Боксерское восстание

| Боксерское восстание | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Китайское имя | |||

| Традиционный китайский | Боксерское восстание | ||

| Упрощенный китайский | Боксерское восстание | ||

| Буквальный смысл | Милиция объединилась в движение за праведность | ||

| |||

| Маньчжурское имя | |||

| маньчжурский сценарий | ᠴᡳᠣᠸᠠᠨ ᠰᡝᡵᡝ ᡝᡥᡝ ᡥᡡᠯᡥᠠ ᡳ ᡶᠠᠴᡠᡥᡡᠨ | ||

| Мёллендорф | песня хулхи в факухуне | ||

Боксерское восстание , также известное как Боксерское восстание или Боксерское восстание — антииностранное, антиимпериалистическое и антихристианское восстание в Северном Китае между 1899 и 1901 годами, ближе к концу династии Цин , организованное Обществом праведников. и «Гармоничные кулаки », известные на английском языке как «Боксеры», поскольку многие из их членов практиковали китайские боевые искусства , которые в то время назывались «китайским боксом». Он потерпел поражение от Альянса восьми стран иностранных держав.

После Первой китайско-японской войны жители Северного Китая опасались расширения иностранных сфер влияния и возмущались распространением привилегий христианских миссионеров , которые использовали их для защиты своих последователей. В 1898 году Северный Китай пережил несколько стихийных бедствий, в том числе наводнение на Желтой реке и засуху, в которых боксеры обвинили иностранное и христианское влияние. Начиная с 1899 года, движение распространилось по Шаньдуну и Северо-Китайской равнине , уничтожая иностранную собственность, такую как железные дороги, а также нападая или убивая христианских миссионеров и китайских христиан . События достигли апогея в июне 1900 года, когда бойцы-боксеры, убежденные в своей неуязвимости для иностранного оружия, собрались в Пекине с лозунгом «Поддержите правительство Цин и истребите иностранцев».

Дипломаты, миссионеры, солдаты и некоторые китайские христиане укрылись в Посольском квартале , который осадили боксеры. Альянс восьми наций, в который вошли американские, австро-венгерские, британские, французские, немецкие, итальянские, японские и российские войска, двинулся в Китай, чтобы снять осаду, и 17 июня штурмовал форт Дагу в Тяньцзине . Вдовствующая императрица Цыси , которая поначалу колебалась, поддержала боксеров и 21 июня издала императорский указ , который де-факто объявлял войну вторгшимся державам. Китайские чиновники были разделены между теми, кто поддерживал боксеров, и теми, кто выступал за примирение во главе с принцем Цин . Верховный главнокомандующий китайских войск маньчжурский генерал Жунлу позже заявил, что действовал для защиты иностранцев. Чиновники южных провинций проигнорировали императорский приказ о борьбе с иностранцами.

Альянс восьми наций, первоначально отвергнутый императорской китайской армией и боксерской милицией, перебросил в Китай 20 000 вооруженных солдат. Они разбили Императорскую армию в Тяньцзине и прибыли в Пекин 14 августа, сняв 55-дневную осаду международных миссий . Последовали бои за столицу и прилегающую сельскую местность, а также в отместку казнили без суда и следствия подозреваемых в том, что они боксеры. Боксерский протокол от 7 сентября 1901 года предусматривал казнь правительственных чиновников, которые поддерживали боксеров, размещение иностранных войск в Пекине и выплату 450 миллионов таэлей серебра — больше, чем ежегодные налоговые поступления правительства — в качестве компенсации . в течение следующих 39 лет восьми странам-оккупантам. Действия династии Цин по подавлению боксерского восстания еще больше ослабили их контроль над Китаем и привели к реформам позднего Цин .

Фон

Христианская миссионерская деятельность

По словам Джона Кинга Фэрбанка : [ 8 ]

Открытие страны в 1860-х годах способствовало огромным усилиям по христианизации Китая. Основываясь на старых [французских] основах, римско-католический истеблишмент к 1894 году насчитывал около 750 европейских миссионеров, 400 местных священников и более полумиллиона прихожан. К 1894 году новая протестантская миссия поддерживала более 1300 миссионеров, в основном британцев и американцев, и содержала около 500 станций — каждая с церковью, жилыми домами, уличными часовнями и обычно небольшой школой и, возможно, больницей или амбулаторией — примерно в 350 различных городах. и города. Тем не менее, они обратили в христианство менее 60 000 китайцев.

Успех в привлечении новообращенных и открытии школ в стране с населением около 400 миллионов человек был ограниченным. [ 9 ] [ 10 ] Миссии столкнулись с растущим гневом, направленным на угрозу культурного империализма. Главным результатом стало Боксерское восстание, в ходе которого миссии были атакованы и тысячи китайских христиан были убиты, чтобы уничтожить влияние Запада.

Происхождение боксеров

возникли «Праведные и гармоничные кулаки» во внутренних районах северной прибрежной провинции Шаньдун . [ 11 ] регион, который долгое время страдал от социальных волнений, религиозных сект и военных обществ. Американские христианские миссионеры, вероятно, были первыми, кто называл хорошо тренированных, спортивных молодых людей «боксерами» из-за боевых искусств, которыми они занимались, и тренировок с оружием, которые они прошли. Их основной практикой был тип духовного одержимости , который включал в себя вращение мечей, жестокие простирания и заклинания божествам. [ 12 ]

Возможности борьбы с западным посягательством были особенно привлекательны для безработных деревенских мужчин, многие из которых были подростками. [ 13 ] Традиция владения и неуязвимости возникла несколько сотен лет назад, но приобрела особое значение против нового мощного оружия Запада. [14] The Boxers, armed with rifles and swords, claimed supernatural invulnerability against cannons, rifle shots, and knife attacks. The Boxer groups popularly claimed that millions of soldiers would descend out of heaven to assist them in purifying China of foreign oppression.[15]

In 1895, despite ambivalence toward their heterodox practices, Yuxian, a Manchu who was the then prefect of Cao Prefecture and would later become provincial governor, cooperated with the Big Swords Society, whose original purpose was to fight bandits.[16] The German Catholic missionaries of the Society of the Divine Word had built up their presence in the area, partially by taking in a significant portion of converts who were "in need of protection from the law".[16] On one occasion in 1895, a large bandit gang defeated by the Big Swords Society claimed to be Catholics to avoid prosecution. "The line between Christians and bandits became increasingly indistinct", remarks historian Paul Cohen.[16]

Some missionaries such as Georg Maria Stenz also used their privileges to intervene in lawsuits. The Big Swords responded by attacking Catholic properties and burning them.[16] As a result of diplomatic pressure in the capital, Yuxian executed several Big Sword leaders but did not punish anyone else. More martial secret societies started emerging after this.[16]

The early years saw a variety of village activities, not a broad movement with a united purpose. Martial folk-religious societies such as the Baguadao ('Eight Trigrams') prepared the way for the Boxers. Like the Red Boxing school or the Plum Flower tradition, the Boxers of Shandong were more concerned with traditional social and moral values, such as filial piety, than with foreign influences. One leader, Zhu Hongdeng (Red Lantern Zhu), started as a wandering healer, specialising in skin ulcers, and gained wide respect by refusing payment for his treatments.[17] Zhu claimed descent from Ming dynasty emperors, since his surname was the surname of the Ming imperial family. He announced that his goal was to "Revive the Qing and destroy the foreigners" (扶清滅洋 fu Qing mie yang).[18]

The enemy was seen as foreign influence. They decided the "primary devils" were the Christian missionaries whilst the "secondary devils" were the Chinese converts to Christianity, which both had either to repent, be driven out or killed.[19][20]

Causes

The Boxer Rebellion was an anti-imperialist movement which sought to expel foreigners from China and end the system of foreign concessions and treaty ports.[11] The rebellion had multiple causes.[21] Escalating tensions caused Chinese to turn against "foreign devils" who engaged in the Scramble for China in the late 19th century.[22][page needed] The Western success at controlling China, growing anti-imperialist sentiment, and extreme weather conditions sparked the movement. A drought followed by floods in Shandong province in 1897–98 forced farmers to flee to cities and seek food.[23]

A major source of discontent in northern China was missionary activity. The Boxers opposed German missionaries in Shandong and in the German concession in Qingdao.[11] The Treaty of Tientsin and the Convention of Peking, signed in 1860 after the Second Opium War, had granted foreign missionaries the freedom to preach anywhere in China and to buy land on which to build churches.[24] There was strong public indignation over the dispossession of Chinese temples that were replaced by Catholic churches which were viewed as deliberately anti-feng shui.[21] A further cause of discontent among Chinese people were the destruction of Chinese burial sites to make way for German railroads and telegraph lines.[21] In response to Chinese protests against German railroads, Germans shot the protestors.[25]

Economic conditions in Shandong also contributed to rebellion.[26] Northern Shandong's economy focused significantly on cotton production and was hampered by the importation of foreign cotton.[26] Traffic along the Grand Canal was also decreasing, further eroding the economy.[26] The area had also experienced periods of drought and flood.[26]

A major precipitating incident was anger at the German Catholic Priest Georg Stenz, who had allegedly serially raped Chinese women in Juye County, Shandong.[21] In an attack known as the Juye Incident, Chinese rebels attempted to kill Stenz in his missionary quarters,[21] but failed to find him and killed two other missionaries. The German Navy's East Asia Squadron dispatched to occupy Jiaozhou Bay on the southern coast of the Shandong peninsula.[27]

In December 1897, Wilhelm declared his intent to seize territory in China, which triggered a "scramble for concessions" by which Britain, France, Russia and Japan also secured their own sphere of influence in China.[28] Germany gained exclusive control of developmental loans, mining, and railway ownership in Shandong province. Russia gained influence of all territory north of the Great Wall,[29] plus the previous tax exemption for trade in Mongolia and Xinjiang,[30] economic powers similar to Germany's over Fengtian, Jilin and Heilongjiang. France gained influence of Yunnan, most of Guangxi and Guangdong, Japan over Fujian. Britain gained influence of the whole Yangtze valley[31] (defined as all provinces adjoining the Yangtze, as well as Henan and Zhejiang[29]), parts of Guangdong and Guangxi provinces and part of Tibet.[32][non-primary source needed] Only Italy's request for Zhejiang was declined by the Chinese government.[31] These do not include the lease and concession territories where the foreign powers had full authority. The Russian government militarily occupied their zone, imposed their law and schools, seized mining and logging privileges, settled their citizens, and even established their municipal administration on several cities.[33]

In October 1898, a group of Boxers attacked the Christian community of Liyuantun village where a temple to the Jade Emperor had been converted into a Catholic church. Disputes had surrounded the church since 1869, when the temple had been granted to the Christian residents of the village. This incident marked the first time the Boxers used the slogan "Support the Qing, destroy the foreigners" (扶清滅洋; fu Qing mie yang) that later characterised them.[34]

The Boxers called themselves the "Militia United in Righteousness" for the first time in October 1899, at the Battle of Senluo Temple, a clash between Boxers and Qing government troops.[35] By using the word "Militia" rather than "Boxers", they distanced themselves from forbidden martial arts sects and tried to give their movement the legitimacy of a group that defended orthodoxy.[36]

Violence toward missionaries and Christians drew sharp responses from diplomats protecting their nationals, including Western seizure of harbors and forts and the moving in of troops in preparation for all-out war, as well as taking control of more land by force or by coerced long-term leases from the Qing.[37] In 1899, the French minister in Beijing helped the missionaries to obtain an edict granting official status to every order in the Roman Catholic hierarchy, enabling local priests to support their people in legal or family disputes and bypass the local officials. After the German government took over Shandong, many Chinese feared that the foreign missionaries and possibly all Christian activities were imperialist attempts at "carving the melon", i.e., to colonise China piece by piece.[38] A Chinese official expressed the animosity towards foreigners succinctly, "Take away your missionaries and your opium and you will be welcome."[39]

In 1899, the Boxer Rebellion developed into a mass movement.[11] The previous year, the Hundred Days' Reform, in which progressive Chinese reformers persuaded the Guangxu Emperor to engage in modernizing efforts, was suppressed by Empress Dowager Cixi and Yuan Shikai.[40] The Qing political elite struggled with the question of how to retain its power.[41] The Qing government came to view the Boxers as a means to help oppose foreign powers.[41] The national crisis was widely perceived as caused by "foreign aggression" inside,[42] even though afterwards a majority of Chinese were grateful for the actions of the alliance.[43][page needed] The Qing government was corrupt, common people often faced extortions from government officials and the government offered no protection from the violent actions of the Boxers.[43]

Qing forces

The military of the Qing dynasty had been dealt a severe blow by the First Sino-Japanese War and this had prompted military reform that was still in its early stages when the Boxer rebellion occurred and they were expected to fight. The bulk of the fighting was conducted by the forces already around Zhili with troops from other provinces only arriving after the main fighting had ended.[44]

| Army | The Boards of

War/Revenue (field troops only) |

Russian General

Staff (field troops only) |

E.H. Parker

(Zhili alone) |

The London Times

(Zhili alone) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 360,000 | 205,000 | 125,000–130,000 | 110,000–140,000 |

The failure of the Qing forces to withstand the Allied forces was not surprising given the limited time for reform and the fact that the best troops of China were not committed to the fight, remaining instead in Huguang and Shandong. The officer corps was particularly deficient; many lacked basic knowledge of strategy and tactics, and even those with training had not actively commanded troops in the field. In addition, the regular soldiers were noted for their poor marksmanship and inaccuracy, while cavalry was ill-organised and was not utilised to its full extent. Tactically, the Chinese still retained their belief in the superiority of defence, often withdrawing as soon as they were flanked, a tendency attributable to their lack of combat experience and training as well as a lack of initiative from commanders who would rather retreat than counterattack. However, accusations of cowardice were minimal; this was a marked improvement from the Sino-Japanese War of 1894–1895, as Chinese troops did not flee en masse as before. If led by courageous officers, the troops would often fight to the death as occurred under Nie Shicheng and Ma Yukun.[45]

On the other hand, Chinese artillery was well-regarded, and caused far more casualties than the infantry at Tientsin, and proving themselves superior to Allied artillery in counter-battery fire. The infantry, for their part, were commended for their good usage of cover and concealment in addition to their tenacity in resistance[45]

The Boxers also targeted Jewish groups in the region destroying their reputation and leading to Britain temporarily vacating their civilian workers from the front lines.

Boxer War

Intensifying crisis

In January 1900, with a majority of conservatives in the imperial court, Cixi changed her position on the Boxers and issued edicts in their defence, causing protests from foreign powers. Cixi urged provincial authorities to support the Boxers, although few did so.[46] In spring 1900, the Boxer movement spread rapidly north from Shandong into the countryside near Beijing. Boxers burned Christian churches, killed Chinese Christians and intimidated Chinese officials who stood in their way. American Minister Edwin H. Conger cabled Washington, "the whole country is swarming with hungry, discontented, hopeless idlers".[47]

On 30 May the diplomats, led by British Minister Claude Maxwell MacDonald, requested that foreign soldiers come to Beijing to defend the legations. The Chinese government reluctantly acquiesced, and the next day a multinational force of 435 navy troops from eight countries debarked from warships and travelled by train from the Taku Forts to Beijing. They set up defensive perimeters around their respective missions.[47]

On 5 June 1900, the railway line to Tianjin was cut by Boxers in the countryside, and Beijing was isolated. On 11 June, at Yongdingmen, the secretary of the Japanese legation, Sugiyama Akira, was attacked and killed by the forces of General Dong Fuxiang, who were guarding the southern part of the Beijing walled city.[48] Armed with Mauser rifles but wearing traditional uniforms,[49] Dong's troops had threatened the foreign legations in the fall of 1898 soon after arriving in Beijing,[50] so much that United States Marines had been called to Beijing to guard the legations.[51]

Wilhelm was so alarmed by the Chinese Muslim troops that he requested Ottoman caliph Abdul Hamid II to find a way to stop the Muslim troops from fighting.[citation needed] Abdul Hamid agreed to the Kaiser's request and sent Enver Pasha (not to be confused with the later Young Turk leader) to China in 1901, but the rebellion was over by that time.[52][53]

On 11 June, the first Boxer was seen in the Peking Legation Quarter. The German Minister Clemens von Ketteler and German soldiers captured a Boxer boy and inexplicably executed him.[54] In response, thousands of Boxers burst into the walled city of Beijing that afternoon and burned many of the Christian churches and cathedrals in the city, burning some victims alive.[55] American and British missionaries took refuge in the Methodist Mission, and an attack there was repulsed by US Marines. The soldiers at the British Embassy and German legations shot and killed several Boxers.[56] The Kansu Braves and Boxers, along with other Chinese, then attacked and killed Chinese Christians around the legations in revenge for foreign attacks on Chinese.[57]

Seymour Expedition

As the situation grew more violent, the Eight Powers authorities at Dagu dispatched a second multinational force to Beijing on 10 June 1900. This force of 2,000 sailors and marines was under the command of Vice Admiral Edward Hobart Seymour, the largest contingent being British. The force moved by train from Dagu to Tianjin with the agreement of the Chinese government, but the railway had been severed between Tianjin and Beijing. Seymour resolved to continue forward by rail to the break and repair the railway, or progress on foot from there, if necessary, as it was only 120 km from Tianjin to Beijing. The court then replaced Prince Qing at the Zongli Yamen with Manchu Prince Duan, a member of the imperial Aisin Gioro clan (foreigners called him a "Blood Royal"), who was anti-foreigner and pro-Boxer. He soon ordered the Imperial army to attack the foreign forces. Confused by conflicting orders from Beijing, General Nie Shicheng let Seymour's army pass by in their trains.[58]

After leaving Tianjin, the force quickly reached Langfang, but the railway was destroyed there. Seymour's engineers tried to repair the line, but the force found itself surrounded, as the railway in both behind directions was destroyed. They were attacked from all sides by Chinese irregulars and imperial troops. Five thousand of Dong Fuxiang's Gansu Braves and an unknown number of Boxers won a costly but major victory over Seymour's troops at the Battle of Langfang on 18 June.[59][60] The Seymour force could not locate the Chinese artillery, which was raining shells upon their positions.[61][non-primary source needed] Chinese troops employed mining, engineering, flooding, and simultaneous attacks. The Chinese also employed pincer movements, ambushes, and sniping with some success.[62][non-primary source needed]

On 18 June, Seymour learned of attacks on the Legation Quarter in Beijing, and decided to continue advancing, this time along the Beihe River, toward Tongzhou, 25 km (16 mi) from Beijing. By 19 June, the force was halted by progressively stiffening resistance and started to retreat southward along the river with over 200 wounded. The force was now very low on food, ammunition, and medical supplies. They happened upon The Great Hsi-Ku Arsenal, a hidden Qing munitions cache of which the Eight Powers had had no knowledge until then.

There they dug in and awaited rescue. A Chinese servant slipped through the Boxer and Imperial lines, reached Tianjin, and informed the Eight Powers of Seymour's predicament. His force was surrounded by Imperial troops and Boxers, attacked nearly around the clock, and at the point of being overrun. The Eight Powers sent a relief column from Tianjin of 1,800 men (900 Russian troops from Port Arthur, 500 British seamen, and other assorted troops). On 25 June the relief column reached Seymour. The Seymour force destroyed the Arsenal: they spiked the captured field guns and set fire to any munitions that they could not take (an estimated £3 million worth). The Seymour force and the relief column marched back to Tientsin, unopposed, on 26 June. Seymour's casualties during the expedition were 62 killed and 228 wounded.[63]

Conflict within the Qing imperial court

Meanwhile, in Beijing, on 16 June, Empress Dowager Cixi summoned the imperial court for a mass audience and addressed the choice between using the Boxers to evict the foreigners from the city and seeking a diplomatic solution. In response to a high official who doubted the efficacy of the Boxers, Cixi replied that both sides of the debate at the imperial court realised that popular support for the Boxers in the countryside was almost universal and that suppression would be both difficult and unpopular, especially when foreign troops were on the march.[64][65]

Siege of the Beijing legations

On 15 June, Qing imperial forces deployed electric naval mine in the Beihe River to prevent the Eight-Nation Alliance from sending ships to attack.[66][non-primary source needed] With a difficult military situation in Tianjin and a total breakdown of communications between Tianjin and Beijing, the allied nations took steps to reinforce their military presence significantly. On 17 June they took the Dagu Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin, and from there brought increasing numbers of troops on shore. When Cixi received an ultimatum that same day demanding that China surrender total control over all its military and financial affairs to foreigners,[67] she defiantly stated before the entire Grand Council, "Now they [the Powers] have started the aggression, and the extinction of our nation is imminent. If we just fold our arms and yield to them, I would have no face to see our ancestors after death. If we must perish, why don't we fight to the death?"[68] It was at this point that Cixi began to blockade the legations with the armies of the Peking Field Force, which began the siege. Cixi stated that "I have always been of the opinion, that the allied armies had been permitted to escape too easily in 1860. Only a united effort was then necessary to have given China the victory. Today, at last, the opportunity for revenge has come", and said that millions of Chinese would join the cause of fighting the foreigners since the Manchus had provided "great benefits" on China.[69] On receipt of the news of the attack on the Dagu Forts on 19 June, Empress Dowager Cixi immediately sent an order to the legations that the diplomats and other foreigners depart Beijing under escort of the Chinese army within 24 hours.[70]

The next morning, diplomats from the besieged legations met to discuss the Empress's offer. The majority quickly agreed that they could not trust the Chinese army. Fearing that they would be killed, they agreed to refuse the Empress's demand. The German Imperial Envoy, Baron Clemens von Ketteler, was infuriated with the actions of the Chinese army troops and determined to take his complaints to the royal court. Against the advice of the fellow foreigners, the baron left the legations with a single aide and a team of porters to carry his sedan chair. On his way to the palace, von Ketteler was killed on the streets of Beijing by a Manchu captain.[71] His aide managed to escape the attack and carried word of the baron's death back to the diplomatic compound. At this news, the other diplomats feared they also would be murdered if they left the legation quarter and they chose to continue to defy the Chinese order to depart Beijing. The legations were hurriedly fortified. Most of the foreign civilians, which included a large number of missionaries and businessmen, took refuge in the British legation, the largest of the diplomatic compounds.[72] Chinese Christians were primarily housed in the adjacent palace (Fu) of Prince Su, who was forced to abandon his property by the foreign soldiers.[73]

On 21 June, Cixi issued an imperial decree stating that hostilities had begun and ordering the regular Chinese army to join the Boxers in their attacks on the invading troops. This was a de facto declaration of war, but the Allies also made no formal declaration of war.[74] Regional governors in the south, who commanded substantial modernised armies, such as Li Hongzhang at Guangzhou, Yuan Shikai in Shandong, Zhang Zhidong[75] at Wuhan, and Liu Kunyi at Nanjing, formed the Mutual Defense Pact of the Southeastern Provinces.[76] They refused to recognise the imperial court's declaration of war, which they declared a luan-ming (illegitimate order) and withheld knowledge of it from the public in the south. Yuan Shikai used his own forces to suppress Boxers in Shandong, and Zhang entered into negotiations with the foreigners in Shanghai to keep his army out of the conflict. The neutrality of these provincial and regional governors left the majority of Chinese military forces out of the conflict.[77] The republican revolutionary Sun Yat-sen even took the opportunity to submit a proposal to Li Hongzhang to declare an independent democratic republic, although nothing came of the suggestion.[78]

The legations of the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, Austria-Hungary, Spain, Belgium, the Netherlands, the United States, Russia and Japan were located in the Beijing Legation Quarter south of the Forbidden City. The Chinese army and Boxer irregulars besieged the Legation Quarter from 20 June to 14 August 1900. A total of 473 foreign civilians, 409 soldiers, marines and sailors from eight countries, and about 3,000 Chinese Christians took refuge there.[79] Under the command of the British minister to China, Claude Maxwell MacDonald, the legation staff and military guards defended the compound with small arms, three machine guns, and one old muzzle-loaded cannon, which was nicknamed the International Gun because the barrel was British, the carriage Italian, the shells Russian and the crew American. Chinese Christians in the legations led the foreigners to the cannon and it proved important in the defence. Also under siege in Beijing was the Northern Cathedral (Beitang) of the Catholic Church. The cathedral was defended by 43 French and Italian soldiers, 33 Catholic foreign priests and nuns, and about 3,200 Chinese Catholics. The defenders suffered heavy casualties from lack of food and from mines which the Chinese exploded in tunnels dug beneath the compound.[80] The number of Chinese soldiers and Boxers besieging the Legation Quarter and the Beitang is unknown. [81] Zaiyi's bannermen in the Tiger and Divine Corps led attacks against the Catholic cathedral church.[82][non-primary source needed]

On 22 and 23 June, Chinese soldiers and Boxers set fire to areas north and west of the British Legation, using it as a "frightening tactic" to attack the defenders. The nearby Hanlin Academy, a complex of courtyards and buildings that housed "the quintessence of Chinese scholarship ... the oldest and richest library in the world", caught fire. Each side blamed the other for the destruction of the invaluable books it contained.[83]

After the failure to burn out the foreigners, the Chinese army adopted an anaconda-like strategy. The Chinese built barricades surrounding the Legation Quarter and advanced, brick by brick, on the foreign lines, forcing the foreign legation guards to retreat a few feet at a time. This tactic was especially used in the Fu, defended by Japanese and Italian sailors and soldiers, and inhabited by most of the Chinese Christians. Fusillades of bullets, artillery and firecrackers were directed against the Legations almost every night—but did little damage. Sniper fire took its toll among the foreign defenders. Despite their numerical advantage, the Chinese did not attempt a direct assault on the Legation Quarter although in the words of one of the besieged, "it would have been easy by a strong, swift movement on the part of the numerous Chinese troops to have annihilated the whole body of foreigners ... in an hour".[84][non-primary source needed] American missionary Francis Dunlap Gamewell and his crew of "fighting parsons" fortified the Legation Quarter,[85][non-primary source needed] but impressed Chinese Christians to do most of the physical labour of building defences.[86][non-primary source needed]

The Germans and the Americans occupied perhaps the most crucial of all defensive positions: the Tartar Wall. Holding the top of the 45 ft (14 m) tall and 40 ft (12 m) wide wall was vital. The German barricades faced east on top of the wall and 400 yd (370 m) west were the west-facing American positions. The Chinese advanced toward both positions by building barricades even closer. "The men all feel they are in a trap", said the US commander Capt. John Twiggs Myers, "and simply await the hour of execution".[87] On 30 June, the Chinese forced the Germans off the Wall, leaving the American Marines alone in its defence. In June 1900, one American described the scene of 20,000 Boxers storming the walls:[88][88]

Their yells were deafening, while the roar of gongs, drums, and horns sounded like thunder…. They waved their swords and stamped on the ground with their feet. They wore red turbans, sashes, and garters over blue cloth…. They were now only twenty yards from our gate. Three or four volleys from the Lebel rifles of our marines left more than fifty dead on the ground.

At the same time, a Chinese barricade was advanced to within a few feet of the American positions, and it became clear that the Americans had to abandon the wall or force the Chinese to retreat. At 2 am on 3 July 56 British, Russian and American marines and sailors, under the command of Myers, launched an assault against the Chinese barricade on the wall. The attack caught the Chinese sleeping, killed about 20 of them, and expelled the rest of them from the barricades.[89][non-primary source needed] The Chinese did not attempt to advance their positions on the Tartar Wall for the remainder of the siege.[90][non-primary source needed]

Sir Claude MacDonald said 13 July was the "most harassing day" of the siege.[91] The Japanese and Italians in the Fu were driven back to their last defence line. The Chinese detonated a mine beneath the French Legation pushing the French and Austrians out of most of the French Legation.[91] On 16 July, the most capable British officer was killed and the journalist George Ernest Morrison was wounded.[92] American Minister Edwin H. Conger established contact with the Chinese government and on 17 July, and an armistice was declared by the Chinese.[93][non-primary source needed]

Infighting among officials and commanders

General Ronglu concluded that it was futile to fight all of the powers simultaneously and declined to press home the siege.[94] Zaiyi wanted artillery for Dong's troops to destroy the legations. Ronglu blocked the transfer of artillery to Zaiyi and Dong, preventing them from attacking.[citation needed] Ronglu forced Dong Fuxiang and his troops to pull back from completing the siege and destroying the legations, thereby saving the foreigners and making diplomatic concessions.[95] Ronglu and Prince Qing sent food to the legations and used their bannermen to attack the Gansu Braves of Dong Fuxiang and the Boxers who were besieging the foreigners. They issued edicts ordering the foreigners to be protected, but the Gansu warriors ignored it, and fought against bannermen who tried to force them away from the legations. The Boxers also took commands from Dong Fuxiang.[96] Ronglu also deliberately hid an Imperial Decree from Nie Shicheng. The Decree ordered him to stop fighting the Boxers because of the foreign invasion, and also because the population was suffering. Due to Ronglu's actions, Nie continued to fight the Boxers and killed many of them even as the foreign troops were making their way into China. Ronglu also ordered Nie to protect foreigners and save the railway from the Boxers.[97] Because parts of the railway were saved under Ronglu's orders, the foreign invasion army was able to transport itself into China quickly. Nie committed thousands of troops against the Boxers instead of against the foreigners, but was already outnumbered by the Allies by 4,000 men. He was blamed for attacking the Boxers, and decided to sacrifice his life at Tietsin by walking into the range of Allied guns.[98]

Xu Jingcheng, who had served as the envoy to many of the same states under siege in the Legation Quarter, argued that "the evasion of extraterritorial rights and the killing of foreign diplomats are unprecedented in China and abroad".[99][page needed] Xu and five other officials urged Empress Dowager Cixi to order the repression of Boxers, the execution of their leaders, and a diplomatic settlement with foreign armies. The Empress Dowager was outraged, and sentenced Xu and the five others to death for "willfully and absurdly petitioning the imperial court" and "building subversive thought". They were executed on 28 July 1900 and their severed heads placed on display at Caishikou Execution Grounds in Beijing.[100]

Reflecting this vacillation, some Chinese soldiers were quite liberally firing at foreigners under siege from its very onset. Cixi did not personally order imperial troops to conduct a siege, and on the contrary had ordered them to protect the foreigners in the legations. Prince Duan led the Boxers to loot his enemies within the imperial court and the foreigners, although imperial authorities expelled Boxers after they were let into the city and went on a looting rampage against both the foreign and the Qing imperial forces. Older Boxers were sent outside Beijing to halt the approaching foreign armies, while younger men were absorbed into the Muslim Gansu army.[101]

With conflicting allegiances and priorities motivating the various forces inside Beijing, the situation in the city became increasingly confused. The foreign legations continued to be surrounded by both Qing imperial and Gansu forces. While Dong's Gansu army, now swollen by the addition of the Boxers, wished to press the siege, Ronglu's imperial forces seem to have largely attempted to follow Cixi's decree and protect the legations. However, to satisfy the conservatives in the imperial court, Ronglu's men also fired on the legations and let off firecrackers to give the impression that they, too, were attacking the foreigners. Inside the legations and out of communication with the outside world, the foreigners simply fired on any targets that presented themselves, including messengers from the imperial court, civilians and besiegers of all persuasions.[102] Dong Fuxiang was denied artillery held by Ronglu which stopped him from levelling the legations, and when he complained to Empress Dowager Cixi on 23 June, she dismissively said that "Your tail is becoming too heavy to wag." The Alliance discovered large amounts of unused Chinese Krupp guns and shells after the siege was lifted.[103]

Gaselee Expedition

Foreign navies started building up their presence along the northern China coast from the end of April 1900. Several international forces were sent to the capital, with varying success, and the Chinese forces were ultimately defeated by the Alliance. Independently, the Netherlands dispatched three cruisers in July to protect its citizens in Shanghai.[104]

British Lieutenant-General Alfred Gaselee acted as the commanding officer of the Eight-Nation Alliance, which eventually numbered 55,000. Japanese forces, led by Fukushima Yasumasa and Yamaguchi Motomi and numbering over 20,840 men, made up the majority of the expeditionary force.[105] French forces in the campaign, led by general Henri-Nicolas Frey, consisted mostly of inexperienced Vietnamese and Cambodian conscripts from French Indochina.[106] The "First Chinese Regiment" (Weihaiwei Regiment) which was praised for its performance, consisted of Chinese collaborators serving in the British military.[107] Notable events included the seizure of the Dagu Forts commanding the approaches to Tianjin and the boarding and capture of four Chinese destroyers by British Commander Roger Keyes. Among the foreigners besieged in Tianjin was a young American mining engineer named Herbert Hoover, who would go on to become the 31st President of the United States.[108][109]

The international force captured Tianjin on 14 July. The international force suffered its heaviest casualties of the Boxer Rebellion in the Battle of Tientsin.[110] With Tianjin as a base, the international force marched from Tianjin to Beijing (about 120 km (75 mi)), with 20,000 allied troops. On 4 August, there were approximately 70,000 Qing imperial troops and anywhere from 50,000 to 100,000 Boxers along the way. The allies only encountered minor resistance, fighting battles at Beicang and Yangcun. At Yangcun, Russian general Nikolai Linevich led the 14th Infantry Regiment of the US and British troops in the assault. The weather was a major obstacle. Conditions were extremely humid with temperatures sometimes reaching 42 °C (108 °F). These high temperatures and insects plagued the Allies. Soldiers became dehydrated and horses died. Chinese villagers killed Allied troops who searched for wells.[111]

The heat killed Allied soldiers, who foamed at the mouth. The tactics along the way were gruesome on either side. Allied soldiers beheaded already dead Chinese corpses, bayoneted or beheaded live Chinese civilians, and raped Chinese girls and women.[112] Cossacks were reported to have killed Chinese civilians almost automatically and Japanese kicked a Chinese soldier to death.[113] The Chinese responded to the Alliance's atrocities with similar acts of violence and cruelty, especially towards captured Russians.[112] Lieutenant Smedley Butler saw the remains of two Japanese soldiers nailed to a wall, who had their tongues cut off and their eyes gouged.[114] Lieutenant Butler was wounded during the expedition in the leg and chest, later receiving the Brevet Medal in recognition for his actions.

The international force reached Beijing on 14 August. Following Beiyang army's defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War, the Chinese government had invested heavily in modernising the imperial army, which was equipped with modern Mauser repeater rifles and Krupp artillery. Three modernised divisions consisting of Manchu bannermen protected the Beijing Metropolitan region. Two of them were under the command of the anti-Boxer Prince Qing and Ronglu, while the anti-foreign Prince Duan commanded the ten-thousand-strong Hushenying, or "Tiger Spirit Division", which had joined the Gansu Braves and Boxers in attacking the foreigners. It was a Hushenying captain who had assassinated the German diplomat, Ketteler. The Tenacious Army under Nie Shicheng received Western style training under German and Russian officers in addition to their modernised weapons and uniforms. They effectively resisted the Alliance at the Battle of Tientsin before retreating and astounded the Alliance forces with the accuracy of their artillery during the siege of the Tianjin concessions (the artillery shells failed to explode upon impact due to corrupt manufacturing). The Gansu Braves under Dong Fuxiang, which some sources described as "ill disciplined", were armed with modern weapons but were not trained according to Western drill and wore traditional Chinese uniforms. They led the defeat of the Alliance at Langfang in the Seymour Expedition and were the most ferocious in besieging the Legations in Beijing. The British won the race among the international forces to be the first to reach the besieged Legation Quarter. The US was able to play a role due to the presence of UD ships and troops stationed in Manila since the US conquest of the Philippines during the Spanish–American War and the subsequent Philippine–American War. The US military refers to this as the China Relief Expedition. United States Marines scaling the walls of Beijing is an iconic image of the Boxer Rebellion.[115]

The British Army reached the legation quarter on the afternoon of 14 August and relieved the Legation Quarter. The Beitang was relieved on 16 August, first by Japanese soldiers and then, officially, by the French.[116]

Qing court flight to Xi'an

As the foreign armies reached Beijing, the Qing court fled to Xi'an, with Cixi disguised as a Buddhist nun.[117] The journey was made all the more arduous by the lack of preparation, but the Empress Dowager insisted this was not a retreat, rather a "tour of inspection". After weeks of travel, the party arrived in Xi'an, beyond protective mountain passes where the foreigners could not reach, deep in Chinese Muslim territory and protected by the Gansu Braves. The foreigners had no orders to pursue Cixi, so they decided to stay put.[118]

Russian invasion of Manchuria

The Russian Empire and the Qing Dynasty had maintained a long peace, starting with the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689, but Russian forces took advantage of Chinese defeats to impose the Aigun Treaty of 1858 and the Treaty of Peking of 1860 which ceded formerly Chinese territory in Manchuria to Russia, much of which is held by Russia to the present day (Primorye). The Russians aimed for control over the Amur River for navigation, and the all-weather ports of Dairen and Port Arthur in the Liaodong peninsula. The rise of Japan as an Asian power provoked Russia's anxiety, especially in light of expanding Japanese influence in Korea. Following Japan's victory in the First Sino-Japanese War of 1895, the Triple Intervention of Russia, Germany and France forced Japan to return the territory won in Liaodong, leading to a de facto Sino-Russian alliance.

Local Chinese in Manchuria were incensed at these Russian advances and began to harass Russians and Russian institutions, such as the Chinese Eastern Railway, which was guarded by Russian troops under Pavel Mishchenko. In June 1900, the Chinese bombarded the town of Blagoveshchensk on the Russian side of the Amur. The Russian government, at the insistence of war minister Aleksey Kuropatkin, used the pretext of Boxer activity to move some 200,000 troops led by Paul von Rennenkampf into the area to crush the Boxers. The Chinese used arson to destroy a bridge carrying a railway and a barracks on 27 July. The Boxer attacks on Chinese Eastern Railway and burned the Yantai mines.[119]

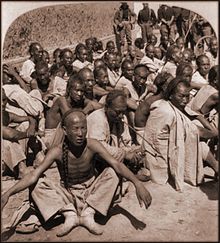

Massacre of missionaries and Chinese Christians

A total of 136 Protestant missionaries, 53 children, 47 Catholic priests and nuns, 30,000 Chinese Catholics, 2,000 Chinese Protestants, and 200–400 of the 700 Russian Orthodox Christians in Beijing are estimated to have been killed during the uprising. The Protestant dead were collectively termed the China Martyrs of 1900.[120]

Orthodox, Protestant, and Catholic missionaries and their Chinese parishioners were massacred throughout northern China, some by Boxers and others by government troops and authorities. After the declaration of war on Western powers in June 1900, Yuxian, who had been named governor of Shanxi in March of that year, implemented a brutal anti-foreign and anti-Christian policy. On 9 July, reports circulated that he had executed forty-four foreigners (including women and children) from missionary families whom he had invited to the provincial capital Taiyuan under the promise to protect them.[121][122] Although the purported eyewitness accounts have recently been questioned as improbable, this event became a notorious symbol of Chinese anger, known as the Taiyuan Massacre.[123]

The England-based Baptist Missionary Society opened its mission in Shanxi in 1877. In 1900, all its missionaries there were killed, along with all 120 converts.[124] By the summer's end, more foreigners and as many as 2,000 Chinese Christians had been put to death in the province. Journalist and historical writer Nat Brandt has called the massacre of Christians in Shanxi "the greatest single tragedy in the history of Christian evangelicalism".[125]

Some 222 Russian–Chinese martyrs, including Chi Sung as St. Metrophanes, were locally canonised as New Martyrs on 22 April 1902, after Archimandrite Innocent (Fugurovsky), head of the Russian Orthodox Mission in China, solicited the Most Holy Synod to perpetuate their memory. This was the first local canonisation for more than two centuries.[126]

Aftermath

Allied occupation and atrocities

The Eight Nation Alliance occupied Zhili province while Russia occupied Manchuria, but the rest of China was not occupied due to the actions of several Han governors who formed the Mutual Protection of Southeast China that refused to obey the declaration of war and kept their armies and provinces out of the war. Zhang Zhidong told Everard Fraser, the Hankou-based British consul general, that he despised Manchus in order that the Eight Nation Alliance would not occupy provinces under the Mutual Defense Pact.[127]

Beijing, Tianjin and Zhili province were occupied for more than one year by the international expeditionary force under the command of German Field Marshal Alfred von Waldersee, who had initially been appointed commander of the Eight-Nation Alliance during the rebellion but did not arrive in China until after most of the fighting had ended. The Americans and British paid General Yuan Shikai and his army (the Right Division) to help the Eight Nation Alliance suppress the Boxers. Yuan Shikai's forces killed tens of thousands of people in their anti-Boxer campaign in Zhili Province and Shandong after the Alliance captured Beijing.[128] The majority of the hundreds of thousands of people living in inner Beijing during the Qing were Manchus and Mongol bannermen from the Eight Banners after they were moved there in 1644, when Han Chinese were expelled.[129][130] Sawara Tokusuke, a Japanese journalist, wrote in "Miscellaneous Notes about the Boxers" about the rapes of Manchu and Mongol banner girls. He alleged that soldiers of the Eight-Nation Alliance raped a large number of women in Peking, including all seven daughters of Viceroy Yulu of the Hitara clan. Likewise, a daughter and a wife of Mongol banner noble Chongqi of the Alute clan were allegedly gang-raped by soldiers of the Eight-Nation Alliance.[131] Chongqi killed himself on 26 August 1900, and some other relatives, including his son, Baochu, did likewise shortly afterward.[132]

During attacks on suspected Boxer areas from September 1900 to March 1901, European and American forces engaged in tactics which included public decapitations of Chinese with suspected Boxer sympathies, systematic looting, routine shooting of farm animals and crop destruction, destruction of religion buildings and public buildings, burning of religious texts, and widespread rape of Chinese women and girls.[133]

Contemporary British and American observers levelled their greatest criticism at German, Russian, and Japanese troops for their ruthlessness and willingness to execute Chinese of all ages and backgrounds, sometimes burning villages and killing their entire populations.[134] The German force arrived too late to take part in the fighting but undertook punitive expeditions to villages in the countryside. According to missionary Arthur Henderson Smith, in addition to burning and looting, Germans "cut off the heads of many Chinese within their jurisdiction, many of them for absolutely trivial offenses".[135] US Army Lieutenant C. D. Rhodes reported that German and French soldiers set fire to buildings where innocent peasants were sheltering and would shoot and bayonet peasants who fled the burning buildings.[136] According to Australian soldiers, Germans extorted ransom payments from villages in exchange for not torching their homes and crops.[136] British journalist George Lynch wrote that German and Italian soldiers engaged in a practice of raping Chinese women and girls before burning their villages.[137] According to Lynch, German soldiers would attempt to cover up these atrocities by throwing rape victims into wells as staged suicides.[137] Lynch said, "There are things that I must not write, and that may not be printed in England, which would seem to show that this Western civilisation of ours is merely a veneer over savagery".[138]

On 27 July, during departure ceremonies for the German relief force, Kaiser Wilhelm II included an impromptu but intemperate reference to the Hun invaders of continental Europe:

Should you encounter the enemy, he will be defeated! No quarter will be given! Prisoners will not be taken! Whoever falls into your hands is forfeited. Just as a thousand years ago the Huns under their King Attila made a name for themselves, one that even today makes them seem mighty in history and legend, may the name German be affirmed by you in such a way in China that no Chinese will ever again dare to look cross-eyed at a German.[139]

One newspaper called the aftermath of the siege a "carnival of ancient loot", and others called it "an orgy of looting" by soldiers, civilians and missionaries. These characterisations called to mind the sacking of the Summer Palace in 1860.[140] Each nationality accused the others of being the worst looters. An American diplomat, Herbert G. Squiers, filled several railway carriages with loot and artefacts. The British Legation held loot auctions every afternoon and proclaimed, "Looting on the part of British troops was carried out in the most orderly manner." However, one British officer noted, "It is one of the unwritten laws of war that a city which does not surrender at the last and is taken by storm is looted." For the rest of 1900 and 1901, the British held loot auctions every day except Sunday in front of the main-gate to the British Legation. Many foreigners, including Claude Maxwell MacDonald and Lady Ethel MacDonald and George Ernest Morrison of The Times, were active bidders among the crowd. Many of these looted items ended up in Europe.[138] The Catholic Beitang or North Cathedral was a "salesroom for stolen property".[141] The American general Adna Chaffee banned looting by American soldiers, but the ban was ineffectual.[142] According to Chaffee, "it is safe to say that where one real Boxer has been killed, fifty harmless coolies or laborers, including not a few women and children, have been slain".[135]

A few Western missionaries took an active part in calling for retribution. To provide restitution to missionaries and Chinese Christian families whose property had been destroyed, William Scott Ament, a missionary of American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, guided American troops through villages to punish those he suspected of being Boxers and confiscate their property. When Mark Twain read of this expedition, he wrote a scathing essay, "To the Person Sitting in Darkness", that attacked the "Reverend bandits of the American Board," especially targeting Ament, one of the most respected missionaries in China.[143] The controversy was front-page news during much of 1901. Ament's counterpart on the distaff side was British missionary Georgina Smith, who presided over a neighbourhood in Beijing as judge and jury.[144]

While one historical account reported that Japanese troops were astonished by other Alliance troops raping civilians,[145] others noted that Japanese troops were "looting and burning without mercy", and that Chinese "women and girls by hundreds have committed suicide to escape a worse fate at the hands of Russian and Japanese brutes".[146] Roger Keyes, who commanded the British destroyer Fame and accompanied the Gaselee Expedition, noted that the Japanese had brought their own "regimental wives" (prostitutes) to the front to keep their soldiers from raping Chinese civilians.[147]

The Daily Telegraph journalist E. J. Dillon stated [where?] that he witnessed the mutilated corpses of Chinese women who were raped and killed by the Alliance troops. The French commander dismissed the rapes, attributing them to "gallantry of the French soldier".[where?] According to U.S. Captain Grote Hutcheson, French forces burned each village they encountered during a 99-mile march and planted the French flag in the ruins.[148]

Many bannermen supported the Boxers, and shared their anti-foreign sentiment.[149] Bannermen had been devastated in the First Sino-Japanese War in 1895 and Banner armies were destroyed while resisting the invasion. In the words of historian Pamela Crossley, their living conditions went "from desperate poverty to true misery".[150] When thousands of Manchus fled south from Aigun during the fighting in 1900, their cattle and horses were stolen by Russian Cossacks who then burned their villages and homes to ashes.[151] Manchu Banner armies were destroyed while resisting the invasion, many annihilated by Russians. Manchu Shoufu killed himself during the battle of Peking and the Manchu Lao She's father was killed by Western soldiers in the battle as the Manchu banner armies of the Center Division of the Guards Army, Tiger Spirit Division and Peking Field Force in the Metropolitan banners were slaughtered by the western soldiers. The Inner-city Legation Quarters and Catholic cathedral (Church of the Saviour, Beijing) were both attacked by Manchu bannermen. Manchu bannermen were slaughtered by the Eight Nation Alliance all over Manchuria and Beijing because most of the Manchu bannermen supported the Boxers.[81]The clan system of the Manchus in Aigun was obliterated by the despoliation of the area at the hands of the Russian invaders.[152] There were 1,266 households including 900 Daurs and 4,500 Manchus in Sixty-Four Villages East of the River and Blagoveshchensk until the Blagoveshchensk massacre and Sixty-Four Villages East of the River massacre committed by Russian Cossack soldiers.[153] Many Manchu villages were burned by Cossacks in the massacre according to Victor Zatsepine.[154]

Manchu royals, officials and officers like Yuxian, Qixiu, Zaixun, Prince Zhuang and Captain Enhai were executed or forced to commit suicide by the Eight Nation Alliance. Manchu official Gangyi's execution was demanded, but he already died.[155] Japanese soldiers arrested Qixiu before he was executed.[156] Zaixun, Prince Zhuang was forced to commit suicide on 21 February 1901.[157][158] They executed Yuxian on 22 February 1901.[159][160] On 31 December 1900 German soldiers beheaded the Manchu captain Enhai for killing Clemens von Ketteler.[161][81]

Indemnity

After the capture of Peking by the foreign armies, some of Cixi's advisers advocated that the war be carried on, arguing that China could have defeated the foreigners as it was disloyal and traitorous people within China who allowed Beijing and Tianjin to be captured by the Allies, and that the interior of China was impenetrable. They also recommended that Dong Fuxiang continue fighting. The Empress Dowager Cixi was practical however, and decided that the terms were generous enough for her to acquiesce when she was assured of her continued reign after the war and that China would not be forced to cede any territory.[162]

On 7 September 1901, the Qing imperial court agreed to sign the Boxer Protocol, also known as Peace Agreement between the Eight-Nation Alliance and China. The protocol ordered the execution of 10 high-ranking officials linked to the outbreak and other officials who were found guilty for the slaughter of foreigners in China. Alfons Mumm, Ernest Satow, and Komura Jutaro signed on behalf of Germany, Britain, and Japan, respectively.

China was fined war reparations of 450,000,000 taels of fine silver (approx.540,000,000 troy ounces (17,000 t)) for the loss that it caused. The reparation was to be paid by 1940, within 39 years, and would be 982,238,150 taels with interest (4 per cent per year) included. The existing tariff increased from 3.18 to 5 per cent, and formerly duty-free merchandise was newly taxed, to help meet these indemnity demands. The sum of reparations was estimated by the Chinese population size (roughly 450 million in 1900) at one tael per person. Chinese customs income and salt taxes guaranteed the reparation.[163] China paid 668,661,220 taels of silver from 1901 to 1939 – equivalent in 2010 to approx.US$61 billion on a purchasing-power-parity basis.[164]

A large portion of the reparations paid to the United States was diverted to pay for the education of Chinese students in US universities under the Boxer Indemnity Scholarship Program. To prepare the students chosen for this program, an institute was established to teach the English language and to serve as a preparatory school. When the first of these students returned to China, they undertook the teaching of subsequent students; from this institute was born Tsinghua University.

The US China Inland Mission lost more members than any other missionary agency: 58 adults and 21 children were killed.[165][page needed][non-primary source needed] However, in 1901, when the allied nations were demanding compensation from the Chinese government, Hudson Taylor refused to accept payment for loss of property or life, in order to demonstrate the meekness and gentleness of Christ to the Chinese.[165][page needed][non-primary source needed]

The Belgian Catholic vicar apostolic of Ordos wanted foreign troops garrisoned in Inner Mongolia, but the Governor refused. Bermyn petitioned the Manchu Enming to send troops to Hetao where Prince Duan's Mongol troops and General Dong Fuxiang's Muslim troops allegedly threatened Catholics. It turned out that Bermyn had created the incident as a hoax.[166][167] Western Catholic missionaries forced Mongols to give up their land to Han Chinese Catholics as part of the Boxer indemnities according to Mongol historian Shirnut Sodbilig.[168] Mongols had participated in attacks against Catholic missions in the Boxer rebellion.[169]

Правительство Цин не капитулировало перед всеми иностранными требованиями. Маньчжурский губернатор Юйсянь был казнен, но императорский двор отказался казнить ханьского китайского генерала Дун Фусяна, хотя он также поощрял убийства иностранцев во время восстания. [170] Вдовствующая императрица Цыси вмешалась, когда Альянс потребовал его казни, а Дуна просто обналичили и отправили домой. [ 171 ] Вместо этого Донг жил в роскоши и власти в «изгнании» в своей родной провинции Ганьсу. [ 172 ] После смерти Дуна в 1908 году все лишенные его почести были восстановлены, и ему было дано полное военное захоронение. [ 172 ] Компенсация так и не была выплачена полностью и была отменена во время Второй мировой войны. [ 173 ]

Долгосрочные последствия

Оккупация Пекина иностранными державами и провал восстания еще больше подорвали поддержку государства Цин. [ 173 ] Поддержка реформ уменьшилась, а поддержка революции возросла. [ 173 ] За десять лет после Боксерского восстания восстания в Китае усилились, особенно на юге. [ 173 ] Поддержка выросла для Тунмэнхуэй , союза антицинских групп, который позже стал Гоминьданом . [ 173 ]

Цыси была возвращена в Пекин, поскольку иностранные державы полагали, что сохранение правительства Цин - лучший способ контролировать Китай. [ 174 ] Государство Цин предприняло дальнейшие усилия по реформированию . [ 173 ] Он отменил имперские экзамены в 1905 году и стремился постепенно ввести консультативные собрания. [ 175 ] Наряду с формированием новых военных и полицейских организаций, реформы также упростили центральную бюрократию и положили начало обновлению налоговой политики. [ 176 ] Эти усилия не смогли сохранить династию Цин, которая была свергнута в результате Синьхайской революции 1911 года . [ 175 ]

В октябре 1900 года Россия оккупировала провинции Маньчжурию. [ 177 ] шаг, который поставил под угрозу надежды англо-американцев на сохранение открытости страны для торговли в рамках Политики открытых дверей .

Историк Уолтер Лафебер утверждает, что решение президента Уильяма МакКинли послать 5000 американских солдат для подавления восстания знаменует собой «истоки современных президентских военных полномочий»: [ 178 ]

МакКинли сделал исторический шаг в создании новой президентской власти 20 века. Он направил пять тысяч солдат, не посоветовавшись с Конгрессом, не говоря уже о том, чтобы получить объявление войны, для борьбы с боксерами, которых поддерживало китайское правительство... Президенты ранее использовали такую силу против неправительственных групп, которые угрожали интересам и гражданам США. . Однако теперь его использовали против признанных правительств и без соблюдения положений Конституции о том, кто должен объявлять войну .

Артур М. Шлезингер-младший согласился и написал: [ 179 ]

Вмешательство в Китай ознаменовало начало решающего изменения в использовании президентских вооруженных сил за рубежом. В XIX веке военная сила, применявшаяся без санкции Конгресса, обычно использовалась против неправительственных организаций. Теперь его начали использовать против суверенных государств, причем, в случае Теодора Рузвельта , с меньшими консультациями, чем когда-либо.

Анализ боксеров

С самого начала мнения разошлись относительно того, следует ли считать боксеров антиимпериалистическими, патриотическими и протонационалистическими или отсталыми, иррациональными и бесполезными противниками неизбежных перемен. Историк Джозеф В. Эшерик комментирует, что «путаница в отношении Боксерского восстания - это не просто вопрос популярных заблуждений», поскольку «в современной истории Китая нет ни одного серьезного инцидента, диапазон профессиональных интерпретаций которого был бы столь же велик». [ 180 ]

Боксеры вызвали осуждение со стороны тех, кто хотел модернизировать Китай в соответствии с западной моделью цивилизации. Сунь Ятсен , считающийся отцом-основателем современного Китая, в то время работал над свержением династии Цин, но считал, что правительство распространяло слухи, которые «вызывали замешательство среди населения» и активизировали боксерское движение. Он выступил с «резкой критикой» «антиностранизма и мракобесия» боксеров. Сан похвалил боксеров за их «дух сопротивления», но назвал их «бандитами». Студенты, обучающиеся в Японии, были настроены неоднозначно. Некоторые заявили, что, хотя восстание началось с невежественных и упрямых людей, их убеждения были смелыми и праведными и могли быть преобразованы в силу за независимость. [ 181 ] После падения династии Цин в 1911 году китайцы-националисты стали более симпатизировать боксерам. В 1918 году Сунь похвалил их боевой дух и сказал, что боксеры были мужественными и бесстрашными в смертельной борьбе против армий Альянса, особенно в битве при Янцуне . [ 182 ] Китайские либералы, такие как Ху Ши , призывавшие Китай к модернизации, по-прежнему осуждали боксеров за их иррациональность и варварство. [ 183 ] Лидер новую культуру Движения за Чэнь Дусю простил «варварство боксера… учитывая преступления, совершенные иностранцами в Китае», и заявил, что именно те «подчиненные иностранцам» действительно «заслужили наше негодование». [ 184 ]

В других странах взгляды на боксеров были сложными и противоречивыми. Марк Твен говорил, что «боксер – патриот. Он любит свою страну больше, чем страны других людей. Я желаю ему успеха». [ 185 ] Русский писатель Лев Толстой также похвалил боксеров и обвинил Николая II в России и Вильгельма II в Германии в том, что они несут главную ответственность за грабежи, изнасилования, убийства и «христианскую жестокость» российских и западных войск. [ 186 ] Русский революционер Владимир Ленин высмеивал утверждение российского правительства о том, что оно защищает христианскую цивилизацию: «Бедное имперское правительство! Такое по-христиански бескорыстное, но в то же время так несправедливо оклеветанное! Несколько лет назад оно бескорыстно захватило Порт-Артур, а теперь оно бескорыстно захватывает Маньчжурию; бескорыстно наводнил приграничные провинции Китая ордами подрядчиков, инженеров и офицеров, которые своим поведением вызвали негодование даже китайцев, известных своей покорностью». [ 187 ] Российская газета «Амурский край» раскритиковала убийство невинных мирных жителей и заявила, что сдержанность была бы более пристойна «цивилизованной христианской нации», спрашивая: «Что нам сказать цивилизованным людям? Нам придется сказать им: «Не считайте мы больше как братья. Мы подлые и ужасные люди, мы убили тех, кто прятался у нас, кто искал нашей защиты». [ 188 ] Он также рассматривал Боксерское восстание как одну из первых попыток рабочего класса и китайского пролетариата свергнуть иностранных империалистических угнетателей и видел в них одну из авангардных пролетарских сил, борющихся за свою свободу против империализма (так же, как это рассматривалось Карл Маркс и Фридрих Энгельс). [ 189 ]

Слева : два пехотинца Новой Императорской Армии . Спереди : барабанщик регулярной армии. На багажнике сидит: полевой артиллерист. Справа : Боксеры.

Некоторые американские церковники высказались в поддержку боксеров. В 1912 году евангелист Джордж Ф. Пятидесятник сказал, что восстание боксеров было:

«патриотическое движение по изгнанию «иностранных дьяволов» – всего лишь – иностранных дьяволов». «Предположим, — сказал он, — что великие нации Европы соберут свои флоты, придут сюда, захватят Портленд, двинутся к Бостону, затем к Нью-Йорку, затем к Филадельфии и так далее по Атлантическому побережью и вокруг Предположим, они овладели этими портовыми городами, выгнали наших людей вглубь страны, построили огромные склады и фабрики, наняли группу развратных агентов и спокойно уведомили наш народ, что отныне они будут управлять торговлей страны? Разве у нас не было бы боксерского движения, которое изгнало бы этих иностранных европейских христианских дьяволов из нашей страны?» [ 190 ]

Индийский бенгальец Рабиндранат Тагор напал на европейских колонизаторов. [ 191 ] Ряд индийских солдат Британской индийской армии сочувствовали делу боксеров, и в 1994 году индийские военные вернули Китаю колокол, украденный британскими солдатами в Храме Неба. [ 192 ]

События также оставили более долгосрочные последствия. Историк Роберт Бикерс отметил, что боксерское восстание послужило для британского правительства эквивалентом индийского восстания 1857 года и взбудоражило желтую опасность среди британской общественности. Он добавляет, что более поздние события, такие как Северная экспедиция 1920-х годов и даже деятельность Красной гвардии в 1960-е годы, воспринимались как стоящие в тени боксеров. [ 193 ]

Учебники по истории на Тайване и в Гонконге часто представляют боксеров как иррациональных, но учебники центрального правительства в материковом Китае описывают боксерское движение как антиимпериалистическое, патриотическое крестьянское движение, которое потерпело неудачу из-за отсутствия руководства со стороны современного рабочего класса – и Международная армия как сила вторжения. Однако в последние десятилетия крупномасштабные проекты деревенских интервью и исследования архивных источников побудили китайских историков взглянуть на ситуацию более детально. Некоторые некитайские ученые, такие как Джозеф Эшерик, считали это движение антиимпериалистическим, но другие считают, что концепция «националистического» является анахронизмом, поскольку китайская нация еще не сформировалась, а боксеры больше интересовались региональными проблемами. Недавнее исследование Пола Коэна включает обзор «Боксеры как миф», который показывает, как их память использовалась в Китае в 20-м веке для изменения образа жизни от Движения за новую культуру до Культурной революции . [ 194 ]

В последние годы вопрос боксеров обсуждается в Китайской Народной Республике. В 1998 году ученый-критик Ван И утверждал, что у боксеров есть общие черты с экстремизмом Культурной революции . Оба события имели внешнюю цель «ликвидацию всех вредных вредителей» и внутреннюю цель «устранение всех плохих элементов», и что эти отношения коренятся в «культурном мракобесии». Ван объяснил своим читателям изменения в отношении к боксерам от осуждения « Движения четвертого мая» до одобрения, выраженного Мао Цзэдуном во время Культурной революции. [ 195 ] В 2006 году Юань Вэйши , профессор философии Университета Чжуншань в Гуанчжоу, написал, что боксеры своими «преступными действиями принесли невыразимые страдания нации и ее народу! Это все факты, которые всем известны, и это национальный позор, что Китайский народ не может забыть». [ 196 ] Юань обвинил учебники истории в том, что им не хватает нейтралитета, поскольку они представляли боксерское восстание как «великолепный подвиг патриотизма», а не мнение о том, что большинство боксерских повстанцев были жестокими. [ 197 ] В ответ некоторые назвали Юань Вэйши «предателем» ( Ханьцзянь ). [ 198 ]

Терминология

Название «Боксерское восстание», заключает Джозеф В. Эшерик , современный историк, действительно является «неправильным термином», поскольку боксеры «никогда не восставали против маньчжурских правителей Китая и их династии Цин» и «наиболее распространенный боксерский лозунг во всем мире». история движения заключалась в следующем: «поддержи Цин, уничтожь иностранцев», где «иностранный» явно означал иностранную религию, христианство, и обращенных в него китайцев, а также самих иностранцев». Он добавляет, что только после того, как движение было подавлено интервенцией союзников, иностранные державы и влиятельные китайские чиновники осознали, что Цин придется оставаться правительством Китая, чтобы поддерживать порядок и собирать налоги для выплаты контрибуции. Поэтому, чтобы сохранить лицо вдовствующей императрицы и членов императорского двора, все утверждали, что боксеры были мятежниками и что единственная поддержка, которую боксеры получили от императорского двора, исходила от нескольких маньчжурских принцев. Эшерик заключает, что термин «восстание» возник «чисто политически и оппортунистически», но он имел замечательную стойкость, особенно в популярных источниках. [ 199 ]

6 июня 1900 года лондонская газета «Таймс» использовала термин «восстание» в кавычках, предположительно, чтобы указать, что, по ее мнению, восстание на самом деле было спровоцировано вдовствующей императрицей Цыси. [ 200 ] Историк Ланьсинь Сян называет это восстание «так называемым «боксерским восстанием » , а также заявляет, что «хотя крестьянское восстание не было чем-то новым в истории Китая, война против самых могущественных государств мира была таковой». [ 201 ] В других недавних западных работах восстание называется «Боксерским движением», «Боксерской войной» или «Движением Ихэтуань», тогда как китайские исследователи называют его 义和团运动 (Ихэтуань юньдун), то есть «Движение Ихэтуань». Обсуждая общие и юридические последствия используемой терминологии, немецкий ученый Торальф Кляйн отмечает, что все термины, включая китайские, являются «посмертными интерпретациями конфликта». Он утверждает, что каждый термин, будь то «восстание», «восстание» или «движение», подразумевает разное определение конфликта. Даже термин «Боксерская война», который часто используется учеными на Западе, вызывает вопросы. Ни одна из сторон не сделала официального объявления войны. В императорских указах от 21 июня говорилось о начале военных действий и предписывалось регулярной китайской армии присоединиться к боксерам против армий союзников. Это было фактическое объявление войны. Войска союзников вели себя как солдаты, организовавшие карательную экспедицию в колониальном стиле, а не как солдаты, ведущие объявленную войну с юридическими ограничениями. Союзники воспользовались тем фактом, что Китай не подписал «Законы и обычаи сухопутной войны», ключевой документ, подписанный на конференции 1899 года. Гаагская мирная конференция . Они утверждали, что Китай нарушил положения, которые они сами игнорировали. [ 74 ]

Существует также разница в терминах, касающихся комбатантов. В первых сообщениях, пришедших из Китая в 1898 году, деревенские активисты назывались «Ихэцюань» (Уэйд-Джайлз: И Хо Чуань). Самое раннее использование термина «боксер» содержится в письме миссионерки Грейс Ньютон, написанном в Шаньдуне в сентябре 1899 года. Контекст письма ясно показывает, что на момент его написания слово «боксер» уже было широко известным термином, вероятно, придуманным Артуром Хендерсоном Смитом или Генри Портером, двумя миссионерами, также проживавшими в Шаньдуне. [ 202 ] Смит написал в своей книге 1902 года, что это имя: [ 203 ]

И Хо Цюань ... буквально означает «Кулаки» ( Цюань ) Праведности (или Общественной) ( И ) Гармонии ( Хо ), явно намекая на силу объединенной силы, которая должна была быть выдвинута. Поскольку китайская фраза «кулаки и ноги» означает бокс и борьбу, для приверженцев секты не было более подходящего термина, чем «боксеры» — обозначение, впервые использованное одним или двумя миссионерскими корреспондентами иностранных журналов в Китае. позже общепринятый из-за сложности создания лучшего.

Изображение в СМИ

К 1900 году появилось множество новых форм средств массовой информации, в том числе иллюстрированные газеты и журналы, открытки, плакаты и рекламные объявления, все из которых представляли изображения боксеров и вторгающихся армий. [ 204 ] Восстание освещалось в зарубежной иллюстрированной прессе художниками и фотографами. Также были опубликованы картины и гравюры, в том числе японские гравюры. [ 205 ] В последующие десятилетия боксеры были постоянным предметом комментариев. Выборка включает в себя:

- Лю Э , Путешествие Лао Цаня [ 206 ] сочувственно показывает честного чиновника, пытающегося провести реформы, и изображает боксеров как сектантских повстанцев.

- Фильм 1963 года « 55 дней в Пекине» режиссёра Николаса Рэя с Чарлтоном Хестоном , Авой Гарднер и Дэвидом Нивеном в главных ролях . [ 207 ]

- В 1975 году гонконгская студия братьев Шоу выпустила фильм «Восстание боксеров» ( китайский : 八國聯軍 ; пиньинь : багуо liánjūn ; Уэйд-Джайлз : Па Го Лиен Чун ; букв. «Союзная армия восьми наций») под руководством режиссера Чанг Че . [ 208 ]

- «Последняя императрица» (Бостон, 2007) Книга Анчи Мин описывает долгое правление вдовствующей императрицы Цыси , в котором осада дипломатических миссий является одним из кульминационных событий романа.

- Мо Яня» — «Сандаловая смерть роман, рассказанный с точки зрения жителей деревни во время восстания боксеров. [ 209 ]

См. также

- Гэнцзы Гуобянь Танци

- Императорский Указ о событиях, приведших к подписанию Боксерского протокола

- Список публикаций 1900–1930 годов о боксерском восстании

- Собор Сисику

Ссылки

Цитаты

- ^ Jump up to: а б Харрингтон (2001) , с. 29.

- ^ «Китайская экспедиция помощи (боксерское восстание), 1900–1901» . Музей ветеранов и мемориальный центр . Архивировано из оригинала 16 июля 2014 года . Проверено 20 марта 2017 г.

- ^ Pronin, Alexander (7 November 2000). Война с Желтороссией (in Russian) . Kommersant . Retrieved 6 July 2018.

- ^ Сюй, Иммануэль CY (1978). «Международные отношения позднего Цина, 1866–1905». В Фэрбенке, Джон Кинг (ред.). Кембриджская история Китая . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 127. ИСБН 978-0-521-22029-3 .

- ^ Сян (2003) , стр. 248 .

- ^ Хаммонд Атлас ХХ века . Хаммонд. 1996. ISBN 9780843711493 .

- ^ «Боксерский бунт» . Британская энциклопедия .

- ^ Фэрбанк, Джон Кинг (1983) [1948]. США и Китай . Американская библиотека внешней политики (4-е изд.). Кембридж, Массачусетс: Издательство Гарвардского университета. п. 202. ИСБН 978-0-674-92438-3 .

- ^ Найджел Далзил, Исторический атлас Британской империи пингвинов (2006), стр. 102–103.

- ^ Эндрю Н. Портер, изд. Имперские горизонты британских протестантских миссий, 1880–1914 гг. (Эрдманс, 2003).

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Хаммонд (2023) , с. 131.

- ^ Томпсон (2009) , с. 7.

- ^ Коэн (1997) , с. 114 .

- ^ Эшерик (1987) , стр. xii, 54–59, 96, сл. .

- ^ Сян (2003) , стр. 114 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Коэн (1997) , стр. 19–20.

- ^ Коэн (1997) , стр. 27–30 .

- ^ Сян (2003) , стр. 115 .

- ^ Перселл, Виктор (2010). Боксерское восстание: предыстория . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 125. ИСБН 978-0-521-14812-2 .

- ^ Престон (2000) , с. 25 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Дрисколл (2020) , с. 211.

- ^ Бикерс, Роберт (2011). Борьба за Китай: иностранные дьяволы в империи Цин, 1832–1914 гг . Пингвин.

- ^ Томпсон (2009) , с. 9.

- ^ Эшерик (1987) , с. 77.

- ^ Шуман (2021) , с. 271.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Шуман (2021) , с. 270.

- ^ Эшерик (1987) , с. 123 .

- ^ Эшерик (1987) , стр. 129–130.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Даллин, Дэвид Дж. (2013). «Второй путь к Тихому океану, секция Порт-Артур». Возвышение России в Азии . Читайте книги. ISBN 978-1-4733-8257-2 .

- ^ Пейн, СКМ (1996). «Китайская дипломатия в смятении: Ливадийский договор» . Имперские соперники: Китай, Россия и их спорная граница . Я Шарп. п. 162 . ISBN 978-1-56324-724-8 . Проверено 22 февраля 2018 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Ло Джиу-Хва, Апшур (2008). Энциклопедия всемирной истории, Акерман-Шредер-Терри-Хва Ло, 2008: Энциклопедия всемирной истории . Энциклопедия всемирной истории. Том. 7. Факт в деле. стр. 87–88.