Луизиана

Луизиана

| |

|---|---|

| Штат Луизиана Штат Луизиана ( французский ) Штат Луизиана ( испанский ) Létat de Lalwizyàn ( луизианский креольский ) | |

Прозвища :

| |

| Девиз(ы) : Союз, Справедливость, Уверенность | |

Гимн:

| |

Карта Соединенных Штатов с выделенной Луизианой | |

| Страна | Соединенные Штаты |

| До государственности | территории Орлеана и Луизианы Покупка |

| Принят в Союз | 30 апреля 1812 г ) |

| Капитал | Батон-Руж |

| Крупнейший город | Новый Орлеан [ 1 ] [ 2 ] [ 3 ] |

| Самый большой округ или его эквивалент | Приход Восточный Батон-Руж |

| Крупнейшие метро и городские районы | Большой Новый Орлеан |

| Правительство | |

| • Губернатор | Джефф Лэндри ( R ) |

| • Вице-губернатор | Билли Нунгессер (справа) |

| Законодательная власть | Законодательная власть |

| • Верхняя палата | Сенат |

| • Нижняя палата | Палата представителей |

| судебная власть | Верховный суд Луизианы |

| Сенаторы США | Билл Кэссиди (справа) Джон Кеннеди (справа) |

| Делегация Палаты представителей США | 5 республиканцев 1 демократ ( список ) |

| Область | |

| • Общий | 52,124 [ 4 ] [ 5 ] квадратных миль (135 000 км²) 2 ) |

| • Земля | 43 204 квадратных миль (111 898 км ) 2 ) |

| • Вода | 8920 квадратных миль (23102 км²) 2 ) 15% |

| • Классифицировать | 31-е |

| Размеры | |

| • Длина | 380 миль (610 км) |

| • Ширина | 130 миль (231 км) |

| Высота | 100 футов (30 м) |

| Самая высокая точка | 535 футов (163 м) |

| Самая низкая высота | −8 футов (−2,5 м) |

| Население (2020) | |

| • Общий | 4,657,757 |

| • Классифицировать | 25-е |

| • Плотность | 106,9/кв. миль (41,3/км) 2 ) |

| • Классифицировать | 29-е |

| • Средний доход домохозяйства | $49,973 [ 5 ] |

| • Рейтинг дохода | 47-е место |

| Демонимы | Луизианский Луизиана (каджунское или креольское наследие) Луизиано (испанские потомки во время правления Новой Испании ) |

| Язык | |

| • Официальный язык | Ничего не предусмотрено конституцией; Луизианский французский (особый статус в соответствии с CODOFIL ) |

| • Разговорный язык | По состоянию на 2010 год [ 7 ]

|

| Часовой пояс | UTC– 06:00 ( центральное время ) |

| • Лето ( летнее время ) | UTC– 05:00 ( CDT ) |

| Аббревиатура USPS | ТО |

| Код ISO 3166 | США-Лос-Анджелес |

| Традиционная аббревиатура | . |

| Широта | От 28° 56′ с.ш. до 33° 01′ с.ш. |

| Долгота | От 88° 49′ з.д. до 94° 03′ з.д. |

| Веб-сайт | Луизиана |

| Список государственных символов | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Живые знаки отличия | |

| Птица | Коричневый пеликан |

| Порода собаки | Леопардовая собака Катахула |

| Рыба | Краппи |

| Цветок | Магнолия |

| Насекомое | медоносная пчела |

| млекопитающее | Черный медведь |

| Рептилия | Аллигатор |

| Дерево | Лысый кипарис |

| Неодушевленные знаки различия | |

| Напиток | Кофе |

| Ископаемое | Окаменевшая пальма |

| драгоценный камень | Агат |

| Инструмент | Диатонический аккордеон |

| Указатель государственного маршрута | |

| |

| Государственный квартал | |

Выпущен в 2002 году | |

| Списки государственных символов США | |

Луизиана [ произношение 1 ] (Французский: Луизиана [lwizjan] ; Испанский: Луизиана [lwiˈsjana] ; Луизианский креольский : Луизиана ) [ б ] — штат в регионах Глубокий Юг и Южно-Центральный США регион . Он граничит с Техасом на западе, Арканзасом на севере и Миссисипи на востоке. Из 50 штатов США он занимает 20-е место по площади и 25-е по численности населения , с населением около 4,6 миллиона человек. Отражая свое французское наследие , Луизиана является единственным штатом США с политическими подразделениями, называемыми приходами , которые эквивалентны округам , что делает ее одним из двух штатов США, не разделенных на округа (вторым является Аляска и ее районы ). Батон-Руж — столица штата, а Новый Орлеан , регион французской Луизианы , — его крупнейший город с населением около 383 000 человек. [ 10 ] Луизиана имеет береговую линию с Мексиканским заливом на юге; большая часть его восточной границы очерчена рекой Миссисипи .

Большая часть земель Луизианы образовалась из отложений, смытых рекой Миссисипи, оставивших огромные дельты и обширные территории прибрежных болот и болот . [ 11 ] Они содержат богатую южную биоту , включая таких птиц, как ибисы и цапли , многие виды древесных лягушек , таких как признанная штатом американская зеленая древесная лягушка , а также такие рыбы, как осетр и веслонос . Более возвышенные районы, особенно на севере, содержат большое разнообразие экосистем, таких как высокотравные прерии , длиннолиственные сосновые леса и влажные саванны ; они поддерживают исключительно большое количество видов растений, включая многие виды наземных орхидей и плотоядных растений . Более половины штата покрыто лесами.

Луизиана расположена в месте слияния речной системы Миссисипи и Мексиканского залива. Его расположение и биоразнообразие привлекали различные группы коренных народов за тысячи лет до прибытия европейцев в 17 веке. В Луизиане проживает восемнадцать индейских племен — больше, чем в любом южном штате, — из которых четыре признаны на федеральном уровне, а десять — на уровне штата. [ 12 ] Французы заявили права на эту территорию в 1682 году, и она стала политическим, торговым и населенным центром более крупной колонии Новая Франция . С 1762 по 1801 год Луизиана находилась под властью Испании, ненадолго вернулась под власть Франции, а затем была продана Наполеоном принята США в 1803 году. В 1812 году она была в Союз как 18-й штат. После обретения статуса штата Луизиана увидела приток поселенцев из восточной части США, а также иммигрантов из Вест-Индии, Германии и Ирландии. Он пережил сельскохозяйственный бум, особенно хлопка и сахарного тростника, которые выращивались в основном рабами из Африки. Будучи рабовладельческим штатом, Луизиана была одним из первых семи членов Конфедеративных Штатов Америки во время Гражданской войны в США .

Уникальное французское наследие Луизианы отражено в ее топонимах, диалектах, обычаях, демографии и правовой системе. По сравнению с остальной частью юга США, Луизиана многоязычна и многокультурна, отражая смесь Луизианской французской ( каджунской , креольской ), испанской , франко-канадской , академической , креольской культур Сен-Доминго , коренных американцев и западноафриканских культур (как правило, потомков рабов , украденных в XVIII веке); Среди более поздних мигрантов - филиппинцы и вьетнамцы. В после Гражданской войны условиях англо-американцы усилили давление на англицизацию , и в 1921 году английский язык вскоре стал единственным языком обучения в школах Луизианы, прежде чем в 1974 году была возрождена политика многоязычия. [ 13 ] [ 14 ] В Луизиане никогда не было официального языка, и в конституции штата перечислено «право людей сохранять, развивать и продвигать свое историческое, языковое и культурное происхождение». [ 13 ]

Судя по средним показателям по стране, Луизиана часто занимает последнее место среди штатов США по уровню здравоохранения. [ 15 ] образование, [ 16 ] [ 17 ] [ 18 ] [ 19 ] и развитие, с высоким уровнем бедности [ 20 ] [ 21 ] [ 22 ] и убийство . В 2018 году Луизиана была признана наименее здоровым штатом в стране с высоким уровнем смертности, связанной с наркотиками . Здесь также самый высокий уровень убийств в Соединенных Штатах, по крайней мере, с 1990-х годов. [ 23 ] [ 24 ] [ 25 ]

Этимология

[ редактировать ]Луизиана была названа в честь Людовика XIV , короля Франции с 1643 по 1715 год. Когда Рене-Робер Кавелье, сьер де ла Саль, заявил права на территорию, истощенную рекой Миссисипи , для Франции, он назвал ее Ла Луизианой . [ 26 ] Суффикс –ana (или –ane) – это латинский суффикс, который может относиться к «информации, относящейся к конкретному человеку, предмету или месту». Таким образом, грубо говоря, Луи + ана несет в себе идею «родственного Луи». Когда-то часть французской колониальной империи , территория Луизианы простиралась от современного залива Мобил до севера от современной границы Канады и США включая небольшую часть того, что сейчас является канадскими провинциями Альберта , и Саскачеван .

История

[ редактировать ]Доколониальная история

[ редактировать ]

Территория Луизианы является местом зарождения культуры курганных строителей в период средней архаики , в 4-м тысячелетии до нашей эры . Места Кейни и Френчменс-Бенд были надежно датированы 5600–5000 годами назад (около 3700–3100 лет до н.э.), что свидетельствует о том, что сезонные охотники-собиратели примерно в это время организовывали строительство сложных земляных сооружений на территории современной северной Луизианы. На территории Уотсон-Брейк недалеко от современного Монро есть комплекс из одиннадцати курганов; он был построен около 5400 г. до н.э. (3500 г. до н.э.). [ 27 ] Эти открытия опровергли предыдущие предположения археологов о том, что такие сложные курганы были построены только культурами более оседлых народов, которые зависели от выращивания кукурузы. Местонахождение Хеджепет в приходе Линкольн появилось позднее и датируется 5200–4500 гг. До н.э. (3300–2600 гг. до н.э.). [ 28 ]

Почти 2000 лет спустя точка бедности была построена ; это самый большой и самый известный памятник поздней архаики в штате. Рядом с ним возник город современного Эппса . Культура Точки Бедности, возможно, достигла своего пика около 1500 г. до н.э., что сделало ее первой сложной культурой и, возможно, первой племенной культурой в Северной Америке. [ 29 ] Это продолжалось примерно до 700 г. до н.э.

За культурой Точки Бедности последовали культуры Чефункте и Озерных Бакланов периода Чула , местные проявления периода Раннего Леса . Культура Чефункте была первым народом в районе Луизианы, который начал производить большое количество керамики. [ 30 ] Эти культуры просуществовали до 200 года нашей эры. Период Среднего Леса начался в Луизиане с культуры Марксвилля в южной и восточной части штата, простирающейся через реку Миссисипи на восток вокруг Натчеза, [ 31 ] и культура Фурш-Малин в северо-западной части штата. Культура Марксвилля была названа в честь доисторического индейского памятника Марксвилл в приходе Авойель .

Эти культуры были современниками культур Хоупвелла современных Огайо и Иллинойса и участвовали в Сети обмена Хоупвелла. Торговля с народами юго-запада принесла лук и стрелы . [ 32 ] В это время были построены первые курганы . [ 33 ] Политическая власть начала консолидироваться, поскольку первые курганы-платформы в ритуальных центрах были построены для развития наследственного политического и религиозного лидерства. [ 33 ]

К 400 году период позднего леса начался с культуры Бэйтауна , культуры Тройвилля и прибрежного Тройвилля в период Бэйтауна, а на смену ему пришли культуры Коулс-Крик . Там, где жители Бэйтауна строили рассредоточенные поселения, жители Тройвилля вместо этого продолжали строить крупные центры земляных работ. [ 34 ] [ 35 ] [ 36 ] Население резко возросло, и есть убедительные доказательства растущей культурной и политической сложности. Многие памятники Коулс-Крик были возведены на месте погребальных курганов более раннего лесного периода. Ученые предполагают, что возникающие элиты символически и физически присваивали умерших предков, чтобы подчеркнуть и продемонстрировать свой собственный авторитет. [37]

The Mississippian period in Louisiana was when the Plaquemine and the Caddoan Mississippian cultures developed, and the peoples adopted extensive maize agriculture, cultivating different strains of the plant by saving seeds, selecting for certain characteristics, etc. The Plaquemine culture in the lower Mississippi River Valley in western Mississippi and eastern Louisiana began in 1200 and continued to about 1600. Examples in Louisiana include the Medora site, the archaeological type site for the culture in West Baton Rouge Parish whose characteristics helped define the culture,[38] the Atchafalaya Basin Mounds in St. Mary Parish,[39] the Fitzhugh Mounds in Madison Parish,[40] the Scott Place Mounds in Union Parish,[41] and the Sims site in St. Charles Parish.[42]

Plaquemine culture was contemporaneous with the Middle Mississippian culture that is represented by its largest settlement, the Cahokia site in Illinois east of St. Louis, Missouri. At its peak Cahokia is estimated to have had a population of more than 20,000. The Plaquemine culture is considered ancestral to the historic Natchez and Taensa peoples, whose descendants encountered Europeans in the colonial era.[43]

By 1000 in the northwestern part of the state, the Fourche Maline culture had evolved into the Caddoan Mississippian culture. The Caddoan Mississippians occupied a large territory, including what is now eastern Oklahoma, western Arkansas, northeast Texas, and northwest Louisiana. Archaeological evidence has demonstrated that the cultural continuity is unbroken from prehistory to the present. The Caddo and related Caddo-language speakers in prehistoric times and at first European contact were the direct ancestors of the modern Caddo Nation of Oklahoma of today.[44] Significant Caddoan Mississippian archaeological sites in Louisiana include Belcher Mound Site in Caddo Parish and Gahagan Mounds Site in Red River Parish.[45]

Many current place names in Louisiana, including Atchafalaya, Natchitouches (now spelled Natchitoches), Caddo, Houma, Tangipahoa, and Avoyel (as Avoyelles), are transliterations of those used in various Native American languages.

Exploration and colonization by Europeans

[edit]The first European explorers to visit Louisiana came in 1528 when a Spanish expedition led by Pánfilo de Narváez located the mouth of the Mississippi River. In 1542, Hernando de Soto's expedition skirted to the north and west of the state (encountering Caddo and Tunica groups) and then followed the Mississippi River down to the Gulf of Mexico in 1543. Spanish interest in Louisiana faded away for a century and a half.[46]

In the late 17th century, French and French Canadian expeditions, which included sovereign, religious and commercial aims, established a foothold on the Mississippi River and Gulf Coast. With its first settlements, France laid claim to a vast region of North America and set out to establish a commercial empire and French nation stretching from the Gulf of Mexico to Canada.

In 1682, the French explorer Robert Cavelier de La Salle named the region Louisiana to honor King Louis XIV of France. The first permanent settlement, Fort Maurepas (now Ocean Springs, Mississippi), was founded in 1699 by Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville, a French military officer from New France. By then the French had also built a small fort at the mouth of the Mississippi at a settlement they named La Balise (or La Balize), "seamark" in French. By 1721, they built a 62-foot (19 m) wooden lighthouse-type structure here to guide ships on the river.[47]

A royal ordinance of 1722—following the Crown's transfer of the Illinois Country's governance from Canada to Louisiana—may have featured the broadest definition of Louisiana: all land claimed by France south of the Great Lakes between the Rocky Mountains and the Alleghenies.[48] A generation later, trade conflicts between Canada and Louisiana led to a more defined boundary between the French colonies; in 1745, Louisiana governor general Vaudreuil set the northern and eastern bounds of his domain as the Wabash valley up to the mouth of the Vermilion River (near present-day Danville, Illinois); from there, northwest to le Rocher on the Illinois River, and from there west to the mouth of the Rock River (at present day Rock Island, Illinois).[48] Thus, Vincennes and Peoria were the limit of Louisiana's reach; the outposts at Ouiatenon (on the upper Wabash near present-day Lafayette, Indiana), Chicago, Fort Miamis (near present-day Fort Wayne, Indiana), and Prairie du Chien, Wisconsin, operated as dependencies of Canada.[48]

The settlement of Natchitoches (along the Red River in present-day northwest Louisiana) was established in 1714 by Louis Juchereau de St. Denis,[49] making it the oldest permanent European settlement in the modern state of Louisiana. The French settlement had two purposes: to establish trade with the Spanish in Texas via the Old San Antonio Road, and to deter Spanish advances into Louisiana. The settlement soon became a flourishing river port and crossroads, giving rise to vast cotton kingdoms along the river that were worked by imported African slaves. Over time, planters developed large plantations and built fine homes in a growing town. This became a pattern repeated in New Orleans and other places, although the commodity crop in the south was primarily sugar cane.

Louisiana's French settlements contributed to further exploration and outposts, concentrated along the banks of the Mississippi and its major tributaries, from Louisiana to as far north as the region called the Illinois Country, around present-day St. Louis, Missouri. The latter was settled by French colonists from Illinois.

Initially, Mobile and then Biloxi served as the capital of La Louisiane.[50][51] Recognizing the importance of the Mississippi River to trade and military interests, and wanting to protect the capital from severe coastal storms, France developed New Orleans from 1722 as the seat of civilian and military authority south of the Great Lakes. From then until the United States acquired the territory in the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, France and Spain jockeyed for control of New Orleans and the lands west of the Mississippi.

In the 1720s, German immigrants settled along the Mississippi River, in a region referred to as the German Coast.

France ceded most of its territory east of the Mississippi to Great Britain in 1763, in the aftermath of Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War (generally referred to in North America as the French and Indian War). This included the lands along the Gulf Coast and north of Lake Pontchartrain to the Mississippi River, which became known as British West Florida. The rest of Louisiana west of the Mississippi, as well as the "isle of New Orleans", had become a colony of Spain by the Treaty of Fontainebleau (1762). The transfer of power on either side of the river would be delayed until later in the decade.

In 1765, during Spanish rule, several thousand Acadians from the French colony of Acadia (now Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island) made their way to Louisiana after having been expelled from Acadia by the British government after the French and Indian War. They settled chiefly in the southwestern Louisiana region now called Acadiana. The governor Luis de Unzaga y Amézaga,[52] eager to gain more settlers, welcomed the Acadians, who became the ancestors of Louisiana's Cajuns.

Spanish Canary Islanders, called Isleños, emigrated from the Canary Islands of Spain to Louisiana under the Spanish crown between 1778 and 1783.[53] In 1800, France's Napoleon Bonaparte reacquired Louisiana from Spain in the Treaty of San Ildefonso, an arrangement kept secret for two years.

Expansion of slavery

[edit]

Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville brought the first two African slaves to Louisiana in 1708, transporting them from a French colony in the West Indies. In 1709, French financier Antoine Crozat obtained a monopoly of commerce in La Louisiane, which extended from the Gulf of Mexico to what is now Illinois. According to historian Hugh Thomas, "that concession allowed him to bring in a cargo of blacks from Africa every year".[54] Starting in 1719, traders began to import slaves in higher numbers; two French ships, the Du Maine and the Aurore, arrived in New Orleans carrying more than 500 black slaves coming from Africa. Previous slaves in Louisiana had been transported from French colonies in the West Indies. By the end of 1721, New Orleans counted 1,256 inhabitants, of whom about half were slaves.[citation needed]

In 1724, the French government issued a law called the Code Noir ("Black Code" in English) which regulated the interaction of whites (blancs) and blacks (noirs) in its colony of Louisiana (which was much larger than the current state of Louisiana).[55]

The Louisiana Black Code of 1806 made the cruel punishment of slaves a crime.[56]

Fugitive slaves, called maroons, could easily hide in the backcountry of the bayous and survive in small settlements.[57] The word "maroon" comes from the Spanish "cimarron", meaning which means "fierce" or "unruly."[58]

In the late 18th century, the last Spanish governor of the Louisiana territory wrote:

Truly, it is impossible for lower Louisiana to get along without slaves and with the use of slaves, the colony had been making great strides toward prosperity and wealth.[59]

When the United States purchased Louisiana in 1803, it was soon accepted that slaves could be brought to Louisiana as easily as they were brought to neighboring Mississippi, though it violated U.S. law to do so.[59] Despite demands by United States Rep. James Hillhouse and by the pamphleteer Thomas Paine to enforce existing federal law against slavery in the newly acquired territory,[59] slavery prevailed because it was the source of great profits and the lowest-cost labor.

At the start of the 19th century, Louisiana was a small producer of sugar with a relatively small number of slaves, compared to Saint-Domingue and the West Indies. It soon thereafter became a major sugar producer as new settlers arrived to develop plantations. William C. C. Claiborne, Louisiana's first United States governor, said African slave labor was needed because white laborers "cannot be had in this unhealthy climate."[60] Hugh Thomas wrote that Claiborne was unable to enforce the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade, which the U.S. and Great Britain enacted in 1807. The United States continued to protect the domestic slave trade, including the coastwise trade—the transport of slaves by ship along the Atlantic Coast and to New Orleans and other Gulf ports.

By 1840, New Orleans had the biggest slave market in the United States, which contributed greatly to the economy of the city and of the state. New Orleans had become one of the wealthiest cities, and the third largest city, in the nation.[61] The ban on the African slave trade and importation of slaves had increased demand in the domestic market. During the decades after the American Revolutionary War, more than one million enslaved African Americans underwent forced migration from the Upper South to the Deep South, two thirds of them in the slave trade. Others were transported by their owners as slaveholders moved west for new lands.[62][63]

With changing agriculture in the Upper South as planters shifted from tobacco to less labor-intensive mixed agriculture, planters had excess laborers. Many sold slaves to traders to take to the Deep South. Slaves were driven by traders overland from the Upper South or transported to New Orleans and other coastal markets by ship in the coastwise slave trade. After sales in New Orleans, steamboats operating on the Mississippi transported slaves upstream to markets or plantation destinations at Natchez and Memphis.

Interestingly, for a slave-state, Louisiana harbored escaped Filipino slaves from the Manila Galleons.[64][65][66][67] The members of the Filipino community were then commonly referred to as Manila men, or Manilamen, and later Tagalas,[68] as they were free when they created the oldest settlement of Asians in the United States in the village of Saint Malo, Louisiana,[68][69][70][71] the inhabitants of which, even joined the United States in the War of 1812 against the British Empire while they were being led by the French-American Jean Lafitte.[70]

Asylum and influence of Creoles from Saint-Domingue

[edit]

Spanish occupation of Louisiana lasted from 1769 to 1800.[72] Beginning in the 1790s, waves of immigration took place from Saint-Domingue as refugees poured over following a slave rebellion that started during the French Revolution of Saint-Domingue in 1791. Over the next decade, thousands of refugees landed in Louisiana from the island, including Europeans, Creoles, and Africans, some of the latter brought in by each free group. They greatly increased the French-speaking population in New Orleans and Louisiana, as well as the number of Africans, and the slaves reinforced African culture in the city.[73]

Anglo-American officials initially made attempts to keep out the additional Creoles of color, but the Louisiana Creoles wanted to increase the Creole population: more than half of the refugees eventually settled in Louisiana, and the majority remained in New Orleans.[74]

Pierre Clément de Laussat (Governor, 1803) said: "Saint-Domingue was, of all our colonies in the Antilles, the one whose mentality and customs influenced Louisiana the most."[75]

Purchase by the United States

[edit]When the United States won its independence from Great Britain in 1783, one of its major concerns was having a European power on its western boundary, and the need for unrestricted access to the Mississippi River. As American settlers pushed west, they found that the Appalachian Mountains provided a barrier to shipping goods eastward. The easiest way to ship produce was to use a flatboat to float it down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers to the port of New Orleans, where goods could be put on ocean-going vessels. The problem with this route was that the Spanish owned both sides of the Mississippi below Natchez.

Napoleon's ambitions in Louisiana involved the creation of a new empire centered on the Caribbean sugar trade. By the terms of the Treaty of Amiens of 1802, Great Britain returned control of the islands of Martinique and Guadeloupe to the French. Napoleon looked upon Louisiana as a depot for these sugar islands, and as a buffer to U.S. settlement. In October 1801 he sent a large military force to take back Saint-Domingue, then under control of Toussaint Louverture after the Haitian Revolution. When the army led by Napoleon's brother-in-law Leclerc was defeated, Napoleon decided to sell Louisiana.[77]

Thomas Jefferson, third president of the United States, was disturbed by Napoleon's plans to re-establish French colonies in North America. With the possession of New Orleans, Napoleon could close the Mississippi to U.S. commerce at any time. Jefferson authorized Robert R. Livingston, U.S. minister to France, to negotiate for the purchase of the city of New Orleans, portions of the east bank of the Mississippi,[78] and free navigation of the river for U.S. commerce. Livingston was authorized to pay up to $2 million.

An official transfer of Louisiana to French ownership had not yet taken place, and Napoleon's deal with the Spanish was a poorly kept secret on the frontier. On October 18, 1802, however, Juan Ventura Morales, acting intendant of Louisiana, made public the intention of Spain to revoke the right of deposit at New Orleans for all cargo from the United States. The closure of this vital port to the United States caused anger and consternation. Commerce in the west was virtually blockaded. Historians believe the revocation of the right of deposit was prompted by abuses by the Americans, particularly smuggling, and not by French intrigues as was believed at the time. President Jefferson ignored public pressure for war with France, and appointed James Monroe a special envoy to Napoleon, to assist in obtaining New Orleans for the United States. Jefferson also raised the authorized expenditure to $10 million.[79]

However, on April 11, 1803, French foreign minister Talleyrand surprised Livingston by asking how much the United States was prepared to pay for the entirety of Louisiana, not just New Orleans and the surrounding area (as Livingston's instructions covered). Monroe agreed with Livingston that Napoleon might withdraw this offer at any time (leaving them with no ability to obtain the desired New Orleans area), and that approval from President Jefferson might take months, so Livingston and Monroe decided to open negotiations immediately. By April 30, they closed a deal for the purchase of the entire Louisiana territory of 828,000 square miles (2,100,000 km2) for sixty million Francs (approximately $15 million).[79]

Part of this sum, $3.5 million, was used to forgive debts owed by France to the United States.[80] The payment was made in United States bonds, which Napoleon sold at face value to the Dutch firm of Hope and Company, and the British banking house of Baring, at a discount of 87+1⁄2 per each $100 unit. As a result, France received only $8,831,250 in cash for Louisiana. English banker Alexander Baring conferred with Marbois in Paris, shuttled to the United States to pick up the bonds, took them to Britain, and returned to France with the money—which Napoleon used to wage war against Baring's own country.

When news of the purchase reached the United States, Jefferson was surprised. He had authorized the expenditure of $10 million for a port city, and instead received treaties committing the government to spend $15 million on a land package which would double the size of the country. Jefferson's political opponents in the Federalist Party argued the Louisiana purchase was a worthless desert,[81] and that the U.S. constitution did not provide for the acquisition of new land or negotiating treaties without the consent of the federal legislature. What really worried the opposition was the new states which would inevitably be carved from the Louisiana territory, strengthening western and southern interests in U.S. Congress, and further reducing the influence of New England Federalists in national affairs. President Jefferson was an enthusiastic supporter of westward expansion, and held firm in his support for the treaty. Despite Federalist objections, the U.S. Senate ratified the Louisiana treaty on October 20, 1803.

By statute enacted on October 31, 1803, President Thomas Jefferson was authorized to take possession of the territories ceded by France and provide for initial governance.[82] A transfer ceremony was held in New Orleans on November 29, 1803. Since the Louisiana territory had never officially been turned over to the French, the Spanish took down their flag, and the French raised theirs. The following day, General James Wilkinson accepted possession of New Orleans for the United States. The Louisiana Territory, purchased for less than three cents an acre, doubled the size of the United States overnight, without a war or the loss of a single American life, and set a precedent for the purchase of territory. It opened the way for the eventual expansion of the United States across the continent to the Pacific Ocean.

Shortly after the United States took possession, the area was divided into two territories along the 33rd parallel north on March 26, 1804, thereby organizing the Territory of Orleans to the south and the District of Louisiana (subsequently formed as the Louisiana Territory) to the north.[83]

Statehood

[edit]Louisiana became the eighteenth U.S. state on April 30, 1812; the Territory of Orleans became the State of Louisiana and the Louisiana Territory was simultaneously renamed the Missouri Territory.[84]

At its creation, the state of Louisiana did not include the area north and east of the Mississippi River known as the Florida Parishes. On April 14, 1812, Congress had authorized Louisiana to expand its borders to include the Florida Parishes,[85][86] but the border change required approval of the state legislature, which it did not give until August 4.[87] For the roughly three months in between, the northern border of eastern Louisiana was the course of Bayou Manchac and the middle of Lake Maurepas and Lake Pontchartrain.[88]

From 1824 to 1861, Louisiana moved from a political system based on personality and ethnicity to a distinct two-party system, with Democrats competing first against Whigs, then Know Nothings, and finally only other Democrats.[89]

Secession and the Civil War

[edit]

According to the 1860 census, 331,726 people were enslaved, nearly 47% of the state's total population of 708,002.[90] The strong economic interest of elite whites in maintaining the slave society contributed to Louisiana's decision to secede from the Union on January 26, 1861.[91] It followed other U.S. states in seceding after the election of Abraham Lincoln as president of the United States. Louisiana's secession was announced on January 26, 1861, and it became part of the Confederate States of America.

The state was quickly defeated in the Civil War, a result of Union strategy to cut the Confederacy in two by controlling the Mississippi River. Federal troops captured New Orleans on April 25, 1862. Because a large part of the population had Union sympathies (or compatible commercial interests), the federal government took the unusual step of designating the areas of Louisiana under federal control as a state within the Union, with its own elected representatives to the U.S. Congress.[92][93]

Post–Civil War to mid–20th century

[edit]

Following the American Civil War and emancipation of slaves, violence rose in the southern U.S. as the war was carried on by insurgent private and paramilitary groups. During the initial period after the war, there was a massive rise in black participation in terms of voting and holding political office. Louisiana saw the United States' first and second black governors with Oscar Dunn and P.B.S. Pinchback, with 125 black members of the state legislature being elected during this time, while Charles E. Nash was elected to represent the state's 6th Congressional District in the U.S. House of Representatives. Eventually former Confederates came to dominate the state legislature after the end of Reconstruction and federal occupation in the late 1870s, and black codes were implemented to regulate freedmen and increasingly restricted the right to vote. They refused to extend voting rights to African Americans who had been free before the war and had sometimes obtained education and property (as in New Orleans).

Following the Memphis riots of 1866 and the New Orleans riot the same year, the Fourteenth Amendment was passed that provided suffrage and full citizenship for freedmen. Congress passed the Reconstruction Act, establishing military districts for those states where conditions were considered the worst, including Louisiana. It was grouped with Texas in what was administered as the Fifth Military District.[94]

African Americans began to live as citizens with some measure of equality before the law. Both freedmen and people of color who had been free before the war began to make more advances in education, family stability and jobs. At the same time, there was tremendous social volatility in the aftermath of war, with many whites actively resisting defeat and the free labor market. White insurgents mobilized to enforce white supremacy, first in Ku Klux Klan chapters.

By 1877, when federal forces were withdrawn, white Democrats in Louisiana and other states had regained control of state legislatures, often by paramilitary groups such as the White League, which suppressed black voting through intimidation and violence. Following Mississippi's example in 1890, in 1898, the white Democratic, planter-dominated legislature passed a new constitution that effectively disfranchised people of color by raising barriers to voter registration, such as poll taxes, residency requirements and literacy tests. The effect was immediate and long lasting. In 1896, there were 130,334 black voters on the rolls and about the same number of white voters, in proportion to the state population, which was evenly divided.[95]

The state population in 1900 was 47% African American: a total of 652,013 citizens. Many in New Orleans were descendants of Creoles of color, the sizeable population of free people of color before the Civil War.[96] By 1900, two years after the new constitution, only 5,320 black voters were registered in the state. Because of disfranchisement, by 1910 there were only 730 black voters (less than 0.5 percent of eligible African-American men), despite advances in education and literacy among blacks and people of color.[97] Blacks were excluded from the political system and also unable to serve on juries. White Democrats had established one-party Democratic rule, which they maintained in the state for decades deep into the 20th century until after congressional passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act provided federal oversight and enforcement of the constitutional right to vote.

In the early decades of the 20th century, thousands of African Americans left Louisiana in the Great Migration north to industrial cities for jobs and education, and to escape Jim Crow society and lynchings. The boll weevil infestation and agricultural problems cost many sharecroppers and farmers their jobs. The mechanization of agriculture also reduced the need for laborers. Beginning in the 1940s, blacks went west to California for jobs in its expanding defense industries.[98]

In 1920 the state had no continuous paved roads running east to west or north to south which traversed the entire state.[99]

During some of the Great Depression, Louisiana was led by Governor Huey Long. He was elected to office on populist appeal. His public works projects provided thousands of jobs to people in need, and he supported education and increased suffrage for poor whites, but Long was criticized for his allegedly demagogic and autocratic style. He extended patronage control through every branch of Louisiana's state government. Especially controversial were his plans for wealth redistribution in the state. Long's rule ended abruptly when he was assassinated in the state capitol in 1935.[100]

Mid–20th century to present

[edit]Mobilization for World War II created jobs in the state. But thousands of other workers, black and white alike, migrated to California for better jobs in its burgeoning defense industry. Many African Americans left the state in the Second Great Migration, from the 1940s through the 1960s to escape social oppression and seek better jobs. The mechanization of agriculture in the 1930s had sharply cut the need for laborers. They sought skilled jobs in the defense industry in California, better education for their children, and living in communities where they could vote.[101]

On November 26, 1958, at Chennault Air Force Base, a USAF B-47 bomber with a nuclear weapon on board developed a fire while on the ground. The aircraft wreckage and the site of the accident were contaminated after a limited explosion of non-nuclear material.[102]

In the 1950s the state created new requirements for a citizenship test for voter registration. Despite opposition by the States' Rights Party (Dixiecrats), downstate black voters had begun to increase their rate of registration, which also reflected the growth of their middle classes. In 1960 the state established the Louisiana State Sovereignty Commission, to investigate civil rights activists and maintain segregation.[103]

Despite this, gradually black voter registration and turnout increased to 20% and more, and it was 32% by 1964, when the first national civil rights legislation of the era was passed.[104] The percentage of black voters ranged widely in the state during these years, from 93.8% in Evangeline Parish to 1.7% in Tensas Parish, for instance, where there were intense white efforts to suppress the vote in the black-majority parish.[105]

Violent attacks on civil rights activists in two mill towns were catalysts to the founding of the first two chapters of the Deacons for Defense and Justice in late 1964 and early 1965, in Jonesboro and Bogalusa, respectively. Made up of veterans of World War II and the Korean War, they were armed self-defense groups established to protect activists and their families. Continued violent white resistance in Bogalusa to blacks trying to use public facilities in 1965, following passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, caused the federal government to order local police to protect the activists.[106] Other chapters were formed in Mississippi and Alabama.

By 1960 the proportion of African Americans in Louisiana had dropped to 32%. The 1,039,207 black citizens were still suppressed by segregation and disfranchisement.[107] African Americans continued to suffer disproportionate discriminatory application of the state's voter registration rules. Because of better opportunities elsewhere, from 1965 to 1970, blacks continued to migrate out of Louisiana, for a net loss of more than 37,000 people. Based on official census figures, the African American population in 1970 stood at 1,085,109, a net gain of more than 46,000 people compared to 1960. During the latter period, some people began to migrate to cities of the New South for opportunities.[108] Since that period, blacks entered the political system and began to be elected to office, as well as having other opportunities.

On May 21, 1919, the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, giving women full rights to vote, was passed at a national level, and was made the law throughout the United States on August 18, 1920. Louisiana finally ratified the amendment on June 11, 1970.[109]

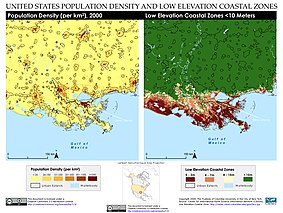

Due to its location on the Gulf Coast, Louisiana has regularly suffered the effects of tropical storms and damaging hurricanes. On August 29, 2005, New Orleans and many other low-lying parts of the state along the Gulf of Mexico were hit by the catastrophic Hurricane Katrina.[110] It caused widespread damage due to breaching of levees and large-scale flooding of more than 80% of the city. Officials had issued warnings to evacuate the city and nearby areas, but tens of thousands of people, mostly African Americans, stayed behind, many of them stranded. Many people died and survivors suffered through the damage of the widespread floodwaters.

In July 2016 the shooting of Alton Sterling sparked protests throughout the state capital of Baton Rouge.[111][112] In August 2016, an unnamed storm dumped trillions of gallons of rain on southern Louisiana, including the cities of Denham Springs, Baton Rouge, Gonzales, St. Amant and Lafayette, causing catastrophic flooding.[113] An estimated 110,000 homes were damaged and thousands of residents were displaced.[114][115] In 2019, three Louisiana black churches were destroyed by arson.[116][117][118]

The first case of COVID-19 in Louisiana was announced on March 9, 2020.[119] As of October 27, 2020, there had been 180,069 confirmed cases; 5,854 people have died of COVID-19.[120][needs update]

Geography

[edit]

Louisiana is bordered to the west by Texas; to the north by Arkansas; to the east by Mississippi; and to the south by the Gulf of Mexico. The state may properly be divided into two parts, the uplands of the north (the region of North Louisiana), and the alluvial along the coast (the Central Louisiana, Acadiana, Florida Parishes, and Greater New Orleans regions). The alluvial region includes low swamp lands, coastal marshlands and beaches, and barrier islands that cover about 12,350 square miles (32,000 km2). This area lies principally along the Gulf of Mexico and the Mississippi River, which traverses the state from north to south for a distance of about 600 mi (970 km) and empties into the Gulf of Mexico; also in the state are the Red River; the Ouachita River and its branches; and other minor streams (some of which are called bayous).

The breadth of the alluvial region along the Mississippi is 10–60 miles (16–97 km), and along the other rivers, the alluvial region averages about 10 miles (16 km) across. The Mississippi River flows along a ridge formed by its natural deposits (known as a levee), from which the lands decline toward a river beyond at an average fall of six feet per mile (3 m/km). The alluvial lands along other streams present similar features.

The higher and contiguous hill lands of the north and northwestern part of the state have an area of more than 25,000 square miles (65,000 km2). They consist of prairie and woodlands. The elevations above sea level range from 10 feet (3 m) at the coast and swamp lands to 50–60 feet (15–18 m) at the prairie and alluvial lands. In the uplands and hills, the elevations rise to Driskill Mountain, the highest point in the state only 535 feet (163 m) above sea level. From 1932 to 2010 the state lost 1,800 square miles due to rises in sea level and erosion. The Louisiana Coastal Protection and Restoration Authority (CPRA) spends around $1 billion per year to help shore up and protect Louisiana shoreline and land in both federal and state funding.[121][122]

Besides the waterways named, there are the Sabine, forming the western boundary; and the Pearl, the eastern boundary; the Calcasieu, the Mermentau, the Vermilion, Bayou Teche, the Atchafalaya, the Boeuf, Bayou Lafourche, the Courtableau River, Bayou D'Arbonne, the Macon River, the Tensas, Amite River, the Tchefuncte, the Tickfaw, the Natalbany River, and a number of other smaller streams, constituting a natural system of navigable waterways, aggregating over 4,000 miles (6,400 km) long.

The state also has political jurisdiction over the approximately 3-mile (4.8 km)-wide portion of subsea land of the inner continental shelf in the Gulf of Mexico. Through a peculiarity of the political geography of the United States, this is substantially less than the 9-mile (14 km)-wide jurisdiction of nearby states Texas and Florida, which, like Louisiana, have extensive Gulf coastlines.[123]

The southern coast of Louisiana in the United States is among the fastest-disappearing areas in the world. This has largely resulted from human mismanagement of the coast (see Wetlands of Louisiana). At one time, the land was added to when spring floods from the Mississippi River added sediment and stimulated marsh growth; the land is now shrinking. There are multiple causes.[124][125]

Artificial levees block spring flood water that would bring fresh water and sediment to marshes. Swamps have been extensively logged, leaving canals and ditches that allow salt water to move inland. Canals dug for the oil and gas industry also allow storms to move sea water inland, where it damages swamps and marshes. Rising sea waters have exacerbated the problem. Some researchers estimate that the state is losing a landmass equivalent to 30 football fields every day. There are many proposals to save coastal areas by reducing human damage, including restoring natural floods from the Mississippi. Without such restoration, coastal communities will continue to disappear.[126] And as the communities disappear, more and more people are leaving the region.[127] Since the coastal wetlands support an economically important coastal fishery, the loss of wetlands is adversely affecting this industry.

The Gulf of Mexico 'dead zone' off the coast of Louisiana is the largest recurring hypoxic zone in the United States. It was 8,776 square miles (22,730 km2) in 2017, the largest ever recorded.[128]

Geology

[edit]The oldest rocks in Louisiana are exposed in the north, in areas such as the Kisatchie National Forest. The oldest rocks date back to the early Cenozoic Era, some 60 million years ago.[129] The youngest parts of the state were formed during the last 12,000 years as successive deltas of the Mississippi River: the Maringouin, Teche, St. Bernard, Lafourche, the modern Mississippi, and now the Atchafalaya.[130] The sediments were carried from north to south by the Mississippi River.

Between the tertiary rocks of the north, and the relatively new sediments along the coast, is a vast belt known as the Pleistocene Terraces. Their age and distribution can be largely related to the rise and fall of sea levels during past ice ages. The northern terraces have had sufficient time for rivers to cut deep channels, while the newer terraces tend to be much flatter.[131]

Salt domes are also found in Louisiana. Their origin can be traced back to the early Gulf of Mexico when the shallow ocean had high rates of evaporation. There are several hundred salt domes in the state; one of the most familiar is Avery Island, Louisiana.[132] Salt domes are important not only as a source of salt; they also serve as underground traps for oil and gas.[133]

Flora and fauna

[edit]Climate

[edit]Louisiana has a humid subtropical climate (Köppen climate classification Cfa), with long, hot, humid summers and short, mild winters. The subtropical characteristics of the state are due to its low latitude, low lying topography, and the influence of the Gulf of Mexico, which at its farthest point is no more than 200 mi (320 km) away.

Rain is frequent throughout the year, although from April to September is slightly wetter than the rest of the year, which is the state's wet season. There is a dip in precipitation in October. In summer, thunderstorms build during the heat of the day and bring intense but brief, tropical downpours. In winter, rainfall is more frontal and less intense.

Summers in southern Louisiana have high temperatures from June through September averaging 90 °F (32 °C) or more, and overnight lows averaging above 70 °F (21 °C). At times, temperatures in the 90s °F (32–37 °C), combined with dew points in the upper 70s °F (24–26 °C), create sensible temperatures over 120 °F (49 °C). The humid, thick, jungle-like heat in southern Louisiana is a famous subject of countless stories and movies.

Temperatures are generally warm in the winter in the southern part of the state, with highs around New Orleans, Baton Rouge, the rest of southern Louisiana, and the Gulf of Mexico averaging 66 °F (19 °C). The northern part of the state is mildly cool in the winter, with highs averaging 59 °F (15 °C). The overnight lows in the winter average well above freezing throughout the state, with 46 °F (8 °C) the average near the Gulf and an average low of 37 °F (3 °C) in the winter in the northern part of the state.

On occasion, cold fronts from low-pressure centers to the north, reach Louisiana in winter. Low temperatures near 20 °F (−7 °C) occur on occasion in the northern part of the state but rarely do so in the southern part of the state. Snow is rare near the Gulf of Mexico, although residents in the northern parts of the state might receive a dusting of snow a few times each decade.[134][135][136][137] Louisiana's highest recorded temperature is 114 °F (46 °C) in Plain Dealing on August 10, 1936, while the coldest recorded temperature is −16 °F (−27 °C) at Minden on February 13, 1899.

Louisiana is often affected by tropical cyclones and is very vulnerable to strikes by major hurricanes, particularly the lowlands around and in the New Orleans area. The unique geography of the region, with the many bayous, marshes and inlets, can result in water damage across a wide area from major hurricanes. The area is also prone to frequent thunderstorms, especially in the summer.[138]

The entire state averages over 60 days of thunderstorms a year, more than any other state except Florida. Louisiana averages 27 tornadoes annually. The entire state is vulnerable to a tornado strike, with the extreme southern portion of the state slightly less so than the rest of the state. Tornadoes are more common from January to March in the southern part of the state, and from February through March in the northern part of the state.[138] Louisiana is partially within the area of tornado activity called Dixie Alley, and the state has tornadoes which tend to be unpredictable but localized.[139]

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sept | Oct | Nov | Dec | Annual | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shreveport[140] | 47.0/8.3 | 50.8/10.4 | 58.1/14.5 | 65.5/18.6 | 73.4/23.0 | 80.0/26.7 | 83.2/28.4 | 83.3/28.5 | 77.1/25.1 | 66.6/19.2 | 56.6/13.7 | 48.3/9.1 | 65.9/18.8 |

| Monroe[140] | 46.3/7.9 | 50.3/10.2 | 57.8/14.3 | 65.6/18.7 | 73.9/23.3 | 80.4/26.9 | 82.8/28.2 | 82.5/28.1 | 76.5/24.7 | 66.0/18.9 | 56.3/13.5 | 48.0/8.9 | 65.5/18.6 |

| Alexandria[140] | 48.5/9.2 | 52.1/11.2 | 59.3/15.2 | 66.4/19.1 | 74.5/23.6 | 80.7/27.1 | 83.2/28.4 | 83.2/28.4 | 78.0/25.6 | 68.0/20.0 | 58.6/14.8 | 50.2/10.1 | 66.9/19.4 |

| Lake Charles[141] | 51.8/11.0 | 55.0/12.8 | 61.4/16.3 | 68.1/20.1 | 75.6/24.2 | 81.1/27.3 | 82.9/28.3 | 83.0/28.3 | 78.7/25.9 | 70.1/21.2 | 61.1/16.2 | 53.8/12.1 | 68.6/20.3 |

| Lafayette[141] | 51.8/11.0 | 55.2/12.9 | 61.5/16.4 | 68.3/20.2 | 75.9/24.4 | 81.0/27.2 | 82.8/28.2 | 82.9/28.3 | 78.5/25.8 | 69.7/20.9 | 61.0/16.1 | 53.7/12.1 | 68.5/20.3 |

| Baton Rouge[142] | 51.3/10.7 | 54.6/12.6 | 61.1/16.2 | 67.6/19.8 | 75.2/24.0 | 80.7/27.1 | 82.5/28.1 | 82.5/28.1 | 78.1/25.6 | 68.9/20.5 | 60.0/15.6 | 52.9/11.6 | 68.0/20.0 |

| New Orleans[142] | 54.3/12.4 | 57.6/14.2 | 63.6/17.6 | 70.1/21.2 | 77.5/25.3 | 82.4/28.0 | 84.0/28.9 | 84.1/28.9 | 80.2/26.8 | 72.2/22.3 | 63.5/17.5 | 56.2/13.4 | 70.3/21.3 |

Publicly owned land

[edit]

Owing to its location and geology, the state has high biological diversity. Some vital areas, such as southwestern prairie, have experienced a loss in excess of 98 percent. The pine flatwoods are also at great risk, mostly from fire suppression and urban sprawl. There is not yet a properly organized system of natural areas to represent and protect Louisiana's biological diversity. Such a system would consist of a protected system of core areas linked by biological corridors, such as Florida is planning.[143]

Louisiana contains a number of areas which, to varying degrees, prevent people from using them.[144] In addition to National Park Service areas and a United States National Forest, Louisiana operates a system of state parks, state historic sites, one state preservation area, one state forest, and many Wildlife Management Areas.

One of Louisiana's largest government-owned areas is Kisatchie National Forest. It is some 600,000 acres in area, more than half of which is flatwoods vegetation, which supports many rare plant and animal species.[145] These include the Louisiana pinesnake and red-cockaded woodpecker. The system of government-owned cypress swamps around Lake Pontchartrain is another large area, with southern wetland species including egrets, alligators, and sturgeon. At least 12 core areas would be needed to build a "protected areas system" for the state; these would range from southwestern prairies, to the Pearl River Floodplain in the east, to the Mississippi River alluvial swamps in the north. Additionally, the state operates a system of 22 state parks, 17 state historic sites and one state preservation area; in these lands, Louisiana maintains a diversity of fauna and flora.

National Park Service

[edit]Historic or scenic areas managed, protected, or recognized by the National Park Service include:

- Atchafalaya National Heritage Area in Ascension Parish;

- Cane River National Heritage Area near Natchitoches;

- Cane River Creole National Historical Park near Natchitoches;

- Jean Lafitte National Historical Park and Preserve, headquartered in New Orleans, with units in St. Bernard Parish, Barataria (Crown Point), and Acadiana (Lafayette);

- Poverty Point National Monument at Delhi, Louisiana; and

- Saline Bayou, a designated National Wild and Scenic River near Winn Parish in northern Louisiana.

U.S. Forest Service

[edit]- Kisatchie National Forest is Louisiana's only national forest. It includes more than 600,000 acres in central and northern Louisiana with large areas of flatwoods and longleaf pine forest.[146][147]

Major cities

[edit]Louisiana contains 308 incorporated municipalities, consisting of four consolidated city-parishes, and 304 cities, towns, and villages. Louisiana's municipalities cover only 7.9% of the state's land mass but are home to 45.3% of its population.[148] The majority of urban Louisianians live along the coast or in northern Louisiana. The oldest permanent settlement in the state is Nachitoches.[149] Baton Rouge, the state capital, is the second-largest city in the state. The most populous city is New Orleans. As defined by the U.S. Census Bureau, Louisiana contains 10 metropolitan statistical areas. Major areas include Greater New Orleans, Greater Baton Rouge, Lafayette, Shreveport–Bossier City, and Slidell.

| Rank | Name | Parish | Pop. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

New Orleans  Baton Rouge |

1 | New Orleans | Orleans | 383,997 |  Shreveport  Lafayette | ||||

| 2 | Baton Rouge | East Baton Rouge | 227,470 | ||||||

| 3 | Shreveport | Caddo | 187,593 | ||||||

| 4 | Lafayette | Lafayette | 121,374 | ||||||

| 5 | Lake Charles | Calcasieu | 84,872 | ||||||

| 6 | Kenner | Jefferson | 66,448 | ||||||

| 7 | Bossier City | Bossier | 62,701 | ||||||

| 8 | Monroe | Ouachita | 47,702 | ||||||

| 9 | Alexandria | Rapides | 45,275 | ||||||

| 10 | Houma | Terrebonne | 33,406 | ||||||

Demographics

[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1810 | 76,556 | — | |

| 1820 | 153,407 | 100.4% | |

| 1830 | 215,739 | 40.6% | |

| 1840 | 352,411 | 63.4% | |

| 1850 | 517,762 | 46.9% | |

| 1860 | 708,002 | 36.7% | |

| 1870 | 726,915 | 2.7% | |

| 1880 | 939,946 | 29.3% | |

| 1890 | 1,118,588 | 19.0% | |

| 1900 | 1,381,625 | 23.5% | |

| 1910 | 1,656,388 | 19.9% | |

| 1920 | 1,798,509 | 8.6% | |

| 1930 | 2,101,593 | 16.9% | |

| 1940 | 2,363,516 | 12.5% | |

| 1950 | 2,683,516 | 13.5% | |

| 1960 | 3,257,022 | 21.4% | |

| 1970 | 3,641,306 | 11.8% | |

| 1980 | 4,205,900 | 15.5% | |

| 1990 | 4,219,973 | 0.3% | |

| 2000 | 4,468,976 | 5.9% | |

| 2010 | 4,533,372 | 1.4% | |

| 2020 | 4,657,757 | 2.7% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 4,573,749 | −1.8% | |

| Sources: 1910–2020[151] | |||

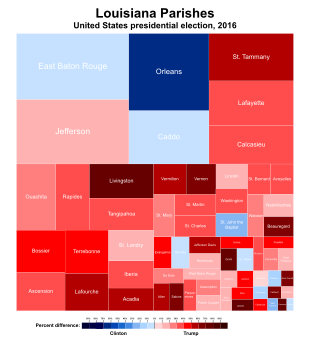

The majority of the state's population lives in southern Louisiana, spread throughout Greater New Orleans, the Florida Parishes, and Acadiana,[152][153][154] while Central and North Louisiana have been stagnating and losing population.[155] From the 2020 U.S. census, Louisiana had an apportioned population of 4,661,468.[156][157][158] Its resident population was 4,657,757 as of 2020.[159] In 2010, the state of Louisiana had a population of 4,533,372, up from 76,556 in 1810.

Despite historically positive trends of population growth leading up to the 2020 census, Louisiana began to experience population decline and stagnation since 2021, with Southwest Louisiana's Calcasieu and Cameron parishes losing more than 5% of their populations individually.[160] Experiencing decline due to deaths and emigration to other states outpacing births and in-migration,[161][162][163][164] Louisiana's 2022 census-estimated population was 4,590,241.[165]

According to immigration statistics in 2019, approximately 4.2% of Louisianians were immigrants, while 2% were native-born U.S. citizens with at least one immigrant parent. The majority of Louisianian immigrants came from Honduras (18.8%), Mexico (13.6%), Vietnam (11.3%), Cuba (5.8%), and India (4.4%); an estimated 29.4% were undocumented immigrants.[166] Its documented and undocumented population collectively paid $1.2 billion in taxes.[166] New Orleans has been defined as a sanctuary city.[167][168][169]

The population density of the state is 104.9 people per square mile.[170] The center of population of Louisiana is located in Pointe Coupee Parish, in the city of New Roads.[171] According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 7,373 homeless people in Louisiana.[172][173]

Race and ethnicity

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[174] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 55.8% | 58.7% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 31.2% | 32.6% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[c] | — | 6.9% | ||

| Asian | 1.8% | 2.3% | ||

| Native American | 0.6% | 1.9% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.04% | 0.1% | ||

| Other | 0.4% | 1.1% | ||

Several American Indian tribes such as the Atakapa and Caddo inhabited Louisiana before European colonization, concentrated along the Red River and Gulf of Mexico.[175][176][177][178] At the beginning of French and Spanish colonization of Louisiana, white and black Americans began to move into the area.[179][180] From French and Spanish rule in Louisiana, they were joined by Filipinos, Germans and Spaniards both slave and free, who settled in enclaves within the Greater New Orleans region and Acadiana;[181][182][183][184] some of the Spanish-descended communities became the Isleños of St. Bernard Parish.[53]

By the 19th and 20th centuries, the state's most-populous racial and ethnic group fluctuated between white and black Americans; 47% of the population was black or African American in 1900.[185] The black Louisianian population declined following migration to states including New York and California in efforts to flee Jim Crow regulations.[186]

At the end of the 20th century, Louisiana's population has experienced diversification again, and its non-Hispanic or non-Latino American white population has been declining.[153] Since 2020, the black or African American population have made up the largest non-white share of youths.[187] Hispanic and Latino Americans have also increased as the second-largest racial and ethnic composition in the state, making up nearly 7% of Louisiana's population at the 2020 census.[153] As of 2018,[188] the largest single Hispanic and Latino American ethnicity were Mexican Americans (2.0%), followed by Puerto Ricans (0.3%) and Cuban Americans (0.2%). Other Hispanic and Latino Americans altogether made up 2.6% of Louisiana's Hispanic or Latino American population. The Asian American and multiracial communities have also experienced rapid growth,[153] with many of Louisiana's multiracial population identifying as Cajun or Louisiana Creole.[189]

At the 2019 American Community Survey, the largest ancestry groups of Louisiana were African American (31.4%), French (9.6%), German (6.2%), English (4.6%), Italian (4.2%), and Scottish (0.9%).[190] African American and French heritage have been dominant since colonial Louisiana. As of 2011, 49.0% of Louisiana's population younger than age 1 were minorities.[191]

Religion

[edit]As an ethnically and culturally diverse state, pre-colonial, colonial and present-day Louisianians have adhered to a variety of religions and spiritual traditions; pre-colonial and colonial Louisianian peoples practiced various Native American religions alongside Christianity through the establishment of Spanish and French missions;[193] and other faiths including Haitian Vodou and Louisiana Voodoo were introduced to the state and are practiced to the present day.[194] In the colonial and present-day U.S. state of Louisiana, Christianity grew to become its predominant religion, representing 84% of the adult population in 2014 and 76.5% in 2020,[195][196] during two separate studies by the Pew Research Center and Public Religion Research Institute.

Among its Christian population—and in common with other southern U.S. states—the majority, particularly in the north of the state, belong to various Protestant denominations. Protestantism was introduced to the state in the 1800s, with Baptists establishing two churches in 1812, followed by Methodists; Episcopalians first entered the state by 1805.[197] Protestant Christians made up 57% of the state's adult population at the 2014 Pew Research Center study, and 53% at the 2020 Public Religion Research Institute's study. Protestants are concentrated in North Louisiana, Central Louisiana, and the northern tier of the Florida Parishes.

Because of French and Spanish heritage, and their descendants the Creoles, and later Irish, Italian, Portuguese and German immigrants, southern Louisiana and Greater New Orleans are predominantly Catholic in contrast; according to the 2020 Public Religion Research Institute study, 22% of the adult population were Catholic.[196] Since Creoles were the first settlers, planters and leaders of the territory, they have traditionally been well represented in politics; for instance, most of the early governors were Creole Catholics, instead of Protestants.[193] As Catholics continue to constitute a significant fraction of Louisiana's population, they have continued to be influential in state politics. The high proportion and influence of the Catholic population makes Louisiana distinct among southern states.[d] The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of New Orleans, Diocese of Baton Rouge, and Diocese of Lafayette in Louisiana are the largest Catholic jurisdictions in the state, located within the Greater New Orleans, Greater Baton Rouge, and Lafayette metropolitan statistical areas.

Louisiana was among the southern states with a significant Jewish population before the 20th century; Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia also had influential Jewish populations in some of their major cities from the 18th and 19th centuries. The earliest Jewish colonists were Sephardic Jews who immigrated to the Thirteen Colonies. Later in the 19th century, German Jews began to immigrate, followed by those from eastern Europe and the Russian Empire in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Jewish communities have been established in the state's larger cities, notably New Orleans and Baton Rouge.[198][199] The most significant of these is the Jewish community of the New Orleans area. In 2000, before the 2005 Hurricane Katrina, its population was about 12,000. Dominant Jewish movements in the state include Orthodox and Reform Judaism; Reform Judaism was the largest Jewish tradition in the state according to the Association of Religion Data Archives in 2020, representing some 5,891 Jews.[200] Prominent Jews in Louisiana's political leadership have included Whig (later Democrat) Judah P. Benjamin, who represented Louisiana in the U.S. Senate before the American Civil War and then became the Confederate secretary of state; Democrat-turned-Republican Michael Hahn who was elected as governor, serving 1864–1865 when Louisiana was occupied by the Union Army, and later elected in 1884 as a U.S. congressman;[201] Democrat Adolph Meyer, Confederate Army officer who represented the state in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1891 until his death in 1908; Republican secretary of state Jay Dardenne, and Republican (Democrat before 2011) attorney general Buddy Caldwell.

Other non-Christian and non-Jewish religions with a continuous, historical presence in the state have been Islam, Buddhism and Hinduism. In the Shreveport–Bossier City metropolitan area, Muslims made up an estimated 14% of Louisiana's total Muslim population as of 2014.[202] In 2020, the Association of Religion Data Archives estimated there were 24,732 Muslims living in the state.[200] The largest Islamic denominations in the major metropolises of Louisiana were Sunni Islam, non-denominational Islam and Quranism, Shia Islam, and the Nation of Islam.[203]

Among Louisiana's irreligious community, 2% affiliated with atheism and 13% claimed no religion as of 2014; an estimated 10% of the state's population practiced nothing in particular at the 2014 study. According to the Public Religion Research Institute in 2020, 19% were religiously unaffiliated.[196]

Economy

[edit]

Louisiana's population, agricultural products, abundance of oil and natural gas, and southern Louisiana's medical and technology corridors have contributed to its growing and diversifying economy.[204] In 2014, Louisiana was ranked as one of the most small business friendly states, based on a study drawing upon data from more than 12,000 small business owners.[205] The state's principal agricultural products include seafood (it is the biggest producer of crawfish in the world, supplying approximately 90%), cotton, soybeans, cattle, sugarcane, poultry and eggs, dairy products, and rice. Among its energy and other industries, chemical products, petroleum and coal products, processed foods, transportation equipment, and paper products have contributed to a significant portion of the state's GSP. Tourism and gaming are also important elements in the economy, especially in Greater New Orleans.[206]

The Port of South Louisiana, located on the Mississippi River between New Orleans and Baton Rouge, was the largest volume shipping port in the Western Hemisphere and 4th largest in the world, as well as the largest bulk cargo port in the U.S. in 2004.[207] The Port of South Louisiana continued to be the busiest port by tonnage in the U.S. through 2018.[208] South Louisiana was number 15 among world ports in 2016.[209]

New Orleans, Shreveport, and Baton Rouge are home to a thriving film industry.[210] State financial incentives since 2002 and aggressive promotion have given Louisiana the nickname "Hollywood South". Because of its distinctive culture within the United States, only Alaska is Louisiana's rival in popularity as a setting for reality television programs.[211] In late 2007 and early 2008, a 300,000-square-foot (28,000 m2) film studio was scheduled to open in Tremé, with state-of-the-art production facilities, and a film training institute.[212] Tabasco sauce, which is marketed by one of the United States' biggest producers of hot sauce, the McIlhenny Company, originated on Avery Island.[213]

From 2010 to 2020, Louisiana's gross state product increased from $213.6 billion to $253.3 billion, the 26th highest in the United States at the time.[214][215] As of 2020, its GSP is greater than the GDPs of Greece, Peru, and New Zealand. Ranking 41st in the United States with a per capita personal income of $30,952 in 2014,[216][217] its residents per capita income decreased to $28,662 in 2019.[218] The median household income was $51,073, while the national average was $65,712 at the 2019 American Community Survey.[219] In July 2017, the state's unemployment rate was 5.3%;[220] it decreased to 4.4% in 2019.[221]

Louisiana has three personal income tax brackets, ranging from 2% to 6%. The state sales tax rate is 4.45%, and parishes can levy additional sales tax on top of this. The state also has a use tax, which includes 4% to be distributed to local governments. Property taxes are assessed and collected at the local level. Louisiana is a subsidized state, and Louisiana taxpayers receive more federal funding per dollar of federal taxes paid compared to the average state.[222] Per dollar of federal tax collected in 2005, Louisiana citizens received approximately $1.78 in the way of federal spending. This ranks the state fourth highest nationally and represents a rise from 1995 when Louisiana received $1.35 per dollar of taxes in federal spending (ranked seventh nationally). Neighboring states and the amount of federal spending received per dollar of federal tax collected were: Texas ($0.94), Arkansas ($1.41), and Mississippi ($2.02). Federal spending in 2005 and subsequent years since has been exceptionally high due to the recovery from Hurricane Katrina.

Culture

[edit]Louisiana is home to many cultures; especially notable are the distinct cultures of the Louisiana Creoles and Cajuns, descendants of French and Spanish settlers in colonial Louisiana.

African culture

[edit]The French colony of La Louisiane struggled for decades to survive. Conditions were harsh, the climate and soil were unsuitable for certain crops the colonists knew, and they suffered from regional tropical diseases. Both colonists and the slaves they imported had high mortality rates. The settlers kept importing slaves, which resulted in a high proportion of native Africans from West Africa, who continued to practice their culture in new surroundings. As described by historian Gwendolyn Midlo Hall, they developed a marked Afro-Creole culture in the colonial era.[223][224]

At the turn of the 18th century and in the early 1800s, New Orleans received a major influx of White and mixed-race refugees fleeing the violence of the Haitian Revolution, many of whom brought their slaves with them.[225] This added another infusion of African culture to the city, as more slaves in Saint-Domingue were from Africa than in the United States. They strongly influenced the African-American culture of the city in terms of dance, music and religious practices.

Creole culture

[edit]

Creole culture is an amalgamation of French, African, Spanish (and other European), and Native American cultures.[226] Creole comes from the Portuguese word crioulo; originally it referred to a colonist of European (specifically French) descent who was born in the New World, in comparison to immigrants from France.[227] The oldest Louisiana manuscript to use the word "Creole", from 1782, applied it to a slave born in the French colony.[228] But originally it referred more generally to the French colonists born in Louisiana.

Over time, there developed in the French colony a relatively large group of Creoles of Color (gens de couleur libres), who were primarily descended from African slave women and French men (later other Europeans became part of the mix, as well as some Native Americans). Often the French would free their concubines and mixed-race children, and pass on social capital to them.[229] They might educate sons in France, for instance, and help them enter the French Army. They also settled capital or property on their mistresses and children. The free people of color gained more rights in the colony and sometimes education; they generally spoke French and were Roman Catholic. Many became artisans and property owners. Over time, the term "Creole" became associated with this class of Creoles of color, many of whom achieved freedom long before the American Civil War.

Wealthy French Creoles generally maintained town houses in New Orleans as well as houses on their large sugar plantations outside town along the Mississippi River. New Orleans had the largest population of free people of color in the region; they could find work there and created their own culture, marrying among themselves for decades.

Acadian culture

[edit]The ancestors of Cajuns immigrated mostly from west central France to New France, where they settled in the Atlantic provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, known originally as the French colony of Acadia. After the British defeated France in the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War) in 1763, France ceded its territory east of the Mississippi River to Britain. After the Acadians refused to swear an oath of loyalty to the British Crown, they were expelled from Acadia, and made their way to places such as France, Britain, and New England.[230]

Other Acadians covertly remained in British North America or moved to New Spain. Many Acadians settled in southern Louisiana in the region around Lafayette and the LaFourche Bayou country. They developed a distinct rural culture there, different from the French Creole colonists of New Orleans. Intermarrying with others in the area, they developed what was called Cajun music, cuisine and culture.

Isleño culture

[edit]

A third distinct culture in Louisiana is that of the Isleños. Its members are descendants of colonists from the Canary Islands who settled in Spanish Louisiana between 1778 and 1783 and intermarried with other communities such as Frenchmen, Acadians, Creoles, Spaniards, and other groups, mainly through the 19th and early 20th centuries.

In Louisiana, the Isleños originally settled in four communities which included Galveztown, Valenzuela, Barataria, and San Bernardo. The large migration of Acadian refugees to Bayou Lafourche led to the rapid gallicization of the Valenzuela community while the community of San Bernardo (Saint Bernard) was able to preserve much of its unique culture and language into the 21st century. The transmission of Spanish and other customs has completely halted in St. Bernard with those having competency in Spanish being octogenarians.[231]

Through the centuries, the various Isleño communities of Louisiana have kept alive different elements of their Canary Islander heritage while also adopting and building upon the customs and traditions of the communities that surround them. Today two heritage associates exist for the communities: Los Isleños Heritage and Cultural Society of St. Bernard as well as the Canary Islanders Heritage Society of Louisiana. The Fiesta de los Isleños is celebrated annually in St. Bernard Parish which features heritage performances from local groups and the Canary Islands.[232]

Education

[edit]

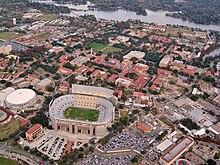

Despite ranking as the third-least educated state as of 2023, preceded by Mississippi and West Virginia,[19] Louisiana is home to over 40 public and private colleges and universities including: Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge; Louisiana Tech University in Ruston, the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in Lafayette; and Tulane University in New Orleans. Louisiana State University is the largest and most comprehensive university in Louisiana;[233] Louisiana Tech University is one the most well regarded universities in Louisiana;[234][235][236] the University of Louisiana at Lafayette is the second largest by enrollment. The University of Louisiana at Lafayette became an R1 university in December 2021.[237] Tulane University is a major private research university and the wealthiest university in Louisiana with an endowment over $1.1 billion.[238] Tulane is also highly regarded for its academics nationwide, consistently ranked in the top 50 on U.S. News & World Report's list of best national universities.[239]

Louisiana's two oldest and largest historically black colleges and universities (HBCUs) are Southern University in Baton Rouge and Grambling State University in Grambling. Both these Southwestern Athletic Conference (SWAC) schools compete against each other in football annually in the much anticipated Bayou Classic during Thanksgiving weekend in the Superdome.[240]

Of note among the education system, the Louisiana Science Education Act was a controversial law passed by the Louisiana Legislature on June 11, 2008, and signed into law by Governor Bobby Jindal on June 25.[241] The act allowed public school teachers to use supplemental materials in the science classroom which are critical of established science on such topics as the theory of evolution and global warming.[242][243]