Ислам в Индии

| |

| Общая численность населения | |

|---|---|

| в. 200 миллионов (14,61% населения) [ 2 ] ( оценка переписи 2021 г.) | |

| Регионы со значительной численностью населения | |

| Уттар-Прадеш | 38,483,970 [ 3 ] |

| Западная Бенгалия | 24,654,830 [ 3 ] |

| Bihar | 17,557,810[3] |

| Maharashtra | 12,971,150[3] |

| Assam | 10,679,350[3] |

| Kerala | 8,873,470[3] |

| Jammu and Kashmir | 8,567,490[3] |

| Andhra Pradesh (includes present-day Telangana) | 8,082,410[3] |

| Karnataka | 7,893,070[3] |

| Rajasthan | 6,215,380[3] |

| Religions | |

| Majority Sunni Islam with significant Shia and Ahmadiyya minorities[4] | |

| Languages | |

Liturgical

| |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam in India |

|---|

|

| Islam by country |

|---|

|

|

|

Индии Ислам – вторая по величине религия . [ 7 ] при этом 14,2% населения страны, или примерно 172,2 миллиона человек, идентифицируют себя как приверженцы ислама по данным переписи 2011 года. [ 8 ] Индия также занимает третье место по количеству мусульман . в мире [ 9 ] [ 10 ] Большинство мусульман Индии — сунниты , при этом шииты составляют около 15% мусульманского населения. [ 11 ]

Ислам распространился в индийских общинах вдоль арабских прибрежных торговых путей в Гуджарате и вдоль Малабарского побережья вскоре после того, как эта религия возникла на Аравийском полуострове . Ислам пришел во внутренние районы Индийского субконтинента в VII веке, когда арабы завоевали Синд , а затем прибыл в Пенджаб и Северную Индию в XII веке в результате Газневидов и завоевания Гуридов и с тех пор стал частью религиозного и культурного наследия Индии . Мечеть Барвада в Гоге , Гуджарат , построенная до 623 г. н.э., Мечеть Чераман Джума (629 г. н.э.) в Метале , Керала и Палая Джумма Палли (или Старая Джумма Масджид, 628–630 гг. н.э.) в Килакарае , Тамил Наду - три из первых мечетей. в Индии , построенные мореплавателями арабскими купцами- . [12][13][14][15][16] According to the legend of Cheraman Perumals, the first Indian mosque was built in 624 CE at Kodungallur in present-day Kerala with the mandate of the last ruler (the Tajudeen Cheraman Perumal) of the Chera dynasty, who converted to Islam during the lifetime of Muhammad (c. 570–632). Similarly, Tamil Muslims on the eastern coasts also claim that they converted to Islam in Muhammad's lifetime. The local mosques date to the early 700s.[17]

History

Origins

The vast majority of the Muslims in India belong to South Asian ethnic groups. However, some Indian Muslims were found with detectable, traceable levels of gene flow from outside, primarily from the Middle East and Central Asia.[18][19][20] However, they are found in very low levels.[20] Sources indicate that the castes among Muslims developed as the result of the concept of Kafa'a.[21][22][23] Those who are referred to as Ashrafs are presumed to have a superior status derived from their foreign Arab ancestry,[24][25] while the Ajlafs are assumed to be converts from Hinduism, and have a lower status.

Many of these ulema also believed that it is best to marry within one's own caste. The practice of endogamous marriage in one's caste is strictly observed in India.[26][27] In two of the three genetic studies referenced here, in which is described that samples were taken from several regions of India's Muslim communities, it was again found that the Muslim population was overwhelmingly similar to the local non-Muslims associated, with some having minor but still detectable levels of gene flow from outside, primarily from Iran and Central Asia, rather than directly from the Arabian peninsula.[19]

Research on the comparison of Y chromosomes of Indian Muslims with other Indian groups was published in 2005.[19][20] In this study 124 Sunnis and 154 Shias of Uttar Pradesh were randomly selected for their genetic evaluation. Other than Muslims, Hindu higher and middle caste group members were also selected for the genetic analysis. Out of 1021 samples in this study, only 17 samples showed E haplogroup and all of them were Shias. The very minor increased frequency however, does place these Shias, solely with regards to their haplogroups, closer to Iraqis, Turks and Palestinians.[19][20]

Early history of Islam in India

Trade relations have existed between Arabia and the Indian subcontinent since ancient times. Even in the pre-Islamic era, Arab traders used to visit the Konkan-Gujarat coast and Malabar Coast, which linked them with the ports of Southeast Asia. Newly Islamised Arabs were Islam's first contact with India. Historians Elliot and Dowson say in their book The History of India, as Told by Its Own Historians, that the first ship bearing Muslim travellers was seen on the Indian coast as early as 630 CE. H. G. Rawlinson in his book Ancient and Medieval History of India[28] claims that the first Arab Muslims settled on the Indian coast in the last part of the 7th century CE. (Zainuddin Makhdoom II "Tuhafat Ul Mujahideen" is also a reliable work.)[29] This fact is corroborated by J. Sturrock in his Madras District Manuals[30] and by Haridas Bhattacharya in Cultural Heritage of India Vol. IV.[31] With the advent of Islam Arabs became a prominent cultural force in the world. Arab merchants and traders became the carriers of the new religion and they propagated it wherever they went.[32]

According to popular tradition, Islam was brought to Lakshadweep islands, situated just to the west of Malabar Coast, by Ubaidullah in 661 CE. His grave is believed to be located on the island of Andrott.[33] A few Umayyad (661–750 CE) coins were discovered from Kothamangalam in the eastern part of Ernakulam district, Kerala.[34] According to Kerala Muslim tradition, the Masjid Zeenath Baksh at Mangalore is one of the oldest mosques in the Indian subcontinent.[35] According to the Legend of Cheraman Perumals, the first Indian mosque was built in 624 CE at Kodungallur in present-day Kerala with the mandate of the last the ruler (the Cheraman Perumal) of Chera dynasty, who converted to Islam during the lifetime of the Islamic prophet Muhammad (c. 570–632).[36][37][38][39] According to Qissat Shakarwati Farmad, the Masjids at Kodungallur, Kollam, Madayi, Barkur, Mangalore, Kasaragod, Kannur, Dharmadam, Panthalayini, and Chaliyam, were built during the era of Malik Dinar, and they are among the oldest Masjids in the Indian subcontinent.[40] It is believed that Malik Dinar died at Thalangara in Kasaragod town.[41]

The first Indian mosque, Cheraman Juma Mosque, is thought to have been built in 629 CE by Malik Deenar[42] although some historians say the first mosque was in Gujarat in between 610 and 623 CE.[43] In Malabar, the Mappilas may have been the first community to convert to Islam.[44] Intensive missionary activities were carried out along the coast and many other natives embraced Islam. According to legend, two travellers from India, Moulai Abdullah (formerly known as Baalam Nath) and Maulai Nuruddin (Rupnath), went to the court of Imam Mustansir (427–487 AH)/(1036–1094 CE) and were so impressed that they converted to Islam and came back to preach in India in 467 AH/1073 CE. Moulai Ahmed was their companion. Abadullah was the first Wali-ul-Hind (saint of India). He came across a married couple named Kaka Akela and Kaki Akela who became his first converts in the Taiyabi (Bohra) community.[citation needed]

Arab–Indian interactions

Historical evidence shows that Arabs and Muslims interacted with Indians from the early days of Islam and possibly before the arrival of Islam in Arab regions. Arab traders transmitted the numeral system developed by Indians to the Middle East and Europe.[citation needed]

Many Sanskrit books were translated into Arabic as early as the 8th century. George Saliba in his book "Islamic Science and the Making of the European Renaissance", writes that "some major Sanskrit texts began to be translated during the reign of the second Abbasid caliph al-Mansur (r. 754–775), if not before; some texts on logic even before that, and it has been generally accepted that the Persian and Sanskrit texts, few as they were, were indeed the first to be translated."[45]

Commercial intercourse between Arabia and India had gone on from time immemorial, with for example the sale of dates and aromatic herbs by Arabs traders who came to Indian shores every spring with the advent of the monsoon breeze. People living on the western coast of India were as familiar with the annual coming of Arab traders as they were with the flocks of monsoon birds; they were as ancient a phenomenon as the monsoon itself. However, whereas monsoon birds flew back to Africa after a sojourn of few months, not all traders returned to their homes in the desert; many married Indian women and settled in India.[46]

The advent of Muhammad (569–632 CE) changed the idolatrous and easy-going Arabs into a nation unified by faith and fired with zeal to spread the gospel of Islam. The merchant seamen who brought dates year after year now brought a new faith with them. The new faith was well received by South India. Muslims were allowed to build mosques, intermarry with Indian women, and very soon an Indian-Arabian community came into being. Early in the 9th century, Muslim missionaries gained a notable convert in the person of the King of Malabar.[46]

According to Derryl N. Maclean, a link between Sindh(currently province of Pakistan) and early partisans of Ali or proto-Shi'ites can be traced to Hakim ibn Jabalah al-Abdi, a companion of Muhammad, who traveled across Sind to Makran in the year 649 CE and presented a report on the area to the Caliph. He supported Ali, and died in the Battle of the Camel alongside Sindhi Jats.[47] He was also a poet and few couplets of his poem in praise of Ali ibn Abu Talib have survived, as reported in Chachnama.[48][a]

During the reign of Ali, many Jats came under the influence of Islam.[51] Harith ibn Murrah Al-abdi and Sayfi ibn Fil' al-Shaybani, both officers of Ali's army, attacked Sindhi bandits and chased them to Al-Qiqan (present-day Quetta) in the year 658.[52] Sayfi was one of the seven partisans of Ali who were beheaded alongside Hujr ibn Adi al-Kindi[53] in 660 CE, near Damascus.

Political history of Islam in India

Muhammad bin Qasim (672 CE) at the age of 17 was the first Muslim general to invade the Indian subcontinent, managing to reach Sindh. In the first half of the 8th century CE, a series of battles took place between the Umayyad Caliphate and the Indian kingdoms; resulted in Umayyad campaigns in India checked and contained to Sindh.[54][b] Around the 10th century, Muslim Central Asian nomadic empire, the Ghaznavids, under Mahmud of Ghazni (971–1030 CE), was the second, much more ferocious invader, using swift-horse cavalry and raising vast armies united by ethnicity and religion, repeatedly overran South Asia's north-western plains. Eventually, under the Ghurids, the Muslim army broke into the North Indian Plains, which lead to the establishment of the Islamic Delhi Sultanate in 1206 by the slaves of the Ghurid dynasty.[55] The sultanate was to control much of North India and to make many forays into South India. However, internal squabbling resulted in the decline of the sultanate, and new Muslim sultanates such as the Bengal Sultanate in the east breaking off,[56] while in the Deccan the Urdu-speaking colonists from Delhi, who carried the Urdu language to the Deccan, founded the Bahmanid Empire.[57] In 1339, Shah Mir became the first Muslim ruler of Kashmir, inaugurating the Salatin-i-Kashmir or Shah Mir dynasty.[58]

Under the Delhi Sultanate, there was a synthesis of Indian civilization with that of Islamic civilization, and the integration of the Indian subcontinent with a growing world system and wider international networks spanning large parts of Afro-Eurasia, which had a significant impact on Indian culture and society.[59] The time period of their rule included the earliest forms of Indo-Islamic architecture,[60][61] increased growth rates in India's population and economy,[62] and the emergence of the Hindustani language.[63] The Delhi Sultanate was also responsible for repelling the Mongol Empire's potentially devastating invasions of India in the 13th and 14th centuries.[64] The period coincided with a greater use of mechanical technology in the Indian subcontinent. From the 13th century onwards, India began widely adopting mechanical technologies from the Islamic world, including water-raising wheels with gears and pulleys, machines with cams and cranks,[65] papermaking technology,[66] and the spinning wheel.[67]

In the early 16th century, northern India, being then under mainly Muslim rulers,[68] fell again to the superior mobility and firepower of a new generation of Central Asian warriors.[69] The resulting Mughal Empire did not stamp out the local societies it came to rule, but rather balanced and pacified them through new administrative practices[70] and diverse and inclusive ruling elites,[71] leading to more systematic, centralised, and uniform rule.[72] Eschewing tribal bonds and Islamic identity, especially under Akbar, the Mughals united their far-flung realms through loyalty, expressed through a Persianised culture, to an emperor who had near-divine status.[71] The Mughal state's economic policies, deriving most revenues from agriculture[73] and mandating that taxes be paid in the well-regulated silver currency,[74] caused peasants and artisans to enter larger markets.[72] The relative peace maintained by the empire during much of the 17th century was a factor in India's economic expansion,[72] resulting in greater patronage of painting, literary forms, textiles, and architecture.[75] The Mughal Empire was the world's largest economy in the 17th century, larger than Qing China and Western Europe, with Mughal India producing about a quarter of the world's economic and industrial output.[76][77]

In the 18th century, Mughal power had become severely limited. By the mid-18th century, the Marathas had routed Mughal armies and invaded several Mughal provinces from the Punjab to Bengal.[78] By this time, the dominant economic powers in the Indian subcontinent were Bengal Subah under the Nawabs of Bengal and the South Indian Kingdom of Mysore under Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, before the former was devastated by the Maratha invasions of Bengal,[79][80] leading to the economy of the Kingdom of Mysore overtaking Bengal.[81] The British East India Company conquered Bengal in 1757 and then Mysore in the late 18th century. The last Mughal emperor, Bahadur Shah II, had authority over only the city of Old Delhi (Shahjahanabad), before he was exiled to Burma by the British Raj after the Indian Rebellion of 1857.[citation needed]

-

Last Mughal Emperor Bahadur Shah II with sons Mirza Jawan Bakht & Mirza Shah Abbas

-

Durbar Procession of Mughal Emperor Akbar Shah II in British India

Role in the Indian independence movement

The contribution of Muslim revolutionaries, poets and writers is documented in the history of India's struggle for independence. Titumir raised a revolt against the British Raj. Abul Kalam Azad, Hakim Ajmal Khan and Rafi Ahmed Kidwai are other Muslims who engaged in this endeavour.[citation needed] Ashfaqulla Khan of Shahjahanpur conspired to loot the British treasury at Kakori(Lucknow) (See Kakori conspiracy).[citation needed] Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan (popularly known as "Frontier Gandhi") was a noted nationalist who spent 45 of his 95 years of life in jail; Barakatullah of Bhopal was one of the founders of the Ghadar Party, which created a network of anti-British organisations; Syed Rahmat Shah of the Ghadar Party worked as an underground revolutionary in France and was hanged for his part in the unsuccessful Ghadar Mutiny in 1915; Ali Ahmad Siddiqui of Faizabad (UP) planned the Indian Mutiny in Malaya and Burma, along with Syed Mujtaba Hussain of Jaunpur, and was hanged in 1917; Vakkom Abdul Khadir of Kerala participated in the "Quit India" struggle in 1942 and was hanged; Umar Subhani, an industrialist and millionaire from Bombay, provided Mahatma Gandhi with Congress expenses and ultimately died for the cause of independence. Among Muslim women, Hazrat Mahal, Asghari Begum, and Bi Amma contributed in the struggle for independence from the British.[citation needed]

Other famous Muslims who fought for independence against British rule were Abul Kalam Azad, Mahmud al-Hasan of Darul Uloom Deoband, who was implicated in the famous Silk Letter Movement to overthrow the British through an armed struggle, Husain Ahmad Madani, former Shaikhul Hadith of Darul Uloom Deoband, Ubaidullah Sindhi, Hakim Ajmal Khan, Hasrat Mohani, Syed Mahmud, Ahmadullah Shah, Professor Maulavi Barkatullah, Maghfoor Ahmad Ajazi, Zakir Husain, Saifuddin Kitchlew, Vakkom Abdul Khadir, Manzoor Abdul Wahab, Bahadur Shah Zafar, Hakeem Nusrat Husain, Khan Abdul Gaffar Khan, Abdul Samad Khan Achakzai, Colonel Shahnawaz, Mukhtar Ahmed Ansari, Rafi Ahmed Kidwai, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed, Ansar Harwani, Tak Sherwani, Nawab Viqarul Mulk, Nawab Mohsinul Mulk, Mustsafa Husain, V. M. Obaidullah, S.R. Rahim, Badruddin Tyabji, Abid Hasan and Moulvi Abdul Hamid.[82][83]

Until 1920, Muhammad Ali Jinnah, later the founder of Pakistan, was a member of the Indian National Congress and was part of the independence struggle. Muhammad Iqbal, poet and philosopher, was a strong proponent of Hindu–Muslim unity and an undivided India, perhaps until 1930. Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy was also active in the Indian National Congress in Bengal, during his early political career. Mohammad Ali Jouhar and Shaukat Ali struggled for the emancipation of the Muslims in the overall Indian context, and struggled for independence alongside Mahatma Gandhi and Abdul Bari of Firangi Mahal. Until the 1930s, the Muslims of India broadly conducted their politics alongside their countrymen, in the overall context of an undivided India.[citation needed]

Partition of India

I find no parallel in history for a body of converts and their descendants claiming to be a nation apart from the parent stock.

— Mahatma Gandhi, opposing the division of India on the basis of religion in 1944.[84]

The partition of India was the partition of British India led to the creation of the dominions of Pakistan (that later split into the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and the People's Republic of Bangladesh) and India (later Republic of India). The Indian Independence Act 1947 had decided 15 August 1947, as the appointed date for the partition. However, Pakistan celebrates its day of creation on 14 August.[citation needed]

The partition of India was set forth in the Act and resulted in the dissolution of the British Indian Empire and the end of the British Raj. It resulted in a struggle between the newly constituted states of India and Pakistan and displaced up to 12.5 million people with estimates of loss of life varying from several hundred thousand to a million (most estimates of the numbers of people who crossed the boundaries between India and Pakistan in 1947 range between 10 and 12 million).[85] The violent nature of the partition created an atmosphere of mutual hostility and suspicion between India and Pakistan that plagues their relationship to this day.[citation needed]

The partition included the geographical division of the Bengal province into East Bengal, which became part of Pakistan (from 1956, East Pakistan). West Bengal became part of India, and a similar partition of the Punjab province became West Punjab (later the Pakistani Punjab and Islamabad Capital Territory) and East Punjab (later the Indian Punjab, as well as Haryana and Himachal Pradesh). The partition agreement also included the division of Indian government assets, including the Indian Civil Service, the Indian Army, the Royal Indian Navy, the Indian railways and the central treasury, and other administrative services.[citation needed]

The two self-governing countries of India and Pakistan legally came into existence at the stroke of midnight on 14–15 August 1947. The ceremonies for the transfer of power were held a day earlier in Karachi, at the time the capital of the new state of Pakistan, so that the last British Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten of Burma, could attend both the ceremony in Karachi and the ceremony in Delhi. Thus, Pakistan's Independence Day is celebrated on 14 August and India's on 15 August.[citation needed]

After Partition of India in 1947, two-thirds of the Muslims resided in Pakistan (both east and West Pakistan) but a third resided in India.[86] Based on 1951 census of displaced persons, 7,226,000 Muslims went to Pakistan (both West and East) from India while 7,249,000 Hindus and Sikhs moved to India from Pakistan (both West and East).[87] Some critics allege that British haste in the partition process increased the violence that followed.[88] Because independence was declared prior to the actual Partition, it was up to the new governments of India and Pakistan to keep public order. No large population movements were contemplated; the plan called for safeguards for minorities on both sides of the new border. It was a task at which both states failed. There was a complete breakdown of law and order; many died in riots, massacre, or just from the hardships of their flight to safety. What ensued was one of the largest population movements in recorded history. According to Richard Symonds: At the lowest estimate, half a million people perished and twelve million became homeless.[89]

However, many argue that the British were forced to expedite the Partition by events on the ground.[90] Once in office, Mountbatten quickly became aware if Britain were to avoid involvement in a civil war, which seemed increasingly likely, there was no alternative to partition and a hasty exit from India.[90] Law and order had broken down many times before Partition with much bloodshed on both sides. A massive civil war was looming by the time Mountbatten became Viceroy. After the Second World War, Britain had limited resources,[90] perhaps insufficient to the task of keeping order. Another viewpoint is that while Mountbatten may have been too hasty he had no real options left and achieved the best he could under difficult circumstances.[91] The historian Lawrence James concurs that in 1947 Mountbatten was left with no option but to cut and run. The alternative seemed to be involvement in a potentially bloody civil war from which it would be difficult to get out.[92]

Demographics

With around 204 million Muslims (2019 estimate), India's Muslim population is the world's third-largest[93][94][95] and the world's largest Muslim-minority population.[96] India is home to 10.9% of the world's Muslim population.[93][97] According to Pew Research Center, there can be 213 million Muslims in 2020, India's 15% population.[98][99] Indian Muslim have a fertility rate of 2.36, the highest in the nation as per as according to year 2019-21 estimation.[100] While Government of India at Lok Sabha have estimated the Muslim population at 19.75 to 20 crore for 2023 year, out of 138.8 to 140.0 crore total population, thus constituting around (14.22%–14.28%) of the nation's population respectively.[1][101][102][103][104][105]

Muslim populations (top 5 countries) Est. 2020[94][106][93][107][108][109]

| Country | Muslim Population | Percentage of Total Muslim Population |

|---|---|---|

| 231,070,000 | 12.2% | |

| 233,046,950 | 11.2% | |

| 207,000,000 | 10.9% | |

| 153,700,000 | 9.20% | |

| 110,263,500 | 5.8% |

Muslims represent a majority of the local population in Lakshadweep (96.2%) and Jammu and Kashmir (68.3%). The largest concentration – about 47% of all Muslims in India, live in the three states of Uttar Pradesh, West Bengal, and Bihar. High concentrations of Muslims are also found in the states of Andhra Pradesh, Assam, Delhi, Gujarat, Jharkhand, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Manipur, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Tripura, and Uttarakhand.[110]

Percentage by states

|

|

As of 2021[update], Muslims comprise the majority of the population in the only Indian union territory of Jammu and Kashmir and in a Union territory Lakshadweep.[111] In 110 minority-concentrated districts, at least a fifth of the population are Muslim.[112]

Population growth rate

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parts of Assam were not included in the 1981 census data due to violence in some districts.[citation needed] Jammu and Kashmir was not included in the 1991 census data due to militant activity in the state.[citation needed] Source: [113][111] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Region-wise distribution of Muslims leaving for Pakistan (1951 Census) [114] -

| Region | Population | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| East Punjab | 5.3 million | 73.61% |

| Uttar Pradesh, Delhi, Rajasthan, and other parts of India | 1.2 million | 16.67% |

| West Bengal and Bihar | 7 lakh | 9.72% |

| Total | 7.2 million | 100% |

After India's independence and the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the Muslim population in India declined from 42,400,000 in 1941 to 35,400,000 in the 1951 census, due to the Partition of India.[113] The Pakistan Census, 1951 identified the number of displaced persons in the country at 7,226,600, presumably all Muslims refugees who had entered Pakistan from India.[115][116] Around 35 million Muslims stayed back after Partition as Jawaharlal Nehru (then the Prime Minister of India) have ensured the confidence that they would be treated fairly in this democratic nation.[117][118]

In the 1941 Census, there were 94.5 million Muslims living in the Undivided India (inc. Pakistan and Bangladesh), comprising 24 percent of the population. Partition, in fact, has eventually drained India of 60% of its Muslim population respectively.[119][120]

In the absence of Partition, a United India would have boasted a population nearing 1.69 billion, with Muslims constituting approximately 35%, equating to roughly 591.56 million individuals, thus positioning it as the world's most populous Muslim-majority nation, surpassing the Arab world and Indonesia.[121]

Former Minister of Law and Justice of India, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar during partition, have advocated for a full population exchange between the Muslim and Hindu minorities of India and Pakistan for maintenance of law, order and peace in both the newly formed nations by citing- "That the transfer of minorities is the only lasting remedy for communal peace is beyond doubt" in his own written book "Pakistan or partition of India" respectively.[122][123][124][125]

However, a complete population exchange did not occur and was made impossible due to the earlier signing of the Liaquat–Nehru Pact in 1950, which sealed the borders of both nations completely. Ultimately, this led to the cessation of migration of refugees from both sides.[126][127] As a result of this, a large number of Muslims in India, a significant number of Hindus in East Pakistan (present-day Bangladesh) and a minuscule number of Hindus in the Sindh province of West Pakistan remained. Meanwhile, the East Punjab state of India and the West Punjab province of Pakistan saw a full population exchange between Muslim and Hindu/Sikh minorities during the time of Partition.[128]

Illegal immigrants

India is the home of some 40,000 illegal Rohingya Muslim refugees, with approximately 18,000 registered with the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). But even people with refugee cards are being detained across India due to security concerns.[129] A small number of Uyghurs also reside in India, primarily in Jammu and Kashmir. Around 1,000 illegal Uyghur refugees arrived in India in 1949 to escape the communist regime.[130] On 17 November 2016, Union Minister of State for Home, Kiren Rijiju, stated in the Rajya Sabha that, according to available inputs, there are around 20 million (2 crore) illegal Bangladeshi migrants staying in India.[131] Illegal immigrants in Assam are estimated to number between 16 lakh and 84 lakh, in a total population of 3.12 crore according to the 2011 Census.[132] A report published by DNA has revealed that the Bangladeshi-origin Muslim population has grown to 5–7% in bordering districts of Assam and Bengal simultaneously.[133][134] Muminul Aowal, an eminent Assamese Muslim Minority Development Board Chairman, has reported that Assam has about 1.3 crore Muslims of which around 90 lakh are of Bangladeshi origin.[135] According to Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma, among the 19 lakh individuals excluded from the Assam National Register of Citizens, 7 lakh are Muslims.[136] Dr. Kuntal Kanti Chattoraj, HOD of the Department of Geography at P.R.M.S. Mahavidyalaya, Bankura, has revealed that an estimated 6.28 million Bangladeshi Muslims have infiltrated into West Bengal over the decades.[137]

Projections

Muslims in India have a much higher total fertility rate (TFR) compared to that of other religious communities in the country.[138] Because of higher birthrates the percentage of Muslims in India has risen from about 9.8% in 1951 to 14.2% by 2011.[139] However, since 1991, the largest decline in fertility rates among all religious groups in India has occurred among Muslims.[140] The Sachar Committee Report shows that the Muslim Population Growth has slowed down and will be on par with national averages.[141] The Sachar Committee Report estimated that the Muslim proportion will stabilise at between 17% and 21% of the Indian population by 2100.[142] Pew Research Center have projected that India will have 311 million Muslims by 2050, out of total 1.668 billion people, thus constituting 18.4% of the country's population.[143][144] United Nations have projected India's future population. It will rise to 170.53 crore by 2050, and then it will decline to 165.97 crore by 2100 year respectively.[145]

Religiosity

On 29 June 2021, Pew Research Center reports on Religiosity have been published, where they completed 29,999 face-to-face interviews with non-institutionalized adults ages 18 and older living in 26 states and three union territories across India. They interviewed 3,336 Muslims and found that 79% of those interviewed believed in the existence of God with absolute certainty, 12% believes in the existence of God with less certainty and 6% of the Indian Muslims have declared themselves as Atheists by citing that they don't believe in any God. However 91% of Muslim interviewed have said religion plays a big part in their lives[146][147][148]

CSDS study reports, have found that Indian Muslims have become ‘less religious’ since 2016. In that same year, the study founds that 97 per cent of Muslim respondents have said that they prayed regularly. However, in 2021, it was found that only 86 per cent of Muslim youth prayed regularly which is an absolute decline of 11 percentage points from the last five years respectively.[149]

Social and economic reasons behind population growth[150]

| Census information for 2011: Hindu and Muslim compared.[151] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Hindus | Muslims |

| % total of population 2011 | 79.8 | 14.2 |

| 10-yr. Growth % (est. 2001–11) | 16.8 | 24.6 |

| Sex ratio* | 939 | 951 |

| Literacy rate (avg. 64.8) | 63.6 | 57.9 |

| Work Participation Rate | 41 | 33 |

| Urban sex ratio | 894 | 907 |

| Child sex ratio (0–6 yrs.) | 913 | 943 |

According to sociologists Roger and Patricia Jeffery, socio-economic conditions rather than religious determinism is the main reason for higher Muslim birthrates. Indian Muslims are poorer and less educated compared to their Hindu counterparts.[152] Noted Indian sociologist, B. K. Prasad, argues that since India's Muslim population is more urban compared to their Hindu counterparts, infant mortality rates among Muslims is about 12% lower than those among Hindus.[153]

However, other sociologists point out that religious factors can explain high Muslim birthrates. Surveys indicate that Muslims in India have been relatively less willing to adopt family planning measures and that Muslim women have a larger fertility period since they get married at a much younger age compared to Hindu women.[154]

On the other hand, it is also documented that Muslims tend to adopt family planning measures.[155] A study conducted by K. C. Zacharia in Kerala in 1983 revealed that on average, the number of children born to a Muslim woman was 4.1 while a Hindu woman gave birth to only 2.9 children. Religious customs and marriage practices were cited as some of the reasons behind the high Muslim birth rate.[156] According to Paul Kurtz, Muslims in India are much more resistant to modern contraception than are Hindus and, as a consequence, the decline in fertility rate among Hindu women is much higher compared to that of Muslim women.[157][158]

The National Family and Health survey conducted in 1998–99 highlighted that Indian Muslim couples consider a substantially higher number of children to be ideal for a family as compared to Hindu couples in India.[159] The same survey also pointed out that percentage of couples actively using family planning measures was more than 49% among Hindus against 37% among Muslims. According to a district wise fertility study by Saswata Ghosh, Muslim TFR (total fertility rate) is closer to that of the Hindu community in most southern states. Also TFR tends to be high for both communities in Northern states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. This study was based on the last census of the country from 2011.[160]

Denominations

There are two major denominations amongst Indian Muslims: Sunni and Shia. The majority of Indian Muslims (over 85%) belong to the Sunni branch of Islam,[11][161] while a minority (over 13%) belong to the Shia branch.[162][11]

Sunni

The majority of Indian Sunnis follow the Barelvi movement which was founded in 1904 by Ahmed Razi Khan of Bareilly in defense of traditional Islam as understood and practised in South Asia and in reaction to the revivalist attempts of the Deobandi movement.[163][164] In the 19th century the Deobandi, a revivalist movement in Sunni Islam was established in India. It is named after Deoband a small town northeast of Delhi, where the original madrasa or seminary of the movement was founded. From its early days this movement has been influenced by Wahhabism.[165][166][167]

In the coastal Konkan region of Maharashtra, the local Konkani Muslims follow the Shafi'i school of Sunni Islamic jurisprudence.[168][169]

Shia

Shia Muslims are a large minority among India's Muslims forming about 13% of the total Muslim population.[11] However, there has been no particular census conducted in India regarding sects, but Indian sources like Times of India and Daily News and Analysis reported Indian Shia population in mid 2005–2006 to be up to 25% of the entire Muslim population of India which accounts them in numbers between 40,000,000[170][171] to 50,000,000[172] of 157,000,000 Indian Muslim population.[173] However, as per an estimation of one reputed Shia NGO Alimaan Trust, India's Shia population in early 2000 was around 30 million with Sayyids comprising just a tenth of the Shia population.[174] According to some national and international sources Indian Shia population is the world's second-largest after Iran.[175][176][177][178][179][180]

Bohra

Bohra Shia was established in Gujarat in the second half of the 11th century. This community's belief system originates in Yemen, evolved from the Fatimid were persecuted due to their adherence to Fatimid Shia Islam – leading the shift of Dawoodi Bohra to India. After occultation of their 21st Fatimid Imam Tayyib, they follow Dai as representative of Imam which are continued till date.[citation needed]

Dā'ī Zoeb appointed Maulai Yaqoob (after the death of Maulai Abdullah), who was the second Walī al-Hind of the Fatimid dawat. Moulai Yaqoob was the first person of Indian origin to receive this honour under the Dā'ī. He was the son of Moulai Bharmal, minister of Hindu Solanki King Jayasimha Siddharaja (Anhalwara, Patan). With Minister Moulai Tarmal, they had honoured the Fatimid dawat along with their fellow citizens on the call of Moulai Abdullah. Syedi Fakhruddin, son of Moulai Tarmal, was sent to western Rajasthan, India, and Moulai Nuruddin went to the Deccan (death: Jumadi al-Ula 11 at Don Gaum, Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India).[citation needed]

One Dai succeeded another until the 23rd Dai in Yemen. In India also Wali-ul-Hind were appointed by them one after another until Wali-ul-Hind Moulai Qasim Khan bin Hasan (11th and last Wali-ul-Hind, d. 950 AH, Ahmedabad).[citation needed]

Due to persecution by the local Zaydi Shi'a ruler in Yemen, the 24th Dai, Yusuf Najmuddin ibn Sulaiman (d. 1567 CE), moved the whole administration of the Dawat (mission) to India. The 25th Dai Jalal Shamshuddin (d. 1567 CE) was first dai to die in India. His mausoleum is in Ahmedabad, India. The Dawat subsequently moved from Ahmedabad to Jamnagar[181] Mandvi, Burhanpur, Surat and finally to Mumbai and continues there to the present day, currently headed by 53rd Dai.[citation needed]

Asaf Ali Asghar Fyzee was a Bohra and 20th century Islamic scholar from India who promoted modernization and liberalization of Islam through his writings. He argued that with changing time modern reforms in Islam are necessary without compromising on basic "spirit of Islam".[182][183][184]

Khojas

The Khojas are a group of diverse people who converted to Islam in South Asia. In India, most Khojas live in the states of Gujarat, Maharashtra, Rajasthan, and the city of Hyderabad. Many Khojas have also migrated and settled over the centuries in East Africa, Europe, and North America. The Khoja were by then adherents of Nizari Ismailism branch of Shi'ism. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, particularly in the aftermath of the Aga Khan case, a significant minority separated and adopted Twelver Shi'ism or Sunni Islam, while the majority remained Nizārī Ismā'īlī.[185]

Sufis

Sufis (Islamic mystics) played an important role in the spread of Islam in India. They were very successful in spreading Islam, as many aspects of Sufi belief systems and practices had their parallels in Indian philosophical literature, in particular nonviolence and monism. The Sufis' orthodox approach towards Islam made it easier for Hindus to practice. Sulthan Syed Ibrahim Shaheed, Hazrat Khawaja Muin-ud-din Chishti, Qutbuddin Bakhtiar Kaki, Nizamuddin Auliya, Shah Jalal, Amir Khusrow, Alauddin Sabir Kaliyari, Shekh Alla-ul-Haq Pandwi, Ashraf Jahangir Semnani, Waris Ali Shah, Ata Hussain Fani Chishti trained Sufis for the propagation of Islam in different parts of India. The Sufi movement also attracted followers from the artisan and untouchable communities; they played a crucial role in bridging the distance between Islam and the indigenous traditions. Ahmad Sirhindi, a prominent member of the Naqshbandi Sufi advocated the peaceful conversion of Hindus to Islam.[186]

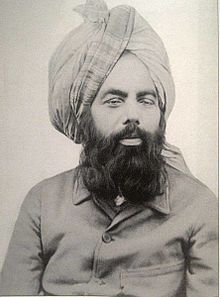

Ahmadiyya

The Ahmadiyya movement was founded in 1889 by Mirza Ghulam Ahmad of Qadian. He claimed to be the promised messiah and mahdi awaited by the Muslims and obtained a considerable number of followers initially within the United Provinces, the Punjab and Sindh.[187] Ahmadis claim the Ahmadiyya movement to embody the latter day revival of Islam and the movement has also been seen to have emerged as an Islamic religious response to the Christian and Arya Samaj missionary activity that was widespread in 19th century India. After the death of Ghulam Ahmad, his successors directed the Ahmadiyya Community from Qadian which remained the headquarters of the community until 1947 with the creation of Pakistan. The movement has grown in organisational strength and in its own missionary programme and has expanded to over 200 countries as of 2014 but has received a largely negative response from mainstream Muslims who see it as heretical, due mainly to Ghulam Ahmad's claim to be a prophet within Islam.[188]

Ahmaddiya have been identified as sects of Islam in 2011 Census of India apart from Sunnis, Shias, Bohras and Agakhanis.[189][190][191][192] India has a significant Ahmadiyya population.[193] Most of them live in Rajasthan, Odisha, Haryana, Bihar, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, and a few in Punjab in the area of Qadian. In India, Ahmadis are considered to be Muslims by the Government of India (unlike in neighbouring Pakistan). This recognition is supported by a court verdict (Shihabuddin Koya vs. Ahammed Koya, A.I.R. 1971 Ker 206).[194][195] There is no legislation that declares Ahmadis non-Muslims or limits their activities,[195] but they are not allowed to sit on the All India Muslim Personal Law Board, a body of religious leaders India's government recognises as representative of Indian Muslims.[196] Ahmadiyya are estimated to be from 60,000 to 1 million in India.[197]

Quranists

Non-sectarian Muslims who reject the authority of hadith, known as Quranists, Quraniyoon, or Ahle Quran, are also present in India. In South Asia during the 19th century, the Ahle Quran movement formed partially in reaction to the Ahle Hadith movement whom they considered to be placing too much emphasis on hadith. Notable Indian Quranists include Chiragh Ali, Aslam Jairajpuri, Khwaja Kamal-ud-Din, and Abdullah Chakralawi.[198]

Islamic traditions in India

Sufism is a mystical dimension of Islam, often complementary with the legalistic path of the sharia had a profound impact on the growth of Islam in India. A Sufi attains a direct vision of oneness with God, often on the edges of orthodox behaviour, and can thus become a Pir (living saint) who may take on disciples (murids) and set up a spiritual lineage that can last for generations. Orders of Sufis became important in India during the thirteenth century following the ministry of Moinuddin Chishti (1142–1236), who settled in Ajmer and attracted large numbers of converts to Islam because of his holiness. His Chishti Order went on to become the most influential Sufi lineage in India, although other orders from Central Asia and Southwest Asia also reached India and played a major role in the spread of Islam. In this way, they created a large literature in regional languages that embedded Islamic culture deeply into older South Asian traditions.[citation needed]

Intra-Muslim relations

Shia–Sunni relations

The Sunnis and Shia are the biggest Muslim groups by denomination. Although the two groups remain cordial, there have been instances of conflict between the two groups, especially in the city of Lucknow.[199]

Society and culture

Religious administration

The religious administration of each state is headed by the Mufti of the State under the supervision of the Grand Mufti of India, the most senior, most influential religious authority and spiritual leader of Muslims in India. The system is executed in India from the Mughal[citation needed] period.[200][201]

Muslim institutes

There are several well established Muslim institutions in India. Here is a list of reputed institutions established by Muslims in India.

Modern universities and institutes

- Al-Ameen Educational Society

- Aliah University

- Aligarh Muslim University

- Jamia Markazu Saqafathi Sunniyya

- Ma'dinu Ssaquafathil Islamiyya

- B.S. Abdur Rahman Crescent Institute of Science and Technology

- Darul Huda Islamic University

- Darul Uloom Deoband

- Darul Uloom Nadwatul Ulama

- Farook College, Kozhikode

- Ibn Sina Academy of Medieval Medicine and Sciences

- Integral University

- Jamal Mohamed College, Tiruchirappalli

- Hamdard University, Delhi

- Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi

- Karim City College, Jamshedpur

- M.S.S. Wakf Board College, Madurai (The only college in India run by a State Wakf Board)

- Madeenathul Uloom Arabic College, Pulikkal, Malappuram

- Maulana Azad National Urdu University Hyderabad

- Maulana Mazharul Haque Arabic and Persian University, Patna, Bihar

- Maulana Azad College of Arts and Science, Aurangabad

- Muslim Educational Association of Southern India

- Muslim Educational Society, Kerala

- Nellai College of Engineering, Tirunelveli

- Osmania University, Hyderabad

- Pocker Sahib Memorial Orphanage College, Tirurangadi

- Thangal Kunju Musaliar College of Engineering, Kollam

Traditional Islamic universities

- Aljamea-tus-Saifiyah, Bohra

- Al Jamiatul Ashrafia, Barelvi

- Jamia Darussalam, Oomerabad

- Al-Jame-atul-Islamia, Uttar Pradesh

- Jamia Nizamia, Hyderabad

- Manzar-e-Islam, Bareilly

- Markazu Saqafathi Sunniyya, Kerala

- Raza Academy

Leadership and organisations

- The Ajmer Sharif Dargah and Dargah-e-Ala Hazrat at Bareilly Shareef are prime center of Sufi oriented Sunni Muslims of India.[202]

- Indian Shia Muslims form a substantial minority within the Muslim community of India comprising between 25 and 31% of total Muslim population in an estimation done during mid-2005 to 2006 of the then Indian Muslim population of 157 million. Sources like The Times of India and DNA reported Indian Shia population during that period between 40,000,000[170][171] to 50,000,000[172] of 157,000,000 Indian Muslim population.

- The Deobandi movement, another section of the Sunni Muslim population, originate from the Darul Uloom Deoband, an influential religious seminary in the district of Saharanpur of Uttar Pradesh. The Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, founded by Deobandi scholars in 1919, became a political mouthpiece for the Darul Uloom.[203]

- The Jamaat-e-Islami Hind, founded in 1941, advocates the establishment of an Islamic government and has been active in promoting education, social service and ecumenical outreach to the community.[204]

Caste system among Indian Muslims

Although Islam does not recognize any castes, the caste system among South Asian Muslims refers to units of social stratification that have developed among Muslims in South Asia.[205]

Stratification

In some parts of South Asia, the Muslims are divided as Ashrafs and Ajlafs.[206][207] Ashrafs claim to be derived from their foreign ancestry.[24][25] They, in turn, are divided into a number of occupational castes.[208][25]

Barrani was specific in his recommendation that the "sons of Mohamed" [i.e. Sayyid] be given a higher social status than the others.[209] His most significant contribution in the fatwa was his analysis of the castes with respect to Islam.[209] His assertion was that castes would be mandated through state laws or "Zawabi" and would carry precedence over Sharia law whenever they were in conflict.[209] Every act which is "contaminated with meanness and based on ignominity, comes elegantly [from the Ajlaf]".[209] He sought appropriate religious sanction to that effect.[23] Barrani also developed an elaborate system of promotion and demotion of imperial officers ("Wazirs") that was primarily on the basis of their caste.[209]

In addition to the ashraf/ajlaf divide, there is also the arzal caste among Muslims,[210] who were regarded by anti-caste activists like Babasaheb Ambedkar as the equivalent of untouchables.[211] The term "Arzal" stands for "degraded" and the Arzal castes are further subdivided into Bhanar, Halalkhor, Hijra, Kasbi, Lalbegi, Maugta, Mehtar etc.[211][212] They are relegated to "menial" professions such as scavenging and carrying night soil.[213]

Some South Asian Muslims have been known to stratify their society according to qaums.[214] Studies of Bengali Muslims in India indicate that the concepts of purity and impurity exist among them and are applicable in inter-group relationships, as the notions of hygiene and cleanliness in a person are related to the person's social position and not to his/her economic status.[25] Muslim Rajput is another caste distinction among Indian Muslims.

Some of the upper and middle caste Muslim communities include Syed, Shaikh, Shaikhzada, Khanzada, Pathan, Mughal, and Malik.[215] Genetic data has also supported this stratification.[216] In three genetic studies representing the whole of South Asian Muslims, it was found that the Muslim population was overwhelmingly similar to the local non-Muslims associated with minor but still detectable levels of gene flow from outside, primarily from Iran and Central Asia, rather than directly from the Arabian Peninsula.[19]

The Sachar Committee's report commissioned by the government of India and released in 2006, documents the continued stratification in Muslim society.[citation needed]

Interaction and mobility

Data indicates that the castes among Muslims have never been as rigid as that among Hindus.[217] They have good interactions with the other communities. They participate in marriages and funerals and other religious and social events in other communities. Some of them also had inter-caste marriages since centuries but mostly they preferred to marry in the same caste with a significant number of marriages being consanguineous.[citation needed] In Bihar state of India, cases had been reported in which the higher caste Muslims have opposed the burials of lower caste Muslims in the same graveyard.[215]

Criticism

Some Muslim scholars have tried to reconcile and resolve the "disjunction between Quranic egalitarianism and Indian Muslim social practice" through theorizing it in different ways and interpreting the Quran and Sharia to justify casteism.[23]

While some scholars theorize that Muslim castes are not as acute in their discrimination as that among Hindus,[23][217] Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar argued otherwise, arguing the social evils in Muslim society were "worse than those seen in Hindu society".[211] He was critical of Ashraf antipathy towards the Ajlaf and Arzal and attempts to palliate sectarian divisions. He condemned the Indian Muslim community of being unable to reform like Muslims in other countries such as Turkey did during the early decades of the twentieth century.[211]

Segregation

Segregation of Indian Muslims from other communities began in the mid-1970s when the first communal riots occurred. This was heightened after the 1989 Bhagalpur violence in Bihar and became a trend after the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992. Soon several major cities developed ghettos, or segregated areas, where the Muslim population moved into.[218] This trend, however, did not help with the anticipated security the anonymity of ghetto was thought to have provided. During the 2002 Gujarat riots, several such ghettos became easy targets for the rioting mobs, as they enabled the profiling of residential colonies.[219][220][221][222] This kind of ghettoisation can be seen in Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata and many cities of Gujarat where a clear socio-cultural demarcation exists between Hindu-dominated and Muslim-dominated neighbourhoods.[citation needed]

In places like Gujarat, riots and alienation of Muslims have led to large-scale ghettoisation of the community. For example, the Juhapura area of Ahmadabad has swelled from 250,000 to 650,000 residents since 2002 riots. Muslims in Gujarat have no option but to head to a ghetto, irrespective of their economic and professional status.[223]

An increase in ghetto living has also shown a strengthening of stereotyping due to a lack of cross-cultural interaction, and reduction in economic and educational opportunities at large. Secularism in India is being seen by some as a favour to the Muslims, and not an imperative for democracy.[224][225][226]

Consanguineous marriages

The NFHS (National Family Health Survey) on 1992-93 showed that 22 per cent of marriages in India were consanguineous, with the highest per cent recorded in Jammu and Kashmir, a Muslim majority state. Post partition percentage of consanguineous marriages in Delhi Sunni Muslims has risen to 37.84 per cent. As per Nasir, such unions are perceived to be exploitative as they perpetuate the existing power structures within the family.[227]

Art and architecture

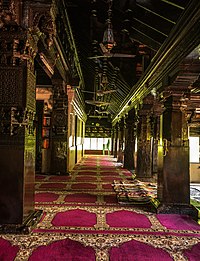

-

A rebuilt structure of the old Cheraman Juma Mosque, Kerala, which is often considered as the first Masjid of India

-

Asafi Imambargah, also known as Bara Imambara at Lucknow

-

The Humayun's Tomb in Delhi

-

Gol Gumbaz at Bijapur, Karnataka, has the second largest pre-modern dome in the world after the Byzantine Hagia Sophia.

-

400-year-old Makkah Masjid, Hyderabad. (Photo: 1885)

-

The Asafi Mosque within the Asafi Imambargah Complex at Lucknow

-

The Rumi Darwaza at Lucknow

-

Gole-Gumma, Mousoleum of Nawab Wahab Khan, Kurnool, Andhra Pradesh

Architecture of India took new shape with the advent of Islamic rule in India towards the end of the 12th century CE. New elements were introduced into the Indian architecture that include: use of shapes (instead of natural forms); inscriptional art using decorative lettering or calligraphy; inlay decoration and use of coloured marble, painted plaster and brightly coloured glazed tiles. Quwwat-ul-Islam Mosque built in 1193 CE was the first mosque to be built in the Indian subcontinent; its adjoining "Tower of Victory", the Qutb Minar also started around 1192 CE, which marked the victory of Muhammad of Ghor and his general Qutb al-Din Aibak, from Ghazni, Afghanistan, over local Rajput kings, is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Delhi.[citation needed]

In contrast to the indigenous Indian architecture which was of the trabeate order, i.e. all spaces were spanned by means of horizontal beams, the Islamic architecture was arcuate, i.e. an arch or dome was adopted as a method of bridging a space. The concept of arch or dome was not invented by the Muslims but was, in fact, borrowed and further perfected by them from the architectural styles of the post-Roman period. Muslims used a cementing agent in the form of mortar for the first time in the construction of buildings in India. They further put to use certain scientific and mechanical formulae, which were derived by experience of other civilisations, in their constructions in India. Such use of scientific principles helped not only in obtaining greater strength and stability of the construction materials but also provided greater flexibility to the architects and builders. One fact that must be stressed here is that, the Islamic elements of architecture had already passed through different experimental phases in other countries like Egypt, Iran and Iraq before these were introduced in India. Unlike most Islamic monuments in these countries, which were largely constructed in brick, plaster and rubble, the Indo-Islamic monuments were typical mortar-masonry works formed of dressed stones. It must be emphasized that the development of the Indo-Islamic architecture was greatly facilitated by the knowledge and skill possessed by the Indian craftsmen, who had mastered the art of stonework for centuries and used their experience while constructing Islamic monuments in India.[citation needed]

Islamic architecture in India can be divided into two parts: religious and secular. Mosques and Tombs represent the religious architecture, while palaces and forts are examples of secular Islamic architecture. Forts were essentially functional, complete with a little township within and various fortifications to engage and repel the enemy.[citation needed]

Mosques

There are more than 300,000 active mosques in India, which is higher than any other country, including the Muslim world.[228] The mosque or masjid is a representation of Muslim art in its simplest form. The mosque is basically an open courtyard surrounded by a pillared verandah, crowned off with a dome. A mihrab indicates the direction of the qibla for prayer. Towards the right of the mihrab stands the minbar or pulpit from where the Imam presides over the proceedings. An elevated platform, usually a minaret from where the Faithful are summoned to attend prayers is an invariable part of a mosque. Large mosques where the faithful assemble for the Friday prayers are called the Jama Masjids.[citation needed]

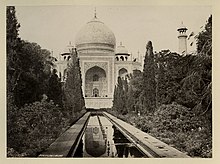

Tombs and mausoleum

The tomb or maqbara could range from being a simple affair (Aurangazeb's grave) to an awesome structure enveloped in grandeur (Taj Mahal). The tomb usually consists of a solitary compartment or tomb chamber known as the huzrah in whose centre is the cenotaph or zarih. This entire structure is covered with an elaborate dome. In the underground chamber lies the mortuary or the maqbara, in which the corpse is buried in a grave or qabr. Smaller tombs may have a mihrab, although larger mausoleums have a separate mosque located at a distance from the main tomb. Normally the whole tomb complex or rauza is surrounded by an enclosure. The tomb of a Muslim saint is called a dargah. Almost all Islamic monuments were subjected to free use of verses from the Quran and a great amount of time was spent in carving out minute details on walls, ceilings, pillars and domes.[citation needed]

Styles of Islamic architecture in India

Islamic architecture in India can be classified into three sections: Delhi or the imperial style (1191–1557 CE); the provincial style, encompassing the surrounding areas like Ahmedabad, Jaunpur and the Deccan; and the Mughal architecture style (1526–1707 CE).[229]

Law, politics, and government

Certain civil matters of jurisdiction for Muslims such as marriage, inheritance and waqf properties are governed by the Muslim Personal Law,[230] which was developed during British rule and subsequently became part of independent India with some amendments.[231][232] Indian Muslim personal law is not developed as a Sharia law but as an interpretation of existing Muslim laws as part of common law. The Supreme Court of India has ruled that Sharia or Muslim law holds precedence for Muslims over Indian civil law in such matters.[233]

Muslims in India are governed by "The Muslim Personal Law (Shariat) Application Act, 1937."[234] It directs the application of Muslim Personal Law to Muslims in marriage, mahr (dower), divorce, maintenance, gifts, waqf, wills and inheritance.[231] The courts generally apply the Hanafi Sunni law for Sunnis; Shia Muslims are independent of Sunni law for those areas where Shia law differs substantially from Sunni practice.[citation needed]

The Indian constitution provides equal rights to all citizens irrespective of their religion. Article 44 of the constitution recommends a uniform civil code. However, attempts by successive political leadership in the country to integrate Indian society under a common civil code is strongly resisted and is viewed by Indian Muslims as an attempt to dilute the cultural identity of the minority groups of the country. The All India Muslim Personal Law Board was established for the protection and continued applicability of "Muslim Personal Law", i.e. Shariat Application Act in India. The Sachar Committee was asked to report about the condition of Muslims in India in 2005. Almost all the recommendations of the Sachar Committee have been implemented.[235][236]

The following laws/acts of Indian legislation are applicable to Muslims in India (except in the state of Goa) regarding matters of marriage, succession, inheritance, child adoption etc.

- Muslim Personal Law Sharia Application Act, 1937

- The Dissolution of Muslim Marriages Act, 1939

- Muslim Women (Protection of Rights on Divorce) Act, 1986

Note: the above laws are not applicable in the state of Goa. The Goa civil code, also called the Goa Family Law, is the set of civil laws that governs the residents of the Indian state of Goa. In India, as a whole, there are religion-specific civil codes that separately govern adherents of different religions. Goa is an exception to that rule, in that a single secular code/law governs all Goans, irrespective of religion, ethnicity or linguistic affiliation. The above laws are also not applicable to Muslims throughout India who had civil marriages under the Special Marriage Act, 1954.[citation needed]

Bharatiya Muslim Mahila Andolan is an Indian Muslim women's organisation in India. It released a draft on 23 June 2014, 'Muslim Marriage and Divorce Act', recommending that polygamy be made illegal in the Muslim Personal Law of India.[237]

Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019 was proposed for the changes in the citizenship and immigration norms of the country by relaxing the requirements for Indian citizenship. The applicability of the amendments are debated in news as it is on religious lines (excluding Muslims).[238][239][240]

India's Constitution and Parliament have protected the rights of Muslims but, according to some sources,[241][242][243] there has been a growth in a 'climate of fear' and 'targeting of dissenters' under the Bharatiya Janata Party and Modi ministry, affecting the feelings of security and tolerance amongst Indian Muslims. However, these allegations are not universally supported.[244]

Active Muslim political parties

- All India Majlis-e-Ittehadul Muslimeen (AIMIM), led by Asaduddin Owaisi; active in states of Telangana, Maharashtra, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Gujarat and Karnataka[245]

- Indian Union Muslim League (IUML), led by E. Ahamed active in Kerala[246]

- All India United Democratic Front (AIUDF), led by Badruddin Ajmal active in Assam state[247]

- Jammu and Kashmir People's Conference (JKPC), founded by Abdul Ghani Lone and Molvi Iftikhar Hussain Ansari.[248][249] Led by Sajjad Lone.[250] It is active in Jammu and Kashmir.

- National Conference (NC) main party of Jammu and Kashmir

- People's Democratic Party (PDP) main party of Jammu and Kashmir

- Apni Party (JKAP) a newly formed party of Jammu and Kashmir

- Peace Party of India of Mohamed Ayub

Muslims in government

India has seen three Muslim presidents and many chief ministers of State Governments have been Muslims. Apart from that, there are and have been many Muslim ministers, both at the centre and at the state level. Out of the 12 Presidents of the Republic of India, three were Muslims – Zakir Husain, Fakhruddin Ali Ahmed and A. P. J. Abdul Kalam. Additionally, Mohammad Hidayatullah, Aziz Mushabber Ahmadi, Mirza Hameedullah Beg and Altamas Kabir held the office of the Chief Justice of India on various occasions since independence. Mohammad Hidayatullah also served as the acting President of India on two separate occasions; and holds the distinct honour of being the only person to have served in all three offices of the President of India, the Vice-President of India and the Chief Justice of India.[251][252]

The former Vice-President of India, Mohammad Hamid Ansari, former Foreign Minister Salman Khurshid and former Director (Head) of the Intelligence Bureau, Syed Asif Ibrahim are Muslims. Ibrahim was the first Muslim to hold this office. From 30 July 2010 to 10 June 2012, Dr. S. Y. Quraishi served as the Chief Election Commissioner of India.[253] He was the first Muslim to serve in this position. Prominent Indian bureaucrats and diplomats include Abid Hussain, Ali Yavar Jung and Asaf Ali. Zafar Saifullah was Cabinet Secretary of the Government of India from 1993 to 1994.[254] Salman Haidar was the Foreign Secretary from 1995 to 1997 and Deputy Permanent Representative of India to the United Nations.[255][256] Tayyab Husain was the only politician in Indian history to serve as a Cabinet Minister in the government of three different states at different times. (Undivided Punjab, Rajasthan, Haryana).[257] Influential Muslim politicians in India include Sheikh Abdullah, Farooq Abdullah and his son Omar Abdullah (former Chief Minister of Jammu and Kashmir), Mufti Mohammad Sayeed, Mehbooba Mufti, Chaudhary Rahim Khan, Sikander Bakht, A. R. Antulay, Ahmed Patel, C. H. Mohammed Koya, A. B. A. Ghani Khan Choudhury, Mukhtar Abbas Naqvi, Salman Khurshid, Saifuddin Soz, E. Ahamed, Ghulam Nabi Azad, Syed Shahnawaz Hussain, Asaduddin Owaisi, Azam Khan and Badruddin Ajmal, Najma Heptulla.

Haj subsidy

The government of India subsidized the cost of the airfare for Indian Hajj pilgrims until it was totally phased out in 2018.[258] The decision to end the subsidy was in order to comply with a Supreme Court of India decision of 2011. Starting in 2011, the amount of government subsidy per person was decreased year on year and ended completely by 2018.[259][260] Maulana Mahmood A. Madani, a member of the Rajya Sabha and general secretary of the Jamiat Ulema-e-Hind, declared that the Hajj subsidy is a technical violation of Islamic Sharia, since the Quran declares that Hajj should be performed by Muslims using their own resources.[261] Influential Muslim lobbies in India have regularly insisted that the Hajj subsidy should be phased out as it is un-Islamic.[262]

Conflict and controversy

Conversion controversy

Considerable controversy exists both in scholarly and public opinion about the conversions to Islam typically represented by the following schools of thought:[263]

- The bulk of Muslims are descendants of migrants from the Iranian Plateau or Arabs.[264][page needed] However this claim is disputed by modern genetic studies on haplotype findings of Y-chromosomal ancestry amongst various Muslim communities in India.[265]

- Conversion of slaves to Islam. Children fathered by Muslim and non-Muslim slaves would be raised Muslim. Non-Muslim women who birthed them would convert to Islam to avoid rejection by their own communities.[266]

- Conversions occurred for non-religious reasons of pragmatism and patronage such as social mobility among the Muslim ruling elite or for relief from taxes[263][264]

- Conversion was a result of the actions of Sunni Sufi saints and involved a genuine change of heart.[263]

- Conversion came from Buddhists and the en masse conversions of lower castes for social liberation and as a rejection of the oppressive Hindu caste strictures.[264]

- A combination, initially made under duress followed by a genuine change of heart.[263]

- As a socio-cultural process of diffusion and integration over an extended period of time into the sphere of the dominant Muslim civilisation and global polity at large.[264]

Embedded within this lies the concept of Islam as a foreign imposition and Hinduism being a natural condition of the natives who resisted, resulting in the failure of the project to Islamize the Indian subcontinent and is highly embroiled within the politics of the partition and communalism in India.[263]

Historians such as Will Durant described Islamic invasions of India as "The bloodiest story in history.[267][268] Jadunath Sarkar contends that several Muslim invaders were waging a systematic jihad against Hindus in India to the effect that "Every device short of massacre in cold blood was resorted to in order to convert heathen subjects".[269] Hindus who converted to Islam were not immune to persecution due to the Muslim Caste System in India established by Ziauddin al-Barani in the Fatawa-i Jahandari,[23] where they were regarded as an "Ajlaf" caste and subjected to discrimination by the "Ashraf" castes.[270] Others argue that, during the Muslim conquests in the Indian subcontinent, Indian-origin religions experienced persecution from various Muslim conquerors[271] who massacred Hindus, Jains and Buddhists, attacked temples and monasteries, and forced conversions on the battlefield.[272]

Disputers of the "conversion by the sword theory" point to the presence of the large Muslim communities found in Southern India, Sri Lanka, Western Burma, Bangladesh, Southern Thailand, Indonesia and Malaysia coupled with the distinctive lack of equivalent Muslim communities around the heartland of historical Muslim empires in the Indian subcontinent as a refutation to the "conversion by the sword theory". The legacy of the Muslim conquest of South Asia is a hotly debated issue and argued even today.[citation needed]

Muslim invaders were not all simply raiders. Later rulers fought on to win kingdoms and stayed to create new ruling dynasties. The practices of these new rulers and their subsequent heirs (some of whom were born to Hindu wives) varied considerably. While some were uniformly hated, others developed a popular following. According to the memoirs of Ibn Battuta who travelled through Delhi in the 14th century, one of the previous sultans had been especially brutal and was deeply hated by Delhi's population. Batuta's memoirs also indicate that Muslims from the Arab world, Persia and Anatolia were often favoured with important posts at the royal courts, suggesting that locals may have played a somewhat subordinate role in the Delhi administration. The term "Turk" was commonly used to refer to their higher social status. S.A.A. Rizvi (The Wonder That Was India – II) however points to Muhammad bin Tughluq as not only encouraging locals but promoting artisan groups such as cooks, barbers and gardeners to high administrative posts. In his reign, it is likely that conversions to Islam took place as a means of seeking greater social mobility and improved social standing.[273]

Numerous temples were destroyed by Muslim conquerors.[274] Richard M. Eaton lists a total of 80 temples that were desecrated by Muslim conquerors,[275] but notes this was not unusual in medieval India where numerous temples were also desecrated by Hindu and Buddhist kings against rival Indian kingdoms during conflicts between devotees of different Hindu deities, and between Hindus, Buddhists and Jains.[276][277][278] He also notes there were many instances of the Delhi Sultanate, which often had Hindu ministers, ordering the protection, maintenance and repairing of temples, according to both Muslim and Hindu sources, and that attacks on temples had significantly declined under the Mughal Empire.[275]

K. S. Lal, in his book Growth of Muslim Population in Medieval India, claimed that between 1000 and 1500 the Indian population decreased by 30 million,[279] but stated his estimates were tentative and did not claim any finality.[280][281][282] His work has come under criticism by historians such as Simon Digby (SOAS, University of London) and Irfan Habib for its agenda and lack of accurate data in pre-census times.[283][284] Different population estimates by economics historians Angus Maddison and Jean-Noël Biraben also indicate that India's population did not decrease between 1000 and 1500, but increased by about 35 million during that time.[285][286] The Indian population estimates from other economic historians including Colin Clark, John D. Durand and Colin McEvedy also show there was a population increase in India between 1000 and 1500.[287][288]

Relations with non-Muslim communities

Muslim–Hindu conflict

- Before 1947

The conflict between Hindus and Muslims in the Indian subcontinent has a complex history which can be said to have begun with the Umayyad Caliphate's invasion of Sindh in 711. The persecution of Hindus during the Islamic expansion in India during the medieval period was characterised by destruction of temples, often illustrated by historians by the repeated destruction of the Hindu Temple at Somnath[289][290] and the anti-Hindu practices of the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.[291] Although there were instances of conflict between the two groups, a number of Hindus worshipped and continue to worship at the tombs of Muslim Sufi Saints.[292]

During the Noakhali riots in 1946, several thousand Hindus were forcibly converted to Islam by Muslim mobs.[293][294]

- From 1947 to 1991

The aftermath of the Partition of India in 1947 saw large scale sectarian strife and bloodshed throughout the nation. Since then, India has witnessed sporadic large-scale violence sparked by underlying tensions between sections of the Hindu and Muslim communities. These include the 1969 Gujarat riots, the 1970 Bhiwandi riots, the 1983 Nellie massacre, and the 1989 Bhagalpur violence. These conflicts stem in part from the ideologies of Hindu nationalism and Islamic extremism. Since independence, India has always maintained a constitutional commitment to secularism.[citation needed]

- Since 1992

The sense of communal harmony between Hindus and Muslims in the post-partition period was compromised greatly by the razing of the Babri Mosque in Ayodhya. The demolition took place in 1992 and was perpetrated by the Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party and organisations like Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, Bajrang Dal, Vishva Hindu Parishad and Shiv Sena. This was followed by tit for tat violence by Muslim and Hindu fundamentalists throughout the country, giving rise to the Bombay riots and the 1993 Bombay bombings.[citation needed]

In the 1998 Prankote massacre, 26 Kashmiri Hindus were beheaded by Islamist militants after their refusal to convert to Islam. The militants struck when the villagers refused demands from the gunmen to convert to Islam and prove their conversion by eating beef.[295]

- Kashmir (1990s)

During the eruption of militancy in the 1990s, following persecution and threats by radical Islamists and militants, the native Kashmiri Hindus were forced into an exodus from Kashmir, a Muslim-majority region in Northern India.[296][297] Mosques issued warnings, telling them to leave Kashmir, convert to Islam or be killed.[298] Approximately 300,000–350,000 pandits left the valley during the mid-80s and the 90s.[299] Many of them have been living in abject conditions in refugee camps of Jammu.[300]

- Gujarat (2002)

One of the most violent events in recent times took place during the Gujarat riots in 2002, where it is estimated one thousand people were killed, most allegedly Muslim. Some sources claim there were approximately 2,000 Muslim deaths.[301] There were also allegations made of state involvement.[301][302] The riots were in retaliation to the Godhra train burning in which 59 Hindu pilgrims returning from the disputed site of the Babri Masjid, were burnt alive in a train fire at the Godhra railway station. Gujarat police claimed that the incident was a planned act carried out by extremist Muslims in the region against the Hindu pilgrims. The Bannerjee commission appointed to investigate this finding declared that the fire was an accident.[303] In 2006 the High Court decided the constitution of such a committee was illegal as another inquiry headed by Justice Nanavati Shah was still investigating the matter.[304]

In 2004, several Indian school textbooks were scrapped by the National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) after they were found to be loaded with anti-Muslim prejudice. The NCERT argued that the books were "written by scholars hand-picked by the previous Hindu nationalist administration". According to The Guardian, the textbooks depicted India's past Muslim rulers "as barbarous invaders and the medieval period as a Dark Age of Islamic colonial rule which snuffed out the glories of the Hindu empire that preceded it".[308] In one textbook, it was purported that the Taj Mahal, the Qutb Minar and the Red Fort – all examples of Islamic architecture – "were designed and commissioned by Hindus".[308]

- West Bengal (2010)

In the 2010 Deganga riots, rioting began on 6 September 2010, when an Islamist mob resorted to arson and violence on the Hindu neighborhoods of Deganga, Kartikpur and Beliaghata under the Deganga police station area. The violence began late in the evening and continued throughout the night into the next morning. The district police, Rapid Action Force, Central Reserve Police Force and Border Security Force all failed to stop the mob violence and the Army was finally deployed.[309][310][311][312] The Army staged a flag march on the Taki Road, while Islamist violence continued unabated in the interior villages off the Taki Road, till Wednesday in spite of the Army's presence and promulgation of prohibitory orders under section 144 of the CrPC.[citation needed]

- Assam (2012)

At least 77 people died[313] and 400,000 people were displaced in the 2012 Assam violence between indigenous Bodos and East Bengal rooted Muslims.[314]

- Delhi (2020)

The 2020 Delhi riots, which left more than 50 dead and hundreds injured,[315][316] were triggered by protests against a citizenship law seen by many critics as anti-Muslim and part of Prime Minister Narendra Modi's Hindu nationalist agenda.[317][318]

Haryana (2023)

The 2023 Haryana riots, stemming from communal clashes during the Brajmandal Yatra pilgrimage, resulted in seven fatalities and over 200 injuries. The violence began when the inclusion of Bajrang Dal activist Monu Manesar, a suspect in the murder of two Muslim men, sparked anger within the Muslim community in Mewat. The BJP government was criticized for allowing Manesar's participation, leading to an organized attack on the procession, triggering retaliatory actions. The government responded with a curfew, internet suspension, and additional troops. Critics blame the BJP government for not preventing the escalation and allowing a potentially volatile situation to unfold.[citation needed]

Muslim–Sikh conflict