Дьявол в христианстве

В христианстве дьявол - олицетворение зла . Он традиционно считается восставшимся против Бога в попытке стать равным Самому Богу. [ А ] Говорят, что он был падшим ангелом , который был изгнан с небес в начале времени, прежде чем Бог создал материальный мир и постоянно противодействует Богу. [ 2 ] [ 3 ] является дьявол Предполагается, что несколькими другими фигурами в Библии, в том числе змея в Эдемском саду , Люцифере , сатане , искушенном Евангелиях , Левиафана и Дракона в Книге Откровения .

Ранние ученые обсудили роль дьявола. Ученые под влиянием неоплатонической космологии , такие как Ориген и Псевдо-Дионисий , изображали дьявола как представляющий дефицит и пустоту, сущность, наиболее отдаленная от божественного. Согласно Августину бегемота , царство дьявола - это не ничто, а низшее царство, стоящее против Бога. Стандартное средневековое изображение дьявола возвращается к Григорию Великому . Он интегрировал дьявола, как первое творение Бога, в христианскую ангельскую иерархию как высшую из ангелов (либо херувим , либо серафт ), которые упали далеко, в глубину ада и стали лидером демонов . [ 4 ]

Since the early Reformation period, the devil has been imagined as an increasingly powerful entity, with not only a lack of goodness but also a conscious will against God, his word, and his creation. Simultaneously, some reformists have interpreted the devil as a mere metaphor for humans' inclination to sin — thereby downgrading his importance. While the devil has played no significant role for most scholars in the Modern Era, he has become important again in contemporary Christianity.

At various times in history, certain Gnostic sects such as the Cathars and the Bogomils, as well as theologians like Marcion and Valentinus, have believed that the devil was involved in creation. Today these views are not part of mainstream Christianity.

Old Testament

[edit]Satan in the Old Testament

[edit]

The Hebrew term śāṭān (Hebrew: שָּׂטָן) was originally a common noun meaning "accuser" or "adversary" that was applicable to both human and heavenly adversaries.[5][6] The term is derived from a verb meaning primarily "to obstruct, oppose".[7] [8] Throughout the Hebrew Bible, it refers most frequently to ordinary human adversaries.[9][10][6] However, 1 Samuel 29:4; 2 Samuel 19:22; 1 Kings 5:4; 1 Kings 11:14, 23, 25; Psalms 109:6 and Numbers 22:22, 32 use the same term to refer to the angel of the Lord. This concept of a heavenly being as an adversary to humans evolved into the personified evil of "a being with agency" called the Satan 18 times in Job 1–2 and Zechariah 3.[9]

Both Hebrew and Greek have definite articles that are used to differentiate between common and proper nouns, but they are used in opposite ways: in Hebrew, the article designates a common noun, whereas in Greek, the article signals an individual's name (a proper noun).[11] For example, in the Hebrew book of Job, one of the angels is referred to as a satan, "an adversary", but in the Greek Septuagint, which was used by the early Christians, whenever "the Satan" (Ha-Satan) appears with a definite article, it specifically refers to the individual known as the heavenly accuser whose personal name is Satan.[10] In some cases it is unclear which is intended.[11]

Henry A. Kelly says that "almost all modern translators and interpreters" of 1 Chronicles 21:1 (in which satan occurs without the definite article) agree the verse contains "the proper name of a specific being appointed to the office of adversary".[12][13] Thomas Farrar writes that "In all three cases, satan was translated in the Septuagint as diabolos, and in the case of Job and Zechariah, with ho diabolos (the accuser; the slanderer). In all three of these passages there is general agreement among Old Testament scholars that the referent of the word satan is an angelic being".[10][6]

In the early rabbinic literature, Satan is never referred to as "the Evil one, the Enemy, belial, Mastema or Beelzebul".[14] No Talmudic source depicts Satan as a rebel against God or as a fallen angel or predicts his end.[14] Ancient Jewish text depicts Satan as an agent of God, a spy, a stool-pigeon, a prosecutor of mankind and even a hangman. He descends to earth to test men's virtue and lead them astray, then rises to Heaven to accuse them.[14]

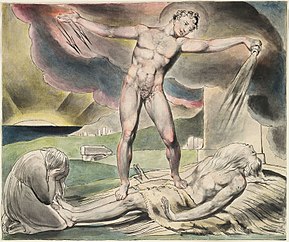

In the Book of Job, Job is a righteous man favored by God.[15] Job 1:6–8[16] describes the "sons of God" (bənê hā'ĕlōhîm) presenting themselves before God:[15]

"Sons of God" is a description of 'angels' as supernatural heavenly beings, "ministers of Yahweh, able under His direction to intervene in the affairs of men, enjoying a closer union with Yahweh than is the lot of men. They appear in the earliest books of the Old Testament as well as in the later... They appear in prophetical and sapiential literature as well as in the historical books; they appear in the primitive history and in the most recent history... they usually appear in the Old Testament in the capacity of God's agents to men; otherwise they appear as the heavenly court of Yahweh. They are sent to men to communicate God's message, to destroy, to save, to help, to punish. ...The angels are in complete submission to the will of God... Whenever they appear among men, it is to execute the will of Yahweh."[17]

God asks one of them where he has been. Satan replies that he has been roaming around the earth.[15] God asks, "Have you considered My servant Job?"[15] Satan thinks Job only loves God because he has been blessed, so he requests that God test the sincerity of Job's love for God through suffering, expecting Job to abandon his faith.[18] God consents; Satan destroys Job's family, health, servants and flocks, yet Job refuses to condemn God.[18] At the end, God returned to Job twice what he had lost. This is one of the two Old Testament passages, along with Zechariah 3, where the Hebrew ha-Satan (the Adversary) becomes the Greek ho diabolos (the Slanderer) in the Greek Septuagint used by the early Christian church.[19]

A satan is involved in King David's census and Christian teachings about this satan varies, just as the pre-exilic account of 2 Samuel and the later account of 1 Chronicles present differing perspectives:

And again the anger of the LORD was kindled against Israel, and He moved David against them, saying: 'Go, number Israel and Judah.'

— 2 Samuel 24:1[20]

However, Satan rose up against Israel, and moved David to number Israel.

— 1 Chronicles 21:1[21]

According to some teachings, this term refers to a human being, who bears the title satan while others argue that it indeed refers to a heavenly supernatural agent, an angel.[22] Since the satan is sent by the will of God, his function resembles less the devilish enemy of God. Even if it is accepted that this satan refers to a supernatural agent, it is not necessarily implied this is the Satan. However, since the role of the figure is identical to that of the devil, viz. leading David into sin, most commentators and translators agree that David's satan is to be identified with Satan and the Devil.[23]

Zechariah's vision of recently deceased Joshua the High Priest depicts a dispute in the heavenly throne room between Satan and the Angel of the Lord (Zechariah 3:1–2).[24] The scene describes Joshua the High Priest dressed in filthy rags, representing the nation of Judah and its sins,[25] on trial with God as the judge and Satan standing as the prosecutor.[25] Yahweh rebukes Satan[25] and orders that Joshua be given clean clothes, representing God's forgiveness of Judah's sins.[25] Goulder (1998) views the vision as related to opposition from Sanballat the Horonite.[26] Again, Satan acts in accordance with God's will. The text implies he functions both as God's accuser and as his executioner.[27]

Identified with the Devil

[edit]Some parts of the Bible, which do not originally refer to an evil spirit or Satan, have been retroactively interpreted as references to the devil.[28]

The serpent

[edit]Genesis 3 mentions the serpent in the Garden of Eden, which tempts Adam and Eve into eating the forbidden fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thus causing their expulsion from the Garden. God rebukes the serpent, stating: "I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your offspring and hers; he will strike your head, and you will strike his heel" (Genesis 3:14–15).[29] Although the Book of Genesis never mentions Satan,[30] Christians have traditionally interpreted the serpent in the Garden of Eden as the devil due to Revelation 12:9,[31] which describes the devil as "that ancient serpent called the Devil, or Satan, the one deceiving the whole world; was thrown down to the earth with all his angels."[32][6] This chapter is used not only to explain the fall of mankind but also to remind the reader of the enmity between Satan and humanity. It is further interpreted as a prophecy regarding Jesus' victory over the devil, with reference to the child of a woman, striking the head of the serpent.[33]

Lucifer

[edit]

The idea of fallen angels was familiar in pre-Christian Hebrew thought from the Book of the Watchers, according to which angels who impregnated human women were cast out of heaven. The Babylonian/Hebrew myth of a rising star, as the embodiment of a heavenly being who is thrown down for his attempt to ascend into the higher planes of the gods, is also found in the Bible, (Isaiah 14:12–15)[34] was accepted by early Christians, and interpreted as a fallen angel.[35]

Aquila of Sinope derives the word hêlêl, the Hebrew name for the morning star, from the verb yalal (to lament). This derivation was adopted as a proper name for an angel who laments the loss of his former beauty.[36] The Christian church fathers—for example Saint Jerome, in his Vulgate—translated this as Lucifer. The equation of Lucifer with the fallen angel probably occurred in 1st-century Palestinian Judaism.[37] The church fathers brought the fallen lightbringer Lucifer into connection with the devil on the basis of a saying of Jesus in the Gospel of Luke (10.18 EU): "I saw Satan fall from heaven like lightning."[35]

In his work De principiis Proemium and in a homily on Book XII, the Christian scholar Origen compared the morning star Eosphorus-Lucifer with the devil. According to Origen, Helal-Eosphorus-Lucifer fell into the abyss as a heavenly spirit after he tried to equate himself with God. Cyprian c. 400, Jerome c. 345–420),[38] Ambrosius c. 340–397, and a few other church fathers essentially subscribed to this view. They viewed this earthly overthrow of a pagan king of Babylon as a clear indication of the heavenly overthrow of Satan.[39] In contrast, the church fathers Hieronymus, Cyrillus of Alexandria (412–444), and Eusebius c. 260–340 saw in Isaiah's prophecy only the mystifying end of a Babylonian king.

Cherub in Eden

[edit]Some scholars use Ezekiel's cherub in Eden to support the Christian doctrine of the devil:[40]

You were in Eden, the garden of God; every precious stone adorned you: ruby, topaz, emerald, chrysolite, onyx, jasper, sapphire, turquoise, and beryl. Gold work of tambourines and of pipes was in you. In the day that you were created they were prepared. You were the anointed cherub who covers: and I set you, so that you were on the holy mountain of God; you have walked up and down in the midst of the stones of fire. You were perfect in your ways from the day that you were created, until unrighteousness was found in you.

— Ezekiel 28:13–15[41]

This description is used to establish major characteristics of the devil: that he was created good as a high ranking angel, that he lived in Eden, and that he turned evil on his own accord. The Church Fathers argued that, therefore, God is not to be blamed for evil but rather the devil's abuse of free will.[42]

Belial

[edit]In the Old Testament, the term belial (Hebrew: בְלִיַּעַל, romanized: bĕli-yaal), with the broader meaning of worthlessness[43] denotes those who work against God or at least against God's order.[44] In Deuteronomy 13:14 those who tempt people into worshiping something other than Yahweh are related to belial. In 1 Samuel 2:12, the sons of Eli are called belial for not recognizing Yahweh and violating sacrifice rituals.[45] In Psalm 18:4 and Psalm 41:8, belial appears in the context of death and disease. In the Old Testament, both Satan and belial make it difficult for men to live in harmony with God's will.[46] Belial is thus another template for the later conception of the devil.[47] On the one hand, both Satan and belial cause hardship for humans, but while belial opposes God, represents chaos and death, and stands outside of God's cosmos, Satan, on the other hand, accuses what opposes God. Satan punishes what belial stands for.[47] Unlike Satan, belial is not an independent entity, but an abstraction.[48]

Intertestamental texts

[edit]Although not part of the canonical Bible, intertestamental writings shaped the early Christian worldview and influenced the interpretation of the Biblical texts. Until the third century, Christians still referred to these stories to explain the origin of evil in the world.[49] Accordingly, evil entered the world by apostate angels, who lusted after women and taught sin to mankind. The Book of Enoch and the Book of Jubilees are still accepted as canonical by the Ethiopian Church.[50] Many Church Fathers accepted their views about fallen angels, though they excluded Satan from these angels. Satan instead, fell after tempting Eve in the Garden of Eden.[51] Satan was being used as a proper name in the apocryphal Jewish writings such as the Book of Jubilees 10:11; 23:29; 50:5, the Testament of Job, and The Assumption of Moses which are contemporary to the writing of the New Testament.[52]

Book of Enoch

[edit]The Book of Enoch, estimated to date from about 300–200 BC, to 100 BC,[53] tells of a group of angels called the Watchers. The Watchers fell in love with human women and descended to earth to have intercourse with them, resulting in giant offspring.[54] On earth, these fallen angels further teach the secrets of heaven like warcraft, blacksmithing, and sorcery.[54] There is no specific devilish leader, as the fallen angels act independently after they descend to earth, but eminent among these angels are Shemyaza and Azazel.[44] Only Azazel is rebuked by the prophet Enoch himself for instructing illicit arts, as stated in 1 Enoch 13:1.[55] According to 1 Enoch 10:6, God sent the archangel Raphael to chain Azazel in the desert Dudael as punishment.

Satan, on the other hand, appears as a leader of a class of angels. Satan is not among the fallen angels but rather a tormentor for both sinful men and sinful angels. The fallen angels are described as "having followed the way of Satan", implying that Satan led them into their sinful ways, but Satan and his angels are clearly in the service of God, akin to Satan in the Book of Job. Satan and his lesser satans act as God's executioners: they tempt into sin, accuse sinners for their misdeeds, and finally execute divine judgment as angels of punishment.[56]

Book of Jubilees

[edit]The Book of Jubilees also identifies the Bene Elohim ("sons of God") in Genesis 6 with the offspring of fallen angels, adhering to the Watcher myth known from the Book of Enoch. Throughout the book, another wicked angel called Mastema is prominent. Mastema asks God to spare a tenth of the demons and assign them under his domain so that he might prove humanity to be sinful and unworthy. Mastema is the first figure who unites the concept Satan and Belial. Morally questionable actions ascribed to God in the Old Testament, like environmental disasters and tempting Abraham, are ascribed to Mastema instead, establishing a satanic character distant from the will of God in contrast to early Judaism. Still, the text implies that Mastema is a creature of God, although contravening his will. In the end times, he will be extinguished.[57]

New Testament

[edit]Gospels

[edit]

The devil figures much more prominently in the New Testament and in Christian theology than in the Old Testament and Judaism. Religion scholar William Caldwell writes that "In the Old Testament we have seen that the figure of Satan is vague. ... In reaching the New Testament we are struck by the unitariness, clearness, and definiteness of the outline of Satan."[58] The New Testament Greek word for the devil, satanas, which occurs 38 times in 36 verses, is not actually a Greek word: it is transliterated from Aramaic, but is ultimately derived from Hebrew.[52] Scholars agree that "Satan" is always a proper name in the New Testament.[52] In Mark 1:13 "ho Satanas" is a proper name that identifies a particular being with a distinct personality:[59]

The figure whom Mark designates as the perpetrator of Jesus' Wilderness temptation, whether called Satan or one of a host of other names, was not an 'unknown quantity'. On the contrary, in Mark's time and in the thought world which Mark and his audience shared, Satan's identity and the activities characteristic of him were both well-defined and widely known.[60]

Although in later Christian theology, the devil and his fellow fallen angels are often merged into one category of demonic spirits, the devil is a unique entity throughout the New Testament.[61] The devil is not only a tempter but perhaps rules over the kingdoms of earth.[62] In the temptation of Christ (Matthew 4:8–9 and Luke 4:6–7),[63] the devil offers all kingdoms of the earth to Jesus, implying they belong to him.[64] Since Jesus does not dispute this offer, it may indicate that the authors of those gospels believed this to be true.[64] This interpretation is, however, not shared by all, as Irenaeus argued that, since the devil was a liar since the beginning, he also lied here and that all kingdoms in fact belong to God, referring to Proverbs 21.[65][66] This event is described in all three synoptic gospels, (Matthew 4:1–11,[67] Mark 1:12–13[68] and Luke 4:1–13).[69]

Other adversaries of Jesus are ordinary humans although influence by the devil is suggested. John 8:40[70] speaks about the Pharisees as the "offspring of the devil". John 13:2[71] states that the devil entered Judas Iscariot before Judas' betrayal (Luke 22:3).[72][73] In all three synoptic gospels (Matthew 9:22–29,[74] Mark 3:22–30[75] and Luke 11:14–20),[76] Jesus' critics accuse him of gaining his power to cast out demons from Beelzebub, the devil. In response, Jesus says that a house divided against itself will fall, and that there would be no reason for the devil to allow one to defeat the devil's works with his own power.[77]

Acts and epistles

[edit]The Epistle of Jude makes reference to an incident where the Archangel Michael argued with the devil over the body of Moses (Jude 1:9).[78] According to the First Epistle of Peter, "Like a roaring lion your adversary the devil prowls around, looking for someone to devour" (1 Peter 5:8).[79] The authors of the Second Epistle of Peter and the Epistle of Jude believe that God prepares judgment for the devil and his fellow fallen angels, who are bound in darkness until the Divine retribution.[80]

In the Epistle to the Romans, the inspirer of sin is also implied to be the author of death.[80] The Epistle to the Hebrews speaks of the devil as the one who has the power of death but is defeated through the death of Jesus (Hebrews 2:14).[81][82] In the Second Epistle to the Corinthians, Paul the Apostle warns that Satan is often disguised as an angel of light.[80]

Revelation

[edit]

The Book of Revelation describes a battle in heaven (Revelation 12:7–10)[83] between a dragon/serpent "called the devil, or Satan" and the archangel Michael resulting in the dragon's fall. Here, the devil is described with features similar to primordial chaos monsters, like the Leviathan in the Old Testament.[61] The identification of this serpent as Satan supports identification of the serpent in Genesis with the devil.[84] Thomas Aquinas, Rupert of Deutz and Gregory the Great (among others) interpreted this battle as occurring after the devil sinned by aspiring to be independent of God. In consequence, Satan and the evil angels are hurled down from heaven by the good angels under leadership of Michael.[85]

Before Satan was cast down from heaven, he was accusing humans for their sins (Revelation 12:10).[86][61] After 1,000 years, the devil would rise again, just to be defeated and cast into the Lake of Fire (Revelation 20:10).[87][88] An angel of the abyss called Abaddon, mentioned in Revelation 9:11,[89] is described as its ruler and is often thought of as the originator of sin and an instrument of punishment. For these reasons, Abaddon is also identified with the devil.[90]

Christian teachings

[edit]The concept of fallen angels is of pre-Christian origin. Fallen angels appear in writings such as the Book of Enoch, the Book of Jubilees and arguably in Genesis 6:1–4. Christian tradition and theology interpreted the myth about a rising star, thrown into the underworld, originally told about a Babylonian king (Isaiah 14:12) as also referring to a fallen angel.[91] The devil is generally identified with Satan, the accuser in the Book of Job.[92] Only rarely are Satan and the devil depicted as separate entities.[93]

Much of the lore of the devil is not biblical. It stems from post-medieval Christian expansions on the scriptures influenced by medieval and pre-medieval popular mythology.[94] In the Middle Ages there was a great deal of adaptation of biblical material, in the vernacular languages, that often employed additional literary forms like drama to convey important ideas to an audience unable to read the Latin for themselves.[95] They sometimes expanded the biblical text with additions, explanatory developments or omissions.[96] The Bible has silences: questions it does not address. For example, in the Bible, the fruit Adam and Eve ate is not defined; the apple is part of folklore.[97] Medieval Europe was well equipped to explain the silences of the Bible.[98] In addition to the use of world history and the expansion of Biblical books, additional vehicles for the adornment of Biblical tales were popular sagas, legends, and fairy tales. These provided elaborate views of a dualistic creation where the Devil vies with God, and creates disagreeable imitations of God's creatures like lice, apes, and women.[99] The Devil in certain Russian tales had to intrigue his way on board the Ark in order to keep from drowning.[100] The ability of the Devil, in folk-tale, to appear in any animal form, to change form, or to become invisible, all such powers while nowhere mentioned in the Bible itself, have been assigned to the devil by medieval ecclesiasticism without dispute.[101]

Maximus the Confessor argued that the purpose of the devil is to teach humans how to distinguish between virtue and sin. Since, according to Christian teachings, the devil was cast out of the heavenly presence (unlike the Jewish Satan, who still functions as an accuser angel at service of God), Maximus explained how the devil could still talk to God, as told in the Book of Job, despite being banished. He argues that, as God is omnipresent within the cosmos, Satan was in God's presence when he uttered his accusation towards Job without being in the heavens. Only after the Day of Judgement, when the rest of the cosmos reunites with God, the devil, his demons, and all whose who cling to evil and unreality will exclude themselves eternally from God and suffer from this separation.[102]

Christians have understood the devil as the personification of evil, the author of lies and the promoter of evil, and as a metaphor of human evil. However, the devil can go no further than God, or human freedom, allows, resulting in the problem of evil. Christian scholars have offered three main theodicies of why a good God might need to allow evil in the world. These are based on the free will of humankind,[103] a self-limiting God,[104] and the observation that suffering has "soul-making" value.[105] Christian theologians do not blame evil solely on the devil, as this creates a kind of Manichean dualism that, nevertheless, still has popular support.[106]

Origen

[edit]Origen was probably the first author to use Lucifer as a proper name for the devil. In his work De principiis Proemium and in a homily on Book XII, he compared the morning star Eosphorus-Lucifer—probably based on the Life of Adam and Eve—with the devil or Satan. Origen took the view that Helal-Eosphorus-Lucifer, originally mistaken for Phaeton, fell into the abyss as a heavenly spirit after he tried to equate himself with God. Cyprian (around 400), Ambrosius (around 340–397) and a few other church fathers essentially subscribed to this view which was borrowed from a Hellenistic myth.[35]

According to Origen, God created rational creatures first then the material world. The rational creatures are divided into angels and humans, both endowed with free will,[107] and the material world is a result of their choices.[108][109] The world, also inhabited by the devil and his angels, manifests all kinds of destruction and suffering too. Origen opposed the Valentinian view that suffering in the world is beyond God's grasp, and the devil is an independent actor. Therefore, the devil is only able to pursue evil as long as God allows. Evil has no ontological reality, but is defined by deficits or a lack of existence, in Origen's cosmology. Therefore, the devil is considered most remote from the presence of God, and those who adhere to the devil's will follow the devil's removal from God's presence.[110]

Origen has been accused by Christians of teaching salvation for the devil. However, in defense of Origen, scholars have argued apocatastasis for the devil is based on a misinterpretation of his universalism. Accordingly, it is not the devil, as the principle of evil, the personification of death and sin, but the angel, who introduced them in the first place, who will be restored after this angel abandons his evil will.[111]

Augustine

[edit]Augustine of Hippo's work, Civitas Dei (5th century), and his subsequent work On Free Will became major influences in Western demonology into the Middle Ages and even into the Reformation era, influencing notable Reformation theologians such as John Calvin and Martin Luther.[112][113] For Augustine, the rebellion of Satan was the first and final cause of evil; thus, he rejected earlier teachings about Satan having fallen when the world was already created.[114][115] In his Civitas Dei, he describes two cities (Civitates) distinct from and opposed to each other like light and darkness.[116] The earthly city is influenced by the sin of the devil and is inhabited by wicked men and demons (fallen angels) who are led by the devil. On the other hand, the heavenly city is inhabited by righteous men and the angels led by God.[116] Although his ontological division into two different kingdoms shows a resemblance to Manichean dualism, Augustine differs in regard to the origin and power of evil. He argues that evil came first into existence by the free will of the devil[117] and has no independent ontological existence. Augustine always emphasized the sovereignty of God over the devil[118] who can only operate within his God-given framework.[115]

Augustine wrote that angels sinned under differing circumstances than humans did, resulting in different consequences for their actions. Human sins are the result of circumstances an individual may or may not be responsible for, such as original sin. The person is responsible for their decisions, but not the environment or conditions in which their decisions are made. The angels who became demons had lived in Heaven; their environment was grounded and surrounded by the divine; they should have loved God more than themselves, but they delighted in their own power, and loved themselves more, sinning "spontaneously". Because they sinned "through their own initiative, without being tempted or persuaded by anyone else, they cannot repent and be saved through the intervention of another. Hence they are eternally fixed in their self-love (De lib. arb. 3.10.29–31)".[119][120] Since the sin of the devil is intrinsic to his nature, Augustine argues that the devil must have turned evil immediately after his creation.[121] Thus the devil's attempt to take God's throne is not an assault on the gates of heaven, but a turn to solipsism in which the devil becomes God in his world.[122]

Further, Augustine rejects the idea that envy could have been the first sin (as some early Christians believed, evident from sources like Cave of Treasures in which Satan has fallen because he envies humans and refused to prostrate himself before Adam), since pride ("loving yourself more than others and God") must precede envy ("hatred for the happiness of others").[123] Such sins are described as removal from God's presence. The devil's sin does not give evil a positive value, since evil is, according to Augustinian theodicy, merely a byproduct of creation. The spirits have all been created in the love of God, but the devil valued himself more, thereby abandoning his position for a lower good. Less clear is Augustine about the reason for the devil's choosing to abandon God's love. In some works, he argued that it is God's grace that gives the angels a deeper understanding of God's nature and the order of the cosmos. Illuminated by God-given grace, they became incapable of feeling any desire for sin. The other angels, however, are not blessed with grace and act sinfully.[124]

Anselm of Canterbury

[edit]Anselm of Canterbury describes the reason for the devil's fall in his De Casu Diaboli ("On the Devil's Fall"). Breaking with Augustine's diabology, he absolved God from pre-determinism and causing the devil to sin. Like earlier theologians, Anselm explained evil as nothingness, or something people can merely ascribe to something to negate its existence that has no substance in itself. God gave the devil free will, but has not caused the devil to sin by creating the condition to abuse this gift. Anselm invokes the idea of grace, bestowed upon the angels.[125] According to Anselm, grace was also offered to Lucifer, but the devil willingly refused to receive the gift from God. Anselm argues further that all rational creatures strive for good, since it is the definition of good to be desired by rational creatures, so Lucifer's wish to become equal to God is actually in accordance with God's plan.[126][b] The devil deviates from God's plans when he wishes to become equal to God by his own efforts without relying on God's grace.[126]

Anselm also played an important role in shifting Christian theology further away from the ransom theory of atonement, the belief that Jesus' crucifixion was a ransom paid to Satan, in favor of the satisfaction theory.[128] According to this view, humanity sinned by violating the cosmic harmony God created. To restore this harmony, humanity needed to pay something they did not owe to God. But since humans could not pay the price, God had to send Jesus, who is both God and human, to sacrifice himself.[129] The devil does not play an important role in this theory of atonement any longer. In Anselm's theology, the devil features more as an example of the abuse of free will than as a significant actor in the cosmos.[130] He is not necessary to explain either the fall or the salvation of humanity.[131]

History

[edit]Early Christianity

[edit]

The notion of fallen angels already existed, but had no unified narrative in Pre-Christian times. In 1 Enoch, Azazel and his host of angels came to earth in human shape and taught forbidden arts resulting in sin. In the Apocalypse of Abraham, Azazel is described with his own Kavod (Magnificence), a term usually used for the Divine in apocalyptic literature, already indicating the devil as anti-thesis of God, with the devil's kingdom on earth and God's kingdom in heaven.[132] In the Life of Adam and Eve, Satan was cast out of heaven for his refusal to prostrate himself before man, likely the most common explanation for Satan's fall in Proto-orthodox Christianity.[133]

Christianity, however, depicted the fall of angels as an event prior to the creation of humans. The devil becomes considered a rebel against God, by claiming divinity for himself; he is allowed to have temporary power over the world. Thus, in prior depictions of the fallen angels, the evil angel's misdemeanor is directed downwards (to man on earth) while, with Christianity, the devil's sin is directed upwards (to God).[35] Although the devil is considered to be inherently evil, influential Christian scholars, like Augustine and Anselm of Canterbury, agree that the devil had been created good but, at some point, had freely chosen evil, resulting in his fall.

In early Christianity, some movements postulated a distinction between the God of Law, creator of the world and the God of Jesus Christ. Such positions were held by Marcion, Valentinus, the Basilides and Ophites, who denied the Old Testamental deity to be the true God, arguing that the descriptions of the Jewish deity are blasphemous for God. They were opposed by those like Irenaeus, Tertullian and Origen who argued that the deity presented by Jesus and the God of Jews are the same, and who, in turn, accused such movements as blaspheming against God by asserting a power higher than the Creator. As evident from Origen's On the First Principles, those who denied the Old Testamental deity to be the true God argued that God can only be good and cannot be subject to inferior emotions like anger and jealousy. Instead, they accused him of self-deification, thus identifying him with Lucifer (Hêlêl), the opponent of Jesus and ruler of the world.[134]

However, not all dualistic movements equated the Creator with the devil. In Valentinianism, the Creator is merely ignorant, but not evil, trying to fashion the world as good as he can, but lacking the proper power to maintain its goodness.[135] Irenaeus writes in Against Heresies that, according to the Valentinian cosmological system, Satan was the left-hand ruler,[136] but actually superior to the Creator, because he would consist of spirit, while the Creator of inferior matter.[137][135]

Byzantium

[edit]

Byzantine understanding of the devil derived mostly from the church fathers of the first five centuries. Due to the focus on monasticism, mysticism and negative theology, which were more unifying than Western traditions, the devil played only a marginal role in Byzantine theology.[139] Within such monistic cosmology, evil was considered as a deficiency having no real ontological existence. Thus the devil became the entity most remote from God, as described by Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite.[140]

John Climacus detailed the traps of the devil in his monastic treatise The Ladder of Paradise. The first trap of the devil and his demons is to prevent people from performing good actions. In the second, one performs good but not in accordance with God's will. In the third, one becomes proud of one's good actions. Only by recognizing that all the good that one can perform comes from God can the last and most dangerous trap be avoided.[102]

John of Damascus, whose works also affected Western scholastic traditions, provided a rebuttal to Dualistic cosmology. Against dualistic religions like Manichaeism, he argued that, if the devil was a principle independent from God and there are two principles, they must be in complete opposition. But if they exist, according to John, they both share the trait of existence, resulting in only one principle (of existence) again.[141] Influenced by John the Evangelist, he further emphasized the metaphors of light for good and darkness for evil.[142] Like darkness, deprivation of good results in one's becoming non-existent and darker.[141]

Byzantine theology does not consider the devil as redeemable. Since the devil is a spirit, the devil and his angels cannot have a change in their will, just as humans turned into spirits after death are not able to change their attitude either.[143]

Early Middle Ages

[edit]

Although the teachings of Augustine, who rejected the Enochian writings and associated the devil with pride instead of envy, are usually considered to be the most fundamental depictions of the devil in medieval Christianity, some concepts like regarding evil as the mere absence of good, were far too subtle to be embraced by most theologians during the Early Middle Ages. They sought a more concrete image of evil to represent spiritual struggle and pain, so the devil became more of a concrete entity. From the 4th through the 12th centuries, Christian ideas combined with European pagan beliefs, creating a vivid folklore about the devil and introducing new elements. Although theologians usually conflated demons, satans and the devil, medieval demonology fairly consistently distinguished between Lucifer, the fallen angel fixed in hell, and the mobile Satan executing his will.[144]

Teutonic gods were often considered demons or even the devil. In the Flateyjarbók, Odin is explicitly described as another form of the devil, whom the pagans worshiped and to whom they sacrificed.[145] Everything sacred to pagans or the foreign deities was usually perceived as sacred for the devil and feared by Christians.[146] Many pagan nature spirits like dwarfs and elves became seen as demons, although a difference remained between monsters and demons. The monsters, regarded as distorted humans, probably without souls, were created so that people might be grateful to God that they did not suffer in such a state; they ranked above demons in existence and still claimed a small degree of beauty and goodness as they had not turned away from God.[147]

It was widely accepted that people could make a deal with the devil[148] by which the devil would attempt to catch the soul of a human. Often, the human would have to renounce faith in Christ. But the devil could easily be tricked by courage and common sense and therefore often remained as a comic relief character in folkloric stories.[149] In many German folktales, the devil replaces the role of a deceived giant, known from pagan tales.[150] For example, the devil builds a bridge in exchange for the first passing being's soul, then people let a dog pass the bridge first and the devil is cheated.[151]

Pope Gregory the Great's doctrines about the devil became widely accepted during the Medieval period and, combined with Augustine's view, became the standard account of the devil. Gregory described the devil as the first creation of God. He was a cherub and leader of the angels (contrary to the Byzantine writer Pseudo-Dionysius, who did not place the devil among the angelic hierarchy).[152] Gregory and Augustine agreed with the idea that the devil fell because of his own will; nevertheless, God held ultimate control over the cosmos. To support his argument, Gregory paraphrases parts of the Old Testament according to which God sends an evil spirit. However, the devils' will is indeed unjust; God merely diverts the evil deeds to justice.[153] For Gregory, the devil is thus also the tempter. The tempter incites, but it is the human will that consents to sin. The devil is only responsible for the first stage of sinning.[154]

Cathars and Bogomiles

[edit]

The revival of dualism in the 12th century by Catharism deeply influenced Christian perceptions on the devil.[155] What is known of the Cathars largely comes in what is preserved by the critics in the Catholic Church which later destroyed them in the Albigensian Crusade. Alain de Lille, c. 1195, accused the Cathars of believing in two gods, one of light and one of darkness.[156] Durand de Huesca, responding to a Cathar tract c. 1220 indicates that they regarded the physical world as the creation of Satan.[157] A former Italian Cathar turned Dominican, Sacchoni in 1250 testified to the Inquisition that his former co-religionists believed that the devil made the world and everything in it.[158]

Catharism probably roots in Bogomilism, founded by Theophilos in the 10th century, who in turn owed many ideas to the earlier Paulicians in Armenia and the Near East and had strong impact on the history of the Balkans. Their true origin probably lies within earlier sects such as Nestorianism, Marcionism and Borboritism, who all share the notion of a docetic Jesus. Like these earlier movements, Bogomilites agree upon a dualism between body and soul, matter and spirit, and a struggle between good and evil. Rejecting most of the Old Testament, they opposed the established Catholic Church whose deity they considered to be the devil. Among the Cathars, there have been both an absolute dualism (shared with Bogomilites and early Christian Gnosticism) and mitigated dualism as part of their own interpretation.[159]

Mitigated dualists are closer to Christianity, regarding Lucifer as an angel created (through emanation, since by rejecting the Old Testament, they rejected creation ex nihilo) by God, with Lucifer falling because of his own will. On the other hand, absolute dualists regard Lucifer as the eternal principle of evil, not part of God's creation. Lucifer forced the good souls into bodily shape, and imprisoned them in his kingdom. Following the absolute dualism, neither the souls of the heavenly realm nor the devil and his demons have free will but merely follow their nature, thus rejecting the Christian notion of sin.[160]

The Catholic church reacted to spreading dualism in the Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215), by affirming that God created everything from nothing; that the devil and his demons were created good, but turned evil by their own will; that humans yielded to the devil's temptations, thus falling into sin; and that, after Resurrection, the damned will suffer along with the devil, while the saved enjoy eternity with Christ.[161] Only a few theologians from the University of Paris, in 1241, proposed the contrary assertion, that God created the devil evil and without his own decision.[162]

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, parts of Bogomil Dualism remained in Balkan folklore concerning creation: before God created the world, he meets a goose on the eternal ocean. The name of the Goose is reportedly Satanael and it claims to be a god. When God asks Satanael who he is, the devil answers "the god of gods". God requests that the devil then dive to the bottom of the sea to carry some mud, and from this mud, they fashioned the world. God created his angels, and the devil created his demons. Later, the devil tries to assault god but is thrown into the abyss. He remains lurking on the creation of God and planning another attack on heaven.[163] This myth shares some resemblance with Pre-Islamic Turkic creation myths as well as Bogomilite thoughts.[164]

The Reformation

[edit]

From the beginning of the early modern period (around the 1400s), Christians started to imagine the devil as an increasingly powerful entity, constantly leading people into falsehood. Jews, witches, heretics and people affected by leprosy were often associated with the devil.[165] The Malleus Maleficarum, a popular and extensive work on witch-hunting, was written in 1486. Protestants and the Catholic Church began to accuse each other of teaching false doctrines and unwittingly falling for the traps of the devil. Both Catholics and Protestants reformed Christian society by shifting their major ethical concerns from avoiding the seven deadly sins to observing the Ten Commandments.[166] Thus disloyalty to God, which was seen as disloyalty to the church, and idolatry became the greatest sins, making the devil increasingly dangerous. Some reform movements and early humanists often rejected the concept of a personal devil. For example, Voltaire dismissed belief in the devil as superstition.[167]

Early Protestant thought

[edit]

Martin Luther taught that the devil was real, personal and powerful.[168] Evil was not a deficit of good, but the presumptuous will against God, his word and his creation.[169] He also affirmed the reality of witchcraft caused by the devil. However, he denied the reality of witches' flight and metamorphoses, regarded as imagination instead.[c] The devil could also possess someone. He opined that the possessed might feel the devil in himself, as a believer feels the Holy Spirit in his body.[d] In his Theatrum Diabolorum, Luther lists several hosts of greater and lesser devils. Greater devils would incite to greater sins, like unbelief and heresy, while lesser devils to minor sins like greed and fornication. Among these devils also appears Asmodeus known from the Book of Tobit.[e] These anthropomorphic devils are used as stylistic devices for his audience, although Luther regards them as different manifestations of one spirit (i.e. the devil).[f]

Calvin taught the traditional view of the devil as a fallen angel. Calvin repeats the simile of Saint Augustine: "Man is like a horse, with either God or the Devil as rider."[172] In interrogation of Servetus who had said that all creation was part of God, Calvin asked: "what of the Devil?" Servetus responded that "all things are a part and portion of God".[173]

Protestants regarded the teachings of the Catholic Church as undermined by Satan's agency, since they were seen as having replaced the teachings of the Bible with invented customs. Unlike heretics and witches, Protestants saw Catholics as following Satan unconsciously.[174] By abandoning the ceremonial rituals and intercession upheld by the Catholic Church, reformers emphasized individual resistance against the temptations of the devil.[174] Among Luther's teachings to ward off the devil was a recommendation of music since "the Devil cannot stand gaiety."[175]

Anabaptists and Dissenters

[edit]David Joris was the first of the Anabaptists to suggest the devil was only an allegory (c. 1540); this view found a small but persistent following in the Netherlands.[165] The devil as a fallen angel symbolized Adam's fall from God's grace and Satan represented a power within man.[165]

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) used the devil as a metaphor. The devil, Satan and similar figures mentioned throughout the Bible, refer in his work Leviathan to offices or qualities but not individual beings.[176]

However, these views remained very much a minority view at this time. Daniel Defoe in his The Political History of the Devil (1726) describes such views as a form of "practical atheism". Defoe wrote "those who believe there is a God, [...] acknowledge the debt of homage which mankind owes [...] to nature, and to believe the existence of the Devil is a like debt to reason".[177]

In the Modern Era

[edit]

With the increasing influence of positivism, scientism and nihilism in the modern era, both the concept of God and the devil have become less relevant for many.[178] However, Gallup has reported that "Regardless of political belief, religious inclination, education, or region, most Americans believe that the devil exists."[179]

Many Christian theologians have interpreted the devil as being within its original cultural context a symbol of psychological forces. Many dropped the concept of the devil as an unnecessary assumption: they say that the devil does not add much to solving the problem of evil since, whether or not the angels sinned before men, the question remains how evil entered the world in the first place.[180]

Rudolf Bultmann taught that Christians need to reject belief in a literal devil as part of formulating an authentic faith in today's world.[ 181 ]

Напротив, работы таких писателей, как Джеффри Бертон Рассел, сохраняют веру в буквальное личное падшее существо. [ 182 ] Рассел утверждает, что богословы, которые отвергают буквального дьявола (как Бультманн), упускают из виду тот факт, что дьявол является неотъемлемой частью Нового Завета от его происхождения. [ 183 ]

Христианский богослов Карл Барт описывает дьявола ни как человека, ни как просто психологическую силу, а как природу противодействует добру. Он включает в себя дьявола в свою тройную космологию: есть Бог, Божье творение и ничто . Небытие не является отсутствием существования, а плоскостью существования, в котором Бог снимает Свою творческую силу. Он изображен как хаос, противостоящий реальному существу, искажая структуру космоса и получает влияние на человечество. В отличие от дуализма, Барт утверждал, что противодействие реальности влечет за собой реальность, так что существование дьявола зависит от существования Бога и не является независимым принципом. [ 184 ]

Современные взгляды

[ редактировать ]Католическая церковь

[ редактировать ]В то время как католическая церковь не уделяла особого внимания дьяволу в современный период, некоторые современные католические учения начали восстанавливать дьявола. [ G ]

Папа Павел VI выразил обеспокоенность по поводу влияния дьявола в 1972 году, заявив, что «дым сатаны пробился в храм Бога через какую -то трещину». [ 186 ] Однако Иоанн Павел II рассматривал поражение сатаны как неизбежное. [ 187 ]

Папа Франциск возобновил фокус на дьявола в начале 2010 -х годов, заявив, среди многих других заявлений, что «дьявол умный, он знает больше богословия, чем все теологи вместе». [ 188 ] Журналистка Синди Вуден прокомментировала распространенность дьявола в учениях Папы Франциска, отметив, что Фрэнсис считает, что дьявол настоящий. [ 189 ] Во время утреннего проповеди в часовне Domus Sanctae Marthae , в 2013 году, понтифик сказал:

Дьявол не миф, а настоящий человек. Нужно отреагировать на дьявол, как и Иисус, который ответил со Словом Божьим. С принцем этого мира не может диалога. Диалог необходим среди нас, это необходимо для мира [...] Диалог рождается из благотворительности, от любви. Но с этим принцем не может диалога; Можно ответить только Словом Божьим, которое защищает нас. [ 190 ]

В 2019 году Артуро Соса , превосходный генерал Общества Иисуса , сказал, что сатана - символ, олицетворение зла, но не человек, а не «личная реальность»; Четыре месяца спустя он сказал, что дьявол реальна, а его сила - злобная сила. [ 191 ]

Унитарии и Кристадельфийцы

[ редактировать ]Либеральное христианство часто рассматривает дьявол метафорически и в переносном смысле . Дьявол рассматривается как представляющий человеческий грех и искушение, а также любую человеческую систему, противостоящую Богу. [ 192 ] Ранние унитарии и несогласные, такие как Натаниэль Ларднер , Ричард Мид , Хью Фармер , Уильям Эшдаун и Джон Симпсон , и Джон Эппс учил, что чудесные исцеления Библии были реальными, но дьявол был аллегорией , а демоны только медицинский язык день. Такие взгляды преподаются сегодня христадельфийцами [ 193 ] и церковь благословенной надежды . Унитарии и христадельфийцы, которые отвергают Троицу, Бессмертие души и божественность Христа, также отвергают веру в олицетворенное зло. [ 194 ]

Харизматические движения

[ редактировать ]Харизматические движения рассматривают дьявол как личного и реального характера, отвергая все более метафорическое и историческое переосмысление дьявола в современный период как небиблейскую и противоречащую жизни Иисуса . Люди, которые сдаются королевству дьявола, находятся под угрозой одержимыми его демонами . [ 195 ]

По деноминации

[ редактировать ]католицизм

[ редактировать ]

Катехизис католической церкви утверждает, что Церковь считает дьявола, созданного как хорошего ангела Богом, и его и его собратья по свободной воле падших ангелов упали из Божьей благодати. [ 196 ] Сатана не бесконечно мощное существо. Хотя он ангел и, следовательно, чистый дух, он тем не менее считается существом. Действия сатаны разрешены Божественным Провиденсом . [ 196 ] Католицизм отвергает апокатастази , примирение с Богом, предложенное отцом церкви Ориген. [ 197 ]

традиции существует ряд молитв и практики против дьявола В рамках католической церковной . [ 198 ] [ 199 ] включает Молитва Господа в себя ходатайство о том, чтобы быть доставленным «от злого», но также существует ряд других конкретных молитв.

Молитва Святого Михаила специально просит католиков защищать «от зла и ловушки дьявола». Учитывая, что некоторые из сообщений от Богоматери Фатимы были связаны Святой Престолом с «конечными временами», [ 200 ] Некоторые католические авторы пришли к выводу, что ангел, упомянутый в сообщениях Фатимы, - это Майкл Архангел, который побеждает дьявола на войне на небесах . [ 201 ] [ 202 ] Тимоти Тиндал-Робертсон занимает позицию, что освящение России было шагом в возможном поражении сатаны Архангелом Майклом. [ 203 ]

Процесс экзорцизма используется в католической церкви против дьявола и демонического владения . Согласно катехизису католической церкви , «Иисус исполнил экзорцизмы, и от него церковь получила власть и должность изгнания». [ 204 ] Габриэле Аморт , который до смерти в 2016 году в 2016 году главный экзорцист , Римской епархии предупредил против игнорирования сатаны, говоря: «Тот, кто отрицает сатану, также отрицает грех и больше не понимает действия Христа». [ 205 ]

Католическая церковь рассматривает битву против дьявола как продолжающуюся. Во время визита 24 мая 1987 года в Архангел святилище Святого Михаила Папа Иоанн Павел II сказал: [ 205 ]

Битва против дьявола, которая является главной задачей Святого Михаила Архангела, до сих пор сражается сегодня, потому что дьявол все еще жив и активен в мире. Зло, которое окружает нас сегодня, расстройства, которые преследуют наше общество, несоответствие человека и разбитость, являются не только результатами первоначального греха, но и результатом распространенного и темного действия сатаны.

Восточные православные виды

[ редактировать ]

В восточной православии дьявол является неотъемлемой частью христианской космологии. Существование дьявола воспринимается всерьез и не подвергается вопросу. [ 206 ] Согласно восточной православной христианской традиции, есть три врага человечества: смерть, грех и сатана. [ 207 ] В отличие от западного христианства, грех рассматривается не как преднамеренный выбор, а как универсальная и неизбежная слабость. [ 207 ] Грех поворачивается от Бога к себе, формы эгоизма и неблагодарности, ведущей от Бога к смерти и ничто. [ 208 ] Люцифер изобрел грех, приведя к смерти и сначала представил его ангелам, которые были созданы до материального мира, а затем в человечество. Люцифер, считавший бывшим сияющим архангелом, потерял свет после своего падения и стал темным сатаном (врагом). [ 209 ]

Восточная православия утверждает, что Бог не создал смерти, но что он был подкреплен дьяволом через девианство с праведного способа (любовь Бога и благодарность). [ 210 ] В некотором смысле, это было место, где Бог не был, потому что Он не мог умереть, но это была неизбежная тюрьма для всего человечества до Христа. До воскресения Христа можно сказать, что у человечества есть повод бояться дьявола, так как он был существом, которое могло отделить человечество от Бога и источник жизни - потому что Бог не мог войти в аду, и человечество не могло избежать этого.

Оказавшись в Аиде, православный держит, что Христос - добрый и справедливый - предоставил жизнь и воскресение всем, кто хотел следовать за ним. В результате дьявол был свергнут и больше не может удержать человечество. С испорченной тюрьмой у дьявола есть только власть над тем, кто свободно выбирает его и грех. [ 211 ]

Евангельские протестанты

[ редактировать ]Евангельские протестанты согласны с тем, что сатана - это реальная, созданная, полностью отданная злу, и что зло - это то, что противостоит Богу или не пожелает Богом. Евангелисты подчеркивают силу и участие сатаны в историю в различной степени; Некоторые практически игнорируют сатану и другие, которые наслаждаются спекуляциями о духовной войне против этой личной силы тьмы. [ 212 ] По словам Сореглеля, Мартин Лютер избежал «обширного обращения с местом ангелов в небесной иерархии или в христианской богословии». [ 213 ] Современные протестанты продолжаются аналогичным образом, так как считается ни полезным, ни необходимым для знания. [ 214 ]

Свидетели Иеговы

[ редактировать ]Свидетели Иеговы считают, что сатана изначально был совершенным ангелом, который развил чувства самооценки и жаждет поклонения, принадлежавшего Богу. Сатана убедил Адама и Евы повиноваться ему, а не Богу, подняв эту проблему - часто называется «противоречием» - будет ли люди, полученные свободной волей , подчиняются Богу как под искушением, так и преследованием. Говорят, что проблема заключается в том, может ли Бог по праву утверждать, что он суверен Вселенной. [ 215 ] [ 216 ] Вместо того, чтобы уничтожить сатану, Бог решил проверить верность остального человечества и доказать остальному творению, что сатана был лжецом. [ 217 ] [ 218 ] Свидетели Иеговы считают, что сатана является главным противником Бога [ 218 ] и невидимый правитель мира. [ 215 ] [ 216 ] Они считают, что демоны были изначально ангелами, которые восстали против Бога и взяли сторону сатаны в полемике. [ 219 ]

Свидетели Иеговы не верят, что сатана живет в аду или что ему было дано ответственность за наказание нечестивых. Говорят, что сатана и его демоны были сбиты с небес на землю в 1914 году, отмечая начало « последних дней ». [ 215 ] [ 220 ] Свидетели считают, что сатана и его демоны влияют на людей, организации и нации, и что они являются причиной человеческих страданий. В Армагеддоне сатана должен быть связан в течение 1000 лет, а затем дает краткую возможность ввести в заблуждение совершенного человечества, прежде чем быть уничтоженным. [ 221 ]

Последний день Святые

[ редактировать ]В мормонизме дьявол-это реальное существо, буквальный духовный Сын Божий, у которого когда-то была ангельская власть, но восстал и упал до создания земли в добытной жизни . В то время он убедил третью часть духовных детей Божьих, чтобы восстать с ним. Это противоречило плану спасения, отстаиваемого Иеговой (Иисус Христос). Теперь дьявол пытается убедить человечество сделать зло ( доктрина и заветы 76: 24–29 ). Человечество может преодолеть это через веру в Иисуса Христа и послушание Евангелию. [ 222 ]

Святые последних дней традиционно рассматривают Люцифера как предсмертное имя дьявола. Мормонское богословие учит, что в небесном совете Люцифер восстал против плана Бога Отца и впоследствии был изгнан. [ 223 ] Мормонское Писание гласит:

И это мы также видели, и записывались, что Ангел Божий, который находился в власти в присутствии Бога, который восстал против единственного порожденного сына, которого любил Отец и который был в груди Отца, был устремлен из Присутствие Бога и Сына, и его называли погибшей, потому что небеса плакали над ним - он был Люцифером, сыном утра. И мы видим, и вот, он упал! упал, даже сын утра! И пока мы были в духе, Господь повелел нам, что мы должны написать видение; ибо мы увидели сатану, этого старого змея, даже дьявола, который восстал против Бога и стремился взять Царство нашего Бога и Его Христа - где бы он ни был, он исполняет войну со святыми Божьими и охватывает их вокруг ( Учение и Заветы 76: 25–29 )

После того, как он стал сатаном своим падением, Люцифер «поднимается вверх и вниз, чтобы позади на землю, стремясь уничтожить души людей» ( Доктрина и Заветы 10:27 ). Мормоны считают Исаию 14:12, чтобы ссылаться как на короля вавилонян, так и дьявола. [ 224 ] [ 225 ]

Богословские споры

[ редактировать ]Ангельская иерархия

[ редактировать ]Дьявол может быть либо херувимом , либо серафом . Христианские писатели часто не определились, из какого порядка ангелов упал дьявол. В то время как дьявол отождествляется с херувимом в Иезекииле 28: 13–15, [ 226 ] Это конфликт с мнением, что дьявол был одним из самых высоких ангелов, которые, по словам Псевдо-Дионизиуса , серафима. [ 227 ] Томас Аквинский цитирует Григория Великого , который заявил, что сатана «превзошел [ангелов] все в славе». [ 228 ] Утверждая, что чем выше ангел, тем больше вероятность того, что он стал виновным в гордости, [ 229 ] [ 227 ] Дьявол будет серафом. Но Аквинский держал грех, несовместимый с огненной любовью, характерной для серафа, но возможный для херувима, основной характеристикой которой является ошибочное знание. В соответствии с Иезекиилем он приходит к выводу, что дьявол был самым знающим из ангелов, херувимов. [ 227 ]

Ад

[ редактировать ]

Христианство не определилось, не попал ли дьявол сразу же в ад или ему дана передышка до дня суда. [ 230 ] Несколько христианских авторов, среди которых Данте Алигьери и Джон Милтон изобразили дьявола как жителя в аду. Это в отличие от частей Библии, которые описывают дьявола как путешествуя по земле, как Иов 1: 6–7 [ 231 ] и 1 Петра 5: 8, [ 232 ] обсуждается выше. С другой стороны, 2 Петра 2: 4 [ 233 ] говорит о грешных ангелах, прикованных в аду. [ 234 ] По крайней мере, согласно Откровению 20:10, [ 87 ] Дьявол брошен в озеро Огненное и Серу. Богословы не согласны, бродит ли дьявол по воздуху земли или упал под землю в ад, [ 235 ] И все же оба взгляда согласны с тем, что дьявол будет в аду после Судного дня.

Если дьявол связан в аду, возникает вопрос, как он все еще может появиться людям на земле. В какой -то литературе дьявол только посылает своих меньших демонов или сатаны исполнять его волю, в то время как он остается цепью в аду. [ 236 ] [ 237 ] Другие утверждают, что дьявол прикован, но берет с собой свои цепи, когда он поднимается на поверхность земли. [ 230 ] Григорий Великий пытался разрешить этот конфликт, заявив, что независимо от того, где дьявол живет пространственно, отделение от самого Бога - это состояние ада. [ 238 ] Беде заявляет, что в своем комментарии к Посланию Джеймса (3.6) , где бы ни двигались дьявол и его ангелы, они несут с собой мучительное пламя ада, как человек с лихорадкой. [ 239 ]

Греховность ангелов

[ редактировать ]Некоторые богословы считают, что ангелы не могут грешить, потому что грех приносит смерть, а ангелы не могут умереть. [ 240 ]

Поддержите идею о том, что английский может грешить, Томас Аквинский , в своем Summa TheLogiae Вопрос 63 Статья 1, Документ:

Ангел или любое другое рациональное существо, рассматриваемое в его собственной природе, может грешить; и для любого существа, которое оно не принадлежит, не грешит, такое существо имеет как дар благодати, а не от состояния природы. Причина этого в том, что грехивание - это не что иное, как отклонение от той прямоты, которое должно иметь акт ; Говорим ли мы о грехе в природе, искусстве или морали. Только этот поступок, правило которого является самой достоинством агента, никогда не может лишить прямоты. Если бы ремесленник рукой самой гравировкой, он не смог выгравировать древесину иначе, чем справедливо; Но если правила будет судить по правильности гравюры, то гравюра может быть правильной или неисправной.

Далее он делит ангельские ордена, которые отличаются псевдодионисом, на ошибочные и непогрешимые, основываясь на том, упоминает ли Библия их по отношению к демонике или нет. Он приходит к выводу, что, поскольку серафим (высший порядок) и престолы (третий по величине) никогда не упоминаются как дьяволы, они не могут грешить. Напротив, Библия говорит о херувиме (второй по величине порядку) и о силах (шестой по величине) по отношению к дьяволу. Он приходит к выводу, что атрибуты, представленные непогрешимыми ангелами, как благотворительность, могут быть только хорошими, в то время как атрибуты, представленные херубимом и силами, могут быть как хорошими, так и плохими. [ 241 ]

Аквинский приходит к выводу, что, хотя ангелы не могут поддаваться телесным желаниям, как интеллектуальные существа, которые они могут грешить в результате своей воли, основанной на разуме. [ 242 ] Грехи, приписываемые дьяволу, включают гордость, зависть и даже жажду, потому что Люцифер любил себя больше, чем все остальное. Первоначально, после того, как ангелы осознали свое существование, они решили за или против зависимости от Бога, а добрые и злые ангелы были отделены друг от друга после короткой задержки после их творения. [ 243 ] Точно так же, Питер Ломбард пишет в своих предложениях , все ангелы были созданы как хорошие духи, имели короткий интервал свободного решения, а некоторые выбирают любовь и, таким образом, были вознаграждены благодати Богом, в то время как другие выбирают грех (гордость или зависть) и стали демоны. [ 244 ]

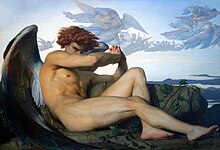

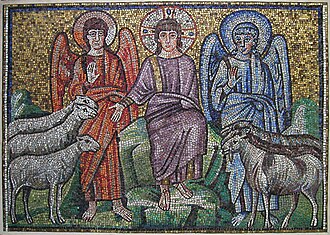

Иконография и литература

[ редактировать ]Изображения

[ редактировать ]

Самое раннее представление дьявола может быть мозаикой в базилике Сант'Аполлинаре Нуово в Равенне с 6 -го века в форме Голубого ангела. [ 245 ] Синий и фиолетовый были общими цветами для дьявола в раннем средневековье, отражая его тело, состоящее из воздуха под небесами, которые, как считается, состоят из более толстого материала, чем эфирный огонь небес, из -за того, что хорошие ангелы изготавливаются и, следовательно, окрашены красным. Первое появление дьявола как черное, а не синее было в 9 веке. [ 246 ] [ 247 ] Только позже дьявол стал ассоциироваться с красным цветом, чтобы отразить кровь или пожары ада. [ 247 ]

До 11 -го века дьявол часто проявлялся в искусстве как человеческий или черный ИМП. Гуманоидный дьявол часто носил белые одежды и пернатые крылья, похожие на птицы, или появлялся как старик в тунике. [ 248 ] Бесс были изображены как крошечные деформированные существа. Когда гуманоидные особенности объединялись с чудовищными в течение 11 -го века, чудовище ИМП постепенно превратилось в гротеск. [ 249 ] Рога стали общим мотивом, начиная с 11 века. Дьявола часто изображали как голые ношения только набедренных порезов, символизируя сексуальность и дикость. [ 250 ]

В частности, в средневековом периоде дьявол часто показали, что имели рога, задних кварталов козы и с хвостом. Он также был изображен как ношение виночки , [ 251 ] чтобы мучить проклятых, что частично происходит от Тридента Посейдона Реализация, используемая в аду , . [ 252 ] Изображения, похожие на коз, напоминают древнюю греческую кастрюлю божества . [ 252 ] Пан, в частности, очень похожа на европейского дьявола в конце средневековья. Неизвестно, будут ли эти функции непосредственно взяты из PAN или христиане по совпадению, приводятся к образу, похожий на PAN. [ 253 ] Изображение дьявола как сатира, подобного существом с 11-го века. [ 253 ]

Поэты, такие как Джеффри Чосер, цвет связывали зеленый с дьяволом, хотя в наше время цвет красный . [ 254 ]

Данте Ад

[ редактировать ]

Изображение дьявола в Адде Алигьери отражает Данте раннюю христианскую неоплатоническую мысль. Данте структурирует его космологию морально; Бог за пределами небес и дьявол на дне ада под землей. В тюрьму в середине земли дьявол становится центром материального и греховного мира, в котором протягивается вся греховность. В противоположность Богу, которого Данте изображает как любовь и свет, Люцифер заморожен и изолирован в последнем круге ада. Почти неподвижный, более жалкий, глупый и отталкивающий, чем ужасающий, дьявол представляет зло [ 255 ] в смысле отсутствия вещества. В соответствии с платонической/христианской традицией, его гигантская внешность указывает на отсутствие силы, поскольку чистое вещество считалось самым дальним от Бога и наиболее близким к необразованию. [ 4 ]

Дьявол описывается как огромный изверг, чьи ягодицы заморожены во льду. У него есть три лица, которые жуют трех предателей Иуды, Кассия и Брута. Сам Люцифер также обвиняется в измене за то, что он перевернулся против своего создателя. Ниже каждого из его лиц у Люцифера есть пара крыльев летучих мышей, еще один символ тьмы. [ 256 ]

Джон Милтон в раю потерян

[ редактировать ]

В Джона Милтона » , «Эпическом стихотворении , потерянном в раю эпохи сатана-один из главных героев, возможно, антигерой . [ 257 ] В соответствии с христианским богословием, сатана восстал против Бога и впоследствии был изгнан с небес вместе со своими собратьями -ангелами. Милтон ломается с предыдущими авторами, которые изображают сатану как гротескную фигуру; [ 257 ] Вместо этого он становится убедительным и харизматическим лидером, который, даже в аду, убедил других падших ангелов создать свое собственное королевство. Неясно, является ли сатана героем, поворачивающимся против несправедливого правителя (Бога) или дурака, который ведет себя и своих последователей к проклятию в тщетной попытке стать равным Богу. Милтон использует несколько языческих изображений, чтобы изобразить демонов, и сам сатана, возможно, напоминает древнего легендарного героя Энеаса . [ 258 ] Сатана - не то, как дьявол, известный из христианского богословия, чем морально амбивалентный персонаж с сильными и слабыми сторонами, вдохновленным христианским дьяволом. [ 259 ]

Смотрите также

[ редактировать ]- Angra Mainyu

- Чернобог

- Дьявол в популярной культуре - включает в себя ссылки на Милтона » «Потерянный рай , Гете » «Фауст , « » Синтапские буквы и т. Д.

- Dystheism

- Злой демон

- Экзорцизм в христианстве

- Дьявол

- Неспособный

- Мара (демон)

- Молитва Святому Михаилу

- Шайтан

- Духовный мир

- Дьявольный фермерский дом

Примечания

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Желая быть равным Богу в Его высокомериях, Люцифер отменяет разницу между Богом и Ангелами, созданными им, и, таким образом сохраняется с обращенными позициями) ». [ 1 ]

- ^ «Стремление рациональных существ к равенству с Богом полностью соответствует божественной воле, чтобы создать, если оно преследуется, потому что она соответствует воле Бога. Это именно там, где находится« расстройство »воли Люцифера: он приравнивает Сам с Богом, потому что он делает это своей собственной волей ( Propria voluntas ), которая не была подчинена кем -либо, разыскиваемой ». [ 127 ]

- ^ «Однако реформатор отвергает реальность полета ведьм или трансформацию и метаморфозу людей в другие формы и приписывает такие идеи не дьяволу, а человеческому воображению». [ 170 ]

- ^ «Реформатор думает о владении дьявола как о возможности, и он чувствует, как он наполняет человеческое тело, похожее на то, как он чувствует божественный дух для себя и, таким образом, считает себя инструментом Бога». [ 170 ]

- ^ «Реформатор интерпретирует книгу Тобита как драму, в которой Асмодеус настаивает на шалости как домашний дьявол». [ 170 ]

- ^ «Таким образом, использование Лютера индивидуальных конкретных дьяволов объясняется необходимостью представить свои мысли таким образом, который является разумным и понятным для масс его современников». [ 171 ]

- ^ «Успех фундаменталистских групп на окраинах католической церкви является такой же частью истории успеха« воскресшего »зла, как и его позиция в некатолических сектах и свободных церквях». [ 185 ]

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Geisenhanslüke, Mein & Overthun 2015 , p. 217

- ^ McCurry, Jeffrey (2006). «Почему дьявол упал: урок в духовном богословии из Аквинского« Сумма теологии » . Новые Блэкфрайарс . 87 (1010): 380–395. doi : 10.1111/j.0028-4289.2006.00155.x . JSTOR 43251053 .

- ^ Гетц 2016 , с. 221

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Рассел 1986 , с. 94–95.

- ^ Kelly 2006 , с. 1–13.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Кампо 2009 , с. 603.

- ^ изд. Баттрик, Джордж Артур ; Словарь Библии переводчика, иллюстрированная энциклопедия

- ^ Farrar 2014 , с. 10

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Farrar 2014 , p. 7

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Келли 2006 , с. 1–13, 28–29.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Келли 2006 , с. 3

- ^ Farrar 2014 , с. 8

- ^ Келли 2006 , с. 29

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Бамбергер, Бернард Дж. (2010). Падшие ангелы: солдаты царства сатаны . Еврейское публикационное общество. п. 94. ISBN 9780827610477 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Келли 2006 , с. 21

- ^ Работа 1: 6–8

- ^ Маккензи, Джон Л. «Божественное сын ангелов» Католическая библейская квартала, вып. 5, нет. 3, 1943, с. 293–300, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43719713 . Доступ 15 апреля 2022. Страницы 297–299

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Келли 2006 , с. 21–22.

- ^ Келли 2004 , с. 323.

- ^ 2 Царств 24: 1

- ^ 1 Хроники 21: 1

- ^ Стоукс, Райан Э. (2009). «Дьявол заставил Давида сделать это ... или« сделал »он? Природа, идентичность и литературное происхождение« сатаны »в 1 Хрониках 21: 1». Журнал библейской литературы . 128 (1): 98–99. doi : 10.2307/25610168 . JSTOR 25610168 . ProQuest 214610671 .

- ^ Стоукс, Райан Э. (2009). «Дьявол заставил Давида сделать это ... или« сделал »он? Природа, идентичность и литературное происхождение« сатаны »в 1 Хрониках 21: 1». Журнал библейской литературы . 128 (1): 91–106. doi : 10.2307/25610168 . JSTOR 25610168 . ProQuest 214610671 .

- ^ Захария 3: 1–2

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Келли 2006 , с. 24

- ^ Goulder 1998 , p. 197

- ^ Стоукс, Райан Э. (2014). «Сатана, палач YHWH». Журнал библейской литературы . 133 (2): 251–270. doi : 10.15699/jbibllite.133.2.251 . JSTOR 10.15699/JBIBLLITE.133.2.251 . Project Muse 547143 ProQuest 1636846672 .

- ^ Келли 2006 , с. 13

- ^ Бытие 3: 14–15

- ^ Келли 2006 , с. 14

- ^ Откровение 12: 9

- ^ Келли 2006 , с. 152

- ^ Wifall, Walter (1974). «Быт 3: 15 - протевангелия?». Католическая библейская ежеквартально . 36 (3): 361–365. JSTOR 43713761 .

- ^ Исаия 14: 12–15

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Theiтсен 2009 , с. 251.

- ^ Bonnetain 2015 , p. 263.

- ^ «Люцифер - еврейский тккопедия.com» . www.jewishencyclopedia.com . Архивировано из оригинала 5 февраля 2022 года.

- ^ Джером. «Письмо 22: Эустохиум» . Новое Адвент . Архивировано из оригинала 5 февраля 2022 года.

- ^ Frick 2006 , p. 193.

- ^ Библейские знания Комментарий: Ветхий Завет , с. 1283 Джон Ф. Уолвоорд, Уолтер Л. Бейкер, Рой Б. Цук. 1985 "Этот" король "появился в Эдемском саду (ст. 13), был хранением херувимов (ст. 14а), обладал свободным доступом ... Лучшее объяснение состоит в том, что Иезекииль описывал сатану, который был истинным «Король» шины, единственный мотивация ».

- ^ Иезекииль 28: 13–15

- ^ Patmore 2012 , с. 41–53.

- ^ Метцгер, Брюс М.; Куган, Майкл Дэвид, ред. (14 октября 1993 г.). "Белиал" . Оксфордский компаньон в Библию . Издательство Оксфордского университета. п. 77. ISBN 978-0-19-974391-9 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Theobald 2015 , p. 35

- ^ Теобальд 2015 , с. 33.

- ^ Теобальд 2015 , с. 32

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Theobald 2015 , p. 34

- ^ Theobald 2015 , с. 32–35.

- ^ Патриция Крона. Книга наблюдателей в Куране, с. 4

- ^ Stuckenbruck & Boccaccini 2016 , с. 133.

- ^ Келли 2004 , с. 324.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Farrar 2014 , p. 11

- ^ Чарльзворт, Джеймс Х. (2005). «Псевдепиграфа». Энциклопедия христианства . Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. С. 410–421. doi : 10.1163/2211-2685_eco_p.172 . ISBN 978-90-04-14595-5 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Лоуренс, Ричард (1883). «Книга Еноха Пророка» . Архивировано из оригинала 5 февраля 2022 года.

- ^ Boustan & Reed 2004 , p. 60

- ^ Колдуэлл, Уильям (1913). «Доктрина сатаны: II. Сатана в экстра-библейской апокалиптической литературе» . Библейский мир . 41 (2): 98–102. doi : 10.1086/474708 . JSTOR 3142425 . S2CID 144698491 .

- ^ Theobald 2015 , с. 37–39.

- ^ Колдуэлл, Уильям. «Доктрина сатаны: III. В Новом Завете». Библейский мир 41.3 (1913): 167–172. Страница 167

- ^ Farrar 2014 , с. 13

- ^ Гибсон 2004 , с. 58

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Келли 2004 , с. 17

- ^ Манго, Кирилл (1992). "Diabolus byzantinus". Дамбартон Оукс Бумаги . 46 : 215–223. doi : 10.2307/1291654 . JSTOR 1291654 .

- ^ Матфея 4: 8–9 ; Луки 4: 6–7

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Келли 2006 , с. 95

- ^ Притчи 21

- ^ Грант 2006 , с. 130.

- ^ Матфея 4: 1–11

- ^ Марк 1: 12–13

- ^ Луки 4: 1–13

- ^ Иоанна 8:40

- ^ Иоанна 13: 2

- ^ Луки 22: 3

- ^ Pagels, Elaine (1994). Полем Религия 62 (1): 17–58. doi : 10.1093/jaarel/lxii . JSTOR 1465555 .

- ^ Матфея 9: 22–29

- ^ Марк 3: 22–30

- ^ Луки 11: 14–20

- ^ Kelly 2006 , с. 82–83.

- ^ Иуд 1: 9

- ^ 1 Петра 5: 8

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Conybeare, FC (1896). «Демонология Нового Завета. Я». Еврейский ежеквартальный обзор . 8 (4): 576–608. doi : 10.2307/1450195 . JSTOR 1450195 .

- ^ Евреям 2:14

- ^ Келли 2006 , с. 30

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Откровение 12: 7–10

- ^ Tyneh 2003 , p. 48

- ^ Рассел 1986 , с. 201–202.

- ^ Откровение 12:10

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Откровение 20:10

- ^ Келли 2004 , с. 16

- ^ Откровение 9:11

- ^ Bonnetain 2015 , p. 378.

- ^ Лестер Л. Грабб, введение в иудаизм первого века: еврейская религия и история во втором храме (Continuum International Publishing Group 1996 978-057085061 ) , с. 101

- ^ Рассел 2000 , с. 33.

- ^ Рассел 1986 , с. 11

- ^ Rudwin 1970 , p. 385.

- ^ Мердок 2003 , с. 3

- ^ Мердок 2003 , с. 4

- ^ Utley 1945 , p. 11

- ^ Utley 1945 , p. 10

- ^ Utley 1945 , p. 12

- ^ Utley 1945 , p. 16

- ^ Rudwin 1970 , p. 391-392.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Рассел 1986 , с. 37

- ^ Плюсинга, Элвин (1978). Природа необходимости. Кларендон Пресс. ISBN 9780191037177.P.189

- ^ Скотт, Марк. SM (2015). Пути в Теодици: введение в проблему зла (иллюстрировано, переиздание изд.). Аугсбургские издатели крепости. ISBN 9781451464702.p.143

- ^ Свенсден, Ларс фр. H. (2010). Философия зла. Dalkey Archive Press. П. 51. ISBN 9781564785718.

- ^ Робин Бриггс (2004) Двадцать второй мемориальная лекция Кэтрин Бриггс, ноябрь 2003 г., фольклор, 115: 3, 259–272, doi: 10.1080/0015587042000284257 с.259

- ^ Рамелли, Илария Ле (2012). «Ориген, греческая философия и рождение тринитарного значения« гипостасиса » . Гарвардский богословский обзор . 105 (3): 302–350. doi : 10.1017/s0017816012000120 . JSTOR 23327679 . S2CID 170203381 .

- ^ Koskenniemi & Fröhlich 2013 , тел.

- ^ Tzamalikos 2007 , p. 78

- ^ Рассел 1987 , с. 130–133.

- ^ Рамелли, Илария Ле (1 Janogy 2013). «Ориген в Августине: на парадоксальном приеме». Нумен . 60 (2–3): 280–307. Doi : 10.1163/15685276-12341266 .

- ^ Брэдник 2017 , с. 39, 43.

- ^ Бернс, Дж. Патаут (1988). «Августин о происхождении и прогрессе зла» . Журнал религиозной этики . 16 (1): 17–18. JSTOR 40015076 .

- ^ Schreckenberg & Schubert 1992 , p. 253.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Брэдник 2017 , с. 42

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Хорн 2010 , с. 158

- ^ Бэбкок, Уильям С. (1988). «Августин по греху и моральному агентству». Журнал религиозной этики . 16 (1): 28–55. JSTOR 40015077 .

- ^ Форсайт 1989 , с. 405

- ^ Raymond 2010 , с. 72

- ^ Брэдник 2017 , с. 44