Женщины в науке

| Часть серии о |

| Женщины в обществе |

|---|

|

Присутствие женщин в науке охватывает самые ранние периоды истории науки , когда они внесли значительный вклад. Историки, интересующиеся гендерными вопросами и наукой, исследовали научные усилия и достижения женщин, барьеры, с которыми они столкнулись, а также стратегии, реализованные для того, чтобы их работа была рецензирована и принята в крупных научных журналах и других публикациях. Историческое, критическое и социологическое стало академической дисциплиной исследование этих проблем само по себе .

Участие женщин в медицине имело место в нескольких ранних западных цивилизациях , а изучение натурфилософии в Древней Греции было открыто для женщин. Женщины внесли свой вклад в протонауку алхимию . в первом или втором веках нашей эры. В средние века религиозные монастыри были важным местом образования для женщин, и некоторые из этих сообществ предоставляли женщинам возможность внести свой вклад в научные исследования В 11 веке появились первые университеты ; женщины по большей части были исключены из университетского образования. [ 1 ] За пределами академических кругов ботаника была наукой, которая больше всего выиграла от вклада женщин в раннее Новое время. [ 2 ] , по-видимому, было более либеральным, Отношение к образованию женщин в области медицины в Италии чем в других странах. Первой известной женщиной, занявшей кафедру университета в области научных исследований, была итальянский ученый восемнадцатого века Лаура Басси .

Гендерные роли были в основном детерминистическими в восемнадцатом веке, и женщины добились значительных успехов в науке . В девятнадцатом веке женщины были исключены из большей части формального научного образования, но в этот период их начали допускать в научные общества. В конце девятнадцатого века появление женских колледжей предоставило женщинам-ученым рабочие места и возможности для получения образования. Мария Кюри открыла ученым путь к изучению радиоактивного распада и открыла элементы радий и полоний . [ 3 ] Работая физиком и химиком , она провела новаторские исследования радиоактивного распада и стала первой женщиной, получившей Нобелевскую премию по физике , а также первым человеком, получившим вторую Нобелевскую премию по химии . Шестьдесят женщин были удостоены Нобелевской премии в период с 1901 по 2022 год. Двадцать четыре женщины были удостоены Нобелевской премии по физике, химии, физиологии и медицине. [ 4 ]

Межкультурные перспективы

[ редактировать ]В 1970-е и 1980-е годы появлялось множество книг и статей о женщинах-ученых; практически все опубликованные источники игнорировали цветных женщин и женщин за пределами Европы и Северной Америки . [ 5 ] Создание Фонда Ковалевской в 1985 году и Организации женщин в науке развивающегося мира в 1993 году сделало более заметными ранее маргинализированных женщин-ученых, но даже сегодня существует нехватка информации о нынешних и исторических женщинах в науке в развивающихся странах. По словам академика Энн Хибнер Коблиц : [ 6 ]

Большая часть работ о женщинах-ученых сосредоточена на личностях и научных субкультурах Западной Европы и Северной Америки, а историки женщин в науке неявно или явно предполагали, что наблюдения, сделанные для этих женщин, регионы будут справедливы и для остального мира.

Коблиц сказал, что эти обобщения о женщинах в науке часто не выдерживают критики в разных культурах: [ 7 ]

Научная или техническая область, которая могла бы считаться «неменственной» в одной стране в определенный период, может включать в себя участие многих женщин в другой исторический период или в другой стране. Примером может служить инженерное дело, которое во многих странах считается исключительной прерогативой мужчин, особенно в обычно престижных областях, таких как электротехника или машиностроение. Однако из этого есть исключения. В бывшем Советском Союзе во всех инженерных специальностях был высокий процент женщин, а в Национальном инженерном университете Никарагуа в 1990 году женщины составляли 70% студентов-инженеров.

Исторические примеры

[ редактировать ]Древняя история

[ редактировать ]Участие женщин в области медицины было зафиксировано в нескольких ранних цивилизациях. Древнеегипетский ), описанный в надписи как «женщина - врач Песешет ( ок. 2600–2500 до н.э. надзирательница женщин-врачей». [ 8 ] [ 9 ] — самая ранняя известная женщина-врач в истории науки . [ 10 ] Агамед упоминался Гомером как целитель в Древней Греции перед Троянской войной (ок. 1194–1184 гг. До н. э.). [ 11 ] [ 12 ] [ 13 ] Согласно одной позднеантичной легенде, Агнодика была первой женщиной-врачем, которая легально практиковала в Афинах четвертого века до нашей эры . [ 14 ]

Изучение натурфилософии в Древней Греции было открыто для женщин. Зарегистрированные примеры включают Аглаонику , предсказавшую затмения ; и Феано , математик и врач, которая была ученицей (возможно, также женой) Пифагора и участницей школы в Кротоне , основанной Пифагором, в которую входили многие другие женщины. [ 15 ] Отрывок у Поллукса говорит о тех, кто изобрел процесс чеканки денег, упоминая Фидона и Демодику из Кимы , жену фригийского царя Мидаса и дочь царя Агамемнона из Кимы. [ 16 ] Дочь некоего Агамемнона , царя Эолийской Кимы , вышла замуж за фригийского царя по имени Мидас. [ 17 ] Эта связь, возможно, способствовала грекам «заимствованию» своего алфавита у фригийцев, поскольку формы фригийских букв наиболее близки к надписям Эолиды. [ 17 ]

В период существования вавилонской цивилизации, около 1200 г. до н.э., две парфюмерки по имени Таппути-Белатекаллим и -нину (первая половина ее имени неизвестна) смогли получать эссенции растений с помощью процедур экстракции и дистилляции. [ 18 ] Во времена египетской династии женщины занимались прикладной химией, например, изготовлением пива и приготовлением лекарственных соединений. [ 19 ] Было зарегистрировано, что женщины внесли большой вклад в алхимию . [ 19 ] Многие из них жили в Александрии примерно в I или II веках нашей эры, где гностическая традиция привела к тому, что вклад женщин стал цениться. Самой известной женщине-алхимику Марии Еврейке приписывают изобретение нескольких химических инструментов, в том числе пароварки ( паровой бани ); усовершенствование или создание перегонного оборудования того времени. [ 19 ] [ 20 ] Такое перегонное оборудование называлось керотакис (простой перегонный аппарат) и трибикос (сложное перегонное устройство). [ 19 ]

Гипатия Александрийская (ок. 350–415 гг. н. э.), дочь Теона Александрийского , была философом, математиком и астрономом. [ 21 ] [ 22 ] Она первая женщина-математик, о которой сохранились подробные сведения. [ 22 ] Гипатии приписывают написание нескольких важных комментариев по геометрии , алгебре и астрономии . [ 15 ] [ 23 ] Гипатия была главой философской школы и учила множество учеников. [ 24 ] В 415 году она оказалась втянутой в политический спор между Кириллом , епископом Александрии, и Орестом , римским губернатором, в результате которого толпа сторонников Кирилла раздела ее, расчленила и сожгла части ее тела. [ 24 ]

Средневековая Европа

[ редактировать ]

Ранние периоды европейского Средневековья , также известные как Темные века , были отмечены упадком Римской империи . Латинский Запад столкнулся с большими трудностями, которые резко повлияли на интеллектуальное производство континента. Хотя природа по-прежнему рассматривалась как система, которую можно постичь в свете разума, инновационных научных исследований было мало. [ 25 ] Арабский мир заслуживает похвалы за сохранение научных достижений. Арабские ученые создали оригинальные научные работы и создали копии рукописей классического периода . [ 26 ] В этот период христианство пережило период возрождения, и в результате получила поддержку западная цивилизация. Частично это явление произошло благодаря монастырям и женским монастырям, которые воспитывали навыки чтения и письма, а также монахам и монахиням, которые собирали и копировали важные сочинения, созданные учеными прошлого. [ 26 ] [ нужна ссылка ]

Как упоминалось ранее, монастыри были важным местом образования для женщин в этот период, поскольку монастыри и женские монастыри поощряли навыки чтения и письма, а некоторые из этих сообществ предоставляли женщинам возможность внести свой вклад в научные исследования. [ 26 ] Примером может служить немецкая настоятельница Хильдегард Бингенская (1098–1179 гг.), известный философ и ботаник, чьи плодотворные труды включают исследования различных научных предметов, включая медицину, ботанику и естествознание (ок. 1151–1158). [ 27 ] Другой известной немецкой настоятельницей была Хросвита Гандерсхаймская (935–1000 гг. н.э.). [ 26 ] это также помогло побудить женщин быть интеллектуальными. Однако с ростом числа и влияния женских монастырей духовная иерархия, состоящая исключительно из мужчин, не приветствовалась по отношению к ним, и, таким образом, это разожгло конфликт, вызвав негативную реакцию против продвижения женщин. Это повлияло на многие религиозные ордена, закрытые для женщин и распустившие свои женские монастыри, и в целом лишив женщин возможности научиться читать и писать. При этом мир науки стал закрытым для женщин, что ограничило влияние женщин в науке. [ 26 ]

В XI веке первые университеты появились . Женщины по большей части были исключены из университетского образования. [ 1 ] Однако были и некоторые исключения. Итальянский университет Болоньи разрешил женщинам посещать лекции с момента его основания, в 1088 году. [ 28 ]

Отношение к образованию женщин в области медицины в Италии, по-видимому, было более либеральным, чем в других странах. Предполагается, что врач Тротула ди Руджеро занимала кафедру в Медицинской школе Салерно в 11 веке, где она обучала многих знатных итальянских женщин, группу, которую иногда называют « дамами Салерно ». [ 20 ] Тротуле также часто приписывают несколько влиятельных текстов по женской медицине, посвященных акушерству и гинекологии , среди прочего, .

Доротея Букка была еще одним выдающимся итальянским врачом. С 1390 года она возглавляла кафедру философии и медицины в Болонском университете более сорока лет. [ 28 ] [ 29 ] [ самостоятельно опубликованный источник? ] [ 30 ] [ 31 ] Среди других итальянских женщин, чей вклад в медицину был зарегистрирован, - Абелла , Якобина Феличи , Алессандра Джилиани , Ребекка де Гуарна , Маргарита , Меркуриада (14 век), Констанция Календа , Кальрис ди Дуризио (15 век), Констанца , Мария Инкарната и Томасия де Маттио. . [ 29 ] [ 32 ]

Несмотря на успех некоторых женщин, в Средние века были заметны культурные предубеждения, влиявшие на их образование и участие в науке. Например, святой Фома Аквинский , христианский учёный, писал, говоря о женщинах: «Она психически неспособна занимать властную должность». [ 1 ]

Научные революции 1600-х и 1700-х годов

[ редактировать ]

Маргарет Кавендиш , аристократка семнадцатого века, принимала участие в некоторых из наиболее важных научных дебатов того времени. Однако она не была принята в члены Английского королевского общества , хотя однажды ей разрешили присутствовать на собрании. Она написала ряд работ по научным вопросам, в том числе «Наблюдения за экспериментальной философией» (1666) и «Основы естественной философии» . В этих работах она особенно критически относилась к растущему убеждению, что люди благодаря науке являются хозяевами природы. Работа 1666 года была попыткой повысить женский интерес к науке. Наблюдения послужили критикой экспериментальной науки Бэкона и критиковали микроскопы как несовершенные машины. [33]

Isabella Cortese, an Italian alchemist, is most known for her book I secreti della signora Isabella Cortese or The Secrets of Isabella Cortese. Cortese was able to manipulate nature in order to create several medicinal, alchemy and cosmetic "secrets" or experiments.[34] Isabella's book of secrets belongs to a larger book of secrets that became extremely popular among the elite during the 16th century. Despite the low percentage of literate women during Cortese's era, the majority of alchemical and cosmetic "secrets" in the book of secrets were geared towards women. This included but was not limited to pregnancy, fertility, and childbirth.[34]

Sophia Brahe, sister of Tycho Brahe, was a Danish Horticulturalist. Brahe was trained by her older brother in chemistry and horticulture but taught herself astronomy by studying books in German. Sophia visited her brother in the Uranienborg on numerous occasions and assisted on his project the De nova stella. Her observations lead to the discovery of the Supernova SN 1572 which helped refute the geocentric model of the universe.[35]

Tycho Wrote the Urania Titani about his sister Sophia and her husband Erik. The Urania presented Sophia and the Titan represented Erik. Tycho used this poem in order to show his appreciation for his sister and all of her work.

In Germany, the tradition of female participation in craft production enabled some women to become involved in observational science, especially astronomy. Between 1650 and 1710, women were 14% of German astronomers.[36] The most famous female astronomer in Germany was Maria Winkelmann. She was educated by her father and uncle and received training in astronomy from a nearby self-taught astronomer. Her chance to be a practising astronomer came when she married Gottfried Kirch, Prussia's foremost astronomer. She became his assistant at the astronomical observatory operated in Berlin by the Academy of Science. She made original contributions, including the discovery of a comet. When her husband died, Winkelmann applied for a position as assistant astronomer at the Berlin Academy – for which she had experience. As a woman – with no university degree – she was denied the post. Members of the Berlin Academy feared that they would establish a bad example by hiring a woman. "Mouths would gape", they said.[37]

Winkelmann's problems with the Berlin Academy reflect the obstacles women faced in being accepted in scientific work, which was considered to be chiefly for men. No woman was invited to either the Royal Society of London nor the French Academy of Sciences until the twentieth century. Most people in the seventeenth century viewed a life devoted to any kind of scholarship as being at odds with the domestic duties women were expected to perform.

A founder of modern botany and zoology, the German Maria Sibylla Merian (1647–1717), spent her life investigating nature. When she was thirteen, Sibylla began growing caterpillars and studying their metamorphosis into butterflies. She kept a "Study Book" which recorded her investigations into natural philosophy. In her first publication, The New Book of Flowers, she used imagery to catalog the lives of plants and insects. After her husband died, and her brief stint of living in Siewert, she and her daughter journeyed to Paramaribo for two years to observe insects, birds, reptiles, and amphibians.[38] She returned to Amsterdam and published The Metamorphosis of the Insects of Suriname, which "revealed to Europeans for the first time the astonishing diversity of the rain forest."[39][40] She was a botanist and entomologist who was known for her artistic illustrations of plants and insects. Uncommon for that era, she traveled to South America and Surinam, where, assisted by her daughters, she illustrated the plant and animal life of those regions.[41]

Overall, the Scientific Revolution did little to change people's ideas about the nature of women – more specifically – their capacity to contribute to science just as men do. According to Jackson Spielvogel, 'Male scientists used the new science to spread the view that women were by nature inferior and subordinate to men and suited to play a domestic role as nurturing mothers. The widespread distribution of books ensured the continuation of these ideas'.[42]

Eighteenth century

[edit]

Although women excelled in many scientific areas during the eighteenth century, they were discouraged from learning about plant reproduction. Carl Linnaeus' system of plant classification based on sexual characteristics drew attention to botanical licentiousness, and people feared that women would learn immoral lessons from nature's example. Women were often depicted as both innately emotional and incapable of objective reasoning, or as natural mothers reproducing a natural, moral society.[43]

The eighteenth century was characterized by three divergent views towards woman: that women were mentally and socially inferior to men, that they were equal but different, and that women were potentially equal in both mental ability and contribution to society.[44] While individuals such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau believed women's roles were confined to motherhood and service to their male partners, the Enlightenment was a period in which women experienced expanded roles in the sciences.[45]

The rise of salon culture in Europe brought philosophers and their conversation to an intimate setting where men and women met to discuss contemporary political, social, and scientific topics.[46] While Jean-Jacques Rousseau attacked women-dominated salons as producing 'effeminate men' that stifled serious discourse, salons were characterized in this era by the mixing of the sexes.[47]

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu defied convention by introducing smallpox inoculation through variolation to Western medicine after witnessing it during her travels in the Ottoman Empire.[48][49] In 1718 Wortley Montague had her son inoculated[49] and when in 1721 a smallpox epidemic struck England, she had her daughter inoculated.[50] This was the first such operation done in Britain.[49] She persuaded Caroline of Ansbach to test the treatment on prisoners.[50] Princess Caroline subsequently inoculated her two daughters in 1722.[49] Under a pseudonym, Wortley Montague published an article describing and advocating in favor of inoculation in September 1722.[51]

After publicly defending forty nine theses[52] in the Palazzo Pubblico, Laura Bassi was awarded a doctorate of philosophy in 1732 at the University of Bologna.[53] Thus, Bassi became the second woman in the world to earn a philosophy doctorate after Elena Cornaro Piscopia in 1678, 54 years prior. She subsequently defended twelve additional theses at the Archiginnasio, the main building of the University of Bologna which allowed her to petition for a teaching position at the university.[53] In 1732 the university granted Bassi's professorship in philosophy, making her a member of the Academy of the Sciences and the first woman to earn a professorship in physics at a university in Europe[53] But the university held the value that women were to lead a private life and from 1746 to 1777 she gave only one formal dissertation per year ranging in topic from the problem of gravity to electricity.[52] Because she could not lecture publicly at the university regularly, she began conducting private lessons and experiments from home in the year of 1749.[52] However, due to her increase in responsibilities and public appearances on behalf of the university, Bassi was able to petition for regular pay increases, which in turn was used to pay for her advanced equipment. Bassi earned the highest salary paid by the University of Bologna of 1,200 lire.[54] In 1776, at the age of 65, she was appointed to the chair in experimental physics by the Bologna Institute of Sciences with her husband as a teaching assistant.[52]

According to Britannica, Maria Gaetana Agnesi is "considered to be the first woman in the Western world to have achieved a reputation in mathematics."[55] She is credited as the first woman to write a mathematics handbook, the Instituzioni analitiche ad uso della gioventù italiana, (Analytical Institutions for the Use of Italian Youth). Published in 1748 it "was regarded as the best introduction extant to the works of Euler."[56][57] The goal of this work was, according to Agnesi herself, to give a systematic illustration of the different results and theorems of infinitesimal calculus.[58] In 1750 she became the second woman to be granted a professorship at a European university. Also appointed to the University of Bologna she never taught there.[56][59]

The German Dorothea Erxleben was instructed in medicine by her father from an early age[60] and Bassi's university professorship inspired Erxleben to fight for her right to practise medicine. In 1742 she published a tract arguing that women should be allowed to attend university.[61] After being admitted to study by a dispensation of Frederick the Great,[60] Erxleben received her M.D. from the University of Halle in 1754.[61] She went on to analyse the obstacles preventing women from studying, among them housekeeping and children.[60] She became the first female medical doctor in Germany.[62]

In 1741–42 Charlotta Frölich became the first woman to be published by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences with three books in agricultural science. In 1748 Eva Ekeblad became the first woman inducted into that academy.[63] In 1746 Ekeblad had written to the academy about her discoveries of how to make flour and alcohol out of potatoes.[64][65] Potatoes had been introduced into Sweden in 1658 but had been cultivated only in the greenhouses of the aristocracy. Ekeblad's work turned potatoes into a staple food in Sweden, and increased the supply of wheat, rye and barley available for making bread, since potatoes could be used instead to make alcohol. This greatly improved the country's eating habits and reduced the frequency of famines.[65] Ekeblad also discovered a method of bleaching cotton textile and yarn with soap in 1751,[64] and of replacing the dangerous ingredients in cosmetics of the time by using potato flour in 1752.[65]

Émilie du Châtelet, a close friend of Voltaire, was the first scientist to appreciate the significance of kinetic energy, as opposed to momentum. She repeated and described the importance of an experiment originally devised by Willem 's Gravesande showing the impact of falling objects is proportional not to their velocity, but to the velocity squared. This understanding is considered to have made a profound contribution to Newtonian mechanics.[66] In 1749 she completed the French translation of Newton's Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica (the Principia), including her derivation of the notion of conservation of energy from its principles of mechanics. Published ten years after her death, her translation and commentary of the Principia contributed to the completion of the scientific revolution in France and to its acceptance in Europe.[67]

Marie-Anne Pierrette Paulze and her husband Antoine Lavoisier rebuilt the field of chemistry, which had its roots in alchemy and at the time was a convoluted science dominated by George Stahl's theory of phlogiston. Paulze accompanied Lavoisier in his lab, making entries into lab notebooks and sketching diagrams of his experimental designs. The training she had received allowed her to accurately and precisely draw experimental apparatuses, which ultimately helped many of Lavoisier's contemporaries to understand his methods and results. Paulze translated various works about phlogiston into French. One of her most important translation was that of Richard Kirwan's Essay on Phlogiston and the Constitution of Acids, which she both translated and critiqued, adding footnotes as she went along and pointing out errors in the chemistry made throughout the paper.[68] Paulze was instrumental in the 1789 publication of Lavoisier's Elementary Treatise on Chemistry, which presented a unified view of chemistry as a field. This work proved pivotal in the progression of chemistry, as it presented the idea of conservation of mass as well as a list of elements and a new system for chemical nomenclature. She also kept strict records of the procedures followed, lending validity to the findings Lavoisier published.

The astronomer Caroline Herschel was born in Hanover but moved to England where she acted as an assistant to her brother, William Herschel. Throughout her writings, she repeatedly made it clear that she desired to earn an independent wage and be able to support herself. When the crown began paying her for her assistance to her brother in 1787, she became the first woman to do so at a time when even men rarely received wages for scientific enterprises—to receive a salary for services to science.[69] During 1786–97 she discovered eight comets, the first on 1 August 1786. She had unquestioned priority as discoverer of five of the comets[69][70] and rediscovered Comet Encke in 1795.[71] Five of her comets were published in Philosophical Transactions, a packet of paper bearing the superscription, "This is what I call the Bills and Receipts of my Comets" contains some data connected with the discovery of each of these objects. William was summoned to Windsor Castle to demonstrate Caroline's comet to the royal family.[72] Caroline Herschel is often credited as the first woman to discover a comet; however, Maria Kirch discovered a comet in the early 1700s, but is often overlooked because at the time, the discovery was attributed to her husband, Gottfried Kirch.[73]

Nineteenth century

[edit]Early nineteenth century

[edit]

Science remained a largely amateur profession during the early part of the nineteenth century. Botany was considered a popular and fashionable activity, and one particularly suitable to women. In the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, it was one of the most accessible areas of science for women in both England and North America.[74][75][76]

However, as the nineteenth century progressed, botany and other sciences became increasingly professionalized, and women were increasingly excluded. Women's contributions were limited by their exclusion from most formal scientific education, but began to be recognized through their occasional admittance into learned societies during this period.[76][74]

Scottish scientist Mary Fairfax Somerville carried out experiments in magnetism, presenting a paper entitled 'The Magnetic Properties of the Violet Rays of the Solar Spectrum' to the Royal Society in 1826, the second woman to do so. She also wrote several mathematical, astronomical, physical and geographical texts, and was a strong advocate for women's education. In 1835, she and Caroline Herschel were the first two women elected as Honorary Members of the Royal Astronomical Society.[77]

English mathematician Ada, Lady Lovelace, a pupil of Somerville, corresponded with Charles Babbage about applications for his analytical engine. In her notes (1842–3) appended to her translation of Luigi Menabrea's article on the engine, she foresaw wide applications for it as a general-purpose computer, including composing music. She has been credited as writing the first computer program, though this has been disputed.[78]

In Germany, institutes for "higher" education of women (Höhere Mädchenschule, in some regions called Lyzeum) were founded at the beginning of the century.[79] The Deaconess Institute at Kaiserswerth was established in 1836 to instruct women in nursing. Elizabeth Fry visited the institute in 1840 and was inspired to found the London Institute of Nursing, and Florence Nightingale studied there in 1851.[80]

In the US, Maria Mitchell made her name by discovering a comet in 1847, but also contributed calculations to the Nautical Almanac produced by the United States Naval Observatory. She became the first woman member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1848 and of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1850.

Other notable female scientists during this period include:[15]

- in Britain, Mary Anning (paleontologist), Anna Atkins (botanist), Janet Taylor (astronomer)

- in France, Marie-Sophie Germain (mathematician), Jeanne Villepreux-Power (marine biologist)

Late 19th century in western Europe

[edit]The latter part of the 19th century saw a rise in educational opportunities for women. Schools aiming to provide education for girls similar to that afforded to boys were founded in the UK, including the North London Collegiate School (1850), Cheltenham Ladies' College (1853) and the Girls' Public Day School Trust schools (from 1872). The first UK women's university college, Girton, was founded in 1869, and others soon followed: Newnham (1871) and Somerville (1879).

The Crimean War (1854–1856) contributed to establishing nursing as a profession, making Florence Nightingale a household name. A public subscription allowed Nightingale to establish a school of nursing in London in 1860, and schools following her principles were established throughout the UK.[80] Nightingale was also a pioneer in public health as well as a statistician.

James Barry became the first British woman to gain a medical qualification in 1812, passing as a man. Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was the first openly female Briton to qualify medically, in 1865. With Sophia Jex-Blake, American Elizabeth Blackwell and others, Garret Anderson founded the first UK medical school to train women, the London School of Medicine for Women, in 1874.

Annie Scott Dill Maunder was a pioneer in astronomical photography, especially of sunspots. A mathematics graduate of Girton College, Cambridge, she was first hired (in 1890) to be an assistant to Edward Walter Maunder, discoverer of the Maunder Minimum, the head of the solar department at Greenwich Observatory. They worked together to observe sunspots and to refine the techniques of solar photography. They married in 1895. Annie's mathematical skills made it possible to analyse the years of sunspot data that Maunder had been collecting at Greenwich. She also designed a small, portable wide-angle camera with a 1.5-inch-diameter (38 mm) lens. In 1898, the Maunders traveled to India, where Annie took the first photographs of the Sun's corona during a solar eclipse. By analysing the Cambridge records for both sunspots and geomagnetic storm, they were able to show that specific regions of the Sun's surface were the source of geomagnetic storms and that the Sun did not radiate its energy uniformly into space, as William Thomson, 1st Baron Kelvin had declared.[81]

In Prussia women could go to university from 1894 and were allowed to receive a PhD. In 1908 all remaining restrictions for women were terminated.

Alphonse Rebière published a book in 1897, in France, entitled Les Femmes dans la science (Women in Science) which listed the contributions and publications of women in science.[82]

Other notable female scientists during this period include:[15][83]

- in Britain, Hertha Marks Ayrton (mathematician, engineer), Margaret Huggins (astronomer), Beatrix Potter (mycologist)

- in France, Dorothea Klumpke-Roberts (American-born astronomer)

- in Germany, Amalie Dietrich (naturalist), Agnes Pockels (physicist)

- in Russia and Sweden, Sofia Kovalevskaya (mathematician)

Late nineteenth-century Russians

[edit]In the second half of the 19th century, a large proportion of the most successful women in the STEM fields were Russians. Although many women received advanced training in medicine in the 1870s,[84] in other fields women were barred and had to go to western Europe—mainly Switzerland—in order to pursue scientific studies. In her book about these "women of the [eighteen] sixties" (шестидесятницы), as they were called, Ann Hibner Koblitz writes:[85]: 11

To a large extent, women's higher education in continental Europe was pioneered by this first generation of Russian women. They were the first students in Zürich, Heidelberg, Leipzig, and elsewhere. Theirs were the first doctorates in medicine, chemistry, mathematics, and biology.

Among the successful scientists were Nadezhda Suslova (1843–1918), the first woman in the world to obtain a medical doctorate fully equivalent to men's degrees; Maria Bokova-Sechenova (1839–1929), a pioneer of women's medical education who received two doctoral degrees, one in medicine in Zürich and one in physiology in Vienna; Iulia Lermontova (1846–1919), the first woman in the world to receive a doctoral degree in chemistry; the marine biologist Sofia Pereiaslavtseva (1849–1903), director of the Sevastopol Biological Station and winner of the Kessler Prize of the Russian Society of Natural Scientists; and the mathematician Sofia Kovalevskaia (1850–1891), the first woman in 19th century Europe to receive a doctorate in mathematics and the first to become a university professor in any field.[85]

Late nineteenth century in the United States

[edit]In the later nineteenth century the rise of the women's college provided jobs for women scientists, and opportunities for education.

Women's colleges produced a disproportionate number of women who went on for PhDs in science. Many coeducational colleges and universities also opened or started to admit women during this period; such institutions included just over 3000 women in 1875, by 1900 numbered almost 20,000.[83]

An example is Elizabeth Blackwell, who became the first certified female doctor in the US when she graduated from Geneva Medical College in 1849.[86] With her sister, Emily Blackwell, and Marie Zakrzewska, Blackwell founded the New York Infirmary for Women and Children in 1857 and the first women's medical college in 1868, providing both training and clinical experience for women doctors. She also published several books on medical education for women.

In 1876, Elizabeth Bragg became the first woman to graduate with a civil engineering degree in the United States, from the University of California, Berkeley.[87]

Early twentieth century

[edit]Europe before World War II

[edit]Marie Skłodowska-Curie, the first woman to win a Nobel prize in 1903 (physics), went on to become a double Nobel prize winner in 1911, both for her work on radiation. She was the first person to win two Nobel prizes, a feat accomplished by only three others since then. She also was the first woman to teach at Sorbonne University in Paris.[88]

Alice Perry is understood to be the first woman to graduate with a degree in civil engineering in the then United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, in 1906 at Queen's College, Galway, Ireland.[89]

Lise Meitner played a major role in the discovery of nuclear fission. As head of the physics section at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute in Berlin she collaborated closely with the head of chemistry Otto Hahn on atomic physics until forced to flee Berlin in 1938. In 1939, in collaboration with her nephew Otto Frisch, Meitner derived the theoretical explanation for an experiment performed by Hahn and Fritz Strassman in Berlin, thereby demonstrating the occurrence of nuclear fission. The possibility that Fermi's bombardment of uranium with neutrons in 1934 had instead produced fission by breaking up the nucleus into lighter elements, had actually first been raised in print in 1934, by chemist Ida Noddack (co-discover of the element rhenium), but this suggestion had been ignored at the time, as no group made a concerted effort to find any of these light radioactive fission products.

Maria Montessori was the first woman in Southern Europe to qualify as a physician.[90] She developed an interest in the diseases of children and believed in the necessity of educating those recognized to be ineducable. In the case of the latter she argued for the development of training for teachers along Froebelian lines and developed the principle that was also to inform her general educational program, which is the first the education of the senses, then the education of the intellect. Montessori introduced a teaching program that allowed defective children to read and write. She sought to teach skills not by having children repeatedly try it, but by developing exercises that prepare them.[91]

Emmy Noether revolutionized abstract algebra, filled in gaps in relativity, and was responsible for a critical theorem about conserved quantities in physics. One notes that the Erlangen program attempted to identify invariants under a group of transformations. On 16 July 1918, before a scientific organization in Göttingen, Felix Klein read a paper written by Emmy Noether, because she was not allowed to present the paper herself. In particular, in what is referred to in physics as Noether's theorem, this paper identified the conditions under which the Poincaré group of transformations (now called a gauge group) for general relativity defines conservation laws.[92] Noether's papers made the requirements for the conservation laws precise. Among mathematicians, Noether is best known for her fundamental contributions to abstract algebra, where the adjective noetherian is nowadays commonly used on many sorts of objects.

Mary Cartwright was a British mathematician who was the first to analyze a dynamical system with chaos.[93] Inge Lehmann, a Danish seismologist, first suggested in 1936 that inside the Earth's molten core there may be a solid inner core.[94] Women such as Margaret Fountaine continued to contribute detailed observations and illustrations in botany, entomology, and related observational fields. Joan Beauchamp Procter, an outstanding herpetologist, was the first woman Curator of Reptiles for the Zoological Society of London at London Zoo.

Florence Sabin was an American medical scientist. Sabin was the first woman faculty member at Johns Hopkins in 1902, and the first woman full-time professor there in 1917.[95] Her scientific and research experience is notable. Sabin published over 100 scientific papers and multiple books.[95]

United States before and during World War II

[edit]Women moved into science in significant numbers by 1900, helped by the women's colleges and by opportunities at some of the new universities. Margaret Rossiter's books Women Scientists in America: Struggles and Strategies to 1940 and Women Scientists in America: Before Affirmative Action 1940–1972 provide an overview of this period, stressing the opportunities women found in separate women's work in science.[96][97]

In 1892, Ellen Swallow Richards called for the "christening of a new science" – "oekology" (ecology) in a Boston lecture. This new science included the study of "consumer nutrition" and environmental education. This interdisciplinary branch of science was later specialized into what is currently known as ecology, while the consumer nutrition focus split off and was eventually relabeled as home economics,[98][99] which provided another avenue for women to study science. Richards helped to form the American Home Economics Association, which published a journal, the Journal of Home Economics, and hosted conferences. Home economics departments were formed at many colleges, especially at land grant institutions. In her work at MIT, Ellen Richards also introduced the first biology course in its history as well as the focus area of sanitary engineering.

Women also found opportunities in botany and embryology. In psychology, women earned doctorates but were encouraged to specialize in educational and child psychology and to take jobs in clinical settings, such as hospitals and social welfare agencies.

In 1901, Annie Jump Cannon first noticed that it was a star's temperature that was the principal distinguishing feature among different spectra.[dubious – discuss] This led to re-ordering of the ABC types by temperature instead of hydrogen absorption-line strength. Due to Cannon's work, most of the then-existing classes of stars were thrown out as redundant. Afterward, astronomy was left with the seven primary classes recognized today, in order: O, B, A, F, G, K, M;[100] that has since been extended.

Henrietta Swan Leavitt first published her study of variable stars in 1908. This discovery became known as the "period-luminosity relationship" of Cepheid variables.[102] Our picture of the universe was changed forever, largely because of Leavitt's discovery.

The accomplishments of Edwin Hubble, renowned American astronomer, were made possible by Leavitt's groundbreaking research and Leavitt's Law. "If Henrietta Leavitt had provided the key to determine the size of the cosmos, then it was Edwin Powell Hubble who inserted it in the lock and provided the observations that allowed it to be turned", wrote David H. and Matthew D.H. Clark in their book Measuring the Cosmos.[103]

Hubble often said that Leavitt deserved the Nobel for her work.[104] Gösta Mittag-Leffler of the Swedish Academy of Sciences had begun paperwork on her nomination in 1924, only to learn that she had died of cancer three years earlier[105] (the Nobel prize cannot be awarded posthumously).

In 1925, Harvard graduate student Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin demonstrated for the first time from existing evidence on the spectra of stars that stars were made up almost exclusively of hydrogen and helium, one of the most fundamental theories in stellar astrophysics.[100][102]

Canadian-born Maud Menten worked in the US and Germany. Her most famous work was on enzyme kinetics together with Leonor Michaelis, based on earlier findings of Victor Henri. This resulted in the Michaelis–Menten equations. Menten also invented the azo-dye coupling reaction for alkaline phosphatase, which is still used in histochemistry. She characterised bacterial toxins from B. paratyphosus, Streptococcus scarlatina and Salmonella ssp., and conducted the first electrophoretic separation of proteins in 1944. She worked on the properties of hemoglobin, regulation of blood sugar level, and kidney function.

World War II brought some new opportunities. The Office of Scientific Research and Development, under Vannevar Bush, began in 1941 to keep a registry of men and women trained in the sciences. Because there was a shortage of workers, some women were able to work in jobs they might not otherwise have accessed. Many women worked on the Manhattan Project or on scientific projects for the United States military services. Women who worked on the Manhattan Project included Leona Woods Marshall, Katharine Way, and Chien-Shiung Wu. It was actually Wu who confirmed Enrico Fermi's hypothesis through her earlier draft that Xe-135 impeded the B reactor from working. The adjustments made would quickly let the project resume its course.[106][107]

Wu would later also confirm Albert Einstein's EPR Paradox in the first experimental corroboration, and prove the first violation of Parity and Charge Conjugate Symmetry, thereby laying the conceptual basis for the future Standard model of Particle Physics, and the rapid development of the new field.[108]

Women in other disciplines looked for ways to apply their expertise to the war effort. Three nutritionists, Lydia J. Roberts, Hazel K. Stiebeling, and Helen S. Mitchell, developed the Recommended Dietary Allowance in 1941 to help military and civilian groups make plans for group feeding situations. The RDAs proved necessary, especially, once foods began to be rationed. Rachel Carson worked for the United States Bureau of Fisheries, writing brochures to encourage Americans to consume a wider variety of fish and seafood. She also contributed to research to assist the Navy in developing techniques and equipment for submarine detection.

Women in psychology formed the National Council of Women Psychologists, which organized projects related to the war effort. The NCWP elected Florence Laura Goodenough president. In the social sciences, several women contributed to the Japanese Evacuation and Resettlement Study, based at the University of California. This study was led by sociologist Dorothy Swaine Thomas, who directed the project and synthesized information from her informants, mostly graduate students in anthropology. These included Tamie Tsuchiyama, the only Japanese-American woman to contribute to the study, and Rosalie Hankey Wax.

In the United States Navy, female scientists conducted a wide range of research. Mary Sears, a planktonologist, researched military oceanographic techniques as head of the Hydgrographic Office's Oceanographic Unit. Florence van Straten, a chemist, worked as an aerological engineer. She studied the effects of weather on military combat. Grace Hopper, a mathematician, became one of the first computer programmers for the Mark I computer. Mina Spiegel Rees, also a mathematician, was the chief technical aide for the Applied Mathematics Panel of the National Defense Research Committee.

Gerty Cori was a biochemist who discovered the mechanism by which glycogen, a derivative of glucose, is transformed in the muscles to form lactic acid, and is later reformed as a way to store energy. For this discovery she and her colleagues were awarded the Nobel prize in 1947, making her the third woman and the first American woman to win a Nobel Prize in science. She was the first woman ever to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Cori is among several scientists whose works are commemorated by a U.S. postage stamp.[109]

Late 20th century to early 21st century

[edit]

Nina Byers notes that before 1976, fundamental contributions of women to physics were rarely acknowledged. Women worked unpaid or in positions lacking the status they deserved. That imbalance is gradually being redressed.[citation needed]

In the early 1980s, Margaret Rossiter presented two concepts for understanding the statistics behind women in science as well as the disadvantages women continued to suffer. She coined the terms "hierarchical segregation" and "territorial segregation." The former term describes the phenomenon in which the further one goes up the chain of command in the field, the smaller the presence of women. The latter describes the phenomenon in which women "cluster in scientific disciplines."[110]: 33–34

A recent book titled Athena Unbound provides a life-course analysis (based on interviews and surveys) of women in science from early childhood interest, through university, graduate school and the academic workplace. The thesis of this book is that "Women face a special series of gender related barriers to entry and success in scientific careers that persist, despite recent advances".[111]

The L'Oréal-UNESCO Awards for Women in Science were set up in 1998, with prizes alternating each year between the materials science and life sciences. One award is given for each geographical region of Africa and the Middle East, Asia-Pacific, Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, and North America. By 2017, these awards had recognised almost 100 laureates from 30 countries. Two of the laureates have gone on to win the Nobel Prize, Ada Yonath (2008) and Elizabeth Blackburn (2009). Fifteen promising young researchers also receive an International Rising Talent fellowship each year within this programme.

Europe after World War II

[edit]South-African born physicist and radiobiologist Tikvah Alper(1909–95), working in the UK, developed many fundamental insights into biological mechanisms, including the (negative) discovery that the infective agent in scrapie could not be a virus or other eukaryotic structure.

French virologist Françoise Barré-Sinoussi performed some of the fundamental work in the identification of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) as the cause of AIDS, for which she shared the 2008 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

In July 1967, Jocelyn Bell Burnell discovered evidence for the first known radio pulsar, which resulted in the 1974 Nobel Prize in Physics for her supervisor. She was president of the Institute of Physics from October 2008 until October 2010.

Astrophysicist Margaret Burbidge was a member of the B2FH group responsible for originating the theory of stellar nucleosynthesis, which explains how elements are formed in stars. She has held a number of prestigious posts, including the directorship of the Royal Greenwich Observatory.

Mary Cartwright was a mathematician and student of G. H. Hardy. Her work on nonlinear differential equations was influential in the field of dynamical systems.

Rosalind Franklin was a crystallographer, whose work helped to elucidate the fine structures of coal, graphite, DNA and viruses. In 1953, the work she did on DNA allowed Watson and Crick to conceive their model of the structure of DNA. Her photograph of DNA gave Watson and Crick a basis for their DNA research, and they were awarded the Nobel Prize without giving due credit to Franklin, who had died of cancer in 1958.

Jane Goodall is a British primatologist considered to be the world's foremost expert on chimpanzees and is best known for her over 55-year study of social and family interactions of wild chimpanzees. She is the founder of the Jane Goodall Institute and the Roots & Shoots programme.

Dorothy Hodgkin analyzed the molecular structure of complex chemicals by studying diffraction patterns caused by passing X-rays through crystals. She won the 1964 Nobel prize for chemistry for discovering the structure of vitamin B12, becoming the third woman to win the prize for chemistry.[112]

Irène Joliot-Curie, daughter of Marie Curie, won the 1935 Nobel Prize for chemistry with her husband Frédéric Joliot for their work in radioactive isotopes leading to nuclear fission. This made the Curies the family with the most Nobel laureates to date.

Palaeoanthropologist Mary Leakey discovered the first skull of a fossil ape on Rusinga Island and also a noted robust Australopithecine.

Italian neurologist Rita Levi-Montalcini received the 1986 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of Nerve growth factor (NGF). Her work allowed for a further potential understanding of different diseases such as tumors, delayed healing, malformations, and others.[113] This research led to her winning the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine alongside Stanley Cohen in 1986. While making advancements in medicine and science, Rita Levi-Montalcini was also active politically throughout her life.[114] She was appointed a Senator for Life in the Italian Senate in 2001 and is the oldest Nobel laureate ever to have lived.

Zoologist Anne McLaren conducted studied in genetics which led to advances in in vitro fertilization. She became the first female officer of the Royal Society in 331 years.

Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1995 for research on the genetic control of embryonic development. She also started the Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard Foundation (Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard Stiftung), to aid promising young female German scientists with children.

Bertha Swirles was a theoretical physicist who made a number of contributions to early quantum theory. She co-authored the well-known textbook Methods of Mathematical Physics with her husband Sir Harold Jeffreys.

United States after World War II

[edit]Kay McNulty, Betty Jennings, Betty Snyder, Marlyn Wescoff, Fran Bilas and Ruth Lichterman were six of the original programmers for the ENIAC, the first general purpose electronic computer.[115]

Linda B. Buck is a neurobiologist who was awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine along with Richard Axel for their work on olfactory receptors.

Rachel Carson was a marine biologist from the United States. She is credited with being the founder of the environmental movement.[116] The biologist and activist published Silent Spring, a work on the dangers of pesticides, in 1962. The publishing of her environmental science book led to the questioning of usage of harmful pesticides and other chemicals in agricultural settings.[116] This led to a campaign to attempt to ultimately discredit Carson. However, the federal government called for a review of DDT which concluded with DDT being banned.[117] Carson later passed away from cancer in 1964 at 57 years old.[117]

Eugenie Clark, popularly known as The Shark Lady, was an American ichthyologist known for her research on poisonous fish of the tropical seas and on the behavior of sharks.[118]

Ann Druyan is an American writer, lecturer and producer specializing in cosmology and popular science. Druyan has credited her knowledge of science to the 20 years she spent studying with her late husband, Carl Sagan, rather than formal academic training.[citation needed] She was responsible for the selection of music on the Voyager Golden Record for the Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 exploratory missions. Druyan also sponsored the Cosmos 1 spacecraft.

Gertrude B. Elion was an American biochemist and pharmacologist, awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1988 for her work on the differences in biochemistry between normal human cells and pathogens.

Sandra Moore Faber, with Robert Jackson, discovered the Faber–Jackson relation between luminosity and stellar dispersion velocity in elliptical galaxies. She also headed the team which discovered the Great Attractor, a large concentration of mass which is pulling a number of nearby galaxies in its direction.

Zoologist Dian Fossey worked with gorillas in Africa from 1967 until her murder in 1985.

Astronomer Andrea Ghez received a MacArthur "genius grant" in 2008 for her work in surmounting the limitations of earthbound telescopes.[119]

Maria Goeppert Mayer was the second female Nobel Prize winner in Physics, for proposing the nuclear shell model of the atomic nucleus. Earlier in her career, she had worked in unofficial or volunteer positions at the university where her husband was a professor. Goeppert Mayer is one of several scientists whose works are commemorated by a U.S. postage stamp.[120]

Sulamith Low Goldhaber and her husband Gerson Goldhaber formed a research team on the K meson and other high-energy particles in the 1950s.

Carol Greider and the Australian born Elizabeth Blackburn, along with Jack W. Szostak, received the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for the discovery of how chromosomes are protected by telomeres and the enzyme telomerase.

Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper developed the first computer compiler while working for the Eckert Mauchly Computer Corporation, released in 1952.

Deborah S. Jin's team at JILA, in Boulder, Colorado, in 2003 produced the first fermionic condensate, a new state of matter.

Stephanie Kwolek, a researcher at DuPont, invented poly-paraphenylene terephthalamide – better known as Kevlar.

Lynn Margulis is a biologist best known for her work on endosymbiotic theory, which is now generally accepted for how certain organelles were formed.

Barbara McClintock's studies of maize genetics demonstrated genetic transposition in the 1940s and 1950s. Before then, McClintock obtained her PhD from Cornell University in 1927. Her discovery of transposition provided a greater understanding of mobile loci within chromosomes and the ability for genetics to be fluid.[121] She dedicated her life to her research, and she was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1983. McClintock was the first American woman to receive a Nobel Prize that was not shared by anyone else.[121] McClintock is one of several scientists whose works are commemorated by a U.S. postage stamp.[122]

Nita Ahuja is a renowned surgeon-scientist known for her work on CIMP in cancer, she is currently the Chief of surgical oncology at Johns Hopkins Hospital. First woman ever to be the Chief of this prestigious department.

Carolyn Porco is a planetary scientist best known for her work on the Voyager program and the Cassini–Huygens mission to Saturn. She is also known for her popularization of science, in particular space exploration.

Physicist Helen Quinn, with Roberto Peccei, postulated Peccei-Quinn symmetry. One consequence is a particle known as the axion, a candidate for the dark matter that pervades the universe. Quinn was the first woman to receive the Dirac Medal by the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) and the first to receive the Oskar Klein Medal.

Lisa Randall is a theoretical physicist and cosmologist, best known for her work on the Randall–Sundrum model. She was the first tenured female physics professor at Princeton University.

Sally Ride was an astrophysicist and the first American woman, and then-youngest American, to travel to outer space. Ride wrote or co-wrote several books on space aimed at children, with the goal of encouraging them to study science.[123][124] Ride participated in the Gravity Probe B (GP-B) project, which provided more evidence that the predictions of Albert Einstein's general theory of relativity are correct.[125]

Through her observations of galaxy rotation curves, astronomer Vera Rubin discovered the Galaxy rotation problem, now taken to be one of the key pieces of evidence for the existence of dark matter. She was the first female allowed to observe at the Palomar Observatory.

Sara Seager is a Canadian-American astronomer who is currently a professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and known for her work on extrasolar planets.

Astronomer Jill Tarter is best known for her work on the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. Tarter was named one of the 100 most influential people in the world by Time Magazine in 2004.[126] She is the former director of SETI.[127]

Rosalyn Yalow was the co-winner of the 1977 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine (together with Roger Guillemin and Andrew Schally) for development of the radioimmunoassay (RIA) technique.

Australia after World War II

[edit]- Amanda Barnard, an Australia-based theoretical physicist specializing in nanomaterials, winner of the Malcolm McIntosh Prize for Physical Scientist of the Year.

- Isobel Bennett, was one of the first women to go to Macquarie Island with the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (ANARE). She is one of Australia's best known marine biologists.

- Dorothy Hill, an Australian geologist who became the first female Professor at an Australian university.

- Ruby Payne-Scott, was an Australian who was an early leader in the fields of radio astronomy and radiophysics. She was one of the first radio astronomers and the first woman in the field.

- Penny Sackett, an astronomer who became the first female Chief Scientist of Australia in 2008. She is a US-born Australian citizen.

- Fiona Stanley, winner of the 2003 Australian of the Year award, is an epidemiologist noted for her research into child and maternal health, birth disorders, and her work in the public health field.

- Michelle Simmons, winner of the 2018 Australian of the Year award, is a quantum physicist known for her research and leadership on atomic-scale silicon quantum devices.

Israel after World War II

[edit]- Ada Yonath, the first woman from the Middle East to win a Nobel prize in the sciences, was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2009 for her studies on the structure and function of the ribosome.

Latin America

Maria Nieves Garcia-Casal, the first scientist and nutritionist woman from Latin America to lead the Latin America Society of Nutrition.

Angela Restrepo Moreno is a microbiologist from Colombia. She first gained interest in tiny organisms when she had the opportunity to view them through a microscope that belonged to her grandfather.[128] While Restrepo has a variety of research, her main area of research is fungi and their causes of diseases.[128] Her work led her to develop research on a disease caused by fungi that has only been diagnosed in Latin America but was originally found in Brazil: Paracoccidioidomycosis.[128] Research groups also developed by Restrepo have begun studying two routes: the relationship between humans, fungi, and the environment and also how the cells within the fungi work.[128]

Along with her research, Restrepo co-founded a non-profit that is devoted to scientific research named Corporation for Biological Research (CIB).[128] Angela Restrepo Moreno was awarded the SCOPUS Prize in 2007 for her numerous publications.[128] She currently resides in Colombia and continues her research.

Susana López Charretón was born in Mexico City, Mexico in 1957. She is a virologist whose area of study focused on the rotavirus.[129] When she initially began studying rotavirus, it had only been discovered four years earlier.[129] Charretón's main job was to study how the virus entered cells and its ways of multiplying.[129] Because of her, and several others, work other scientists were able to learn about more details of the virus.[129] Now, her research focuses on the virus's ability to recognize the cells it infects.[129] Along with her husband, Charretón was awarded the Carlos J. Finlay Prize for Microbiology in 2001.[129] She also received the Loreal-UNESCO prize titled "Woman in Science" in 2012.[129] Charretón has also received several other awards for her research.

Liliana Quintanar Vera is a Mexican chemist. Currently a researcher at the Department of Chemistry of the Center of Investigation and Advanced Studies, Vera's research currently focuses on neurodegenerative diseases like Parkinson's, Alzheimer's, and prion disease and also on degenerative diseases like diabetes and cataracts.[130] For this research she focused on how copper interacts with the proteins of the neurodegenerative diseases mentioned before.[131]

Liliana's awards include the Mexican Academy of Sciences Research Prize for Science in 2017, the Marcos Moshinsky Chair award in 2016, the Fulbright Scholarship in 2014, and the L'Oréal-UNESCO For Women in Science Award in 2007.[130]

Nobel laureates

[edit]The Nobel Prize and Prize in Economic Sciences have been awarded to women 61 times between 1901 and 2022. One woman, Marie Sklodowska-Curie, has been honored twice, with the 1903 Nobel Prize in Physics and the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. This means that 60 women in total have been awarded the Nobel Prize between 1901 and 2022. 25 women have been awarded the Nobel Prize in physics, chemistry, physiology or medicine.[4]

Chemistry

[edit]- 2022 – Carolyn Bertozzi

- 2020 – Emmanuelle Charpentier, Jennifer Doudna

- 2018 – Frances Arnold

- 2009 – Ada E. Yonath

- 1964 – Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin

- 1935 – Irène Joliot-Curie

- 1911 – Marie Sklodowska-Curie

Physics

[edit]- 2023 – Anne L'Huillier

- 2020 – Andrea Ghez

- 2018 – Donna Strickland

- 1963 – Maria Goeppert-Mayer

- 1903 – Marie Sklodowska-Curie

Physiology or Medicine

[edit]- 2023 – Katalin Karikó

- 2015 – Youyou Tu

- 2014 – May-Britt Moser

- 2009 – Elizabeth H. Blackburn

- 2009 – Carol W. Greider

- 2008 – Françoise Barré-Sinoussi

- 2004 – Linda B. Buck

- 1995 – Christiane Nüsslein-Volhard

- 1988 – Gertrude B. Elion

- 1986 – Rita Levi-Montalcini

- 1983 – Barbara McClintock

- 1977 – Rosalyn Yalow

- 1947 – Gerty Cori

- 2014 – Maryam Mirzakhani (12 May 1977 – 14 July 2017), the first woman to have won the prize, was an Iranian mathematician and a professor of mathematics at Stanford University.

- 2022 – Maryna Viazovska[132]

Statistics

[edit]The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. (April 2013) |

Statistics are used to indicate disadvantages faced by women in science, and also to track positive changes of employment opportunities and incomes for women in science.[110]: 33

Situation in the 1990s

[edit]Women appear to do less well than men (in terms of degree, rank, and salary) in the fields that have been traditionally dominated by women, such as nursing. In 1991 women attributed 91% of the PhDs in nursing, and men held 4% of full professorships in nursing.[citation needed] In the field of psychology, where women earn the majority of PhDs, women do not fill the majority of high rank positions in that field.[133][citation needed]

Women's lower salaries in the scientific community are also reflected in statistics. According to the data provided in 1993, the median salaries of female scientists and engineers with doctoral degrees were 20% less than men.[110]: 35 [needs update] This data can be explained[who?] as there was less participation of women in high rank scientific fields/positions and a female majority in low-paid fields/positions. However, even with men and women in the same scientific community field, women are typically paid 15–17% less than men.[citation needed] In addition to the gender gap, there were also salary differences between ethnicity: African-American women with more years of experiences earn 3.4% less than European-American women with similar skills, while Asian women engineers out-earn both Africans and Europeans.[134][needs update]

Women are also under-represented in the sciences as compared to their numbers in the overall working population. Within 11% of African-American women in the workforce, 3% are employed as scientists and engineers.[clarification needed] Hispanics made up 8% of the total workers in the US, 3% of that number are scientists and engineers. Native Americans participation cannot be statistically measured.[citation needed]

Women tend to earn less than men in almost all industries, including government and academia.[citation needed] Women are less likely to be hired in highest-paid positions.[citation needed] The data showing the differences in salaries, ranks, and overall success between the genders is often claimed[who?] to be a result of women's lack of professional experience. The rate of women's professional achievement is increasing. In 1996, the salaries for women in professional fields increased from 85% to 95% relative to men with similar skills and jobs. Young women between the age of 27 and 33 earned 98%, nearly as much as their male peers.[needs update] In the total workforce of the United States, women earn 74% as much as their male counterparts (in the 1970s they made 59% as much as their male counterparts).[110]: 33–37 [needs update]

Claudia Goldin, Harvard concludes in A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter – "The gender gap in pay would be considerably reduced and might vanish altogether if firms did not have an incentive to disproportionately reward individuals who labored long hours and worked particular hours."[135]

Research on women's participation in the "hard" sciences such as physics and computer science speaks of the "leaky pipeline" model, in which the proportion of women "on track" to potentially becoming top scientists fall off at every step of the way, from getting interested in science and maths in elementary school, through doctorate, postdoctoral, and career steps. The leaky pipeline also applies in other fields. In biology, for instance, women in the United States have been getting Masters degrees in the same numbers as men for two decades, yet fewer women get PhDs; and the numbers of women principal investigators have not risen.[136]

What may be the cause of this "leaky pipeline" of women in the sciences?[tone] It is important to look at factors outside of academia that are occurring in women's lives at the same time they are pursuing their continued education and career search. The most outstanding factor that is occurring at this crucial time is family formation. As women are continuing their academic careers, they are also stepping into their new role as a wife and mother. These traditionally require at large time commitment and presence outside work. These new commitments do not fare well for the person looking to attain tenure. That is why women entering the family formation period of their life are 35% less likely to pursue tenure positions after receiving their PhD's than their male counterparts.[137]

In the UK, women occupied over half the places in science-related higher education courses (science, medicine, maths, computer science and engineering) in 2004–5.[138] However, gender differences varied from subject to subject: women substantially outnumbered men in biology and medicine, especially nursing, while men predominated in maths, physical sciences, computer science and engineering.

In the US, women with science or engineering doctoral degrees were predominantly employed in the education sector in 2001, with substantially fewer employed in business or industry than men.[139] According to salary figures reported in 1991, women earn anywhere between 83.6 percent to 87.5 percent that of a man's salary.[needs update] An even greater disparity between men and women is the ongoing trend that women scientists with more experience are not as well-compensated as their male counterparts. The salary of a male engineer continues to experience growth as he gains experience whereas the female engineer sees her salary reach a plateau.[140]

Women, in the United States and many European countries, who succeed in science tend to be graduates of single-sex schools.[110]: Chapter 3 [needs update] Women earn 54% of all bachelor's degrees in the United States and 50% of those are in science. 9% of US physicists are women.[110]: Chapter 2 [needs update]

Overview of situation in 2013

[edit]

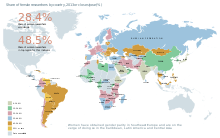

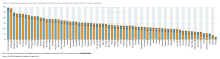

In 2013, women accounted for 53% of the world's graduates at the bachelor's and master's level and 43% of successful PhD candidates but just 28% of researchers. Women graduates are consistently highly represented in the life sciences, often at over 50%. However, their representation in the other fields is inconsistent. In North America and much of Europe, few women graduate in physics, mathematics and computer science but, in other regions, the proportion of women may be close to parity in physics or mathematics. In engineering and computer sciences, women consistently trail men, a situation that is particularly acute in many high-income countries.[141]

In decision-making

[edit]As of 2015, each step up the ladder of the scientific research system saw a drop in female participation until, at the highest echelons of scientific research and decision-making, there were very few women left. In 2015, the EU Commissioner for Research, Science and Innovation Carlos Moedas called attention to this phenomenon, adding that the majority of entrepreneurs in science and engineering tended to be men. In 2013, the German government coalition agreement introduced a 30% quota for women on company boards of directors.[141]

In 2010, women made up 14% of university chancellors and vice-chancellors at Brazilian public universities and 17% of those in South Africa in 2011.[142][143] As of 2015, in Argentina, women made up 16% of directors and vice-directors of national research centres and, in Mexico, 10% of directors of scientific research institutes at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.[144][145] In the US, numbers are slightly higher at 23%. In the EU, less than 16% of tertiary institutions were headed by a woman in 2010 and just 10% of universities. In 2011, at the main tertiary institution for the English-speaking Caribbean, the University of the West Indies, women represented 51% of lecturers but only 32% of senior lecturers and 26% of full professors . A 2018 review of the Royal Society of Britain by historians Aileen Fyfe and Camilla Mørk Røstvik produced similarly low numbers,[146] with women accounting for more than 25% of members in only a handful of countries, including Cuba, Panama and South Africa. As of 2015, the figure for Indonesia was 17%.[141][147][148]

Women in life sciences

[edit]In life sciences, women researchers have achieved parity (45–55% of researchers) in many countries. In some, the balance even now tips in their favour. Six out of ten researchers are women in both medical and agricultural sciences in Belarus and New Zealand, for instance. More than two-thirds of researchers in medical sciences are women in El Salvador, Estonia, Kazakhstan, Latvia, the Philippines, Tajikistan, Ukraine and Venezuela.[141]

There has been a steady increase in female graduates in agricultural sciences since the turn of the century. In sub-Saharan Africa, for instance, numbers of female graduates in agricultural science have been increasing steadily, with eight countries reporting a share of women graduates of 40% or more: Lesotho, Madagascar, Mozambique, Namibia, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Swaziland and Zimbabwe. The reasons for this surge are unclear, although one explanation may lie in the growing emphasis on national food security and the food industry. Another possible explanation is that women are highly represented in biotechnology. For example, in South Africa, women were underrepresented in engineering (16%) in 2004 and in 'natural scientific professions' (16%) in 2006 but made up 52% of employees working in biotechnology-related companies.[141]

Women play an increasing role in environmental sciences and conservation biology. In fact, women played a foremost role in the development of these disciplines. Silent Spring by Rachel Carson proved an important impetus to the conservation movement and the later banning of chemical pesticides. Women played an important role in conservation biology including the famous work of Dian Fossey, who published the famous Gorillas in the Mist and Jane Goodall who studied primates in East Africa. Today women make up an increasing proportion of roles in the active conservation sector. A recent survey of those working in the Wildlife Trusts in the U.K., the leading conservation organisation in England, found that there are nearly as many women as men in practical conservation roles.[149]

In engineering and related fields

[edit]Women are consistently underrepresented in engineering and related fields. In Israel, for instance, where 28% of senior academic staff are women, there are proportionately many fewer in engineering (14%), physical sciences (11%), mathematics and computer sciences (10%) but dominate education (52%) and paramedical occupations (63%). In Japan and the Republic of Korea, women represent just 5% and 10% of engineers.[141]

For women who are pursuing STEM major careers, these individuals often face gender disparities in the work field, especially in regards to science and engineering. It has become more common for women to pursue undergraduate degrees in science, but are continuously discredited in salary rates and higher ranking positions. For example, men show a greater likelihood of being selected for an employment position than a woman.[150]

In Europe and North America, the number of female graduates in engineering, physics, mathematics and computer science is generally low. Women make up just 19% of engineers in Canada, Germany and the US and 22% in Finland, for example. However, 50% of engineering graduates are women in Cyprus, 38% in Denmark and 36% in the Russian Federation, for instance.[141]

In many cases, engineering has lost ground to other sciences, including agriculture. The case of New Zealand is fairly typical. Here, women jumped from representing 39% to 70% of agricultural graduates between 2000 and 2012, continued to dominate health (80–78%) but ceded ground in science (43–39%) and engineering (33–27%).[141]

In a number of developing countries, there is a sizable proportion of women engineers. At least three out of ten engineers are women, for instance, in Costa Rica, Vietnam and the United Arab Emirates (31%), Algeria (32%), Mozambique (34%), Tunisia (41%) and Brunei Darussalam (42%). In Malaysia (50%) and Oman (53%), women are on a par with men. Of the 13 sub-Saharan countries reporting data, seven have observed substantial increases (more than 5%) in women engineers since 2000, namely: Benin, Burundi, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Mozambique and Namibia.[141]

Of the seven Arab countries reporting data, four observe a steady percentage or an increase in female engineers (Morocco, Oman, Palestine and Saudi Arabia). In the United Arab Emirates, the government has made it a priority to develop a knowledge economy, having recognized the need for a strong human resource base in science, technology and engineering. With just 1% of the labour force being Emirati, it is also concerned about the low percentage of Emirati citizens employed in key industries. As a result, it has introduced policies promoting the training and employment of Emirati citizens, as well as a greater participation of Emirati women in the labour force. Emirati female engineering students have said that they are attracted to a career in engineering for reasons of financial independence, the high social status associated with this field, the opportunity to engage in creative and challenging projects and the wide range of career opportunities.[141]

An analysis of computer science shows a steady decrease in female graduates since 2000 that is particularly marked in high-income countries. Between 2000 and 2012, the share of women graduates in computer science slipped in Australia, New Zealand, the Republic of Korea and USA. In Latin America and the Caribbean, the share of women graduates in computer science dropped by between 2 and 13 percentage points over this period for all countries reporting data.[141]

There are exceptions. In Denmark, the proportion of female graduates in computer science increased from 15% to 24% between 2000 and 2012 and Germany saw an increase from 10% to 17%. These are still very low levels. Figures are higher in many emerging economies. In Turkey, for instance, the proportion of women graduating in computer science rose from a relatively high 29% to 33% between 2000 and 2012.[141]

The Malaysian information technology (IT) sector is made up equally of women and men, with large numbers of women employed as university professors and in the private sector. This is a product of two historical trends: the predominance of women in the Malay electronics industry, the precursor to the IT industry, and the national push to achieve a 'pan-Malayan' culture beyond the three ethnic groups of Indian, Chinese and Malay. Government support for the education of all three groups is available on a quota basis and, since few Malay men are interested in IT, this leaves more room for women. Additionally, families tend to be supportive of their daughters' entry into this prestigious and highly remunerated industry, in the interests of upward social mobility. Malaysia's push to develop an endogenous research culture should deepen this trend.[141]

In India, the substantial increase in women undergraduates in engineering may be indicative of a change in the 'masculine' perception of engineering in the country. It is also a product of interest on the part of parents, since their daughters will be assured of employment as the field expands, as well as an advantageous marriage. Other factors include the 'friendly' image of engineering in India and the easy access to engineering education resulting from the increase in the number of women's engineering colleges over the last two decades.[141]

In space