ЛГБТ -история

| ЛГБТ -история | |

|---|---|

Статуя Александра Вуда , Торонто, Канада Natalie Barney historical marker, Dayton, Ohio Anne Lister plaque, York, England Stonewall Inn Plaque, New York City, New York |

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ topics |

|---|

|

|

История ЛГБТК восходит к первым зарегистрированным случаям однополой любви, разнообразных гендерных идентичностей и сексуальности в древних цивилизациях, в которой участвуют история и культуры лесбиянок , геев , бисексуалов , транссексуалов и странных ( ЛГБТ ) по всему миру. То, что сохранилось после многих веков преследований, вызванных стыдом, подавлением и секретностью, - только в последние десятилетия преследуется и переплетается в более основные исторические повествования.

В 1994 году в Соединенных Штатах началось ежегодное соблюдение Месяца истории ЛГБТ , и с тех пор он был поднят в других странах. Это соблюдение включает в себя освещение истории людей, прав ЛГБТ и связанных с ними движений гражданских прав . В октябре отмечается в Соединенных Штатах, включив национальный день выхода 11 октября. [ 1 ] В Соединенном Королевстве он наблюдался в течение февраля с 2005 года, что совпадает с отменой раздела 28 в 2003 году, которая запретила местным властям «содействовать» гомосексуализму. [2][3] A celebrated achievement in LGBTQ history occurred when Queen Beatrix signed a law making Netherlands the first country to legalize same-sex marriage in 2001.[4]

East Asia

China and Taiwan

Male homosexuality has been acknowledged in China since ancient times and was mentioned in many famous works of Chinese literature. Confucianism, being primarily a social and political philosophy, focused little on sexuality, whether homosexual or heterosexual. In contrast, the role of women is given little positive emphasis in Chinese history, with records of lesbianism being especially rare. Still, there are also descriptions of lesbians in some history books.[5]: 174

Chinese literature recorded multiple anecdotes of men engaging in homosexual relationships. In the story of the leftover peach (余桃), set during the Spring and Autumn Era, the historian Han Fei recorded an anecdote in the relationship of Mizi Xia (彌子瑕) and Duke Ling of Wei (衛靈公) in which Mizi Xia shared an especially delicious peach with his lover.[5]: 32

The story of the cut sleeve (断袖) recorded the Emperor Ai of Han sharing a bed with his lover, Dong Xian (董賢); when Emperor Ai woke up later, he carefully cut off his sleeve, so as not to awake Dong, who had fallen asleep on top of it.[5]: 46 Scholar Pan Guangdan (潘光旦) came to the conclusion that many emperors in the Han dynasty had one or more male sex partners.[6] However, except in unusual cases, such as Emperor Ai, the men named for their homosexual relationships in the official histories appear to have had active heterosexual lives as well.

With the rise of the Tang dynasty, China became increasingly influenced by the sexual morals of foreigners from Western and Central Asia, and female companions began to replace male companions in terms of power and familial standings.[5] The following Song dynasty was the last dynasty to include a chapter on male companions of the emperors in official documents.[5] During these dynasties, the general attitude toward homosexuality was still tolerant, but male lovers were increasingly seen as less legitimate compared to wives and men were usually expected to get married and continue the family line.[7]

During the Ming dynasty, it is said that the Zhengde Emperor had a homosexual relationship with a Muslim leader named Sayyid Husain.[8][9] In later Ming dynasty, homosexuality began to be referred to as the "southern custom" due to the fact that Fujian was the site of a unique system of male marriages, attested to by the scholar-bureaucrat Shen Defu and the writer Li Yu, and mythologized by in the folk tale, The Leveret Spirit.

The Qing dynasty instituted the first law against consensual, non-monetized homosexuality in China. However, the punishment designated, which included a month in prison and 100 heavy blows, was actually the lightest punishment which existed in the Qing legal system.[5]: 144 In Dream of the Red Chamber, written during the Qing dynasty, instances of same-sex affection and sexual interactions described seem as familiar to observers in the present as do equivalent stories of romances between heterosexual people during the same period.[citation needed]

Significant efforts to suppress homosexuality in China began with the Self-Strengthening Movement, when homophobia was imported to China along with Western science and philosophy.[10]

In 2006, a shrine for the god of homosexual love, Tu'er Shen, was established in Taiwan centuries after the original temple was destroyed in Fujian by the Chinese government in the 17th century.[11] Thousands of queer pilgrims have flocked the site to pray for good fortune in love.[12] In 2019, Taiwan became the first country in the region to legalize marriage equality.[13]

Japan and Korea

Pre-Meiji Japan

Records of men who have sex with men in Japan date back to ancient times. However, they became most apparent to scholars during the Edo period. Historical practises of homosexuality is usually referred to in Japan as wakashudō (若衆道, lit. 'way of the wakashū') and nanshoku (男色, lit. 'male colors').[14] The institution of wakashudō in Japan is in many ways similar to pederasty in ancient Greece. Older men usually engaged in romantic and sexual relationships with younger men (the wakashū), usually in their teens.[15][16]

In the classic Japanese literature The Tale of Genji, written in the Heian Era, men are frequently moved by the beauty of young boys. In one scene the hero is rejected by a lady and instead sleeps with her young brother: "Genji pulled the boy down beside him ... Genji, for his part, or so one is informed, found the boy more attractive than his chilly sister".[17] Some references also contain references to emperors involved in homosexual relationships and to "handsome boys retained for sexual purposes" by emperors.[18] In other literary works can be found references to what Leupp has called "problems of gender identity",[19] such as the story of a youth's falling in love with a girl who is actually a cross-dressing male. Japanese shunga are erotic pictures which include same-sex and opposite-sex love.

Post Meiji Japan

As Japan started it process of westernizing during the Meiji era, homophobia was imported from western sources into Japan and animosity towards same-sex practices started growing.[16] In 1873 Ministry of Justice passed the keikan (鶏姦) code, a sodomy law criminalizing homosexual practices.[14]

Korea

Several members of Korea's nobility class and Buddhist monks have been known to declare their attraction to members of the same sex.[20] Some Korean emperors from a thousand years ago were also known for having male lovers.[21][22]

Southeast Asia and the Pacific

In Thailand, homosexuality has been documented as early as the Ayutthaya period (1351 to 1767). Temple murals have been found which depict same-sex relations between men and between women.[23] Concubines from the royal Thai family were known in the ‘Samutthakhot Kham Chan’ (สมุทรโฆษคำฉันท์), Thai literature from Ayuttaya times, to have lesbian relationships.[24] Records of homosexuality are present since at least the 14th century in Vietnam.[25] In the Philippines, same-sex marriage was documented as normalized as early as the 1500s through the Boxer Codex, while various texts have elaborated on the powerful roles gender non-conforming peoples had prior to Spanish colonization.[26] Many of these gender non-conforming people became shamans known as babaylan, whose social status were on par with the ruling nobility.[27][28] In Indonesia, the Serat Centhini records the prevalence of bisexuality and homosexuality in Javanese culture.[29] Homosexuality has also been recorded as part of numerous indigenous cultures throughout Indonesia, where each culture has specific terminologies for gender non-conforming peoples, many of whom had high roles in society.[30]

Under British colonial rule, the British imposed Section 377 or its equivalent over territories it colonized in Asia, including Myanmar, Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei. The law has left an anti-LGBTQ legacy in the countries that Britain colonized.[31][32] In Cambodia, homosexuality and same-sex marriages are openly supported by the monarchy, which has called on its government to legalize marriage equality.[33] In East Timor, Asia's youngest independent country since 2002, prime ministers and presidents have openly supported the LGBTQ community since 2017 when the nation celebrated its first pride march with religious and political leaders backing the movement.[34]

In some societies of Melanesia, especially in Papua New Guinea, same-sex relationships were, until the middle of the last century, an integral part of the culture.[35] Third gender concepts are prevalent in Polynesia, such as Samoa, where traditional same-sex marriage have been documented and trans people are widely accepted prior to colonization.[36][37] In Australia, non-binary concepts have been recorded in the culture of the indigenous Aboriginal peoples since pre-colonial times,[38] while homosexual terminologies are indigenous to Tiwi Islanders.[39] In New Zealand, Maori culture has records of homosexuality through their indigenous epics, where queer people are referred to as takatāpui.[40] In Hawaii, queer people, referred to as māhū, are widely accepted since pre-colonial times. Intimate same-sex relationships, referred as moe aikāne, are supported by indigenous rulers or chieftains without any form of stigma.[41] British colonialism and Christian churches have left an anti-LGBTQ legacy in parts of the Pacific due to the aggressive discriminatory impositions of Western conservatism on the region.[42]

South Asia

The earliest references to homophobia in South Asia are from Zoroastrianism around 250 BC. During the Parthian Empire, which encompassed the region currently known as Pakistan, the Zoroastrian text Vendidad was written. It contains provisions that are part of sexual code promoting procreative sexuality that is interpreted to prohibit same-sex intercourse as sinful. Ancient commentary on this passage suggests that those engaging in sodomy could be killed without permission from a high priest. These prohobitions had an influence during the implementations of other religions in the region such as during the spread of Buddhism in Central Asia, and eventually supplanted by the domination of Islam and Sharia Law.[43][44][45][46][47]

Homophobia was notably introduced to the region that now encompasses India through Islam, though the totality of homophobic laws was introduced during British colonialsm. Homophobic laws were only introduced to parts of South India and Sri Lanka through colonialism and not Islam.[48]

India

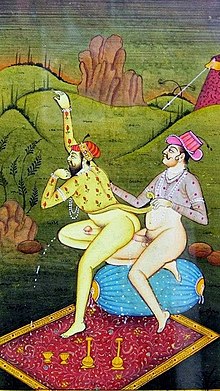

Throughout Hindu and Vedic texts there are many descriptions of saints, demigods, and even the Supreme Lord transcending gender norms and manifesting multiple combinations of sex and gender. There are several instances in ancient Indian epic poetry of same sex depictions and unions by gods and goddesses. There are several stories of depicting love between the same sex especially among kings and queens. Kamasutra, the ancient Hinduism based Indian treatise on love talks about feelings for the same sex. There are several depictions of same-sex sexual acts in Hindu temples like Khajuraho.[49] Currently one of the earliest discovered references to homosexuality in South Asia comes from a Hindu medical journal written in the holy city of Varanasi in 600 BCE, which describes the concept of homosexuality and transexuality in a neutral manner.[50][51][52]

In South Asia the Hijra are a caste of third gender or transgender people who live a feminine role. Hijra may be born male or intersex, and some may have been born female.[53]

Middle East and North Africa

Abbasid Caliphate

In the age of the Abbasid Caliphate, some references and anecdotes to same-sex love affairs and social views on gender and sexuality can be found in literary texts such as recorded poems.

In Jawāmiʿ al-ladhdha, a 10th century erotic compendium, individual proponents discuss their sexual preferences in contributed poems. Female poets, describe tribadism as a form of sexual gratification without the concomitant loss of reputation or risk of pregnancy.[54] Other poets such as Abu'l-'Anbas Saymari, who is said to have written a book about lesbians and passive sodomites that has not survived to this day, described same-sex intercourse between two women as compatible due to the similarity of both love bodies and the equality of their relationship to other women.[54]

The categorisation of different sex acts in Arabic-Islamic culture, was named according to the act rather than a particular orientation. A possible distinction according to El-Rouayheb is that of the active and passive part during the sexual intercourse.[55] Thus, the act of two women haven intercourse was known as saḥḥāqāt, derived from saḥq for rubbing - in theory regardless of the gender identity of the partner.[56][54]

An example of described homosexuality between men are the two poets Abū Nuwās and al-Buturī known for their affection for slave boys (ghulām) or socially inferior boys. In one story, al-Buturī's is selling Nasīm, a slave boy, to the son of a vizier, only to regret it later and buy him back at great financial sacrifice.[57]

Abū Nuwās explicitly describes his affection for young male lovers in his poems, often referring to socially subordinate boys such as Christian tavern boys, student from mosques, or apprentices in the bureaucracy.[58]

Egypt

Ancient Egypt

The duo Khnumhotep and Niankhkhnum, manicurists in the Palace of King Niuserre during the Fifth Dynasty of Egyptian pharaohs, c. 2400 BCE,[59] are speculated to have been gay based on a representation of them embracing nose-to-nose in their shared tomb, though critics say that they were likely brothers. King Neferkare and General Sasenet, a Middle Kingdom story, has an intriguing plot revolving around a king's clandestine gay affair with one of his generals. It may reference the actual Pharaoh Pepi II, but critics say that the story may have been written to tarnish what was considered to be a unloved monarch.[60][61]

Coptic Egypt

The sixth- or seventh-century Ashmolean Parchment AN 1981.940 provides the only example in Coptic language of a love spell between men. This vellum leaf contains an incantation by a man named Apapolo, the son of Noah, to compel the presence and love of another man Phello, the son of Maure. Phello will be restless until he finds Apapolo and satisfies the latter's desire.[62][63]

Medieval Egypt

Sunni Islam eventually supplanted Christianity as the dominant religion of Egypt in the centuries following the Muslim conquest of Egypt. The native Egyptian population was tolerant of homosexual behaviors, but Islamic religious authority was discouraging of homosexual behaviors and non-traditional gender roles.[64] However, Islamic law tolerated a smaller subsection of homosexual behaviors of pederasty, as the attraction to feminine male youth was viewed as natural and compatible with traditional Muslim gender roles.[65][66][67]

Early modern Egypt

The Siwa Oasis was of special interest to anthropologists and sociologists because of its historical acceptance of male homosexuality. Some argue the practice arose because from ancient times unmarried men and adolescent boys were required to live and work together outside the town of Shali, secluded for several years from any access to available women. In 1900, the German egyptologist George Steindorff reported that, "the feast of marrying a boy was celebrated with great pomp, and the money paid for a boy sometimes amounted to fifteen pound, while the money paid for a woman was a little over one pound."[68][better source needed] The archaeologist Count Byron de Prorok reported in 1937 that "an enthusiasm could not have been approached even in Sodom... Homosexuality was not merely rampant, it was raging...Every dancer had his boyfriend...[and] chiefs had harems of boys.[69][better source needed]

Walter Cline noted that, "all normal Siwan men and boys practice sodomy...the natives are not ashamed of this; they talk about it as openly as they talk about love of women, and many if not most of their fights arise from homosexual competition....Prominent men lend their sons to each other. All Siwans know the matings which have taken place among their sheiks and their sheiks' sons....Most of the boys used in sodomy are between twelve and eighteen years of age."[70][better source needed] In the late 1940s, a Siwan merchant told the visiting British novelist Robin Maugham that the Siwan men "will kill each other for boy. Never for a woman".[71][better source needed]

Assyria

The Middle Assyrian Law Codes (1075 BCE) state: If a man has intercourse with his brother-in-arms, they shall turn him into a eunuch.[72] This is the earliest known law condemning the act of male-to-male intercourse in the military.[73] Despite these laws, sex crimes were punished identically whether they were homosexual or heterosexual in the Assyrian society.[74] Freely pictured art of anal intercourse, practiced as part of a religious ritual, dated from the third millennium BCE and onwards.[75]

Furthermore, the article 'Homosexualität' in Reallexicon der Assyriologie states,

Homosexuality in itself is thus nowhere condemned as licentiousness, as immorality, as social disorder, or as transgressing any human or divine law. Anyone could practice it freely, just as anyone could visit a prostitute, provided it was done without violence and without compulsion, and preferably as far as taking the passive role was concerned, with specialists. That there was nothing religiously amiss with homosexual love between men is seen by the fact that they prayed for divine blessing on it. It seems clear that the Mesopotamians saw nothing wrong in homosexual acts between consenting adults.[76][77][78]

Israel

The ancient Law of Moses (the Torah) forbids men from lying with men (i.e., from having intercourse) in Leviticus 18 and gives a story of attempted homosexual rape in Genesis 19, in the story of Sodom and Gomorrah, after which the cities were soon destroyed with "brimstone and fire, from the Lord"[79][80][page needed] and the death penalty was prescribed to its inhabitants and to Lot's wife who was tuned into a pillar of salt because she turned back to watch the cities' destruction.[81][82][better source needed] In Deuteronomy 22:5, cross-dressing is condemned as "abominable".[83][84]

Persia

In pre-modern Islam there was a "widespread conviction that beardless youths possessed a temptation to adult men as a whole, and not merely to a small minority of deviants."[85]

Muslim—often Sufi—poets in medieval Arab lands and in Persia wrote odes to the beautiful wine boys who served them in the taverns. In many areas the practice survived into modern times, as documented by Richard Francis Burton, André Gide, and others. Homoerotic themes were present in poetry and other literature written by some Muslims from the medieval period onward and which celebrated love between men. In fact these were more common than expressions of attraction to women.[86]

Turkey

The Ottoman Empire

In a world before sexual preferences defined identity, men who desired other men were not thought of as members of a biologically determined, distinctive subculture with a constant nature. Because men and women were not thought of as opposites, same-sex relationships were not considered to go against nature. (In fact, women were thought of as biologically imperfect men.)[87]

Pre-Columbian Americas

George Catlin's painting/interpretation of Sac and Fox Nation people, which he titled Dance to the Berdache [sic]. George Catlin (1796–1872); Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC

Among Indigenous peoples of the Americas prior to European colonization, a number of nations had respected roles for homosexual, bisexual, and gender-nonconforming individuals; in some Indigenous communities, these social and spiritual roles are still observed.[88] While the Indigenous cultures that preserve (or have adopted) these roles have their own names, in their own languages, for these individuals,[89] a modern, pan-Indian term that some have adopted is "Two-Spirit".[90] In a traditional culture that holds these roles as sacred, these individuals are recognized early in life, raised in the appropriate manner, learning from the Elders the customs, spiritual, and social duties fulfilled by these people in the community.[88] While this new term has not been universally accepted—it has been criticized as a term of erasure by traditional communities who already have their own terms for the people being grouped under this new term, and by those who reject what they call the "western" binary implications, such as implying that Natives believe these individuals are "both male and female"[91]—it has generally received more acceptance and use than the anthropological term it replaced.[90][92][93]

Sub-Saharan Africa

Lesotho

Anthropologists Stephen Murray and Will Roscoe reported that women in Lesotho engaged in socially sanctioned "long term, erotic relationships", named motsoalle (lit. 'Special Friend').[94][page needed] Often, a motsoalle relationship was acknowledged publicly with a ritual feast and with the community fully aware of the women's commitment to one another.[95] Motsoalle relationships commonly existed among school girls where it functioned like a type of "puppy love" or mentorship.[96]

However, different from the western notion of lesbianism, motsoalle relationships are not seen as an "alternative to heterosexual marriage".[97] Women in motsoalle relationships are still expected to "marry men and conform, or appear to conform, to gender expectations."[98] Motsoalle relationships are usually not seen as proper sexual and romantic relationship due to the Sesotho notion of sex, where an act is not considered a sex act if one partner was not male.[99]

As Lesotho became more modernized, those communities were exposed to Western culture and thus homophobia.[100] Anthropologist K. Limakatsuo Kendall hypothesizes that as Western ideas spread, the idea that women could be sexual with one another, coupled with homophobia, began to erase the motsoalle relationships.[100] By the 1980s, the ritual feasts that were once celebrated by the community for motsoalles had vanished.[101] Today, motsoalle relationships have largely disappeared.[102]

Azande

Among the Zande people of Congo, there was a social institution similar to pederasty in Ancient Greece. E. E. Evans-Pritchard also recorded that male Azande warriors routinely took on boy-wives between the ages of twelve and twenty, who helped with household tasks and participated in intercrural sex with their older husbands. The practice had died out by the early 20th century, after Europeans had gained control of African countries, but was recounted to Evans-Pritchard by the elders with whom he spoke.[103]

During the 1930s Evans-Pritchard recorded information about sexual relationships between women, based on reports from male Azande.[104]: 55 According to male Azande, women would take female lovers in order to seek out pleasure and that partners would penetrate each other using bananas or a food item carved into the shape of a phallus.[104]: 55 They also reported that the daughter of a ruler may be given a female slave as a sexual partner.[104]: 55 Evans-Pritchard also recorded that the male Azande were fearful of women taking on female lovers, as they might view men as unnecessary.[104]

Europe

Classical antiquity

Ancient Celts

According to Aristotle, although most "belligerent nations" were strongly influenced by their women, the Celts were unusual among them because their men openly preferred male lovers (Politics II 1269b).[105] H. D. Rankin in Celts and the Classical World notes that "Athenaeus echoes this comment (603a) and so does Ammianus (30.9). It seems to be the general opinion of antiquity."[106] In book XIII of his Deipnosophists, the Roman Greek rhetorician and grammarian Athenaeus, repeating assertions made by Diodorus Siculus in the first century BCE (Bibliotheca historica 5:32), wrote that Celtic women were beautiful but that the men preferred to sleep together. Diodorus went further, stating that "the young men will offer themselves to strangers and are insulted if the offer is refused". Rankin argues that the ultimate source of these assertions is likely to be Poseidonius and speculates that these authors may be recording male "bonding rituals".[107]

Ancient Greece

Same-sex relationships did not replace marriage between man and woman, but occurred before and beside it.[109] A mature man would not usually have a mature male mate (with exceptions such as Alexander the Great and the same-aged Hephaestion) but the older man would usually be the erastes (lover) to a young eromenos (loved one). Kenneth J. Dover, followed by Michel Foucault and Halperin, assumed that it was considered improper for the eromenos to feel desire, as that would not be masculine. However, Dover's claim has been questioned in light of evidence of love poetry which suggests a more emotional connection than earlier researchers liked to acknowledge.[citation needed] The ideal held that both partners would be inspired by love symbolized by Eros, the erastes unselfishly providing education, guidance, and appropriate gifts to his eromenos, who became his devoted pupil and assistant, while the sexuality theoretically remained short of penetrative acts and supposedly would consist primarily of the act of frottage or intercrural sex.[110] Although this was the ideal, realistically speaking, it is probable that in many such relationships fellatio and penetrative anal intercourse did occur.[original research?] The hoped-for result was the mutual improvement of both erastes and eromenos, each doing his best to excel in order to be worthy of the other.[citation needed]

Men could also seek adolescent boys as partners as shown by some of the earliest documents concerning same-sex pederastic relationships, which come from ancient Greece. Often they were favored over women.[111] Though slave boys could be bought, free boys had to be courted, and ancient materials suggest that the father also had to consent to the relationship.[citation needed]

Same-sex relationships were a social institution variously constructed over time and from one city to another. The formal practice, an erotic yet often restrained relationship between a free adult male and a free adolescent was valued for its pedagogic benefits and as a means of population control, though occasionally was blamed for causing disorder.[citation needed] Plato praised its benefits in his early writings [e.g., Phaedrus in the Symposium (385–370 BCE)] but in his late works proposed its prohibition [e.g., in Laws (636D & 835E)]).[112] In the Symposium (182B-D), Plato equates acceptance of homosexuality with democracy and its suppression with despotism, and wrote that homosexuality "is shameful to barbarians because of their despotic governments, just as philosophy and athletics are, since it is apparently not in best interests of such rulers to have great ideas engendered in their subjects, or powerful friendships or physical unions, all of which love is particularly apt to produce".[113] Aristotle, in the Politics, dismissed Plato's ideas about abolishing homosexuality; he explains that barbarians like the Celts accorded it a special honor, while the Cretans used it to regulate the population.[113]

Sappho, born on the island of Lesbos, was included by later Greeks in the canonical list of nine lyric poets. The adjectives deriving from her name and place of birth (Sapphic and Lesbian) came to be applied to female homosexuality beginning in the 19th century.[114][115] Sappho's poetry centers on passion and love for various personages and both genders. The narrators of many of her poems speak of infatuations and love (sometimes requited, sometimes not) for various females, but descriptions of physical acts between women are few and subject to debate.[116][117]

Ancient Rome

In Ancient Greece and Phrygia, and later in the Roman Republic, the Goddess Cybele was worshiped by a cult of people who castrated themselves, and thereafter took female dress and referred to themselves as female.[119][120] These early transgender figures have also been referred by several authors as early role models.[121][122]

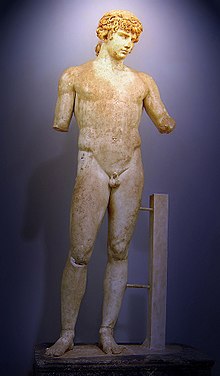

In Ancient Rome the young male body remained a focus of male sexual attention, but relationships were between older free men and slaves or freed youths who took the receptive role in sex. The Hellenophile emperor Hadrian is renowned for his relationship with Antinous.

In Roman patriarchal society, it was socially acceptable for an adult male citizen to take the penetrative role in same-sex relations. Freeborn male minors were strictly protected from sexual predators (see Lex Scantinia), and men who willingly played the "passive" role in homosexual relations were disparaged. No law or moral censure was directed against homosexual behaviors as such, as long as the citizen took the dominant role with a partner of lower status such as a slave, prostitute, or someone considered infamis, of no social standing.

The Roman emperor Elagabalus is depicted as transgender by some modern writers. Elagabalus was said to be "delighted to be called the mistress, the wife, the queen of Hierocles." Supposedly, great wealth was offered to any surgeon who was able to give Elagabalus female genitalia.

During the Renaissance, wealthy cities in northern Italy—Florence and Venice in particular—were renowned for their widespread practice of same-sex love, engaged in by a considerable part of the male population and constructed along the classical pattern of Greece and Rome.[123][124] Attitudes toward homosexual behavior changed when the Empire fell under Christian rule; see for instance legislation of Justinian I.

The Middle Ages

According to John Boswell, author of Christianity, Social Tolerance and Homosexuality,[125] there were same-sex Christian monastic communities and other religious orders in which homosexuality thrived. According to Chauncey et al. (1989), the book "offered a revolutionary interpretation of the Western tradition, arguing that the Roman Catholic Church had not condemned gay people throughout its history, but rather, at least until the twelfth century, had alternately evinced no special concern about homosexuality or actually celebrated love between men." Boswell was also the author of Same-Sex Unions in Pre-Modern Europe (New York: Villard, 1994) in which he argues that the adelphopoiia liturgy was evidence that attitude of the Christian church towards homosexuality has changed over time, and that early Christians did on occasion accept same-sex relationships.[126] His work attracted great controversy, as it was seen by many as merely an attempt for Boswell to justify his homosexuality and Roman Catholic faith. For instance, R. W. Southern points out that homosexuality had been condemned extensively by religious leaders and medieval scholars well before the 12th century; he also points to the penitentials which were common in early medieval society, and many of which include homosexuality as among the serious sins.[127]

Bennett and Froide, in Singlewomen in the European Past, note: "Other single women found emotional comfort and sexual pleasure with women. The history of same-sex relations between women in medieval and early modern Europe is exceedingly difficult to study, but there can be no doubt of its existence. Church leaders worried about lesbian sex; women expressed, practiced, and were sometimes imprisoned or even executed for same-sex love; and some women cross-dressed in order to live with other women as married couples." They go on to note that even the seemingly modern word "lesbian" has been traced back as far as 1732, and discuss lesbian subcultures, but add, "Nevertheless, we certainly should not equate the single state with lesbian practices." While same-sex relationships among men were highly documented and condemned, "Moral theologians did not pay much attention to the question of what we would today call lesbian sex, perhaps because anything that did not involve a phallus did not fall within the bounds of their understanding of the sexual. Some legislation against lesbian relations can be adduced for the period, mainly involving the use of "instruments," in other words, dildoes."[128]

Throughout the majority of Christian history, most Christian theologians and denominations have considered homosexual behavior as immoral or sinful.[129][130] Persecutions against homosexuality rose during the High Middle Ages, reaching their height during the Medieval Inquisitions, when the sects of Cathars and Waldensians were accused of fornication and sodomy, alongside accusations of satanism. In 1307, accusations of sodomy and homosexuality were major charges leveled during the Trial of the Knights Templar.[131] The theologian Thomas Aquinas was influential in linking condemnations of homosexuality with the idea of natural law, arguing that "special sins are against nature, as, for instance, those that run counter to the intercourse of male and female natural to animals, and so are peculiarly qualified as unnatural vices."[132]

The Renaissance

The Renaissance saw intense oppression of homosexual relationships by the Roman Catholic Church. Homosexual activity radically passes from being completely legal in most of Europe to incurring the death penalty in most European states.[133] In France, first-offending sodomites lost their testicles, second offenders lost their penis, and third offenders were burned. Women caught in same-sex acts would be mutilated and executed as well.[134] Thomas Aquinas argued that sodomy was second only to murder in the ranking of sins.[134] The church used every means at its disposal to fight what it considered to be the "corruption of sodomy". Men were fined or jailed; boys were flogged. The harshest punishments, such as burning at the stake, were usually reserved for crimes committed against the very young, or by violence. The Spanish Inquisition begins in 1480, sodomites were stoned, castrated, and burned. Between 1540 and 1700, more than 1,600 people were prosecuted for sodomy.[134] In 1532 the Holy Roman Empire made sodomy punishable by death.[134] The following year King Henry VIII passed the Buggery Act 1533 making all male-male sexual activity punishable by death.[135]

Florentine homosexuality

Florence had a homosexual subculture, which included age-structured relationships.[136] In 1432 the city established Gli Ufficiali di Notte (The Officers of the Night) to root out the practice of sodomy. From that year until 1502, the number of men charged with sodomy numbered more than 17,000, of whom 3,000 were convicted. This number also included heterosexual sodomy.[137]

Association of homosexuality with foreignness

The reputation of Florence is reflected in the fact that the Germans adopted the word Florenzer to refer to a "sodomite".[137][138][page needed] The association of foreignness with homosexuality gradually became a cornerstone of homophobic rhetoric throughout Europe, and it was used in a calumnious perspective. For example, the French would call "homosexuality" the "Italian vice" in the 16th and 17th centuries, the "English vice" in the 18th century, the mœurs orientales (oriental mores) in the 19th century, and the "German vice" starting from 1870 and into the 20th century.[139]

Modern Europe

Psychology and terminology shifts

The developing field of psychology was the first way homosexuality could be directly addressed aside from Biblical condemnation. In Europe, homosexuality had been part of case studies since the 1790s with Johann Valentin Müller's work.[140] The studies of this era tended to be rigorous examination of "criminals", looking to confirm guilt and establish patterns for future prosecutions. Ambroise Tardieu in France believed he could identify "pederasts" affirming that the sex organs are altered by homosexuality in his 1857 publishing.[141][page needed] François Charles's exposé, Les Deux Prostitutions: études de pathologie sociale ("The Two Prostitutions: Study of the Social Pathology"), developed methods for police to persecute through meticulous documentation of homosexuality.[141] Others include Johann Caspar and Otto Westphal, Karl Heinrich Ulrichs. Richard von Krafft-Ebing's 1886 publication, Psychopathia Sexualis, was the most widely translated work of this kind.[141] He and Ulrichs believed that homosexuality was congenitally based, but Krafft-Ebing differed; in that, he asserted that homosexuality was a symptom of other psychopathic behavior that he viewed to be an inherited disposition to degeneracy.[141]

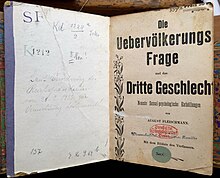

Degeneracy became a widely acknowledged theory for homosexuality during the 1870s and 1880s.[141] It spoke to the eugenic and Social Darwinist theories of the late 19th century. Benedict Augustin Morel is considered the father of degeneracy theory.[141] His theories posit that physical, intellectual, and moral abnormalities come from disease, urban over-population, malnutrition, alcohol, and other failures of his contemporary society.[141]

An important shift in the terminology of homosexuality was brought about by the development of psychology's inquisition into homosexuality. "Contrary sexual feeling",[141] as Westphal's phrased it, and the word "homosexual" itself made their way into the Western lexicons. Homosexuality had a name aside from the ambiguous term "sodomy" and the elusive "abomination". As Michel Foucault phrases it, "the sodomite had been a temporary aberration; the homosexual was now a species."[141]

Historical science shifts

To this day, historians are still arguing about the question of the Sexuality of Frederick the Great (1712–1786), which essentially revolves around the taboo of whether the myth of one of the greatest war heroes in world history is allowed to be psychologically deconstructed.[142]

Homosexuality in Modern Great Britain

Following the codification of anti-sodomy laws with the Buggery Act 1533, homosexual sex and relationships were greatly looked down upon and civilly prosecuted.[143] Although section 61 of the Offences Against the Person Act 1861 removed the death penalty for homosexuality, male homosexual acts remained illegal and were punishable by imprisonment.[143]

In contrast, lesbian relationships were frequently overlooked and legal codes that targeted homosexuality often did not cover sapphic love.[144][page needed] In one Scottish court case, a judge deemed sexual relationships between two women imaginary.[145] Only in cases where women broke gender roles and crossed into masculinity were they punished with public whippings and banishment, much less severe than their gay male counterparts.[146] However, Ballads celebrating cross-dressing female soldiers circulated during the Napoleonic Wars, frequently depicting women donning male garb flirting with men and occasionally even "female husbands" would appear.[147]

Various authors wrote on the topic of homosexuality. In 1735, Conyers Place wrote "Reason Insufficient Guide to Conduct Mankind in Religion".[148] In 1749, Thomas Cannon wrote "Ancient and Modern Pederasty Investigated and Exemplified".[149] In August, 1772, The Morning Chronicle publishes a series of letters to the editor about the trial of Captain Robert Jones.[150][151] In 1773, Charles Crawford wrote "A Dissertation on the Phaedon of Plato".[152]

Molly houses appeared in 18th century London and other large cities. A Molly house is an archaic 18th century English term for a tavern or private room where homosexual and cross-dressing men could meet each other and possible sexual partners. Patrons of the Molly house would sometimes enact mock weddings, sometimes with the bride giving birth. Margaret Clap (?–c. 1726), better known as Mother Clap, ran such a Molly house from 1724 to 1726 in Holborn, London. She was also heavily involved in the ensuing legal battles after her premises were raided by the police and shut down. Molly houses were perhaps the first precursors to the modern gay bar.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, male commentary on lesbian relationships became more common and increasingly eroticized.[153] The publication of Anne Lister's diaries revealed that as early as 1820, educated women had covert sexual and romantic relationships with other women, often while married to men and presenting as close female friendships.[154][145] Intensely emotional friendships between women were normal in England, making it difficult for scholars to definitively identify same-sex relationships.[155] However, modern scholars suspect that lesbian subscripts exist within much of the literature published by women, as female characters yearn romantically after other female characters, but that passion is silenced.[156] This is reflected by a large body of same-sex love poetry was written by women.[157]

Oscar Wilde

Oscar Wilde, the Irish author and playwright, played an important role in bringing homosexuality into the public eye. The scandal in British society and subsequent court case from 1895 to 1896 was highly discussed not only in Europe, but also in America, although newspapers like the New York Times concentrated on the question of blackmail, only alluding to the homosexual aspects as having "a curious meaning", in the first publication on April 4, 1895.[158] After Wilde's arrest, the April 6 New York Times discussed Wilde's case as a question of "immorality" and did not specifically address homosexuality, discussing the men "some as young as 18" that were brought up as witnesses.[159] Inspired by Wilde's renown and homosexuality, gay activist Craig Rodwell founded the first United States LGBTQ bookstore on November 24, 1967, and called it the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop.

Alan Turing

In Britain, the view of homosexuality as the mark of a deviant mind was not limited to the psychiatric wards of hospitals but also the courts. An extremely famous case was that of Alan Turing, a British mathematician and theoretician. During WWII, Turing worked at Bletchley Park and was one of the major architects of the Colossus computer, designed to break the Enigma codes of the Nazi war machine. For the success of this, he was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1945.[160] In spite of all his brilliance and the services rendered to his country, Turing was also openly homosexual and in the early 1950s this fact came to the attention of the British government when he was arrested under section 11 of an 1885 statute on "gross indecency".[161] At the time there was great fear that Turing's sexuality could be exploited by Soviet spies, and so he was sentenced to choosing between jail and injections of synthetic estrogen. The choice of the latter led him to massive depression and dying at the age of 41 after biting into an allegedly poisoned apple.[162] Although it is popularly believed that Turing committed suicide, his death was also consistent with accidental poisoning.[163] It is estimated that an additional 50–75,000 men were persecuted under this law, with only partial repeal taking place in 1967 and the final measure of it in 2003.[164]

Decriminalization of homosexuality in France

Written on July 21, 1776, the Letter LXIII became infamous for its frank talk of human sexuality. Mathieu-François Pidansat de Mairobert published the letter in his 1779 book, "L'Espion Anglois, Ou Correspondance Secrete Entre Milord All'eye et Milord Alle'ar" (aka "L'Observateur Anglais or L'Espion Anglais") ("The English Spy, or Secret Correspondence Between my Lord All'eye and my Lord Alle'ar [aka The English Observer or The English Spy]").[165]

In 1791, Revolutionary France (and Andorra) adopted the French Penal Code of 1791 which no longer criminalized sodomy. France thus became the first West European country to decriminalize homosexual acts between consenting adults.[166] Globally, various countries such as Madagascar have never criminalized homosexual activity.[167]

Soviet Union

The Soviet government of the Russian Soviet Republic (RSFSR) decriminalised homosexuality in December 1917, following the October Revolution and the discarding of the Legal Code of Tsarist Russia.[168]

The legalisation of homosexuality was confirmed in the RSFSR Penal Code of 1922, and following its redrafting in 1926. According to Dan Healey, archival material that became widely available following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 "demonstrates a principled intent to decriminalize the act between consenting adults, expressed from the earliest efforts to write a socialist criminal code in 1918 to the eventual adoption of legislation in 1922."[169]

The Bolsheviks also rescinded Tsarist legal bans on homosexual civil and political rights, especially in the area of state employment. In 1918, Georgy Chicherin, a homosexual man who kept his homosexuality hidden, was appointed as People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the RSFSR. In 1923, Chicherin was also appointed People's Commissar for Foreign Affairs of the USSR, a position he held until 1930.[170]

In the early 1920s, the Soviet government and scientific community took a great deal of interest in sexual research, sexual emancipation and homosexual emancipation. In January 1923, the Soviet Union sent delegates from the Commissariat of Health led by Commissar of Health Semashko[171] to the German Institute for Sexual Research as well as to some international conferences on human sexuality between 1921 and 1930, where they expressed support for the legalisation of adult, private and consensual homosexual relations and the improvement of homosexual rights in all nations.[168][171] In both 1923 and 1925, Dr. Grigorii Batkis, director of the Institute for Social Hygiene in Moscow, published a report, The Sexual Revolution in Russia, which stated that homosexuality was "perfectly natural" and should be legally and socially respected.[172][171] In the Soviet Union itself, the 1920s saw developments in serious Soviet research on sexuality in general, sometimes in support of the progressive idea of homosexuality as a natural part of human sexuality, such as the work of Dr. Batkis prior to 1928.[173][174] Such delegations and research were sent and authorised and supported by the People's Commissariat for Health under Commissar Semashko.[168][174]

Modern Germany

Emancipation movement (1890s–1934)

Prior to the Third Reich, Berlin was a liberal city, with many gay bars, nightclubs and cabarets. There were even many drag bars where tourists straight and gay would enjoy female impersonation acts. Hitler decried cultural degeneration, prostitution and syphilis in his book Mein Kampf, blaming at least some of the phenomena on Jews.

Berlin also had the most active LGBTQ rights movements in the world at the time. Jewish doctor Magnus Hirschfeld had co-founded the Scientific-Humanitarian Committee (Wissenschaftlich-humanitäres Komitee, WhK) in Berlin in 1897 to campaign against the notorious "Paragraph 175" of the Penal Code that made sex between men illegal. It also sought social recognition of homosexual and transgender men and women. It was the first public gay rights organization. The Committee had branches in several other countries, thereby being the first international LGBTQ organization, although on a small scale.

In 1919, Hirschfeld had also co-founded the Institut für Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sex Research), a private sexology research institute. It had a research library and a large archive, and included a marriage and sex counseling office. In addition, the institute was a pioneer worldwide in the call for civil rights and social acceptance for homosexual and transgender people. As a leading city for homosexuals during the 1920s, Berlin had clubs and even newspapers for both lesbians and gay men. The lesbian magazine Die Freundin was started by Friedrich Radszuweit and the gay men's magazine Der Eigene had already started in 1896 as the world's first gay magazine. The first gay demonstration ever took place in Nollendorfplatz in 1922 in Berlin,[175] gathering 400 homosexuals.[citation needed]

Nazi Germany

Under the rule of Nazi Germany, about 50,000 men were sentenced because of their homosexuality and thousands of them died in concentration camps.[176] Gay men were viewed as "inferior" and "animalistic".[177] Conditions for gay men in the camps were especially rough; they faced not only persecution from German soldiers, but also other prisoners, and many gay men were reported to die of beatings.[178] Female homosexuality was not, technically, a crime and thus gay women were generally not treated as harshly as gay men.[179] Although there are some scattered reports that gay women were sometimes imprisoned for their sexuality, most would have been imprisoned for other reasons, i.e. "anti-social".

Decriminalization of homosexuality in Germany

West Germany inherited Paragraph 175 after World War II, which remained on the books until 1969. The first kiss between two men on German television was shown in Rosa von Praunheim's film It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives (1971). This film marks the beginning of the German modern gay liberation movement. In 1993, the last parts of Paragraph 175 were deleted and Germany enacted an equal age of consent.

United States

This article may lend undue weight to certain ideas, incidents, or controversies. (December 2021) |

18th and 19th century

Before the American Civil War and the massive population growth of the Post-Civil War America, the majority of the American population was rural. Homosexuality remained an unseen and taboo concept in society, and the word "homosexuality" was not coined until 1868 In a letter to Karl Heinrich Ulrichs[180] by German-Hungarian Karoly Maria Kertbeny (who advocated decriminalization).[181] During this era, homosexuality fell under the umbrella term "sodomy" that comprised all forms of nonproductive sexuality (masturbation and oral sex were sometimes excluded). Without urban sub-cultures or a name for self-definition, group identification and self-consciousness was unlikely.[182]

Mainstream interpretation of Leviticus 20:13, Romans 1:26–7 and the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah were the justification for the severe penalties facing those accused of "sodomy".[182] Most of the laws around homosexuality in the colonies were derived from the English laws of "buggery", and the punishment in all American colonies was death. The penalty for attempted sodomy (both homosexuality and bestiality) was prison, whipping, banishment, or fines. Thomas Jefferson suggested castration as the punishment for sodomy, rape, and polygamy in a proposed revision of the Virginia criminal code near the end of the 18th century.[182]

Pennsylvania was the first state to repeal the death penalty for "sodomy" in 1786 and within a generation all the other colonies followed suit (except North and South Carolina that repealed after the Civil War).[182] Along with the removal of the death penalty during this generation, legal language shifted away from that of damnation to more dispassionate terms like "unmentionable" or "abominable" acts.[182] Aside from sodomy and "attempted sodomy" court cases and a few public scandals, homosexuality was seen as peripheral in mainstream society. Lesbianism had no legal definition largely given Victorian notions of female sexuality.[182]

A survey of sodomy law enforcement during the nineteenth century suggests that a significant minority of cases did not specify the gender of the "victim" or accused. Most cases were argued as non-consensual or rape.[183] The first prosecution for consensual sex between people of the same gender was not until 1880.[183] In response to increasing visibility of alternative genders, gender bending, and homosexuality, a host of laws against vagrancy, public indecency, disorderly conduct, and indecent exposure was introduced across the United States. "Sodomy" laws also shifted in many states over the beginning of the twentieth century to address homosexuality specifically (many states during the twentieth century made heterosexual anal intercourse legal).[183] In some states, these laws would last until they were repealed by the Supreme Court in 2003 with the Lawrence decision.[183]

Male ideal and the 19th century

This section relies largely or entirely upon a single source. (June 2021) |

Male homosexuality found its first social foothold in the 19th century not in sexuality or homoerotica, but in idealized conception of the wholesome and loving male friendship during the 19th century. Or as contemporary author Theodore Winthrop in Cecil Dreeme writes, "a friendship I deemed more precious than the love of women."[182] This ideal came from and was enforced by the male-centric institutions of boy's boarding schools, all-male colleges, the military, the frontier, etc.—fictional and non-fiction accounts of passionate male friendships became a theme present in American Literature and social conceptions of masculinity.[182]

New York, as America's largest city exponentially growing during the 19th century (doubling from 1800 to 1820 and again by 1840 to a population of 300,000), saw the beginnings of a homosexual subculture concomitantly growing with the population.[182] Continuing the theme of loving male friendship, the American poet, Walt Whitman arrived in New York in 1841.[182] He was immediately drawn to young working-class men found in certain parks, public baths, the docks, and some bars and dance halls.[182] He kept records of the men and boys, usually noting their ages, physical characteristics, jobs, and origins.[182] Dispersed in his praise of the city are moments of male admiration, such as in Calamus—"frequent and swift flash of eyes offering me robust, athletic love" or in poem Crossing Brooklyn Ferry, where he writes:

"Was call'd by my nighest name by clear loud voices of young men as they saw me / approaching or passing, / Felt their arms on my neck as I stood, or the negligent leaning of their flesh against me as / I sat, / Saw many I loved in the street or ferry-boat or public assembly, yet never told them a / word, / Lived the same life with the rest, the same old laughing, gnawing, sleeping, / Play'd the part that still looks back on the actor or actress, / The same old role, the role that is what we make it, as great as we like, / Or as small as we like, or both great and small."[182]

Sometimes Whitman's writing verged on explicit, such as in his poem, Native Moments—"I share the midnight orgies of young men / I pick out some low person for my dearest friend. He shall be lawless, rude, illiterate."[182] Poems like these and Calamus (inspired by Whitman's treasured friends and possible lover, Fred Vaughan who lived with the Whitman family in the 1850s) and the general theme of manly love, functioned as a pseudonym for homosexuality.[182] The developing sub-community had a coded voice to draw more homosexuals to New York and other growing American urban centers. Whitman did, however, in 1890 denounce any sexuality in the comradeship of his works, and historians debate whether he was homosexual, bisexual, etc.[182] But this denouncement shows that homosexuality had become a public question by the end of the 19th century.[182]

Twenty years after Whitman came to New York, Horatio Alger continued the theme of manly love in his stories of the young Victorian self-made man.[182] He came to New York fleeing from a public scandal with a young man in Cape Cod that forced him to leave the ministry, in 1866.[182]

Late 19th century

We'wha (1849–1896) was a notable Zuni weaver, potter and lhamana. Raised as a boy, they would later spend part of their life dressing and living in the roles usually filled by women in Zuni culture, later living and working in roles filled by men, changing depending on the situation. Anthropologist Matilda Coxe Stevenson, a friend of We'wha's who wrote extensively about the Zuni, hosted We'wha and the Zuni delegation when We'wha was chosen as an official emissary to Washington, D.C., in 1886. During this time they met President Grover Cleveland. We'wha had at least one husband, was trained in the customs and rites for the ceremonies for both men and women, and was a respected member of their community. Friends who documented their life used both pronouns for We'wha.[184][185]

Early 20th century

In 1908, the first American defense of homosexuality was published.[141] The Intersexes: A History of Similisexualism as a Problem in Social Life, was written by Edward Stevenson under the pseudonym Xavier Mayne.[141] This 600-page defense detailed Classical examples, but also modern literature and the homosexual subcultures of urban life.[141] He dedicated the novel to Krafft-Ebing because he argued homosexuality was inherited and, in Stevenson's view and not necessarily Krafft-Ebing's, should not face prejudice. He also wrote one of the first homosexual novels—Imre: A Memorandum.[141] Also in this era, the earliest known open homosexual in the United States, Claude Hartland, wrote an account of his sexual history.[186] He affirmed that he wrote it to affront the naivety surrounding sexuality. It was in response to the ignorance he saw while being treated by doctors and psychologists that failed to "cure" him.[186] Hartland wished his attraction to men could be solely "spiritual", but could not escape the "animal".[186]

By this time, society was slowly becoming aware of the homosexual subculture. In an 1898 lecture in Massachusetts, a doctor gave a lecture on this development in modern cities.[141] With a population around three million at the turn of the 20th century, New York's queer subculture had a strong sense of self-definition and began redefining itself on its own terms. "Middle class queer", "fairies", were among the terminology of the underground world of the Lower East Side.[141] But with this growing public presence, backlash occurred. The YMCA, who ironically promoted a similar image to that of the Whitman's praise of male brotherhood and athletic prowess, took a chief place in the purity campaigns of the epoch. Anthony Comstock, a salesman and leader of YMCA in Connecticut and later head of his own New York Society for the Suppression of Vice successfully pressed Congress and many state legislatures to pass strict censorship laws.[141] Ironically, the YMCA became a site of homosexual conduct. In 1912, a scandal hit Oregon where more than 50 men, many prominent in the community, were arrested for homosexual activity. In reaction to this scandal conflicting with public campaigns, YMCA leadership began to look the other way on this conduct.[citation needed]

1920s

The 1920s ushered in a new era of social acceptance of minorities and homosexuals, at least in heavily urbanized areas. This was reflected in many of the films (see Pre-Code) of the decade that openly made references to homosexuality. Even popular songs poked fun at the new social acceptance of homosexuality. One of these songs had the title "Masculine Women, Feminine Men".[187] It was released in 1926 and recorded by numerous artists of the day and included the following lyrics:[188]

Masculine women, Feminine men

Which is the rooster, which is the hen?

It's hard to tell 'em apart today! And, say!

Sister is busy learning to shave,

Brother just loves his permanent wave,

It's hard to tell 'em apart today! Hey, hey!

Girls were girls and boys were boys when I was a tot,

Now we don't know who is who, or even what's what!

Knickers and trousers, baggy and wide,

Nobody knows who's walking inside,

Those masculine women and feminine men![189]

Homosexuals received a level of acceptance that was not seen again until the 1970s. Until the early 1930s, gay clubs were openly operated, commonly known as "pansy clubs". The relative liberalism of the decade is demonstrated by the fact that the actor William Haines, regularly named in newspapers and magazines as the number-one male box-office draw, openly lived in a gay relationship with his lover, Jimmie Shields.[190] Other popular gay actors/actresses of the decade included Alla Nazimova and Ramon Novarro.[191] In 1927, Mae West wrote a play about homosexuality called The Drag, and alluded to the work of Karl Heinrich Ulrichs. It was a box-office success. West regarded talking about sex as a basic human rights issue, and was also an early advocate of gay rights. With the return of conservatism in the 1930s, the public grew intolerant of homosexuality, and gay actors were forced to choose between retiring or agreeing to hide their sexuality.

Late 1930s

By 1935, the United States had become conservative once again. Victorian values and morals, which had been widely ridiculed during the 1920s, became fashionable once again. During this period, life was harsh for homosexuals as they were forced to hide their behavior and identity in order to escape ridicule and even imprisonment. Many laws were passed against homosexuals during this period, and it was declared to be a mental illness. Many police forces conducted operations to arrest homosexuals by using young undercover cops to get them to make propositions to them.[192]

By the 1930s both fruit and fruitcake as well as numerous other words were seen as not only negative but also to mean male homosexual,[193] although probably not universally. LGBTQ people were widely diagnosed as diseased with the potential for being cured, thus were regularly "treated" with castration,[194][195][196] lobotomies,[196][197] pudic nerve surgery,[198] and electroshock treatment.[199][200] So transferring the meaning of fruitcake, nutty, to someone who is deemed insane, or crazy, may have seemed rational at the time and many apparently believed that LGBTQ people were mentally unsound. In the United States, psychiatric institutions ("mental hospitals") where many of these procedures were carried out were called fruitcake factories while in 1960s Australia they were called fruit factories.[201]

World War II

As the US entered World War II in 1941, women were provided opportunities to volunteer for their country and almost 250,000 women served in the armed forces, mostly in the Women's Army Corps (WAC), two-thirds of whom were single and under the age of twenty-five.[202] Women were recruited with posters showing muscular, short-haired women wearing tight-fitting tailored uniforms.[202] Many lesbians joined the WAC to meet other women and to do men's work.[202][203] Few were rejected for lesbianism, and found that being strong or having masculine appearance – characteristics associated with homosexual women – aided in the work as mechanics and motor vehicle operators.[202] A popular Fleischmann's Yeast advertisement showed a WAC riding a motorcycle with the heading This is no time to be frail.[202][204] Some recruits appeared at their inductions wearing men's clothing and their hair slicked back in the classic butch style of out lesbians of the time.[202] Post-war many women including lesbians declined opportunities to return to traditional gender roles and helped redefine societal expectations that fed the women's movement, Civil Rights Movement and gay liberation movement. The war effort greatly shifted American culture and by extension representations in entertainment of both the nuclear family and LGBTQ people. In mostly same sex quarters service members were more easily able to express their interests and find willing partners of all sexualities.

From 1942 to 1947, WWII conscientious objectors in the US assigned to psychiatric hospitals under Civilian Public Service exposed abuses throughout the psychiatric care system and were instrumental in reforms of the 1940s and 1950s.[205]

Lavender Scare

The Lavender Scare was an early example of institutionalized homophobia, resulting from a moral panic over the employment of homosexuals in the government, particularly the State Department. A key aspect of the moral panic was the idea that homosexuals were particularly vulnerable to communist blackmail and so constituted a security risk.[206] However, issues of morality were also present, with homosexuals being accused of lacking moral fiber and emotional stability.[207]

Stonewall riots

Although the June 28, 1969, Stonewall riots are generally considered the starting point of the modern gay liberation movement, a number of demonstrations and actions took place before that date. These actions, often organized by local homophile organizations but sometimes spontaneous, addressed concerns ranging from anti-gay discrimination in employment and public accommodations to the exclusion of homosexuals from the United States military to police harassment to the treatment of homosexuals in revolutionary Cuba. The early actions have been credited with preparing the LGBTQ community for Stonewall and contributing to the riots' symbolic power. See: List of LGBT actions in the United States prior to the Stonewall riots

In the autumn of 1959, the police force of New York City's Wagner administration began closing down the city's gay bars, which had numbered almost two dozen in Manhattan at the beginning of the year. This crackdown was largely the result of a sustained campaign by the right-wing NY Mirror newspaper columnist Lee Mortimer. Existing gay bars were quickly closed and new ones lasted only a short time. The election of John Lindsay in 1965 signaled a major shift in city politics, and a new attitude toward sexual mores began changing the social atmosphere of New York. On April 21, 1966, Dick Leitsch, Craig Rodwell president and vice president respectively of the New York Mattachine Society and Mattachine activist John Timmons staged the Sip-In at Julius' Bar on West 10th Street in Greenwich Village. This resulted in the anti-gay accommodation rules of the NY State Liquor Authority being overturned in subsequent court actions. These SLA provisions declared that it was illegal for homosexuals to congregate and be served alcoholic beverages in bars. An example of when these laws had been upheld is in 1940 when Gloria's, a bar that had been closed for such violations, fought the case in court and lost. Prior to this change in the law, the business of running a gay bar had to involve paying bribes to the police and Mafia. As soon as the law was altered, the SLA ceased closing legally licensed gay bars and such bars could no longer be prosecuted for serving gays and lesbians. Mattachine pressed this advantage very quickly and Mayor Lindsay was confronted with the issue of police entrapment in gay bars, resulting in this practice being stopped. On the heels of this victory, the mayor cooperated in getting questions about homosexuality removed from NYC hiring practices. The police and fire departments resisted the new policy, however, and refused to cooperate.[208]

The result of these changes in the law, combined with the open social- and sexual-attitudes of the late Sixties, led to the increased visibility of gay life in New York. Several licensed gay bars were in operation in Greenwich Village and the Upper West Side, as well as illegal, unlicensed places serving alcohol, such as the Stonewall Inn and the Snakepit, both in Greenwich Village. The Stonewall riots were a series of violent conflicts between gay men, drag queens, transsexuals, and lesbians against a police officer raid in New York City. The first night of rioting began on Friday, June 27, 1969, at about 1:20 am, when police raided the Stonewall Inn, a gay bar operating without a state license in Greenwich Village. Stonewall is considered a turning point for the modern gay rights movement worldwide. Newspaper coverage of the events was minor in the city, since, in the Sixties, huge marches and mass rioting had become commonplace and the Stonewall disturbances were relatively small. It was the commemorative march one year later, organized by the impetus of Craig Rodwell, owner of the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop, which drew 5,000 marchers up New York City's Sixth Avenue, that drew nationwide publicity and put the Stonewall events on the historical map and led to the modern-day pride marches. A new period of liberalism in the late 1960s began a new era of more social acceptance for homosexuality which lasted until the late 1970s. In the 1970s, the popularity of disco music and its culture in many ways made society more accepting of gays and lesbians. On June 27, 2019, the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor was inaugurated at the Stonewall Inn, as part of the Stonewall National Monument.[208]

1980s

This section's factual accuracy is disputed. (May 2014) |

The 1980s in LGBTQ history are marked with the emergence of HIV. During the early period of the outbreak of HIV, the epidemic of HIV was commonly linked to gay men.

In the 1980s a renewed conservative movement spawned a new anti-gay movement in the United States, particularly with the help of the Religious Right (Evangelicals in particular), however, by the later part of the decade the general public started to show more sympathy and even tolerance for gays as the toll for AIDS related deaths continued to rise to include heterosexuals as well as cultural icons such as Rock Hudson and Liberace, who also died from the condition. Also, despite the more conservative period, life in general for gays and lesbians was considerably better in contrast to the pre-Stonewall era.[citation needed]

Testifying to improved conditions, a 1991 Wall Street Journal survey found that homosexuals, in comparison with average Americans, were three times more likely to be college graduates, three times more likely to hold professional or managerial positions, with average salaries $30,000 higher than the norm.[209]

Decriminalization of homosexuality in the US (1961–2011)

The first US state to decriminalize sodomy was Illinois in 1961.[210] It was not until 1969 that another state would follow (Connecticut), but the 1970s and 80s saw the decriminalization throughout the majority of the United States. The 14 states that did not repeal these laws until 2003 were forced to by the landmark United States Supreme Court case Lawrence v. Texas.

Трансгендерные права

Бруклинский марш освобождения, крупнейшая демонстрация трансгендеров в истории ЛГБТ, состоялась 14 июня 2020 года, простирающуюся от Гранд-Армейской Плаза до Форт Грин, Бруклин , сосредоточилась на поддержке жизни чернокожих трансгендеров, что привело к тому, что около 15 000 до 20 000 участников. [ 211 ] [ 212 ]

Школы

Несколько государственных школ открылись с определенной миссией по созданию «безопасного» места для ЛГБТ -студентов и союзников, включая школу Харви Милк в Нью -Йорке и Школу альянса Милуоки среднюю . Кампус средней школы социальной справедливости предлагается для Чикаго, [ 213 ] и ряд частных школ также определили как «дружелюбные к геям», такие как средняя школа Элизабет Ирвин в Нью -Йорке.

В 2012 году впервые два американских школьных округа отметили месяц истории ЛГБТ ; Школьный округ округа Бровард во Флориде подписал резолюцию в сентябре в поддержку лесбиянок, геев, бисексуалов и трансгендерных американцев, а затем в том же году школьного округа Лос-Анджелеса, второго по величине Америки. [ 214 ]

Однополые браки

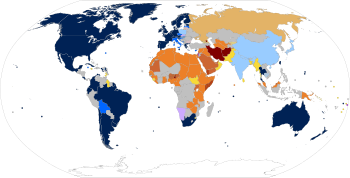

| Однополые половые сношения незаконно. Штрафы: | |

Тюрьма; Смерть не соблюдается | |

Смерть при ополченцах | Тюрьма, с арестами или задержанием |

Тюрьма, не применяется 1 | |

| Однополые половые сношения законно. Признание профсоюзов: | |

Экстратерриториальный брак 2 | |

Ограниченная иностранная | Дополнительная сертификация |

Никто | Ограничения выражения, а не применяются |

Ограничения связи с арестами или задержанием | |

1 Никакого заключения за последние три года или мораторий по закону.

2 Брак недоступен на местном уровне. Некоторые юрисдикции могут выполнять другие типы партнерств.

В конце 20-го и начала 21-го веков в ряде стран стал растущее движение, чтобы рассматривать брак как право, которое должно быть распространено на однополые пары . Юридическое признание брачного союза открывает широкий спектр прав, включая социальное обеспечение , налогообложение, наследство и другие льготы, недоступные для пар, не женатых, в глазах закона. Ограничение юридического признания парами противоположных полов мешает однополым парам получить доступ к юридической выгоде брака. Хотя определенные права могут быть воспроизведены юридическими средствами, отличными от брака (например, путем вытягивания контрактов), многие не могут, такие как наследование, посещение в больнице и иммиграция. Отсутствие юридического признания также затрудняет однополые пары усыновлять детей. [ Цитация необходима ]

Первой страной, которая легализует однополые браки, были Нидерланды (2001) при королеве Беатрикс , [ 215 ] В то время как первые браки были выполнены в мэрии Амстердама 1 апреля 2001 года. По состоянию на июль 2022 г. [update], однополые браки являются законными в национальном уровне в тридцати одной странах: Нидерланды (2001), Бельгия (2003), Испания и Канада (2005), Южная Африка (2006), Норвегия и Швеция (2009), Португалия , Исландия и Аргентина (2010), Дания (2012), Бразилия , Франция , Уругвай , Новая Зеландия (2013), Великобритания (без Северной Ирландии 2015) и Люксембург (2014), Ирландия (2015), Колумбия (2016), Финляндия , Германия (2017 ), Мальта (2017), Австралия (2018), Тайвань , Эквадор , Австрия (2019), Коста -Рика (2020), Чили , Швейцария и Словения (2022). В Мексике однополые браки признаются во всех штатах, но выступали только в Мехико , где он вступил в силу 4 марта 2010 года. [ 216 ] [ 217 ]

Однополые браки были эффективно легализованы в Соединенных Штатах 26 июня 2015 года после Верховного суда США решения по делу Obergefell v. Hodges . [ 218 ] [ 219 ] До того, как Obergefell решения в низком суде, законодательство штата и популярные референдумы уже узаконили однополые браки до некоторой степени в 38 из 50 штатов США , в состав которого было около 70% населения США. Федеральные льготы ранее были предоставлены на законно женатых однополых пары после решения Верховного суда в июне 2013 года в Соединенных Штатах против Виндзора .

Студенческие группы

С середины 1970-х годов учащиеся средних школ и университетов организовали группы ЛГБТ, часто называемые альянсами геев (GSA) в своих школах. [ 220 ] Группы формируются, чтобы обеспечить поддержку студентам ЛГБТ и для повышения осведомленности о проблемах ЛГБТ в местном сообществе. В 1990 году студенческая группа назвала остальные десяти процентиля ( иврит : Ки: העשירון האחר ) была основана группа учителей и учеников в ивритском университете Иерусалима , став первой ЛГБТ -организацией в Иерусалиме . Часто такие группы были запрещены или запрещены встречаться или получать такое же признание, что и другие студенческие группы. Например, в сентябре 2006 года в Калифорнии в Калифорнии кратко попытались запретить школу GSA, альянс Гей-Страйт Университета Туро. После демонстраций учащихся и протеста поддержки Американской ассоциации студентов -медиков , медицинской ассоциации геев и лесбиянок и Вальехо городского совета , Университет Туро отозвал свой отзыв в школе GSA. Далее университет подтвердил свою приверженность недискриминации, основанной на сексуальной ориентации.

В апреле 2016 года сеть GSA изменила свое имя с сети Alliance Gay-Straight на сеть Alliance Geals & Sextianty, чтобы быть более инклюзивными и отражающими молодежь, которая составляет организацию.

Историческое исследование гомосексуализма

19 -го века и начало 20 -го века

Когда в конце 19 -го века Генрих Хоссли и Хульрихс начали свою новаторскую гомосексуальную стипендию, они обнаружили мало на пути всесторонних исторических данных, за исключением материала из древней Греции и Ислама. [ 221 ] Некоторая другая информация была добавлена английскими учеными Ричардом Бертоном и Хавелоком Эллисом . В Германии Альберт Молл опубликовал том, содержащий списки известных гомосексуалистов. Однако к концу столетия, когда был сформирован Берлинский научный комитет, был понят, что должен быть проведен комплексный библиографический поиск. Результаты этого расследования были включены в объемы меховой сексуалы Jahrbuch Zwischenstufen и Magnus Hirschfeld's Die Homosexualität des Mannes und Des Weibes (1914). Великая депрессия и рост нацизма положили конец самым серьезным гомосексуальным исследованиям.

1950 -е и 1960 -е годы

В рамках роста современного гей -движения в Южной Калифорнии ряд исторических статей попадали в такие периодические издания такого движения, как лестница , Mattachine Review и один квартал . Во Франции Аркади под редакцией Андре Бодри опубликовала значительное количество исторических материалов. Почти без исключения ученые университета боялись прикоснуться к предмету. В результате большая часть работы была проделана автодидактами, работающими в не идеальных условиях. Поскольку большая часть этой стипендии была сделана под эгидой движения, она, как правило, отражала соответствующие проблемы; Скомпилируйте краткую несправедливость и биографические наброски образцовых геев и женщин прошлого.

Атмосфера 1960 -х годов изменила вещи. Сексуальная революция сделала человеческую сексуальность подходящим объектом исследований. Появился новый акцент на социальной и интеллектуальной истории, в значительной степени проистекая из группы по всей французской периодической анналяй . несколько полезных синтезов мировой истории гомосексуализма Хотя появилось , много материала, особенно из ислама , Китая и других незападных культур, еще не было должным образом изучено и опубликовано, так что, несомненно, они будут заменены. [ 222 ]

Школьные учебные программы