Юго-Восточная Азия

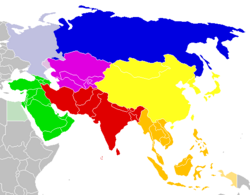

Геополитическая карта Юго-Восточной Азии, включая Западную Новую Гвинею , которая географически является частью Океании. | |

| Область | 4 545 792 км 2 (1755140 квадратных миль) |

|---|---|

| Население | 675 796 065 ( 3-е место ) [ 1 ] [ 2 ] |

| Плотность населения | 135.6/km2 (351/кв. миль) |

| GDP (PPP) | $9.727 trillion[3] |

| GDP (nominal) | $3.317 trillion (exchange rate)[4] |

| GDP per capita | $5,017 (exchange rate)[4] |

| HDI | |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Religions | Animism, Buddhism, Christianity, Confucianism, Hinduism, Islam, Tai folk religion, Taoism, and Vietnamese folk religion Note: does not indicate majority or minority |

| Demonym | Southeast Asian |

| Countries | |

| Dependencies | |

| Languages | Official languages Other native languages |

| Time zones | 5 time zones |

| Internet TLD | .bn, .id, .kh, .la, .mm, .my, .ph, .sg, .th, .tl, .vn |

| Calling code | Zone 6, 8 & 9 |

| Largest cities | Capital cities Largest cities |

| UN M49 code | 035 – South-eastern Asia142 – Asia001 – World |

Юго-Восточная Азия [ а ] — географический восточный регион Азии юго - , состоящий из регионов, расположенных к югу от Китая , к востоку от Индийского субконтинента и к северо-западу от материковой части Австралии , входящей в состав Океании . [ 5 ] Юго-Восточная Азия граничит на севере с Восточной Азией , на западе с Южной Азией и Бенгальским заливом , на востоке с Океанией и Тихим океаном , на юге с Австралией и Индийским океаном . Помимо Британской территории в Индийском океане и двух из 26 атоллов Мальдивских островов в Южной Азии, Морская Юго-Восточная Азия является единственным субрегионом Азии, частично лежащим в Южном полушарии . Материковая часть Юго-Восточной Азии полностью находится в Северном полушарии . Восточный Тимор и южная часть Индонезии — это части Юго-Восточной Азии, расположенные к югу от экватора .

Этот регион расположен недалеко от пересечения геологических плит , где наблюдается сильная сейсмическая и вулканическая активность. [ 6 ] Плита Сунда — главная плита региона, объединяющая почти все страны Юго-Восточной Азии, за исключением Мьянмы , северного Таиланда , северного Лаоса , северного Вьетнама и северного Лусона на Филиппинах , в то время как плита Сунда включает только западную Индонезию и вплоть до восточного побережья. Индонезийская провинция Бали . Горные хребты в Мьянме, Таиланде , на полуострове Малайзия и индонезийские острова Суматра , Ява , Бали , Малые Зондские острова и Тимор входят в состав Альпийского пояса , а острова Филиппин и Индонезии, а также Восточный Тимор — в состав Альпийского пояса. Тихоокеанского огненного кольца . Оба сейсмических пояса встречаются в Индонезии, в результате чего в этом регионе относительно часто происходят землетрясения и извержения вулканов, особенно на Филиппинах и в Индонезии . [7]

It covers about 4,500,000 km2 (1,700,000 sq mi), which is 8% of Eurasia and 3% of Earth's total land area. Its total population is more than 675 million, about 8.5% of the world's population. It is the third most populous geographical region in Asia after South Asia and East Asia.[8] The region is culturally and ethnically diverse, with hundreds of languages spoken by different ethnic groups.[9] Ten countries in the region are members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), a regional organisation established for economic, political, military, educational, and cultural integration among its members.[10]

Southeast Asia is one of the most culturally diverse regions of the world. There are many different languages and ethnicities in the region. Historically, Southeast Asia was significantly influenced by Indian, Chinese, Muslim, and colonial cultures, which became core components of the region's cultural and political institutions. Most modern Southeast Asian countries were colonised by European powers. European colonisation exploited natural resources and labour from the lands they conquered, and attempted to spread European institutions to the region.[11] Several Southeast Asian countries were also briefly occupied by the Japanese Empire during World War II. The aftermath of World War II saw most of the region decolonised. Today, Southeast Asia is predominantly governed by independent states.[12]

Definition

The region, together with part of South Asia, was well known by Europeans as the East Indies or simply the Indies until the 20th century. Chinese sources referred to the region as Nanyang ("南洋"), which literally means the "Southern Ocean". The mainland section of Southeast Asia was referred to as Indochina by European geographers due to its location between China and the Indian subcontinent and its having cultural influences from both neighbouring regions. In the 20th century, however, the term became more restricted to territories of the former French Indochina (Cambodia, Laos, and Vietnam). The maritime section of Southeast Asia is also known as the Malay Archipelago, a term derived from the European concept of a Malay race.[13] Another term for Maritime Southeast Asia is Insulindia (Indian Islands), used to describe the region between Indochina and Australasia.[14]

The term "Southeast Asia" was first used in 1839 by American pastor Howard Malcolm in his book Travels in South-Eastern Asia. Malcolm only included the Mainland section and excluded the Maritime section in his definition of Southeast Asia.[15] The term was officially used in the midst of World War II by the Allies, through the formation of South East Asia Command (SEAC) in 1943.[16] SEAC popularised the use of the term "Southeast Asia", although what constituted Southeast Asia was not fixed; for example, SEAC excluded the Philippines and a large part of Indonesia while including Ceylon. However, by the late 1970s, a roughly standard usage of the term "Southeast Asia" and the territories it encompasses had emerged.[17] Although from a cultural or linguistic perspective the definitions of "Southeast Asia" may vary, the most common definitions nowadays include the area represented by the countries (sovereign states and dependent territories) listed below.

Ten of the eleven states of Southeast Asia are members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), while East Timor is an observer state. Papua New Guinea has stated that it might join ASEAN, and is currently an observer. Sovereignty issues exist over some islands in the South China Sea.

Political divisions

Sovereign states

| State | Area (km2) |

Population (2020)[18] |

Density (/km2) |

GDP (nominal), billion USD (2022)[4] |

GDP (PPP), billion Int$ (2022)[4] |

GDP (nominal) per capita, USD (2022)[4] |

GDP (PPP) per capita, Int$ (2022)[4] |

HDI (2021)[19] |

Capital |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5,765[20] | 449,002 | 77 | 16.639 | 31.142 | $37,667 | $70,500 | 0.829 | Bandar Seri Begawan | |

| 181,035[21] | 16,718,965 | 92 | 28.544 | 89.570 | $1,784 | $5,600 | 0.593 | Phnom Penh | |

| 14,874[22] | 1,320,942 | 89 | 3.659 | 7.502 | $2,671 | $5,478 | 0.607 | Dili | |

| 1,904,569[23] | 273,753,191 | 144 | 1,318.807 | 4,036.878 | $4,798 | $14,687 | 0.705 | Jakarta | |

| 236,800[24] | 7,425,057 | 31 | 15.304 | 68.843 | $2,046 | $9,207 | 0.607 | Vientiane | |

| 329,847[25] | 33,573,874 | 102 | 407.923 | 1,134.671 | $12,364 | $34,391 | 0.803 | Kuala Lumpur * | |

| 676,578[26] | 53,798,084 | 80 | 56.757 | 261.170 | $1,053 | $4,846 | 0.585 | Nay Pyi Taw | |

| 300,000[27] | 115,559,009 | 380 | 404.261 | 1,171.162 | $3,623 | $10,497 | 0.699 | Manila | |

| 719.2[28] | 5,921,231 | 8,261 | 466.789 | 719.080 | $82,807 | $127,563 | 0.939 | Singapore | |

| 513,120[29] | 71,601,103 | 140 | 536.160 | 1,482.347 | $7,650 | $21,152 | 0.800 | Bangkok | |

| 331,210[30] | 97,468,029 | 294 | 406.452 | 1,321.249 | $4,086 | $13,283 | 0.703 | Hanoi |

* Administrative centre in Putrajaya.

Geographical divisions

Southeast Asia is geographically divided into two subregions, namely Mainland Southeast Asia (or the Indochinese Peninsula) and Maritime Southeast Asia.

Mainland Southeast Asia includes:

- Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam:

- Myanmar, Thailand and West Malaysia:

Maritime Southeast Asia includes:

While Peninsular Malaysia is geographically situated in Mainland Southeast Asia, it shares many similar cultural and ecological affinities with surrounding islands, thus it is often grouped with them as part of Maritime Southeast Asia.[33] Geographically, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands of India is also considered a part of Maritime Southeast Asia. Eastern Bangladesh and Northeast India have strong cultural ties with Mainland Southeast Asia and are sometimes considered transregional areas between South Asia and Southeast Asia.[34] To the east, Hong Kong is sometimes regarded as part of Southeast Asia.[35][36][37][38][39][40][41] Similarly, Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands have strong cultural ties with Maritime Southeast Asia and are sometimes considered transregional areas between Southeast Asia and Australia/Oceania. On some occasions, Sri Lanka has been considered a part of Southeast Asia because of its cultural and religious ties to Mainland Southeast Asia.[17][42] The eastern half of the island of New Guinea, which is not a part of Indonesia, namely, Papua New Guinea, is sometimes included as a part of Maritime Southeast Asia, and so are Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and Palau, which were all parts of the Spanish East Indies with strong cultural and linguistic ties to the region, specifically, the Philippines.[43]

East Timor and the eastern half of Indonesia (east of the Wallace Line in the region of Wallacea) are considered to be geographically associated with Oceania due to their distinctive faunal features. Geologically, the island of New Guinea and its surrounding islands are considered as parts of the Australian continent, connected via the Sahul Shelf. Both Christmas Island and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands are located on the Australian Plate, south of the Sunda Trench. Even though they are geographically closer to Maritime Southeast Asia than mainland Australia, these two Australian external territories are not geologically associated with Asia as none of them is actually on the Sunda Plate. The UN Statistics Division's geoscheme, which is a UN political geography tool created specifically for statistical purposes,[44] has classified both island territories as parts of Oceania, under the UNSD subregion "Australia and New Zealand" (Australasia). Some definitions of Southeast Asia may include Taiwan. Taiwan has sometimes been included in Southeast Asia as well as East Asia but is not a member of ASEAN.[45] Likewise, a similar argument could be applied to some southern parts of mainland China, as well as Hong Kong and Macau, may also considered as part of Southeast Asia as well as East Asia but are not members of ASEAN.[35]

History

Prehistory

The region was already inhabited by Homo erectus from approximately 1,500,000 years ago during the Middle Pleistocene age.[46] Distinct Homo sapiens groups, ancestral to Eastern non-African (related to East Asians as well as Papuans) populations, reached the region by between 50,000BC to 70,000BC, with some arguing earlier.[47][48] Rock art (parietal art) dating from 40,000 years ago (which is currently the world's oldest) has been discovered in the caves of Borneo.[49] Homo floresiensis also lived in the area up until at least 50,000 years ago, after which they became extinct.[50] During much of this time the present-day islands of western Indonesia were joined into a single landmass known as Sundaland due to lower sea levels.

Ancient remains of hunter-gatherers in Maritime Southeast Asia, such as one Holocene hunter-gatherer from South Sulawesi, had ancestry from both the Papuan-related and East Asian-related branches of the Eastern non-African lineage. The hunter-gatherer individual had approximately ~50% "Basal-East Asian" ancestry, and was positioned in between modern East Asians and Papuans of Oceania. The authors concluded that East Asian-related ancestry expanded from Mainland Southeast Asia into Maritime Southeast Asia much earlier than previously suggested, as early as 25,000BC, long before the expansion of Austroasiatic and Austronesian groups.[51]

Distinctive Basal-East Asian (East-Eurasian) ancestry was recently found to have originated in Mainland Southeast Asia at ~50,000BC, and expanded through multiple migration waves southwards and northwards respectively. Geneflow of East Asian-related ancestry into Maritime Southeast Asia and Oceania could be estimated to ~25,000BC (possibly also earlier). The pre-Neolithic Papuan-related populations of Maritime Southeast Asia were largely replaced by the expansion of various East Asian-related populations, beginning about 50,000BC to 25,000BC years ago from Mainland Southeast Asia. The remainders, known as Negritos, form small minority groups in geographically isolated regions. Southeast Asia was dominated by East Asian-related ancestry already in 15,000BC, predating the expansion of Austroasiatic and Austronesian peoples.[48]

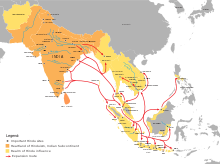

In the late Neolithic, the Austronesian peoples, who form the majority of the modern population in Brunei, Indonesia, East Timor, Malaysia, and the Philippines, migrated to Southeast Asia from Taiwan in the first seaborne human migration known as the Austronesian Expansion. They arrived in the northern Philippines between 7,000 BC to 2,200 BC and rapidly spread further into the Northern Mariana Islands and Borneo by 1500 BC; Island Melanesia by 1300 BC; and to the rest of Indonesia, Malaysia, southern Vietnam, and Palau by 1000 BC.[52][53] They often settled along coastal areas, replacing and assimilating the diverse preexisting peoples.[54][55][48]

The Austronesian peoples of Southeast Asia have been seafarers for thousands of years. They spread eastwards to Micronesia and Polynesia, as well as westwards to Madagascar, becoming the ancestors of modern-day Malagasy people, Micronesians, Melanesians, and Polynesians.[56] Passage through the Indian Ocean aided the colonisation of Madagascar, as well as commerce between Western Asia, eastern coast of India and Chinese southern coast.[56] Gold from Sumatra is thought to have reached as far west as Rome. Pliny the Elder wrote in his Natural History about Chryse and Argyre, two legendary islands rich in gold and silver, located in the Indian Ocean. Their vessels, such as the vinta, were capable to sail across the ocean. Magellan's voyage records how much more manoeuvrable their vessels were, as compared to the European ships.[57] A slave from the Sulu Sea was believed to have been used in Magellan's voyage as a translator.

Studies presented by the Human Genome Organisation (HUGO) through genetic studies of the various peoples of Asia show empirically that there was a single migration event from Africa, whereby the early people travelled along the south coast of Asia, first entered the Malay peninsula 50,000–90,000 years ago. The Orang Asli, in particular the Semang who show Negrito characteristics, are the direct descendants of these earliest settlers of Southeast Asia. These early people diversified and travelled slowly northwards to China, and the populations of Southeast Asia show greater genetic diversity than the younger population of China.[58][59]

Solheim and others have shown evidence for a Nusantao maritime trading network ranging from Vietnam to the rest of the archipelago as early as 5000 BC to 1 AD.[60] The Bronze Age Dong Son culture flourished in Northern Vietnam from about 1000 BC to 1 BC. Its influence spread to other parts Southeast Asia.[61][62][63] The region entered the Iron Age era in 500 BC, when iron was forged also in northern Vietnam still under Dong Son, due to its frequent interactions with neighbouring China.[46]

Most Southeast Asian people were originally animist, engaged in ancestors, nature, and spirits worship. These belief systems were later supplanted by Hinduism and Buddhism after the region, especially coastal areas, came under contact with Indian subcontinent during the first century.[64] Indian Brahmins and traders brought Hinduism to the region and made contacts with local courts.[65] Local rulers converted to Hinduism or Buddhism and adopted Indian religious traditions to reinforce their legitimacy, elevate ritual status above their fellow chief counterparts and facilitate trade with South Asian states. They periodically invited Indian Brahmins into their realms and began a gradual process of Indianisation in the region.[66][67][68] Shaivism was the dominant religious tradition of many southern Indian Hindu kingdoms during the first century. It then spread into Southeast Asia via Bay of Bengal, Indochina, then Malay Archipelago, leading to thousands of Shiva temples on the islands of Indonesia as well as Cambodia and Vietnam, co-evolving with Buddhism in the region.[69][70] Theravada Buddhism entered the region during the third century, via maritime trade routes between the region and Sri Lanka.[71] Buddhism later established a strong presence in Funan region in the fifth century. In present-day mainland Southeast Asia, Theravada is still the dominant branch of Buddhism, practised by the Thai, Burmese, and Cambodian Buddhists. This branch was fused with the Hindu-influenced Khmer culture. Mahayana Buddhism established presence in Maritime Southeast Asia, brought by Chinese monks during their transit in the region en route to Nalanda.[66] It is still the dominant branch of Buddhism practised by Indonesian and Malaysian Buddhists.

The spread of these two Indian religions confined the adherents of Southeast Asian indigenous beliefs into remote inland areas. The Maluku Islands and New Guinea were never Indianised and its native people were predominantly animists until the 15th century when Islam began to spread in those areas.[72] While in Vietnam, Buddhism never managed to develop strong institutional networks due to strong Chinese influence.[73] In present-day Southeast Asia, Vietnam is the only country where its folk religion makes up the plurality.[74][75] Recently, Vietnamese folk religion is undergoing a revival with the support of the government.[76] Elsewhere, there are ethnic groups in Southeast Asia that resisted conversion and still retain their original animist beliefs, such as the Dayaks in Kalimantan, the Igorots in Luzon, and the Shans in eastern Myanmar.[77]

Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms era

After the region came under contact with the Indian subcontinent c. 400 BCE, it began a gradual process of Indianisation where Indian ideas such as religions, cultures, architectures, and political administrations were brought by traders and religious figures and adopted by local rulers. In turn, Indian Brahmins and monks were invited by local rulers to live in their realms and help transforming local polities to become more Indianised, blending Indian and indigenous traditions.[78][67][68] Sanskrit and Pali became the elite language of the region, which effectively made Southeast Asia part of the Indosphere.[79] Most of the region had been Indianised during the first centuries, while the Philippines later Indianised c. ninth century when Kingdom of Tondo was established in Luzon.[80] Vietnam, especially its northern part, was never fully Indianised due to the many periods of Chinese domination it experienced.[81]

The first Indian-influenced polities established in the region were the Pyu city-states that already existed circa second century BCE, located in inland Myanmar. It served as an overland trading hub between India and China.[82] Theravada Buddhism was the predominant religion of these city states, while the presence of other Indian religions such as Mahayana Buddhism and Hinduism were also widespread.[83][84] In the first century, the Funan states centered in Mekong Delta were established, encompassed modern-day Cambodia, southern Vietnam, Laos, and eastern Thailand. It became the dominant trading power in mainland Southeast Asia for about five centuries, provided passage for Indian and Chinese goods and assumed authority over the flow of commerce through Southeast Asia.[56] In maritime Southeast Asia, the first recorded Indianised kingdom was Salakanagara, established in western Java circa second century CE. This Hindu kingdom was known by the Greeks as Argyre (Land of Silver).[85]

By the fifth century CE, trade networking between East and West was concentrated in the maritime route. Foreign traders were starting to use new routes such as Malacca and Sunda Strait due to the development of maritime Southeast Asia. This change resulted in the decline of Funan, while new maritime powers such as Srivijaya, Tarumanagara, and Mataram emerged. Srivijaya especially became the dominant maritime power for more than 5 centuries, controlling both Strait of Malacca and Sunda Strait.[56] This dominance started to decline when Srivijaya were invaded by Chola Empire, a dominant maritime power of Indian subcontinent, in 1025.[86] The invasion reshaped power and trade in the region, resulted in the rise of new regional powers such as the Khmer Empire and Kahuripan.[87] Continued commercial contacts with the Chinese Empire enabled the Cholas to influence the local cultures. Many of the surviving examples of the Hindu cultural influence found today throughout Southeast Asia are the result of the Chola expeditions.[note 2]

As Srivijaya influence in the region declined, The Hindu Khmer Empire experienced a golden age during the 11th to 13th century CE. The empire's capital Angkor hosts majestic monuments—such as Angkor Wat and Bayon. Satellite imaging has revealed that Angkor, during its peak, was the largest pre-industrial urban centre in the world.[89] The Champa civilisation was located in what is today central Vietnam, and was a highly Indianised Hindu Kingdom. The Vietnamese launched a massive conquest against the Cham people during the 1471 Vietnamese invasion of Champa, ransacking and burning Champa, slaughtering thousands of Cham people, and forcibly assimilating them into Vietnamese culture.[90]

During the 13th century CE, the region experienced Mongol invasions, affected areas such as Vietnamese coast, inland Burma and Java. In 1258, 1285 and 1287, the Mongols tried to invade Đại Việt and Champa.[91] The invasions were unsuccessful, yet both Dai Viet and Champa agreed to become tributary states to Yuan dynasty to avoid further conflicts.[92] The Mongols also invaded Pagan Kingdom in Burma from 1277 to 1287, resulted in fragmentation of the Kingdom and rise of smaller Shan States ruled by local chieftains nominally submitted to Yuan dynasty.[93][94] However, in 1297, a new local power emerged. Myinsaing Kingdom became the real ruler of Central Burma and challenged the Mongol rule. This resulted in the second Mongol invasion of Burma in 1300, which was repulsed by Myinsaing.[95][96] The Mongols would later in 1303 withdrawn from Burma.[97] In 1292, The Mongols sent envoys to Singhasari Kingdom in Java to ask for submission to Mongol rule. Singhasari rejected the proposal and injured the envoys, enraged the Mongols and made them sent a large invasion fleet to Java. Unbeknownst to them, Singhasari collapsed in 1293 due to a revolt by Kadiri, one of its vassals. When the Mongols arrived in Java, a local prince named Raden Wijaya offered his service to assist the Mongols in punishing Kadiri. After Kadiri was defeated, Wijaya turned on his Mongol allies, ambushed their invasion fleet and forced them to immediately leave Java.[98][99]

After the departure of the Mongols, Wijaya established the Majapahit Empire in eastern Java in 1293. Majapahit would soon grow into a regional power. Its greatest ruler was Hayam Wuruk, whose reign from 1350 to 1389 marked the empire's peak when other kingdoms in the southern Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Sumatra, and Bali came under its influence. Various sources such as the Nagarakertagama also mention that its influence spanned over parts of Sulawesi, Maluku, and some areas of western New Guinea and southern Philippines, making it one of the largest empire to ever exist in Southeast Asian history.[100]: 107 By the 15th century CE however, Majapahit's influence began to wane due to many war of successions it experienced and the rise of new Islamic states such as Samudera Pasai and Malacca Sultanate around the strategic Strait of Malacca. Majapahit then collapsed around 1500. It was the last major Hindu kingdom and the last regional power in the region before the arrival of the Europeans.[101][102]

Spread of Islam

Islam began to make contacts with Southeast Asia in the eighth-century CE, when the Umayyads established trade with the region via sea routes.[103][104][105] However its spread into the region happened centuries later. In the 11th century, a turbulent period occurred in the history of Maritime Southeast Asia. The Indian Chola navy crossed the ocean and attacked the Srivijaya kingdom of Sangrama Vijayatungavarman in Kadaram (Kedah); the capital of the powerful maritime kingdom was sacked and the king was taken captive. Along with Kadaram, Pannai in present-day Sumatra and Malaiyur and the Malayan peninsula were attacked too. Soon after that, the king of Kedah Phra Ong Mahawangsa became the first ruler to abandon the traditional Hindu faith, and converted to Islam with the Sultanate of Kedah established in 1136. Samudera Pasai converted to Islam in 1267, the King of Malacca Parameswara married the princess of Pasai, and the son became the first sultan of Malacca. Soon, Malacca became the center of Islamic study and maritime trade, and other rulers followed suit. Indonesian religious leader and Islamic scholar Hamka (1908–1981) wrote in 1961: "The development of Islam in Indonesia and Malaya is intimately related to a Chinese Muslim, Admiral Zheng He."[106]

There are several theories to the Islamization process in Southeast Asia. Another theory is trade. The expansion of trade among West Asia, India and Southeast Asia helped the spread of the religion as Muslim traders from Southern Yemen (Hadramout) brought Islam to the region with their large volume of trade. Many settled in Indonesia, Singapore, and Malaysia. This is evident in the Arab-Indonesian, Arab-Singaporean, and Arab-Malay populations who were at one time very prominent in each of their countries. Finally, the ruling classes embraced Islam and that further aided the permeation of the religion throughout the region. The ruler of the region's most important port, Malacca Sultanate, embraced Islam in the 15th century, heralding a period of accelerated conversion of Islam throughout the region as Islam provided a positive force among the ruling and trading classes. Gujarati Muslims played a pivotal role in establishing Islam in Southeast Asia.[107]

Trade and colonization

Trade among Southeast Asian countries has a long tradition. The consequences of colonial rule, struggle for independence, and in some cases war influenced the economic attitudes and policies of each country.[108]

Chinese

From 111 BC to 938 AD northern Vietnam was under Chinese rule. Vietnam was successfully governed by a series of Chinese dynasties including the Han, Eastern Han, Eastern Wu, Cao Wei, Jin, Liu Song, Southern Qi, Liang, Sui, Tang, and Southern Han. Records from Magellan's voyage show that Brunei possessed more cannon than European ships, so the Chinese must have been trading with them.[57]

Malaysian legend has it that a Chinese Ming emperor sent a princess, Hang Li Po, to Malacca, with a retinue of 500, to marry Sultan Mansur Shah after the emperor was impressed by the wisdom of the sultan. Hang Li Poh's Well (constructed 1459) is now a tourist attraction there, as is Bukit Cina, where her retinue settled.

The strategic value of the Strait of Malacca, which was controlled by Sultanate of Malacca in the 15th and early 16th century, did not go unnoticed by Portuguese writer Tomé Pires, who wrote in the Suma Oriental: "Whoever is lord of Malacca has his hand on the throat of Venice."[109] (Venice was a major European trading partner, and goods were transported there via the Straight.)

European

Western influence started to enter in the 16th century, with the arrival of the Portuguese in Malacca, Maluku and the Philippines, the latter being settled by the Spanish years later, which they used to trade between Asia and Latin America. Throughout the 17th and 18th centuries the Dutch established the Dutch East Indies; the French Indochina; and the British Strait Settlements. By the 19th century, all Southeast Asian countries were colonised except for Thailand.

European explorers were reaching Southeast Asia from the west and from the east. Regular trade between the ships sailing east from the Indian Ocean and south from mainland Asia provided goods in return for natural products, such as honey and hornbill beaks from the islands of the archipelago. Before the eighteenth and nineteenth century, the Europeans mostly were interested in expanding trade links. For the majority of the populations in each country, there was comparatively little interaction with Europeans and traditional social routines and relationships continued. For most, a life with subsistence-level agriculture, fishing and, in less developed civilisations, hunting and gathering was still hard.[110]

Europeans brought Christianity allowing Christian missionaries to become widespread. Thailand also allowed Western scientists to enter its country to develop its own education system as well as start sending Royal members and Thai scholars to get higher education from Europe and Russia.

Japanese

During World War II, Imperial Japan invaded most of the former western colonies under the concept of "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere". However, the Shōwa occupation regime committed violent actions against civilians such as live human experimentation,[111][112][113][114][115][116][117] sexual slavery under the brutal "comfort women" system,[118] [119] [120][121][122] the Manila massacre and the implementation of a system of forced labour, such as the one involving four to ten million romusha in Indonesia.[123] A later UN report stated that four million people died in Indonesia as a result of famine and forced labour during the Japanese occupation.[124] The Allied powers who then defeated Japan (and other allies of Axis) in the South-East Asian theatre of World War II then contended with nationalists to whom the occupation authorities had granted independence.

Indian

Gujarat, India had a flourishing trade relationship with Southeast Asia in the 15th and 16th centuries.[107] The trade relationship with Gujarat declined after the Portuguese invasion of Southeast Asia in the 17th century.[107]

American

The United States took the Philippines from Spain in 1898. Internal autonomy was granted in 1934, and independence in 1946.[125]

Contemporary history

Most countries in the region maintain national autonomy. Democratic forms of government are practised in most Southeast Asian countries and human rights is recognised but dependent on each nation state. Socialist or communist countries in Southeast Asia include Vietnam and Laos. ASEAN provides a framework for the integration of commerce and regional responses to international concerns.

China has asserted broad claims over the South China Sea, based on its nine-dash line, and has built artificial islands in an attempt to bolster its claims. China also has asserted an exclusive economic zone based on the Spratly Islands. The Philippines challenged China in the Permanent Court of Arbitration in The Hague in 2013, and in Philippines v. China (2016), the Court ruled in favour of the Philippines and rejected China's claims.[126][127]

Geography

Indonesia is the largest country in Southeast Asia and is also the largest archipelago in the world by size (according to the CIA World Factbook). Geologically, the Indonesian Archipelago is one of the most volcanically active regions in the world. Geological uplifts in the region have also produced some impressive mountains, culminating in Puncak Jaya in Papua, Indonesia at 5,030 metres (16,503 feet), on the island of New Guinea; it is the only place where ice glaciers can be found in Southeast Asia. The highest mountain in Southeast Asia is Hkakabo Razi at 5,967 metres (19,577 feet) and can be found in northern Burma sharing the same range of its parent peak, Mount Everest.

The South China Sea is the major body of water within Southeast Asia. The Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia, and Singapore, have integral rivers that flow into the South China Sea.

Mayon Volcano, despite being dangerously active, holds the record of the world's most perfect cone which is built from past and continuous eruption.[128]

Boundaries

Geographically, Southeast Asia is bounded to the southeast by the Australian continent, the boundary between these two regions is most often considered to run through Wallacea.

Geopolitically, the boundary lies between Papua New Guinea and the Indonesian region of Western New Guinea (Papua and West Papua). Both countries share the island of New Guinea.

Islands to the east of the Philippines make up the region of Micronesia. These islands are not biogeographically, geologically or historically linked to mainland Asia, and are considered part of Oceania by the United Nations, The World Factbook and other organisations.[129] The Oceania region is politically represented through the Pacific Islands Forum, a governing body which, up until 2022, included Australia, New Zealand and all independent territories in Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. Several countries of Maritime Southeast Asia, such as Indonesia and the Philippines, are dialogue partners of the Pacific Islands Forum, but none have full membership.[130]

Maritime Southeast Asia was often grouped with Australia and Oceania in the mid to late 1800s, rather than with mainland Asia.[131] The term Oceania came into usage at the beginning of the 1800s, and the earlier definitions predated the advent of concepts such as Wallacea.

The non-continental Australian external territories of Christmas Island and Cocos (Keeling) Islands are sometimes considered part of Maritime Southeast Asia, as they lie in much closer proximity to western Indonesia than they do to mainland Australia.[132][133][134] They have a multicultural mix of inhabitants with Asian and European Australian ancestry, and were uninhabited when discovered by the British during the 17th century.[135][136] The islands lie within the bounds of the Australian Plate, and are defined by the World Factbook as the westernmost extent of Oceania.[137][138] The United Nations also include these islands in their definition of Oceania, under the same subregion as Australia and New Zealand.[129]

Climate

Most of Southeast Asia have a tropical climate that is hot and humid all year round with plentiful rainfall. The majority of Southeast Asia has a wet and dry season caused by seasonal shifts in winds or monsoons. The tropical rain belt causes additional rainfall during the monsoon season. The rainforest is the second largest on Earth (with the Amazon rainforest being the largest). Exceptions to the typical tropical climate and forest vegetation are:

- Northern Vietnam (including Hanoi) with a subtropical climate that is sometimes influenced by cold waves which move from the northeast and the Siberian High

- the northern part of Central Vietnam also is occasionally influenced by cold waves

- mountain areas in the northern region and the higher islands, where high altitudes lead to milder temperatures

- the “dry zone” of central Myanmar in the rain shadow of the Arakan Mountains, where annual rainfall can be as low as 600 millimetres or 24 inches, which under the hot temperatures that prevail is dry enough to qualify as semi-arid.

- Southern areas in South Central Coast of Vietnam is marked with hot semi-arid climate due to weak monsoon activities and high temperature throughout the year. Annual rainfall of this region varies between 400 millimetres or 16 inches to 800 millimetres or 31 inches, with an 8-month dry season.

Climate change

Southeast Asia lags behind on mitigation measures,[140] even though it is one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change in the world.[141] Climate change has already caused an increase in heavy precipitation events (defined as 400 mm or more in a day)[142]: 1464 and greater increases are expected in this region. Changes in rainfall and runoff will also affect the quality of water supply used by the irrigation systems.[143] Under a high-warming scenario, heat-related deaths in the region could increase by 12.7% by 2100.[142]: 1508 Among the elderly in Malaysia, annual heat-related deaths may go from less than 1 per 100,000 to 45 per 100,000.[144]: 1 [145]: 23

Sea level rise is a serious threat. Along Philippine coasts, it occurs three times faster than the global average,[146] while 199 out of 514 cities and districts in Indonesia could be affected by tidal flooding by 2050.[147] Bangkok, Ho Chi Minh City and Jakarta are amongst the 20 coastal cities which would have the world's highest annual flood losses in the year 2050.[142] Due to land subsidence, Jakarta is sinking so much (up to 28 cm (11 in) per year between 1982 and 2010 in some areas[148]) that by 2019, the government had committed to relocate the capital of Indonesia to another city.[149]

Climate change is also likely to pose a serious threat to the region's fisheries:[141] 3.35 million fishers in the Southeast Asia are reliant on coral reefs,[142]: 1479 and yet those reefs are highly vulnerable to even low-emission climate change and will likely be lost if global warming exceeds 1.5 °C (2.7 °F)[150][151] By 2050–2070, around 30% of the region's aquaculture area and 10-20% of aquaculture production may be lost.[142]: 1491

Environment

The vast majority of Southeast Asia falls within the warm, humid tropics, and its climate generally can be characterized as monsoonal. The animals of Southeast Asia are diverse; on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra, the orangutan, the Asian elephant, the Malayan tapir, the Sumatran rhinoceros and the Bornean clouded leopard can also be found. Six subspecies of the binturong or bearcat exist in the region, though the one endemic to the island of Palawan is now classed as vulnerable.

Tigers of three different subspecies are found on the island of Sumatra (the Sumatran tiger), in peninsular Malaysia (the Malayan tiger), and in Indochina (the Indochinese tiger); all of which are endangered species.

The Komodo dragon is the largest living species of lizard and inhabits the islands of Komodo, Rinca, Flores, and Gili Motang in Indonesia.

The Philippine eagle is the national bird of the Philippines. It is considered by scientists as the largest eagle in the world,[152] and is endemic to the Philippines' forests.

The wild water buffalo, and on various islands related dwarf species of Bubalus such as anoa were once widespread in Southeast Asia; nowadays the domestic Asian water buffalo is common across the region, but its remaining relatives are rare and endangered.

The mouse deer, a small tusked deer as large as a toy dog or cat, mostly can be found on Sumatra, Borneo (Indonesia), and in Palawan (Philippines). The gaur, a gigantic wild ox larger than even wild water buffalo, is found mainly in Indochina. There is very little scientific information available regarding Southeast Asian amphibians.[153]

Birds such as the green peafowl and drongo live in this subregion as far east as Indonesia. The babirusa, a four-tusked pig, can be found in Indonesia as well. The hornbill was prized for its beak and used in trade with China. The horn of the rhinoceros, not part of its skull, was prized in China as well.

The Indonesian Archipelago is split by the Wallace Line. This line runs along what is now known to be a tectonic plate boundary, and separates Asian (Western) species from Australasian (Eastern) species. The islands between Java/Borneo and Papua form a mixed zone, where both types occur, known as Wallacea. As the pace of development accelerates and populations continue to expand in Southeast Asia, concern has increased regarding the impact of human activity on the region's environment. A significant portion of Southeast Asia, however, has not changed greatly and remains an unaltered home to wildlife. The nations of the region, with only a few exceptions, have become aware of the need to maintain forest cover not only to prevent soil erosion but to preserve the diversity of flora and fauna. Indonesia, for example, has created an extensive system of national parks and preserves for this purpose. Even so, such species as the Javan rhinoceros face extinction, with only a handful of the animals remaining in western Java.

The shallow waters of the Southeast Asian coral reefs have the highest levels of biodiversity for the world's marine ecosystems, where coral, fish, and molluscs abound. According to Conservation International, marine surveys suggest that the marine life diversity in the Raja Ampat (Indonesia) is the highest recorded on Earth. Diversity is considerably greater than any other area sampled in the Coral Triangle composed of Indonesia, the Philippines, and Papua New Guinea. The Coral Triangle is the heart of the world's coral reef biodiversity, the Verde Passage is dubbed by Conservation International as the world's "center of the center of marine shore fish biodiversity". The whale shark, the world's largest species of fish and 6 species of sea turtles can also be found in the South China Sea and the Pacific Ocean territories of the Philippines.

The trees and other plants of the region are tropical; in some countries where the mountains are tall enough, temperate-climate vegetation can be found. These rainforest areas are currently being logged-over, especially in Borneo.

While Southeast Asia is rich in flora and fauna, Southeast Asia is facing severe deforestation which causes habitat loss for various endangered species such as orangutan and the Sumatran tiger. Predictions have been made that more than 40% of the animal and plant species in Southeast Asia could be wiped out in the 21st century.[154] At the same time, haze has been a regular occurrence. The two worst regional hazes were in 1997 and 2006 in which multiple countries were covered with thick haze, mostly caused by "slash and burn" activities in Sumatra and Borneo. In reaction, several countries in Southeast Asia signed the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution to combat haze pollution.

The 2013 Southeast Asian Haze saw API levels reach a hazardous level in some countries. Muar experienced the highest API level of 746 on 23 June 2013 at around 7 am.[155]

Economy

Even prior to the penetration of European interests, Southeast Asia was a critical part of the world trading system. A wide range of commodities originated in the region, but especially important were spices such as pepper, ginger, cloves, and nutmeg. The spice trade initially was developed by Indian and Arab merchants, but it also brought Europeans to the region. First, Spaniards (Manila galleon) who sailed from the Americas and Kingdom of Portugal, then the Dutch, and finally the British and French became involved in this enterprise in various countries. The penetration of European commercial interests gradually evolved into annexation of territories, as traders lobbied for an extension of control to protect and expand their activities. As a result, the Dutch moved into Indonesia, the British into Malaya and parts of Borneo, the French into Indochina, and the Spanish and the US into the Philippines. An economic effect of this imperialism was the shift in the production of commodities. For example, the rubber plantations of Malaysia, Java, Vietnam, and Cambodia, the tin mining of Malaya, the rice fields of the Mekong Delta in Vietnam, and the Irrawaddy River delta in Burma, were a response to the powerful market demands.[156]

The overseas Chinese community has played a large role in the development of the economies in the region. The origins of Chinese influence can be traced to the 16th century, when Chinese migrants from southern China settled in Indonesia, Thailand, and other Southeast Asian countries.[157] Chinese populations in the region saw a rapid increase following the Communist Revolution in 1949, which forced many refugees to emigrate outside of China.[158]

In 2022, Malaysian petroleum industry through its oil and gas company, Petronas, was ranked eighth in the world by the Brandirectory.[159]

Seventeen telecommunications companies contracted to build the Asia-America Gateway submarine cable to connect Southeast Asia to the US[160] This is to avoid disruption of the kind caused by the cutting of the undersea cable from Taiwan to the US in the 2006 Hengchun earthquakes.

Tourism has been a key factor in economic development for many Southeast Asian countries, especially Cambodia. According to UNESCO, "tourism, if correctly conceived, can be a tremendous development tool and an effective means of preserving the cultural diversity of our planet."[161] Since the early 1990s, "even the non-ASEAN nations such as Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam and Burma, where the income derived from tourism is low, are attempting to expand their own tourism industries."[162] In 1995, Singapore was the regional leader in tourism receipts relative to GDP at over 8%. By 1998, those receipts had dropped to less than 6% of GDP while Thailand and Lao PDR increased receipts to over 7%. Since 2000, Cambodia has surpassed all other ASEAN countries and generated almost 15% of its GDP from tourism in 2006.[163] Furthermore, Vietnam is considered as a growing power in Southeast Asia due to its large foreign investment opportunities and the booming tourism sector.

By the early 21st century, Indonesia had grown to an emerging market economy, becoming the largest economy in the region. It was classified a newly industrialised country and is the region's singular member of the G-20 major economies.[164] Indonesia's estimated gross domestic product (GDP) for 2020 was US$1,088.8 billion (nominal) or $3,328.3 billion (PPP) with per capita GDP of US$4,038 (nominal) or $12,345 (PPP).[165] By GDP per capita in 2023, Singapore is the leading nation in the region with US$84,500 (nominal) or US$140,280 (PPP), followed by Brunei with US$41,713 (nominal) or US$79,408 (PPP) and Malaysia with US$13,942 (nominal) or US$33,353 (PPP).[166] Besides that, Malaysia has the lowest cost of living in the region, followed by Brunei and Vietnam.[167] On the contrary, Singapore is the costliest country in the region, followed by Thailand and the Philippines.[167]

Stock markets in Southeast Asia have performed better than other bourses in the Asia-Pacific region in 2010, with the Philippines' PSE leading the way with 22 per cent growth, followed by Thailand's SET with 21 per cent and Indonesia's JKSE with 19 per cent.[168][169]

Southeast Asia's GDP per capita is US$4,685 according to a 2020 International Monetary Fund estimates, which is comparable to South Africa, Iraq, and Georgia.[170]

| Country | Currency | Population (2020)[18][171] |

Nominal GDP (2020) $ billion[172] |

GDP per capita (2020)[170] |

GDP growth (2020)[173] |

Inflation (2020)[174] |

Main industries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B$ Brunei dollar | 437,479 | $10.647 | $23,117 | 0.1% | 0.3% | Petroleum, Petrochemicals, Fishing | |

| ៛ Riel US$ US Dollar | 16,718,965 | $26.316 | $1,572 | -2.8% | 2.5% | Clothing, Gold, Agriculture | |

| US$ US dollar | 1,318,445 | $1.920 | $1,456 | -6.8% | 0.9% | Petroleum, Coffee, Electronics | |

| Rp Rupiah | 270,203,917[171] | $1,088.768 | $4,038 | -1.5% | 2.1% | Coal, Petroleum, Palm oil | |

| ₭ Kip | 7,275,560 | $18.653 | $2,567 | 0.2% | 6.5% | Copper, Electronics, Tin | |

| RM Ringgit | 32,365,999 | $336.330 | $10,192 | -6% | -1.1% | Electronics, Petroleum, Petrochemicals, Palm oil, Automotive | |

| K Kyat | 54,409,800 | $70.890 | $1,333 | 2% | 6.1% | Natural gas, Agriculture, Clothing | |

| ₱ Peso | 109,581,078 | $367.362 | $3,373 | -8.3% | 2.4% | Electronics, Timber, Automotive | |

| S$ Singapore dollar | 5,850,342 | $337.451 | $58,484 | -6% | -0.4% | Electronics, Petroleum, Chemicals | |

| ฿ Baht | 69,799,978 | $509.200 | $7,295 | -7.1% | -0.4% | Electronics, Automotive, Rubber | |

| ₫ Đồng | 97,338,579 | $340.602 | $3,498 | 2.9% | 3.8% | Electronics, Clothing, Petroleum |

Energy

Traditionally, the Southeast Asian economy has heavily relied on fossil fuels. However, it has begun transitioning towards clean energy. The region possesses significant renewable energy potential, including solar, wind, hydro, and pumped hydro energy storage. Modeling indicates that it could achieve a 97% share of solar and wind energy in the electricity mix at competitive costs ranging from $US 55 to $115 per megawatt-hour.[175]

The energy transition in Southeast Asia can be characterized as demanding, doable, and dependent.[176] This implies the presence of substantial challenges, including financial, technical, and institutional barriers. However, it is feasible, as evidenced by Vietnam's remarkable achievement of installing about 20 GW of solar and wind power in just three years.[177] International cooperation plays a crucial role in facilitating this transition.[176]

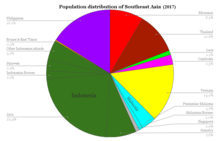

Demographics

Southeast Asia has an area of approximately 4,500,000 square kilometres (1,700,000 sq mi). As of 2021, around 676 million people live in the region, more than a fifth live (143 million) on the Indonesian island of Java, the most densely populated large island in the world. Indonesia is the most populous country with 274 million people (~40% of South East Asia), and also the fourth most populous country in the world. The distribution of the religions and people is diverse in Southeast Asia and varies by country. Some 30 million overseas Chinese also live in Southeast Asia, most prominently in Christmas Island, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, and also as the Hoa in Vietnam. People of Southeast Asian origins are known as Southeast Asians or Aseanites.

Ethnic groups

The peoples of Southeast Asia are mainly divided into four major ethnolinguistic groups: the Austronesian, Austroasiatic (or Mon-Khmers), Tai (part of the wider Kra-Dai family) and Tibeto-Burman (part of greater Sino-Tibetan language family) peoples. There is also a smaller but significant number of Hmong-Mien, Chinese, Dravidians, Indo-Aryans, Eurasians and Papuans, which also contributes to the diversity of peoples in the region.

The Aslians and Negritos were believed to be one of the earliest inhabitants in the region. They are genetically related to Papuans in Eastern Indonesia, East Timor and Australian Aborigines. In modern times, the Javanese are the largest ethnic group in Southeast Asia, with more than 100 million people, mostly concentrated in Java, Indonesia. The second-largest ethnic group in Southeast Asia are the Vietnamese (Kinh people) with around 86 million people, mainly inhabiting Vietnam but also forming a significant minority in neighbouring Cambodia and Laos. The Thais are the third largest with around 59 million people, forming the majority in Thailand.

Indonesia is politically and culturally dominated by the Javanese and Sundanese ethnic groups (both native to Java), but the country also has hundreds of ethnic groups scattered throughout the archipelago, such as the Madurese, Minangkabau, Acehnese, Bugis, Balinese, Dayak, Batak, Malay and Ambonese peoples.

In Malaysia, the country is demographically divided into Malays, who make up more than half of the country's population; the Chinese, at around 22%; other Bumiputeras, at 12%; and Indians, at around 6%. In East Malaysia, the Dayaks (mainly Ibans and Bidayuhs) make up the majority in the state of Sarawak, while the Kadazan-Dusuns make up the majority in Sabah. In Labuan, the Bruneian Malays and Kedayans are the largest groups. Overall, the Malays are the majority in Malaysia and Brunei and form a significant minority in Indonesia, Southern Thailand, Myanmar, and Singapore. In Singapore, the demographics of the country is similar to that of its West Malaysian counterparts but instead of Malays, it is the Chinese that are the majority, while the Malays are the second largest group and Indians third largest.

Within the Philippines, the country has no majority ethnic groups; but the four largest ethnolinguistic groups in the country are the Visayans (mainly Cebuanos, Warays and Hiligaynons), Tagalogs, Ilocanos and Bicolanos. Besides the major four, there are also the Moro peoples of Mindanao, consisting of the Tausug, Maranao, Yakan and Maguindanao. Other regional groups in the country are the Kapampangans, Pangasinans, Surigaonons, Ifugao, Kalinga, Kamayo, Cuyonon and Ivatan.

In mainland Southeast Asia, the Burmese accounts for more than two-thirds of the population in Myanmar, but the country also has several regional ethnic groups which mainly live in states that are specifically formed for ethnic minorities. The major regional ethnic groups in Myanmar are the Tai-speaking Shan people, Karen people, Rakhine people, Chin people, Kayah people and Indo-Aryan-speaking Rohingya people living on the westernmost part of the country near the border with Bangladesh. In neighbouring Thailand, the Thais are the largest ethnic group in the country but is divided into several regional Tai groups such as Central Thais, Northern Thais or Lanna, Southern Thais or Pak Thai, and Northeastern Thai or Isan people (which is ethnically more closely related to Lao people than to Central Thais), each have their own unique dialects, history and culture. Besides the Thais, Thailand is also home to more than 70 ethnolinguistic groups of which the largest being Patani Malays, Northern Khmers, Karen, Hmongs and Chinese.

Cambodia is one of the most homogeneous countries in the area, with Khmers forming more than 90% of the population but the country also has a large number of ethnic Chams, Vietnamese and various inland tribes categorised under the term Khmer Loeu (Hill Khmers).

Religion

-

Spirit houses are common in areas of Southeast Asia where Animism is a held belief.

-

Cebu Metropolitan Cathedral in Cebu City, Philippines, the ecclesiastical seat of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cebu

-

A Protestant church in Indonesia. Indonesia has the largest Protestant population in Southeast Asia.

Religion in Southeast Asia (2020)[178]

Countries in Southeast Asia practice many different religions and the region is home to many world religions including Abrahamic, Indian, East Asian and Iranian religions. By population, Islam is the most practised faith with approximately 240 million adherents, or about 40% of the entire population, concentrated in Indonesia, Brunei, Malaysia, Southern Thailand and in the Southern Philippines. Indonesia is the most populous Muslim-majority country in the world. Meanwhile, Islam is constitutionally the official religion in Malaysia and Brunei.[179][180] The majority of the Muslim population is Sunni, but there are also significant Shia populations in Thailand and Indonesia. A minority are Sufi or Ahmadiyya Muslims.

There are approximately 190-205 million Buddhists in Southeast Asia, making it the second-largest religion in the region. Approximately 28 to 35% of the world's Buddhists reside in Southeast Asia. Buddhism is predominant in Vietnam, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Myanmar and Singapore, and adherents may come from Theravada or Mahayana schools. Ancestor worship and Confucianism are also widely practised in Vietnam and Singapore. Taoism and Chinese folk religions such as Mazuism are also widely practised by the overseas Chinese community in Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand. In certain cases, they may include Chinese or local deities in their worshipping practises such as Tua Pek Kong, Datuk Keramat and many more.

Christianity is predominant in the Philippines, eastern Indonesia, East Malaysia, and East Timor. The Philippines has the largest Roman Catholic population in Asia.[181] East Timor is also predominantly Roman Catholic due to a history of Indonesian[182] and Portuguese rule. In October 2019, the number of Christians, both Catholic and Protestant, in Southeast Asia reached 156 million, of which 97 million came from the Philippines, 29 million from Indonesia, 11 million from Vietnam, and the rest from Malaysia, Myanmar, East Timor, Singapore, Laos, Cambodia and Brunei. In addition, Eastern Orthodox Christianity can also be found in the region. In addition, Judaism is practised in certain countries such as in the Philippines, Singapore and Indonesia due to the presence of Jewish diaspora. There is a small population of Parsis in Singapore who practise Zoroastrianism, and Baháʼí is also practised by very small population in Malaysia, Vietnam, Singapore and Thailand.

No individual Southeast Asian country is religiously homogeneous. Some groups are protected de facto by their isolation from the rest of the world.[183] In the world's most populous Muslim nation, Indonesia, Hinduism is dominant on islands such as Bali. Christianity also predominates in the rest of the part of the Philippines, New Guinea, Flores and Timor. Pockets of Hindu population can also be found around Southeast Asia in Singapore, Malaysia, etc. Garuda, the phoenix who is the mount (vahanam) of Vishnu, is a national symbol in both Thailand and Indonesia; in the Philippines, gold images of Garuda have been found on Palawan; gold images of other Hindu gods and goddesses have also been found on Mindanao. Balinese Hinduism is somewhat different from Hinduism practised elsewhere, as animism and local culture is incorporated into it. Meanwhile, Hindu community in Malaysia and Singapore are mostly South Indian diaspora, hence the practices are closely related to the Indian Hinduism. Additionally, Sikhism is also practised by significant population especially in Malaysia and Singapore by North Indian diaspora specifically from Punjab region. Small population of the Indian diaspora in the region are Jains and can be found in Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand and Indonesia. Christians can also be found throughout Southeast Asia; they are in the majority in East Timor and the Philippines, Asia's largest Christian nation. In addition, there are also older tribal religious practices in remote areas of Sarawak in East Malaysia, Highland Philippines, and Papua in eastern Indonesia. In Burma, Sakka (Indra) is revered as a Nat. In Vietnam, Mahayana Buddhism is practised, which is influenced by native animism but with a strong emphasis on ancestor worship. Vietnamese folk religions are practised by majority of population in Vietnam. Caodaism, a monotheistic syncretic new religious movement, is also practised by less than one percent of the population in Vietnam. Due to the presence of Japanese diaspora in the region, the practice of Shinto has growingly made appearance in certain countries such as in Thailand.

The religious composition for each country is as follows: Some values are taken from the CIA World Factbook:[184]

| Country | Religions |

|---|---|

| Islam (81%), Buddhism, Christianity, others (indigenous beliefs, etc.) | |

| Buddhism (97%), Islam, Christianity, Animism, others | |

| Roman Catholicism (97%), Protestantism, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism | |

| Islam (87%), Protestantism (7.6%), Roman Catholicism (3.12%), Hinduism (1.74%), Buddhism (0.77%), Confucianism (0.03%), others (0.4%)[185][186] | |

| Buddhism (67%), Animism, Christianity, others | |

| Islam (61.3%), Buddhism, Christianity, Hinduism, Animism | |

| Buddhism (89%), Islam, Christianity, Hinduism, Animism, others | |

| Roman Catholicism (80.6%), Islam (6.9%-11%),[187] Evangelicals (2.7%), Iglesia ni Cristo (Church of Christ) (2.4%), Members Church of God International (1.0%), Other Protestants (2.8%), Buddhism (0.05%-2%),[188] Animism (0.2%-1.25%), others (1.9%)[189] | |

| Buddhism (31.1%), Christianity (18.9%), Islam (15.6%), Taoism (8.8%), Hinduism (5%), others (20.6%) | |

| Buddhism (93.5%), Islam (5.4%), Christianity (1.13%), Hinduism (0.02%), others (0.003%) | |

| Vietnamese folk religion (45.3%), Buddhism (16.4%), Christianity (8.2%), Other (0.4%), Unaffiliated (29.6%)[190] |

Languages

Each of the languages has been influenced by cultural pressures due to trade, immigration, and historical colonisation as well. There are nearly 800 native languages in the region.

The language composition for each country is as follows (with official languages in bold):

| Country/Region | Languages |

|---|---|

| Malay, English, Chinese, Tamil, Indonesian and indigenous Bornean dialects (Iban, Murutic language, Lun Bawang.)[191] | |

| Khmer, English, French, Teochew, Vietnamese, Cham, Mandarin, others[192] | |

| Portuguese, Tetum, Mambae, Makasae, Tukudede, Bunak, Galoli, Kemak, Fataluku, Baikeno, others[193] | |

| Indonesian, Javanese, Sundanese, Batak, Minangkabau, Buginese, Banjar, Papuan, Dayak, Acehnese, Ambonese, Balinese, Betawi, Madurese, Musi, Manado, Sasak, Makassarese, Batak Dairi, Karo, Mandailing, Jambi Malay, Mongondow, Gorontalo, Ngaju, Kenyah, Nias, North Moluccan, Uab Meto, Bima, Manggarai, Toraja-Sa'dan, Komering, Tetum, Rejang, Muna, Sumbawa, Bangka Malay, Osing, Gayo, Bungku-Tolaki languages, Moronene, Bungku, Bahonsuai, Kulisusu, Wawonii, Mori Bawah, Mori Atas, Padoe, Tomadino, Lewotobi, Tae', Mongondow, Lampung, Tolaki, Ma'anyan, Simeulue, Gayo, Buginese, Mandar, Minahasan, Enggano, Ternate, Tidore, Mairasi, East Cenderawasih Language, Lakes Plain Languages, Tor-Kwerba, Nimboran, Skou/Sko, Border languages, Senagi, Pauwasi, Mandarin, Hokkien, Cantonese, Hakka, Teochew, Tamil, Punjabi, and Arabic.

Indonesia has over 700 languages in over 17,000 islands across the archipelago, making Indonesia the second most linguistically diverse country on the planet,[194] slightly behind Papua New Guinea. The official language of Indonesia is Indonesian (Bahasa Indonesia), widely used in educational, political, economic, and other formal situations. In daily activities and informal situations, most Indonesians speak in their local language(s). For more details, see: Languages of Indonesia. | |

| Lao, French, Thai, Vietnamese, Hmong, Miao, Mien, Dao, Shan and others[195] | |

| Malaysian, English, Mandarin, Tamil, Daro-Matu, Kedah Malay, Sabah Malay, Brunei Malay, Kelantan Malay, Pahang Malay, Acehnese, Javanese, Minangkabau, Banjar, Buginese, Tagalog, Hakka, Cantonese, Hokkien, Teochew, Fuzhounese, Telugu, Bengali, Punjabi, Sinhala, Malayalam, Arabic, Brunei Bisaya, Okolod, Kota Marudu Talantang, Kelabit, Lotud, Terengganu Malay, Semelai, Thai, Iban, Kadazan, Dusun, Kristang, Bajau, Jakun, Mah Meri, Batek, Melanau, Semai, Temuan, Lun Bawang, Temiar, Penan, Tausug, Iranun, Lundayeh/Lun Bawang, and others[196] see: Languages of Malaysia | |

| Burmese, Shan, Kayin (Karen), Rakhine, Kachin, Chin, Mon, Kayah, Chinese and other ethnic languages.[197][198] | |

| Filipino (Tagalog), English, Bisayan languages (Aklanon, Cebuano, Kinaray-a, Capiznon, Hiligaynon, Waray, Masbateño, Romblomanon, Cuyonon, Surigaonon, Butuanon, Tausug), Ivatan, Ilocano, Ibanag, Pangasinan, Kapampangan, Bikol, Sama-Bajaw, Maguindanao, Maranao, Spanish, Chavacano and others[199] | |

| English, Malay, Mandarin Chinese, Tamil, Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, Japanese, Telugu, Malayalam, Punjabi, Indonesian, Boyanese, Buginese, Javanese, Balinese, Singlish creole and others[200] | |

| Thai, Isan, Northern Khmer, Malay, Karen, Hmong, Teochew, Minnan, Hakka, Yuehai, Burmese, Mien, Tamil, Bengali, Urdu, Arabic, Shan, Lue, Phutai, Mon and others[201] | |

| Vietnamese, Cantonese, Khmer, Hmong, Tai, Cham and others[202] |

Cities

- Brunei-Muara (Bandar Seri Begawan/Muara),

Brunei

Brunei - Phnom Penh City (Phnom Penh/Kandal),

Cambodia

Cambodia - Dili (Dili),

East Timor

East Timor - Jabodetabek (Jakarta/Bogor/Depok/Tangerang/South Tangerang/Bekasi),

Indonesia

Indonesia - Gerbangkertosusila (Surabaya/Sidoarjo/Gresik/Mojokerto/Lamongan/Bangkalan),

Indonesia

Indonesia - Bandung metropolitan area (Bandung/Cimahi/Sumedang/West Bandung),

Indonesia

Indonesia - Vientiane Prefecture (Vientiane/Tha Ngon),

Laos

Laos - Greater Kuala Lumpur/Klang Valley (Kuala Lumpur/Selangor),

Malaysia

Malaysia - George Town Conurbation (Penang/Kedah/Perak),

Malaysia

Malaysia - Iskandar Malaysia (Johor),

Malaysia

Malaysia - Yangon Region (Yangon/Thanlyin),

Myanmar

Myanmar - Metro Manila (Manila/Quezon City/Makati/Taguig/Pasay/Caloocan and 11 others),

Philippines

Philippines - Метро Давао ( Давао-Сити / Дигос / Тагум / Остров-сад-город Самал ) ,

Филиппины

Филиппины - Метро Себу ( Себу / Мандауэ / Лапу-Лапу / Талисай и еще 11 )

Филиппины

Филиппины - Сингапур ,

Сингапур

Сингапур - Столичный регион Бангкока ( Бангкок / Нонтхабури / Самутпракан / Патхумтхани / Самутсакхон / Накхонпатхом ) ,

Таиланд

Таиланд - Восточный экономический коридор ( Чаченгсао / Чонбури / Районг ) ,

Таиланд

Таиланд - Агломерация Хошимина ( Хошимин / Вунгтау / Биньзыонг / Донгнай ) ,

Вьетнам

Вьетнам - Столичный регион Ханой ( Ханой / Хайфон / Халонг ) ,

Вьетнам

Вьетнам - Город Дананг ( Дананг / Хойан / Хюэ ) ,

Вьетнам

Вьетнам

- Ночные горизонты

-

Куала-Лумпур , Малайзия

-

Бангкок , Таиланд

-

Манила , Филиппины

-

Хошимин , Вьетнам

-

Джакарта , Индонезия

Культура

Культура Юго-Восточной Азии разнообразна: на материковой части Юго-Восточной Азии культура представляет собой смесь бирманской, камбоджийской, лаосской, тайской ( индийской ) и вьетнамской ( китайской ) культур. В то время как в Индонезии, на Филиппинах, в Сингапуре и Малайзии культура представляет собой смесь коренных австронезийских , индийских, исламских, западных и китайских культур. Кроме того, Бруней демонстрирует сильное влияние Аравии. Вьетнам и Сингапур демонстрируют большее влияние Китая [ 203 ] в том, что Сингапур, хотя географически и является страной Юго-Восточной Азии, является домом для значительного китайского большинства, а Вьетнам находился в сфере влияния Китая на протяжении большей части своей истории. Индийское влияние в Сингапуре наиболее заметно проявляется через тамильских мигрантов, [ 204 ] что в некоторой степени повлияло на кухню Сингапура . На протяжении всей истории Вьетнам не имел прямого влияния со стороны Индии – только через контакты с народами тайцев, кхмеров и чамов. Более того, Вьетнам также относят к культурной сфере Восточной Азии наряду с Китаем, Кореей и Японией из-за большого влияния Китая, заложенного в их культуру и образ жизни.

Рисовые поля существовали в Юго-Восточной Азии на протяжении тысячелетий, по всему субрегиону. Некоторые впечатляющие примеры таких рисовых полей можно найти на рисовых террасах Банауэ в горах Лусона на Филиппинах . Уход за этими чеками очень трудоемкий. Рисовые поля хорошо подходят для муссонного климата региона.

Дома на сваях можно найти по всей Юго-Восточной Азии, от Таиланда и Вьетнама до Борнео, Лусона на Филиппинах и Папуа-Новой Гвинеи. В регионе развита разнообразная металлообработка, особенно в Индонезии. Сюда входит оружие, такое как отличительный крис , и музыкальные инструменты, такие как гамелан .

Влияния

Основное культурное влияние региона оказало некое сочетание ислама , Индии и Китая . На Филиппинах ярко выражено разнообразное культурное влияние, обусловленное, в частности, периодом испанского и американского правления, контактами с культурами, находящимися под влиянием Индии, а также эпохой китайской и японской торговли.

Как правило, на народы, которые ели пальцами, скорее всего повлияла, например, культура Индии, чем культура Китая, где народы ели палочками ; чай как напиток можно найти по всему региону. Рыбные соусы, характерные для этого региона, обычно различаются.

Искусство

Искусство Юго-Восточной Азии имеет сходство с искусством других регионов. Танец в большей части Юго-Восточной Азии включает в себя движения рук и ног, чтобы выразить эмоции танца и смысл истории, которую балерина собирается рассказать публике. Большая часть Юго-Восточной Азии представила танец на своем дворе; в частности, камбоджийский королевский балет представлял их в начале седьмого века, до появления Кхмерской империи , находившейся под сильным влиянием индийского индуизма. Танец Апсара , известный сильными движениями рук и ног, является прекрасным примером индуистского символического танца.

Кукольный театр и игры теней также были излюбленной формой развлечения в прошлые века, самым известным из которых был ваянг из Индонезии. Искусство и литература в некоторых странах Юго-Восточной Азии находятся под сильным влиянием индуизма, пришедшего к ним много веков назад. Индонезия, несмотря на широкомасштабное обращение в ислам, который выступает против определенных форм искусства, сохранила многие формы индуистских практик, культуры, искусства и литературы. Примером может служить ваянг кулит (теневая марионетка) и литература, подобная Рамаяне . Шоу ваянг кулит было признано ЮНЕСКО 7 ноября 2003 года шедевром устного и нематериального наследия человечества .

Было отмечено, что кхмерское и индонезийское классическое искусство было связано с изображением жизни богов, но для ума Юго-Восточной Азии жизнь богов была жизнью самих народов — радостной, земной, но божественной. Тайцы монских , поздно пришедшие в Юго-Восточную Азию, принесли с собой некоторые китайские художественные традиции, но вскоре отказались от них в пользу кхмерских и традиций , и единственными признаками их более раннего контакта с китайским искусством были стиль их храмов. особенно сужающаяся крыша и их лаковые изделия .

Музыка

Традиционная музыка Юго-Восточной Азии столь же разнообразна, как и ее многочисленные этнические и культурные подразделения. Основные стили традиционной музыки включают придворную музыку, народную музыку, музыкальные стили небольших этнических групп и музыку, на которую повлияли жанры за пределами географического региона.

Из придворных и народных жанров гонговых колоколов большинство составляют ансамбли и оркестры (исключение составляют равнинные районы Вьетнама). Оркестры гамелана и ангклунга из Индонезии ; ансамбли пипхат и пинпеат Таиланда и Камбоджи; и ансамбли кулинтанг на юге Филиппин, Борнео , Сулавеси и Тимора — три основных различных стиля музыкальных жанров, которые повлияли на другие традиционные музыкальные стили в регионе. Струнные инструменты также популярны в регионе.

18 ноября 2010 года ЮНЕСКО официально признала ангклунг шедевром устного и нематериального наследия человечества и призвала индонезийский народ и правительство охранять, передавать, продвигать представления и поощрять мастерство изготовления ангклунга .

Письмо

История Юго-Восточной Азии привела к появлению множества разных авторов, писавших об этом регионе как внутри страны, так и за ее пределами.

Некоторые из самых ранних систем письма Юго-Восточной Азии произошли от систем письма Индии . Это видно через брахмические формы письма, присутствующие в регионе, такие как балийское письмо, изображенное на расщепленных пальмовых листьях, называемых лонтар (см. изображение слева — увеличьте изображение, чтобы увидеть надпись на плоской стороне и украшение на обратной стороне). сторона).

Древность этой формы письма простирается до изобретения бумаги примерно в 100 году в Китае. Обратите внимание, что каждая секция пальмового листа состояла всего из нескольких строк, написанных вдоль листа и связанных шпагатом с другими секциями. Внешняя часть была украшена. Алфавиты Юго-Восточной Азии, как правило, были abugidas до прихода европейцев, которые использовали слова, которые также оканчивались на согласные, а не только на гласные. Другие формы официальных документов, в которых не использовалась бумага, включали яванские свитки с медными пластинами. В тропическом климате Юго-Восточной Азии этот материал был бы более прочным, чем бумага.

В Малайзии, Брунее и Сингапуре малайский язык теперь обычно пишется латиницей. То же явление присутствует в индонезийском языке, хотя используются разные стандарты написания (например, «Текси» на малайском языке и «Такси» на индонезийском языке для слова «Такси»).

Использование китайских иероглифов в прошлом и настоящем наблюдается только во Вьетнаме, а в последнее время – в Сингапуре и Малайзии. Принятие чо Хан во Вьетнаме относится примерно к 111 г. до н.э., когда он был оккупирован китайцами. Вьетнамский сценарий под названием chữ Nôm использовал модифицированный chữ Hán для выражения вьетнамского языка. И Тё Хан, и Тё Ном использовались вплоть до начала 20 века.

Рапа-нуи — австронезийский язык, подобный языкам индонезийского, тагальского и многих других языков Юго-Восточной Азии. Предполагается, что Ронгоронго является письменностью Рапа-Нуи, и, если это будет доказано, оно станет одним из очень немногих изобретений письменности в истории человечества. [ 205 ]

Спорт

Ассоциативный футбол — самый популярный вид спорта в регионе. Федерация футбола АСЕАН , основной регулирующий орган региона, была создана 31 января 1984 года в Джакарте , Индонезия. Чемпионат AFF является крупнейшим футбольным соревнованием в регионе с момента его открытия в 1996 году . Таиланд имеет наибольшее количество титулов в соревновании - семь титулов. Действующим победителем является Таиланд, победивший Вьетнам в финале 2022 года . Таиланд больше всего участвовал в Кубке Азии АФК в то время как самый высокий результат в Кубке Азии для команды Юго-Восточной Азии - второе место в 1968 году Мьянмы - 7 , в Иране . Индонезия — единственная команда Юго-Восточной Азии, которая играла на чемпионате мира по футболу 1938 года под названием Голландская Ост-Индия .

См. также

- Ассоциация государств Юго-Восточной Азии (АСЕАН)

- Глобальный юго-восток

- Список нынешних глав государств и правительств

- Список первых в Юго-Восточной Азии

- Наращивание военной мощи в Юго-Восточной Азии

- Тихоокеанская Азия

- Организация Договора Юго-Восточной Азии

- Игры Юго-Восточной Азии

- Экономика Тигренка

Примечания

- ^ Трансконтинентальная страна .

- ^ Великий храмовый комплекс в Прамбанане в Индонезии имеет ряд сходств с архитектурой Южной Индии. [ 88 ]

- ^ Также пишется Юго-Восточная Азия и Юго-Восточная Азия, а также известна как Юго-Восточная Азия, Юго-Восточная Азия или ЮВА.

Ссылки

Цитаты

- ^ «Перспективы мирового народонаселения 2022» . Департамент ООН по экономическим и социальным вопросам , Отдел народонаселения . Проверено 17 июля 2022 г.

- ^ «Перспективы мирового населения на 2022 год: Демографические показатели по регионам, субрегионам и странам ежегодно на 1950–2100 годы» (XSLX) («Общая численность населения по состоянию на 1 июля (тысяч)»). Департамент ООН по экономическим и социальным вопросам , Отдел народонаселения . Проверено 17 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Сообщество АСЕАН в цифрах (ACIF), 2013 г. (PDF) (6-е изд.). Джакарта: АСЕАН. Февраль 2014. с. 1. ISBN 978-602-7643-73-4 . Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 4 сентября 2015 года . Проверено 9 мая 2015 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д и ж «База данных «Перспективы мировой экономики», апрель 2023 г.» . Международный валютный фонд. Апрель 2022 года . Проверено 22 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Клаус Кестле (10 сентября 2013 г.). «Карта региона Юго-Восточной Азии» . Онлайн-проект Наций . Один мир – нации онлайн. Архивировано из оригинала 20 сентября 2013 года . Проверено 10 сентября 2013 г.

Юго-Восточная Азия — это обширный субрегион Азии, географически расположенный к востоку от Индийского субконтинента, к югу от Китая и к северо-западу от Австралии. Регион расположен между Индийским океаном и Бенгальским заливом на западе, Филиппинским морем, Южно-Китайским морем и Тихим океаном на востоке.

- ^ Уэлли, Патрик Л.; Ньюхолл, Кристофер Г.; Брэдли, Кайл Э. (2015). «Частота взрывных извержений вулканов в Юго-Восточной Азии» . Бюллетень вулканологии . 77 (1): 1. Бибкод : 2015BVol...77....1W . дои : 10.1007/s00445-014-0893-8 . ISSN 0258-8900 . ПМЦ 4470363 . ПМИД 26097277 .

- ^ Честер, Рой (16 июля 2008 г.). Горнило созидания, колыбель разрушения: путешествие к месту рождения землетрясений, вулканов и цунами . АМАКОМ. ISBN 978-0-8144-0920-6 .

- ^ «Население Азии (2018)» . worldometers.info . Архивировано из оригинала 6 января 2019 года . Проверено 30 декабря 2018 г.

- ^ Зиде; Бейкер, Норман Х.; Милтон Э. (1966). Исследования по сравнительному австроазиатскому языкознанию . Изучение иностранного языка.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ «Государства-члены АСЕАН» . АСЕАН . Архивировано из оригинала 10 августа 2019 года . Проверено 27 августа 2017 г.

- ^ «Экономическое влияние колониализма» . ЦЭПР . 30 января 2017 г.

- ^ Пасенг, Рохайати. «Исследовательские путеводители: исследовательский путеводитель по Юго-Восточной Азии: империализм, колониализм и национализм» . guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu . Проверено 9 июля 2022 г.

- ^ Уоллес, Альфред Рассел (1869). Малайский архипелаг . Лондон: Макмиллан. п. 1.

- ^ Лах; Ван Клей, Дональд Ф.; Эдвин Дж (1998). Азия в процессе создания Европы, Том III . Чикаго: Издательство Чикагского университета. ISBN 978-0-226-46768-9 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Элиот, Джошуа; Бикерстет, Джейн; Баллард, Себастьян (1996). Справочник по Индонезии, Малайзии и Сингапуру . Нью-Йорк: Публикации о торговле, торговле и путешествиях.

- ^ Парк; Король Сын У; Виктор Т. (2013). Историческая конструкция исследований Юго-Восточной Азии: Корея и за ее пределами . Сингапур: Институт исследований Юго-Восточной Азии. ISBN 978-981-4414-58-6 .

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: несколько имен: список авторов ( ссылка ) - ^ Перейти обратно: а б Эммерсон, Дональд К. (1984). «Юго-Восточная Азия: что в названии?». Журнал исследований Юго-Восточной Азии . 15 (1): 1–21. дои : 10.1017/S0022463400012182 . JSTOR 20070562 . S2CID 162530182 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Население Юго-Восточной Азии (ЖИВОЕ)» . Мирометры/. 6 февраля 2020 года. Архивировано из оригинала 19 августа 2013 года . Проверено 6 февраля 2020 г.