавучести. Это не так срочно, как чрезвычайные ситуации с дыханием, но может представлять определенный риск для жизни.

Потеря ориентира в пещере или затонувший корабль, когда выход находится вне поля зрения. Приятель может помочь в зависимости от обстоятельств.

Обучение и сертификация

[ редактировать ]

Обучение подводному плаванию обычно проводится квалифицированным инструктором, который является членом одного или нескольких агентств по сертификации дайверов или зарегистрирован в государственном органе. Базовая подготовка дайверов влечет за собой освоение навыков, необходимых для безопасного ведения деятельности в подводной среде, и включает процедуры и навыки использования водолазного снаряжения, техники безопасности, экстренной самопомощи и процедур спасения, планирования погружений и использования таблиц для погружений. или персональный дайв-компьютер . [ 6 ]

Навыки подводного плавания, которые обычно изучает дайвер начального уровня, включают: [ 6 ] [ 117 ]

- Подготовка и одевание гидрокостюма

- плавания перед погружением Сборка и проверка комплекта для подводного .

- Входы и выходы между водой и берегом или лодкой.

- Дыхание через регулируемый клапан

- Восстановление и очистка регулирующего клапана.

- Удаление воды из маски и замена смещенной маски.

- Контроль плавучести с помощью гирь и компенсатора плавучести .

- Техника плавников, подводная мобильность и маневрирование.

- Осуществление безопасных и контролируемых спусков и подъемов .

- Выравнивание ушей и других воздушных пространств.

- Помощь другому дайверу путем подачи воздуха из собственного запаса или получения воздуха, подаваемого другим дайвером.

- Как вернуться на поверхность без травм в случае прекращения подачи воздуха.

- Использование систем аварийного газоснабжения (профессиональные водолазы).

- Сигналы руками для ныряния, используемые для общения под водой . Профессиональные дайверы также научатся другим методам общения.

- Навыки управления погружениями, такие как контроль глубины и времени, а также подача дыхательного газа.

- Процедуры погружения с напарником , включая реакцию на разделение напарника под водой.

- Базовое планирование погружения, касающееся выбора точек входа и выхода, запланированной максимальной глубины и времени пребывания в бездекомпрессионных пределах.

- Может быть включено ограниченное признание опасностей, действий в чрезвычайных ситуациях и медицинской эвакуации.

- Как адаптироваться к сильному течению

- Возможность снимать и повторно прикреплять снаряжение под водой.

- Может достигать нейтральной плавучести