Ботаника

| Part of a series on |

| Biology |

|---|

Ботаника , также называемая наукой о растениях (или науками о растениях ), биологией растений или фитологией , — это наука о жизни растений и раздел биологии . Ботаник , , ученый-растениевед или фитолог — это ученый специализирующийся в этой области. Термин «ботаника» происходит от древнегреческого слова βοτάνη ( botanē ), означающего « пастбище », « травы », « трава » или « корм »; βοτάνη , в свою очередь, происходит от βόσκειν ( боскейн ), «кормить» или «пастись » . [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] Традиционно к ботанике относится также изучение грибов и водорослей соответственно микологов и физиков , причем изучение этих трех групп организмов остается в сфере интересов Международного ботанического конгресса . В настоящее время ботаники (в строгом смысле слова) изучают около 410 000 видов наземных растений , из которых около 391 000 видов являются сосудистыми (в том числе около 369 000 видов цветковых растений ), [ 4 ] и около 20 000 — мохообразные . [ 5 ]

Ботаника зародилась в доисторические времена как травничество , когда древние люди пытались идентифицировать – а затем выращивать – растения, которые были съедобными, ядовитыми и, возможно, лекарственными, что сделало ее одним из первых начинаний человечества. Средневековые лечебные сады , часто пристроенные к монастырям , содержали растения, возможно, имеющие лечебную ценность. Они были предшественниками первых ботанических садов при университетах , основанных с 1540-х годов. Одним из первых был Падуанский ботанический сад . Эти сады способствовали академическому изучению растений. Усилия по каталогизации и описанию их коллекций положили начало систематике растений и привели в 1753 году к биномиальной системе номенклатуры Карла Линнея , которая используется и по сей день для обозначения всех биологических видов.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, new techniques were developed for the study of plants, including methods of optical microscopy and live cell imaging, electron microscopy, analysis of chromosome number, plant chemistry and the structure and function of enzymes and other proteins. In the last two decades of the 20th century, botanists exploited the techniques of molecular genetic analysis, including genomics and proteomics and DNA sequences to classify plants more accurately.

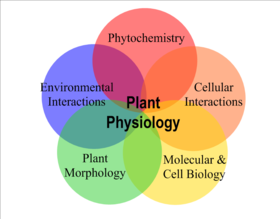

Modern botany is a broad, multidisciplinary subject with contributions and insights from most other areas of science and technology. Research topics include the study of plant structure, growth and differentiation, reproduction, biochemistry and primary metabolism, chemical products, development, diseases, evolutionary relationships, systematics, and plant taxonomy. Dominant themes in 21st century plant science are molecular genetics and epigenetics, which study the mechanisms and control of gene expression during differentiation of plant cells and tissues. Botanical research has diverse applications in providing staple foods, materials such as timber, oil, rubber, fibre and drugs, in modern horticulture, agriculture and forestry, plant propagation, breeding and genetic modification, in the synthesis of chemicals and raw materials for construction and energy production, in environmental management, and the maintenance of biodiversity.

History

[edit]Early botany

[edit]

Botany originated as herbalism, the study and use of plants for their possible medicinal properties.[6] The early recorded history of botany includes many ancient writings and plant classifications. Examples of early botanical works have been found in ancient texts from India dating back to before 1100 BCE,[7][8] Ancient Egypt,[9] in archaic Avestan writings, and in works from China purportedly from before 221 BCE.[7][10]

Modern botany traces its roots back to Ancient Greece specifically to Theophrastus (c. 371–287 BCE), a student of Aristotle who invented and described many of its principles and is widely regarded in the scientific community as the "Father of Botany".[11] His major works, Enquiry into Plants and On the Causes of Plants, constitute the most important contributions to botanical science until the Middle Ages, almost seventeen centuries later.[11][12]

Another work from Ancient Greece that made an early impact on botany is De materia medica, a five-volume encyclopedia about preliminary herbal medicine written in the middle of the first century by Greek physician and pharmacologist Pedanius Dioscorides. De materia medica was widely read for more than 1,500 years.[13] Important contributions from the medieval Muslim world include Ibn Wahshiyya's Nabatean Agriculture, Abū Ḥanīfa Dīnawarī's (828–896) the Book of Plants, and Ibn Bassal's The Classification of Soils. In the early 13th century, Abu al-Abbas al-Nabati, and Ibn al-Baitar (d. 1248) wrote on botany in a systematic and scientific manner.[14][15][16]

In the mid-16th century, botanical gardens were founded in a number of Italian universities. The Padua botanical garden in 1545 is usually considered to be the first which is still in its original location. These gardens continued the practical value of earlier "physic gardens", often associated with monasteries, in which plants were cultivated for suspected medicinal uses. They supported the growth of botany as an academic subject. Lectures were given about the plants grown in the gardens. Botanical gardens came much later to northern Europe; the first in England was the University of Oxford Botanic Garden in 1621.[17]

German physician Leonhart Fuchs (1501–1566) was one of "the three German fathers of botany", along with theologian Otto Brunfels (1489–1534) and physician Hieronymus Bock (1498–1554) (also called Hieronymus Tragus).[18][19] Fuchs and Brunfels broke away from the tradition of copying earlier works to make original observations of their own. Bock created his own system of plant classification.

Physician Valerius Cordus (1515–1544) authored a botanically and pharmacologically important herbal Historia Plantarum in 1544 and a pharmacopoeia of lasting importance, the Dispensatorium in 1546.[20] Naturalist Conrad von Gesner (1516–1565) and herbalist John Gerard (1545–c. 1611) published herbals covering the supposed medicinal uses of plants. Naturalist Ulisse Aldrovandi (1522–1605) was considered the father of natural history, which included the study of plants. In 1665, using an early microscope, Polymath Robert Hooke discovered cells (a term he coined) in cork, and a short time later in living plant tissue.[21]

Early modern botany

[edit]

During the 18th century, systems of plant identification were developed comparable to dichotomous keys, where unidentified plants are placed into taxonomic groups (e.g. family, genus and species) by making a series of choices between pairs of characters. The choice and sequence of the characters may be artificial in keys designed purely for identification (diagnostic keys) or more closely related to the natural or phyletic order of the taxa in synoptic keys.[22] By the 18th century, new plants for study were arriving in Europe in increasing numbers from newly discovered countries and the European colonies worldwide. In 1753, Carl Linnaeus published his Species Plantarum, a hierarchical classification of plant species that remains the reference point for modern botanical nomenclature. This established a standardised binomial or two-part naming scheme where the first name represented the genus and the second identified the species within the genus.[23] For the purposes of identification, Linnaeus's Systema Sexuale classified plants into 24 groups according to the number of their male sexual organs. The 24th group, Cryptogamia, included all plants with concealed reproductive parts, mosses, liverworts, ferns, algae and fungi.[24]

Botany was originally a hobby for upper class women. These women would collect and paint flowers and plants from around the world with scientific accuracy. The paintings were used to record many species that could not be transported or maintained in other environments. Marianne North illustrated over 900 species in extreme detail with watercolor and oil paintings.[25] Her work and many other women's botany work was the beginning of popularizing botany to a wider audience.

Increasing knowledge of plant anatomy, morphology and life cycles led to the realisation that there were more natural affinities between plants than the artificial sexual system of Linnaeus. Adanson (1763), de Jussieu (1789), and Candolle (1819) all proposed various alternative natural systems of classification that grouped plants using a wider range of shared characters and were widely followed. The Candollean system reflected his ideas of the progression of morphological complexity and the later Bentham & Hooker system, which was influential until the mid-19th century, was influenced by Candolle's approach. Darwin's publication of the Origin of Species in 1859 and his concept of common descent required modifications to the Candollean system to reflect evolutionary relationships as distinct from mere morphological similarity.[26]

Botany was greatly stimulated by the appearance of the first "modern" textbook, Matthias Schleiden's Grundzüge der Wissenschaftlichen Botanik, published in English in 1849 as Principles of Scientific Botany.[27] Schleiden was a microscopist and an early plant anatomist who co-founded the cell theory with Theodor Schwann and Rudolf Virchow and was among the first to grasp the significance of the cell nucleus that had been described by Robert Brown in 1831.[28] In 1855, Adolf Fick formulated Fick's laws that enabled the calculation of the rates of molecular diffusion in biological systems.[29]

Late modern botany

[edit]Building upon the gene-chromosome theory of heredity that originated with Gregor Mendel (1822–1884), August Weismann (1834–1914) proved that inheritance only takes place through gametes. No other cells can pass on inherited characters.[30] The work of Katherine Esau (1898–1997) on plant anatomy is still a major foundation of modern botany. Her books Plant Anatomy and Anatomy of Seed Plants have been key plant structural biology texts for more than half a century.[31][32]

The discipline of plant ecology was pioneered in the late 19th century by botanists such as Eugenius Warming, who produced the hypothesis that plants form communities, and his mentor and successor Christen C. Raunkiær whose system for describing plant life forms is still in use today. The concept that the composition of plant communities such as temperate broadleaf forest changes by a process of ecological succession was developed by Henry Chandler Cowles, Arthur Tansley and Frederic Clements. Clements is credited with the idea of climax vegetation as the most complex vegetation that an environment can support and Tansley introduced the concept of ecosystems to biology.[33][34][35] Building on the extensive earlier work of Alphonse de Candolle, Nikolai Vavilov (1887–1943) produced accounts of the biogeography, centres of origin, and evolutionary history of economic plants.[36]

Particularly since the mid-1960s there have been advances in understanding of the physics of plant physiological processes such as transpiration (the transport of water within plant tissues), the temperature dependence of rates of water evaporation from the leaf surface and the molecular diffusion of water vapour and carbon dioxide through stomatal apertures. These developments, coupled with new methods for measuring the size of stomatal apertures, and the rate of photosynthesis have enabled precise description of the rates of gas exchange between plants and the atmosphere.[37][38] Innovations in statistical analysis by Ronald Fisher,[39] Frank Yates and others at Rothamsted Experimental Station facilitated rational experimental design and data analysis in botanical research.[40] The discovery and identification of the auxin plant hormones by Kenneth V. Thimann in 1948 enabled regulation of plant growth by externally applied chemicals. Frederick Campion Steward pioneered techniques of micropropagation and plant tissue culture controlled by plant hormones.[41] The synthetic auxin 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid or 2,4-D was one of the first commercial synthetic herbicides.[42]

20th century developments in plant biochemistry have been driven by modern techniques of organic chemical analysis, such as spectroscopy, chromatography and electrophoresis. With the rise of the related molecular-scale biological approaches of molecular biology, genomics, proteomics and metabolomics, the relationship between the plant genome and most aspects of the biochemistry, physiology, morphology and behaviour of plants can be subjected to detailed experimental analysis.[43] The concept originally stated by Gottlieb Haberlandt in 1902[44] that all plant cells are totipotent and can be grown in vitro ultimately enabled the use of genetic engineering experimentally to knock out a gene or genes responsible for a specific trait, or to add genes such as GFP that report when a gene of interest is being expressed. These technologies enable the biotechnological use of whole plants or plant cell cultures grown in bioreactors to synthesise pesticides, antibiotics or other pharmaceuticals, as well as the practical application of genetically modified crops designed for traits such as improved yield.[45]

Modern morphology recognises a continuum between the major morphological categories of root, stem (caulome), leaf (phyllome) and trichome.[46] Furthermore, it emphasises structural dynamics.[47] Modern systematics aims to reflect and discover phylogenetic relationships between plants.[48][49][50][51] Modern Molecular phylogenetics largely ignores morphological characters, relying on DNA sequences as data. Molecular analysis of DNA sequences from most families of flowering plants enabled the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group to publish in 1998 a phylogeny of flowering plants, answering many of the questions about relationships among angiosperm families and species.[52] The theoretical possibility of a practical method for identification of plant species and commercial varieties by DNA barcoding is the subject of active current research.[53][54]

Branches of botany

[edit]Botany is divided along several axes.

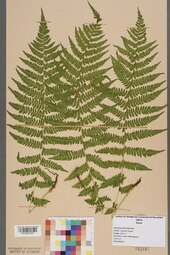

Some subfields of botany relate to particular groups of organisms. Divisions related to the broader historical sense of botany include bacteriology, mycology (or fungology) and phycology - the study of bacteria, fungi and algae respectively - with lichenology as a subfield of mycology. The narrower sense of botany in the sense of the study of embryophytes (land plants) is disambiguated as phytology. Bryology is the study of mosses (and in the broader sense also liverworts and hornworts). Pteridology (or filicology) is the study of ferns and allied plants. A number of other taxa of ranks varying from family to subgenus have terms for their study, including agrostology (or graminology) for the study of grasses, synantherology for the study of composites, and batology for the study of brambles.

Study can also be divided by guild rather than clade or grade. Dendrology is the study of woody plants.

Many divisions of biology have botanical subfields. These are commonly denoted by prefixing the word plant (e.g. plant taxonomy, plant ecology, plant anatomy, plant morphology, plant systematics, plant ecology), or prefixing or substituting the prefix phyto- (e.g. phytochemistry, phytogeography). The study of fossil plants is palaeobotany. Other fields are denoted by adding or substituting the word botany (e.g. systematic botany).

Phytosociology is a subfield of plant ecology that classifies and studies communities of plants.

The intersection of fields from the above pair of categories gives rise to fields such as bryogeography (the study of the distribution of mosses).

Different parts of plants also give rise to their own subfields, including xylology, carpology (or fructology) and palynology, these been the study of wood, fruit and pollen/spores respectively.

Botany also overlaps on the one hand with agriculture, horticulture and silviculture, and on the other hand with medicine and pharmacology, giving rise to fields such as agronomy, horticultural botany, phytopathology and phytopharmacology.

Scope and importance

[edit]

The study of plants is vital because they underpin almost all animal life on Earth by generating a large proportion of the oxygen and food that provide humans and other organisms with aerobic respiration with the chemical energy they need to exist. Plants, algae and cyanobacteria are the major groups of organisms that carry out photosynthesis, a process that uses the energy of sunlight to convert water and carbon dioxide[55] into sugars that can be used both as a source of chemical energy and of organic molecules that are used in the structural components of cells.[56] As a by-product of photosynthesis, plants release oxygen into the atmosphere, a gas that is required by nearly all living things to carry out cellular respiration. In addition, they are influential in the global carbon and water cycles and plant roots bind and stabilise soils, preventing soil erosion.[57] Plants are crucial to the future of human society as they provide food, oxygen, biochemicals, and products for people, as well as creating and preserving soil.[58]

Historically, all living things were classified as either animals or plants[59] and botany covered the study of all organisms not considered animals.[60] Botanists examine both the internal functions and processes within plant organelles, cells, tissues, whole plants, plant populations and plant communities. At each of these levels, a botanist may be concerned with the classification (taxonomy), phylogeny and evolution, structure (anatomy and morphology), or function (physiology) of plant life.[61]

The strictest definition of "plant" includes only the "land plants" or embryophytes, which include seed plants (gymnosperms, including the pines, and flowering plants) and the free-sporing cryptogams including ferns, clubmosses, liverworts, hornworts and mosses. Embryophytes are multicellular eukaryotes descended from an ancestor that obtained its energy from sunlight by photosynthesis. They have life cycles with alternating haploid and diploid phases. The sexual haploid phase of embryophytes, known as the gametophyte, nurtures the developing diploid embryo sporophyte within its tissues for at least part of its life,[62] even in the seed plants, where the gametophyte itself is nurtured by its parent sporophyte.[63] Other groups of organisms that were previously studied by botanists include bacteria (now studied in bacteriology), fungi (mycology) – including lichen-forming fungi (lichenology), non-chlorophyte algae (phycology), and viruses (virology). However, attention is still given to these groups by botanists, and fungi (including lichens) and photosynthetic protists are usually covered in introductory botany courses.[64][65]

Palaeobotanists study ancient plants in the fossil record to provide information about the evolutionary history of plants. Cyanobacteria, the first oxygen-releasing photosynthetic organisms on Earth, are thought to have given rise to the ancestor of plants by entering into an endosymbiotic relationship with an early eukaryote, ultimately becoming the chloroplasts in plant cells. The new photosynthetic plants (along with their algal relatives) accelerated the rise in atmospheric oxygen started by the cyanobacteria, changing the ancient oxygen-free, reducing, atmosphere to one in which free oxygen has been abundant for more than 2 billion years.[66][67]

Among the important botanical questions of the 21st century are the role of plants as primary producers in the global cycling of life's basic ingredients: energy, carbon, oxygen, nitrogen and water, and ways that our plant stewardship can help address the global environmental issues of resource management, conservation, human food security, biologically invasive organisms, carbon sequestration, climate change, and sustainability.[68]

Human nutrition

[edit]

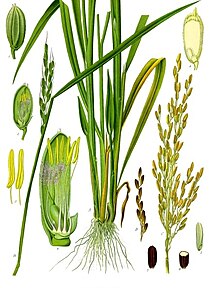

Virtually all staple foods come either directly from primary production by plants, or indirectly from animals that eat them.[69] Plants and other photosynthetic organisms are at the base of most food chains because they use the energy from the sun and nutrients from the soil and atmosphere, converting them into a form that can be used by animals. This is what ecologists call the first trophic level.[70] The modern forms of the major staple foods, such as hemp, teff, maize, rice, wheat and other cereal grasses, pulses, bananas and plantains,[71] as well as hemp, flax and cotton grown for their fibres, are the outcome of prehistoric selection over thousands of years from among wild ancestral plants with the most desirable characteristics.[72]

Botanists study how plants produce food and how to increase yields, for example through plant breeding, making their work important to humanity's ability to feed the world and provide food security for future generations.[73] Botanists also study weeds, which are a considerable problem in agriculture, and the biology and control of plant pathogens in agriculture and natural ecosystems.[74] Ethnobotany is the study of the relationships between plants and people. When applied to the investigation of historical plant–people relationships ethnobotany may be referred to as archaeobotany or palaeoethnobotany.[75] Some of the earliest plant-people relationships arose between the indigenous people of Canada in identifying edible plants from inedible plants. This relationship the indigenous people had with plants was recorded by ethnobotanists.[76]

Plant biochemistry

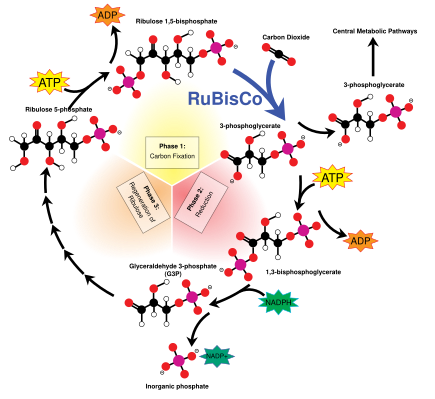

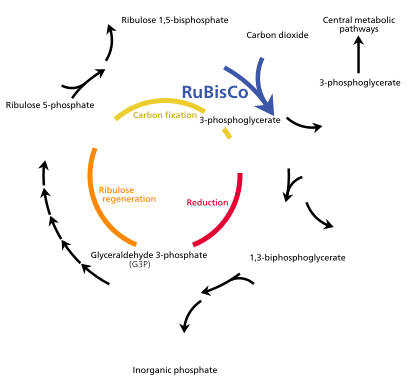

[edit]Plant biochemistry is the study of the chemical processes used by plants. Some of these processes are used in their primary metabolism like the photosynthetic Calvin cycle and crassulacean acid metabolism.[77] Others make specialised materials like the cellulose and lignin used to build their bodies, and secondary products like resins and aroma compounds.

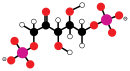

Plants and various other groups of photosynthetic eukaryotes collectively known as "algae" have unique organelles known as chloroplasts. Chloroplasts are thought to be descended from cyanobacteria that formed endosymbiotic relationships with ancient plant and algal ancestors. Chloroplasts and cyanobacteria contain the blue-green pigment chlorophyll a.[78] Chlorophyll a (as well as its plant and green algal-specific cousin chlorophyll b)[a] absorbs light in the blue-violet and orange/red parts of the spectrum while reflecting and transmitting the green light that we see as the characteristic colour of these organisms. The energy in the red and blue light that these pigments absorb is used by chloroplasts to make energy-rich carbon compounds from carbon dioxide and water by oxygenic photosynthesis, a process that generates molecular oxygen (O2) as a by-product.

The light energy captured by chlorophyll a is initially in the form of electrons (and later a proton gradient) that's used to make molecules of ATP and NADPH which temporarily store and transport energy. Their energy is used in the light-independent reactions of the Calvin cycle by the enzyme rubisco to produce molecules of the 3-carbon sugar glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate (G3P). Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate is the first product of photosynthesis and the raw material from which glucose and almost all other organic molecules of biological origin are synthesised. Some of the glucose is converted to starch which is stored in the chloroplast.[82] Starch is the characteristic energy store of most land plants and algae, while inulin, a polymer of fructose is used for the same purpose in the sunflower family Asteraceae. Some of the glucose is converted to sucrose (common table sugar) for export to the rest of the plant.

Unlike in animals (which lack chloroplasts), plants and their eukaryote relatives have delegated many biochemical roles to their chloroplasts, including synthesising all their fatty acids,[83][84] and most amino acids.[85] The fatty acids that chloroplasts make are used for many things, such as providing material to build cell membranes out of and making the polymer cutin which is found in the plant cuticle that protects land plants from drying out. [86]

Plants synthesise a number of unique polymers like the polysaccharide molecules cellulose, pectin and xyloglucan[87] from which the land plant cell wall is constructed.[88] Vascular land plants make lignin, a polymer used to strengthen the secondary cell walls of xylem tracheids and vessels to keep them from collapsing when a plant sucks water through them under water stress. Lignin is also used in other cell types like sclerenchyma fibres that provide structural support for a plant and is a major constituent of wood. Sporopollenin is a chemically resistant polymer found in the outer cell walls of spores and pollen of land plants responsible for the survival of early land plant spores and the pollen of seed plants in the fossil record. It is widely regarded as a marker for the start of land plant evolution during the Ordovician period.[89] The concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere today is much lower than it was when plants emerged onto land during the Ordovician and Silurian periods. Many monocots like maize and the pineapple and some dicots like the Asteraceae have since independently evolved[90] pathways like Crassulacean acid metabolism and the C4 carbon fixation pathway for photosynthesis which avoid the losses resulting from photorespiration in the more common C3 carbon fixation pathway. These biochemical strategies are unique to land plants.

Medicine and materials

[edit]Phytochemistry is a branch of plant biochemistry primarily concerned with the chemical substances produced by plants during secondary metabolism.[91] Some of these compounds are toxins such as the alkaloid coniine from hemlock. Others, such as the essential oils peppermint oil and lemon oil are useful for their aroma, as flavourings and spices (e.g., capsaicin), and in medicine as pharmaceuticals as in opium from opium poppies. Many medicinal and recreational drugs, such as tetrahydrocannabinol (active ingredient in cannabis), caffeine, morphine and nicotine come directly from plants. Others are simple derivatives of botanical natural products. For example, the pain killer aspirin is the acetyl ester of salicylic acid, originally isolated from the bark of willow trees,[92] and a wide range of opiate painkillers like heroin are obtained by chemical modification of morphine obtained from the opium poppy.[93] Popular stimulants come from plants, such as caffeine from coffee, tea and chocolate, and nicotine from tobacco. Most alcoholic beverages come from fermentation of carbohydrate-rich plant products such as barley (beer), rice (sake) and grapes (wine).[94] Native Americans have used various plants as ways of treating illness or disease for thousands of years.[95] This knowledge Native Americans have on plants has been recorded by enthnobotanists and then in turn has been used by pharmaceutical companies as a way of drug discovery.[96]

Plants can synthesise coloured dyes and pigments such as the anthocyanins responsible for the red colour of red wine, yellow weld and blue woad used together to produce Lincoln green, indoxyl, source of the blue dye indigo traditionally used to dye denim and the artist's pigments gamboge and rose madder.

Sugar, starch, cotton, linen, hemp, some types of rope, wood and particle boards, papyrus and paper, vegetable oils, wax, and natural rubber are examples of commercially important materials made from plant tissues or their secondary products. Charcoal, a pure form of carbon made by pyrolysis of wood, has a long history as a metal-smelting fuel, as a filter material and adsorbent and as an artist's material and is one of the three ingredients of gunpowder. Cellulose, the world's most abundant organic polymer,[97] can be converted into energy, fuels, materials and chemical feedstock. Products made from cellulose include rayon and cellophane, wallpaper paste, biobutanol and gun cotton. Sugarcane, rapeseed and soy are some of the plants with a highly fermentable sugar or oil content that are used as sources of biofuels, important alternatives to fossil fuels, such as biodiesel.[98] Sweetgrass was used by Native Americans to ward off bugs like mosquitoes.[99] These bug repelling properties of sweetgrass were later found by the American Chemical Society in the molecules phytol and coumarin.[99]

Plant ecology

[edit]

Plant ecology is the science of the functional relationships between plants and their habitats – the environments where they complete their life cycles. Plant ecologists study the composition of local and regional floras, their biodiversity, genetic diversity and fitness, the adaptation of plants to their environment, and their competitive or mutualistic interactions with other species.[101] Some ecologists even rely on empirical data from indigenous people that is gathered by ethnobotanists.[102] This information can relay a great deal of information on how the land once was thousands of years ago and how it has changed over that time.[102] The goals of plant ecology are to understand the causes of their distribution patterns, productivity, environmental impact, evolution, and responses to environmental change.[103]

Plants depend on certain edaphic (soil) and climatic factors in their environment but can modify these factors too. For example, they can change their environment's albedo, increase runoff interception, stabilise mineral soils and develop their organic content, and affect local temperature. Plants compete with other organisms in their ecosystem for resources.[104][105] They interact with their neighbours at a variety of spatial scales in groups, populations and communities that collectively constitute vegetation. Regions with characteristic vegetation types and dominant plants as well as similar abiotic and biotic factors, climate, and geography make up biomes like tundra or tropical rainforest.[106]

Herbivores eat plants, but plants can defend themselves and some species are parasitic or even carnivorous. Other organisms form mutually beneficial relationships with plants. For example, mycorrhizal fungi and rhizobia provide plants with nutrients in exchange for food, ants are recruited by ant plants to provide protection,[107] honey bees, bats and other animals pollinate flowers[108][109] and humans and other animals[110] act as dispersal vectors to spread spores and seeds.

Plants, climate and environmental change

[edit]Plant responses to climate and other environmental changes can inform our understanding of how these changes affect ecosystem function and productivity. For example, plant phenology can be a useful proxy for temperature in historical climatology, and the biological impact of climate change and global warming. Palynology, the analysis of fossil pollen deposits in sediments from thousands or millions of years ago allows the reconstruction of past climates.[111] Estimates of atmospheric CO2 concentrations since the Palaeozoic have been obtained from stomatal densities and the leaf shapes and sizes of ancient land plants.[112] Ozone depletion can expose plants to higher levels of ultraviolet radiation-B (UV-B), resulting in lower growth rates.[113] Moreover, information from studies of community ecology, plant systematics, and taxonomy is essential to understanding vegetation change, habitat destruction and species extinction.[114]

Genetics

[edit]

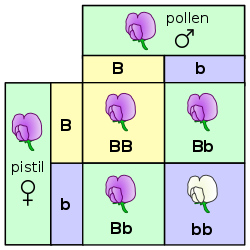

Inheritance in plants follows the same fundamental principles of genetics as in other multicellular organisms. Gregor Mendel discovered the genetic laws of inheritance by studying inherited traits such as shape in Pisum sativum (peas). What Mendel learned from studying plants has had far-reaching benefits outside of botany. Similarly, "jumping genes" were discovered by Barbara McClintock while she was studying maize.[115] Nevertheless, there are some distinctive genetic differences between plants and other organisms.

Species boundaries in plants may be weaker than in animals, and cross species hybrids are often possible. A familiar example is peppermint, Mentha × piperita, a sterile hybrid between Mentha aquatica and spearmint, Mentha spicata.[116] The many cultivated varieties of wheat are the result of multiple inter- and intra-specific crosses between wild species and their hybrids.[117] Angiosperms with monoecious flowers often have self-incompatibility mechanisms that operate between the pollen and stigma so that the pollen either fails to reach the stigma or fails to germinate and produce male gametes.[118] This is one of several methods used by plants to promote outcrossing.[119] In many land plants the male and female gametes are produced by separate individuals. These species are said to be dioecious when referring to vascular plant sporophytes and dioicous when referring to bryophyte gametophytes.[120]

Charles Darwin in his 1878 book The Effects of Cross and Self-Fertilization in the Vegetable Kingdom[121] at the start of chapter XII noted "The first and most important of the conclusions which may be drawn from the observations given in this volume, is that generally cross-fertilisation is beneficial and self-fertilisation often injurious, at least with the plants on which I experimented." An important adaptive benefit of outcrossing is that it allows the masking of deleterious mutations in the genome of progeny. This beneficial effect is also known as hybrid vigor or heterosis. Once outcrossing is established, subsequent switching to inbreeding becomes disadvantageous since it allows expression of the previously masked deleterious recessive mutations, commonly referred to as inbreeding depression.

Unlike in higher animals, where parthenogenesis is rare, asexual reproduction may occur in plants by several different mechanisms. The formation of stem tubers in potato is one example. Particularly in arctic or alpine habitats, where opportunities for fertilisation of flowers by animals are rare, plantlets or bulbs, may develop instead of flowers, replacing sexual reproduction with asexual reproduction and giving rise to clonal populations genetically identical to the parent. This is one of several types of apomixis that occur in plants. Apomixis can also happen in a seed, producing a seed that contains an embryo genetically identical to the parent.[122]

Most sexually reproducing organisms are diploid, with paired chromosomes, but doubling of their chromosome number may occur due to errors in cytokinesis. This can occur early in development to produce an autopolyploid or partly autopolyploid organism, or during normal processes of cellular differentiation to produce some cell types that are polyploid (endopolyploidy), or during gamete formation. An allopolyploid plant may result from a hybridisation event between two different species. Both autopolyploid and allopolyploid plants can often reproduce normally, but may be unable to cross-breed successfully with the parent population because there is a mismatch in chromosome numbers. These plants that are reproductively isolated from the parent species but live within the same geographical area, may be sufficiently successful to form a new species.[123] Some otherwise sterile plant polyploids can still reproduce vegetatively or by seed apomixis, forming clonal populations of identical individuals.[123] Durum wheat is a fertile tetraploid allopolyploid, while bread wheat is a fertile hexaploid. The commercial banana is an example of a sterile, seedless triploid hybrid. Common dandelion is a triploid that produces viable seeds by apomictic seed.

As in other eukaryotes, the inheritance of endosymbiotic organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts in plants is non-Mendelian. Chloroplasts are inherited through the male parent in gymnosperms but often through the female parent in flowering plants.[124]

Molecular genetics

[edit]

A considerable amount of new knowledge about plant function comes from studies of the molecular genetics of model plants such as the Thale cress, Arabidopsis thaliana, a weedy species in the mustard family (Brassicaceae).[91] The genome or hereditary information contained in the genes of this species is encoded by about 135 million base pairs of DNA, forming one of the smallest genomes among flowering plants. Arabidopsis was the first plant to have its genome sequenced, in 2000.[125] The sequencing of some other relatively small genomes, of rice (Oryza sativa)[126] and Brachypodium distachyon,[127] has made them important model species for understanding the genetics, cellular and molecular biology of cereals, grasses and monocots generally.

Model plants such as Arabidopsis thaliana are used for studying the molecular biology of plant cells and the chloroplast. Ideally, these organisms have small genomes that are well known or completely sequenced, small stature and short generation times. Corn has been used to study mechanisms of photosynthesis and phloem loading of sugar in C4 plants.[128] The single celled green alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, while not an embryophyte itself, contains a green-pigmented chloroplast related to that of land plants, making it useful for study.[129] A red alga Cyanidioschyzon merolae has also been used to study some basic chloroplast functions.[130] Spinach,[131] peas,[132] soybeans and a moss Physcomitrella patens are commonly used to study plant cell biology.[133]

Agrobacterium tumefaciens, a soil rhizosphere bacterium, can attach to plant cells and infect them with a callus-inducing Ti plasmid by horizontal gene transfer, causing a callus infection called crown gall disease. Schell and Van Montagu (1977) hypothesised that the Ti plasmid could be a natural vector for introducing the Nif gene responsible for nitrogen fixation in the root nodules of legumes and other plant species.[134] Today, genetic modification of the Ti plasmid is one of the main techniques for introduction of transgenes to plants and the creation of genetically modified crops.

Epigenetics

[edit]Epigenetics is the study of heritable changes in gene function that cannot be explained by changes in the underlying DNA sequence[135] but cause the organism's genes to behave (or "express themselves") differently.[136] One example of epigenetic change is the marking of the genes by DNA methylation which determines whether they will be expressed or not. Gene expression can also be controlled by repressor proteins that attach to silencer regions of the DNA and prevent that region of the DNA code from being expressed. Epigenetic marks may be added or removed from the DNA during programmed stages of development of the plant, and are responsible, for example, for the differences between anthers, petals and normal leaves, despite the fact that they all have the same underlying genetic code. Epigenetic changes may be temporary or may remain through successive cell divisions for the remainder of the cell's life. Some epigenetic changes have been shown to be heritable,[137] while others are reset in the germ cells.

Epigenetic changes in eukaryotic biology serve to regulate the process of cellular differentiation. During morphogenesis, totipotent stem cells become the various pluripotent cell lines of the embryo, which in turn become fully differentiated cells. A single fertilised egg cell, the zygote, gives rise to the many different plant cell types including parenchyma, xylem vessel elements, phloem sieve tubes, guard cells of the epidermis, etc. as it continues to divide. The process results from the epigenetic activation of some genes and inhibition of others.[138]

Unlike animals, many plant cells, particularly those of the parenchyma, do not terminally differentiate, remaining totipotent with the ability to give rise to a new individual plant. Exceptions include highly lignified cells, the sclerenchyma and xylem which are dead at maturity, and the phloem sieve tubes which lack nuclei. While plants use many of the same epigenetic mechanisms as animals, such as chromatin remodelling, an alternative hypothesis is that plants set their gene expression patterns using positional information from the environment and surrounding cells to determine their developmental fate.[139]

Epigenetic changes can lead to paramutations, which do not follow the Mendelian heritage rules. These epigenetic marks are carried from one generation to the next, with one allele inducing a change on the other.[140]

Plant evolution

[edit]

The chloroplasts of plants have a number of biochemical, structural and genetic similarities to cyanobacteria, (commonly but incorrectly known as "blue-green algae") and are thought to be derived from an ancient endosymbiotic relationship between an ancestral eukaryotic cell and a cyanobacterial resident.[141][142][143][144]

The algae are a polyphyletic group and are placed in various divisions, some more closely related to plants than others. There are many differences between them in features such as cell wall composition, biochemistry, pigmentation, chloroplast structure and nutrient reserves. The algal division Charophyta, sister to the green algal division Chlorophyta, is considered to contain the ancestor of true plants.[145] The Charophyte class Charophyceae and the land plant sub-kingdom Embryophyta together form the monophyletic group or clade Streptophytina.[146]

Nonvascular land plants are embryophytes that lack the vascular tissues xylem and phloem. They include mosses, liverworts and hornworts. Pteridophytic vascular plants with true xylem and phloem that reproduced by spores germinating into free-living gametophytes evolved during the Silurian period and diversified into several lineages during the late Silurian and early Devonian. Representatives of the lycopods have survived to the present day. By the end of the Devonian period, several groups, including the lycopods, sphenophylls and progymnosperms, had independently evolved "megaspory" – their spores were of two distinct sizes, larger megaspores and smaller microspores. Their reduced gametophytes developed from megaspores retained within the spore-producing organs (megasporangia) of the sporophyte, a condition known as endospory. Seeds consist of an endosporic megasporangium surrounded by one or two sheathing layers (integuments). The young sporophyte develops within the seed, which on germination splits to release it. The earliest known seed plants date from the latest Devonian Famennian stage.[147][148] Following the evolution of the seed habit, seed plants diversified, giving rise to a number of now-extinct groups, including seed ferns, as well as the modern gymnosperms and angiosperms.[149] Gymnosperms produce "naked seeds" not fully enclosed in an ovary; modern representatives include conifers, cycads, Ginkgo, and Gnetales. Angiosperms produce seeds enclosed in a structure such as a carpel or an ovary.[150][151] Ongoing research on the molecular phylogenetics of living plants appears to show that the angiosperms are a sister clade to the gymnosperms.[152]

Plant physiology

[edit]

Plant physiology encompasses all the internal chemical and physical activities of plants associated with life.[153] Chemicals obtained from the air, soil and water form the basis of all plant metabolism. The energy of sunlight, captured by oxygenic photosynthesis and released by cellular respiration, is the basis of almost all life. Photoautotrophs, including all green plants, algae and cyanobacteria gather energy directly from sunlight by photosynthesis. Heterotrophs including all animals, all fungi, all completely parasitic plants, and non-photosynthetic bacteria take in organic molecules produced by photoautotrophs and respire them or use them in the construction of cells and tissues.[154] Respiration is the oxidation of carbon compounds by breaking them down into simpler structures to release the energy they contain, essentially the opposite of photosynthesis.[155]

Molecules are moved within plants by transport processes that operate at a variety of spatial scales. Subcellular transport of ions, electrons and molecules such as water and enzymes occurs across cell membranes. Minerals and water are transported from roots to other parts of the plant in the transpiration stream. Diffusion, osmosis, and active transport and mass flow are all different ways transport can occur.[156] Examples of elements that plants need to transport are nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and sulfur. In vascular plants, these elements are extracted from the soil as soluble ions by the roots and transported throughout the plant in the xylem. Most of the elements required for plant nutrition come from the chemical breakdown of soil minerals.[157] Sucrose produced by photosynthesis is transported from the leaves to other parts of the plant in the phloem and plant hormones are transported by a variety of processes.

Plant hormones

[edit]

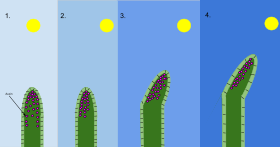

2 Когда солнце находится под углом и светит только на одну сторону побега, ауксин перемещается на противоположную сторону и стимулирует там удлинение клеток .

3 и 4. Дополнительный рост на этой стороне заставляет побег наклоняться к солнцу . [ 158 ]

Растения не пассивны, а реагируют на внешние сигналы, такие как свет, прикосновение и травмы, перемещаясь или растущих в направлении раздражителя или от него, в зависимости от обстоятельств. Осязаемыми свидетельствами сенсорной чувствительности являются почти мгновенное разрушение листочков Mimosa pudica , ловушки для насекомых венеринской мухоловки и пузырчатки , а также поллинии орхидей. [ 159 ]

Гипотеза о том, что рост и развитие растений координируется растительными гормонами или регуляторами роста растений, впервые возникла в конце 19 века. Дарвин экспериментировал с движением побегов и корней растений к свету. [ 160 ] и гравитация , и пришел к выводу: «Едва ли будет преувеличением сказать, что кончик корешка… действует как мозг одного из низших животных… направляя несколько движений». [ 161 ] Примерно в то же время роль ауксинов (от греч. auxein — расти) в контроле роста растений впервые обозначила голландский учёный Фриц Вент . [ 162 ] Первый известный ауксин, индол-3-уксусная кислота (ИУК), способствующий росту клеток, был выделен из растений лишь примерно 50 лет спустя. [ 163 ] Это соединение опосредует тропическую реакцию побегов и корней на свет и силу тяжести. [ 164 ] Открытие в 1939 году того, что каллус растений можно поддерживать в культуре, содержащей ИУК, а затем наблюдение в 1947 году, что его можно стимулировать к образованию корней и побегов путем контроля концентрации гормонов роста, стали ключевыми шагами в развитии биотехнологии растений и генетической модификации. . [ 165 ]

Цитокинины — это класс растительных гормонов, названных в честь их контроля деления клеток (особенно цитокинеза ). Природный цитокинин зеатин был обнаружен в кукурузе Zea mays и является производным пурина аденина . Зеатин вырабатывается в корнях и транспортируется в побеги в ксилеме, где способствует делению клеток, развитию почек и зеленению хлоропластов. [ 166 ] [ 167 ] Гибберелины представляют , такие как гибберелиновая кислота, собой дитерпены, синтезируемые из ацетил-КоА по мевалонатному пути . Они участвуют в прорастании и нарушении покоя семян, в регулировании высоты растений путем контроля удлинения стебля и контроля цветения. [ 168 ] Абсцизовая кислота (АБК) встречается во всех наземных растениях, кроме печеночников, и синтезируется из каротиноидов в хлоропластах и других пластидах. Он ингибирует деление клеток, способствует созреванию и покою семян, а также способствует закрытию устьиц. Он был назван так потому, что первоначально считалось, что он контролирует отпадение . [ 169 ] Этилен — газообразный гормон, вырабатываемый во всех тканях высших растений из метионина . Теперь известно, что это гормон, который стимулирует или регулирует созревание и опадение плодов. [ 170 ] [ 171 ] и он, или синтетический регулятор роста этефон , который быстро метаболизируется с образованием этилена, используются в промышленных масштабах для ускорения созревания хлопка, ананасов и других климактерических культур.

Другой класс фитогормонов — жасмонаты , впервые выделенные из масла Jasminum grandiflorum. [ 172 ] который регулирует реакцию на рану у растений, разблокируя экспрессию генов, необходимых для системной приобретенной реакции устойчивости к атаке патогенов. [ 173 ]

Помимо того, что свет является основным источником энергии для растений, он действует как сигнальное устройство, предоставляя растению информацию, например, сколько солнечного света растение получает каждый день. Это может привести к адаптивным изменениям в процессе, известном как фотоморфогенез . Фитохромы — фоторецепторы растений, чувствительные к свету. [ 174 ]

Анатомия и морфология растений

[ редактировать ]

Анатомия растений — это изучение строения растительных клеток и тканей, тогда как морфология растений — это изучение их внешней формы. [ 175 ] Все растения являются многоклеточными эукариотами, их ДНК хранится в ядрах. [ 176 ] [ 177 ] К характерным особенностям растительных клеток , отличающим их от клеток животных и грибов, относятся первичная клеточная стенка, состоящая из полисахаридов целлюлозы , гемицеллюлозы и пектина . [ 178 ] более крупные вакуоли , чем в клетках животных, и наличие пластид с уникальными фотосинтетическими и биосинтетическими функциями, как в хлоропластах. Другие пластиды содержат продукты хранения, такие как крахмал ( амилопласты ) или липиды ( элайопласты ). Уникально, клетки стрептофитов и клетки зеленых водорослей отряда Trentepohliales. [ 179 ] делятся путем построения фрагмопласта в качестве шаблона для построения клеточной пластинки на поздних стадиях клеточного деления . [ 82 ]

Тела сосудистых растений , включая плауны , папоротники и семенные растения ( голосеменные и покрытосеменные ), обычно имеют надземную и подземную подсистемы. Побеги с состоят из стеблей зелеными фотосинтезирующими листьями и репродуктивными структурами. Подземные васкуляризированные корни несут корневые волоски и обычно лишены хлорофилла. на кончиках [ 181 ] Несосудистые растения, печеночники , роголистники и мхи не образуют проникающих в землю сосудистых корней, и большая часть растений участвует в фотосинтезе. [ 182 ] Поколение спорофитов у печеночников не является фотосинтезирующим, но может частично удовлетворять свои энергетические потребности за счет фотосинтеза у мхов и роголистников. [ 183 ]

Корневая система и система побегов взаимозависимы: обычно нефотосинтетическая корневая система зависит от побеговой системы для питания, а обычно фотосинтетическая побеговая система зависит от воды и минералов корневой системы. [ 181 ] Клетки каждой системы способны создавать клетки другой и давать придаточные побеги или корни. [ 184 ] Столоны и клубни являются примерами побегов, у которых могут образовываться корни. [ 185 ] Корни, которые распространяются близко к поверхности, например, у ивы, могут дать побеги и, в конечном итоге, новые растения. [ 186 ] В случае потери одной из систем другая часто может восстановить ее. Фактически, из одного листа можно вырастить целое растение, как в случае с растениями секты Streptocarpus . Сенполия , [ 187 ] или даже одну клетку , которая может дедифференцироваться в каллус (массу неспециализированных клеток), из которого может вырасти новое растение. [ 184 ] У сосудистых растений ксилема и флоэма являются проводящими тканями, которые транспортируют ресурсы между побегами и корнями. Корни часто приспособлены для хранения пищевых продуктов, таких как сахар или крахмал . [ 181 ] как в сахарной свекле и моркови. [ 186 ]

Стебли в основном обеспечивают поддержку листьям и репродуктивным структурам, но могут хранить воду в суккулентных растениях, таких как кактусы картофеля , пищу, как в клубнях , или размножаться вегетативно, как в столонах растений клубники , или в процессе отводков . [ 188 ] Листья собирают солнечный свет и осуществляют фотосинтез . [ 189 ] Большие, плоские, гибкие, зеленые листья называются лиственными. [ 190 ] Голосеменные растения , такие как хвойные , саговники , гинкго и гнетофиты, представляют собой семенные растения с открытыми семенами. [ 191 ] Покрытосеменные – это семенные растения , которые дают цветы и имеют закрытые семена. [ 150 ] Древесные растения, такие как азалии и дубы , проходят вторичную фазу роста, в результате которой образуются два дополнительных типа тканей: древесина (вторичная ксилема ) и кора (вторичная флоэма и пробка ). Все голосеменные и многие покрытосеменные растения являются древесными растениями. [ 192 ] Некоторые растения размножаются половым путем, некоторые бесполым, а некоторые - обоими способами. [ 193 ]

Хотя ссылки на основные морфологические категории, такие как корень, стебель, лист и трихома, полезны, следует иметь в виду, что эти категории связаны через промежуточные формы, так что в результате получается континуум между категориями. [ 194 ] Более того, структуры можно рассматривать как процессы, то есть комбинации процессов. [ 47 ]

Систематическая ботаника

[ редактировать ]

Систематическая ботаника является частью систематической биологии, которая занимается ареалом и разнообразием организмов и их взаимоотношениями, в частности, определяемыми их эволюционной историей. [ 195 ] Он включает или связан с биологической классификацией, научной таксономией и филогенетикой . Биологическая классификация — это метод, с помощью которого ботаники группируют организмы в такие категории, как роды или виды . Биологическая классификация — это форма научной систематики . Современная систематика уходит корнями в работы Карла Линнея , который сгруппировал виды по общим физическим характеристикам. С тех пор эти группировки были пересмотрены, чтобы лучше соответствовать дарвиновскому принципу общего происхождения – группировке организмов по происхождению, а не по поверхностным характеристикам . Хотя ученые не всегда сходятся во мнении относительно того, как классифицировать организмы, молекулярная филогенетика , которая использует последовательности ДНК в качестве данных, привела к множеству недавних пересмотров эволюционных направлений и, вероятно, будет продолжать это делать. Доминирующая система классификации называется таксономией Линнея . Он включает ранги и биномиальную номенклатуру . Номенклатура ботанических организмов кодифицирована в Международном кодексе номенклатуры водорослей, грибов и растений. (ICN) и находится в ведении Международного ботанического конгресса . [ 196 ] [ 197 ]

Королевство Plantae принадлежит к домену Eukaryota и рекурсивно разбивается до тех пор, пока каждый вид не будет классифицирован отдельно. Порядок такой: Королевство ; Тип (или отдел); Сорт ; Заказ ; Семья ; Род (множественное число родов ); Разновидность . Научное название растения представляет его род и виды внутри рода, в результате чего для каждого организма создается единое всемирное название. [ 197 ] Например, тигровая лилия — Lilium columbianum . Lilium — это род, а columbianum — видовой эпитет . Сочетание и есть название вида. При написании научного названия организма первую букву рода следует писать с заглавной буквы, а весь видовой эпитет писать строчными. Кроме того, весь термин обычно выделяется курсивом (или подчеркивается, если курсив недоступен). [ 198 ] [ 199 ] [ 200 ]

Эволюционные связи и наследственность группы организмов называют ее филогенией . Филогенетические исследования пытаются обнаружить филогении. Основной подход заключается в использовании сходств на основе общего наследования для определения отношений. [ 201 ] Например, виды перескии — это деревья или кусты с выступающими листьями. Они явно не похожи на типичный безлистный кактус, такой как эхинокактус . Однако и у Pereskia , и у Echinocactus есть шипы, образующиеся из ареол (узкоспециализированных подушечек), что позволяет предположить, что эти два рода действительно связаны. [ 202 ] [ 203 ]

Оценка отношений на основе общих признаков требует осторожности, поскольку растения могут походить друг на друга в результате конвергентной эволюции , в которой признаки возникли независимо. Некоторые молочайные имеют безлистные округлые тела, приспособленные к сохранению воды, подобные телам шаровидных кактусов, но такие особенности, как структура их цветков, ясно показывают, что эти две группы не связаны тесно. Кладистический метод использует систематический подход к признакам, различая те, которые не несут никакой информации об общей эволюционной истории – например, те, которые развивались отдельно в разных группах ( гомоплазии ) или оставшиеся от предков ( плезиоморфии ) – и производные признаки, которые были передающиеся от нововведений от общего предка ( апоморфии ). Только производные признаки, такие как ареолы кактусов, образующие шипы, служат доказательством происхождения от общего предка. Результаты кладистического анализа выражаются в виде кладограмм : древовидных диаграмм, показывающих закономерности эволюционного ветвления и происхождения. [ 204 ]

С 1990-х годов преобладающим подходом к построению филогений живых растений была молекулярная филогенетика , которая использует молекулярные признаки, особенно последовательности ДНК , а не морфологические признаки, такие как наличие или отсутствие шипов и ареол. Разница в том, что генетический код сам по себе используется для определения эволюционных отношений, а не косвенно, через признаки, которые он порождает. Клайв Стейс описывает это как «прямой доступ к генетической основе эволюции». [ 205 ] В качестве простого примера: до использования генетических данных считалось, что грибы либо являются растениями, либо более тесно связаны с растениями, чем с животными. Генетические данные свидетельствуют о том, что истинные эволюционные взаимоотношения многоклеточных организмов показаны на кладограмме ниже: грибы более тесно связаны с животными, чем с растениями. [ 206 ]

| |||||||||||||

В 1998 году Группа филогении покрытосеменных опубликовала филогению цветковых растений, основанную на анализе последовательностей ДНК большинства семейств цветковых растений. В результате этой работы на многие вопросы, например, какие семейства представляют самые ранние ветви покрытосеменных . теперь получены ответы [ 52 ] Исследование того, как виды растений связаны друг с другом, позволяет ботаникам лучше понять процесс эволюции растений. [ 207 ] Несмотря на изучение модельных растений и растущее использование данных ДНК, систематики продолжают работать и дискутировать о том, как лучше всего классифицировать растения по различным таксонам . [ 208 ] Технологические разработки, такие как компьютеры и электронные микроскопы, значительно повысили уровень детализации изучаемых данных и скорость анализа данных. [ 209 ]

Символы

[ редактировать ]В ботанике в настоящее время используются несколько символов. Ряд других устарели; например, Линней использовал планетарные символы ⟨♂⟩ (Марс) для двулетних растений, ⟨♃⟩ (Юпитер) для травянистых многолетних растений и ⟨♄⟩ (Сатурн) для древесных многолетних растений, исходя из периодов обращения планет 2, 12 и 30. годы; и Уиллд использовал ⟨♄⟩ (Сатурн) для среднего рода в дополнение к ⟨☿⟩ (Меркурий) для гермафродита. [ 210 ] Следующие символы по-прежнему используются: [ 211 ]

- ♀ женщина

- ♂ мужчина

- ⚥ гермафродит/бисексуал

- ⚲ вегетативное (бесполое) размножение

- ◊ пол неизвестен

- ☉ ежегодный

- ⚇ биеннале

- ♾ многолетник

- ☠ ядовитый

- 🛈 дополнительная информация

- × гибридный гибрид

- + привитой гибрид

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Отрасли ботаники

- Эволюция растений

- Словарь ботанических терминов

- Глоссарий морфологии растений

- Список журналов по ботанике

- Список ботаников

- Список ботанических садов

- Список ботаников по сокращению авторов

- Список одомашненных растений

- Список цветов

- Список систем систематики растений

- Очерк ботаники

- Хронология британской ботаники

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ Хлорофилл b также содержится в некоторых цианобактериях. Ряд других хлорофиллов существует у цианобактерий и некоторых групп водорослей, но ни один из них не обнаружен в наземных растениях. [ 79 ] [ 80 ] [ 81 ]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Лидделл и Скотт 1940 .

- ^ Горд и Хедрик 2001 , с. 134.

- ^ Интернет-словарь этимологии 2012 .

- ^ RGB Кью 2016 .

- ^ Список растений и 2013 .

- ^ Самнер 2000 , с. 16.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Рид 1942 , стр. 7-29.

- ^ Оберлис 1998 , с. 155.

- ^ Манниш 2006 .

- ^ Нидхэм, Лу и Хуанг 1986 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Грин 1909 , стр. 140–142.

- ^ Беннетт и Хаммонд 1902 , с. 30.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , с. 532.

- ^ Далал 2010 , с. 197.

- ^ Панаино 2002 , с. 93.

- ^ Леви 1973 , с. 116.

- ^ Хилл 1915 .

- ^ Национальный музей Уэльса 2007 .

- ↑ Yaniv & Bachrach 2005 , p. 157.

- ^ Спраг и Спраг, 1939 .

- ^ Вагонер 2001 .

- ^ Шарф 2009 , стр. 73–117.

- ^ Капон 2005 , стр. 220–223.

- ^ Hoek, Mann & Jahns 2005 , стр. 9.

- ^ Росс, Эйлса (22 апреля 2015 г.). «Викторианская джентльменка, задокументировавшая 900 видов растений» . Атлас Обскура . Проверено 5 июня 2024 г.

- ^ Старр 2009 , стр. 299–.

- ^ Мортон 1981 , с. 377.

- ^ Харрис 2000 , стр. 76–81.

- ^ Смолл 2012 , стр. 118–.

- ^ Карп 2009 , с. 382.

- ^ Национальный научный фонд 1989 .

- ^ Чаффи 2007 , стр. 481–482.

- ^ Тэнсли 1935 , стр. 299–302.

- ^ Уиллис 1997 , стр. 267–271.

- ^ Мортон 1981 , с. 457.

- ^ де Кандоль 2006 , стр. 9–25, 450–465.

- ^ Ясечко и др. 2013 , стр. 347–350.

- ^ Нобелевская премия 1983 г. , с. 608

- ^ Йейтс и Мазер 1963 , стр. 91–129.

- ^ Финни 1995 , стр. 554–573.

- ^ Кокинг 1993 .

- ^ Казенс и Мортимер 1995 .

- ^ Эрхардт и Фроммер 2012 , стр. 1–21.

- ^ Хаберландт 1902 , стр. 69–92.

- ^ Леонелли и др. 2012 .

- ^ Саттлер и Янг 1992 , стр. 249–262.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Саттлер 1992 , стр. 708–714.

- ^ Эрешефский 1997 , стр. 493–519.

- ^ Грей и Сарджент 1889 , стр. 292–293.

- ^ Медбери 1993 , стр. 14–16.

- ^ Джадд и др. 2002 , стр. 347–350.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бургер 2013 года .

- ^ Кресс и др. 2005 , стр. 8369–8374.

- ^ Янзен и др. 2009 , стр. 12794–12797.

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , стр. 186–187.

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , с. 1240.

- ^ Порыв 1996 .

- ^ Ботанический сад Миссури 2009 .

- ^ Чепмен и др. 2001 , с. 56.

- ^ Бразелтон 2013 .

- ^ Бен-Менахем 2009 , с. 5368.

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , с. 602.

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , стр. 619–620.

- ^ Капон 2005 , стр. 10–11.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 1–3.

- ^ Кливлендский музей естественной истории, 2012 .

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , стр. 516–517.

- ^ Ботаническое общество Америки, 2013 .

- ^ Бен-Менахем 2009 , стр. 5367–5368.

- ^ Бутц 2007 , стр. 534–553.

- ^ Стовер и Симмондс 1987 , стр. 106–126.

- ^ Зохари и Хопф 2000 , стр. 20–22.

- ^ Флорос, Ньюсом и Фишер 2010 .

- ^ Шенинг 2005 .

- ^ Ачарья и Аншу 2008 , с. 440.

- ^ Кунляйн и Тернер 1991 .

- ^ Lüttge 2006 , стр. 7–25.

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , стр. 190–193.

- ^ Ким и Арчибальд 2009 , стр. 1–39.

- ^ Хоу и др. 2008 , стр. 2675–2685.

- ^ Такаити 2011 , стр. 1101–1118.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Льюис и МакКорт 2004 , стр. 1535–1556.

- ^ Падманабхан и Динеш-Кумар 2010 , стр. 1368–1380.

- ^ Шнурр и др. 2002 , стр. 1700–1709.

- ^ Ферро и др. 2002 , стр. 11487–11492.

- ^ Колаттукуди 1996 , стр. 83–108.

- ^ Фрай 1989 , стр. 1–11.

- ^ Томпсон и Фрай 2001 , стр. 23–34.

- ^ Кенрик и Крейн 1997 , стр. 33–39.

- ^ Говик и Вестхофф 2010 , стр. 56–63.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Бендерот и др. 2006 , стр. 9118–9123.

- ^ Джеффрис 2005 , стр. 38–40.

- ^ Манн 1987 , стр. 186–187.

- ^ Медицинский центр Университета Мэриленда, 2011 г.

- ^ Денсмор 1974 .

- ^ Маккатчеон и др. 1992 год .

- ^ Клемм и др. 2005

- ^ Шарлеманн и Лоранс 2008 , стр. 52–53.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Вашингтон Пост, 18 августа 2015 г.

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , с. 794.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 786–818.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б TeachEthnobotany (12 июня 2012 г.), Выращивание пейота коренными американцами: прошлое, настоящее и будущее , заархивировано из оригинала 28 октября 2021 г. , получено 5 мая 2016 г.

- ^ Берроуз 1990 , стр. 1–73.

- ^ Аддельсон 2003 .

- ^ Грайм и Ходжсон 1987 , стр. 283–295.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 819–848.

- ^ Эррера и Пеллмир 2002 , стр. 211–235.

- ^ Проктор и Йео 1973 , с. 479.

- ^ Эррера и Пеллмир 2002 , стр. 157–185.

- ^ Эррера и Пеллмир 2002 , стр. 185–210.

- ^ Беннетт и Уиллис 2001 , стр. 5–32.

- ^ Beerling, Osborne & Chaloner 2001 , стр. 287–394.

- ^ Бьорн и др. 1999 , стр. 449–454.

- ^ Бен-Менахем 2009 , стр. 5369–5370.

- ^ Бен-Менахем 2009 , с. 5369.

- ^ Стейс 2010b , стр. 629–633.

- ^ Хэнкок 2004 , стр. 190–196.

- ^ Соботка, Сакова и Курн 2000 , стр. 103–112.

- ^ Реннер и Риклефс 1995 , стр. 596–606.

- ^ Порли и Ходжеттс 2005 , стр. 2–3.

- ^ Дарвин, CR 1878. Эффекты перекрестного и самооплодотворения в растительном царстве. Лондон: Джон Мюррей». darwin-online.org.uk.

- ^ Савидан 2000 , стр. 13–86.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , стр. 495–496.

- ^ Моргенсен 1996 , стр. 383–384.

- ^ Инициатива по геному арабидопсиса 2000 , стр. 796–815.

- ^ Девос и Гейл 2000 .

- ^ Калифорнийский университет в Дэвисе, 2012 г.

- ^ Руссин и др. 1996 , стр. 645–658.

- ^ Роше, Гольдшмидт-Клермон и Мерчант 1998 , стр. 550.

- ^ Глинн и др. 2007 , стр. 451–461.

- ^ Поссингем и Роуз 1976 , стр. 295–305.

- ^ Сан и др. 2002 , стр. 95–100.

- ^ Heinhorst & Cannon 1993 , стр. 1–9.

- ^ Шелл и Ван Монтегю 1977 , стр. 159–179.

- ^ Берд 2007 , стр. 396–398.

- ^ Хантер 2008 .

- ^ Спектор 2012 , с. 8.

- ^ Рейк 2007 , стр. 425–432.

- ^ Коста и Шоу 2007 , стр. 101–106.

- ^ Конус и Ведова 2004 .

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 552–581.

- ^ Коупленд 1938 , стр. 383–420.

- ^ Вёзе и др. 1977 , стр. 305–311.

- ^ Кавальер-Смит 2004 , стр. 1251–1262.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 617–654.

- ^ Беккер и Марин 2009 , стр. 999–1004.

- ^ Fairon-Demaret 1996 , стр. 217–233.

- ^ Стюарт и Ротвелл 1993 , стр. 279–294.

- ^ Тейлор, Тейлор и Крингс 2009 , глава 13.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маусет 2003 , стр. 720–750.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 751–785.

- ^ Ли и др. 2011 , с. е1002411.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 278–279.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 280–314.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 315–340.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 341–372.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 373–398.

- ^ Маусет 2012 , с. 351.

- ^ Дарвин 1880 , стр. 129–200.

- ^ Дарвин 1880 , стр. 449–492.

- ^ Дарвин 1880 , с. 573.

- ^ Растительные гормоны 2013 .

- ^ Вент и Тиманн 1937 , стр. 110–112.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 411–412.

- ^ Сассекс 2008 , стр. 1189–1198.

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , стр. 827–830.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 411–413.

- ^ Тайз и Зейгер 2002 , стр. 461–492.

- ^ Тайз и Зейгер 2002 , стр. 519–538.

- ^ Линь, Чжун и Грирсон 2009 , стр. 331–336.

- ^ Тайз и Зейгер 2002 , стр. 539–558.

- ^ Демол, Ледерер и Мерсье 1962 , стр. 675–685.

- ^ Ниже и др. 2007 , стр. 666–671.

- ^ Ру 1984 , стр. 25–29.

- ^ Рэйвен, Эверт и Эйххорн 2005 , стр. 9.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 433–467.

- ^ Национальный центр биотехнологической информации, 2004 г.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 62–81.

- ^ Лопес-Баутиста, Уотерс и Чепмен 2003 , стр. 1715–1718.

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , стр. 630, 738.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , с. 739.

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , стр. 607–608.

- ^ Ольха 2012 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , стр. 812–814.

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , с. 740.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маусет 2003 , стр. 185–208.

- ^ Митила и др. 2003 , стр. 408–414.

- ^ Кэмпбелл и др. 2008 , с. 741.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 114–153.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 154–184.

- ^ Капон 2005 , с. 11.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 209–243.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 244–277.

- ^ Саттлер и Янг 1992 , стр. 249–269.

- ^ Лилберн и др. 2006 год .

- ^ Макнил и др. 2011 , с. Преамбула, п. 7.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б Маусет 2003 , стр. 528–551.

- ^ Маусет 2003 , стр. 528–555.

- ^ Международная ассоциация таксономии растений 2006 .

- ^ Силин-Робертс 2000 , с. 198.

- ^ Маусет 2012 , стр. 438–444.

- ^ Маусет 2012 , стр. 446–449.

- ^ Андерсон 2001 , стр. 26–27.

- ^ Маусет 2012 , стр. 442–450.

- ^ Стейс 2010a , с. 104.

- ^ Маусет 2012 , с. 453.

- ^ Чейз и др. 2003 , стр. 399–436.

- ^ Капон 2005 , с. 223.

- ^ Мортон 1981 , стр. 459–459.

- ^ Линдли 1848 .

- ^ Симпсоны 2010 .

Источники

[ редактировать ]- Ачарья, Дипак; Аншу, Шривастава (2008). Лекарственные травы коренных народов: племенные рецептуры и традиционные методы лечения травами . Джайпур, Индия: Издательство Aavishkar. ISBN 978-81-7910-252-7 .

- Аддельсон, Барбара (декабрь 2003 г.). «Естественно-научный институт ботаники и экологии для учителей начальных классов» . Международная организация по охране ботанических садов. Архивировано из оригинала 23 мая 2013 года . Проверено 8 июня 2013 г.

- Андерсон, Эдвард Ф. (2001). Семья Кактусов . Пентленд, Орегон: Timber Press. ISBN 978-0-88192-498-5 .

- Армстронг, Джорджия; Херст, Дж. Э. (1996). «Каротиноиды 2: генетика и молекулярная биология биосинтеза каротиноидных пигментов» . ФАСЕБ Дж . 10 (2): 228–237. дои : 10.1096/fasebj.10.2.8641556 . ПМИД 8641556 . S2CID 22385652 .

- Беккер, Буркхард; Марин, Биргер (2009). «Водоросли-стрептофиты и происхождение эмбриофитов» . Анналы ботаники . 103 (7): 999–1004. дои : 10.1093/aob/mcp044 . ПМК 2707909 . ПМИД 19273476 .

- Берлинг, диджей ; Осборн, CP; Чалонер, WG (2001). «Эволюция формы листьев наземных растений, связанная с уменьшением содержания CO2 в атмосфере в позднепалеозойскую эру» (PDF) . Природа . 410 (6826): 352–354. Бибкод : 2001Natur.410..352B . дои : 10.1038/35066546 . ПМИД 11268207 . S2CID 4386118 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 20 сентября 2010 г. Проверено 14 декабря 2018 г.

- Бендерот, Маркус; Текстор, Сюзанна; Виндзор, Аарон Дж.; Митчелл-Олдс, Томас; Гершензон, Джонатан; Кройманн, Юрген (июнь 2006 г.). «Положительный отбор, способствующий диверсификации вторичного метаболизма растений» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 103 (24): 9118–9123. Бибкод : 2006PNAS..103.9118B . дои : 10.1073/pnas.0601738103 . JSTOR 30051907 . ПМЦ 1482576 . ПМИД 16754868 .

- Бен-Менахем, Ари (2009). Историческая энциклопедия естественных и математических наук . Том. 1. Берлин: Шпрингер-Верлаг. ISBN 978-3-540-68831-0 .

- Беннетт, Чарльз Э.; Хаммонд, Уильям А. (1902). Персонажи Теофраста – Введение . Лондон: Longmans, Green и Co. Архивировано из оригинала 10 февраля 2023 года . Проверено 27 июня 2012 г.

- Беннетт, К.Д.; Уиллис, К.Дж. (2001). «Пыльца». В Смоле, Джон П.; Биркс, Х. Джон Б. (ред.). Отслеживание изменений окружающей среды с использованием озерных отложений . Том. 3: Наземные, водорослевые и кремнистые индикаторы. Дордрехт, Германия: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- Берд, Адриан (май 2007 г.). «Представления об эпигенетике» . Природа . 447 (7143): 396–398. Бибкод : 2007Natur.447..396B . дои : 10.1038/nature05913 . ПМИД 17522671 . S2CID 4357965 .

- Бьёрн, Лоу; Каллаган, ТВ; Герке, К.; Йохансон, У.; Сонессон, М. (ноябрь 1999 г.). «Разрушение озона, ультрафиолетовое излучение и жизнь растений». Хемосфера – наука о глобальных изменениях . 1 (4): 449–454. Бибкод : 1999ChGCS...1..449B . дои : 10.1016/S1465-9972(99)00038-0 .

- Смелый, ХК (1977). Царство растений (4-е изд.). Энглвуд Клиффс, Нью-Джерси: Прентис-Холл. ISBN 978-0-13-680389-8 .

- Бразелтон, JP (2013). «Что такое биология растений?» . Университет Огайо. Архивировано из оригинала 24 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 3 июня 2013 г.

- Бургер, Уильям К. (2013). «Происхождение покрытосеменных: сценарий сначала для однодольных» . Чикаго: Полевой музей. Архивировано из оригинала 23 октября 2012 г. Проверено 15 июня 2013 г.

- Берроуз, WJ (1990). Процессы изменения растительности . Лондон: Анвин Хайман. ISBN 978-0-04-580013-1 .

- Батц, Стивен Д. (2007). Наука о системах Земли (2-е изд.). Клифтон-Парк, Нью-Йорк: Обучение Делмара Сенгеджа. ISBN 978-1-4180-4122-9 .

- Кэмпбелл, Нил А.; Рис, Джейн Б.; Урри, Лиза Андреа; Каин, Майкл Л.; Вассерман, Стивен Александер; Минорский, Петр Васильевич; Джексон, Роберт Брэдли (2008). Биология (8-е изд.). Сан-Франциско: Пирсон – Бенджамин Каммингс. ISBN 978-0-321-54325-7 .

- де Кандоль, Альфонс (2006). Происхождение культурных растений . Национальный парк Глейшер, Монтана: Издательство Кессинджер. ISBN 978-1-4286-0946-4 .

- Капон, Брайан (2005). Ботаника для садоводов (2-е изд.). Портленд, Орегон: Издательство Timber Publishing. ISBN 978-0-88192-655-2 .

- Кавальер-Смит, Томас (2004). «Только шесть королевств жизни» (PDF) . Труды Лондонского королевского общества Б. 271 (1545): 1251–1262. дои : 10.1098/rspb.2004.2705 . ПМК 1691724 . ПМИД 15306349 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 10 января 2011 г. Проверено 1 апреля 2012 г.

- Чаффи, Найджел (2007). «Анатомия растений Исава, меристемы, клетки и ткани тела растения: их структура, функции и развитие» . Анналы ботаники . 99 (4): 785–786. дои : 10.1093/aob/mcm015 . ПМК 2802946 .

- Чепмен, Жасмин; Хорсфолл, Питер; О'Брайен, Пэт; Мерфи, Ян; Макдональд, Аверил (2001). Научная сеть . Челтнем, Великобритания: Нельсон Торнс. ISBN 978-0-17-438746-6 .

- Чейз, Марк В.; Бремер, Биргитта; Бремер, Коре; Раскрытие, Джеймс Л.; Солтис, Дуглас Э.; Солтис, Памела С.; Стивенс, Питер С. (2003). «Обновление классификации групп филогении покрытосеменных для отрядов и семейств цветковых растений: APG II» (PDF) . Ботанический журнал Линнеевского общества . 141 (4): 399–436. doi : 10.1046/j.1095-8339.2003.t01-1-00158.x . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 3 марта 2016 г. Проверено 1 апреля 2012 г.

- Чини, А.; Фонсека, С.; Фернандес, Г.; Ади, Б.; Чико, Дж. М.; Лоуренс, О.; Гарсия-Женат, Г.; Лопес-Стекловар, И.; Лозано, FM; Понсе, MR; Миколь, Дж.Л.; Солано, Р. (2007). «Семейство репрессоров JAZ в передаче сигналов жасмоната». Природа 448 (7154): 666–671. Бибкод : 2007Nature.448..666C . дои : 10.1038/nature06006 . ПМИД 17637675 . S2CID 4383741 .

- Кокинг, Эдвард К. (18 октября 1993 г.). «Некролог: профессор ФК Стюард» . Независимый . Лондон. Архивировано из оригинала 9 ноября 2012 года . Проверено 5 июля 2013 г.

- Коун, Карен С.; Ведова, Крис Б. Делла (1 июня 2004 г.). «Парамутация: связь хроматина» . Растительная клетка . 16 (6): 1358–1364. дои : 10.1105/tpc.160630 . ISSN 1040-4651 . ПМК 490031 . ПМИД 15178748 .

- Коупленд, Герберт Фолкнер (1938). «Царства организмов». Ежеквартальный обзор биологии . 13 (4): 383–420. дои : 10.1086/394568 . S2CID 84634277 .

- Коста, Сильвия; Шоу, Питер (март 2007 г.). « Клетки с открытым мышлением: как клетки могут изменить судьбу» (PDF) . Тенденции в клеточной биологии . 17 (3): 101–106. дои : 10.1016/j.tcb.2006.12.005 . ПМИД 17194589 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF)) 15 декабря 2013 г.

- Казенс, Роджер; Мортимер, Мартин (1995). Динамика популяций сорняков . Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-0-521-49969-9 . Архивировано из оригинала 10 февраля 2023 г. Проверено 27 июня 2015 г.

- Даллал, Ахмад (2010). Ислам, наука и вызов истории . Нью-Хейвен, Коннектикут: Издательство Йельского университета. ISBN 978-0-300-15911-0 . Архивировано из оригинала 10 февраля 2023 г. Проверено 6 октября 2020 г.

- Дарвин, Чарльз (1880). Сила движения растений (PDF) . Лондон: Мюррей. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 14 октября 2016 г. Проверено 14 июля 2013 г.

- Демол, Э.; Ледерер, Э.; Мерсье, Д. (1962). «Выделение и определение структуры метилжасмоната, характерного пахучего компонента жасминового масла. Выделение и определение структуры метилжасмоната, характерного пахучего компонента жасминового масла». Helvetica Chimica Acta . 45 (2): 675–685. дои : 10.1002/hlca.19620450233 .

- Денсмор, Фрэнсис (1974). Как индейцы используют дикие растения в пищу, в медицине и в ремеслах . Дуврские публикации. ISBN 978-0-486-13110-8 .

- Девос, Кэтриен М .; Гейл, доктор медицины (май 2000 г.). «Взаимоотношения генома: модель травы в текущих исследованиях» . Растительная клетка . 12 (5): 637–646. дои : 10.2307/3870991 . JSTOR 3870991 . ПМК 139917 . ПМИД 10810140 . Архивировано из оригинала 7 июня 2008 г. Проверено 29 июня 2009 г.

- Эрхардт, Д.В.; Фроммер, Всемирный банк (февраль 2012 г.). «Новые технологии для растениеводства 21 века» . Растительная клетка . 24 (2): 374–394. дои : 10.1105/tpc.111.093302 . ПМК 3315222 . ПМИД 22366161 .

- Эрешефски, Марк (1997). «Эволюция линнеевской иерархии». Биология и философия . 12 (4): 493–519. дои : 10.1023/А:1006556627052 . S2CID 83251018 .

- Ферро, Мириам; Сальви, Даниэль; Ривьер-Ролан, Элен; Верма, Тьерри; и др. (20 августа 2002 г.). «Интегральные мембранные белки оболочки хлоропластов: идентификация и субклеточная локализация новых переносчиков» . Труды Национальной академии наук Соединенных Штатов Америки . 99 (17): 11487–11492. Бибкод : 2002PNAS...9911487F . дои : 10.1073/pnas.172390399 . ПМЦ 123283 . ПМИД 12177442 .

- Фэйрон-Демаре, Мюриэль (октябрь 1996 г.). « Dorinnotheca streelii Fairon-Demaret, gen. et sp. nov. , новое раннесеменное растение из верхнего фамена Бельгии». Обзор палеоботаники и палинологии . 93 (1–4): 217–233. Бибкод : 1996RPaPa..93..217F . дои : 10.1016/0034-6667(95)00127-1 .

- Финни, диджей (ноябрь 1995 г.). «Фрэнк Йейтс, 12 мая 1902 г. - 17 июня 1994 г.». Биографические мемуары членов Королевского общества . 41 : 554–573. дои : 10.1098/rsbm.1995.0033 . JSTOR 770162 . S2CID 26871863 .

- Флорос, Джон Д.; Ньюсом, Розетта; Фишер, Уильям (2010). «Накормить мир сегодня и завтра: важность пищевой науки и технологий» (PDF) . Институт пищевых технологов. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 16 февраля 2012 года . Проверено 1 марта 2012 г.

- Фрай, Южная Каролина (1989). «Структура и функции ксилоглюкана». Журнал экспериментальной биологии . 40 .