Охота

Охота - это человеческая практика поиска, преследования, захвата и убийства дикой природы или диких животных . [ 10 ] Наиболее распространенные причины охоты людей - это получить тело животного для мяса и полезных продуктов животного происхождения ( мех / шкура , кости / клыки , рог / рога и т. Д.), Для отдыха / таксидермии (см. Трофейную охоту ), хотя это может Также делаются по изобретательным причинам, таким как удаление хищников, опасных для людей, или домашних животных (например, охота на волков ), для устранения вредителей и неприятностей животных , которые повреждают культуры / скот / птица или распространять болезнь (см. Varminting ), для торговли / туризма (см. Safari или ), или для экологического сохранения против перенаселения и инвазивных видов (обычно называемый отбор ).

Охотники на отдых виды обычно называют игрой и обычно являются млекопитающими и птицами . Человек, участвующий в охоте, является охотником или (менее часто) охотником ; используемая Природная зона, для охоты, называется игровым резервом ; А опытный охотник, который помогает организовать охоту и/или управлять игровым резервом, также известен как игрока .

Hunting activities by humans arose in Homo erectus or earlier, in the order of millions of years ago. Hunting has become deeply embedded in various human cultures and was once an important part of rural economies—classified by economists as part of primary production alongside forestry, agriculture, and fishery. Modern regulations (see game law) distinguish lawful hunting activities from illegal poaching, which involves the unauthorised and unregulated killing, trapping, or capture of animals.

Apart from food provision, hunting can be a means of population control. Hunting advocates state that regulated hunting can be a necessary component[11] of modern wildlife management, for example to help maintain a healthy proportion of animal populations within an environment's ecological carrying capacity when natural checks such as natural predators are absent or insufficient,[12][13] or to provide funding for breeding programs and maintenance of natural reserves and conservation parks. However, excessive hunting has also heavily contributed to the endangerment, extirpation and extinction of many animals.[14][15] Some animal rights and anti-hunting activists regard hunting as a cruel, perverse and unnecessary blood sport.[16][17] Certain hunting practices, such as canned hunts and ludicrously paid/bribed trophy tours (especially to poor countries), are considered unethical and exploitative even by some hunters.

Marine mammals such as whales and pinnipeds are also targets of hunting, both recreationally and commercially, often with heated controversies regarding the morality, ethics and legality of such practices. The pursuit, harvesting or catch and release of fish and aquatic cephalopods and crustaceans is called fishing, which however is widely accepted and not commonly categorised as a form of hunting. It is also not considered hunting to pursue animals without intent to kill them, as in wildlife photography, birdwatching, or scientific-research activities which involve tranquilizing or tagging of animals, although green hunting is still called so. The practices of netting or trapping insects and other arthropods for trophy collection, or the foraging or gathering of plants and mushrooms, are also not regarded as hunting.[18]

Skillful tracking and acquisition of an elusive target has caused the word hunt to be used in the vernacular as a metaphor for searching and obtaining something, as in "treasure hunting", "bargain hunting", "hunting for votes" and even "hunting down" corruption and waste.

Etymology

[edit]The word hunt serves as both a noun ("the act, the practice, or an instance of hunting") and a verb ("to pursue for food or in sport").[19] The noun has been dated to the early 12th century, from the verb hunt. Old English had huntung, huntoþ.[20] The meaning of "a body of persons associated for the purpose of hunting with a pack of hounds" is first recorded in the 1570s. "The act of searching for someone or something" is from about 1600.[20]

The verb, Old English huntian "to chase game" (transitive and intransitive), perhaps developed from hunta "hunter," is related to hentan "to seize," from Proto-Germanic huntojan (the source also of Gothic hinþan "to seize, capture," Old High German hunda "booty"), which is of uncertain origin. The general sense of "search diligently" (for anything) is first recorded c. 1200.[21]

Types

[edit]- Recreational hunting, also known as trophy hunting, sport hunting or "sporting"

- Big game hunting

- Medium/small game hunting

- Fowling

- Pest control/nuisance management

- Commercial hunting and traditional sustenance hunting

- Other

History

[edit]

Lower to Middle Paleolithic

[edit]Hunting has a long history. It predates the emergence of Homo sapiens (anatomically modern humans) and may even predate the genus Homo.

The oldest undisputed evidence for hunting dates to the Early Pleistocene, consistent with the emergence and early dispersal of Homo erectus about 1.7 million years ago (Acheulean).[22] While it is undisputed that Homo erectus were hunters, the importance of this for the emergence of Homo erectus from its australopithecine ancestors, including the production of stone tools and eventually the control of fire, is emphasised in the so-called "hunting hypothesis" and de-emphasised in scenarios that stress omnivory and social interaction.

There is no direct evidence for hunting predating Homo erectus, in either Homo habilis or in Australopithecus. The early hominid ancestors of humans were probably frugivores or omnivores, with a partially carnivorous diet from scavenging rather than hunting. Evidence for australopithecine meat consumption was presented in the 1990s.[23] It has nevertheless often been assumed that at least occasional hunting behaviour may have been present well before the emergence of Homo.This can be argued on the basis of comparison with chimpanzees, the closest extant relatives of humans, who also engage in hunting, indicating that the behavioural trait may have been present in the Chimpanzee–human last common ancestor as early as 5 million years ago. The common chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) regularly engages in troop predation behaviour, where bands of beta males are led by an alpha male. Bonobos (Pan paniscus) have also been observed to occasionally engage in group hunting,[24] although more rarely than Pan troglodytes, mainly subsisting on a frugivorous diet.[25] Indirect evidence for Oldowan era hunting, by early Homo or late Australopithecus, has been presented in a 2009 study based on an Oldowan site in southwestern Kenya.[26]

Louis Binford (1986) criticised the idea that early hominids and early humans were hunters. On the basis of the analysis of the skeletal remains of the consumed animals, he concluded that hominids and early humans were mostly scavengers, not hunters,[27] Blumenschine (1986) proposed the idea of confrontational scavenging, which involves challenging and scaring off other predators after they have made a kill, which he suggests could have been the leading method of obtaining protein-rich meat by early humans.[28]

Stone spearheads dated as early as 500,000 years ago were found in South Africa.[29] Wood does not preserve well, however, and Craig Stanford, a primatologist and professor of anthropology at the University of Southern California, has suggested that the discovery of spear use by chimpanzees probably means that early humans used wooden spears as well, perhaps, five million years ago.[30] The earliest dated find of surviving wooden hunting spears dates to the very end of the Lower Paleolithic, just before 300,000 years ago. The Schöningen spears, found in 1976 in Germany, are associated with Homo heidelbergensis.[31]

The hunting hypothesis sees the emergence of behavioral modernity in the Middle Paleolithic as directly related to hunting, including mating behaviour, the establishment of language, culture, and religion, mythology and animal sacrifice. Sociologist David Nibert of Wittenberg University argues that the emergence of the organized hunting of animals undermined the communal, egalitarian nature of early human societies, with the status of women and less powerful males declining as the status of men quickly became associated with their success at hunting, which also increased human violence within these societies.[32] However, 9000-year-old remains of a female hunter along with a toolkit of projectile points and animal processing implements were discovered at the Andean site of Wilamaya Patjxa, Puno District in Peru.[33]

Upper Paleolithic to Mesolithic

[edit]

Evidence exists that hunting may have been one of the multiple, or possibly main, environmental factors leading to the Holocene extinction of megafauna and their replacement by smaller herbivores.[34][35]

In some locations, such as Australia, humans are thought to have played a very significant role in the extinction of the Australian megafauna that was widespread prior to human occupation.[36][37][38]

Hunting was a crucial component of hunter-gatherer societies before the domestication of livestock and the dawn of agriculture, beginning about 11,000 years ago in some parts of the world. In addition to the spear, hunting weapons developed during the Upper Paleolithic include the atlatl (a spear-thrower; before 30,000 years ago) and the bow (18,000 years ago). By the Mesolithic, hunting strategies had diversified with the development of these more far-reaching weapons and the domestication of the dog about 15,000 years ago. Evidence puts the earliest known mammoth hunting in Asia with spears to approximately 16,200 years ago.[39]

Many species of animals have been hunted throughout history. One theory is that in North America and Eurasia, caribou and wild reindeer "may well be the species of single greatest importance in the entire anthropological literature on hunting"[40] (see also Reindeer Age), although the varying importance of different species depended on the geographic location.

Mesolithic hunter-gathering lifestyles remained prevalent in some parts of the Americas, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Siberia, as well as all of Australia, until the European Age of Discovery. They still persist in some tribal societies, albeit in rapid decline. Peoples that preserved Paleolithic hunting-gathering until the recent past include some indigenous peoples of the Amazonas (Aché), some Central and Southern African (San people), some peoples of New Guinea (Fayu), the Mlabri of Thailand and Laos, the Vedda people of Sri Lanka, and a handful of uncontacted peoples. In Africa, one of the last remaining hunter-gatherer tribes are the Hadza of Tanzania.[41]

Neolithic and Antiquity

[edit]

Even as animal domestication became relatively widespread and after the development of agriculture, hunting usually remained a significant contributor to the human food-supply. The supplementary meat and materials from hunting included protein, bone for implements, sinew for cordage, fur, feathers, rawhide and leather used in clothing.

Hunting is still vital in marginal climates, especially those unsuited for pastoral uses or for agriculture.[42] For example, Inuit in the Arctic trap and hunt animals for clothing and use the skins of sea mammals to make kayaks, clothing, and footwear.

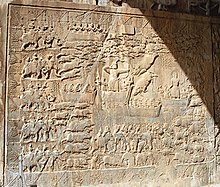

On ancient reliefs, especially from Mesopotamia, kings are often depicted by sculptors as hunters of big game such as lions and are often portrayed hunting from a war chariot - early examples of royalty symbolically and militaristically engaging in hunting[43] as "the sport of kings".[44] The cultural and psychological importance of hunting in ancient societies is represented by deities such as the horned god Cernunnos and lunar goddesses of classical antiquity, the Greek Artemis or Roman Diana. Taboos are often related[citation needed] to hunting, and mythological association of prey species with a divinity could be reflected in hunting restrictions such as a reserve surrounding a temple. Euripides' tale of Artemis and Actaeon, for example, may be seen as a caution against disrespect of prey or against impudent boasting.

With the domestication of the dog, birds of prey, and the ferret, various forms of animal-aided hunting developed, including venery (scent-hound hunting, such as fox hunting), coursing (sight-hound hunting), falconry, and ferreting. While these are all associated[citation needed] with medieval hunting, over time, various dog breeds were selected by humans for very precise tasks during the hunt, reflected in such names as "pointer" and "setter".

Pastoral and agricultural societies

[edit]

Even as agriculture and animal husbandry became more prevalent, hunting often remained as a part of human culture where the environment and social conditions allowed. Hunter-gatherer societies persisted, even when increasingly confined to marginal areas. And within agricultural systems, hunting served to kill animals that prey upon domestic and wild animals or to attempt to extirpate animals seen by humans as competition for resources such as water or forage.

When hunting moved from a subsistence activity to a selective one, two trends emerged:

- the development of the role of the specialist hunter, with special training and equipment

- the option of hunting as a "sport" for members of an upper social class

The meaning of the word game in Middle English evolved to include an animal which is hunted. As the domestication of animals for meat grew, subsistence hunting remained among the lowest classes; however, the stylised pursuit of game in European societies became a luxury. Dangerous hunting, such as for lions or wild boars, often done on horseback or from a chariot, had a function similar to tournaments and manly sports. Hunting ranked as an honourable, somewhat competitive pastime to help the aristocracy practice skills of war in times of peace.[45]

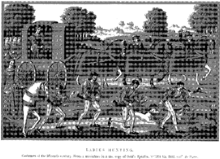

In most parts of medieval Europe, the upper class obtained the sole rights to hunt in certain areas of a feudal territory. Game in these areas was used as a source of food and furs, often provided via professional huntsmen, but it was also expected to provide a form of recreation for the aristocracy. The importance of this proprietary view of game can be seen in the Robin Hood legends, in which one of the primary charges against the outlaws is that they "hunt the King's deer". In contrast, settlers in Anglophone colonies gloried democratically in hunting for all.[46]

In medieval Europe, hunting was considered by Johannes Scotus Eriugena to be part of the set of seven mechanical arts.[47]

Use of dog

[edit]

Although various other animals have been used to aid the hunter, such as ferrets, the dog has assumed many very important uses to the hunter. The domestication of the dog has led to a symbiotic relationship in which the dog's independence from humans is deferred. Though dogs can survive independently of humans, and in many cases do ferally, when raised or adopted by humans the species tends to defer to its control in exchange for habitation, food and support.[48]

Dogs today are used to find, chase, retrieve, and sometimes kill game. Dogs allow humans to pursue and kill prey that would otherwise be very difficult or dangerous to hunt. Different breeds of specifically bred hunting dog are used for different types of hunting. Waterfowl are commonly hunted using retrieving dogs such as the Labrador Retriever, the Golden Retriever, the Chesapeake Bay Retriever, the Brittany Spaniel, and other similar breeds. Game birds are flushed out using flushing spaniels such as the English Springer Spaniel, the various Cocker Spaniels and similar breeds.

The hunting of wild mammals in England and Wales with dogs was banned under the Hunting Act 2004. The wild mammals include fox, hare, deer and mink. There are, however, exceptions in the Act.[49] Nevertheless, there have been numerous attempts on behalf of activists, pressure groups, etc. to revoke the act over the last two decades.[50] [51] [52]

Religion

[edit]Many prehistoric deities are depicted as predators or prey of humans, often in a zoomorphic form, perhaps alluding to the importance of hunting for most Palaeolithic cultures.

In many pagan religions, specific rituals are conducted before or after a hunt; the rituals done may vary according to the species hunted or the season the hunt is taking place.[citation needed] Often a hunting ground, or the hunt for one or more species, was reserved or prohibited in the context of a temple cult.[citation needed] In Roman religion, Diana is the goddess of the hunt.[53]

Indian and Eastern religions

[edit]

Hindu scriptures describe hunting as an occupation, as well as a sport of the kingly. Even figures considered divine are described to have engaged in hunting. One of the names of the god Shiva is Mrigavyadha (deer-slayer).[54] The word Mriga, in many Indian languages including Malayalam, not only stands for deer, but for all animals and animal instincts (Mriga Thrishna). Shiva, as Mrigavyadha, is the one who destroys the animal instincts in human beings. In the epic Ramayana, Dasharatha, the father of Rama, is said to have the ability to hunt in the dark. During one of his hunting expeditions, he accidentally killed Shravana, mistaking him for game. During Rama's exile in the forest, Ravana kidnapped his wife, Sita, from their hut, while Rama was asked by Sita to capture a golden deer, and his brother Lakshman went after him. According to the Mahabharat, Pandu, the father of the Pandavas, accidentally killed the sage Kindama and his wife with an arrow, mistaking them for a deer.[citation needed]

Jainism teaches followers to have tremendous respect for all of life. Prohibitions for hunting and meat eating are the fundamental conditions for being a Jain.[55]

Buddhism's first precept is the respect for all sentient life. The general approach by all Buddhists is to avoid killing any living animals. Buddha explained the issue by saying "all fear death; comparing others with oneself, one should neither kill nor cause to kill."[56]

In Sikhism, only meat obtained from hunting, or slaughtered with the Jhatka is permitted. The Sikh gurus, especially Guru Hargobind and Guru Gobind Singh were ardent hunters. Many old Sikh Rehatnamas like Prem Sumarag, recommend hunting wild boar and deer. However, among modern Sikhs, the practice of hunting has died down; some even saying that all meat is forbidden.

Christianity, Judaism, and Islam

[edit]

From early Christian times, hunting has been forbidden to Roman Catholic Church clerics. Thus the Corpus Juris Canonici (C. ii, X, De cleric. venat.) says, "We forbid to all servants of God hunting and expeditions through the woods with hounds; and we also forbid them to keep hawks or falcons." The Fourth Council of the Lateran, held under Pope Innocent III, decreed (canon xv): "We interdict hunting or hawking to all clerics." The decree of the Council of Trent is worded more mildly: "Let clerics abstain from illicit hunting and hawking" (Sess. XXIV, De reform., c. xii), which seems to imply that not all hunting is illicit, and canonists generally make a distinction declaring noisy (clamorosa) hunting unlawful, but not quiet (quieta) hunting.[57]

Ferraris gives it as the general sense of canonists that hunting is allowed to clerics if it be indulged in rarely and for sufficient cause, as necessity, utility or "honest" recreation, and with that moderation which is becoming to the ecclesiastical state. Ziegler, however, thinks that the interpretation of the canonists is not in accordance with the letter or spirit of the laws of the church.[57]

Nevertheless, although a distinction between lawful and unlawful hunting[58] is undoubtedly permissible, it is certain that a bishop can absolutely prohibit all hunting to the clerics of his diocese, as was done by synods at Milan, Avignon, Liège, Cologne, and elsewhere. Benedict XIV declared that such synodal decrees are not too severe, as an absolute prohibition of hunting is more conformable to the ecclesiastical law. In practice, therefore, the synodal statutes of various localities must be consulted to discover whether they allow quiet hunting or prohibit it altogether.[57] Small-scale hunting as a family or subsistence farming activity is recognised by Pope Francis in his encyclical letter, Laudato si', as a legitimate and valuable aspect of employment within the food production system.[59]

Hunting is not forbidden in Jewish law, although there is an aversion to it. The great 18th-century authority Rabbi Yechezkel Landau after a study concluded although "hunting would not be considered cruelty to animals insofar as the animal is generally killed quickly and not tortured... There is an unseemly element in it, namely cruelty." The other issue is that hunting can be dangerous and Judaism places an extreme emphasis on the value of human life.[60][61]

Islamic Sharia Law permits hunting of lawful animals and birds if they cannot be easily caught and slaughtered. However, this is only for the purpose of food and not for trophy hunting.[62]

National traditions

[edit]East Africa

[edit]

A safari, from a Swahili word meaning "journey, expedition,"[63] especially in Africa, is defined as a journey to see or kill animals in their natural environment, most commonly in East Africa.[64] Safari as a distinctive way of hunting was popularized by the US author Ernest Hemingway and President Theodore Roosevelt.[65] A safari may consist of a several-days—or even weeks-long journey, with camping in the bush or jungle, while pursuing big game. Nowadays, it is often used to describe hunting tours through African wildlife.[66]

Hunters are usually tourists, accompanied by licensed and highly regulated professional hunters, local guides, skinners, and porters in more difficult terrains.[citation needed] A special safari type is the solo-safari, where all the license acquiring, stalking, preparation, and outfitting is done by the hunter himself.[67]

Indian subcontinent

[edit]

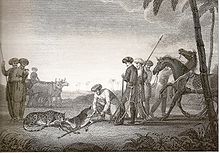

During the feudal and colonial times in British India, hunting or shikar was regarded as a regal sport in the numerous princely states, as many maharajas and nawabs, as well as British officers, maintained a whole corps of shikaris (big-game hunters), who were native professional hunters. They would be headed by a master of the hunt, who might be styled mir-shikar. Often, they recruited the normally low-ranking local tribes because of their traditional knowledge of the environment and hunting techniques. Big game, such as Bengal tigers, might be hunted from the back of an Indian elephant.

Regional social norms are generally antagonistic to hunting, while a few sects, such as the Bishnoi, lay special emphasis on the conservation of particular species, such as the antelope. India's Wildlife Protection Act of 1972 bans the killing of all wild animals. However, the Chief Wildlife Warden may, if satisfied that any wild animal from a specified list has become dangerous to human life or is so disabled or diseased as to be beyond recovery, permit any person to hunt such an animal. In this case, the body of any wild animal killed or wounded becomes government property.[68]

The practice among the soldiers in British India during the 1770s of going out to hunt snipes, a shorebird considered extremely challenging for hunters due to its alertness, camouflaging colour and erratic flight behavior, is believed to be the origin of the modern word for sniper, as snipe-hunters needed to be stealthy in addition to having tracking skills and marksmanship.[69][70] The term was used in the nineteenth century, and had become common usage by the First World War.

United Kingdom

[edit]

Unarmed fox hunting on horseback with hounds is the type of hunting most closely associated with the United Kingdom; in fact, "hunting" without qualification implies fox hunting.[72] What in other countries is called "hunting" is called "shooting" (birds)[73] or "stalking" (deer)[74] in Britain. Fox hunting is a social activity for the upper classes, with roles strictly defined by wealth and status.[75][76] Similar to fox hunting in many ways is the chasing of hares with hounds. Pairs of sighthounds (or long-dogs), such as greyhounds, may be used to pursue a hare in coursing, where the greyhounds are marked as to their skill in coursing the hare (but are not intended to actually catch it), or the hare may be pursued with scent hounds such as beagles or harriers. Other sorts of foxhounds may also be used for hunting stags (deer) or mink.[citation needed] Deer stalking with rifles is carried out on foot without hounds, using stealth.[11]

These forms of hunting have been controversial in the UK. Animal welfare supporters believe that hunting causes unnecessary suffering to foxes, horses, and hounds. Proponents argue that the activity is a historical tradition. Using dogs to chase wild mammals was made illegal in February 2005 by the Hunting Act 2004; there were a number of exemptions (under which the activity may not be illegal) in the act for hunting with hounds, but no exemptions at all for hare-coursing.[74]

Shooting traditions

[edit]Game birds, especially pheasants, are shot with shotguns for sport in the UK; the British Association for Shooting and Conservation says that over a million people per year participate in shooting, including game shooting, clay pigeon shooting, and target shooting.[77] Shooting as practiced in Britain, as opposed to traditional hunting, requires little questing for game—around thirty-five million birds are released onto shooting estates every year, some having been factory farmed. Shoots can be elaborate affairs with guns placed in assigned positions and assistants to help load shotguns. When in position, "beaters" move through the areas of cover, swinging sticks or flags to drive the game out. Such events are often called "drives". The open season for grouse in the UK begins on 12 August, the so-called Glorious Twelfth. The definition of game in the United Kingdom is governed by the Game Act 1831 (1 & 2 Will. 4. c. 32).

A similar tradition, ojeo [es], exists in Spain.

United States

[edit]

North American hunting pre-dates the United States by thousands of years and was an important part of many pre-Columbian Native American cultures. Native Americans retain some hunting rights and are exempt from some laws as part of Indian treaties and otherwise under federal law[78]—examples include eagle feather laws and exemptions in the Marine Mammal Protection Act. This is considered particularly important in Alaskan native communities.

Gun usage in hunting is typically regulated by game category, area within the state, and time period. Regulations for big-game hunting often specify a minimum caliber or muzzle energy for firearms. The use of rifles is often banned for safety reasons in areas with high population densities or limited topographic relief. Regulations may also limit or ban the use of lead in ammunition because of environmental concerns. Specific seasons for bow hunting or muzzle-loading black-powder guns are often established to limit competition with hunters using more effective weapons.

Hunting in the United States is not associated with any particular class or culture; a 2006 poll showed seventy-eight per cent of Americans supported legal hunting,[79] although relatively few Americans actually hunt. At the beginning of the 21st century, just six per cent of Americans hunted. Southerners in states along the eastern seaboard hunted at a rate of five per cent, slightly below the national average, and while hunting was more common in other parts of the South at nine per cent, these rates did not surpass those of the Plains states, where twelve per cent of Midwesterners hunted. Hunting in other areas of the country fell below the national average.[80] Overall, in the 1996–2006 period, the number of hunters over the age of sixteen declined by ten per cent, a drop attributable to a number of factors including habitat loss and changes in recreation habits.[81]

The principles of the fair chase[82] have been a part of the American hunting tradition for over one hundred years. The role of the hunter-conservationist, popularised by Theodore Roosevelt, and perpetuated by Roosevelt's formation of the Boone and Crockett Club, has been central to the development of the modern fair chase tradition. Beyond Fair Chase: The Ethic and Tradition of Hunting, a book by Jim Posewitz, describes fair chase:

"Fundamental to ethical hunting is the idea of fair chase. This concept addresses the balance between the hunter and the hunted. It is a balance that allows hunters to occasionally succeed while animals generally avoid being taken."[83]

When Internet hunting was introduced in 2005, allowing people to hunt over the Internet using remotely controlled guns, the practice was widely criticised by hunters as violating the principles of fair chase. As a representative of the National Rifle Association of America (NRA) explained, "The NRA has always maintained that fair chase, being in the field with your firearm or bow, is an important element of hunting tradition. Sitting at your desk in front of your computer, clicking at a mouse, has nothing to do with hunting."[84]

Animals such as blackbuck, nilgai, axis deer, fallow deer, zebras, barasingha, gazelle and many other exotic game species can now be found on game farms and ranches in Texas, where they were introduced for sport hunting. These hunters can be found paying in excess of $10,000 to take trophy animals on these controlled ranches.[85]

Russia

[edit]The Russian imperial hunts evolved from hunting traditions of early Russian rulers—Grand Princes and Tsars—under the influence of hunting customs of European royal courts. The imperial hunts were organised mainly in Peterhof, Tsarskoye Selo, and Gatchina.

Australia

[edit]Hunting in Australia has evolved around the hunting and eradication of various animals considered to be pests or invasive species . All native animals are protected by law, and certain species such as kangaroos and ducks can be hunted by licensed shooters but only under a special permit on public lands during open seasons. The introduced species that are targeted include European rabbits, red foxes, deer (sambar, hog, red, fallow, chital and rusa), feral cats, pigs, goats, brumbies, donkeys and occasionally camels, as well as introduced upland birds such as quails, pheasants and partridges.

New Zealand

[edit]New Zealand has a strong hunting culture.[86] When humans arrived, the only mammals present on the islands making up New Zealand were bats, although seals and other marine mammals were present along the coasts. However, when humans arrived they brought other species with them. Polynesian voyagers introduced kuri (dogs), kiore (Polynesian rats), as well as a range of plant species. European explorers further added to New Zealand's biota, particularly pigs which were introduced by either Captain Cook or the French explorer De Surville in the 1700s.[87][88] During the nineteenth century, as European colonisation took place, acclimatisation societies were established. The societies introduced a large number of species with no use other than as prey for hunting.[89] Species that adapted well to the New Zealand terrain include deer, pigs, goats, hare, tahr and chamois. With wilderness areas, suitable forage, and no natural predators, their populations exploded. Government agencies view the animals as pests due to their effects on the natural environment and on agricultural production, but hunters view them as a resource.

Iran

[edit]

Iranian tradition regarded hunting as an essential part of a prince's education,[90] and hunting was well recorded for the education of the upper-class youths during pre-Islamic Persia. As of October 2020, a hunting licensee costs $20,000. The Department of Environment although do not report the number of permits issued.[91]

Japan

[edit]The numbers of licensed hunters in Japan, including those using snares and guns, is generally decreasing, while their average age is increasing. As of 2010[update], there were approximately 190,000 registered hunters, approximately 65% of whom were sixty years old or older.[92]

Trinidad and Tobago

[edit]There is a very active tradition of hunting small to medium-sized wild game in Trinidad and Tobago. Hunting is carried out with firearms, slingshots and cage traps, and sometimes aided by the use of hounds. The illegal use of trap guns and snare nets also occurs. With approximately 12,000 to 13,000 hunters applying for and being granted hunting permits in recent years, there is some concern that the practice might not be sustainable. In addition, there are at present no bag limits and the open season is comparatively very long (5 months – October to February inclusive). As such hunting pressure from legal hunters is very high. Added to that, there is a thriving and very lucrative black market for poached wild game (sold and enthusiastically purchased as expensive luxury delicacies) and the numbers of commercial poachers in operation is unknown but presumed to be fairly high. As a result, the populations of the five major mammalian game species (red-rumped agouti, lowland paca, nine-banded armadillo, collared peccary and red brocket deer) are thought to be relatively low when compared to less-hunted regions in nearby mainland South America (although scientifically conducted population studies are only just recently being conducted as of 2013[update]). It appears that the red brocket deer population has been extirpated in Tobago as a result of over-hunting. By some time in the mid 20th century another extirpation due to over-hunting occurred in Trinidad with its population of horned screamer (a large game bird). Various herons, ducks, doves, the green iguana, the cryptic golden tegu, the spectacled caiman, the common opossum and the capybara are also commonly hunted and poached. There is also some poaching of 'fully protected species', including red howler monkey and capuchin monkeys, southern tamandua, Brazilian porcupine, yellow-footed tortoise, the critically endangered island endemic Trinidad piping guan and even one of the national birds, the scarlet ibis. Legal hunters pay relatively small fees to obtain hunting licenses and undergo no official basic conservation biology or hunting-ethics/fair chase training and are not assessed regarding their knowledge and comprehension of the local wildlife conservation laws. There is presumed to be relatively little subsistence hunting in the country (with most hunting for either sport or commercial profit). The local wildlife management authorities are under-staffed and under-funded, and as such little in the way of enforcement is done to uphold existing wildlife management laws, with hunting/poaching occurring both in and out of season and even in wildlife sanctuaries. There is some indication that the government is beginning to take the issue of wildlife management more seriously, with well drafted legislation being brought before Parliament in 2015. It remains to be seen if the drafted legislation will be fully adopted and financially supported by the current and future governments, and if the general populace will move towards a greater awareness of the importance of wildlife conservation and change the culture of wanton consumption to one of sustainable management.

Wildlife management

[edit]

Hunting is claimed to give resource managers an important tool[93][94] in managing populations that might exceed the carrying capacity of their habitat and threaten the well-being of other species, or, in some instances, damage human health or safety.[95]

In some cases, hunting actually can increase the population of predators such as coyotes by removing territorial bounds that would otherwise be established, resulting in excess neighbouring migrations into an area, thus artificially increasing the population.[96] Hunting advocates[who?] assert that hunting reduces intraspecific competition for food and shelter, reducing mortality among the remaining animals. Some environmentalists assert[who?] that (re)introducing predators would achieve the same end with greater efficiency and less negative effect, such as introducing significant amounts of free lead into the environment and food chain.

In the United States, wildlife managers are frequently part of hunting regulatory and licensing bodies, where they help to set rules on the number, manner and conditions in which game may be hunted.

Management agencies sometimes rely on hunting to control specific animal populations, as has been the case with deer in North America. These hunts may sometimes be carried out by professional shooters, although others may include amateur hunters. Many US city and local governments hire professional and amateur hunters each year to reduce populations of animals such as deer that are becoming hazardous in a restricted area, such as neighbourhood parks and metropolitan open spaces.

A large part of managing populations involves managing the number and, sometimes, the size or age of animals harvested so as to ensure the sustainability of the population. Tools that are frequently used to control harvest are bag limits and season closures, although gear restrictions such as archery-only seasons are becoming increasingly popular in an effort to reduce hunter success rates in countries that rely on bag limits per hunter instead of per area.[97][98][99][100]

Laws

[edit]Illegal hunting and harvesting of wild species contrary to local and international conservation and wildlife management laws is called poaching. Game preservation is one of the tactics used to prevent poaching. Violations of hunting laws and regulations involving poaching are normally punishable by law.[101] Punishment can include confiscation of equipment, fines or a prison sentence.

Right to hunt

[edit]The right to hunt—sometimes in combination with the right to fish—is protected implicitly, as a consequence of the right of ownership,[102] or explicitly, as a right on its own,[103][104] in a number of jurisdictions. For instance, as of 2019, a total of 22 U.S. states explicitly recognize a subjective right to hunt in their constitutions.[104][105]

Bag limits

[edit]

Bag limits are provisions under the law that control how many animals of a given species or group of species can be killed, although there are often species for which bag limits do not apply. There are also jurisdictions where bag limits are not applied at all or are not applied under certain circumstances. The phrase bag limits come from the custom among hunters of small game to carry successful kills in a small basket, similar to a fishing creel.

Where bag limits are used, there can be daily or seasonal bag limits; for example, ducks can often be harvested at a rate of six per hunter per day.[106] Big game, like moose, most often have a seasonal bag limit of one animal per hunter.[citation needed] Bag limits may also regulate the size, sex, or age of animal that a hunter can kill. In many cases, bag limits are designed to allocate harvest among the hunting population more equitably rather than to protect animal populations, as protecting the population would necessitate regional density-dependent maximum bags.

Closed and open season

[edit]A closed season is a time during which hunting an animal of a given species is contrary to law. Typically, closed seasons are designed to protect a species when they are most vulnerable or to protect them during their breeding season.[107] By extension, the period that is not the closed season is known as the open season.

Methods

[edit]

Historical, subsistence, and sport hunting techniques can differ radically, with modern hunting regulations often addressing issues of where, when, and how hunts are conducted. Techniques may vary depending on government regulations, a hunter's personal ethics, local custom, hunting equipment, and the animal being hunted. Often a hunter will use a combination of more than one technique. Laws may forbid sport hunters from using some methods used primarily in poaching and wildlife management.

- Baiting is the use of decoys, lures, scent, or food.

- Battue involves scaring animals (by beating sticks) into a killing zone or ambush.

- Beagling is the use of beagles in hunting rabbits, and sometimes in hunting foxes.

- Beating uses human beaters to flush out game from an area or drive it into position.

- Stand hunting or blind hunting is waiting for animals from a concealed or elevated position, for example from tree stands, hunting blinds or other types of shooting stands.

- Calling is the use of animal noises to attract or drive animals.

- Camouflage is the use of visual or odour concealment to blend with the environment.

- Dogs may be used to course or to help flush, herd, drive, track, point at, pursue, or retrieve prey.

- Driving is the herding of animals in a particular direction, usually toward another hunter in the group.

- Falconry is the hunting of wild animals in their natural state and habitat by means of a trained bird of prey.

- Flushing is the practice of scaring animals from concealed areas.

- Ghillie suit is a type of gear a person can wear to blend with environment.[108]

- Glassing is the use of optics, such as binoculars, to locate animals more easily.

- Glue is an indiscriminate passive form to kill birds.[109]

- Internet hunting is a method of hunting over the Internet using webcams and remotely controlled guns.

- Netting involves using nets, including active netting with the use of cannon nets and rocket nets.

- Persistence hunting is the use of running and tracking to pursue the prey to exhaustion.[110]

- Posting is done by sitting or standing in a particular place with the intentions of intercepting your game of choice along their travel corridor.[111]

- Scouting for game is typically done prior to a hunt and will ensure the desired species are in a chosen area. Looking for animal sign such as tracks, scat, etc.... and utilizing "trail cameras" are commonly used tactics while scouting.

- Shooting is the use of a ranged weapon such as a gun, bow, crossbow, or slingshot.

- Solunar theory says that animals move according to the location of the moon in comparison to their bodies and is said to have been used long before this by hunters to know the best times to hunt their desired game.[112]

- Spotlighting or shining is the use of artificial light to find or blind animals before killing.

- Stalking or still hunting is the practice of walking quietly in search of animals or in pursuit of an individual animal.

- Tracking is the practice of reading physical evidence in pursuing animals.

- Trapping is the use of devices such as snares, pits, and deadfalls to capture or kill an animal.

Statistics

[edit]Table

[edit]| Country | Hunters | Population

(millions) |

Hunters as percentage of

the total population |

Relation

hunters/inhabitants |

Area (km2) | Hunters per km2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2,482,678 | 34.7 | 7.15 | 1:14 | 9,984,670 | 0.25 | |

| 308,000 | 5.2 | 5.92 | 1:17 | 338,448 | 0.91 | |

| 45,000 | 0.8 | 5.63 | 1:18 | 5,896 | 7.63 | |

| 190,000 | 4.7 | 4.04 | 1:25 | 385,207 | 0.49 | |

| 15,000 | 0.4 | 3.75 | 1:27 | 316 | 47.47 | |

| 11,453,000 | 323.1 | 3.54 | 1:28 | 9,826,675 | 1.17 | |

| 290,000 | 9.0 | 3.22 | 1:31 | 447,435 | 0.65 | |

| 165,000 | 5.5 | 3.00 | 1:33 | 42,921 | 3.84 | |

| 104,000 | 4.2 | 2.48 | 1:46 | 70,273 | 1.48 | |

| 235,000 | 10.7 | 2.20 | 1:46 | 131,957 | 1.78 | |

| 980,000 | 45.0 | 2.18 | 1:46 | 505,970 | 1.94 | |

| 230,000 | 10.7 | 2.15 | 1:47 | 92,212 | 2.49 | |

| 1,331,000 | 64.1 | 2.08 | 1:48 | 543,965 | 2.45 | |

| 2,800,000 | 143.2 | 1.96 | 1:51 | 17,125,200 | 0.16 | |

| 110,000 | 7.7 | 1.43 | 1:70 | 110,994 | 0.99 | |

| 118,000 | 8.3 | 1.42 | 1:70 | 83,879 | 1.41 | |

| 800,000 | 61.1 | 1.31 | 1:76 | 242,495 | 3.30 | |

| 750,000 | 58.1 | 1.29 | 1:77 | 301,338 | 2.49 | |

| 16,600 | 1.3 | 1.28 | 1:78 | 45,339 | 0.37 | |

| 55,000 | 4.5 | 1.22 | 1:82 | 56,594 | 0.97 | |

| 22,000 | 2.0 | 1.10 | 1:91 | 20,273 | 1.09 | |

| 25,000 | 2.3 | 1.09 | 1:92 | 64,589 | 0.39 | |

| 110,000 | 10.2 | 1.08 | 1:93 | 78,866 | 1.39 | |

| 55,000 | 5.4 | 1.02 | 1:98 | 49,034 | 1.12 | |

| 32,000 | 3.6 | 0.89 | 1:113 | 65,300 | 0.49 | |

| 55,000 | 9.9 | 0.56 | 1:180 | 93,036 | 0.59 | |

| 351,000 | 82.5 | 0.43 | 1:235 | 357,578 | 0.98 | |

| 2,000 | 0.5 | 0.40 | 1:250 | 2,586 | 0.77 | |

| 30,000 | 7.6 | 0.39 | 1:253 | 41,285 | 0.73 | |

| 106,000 | 38.5 | 0.28 | 1:363 | 312,696 | 0.34 | |

| 60,000 | 22.2 | 0.27 | 1:370 | 238,391 | 0.25 | |

| 23,000 | 10.4 | 0.22 | 1:452 | 30,688 | 0.75 | |

| 28,170 | 16.7 | 0.17 | 1:593 | 41,543 | 0.68 |

Graph

[edit]Trophy hunting

[edit]

Trophy hunting is the selective seeking and killing of wild game animals to take trophies for personal collection, bragging rights or as a status symbol. It may also include the controversial hunting of captive or semi-captive animals expressly bred and raised under controlled or semi-controlled conditions so as to attain trophy characteristics; this is sometimes known as canned hunts.[118]

History

[edit]In the 19th century, southern and central European sport hunters often pursued game only for a trophy, usually the head or pelt of an animal, which was then displayed as a sign of prowess. The rest of the animal was typically discarded. Some cultures, however, disapprove of such waste. In Nordic countries, hunting for trophies was—and still is—frowned upon. Hunting in North America in the 19th century was done primarily as a way to supplement food supplies, although it is now undertaken mainly for sport.[citation needed] The safari method of hunting was a development of sport hunting that saw elaborate travel in Africa, India and other places in pursuit of trophies. In modern times, trophy hunting persists and is a significant industry in some areas.[citation needed]

Conservation tool

[edit]According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, hunting "provides an economic incentive" for ranchers to continue to breed those species, and that hunting "reduces the threat of the species' extinction."[119][120]

A scientific study in the journal, Biological Conservation, states that trophy hunting is of "major importance to conservation in Africa by creating economic incentives for conservation over vast areas, including areas which may be unsuitable for alternative wildlife-based land uses such as photographic ecotourism."[121] However, another study states that less than 3% of a trophy hunters' expenditures reach the local level, meaning that the economic incentive and benefit is "minimal, particularly when we consider the vast areas of land that hunting concessions occupy."[122]

Financial incentives from trophy hunting effectively more than double the land area that is used for wildlife conservation, relative to what would be conserved relying on national parks alone according to Biological Conservation,[121] although local communities usually derive no more than 18 cents per hectare from trophy hunting.[122]

Trophy hunting has been considered essential for providing economic incentives to conserve large carnivores according to research studies in Conservation Biology,[123] Journal of Sustainable Tourism,[124] Wildlife Conservation by Sustainable Use,[125] and Animal Conservation.[123][126] Studies by the Centre for Responsible Tourism[127] and the IUCN state that ecotourism, which includes more than hunting, is a superior economic incentive, generating twice the revenue per acre and 39 times more permanent employment.[128] At the cross-section of trophy hunting, ecotourism and conservation is green hunting, a trophy hunting alternative where hunters pay to dart animals that need to be tranquilized for conservation projects.[129]

The U.S. House Committee on Natural Resources in 2016 concluded that trophy hunting may be contributing to the extinction of certain animals.[130] Animal welfare organizations, including the International Fund for Animal Welfare, claim that trophy hunting is a key factor in the "silent extinction" of giraffes.[131]

According to a national survey that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service conducts every five years, fewer people are hunting, even as population rises. National Public Radio reported, a graph shows 2016 statistics, that only about 5 per cent of Americans, 16 years old and older, actually hunt, which is half of what it was 50 years ago. The decline in popularity of hunting is expected to accelerate over the next decade, which threatens how US will pay for conservation. [132]

Controversy

[edit]Trophy hunting is most often criticised when it involves rare or endangered animals.[133] Opponents may also see trophy hunting as an issue of morality[134] or animal cruelty, criticising the killing of living creatures for recreation. Victorian era dramatist W. S. Gilbert remarked, "Deer-stalking would be a very fine sport if only the deer had guns."[135]

There is also debate about the extent to which trophy hunting benefits the local economy. Hunters pay substantial fees to the game outfitters and hunting guides which contributes to the local economy and provides value to animals that would otherwise be seen as competition for grazing, livestock, and crops.[136] However, the argument is disputed by animal welfare organizations and other opponents of trophy hunting.[137][138] It is argued that the animals are worth more to the community for ecotourism than hunting.[139][140]

Economics

[edit]

A variety of industries benefit from hunting and support hunting on economic grounds. In Tanzania, it is estimated that a safari hunter spends fifty to one hundred times that of the average ecotourist. While the average photo tourist may seek luxury accommodation, the average safari hunter generally stays in tented camps. Safari hunters are also more likely to use remote areas, uninviting to the typical ecotourist. Advocates argue that these hunters allow for anti-poaching activities and revenue for local communities.[citation needed]

In the United Kingdom, the game hunting of birds as an industry is said to be extremely important to the rural economy. The Cobham Report of 1997 suggested it to be worth around £700 million, and hunting and shooting lobby groups claimed it to be worth over a billion pounds less than ten years later.[citation needed]

Hunting also has a significant financial impact in the United States, with many companies specialising in hunting equipment or speciality tourism. Many different technologies have been created to assist hunters. Today's hunters come from a broad range of economic, social, and cultural backgrounds. In 2001, over thirteen million hunters averaged eighteen days hunting, and spent over $20.5 billion on their sport.[141] In the US, proceeds from hunting licenses contribute to state game management programs, including preservation of wildlife habitat.

Hunting contributes to a portion of caloric intake of people and may have positive impacts on greenhouse gas emissions by avoidance of utilization of meat raised under industrial methods.[142]

Environmental problems

[edit]

Lead bullets that miss their target or remain in an unretrieved carcass could become a toxicant in the environment but lead in ammunition because of its metallic form has a lower solubility and higher resistance to corrosion than other forms of lead making it hardly available to biological systems.[143] Waterfowl or other birds may ingest the lead and poison themselves with the neurotoxicant, but studies have demonstrated that effects of lead in ammunition are negligible on animal population size and growth.[144][145] Since 1991, US federal law forbids lead shot in waterfowl hunts, and 30 states have some type of restriction.[146]

In December 2014, a federal appeals court denied a lawsuit by environmental groups that the EPA must use the Toxic Substances Control Act to regulate lead in shells and cartridges. The groups sought EPA to regulate "spent lead", yet the court found EPA could not regulate spent lead without also regulating cartridges and shells.[147]

Conservation

[edit]This article may be unbalanced toward certain viewpoints. (May 2012) |

Hunters have been driving forces throughout history in the movement to ensure the preservation of wildlife habitats and wildlife for further hunting.[149] However, excessive hunting and poachers have also contributed heavily to the endangerment, extirpation and extinction of many animals, such as the quagga, the great auk, Steller's sea cow, the thylacine, the bluebuck, the Arabian oryx, the Caspian and Javan tigers, the markhor, the Sumatran rhinoceros, the bison, the North American cougar, the Altai argali sheep, the Asian elephant and many more, primarily for commercial sale or sport. All these animals have been hunted to endangerment or extinction.[161] Poaching currently threatens bird and mammalian populations around the world.[162][163][164] The 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services lists the direct exploitation of organisms, including hunting, as the second leading cause of biodiversity loss, after land use for agriculture.[165] In 2022, IPBES released another report which stated that unsustainable hunting, along with unsustainable logging and fishing, are primary drivers of the global extinction crisis.[166] A 2023 study published in BioScience posited that the prioritizing of hunting by state agencies in the United States over the rewinding of key species is "reinforcing" the loss of biodiversity.[167]

Законодательство

[ редактировать ]

Питман -Робертсон Закон о восстановлении дикой природы 1937 года

[ редактировать ]В 1937 году американские охотники успешно лоббировали Конгресс США, чтобы принять Закон о восстановлении дикой природы Питтмана-Робертсона , который положил налог на одиннадцать процентов на все охотничье оборудование. Этот налог на себя в настоящее время генерирует более 700 миллионов долларов в год и используется исключительно для создания, восстановления и защиты средств обитания дикой природы. [ 168 ] Этот акт назван в честь сенатора Невады Ки Питтмана и конгрессмена Вирджинии Абсалом Уиллис Робертсон .

Федеральная программа штампов

[ редактировать ]16 марта 1934 года президент Франклин Д. Рузвельт подписал Закон об охотничьих штампах с миграционными птицами, который требует ежегодной покупки штампов всех охотников в возрасте старше шестнадцати лет. Марки создаются от имени программы почтовой службой США и изображают художественные работы дикой природы, выбранные в рамках ежегодного конкурса. Они играют важную роль в сохранении среды обитания , потому что девяносто восемь процентов всех средств, полученных в результате их продажи, идут непосредственно к покупке или аренде среды обитания водно-болотных угодий для защиты в национальной системе убежища дикой природы . [ 169 ] В дополнение к водоплавающим птицам, по оценкам, треть исчезающих видов страны ищут пищу и укрытие в районах, защищенных с использованием средств для утки. [ 170 ]

С 1934 года продажа федеральных утиных штампов принесла 670 миллионов долларов и помогла приобрести или арендовать 5 200 000 акров (8 100 кв. Миль; 21 000 км. 2 ) среды обитания. Марки служат лицензией на охоту за перелетными птицами, входным проходом для всех национальных зон охраны дикой природы, а также считаются предметами для коллекционеров, часто приобретаемых по эстетическим причинам за пределами общин охоты и птиц. Хотя не охотники покупают значительное количество штампов утки, восемьдесят семь процентов их продаж предоставляются охотниками. Распределение средств управляется Комиссией по сохранению перелетных птиц (MBCC). [ 171 ]

Разновидность

[ редактировать ]Аравийский Орикс

[ редактировать ]Аравийский Oryx , вид большой антилопы , когда -то населял большую часть пустынных районов Ближнего Востока. [ 155 ] На местных бедуинских племенах давно охотились на Oryx, используя верблюдов и стрел. Разведка нефти сделала среду обитания все более доступной, и поразительный вид вида сделал ее (наряду с тесно связанными насадками Oryx и Addax) популярным карьером для охотников за спортом, включая иностранных руководителей нефтяных компаний. [ 172 ] Использование автомобилей и мощных винтовок разрушило их единственное преимущество: скорость, и они вымерли в дикой природе исключительно из-за охоты на спорт в 1972 году. Орикс с природом насаждений последовал примеру, в то время как аддакс подвергся критике подвергнут угрозе исчезновения. [ 173 ] Тем не менее, арабский Oryx теперь вернулся и был обновлен с «вымершего в дикой природе» до «уязвимых» из -за усилий по сохранению, таких как разведение в неволе. [ 174 ]

Мархор

[ редактировать ]Марххор Центральной является исчезающим видом дикого коз, который обитает в горах Азии и Пакистана . Колонизация дала британским охотникам за этих регионов Британии спортом доступ к видам, и на них охотились сильно, почти до такой степени исчезновения. Только их готовность размножаться в неволе и неосведомленность их гористой среды обитания предотвратила это. Несмотря на эти факторы, Марххор все еще находится под угрозой исчезновения. [ 175 ]

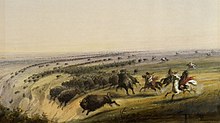

Американский бизон

[ редактировать ]Американский бизон - это большой бовид , который населял большую часть западной Северной Америки до 1800 -х годов, живя в прериях в больших стадах. Тем не менее, обширные стада бизонов привлекли охотников за рынком, которые убили десятки бизонов только за шкуры, оставляя остальных гнить. Тысячи этих охотников быстро устранили стада бизонов, доведя население с нескольких миллионов миллионов в начале 1800 -х годов до нескольких сотен к 1880 -м годам. Усилия по сохранению позволили населению увеличиться, но бизон остается почти опасным из-за отсутствия среды обитания. [ 176 ]

Белый носорог

[ редактировать ]Журнал международного законодательства и политики дикой природы цитирует, что легализация охоты на белых носорогов в Южной Африке побудила частных землевладельцев вновь ввести виды на свои земли. В результате в стране наблюдалось увеличение белых носорогов с менее чем ста, чем у людей до более чем 11 000, даже если ограниченное число было убито в качестве трофеев. [ 177 ]

Тем не менее, незаконная охота на носорогов на их рога очень вредна для населения и в настоящее время растет во всем мире, [ 178 ] С той только в Южной Африке было убито 100444, согласно последней оценке. [ 179 ] Белый носорог (наряду с другими 4 видами носорога) браконьерство из -за убеждений в том, что рога носорога могут быть использованы для лечения рака, артрита и других заболеваний и болезней, даже если они научно доказаны. [ 180 ]

Другие виды

[ редактировать ]По словам Ричарда Конниффа , Намибия является домом для 1750 из примерно 5000 черных носорогов, выживающих в дикой природе, потому что она позволяет охотиться на трофей различных видов. Население Горного зебры Намибии увеличилось до 27 000 с 1000 в 1982 году. Слоны, которые «застреляются в других местах для своей слоновой кости», добрались до 20 000 из 15 000 в 1995 году. Львы, которые были на грани вымирания «от Сенегала до Кения». , увеличиваются в Намибии. [ 181 ]

Напротив, Ботсвана в 2012 году запретила охоту на трофей после ускоряющего снижения дикой природы. [ 182 ] Количество антилопы, упавших по всей Ботсване, с результирующим снижением чисел хищников, в то время как числа слонов оставались стабильными, а числа бегемота выросли. По данным правительства Ботсваны, охота на трофей, по крайней мере, отчасти виноват в этом, но также виноваты многие другие факторы, такие как браконьерство, засуха и потеря среды обитания. [ 183 ] Уганда недавно сделала то же самое, утверждая, что «доля преимуществ охоты на спортивную охоту была однобокой и вряд ли сможет удержать браконьерство или улучшить способность [Уганды] для управления запасами дикой природы». [ 184 ] В 2020 году Ботсвана вновь открыла охоту на трофей на общественных землях. [ 185 ]

Исследования

[ редактировать ]

Исследование, опубликованное Обществом дикой природы, пришло к выводу, что охота и ловушка являются экономически эффективными инструментами, которые уменьшают ущерб дикой природе за счет сокращения популяции ниже способности окружающей среды, чтобы перенести ее и изменяя поведение животных, чтобы помешать им нанести ущерб. Кроме того, в исследовании говорится, что прекращение охоты может привести к серьезному вреду дикой природе, стоимость сельской собственности падает и стимул землевладельцев для поддержания естественной среды обитания для уменьшения. [ 186 ]

Хотя вырубка лесов и деградация лесов долгое время считались наиболее значительной угрозой для тропического биоразнообразия, по всей Юго -Восточной Азии (Северо -Восточная Индия, Индокитай, Сандаленд, Филиппины) в значительных районах естественной среды обитания мало диких животных (> 1 кг), бара толерантные виды. [ 187 ] [ 188 ] [ 189 ]

Оппозиция

[ редактировать ]Активисты по защите прав животных утверждали, что убийство животных за спорт неэтично, жестоко и ненуж. [ 16 ] Они отмечают страдания и жестокость, причиненные животным, охотящимися на спорт: «Многие животные терпят длительные, болезненные смерти, когда они пострадали, но не убиты охотниками. Охота нарушает миграцию и схемы спячки и уничтожает семьи». [ 16 ] Активисты по защите прав животных также комментируют, что охота не требуется для поддержания экологического баланса , и что «природа заботится о своем собственном». [ 16 ] Они говорят, что охота может быть борется на общественных землях, «распространяемых [оленя, репеллента или человеческих волос (из парикмахерских) вблизи охотничьих районов». [ 16 ] Активисты по защите прав животных также утверждают, что охота является видовой : [ 17 ]

Пытаются ли охотники оправдать свое убийство, сославшись на человеческие смерти, вызванные дикими животными, делая заявления о природе, утверждая, что приемлемо охотиться до тех пор, пока тела животных едят, или просто из -за удовольствия, которые он приносит им, факт Остается, что охота морально неприемлема, если мы рассмотрим интересы нечеловеческих животных. Охотники животные терпят страх и боль, а затем лишены своей жизни. Понимание несправедливости видовизма и интересов нечеловеческих животных дает понять, что человеческое удовольствие не может оправдать боль нечеловеческих животных. [ 17 ]

В искусстве

[ редактировать ]

-

Охота в чаще папируса, роспись из гробницы в Фивах, Египет , до 1350 г. до н.э.

-

Человек охотится на кабана, римская мозаика, 4 века н.э.

-

Vittore Carpaccio , Laguna Hunt (Охота в лагуне) , c. 1490

-

Piero di Cosimo ,

Охотничья сцена , 1508 -

Лукас Крэнах Старший , охота на оленя с избирателем Фридриха Мудрый , 1529

-

Питер Пол Рубенс , Бегемот и охота за крокодилом , ок. 1615

-

Питер Пол Рубенс, Tiger и Lion Hunt , 1618

-

Чарльз Андре Ван Лу , Халте де Часс (Остановка продолжительностью охоты) , 1737

-

Франциско Гойя , Стрелка перепели , 1775

-

Эдвард Уолхаус Марк, Caimán del Magadalena , 1843 - 1856

-

Густав Курбе, Охотный завтрак , 1858

-

Eugène Delaroix , Lion Hunt (Hunt Lion) , 1858

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Авиационное путешествие с огнестрельным оружием и боеприпасами

- Браконьерство

- Анти-охота

- Бэмби эффект

- Кровавый спорт

- Хонтинг

- Бушечные продукты

- Пустоши

- Гнаться

- Дефунация

- Федерация ассоциаций по охоте и сохранению ЕС

- Походное оборудование

- Охота на человека

- Ассоциация диверсионеров охоты (HSA)

- Охотничий рог

- Охотниковое оружие

- Нимрод

- Исав

- Сэр Гавейн и зеленый рыцарь

- Tapetum Lucidum Eyeshine

- Звук его рога

- Дикая местность

- Охота на большую игру

- Сафари

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Оксфордский словарь английского языка . Стивенсон, Ангус (3 изд.). Оксфорд: издательство Оксфордского университета. 2010. С. 856. ISBN 9780199571123 Полем OCLC 729551189 .

«Охота [...] преследовать и убить (дикое животное) за спорт или еду [...]»; «Охота [...] деятельность охоты на диких животных или игры».

{{cite book}}: Cs1 maint: другие ( ссылка ) - ^ Петерсон, М. Нильс (2019), «Охота», в Фат -Фат, Брайан Д. (ред.), Энциклопедия экологии , вып. 3 (2 изд.), Elsevier, pp. 438–440, doi : 10.1016/b978-0-12-409548-9.11168-6 , ISBN 978-0-444-64130-4 Охота

- это практика преследования, захвата или убийства дикой природы.

- ^ Парк, Крис; Аллаби, Майкл (2013). Словарь окружающей среды и сохранения (2 изд.). Оксфорд: издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 208. ISBN 978-0-19-964166-6 Полем OCLC 993020467 .

Охота на активность поиска и убийства или захвата диких животных за еду, шкуры или в качестве полевого спорта.

- ^ Neves-Garca, Katja (2007). "Охота". В Роббинсе, Пол (ред.). Энциклопедия окружающей среды и общества . Тол. 3. Тысяча дубов: мудреца публикации. С. 894–896. ISBN 978-1-4129-5627-7 Полем OCLC 228071686 .

В очень общем плане охота относится к деятельности по преследованию и убийству свободных животных.

- ^ Коллин, PH (Питер Ходжсон) (2009). Словарь окружающей среды и экологии: более 7000 терминов четко определены . Блумсбери ссылка (5 изд.). Лондон: Блумсбери. п. 108. ISBN 978-1-4081-0222-0 Полем OCLC 191700369 .

Охота [...] активность следования и убийства диких животных для спорта

- ^ «Охота | Значение в Кембриджском английском словаре» . Кембриджский английский словарь . Архивировано с оригинала 10 декабря 2019 года . Получено 10 декабря 2019 года .

охота [...] погоня за животным или птицей за еду, спорт или прибыль

- ^ «Определение охоты и значение | Коллинз английский словарь» . Коллинз английский словарь . Архивировано с оригинала 10 декабря 2019 года . Получено 10 декабря 2019 года .

Охота - это погоня и убийство диких животных людей или других животных, за еду или как спорт.

- ^ «Охота | История, методы и управление» . Энциклопедия Британская . Архивировано с оригинала 10 декабря 2019 года . Получено 10 декабря 2019 года .

Охота, спорт, который включает в себя поиск, преследование и убийство диких животных и птиц, называемых Game и Game Birds, [...]

- ^ Cartmill, Matt (1996). Вид на смерть утром: охота и природа через историю (1 изд.). Кембридж, Массачусетс: издательство Гарвардского университета. ISBN 9780674029255 Полем OCLC 298105066 .

- ^ [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] [ 4 ] [ 5 ] [ 6 ] [ 7 ] [ 8 ] [ 9 ]

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Уильямс, Тед. «Разыскивается: больше охотников», журнал Audubon , март 2002 года, полученная копия 26 октября 2007 года.

- ^ «Районы охоты на отдых» . doc.govt.nz. Архивировано из оригинала 13 августа 2019 года . Получено 13 августа 2019 года .

- ^ Харпер, Крейг А. «Руководство по управлению качеством оленей для реализации» (PDF) . Служба расширения сельского хозяйства, Университет Теннесси. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 12 сентября 2006 года . Получено 20 декабря 2006 года .

- ^ Nugent, Грэм; Чокенот, Дэвид (2004). «Сравнение экономической эффективности коммерческого сбора урожая, финансируемого государством и охотой на оленей в Новой Зеландии». Бюллетень общества дикой природы . 32 (2): 481–492. doi : 10.2193/0091-7648 (2004) 32 [481: ccochs] 2.0.co; 2 . ISSN 0091-7648 . JSTOR 3784988 . S2CID 86110872 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный "Красная обзор списка". Красный список IUCN. Международный союз сохранения природы. Получено 8 сентября 2010 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый и «Почему спортивная охота является жестокой и ненужной» . Пета 15 декабря 2003 года. Архивировано с оригинала 23 ноября 2013 года . Получено 20 марта 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в "Охота" . Этика животных . Архивировано с оригинала 9 сентября 2017 года . Получено 20 марта 2020 года .

- ^ «10 Охота - обзоры охотничьего оборудования и руководство по покупке» . Архивировано из оригинала 20 февраля 2023 года . Получено 20 февраля 2023 года .

- ^ «Определение охоты» . www.merriam-webster.com . 24 мая 2023 года. Архивировано с оригинала 20 февраля 2023 года . Получено 4 июня 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Охота | Этимология, происхождение и смысл охоты этимонлинином» . www.etymonline.com . Архивировано из оригинала 4 июня 2023 года . Получено 4 июня 2023 года .

- ^ Харпер, Дуглас. "Охота" . Онлайн этимологический словарь . Получено 24 декабря 2016 года .

- ^ Гаудзински, S (2004). «Схемы прожиточного минимума ранних плейстоценовых гоминидов в леванте - тафономические доказательства из« Убейдья »(Израиль)». Журнал археологической науки . 31 (1): 65–75. Bibcode : 2004jarsc..31 ... 65G . doi : 10.1016/s0305-4403 (03) 00100-6 . ISSN 0305-4403 . Полем Рабинович, Р.; Gaudzinski-Windheuser, S.; Горен-Инбар, Н. (2008). «Систематическое наращивание оленей Fallow (DAMA) на раннем среднем плейстоценовом ахеулианском участке Гесшера Бенота Яки (Израиль)». Журнал человеческой эволюции . 54 (1): 134–49. Bibcode : 2008jhume..54..134r . doi : 10.1016/j.jhevol.2007.07.007 . PMID 17868780 .

- ^ 1992 Исследования микроэлементов стронция/кальциевых соотношений у надежных австралопитециновых окаменелостей предположили возможность потребления животных, как и 1994 год с использованием стабильного изотопного анализа углерода. Биллингс, Том. «Сравнительная анатомия и физиология, поднятые до настоящего времени - содержится, часть 3B» . Архивировано из оригинала 15 декабря 2006 года . Получено 6 января 2007 года .

- ^ «Бонобо охотятся на других приматов» . LivesCience.com . 2008. Архивировано из оригинала 15 ноября 2021 года . Получено 5 августа 2012 года .

- ^ Кортни Лэйрд. «Социальный интервал Бонобо» . Дэвидсон колледж . Архивировано из оригинала 23 января 2008 года . Получено 10 марта 2008 года .

- ^ Plummer, TW, Bishop, L., Ditchfield, P., Kingston, J., Ferraro, J., Hertel, F. & D. Braun (2009). «Экологический контекст деятельности Oldowan Hominin на юге Канджеры, Кения». В: Hovers, E. & D. Braun (Eds.), Междисциплинарные подходы к пониманию Oldowan , Springer, Dordrecht, с. 149–60. Том Пламмер, «Трудные вещи культуры: археология Олдэна на юге Канджеры, Кения», архивировано 14 ноября 2021 года в The Wayback Machine , Популярная археология , июнь 2012 года.

- ^ Бинфорд, Луи (1986). «Человеческие предки: изменение взглядов на их поведение». Журнал антропологической археологии . 4 (4): 292–327. doi : 10.1016/0278-4165 (85) 90009-1 .

- ^ 1986) Robert J. ( Blumenschine , Оксфорд, Англия: бар

- ^ Монте Морин, «Копье с каменным наконечником может иметь гораздо более раннее происхождение» , Los Angeles Times , 16 ноября 2012 г.

- ^ Рик Вайс, «Чимп, наблюдающая, что делает свое собственное оружие», архивировав 15 ноября 2021 года на машине Wayback , The Washington Post , 22 февраля 2007 г.

- ^ Thieme, Hartmut (1997). «Нижние палеолитические охотничьи копья из Германии». Природа . 385 (6619): 807–810. Bibcode : 1997natur.385..807t . doi : 10.1038/385807a0 . PMID 9039910 . S2CID 4283393 . [1] Архивировано 21 июля 2017 года на машине Wayback .

- ^ Ниберт, Дэвид (2013). Угнетение животных и насилие человека: кубик, капитализм и глобальный конфликт . Издательство Колумбийского университета . п. 10. ISBN 978-0231151894 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 26 марта 2023 года . Получено 18 апреля 2023 года .

- ^ Рэндалл Хаас; и др. (2020). «Женщины -охотники о ранней Америке». Тол. 6, нет. 45. Science Advances. doi : 10.1126/sciadv.abd0310 .

- ^ Сурувелл, Тодд; Николь Waguespack; П. Джеффри Брантингем (13 апреля 2005 г.). «Глобальные археологические данные для хобосквидических избыточков» . Труды Национальной академии наук . 102 (17): 6231–36. Bibcode : 2005pnas..102.6231S . doi : 10.1073/pnas.0501947102 . PMC 1087946 . PMID 15829581 .

- ^ Дембитцер, Джейкоб; Баркай, побежал; Бен-Дор, Мики; Мейри, Шай (2022). «Levantine Overkill: 1,5 миллиона лет охоты на распределение размеров тела» . Кватернарные науки обзоры . 276 : 107316. BIBCODE : 2022QSRV..27607316D . doi : 10.1016/j.quascirev.2021.107316 . S2CID 245236379 . Архивировано из оригинала 22 декабря 2021 года . Получено 22 декабря 2021 года .

- ^ Миллер, GH (2005). «Экосистемный коллапс в Плейстоценовой Австралии и человеческая роль в вымирании мегафауна» (PDF) . Наука . 309 (5732): 287–90. Bibcode : 2005sci ... 309..287m . doi : 10.1126/science.1111288 . PMID 16002615 . S2CID 22761857 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 7 января 2023 года . Получено 3 января 2023 года .

- ^ Придо, GJ; и др. (2007). «Адаптированная засушливая средняя плейстоценовая фауна от юго-центральной Австралии». Природа . 445 (7126): 422–25. Bibcode : 2007natur.445..422p . doi : 10.1038/nature05471 . PMID 17251978 . S2CID 4429899 .

- ^ Saltré, F.; Chadoeuf, J.; Петерс, KJ; Макдауэлл, MC; Фридрих, Т.; Timmermann, A.; Ulm, S.; Брэдшоу, CJ (2019). «Климатическое взаимодействие и человеческое взаимодействие, связанное с юго-восточной австралийской мегафауна, схемы вымирания» . Природная связь . 10 (1): 5311. Bibcode : 2019natco..10.5311s . doi : 10.1038/s41467-019-13277-0 . PMC 6876570 . PMID 31757942 .

- ^ Zenin, Vasiliy N.; Евгений Н. Машенко; Сергей В. Лешчинский; Александр Ф. Павлов; Питер М. Гроот; Мари-Джози Надо (24–29 мая 2003 г.). «Первое прямое доказательство мамонтовой охоты в Азии (сайт Луговской, Западная Сибири) (L)» . 3 -я Международная конференция Мамонта . Доусон -Сити, Территория Юкона, Канада: правительство Юкона. Архивировано с оригинала 17 ноября 2006 года . Получено 1 января 2007 года .

- ^ «В Северной Америке и Евразии вид долгое время был важным ресурсом - во многих областях наиболее важным ресурсом - для народов, населяющих северные бореальные леса и регионы Тундры. Известная человеческая зависимость от карибу/диких оленей имеет долгую историю, начиная с Средний плейстоцен (Банфилд 1961: 170; Куртен, 1968: 170) и продолжая до настоящего времени. десятки тысяч лет ". Берч, Эрнест С. младший (1972). «Карибу/дикий оленей как человеческий ресурс». Американская древность . 37 (3): 339–68. doi : 10.2307/278435 . JSTOR 278435 . S2CID 161921691 .

- ^ «Природа охраны» . Природа охраняемость . Архивировано из оригинала 3 июля 2018 года . Получено 15 сентября 2016 года .

- ^ Портер, VI (2018). Мистики Мелодии . Питтсбург, Пенсильвания: Dorrance Publishing. п. 48. ISBN 978-1-4809-5591-2 .

- ^ Allsen, Thomas T. (2011) [2006]. Королевская охота в истории Евразии . Встречи с Азией. Филадельфия: Университет Пенсильвании Пресс. ISBN 9780812201079 Полем Получено 27 марта 2023 года .

- ^ Коннор, Стивен (15 ноября 2011 г.). «Победа». Философия спорта . Лондон: Reaktion Books. ISBN 9781861899736 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 27 марта 2023 года . Получено 27 марта 2023 года .

Начиная с классических времен, игры и спорт рассматривались как обучение для реального боя. Самым важным и устойчивым посредником между битвой и спортом была охота, один из нескольких видов спорта регулярно назначал «спорт королей».

- ^

Макиавелли предоставляет обоснование, если не происхождение, благородной охоты:

Макиавелли, Никколо (1531). «Дискурсы в первом десятилетии Тита Ливиуса, книга 3» . В Гилберте, Аллан (ред.). Макиавелли: Главные работы и другие . Тол. 1. Duke University Press (опубликовано 1989). п. 516. ISBN 978-0-8223-8157-0 Полем Получено 27 декабря 2013 года .

[...] Охотничьи экспедиции, как ксенофонт простым, являются изображениями войны; Поэтому для мужчин ранга такая деятельность является почетной и необходимой.

- ^

Данлэп, Томас Р. (1999). «Передача миров: европейские модели в новых землях» . Природа и английская диаспора: окружающая среда и история в Соединенных Штатах, Канаде, Австралии и Новой Зеландии . Исследования по окружающей среде и истории. Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 61 . ISBN 978-0-521-65700-6 Полем Получено 24 декабря 2013 года .

Поселенцы приняли охоту на спорт, так как они делали другие элементы британской культуры, но им пришлось адаптировать ее. Социальные обстоятельства и биологические реалии изменили его и дали ему новое значение. Не было элитного монополизирующего доступа к земле. Действительно, великая привлекательность и хвастовство этих наций были земли для всех.

- ^ В своем комментарии к работе Мартинуса Капеллы начала 5-го века, брак филологии и Меркурия , одного из основных источников средневекового размышлений об гуманитарных науках.

- ^ «Руководство по охоте >> прочитать перед охотой» . Охотник . Архивировано из оригинала 14 ноября 2021 года . Получено 15 декабря 2017 года .

- ^ «Охота с собаками« дефра » . Defra.gov.uk. 18 февраля 2005 года. Архивировано с оригинала 22 февраля 2013 года . Получено 20 апреля 2012 года .

- ^ «Почему мы должны продолжать кампанию за отмену Закона о охоте 2004 года» . www.vote-ok.co.uk . Получено 12 августа 2024 года .

- ^ «Ошибочный и бесполезный: время отменить охотничий акт» . www.oxfordstudent.com . Получено 12 августа 2024 года .

- ^ «Английские голоса за английские законы могут положить конец запрету на охоту» . Телеграф . Получено 12 августа 2024 года .

- ^ «Диана - римская религия» . Encyclopædia britannica.com . Архивировано из оригинала 8 января 2022 года . Получено 21 декабря 2021 года .

- ^ Каппеллер, Карл (1891). Санскритский английский словарь, основанный на лексиконах Санкт-Петербурга; Полем Страссбург: Карл Дж. Трюбнер. п. 418.

- ^ «Джайнизм - ненасилие, джива, аджива, три драгоценные камни, калпа | Британия» . www.britannica.com . Архивировано с оригинала 19 ноября 2022 года . Получено 4 июня 2023 года .

- ^ «Будда преподавал ненасилие, а не пацифизм» . www.buddhistinquiry.org . Архивировано из оригинала 23 марта 2023 года . Получено 4 июня 2023 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Католическая энциклопедия: охота» . www.newadvent.org . Архивировано из оригинала 29 декабря 2021 года . Получено 29 декабря 2021 года .

- ^ «Каноны на охоте» . Католические ответы . Архивировано с оригинала 6 сентября 2015 года . Получено 23 марта 2022 года .