гомосексуальность

| Сексуальная ориентация |

|---|

|

| Сексуальная ориентация |

| Связанные термины |

| Исследовать |

| Animals |

| Related topics |

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

Гомосексуализм – это сексуальное влечение , романтическое влечение или сексуальное поведение между представителями одного и того же пола или пола . [1] [2] [3] Как сексуальная ориентация , гомосексуализм представляет собой «стойкую модель эмоционального, романтического и/или сексуального влечения» исключительно к людям того же пола или гендера. [4] Это «также относится к чувству идентичности человека, основанному на этих влечениях, соответствующем поведении и членстве в сообществе других людей , которые разделяют эти влечения». [5] [6]

Наряду с бисексуальностью и гетеросексуальностью , гомосексуализм является одной из трёх основных категорий сексуальной ориентации в гетеросексуально-гомосексуальном континууме . [5] Ученые еще не знают точную причину сексуальной ориентации, но они предполагают, что она вызвана сложным взаимодействием генетических , гормональных и экологических влияний , и не рассматривают это как выбор. [7] [8] [9] Хотя ни одна теория причин сексуальной ориентации еще не получила широкой поддержки, ученые отдают предпочтение теориям, основанным на биологии . [7][8] There is considerably more evidence supporting nonsocial, biological causes of sexual orientation than social ones, especially for males.[10][11][12] There is no substantive evidence which suggests parenting or early childhood experiences play a role with regard to sexual orientation.[13] While some believe that homosexual activity is unnatural,[14] scientific research shows that homosexuality is a normal and natural variation in human sexuality and is not in and of itself a source of negative psychological effects.[5][15] There is insufficient evidence to support the use of psychological interventions to change sexual orientation.[16][17]

The most common terms for homosexual people are lesbian for females and gay for males, but the term gay also commonly refers to both homosexual females and males. The percentage of people who are gay or lesbian and the proportion of people who are in same-sex romantic relationships or have had same-sex sexual experiences are difficult for researchers to estimate reliably for a variety of reasons, including many gay and lesbian people not openly identifying as such due to prejudice or discrimination such as homophobia and heterosexism.[18] Homosexual behavior has also been documented in many non-human animal species,[24] though humans are one of only two species known to exhibit a homosexual orientation (the other is sheep).[10]

Many gay and lesbian people are in committed same-sex relationships. These relationships are equivalent to heterosexual relationships in essential psychological respects.[6] Homosexual relationships and acts have been admired as well as condemned throughout recorded history, depending on the form they took and the culture in which they occurred.[25] Since the end of the 20th century, there has been a global movement towards freedom and equality for gay people, including the introduction of anti-bullying legislation to protect gay children at school, legislation ensuring non-discrimination, equal ability to serve in the military, equal access to health care, equal ability to adopt and parent, and the establishment of marriage equality.

Etymology

Attic red-figure cup from Tarquinia, 480 BC (Boston Museum of Fine Arts)

The word homosexual is a Greek and Latin hybrid, with the first element derived from Greek ὁμός homos, "same" (not related to the Latin homo, "man", as in Homo sapiens), thus connoting sexual acts and affections between members of the same sex, including lesbianism.[26][27] The first known appearance of homosexual in print is found in an 1868 letter to Karl Heinrich Ulrichs by the Austrian-born novelist Karl-Maria Kertbeny.[28][29] arguing against a Prussian anti-sodomy law.[29][30] In 1886, the psychiatrist Richard von Krafft-Ebing used the terms homosexual and heterosexual in his book Psychopathia Sexualis. Krafft-Ebing's book was so popular among both laymen and doctors that the terms heterosexual and homosexual became the most widely accepted terms for sexual orientation.[31][32] As such, the current use of the term has its roots in the broader 19th-century tradition of personality taxonomy.

Many modern style guides in the U.S. recommend against using homosexual as a noun, instead using gay man or lesbian.[33][citation needed] Similarly, some recommend completely avoiding usage of homosexual as it has a negative, clinical history and because the word only refers to one's sexual behavior (as opposed to romantic feelings) and thus it has a negative connotation.[33] Gay and lesbian are the most common alternatives. The first letters are frequently combined to create the initialism LGBT (sometimes written as GLBT), in which B and T refer to bisexual and transgender people.

Gay especially refers to male homosexuality,[34] but may be used in a broader sense to refer to all LGBT people. In the context of sexuality, lesbian refers only to female homosexuality. The word lesbian is derived from the name of the Greek island Lesbos, where the poet Sappho wrote largely about her emotional relationships with young women.[35][36]

Although early writers also used the adjective homosexual to refer to any single-sex context (such as an all-girls school), today the term is used exclusively in reference to sexual attraction, activity, and orientation. The term homosocial is now used to describe single-sex contexts that are not specifically sexual. There is also a word referring to same-sex love, homophilia.

Some synonyms for same-sex attraction or sexual activity include men who have sex with men or MSM (used in the medical community when specifically discussing sexual activity) and homoerotic (referring to works of art).[37][38] Pejorative terms in English include queer, faggot, fairy, poof, poofter[39] and homo.[40][41][42][43] Beginning in the 1990s, some of these have been reclaimed as positive words by gay men and lesbians, as in the usage of queer studies, queer theory, and even the popular American television program Queer Eye for the Straight Guy.[44] The word homo occurs in many other languages without the pejorative connotations it has in English.[45] As with ethnic slurs and racial slurs, the use of these terms can still be highly offensive. The range of acceptable use for these terms depends on the context and speaker.[46] Conversely, gay, a word originally embraced by homosexual men and women as a positive, affirmative term (as in gay liberation and gay rights),[47] came into widespread pejorative use among young people in the early 2000s.[48]

The American LGBT rights organization GLAAD advises the media to avoid using the term homosexual to describe gay people or same-sex relationships as the term is "frequently used by anti-gay extremists to denigrate gay people, couples and relationships".[49]

History

Some scholars argue that the term "homosexuality" is problematic when applied to ancient cultures since, for example, neither Greeks or Romans possessed any one word covering the same semantic range as the modern concept of "homosexuality".[50][51] Nor did there exist a distinction of lifestyle or differentiation of psychological or behavioral profiles in the ancient world.[52] However, there were diverse sexual practices that varied in acceptance depending on time and place.[50] In ancient Greece, the pattern of adolescent boys engaging in sexual practices with older males did not constitute a homosexual identity in the modern sense since such relations were seen as phases in life, not permanent orientations, since later on the younger partners would commonly marry females and reproduce.[53] Other scholars argue that there are significant continuities between ancient and modern homosexuality.[54][55]

In cultures influenced by Abrahamic religions, the law and the church established sodomy as a transgression against divine law or a crime against nature. The condemnation of anal sex between males, however, predates Christian belief. Throughout the majority of Christian history, most Christian theologians and denominations have considered homosexual behavior as immoral or sinful.[56][57] Condemnation was frequent in ancient Greece; for instance, the idea of male anal sex being "unnatural" is described by a character of Plato's,[58] though he had earlier written of the benefits of homosexual relationships.[59]

Many historical figures, including Socrates, Lord Byron, Edward II, and Hadrian,[60] have had terms such as gay or bisexual applied to them. Some scholars have regarded uses of such modern terms on people from the past as an anachronistic introduction of a contemporary construction of sexuality that would have been foreign to their times.[61][52] Other scholars see continuity instead.[62][55][54]

In social science, there has been a dispute between "essentialist" and "constructionist" views of homosexuality. The debate divides those who believe that terms such as "gay" and "straight" refer to objective, culturally invariant properties of persons from those who believe that the experiences they name are artifacts of unique cultural and social processes. "Essentialists" typically believe that sexual preferences are determined by biological forces, while "constructionists" assume that sexual desires are learned.[63] The philosopher of science Michael Ruse has stated that the social constructionist approach, which is influenced by Foucault, is based on a selective reading of the historical record that confuses the existence of homosexual people with the way in which they are labelled or treated.[64]

Africa

The first record of a possible homosexual couple in history is commonly regarded as Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum, an ancient Egyptian male couple, who lived around 2400 BCE. The pair are portrayed in a nose-kissing position, the most intimate pose in Egyptian art, surrounded by what appear to be their heirs. The anthropologists Stephen Murray and Will Roscoe reported that women in Lesotho engaged in socially sanctioned "long term, erotic relationships" called motsoalle.[65] The anthropologist E. E. Evans-Pritchard also recorded that male Azande warriors in the northern Congo routinely took on young male lovers between the ages of twelve and twenty, who helped with household tasks and participated in intercrural sex with their older husbands.[66]

Americas

Indigenous cultures

Sac and Fox Nation ceremonial dance to celebrate the two-spirit person. George Catlin (1796–1872); Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

As is true of many other non-Western cultures, it is difficult to determine the extent to which Western notions of sexual orientation and gender identity apply to Pre-Columbian cultures. Evidence of homoerotic sexual acts and transvestism has been found in many pre-conquest civilizations in Latin America, such as the Aztecs, Mayas, Quechuas, Moches, Zapotecs, the Incas, and the Tupinambá of Brazil.[67][68][69]

The Spanish conquerors were horrified to discover sodomy openly practiced among native peoples, and attempted to crush it out by subjecting the berdaches (as the Spanish called them) under their rule to severe penalties, including public execution, burning and being torn to pieces by dogs.[70] The Spanish conquerors talked extensively of sodomy among the natives to depict them as savages and hence justify their conquest and forceful conversion to Christianity. As a result of the growing influence and power of the conquerors, many native cultures started condemning homosexual acts themselves.[citation needed]

Among some of the indigenous peoples of the Americas in North America prior to European colonization, a relatively common form of same-sex sexuality centered around the figure of the Two-Spirit individual (the term itself was coined only in 1990).[citation needed] Typically, this individual was recognized early in life, given a choice by the parents to follow the path and, if the child accepted the role, raised in the appropriate manner, learning the customs of the gender it had chosen. Two-Spirit individuals were commonly shamans and were revered as having powers beyond those of ordinary shamans. Their sexual life was with the ordinary tribe members of the same sex.[citation needed]

During the colonial times following the European invasion, homosexuality was prosecuted by the Inquisition, sometimes leading to death sentences on the charges of sodomy, and the practices became clandestine. Many homosexual individuals went into heterosexual marriages to maintain appearances, and many joined the (unmarried) Catholic clergy to escape public scrutiny of their lack of interest in the opposite sex.[citation needed]

Canada

During the colonial period, both the French and the British criminalised same-sex sexual relations. Anal sex between males was a capital offence.[71] Post-Confederation, anal sex and acts of "gross indecency" continued to be criminal offences, but were no longer capital offences.[72] Individuals were prosecuted for same-sex sexual activity as late as the 1960s, which led to the federal Parliament amending the Criminal Code in 1969 to provide that anal sex between consenting adults in private (defined as only two persons) was not a criminal offence. In advocating for the law, the then-Minister of Justice, Pierre Trudeau, said: "The state has no place in the bedrooms of the nation."[73]

In 1995, the Supreme Court of Canada held that sexual orientation is a protected personal characteristic under the equality clause of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.[74] The federal Parliament and provincial legislatures began to amend their laws to treat same-sex relations in the same way as opposite-sex relations. Beginning in 2003, the courts in Canada began to rule that excluding same-sex couples from marriage violated the equality clause of the Charter. In 2005, the federal Parliament enacted the Civil Marriage Act, which legalised same-sex marriage across Canada.[75]

Canada has been referred to as the most gay-friendly country in the world, ranked first in the Gay Travel Index chart in 2018, and among the five safest in Forbes magazine in 2019.[76][77] It was also ranked first in Asher & Lyric's LGBTQ+ Danger Index in a 2021 update.[78]

United States

In 1986, the Supreme Court of the United States ruled in Bowers v. Hardwick that a state could criminalize sodomy, but, in 2003, overturned itself in Lawrence v. Texas and thereby legalized homosexual activity throughout the United States of America.

It is only since the 2010s that census forms and political conditions have facilitated the visibility and enumeration of same-sex relationships.[79]

Same-sex marriage in the United States expanded from one state in 2004 to all 50 states in 2015, through various state court rulings, state legislation, direct popular votes (referendums and initiatives), and federal court rulings.

East Asia

In East Asia, same-sex love has been referred to since the earliest recorded history.

Homosexuality in China, known as the passions of the cut peach and various other euphemisms, has been recorded since approximately 600 BCE. Homosexuality was mentioned in many famous works of Chinese literature. The instances of same-sex affection and sexual interactions described in the classical novel Dream of the Red Chamber seem as familiar to observers in the present as do equivalent stories of romances between heterosexual people during the same period. Ming dynasty literature, such as Bian Er Chai (弁而釵/弁而钗), portray homosexual relationships between men as more enjoyable and more "harmonious" than heterosexual relationships.[80] Writings from the Liu Song dynasty by Wang Shunu claimed that homosexuality was as common as heterosexuality in the late 3rd century.[81]

Opposition to homosexuality in China originates in the medieval Tang dynasty (618–907), attributed to the rising influence of Christian and Islamic values,[82] but did not become fully established until the Westernization efforts of the late Qing dynasty and the Republic of China.[83]

South Asia

South Asia has a recorded and verifiable history of homosexuality going back to at least 1200 BC. Hindu medical texts written in India from this period document homosexual acts and attempt to explain the cause in a neutral/scientific manner.[84][85][86] Numerous artworks and literary works from this period also describe homosexuality.[87][88][89][90]

The Pali Cannon, written in Sri Lanka between 600 BC and 100 BC, states that sexual relations, whether of homosexual or of heterosexual nature, is forbidden in the monastic code, and states that any acts of soft homosexual sex (such as masturbation and interfumeral sex) does not entail a punishment but must be confessed to the monastery. These codes apply to monks only and not to the general population.[91][92] The Kama Sutra written in India around 200 AD also described numerous homosexual sex acts positively.[93]

There were no legal restrictions on homosexuality or transsexuality for the general population prior to early modern period and colonialism, however certain dharmic moral codes forbade sexual misconduct (of both heterosexual and homosexual nature) among the upper class of persists and monks, and religious codes of foreign religions such as Christianity and Islam imposed homophobic rules on their populations.[94][95]

Hinduism describes a third gender that is equal to other genders and documentation of the third gender are found in ancient Hindu and Buddhist medical texts.[96] There are certain characters in the Mahabharata who, according to some versions of the epic, change genders, such as Shikhandi, who is sometimes said to be born as a female but identifies as male and eventually marries a woman. Bahuchara Mata is the goddess of fertility, worshipped by hijras as their patroness.

Historians have long argued that pre-colonial Indian society did not criminalise same-sex relationships, nor did it view such relations as immoral or sinful. Hinduism has traditionally portrayed homosexuality as natural and joyful.

Europe

Classical period

The earliest Western documents (in the form of literary works, art objects, and mythographic materials) concerning same-sex relationships are derived from ancient Greece.

In regard to male homosexuality, such documents depict an at times complex understanding in which relationships with women and relationships with adolescent boys could be a part of a normal man's love life. Same-sex relationships were a social institution variously constructed over time and from one city to another. The formal practice, an erotic yet often restrained relationship between a free adult male and a free adolescent, was valued for its pedagogic benefits and as a means of population control, though occasionally blamed for causing disorder. Plato praised its benefits in his early writings[59] but in his late works proposed its prohibition.[97] Aristotle, in the Politics, dismissed Plato's ideas about abolishing homosexuality (2.4); he explains that barbarians like the Celts accorded it a special honor (2.6.6), while the Cretans used it to regulate the population (2.7.5).[98]

Some scholars argue that there are examples of homosexual love in ancient literature, such as Achilles and Patroclus in the Iliad.[99]

Little is known of female homosexuality in antiquity. Sappho, born on the island of Lesbos, was included by later Greeks in the canonical list of nine lyric poets. The adjectives deriving from her name and place of birth (Sapphic and Lesbian) came to be applied to female homosexuality beginning in the 19th century.[100][101] Sappho's poetry centers on passion and love for various personages and both genders. The narrators of many of her poems speak of infatuations and love (sometimes requited, sometimes not) for various females, but descriptions of physical acts between women are few and subject to debate.[102][103]

In Ancient Rome, the young male body remained a focus of male sexual attention, but relationships were between older free men and slaves or freed youths who took the receptive role in sex. The Hellenophile emperor Hadrian is renowned for his relationship with Antinous, but the Christian emperor Theodosius I decreed a law on 6 August 390, condemning passive males to be burned at the stake. Notwithstanding these regulations taxes on brothels with boys available for homosexual sex continued to be collected until the end of the reign of Anastasius I in 518. Justinian, towards the end of his reign, expanded the proscription to the active partner as well (in 558), warning that such conduct can lead to the destruction of cities through the "wrath of God".[citation needed]

Renaissance

During the Renaissance, wealthy cities in northern Italy—Florence and Venice in particular—were renowned for their widespread practice of same-sex love, engaged in by a considerable part of the male population and constructed along the classical pattern of Greece and Rome.[104][105] But even as many of the male population were engaging in same-sex relationships, the authorities, under the aegis of the Officers of the Night court, were prosecuting, fining, and imprisoning a good portion of that population.

From the second half of the 13th century, death was the punishment for male homosexuality in most of Europe.[106]The relationships of socially prominent figures, such as King James I and the Duke of Buckingham, served to highlight the issue, including in anonymously authored street pamphlets: "The world is chang'd I know not how, For men Kiss Men, not Women now;...Of J. the First and Buckingham: He, true it is, his Wives Embraces fled, To slabber his lov'd Ganimede" (Mundus Foppensis, or The Fop Display'd, 1691).

Modern period

Love Letters Between a Certain Late Nobleman and the Famous Mr. Wilson was published in 1723 in England, and is presumed by some modern scholars to be a novel. The 1749 edition of John Cleland's popular novel Fanny Hill includes a homosexual scene, but this was removed in its 1750 edition. Also in 1749, the earliest extended and serious defense of homosexuality in English, Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplified, written by Thomas Cannon, was published, but was suppressed almost immediately. It includes the passage, "Unnatural Desire is a Contradiction in Terms; downright Nonsense. Desire is an amatory Impulse of the inmost human Parts."[107] Around 1785 Jeremy Bentham wrote another defense, but this was not published until 1978.[108] Executions for sodomy continued in the Netherlands until 1803, and in England until 1835, James Pratt and John Smith being the last Englishmen to be so hanged.

To this day, historians are still arguing about the question of the Sexuality of Frederick the Great (1712−1786), which essentially revolves around the taboo of whether the myth of one of the greatest war heroes in world history is allowed to be psychologically deconstructed.

Between 1864 and 1880 Karl Heinrich Ulrichs published a series of 12 tracts, which he collectively titled Research on the Riddle of Man-Manly Love. In 1867, he became the first self-proclaimed homosexual person to speak out publicly in defense of homosexuality when he pleaded at the Congress of German Jurists in Munich for a resolution urging the repeal of anti-homosexual laws.[18] Sexual Inversion by Havelock Ellis, published in 1896, challenged theories that homosexuality was abnormal, as well as stereotypes, and insisted on the ubiquity of homosexuality and its association with intellectual and artistic achievement.[109]

Although medical texts like these (written partly in Latin to obscure the sexual details) were not widely read by the general public, they did lead to the rise of Magnus Hirschfeld's Scientific-Humanitarian Committee, which campaigned from 1897 to 1933 against anti-sodomy laws in Germany, as well as a much more informal, unpublicized movement among British intellectuals and writers, led by such figures as Edward Carpenter and John Addington Symonds. Beginning in 1894 with Homogenic Love, Socialist activist and poet Edward Carpenter wrote a string of pro-homosexual articles and pamphlets, and "came out" in 1916 in his book My Days and Dreams. In 1900, Elisar von Kupffer published an anthology of homosexual literature from antiquity to his own time, Lieblingminne und Freundesliebe in der Weltliteratur.

Middle East

There are a handful of accounts by Arab travelers to Europe during the mid-1800s. Two of these travelers, Rifa'ah al-Tahtawi and Muhammad as-Saffar, show their surprise that the French sometimes deliberately mistranslated love poetry about a young boy, instead referring to a young female, to maintain their social norms and morals.[110]

Israel is considered the most tolerant country in the Middle East and Asia to homosexuals,[111] with Tel Aviv being named "the gay capital of the Middle East"[112] and considered one of the most gay friendly cities in the world.[113] The annual Pride Parade in support of homosexuality takes place in Tel Aviv.[114]

On the other hand, many governments in the Middle East often ignore, deny the existence of, or criminalize homosexuality. Homosexuality is illegal in almost all Muslim countries.[115] Same-sex intercourse officially carries the death penalty in several Muslim nations: Saudi Arabia, Iran, Mauritania, northern Nigeria, and Yemen.[116] Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, during his 2007 speech at Columbia University, asserted that there were no gay people in Iran. However, the probable reason is that they keep their sexuality a secret for fear of government sanction or rejection by their families.[117]

Pre-Islamic period

In ancient Sumer, a set of priests known as gala worked in the temples of the goddess Inanna, where they performed elegies and lamentations.[119]: 285 Gala took female names, spoke in the eme-sal dialect, which was traditionally reserved for women, and appear to have engaged in homosexual intercourse.[120] The Sumerian sign for gala was a ligature of the signs for "penis" and "anus".[120] One Sumerian proverb reads: "When the gala wiped off his ass [he said], 'I must not arouse that which belongs to my mistress [i.e., Inanna].'"[120] In later Mesopotamian cultures, kurgarrū and assinnu were servants of the goddess Ishtar (Inanna's East Semitic equivalent), who dressed in female clothing and performed war dances in Ishtar's temples.[120] Several Akkadian proverbs seem to suggest that they may have also engaged in homosexual intercourse.[120]

In ancient Assyria, homosexuality was present and common; it was also not prohibited, condemned, nor looked upon as immoral or disordered. Some religious texts contain prayers for divine blessings on homosexual relationships. The Almanac of Incantations contained prayers favoring on an equal basis the love of a man for a woman, of a woman for a man, and of a man for man.[citation needed]

South Pacific

In some societies of Melanesia, especially in Papua New Guinea, same-sex relationships were an integral part of the culture until the mid-1900s. The Etoro and Marind-anim for example, viewed heterosexuality as unclean and celebrated homosexuality instead. In some traditional Melanesian cultures a prepubertal boy would be paired with an older adolescent who would become his mentor and who would "inseminate" him (orally, anally, or topically, depending on the tribe) over a number of years in order for the younger to also reach puberty. Many Melanesian societies, however, have become hostile towards same-sex relationships since the introduction of Christianity by European missionaries.[121]

Sexuality and identity

Behavior and desire

The American Psychological Association, the American Psychiatric Association, and the National Association of Social Workers identify sexual orientation as "not merely a personal characteristic that can be defined in isolation. Rather, one's sexual orientation defines the universe of persons with whom one is likely to find the satisfying and fulfilling relationships":[6]

Sexual orientation is commonly discussed as a characteristic of the individual, like biological sex, gender identity, or age. This perspective is incomplete because sexual orientation is always defined in relational terms and necessarily involves relationships with other individuals. Sexual acts and romantic attractions are categorized as homosexual or heterosexual according to the biological sex of the individuals involved in them, relative to each other. Indeed, it is by acting—or desiring to act—with another person that individuals express their heterosexuality, homosexuality, or bisexuality. This includes actions as simple as holding hands with or kissing another person. Thus, sexual orientation is integrally linked to the intimate personal relationships that human beings form with others to meet their deeply felt needs for love, attachment, and intimacy. In addition to sexual behavior, these bonds encompass nonsexual physical affection between partners, shared goals and values, mutual support, and ongoing commitment.[6]

The Kinsey scale, also called the Heterosexual-Homosexual Rating Scale,[122] attempts to describe a person's sexual history or episodes of his or her sexual activity at a given time. It uses a scale from 0, meaning exclusively heterosexual, to 6, meaning exclusively homosexual. In both the Male and Female volumes of the Kinsey Reports, an additional grade, listed as "X", has been interpreted by scholars to indicate asexuality.[123]

Sexual identity and sexual fluidity

Often, sexual orientation and sexual identity are not distinguished, which can impact accurately assessing sexual identity and whether or not sexual orientation is able to change; sexual orientation identity can change throughout an individual's life, and may or may not align with biological sex, sexual behavior or actual sexual orientation.[124][125][126] Sexual orientation is stable and unlikely to change for the vast majority of people, but some research indicates that some people may experience change in their sexual orientation, and this is more likely for women than for men.[127] The American Psychological Association distinguishes between sexual orientation (an innate attraction) and sexual orientation identity (which may change at any point in a person's life).[128]

Same-sex relationships

People with a homosexual orientation can express their sexuality in a variety of ways, and may or may not express it in their behaviors.[5] Many have sexual relationships predominantly with people of their own sex, though some have sexual relationships with those of the opposite sex, bisexual relationships, or none at all (celibacy).[5] Studies have found same-sex and opposite-sex couples to be equivalent to each other in measures of satisfaction and commitment in relationships, that age and sex are more reliable than sexual orientation as a predictor of satisfaction and commitment to a relationship, and that people who are heterosexual or homosexual share comparable expectations and ideals with regard to romantic relationships.[129][130][131]

Coming out of the closet

Coming out (of the closet) is a phrase referring to one's disclosure of their sexual orientation or gender identity, and is described and experienced variously as a psychological process or journey.[132] Generally, coming out is described in three phases. The first phase is that of "knowing oneself", and the realization emerges that one is open to same-sex relations.[133] This is often described as an internal coming out. The second phase involves one's decision to come out to others, e.g. family, friends, or colleagues. The third phase more generally involves living openly as an LGBT person.[134] In the United States today, people often come out during high school or college age. At this age, they may not trust or ask for help from others, especially when their orientation is not accepted in society. Sometimes their own families are not even informed.

According to Rosario, Schrimshaw, Hunter, Braun (2006), "the development of a lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB) sexual identity is a complex and often difficult process. Unlike members of other minority groups (e.g., ethnic and racial minorities), most LGB individuals are not raised in a community of similar others from whom they learn about their identity and who reinforce and support that identity. Rather, LGB individuals are often raised in communities that are either ignorant of or openly hostile toward homosexuality."[125]

Outing is the practice of publicly revealing the sexual orientation of a closeted person.[135] Notable politicians, celebrities, military service people, and clergy members have been outed, with motives ranging from malice to political or moral beliefs. Many commentators oppose the practice altogether,[136] while some encourage outing public figures who use their positions of influence to harm other gay people.[137]

Homoromanticism

Homosexuality is not to be confused with homoromanticism, which is the romantic attraction to the same sex or gender.[138] Most people who are homosexual are also homoromantic, but some people under the asexual spectrum, do not experience, or experience limited homosexuality. For example, homoromantic heterosexuals are described as "romantically attracted to the same or a similar gender while only being sexually attracted to the opposite gender".[139]

Demographics

In their 2016 literature review, Bailey et al. stated that they "expect that in all cultures ... a minority of individuals are sexually predisposed (whether exclusively or non-exclusively) to the same sex." They state that there is no persuasive evidence that the demographics of sexual orientation have varied much across time or place.[10] Men are more likely to be exclusively homosexual than to be equally attracted to both sexes, while the opposite is true for women.[10][11][12]

Surveys in Western cultures find, on average, that about 93% of men and 87% of women identify as completely heterosexual, 4% of men and 10% of women as mostly heterosexual, 0.5% of men and 1% of women as evenly bisexual, 0.5% of men and 0.5% of women as mostly homosexual, and 2% of men and 0.5% of women as completely homosexual.[10] An analysis of 67 studies found that the lifetime prevalence of sex between men (regardless of orientation) was 3–5% for East Asia, 6–12% for South and South East Asia, 6–15% for Eastern Europe, and 6–20% for Latin America.[140] The International HIV/AIDS Alliance estimates that worldwide between 3 and 16% of men have had some form of sex with another man at least once during their lifetime.[141]

According to major studies, 2% to 11% of people have had some form of same-sex sexual contact within their lifetime;[142][143][144][145][146] this percentage rises to 16–21% when either or both same-sex attraction and behavior are reported.[146]

According to the 2021 United States Census, there were about 1.2 million same-sex couple households.[147] In the United States, according to a report by The Williams Institute in April 2011, 3.5% or approximately 9 million of the adult population identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual.[148] A 2013 study by the CDC, in which over 34,000 Americans were interviewed, puts the percentage of self-identifying lesbians and gay men at 1.6%, and of bisexuals at 0.7%.[149]

In October 2012, Gallup started conducting annual surveys to study the demographics of LGBT people, determining that 3.4% (±1%) of adults identified as LGBT in the United States.[150] It was the nation's largest poll on the issue at the time.[151][152] In 2017, the percentage was estimated to have risen to 4.5% of adults, with the increase largely driven by millennials. The poll attributes the rise to greater willingness of younger people to reveal their sexual identity.[153]

Measuring the prevalence of homosexuality presents difficulties. It is necessary to consider the measuring criteria that are used, the cutoff point and the time span taken to define a sexual orientation.[18] Many people, despite having same-sex attractions, may be reluctant to identify themselves as gay or bisexual. The research must measure some characteristic that may or may not be defining of sexual orientation. The number of people with same-sex desires may be larger than the number of people who act on those desires, which in turn may be larger than the number of people who self-identify as gay, lesbian, or bisexual.[154]

Reliable data as to the size of the gay and lesbian population are of value in informing public policy.[154] For example, demographics are of help in calculating the costs and benefits of domestic partnership benefits, of the impact of legalizing gay adoption, and of the impact of the U.S. military's former Don't Ask Don't Tell policy.[154] Further, knowledge of the size of the "gay and lesbian population holds promise for helping social scientists understand a wide array of important questions—questions about the general nature of labor market choices, accumulation of human capital, specialization within households, discrimination, and decisions about geographic location."[154]

Psychology

The American Psychological Association, the American Psychiatric Association, and the National Association of Social Workers state:

In 1952, when the American Psychiatric Association published its first Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, homosexuality was included as a disorder. Almost immediately, however, that classification began to be subjected to critical scrutiny in research funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. That study and subsequent research consistently failed to produce any empirical or scientific basis for regarding homosexuality as a disorder or abnormality, rather than a normal and healthy sexual orientation. As results from such research accumulated, professionals in medicine, mental health, and the behavioral and social sciences reached the conclusion that it was inaccurate to classify homosexuality as a mental disorder and that the DSM classification reflected untested assumptions based on once-prevalent social norms and clinical impressions from unrepresentative samples comprising patients seeking therapy and individuals whose conduct brought them into the criminal justice system.

In recognition of the scientific evidence,[155] the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from the DSM in 1973, stating that "homosexuality per se implies no impairment in judgment, stability, reliability, or general social or vocational capabilities." After thoroughly reviewing the scientific data, the American Psychological Association adopted the same position in 1975, and urged all mental health professionals "to take the lead in removing the stigma of mental illness that has long been associated with homosexual orientations." The National Association of Social Workers has adopted a similar policy.

Thus, mental health professionals and researchers have long recognized that being homosexual poses no inherent obstacle to leading a happy, healthy, and productive life, and that the vast majority of gay and lesbian people function well in the full array of social institutions and interpersonal relationships.[6]

The consensus of research and clinical literature demonstrates that same-sex sexual and romantic attractions, feelings, and behaviors are normal and positive variations of human sexuality.[156] There is now a large body of research evidence that indicates that being gay, lesbian or bisexual is compatible with normal mental health and social adjustment.[13] The World Health Organization's ICD-9 (1977) listed homosexuality as a mental illness; it was removed from the ICD-10, endorsed by the Forty-third World Health Assembly on 17 May 1990.[157][158][159] Like the DSM-II, the ICD-10 added ego-dystonic sexual orientation to the list, which refers to people who want to change their gender identities or sexual orientation because of a psychological or behavioral disorder (F66.1). The Chinese Society of Psychiatry removed homosexuality from its Chinese Classification of Mental Disorders in 2001 after five years of study by the association.[160] According to the Royal College of Psychiatrists "This unfortunate history demonstrates how marginalisation of a group of people who have a particular personality feature (in this case homosexuality) can lead to harmful medical practice and a basis for discrimination in society."[13]

Most lesbian, gay, and bisexual people who seek psychotherapy do so for the same reasons as heterosexual people (stress, relationship difficulties, difficulty adjusting to social or work situations, etc.); their sexual orientation may be of primary, incidental, or no importance to their issues and treatment. Whatever the issue, there is a high risk for anti-gay bias in psychotherapy with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients.[161] Psychological research in this area has been relevant to counteracting prejudicial ("homophobic") attitudes and actions, and to the LGBT rights movement generally.[162]

The appropriate application of affirmative psychotherapy is based on the following scientific facts:[156]

- Same-sex sexual attractions, behavior, and orientations per se are normal and positive variants of human sexuality; in other words, they are not indicators of mental or developmental disorders.

- Homosexuality and bisexuality are stigmatized, and this stigma can have a variety of negative consequences (e.g., minority stress) throughout the life span (D'Augelli & Patterson, 1995; DiPlacido, 1998; Herek & Garnets, 2007; Meyer, 1995, 2003).

- Same-sex sexual attractions and behavior can occur in the context of a variety of sexual orientations and sexual orientation identities (Diamond, 2006; Hoburg et al., 2004; Rust, 1996; Savin-Williams, 2005).

- Gay men, lesbians, and bisexual individuals can live satisfying lives as well as form stable, committed relationships and families that are equivalent to heterosexual relationships in essential respects (APA, 2005c; Kurdek, 2001, 2003, 2004; Peplau & Fingerhut, 2007).

- There are no empirical studies or peer-reviewed research that support theories attributing same-sex sexual orientation to family dysfunction or trauma (Bell et al., 1981; Bene, 1965; Freund & Blanchard, 1983; Freund & Pinkava, 1961; Hooker, 1969; McCord et al., 1962; D. K. Peters & Cantrell, 1991; Siegelman, 1974, 1981; Townes et al., 1976).

Sexual orientation change efforts

There are no studies of adequate scientific rigor that conclude that sexual orientation change efforts work to change a person's sexual orientation. Those efforts have been controversial due to tensions between the values held by some faith-based organizations, on the one hand, and those held by LGBT rights organizations and professional and scientific organizations and other faith-based organizations, on the other.[16] The longstanding consensus of the behavioral and social sciences and the health and mental health professions is that homosexuality per se is a normal and positive variation of human sexual orientation, and therefore not a mental disorder.[16] The American Psychological Association says that "most people experience little or no sense of choice about their sexual orientation".[163]Some individuals and groups have promoted the idea of homosexuality as symptomatic of developmental defects or spiritual and moral failings and have argued that sexual orientation change efforts, including psychotherapy and religious efforts, could alter homosexual feelings and behaviors. Many of these individuals and groups appeared to be embedded within the larger context of conservative religious political movements that have supported the stigmatization of homosexuality on political or religious grounds.[16]

No major mental health professional organization has sanctioned efforts to change sexual orientation and virtually all of them have adopted policy statements cautioning the profession and the public about treatments that purport to change sexual orientation. These include the American Psychiatric Association, American Psychological Association, American Counseling Association, National Association of Social Workers in the U.S.,[164] the Royal College of Psychiatrists,[165] and the Australian Psychological Society.[166] The American Psychological Association and the Royal College of Psychiatrists expressed concerns that the positions espoused by NARTH are not supported by the science and create an environment in which prejudice and discrimination can flourish.[165][167]

The American Psychiatric Association says "individuals maybe become aware at different points in their lives that they are heterosexual, gay, lesbian, or bisexual" and "opposes any psychiatric treatment, such as 'reparative' or 'conversion' therapy, which is based upon the assumption that homosexuality per se is a mental disorder, or based upon a prior assumption that the patient should change his/her homosexual orientation". They do, however, encourage gay affirmative psychotherapy.[168] Similarly, the American Psychological Association is doubtful about the effectiveness and side-effect profile of sexual orientation change efforts, including conversion therapy.[169]

The American Psychological Association "encourages mental health professionals to avoid misrepresenting the efficacy of sexual orientation change efforts by promoting or promising change in sexual orientation when providing assistance to individuals distressed by their own or others' sexual orientation and concludes that the benefits reported by participants in sexual orientation change efforts can be gained through approaches that do not attempt to change sexual orientation".[16]

Causes

Although scientists favor biological models for the cause of sexual orientation,[7] they do not believe that the development of sexual orientation is the result of any one factor. They generally believe that it is determined by a complex interplay of biological and environmental factors, and is shaped at an early age.[5] There is considerably more evidence supporting nonsocial, biological causes of sexual orientation than social ones, especially for males.[10][8] There is no substantive evidence which suggests parenting or early childhood experiences play a role with regard to sexual orientation.[13] Scientists do not believe that sexual orientation is a choice.[7][9]

The American Academy of Pediatrics stated in Pediatrics in 2004:

There is no scientific evidence that abnormal parenting, sexual abuse, or other adverse life events influence sexual orientation. Current knowledge suggests that sexual orientation is usually established during early childhood.[7][170]

The American Psychological Association, American Psychiatric Association, and National Association of Social Workers stated in 2006:

Currently, there is no scientific consensus about the specific factors that cause an individual to become heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual—including possible biological, psychological, or social effects of the parents' sexual orientation. However, the available evidence indicates that the vast majority of lesbian and gay adults were raised by heterosexual parents and the vast majority of children raised by lesbian and gay parents eventually grow up to be heterosexual.[5]

"Gay genes"

Despite numerous attempts, no "gay gene" has been identified. However, there is substantial evidence for a genetic basis of homosexuality, especially in males, based on twin studies; some association with regions of Chromosome 8, the Xq28 locus on the X chromosome, and other sites across many chromosomes.[171]

| Chromosome | Location | Associated genes | Sex | Study1 | Origin | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X chromosome | Xq28 | Speculative | male only | Hamer et al. 1993 | genetic | |

| Chromosome 1 | 1p36 | both sexes | Ellis et al. 2008 | potential genetic linkage2 | ||

| Chromosome 4 | 4p14 | female only | Ganna et al. 2019 | |||

| Chromosome 7 | 7q31 | both sexes | Ganna et al. 2019 | |||

| Chromosome 8 | 8p12 | NKAIN3 | male only | Mustanski et al. 2005 | ||

| Chromosome 9 | 9q34 | ABO | both sexes | Ellis et al. 2008 | potential genetic linkage2 | |

| Chromosome 11 | 11q12 | OR51A7 (speculative) | male only | Ganna et al. 2019 | Olfactory system in mating preferences | |

| Chromosome 12 | 12q21 | both sexes | Ganna et al. 2019 | |||

| Chromosome 13 | 13q31 | SLITRK6 | male only | Sanders et al. 2017 | Diencephalon-associated gene | |

| Chromosome 14 | 14q31 | TSHR | male only | Sanders et al. 2017 | ||

| Chromosome 15 | 15q21 | TCF12 | male only | Ganna et al. 2019 | ||

1Reported primary studies are not conclusive evidence of any relationship. 2Not believed to be causal. | ||||||

Starting in the 2010s, potential epigenetic factors have become a topic of increased attention in genetic research on sexual orientation. A study presented at the ASHG 2015 Annual Meeting found that the methylation pattern in nine regions of the genome appeared very closely linked to sexual orientation, with a resulting algorithm using the methylation pattern to predict the sexual orientation of a control group with almost 70% accuracy.[172][173]

Research into the causes of homosexuality plays a role in political and social debates and also raises concerns about genetic profiling and prenatal testing.[174]

Evolutionary perspectives

Since homosexuality tends to lower reproductive success, and since there is considerable evidence that human sexual orientation is genetically influenced, it is unclear how it is maintained in the population at a relatively high frequency.[175] There are many possible explanations, such as genes predisposing to homosexuality also conferring advantage in heterosexuals, a kin selection effect, social prestige, and more.[176] A 2009 study also suggested a significant increase in fecundity in the females related to homosexual people from the maternal line (but not in those related from the paternal one).[177]

Parenting

Scientific research has been generally consistent in showing that lesbian and gay parents are as fit and capable as heterosexual parents, and their children are as psychologically healthy and well-adjusted as children reared by heterosexual parents.[178][179][180] According to scientific literature reviews, there is no evidence to the contrary.[6][181][182][183][184]

Some research has examined the sexual orientation of children raised by same-sex couples. A 2005 review of studies by Charlotte J. Patterson for the American Psychological Association did not find higher rates of homosexuality among the children of lesbian or gay parents.[185] According to Bailey et al. 2016, available data do not suggest higher rates of non-heterosexuality among children of same-sex couples. However, they state that even given a modest heritability of sexual orientation, it would be expected that biological children of non-heterosexuals would be more likely to have a non-heterosexual orientation due to genes alone.[186] According to a 2011 data, 80% of the children being raised by same-sex couples in the US are their own biological children.[187] In addition, accepting social environments may facilitate the open expression of individuals same-sex attraction.[188] Thus, it is necessary to control for various confounding factors.[186] One study by Bailey et al. found that the sexual orientation of sons raised by gay men was not related to length of time they had lived with their fathers (social theories of homosexuality would predict sons who lived with a gay father the longest would be most likely to be gay).[189] The Bailey et al. review conclude that social environmental influence on male sexual orientation is not well supported, while it remains more plausible for female sexual orientation.[188]

Health

Physical

The terms "men who have sex with men" (MSM) and "women who have sex with women" (WSW) refer to people who engage in sexual activity with others of the same sex regardless of how they identify themselves—as many choose not to accept social identities as lesbian, gay and bisexual.[190][191][192][193][194] These terms are often used in medical literature and social research to describe such groups for study, without needing to consider the issues of sexual self-identity. The terms are seen as problematic by some, however, because they "obscure social dimensions of sexuality; undermine the self-labeling of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people; and do not sufficiently describe variations in sexual behavior".[195]

In contrast to its benefits, sexual behavior can be a disease vector. Safe sex is a relevant harm reduction philosophy.[196] Many countries currently prohibit men who have sex with men from donating blood; the policy of the United States Food and Drug Administration states that "they are, as a group, at increased risk for HIV, hepatitis B and certain other infections that can be transmitted by transfusion."[197]

Public health

These safer sex recommendations are agreed upon by public health officials for women who have sex with women to avoid sexually transmitted infections (STIs):

- Avoid contact with a partner's menstrual blood and with any visible genital lesions.

- Cover sex toys that penetrate more than one person's vagina or anus with a new condom for each person; consider using different toys for each person.

- Use a barrier (e.g., latex sheet, dental dam, cut-open condom, plastic wrap) during oral sex.

- Use latex or vinyl gloves and lubricant for any manual sex that might cause bleeding.[198]

These safer sex recommendations are agreed upon by public health officials for men who have sex with men to avoid sexually transmitted infections:

- Avoid contact with a partner's bodily fluids and with any visible genital lesions.

- Use condoms for anal and oral sex.

- Use a barrier (e.g., latex sheet, dental dam, cut-open condom) during anal–oral sex.

- Cover sex toys that penetrate more than one person's anus with a new condom for each person; consider using different toys for each person.

- Use latex or vinyl gloves and lubricant for any manual sex that might cause bleeding.[199][200]

Mental

When it was first described in medical literature, homosexuality was often approached from a view that sought to find an inherent psychopathology as its root cause. Much literature on mental health and homosexual patients centered on their depression, substance abuse, and suicide. Although these issues exist among people who are non-heterosexual, discussion about their causes shifted after homosexuality was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) in 1973. Instead, social ostracism, legal discrimination, internalization of negative stereotypes, and limited support structures indicate factors homosexual people face in Western societies that often adversely affect their mental health.[201]Stigma, prejudice, and discrimination stemming from negative societal attitudes toward homosexuality lead to a higher prevalence of mental health disorders among lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals compared to their heterosexual peers.[202] Evidence indicates that the liberalization of these attitudes is associated with a decrease in such mental health risks among younger sexual minority people.[203]

Gay and lesbian youth

Gay and lesbian youth bear an increased risk of suicide, substance abuse, school problems, and isolation because of a "hostile and condemning environment, verbal and physical abuse, rejection and isolation from family and peers".[204] Further, LGBT youths are more likely to report psychological and physical abuse by parents or caretakers, and more sexual abuse. Suggested reasons for this disparity are that (1) LGBT youths may be specifically targeted on the basis of their perceived sexual orientation or gender non-conforming appearance, and (2) that "risk factors associated with sexual minority status, including discrimination, invisibility, and rejection by family members...may lead to an increase in behaviors that are associated with risk for victimization, such as substance abuse, sex with multiple partners, or running away from home as a teenager."[205]

Crisis centers in larger cities and information sites on the Internet have arisen to help youth and adults.[206] The Trevor Project, a suicide prevention helpline for gay youth, was established following the 1998 airing on HBO of the Academy Award winning short film Trevor.[207]

Law and politics

Legality

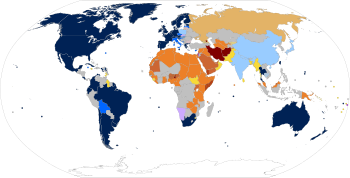

| Same-sex intercourse illegal. Penalties: | |

Prison; death not enforced | |

Death under militias | Prison, with arrests or detention |

Prison, not enforced1 | |

| Same-sex intercourse legal. Recognition of unions: | |

Extraterritorial marriage2 | |

Limited foreign | Optional certification |

None | Restrictions of expression |

Restrictions of association with arrest or detention | |

1No imprisonment in the past three years or moratorium on law.

2Marriage not available locally. Some jurisdictions may perform other types of partnerships.

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT rights |

|---|

|

| Lesbian ∙ Gay ∙ Bisexual ∙ Transgender |

Most nations do not prohibit consensual sex between unrelated persons above the local age of consent. Some jurisdictions further recognize identical rights, protections, and privileges for the family structures of same-sex couples, including marriage. Some countries and jurisdictions mandate that all individuals restrict themselves to heterosexual activity and disallow homosexual activity via sodomy laws. Offenders can face the death penalty in Islamic countries and jurisdictions ruled by sharia. There are, however, often significant differences between official policy and real-world enforcement.

Although homosexual acts were decriminalized in some parts of the Western world, such as Poland in 1932, Denmark in 1933, Sweden in 1944, and England and Wales in 1967, it was not until the mid-1970s that the gay community first began to achieve limited civil rights in some developed countries. A turning point was reached in 1973 when the American Psychiatric Association, which previously listed homosexuality in the DSM-I in 1952, removed homosexuality in the DSM-II, in recognition of scientific evidence.[6] In 1977, Quebec became the first state-level jurisdiction in the world to prohibit discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. During the 1980s and 1990s, several developed countries enacted laws decriminalizing homosexual behavior and prohibiting discrimination against lesbian and gay people in employment, housing, and services. On the other hand, many countries today in the Middle East and Africa, as well as several countries in Asia, the Caribbean and the South Pacific, outlaw homosexuality. In 2013, the Supreme Court of India upheld Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code,[208] but in 2018 overturned itself and legalized homosexual activity in India.[209] Ten countries or jurisdictions, all of which are predominantly Islamic and governed according to sharia law, have imposed the death penalty for homosexuality. These include Afghanistan, Iran, Brunei, Mauritania, Saudi Arabia, and several regions in Nigeria and Jubaland.[210][211][212][213][214][215]

Laws against sexual orientation discrimination

United States

- Employment discrimination refers to discriminatory employment practices such as bias in hiring, promotion, job assignment, termination, and compensation, and various types of harassment. In the United States there is "very little statutory, common law, and case law establishing employment discrimination based upon sexual orientation as a legal wrong."[216] Some exceptions and alternative legal strategies are available. President Bill Clinton's Executive Order 13087 (1998) prohibits discrimination based on sexual orientation in the competitive service of the federal civilian workforce,[217] and federal non-civil service employees may have recourse under the Due Process Clause of the U.S. Constitution.[218] Private sector workers may have a Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 action under a quid pro quo sexual harassment theory,[219] a "hostile work environment" theory,[220] a sexual stereotyping theory,[221] or others.[216]

- Housing discrimination refers to discrimination against potential or current tenants by landlords. In the United States, there is no federal law against such discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation or gender identity, but at least thirteen states and many major cities have enacted laws prohibiting it.[222]

- Hate crimes (also known as bias crimes) are crimes motivated by homophobia, or bias against an identifiable social group, usually groups defined by race (human classification), religion, sexual orientation, disability, ethnicity, nationality, age, gender, gender identity, or political affiliation. In the United States, 45 states and the District of Columbia have statutes criminalizing various types of bias-motivated violence or intimidation (the exceptions are AZ, GA, IN, SC, and WY). Each of these statutes covers bias on the basis of race, religion, and ethnicity; 32 of them cover sexual orientation, 28 cover gender, and 11 cover transgender/gender-identity.[223] In October 2009, the Matthew Shepard and James Byrd Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, which "...gives the Justice Department the power to investigate and prosecute bias-motivated violence where the perpetrator has selected the victim because of the person's actual or perceived race, color, religion, national origin, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or disability", was signed into law and makes hate crime based on sexual orientation, amongst other offenses, a federal crime in the United States.[224]

European Union

In the European Union, discrimination of any type based on sexual orientation or gender identity is illegal under the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.[225]

Political activism

This section needs additional citations for verification. (January 2018) |

Since the 1960s, many LGBT people in the West, particularly those in major metropolitan areas, have developed a so-called gay culture. To many,[who?] gay culture is exemplified by the gay pride movement, with annual parades and displays of rainbow flags. Yet not all LGBT people choose to participate in "queer culture", and many gay men and women specifically decline to do so. To some[who?] it seems to be a frivolous display, perpetuating gay stereotypes.

With the outbreak of AIDS in the early 1980s, many LGBT groups and individuals organized campaigns to promote efforts in AIDS education, prevention, research, patient support, and community outreach, as well as to demand government support for these programs.

The death toll wrought by the AIDS epidemic at first seemed to slow the progress of the gay rights movement, but in time it galvanized some parts of the LGBT community into community service and political action, and challenged the heterosexual community to respond compassionately. Major American motion pictures from this period that dramatized the response of individuals and communities to the AIDS crisis include An Early Frost (1985), Longtime Companion (1990), And the Band Played On (1993), Philadelphia (1993), and Common Threads: Stories from the Quilt (1989).

Publicly gay politicians have attained numerous government posts, even in countries that had sodomy laws in their recent past. Examples include Guido Westerwelle, Germany's Vice-Chancellor; Pete Buttigieg, the United States Secretary of Transportation, Peter Mandelson, a British Labour Party cabinet minister and Per-Kristian Foss, formerly Norwegian Minister of Finance.

LGBT movements are opposed by a variety of individuals and organizations. Some social conservatives believe that all sexual relationships with people other than an opposite-sex spouse undermine the traditional family[226] and that children should be reared in homes with both a father and a mother.[227][228] Some argue that gay rights may conflict with individuals' freedom of speech,[229][230] religious freedoms in the workplace,[231][232] the ability to run churches,[233] charitable organizations[234][235] and other religious organizations[236] in accordance with one's religious views, and that the acceptance of homosexual relationships by religious organizations might be forced through threatening to remove the tax-exempt status of churches whose views do not align with those of the government.[237][238][239][240] Some critics charge that political correctness has led to the association of sex between males and HIV being downplayed.[241]

Military service

Policies and attitudes toward gay and lesbian military personnel vary widely around the world. Some countries allow gay men, lesbians, and bisexual people to serve openly and have granted them the same rights and privileges as their heterosexual counterparts. Many countries neither ban nor support LGB service members. A few countries continue to ban homosexual personnel outright.[citation needed]

Most Western military forces have removed policies excluding sexual minority members. Of the 26 countries that participate militarily in NATO, more than 20 permit openly gay, lesbian and bisexual people to serve. Of the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, three (United Kingdom, France and United States) do so. The other two generally do not: China bans gay and lesbian people outright, Russia excludes all gay and lesbian people during peacetime but allows some gay men to serve in wartime (see below). Israel is the only country in the Middle East region that allows openly LGB people to serve in the military.[citation needed]

According to the American Psychological Association, empirical evidence fails to show that sexual orientation is germane to any aspect of military effectiveness including unit cohesion, morale, recruitment and retention.[242] Sexual orientation is irrelevant to task cohesion, the only type of cohesion that critically predicts the team's military readiness and success.[243]

Society and sociology

Public opinion

Societal acceptance of non-heterosexual orientations such as homosexuality is lowest in Asian, African and Eastern European countries,[244][245] and is highest in Western Europe, Australia, and the Americas. Western society has become increasingly accepting of homosexuality since the 1990s. In 2017, Professor Amy Adamczyk contended that these cross-national differences in acceptance can be largely explained by three factors: the relative strength of democratic institutions, the level of economic development, and the religious context of the places where people live.[246]

Non-acceptance of the sexual identity of LGBTQ+ by the official laws of some countries, as well as the lack of teaching correct behavior towards homosexuals, has led to the formation of societal misconceptions about this group.[citation needed]

These stereotypical beliefs of the people against the LGBTQ+ community have caused rejection and discriminatory behavior against them. Various researches have shown that LGBTQ+ people in societies that do not recognize homosexuality as a sexual identity of such group feel insecure, psychological pressure and isolated from the society.[247][248][249][250] Kameel Ahmady, an anthropologist and social researcher, who along with team conducted a fieldwork study in Iran with the aim of understanding the attitude of the Iranian LGBTQ+ community towards their position in the Iranian society, believes that the traditional and religious structure of the society, along with the legal obstacles and restrictions, has caused this groups to not to be able to express themselves and often suppressing their gender identity.[251][252][253][254][255][256] Legal restrictions such as imprisonment, fear of execution, not been to allowed employment in governmental jobs, along with informal restrictions such as sexual abuse in society, exclusion from family and social groups, verbal and public humiliation, etc., have all made life difficult for the LGBTQ+ groups.[257][258][259][252]

Relationships

In 2006, the American Psychological Association, American Psychiatric Association and National Association of Social Workers stated in an amicus brief presented to the Supreme Court of California: "Gay men and lesbians form stable, committed relationships that are equivalent to heterosexual relationships in essential respects. The institution of marriage offers social, psychological, and health benefits that are denied to same-sex couples. By denying same-sex couples the right to marry, the state reinforces and perpetuates the stigma historically associated with homosexuality. Homosexuality remains stigmatized, and this stigma has negative consequences. California's prohibition on marriage for same-sex couples reflects and reinforces this stigma". They concluded: "There is no scientific basis for distinguishing between same-sex couples and heterosexual couples with respect to the legal rights, obligations, benefits, and burdens conferred by civil marriage."[6]

Religion

Though the relationship between homosexuality and religion is complex, current authoritative bodies and doctrines of the world's largest religions view homosexual behaviour negatively.[citation needed] This can range from quietly discouraging homosexual activity, to explicitly forbidding same-sex sexual practices among adherents and actively opposing social acceptance of homosexuality. Some teach that homosexual desire itself is sinful,[260] others state that only the sexual act is a sin,[261] while others are completely accepting of gays and lesbians.[262] Some claim that homosexuality can be overcome through religious faith and practice. On the other hand, voices exist within many of these religions that view homosexuality more positively, and liberal religious denominations may bless same-sex marriages. Some view same-sex love and sexuality as sacred, and a mythology of same-sex love can be found throughout the world.[263]

Discrimination

Gay bullying

Gay bullying can be the verbal or physical abuse against a person who is perceived by the aggressor to be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or generally queer, including persons who are actually heterosexual or of non-specific or unknown sexual orientation. In the US, teenage students heard anti-gay slurs such as "homo", "faggot" and "sissy" about 26 times a day on average, or once every 14 minutes, according to a 1998 study by Mental Health America (formerly National Mental Health Association).[264]

Heterosexism and homophobia

In many cultures, homosexual people are frequently subject to prejudice and discrimination. A 2011 Dutch study concluded that 49% of Holland's youth and 58% of youth foreign to the country reject homosexuality.[265] Similar to other minority groups they can also be subject to stereotyping. These attitudes tend to be due to forms of homophobia and heterosexism (negative attitudes, bias, and discrimination in favor of opposite-sex sexuality and relationships). Heterosexism can include the presumption that everyone is heterosexual or that opposite-sex attractions and relationships are the norm and therefore superior. Homophobia is a fear of, aversion to, or discrimination against homosexual people. It manifests in different forms, and a number of different types have been postulated, among which are internalized homophobia, social homophobia, emotional homophobia, rationalized homophobia, and others.[266] Similar is lesbophobia (specifically targeting lesbians) and biphobia (against bisexual people). When such attitudes manifest as crimes they are often called hate crimes and gay bashing.

Negative stereotypes characterize LGB people as less romantically stable and more likely to abuse children, but there is no scientific basis to such assertions. Gay men and lesbians form stable, committed relationships that are equivalent to heterosexual relationships in essential respects.[6] Sexual orientation does not affect the likelihood that people will abuse children.[267][268][269] Claims that there is scientific evidence to support an association between being gay and being a pedophile are based on misuses of those terms and misrepresentation of the actual evidence.[268]

Violence against homosexuals

In the United States, the FBI reported that 20.4% of hate crimes reported to law enforcement in 2011 were based on sexual orientation bias. 56.7% of these crimes were based on bias against homosexual men. 11.1% were based on bias against homosexual women. 29.6% were based on anti-homosexual bias without regard to gender.[270] The 1998 murder of Matthew Shepard, a gay student, is a notorious such incident in the U.S. LGBT people, especially lesbians, may become the victims of "corrective rape", a violent crime with the supposed aim of making them heterosexual. In certain parts of the world, LGBT people are also at risk of "honor killings" perpetrated by their families or relatives.[271][272][273]

In Morocco, a constitutional monarchy following Islamic laws, homosexual acts are a punishable offence. With a population hostile towards LGBT people, the country has witnessed public demonstrations against homosexuals, public denunciations of presumed homosexual individuals, as well as violent intrusions in private homes. The community in the country is exposed to additional risk of prejudice, social rejection and violence, with a greater impossibility of obtaining protection even from the police.[274]

Homosexual behavior in other animals

Homosexual and bisexual behaviors occur in a number of other animal species. Such behaviors include sexual activity, courtship, affection, pair bonding, and parenting,[22] and are widespread; a 1999 review by researcher Bruce Bagemihl shows that homosexual behavior has been documented in about 500 species, ranging from primates to gut worms.[22][23] Animal sexual behavior takes many different forms, even within the same species. The motivations for and implications of these behaviors have yet to be fully understood, since most species have yet to be fully studied.[276] According to Bagemihl, "the animal kingdom [does] it with much greater sexual diversity—including homosexual, bisexual and nonreproductive sex—than the scientific community and society at large have previously been willing to accept".[277] According to Bailey et al., humans and domestic sheep are the only animals conclusively proven to exhibit a homosexual orientation.[10]

A review paper by N. W. Bailey and Marlene Zuk looking into studies of same-sex sexual behaviour in animals challenges the view that such behaviour lowers reproductive success, citing several hypotheses about how same-sex sexual behavior might be adaptive; these hypotheses vary greatly among different species.[278]

In October 2023, biologists reported studies of animals (over 1,500 different species) that found same-sex behavior (not necessarily related to human orientation) may help improve social stability by reducing conflict within the groups studied.[279][280]

See also

- LGBT rights by country or territory

- LGBT rights at the United Nations

- Anti-LGBT rhetoric

- Biology and sexual orientation

- Fraternal birth order and male sexual orientation

- Gender dysphoria

- Hate speech

- Human male sexuality

- List of nonfiction books about homosexuality

- List of gay, lesbian or bisexual people

- Religion and sexuality

- Riddle homophobia scale

- Sexual practices between men

- Sexual practices between women

- Sexuality and gender identity-based cultures

- LGBT music

Notes

- ^ "Definitions Related to Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity in APA Documents" (PDF). American Psychological Association. 2015. p. 6. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 April 2022. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

Sexual orientation refers to the sex of those to whom one is sexually and romantically attracted. ... [It is] one's enduring sexual attraction to male partners, female partners, or both. Sexual orientation may be heterosexual, samesex (gay or lesbian), or bisexual. ... A person may be attracted to men, women, both, neither, or to people who are genderqueer, androgynous, or have other gender identities. Individuals may identify as lesbian, gay, heterosexual, bisexual, queer, pansexual, or asexual, among others. ... Categories of sexual orientation typically have included attraction to members of one's own sex (gay men or lesbians), attraction to members of the other sex (heterosexuals), and attraction to members of both sexes (bisexuals). While these categories continue to be widely used, research has suggested that sexual orientation does not always appear in such definable categories and instead occurs on a continuum .... Some people identify as pansexual or queer in terms of their sexual orientation, which means they define their sexual orientation outside of the gender binary of 'male' and 'female' only.

- ^ Eric B. Shiraev; David A. Levy (2016). Cross-Cultural Psychology: Critical Thinking and Contemporary Applications, Sixth Edition. Taylor & Francis. p. 216. ISBN 978-1134871315. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.

Sexual orientation refers to romantic or sexual attraction to people of a specific sex or gender. ... Heterosexuality, along with bisexuality and homosexuality are at least three main categories of the continuum of sexual orientation. ... Homosexuality is a romantic or sexual attraction between persons of the same sex or gender.

- ^ James R. Lehman; Kristine Diaz; Henry Ng; Elizabeth M. Petty; Meena Thatikunta; Kristen Eckstrand, eds. (2019). The Equal Curriculum: The Student and Educator Guide to LGBTQ Health. Springer Nature. p. 5. ISBN 978-3030240257. Archived from the original on 24 November 2021. Retrieved 15 September 2021.