Конкистадор

Конкистадоры ( / kɒnˈk n ɪstədɔːrz k ( w ) ɪstədɔːrz / , США также /- ˈ k iː s -, k ˈ ɒ ŋ - / ) или конкистадоры [ 1 ] ( Испанский: [koŋkistaˈðoɾes] , Португальский: [kõkiʃtɐˈðoɾɨʃ, kõkistɐˈdoɾis] ; буква «завоеватели») — термин, используемый для обозначения испанских и португальских солдат и исследователей, которые совершали завоевания и исследования эпохи Великих географических открытий . [ 2 ] [ 3 ] Конкистадоры отправились за пределы Пиренейского полуострова в Америку , Океанию , Африку и Азию , основав новые колонии и торговые пути . Они привели большую часть « Нового Света » под власть Испании и Португалии.

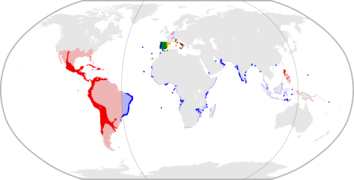

After Christopher Columbus' arrival in the West Indies in 1492, the Spanish, usually led by hidalgos from the west and south of Spain, began building a colonial empire in the Caribbean using colonies such as Santo Domingo, Cuba, and Puerto Rico as their main bases. From 1519 to 1521, Hernán Cortés led the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire, ruled by Moctezuma II. From the territories of the Aztec Empire, conquistadors expanded Spanish rule to northern Central America and parts of what is now the southern and western United States, and from Mexico sailing the Pacific Ocean to the Spanish East Indies. Other conquistadors took over the Inca Empire after crossing the Isthmus of Panama and sailing the Pacific to northern Peru. From 1532 to 1572, Francisco Pizarro succeeded in subduing this empire in a manner similar to Cortés. Subsequently, other conquistadores used Peru as a base for conquering much of Ecuador and Chile. Central Colombia, home of the Muisca was conquered by licentiate Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, а его северные районы исследовали Родриго де Бастидас , Алонсо де Охеда , Хуан де ла Коса , Педро де Эредиа и другие. На юго-западе Колумбии, Боливии и Аргентины конкистадоры из Перу объединили группы с другими конкистадорами, прибывшими напрямую из Карибского бассейна и Рио-де-ла-Плата ( Парагвай) соответственно. Все эти завоевания заложили основу современной латиноамериканской Америки и испаносферы .

Spanish conquistadors also made significant explorations into the Amazon Jungle, Patagonia, the interior of North America, and the discovery and exploration of the Pacific Ocean. Conquistadors founded numerous cities, some of them in locations with pre-existing settlements, such as Cusco and Mexico City. Conquistadors in the service of the Portuguese Crown led numerous conquests and visits in the name of the Portuguese Empire across South America and Africa, going "anticlockwise" along the continent's coast right up to the Red Sea, as well as commercial colonies in Asia, founding the origins of modern Portuguese-speaking world. Notable Portuguese conquistadors include Afonso de Albuquerque who led conquests across India, the Persian Gulf, the East Indies, and East Africa; and Filipe de Brito e Nicote who led conquests into Burma.

Conquest

[edit]

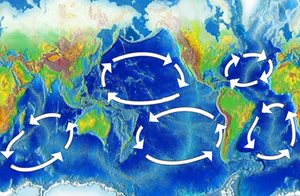

Portugal established a route to China in the early 16th century, sending ships via the southern coast of Africa and founding numerous coastal enclaves along the route. Following the discovery in 1492 by Spaniards of the New World with Italian explorer Christopher Columbus' first voyage there and the first circumnavigation of the world by Ferdinand Magellan in 1521, expeditions led by conquistadors in the 16th century established trading routes linking Europe with all these areas.[5]

The Age of Discovery was hallmarked in 1519, shortly after the European discovery of the Americas, when Hernán Cortés began his conquest of the Aztec Empire.[6] As the Spaniards, motivated by gold and fame, established relations and war with the Aztecs, the slow progression of conquest, erection of towns, and cultural dominance over the natives brought more Spanish troops and support to modern-day Mexico. As trading routes over the seas were established by the works of Columbus, Magellan, and Elcano, land support system was established as the trails of Cortés' conquest to the capital.

Human infections gained worldwide transmission vectors for the first time: from Africa and Eurasia to the Americas and vice versa.[7][8][9] The spread of Old World diseases, including smallpox, influenza, and typhus, led to the deaths of many indigenous inhabitants of the New World.

In the 16th century, perhaps 240,000 Spaniards entered American ports.[10][11] By the late 16th century, gold and silver imports from the Americas provided one-fifth of Spain's total budget.[12]

Background

[edit]

Contrary to popular belief, many conquistadors were not trained warriors, but mostly artisans, lesser nobility or farmers seeking an opportunity to advance themselves in the new world since they had limited opportunities in Spain.[13] A few also had crude firearms known as arquebuses. Their units (compañia) would often specialize in forms of combat that required long periods of training that were too costly for informal groups. Their armies were mostly composed of Spanish troops, as well as soldiers from other parts of Europe and Africa.

Native allied troops were largely infantry equipped with armament and armour that varied geographically. Some groups consisted of young men without military experience, Catholic clergy who helped with administrative duties, and soldiers with military training. These native forces often included African slaves and Native Americans, some of whom were also slaves. They were not only made to fight in the battlefield but also to serve as interpreters, informants, servants, teachers, physicians, and scribes. India Catalina and Malintzin were Native American women slaves who were forced to work for the Spaniards.[citation needed]

Castilian law prohibited foreigners and non-Catholics from settling in the New World. However, not all conquistadors were Castilian. Many foreigners Hispanicised their names and/or converted to Catholicism to serve the Castilian Crown. For example, Ioánnis Fokás (known as Juan de Fuca) was a Castilian of Greek origin who discovered the strait that bears his name between Vancouver Island and Washington state in 1592. German-born Nikolaus Federmann, Hispanicised as Nicolás de Federmán, was a conquistador in Venezuela and Colombia. The Venetian Sebastiano Caboto was Sebastián Caboto, Georg von Speyer Hispanicised as Jorge de la Espira, Eusebio Francesco Chini Hispanicised as Eusebio Kino, Wenceslaus Linck was Wenceslao Linck, Ferdinand Konščak, was Fernando Consag, Amerigo Vespucci was Américo Vespucio, and the Portuguese Aleixo Garcia was known as Alejo García in the Castilian army.

The origin of many people in mixed expeditions was not always distinguished. Various occupations, such as sailors, fishermen, soldiers and nobles employed different languages (even from unrelated language groups), so that crew and settlers of Iberian empires recorded as Galicians from Spain were actually using Portuguese, Basque, Catalan, Italian and Languedoc languages, which were wrongly identified.

Castilian law banned Spanish women from travelling to America unless they were married and accompanied by a husband. Women who travelled thus include María de Escobar, María Estrada, Marina Vélez de Ortega, Marina de la Caballería, Francisca de Valenzuela, Catalina de Salazar. Some conquistadors married Native American women or had illegitimate children.

European young men enlisted in the army because it was one way out of poverty. Catholic priests instructed the soldiers in mathematics, writing, theology, Latin, Greek, and history, and wrote letters and official documents for them. King's army officers taught military arts. An uneducated young recruit could become a military leader, elected by their fellow professional soldiers, perhaps based on merit. Others were born into hidalgo families, and as such they were members of the Spanish nobility with some studies but without economic resources. Even some rich nobility families' members became soldiers or missionaries, but mostly not the firstborn heirs.

The two most famous conquistadors were Hernán Cortés who conquered the Aztec Empire and Francisco Pizarro who led the conquest of the Inca Empire. They were second cousins born in Extremadura, where many of the Spanish conquerors were born.

Catholic religious orders that participated and supported the exploration, evangelizing and pacifying, were mostly Dominicans, Carmelites, Franciscans and Jesuits, for example Francis Xavier, Bartolomé de Las Casas, Eusebio Kino, Juan de Palafox y Mendoza or Gaspar da Cruz. In 1536, Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas went to Oaxaca to participate in a series of discussions and debates among the Bishops of the Dominican and Franciscan orders. The two orders had very different approaches to the conversion of the Indians. The Franciscans used a method of mass conversion, sometimes baptizing many thousands of Indians in a day. This method was championed by prominent Franciscans such as Toribio de Benavente.

The conquistadors took many different roles, including religious leader, harem keeper, King or Emperor, deserter and Native American warrior. Caramuru was a Portuguese settler in the Tupinambá Indians. Gonzalo Guerrero was a Maya war leader for Nachan Can, Lord of Chactemal. Gerónimo de Aguilar, who had taken holy orders in his native Spain, was captured by Maya lords too, and later was a soldier with Hernán Cortés. Francisco Pizarro had children with more than 40 women, many of whom were ñusta. The chroniclers Pedro Cieza de León, Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés, Diego Durán, Juan de Castellanos and friar Pedro Simón wrote about the Americas.

After Mexico fell, Hernán Cortés's enemies Bishop Fonseca, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar, Diego Columbus and Francisco Garay[14] were mentioned in Cortés' fourth letter to the King in which he describes himself as the victim of a conspiracy.

The division of the booty produced bloody conflicts, such as the one between Pizarro and De Almagro. After present-day Peruvian territories fell to Spain, Francisco Pizarro dispatched El Adelantado, Diego de Almagro, before they became enemies to the Inca Empire's northern city of Quito to claim it. Their fellow conquistador Sebastián de Belalcázar, who had gone forth without Pizarro's approval, had already reached Quito. The arrival of Pedro de Alvarado from the lands known today as Mexico in search of Inca gold further complicated the situation for De Almagro and Belalcázar. De Alvarado left South America in exchange for monetary compensation from Pizarro. De Almagro was executed in 1538, by Hernando Pizarro's orders. In 1541, supporters of Diego Almagro II assassinated Francisco Pizarro in Lima. In 1546, De Belalcázar ordered the execution of Jorge Robledo, who governed a neighbouring province in yet another land-related vendetta. De Belalcázar was tried in absentia, convicted and condemned for killing Robledo and for other offenses pertaining to his involvement in the wars between armies of conquistadors. Pedro de Ursúa was killed by his subordinate Lope de Aguirre who crowned himself king while searching for El Dorado. In 1544, Lope de Aguirre and Melchor Verdugo (a converso Jew) were at the side of Peru's first viceroy Blasco Núñez Vela, who had arrived from Spain with orders to implement the New Laws and suppress the encomiendas. Gonzalo Pizarro, another brother of Francisco Pizarro, rose in revolt, killed viceroy Blasco Núñez Vela and most of his Spanish army in the battle in 1546, and Gonzalo attempted to have himself crowned king.

The Emperor commissioned bishop Pedro de la Gasca to restore the peace, naming him president of the Audiencia and providing him with unlimited authority to punish and pardon the rebels. Gasca repealed the New Laws, the issue around which the rebellion had been organized. Gasca convinced Pedro de Valdivia, explorer of Chile, Alonso de Alvarado another searcher for El Dorado, and others that if he were unsuccessful, a royal fleet of 40 ships and 15,000 men was preparing to sail from Seville in June.[clarification needed]

History

[edit]

Early Portuguese period

[edit]Infante Dom Henry the Navigator of Portugal, son of King João I, became the main sponsor of exploration travels. In 1415, Portugal conquered Ceuta, its first overseas colony.

Throughout the 15th century, Portuguese explorers sailed the coast of Africa, establishing trading posts for tradable commodities such as firearms, spices, silver, gold, and slaves crossing Africa and India. In 1434 the first consignment of slaves was brought to Lisbon; slave trading was the most profitable branch of Portuguese commerce until the Indian subcontinent was reached. Due to the importation of the slaves as early as 1441, the kingdom of Portugal was able to establish a number of population of slaves throughout the Iberia due to its slave markets' dominance within Europe. Before the Age of Conquest began, the continental Europe already associated darker skin color with slave-class, attributing to the slaves of African origins. This sentiment traveled with the conquistadors when they began their explorations into the Americas. The predisposition inspired a lot of the entradas to seek slaves as part of the conquest.

Birth of the Spanish Kingdom

[edit]After his father's death in 1479, Ferdinand II of Aragón married Isabella of Castile, unifying both kingdoms and creating the Kingdom of Spain. He later tried to incorporate the kingdom of Portugal by marriage. Notably, Isabella supported Columbus's first voyage that launched the spanish conquistadors into action.

The Iberian Peninsula was largely divided before the hallmark of this marriage. Five independent kingdoms: Portugal in the West, Aragon and Navarre in the East, Castile in the large center, and Granada in the south, all had independent sovereignty and competing interests. The conflict between Christians and Muslims to control Iberia, which started with North Africa's Muslim invasion in 711, lasted from the years 718 to 1492.[6] Christians, fighting for control, successfully pushed the Muslims back to Granada, which was the Muslims' last control of the Iberian Peninsula.

The marriage between Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabel of Castile resulted in joint rule by the spouses of the two kingdoms, honoured as the "Catholic Monarchs" by Pope Alexander VI.[6] Together, the Crown Kings saw about the fall of Granada, victory over the Muslim minority, and expulsion or forcibly converted Jews and non-Christians to turn Iberia into a religious homogeneity.

Treaties

[edit]The 1492 discovery of the New World by Spain rendered desirable a delimitation of the Spanish and Portuguese spheres of exploration. Thus dividing the world into two areas of exploration and colonization. This was settled by the Treaty of Tordesillas (7 June 1494) which modified the delimitation authorized by Pope Alexander VI in two bulls issued on 4 May 1493. The treaty gave to Portugal all lands which might be discovered east of a meridian drawn from the Arctic Pole to the Antarctic, at a distance of 370 leagues (1,800 km) west of Cape Verde. Spain received the lands west of this line.

The known means of measuring longitude were so inexact that the line of demarcation could not in practice be determined,[15] subjecting the treaty to diverse interpretations. Both the Portuguese claim to Brazil and the Spanish claim to the Moluccas depended on the treaty. It was particularly valuable to the Portuguese as a recognition of their new-found,[clarification needed] particularly when, in 1497–1499, Vasco da Gama completed the voyage to India.

Later, when Spain established a route to the Indies from the west, Portugal arranged a second treaty, the Treaty of Zaragoza.

Spanish exploration

[edit]Colonization of the Caribbean, Mesoamerica, and South America

[edit]Sevilla la Nueva, established in 1509, was the first Spanish settlement on the island of Jamaica, which the Spaniards called Isla de Santiago. The capital was in an unhealthy location[16] and consequently moved around 1534 to the place they called "Villa de Santiago de la Vega", later named Spanish Town, in present-day Saint Catherine Parish.[17]

After first landing on "Guanahani" in the Bahamas, Columbus found the island which he called "Isla Juana", later named Cuba.[18] In 1511, the first Adelantado of Cuba, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar founded the island's first Spanish settlement at Baracoa; other towns soon followed, including Havana, which was founded in 1515.

After he pacified Hispaniola, where the native Indians had revolted against the administration of governor Nicolás de Ovando, Diego Velázquez de Cuéllar led the conquest of Cuba in 1511 under orders from Viceroy Diego Columbus and was appointed governor of the island. As governor he authorized expeditions to explore lands further west, including the 1517 Francisco Hernández de Córdoba expedition to Yucatán. Diego Velázquez, ordered expeditions, one led by his nephew, Juan de Grijalva, to Yucatán and the Hernán Cortés expedition of 1519. He initially backed Cortés's expedition to Mexico, but because of his personal enmity for Cortés later ordered Pánfilo de Narváez to arrest him. Grijalva was sent out with four ships and some 240 men.[19]

Hernán Cortés, led an expedition (entrada) to Mexico, which included Pedro de Alvarado and Bernardino Vázquez de Tapia. The Spanish campaign against the Aztec Empire had its final victory on 13 August 1521, when a coalition army of Spanish forces and native Tlaxcalan warriors led by Cortés and Xicotencatl the Younger captured the emperor Cuauhtemoc and Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire. The fall of Tenochtitlan marks the beginning of Spanish rule in central Mexico, and they established their capital of Mexico City on the ruins of Tenochtitlan. The Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire was one of the most significant events in world history.

In 1516, Juan Díaz de Solís, discovered the estuary formed by the confluence of the Uruguay River and the Paraná River.

In 1517, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba sailed from Cuba in search of slaves along the coast of Yucatán.[20][21] The expedition returned to Cuba to report on the discovery of this new land.

After receiving notice from Juan de Grijalva of gold in the area of what is now Tabasco, the governor of Cuba, Diego de Velasquez, sent a larger force than had previously sailed, and appointed Cortés as Captain-General of the Armada. Cortés then applied all of his funds, mortgaged his estates and borrowed from merchants and friends to outfit his ships. Velásquez may have contributed to the effort, but the government of Spain offered no financial support.[22]

Pedro Arias Dávila, Governor of the Island La Española was descended from a converso's family. In 1519 Dávila founded Darién, then in 1524 he founded Panama City and moved his capital there laying the basis for the exploration of South America's west coast and the subsequent conquest of Peru. Dávila was a soldier in wars against Moors at Granada in Spain, and in North Africa, under Pedro Navarro intervening in the Conquest of Oran. At the age of nearly seventy years he was made commander in 1514 by Ferdinand of the largest Spanish expedition.

Dávila sent Gil González Dávila to explore northward, and Pedro de Alvarado to explore Guatemala. In 1524 he sent another expedition with Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, executed there in 1526 by Dávila, by then aged over 85. Dávila's daughters married Rodrigo de Contreras and conquistador of Florida and Mississippi, the Governor of Cuba Hernando de Soto.

Dávila made an agreement with Francisco Pizarro and Diego de Almagro, which brought about the discovery of Peru, but withdrew in 1526 for a small compensation, having lost confidence in the outcome. In 1526 Dávila was superseded as Governor of Panama by Pedro de los Ríos, but became governor in 1527 of León in Nicaragua.

An expedition commanded by Pizarro and his brothers explored south from what is today Panama, reaching Inca territory by 1526.[23] After one more expedition in 1529, Pizarro received royal approval to conquer the region and be its viceroy. The approval read: "In July 1529 the queen of Spain signed a charter allowing Pizarro to conquer the Inca. Pizarro was named governor and captain of all conquests in New Castile."[24] The Viceroyalty of Peru was established in 1542, encompassing all Spanish holdings in South America.

In early 1536, the Adelantado of Canary Islands, Pedro Fernández de Lugo, arrived to Santa Marta, a city founded in 1525 by Rodrigo de Bastidas in modern-day Colombia, as governor. After some expeditions to the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta, Fernández de Lugo sent an expedition to the interior of the territory, initially looking for a land path to Peru following the Magdalena River. This expedition was commanded by Licentiate Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada, who ended up discovering and conquering the indigenous Muisca, and establishing the New Kingdom of Granada, which almost two centuries would be a viceroyalty. Jiménez de Quesada also founded the capital of Colombia, Santafé de Bogotá.

Juan Díaz de Solís arrived again to the renamed Río de la Plata, literally river of the silver, after the Incan conquest. He sought a way to transport the Potosi's silver to Europe. For a long time due to the Incan silver mines, Potosí was the most important site in Colonial Spanish America, located in the current department of Potosí in Bolivia[25] and it was the location of the Spanish colonial mint. The first settlement in the way was the fort of Sancti Spiritu, established in 1527 next to the Paraná River. Buenos Aires was established in 1536, establishing the Governorate of the Río de la Plata.[26]

Africans were also conquistadors in the early conquest campaigns in the Caribbean and Mexico. In the 1500s there were enslaved black and free black[clarification needed] sailors on Spanish ships crossing the Atlantic and developing new routes of conquest and trade in the Americas.[27] After 1521, the wealth and credit generated by the acquisition of the Aztec Empire funded auxiliary forces of black conquistadors that could number as many as five hundred. Spaniards recognized the value of these fighters. [citation needed]

One of the black conquistadors who fought against the Aztecs and survived the destruction of their empire was Juan Garrido. Born in Africa, Garrido lived as a young slave in Portugal before being sold to a Spaniard and acquiring his freedom fighting in the conquests of Puerto Rico, Cuba, and other islands. He fought as a free servant or auxiliary, participating in Spanish expeditions to other parts of Mexico (including Baja California) in the 1520s and 1530s. Granted a house plot in Mexico City, he raised a family there, working at times as a guard and town crier. He claimed to have been the first person to plant wheat in Mexico.[28]

Sebastian Toral was an African slave and one of the first black conquistadors in the New World. While a slave, he went with his Spanish owner on a campaign. He was able to earn his freedom during this service. He continued as a free conquistador with the Spaniards to fight the Maya in Yucatán in 1540. After the conquests he settled in the city of Mérida in the newly formed colony of Yucatán with his family. In 1574, the Spanish crown ordered that all slaves and free blacks in the colony had to pay a tribute to the crown. However, Toral wrote in protest of the tax based on his services during his conquests. The Spanish king responded that Toral need not pay the tax because of his service. Toral died a veteran of three transatlantic voyages and two Conquest expeditions, a man who had successfully petitioned the great Spanish King, walked the streets of Lisbon, Seville, and Mexico City, and helped found a capital city in the Americas.[29]

Juan Valiente was born in West Africa and purchased by Portuguese traders from African slavers. Around 1530 he was purchased by Alonso Valiente to be a slaved domestic servant in Puebla, Mexico. In 1533, Juan Valiente made a deal with his owner to allow him to be a conquistador for four years with the agreement that all earnings would come back to Alonso. He fought for many years in Chile and Peru. By 1540, he was a captain, horseman, and partner in Pedro de Valdivia's company in Chile. He was later awarded an estate in Santiago; a city he would help Valdivia found. Both Alonso and Valiente tried to contact the other to make an agreement about Valiente's manumission and send Alonso his awarded money. They were never able to reach each other and Valiente died in 1553 in the Battle of Tucapel.[30]

Other black conquistadors include Pedro Fulupo, Juan Bardales, Antonio Pérez, and Juan Portugués. Pedro Fulupo was a black slave that fought in Costa Rica. Juan Bardales was an African slave that fought in Honduras and Panama. For his service he was granted manumission and a pension of 50 pesos. Antonio Pérez was from North Africa, and a free black. He joined the conquest in Venezuela and was made a captain. Juan Portugués fought in the conquests in Venezuela.[30]

North America colonization

[edit]

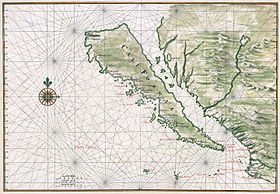

During the 1500s, the Spanish began to travel through and colonize North America. They were looking for gold in foreign kingdoms. By 1511 there were rumours of undiscovered lands to the northwest of Hispaniola. Juan Ponce de León equipped three ships with at least 200 men at his own expense and set out from Puerto Rico on 4 March 1513 to Florida and surrounding coastal area. Another early motive was the search for the Seven Cities of Gold, or "Cibola", rumoured to have been built by Native Americans somewhere in the desert Southwest. In 1536 Francisco de Ulloa, the first documented European to reach the Colorado River, sailed up the Gulf of California and a short distance into the river's delta.[31]

The Basques were fur trading, fishing cod and whaling in Terranova (Labrador and Newfoundland) in 1520,[32] and in Iceland by at least the early 17th century.[33][34] They established whaling stations at the former, mainly in Red Bay,[35] and probably established some in the latter as well. In Terranova they hunted bowheads and right whales, while in Iceland[36] they appear to have only hunted the latter. The Spanish fishery in Terranova declined over conflicts between Spain and other European powers during the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

In 1524, the Portuguese Estêvão Gomes, who had sailed in Ferdinand Magellan's fleet, explored Nova Scotia, sailing South through Maine, where he entered New York Harbor and the Hudson River and eventually reached Florida in August 1525. As a result of his expedition, the 1529 Diego Ribeiro world map outlined the East coast of North America almost perfectly.[citation needed]

The Spaniard Cabeza de Vaca was the leader of the Narváez expedition of 600 men[37] that between 1527 and 1535 explored the mainland of North America. From Tampa Bay, Florida, on 15 April 1528, they marched through Florida. Traveling mostly on foot, they crossed Texas, New Mexico and Arizona, and Mexican states of Tamaulipas, Nuevo León and Coahuila. After several months of fighting native inhabitants through wilderness and swamp, the party reached Apalachee Bay with 242 men. They believed they were near other Spaniards in Mexico, but there was in fact 1500 miles of coast between them. They followed the coast westward, until they reached the mouth of the Mississippi River near to Galveston Island.[citation needed]

Later they were enslaved for a few years by various Native American tribes of the upper Gulf Coast. They continued through Coahuila and Nueva Vizcaya; then down the Gulf of California coast to what is now Sinaloa, Mexico, over a period of roughly eight years. They spent years enslaved by the Ananarivo of the Louisiana Gulf Islands. Later they were enslaved by the Hans, the Capoques and others. In 1534 they escaped into the American interior, contacting other Native American tribes along the way. Only four men, Cabeza de Vaca, Andrés Dorantes de Carranza, Alonso del Castillo Maldonado, and an enslaved Moroccan Berber named Estevanico, survived and escaped to reach Mexico City. In 1539, Estevanico was one of four men who accompanied Marcos de Niza as a guide in search of the fabled Seven Cities of Cibola, preceding Coronado. When the others were struck ill, Estevanico continued alone, opening up what is now New Mexico and Arizona. He was killed at the Zuni village of Hawikuh in present-day New Mexico.[citation needed]

The viceroy of New Spain Antonio de Mendoza, for whom is named the Codex Mendoza, commissioned several expeditions to explore and establish settlements in the northern lands of New Spain in 1540–1542. Francisco Vázquez de Coronado reached Quivira in central Kansas. Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo explored the western coastline of Alta California in 1542–1543. Vázquez de Coronado's 1540–1542 expedition began as a search for the fabled Cities of Gold, but after learning from natives in New Mexico of a large river to the west, he sent García López de Cárdenas to lead a small contingent to find it. With the guidance of Hopi Indians, Cárdenas and his men became the first outsiders to see the Grand Canyon.[38] However, Cárdenas was reportedly unimpressed with the canyon, assuming the width of the Colorado River at six feet (1.8 m) and estimating 300-foot-tall (91 m) rock formations to be the size of a person. After unsuccessfully attempting to descend to the river, they left the area, defeated by the difficult terrain and torrid weather.[39]

In 1540, Hernando de Alarcón and his fleet reached the mouth of the Colorado River, intending to provide additional supplies to Coronado's expedition. Alarcón may have sailed the Colorado as far upstream as the present-day California–Arizona border. However, Coronado never reached the Gulf of California, and Alarcón eventually gave up and left. Melchior Díaz reached the delta in the same year, intending to establish contact with Alarcón, but the latter was already gone by the time of Díaz's arrival. Díaz named the Colorado River Río del Tizón, while the name Colorado ("Red River") was first applied to a tributary of the Gila River.

In 1540, expeditions under Hernando de Alarcon and Melchior Diaz visited the area of Yuma and immediately saw the natural crossing of the Colorado River from Mexico to California by land as an ideal spot for a city, as the Colorado River narrows to slightly under 1000 feet wide in one small point. Later military expeditions that crossed the Colorado River at the Yuma Crossing include Juan Bautista de Anza's (1774).

The marriage between Luisa de Abrego, a free black domestic servant from Seville and Miguel Rodríguez, a white Segovian conquistador in 1565 in St. Augustine (Spanish Florida), is the first known and recorded Christian marriage anywhere in the continental United States.[40]

The Chamuscado and Rodríguez Expedition explored New Mexico in 1581–1582. They explored a part of the route visited by Coronado in New Mexico and other parts in the southwestern United States between 1540 and 1542.

The viceroy of New Spain Don Diego García Sarmiento sent another expedition in 1648 to explore, conquer and colonize the Californias.

Asia and Oceania colonization, and Pacific exploration

[edit]In 1525, Charles I of Spain ordered an expedition led by friar García Jofre de Loaísa to go to Asia by the western route to colonize the Maluku Islands (known as Spice Islands, now part of Indonesia), thus crossing first the Atlantic and then the Pacific oceans. Ruy López de Villalobos sailed to the Philippines in 1542–1543. From 1546 to 1547 Francis Xavier worked in Maluku among the peoples of Ambon Island, Ternate, and Morotai, and laid the foundations for the Christian religion there.

In 1564, Miguel López de Legazpi was commissioned by the viceroy of New Spain, Luís de Velasco, to explore the Maluku Islands where Magellan and Ruy López de Villalobos had landed in 1521 and 1543, respectively. The expedition was ordered by Philip II of Spain, after whom the Philippines had earlier been named by Villalobos. El Adelantado Legazpi established settlements in the East Indies and the Pacific Islands in 1565. He was the first governor-general of the Spanish East Indies. After obtaining peace with various indigenous tribes, López de Legazpi made the Philippines the capital in 1571.[clarification needed]

The Spanish settled and took control of Tidore in 1603 to trade spices and counter Dutch encroachment in the archipelago of Maluku. The Spanish presence lasted until 1663, when the settlers and military were moved back to the Philippines. Part of the Ternatean population chose to leave with the Spanish, settling near Manila in what later became the municipality of Ternate. Spanish galleons traveled across the Pacific Ocean between Acapulco in Mexico and Manila.

In 1542, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo traversed the coast of California and named many of its features. In 1601, Sebastián Vizcaíno mapped the coastline in detail and gave new names to many features. Martín de Aguilar, lost from the expedition led by Sebastián Vizcaíno, explored the Pacific coast as far north as Coos Bay in present-day Oregon.[41]

Since the 1549 arrival to Kagoshima (Kyushu) of a group of Jesuits with St. Francis Xavier missionary and Portuguese traders, Spain was interested in Japan. In this first group of Jesuit missionaries were included Spaniards Cosme de Torres and Juan Fernandez.

In 1611, Sebastián Vizcaíno surveyed the east coast of Japan and from the year of 1611 to 1614 he was ambassador of King Felipe III in Japan returning to Acapulco in the year of 1614.[citation needed] In 1608, he was sent to search for two mythical islands called Rico de Oro (island of gold) and Rico de Plata (island of silver).[42]

Portuguese exploration

[edit]

As a seafaring people in the south-westernmost region of Europe, the Portuguese became natural leaders of exploration during the Middle Ages. Faced with the options of either accessing other European markets by sea, by exploiting its seafaring prowess, or by land, and facing the task of crossing Castile and Aragon territory, it is not surprising that goods were sent via the sea to England, Flanders, Italy and the Hanseatic league towns.[citation needed]

One important reason was the need for alternatives to the expensive eastern trade routes that followed the Silk Road. Those routes were dominated first by the republics of Venice and Genoa, and then by the Ottoman Empire after the conquest of Constantinople in 1453. The Ottomans barred European access. For decades the Spanish Netherlands ports produced more revenue than the colonies since all goods brought from Spain, Mediterranean possessions, and the colonies were sold directly there to neighbouring European countries: wheat, olive oil, wine, silver, spice, wool and silk were big businesses.[citation needed]

The gold brought home from Guinea stimulated the commercial energy of the Portuguese, and its European neighbours, especially Spain. Apart from their religious and scientific aspects, these voyages of discovery were highly profitable.

They had benefited from Guinea's connections with neighbouring Iberians and north African Muslim states. Due to these connections, mathematicians and experts in naval technology appeared in Portugal. Portuguese and foreign experts made several breakthroughs in the fields of mathematics, cartography and naval technology.

Under Afonso V (1443–1481), surnamed the African, the Gulf of Guinea was explored as far as Cape St. Catherine (Cabo Santa Caterina),[44][45][46] and three expeditions in 1458, 1461 and 1471, were sent to Morocco; in 1471 Arzila (Asila) and Tangier were captured from the Moors. Portuguese explored the Atlantic, Indian and Pacific Oceans before the Iberian Union period (1580–1640). Under John II (1481–1495) the fortress of São Jorge da Mina, the modern Elmina, was founded for the protection of the Guinea trade. Diogo Cão, or Can, discovered the Congo in 1482 and reached Cape Cross in 1486.

In 1483, Diogo Cão sailed up the uncharted Congo River, finding Kongo villages and becoming the first European to encounter the Kongo kingdom.[47]

On 7 May 1487, two Portuguese envoys, Pero da Covilhã and Afonso de Paiva, were sent traveling secretly overland to gather information on a possible sea route to India, but also to inquire about Prester John. Covilhã managed to reach Ethiopia. Although well received, he was forbidden to depart. Bartolomeu Dias crossed the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, thus proving that the Indian Ocean was accessible by sea.

In 1498, Vasco da Gama reached India. In 1500, Pedro Álvares Cabral discovered Brazil, claiming it for Portugal.[48] In 1510, Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Goa in India, Ormuz in the Persian Strait, and Malacca. The Portuguese sailors sailed eastward to such places as Taiwan, Japan, and the island of Timor. Several writers have also suggested the Portuguese were the first Europeans to discover Australia and New Zealand.[49][50][51][52][53]

Álvaro Caminha, in Cape Verde islands, who received the land as a grant from the crown, established a colony with Jews forced to stay on São Tomé Island. Príncipe island was settled in 1500 under a similar arrangement. Attracting settlers proved difficult; however, the Jewish settlement was a success and their descendants settled many parts of Brazil.[54]

From their peaceful settlings in secured islands along Atlantic Ocean (archipelagos and islands such as Madeira, the Azores, Cape Verde, São Tomé, Príncipe, and Annobón) they travelled to coastal enclaves trading almost every goods of African and Islander areas like spices (hemp, opium, garlic), wine, dry fish, dried meat, toasted flour, leather, fur of tropical animals and seals, whaling ... but mainly ivory, black slaves, gold and hardwoods. They maintaining trade ports in Congo (M'banza), Angola, Natal (City of Cape Good Hope, in Portuguese "Cidade do Cabo da Boa Esperança"), Mozambique (Sofala), Tanzania (Kilwa Kisiwani), Kenya (Malindi) to Somalia. The Portuguese following the maritime trade routes of Muslims and Chinese traders, sailed the Indian Ocean. They were on Malabar Coast since 1498 when Vasco da Gama reached Anjadir, Kannut, Kochi and Calicut.

Da Gama in 1498 marked the beginning of Portuguese influence in Indian Ocean. In 1503 or 1504, Zanzibar became part of the Portuguese Empire when Captain Ruy Lourenço Ravasco Marques landed and demanded and received tribute from the sultan in exchange for peace.[55]: page: 99 Zanzibar remained a possession of Portugal for almost two centuries. It initially became part of the Portuguese province of Arabia and Ethiopia and was administered by a governor general. Around 1571, Zanzibar became part of the western division of the Portuguese empire and was administered from Mozambique.[56]: 15 It appears, however, that the Portuguese did not closely administer Zanzibar. The first English ship to visit Unguja, the Edward Bonaventure in 1591, found that there was no Portuguese fort or garrison. The extent of their occupation was a trade depot where produce was purchased and collected for shipment to Mozambique. "In other respects, the affairs of the island were managed by the local 'king,' the predecessor of the Mwinyi Mkuu of Dunga."[57]: 81 This hands-off approach ended when Portugal established a fort on Pemba around 1635 in response to the Sultan of Mombasa's slaughter of Portuguese residents several years earlier.

After 1500: West and East Africa, Asia, and the Pacific

[edit]In west Africa Cidade de Congo de São Salvador was founded some time after the arrival of the Portuguese, in the pre-existing capital of the local dynasty ruling at that time (1483), in a city of the Luezi River valley. Portuguese were established supporting one Christian local dynasty ruling suitor.

When Afonso I of Kongo was established the Roman Catholic Church in Kongo kingdom. By 1516, Afonso I sent various of his children and nobles to Europe to study, including his son Henrique Kinu a Mvemba, who was elevated to the status of bishop in 1518. Afonso I wrote a series of letters to the kings of Portugal Manuel I and João III of Portugal concerning to the behavior of the Portuguese in his country and their role in the developing slave trade, complaining of Portuguese complicity in purchasing illegally enslaved people and the connections between Afonso's men, Portuguese mercenaries in Kongo's service and the capture and sale of slaves by Portuguese.[58]

The aggregate of Portugal's colonial holdings in India were Portuguese India. The period of European contact of Ceylon began with the arrival of Portuguese soldiers and explorers of the expedition of Lourenço de Almeida, the son of Francisco de Almeida, in 1505.[59] The Portuguese founded a fort at the port city of Colombo in 1517 and gradually extended their control over the coastal areas and inland. In a series of military conflicts, political manoeuvres and conquests, the Portuguese extended their control over the Sinhalese kingdoms, including Jaffna (1591),[60] Raigama (1593), Sitawaka (1593), and Kotte (1594,)[61] but the aim of unifying the entire island under Portuguese control failed.[62] The Portuguese, led by Pedro Lopes de Sousa, launched a full-scale military invasion of the Kingdom of Kandy in the Danture campaign of 1594. The invasion was a disaster for the Portuguese, with their entire army wiped out by Kandyan guerrilla warfare.[63][64]

More envoys were sent in 1507 to Ethiopia, after Socotra was taken by the Portuguese. As a result of this mission, and facing Muslim expansion, Queen Regent Eleni of Ethiopia sent ambassador Mateus to King Manuel I of Portugal and to the Pope, in search of a coalition. Mateus reached Portugal via Goa, having returned with a Portuguese embassy, along with priest Francisco Álvares in 1520. Francisco Álvares book, which included the testimony of Covilhã, the Verdadeira Informação das Terras do Preste João das Indias ("A True Relation of the Lands of Prester John of the Indies") was the first direct account of Ethiopia, greatly increasing European knowledge at the time, as it was presented to the pope, published and quoted by Giovanni Battista Ramusio.[65]

In 1509, the Portuguese under Francisco de Almeida won a critical victory in the Battle of Diu against a joint Mamluk and Arab fleet sent to counteract their presence in the Arabian Sea. The retreat of the Mamluks and Arabs enabled the Portuguese to implement their strategy of controlling the Indian Ocean.[66]

Afonso de Albuquerque set sail in April 1511 from Goa to Malacca with a force of 1,200 men and seventeen or eighteen ships.[67] Following his capture of the city on 24 August 1511, it became a strategic base for Portuguese expansion in the East Indies; consequently the Portuguese were obliged to build a fort they named A Famosa to defend it. That same year, the Portuguese, desiring a commercial alliance, sent an ambassador, Duarte Fernandes, to the Kingdom of Ayutthaya, where he was well received by King Ramathibodi II.[68] In 1526, a large force of Portuguese ships under the command of Pedro Mascarenhas was sent to conquer Bintan, where Sultan Mahmud was based. Earlier expeditions by Diogo Dias and Afonso de Albuquerque had explored that part of the Indian Ocean, and discovered several islands new to Europeans. Mascarenhas served as Captain-Major of the Portuguese colony of Malacca from 1525 to 1526, and as viceroy of Goa, capital of the Portuguese possessions in Asia, from 1554 until his death in 1555. He was succeeded by Francisco Barreto, who served with the title of "governor-general".[69]

To enforce a trade monopoly, Muscat, and Hormuz in the Persian Gulf, were seized by Afonso de Albuquerque in 1507, and in 1507 and 1515, respectively. He also entered into diplomatic relations with Persia. In 1513 while trying to conquer Aden, an expedition led by Albuquerque cruised the Red Sea inside the Bab al-Mandab, and sheltered at Kamaran island. In 1521, a force under António Correia conquered Bahrain, ushering in a period of almost eighty years of Portuguese rule of the Persian Gulf.[70] In the Red Sea, Massawa was the most northerly point frequented by the Portuguese until 1541, when a fleet under Estevão da Gama penetrated as far as Suez.

In 1511, the Portuguese were the first Europeans to reach the city of Guangzhou by the sea, and they settled on its port for a commercial monopoly of trade with other nations. They were later expelled from their settlements, but they were allowed the use of Macau, which was also occupied in 1511, and to be appointed in 1557 as the base for doing business with Guangzhou. The quasi-monopoly on foreign trade in the region would be maintained by the Portuguese until the early seventeenth century, when the Spanish and Dutch arrived.

The Portuguese Diogo Rodrigues explored the Indian Ocean in 1528, he explored the islands of Réunion, Mauritius, and Rodrigues, naming it the Mascarene or Mascarenhas Islands, after his countryman Pedro Mascarenhas, who had been there before. The Portuguese presence disrupted and reorganised the Southeast Asian trade, and in eastern Indonesia they introduced Christianity.[71] After the Portuguese annexed Malacca in August 1511, one Portuguese diary noted 'it is thirty years since they became Moors'–[72] giving a sense of the competition then taking place between Islamic and European influences in the region. Afonso de Albuquerque learned of the route to the Banda Islands and other "Spice Islands", and sent an exploratory expedition of three vessels under the command of António de Abreu, Simão Afonso Bisigudo and Francisco Serrão.[73] On the return trip, Francisco Serrão was shipwrecked at Hitu Island (northern Ambon) in 1512. There he established ties with the local ruler who was impressed with his martial skills. The rulers of the competing island states of Ternate and Tidore also sought Portuguese assistance and the newcomers were welcomed in the area as buyers of supplies and spices during a lull in the regional trade due to the temporary disruption of Javanese and Malay sailings to the area following the 1511 conflict in Malacca. The spice trade soon revived but the Portuguese would not be able to fully monopolize nor disrupt this trade.[74]

Allying himself with Ternate's ruler, Serrão constructed a fortress on that tiny island and served as the head of a mercenary band of Portuguese seamen under the service of one of the two local feuding sultans who controlled most of the spice trade. Such an outpost far from Europe generally only attracted the most desperate and avaricious, and as such the feeble attempts at Christianization only strained relations with Ternate's Muslim ruler.[74] Serrão urged Ferdinand Magellan to join him in Maluku, and sent the explorer information about the Spice Islands. Both Serrão and Magellan, however, perished before they could meet one another, with Magellan dying in battle in Macatan.[74] In 1535 Sultan Tabariji was deposed and sent to Goa in chains, where he converted to Christianity and changed his name to Dom Manuel. After being declared innocent of the charges against him he was sent back to reassume his throne, but died en route at Malacca in 1545. He had however, already bequeathed the island of Ambon to his Portuguese godfather Jordão de Freitas. Following the murder of Sultan Hairun at the hands of the Europeans, the Ternateans expelled the hated foreigners in 1575 after a five-year siege.

The Portuguese first landed in Ambon in 1513, but it only became the new centre for their activities in Maluku following the expulsion from Ternate. European power in the region was weak and Ternate became an expanding, fiercely Islamic and anti-European state under the rule of Sultan Baab Ullah (r. 1570–1583) and his son Sultan Said.[75] The Portuguese in Ambon, however, were regularly attacked by native Muslims on the island's northern coast, in particular Hitu which had trading and religious links with major port cities on Java's north coast. Altogether, the Portuguese never had the resources or manpower to control the local trade in spices, and failed in attempts to establish their authority over the crucial Banda Islands, the nearby centre of most nutmeg and mace production. Following Portuguese missionary work, there have been large Christian communities in eastern Indonesia particularly among the Ambonese.[75] By the 1560s there were 10,000 Catholics in the area, mostly on Ambon, and by the 1590s there were 50,000 to 60,000, although most of the region surrounding Ambon remained Muslim.[75]

Mauritius was visited by the Portuguese between 1507 (by Diogo Fernandes Pereira) and 1513. The Portuguese took no interest in the isolated Mascarene islands. Their main African base was in Mozambique, and therefore the Portuguese navigators preferred to use the Mozambique Channel to go to India. The Comoros at the north proved to be a more practical port of call.

North America

[edit]

Based on the Treaty of Tordesillas, Manuel I claimed territorial rights in the area visited by John Cabot in 1497 and 1498.[76] To that end, in 1499 and 1500, the Portuguese mariner João Fernandes Lavrador visited the northeast Atlantic coast and Greenland and the north Atlantic coast of Canada, which accounts for the appearance of "Labrador" on topographical maps of the period.[77] Subsequently, in 1501 and 1502 the Corte-Real brothers explored and charted Greenland and the coasts of present-day Newfoundland and Labrador, claiming these lands as part of the Portuguese Empire. Whether or not the Corte-Reals expeditions were also inspired by or continuing the alleged voyages of their father, João Vaz Corte-Real (with other Europeans) in 1473, to Terra Nova do Bacalhau (Newfoundland of the Codfish), remains controversial, as the 16th century accounts of the 1473 expedition differ considerably. In 1520–1521, João Álvares Fagundes was granted donatary rights to the inner islands of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Accompanied by colonists from mainland Portugal and the Azores, he explored Newfoundland and Nova Scotia (possibly reaching the Bay of Fundy on the Minas Basin[78]), and established a fishing colony on Cape Breton Island, that would last some years or until at least 1570s, based on contemporary accounts.[79]

South America

[edit]

Brazil was claimed by Portugal in April 1500, on the arrival of the Portuguese fleet commanded by Pedro Álvares Cabral.[80] The Portuguese encountered natives divided into several tribes. The first settlement was founded in 1532. Some European countries, especially France, were also sending excursions to Brazil to extract brazilwood. Worried about the foreign incursions and hoping to find mineral riches, the Portuguese crown decided to send large missions to take possession of the land and combat the French. In 1530, an expedition led by Martim Afonso de Sousa arrived to patrol the entire coast, ban the French, and to create the first colonial villages, like São Vicente, at the coast. As time passed, the Portuguese created the Viceroyalty of Brazil. Colonization was effectively begun in 1534, when Dom João III divided the territory into twelve hereditary captaincies,[81][82] a model that had previously been used successfully in the colonization of the Madeira Island, but this arrangement proved problematic and in 1549 the king assigned a Governor-General to administer the entire colony,[82][83] Tomé de Sousa.

The Portuguese frequently relied on the help of Jesuits and European adventurers who lived together with the aborigines and knew their languages and culture, such as João Ramalho, who lived among the Guaianaz tribe near today's São Paulo, and Diogo Álvares Correia, who lived among the Tupinamba natives near today's Salvador de Bahia.

The Portuguese assimilated some of the native tribes[84] while others were enslaved or exterminated in long wars or by European diseases to which they had no immunity.[85][86] By the mid-16th century, sugar had become Brazil's most important export[87][88] and the Portuguese imported African slaves[89][90] to produce it.

Mem de Sá was the third Governor-General of Brazil in 1556, succeeding Duarte da Costa, in Salvador of Bahia when France founded several colonies. Mem de Sá was supporting of Jesuit priests, Fathers Manuel da Nóbrega and José de Anchieta, who founded São Vicente in 1532, and São Paulo, in 1554.

French colonists tried to settle in present-day Rio de Janeiro, from 1555 to 1567, the so-called France Antarctique episode, and in present-day São Luís, from 1612 to 1614 the so-called France Équinoxiale. Through wars against the French the Portuguese slowly expanded their territory to the southeast, taking Rio de Janeiro in 1567, and to the northwest, taking São Luís in 1615.[91]

The Dutch sacked Bahia in 1604, and temporarily captured the capital Salvador.

In the 1620s and 1630s, the Dutch West India Company established many trade posts or colonies. The Spanish silver fleet, which carried silver from Spanish colonies to Spain, were seized by Piet Heyn in 1628. In 1629 Suriname and Guyana were established.[clarification needed] In 1630 the West India Company conquered part of Brazil, and the colony of New Holland (capital Mauritsstad, present-day Recife) was founded.

John Maurice of Nassau prince of Nassau-Siegen, was appointed as the governor of the Dutch possessions in Brazil in 1636 by the Dutch West India Company on recommendation of Frederick Henry. He landed at Recife, the port of Pernambuco and the chief stronghold of the Dutch, in January 1637. By a series of successful expeditions, he gradually extended the Dutch possessions from Sergipe on the south to São Luís de Maranhão in the north.

In 1624 most of the inhabitants of the town Pernambuco (Recife), in the future Dutch colony of Brazil were Sephardic Jews who had been banned by the Portuguese Inquisition to this town at the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. As some years afterward the Dutch in Brazil appealed to Holland for craftsmen of all kinds, many Jews went to Brazil; about 600 Jews left Amsterdam in 1642, accompanied by two distinguished scholars – Isaac Aboab da Fonseca and Moses Raphael de Aguilar. In the struggle between Holland and Portugal for the possession of Brazil the Dutch were supported by the Jews.

From 1630 to 1654, the Dutch set up more permanently in the Nordeste and controlled a long stretch of the coast most accessible to Europe, without, however, penetrating the interior. But the colonists of the Dutch West India Company in Brazil were in a constant state of siege, in spite of the presence in Recife of John Maurice of Nassau as governor. After several years of open warfare, the Dutch formally withdrew in 1661.

Portuguese sent military expeditions to the Amazon rainforest and conquered British and Dutch strongholds,[92] founding villages and forts from 1669.[93] In 1680 they reached the far south and founded Sacramento on the bank of the Rio de la Plata, in the Eastern Strip region (present-day Uruguay).[94]

In the 1690s, gold was discovered by explorers in the region that would later be called Minas Gerais (General Mines) in current Mato Grosso and Goiás.

Before the Iberian Union period (1580–1640), Spain tried to prevent Portuguese expansion into Brazil with the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas. After the Iberian Union period, the Eastern Strip were settled by Portugal. This was disputed in vain, and in 1777 Spain confirmed Portuguese sovereignty.

Iberian Union period (1580–1640)

[edit]

In 1578, the Saadi sultan Ahmad al-Mansur, contemporary of Queen Elizabeth I, defeated Portugal at the Battle of Ksar El Kebir, beating the young king Sebastian I, a devout Christian who believed in the crusade to defeat Islam. Portugal had landed in North Africa after Abu Abdallah asked him to help recover the Saadian throne. Abu Abdallah's uncle, Abd Al-Malik, had taken it from Abu Abdallah with Ottoman Empire support. The defeat of Abu Abdallah and the death of Portugal's king led to the end of the Portuguese Aviz dynasty and later to the integration of Portugal and its empire at the Iberian Union for 60 years under Sebastian's uncle Philip II of Spain. Philip was married to his relative Mary I cousin of his father, due to this, Philip was King of England and Ireland[95] in a dynastic union with Spain.

As a result of the Iberian Union, Phillip II's enemies became Portugal's enemies, such as the Dutch in the Dutch–Portuguese War, England or France. The English-Spanish wars of 1585–1604 were clashes not only in English and Spanish ports or on the sea between them but also in and around the present-day territories of Florida, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, and Panama. War with the Dutch led to invasions of many countries in Asia, including Ceylon and commercial interests in Japan, Africa (Mina), and South America. Even though the Portuguese were unable to capture the entire island of Ceylon, they were able to control its coastal regions for a considerable time.

From 1580 to 1670 mostly, the Bandeirantes in Brazil focused on slave hunting, then from 1670 to 1750 they focused on mineral wealth. Through these expeditions and the Dutch–Portuguese War, Colonial Brazil expanded from the small limits of the Tordesilhas Line to roughly the same borders as current Brazil.

In the 17th century, taking advantage of this period of Portuguese weakness, the Dutch occupied many Portuguese territories in Brazil. John Maurice, Prince of Nassau-Siegen was appointed as the governor of the Dutch possessions in Brazil in 1637 by the Dutch West India Company. He landed at Recife, the port of Pernambuco, in January 1637. In a series of expeditions, he gradually expanded from Sergipe on the south to São Luís de Maranhão in the north. He likewise conquered the Portuguese possessions of Elmina Castle, Saint Thomas, and Luanda and Angola. The Dutch intrusion into Brazil was long lasting and troublesome to Portugal. The Seventeen Provinces captured a large portion of the Brazilian coast including the provinces of Bahia, Pernambuco, Paraíba, Rio Grande do Norte, Ceará, and Sergipe, while Dutch privateers sacked Portuguese ships in both the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. The large area of Bahia and its city, the strategically important Salvador, was recovered quickly by an Iberian military expedition in 1625.

After the dissolution of the Iberian Union in 1640, Portugal re-established authority over its lost territories including remaining Dutch controlled areas. The other smaller, less developed areas were recovered in stages and relieved of Dutch piracy in the next two decades by local resistance and Portuguese expeditions.

Spanish Formosa was established in Taiwan, first by Portugal in 1544 and later renamed and repositioned by Spain in Keelung. It became a natural defence site for the Iberian Union. The colony was designed to protect Spanish and Portuguese trade from interference by the Dutch base in the south of Taiwan. The Spanish colony was short-lived due to the unwillingness of Spanish colonial authorities in Manila to defend it.

Disease in the Americas

[edit]

While technological superiority, military strategy and forging local alliances played an important role in the victories of the conquistadors in the Americas, their conquest was greatly facilitated by Old World diseases: smallpox, chicken pox, diphtheria, typhus, influenza, measles, malaria, and yellow fever. The diseases were carried to distant tribes and villages. This typical path of disease transmission moved much faster than the conquistadors, so that as they advanced, resistance weakened.[citation needed] Epidemic disease is commonly cited as the primary reason for the population collapse. The American natives lacked immunity to these infections.[96]

When Francisco Coronado and the Spaniards first explored the Rio Grande Valley in 1540, in modern New Mexico, some of the chieftains complained of new diseases that affected their tribes. Cabeza de Vaca reported that in 1528, when the Spanish landed in Texas, "half the natives died from a disease of the bowels and blamed us."[97] When the Spanish conquistadors arrived in the Incan empire, a large portion of the population had already died in a smallpox epidemic. The first epidemic was recorded in 1529 and killed the emperor Huayna Capac, the father of Atahualpa. Further epidemics of smallpox broke out in 1533, 1535, 1558 and 1565, as well as typhus in 1546, influenza in 1558, diphtheria in 1614 and measles in 1618.[98]: 133

Recently developed tree-ring evidence shows that the illness which reduced the population in Aztec Mexico was aided by a great drought in the 16th century, and which continued through the arrival of the Spanish conquest.[99][100] This has added to the body of epidemiological evidence indicating that cocoliztli epidemics (Nahuatl name for viral haemorrhagic fever) were indigenous fevers transmitted by rodents and aggravated by the drought. The cocoliztli epidemic from 1545 to 1548 killed an estimated 5 to 15 million people, or up to 80% of the native population. The cocoliztli epidemic from 1576 to 1578 killed an estimated, additional 2 to 2.5 million people, or about 50% of the remainder.[101][102]

The American researcher Henry Dobyns said that 95% of the total population of the Americas died in the first 130 years,[103] and that 90% of the population of the Inca Empire died in epidemics.[104] Cook and Borah of the University of California at Berkeley believe that the indigenous population in Mexico declined from 25.2 million in 1518 to 700,000 people in 1623, less than 3% of the original population.[105]

Mythic lands

[edit]The conquistadors found new animal species, but reports confused these with monsters such as giants, dragons, or ghosts.[106] Stories about castaways on mysterious islands were common.

An early motive for exploration was the search for Cipango, the place where gold was born. Cathay and Cibao were later goals. The Seven Cities of Gold, or "Cibola", was rumoured to have been built by Native Americans somewhere in the desert Southwest.[107][108] As early as 1611, Sebastián Vizcaíno surveyed the east coast of Japan and searched for two mythical islands called Rico de Oro ('Rich in Gold') and Rico de Plata ('Rich in Silver').

Books such as The Travels of Marco Polo fuelled rumours of mythical places. Stories included the half-fabulous Christian Empire of "Prester John", the kingdom of the White Queen on the "Western Nile" (Sénégal River), the Fountain of Youth, cities of Gold in North and South America such as Quivira, Zuni-Cibola Complex, and El Dorado, and wonderful kingdoms of the Ten Lost Tribes and women called Amazons. In 1542, Francisco de Orellana reached the Amazon River, naming it after a tribe of warlike women he claimed to have fought there. Others claimed that the similarity between Indio and Iudio, the Spanish-language word for 'Jew' around 1500, revealed the indigenous peoples' origin. Portuguese traveller Antonio de Montezinos reported that some of the Lost Tribes were living among the Native Americans of the Andes in South America. Gonzalo Fernández de Oviedo y Valdés wrote that Ponce de León was looking for the waters of Bimini to cure his aging.[109] A similar account appears in Francisco López de Gómara's Historia General de las Indias of 1551.[110] Then in 1575, Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda, a shipwreck survivor who had lived with the Native Americans of Florida for 17 years, published his memoir in which he locates the Fountain of Youth in Florida, and says that Ponce de León was supposed to have looked for them there.[111] This land[clarification needed] somehow also became confused with the Boinca or Boyuca mentioned by Juan de Solis, although Solis's navigational data placed it in the Gulf of Honduras.

Sir Walter Raleigh and some Italian, Spanish, Dutch, French and Portuguese expeditions were looking for the wonderful Guiana empire that gave its name to the present day countries of the Guianas.

Several expeditions went in search of these fabulous places, but returned empty-handed, or brought less gold than they had hoped. They found other precious metals such as silver, which was particularly abundant in Potosí, in modern-day Bolivia. They discovered new routes, ocean currents, trade winds, crops, spices and other products. In the sail era knowledge of winds and currents was essential, for example, the Agulhas current long prevented Portuguese sailors from reaching India. Various places in Africa and the Americas have been named after the imagined cities made of gold, rivers of gold and precious stones.

Shipwrecked off Santa Catarina island in present-day Brazil, Aleixo Garcia living among the Guaranís heard tales of a "White King" who lived to the west, ruling cities of incomparable riches and splendour. Marching westward in 1524 to find the land of the "White King", he was the first European to cross South America from the East. He discovered a great waterfall[clarification needed] and the Chaco Plain. He managed to penetrate the outer defences of the Inca Empire on the hills of the Andes, in present-day Bolivia, the first European to do so, eight years before Francisco Pizarro. Garcia looted a booty of silver. When the army of Huayna Cápac arrived to challenge him, Garcia then retreated with the spoils, only to be assassinated by his Indian allies near San Pedro on the Paraguay River.

Secrecy

[edit]

The Spanish discovery of what they thought at that time was India, and the constant competition of Portugal and Spain led to a desire for secrecy about every trade route and every colony. As a consequence, many documents that could reach other European countries included fake dates and faked facts, to mislead any other nation's possible efforts. For example, the Island of California refers to a famous cartographic error propagated on many maps during the 17th and 18th centuries, despite contradictory evidence from various explorers. The legend was initially infused with the idea that California was a terrestrial paradise, peopled by black Amazons.

The tendency to secrecy and falsification of dates casts doubts about the authenticity of many primary sources. Several historians[clarification needed] have hypothesized that John II may have known of the existence of Brazil and North America as early as 1480, thus explaining his wish in 1494 at the signing of the Treaty of Tordesillas, to push the line of influence further west. Many historians suspect that the real documents would have been placed in the Library of Lisbon.[clarification needed] Unfortunately, a fire following the 1755 Lisbon earthquake destroyed nearly all of the library's records, but an extra copy[clarification needed] available in Goa was transferred to Lisbon's Tower of Tombo, during the following 100 years. The Corpo Cronológico (Chronological Corpus), a collection of manuscripts on the Portuguese explorations and discoveries in Africa, Asia and Latin America, was inscribed on UNESCO's Memory of the World Register in 2007 in recognition of its historical value "for acquiring knowledge of the political, diplomatic, military, economic and religious history of numerous countries at the time of the Portuguese Discoveries."[112]

Financing and governance

[edit]

Ferdinand II King of Aragon and Regent of Castile, incorporated the American territories into the Kingdom of Castile and then withdrew the authority granted to governor Christopher Columbus and the first conquistadors. He established direct royal control with the Council of the Indies, the most important administrative organ of the Spanish Empire, both in the Americas and in Asia. After unifying Castile, Ferdinand introduced to Castile many laws, regulations and institutions such as the Inquisition, that were typical in Aragon. These laws were later used in the new lands.

The Laws of Burgos, created in 1512–1513, were the first codified set of laws governing the behavior of settlers in Spanish colonial America, particularly with regards to Native Americans. They forbade the maltreatment of indigenous people, and endorsed their conversion to Catholicism.

The evolving structure of colonial government was not fully formed until the third quarter of the 16th century; however, los Reyes Católicos designated Juan Rodríguez de Fonseca to study the problems related to the colonization process. Rodríguez de Fonseca effectively became minister for the Indies and laid the foundations for the creation of a colonial bureaucracy, combining legislative, executive and judicial functions. Rodríguez de Fonseca presided over the council, which contained a number of members of the Council of Castile (Consejo de Castilla), and formed a Junta de Indias of about eight counsellors. Emperor Charles V was already using the term "Council of the Indies" in 1519.

Корона сохранила за собой важные инструменты вмешательства. В «капитулясионе» четко указывалось, что завоеванные территории принадлежат Короне, а не отдельному лицу. С другой стороны, уступки позволяли Короне направлять завоевания Компаний на определенные территории в зависимости от их интересов. Кроме того, руководитель экспедиции получил четкие инструкции о своих обязанностях по отношению к армии, туземному населению, роду военных действий. Письменный отчет о результатах был обязательным. В армии был королевский чиновник «ведор». «Веедор», или нотариус, следил за тем, чтобы они выполняли приказы и инструкции, и сохранял королевскую долю добычи.

На практике капитан имел почти неограниченную власть. Помимо короны и конкистадора, они были очень важными покровителями, которым было поручено предвидеть деньги капитану и гарантировать оплату обязательств.

Вооруженные группы различными способами искали припасы и средства. Финансирование запрашивалось у короля, делегатов короны, дворянства, богатых купцов или самих войск. Более профессиональные кампании финансировались Короной. Кампании иногда инициировались неопытными губернаторами, потому что в испанской колониальной Америке офисы покупались или передавались родственникам или друзьям. Иногда экспедиция конкистадоров представляла собой группу влиятельных людей, которые набирали и снаряжали своих бойцов, обещая долю добычи.

Помимо исследований, в которых преобладали Испания и Португалия, другие части Европы также способствовали колонизации Нового Света. Документально подтверждено, что король Карл I получил ссуды от немецкой семьи Вельзеров для финансирования экспедиции в Венесуэлу за золотом. [ 6 ] Поскольку многочисленные вооруженные группы стремились начать исследования еще в эпоху завоеваний, Корона оказалась в долгах, что дало иностранным европейским кредиторам возможность финансировать исследования.

Конкистадор брал в долг как можно меньше, предпочитая вкладывать все свое имущество. Иногда каждый солдат привозил свое снаряжение и припасы, иногда солдаты получали снаряжение в качестве аванса от конкистадора.

Братья Пинсон , моряки « Тинто - Одиэль», участвовали в начинании Колумба. [ 113 ] Они также поддерживали проект экономически, предоставляя деньги из своего личного состояния. [ 114 ]

В число спонсоров входили правительства, король, наместники и местные губернаторы, которых поддерживали богатые люди. Вклад каждого человека обуславливал последующий раздел добычи, получая часть пешки (лансеро, пикеро, алабардеро, роделеро) и дважды всадника (кабальеро) — владельца лошади. [ нужны разъяснения ] Иногда часть добычи состояла из женщин и/или рабов. Даже собаки, которые сами по себе являются важным оружием войны, в некоторых случаях награждались. Раздел добычи привел к конфликтам, таким как конфликт между Писарро и Альмагро.

Военные преимущества

[ редактировать ]

Несмотря на то, что конкистадоры значительно превосходили численностью на чужой и неизвестной территории, они имели несколько военных преимуществ перед завоеванными ими коренными народами, а военная стратегия и тактика в основном были усвоены из 781-летней войны Реконкисты .

Стратегия

[ редактировать ]Одним из факторов была способность конкистадоров манипулировать политической ситуацией между коренными народами и заключать союзы против более крупных империй. Чтобы победить цивилизацию инков , они поддержали одну сторону гражданской войны. Испанцы свергли цивилизацию ацтеков , объединившись с туземцами, порабощенными более могущественными соседними племенами и королевствами. Эта тактика использовалась испанцами, например, во время Гранадской войны , завоевания Канарских островов и завоевания Наварры . На протяжении всего завоевания коренное население значительно превосходило конкистадоров по численности; войска конкистадоров никогда не превышали 2% коренного населения. Армия, с которой Эрнан Кортес осадил Теночтитлан , состояла из 200 000 солдат, из которых менее 1% составляли испанцы. [ 98 ] : 178

Тактика

[ редактировать ]Испанские и португальские войска были способны быстро перемещаться на большие расстояния по чужой земле, что позволяло быстро маневрировать и застать врасплох превосходящие по численности силы. Войны велись в основном между кланами, изгоняющими незваных гостей. На суше эти войны сочетали некоторые европейские методы с методами мусульманских бандитов в Аль-Андалусе . Эта тактика заключалась в том, что небольшие группы пытались застать своих противников врасплох, устроив засаду.

В Момбасе прибегнул к нападению на арабские торговые суда, которые , Васко да Гама как правило, представляли собой невооруженные торговые суда без тяжелых пушек.

Оружие и животные

[ редактировать ]Оружие

[ редактировать ]

Испанские конкистадоры в Америке широко использовали мечи , пики и арбалеты , причем аркебузы получили распространение лишь с 1570-х годов. [ 115 ] Нехватка огнестрельного оружия не помешала конкистадорам первыми использовать конные аркебузиры, раннюю форму драгун . [ 115 ] В 1540-х годах Франсиско де Карвахалем использование огнестрельного оружия во время гражданской войны в Испании в Перу стало прообразом техники залпового огня , которая получила развитие в Европе много десятилетий спустя. [ 115 ]

Животные

[ редактировать ]

Животные были еще одним важным фактором испанского триумфа. С одной стороны, появление лошадей и других домашних вьючных животных обеспечило им большую мобильность, неизвестную в индийских культурах. Однако в горах и джунглях испанцы были менее способны использовать узкие индейские дороги и мосты, предназначенные для пешеходного движения, которые иногда были не шире нескольких футов. В таких местах, как Аргентина , Нью-Мексико и Калифорния , коренные жители учились верховой езде, скотоводству и выпасу овец. Использование новых методов коренными народами позже стало спорным фактором местного сопротивления колониальному и американскому правительствам. [ нужна ссылка ]

Испанцы также умели разводить собак для войны, охоты и защиты. Мастифы , , боевые собаки испанские [ 116 ] а овчарки, которых они использовали в бою, были эффективным психологическим оружием против туземцев, которые во многих случаях никогда не видели домашних собак. Хотя у некоторых коренных народов во время завоевания Америки были домашние собаки, испанские конкистадоры использовали испанских мастифов и других молоссов в битвах против таино , ацтеков и майя . Этих специально обученных собак боялись из-за их силы и свирепости. Сильнейшие крупные породы собак с широкой пастью специально дрессировались для боя. Этих боевых собак использовали против едва одетых солдат. Это были бронированные собаки, обученные убивать и потрошить. [ 117 ]

Самой известной из этих боевых собак был талисман Понсе де Леона по кличке Бесеррильо , первая европейская собака, которая, как известно, достигла Северной Америки; [ нужна ссылка ] другая известная собака по имени Леонсико , сын Бесерильо , и первая европейская собака, которая, как известно, увидела Тихий океан, была талисманом Васко Нуньеса де Бальбоа и сопровождала его в нескольких экспедициях.

Морская наука

[ редактировать ]

Последовательные экспедиции и опыт испанских и португальских лоцманов привели к быстрому развитию европейской морской науки.

Навигация

[ редактировать ]В тринадцатом веке ориентировались по положению солнца. Для навигации по небесам, как и другие европейцы, они использовали греческие инструменты, такие как астролябия и квадрант , которые они сделали проще и проще. Они также создали перекрестный посох , или трость Иакова , для измерения на море высоты Солнца и других звезд. стал Южный Крест символом после прибытия Жоао де Сантарена и Педро Эскобара в Южное полушарие в 1471 году, начав его использование в небесной навигации. Результаты менялись в течение года, что требовало корректировок. Для решения этой проблемы португальцы использовали астрономические таблицы ( эфемериды ), ценный инструмент океанской навигации, широко распространившийся в пятнадцатом веке. Эти таблицы произвели революцию в навигации, позволив рассчитывать широту . Таблицы Вечного Альманаха астронома Авраама Сакуто , опубликованные в Лейрии в 1496 году, использовались вместе с улучшенной астролябией Васко да Гамой и Педро Альварешем Кабралем .

Дизайн корабля

[ редактировать ]

Кораблем, который действительно положил начало первой фазе открытий вдоль африканского побережья, была португальская каравелла . Иберийцы быстро приняли его для своего торгового флота. Это была разработка на основе африканских рыбацких лодок. Они были маневренными и легкими в навигации, имели водоизмещение от 50 до 160 тонн и имели от одной до трех мачт, а также латинские треугольные паруса, позволяющие поднимать стрелу . Каравелла особенно выиграла от большей способности поворачивать поворот . Ограниченная вместимость груза и экипажа была их главным недостатком, но не помешала успеху. Ограниченное пространство для экипажа и грузового пространства изначально было приемлемым, потому что в качестве исследовательских кораблей их «грузом» было то, что было в открытиях исследователя о новой территории, которая занимала пространство только одного человека. [ 118 ] Среди знаменитых каравелл — Беррио и Каравела Благовещения . Колумб также использовал их в своих путешествиях.