Локхид Мартин F-35 Лайтнинг II

| F-35 Лайтнинг II | |

|---|---|

| |

| F-35A Lightning II выполняет испытательный полет над Форт-Уэртом в октябре 2015 года. | |

| Роль | Многоцелевой истребитель |

| Национальное происхождение | Соединенные Штаты |

| Производитель | Локхид Мартин |

| Первый полет | 15 декабря 2006 г ( F-35A ) |

| Введение | |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | United States Air Force |

| Produced | 2006–present |

| Number built | 1,000+[4] |

| Developed from | Lockheed Martin X-35 |

Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II — американское семейство одноместных одномоторных невидимок многоцелевых боевых самолетов- , предназначенных для завоевания превосходства в воздухе и выполнения ударных задач; он также обладает радиоэлектронной борьбы и разведки, наблюдения и рекогносцировки возможностями . Lockheed Martin является основным подрядчиком по производству F-35 вместе с основными партнерами Northrop Grumman и BAE Systems . Самолет имеет три основных варианта: с обычным взлетом и посадкой (CTOL) F-35A, с коротким взлетом и вертикальной посадкой (STOVL) F-35B и палубный (CV/ CATOBAR ) F-35C.

The aircraft descends from the Lockheed Martin X-35, which in 2001 beat the Boeing X-32 to win the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program. Its development is principally funded by the United States, with additional funding from program partner countries from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and close U.S. allies, including the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, Italy, Norway, Denmark, the Netherlands, and formerly Turkey.[5][6][7] Several other countries have also ordered, or are considering ordering, the aircraft. The program has drawn criticism for its unprecedented size, complexity, ballooning costs, and delayed deliveries.[8][N 1] The acquisition strategy of concurrent production of the aircraft while it was still in development and testing led to expensive design changes and retrofits.[10][11]

The F-35 first flew in 2006 and entered service with the U.S. Marine Corps F-35B in July 2015, followed by the U.S. Air Force F-35A in August 2016 and the U.S. Navy F-35C in February 2019.[1][2][3] The aircraft was first used in combat in 2018 by the Israeli Air Force.[12] The U.S. plans to buy 2,456 F-35s through 2044, which will represent the bulk of the crewed tactical aviation of the U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps for several decades; the aircraft is planned to be a cornerstone of NATO and U.S.-allied air power and to operate until 2080.[13][14][15]

Development

[edit]Program origins

[edit]The F-35 was the product of the Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) program, which was the merger of various combat aircraft programs from the 1980s and 1990s. One progenitor program was the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) Advanced Short Take-Off/Vertical Landing (ASTOVL) which ran from 1983 to 1994; ASTOVL aimed to develop a Harrier jump jet replacement for the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) and the U.K. Royal Navy. Under one of ASTOVL's classified programs, the Supersonic STOVL Fighter (SSF), Lockheed Skunk Works conducted research for a stealthy supersonic STOVL fighter intended for both U.S. Air Force (USAF) and USMC; a key technology explored was the shaft-driven lift fan (SDLF) system. Lockheed's concept was a single-engine canard delta aircraft weighing about 24,000 lb (11,000 kg) empty. ASTOVL was rechristened as the Common Affordable Lightweight Fighter (CALF) in 1993 and involved Lockheed, McDonnell Douglas, and Boeing.[16][17]

The end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 caused considerable reductions in Department of Defense (DoD) spending and subsequent restructuring. In 1993, the Joint Advanced Strike Technology (JAST) program emerged following the cancellation of the USAF's Multi-Role Fighter (MRF) and U.S. Navy's (USN) Advanced Attack/Fighter (A/F-X) programs. MRF, a program for a relatively affordable F-16 replacement, was scaled back and delayed due to post–Cold War defense posture easing F-16 fleet usage and thus extending its service life as well as increasing budget pressure from the F-22 Advanced Tactical Fighter (ATF) program. The A/F-X, initially known as the Advanced-Attack (A-X), began in 1991 as the USN's follow-on to the Advanced Tactical Aircraft (ATA) program for an A-6 replacement; the ATA's resulting A-12 Avenger II had been canceled due to technical problems and cost overruns in 1991. In the same year, the termination of the Naval Advanced Tactical Fighter (NATF), a naval development of USAF's ATF program to replace the F-14, resulted in additional fighter capability being added to A-X, which was then renamed A/F-X. Amid increased budget pressure, the DoD's Bottom-Up Review (BUR) in September 1993 announced MRF's and A/F-X's cancellations, with applicable experience brought to the emerging JAST program.[17] JAST was not meant to develop a new aircraft, but rather to develop requirements, mature technologies, and demonstrate concepts for advanced strike warfare.[18]

As JAST progressed, the need for concept demonstrator aircraft by 1996 emerged, which would coincide with the full-scale flight demonstrator phase of ASTOVL/CALF. Because the ASTOVL/CALF concept appeared to align with the JAST charter, the two programs were eventually merged in 1994 under the JAST name, with the program now serving the USAF, USMC, and USN.[18] JAST was subsequently renamed to Joint Strike Fighter (JSF) in 1995, with STOVL submissions by McDonnell Douglas, Northrop Grumman, Lockheed Martin,[N 2] and Boeing. The JSF was expected to eventually replace large numbers of multi-role and strike fighters in the inventories of the US and its allies, including the Harrier, F-16, F/A-18, A-10, and F-117.[19]

International participation is a key aspect of the JSF program, starting with United Kingdom participation in the ASTOVL program. Many international partners requiring modernization of their air forces were interested in the JSF. The United Kingdom joined JAST/JSF as a founding member in 1995 and thus became the only Tier 1 partner of the JSF program;[20] Italy, the Netherlands, Denmark, Norway, Canada, Australia, and Turkey joined the program during the Concept Demonstration Phase (CDP), with Italy and the Netherlands being Tier 2 partners and the rest Tier 3. Consequently, the aircraft was developed in cooperation with international partners and available for export.[21]

JSF competition

[edit]Boeing and Lockheed Martin were selected in early 1997 for CDP, with their concept demonstrator aircraft designated X-32 and X-35 respectively; the McDonnell Douglas team was eliminated and Northrop Grumman and British Aerospace joined the Lockheed Martin team. Each firm would produce two prototype air vehicles to demonstrate conventional takeoff and landing (CTOL), carrier takeoff and landing (CV), and STOVL.[N 3] Lockheed Martin's design would make use of the work on the SDLF system conducted under the ASTOVL/CALF program. The key aspect of the X-35 that enabled STOVL operation, the SDLF system consists of the lift fan in the forward center fuselage that could be activated by engaging a clutch that connects the driveshaft to the turbines and thus augmenting the thrust from the engine's swivel nozzle. Research from prior aircraft incorporating similar systems, such as the Convair Model 200,[N 4] Rockwell XFV-12, and Yakovlev Yak-141, were also taken into consideration.[23][24][25] By contrast, Boeing's X-32 employed direct lift system that the augmented turbofan would be reconfigured to when engaging in STOVL operation.

Lockheed Martin's commonality strategy was to replace the STOVL variant's SDLF with a fuel tank and the aft swivel nozzle with a two-dimensional thrust vectoring nozzle for the CTOL variant.[N 5] STOVL operation is made possible through a patented shaft-driven LiftFan propulsion system.[26] This would enable identical aerodynamic configuration for the STOVL and CTOL variants, while the CV variant would have an enlarged wing to reduce landing speed for carrier recovery. Due to aerodynamic characteristics and carrier recovery requirements from the JAST merger, the design configuration settled on a conventional tail compared to the canard delta design from the ASTOVL/CALF; notably, the conventional tail configuration offers much lower risk for carrier recovery compared to the ASTOVL/CALF canard configuration, which was designed without carrier compatibility in mind. This enabled greater commonality between all three variants, as the commonality goal was important at this design stage.[27] Lockheed Martin's prototypes would consist of the X-35A for demonstrating CTOL before converting it to the X-35B for STOVL demonstration and the larger-winged X-35C for CV compatibility demonstration.[28]

The X-35A first flew on 24 October 2000 and conducted flight tests for subsonic and supersonic flying qualities, handling, range, and maneuver performance.[29] After 28 flights, the aircraft was then converted into the X-35B for STOVL testing, with key changes including the addition of the SDLF, the three-bearing swivel module (3BSM), and roll-control ducts. The X-35B would successfully demonstrate the SDLF system by performing stable hover, vertical landing, and short takeoff in less than 500 ft (150 m).[27][30] The X-35C first flew on 16 December 2000 and conducted field landing carrier practice tests.[29]

On 26 October 2001, Lockheed Martin was declared the winner and was awarded the System Development and Demonstration (SDD) contract; Pratt & Whitney was separately awarded a development contract for the F135 engine for the JSF.[31] The F-35 designation, which was out of sequence with standard DoD numbering, was allegedly determined on the spot by program manager Major General Mike Hough; this came as a surprise even to Lockheed Martin, which had expected the F-24 designation for the JSF.[32]

Design and production

[edit]

As the JSF program moved into the System Development and Demonstration phase, the X-35 demonstrator design was modified to create the F-35 combat aircraft. The forward fuselage was lengthened by 5 inches (13 cm) to make room for mission avionics, while the horizontal stabilizers were moved 2 inches (5.1 cm) aft to retain balance and control. The diverterless supersonic inlet changed from a four-sided to a three-sided cowl shape and was moved 30 inches (76 cm) aft. The fuselage section was fuller, the top surface raised by 1 inch (2.5 cm) along the centerline to accommodate weapons bays. Following the designation of the X-35 prototypes, the three variants were designated F-35A (CTOL), F-35B (STOVL), and F-35C (CV), all with a design service life of 8,000 hours. Prime contractor Lockheed Martin performs overall systems integration and final assembly and checkout (FACO) at Fort Worth, Texas,[N 6] while Northrop Grumman and BAE Systems supply components for mission systems and airframe.[33][34]

Adding the systems of a fighter aircraft added weight. The F-35B gained the most, largely due to a 2003 decision to enlarge the weapons bays for commonality between variants; the total weight growth was reportedly up to 2,200 pounds (1,000 kg), over 8%, causing all STOVL key performance parameter (KPP) thresholds to be missed.[35] In December 2003, the STOVL Weight Attack Team (SWAT) was formed to reduce the weight increase; changes included thinned airframe members, smaller weapons bays and vertical stabilizers, less thrust fed to the roll-post outlets, and redesigning the wing-mate joint, electrical elements, and the airframe immediately aft of the cockpit. The inlet was also revised to accommodate more powerful, greater mass flow engines.[36][37] Many changes from the SWAT effort were applied to all three variants for commonality. By September 2004, these efforts had reduced the F-35B's weight by over 3,000 pounds (1,400 kg), while the F-35A and F-35C were reduced in weight by 2,400 pounds (1,100 kg) and 1,900 pounds (860 kg) respectively.[27][38] The weight reduction work cost $6.2 billion and caused an 18-month delay.[39]

The first F-35A, designated AA-1, was rolled out at Fort Worth on 19 February 2006 and first flew on 15 December 2006.[N 7][40] In 2006, the F-35 was given the name "Lightning II" after the Lockheed P-38 Lightning of World War II.[41] Some USAF pilots have nicknamed the aircraft "Panther" instead.[42]

The aircraft's software was developed as six releases, or Blocks, for SDD. The first two Blocks, 1A and 1B, readied the F-35 for initial pilot training and multi-level security. Block 2A improved the training capabilities, while 2B was the first combat-ready release planned for the USMC's Initial Operating Capability (IOC). Block 3i retains the capabilities of 2B while having new Technology Refresh 2 (TR-2) hardware and was planned for the USAF's IOC. The final release for SDD, Block 3F, would have full flight envelope and all baseline combat capabilities. Alongside software releases, each block also incorporates avionics hardware updates and air vehicle improvements from flight and structural testing.[43] In what is known as "concurrency", some low rate initial production (LRIP) aircraft lots would be delivered in early Block configurations and eventually upgraded to Block 3F once development is complete.[44] After 17,000 flight test hours, the final flight for the SDD phase was completed in April 2018.[45] Like the F-22, the F-35 has been targeted by cyberattacks and technology theft efforts, as well as potential vulnerabilities in the integrity of the supply chain.[46][47][48]

Testing found several major problems: early F-35B airframes were vulnerable to premature cracking,[N 8] the F-35C arrestor hook design was unreliable, fuel tanks were too vulnerable to lightning strikes, the helmet display had problems, and more. Software was repeatedly delayed due to its unprecedented scope and complexity. In 2009, the DoD Joint Estimate Team (JET) estimated that the program was 30 months behind the public schedule.[49][50] In 2011, the program was "re-baselined"; that is, its cost and schedule goals were changed, pushing the IOC from the planned 2010 to July 2015.[51][52] The decision to simultaneously test, fix defects, and begin production was criticized as inefficient; in 2014, Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition Frank Kendall called it "acquisition malpractice".[53] The three variants shared just 25% of their parts, far below the anticipated commonality of 70%.[54] The program received considerable criticism for cost overruns and for the total projected lifetime cost, as well as quality management shortcomings by contractors.[55][56]

The JSF program was expected to cost about $200 billion for acquisition in base-year 2002 dollars when SDD was awarded in 2001.[57][58] As early as 2005, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) had identified major program risks in cost and schedule.[59] The costly delays strained the relationship between the Pentagon and contractors.[60] By 2017, delays and cost overruns had pushed the F-35 program's expected acquisition costs to $406.5 billion, with total lifetime cost (i.e., to 2070) to $1.5 trillion in then-year dollars which also includes operations and maintenance.[61][62][63] The F-35A's unit cost for LRIP Lot 13 was $79.2 million.[64] Delays in development and operational test and evaluation, including integration into the Joint Simulation Environment, pushed full-rate production decision from the end of 2019 to March 2024, although actual production rate had already approached the full rate by 2020; full rate at the Fort Worth plant is 156 aircraft annually.[65][66]

Upgrades and further development

[edit]

The F-35 is expected to be continually upgraded over its lifetime. The first combat-capable Block 2B configuration, which had basic air-to-air and strike capabilities, was declared ready by the USMC in July 2015.[1] The Block 3F configuration began operational test and evaluation (OT&E) in December 2018 and its completion in late 2023 concluded SDD in March 2024.[67] The F-35 program is also conducting sustainment and upgrade development, with early aircraft from LRIP lot 2 onwards gradually upgraded to the baseline Block 3F standard by 2021.[68][needs update]

With Block 3F as the final build for SDD, the first major upgrade program is Block 4 which began development in 2019 and was initially captured under the Continuous Capability Development and Delivery (C2D2) program. Block 4 is expected to enter service in incremental steps from the late 2020s to early 2030s and integrates additional weapons, including those unique to international customers, improved sensor capabilities including the new AN/APG-85 AESA radar and additional ESM bandwidth, and add Remotely Operated Video Enhanced Receiver (ROVER) support.[69][70] C2D2 also places greater emphasis on agile software development to enable quicker releases.[71]

Key enablers of Block 4 are Technology Refresh 3 (TR-3) avionics hardware, which consist of new display, core processor, and memory modules to support increased processing requirements, and an engine upgrade that increases the amount of cooling available to support the additional mission systems. The engine upgrade effort explored both improvements to the F135 as well as significantly more power and efficient adaptive cycle engines. In 2018, General Electric and Pratt & Whitney were awarded contracts to develop adaptive cycle engines for potential application in the F-35,[N 9] and in 2022, the F-35 Adaptive Engine Replacement program was launched to integrate them.[72][73] However, in 2023 the USAF chose an improved F135 under the Engine Core Upgrade (ECU) program over an adaptive cycle engine due to cost as well as concerns over risk of integrating the new engine, initially designed for the F-35A, on the B and C.[74] Difficulties with the new TR-3 hardware, including regression testing, have caused delays to Block 4 as well as a halt in aircraft deliveries from 2023 to 2024.[75][76]

Defense contractors have offered upgrades to the F-35 outside of official program contracts. In 2013, Northrop Grumman disclosed its development of a directional infrared countermeasures suite, named Threat Nullification Defensive Resource (ThNDR). The countermeasure system would share the same space as the Distributed Aperture System (DAS) sensors and acts as a laser missile jammer to protect against infrared-homing missiles.[77]

Israel operates a unique subvariant of the F-35A, designated the F-35I, that is designed to better interface with and incorporate Israeli equipment and weapons. The Israeli Air Force also has their own F-35I test aircraft that provides more access to the core avionics to include their own equipment.[78]

Procurement and international participation

[edit]The United States is the primary customer and financial backer, with planned procurement of 1,763 F-35As for the USAF, 353 F-35Bs and 67 F-35Cs for the USMC, and 273 F-35Cs for the USN.[13] Additionally, the United Kingdom, Italy, the Netherlands, Turkey, Australia, Norway, Denmark and Canada have agreed to contribute US$4.375 billion towards development costs, with the United Kingdom contributing about 10% of the planned development costs as the sole Tier 1 partner.[20] The initial plan was that the U.S. and eight major partner countries would acquire over 3,100 F-35s through 2035.[79] The three tiers of international participation generally reflect financial stake in the program, the amount of technology transfer and subcontracts open for bid by national companies, and the order in which countries can obtain production aircraft.[80] Alongside program partner countries, Israel and Singapore have joined as Security Cooperative Participants (SCP).[81][82][83] Sales to SCP and non-partner states, including Belgium, Japan, and South Korea, are made through the Pentagon's Foreign Military Sales program.[7][84] Turkey was removed from the F-35 program in July 2019 over security concerns following its purchase of a Russian S-400 surface-to-air missile system.[85][86][N 10]

Design

[edit]Overview

[edit]The F-35 is a family of single-engine, supersonic, stealth multirole fighters.[88] The second fifth-generation fighter to enter US service and the first operational supersonic STOVL stealth fighter, the F-35 emphasizes low observables, advanced avionics and sensor fusion that enable a high level of situational awareness and long range lethality;[89][90][91] the USAF considers the aircraft its primary strike fighter for conducting suppression of enemy air defense (SEAD) missions, owing to the advanced sensors and mission systems.[92]

The F-35 has a wing-tail configuration with two vertical stabilizers canted for stealth. Flight control surfaces include leading-edge flaps, flaperons,[N 11] rudders, and all-moving horizontal tails (stabilators); leading edge root extensions or chines[93] also run forwards to the inlets. The relatively short 35-foot wingspan of the F-35A and F-35B is set by the requirement to fit inside USN amphibious assault ship parking areas and elevators; the F-35C's larger wing is more fuel efficient.[94][95] The fixed diverterless supersonic inlets (DSI) use a bumped compression surface and forward-swept cowl to shed the boundary layer of the forebody away from the inlets, which form a Y-duct for the engine.[96] Structurally, the F-35 drew upon lessons from the F-22; composites comprise 35% of airframe weight, with the majority being bismaleimide and composite epoxy materials as well as some carbon nanotube-reinforced epoxy in later production lots.[97][98][99] The F-35 is considerably heavier than the lightweight fighters it replaces, with the lightest variant having an empty weight of 29,300 lb (13,300 kg); much of the weight can be attributed to the internal weapons bays and the extensive avionics carried.[100]

While lacking the kinematic performance of the larger twin-engine F-22, the F-35 is competitive with fourth-generation fighters such as the F-16 and F/A-18, especially when they carry weapons because the F-35's internal weapons bay eliminates drag from external stores.[101] All variants have a top speed of Mach 1.6, attainable with full internal payload. The Pratt & Whitney F135 engine gives good subsonic acceleration and energy, with supersonic dash in afterburner. The F-35, while not a "supercruising" aircraft, can fly at Mach 1.2 for a dash of 150 miles (240 km) with afterburners. This ability can be useful in battlefield situations.[102] The large stabilitors, leading edge extensions and flaps, and canted rudders provide excellent high alpha (angle-of-attack) characteristics, with a trimmed alpha of 50°. Relaxed stability and triplex-redundant fly-by-wire controls provide excellent handling qualities and departure resistance.[103][104] Having over double the F-16's internal fuel, the F-35 has a considerably greater combat radius, while stealth also enables a more efficient mission flight profile.[105]

Sensors and avionics

[edit]

The F-35's mission systems are among the most complex aspects of the aircraft. The avionics and sensor fusion are designed to improve the pilot's situational awareness and command-and-control capabilities and facilitate network-centric warfare.[88][106] Key sensors include the Northrop Grumman AN/APG-81 active electronically scanned array (AESA) radar, BAE Systems AN/ASQ-239 Barracuda electronic warfare system, Northrop Grumman/Raytheon AN/AAQ-37 Electro-optical Distributed Aperture System (DAS), Lockheed Martin AN/AAQ-40 Electro-Optical Targeting System (EOTS) and Northrop Grumman AN/ASQ-242 Communications, Navigation, and Identification (CNI) suite. The F-35 was designed for its sensors to work together to provide a cohesive image of the local battlespace; for example, the APG-81 radar also acts as a part of the electronic warfare system.[107]

Much of the F-35's software was developed in C and C++ programming languages, while Ada83 code from the F-22 was also used; the Block 3F software has 8.6 million lines of code.[108][109] The Green Hills Software Integrity DO-178B real-time operating system (RTOS) runs on integrated core processors (ICPs); data networking includes the IEEE 1394b and Fibre Channel buses.[110][111] The avionics use commercial off-the-shelf (COTS) components when practical to make upgrades cheaper and more flexible; for example, to enable fleet software upgrades for the software-defined radio (SDR) systems.[112][113][114] The mission systems software, particularly for sensor fusion, was one of the program's most difficult parts and responsible for substantial program delays.[N 12][116][117]

The APG-81 radar uses electronic scanning for rapid beam agility and incorporates passive and active air-to-air modes, strike modes, and synthetic aperture radar (SAR) capability, with multiple target track-while-scan at ranges in excess of 80 nmi (150 km). The antenna is tilted backwards for stealth.[118] Complementing the radar is the AAQ-37 DAS, which consists of six infrared sensors that provide all-aspect missile launch warning and target tracking; the DAS acts as a situational awareness infrared search-and-track (SAIRST) and gives the pilot spherical infrared and night-vision imagery on the helmet visor.[119] The ASQ-239 Barracuda electronic warfare system has ten radio frequency antennas embedded into the edges of the wing and tail for all-aspect radar warning receiver (RWR). It also provides sensor fusion of radio frequency and infrared tracking functions, geolocation threat targeting, and multispectral image countermeasures for self-defense against missiles. The electronic warfare system can detect and jam hostile radars.[120] The AAQ-40 EOTS is mounted behind a faceted low-observable window under the nose and performs laser targeting, forward-looking infrared (FLIR), and long range IRST functions.[121] The ASQ-242 CNI suite uses a half dozen physical links, including the directional Multifunction Advanced Data Link (MADL), for covert CNI functions.[122][123] Through sensor fusion, information from radio frequency receivers and infrared sensors are combined to form a single tactical picture for the pilot. The all-aspect target direction and identification can be shared via MADL to other platforms without compromising low observability, while Link 16 enables communication with older systems.[124]

The F-35 was designed to accept upgrades to its processors, sensors, and software over its lifespan. Technology Refresh 3, which includes a new core processor and a new cockpit display, is planned for Lot 15 aircraft.[125] Lockheed Martin has offered the Advanced EOTS for the Block 4 configuration; the improved sensor fits into the same area as the baseline EOTS with minimal changes.[126] In June 2018, Lockheed Martin picked Raytheon for improved DAS.[127] The USAF has studied the potential for the F-35 to orchestrate attacks by unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs) via its sensors and communications equipment.[128]

A new radar called the AN/APG-85 is planned for Block 4 F-35s.[129] According to the JPO, the new radar will be compatible with all three major F-35 variants. However, it is unclear if older aircraft will be retrofitted with the new radar.[129]

Stealth and signatures

[edit]

Stealth is a key aspect of the F-35's design, and radar cross-section (RCS) is minimized through careful shaping of the airframe and the use of radar-absorbent materials (RAM); visible measures to reduce RCS include alignment of edges and continuous curvature of surfaces, serration of skin panels, and the masking of the engine face and turbine. Additionally, the F-35's diverterless supersonic inlet (DSI) uses a compression bump and forward-swept cowl rather than a splitter gap or bleed system to divert the boundary layer away from the inlet duct, eliminating the diverter cavity and further reducing radar signature.[96][130] The RCS of the F-35 has been characterized as lower than a metal golf ball at certain frequencies and angles; in some conditions, the F-35 compares favorably to the F-22 in stealth.[131][132][133] For maintainability, the F-35's stealth design took lessons from earlier stealth aircraft such as the F-22; the F-35's radar-absorbent fibermat skin is more durable and requires less maintenance than older topcoats.[134] The aircraft also has reduced infrared and visual signatures as well as strict controls of radio frequency emitters to prevent their detection.[135][136][137] The F-35's stealth design is primarily focused on high-frequency X-band wavelengths;[138] low-frequency radars can spot stealthy aircraft due to Rayleigh scattering, but such radars are also conspicuous, susceptible to clutter, and lack precision.[139][140][141] To disguise its RCS, the aircraft can mount four Luneburg lens reflectors.[142]

Noise from the F-35 caused concerns in residential areas near potential bases for the aircraft, and residents near two such bases—Luke Air Force Base, Arizona, and Eglin Air Force Base (AFB), Florida—requested environmental impact studies in 2008 and 2009 respectively.[143] Although the noise levels, in decibels, were comparable to those of prior fighters such as the F-16, the F-35's sound power is stronger—particularly at lower frequencies.[144] Subsequent surveys and studies have indicated that the noise of the F-35 was not perceptibly different from the F-16 and F/A-18E/F, though the greater low-frequency noise was noticeable for some observers.[145][146][147]

Cockpit

[edit]

The glass cockpit was designed to give the pilot good situational awareness. The main display is a 20-by-8-inch (50 by 20 cm) panoramic touchscreen, which shows flight instruments, stores management, CNI information, and integrated caution and warnings; the pilot can customize the arrangement of the information. Below the main display is a smaller stand-by display.[148] The cockpit has a speech-recognition system developed by Adacel.[149] The F-35 does not have a head-up display; instead, flight and combat information is displayed on the visor of the pilot's helmet in a helmet-mounted display system (HMDS).[150] The one-piece tinted canopy is hinged at the front and has an internal frame for structural strength. The Martin-Baker US16E ejection seat is launched by a twin-catapult system housed on side rails.[151] There is a right-hand side stick and throttle hands-on throttle-and-stick system. For life support, an onboard oxygen-generation system (OBOGS) is fitted and powered by the Integrated Power Package (IPP), with an auxiliary oxygen bottle and backup oxygen system for emergencies.[152]

The Vision Systems International[N 13] helmet display is a key piece of the F-35's human-machine interface. Instead of the head-up display mounted atop the dashboard of earlier fighters, the HMDS puts flight and combat information on the helmet visor, allowing the pilot to see it no matter which way they are facing.[153] Infrared and night vision imagery from the Distributed Aperture System can be displayed directly on the HMDS and enables the pilot to "see through" the aircraft. The HMDS allows an F-35 pilot to fire missiles at targets even when the nose of the aircraft is pointing elsewhere by cuing missile seekers at high angles off-boresight.[154][155] Each helmet costs $400,000.[156] The HMDS weighs more than traditional helmets, and there is concern that it can endanger lightweight pilots during ejection.[157]

Due to the HMDS's vibration, jitter, night-vision and sensor display problems during development, Lockheed Martin and Elbit issued a draft specification in 2011 for an alternative HMDS based on the AN/AVS-9 night vision goggles as backup, with BAE Systems chosen later that year.[158][159] A cockpit redesign would be needed to adopt an alternative HMDS.[160][161] Following progress on the baseline helmet, development on the alternative HMDS was halted in October 2013.[162][163] In 2016, the Gen 3 helmet with improved night vision camera, new liquid crystal displays, automated alignment and software enhancements was introduced with LRIP lot 7.[162]

Armament

[edit]

To preserve its stealth shaping, the F-35 has two internal weapons bays each with two weapons stations. The two outboard weapon stations each can carry ordnance up to 2,500 lb (1,100 kg), or 1,500 lb (680 kg) for the F-35B, while the two inboard stations carry air-to-air missiles. Air-to-surface weapons for the outboard station include the Joint Direct Attack Munition (JDAM), Paveway series of bombs, Joint Standoff Weapon (JSOW), and cluster munitions (Wind Corrected Munitions Dispenser). The station can also carry multiple smaller munitions such as the GBU-39 Small Diameter Bombs (SDB), GBU-53/B SDB II, and SPEAR 3; up to four SDBs can be carried per station for the F-35A and F-35C, and three for the F-35B.[164][165][166] The F-35A achieved certification to carry the B61 Mod 12 nuclear bomb in October 2023.[167] The inboard station can carry the AIM-120 AMRAAM and eventually the AIM-260 JATM. Two compartments behind the weapons bays contain flares, chaff, and towed decoys.[168]

The aircraft can use six external weapons stations for missions that do not require stealth.[169] The wingtip pylons each can carry an AIM-9X or AIM-132 ASRAAM and are canted outwards to reduce their radar cross-section.[170][171] Additionally, each wing has a 5,000 lb (2,300 kg) inboard station and a 2,500 lb (1,100 kg) middle station, or 1,500 lb (680 kg) for F-35B. The external wing stations can carry large air-to-surface weapons that would not fit inside the weapons bays such as the AGM-158 Joint Air to Surface Standoff Missile (JASSM) cruise missile. An air-to-air missile load of eight AIM-120s and two AIM-9s is possible using internal and external weapons stations; a configuration of six 2,000 lb (910 kg) bombs, two AIM-120s and two AIM-9s can also be arranged.[154][172][173] The F-35 is armed with a 25 mm GAU-22/A rotary cannon, a lighter four-barrel variant of the GAU-12/U Equalizer.[174] On the F-35A this is mounted internally near the left wing root with 182 rounds carried;[citation needed] the gun is more effective against ground targets than the 20 mm gun carried by other USAF fighters.[dubious – discuss][citation needed] In 2020, a USAF report noted "unacceptable" accuracy problems with the GAU-22/A on the F-35A. These were due to "misalignments" in the gun's mount, which was also susceptible to cracking.[175] These problems were resolved by 2024.[176] The F-35B and F-35C have no internal gun and instead can use a Terma A/S multi-mission pod (MMP) carrying the GAU-22/A and 220 rounds; the pod is mounted on the centerline of the aircraft and shaped to reduce its radar cross-section.[174][177][verification needed] In lieu of the gun, the pod can also be used for different equipment and purposes, such as electronic warfare, aerial reconnaissance, or rear-facing tactical radar.[178][179] The pod was not susceptible to the accuracy issues that once plagued the gun on the F-35A variant,[175] though was apparently not problem-free.[176]

Lockheed Martin is developing a weapon rack called Sidekick that would enable the internal outboard station to carry two AIM-120s, thus increasing the internal air-to-air payload to six missiles, currently offered for Block 4.[180][181] Block 4 will also have a rearranged hydraulic line and bracket to allow the F-35B to carry four SDBs per internal outboard station; integration of the MBDA Meteor is also planned.[182][183] The USAF and USN are planning to integrate the AGM-88G AARGM-ER internally in the F-35A and F-35C.[184] Norway and Australia are funding an adaptation of the Naval Strike Missile (NSM) for the F-35; designated Joint Strike Missile (JSM), two missiles can be carried internally with an additional four externally.[185] Both hypersonic missiles and direct energy weapons such as solid-state laser are currently being considered as future upgrades.[N 14][189] Lockheed Martin is studying integrating a fiber laser that uses spectral beam combining multiple individual laser modules into a single high-power beam, which can be scaled to various levels.[190]

The USAF plans for the F-35A to take up the close air support (CAS) mission in contested environments; amid criticism that it is not as well suited as a dedicated attack platform, USAF chief of staff Mark Welsh placed a focus on weapons for CAS sorties, including guided rockets, fragmentation rockets that shatter into individual projectiles before impact, and more compact ammunition for higher capacity gun pods.[191] Fragmentary rocket warheads create greater effects than cannon shells as each rocket creates a "thousand-round burst", delivering more projectiles than a strafing run.[192]

Engine

[edit]The aircraft is powered by a single Pratt & Whitney F135 low-bypass augmented turbofan with rated thrust of 28,000 lbf (125 kN) at military power and 43,000 lbf (191 kN) with afterburner. Derived from the Pratt & Whitney F119 used by the F-22, the F135 has a larger fan and higher bypass ratio to increase subsonic thrust and fuel efficiency, and unlike the F119, is not optimized for supercruise.[193] The engine contributes to the F-35's stealth by having a low-observable augmenter, or afterburner, that incorporates fuel injectors into thick curved vanes; these vanes are covered by ceramic radar-absorbent materials and mask the turbine. The stealthy augmenter had problems with pressure pulsations, or "screech", at low altitude and high speed early in its development.[194] The low-observable axisymmetric nozzle consists of 15 partially overlapping flaps that create a sawtooth pattern at the trailing edge, which reduces radar signature and creates shed vortices that reduce the infrared signature of the exhaust plume.[195] Due to the engine's large dimensions, the U.S. Navy had to modify its underway replenishment system to facilitate at-sea logistics support.[196] The F-35's Integrated Power Package (IPP) performs power and thermal management and integrates environment control, auxiliary power unit, engine starting, and other functions into a single system.[197]

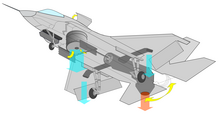

The F135-PW-600 variant for the F-35B incorporates the Shaft-Driven Lift Fan (SDLF) to allow STOVL operations. Designed by Lockheed Martin and developed by Rolls-Royce, the SDLF, also known as the Rolls-Royce LiftSystem, consists of the lift fan, drive shaft, two roll posts, and a "three-bearing swivel module" (3BSM). The nozzle features three bearings resembling a short cylinder with nonparallel bases. As the toothed edges are rotated by motors, the nozzle swivels from being linear with the engine to being perpendicular. The thrust vectoring 3BSM nozzle allows the main engine exhaust to be deflected downward at the tail of the aircraft and is moved by a "fueldraulic" actuator that uses pressurized fuel as the working fluid.[198][199][200] Unlike the Harrier's Pegasus engine that entirely uses direct engine thrust for lift, the F-35B's system augments the swivel nozzle's thrust with the lift fan; the fan is powered by the low-pressure turbine through a drive shaft when engaged with a clutch and placed near the front of the aircraft to provide a torque countering that of the 3BSM nozzle.[201][202][203] Roll control during slow flight is achieved by diverting unheated engine bypass air through wing-mounted thrust nozzles called roll posts.[204][205]

An alternative engine, the General Electric/Rolls-Royce F136, was being developed in the 2000s; originally, F-35 engines from Lot 6 onward were competitively tendered. Using technology from the General Electric YF120, the F136 was claimed to have a greater temperature margin than the F135 due to the higher mass flow design making full use of the inlet.[36][206] The F136 was canceled in December 2011 due to lack of funding.[207][208]

The F-35 is expected to receive propulsion upgrades over its lifecycle to adapt to emerging threats and enable additional capabilities. In 2016, the Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP) was launched to develop and test adaptive cycle engines, with one major potential application being the re-engining of the F-35; in 2018, both GE and P&W were awarded contracts to develop 45,000 lbf (200 kN) thrust class demonstrators, with the designations XA100 and XA101 respectively.[72] In addition to potential re-engining, P&W is also developing improvements to the baseline F135; the Engine Core Upgrade (ECU) is an update to the power module, originally called Growth Option 1.0 and then Engine Enhancement Package, that improves engine thrust and fuel burn by 5% and bleed air cooling capacity by 50% to support Block 4.[209][210][211] The F135 ECU was selected over AETP engines in 2023 to provide additional power and cooling for the F-35. Although GE had expected that the more revolutionary XA100 could enter service with the F-35A and C by 2027 and could be adapted for the F-35B, the increased cost and risk caused the USAF to choose the F135 ECU instead.[212][74]

Maintenance and logistics

[edit]The F-35 is designed to require less maintenance than prior stealth aircraft. Some 95% of all field-replaceable parts are "one deep"—that is, nothing else needs to be removed to reach the desired part; for instance, the ejection seat can be replaced without removing the canopy. The F-35 has a fibermat radar-absorbent material (RAM) baked into the skin, which is more durable, easier to work with, and faster to cure than older RAM coatings; similar coatings are being considered for application on older stealth aircraft such as the F-22.[134][213][214] Skin corrosion on the F-22 led to the F-35 using a less galvanic corrosion-inducing skin gap filler, fewer gaps in the airframe skin needing filler, and better drainage.[215] The flight control system uses electro-hydrostatic actuators rather than traditional hydraulic systems; these controls can be powered by lithium-ion batteries in case of emergency.[216][217] Commonality between variants led to the USMC's first aircraft maintenance Field Training Detachment, which applied USAF lessons to their F-35 operations.[218]

The F-35 was initially supported by a computerized maintenance management system named Autonomic Logistics Information System (ALIS). In concept, any F-35 can be serviced at any maintenance facility and all parts can be globally tracked and shared as needed.[219] Due to numerous problems,[220] such as unreliable diagnoses, excessive connectivity requirements, and security vulnerabilities, ALIS is being replaced by the cloud-based Operational Data Integrated Network (ODIN).[221][222][223] From September 2020, ODIN base kits (OBKs)[224] were running ALIS software, as well as ODIN software, first at Marine Corps Air Station (MCAS) Yuma, Arizona, then at Naval Air Station Lemoore, California, in support of Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 125 on 16 July 2021, and then Nellis Air Force Base, Nevada, in support of the 422nd Test and Evaluation Squadron (TES) on 6 August 2021. In 2022, over a dozen more OBK sites will replace the ALIS's Standard Operating Unit unclassified (SOU-U) servers.[225] OBK performance is double that of ALIS.[226][225][224]

Operational history

[edit]Testing

[edit]The first F-35A, AA-1, conducted its engine run in September 2006 and first flew on 15 December 2006.[227] Unlike all subsequent aircraft, AA-1 did not have the weight optimization from SWAT; consequently, it mainly tested subsystems common to subsequent aircraft, such as the propulsion, electrical system, and cockpit displays. This aircraft was retired from flight testing in December 2009 and was used for live-fire testing at NAS China Lake.[228]

The first F-35B, BF-1, flew on 11 June 2008, while the first weight-optimized F-35A and F-35C, AF-1 and CF-1, flew on 14 November 2009 and 6 June 2010 respectively. The F-35B's first hover was on 17 March 2010, followed by its first vertical landing the next day.[229] The F-35 Integrated Test Force (ITF) consisted of 18 aircraft at Edwards Air Force Base and Naval Air Station Patuxent River. Nine aircraft at Edwards, five F-35As, three F-35Bs, and one F-35C, performed flight sciences testing such as F-35A envelope expansion, flight loads, stores separation, as well as mission systems testing. The other nine aircraft at Patuxent River, five F-35Bs and four F-35Cs, were responsible for F-35B and C envelope expansion and STOVL and CV suitability testing. Additional carrier suitability testing was conducted at Naval Air Warfare Center Aircraft Division at Lakehurst, New Jersey. Two non-flying aircraft of each variant were used to test static loads and fatigue.[230] For testing avionics and mission systems, a modified Boeing 737-300 with a duplication of the cockpit, the Lockheed Martin CATBird has been used.[181] Field testing of the F-35's sensors were conducted during Exercise Northern Edge 2009 and 2011, serving as significant risk-reduction steps.[231][232]

Flight tests revealed several serious deficiencies that required costly redesigns, caused delays, and resulted in several fleet-wide groundings. In 2011, the F-35C failed to catch the arresting wire in all eight landing tests; a redesigned tail hook was delivered two years later.[233][234] By June 2009, many of the initial flight test targets had been accomplished but the program was behind schedule.[235] Software and mission systems were among the biggest sources of delays for the program, with sensor fusion proving especially challenging.[117] In fatigue testing, the F-35B suffered several premature cracks, requiring a redesign of the structure.[236] A third non-flying F-35B is currently planned to test the redesigned structure. The F-35B and C also had problems with the horizontal tails suffering heat damage from prolonged afterburner use.[N 15][239][240] Early flight control laws had problems with "wing drop"[N 16] and also made the airplane sluggish, with high angles-of-attack tests in 2015 against an F-16 showing a lack of energy.[241][242]

At-sea testing of the F-35B was first conducted aboard USS Wasp. In October 2011, two F-35Bs conducted three weeks of initial sea trials, called Development Test I.[243] The second F-35B sea trials, Development Test II, began in August 2013, with tests including nighttime operations; two aircraft completed 19 nighttime vertical landings using DAS imagery.[244][245] The first operational testing involving six F-35Bs was done on the Wasp in May 2015. The final Development Test III on USS America involving operations in high sea states was completed in late 2016.[246] A Royal Navy F-35 conducted the first "rolling" landing on board HMS Queen Elizabeth in October 2018.[247]

After the redesigned tail hook arrived, the F-35C's carrier-based Development Test I began in November 2014 aboard USS Nimitz and focused on basic day carrier operations and establishing launch and recovery handling procedures.[248] Development Test II, which focused on night operations, weapons loading, and full power launches, took place in October 2015. The final Development Test III was completed in August 2016, and included tests of asymmetric loads and certifying systems for landing qualifications and interoperability.[249] Operational test of the F-35C was conducted in 2018 and the first operational squadron achieved safe-for-flight milestone that December, paving the way for its introduction in 2019.[3][250]

The F-35's reliability and availability have fallen short of requirements, especially in the early years of testing. The ALIS maintenance and logistics system was plagued by excessive connectivity requirements and faulty diagnoses. In late 2017, the GAO reported the time needed to repair an F-35 part averaged 172 days, which was "twice the program's objective," and that shortage of spare parts was degrading readiness.[251] In 2019, while individual F-35 units have achieved mission-capable rates of over the target of 80% for short periods during deployed operations, fleet-wide rates remained below target. The fleet availability goal of 65% was also not met, although the trend shows improvement. Internal gun accuracy of the F-35A was unacceptable until misalignment issues were addressed by 2024.[239][252] As of 2020, the number of the program's most serious issues have been decreased by half.[253][176]

Operational test and evaluation (OT&E) with Block 3F, the final configuration for SDD, began in December 2018, but its completion was delayed particularly by technical problems in integration with the DOD's Joint Simulation Environment (JSE);[254] the F-35 finally completed all JSE trials in September 2023.[66]

United States

[edit]Training

[edit]

The F-35A and F-35B were cleared for basic flight training in early 2012, although there were concerns over safety and performance due to lack of system maturity at the time.[255][256][257] During the Low Rate Initial Production (LRIP) phase, the three U.S. military services jointly developed tactics and procedures using flight simulators, testing effectiveness, discovering problems and refining design. On 10 September 2012, the USAF began an operational utility evaluation (OUE) of the F-35A, including logistical support, maintenance, personnel training, and pilot execution.[258][259]

The USMC F-35B Fleet Replacement Squadron (FRS) was initially based at Eglin AFB in 2012 alongside USAF F-35A training units, before moving to MCAS Beaufort in 2014 while another FRS was stood up at MCAS Miramar in 2020.[260][261] The USAF F-35A basic course is held at Eglin AFB and Luke AFB; in January 2013, training began at Eglin with capacity for 100 pilots and 2,100 maintainers at once.[262] Additionally, the 6th Weapons Squadron of the USAF Weapons School was activated at Nellis AFB in June 2017 for F-35A weapons instructor curriculum while the 65th Aggressor Squadron was reactivated with the F-35A in June 2022 to expand training against adversary stealth aircraft tactics.[263] The USN stood up its F-35C FRS in 2012 with VFA-101 at Eglin AFB, but operations would later be transferred and consolidated under VFA-125 at NAS Lemoore in 2019.[264] The F-35C was introduced to the Strike Fighter Tactics Instructor course, or TOPGUN, in 2020 and the additional capabilities of the aircraft greatly revamped the course syllabus.[265]

U.S. Marine Corps

[edit]On 16 November 2012, the USMC received the first F-35B of VMFA-121 at MCAS Yuma.[266] The USMC declared Initial Operational Capability (IOC) for the F-35B in the Block 2B configuration on 31 July 2015 after operational trials, with some limitations in night operations, mission systems, and weapons carriage.[1][267] USMC F-35Bs participated in their first Red Flag exercise in July 2016 with 67 sorties conducted.[268] The first F-35B deployment occurred in 2017 at MCAS Iwakuni, Japan; combat employment began in July 2018 from the amphibious assault ship USS Essex, with the first combat strike on 27 September 2018 against a Taliban target in Afghanistan.[269]

In addition to deploying F-35Bs on amphibious assault ships, the USMC plans to disperse the aircraft among austere forward-deployed bases with shelter and concealment to enhance survivability while remaining close to a battlespace. Known as distributed STOVL operations (DSO), F-35Bs would operate from temporary bases in allied territory within hostile missile engagement zones and displace inside the enemy's 24- to 48-hour targeting cycle; this strategy allows F-35Bs to rapidly respond to operational needs, with mobile forward arming and refueling points (M-FARPs) accommodating KC-130 and MV-22 Osprey aircraft to rearm and refuel the jets, as well as littoral areas for sea links of mobile distribution sites. For higher echelons of maintenance, F-35Bs would return from M-FARPs to rear-area friendly bases or ships. Helicopter-portable metal planking is needed to protect unprepared roads from the F-35B's exhaust; the USMC are studying lighter heat-resistant options.[270] These operations have become part of the larger USMC Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) concept.[271]

The first USMC F-35C squadron, VMFA-314, achieved Full Operational Capability in July 2021 and was first deployed on board the USS Abraham Lincoln as a part of Carrier Air Wing 9 in January 2022.[272]

U.S. Air Force

[edit]USAF F-35A in the Block 3i configuration achieved IOC with the USAF's 34th Fighter Squadron at Hill Air Force Base, Utah on 2 August 2016.[2] F-35As conducted their first Red Flag exercise in 2017; system maturity had improved and the aircraft scored a kill ratio of 15:1 against an F-16 aggressor squadron in a high-threat environment.[273] The first USAF F-35A deployment occurred on 15 April 2019 to Al Dhafra Air Base, UAE.[274] On 27 April 2019, USAF F-35As were first used in combat in an airstrike on an Islamic State tunnel network in northern Iraq.[275]

For European basing, RAF Lakenheath in the UK was chosen as the first installation to station two F-35A squadrons, with 48 aircraft adding to the 48th Fighter Wing's existing F-15C and F-15E squadrons. The first aircraft of the 495th Fighter Squadron arrived in 15 December 2021.[276][277]

The F-35's operating cost is higher than some older USAF tactical aircraft. In fiscal year 2018, the F-35A's cost per flight hour (CPFH) was $44,000, a number that was reduced to $35,000 in 2019.[278] For comparison, in 2015 the CPFH of the A-10 was $17,716; the F-15C, $41,921; and the F-16C, $22,514.[279] Lockheed Martin hopes to reduce it to $25,000 by 2025 through performance-based logistics and other measures.[280]

U.S. Navy

[edit]The USN achieved operational status with the F-35C in Block 3F on 28 February 2019.[3] On 2 August 2021, the F-35C of VFA-147, as well as the CMV-22 Osprey, embarked on their maiden deployments as part of Carrier Air Wing 2 on board the USS Carl Vinson.[281]

United Kingdom

[edit]

The United Kingdom's Royal Air Force and Royal Navy operate the F-35B. Called Lightning in British service,[282] it has replaced the Harrier GR9, retired in 2010, and Tornado GR4, retired in 2019. The F-35 is to be Britain's primary strike aircraft for the next three decades. One of the Royal Navy's requirements was a Shipborne Rolling and Vertical Landing (SRVL) mode to increase maximum landing weight by using wing lift during landing.[283][284] Like the Italian Navy, British F-35Bs use ski-jumps to fly from their aircraft carriers, HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales. British F-35Bs are not intended to use the Brimstone 2 missile.[285] In July 2013, Chief of the Air Staff Air Chief Marshal Sir Stephen Dalton announced that No. 617 (The Dambusters) Squadron would be the RAF's first operational F-35 squadron.[286][287]

The first British F-35 squadron was No. 17 (Reserve) Test and Evaluation Squadron (TES), which stood up on 12 April 2013 as the plane's Operational Evaluation Unit.[288] By June 2013, the RAF had received three F-35s of the 48 on order, initially based at Eglin Air Force Base.[289] In June 2015, the F-35B undertook its first launch from a ski-jump at NAS Patuxent River.[290] On 5 July 2017, it was announced the second UK-based RAF squadron would be No. 207 Squadron,[291] which reformed on 1 August 2019 as the Lightning Operational Conversion Unit.[292] No. 617 Squadron reformed on 18 April 2018 during a ceremony in Washington, D.C., becoming the first RAF front-line squadron to operate the type;[293] receiving its first four F-35Bs on 6 June, flying from MCAS Beaufort to RAF Marham.[294] On 10 January 2019, No. 617 Squadron and its F-35s were declared combat-ready.[295]

April 2019 saw the first overseas deployment of a UK F-35 squadron when No. 617 Squadron went to RAF Akrotiri, Cyprus.[296] This reportedly led on 25 June 2019 to the first combat use of an RAF F-35B: an armed reconnaissance flight searching for Islamic State targets in Iraq and Syria.[297] In October 2019, the Dambusters and No. 17 TES F-35s were embarked on HMS Queen Elizabeth for the first time.[298] No. 617 Squadron departed RAF Marham on 22 January 2020 for their first Exercise Red Flag with the Lightning.[299] As of November 2022, 26 F-35Bs were based in the United Kingdom (with 617 and 207 Squadrons) and a further three were permanently based in the United States (with 17 Squadron) for testing and evaluation purposes.[300]

The UK's second operational squadron is the Fleet Air Arm's 809 Naval Air Squadron, which stood up in December 2023.[301][302][303]

Australia

[edit]

Australia's first F-35, designated A35-001, was manufactured in 2014, with flight training provided through international Pilot Training Centre (PTC) at Luke Air Force Base in Arizona.[304] The first two F-35s were unveiled to the Australian public on 3 March 2017 at the Avalon Airshow.[305] By 2021, the Royal Australian Air Force had accepted 26 F-35As, with nine in the US and 17 operating at No 3 Squadron and No 2 Operational Conversion Unit at RAAF Base Williamtown.[304] With 41 trained RAAF pilots and 225 trained technicians for maintenance, the fleet was declared ready to deploy on operations.[306] It was originally expected that Australia would receive all 72 F-35s by 2023,[305] but as of February 2024 Australia has received 63 aircraft. Its final nine aircraft are expected in 2024, and are expected to be the TR-3 version.[307]

Israel

[edit]The Israeli Air Force (IAF) declared the F-35 operationally capable on 6 December 2017.[308] According to Kuwaiti newspaper Al Jarida, in July 2018, a test mission of at least three IAF F-35s flew to Iran's capital Tehran and back to Tel Aviv. While publicly unconfirmed, regional leaders acted on the report; Iran's supreme leader Ali Khamenei reportedly fired the air force chief and commander of Iran's Revolutionary Guard Corps over the mission.[309][310]

On 22 May 2018, IAF chief Amikam Norkin said that the service had employed their F-35Is in two attacks on two battle fronts, marking the first combat operation of an F-35 by any country.[12][311] Norkin said it had been flown "all over the Middle East", and showed photos of an F-35I flying over Beirut in daylight.[312] In July 2019, Israel expanded its strikes against Iranian missile shipments; IAF F-35Is allegedly struck Iranian targets in Iraq twice.[313]

In November 2020, the IAF announced the delivery of a unique F-35I testbed aircraft among a delivery of four aircraft received in August, to be used to test and integrate Israeli-produced weapons and electronic systems on F-35s received later. This is the only example of a testbed F-35 delivered to a non-US air force.[314][315]

On 11 May 2021, eight IAF F-35Is took part in an attack on 150 targets in Hamas' rocket array, including 50–70 launch pits in the northern Gaza Strip, as part of Operation Guardian of the Walls.[316]

On 6 March 2022, the IDF stated that on 15 March 2021, F-35Is shot down two Iranian drones carrying weapons to the Gaza Strip.[317] This was the first operational shoot down and interception carried out by the F-35. They were also used in the Israel–Hamas war.[318][319][320]

On 2 November 2023, the IDF posted on social media that they used an F-35I to shoot down a Houthi cruise missile over the Red Sea that was fired from Yemen during the Israel-Hamas War.[321]

Italy

[edit]Italy's F-35As were declared to have reached initial operational capability (IOC) on 30 November 2018. At the time Italy had taken delivery of 10 F-35As and one F-35B, with 2 F-35As and the one F-35B being stationed in the U.S. for training, the remaining 8 F-35As were stationed in Amendola.[322]

Japan

[edit]Japan's F-35As were declared to have reached initial operational capability (IOC) on 29 March 2019. At the time Japan had taken delivery of 10 F-35As stationed in Misawa Air Base. Japan plans to eventually acquire a total of 147 F-35s, which will include 42 F-35Bs. It plans to use the latter variant to equip Japan's Izumo-class multi-purpose destroyers.[323][324]

Norway

[edit]

On 6 November 2019 Norway declared initial operational capability (IOC) for its fleet of 15 F-35As out of a planned 52 F-35As.[325] On 6 January 2022 Norway's F-35As replaced its F-16s for the NATO quick reaction alert mission in the high north.[326]

On 22 September 2023, two F-35As from the Royal Norwegian Air Force landed on a motorway near Tervo, Finland, showing, for the first time, that F-35As can operate from paved roads. Unlike the F-35B they cannot land vertically. The fighters were also refueled with their engines running. Commander of the Royal Norwegian Air Force, Major General Rolf Folland, said: "Fighter jets are vulnerable on the ground, so by being able to use small airfields – and now motorways – (this) increases our survivability in war,"[327]

Netherlands

[edit]On 27 December 2021 the Netherlands declared initial operational capability (IOC) for its fleet of 24 F-35As that it has received to date from its order for 46 F-35As.[328] In 2022, the Netherlands announced they will order an additional six F-35s, totaling 52 aircraft ordered.[329]

Variants

[edit]The F-35 was designed with three initial variants – the F-35A, a CTOL land-based version; the F-35B, a STOVL version capable of use either on land or on aircraft carriers; and the F-35C, a CATOBAR carrier-based version. Since then, there has been work on the design of nationally specific versions for Israel and Canada.

F-35A

[edit]The F-35A is the conventional take-off and landing (CTOL) variant intended for the USAF and other air forces. It is the smallest, lightest version and capable of 9 g, the highest of all variants.

Although the F-35A currently conducts aerial refueling via boom and receptacle method, the aircraft can be modified for probe-and-drogue refueling if needed by the customer.[330][331] A drag chute pod can be installed on the F-35A, with the Royal Norwegian Air Force being the first operator to adopt it.[332]

F-35B

[edit]

The F-35B is the short take-off and vertical landing (STOVL) variant of the aircraft. Similar in size to the A variant, the B sacrifices about a third of the A variant's fuel volume to accommodate the shaft-driven lift fan (SDLF).[333][334] This variant is limited to 7 g. Unlike other variants, the F-35B has no landing hook. The "STOVL/HOOK" control instead engages conversion between normal and vertical flight.[335][336] The F-35B is capable of Mach 1.6 (1,976 km/h) and can perform vertical and/or short take-off and landing (V/STOL).[204]

F-35C

[edit]The F-35C is a carrier-based variant designed for catapult-assisted take-off, barrier arrested recovery operations from aircraft carriers. Compared to the F-35A, the F-35C features larger wings with foldable wingtip sections, larger control surfaces for improved low-speed control, stronger landing gear for the stresses of carrier arrested landings, a twin-wheel nose gear, and a stronger tailhook for use with carrier arrestor cables.[234] The larger wing area allows for decreased landing speed while increasing both range and payload. The F-35C is limited to 7.5 g.[337]

F-35I "Adir"

[edit]The F-35I Adir (Hebrew: אדיר, meaning "Awesome",[338] or "Mighty One"[339]) is an F-35A with unique Israeli modifications. The US initially refused to allow such changes before permitting Israel to integrate its own electronic warfare systems, including sensors and countermeasures. The main computer has a plug-and-play function for add-on systems; proposals include an external jamming pod, and new Israeli air-to-air missiles and guided bombs in the internal weapon bays.[340][341] A senior IAF official said that the F-35's stealth may be partly overcome within 10 years despite a 30 to 40-year service life, thus Israel's insistence on using their own electronic warfare systems.[342] Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) has considered a two-seat F-35 concept; an IAI executive noted: "There is a known demand for two seats not only from Israel but from other air forces".[343] IAI plans to produce conformal fuel tanks.[344]

Israel has ordered a total of 75 F-35Is, with 36 already delivered as of November 2022.[345][346]

Proposed variants

[edit]CF-35

[edit]The Canadian CF-35 was a proposed variant that would differ from the F-35A through the addition of a drogue parachute and the potential inclusion of an F-35B/C-style refueling probe.[332][347] In 2012, it was revealed that the CF-35 would employ the same boom refueling system as the F-35A.[348] One alternative proposal would have been the adoption of the F-35C for its probe refueling and lower landing speed; however, the Parliamentary Budget Officer's report cited the F-35C's limited performance and payload as being too high a price to pay.[349] Following the 2015 Federal Election the Liberal Party, whose campaign had included a pledge to cancel the F-35 procurement,[350] formed a new government and commenced an open competition to replace the existing CF-18 Hornet.[351] The CF-35 variant was deemed too expensive to develop, and was never considered. The Canadian government decided to not pursue any other modifications in the Future Fighter Capability Project, and instead focused on the potential procurement of the existing F-35A variant.[352]

On 28 March 2022, the Canadian Government began negotiations with Lockheed Martin for 88 F-35As[353] to replace the aging fleet of CF-18 fighters starting in 2025.[354] The aircraft are reported to cost up to CA$19bn total with a life-cycle cost estimated at CA$77bn over the course of the F-35 program.[355][356] On 9 January 2023, Canada formally confirmed the purchase of 88 aircraft. The initial delivery to the Royal Canadian Air Force in 2026 will be 4 aircraft, followed by 6 aircraft each in 2027-2028, and the rest to be delivered by 2032.[357][358] The additional characteristics confirmed for the CF-35 included the drag chute pod for landings at short/icy arctic runways, as well as the 'sidekick' system, which allows the CF-35 to carry up to 6 x AIM-120D missiles internally (instead of the typical internal capacity of 4 x AIM-120 missiles on other variants).[359]

New export variant

[edit]In December 2021, it was reported that Lockheed Martin was developing a new variant for an unspecified foreign customer. The Department of Defense released US$49 million in funding for this work.[360]

Operators

[edit]

Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II Australian procurement

- Royal Australian Air Force – 63 F-35A delivered as of October 2023[update], of 72 ordered.[361]

- Belgian Air Component – 1 officially delivered[362] (but none has left the US as of March 2024[363]), 34 F-35A planned as of 2019[update].[364][365]

- Royal Canadian Air Force - 88 F-35As (Block 4) ordered on 9 January 2023. The first 4 are expected to be delivered in 2026, 6 in 2027, another 6 in 2028, and the rest delivered by 2032.[366] This will phase out the CF-18s that were delivered in the 1980s.[367][368]

- Royal Danish Air Force – 10 F-35As delivered (including 6 stationed at Luke AFB for training) of the 27 planned for the RDAF.[369][370][371][372]

- Finnish Air Force – F-35A Block 4 selected via the HX Fighter Program to replace the current F/A-18 Hornets.[373][374] 64 F-35As on order as of 2022.[375]

- German Air Force – 35 F-35A ordered as of 2023[update],[376][377] with an order for 10 more being considered as of 2024.[378]

- Hellenic Air Force – 20 F-35As on order, with expected delivery in late 2027 to early 2028.[379] An option for another additional 20 aircraft is also included.[380]

- Israeli Air Force – 39 delivered as of July 2023[update] (F-35I "Adir").[381] Includes one F-35 testbed aircraft for indigenous Israeli weapons, electronics and structural upgrades, designated (AS-15).[382][383] A total of 75 ordered.[384]

- Italian Air Force – 17 F-35As and 3 F-35B delivered as of April 2023[update][385] of 60 F-35As and 15 F-35Bs ordered for the Italian Air Force.[386][387][388]

- Italian Navy – 3 delivered as of April 2023[update], out of 15 F-35Bs ordered for the Italian Navy.[386][387][388]

- Japan Air Self-Defense Force – 27 F-35As operational as of March 2022 with a total order of 147, including 105 F-35As and 42 F-35Bs.[389][390][391][392]

- Royal Netherlands Air Force – 39 F-35As delivered and operational, of which 8 trainer aircraft based at Luke Air Force Base in the USA.[328] 52 F-35As ordered in total.[393][394][395]

- Royal Norwegian Air Force – 31 F-35As delivered and operational, of which 21 are in Norway and 10 are based in the US for training as of 11 August 2021[396] of 52 F-35As planned in total.[397] They differ from other F-35A through the addition of a drogue parachute.[398]

- Polish Air Force – 32 F-35A Block 4 jets with "Technology Refresh 3" software update and drogue parachutes were ordered on 31 January 2020.[399][400] The deliveries are expected to begin in 2024 and conclude in 2030. There are plans for two more squadrons consisting of 16 jets each, for a total of 32 additional F-35s.[401]

- Republic of Korea Air Force – 40 F-35As ordered and delivered as of January 2022,[402] with 25 more ordered in September 2023.[403][404][405][406]

- Republic of Korea Navy – about 20 F-35Bs planned.[407][408] It has not yet been approved by South Korean parliament.[409]

- Republic of Singapore Air Force – 12 F-35Bs on order as of February 2024 with first 4 to be delivered in 2026; The other 8 are to be delivered in 2028. 8 F-35As have been ordered, and are expected to arrive by 2030.[410][411]

- Swiss Air Force – 36 F-35A ordered to replace the current F-5E/F Tiger II and F/A-18C/D Hornet. Deliveries will begin in 2027 and conclude in 2030.[412][413]

- Royal Air Force and Royal Navy (owned by the RAF but jointly operated) – 34 F-35Bs received[414][415][416] with 30 in the UK after the loss of one aircraft in November 2021;[300][417][418][419] the other three are in the US where they are used for testing and training.[420] 42 (24 FOC fighters and 18 training aircraft) originally intended to be fast-tracked by 2023;[421][422] A total of 48 ordered as of 2021; a total of 138 were originally planned, the expectation in 2021 was to eventually reach around 60 or 80.[423] In 2022, it was announced that the UK would acquire 74 F-35Bs, with a decision on whether or not to go beyond that number, including the possibility of reviving the original plan of 138 aircraft, to be made in the mid-2020s.[424] In February 2024 the United Kingdom appeared to signal a reaffirmation of its commitment to procure 138 F-35B aircraft, as per the original plan.[425]

- United States Air Force – 302 delivered with 1,763 F-35As planned[426]

- United States Marine Corps – 112 F-35B/C delivered[427] with 353 F-35Bs and 67 F-35Cs planned[428]

- United States Navy – 30 delivered[427] with 273 F-35Cs planned[428]

Potential operators

[edit]- Czech Air Force – The U.S. State Department approved a possible sale to the Czech Republic of F-35 aircraft, munitions and related equipment worth up to $5.62 billion, according to a 29 June 2023 announcement.[429] On 29 January 2024, the Czech government signed a memorandum of understanding with the U.S. for the purchase of 24 F-35A fighters.[430]

- Romanian Air Force – Romania plans to buy 48 F-35 aircraft in two phases.[431] The first phase of the purchase, involving 32 F-35 aircraft, was approved by the Romanian Parliament with an estimated cost of $6.5 billion.[432]

- Portuguese Air Force — In April 2024, General João Cartaxo Alves, chief of staff of the Portuguese Air Force, said his country would switch from the F-16 to the F-35, a process that he said "had already begun", would take 20 years, and would ultimately cost 5.5 billion euros.[433]

Order and approval cancellations

[edit]- Republic of China Air Force – Taiwan has requested to buy the F-35 from the US. However this has been rejected by the US in fear of a critical response from China.[434] In March 2009 Taiwan again was looking to buy U.S. fifth-generation fighter jets. However, in September 2011, during a visit to the US, the Deputy Minister of National Defense of Taiwan confirmed that while the country was busy upgrading its current F-16s it was still also looking to procure a next-generation aircraft such as the F-35. This received the usual critical response from China.[435] Taiwan renewed its push for an F-35 purchase during Donald Trump's presidency in early 2017, again causing criticism from China.[436] In March 2018, Taiwan once again reiterated its interest in the F-35 in light of an anticipated round of arms procurement from the United States. The F-35B STOVL variant is reportedly the political favorite as it would allow the Republic of China Air Force to continue operations after its limited number of runways were to be bombed in an escalation with the People's Republic of China.[437] In April 2018 however it became clear that the U.S. government was reluctant about selling the F-35 to Taiwan over worries of Chinese spies within the Taiwanese Armed Forces, possibly compromising classified data concerning the aircraft and granting Chinese military officials access. In November 2018, it was reported that Taiwanese military leadership had abandoned the procurement of the F-35 in favor of a larger number of F-16V Viper aircraft. The decision was reportedly motivated by concerns about industry independence, as well as cost and previously raised espionage concerns.[438]

- Royal Thai Air Force – 8 or 12 planned to replace F-16A/B Block 15 ADF in service. On 12 January 2022, Thailand's cabinet approved a budget for the first four F-35A, estimated at 13.8 billion baht in FY2023.[439][440][441] On 22 May 2023, the United States Department of Defense implied it will turn down Thailand's bid to buy F-35 fighters, and instead offer F-16 Block 70/72 Viper and F-15EX Eagle II fighters, a Royal Thai Air Force source said.[442]

- Turkish Air Force – 30 were ordered,[443] of up to 100 total planned.[444][445] Future purchases have been banned by the U.S. with contracts canceled by early 2020, following Turkey's decision to buy the S-400 missile system from Russia.[446] Six of Turkey's 30 ordered F-35As were completed as of 2019 (they are still kept in a hangar in the United States as of 2023[447][448] and so far haven't been transferred to the USAF, despite a modification in the 2020 Fiscal Year defense budget by the U.S. Congress which gives authority to do so if necessary),[449][450] and two more were at the assembly line in 2020.[449][450] The first four F-35As were delivered to Luke Air Force Base in 2018[451] and 2019[452] for the training of Turkish pilots.[453][454] On July 20, 2020, the U.S. government had formally approved the seizure of eight F-35As originally bound for Turkey and their transfer to the USAF, together with a contract to modify them to USAF specifications.[455] The U.S. has not refunded the $1.4 billion payment made by Turkey for purchasing the F-35A fighters as of January 2023.[447][448] On 1 February 2024, the United States expressed willingness to readmit Turkey into the F-35 program if Turkey agrees to give up its S-400 system.[456]

- United Arab Emirates Air Force – Up to 50 F-35As planned.[457] But on 27 January 2021, the Biden administration temporarily suspended the F-35 sales to the UAE.[458] After pausing the bill to review the sale, the Biden administration confirmed to move forward with the deal on 13 April 2021.[459] In December 2021 UAE withdrew from purchasing F-35s as they did not agree to the additional terms of the transaction from the US.[460][461]

Accidents and notable incidents

[edit]Various models of the F-35 have been involved in incidents since 2014. They have often involved operator error or mechanical issues, which has set back the program.[462] In comparison to most military aircraft, however, it is described as being safe.[463]

Specifications (F-35A)

[edit]

Data from Lockheed Martin: F-35 specifications,[464][465][466][467] Lockheed Martin: F-35 weaponry,[468] Lockheed Martin: F-35 Program Status,[105] F-35 Program brief,[154] FY2019 Select Acquisition Report (SAR),[337] Director of Operational Test & Evaluation[469]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 51.4 ft (15.7 m)

- Wingspan: 35 ft (11 m)

- Height: 14.4 ft (4.4 m)

- Wing area: 460 sq ft (43 m2)

- Aspect ratio: 2.66

- Empty weight: 29,300 lb (13,290 kg)

- Gross weight: 49,540 lb (22,471 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 65,918 lb (29,900 kg) [470]

- Fuel capacity: 18,250 lb (8,278 kg) internal

- Powerplant: 1 × Pratt & Whitney F135-PW-100 afterburning turbofan, 28,000 lbf (125 kN) thrust dry, 43,000 lbf (191 kN) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: Mach 1.6 at high altitude

- Mach 1.06, 700 knots (806 mph; 1,296 km/h) at sea level

- Range: 1,500 nmi (1,700 mi, 2,800 km)

- Combat range: 669 nmi (770 mi, 1,239 km) interdiction mission (air-to-surface) on internal fuel

- 760 nmi (870 mi; 1,410 km), air-to-air configuration on internal fuel[471]

- Service ceiling: 50,000 ft (15,000 m)

- g limits: +9.0

- Wing loading: 107.7 lb/sq ft (526 kg/m2) at gross weight

- Thrust/weight: 0.87 at gross weight (1.07 at loaded weight with 50% internal fuel)

Armament

- Guns: 1 × 25 mm GAU-22/A 4-barrel rotary cannon, 180 rounds[N 17]

- Hardpoints: 4 × internal stations, 6 × external stations on wings with a capacity of 5,700 pounds (2,600 kg) internal, 15,000 pounds (6,800 kg) external, 18,000 pounds (8,200 kg) total weapons payload, with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Missiles:

- Air-to-air missiles:

- AIM-9X Sidewinder

- AIM-120 AMRAAM

- AIM-132 ASRAAM

- AIM-260 JATM (To be integrated)[472]

- MBDA Meteor (Block 4, for F-35B, not before 2027)[473][182][474]

- Air-to-surface missiles:

- AGM-88G AARGM-ER (Block 4)

- AGM-158 JASSM[173]

- AGM-179 JAGM

- SPEAR 3 (Block 4, in development, integration contracted)[166][474]

- Stand-in Attack Weapon (SiAW)[475]

- Anti-ship missiles:

- AGM-158C LRASM[476] (being integrated)

- Joint Strike Missile (integration in progress)[477]

- Air-to-air missiles:

- Bombs:

- Missiles:

Avionics

- AN/APG-81 or AN/APG-85 (Lot 17 onwards) AESA radar[479][480]

- AN/AAQ-40 Electro-Optical Targeting System[481]

- AN/AAQ-37 Electro-Optical Distributed Aperture System[482]

- AN/ASQ-239 Barracuda electronic warfare/electronic countermeasures system[483]

- AN/ASQ-242 CNI suite, which includes

- Harris Corporation Multifunction Advanced Data Link (MADL) communication system

- Link 16 data link

- SINCGARS

- An IFF interrogator and transponder

- HAVE QUICK

- AM, VHF, UHF AM, and UHF FM Radio

- GUARD survival radio

- A radar altimeter