Неонацизм

| Часть серии о |

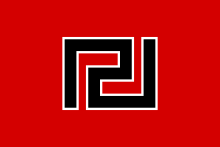

| нацизм |

|---|

| Part of a series on |

| Neo-fascism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Terrorism |

|---|

Неонацизм включает в себя воинственные, социальные и политические движения, возникшие после Второй мировой войны и стремящиеся возродить и восстановить нацистскую идеологию . Неонацисты используют свою идеологию для пропаганды ненависти и расового превосходства (часто белого превосходства ), для нападения на расовые и этнические меньшинства (часто антисемитизм и исламофобия ), а в некоторых случаях для создания фашистского государства . [ 1 ] [ 2 ]

Неонацизм — это глобальное явление, имеющее организованное представительство во многих странах и международных сетях. Он заимствует элементы из нацистской доктрины, включая антисемитизм, ультранационализм , расизм , ксенофобию , эйлизм , гомофобию , антикоммунизм и создание « Четвертого рейха ». Отрицание Холокоста распространено в неонацистских кругах.

Neo-Nazis regularly display Nazi symbols and express admiration for Adolf Hitler and other Nazi leaders. In some European and Latin American countries, laws prohibit the expression of pro-Nazi, racist, antisemitic, or homophobic views. Nazi-related symbols are banned in many European countries (especially Germany) in an effort to curtail neo-Nazism.[3]

Definition

The term neo-Nazism describes any post-World War II militant, social or political movements seeking to revive the ideology of Nazism in whole or in part.[4][5]

The term 'neo-Nazism' can also refer to the ideology of these movements, which may borrow elements from Nazi doctrine, including ultranationalism, anti-communism, racism, ableism, xenophobia, homophobia, antisemitism, up to initiating the Fourth Reich. Holocaust denial is a common feature, as is the incorporation of Nazi symbols and admiration of Adolf Hitler.

Neo-Nazism is considered a particular form of far-right politics and right-wing extremism.[6]

Hyperborean racial doctrine

Neo-Nazi writers have posited a spiritual, esoteric doctrine of race, which moves beyond the primarily Darwinian-inspired materialist scientific racism popular mainly in the Anglosphere during the 20th century. Figures influential in the development of neo-Nazi racism,[citation needed] such as Miguel Serrano and Julius Evola (writers who are described by critics of Nazism such as the Southern Poverty Law Center as influential within what it presents as parts of "the bizarre fringes of National Socialism, past and present"),[7] claim that the Hyperborean ancestors of the Aryans were in the distant past, far higher beings than their current state, having suffered from "involution" due to mixing with the "Telluric" peoples; supposed creations of the Demiurge. Within this theory, if the "Aryans" are to return to the Golden Age of the distant past, they need to awaken the memory of the blood. An extraterrestrial origin of the Hyperboreans is often claimed. These theories draw influence from Gnosticism and Tantrism, building on the work of the Ahnenerbe. Within this racist theory, Jews are held up as the antithesis of nobility, purity and beauty.

Ecology and environmentalism

Neo-Nazism generally aligns itself with a blood and soil variation of environmentalism, which has themes in common with deep ecology, the organic movement and animal protectionism.[8][9] This tendency, sometimes called "ecofascism", was represented in the original German Nazism by Richard Walther Darré who was the Reichsminister of Food from 1933 until 1942.[10]

History

Germany and Austria, 1945–1950s

Following the defeat of Nazi Germany, the political ideology of the ruling party, Nazism, was in complete disarray. The final leader of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP) was Martin Bormann. He died on 2 May 1945 during the Battle of Berlin, but the Soviet Union did not reveal his death to the rest of the world, and his ultimate fate remained a mystery for many years. Conspiracy theories emerged about Hitler himself, that he had secretly survived the war and fled to South America or elsewhere.

The Allied Control Council officially dissolved the NSDAP on 10 October 1945, marking the end of "Old" Nazism. A process of denazification began, and the Nuremberg trials took place, where many major leaders and ideologues were condemned to death by October 1946, others committed suicide.

In both the East and West, surviving ex-party members and military veterans assimilated to the new reality and had no interest in constructing a "neo-Nazism".[citation needed] However, during the 1949 West German elections a number of Nazi advocates such as Fritz Rössler had infiltrated the national conservative Deutsche Rechtspartei, which had 5 members elected. Rössler and others left to found the more radical Socialist Reich Party (SRP) under Otto Ernst Remer. At the onset of the Cold War, the SRP favoured the Soviet Union over the United States.[citation needed]

In Austria, national independence had been restored, and the Verbotsgesetz 1947 explicitly criminalised the NSDAP and any attempt at restoration. West Germany adopted a similar law to target parties it defined as anti-constitutional; Article 21 Paragraph 2 in the Basic Law, banning the SRP in 1952 for being opposed to liberal democracy.

As a consequence, some members of the nascent movement of German neo-Nazism joined the Deutsche Reichspartei of which Hans-Ulrich Rudel was the most prominent figure. Younger members founded the Wiking-Jugend modelled after the Hitler Youth. The Deutsche Reichspartei stood for elections from 1953 until 1961 fetching around 1% of the vote each time.[citation needed] Rudel befriended French-born Savitri Devi, who was a proponent of Esoteric Nazism. In the 1950s she wrote a number of books, such as Pilgrimage (1958), which concerns prominent Third Reich sites, and The Lightning and the Sun (1958), in which she claims that Adolf Hitler was an avatar of the God Vishnu. She was not alone in this reorientation of Nazism towards its Thulean-roots; the Artgemeinschaft, founded by former SS member Wilhelm Kusserow, attempted to promote a new paganism.[citation needed] In the German Democratic Republic (East Germany) a former member of SA, Wilhelm Adam, founded the National Democratic Party of Germany. It reached out to those attracted by the Nazi Party before 1945 and provide them with a political outlet, so that they would not be tempted to support the far-right again or turn to the anti-communist Western Allies.[citation needed] Joseph Stalin wanted to use them to create a new pro-Soviet and anti-Western strain in German politics.[11] According to top Soviet diplomat Vladimir Semyonov, Stalin even suggested that they could be allowed to continue publishing their own newspaper, Völkischer Beobachter.[11] While in Austria, former SS member Wilhelm Lang founded an esoteric group known as the Vienna Lodge; he popularised Nazism and occultism such as the Black Sun and ideas of Third Reich survival colonies below the polar ice caps.[citation needed]

With the onset of the Cold War, the allied forces had lost interest in prosecuting anyone as part of the denazification.[12] In the mid-1950s this new political environment allowed Otto Strasser, an NS activist on the left of the NSDAP, who had founded the Black Front to return from exile. In 1956, Strasser founded the German Social Union as a Black Front successor, promoting a Strasserite "nationalist and socialist" policy, which dissolved in 1962 due to lack of support. Other Third Reich associated groups were the HIAG and Stille Hilfe dedicated to advancing the interests of Waffen-SS veterans and rehabilitating them into the new democratic society. However, they did not claim to be attempting to restore Nazism, instead functioning as lobbying organizations for their members before the government and the two main political parties (the conservative CDU/CSU and the Nazis' one-time archenemies, the Social Democratic Party)

Many bureaucrats who served under the Third Reich continued to serve in German administration after the war. According to the Simon Wiesenthal Center, many of the more than 90,000 Nazi war criminals recorded in German files were serving in positions of prominence under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer.[13][14] Not until the 1960s were the former concentration camp personnel prosecuted by West Germany in the Belzec trial, Frankfurt Auschwitz trials, Treblinka trials, Chełmno trials, and the Sobibór trial.[15] However, the government had passed laws prohibiting Nazis from publicly expressing their beliefs.

"Universal National Socialism", 1950s–1970s

This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2022) |

Neo-Nazism found expression outside of Germany, including in countries who fought against the Third Reich during the Second World War, and sometimes adopted pan-European or "universal" characteristics, beyond the parameters of German nationalism.[citation needed] The two main tendencies, with differing styles and even worldviews, were the followers of the American Francis Parker Yockey, who was fundamentally anti-American and advocated for a pan-European nationalism, and those of George Lincoln Rockwell, an American conservative.[nb 1][citation needed]

Yockey, a neo-Spenglerian author, had written Imperium: The Philosophy of History and Politics (1949) dedicated to "the hero of the twentieth century" (namely, Adolf Hitler) and founded the European Liberation Front. He was interested more in the destiny of Europe; to this end, he advocated a National Bolshevik-esque red-brown alliance against American culture and influenced 1960s figures such as SS-veteran Jean-François Thiriart. Yockey was also fond of Arab nationalism, in particular Gamal Abdel Nasser, and saw Fidel Castro's Cuban Revolution as a positive, visiting officials there. Yockey's views impressed Otto Ernst Remer and the radical traditionalist philosopher Julius Evola. He was constantly hounded by the FBI and was eventually arrested in 1960, before committing suicide. Domestically, Yockey's biggest sympathisers were the National Renaissance Party, including James H. Madole, H. Keith Thompson and Eustace Mullins (protégé of Ezra Pound) and the Liberty Lobby of Willis Carto.[citation needed]

Rockwell, an American conservative, was first politicised in the anti-communism and anti-racial integration movements before becoming anti-Jewish. In response to his opponents calling him a "Nazi", he theatrically appropriated the aesthetic elements of the NSDAP, to "own" the intended insult. In 1959, Rockwell founded the American Nazi Party and instructed his members to dress in imitation SA-style brown shirts, while flying the flag of the Third Reich. In contrast to Yockey, he was pro-American and cooperated with FBI requests, despite the party being targeted by COINTELPRO due to the mistaken belief that they were agents of Nasser's Egypt during a brief intelligence "brown scare".[nb 2] Later leaders of American white nationalism came to politics through the ANP, including a teenage David Duke and William Luther Pierce of the National Alliance, although they soon distanced themselves from explicit self-identification with neo-Nazism.[citation needed]

In 1961, the World Union of National Socialists was founded by Rockwell and Colin Jordan of the British National Socialist Movement, adopting the Cotswold Declaration. French socialite Françoise Dior was involved romantically with Jordan and his deputy John Tyndall and a friend of Savitri Devi, who also attended the meeting. The National Socialist Movement wore quasi-SA uniforms, was involved in streets conflicts with the Jewish 62 Group. In the 1970s, Tyndall's earlier involvement with neo-Nazism would come back to haunt the National Front, which he led, as they attempted to ride a wave of anti-immigration populism and concerns over British national decline. Televised exposes on This Week in 1974 and World in Action in 1978, showed their neo-Nazi pedigree and damaged their electoral chances. In 1967, Rockwell was killed by a disgruntled former member. Matthias Koehl took control of the ANP, and strongly influenced by Savitri Devi, gradually transformed it into an esoteric group known as the New Order.[citation needed]

In Franco's Spain, certain SS refugees most notably Otto Skorzeny, Léon Degrelle and the son of Klaus Barbie became associated with CEDADE (Círculo Español de Amigos de Europa), an organisation which disseminated Third Reich apologetics out of Barcelona. They intersected with neo-Nazi advocates from Mark Fredriksen in France to Salvador Borrego in Mexico. In the post-fascist Italian Social Movement splinter groups such as Ordine Nuovo and Avanguardia Nazionale, involved in the "Years of Lead" considered Nazism a reference. Franco Freda created a "Nazi-Maoist" synthesis.

In Germany itself, the various Third Reich nostalgic movements coalesced around the National Democratic Party of Germany in 1964 and in Austria the National Democratic Party in 1967 as the primary sympathisers of the NSDAP past, although more publicly cautious than earlier groups.[citation needed]

Holocaust denial and subcultures, 1970s–1990s

Holocaust denial, the claim that six million Jews were not deliberately and systematically exterminated as an official policy of the Third Reich and Adolf Hitler, became a more prominent feature of neo-Nazism in the 1970s. Before this time, Holocaust denial had long existed as a sentiment among neo-Nazis, but it had not yet been systematically articulated as a theory with a bibliographical canon. Few of the major theorists of Holocaust denial (who call themselves "revisionists") can be uncontroversially classified as outright neo-Nazis (though some works such as those of David Irving forward a clearly sympathetic view of Hitler and the publisher Ernst Zündel was deeply tied to international neo-Nazism), however, the main interest of Holocaust denial to neo-Nazis was their hope that it would help them rehabilitate their political ideology in the eyes of the general public. Did Six Million Really Die? (1974) by Richard Verrall and The Hoax of the Twentieth Century (1976) by Arthur Butz are popular examples of Holocaust denial material.

Key developments in international neo-Nazism during this time include the radicalisation of the Vlaamse Militanten Orde under former Hitler Youth member Bert Eriksson. They began hosting an annual conference; the "Iron Pilgrimage"; at Diksmuide, which drew kindred ideologues from across Europe and beyond. As well as this, the NSDAP/AO under Gary Lauck arose in the United States in 1972 and challenged the international influence of the Rockwellite WUNS. Lauck's organisation drew support from the National Socialist Movement of Denmark of Povl Riis-Knudsen and various German and Austrian figures who felt that the "National Democratic" parties were too bourgeois and insufficiently Nazi in orientation. This included Michael Kühnen, Christian Worch, Bela Ewald Althans and Gottfried Küssel of the 1977-founded ANS/NS which called for the establishment of a Germanic Fourth Reich. Some ANS/NS members were imprisoned for planning paramilitary attacks on NATO bases in Germany and planning to liberate Rudolf Hess from Spandau Prison. The organisation was officially banned in 1983 by the Minister of the Interior.

During the late 1970s, a British subculture came to be associated with neo-Nazism; the skinheads. Portraying an ultra-masculine, crude and aggressive image, with working-class references, some of the skinheads joined the British Movement under Michael McLaughlin (successor of Colin Jordan), while others became associated with the National Front's Rock Against Communism project which was meant to counter the SWP's Rock Against Racism. The most significant music group involved in this project was Skrewdriver, led by Ian Stuart Donaldson. Together with ex-BM member Nicky Crane, Donaldson founded the international Blood & Honour network in 1987. By 1992 this network, with input from Harold Covington, had developed a paramilitary wing; Combat 18, which intersected with football hooligan firms such as the Chelsea Headhunters. The neo-Nazi skinhead movement spread to the United States, with groups such as the Hammerskins. It was popularised from 1986 onwards by Tom Metzger of the White Aryan Resistance. Since then it has spread across the world. Films such as Romper Stomper (1992) and American History X (1998) would fix a public perception that neo-Nazism and skinheads were synonymous.

New developments also emerged on the esoteric level, as former Chilean diplomat Miguel Serrano built on the works of Carl Jung, Otto Rahn, Wilhelm Landig, Julius Evola and Savitri Devi to bind together and develop already existing theories. Serrano had been a member of the National Socialist Movement of Chile in the 1930s and from the early days of neo-Nazism, he had been in contact with key figures across Europe and beyond. Despite this, he was able to work as an ambassador to numerous countries until the rise of Salvador Allende. In 1984 he published his book Adolf Hitler: The Ultimate Avatar. Serrano claimed that the Aryans were extragalactic beings who founded Hyperborea and lived the heroic life of Bodhisattvas, while the Jews were created by the Demiurge and were concerned only with coarse materialism. Serrano claimed that a new Golden Age can be attained if the Hyperboreans repurify their blood (supposedly the light of the Black Sun) and restore their "blood-memory." As with Savitri Devi before him, Serrano's works became a key point of reference in neo-Nazism.

Lifting of the Iron Curtain, 1990s–present

With the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union during the early 1990s, neo-Nazism began to spread its ideas in the East, as hostility to the triumphant liberal order was high and revanchism a widespread feeling. In Russia, during the chaos of the early 1990s, an amorphous mixture of KGB hardliners, Orthodox neo-Tsarist nostalgics (i.e., Pamyat) and explicit neo-Nazis found themselves strewn together in the same camp. They were united by opposition to the influence of the United States, against the liberalising legacy of Mikhail Gorbachev's perestroika and on the Jewish question, Soviet Zionology merged with a more explicit anti-Jewish sentiment. The most significant organisation representing this was Russian National Unity under the leadership of Alexander Barkashov, where black-uniform clad Russians marched with a red flag incorporating the Swastika under the banner of Russia for Russians. These forces came together in a last gasp effort to save the Supreme Soviet of Russia against Boris Yeltsin during the 1993 Russian constitutional crisis. As well as events in Russia, in newly independent ex-Soviet states, annual commemorations for SS volunteers now took place; particularly in Latvia, Estonia and Ukraine.

The Russian developments excited German neo-Nazism who dreamed of a Berlin–Moscow alliance against the supposedly "decadent" Atlanticist forces; a dream which had been thematic since the days of Remer.[citation needed] Zündel visited Russia and met with ex-KGB general Aleksandr Stergilov and other Russian National Unity members. Despite these initial aspirations, international neo-Nazism and its close affiliates in ultra-nationalism would be split over the Bosnian War between 1992 and 1995, as part of the breakup of Yugoslavia. The split would largely be along ethnic and sectarian lines. The Germans and the French would largely back the Western Catholic Croats (Lauck's NSDAP/AO explicitly called for volunteers, which Kühnen's Free German Workers' Party answered and the French formed the "Groupe Jacques Doriot"), while the Russians and the Greeks would back the Orthodox Serbs (including Russians from Barkashov's Russian National Unity, Eduard Limonov's National Bolshevik Front and Golden Dawn members joined the Greek Volunteer Guard). Indeed, the revival of National Bolshevism was able to steal some of the thunder from overt Russian neo-Nazism, as ultra-nationalism was wedded with veneration of Joseph Stalin in place of Adolf Hitler, while still also flirting with Nazi aesthetics.

Analogous European movements

Outside Germany, in other countries which were involved with the Axis powers and had their own native ultra-nationalist movements, which sometimes collaborated with the Third Reich but were not technically German-style National Socialists, revivalist and nostalgic movements have emerged in the post-war period which, as neo-Nazism has done in Germany, seek to rehabilitate their various loosely associated ideologies. These movements include neo-fascists and post-fascists in Italy; Vichyites, Pétainists and "national Europeans" in France; Ustaše sympathisers in Croatia; neo-Chetniks in Serbia; Iron Guard revivalists in Romania; Hungarists and Horthyists in Hungary and others.[16]

Issues

Ex-Nazis in mainstream politics

The most significant case on an international level was the election of Kurt Waldheim to the Presidency of Austria in 1986. It came to light that Waldheim had been a member of the National Socialist German Students' League, the SA and served as an intelligence officer during the Second World War. Following this he served as an Austrian diplomat and was the Secretary-General of the United Nations from 1972 until 1981. After revelations of Waldheim's past were made by an Austrian journalist, Waldheim clashed with the World Jewish Congress on the international stage. Waldheim's record was defended by Bruno Kreisky, an Austrian Jew who served as Chancellor of Austria. The legacy of the affair lingers on, as Victor Ostrovsky has claimed the Mossad doctored the file of Waldheim to implicate him in war crimes.[citation needed]

Contemporary right-wing populism

Some critics have sought to draw a connection between Nazism and modern right-wing populism in Europe, but the two are not widely regarded as interchangeable by most academics. In Austria, the Freedom Party of Austria (FPÖ) served as a shelter for ex-Nazis almost from its inception.[17] In 1980, scandals undermined Austria's two main parties and the economy stagnated. Jörg Haider became leader of the FPÖ and offered partial justification for Nazism, calling its employment policy effective. In the 1994 Austrian election, the FPÖ won 22 percent of the vote, as well as 33 percent of the vote in Carinthia and 22 percent in Vienna; showing that it had become a force capable of reversing the old pattern of Austrian politics.[18]

Historian Walter Laqueur writes that even though Haider welcomed former Nazis at his meetings and went out of his way to address Schutzstaffel (SS) veterans, the FPÖ is not a fascist party in the traditional sense, since it has not made anti-communism an important issue, and it does not advocate the overthrow of the democratic order or the use of violence. In his view, the FPÖ is "not quite fascist", although it is part of a tradition, similar to that of 19th-century Viennese mayor Karl Lueger, which involves nationalism, xenophobic populism, and authoritarianism.[19] Haider, who in 2005 left the Freedom Party and formed the Alliance for Austria's Future, was killed in a traffic accident in October 2008.[20]

Barbara Rosenkranz, the Freedom Party's candidate in Austria's 2010 presidential election, was controversial for having made allegedly pro-Nazi statements.[21] Rosenkranz is married to Horst Rosenkranz, a key member of a banned neo-Nazi party, who is known for publishing far-right books. Rosenkranz says she cannot detect anything "dishonourable" in her husband's activities.[22]

Around the world

Europe

Armenia

The Armenian-Aryan Racialist Political Movement is a National Socialist movement in Armenia. It was founded in 2021 and supports Aryanism, Antisemitism, and White supremacy.[23]

Belgium

A Belgian neo-Nazi organization, Bloed, Bodem, Eer en Trouw (Blood, Soil, Honour and Loyalty), was created in 2004 after splitting from the international network (Blood and Honour). The group rose to public prominence in September 2006, after 17 members (including 11 soldiers) were arrested under the December 2003 anti-terrorist laws and laws against racism, antisemitism and supporters of censorship. According to Justice Minister Laurette Onkelinx and Interior Minister Patrick Dewael, the suspects (11 of whom were members of the military) were preparing to launch terrorist attacks in order to "destabilize" Belgium.[24] According to the journalist Manuel Abramowicz, of the Resistances,[25] the extremists of the radical right have always had as its aim to "infiltrate the state mechanisms," including the army in the 1970s and the 1980s, through Westland New Post and the Front de la Jeunesse.[26]

A police operation, which mobilized 150 agents, searched five military barracks (in Leopoldsburg near the Dutch border, Kleine-Brogel, Peer, Brussels (Royal military school) and Zedelgem) as well as 18 private addresses in Flanders. They found weapons, munitions, explosives and a homemade bomb large enough to make "a car explode". The leading suspect, B.T., was organizing the trafficking of weapons and was developing international links, in particular with the Dutch far-right movement De Nationale Alliantie.[27]

Bosnia and Herzegovina

The neo-Nazi white nationalist organization Bosanski Pokret Nacionalnog Ponosa (Bosnian Movement of National Pride) was founded in Bosnia and Herzegovina in July 2009. Its model is the Waffen-SS Handschar Division, which was composed of Bosniak volunteers.[28] It proclaimed its main enemies to be "Jews, Roma, Serbian Chetniks, the Croatian separatists, Josip Broz Tito, Communists, homosexuals and blacks".[29] Its ideology is a mixture of Bosnian nationalism, National Socialism and white nationalism. It says "Ideologies that are not welcome in Bosnia are: Zionism, Islamism, communism, capitalism. The only ideology good for us is Bosnian nationalism because it secures national prosperity and social justice..."[30] The group is led by a person nicknamed Sauberzwig, after the commander of the 13th SS Handschar. The group's strongest area of operations is in the Tuzla area of Bosnia.

Bulgaria

The primary neo-Nazi political party to receive attention in post-WWII Bulgaria is the Bulgarian National Union – New Democracy.[citation needed]

On 13 February of every year since 2003, Bulgarian neo-Nazis and like-minded far-right nationalists gather at Sofia to honor Hristo Lukov, a late World War II general known for his antisemitic and pro-Nazi stance. From 2003 to 2019, the annual event was hosted by Bulgarian National Union.[31][32][33]

Croatia

Neo-Nazis in Croatia base their ideology on the writings of Ante Pavelić and the Ustaše, a fascist anti-Yugoslav separatist movement.[34] The Ustaše regime committed a genocide against Serbs, Jews and Roma. At the end of World War II, many Ustaše members fled to the West, where they found sanctuary and continued their political and terrorist activities (which were tolerated due to Cold War hostilities).[35][36]

In 1999, Zagreb's Square of the Victims of Fascism was renamed Croatian Nobles Square, provoking widespread criticism of Croatia's attitude towards the Holocaust.[37] In 2000, the Zagreb City Council again renamed the square into Square of the Victims of Fascism.[38] Many streets in Croatia were renamed after the prominent Ustaše figure Mile Budak, which provoked outrage amongst the Serbian minority. Since 2002, there has been a reversal of this development, and streets with the name of Mile Budak or other persons connected with the Ustaše movement are few or non-existent.[39] A plaque in Slunj with the inscription "Croatian Knight Jure Francetić" was erected to commemorate Francetić, the notorious Ustaše leader of the Black Legion. The plaque remained there for four years, until it was removed by the authorities.[39][40]

In 2003, Croatian penal code was amended with provisions prohibiting the public display of Nazi symbols, the propagation of Nazi ideology, historical revisionism and holocaust denial but the amendments were annulled in 2004 since they were not enacted in accordance with a constitutionally prescribed procedure.[41] Nevertheless, since 2006 Croatian penal code explicitly prohibits any type of hate crime based on race, color, gender, sexual orientation, religion or national origin.[42]

There have been instances of hate speech in Croatia, such as the use of the phrase Srbe na vrbe! ("[Hang] Serbs on the willow trees!").[citation needed] In 2004, an Orthodox church was spray-painted with pro-Ustaše graffiti.[43][44] During some protests in Croatia, supporters of Ante Gotovina and other at the time suspected war criminals (all acquitted in 2012) have carried nationalist symbols and pictures of Pavelić.[45] On 17 May 2007, a concert in Zagreb by Thompson, a popular Croatian singer, was attended by 60,000 people, some of them wearing Ustaše uniforms. Some gave Ustaše salutes and shouted the Ustaše slogan "Za dom spremni" ("For the homeland – ready!"). This event prompted the Simon Wiesenthal Center to publicly issue a protest to the Croatian president.[46][47][48][49][50] Cases of displaying Ustashe memorabilia have been recorded at the Bleiburg commemoration held annually in Austria.[51]

Czech Republic

The government of the Czech Republic strictly punishes neo-Nazism (Czech: Neonacismus). According to a report by the Ministry of the Interior of the Czech Republic, neo-Nazis committed more than 211 crimes in 2013. The Czech Republic has various neo-Nazi groups. One of them is the group Wotan Jugend, based in Germany.

Denmark

The National Socialist Movement of Denmark was formed in 1991, and was formally a neo nazi party, that would actively promote the nazi ideology in Denmark. The party did not gain any political influence, and were regarded as a failed political project by neo nazi expert Frede Farmand.[52] Long time party leader Johnni Hansen was replaced by Esben Rohde Kristensen in 2010, which resulted in a large amount of party members leaving the party. While the party never has been formally dissolved, there has been very little activity from its core member since 2010.[53] Former neo nazi Daniel Carlsen formed the small national party Party of the Danes in 2011, which officially rejected nazism, but were none the less categorized as such by professor in politics Peter Nedergaard.[54][55]It was dissolved in 2017 after its founder Daniel Stockholm announced retirement from politics.[56]

Estonia

In 2006, Roman Ilin, a Jewish theatre director from St. Petersburg, Russia, was attacked by neo-Nazis when returning from a tunnel after a rehearsal. Ilin subsequently accused Estonian police of indifference after filing the incident.[57] When a dark-skinned French student was attacked in Tartu, the head of an association of foreign students claimed that the attack was characteristic of a wave of neo-Nazi violence. An Estonian police official, however, stated that there were only a few cases involving foreign students over the previous two years.[58] In November 2006, the Estonian government passed a law banning the display of Nazi symbols.[59]

The 2008 United Nations Human Rights Council Special Rapporteur's Report noted that community representatives and non-governmental organizations devoted to human rights had pointed out that neo-Nazi groups were active in Estonia—particularly in Tartu—and had perpetrated acts of violence against non-European minorities.[60]

The neo-Nazi terrorist organization Feuerkrieg Division was found and operates in the country, with some members of the Conservative People's Party of Estonia having been linked to the Feuerkrieg Division.[61][62][63]

Finland

In Finland, neo-Nazism is often connected to the 1930s and 1940s fascist and pro-Nazi Patriotic People's Movement (IKL), its youth movement Blues-and-Blacks and its predecessor Lapua Movement. Post-war fascist groups such as Patriotic People's Movement (1993), Patriotic People's Front, Patriotic National Movement, Blue-and-Black Movement and many others consciously copy the style of the movement and look up to its leaders as inspiration. A Finns Party councillor and police officer in Seinäjoki caused small scandal wearing the fascist blue-and-black uniform.[65][66]

During the Cold War, all partied deemed fascist were banned according to the Paris Peace Treaties and all former fascist activists had to find new political homes.[67] Despite Finlandization, many continued in public life. Three former members of the Waffen SS served as ministers; the Finnish SS Battalion officers Sulo Suorttanen (Centre Party) and Pekka Malinen (People's Party) as well as Mikko Laaksonen (Social Democrat), a soldier in the Finnish SS-Company, formed of pro-Nazi defectors.[68][69] Neo-Nazi activism was limited to small illegal groups like the clandestine Nazi occultist group led by Pekka Siitoin who made headlines after arson and bombing of the printing houses of the Communist Party of Finland. His associates also sent letter bombs to leftists, including to the headquarters of the Finnish Democratic Youth League.[70] Another group called the "New Patriotic People's Movement" bombed the left-wing Kansan Uutiset newspaper and the embassy of communist Bulgaria.[71][72][73] Member of the Nordic Realm Party Seppo Seluska was convicted of the torture and murder of a gay Jewish person.[74][75][76]

The skinhead culture gained momentum during the late 1980s and peaked during the late 1990s. In 1991, Finland received a number of Somali immigrants who became the main target of Finnish skinhead violence in the following years, including four attacks using explosives and a racist murder. Asylum seeker centres were attacked, in Joensuu skinheads would force their way into an asylum seeker centre and start shooting with shotguns. At worst Somalis were assaulted by 50 skinheads at the same time.[77][78]

The most prominent neo-Nazi group is the Nordic Resistance Movement, which is tied to multiple murders, attempted murders and assaults of political enemies was found in 2006 and proscribed in 2019.[79] The second biggest Finnish party, the Finns Party politicians have frequently supported far-right and neo-Nazi movements such as the Finnish Defense League, Soldiers of Odin, Nordic Resistance Movement, Rajat Kiinni (Close the Borders), and Suomi Ensin (Finland First).[80]

The NRM and other far-right nationalist parties organize an annual torch march demonstration in Helsinki in memory of the Finnish SS-battalion on the Finnish independence day which ends at the Hietaniemi cemetery where members visit the tomb of Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim and the monument to the Finnish SS Battalion.[81][82] The event is protested by antifascists, leading to counterdemonstrators being violently assaulted by NRM members who act as security. The demonstration attracts close to 3,000 participants according to the estimates of the police and hundreds of officers patrol Helsinki to prevent violent clashes.[83][84][85]

France

In France, the most enthusiastic collaborationists during the German occupation of France had been the National Popular Rally of Marcel Déat (former SFIO members) and the French Popular Party of Jacques Doriot (former French Communist Party members). These two groups, like the Germans, saw themselves as combining ultra-nationalism and socialism. In the south there existed the vassal state of Vichy France under the military "Hero of the Verdun", Marshal Philippe Pétain whose Révolution nationale emphasised an authoritarian Catholic conservative politics. Following the liberation of France and the creation of the Fourth French Republic, collaborators were prosecuted during the épuration légale and nearly 800 put to death for treason under Charles de Gaulle.

In the aftermath of the Second World War, the main concern of the French radical right was the collapse of the French Empire, in particular the Algerian War, which led to the creation of the OAS. Outside of this, individual fascistic activists such as Maurice Bardèche (brother-in-law of Robert Brasillach), as well as SS-veterans Saint-Loup and René Binet, were active in France and involved in the European Social Movement and later the New European Order, alongside similar groups from across Europe. Early neo-fascist groups included Jeune Nation, which introduced the Celtic cross into use by radical right groups (an association which would spread internationally). A "neither East, nor West" pan-Europeanism was most popular among French fascistic activists until the late 1960s, partly motivated by feelings of national vulnerability following the collapse of their empire; thus the Belgian SS-veteran Jean-François Thiriart's group Jeune Europe also had a considerable French contingent.

It was the 1960s, during the Fifth French Republic, that a considerable upturn in French neo-fascism occurred; some of it in response to the Protests of 1968. The most explicitly pro-Nazi of these was the FANE of Mark Fredriksen. Neo-fascist groups included Pierre Sidos' Occident, the Ordre Nouveau (which was banned after violent clashes with the Trotskyist LCR) and the student-based Groupe Union Défense. A number of these activists such as François Duprat were instrumental in founding the Front National under Jean-Marie Le Pen; but the FN also included a broader selection from the French hard-right, including not only these neo-fascist elements, but also Catholic integrists, monarchists, Algerian War veterans, Poujadists and national-conservatives. Others from these neo-fascist micro-groups formed the Parti des forces nouvelles working against Le Pen.

Within the FN itself, Duprat founded the FANE-backed Groupes nationalistes révolutionnaires faction, until his 1978 assassination. The subsequent history of the French hard right has been the conflict between the national-conservative controlled FN and "national revolutionary" (fascistic and National Bolshevik) splinter or opposition groups. The latter include groups in the tradition of Thiriart and Duprat, such as the Parti communautaire national-européen, Troisième voie, the Nouvelle Résistance of Christian Bouchet,[86] Unité Radicale and most recently Bloc identitaire. Direct splits from the FN include the 1987 founded FANE-revival Parti nationaliste français et européen, which was disbanded in 2000. Neo-Nazi organizations are outlawed in the Fifth French Republic, yet a significant number of them still exist.[87]

Germany

Following the failure of the National Democratic Party of Germany in the election of 1969, small groups committed to the revival of Nazi ideology began to emerge in Germany. The NPD splintered, giving rise to paramilitary Wehrsportgruppe. These groups attempted to organize under a national umbrella organization, the Action Front of National Socialists/National Activists.[88] Neo-Nazi movements in East Germany began as a rebellion against the Communist regime; the banning of Nazi symbols helped neo-Nazism to develop as an anti-authoritarian youth movement.[89] Mail order networks developed to send illegal Nazi-themed music cassettes and merchandise to Germany.[90]

Turks in Germany have been victims of neo-Nazi violence on several occasions. In 1992, two young girls were killed in the Mölln arson attack along with their grandmother; nine others were injured.[91][92] In 1993, five Turks were killed in the Solingen arson attack.[93] In response to the fire Turkish youth in Solingen rioted chanting "Nazis out!" and "We want Nazi blood". In other parts of Germany police had to intervene to protect skinheads from assault.[94] The Hoyerswerda riots and Rostock-Lichtenhagen riots targeting migrants and ethnic minorities living in Germany also took place during the 1990s.[88]

Between 2000 and 2007, eight Turkish immigrants, one Greek and a German policewoman were murdered by the neo-Nazi National Socialist Underground.[95] The NSU has its roots in the former East German area of Thuringia, which The Guardian identified as "one of the heartlands of Germany's radical right". The German intelligence services have been criticized for extravagant distributions of cash to informants within the far-right movement. Tino Brandt publicly boasted on television that he had received around €100,000 in funding from the German state. Though Brandt did not give the state "useful information", the funding supported recruitment efforts in Thuringia during the early 1990s. (Brandt was eventually sentenced to five and a half years in prison on for 66 counts of child prostitution and child sexual abuse).[96]

Police were only able to locate the killers when they were tipped off following a botched bank robbery in Eisenach. As the police closed in on them, the two men committed suicide. They had evaded capture for 13 years. Beate Zschäpe, who had been living with the two men in Zwickau, turned herself in to the German authorities a few days later. Zschäpe's trial began in May 2013; she was charged with nine counts of murder. She pleaded "not guilty". According to The Guardian, the NSU may have enjoyed protection and support from certain "elements of the state". Anders Behring Breivik, a fan of Zschäpe's, reportedly sent her a letter from prison in 2012.[96]

According to the annual report of Germany's interior intelligence service (Verfassungsschutz) for 2012, at the time there were 26,000 right-wing extremists living in Germany, including 6,000 neo-Nazis.[97] In January 2020, Combat 18 was banned in Germany, and raids directed against the organization were made across the country.[98] In March 2020, United German Peoples and Tribes, which is part of Reichsbürger, a neo-Nazi movement that rejects the German state as a legal entity, was raided by the German police.[99] Holocaust denial is a crime, according to the German Criminal Code (Strafgesetzbuch § 86a) and § 130 (public incitement).[citation needed]

Greece

This section needs to be updated. (April 2024) |

The far-right political party Golden Dawn (Χρυσή Αυγή – Chrysi Avyi) is generally labelled neo-Nazi, although the group rejects this label.[100] A few Golden Dawn members participated in the Bosnian War in the Greek Volunteer Guard (GVG) and were present in Srebrenica during the Srebrenica massacre.[101][102] The party has its roots in Papadopoulos' regime.

There is often collaboration between the state and neo-Nazi elements in Greece.[103] In 2018, during the trial of sixty-nine members of the Golden Dawn party, evidence was presented of the close ties between the party and the Hellenic Police.[104]

Golden Dawn has spoken out in favour of the Assad regime in Syria,[105] and the Strasserist group Black Lily have claimed to have sent mercenaries to Syria to fight alongside the Syrian regime, specifically mentioning their participation in the Battle of al-Qusayr.[106] In the 6 May 2012 legislative election, Golden Dawn received 6.97% of the votes, entering the Greek parliament for the first time with 21 representatives, but when the elected parties were unable to form a coalition government a second election was held in June 2012. Golden Dawn received 6.92% of the votes in the June election and entered the Greek parliament with 18 representatives.

Since 2008, neo-Nazi violence in Greece has targeted immigrants, leftists and anarchist activists. In 2009, certain far-right groups announced that Agios Panteleimonas in Athens was off limits to immigrants. Neo-Nazi patrols affiliated with the Golden Dawn party began attacking migrants in this neighborhood. The violence continued escalating through 2010.[103] In 2013, after the murder of anti-fascist rapper Pavlos Fyssas, the number of hate crimes in Greece declined for several years until 2017. Many of the crimes in 2017 have been attributed to other groups like the Crypteia Organisation and Combat 18 Hellas.[104]

Hungary

In Hungary, the historical political party which allied itself ideologically with German National Socialism and drew inspiration from it, was the Arrow Cross Party of Ferenc Szálasi. They referred to themselves explicitly as National Socialists and within Hungarian politics this tendency is known as Hungarism.[citation needed] After the Second World War, exiles such as Árpád Henney kept the Hungarist tradition alive. Following the fall of the Hungarian People's Republic in 1989, which was a Marxist–Leninist state and a member of the Warsaw Pact, many new parties emerged. Amongst these was the Hungarian National Front of István Győrkös, which was a Hungarist party and considered itself the heirs of Arrow Cross-style National Socialism (a self-description they explicitly embraced).[citation needed] In the 2000s, Győrkös' movement moved closer to a national bolshevist and neo-Eurasian position, aligned with Aleksandr Dugin, cooperating with the Hungarian Workers' Party. Some Hungarists opposed this and founded the Pax Hungarica Movement.

In modern Hungary, the ultranationalist Jobbik is regarded by some scholars as a neo-Nazi party; for example, it has been termed as such by Randolph L. Braham.[107] The party denies being neo-Nazi, although "there is extensive proof that the leading members of the party made no effort to hide their racism and anti-Semitism."[108] Rudolf Paksa, a scholar of the Hungarian far-right, describes Jobbik as "anti-Semitic, racist, homophobic and chauvinistic" but not as neo-Nazi because it does not pursue the establishment of a totalitarian regime.[108] Historian Krisztián Ungváry writes that "It is safe to say that certain messages of Jobbik can be called open neo-Nazi propaganda. However, it is quite certain that the popularity of the party is not due to these statements."[109]

Italy

During the 1950s, the neo-fascist Italian Social Movement moved closer to bourgeois conservative politics on the domestic front, which led to radical youths founding hardline splinter groups, such as Pino Rauti's Ordine Nuovo (later succeeded by Ordine Nero) and Stefano Delle Chiaie's Avanguardia Nazionale. These organisations were influenced by the esotericism of Julius Evola and considered the Waffen-SS and Romanian leader Corneliu Zelea Codreanu a reference, moving beyond Italian fascism. They were implicated in paramiliary attacks during the late 1960s to the early 1980s, such as the Piazza Fontana bombing. Delle Chiaie had even assisted Junio Valerio Borghese in a failed 1970 coup attempt known as the Golpe Borghese, which attempted to reinstate a fascist state in Italy.

Ireland

The National Socialist Irish Workers Party, a small party, was active between 1968 and the late 1980s, producing neo-Nazi propaganda pamphlets and sending threatening messages to Jews and Black people living in Ireland.[110]

Netherlands

Noteworthy neo-Nazi movements and parties in the Netherlands include the National European Social Movement (NESB), the Dutch People's Union (NVU),[111] the Centre Party/Centre Party '86 (CP/CP'86),[112] the National Alliance (NA),[113] and the Nationalist People's Movement (NVB). Individuals of note have included Waffen-SS volunteer and NESB founder Paul van Tienen, war-time collaborator and NESB co-founder Jan Wolthuis, former NVU member Bernhard Postma, the "Black Widow" Florentine Rost van Tonningen, former NVU leader Joop Glimmerveen,[114] CP/CP'86 member and NVB leader Wim Beaux, former CP/CP'86 member and NA leader Jan Teijn, former NVU member and "Hitler-lookalike"[115] Stefan Wijkamp, former CP'86 member and current NVU leader Constant Kusters,[114] and former NVU member and NA leader Virginia Kapić.

Both the General Intelligence and Security Service[116] and non-governmental initiatives such as the far-left anti-fascist research group Kafka research neo-Nazism and other forms of political extremism and have attested to the local presence of international movements such as Blood & Honour,[117][118] Combat 18,[119] the Racial Volunteer Force,[120] and The Base,[121] and expressed concern at the online dissemination of alt-right and far-right accelerationist thought in the Netherlands.[122]

Poland

Under the Polish Constitution promoting any totalitarian system such as Nazism, fascism, or communism, as well as inciting violence and/or racial hatred is illegal.[123] This was further re-enforced in the Polish Penal Code where discrediting any group or persons on national, religious, or racial grounds carries a sentence of 3 years.[124]

Although several small far-right and anti-semitic organisations exist, most notably NOP and ONR (both of which exist legally), they frequently adhere to Polish nationalism and National Democracy, in which Nazism is generally considered to be against ultra-nationalist principles, and although they are classed as nationalist and fascist movements, they are at the same time considered anti-Nazi. Some of their elements may resemble neo-Nazi features, but these groups frequently dissociate themselves from Nazi elements, claiming that such acts are unpatriotic and they argue that Nazism misappropriated or slightly altered several pre-existing symbols and features, such as distinguishing the Roman salute from the Nazi salute.[125]

Self-declared neo-Nazi movements in Poland frequently treat Polish culture and traditions with contempt, are anti-Christian and translate various texts from German, meaning they are considered movements favouring Germanisation.[126]

According to several reporter investigations, the Polish government turns a blind eye to these groups, and they are free to spread their ideology, frequently dismissing their existence as conspiracy theories, dismissing acts political provocations, deeming them too insignificant to pose a threat, or attempting to justify or diminish the seriousness of their actions.[127][128][129][130]

Russia

Some observers have noted a subjective irony of Russians embracing Nazism, because one of Hitler's ambitions at the start of World War II was the Generalplan Ost (Master Plan East) which envisaged to exterminate, expel, or enslave most or all Slavs from central and eastern Europe (e.g., Russians, Ukrainians, Poles etc.).[131] At the end of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, over 25 million Soviet citizens had died.[132]

The first reports of neo-Nazi organizations in the USSR appeared in the second half of the 1950s. In some cases, the participants were attracted primarily by the aesthetics of Nazism (rituals, parades, uniforms, the cult of physical fitness, architecture). Other organizations were more interested in the ideology of the Nazis, their program, and the image of Adolf Hitler.[133] The formation of neo-Nazism in the USSR dates back to the turn of the 1960s and 1970s; during this period, these organizations still preferred to operate underground.

Modern Russian neo-paganism took shape in the second half of the 1970s[134] and is associated with the activities of supporters of antisemitism, especially the Moscow Arabist Valery Yemelyanov (also known as "Velemir") and the former dissident and neo-Nazi activist Alexey Dobrovolsky (also known as "Dobroslav").

In Soviet times, the founder of the movement of Peterburgian Vedism (a branch of Slavic neopaganism) Viktor Bezverkhy (Ostromysl) revered Hitler and Heinrich Himmler and propagated racial and antisemitic theories in a narrow circle of his students, calling for the deliverance of mankind from "inferior offspring", allegedly arising from interracial marriages. He called such "inferior people" "bastards", referred to them as "Zhyds, Indians or gypsies and mulattoes" and believed that they prevent society from achieving social justice.

The first public manifestations of neo-Nazis in Russia took place in 1981 in Kurgan, and then in Yuzhnouralsk, Nizhny Tagil, Sverdlovsk, and Leningrad.[135][136]

In 1982, on Hitler's birthday, a group of Moscow high school students held a Nazi demonstration on Pushkinskaya Square.[135]

Russian National Unity (RNE) was a Neo-Nazi group founded in 1990 and was led by Alexander Barkashov, who claimed to have members in 250 cities. RNE adopted the swastika as its symbol, and sees itself as the avant-garde of a coming national revolution. It is critical of other major far-right organizations, such as the Liberal Democratic Party of Russia (LDPR). As of 1997, the members RNE were called Soratnik (comrades in arms), receive combat training at locations near Moscow, and many of them work as security officers or armed guards.[137] RNE was banned in 1999 by Moscow's court in 1999,[138] after which the group faded away.[139][140]

In 2007, it was claimed that Russian neo-Nazis accounted for "half of the world's total".[141][142]

On 15 August 2007, Russian authorities arrested a student for allegedly posting a video on the Internet which appears to show two migrant workers being beheaded in front of a red and black swastika flag.[143] Alexander Verkhovsky, the head of a Moscow-based center that monitors hate crime in Russia, said, "It looks like this is the real thing. The killing is genuine ... There are similar videos from the Chechen war. But this is the first time the killing appears to have been done intentionally."[144]

Atomwaffen Division Russland was a neo-Nazi terrorist group in Russia found by Russian officials to have been tied to multiple mass murder plots. AWDR was founded by former members of defunct National Socialist Society responsible for 27 murders and AWDR is connected to local chapter of the Order of Nine Angles responsible for rapes, ritual murders and drug trafficking. The Russian authorities raided an Atomwaffen compound in Ulan-Ude and uncovered illegal weapons and explosives.[145][146][147][148]

Serbia

An example of neo-Nazism in Serbia is the group Nacionalni stroj. In 2006 charges were brought against 18 leading members.[149][150][151] Besides political parties, there are a few militant neo-Nazi organizations in Serbia, such as Blood & Honour Serbia and Combat 18.[152]

Slovakia

The Slovak political party Kotlebists – People's Party Our Slovakia, which is represented in the National Council and European Parliament, is widely characterized as neo-Nazi.[153][154][155] Kotleba has softened its image over time and now disputes that is fascist or neo-Nazi, even suing a media outlet that described it as neo-Nazi. As of 2020, the party spokesperson was Ondrej Durica, a former member of the neo-Nazi band Biely Odpor (White Resistance). 2020 candidate Andrej Medvecky was convicted of attacking a black man while shouting racial slurs; another candidate, Anton Grňo, was fined for making a fascist salute. The party still celebrates 14 March, the anniversary of the founding of the fascist first Slovak Republic.[156] In 2020, party leader Marian Kotleba was facing trial for writing checks for 1,488 euros, alleged to be a reference to Fourteen Words and Heil Hitler.[157]

Spain

Spanish neo-Nazism is often connected to the country's Francoist and Falangist past, and nurtured by the ideology of the National Catholicism.[158][159]

According to a study by the newspaper ABC, black people are the ones who have suffered the most attacks by neo-Nazi groups, followed by Maghrebis and Latin Americans. They have also caused deaths in the anti-fascist group, such as the murder of the Madrid-born sixteen-year-old Carlos Palomino on 11 November 2007, stabbed with a knife by a soldier in the Legazpi metro station (Madrid).[160]

There have been other neo-Nazi cultural organizations such as the Spanish Circle of Friends of Europe (CEDADE) and the Circle of Indo-European Studies (CEI).[161]

The extreme right has little electoral support, with the presence of these groups of 0.36% (if the Plataforma per Catalunya (PxC) party is excluded with 66007 votes (0.39%), according to the voting data of the European elections of 2014. The first extreme right party FE de las JONS obtains 0.13% of the votes (21 577 votes), after doubling its results after the crisis; this is followed by the far-right party La España en Marcha (LEM) with 0.1% of the votes, National Democracy (DN) of the far-right with 0.08%, Republican Social Movement (MSR) (far-right) with 0.05% of the votes.[162]

Sweden

Neo-Nazi activities in Sweden have previously been limited to white supremacist groups, few of which have a membership over a few hundred members.[163] The main neo-Nazi organization is the Nordic Resistance Movement, a political movement which engages in martial arts training and paramilitary exercises[164] and which has been called a terrorist group.[165] They are also active in Norway and Denmark; the branch in Finland was banned in 2019.

Switzerland

The neo-Nazi and white power skinhead scene in Switzerland has seen significant growth in the 1990s and 2000s.[166] It is reflected in the foundation of the Partei National Orientierter Schweizer in 2000, which resulted in an improved organizational structure of the neo-Nazi and white supremacist scene.

Ukraine

In 1991, the Social-National Party of Ukraine (SNPU) was founded.[167] The party combined radical nationalism and neo-Nazi features.[168][169] The SNPU was characterized as a radical right-wing populist party that combined elements of ethnic ultranationalism and anti-communism. During the 1990s, it was accused of neo-Nazism due to the party's recruitment of skinheads and usage of neo-Nazi symbols.[170][171][172] When Oleh Tyahnybok was elected party leader in 2004, he made efforts to moderate the party's image by changing the party's name to All-Ukrainian Association "Svoboda", changing its symbols and expelling neo-Nazi and neofascist groups.[173][174] Some commentators continued to consider it neo-Nazi: in 2016, The Nation reported that "in Ukrainian municipal elections held [in October 2015], the neo-Nazi Svoboda party won 10 percent of the vote in Kyiv and placed second in Lviv. The Svoboda party's candidate won the mayoral election in the city of Konotop."[175] In 2015, the Svoboda party mayor in Konotop reportedly had the number "14/88" displayed on his car and refused to display the city's official flag because it contains a star of David, and has implied that Jews were responsible for the Holodomor.[168]

The topic of Ukrainian nationalism and its alleged relationship to neo-Nazism came to the fore in polemics about the more radical elements involved in the Euromaidan protests and subsequent Russo-Ukrainian War from 2014 onward.[169] Some Russian, Latin American, U.S. and Israeli media have portrayed the Ukrainian nationalists in the conflict as neo-Nazi.[176]

The Azov Battalion, founded in 2014, has been described as a far-right militia,[177][178] with connections to neo-Nazism[179] and members wearing neo-Nazi and SS symbols and regalia, as well as expressing neo-Nazi views.[180][181]

According to Vyacheslav Likhachev of the Institut français des relations internationales, members of far-right (including neo-Nazi) groups played an important role on the pro-Russian side, arguably more so than on the Ukrainian side, especially during early 2014.[182][183] Members and former members of the National Bolshevik Party, Russian National Unity (RNU), Eurasian Youth Union, and Cossack groups participated in recruitment of the separatists.[182][184][185][186] A former RNU member, Pavel Gubarev, was founder of the Donbas People's Militia and first "governor" of the Donetsk People's Republic.[182][187] RNU is particularly linked to the Russian Orthodox Army,[182] one of a number of separatist units described as "pro-Tsarist" and "extremist" Orthodox nationalists.[188][182] 'Rusich' is part of the Wagner Group, a Russian mercenary group in Ukraine which has been linked to far-right extremism.[189][190] Afterward, the pro-Russian far-right groups became less important in Donbas and the need for Russian radical nationalists started to disappear.[182]

The radical nationalist group С14, whose members openly expressed neo-Nazi views, gained notoriety in 2018 for being involved in violent attacks on Romany camps.[191][192][193]

United Kingdom

In 1962, the British neo-Nazi activist Colin Jordan formed the National Socialist Movement (NSM) which later became the British Movement (BM) in 1968.[194][195]

John Tyndall, a long-term neo-Nazi activist in the UK, led a break-away from the National Front to form an openly neo-Nazi party named the British National Party.[196] In the 1990s, the party formed a group for protecting its meetings named Combat 18,[197] which later grew too violent for the party to control and began to attack members of the BNP who were not perceived as supportive of neo-Nazism.[198] Under the subsequent leadership of Nick Griffin, the BNP distanced itself from neo-Nazism, although many members (including Griffin himself) have been accused of links to other neo-Nazi groups.[199]

Sonnenkrieg Division is a neo-Nazi terrorist organization in the United Kingdom, linked to international Atomwaffen Division network. Multiple members have been jailed for plotting terror attacks against minorities. Sonnenkrieg Division has been proscribed as a terrorist organization in United Kingdom and Australia. Sonnenkrieg Division is also closely tied with the Order of Nine Angles linked to the Murders of Bibaa Henry and Nicole Smallman.[200][201][202]

The UK has also been a source of neo-Nazi music, such as the band Skrewdriver.[203]

Asia

Iran

Several neo-Nazi groups were active in Iran, although they are now defunct. Advocates of Nazism continue to exist in Iran and are mainly based on the Internet.[204][205]

Israel

Neo-Nazi activity is not common or widespread in Israel, and the few reported activities have all been the work of extremists, who were punished severely. One notable case is that of Patrol 36, a cell in Petah Tikva made up of eight teenage immigrants from the former Soviet Union who had been attacking foreign workers and gay people, and vandalizing synagogues with Nazi images.[206][207] These neo-Nazis were reported to have operated in cities across Israel, and have been described as being influenced by the rise of neo-Nazism in Europe;[206][207][208] mostly influenced by similar movements in Russia and Ukraine, as the rise of the phenomenon is widely credited to immigrants from those two states, the largest sources of emigration to Israel.[209] Widely publicized arrests have led to a call to reform the Law of Return to permit the revocation of Israeli citizenship for—and the subsequent deportation of—neo-Nazis.[207]

Japan

Since 1982, the neo-Nazi National Socialist Japanese Workers' Party has operated in Japan, currently under the leadership of Kazunari Yamada, who has praised Hitler and denied the Holocaust.[210]

Mongolia

From 2008, Mongolian neo-Nazi groups have defaced buildings in Ulaanbaatar, smashed Chinese shopkeepers' windows, and killed Chinese immigrants. The neo-Nazi Mongols' targets for violence are Chinese, Koreans,[211] Mongol women who have sex with Chinese men, and LGBT people.[212] They wear Nazi uniforms and revere the Mongol Empire and Genghis Khan. Though Tsagaan Khass leaders say they do not support violence, they are self-proclaimed Nazis. "Adolf Hitler was someone we respect. He taught us how to preserve national identity," said the 41-year-old co-founder, who calls himself Big Brother. "We don't agree with his extremism and starting the Second World War. We are against all those killings, but we support his ideology. We support nationalism rather than fascism." Some have ascribed it to poor historical education.[211]

Taiwan

The National Socialism Association (NSA) is a neo-Nazi political organisation founded in Taiwan in September 2006 by Hsu Na-chi (Chinese: 許娜琦), at that time a 22-year-old female political science graduate of Soochow University. The NSA has an explicit stated goal of obtaining the power to govern the state. The Simon Wiesenthal Centre condemned the National Socialism Association on 13 March 2007 for championing the former Nazi dictator and blaming democracy for social unrest in Taiwan.[213]

Turkey

A neo-Nazi group existed in 1969 in İzmir, when a group of former Republican Villagers Nation Party members (precursor party of the Nationalist Movement Party) founded the association "Nasyonal Aktivite ve Zinde İnkişaf" (National Activity and Vigorous Development). The club maintained two combat units. The members wore SA uniforms and used the Hitler salute. One of the leaders (Gündüz Kapancıoğlu) was re-admitted to the Nationalist Movement Party in 1975.[214]

Apart from neo-fascist[215][216][217][218][219] Grey Wolves and the Turkish ultranationalist[220][221][222] Nationalist Movement Party, there are some neo-Nazi organizations in Turkey such as the Turkish Nazi Party[223] or the National Socialist Party of Turkey, which are mainly based on the Internet.[224][225][226]

Americas

Brazil

Several Brazilian neo-Nazi gangs appeared in the 1990s in Southern and Southeastern Brazil, regions with mostly white people, with their acts gaining more media coverage and public notoriety in the 2010s.[227][228][229][230] Some members of Brazilian neo-Nazi groups have been associated with football hooliganism.[231] Their targets have included African, South American and Asian immigrants; Jews, Muslims, Catholics and atheists; Afro-Brazilians and internal migrants with origins in the northern regions of Brazil (who are mostly brown-skinned or Afro-Brazilian);[232][233] homeless people, prostitutes; recreational drug users; feminists and—more frequently reported in the media—gay people, bisexuals, and transgender and third-gender people.[230][234][235] News of their attacks has played a role in debates about anti-discrimination laws in Brazil (including to some extent hate speech laws) and the issues of sexual orientation and gender identity.[236][237][238]

Canada

Neo-Nazism in Canada began with the formation of the Canadian Nazi Party in 1965. In the 1970s and 1980s, neo-Nazism continued to spread in the country as organizations including the Western Guard Party and Church of the Creator (later renamed Creativity) promoted white supremacist ideals.[239] Founded in the United States in 1973, Creativity calls for white people to wage racial holy war (Rahowa) against Jews and other perceived enemies.[240]

Don Andrews founded the Nationalist Party of Canada in 1977. The purported goals of the unregistered party are "the promotion and maintenance of European Heritage and Culture in Canada," but the party is known for anti-Semitism and racism. Many influential neo-Nazi Leaders, such as Wolfgang Droege, were affiliated with the party, but many of its members left to join the Heritage Front, which was founded in 1989.[241]

Droege founded the Heritage Front in Toronto at a time when leaders of the white supremacist movement were "disgruntled about the state of the radical right" and wanted to unite unorganized groups of white supremacists into an influential and efficient group with common objectives.[241] Plans for the organization began in September 1989, and the formation of the Heritage Front was formally announced a couple of months later in November. In the 1990s, George Burdi of Resistance Records and the band Rahowa popularized the Creativity movement and the white power music scene.[242]

On September 18, 2020, Toronto Police arrested 34-year-old Guilherme "William" Von Neutegem and charged him with the murder of Mohamed-Aslim Zafis. Zafis was the caretaker of a local mosque who was found dead with his throat cut. The Toronto Police Service said the killing is possibly connected to the stabbing murder of Rampreet Singh a few days prior a short distance from the spot where Zafis' murder took place. Von Neutegem is a member of the Order of Nine Angles and social media accounts established as belonging to him promote the group and included recordings of Von Neutegem performing satanic chants. In his home there was also an altar with the symbol of the O9A adorning a monolith.[243] According to Evan Balgord of the Canadian Anti-Hate Network, they are aware of more O9A members in Canada and their affiliated organization Northern Order.[244][245] Northern Order is a proscribed[246] neo-Nazi terrorist organization in Canada. NO members have been arrested for trafficking explosives and firearms, and NO has active members of the Canadian Armed Forces as its members and even a member of the CJIRU was identified as a member.[247][248][249]

Controversy and dissention has left many Canadian neo-Nazi organizations dissolved or weakened.[241]

Chile

After the dissolution of the National Socialist Movement of Chile (MNSCH) in 1938, notable former members of MNSCH migrated into Partido Agrario Laborista (PAL), obtaining high positions.[250] Not all former MNSCH members joined the PAL; some continued to form parties that followed the MNSCH model until 1952.[250] A new old-school Nazi party was formed in 1964 by school teacher Franz Pfeiffer.[250] Among the activities of this group were the organization of a Miss Nazi beauty contest and the formation of a Chilean branch of the Ku Klux Klan.[250] The party disbanded in 1970. Pfeiffer attempted to restart it in 1983 in the wake of a wave of protests against the Augusto Pinochet regime.[250]

Nicolás Palacios considered the "Chilean race" to be a mix of two bellicose master races: the Visigoths of Spain and the Mapuche (Araucanians) of Chile.[251] Palacios traces the origins of the Spanish component of the "Chilean race" to the coast of the Baltic Sea, specifically to Götaland in Sweden,[251] one of the supposed homelands of the Goths. Palacios claimed that both the blonde-haired and the bronze-coloured Chilean Mestizo share a "moral physonomy" and a masculine psychology.[252] He opposed immigration from Southern Europe, and argued that Mestizos who are derived from south Europeans lack "cerebral control" and are a social burden.[253]

Costa Rica

Several fringe neo-Nazi groups have existed in Costa Rica, some with online presence since around 2003.[254][255] The groups normally target Jewish Costa Ricans, Afro-Costa Ricans, Communists, gay people and especially Nicaraguan and Colombian immigrants. In 2012 the media discovered the existence of a neo-Nazi police officer inside the Public Force of Costa Rica, for which he was fired and would later commit suicide in April 2016 due to lack of job opportunities and threats from anti-fascists.[256][257][258][259]

In 2015, the Simon Wiesenthal Center asked the Costa Rican government to shut down a store in San José that sells Nazi paraphernalia, Holocaust denial books and other products associated with Nazism.[260]

In 2018, a series of pages on the social network Facebook of neo-Nazi inclination openly or discreetly carried out a vast campaign instigating xenophobic hatred by recycling old news or posting fake news to take advantage of an anti-immigrant sentiment after three homicides of tourists allegedly committed by migrants (although from one of the homicides the suspect is Costa Rican).[261] A rally against the country's migration policy was held on 19 August 2018, in which neo-Nazi and hooligans took part. Although not all participants were linked these groups and the majority of participants were peaceful, the protest turned violent and the Public Force intervened with 44 arrested (36 Costa Ricans and the rest Nicaraguans).[262][263] Authorities confiscated sharp weapons, Molotov cocktails and other items from the neo-Nazis, who also carried swastika flags.[264] A subsequent anti-xenophobic march and solidarity with the Nicaraguan refugees was organized a week later with more assistance. A second anti-migration demonstration, with the explicit exclusion of neo-Nazis and hooligans, was carried out in September with similar assistance.[265] In 2019 Facebook pages of extreme right-wing tendencies and anti-immigration position as Deputy 58, Costa Rican Resistance and Salvation Costa Rica called an anti-government demonstration on 1 May with small attendance.[266][267]

Peru

Peru has been home to a handful of neo-Nazi groups, most notably the National Socialist Movement "Peru Awake", the National Socialist Tercios of New Castile, and the Peruvian National Socialist Union.[268][269][270]

United States

There are several neo-Nazi groups in the United States. The National Socialist Movement (NSM), with about 400 members in 32 states,[271] is currently the largest neo-Nazi organization in the US.[272] After World War II, new organizations formed with varying degrees of support for Nazi principles. The National States' Rights Party, founded in 1958 by Edward Reed Fields and J. B. Stoner, countered racial integration in the Southern United States with Nazi-inspired publications and iconography. The American Nazi Party, founded by George Lincoln Rockwell in 1959, achieved high-profile coverage in the press through its public demonstrations.[273]

The ideology of James H. Madole, leader of the National Renaissance Party, was influenced by Blavatskian Theosophy. Helena Blavatsky developed a racial theory of evolution, holding that the white race was the "fifth rootrace" called the Aryan Race. According to Blavatsky, Aryans had been preceded by Atlanteans who had perished in the flood that sunk the continent Atlantis. The three races that preceded the Atlanteans, in Blavatsky's view, were proto-humans; these were the Lemurians, Hyperboreans and the first Astral rootrace. It was on this foundation that Madole based his claims that the Aryan Race has been worshiped as "White Gods" since time immemorial and proposed a governance structure based on the Hindu Laws of Manu and its hierarchical caste system.[274]

The First Amendment to the United States Constitution guarantees freedom of speech, which the courts have interpreted very broadly to include hate speech, severely limiting the government's authority to suppress it.[275] This allows political organizations great latitude in expressing Nazi, racist, and antisemitic views. A landmark First Amendment case was National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie, in which neo-Nazis threatened to march in a predominantly Jewish suburb of Chicago. The march never took place in Skokie, but the court ruling allowed the neo-Nazis to stage a series of demonstrations in Chicago.

The Institute for Historical Review, formed in 1978, is a Holocaust denial body associated with neo-Nazism.[276]

Organizations which report upon neo-Nazi activities in the U.S., which may involve attacking and harassing minorities, include the American organizations Anti-Defamation League and the Southern Poverty Law Center.[277]

In 2020, the FBI reclassified neo-Nazis to the same threat level as ISIS. Chris Wray, the Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, stated "Not only is the terror threat diverse, it's unrelenting."[278][279]

In 2022, famous rapper Kanye West stated that he identifies as a Nazi, denying the Holocaust and praising the policies of Adolf Hitler.[280]

Uruguay

In 1998, a group of people belonging to the "Joseph Goebbels Movement" tried to burn down a synagogue, which also served as a Hebrew school, in the Pocitos neighborhood of Montevideo in Uruguay; an antisemitic pamphlet signed by the group was found in the building after the quick action of firefighters saved it. Another group, the racist and antisemitic neo-Nazi Euroamerikaners group, founded in 1996, said when they were interviewed by the newspaper La República de Montevideo that they had no involvement with the attack on the synagogue, but revealed that they maintain contacts with a group called Poder Blanco ("White Power"), also Uruguayan, as well as with neo-Nazi groups from Argentina and several European countries. Through the Internet they have received the solidarity of the Patria pro-fascist group, based in Spain. They also said that in the city of Canelones, Uruguay, fifty kilometers from Montevideo, there is a clandestine "Aryan church" which uses rituals taken from the Ku Klux Klan. The Euroamerikaners declared that they did not tolerate interracial or gay couples. One of the militants said in the interview that "... if we see a black man with a white woman, we break them up ...". Other neo-Nazi incidents in Uruguay in 1998 included the bombing of a Jewish-owned small business in February, which injured two people, and the appearance of posters celebrating the anniversary of Hitler's birthday in April.[281]

Africa

South Africa

Several groups in South Africa, such as Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging and Blanke Bevrydingsbeweging, have often been described as neo-Nazi.[282] Eugène Terre'Blanche was a prominent South African neo-Nazi leader who was murdered in 2010.[283]

Oceania

There were a number of now-defunct Australian neo-Nazi groups, such as the Australian National Socialist Party (ANSP), which was formed in 1962 and merged into the National Socialist Party of Australia (1968–1970s), originally a splinter group, in 1968,[284] and Jack van Tongeren's Australian Nationalist Movement.[284]

White supremacist organisations active in Australia as of 2016 included local chapters of the Aryan Nations.[285] Blair Cottrell, former leader of the United Patriots Front, has tried to distance himself from neo-Nazism, but he has nevertheless been accused of expressing "pro-Nazi views".[286] Australian Security Intelligence Organisation director Mike Burgess said in February 2020 that neo-Nazis pose a "real threat" to Australia's security. Burgess maintained that there is a growing threat from the extreme right, and that its supporters "regularly meet to salute Nazi flags, inspect weapons, train in combat and share their hateful ideology".[287] In June 2022, the Australian state Victoria banned display of the swastika symbol. Under the new law, individuals who intentionally exhibit the symbol may face up to a year in jail or a A$22,000 (£12,300; $15,000) fine. The state of Victoria already has laws against hate speech, but they have been criticized for having weaknesses. The call for reform of these laws grew stronger in 2020 when a couple flew a swastika flag over their home, causing outrage in the community."[288]

In New Zealand, historical neo-Nazi organisations include Unit 88[289] and the National Socialist Party of New Zealand.[290] White nationalist organisations such as the New Zealand National Front and Action Zealandia have faced accusations of neo-Nazism.[291]

See also

- Alt-right – Far-right white nationalist movement

- The Believer – 2001 film by Henry Bean

- The Daily Stormer – US neo-Nazi commentary & message board

- Far-right subcultures – Far right groups and organisations