ВИЧ/СПИД

| ВИЧ/СПИД | |

|---|---|

| Другие имена | ВИЧ-инфекция, ВИЧ-инфекция [1] [2] |

| |

| Красная лента является символом солидарности и людьми , с ВИЧ-положительными людьми живущими со СПИДом. [3] | |

| Специальность | Инфекционные болезни , иммунология |

| Симптомы | Ранние : гриппоподобное заболевание. [4] Позже : увеличение лимфатических узлов , лихорадка, потеря веса. [4] |

| Осложнения | Оппортунистические инфекции , опухоли [4] |

| Продолжительность | Пожизненный [4] |

| Причины | Вирус иммунодефицита человека (ВИЧ) [4] |

| Факторы риска | Незащищенный анальный или вагинальный секс, наличие другой инфекции, передающейся половым путем , совместное использование игл , медицинские процедуры, включающие нестерильные разрезы или пирсинг, а также травмы от уколов иглой. [4] |

| Метод диагностики | Анализы крови [4] |

| Профилактика | Безопасный секс , обмен игл , мужское обрезание , доконтактная профилактика , постконтактная профилактика [4] |

| Уход | Антиретровирусная терапия [4] |

| Прогноз | Ожидаемая продолжительность жизни, близкая к нормальной, при лечении [5] [6] Ожидаемая продолжительность жизни 11 лет без лечения [7] |

| Частота | Всего 71,3 млн – 112,8 млн случаев [8] 1,3 миллиона новых случаев (2022 г.) [8] 39,9 миллиона человек, живущих с ВИЧ (2022 г.) [8] |

| Летальные исходы | Всего 42,3 миллиона смертей [8] 630,000 (2023) [8] |

Вирус иммунодефицита человека ( ВИЧ ) [9] [10] [11] это ретровирус [12] который атакует иммунную систему . С этим можно справиться с помощью лечения. Без лечения это может привести к целому ряду заболеваний, включая синдром приобретенного иммунодефицита ( СПИД ). [5]

Эффективное лечение ВИЧ -положительных людей (людей, живущих с ВИЧ ) включает в себя пожизненный курс лечения, направленный на подавление вируса, что делает вирусную нагрузку неопределяемой. От ВИЧ не существует вакцины или лекарства. ВИЧ-положительный человек, проходящий лечение, может рассчитывать на то, что проживет нормальную жизнь и умрет от вируса, а не от него. [5] [6]

Лечение рекомендуется сразу после установления диагноза. [13]

ВИЧ-положительный человек, имеющий неопределяемую вирусную нагрузку в результате длительного лечения, фактически не имеет риска передачи ВИЧ половым путем. [14] [15] Кампании ЮНЭЙДС и организаций по всему миру преподносят это как «Необнаружимо = Непередаваемо» . [16]

Без лечения инфекция может повлиять на иммунную систему и в конечном итоге перерасти в СПИД , что иногда занимает много лет. После первоначального заражения человек может не замечать никаких симптомов или может испытывать кратковременный период гриппоподобного заболевания . [4] В течение этого периода человек может не знать, что он ВИЧ-положителен, но он сможет передать вирус . Обычно за этим периодом следует длительный инкубационный период без каких-либо симптомов. [5] В конечном итоге ВИЧ-инфекция увеличивает риск развития других инфекций, таких как туберкулез , а также других оппортунистических инфекций и опухолей , которые редко встречаются у людей с нормальной иммунной функцией. [4] Поздняя стадия часто также связана с непреднамеренной потерей веса . [5] Без лечения человек, живущий с ВИЧ, может рассчитывать прожить 11 лет. [7] Раннее тестирование может показать, необходимо ли лечение, чтобы остановить это прогрессирование и предотвратить заражение других.

ВИЧ передается в основном при незащищенном сексе (включая анальный и вагинальный секс ), зараженных иглах для подкожных инъекций или при переливании крови , а также от матери к ребенку во время беременности , родов или грудного вскармливания. [17] Некоторые жидкости организма, такие как слюна, пот и слезы, не передают вирус. [18] Оральный секс имеет небольшой риск передачи вируса. [19]

Способы избежать заражения ВИЧ и предотвращения распространения включают безопасный секс , лечение для предотвращения инфекции (« ПКП »), лечение для остановки инфекции у недавно подвергшихся заражению (« ПКП »), [4] лечение инфицированных и программы обмена игл . Заболевание ребенка часто можно предотвратить, давая антиретровирусные препараты и матери, и ребенку . [4]

Признанный во всем мире в начале 1980-х годов, [20] ВИЧ/СПИД оказал большое влияние на общество как как болезнь, так и как источник дискриминации . [21] Болезнь также имеет большие экономические последствия . [21] Существует множество заблуждений о ВИЧ/СПИДе , например, убеждение, что он может передаваться при случайном несексуальном контакте. [22] Заболевание стало предметом многих споров, связанных с религией , включая позицию католической церкви, не поддерживающую использование презервативов в качестве профилактики. [23] С момента своего обнаружения в 1980-х годах он привлек международное медицинское и политическое внимание, а также крупномасштабное финансирование. [24]

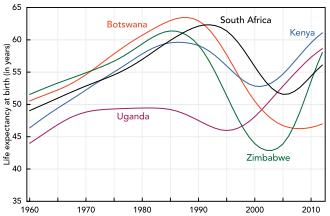

ВИЧ перешел от других приматов к человеку в западно-центральной Африке в начале-середине 20 века. [25] СПИД был впервые признан Центрами США по контролю и профилактике заболеваний (CDC) в 1981 году, а его причина – ВИЧ-инфекция – была выявлена в начале десятилетия. [20] По оценкам, с момента первого выявления СПИДа до 2021 года это заболевание стало причиной не менее 40 миллионов смертей во всем мире. [26] В 2021 году во всем мире зарегистрировано 650 000 смертей и около 38 миллионов человек, живущих с ВИЧ. [8] По оценкам, 20,6 миллиона этих людей живут в восточной и южной Африке. [27] ВИЧ/СПИД считается пандемией — вспышкой заболевания, охватывающей большую территорию и активно распространяющейся. [28]

Национальные институты здравоохранения США (NIH) и Фонд Гейтса пообещали выделить 200 миллионов долларов на разработку глобального лекарства от СПИДа. [29] не существует Хотя лекарства или вакцины , антиретровирусное лечение может замедлить течение заболевания и привести к почти нормальной продолжительности жизни. [5] [6]

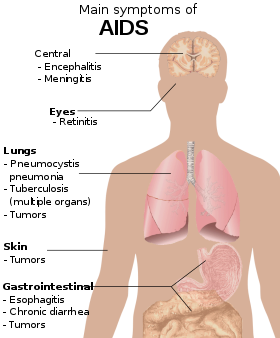

Признаки и симптомы

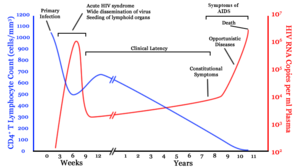

Выделяют три основные стадии ВИЧ- инфекции: острая инфекция, клиническая латентная стадия и СПИД. [1] [30]

Первая основная стадия: острая инфекция.

Начальный период после заражения ВИЧ называется острым ВИЧ, первичным ВИЧ или острым ретровирусным синдромом. [30] [31] У многих людей через 2–4 недели после заражения развивается такое заболевание, как грипп , мононуклеоз или железистая лихорадка, в то время как у других нет серьезных симптомов. [32] [33] Симптомы возникают в 40–90% случаев и чаще всего включают лихорадку , увеличение болезненных лимфатических узлов , воспаление горла , сыпь , головную боль, усталость и/или язвы во рту и половых органах. [31] [33] Сыпь, возникающая в 20–50% случаев, появляется на туловище и имеет классический макулопапулезный характер . [34] также развиваются оппортунистические инфекции . У некоторых людей на этом этапе [31] Могут возникнуть желудочно-кишечные симптомы, такие как рвота или диарея . [33] Также встречаются неврологические симптомы периферической нейропатии или синдрома Гийена-Барре . [33] Продолжительность симптомов варьируется, но обычно составляет одну или две недели. [33]

These symptoms are not often recognized as signs of HIV infection. Family doctors or hospitals can misdiagnose cases as one of the many common infectious diseases with similar symptoms. Someone with an unexplained fever who may have been recently exposed to HIV should consider testing to find out if they have been infected.[33]

Second main stage: clinical latency

The initial symptoms are followed by a stage called clinical latency, asymptomatic HIV, or chronic HIV.[1] Without treatment, this second stage of the natural history of HIV infection can last from about three years[35] to over 20 years[36] (on average, about eight years).[37] While typically there are few or no symptoms at first, near the end of this stage many people experience fever, weight loss, gastrointestinal problems and muscle pains.[1] Between 50% and 70% of people also develop persistent generalized lymphadenopathy, characterized by unexplained, non-painful enlargement of more than one group of lymph nodes (other than in the groin) for over three to six months.[30]

Although most HIV-1 infected individuals have a detectable viral load and in the absence of treatment will eventually progress to AIDS, a small proportion (about 5%) retain high levels of CD4+ T cells (T helper cells) without antiretroviral therapy for more than five years.[33][38] These individuals are classified as "HIV controllers" or long-term nonprogressors (LTNP).[38] Another group consists of those who maintain a low or undetectable viral load without anti-retroviral treatment, known as "elite controllers" or "elite suppressors". They represent approximately 1 in 300 infected persons.[39]

Third main stage: AIDS

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is defined as an HIV infection with either a CD4+ T cell count below 200 cells per μL or the occurrence of specific diseases associated with HIV infection.[33] In the absence of specific treatment, around half of people infected with HIV develop AIDS within ten years.[33] The most common initial conditions that alert to the presence of AIDS are pneumocystis pneumonia (40%), cachexia in the form of HIV wasting syndrome (20%), and esophageal candidiasis.[33] Other common signs include recurrent respiratory tract infections.[33]

Opportunistic infections may be caused by bacteria, viruses, fungi, and parasites that are normally controlled by the immune system.[40] Which infections occur depends partly on what organisms are common in the person's environment.[33] These infections may affect nearly every organ system.[41]

People with AIDS have an increased risk of developing various viral-induced cancers, including Kaposi's sarcoma, Burkitt's lymphoma, primary central nervous system lymphoma, and cervical cancer.[34] Kaposi's sarcoma is the most common cancer, occurring in 10% to 20% of people with HIV.[42] The second-most common cancer is lymphoma, which is the cause of death of nearly 16% of people with AIDS and is the initial sign of AIDS in 3% to 4%.[42] Both these cancers are associated with human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8).[42] Cervical cancer occurs more frequently in those with AIDS because of its association with human papillomavirus (HPV).[42] Conjunctival cancer (of the layer that lines the inner part of eyelids and the white part of the eye) is also more common in those with HIV.[43]

Additionally, people with AIDS frequently have systemic symptoms such as prolonged fevers, sweats (particularly at night), swollen lymph nodes, chills, weakness, and unintended weight loss.[44] Diarrhea is another common symptom, present in about 90% of people with AIDS.[45] They can also be affected by diverse psychiatric and neurological symptoms independent of opportunistic infections and cancers.[46]

Transmission

| Exposure route | Chance of infection | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood transfusion | 90%[47] | |||

| Childbirth (to child) | 25%[48][clarification needed] | |||

| Needle-sharing injection drug use | 0.67%[49] | |||

| Percutaneous needle stick | 0.30%[50] | |||

| Receptive anal intercourse* | 0.04–3.0%[51] | |||

| Insertive anal intercourse* | 0.03%[52] | |||

| Receptive penile-vaginal intercourse* | 0.05–0.30%[51][53] | |||

| Insertive penile-vaginal intercourse* | 0.01–0.38%[51][53] | |||

| Receptive oral intercourse*§ | 0–0.04%[51] | |||

| Insertive oral intercourse*§ | 0–0.005%[54] | |||

| * assuming no condom use § source refers to oral intercourse performed on a man | ||||

HIV is spread by three main routes: sexual contact, significant exposure to infected body fluids or tissues, and from mother to child during pregnancy, delivery, or breastfeeding (known as vertical transmission).[17] There is no risk of acquiring HIV if exposed to feces, nasal secretions, saliva, sputum, sweat, tears, urine, or vomit unless these are contaminated with blood.[55] It is also possible to be co-infected by more than one strain of HIV—a condition known as HIV superinfection.[56]

Sexual

The most frequent mode of transmission of HIV is through sexual contact with an infected person.[17] However, an HIV-positive person who has an undetectable viral load as a result of long-term treatment has effectively no risk of transmitting HIV sexually.[14][15] The existence of functionally noncontagious HIV-positive people on antiretroviral therapy was controversially publicized in the 2008 Swiss Statement, and has since become accepted as medically sound.[57]

Globally, the most common mode of HIV transmission is via sexual contacts between people of the opposite sex;[17] however, the pattern of transmission varies among countries. As of 2017[update], most HIV transmission in the United States occurred among men who had sex with men (82% of new HIV diagnoses among males aged 13 and older and 70% of total new diagnoses).[58][59] In the US, gay and bisexual men aged 13 to 24 accounted for an estimated 92% of new HIV diagnoses among all men in their age group and 27% of new diagnoses among all gay and bisexual men.[60]

With regard to unprotected heterosexual contacts, estimates of the risk of HIV transmission per sexual act appear to be four to ten times higher in low-income countries than in high-income countries.[61] In low-income countries, the risk of female-to-male transmission is estimated as 0.38% per act, and of male-to-female transmission as 0.30% per act; the equivalent estimates for high-income countries are 0.04% per act for female-to-male transmission, and 0.08% per act for male-to-female transmission.[61] The risk of transmission from anal intercourse is especially high, estimated as 1.4–1.7% per act in both heterosexual and homosexual contacts.[61][62] While the risk of transmission from oral sex is relatively low, it is still present.[63] The risk from receiving oral sex has been described as "nearly nil";[64] however, a few cases have been reported.[65] The per-act risk is estimated at 0–0.04% for receptive oral intercourse.[66] In settings involving prostitution in low-income countries, risk of female-to-male transmission has been estimated as 2.4% per act, and of male-to-female transmission as 0.05% per act.[61]

Risk of transmission increases in the presence of many sexually transmitted infections[67] and genital ulcers.[61] Genital ulcers appear to increase the risk approximately fivefold.[61] Other sexually transmitted infections, such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis, and bacterial vaginosis, are associated with somewhat smaller increases in risk of transmission.[66]

The viral load of an infected person is an important risk factor in both sexual and mother-to-child transmission.[68] During the first 2.5 months of an HIV infection a person's infectiousness is twelve times higher due to the high viral load associated with acute HIV.[66] If the person is in the late stages of infection, rates of transmission are approximately eightfold greater.[61]

Commercial sex workers (including those in pornography) have an increased likelihood of contracting HIV.[69][70] Rough sex can be a factor associated with an increased risk of transmission.[71] Sexual assault is also believed to carry an increased risk of HIV transmission as condoms are rarely worn, physical trauma to the vagina or rectum is likely, and there may be a greater risk of concurrent sexually transmitted infections.[72]

Body fluids

The second-most frequent mode of HIV transmission is via blood and blood products.[17] Blood-borne transmission can be through needle-sharing during intravenous drug use, needle-stick injury, transfusion of contaminated blood or blood product, or medical injections with unsterilized equipment. The risk from sharing a needle during drug injection is between 0.63% and 2.4% per act, with an average of 0.8%.[73] The risk of acquiring HIV from a needle stick from an HIV-infected person is estimated as 0.3% (about 1 in 333) per act and the risk following mucous membrane exposure to infected blood as 0.09% (about 1 in 1000) per act.[55] This risk may, however, be up to 5% if the introduced blood was from a person with a high viral load and the cut was deep.[74] In the United States, intravenous drug users made up 12% of all new cases of HIV in 2009,[75] and in some areas more than 80% of people who inject drugs are HIV-positive.[17]

HIV is transmitted in about 90% of blood transfusions using infected blood.[47] In developed countries the risk of acquiring HIV from a blood transfusion is extremely low (less than one in half a million) where improved donor selection and HIV screening is performed;[17] for example, in the UK the risk is reported at one in five million[76] and in the United States it was one in 1.5 million in 2008.[77] In low-income countries, only half of transfusions may be appropriately screened (as of 2008),[78] and it is estimated that up to 15% of HIV infections in these areas come from transfusion of infected blood and blood products, representing between 5% and 10% of global infections.[17][79] It is possible to acquire HIV from organ and tissue transplantation, although this is rare because of screening.[80]

Unsafe medical injections play a role in HIV spread in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2007, between 12% and 17% of infections in this region were attributed to medical syringe use.[81] The World Health Organization estimates the risk of transmission as a result of a medical injection in Africa at 1.2%.[81] Risks are also associated with invasive procedures, assisted delivery, and dental care in this area of the world.[81]

People giving or receiving tattoos, piercings, and scarification are theoretically at risk of infection but no confirmed cases have been documented.[82] It is not possible for mosquitoes or other insects to transmit HIV.[83]

Mother-to-child

HIV can be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy, during delivery, or through breast milk, resulting in the baby also contracting HIV.[17][84] As of 2008, vertical transmission accounted for about 90% of cases of HIV in children.[85] In the absence of treatment, the risk of transmission before or during birth is around 20%, and in those who also breastfeed 35%.[85] Treatment decreases this risk to less than 5%.[86]

Antiretrovirals when taken by either the mother or the baby decrease the risk of transmission in those who do breastfeed.[87] If blood contaminates food during pre-chewing it may pose a risk of transmission.[82] If a woman is untreated, two years of breastfeeding results in an HIV/AIDS risk in her baby of about 17%.[88] Due to the increased risk of death without breastfeeding in many areas in the developing world, the World Health Organization recommends either exclusive breastfeeding or the provision of safe formula.[88] All women known to be HIV-positive should be taking lifelong antiretroviral therapy.[88]

Virology

HIV is the cause of the spectrum of disease known as HIV/AIDS. HIV is a retrovirus that primarily infects components of the human immune system such as CD4+ T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells. It directly and indirectly destroys CD4+ T cells.[89]

HIV is a member of the genus Lentivirus,[90] part of the family Retroviridae.[91] Lentiviruses share many morphological and biological characteristics. Many species of mammals are infected by lentiviruses, which are characteristically responsible for long-duration illnesses with a long incubation period.[92] Lentiviruses are transmitted as single-stranded, positive-sense, enveloped RNA viruses. Upon entry into the target cell, the viral RNA genome is converted (reverse transcribed) into double-stranded DNA by a virally encoded reverse transcriptase that is transported along with the viral genome in the virus particle. The resulting viral DNA is then imported into the cell nucleus and integrated into the cellular DNA by a virally encoded integrase and host co-factors.[93] Once integrated, the virus may become latent, allowing the virus and its host cell to avoid detection by the immune system.[94] Alternatively, the virus may be transcribed, producing new RNA genomes and viral proteins that are packaged and released from the cell as new virus particles that begin the replication cycle anew.[95]

HIV is now known to spread between CD4+ T cells by two parallel routes: cell-free spread and cell-to-cell spread, i.e. it employs hybrid spreading mechanisms.[96] In the cell-free spread, virus particles bud from an infected T cell, enter the blood/extracellular fluid and then infect another T cell following a chance encounter.[96] HIV can also disseminate by direct transmission from one cell to another by a process of cell-to-cell spread.[97][98] The hybrid spreading mechanisms of HIV contribute to the virus' ongoing replication against antiretroviral therapies.[96][99]

Two types of HIV have been characterized: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the virus that was originally discovered (and initially referred to also as LAV or HTLV-III). It is more virulent, more infective,[100] and is the cause of the majority of HIV infections globally. The lower infectivity of HIV-2 as compared with HIV-1 implies that fewer people exposed to HIV-2 will be infected per exposure. Because of its relatively poor capacity for transmission, HIV-2 is largely confined to West Africa.[101]

Pathophysiology

After the virus enters the body, there is a period of rapid viral replication, leading to an abundance of virus in the peripheral blood. During primary infection, the level of HIV may reach several million virus particles per milliliter of blood.[102] This response is accompanied by a marked drop in the number of circulating CD4+ T cells. The acute viremia is almost invariably associated with activation of CD8+ T cells, which kill HIV-infected cells, and subsequently with antibody production, or seroconversion. The CD8+ T cell response is thought to be important in controlling virus levels, which peak and then decline, as the CD4+ T cell counts recover. A good CD8+ T cell response has been linked to slower disease progression and a better prognosis, though it does not eliminate the virus.[103]

Ultimately, HIV causes AIDS by depleting CD4+ T cells. This weakens the immune system and allows opportunistic infections. T cells are essential to the immune response and without them, the body cannot fight infections or kill cancerous cells. The mechanism of CD4+ T cell depletion differs in the acute and chronic phases.[104] During the acute phase, HIV-induced cell lysis and killing of infected cells by CD8+ T cells accounts for CD4+ T cell depletion, although apoptosis may also be a factor. During the chronic phase, the consequences of generalized immune activation coupled with the gradual loss of the ability of the immune system to generate new T cells appear to account for the slow decline in CD4+ T cell numbers.[105]

Although the symptoms of immune deficiency characteristic of AIDS do not appear for years after a person is infected, the bulk of CD4+ T cell loss occurs during the first weeks of infection, especially in the intestinal mucosa, which harbors the majority of the lymphocytes found in the body.[106] The reason for the preferential loss of mucosal CD4+ T cells is that the majority of mucosal CD4+ T cells express the CCR5 protein which HIV uses as a co-receptor to gain access to the cells, whereas only a small fraction of CD4+ T cells in the bloodstream do so.[107] A specific genetic change that alters the CCR5 protein when present in both chromosomes very effectively prevents HIV-1 infection.[108]

HIV seeks out and destroys CCR5 expressing CD4+ T cells during acute infection.[109] A vigorous immune response eventually controls the infection and initiates the clinically latent phase. CD4+ T cells in mucosal tissues remain particularly affected.[109] Continuous HIV replication causes a state of generalized immune activation persisting throughout the chronic phase.[110] Immune activation, which is reflected by the increased activation state of immune cells and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, results from the activity of several HIV gene products and the immune response to ongoing HIV replication. It is also linked to the breakdown of the immune surveillance system of the gastrointestinal mucosal barrier caused by the depletion of mucosal CD4+ T cells during the acute phase of disease.[111]

Diagnosis

| Blood test | Days |

|---|---|

| Antibody test (rapid test, ELISA 3rd gen) | 23–90 |

| Antibody and p24 antigen test (ELISA 4th gen) | 18–45 |

| PCR | 10–33 |

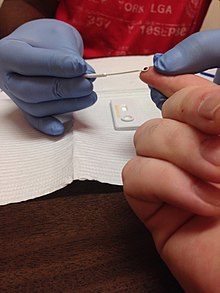

HIV/AIDS is diagnosed via laboratory testing and then staged based on the presence of certain signs or symptoms.[31] HIV screening is recommended by the United States Preventive Services Task Force for all people 15 years to 65 years of age, including all pregnant women.[113] Additionally, testing is recommended for those at high risk, which includes anyone diagnosed with a sexually transmitted illness.[34][113] In many areas of the world, a third of HIV carriers only discover they are infected at an advanced stage of the disease when AIDS or severe immunodeficiency has become apparent.[34]

HIV testing

Most people infected with HIV develop seroconverted (antigen-specific) antibodies within three to twelve weeks after the initial infection.[33] Diagnosis of primary HIV before seroconversion is done by measuring HIV-RNA or p24 antigen.[33] Positive results obtained by antibody or PCR testing are confirmed either by a different antibody or by PCR.[31]

Antibody tests in children younger than 18 months are typically inaccurate, due to the continued presence of maternal antibodies.[114] Thus HIV infection can only be diagnosed by PCR testing for HIV RNA or DNA, or via testing for the p24 antigen.[31] Much of the world lacks access to reliable PCR testing, and people in many places simply wait until either symptoms develop or the child is old enough for accurate antibody testing.[114] In sub-Saharan Africa between 2007 and 2009, between 30% and 70% of the population were aware of their HIV status.[115] In 2009, between 3.6% and 42% of men and women in sub-Saharan countries were tested;[115] this represented a significant increase compared to previous years.[115]

Classifications

Two main clinical staging systems are used to classify HIV and HIV-related disease for surveillance purposes: the WHO disease staging system for HIV infection and disease,[31] and the CDC classification system for HIV infection.[116] The CDC's classification system is more frequently adopted in developed countries. Since the WHO's staging system does not require laboratory tests, it is suited to the resource-restricted conditions encountered in developing countries, where it can also be used to help guide clinical management. Despite their differences, the two systems allow a comparison for statistical purposes.[30][31][116]

The World Health Organization first proposed a definition for AIDS in 1986.[31] Since then, the WHO classification has been updated and expanded several times, with the most recent version being published in 2007.[31] The WHO system uses the following categories:

- Primary HIV infection: May be either asymptomatic or associated with acute retroviral syndrome[31]

- Stage I: HIV infection is asymptomatic with a CD4+ T cell count (also known as CD4 count) greater than 500 per microlitre (μL or cubic mm) of blood.[31] May include generalized lymph node enlargement.[31]

- Stage II: Mild symptoms, which may include minor mucocutaneous manifestations and recurrent upper respiratory tract infections. A CD4 count of less than 500/μL[31]

- Stage III: Advanced symptoms, which may include unexplained chronic diarrhea for longer than a month, severe bacterial infections including tuberculosis of the lung, and a CD4 count of less than 350/μL[31]

- Stage IV or AIDS: severe symptoms, which include toxoplasmosis of the brain, candidiasis of the esophagus, trachea, bronchi, or lungs, and Kaposi's sarcoma. A CD4 count of less than 200/μL[31]

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also created a classification system for HIV, and updated it in 2008 and 2014.[116][117] This system classifies HIV infections based on CD4 count and clinical symptoms, and describes the infection in five groups.[117] In those greater than six years of age it is:[117]

- Stage 0: the time between a negative or indeterminate HIV test followed less than 180 days by a positive test

- Stage 1: CD4 count ≥ 500 cells/μL and no AIDS-defining conditions

- Stage 2: CD4 count 200 to 500 cells/μL and no AIDS-defining conditions

- Stage 3: CD4 count ≤ 200 cells/μL or AIDS-defining conditions

- Unknown: if insufficient information is available to make any of the above classifications.

For surveillance purposes, the AIDS diagnosis still stands even if, after treatment, the CD4+ T cell count rises to above 200 per μL of blood or other AIDS-defining illnesses are cured.[30]

Prevention

Sexual contact

Consistent condom use reduces the risk of HIV transmission by approximately 80% over the long term.[118] When condoms are used consistently by a couple in which one person is infected, the rate of HIV infection is less than 1% per year.[119] There is some evidence to suggest that female condoms may provide an equivalent level of protection.[120] Application of a vaginal gel containing tenofovir (a reverse transcriptase inhibitor) immediately before sex seems to reduce infection rates by approximately 40% among African women.[121] By contrast, use of the spermicide nonoxynol-9 may increase the risk of transmission due to its tendency to cause vaginal and rectal irritation.[122]

Circumcision in sub-Saharan Africa "reduces the acquisition of HIV by heterosexual men by between 38% and 66% over 24 months".[123] Owing to these studies, both the World Health Organization and UNAIDS recommended male circumcision in 2007 as a method of preventing female-to-male HIV transmission in areas with high rates of HIV.[124] However, whether it protects against male-to-female transmission is disputed,[125][126] and whether it is of benefit in developed countries and among men who have sex with men is undetermined.[127][128][129]

Programs encouraging sexual abstinence do not appear to affect subsequent HIV risk.[130] Evidence of any benefit from peer education is equally poor.[131] Comprehensive sexual education provided at school may decrease high-risk behavior.[132][133] A substantial minority of young people continues to engage in high-risk practices despite knowing about HIV/AIDS, underestimating their own risk of becoming infected with HIV.[134] Voluntary counseling and testing people for HIV does not affect risky behavior in those who test negative but does increase condom use in those who test positive.[135] Enhanced family planning services appear to increase the likelihood of women with HIV using contraception, compared to basic services.[136] It is not known whether treating other sexually transmitted infections is effective in preventing HIV.[67]

Pre-exposure

Antiretroviral treatment among people with HIV whose CD4 count ≤ 550 cells/μL is a very effective way to prevent HIV infection of their partner (a strategy known as treatment as prevention, or TASP).[137] TASP is associated with a 10- to 20-fold reduction in transmission risk.[137][138] Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV ("PrEP") with a daily dose of the medications tenofovir, with or without emtricitabine, is effective in people at high risk including men who have sex with men, couples where one is HIV-positive, and young heterosexuals in Africa.[121][139] It may also be effective in intravenous drug users, with a study finding a decrease in risk of 0.7 to 0.4 per 100 person years.[140] The USPSTF, in 2019, recommended PrEP in those who are at high risk.[141]

Universal precautions within the health care environment are believed to be effective in decreasing the risk of HIV.[142] Intravenous drug use is an important risk factor, and harm reduction strategies such as needle-exchange programs and opioid substitution therapy appear effective in decreasing this risk.[143][144]

Post-exposure

A course of antiretrovirals administered within 48 to 72 hours after exposure to HIV-positive blood or genital secretions is referred to as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP).[145] The use of the single agent zidovudine reduces the risk of an HIV infection five-fold following a needle-stick injury.[145] As of 2013[update], the prevention regimen recommended in the United States consists of three medications—tenofovir, emtricitabine and raltegravir—as this may reduce the risk further.[146]

PEP treatment is recommended after a sexual assault when the perpetrator is known to be HIV-positive, but is controversial when their HIV status is unknown.[147] The duration of treatment is usually four weeks[148] and is frequently associated with adverse effects—where zidovudine is used, about 70% of cases result in adverse effects such as nausea (24%), fatigue (22%), emotional distress (13%) and headaches (9%).[55]

Mother-to-child

Programs to prevent the vertical transmission of HIV (from mothers to children) can reduce rates of transmission by 92–99%.[85][143] This primarily involves the use of a combination of antiviral medications during pregnancy and after birth in the infant, and potentially includes bottle feeding rather than breastfeeding.[85][149] If replacement feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable and safe, mothers should avoid breastfeeding their infants; however, exclusive breastfeeding is recommended during the first months of life if this is not the case.[150] If exclusive breastfeeding is carried out, the provision of extended antiretroviral prophylaxis to the infant decreases the risk of transmission.[151] In 2015, Cuba became the first country in the world to eradicate mother-to-child transmission of HIV.[152]

Vaccination

Currently there is no licensed vaccine for HIV or AIDS.[6] The most effective vaccine trial to date, RV 144, was published in 2009; it found a partial reduction in the risk of transmission of roughly 30%, stimulating some hope in the research community of developing a truly effective vaccine.[153]

Treatment

There is currently no cure, nor an effective HIV vaccine. Treatment consists of highly active antiretroviral therapy (ART), which slows progression of the disease.[154] As of 2022, 39 million people globally were living with HIV, and 29.8 million people were accessing ART.[155] Treatment also includes preventive and active treatment of opportunistic infections. As of July 2022[update], four people have been successfully cleared of HIV.[156][157][158] Rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy within one week of diagnosis appear to improve treatment outcomes in low and medium-income settings and is recommend for newly diagnosed HIV patients.[159][160]

Antiviral therapy

Current ART options are combinations (or "cocktails") consisting of at least three medications belonging to at least two types, or "classes", of antiretroviral agents.[161] There are eight classes of antiretroviral agents (ARVs), and over 30 individual drugs: nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs), non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase, inhibitors (NNRTIs), protease inhibitors (PIs), integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INSTIs), a fusion inhibitor, a CCR5 antagonist, a CD4 T lymphocyte (CD4) post-attachment inhibitor, and a gp120 attachment inhibitor. There are also two drugs, ritonavir (RTV) and cobicistat (COBI) which can be used as pharmacokinetic (PK) enhancers (or boosters) to improve the PK profiles of PIs and the INSTI elvitegravir (EVG).[162] Depending on the guidelines being followed, initial treatment generally consists of two nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors along with a third ARV, either an integrase strand transfer inhibitor (INSTI), a non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI), or a protease inhibitor with a pharmacokinetic enhancer (also known as a booster).[162]

The World Health Organization and the United States recommend antiretrovirals in people of all ages (including pregnant women) as soon as the diagnosis is made, regardless of CD4 count.[13][163][164] Once treatment is begun, it is recommended that it is continued without breaks or "holidays".[34] Many people are diagnosed only after treatment ideally should have begun.[34] The desired outcome of treatment is a long-term plasma HIV-RNA count below 50 copies/mL.[34] Levels to determine if treatment is effective are initially recommended after four weeks and once levels fall below 50 copies/mL checks every three to six months are typically adequate.[34] Inadequate control is deemed to be greater than 400 copies/mL.[34] Based on these criteria treatment is effective in more than 95% of people during the first year.[34]

Benefits of treatment include a decreased risk of progression to AIDS and a decreased risk of death.[165] In the developing world, treatment also improves physical and mental health.[166] With treatment, there is a 70% reduced risk of acquiring tuberculosis.[161] Additional benefits include a decreased risk of transmission of the disease to sexual partners and a decrease in mother-to-child transmission.[161][167] The effectiveness of treatment depends to a large part on compliance.[34] Reasons for non-adherence to treatment include poor access to medical care,[168] inadequate social supports, mental illness and drug abuse.[169] The complexity of treatment regimens (due to pill numbers and dosing frequency) and adverse effects may reduce adherence.[170] Even though cost is an important issue with some medications,[171] 47% of those who needed them were taking them in low- and middle-income countries as of 2010[update],[172] and the rate of adherence is similar in low-income and high-income countries.[173]

Specific adverse events are related to the antiretroviral agent taken.[174] Some relatively common adverse events include: lipodystrophy syndrome, dyslipidemia, and diabetes mellitus, especially with protease inhibitors.[30] Other common symptoms include diarrhea,[174][175] and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease.[176] Newer recommended treatments are associated with fewer adverse effects.[34] Certain medications may be associated with birth defects and therefore may be unsuitable for women hoping to have children.[34]

Treatment recommendations for children are somewhat different from those for adults. The World Health Organization recommends treating all children less than five years of age; children above five are treated like adults.[177] The United States guidelines recommend treating all children less than 12 months of age and all those with HIV RNA counts greater than 100,000 copies/mL between one year and five years of age.[178]

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended the granting of marketing authorizations for two new antiretroviral (ARV) medicines, rilpivirine (Rekambys) and cabotegravir (Vocabria), to be used together for the treatment of people with human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection.[179] The two medicines are the first ARVs that come in a long-acting injectable formulation.[179] This means that instead of daily pills, people receive intramuscular injections monthly or every two months.[179]

The combination of Rekambys and Vocabria injection is intended for maintenance treatment of adults who have undetectable HIV levels in the blood (viral load less than 50 copies/mL) with their current ARV treatment, and when the virus has not developed resistance to a certain class of anti-HIV medicines called non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) and integrase strand transfer inhibitors (INIs).[179]

Cabotegravir combined with rilpivirine (Cabenuva) is a complete regimen for the treatment of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) infection in adults to replace a current antiretroviral regimen in those who are virologically suppressed on a stable antiretroviral regimen with no history of treatment failure and with no known or suspected resistance to either cabotegravir or rilpivirine.[180][181]

Opportunistic infections

Measures to prevent opportunistic infections are effective in many people with HIV/AIDS. In addition to improving current disease, treatment with antiretrovirals reduces the risk of developing additional opportunistic infections.[174]

Adults and adolescents who are living with HIV (even on anti-retroviral therapy) with no evidence of active tuberculosis in settings with high tuberculosis burden should receive isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT); the tuberculin skin test can be used to help decide if IPT is needed.[182] Children with HIV may benefit from screening for tuberculosis.[183] Vaccination against hepatitis A and B is advised for all people at risk of HIV before they become infected; however, it may also be given after infection.[184]

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole prophylaxis between four and six weeks of age, and ceasing breastfeeding of infants born to HIV-positive mothers, is recommended in resource-limited settings.[185] It is also recommended to prevent PCP when a person's CD4 count is below 200 cells/uL and in those who have or have previously had PCP.[186] People with substantial immunosuppression are also advised to receive prophylactic therapy for toxoplasmosis and MAC.[187] Appropriate preventive measures reduced the rate of these infections by 50% between 1992 and 1997.[188] Influenza vaccination and pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine are often recommended in people with HIV/AIDS with some evidence of benefit.[189][190]

Diet

The World Health Organization (WHO) has issued recommendations regarding nutrient requirements in HIV/AIDS.[191] A generally healthy diet is promoted. Dietary intake of micronutrients at RDA levels by HIV-infected adults is recommended by the WHO; higher intake of vitamin A, zinc, and iron can produce adverse effects in HIV-positive adults, and is not recommended unless there is documented deficiency.[191][192][193][194] Dietary supplementation for people who are infected with HIV and who have inadequate nutrition or dietary deficiencies may strengthen their immune systems or help them recover from infections; however, evidence indicating an overall benefit in morbidity or reduction in mortality is not consistent.[195]

People with HIV/AIDS are up to four times more likely to develop type 2 diabetes than those who are not tested positive with the virus.[196]

Evidence for supplementation with selenium is mixed with some tentative evidence of benefit.[197] For pregnant and lactating women with HIV, multivitamin supplement improves outcomes for both mothers and children.[198] If the pregnant or lactating mother has been advised to take anti-retroviral medication to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission, multivitamin supplements should not replace these treatments.[198] There is some evidence that vitamin A supplementation in children with an HIV infection reduces mortality and improves growth.[199]

Alternative medicine

In the US, approximately 60% of people with HIV use various forms of complementary or alternative medicine,[200] whose effectiveness has not been established.[201] There is not enough evidence to support the use of herbal medicines.[202] There is insufficient evidence to recommend or support the use of medical cannabis to try to increase appetite or weight gain.[203]

Prognosis

HIV/AIDS has become a chronic rather than an acutely fatal disease in many areas of the world.[204] Prognosis varies between people, and both the CD4 count and viral load are useful for predicted outcomes.[33] Without treatment, average survival time after infection with HIV is estimated to be 9 to 11 years, depending on the HIV subtype.[7] After the diagnosis of AIDS, if treatment is not available, survival ranges between 6 and 19 months.[205][206] ART and appropriate prevention of opportunistic infections reduces the death rate by 80%, and raises the life expectancy for a newly diagnosed young adult to 20–50 years.[204][207][208] This is between two thirds[207] and nearly that of the general population.[34][209] If treatment is started late in the infection, prognosis is not as good:[34] for example, if treatment is begun following the diagnosis of AIDS, life expectancy is ~10–40 years.[34][204] Half of infants born with HIV die before two years of age without treatment.[185][210]

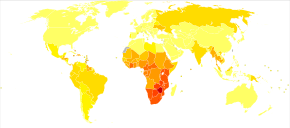

| no data ≤ 10 10–25 25–50 50–100 | 100–500 500–1000 1,000–2,500 2,500–5,000 5,000–7500 | 7,500–10,000 10,000–50,000 ≥ 50,000 |

The primary causes of death from HIV/AIDS are opportunistic infections and cancer, both of which are frequently the result of the progressive failure of the immune system.[188][211] Risk of cancer appears to increase once the CD4 count is below 500/μL.[34] The rate of clinical disease progression varies widely between individuals and has been shown to be affected by a number of factors such as a person's susceptibility and immune function;[212] their access to health care, the presence of co-infections;[205][213] and the particular strain (or strains) of the virus involved.[214][215]

Tuberculosis co-infection is one of the leading causes of sickness and death in those with HIV/AIDS being present in a third of all HIV-infected people and causing 25% of HIV-related deaths.[216] HIV is also one of the most important risk factors for tuberculosis.[217] Hepatitis C is another very common co-infection where each disease increases the progression of the other.[218] The two most common cancers associated with HIV/AIDS are Kaposi's sarcoma and AIDS-related non-Hodgkin's lymphoma.[211] Other cancers that are more frequent include anal cancer, Burkitt's lymphoma, primary central nervous system lymphoma, and cervical cancer.[34][219]

Even with anti-retroviral treatment, over the long term HIV-infected people may experience neurocognitive disorders,[220] osteoporosis,[221] neuropathy,[222] cancers,[223][224] nephropathy,[225] and cardiovascular disease.[175] Some conditions, such as lipodystrophy, may be caused both by HIV and its treatment.[175]

Epidemiology

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

HIV/AIDS is considered a global pandemic.[227] As of 2022[update], approximately 39.0 million people worldwide are living with HIV, the number of new infections that year being about 1.3 million.[155] This is down from 2.1 million new infections in 2010.[155] Among new infections, 46% are in women and are children globally.[155] There were 630,000 AIDS related deaths in 2022, down from a peak of 2 million in 2005.[155]

Among persons living with HIV (PLWH), the largest proportion reside in eastern and southern Africa (20.6 million, 54.6%). This region also had the highest rate of adult and child deaths due to AIDS in 2020 (310,000, 46.6%). Sub-Saharan African adolescent girls and young women (aged 15–24 years) account for 77% of new infections among this age-range globally.[155] Here, in contrast to other regions, adolescent girls and young women are three times more likely to acquire HIV than age-matched males.[155] Despite these statistics, overall, new HIV infections and AIDS-related deaths have substantially decreased in this region since 2010.[228]

Eastern Europe and central Asia has observed a 43% increase in new HIV infections and 32% increase in AIDS-related deaths since 2010, the highest of all global regions.[228] These infections are predominantly distributed in persons who inject drugs, with gay men and other men who have sex with men or persons who engage in transaction sex the second and third populations most impacted in this region.[228]

At the end of 2019, United States indicated that approximately 1.2 million people aged ≥13 years were living with HIV, resulting in about 18,500 deaths in 2020.[229] There were 34,800 estimated new infections in the US in 2019, 53% of which were in the southern region of the country.[229] In addition to geographic location, significant disparities in HIV incidence exist among men, Black or Hispanic populations, and men who reported male-to-male sexual contact. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimated that in that year, 158,500 people or 13% of infected Americans were unaware of their infection.[229]

In the United Kingdom as of 2015[update], there were approximately 101,200 cases which resulted in 594 deaths.[230] In Canada as of 2008, there were about 65,000 cases causing 53 deaths.[231] Between the first recognition of AIDS (in 1981) and 2009, it has led to nearly 30 million deaths.[232] Rates of HIV are lowest in North Africa and the Middle East (0.1% or less), East Asia (0.1%), and Western and Central Europe (0.2%).[233] The worst-affected European countries, in 2009 and 2012 estimates, are Russia, Ukraine, Latvia, Moldova, Portugal and Belarus, in decreasing order of prevalence.[234]

Groups at higher risk of acquiring HIV include persons who engage in transactional sex, gay men and other men who have sex with men, persons who inject drugs, transgender persons, and those who are incarcerated or detained.[155]

History

Discovery

The first news story on the disease appeared on May 18, 1981, in the gay newspaper New York Native.[235][236] AIDS was first clinically reported on June 5, 1981, with five cases in the United States.[42][237] The initial cases were a cluster of injecting drug users and gay men with no known cause of impaired immunity who showed symptoms of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP), a rare opportunistic infection that was known to occur in people with very compromised immune systems.[238] Soon thereafter, a large number of homosexual men developed a generally rare skin cancer called Kaposi's sarcoma (KS).[239][240] Many more cases of PCP and KS emerged, alerting U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and a CDC task force was formed to monitor the outbreak.[241]

In the early days, the CDC did not have an official name for the disease, often referring to it by way of diseases associated with it, such as lymphadenopathy, the disease after which the discoverers of HIV originally named the virus.[242][243] They also used Kaposi's sarcoma and opportunistic infections, the name by which a task force had been set up in 1981.[244] At one point the CDC referred to it as the "4H disease", as the syndrome seemed to affect heroin users, homosexuals, haemophiliacs, and Haitians.[245][246] The term GRID, which stood for gay-related immune deficiency, had also been coined.[247] However, after determining that AIDS was not isolated to the gay community,[244] it was realized that the term GRID was misleading, and the term AIDS was introduced at a meeting in July 1982.[248] By September 1982 the CDC started referring to the disease as AIDS.[249]

In 1983, two separate research groups led by Robert Gallo and Luc Montagnier declared that a novel retrovirus may have been infecting people with AIDS, and published their findings in the same issue of the journal Science.[250][243] Gallo claimed a virus which his group had isolated from a person with AIDS was strikingly similar in shape to other human T-lymphotropic viruses (HTLVs) that his group had been the first to isolate. Gallo's group called their newly isolated virus HTLV-III. At the same time, Montagnier's group isolated a virus from a person presenting with swelling of the lymph nodes of the neck and physical weakness, two characteristic symptoms of AIDS. Contradicting the report from Gallo's group, Montagnier and his colleagues showed that core proteins of this virus were immunologically different from those of HTLV-I. Montagnier's group named their isolated virus lymphadenopathy-associated virus (LAV).[241] As these two viruses turned out to be the same, in 1986, LAV and HTLV-III were renamed HIV.[251]

Origins

The origin of HIV / AIDS and the circumstances that led to its emergence remain unsolved.[252]

Both HIV-1 and HIV-2 are believed to have originated in non-human primates in West-central Africa and were transferred to humans in the early 20th century.[25] HIV-1 appears to have originated in southern Cameroon through the evolution of SIV(cpz), a simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) that infects wild chimpanzees (HIV-1 descends from the SIVcpz endemic in the chimpanzee subspecies Pan troglodytes troglodytes).[253][254] The closest relative of HIV-2 is SIV (smm), a virus of the sooty mangabey (Cercocebus atys atys), an Old World monkey living in coastal West Africa (from southern Senegal to western Ivory Coast).[101] New World monkeys such as the owl monkey are resistant to HIV-1 infection, possibly because of a genomic fusion of two viral resistance genes.[255] HIV-1 is thought to have jumped the species barrier on at least three separate occasions, giving rise to the three groups of the virus, M, N, and O.[256]

There is evidence that humans who participate in bushmeat activities, either as hunters or as bushmeat vendors, commonly acquire SIV.[257] However, SIV is a weak virus which is typically suppressed by the human immune system within weeks of infection. It is thought that several transmissions of the virus from individual to individual in quick succession are necessary to allow it enough time to mutate into HIV.[258] Furthermore, due to its relatively low person-to-person transmission rate, SIV can only spread throughout the population in the presence of one or more high-risk transmission channels, which are thought to have been absent in Africa before the 20th century.[259]

Specific proposed high-risk transmission channels, allowing the virus to adapt to humans and spread throughout society, depend on the proposed timing of the animal-to-human crossing. Genetic studies of the virus suggest that the most recent common ancestor of the HIV-1 M group dates back to c. 1910.[260] Proponents of this dating link the HIV epidemic with the emergence of colonialism and growth of large colonial African cities, leading to social changes, including a higher degree of sexual promiscuity, the spread of prostitution, and the accompanying high frequency of genital ulcer diseases (such as syphilis) in nascent colonial cities.[261] While transmission rates of HIV during vaginal intercourse are low under regular circumstances, they are increased manyfold if one of the partners has a sexually transmitted infection causing genital ulcers. Early 1900s colonial cities were notable for their high prevalence of prostitution and genital ulcers, to the degree that, as of 1928, as many as 45% of female residents of eastern Kinshasa were thought to have been prostitutes, and, as of 1933, around 15% of all residents of the same city had syphilis.[261]

An alternative view holds that unsafe medical practices in Africa after World War II, such as unsterile reuse of single-use syringes during mass vaccination, antibiotic and anti-malaria treatment campaigns, were the initial vector that allowed the virus to adapt to humans and spread.[258][262][263]

The earliest well-documented case of HIV in a human dates back to 1959 in the Congo.[264] The virus may have been present in the U.S. as early as the mid-to-late 1950s, as a sixteen-year-old male named Robert Rayford presented with symptoms in 1966 and died in 1969. In the 1970s, there were cases of getting parasites and becoming sick with what was called "gay bowel disease", but what is now suspected to have been AIDS.[265]

The earliest retrospectively described case of AIDS is believed to have been in Norway beginning in 1966, that of Arvid Noe.[266] In July 1960, in the wake of Congo's independence, the United Nations recruited Francophone experts and technicians from all over the world to assist in filling administrative gaps left by Belgium, who did not leave behind an African elite to run the country. By 1962, Haitians made up the second-largest group of well-educated experts (out of the 48 national groups recruited), that totaled around 4,500 in the country.[267][268] Dr. Jacques Pépin, a Canadian author of The Origins of AIDS, stipulates that Haiti was one of HIV's entry points to the U.S. and that a Haitian may have carried HIV back across the Atlantic in the 1960s.[268] Although there was known to have been at least one case of AIDS in the U.S. from 1966,[269] the vast majority of infections occurring outside sub-Saharan Africa (including the U.S.) can be traced back to a single unknown individual who became infected with HIV in Haiti and brought the infection to the U.S. at some time around 1969.[252] The epidemic rapidly spread among high-risk groups (initially, sexually promiscuous men who have sex with men). By 1978, the prevalence of HIV-1 among gay male residents of New York City and San Francisco was estimated at 5%, suggesting that several thousand individuals in the country had been infected.[252]

Society and culture

Stigma

AIDS stigma exists around the world in a variety of ways, including ostracism, rejection, discrimination and avoidance of HIV-infected people; compulsory HIV testing without prior consent or protection of confidentiality; violence against HIV-infected individuals or people who are perceived to be infected with HIV; and the quarantine of HIV-infected individuals.[21] Stigma-related violence or the fear of violence prevents many people from seeking HIV testing, returning for their results, or securing treatment, possibly turning what could be a manageable chronic illness into a death sentence and perpetuating the spread of HIV.[271]

AIDS stigma has been further divided into the following three categories:

- Instrumental AIDS stigma—a reflection of the fear and apprehension that are likely to be associated with any deadly and transmissible illness.[272]

- Symbolic AIDS stigma—the use of HIV/AIDS to express attitudes toward the social groups or lifestyles perceived to be associated with the disease.[272]

- Courtesy AIDS stigma—stigmatization of people connected to the issue of HIV/AIDS or HIV-positive people.[273]

Often, AIDS stigma is expressed in conjunction with one or more other stigmas, particularly those associated with homosexuality, bisexuality, promiscuity, prostitution, and intravenous drug use.[274]

In many developed countries, there is an association between AIDS and homosexuality or bisexuality, and this association is correlated with higher levels of sexual prejudice, such as anti-homosexual or anti-bisexual attitudes.[275] There is also a perceived association between AIDS and all male-male sexual behavior, including sex between uninfected men.[272] However, the dominant mode of spread worldwide for HIV remains heterosexual transmission.[276]

The NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt was conceived in 1985 to celebrate the lives of those who had died of AIDS when stigma prevented many from receiving funerals. It is now cared for by the National AIDS Memorial in San Francisco.

In 2003, as part of an overall reform of marriage and population legislation, it became legal for those diagnosed with AIDS to marry in China.[277]

In 2013, the U.S. National Library of Medicine developed a traveling exhibition titled Surviving and Thriving: AIDS, Politics, and Culture;[278] this covered medical research, the U.S. government's response, and personal stories from people with AIDS, caregivers, and activists.[279]

Stigma has proved an obstacle to the update of PrEP. Within the MSM community, the greatest barrier to PrEP use has been the stigma surrounding HIV and gay men. Gay men on PrEP have experienced "slut-shaming".[280][281] Numerous other barriers have been identified, including lack of quality LGBTQ care, cost, and adherence to medication use.[282]

Economic impact

HIV/AIDS affects the economics of both individuals and countries.[283] The gross domestic product of the most affected countries has decreased due to the lack of human capital.[283][284] Without proper nutrition, health care and medicine, large numbers of people die from AIDS-related complications. Before death they will not only be unable to work, but will also require significant medical care. It is estimated that as of 2007 there were 12 million AIDS orphans.[283] Many are cared for by elderly grandparents.[285]

Returning to work after beginning treatment for HIV/AIDS is difficult, and affected people often work less than the average worker. Unemployment in people with HIV/AIDS also is associated with suicidal ideation, memory problems, and social isolation. Employment increases self-esteem, sense of dignity, confidence, and quality of life for people with HIV/AIDS. Anti-retroviral treatment may help people with HIV/AIDS work more, and may increase the chance that a person with HIV/AIDS will be employed (low-quality evidence).[286]

By affecting mainly young adults, AIDS reduces the taxable population, in turn reducing the resources available for public expenditures such as education and health services not related to AIDS, resulting in increasing pressure on the state's finances and slower growth of the economy. This causes a slower growth of the tax base, an effect that is reinforced if there are growing expenditures on treating the sick, training (to replace sick workers), sick pay, and caring for AIDS orphans. This is especially true if the sharp increase in adult mortality shifts the responsibility from the family to the government in caring for these orphans.[285]

At the household level, AIDS causes both loss of income and increased spending on healthcare. A study in Côte d'Ivoire showed that households having a person with HIV/AIDS spent twice as much on medical expenses as other households. This additional expenditure also leaves less income to spend on education and other personal or family investment.[287]

Religion and AIDS

The topic of religion and AIDS has become highly controversial, primarily because some religious authorities have publicly declared their opposition to the use of condoms.[288][289] The religious approach to prevent the spread of AIDS, according to a report by American health expert Matthew Hanley titled The Catholic Church and the Global AIDS Crisis, argues that cultural changes are needed, including a re-emphasis on fidelity within marriage and sexual abstinence outside of it.[289]

Some religious organizations have claimed that prayer can cure HIV/AIDS. In 2011, the BBC reported that some churches in London were claiming that prayer would cure AIDS, and the Hackney-based Centre for the Study of Sexual Health and HIV reported that several people stopped taking their medication, sometimes on the direct advice of their pastor, leading to many deaths.[290] The Synagogue Church Of All Nations advertised an "anointing water" to promote God's healing, although the group denies advising people to stop taking medication.[290]

Media portrayal

One of the first high-profile cases of AIDS was the American gay actor Rock Hudson. He had been diagnosed during 1984, announced that he had had the virus on July 25, 1985, and died a few months later on October 2, 1985.[291] Another notable British casualty of AIDS that year was Nicholas Eden, a gay politician and son of former prime minister Anthony Eden.[292] On November 24, 1991, British rock star Freddie Mercury died from an AIDS-related illness, having revealed the diagnosis only on the previous day.[293]

One of the first high-profile heterosexual cases of the virus was American tennis player Arthur Ashe. He was diagnosed as HIV-positive on August 31, 1988, having contracted the virus from blood transfusions during heart surgery earlier in the 1980s. Further tests within 24 hours of the initial diagnosis revealed that Ashe had AIDS, but he did not tell the public about his diagnosis until April 1992.[294] He died as a result on February 6, 1993, aged 49.[295]

Therese Frare's photograph of gay activist David Kirby, as he lay dying from AIDS while surrounded by family, was taken in April 1990. Life magazine said the photo became the one image "most powerfully identified with the HIV/AIDS epidemic." The photo was displayed in Life, was the winner of the World Press Photo, and acquired worldwide notoriety after being used in a United Colors of Benetton advertising campaign in 1992.[296]

Many famous artists and AIDS activists such as Larry Kramer, Diamanda Galás and Rosa von Praunheim[297] campaign for AIDS education and the rights of those affected. These artists worked with various media formats.

Criminal transmission

Criminal transmission of HIV is the intentional or reckless infection of a person with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Some countries or jurisdictions, including some areas of the United States, have laws that criminalize HIV transmission or exposure.[298] Others may charge the accused under laws enacted before the HIV pandemic.

In 1996, Ugandan-born Canadian Johnson Aziga was diagnosed with HIV; he subsequently had unprotected sex with eleven women without disclosing his diagnosis. By 2003, seven had contracted HIV; two died from complications related to AIDS.[299][300] Aziga was convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.[301]

Misconceptions

There are many misconceptions about HIV and AIDS. Three misconceptions are that AIDS can spread through casual contact, that sexual intercourse with a virgin will cure AIDS,[302][303][304] and that HIV can infect only gay men and drug users.[305][306] In 2014, some among the British public wrongly thought one could get HIV from kissing (16%), sharing a glass (5%), spitting (16%), a public toilet seat (4%), and coughing or sneezing (5%).[307] Other misconceptions are that any act of anal intercourse between two uninfected gay men can lead to HIV infection, and that open discussion of HIV and homosexuality in schools will lead to increased rates of AIDS.[308][309]

A small group of individuals continue to dispute the connection between HIV and AIDS,[310] the existence of HIV itself, or the validity of HIV testing and treatment methods.[311][312] These claims, known as AIDS denialism, have been examined and rejected by the scientific community.[313] However, they have had a significant political impact, particularly in South Africa, where the government's official embrace of AIDS denialism (1999–2005) was responsible for its ineffective response to that country's AIDS epidemic, and has been blamed for hundreds of thousands of avoidable deaths and HIV infections.[314][315][316]

Several discredited conspiracy theories have held that HIV was created by scientists, either inadvertently or deliberately. Operation INFEKTION was a worldwide Soviet active measures operation to spread the claim that the United States had created HIV/AIDS. Surveys show that a significant number of people believed—and continue to believe—in such claims.[317]

Research

HIV/AIDS research includes all medical research which attempts to prevent, treat, or cure HIV/AIDS, along with fundamental research about the nature of HIV as an infectious agent, and about AIDS as the disease caused by HIV.

Many governments and research institutions participate in HIV/AIDS research. This research includes behavioral health interventions such as sex education, and drug development, such as research into microbicides for sexually transmitted diseases, HIV vaccines, and antiretroviral drugs. Other medical research areas include the topics of pre-exposure prophylaxis, post-exposure prophylaxis, and circumcision and HIV. Public health officials, researchers, and programs can gain a more comprehensive picture of the barriers they face, and the efficacy of current approaches to HIV treatment and prevention, by tracking standard HIV indicators.[318] Use of common indicators is an increasing focus of development organizations and researchers.[319][320]

References

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "What Are HIV and AIDS?". HIV.gov. May 15, 2017. Archived from the original on September 22, 2019. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ "HIV Classification: CDC and WHO Staging Systems". AIDS Education & Training Center Program. Archived from the original on October 18, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ "Wear your red ribbon this World AIDS Day". UNAIDS. Archived from the original on September 10, 2017. Retrieved September 10, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m "HIV/AIDS Fact sheet N°360". World Health Organization. November 2015. Archived from the original on February 17, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "About HIV/AIDS". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). December 6, 2015. Archived from the original on February 24, 2016. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d UNAIDS (May 18, 2012). "The quest for an HIV vaccine". Archived from the original on May 24, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c UNAIDS, World Health Organization (December 2007). "2007 AIDS epidemic update" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2008. Retrieved March 12, 2008.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f "Global HIV & AIDS statistics — 2022 fact sheet". UNAIDS. Archived from the original on December 4, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ Sepkowitz KA (June 2001). "AIDS – the first 20 years". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (23): 1764–72. doi:10.1056/NEJM200106073442306. ISSN 0028-4793. PMID 11396444.

- ^ Krämer A, Kretzschmar M, Krickeberg K (2010). Modern infectious disease epidemiology concepts, methods, mathematical models, and public health (Online-Ausg. ed.). New York: Springer. p. 88. ISBN 978-0-387-93835-6. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Kirch W (2008). Encyclopedia of Public Health. New York: Springer. pp. 676–77. ISBN 978-1-4020-5613-0. Archived from the original on September 11, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ "Retrovirus Definition". AIDSinfo. Archived from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved December 28, 2019.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV (PDF). World Health Organization. 2015. p. 13. ISBN 978-92-4-150956-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 14, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b McCray E, Mermin J (September 27, 2017). "Dear Colleague: September 27, 2017". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Archived from the original on January 30, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to: a b LeMessurier J, Traversy G, Varsaneux O, Weekes M, Avey MT, Niragira O, et al. (November 19, 2018). "Risk of sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus with antiretroviral therapy, suppressed viral load and condom use: a systematic review". Canadian Medical Association Journal. 190 (46): E1350–E1360. doi:10.1503/cmaj.180311. PMC 6239917. PMID 30455270.

- ^ "Undetectable = untransmittable". UNAIDS. Archived from the original on December 11, 2023. Retrieved August 26, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Rom WN, Markowitz SB, eds. (2007). Environmental and occupational medicine (4th ed.). Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 745. ISBN 978-0-7817-6299-1. Archived from the original on September 11, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ "HIV and Its Transmission". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2003. Archived from the original on February 4, 2005. Retrieved May 23, 2006.

- ^ "Preventing Sexual Transmission of HIV". HIV.gov. April 9, 2021. Archived from the original on February 1, 2022. Retrieved February 1, 2022.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Gallo RC (October 2006). "A reflection on HIV/AIDS research after 25 years". Retrovirology. 3 (1): 72. doi:10.1186/1742-4690-3-72. PMC 1629027. PMID 17054781.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c "The impact of AIDS on people and societies" (PDF). 2006 Report on the global AIDS epidemic. UNAIDS. 2006. ISBN 978-92-9173-479-5. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 4, 2006. Retrieved June 16, 2006.

- ^ Endersby J (2016). "Myth Busters". Science. 351 (6268): 35. Bibcode:2016Sci...351...35E. doi:10.1126/science.aad2891. S2CID 51608938. Archived from the original on February 22, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ McCullom R (February 26, 2013). "An African Pope Won't Change the Vatican's Views on Condoms and AIDS". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on March 8, 2016. Retrieved February 14, 2016.

- ^ Harden VA (2012). AIDS at 30: A History. Potomac Books Inc. p. 324. ISBN 978-1-59797-294-9.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Sharp PM, Hahn BH (September 2011). "Origins of HIV and the AIDS pandemic". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 1 (1): a006841. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006841. PMC 3234451. PMID 22229120.

- ^ "HIV Statistics Overview (International Statistics)". U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2018. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018. Retrieved May 9, 2021.

- ^ "Fact Sheet – World AIDS Day 2019" (PDF). UNAIDS. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019.

- ^ Kallings LO (March 2008). "The first postmodern pandemic: 25 years of HIV/AIDS". Journal of Internal Medicine. 263 (3): 218–43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01910.x. PMID 18205765. S2CID 205339589.(subscription required)

- ^ "NIH launches new collaboration to develop gene-based cures for sickle cell disease and HIV on global scale". National Institutes of Health (NIH). October 23, 2019. Archived from the original on September 4, 2021. Retrieved September 24, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f Mandell, Bennett, and Dolan (2010). Chapter 121.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p WHO case definitions of HIV for surveillance and revised clinical staging and immunological classification of HIV-related disease in adults and children (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2007. pp. 6–16. ISBN 978-92-4-159562-9. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 31, 2013.

- ^ Diseases and disorders. Tarrytown, NY: Marshall Cavendish. 2008. p. 25. ISBN 978-0-7614-7771-6. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Mandell, Bennett, and Dolan (2010). Chapter 118.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r Vogel M, Schwarze-Zander C, Wasmuth JC, Spengler U, Sauerbruch T, Rockstroh JK (July 2010). "The treatment of patients with HIV". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 107 (28–29): 507–15, quiz 516. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2010.0507. PMC 2915483. PMID 20703338.

- ^ Evian C (2006). Primary HIV/AIDS care: a practical guide for primary health care personnel in a clinical and supportive setting (Updated 4th ed.). Houghton [South Africa]: Jacana. p. 29. ISBN 978-1-77009-198-6. Archived from the original on September 11, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Hicks CB (2001). Reeders JW, Goodman PC (eds.). Radiology of AIDS. Berlin [u.a.]: Springer. p. 19. ISBN 978-3-540-66510-6. Archived from the original on May 9, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Elliott T (2012). Lecture Notes: Medical Microbiology and Infection. John Wiley & Sons. p. 273. ISBN 978-1-118-37226-5. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved June 27, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Blankson JN (March 2010). "Control of HIV-1 replication in elite suppressors". Discovery Medicine. 9 (46): 261–66. PMID 20350494.

- ^ Walker BD (August–September 2007). "Elite control of HIV Infection: implications for vaccines and treatment". Topics in HIV Medicine. 15 (4): 134–36. PMID 17720999.

- ^ Holmes CB, Losina E, Walensky RP, Yazdanpanah Y, Freedberg KA (March 2003). "Review of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-related opportunistic infections in sub-Saharan Africa". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 36 (5): 652–62. doi:10.1086/367655. PMID 12594648.

- ^ Chu C, Selwyn PA (February 2011). "Complications of HIV infection: a systems-based approach". American Family Physician. 83 (4): 395–406. PMID 21322514.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Mandell, Bennett, and Dolan (2010). Chapter 169.

- ^ Mittal R, Rath S, Vemuganti GK (July 2013). "Ocular surface squamous neoplasia – Review of etio-pathogenesis and an update on clinico-pathological diagnosis". Saudi Journal of Ophthalmology. 27 (3): 177–86. doi:10.1016/j.sjopt.2013.07.002. PMC 3770226. PMID 24227983.

- ^ "AIDS". MedlinePlus. Archived from the original on June 18, 2012. Retrieved June 14, 2012.

- ^ Sestak K (July 2005). "Chronic diarrhea and AIDS: insights into studies with non-human primates". Current HIV Research. 3 (3): 199–205. doi:10.2174/1570162054368084. PMID 16022653.

- ^ Murray ED, Buttner N, Price BH (2012). "Depression and Psychosis in Neurological Practice". In Bradley WG, Daroff RB, Fenichel GM, Jankovic J (eds.). Bradley's Neurology in Clinical Practice: Expert Consult – Online and Print, 6e (Bradley, Neurology in Clinical Practice e-dition 2v Set). Vol. 1 (6th ed.). Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 101. ISBN 978-1-4377-0434-1.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Donegan E, Stuart M, Niland JC, Sacks HS, Azen SP, Dietrich SL, et al. (November 15, 1990). "Infection with Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1 (HIV-1) among Recipients of Antibody-Positive Blood Donations". Annals of Internal Medicine. 113 (10): 733–739. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-113-10-733. Retrieved May 11, 2020.

- ^ Coovadia H (2004). "Antiretroviral agents—how best to protect infants from HIV and save their mothers from AIDS". N. Engl. J. Med. 351 (3): 289–292. doi:10.1056/NEJMe048128. PMID 15247337.

- ^ Smith DK, Grohskopf LA, Black RJ, Auerbach JD, Veronese F, Struble KA, et al. (January 21, 2005). "Antiretroviral postexposure prophylaxis after sexual, injection-drug use, or other nonoccupational exposure to HIV in the United States: recommendations from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services". MMWR. Recommendations and reports : Morbidity and mortality weekly report. Recommendations and reports / Centers for Disease Control. 54 (RR-2): 1–20. PMID 15660015.

- ^ Kripke C (August 1, 2007). "Antiretroviral prophylaxis for occupational exposure to HIV". American Family Physician. 76 (3): 375–6. PMID 17708137.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d Dosekun O, Fox J (July 2010). "An overview of the relative risks of different sexual behaviours on HIV transmission". Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 5 (4): 291–7. doi:10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a88a3. PMID 20543603.

- ^ Cunha B (2012). Antibiotic Essentials 2012 (11 ed.). Jones & Bartlett Publishers. p. 303. ISBN 9781449693831.