Психология

| Часть серии о |

| Психология |

|---|

Психология – это научное исследование разума и поведения . [1] [2] Его предмет включает в себя поведение людей и нелюдей, как сознательные , так и бессознательные явления, а также психические процессы, такие как мысли , чувства и мотивы . Психология — это академическая дисциплина огромного масштаба, пересекающая границы между естественными и социальными науками . Биологические психологи стремятся понять возникающие свойства мозга, связывая эту дисциплину с нейробиологией . Как социологи, психологи стремятся понять поведение отдельных лиц и групп. [3] [4]

Профессиональный практик или исследователь, занимающийся этой дисциплиной, называется психологом . Некоторых психологов также можно отнести к ученым -бихевиористам или когнитивистам . Некоторые психологи пытаются понять роль психических функций в индивидуальном и социальном поведении . Другие исследуют физиологические и нейробиологические процессы, лежащие в основе когнитивных функций и поведения.

Психологи участвуют в исследованиях восприятия , познания , внимания , эмоций , интеллекта , субъективных переживаний , мотивации , функционирования мозга и личности . Интересы психологов распространяются на межличностные отношения , психологическую устойчивость , устойчивость семьи и другие области социальной психологии . Они также рассматривают бессознательное. [5] Психологи-исследователи используют эмпирические методы для вывода причинно-следственных и корреляционных связей между психосоциальными переменными . Некоторые, но не все, клинические и консультирующие психологи полагаются на символическую интерпретацию .

Хотя психологические знания часто применяются для оценки и лечения проблем психического здоровья, они также направлены на понимание и решение проблем в нескольких сферах человеческой деятельности. По мнению многих, психология в конечном итоге стремится принести пользу обществу. [6] [7] [8] Многие психологи участвуют в той или иной терапевтической роли, практикуя психотерапию в клинических, консультационных или школьных учреждениях. Другие психологи проводят научные исследования по широкому кругу тем, связанных с психическими процессами и поведением. Обычно последняя группа психологов работает в академических учреждениях (например, в университетах, медицинских школах или больницах). Другая группа психологов работает на производстве и в организациях . [9] Третьи участвуют в работе в области человеческого развития , старения, спорта , здравоохранения, судебной медицины , образования и средств массовой информации .

Этимология и определения

Слово психология происходит от греческого слова psyche , означающего дух или душу . Последняя часть слова «психология» происходит от -λογία -logia , что означает «изучение» или «исследование». [10] Слово психология впервые было использовано в эпоху Возрождения. [11] В своей латинской форме psychiologia она была впервые использована хорватским гуманистом и латинистом Марко Маруличем в его книге Psichiologia deratione animae humanae ( «Психология о природе человеческой души ») в десятилетии 1510-1520 годов. [11] [12] Самая ранняя известная ссылка на слово «психология» на английском языке была сделана Стивеном Бланкартом в 1694 году в «Физическом словаре» . В словаре упоминаются « Анатомия , изучающая Тело, и Психология, изучающая Душу». [13]

Ψ ( пси ) , первая буква греческого слова «психика» , от которого происходит термин «психология», обычно ассоциируется с областью психологии.

В 1890 году Уильям Джеймс определил психологию как «науку о психической жизни, как о ее явлениях, так и об их состояниях». [14] Это определение пользовалось широким распространением на протяжении десятилетий. Однако это значение оспаривалось, в частности, радикальными бихевиористами , такими как Джон Б. Уотсон , который в 1913 году утверждал, что эта дисциплина является естественной наукой , теоретической целью которой «является предсказание и контроль поведения». [15] Поскольку Джеймс дал определение «психологии», этот термин в большей степени подразумевает научные эксперименты. [16] [15] Народная психология — это понимание психических состояний и поведения людей, которого придерживаются обычные люди , в отличие от понимания профессиональных психологов. [17]

История

Древние цивилизации Египта, Греции, Китая, Индии и Персии занимались философским изучением психологии. В Древнем Египте папирус Эберса упоминал депрессию и расстройства мышления. [18] Историки отмечают, что греческие философы, в том числе Фалес , Платон и Аристотель (особенно в его трактате «О душе» ), [19] обратился к работе ума. [20] Еще в IV веке до нашей эры греческий врач Гиппократ предположил, что психические расстройства имеют физические, а не сверхъестественные причины. [21] В 387 г. до н. э. Платон предположил, что мозг — это место, где происходят психические процессы, а в 335 г. до н. э. Аристотель предположил, что это сердце. [22]

В Китае психологическое понимание выросло из философских трудов Лао-цзы и Конфуция , а позднее из доктрин буддизма . [23] Этот массив знаний включает в себя идеи, полученные в результате самоанализа и наблюдения, а также методы сосредоточенного мышления и действия. Он создает вселенную с точки зрения разделения физической реальности и ментальной реальности, а также взаимодействия между физическим и ментальным. [ нужна ссылка ] Китайская философия также делала упор на очищении ума, чтобы увеличить добродетель и силу. Древний текст, известный как « Классика внутренней медицины Желтого императора», определяет мозг как связующее звено мудрости и ощущений, включает теории личности, основанные на балансе инь-ян , и анализирует психические расстройства с точки зрения физиологических и социальных нарушений равновесия. Китайская наука, изучавшая мозг, получила развитие во времена династии Цин благодаря работам получивших западное образование Фан Ичжи (1611–1671), Лю Чжи (1660–1730) и Ван Цинжэня (1768–1831). Ван Цинжэнь подчеркнул важность мозга как центра нервной системы, связал психические расстройства с заболеваниями головного мозга, исследовал причины сновидений и бессонницы и выдвинул теорию латерализации полушарий в функции мозга. [24]

Под влиянием индуизма индийская философия исследовала различия в типах сознания. Центральной идеей Упанишад и других ведических текстов, которые легли в основу индуизма, было различие между преходящим мирским «я» человека и его вечной, неизменной душой . Различные доктрины индуизма и буддизма бросили вызов этой иерархии личностей, но все они подчеркивали важность достижения более высокого осознания. Йога включает в себя ряд техник, используемых для достижения этой цели. Теософия , религия, основанная русско-американским философом Еленой Блаватской , черпала вдохновение из этих доктрин во время ее пребывания в Британской Индии . [25] [26]

Психология представляла интерес для мыслителей эпохи Просвещения в Европе. В Германии Готфрид Вильгельм Лейбниц (1646–1716) применил свои принципы исчисления к разуму, утверждая, что умственная деятельность происходит в неделимом континууме. Он предположил, что разница между сознательным и бессознательным осознанием является лишь вопросом степени. Кристиан Вольф определил психологию как отдельную науку, написав Psychologia Empirica в 1732 году и Psychologia Rationalis в 1734 году. Иммануил Кант выдвинул идею антропологии как дисциплины, важным подразделом которой является психология. Кант, однако, явно отверг идею экспериментальной психологии , написав, что «эмпирическое учение о душе также никогда не может приблизиться к химии даже как к систематическому искусству анализа или экспериментальному учению, ибо в ней многообразие внутреннего наблюдения может быть выделено только путем простого разделения в мышлении, и тогда он не может быть разделен и воссоединен по желанию (но еще меньше другой мыслящий субъект позволяет экспериментировать над собой для достижения нашей цели), и даже наблюдение само по себе уже изменяет и смещает состояние наблюдаемого. объект."

В 1783 году Фердинанд Юбервассер (1752–1812) назначил себя профессором эмпирической психологии и логики и читал лекции по научной психологии, хотя эти разработки вскоре были омрачены наполеоновскими войнами . [27] В конце наполеоновской эпохи прусские власти закрыли Старый университет Мюнстера. [27] Однако, посоветовавшись с философами Гегелем и Гербартом , в 1825 году прусское государство сделало психологию обязательной дисциплиной в своей быстро расширяющейся и очень влиятельной системе образования . Однако эта дисциплина еще не охватывала экспериментирование. [28] В Англии ранняя психология включала френологию и реакцию на социальные проблемы, включая алкоголизм, насилие и переполненные «сумасшедшие» приюты в стране. [29]

Начало экспериментальной психологии

Философ Джон Стюарт Милль считал, что человеческий разум открыт для научных исследований, даже если наука в некотором смысле неточна. [30] Милль предложил «ментальную химию », в которой элементарные мысли могли объединяться в идеи большей сложности. [30] Густав Фехнер начал проводить психофизические исследования в Лейпциге в 1830-х годах. Он сформулировал принцип, согласно которому человеческое восприятие стимула изменяется логарифмически в зависимости от его интенсивности. [31] : 61 Этот принцип стал известен как закон Вебера-Фехнера . Фехнера 1860 года «Элементы психофизики» бросили вызов негативному взгляду Канта на проведение количественных исследований разума. [32] [28] Достижением Фехнера было показать, что «психическим процессам можно не только придать числовые значения, но и измерить их экспериментальными методами». [28] В Гейдельберге Герман фон Гельмгольц проводил параллельные исследования сенсорного восприятия и обучал физиолога Вильгельма Вундта . Вундт, в свою очередь, приехал в Лейпцигский университет, где основал психологическую лабораторию, которая подарила миру экспериментальную психологию. Вундт сосредоточился на разбиении психических процессов на самые основные компоненты, отчасти руководствуясь аналогией с недавними достижениями в химии и успешными исследованиями элементов и структуры материалов. [33] Пауль Флехсиг и Эмиль Крепелин вскоре создали в Лейпциге еще одну влиятельную лабораторию, лабораторию, связанную с психологией, которая больше ориентировалась на экспериментальную психиатрию. [28]

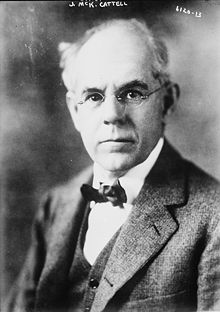

Джеймс Маккин Кеттелл , профессор психологии Пенсильванского и Колумбийского университетов и сооснователь Psychoological Review , был первым профессором психологии в США .

Немецкий психолог Герман Эббингауз , исследователь из Берлинского университета , внес свой вклад в эту область в XIX веке. Он был пионером экспериментального исследования памяти и разработал количественные модели обучения и забывания. [34] В начале 20 века Вольфганг Колер , Макс Вертхаймер и Курт Коффка стали соучредителями школы гештальт-психологии Фрица Перлза . Подход гештальт-психологии основан на идее, что люди воспринимают вещи как единое целое. Вместо того, чтобы сводить мысли и поведение на более мелкие составные элементы, как в структурализме, гештальтисты утверждали, что весь опыт важен и отличается от суммы его частей.

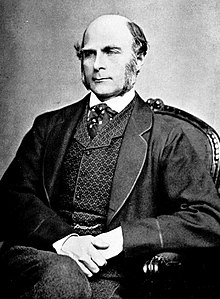

Психологи в Германии, Дании, Австрии, Англии и США вскоре последовали примеру Вундта в создании лабораторий. [35] Дж. Стэнли Холл , американец, который учился у Вундта, основал психологическую лабораторию, которая стала влиятельной на международном уровне. Лаборатория располагалась в Университете Джонса Хопкинса . Холл, в свою очередь, обучал Юдзиро Мотору , который принес экспериментальную психологию с упором на психофизику в Императорский университет Токио . [36] Ассистент Вундта, Хьюго Мюнстерберг , преподавал психологию в Гарварде таким студентам, как Нарендра Нат Сен Гупта , который в 1905 году основал факультет психологии и лабораторию в Калькуттском университете . [25] Ученики Вундта Уолтер Дилл Скотт , Лайтнер Уитмер и Джеймс Маккин Кеттелл работали над разработкой тестов умственных способностей. Кеттелл, который также учился у евгениста Фрэнсиса Гальтона , впоследствии основал Психологическую корпорацию . Уитмер сосредоточился на умственном тестировании детей; Скотт, о подборе сотрудников. [31] : 60

Другой ученик Вундта, англичанин Эдвард Титченер , создал программу психологии в Корнелльском университете и выдвинул « структуралистскую » психологию. Идея структурализма заключалась в анализе и классификации различных аспектов сознания, прежде всего с помощью метода самоанализа . [37] Уильям Джеймс, Джон Дьюи и Харви Карр выдвинули идею функционализма , экспансивного подхода к психологии, который подчеркивал дарвиновскую идею о полезности поведения для человека. В 1890 году Джеймс написал влиятельную книгу «Принципы психологии» , в которой подробно остановился на структурализме. Он незабываемо описал « поток сознания ». Идеи Джеймса заинтересовали многих американских студентов новой дисциплиной. [37] [14] [31] : 178–82 Дьюи объединил психологию с общественными проблемами, в первую очередь путем продвижения прогрессивного образования , привития моральных ценностей детям и ассимиляции иммигрантов. [31] : 196–200

Другое направление экспериментализма, более тесно связанное с физиологией, возникло в Южной Америке под руководством Орасио Г. Пиньеро из Университета Буэнос-Айреса . [38] В России исследователи также уделяли больше внимания биологическим основам психологии, начиная с эссе Ивана Сеченова 1873 года «Кто и как развивать психологию?» Сеченов выдвинул идею мозговых рефлексов и агрессивно продвигал детерминистический взгляд на человеческое поведение. [39] Российско-советский физиолог Иван Павлов обнаружил у собак процесс обучения, который позже был назван « классическим обусловливанием », и применил этот процесс к людям. [40]

Консолидация и финансирование

Одним из первых психологических обществ было La Société de Psychologie Physiologique во Франции, которое существовало с 1885 по 1893 год. Первое заседание Международного психологического конгресса, спонсируемого Международным союзом психологических наук, состоялось в Париже в августе 1889 года в разгар Всемирная выставка, посвященная столетию Французской революции. Уильям Джеймс был одним из трех американцев среди 400 участников. Американская психологическая ассоциация (АПА) была основана вскоре после этого, в 1892 году. Международный конгресс продолжал проводиться в разных местах Европы и с широким международным участием. Шестой конгресс, состоявшийся в Женеве в 1909 году, включал доклады на русском, китайском и японском языках, а также на эсперанто . После перерыва из-за Первой мировой войны в Оксфорде собрался Седьмой конгресс, в котором приняли участие победившие в войне англо-американцы. В 1929 году в Йельском университете в Нью-Хейвене, штат Коннектикут, состоялся Конгресс, на котором присутствовали сотни членов АПА. [35] Императорский университет Токио возглавил путь распространения новой психологии на Восток. Новые идеи о психологии распространились из Японии в Китай. [24] [36]

Американская психология получила статус после вступления США в Первую мировую войну. Постоянный комитет, возглавляемый Робертом Йерксом, провел психологические тесты (« Армия Альфа » и « Армия Бета ») почти 1,8 миллионам солдат. [41] Впоследствии семья Рокфеллеров через Совет по исследованиям в области социальных наук начала предоставлять финансирование поведенческих исследований. [42] [43] Благотворительные организации Рокфеллера финансировали Национальный комитет психической гигиены, который распространял концепцию психических заболеваний и лоббировал применение идей психологии к воспитанию детей. [41] [44] Через Бюро социальной гигиены, а затем через финансирование Альфреда Кинси , фонды Рокфеллера помогли организовать исследования сексуальности в США. [45] Под влиянием Бюро регистрации евгеники , финансируемого Дрейпером , финансируемого Карнеги, Фонда пионеров , и других учреждений, евгеническое движение также повлияло на американскую психологию. В 1910-х и 1920-х годах евгеника стала стандартной темой на уроках психологии. [46] В отличие от США, в Великобритании психология встречалась с антагонизмом со стороны научных и медицинских учреждений, и до 1939 года в университетах Англии было всего шесть кафедр психологии. [47]

Во время Второй мировой войны и «холодной войны» военные и разведывательные службы США зарекомендовали себя как ведущие спонсоры психологии через вооруженные силы и в новом разведывательном агентстве Управления стратегических служб . Психолог Мичиганского университета Дорвин Картрайт сообщил, что университетские исследователи начали крупномасштабные пропагандистские исследования в 1939–1941 годах. Он заметил, что «в последние несколько месяцев войны социальный психолог стал главным ответственным за определение еженедельной пропагандистской политики правительства Соединенных Штатов». Картрайт также писал, что психологи играют важную роль в управлении отечественной экономикой. [48] Армия внедрила новый общий классификационный тест для оценки способностей миллионов солдат. Армия также участвовала в крупномасштабных психологических исследованиях морального духа и психического здоровья солдат . [49] В 1950-х годах Фонд Рокфеллера и Фонд Форда сотрудничали с Центральным разведывательным управлением (ЦРУ) для финансирования исследований в области психологической войны . [50] В 1965 году общественная полемика привлекла внимание к армейскому проекту «Камелот» , «Манхэттенскому проекту» социальных наук , в рамках которого психологи и антропологи привлекались к анализу планов и политики зарубежных стран в стратегических целях. [51] [52]

В Германии после Первой мировой войны психология имела институциональную власть через армию, которая впоследствии была расширена вместе с остальной армией во времена нацистской Германии . [28] Под руководством Германа Геринга двоюродного брата Матиаса Геринга Берлинский психоаналитический институт был переименован в Институт Геринга. Психоаналитики-фрейдисты были изгнаны и преследовались в соответствии с антиеврейской политикой нацистской партии , и всем психологам пришлось дистанцироваться от Фрейда и Адлера , основателей психоанализа , которые также были евреями. [53] Институт Геринга хорошо финансировался на протяжении всей войны, ему было поручено создать «Новую немецкую психотерапию». Эта психотерапия была направлена на то, чтобы привести подходящих немцев в соответствие с общими целями Рейха. Как описал один врач: «Несмотря на важность анализа, духовное руководство и активное сотрудничество пациента представляют собой лучший способ преодолеть индивидуальные психические проблемы и подчинить их требованиям Volk и Gemeinschaft » . Психологи должны были обеспечить Seelenführung [букв. руководство душой], руководство разумом, чтобы интегрировать людей в новое видение немецкого сообщества. [54] Харальд Шульц-Хенке объединил психологию с нацистской теорией биологии и расового происхождения, критикуя психоанализ как исследование слабых и уродливых. [55] Йоханнес Генрих Шульц , немецкий психолог, получивший признание за разработку техники аутогенной тренировки , активно выступал за стерилизацию и эвтаназию мужчин, считающихся генетически нежелательными, и разработал методы, облегчающие этот процесс. [56]

После войны были созданы новые учреждения, хотя некоторые психологи из-за своей нацистской принадлежности были дискредитированы. Александр Мичерлих основал известный журнал по прикладному психоанализу под названием «Психея» . При финансовой поддержке Фонда Рокфеллера Мичерлих основал первое отделение клинической психосоматической медицины в Гейдельбергском университете. В 1970 году психология была интегрирована в обязательную программу обучения студентов-медиков. [57]

После русской революции большевики пропагандировали психологию как способ создания «нового человека» социализма. Следовательно, факультеты психологии университетов подготовили большое количество студентов по психологии. По завершении обучения этим студентам открывались должности в школах, на рабочих местах, в учреждениях культуры и в армии. Российское государство уделяло особое внимание почвоведению и изучению развития детей. Лев Выготский стал видным специалистом в области детского развития. [39] Большевики также пропагандировали свободную любовь и приняли доктрину психоанализа как противоядие от сексуальных репрессий. [58] : 84–6 [59] Хотя в 1936 году педология и тестирование интеллекта вышли из моды, психология сохранила свое привилегированное положение как инструмент Советского Союза. [39] Сталинские чистки нанесли тяжелый урон и посеяли атмосферу страха в профессии, как и везде в советском обществе. [58] : 22 После Второй мировой войны были осуждены еврейские психологи прошлого и настоящего, в том числе Лев Выготский , А.Р. Лурия и Арон Залкинд; Иван Павлов (посмертно) и сам Сталин прославлялись как герои советской психологии. [58] : 25–6, 48–9 Советские ученые пережили определенную либерализацию во время хрущевской оттепели . Темы кибернетики, лингвистики и генетики снова стали приемлемыми. Появилась новая область инженерной психологии . Эта область включала изучение психических аспектов сложных профессий (таких как пилот и космонавт). Междисциплинарные исследования стали популярными, и такие ученые, как Георгий Щедровицкий, разработали системные подходы к человеческому поведению. [58] : 27–33

Китайская психология двадцатого века первоначально создавала себя по образцу психологии США, с переводами американских авторов, таких как Уильям Джеймс, созданием университетских факультетов психологии и журналов, а также созданием групп, включая Китайскую ассоциацию психологического тестирования (1930) и Китайское психологическое общество. (1937). Китайским психологам было предложено сосредоточиться на образовании и изучении языков. Китайских психологов привлекла идея о том, что образование сделает возможным модернизацию. Джон Дьюи, читавший лекции перед китайской аудиторией в период с 1919 по 1921 год, оказал значительное влияние на психологию в Китае. Канцлер Цай Юаньпэй представил его в Пекинском университете как более великого мыслителя, чем Конфуций. Го Цзин-ян, получивший докторскую степень в Калифорнийском университете в Беркли, стал президентом Чжэцзянского университета и популяризировал бихевиоризм . [60] : 5–9 После того, как Коммунистическая партия Китая получила контроль над страной, сталинистский Советский Союз стал основным влиянием, при этом марксизм-ленинизм стал ведущей социальной доктриной, а павловская теория обусловила одобренные средства изменения поведения. Китайские психологи разработали ленинскую модель «рефлексивного» сознания, предвидя «активное сознание» ( пиньинь : цзы-чуэ ненг-дун-ли ), способное преодолевать материальные условия посредством упорного труда и идеологической борьбы. Они разработали концепцию «признания» ( пиньинь : jen-shih ), которая относилась к интерфейсу между индивидуальным восприятием и социально принятым мировоззрением; несоответствие партийной доктрине было «неправильным признанием». [60] : 9–17 Психологическое образование было централизовано в рамках Китайской академии наук и контролировалось Государственным советом . В 1951 году в академии было создано Отделение психологических исследований, которое в 1956 году стало Институтом психологии. Поскольку большинство ведущих психологов получили образование в Соединенных Штатах, первой заботой академии было перевоспитание этих психологов в соответствии с советскими доктринами. Детская психология и педагогика с целью национально сплоченного образования оставались центральной целью дисциплины. [60] : 18–24

Женщины в психологии

1900 - 1949

Женщины в начале 1900-х годов начали делать ключевые открытия в мире психологии. В 1923 году Анна Фрейд [61] дочь Зигмунда Фрейда , основанная на работе своего отца, использующая различные защитные механизмы (отрицание, подавление и подавление) для психоанализа детей. Она считала, что как только ребенок достигнет латентного периода , детский анализ можно будет использовать в качестве метода терапии . Она заявила, что важно уделять внимание окружению ребенка, поддерживать его развитие и предотвращать неврозы . Она считала, что ребенка следует признавать как личность, имеющую собственные права, и каждое занятие должно учитывать его конкретные потребности. Она поощряла рисование, свободное передвижение и самовыражение любым способом. Это помогло построить прочный терапевтический альянс с детьми-пациентами, что позволяет психологам наблюдать за их нормальным поведением. Она продолжила свои исследования влияния детей после разлучения семьи, детей из социально-экономически неблагополучных семей и всех стадий детского развития от младенчества до подросткового возраста.

Functional periodicity, the belief women are mentally and physically impaired during menstruation, impacted women's rights because employers were less likely to hire them due to the belief they would be incapable of working for 1 week a month. Leta Stetter Hollingworth wanted to prove this hypothesis and Edward L. Thorndike's theory, that women have lesser psychological and physical traits than men and were simply mediocre, incorrect. Hollingworth worked to prove differences were not from male genetic superiority, but from culture. She also included the concept of women's impairment during menstruation in her research. She recorded both women and men performances on tasks (cognitive, perceptual, and motor) for three months. No evidence was found of decreased performance due to a woman's menstrual cycle.[62] She also challenged the belief intelligence is inherited and women here are intellectually inferior to men. She stated that women do not reach positions of power due to the societal norms and roles they are assigned. As she states in her article, "Variability as related to sex differences in achievement: A Critique",[63] the largest problem women have is the social order that was built due to the assumption women have less interests and abilities than men. To further prove her point, she completed another experiment with infants who have not been influenced by the environment of social norms, like the adult male getting more opportunities than women. She found no difference between infants besides size. After this research proved the original hypothesis wrong, Hollingworth was able to show there is no difference between the physiological and psychological traits of men and women, and women are not impaired during menstruation.[64]

The first half of the 1900s was filled with new theories and it was a turning point for women's recognition within the field of psychology. In addition to the contributions made by Leta Stetter Hollingworth and Anna Freud, Mary Whiton Calkins invented the paired associates technique of studying memory and developed self-psychology.[65] Karen Horney developed the concept of "womb envy" and neurotic needs.[66] Psychoanalyst Melanie Klein impacted developmental psychology with her research of play therapy.[67] These great discoveries and contributions were made during struggles of sexism, discrimination, and little recognition for their work.

1950 - 1999

Women in the second half of the 20th century continued to do research that had large-scale impacts on the field of psychology. Mary Ainsworth's work centered around attachment theory. Building off fellow psychologist John Bowlby, Ainsworth spent years doing fieldwork to understand the development of mother-infant relationships. In doing this field research, Ainsworth developed the Strange Situation Procedure, a laboratory procedure meant to study attachment style by separating and uniting a child with their mother several different times under different circumstances. These field studies are also where she developed her attachment theory and the order of attachment styles, which was a landmark for developmental psychology.[68][69] Because of her work, Ainsworth became one of the most cited psychologists of all time.[70] Mamie Phipps Clark was another woman in psychology that changed the field with her research. She was one of the first African-Americans to receive a doctoral degree in psychology from Columbia University, along with her husband, Kenneth Clark. Her master's thesis, "The Development of Consciousness in Negro Pre-School Children," argued that black children's self-esteem was negatively impacted by racial discrimination. She and her husband conduced research building off her thesis throughout the 1940s. These tests, called the doll tests, asked young children to choose between identical dolls whose only difference was race, and they found that the majority of the children preferred the white dolls and attributed positive traits to them. Repeated over and over again, these tests helped to determine the negative effects of racial discrimination and segregation on black children's self-image and development. In 1954, this research would help decide the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision, leading to the end of legal segregation across the nation. Clark went on to be an influential figure in psychology, her work continuing to focus on minority youth.[71]

As the field of psychology developed throughout the latter half of the 20th century, women in the field advocated for their voices to be heard and their perspectives to be valued. Second-wave feminism did not miss psychology. An outspoken feminist in psychology was Naomi Weisstein, who was an accomplished researcher in psychology and neuroscience, and is perhaps best known for her paper, "Kirche, Kuche, Kinder as Scientific Law: Psychology Constructs the Female." Psychology Constructs the Female criticized the field of psychology for centering men and using biology too much to explain gender differences without taking into account social factors.[72] Her work set the stage for further research to be done in social psychology, especially in gender construction.[73] Other women in the field also continued advocating for women in psychology, creating the Association for Women in Psychology to criticize how the field treated women. E. Kitsch Child, Phyllis Chesler, and Dorothy Riddle were some of the founding members of the organization in 1969.[74][75]

The latter half of the 20th century further diversified the field of psychology, with women of color reaching new milestones. In 1962, Martha Bernal became the first Latina woman to get a Ph.D. in psychology. In 1969, Marigold Linton, the first Native American woman to get a Ph.D. in psychology, founded the National Indian Education Association. She was also a founding member of the Society for Advancement of Chicanos and Native Americans in Science. In 1971, The Network of Indian Psychologists was established by Carolyn Attneave. Harriet McAdoo was appointed to the White House Conference on Families in 1979.[76]

2000 - Current

Babette Rothschild, a clinical social worker, invented Somatic Trauma Therapy. Somatic Trauma Therapy utilizes the body to experience, process, and heal from traumatic experiences. To spread her technique she wrote several books, the most prominent being The Body Remembers: The Psychophysiology of Trauma, Trauma, and Trauma Treatment[77], which was published in 2000.[78]

Dr. Tara Brach has written several bestselling books that combine Western and Eastern psychology. She founded the Insight Meditation Community of Washington in 1998 and co-founded two teaching programs, Banyan, and the Mindfulness Mediation Teacher Training Program. The latter has served people from 74 different countries.[79]

Dr. Kay Redfield Jamison, named one of Time Magazine's "Best Doctors in the United States" is a lecturer, psychologist, and writer. She is known for her vast modern contributions to bipolar disorder and her books An Unquiet Mind[80] (Published 1995) and Nothing Was the Same[81] (Published in 2009). Having Bipolar Disorder herself, she has written several memoirs about her experience with suicidal thoughts, manic behaviors, depression, and other issues that arise from being Bipolar.[78]

Dr. Angela Neal-Barnett views psychology through a Black lens and dedicated her career to focusing on the anxiety of African American women. She founded the organization Rise Sally Rise which helps Black women cope with anxiety. She published her work Soothe Your Nerves: The Black Woman's Guide to Understanding and Overcoming Anxiety, Panic and Fear[82] in 2003.[78]

In 2003 Kristin Neff founded the Self Compassion Scale, a tool for therapists to use to measure their compassion for themselves. In addition to this, she has written several books the most relevant being Self Compassion: The Proven Power to Being Kind to Yourself[83] (Published in 2011) and Fierce Self-Compassion: How Women Can Harness Kindness to Speak Up, Claim Their Power and Thrive[84] (Published in 2021).[78]

In 2002 Dr. Teresa LaFromboise, former president of the Society of Indian Psychologists, received the APA's Distinguished Career Contribution to Research Award from the Society for the Psychological Study of Culture Ethnicity, and Race for her research on suicide prevention. She was the first person to lead an intervention for Native American children and adolescents that utilized evidence-based suicide prevention. She has spent her career dedicated to aiding racial and ethnic minority youth cope with cultural adjustment and pressures.[85]

Dr. Shari Miles-Cohen, a psychologist and political activist has applied a black, feminist, and class lens to all her psychological studies. Aiding progressive and women's issues, she has been the executive director for many NGOs. In 2007 she became the Senior Director of the Women's Programs Office of the American Psychological Association. Therefore, she was one of the creators of the APA's "Women in Psychology Timeline" which features the accomplishments of women of color in psychology. She is well known for co-editing Eliminating Inequities for Women with Disabilities: An Agenda for Health and Wellness[86] (published in 2016), her article published in the Women's Reproductive Health Journal about women of color's struggle with pregnancy and postpartum (Published in 2018), and co-authoring the award-winning "APA Handbook of the Psychology of Women" (published in 2019).[87]

Disciplinary organizations

Institutions

In 1920, Édouard Claparède and Pierre Bovet created a new applied psychology organization called the International Congress of Psychotechnics Applied to Vocational Guidance, later called the International Congress of Psychotechnics and then the International Association of Applied Psychology.[35] The IAAP is considered the oldest international psychology association.[88] Today, at least 65 international groups deal with specialized aspects of psychology.[88] In response to male predominance in the field, female psychologists in the U.S. formed the National Council of Women Psychologists in 1941. This organization became the International Council of Women Psychologists after World War II and the International Council of Psychologists in 1959. Several associations including the Association of Black Psychologists and the Asian American Psychological Association have arisen to promote the inclusion of non-European racial groups in the profession.[88]

The International Union of Psychological Science (IUPsyS) is the world federation of national psychological societies. The IUPsyS was founded in 1951 under the auspices of the United Nations Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization (UNESCO).[35][89] Psychology departments have since proliferated around the world, based primarily on the Euro-American model.[25][89] Since 1966, the Union has published the International Journal of Psychology.[35] IAAP and IUPsyS agreed in 1976 each to hold a congress every four years, on a staggered basis.[88]

IUPsyS recognizes 66 national psychology associations and at least 15 others exist.[88] The American Psychological Association is the oldest and largest.[88] Its membership has increased from 5,000 in 1945 to 100,000 in the present day.[37] The APA includes 54 divisions, which since 1960 have steadily proliferated to include more specialties. Some of these divisions, such as the Society for the Psychological Study of Social Issues and the American Psychology–Law Society, began as autonomous groups.[88]

The Interamerican Psychological Society, founded in 1951, aspires to promote psychology across the Western Hemisphere. It holds the Interamerican Congress of Psychology and had 1,000 members in year 2000. The European Federation of Professional Psychology Associations, founded in 1981, represents 30 national associations with a total of 100,000 individual members. At least 30 other international organizations represent psychologists in different regions.[88]

In some places, governments legally regulate who can provide psychological services or represent themselves as a "psychologist."[90] The APA defines a psychologist as someone with a doctoral degree in psychology.[91]

Boundaries

Early practitioners of experimental psychology distinguished themselves from parapsychology, which in the late nineteenth century enjoyed popularity (including the interest of scholars such as William James). Some people considered parapsychology to be part of "psychology." Parapsychology, hypnotism, and psychism were major topics at the early International Congresses. But students of these fields were eventually ostracized, and more or less banished from the Congress in 1900–1905.[35] Parapsychology persisted for a time at Imperial University in Japan, with publications such as Clairvoyance and Thoughtography by Tomokichi Fukurai, but it was mostly shunned by 1913.[36]

As a discipline, psychology has long sought to fend off accusations that it is a "soft" science. Philosopher of science Thomas Kuhn's 1962 critique implied psychology overall was in a pre-paradigm state, lacking agreement on the type of overarching theory found in mature hard sciences such as chemistry and physics.[92] Because some areas of psychology rely on research methods such as self-reports in surveys and questionnaires, critics asserted that psychology is not an objective science. Skeptics have suggested that personality, thinking, and emotion cannot be directly measured and are often inferred from subjective self-reports, which may be problematic. Experimental psychologists have devised a variety of ways to indirectly measure these elusive phenomenological entities.[93][94][95]

Divisions still exist within the field, with some psychologists more oriented towards the unique experiences of individual humans, which cannot be understood only as data points within a larger population. Critics inside and outside the field have argued that mainstream psychology has become increasingly dominated by a "cult of empiricism", which limits the scope of research because investigators restrict themselves to methods derived from the physical sciences.[96]: 36–7 Feminist critiques have argued that claims to scientific objectivity obscure the values and agenda of (historically) mostly male researchers.[41] Jean Grimshaw, for example, argues that mainstream psychological research has advanced a patriarchal agenda through its efforts to control behavior.[96]: 120

Major schools of thought

Biological

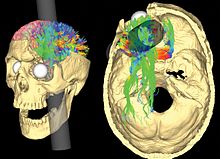

Psychologists generally consider biology the substrate of thought and feeling, and therefore an important area of study. Behaviorial neuroscience, also known as biological psychology, involves the application of biological principles to the study of physiological and genetic mechanisms underlying behavior in humans and other animals. The allied field of comparative psychology is the scientific study of the behavior and mental processes of non-human animals.[97] A leading question in behavioral neuroscience has been whether and how mental functions are localized in the brain. From Phineas Gage to H.M. and Clive Wearing, individual people with mental deficits traceable to physical brain damage have inspired new discoveries in this area.[98] Modern behavioral neuroscience could be said to originate in the 1870s, when in France Paul Broca traced production of speech to the left frontal gyrus, thereby also demonstrating hemispheric lateralization of brain function. Soon after, Carl Wernicke identified a related area necessary for the understanding of speech.[99]: 20–2

The contemporary field of behavioral neuroscience focuses on the physical basis of behavior. Behaviorial neuroscientists use animal models, often relying on rats, to study the neural, genetic, and cellular mechanisms that underlie behaviors involved in learning, memory, and fear responses.[100] Cognitive neuroscientists, by using neural imaging tools, investigate the neural correlates of psychological processes in humans. Neuropsychologists conduct psychological assessments to determine how an individual's behavior and cognition are related to the brain. The biopsychosocial model is a cross-disciplinary, holistic model that concerns the ways in which interrelationships of biological, psychological, and socio-environmental factors affect health and behavior.[101]

Evolutionary psychology approaches thought and behavior from a modern evolutionary perspective. This perspective suggests that psychological adaptations evolved to solve recurrent problems in human ancestral environments. Evolutionary psychologists attempt to find out how human psychological traits are evolved adaptations, the results of natural selection or sexual selection over the course of human evolution.[102]

The history of the biological foundations of psychology includes evidence of racism. The idea of white supremacy and indeed the modern concept of race itself arose during the process of world conquest by Europeans.[103] Carl von Linnaeus's four-fold classification of humans classifies Europeans as intelligent and severe, Americans as contented and free, Asians as ritualistic, and Africans as lazy and capricious. Race was also used to justify the construction of socially specific mental disorders such as drapetomania and dysaesthesia aethiopica—the behavior of uncooperative African slaves.[104] After the creation of experimental psychology, "ethnical psychology" emerged as a subdiscipline, based on the assumption that studying primitive races would provide an important link between animal behavior and the psychology of more evolved humans.[105]

Behaviorist

A tenet of behavioral research is that a large part of both human and lower-animal behavior is learned. A principle associated with behavioral research is that the mechanisms involved in learning apply to humans and non-human animals. Behavioral researchers have developed a treatment known as behavior modification, which is used to help individuals replace undesirable behaviors with desirable ones.

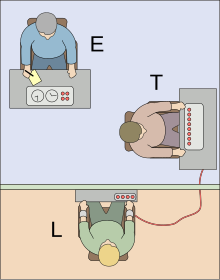

Early behavioral researchers studied stimulus–response pairings, now known as classical conditioning. They demonstrated that when a biologically potent stimulus (e.g., food that elicits salivation) is paired with a previously neutral stimulus (e.g., a bell) over several learning trials, the neutral stimulus by itself can come to elicit the response the biologically potent stimulus elicits. Ivan Pavlov—known best for inducing dogs to salivate in the presence of a stimulus previously linked with food—became a leading figure in the Soviet Union and inspired followers to use his methods on humans.[39] In the United States, Edward Lee Thorndike initiated "connectionist" studies by trapping animals in "puzzle boxes" and rewarding them for escaping. Thorndike wrote in 1911, "There can be no moral warrant for studying man's nature unless the study will enable us to control his acts."[31]: 212–5 From 1910 to 1913 the American Psychological Association went through a sea change of opinion, away from mentalism and towards "behavioralism." In 1913, John B. Watson coined the term behaviorism for this school of thought.[31]: 218–27 Watson's famous Little Albert experiment in 1920 was at first thought to demonstrate that repeated use of upsetting loud noises could instill phobias (aversions to other stimuli) in an infant human,[15][106] although such a conclusion was likely an exaggeration.[107] Karl Lashley, a close collaborator with Watson, examined biological manifestations of learning in the brain.[98]

Clark L. Hull, Edwin Guthrie, and others did much to help behaviorism become a widely used paradigm.[37] A new method of "instrumental" or "operant" conditioning added the concepts of reinforcement and punishment to the model of behavior change. Radical behaviorists avoided discussing the inner workings of the mind, especially the unconscious mind, which they considered impossible to assess scientifically.[108] Operant conditioning was first described by Miller and Kanorski and popularized in the U.S. by B.F. Skinner, who emerged as a leading intellectual of the behaviorist movement.[109][110]

Noam Chomsky published an influential critique of radical behaviorism on the grounds that behaviorist principles could not adequately explain the complex mental process of language acquisition and language use.[111][112] The review, which was scathing, did much to reduce the status of behaviorism within psychology.[31]: 282–5 Martin Seligman and his colleagues discovered that they could condition in dogs a state of "learned helplessness", which was not predicted by the behaviorist approach to psychology.[113][114] Edward C. Tolman advanced a hybrid "cognitive behavioral" model, most notably with his 1948 publication discussing the cognitive maps used by rats to guess at the location of food at the end of a maze.[115] Skinner's behaviorism did not die, in part because it generated successful practical applications.[112]

The Association for Behavior Analysis International was founded in 1974 and by 2003 had members from 42 countries. The field has gained a foothold in Latin America and Japan.[116] Applied behavior analysis is the term used for the application of the principles of operant conditioning to change socially significant behavior (it supersedes the term, "behavior modification").[117]

Cognitive

Green Red Blue

Purple Blue Purple

Blue Purple Red

Green Purple Green

The Stroop effect is the fact that naming the color of the first set of words is easier and quicker than the second.

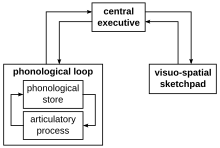

Cognitive psychology involves the study of mental processes, including perception, attention, language comprehension and production, memory, and problem solving.[118] Researchers in the field of cognitive psychology are sometimes called cognitivists. They rely on an information processing model of mental functioning. Cognitivist research is informed by functionalism and experimental psychology.

Starting in the 1950s, the experimental techniques developed by Wundt, James, Ebbinghaus, and others re-emerged as experimental psychology became increasingly cognitivist and, eventually, constituted a part of the wider, interdisciplinary cognitive science.[119][120] Some called this development the cognitive revolution because it rejected the anti-mentalist dogma of behaviorism as well as the strictures of psychoanalysis.[120]

Albert Bandura helped along the transition in psychology from behaviorism to cognitive psychology. Bandura and other social learning theorists advanced the idea of vicarious learning. In other words, they advanced the view that a child can learn by observing the immediate social environment and not necessarily from having been reinforced for enacting a behavior, although they did not rule out the influence of reinforcement on learning a behavior.[121]

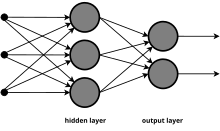

Technological advances also renewed interest in mental states and mental representations. English neuroscientist Charles Sherrington and Canadian psychologist Donald O. Hebb used experimental methods to link psychological phenomena to the structure and function of the brain. The rise of computer science, cybernetics, and artificial intelligence underlined the value of comparing information processing in humans and machines.

A popular and representative topic in this area is cognitive bias, or irrational thought. Psychologists (and economists) have classified and described a sizeable catalog of biases which recur frequently in human thought. The availability heuristic, for example, is the tendency to overestimate the importance of something which happens to come readily to mind.[122]

Elements of behaviorism and cognitive psychology were synthesized to form cognitive behavioral therapy, a form of psychotherapy modified from techniques developed by American psychologist Albert Ellis and American psychiatrist Aaron T. Beck.

On a broader level, cognitive science is an interdisciplinary enterprise involving cognitive psychologists, cognitive neuroscientists, linguists, and researchers in artificial intelligence, human–computer interaction, and computational neuroscience. The discipline of cognitive science covers cognitive psychology as well as philosophy of mind, computer science, and neuroscience.[123] Computer simulations are sometimes used to model phenomena of interest.

Social

Social psychology is concerned with how behaviors, thoughts, feelings, and the social environment influence human interactions.[124] Social psychologists study such topics as the influence of others on an individual's behavior (e.g. conformity, persuasion) and the formation of beliefs, attitudes, and stereotypes about other people. Social cognition fuses elements of social and cognitive psychology for the purpose of understanding how people process, remember, or distort social information. The study of group dynamics involves research on the nature of leadership, organizational communication, and related phenomena. In recent years, social psychologists have become interested in implicit measures, mediational models, and the interaction of person and social factors in accounting for behavior. Some concepts that sociologists have applied to the study of psychiatric disorders, concepts such as the social role, sick role, social class, life events, culture, migration, and total institution, have influenced social psychologists.[125]

Psychoanalytic

Psychoanalysis is a collection of theories and therapeutic techniques intended to analyze the unconscious mind and its impact on everyday life. These theories and techniques inform treatments for mental disorders.[126][127][128] Psychoanalysis originated in the 1890s, most prominently with the work of Sigmund Freud. Freud's psychoanalytic theory was largely based on interpretive methods, introspection, and clinical observation. It became very well known, largely because it tackled subjects such as sexuality, repression, and the unconscious.[58]: 84–6 Freud pioneered the methods of free association and dream interpretation.[129][130]

Psychoanalytic theory is not monolithic. Other well-known psychoanalytic thinkers who diverged from Freud include Alfred Adler, Carl Jung, Erik Erikson, Melanie Klein, D.W. Winnicott, Karen Horney, Erich Fromm, John Bowlby, Freud's daughter Anna Freud, and Harry Stack Sullivan. These individuals ensured that psychoanalysis would evolve into diverse schools of thought. Among these schools are ego psychology, object relations, and interpersonal, Lacanian, and relational psychoanalysis.

Psychologists such as Hans Eysenck and philosophers including Karl Popper sharply criticized psychoanalysis. Popper argued that psychoanalysis was not falsifiable (no claim it made could be proven wrong) and therefore inherently not a scientific discipline,[131] whereas Eysenck advanced the view that psychoanalytic tenets had been contradicted by experimental data. By the end of the 20th century, psychology departments in American universities mostly had marginalized Freudian theory, dismissing it as a "desiccated and dead" historical artifact.[132] Researchers such as António Damásio, Oliver Sacks, and Joseph LeDoux; and individuals in the emerging field of neuro-psychoanalysis have defended some of Freud's ideas on scientific grounds.[133]

Existential-humanistic

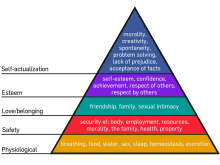

Humanistic psychology, which has been influenced by existentialism and phenomenology,[135] stresses free will and self-actualization.[136] It emerged in the 1950s as a movement within academic psychology, in reaction to both behaviorism and psychoanalysis.[137] The humanistic approach seeks to view the whole person, not just fragmented parts of the personality or isolated cognitions.[138] Humanistic psychology also focuses on personal growth, self-identity, death, aloneness, and freedom. It emphasizes subjective meaning, the rejection of determinism, and concern for positive growth rather than pathology. Some founders of the humanistic school of thought were American psychologists Abraham Maslow, who formulated a hierarchy of human needs, and Carl Rogers, who created and developed client-centered therapy.

Later, positive psychology opened up humanistic themes to scientific study. Positive psychology is the study of factors which contribute to human happiness and well-being, focusing more on people who are currently healthy. In 2010, Clinical Psychological Review published a special issue devoted to positive psychological interventions, such as gratitude journaling and the physical expression of gratitude. It is, however, far from clear that positive psychology is effective in making people happier.[139][140] Positive psychological interventions have been limited in scope, but their effects are thought to be somewhat better than placebo effects.

The American Association for Humanistic Psychology, formed in 1963, declared:

Humanistic psychology is primarily an orientation toward the whole of psychology rather than a distinct area or school. It stands for respect for the worth of persons, respect for differences of approach, open-mindedness as to acceptable methods, and interest in exploration of new aspects of human behavior. As a "third force" in contemporary psychology, it is concerned with topics having little place in existing theories and systems: e.g., love, creativity, self, growth, organism, basic need-gratification, self-actualization, higher values, being, becoming, spontaneity, play, humor, affection, naturalness, warmth, ego-transcendence, objectivity, autonomy, responsibility, meaning, fair-play, transcendental experience, peak experience, courage, and related concepts.[141]

Existential psychology emphasizes the need to understand a client's total orientation towards the world. Existential psychology is opposed to reductionism, behaviorism, and other methods that objectify the individual.[136] In the 1950s and 1960s, influenced by philosophers Søren Kierkegaard and Martin Heidegger, psychoanalytically trained American psychologist Rollo May helped to develop existential psychology. Existential psychotherapy, which follows from existential psychology, is a therapeutic approach that is based on the idea that a person's inner conflict arises from that individual's confrontation with the givens of existence. Swiss psychoanalyst Ludwig Binswanger and American psychologist George Kelly may also be said to belong to the existential school.[142] Existential psychologists tend to differ from more "humanistic" psychologists in the former's relatively neutral view of human nature and relatively positive assessment of anxiety.[143] Existential psychologists emphasized the humanistic themes of death, free will, and meaning, suggesting that meaning can be shaped by myths and narratives; meaning can be deepened by the acceptance of free will, which is requisite to living an authentic life, albeit often with anxiety with regard to death.[144]

Austrian existential psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl drew evidence of meaning's therapeutic power from reflections upon his own internment.[145] He created a variation of existential psychotherapy called logotherapy, a type of existentialist analysis that focuses on a will to meaning (in one's life), as opposed to Adler's Nietzschean doctrine of will to power or Freud's will to pleasure.[146]

Themes

Personality

Personality psychology is concerned with enduring patterns of behavior, thought, and emotion. Theories of personality vary across different psychological schools of thought. Each theory carries different assumptions about such features as the role of the unconscious and the importance of childhood experience. According to Freud, personality is based on the dynamic interactions of the id, ego, and super-ego.[147] By contrast, trait theorists have developed taxonomies of personality constructs in describing personality in terms of key traits. Trait theorists have often employed statistical data-reduction methods, such as factor analysis. Although the number of proposed traits has varied widely, Hans Eysenck's early biologically based model suggests at least three major trait constructs are necessary to describe human personality, extraversion–introversion, neuroticism-stability, and psychoticism-normality. Raymond Cattell empirically derived a theory of 16 personality factors at the primary-factor level and up to eight broader second-stratum factors.[148][149][150][151]Since the 1980s, the Big Five (openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism) emerged as an important trait theory of personality.[152] Dimensional models of personality are receiving increasing support, and a version of dimensional assessment has been included in the DSM-V. However, despite a plethora of research into the various versions of the "Big Five" personality dimensions, it appears necessary to move on from static conceptualizations of personality structure to a more dynamic orientation, acknowledging that personality constructs are subject to learning and change over the lifespan.[153][154]

An early example of personality assessment was the Woodworth Personal Data Sheet, constructed during World War I. The popular, although psychometrically inadequate, Myers–Briggs Type Indicator[155] was developed to assess individuals' "personality types" according to the personality theories of Carl Jung. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), despite its name, is more a dimensional measure of psychopathology than a personality measure.[156] California Psychological Inventory contains 20 personality scales (e.g., independence, tolerance).[157] The International Personality Item Pool, which is in the public domain, has become a source of scales that can be used personality assessment.[158]

Unconscious mind

Study of the unconscious mind, a part of the psyche outside the individual's awareness but that is believed to influence conscious thought and behavior, was a hallmark of early psychology. In one of the first psychology experiments conducted in the United States, C.S. Peirce and Joseph Jastrow found in 1884 that research subjects could choose the minutely heavier of two weights even if consciously uncertain of the difference.[159] Freud popularized the concept of the unconscious mind, particularly when he referred to an uncensored intrusion of unconscious thought into one's speech (a Freudian slip) or to his efforts to interpret dreams.[160] His 1901 book The Psychopathology of Everyday Life catalogs hundreds of everyday events that Freud explains in terms of unconscious influence. Pierre Janet advanced the idea of a subconscious mind, which could contain autonomous mental elements unavailable to the direct scrutiny of the subject.[161]

The concept of unconscious processes has remained important in psychology. Cognitive psychologists have used a "filter" model of attention. According to the model, much information processing takes place below the threshold of consciousness, and only certain stimuli, limited by their nature and number, make their way through the filter. Much research has shown that subconscious priming of certain ideas can covertly influence thoughts and behavior.[161] Because of the unreliability of self-reporting, a major hurdle in this type of research involves demonstrating that a subject's conscious mind has not perceived a target stimulus. For this reason, some psychologists prefer to distinguish between implicit and explicit memory. In another approach, one can also describe a subliminal stimulus as meeting an objective but not a subjective threshold.[162]

The automaticity model of John Bargh and others involves the ideas of automaticity and unconscious processing in our understanding of social behavior,[163][164] although there has been dispute with regard to replication.[165][166]Some experimental data suggest that the brain begins to consider taking actions before the mind becomes aware of them.[167] The influence of unconscious forces on people's choices bears on the philosophical question of free will. John Bargh, Daniel Wegner, and Ellen Langer describe free will as an illusion.[163][164][168]

Motivation

Some psychologists study motivation or the subject of why people or lower animals initiate a behavior at a particular time. It also involves the study of why humans and lower animals continue or terminate a behavior. Psychologists such as William James initially used the term motivation to refer to intention, in a sense similar to the concept of will in European philosophy. With the steady rise of Darwinian and Freudian thinking, instinct also came to be seen as a primary source of motivation.[169] According to drive theory, the forces of instinct combine into a single source of energy which exerts a constant influence. Psychoanalysis, like biology, regarded these forces as demands originating in the nervous system. Psychoanalysts believed that these forces, especially the sexual instincts, could become entangled and transmuted within the psyche. Classical psychoanalysis conceives of a struggle between the pleasure principle and the reality principle, roughly corresponding to id and ego. Later, in Beyond the Pleasure Principle, Freud introduced the concept of the death drive, a compulsion towards aggression, destruction, and psychic repetition of traumatic events.[170] Meanwhile, behaviorist researchers used simple dichotomous models (pleasure/pain, reward/punishment) and well-established principles such as the idea that a thirsty creature will take pleasure in drinking.[169][171] Clark Hull formalized the latter idea with his drive reduction model.[172]

Hunger, thirst, fear, sexual desire, and thermoregulation constitute fundamental motivations in animals.[171] Humans seem to exhibit a more complex set of motivations—though theoretically these could be explained as resulting from desires for belonging, positive self-image, self-consistency, truth, love, and control.[173][174]

Motivation can be modulated or manipulated in many different ways. Researchers have found that eating, for example, depends not only on the organism's fundamental need for homeostasis—an important factor causing the experience of hunger—but also on circadian rhythms, food availability, food palatability, and cost.[171] Abstract motivations are also malleable, as evidenced by such phenomena as goal contagion: the adoption of goals, sometimes unconsciously, based on inferences about the goals of others.[175] Vohs and Baumeister suggest that contrary to the need-desire-fulfillment cycle of animal instincts, human motivations sometimes obey a "getting begets wanting" rule: the more you get a reward such as self-esteem, love, drugs, or money, the more you want it. They suggest that this principle can even apply to food, drink, sex, and sleep.[176]

Development psychology

Developmental psychology is the scientific study of how and why the thought processes, emotions, and behaviors of humans change over the course of their lives.[177] Some credit Charles Darwin with conducting the first systematic study within the rubric of developmental psychology, having published in 1877 a short paper detailing the development of innate forms of communication based on his observations of his infant son.[178] The main origins of the discipline, however, are found in the work of Jean Piaget. Like Piaget, developmental psychologists originally focused primarily on the development of cognition from infancy to adolescence. Later, developmental psychology extended itself to the study cognition over the life span. In addition to studying cognition, developmental psychologists have also come to focus on affective, behavioral, moral, social, and neural development.

Developmental psychologists who study children use a number of research methods. For example, they make observations of children in natural settings such as preschools[179] and engage them in experimental tasks.[180] Such tasks often resemble specially designed games and activities that are both enjoyable for the child and scientifically useful. Developmental researchers have even devised clever methods to study the mental processes of infants.[181] In addition to studying children, developmental psychologists also study aging and processes throughout the life span, including old age.[182] These psychologists draw on the full range of psychological theories to inform their research.[177]

Genes and environment

All researched psychological traits are influenced by both genes and environment, to varying degrees.[183][184] These two sources of influence are often confounded in observational research of individuals and families. An example of this confounding can be shown in the transmission of depression from a depressed mother to her offspring. A theory based on environmental transmission would hold that an offspring, by virtue of their having a problematic rearing environment managed by a depressed mother, is at risk for developing depression. On the other hand, a hereditarian theory would hold that depression risk in an offspring is influenced to some extent by genes passed to the child from the mother. Genes and environment in these simple transmission models are completely confounded. A depressed mother may both carry genes that contribute to depression in her offspring and also create a rearing environment that increases the risk of depression in her child.[185]

Behavioral genetics researchers have employed methodologies that help to disentangle this confound and understand the nature and origins of individual differences in behavior.[102] Traditionally the research has involved twin studies and adoption studies, two designs where genetic and environmental influences can be partially un-confounded. More recently, gene-focused research has contributed to understanding genetic contributions to the development of psychological traits.

The availability of microarray molecular genetic or genome sequencing technologies allows researchers to measure participant DNA variation directly, and test whether individual genetic variants within genes are associated with psychological traits and psychopathology through methods including genome-wide association studies. One goal of such research is similar to that in positional cloning and its success in Huntington's: once a causal gene is discovered biological research can be conducted to understand how that gene influences the phenotype. One major result of genetic association studies is the general finding that psychological traits and psychopathology, as well as complex medical diseases, are highly polygenic,[186][187][188][189][190] where a large number (on the order of hundreds to thousands) of genetic variants, each of small effect, contribute to individual differences in the behavioral trait or propensity to the disorder. Active research continues to work toward understanding the genetic and environmental bases of behavior and their interaction.

Applications

Psychology encompasses many subfields and includes different approaches to the study of mental processes and behavior.

Psychological testing

Psychological testing has ancient origins, dating as far back as 2200 BC, in the examinations for the Chinese civil service. Written exams began during the Han dynasty (202 BC – AD 200). By 1370, the Chinese system required a stratified series of tests, involving essay writing and knowledge of diverse topics. The system was ended in 1906.[191]: 41–2 In Europe, mental assessment took a different approach, with theories of physiognomy—judgment of character based on the face—described by Aristotle in 4th century BC Greece. Physiognomy remained current through the Enlightenment, and added the doctrine of phrenology: a study of mind and intelligence based on simple assessment of neuroanatomy.[191]: 42–3

When experimental psychology came to Britain, Francis Galton was a leading practitioner. By virtue of his procedures for measuring reaction time and sensation, he is considered an inventor of modern mental testing (also known as psychometrics).[191]: 44–5 James McKeen Cattell, a student of Wundt and Galton, brought the idea of psychological testing to the United States, and in fact coined the term "mental test".[191]: 45–6 In 1901, Cattell's student Clark Wissler published discouraging results, suggesting that mental testing of Columbia and Barnard students failed to predict academic performance.[191]: 45–6 In response to 1904 orders from the Minister of Public Instruction, One example of an observational study was run by Arthur Bandura. This observational study focused on children who were exposed to an adult exhibiting aggressive behaviors and their reaction to toys versus other children who were not exposed to these stimuli. The result shows that children who had seen the adult acting aggressively towards a toy, in turn, were aggressive towards their own toy when put in a situation that frustrated them.[192] psychologists Alfred Binet and Théodore Simon developed and elaborated a new test of intelligence in 1905–1911. They used a range of questions diverse in their nature and difficulty. Binet and Simon introduced the concept of mental age and referred to the lowest scorers on their test as idiots. Henry H. Goddard put the Binet-Simon scale to work and introduced classifications of mental level such as imbecile and feebleminded. In 1916, (after Binet's death), Stanford professor Lewis M. Terman modified the Binet-Simon scale (renamed the Stanford–Binet scale) and introduced the intelligence quotient as a score report.[191]: 50–56 Based on his test findings, and reflecting the racism common to that era, Terman concluded that intellectual disability "represents the level of intelligence which is very, very common among Spanish-Indians and Mexican families of the Southwest and also among negroes. Their dullness seems to be racial."[193]

Following the Army Alpha and Army Beta tests, which was developed by psychologist Robert Yerkes in 1917 and then used in World War 1 by industrial and organizational psychologists for large-scale employee testing and selection of military personnel.[194] Mental testing also became popular in the U.S., where it was applied to schoolchildren. The federally created National Intelligence Test was administered to 7 million children in the 1920s. In 1926, the College Entrance Examination Board created the Scholastic Aptitude Test to standardize college admissions.[191]: 61 The results of intelligence tests were used to argue for segregated schools and economic functions, including the preferential training of Black Americans for manual labor. These practices were criticized by Black intellectuals such a Horace Mann Bond and Allison Davis.[193] Eugenicists used mental testing to justify and organize compulsory sterilization of individuals classified as mentally retarded (now referred to as intellectual disability).[46] In the United States, tens of thousands of men and women were sterilized. Setting a precedent that has never been overturned, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the constitutionality of this practice in the 1927 case Buck v. Bell.[195]

Today mental testing is a routine phenomenon for people of all ages in Western societies.[191]: 2 Modern testing aspires to criteria including standardization of procedure, consistency of results, output of an interpretable score, statistical norms describing population outcomes, and, ideally, effective prediction of behavior and life outcomes outside of testing situations.[191]: 4–6 Psychological testing is regularly used in forensic contexts to aid legal judgments and decisions.[196] Developments in psychometrics include work on test and scale reliability and validity.[197] Developments in item-response theory,[198] structural equation modeling,[199] and bifactor analysis[200] have helped in strengthening test and scale construction.

Mental health care

The provision of psychological health services is generally called clinical psychology in the U.S. Sometimes, however, members of the school psychology and counseling psychology professions engage in practices that resemble that of clinical psychologists. Clinical psychologists typically include people who have graduated from doctoral programs in clinical psychology. In Canada, some of the members of the abovementioned groups usually fall within the larger category of professional psychology. In Canada and the U.S., practitioners get bachelor's degrees and doctorates; doctoral students in clinical psychology usually spend one year in a predoctoral internship and one year in postdoctoral internship. In Mexico and most other Latin American and European countries, psychologists do not get bachelor's and doctoral degrees; instead, they take a three-year professional course following high school.[91] Clinical psychology is at present the largest specialization within psychology.[201] It includes the study and application of psychology for the purpose of understanding, preventing, and relieving psychological distress, dysfunction, and/or mental illness. Clinical psychologists also try to promote subjective well-being and personal growth. Central to the practice of clinical psychology are psychological assessment and psychotherapy although clinical psychologists may also engage in research, teaching, consultation, forensic testimony, and program development and administration.[202]

Credit for the first psychology clinic in the United States typically goes to Lightner Witmer, who established his practice in Philadelphia in 1896. Another modern psychotherapist was Morton Prince, an early advocate for the establishment of psychology as a clinical and academic discipline.[201] In the first part of the twentieth century, most mental health care in the United States was performed by psychiatrists, who are medical doctors. Psychology entered the field with its refinements of mental testing, which promised to improve the diagnosis of mental problems. For their part, some psychiatrists became interested in using psychoanalysis and other forms of psychodynamic psychotherapy to understand and treat the mentally ill.[41][203]

Psychotherapy as conducted by psychiatrists blurred the distinction between psychiatry and psychology, and this trend continued with the rise of community mental health facilities. Some in the clinical psychology community adopted behavioral therapy, a thoroughly non-psychodynamic model that used behaviorist learning theory to change the actions of patients. A key aspect of behavior therapy is empirical evaluation of the treatment's effectiveness. In the 1970s, cognitive-behavior therapy emerged with the work of Albert Ellis and Aaron Beck. Although there are similarities between behavior therapy and cognitive-behavior therapy, cognitive-behavior therapy required the application of cognitive constructs. Since the 1970s, the popularity of cognitive-behavior therapy among clinical psychologists increased. A key practice in behavioral and cognitive-behavioral therapy is exposing patients to things they fear, based on the premise that their responses (fear, panic, anxiety) can be deconditioned.[204]

Mental health care today involves psychologists and social workers in increasing numbers. In 1977, National Institute of Mental Health director Bertram Brown described this shift as a source of "intense competition and role confusion."[41] Graduate programs issuing doctorates in clinical psychology emerged in the 1950s and underwent rapid increase through the 1980s. The PhD degree is intended to train practitioners who could also conduct scientific research. The PsyD degree is more exclusively designed to train practitioners.[91]

Some clinical psychologists focus on the clinical management of patients with brain injury. This subspecialty is known as clinical neuropsychology. In many countries, clinical psychology is a regulated mental health profession. The emerging field of disaster psychology (see crisis intervention) involves professionals who respond to large-scale traumatic events.[205]

The work performed by clinical psychologists tends to be influenced by various therapeutic approaches, all of which involve a formal relationship between professional and client (usually an individual, couple, family, or small group). Typically, these approaches encourage new ways of thinking, feeling, or behaving. Four major theoretical perspectives are psychodynamic, cognitive behavioral, existential–humanistic, and systems or family therapy. There has been a growing movement to integrate the various therapeutic approaches, especially with an increased understanding of issues regarding culture, gender, spirituality, and sexual orientation. With the advent of more robust research findings regarding psychotherapy, there is evidence that most of the major therapies have equal effectiveness, with the key common element being a strong therapeutic alliance.[206][207] Because of this, more training programs and psychologists are now adopting an eclectic therapeutic orientation.[208][209][210][211][212]

Diagnosis in clinical psychology usually follows the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).[213] The study of mental illnesses is called abnormal psychology.

Education

Educational psychology is the study of how humans learn in educational settings, the effectiveness of educational interventions, the psychology of teaching, and the social psychology of schools as organizations. Educational psychologists can be found in preschools, schools of all levels including post secondary institutions, community organizations and learning centers, Government or private research firms, and independent or private consultant.[214] The work of developmental psychologists such as Lev Vygotsky, Jean Piaget, and Jerome Bruner has been influential in creating teaching methods and educational practices. Educational psychology is often included in teacher education programs in places such as North America, Australia, and New Zealand.