Селегилин

Селегилин , также известный как L -депренил под торговыми марками Eldepryl , Zelapar и Emsam и продаваемый , среди прочего, , представляет собой лекарство , которое используется при лечении болезни Паркинсона и большого депрессивного расстройства . [4] [6] [8] [3] Он также был изучен по ряду других показаний, но не был официально одобрен для какого-либо другого использования. [20] [21] Лекарство в форме, разрешенной для лечения депрессии, имеет умеренную эффективность при этом состоянии, аналогичную эффективности других антидепрессантов . [21] [22] [23] Селегилин выпускается в виде проглатываемой таблетки или капсулы. [4] [5] или перорально распадающаяся таблетка (ODT) [6] [7] при болезни Паркинсона и в виде пластыря на кожу при депрессии. [8] [9]

Побочные эффекты селегилина, возникающие чаще, чем при приеме плацебо, включают бессонницу , среди прочего , , сухость во рту , головокружение , нервозность , ненормальные сновидения и реакции в месте применения (в форме пластыря). [21] [22] [24] [4] [8] В высоких дозах селегилин может вызывать опасные взаимодействия с пищей и лекарствами , такие как тирамин -связанная «сырная реакция» или гипертонический криз и риск серотонинового синдрома . [9] [25] [5] Однако дозы в пределах одобренного клинического диапазона, по-видимому, практически не имеют риска такого взаимодействия. [9][25][5] In addition, the ODT and transdermal patch forms of selegiline have reduced risks of such interactions compared to the conventional oral form.[7][9] Selegiline has no known misuse potential or dependence liability and is not a controlled substance.[26][27][28][29][8]

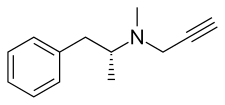

Selegiline acts as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI) and thereby increases levels of monoamine neurotransmitters in the brain.[30][11][25][5] At typical clinical doses used for Parkinson's disease, selegiline is a selective and irreversible inhibitor of monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B), increasing brain levels of dopamine.[30][11][25][5] At higher doses, it loses its specificity for MAO-B and also inhibits monoamine oxidase A (MAO-A), which increases serotonin and norepinephrine levels in the brain as well.[30][11][25][5] In addition to its MAOI activity, selegiline is a catecholaminergic activity enhancer (CAE) and enhances the impulse-mediated release of norepinephrine and dopamine in the brain.[31][32][33][34][25] This action may be mediated by TAAR1 agonism.[35][36][37] After administration, selegiline partially metabolizes into levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine, which act as norepinephrine releasing agents (NRAs) and may contribute to its therapeutic and adverse effects.[38][28][39] The levels of these metabolites are much lower with the ODT and transdermal patch forms of selegiline.[7][9] Chemically, selegiline is a substituted amphetamine,[40] a derivative of methamphetamine,[40] and the purified levorotatory enantiomer of deprenyl (the racemic form).[41][20]

Deprenyl was discovered and studied in the early 1960s.[41][20] Subsequently, selegiline was purified from deprenyl and was studied and developed itself.[41] Selegiline was first introduced for medical use in Hungary in 1977.[42] It was subsequently approved in the United Kingdom in 1982 and in the United States in 1989.[42][43] The ODT was approved in the United States in 2006 and in the European Union in 2010, while the patch was introduced in the United States in 2006.[42][20] Selegiline was the first selective MAO-B inhibitor to be discovered and marketed.[13][44][45] In addition to its medical use, there has been interest in selegiline as a potential anti-aging drug and nootropic.[46] However, effects of this sort are controversial and uncertain.[47][48][49][50] Generic versions of selegiline are available in the case of the conventional oral form but not in the case of the ODT or transdermal patch forms.[51][52]

Medical uses

[edit]Parkinson's disease

[edit]In its oral and ODT forms, selegiline is used to treat symptoms of Parkinson's disease (PD).[4][6] It is most often used as an adjunct to medications such as levodopa (L-DOPA), although it has been used off-label as a monotherapy.[53][54] The rationale for adding selegiline to levodopa is to decrease the required dose of levodopa and thus reduce the motor complications of levodopa therapy.[55] Selegiline delays the point when levodopa treatment becomes necessary from about 11 months to about 18 months after diagnosis.[56] There is some evidence that selegiline acts as a neuroprotective and reduces the rate of disease progression, though this is disputed.[54][55] In addition to parkinsonism, selegiline can improve symptoms of depression in people with Parkinson's disease.[57][58] There is evidence that selegiline may be more effective than rasagiline in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[20][35][59] This may be due to pharmacological differences between the drugs, such as the catecholaminergic activity enhancer (CAE) actions of selegiline which rasagiline lacks.[20][35][59][32]

Depression

[edit]Selegiline is used as an antidepressant in the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD).[8][21] Both the oral selegiline and transdermal selegiline patch formulations are used in the treatment of depression.[21] However, oral selegiline is not approved for depression and is used off-label for this indication, while the transdermal patch is specifically licensed for treatment of depression.[4][8] Both standard clinical doses of oral selegiline (up to 10 mg/day) and higher doses of oral selegiline (e.g., 30 to 60 mg/day) have been used to treat depression, with the lower doses selectively inhibiting MAO-B and the higher doses producing dual inhibition of both MAO-A and MAO-B.[9][21] Unlike oral selegiline, transdermal selegiline bypasses first-pass metabolism, thereby avoiding inhibition of gastrointestinal and hepatic MAO-A and minimizing the risk of food and drug interactions, whilst still allowing for selegiline to reach the brain and inhibit MAO-B.[9]

A 2023 systematic review and meta-analysis evaluated the effectiveness and safety of selegiline in the treatment of psychiatric disorders including depression.[21] It included both randomized and non-randomized published clinical studies.[21] The meta-analysis found that selegiline was more effective than placebo in terms of reduction in depressive symptoms (SMD = −0.96, k = 10, n = 1,308), response rates for depression improvement (RR = 1.61, k = 9, n = 1,238), and response rates for improvement of depression with atypical features (RR = 2.23, k = 3, n = 136).[21] Oral selegiline was significantly more effective than the selegiline patch in terms of depressive symptom improvement (SMD = −1.49, k = 6, n = 282 vs. SMD = −0.27, k = 4, n = 1,026, respectively; p = 0.03).[21] However, this was largely due to older and less methodologically rigorous trials that were at high risk for bias.[21] Oral selegiline studies also often employed much higher doses than usual, for instance 20 to 60 mg/day.[21] The quality of evidence of selegiline for depression was rated as very low overall, very low for oral selegiline, and low to moderate for transdermal selegiline.[21] For comparison, meta-analyses of other antidepressants for depression have found a mean effect size of about 0.3 (a small effect),[23][60] which is similar to that with transdermal selegiline.[21]

In two pivotal regulatory clinical trials of 6 to 8 weeks duration, the selegiline transdermal patch decreased scores on depression rating scales (specifically the 17- and 28-item HDRS) by 9.0 to 10.9 points, whereas placebo decreased scores by 6.5 to 8.6 points, giving placebo-subtracted differences attributable to selegiline of 2.4 to 2.5 points.[8] A 2013 quantitative review of the transdermal selegiline patch for depression, which pooled the results of these two trials, found that the placebo-subtracted number needed to treat (NNT) was 11 in terms of depression response (>50% reduction in symptoms) and 9 in terms of remission of depression (score of ≤10 on the MADRS).[22] For comparison, other antidepressants, including fluoxetine, paroxetine, duloxetine, vilazodone, adjunctive aripiprazole, olanzapine/fluoxetine, and extended-release quetiapine, have NNTs ranging from 6 to 8 in terms of depression response and 7 to 14 in terms of depression remission.[22] On the basis of these results, it was concluded that transdermal selegiline has similar effectiveness to other antidepressants.[22][61] NNTs are measures of effect size and indicate how many individuals would need to be treated in order to encounter one additional outcome of interest.[22] Lower NNTs are better, and NNTs corresponding to Cohen's d effect sizes have been defined as 2.3 for a large effect (d = 0.8), 3.6 for a medium effect (d = 0.5), and 8.9 for a small effect (d = 0.2).[22] The effectiveness of transdermal selegiline for depression relative to side effects and discontinuation was considered to be favorable.[22]

While several large regulatory clinical trials of transdermal selegiline versus placebo for depression have been conducted, there is a lack of trials comparing selegiline to other antidepressants.[52][61] Although multiple doses of transdermal selegiline were assessed, a dose–response relationship for depression was never established.[52][61] Transdermal selegiline has shown similar clinical effectiveness in the treatment of atypical depression relative to typical depression and in the treatment of anxious depression relative to non-anxious depression.[52][62][61]

Transdermal selegiline does not cause sexual dysfunction and may improve certain domains of sexual function, for instance sexual interest, maintaining interest during sex, and sexual satisfaction.[63] These benefits were apparent in women but not in men.[63] The lack of sexual dysfunction with transdermal selegiline is in contrast to many other antidepressants, such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), which are associated with high rates of sexual dysfunction.[64]

Transdermal selegiline patches have been underutilized in the treatment of depression compared to other antidepressants.[52][61] A variety of factors contributing to this underutilization have been identified.[52] One major factor is the very high cost of transdermal selegiline, which is often not covered by insurance and frequently proves to be prohibitive.[52][61] Conversely, other widely available antidepressants are much cheaper in comparison.[52][61]

Available forms

[edit]Selegiline is available in the following three pharmaceutical forms:[51]

- Oral tablets and capsules 5 mg (brand names Eldepryl, Jumex, and generics) – indicated for Parkinson's disease[4][5][42]

- Orally disintegrating tablets (ODTs) 1.25 mg (brand name Zelapar) – indicated for Parkinson's disease[6][7]

- Transdermal patches 6, 9, and 12 mg/24 hours (brand name Emsam) – indicated for major depressive disorder[8][9][12][24][61]

The transdermal patch form is also known as the "selegiline transdermal system" or "STS" and is applied once daily.[9][12][24][61][8] They are 20, 30, or 40 cm2 in size and contain a total of 20, 30, or 40 mg selegiline per patch (so 20 mg/20 cm2, 30 mg/30 cm2, and 40 mg/40 cm2), respectively.[8][61] The selegiline transdermal patch is a matrix-type adhesive patch with a three-layer structure.[8][61] It is the only approved non-oral MAOI, having reduced dietary restrictions and side effects in comparison to oral MAOIs, and is also the only approved non-oral first-line antidepressant.[61] The selegiline patch can be useful for those who have difficulty tolerating oral medications.[61]

Contraindications

[edit]Selegiline is contraindicated with serotonergic antidepressants including selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), with serotonergic opioids like meperidine, tramadol, and methadone, with other monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) such as linezolid, phenelzine, and tranylcypromine, and with dextromethorphan, St. John's wort, cyclobenzaprine, pentazocine, propoxyphene, and carbamazepine.[6][8][4] Combination of selegiline with serotonergic agents may cause serotonin syndrome, while combination of selegiline with adrenergic or sympathomimetic agents like ephedrine or amphetamines may cause hypertensive crisis.[6][8] Long washout periods are required before starting and stopping these medications with discontinuation or initiation of selegiline.[6][8][4][61]

Consumption of tyramine-rich foods can result in hypertensive crisis with selegiline, also known as the "cheese effect" or "cheese reaction" due to the high amounts of tyramine present in some cheeses.[6][11][44][65] Examples of other foods that may have high amounts of tyramine and similar substances include yeast products, chicken liver, snails, pickled herring, red wines, some beers, canned figs, broad beans, chocolate, and cream products.[65]

The preceding drug and food contraindications are dependent on selegiline dose and route, and hence are not necessarily absolute contraindications.[4][6][5][7][9] While high oral doses of selegiline (≥20 mg/day) can cause such interactions, oral doses within the approved clinical range (≤10 mg/day) appear to have little to no risk of these interactions.[9][25][5] In addition, the ODT and transdermal forms of selegiline have reduced risks of such interactions compared to the conventional oral form.[7][9]

Selegiline is also contraindicated in children less than 12 years of age and in people with pheochromocytoma, both due to heightened risk of hypertensive crisis.[8] For all human uses and all forms, selegiline is pregnancy category C, meaning that studies in pregnant animals have shown adverse effects on the fetus but there are no adequate studies in humans.[4][8]

Side effects

[edit]Side effects of the tablet form in conjunction with levodopa include, in decreasing order of frequency, nausea, hallucinations, confusion, depression, loss of balance, insomnia, increased involuntary movements, agitation, slow or irregular heart rate, delusions, hypertension, new or increased angina pectoris, and syncope.[4] Most of the side effects are due to a high dopamine levels, and can be alleviated by reducing the dose of levodopa.[3] Selegiline can also cause cardiovascular side effects such as orthostatic hypotension, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, and other types of cardiac arrhythmias.[66]

The main side effects of the patch form for depression include application-site reactions, insomnia, dry mouth, dizziness, nervousness, and abnormal dreams.[8][24] The selegiline patch carries a black box warning about a possible increased risk of suicide, especially for young people,[8] as do all antidepressants since 2007.[67]

Side effects of selegiline that have been identified as occurring significantly more often than with placebo in meta-analyses for psychiatric disorders have included dry mouth (RR = 1.58), insomnia (RR = 1.61, NNH = 19), and application site reactions with the transdermal form (RR = 1.81, NNH = 7).[21][22] No significant diarrhea, headache, dizziness, nausea, sexual dysfunction, or weight gain were apparent in these meta-analyses.[21][22]

Selegiline, including in its oral, ODT, and patch forms, has been found to cause hypotension or orthostatic hypotension in some individuals.[4][6][8] In a clinical trial, the rate of systolic orthostatic hypotension was 21% versus 9% with placebo and the rate of diastolic orthostatic hypotension was 12% versus 4% with placebo in people with Parkinson's disease taking the ODT form of selegiline.[6] The risk of hypotension is greater at the start of treatment and in the elderly (3% vs. 0% with placebo).[6] The rate of hypotension or orthostatic hypotension with the selegiline patch was 2.2% versus 0.5% with placebo in clinical trials of people with depression.[24] Significant orthostatic blood pressure changes (≥10 mm Hg decrease) occurred in 9.8% versus 6.7% with placebo, but most of these cases were asymptomatic and heart rate was unchanged.[24][68] The rates of other orthostatic hypotension-related side effects in this population were dizziness or vertigo 4.9% versus 3.1% with placebo and fainting 0.5% versus 0.0% with placebo.[24] It is said that orthostatic hypotension is rarely seen with the selegiline transdermal patch compared to oral MAOIs.[52] Caution is advised against rapidly rising after sitting or lying, especially after prolonged periods or at the start of treatment, as this can result in fainting.[6][27][68] Falls are of particular concern in the elderly.[68] MAOIs like selegiline may lower blood pressure by increasing dopamine levels and activating dopamine receptors, by increasing levels of the false neurotransmitter octopamine, and/or by other mechanisms.[69]

Meta-analyses published in the 1990s found that the addition of selegiline to levodopa increased mortality in people with Parkinson's disease.[27] However, several subsequent meta-analyses with more trials and patients found no increase in mortality with selegiline added to levodopa.[27][70][71] If selegiline does increase mortality, it has been theorized that this may be due to cardiovascular side effects, such as its amphetamine-related sympathomimetic effects and its MAO inhibition-related hypotension.[72] Although selegiline does not seem to increase mortality, it appears to worsen cognition in people with Parkinson's disease over time.[73] Conversely, rasagiline does not seem to do so and can enhance cognition.[73]

Rarely, selegiline has been reported to induce or exacerbate impulse control disorders, pathological gambling, hypersexuality, and paraphilias in people with Parkinson's disease.[74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81] However, MAO-B inhibitors like selegiline causing impulse control disorders is uncommon and controversial.[74][75] Selegiline has also been reported to activate or worsen rapid eye movement (REM) sleep behavior disorder (RBD) in some people with Parkinson's disease.[82][83][84]

Selegiline has shown little or no misuse potential in humans or monkeys.[26][27][28][85][86][87] Likewise, it has no dependence potential in rodents.[29] This is in spite of its amphetamine active metabolites, levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine, and is in contrast to agents like dextroamphetamine and dextromethamphetamine.[27][28][29][86][87] However, selegiline can strongly potentiate the reinforcing effects of exogenous β-phenethylamine by inhibiting its MAO-B-mediated metabolism.[28] Misuse of the combination of selegiline and β-phenethylamine has been reported.[88][89]

Overdose

[edit]Little information is available about clinically significant selegiline overdose.[4] The drug has been studied clinically at doses as high as 60 mg/day orally,[90][21] 10 mg/day as an ODT,[7] and 12 mg/24 hours as a transdermal patch.[9] In addition, deprenyl (the racemic form) has been clinically studied orally at doses as large as 100 mg/day.[30] During clinical development of oral selegiline, some individuals who were exposed to doses of 600 mg developed severe hypotension and psychomotor agitation.[4][6] Overdose may result in non-selective inhibition of both MAO-A and MAO-B and may be similar to overdose of other non-selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) like phenelzine, isocarboxazid, and tranylcypromine.[4][6] Serotonin syndrome, hypertensive crisis, and/or death may occur with overdose.[4][6][8] No specific antidote to selegiline overdose is available.[8]

Interactions

[edit]Serotonin syndrome and hypertensive crisis

[edit]Both the oral and patch forms of selegiline come with strong warnings against combining it with drugs that could produce serotonin syndrome, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and the cough medicine dextromethorphan.[4][8][91] Selegiline in combination with the opioid analgesic pethidine is not recommended, as it can lead to severe adverse effects.[91] Several other synthetic opioids such as tramadol and methadone, as well as various triptans, are also contraindicated due to potential for serotonin syndrome.[92][93]

All three forms of selegiline carry warnings about food restrictions to avoid hypertensive crisis that are associated with MAOIs.[4][6][8] The patch form was created in part to overcome food restrictions; clinical trials showed that it was successful.[22][8] Additionally, in post-marketing surveillance from April 2006 to October 2010, only 13 self-reports of possible hypertensive events or hypertension were made out of 29,141 exposures to the drug, and none were accompanied by objective clinical data.[22] The lowest dose of the patch method of delivery, 6 mg/24 hours, does not require any dietary restrictions.[94] Higher doses of the patch and oral formulations, whether in combination with the older non-selective MAOIs or in combination with the reversible MAO-A inhibitor (RIMA) moclobemide, require a low-tyramine diet.[91]

A study found that selegiline in transdermal patch form did not importantly modify the pharmacodynamic effects or pharmacokinetics of the sympathomimetic agents pseudoephedrine and phenylpropanolamine.[9][95] Likewise, oral selegiline at an MAO-B-selective dosage did not appear to modify the pharmacodynamic effects or pharmacokinetics of intravenous methamphetamine in another study.[96][97] Conversely, selegiline, also at MAO-B-selective doses, has been found to reduce the physiological and euphoric subjective effects of cocaine whilst not affecting its pharmacokinetics in some studies but not in others.[98][99][100][101][102][103] Cautious safe combination of MAOIs like selegiline with stimulants like lisdexamfetamine has been reported.[104][105][106] However, a hypertensive crisis with selegiline and ephedrine has also been reported.[4] The selegiline drug labels warn about combination of selegiline with indirectly-acting sympathomimetic agents, like amphetamines, ephedrine, pseudoephedrine, and phenylpropanolamine, due to the potential risk of hypertensive crisis, and recommend monitoring blood pressure with such combinations.[6][8] The combination of selegiline with certain other medications, like phenylephrine and buspirone, is also warned against for similar reasons.[8][12][107][68] In the case of phenylephrine, this drug is substantially metabolized by monoamine oxidase, including by both MAO-A and MAO-B.[108][109]

Besides norepinephrine releasing agents, selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (NRIs) may be safe in combination with MAOIs like selegiline.[110][111][112] Potent NRIs, such as reboxetine, desipramine, protriptyline, and nortriptyline, can reduce or block the pressor effects of tyramine, including in those taking MAOIs.[110][111][112] This is by inhibiting the norepinephrine transporter (NET) and preventing entry of tyramine into presynaptic noradrenergic neurons where tyramine induces the release of norepinephrine.[110][111][112] As a result, NRIs may reduce the risk of tyramine-related hypertensive crisis in people taking MAOIs.[110][111][112] Norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitors (NDRIs), like methylphenidate and bupropion, are also considered to be safe in combination with MAOIs.[113] However, initiation at low doses and slow upward dose titration is advisable in the case of both NRIs and NDRIs due to possible potentiation of their effects and side effects by MAOIs.[113]

Cytochrome P450 inhibitors and inducers

[edit]The cytochrome P450 enzymes involved in the metabolism of selegiline have not been fully elucidated.[5][18] CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 metabolizer phenotypes did not significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of selegiline, suggesting that these enzymes are minimally involved in its metabolism and that inhibitors and inducers of these enzymes would not importantly affect its pharmacokinetics.[18][40][114][115] However, although most pharmacokinetic variables were unaffected, overall exposure to selegiline's metabolite levomethamphetamine was 46% higher in CYP2D6 poor metabolizers compared to extensive metabolizers and exposure to its metabolite desmethylselegiline was 68% higher in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers compared to extensive metabolizers.[40][114][115] As with the cases of CYP2D6 and CYP2C19, the strong CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 inhibitor itraconazole has minimal impact on the pharmacokinetics of selegiline, suggesting lack of major involvement of this enzyme as well.[18][116][6] On the other hand, the anticonvulsant carbamazepine, which is known to act as a strong inducer of CYP3A enzymes,[117] has paradoxically been found to increase exposure to selegiline and its metabolites levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine by approximately 2-fold (with selegiline used as the transdermal patch form).[8][9] One enzyme thought to be majorly involved in the metabolism of selegiline based on in-vitro studies is CYP2B6.[5][18][9][19] However, there are no clinical studies of different CYP2B6 metabolizer phenotypes or of CYP2B6 inhibitors or inducers on the pharmacokinetics of selegiline.[44] In addition to CYP2B6, CYP2A6 may be involved in the metabolism of selegiline to a lesser extent.[44][118]

Birth control pills containing the synthetic estrogen ethinylestradiol and a progestin like gestodene or levonorgestrel have been found to increase peak levels and overall exposure to oral selegiline by 10- to 20-fold.[18][119][120] High levels of selegiline can lead to loss of MAO-B selectivity and inhibition of MAO-A as well.[18][120] This increases susceptibility to side effects and interactions of non-selective monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), such as tyramine-induced hypertensive crisis and serotonin toxicity when combined with serotonergic medications.[18][120] However, this study had a small sample size of four individuals as well as other methodological limitations.[18][120] The precise mechanism underlying the interaction is unknown, but is likely related to cytochrome P450 inhibition and consequent inhibition of selegiline first-pass metabolism by ethinylestradiol.[18] In contrast to birth control pills containing ethinylestradiol, menopausal hormone therapy with estradiol and levonorgestrel did not modify peak levels of selegiline and only modestly increased overall exposure (+59%).[18][119][121] Hence, menopausal hormone therapy does not pose the same risk of interaction as ethinylestradiol-containing birth control pills when taken together with selegiline.[119][121]

Overall exposure to selegiline with oral selegiline has been found to be 23-fold lower in people taking anticonvulsants known to strongly activate drug-metabolizing enzymes.[122] The anticonvulsants included phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and amobarbital.[122] In a previous study however, carbamazepine specifically did not reduce selegiline exposure.[8][9] Phenobarbital and certain other anticonvulsants are known to strongly induce CYP2B6, one of the major enzymes believed to be involved in selegiline metabolism.[122] As such, it was concluded that strong CYP2B6 induction was most likely responsible for the dramatically reduced exposure to selegiline observed in the study.[122]

Selegiline inhibition of cytochrome P450 enzymes

[edit]Selegiline has been reported to inhibit several cytochrome P450 enzymes, including CYP2D6, CYP3A4/5, CYP2C19, CYP2B6, and CYP2A6.[8][123] It is a mechanism-based inhibitor (suicide inhibitor) of CYP2B6 and has been said to "potently" or "strongly" inhibit this enzyme in vitro.[124][123][125][126] It may inhibit the metabolism of bupropion, a major CYP2B6 substrate, into its active metabolite hydroxybupropion.[124][123][125] However, a study predicted that inhibition of CYP2B6 by selegiline would non-significantly affect exposure to bupropion.[126] Selegiline has not been listed or described as a clinically significant CYP2B6 inhibitor by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as of 2023.[117][8] One small study observing three patients found that selegiline was safe and well-tolerated in combination with bupropion.[125][127] In addition to CYP2B6 and other cytochrome P450 enzymes, selegiline is a potent mechanism-based inhibitor of CYP2A6 and may increase exposure to nicotine (a major CYP2A6 substrate).[128][129] By inhibiting cytochrome P450 enzymes like CYP2B6 and CYP1A2, selegiline may inhibit its own metabolism and thereby interact with itself.[129][130]

Other interactions

[edit]Dopamine antagonists like antipsychotics or metoclopramide, which block dopamine receptors and thereby antagonize the dopaminergic effects of selegiline, could potentially reduce the effectiveness of the medication.[6] Dopamine-depleting agents like reserpine and tetrabenazine, by reducing dopamine levels, can also oppose the effectiveness of dopaminergic medications like selegiline.[131]

Pharmacology

[edit]Pharmacodynamics

[edit]Monoamine oxidase inhibitor

[edit]Selegiline acts as an enzyme inhibitor of the enzyme monoamine oxidase (MAO) and hence is known as a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI).[30][11][25][5] There are two types of MAO, MAO-A and MAO-B.[30][11][25][5] MAO-A metabolizes the monoamine neurotransmitters serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine as well as trace amines like tyramine, whereas MAO-B metabolizes dopamine and the trace amine β-phenethylamine.[30][11][25][5] At lower concentrations and at typical clinical doses (≤10 mg/day), selegiline selectively inhibits MAO-B.[30][11][25][5] Conversely, at higher concentrations and doses (≥20 mg/day), selegiline additionally inhibits MAO-A.[30][11][25][5] By selectively inhibiting MAO-B, selegiline increases levels of dopamine in the brain and thereby increases dopaminergic neurotransmission.[30][11][25][5] At higher doses, by inhibiting both MAO-A and MAO-B, selegiline increases brain levels of serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine and thereby increases serotonergic, dopaminergic, and noradrenergic neurotransmission.[30][11][25][5] Selegiline is an irreversible mechanism-based inhibitor (suicide inhibitor) of MAO that acts by covalently binding to the active site of the enzyme and thereby disabling it.[30][11][25][5][66]

Selegiline is thought to exert its therapeutic effects in the treatment of the motor symptoms of Parkinson's disease by increasing dopamine levels in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) of the basal ganglia, which projects to the caudate nucleus and putamen of the striatum, thereby enhancing the signaling of the nigrostriatal pathway.[66][30][132][133][17] In addition to the nigrostriatal pathway, selegiline may also influence and potentiate other dopaminergic pathways and areas, including the mesolimbic pathway, mesocortical pathway, tuberoinfundibular pathway, and chemoreceptor trigger zone, which may also be involved in its effects as well as side effects.[134][135][136] Selegiline and other MAO-B inhibitors may additionally improve non-motor symptoms in Parkinson's disease, for instance depression and motivational deficits, by increasing dopamine levels.[66] Selegiline may have some disease-modifying neuroprotective effects in Parkinson's disease by inhibiting the MAO-B-mediated oxidation of dopamine into reactive oxygen species that damage dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway via oxidative stress.[137][66] However, the pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease is complex and multifacted, and MAO-B inhibitors may only slow the progression of the disease and do not halt it.[137][66]

Selegiline almost completely inhibits MAO-B in blood platelets at a dosage of 10 mg/day.[7] Following a single 5 or 10 mg oral dose of selegiline, 86 to 90% of MAO-B activity in platelets was inhibited within 2 to 4 hours and 98% of activity was inhibited after 24 hours.[5][30] Inhibition of platelet MAO-B activity persisted at above 90% for 5 days and almost 14 days were required before activity returned to baseline.[5][30] A lower dose of selegiline of 1 mg/day for 10 days also inhibited platelet MAO-B activity by about 75 to 100% in three individuals.[30][138] Similarly, 2.5 mg/day selegiline inhibited platelet MAO-B by 95% within 4 days.[139] The recommended dosing schedule of selegiline in Parkinson's disease (10 mg/day) has been described as somewhat questionable and potentially excessive from a pharmacological standpoint.[140][139] Selegiline could be effective at lower doses, like 2.5 mg/day.[141][139] However, optimal effectiveness of selegiline in Parkinson's disease seems to require a dosage of 10 mg/day and its effectiveness lasts only about 2 to 3 days following discontinuation.[30][142] It is assumed that peripheral and brain MAO-B are inhibited with selegiline to similar extents.[50][69][30] Accordingly, selegiline at an MAO-B-selective dosage of 10 mg/day has been found to inhibit brain MAO-B by more than 90% in postmortem individuals with Parkinson's disease.[13][38][143][144] This dosage of selegiline has been found in such individuals to produce increases in brain levels of dopamine of 23 to 350% and of β-phenethylamine of 1,200 to 3,400% depending on the brain area and the study.[25][30][145][143][146][147] Brain MAO-B levels recover slowly upon discontinuation of selegiline, with a half-time of brain MAO-B synthesis and recovery of approximately 40 days in humans.[25][144]

Selegiline is about 500 to 1,000 times more potent in inhibiting MAO-B than MAO-A in vitro and about 100 times more potent in vivo in rodents.[30][11][50] The clinical selectivity of selegiline for MAO-B is lost at doses of the drug above 20 mg/day.[30] In a study of post-mortem individuals who were on selegiline 10 mg/day, MAO-A activity in the brain was inhibited by 38 to 86%.[30][25] A more recent study using positron emission tomography (PET) imaging similarly found inhibition of brain MAO-A by 33 to 70% in humans.[42][148] However, while brain dopamine and β-phenethylamine levels are substantially increased at this dosage, brain levels of serotonin and its metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) remain unchanged.[25][30][145] It has been found in animal studies that brain MAO-A must be inhibited by nearly 85% before serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine levels increase and result in increased functional activity as well as accompanying behavioral changes.[25][149] Selegiline at an oral dosage of 10 mg/day does not cause the "cheese effect" as assessed by oral tyramine and β-phenethylamine challenge tests.[5] These findings indicate that selegiline does not importantly inhibit MAO-A at a dosage of 10 mg/day.[5] However, a dosage of 20 mg/day selegiline did increase the pressor effect of tyramine, indicating that doses this high and above can significantly inhibit MAO-A.[25] The "cheese reaction" is known to be specifically dependent on inhibition of intestinal MAO-A.[30][25]

Besides increasing brain dopamine levels via MAO-B inhibition, selegiline strongly increases endogenous levels of β-phenethylamine, a major substrate of MAO-B.[30] Levels of β-phenethylamine in the brain are increased 10- to 30-fold and levels in urine are increased 20- to 90-fold.[30][145][150] β-Phenethylamine is normally present in small amounts in the brain and urine and has been referred to as "endogenous amphetamine".[30][151] Similarly to amphetamines, it induces the release of norepinephrine and dopamine and produces psychostimulant effects.[30] Selegiline also strongly increases levels of β-phenethylamine with exogenous administration of β-phenethylamine.[30] The increase in endogenous levels of β-phenethylamine with selegiline might be involved in its effects, for instance claimed "psychic energizing" and mood-lifting effects as well as its effectiveness in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[152][46][153] In contrast to amphetamine psychostimulants however, selegiline is thought to have little or no misuse potential.[46][85]

The MAO-B inhibition of deprenyl lies mainly in selegiline (L-deprenyl), which is 150-fold more potent than D-deprenyl at inhibiting MAO-B.[38][154] Besides selegiline itself, desmethylselegiline, one of its major metabolites, is pharmacologically active.[38][155] Compared to selegiline, desmethylselegiline is 60-fold less potent in inhibiting MAO-B in vitro, but is only 3- to 6-fold less potent in vivo.[5][155] Although desmethylselegiline levels with selegiline therapy are low, selegiline and desmethylselegiline are highly potent MAO-B inhibitors due to the irreversible nature of their inhibition.[30] As such, desmethylselegiline may contribute significantly to the MAO-B inhibition with selegiline.[30]

Findings from a 2021 study suggest that MAO-A is solely or almost entirely responsible for the striatal metabolism of dopamine rather than MAO-B.[156][157][158] Conversely, MAO-B was found to regulate tonic γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels.[156][157][158] These findings may warrant a rethinking of the pharmacological actions of MAO-B inhibitors like selegiline in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[156][157][158]

Catecholaminergic activity enhancer

[edit]Selegiline has been found to act as a catecholaminergic activity enhancer (CAE).[31][32][33] It selectively enhances the activity of noradrenergic and dopaminergic neurons and does not affect the activity of serotonergic neurons.[159][34][25] The CAE actions of selegiline are distinct from those of catecholamine releasing agents like amphetamines.[31][32][33] Conversely, the actions are shared with certain trace amines like β-phenethylamine and tryptamine.[160][36] Selegiline and other CAEs enhance only impulse propogation-mediated release of catecholamines.[31][33] In relation to this, they lack the misuse potential of amphetamines.[31][32] Selegiline is active as a CAE at far lower concentrations and doses than those at which it starts to inhibit the monoamine oxidases.[159][161][25] For example, selegiline given subcutaneously in rodents selectively inhibits MAO-B with a single dose of at least 0.2 mg/kg, whereas CAE effects are apparent for noradrenergic neurons at a dose of 0.01 mg/kg (+42% activity) and for dopaminergic neurons at a dose of 0.025 mg/kg (+17% activity) (i.e., 8- to 20-fold lower doses).[25][note 1][159] Monoamine activity enhancers (MAEs) show a peculiar and characteristic bimodal concentration–response relationship, with two bell-shaped curves of activity across tested concentration ranges.[36][163][159][164] Selegiline is presently the only registered pharmaceutical medication with CAE actions that lacks concomitant potent catecholamine releasing effects.[160][159][165]

Other MAEs besides selegiline, like phenylpropylaminopentane (PPAP) and benzofuranylpropylaminopentane (BPAP), have been developed.[33][160] PPAP was derived from selegiline (and by extension from β-phenethylamine), while BPAP was derived from tryptamine.[160] These compounds are more potent and selective in their MAE actions than selegiline.[160][36] In addition, BPAP is an activity enhancer of not only catecholaminergic neurons but also of serotonergic neurons.[34] Unlike selegiline, PPAP and BPAP lack the MAO inhibition and amphetamine metabolites of selegiline, although BPAP has also been found to inhibit the reuptake of dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin.[160][166]

The actions of MAEs including selegiline may be due to TAAR1 agonism.[167][35] TAAR1 agonists have been found to enhance the release of monoamine neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin analogously to MAEs;[168][169][35] trace amines like β-phenethylamine and tryptamine are known to act as both TAAR1 agonists and MAEs;[168][169] and the TAAR1 antagonist EPPTB has been shown to reverse the CAE effects of BPAP and selegiline, among other findings.[167][35] However, it has yet to be determined whether MAEs like BPAP and selegiline actually directly bind to and activate the TAAR1.[37][35] Moreover, in an older study of MAO-B knockout mice, no non-MAO binding of radiolabeled selegiline was detected in the brain, suggesting that this agent might not act directly via a macromolecular target in terms of its MAE effects.[170][171][172] In any case, selegiline's active metabolites levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine have been confirmed to bind to and activate the TAAR1.[173][174][175] As with selegiline, levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine are also CAEs, although levomethamphetamine is 1- to 10-fold less potent in this action than selegiline itself.[32][25][176][177][160][35] Another metabolite of selegiline, desmethylselegiline, has been found to act as a CAE as well.[178][179] TAAR1 agonists like ulotaront and ralmitaront are under investigation for treatment of a variety of psychiatric disorders, such as depression and schizophrenia.[180][181]

In contrast to selegiline, rasagiline is devoid of CAE actions.[20][178] In fact, it actually inhibits the CAE effects of selegiline.[35] This may explain differences in effectiveness between selegiline and rasagiline in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[20][35][59] According to József Knoll, one of the original developers of selegiline, the CAE effect of selegiline may be more important than MAO-B inhibition in terms of effectiveness for Parkinson's disease.[32] Rasagiline may act as a TAAR1 antagonist to mediate its anti-CAE effects.[159][35] However, as with selegiline, binding to and modulation of the TAAR1 by rasagiline still requires confirmation.[35]

Selegiline has potent pro-sexual or aphrodisiac effects in male rodents.[30][182][183][184] The pro-sexual effects of selegiline are stronger than those of dopamine agonists like apomorphine and bromocriptine and high doses of amphetamine.[30][182][184] These effects are not shared with other MAO-B inhibitors or the MAO-A inhibitor clorgiline and hence do not appear to be related to MAO inhibition.[30][183] Instead, the CAE actions of selegiline have been implicated in the pro-sexual effects.[20][160] Although selegiline has shown potent pro-sexual effects in rodents, these effects were not subsequently confirmed in primates.[30][185] In humans, selegiline for depression shows minimal pro-sexual effects in men, though it did significantly enhance several areas of sexual function in women.[63] However, this may have been due to improvement in depression.[63]

Catecholamine releasing agent

[edit]Levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine are major metabolites of selegiline and are also pharmacologically active.[38][39] They are sympathomimetic and psychostimulant agents that work by inducing the release of norepinephrine and dopamine in the body and brain.[38][39][186]

The involvement of levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine in the effects of selegiline is controversial.[28] The levels of these metabolites are relatively low and are potentially below pharmacological concentrations at typical clinical doses of selegiline.[30][4] In any case, both beneficial and harmful effects of these metabolites have been postulated.[28] It is unknown whether the metabolites are involved in the effectiveness of selegiline in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[30] It has been said that the amphetamine metabolites of selegiline might improve fatigue, but could also produce cardiovascular side effects like increased heart rate and blood pressure and reportedly may be able to cause insomnia, euphoria, psychiatric disturbances, and psychosis.[38][7][17] It is unknown what concentrations of levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine produce sympathomimetic and other effects in humans and whether such concentrations are achieved with selegiline therapy.[38] However, cardiovascular side effects of selegiline have been found clinically and have been attributed to its amphetamine metabolites.[187][50] For comparison, rasagiline, which lacks amphetamine metabolites, has shown fewer adverse effects in clinical studies.[187][50][188] Animal studies suggest that selegiline's amphetamine metabolites may indeed be involved in its effects, such as arousal, wakefulness, locomotor activity, and sympathomimetic effects.[189][190][153][191][192]

Whereas the psychostimulants dextromethamphetamine and dextroamphetamine are relatively balanced releasers of dopamine and norepinephrine, levomethamphetamine is about 15- to 20-fold more potent in releasing norepinephrine relative to dopamine in vitro.[193][39][194][195][196] Levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine are similar to dextromethamphetamine and dextroamphetamine in their potencies as norepinephrine releasers in rodents in vivo.[186][197][196][198] Conversely, levomethamphetamine is dramatically less potent as a dopamine releaser than dextromethamphetamine in vivo, whereas levoamphetamine is 3- to 5-fold less potent as a dopamine releaser compared to dextroamphetamine.[197][186][198] Relatedly, levoamphetamine is substantially more potent as a dopamine releaser and stimulant than levomethamphetamine in rodents.[197][198] In relation to the preceding findings, levomethamphetamine acts more as a selective norepinephrine releasing agent and levoamphetamine as an imbalanced and norepinephrine-preferring releasing agent of norepinephrine and dopamine than as balanced dual releasers of these catecholamine neurotransmitters.[39][197][186][195][38][194] In accordance with the results of catecholamine release studies, levomethamphetamine is 2- to 10-fold or more less potent than dextromethamphetamine in terms of psychostimulant-like effects in rodents,[199][200][201] whereas levoamphetamine is 1- to 4-fold less potent than dextroamphetamine in its stimulating and reinforcing effects in monkeys and humans.[186][30][202]

In clinical studies, levomethamphetamine at oral doses of 1 to 10 mg has been found not to affect subjective drug responses, heart rate, blood pressure, core temperature, electrocardiography, respiration rate, oxygen saturation, or other clinical parameters.[203][204] As such, doses of levomethamphetamine of less than or equal to 10 mg appear to have no significant physiological or subjective effects.[203][204] However, higher doses of levomethamphetamine, for instance 0.25 to 0.5 mg/kg (mean doses of ~18–37 mg) intravenously, have been reported to produce significant pharmacological effects, including increased heart rate and blood pressure, increased respiration rate, and subjective effects like intoxication and drug liking.[203][195] On the other hand, in contrast to dextroamphetamine and dextromethamphetamine, levomethamphetamine also produces subjective "bad" or aversive drug effects.[194][195] Unlike the case of levomethamphetamine, oral doses of levoamphetamine of as low as 5 mg and above have been assessed and reported to produce significant pharmacological effects, for instance on wakefulness and mood.[205][202][note 2][206][207] With a 10 mg oral dose of selegiline, about 2 to 6 mg levomethamphetamine and 1 to 3 mg levoamphetamine is excreted in urine.[7][5][17]

The amphetamine metabolites of selegiline being involved in its effectiveness in the treatment of Parkinson's disease has been deemed unlikely.[30] High doses of levoamphetamine, for instance 50 mg/day, have been reported to be slightly effective in the treatment of Parkinson's disease.[30][17][207] It has been postulated that amphetamines are limitedly effective for Parkinson's disease as there is inadequate presynaptic dopamine to be released in patients with the condition.[205][207] In any case, this effectiveness of high doses of levoamphetamine could not be relevant to selegiline, which is administered at a dose of 10 mg/day.[30] In one clinical study, levels of the amphetamine metabolites of selegiline were manipulated and there were no changes in clinical symptoms of Parkinson's disease.[30][208] This led the researchers to conclude that the beneficial clinical effects of selegiline in Parkinson's disease were not due to its amphetamine metabolites.[30][208] It is possible that there could be some small synergistic beneficial effect of selegiline with its amphetamine metabolites, but this has been considered improbable.[30]

Methamphetamine is directly neurotoxic to dopaminergic neurons at high concentrations and doses.[209] Such toxicity is unfavorable generally, but it is particularly concerning in the context of Parkinson's disease due to the potential for sufficiently high concentrations of methamphetamine to further exarcebate neurodegeneration along the nigrostriatal pathway.[210][211][28] However, as previously described, levomethamphetamine is a significantly weaker monoamine releaser and psychostimulant than dextromethamphetamine.[210][39][28] Circulating levels of levomethamphetamine associated with clinically relevant doses of selegiline are far lower than concentrations of racemic or dextrorotatory methamphetamine that are known to be neurotoxic to dopaminergic neurons.[209][28] As such, dopaminergic neurotoxicity from selegiline's levomethamphetamine metabolite has been deemed unlikely.[28]

Newer formulations of selegiline, such as the ODT and transdermal patch forms, have been developed which strongly reduce formation of the amphetamine metabolites and their associated effects.[7][9] In addition, other MAO-B inhibitors that do not metabolize into amphetamines or monoamine releasing agents, like rasagiline and safinamide, have been developed and introduced.[38][212]

Dopaminergic neuroprotection

[edit]Starting around the age of 45, dopamine content in the caudate nucleus decreases at a rate of about 13% per decade, and this neurodegeneration extends to the nigrostriatal dopaminergic pathway in general.[20][32][213][133][214][215][216] This is a very high rate of neuronal decay relative to brain aging generally.[32] Similarly, age-related decay of mesolimbic dopaminergic neurons as well as noradrenergic neurons is substantially slower than in the nigrostriatal pathway.[32][215] Symptoms of Parkinson's disease are known to develop when the dopamine content of the caudate nucleus drops below 30% of the normal level.[32][213][214][133] Loss of striatal dopamine reaches a level of 40% in healthy people by the age of 75, whereas in people with Parkinson's disease, the loss is around 70% at diagnosis and more than 90% at death.[32] Only about 0.1% of the human population develops Parkinson's disease.[214][133][32] In these individuals, the nigrostriatal pathway deteriorates more rapidly and prematurely than usual, for instance at a rate of 30 to 90% loss of dopamine content per decade.[214][133] However, it is thought that if humans lived much longer than the average lifespan, everyone would eventually develop Parkinson's disease.[214][133] Besides the nigrostriatal pathway, there is also considerable, albeit lesser, loss of dopaminergic neurons in people with Parkinson's disease in other pathways and areas, like the mesolimbic and mesocortical pathways.[215] There is even substantial loss of dopamine in non-brain tissues, like the adrenal cortex and retina, implicating a generalized degeneration of the whole dopamine system.[215]

The progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the nigrostriatal pathway as well as other areas has implications not only for motor control and risk of Parkinson's disease but also for cognition, emotion, learning, sexual activity, and other processes.[20][32][215] Dopamine itself is thought to play a major role in this degeneration by metabolism into reactive oxygen species that damage dopaminergic neurons.[32] Age-related degeneration of nigrostriatal dopaminergic neurons is similar in rodents and humans.[32][213] Selegiline has been found to attenuate the age-related morphological changes in the nigrostriatal pathway of rodents and to produce accompanying preservations of cognitive and sexual functions.[20][32][213] These protective effects may be mediated by activities of selegiline including its MAO-B inhibition, its catetcholaminergic activity enhancer effects, and other actions.[20][32][213] According to József Knoll and Ildikó Miklya, two of the developers of selegiline, the drug may act as a neuroprotective and may be able to modestly slow the rate of age-related loss of dopamine signaling in humans.[20][32][161][163][217] Knoll has advocated for the widespread use of a low dose of selegiline (1 mg/day or 10–15 mg/week) in the healthy population for such purposes and has used this himself.[213][160][214][161][218] However, antiaging and anti-neurodegenerative effects of selegiline in humans have not been clearly demonstrated as of present and this theory remains to be substantiated.[50][20]

Other actions

[edit]Selegiline has a weak norepinephrine, dopamine, and serotonin-releasing effects, weakly blocks dopamine receptors, and weakly inhibits the reuptake of norepinephrine.[30][219][192] However, these actions are largely of very low potency and are of questionable clinical significance.[30] On the basis of positron emission tomography (PET) research with the ODT and patch formulations of selegiline, the drug does not significantly inhibit the brain dopamine transporter (DAT) in humans at clinical doses.[148]

Selegiline appears to activate σ1 receptors, having a relatively high affinity for these receptors of approximately 400 nM.[220][221]

Selegiline and its metabolite desmethylselegiline have been reported to directly bind to and inhibit glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH).[38][222][223] This might play a modulating role in the clinical effectiveness of selegiline for Parkinson's disease.[38][222][223]

Unlike some of the hydrazine MAOIs like phenelzine and isocarboxazid, selegiline does not inhibit semicarbazide-sensitive amine oxidase (SSAO; also known as primary amine oxidase (PrAO) or as diamine oxidase (DAO)) nor does it pose a risk of vitamin B6 deficiency.[44] As a result, selegiline does not have risks of the side effects of these actions.[44]

Selegiline has been reported to inhibit several cytochrome P450 enzymes, including CYP2D6, CYP3A4/5, CYP2C19, CYP2B6, and CYP2A6.[8][123]

Pharmacokinetics

[edit]Absorption

[edit]Selegiline has an oral bioavailability of about 4 to 10%.[5][11][12][224] The average time to peak levels of selegiline is 0.6 to 1.4 hours in different studies, with a range of about 0.5 to 1.5 hours in one study.[5]

The circulating levels of selegiline and its metabolites following a single 10 mg oral dose have been studied.[5] The metabolites of selegiline include desmethylselegiline, levomethamphetamine, and levoamphetamine.[5] The average peak concentrations of selegiline across several studies ranged from 0.84 ± 0.6 μg/L to 2.2 ± 1.2 μg/L and the AUC levels ranged from 1.26 ± 1.19 μg⋅h/L to 2.17 ± 2.59 μg⋅h/L.[5] In the case of desmethylselegiline, the time to peak has been reported to be 0.8 ± 0.2 hours, the peak levels were 7.84 ± 2.11 μg/L to 13.4 ± 3.2 μg/L, and the area-under-the-curve (AUC) levels were 15.05 ± 4.37 μg⋅h/L to 40.3 ± 10.7 μg⋅h/L.[5] For levomethamphetamine, the peak levels were 10.2 ± 1.5 μg/L and the AUC levels were 150.2 ± 21.6 μg⋅h/L, whereas for levoamphetamine, the peak levels were 3.6 ± 2.9 μg/L and the AUC levels were 61.7 ± 44.0 μg⋅h/L.[5] For comparison, following a single 10 mg oral dose of dextromethamphetamine or dextroamphetamine, peak levels of these agents have been reported to range from 14 to 90 μg/L and from 15 to 34 μg/L, respectively.[225] Time to peak for levomethamphetamine has been reported to be 0.75 to 6 hours and for levoamphetamine has been reported to be 2.5 to 12 hours in people with different CYP2D6 metabolizer phenotypes.[40][114] Levels of desmethylselegiline, levomethamphetamine, and levoamphetamine are 4- to almost 20-fold higher than maximal selegiline levels with oral selegiline therapy.[115][4]

With repeated administration of selegiline, there is an accumulation of selegiline and its metabolites.[5] With a dosage of 10 mg once a day or 5 mg twice daily, peak levels of selegiline were 1.59 ± 0.89 μg/L to 2.33 ± 1.76 μg/L and AUC levels of selegiline were 6.92 ± 5.39 μg⋅h/L to 7.84 ± 5.43 μg⋅h/L after 1 week of treatment.[5] This equated to a 1.9- to 2.6-fold accumulation in peak levels and a 3.6- to 5.5-fold accumulation in AUC levels.[5] The metabolites of selegiline accumulate to a smaller extent than selegiline.[5] The AUC levels of desmethylselegiline increased by 1.5-fold and the peak and AUC levels of levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine increased by 2-fold following 1 week of treatment with selegiline.[5] Selegiline appears to inhibit its own metabolism and that of desmethylselegiline with continuous use.[129][130]

The oral bioavailability of selegiline increases when it is ingested together with a fatty meal, as the molecule is fat-soluble.[3][226] There is a 3-fold increase in peak levels of selegiline and a 5-fold increase in AUC levels when it is taken orally with food.[5][4] The elimination half-life of selegiline is unchanged when it is taken with food.[5] In contrast to selegiline itself, the pharmacokinetics of its metabolites, desmethylselegililne, levomethamphetamine, and levoamphetamine, are unchanged when selegiline is taken with food.[5]

Distribution

[edit]The apparent volume of distribution of selegiline is 1,854 ± 824 L.[5] Selegiline and its metabolites rapidly cross the blood–brain barrier and enter the brain, where they are most concentrated in the thalamus, basal ganglia, midbrain, and cingulate gyrus.[54][8] Selegiline especially accumulates in brain areas with high MAO-B content, such as the thalamus, striatum, cortex, and brainstem.[25] Concentrations of selegiline's metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) are similar to those in blood, suggesting that accumulation in the brain over peripheral tissues does not occur.[25]

No data were originally available on the plasma protein binding of selegiline.[5] It has been stated that the plasma protein binding of selegiline is 94%, but it has been said that there is no actual evidence to support this figure.[5] Subsequent research found that its plasma protein binding is 85 to 90%.[9][8][6]

Metabolism

[edit]Selegiline is metabolized in the intestines, liver, and other tissues.[5][25] More than 90% of orally administered selegiline is metabolized prior to reaching the bloodstream due to strong first-pass metabolism.[7] Selegiline (L-N-propargylmethamphetamine) is metabolized by N-demethylation into levomethamphetamine and by N-depropargylation into desmethylselegiline (L-N-propargylamphetamine).[9][44] Subsequently, levomethamphetamine is further metabolized into levoamphetamine by N-demethylation and desmethylselegiline is further metabolized into levoamphetamine by N-depropargylation.[7][44] Levomethamphetamine, levoamphetamine, and desmethylselegiline constitute the three major or primary metabolites of selegiline.[9][5][25] No racemization occurs in the metabolism of selegiline or its metabolites; that is, the levorotatory enantiomers are not converted into the dextrorotatory enantiomers, such as D-deprenyl, dextromethamphetamine, or dextroamphetamine.[11] Following their formation, the amphetamine metabolites of selegiline are also metabolized via hydroxylation and then conjugation via glucuronidation.[44] Besides the preceding metabolites, selegiline-N-oxide and formaldehyde are also known to be formed.[162] More than 40 minor metabolites of selegiline have been either detected or proposed.[162] Due to the amphetamine metabolites of selegiline, people taking selegiline may test positive for "amphetamine" or "methamphetamine" on drug screening tests.[227][228]

The exact cytochrome P450 enzymes responsible for the metabolism of selegiline have not been fully elucidated.[18] CYP2B6, CYP2C9, and CYP3A are thought to be significantly involved in the metabolism of selegiline on the basis of in vitro studies.[9][19][40] Other cytochrome P450 enzymes, including CYP1A2, CYP2A6, CYP2C8, CYP2D6, CYP2C19, and CYP2E1, may also be involved.[9][11][19][40] One review concluded that CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 are the leading candidates in selegiline metabolism.[18] CYP2B6 is thought to N-demethylate selegiline into desmethylselegiline and CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 are thought to N-depropargylate selegiline into levomethamphetamine.[9][19] Additionally, CYP2B6 and CYP2C19 are thought to metabolize desmethylselegiline into levoamphetamine and CYP2B6 is thought to N-demethylate levomethamphetamine into levoamphetamine.[9][19] CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 metabolizer phenotypes did not significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of selegiline, suggesting that these enzymes are minimally involved in its metabolism.[18][40][114][115] However, although most pharmacokinetic variables were unaffected, AUC levels of levomethamphetamine were 46% higher and its elimination half-life 33% longer in CYP2D6 poor metabolizers compared to extensive metabolizers and desmethylselegiline AUC levels were 68% higher in CYP2C19 poor metabolizers compared to extensive metabolizers.[40][114][115] As with CYP2D6 and CYP2C19, CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 are unlikely to be majorly involved in the metabolism of selegiline as the strong inhibitor itraconazole has minimal impact on its pharmacokinetics.[18][116][6]

Elimination

[edit]Selegiline administered orally is recovered 87% in urine and 15% in feces as the unchanged parent drug and its metabolites.[15][7][16] Of selegiline excreted in urine, 20 to 63% is excreted as levomethamphetamine, 9 to 26% as levoamphetamine, 1% as desmethylselegiline, and 0.01 to 0.03% at unchanged selegiline.[7][5][17] In the case of levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine, with an oral dose of 10 mg selegiline, this would be amounts of about 2 to 6 mg levomethamphetamine and about 1 to 3 mg levoamphetamine.[7][17] The near-absence of unchanged excreted selegiline indicates that selegiline is essentially completely metabolized prior to its excretion.[5][7]

The average elimination half-life of selegiline after a single oral dose ranges from 1.2 to 1.9 hours across studies.[5] With repeated administration, the half-life of selegiline increases to 7.7 ± 12.6 hours to 9.6 ± 13.6 hours.[5] The elimination half-life of selegiline's metabolite, desmethylselegiline, has been reported to range from 2.2 ± 0.6 hours to 3.8 hours.[5] The half-lives of its metabolites levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine have been reported to be 14 hours and 16 hours, respectively.[5] In another study, their half-lives were 11.6 to 15.4 hours and 17.0 to 18.1 hours, respectively, in people with different CYP2D6 metabolizer phenotypes.[40][114] Following repeated administration, the half-life of desmethylselegiline increased from 3.8 hours with the first dose to 9.5 hours following 1 week of daily selegiline doses.[5] Selegiline is a known inhibitor of several cytochrome P450 enzymes, such as CYP2B6 and CYP2A6.[124][123][125][129] It appears to inhibit its own metabolism and the metabolism of its metabolite desmethylselegiline.[129][130]

The oral clearance of selegiline is 59.4 ± 43.7 L/min.[5] This is described as very high and as almost 30-fold higher than hepatic blood flow.[5] The renal clearance of selegiline is 0.0072 L/h and is very low compared to its oral clearance.[5] These findings suggest that selegiline is extensively metabolized not only by the liver but also by non-hepatic tissues.[5]

Orally disintegrating tablet

[edit]Selegiline as an orally disintegrating tablet (ODT) is absorbed primarily buccally instead of being swallowed orally.[6][14] It was found to have 5- to 8-fold higher bioavailability, more consistent blood levels, and to produce fewer amphetamine metabolites than the standard oral tablet form.[14][13] It achieves blood levels of selegiline at a dose of 1.25 mg/day that are similar to those with conventional oral selegiline at a dose of 10 mg/day.[7] In addition, there is an at least 90% reduction in metabolites of selegiline including desmethylselegiline, levomethamphetamine, and levoamphetamine with the ODT formulation of selegiline compared to conventional oral selegiline.[7] Hence, levels of these metabolites are 10-fold lower with the ODT formulation.[187] The levels of amphetamine metabolites with the ODT formulation have been regarded as negligible.[6] This formulation of selegiline retains selectivity for MAO-B over MAO-A and likewise does not cause the "cheese effect" with consumption of tyramine-rich foods.[7]

Transdermal patch

[edit]The selegiline transdermal patch is indicated for application to the upper torso, upper thigh, or the outer upper arm once every 24 hours.[8] With application, an average of 25 to 30% (range 10 to 14%) of the selegiline content of the patch is delivered systemically over 24 hours.[9][8] This equates to about 0.3 mg selegiline per cm2 over 24 hours.[9] The patch has approximately 75% bioavailability, compared to 4 to 10% with the conventional oral form.[9][12] Transdermal selegiline results in significantly higher exposure to selegiline and lower exposure to all metabolites compared to conventional oral selegiline.[9] Selegiline levels are 50-fold higher and exposure to its metabolites 70% lower with the transdermal patch compared to oral administration at equivalent doses.[9] These differences are due to extensive first-pass metabolism with the oral form and the bypassing and absence of the first pass with the patch form.[9][12] Selegiline absorption and levels have been found to be equivalent when applied to the upper torso versus the upper thigh.[8] The drug does not accumulate in skin and is not significantly metabolized in skin.[8]

Hepatic and renal impairment

[edit]The United States drug label for oral selegiline states that no information is available on this formulation of the drug in the context of hepatic or renal impairment.[4] Conversely, the transdermal patch drug label states that no pharmacokinetic differences in selegiline and its metabolites were observed in mild or moderate liver impairment nor in mild, moderate, or severe renal impairment.[8] As such, the label states that dosage adjustment is not needed in these contexts.[8] Severe hepatic impairment and end-stage renal impairment were not studied.[8] In the case of the ODT formulation of selegiline, its drug label states that the dosage of selegiline should be reduced in mild and moderate hepatic impairment, whereas no dosage adjustment is required in mild to moderate renal impairment.[6] The label additionally states that ODT selegiline is not recommended in severe hepatic impairment nor in severe or end-stage renal impairment.[6] In clinical studies described by the ODT label, selegiline exposure was 1.5-fold higher and desmethylselegiline exposure 1.4-fold higher in mild hepatic impairment, selegiline exposure was 1.5-fold higher and desmethylselegiline exposure 1.8-fold higher in moderate hepatic impairment, and selegiline exposure was 4-fold higher and desmethylselegiline exposure 1.25-fold higher in severe hepatic impairment.[6] Conversely, levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine exposures were not modified by hepatic impairment.[6] In the case of renal impairment, selegiline and desmethylselegiline levels were not substantially different in mild and moderate renal impairment and selegiline levels were likewise not substantially different in end-stage renal impairment.[6] However, levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine exposures were increased by 34 to 67% in moderate renal impairment and by approximately 4-fold in end-stage renal impairment.[6]

In a published clinical study, hepatic and renal function were reported to more dramatically influence the pharmacokinetics of selegiline in the case of oral selegiline.[229][230][122] The pharmacokinetics of selegiline's major metabolites, desmethylselegiline, levomethamphetamine, and levoamphetamine, were also affected, but to a much lesser extent compared to selegiline itself.[122] AUC levels of selegiline relative to normal control subjects were 18-fold higher in people with hepatic impairment, 23-fold lower in people with drug-induced liver dysfunction, and 6-fold higher in people with renal impairment.[230][122] The drug-induced liver dysfunction group consisted of people taking a variety of anticonvulsants, including phenobarbital, phenytoin, carbamazepine, and amobarbital, that are known to strongly activate drug-metabolizing enzymes.[122] However, in a previous study, carbamazepine specifically did not reduce selegiline exposure.[8][9] Phenobarbital and certain other anticonvulsants are known to strongly induce CYP2B6, one of the major enzymes thought to be involved in the metabolism of selegiline, and it was concluded by the study authors that induction of this enzyme was the most likely explanation of the dramatically reduced exposure to selegiline in the drug-induced liver dysfunction group.[122] Because of these increased exposures, subsequent literature reviews citing the study have stated that selegiline (route/form not specified) is not recommended in people with moderate or severe liver impairment or with renal impairment.[119][231]

Chemistry

[edit]Selegiline is a substituted phenethylamine and amphetamine derivative.[40] It is also known as (R)-(–)-N,α-dimethyl-N-(2-propynyl)phenethylamine, (R)-(–)-N-methyl-N-2-propynylamphetamine, or N-propargyl-L-methamphetamine.[232][233][234][7] Selegiline (L-deprenyl) is the enantiopure levorotatory enantiomer of the racemic mixture deprenyl, whereas D-deprenyl is the dextrorotatory enantiomer.[41][20] Selegiline is a derivative of levomethamphetamine (L-methamphetamine), the levorotatory enantiomer of the psychostimulant and sympathomimetic agent methamphetamine (N-methylamphetamine), with a propargyl group attached to the nitrogen atom of the molecule.[61]

Selegiline is a small-molecule compound, with the molecular formula C13H17N and a low molecular weight of 187.281 g/mol.[232][233][234][4][61] It has high lipophilicity, with an experimental log P of 2.7 and predicted log P values of 2.9 to 3.1.[232][233][234][61] Pharmaceutically, selegiline is used almost always as the hydrochloride salt, though the free base form has also been used.[4][235] At room temperature, selegiline hydrochloride is a white to near white crystalline powder.[4] Selegiline hydrochloride is freely soluble in water, chloroform, and methanol.[4]

Analogues

[edit]Selegiline is a close analogue of methamphetamine and amphetamine, and in fact produces their levorotatory forms, levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine, as metabolites.[38][28] Selegiline is structurally similar to the antihypertensive agent pargyline (N-methyl-N-propargylbenzylamine), an earlier non-selective MAOI of the phenylalkylamine group.[236][33] Besides selegiline and pargyline, another clinically used MAOI of the phenylalkylamine and amphetamine families is the antidepressant tranylcypromine (trans-2-phenylcyclopropylamine).[44] Tranylcypromine can be conceptualized as a cyclized amphetamine and has amphetamine-like actions at high doses similarly to selegiline.[44][237][238] Another notable analogue of selegiline is 4-fluoroselegiline, a variation of selegiline in which one of the hydrogen atoms of the phenyl ring has been replaced with a fluorine atom.[239] A large number of other analogues of selegiline derived via structural modification have been synthesized and characterized.[240][239][241][242]

Rasagiline (N-propargyl-1(R)-aminoindan) is an analogue of selegiline in which the amphetamine base structure has been replaced with a 1-aminoindan structure and the N-methyl group has been removed.[38] Like selegiline, it is also a selective MAO-B inhibitor and used to treat Parkinson's disease.[38] In contrast to selegiline however, rasagiline lacks the amphetamine metabolites and activity of selegiline.[38] A further derivative of rasagiline, ladostigil ([N-propargyl-(3R)-aminoindan-5-yl]-N-propylcarbamate), a dual MAO-B inhibitor and acetylcholinesterase inhibitor, was developed for treatment of Alzheimer's disease and other conditions but was ultimately never introduced for medical use.[243]

Synthesis

[edit]Selegiline can be synthesized by the alkylation of levomethamphetamine using propargyl bromide.[44][244][245][246][247]

History

[edit]Following the discovery in 1952 that the tuberculosis drug iproniazid elevated the mood of people taking it, and the subsequent discovery that the effect was likely due to inhibition of monoamine oxidase (MAO) and elevation of monoamine neurotransmitters in the brain, many people and companies started trying to discover monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) to use as antidepressants.[11][248] Deprenyl, the racemic form of selegiline, was synthesized and discovered by Zoltan Ecseri at the Chinoin Pharmaceutical Company (part of Sanofi since 1993) in Budapest, Hungary.[11][249] Chinoin received a patent on the drug in 1962 and the compound was first published in the scientific literature in English in 1965.[11][250] Chinoin researchers had been studying substituted amphetamines since 1960, and decided to try synthesizing amphetamines that acted as MAOIs.[65] It had been known that methamphetamine was a reversible inhibitor of MAO.[65] Deprenyl, also known as N-propargyl-N-methylamphetamine,[33] is closely related to and inspired by pargyline (N-propargyl-N-methylbenzylamine), another MAOI that had been synthesized earlier.[11][65][251] Deprenyl was initially referred to by the chemical name phenylisopropylmethylpropinylamine and the developmental code name E-250.[11][250] Work on the biology and effects of E-250 in animals and humans was conducted by a group led by József Knoll at Semmelweis University, which was also in Budapest.[11]

Deprenyl is a racemic compound (a mixture of two isomers called enantiomers).[11][65] Further work determined that the levorotatory enantiomer was a more potent MAOI, which was published in 1967, and subsequent work was done with the single enantiomer L-deprenyl.[11][65][154][218] In 1968, it was discovered by Johnston that monoamine oxidase exists in multiple forms.[11][65][252] In 1971, Knoll showed that selegiline highly selectively inhibits the B-isoform of monoamine oxidase (MAO-B) and proposed that it is unlikely to cause the infamous "cheese effect" (hypertensive crisis resulting from consuming foods containing tyramine) that occurs with non-selective MAOIs.[11][65][253] The lack of potentiation of tyramine effect by deprenyl had previously been reported in 1966 and 1968 studies, but could not be mechanistically explained until after the existence of multiple forms of MAO was discovered.[11][65][254] Selegiline was the first selective MAO-B inhibitor to be discovered[13] and is described as prototypical of these agents.[44][45]

Deprenyl and selegiline were initially studied as antidepressants for treatment of depression.[160][250] Deprenyl was first found to be effective for depression from 1965 to 1967,[160][255][256] while selegiline was first found to be effective for depression in 1971 and this was further corroborated in 1980.[160][257][258] A 1984 study that combined selegiline with phenylalanine reported remarkably high effectiveness in the treatment of depression similar to that with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).[160][259] However, selegiline in its original oral form was never further developed or approved for the treatment of depression.[160]

A few years after the discovery that selegiline was a selective MAO-B inhibitor, two Parkinson's disease researchers based in Vienna, Peter Riederer and Walther Birkmayer, realized that selegiline could be useful in Parkinson's disease. One of their colleagues, Moussa B. H. Youdim, visited Knoll in Budapest and took selegiline from him to Vienna. In 1975, Birkmayer's group published the first paper on the effect of selegiline in Parkinson's disease.[218][260]

Speculation that selegiline could be useful as an anti-aging drug or aphrodisiac based on animal studies began in the 1970s.[261]

Selegiline was first introduced for clinical use in Hungary in 1977.[42] It was approved in the oral pill form under the brand name Jumex to treat Parkinson's disease.[42] The drug was then introduced in the United Kingdom in 1982.[42] In 1987, Somerset Pharmaceuticals in New Jersey, which had acquired the rights to develop selegiline in the United States, filed a New Drug Application (NDA) with the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to market the drug for Parkinson's disease in this country.[43] While the NDA was under review, Somerset was acquired in a joint venture by two generic drug companies, Mylan and Bolan Pharmaceuticals.[43] Selegiline was approved for Parkinson's disease by the FDA in 1989.[43]

It had been known since the mid-1960s that high doses of deprenyl had psychostimulant effects.[30][11][250][256] Selegiline was first shown to metabolize into levomethamphetamine and levoamphetamine in humans in 1978.[28][262] The involvement of these metabolites in the effects and side effects of selegiline has remained controversial and unresolved in the decades afterwards.[28][38] In any case, concerns about these metabolites have contributed to the development of newer MAO-B inhibitors like rasagiline and safinamide that lack such metabolites.[38][212]

The catecholaminergic activity enhancer (CAE) effects of selegiline became well-characterized and distinctly named in 1994.[159][32][25][178][20][34][177][176][263] These effects had been observed much earlier, dating back to the 1960s and 1970s, but were not properly distinguished from the other actions of selegiline, like MAO-B inhibition, until the 1990s.[32][25][34][159] More potent, selective, and/or expansive monoamine activity enhancers (MAEs), like phenylpropylaminopentane (PPAP) and benzofuranylpropylaminopentane (BPAP), were derived from selegiline and other compounds and were first described in 1992 and 1999, respectively.[33][36][171][160] These drugs had been proposed for potential treatment of psychiatric disorders like depression as well as for Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease, but were never developed or marketed.[264][34][36][163][160]

In the 1990s, J. Alexander Bodkin at McLean Hospital, an affiliate of Harvard Medical School, began a collaboration with Somerset to develop delivery of selegiline via a transdermal patch in order to avoid the well known dietary restrictions of MAOIs.[261][265][266] Somerset obtained FDA approval to market the patch for depression in 2006.[267] Similarly, the orally disintegrating tablet (ODT) form of selegiline, marketed under the brand name Zelapar, was approved for Parkinson's disease in the United States in 2006 and in the European Union in 2010.[42]

Binding to and agonism of the trace amine-associated receptors (TAARs) as the mechanism responsible for the MAE effects of selegiline and related MAEs like PPAP and BPAP was first suggested in the early 2000s following the discovery of the TAARs.[36][163][37] Activation of the TAAR1 as the mechanism of the MAE effects was first clearly substantiated in 2022.[167][35] TAAR1 agonists like ulotaront and ralmitaront are under development for treatment of various psychiatric disorders as of 2023.[180][181]

Society and culture

[edit]Names