Бразилия

Федеративная Республика Бразилия Федеративная Республика Бразилия | |

|---|---|

| Девиз: Порядок и прогресс «Порядок и прогресс» | |

| Гимн: Государственный гимн Бразилии «Гимн Бразилии» | |

Национальная печать

| |

| |

| Капитал | Бразилиа 15 ° 47' ю.ш., 47 ° 52' з.д. / 15,783 ° ю.ш., 47,867 ° з.д. |

| Крупнейший город | Сан-Паулу 23 ° 33' ю.ш., 46 ° 38' з.д. / 23,550 ° ю.ш., 46,633 ° з.д. |

| Официальный язык и национальный язык | португальский |

| Признанные региональные языки | См. региональные официальные языки |

| Этнические группы (2022) [ 2 ] |

|

| Религия |

|

| Демон(ы) | Бразильский |

| Правительство | Федеративная президентская республика |

| Лула да Силва | |

| Джеральдо Алкмин | |

| Артур Лира | |

| Родриго Пачеко | |

| Луис Роберто Баррозу | |

| Законодательная власть | Национальный Конгресс |

| Федеральный Сенат | |

| Палата депутатов | |

| Независимость из Португалии | |

• Заявлено | 7 сентября 1822 г. |

| 29 августа 1825 г. | |

| 15 ноября 1889 г. | |

| 5 октября 1988 г. | |

| Область | |

• Общий | 8 515 767 км 2 (3 287 956 квадратных миль) ( 5-е место ) |

• Вода (%) | 0.65 |

| Население | |

• Оценка на 2024 год | |

• 2022 года Перепись | |

• Плотность | 23.8 [ 7 ] /км 2 (61,6/кв. миль) ( 193-е место ) |

| ВВП ( ГЧП ) | оценка на 2024 год |

• Общий | |

• На душу населения | |

| ВВП (номинальный) | оценка на 2024 год |

• Общий | |

• На душу населения | |

| Джини (2022) | высокое неравенство |

| ИЧР (2022) | высокий ( 89-й ) |

| Валюта | Реал (R$) ( BRL ) |

| Часовой пояс | UTC от −2 до −5 ( BRT ) |

| Летнее время не наблюдается. | |

| Формат даты | дд/мм/гггг ( CE ) |

| Ведущая сторона | верно |

| Код вызова | +55 |

| Код ISO 3166 | БР |

| Интернет-ДВУ | .br |

Бразилия , [ б ] официально Федеративная Республика Бразилия , [ с ] Это самая большая и самая восточная страна Южной Америки и Латинской Америки . Это пятая по величине страна в мире по площади и седьмая по численности населения . Столица — Бразилиа , а самый густонаселенный город — Сан-Паулу . Бразилия – федерация, состоящая из 26 штатов и федерального округа . Это единственная страна в Америке , где португальский является официальным языком . [ 12 ] [ 13 ] и этнически разнообразных стран мира Бразилия входит в число самых многокультурных благодаря более чем столетней массовой иммиграции со всего мира . [ 14 ]

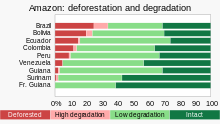

Бразилия, ограниченная Атлантическим океаном на востоке , имеет береговую линию длиной 7491 километр (4655 миль). [ 15 ] Занимая примерно половину территории Южной Америки, он граничит со всеми другими странами и территориями континента, за исключением Эквадора и Чили . [ 16 ] в Бразилии Бассейн Амазонки включает в себя обширные тропические леса , где обитает разнообразная дикая природа , разнообразные экологические системы и обширные природные ресурсы, охватывающие многочисленные охраняемые места обитания . [ 15 ] Это уникальное экологическое наследие ставит Бразилию на первое место среди 17 стран с мегаразнообразием . Природное богатство страны также является предметом значительного глобального интереса, поскольку деградация окружающей среды (в результате таких процессов, как вырубка лесов ) оказывает прямое воздействие на глобальные проблемы, такие как изменение климата и утрата биоразнообразия .

территория современной Бразилии была населена многочисленными племенными народами. До высадки исследователя Педру Альвареша Кабрала в 1500 году Бразилия, на которую впоследствии претендовала Португальская империя , оставалась португальской колонией до 1808 года, когда столица империи была перенесена из Лиссабона. в Рио-де-Жанейро . В 1815 году колония была возведена в ранг королевства после образования Соединенного Королевства Португалии, Бразилии и Алгарви . Независимость была достигнута в 1822 году с созданием Бразильской империи , унитарного государства, управляемого конституционной монархией и парламентской системой . Ратификация первой конституции в 1824 году привела к формированию двухпалатного законодательного органа, ныне называемого Национальным конгрессом . Рабство было отменено в 1888 году. Страна стала президентской республикой в 1889 году после военного переворота . Авторитарная военная диктатура возникла в 1964 году и правила до 1985 года, после чего возобновилось гражданское управление. Бразилии Действующая конституция , сформулированная в 1988 году, определяет ее как демократическую федеративную республику . [ 17 ] Благодаря своей богатой культуре и истории страна занимает тринадцатое место в мире по количеству ЮНЕСКО объектов Всемирного наследия . [ 18 ]

Бразилия – региональная и средняя держава . [ 19 ] [ 20 ] [ 21 ] это развивающаяся сила [ 22 ] [ 23 ] [ 24 ] [ 25 ] и входящий в НАТО главный союзник США, не . [ 26 ] Относится к развивающейся стране с высоким индексом человеческого развития . [ 27 ] Бразилия считается страной с развитой развивающейся экономикой . [ 28 ] имея восьмой по величине ВВП в мире как в номинальном выражении, так и в выражении по ППС — самый большой в Латинской Америке и Южном полушарии . [ 8 ] [ 29 ] как экономика с доходом выше среднего Классифицируется Всемирным банком . [ 30 ] и новая индустриальная страна по версии МВФ , [ 31 ] Бразилия имеет самую большую долю богатства и самую сложную экономику в Южной Америке. в мире Это также одна из крупнейших житниц , являющаяся крупнейшим производителем кофе за последние 150 лет. [ 32 ] Несмотря на свой растущий экономический и глобальный статус, страна продолжает сталкиваться с высоким уровнем коррупции , преступности и социального неравенства . Бразилия является одним из основателей ООН , G20 , БРИКС , G4 , Mercosul , Организации американских государств , Организации иберо-американских государств и Сообщества португалоязычных стран . Бразилия также является государством-наблюдателем в Лиге арабских государств . [ 33 ]

Этимология

Слово Бразилия , вероятно, происходит от португальского слова, обозначающего бразильское дерево , дерево, которое когда-то обильно росло вдоль побережья Бразилии. [ 34 ] По-португальски бразильское дерево называется pau-brasil , причем слово brasil обычно имеет этимологию «красный, как угли », образованную от brasa («уголок») и суффикса -il (от -iculum или -ilium ). [ 35 ] Альтернативно было высказано предположение, что это народная этимология слова, обозначающего растение, родственного арабскому или азиатскому слову, обозначающему красное растение. [ 36 ] Поскольку бразильская древесина дает темно-красный краситель, она высоко ценилась в европейской текстильной промышленности и была первым коммерчески используемым продуктом из Бразилии. [ 37 ] заготавливали огромное количество бразильской древесины , которые продавали древесину европейским торговцам (в основном португальцам, но также и французам) в обмен на различные европейские потребительские товары. На протяжении XVI века коренные народы (в основном тупи ) на бразильском побережье [ 38 ]

Официальным португальским названием этой земли в оригинальных португальских записях было «Земля Святого Креста» ( Terra da Santa Cruz ). [ 39 ] но европейские моряки и купцы обычно называли ее «Землей Бразилии» ( Terra do Brasil ) из-за торговли бразильским лесом. [ 40 ] Популярное название затмило и в конечном итоге вытеснило официальное португальское название. Некоторые первые моряки называли это место «Землей попугаев». [ 41 ]

На языке гуарани , официальном языке Парагвая , Бразилия называется «Пиндорама», что означает «земля пальм». [ 42 ]

История

Докабралинская эпоха

Некоторые из самых ранних человеческих останков, найденных в Америке , «Женщина Лузия» , были найдены в районе Педро Леопольдо , штат Минас-Жерайс, и представляют собой свидетельства человеческого проживания, насчитывающего по меньшей мере 11 000 лет. [ 44 ] [ 45 ] Самая ранняя керамика , когда-либо найденная в Западном полушарии, была раскопана в бассейне Амазонки в Бразилии и датирована радиоуглеродом 8000 лет назад (6000 г. до н.э.). Керамика была найдена недалеко от Сантарема и свидетельствует о том, что в этом регионе существовала сложная доисторическая культура. [ 46 ] Культура Марахоара процветала в Маражо в дельте Амазонки с 400 по 1400 год нашей эры, развивая сложную керамику, социальное расслоение , большое население, строительство курганов и сложные социальные образования, такие как вождества . [ 47 ]

Примерно во время прибытия португальцев на территории нынешней Бразилии проживало коренное население, составлявшее, по оценкам, 7 миллионов человек. [ 48 ] в основном полукочевые люди, которые существовали за счет охоты, рыболовства, собирательства и кочевого земледелия. Население состояло из нескольких крупных коренных этнических групп (например, тупи , гуарани , гесов и араваков ). Народ тупи подразделялся на тупиникинов и тупинамбас . [ 49 ]

До прихода европейцев границы между этими группами и их подгруппами обозначались войнами, возникавшими из-за различий в культуре, языке и моральных убеждениях. [ 50 ] Эти войны также включали крупномасштабные военные действия на суше и на воде с каннибалистическими ритуалами над военнопленными . [ 51 ] [ 52 ] Хотя наследственность имела некоторый вес, лидерство было статусом, который скорее приобретался с течением времени, чем присваивался в церемониях преемственности и соглашениях. [ 50 ] Рабство среди коренных народов имело иное значение, чем для европейцев, поскольку оно возникло из разнообразной социально-экономической организации, в которой асимметрия трансформировалась в родственные отношения. [ 53 ]

Португальская колонизация

После Тордесильясского договора 1494 года земля, которая сейчас называется Бразилией, была передана Португальской империи 22 апреля 1500 года с прибытием португальского флота под командованием Педро Альвареша Кабрала . [ 55 ] Португальцы столкнулись с коренными народами, разделенными на несколько этнических обществ, большинство из которых говорили на языках семьи тупи-гуарани и воевали между собой. [ 56 ] Хотя первое поселение было основано в 1532 году, колонизация фактически началась в 1534 году, когда король Португалии Иоанн III разделил территорию на пятнадцать частных и автономных капитанов . [ 57 ] [ 58 ]

Однако децентрализованные и неорганизованные тенденции капитанов оказались проблематичными, и в 1549 году португальский король реструктурировал их в Генерал-губернаторство Бразилии в городе Сальвадор , который стал столицей единой и централизованной португальской колонии в Южной Америке. [ 58 ] [ 59 ] В первые два столетия колонизации коренные и европейские группы жили в постоянной войне, создавая оппортунистические союзы, чтобы получить преимущества друг против друга. [ 60 ] [ 61 ] [ 62 ] [ 63 ]

К середине 16 века тростниковый сахар стал самым важным экспортным товаром Бразилии. [ 56 ] [ 64 ] в то время как рабы приобретаются в странах Африки к югу от Сахары на невольничьем рынке Западной Африки. [ 65 ] (не только от португальских союзников из их колоний в Анголе и Мозамбике ), стал его крупнейшим импортом, [ 66 ] [ 67 ] чтобы справиться с плантациями сахарного тростника из-за растущего международного спроса на бразильский сахар. [ 68 ] [ 69 ] В период с 1500 по 1800 год Бразилия получила более 2,8 миллиона рабов из Африки. [ 70 ]

К концу 17 века экспорт сахарного тростника начал снижаться. [ 71 ] а открытие золота бандейрантами в 1690-х годах стало новой основой экономики колонии, способствуя золотой лихорадке. [ 72 ] что привлекло в Бразилию тысячи новых поселенцев из Португалии и всех португальских колоний по всему миру. [ 73 ] This increased level of immigration in turn caused some conflicts between newcomers and old settlers.[74]

Portuguese expeditions known as bandeiras gradually expanded Brazil's original colonial frontiers in South America to its approximately current borders.[75][76] In this era other European powers tried to colonize parts of Brazil, in incursions that the Portuguese had to fight, notably the French in Rio during the 1560s, in Maranhão during the 1610s, and the Dutch in Bahia and Pernambuco, during the Dutch–Portuguese War, after the end of Iberian Union.[77]

The Portuguese colonial administration in Brazil had two objectives that would ensure colonial order and the monopoly of Portugal's wealthiest and largest colony: to keep under control and eradicate all forms of slave rebellion and resistance, such as the Quilombo of Palmares,[78] and to repress all movements for autonomy or independence, such as the Minas Gerais Conspiracy.[79]

Elevation to kingdom

In late 1807, Spanish and Napoleonic forces threatened the security of continental Portugal, causing Prince Regent John, in the name of Queen Maria I, to move the royal court from Lisbon to Rio de Janeiro.[80] There they established some of Brazil's first financial institutions, such as its local stock exchanges[81] and its National Bank, additionally ending the Portuguese monopoly on Brazilian trade and opening Brazil's ports to other nations. In 1809, in retaliation for being forced into exile, the Prince Regent ordered the conquest of French Guiana.[82]

With the end of the Peninsular War in 1814, the courts of Europe demanded that Queen Maria I and Prince Regent John return to Portugal, deeming it unfit for the head of an ancient European monarchy to reside in a colony. In 1815, to justify continuing to live in Brazil, where the royal court had thrived for six years, the Crown established the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarves, thus creating a pluricontinental transatlantic monarchic state.[83] However, the leadership in Portugal, resentful of the new status of its larger colony, continued to demand the return of the court to Lisbon (see Liberal Revolution of 1820). In 1821, acceding to the demands of revolutionaries who had taken the city of Porto,[84] John VI departed for Lisbon. There he swore an oath to the new constitution, leaving his son, Prince Pedro de Alcântara, as Regent of the Kingdom of Brazil.[85]

Independent empire

Tensions between Portuguese and Brazilians increased and the Portuguese Cortes, guided by the new political regime imposed by the Liberal Revolution, tried to re-establish Brazil as a colony.[86] The Brazilians refused to yield, and Prince Pedro decided to stand with them, declaring the country's independence from Portugal on 7 September 1822.[87] A month later, Prince Pedro was declared the first Emperor of Brazil, with the royal title of Dom Pedro I, resulting in the founding of the Empire of Brazil.[88]

The Brazilian War of Independence, which had already begun along this process, spread through the northern, northeastern regions and in the Cisplatina province.[89] The last Portuguese soldiers surrendered on 8 March 1824;[90] Portugal officially recognized Brazilian independence on 29 August 1825.[91]

On 7 April 1831, worn down by years of administrative turmoil and political dissent with both liberal and conservative sides of politics, including an attempt of republican secession[92] and unreconciled to the way that absolutists in Portugal had given in the succession of King John VI, Pedro I departed for Portugal to reclaim his daughter's crown after abdicating the Brazilian throne in favor of his five-year-old son and heir (Dom Pedro II).[93]

As the new Emperor could not exert his constitutional powers until he came of age, a regency was set up by the National Assembly.[94] In the absence of a charismatic figure who could represent a moderate face of power, during this period a series of localized rebellions took place, such as the Cabanagem in Grão-Pará, the Malê Revolt in Salvador, the Balaiada (Maranhão), the Sabinada (Bahia), and the Ragamuffin War, which began in Rio Grande do Sul and was supported by Giuseppe Garibaldi. These emerged from the provinces' dissatisfaction with the central power, coupled with old and latent social tensions peculiar to a vast, slaveholding and newly independent nation state.[95] This period of internal political and social upheaval, which included the Praieira revolt in Pernambuco, was overcome only at the end of the 1840s, years after the end of the regency, which occurred with the premature coronation of Pedro II in 1841.[96]

During the last phase of the monarchy, internal political debate centered on the issue of slavery. The Atlantic slave trade was abandoned in 1850,[97] as a result of the British Aberdeen Act and the Eusébio de Queirós Law, but only in May 1888, after a long process of internal mobilization and debate for an ethical and legal dismantling of slavery in the country, was the institution formally abolished with the approval of the Golden Law.[98]

The foreign-affairs policies of the monarchy dealt with issues with the countries of the Southern Cone with whom Brazil had borders. Long after the Cisplatine War that resulted in the independence of Uruguay,[99] Brazil won three international wars during the 58-year reign of Pedro II: the Platine War, the Uruguayan War and the devastating Paraguayan War, the largest war effort in Brazilian history.[100][101]

Although there was no desire among the majority of Brazilians to change the country's form of government,[102] on 15 November 1889, in disagreement with the majority of the Imperial Army officers, as well as with rural and financial elites (for different reasons), the monarchy was overthrown by a military coup.[103] A few days later, the national flag was replaced with a new design that included the national motto "Ordem e Progresso", influenced by positivism. 15 November is now Republic Day, a national holiday.[104]

Early republic

The early republican government was a military dictatorship, with the army dominating affairs both in Rio de Janeiro and in the states. Freedom of the press disappeared and elections were controlled by those in power.[105] Not until 1894, following an economic crisis and a military one, did civilians take power, remaining there until October 1930.[106][107][108]

If in relation to its foreign policy, the country in this first republican period maintained a relative balance characterized by a success in resolving border disputes with neighboring countries,[109] only broken by the Acre War (1899–1902) and its involvement in World War I (1914–1918),[110][111][112] followed by a failed attempt to exert a prominent role in the League of Nations;[113] Internally, from the crisis of Encilhamento[114][115][116] and the Navy Revolts,[117] a prolonged cycle of financial, political and social instability began until the 1920s, keeping the country besieged by various rebellions, both civilian[118][119][120] and military.[121][122][123]

Little by little, a cycle of general instability sparked by these crises undermined the regime to such an extent that in the wake of the murder of his running mate, the defeated opposition presidential candidate Getúlio Vargas, supported by most of the military, successfully led the Revolution of 1930.[124][125] Vargas and the military were supposed to assume power temporarily, but instead closed down Congress, extinguished the Constitution, ruled with emergency powers and replaced the states' governors with his own supporters.[126][127]

In the 1930s, three attempts to remove Vargas and his supporters from power failed. The first was the Constitutionalist Revolution in 1932, led by the São Paulo's oligarchy. The second was a Communist uprising in November 1935, and the last one a putsch attempt by local fascists in May 1938.[128][129][130] The 1935 uprising created a security crisis in which Congress transferred more power to the executive branch. The 1937 coup d'état resulted in the cancellation of the 1938 election and formalized Vargas as dictator, beginning the Estado Novo era. During this period, government brutality and censorship of the press increased.[131]

During World War II, Brazil remained neutral until August 1942, when the country suffered retaliation by Nazi Germany and Fascist Italy in a strategic dispute over the South Atlantic, and, therefore, entered the war on the allied side.[132][133][134] In addition to its participation in the battle of the Atlantic, Brazil also sent an expeditionary force to fight in the Italian campaign.[135]

With the Allied victory in 1945 and the end of the fascist regimes in Europe, Vargas's position became unsustainable, and he was swiftly overthrown in another military coup, with democracy "reinstated" by the same army that had ended it 15 years earlier.[136] Vargas committed suicide in August 1954 amid a political crisis, after having returned to power by election in 1950.[137][138]

Contemporary era

Several brief interim governments followed Vargas's suicide.[139] Juscelino Kubitschek became president in 1956 and assumed a conciliatory posture towards the political opposition that allowed him to govern without major crises.[140] The economy and industrial sector grew remarkably,[141] but his greatest achievement was the construction of the new capital city of Brasília, inaugurated in 1960.[142] Kubitschek's successor, Jânio Quadros, resigned in 1961 less than a year after taking office.[143] His vice-president, João Goulart, assumed the presidency, but aroused strong political opposition[144] and was deposed in April 1964 by a coup that resulted in a military dictatorship.[145]

The new regime was intended to be transitory[146] but gradually closed in on itself and became a full dictatorship with the promulgation of the Fifth Institutional Act in 1968.[147] Oppression was not limited to those who resorted to guerrilla tactics to fight the regime, but also reached institutional opponents, artists, journalists and other members of civil society,[148][149] inside and outside the country through the infamous "Operation Condor".[150][151] Like other brutal authoritarian regimes, due to an economic boom, known as the "economic miracle", the regime reached a peak in popularity in the early 1970s.[152]

Slowly, however, the wear and tear of years of dictatorial power that had not slowed the repression, even after the defeat of the leftist guerrillas.[153] The inability to deal with the economic crises of the period and popular pressure made an opening policy inevitable, which from the regime side was led by Generals Ernesto Geisel and Golbery do Couto e Silva.[154] With the enactment of the Amnesty Law in 1979, Brazil began a slow return to democracy, which was completed during the 1980s.[96]

Civilians returned to power in 1985 when José Sarney assumed the presidency. He became unpopular during his tenure through failure to control the economic crisis and hyperinflation he inherited from the military regime.[155] Sarney's unsuccessful government led to the election in 1989 of the almost-unknown Fernando Collor, who was subsequently impeached by the National Congress in 1992.[156] Collor was succeeded by his vice-president, Itamar Franco, who appointed Fernando Henrique Cardoso Minister of Finance. In 1994, Cardoso produced a highly successful Plano Real,[157] that, after decades of failed economic plans made by previous governments attempting to curb hyperinflation, finally stabilized the Brazilian economy.[158][159] Cardoso won the 1994 election, and again in 1998.[160]

The peaceful transition of power from Cardoso to his main opposition leader, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva (elected in 2002 and re-elected in 2006), was seen as proof that Brazil had achieved a long-sought political stability.[161][162] However, sparked by indignation and frustrations accumulated over decades from corruption, police brutality, inefficiencies of the political establishment and public service, numerous peaceful protests erupted in Brazil from the middle of first term of Dilma Rousseff, who had succeeded Lula after winning election in 2010 and again in 2014 by narrow margins.[163][164]

Rousseff was impeached by the Brazilian Congress in 2016, halfway into her second term,[165][166] and replaced by her Vice-president Michel Temer, who assumed full presidential powers after Rousseff's impeachment was accepted on 31 August. Large street protests for and against her took place during the impeachment process.[167] The charges against her were fueled by political and economic crises along with evidence of involvement with politicians from all the primary political parties. In 2017, the Supreme Court requested the investigation of 71 Brazilian lawmakers and nine ministers of President Michel Temer's cabinet who were allegedly linked to the Petrobras corruption scandal.[168] President Temer himself was also accused of corruption.[169] According to a 2018 poll, 62% of the population said that corruption was Brazil's biggest problem.[170]

In the fiercely disputed 2018 elections, the controversial conservative candidate Jair Bolsonaro of the Social Liberal Party (PSL) was elected president, winning in the second round Fernando Haddad, of the Workers Party (PT), with the support of 55.13% of the valid votes.[171] In the early 2020s, Brazil became one of the hardest hit countries during the COVID-19 pandemic, receiving the second-highest death toll worldwide after the United States.[172] In May 2021, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva stated that he would run for a third term in the 2022 Brazilian general election against Bolsonaro.[173] On October 2022, Lula was in first place in first round, with 48.43% of the support from the electorate, and received 50.90% of the votes in the second round.[174][175] On 8 January 2023, a week after Lula's inauguration, a mob of Bolsonaro's supporters attacked Brazil's federal government buildings in the capital, Brasília, after several weeks of unrest.[176][177]

Geography

Brazil occupies a large area along the eastern coast of South America and includes much of the continent's interior,[178] sharing land borders with Uruguay to the south; Argentina and Paraguay to the southwest; Bolivia and Peru to the west; Colombia to the northwest; and Venezuela, Guyana, Suriname and France (French overseas region of French Guiana) to the north. It shares a border with every South American country except Ecuador and Chile.[15]

The brazilian territory also encompasses a number of oceanic archipelagos, such as Fernando de Noronha, Rocas Atoll, Saint Peter and Paul Rocks, and Trindade and Martim Vaz.[15] Its size, relief, climate, and natural resources make Brazil geographically diverse.[178] Including its Atlantic islands, Brazil lies between latitudes 6°N and 34°S, and longitudes 28° and 74°W.[15]

Brazil is the fifth largest country in the world, and third largest in the Americas, with a total area of 8,515,767.049 km2 (3,287,956 sq mi),[179] including 55,455 km2 (21,411 sq mi) of water. North to South, Brazil is also the longest country in the world, spanning 4,395 km (2,731 mi) from north to south,[15] and the only country in the world that has the equator and the Tropic of Capricorn running through it.[15] It spans four time zones; from UTC−5 comprising the state of Acre and the westernmost portion of Amazonas, to UTC−4 in the western states, to UTC−3 in the eastern states (the national time) and UTC−2 in the Atlantic islands.[180]

Climate

The climate of Brazil comprises a wide range of weather conditions across a large area and varied topography, but most of the country is tropical.[15] According to the Köppen system, Brazil hosts six major climatic subtypes: desert, equatorial, tropical, semiarid, oceanic and subtropical. The different climatic conditions produce environments ranging from equatorial rainforests in the north and semiarid deserts in the northeast, to temperate coniferous forests in the south and tropical savannas in central Brazil.[181] Many regions have starkly different microclimates.[182][183]

An equatorial climate characterizes much of northern Brazil. There is no real dry season, but there are some variations in the period of the year when most rain falls.[181] Temperatures average 25 °C (77 °F),[183] with more significant temperature variation between night and day than between seasons.[182] Over central Brazil rainfall is more seasonal, characteristic of a savanna climate.[182] This region is as extensive as the Amazon basin but has a very different climate as it lies farther south at a higher altitude.[181] In the interior northeast, seasonal rainfall is even more extreme.[184] South of Bahia, near the coasts, and more southerly most of the state of São Paulo, the distribution of rainfall changes, with rain falling throughout the year.[181] The south enjoys subtropical conditions, with cool winters and average annual temperatures not exceeding 18 °C (64.4 °F);[183] winter frosts and snowfall are not rare in the highest areas.[181][182]

The semiarid climatic region generally receives less than 800 millimeters (31.5 in) of rain,[184] most of which generally falls in a period of three to five months of the year[185] and occasionally less than this, creating long periods of drought.[182] Brazil's 1877–78 Grande Seca (Great Drought), the worst in Brazil's history,[186] caused approximately half a million deaths.[187] A similarly devastating drought occurred in 1915.[188]

In 2020 the government of Brazil pledged to reduce its annual greenhouse gases emissions by 43% by 2030. It also set as indicative target of reaching carbon neutrality by 2060 if the country gets 10 billion dollars per year.[189]

Topography and hydrography

Brazilian topography is also diverse and includes hills, mountains, plains, highlands, and scrublands. Much of the terrain lies between 200 meters (660 ft) and 800 meters (2,600 ft) in elevation.[190] The main upland area occupies most of the southern half of the country.[190] The northwestern parts of the plateau consist of broad, rolling terrain broken by low, rounded hills.[190]

The southeastern section is more rugged, with a complex mass of ridges and mountain ranges reaching elevations of up to 1,200 meters (3,900 ft).[190] These ranges include the Mantiqueira and Espinhaço mountains and the Serra do Mar.[190] In the north, the Guiana Highlands form a major drainage divide, separating rivers that flow south into the Amazon Basin from rivers that empty into the Orinoco River system, in Venezuela, to the north. The highest point in Brazil is the Pico da Neblina at 2,994 meters (9,823 ft), and the lowest is the Atlantic Ocean.[15]

Brazil has a dense and complex system of rivers, one of the world's most extensive, with eight major drainage basins, all of which drain into the Atlantic.[191] Major rivers include the Amazon (the world's second-longest river and the largest in terms of volume of water), the Paraná and its major tributary the Iguaçu (which includes the Iguazu Falls), the Negro, São Francisco, Xingu, Madeira and Tapajós rivers.[191]

Biodiversity and conservation

The wildlife of Brazil comprises all naturally occurring animals, plants, and fungi in the South American country. Home to 60% of the Amazon rainforest, which accounts for approximately one-tenth of all species in the world,[192] Brazil is considered to have the greatest biodiversity of any country on the planet, containing over 70% of all animal and plant species catalogued.[193] Brazil has the most known species of plants (55,000), freshwater fish (3,000), and mammals (over 689).[194] It also ranks third on the list of countries with the most bird species (1,832) and second with the most reptile species (744).[194] The number of fungal species is unknown but is large.[195] Brazil is second only to Indonesia as the country with the most endemic species.[196]

Brazil's large territory comprises different ecosystems, such as the Amazon rainforest, recognized as having the greatest biological diversity in the world,[197] with the Atlantic Forest and the Cerrado, sustaining the greatest biodiversity.[198] In the south, the Araucaria moist forests grow under temperate conditions.[198] The rich wildlife of Brazil reflects the variety of natural habitats. Scientists estimate that the total number of plant and animal species in Brazil could approach four million, mostly invertebrates.[198] Larger mammals include carnivores pumas, jaguars, ocelots, rare bush dogs, and foxes, and herbivores peccaries, tapirs, anteaters, sloths, opossums, and armadillos. Deer are plentiful in the south, and many species of New World monkeys are found in the northern rain forests.[198][199]

More than one-fifth of the Amazon rainforest in Brazil has been completely destroyed, and more than 70 mammals are endangered.[194] The threat of extinction comes from several sources, including deforestation and poaching. Extinction is even more problematic in the Atlantic Forest, where nearly 93% of the forest has been cleared.[201] Of the 202 endangered animals in Brazil, 171 are in the Atlantic Forest.[202] The Amazon rainforest has been under direct threat of deforestation since the 1970s because of rapid economic and demographic expansion. Extensive legal and illegal logging destroy forests the size of a small country per year, and with it a diverse series of species through habitat destruction and habitat fragmentation.[203] Since 1970, over 600,000 square kilometers (230,000 sq mi) of the Amazon rainforest have been cleared by logging.[204]

In 2017, preserved native vegetation occupies 61% of the Brazilian territory. Agriculture occupied only 8% of the national territory and pastures 19.7%.[205] In terms of comparison, in 2019, although 43% of the entire European continent has forests, only 3% of the total forest area in Europe is of native forest.[206] Brazil has a strong interest in conservation as its agriculture sector directly depends on its forests.[207]

Government and politics

The form of government is a democratic federative republic, with a presidential system.[17] The president is both head of state and head of government of the Union and is elected for a four-year term,[17] with the possibility of re-election for a second successive term. The current president is Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva.[208] The President appoints the Ministers of State, who assist in government.[17]

Legislative houses in each political entity are the main source of law in Brazil. The National Congress is the Federation's bicameral legislature, consisting of the Chamber of Deputies and the Federal Senate. Judiciary authorities exercise jurisdictional duties almost exclusively. In 2021, the Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index categorized Brazil as a "flawed democracy", ranking 46th in the report,[209] and Freedom House classified it as a free country at Freedom in the World report.[210]

The political-administrative organization of the Federative Republic of Brazil comprises the Union, the states, the Federal District, and the municipalities.[17] The Union, the states, the Federal District, and the municipalities, are the "spheres of government". The federation is set on five fundamental principles: sovereignty, citizenship, dignity of human beings, the social values of labor and freedom of enterprise, and political pluralism.[17]

The classic tripartite branches of government (executive, legislative and judicial under a checks and balances system) are formally established by the Constitution.[17] The executive and legislative are organized independently in all three spheres of government, while the judiciary is organized only at the federal and state and Federal District spheres. All members of the executive and legislative branches are directly elected.[211][212][213]

For most of its democratic history, Brazil has had a multi-party system, with proportional representation. Voting is compulsory for the literate between 18 and 70 years old and optional for illiterates and those between 16 and 18 or beyond 70.[17] The country has around 30 registered political parties. Twenty political parties are represented in Congress. It is common for politicians to switch parties, and thus the proportion of congressional seats held by particular parties changes regularly.[214]

Law

Brazilian law is based on the civil law legal system[215] and civil law concepts prevail over common law practice. Most of Brazilian law is codified, although non-codified statutes also represent a substantial part, playing a complementary role. Court decisions set out interpretive guidelines; however, they are seldom binding on other specific cases. Doctrinal works and the works of academic jurists have strong influence in law creation and in law cases. Judges and other judicial officials are appointed after passing entry exams.[211]

The legal system is based on the Federal Constitution, promulgated on 5 October 1988, and the fundamental law of Brazil. All other legislation and court decisions must conform to its rules.[216] As of July 2022[update], there have been 124 amendments.[217] The highest court is the Supreme Federal Court. States have their own constitutions, which must not contradict the Federal Constitution.[218] Municipalities and the Federal District have "organic laws" (leis orgânicas), which act in a similar way to constitutions.[219] Legislative entities are the main source of statutes, although in certain matters judiciary and executive bodies may enact legal norms.[17] Jurisdiction is administered by the judiciary entities, although in rare situations the Federal Constitution allows the Federal Senate to pass on legal judgments.[17] There are also specialized military, labor, and electoral courts.[17]

Military

The armed forces of Brazil are the largest in Latin America by active personnel and the largest in terms of military equipment.[220] The country was considered the 9th largest military power on the planet in 2021.[221][222] It consists of the Brazilian Army (including the Army Aviation Command), the Brazilian Navy (including the Marine Corps and Naval Aviation), and the Brazilian Air Force. Brazil's conscription policy gives it one of the world's largest military forces, estimated at more than 1.6 million reservists annually.[223]

Numbering close to 236,000 active personnel,[224] the Brazilian Army has the largest number of armored vehicles in South America, including armored transports and tanks.[225] The states' Military Police and the Military Firefighters Corps are described as an ancillary forces of the Army by the constitution, but are under the control of each state's governor.[17]

Brazil's navy once operated some of the most powerful warships in the world with the two Minas Geraes-class dreadnoughts, sparking a naval arms race between Argentina, Brazil, and Chile.[226] Today, it is a green water force and has a group of specialized elite in retaking ships and naval facilities, GRUMEC, unit specially trained to protect Brazilian oil platforms along its coast.[227] As of 2022[update], it is the only navy in Latin America that operates a helicopter carrier, NAM Atlântico, and one of twelve navies in the world to operate or have one under construction.[228]

The Air Force is the largest in Latin America and has about 700 crewed aircraft in service and effective about 67,000 personnel.[229]

Foreign policy

Brazil's international relations are based on Article 4 of the Federal Constitution, which establishes non-intervention, self-determination, international cooperation and the peaceful settlement of conflicts as the guiding principles of Brazil's relationship with other countries and multilateral organizations.[230] According to the Constitution, the President has ultimate authority over foreign policy, while the Congress is tasked with reviewing and considering all diplomatic nominations and international treaties, as well as legislation relating to Brazilian foreign policy.[231]

Brazil's foreign policy is a by-product of the country's position as a regional power in Latin America, a leader among developing countries, and an emerging world power.[232] Brazilian foreign policy has generally been based on the principles of multilateralism, peaceful dispute settlement, and non-intervention in the affairs of other countries.[233] Brazil is a founding member state of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), also known as the Lusophone Commonwealth, an international organization and political association of Lusophone nations.

An increasingly well-developed tool of Brazil's foreign policy is providing aid as a donor to other developing countries.[234] Brazil does not just use its growing economic strength to provide financial aid, but it also provides high levels of expertise and most importantly of all, a quiet non-confrontational diplomacy to improve governance levels.[234] Total aid is estimated to be around $1 billion per year, which includes.[234] In addition, Brazil already managed a peacekeeping mission in Haiti ($350 million) and makes in-kind contributions to the World Food Programme ($300 million).[234] This is in addition to humanitarian assistance and contributions to multilateral development agencies. The scale of this aid places it on par with China and India.[234] The Brazilian South-South aid has been described as a "global model in waiting".[235]

Law enforcement and crime

In Brazil, the Constitution establishes six different police agencies for law enforcement: Federal Police Department, Federal Highway Police, Federal Railroad Police, Federal, District and State Penal Police (included by the Constitutional Amendment No. 104, of 2019), Military Police and Civil Police. Of these, the first three are affiliated with federal authorities, the last two are subordinate to state governments and the Penal Police can be subordinated to the federal or state/district government. All police forces are overseen by the executive branch of the federal or state government.[17] The National Public Security Force also can act in public disorder situations arising anywhere in the country.[236]

The country has high levels of violent crime, such as gun violence and homicides. In 2012, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated the number of 32 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, one of the highest rates of homicide of the world.[237] The number considered acceptable by the WHO is about 10 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants.[238] In 2018, Brazil had a record 63,880 murders.[239] However, there are differences between the crime rates in the Brazilian states. While in São Paulo the homicide rate registered in 2013 was 10.8 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants, in Alagoas it was 64.7 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants.[240]

Brazil also has high levels of incarceration. It had the third largest prison population in the world of approximately 700,000 prisoners as of June 2014, which put it only behind the United States (2,228,424) and China (1,701,344).[241] The high number of prisoners eventually overloaded the Brazilian prison system, leading to a shortfall of about 200,000 accommodations.[242]

Human rights

LGBT rights are generally supported within Brazil,[243][244] and same-sex marriage has been fully recognized since 2013.[245] However, police violence and gender-based discrimination remain prevalent throughout the nation.[246][247] Brazil has one of the highest Gini coefficient rankings in Latin America.[9]

Political subdivisions

| States of Brazil and Regions of Brazil |

Brazil is a federation composed of 26 states, one federal district, and the 5,570 municipalities.[17] States have autonomous administrations, collect their own taxes and receive a share of taxes collected by the Federal government. They have a governor and a unicameral legislative body elected directly by their voters. They also have independent Courts of Law for common justice. Despite this, states have much less autonomy to create their own laws than in other federal states such as the United States. For example, criminal and civil laws can be voted by only the federal bicameral Congress and are uniform throughout the country.[17]

The states and the federal district are grouped into regions: Northern, Northeast, Central-West, Southeast and Southern. The Brazilian regions are merely geographical, not political or administrative divisions, and they do not have any specific form of government. Although defined by law, Brazilian regions serve mainly statistical purposes, and also to define the distribution of federal funds in development projects.

Municipalities, as the states, have autonomous administrations, collect their own taxes and receive a share of taxes collected by the federal and state government.[17] Each has an elected mayor and legislative body, but no separate Court of Law. Indeed, a Court of Law organized by the state can encompass many municipalities in a single justice administrative division called comarca (county).

Brazil's constitution also provides for the creation of federal territories, which are administrative divisions directly controlled by the federal government. However, there are currently no federal territories in the country, as the 1988 Constitution abolished the last three: Amapá and Roraima (which gained statehood status) and Fernando de Noronha, which became a state district of Pernambuco.[248][249]

Economy

Brazil's upper-middle income mixed market economy is rich in natural resources.[253] It has the largest national economy in Latin America, the eighth-largest economy in the world by nominal GDP, and the eighth-largest by PPP. After rapid growth in preceding decades, the country entered an ongoing recession in 2014 amid a political corruption scandal and nationwide protests. A developing country, Brazil has a labor force of roughly 100 million,[254] which is the world's fifth-largest; with a high unemployment rate of 14.4% as of 2021[update].[255] Its foreign exchange reserves are the tenth-highest in the world.[256] The B3 in São Paulo is the largest stock exchange of Latin America by market capitalization. In regards to poverty, about 1.9% of the total population lives at $2.15 a day,[257] while about 19% live at $6.85 a day.[258] Brazil's economy suffers from endemic corruption and high income inequality.[259] The Brazilian real is the national currency.

Brazil's diversified economy includes agriculture, industry, and a wide range of services.[260] The large service sector accounts for about 72.7% of total GDP, followed by the industrial sector (20.7%), while the agriculture sector is by far the smallest, making up 6.6% of total GDP.[261]

Brazil is one of the largest producers of various agricultural commodities,[262] and also has a large cooperative sector that provides 50% of the food in the country.[263] It has been the world's largest producer of coffee for the last 150 years.[32] Brazil is the world's largest producer of sugarcane, soy, coffee and orange; is one of the top 5 producers of maize, cotton, lemon, tobacco, pineapple, banana, beans, coconut, watermelon and papaya; and is one of the top 10 world producers of cocoa, cashew, mango, rice, tomato, sorghum, tangerine, avocado, persimmon, and guava, among others. Regarding livestock, it is one of the 5 largest producers of chicken meat, beef, pork and cow's milk in the world.[264] In the mining sector, Brazil is among the largest producers of iron ore, copper, gold,[265] bauxite, manganese, tin, niobium,[266] and nickel. In terms of precious stones, Brazil is the world's largest producer of amethyst, topaz, agate and one of the main producers of tourmaline, emerald, aquamarine, garnet and opal.[267][268] The country is a major exporter of soy, iron ore, pulp (cellulose), maize, beef, chicken meat, soybean meal, sugar, coffee, tobacco, cotton, orange juice, footwear, airplanes, cars, vehicle parts, gold, ethanol, semi-finished iron, among other products.[269][270]

Brazil is the world's 24th-largest exporter and 26th-largest importer as of 2021[update].[271][272] China is its largest trading partner, accounting for 32% of the total trade. Other large trading partners include the United States, Argentina, the Netherlands and Canada.[273] Its automotive industry is the eighth-largest in the world.[274] In the food industry, Brazil was the second-largest exporter of processed foods in the world in 2019.[275] The country was the second-largest producer of pulp in the world and the eighth-largest producer of paper in 2016.[276] In the footwear industry, Brazil was the fourth-largest producer in 2019.[277] It was also the ninth-largest producer of steel in the world.[278][279][280] In 2018, the chemical industry of Brazil was the eighth-largest in the world.[281][282][283] Although, it was among the five largest world producers in 2013, Brazil's textile industry is very little integrated into world trade.[284]

The tertiary sector (trade and services) represented 75.8% of the country's GDP in 2018, according to the IBGE. The service sector was responsible for 60% of GDP and trade for 13%. It covers a wide range of activities: commerce, accommodation and catering, transport, communications, financial services, real estate activities and services provided to businesses, public administration (urban cleaning, sanitation, etc.) and other services such as education, social and health services, research and development, sports activities, etc., since it consists of activities complementary to other sectors.[285][286] Micro and small businesses represent 30% of the country's GDP. In the commercial sector, for example, they represent 53% of the GDP within the activities of the sector.[287]

Tourism

Tourism in Brazil is a growing sector and key to the economy of several regions of the country. The country had 6.36 million visitors in 2015, ranking in terms of the international tourist arrivals as the main destination in South America and second in Latin America after Mexico.[288] Revenues from international tourists reached US$6 billion in 2010, showing a recovery from the 2008–2009 economic crisis.[289] Historical records of 5.4 million visitors and US$6.8 billion in receipts were reached in 2011.[290][291] In the list of world tourist destinations, in 2018, Brazil was the 48th most visited country, with 6.6 million tourists (and revenues of 5.9 billion dollars).[292]

Natural areas are its most popular tourism product, a combination of ecotourism with leisure and recreation, mainly sun and beach, and adventure travel, as well as cultural tourism. Among the most popular destinations are the Amazon Rainforest, beaches and dunes in the Northeast Region, the Pantanal in the Center-West Region, beaches at Rio de Janeiro and Santa Catarina, cultural tourism in Minas Gerais and business trips to São Paulo.[293]

In terms of the 2015 Travel and Tourism Competitiveness Index (TTCI), which is a measurement of the factors that make it attractive to develop business in the travel and tourism industry of individual countries, Brazil ranked in the 28th place at the world's level, third in the Americas, after Canada and United States.[294][295]

Domestic tourism is a key market segment for the tourism industry in Brazil. In 2005, 51 million Brazilian nationals made ten times more trips than foreign tourists and spent five times more money than their international counterparts.[296] The main destination states in 2023 were São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Rio Grande do Sul.[297][298] The main source of tourists for the entire country is São Paulo state.[299] In terms of tourism revenues, the top earners by state were São Paulo and Bahia.[300] For 2005, the three main trip purposes were visiting friends and family (53.1%), sun and beach (40.8%), and cultural tourism (12.5%).[301]

Science and technology

Technological research in Brazil is largely carried out in public universities and research institutes, with the majority of funding for basic research coming from various government agencies.[302] Brazil's most esteemed technological hubs are the Oswaldo Cruz Institute, the Butantan Institute, the Air Force's Aerospace Technical Center, the Brazilian Agricultural Research Corporation and the National Institute for Space Research.[303][304]

The Brazilian Space Agency has the most advanced space program in Latin America, with significant resources to launch vehicles, and manufacture of satellites.[305] Owner of relative technological sophistication, the country develops submarines, aircraft, as well as being involved in space research, having a Vehicle Launch Center Light and being the only country in the Southern Hemisphere the integrate team building International Space Station (ISS).[306]

The country is also a pioneer in the search for oil in deep water, from where it extracts 73% of its reserves. Uranium is enriched at the Resende Nuclear Fuel Factory, mostly for research purposes (as Brazil obtains 88% of its electricity from hydroelectricity[307]) and the country's first nuclear submarine is expected to be launched in 2029.[308]

Brazil is one of the three countries in Latin America[309] with an operational Synchrotron Laboratory, a research facility on physics, chemistry, material science and life sciences, and Brazil is the only Latin American country to have a semiconductor company with its own fabrication plant, the CEITEC.[310] According to the Global Information Technology Report 2009–2010 of the World Economic Forum, Brazil is the world's 61st largest developer of information technology.[311] Brazil was ranked 49th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023, up from 66th in 2019.[312][313][314]

Among the most renowned Brazilian inventors are priests Bartolomeu de Gusmão, Landell de Moura and Francisco João de Azevedo, besides Alberto Santos-Dumont,[315] Evaristo Conrado Engelberg,[316] Manuel Dias de Abreu,[317] Andreas Pavel[318] and Nélio José Nicolai.[319] Brazilian science is represented by the likes of César Lattes (Brazilian physicist Pathfinder of Pi Meson),[320] Mário Schenberg (considered the greatest theoretical physicist of Brazil),[321] José Leite Lopes (only Brazilian physicist holder of the UNESCO Science Prize),[322] Artur Ávila (the first Latin American winner of the Fields Medal)[323] and Fritz Müller (pioneer in factual support of the theory of evolution by Charles Darwin).[324]

Energy

Brazil is the world's ninth largest energy consumer.[325] Much of its energy comes from renewable sources, particularly hydroelectricity and ethanol; the Itaipu Dam is the world's largest hydroelectric plant by energy generation,[326] and the country has other large plants such as Belo Monte and Tucuruí. The first car with an ethanol engine was produced in 1978 and the first airplane engine running on ethanol in 2005.[327]

At the end of 2021 Brazil was the 2nd country in the world in terms of installed hydroelectric power (109.4 GW) and biomass (15.8 GW), the 7th country in the world in terms of installed wind power (21.1 GW) and the 14th country in the world in terms of installed solar power (13.0 GW)—on track to also become one of the top 10 in the world in solar energy.[328] At the end of 2021, Brazil was the 4th largest producer of wind energy in the world (72 TWh), behind only China, the United States and Germany, and the 11th largest producer of solar energy in the world (16.8 TWh).[329]

The main characteristic of the Brazilian energy matrix is that it is much more renewable than that of the world. While in 2019 the world matrix was only 14% made up of renewable energy, Brazil's was at 45%. Petroleum and oil products made up 34.3% of the matrix; sugar cane derivatives, 18%; hydraulic energy, 12.4%; natural gas, 12.2%; firewood and charcoal, 8.8%; varied renewable energies, 7%; mineral coal, 5.3%; nuclear, 1.4%, and other non-renewable energies, 0.6%.[330]

In the electric energy matrix, the difference between Brazil and the world is even greater: while the world only had 25% of renewable electric energy in 2019, Brazil had 83%. The Brazilian electric matrix was composed of: hydraulic energy, 64.9%; biomass, 8.4%; wind energy, 8.6%; solar energy, 1%; natural gas, 9.3%; oil products, 2%; nuclear, 2.5%; coal and derivatives, 3.3%.[330] Brazil has the largest electricity sector in Latin America. Its capacity at the end of 2021 was 181,532 MW.[331]

As for oil, the Brazilian government has embarked on a program over the decades to reduce dependence on imported oil, which previously accounted for more than 70% of the country's oil needs. Brazil became self-sufficient in oil in 2006–2007. In 2021, the country closed the year as the 7th oil producer in the world, with an average of close to three million barrels per day, becoming an exporter of the product.[332][333]

Transportation

Brazilian roads are the primary carriers of freight and passenger traffic. The road system totaled 1,720,000 km (1,068,758 mi) in 2019.[336] The total of paved roads increased from 35,496 km (22,056 mi) in 1967 to 215,000 km (133,595 mi) in 2018.[337][338]

Brazil's railway system has been declining since 1945, when emphasis shifted to highway construction. The country's total railway track length was 30,576 km (18,999 mi) in 2015,[339] as compared with 31,848 km (19,789 mi) in 1970, making it the ninth largest network in the world. Most of the railway system belonged to the Federal Railroad Network Corporation (RFFSA), which was privatized in 2007.[340] The São Paulo Metro began operating on 14 September 1974 as the first underground transit system in Brazil.[341]

There are about 2,500 airports in Brazil, including landing fields: the second largest number in the world, after the United States.[342] São Paulo–Guarulhos International Airport, near São Paulo, is the largest and busiest airport with nearly 43 million passengers annually, while handling the vast majority of commercial traffic for the country.[343][344]

For freight transport waterways are of importance, e.g. the industrial zones of Manaus can be reached only by means of the Solimões–Amazonas waterway (3,250 kilometers or 2,020 miles in length, with a minimum depth of six meters or 20 feet). The country also has 50,000 kilometers (31,000 miles) of waterways.[345] Coastal shipping links widely separated parts of the country. Bolivia and Paraguay have been given free ports at Santos. Of the 36 deep-water ports, Santos, Itajaí, Rio Grande, Paranaguá, Rio de Janeiro, Sepetiba, Vitória, Suape, Manaus, and São Francisco do Sul are the most important.[346] Bulk carriers have to wait up to 18 days before being serviced, container ships 36.3 hours on average.[347]

Demographics

The population of Brazil, as recorded by the 2008 PNAD, was approximately 190 million[348] (22.31 inhabitants per square kilometer or 57.8/sq mi), with a ratio of men to women of 0.95:1[349] and 83.75% of the population defined as urban.[350] The population is heavily concentrated in the Southeastern (79.8 million inhabitants) and Northeastern (53.5 million inhabitants) regions, while the two most extensive regions, the Center-West and the North, which together make up 64.12% of the Brazilian territory, have a total of only 29.1 million inhabitants.

The first census in Brazil was carried out in 1872 and recorded a population of 9,930,478.[351] From 1880 to 1930, 4 million Europeans arrived.[352] Brazil's population increased significantly between 1940 and 1970, because of a decline in the mortality rate, even though the birth rate underwent a slight decline. In the 1940s the annual population growth rate was 2.4%, rising to 3.0% in the 1950s and remaining at 2.9% in the 1960s, as life expectancy rose from 44 to 54 years[353] and to 72.6 years in 2007.[354] It has been steadily falling since the 1960s, from 3.04% per year between 1950 and 1960 to 1.05% in 2008 and is expected to fall to a negative value of –0.29% by 2050[355] thus completing the demographic transition.[356]

In 2008, the illiteracy rate was 11.48%.[357]

Race and ethnicity

Race and ethnicity in Brazil 2022

According to the National Research by Household Sample (PNAD) of 2022, 45.3% of the population (92,1 million) described themselves as Mixed (officially called brown or pardo), 43.5% (88,2 million) as White, 10.2% (20,7 million) as Black, 0.6% (1,2 million) as Indigenous and 0.4% (850 thousand) as East Asian (officially called yellow or amarela).[358]

Since the arrival of the Portuguese in 1500, considerable genetic mixing between Amerindians, Europeans, and Africans has taken place in all regions of the country: European ancestry being dominant nationwide according to the vast majority of all autosomal studies undertaken covering the entire population, accounting for between 65% and 77%,[359][360][361][362] while the African ancestry among the Brazilians are estimated that 14.30% to 25%[361][363] and more than 80% of Brazilians have over 10% African ancestry,[364] and the Indigenous ancestry is significant and present in all regions of Brazil.[365][366][367][368][369][370][371][372]

From the 19th century, Brazil opened its borders to immigration. About five million people from over 60 countries migrated to Brazil between 1808 and 1972, most of them of Portuguese, Italian, Spanish, German, English, Ukrainian, Polish, Jewish, African, Armenian, Russian, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Arab origin.[373][374][375] Brazil has the second largest Jewish community in Latin America making up 0.06% of its population.[376] Outside in the Arab world, Brazil also has the largest population of Arab ancestry in the world, with 15–20 million people.[377][378] According to Brazil's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Brazil is a home to a Lebanese diaspora of 7 million to 10 million, surpassing the population of Lebanese individuals residing in Lebanon.[379]

Brazilian society is more markedly divided by social class lines, although a high income disparity is found between race groups, so racism and classism often overlap. The brown population (officially called pardo in Portuguese, also colloquially moreno)[380][381] is a broad category that includes caboclos (assimilated Amerindians in general, and descendants of Whites and Natives), mulatos (descendants of primarily Whites and Afro-Brazilians) and cafuzos (descendants of Afro-Brazilians and Natives).[380][381][382][383][384] Higher percents of Blacks, mulattoes and tri-racials can be found in the eastern coast of the Northeastern region from Bahia to Paraíba[384][385] and also in northern Maranhão,[386][387] southern Minas Gerais[388] and in eastern Rio de Janeiro.[384][388]

People of considerable Amerindian ancestry form the majority of the population in the Northern, Northeastern and Center-Western regions.[389] In 2007, the National Indian Foundation estimated that Brazil has 67 different uncontacted tribes, up from their estimate of 40 in 2005. Brazil is believed to have the largest number of uncontacted peoples in the world.[390]

Religion

Religion in Brazil (2010 Census)

Christianity is the country's predominant faith, with Roman Catholicism being its largest denomination. Brazil has the world's largest Catholic population.[391][392] According to the 2010 Demographic Census (the PNAD survey does not inquire about religion), 64.63% of the population followed Roman Catholicism; 22.2% Protestantism; 2.0% Kardecist spiritism; 3.2% other religions, undeclared or undetermined; while 8.0% had no religion.[393]

Religion in Brazil was formed from the meeting of the Catholic Church with the religious traditions of enslaved African peoples and indigenous peoples.[394] This confluence of faiths during the Portuguese colonization of Brazil led to the development of a diverse array of syncretistic practices within the overarching umbrella of Brazilian Catholic Church, characterized by traditional Portuguese festivities.[395]

Religious pluralism increased during the 20th century,[396] and the Protestant community has grown to include over 22% of the population.[397] The most common Protestant denominations are Evangelical Pentecostal ones. Other Protestant branches with a notable presence in the country include the Baptists, Seventh-day Adventists, Lutherans and the Reformed tradition.[398]

In recent decades, Protestantism, particularly in forms of Pentecostalism and Evangelicalism, has spread in Brazil, while the proportion of Catholics has dropped significantly.[399] After Protestantism, individuals professing no religion are also a significant group, exceeding 8% of the population as of the 2010 census. The cities of Boa Vista, Salvador, and Porto Velho have the greatest proportion of Irreligious residents in Brazil. Teresina, Fortaleza, and Florianópolis were the most Roman Catholic in the country.[400] Greater Rio de Janeiro, not including the city proper, is the most irreligious and least Roman Catholic Brazilian periphery, while Greater Porto Alegre and Greater Fortaleza are on the opposite sides of the lists, respectively.[400]

In October 2009, the Brazilian Senate approved and enacted by the President of Brazil in February 2010, an agreement with the Vatican, in which the Legal Statute of the Catholic Church in Brazil is recognized.[401][402]

Health

The Brazilian public health system, the Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saúde – SUS), is managed and provided by all levels of government,[403] being the largest system of this type in the world.[404] On the other hand, private healthcare systems play a complementary role.[405]

Public health services are universal and offered to all citizens of the country for free. However, the construction and maintenance of health centers and hospitals are financed by taxes, and the country spends about 9% of its GDP on expenditures in the area. In 2012, Brazil had 1.85 doctors and 2.3 hospital beds for every 1,000 inhabitants.[406][407]

Despite all the progress made since the creation of the universal health care system in 1988, there are still several public health problems in Brazil. In 2006, the main points to be solved were the high infant (2.51%) and maternal mortality rates (73.1 deaths per 1000 births).[408]

The number of deaths from noncommunicable diseases, such as cardiovascular diseases (151.7 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants) and cancer (72.7 deaths per 100,000 inhabitants), also has a considerable impact on the health of the Brazilian population. Finally, external but preventable factors such as car accidents, violence and suicide caused 14.9% of all deaths in the country.[408] The Brazilian health system was ranked 125th among the 191 countries evaluated by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2000.[409]

Education

The Federal Constitution and the Law of Guidelines and Bases of National Education determine that the Union, the states, the Federal District, and the municipalities must manage and organize their respective education systems. Each of these public educational systems is responsible for its own maintenance, which manages funds as well as the mechanisms and funding sources. The constitution reserves 25% of the state budget and 18% of federal taxes and municipal taxes for education.[410]

According to the IBGE, in 2019, the literacy rate of the population was 93.4%, meaning that 11.3 million (6.6% of population) people are still illiterate in the country, with some states such as Rio de Janeiro and Santa Catarina reaching around 97% of literacy rate;[411] functional illiteracy has reached 21.6% of the population.[412] Illiteracy is higher in the Northeast, where 13.87% of the population is illiterate, while the South, has 3.3% of its population illiterate.[413][411]

Brazil's private institutions tend to be more exclusive and offer better quality education, so many high-income families send their children there. The result is a segregated educational system that reflects extreme income disparities and reinforces social inequality. However, efforts to change this are making impacts.[414]

The University of São Paulo is the second best university in Latin America, according to recent 2019 QS World University Rankings. Of the top 20 Latin American universities, eight are Brazilian. Most of them are public. Attending an institution of higher education is required by Law of Guidelines and Bases of Education. Kindergarten, elementary and medium education are required of all students.[415]

Language

The official language of Brazil is Portuguese (Article 13 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Brazil), which almost all of the population speaks and is virtually the only language used in newspapers, radio, television, and for business and administrative purposes. Brazil is the only Portuguese-speaking nation in the Americas, making the language an important part of Brazilian national identity and giving it a national culture distinct from those of its Spanish-speaking neighbors.[416]

Brazilian Portuguese has had its own development, mostly similar to 16th-century Central and Southern dialects of European Portuguese[417] (despite a very substantial number of Portuguese colonial settlers, and more recent immigrants, coming from Northern regions, and in minor degree Portuguese Macaronesia), with a few influences from the Amerindian and African languages, especially West African and Bantu restricted to the vocabulary only.[418] As a result, the language is somewhat different, mostly in phonology, from the language of Portugal and other Portuguese-speaking countries (the dialects of the other countries, partly because of the more recent end of Portuguese colonialism in these regions, have a closer connection to contemporary European Portuguese). These differences are comparable to those between American and British English.[418]

The 2002 sign language law[419] requires government authorities and public agencies to accept and provide information in Língua Brasileira dos Sinais or "LIBRAS", the Brazilian Sign Language, while a 2005 presidential edict[420] extends this to require teaching of the language as a part of the education and speech and language pathology curricula. LIBRAS teachers, instructors and translators are recognized professionals. Schools and health services must provide access ("inclusion") to deaf people.[421]

Minority languages are spoken throughout the nation. One hundred and eighty Amerindian languages are spoken in remote areas and a significant number of other languages are spoken by immigrants and their descendants.[418] In the municipality of São Gabriel da Cachoeira, Nheengatu (a currently endangered South American creole language—or an 'anti-creole', according to some linguists—with mostly Indigenous Brazilian languages lexicon and Portuguese-based grammar that, together with its southern relative língua geral paulista, once was a major lingua franca in Brazil,[422] being replaced by Portuguese only after governmental prohibition led by major political changes),[excessive detail?] Baniwa and Tucano languages had been granted co-official status with Portuguese.[423]

There are significant communities of German (mostly the Brazilian Hunsrückisch, a High German language dialect) and Italian (mostly the Talian, a Venetian dialect) origins in the Southern and Southeastern regions, whose ancestors' native languages were carried along to Brazil, and which, still alive there, are influenced by the Portuguese language.[424][425] Talian is officially a historic patrimony of Rio Grande do Sul,[426] and two German dialects possess co-official status in a few municipalities.[427] Italian is also recognized as ethnic language in the Santa Teresa microregion and Vila Velha (Espirito Santo state), and is taught as mandatory second language at school.[428]

Urbanization

According to IBGE (Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics) urban areas already concentrate 84.35% of the population, while the Southeast region remains the most populated one, with over 80 million inhabitants.[429] The largest urban agglomerations in Brazil are São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Belo Horizonte—all in the Southeastern Region—with 21.1, 12.3, and 5.1 million inhabitants respectively.[430][431][432] The majority of state capitals are the largest cities in their states, except for Vitória, the capital of Espírito Santo, and Florianópolis, the capital of Santa Catarina.[433]

Largest urban agglomerations in Brazil

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | State | Pop. | Rank | Name | State | Pop. | ||

São Paulo  Rio de Janeiro |

1 | São Paulo | São Paulo | 21,314,716 | 11 | Belém | Pará | 2,157,180 |  Belo Horizonte  Recife |

| 2 | Rio de Janeiro | Rio de Janeiro | 12,389,775 | 12 | Manaus | Amazonas | 2,130,264 | ||

| 3 | Belo Horizonte | Minas Gerais | 5,142,260 | 13 | Campinas | São Paulo | 2,105,600 | ||

| 4 | Recife | Pernambuco | 4,021,641 | 14 | Vitória | Espírito Santo | 1,837,047 | ||

| 5 | Brasília | Federal District | 3,986,425 | 15 | Baixada Santista | São Paulo | 1,702,343 | ||

| 6 | Porto Alegre | Rio Grande do Sul | 3,894,232 | 16 | São José dos Campos | São Paulo | 1,572,943 | ||

| 7 | Salvador | Bahia | 3,863,154 | 17 | São Luís | Maranhão | 1,421,569 | ||

| 8 | Fortaleza | Ceará | 3,594,924 | 18 | Natal | Rio Grande do Norte | 1,349,743 | ||

| 9 | Curitiba | Paraná | 3,387,985 | 19 | Maceió | Alagoas | 1,231,965 | ||

| 10 | Goiânia | Goiás | 2,347,557 | 20 | João Pessoa | Paraíba | 1,168,941 | ||

Culture

The core culture of Brazil is derived from Portuguese culture, because of its strong colonial ties with the Portuguese Empire.[437] Among other influences, the Portuguese introduced the Portuguese language, Roman Catholicism and colonial architectural styles. The culture was also strongly influenced by African, indigenous and non-Portuguese European cultures and traditions.[438]

Some aspects of Brazilian culture were influenced by the contributions of Italian, German and other European as well as Japanese, Jewish and Arab immigrants who arrived in large numbers in the South and Southeast of Brazil during the 19th and 20th centuries.[439] The indigenous Amerindians influenced Brazil's language and cuisine; and the Africans influenced language, cuisine, music, dance and religion.[440]

Brazilian art has developed since the 16th century into different styles that range from Baroque (the dominant style in Brazil until the early 19th century)[441][442] to Romanticism, Modernism, Expressionism, Cubism, Surrealism and Abstractionism. Brazilian cinema dates back to the birth of the medium in the late 19th century and has gained a new level of international acclaim since the 1960s.[443]

Architecture

The architecture of Brazil is influenced by Europe, especially Portugal. It has a history that goes back 500 years to the time, when Pedro Álvares Cabral landed in Brazil in 1500. Portuguese colonial architecture was the first wave of architecture to go to Brazil.[444] It is the basis for all Brazilian architecture of later centuries.[445] In the 19th century during the time of the Empire of Brazil, the country followed European trends and adopted Neoclassical and Gothic Revival architecture. Then in the 20th century especially in Brasília, Brazil experimented with Modernist architecture.

The colonial architecture of Brazil dates to the early 16th century when Brazil was first explored, conquered and settled by the Portuguese. The Portuguese built architecture familiar to them in Europe in their aim to colonize Brazil. They built Portuguese colonial architecture which included churches, civic architecture including houses and forts in Brazilian cities and the countryside.[446]

During 19th century, Brazilian architecture saw the introduction of more European styles to Brazil such as Neoclassical and Gothic Revival architecture. This was usually mixed with Brazilian influences from their own heritage which produced a unique form of Brazilian architecture.[446]

In the 1950s, the modernist architecture was introduced when Brasília was built as new federal capital in the interior of Brazil to help develop the interior. The architect Oscar Niemeyer idealized and built government buildings, churches and civic buildings in the modernist style.[447]

Music

The music of Brazil was formed mainly from the fusion of European, Native Indigenous, and African elements.[448] Until the nineteenth century, Portugal was the gateway to most of the influences that built Brazilian music, although many of these elements were not of Portuguese origin, but generally European. The first was José Maurício Nunes Garcia, author of sacred pieces with influence of Viennese classicism.[449] The major contribution of the African element was the rhythmic diversity and some dances and instruments that had a bigger role in the development of popular music and folk, flourishing especially in the twentieth century.[448]

Popular music since the late eighteenth century began to show signs of forming a characteristically Brazilian sound, with samba considered the most typical and on the UNESCO cultural heritage list.[450] Samba-reggae, Maracatu, Frevo and Afoxê are four music traditions that have been popularized by their appearance in the annual Brazilian Carnivals.[451] Capoeira is usually played with its own music referred to as capoeira music, which is usually considered to be a call-and-response type of folk music.[452] Forró is a type of folk music prominent during the Festa Junina in northeastern Brazil.[453] Jack A. Draper III, a professor of Portuguese at the University of Missouri,[454] argues that Forró was used as a way to subdue feelings of nostalgia for a rural lifestyle.[455]

Choro is a very popular music instrumental style. Its origins are in 19th-century Rio de Janeiro. In spite of the name, the style often has a fast and happy rhythm, characterized by virtuosity, improvisation, subtle modulations and full of syncopation and counterpoint.[456] Bossa nova is also a well-known style of Brazilian music developed and popularized in the 1950s and 1960s.[457] The phrase "bossa nova" means literally 'new trend'.[458] A lyrical fusion of samba and jazz, bossa nova acquired a large following starting in the 1960s.[459] Some Brazilian music artists have achieved international success, for example: Villa-Lobos, Tom Jobim, João Gilberto, Sergio Mendes, Eumir Deodato, Kaoma, Sepultura, Olodum and CSS.

Literature

Brazilian literature dates back to the 16th century, to the writings of the first Portuguese explorers in Brazil, such as Pero Vaz de Caminha, filled with descriptions of fauna, flora and commentary about the indigenous population that fascinated European readers.[460]