Human rights

| Rights |

|---|

|

| Theoretical distinctions |

| Human rights |

| Rights by beneficiary |

| Other groups of rights |

Human rights are moral principles or norms[1] for standards of human behaviour and are regularly protected as substantive rights in substantive law, municipal and international law.[2] They are commonly understood as inalienable,[3] fundamental rights "to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being"[4] and which are "inherent in all human beings",[5] regardless of their age, ethnic origin, location, language, religion, ethnicity, or any other status.[3] They are applicable everywhere and at every time in the sense of being universal,[1] and they are egalitarian in the sense of being the same for everyone.[3] They are regarded as requiring empathy and the rule of law,[6] and imposing an obligation on persons to respect the human rights of others;[1][3] it is generally considered that they should not be taken away except as a result of due process based on specific circumstances.[3]

The doctrine of human rights has been highly influential within international law and global and regional institutions.[3] The precise meaning of the term right is controversial and is the subject of continued philosophical debate.[7] While there is consensus that human rights encompass a wide variety of rights,[5] such as the right to a fair trial, protection against enslavement, prohibition of genocide, free speech,[8] or a right to education, there is disagreement about which of these particular rights should be included within the general framework of human rights;[1] some thinkers suggest that human rights should be a minimum requirement to avoid the worst-case abuses, while others see it as a higher standard.[1][9]

Many of the basic ideas that animated the human rights movement developed in the aftermath of the Second World War and the events of the Holocaust,[6] culminating in the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Paris by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948.[10] Ancient peoples did not have the same modern-day conception of universal human rights.[11] The true forerunner of human rights discourse was the concept of natural rights, which first appeared as part of the medieval natural law tradition, and developed in new directions during the European Enlightenment with such philosophers as John Locke, Francis Hutcheson, and Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, and which featured prominently in the political discourse of the American Revolution and the French Revolution.[6] From this foundation, the modern human rights arguments emerged over the latter half of the 20th century,[12] possibly as a reaction to slavery, torture, genocide, and war crimes.[6]

History

This section needs expansion with: More information about human rights prior to the Enlightenment. You can help by adding to it. (May 2022) |

Many of the basic ideas that animated the human rights movement developed in the aftermath of the Second World War and the events of the Holocaust,[6] culminating in the adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Paris by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948.[13]

Ancient peoples did not have the same modern-day conception of universal human rights.[11] However, the concept has in some sense existed for centuries, although not in the same way as today.[11][14][15][16]

The true forerunner of human rights discourse was the concept of natural rights, which first appeared as part of the medieval natural law tradition. It developed in new directions during the European Enlightenment with such philosophers as John Locke, Francis Hutcheson, and Jean-Jacques Burlamaqui, and featured prominently in the political discourse of the American Revolution and the French Revolution.[6] From this foundation, the modern human rights arguments emerged over the latter half of the 20th century,[12] possibly as a reaction to slavery, torture, genocide, and war crimes.[6]

The medieval natural law tradition was heavily influenced by the writings of St Paul's early Christian thinkers such as St Hilary of Poitiers, St Ambrose, and St Augustine.[17] Augustine was among the earliest to examine the legitimacy of the laws of man, and attempt to define the boundaries of what laws and rights occur naturally based on wisdom and conscience, instead of being arbitrarily imposed by mortals, and if people are obligated to obey laws that are unjust.[18]

Spanish scholasticism insisted on a subjective vision of law during the 16th and 17th centuries: Luis de Molina, Domingo de Soto and Francisco Vitoria, members of the School of Salamanca, defined law as a moral power over one's own.50 Although they maintained at the same time, the idea of law as an objective order, they stated that there are certain natural rights, mentioning both rights related to the body (right to life, to property) and to the spirit (right to freedom of thought, dignity). The jurist Vázquez de Menchaca, starting from an individualist philosophy, was decisive in the dissemination of the term iura naturalia. This natural law thinking was supported by contact with American civilizations and the debate that took place in Castile about the just titles of the conquest and, in particular, the nature of the indigenous people. In the Castilian colonization of America, it is often stated, measures were applied in which the germs of the idea of Human Rights are present, debated in the well-known Valladolid Debate that took place in 1550 and 1551. The thought of the School of Salamanca, especially through Francisco Vitoria, also contributed to the promotion of European natural law.

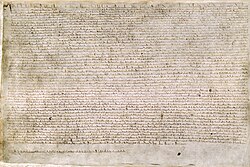

From this foundation, the modern human rights arguments emerged over the latter half of the 20th century.[12] Magna Carta is an English charter originally issued in 1215 which influenced the development of the common law and many later constitutional documents related to human rights, such as the 1689 English Bill of Rights, the 1789 United States Constitution, and the 1791 United States Bill of Rights.[19]

17th century English philosopher John Locke discussed natural rights in his work, identifying them as being "life, liberty, and estate (property)", and argued that such fundamental rights could not be surrendered in the social contract. In Britain in 1689, the English Bill of Rights and the Scottish Claim of Right each made a range of oppressive governmental actions, illegal.[20] Two major revolutions occurred during the 18th century, in the United States (1776) and in France (1789), leading to the United States Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen respectively, both of which articulated certain human rights. Additionally, the Virginia Declaration of Rights of 1776 encoded into law a number of fundamental civil rights and civil freedoms.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.

— United States Declaration of Independence, 1776

1800 to World War I

Philosophers such as Thomas Paine, John Stuart Mill, and Hegel expanded on the theme of universality during the 18th and 19th centuries. In 1831, William Lloyd Garrison wrote in a newspaper called The Liberator that he was trying to enlist his readers in "the great cause of human rights",[21] so the term human rights probably came into use sometime between Paine's The Rights of Man and Garrison's publication. In 1849 a contemporary, Henry David Thoreau, wrote about human rights in his treatise On the Duty of Civil Disobedience which was later influential on human rights and civil rights thinkers. United States Supreme Court Justice David Davis, in his 1867 opinion for Ex Parte Milligan, wrote "By the protection of the law, human rights are secured; withdraw that protection and they are at the mercy of wicked rulers or the clamor of an excited people."[22]

Many groups and movements have managed to achieve profound social changes over the course of the 20th century in the name of human rights. In Western Europe and North America, labour unions brought about laws granting workers the right to strike, establishing minimum work conditions and forbidding or regulating child labour. The women's rights movement succeeded in gaining for many women the right to vote. National liberation movements in many countries succeeded in driving out colonial powers. One of the most influential was Mahatma Gandhi's leadership of the Indian independence movement. Movements by long-oppressed racial and religious minorities succeeded in many parts of the world, among them the civil rights movement, and more recent diverse identity politics movements, on behalf of women and minorities in the United States.[23]

The foundation of the International Committee of the Red Cross, the 1864 Lieber Code and the first of the Geneva Conventions in 1864 laid the foundations of International humanitarian law, to be further developed following the two World Wars.

Between World War I and World War II

The League of Nations was established in 1919 at the negotiations over the Treaty of Versailles following the end of World War I. The League's goals included disarmament, preventing war through collective security, settling disputes between countries through negotiation, diplomacy and improving global welfare. Enshrined in its Charter was a mandate to promote many of the rights which were later included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The League of Nations had mandates to support many of the former colonies of the Western European colonial powers during their transition from colony to independent state. Established as an agency of the League of Nations, and now part of United Nations, the International Labour Organization also had a mandate to promote and safeguard certain of the rights later included in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR):

the primary goal of the ILO today is to promote opportunities for women and men to obtain decent and productive work, in conditions of freedom, equity, security and human dignity.

— Report by the Director General for the International Labour Conference 87th Session

After World War II

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a non-binding declaration adopted by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948,[25] partly in response to the events of World War II. The UDHR urges member states to promote a number of human, civil, economic and social rights, asserting these rights are part of the "foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world". The declaration was the first international legal effort to limit the behavior of states and make sure they did their duties to their citizens following the model of the rights-duty duality.

... recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world

— Preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948

The UDHR was framed by members of the Human Rights Commission, with Eleanor Roosevelt as chair, who began to discuss an International Bill of Rights in 1947. The members of the Commission did not immediately agree on the form of such a bill of rights, and whether, or how, it should be enforced. The Commission proceeded to frame the UDHR and accompanying treaties, but the UDHR quickly became the priority.[26] Canadian law professor John Humprey and French lawyer René Cassin were responsible for much of the cross-national research and the structure of the document respectively, where the articles of the declaration were interpretative of the general principle of the preamble. The document was structured by Cassin to include the basic principles of dignity, liberty, equality and brotherhood in the first two articles, followed successively by rights pertaining to individuals; rights of individuals in relation to each other and to groups; spiritual, public and political rights; and economic, social and cultural rights. The final three articles place, according to Cassin, rights in the context of limits, duties and the social and political order in which they are to be realized.[26] Humphrey and Cassin intended the rights in the UDHR to be legally enforceable through some means, as is reflected in the third clause of the preamble:[26]

Whereas it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have recourse, as a last resort, to rebellion against tyranny and oppression, that human rights should be protected by the rule of law.

— Preamble to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, 1948

Some of the UDHR was researched and written by a committee of international experts on human rights, including representatives from all continents and all major religions, and drawing on consultation with leaders such as Mahatma Gandhi.[27] The inclusion of both civil and political rights and economic, social, and cultural rights was predicated on the assumption that basic human rights are indivisible and that the different types of rights listed are inextricably linked.[26][28] Although this principle was not opposed by any member states at the time of adoption (the declaration was adopted unanimously, with the abstention of the Soviet bloc, apartheid South Africa, and Saudi Arabia), this principle was later subject to significant challenges.[28] On the issue of the term universal, the declarations did not apply to domestic discrimination or racism.[29] Henry J. Richardson III argued:[30]

- All major governments at the time of drafting the U.N. charter and the Universal declaration did their best to ensure, by all means known to domestic and international law, that these principles had only international application and carried no legal obligation on those governments to be implemented domestically. All tacitly realized that for their own discriminated-against minorities to acquire leverage on the basis of legally being able to claim enforcement of these wide-reaching rights would create pressures that would be political dynamite.

The onset of the Cold War soon after the UDHR was conceived brought to the fore divisions over the inclusion of both economic and social rights and civil and political rights in the declaration. Capitalist states tended to place strong emphasis on civil and political rights (such as freedom of association and expression), and were reluctant to include economic and social rights (such as the right to work and the right to join a union). Socialist states placed much greater importance on economic and social rights and argued strongly for their inclusion.[31] Because of the divisions over which rights to include and because some states declined to ratify any treaties including certain specific interpretations of human rights, and despite the Soviet bloc and a number of developing countries arguing strongly for the inclusion of all rights in a Unity Resolution, the rights enshrined in the UDHR were split into two separate covenants, allowing states to adopt some rights and derogate others. Although this allowed the covenants to be created, it denied the proposed principle that all rights are linked, which was central to some interpretations of the UDHR.[31][32] Although the UDHR is a non-binding resolution, it is now considered to be a central component of international customary law which may be invoked under appropriate circumstances by state judiciaries and other judiciaries.[33]

Human Rights Treaties

In 1966, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) were adopted by the United Nations, between them making the rights contained in the UDHR binding on all states.[a] They came into force only in 1976, when they were ratified by a sufficient number of countries (despite achieving the ICCPR, a covenant including no economic or social rights, the US only ratified the ICCPR in 1992).[34] The ICESCR commits 155 state parties to work toward the granting of economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR) to individuals.

Numerous other treaties (pieces of legislation) have been offered at the international level. They are generally known as human rights instruments. Some of the most significant are:

- Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (adopted 1948, entry into force: 1951) unhchr.ch

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) (adopted 1966, entry into force: 1969) unhchr.ch

- Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) (entry into force: 1981) Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women

- United Nations Convention Against Torture (CAT) (adopted 1984, entry into force: 1984)[35]

- Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) (adopted 1989, entry into force: 1989) Convention on the Rights of the Child | UNICEF Archived 26 April 2019 at the Wayback Machine

- International Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of their Families (ICRMW) (adopted 1990)

- Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (ICC) (entry into force: 2002)

Including environmental rights

In 2021 the United Nations Human Rights Council officially recognized "having a clean, healthy and sustainable environment" as a human right.[36] In April 2024, the European Court of Human Rights ruled, for the first time in history, that the Swiss government had violated human rights by not acting strongly enough to stop climate change.[37]

Promotion strategies

Military force

Responsibility to protect refers to a doctrine for United Nations member states to intervene to protect populations from atrocities. It has been cited as justification in the use of recent military interventions. An example of an intervention that is often criticized is the 2011 military intervention in the First Libyan Civil War by NATO and Qatar where the goal of preventing atrocities is alleged to have taken upon itself the broader mandate of removing the target government.[38][39]

Economic actions

Economic sanctions are often levied upon individuals or states who commit human rights violations. Sanctions are often criticized for its feature of collective punishment in hurting a country's population economically in order dampen that population's view of its government.[40][41] It is also argued that, counterproductively, sanctions on offending authoritarian governments strengthen that government's position domestically as governments would still have more mechanisms to find funding than their critics and opposition, who become further weakened.[42]

The risk of human rights violations increases with the increase in financially vulnerable populations. Girls from poor families in non-industrialized economies are often viewed as a financial burden on the family and marriage of young girls is often driven in the hope that daughters will be fed and protected by wealthier families.[43] Female genital mutilation and force-feeding of daughters is argued to be similarly driven in large part to increase their marriage prospects and thus their financial security by achieving certain idealized standards of beauty.[44] In certain areas, girls requiring the experience of sexual initiation rites with men and passing sex training tests on girls are designed to make them more appealing as marriage prospects.[45] Measures to help the economic status of vulnerable groups in order to reduce human rights violations include girls' education and guaranteed minimum incomes and conditional cash transfers, such as Bolsa familia which subsidize parents who keep children in school rather than contributing to family income, has successfully reduced child labor.[46]

Informational strategies

Human rights abuses are monitored by United Nations committees, national institutions and governments and by many independent non-governmental organizations, such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, World Organisation Against Torture, Freedom House, International Freedom of Expression Exchange and Anti-Slavery International. These organisations collect evidence and documentation of human rights abuses and apply pressure to promote human rights. Educating people on the concept of human rights has been argued as a strategy to prevent human rights abuses.[47]

Legal instruments

Many examples of legal instruments at the international, regional and national level described below are designed to enforce laws securing human rights.

Protection at the international level

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is the only multilateral governmental agency with universally accepted international jurisdiction for universal human rights legislation.[48] All UN organs have advisory roles to the United Nations Security Council and the United Nations Human Rights Council, and there are numerous committees within the UN with responsibilities for safeguarding different human rights treaties. The most senior body of the UN with regard to human rights is the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. The United Nations has an international mandate to:

... achieve international co-operation in solving international problems of an economic, social, cultural, or humanitarian character, and in promoting and encouraging respect for human rights and for fundamental freedoms for all without distinction as to race, sex, language, or religion.

— Article 1–3 of the Charter of the United Nations

Human Rights Council

The UN Human Rights Council, created in 2005, has a mandate to investigate alleged human rights violations.[49] 47 of the 193 UN member states sit on the council, elected by simple majority in a secret ballot of the United Nations General Assembly. Members serve a maximum of six years and may have their membership suspended for gross human rights abuses. The council is based in Geneva, and meets three times a year; with additional meetings to respond to urgent situations.[50] Independent experts (rapporteurs) are retained by the council to investigate alleged human rights abuses and to report to the council. The Human Rights Council may request that the Security Council refer cases to the International Criminal Court (ICC) even if the issue being referred is outside the normal jurisdiction of the ICC.[b]

United Nations treaty bodies

In addition to the political bodies whose mandate flows from the UN charter, the UN has set up a number of treaty-based bodies, comprising committees of independent experts who monitor compliance with human rights standards and norms flowing from the core international human rights treaties. They are supported by and are created by the treaty that they monitor, With the exception of the CESCR, which was established under a resolution of the Economic and Social Council to carry out the monitoring functions originally assigned to that body under the Covenant, they are technically autonomous bodies, established by the treaties that they monitor and accountable to the state parties of those treaties – rather than subsidiary to the United Nations, though in practice they are closely intertwined with the United Nations system and are supported by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNHCHR) and the UN Centre for Human Rights.[51]

- The Human Rights Committee promotes participation with the standards of the ICCPR. The members of the committee express opinions on member countries and make judgments on individual complaints against countries which have ratified an Optional Protocol to the treaty. The judgments, termed "views", are not legally binding. The member of the committee meets around three times a year to hold sessions[52]

- The Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights monitors the ICESCR and makes general comments on ratifying countries performance. It will have the power to receive complaints against the countries that opted into the Optional Protocol once it has come into force. Unlike the other treaty bodies, the economic committee is not an autonomous body responsible to the treaty parties, but directly responsible to the Economic and Social Council and ultimately to the General Assembly. This means that the Economic Committee faces particular difficulties at its disposal only relatively "weak" means of implementation in comparison to other treaty bodies.[53] Particular difficulties noted by commentators include: perceived vagueness of the principles of the treaty, relative lack of legal texts and decisions, ambivalence of many states in addressing economic, social and cultural rights, comparatively few non-governmental organisations focused on the area and problems with obtaining relevant and precise information.[53][54]

- The Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination monitors the CERD and conducts regular reviews of countries' performance. It can make judgments on complaints against member states allowing it, but these are not legally binding. It issues warnings to attempt to prevent serious contraventions of the convention.

- The Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women monitors the CEDAW. It receives states' reports on their performance and comments on them, and can make judgments on complaints against countries which have opted into the 1999 Optional Protocol.

- The Committee Against Torture monitors the CAT and receives states' reports on their performance every four years and comments on them. Its subcommittee may visit and inspect countries which have opted into the Optional Protocol.

- The Committee on the Rights of the Child monitors the CRC and makes comments on reports submitted by states every five years. It does not have the power to receive complaints.

- The Committee on Migrant Workers was established in 2004 and monitors the ICRMW and makes comments on reports submitted by states every five years. It will have the power to receive complaints of specific violations only once ten member states allow it.

- The Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was established in 2008 to monitor the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. It has the power to receive complaints against the countries which have opted into the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities.

- The Committee on Enforced Disappearances monitors the ICPPED. All States parties are obliged to submit reports to the committee on how the rights are being implemented. The Committee examines each report and addresses its concerns and recommendations to the State party in the form of "concluding observations".

Each treaty body receives secretariat support from the Human Rights Council and Treaties Division of Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights (OHCHR) in Geneva except CEDAW, which is supported by the Division for the Advancement of Women (DAW). CEDAW formerly held all its sessions at United Nations headquarters in New York but now frequently meets at the United Nations Office in Geneva; the other treaty bodies meet in Geneva. The Human Rights Committee usually holds its March session in New York City. The human rights enshrined in the UDHR, the Geneva Conventions and the various enforced treaties of the United Nations are enforceable in law. In practice, many rights are very difficult to legally enforce due to the absence of consensus on the application of certain rights, the lack of relevant national legislation or of bodies empowered to take legal action to enforce them.

International courts

There exist a number of internationally recognized organisations with worldwide mandate or jurisdiction over certain aspects of human rights:

- The International Court of Justice (ICJ) is the United Nations' primary judiciary body.[55] It has worldwide jurisdiction. It is directed by the Security Council. The ICJ settles disputes between nations. The ICJ does not have jurisdiction over individuals.

- The International Criminal Court (ICC) is the body responsible for investigating and punishing war crimes, and crimes against humanity when such occur within its jurisdiction, with a mandate to bring to justice perpetrators of such crimes that occurred after its creation in 2002. A number of UN members have not joined the court and the ICC does not have jurisdiction over their citizens, and others have signed but not yet ratified the Rome Statute, which established the court.[56]

The ICC and other international courts (see Regional human rights below) exist to take action where the national legal system of a state is unable to try the case itself. If national law is able to safeguard human rights and punish those who breach human rights legislation, it has primary jurisdiction by complementarity. Only when all local remedies have been exhausted does international law take effect.[57]

Regional human rights regimes

In over 110 countries, national human rights institutions (NHRIs) have been set up to protect, promote or monitor human rights with jurisdiction in a given country.[58] Although not all NHRIs are compliant with the Paris Principles,[59] the number and effect of these institutions is increasing.[60] The Paris Principles were defined at the first International Workshop on National Institutions for the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights in Paris on 7–9 October 1991, and adopted by United Nations Human Rights Commission Resolution 1992/54 of 1992 and the General Assembly Resolution 48/134 of 1993. The Paris Principles list a number of responsibilities for national institutions.[61]

Africa

The African Union (AU) is a continental union consisting of fifty-five African states.[62] Established in 2001, the AU's purpose is to help secure Africa's democracy, human rights, and a sustainable economy, especially by bringing an end to intra-African conflict and creating an effective common market.[63] The African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights (ACHPR) is a quasi-judicial organ of the African Union tasked with promoting and protecting human rights and collective (peoples') rights throughout the African continent as well as interpreting the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights and considering individual complaints of violations of the Charter. The commission has three broad areas of responsibility:[64]

- Promoting human and peoples' rights

- Protecting human and peoples' rights

- Interpreting the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights

In pursuit of these goals, the commission is mandated to "collect documents, undertake studies and researches on African problems in the field of human and peoples, rights, organise seminars, symposia and conferences, disseminate information, encourage national and local institutions concerned with human and peoples' rights and, should the case arise, give its views or make recommendations to governments" (Charter, Art. 45).[64]

With the creation of the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights (under a protocol to the Charter which was adopted in 1998 and entered into force in January 2004), the commission will have the additional task of preparing cases for submission to the Court's jurisdiction.[65] In a July 2004 decision, the AU Assembly resolved that the future Court on Human and Peoples' Rights would be integrated with the African Court of Justice. The Court of Justice of the African Union is intended to be the "principal judicial organ of the Union" (Protocol of the Court of Justice of the African Union, Article 2.2).[66] Although it has not yet been established, it is intended to take over the duties of the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights, as well as act as the supreme court of the African Union, interpreting all necessary laws and treaties. The Protocol establishing the African Court on Human and Peoples' Rights entered into force in January 2004,[67] but its merging with the Court of Justice has delayed its establishment. The Protocol establishing the Court of Justice will come into force when ratified by 15 countries.[68]

There are many countries in Africa accused of human rights violations by the international community and NGOs.[69]

Americas

The Organization of American States (OAS) is an international organization, headquartered in Washington, D.C., United States. Its members are the thirty-five independent states of the Americas. Over the course of the 1990s, with the end of the Cold War, the return to democracy in Latin America, and the thrust toward globalization, the OAS made major efforts to reinvent itself to fit the new context. Its stated priorities now include the following:[70]

- Strengthening democracy

- Working for peace

- Protecting human rights

- Combating corruption

- The rights of Indigenous Peoples

- Promoting sustainable development

The Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (the IACHR) is an autonomous organ of the Organization of American States, also based in Washington, D.C. Along with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, based in San José, Costa Rica, it is one of the bodies that comprise the inter-American system for the promotion and protection of human rights.[71] The IACHR is a permanent body which meets in regular and special sessions several times a year to examine allegations of human rights violations in the hemisphere. Its human rights duties stem from three documents:[72]

- the American Convention on Human Rights

- the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man

- the Charter of the Organization of American States

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights was established in 1979 with the purpose of enforcing and interpreting the provisions of the American Convention on Human Rights. Its two main functions are thus adjudicatory and advisory. Under the former, it hears and rules on the specific cases of human rights violations referred to it. Under the latter, it issues opinions on matters of legal interpretation brought to its attention by other OAS bodies or member states.[73]

Asia

There are no Asia-wide organisations or conventions to promote or protect human rights. Countries vary widely in their approach to human rights and their record of human rights protection.[74][75] The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)[76] is a geo-political and economic organization of 10 countries located in Southeast Asia, which was formed in 1967 by Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand.[77] The organisation now also includes Brunei Darussalam, Vietnam, Laos, Myanmar and Cambodia.[76] In October 2009, the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights was inaugurated,[78] and subsequently, the ASEAN Human Rights Declaration was adopted unanimously by ASEAN members on 18 November 2012.[79]

The Arab Charter on Human Rights (ACHR) was adopted by the Council of the League of Arab States on 22 May 2004.[80]

Europe

The Council of Europe, founded in 1949, is the oldest organisation working for European integration. It is an international organisation with legal personality recognised under public international law and has observer status with the United Nations. The seat of the Council of Europe is in Strasbourg in France. The Council of Europe is responsible for both the European Convention on Human Rights and the European Court of Human Rights.[81] These institutions bind the council's members to a code of human rights which, though strict, are more lenient than those of the United Nations charter on human rights. The council also promotes the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages and the European Social Charter.[82] Membership is open to all European states which seek European integration, accept the principle of the rule of law and are able and willing to guarantee democracy, fundamental human rights and freedoms.[83]

The Council of Europe is an organisation that is not part of the European Union, but the latter is expected to accede to the European Convention and potentially the Council itself. The EU has its own human rights document; the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.[84] The European Convention on Human Rights defines and guarantees since 1950 human rights and fundamental freedoms in Europe.[85] All 47 member states of the Council of Europe have signed this convention and are therefore under the jurisdiction of the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg.[85] In order to prevent torture and inhuman or degrading treatment (Article 3 of the convention), the European Committee for the Prevention of Torture was established.[86]

Philosophies of human rights

| Rights |

|---|

|

| Theoretical distinctions |

| Human rights |

| Rights by beneficiary |

| Other groups of rights |

Several theoretical approaches have been advanced to explain how and why human rights become part of social expectations. One of the oldest Western philosophies on human rights is that they are a product of a natural law, stemming from different philosophical or religious grounds. Other theories hold that human rights codify moral behavior which is a human social product developed by a process of biological and social evolution (associated with David Hume). Human rights are also described as a sociological pattern of rule setting (as in the sociological theory of law and the work of Max Weber). These approaches include the notion that individuals in a society accept rules from legitimate authority in exchange for security and economic advantage (as in John Rawls) – a social contract.

Natural rights

Natural law theories base human rights on a "natural" moral, religious or even biological order which is independent of transitory human laws or traditions. Socrates and his philosophic heirs, Plato and Aristotle, posited the existence of natural justice or natural right (dikaion physikon, δικαιον φυσικον, Latin ius naturale). Of these, Aristotle is often said to be the father of natural law,[87] although evidence for this is due largely to the interpretations of his work by Thomas Aquinas.[88] The development of this tradition of natural justice into one of natural law is usually attributed to the Stoics.[89]

Some of the early Church fathers sought to incorporate the until then pagan concept of natural law into Christianity. Natural law theories have featured greatly in the philosophies of Thomas Aquinas, Francisco Suárez, Richard Hooker, Thomas Hobbes, Hugo Grotius, Samuel von Pufendorf, and John Locke. In the 17th century, Thomas Hobbes founded a contractualist theory of legal positivism on what all men could agree upon: what they sought (happiness) was subject to contention, but a broad consensus could form around what they feared (violent death at the hands of another). The natural law was how a rational human being, seeking to survive and prosper, would act. It was discovered by considering humankind's natural rights, whereas previously it could be said that natural rights were discovered by considering the natural law. In Hobbes' opinion, the only way natural law could prevail was for men to submit to the commands of the sovereign. In this lay the foundations of the theory of a social contract between the governed and the governor.

Hugo Grotius based his philosophy of international law on natural law. He wrote that "even the will of an omnipotent being cannot change or abrogate" natural law, which "would maintain its objective validity even if we should assume the impossible, that there is no God or that he does not care for human affairs." (De iure belli ac pacis, Prolegomeni XI). This is the famous argument etiamsi daremus (non-esse Deum), that made natural law no longer dependent on theology. John Locke incorporated natural law into many of his theories and philosophy, especially in Two Treatises of Government. Locke turned Hobbes' prescription around, saying that if the ruler went against natural law and failed to protect "life, liberty, and property," people could justifiably overthrow the existing state and create a new one.

Бельгийский философ права Франк ван Дун — один из тех, кто разрабатывает светскую концепцию естественного права в либеральной традиции. [90] There are also emerging and secular forms of natural law theory that define human rights as derivative of the notion of universal human dignity.[91] Термин «права человека» заменил по популярности термин « естественные права », поскольку права все реже и реже рассматриваются как требующие естественного закона для своего существования. [92]

Другие теории прав человека

Философ Джон Финнис утверждает, что права человека оправданы на основании их инструментальной ценности в создании необходимых условий для человеческого благополучия. [93] [94] Теории интересов подчеркивают обязанность уважать права других людей исходя из собственных интересов:

Закон о правах человека, применяемый к гражданам государства, служит интересам государства, например, сводя к минимуму риск насильственного сопротивления и протеста, а также сохраняя управляемым уровень недовольства правительством.

- Нирадж Натвани, Переосмысление закона о беженцах [95]

Биологическая альтруизме теория рассматривает сравнительное репродуктивное преимущество социального поведения человека, основанного на эмпатии и , в контексте естественного отбора . [96] [97] [98] Философ Чжао Тинъян утверждает, что традиционная система прав человека не может быть универсальной, поскольку она возникла из случайных аспектов западной культуры, и что концепция неотъемлемых и безусловных прав человека находится в противоречии с принципом справедливости . Он предлагает альтернативную структуру под названием «кредит прав человека», в которой права связаны с обязанностями. [99] [100]

Концепции в области прав человека

Неделимость и категоризация прав

Наиболее распространенной категоризацией прав человека является разделение их на гражданские и политические права, а также экономические, социальные и культурные права. Гражданские и политические права закреплены в статьях 3–21 Всеобщей декларации прав человека и МПГПП. Экономические, социальные и культурные права закреплены в статьях 22–28 Всеобщей декларации прав человека и МПЭСКП. ВДПЧ включала как экономические, социальные и культурные права, так и гражданские и политические права, поскольку она была основана на принципе, согласно которому различные права могут успешно существовать только в сочетании:

Идеал свободных людей, пользующихся гражданской и политической свободой и свободой от страха и нужды, может быть достигнут только в том случае, если будут созданы условия, при которых каждый сможет пользоваться своими гражданскими и политическими правами, а также своими социальными, экономическими и культурными правами.

— Международный пакт о гражданских и политических правах и Международный пакт об экономических, социальных и культурных правах , 1966 г.

Это считается правдой, поскольку без гражданских и политических прав общественность не может отстаивать свои экономические, социальные и культурные права. Аналогичным образом, без средств к существованию и работающего общества общество не может отстаивать или использовать гражданские или политические права (известный как тезис о полном животе ).

Несмотря на то, что ВДПЧ принята сторонами, подписавшими ВДПЧ, большинство из них на практике не придают равного значения различным типам прав. Западные культуры часто отдают приоритет гражданским и политическим правам, иногда в ущерб экономическим и социальным правам, таким как право на труд, образование, здравоохранение и жилье. Например, в США не существует всеобщего доступа к бесплатному медицинскому обслуживанию на месте. [101] Это не означает, что западные культуры полностью игнорировали эти права (государства всеобщего благосостояния, существующие в Западной Европе, являются тому подтверждением). Аналогичным образом, страны бывшего советского блока и страны Азии, как правило, отдавали приоритет экономическим, социальным и культурным правам, но часто не обеспечивали гражданские и политические права.

Другая классификация, предложенная Карелом Васаком , заключается в том, что существует три поколения прав человека : гражданские и политические права первого поколения (право на жизнь и участие в политической жизни), экономические, социальные и культурные права второго поколения (право на существование) и третье поколение. - права солидарности поколений (право на мир, право на чистую окружающую среду). Из этих поколений третье поколение является наиболее обсуждаемым и не имеет ни юридического, ни политического признания. Эта категоризация противоречит принципу неделимости прав, поскольку неявно утверждает, что одни права могут существовать без других. Однако приоритезация прав по прагматическим соображениям является широко признанной необходимостью. Эксперт по правам человека Филип Олстон утверждает:

Если каждый возможный элемент прав человека будет считаться важным или необходимым, то ничто не будет рассматриваться как действительно важное. [102]

— Филип Олстон

Он и другие призывают к осторожности при определении приоритетности прав:

... призыв к расстановке приоритетов не означает, что можно игнорировать любые очевидные нарушения прав. [102]

— Филип Олстон

Приоритеты, где это необходимо, должны соответствовать основным концепциям (таким как разумные попытки постепенной реализации) и принципам (таким как недискриминация, равенство и участие). [103]

— Оливия Болл , Пол Гриди

Некоторые права человека считаются « неотъемлемыми правами ». Термин «неотчуждаемые права» (или «неотчуждаемые права») относится к «набору прав человека, которые являются фундаментальными, не предоставляются человеческой властью и не могут быть отменены».

Приверженность международному сообществу принципу неделимости была подтверждена в 1995 году:

Все права человека универсальны, неделимы, взаимозависимы и взаимосвязаны. Международное сообщество должно относиться к правам человека во всем мире справедливо и равно, на одинаковой основе и с одинаковым вниманием.

— Венская декларация и Программа действий , Всемирная конференция по правам человека, 1995 г.

Это заявление было вновь одобрено на Всемирном саммите 2005 года в Нью-Йорке (пункт 121).

Универсализм против культурного релятивизма

Всеобщая декларация прав человека по определению закрепляет права, которые в равной степени применимы ко всем людям, к какому бы географическому местоположению, государству, расе или культуре они ни принадлежали. Сторонники культурного релятивизма предполагают, что не все права человека универсальны и даже противоречат некоторым культурам и угрожают их выживанию. Права, которые чаще всего оспариваются с помощью релятивистских аргументов, — это права женщин. Например, калечащие операции на женских половых органах встречаются в различных культурах Африки, Азии и Южной Америки. Это не предписано какой-либо религией, но стало традицией во многих культурах. Большая часть международного сообщества считает это нарушением прав женщин и девочек, а в некоторых странах оно объявлено вне закона.

Некоторые описывают универсализм как культурный, экономический или политический империализм. В частности, часто утверждается, что концепция прав человека фундаментально коренится в политически либеральном мировоззрении, которое, хотя и является общепринятым в Европе, Японии или Северной Америке, не обязательно принимается в качестве стандарта в других странах. Например, в 1981 году представитель Ирана в Организации Объединенных Наций Саид Раджаи-Хорассани сформулировал позицию своей страны в отношении ВДПЧ, заявив, что ВДПЧ представляет собой « светское понимание иудео-христианской традиции», которое не может быть реализуются мусульманами без нарушения исламского закона. [104] Бывшие премьер-министры Сингапура Ли Куан Ю и Малайзии азиатские Махатхир Мохамад в 1990-е годы заявляли, что ценности существенно отличаются от западных и включают в себя чувство лояльности и отказ от личных свобод ради социальной стабильности и процветания. и поэтому авторитарное правительство более уместно в Азии, чем демократия. Этой точке зрения возражает бывший заместитель Махатхира:

Сказать, что свобода является западной или неазиатской, значит оскорбить наши традиции, а также наших предков, которые отдали свои жизни в борьбе с тиранией и несправедливостью.

- Анвар Ибрагим , в своей программной речи на Азиатском форуме прессы под названием «СМИ и общество в Азии» , 2 декабря 1994 г.

Лидер сингапурской оппозиции Чи Сун Хуан также заявляет, что утверждение о том, что азиаты не хотят прав человека, является расизмом. [105] [106] Часто апеллируют к тому факту, что влиятельные мыслители в области прав человека, такие как Джон Локк и Джон Стюарт Милль , все были выходцами с Запада, и что некоторые из них действительно участвовали в управлении империями. [107] [108] Релятивистские аргументы, как правило, игнорируют тот факт, что современные права человека являются новыми для всех культур, начиная с ВДПЧ в 1948 году. Они также не учитывают тот факт, что ВДПЧ была разработана людьми, принадлежащими к самым разным культурам и традициям, включая католик из США, китайский философ-конфуцианец, французский сионист и представитель Лиги арабских государств, среди прочих, и опирался на советы таких мыслителей, как Махатма Ганди. [28]

Майкл Игнатьефф утверждал, что культурный релятивизм — это почти исключительно аргумент, используемый теми, кто обладает властью в культурах, которые нарушают права человека, и что те, чьи права человека нарушены, бессильны. [109] Это отражает тот факт, что трудность в оценке универсализма и релятивизма заключается в том, кто утверждает, что представляет конкретную культуру. Хотя спор между универсализмом и релятивизмом далек от завершения, это академическая дискуссия, поскольку все международные документы по правам человека придерживаются принципа универсальной применимости прав человека. Всемирный саммит 2005 года подтвердил приверженность международного сообщества этому принципу:

Универсальный характер прав и свобод человека не подлежит сомнению.

- Всемирный саммит 2005 г., параграф 120.

Универсальная юрисдикция против государственного суверенитета

Универсальная юрисдикция является спорным принципом в международном праве, согласно которому государства претендуют на уголовную юрисдикцию в отношении лиц, предполагаемые преступления которых были совершены за пределами государства, осуществляющего преследование, независимо от гражданства, страны проживания или каких-либо других отношений со страной, осуществляющей преследование. Государство поддерживает свое утверждение на том основании, что совершенное преступление считается преступлением против всех, за которое любое государство имеет право наказывать. Таким образом, концепция универсальной юрисдикции тесно связана с идеей о том, что определенные международные нормы являются erga omnes или обязаны всему мировому сообществу, а также с концепцией jus cogens . В 1993 году Бельгия приняла закон об универсальной юрисдикции , предоставляющий юрисдикцию своего суда в отношении преступлений против человечности в других странах, а в 1998 году Аугусто Пиночет был арестован в Лондоне после предъявления обвинения испанским судьей Бальтасаром Гарсоном в соответствии с принципом универсальной юрисдикции. [110] Этот принцип поддерживается Amnesty International и другими правозащитными организациями , поскольку они считают, что определенные преступления представляют угрозу международному сообществу в целом, и у сообщества есть моральный долг действовать, но другие, в том числе Генри Киссинджер , утверждают, что государственный суверенитет имеет первостепенное значение. , поскольку нарушения прав, совершенные в других странах, находятся за пределами суверенных интересов государств и потому что государства могут использовать этот принцип по политическим причинам. [111]

Государственные и негосударственные субъекты

Компании, НПО, политические партии, неформальные группы и отдельные лица известны как негосударственные субъекты . Негосударственные субъекты также могут нарушать права человека, но на них не распространяется действие других законов о правах человека, кроме международного гуманитарного права, которое применяется к отдельным лицам. Транснациональные компании играют все более важную роль в мире и несут ответственность за большое количество нарушений прав человека. [112] Хотя правовая и моральная среда, окружающая действия правительств, достаточно хорошо развита, ситуация вокруг транснациональных компаний противоречива и нечетко определена. Транснациональные компании часто рассматривают свою основную ответственность как перед своими акционерами , а не перед теми, кого затронули их действия. Такие компании часто превышают экономику государств, в которых они работают, и могут обладать значительной экономической и политической властью. Не существует международных договоров, специально регулирующих поведение компаний в отношении прав человека, а национальное законодательство очень разнообразно. Жан Зиглер , специальный докладчик Комиссии ООН по правам человека по вопросу о праве на питание, заявил в докладе 2003 года:

Растущая мощь транснациональных корпораций и расширение их власти посредством приватизации, дерегулирования и сворачивания государства также означают, что сейчас настало время разработать обязательные правовые нормы, которые обязывают корпорации соблюдать стандарты прав человека и ограничивают потенциальные злоупотребления их властным положением. . [113]

— Жан Зиглер

В августе 2003 года Подкомиссия Комиссии по правам человека по поощрению и защите прав человека подготовила проект Норм об ответственности транснациональных корпораций и других предприятий в отношении прав человека . [114] Они были рассмотрены Комиссией по правам человека в 2004 году, но не имеют обязательного статуса для корпораций и не контролируются. [115] Кроме того, цель 10 устойчивого развития Организации Объединенных Наций направлена на существенное сокращение неравенства к 2030 году посредством принятия соответствующего законодательства. [116]

Права человека в чрезвычайных ситуациях

За исключением не допускающих отступлений прав человека (международные конвенции классифицируют право на жизнь, право на свободу от рабства, право на свободу от пыток и право на свободу от ретроактивного применения уголовных законов как не допускающие отступлений) , [117] ООН признает, что права человека могут быть ограничены или даже отодвинуты в сторону во время чрезвычайного положения в стране, хотя и уточняет:

Чрезвычайная ситуация должна быть реальной, затрагивать все население и представлять угрозу самому существованию нации. Объявление чрезвычайного положения также должно быть крайней мерой и временной мерой.

- Организация Объединенных Наций, Ресурс [117]

Права, от которых нельзя отступать ни при каких обстоятельствах по соображениям национальной безопасности, известны как императивные нормы или jus cogens . Такие обязательства по международному праву обязательны для всех государств и не могут быть изменены договором.

Критика

Критики точки зрения, согласно которой права человека универсальны, утверждают, что права человека — это западная концепция, которая «исходит из европейского, иудео-христианского наследия и/или наследия Просвещения (обычно называемого западным) и не может быть реализована другими культурами, которые не подражают условия и ценности «западных» обществ». [118] Правые критики прав человека утверждают, что это «нереалистичные и неисполнимые нормы и неуместное посягательство на государственный суверенитет», в то время как левые критики прав человека утверждают, что они не «способны достичь прогрессивных целей или препятствуют лучшим подходам к достижению прогрессивных целей». . [119]

См. также

- Права животных

- Гражданские свободы

- Движение за права глухих

- Движение за права инвалидов

- Дискриминация

- Право человека на воду и санитарию

- Трудовые права

- Права ЛГБТ по странам или территориям

- Список правозащитных организаций

- Список наград в области прав человека

- Права меньшинств

- Потребности

- Права заключенных

- Праведность

- Права на благосостояние

Пояснительные примечания

Примечания

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и Джеймс Никель, при содействии Томаса Погге, MBE Смита и Лейфа Венара, 13 декабря 2013 г., Стэнфордская энциклопедия философии, права человека . Архивировано 5 августа 2019 г. в Wayback Machine . Проверено 14 августа 2014 г.

- ^ Никель (2010) .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж Организация Объединенных Наций, Управление Верховного комиссара по правам человека, Что такое права человека? Архивировано 19 августа 2014 года в Wayback Machine . Проверено 14 августа 2014 г.

- ^ Сепульведа и др. (2004) , с. 3.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Бернс Х. Уэстон, 20 марта 2014 г., Британская энциклопедия, права человека . Архивировано 18 мая 2015 г. в Wayback Machine . Проверено 14 августа 2014 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д и ж г Гэри Дж. Басс (книжный рецензент), Сэмюэл Мойн (автор рецензируемой книги), 20 октября 2010 г., The New Republic, The Old New Thing . Архивировано 12 сентября 2015 г. в Wayback Machine . Проверено 14 августа 2014 г.

- ^ Шоу (2008) , с. 265.

- ↑ Словарь Macmillan, права человека – определение. Архивировано 19 августа 2014 года в Wayback Machine . Проверено 14 августа 2014 г., «права, которые каждый должен иметь в обществе, включая право выражать мнение о правительстве или на защиту от вреда».

- ^ Международное техническое руководство по сексуальному образованию: научно обоснованный подход (PDF) . Париж: ЮНЕСКО. 2018. с. 16. ISBN 978-9231002595 . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 13 ноября 2018 года . Проверено 23 февраля 2018 г.

- ^ Симмонс, Бет А. (2009). Мобилизация в защиту прав человека: международное право во внутренней политике . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 23. ISBN 978-1139483483 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Фриман (2002) , стр. 15–17.

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Мойн (2010) , с. 8.

- ^ Симмонс, Бет А. (2009). Мобилизация в защиту прав человека: международное право во внутренней политике . Издательство Кембриджского университета. п. 23. ISBN 978-1139483483 .

- ^ Сутто, Марко (2019). «Эволюция прав человека, краткая история» . Журнал КЭГПУ . 2019 (3): 18–21. doi : 10.32048/Coespumagazine3.19.3 . Архивировано из оригинала 6 марта 2023 года . Проверено 6 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Краткая история прав человека» . Архивировано из оригинала 6 марта 2023 года . Проверено 6 марта 2023 г.

- ^ «Международное право прав человека: Краткая история» . Архивировано из оригинала 14 марта 2023 года . Проверено 6 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Карлайл, AJ (1903). История средневековой политической теории на Западе . Том. 1. Нью-Йорк: Сыновья Г.П. Патнэма. п. 83. Архивировано из оригинала 8 июня 2016 года.

- ^ «Августин о законе и порядке — Lawexplores.com» .

- ^ Хейзелтин, HD (1917). «Влияние Великой хартии вольностей на конституционное развитие Америки». В Молдене, Генри Эллиот (ред.). Очерки памяти Великой хартии вольностей . БиблиоБазар. ISBN 978-1116447477 .

- ^ «Неписаная конституция Великобритании» . Британская библиотека. Архивировано из оригинала 8 сентября 2021 года . Проверено 27 ноября 2015 г.

Ключевой вехой является Билль о правах (1689 г.), который установил верховенство парламента над короной... предусматривая регулярные заседания парламента, свободные выборы в палату общин, свободу слова в парламентских дебатах и некоторые основные права человека. наиболее известная свобода от «жестокого или необычного наказания».

- ^ Майер (2000) , с. 110.

- ^ « Ex Parte Milligan , 71 US 2, 119. (полный текст)» (PDF) . Декабрь 1866 года. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 7 марта 2008 года . Проверено 28 декабря 2007 г.

- ^ Креншоу, Кимберл (1991). «Картирование границ: интерсекциональность, политика идентичности и насилие в отношении цветных женщин» . Стэнфордский юридический обзор . 43 (6): 1241–1299. дои : 10.2307/1229039 . ISSN 0038-9765 . JSTOR 1229039 .

- ↑ Элеонора Рузвельт: Обращение к Генеральной Ассамблее Организации Объединенных Наций. Архивировано 22 июня 2017 года в Wayback Machine, 10 декабря 1948 года в Париже, Франция.

- ^ (A/RES/217, 10 декабря 1948 г., Дворец Шайо, Париж)

- ^ Jump up to: а б с д Глендон, Мэри Энн (июль 2004 г.). «Верховенство закона во Всеобщей декларации прав человека» . Журнал Северо-Западного университета по международным правам человека . 2 (5). Архивировано из оригинала 20 июля 2011 года . Проверено 7 января 2008 г.

- ^ Глендон (2001) .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Болл и Гриди (2007) , с. 34.

- ^ Пол Гордон Лорен , «Первые принципы расового равенства: история, политика и дипломатия положений о правах человека в Уставе Организации Объединенных Наций», Human Rights Quarterly 5 (1983): 1–26.

- ^ Генри Дж. Ричардсон III, «Черные люди, технократия и юридический процесс: мысли, страхи и цели», в «Государственной политике для черного сообщества», изд. Маргерит Росс Барнетт и Джеймс А. Хефнер (Порт Вашингтон, штат Нью-Йорк: Alfred Publishing, 1976), стр. 179.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Болл и Гриди (2007) , с. 35.

- ^ Литтман, Дэвид Г. (19 января 2003 г.). «Права человека и человеческие ошибки» . Национальное обозрение . Архивировано из оригинала 11 января 2008 года . Проверено 7 января 2008 г.

Основная цель Всеобщей декларации прав человека 1948 года (ВДПЧ) заключалась в создании основы для универсального кодекса, основанного на взаимном согласии. Первые годы существования Организации Объединенных Наций были омрачены расколом между западной и коммунистической концепциями прав человека, хотя ни одна из сторон не ставила под сомнение концепцию универсальности. Дебаты были сосредоточены на том, какие «права» – политические, экономические и социальные – должны быть включены в универсальные инструменты.

- ^ Болл и Гриди (2007) , с. [ нужна страница ] .

- ^ Болл и Гриди (2007) , с. 37.

- ^ «Конвенция против пыток» . УВКПЧ . 10 декабря 1984 года. Архивировано из оригинала 27 марта 2013 года . Проверено 14 августа 2021 г.

- ^ «Доступ к здоровой окружающей среде объявлен правом человека Советом ООН по правам человека» . Объединенные Нации . 8 октября 2021 г. Проверено 21 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Шарп, Александра. «Швейцарские женщины одержали знаменательную климатическую победу» . Внешняя политика . Проверено 21 апреля 2024 г.

- ^ Акбарзаде, Шахрам; Саба, Ариф (2020). «Паралич ООН в Сирии: ответственность по защите или смена режима?». Международная политика . 56 (4): 536–550. дои : 10.1057/s41311-018-0149-x . ISSN 1384-5748 . S2CID 150004890 .

- ^ Эмерсон, Майкл (1 декабря 2011 г.). «Ответственность за защиту и смену режима» (PDF) . Центр исследований европейской политики. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 6 июня 2022 года . Проверено 4 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Хабибзаде, Фаррох (2018). «Экономические санкции: оружие массового поражения» . Ланцет . 392 (10150): 816–817. дои : 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31944-5 . ПМИД 30139528 . S2CID 52074513 .

- ^ Мюллер, Джон; Мюллер, Карл (1999). «Санкции массового уничтожения». Иностранные дела . 78 (3): 43–53. дои : 10.2307/20049279 . JSTOR 20049279 .

- ^ Несрин Малик (3 июля 2018 г.). «Санкции против Судана не нанесли вреда репрессивному правительству — они ему помогли» . Внешняя политика . Архивировано из оригинала 5 мая 2022 года . Проверено 5 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Дэвис, Лиззи (30 апреля 2022 г.). «Засуха в Эфиопии привела к резкому увеличению числа детских браков, предупреждает ЮНИСЕФ» . Хранитель . Архивировано из оригинала 12 мая 2022 года . Проверено 11 мая 2022 г.

- ^ «Использование образования для прекращения калечащих операций и обрезания женских половых органов во всем мире» (PDF) . Международный центр исследований женщин. п. 3. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 6 октября 2022 г. Проверено 11 мая 2022 г.

Финансовая стабильность женщин и девочек, живущих в районах, где распространено КЖПО/К, часто зависит от брака. В результате КЖПО/О рассматривается как способ гарантировать статус женщины, давая ей возможность иметь детей социально приемлемым способом и обеспечивая ей экономическую безопасность, обычно предоставляемую мужем. Родители, решившие обрезать своих дочерей, считают свое решение необходимым, если не полезным, для будущих перспектив замужества дочери, учитывая финансовые и социальные ограничения, с которыми они могут столкнуться.

- ^ Ахмед, Бениш (20 января 2014 г.). «Противостояние сексуальному обряду в Малави» . Атлантика . Архивировано из оригинала 2 декабря 2019 года . Проверено 11 мая 2022 г.

- ^ «Как остановить работу детей – сосредоточьтесь на сокращении бедности и помощи родителям, а не наказывании их» . Экономист . 18 сентября 2021 г. Архивировано из оригинала 12 мая 2022 г. Проверено 11 мая 2022 г.

- ^ «Холокост — ключ к пониманию ИГИЛ, — говорит глава ООН по правам человека» . Гаарец . 7 февраля 2015 г. Архивировано из оригинала 9 мая 2022 г. Проверено 8 мая 2022 г.

- ^ Болл и Гриди (2007) , с. 92.

- ^ «Совет по правам человека» . Центр новостей ООН. Архивировано из оригинала 13 сентября 2018 года . Проверено 14 мая 2007 г.

- ^ Болл и Гриди (2007) , с. 95.

- ^ Шоу (2008) , с. 311.

- ^ «Введение в комитет» . УВКПЧ . Архивировано из оригинала 7 марта 2022 года . Проверено 6 октября 2017 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б Шоу (2008) , с. 309.

- ^ Олстон, Филип, изд. (1992). Организация Объединенных Наций и права человека: критическая оценка . Оксфорд: Кларендон Пресс. п. 474. ИСБН 978-0198254508 .

- ^ «Cour Internationale de Justice – Международный суд | Международный суд» . icj-cij.org . Архивировано из оригинала 2 июля 2019 года . Проверено 27 августа 2019 г.

- ^ Организация Объединенных Наций. Многосторонние договоры, сданные на хранение Генеральному секретарю: Римский статут Международного уголовного суда . Архивировано 9 мая 2008 года в Wayback Machine . Проверено 8 июня 2007 г.

- ^ «Ресурс, часть II: Международная система прав человека» . Объединенные Нации. Архивировано из оригинала 21 января 2008 года . Проверено 31 декабря 2007 г.

- ^ «Форум национальных правозащитных институтов – международный форум исследователей и практиков в области национальных прав человека» . Архивировано из оригинала 15 сентября 2002 года . Проверено 6 сентября 2007 г.

- ^ «Диаграмма статуса национальных учреждений» (PDF) . Форум национальных правозащитных учреждений. Ноябрь 2007 г. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 16 февраля 2008 г. . Проверено 6 января 2008 г.

Аккредитован Международным координационным комитетом национальных учреждений по поощрению прав человека.

В соответствии с Парижскими принципами и Правилами процедуры Подкомитета ICC ICC использует следующие классификации аккредитации:

Ответ: Соблюдение Парижских принципов;

A(R): Аккредитация с резервом – предоставляется в случае предоставления недостаточной документации для присвоения статуса А;

B: Статус наблюдателя – не полностью соответствует Парижским принципам или предоставлено недостаточно информации для принятия решения;

C: Несоответствие Парижским принципам. - ^ «ЮРИДОКС» . Архивировано из оригинала 20 апреля 2019 года . Проверено 24 апреля 2019 г.

- ^ «Национальные правозащитные учреждения – реализация прав человека», исполнительный директор Мортен Кьерум, Датский институт прав человека, 2003. ISBN 8790744721 , с. 6

- ^ «Государства-члены АС» . Африканский союз. Архивировано из оригинала 5 января 2008 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ «АУ в двух словах» . Архивировано из оригинала 30 декабря 2007 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Мандат Африканской комиссии по правам человека и народов» . Архивировано из оригинала 20 января 2008 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Протокол к Африканской хартии прав человека и народов о создании Африканского суда по правам человека и народов» . Архивировано из оригинала 2 марта 2012 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Протокол Суда Африканского Союза» (PDF) . Африканский союз. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 24 июля 2011 года . Проверено 4 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Открытое письмо председателю Африканского союза (АС) с просьбой дать разъяснения и заверения в том, что создание эффективного Африканского суда по правам человека и народов не будет отложено или подорвано» (PDF) . Международная амнистия. 5 августа 2004 г. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 18 февраля 2008 г. . Проверено 28 января 2019 г.

- ^ «Африканский суд» . Африканские международные суды и трибуналы. Архивировано из оригинала 26 июля 2013 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Африка» . Хьюман Райтс Вотч. Архивировано из оригинала 19 июля 2019 года . Проверено 20 июля 2019 г.

- ^ «Ключевые проблемы ОАГ» . Архивировано из оригинала 3 декабря 2007 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Справочник органов ОАГ» . Организация американских государств. Архивировано из оригинала 20 января 2008 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Что такое МАКПЧ?» . Межамериканская комиссия по правам человека. Архивировано из оригинала 14 января 2008 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Домашняя страница Межамериканского суда по правам человека» . Межамериканский суд по правам человека. Архивировано из оригинала 27 октября 2007 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ Репуччи, Сара; Слиповиц, Эми (2021). «Демократия в осаде» (PDF) . Свобода в мире . Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 10 декабря 2021 года . Проверено 27 марта 2021 г.

Экспорт Пекином антидемократической тактики, финансового принуждения и физического запугивания привел к эрозии демократических институтов и защиты прав человека во многих странах... Политические права и гражданские свободы в стране ухудшились с тех пор, как Нарендра Моди стал премьер-министром в 2014 году, когда усиление давления на правозащитные организации, растущее запугивание ученых и журналистов, а также волна фанатичных нападений, включая линчевания, направленных на мусульман.

- ^ «Отчеты о демократии | V-Dem» . v-dem.net . Архивировано из оригинала 30 июня 2021 года . Проверено 7 июля 2021 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Обзор – Ассоциация государств Юго-Восточной Азии» . Архивировано из оригинала 11 ноября 2002 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ Бангкокская декларация . Викиисточник. Проверено 14 марта 2007 г.

- ^ «Межправительственная комиссия АСЕАН по правам человека (AICHR)» . АСЕАН . Архивировано из оригинала 21 апреля 2021 года . Проверено 21 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ «Декларация прав человека АСЕАН (AHRD) и Пномпеньское заявление о принятии AHRD и ее переводах» (PDF) . АСЕАН . 2013. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 10 сентября 2016 года . Проверено 21 апреля 2021 г.

- ^ «Английская версия Статута Арабского суда по правам человека» . acihl.org . АЦИХЛ. Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2021 года . Проверено 14 декабря 2020 г.

- ^ «Совет Европы по правам человека» . Совет Европы. Архивировано из оригинала 20 июля 2010 года . Проверено 4 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Социальная Хартия» . Совет Европы. Архивировано из оригинала 29 июля 2012 года . Проверено 4 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Кратко о Совете Европы» . Архивировано из оригинала 24 ноября 2003 года . Проверено 4 января 2008 г.

- ^ Юнкер, Жан-Клод (11 апреля 2006 г.). «Совет Европы – Европейский Союз: «Единственная цель Европейского континента» » (PDF) . Совет Европы. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 1 мая 2011 года . Проверено 4 января 2008 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Историческая справка Европейского суда по правам человека» . Европейский суд по правам человека. Архивировано из оригинала 22 декабря 2007 года . Проверено 4 января 2008 г.

- ^ «О Европейском комитете по предотвращению пыток» . Европейский комитет по предотвращению пыток. Архивировано из оригинала 2 января 2008 года . Проверено 4 января 2008 г.

- ^ Шелленс (1959) .

- ^ Яффо (1979) .

- ^ Силлс (1968, 1972) Естественный закон

- ^ Ван Дун, Фрэнк. «Естественный закон» . Архивировано из оригинала 13 декабря 2007 года . Проверено 28 декабря 2007 г.

- ^ Коэн (2007) .

- ^ Уэстон, Бернс Х. «Права человека» . Британская энциклопедия Online, стр. 2. Архивировано из оригинала 18 декабря 2007 года . Проверено 18 мая 2006 г.

- ^ Фэган, Эндрю (2006). «Права человека» . Интернет-энциклопедия философии . Архивировано из оригинала 14 апреля 2009 года . Проверено 1 января 2008 г.

- ^ Финнис (1980) .

- ^ Натвани (2003) , с. 25.

- ^ Арнхарт (1998) .

- ^ Клейтон и Шлосс (2004) .

- ^ Пол, Миллер, Пол (2001): Арнхарт, Ларри. Томистический естественный закон как дарвиновское естественное право стр.1

- ^ Хан, Сан-Джин (2020). «Универсальный, но негегемонистский подход к правам человека в международной политике». Конфуцианство и рефлексивная современность: возвращение сообщества к правам человека в эпоху общества глобального риска . стр. 102–117. дои : 10.1163/9789004415492_008 . ISBN 978-9004415492 . S2CID 214310918 . Проверено 10 марта 2023 г.

- ^ Чжао Тинъян. « Продвинутые права человека»: незападная теория универсальных прав человека» . Архивировано из оригинала 18 мая 2021 года.

- ^ Свет (2002) .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Олстон (2005) , с. 807.

- ^ Болл и Гриди (2007) , с. 42.

- ^ Литтман (1999) .

- ^ Болл и Гриди (2007) , с. 25.

- ^ Чи, SJ (3 июля 2003 г.). Права человека: грязные слова в Сингапуре . Конференция «Активация прав человека и многообразия» (Байрон-Бей, Австралия).

- ^ Туник (2006) .

- ^ Ян (2005) .

- ^ Игнатьев (2001) , с. 68.

- ^ Болл и Гриди (2007) , с. 70.

- ^ Киссинджер, Генри (июль – август 2001 г.). «Ловушка универсальной юрисдикции» . Иностранные дела . 80 (4): 86–96. дои : 10.2307/20050228 . JSTOR 20050228 . Архивировано из оригинала 14 января 2009 года . Проверено 6 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Корпорации и права человека» . Хьюман Райтс Вотч. Архивировано из оригинала 14 ноября 2008 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Транснациональные корпорации должны соблюдать стандарты прав человека – эксперт ООН» . Центр новостей ООН. 13 октября 2003 г. Архивировано из оригинала 21 января 2008 г. Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Нормы об ответственности транснациональных корпораций и других предприятий в отношении прав человека» . Подкомиссия ООН по поощрению и защите прав человека. Архивировано из оригинала 12 сентября 2016 года . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Отчет Экономического и Социального Совета о шестидесятой сессии Комиссии (E/CN.4/2004/L.11/Add.7)» (PDF) . Комиссия ООН по правам человека. п. 81. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 16 февраля 2008 г. . Проверено 3 января 2008 г.

- ^ «Цель 10» . ПРООН . Архивировано из оригинала 27 ноября 2020 года . Проверено 23 сентября 2020 г.

- ^ Jump up to: а б «Ресурс, часть II: Права человека в чрезвычайных ситуациях» . Объединенные Нации. Архивировано из оригинала 21 декабря 2007 года . Проверено 31 декабря 2007 г.

- ^ Шахид, Ахмед; Рихтер, Роуз Пэррис (17 октября 2018 г.). «Являются ли «права человека» западной концепцией?» . Глобальная обсерватория МИП . Архивировано из оригинала 10 июля 2022 года . Проверено 11 августа 2022 г.

- ^ Силк, Джеймс (23 июня 2021 г.). «О чем мы на самом деле говорим, когда говорим о правах человека?» . OpenGlobalRights . Архивировано из оригинала 11 августа 2022 года . Проверено 11 августа 2022 г.

Ссылки и дальнейшее чтение

- Международная амнистия (2004). Отчет Amnesty International . Международная амнистия. ISBN 0862103541 , 1887204407

- Олстон, Филип (2005). «Корабли, проходящие в ночи: современное состояние дебатов о правах человека и развитии сквозь призму целей развития тысячелетия». Ежеквартальный журнал по правам человека . 27 (3): 755–829. дои : 10.1353/hrq.2005.0030 . S2CID 145803790 .

- Арнхарт, Ларри (1998). Дарвиновское естественное право: биологическая этика человеческой природы . СУНИ Пресс. ISBN 0791436934 .

- Болл, Оливия; Гриди, Пол (2007). Серьезное руководство по правам человека . Новый интернационалист. ISBN 978-1904456452 .

- Бейтц, Чарльз Р. (2009). Идея прав человека . Оксфорд: Издательство Оксфордского университета. ISBN 978-0-19-957245-8 .

- Чаухан, ОП (2004). Права человека: продвижение и защита . Публикации Anmol PVT. ООО. ISBN 812612119X .

- Клейтон, Филип; Шлосс, Джеффри (2004). Эволюция и этика: человеческая мораль в биологической и религиозной перспективе . Вм. Издательство Б. Эрдманс. ISBN 0802826954 .

- Коуп К., Крэбтри К. и Фарисс К. (2020). «Модели разногласий в показателях государственных репрессий» Политологические исследования и методы , 8 (1), 178–187. два : 10.1017/psrm.2018.62

- Кросс, Фрэнк Б. «Значение закона в защите прав человека». International Review of Law and Economics 19.1 (1999): 87–98 онлайн. Архивировано 22 апреля 2021 года в Wayback Machine .

- Давенпорт, Кристиан (2007). Государственные репрессии и политический порядок. Ежегодный обзор политической науки.

- Доннелли, Джек. (2003). Всеобщие права человека в теории и практике. 2-е изд. Итака и Лондон: Издательство Корнельского университета. ISBN 0801487765

- Финнис, Джон (1980). Естественный закон и естественные права . Оксфорд: Кларендон Пресс. ISBN 0198761104 .

- Фомеран, Жак. ред. Исторический словарь прав человека (2021 г.), отрывок

- Форсайт, Дэвид П. (2000). Права человека в международных отношениях. Кембридж: Издательство Кембриджского университета. Международная организация прогресса. ISBN 3900704082

- Фридман, Линн П.; Айзекс, Стивен Л. (январь – февраль 1993 г.). «Права человека и репродуктивный выбор». Исследования по планированию семьи Том 24 (№ 1): с. 18–30 JSTOR 2939211

- Фриман, Майкл (2002). Права человека: междисциплинарный подход . Уайли. ISBN 978-0-7456-2356-6 .

- Глендон, Мэри Энн (2001). Новый мир: Элеонора Рузвельт и Всеобщая декларация прав человека . Random House of Canada Ltd. ISBN 0375506926 .

- Горман, Роберт Ф. и Эдвард С. Михалканин, ред. Исторический словарь прав человека и гуманитарных организаций (2007) , отрывок

- Компания Houghton Miffin (2006). Словарь американского наследия английского языка . Хоутон Миффин. ISBN 0618701737

- Игнатьев, Михаил (2001). Права человека как политика и идолопоклонство . Принстон и Оксфорд: Издательство Принстонского университета. ISBN 0691088934 .

- Ишай, Мишлин. истории прав человека: от древних времен до эпохи глобализации (U of California Press, 2008). Отрывок из

- Мойн, Сэмюэл (2010). Последняя утопия: права человека в истории . Издательство Гарвардского университета. ISBN 978-0-674-04872-0 .