Вода

| |||

| |||

| |||

| Имена | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| IUPAC name Water | |||

| Systematic IUPAC name Oxidane | |||

Other names

| |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol) | |||

| 3587155 | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| DrugBank | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.028.902 | ||

| EC Number |

| ||

| 117 | |||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID | |||

| RTECS number |

| ||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |||

| Properties | |||

| H 2O | |||

| Molar mass | 18.01528(33) g/mol | ||

| Appearance | Almost colorless or white crystalline solid, almost colorless liquid, with a hint of blue, colorless gas[3] | ||

| Odor | Odorless | ||

| Density | |||

| Melting point | 0.00 °C (32.00 °F; 273.15 K) [b] | ||

| Boiling point | 99.98 °C (211.96 °F; 373.13 K)[16][b] | ||

| Solubility | Poorly soluble in haloalkanes, aliphatic and aromatic hydrocarbons, ethers.[7] Improved solubility in carboxylates, alcohols, ketones, amines. Miscible with methanol, ethanol, propanol, isopropanol, acetone, glycerol, 1,4-dioxane, tetrahydrofuran, sulfolane, acetaldehyde, dimethylformamide, dimethoxyethane, dimethyl sulfoxide, acetonitrile. Partially miscible with diethyl ether, methyl ethyl ketone, dichloromethane, ethyl acetate, bromine. | ||

| Vapor pressure | 3.1690 kilopascals or 0.031276 atm at 25 °C[8] | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 13.995[9][10][a] | ||

| Basicity (pKb) | 13.995 | ||

| Conjugate acid | Hydronium H3O+ (pKa = 0) | ||

| Conjugate base | Hydroxide OH– (pKb = 0) | ||

| Thermal conductivity | 0.6065 W/(m·K)[13] | ||

Refractive index (nD) | 1.3330 (20 °C)[14] | ||

| Viscosity | 0.890 mPa·s (0.890 cP)[15] | ||

| Structure | |||

| Hexagonal | |||

| C2v | |||

| Bent | |||

| 1.8546 D[17] | |||

| Thermochemistry | |||

Heat capacity (C) | 75.385 ± 0.05 J/(mol·K)[16] | ||

Std molar entropy (S⦵298) | 69.95 ± 0.03 J/(mol·K)[16] | ||

Std enthalpy of formation (ΔfH⦵298) | −285.83 ± 0.04 kJ/mol[7][16] | ||

Gibbs free energy (ΔfG⦵) | −237.24 kJ/mol[7] | ||

| Hazards | |||

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |||

Main hazards | Drowning Avalanche (as snow) Water intoxication | ||

| NFPA 704 (fire diamond) | |||

| Flash point | Non-flammable | ||

| Safety data sheet (SDS) | SDS | ||

| Related compounds | |||

Other cations | |||

Related solvents | |||

| Supplementary data page | |||

| Water (data page) | |||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |||

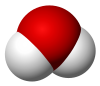

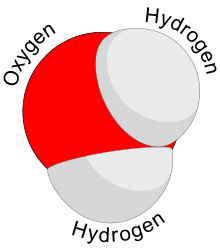

Вода – неорганическое соединение с химической формулой Н 2 О. Это прозрачный, безвкусный, без запаха, [с] и почти бесцветное химическое вещество , являющееся основной составляющей и гидросферы Земли растворитель жидкостей всех известных живых организмов (в которых оно действует как ). [19] ). Он жизненно важен для всех известных форм жизни , несмотря на то, что он не обеспечивает пищевой энергией и органическими микроэлементами . Его химическая формула, H 2 O , указывает на то, что каждая его молекула содержит один атом кислорода и два водорода атома , соединенных ковалентными связями . Атомы водорода присоединены к атому кислорода под углом 104,45°. [20] В жидкой форме, H 2 O также называют «Водой» при стандартной температуре и давлении .

Поскольку окружающая среда Земли относительно близка к тройной точке воды , вода существует на Земле в твердом состоянии , жидкости и газе . [21] Образует осадки в виде дождя и аэрозоли в виде тумана . Облака состоят из взвешенных капель воды и льда , его твердого состояния. Мелко измельченный кристаллический лед может выпадать в виде снега . Газообразное состояние воды — пар или водяной пар .

Water covers about 71% of the Earth's surface, with seas and oceans making up most of the water volume (about 96.5%).[22] Small portions of water occur as groundwater (1.7%), in the glaciers and the ice caps of Antarctica and Greenland (1.7%), and in the air as vapor, clouds (consisting of ice and liquid water suspended in air), and precipitation (0.001%).[23][24] Water moves continually through the water cycle of evaporation, transpiration (evapotranspiration), condensation, precipitation, and runoff, usually reaching the sea.

Water plays an important role in the world economy. Approximately 70% of the fresh water used by humans goes to agriculture.[25] Fishing in salt and fresh water bodies has been, and continues to be, a major source of food for many parts of the world, providing 6.5% of global protein.[26] Much of the long-distance trade of commodities (such as oil, natural gas, and manufactured products) is transported by boats through seas, rivers, lakes, and canals. Large quantities of water, ice, and steam are used for cooling and heating in industry and homes. Water is an excellent solvent for a wide variety of substances, both mineral and organic; as such, it is widely used in industrial processes and in cooking and washing. Water, ice, and snow are also central to many sports and other forms of entertainment, such as swimming, pleasure boating, boat racing, surfing, sport fishing, diving, ice skating, snowboarding, and skiing.

Etymology

The word water comes from Old English wæter, from Proto-Germanic *watar (source also of Old Saxon watar, Old Frisian wetir, Dutch water, Old High German wazzar, German Wasser, vatn, Gothic 𐍅𐌰𐍄𐍉 (wato)), from Proto-Indo-European *wod-or, suffixed form of root *wed- ('water'; 'wet').[27] Also cognate, through the Indo-European root, with Greek ύδωρ (ýdor; from Ancient Greek ὕδωρ (hýdōr), whence English 'hydro-'), Russian вода́ (vodá), Irish uisce, and Albanian ujë.

History

On Earth

One factor in estimating when water appeared on Earth is that water is continually being lost to space. H2O molecules in the atmosphere are broken up by photolysis, and the resulting free hydrogen atoms can sometimes escape Earth's gravitational pull. When the Earth was younger and less massive, water would have been lost to space more easily. Lighter elements like hydrogen and helium are expected to leak from the atmosphere continually, but isotopic ratios of heavier noble gases in the modern atmosphere suggest that even the heavier elements in the early atmosphere were subject to significant losses.[28] In particular, xenon is useful for calculations of water loss over time. Not only is it a noble gas (and therefore is not removed from the atmosphere through chemical reactions with other elements), but comparisons between the abundances of its nine stable isotopes in the modern atmosphere reveal that the Earth lost at least one ocean of water early in its history, between the Hadean and Archean eons.[29][clarification needed]

Any water on Earth during the latter part of its accretion would have been disrupted by the Moon-forming impact (~4.5 billion years ago), which likely vaporized much of Earth's crust and upper mantle and created a rock-vapor atmosphere around the young planet.[30][31] The rock vapor would have condensed within two thousand years, leaving behind hot volatiles which probably resulted in a majority carbon dioxide atmosphere with hydrogen and water vapor. Afterward, liquid water oceans may have existed despite the surface temperature of 230 °C (446 °F) due to the increased atmospheric pressure of the CO2 atmosphere. As the cooling continued, most CO2 was removed from the atmosphere by subduction and dissolution in ocean water, but levels oscillated wildly as new surface and mantle cycles appeared.[32]

Geological evidence also helps constrain the time frame for liquid water existing on Earth. A sample of pillow basalt (a type of rock formed during an underwater eruption) was recovered from the Isua Greenstone Belt and provides evidence that water existed on Earth 3.8 billion years ago.[33] In the Nuvvuagittuq Greenstone Belt, Quebec, Canada, rocks dated at 3.8 billion years old by one study[34] and 4.28 billion years old by another[35] show evidence of the presence of water at these ages.[33] If oceans existed earlier than this, any geological evidence has yet to be discovered (which may be because such potential evidence has been destroyed by geological processes like crustal recycling). More recently, in August 2020, researchers reported that sufficient water to fill the oceans may have always been on the Earth since the beginning of the planet's formation.[36][37][38]

Unlike rocks, minerals called zircons are highly resistant to weathering and geological processes and so are used to understand conditions on the very early Earth. Mineralogical evidence from zircons has shown that liquid water and an atmosphere must have existed 4.404 ± 0.008 billion years ago, very soon after the formation of Earth.[39][40][41][42] This presents somewhat of a paradox, as the cool early Earth hypothesis suggests temperatures were cold enough to freeze water between about 4.4 billion and 4.0 billion years ago. Other studies of zircons found in Australian Hadean rock point to the existence of plate tectonics as early as 4 billion years ago. If true, that implies that rather than a hot, molten surface and an atmosphere full of carbon dioxide, early Earth's surface was much as it is today (in terms of thermal insulation). The action of plate tectonics traps vast amounts of CO2, thereby reducing greenhouse effects, leading to a much cooler surface temperature and the formation of solid rock and liquid water.[43]Properties

Water (H2O) is a polar inorganic compound. At room temperature it is a tasteless and odorless liquid, nearly colorless with a hint of blue. This simplest hydrogen chalcogenide is by far the most studied chemical compound and is described as the "universal solvent" for its ability to dissolve many substances.[44][45] This allows it to be the "solvent of life":[46] indeed, water as found in nature almost always includes various dissolved substances, and special steps are required to obtain chemically pure water. Water is the only common substance to exist as a solid, liquid, and gas in normal terrestrial conditions.[47]

States

Along with oxidane, water is one of the two official names for the chemical compound H

2O;[48] it is also the liquid phase of H

2O.[49] The other two common states of matter of water are the solid phase, ice, and the gaseous phase, water vapor or steam. The addition or removal of heat can cause phase transitions: freezing (water to ice), melting (ice to water), vaporization (water to vapor), condensation (vapor to water), sublimation (ice to vapor) and deposition (vapor to ice).[50]

Density

Water differs from most liquids in that it becomes less dense as it freezes.[d] In 1 atm pressure, it reaches its maximum density of 999.972 kg/m3 (62.4262 lb/cu ft) at 3.98 °C (39.16 °F), or almost 1,000 kg/m3 (62.43 lb/cu ft) at almost 4 °C (39 °F).[52][53] The density of ice is 917 kg/m3 (57.25 lb/cu ft), an expansion of 9%.[54][55] This expansion can exert enormous pressure, bursting pipes and cracking rocks.[56]

In a lake or ocean, water at 4 °C (39 °F) sinks to the bottom, and ice forms on the surface, floating on the liquid water. This ice insulates the water below, preventing it from freezing solid. Without this protection, most aquatic organisms residing in lakes would perish during the winter.[57]

Magnetism

Water is a diamagnetic material.[58] Though interaction is weak, with superconducting magnets it can attain a notable interaction.[58]

Phase transitions

At a pressure of one atmosphere (atm), ice melts or water freezes (solidifies) at 0 °C (32 °F) and water boils or vapor condenses at 100 °C (212 °F). However, even below the boiling point, water can change to vapor at its surface by evaporation (vaporization throughout the liquid is known as boiling). Sublimation and deposition also occur on surfaces.[50] For example, frost is deposited on cold surfaces while snowflakes form by deposition on an aerosol particle or ice nucleus.[59] In the process of freeze-drying, a food is frozen and then stored at low pressure so the ice on its surface sublimates.[60]

The melting and boiling points depend on pressure. A good approximation for the rate of change of the melting temperature with pressure is given by the Clausius–Clapeyron relation:

where and are the molar volumes of the liquid and solid phases, and is the molar latent heat of melting. In most substances, the volume increases when melting occurs, so the melting temperature increases with pressure. However, because ice is less dense than water, the melting temperature decreases.[51] In glaciers, pressure melting can occur under sufficiently thick volumes of ice, resulting in subglacial lakes.[61][62]

The Clausius-Clapeyron relation also applies to the boiling point, but with the liquid/gas transition the vapor phase has a much lower density than the liquid phase, so the boiling point increases with pressure.[63] Water can remain in a liquid state at high temperatures in the deep ocean or underground. For example, temperatures exceed 205 °C (401 °F) in Old Faithful, a geyser in Yellowstone National Park.[64] In hydrothermal vents, the temperature can exceed 400 °C (752 °F).[65]

At sea level, the boiling point of water is 100 °C (212 °F). As atmospheric pressure decreases with altitude, the boiling point decreases by 1 °C every 274 meters. High-altitude cooking takes longer than sea-level cooking. For example, at 1,524 metres (5,000 ft), cooking time must be increased by a fourth to achieve the desired result.[66] Conversely, a pressure cooker can be used to decrease cooking times by raising the boiling temperature.[67] In a vacuum, water will boil at room temperature.[68]

Triple and critical points

On a pressure/temperature phase diagram (see figure), there are curves separating solid from vapor, vapor from liquid, and liquid from solid. These meet at a single point called the triple point, where all three phases can coexist. The triple point is at a temperature of 273.16 K (0.01 °C; 32.02 °F) and a pressure of 611.657 pascals (0.00604 atm; 0.0887 psi);[69] it is the lowest pressure at which liquid water can exist. Until 2019, the triple point was used to define the Kelvin temperature scale.[70][71]

The water/vapor phase curve terminates at 647.096 K (373.946 °C; 705.103 °F) and 22.064 megapascals (3,200.1 psi; 217.75 atm).[72] This is known as the critical point. At higher temperatures and pressures the liquid and vapor phases form a continuous phase called a supercritical fluid. It can be gradually compressed or expanded between gas-like and liquid-like densities; its properties (which are quite different from those of ambient water) are sensitive to density. For example, for suitable pressures and temperatures it can mix freely with nonpolar compounds, including most organic compounds. This makes it useful in a variety of applications including high-temperature electrochemistry and as an ecologically benign solvent or catalyst in chemical reactions involving organic compounds. In Earth's mantle, it acts as a solvent during mineral formation, dissolution and deposition.[73][74]

Phases of ice and water

The normal form of ice on the surface of Earth is ice Ih, a phase that forms crystals with hexagonal symmetry. Another with cubic crystalline symmetry, ice Ic, can occur in the upper atmosphere.[75] As the pressure increases, ice forms other crystal structures. As of 2024, twenty have been experimentally confirmed and several more are predicted theoretically.[76] The eighteenth form of ice, ice XVIII, a face-centred-cubic, superionic ice phase, was discovered when a droplet of water was subject to a shock wave that raised the water's pressure to millions of atmospheres and its temperature to thousands of degrees, resulting in a structure of rigid oxygen atoms in which hydrogen atoms flowed freely.[77][78] When sandwiched between layers of graphene, ice forms a square lattice.[79]

The details of the chemical nature of liquid water are not well understood; some theories suggest that its unusual behaviour is due to the existence of two liquid states.[53][80][81][82]

Taste and odor

Pure water is usually described as tasteless and odorless, although humans have specific sensors that can feel the presence of water in their mouths,[83][84] and frogs are known to be able to smell it.[85] However, water from ordinary sources (including mineral water) usually has many dissolved substances that may give it varying tastes and odors. Humans and other animals have developed senses that enable them to evaluate the potability of water in order to avoid water that is too salty or putrid.[86]

Color and appearance

Pure water is visibly blue due to absorption of light in the region c. 600–800 nm.[87] The color can be easily observed in a glass of tap-water placed against a pure white background, in daylight. The principal absorption bands responsible for the color are overtones of the O–H stretching vibrations. The apparent intensity of the color increases with the depth of the water column, following Beer's law. This also applies, for example, with a swimming pool when the light source is sunlight reflected from the pool's white tiles.

In nature, the color may also be modified from blue to green due to the presence of suspended solids or algae.

In industry, near-infrared spectroscopy is used with aqueous solutions as the greater intensity of the lower overtones of water means that glass cuvettes with short path-length may be employed. To observe the fundamental stretching absorption spectrum of water or of an aqueous solution in the region around 3,500 cm−1 (2.85 μm)[88] a path length of about 25 μm is needed. Also, the cuvette must be both transparent around 3500 cm−1 and insoluble in water; calcium fluoride is one material that is in common use for the cuvette windows with aqueous solutions.

The Raman-active fundamental vibrations may be observed with, for example, a 1 cm sample cell.

Aquatic plants, algae, and other photosynthetic organisms can live in water up to hundreds of meters deep, because sunlight can reach them.Practically no sunlight reaches the parts of the oceans below 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) of depth.

The refractive index of liquid water (1.333 at 20 °C (68 °F)) is much higher than that of air (1.0), similar to those of alkanes and ethanol, but lower than those of glycerol (1.473), benzene (1.501), carbon disulfide (1.627), and common types of glass (1.4 to 1.6). The refraction index of ice (1.31) is lower than that of liquid water.

Molecular polarity

In a water molecule, the hydrogen atoms form a 104.5° angle with the oxygen atom. The hydrogen atoms are close to two corners of a tetrahedron centered on the oxygen. At the other two corners are lone pairs of valence electrons that do not participate in the bonding. In a perfect tetrahedron, the atoms would form a 109.5° angle, but the repulsion between the lone pairs is greater than the repulsion between the hydrogen atoms.[89][90] The O–H bond length is about 0.096 nm.[91]

Other substances have a tetrahedral molecular structure, for example methane (CH

4) and hydrogen sulfide (H

2S). However, oxygen is more electronegative than most other elements, so the oxygen atom has a negative partial charge while the hydrogen atoms are partially positively charged. Along with the bent structure, this gives the molecule an electrical dipole moment and it is classified as a polar molecule.[92]

Water is a good polar solvent, dissolving many salts and hydrophilic organic molecules such as sugars and simple alcohols such as ethanol. Water also dissolves many gases, such as oxygen and carbon dioxide—the latter giving the fizz of carbonated beverages, sparkling wines and beers. In addition, many substances in living organisms, such as proteins, DNA and polysaccharides, are dissolved in water. The interactions between water and the subunits of these biomacromolecules shape protein folding, DNA base pairing, and other phenomena crucial to life (hydrophobic effect).

Many organic substances (such as fats and oils and alkanes) are hydrophobic, that is, insoluble in water. Many inorganic substances are insoluble too, including most metal oxides, sulfides, and silicates.

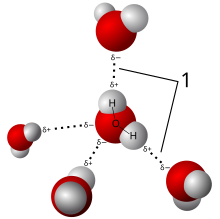

Hydrogen bonding

Because of its polarity, a molecule of water in the liquid or solid state can form up to four hydrogen bonds with neighboring molecules. Hydrogen bonds are about ten times as strong as the Van der Waals force that attracts molecules to each other in most liquids. This is the reason why the melting and boiling points of water are much higher than those of other analogous compounds like hydrogen sulfide. They also explain its exceptionally high specific heat capacity (about 4.2 J/(g·K)), heat of fusion (about 333 J/g), heat of vaporization (2257 J/g), and thermal conductivity (between 0.561 and 0.679 W/(m·K)). These properties make water more effective at moderating Earth's climate, by storing heat and transporting it between the oceans and the atmosphere. The hydrogen bonds of water are around 23 kJ/mol (compared to a covalent O-H bond at 492 kJ/mol). Of this, it is estimated that 90% is attributable to electrostatics, while the remaining 10% is partially covalent.[93]

These bonds are the cause of water's high surface tension[94] and capillary forces. The capillary action refers to the tendency of water to move up a narrow tube against the force of gravity. This property is relied upon by all vascular plants, such as trees.[citation needed]

Self-ionization

Water is a weak solution of hydronium hydroxide—there is an equilibrium 2H

2O ⇌ H

3O+

+ OH−

, in combination with solvation of the resulting hydronium and hydroxide ions.

Electrical conductivity and electrolysis

Pure water has a low electrical conductivity, which increases with the dissolution of a small amount of ionic material such as common salt.

Liquid water can be split into the elements hydrogen and oxygen by passing an electric current through it—a process called electrolysis. The decomposition requires more energy input than the heat released by the inverse process (285.8 kJ/mol, or 15.9 MJ/kg).[96]

Mechanical properties

Liquid water can be assumed to be incompressible for most purposes: its compressibility ranges from 4.4 to 5.1×10−10 Pa−1 in ordinary conditions.[97] Even in oceans at 4 km depth, where the pressure is 400 atm, water suffers only a 1.8% decrease in volume.[98]

The viscosity of water is about 10−3 Pa·s or 0.01 poise at 20 °C (68 °F), and the speed of sound in liquid water ranges between 1,400 and 1,540 meters per second (4,600 and 5,100 ft/s) depending on temperature. Sound travels long distances in water with little attenuation, especially at low frequencies (roughly 0.03 dB/km for 1 kHz), a property that is exploited by cetaceans and humans for communication and environment sensing (sonar).[99]

Reactivity

Metallic elements which are more electropositive than hydrogen, particularly the alkali metals and alkaline earth metals such as lithium, sodium, calcium, potassium and cesium displace hydrogen from water, forming hydroxides and releasing hydrogen. At high temperatures, carbon reacts with steam to form carbon monoxide and hydrogen.[citation needed]

On Earth

Hydrology is the study of the movement, distribution, and quality of water throughout the Earth. The study of the distribution of water is hydrography. The study of the distribution and movement of groundwater is hydrogeology, of glaciers is glaciology, of inland waters is limnology and distribution of oceans is oceanography. Ecological processes with hydrology are in the focus of ecohydrology.

The collective mass of water found on, under, and over the surface of a planet is called the hydrosphere. Earth's approximate water volume (the total water supply of the world) is 1.386 billion cubic kilometres (333 million cubic miles).[23]

Liquid water is found in bodies of water, such as an ocean, sea, lake, river, stream, canal, pond, or puddle. The majority of water on Earth is seawater. Water is also present in the atmosphere in solid, liquid, and vapor states. It also exists as groundwater in aquifers.

Water is important in many geological processes. Groundwater is present in most rocks, and the pressure of this groundwater affects patterns of faulting. Water in the mantle is responsible for the melt that produces volcanoes at subduction zones. On the surface of the Earth, water is important in both chemical and physical weathering processes. Water, and to a lesser but still significant extent, ice, are also responsible for a large amount of sediment transport that occurs on the surface of the earth. Deposition of transported sediment forms many types of sedimentary rocks, which make up the geologic record of Earth history.

Water cycle

The water cycle (known scientifically as the hydrologic cycle) is the continuous exchange of water within the hydrosphere, between the atmosphere, soil water, surface water, groundwater, and plants.

Water moves perpetually through each of these regions in the water cycle consisting of the following transfer processes:

- evaporation from oceans and other water bodies into the air and transpiration from land plants and animals into the air.

- precipitation, from water vapor condensing from the air and falling to the earth or ocean.

- runoff from the land usually reaching the sea.

Most water vapors found mostly in the ocean returns to it, but winds carry water vapor over land at the same rate as runoff into the sea, about 47 Tt per year whilst evaporation and transpiration happening in land masses also contribute another 72 Tt per year. Precipitation, at a rate of 119 Tt per year over land, has several forms: most commonly rain, snow, and hail, with some contribution from fog and dew.[100] Dew is small drops of water that are condensed when a high density of water vapor meets a cool surface. Dew usually forms in the morning when the temperature is the lowest, just before sunrise and when the temperature of the earth's surface starts to increase.[101] Condensed water in the air may also refract sunlight to produce rainbows.

Water runoff often collects over watersheds flowing into rivers. Through erosion, runoff shapes the environment creating river valleys and deltas which provide rich soil and level ground for the establishment of population centers. A flood occurs when an area of land, usually low-lying, is covered with water which occurs when a river overflows its banks or a storm surge happens. On the other hand, drought is an extended period of months or years when a region notes a deficiency in its water supply. This occurs when a region receives consistently below average precipitation either due to its topography or due to its location in terms of latitude.

Water resources

Water resources are natural resources of water that are potentially useful for humans,[102] for example as a source of drinking water supply or irrigation water. Water occurs as both "stocks" and "flows". Water can be stored as lakes, water vapor, groundwater or aquifers, and ice and snow. Of the total volume of global freshwater, an estimated 69 percent is stored in glaciers and permanent snow cover; 30 percent is in groundwater; and the remaining 1 percent in lakes, rivers, the atmosphere, and biota.[103] The length of time water remains in storage is highly variable: some aquifers consist of water stored over thousands of years but lake volumes may fluctuate on a seasonal basis, decreasing during dry periods and increasing during wet ones. A substantial fraction of the water supply for some regions consists of water extracted from water stored in stocks, and when withdrawals exceed recharge, stocks decrease. By some estimates, as much as 30 percent of total water used for irrigation comes from unsustainable withdrawals of groundwater, causing groundwater depletion.[104]

Seawater and tides

Seawater contains about 3.5% sodium chloride on average, plus smaller amounts of other substances. The physical properties of seawater differ from fresh water in some important respects. It freezes at a lower temperature (about −1.9 °C (28.6 °F)) and its density increases with decreasing temperature to the freezing point, instead of reaching maximum density at a temperature above freezing. The salinity of water in major seas varies from about 0.7% in the Baltic Sea to 4.0% in the Red Sea. (The Dead Sea, known for its ultra-high salinity levels of between 30 and 40%, is really a salt lake.)

Tides are the cyclic rising and falling of local sea levels caused by the tidal forces of the Moon and the Sun acting on the oceans. Tides cause changes in the depth of the marine and estuarine water bodies and produce oscillating currents known as tidal streams. The changing tide produced at a given location is the result of the changing positions of the Moon and Sun relative to the Earth coupled with the effects of Earth rotation and the local bathymetry. The strip of seashore that is submerged at high tide and exposed at low tide, the intertidal zone, is an important ecological product of ocean tides.

Effects on life

From a biological standpoint, water has many distinct properties that are critical for the proliferation of life. It carries out this role by allowing organic compounds to react in ways that ultimately allow replication. All known forms of life depend on water. Water is vital both as a solvent in which many of the body's solutes dissolve and as an essential part of many metabolic processes within the body. Metabolism is the sum total of anabolism and catabolism. In anabolism, water is removed from molecules (through energy requiring enzymatic chemical reactions) in order to grow larger molecules (e.g., starches, triglycerides, and proteins for storage of fuels and information). In catabolism, water is used to break bonds in order to generate smaller molecules (e.g., glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids to be used for fuels for energy use or other purposes). Without water, these particular metabolic processes could not exist.

Water is fundamental to both photosynthesis and respiration. Photosynthetic cells use the sun's energy to split off water's hydrogen from oxygen.[105] In the presence of sunlight, hydrogen is combined with CO

2 (absorbed from air or water) to form glucose and release oxygen.[106] All living cells use such fuels and oxidize the hydrogen and carbon to capture the sun's energy and reform water and CO

2 in the process (cellular respiration).

Water is also central to acid-base neutrality and enzyme function. An acid, a hydrogen ion (H+

, that is, a proton) donor, can be neutralized by a base, a proton acceptor such as a hydroxide ion (OH−

) to form water. Water is considered to be neutral, with a pH (the negative log of the hydrogen ion concentration) of 7. Acids have pH values less than 7 while bases have values greater than 7.

Aquatic life forms

Earth's surface waters are filled with life. The earliest life forms appeared in water; nearly all fish live exclusively in water, and there are many types of marine mammals, such as dolphins and whales. Some kinds of animals, such as amphibians, spend portions of their lives in water and portions on land. Plants such as kelp and algae grow in the water and are the basis for some underwater ecosystems. Plankton is generally the foundation of the ocean food chain.

Aquatic vertebrates must obtain oxygen to survive, and they do so in various ways. Fish have gills instead of lungs, although some species of fish, such as the lungfish, have both. Marine mammals, such as dolphins, whales, otters, and seals need to surface periodically to breathe air. Some amphibians are able to absorb oxygen through their skin. Invertebrates exhibit a wide range of modifications to survive in poorly oxygenated waters including breathing tubes (see insect and mollusc siphons) and gills (Carcinus). However, as invertebrate life evolved in an aquatic habitat most have little or no specialization for respiration in water.

- Some of the biodiversity of a coral reef

- Some marine diatoms – a key phytoplankton group

- Squat lobster and Alvinocarididae shrimp at the Von Damm hydrothermal field survive by altered water chemistry.

Effects on human civilization

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2018) |

Civilization has historically flourished around rivers and major waterways; Mesopotamia, one of the so-called cradles of civilization, was situated between the major rivers Tigris and Euphrates; the ancient society of the Egyptians depended entirely upon the Nile. The early Indus Valley civilization (c. 3300 BCE – c. 1300 BCE) developed along the Indus River and tributaries that flowed out of the Himalayas. Rome was also founded on the banks of the Italian river Tiber. Large metropolises like Rotterdam, London, Montreal, Paris, New York City, Buenos Aires, Shanghai, Tokyo, Chicago, and Hong Kong owe their success in part to their easy accessibility via water and the resultant expansion of trade. Islands with safe water ports, like Singapore, have flourished for the same reason. In places such as North Africa and the Middle East, where water is more scarce, access to clean drinking water was and is a major factor in human development.

Health and pollution

Water fit for human consumption is called drinking water or potable water. Water that is not potable may be made potable by filtration or distillation, or by a range of other methods. More than 660 million people do not have access to safe drinking water.[107][108]

Water that is not fit for drinking but is not harmful to humans when used for swimming or bathing is called by various names other than potable or drinking water, and is sometimes called safe water, or "safe for bathing". Chlorine is a skin and mucous membrane irritant that is used to make water safe for bathing or drinking. Its use is highly technical and is usually monitored by government regulations (typically 1 part per million (ppm) for drinking water, and 1–2 ppm of chlorine not yet reacted with impurities for bathing water). Water for bathing may be maintained in satisfactory microbiological condition using chemical disinfectants such as chlorine or ozone or by the use of ultraviolet light.

Water reclamation is the process of converting wastewater (most commonly sewage, also called municipal wastewater) into water that can be reused for other purposes. There are 2.3 billion people who reside in nations with water scarcities, which means that each individual receives less than 1,700 cubic metres (60,000 cu ft) of water annually. 380 billion cubic metres (13×1012 cu ft) of municipal wastewater are produced globally each year.[109][110][111]

Freshwater is a renewable resource, recirculated by the natural hydrologic cycle, but pressures over access to it result from the naturally uneven distribution in space and time, growing economic demands by agriculture and industry, and rising populations. Currently, nearly a billion people around the world lack access to safe, affordable water. In 2000, the United Nations established the Millennium Development Goals for water to halve by 2015 the proportion of people worldwide without access to safe water and sanitation. Progress toward that goal was uneven, and in 2015 the UN committed to the Sustainable Development Goals of achieving universal access to safe and affordable water and sanitation by 2030. Poor water quality and bad sanitation are deadly; some five million deaths a year are caused by water-related diseases. The World Health Organization estimates that safe water could prevent 1.4 million child deaths from diarrhoea each year.[112]

In developing countries, 90% of all municipal wastewater still goes untreated into local rivers and streams.[113] Some 50 countries, with roughly a third of the world's population, also suffer from medium or high water scarcity and 17 of these extract more water annually than is recharged through their natural water cycles.[114] The strain not only affects surface freshwater bodies like rivers and lakes, but it also degrades groundwater resources.

Human uses

Agriculture

The most substantial human use of water is for agriculture, including irrigated agriculture, which accounts for as much as 80 to 90 percent of total human water consumption.[116] In the United States, 42% of freshwater withdrawn for use is for irrigation, but the vast majority of water "consumed" (used and not returned to the environment) goes to agriculture.[117]

Access to fresh water is often taken for granted, especially in developed countries that have built sophisticated water systems for collecting, purifying, and delivering water, and removing wastewater. But growing economic, demographic, and climatic pressures are increasing concerns about water issues, leading to increasing competition for fixed water resources, giving rise to the concept of peak water.[118] As populations and economies continue to grow, consumption of water-thirsty meat expands, and new demands rise for biofuels or new water-intensive industries, new water challenges are likely.[119]

An assessment of water management in agriculture was conducted in 2007 by the International Water Management Institute in Sri Lanka to see if the world had sufficient water to provide food for its growing population.[120] It assessed the current availability of water for agriculture on a global scale and mapped out locations suffering from water scarcity. It found that a fifth of the world's people, more than 1.2 billion, live in areas of physical water scarcity, where there is not enough water to meet all demands. A further 1.6 billion people live in areas experiencing economic water scarcity, where the lack of investment in water or insufficient human capacity make it impossible for authorities to satisfy the demand for water. The report found that it would be possible to produce the food required in the future, but that continuation of today's food production and environmental trends would lead to crises in many parts of the world. To avoid a global water crisis, farmers will have to strive to increase productivity to meet growing demands for food, while industries and cities find ways to use water more efficiently.[121]

Water scarcity is also caused by production of water intensive products. For example, cotton: 1 kg of cotton—equivalent of a pair of jeans—requires 10.9 cubic meters (380 cu ft) water to produce. While cotton accounts for 2.4% of world water use, the water is consumed in regions that are already at a risk of water shortage. Significant environmental damage has been caused: for example, the diversion of water by the former Soviet Union from the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers to produce cotton was largely responsible for the disappearance of the Aral Sea.[122]

- Water requirement per tonne of food product

- Water distribution in subsurface drip irrigation

- Irrigation of field crops

As a scientific standard

On 7 April 1795, the gram was defined in France to be equal to "the absolute weight of a volume of pure water equal to a cube of one-hundredth of a meter, and at the temperature of melting ice".[123] For practical purposes though, a metallic reference standard was required, one thousand times more massive, the kilogram. Work was therefore commissioned to determine precisely the mass of one liter of water. In spite of the fact that the decreed definition of the gram specified water at 0 °C (32 °F)—a highly reproducible temperature—the scientists chose to redefine the standard and to perform their measurements at the temperature of highest water density, which was measured at the time as 4 °C (39 °F).[124]

The Kelvin temperature scale of the SI system was based on the triple point of water, defined as exactly 273.16 K (0.01 °C; 32.02 °F), but as of May 2019 is based on the Boltzmann constant instead. The scale is an absolute temperature scale with the same increment as the Celsius temperature scale, which was originally defined according to the boiling point (set to 100 °C (212 °F)) and melting point (set to 0 °C (32 °F)) of water.

Natural water consists mainly of the isotopes hydrogen-1 and oxygen-16, but there is also a small quantity of heavier isotopes oxygen-18, oxygen-17, and hydrogen-2 (deuterium). The percentage of the heavier isotopes is very small, but it still affects the properties of water. Water from rivers and lakes tends to contain less heavy isotopes than seawater. Therefore, standard water is defined in the Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water specification.

For drinking

The human body contains from 55% to 78% water, depending on body size.[125][user-generated source?] To function properly, the body requires between one and seven liters (0.22 and 1.54 imp gal; 0.26 and 1.85 U.S. gal)[citation needed] of water per day to avoid dehydration; the precise amount depends on the level of activity, temperature, humidity, and other factors. Most of this is ingested through foods or beverages other than drinking straight water. It is not clear how much water intake is needed by healthy people, though the British Dietetic Association advises that 2.5 liters of total water daily is the minimum to maintain proper hydration, including 1.8 liters (6 to 7 glasses) obtained directly from beverages.[126] Medical literature favors a lower consumption, typically 1 liter of water for an average male, excluding extra requirements due to fluid loss from exercise or warm weather.[127]

Healthy kidneys can excrete 0.8 to 1 liter of water per hour, but stress such as exercise can reduce this amount. People can drink far more water than necessary while exercising, putting them at risk of water intoxication (hyperhydration), which can be fatal.[128][129] The popular claim that "a person should consume eight glasses of water per day" seems to have no real basis in science.[130] Studies have shown that extra water intake, especially up to 500 milliliters (18 imp fl oz; 17 U.S. fl oz) at mealtime, was associated with weight loss.[131][132][133][134][135][136] Adequate fluid intake is helpful in preventing constipation.[137]

An original recommendation for water intake in 1945 by the Food and Nutrition Board of the U.S. National Research Council read: "An ordinary standard for diverse persons is 1 milliliter for each calorie of food. Most of this quantity is contained in prepared foods."[138] The latest dietary reference intake report by the U.S. National Research Council in general recommended, based on the median total water intake from US survey data (including food sources): 3.7 liters (0.81 imp gal; 0.98 U.S. gal) for men and 2.7 liters (0.59 imp gal; 0.71 U.S. gal) of water total for women, noting that water contained in food provided approximately 19% of total water intake in the survey.[139]

Specifically, pregnant and breastfeeding women need additional fluids to stay hydrated. The US Institute of Medicine recommends that, on average, men consume 3 liters (0.66 imp gal; 0.79 U.S. gal) and women 2.2 liters (0.48 imp gal; 0.58 U.S. gal); pregnant women should increase intake to 2.4 liters (0.53 imp gal; 0.63 U.S. gal) and breastfeeding women should get 3 liters (12 cups), since an especially large amount of fluid is lost during nursing.[140] Also noted is that normally, about 20% of water intake comes from food, while the rest comes from drinking water and beverages (caffeinated included). Water is excreted from the body in multiple forms; through urine and feces, through sweating, and by exhalation of water vapor in the breath. With physical exertion and heat exposure, water loss will increase and daily fluid needs may increase as well.

Humans require water with few impurities. Common impurities include metal salts and oxides, including copper, iron, calcium and lead,[141][full citation needed] and harmful bacteria, such as Vibrio. Some solutes are acceptable and even desirable for taste enhancement and to provide needed electrolytes.[142]

The single largest (by volume) freshwater resource suitable for drinking is Lake Baikal in Siberia.[143]

Washing

Washing is a method of cleaning, usually with water and soap or detergent. Regularly washing and then rinsing both body and clothing is an essential part of good hygiene and health.[144][145][146]

Often people use soaps and detergents to assist in the emulsification of oils and dirt particles so they can be washed away. The soap can be applied directly, or with the aid of a washcloth.

People wash themselves, or bathe periodically for religious ritual or therapeutic purposes[147] or as a recreational activity.

In Europe, some people use a bidet to wash their external genitalia and the anal region after using the toilet, instead of using toilet paper.[148] The bidet is common in predominantly Catholic countries where water is considered essential for anal cleansing.[149]

More frequent is washing of just the hands, e.g. before and after preparing food and eating, after using the toilet, after handling something dirty, etc. Hand washing is important in reducing the spread of germs.[150][151] Also common is washing the face, which is done after waking up, or to keep oneself cool during the day. Brushing one's teeth is also essential for hygiene and is a part of washing.

'Washing' can also refer to the washing of clothing or other cloth items, like bedsheets, whether by hand or with a washing machine. It can also refer to washing one's car, by lathering the exterior with car soap, then rinsing it off with a hose, or washing cookware.

Transportation

Maritime transport (or ocean transport) or more generally waterborne transport, is the transport of people (passengers) or goods (cargo) via waterways. Freight transport by sea has been widely used throughout recorded history. The advent of aviation has diminished the importance of sea travel for passengers, though it is still popular for short trips and pleasure cruises. Transport by water is cheaper than transport by air or ground,[154] but significantly slower for longer distances. Maritime transport accounts for roughly 80% of international trade, according to UNCTAD in 2020.

Maritime transport can be realized over any distance by boat, ship, sailboat or barge, over oceans and lakes, through canals or along rivers. Shipping may be for commerce, recreation, or military purposes. While extensive inland shipping is less critical today, the major waterways of the world including many canals are still very important and are integral parts of worldwide economies. Particularly, especially any material can be moved by water; however, water transport becomes impractical when material delivery is time-critical such as various types of perishable produce. Still, water transport is highly cost effective with regular schedulable cargoes, such as trans-oceanic shipping of consumer products – and especially for heavy loads or bulk cargos, such as coal, coke, ores, or grains. Arguably, the industrial revolution had its first impacts where cheap water transport by canal, navigations, or shipping by all types of watercraft on natural waterways supported cost-effective bulk transport.

Containerization revolutionized maritime transport starting in the 1970s. "General cargo" includes goods packaged in boxes, cases, pallets, and barrels. When a cargo is carried in more than one mode, it is intermodal or co-modal.Chemical uses

Water is widely used in chemical reactions as a solvent or reactant and less commonly as a solute or catalyst. In inorganic reactions, water is a common solvent, dissolving many ionic compounds, as well as other polar compounds such as ammonia and compounds closely related to water. In organic reactions, it is not usually used as a reaction solvent, because it does not dissolve the reactants well and is amphoteric (acidic and basic) and nucleophilic. Nevertheless, these properties are sometimes desirable. Also, acceleration of Diels-Alder reactions by water has been observed. Supercritical water has recently been a topic of research. Oxygen-saturated supercritical water combusts organic pollutants efficiently.

Heat exchange

Water and steam are a common fluid used for heat exchange, due to its availability and high heat capacity, both for cooling and heating. Cool water may even be naturally available from a lake or the sea. It is especially effective to transport heat through vaporization and condensation of water because of its large latent heat of vaporization. A disadvantage is that metals commonly found in industries such as steel and copper are oxidized faster by untreated water and steam. In almost all thermal power stations, water is used as the working fluid (used in a closed-loop between boiler, steam turbine, and condenser), and the coolant (used to exchange the waste heat to a water body or carry it away by evaporation in a cooling tower). In the United States, cooling power plants is the largest use of water.[155]

In the nuclear power industry, water can also be used as a neutron moderator. In most nuclear reactors, water is both a coolant and a moderator. This provides something of a passive safety measure, as removing the water from the reactor also slows the nuclear reaction down. However other methods are favored for stopping a reaction and it is preferred to keep the nuclear core covered with water so as to ensure adequate cooling.

Fire considerations

Water has a high heat of vaporization and is relatively inert, which makes it a good fire extinguishing fluid. The evaporation of water carries heat away from the fire. It is dangerous to use water on fires involving oils and organic solvents because many organic materials float on water and the water tends to spread the burning liquid.

Use of water in fire fighting should also take into account the hazards of a steam explosion, which may occur when water is used on very hot fires in confined spaces, and of a hydrogen explosion, when substances which react with water, such as certain metals or hot carbon such as coal, charcoal, or coke graphite, decompose the water, producing water gas.

The power of such explosions was seen in the Chernobyl disaster, although the water involved in this case did not come from fire-fighting but from the reactor's own water cooling system. A steam explosion occurred when the extreme overheating of the core caused water to flash into steam. A hydrogen explosion may have occurred as a result of a reaction between steam and hot zirconium.

Some metallic oxides, most notably those of alkali metals and alkaline earth metals, produce so much heat in reaction with water that a fire hazard can develop. The alkaline earth oxide quicklime, also known as calcium oxide, is a mass-produced substance that is often transported in paper bags. If these are soaked through, they may ignite as their contents react with water.[156]

Recreation

Humans use water for many recreational purposes, as well as for exercising and for sports. Some of these include swimming, waterskiing, boating, surfing and diving. In addition, some sports, like ice hockey and ice skating, are played on ice. Lakesides, beaches and water parks are popular places for people to go to relax and enjoy recreation. Many find the sound and appearance of flowing water to be calming, and fountains and other flowing water structures are popular decorations. Some keep fish and other flora and fauna inside aquariums or ponds for show, fun, and companionship. Humans also use water for snow sports such as skiing, sledding, snowmobiling or snowboarding, which require the water to be at a low temperature either as ice or crystallized into snow.

Water industry

The water industry provides drinking water and wastewater services (including sewage treatment) to households and industry. Water supply facilities include water wells, cisterns for rainwater harvesting, water supply networks, and water purification facilities, water tanks, water towers, water pipes including old aqueducts. Atmospheric water generators are in development.

Drinking water is often collected at springs, extracted from artificial borings (wells) in the ground, or pumped from lakes and rivers. Building more wells in adequate places is thus a possible way to produce more water, assuming the aquifers can supply an adequate flow. Other water sources include rainwater collection. Water may require purification for human consumption. This may involve the removal of undissolved substances, dissolved substances and harmful microbes. Popular methods are filtering with sand which only removes undissolved material, while chlorination and boiling kill harmful microbes. Distillation does all three functions. More advanced techniques exist, such as reverse osmosis. Desalination of abundant seawater is a more expensive solution used in coastal arid climates.

The distribution of drinking water is done through municipal water systems, tanker delivery or as bottled water. Governments in many countries have programs to distribute water to the needy at no charge.

Reducing usage by using drinking (potable) water only for human consumption is another option. In some cities such as Hong Kong, seawater is extensively used for flushing toilets citywide in order to conserve freshwater resources.

Polluting water may be the biggest single misuse of water; to the extent that a pollutant limits other uses of the water, it becomes a waste of the resource, regardless of benefits to the polluter. Like other types of pollution, this does not enter standard accounting of market costs, being conceived as externalities for which the market cannot account. Thus other people pay the price of water pollution, while the private firms' profits are not redistributed to the local population, victims of this pollution. Pharmaceuticals consumed by humans often end up in the waterways and can have detrimental effects on aquatic life if they bioaccumulate and if they are not biodegradable.

Municipal and industrial wastewater are typically treated at wastewater treatment plants. Mitigation of polluted surface runoff is addressed through a variety of prevention and treatment techniques.

- A water-carrier in India, 1882. In many places where running water is not available, water has to be transported by people.

- A manual water pump in China

- Water purification facility

Industrial applications

Many industrial processes rely on reactions using chemicals dissolved in water, suspension of solids in water slurries or using water to dissolve and extract substances, or to wash products or process equipment. Processes such as mining, chemical pulping, pulp bleaching, paper manufacturing, textile production, dyeing, printing, and cooling of power plants use large amounts of water, requiring a dedicated water source, and often cause significant water pollution.

Water is used in power generation. Hydroelectricity is electricity obtained from hydropower. Hydroelectric power comes from water driving a water turbine connected to a generator. Hydroelectricity is a low-cost, non-polluting, renewable energy source. The energy is supplied by the motion of water. Typically a dam is constructed on a river, creating an artificial lake behind it. Water flowing out of the lake is forced through turbines that turn generators.

Pressurized water is used in water blasting and water jet cutters. High pressure water guns are used for precise cutting. It works very well, is relatively safe, and is not harmful to the environment. It is also used in the cooling of machinery to prevent overheating, or prevent saw blades from overheating.

Water is also used in many industrial processes and machines, such as the steam turbine and heat exchanger, in addition to its use as a chemical solvent. Discharge of untreated water from industrial uses is pollution. Pollution includes discharged solutes (chemical pollution) and discharged coolant water (thermal pollution). Industry requires pure water for many applications and uses a variety of purification techniques both in water supply and discharge.

Food processing

Boiling, steaming, and simmering are popular cooking methods that often require immersing food in water or its gaseous state, steam.[157] Water is also used for dishwashing. Water also plays many critical roles within the field of food science.

Solutes such as salts and sugars found in water affect the physical properties of water. The boiling and freezing points of water are affected by solutes, as well as air pressure, which is in turn affected by altitude. Water boils at lower temperatures with the lower air pressure that occurs at higher elevations. One mole of sucrose (sugar) per kilogram of water raises the boiling point of water by 0.51 °C (0.918 °F), and one mole of salt per kg raises the boiling point by 1.02 °C (1.836 °F); similarly, increasing the number of dissolved particles lowers water's freezing point.[158]

Solutes in water also affect water activity that affects many chemical reactions and the growth of microbes in food.[159] Water activity can be described as a ratio of the vapor pressure of water in a solution to the vapor pressure of pure water.[158] Solutes in water lower water activity—this is important to know because most bacterial growth ceases at low levels of water activity.[159] Not only does microbial growth affect the safety of food, but also the preservation and shelf life of food.

Water hardness is also a critical factor in food processing and may be altered or treated by using a chemical ion exchange system. It can dramatically affect the quality of a product, as well as playing a role in sanitation. Water hardness is classified based on concentration of calcium carbonate the water contains. Water is classified as soft if it contains less than 100 mg/L (UK)[160] or less than 60 mg/L (US).[161]

According to a report published by the Water Footprint organization in 2010, a single kilogram of beef requires 15 thousand liters (3.3×103 imp gal; 4.0×103 U.S. gal) of water; however, the authors also make clear that this is a global average and circumstantial factors determine the amount of water used in beef production.[162]

Medical use

Water for injection is on the World Health Organization's list of essential medicines.[163]

Distribution in nature

In the universe

Much of the universe's water is produced as a byproduct of star formation. The formation of stars is accompanied by a strong outward wind of gas and dust. When this outflow of material eventually impacts the surrounding gas, the shock waves that are created compress and heat the gas. The water observed is quickly produced in this warm dense gas.[165]

On 22 July 2011, a report described the discovery of a gigantic cloud of water vapor containing "140 trillion times more water than all of Earth's oceans combined" around a quasar located 12 billion light years from Earth. According to the researchers, the "discovery shows that water has been prevalent in the universe for nearly its entire existence".[166][167]

Water has been detected in interstellar clouds within the Milky Way.[168] Water probably exists in abundance in other galaxies, too, because its components, hydrogen, and oxygen, are among the most abundant elements in the universe. Based on models of the formation and evolution of the Solar System and that of other star systems, most other planetary systems are likely to have similar ingredients.

Water vapor

Water is present as vapor in:

- Atmosphere of the Sun: in detectable trace amounts[169]

- Atmosphere of Mercury: 3.4%, and large amounts of water in Mercury's exosphere[170]

- Atmosphere of Venus: 0.002%[171]

- Earth's atmosphere: ≈0.40% over full atmosphere, typically 1–4% at surface; as well as that of the Moon in trace amounts[172]

- Atmosphere of Mars: 0.03%[173]

- Atmosphere of Ceres[174]

- Atmosphere of Jupiter: 0.0004%[175] – in ices only; and that of its moon Europa[176]

- Atmosphere of Saturn – in ices only; Enceladus: 91%[177] and Dione (exosphere)[citation needed]

- Atmosphere of Uranus – in trace amounts below 50 bar

- Atmosphere of Neptune – found in the deeper layers[178]

- Extrasolar planet atmospheres: including those of HD 189733 b[179] and HD 209458 b,[180] Tau Boötis b,[181] HAT-P-11b,[182][183] XO-1b, WASP-12b, WASP-17b, and WASP-19b.[184]

- Stellar atmospheres: not limited to cooler stars and even detected in giant hot stars such as Betelgeuse, Mu Cephei, Antares and Arcturus.[183][185]

- Circumstellar disks: including those of more than half of T Tauri stars such as AA Tauri[183] as well as TW Hydrae,[186][187] IRC +10216[188] and APM 08279+5255,[166][167] VY Canis Majoris and S Persei.[185]

Liquid water

Liquid water is present on Earth, covering 71% of its surface.[22] Liquid water is also occasionally present in small amounts on Mars.[189] Scientists believe liquid water is present in the Saturnian moons of Enceladus, as a 10-kilometre thick ocean approximately 30–40 kilometres below Enceladus' south polar surface,[190][191] and Titan, as a subsurface layer, possibly mixed with ammonia.[192] Jupiter's moon Europa has surface characteristics which suggest a subsurface liquid water ocean.[193] Liquid water may also exist on Jupiter's moon Ganymede as a layer sandwiched between high pressure ice and rock.[194]

Water ice

Water is present as ice on:

- Mars: under the regolith and at the poles.[195][196]

- Earth–Moon system: mainly as ice sheets on Earth and in Lunar craters and volcanic rocks[197] NASA reported the detection of water molecules by NASA's Moon Mineralogy Mapper aboard the Indian Space Research Organization's Chandrayaan-1 spacecraft in September 2009.[198]

- Ceres[199][200][201]

- Jupiter's moons: Europa's surface and also that of Ganymede[202] and Callisto[203][204]

- Saturn: in the planet's ring system[205] and on the surface and mantle of Titan[206] and Enceladus[207]

- Pluto–Charon system[205]

- Comets[208][209] and other related Kuiper belt and Oort cloud objects[210]

And is also likely present on:

Exotic forms

Water and other volatiles probably comprise much of the internal structures of Uranus and Neptune and the water in the deeper layers may be in the form of ionic water in which the molecules break down into a soup of hydrogen and oxygen ions, and deeper still as superionic water in which the oxygen crystallizes, but the hydrogen ions float about freely within the oxygen lattice.[213]

Water and planetary habitability

The existence of liquid water, and to a lesser extent its gaseous and solid forms, on Earth are vital to the existence of life on Earth as we know it. The Earth is located in the habitable zone of the Solar System; if it were slightly closer to or farther from the Sun (about 5%, or about 8 million kilometers), the conditions which allow the three forms to be present simultaneously would be far less likely to exist.[214][215]

Earth's gravity allows it to hold an atmosphere. Water vapor and carbon dioxide in the atmosphere provide a temperature buffer (greenhouse effect) which helps maintain a relatively steady surface temperature. If Earth were smaller, a thinner atmosphere would allow temperature extremes, thus preventing the accumulation of water except in polar ice caps (as on Mars).[citation needed]

The surface temperature of Earth has been relatively constant through geologic time despite varying levels of incoming solar radiation (insolation), indicating that a dynamic process governs Earth's temperature via a combination of greenhouse gases and surface or atmospheric albedo. This proposal is known as the Gaia hypothesis.[citation needed]

The state of water on a planet depends on ambient pressure, which is determined by the planet's gravity. If a planet is sufficiently massive, the water on it may be solid even at high temperatures, because of the high pressure caused by gravity, as it was observed on exoplanets Gliese 436 b[216] and GJ 1214 b.[217]

Law, politics, and crisis

This section needs to be updated. (June 2022) |

Water politics is politics affected by water and water resources. Water, particularly fresh water, is a strategic resource across the world and an important element in many political conflicts. It causes health impacts and damage to biodiversity.

Access to safe drinking water has improved over the last decades in almost every part of the world, but approximately one billion people still lack access to safe water and over 2.5 billion lack access to adequate sanitation.[218] However, some observers have estimated that by 2025 more than half of the world population will be facing water-based vulnerability.[219] A report, issued in November 2009, suggests that by 2030, in some developing regions of the world, water demand will exceed supply by 50%.[220]

1.6 billion people have gained access to a safe water source since 1990.[221] The proportion of people in developing countries with access to safe water is calculated to have improved from 30% in 1970[222] to 71% in 1990, 79% in 2000, and 84% in 2004.[218]

A 2006 United Nations report stated that "there is enough water for everyone", but that access to it is hampered by mismanagement and corruption.[223] In addition, global initiatives to improve the efficiency of aid delivery, such as the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, have not been taken up by water sector donors as effectively as they have in education and health, potentially leaving multiple donors working on overlapping projects and recipient governments without empowerment to act.[224]

The authors of the 2007 Comprehensive Assessment of Water Management in Agriculture cited poor governance as one reason for some forms of water scarcity. Water governance is the set of formal and informal processes through which decisions related to water management are made. Good water governance is primarily about knowing what processes work best in a particular physical and socioeconomic context. Mistakes have sometimes been made by trying to apply 'blueprints' that work in the developed world to developing world locations and contexts. The Mekong river is one example; a review by the International Water Management Institute of policies in six countries that rely on the Mekong river for water found that thorough and transparent cost-benefit analyses and environmental impact assessments were rarely undertaken. They also discovered that Cambodia's draft water law was much more complex than it needed to be.[225]

In 2004, the UK charity WaterAid reported that a child dies every 15 seconds from easily preventable water-related diseases, which are often tied to a lack of adequate sanitation.[226][227]

Since 2003, the UN World Water Development Report, produced by the UNESCO World Water Assessment Programme, has provided decision-makers with tools for developing sustainable water policies.[228] The 2023 report states that two billion people (26% of the population) do not have access to drinking water and 3.6 billion (46%) lack access to safely managed sanitation.[229] People in urban areas (2.4 billion) will face water scarcity by 2050.[228] Water scarcity has been described as endemic, due to overconsumption and pollution.[230] The report states that 10% of the world's population lives in countries with high or critical water stress. Yet over the past 40 years, water consumption has increased by around 1% per year, and is expected to grow at the same rate until 2050. Since 2000, flooding in the tropics has quadrupled, while flooding in northern mid-latitudes has increased by a factor of 2.5.[231] The cost of these floods between 2000 and 2019 was 100,000 deaths and $650 million.[228]

Organizations concerned with water protection include the International Water Association (IWA), WaterAid, Water 1st, and the American Water Resources Association. The International Water Management Institute undertakes projects with the aim of using effective water management to reduce poverty. Water related conventions are United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and Ramsar Convention. World Day for Water takes place on 22 March[232] and World Oceans Day on 8 June.[233]

In culture

Religion

Water is considered a purifier in most religions. Faiths that incorporate ritual washing (ablution) include Christianity,[234] Hinduism, Islam, Judaism, the Rastafari movement, Shinto, Taoism, and Wicca. Immersion (or aspersion or affusion) of a person in water is a central Sacrament of Christianity (where it is called baptism); it is also a part of the practice of other religions, including Islam (Ghusl), Judaism (mikvah) and Sikhism (Amrit Sanskar). In addition, a ritual bath in pure water is performed for the dead in many religions including Islam and Judaism. In Islam, the five daily prayers can be done in most cases after washing certain parts of the body using clean water (wudu), unless water is unavailable (see Tayammum). In Shinto, water is used in almost all rituals to cleanse a person or an area (e.g., in the ritual of misogi).

In Christianity, holy water is water that has been sanctified by a priest for the purpose of baptism, the blessing of persons, places, and objects, or as a means of repelling evil.[235][236]

In Zoroastrianism, water (āb) is respected as the source of life.[237]

Philosophy

The Ancient Greek philosopher Empedocles saw water as one of the four classical elements (along with fire, earth, and air), and regarded it as an ylem, or basic substance of the universe. Thales, whom Aristotle portrayed as an astronomer and an engineer, theorized that the earth, which is denser than water, emerged from the water. Thales, a monist, believed further that all things are made from water. Plato believed that the shape of water is an icosahedron – flowing easily compared to the cube-shaped earth.[238]

The theory of the four bodily humors associated water with phlegm, as being cold and moist. The classical element of water was also one of the five elements in traditional Chinese philosophy (along with earth, fire, wood, and metal).

Some traditional and popular Asian philosophical systems take water as a role-model. James Legge's 1891 translation of the Dao De Jing states, "The highest excellence is like (that of) water. The excellence of water appears in its benefiting all things, and in its occupying, without striving (to the contrary), the low place which all men dislike. Hence (its way) is near to (that of) the Tao" and "There is nothing in the world more soft and weak than water, and yet for attacking things that are firm and strong there is nothing that can take precedence of it—for there is nothing (so effectual) for which it can be changed."[239] Guanzi in the "Shui di" 水地 chapter further elaborates on the symbolism of water, proclaiming that "man is water" and attributing natural qualities of the people of different Chinese regions to the character of local water resources.[240]

Folklore

"Living water" features in Germanic and Slavic folktales as a means of bringing the dead back to life. Note the Grimm fairy-tale ("The Water of Life") and the Russian dichotomy of living and dead water. The Fountain of Youth represents a related concept of magical waters allegedly preventing aging.

Art and activism

Художница и активистка Фредерика Фостер курировала выставку «Ценность воды» в соборе Святого Иоанна Богослова в Нью-Йорке. [241] что положило начало годовой инициативе Собора о нашей зависимости от воды. [242] [243] Самая большая выставка, когда-либо проводившаяся в соборе. [244] в нем приняли участие более сорока художников, в том числе Дженни Хольцер , Роберт Лонго , Марк Ротко , Уильям Кентридж , Эйприл Горник , Кики Смит , Пэт Стейр , Элис Далтон Браун , Тересита Фернандес и Билл Виола . [245] [246] Фостер создал «Думай о воде», [247] [ нужна полная цитата ] экологический коллектив художников, использующих воду в качестве объекта или медиума. В число членов входят Басия Ирландия, [248] [ нужна полная цитата ] Авива Рахмани , Бетси Дэймон , Дайан Бурко , Лейла Доу , Стейси Леви , Шарлотта Коте, [249] Меридель Рубинштейн и Анна Маклауд .

Чтобы отметить 10-летие того, как ООН объявила доступ к воде и санитарии правом человека, благотворительная организация WaterAid наняла десять художников-иллюстраторов, чтобы они продемонстрировали влияние чистой воды на жизнь людей. [250] [251]

Пародия на угарный газ

«Монооксид дигидрогена» — технически правильное, но редко используемое химическое название воды. Это имя использовалось в ряде мистификаций и розыгрышей , высмеивающих научную неграмотность . Это началось в 1983 году, когда , появилась первоапрельская в газете в Дюране, штат Мичиган статья . Ложная история заключалась в опасениях по поводу безопасности этого вещества. [252]

Музыка

Слово «Вода» использовалось многими Флориды из рэперами как своего рода крылатая фраза или импровизация. Среди рэперов, которые сделали это, — BLP Kosher и Ski Mask the Slump God . [253] Чтобы пойти еще дальше, некоторые рэперы написали целые песни, посвященные воде во Флориде, например, песня Дэнни Тауэрса 2023 года «Florida Water». [254] Другие написали целые песни, посвященные воде в целом, например XXXTentacion и Ski Mask the Slump God со своим хитом «H2O».

См. также

- Очерк воды - Обзор и актуальное руководство по воде.

- Вода (страница данных) . Страница химических данных о воде представляет собой набор химических и физических свойств воды.

- Аквафобия – постоянный и ненормальный страх воды.

- Голубая крыша - крыша здания, предназначенная для временного хранения воды.

- Водосборник - устройство для улавливания или направления стоков.

- Право человека на воду и санитарию – право человека, признанное Генеральной Ассамблеей Организации Объединенных Наций в 2010 году.

- Гидроэлектроэнергия - Электроэнергия, вырабатываемая гидроэлектростанциями.

- Энергия морских течений - Извлечение энергии из океанских течений.

- Морская энергия - энергия, запасенная в водах океанов.

- Эффект Мпембы - природное явление, заключающееся в том, что горячая вода замерзает быстрее, чем холодная.

- Пероральная регидратационная терапия - тип восполнения жидкости, используемый для предотвращения и лечения обезвоживания.

- Осмотическая сила - энергия, получаемая за счет разницы в концентрации соли в морской и речной воде.

- Свойства воды – Физические и химические свойства чистой воды.

- Жажда – тяга к питьевой жидкости, испытываемая животными.

- Приливная энергия - технология преобразования энергии приливов в полезные формы энергии.

- Анализ водной щепотки

- Волновая энергия - перенос энергии ветровыми волнами и захват этой энергии для выполнения полезной работы.

- Фильтр для воды – устройство, удаляющее примеси из воды.

Примечания

- ^ Обычно цитируемое значение pK a воды 15,7, используемое в основном в органической химии, неверно. [11] [12]

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б Венская стандартная средняя океанская вода (VSMOW), используемая для калибровки, плавится при 273,1500089(10) К (0,000089(10) °C) и кипит при 373,1339 К (99,9839 °C). Другие изотопные составы плавятся или кипят при немного других температурах.

- ^ см вкуса и запаха . . раздел

- ^ Другие вещества с этим свойством включают висмут , кремний , германий и галлий . [51]

Ссылки

- ^ «Наименование молекулярных соединений» . www.iun.edu . Архивировано из оригинала 24 сентября 2018 года . Проверено 1 октября 2018 г.

Иногда эти соединения имеют родовые или общепринятые названия (например, H2O — «вода»), а также имеют систематические названия (например, H2O, монооксид дигидрогена).

- ^ «Определение гидрола» . Мерриам-Вебстер . Архивировано из оригинала 13 августа 2017 года . Проверено 21 апреля 2019 г.

- ^ Браун К.Л., Смирнов С.Н. (1 августа 1993 г.). «Почему вода голубая?» (PDF) . Журнал химического образования . 70 (8): 612. Бибкод : 1993ЖЧЭд..70..612Б . дои : 10.1021/ed070p612 . ISSN 0021-9584 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 1 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 13 сентября 2023 г.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Танака М., Жирар Дж., Дэвис Р., Пеуто А., Бигнелл Н. (август 2001 г.). «Рекомендуемая таблица плотности воды от 0 C до 40 C на основе недавних экспериментальных отчетов». Метрология . 38 (4): 301–309. дои : 10.1088/0026-1394/38/4/3 .

- ^ Леммон Э.В., Белл И.Х., Хубер М.Л., МакЛинден М.О. «Теплофизические свойства жидких систем». В Линстрем П., Маллард В. (ред.). Интернет-книга NIST по химии, стандартная справочная база данных NIST, номер 69 . Национальный институт стандартов и технологий. дои : 10.18434/T4D303 . Архивировано из оригинала 23 октября 2023 года . Проверено 17 октября 2023 г.

- ^ Лиде 2003 , Свойства льда и переохлажденной воды в разделе 6.

- ↑ Перейти обратно: Перейти обратно: а б с Анатольевич КР. «Свойства вещества: вода» . Архивировано из оригинала 2 июня 2014 года . Проверено 1 июня 2014 г.

- ^ Лиде 2003 , Давление пара воды от 0 до 370 ° C в сек. 6.

- ^ Лиде 2003 , Глава 8: Константы диссоциации неорганических кислот и оснований.

- ^ Вайнгертнер и др. 2016 , с. 13.

- ^ «Что такое рКа Воды» . Калифорнийский университет в Дэвисе . 9 августа 2015 года. Архивировано из оригинала 14 февраля 2016 года . Проверено 9 апреля 2016 г.

- ^ Сильверстайн Т.П., Хеллер С.Т. (17 апреля 2017 г.). «Значения pKa в учебной программе бакалавриата: какова настоящая pKa воды?». Журнал химического образования . 94 (6): 690–695. Бибкод : 2017ЖЧЭд..94..690С . doi : 10.1021/acs.jchemed.6b00623 .

- ^ Рамирес М.Л., Кастро Калифорния, Нагасака Ю., Нагасима А., Ассаэль М.Дж., Уэйкхэм, Вашингтон (1 мая 1995 г.). «Стандартные справочные данные по теплопроводности воды». Журнал физических и химических справочных данных . 24 (3): 1377–1381. Бибкод : 1995JPCRD..24.1377R . дои : 10.1063/1.555963 . ISSN 0047-2689 .

- ^ Lide 2003 , 8 — Концентрационные свойства водных растворов: плотность, показатель преломления, понижение температуры замерзания и вязкость.

- ^ Как и в 2003 году , 6.186.