Болезнь Паркинсона

Болезнь Паркинсона ( ПД ), или просто Паркинсона , представляет собой нейродегенеративное заболевание в основном центральной нервной системы , которая влияет как на моторные , так и немоторные системы организма. Симптомы обычно возникают медленно, и, по мере развития заболевания, немоторные симптомы становятся более распространенными. Обычные симптомы включают тремор , медлительность движения , жесткость и трудности с балансом , совокупно известные как паркинсонизм . Деменция болезни Паркинсона , падения и нейропсихиатрические проблемы , такие как аномалии сна , психоз , перепада настроения или поведенческие изменения, также могут возникнуть на продвинутых этапах.

Большинство случаев болезни Паркинсона являются спорадическими , но было выявлено несколько факторов, способствующих. Патофизиология характеризуется постепенно расширяющейся гибелью нервных клеток , возникающей в субстанции NIGRA , области среднего мозга , которая обеспечивает дофамин базальным ганглиям , системе, участвующему в добровольном моторном контроле . Причина этой гибели клеток плохо изучена, но включает в себя альфа-синуклеина агрегацию в тела Льюи в нейронах . Другие возможные факторы включают генетические и экологические механизмы, лекарства, образ жизни и предыдущие состояния.

Диагноз в основном основан на признаках и симптомах , обычно связанных с двигателем, обнаруженным с помощью неврологического обследования , хотя медицинская визуализация, такая как Нейромеланин МРТ, может поддерживать диагноз. Обычное начало у людей старше 60 лет, из которых затрагивается около одного процента. У тех, кто младше 50, его называют «Раннее ПД».

Лечение не известно; Цель лечения смягчением симптомов. Первоначальное лечение обычно включает в себя L-DOPA , ингибиторы MAO-B или агонисты дофамина . По мере развития заболевания эти лекарства становятся менее эффективными и создают побочный эффект, отмеченный непроизвольными движениями мышц . Диета и определенные формы реабилитации показали некоторую эффективность при улучшении симптомов. Глубокая стимуляция мозга использовалась для снижения тяжелых моторных симптомов, когда лекарства неэффективны. Существует мало доказательств лечения симптомов, связанных с не движением, таких как нарушения сна и нестабильность настроения. Средняя продолжительность жизни почти нормальна.

Классификация и терминология

[ редактировать ]Болезнь Паркинсона (ПД) представляет собой нейродегенеративное заболевание , влияющее как на центральную , так и периферическую нервную систему , характеризующуюся потерей дофаминовых , продуктивных нейронов в области черной субстанции в мозге. [ 7 ] Он классифицируется как синуклеинопатия из-за аномального накопления белка альфа-синуклеина , который агрегирует в тела Lewy в рамках пораженных нейронов. [ 8 ]

Потеря дофамина, продуцирующих нейроны в субстанции, первоначально представляет собой аномалии движения, что приводит к дальнейшей категоризации Паркинсона как расстройства движения . [ 9 ] В 30% случаев прогрессирование заболевания приводит к снижению когнитивных средств, известном как деменция болезни Паркинсона (PDD). [ 10 ] Наряду с деменцией с Lewy Todies , PDD является одним из двух подтипов деменции Lewy Body . [ 11 ]

Четыре кардинальных моторных симптомов Паркинсона - Брейдикинезии (замедленные движения), постуральная нестабильность , жесткость и тремор - называются паркинсонизмом . [ 12 ] [ 13 ] Эти четыре симптомы не являются исключительными для Паркинсона и могут возникнуть во многих других условиях, [ 14 ] [ 15 ] в том числе ВИЧ -инфекция и употребление наркотиков для отдыха . [ 16 ] [ 17 ] Нейродегенеративные заболевания, которые показывают паркинсонизм, но имеют различные особенности, сгруппированы под отдельным зонтиком синдромов Паркинсона-Плюс или, альтернативно, атипичных расстройств паркинсона. [ 18 ] [ 19 ] Болезнь Паркинсона может быть результатом генетических факторов или быть идиопатической , в которой нет четко идентифицируемой причины. Последний, также называемый спорадическим Паркинсоном, составляет около 85–90% случаев. [ 20 ]

Признаки и симптомы

[ редактировать ]Определяющие симптомы влияют на двигательную систему и включают тремор , брадикинезию , жесткость и постуральную нестабильность . Другие симптомы могут влиять на вегетативную или сенсорную нервную систему, настроение , поведение, модели сна и познание. [ 22 ]

Немоторные симптомы могут предшествовать появлению моторных симптомов до 20 лет. К ним относятся запор, аносмия , расстройства настроения и расстройство поведения быстрого сна среди других. [ 23 ] В целом, моторные симптомы, такие как постуральная нестабильность и аномалии походки, имеют тенденцию проявляться по мере развития заболевания. [ 24 ]

Мотор

[ редактировать ]Четыре моторных симптомы считаются кардинальными признаками в PD: тремор, брадикинезия, жесткость и постуральная нестабильность, в совокупности, известные как паркинсонизм . [ 22 ] Тем не менее, другие моторные симптомы распространены.

Тремор является наиболее распространенным знаком представленного и может появляться как в состоянии покоя, так и во время преднамеренного движения с частотой между 4–6 герцами (циклы в секунду). [ 25 ] Тремор PD имеет тенденцию возникать в руках, но также может влиять на другие части тела, такие как ноги, руки, язык или губы. Его часто описывают как « таблетка », тенденция указательного пальца и большого пальца прикоснуться и выполнять круговое движение, которое напоминает о ранней фармацевтической технике ручного приготовления таблеток. Несмотря на то, что он является наиболее заметным знаком, тремор присутствует только в 70–90 процентах случаев. [ 26 ] [ 25 ]

Брейдикинезия часто считается наиболее важной особенностью болезни Паркинсона, а также присутствует в нетипичном паркинсонизме. Он описывает трудности в планировании моторного планирования , начала и выполнения, что приводит к общему замедлению движения с уменьшенной амплитудой, которая влияет на последовательные и одновременные задачи. [ 27 ] Следовательно, это мешает повседневной деятельности, такими как повязка, кормление и купание. [ 28 ] Мышцы лица , участвующие в Брэйдикинезии, приводят к характеристическому снижению экспрессии лица, известной как «маскированное лицо» или гипомимию . [ 29 ]

Жесткость , также называемая строгостью или «жесткостью», является повышенной сопротивлением во время пассивной мобилизации конечности, затрагивающей до 89 процентов случаев. [ 30 ] Обычно это происходит после начала тремора и брейдикинезии с одной или обеих сторон тела и может привести к боли в мышцах или суставе по мере развития заболевания. [ 31 ] По состоянию на 2024 год остается неясным, вызвана ли жесткость различным биомеханическим процессом или является ли это проявлением другого кардинального признака БП. [ 32 ]

Постуральная нестабильность (PI) типична на более поздних стадиях заболевания, что приводит к нарушению баланса и падений , а также второстепенно к переломам костей, таким образом, снижению подвижности и качества жизни. PI отсутствует на начальных этапах и обычно происходит через 10–15 лет после первого диагноза. В течение первых трех лет после начала заболевания PI может указывать на нетипичный паркинсонизм. [ 33 ] Вместе с брейдикинезией и жесткостью она отвечает за типичную походку, характеризующуюся короткими шагами и положениями, предназначенной для перетасовки, и осанкой . [ 34 ]

Другие общие моторные знаки включают в себя невнятный и тихий голос, и почерк, который постепенно постепенно становится меньше . Это последнее может происходить до других типичных симптомов, но точный нейробиологический механизм, и, следовательно, возможные связи с другими симптомами остаются неизвестными. [ 35 ]

Сенсорный

[ редактировать ]Трансформация сенсорной нервной системы может привести к изменениям в ощущении, которые включают нарушение обоняния , нарушенное зрение , боль и парестезию . [ 36 ] Проблемы с визуально -пространственной функцией могут возникнуть и привести к трудностям в распознавании лиц и восприятии ориентации нарисованных линий. [ 37 ]

периферическая невропатия Известно, что присутствует у 55 процентов пациентов с БП. Хотя он отвечает за большую часть парестезии и боли в БП, его роль в постуральной нестабильности и моторных нарушениях плохо изучена. [ 36 ]

Автономный

[ редактировать ]Изменения в вегетативной нервной системе , известной как дисавтономия , связаны с различными симптомами, такими как желудочно -кишечная дисфункция , ортостатическая гипотензия , чрезмерное потоотделение или недержание мочи. [ 38 ]

Проблемы желудочно -кишечного тракта включают запоры, нарушение опорожнения желудка , выработку слюны иммеров и сложность глотания (распространенность до 82 процентов). Осложнения, возникающие в результате дисфагии, включают обезвоживание , недоедание, потерю веса и аспирационную пневмонию . [ 39 ] Все особенности желудочно -кишечного тракта могут быть достаточно серьезными, чтобы вызвать дискомфорт, здоровье опасности, [ 40 ] и усложнить лечение болезней. [ 41 ] Несмотря на то, что они связаны друг с другом, точный механизм этих симптомов остается неизвестным. [ 42 ]

Ортостатическая гипотензия - это устойчивая капля артериального давления, по меньшей мере, на 20 мм рт.ст. или 10 мм рт. Ст. систолическое Низкое кровяное давление может ухудшить перфузию органов, расположенных над сердцем, особенно мозга, что приводит к легкомысленности . Это может в конечном итоге привести к обморочке и связано с более высокой заболеваемостью и смертностью. [ 43 ]

Другие симптомы, связанные с автономными, включают чрезмерное потоотделение, недержание мочи и сексуальную дисфункцию . [ 38 ]

Нейропсихиатрический

[ редактировать ]Нейропсихиатрические симптомы (NP) являются общими и варьируются от легких нарушений до тяжелых нарушений, составляющих аномалии в познании, настроении, поведении или мысли, которые могут мешать ежедневной деятельности, снижать качество жизни и повысить риск поступления в дом престарелых . Известно, что некоторые из них, такие как депрессия и тревога, предшествуют характерным моторным знакам на срок до нескольких лет и могут провести развитие БП, в то время как большинство из них ухудшаются по мере развития болезни. [ 44 ] Исследования показывают, что пациенты с более тяжелыми моторными симптомами подвержены более высокому риску для любых НП. И наоборот, NP могут ухудшить PD. [ 45 ] [ 46 ]

Депрессия является наиболее распространенным НП и встречается почти у половины всех пациентов. Это имеет низкое настроение и отсутствие удовольствия и более распространено у женщин. Диагноз может быть сложным, поскольку некоторые симптомы депрессии, такие как психомоторная задержка , проблемы с памятью или измененный аппетит, имеют сходство с психиатрическими признаками, вызванными БП. [ 45 ] Это может привести к суицидальным идеям , которое более распространено в PD. Тем не менее, самоубийственные попытки сами ниже, чем в общем населении. [ 47 ]

Апатия характеризуется эмоциональным безразличием и возникает примерно в 46 процентах случаев. Диагноз затруднен, так как он может стать нечетким от симптомов депрессии. [ 45 ]

Тревожные расстройства развиваются примерно в 43 процентах случаев. [ 45 ] Наиболее распространенными являются паническое расстройство , генерализованное тревожное расстройство и социальное тревожное расстройство . [ 44 ] Известно, что беспокойство вызывает ухудшение в симптомах БП. [ 46 ]

болезни Паркинсона Психоз (НДП) присутствует примерно в 20 процентах случаев [ 48 ] и включает галлюцинации , иллюзии и бред . Он связан с дофаминергическими препаратами, используемыми для лечения моторных симптомов, более высокой заболеваемости, смертности, снижением поведения, способствующего здоровью, и более длительного пребывания в доме престарелых. Кроме того, это коррелирует с депрессией и может привести к появлению деменции на продвинутых этапах. В отличие от других психотических форм, PDP обычно представляет собой четкий сенсориум . [ 49 ] Это может перекрываться с другими психиатрическими симптомами, что делает диагноз сложным. [ 50 ]

Расстройства импульсного контроля (МКД) можно увидеть примерно у 19 процентов всех пациентов [ 45 ] and, in the context of PD, are grouped along with compulsive behavior and dopamine dysregulation syndrome (DDS) within the broader spectrum of impulsive and compulsive behaviors (ICB). They are characterized by impulsivity and difficulty to control impulsive urges and are positively correlated with the use of dopamine agonists.[51]

Cognitive

[edit]Cognitive disturbances can occur in early stages or before diagnosis, and increase in prevalence and severity with duration of the disease. Ranging from mild cognitive impairment to severe Parkinson's disease dementia, they feature executive dysfunction, slowed cognitive processing speed, and disrupted perception and estimation of time.[52]

Sleep

[edit]Sleep disorders are common in PD and affect about two thirds of all patients.[53] They comprise insomnia, excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS), restless legs syndrome (RLS), REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), and sleep-disordered breathing (SDB), many of which can be worsened by medication. RBD may begin years prior to the initial motor symptoms. Individual presentation of symptoms vary, although most of people affected by PD show an altered circadian rhythm at some point of disease progression.[54][55]

Other

[edit]PD is associated with a variety of skin disorders that include melanoma, seborrheic dermatitis, bullous pemphigoid, and rosacea.[56] Seborrheic dermatitis is recognized as a premotor feature that indicates dysautonomia and demonstrates that PD can be detected not only by changes of nervous tissue, but tissue abnormalities outside the nervous system as well.[57]

Causes and risk factors

[edit]

As of 2024, the underlying cause of PD is unknown,[58] yet is assumed to be influenced primarily by an interaction of genetic and environmental factors.[59] Nonetheless, the most significant risk factor is age with a prevalence of 1 percent in those aged over 65 and approximately 4.3 percent in age over 85.[60] Genetic components comprise SNCA, LRRK2, and PARK2 among others, while environmental risks include exposure to pesticides or heavy metals.[61] Timing of exposure factor may influence the progression or severity of certain stages.[62]: 46 However, caffeine and nicotine exhibit neuroprotective features, hence lowering the risk of PD.[63][64] About 85 percent of cases occur sporadic, meaning that there is no family history.[65]

Genetic

[edit]PD, in a narrow sense, can be seen as a genetic disease; heritability is estimated to lie between 22 and 40 percent,[59] across different ethnicities.[66] Around 15 percent of diagnosed individuals have a family history, from which 5–10 percent can be attributed to a causative risk gene mutation, although harboring one of these mutations may not lead to the disease.[65]

As of 2024, around 90 genetic risk variants across 78 genomic loci have been identified.[67] Notable risk genes include SNCA, LRRK2, and VPS35 for autosomal dominant inheritance, and PRKN, PINK1, and DJ1 for autosomal recessive inheritance.[59] Additionally, mutations in the GBA1 gene, linked to Gaucher's disease, are found in 5–10 percent of PD cases.[68]

Alpha-synuclein (aSyn), a protein encoded by SNCA gene, is thought to be primarily responsible Lewy body aggregation.[69] ASyn activates ATM serine/threonine kinase, a major DNA damage-repair signaling kinase,[70] and non-homologous end joining DNA repair pathway.[70]

Environmental

[edit]Identifying environmental risk factors and causality is difficult due to the disease's often decade-long prodromal period.[62]: 46 Most noteworthy environmental factors include pesticide exposure and contact with heavy metals.

In particular, exposure to pesticides such as paraquat, rotenone, benomyl, and mancozeb causes one in five cases,[71] implying an association with the onset of PD.[62] Risk is increased by co-exposure to, for example, glyphosate and MPTP.[72]

Harmful heavy metals include mainly manganese, iron, lead, mercury,[73] aluminium, and cadmium. On the other hand, magnesium shows neuroprotective features.[74]

Other chemical compounds include trichloroethylene[75] and MPTP.[76]

Other

[edit]Traumatic brain injury is also strongly implicated as a risk factor.[77] Additionally, although the underlying cause is unknown, melanoma is documented to be associated with PD.[78] Low levels of urate in the blood are associated with an increased risk[79] while Helicobacter pylori infection can prevent the absorption of some drugs, including L-DOPA.[80]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Main pathological feature is cell death of dopamine-releasing neurons within, among other regions, the basal ganglia, more precisely pars compacta of substantia nigra and partially striatum, thus impeding nigrostriatal pathway of the dopaminergic system which plays a central role in motor control.[81]

Neuroanatomy

[edit]Three major pathways connect the basal ganglia to other brain areas: direct, indirect, and hyperdirect pathway, all part of the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop.[82]

The direct pathway projects from the neocortex to putamen or caudate nucleus of the striatum, which sends inhibitory GABAergic signals to substantia nigra pars reticulata (SNpr) and internal globus pallidus (GPi).[82] This inhibition reduces GABAergic signaling to ventral lateral (VL) and ventral anterior (VA) nuclei of the thalamus, thereby promoting their projections to the motor cortex.[83]

The indirect pathway projects inhibition from striatum to external globus pallidus (GPe), reducing its GABAergic inhibition of the subthalamic nucleus, pars reticulata and internal globus pallidus. This reduction in inhibition allows the subthalamic nucleus to excite internal globus pallidus and pars reticulata, which in turn inhibit thalamic activity, thereby suppressing excitatory signals to the motor cortex.[82]

The hyperdirect pathway is an additional glutamatergic pathway that projects from the frontal lobe to subthalamic nucleus, modulating basal ganglia activity with rapid excitatory input.[84]

The striatum and other basal ganglia structures contain D1 and D2 receptor neurons that modulate the previously described pathways. Consequently, dopaminergic dysfunction in these systems can disrupt their respective components—motor, oculomotor, associative, limbic, and orbitofrontal circuits (each named for its primary projection area)—leading to symptoms related to movement, attention, and learning in the disease.[85]

Mechanisms

[edit]Alpha-synuclein (aSyn) is a protein involved in synaptic vesicle trafficking, intracellular transport, and neurotransmitter release. In PD, it can be overexpressed, misfolded and subsequently form clumps[86] on axon terminals and other structures inside a neuron, for example the mitochondria and nucleus. This aggregation forms Lewy bodies which are involved in neuronal necrosis and dysfunction of neurotransmitters.[citation needed]

A vicious cycle linked to neurodegeneration involves oxidative stress, mitochondria, and neuroimmune function, particularly inflammation. Normal metabolism of dopamine tends to fail, leading to elevated levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which is cytotoxic and causes cellular damage to lipids, proteins, DNA, and especially mitochondria.[87] Mitochondrial damage triggers neuroinflammatory responses via damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), resulting in aggregation of neuromelanin, and therefore, fueling further neuroinflammation by activating microglia.[88]

Ferroptosis is suggested as another significant mechanism in disease progression. It is characterized by cell death through high levels of lipid hydroperoxide.[89]

Brain cell death

[edit]One mechanism causing brain cell death results from abnormal accumulation of the protein alpha-synuclein bound to ubiquitin in damaged cells. This insoluble protein accumulates inside neurons forming inclusions, known as Lewy bodies.[90][91] These bodies first appear in the olfactory bulb, medulla oblongata and pontine tegmentum; individuals at this stage may be asymptomatic or have early nonmotor symptoms (such as loss of sense of smell or some sleep or automatic dysfunction). As the disease progresses, Lewy bodies develop in the substantia nigra, areas of the midbrain and basal forebrain, and finally, the neocortex.[90] These brain sites are the main places of neuronal degeneration in PD, but Lewy bodies may be protective from cell death (with the abnormal protein sequestered or walled off). Other forms of alpha-synuclein (e.g. oligomers) that are not aggregated into Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites, may in fact be the toxic forms of the protein.[92][91] In people with dementia, a generalized presence of Lewy bodies is common in cortical areas. Neurofibrillary tangles and senile plaques, characteristic of Alzheimer's disease, are uncommon unless the person has dementia.[93][page needed]

Other mechanisms include proteasomal and lysosomal systems dysfunction and reduced mitochondrial activity.[92] Iron accumulation in the substantia nigra is typically observed in conjunction with the protein inclusions. It may be related to oxidative stress, protein aggregation, and neuronal death, but the mechanisms are obscure.[94]

Neuroimmune interaction

[edit]The neuroimmune interaction is heavily implicated in PD pathology. PD and autoimmune disorders share genetic variations and molecular pathways. Some autoimmune diseases may even increase one's risk of developing PD, up to 33% in one study.[95] Autoimmune diseases linked to protein expression profiles of monocytes and CD4+ T cells are linked to PD. Herpes virus infections can trigger autoimmune reactions to alpha-synuclein, perhaps through molecular mimicry of viral proteins.[96] Alpha-synuclein, and its aggregate form, Lewy bodies, can bind to microglia. Microglia can proliferate and be over-activated by alpha-synuclein binding to MHC receptors on inflammasomes, bringing about a release of proinflammatory cytokines like IL-1β, IFNγ, and TNFα.[97]

Activated microglia influence the activation of astrocytes, converting their neuroprotective phenotype to a neurotoxic one. Astrocytes in healthy brains serve to protect neuronal connections. In Parkinson's disease, astrocytes cannot protect the dopaminergic connections in the striatum. Microglia present antigens via MHC-I and MHC-II to T cells. CD4+ T cells, activated by this process, are able to cross the blood brain barrier (BBB) and release more proinflammatory cytokines, like interferon-γ (IFNγ), TNFα, and IL-1β. Mast cell degranulation and subsequent proinflammatory cytokine release is implicated in BBB breakdown in PD. Another immune cell implicated in PD are peripheral monocytes and have been found in the substantia nigra of people with PD. These monocytes can lead to more dopaminergic connection breakdown. In addition, monocytes isolated from people with Parkinson's disease express higher levels of the PD-associated protein, LRRK2, compared with non-PD individuals via vasodilation.[98] In addition, high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-6, can lead to the production of C-reactive protein by the liver, another protein commonly found in people with PD, that can lead to an increase in peripheral inflammation.[99][100]

Peripheral inflammation can affect the gut-brain axis, an area of the body highly implicated in PD. People with PD have altered gut microbiota and colon problems years before motor issues arise.[99][100] Alpha-synuclein is produced in the gut and may migrate via the vagus nerve to the brainstem, and then to the substantia nigra.[undue weight? – discuss][better source needed][101]

Diagnosis

[edit]

Physician's initial assessment is typically based on medical history and neurological examination.[102] They assess motor symptoms (bradykinesia, rest tremors, etc.) using clinical diagnostic criteria. The finding of Lewy bodies in the midbrain on autopsy is usually considered final proof that the person had PD. The clinical course of the illness over time may diverge from PD, requiring that presentation is periodically reviewed to confirm the accuracy of the diagnosis.[102][103]

Multiple causes can occur for parkinsonism or diseases that look similar. Stroke, certain medications, and toxins can cause "secondary parkinsonism" and need to be assessed during visit.[104][103] Parkinson-plus syndromes, such as progressive supranuclear palsy and multiple system atrophy, must be considered and ruled out appropriately to begin a different treatment and disease progression (anti-Parkinson's medications are typically less effective at controlling symptoms in Parkinson-plus syndromes).[102] Faster progression rates, early cognitive dysfunction or postural instability, minimal tremor, or symmetry at onset may indicate a Parkinson-plus disease rather than PD itself.[105]

Medical organizations have created diagnostic criteria to ease and standardize the diagnostic process, especially in the early stages of the disease. The most widely known criteria come from the UK Queen Square Brain Bank for Neurological Disorders and the U.S. National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. The Queen Square Brain Bank criteria require slowness of movement (bradykinesia) plus either rigidity, resting tremor, or postural instability. Other possible causes of these symptoms need to be ruled out. Finally, three or more of the following supportive symptoms are required during onset or evolution: unilateral onset, tremor at rest, progression in time, asymmetry of motor symptoms, response to levodopa for at least five years, the clinical course of at least ten years and appearance of dyskinesias induced by the intake of excessive levodopa.[106] Assessment of sudomotor function through electrochemical skin conductance can be helpful in diagnosing dysautonomia.[107]

When PD diagnoses are checked by autopsy, movement disorders experts are found on average to be 79.6% accurate at initial assessment and 83.9% accurate after refining diagnoses at follow-up examinations. When clinical diagnoses performed mainly by nonexperts are checked by autopsy, the average accuracy is 73.8%. Overall, 80.6% of PD diagnoses are accurate, and 82.7% of diagnoses using the Brain Bank criteria are accurate.[108]

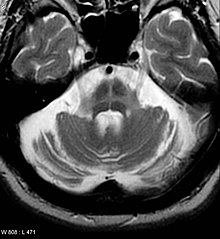

Imaging

[edit]Computed tomography (CT) scans of people with PD usually appear normal.[109] Magnetic resonance imaging has become more accurate in diagnosis of the disease over time, specifically through iron-sensitive T2* and susceptibility weighted imaging sequences at a magnetic field strength of at least 3T, both of which can demonstrate absence of the characteristic 'swallow tail' imaging pattern in the dorsolateral substantia nigra.[110] In a meta-analysis, absence of this pattern was highly sensitive and specific for the disease.[111] A meta-analysis found that neuromelanin-MRI can discriminate individuals with Parkinson's from healthy subjects.[112] Diffusion MRI has shown potential in distinguishing between PD and Parkinson-plus syndromes, as well as between PD motor subtypes,[113] though its diagnostic value is still under investigation.[109] CT and MRI are used to rule out other diseases that can be secondary causes of parkinsonism, most commonly encephalitis and chronic ischemic insults, as well as less-frequent entities such as basal ganglia tumors and hydrocephalus.[109]

The metabolic activity of dopamine transporters in the basal ganglia can be directly measured with positron emission tomography and single-photon emission computed tomography scans. It has shown high agreement with clinical diagnoses of PD.[114] Reduced dopamine-related activity in the basal ganglia can help exclude drug-induced Parkinsonism. This finding is nonspecific and can be seen with both PD and Parkinson-plus disorders.[109] In the United States, DaTSCANs are only FDA approved to distinguish PD or Parkinsonian syndromes from essential tremor.[115]

Iodine-123-meta-iodobenzylguanidine myocardial scintigraphy can help locate denervation of the muscles of the heart which can support a PD diagnosis.[104]

Differential diagnosis

[edit]Secondary parkinsonism – The multiple causes of parkinsonism can be differentiated through careful history, physical examination, and appropriate imaging.[104][116] Other Parkinson-plus syndromes can have similar movement symptoms but have a variety of associated symptoms. Some of these are also synucleinopathies. Lewy body dementia involves motor symptoms with early onset of cognitive dysfunction and hallucinations which precede motor symptoms. Alternatively, multiple systems atrophy or MSA usually has early onset of autonomic dysfunction (such as orthostasis), and may have autonomic predominance, cerebellar symptom predominance, or Parkinsonian predominance.[117]

Other Parkinson-plus syndromes involve tau, rather than alpha-synuclein. These include progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and corticobasal syndrome (CBS). PSP predominantly involves rigidity, early falls, bulbar symptoms, and vertical gaze restriction; it can be associated with frontotemporal dementia symptoms. CBS involves asymmetric parkinsonism, dystonia, alien limb, and myoclonic jerking.[118] Presentation timelines and associated symptoms can help differentiate similar movement disorders from idiopathic Parkinson disease.[medical citation needed]

Vascular parkinsonism is the phenomenon of the presence of Parkinson's disease symptoms combined with findings of vascular events (such as a cerebral stroke). The damaging of the dopaminergic pathways is similar in cause for both vascular parkinsonism and idiopathic PD, and so present with similar symptoms. Differentiation can be made with careful bedside examination, history evaluation, and imaging.[119][120]

Parkinson-plus syndrome – Multiple diseases can be considered part of the Parkinson's plus group, including corticobasal syndrome, multiple system atrophy, progressive supranuclear palsy, and dementia with Lewy bodies. Differential diagnosis can be narrowed down with careful history and physical exam (especially focused on the sequential onset of specific symptoms), progression of the disease, and response to treatment.[121][116] Some key symptoms:[122][116]

- Corticobasal syndrome – levodopa-resistance, myoclonus, dystonia, corticosensory loss, apraxia, and non-fluent aphasia

- Dementia with Lewy bodies – levodopa resistance, cognitive predominance before motor symptoms, and fluctuating cognitive symptoms, (visual hallucinations are common in this disease)

- Essential tremor – This can at first look like parkinsonism, but has key differentiators. In essential tremor, the tremor gets worse with action (improves in PD), a lack of other symptoms is common in PD, and normal DatSCAN is seen.[116]

- Multiple system atrophy – levodopa resistance, rapidly progressive, autonomic failure, stridor, present Babinski sign, cerebellar ataxia, and specific MRI findings

- Progressive supranuclear palsy – levodopa resistance, restrictive vertical gaze, specific MRI findings, and early and different postural difficulties

Prevention

[edit]

As of 2024, no disease-modifying therapies exist that reverse or slow neurodegeneration, processes respectively termed neurorestoration and neuroprotection.[123][124] However, several factors have been found to be associated with a decreased risk.[123] The identification and mechanistic analysis of these factors may guide the development of new therapies.[125]

Exercise—one of the most common recommendations to prevent or delay Parkinson's—may exert a neuroprotective effect.[126] In animal studies investigating the cellular basis, exercise has been found to increase neurotrophic growth factor expression and to reduce alpha-synuclein expression, neuroinflammation, and mitochondrial dysfunction.[127]

Tobacco use and smoking is strongly associated with a decreased risk, reducing the chance of developing PD by 40–60%.[128][129] Various tobacco and smoke components have been hypothesized to be neuroprotective, including nicotine, carbon monoxide, and monoamine oxidase B inhibitors.[130][131] Consumption of coffee, tea, or caffeine is also strongly associated with neuroprotection.[132][133] In laboratory models, caffeine has been shown to be neuroprotective due to its antagonistic interaction with the adenosine A2A receptor, which modulates dopaminergic signaling, synaptic plasticity, synapse formation, and inflammation.[130] Prescribed adrenergic antagonists like terazosin may also reduce risk.[132]

Although findings have varied, usage of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) like ibuprofen may be neuroprotective.[134][135] Calcium channel blockers (CCB) may also have a protective effect, with a 22% risk decrease found in a 2024 meta-analysis of almost 3 million CCB users.[136] Higher blood concentrations of urate—a potent antioxidant—have been proposed to be neuroprotective;[130][137] animal and cell studies have shown that urate can prevent dopaminergic neurodegeneration.[137] Although longitudinal studies observe a slight decrease in PD risk among those who consume alcohol—possibly due to alcohol's urate-increasing effect—alcohol abuse may increase risk.[138][139]

Management

[edit]Despite ongoing research efforts, Parkinson's disease has no known cure. Patients are typically managed by a holistic approach that combines lifestyle modifications with physical therapy. Certain medications may also be used to provide symptomatic relief and improve the patient's quality of life. The medications used in Parkinson's disease work by either increasing endogenous dopamine levels or by directly mimicking dopamine's effect on the patient's brain. Levodopa (L-dopa) is the most effective for motor symptoms and is often combined with a dopa decarboxylase inhibitor (such as carbidopa or benserazide).[140] Other agents include COMT inhibitors, dopamine agonists, and MAO-B inhibitors. The patient's age at disease onset as well as the stage of the disease often help determine which of the aforementioned drug groups is most effective.

Braak staging classifies the degree of pathology in patients with Parkinson's disease into six stages that correlate with early, middle, and late presentations of the disease.[141] Treatment in the first stage aims for an optimal trade-off between symptom control and medication side effects. For example, the administration of levodopa in this stage may be delayed in favor of other agents, such as MAO-B inhibitors and dopamine agonists, due to its notable risk of complications.[142] However, levodopa-related dyskinesias still correlate more strongly with the duration and severity of the disease than the duration of levodopa treatment.[143] A careful consideration of the risks and benefits of starting treatment is crucial to optimize patient outcomes. In the middle stages of Parkinson's disease, the primary aim is to reduce patient symptoms. Episodes of medication overuse or any sudden withdrawals from medication must be promptly managed.[142] If medications prove ineffective, surgery (such as deep brain stimulation or high-intensity focused ultrasound[144]), subcutaneous waking-day apomorphine infusion, and enteral dopa pumps may be useful.[145] Late-stage Parkinson's disease presents challenges requiring a variety of treatments, including those for psychiatric symptoms particularly depression, orthostatic hypotension, bladder dysfunction, and erectile dysfunction.[145] In the final stages of the disease, palliative care is provided to improve a person's quality of life.[146]

A 2020 Cochrane review found no certain evidence that cognitive training is beneficial for people with Parkinson's disease, dementia or mild cognitive impairment.[147] The findings are based on low certainty evidence of seven studies.

No standard treatment for PD-associated anxiety exists.[148][page needed]

Medications

[edit]

Levodopa

[edit]Levodopa is usually the first drug of choice when treating Parkinson's disease and has been the most widely used PD treatment since the 1980s.[142][149] The motor symptoms of PD are the result of reduced dopamine production in the brain's basal ganglia. Dopamine fails to cross the blood–brain barrier so it cannot be taken as a medicine to boost the brain's depleted levels of dopamine. A precursor of dopamine, levodopa, can pass through to the brain where it is readily converted to dopamine. Administration of levodopa temporarily diminishes the motor symptoms of PD.

Only 5–10% of levodopa crosses the blood–brain barrier. Much of the remainder is metabolized to dopamine elsewhere in the body, causing a variety of side-effects, including nausea, vomiting, and orthostatic hypotension.[150] Carbidopa and benserazide are dopa decarboxylase inhibitors that fail to cross the blood–brain barrier and inhibit the conversion of levodopa to dopamine outside the brain, reducing side-effects and improving the availability of levodopa for passage into the brain. One of these drugs is usually taken along with levodopa and is available combined with levodopa in the same pill.[151]

Prolonged use of levodopa is associated with the development of complications, such as involuntary movements (dyskinesias) and fluctuations in the impact of the medication.[142] When fluctuations occur, a person can cycle through phases with good response to medication and reduced PD symptoms ("on state"), and phases with poor response to medication and increased PD symptoms ("off state").[142][152] Using lower doses of levodopa may reduce the risk and severity of these levodopa-induced complications.[153] A former strategy, called "drug holidays", to reduce levodopa-related dyskinesia and fluctuations was to withdraw levodopa medication for some time,[149] which can bring on dangerous side-effects such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome and is discouraged.[142] Most people with PD eventually need levodopa and later develop levodopa-induced fluctuations and dyskinesias.[142] Adverse effects of levodopa, including dyskinesias, may mistakenly influence people affected by the disease and sometimes their healthcare professionals to delay treatment, which reduces potential for optimal results.[medical citation needed]

Levodopa is available in oral, inhalation, and infusion form; inhaled levodopa can be used when oral levodopa therapy has reached a point where "off" periods have increased in length.[154][155]

COMT inhibitors

[edit]

During the course of PD, affected people can experience a wearing-off phenomenon, where a recurrence of symptoms occurs after a dose of levodopa, but right before their next dose.[104] Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) is a protein that degrades levodopa before it can cross the blood–brain barrier and COMT inhibitors allow for more levodopa to cross.[157] They are normally used in the management of later symptoms, but can be used in conjunction with levodopa/carbidopa when a person is experiencing the wearing off-phenomenon with their motor symptoms.[104][149]

Three COMT inhibitors are used to treat adults with PD and end-of-dose motor fluctuations – opicapone, entacapone, and tolcapone.[104] Tolcapone has been available for but its usefulness is limited by possible liver damage complications requiring liver-function monitoring.[158][104][157][122] Entacapone and opicapone cause little alteration to liver function.[157][159][160] Licensed preparations of entacapone contain entacapone alone or in combination with carbidopa and levodopa.[161][122][162] Opicapone is a once-daily COMT inhibitor.[163][104]

Dopamine agonists

[edit]Dopamine agonists that bind to dopamine receptors in the brain have similar effects to levodopa.[142] These were initially used as a complementary therapy to levodopa for individuals experiencing levodopa complications (on-off fluctuations and dyskinesias); they are mainly used on their own as first therapy for the motor symptoms of PD with the aim of delaying the initiation of levodopa therapy, thus delaying the onset of levodopa's complications.[142][164] Dopamine agonists include bromocriptine, pergolide, pramipexole, ropinirole, piribedil, cabergoline, apomorphine, and lisuride.

Though dopamine agonists are less effective than levodopa at controlling PD motor symptoms, they are effective enough to manage these symptoms in the first years of treatment.[165] Dyskinesias due to dopamine agonists are rare in younger people who have PD, but along with other complications, become more common with older age at onset.[165] Thus, dopamine agonists are the preferred initial treatment for younger-onset PD, and levodopa is preferred for older-onset PD.[165]

Dopamine agonists produce side effects, including drowsiness, hallucinations, insomnia, nausea, and constipation.[142][149] Side effects appear with minimal clinically effective doses giving the physician reason to search for a different drug.[142] Agonists have been related to impulse-control disorders (such as increased sexual activity, eating, gambling, and shopping) more strongly than other antiparkinson medications.[166][149]

Apomorphine, a dopamine agonist, may be used to reduce off periods and dyskinesia in late PD.[142] It is administered only by intermittent injections or continuous subcutaneous infusions.[142] Secondary effects such as confusion and hallucinations are common, individuals receiving apomorphine treatment should be closely monitored.[142] Two dopamine agonists administered through skin patches (lisuride and rotigotine) are useful for people in the initial stages and possibly to control off states in those in advanced states.[167][page needed] Due to an increased risk of cardiac fibrosis with ergot-derived dopamine agonists (bromocriptine, cabergoline, dihydroergocryptine, lisuride, and pergolide), they should only be considered for adjunct therapy to levodopa.[149]

MAO-B inhibitors

[edit]MAO-B inhibitors (safinamide, selegiline and rasagiline) increase the amount of dopamine in the basal ganglia by inhibiting the activity of monoamine oxidase B, an enzyme that breaks down dopamine.[142] They have been found to help alleviate motor symptoms when used as monotherapy (on their own); when used in conjunction with levodopa, time spent in the off phase is reduced.[168][149] Selegiline has been shown to delay the need for beginning levodopa, suggesting that it might be neuroprotective and slow the progression of the disease.[169] An initial study indicated that selegiline in combination with levodopa increased the risk of death, but this has been refuted.[170]

Common side effects are nausea, dizziness, insomnia, sleepiness, and (in selegiline and rasagiline) orthostatic hypotension.[169][104] MAO-Bs are known to increase serotonin and cause a potentially dangerous condition known as serotonin syndrome.[169]

Other drugs

[edit]Other drugs such as amantadine may be useful as treatment of motor symptoms, but evidence for use is lacking.[142][171] Anticholinergics should not be used for dyskinesia or motor fluctuations but may be considered topically for drooling.[149] A diverse range of symptoms beyond those related to motor function can be treated pharmaceutically.[172] Examples are the use of quetiapine or clozapine for psychosis, cholinesterase inhibitors or memantine for dementia, and modafinil for excessive daytime sleepiness.[172][173][149] In 2016, pimavanserin was approved for the management of PD psychosis.[174] Doxepin and rasagline may reduce physical fatigue in PD.[175]

Surgery

[edit]

Treating motor symptoms with surgery was once a common practice but the discovery of levodopa has decreased the amount of procedures.[176] Studies have led to great improvements in surgical techniques, so surgery can be used in people with advanced PD for whom drug therapy is no longer sufficient.[176] Surgery for PD can be divided in two main groups – lesional and deep brain stimulation (DBS). Target areas for DBS or lesions include the thalamus, globus pallidus, or subthalamic nucleus.[176] DBS involves the implantation of a medical device called a neurostimulator, which sends electrical impulses to specific parts of the brain. DBS is recommended for people who have PD with motor fluctuations and tremor inadequately controlled by medication, or to those who are intolerant to medication lacking severe neuropsychiatric problems.[177] Other less common surgical therapies involve intentional formation of lesions to suppress overactivity of specific subcortical areas. For example, pallidotomy involves surgical destruction of the globus pallidus to control dyskinesia.[176]

Four areas of the brain have been treated with neural stimulators in PD.[178] These are the globus pallidus interna, thalamus, subthalamic nucleus, and pedunculopontine nucleus. DBS of the globus pallidus interna improves motor function, while DBS of the thalamic DBS improves tremor, but has little impact on bradykinesia or rigidity. DBS of the subthalamic nucleus is usually avoided if a history of depression or neurocognitive impairment is present. DBS of the subthalamic nucleus is associated with a reduction in medication. Pedunculopontine nucleus DBS remains experimental at present. Generally, DBS is associated with 30–60% improvement in motor score evaluations.[178]

Rehabilitation

[edit]Exercise programs are recommended in people with PD and recent reviews (2024) have demonstrated their efficacy.[179][180] Some evidence shows that speech or mobility problems can improve with rehabilitation, although studies are scarce and of low quality.[181][182] Regular physical exercise with or without physical therapy can be beneficial to maintain and improve mobility, flexibility, strength, gait speed, and quality of life.[182] When an exercise program is performed under the supervision of a physiotherapist, more improvements occur in motor symptoms, mental and emotional functions, daily living activities, and quality of life compared with a self-supervised exercise program at home.[183] Clinical exercises may be an effective intervention targeting overall well-being of individuals with Parkinson's. Improvement in motor function and depression may happen.[184]

In improving flexibility and range of motion for people experiencing rigidity, generalized relaxation techniques such as gentle rocking have been found to decrease excessive muscle tension. Other effective techniques to promote relaxation include slow rotational movements of the extremities and trunk, rhythmic initiation, diaphragmatic breathing, and meditation techniques.[185] As for gait and addressing the challenges associated with the disease such as hypokinesia, shuffling, and decreased arm swing, physiotherapists have a variety of strategies to improve functional mobility and safety. Areas of interest concerning gait during rehabilitation programs focus on improving gait speed, the base of support, stride length, and trunk and arm-swing movement. Strategies include using assistive equipment (pole walking and treadmill walking), verbal cueing (manual, visual, and auditory), exercises (marching and PNF patterns), and altering environments (surfaces, inputs, open vs. closed).[186] Strengthening exercises have shown improvements in strength and motor function for people with primary muscular weakness and weakness related to inactivity with mild to moderate PD, but reports show an interaction between strength and the time the medications were taken. Therefore, people with PD should perform exercises 45 minutes to one hour after medications when they are capable.[187] Deep diaphragmatic breathing exercises are beneficial in improving chest-wall mobility and vital capacity decreased by a forward flexed posture and respiratory dysfunctions in advanced PD.[188] Exercise may improve constipation.[189] Whether exercise reduces physical fatigue in PD remains unclear.[175]

Strength training exercise has been shown to increase manual dexterity in people with PD after exercising with manual putty. Improvements in both manual dexterity and strength can have a favorable impact on people with Parkinson's disease, fostering increased independence in daily activities that require grasping objects.[190]

The Lee Silverman voice treatment (LSVT) is one of the most widely practiced treatments for speech disorders associated with PD.[181][191] Speech therapy and specifically LSVT may improve speech.[181] Occupational therapy (OT) aims to promote health and quality of life by helping people with the disease to participate in a large percentage of their daily living activities.[181] Few studies have been conducted on the effectiveness of OT, and their quality is poor, although with some indication that it may improve motor skills and quality of life for the duration of the therapy.[181][192]

Palliative care

[edit]The goal of palliative care is to improve quality of life for both the patient and family by providing relief from the symptoms and stress of illnesses.[193] As Parkinson's is uncurable, treatments focus on slowing decline and improving quality of life and are therefore palliative.[194]

Palliative care should be involved earlier, rather than later, in the disease course.[195][196] Palliative care specialists can help with physical symptoms, emotional factors such as loss of function and jobs, depression, fear, and existential concerns.[195][196][197]

Along with offering emotional support to both the affected person and family, palliative care addresses goals of care. People with PD may have difficult decisions to make as the disease progresses, such as wishes for feeding tube, noninvasive ventilator or tracheostomy, wishes for or against cardiopulmonary resuscitation, and when to use hospice care.[194] Palliative-care team members can help answer questions and guide people with PD on these complex and emotional topics to help them make decisions based on values.[196][198]

Muscles and nerves that control the digestive process may be affected by PD, resulting in constipation and gastroparesis (prolonged emptying of stomach contents).[189] A balanced diet, based on periodical nutritional assessments, is recommended, and should be designed to avoid weight loss or gain and minimize the consequences of gastrointestinal dysfunction.[189] As the disease advances, swallowing difficulties (dysphagia) may appear. Using thickening agents for liquid intake and an upright posture when eating may be useful; both measures reduce the risk of choking. Gastrostomy can be used to deliver food directly into the stomach.[189]

Levodopa and proteins use the same transportation system in the intestine and the blood–brain barrier, thereby competing for access.[189] Taking them together results in reduced effectiveness of the drug.[189] Therefore, when levodopa is introduced, excessive protein consumption is discouraged in favour of a well-balanced Mediterranean diet. In advanced stages, additional intake of low-protein products such as bread or pasta is recommended for similar reasons.[189] To minimize interaction with proteins, levodopa should be taken 30 minutes before meals.[189] At the same time, regimens for PD restrict proteins during breakfast and lunch, allowing protein intake in the evening.[189]

Prognosis

[edit]| Parkinson's subtype | Mean years post-diagnosis until: | |

|---|---|---|

| Severe cognitive or movement abnormalities[note 1] | Death | |

| Mild-motor predominant | 14.3 | 20.2 |

| Intermediate | 8.2 | 13.1 |

| Diffuse malignant | 3.5 | 8.1 |

As Parkinson's is a heterogeneous condition with multiple etiologies, prognistication can be difficult and prognoses can be highly variable.[199][201] On average, life expectancy is reduced in those with Parkinson's, with younger age of onset resulting in greater life expectancy decreases.[202] Although PD subtype categorization is controversial, the 2017 Parkinson's Progression Markers Initiative study identified three broad scorable subtypes of increasing severity and more rapid progression: mild-motor predominant, intermediate, and diffuse malignant. Mean years of survival post diagnosis were 20.2, 13.1, and 8.1.[199]

Around 30% of Parkinson's patients develop dementia, and is 12 times more likely to occur in elderly patients of those with severe PD.[203] Dementia is less likely to arise in patients with tremor-dominant PD.[204] Parkinson's disease dementia is associated with a reduced quality of life in people with PD and their caregivers, increased mortality, and a higher probability of needing nursing home care.[205]

The incidence rate of falls in Parkinson's patients is approximately 45 to 68%, thrice that of healthy individuals, and half of such falls result in serious secondary injuries. Falls increase morbidity and mortality.[206] Around 90% of those with PD develop hypokinetic dysarthria, which worsens with disease progession and can hinder communication.[207] Additionally, over 80% of PD patients develop dysphagia: consequent inhalation of gastric and oropharyngeal secretions can lead to aspiration pneumonia.[208] Aspiration pneumonia is responsible for 70% of deaths in those with PD.[209]

Epidemiology

[edit]

As of 2024, Parkinson's is the second most common neurodegenerative disease and the fastest-growing in total number of cases.[210][211] As of 2023, global prevalence was estimated to be 1.51 per 1000.[212] Although it is around 40% more common in men,[213] age is the dominant predeterminant of Parkinson's.[214] Consequently, as global life expectancy has increased, Parkinson's disease prevalence has also risen, with an estimated increase in cases by 74% from 1990 to 2016.[215] The total number is predicted to rise to over 12 million patients by 2040.[216] Some label this a pandemic.[215]

This increase may be due to a number of global factors, including prolonged life expectancy, increased industrialisation, and decreased smoking.[215] Although genetics is the sole factor in a minority of cases, most cases of Parkinson's are likely a result of gene-environment interactions: concordance studies with twins have found Parkinson's heritability to be just 30%.[213] The influence of multiple genetic and environmental factors complicates epidemiological efforts.[217]

Relative to Europe and North America, disease prevalence is lower in Africa—especially sub-Saharan Africa—but similar in Latin America.[218] Although China is predicted to have nearly half of the global Parkinson's population by 2030,[219] estimates of prevalence in Asia have varied.[218] Potential explanations for these geographic differences include genetic variation, environmental factors, health care access, and life expectancy.[218] Although PD incidence and prevalence may vary by race and ethnicity, significant disparities in care, diagnosis, and study participation limit generalizability and lead to conflicting results.[218][217] Within the United States, high rates of PD have been identified in the Midwest and South, as well as agricultural regions of California, Florida, Pennsylvania, and Texas: collectively termed the "PD belt". It is hypothesized that this is due to localized environmental factors like herbicides, pesticides, and industrial waste.[220]

History

[edit]In 1817, English physician James Parkinson published the first comprehensive medical description of the disease as a neurological syndrome in his monograph An Essay on the Shaking Palsy.[222][223] He presented six clinical cases, inlcuding three he had observed afar near Hoxton Square in London.[224] Parkinson described three cardinal symptoms: tremor, postural instability and "paralysis" (undistinguished from rigidity or bradykinesia), and speculated that the disease was caused by trauma to the spinal cord.[225][226]

There was little discussion or investigation of the "shaking palsy" until 1861, when Frenchman Jean-Martin Charcot—regarded as the father of neurology—began expanding Parkinson's description, adding bradykinesia as one of the four cardinal symptoms.[225][224][226] In 1877, Charcot renamed the disease after Parkinson, as not all patients displayed the tremor suggested by "shaking palsy".[224][226] Subsequent neurologists who made early advances to the understanding of Parkinson's include Armand Trousseau, William Gowers, Samuel Kinnier Wilson, and Wilhelm Erb.[227]

Although Parkinson is typically credited with the first detailed description of PD, many previous texts reference some of the disease's clinical signs.[228] In his essay, Parkinson himself acknowledged partial descriptions by Galen, William Cullen, Johann Juncker, and others.[226] Possible earlier but incomplete descriptions include a Nineteenth Dynasty Egyptian papyrus, the ayurvedic text Charaka Samhita, Ecclesiastes 12:3, and a discussion of tremors by Leonardo da Vinci.[226][229] Multiple traditional Chinese medicine texts may include references to PD, including a discussion in the Yellow Emperor's Internal Classic (c. 425–221 BC) of a disease with symptoms of tremor, stiffness, staring, and stooped posture.[229] In 2009, a systematic description of PD was found in the Hungarian medical text Pax corporis written by Ferenc Pápai Páriz in 1690, some 120 years before Parkinson. Although he correctly described all four cardinal signs, it was only published in Hungarian and was not widely distributed.[230][231]

In 1912, Frederic Lewy described microscopic particles in affected brains, later named Lewy bodies.[232] In 1919, Konstantin Tretiakoff reported that the substantia nigra was the main brain structure affected, corroborated by Rolf Hassler in 1938.[233] The underlying changes in dopamine signaling were identified in the 1950s, largely by Arvid Carlsson and Oleh Hornykiewicz.[234] In 1997, alpha-synuclein was found to be the main component of Lewy bodies by Spillantini, Trojanowski, Goedert, and others.[235] Anticholinergics and surgery were the only treatments until the use of levodopa,[236][237] which, although first synthesized by Casimir Funk in 1911,[238] did not enter clinical use until 1967.[239] By the late 1980s deep brain stimulation introduced by Alim Louis Benabid and colleagues at Grenoble, France, emerged as an additional treatment.[240]

Society and culture

[edit]Social impact

[edit]For some people with PD, masked facial expressions and difficulty moderating facial expressions of emotion or recognizing other people's facial expressions can impact social well-being.[241] As the condition progresses, tremor, other motor symptoms, difficulty communicating, or issues with mobility may interfere with social engagement, causing individuals with PD to feel isolated.[242] Public perception and awareness of PD symptoms such as shaking, hallucinating, slurring speech, and being off balance is lacking in some countries and can lead to stigma.[242]

Cost

[edit]Parts of this article (those related to this subsection) need to be updated. (August 2020) |

The costs of PD to society are high; in 2007, the largest share of direct cost came from inpatient care and nursing homes, while the share coming from medication was substantially lower.[243] Indirect costs are high, due to reduced productivity and the burden on caregivers.[243] In addition to economic costs, PD reduces quality of life of those with the disease and their caregivers.[243]

A study based on 2017 data estimated the US economic PD burden at $51.9 billion, including direct medical costs of $25.4 billion and $26.5 billion in indirect and non-medical costs. The projected total economic burden surpasses $79 billion by 2037. These findings highlight the need for interventions to reduce PD incidence, delay disease progression, and alleviate symptom burden that may reduce the future economic burden of PD.[244]

Advocacy

[edit]

The birthday of James Parkinson, 11 April, has been designated as World Parkinson's Day.[245] A red tulip was chosen by international organizations as the symbol of the disease in 2005; it represents the 'James Parkinson' tulip cultivar, registered in 1981 by a Dutch horticulturalist.[246]

Advocacy organizations include the National Parkinson Foundation, which has provided more than $180 million in care, research, and support services since 1982,[247] Parkinson's Disease Foundation, which has distributed more than $115 million for research and nearly $50 million for education and advocacy programs since its founding in 1957 by William Black;[248][249] the American Parkinson Disease Association, founded in 1961;[250] and the European Parkinson's Disease Association, founded in 1992.[251]

Notable cases

[edit]

In the 21st century, the diagnosis of Parkinson's among notable figures has increased the public's understanding of the disorder.[252]

Actor Michael J. Fox was diagnosed with PD at 29 years old,[253] and has used his diagnosis to increase awareness of the disease.[254] To illustrate the effects of the disease, Fox has appeared without medication in television roles and before the United States Congress.[255] The Michael J. Fox Foundation, which he founded in 2000, has raised over $2 billion for Parkinson's research.[256] Boxer Muhammad Ali showed signs of PD when he was 38, but was undiagnosed until he was 42, and has been called the "world's most famous Parkinson's patient".[257] Whether he had PD or parkinsonism related to boxing is unresolved.[258][259] Cyclist and Olympic medalist Davis Phinney, diagnosed with Parkinson's at 40, started the Davis Phinney Foundation in 2004 to support PD research.[260][261] Deng Xiaoping, former paramount leader of China, had advanced Parkinson's disease.[262][263][264]

At the time of his suicide in 2014, Robin Williams, the American actor and comedian, had been diagnosed with PD,[265] but his autopsy revealed dementia with Lewy bodies, highlighting difficulties in accurate diagnosis.[265][266][267][268][269]

Clinical research

[edit]Parts of this article (those related to this subsection) need to be updated. (July 2020) |

As of 2022[update], no disease-modifying drugs (drugs that target the causes or damage) are approved for Parkinson's, so this is a major focus of Parkinson's research.[270][271] Active research directions include the search for new animal models of the disease and studies of the potential usefulness of gene therapy, stem cell transplants, and neuroprotective agents.[272] To aid in earlier diagnosis, research criteria for identifying prodromal biomarkers of the disease have been established.[273]

Gene therapy

[edit]Gene therapy typically involves the use of a noninfectious virus[274] to shuttle genetic material into a part of the brain. Approaches have involved the expression of growth factors to prevent damage (Neurturin – a GDNF-family growth factor), and enzymes such as glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD – the enzyme that produces GABA), tyrosine hydroxylase (the enzyme that produces L-DOPA) and catechol-O-methyl transferase (COMT – the enzyme that converts L-DOPA to dopamine). No safety concerns have been reported but the approaches have largely failed in phase two clinical trials.[272] The delivery of GAD showed promise in phase two trials in 2011, but while effective at improving motor function, was inferior to DBS. Follow-up studies in the same cohort have suggested persistent improvement.[275]

Neuroprotective treatments

[edit]A vaccine that primes the human immune system to destroy alpha-synuclein, PD01A, entered clinical trials and a phase one report in 2020 suggested safety and tolerability.[276][277] In 2018, an antibody, PRX002/RG7935, showed preliminary safety evidence in stage I trials supporting continuation to stage II trials.[278]

Cell-based therapies

[edit]In contrast to other neurodegenerative disorders, many Parkinson's symptoms can be attributed to the loss of a single cell type: mesencephalic dopaminergic (DA) neurons. Consequently, DA neuron regeneration is a promising therapeutic approach.[279] Although most initial research sought to generate DA neuron precursor cells from fetal brain tissue,[280] pluripotent stem cells—particularly induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs)—have become an increasingly popular tissue source.[281][282]

Both fetal and iPSC-derived DA neurons have been transplanted into patients in clinical trials.[283][284]: 1926 Although some patients see improvements, the results are highly variable. Adverse effects, such as dyskinesia arising from excess dopamine release by the transplanted tissues, have also been observed.[285][286]

Pharmaceutical

[edit]Antagonists of adenosine receptors (specifically A2A) have been explored for Parkinson's.[287] Of these, istradefylline has emerged as the most successful medication and was approved for medical use in the United States in 2019.[288] It is approved as an add-on treatment to the levodopa/carbidopa regime.[288] LRRK2 kinase inhibitors are also of interest.[289]

Pathophysiology

[edit]Neurodegeneration is proposed to originate in the brainstem and olfactory bulb.[290]

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Jump up to: a b c "Parkinson's Disease Information Page". NINDS. 30 June 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2016.

- ^ Truong & Bhidayasiri 2016, p. 188.

- ^ Ferri 2010, Chapter P.

- ^ Koh J, Ito H (January 2017). "Differential diagnosis of Parkinson's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders". Nihon Rinsho. Japanese Journal of Clinical Medicine. 75 (1): 56–62. PMID 30566295.

- ^ Sveinbjornsdottir S (October 2016). "The clinical symptoms of Parkinson's disease". Journal of Neurochemistry. 139 (Suppl 1): 318–324. doi:10.1111/jnc.13691. PMID 27401947.

- ^ Ou Z, Pan J, Tang S, Duan D, Yu D, Nong H, et al. (7 December 2021). "Global Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Years Lived With Disability of Parkinson's Disease in 204 Countries/Territories From 1990 to 2019". Frontiers in Public Health. 9: 776847. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2021.776847. PMC 8688697. PMID 34950630.

- ^ Ramesh & Arachchige 2023, pp. 200–201, 203.

- ^ Calabresi et al. 2023, pp. 1, 5.

- ^ National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

- ^ Wallace et al. 2021, p. 149.

- ^ Hansen et al. 2019, p. 635.

- ^ Bhattacharyya 2017, p. 7.

- ^ Stanford University School Medicine.

- ^ Bologna, Truong & Jankovic 2022, pp. 1–6.

- ^ Limphaibool et al. 2019, pp. 1–2.

- ^ Leta et al. 2022, p. 1122.

- ^ Langston 2017, p. S11.

- ^ Prajjwal et al. 2024, pp. 1–3.

- ^ Olfatia, Shoeibia & Litvanb 2019, p. 101.

- ^ Dolgacheva, Zinchenko & Goncharov 2022, p. 2.

- ^ Connie T, Aderinola TB, Ong TS, Goh MKO, Erfianto B, Purnama B (12 December 2022). "Pose-Based Gait Analysis for Diagnosis of Parkinson's Disease". Algorithms. 15 (12). MDPI AG: 474. doi:10.3390/a15120474.

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Parkinson's disease - Symptoms". National Health Service. 3 November 2022. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Leite Silva AB, Gonçalves de Oliveira RW, Diógenes GP, de Castro Aguiar MF, Sallem CC, Lima MP, et al. (February 2023). "Premotor, nonmotor and motor symptoms of Parkinson's Disease: A new clinical state of the art". Ageing Research Reviews. 84: 101834. doi:10.1016/j.arr.2022.101834. PMID 36581178.

- ^ De Carolis L, Galli S, Bianchini E, Rinaldi D, Raju M, Caliò B, et al. (January 2023). "Age at Onset Influences Progression of Motor and Non-Motor Symptoms during the Early Stage of Parkinson's Disease: A Monocentric Retrospective Study". Brain Sciences. 13 (2): 157. doi:10.3390/brainsci13020157. PMC 9954489. PMID 36831700.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Abusrair AH, Elsekaily W, Bohlega S (13 September 2022). "Tremor in Parkinson's Disease: From Pathophysiology to Advanced Therapies". Tremor and Other Hyperkinetic Movements. 12 (1): 29. doi:10.5334/tohm.712. PMC 9504742. PMID 36211804.

- ^ "Tremor". Parkinson's Foundation. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Bologna M, Paparella G, Fasano A, Hallett M, Berardelli A (March 2020). "Evolving concepts on bradykinesia". Brain. 143 (3): 727–750. doi:10.1093/brain/awz344. PMC 8205506. PMID 31834375.

- ^ "What Is Bradykinesia?". Cleveland Clinic. 30 November 2023. Retrieved 2 May 2024.

- ^ "Facial Masking". Parkinson's Foundation. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Ferreira-Sánchez MD, Moreno-Verdú M, Cano-de-la-Cuerda R (February 2020). "Quantitative Measurement of Rigidity in Parkinson´s Disease: A Systematic Review". Sensors. 20 (3): 880. Bibcode:2020Senso..20..880F. doi:10.3390/s20030880. PMC 7038663. PMID 32041374.

- ^ "Rigidity". Parkinson's Foundation. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Asci F, Falletti M, Zampogna A, Patera M, Hallett M, Rothwell J, et al. (September 2023). "Rigidity in Parkinson's disease: evidence from biomechanical and neurophysiological measures". Brain. 146 (9): 3705–3718. doi:10.1093/brain/awad114. PMC 10681667. PMID 37018058.

- ^ Becker D, Maric A, Schreiner SJ, Büchele F, Baumann CR, Waldvogel D (2 December 2022). Ahmed S (ed.). "Onset of Postural Instability in Parkinson's Disease Depends on Age rather than Disease Duration". Parkinson's Disease. 2022: 6233835. doi:10.1155/2022/6233835. PMC 9734006. PMID 36506486.

- ^ "Postural Instability (Balance & Falls)". Parkinson's Foundation. Retrieved 29 April 2024.

- ^ Eklund M, Nuuttila S, Joutsa J, Jaakkola E, Mäkinen E, Honkanen EA, et al. (July 2022). "Diagnostic value of micrographia in Parkinson's disease: a study with [123I]FP-CIT SPECT". Journal of Neural Transmission. 129 (7): 895–904. doi:10.1007/s00702-022-02517-1. PMC 9217822. PMID 35624405.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Corrà MF, Vila-Chã N, Sardoeira A, Hansen C, Sousa AP, Reis I, et al. (January 2023). "Peripheral neuropathy in Parkinson's disease: prevalence and functional impact on gait and balance". Brain. 146 (1): 225–236. doi:10.1093/brain/awac026. PMC 9825570. PMID 35088837.

- ^ França M, Parada Lima J, Oliveira A, Rosas MJ, Vicente SG, Sousa C (September 2023). "Visuospatial memory profile of patients with Parkinson's disease". Applied Neuropsychology. Adult: 1–9. doi:10.1080/23279095.2023.2256918. hdl:10216/141606. PMID 37695259.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Palma JA, Kaufmann H (March 2018). "Treatment of autonomic dysfunction in Parkinson disease and other synucleinopathies". Movement Disorders. 33 (3): 372–390. doi:10.1002/mds.27344. PMC 5844369. PMID 29508455.

- ^ Winiker K, Kertscher B (March 2023). "Behavioural interventions for swallowing in subjects with Parkinson's disease: A mixed methods systematic review". International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders. 58 (4): 1375–1404. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12865. PMID 36951546.

- ^ Warnecke T, Schäfer KH, Claus I, Del Tredici K, Jost WH (March 2022). "Gastrointestinal involvement in Parkinson's disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management". npj Parkinson's Disease. 8 (1): 31. doi:10.1038/s41531-022-00295-x. PMC 8948218. PMID 35332158.

- ^ Han MN, Finkelstein DI, McQuade RM, Diwakarla S (January 2022). "Gastrointestinal Dysfunction in Parkinson's Disease: Current and Potential Therapeutics". Journal of Personalized Medicine. 12 (2): 144. doi:10.3390/jpm12020144. PMC 8875119. PMID 35207632.

- ^ Skjærbæk C, Knudsen K, Horsager J, Borghammer P (January 2021). "Gastrointestinal Dysfunction in Parkinson's Disease". Journal of Clinical Medicine. 10 (3): 493. doi:10.3390/jcm10030493. PMC 7866791. PMID 33572547.

- ^ Palma JA, Kaufmann H (February 2020). "Orthostatic Hypotension in Parkinson Disease". Clinics in Geriatric Medicine. 36 (1): 53–67. doi:10.1016/j.cger.2019.09.002. PMC 7029426. PMID 31733702.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hinkle JT, Perepezko K, Gonzalez LL, Mills KA, Pontone GM (January 2021). "Apathy and Anxiety in De Novo Parkinson's Disease Predict the Severity of Motor Complications". Movement Disorders Clinical Practice. 8 (1): 76–84. doi:10.1002/mdc3.13117. PMC 7780944. PMID 33426161.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e Macías-García P, Rashid-López R, Cruz-Gómez ÁJ, Lozano-Soto E, Sanmartino F, Espinosa-Rosso R, et al. (9 May 2022). Aasly J (ed.). "Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Clinically Defined Parkinson's Disease: An Updated Review of Literature". Behavioural Neurology. 2022: 1213393. doi:10.1155/2022/1213393. PMC 9110237. PMID 35586201.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Khatri DK, Choudhary M, Sood A, Singh SB (November 2020). "Anxiety: An ignored aspect of Parkinson's disease lacking attention". Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 131: 110776. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110776. PMID 33152935.

- ^ Weintraub D, Mamikonyan E (September 2019). "The Neuropsychiatry of Parkinson Disease: A Perfect Storm". The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 27 (9): 998–1018. doi:10.1016/j.jagp.2019.03.002. PMC 7015280. PMID 31006550.

- ^ Chendo I, Silva C, Duarte GS, Prada L, Voon V, Ferreira JJ (21 января 2022 года). «Частота и характеристики психоза при болезни Паркинсона: систематический обзор и метаанализ». Журнал болезни Паркинсона . 12 (1): 85–94. doi : 10.3233/jpd-212930 . PMID 34806620 .

- ^ Zhang S, Ma Y (сентябрь 2022 г.). «Новая роль психоза при болезни Паркинсона: от клинической значимости к молекулярным механизмам» . Мировой журнал психиатрии . 12 (9): 1127–1140. doi : 10.5498/wjp.v12.i9.1127 . PMC 9521528 . PMID 36186499 .

- ^ Pahwa R, Isaacson SH, Small GW, Torres-Yaghi Y, Pagan F, Sabbagh M (декабрь 2022 г.). «Скрининг, диагностика и лечение психоза болезни Паркинсона: рекомендации от экспертной группы» . Неврология и терапия . 11 (4): 1571–1582. doi : 10.1007/s40120-022-00388-y . PMC 9362468 . PMID 35906500 .

- ^ De Wit Le, Wilting I, Souverein PC, Van Der Pol P, Egberts TC (май 2022). «Импульсные контрольные расстройства, связанные с дофаминергическими препаратами: анализ диспропорциональности с использованием вигибазы» . Европейская нейропсихофармакология . 58 : 30–38. doi : 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2022.01.113 . PMID 35189453 .

- ^ Gonzalez-Latapi P, Bayram E, Litvan I, Marras C (май 2021). «Когнитивные нарушения при болезни Паркинсона: эпидемиология, клинический профиль, защитные и факторы риска» . Поведенческие науки . 11 (5): 74. doi : 10.3390/bs11050074 . PMC 8152515 . PMID 34068064 .

- ^ «Проблемы со сном Паркинсона» . Клиника Кливленда . Получено 1 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Bollu PC, Sahota P (2017). «Сон и болезнь Паркинсона» . Миссури Медицина . 114 (5): 381–386. PMC 6140184 . PMID 30228640 .

- ^ Dodet P, Houot M, Leu-Semenescu S, Corvol JC, Lehéricy S, Mangone G, et al. (Февраль 2024 г.). «Расстройства сна при болезни Паркинсона, ранняя и множественная проблема» . Болезнь NPJ Паркинсона . 10 (1): 46. doi : 10.1038/s41531-024-00642-0 . PMC 10904863 . PMID 38424131 .

- ^ Ниманн Н., Биллнитцер А., Янкович Дж. (Январь 2021 г.). «Болезнь и кожу Паркинсона». Паркинсонизм и связанные с ним расстройства . 82 : 61–76. doi : 10.1016/j.parkreldis.2020.11.017 . PMID 33248395 .

- ^ Альмихлафи Ма (январь 2024 г.). «Обзор желудочно -кишечных, обонятельных и кожных аномалий у пациентов с болезнью Паркинсона» . Нейронауки . 29 (1): 4–9. doi : 10.17712/nsj.2024.1.20230062 (неактивный 2 мая 2024 г.). PMC 10827020 . PMID 38195133 .

{{cite journal}}: CS1 Maint: doi неактивен с мая 2024 года ( ссылка ) - ^ Vertes AC, Beato MR, Sonne J, Khan Suheb MZ (июнь 2023 г.). «Синдром Паркинсон-Плюс» . Statpearls . Остров сокровищ (Флорида): Statpearls Publishing. PMID 36256760 . Получено 2 мая 2024 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Morris HR, Spillantini MG, Sue CM, Williams-Gray CH (январь 2024 г.). «Патогенез болезни Паркинсона» . Лансет . 403 (10423): 293–304. doi : 10.1016/s0140-6736 (23) 01478-2 . PMID 38245249 .

- ^ Коулман С, Мартин I (16 декабря 2022 года). «Разрушение нейродегенерации болезни Паркинсона: удерживает ли старение?» Анкет Журнал болезни Паркинсона . 12 (8): 2321–2338. doi : 10.3233/jpd-223363 . PMC 9837701 . PMID 36278358 .

- ^ Jaaffar FS, Aizuddin AN, Ahmad N (21 февраля 2024 г.). «Факторы экологического риска болезни Паркинсона: обзор обзора» . Международный журнал исследований общественного здравоохранения . 14 (1): 1823–1831.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Де Миранда Б.Р., Голдман С.М., Миллер Г.В., Гринамир Дж.Т., Дорси Э.Р. (2022). «Предотвращение болезни Паркинсона: повестка дня окружающей среды» . Журнал болезни Паркинсона . 12 (1): 45–68. doi : 10.3233/jpd-212922 . PMC 8842749 . PMID 34719434 . S2CID 240235393 .

- ^ Zhao Y, Yunjia L, Hilde K (23 апреля 2024 г.). «Ассоциация потребления кофе и метаболитов кофеина с предстиагностикой с инцидентной болезнью Паркинсона в популяционной когорте» . Неврология . 102 (8): E209201. doi : 10.1212/wnl.0000000000209201 . PMC 11175631 . PMID 38513162 .

- ^ Rose, Schwarzschild & Gomperts 2024 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Salles PA, Tirapegui JM, Chaná-Cuevas P (22 марта 2024 г.). «Генетика болезни Паркинсона: доминирующие формы и GBA» . Перспективы неврологии . 4 (3): 100153. DOI : 10.1016/j.neurop.2024.100153 .

- ^ Khani M, Cerquera-Cleves C, Kekenadze M, Wild Crea P, Singleton AB, Bandres-Ciga S (май 2024). «На пути к глобальному взгляду на генетику болезни Паркинсона» Анналы неврологии 95 (5): 831–8 Doi : 10.1002/ana . PMC 11060911. 38557965PMID

- ^ Фарроу С.Л., Гокуладхас С., Ширдинг В., Пудихартоно М., Перри Дж.К., Купер А.А. и др. (Февраль 2024 г.). «Идентификация 27 аллельных регуляторных вариантов при болезни Паркинсона с использованием массового параллельного репортерного анализа» . Болезнь NPJ Паркинсона . 10 (1): 44. doi : 10.1038/s41531-024-00659-5 . PMC 10899198 . PMID 38413607 .

- ^ Смит Л, Шапира А.Х. (апрель 2022 г.). « Варианты GBA и болезнь Паркинсона: механизмы и лечение» . Ячейки 11 (8): 1261. doi : 10.3390/cells11081261 . PMC 9029385 . PMID 35455941 .

- ^ Лашуэль Ха (июль 2020 г.). «Содержит ли тела Lewy альфа-синуклеиновые фибриллы? И имеет ли это значение? Краткая история и критический анализ недавних отчетов». Нейробиология болезней . 141 : 104876. DOI : 10.1016/j.nbd.2020.104876 . PMID 32339655 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Abugable AA, Morris JL, Palminha NM, Zaksauskaite R, Ray S, El-Khamisy SF (сентябрь 2019 г.). «Репарация ДНК и неврологическое заболевание: от молекулярного понимания до развития диагностики и модельных организмов» . Репарация ДНК . 81 : 102669. DOI : 10.1016/j.dnarep.2019.102669 . PMID 31331820 .

- ^ Santos-Lobato BL (апрель 2024 г.). «На пути к методологической униформизации исследований в области риска окружающей среды при болезни Паркинсона» . Болезнь NPJ Паркинсона . 10 (1): 86. doi : 10.1038/s41531-024-00709-y . PMC 11024193 . PMID 38632283 .