Париж

Париж | |

|---|---|

| Motto(s): Fluctuat nec mergitur "Tossed by the waves but never sunk" | |

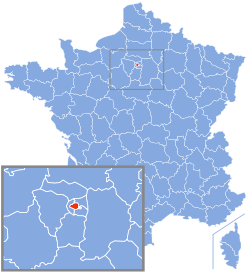

Paris in France | |

Location of Paris | |

| Coordinates: 48°51′24″N 2°21′8″E / 48.85667°N 2.35222°E | |

| Country | France |

| Region | Île-de-France |

| Department | Paris |

| Arrondissement | None |

| Intercommunality | Métropole du Grand Paris |

| Subdivisions | 20 arrondissements |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–2026) | Anne Hidalgo[1] (PS) |

| Area 1 | 105.4 km2 (40.7 sq mi) |

| • Urban (2020) | 2,853.5 km2 (1,101.7 sq mi) |

| • Metro (2020) | 18,940.7 km2 (7,313.0 sq mi) |

| Population (2023)[2] | 2,102,650 |

| • Rank | 9th in Europe 1st in France |

| • Density | 20,000/km2 (52,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban (2019[3]) | 10,858,852 |

| • Urban density | 3,800/km2 (9,900/sq mi) |

| • Metro (Jan. 2017[4]) | 13,024,518 |

| • Metro density | 690/km2 (1,800/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Parisian(s) (en) Parisien(s) (masc.), Parisienne(s) (fem.) (fr), Parigot(s) (masc.), "Parigote(s)" (fem.) (fr, colloquial) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| INSEE/Postal code | 75056 /75001-75020, 75116 |

| Elevation | 28–131 m (92–430 ft) (avg. 78 m or 256 ft) |

| Website | paris |

| 1 French Land Register data, which excludes lakes, ponds, glaciers > 1 km2 (0.386 sq mi or 247 acres) and river estuaries. | |

Париж ( Французское произношение: [paʁi] ) — столица и город Франции крупнейший . Официальная расчетная численность населения составляет 2 102 650 жителей в январе 2023 года. [2] на площади более 105 км 2 (41 кв. миль), [5] Париж — четвертый по величине город в Европейском Союзе и 30-й по густонаселенности город в мире в 2022 году. [6] С 17 века Париж был одним из крупнейших мировых центров финансов , дипломатии , торговли , культуры , моды и гастрономии . За ведущую роль в искусстве и науке , а также за раннюю и обширную систему уличного освещения в 19 веке он стал известен как Город Света. [7]

Город Париж является центром региона -де-Франс Иль , или Парижского региона, с официальной расчетной численностью населения в 12 271 794 человека на январь 2023 года, или около 19% населения Франции. [2] Парижского региона составил ВВП 765 миллиардов евро (1,064 триллиона долларов США, ППС ). [8] in 2021, the highest in the European Union.[9] According to the Economist Intelligence Unit Worldwide Cost of Living Survey, in 2022, Paris was the city with the ninth-highest cost of living in the world.[10]

Paris is a major railway, highway, and air-transport hub served by two international airports: Charles de Gaulle Airport, the third-busiest airport in Europe, and Orly Airport.[11][12] Opened in 1900, the city's subway system, the Paris Métro, serves 5.23 million passengers daily.[13] It is the second-busiest metro system in Europe after the Moscow Metro. Gare du Nord is the 24th-busiest railway station in the world and the busiest outside Japan, with 262 million passengers in 2015.[14] Paris has one of the most sustainable transportation systems[15] and is one of only two cities in the world that received the Sustainable Transport Award twice.[16]

Paris is known for its museums and architectural landmarks: the Louvre received 8.9 million visitors in 2023, on track for keeping its position as the most-visited art museum in the world.[17] The Musée d'Orsay, Musée Marmottan Monet and Musée de l'Orangerie are noted for their collections of French Impressionist art. The Pompidou Centre Musée National d'Art Moderne, Musée Rodin and Musée Picasso are noted for their collections of modern and contemporary art. The historical district along the Seine in the city centre has been classified as a UNESCO World Heritage Site since 1991.[18]

Paris is home to several United Nations organizations including UNESCO, as well as other international organizations such as the OECD, the OECD Development Centre, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, the International Energy Agency, the International Federation for Human Rights, along with European bodies such as the European Space Agency, the European Banking Authority and the European Securities and Markets Authority. The football club Paris Saint-Germain and the rugby union club Stade Français are based in Paris. The 81,000-seat Stade de France, built for the 1998 FIFA World Cup, is located just north of Paris in the neighbouring commune of Saint-Denis. Paris hosts the annual French Open Grand Slam tennis tournament on the red clay of Roland Garros. Paris hosted the Olympic Games in 1900 and 1924 and is currently hosting the 2024 Summer Olympics. The 1938 and 1998 FIFA World Cups, the 2019 FIFA Women's World Cup, the 2007 Rugby World Cup, as well as the 1960, 1984 and 2016 UEFA European Championships were held in Paris. Every July, the Tour de France bicycle race finishes on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées in Paris.

Etymology

The ancient oppidum that corresponds to the modern city of Paris was first mentioned in the mid-1st century BC by Julius Caesar as Luteciam Parisiorum ('Lutetia of the Parisii') and is later attested as Parision in the 5th century AD, then as Paris in 1265.[19][20] During the Roman period, it was commonly known as Lutetia or Lutecia in Latin, and as Leukotekía in Greek, which is interpreted as either stemming from the Celtic root *lukot- ('mouse'), or from *luto- ('marsh, swamp').[21][22][20]

The name Paris is derived from its early inhabitants, the Parisii, a Gallic tribe from the Iron Age and the Roman period.[23] The meaning of the Gaulish ethnonym remains debated. According to Xavier Delamarre, it may derive from the Celtic root pario- ('cauldron').[23] Alfred Holder interpreted the name as 'the makers' or 'the commanders', by comparing it to the Welsh peryff ('lord, commander'), both possibly descending from a Proto-Celtic form reconstructed as *kwar-is-io-.[24] Alternatively, Pierre-Yves Lambert proposed to translate Parisii as the 'spear people', by connecting the first element to the Old Irish carr ('spear'), derived from an earlier *kwar-sā.[20] In any case, the city's name is not related to the Paris of Greek mythology.

Residents of the city are known in English as Parisians and in French as Parisiens ([paʁizjɛ̃] ). They are also pejoratively called Parigots ([paʁiɡo] ).[note 1][25]

History

Origins

The Parisii, a sub-tribe of the Celtic Senones, inhabited the Paris area from around the middle of the 3rd century BC.[26][27] One of the area's major north–south trade routes crossed the Seine on the Île de la Cité, which gradually became an important trading centre.[28] The Parisii traded with many river towns (some as far away as the Iberian Peninsula) and minted their own coins.[29]

The Romans conquered the Paris Basin in 52 BC and began their settlement on Paris's Left Bank.[30] The Roman town was originally called Lutetia (more fully, Lutetia Parisiorum, "Lutetia of the Parisii", modern French Lutèce). It became a prosperous city with a forum, baths, temples, theatres, and an amphitheatre.[31]

By the end of the Western Roman Empire, the town was known as Parisius, a Latin name that would later become Paris in French.[32] Christianity was introduced in the middle of the 3rd century AD by Saint Denis, the first Bishop of Paris: according to legend, when he refused to renounce his faith before the Roman occupiers, he was beheaded on the hill which became known as Mons Martyrum (Latin "Hill of Martyrs"), later "Montmartre", from where he walked headless to the north of the city; the place where he fell and was buried became an important religious shrine, the Basilica of Saint-Denis, and many French kings are buried there.[33]

Clovis the Frank, the first king of the Merovingian dynasty, made the city his capital from 508.[34] As the Frankish domination of Gaul began, there was a gradual immigration by the Franks to Paris and the Parisian Francien dialects were born. Fortification of the Île de la Cité failed to avert sacking by Vikings in 845, but Paris's strategic importance—with its bridges preventing ships from passing—was established by successful defence in the Siege of Paris (885–886), for which the then Count of Paris (comte de Paris), Odo of France, was elected king of West Francia.[35] From the Capetian dynasty that began with the 987 election of Hugh Capet, Count of Paris and Duke of the Franks (duc des Francs), as king of a unified West Francia, Paris gradually became the largest and most prosperous city in France.[33]

High and Late Middle Ages to Louis XIV

By the end of the 12th century, Paris had become the political, economic, religious, and cultural capital of France.[36] The Palais de la Cité, the royal residence, was located at the western end of the Île de la Cité. In 1163, during the reign of Louis VII, Maurice de Sully, bishop of Paris, undertook the construction of the Notre Dame Cathedral at its eastern extremity.

After the marshland between the river Seine and its slower 'dead arm' to its north was filled in from around the 10th century,[37] Paris's cultural centre began to move to the Right Bank. In 1137, a new city marketplace (today's Les Halles) replaced the two smaller ones on the Île de la Cité and Place de Grève (Place de l'Hôtel de Ville).[38] The latter location housed the headquarters of Paris's river trade corporation, an organisation that later became, unofficially (although formally in later years), Paris's first municipal government.

In the late 12th century, Philip Augustus extended the Louvre fortress to defend the city against river invasions from the west, gave the city its first walls between 1190 and 1215, rebuilt its bridges to either side of its central island, and paved its main thoroughfares.[39] In 1190, he transformed Paris's former cathedral school into a student-teacher corporation that would become the University of Paris and would draw students from all of Europe.[40][36]

With 200,000 inhabitants in 1328, Paris, then already the capital of France, was the most populous city of Europe. By comparison, London in 1300 had 80,000 inhabitants.[41] By the early fourteenth century, so much filth had collected inside urban Europe that French and Italian cities were naming streets after human waste. In medieval Paris, several street names were inspired by merde, the French word for "shit".[42]

During the Hundred Years' War, Paris was occupied by England-friendly Burgundian forces from 1418, before being occupied outright by the English when Henry V of England entered the French capital in 1420;[43] in spite of a 1429 effort by Joan of Arc to liberate the city,[44] it would remain under English occupation until 1436.

In the late 16th-century French Wars of Religion, Paris was a stronghold of the Catholic League, the organisers of 24 August 1572 St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in which thousands of French Protestants were killed.[45][46] The conflicts ended when pretender to the throne Henry IV, after converting to Catholicism to gain entry to the capital, entered the city in 1594 to claim the crown of France. This king made several improvements to the capital during his reign: he completed the construction of Paris's first uncovered, sidewalk-lined bridge, the Pont Neuf, built a Louvre extension connecting it to the Tuileries Palace, and created the first Paris residential square, the Place Royale, now Place des Vosges. In spite of Henry IV's efforts to improve city circulation, the narrowness of Paris's streets was a contributing factor in his assassination near Les Halles marketplace in 1610.[47]

During the 17th century, Cardinal Richelieu, chief minister of Louis XIII, was determined to make Paris the most beautiful city in Europe. He built five new bridges, a new chapel for the College of Sorbonne, and a palace for himself, the Palais-Cardinal. After Richelieu's death in 1642, it was renamed the Palais-Royal.[48]

Due to the Parisian uprisings during the Fronde civil war, Louis XIV moved his court to a new palace, Versailles, in 1682. Although no longer the capital of France, arts and sciences in the city flourished with the Comédie-Française, the Academy of Painting, and the French Academy of Sciences. To demonstrate that the city was safe from attack, the king had the city walls demolished and replaced with tree-lined boulevards that would become the Grands Boulevards.[49] Other marks of his reign were the Collège des Quatre-Nations, the Place Vendôme, the Place des Victoires, and Les Invalides.[50]

18th and 19th centuries

Paris grew in population from about 400,000 in 1640 to 650,000 in 1780.[51] A new boulevard named the Champs-Élysées extended the city west to Étoile,[52] while the working-class neighbourhood of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine on the eastern side of the city grew increasingly crowded with poor migrant workers from other regions of France.[53]

Paris was the centre of an explosion of philosophic and scientific activity, known as the Age of Enlightenment. Diderot and D'Alembert published their Encyclopédie in 1751, before the Montgolfier Brothers launched the first manned flight in a hot air balloon on 21 November 1783. Paris was the financial capital of continental Europe, as well the primary European centre for book publishing, fashion and the manufacture of fine furniture and luxury goods.[54] On 22 October 1797, Paris was also the site of the first parachute jump in history, by Garnerin.

In the summer of 1789, Paris became the centre stage of the French Revolution. On 14 July, a mob seized the arsenal at the Invalides, acquiring thousands of guns, with which it stormed the Bastille, a principal symbol of royal authority. The first independent Paris Commune, or city council, met in the Hôtel de Ville and elected a Mayor, the astronomer Jean Sylvain Bailly, on 15 July.[55]

Louis XVI and the royal family were brought to Paris and incarcerated in the Tuileries Palace. In 1793, as the revolution turned increasingly radical, the king, queen and mayor were beheaded by guillotine in the Reign of Terror, along with more than 16,000 others throughout France.[56] The property of the aristocracy and the church was nationalised, and the city's churches were closed, sold or demolished.[57] A succession of revolutionary factions ruled Paris until 9 November 1799 (coup d'état du 18 brumaire), when Napoleon Bonaparte seized power as First Consul.[58]

The population of Paris had dropped by 100,000 during the Revolution, but after 1799 it surged with 160,000 new residents, reaching 660,000 by 1815.[59] Napoleon replaced the elected government of Paris with a prefect that reported directly to him. He began erecting monuments to military glory, including the Arc de Triomphe, and improved the neglected infrastructure of the city with new fountains, the Canal de l'Ourcq, Père Lachaise Cemetery and the city's first metal bridge, the Pont des Arts.[59]

During the Restoration, the bridges and squares of Paris were returned to their pre-Revolution names; the July Revolution in 1830 (commemorated by the July Column on the Place de la Bastille) brought to power a constitutional monarch, Louis Philippe I. The first railway line to Paris opened in 1837, beginning a new period of massive migration from the provinces to the city.[59] In 1848, Louis-Philippe was overthrown by a popular uprising in the streets of Paris. His successor, Napoleon III, alongside the newly appointed prefect of the Seine, Georges-Eugène Haussmann, launched a huge public works project to build wide new boulevards, a new opera house, a central market, new aqueducts, sewers and parks, including the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes.[60] In 1860, Napoleon III annexed the surrounding towns and created eight new arrondissements, expanding Paris to its current limits.[60]

During the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871), Paris was besieged by the Prussian Army. Following several months of blockade, hunger, and then bombardment by the Prussians, the city was forced to surrender on 28 January 1871. After seizing power in Paris on 28 March, a revolutionary government known as the Paris Commune held power for two months, before being harshly suppressed by the French army during the "Bloody Week" at the end of May 1871.[61]

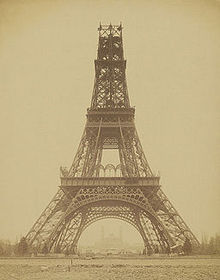

In the late 19th century, Paris hosted two major international expositions: the 1889 Universal Exposition, which featured the new Eiffel Tower, was held to mark the centennial of the French Revolution; and the 1900 Universal Exposition gave Paris the Pont Alexandre III, the Grand Palais, the Petit Palais and the first Paris Métro line.[62] Paris became the laboratory of Naturalism (Émile Zola) and Symbolism (Charles Baudelaire and Paul Verlaine), and of Impressionism in art (Courbet, Manet, Monet, Renoir).[63]

20th and 21st centuries

By 1901, the population of Paris had grown to about 2,715,000.[64] At the beginning of the century, artists from around the world including Pablo Picasso, Modigliani, and Henri Matisse made Paris their home. It was the birthplace of Fauvism, Cubism and abstract art,[65][66] and authors such as Marcel Proust were exploring new approaches to literature.[67]

During the First World War, Paris sometimes found itself on the front line; 600 to 1,000 Paris taxis played a small but highly important symbolic role in transporting 6,000 soldiers to the front line at the First Battle of the Marne. The city was also bombed by Zeppelins and shelled by German long-range guns.[68] In the years after the war, known as Les Années Folles, Paris continued to be a mecca for writers, musicians and artists from around the world, including Ernest Hemingway, Igor Stravinsky, James Joyce, Josephine Baker, Eva Kotchever, Henry Miller, Anaïs Nin, Sidney Bechet[69] and Salvador Dalí.[70]

In the years after the peace conference, the city was also home to growing numbers of students and activists from French colonies and other Asian and African countries, who later became leaders of their countries, such as Ho Chi Minh, Zhou Enlai and Léopold Sédar Senghor.[71]

On 14 June 1940, the German army marched into Paris, which had been declared an "open city".[72] On 16–17 July 1942, following German orders, the French police and gendarmes arrested 12,884 Jews, including 4,115 children, and confined them during five days at the Vel d'Hiv (Vélodrome d'Hiver), from which they were transported by train to the extermination camp at Auschwitz. None of the children came back.[73][74] On 25 August 1944, the city was liberated by the French 2nd Armoured Division and the 4th Infantry Division of the United States Army. General Charles de Gaulle led a huge and emotional crowd down the Champs Élysées towards Notre Dame de Paris and made a rousing speech from the Hôtel de Ville.[75]

In the 1950s and the 1960s, Paris became one front of the Algerian War for independence; in August 1961, the pro-independence FLN targeted and killed 11 Paris policemen, leading to the imposition of a curfew on Muslims of Algeria (who, at that time, were French citizens). On 17 October 1961, an unauthorised but peaceful protest demonstration of Algerians against the curfew led to violent confrontations between the police and demonstrators, in which at least 40 people were killed. The anti-independence Organisation armée secrète (OAS) carried out a series of bombings in Paris throughout 1961 and 1962.[76][77]

In May 1968, protesting students occupied the Sorbonne and put up barricades in the Latin Quarter. Thousands of Parisian blue-collar workers joined the students, and the movement grew into a two-week general strike. Supporters of the government won the June elections by a large majority. The May 1968 events in France resulted in the break-up of the University of Paris into 13 independent campuses.[78] In 1975, the National Assembly changed the status of Paris to that of other French cities and, on 25 March 1977, Jacques Chirac became the first elected mayor of Paris since 1793.[79] The Tour Maine-Montparnasse, the tallest building in the city at 57 storeys and 210 m (689 ft) high, was built between 1969 and 1973. It was highly controversial, and it remains the only building in the centre of the city over 32 storeys high.[80] The population of Paris dropped from 2,850,000 in 1954 to 2,152,000 in 1990, as middle-class families moved to the suburbs.[81] A suburban railway network, the RER (Réseau Express Régional), was built to complement the Métro; the Périphérique expressway encircling the city, was completed in 1973.[82]

Most of the postwar presidents of the Fifth Republic wanted to leave their own monuments in Paris; President Georges Pompidou started the Centre Georges Pompidou (1977), Valéry Giscard d'Estaing began the Musée d'Orsay (1986); President François Mitterrand had the Opéra Bastille built (1985–1989), the new site of the Bibliothèque nationale de France (1996), the Arche de la Défense (1985–1989) in La Défense, as well as the Louvre Pyramid with its underground courtyard (1983–1989); Jacques Chirac (2006), the Musée du quai Branly.[83]

In the early 21st century, the population of Paris began to increase slowly again, as more young people moved into the city. It reached 2.25 million in 2011. In March 2001, Bertrand Delanoë became the first socialist mayor. He was re-elected in March 2008.[84] In 2007, in an effort to reduce car traffic, he introduced the Vélib', a system which rents bicycles. Bertrand Delanoë also transformed a section of the highway along the Left Bank of the Seine into an urban promenade and park, the Promenade des Berges de la Seine, which he inaugurated in June 2013.[85]

In 2007, President Nicolas Sarkozy launched the Grand Paris project, to integrate Paris more closely with the towns in the region around it. After many modifications, the new area, named the Metropolis of Grand Paris, with a population of 6.7 million, was created on 1 January 2016.[86] In 2011, the City of Paris and the national government approved the plans for the Grand Paris Express, totalling 205 km (127 mi) of automated metro lines to connect Paris, the innermost three departments around Paris, airports and high-speed rail (TGV) stations, at an estimated cost of €35 billion.[87] The system is scheduled to be completed by 2030.[88]

In January 2015, Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula claimed attacks across the Paris region.[89][90] 1.5 million people marched in Paris in a show of solidarity against terrorism and in support of freedom of speech.[91] In November of the same year, terrorist attacks, claimed by ISIL,[92] killed 130 people and injured more than 350.[93]

On 22 April 2016, the Paris Agreement was signed by 196 nations of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change in an aim to limit the effects of climate change below 2 °C.[94]

Geography

Location

Paris is located in northern central France, in a north-bending arc of the river Seine, whose crest includes two islands, the Île Saint-Louis and the larger Île de la Cité, which form the oldest part of Paris. The river's mouth on the English Channel (La Manche) is about 233 mi (375 km) downstream from Paris. Paris is spread widely on both banks of the river.[95] Overall, Paris is relatively flat, and the lowest point is 35 m (115 ft) above sea level. Paris has several prominent hills, the highest of which is Montmartre at 130 m (427 ft).[96]

Excluding the outlying parks of Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes, Paris covers an oval measuring about 87 km2 (34 sq mi) in area, enclosed by the 35 km (22 mi) ring road, the Boulevard Périphérique.[97] Paris' last major annexation of outlying territories in 1860 gave it its modern form, and created the 20 clockwise-spiralling arrondissements (municipal boroughs). From the 1860 area of 78 km2 (30 sq mi), the city limits were expanded marginally to 86.9 km2 (33.6 sq mi) in the 1920s. In 1929, the Bois de Boulogne and Bois de Vincennes forest parks were annexed to the city, bringing its area to about 105 km2 (41 sq mi).[98] The metropolitan area is 2,300 km2 (890 sq mi).[95]

Measured from the 'point zero' in front of its Notre-Dame cathedral, Paris by road is 450 km (280 mi) southeast of London, 287 km (178 mi) south of Calais, 305 km (190 mi) southwest of Brussels, 774 km (481 mi) north of Marseille, 385 km (239 mi) northeast of Nantes, and 135 km (84 mi) southeast of Rouen.[99]

Climate

Paris has an oceanic climate within the Köppen climate classification, typical of western Europe. This climate type features cool winters, with frequent rain and overcast skies, and mild to warm summers. Very hot and very cold temperatures and weather extremes are rare in this type of climate.[100]

Summer days are usually mild and pleasant, with average temperatures between 15 and 25 °C (59 and 77 °F), and a fair amount of sunshine.[101] Each year there are a few days when the temperature rises above 32 °C (90 °F). Longer periods of more intense heat sometimes occur, such as the heat wave of 2003 when temperatures exceeded 30 °C (86 °F) for weeks, reached 40 °C (104 °F) on some days, and rarely cooled down at night.[102]

Spring and autumn have, on average, mild days and cool nights, but are changing and unstable. Surprisingly warm or cool weather occurs frequently in both seasons.[103] In winter, sunshine is scarce. Days are cool, and nights are cold but generally above freezing, with low temperatures around 3 °C (37 °F).[104] Light night frosts are quite common, but the temperature seldom dips below −5 °C (23 °F). Paris sometimes sees light snow or flurries with or without accumulation.[105]

Paris has an average annual precipitation of 641 mm (25.2 in), and experiences light rainfall distributed evenly throughout the year. Paris is known for intermittent, abrupt, heavy showers. The highest recorded temperature was 42.6 °C (108.7 °F), on 25 July 2019.[106] The lowest was −23.9 °C (−11.0 °F), on 10 December 1879.[107]

| Climate data for Paris (Parc Montsouris), elevation: 75 m (246 ft), 1991–2020 normals, extremes 1872–present | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 16.1 (61.0) | 21.4 (70.5) | 26.0 (78.8) | 30.2 (86.4) | 34.8 (94.6) | 37.6 (99.7) | 42.6 (108.7) | 39.5 (103.1) | 36.2 (97.2) | 28.9 (84.0) | 21.6 (70.9) | 17.1 (62.8) | 42.6 (108.7) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 7.6 (45.7) | 8.8 (47.8) | 12.8 (55.0) | 16.6 (61.9) | 20.2 (68.4) | 23.4 (74.1) | 25.7 (78.3) | 25.6 (78.1) | 21.5 (70.7) | 16.5 (61.7) | 11.1 (52.0) | 8.0 (46.4) | 16.5 (61.7) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 5.4 (41.7) | 6.0 (42.8) | 9.2 (48.6) | 12.2 (54.0) | 15.6 (60.1) | 18.8 (65.8) | 20.9 (69.6) | 20.8 (69.4) | 17.2 (63.0) | 13.2 (55.8) | 8.7 (47.7) | 5.9 (42.6) | 12.8 (55.0) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) | 3.3 (37.9) | 5.6 (42.1) | 7.9 (46.2) | 11.1 (52.0) | 14.2 (57.6) | 16.2 (61.2) | 16.0 (60.8) | 13.0 (55.4) | 9.9 (49.8) | 6.2 (43.2) | 3.8 (38.8) | 9.2 (48.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.6 (5.7) | −14.7 (5.5) | −9.1 (15.6) | −3.5 (25.7) | −0.1 (31.8) | 3.1 (37.6) | 6.0 (42.8) | 6.3 (43.3) | 1.8 (35.2) | −3.8 (25.2) | −14.0 (6.8) | −23.9 (−11.0) | −23.9 (−11.0) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 47.6 (1.87) | 41.8 (1.65) | 45.2 (1.78) | 45.8 (1.80) | 69.0 (2.72) | 51.3 (2.02) | 59.4 (2.34) | 58.0 (2.28) | 44.7 (1.76) | 55.2 (2.17) | 54.3 (2.14) | 62.0 (2.44) | 634.3 (24.97) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 9.9 | 9.1 | 9.5 | 8.6 | 9.2 | 8.3 | 7.4 | 8.1 | 7.5 | 9.5 | 10.4 | 11.4 | 108.9 |

| Average snowy days | 3.0 | 3.9 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 2.1 | 11.9 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 83 | 78 | 73 | 69 | 70 | 69 | 68 | 71 | 76 | 82 | 84 | 84 | 76 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 59.0 | 83.7 | 134.9 | 177.3 | 201.0 | 203.5 | 222.4 | 215.3 | 174.7 | 118.6 | 69.8 | 56.9 | 1,717 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 22 | 29 | 37 | 43 | 43 | 42 | 46 | 48 | 46 | 35 | 25 | 22 | 37 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 7 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Source 1: Meteo France (snow days 1981–2010),[108] Infoclimat.fr (relative humidity 1961–1990)[109] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (percent sunshine and UV Index)[110] | |||||||||||||

Administration

City government

For almost all of its long history, except for a few brief periods, Paris was governed directly by representatives of the king, emperor, or president of France. In 1974, Paris was granted municipal autonomy by the National Assembly.[111] The first modern elected mayor of Paris was Jacques Chirac, elected March 1977, becoming the city's first mayor since 1871 and only the fourth since 1794. The current mayor is Anne Hidalgo, a socialist, first elected in April 2014,[112] and re-elected in June 2020.[113]

The mayor of Paris is elected indirectly by Paris voters. The voters of each of the city's 20 arrondissements elect members to the Conseil de Paris (Council of Paris), which elects the mayor. The council is composed of 163 members. Each arrondissement is allocated a number of seats dependent upon its population, from 10 members for each of the least-populated arrondissements, to 34 members for the most populated. The council is elected using closed list proportional representation in a two-round system.[114]

Party lists winning an absolute majority in the first round – or at least a plurality in the second round – automatically win half the seats of an arrondissement. The remaining half of seats are distributed proportionally to all lists which win at least 5% of the vote, using the highest averages method.[115] This ensures that the winning party or coalition always wins a majority of the seats, even if they do not win an absolute majority of the vote.[116]

Prior to the 2020 Paris municipal election, each of Paris's 20 arrondissements had its own town hall and a directly elected council (conseil d'arrondissement), which elects an arrondissement mayor.[117] The council of each arrondissement is composed of members of the Conseil de Paris, and members who serve only on the council of the arrondissement. The number of deputy mayors in each arrondissement varies depending upon its population. As of 1996, there were 20 arrondissement mayors and 120 deputy mayors.[111] The creation of Paris Centre, a unified administrative division with a single mayor covering the first four arrondissements, took effect with the said 2020 election. The other 16 arrondissements continue to have their own mayors.[118]

Métropole du Grand Paris

In January 2016, the Métropole du Grand Paris, or simply Grand Paris, came into existence.[119] It is an administrative structure for co-operation between the City of Paris and its nearest suburbs. It includes the City of Paris, plus the communes of the three departments of the inner suburbs, Hauts-de-Seine, Seine-Saint-Denis and Val-de-Marne, plus seven communes in the outer suburbs, including Argenteuil in Val d'Oise and Paray-Vieille-Poste in Essonne, which were added to include the major airports of Paris. The Metropole covers 814 km2 (314 sq mi). In 2015, it had a population of 6.945 million persons.[120][121]

The new structure is administered by a Metropolitan Council of 210 members, not directly elected, but chosen by the councils of the member Communes. By 2020 its basic competencies will include urban planning, housing and protection of the environment.[119][121] In January 2016, Patrick Ollier was elected the first president of the metropolitan council. Though the Metropole has a population of nearly seven million people and accounts for 25 percent of the GDP of France, it has a very small budget: just 65 million Euros, compared with eight billion Euros for the City of Paris.[122]

Regional government

The Region of Île de France, including Paris and its surrounding communities, is governed by the Regional Council, composed of 209 members representing its different communes. In December 2015, a list of candidates of the Union of the Right, a coalition of centrist and right-wing parties, led by Valérie Pécresse, narrowly won the regional election, defeating a coalition of Socialists and ecologists. The Socialists had governed the region for seventeen years. The regional council has 121 members from the Union of the Right, 66 from the Union of the Left and 22 from the extreme right National Front.[123]

National government

As the capital of France, Paris is the seat of France's national government. For the executive, the two chief officers each have their own official residences, which also serve as their offices. The President of the French Republic resides at the Élysée Palace.[124] The Prime Minister's seat is at the Hôtel Matignon.[125][126] Government ministries are located in various parts of the city, many near the Hôtel Matignon.[127]

Both houses of the French Parliament are located on the Rive Gauche. The upper house, the Senate, meets in the Palais du Luxembourg. The more important lower house, the National Assembly, meets in the Palais Bourbon. The President of the Senate, the second-highest public official in France, with the President of the Republic being the sole superior, resides in the Petit Luxembourg, a smaller palace annexe to the Palais du Luxembourg.[128]

France's highest courts are located in Paris. The Court of Cassation, the highest court in the judicial order, which reviews criminal and civil cases, is located in the Palais de Justice on the Île de la Cité.[129] The Conseil d'État, which provides legal advice to the executive and acts as the highest court in the administrative order, judging litigation against public bodies, is located in the Palais-Royal in the 1st arrondissement.[130] The Constitutional Council, an advisory body with ultimate authority on the constitutionality of laws and government decrees, meets in the Montpensier wing of the Palais Royal.[131]

Paris and its region host the headquarters of several international organisations, including UNESCO, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the International Chamber of Commerce, the Paris Club, the European Space Agency, the International Energy Agency, the Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, the European Union Institute for Security Studies, the International Bureau of Weights and Measures, the International Exhibition Bureau, and the International Federation for Human Rights.

Police force

The security of Paris is mainly the responsibility of the Prefecture of Police of Paris, a subdivision of the Ministry of the Interior. It supervises the units of the National Police who patrol the city and the three neighbouring departments. It is also responsible for providing emergency services, including the Paris Fire Brigade. Its headquarters is on Place Louis Lépine on the Île de la Cité.[132]

There are 43,800 officers under the prefecture, and a fleet of more than 6,000 vehicles, including police cars, motorcycles, fire trucks, boats and helicopters.[132] The national police has its own special unit for riot control and crowd control and security of public buildings, called the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité (CRS). Vans of CRS agents are frequently seen in the centre of Paris when there are demonstrations and public events. The police are supported by the National Gendarmerie, a branch of the French Armed Forces. Their police operations are supervised by the Ministry of the Interior.[133]

Crime in Paris is similar to that in most large cities. Violent crime is relatively rare in the city centre. Political violence is uncommon, though very large demonstrations may occur in Paris and other French cities simultaneously. These demonstrations, usually managed by a strong police presence, can turn confrontational and escalate into violence.[134]

Cityscape

Urbanism and architecture

Paris is one of the few world capitals that has rarely seen destruction by catastrophe or war. As a result, even its earliest history is visible in its streetmap, and centuries of rulers adding their respective architectural marks on the capital has resulted in an accumulated wealth of history-rich monuments and buildings whose beauty plays a large part in giving Paris the reputation it has today.[135] At its origin, before the Middle Ages, Paris was composed of several islands and sandbanks in a bend of the Seine. Of those, two remain today: Île Saint-Louis and the Île de la Cité. A third one is the 1827 artificially created Île aux Cygnes.

Modern Paris owes much of its downtown plan and architectural harmony to Napoleon III and his Prefect of the Seine, Baron Haussmann. Between 1853 and 1870 they rebuilt the city centre, created the wide downtown boulevards and squares where the boulevards intersected, imposed standard facades along the boulevards, and required that the facades be built of the distinctive cream-grey "Paris stone". They built the major parks around central Paris.[136] The high residential population of the city centre makes Paris much different from most other major western cities.[137]

Paris's urbanism laws have been under strict control since the early 17th century,[138] particularly where street-front alignment, building height and building distribution is concerned.[138] The 210 m (690 ft) Tour Montparnasse was both Paris's and France's tallest building since 1973,[139] Since 2011, this record has been held by the La Défense quarter Tour First tower in Courbevoie.

Housing

In 2018, the most expensive residential street in Paris by average price per square metre, was Avenue Montaigne, at 22,372 euros per square metre.[140] In 2011, the number of residences in the City of Paris was 1,356,074. Among these, 1,165,541 (85.9 percent) were main residences, 91,835 (6.8 percent) were secondary residences, and the remaining 7.3 percent were empty.[141]

Sixty-two percent of buildings date from 1949 and before, with 20 percent built between 1949 and 1974. 18 percent of Paris buildings were built after 1974.[142] Two-thirds of the city's 1.3 million residences are studio and two-room apartments. Paris averages 1.9 people per residence, a number that has remained constant since the 1980s, which is less than Île-de-France's 2.33 person-per-residence average. Only 33 percent of principal residence Parisians own their habitation, against 47 percent for the wider Île-de-France region. Most of Paris' population rent their residence.[142] In 2017, social or public housing was 19.9 percent Paris' residences. Its distribution varies widely throughout Paris, from 2.6 percent of the housing in the wealthy 7th arrondissement, to 39.9 percent in the 19th arrondissement.[143]

In February 2019, a Paris NGO conducted its annual citywide count of homeless persons. They counted 3,641 homeless persons in Paris, of whom twelve percent were women. More than half had been homeless for more than a year. 2,885 were living in the streets or parks, 298 in train and metro stations, and 756 in other forms of temporary shelter. This was an increase of 588 persons since 2018.[144]

Suburbs

Aside from the 20th-century addition of the Bois de Boulogne, the Bois de Vincennes and the Paris heliport, Paris's administrative limits have remained unchanged since 1860. A greater administrative Seine department had been governing Paris and its suburbs since its creation in 1790, but the rising suburban population had made it difficult to maintain as a unique entity. To address this problem, the parent "District de la région parisienne" ('district of the Paris region') was reorganised into several new departments from 1968: Paris became a department in itself, and the administration of its suburbs was divided between the three new departments surrounding it. The district of the Paris region was renamed "Île-de-France" in 1977, but this abbreviated "Paris region" name is still commonly used today to describe the Île-de-France, and as a vague reference to the entire Paris agglomeration.[145] Long-intended measures to unite Paris with its suburbs began in January 2016, when the Métropole du Grand Paris came into existence.[119]

Paris's disconnect with its suburbs, its lack of suburban transportation, in particular, became all too apparent with the Paris agglomeration's growth. Paul Delouvrier promised to resolve the Paris-suburbs mésentente when he became head of the Paris region in 1961.[146] Two of his most ambitious projects for the Region were the construction of five suburban "villes nouvelles" ("new cities")[147] and the RER commuter train network.[148]

Many other suburban residential districts (grands ensembles) were built between the 1960s and 1970s, to provide a low-cost solution for a rapidly expanding population.[149] These districts were socially mixed at first,[150] but few residents actually owned their homes. The growing economy made these accessible to the middle classes only from the 1970s.[151] Their poor construction quality and their haphazard insertion into existing urban growth contributed to their desertion by those able to move elsewhere, and their repopulation by those with more limited resources.[151]

These areas, quartiers sensibles ("sensitive quarters"), are in northern and eastern Paris, namely around its Goutte d'Or and Belleville neighbourhoods. To the north of Paris, they are grouped mainly in the Seine-Saint-Denis department, and to a lesser extreme to the east in the Val-d'Oise department. Other difficult areas are located in the Seine valley, in Évry et Corbeil-Essonnes (Essonne), in Mureaux, Mantes-la-Jolie (Yvelines), and scattered among social housing districts created by Delouvrier's 1961 "ville nouvelle" political initiative.[152]

The Paris agglomeration's urban sociology is basically that of 19th-century Paris: the wealthy live in the west and southwest, and the middle-to-working classes are in the north and east. The remaining areas are mostly middle-class, dotted with wealthy islands in areas of historical importance, namely Saint-Maur-des-Fossés to the east and Enghien-les-Bains to the north of Paris.[153]

Demographics

| 2019 Census Paris Region | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Île-de-France)[154][155] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

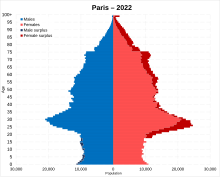

The population of the City of Paris was 2,102,650 in January 2023, down from 2,165,423 in January 2022, according to the INSEE, the French statistical agency. Between 2013 and 2023, the population fell by 122,919, or about five percent. The Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, declared that this illustrated the "de-densification" of the city, creating more green space and less crowding.[156][157] Despite the drop, Paris remains the most densely-populated city in Europe, with 252 residents per hectare, not counting parks.[158] This drop was attributed partly to a lower birth rate, the departure of middle-class residents and the possible loss of housing in Paris, due to short-term rentals for tourism.[159]

Paris is the fourth largest municipality in the European Union, after Berlin, Madrid and Rome. Eurostat places Paris (6.5 million people) behind London (8 million) and ahead of Berlin (3.5 million), based on the 2012 populations of what Eurostat calls "urban audit core cities".[160]The population of Paris today is lower than its historical peak of 2.9 million in 1921.[161] The principal reasons are a significant decline in household size, and a dramatic migration of residents to the suburbs between 1962 and 1975. Factors in the migration included de-industrialisation, high rent, the gentrification of many inner quarters, the transformation of living space into offices, and greater affluence among working families. Paris's population loss came to a temporary halt at the beginning of the 21st century. The population increased from 2,125,246 in 1999 to 2,240,621 in 2012, before declining again slightly in 2017, 2018, and again in 2021.[162][163]

Paris is the core of a built-up area that extends well beyond its limits: commonly referred to as the agglomération Parisienne, and statistically as a unité urbaine (a measure of urban area), the Paris agglomeration's population of 10,785,092 in 2017 made it the largest urban area in the European Union.[164][165] City-influenced commuter activity reaches further, in a statistical aire d'attraction de Paris, "functional area", a statistical method comparable to a metropolitan area,[166]), that had a population of 13,024,518 in 2017,[167] 19.6% of the population of France,[168] and the largest metropolitan area in the Eurozone.[165]

In 2012, according to Eurostat, the EU statistical agency, in 2012 the Commune of Paris was the most densely populated city in the European Union. There were 21,616 people per square kilometre within the city limits, the NUTS-3 statistical area, ahead of Inner London West, which had 10,374 people per square kilometre. In the same census, three departments bordering Paris, Hauts-de-Seine, Seine-Saint-Denis and Val-de-Marne, had population densities of over 10,000 people per square kilometre, ranking among the 10 most densely populated areas of the EU.[169][verification needed]

Migration

Under French law, people born in foreign countries with no French citizenship at birth are defined as immigrants. In the 2012 census, 135,853 residents of the City of Paris were immigrants from Europe, 112,369 were immigrants from the Maghreb, 70,852 from sub-Saharan Africa and Egypt, 5,059 from Turkey, 91,297 from Asia outside Turkey, 38,858 from the Americas, and 1,365 from the South Pacific.[170]

In the Paris Region, 590,504 residents were immigrants from Europe, 627,078 were immigrants from the Maghreb, 435,339 from sub-Saharan Africa and Egypt, 69,338 from Turkey, 322,330 from Asia outside Turkey, 113,363 from the Americas, and 2,261 from the South Pacific.[171]

In 2012, there were 8,810 British citizens and 10,019 United States citizens living in the City of Paris (Ville de Paris), and 20,466 British citizens and 16,408 United States citizens living in the entire Paris Region (Île-de-France).[172][173]

In 2020–2021, about 6 million people, or 41% of the population of the Paris Region, were either immigrants (21%) or had at least one immigrant parent (20%). These figures do not include French people born in Overseas France and their direct descendants.[174]

Religion

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Paris was the largest Catholic city in the world.[175] French census data does not contain information about religious affiliation.[176] In a 2011 survey by the Institut français d'opinion publique (IFOP), a French public opinion research organisation, 61 percent of residents of the Paris Region (Île-de-France) identified themselves as Roman Catholic. In the same survey, 7 percent of residents identified themselves as Muslims, 4 percent as Protestants, 2 percent as Jewish and 25 percent as without religion.

According to the INSEE, between 4 and 5 million French residents were born, or had at least one parent born, in a predominantly Muslim country, particularly Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia. An IFOP survey in 2008 reported that, of immigrants from these predominantly Muslim countries, 25 percent went to the mosque regularly. 41 percent practised the religion, and 34 percent were believers, but did not practice the religion.[177][178] In 2012 and 2013, it was estimated that there were almost 500,000 Muslims in the City of Paris, 1.5 million Muslims in the Île-de-France region and 4 to 5 million Muslims in France.[179][180]

In 2014, the Jewish population of the Paris Region was estimated to be 282,000, the largest concentration of Jews in the world outside of Israel and the United States.[181]

Economy

The economy of the City of Paris is based largely on services and commerce. Of the 390,480 enterprises in Paris, 80.6 percent are engaged in commerce, transportation, and diverse services, 6.5 percent in construction, and 3.8 percent in industry.[185] The story is similar in the Paris Region (Île-de-France): 76.7 percent of enterprises are engaged in commerce and services, and 3.4 percent in industry.[186]

At the 2012 census, 59.5% of jobs in the Paris Region were in market services (12.0% in wholesale and retail trade, 9.7% in professional, scientific, and technical services, 6.5% in information and communication, 6.5% in transportation and warehousing, 5.9% in finance and insurance, 5.8% in administrative and support services, 4.6% in accommodation and food services, and 8.5% in various other market services), 26.9% in non-market services (10.4% in human health and social work activities, 9.6% in public administration and defence, and 6.9% in education), 8.2% in manufacturing and utilities (6.6% in manufacturing and 1.5% in utilities), 5.2% in construction, and 0.2% in agriculture.[187][188]

The Paris Region had 5.4 million salaried employees in 2010, of whom 2.2 million were concentrated in 39 pôles d'emplois or business districts. The largest of these, in terms of number of employees, is known in French as the QCA, or quartier central des affaires. In 2010, it was the workplace of 500,000 salaried employees, about 30 percent of the salaried employees in Paris and 10 percent of those in the Île-de-France. The largest sectors of activity in the central business district were finance and insurance (16 percent of employees in the district) and business services (15 percent). The district includes a large concentration of department stores, shopping areas, hotels and restaurants, as well a government offices and ministries.[189]

The second-largest business district in terms of employment is La Défense, just west of the city. In 2010, it was the workplace of 144,600 employees, of whom 38 percent worked in finance and insurance, 16 percent in business support services. Two other important districts, Neuilly-sur-Seine and Levallois-Perret, are extensions of the Paris business district and of La Défense. Another district, including Boulogne-Billancourt, Issy-les-Moulineaux and the southern part of the 15th arrondissement, is a centre of activity for the media and information technology.[189]

In 2021, the top French companies listed in the Fortune Global 500 all have their headquarters in the Paris Region. Six are in the central business district of the City of Paris, four are close to the city in the Hauts-de-Seine Department, three are in La Défense and one is in Boulogne-Billancourt. Some companies, like Société Générale, have offices in both Paris and La Défense. The Paris Region is France's leading region for economic activity, with a GDP of €765 billion, of which €253 billion was in Paris city.[190] In 2021, its GDP ranked first among the metropolitan regions of the EU, and its per-capita GDP PPP was the 8th highest.[191][192][193] While the Paris region's population accounted for 18.8 percent of metropolitan France in 2019,[194] the Paris region's GDP accounted for 32 percent of metropolitan France's GDP.[195][196]

The Paris Region economy has gradually shifted from industry to high-value-added service industries (finance, IT services) and high-tech manufacturing (electronics, optics, aerospace, etc.).[197] The Paris region's most intense economic activity through the central Hauts-de-Seine department and suburban La Défense business district places Paris's economic centre to the west of the city, in a triangle between the Opéra Garnier, La Défense and the Val de Seine.[197] While the Paris economy is dominated by services, and employment in manufacturing sector has declined sharply, the region remains an important manufacturing centre, particularly for aeronautics, automobiles, and "eco" industries.[197]

In the 2017 worldwide cost of living survey by the Economist Intelligence Unit, based on a survey made in September 2016, Paris ranked as the seventh most expensive city in the world, and the second most expensive in Europe, after Zürich.[198] In 2018, Paris was the most expensive city in the world with Singapore and Hong Kong.[199] Station F is a business incubator for startups, noted as the world's largest startup facility.[200]

Employment and income

In 2007, the majority of Paris's salaried employees filled 370,000 businesses services jobs, concentrated in the north-western 8th, 16th and 17th arrondissements.[201] Paris's financial service companies are concentrated in the central-western 8th and 9th arrondissement banking and insurance district.[201] Paris's department store district in the 1st, 6th, 8th and 9th arrondissements employ ten percent of mostly female Paris workers, with 100,000 of these in the retail trade.[201] Fourteen percent of Parisians worked in hotels and restaurants and other services to individuals.[201]

Nineteen percent of Paris employees work for the State in either administration or education. The majority of Paris's healthcare and social workers work at the hospitals and social housing, concentrated in the peripheral 13th, 14th, 18th, 19th and 20th arrondissements.[201] Outside Paris, the western Hauts-de-Seine department La Défense district specialising in finance, insurance and scientific research district, employs 144,600.[197] The north-eastern Seine-Saint-Denis audiovisual sector has 200 media firms and 10 major film studios.[197]

Paris's manufacturing is mostly focused in its suburbs. Paris has around 75,000 manufacturing workers, most of which are in the textile, clothing, leather goods, and shoe trades.[197] In 2015, the Paris region's 800 aerospace companies employed 100,000.[197] Four hundred automobile industry companies employ another 100,000 workers. Many of these are centred in the Yvelines department, around the Renault and PSA-Citroën plants. This department alone employs 33,000.[197] In 2014, the industry as a whole suffered a major loss, with the closing of a major Aulnay-sous-Bois Citroën assembly plant.[197]

The southern Essonne department specialises in science and technology.[197] The south-eastern Val-de-Marne, with its wholesale Rungis food market, specialises in food processing and beverages.[197] The Paris region's manufacturing decline is quickly being replaced by eco-industries. These employ about 100,000 workers.[197]

Incomes are higher in the Western part of Paris and in the western suburbs, than in the northern and eastern parts of the urban area.[202] While Paris has some of the richest neighbourhoods in France, it also has some of the poorest, mostly on the eastern side of the city. In 2012, 14 percent of households in Paris earned less than €977 per month, the official poverty line. Twenty-five percent of residents in the 19th arrondissement lived below the poverty line. In Paris' wealthiest neighbourhood, the 7th arrondissement, 7 percent lived below the poverty line.[203] The unemployment rate in Paris in the 4th trimester of 2021 was six percent, compared with 7.4 percent in the whole of France. This was the lowest rate in thirteen years.[204][205]

Tourism

Tourism continued to recover in the Paris region in 2022, increasing to 44 million visitors, an increase of 95 percent over 2021, but still 13 percent lower than in 2019.[206]

Greater Paris, comprising Paris and its three surrounding departments, received a record 38 million visitors in 2019, measured by hotel arrivals.[207] These included 12.2 million French visitors. Of the foreign visitors, the greatest number came from the United States (2.6 million), United Kingdom (1.2 million), Germany (981 thousand) and China (711 thousand).[207]

In 2018, measured by the Euromonitor Global Cities Destination Index, Paris was the second-busiest airline destination in the world, with 19.10 million visitors, behind Bangkok (22.78 million) but ahead of London (19.09 million).[208] In 2016, 393,008 workers in Greater Paris, or 12.4 percent of the total workforce, were engaged in tourism-related sectors such as hotels, catering, transport and leisure.[209]

Paris' top cultural attractions in 2022 were the Louvre Museum (7.7 million visitors), the Eiffel Tower (5.8 million visitors), the Musée d'Orsay (3.27 million visitors) and the Centre Pompidou (3 million visitors).[206]

In 2019, Greater Paris had 2,056 hotels, including 94 five-star hotels, with a total of 121,646 rooms.[207] In 2019, in addition to the hotels, Greater Paris had 60,000 homes registered with Airbnb.[207] Under French law, renters of these units must pay the Paris tourism tax. The company paid the city government 7.3 million euros in 2016.[210][full citation needed]

A minuscule fraction of foreign visitors suffer from Paris syndrome, when their experiences do not meet expectations.[211]

Culture

Painting and sculpture

For centuries, Paris has attracted artists from around the world. As a result, Paris has acquired a reputation as the "City of Art".[212] Italian artists were a profound influence on the development of art in Paris in the 16th and 17th centuries, particularly in sculpture and reliefs. Painting and sculpture became the pride of the French monarchy and the French royal family commissioned many Parisian artists to adorn their palaces during the French Baroque and Classicism era. Sculptors such as Girardon, Coysevox and Coustou acquired reputations as the finest artists in the royal court in 17th-century France. Pierre Mignard became the first painter to King Louis XIV during this period. In 1648, the Académie royale de peinture et de sculpture (Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture) was established to accommodate for the dramatic interest in art in the capital. This served as France's top art school until 1793.[213]

Paris was in its artistic prime in the 19th century and early 20th century, when it had a colony of artists established in the city and in art schools associated with some of the finest painters of the times: Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Édouard Manet, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Paul Gauguin, Pierre-Auguste Renoir and others. Paris was central to the development of Romanticism in art, with painters such as Géricault.[213] Impressionism, Art Nouveau, Symbolism, Fauvism, Cubism and Art Deco movements all evolved in Paris.[213] In the late 19th century, many artists in the French provinces and worldwide flocked to Paris to exhibit their works in the numerous salons and expositions and make a name for themselves.[214] Artists such as Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Vincent van Gogh, Paul Cézanne, Jean Metzinger, Albert Gleizes, Henri Rousseau, Marc Chagall, Amedeo Modigliani and many others became associated with Paris.

The most prestigious sculptors who made their reputation in Paris in the modern era are Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi (Statue of Liberty), Auguste Rodin, Camille Claudel, Antoine Bourdelle, Paul Landowski (statue of Christ the Redeemer in Rio de Janeiro) and Aristide Maillol. The Golden Age of the School of Paris ended between the two world wars.

Museums

The Louvre received 2,8 million visitors in 2021, up from 2.7 million in 2020,[215] holding its position as first among the most-visited museums. Its treasures include the Mona Lisa (La Joconde), the Venus de Milo statue, and Liberty Leading the People. The second-most visited museum in the city in 2021, with 1.5 million visitors, was the Centre Georges Pompidou, also known as Beaubourg, which houses the Musée National d'Art Moderne The third most visited Paris museum in 2021 was the National Museum of Natural History with 1,4 million visitors. It is famous for its dinosaur artefacts, mineral collections and its Gallery of Evolution. It was followed by the Musée d'Orsay, featuring 19th century art and the French Impressionists, which had one million visitors. Paris hosts one of the largest science museums in Europe, the Cité des sciences et de l'industrie, (984,000 visitors in 2020). The other most-visited Paris museums in 2021 were the Fondation Louis Vuitton (691,000), the Musée du Quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, featuring the indigenous art and cultures of Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Americas. (616,000); the Musée Carnavalet (History of Paris) (606,000), and the Petit Palais, the art museum of the City of Paris (518,000).[216]

The Musée de l'Orangerie, near both the Louvre and the Orsay, also exhibits Impressionists and Post-Impressionists, including most of Claude Monet's large Water Lilies murals. The Musée national du Moyen Âge, or Cluny Museum, presents Medieval art. The Guimet Museum, or Musée national des arts asiatiques, has one of the largest collections of Asian art in Europe. There are also notable museums devoted to individual artists, including the Musée Picasso, the Musée Rodin and the Musée national Eugène Delacroix.

The military history of France is presented by displays at the Musée de l'Armée at Les Invalides. In addition to the national museums, run by the Ministry of Culture, the City of Paris operates 14 museums, including the Carnavalet Museum on the history of Paris, Musée d'Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, Palais de Tokyo, the House of Victor Hugo, the House of Balzac and the Catacombs of Paris.[217] There are also notable private museums. The Contemporary Art museum of the Louis Vuitton Foundation, designed by architect Frank Gehry, opened in October 2014 in the Bois de Boulogne.

Theatre

The largest opera houses of Paris are the 19th-century Opéra Garnier (historical Paris Opéra) and modern Opéra Bastille; the former tends toward the more classic ballets and operas, and the latter provides a mixed repertoire of classic and modern.[218] In the middle of the 19th century, there were three other active and competing opera houses: the Opéra-Comique (which still exists), Théâtre-Italien and Théâtre Lyrique (which in modern times changed its profile and name to Théâtre de la Ville).[219] Philharmonie de Paris, the modern symphonic concert hall of Paris, opened in January 2015. Another musical landmark is the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées, where the first performances of Diaghilev's Ballets Russes took place in 1913.

Theatre traditionally has occupied a large place in Parisian culture, and many of its most popular actors today are also stars of French television. The oldest and most famous Paris theatre is the Comédie-Française, founded in 1680. Run by the Government of France, it performs mostly French classics at the Salle Richelieu in the Palais-Royal.[220] Other famous theatres include the Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe, also a state institution and theatrical landmark; the Théâtre Mogador; and the Théâtre de la Gaîté-Montparnasse.[221]

The music hall and cabaret are famous Paris institutions. The Moulin Rouge was opened in 1889 and became the birthplace of the dance known as the French Cancan. It helped make famous the singers Mistinguett and Édith Piaf and the painter Toulouse-Lautrec, who made posters for the venue. In 1911, the dance hall Olympia Paris invented the grand staircase as a settling for its shows, competing with its great rival, the Folies Bergère. Its stars in the 1920s included the American singer and dancer Josephine Baker. Later, Olympia Paris presented Dalida, Edith Piaf, Marlene Dietrich, Miles Davis, Judy Garland and the Grateful Dead.

The Casino de Paris presented many famous French singers, including Mistinguett, Maurice Chevalier and Tino Rossi. Other famous Paris music halls include Le Lido, on the Champs-Élysées, opened in 1946; and the Crazy Horse Saloon, featuring strip-tease, dance and magic, opened in 1951. A half dozen music halls exist today in Paris, attended mostly by visitors to the city.[222]

Literature

The first book printed in France, Epistolae ("Letters"), by Gasparinus de Bergamo (Gasparino da Barzizza), was published in Paris in 1470 by the press established by Johann Heynlin. Since then, Paris has been the centre of the French publishing industry, the home of some of the world's best-known writers and poets, and the setting for many classic works of French literature. Paris did not become the acknowledged capital of French literature until the 17th century, with authors such as Boileau, Corneille, La Fontaine, Molière, Racine, Charles Perrault,[223] several coming from the provinces, as well as the foundation of the Académie française.[224] In the 18th century, the literary life of Paris revolved around the cafés and salons; it was dominated by Voltaire, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Pierre de Marivaux and Pierre Beaumarchais.

During the 19th century, Paris was the home and subject for some of France's greatest writers, including Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé, Mérimée, Alfred de Musset, Marcel Proust, Émile Zola, Alexandre Dumas, Gustave Flaubert, Guy de Maupassant and Honoré de Balzac. Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre-Dame inspired the renovation of its setting, the Notre-Dame de Paris.[225] Another of Victor Hugo's works, Les Misérables, described the social change and political turmoil in Paris in the early 1830s.[226] One of the most popular of all French writers, Jules Verne, worked at the Theatre Lyrique and the Paris stock exchange, while he did research for his stories at the National Library.[227]

In the 20th century, the Paris literary community was dominated by figures such as Colette, André Gide, François Mauriac, André Malraux, Albert Camus, and, after World War II, by Simone de Beauvoir and Jean-Paul Sartre. Between the wars it was the home of many important expatriate writers, including Ernest Hemingway, Samuel Beckett, Miguel Ángel Asturias, Alejo Carpentier and, Arturo Uslar Pietri. The winner of the 2014 Nobel Prize in Literature, Patrick Modiano, based most of his literary work on the depiction of the city during World War II and the 1960s–1970s.[228]

Paris is a city of books and bookstores. In the 1970s, 80 percent of French-language publishing houses were found in Paris.[229] It is also a city of small bookstores. There are about 150 bookstores in the 5th arrondissement alone, plus another 250 book stalls along the Seine. Small Paris bookstores are protected against competition from discount booksellers by French law; books, even e-books, cannot be discounted more than five percent below their publisher's cover price.[230]

Music

In the late 12th century, a school of polyphony was established at Notre-Dame. Among the Trouvères of northern France, a group of Parisian aristocrats became known for their poetry and songs. Troubadours, from the south of France, were also popular. During the reign of François I, in the Renaissance era, the lute became popular in the French court. The French royal family and courtiers "disported themselves in masques, ballets, allegorical dances, recitals, and opera and comedy", and a national musical printing house was established.[213] In the Baroque-era, noted composers included Jean-Baptiste Lully, Jean-Philippe Rameau, and François Couperin.[213] The Conservatoire de Musique de Paris was founded in 1795.[231] By 1870, Paris had become an important centre for symphony, ballet and operatic music.

Romantic-era composers (in Paris) include Hector Berlioz, Charles Gounod, Camille Saint-Saëns, Léo Delibes and Jules Massenet, among others.[213] Georges Bizet's Carmen premiered 3 March 1875. Carmen has since become one of the most popular and frequently-performed operas in the classical canon.[232][233] Among the Impressionist composers who created new works for piano, orchestra, opera, chamber music and other musical forms, stand in particular, Claude Debussy, Erik Satie and Maurice Ravel. Several foreign-born composers, such as Frédéric Chopin, Franz Liszt, Jacques Offenbach, Niccolò Paganini, and Igor Stravinsky, established themselves or made significant contributions both with their works and their influence in Paris.

Bal-musette is a style of French music and dance that first became popular in Paris in the 1870s and 1880s; by 1880 Paris had some 150 dance halls.[234] Patrons danced the bourrée to the accompaniment of the cabrette (a bellows-blown bagpipe locally called a "musette") and often the vielle à roue (hurdy-gurdy) in the cafés and bars of the city. Parisian and Italian musicians who played the accordion adopted the style and established themselves in Auvergnat bars,[235] and Paris became a major centre for jazz and still attracts jazz musicians from all around the world to its clubs and cafés.[236]

Paris is the spiritual home of gypsy jazz in particular, and many of the Parisian jazzmen who developed in the first half of the 20th century began by playing Bal-musette in the city.[235] Django Reinhardt rose to fame in Paris, having moved to the 18th arrondissement in a caravan as a young boy, and performed with violinist Stéphane Grappelli and their Quintette du Hot Club de France in the 1930s and 1940s.[237]

Immediately after the War the Saint-Germain-des-Pres quarter and the nearby Saint-Michel quarter became home to many small jazz clubs, including the Caveau des Lorientais, the Club Saint-Germain, the Rose Rouge, the Vieux-Colombier, and the most famous, Le Tabou. They introduced Parisians to the music of Claude Luter, Boris Vian, Sydney Bechet, Mezz Mezzrow, and Henri Salvador. Most of the clubs closed by the early 1960s, as musical tastes shifted toward rock and roll.[238]

Some of the finest manouche musicians in the world are found here playing the cafés of the city at night.[237] Some of the more notable jazz venues include the New Morning, Le Sunset, La Chope des Puces and Bouquet du Nord.[236][237] Several yearly festivals take place in Paris, including the Paris Jazz Festival and the rock festival Rock en Seine.[239] The Orchestre de Paris was established in 1967.[240] December 2015 was the 100th anniversary of the birth of Edith Piaf—widely regarded as France's national chanteuse, as well as being one of France's greatest international stars.[241]

Paris has a big hip hop scene. This music became popular during the 1980s.[242] The presence of a large African and Caribbean community helped to its development, giving political and social status for many minorities.[243]

Cinema

The movie industry was born in Paris when Auguste and Louis Lumière projected the first motion picture for a paying audience at the Grand Café on 28 December 1895.[244] Many of Paris's concert/dance halls were transformed into cinemas when the media became popular beginning in the 1930s. Paris's largest cinema room today is in the Grand Rex theatre with 2,700 seats.[245] Big multiplex cinemas have been built since the 1990s. UGC Ciné Cité Les Halles with 27 screens, MK2 Bibliothèque with 20 screens and UGC Ciné Cité Bercy with 18 screens are among the largest.[246]

Parisians tend to share the same movie-going trends as many of the world's global cities, with cinemas primarily dominated by Hollywood-generated film entertainment. French cinema comes a close second, with major directors (réalisateurs) such as Claude Lelouch, Jean-Luc Godard, and Luc Besson, and the more slapstick/popular genre with director Claude Zidi as an example. European and Asian films are also widely shown and appreciated.[247]

Restaurants and cuisine

Since the late 18th century, Paris has been famous for its restaurants and haute cuisine, food meticulously prepared and artfully presented. A luxury restaurant, La Taverne Anglaise, opened in 1786 in the arcades of the Palais-Royal by Antoine Beauvilliers; it became a model for future Paris restaurants. The restaurant Le Grand Véfour in the Palais-Royal dates from the same period.[248] The famous Paris restaurants of the 19th century, including the Café de Paris, the Rocher de Cancale, the Café Anglais, Maison Dorée and the Café Riche, were mostly located near the theatres on the Boulevard des Italiens. Several of the best-known restaurants in Paris today appeared during the Belle Époque, including Maxim's on Rue Royale, Ledoyen in the gardens of the Champs-Élysées, and the Tour d'Argent on the Quai de la Tournelle.[249]

Today, owing to Paris's cosmopolitan population, every French regional cuisine and almost every national cuisine in the world can be found there; the city has more than 9,000 restaurants.[250] The Michelin Guide has been a standard guide to French restaurants since 1900, awarding its highest award, three stars, to the best restaurants in France. In 2018, of the 27 Michelin three-star restaurants in France, ten are located in Paris. These include both restaurants which serve classical French cuisine, such as L'Ambroisie in the Place des Vosges, and those which serve non-traditional menus, such as L'Astrance, which combines French and Asian cuisines. Several of France's most famous chefs, including Pierre Gagnaire, Alain Ducasse, Yannick Alléno and Alain Passard, have three-star restaurants in Paris.[251][252]

Paris has several other kinds of traditional eating places. The café arrived in Paris in the 17th century, and by the 18th century Parisian cafés were centres of the city's political and cultural life. The Café Procope on the Left Bank dates from this period. In the 20th century, the cafés of the Left Bank, especially Café de la Rotonde and Le Dôme Café in Montparnasse and Café de Flore and Les Deux Magots on Boulevard Saint Germain, all still in business, were important meeting places for painters, writers and philosophers.[249] A bistro is a type of eating place loosely defined as a neighbourhood restaurant with a modest decor and prices and a regular clientele and a congenial atmosphere. Real bistros are increasingly rare in Paris, due to rising costs, competition, and different eating habits of Parisian diners.[253] A brasserie originally was a tavern located next to a brewery, which served beer and food at any hour. Beginning with the Paris Exposition of 1867, it became a popular kind of restaurant which featured beer and other beverages served by young women in the national costume associated with the beverage. Now brasseries, like cafés, serve food and drinks throughout the day.[254]

Fashion

Since the 19th century, Paris has been an international fashion capital, particularly in the domain of haute couture (clothing hand-made to order for private clients).[255] It is home to some of the largest fashion houses in the world, including Dior and Chanel, as well as many other well-known and more contemporary fashion designers, such as Karl Lagerfeld, Jean-Paul Gaultier, Yves Saint Laurent, Givenchy, and Christian Lacroix. Paris Fashion Week, held in January and July in the Carrousel du Louvre among other renowned city locations, is one of the top four events on the international fashion calendar.[256][257] Moreover, Paris is also the home of the world's largest cosmetics company: L'Oréal as well as three of the top five global makers of luxury fashion accessories: Louis Vuitton, Hermés, and Cartier.[258] Most of the major fashion designers have their showrooms along the Avenue Montaigne, between the Champs-Élysées and the Seine.

Photography

The inventor Nicéphore Niépce produced the first permanent photograph on a polished pewter plate in Paris in 1825. In 1839, after the death of Niépce, Louis Daguerre patented the Daguerrotype, which became the most common form of photography until the 1860s.[213] The work of Étienne-Jules Marey in the 1880s contributed considerably to the development of modern photography. Photography came to occupy a central role in Parisian Surrealist activity, in the works of Man Ray and Maurice Tabard.[259][260] Numerous photographers achieved renown for their photography of Paris, including Eugène Atget, noted for his depictions of street scenes, Robert Doisneau, noted for his playful pictures of people and market scenes (among which Le baiser de l'hôtel de ville has become iconic of the romantic vision of Paris), Marcel Bovis, noted for his night scenes, as well as others such as Jacques-Henri Lartigue and Henri Cartier-Bresson.[213] Poster art also became an important art form in Paris in the late nineteenth century, through the work of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jules Chéret, Eugène Grasset, Adolphe Willette, Pierre Bonnard, Georges de Feure, Henri-Gabriel Ibels, Paul Gavarni and Alphonse Mucha.[213]

Media

Paris and its close suburbs are home to numerous newspapers, magazines and publications including Le Monde, Le Figaro, Libération, Le Nouvel Observateur, Le Canard enchaîné, La Croix, Le Parisien (in Saint-Ouen), Les Échos, Paris Match (Neuilly-sur-Seine), Réseaux & Télécoms, Reuters France, l'Équipe (Boulogne-Billancourt) and L'Officiel des Spectacles.[262] France's two most prestigious newspapers, Le Monde and Le Figaro, are the centrepieces of the Parisian publishing industry.[263] Agence France-Presse is France's oldest, and one of the world's oldest, continually operating news agencies. AFP, as it is colloquially abbreviated, maintains its headquarters in Paris, as it has since 1835.[264] France 24 is a television news channel owned and operated by the French government, and is based in Paris.[265] Another news agency is France Diplomatie, owned and operated by the Ministry of Foreign and European Affairs, and pertains solely to diplomatic news and occurrences.[266]

The most-viewed network in France, TF1, is in nearby Boulogne-Billancourt. France 2, France 3, Canal+, France 5, M6 (Neuilly-sur-Seine), Arte, D8, W9, NT1, NRJ 12, La Chaîne parlementaire, France 4, BFM TV, and Gulli are other stations located in and around the capital.[267] Radio France, France's public radio broadcaster, and its various channels, is headquartered in Paris's 16th arrondissement. Radio France Internationale, another public broadcaster is also based in the city.[268] Paris also holds the headquarters of the La Poste, France's national postal carrier.[269]

Holidays and festivals

Bastille Day, a celebration of the storming of the Bastille in 1789, the biggest festival in the city, is a military parade taking place every year on 14 July on the Champs-Élysées, from the Arc de Triomphe to Place de la Concorde. It includes a flypast over the Champs Élysées by the Patrouille de France, a parade of military units and equipment, and a display of fireworks in the evening, the most spectacular being the one at the Eiffel Tower.[270]

Some other yearly festivals are Paris-Plages, a festive summertime event when the Right Bank of the Seine is converted into a temporary beach;[270] Journées du Patrimoine, Fête de la Musique, Techno Parade, Nuit Blanche, Cinéma au clair de lune, Printemps des rues, Festival d'automne, and Fête des jardins. The Carnaval de Paris, one of the oldest festivals in Paris, dates back to the Middle Ages.

Libraries