шумерский язык

| Шумерский | |

|---|---|

| 𒅴𒂠 сделать 15 [1] | |

| |

| Родной для | Шумер и Аккад |

| Область | Месопотамия (современный Ирак ) |

| Эра | Засвидетельствовано с . 2900 г. до н.э. Вышел из народного обихода около 1700 г. до н.э.; использовался как классический язык примерно до 100 г. н.э. [2] |

| Диалекты | |

| Шумеро-аккадская клинопись | |

| Коды языков | |

| ИСО 639-2 | sux |

| ИСО 639-3 | sux |

uga | |

| глоттолог | sume1241 |

Шумерский (шумерский: 𒅴𒂠 , латинизированный: eme-gir 15 [а] , букв. '' родной язык '' [1] ) был языком древнего Шумера . Это один из старейших подтвержденных языков , возникший как минимум в 2900 году до нашей эры. Это изолированный местный язык , на котором говорили в древней Месопотамии , на территории современного Ирака .

Аккадский , семитский язык , постепенно заменил шумерский в качестве основного разговорного языка на территории c. 2000 г. до н.э. (точная дата обсуждается), [5] но шумерский язык продолжал использоваться в качестве священного, церемониального, литературного и научного языка в аккадскоязычных месопотамских государствах, таких как Ассирия и Вавилония , до I века нашей эры. [6] [7] После этого он, похоже, канул в безвестность до 19 века, когда ассириологи начали расшифровывать клинописные надписи и раскопанные таблички , оставленные его носителями.

Несмотря на свое исчезновение, шумерский язык оказал значительное влияние на языки региона. Клинопись , первоначально использовавшаяся для шумерского языка, была широко принята во многих региональных языках , таких как аккадский , эламский , эблаитский , хеттский , хурритский , лувийский и урартский ; он также вдохновил древнеперсидский алфавит , который использовался для написания одноименного языка . Вероятно, наибольшее влияние было на аккадский язык, чья грамматика и словарный запас находились под значительным влиянием шумерского языка. [8]

Этапы

[ редактировать ]

Историю письменности Шумера можно разделить на несколько периодов: [10] [11] [12] [13]

- Протописьменный период – ок. 3200 г. до н.э. – ок. 3000 г. до н.э. [ нужна ссылка ]

- Архаический шумерский язык – ок. 3000 г. до н.э. – ок. 2500 г. до н.э.

- Старый или классический шумерский язык – ок. 2500 г. до н.э. – ок. 2350 г. до н.э.

- Древнеаккадский шумерский – ок. 2350 – 2200 гг. до н.э.

- Неошумерский – ок. 2200 г. до н.э. – ок. 2000 г. до н.э. , далее делится на:

- Ранний неошумерский период ( период Лагаша II) – ок. 2200 г. до н.э. – ок. 2100 г. до н.э.

- Поздний неошумерский период ( период Ура III ) – ок. 2100 г. до н.э. – ок. 2000 г. до н.э.

- Древневавилонский шумерский – ок. 2000 г. до н.э. – ок. 1600 г. до н.э.

- Пост-старовавилонский шумерский - после ок. 1600 г. до н.э.

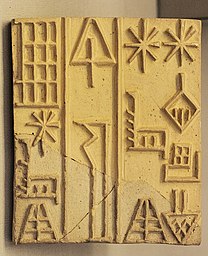

Система пиктографического письма, использовавшаяся в период протописьменного письма (3200 г. до н.э. – 3000 г. до н.э.), соответствующая периодам Урука III и Урука IV в археологии, все еще была настолько элементарной, что среди ученых остаются некоторые разногласия относительно того, является ли язык, написанный на ней, шумерским. вообще, хотя утверждалось, что есть некоторые, хотя и очень редкие, случаи фонетических индикаторов и орфографии, которые показывают, что это так. [14] Тексты этого периода в основном административные; имеется также ряд указателей, которые, по-видимому, использовались для обучения писцов. [10] [15]

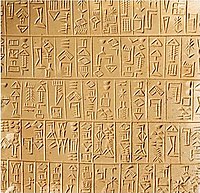

Следующий период, архаический шумерский (3000 г. до н.э. – 2500 г. до н.э.), представляет собой первый этап надписей, в которых указаны грамматические элементы, поэтому идентификация языка является достоверной. Он включает в себя некоторые административные тексты и списки знаков из Ура (ок. 2800 г. до н. э.). Тексты Шуруппака и Абу Салабиха, датированные 2600–2500 гг. до н.э. (так называемый период Фара или ранний династический период IIIa), являются первыми, охватывающими большее разнообразие жанров, включая не только административные тексты и списки знаков, но также заклинания , юридические и литературные тексты (в том числе пословицы и ранние варианты известных произведений «Наставления Шуруппака» и ) « Храмовый гимн Кеш» . Однако написание грамматических элементов остается необязательным, что затрудняет интерпретацию и лингвистический анализ этих текстов. [10] [16]

Древнешумерский период (2500–2350 гг. до н. э.) — первый период, от которого сохранились хорошо понятные тексты. Это соответствует главным образом последней части раннединастического периода (ED IIIb) и, в частности, Первой династии Лагаша , откуда происходит подавляющее большинство сохранившихся текстов. Источники включают важные королевские надписи исторического содержания, а также обширные административные записи. [10] Иногда к древнешумерскому этапу относят также древнеаккадский период (ок. 2350 г. до н. э. – ок. 2200 г. до н. э.), [17] в ходе которого Месопотамия, включая Шумер, была объединена под властью Аккадской империи . В это время аккадский язык функционировал в качестве основного официального языка, но тексты на шумерском (в основном административном) также продолжали создаваться. [10]

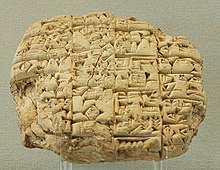

Первая фаза неошумерского периода соответствует времени правления кутиев в Месопотамии ; наиболее важные источники происходят из автономной Второй династии Лагаша, особенно из правления Гудеа , который создал обширные царские надписи. Вторая фаза соответствует объединению Месопотамии под властью Третьей династии Ура , которая наблюдала за «возрождением» использования шумерского языка по всей Месопотамии, используя его в качестве единственного официального письменного языка. Существует богатство текстов, большее, чем когда-либо прежде: помимо чрезвычайно подробных и тщательных административных записей, существует множество королевских надписей, юридических документов, писем и заклинаний. [17] Несмотря на доминирующее положение письменного шумерского языка во времена династии Ура III, остается спорным вопрос о том, в какой степени на нем фактически говорили или уже вымерли в большинстве частей его империи. [5] [18] Некоторые факты были истолкованы как предполагающие, что многие писцы [5] [19] и даже королевский двор фактически использовал аккадский язык в качестве основного разговорного и родного языка. [19] С другой стороны, были представлены доказательства того, что на шумерском языке продолжали говорить местные жители, и он даже оставался доминирующим в качестве повседневного языка в Южной Вавилонии, включая Ниппур и территорию к югу от него. [19] [20] [21]

К старовавилонскому периоду (ок. 2000 – ок. 1600 до н. э.) аккадский язык явно вытеснил шумерский как разговорный язык почти на всей своей первоначальной территории, тогда как шумерский продолжал свое существование как литургический и классический язык для религиозных, художественных и научных целей. Кроме того, утверждалось, что шумерский язык сохранялся как разговорный, по крайней мере, в небольшой части Южной Месопотамии ( Ниппур и его окрестности), по крайней мере, примерно до 1900 г. до н.э. [19] [20] и, возможно, вплоть до 1700 г. до н.э. [5] [19] Тем не менее, кажется очевидным, что подавляющее большинство писцов, писавших на шумерском языке, не были носителями языка, и ошибки, возникшие из-за их родного аккадского языка, становятся очевидными. [22] По этой причине этот период, а также оставшееся время, в течение которого была написана шумерская письменность, иногда называют «постшумерским» периодом. [12] Письменный язык администрации, законов и царских надписей продолжал оставаться шумерским в несомненно семитоязычных государствах-преемниках Ура III в течение так называемого периода Исина-Ларсы (ок. 2000 г. до н.э. - ок. 1750 г. до н.э.). версии . Однако Старая Вавилонская империя в надписях в основном использовала аккадский язык, иногда добавляя шумерские [19] [23]

Древневавилонский период, особенно его ранняя часть, [10] создал чрезвычайно многочисленные и разнообразные шумерские литературные тексты: мифы, эпос, гимны, молитвы, литературу мудрости и письма. Фактически, почти вся сохранившаяся шумерская религиозная и мудрая литература [24] и подавляющее большинство сохранившихся рукописей шумерских литературных текстов в целом [25] [26] [27] можно датировать этим временем, и его часто называют «классическим веком» шумерской литературы. [28] И наоборот, гораздо больше литературных текстов на табличках, сохранившихся со времен Старого Вавилона, написано на шумерском языке, чем на аккадском, хотя это время считается классическим периодом вавилонской культуры и языка. [29] [30] [26] Однако иногда высказывалось предположение, что многие или большинство из этих «старовавилонских шумерских» текстов могут быть копиями произведений, которые были первоначально написаны в предшествующий период Ура III или ранее, а некоторые копии или фрагменты известных произведений или литературных жанров действительно был найден в табличках неошумерского и древнешумерского происхождения. [31] [26] Кроме того, с того времени сохранились некоторые из первых двуязычных шумеро-аккадских лексических списков (хотя списки все еще были обычно одноязычными, а аккадские переводы не стали обычным явлением до позднего средневавилонского периода). [32] существуют также грамматические тексты — по сути, двуязычные парадигмы, в которых перечислены шумерские грамматические формы и их предполагаемые аккадские эквиваленты. [33]

После древневавилонского периода [12] или, по некоторым данным, уже в 1700 г. до н. э., [10] активное использование шумерского языка пришло в упадок. Переписчики продолжали создавать тексты на шумерском языке в более скромном масштабе, но, как правило, с подстрочными аккадскими переводами. [34] и только часть литературы, известной в старовавилонский период, продолжала копироваться после его окончания около 1600 г. до н.э. [24] В средневавилонский период, примерно с 1600 по 1000 гг. до н.э., касситские правители продолжали использовать шумерский язык во многих своих надписях. [35] [36] но аккадский, похоже, занял место шумерского в качестве основного языка текстов, используемых для обучения писцов. [37] а сам их шумерский язык приобретает все более искусственную форму с аккадским влиянием. [24] [38] [39] В некоторых случаях текст даже не предназначался для чтения на шумерском языке; вместо этого он, возможно, служил престижным способом «кодирования» аккадского языка с помощью шумерограмм (ср. японский канбун ). [38] Тем не менее, изучение шумерского языка и копирование шумерских текстов оставались неотъемлемой частью писцовского образования и литературной культуры Месопотамии и окружающих обществ, находящихся под ее влиянием. [35] [36] [40] [41] [б] и она сохраняла эту роль до затмения самой традиции клинописной грамотности в начале нашей эры . Самыми популярными жанрами шумерских текстов после древневавилонского периода были заклинания, литургические тексты и пословицы; среди более длинных текстов классические произведения Лугал-э и Ан-гим . чаще всего копировались [24]

Классификация

[ редактировать ]Шумерский язык широко считается изолированным местным языком . [43] [44] [45] [46] Шумерский язык когда-то широко считался индоевропейским языком , но эта точка зрения была почти повсеместно отвергнута. [47] С момента его расшифровки в начале 20 века ученые пытались связать шумерский язык с самыми разными языками. Поскольку шумерский язык имеет престиж как первый письменность, предположения о языковом родстве иногда имеют националистический оттенок. [48] Были предприняты попытки связать шумерский язык с рядом совершенно разных групп, таких как австроазиатские языки , [49] дравидийские языки , [50] Уральские языки, такие как венгерский и финский , [51] [52] [53] [54] Сино-тибетские языки [55] и тюркские языки (последний продвигается турецкими националистами как часть теории языка Солнца). [56] [57] ). Кроме того, в долгосрочных предложениях предпринимались попытки включить шумерский язык в широкие макросемьи . [58] [59] Подобные предложения практически не пользуются поддержкой среди современных лингвистов, шумерологов и ассириологов и обычно рассматриваются как маргинальные теории . [48]

Было также высказано предположение, что шумерский язык произошел от позднего доисторического креольского языка (Høyrup 1992). [60] Однако не удалось найти убедительных доказательств, а только некоторые типологические особенности, подтверждающие точку зрения Хойрупа. Более распространенная гипотеза предполагает наличие протоевфратского языка , который предшествовал шумерскому языку в Месопотамии и оказывал на него географическое влияние, особенно в форме многосложных слов, которые кажутся «нешумерскими», что заставляет их подозревать, что они являются заимствованными словами , и не прослеживается до них. любой другой известный язык. Существует мало предположений относительно родства этого языка- субстрата или этих языков, и поэтому его лучше всего рассматривать как неклассифицированный . [61] Другие исследователи не согласны с предположением о едином языке-субстрате и утверждают, что здесь задействовано несколько языков. [62] Соответствующее предложение Гордона Уиттакера [63] заключается в том, что язык протолитературных текстов периода позднего Урука ( ок. 3350–3100 до н. э.) на самом деле является ранним индоевропейским языком, который он называет «евфратическим».

Система письма

[ редактировать ]Разработка

[ редактировать ]

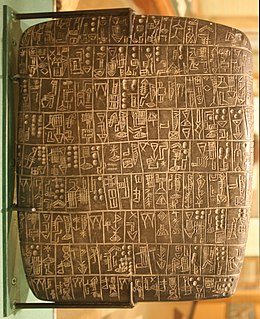

Пиктографическое протописьмо использовалось начиная с ок. 3300 г. до н.э. Неясно, какой основной язык он закодировал, если таковой имеется. К ц. В 2800 г. до н.э. на некоторых табличках стали использоваться слоговые элементы, явно указывающие на связь с шумерским языком. Около 2600 г. до н. э., [64] [65] Клинописные символы создавались с помощью клиновидного стилуса для впечатывания форм во влажную глину. Этот клинописный («клиновидный») способ письма сосуществовал с протоклинописным архаичным способом. Деймель (1922) перечисляет 870 знаков, использовавшихся в раннединастический период IIIa (26 век). В тот же период большой набор логографических знаков был упрощен до логослогического письма, состоящего из нескольких сотен знаков. Розенгартен (1967) перечисляет 468 знаков, использовавшихся в шумерском ( досаргонианском ) Лагаше .

Клинопись была адаптирована к аккадскому письму начиная с середины третьего тысячелетия. В течение длительного периода двуязычного перекрытия активного использования шумерского и аккадского языков эти два языка влияли друг на друга, что отражалось в многочисленных заимствованиях и даже изменениях порядка слов. [66]

Транслитерация

[ редактировать ]В зависимости от контекста клинописный знак может читаться либо как одна из нескольких возможных логограмм , каждая из которых соответствует слову шумерского разговорного языка, либо как фонетический слог (V, VC, CV или CVC), либо как детерминативный (маркер семантической категории, например рода занятий или места). (См. статью Клинопись .) Некоторые шумерские логограммы были написаны множеством клинописных знаков. Эти логограммы называются дири -орфографии, по названию логограммы 𒋛𒀀 ДИРИ , которая пишется знаками 𒋛 СИ и 𒀀 А . При транслитерации текста на табличке будет отображаться только логотипограмма, например слово dirig , а не отдельные знаки компонентов.

Не все эпиграфисты одинаково надежны, и перед публикацией важной обработки текста ученые часто сопоставляют опубликованную транслитерацию с фактической табличкой, чтобы увидеть, следует ли представлять какие-либо знаки, особенно сломанные или поврежденные знаки, по-другому.

Наши знания о прочтении шумерских знаков в значительной степени основаны на лексических списках, составленных для носителей аккадского языка, где они выражены с помощью слоговых знаков. Установленные чтения первоначально были основаны на лексических списках нововавилонского периода , найденных в XIX веке; в 20 веке были опубликованы более ранние списки древневавилонского периода , и некоторые исследователи 21 века перешли к использованию их прочтений. [67] [с] Существуют также различия в степени отражения в транслитерации так называемых «ауслаутов» или «любимых согласных» (согласных в конце морфемы, которые в тот или иной момент истории шумера перестали произноситься). [68] В этой статье в основном использовались версии с выраженными ауслаутами.

Историография

[ редактировать ]Этот раздел нуждается в дополнительных цитатах для проверки . ( декабрь 2023 г. ) |

Ключом к чтению логосложной клинописи послужила Бехистунская надпись , трехъязычная клинопись, написанная на древнеперсидском , эламском и аккадском языках . (Аналогично, ключом к пониманию египетских иероглифов был двуязычный [греческий и египетский с египетским текстом в двух письменностях] Розеттский камень и транскрипция Жана-Франсуа Шампольона в 1822 году.)

В 1838 году Генри Роулинсон , опираясь на работу Георга Фридриха Гротефенда 1802 года , смог расшифровать древнеперсидский раздел Бехистунских надписей, используя свои знания современного персидского языка. Когда он восстановил остальную часть текста в 1843 году, он и другие постепенно смогли перевести его эламскую и аккадскую части, начиная с 37 знаков, которые он расшифровал для древнеперсидского языка. раскопок было обнаружено еще много клинописных текстов Тем временем в результате археологических , в основном на семитском аккадском языке , которые были должным образом расшифрованы.

Однако к 1850 году Эдвард Хинкс заподозрил несемитское происхождение клинописи. Семитские языки структурированы согласно формам согласных , тогда как клинопись при фонетическом функционировании была слоговой , связывая согласные с определенными гласными. Более того, не удалось найти никаких семитских слов, объясняющих слоговые значения, придаваемые определенным знакам. [71] Юлиус Опперт предположил, что несемитский язык предшествовал аккадскому языку в Месопотамии и что носители этого языка развили клинопись.

В 1855 году Роулинсон объявил об открытии несемитских надписей на южных вавилонских памятниках Ниппура , Ларсы и Урука .

В 1856 году Хинкс утверждал, что непереведенный язык имеет агглютинативный характер. Некоторые называли этот язык «скифским», а другие, что сбивает с толку, «аккадским». В 1869 году Опперт предложил название «Шумерский», основанное на известном титуле «Царь Шумера и Аккада», мотивируя это тем, что, если Аккад обозначал семитскую часть королевства, Шумер мог бы обозначать несемитскую пристройку.

Заслуга первого научного подхода к двуязычному шумеро-аккадскому тексту принадлежит Паулю Хаупту , опубликовавшему «Die sumerischen Familiengesetze» («Шумерские семейные законы») в 1879 году. [72]

Эрнест де Сарзек начал раскопки шумерского городища Телло (древний Гирсу, столица штата Лагаш ) в 1877 году и опубликовал первую часть «Découvertes en Chaldée» с транскрипциями шумерских табличек в 1884 году. Пенсильванский университет начал раскопки шумерского Ниппура в 1884 году. 1888.

Классифицированный список шумерских иероглифов Р. Брюннова появился в 1889 году.

и разнообразие фонетических значений, которые знаки могли иметь в шумерском языке, привели к отклонению в понимании языка: парижский востоковед Поразительное количество с Жозеф Галеви 1874 года утверждал, что шумерский язык не является естественным языком, а скорее секретным кодом ( криптолект ) , и более десяти лет ведущие ассириологи боролись по этому вопросу. В течение дюжины лет, начиная с 1885 года, Фридрих Делич принимал аргументы Галеви, не отказываясь от Галеви до 1897 года. [73]

Франсуа Тюро-Данжен, работавший в Лувре в Париже, также внес значительный вклад в расшифровку шумерского языка с помощью публикаций с 1898 по 1938 год, таких как его публикация 1905 года « Les inscriptions de Sumer et d'Akkad» . Шарль Фосси из Коллеж де Франс в Париже был еще одним плодовитым и надежным ученым. Его новаторский вклад в Dictionnaire sumérien-assyrien , Париж, 1905–1907, оказался основой для шумерско-аккадского глоссара Деймеля П. Антона Деймеля 1934 года (том III 4-томного шумерского лексикона ).

В 1908 году Стивен Герберт Лэнгдон подытожил быстрое расширение знаний шумерской и аккадской лексики на страницах журнала Babyloniaca , редактируемого Шарлем Вироло , в статье «Шумерско-ассирийские словари», в которой был сделан обзор ценной новой книги о редких логограммах, написанной Бруно Мейснер. [74] Последующие ученые сочли работу Лэнгдона, включая его табличную транскрипцию, не совсем достоверной.

В 1944 году шумеролог Сэмюэл Ной Крамер представил подробное и доступное для чтения изложение расшифровки шумерского языка в своей «Шумерской мифологии» . [75]

Фридрих Делич опубликовал ученый шумерский словарь и грамматику в форме своих Шумерского глоссария и «Основ шумерской грамматики» , вышедших в 1914 году. [76] Ученик Делича, Арно Пебель , опубликовал грамматику с таким же названием Grundzüge der Sumerischen Grammatik в 1923 году, и в течение 50 лет она была стандартом для студентов, изучающих шумерский язык. Другой весьма влиятельной фигурой в шумерологии на протяжении большей части 20-го века был Адам Фалькенштейн , который разработал грамматику языка надписей Гудеа . [77] Грамматика Побеля была окончательно заменена в 1984 году после публикации книги «Шумерский язык: введение в его историю и грамматическую структуру » Мари-Луизы Томсен . Хотя в шумерской грамматике есть различные моменты, по которым взгляды Томсена не разделяются большинством современных шумерологов, грамматика Томсена (часто с явным упоминанием критических замечаний, выдвинутых Паскалем Аттингером в его книге « Элементы шумерской лингвистики» 1993 года: La Construction de du 11 /e) /di 'ужасный ' ) — отправная точка последних академических дискуссий по шумерской грамматике.

Более поздние монографии по грамматикам шумерского языка включают « Дица-Отто Эдзарда 2003 года Шумерскую грамматику» Брэма Джагерсмы 2010 года и «Описательную грамматику шумерского языка» (в настоящее время в цифровом формате, но вскоре будет напечатана в исправленном виде издательством Oxford University Press). Эссе Петра Михаловского (названное просто «Шумерский») в Кембриджской энциклопедии древних языков мира за 2004 год также было признано хорошим современным грамматическим очерком.

Даже среди разумных шумерологов относительно мало единого мнения по сравнению с состоянием большинства современных или классических языков. В частности, горячо обсуждается вербальная морфология. Помимо общих грамматик, существует множество монографий и статей по отдельным разделам шумерской грамматики, без которых обзор этой области нельзя считать полным.

Основным институциональным лексическим проектом шумерского языка является проект Пенсильванского шумерского словаря , начатый в 1974 году. В 2004 году PSD был выпущен в Интернете как ePSD. В настоящее время проект курирует Стив Тинни. Он не обновлялся онлайн с 2006 года, но Тинни и его коллеги работают над новой редакцией ePSD, рабочий проект которой доступен в Интернете.

Фонология

[ редактировать ]Предполагаемые фонологические и морфологические формы будут заключены в косую черту // и фигурные скобки {} соответственно, а для стандартной ассириологической транскрипции шумерского языка будет использоваться простой текст. Большинство следующих примеров не подтверждены. Также обратите внимание, что, как и большинство других досовременных орфографий, шумерское клинопись сильно варьируется, поэтому транскрипции и примеры клинописи обычно демонстрируют только одну или, самое большее, несколько распространенных графических форм из многих, которые могут встречаться. Орфографическая практика также существенно изменилась в ходе истории шумерского языка: в примерах в статье будут использоваться наиболее фонетически явные засвидетельствованные варианты написания, что обычно означает написание древневавилонского периода или периода Ура III. за исключением случаев, когда используется подлинный пример из другого периода.

Современные знания о шумерской фонологии ошибочны и неполны из-за отсутствия носителей, передачи аккадской фонологии через фильтр и трудностей, связанных с клинописью. Как отмечает И. М. Дьяконов , «когда мы пытаемся выяснить морфонологическую структуру шумерского языка, мы должны постоянно иметь в виду, что мы имеем дело не с языком непосредственно, а реконструируем его из весьма несовершенной мнемонической письменности, которая еще не была изучена». в основном направлен на передачу морфонемики». [78]

Согласные

[ редактировать ]Предполагается, что в раннем шумерском языке были по крайней мере согласные, перечисленные в таблице ниже. Согласные в скобках реконструируются некоторыми учеными по косвенным данным; если они существовали, то были утеряны примерно в период Ура III в конце 3-го тысячелетия до нашей эры.

| двугубный | Альвеолярный | Постальвеолярный | Велар | Глоттальный | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| носовой | м ⟨м⟩ | н ⟨n⟩ | ŋ ⟨g̃⟩ | |||

| взрывной | простой | п ⟨б⟩ | т ⟨д⟩ | k ⟨g⟩ | ( ʔ ) | |

| безнаддувный | пʰ ⟨п⟩ | тʰ ⟨т⟩ | кʰ ⟨к⟩ | |||

| Фрикативный | SS⟩ | ʃ ⟨š⟩ | х ⟨ḫ~ч⟩ | ( ч ) | ||

| Аффрикат | простой | тс ⟨z⟩ | ||||

| безнаддувный | цц ? ⟨ř~доктор⟩ | |||||

| Кран | ɾ ⟨р⟩ | |||||

| Жидкость | л ⟨л⟩ | |||||

| полугласный | ( Дж ) | |||||

- простое распределение шести стоповых согласных в трех местах артикуляции , первоначально отличающееся придыханием . Считается, что в конце 3-го тысячелетия до нашей эры безнаддувные остановки стали озвучиваться в большинстве позиций (хотя и не в конце слова). [79] тогда как безмолвные придыхательные остановки сохраняли свое стремление. [80] [д]

- р ( глухая аспирационная двугубная взрывчатка ),

- т ( глухой аспирационный альвеолярный взрывной ),

- к ( глухая аспирационная велярная взрывчатка ),

- Как правило, глухие придыхательные согласные ( р , т и к ) в конце слова не встречаются. [82]

- б ( глухая безаспирационная двугубная взрывная ), позже звонкая;

- г ( глухой безаспирационный альвеолярный взрывной ), позже звонкий;

- г ( глухой безнаддувный велярный взрывной звук ), позже звонкий.

- фонема , обычно обозначаемая буквой ř (иногда пишется dr ), которая превратилась в /d/ или /r/ после древнеаккадского периода в северном и южном диалектах соответственно. Впервые он был реконструирован как звонкий альвеолярный постукивание /ɾ/, но Брэм Ягерсма утверждает, что это была глухая придыхательная альвеолярная аффриката из-за его отражения в заимствованных словах на аккадском языке, среди других причин: [79] и эту точку зрения разделяет Габор Золёми (2017: 28). Другие предположения, которые были высказаны, заключаются в том, что ř был глухим альвеолярным краном . [83]

- простое распределение трех носовых согласных , распределение которых аналогично стопам:

- м ( носовая двугубная ),

- н ( альвеолярно-носовой ),

- g̃ (часто печатается ĝ из-за ограничений набора текста, все чаще транскрибируется как ŋ ) /ŋ/ (вероятно, велярный носовой , как в si ng , также утверждается, что это лабиовелярный носовой [ŋʷ] или назальный лабиовелярный [84] ).

- набор из трех сибилянтов :

- s , вероятно, глухой альвеолярный фрикативный звук ,

- z , вероятно, глухая бездыханная альвеолярная аффриката , /t͡s/ , как показывают аккадские заимствования от /s/ = [t͡s] к шумерскому /z/ . На раннем шумерском языке это был бы безнаддувный аналог ř . [85] Как и стоп-серии b , d и g , считается, что в конце 3-го тысячелетия в некоторых позициях он стал озвученным /dz/. [86]

- š (обычно описывается как глухой постальвеолярный фрикативный звук , /ʃ/ , как в sh ip [и]

- ḫ ( велярный фрикативный звук , /x/ , иногда пишется <h>)

- две жидкие согласные :

- л ( боковой согласный )

- r ( ротический согласный ), который, как утверждает Ягерсма, был реализован как постукивание [ɾ] из-за различных свидетельств, предполагающих его фонетическое сходство с /t/ и /d/. [89]

На основе графических чередований и заимствований была выдвинута гипотеза о существовании различных других согласных, но ни одна из них не нашла широкого признания. Например, Дьяконов перечисляет доказательства наличия двух боковых фонем, двух ротических, двух задних фрикативов и двух звуков g (исключая велярный носовой) и предполагает фонематическую разницу между согласными, которые опускаются в конце слова (например, g в 𒍠 zag > za 3 ) и оставшиеся согласные (например, g в 𒆷𒀝 lag ). Другие «скрытые» согласные фонемы, которые были предложены, включают полугласные, такие как /j/ и /w/ , [90] и гортанный фрикативный звук /h/ или гортанная смычка , которые могли бы объяснить отсутствие сокращения гласных в некоторых словах. [91] — хотя и против этого высказывались возражения. [92] Недавняя описательная грамматика Брэма Джагерсмы включает /j/ , /h/ и /ʔ/ как неписаные согласные, а голосовая смычка даже служит местоименным префиксом от первого лица. Однако, согласно Ягерсме, эти неписаные согласные были утеряны к периоду Ура III. [93]

Очень часто согласная в конце слова не выражалась на письме и, возможно, опускалась при произношении, поэтому она появлялась только тогда, когда за ней следовала гласная: например, /k/ в родительном падеже , заканчивающемся -ak , не появляется в 𒂍𒈗𒆷 e 2 lugal-la "королевский дом", но это становится очевидным в 𒂍𒈗𒆷𒄰 e 2 lugal-la-kam "(это) дом короля" (сравните связь во французском языке). Ягерсма считает, что отсутствие выраженности согласных в конце слова изначально было в основном графическим условностью. [94] но что в конце 3-го тысячелетия глухие придыхательные остановки и аффрикаты (/pʰ/, /tʰ/, /kʰ/ и /tsʰ/ действительно постепенно терялись в позиции конца слога, как и безнаддувные остановки /d/ и / г/. [95]

гласные

[ редактировать ]Гласные, которые четко различаются клинописью, — это /a/ , /e/ , /i/ и /u/ . Различные исследователи постулировали существование большего количества гласных фонем, таких как /o/ и даже /ɛ/ и /ɔ/ , которые были бы скрыты при передаче через аккадский язык, поскольку этот язык не различает их. [96] [97] Это могло бы объяснить кажущееся существование многочисленных омофонов в транслитерированном шумерском языке, а также некоторые детали явлений, упомянутых в следующем абзаце. [98] Эти гипотезы еще не получили общепринятого признания. [84] Многие ученые установили длину фонематических гласных на основе длины гласных в шумерских заимствованных словах в аккадском языке. [99] [100] случайные так называемые варианты написания плене с дополнительными знаками гласных и некоторыми внутренними свидетельствами чередований. [ф] [100] [102] Однако ученые, верящие в существование фонематической долготы гласных, не считают возможным реконструировать долготу гласных в большинстве шумерских слов. [103] [г]

В старошумерский период южные диалекты (те, которые использовались в городах Лагаш , Умма , Ур и Урук ), [106] которые также предоставляют подавляющее большинство материала с этого этапа, демонстрировали правило гармонии гласных, основанное на высоте гласных или развитом корне языка . [96] По сути, префиксы, содержащие /e/ или /i/, чередуются между /e/ перед слогами, содержащими открытые гласные, и /i/ перед слогами, содержащими закрытые гласные; например 𒂊𒁽 e-kaš 4 "он бежит", но 𒉌𒁺 i 3 -губ "он стоит". Однако некоторые глаголы с основными гласными, написанными с помощью /u/ и /e/, похоже, имеют префиксы с качеством гласных, противоположным тому, которое можно было бы ожидать в соответствии с этим правилом. [час] , что по-разному интерпретировалось как указание на наличие дополнительных гласных фонем в шумерском языке. [96] или просто неправильно реконструированных прочтений отдельных лексем. [106] Префикс множественного числа 3-го лица 𒉈 -ne- также не затрагивается, что, по мнению Ягерсмы, вызвано длиной его гласной. [106] Кроме того, некоторые выступают за правило второй гармонии гласных. [107] [97]

По-видимому, также имеется множество случаев частичной или полной ассимиляции гласной некоторых префиксов и суффиксов с гласной в соседнем слоге, отраженной в письменной форме в некоторые из более поздних периодов, и существует заметная, хотя и не абсолютная, тенденция к образованию двусложных основ. иметь одну и ту же гласную в обоих слогах. [108] Некоторые исследователи интерпретируют эти закономерности как свидетельство более богатого набора гласных. [96] [97] Например, мы находим такие формы, как 𒂵𒁽 g a -kaš 4 «позволь мне бежать», но, начиная с неошумерского периода, иногда встречаются такие варианты написания, как 𒄘𒈬𒊏𒀊𒋧 g u 2 -mu-ra-ab-šum 2 «позволь мне дать это». тебе". По мнению Ягерсмы, эти ассимиляции ограничиваются открытыми слогами. [109] и, как и в случае с гармонией гласных, Ягерсма интерпретирует их отсутствие как результат длины гласных или ударения, по крайней мере, в некоторых случаях. [109] Имеются сведения о различных случаях выпадения гласных, по-видимому, в безударных слогах; в частности, во многих случаях , по-видимому, пропускалась начальная гласная в слове, состоящем более чем из двух слогов . [109] Что-то похожее на сокращение гласных в перерыве (*/aa/, */ia/, */ua/ > a , */ae/ > a , */ie/ > i или e , */ue/ > u или e и т. д.) также очень распространено. [110] Существует некоторая неопределенность и разногласия относительно того, является ли результатом в каждом конкретном случае долгая гласная или гласная просто заменяется/удаляется. [111]

Слоги могут иметь любую из следующих структур: V, CV, VC, CVC. Более сложные слоги, если они были в шумерском языке, клинописным письмом как таковые не выражаются.

Стресс

[ редактировать ]Шумерское ударение обычно считается динамическим, поскольку оно, по-видимому, во многих случаях вызывало пропуски гласных. Мнения по поводу его размещения разнятся. Как утверждает Брэм Джагерсма [112] и подтверждено другими учеными, [113] [114] адаптация аккадских слов шумерского происхождения, по-видимому, позволяет предположить, что шумерское ударение обычно приходилось на последний слог слова, по крайней мере, в форме его цитирования. Менее ясна трактовка форм с грамматическими морфемами. Многие случаи афереза в формах с энклитиками интерпретировались как предполагающие, что то же самое правило во многих случаях справедливо и для фонологического слова, т. е. что ударение может быть перенесено на энклитики; однако тот факт, что многие из этих же энклитиков имеют алломорфы с апокопированными конечными гласными (например, / -ше / ~ /-ш/), позволяет предположить, что они, наоборот, были безударными, когда эти алломорфы возникли. [112] Было также высказано предположение, что частое уподобление гласных неконечных слогов гласной последнего слога слова может быть связано с ударением на нем. [115] Однако ряд суффиксов и энклитик, состоящих из /e/ или начинающихся на /e/, также ассимилируются и редуцируются. [116]

В более ранних исследованиях высказывались несколько иные взгляды и предпринимались попытки сформулировать подробные правила влияния грамматических морфем и словосложения на ударение, но с безрезультатными результатами. Основываясь преимущественно на закономерностях выпадения гласных, Адам Фалькенштейн [117] утверждал, что ударение в мономорфемных словах, как правило, приходится на первый слог, и что то же самое относится без исключения к повторяющимся основам, но что ударение смещается на последний слог в первом члене сложной или идиоматической фразы, на слог, предшествующий (конечный) суффикс/энклитика и на первый слог притяжательной энклитики /-ани/. По его мнению, отдельные глагольные приставки были безударными, но более длинные последовательности глагольных приставок переносили ударение на первый слог. Ягерсма [112] возразил, что многие из примеров элизии Фалькенштейна являются средними, и поэтому, хотя ударение явно приходилось не на рассматриваемый средний слог, примеры не показывают, где оно было .

Joachim Krecher [118] попытались найти больше подсказок в текстах, написанных фонетически, предполагая, что геминации, написание плена и неожиданные «более сильные» качества согласных были ключами к расположению ударения. Используя этот метод, он подтвердил мнение Фалькенштейна о том, что ударение в редуплицированных формах приходится на первый слог и что обычно ударение падает на слог, предшествующий (конечному) суффиксу/энклитике, на предпоследнем слоге многосложной энклитики, такой как -/ani/, -/зунене/ и т. д., на последнем слоге первого члена сложного слова и на первом слоге в последовательности глагольных приставок. Однако он обнаружил, что отдельные глагольные префиксы получали ударение точно так же, как и префиксные последовательности, и что в большинстве приведенных выше случаев часто присутствовало и другое ударение: на основе, к которой были добавлены суффиксы/энклитики, на второй составной член в сложных словах и, возможно, в глагольной основе, в которой префиксы были добавлены к следующим слогам или к ним. Он также не согласился с тем, что ударение мономорфемных слов обычно было начальным, и считал, что нашел свидетельства существования слов как с начальным, так и с конечным ударением; [119] более того, он даже не исключал возможности того, что стресс обычно бывает финальным. [120]

Паскаль Аттингер [121] частично согласился с Кречером, но сомневается, что ударение всегда приходилось на слог, предшествующий суффиксу/энклитике, и утверждает, что в префиксной последовательности ударный слог был не первым, а скорее последним, если он тяжелый, и следующим - в остальных случаях до последнего. Аттингер также отметил, что наблюдаемые закономерности могут быть результатом аккадского влияния – либо из-за языковой конвергенции, когда шумерский язык еще был живым языком, либо, поскольку данные относятся к древневавилонскому периоду, из-за особенности шумерского языка, произносимой носителями языка. Аккадский. На последнее указывает и Ягерсма, который, кроме того, скептически относится к самим предположениям, лежащим в основе метода, использованного Крехером для установления места напряжения. [112]

Орфография

[ редактировать ]Шумерская письменность выражала произношение лишь приблизительно. Часто оно было морфонемным , поэтому большую часть алломорфных вариаций можно было игнорировать. [122] Согласные кода также часто игнорировались при написании, особенно в раннем шумерском языке; например, /mung̃areš/ «они положили это сюда» можно было бы написать 𒈬𒃻𒌷 mu-g̃ar-re 2 . Использование знаков VC для этой цели, создающее более сложные варианты написания, такие как 𒈬𒌦𒃻𒌷𒌍 mu-un-g̃ar-re 2 -eš 3 , стало более распространенным только в неошумерский и особенно в старовавилонский период. [123]

И наоборот, интервокальный согласный, особенно в конце морфемы, за которым следовала морфема, начинающаяся с гласной, обычно «повторялся» за счет использования знака CV для того же согласного; например 𒊬 сар "писать" - 𒊬𒊏 сар-ра "написано". [я] Это приводит к орфографической геминации, которая обычно отражается в шумерологической транслитерации, но фактически не обозначает какое-либо фонологическое явление, такое как длина. [125] [Дж] В этом контексте также важно то, что, как объяснялось выше , многие согласные в конце морфемы, по-видимому, были исключены, если за ними не следовала гласная, на различных этапах истории шумерского языка. В шумерологии их традиционно называют ауслаутами , и они могут выражаться или не выражаться в транслитерации: например, логограмма 𒊮 для /šag/ > /ša(g)/ «сердце» может транслитерироваться как šag 4 или ša 3 . Таким образом, когда перед гласной появляется следующая согласная, можно сказать, что она выражена только следующим знаком: например, 𒊮𒂵 šag 4 -ga «в сердце» также можно интерпретировать как ša 3 -ga . [127]

Конечно, когда звуковая последовательность CVC выражается последовательностью знаков со звуковыми значениями CV-VC, это не обязательно указывает на долгую гласную или последовательность одинаковых гласных. Для обозначения такого явления использовались так называемые «пленные» письма с дополнительным знаком гласной, повторяющим предыдущую гласную, хотя это никогда не делалось систематически. Типичное пленарное письмо включало такую последовательность, как (C)V- V (-VC/CV), например 𒂼𒀀 ama- a для /ama a / < {ama- e } «мать (эргативный падеж)»). [128]

Шумерские тексты различаются по степени использования логограмм или выбора вместо них слогового (фонетического) написания: например, слово 𒃻 g̃ar «ставить» также может быть фонетически записано как 𒂷𒅈 g̃a 2 -ar . Они также различаются по степени выраженности алломорфной вариации, например 𒁀𒄄𒌍 ba-gi 4 - eš или 𒁀𒅖 ba-gi 4 - iš для «они вернулись». Хотя раннее шумерское письмо было в значительной степени логографическим, в неошумерский период наблюдалась тенденция к более фонетическому написанию. [129] Последовательное слоговое написание использовалось при записи диалекта Эмесаль (поскольку обычные логограммы по умолчанию читались на Эмегире) с целью обучения языку и часто для записи заклинаний. [130]

Как уже говорилось, тексты, написанные в архаический шумерский период, сложны для интерпретации, поскольку в них часто опускаются грамматические элементы и определители . [10] [16] Кроме того, во многих литературно-мифологических текстах этого периода используется особый орфографический стиль УД.ГАЛ.НУН, который, по-видимому, основан на замене одних знаков или групп знаков другими. Например, три знака 𒌓 UD, 𒃲 GAL и 𒉣 NUN, в честь которых названа система, заменяются на 𒀭 AN, 𒂗 EN и 𒆤 LIL 2 соответственно, образуя имя бога. д эн-лил 2 . Мотивация этой практики загадочна; Было высказано предположение, что это был своего рода криптография . Тексты, написанные на УД.ГАЛ.НУН, до сих пор понимаются очень плохо и лишь частично. [131] [16] [132]

Грамматика

[ редактировать ]С момента его расшифровки исследование шумерского языка было затруднено не только отсутствием носителей языка, но и относительной скудностью лингвистических данных, очевидным отсутствием близкородственного языка и особенностями письменности. Еще одна часто упоминаемая и парадоксальная проблема изучения шумерского языка заключается в том, что самые многочисленные и разнообразные тексты, написанные с наиболее фонетически ясной и точной орфографией, датируются только периодами, когда сами писцы уже не были носителями языка и часто явно имели меньше языков. чем идеальное владение языком, на котором они писали; и наоборот, на протяжении большей части времени, в течение которого шумерский язык все еще был живым языком, сохранившиеся источники немногочисленны, неизменны и/или написаны с орфографией, которую труднее интерпретировать. [133]

Типологически шумерский язык классифицируется как агглютинативный , эргативный (последовательно так в его номинальной морфологии и расщепленный эргатив в его глагольной морфологии) и субъект-объект-глагол . [134]

Номинальная морфология

[ редактировать ]Существительные фразы

[ редактировать ]Шумерское существительное обычно имеет одно- или двухсложный корень (𒅆 igi «глаз», 𒂍 e 2 «дом, домашнее хозяйство», 𒎏 nin «леди»), хотя есть также некоторые корни с тремя слогами, например 𒆠𒇴 šakanka «рынок». . Существует два семантически предсказуемых грамматических рода , которые традиционно называются одушевленными и неодушевленными, хотя эти названия не выражают точно их принадлежность, как поясняется ниже .

Прилагательные « великий и другие модификаторы следуют за существительным (𒈗𒈤 lugal maḫ король»). Само существительное не склоняется; скорее, грамматические маркеры прикрепляются к именной группе в целом, в определенном порядке. Обычно этот порядок будет следующим:

| существительное | прилагательное | цифра | родительный падеж | относительное предложение | притяжательный маркер | маркер множественного числа | маркер случая |

|---|

Примером может быть: [135]

Притяжательные, множественные и падежные маркеры традиционно называются « суффиксами », но в последнее время их также называют энклитиками. [136] или послелоги . [137]

Пол

[ редактировать ]Оба пола по-разному назывались одушевленными и неодушевленными . [138] [139] [140] [141] человеческие и нечеловеческие , [142] [143] или личное/личное и безличное/неличное. [144] [145] Их назначение семантически предсказуемо: к первому полу относятся люди и боги, ко второму — животные, растения, неживые объекты, абстрактные понятия и группы людей. Поскольку ко второму полу относятся животные, использование терминов «живое» и «неживое» несколько вводит в заблуждение. [144] и обычные, [139] но оно наиболее распространено в литературе, поэтому оно будет сохранено в этой статье.

Есть некоторые незначительные отклонения от правил присвоения пола, например:

1. Слово 𒀩 алан «статуя» можно понимать как одушевленное.

2. Слова, обозначающие рабов, такие как 𒊩𒆳 geme 2 «рабыня» и 𒊕 sag̃ «голова», используемые во вторичном значении «раб», могут рассматриваться как неодушевленные. [146]

3. В басноподобных контекстах, которые часто встречаются в шумерских пословицах, животные обычно рассматриваются как одушевленные. [147]

Число

[ редактировать ]Собственно маркер множественного числа — (𒂊)𒉈 /-(e)ne/. [л] Оно употребляется только с существительными одушевленного рода и его употребление необязательно. Его часто опускают, когда другие части предложения указывают на множественность референта. [150] Таким образом, оно не используется, если существительное модифицировано числительным ( 𒇽 𒁹𒁹𒁹 lu 2 eš 5 «трое мужчин»). Также было замечено, что до периода Ура III маркер обычно не используется в именной группе в абсолютном падеже . [151] [152] [153] если только это не необходимо для устранения неоднозначности. [152] [153] Вместо этого множественность абсолютного участника обычно выражается только формой глагола в предложении: [153] [151] например, 𒇽𒁀𒀄𒀄𒌍 lu 2 ba- zaḫ 3 -zaḫ 3 -eš "мужчины убежали", 𒇽𒅇𒆪𒁉𒌍 lu 2 mu-u 3 -dab 5 -be 2 - eš "Я поймал мужчин". Маркер множественного числа не используется при упоминании группы людей, поскольку группа людей рассматривается как неодушевленная; например, 𒀳 engar «фермер» без маркера множественного числа может относиться к «(группе) фермеров». [150]

Как показано в следующем примере, маркер добавляется в конец фразы даже после придаточного предложения: [150]

лу 2 е 2 -а ба-даб 5 -ба-не

ему

мужчина

еа

дом в

«мужчины, которых поймали в доме»

Точно так же маркер множественного числа обычно (хотя и не всегда) добавляется только один раз, когда целая серия координируемых существительных имеет ссылку во множественном числе: [150]

но сипад шу-ку 6 -е-не

никто

фермер

сипад

пасти

«земледельцы, пастухи и рыбаки»

Другой способ выражения своего рода множественного числа — посредством редупликации существительного: 𒀭𒀭 dig̃ir-dig̃ir «боги», 𒌈𒌈 ib 2 -ib 2 «бедра». Однако обычно считается, что эта конструкция имеет более специализированное значение, по-разному интерпретируемое как целостность («все боги», «оба моих бедра»). [154] [155] или распределение/отдельность («каждый из богов в отдельности»). [156] [157] Особенно часто встречающееся редуплицированное слово 𒆳𒆳 кур-кур «чужие земли» может иметь просто множественное значение, [156] и в очень позднем использовании значение повторения в целом могло быть простым множественным числом. [154]

По крайней мере, несколько прилагательных (в частности, 𒃲 gal «большой» и 𒌉 tur «маленький») также дублируются, когда существительное, которое они изменяют, имеет множественное число: 𒀀𒃲𒃲 a gal-gal «великие воды». [158] В этом случае само существительное не дублируется. [159] Иногда это интерпретируется как выражение простой множественности. [160] в то время как мнение меньшинства состоит в том, что значение этих форм не чисто множественное, а такое же, как и у дублирования существительного. [157] [161]

Два других способа выражения множественности характерны только для очень позднего шумерского употребления и проникли в шумерограммы, используемые в письменности на аккадском и других языках. Один используется с неодушевленными существительными и состоит из модификации существительного прилагательным 𒄭𒀀 ḫi-a «различный» (букв. «смешанный»), например 𒇻𒄭𒀀 udu ḫi-a «овца». [162] Другой - добавление формы 3-го лица множественного числа энклитической связки 𒈨𒌍 -me-eš к существительному (𒈗𒈨𒌍 lugal-me-eš «короли», первоначально «они (которые) являются королями»). [163]

Случай

[ редактировать ]Маркеры дела

[ редактировать ]Общепризнанными маркерами падежа являются: [164]

| случай | окончание | самое распространенное написание [165] | приблизительные английские эквиваленты и функции [166] |

|---|---|---|---|

| абсолютный | /-Ø/ | непереходный субъект или переходный объект | |

| эргативный | /-и/ [м] (в основном с анимацией) [н] | (𒂊 -е ) | переходный субъект |

| директива [the] | /-e/ (только с неодушевленными существами) [п] | (𒂊 -е ) | «в контакте с», «у», «при», «за», «что касается»; причина |

| родительный падеж | /-а(к)/, /-(к)/ [д] [р] | (𒀀 -а ) | "из" |

| эквивалентный | /-Джин/ | 𒁶 - поколение 7 | «как», «как» |

| дательный падеж | /-р(а)/ [с] (только с анимацией) [т] | 𒊏 -ра | «чтобы», «для», «по», причине |

| завершающий [в] | /-(е)ш(е)/ [v] | 𒂠 — 3 | «к», «к», «за», «пока», «в обмен (на)», «вместо того, если», «что касается», «из-за» |

| комитативный | /-д(а)/ [В] | 𒁕 - да | «(вместе) с», «из-за (эмоции)» |

| местный житель [х] | /-а/ [и] (только с неодушевленными) [С] | (𒀀 -а ) | «в/в», «на/на», «около», «посредством», «с (определённым материалом» |

| аблятивный (только с неодушевленными) [аа] | /-лицом/ | 𒋫- та | «от», «поскольку», «путем (посредством)», «в дополнение к»/«с», распределительный («каждый») |

Заключительные гласные большинства вышеупомянутых маркеров могут быть потеряны, если они прикреплены к словам, завершающим гласные.

Кроме того, есть энклитические частицы 𒈾𒀭𒈾 на-ан-на, означающие «без». [185] и (𒀀)𒅗𒉆 (-a)-ka-nam -/akanam/ (на более раннем шумерском языке) или (𒀀)𒆤𒌍 (-a)-ke 4 -eš 2 -/akeš/ «из-за» (на более позднем шумерском языке) . [186]

Обратите внимание, что эти именные падежи Enter взаимодействуют с так называемыми размерными префиксами глагола, которые изменяет существительное, создавая дополнительные значения. имеют дополняющее распространение Хотя дательный и директивный падеж в существительном , тем не менее их можно различить, если принять во внимание глагольные приставки. Аналогичным образом, хотя значения «в (к)» и «на (к)» выражаются одним и тем же именным падежом, их неоднозначность можно устранить с помощью глагольных префиксов. Более подробно это объясняется в разделе Размерные префиксы .

Дополнительные пространственные или временные значения могут быть выражены родительными фразами типа «во главе» = «выше», «на лице» = «перед», «на внешней стороне» = «из-за» и т. д. .:

оставить уду хад 2 -ка

бар

внешняя сторона

туман

овца

«из-за белой овцы»

структуру Встроенную именной группы можно дополнительно проиллюстрировать следующей фразой:

sipad udu siki-ka-ke 4 -ne

сипад

пасти

туман

овца

«пастухи шерстистых овец»

Здесь первая морфема родительного падежа ( -a(k) ) подчиняет 𒋠 siki «шерсть» 𒇻 udu «овца», а вторая подчиненная 𒇻𒋠 udu siki-(a)k «шерстяная овца» (или «шерстистая овца») to 𒉺𒇻 сипад "пастух". [187]

Использование кейса

[ редактировать ]Использование эргативного и абсолютного падежа типично для эргативных языков. Подлежащее непереходного глагола, такого как «прийти», находится в том же падеже, что и объект переходного глагола, такого как «строить», а именно в так называемом абсолютивном падеже. Напротив, подлежащее переходного глагола имеет другой падеж, который называется эргативным . Это можно проиллюстрировать следующими примерами:

In contrast with the verbal morphology, Sumerian nominal morphology consistently follows this ergative principle regardless of tense/aspect, person and mood.

Besides the general meanings of the case forms outlined above, there are many lexically determined and more or less unpredictable uses of specific cases, often governed by a certain verb in a certain sense:

- The comitative is used to express:[188]

- "to run away" (e.g. 𒀄 zaḫ3) or to "take away" (e.g. 𒋼𒀀 kar) from somebody;

- 𒍪 zu "to know/learn something from somebody";

- 𒁲 sa2 "to be equal to somebody" (but the same verb uses the directive in the phrasal verb si ...sa2 "be/put something in order", see Phrasal verbs);

- the meaning "ago" in the construction 𒈬𒁕...𒋫 mu-da X-ta "X years ago" (lit. "since X with the years")[189]

- The directive is used to express:[190]

- the objects of 𒍏 dab6 "surround", 𒊏 raḫ2 "hit", 𒋛 si "fill"[ab], 𒋳 tag "touch"

- 𒈭 daḫ "add something to something"

- 𒄄 gi4 in the sense "bring back something to something"

- 𒍑 us2 "be next to something, follow something"

- 𒅗 dug4 "say something about/concerning something" ({b-i-dug} "say something about this" often seems to have very vague reference, approaching the meaning "say something then")[191]

- The locative with a directive verbal prefix, expressing "on(to)", is used to express:[192]

- 𒆕 řu2 "hold on to something"

- 𒄷𒈿 sa4 "give (as a name)" to somebody/something

- 𒁺 tum2 "be fit for something"

- 𒉚 sa10 "to barter" governs, in the sense to "to buy", the terminative to introduce the seller from whom something is bought, but in another construction it uses the locative for the thing something is bartered for;[193]

- 𒋾 ti "to approach" governs the dative.[194]

For the government of phrasal verbs, see the relevant section.

Pronouns

[edit]The attested personal pronouns are:

| independent | possessive suffix/enclitic | |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person singular | 𒂷(𒂊) g̃e26(-e) | 𒈬 -g̃u10 |

| 2nd person singular | 𒍢 ze2, Old Babylonian 𒍝𒂊 za-e | 𒍪 -zu |

| 3rd person singular animate | 𒀀𒉈 a-ne or 𒂊𒉈 e-ne[ac] | (𒀀)𒉌 -(a)-ni[ad] |

| 3rd person inanimate[ae] | 𒁉 -bi | |

| 1st person plural | (𒈨𒂗𒉈𒂗 me-en-de3-en?, 𒈨 me?)[af] | 𒈨 -me |

| 2nd person plural | (𒈨𒂗𒍢𒂗 me-en-ze2-en?)[ag] | 𒍪𒉈𒉈 -zu-ne-ne |

| 3rd person plural animate | 𒀀/𒂊𒉈𒉈 a/e-ne-ne[ah] | 𒀀/𒂊𒉈𒉈 (-a)-ne-ne[ai], 𒁉 -bi[203] |

The stem vowels of 𒂷(𒂊) g̃e26(-e) and 𒂊 ze2 are assimilated to a following case suffix containing /a/ and then have the forms 𒂷 g̃a- and 𒍝 za-; e.g. 𒍝𒊏 za-ra 'to you (sg.)'.

As far as demonstrative pronouns are concerned, Sumerian most commonly uses the enclitic 𒁉 -bi to express the meaning "this". There are rare instances of other demonstrative enclitics such as 𒂊 -e "this", 𒊺 -še "that" and 𒊑 -re "that". The difference between the three has been explained in terms of increasing distance from the speaker[204] or as a difference between proximity to the speaker, proximity to the listener and distance from both, akin to the Japanese or Latin three-term demonstrative system.[205] The independent demonstrative pronouns are 𒉈𒂗/𒉈𒂊 ne-e(n) "this (thing)" and 𒄯 ur5 "that (thing)";[206] -ne(n) might also be used as another enclitic.[207][aj] "Now" is 𒉌𒉈𒂠 i3-ne-eš2 or 𒀀𒁕𒀠 a-da-al. For "then" and "there", the declined noun phrases 𒌓𒁀 ud-ba "at that time" and 𒆠𒁀 ki-ba "at that place" are used; "so" is 𒄯𒁶 ur5-gen7, lit. "like that".[208]

The interrogative pronouns are 𒀀𒁀 a-ba "who" and 𒀀𒈾 a-na "what" (also used as "whoever" and "whatever" when introducing dependent clauses). The stem for "where" is 𒈨 me-[209] (used in the locative, terminative and ablative to express "where", "whither" and "whence", respectively[210][211][212]) . "When" is 𒇷/𒂗 en3/en,[209] but also the stem 𒈨(𒂊)𒈾 me-(e)-na is attested for "when" (in the emphatic form me-na-am3 and in the terminative me-na-še3 "until when?", "how long?").[213] "How" and "why" are expressed by 𒀀𒈾𒀸 a-na-aš (lit. "what for?") and 𒀀𒁶 a-gen7 "how" (an equative case form, perhaps "like what?").[209] The expected form 𒀀𒈾𒁶 a-na-gen7 is used in Old Babylonian.[211]

An indefinite pronoun is 𒈾𒈨 na-me "any", which is only attested in attributive function until the Old Babylonian period,[214] but may also stand alone in the sense "anyone, anything" in late texts.[215] It can be added to nouns to produce further expressions with pronominal meaning such as 𒇽𒈾𒈨 lu2 na-me "anyone", 𒃻𒈾𒈨 nig̃2 na-me "anything", 𒆠𒈾𒈨 ki na-me "anywhere", 𒌓𒈾𒈨 ud4 na-me "ever, any time". The nouns 𒇽 lu2 "man" and 𒃻 nig̃2 "thing" are also used for "someone, anyone" and "something, anything".[216] With negation, all of these expressions naturally acquire the meanings "nobody", "nothing", "nowhere" and "never".[217]

The reflexive pronoun is 𒅎(𒋼) ni2(-te) "self", which generally occurs with possessive pronouns attached: 𒅎𒈬 ni2-g̃u10 "my-self", etc. The longer form appears in the third person animate (𒅎𒋼𒉌 ni2-te-ni "him/herself", 𒅎𒋼𒉈𒉈 ni2-te-ne-ne "themselves").[218]

Adjectives

[edit]It is controversial whether Sumerian has adjectives at all, since nearly all stems with adjectival meaning are also attested as verb stems and may be conjugated as verbs: 𒈤 maḫ "great" > 𒎏𒀠𒈤 nin al-maḫ "the lady is great".[219][220] Jagersma believes that there is a distinction in that the few true adjectives cannot be negated, and a few stems are different depending on the part of speech: 𒃲 gal "big", but 𒄖𒌌 gu-ul "be big".[221] Furthermore, stems with adjective-like meaning sometimes occur with the nominalizing suffix /-a/, but their behaviour varies in this respect. Some stems appear to require the suffix always: e.g. 𒆗𒂵 kalag-ga "mighty", 𒊷𒂵 sag9-ga "beautiful", 𒁍𒁕 gid2-da "long"[222][223] (these are verbs with adjectival meaning according to Jagersma[224]). Some never take the suffix: e.g. 𒃲 gal "big", 𒌉 tur "small" and 𒈤 maḫ "great"[225] (these are genuine adjectives according to Jagersma[226]). Finally, some alternate: 𒍣 zid "right" often occurs as 𒍣𒁕 zid-da (these are pairs of adjectives and verbs derived from them, respectively, according to Jagersma[227]). In the latter case, attempts have been made to find a difference of meaning between the forms with and without -a; it has been suggested that the form with -a expresses a kind of determination,[228] e.g. zid "righteous, true" vs zid-da "right (not left)", or restrictiveness, e.g. 𒂍𒉋 e2 gibil "a new house" vs 𒂍𒉋𒆷 e2 gibil-la "the new house (as contrasted with the old one)", "a/the newer (kind of) house" or "the newest house", as well as nominalization, e.g. tur-ra "a/the small one" or "a small thing".[229] Other scholars have remained sceptical about the posited contrasts.[230]

A few adjectives, like 𒃲 gal "big" and 𒌉 tur "small" appear to "agree in number" with a preceding noun in the plural by reduplication; with some other adjectives, the meaning seems to be "each of them ADJ". The colour term 𒌓(𒌓) bar6-bar6 / babbar "white" appears to have always been reduplicated, and the same may be true of 𒈪 gig2 (actually giggig) "black".[158]

To express the comparative or superlative degree, various constructions with the word 𒋛𒀀 dirig "exceed"/"excess" are used: X + locative + dirig-ga "which exceeds (all) X", dirig + X + genitive + terminative "exceeding X", lit. "to the excess of X".[231]

Adverbs and adverbial expressions

[edit]Most commonly, adverbial meanings are expressed by noun phrases in a certain case, e.g. 𒌓 ud-ba "then", lit. "at that time".[232]

There are two main ways to form an adverb of manner:

- There is a dedicated adverbiative suffix 𒂠 -eš2,[233] which can be used to derive adverbs from both adjectives and nouns: 𒍣𒉈𒂠 zid-de3-eš2 "rightly", "in the right way",[234] 𒆰𒂠 numun-eš2 'as seeds', 'in the manner of seeds'.[235]

- the enclitic 𒁉 -bi can be added to an adjectival stem: 𒉋𒁉 gibil-bi "newly". This, too, is interpreted by Jagersma as a deadjectival noun with a possessive clitic in the directive case: {gibil.∅.bi-e}, lit. "at its newness".[ak][236]

For pronominal adverbs, see the section on Pronouns.

Numerals

[edit]Sumerian has a combination decimal and sexagesimal system (for example, 600 is 'ten sixties'), so that the Sumerian lexical numeral system is sexagesimal with 10 as a subbase.[237] The cardinal numerals and ways of forming composite numbers are as follows:[238][239][240]

| number | name | explanation notes | cuneiform sign |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | diš/deš (aš, dili[al]) | 𒁹 (𒀸) | |

| 2 | min | 𒈫 | |

| 3 | eš5 | 𒐈, 𒌍 | |

| 4 | limmu | 𒇹, 𒐉, 𒐼 | |

| 5 | ia2/i2 | 𒐊 | |

| 6 | aš[am] | ia2 "five" + aš "one" | 𒐋 |

| 7 | imin/umun5/umin | ia2 "five" + min "two" | 𒅓 |

| 8 | ussu | 𒑄 | |

| 9 | ilimmu | ia2/i2 (5) + limmu (4) | 𒑆 |

| 10 | u | 𒌋 | |

| 11 | u-diš (?) | 𒌋𒁹 | |

| 20 | niš | 𒌋𒌋 | |

| 30 | ušu3 | 𒌋𒌋𒌋 | |

| 40 | nimin | "less two [tens]" | 𒐏 |

| 50 | ninnu | "less ten" | 𒐐 |

| 60 | g̃eš2(d)[241] | 𒐕, 𒐑 | |

| 120 | g̃eš2(d)-min | "two g̃eš2(d)" | 𒐕𒈫 |

| 240 | g̃eš2(d)-limmu | "four g̃eš2(d)" | 𒐕𒐏 |

| 420 | g̃eš2(d)-imin | "seven g̃eš(d)" | 𒐕𒅓 |

| 600 | g̃eš2(d)-u | "ten g̃eš(d)" | 𒐞 |

| 1000 | li-mu-um | borrowed from Akkadian | 𒇷𒈬𒌝 |

| 1200 | g̃eš2(d)-u-min | "two g̃eš2(d)-u" | 𒐞𒈫 |

| 3600 | šar2 | "totality" | 𒊹 |

| 36000 | šar2-u | "ten totalities" | 𒐬 |

| 216000 | šar2 gal | "a big totality" | 𒊹𒃲 |

Ordinal numerals are formed with the suffix 𒄰𒈠 -kam-ma in Old Sumerian and 𒄰(𒈠) -kam(-ma) (with the final vowel still surfacing in front of enclitics) in subsequent periods.[242] However, a cardinal numeral may also have ordinal meaning sometimes.[243]

The syntax of numerals has some peculiarities. Besides just being placed after a noun like other modifiers (𒌉𒐈 dumu eš5 "three children" - which may, however, also be written 𒐈𒌉 3 dumu), the numeral may be reinforced by the copula (𒌉𒐈𒀀𒀭 dumu eš5-am3, lit. "the children, being three". Finally, there is a third construction in which the possessive pronoun 𒁉 -bi is added after the numeral, which gives the whole phrase a definite meaning: 𒌉𒐈𒀀𒁉 dumu eš5-a-bi: "the three children" (lit. "children - the three of them"). The numerals 𒈫 min "two" and 𒐈 eš5 "three" are also supplied with the nominalizing marker -a before the pronoun, as the above example shows.[243]

Fractions are formed with the phrase 𒅆...N...𒅅 igi-N-g̃al2 : "one-Nth"; where 𒅅 g̃al2 may be omitted. "One-half", however, is 𒋗𒊒𒀀 šu-ru-a, later 𒋗𒊑𒀀 šu-ri-a. Another way of expressing fractions was originally limited to weight measures, specifically fractions of the mina (𒈠𒈾 ma-na): 𒑚 šuššana "one-third" (literarlly "two-sixths"), 𒑛 šanabi "two-thirds" (the former two words are of Akkadian origins), 𒑜 gig̃usila or 𒇲𒌋𒂆 la2 gig̃4 u "five-sixths" (literally "ten shekels split off (from the mina)" or "(a mina) minus ten shekels", respectively), 𒂆 gig̃4 "one-sixtieth", lit. "a shekel" (since a shekel is one-sixtieth of a mina). Smaller fractions are formed by combining these: e.g. one-fifth is 𒌋𒁹𒁹𒂆 "12×1/60 = 1/5", and two-fifths are 𒑚𒇹𒂆 "2/3 + (4 × 1/60) = 5/15 + 1/15 = 6/15 = 2/5".[244]

Verbal morphology

[edit]General

[edit]The Sumerian finite verb distinguishes a number of moods and agrees (more or less consistently) with the subject and the object in person, number and gender. The verb chain may also incorporate pronominal references to the verb's other modifiers, which has also traditionally been described as "agreement", although, in fact, such a reference and the presence of an actual modifier in the clause need not co-occur: not only 𒂍𒂠𒌈𒌈𒅆𒁺𒌦 e2-še3 ib2-ši-du-un "I'm going to the house", but also 𒂍𒂠𒉌𒁺𒌦 e2-še3 i3-du-un "I'm going to the house" and simply 𒌈𒅆𒁺𒌦 ib2-ši-du-un "I'm going to it" are possible.[137][245][246] Hence, the term "cross-reference" instead of "agreement" has been proposed. This article will predominantly use the term "agreement".[247][248]

The Sumerian verb also makes a binary distinction according to a category that some regard as tense (past vs present-future), others as aspect (perfective vs imperfective), and that will be designated as TA (tense/aspect) in the following. The two members of the opposition entail different conjugation patterns and, at least for many verbs, different stems; they are theory-neutrally referred to with the Akkadian grammatical terms for the two respective forms – ḫamṭu "quick" and marû "slow, fat".[an] Finally, opinions differ on whether the verb has a passive or a middle voice and how it is expressed.

It is often pointed out that a Sumerian verb does not seem to be strictly limited to only transitive or only intransitive usage: e.g. the verb 𒆭 kur9 can mean both "enter" and "insert / bring in", and the verb 𒌣 de2 can mean both "flow out" and "pour out". This depends simply on whether an ergative participant causing the event is explicitly mentioned (in the clause and in the agreement markers on the verb). Some have even concluded that instead of speaking about intransitive and transitive verbs, it may be better to speak only of intransitive and transitive constructions in Sumerian.[250]

The verbal root is almost always a monosyllable and, together with various affixes, forms a so-called verbal chain which is described as a sequence of about 15 slots, though the precise models differ.[251] The finite verb has both prefixes and suffixes, while the non-finite verb may only have suffixes. Broadly, the prefixes have been divided in three groups that occur in the following order: modal prefixes, "conjugation prefixes", and pronominal and dimensional prefixes.[252] The suffixes are a future or imperfective marker /-ed-/, pronominal suffixes, and an /-a/ ending that nominalizes the whole verb chain. The overall structure can be summarized as follows:

| slot | modal prefix | "conjugation prefixes" | pronominal prefix 1 | dimensional prefix | pronominal prefix 2 | stem | future/imperfective | pronominal suffix | nominalizer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| finite prefix | coordinator prefix | ventive prefix | middle prefix | |||||||||

| common morphemes | /Ø/-, /ḫa/-, /u/-, /ga/-, /nu/-~/la/- | /i/~/e/-, /a/- | -/nga/- | /mu/-, -/m/- | -/ba/- | -/Ø/-, -/e/~/r/-, -/n(n)/-, -/b/- | -/a/-, -/da/-,-/ta/-,-/ši/-,-/i/-,-/ni/- | -/Ø/-, -/e/~/r/-, -/n(n)/-, -/b/- | -/e(d)/- | -/en/ -/en/ -/Ø/, -/e/ -/enden/ | -/a/ | |

Examples using most of the above slots may be:

nu-ub-ši-e-gi4-gi4-a

nu-

NEG-

-i-

-FIN-

-b-

-INAN-

-ši-

-TERM-

-gi4-gi4-

-return.IPFV-

-a

-NMLZ

'(one) who does not bring you back to it'

More than one dimensional prefix may occur within the verb chain. If so, the prefixes are placed in a specific order, which is shown the section Dimensional prefixes below. The "conjugation prefixes" appear to be mutually exclusive to a great extent, since the "finite" prefixes /i/~/e/- and /a/- do not appear before [mu]-, /ba/- and the sequence -/b/-+-/i/-, nor does the realization [mu] appear before /ba-/ or /b-i/. However, it is commonly assumed that the spellings im-, im-ma- and im-mi- are equivalent to {i-} + {-mu-}, {i-} + {-mu-} + {-ba-} and {i-} + {-mu-} + {-bi-}, respectively. According to Jagersma, the reason for the restrictions is that the "finite" prefixes /i/~/e/- and /a/- have been elided prehistorically in open syllables, in front of prefixes of the shape CV (consonant-vowel). The exception is the position in front of the locative prefix -/ni/-, the second person dative 𒊏 /-r-a/ and the second person directive 𒊑 /-r-i/, where the dominant dialect of the Old Babylonian period retains them.[253]

Modal prefixes

[edit]The modal prefixes express modality. Some of them are generally combined with certain TAs; in other cases, the meaning of a modal prefix can depend on the TA.

- /Ø-/ is the prefix of the simple indicative mood; in other words, the indicative is unmarked.

E.g.: 𒅔𒅥 in-gu7 {Ø-i-n-gu} "He ate it."

- 𒉡 nu- and 𒆷 la-, 𒇷 li- (𒉌 li2- in Ur III spelling) have negative meaning and can be translated as "not". The allomorphs /la-/ and /li-/ are used before the "conjugation prefixes" 𒁀 ba- and 𒉈 bi2-, respectively. A following vowel /i/ or /e/ is contracted with the preceding /u/ of nu- with compensatory lengthening (which is often graphically unexpressed): compare 𒉌𒁺 i3-du "he is walking", but /nu-i-du/ > /nuː-du/ 𒉡𒅇𒁺 nu(-u3)-du "he isn't walking". If followed by a consonant, on the other hand, the vowel of nu- appears to have been assimilated to the vowel of the following syllable, because it occasionally appears written as 𒈾 /na-/ in front of a syllable containing /a/.[254]

E.g.: 𒉡𒌦𒅥 nu(-u3)-un-gu7 {nu-i-n-gu} "He didn't eat it."

- 𒄩 ḫa- / 𒃶 ḫe2- has either precative/optative meaning ("let him do X", "may you do X") or affirmative meaning ("he does this indeed"), partly depending on the type of verb. If the verbal form denotes a transitive action, precative meaning is expressed with the marû form, and affirmative with the ḫamṭu form. In contrast, if the verbal form is intransitive or stative, the TA used is always ḫamṭu.[255] Occasionally the precative/optative form is also used in a conditional sense of "if" or "when".[255] According to Jagersma, the base form is 𒄩 ḫa-, but in open syllables the prefix merges with a following conjugation prefix i3- into 𒃶 ḫe2-. Beginning in the later Old Akkadian period, the spelling also shows assimilation of the vowel of the prefix to 𒃶 ḫe2- in front of a syllable containing /e/; in the Ur III period, there is a tendency to generalize the variant 𒃶 ḫe2-, but in addition further assimilation to 𒄷 ḫu- in front of /u/ is attested and graphic expressions of the latter become common in the Old Babylonian period.[256] Other scholars have contended that 𒃶 ḫe2- was the only allomorph in the Archaic Sumerian period[257] and many have viewed it as the main form of the morpheme.[258]

E.g.: 𒃶𒅁𒅥𒂊 ḫe2-eb-gu7-e {ḫa-ib-gu7-e} "let him eat it!"; 𒄩𒀭𒅥 ḫa-an-gu7 "He ate it indeed."

- 𒂵 ga- has cohortative meaning and can be translated as "let me/us do X" or "I will do X". Occasional phonetic spellings show that its vowel is assimilated to following vowels, producing the allomorphs written 𒄄 gi4- and 𒄘 gu2-. It is only used with ḫamṭu stems,[259] but nevertheless uses personal prefixes to express objects, which is otherwise characteristic of the marû conjugation: 𒂵𒉌𒌈𒃻 ga-ni-ib2-g̃ar "let me put it there!".[260] The plural number of the subject was not specially marked until the Old Babylonian period,[260] during which the 1st person plural suffix began to be added: 𒂵𒉌𒌈𒃻𒊑𒂗𒉈𒂗 ga-ni-ib2-g̃ar-re-en-de3-en "let us put it there!".[261]

E.g.: 𒂵𒀊𒅥 ga-ab-gu7 "Let me eat it!"

- 𒅇 u3- has prospective meaning ("after/when/if") and is also used as a mild imperative "Please do X". It is only used with ḫamṭu forms.[259] In open syllables, the vowel of the prefix is assimilated to i3- and a- in front of syllables containing these vowels. The prefix acquires an additional /l/ when located immediately before the stem, resulting in the allomorph 𒅇𒌌 u3-ul-.[262]

E.g.: 𒌦𒅥 un-gu7 "If/when he eats it..."

- 𒈾 na- has prohibitive / negative optative[263] meaning ("Do not do it!"/"He must not do it!"/"May he not do it!") or affirmative meaning ("he did it indeed"), depending on the TA of verb: it almost always expresses negative meaning with the marû TA and affirmative meaning with the ḫamṭu TA.[264][265] In its negative usage, it can be said to function as the negation of the precative/optative ḫa-.[266] In affirmative usage, it has been said to signal an emphatic assertion,[267] but some have also claimed that it expresses reported speech (either "traditional orally transmitted knowledge" or someone else's words)[268] or that it introduces following events/states to which it is logically connected ("as X happened (na-), so/then/therefore Y happened").[269] According to Jagersma and others, "negative na-" and "affirmative na-" are actually two different prefixes, since "negative na-" has the allomorph /nan-/ before a single consonant (written 𒈾𒀭 na-an- or, in front of the labial consonants /b/ and /m/, 𒉆 nam-), whereas "affirmative na-" does not.[270]

E.g.: 𒈾𒀊𒅥𒂊 na-ab-gu7-e "He must not eat it!"; 𒈾𒀭𒅥 na-an-gu7 "He ate it indeed."

- 𒁀𒊏 ba-ra- has emphatic negative meaning ("He certainly does/will not do it")[271] or vetitive meaning ("He should not do it!")[272], although some consider the latter usage rare or non-existent.[273] It can often function as the negation of cohortative ga-[274] and of affirmative ḫa-.[275] It is combined with the marû TA if the verb denies an action (always present or future), and with the ḫamṭu TA if it denies a state (past, present or future) or an action (always in the past).[271] The vetitive meaning requires it to be combined with the marû TA,[276] at least if the action is transitive.[277]

E.g.: 𒁀𒊏𒀊𒅥𒂗 ba-ra-ab-gu7-en "I certainly will not eat it!"; 𒁀𒊏𒀭𒅥 ba-ra-an-gu7 "He certainly didn't eat it."

- 𒉡𒍑 nu-uš- is a rare prefix that has been interpreted as having "frustrative" meaning, i.e. as expressing an unrealizable wish ("If only he would do it!"). It occurs both with ḫamṭu and with marû.[278]

E.g.: 𒉡𒍑𒌈𒅥𒂊 nu-uš-ib2-gu7-e "If only he would eat it!"

- 𒅆 ši-, earlier 𒂠 še3-, is a rare prefix, with unclear and disputed meaning, which has been variously described as affirmative ("he does it indeed"),[279] contrapunctive ("correspondingly", "on his part"[280]), as "reconfirming something that already ha(s) been stated or ha(s) occurred",[281] or as "so", "therefore".[282] It occurs both with ḫamṭu and with marû.[283] In Southern Old Sumerian, the vowel alternated between /e/ before open vowels and /i/ before close ones in accordance with the vowel harmony rule of that dialect; later, it displays assimilation of the vowel in an open syllable,[279] depending on the vowel of the following syllable, to /ša-/ (𒊭 ša- / 𒁺 ša4-) and (first attested in Old Babylonian) to 𒋗 šu-.[281]

E.g.: 𒅆𒅔𒅥 ši-in-gu7 "So/correspondingly/accordingly(?), he ate it."

Although the modal prefixes are traditionally grouped together in one slot in the verbal chain, their behaviour suggests a certain difference in status: only nu- and ḫa- exhibit morphophonemic evidence of co-occurring with a following finite "conjugation prefix", while the others do not and hence seem to be mutually exclusive with it. For this reason, Jagersma separates the first two as "proclitics" and groups the others together with the finite prefix as (non-proclitic) "preformatives".[284]

"Conjugation prefixes"

[edit]The meaning, structure, identity and even the number of the various "conjugation prefixes" have always been a subject of disagreements. The term "conjugation prefix" simply alludes to the fact that a Sumerian finite verb in the indicative mood must (nearly) always contain one of them. Which of these prefixes is used seems to have, more often than not, no effect on its translation into European languages.[285] Proposed explanations of the choice of conjugation prefix usually revolve around the subtleties of spatial grammar, information structure (focus[286]), verb valency, and, most recently, voice.[287] The following description primarily follows the analysis of Jagersma (2010), largely seconded by Zólyomi (2017) and Sallaberger (2023), in its specifics; nonetheless, most of the interpretations in it are held widely, if not universally.[288]

- 𒉌 i3- (Southern Old Sumerian variant: 𒂊 e- in front of open vowels), sometimes described as a finite prefix,[289] appears to have a neutral finite meaning.[290][291] As mentioned above, it generally does not occur in front of a prefix or prefix sequence of the shape CV[292] except, in Old Babylonian Sumerian, in front of the locative prefix 𒉌 -/ni/-, the second person dative 𒊏 -/r-a/- and the second person directive 𒊑 -/r-i/-.[290]

E.g.: 𒅔𒁺 in-ře6 {Ø-i-n-ře} "He brought (it)."

- 𒀀 a-, with the variant 𒀠 al- used in front of the stem[290][293], the other finite prefix, is rare in most Sumerian texts outside of the imperative form,[290] but when it occurs, it usually has stative meaning.[294] It is common in the Northern Old Sumerian dialect, where it can also have a passive meaning.[295][294] According to Jagersma, it was used in the South as well during the Old Sumerian period, but only in subordinate clauses, where it regularly characterized not only stative verbs in ḫamṭu, but also verbs in marû; in the Neo-Sumerian period, only the pre-stem form al- was still used and it no longer occurred with marû forms.[296][ao] Like i3-, the prefix a- does not occur in front of a CV sequence except, in Old Babylonian Sumerian, in front of the locative prefix 𒉌 -/ni/-, the second person dative 𒊏 -/r-a/- and the second person directive 𒊑 -/r-i/-.[290]

E.g.: 𒀠𒁺 al-ře6 "It is/was brought."

- 𒈬 mu- is most commonly considered to be a ventive prefix,[297] expressing movement towards the speaker or proximity to the speaker; in particular, it is an obligatory part of the 1st person dative form 𒈠 ma- (mu- + -a-).[298] However, many of its occurrences appear to express more subtle and abstract nuances or general senses, which different scholars have sought to pinpoint. They have often been derived from "abstract nearness to the speaker" or "involvement of the speaker".[299] It has been suggested, variously, that mu- may be adding nuances of emotional closeness or alignment of the speaker with the agent or other participants of the event,[300] topicality, foregrounding of the event as something essential to the message with a focus on a person,[301] movement or action directed towards an entity with higher social status,[302] prototypical transitivity with its close association with "control, agency, and animacy" as well as focus or emphasis on the role of the agent,[303] telicity as such[304] or that it is attracted by personal dative prefixes in general, as is the Akkadian ventive.[304]

E.g. 𒈬𒌦𒁺 mu-un-ře6 "He brought it here."

- 𒅎 im- and 𒀀𒀭am3- are widely seen as being formally related to mu-[305] and as also having ventive meaning;[306] according to Jagersma, they consist of an allomorph of mu-, namely -/m/-, and the preceding prefixes 𒉌 i3- and 𒀀 a-. In his analysis, these combinations occur in front of a CV sequence, where the vowel -u- of mu- is lost, whereas the historically preceding finite prefix is preserved: */i-mu-ši-g̃en/ > 𒅎𒅆𒁺 im-ši-g̃en "he came for it".[307] In Zólyomi's slightly different analysis, which is supported by Sallaberger, there may also be a -/b/- in the underlying form, which also elicits the allomorph -/m/-: *{i-mu-b-ši-g̃en} > /i-m-b-ši-g̃en/ > /i-m-ši-g̃en/.[308] The vowel of the finite prefix undergoes compensatory lengthening immediately before the stem */i-mu-g̃en/ > 𒉌𒅎𒁺 i3-im-g̃en "he came".[309]

E.g. 𒅎𒁺𒈬 im-tum3-mu {i-mu-b-tum-e} "He will bring it here."

- The vowel of mu- is not elided in front of the locative prefix 𒉌 -ni-, the second person dative 𒊏 /-r-a/ and the second person directive 𒊑 /-r-i/. It may, however, be assimilated to the vowel of the following syllable.[ap] This produces two allomorphs:[310]

- 𒈪 mi- in the sequences 𒈪𒉌 mi-ni- and 𒈪𒊑 mi-ri-.[311]

E.g. 𒈪𒉌𒅔𒁺 mi-ni-in-ře6 "He brought it in here."

- 𒈠 ma- in the sequence 𒈠𒊏 ma-ra-.

E.g. 𒈠𒊏𒀭𒁺 ma-ra-an-ře6 "He brought (it) here to you."