Опиоид

| Опиоид | |

|---|---|

| Класс препарата | |

| |

| Идентификаторы классов | |

| Использовать | Облегчение боли |

| код АТС | N02A |

| Способ действия | Опиоидный рецептор |

| Внешние ссылки | |

| MeSH | D000701 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Опиоиды — это класс наркотиков или имитируют их , которые получают из натуральных веществ, содержащихся в растении опийного мака, . Опиоиды воздействуют на мозг, оказывая различные эффекты, включая облегчение боли. Как класс веществ, они действуют на опиоидные рецепторы , вызывая морфиноподобный эффект. [2] [3]

Термины «опиоид» и «опиат» иногда используются как синонимы, но существуют ключевые различия, основанные на процессах производства этих лекарств. [4]

В медицине они в основном используются для облегчения боли , включая анестезию . [5] Другие медицинские применения включают подавление диареи , заместительную терапию расстройств, вызванных употреблением опиоидов , устранение передозировки опиоидов и подавление кашля . [5] Чрезвычайно сильные опиоиды, такие как карфентанил, разрешены только для использования в ветеринарии . [6] [7] [8] Опиоиды также часто используются в рекреационных целях из-за их эйфорического эффекта или для предотвращения абстиненции . [9] Опиоиды могут привести к смерти и использовались для казней в Соединенных Штатах .

Side effects of opioids may include itchiness, sedation, nausea, respiratory depression, constipation, and euphoria. Long-term use can cause tolerance, meaning that increased doses are required to achieve the same effect, and physical dependence, meaning that abruptly discontinuing the drug leads to unpleasant withdrawal symptoms.[10] The euphoria attracts recreational use, and frequent, escalating recreational use of opioids typically results in addiction. An overdose or concurrent use with other depressant drugs like benzodiazepines commonly results in death from respiratory depression.[11]

Opioids act by binding to opioid receptors, which are found principally in the central and peripheral nervous system and the gastrointestinal tract. These receptors mediate both the psychoactive and the somatic effects of opioids. Opioid drugs include partial agonists, like the anti-diarrhea drug loperamide and antagonists like naloxegol for opioid-induced constipation, which do not cross the blood–brain barrier, but can displace other opioids from binding to those receptors in the myenteric plexus.

Because opioids are addictive and may result in fatal overdose, most are controlled substances. In 2013, between 28 and 38 million people used opioids illicitly (0.6% to 0.8% of the global population between the ages of 15 and 65).[12] In 2011, an estimated 4 million people in the United States used opioids recreationally or were dependent on them.[13] As of 2015, increased rates of recreational use and addiction are attributed to over-prescription of opioid medications and inexpensive illicit heroin.[14][15][16] Conversely, fears about overprescribing, exaggerated side effects, and addiction from opioids are similarly blamed for under-treatment of pain.[17][18]

Terminology

[edit]

Opioids include opiates, an older term that refers to such drugs derived from opium, including morphine itself.[19] Other opioids are semi-synthetic and synthetic drugs such as hydrocodone, oxycodone and fentanyl; antagonist drugs such as naloxone; and endogenous peptides such as endorphins.[20] The terms opiate and narcotic are sometimes encountered as synonyms for opioid. Opiate is properly limited to the natural alkaloids found in the resin of the opium poppy although some include semi-synthetic derivatives.[19][21] Narcotic, derived from words meaning 'numbness' or 'sleep', as an American legal term, refers to cocaine and opioids, and their source materials; it is also loosely applied to any illegal or controlled psychoactive drug.[22][23] In some jurisdictions all controlled drugs are legally classified as narcotics. The term can have pejorative connotations and its use is generally discouraged where that is the case.[24][25]

Medical uses

[edit]Pain

[edit]The weak opioid codeine, in low doses and combined with one or more other drugs, is commonly available in prescription medicines and without a prescription to treat mild pain.[26][27][28] Other opioids are usually reserved for the relief of moderate to severe pain.[27]

Acute pain

[edit]Opioids are effective for the treatment of acute pain (such as pain following surgery).[29] For immediate relief of moderate to severe acute pain, opioids are frequently the treatment of choice due to their rapid onset, efficacy and reduced risk of dependence. However, a new report showed a clear risk of prolonged opioid use when opioid analgesics are initiated for an acute pain management following surgery or trauma.[30] They have also been found to be important in palliative care to help with the severe, chronic, disabling pain that may occur in some terminal conditions such as cancer, and degenerative conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis. In many cases opioids are a successful long-term care strategy for those with chronic cancer pain.

Just over half of all states in the US have enacted laws that restrict the prescribing or dispensing of opioids for acute pain.[31]

Chronic non-cancer pain

[edit]Guidelines have suggested that the risk of opioids is likely greater than their benefits when used for most non-cancer chronic conditions including headaches, back pain, and fibromyalgia.[32] Thus they should be used cautiously in chronic non-cancer pain.[33] If used the benefits and harms should be reassessed at least every three months.[34]

In treating chronic pain, opioids are an option to be tried after other less risky pain relievers have been considered, including paracetamol/acetaminophen or NSAIDs like ibuprofen or naproxen.[35] Some types of chronic pain, including the pain caused by fibromyalgia or migraine, are preferentially treated with drugs other than opioids.[36][37] The efficacy of using opioids to lessen chronic neuropathic pain is uncertain.[38]

Opioids are contraindicated as a first-line treatment for headache because they impair alertness, bring risk of dependence, and increase the risk that episodic headaches will become chronic.[39] Opioids can also cause heightened sensitivity to headache pain.[39] When other treatments fail or are unavailable, opioids may be appropriate for treating headache if the patient can be monitored to prevent the development of chronic headache.[39]

Opioids are being used more frequently in the management of non-malignant chronic pain.[40][41][42] This practice has now led to a new and growing problem with addiction and misuse of opioids.[33][43] Because of various negative effects the use of opioids for long-term management of chronic pain is not indicated unless other less risky pain relievers have been found ineffective. Chronic pain which occurs only periodically, such as that from nerve pain, migraines, and fibromyalgia, frequently is better treated with medications other than opioids.[36] Paracetamol/Tylenol/Acetaminophen and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs including ibuprofen and naproxen are considered safer alternatives.[44] They are frequently used combined with opioids, such as paracetamol combined with oxycodone (Percocet) and ibuprofen combined with hydrocodone (Vicoprofen), which boosts the pain relief but is also intended to deter recreational use.[45][46]

Other

[edit]Cough

[edit]Codeine was once viewed as the "gold standard" in cough suppressants, but this position is now questioned.[47] Some recent placebo-controlled trials have found that it may be no better than a placebo for some causes including acute cough in children.[48][49] As a consequence, it is not recommended for children.[49] Additionally, there is no evidence that hydrocodone is useful in children.[50] Similarly, a 2012 Dutch guideline regarding the treatment of acute cough does not recommend its use.[51] (The opioid analogue dextromethorphan, long claimed to be as effective a cough suppressant as codeine,[52] has similarly demonstrated little benefit in several recent studies.[53])

Low dose morphine may help chronic cough but its use is limited by side effects.[54]

Diarrhea

[edit]In cases of diarrhea-predominate irritable bowel syndrome, opioids may be used to suppress diarrhea. Loperamide is a peripherally selective opioid available without a prescription used to suppress diarrhea.

The ability to suppress diarrhea also produces constipation when opioids are used beyond several weeks.[55] Naloxegol, a peripherally-selective opioid antagonist is now available to treat opioid induced constipation.[56]

Shortness of breath

[edit]Opioids may help with shortness of breath particularly in advanced diseases such as cancer and COPD among others.[57][58] However, findings from two recent systematic reviews of the literature found that opioids were not necessarily more effective in treating shortness of breath in patients who have advanced cancer.[59][60]

Restless legs syndrome

[edit]Though not typically a first line of treatment, opioids, such as oxycodone and methadone, are sometimes used in the treatment of severe and refractory restless legs syndrome.[61]

Hyperalgesia

Opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH) has been evident in patients after chronic opioid exposure.[62][63]

Adverse effects

[edit]Common and short term

Other

- Cognitive effects

- Opioid dependence

- Dizziness

- Loss of appetite

- Delayed gastric emptying

- Decreased sex drive

- Impaired sexual function

- Decreased testosterone levels

- Depression

- Immunodeficiency

- Increased pain sensitivity

- Irregular menstruation

- Increased risk of falls

- Slowed breathing

- Coma

Each year 69,000 people worldwide die of opioid overdose, and 15 million people have an opioid addiction.[65]

In older adults, opioid use is associated with increased adverse effects such as "sedation, nausea, vomiting, constipation, urinary retention, and falls".[66] As a result, older adults taking opioids are at greater risk for injury.[67] Opioids do not cause any specific organ toxicity, unlike many other drugs, such as aspirin and paracetamol. They are not associated with upper gastrointestinal bleeding and kidney toxicity.[68]

Prescription of opioids for acute low back pain and management of osteoarthritis seem to have long-term adverse effects[69][70]

According to the USCDC, methadone was involved in 31% of opioid related deaths in the US between 1999–2010 and 40% as the sole drug involved, far higher than other opioids.[71] Studies of long term opioids have found that many stop them, and that minor side effects were common.[72] Addiction occurred in about 0.3%.[72] In the United States in 2016 opioid overdose resulted in the death of 1.7 in 10,000 people.[73]

Reinforcement disorders

[edit]Tolerance

[edit]Tolerance is a process characterized by neuroadaptations that result in reduced drug effects. While receptor upregulation may often play an important role other mechanisms are also known.[74] Tolerance is more pronounced for some effects than for others; tolerance occurs slowly to the effects on mood, itching, urinary retention, and respiratory depression, but occurs more quickly to the analgesia and other physical side effects. However, tolerance does not develop to constipation or miosis (the constriction of the pupil of the eye to less than or equal to two millimeters). This idea has been challenged, however, with some authors arguing that tolerance does develop to miosis.[75]

Tolerance to opioids is attenuated by a number of substances, including:

- calcium channel blockers[76][77][78]

- intrathecal magnesium[79][80] and zinc[81]

- NMDA antagonists, such as dextromethorphan, ketamine,[82] and memantine.[83]

- cholecystokinin antagonists, such as proglumide[84][85][86]

- Newer agents such as the phosphodiesterase inhibitor ibudilast have also been researched for this application.[87]

Tolerance is a physiologic process where the body adjusts to a medication that is frequently present, usually requiring higher doses of the same medication over time to achieve the same effect. It is a common occurrence in individuals taking high doses of opioids for extended periods, but does not predict any relationship to misuse or addiction.

Physical dependence

[edit]Physical dependence is the physiological adaptation of the body to the presence of a substance, in this case opioid medication. It is defined by the development of withdrawal symptoms when the substance is discontinued, when the dose is reduced abruptly or, specifically in the case of opioids, when an antagonist (e.g., naloxone) or an agonist-antagonist (e.g., pentazocine) is administered. Physical dependence is a normal and expected aspect of certain medications and does not necessarily imply that the patient is addicted.

The withdrawal symptoms for opiates may include severe dysphoria, craving for another opiate dose, irritability, sweating, nausea, rhinorrea, tremor, vomiting and myalgia. Slowly reducing the intake of opioids over days and weeks can reduce or eliminate the withdrawal symptoms.[88] The speed and severity of withdrawal depends on the half-life of the opioid; heroin and morphine withdrawal occur more quickly than methadone withdrawal. The acute withdrawal phase is often followed by a protracted phase of depression and insomnia that can last for months. The symptoms of opioid withdrawal can be treated with other medications, such as clonidine.[89] Physical dependence does not predict drug misuse or true addiction, and is closely related to the same mechanism as tolerance. While there is anecdotal claims of benefit with ibogaine, data to support its use in substance dependence is poor.[90]

Critical patients who received regular doses of opioids experience iatrogenic withdrawal as a frequent syndrome.[91]

Addiction

[edit]Drug addiction is a complex set of behaviors typically associated with misuse of certain drugs, developing over time and with higher drug dosages. Addiction includes psychological compulsion, to the extent that the affected person persists in actions leading to dangerous or unhealthy outcomes. Opioid addiction includes insufflation or injection, rather than taking opioids orally as prescribed for medical reasons.[88]

In European nations such as Austria, Bulgaria, and Slovakia, slow-release oral morphine formulations are used in opiate substitution therapy (OST) for patients who do not well tolerate the side effects of buprenorphine or methadone. Buprenorphine can also be used together with naloxone for a longer treatment of addiction. In other European countries including the UK, this is also legally used for OST although on a varying scale of acceptance.

Slow-release formulations of medications are intended to curb misuse and lower addiction rates while trying to still provide legitimate pain relief and ease of use to pain patients. Questions remain, however, about the efficacy and safety of these types of preparations. Further tamper resistant medications are currently under consideration with trials for market approval by the FDA.[92][93]

The amount of evidence available only permits making a weak conclusion, but it suggests that a physician properly managing opioid use in patients with no history of substance use disorder can give long-term pain relief with little risk of developing addiction, or other serious side effects.[72]

Problems with opioids include the following:

- Some people find that opioids do not relieve all of their pain.[94]

- Some people find that opioids side effects cause problems which outweigh the therapy's benefit.[72]

- Some people build tolerance to opioids over time. This requires them to increase their drug dosage to maintain the benefit, and that in turn also increases the unwanted side effects.[72]

- Long-term opioid use can cause opioid-induced hyperalgesia, which is a condition in which the patient has increased sensitivity to pain.[95]

All of the opioids can cause side effects.[64] Common adverse reactions in patients taking opioids for pain relief include nausea and vomiting, drowsiness, itching, dry mouth, dizziness, and constipation.[64][88]

Nausea and vomiting

[edit]Tolerance to nausea occurs within 7–10 days, during which antiemetics (e.g. low dose haloperidol once at night) are very effective.[citation needed] Due to severe side effects such as tardive dyskinesia, haloperidol is now rarely used. A related drug, prochlorperazine is more often used, although it has similar risks. Stronger antiemetics such as ondansetron or tropisetron are sometimes used when nausea is severe or continuous and disturbing, despite their greater cost. A less expensive alternative is dopamine antagonists such as domperidone and metoclopramide. Domperidone does not cross the blood–brain barrier and produce adverse central antidopaminergic effects, but blocks opioid emetic action in the chemoreceptor trigger zone. This drug is not available in the U.S.

Some antihistamines with anticholinergic properties (e.g. orphenadrine, diphenhydramine) may also be effective. The first-generation antihistamine hydroxyzine is very commonly used, with the added advantages of not causing movement disorders, and also possessing analgesic-sparing properties. Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol relieves nausea and vomiting;[96][97] it also produces analgesia that may allow lower doses of opioids with reduced nausea and vomiting.[98][99]

- 5-HT3 antagonists (e.g. ondansetron)

- Dopamine antagonists (e.g. domperidone)

- Anti-cholinergic antihistamines (e.g. diphenhydramine)

- Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (e.g. dronabinol)

Vomiting is due to gastric stasis (large volume vomiting, brief nausea relieved by vomiting, oesophageal reflux, epigastric fullness, early satiation), besides direct action on the chemoreceptor trigger zone of the area postrema, the vomiting centre of the brain. Vomiting can thus be prevented by prokinetic agents (e.g. domperidone or metoclopramide). If vomiting has already started, these drugs need to be administered by a non-oral route (e.g. subcutaneous for metoclopramide, rectally for domperidone).

- Prokinetic agents (e.g. domperidone)

- Anti-cholinergic agents (e.g. orphenadrine)

Evidence suggests that opioid-inclusive anaesthesia is associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting.[100]

Patients with chronic pain using opioids had small improvements in pain and physically functioning and increased risk of vomiting.[101]

Drowsiness

[edit]Tolerance to drowsiness usually develops over 5–7 days, but if troublesome, switching to an alternative opioid often helps. Certain opioids such as fentanyl, morphine and diamorphine (heroin) tend to be particularly sedating, while others such as oxycodone, tilidine and meperidine (pethidine) tend to produce comparatively less sedation, but individual patients responses can vary markedly and some degree of trial and error may be needed to find the most suitable drug for a particular patient. Otherwise, treatment with CNS stimulants is generally effective.[102][103]

- Stimulants (e.g. caffeine, modafinil, amphetamine, methylphenidate)

Itching

[edit]Itching tends not to be a severe problem when opioids are used for pain relief, but antihistamines are useful for counteracting itching when it occurs. Non-sedating antihistamines such as fexofenadine are often preferred as they avoid increasing opioid induced drowsiness. However, some sedating antihistamines such as orphenadrine can produce a synergistic pain relieving effect permitting smaller doses of opioids be used. Consequently, several opioid/antihistamine combination products have been marketed, such as Meprozine (meperidine/promethazine) and Diconal (dipipanone/cyclizine), and these may also reduce opioid induced nausea.

- Antihistamines (e.g. fexofenadine)

Constipation

[edit]Opioid-induced constipation (OIC) develops in 90 to 95% of people taking opioids long-term.[104] Since tolerance to this problem does not generally develop, most people on long-term opioids need to take a laxative or enemas.[105]

Treatment of OIC is successional and dependent on severity.[106] The first mode of treatment is non-pharmacological, and includes lifestyle modifications like increasing dietary fiber, fluid intake (around 1.5 L (51 US fl oz) per day), and physical activity.[106] If non-pharmacological measures are ineffective, laxatives, including stool softeners (e.g., polyethylene glycol), bulk-forming laxatives (e.g., fiber supplements), stimulant laxatives (e.g., bisacodyl, senna), and/or enemas, may be used.[106] A common laxative regimen for OIC is the combination of docusate and bisacodyl.[106][107][108][needs update] Osmotic laxatives, including lactulose, polyethylene glycol, and milk of magnesia (magnesium hydroxide), as well as mineral oil (a lubricant laxative), are also commonly used for OIC.[107][108]

If laxatives are insufficiently effective (which is often the case),[109] opioid formulations or regimens that include a peripherally-selective opioid antagonist, such as methylnaltrexone bromide, naloxegol, alvimopan, or naloxone (as in oxycodone/naloxone), may be tried.[106][108][110] A 2018 (updated in 2022) Cochrane review found that the evidence was moderate for alvimopan, naloxone, or methylnaltrexone bromide but with increased risk of adverse events.[111] Naloxone by mouth appears to be the most effective.[112] A daily 0.2 mg dose of naldemedine has been shown to significantly improve symptoms in patients with OIC.[113]

Opioid rotation is one method suggested to minimise the impact of constipation in long-term users.[114] While all opioids cause constipation, there are some differences between drugs, with studies suggesting tramadol, tapentadol, methadone and fentanyl may cause relatively less constipation, while with codeine, morphine, oxycodone or hydromorphone constipation may be comparatively more severe.

Respiratory depression

[edit]Respiratory depression is the most serious adverse reaction associated with opioid use, but it usually is seen with the use of a single, intravenous dose in an opioid-naïve patient. In patients taking opioids regularly for pain relief, tolerance to respiratory depression occurs rapidly, so that it is not a clinical problem. Several drugs have been developed which can partially block respiratory depression, although the only respiratory stimulant currently approved for this purpose is doxapram, which has only limited efficacy in this application.[115][116] Newer drugs such as BIMU-8 and CX-546 may be much more effective.[117][118][119][non-primary source needed]

- Respiratory stimulants: carotid chemoreceptor agonists (e.g. doxapram), 5-HT4 agonists (e.g. BIMU8), δ-opioid agonists (e.g. BW373U86) and AMPAkines (e.g. CX717) can all reduce respiratory depression caused by opioids without affecting analgesia, but most of these drugs are only moderately effective or have side effects which preclude use in humans. 5-HT1A agonists such as 8-OH-DPAT and repinotan also counteract opioid-induced respiratory depression, but at the same time reduce analgesia, which limits their usefulness for this application.

- Opioid antagonists (e.g. naloxone, nalmefene, diprenorphine)

The initial 24 hours after opioid administration appear to be the most critical with regard to life-threatening OIRD, but may be preventable with a more cautious approach to opioid use.[120]

Patients with cardiac, respiratory disease and/or obstructive sleep apnoea are at increased risk for OIRD.[121]

Increased pain sensitivity

[edit]Opioid-induced hyperalgesia – where individuals using opioids to relieve pain paradoxically experience more pain as a result of that medication – has been observed in some people. This phenomenon, although uncommon, is seen in some people receiving palliative care, most often when dose is increased rapidly.[122][123] If encountered, rotation between several different opioid pain medications may decrease the development of increased pain.[124][125] Opioid induced hyperalgesia more commonly occurs with chronic use or brief high doses but some research suggests that it may also occur with very low doses.[126][127]

Side effects such as hyperalgesia and allodynia, sometimes accompanied by a worsening of neuropathic pain, may be consequences of long-term treatment with opioid analgesics, especially when increasing tolerance has resulted in loss of efficacy and consequent progressive dose escalation over time. This appears to largely be a result of actions of opioid drugs at targets other than the three classic opioid receptors, including the nociceptin receptor, sigma receptor and Toll-like receptor 4, and can be counteracted in animal models by antagonists at these targets such as J-113,397, BD-1047 or (+)-naloxone respectively.[128] No drugs are currently approved specifically for counteracting opioid-induced hyperalgesia in humans and in severe cases the only solution may be to discontinue use of opioid analgesics and replace them with non-opioid analgesic drugs. However, since individual sensitivity to the development of this side effect is highly dose dependent and may vary depending which opioid analgesic is used, many patients can avoid this side effect simply through dose reduction of the opioid drug (usually accompanied by the addition of a supplemental non-opioid analgesic), rotating between different opioid drugs, or by switching to a milder opioid with a mixed mode of action that also counteracts neuropathic pain, particularly tramadol or tapentadol.[129][130][131]

- NMDA receptor antagonists such as ketamine

- SNRIs such as milnacipran

- Anticonvulsants such as gabapentin or pregabalin

Other adverse effects

[edit]Low sex hormone levels

[edit]Clinical studies have consistently associated medical and recreational opioid use with hypogonadism (low sex hormone levels) in different sexes. The effect is dose-dependent. Most studies suggest that the majority (perhaps as much as 90%) of chronic opioid users develop hypogonadism. A 2015 systematic review and meta-analysis found that opioid therapy suppressed testosterone levels in men by about 165 ng/dL (5.7 nmol/L) on average, which was a reduction in testosterone level of almost 50%.[132] Conversely, opioid therapy did not significantly affect testosterone levels in women.[132] However, opioids can also interfere with menstruation in women by limiting the production of luteinizing hormone (LH). Opioid-induced hypogonadism likely causes the strong association of opioid use with osteoporosis and bone fracture, due to deficiency in estradiol. It also may increase pain and thereby interfere with the intended clinical effect of opioid treatment. Opioid-induced hypogonadism is likely caused by their agonism of opioid receptors in the hypothalamus and the pituitary gland.[133] One study found that the depressed testosterone levels of heroin addicts returned to normal within one month of abstinence, suggesting that the effect is readily reversible and is not permanent.[citation needed] As of 2013[update], the effect of low-dose or acute opioid use on the endocrine system is unclear.[134][135][136][137] Long-term use of opioids can affect the other hormonal systems as well.[134]

Disruption of work

[edit]Use of opioids may be a risk factor for failing to return to work.[138][139]

Persons performing any safety-sensitive task should not use opioids.[140] Health care providers should not recommend that workers who drive or use heavy equipment including cranes or forklifts treat chronic or acute pain with opioids.[140] Workplaces which manage workers who perform safety-sensitive operations should assign workers to less sensitive duties for so long as those workers are treated by their physician with opioids.[140]

People who take opioids long term have increased likelihood of being unemployed.[141] Taking opioids may further disrupt the patient's life and the adverse effects of opioids themselves can become a significant barrier to patients having an active life, gaining employment, and sustaining a career.

In addition, lack of employment may be a predictor of aberrant use of prescription opioids.[142]

Increased accident-proneness

[edit]Opioid use may increase accident-proneness. Opioids may increase risk of traffic accidents[143][144] and accidental falls.[145]

Reduced Attention

Opioids have been shown to reduce attention, more so when used with antidepressants and/or anticonvulsants.[146]

Rare side effects

[edit]Infrequent adverse reactions in patients taking opioids for pain relief include: dose-related respiratory depression (especially with more potent opioids), confusion, hallucinations, delirium, urticaria, hypothermia, bradycardia/tachycardia, orthostatic hypotension, dizziness, headache, urinary retention, ureteric or biliary spasm, muscle rigidity, myoclonus (with high doses), and flushing (due to histamine release, except fentanyl and remifentanil).[88] Both therapeutic and chronic use of opioids can compromise the function of the immune system. Opioids decrease the proliferation of macrophage progenitor cells and lymphocytes, and affect cell differentiation (Roy & Loh, 1996). Opioids may also inhibit leukocyte migration. However the relevance of this in the context of pain relief is not known.

Pregnancy

[edit]Opioid use during pregnancy can have significant implications for both the mother and the developing fetus.

Opioids are a class of drugs that include prescription painkillers (e.g., oxycodone, hydrocodone) and illicit substances like heroin. Opioid use during pregnancy is associated with an increased risk of complications, including an elevated risk of preterm birth, low birth weight, intrauterine growth restriction, and stillbirth. Opioids are substances that can cross the placenta, exposing the developing fetus to the drugs. This exposure can potentially lead to various adverse effects on fetal development, including an increased risk of birth defects. One of the most well-known consequences of maternal opioid use during pregnancy is the risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS). NAS occurs when the newborn experiences withdrawal symptoms after birth due to exposure to opioids in the womb. Maternal opioid use during pregnancy can also have long-term effects on the child's development. These effects may include cognitive and behavioral problems, as well as an increased risk of substance use disorders later in life.Interactions

[edit]Physicians treating patients using opioids in combination with other drugs keep continual documentation that further treatment is indicated and remain aware of opportunities to adjust treatment if the patient's condition changes to merit less risky therapy.[147]

With other depressant drugs

[edit]The concurrent use of opioids with other depressant drugs such as benzodiazepines or ethanol increases the rates of adverse events and overdose.[147] Despite this, opioids and benzodiazepines are concurrently dispensed in many settings.[148][149] As with an overdose of opioid alone, the combination of an opioid and another depressant may precipitate respiratory depression often leading to death.[150] These risks are lessened with close monitoring by a physician, who may conduct ongoing screening for changes in patient behavior and treatment compliance.[147]

Opioid antagonist

[edit]Opioid effects (adverse or otherwise) can be reversed with an opioid antagonist such as naloxone or naltrexone.[151] These competitive antagonists bind to the opioid receptors with higher affinity than agonists but do not activate the receptors. This displaces the agonist, attenuating or reversing the agonist effects. However, the elimination half-life of naloxone can be shorter than that of the opioid itself, so repeat dosing or continuous infusion may be required, or a longer acting antagonist such as nalmefene may be used. In patients taking opioids regularly it is essential that the opioid is only partially reversed to avoid a severe and distressing reaction of waking in excruciating pain. This is achieved by not giving a full dose but giving this in small doses until the respiratory rate has improved. An infusion is then started to keep the reversal at that level, while maintaining pain relief. Opioid antagonists remain the standard treatment for respiratory depression following opioid overdose, with naloxone being by far the most commonly used, although the longer acting antagonist nalmefene may be used for treating overdoses of long-acting opioids such as methadone, and diprenorphine is used for reversing the effects of extremely potent opioids used in veterinary medicine such as etorphine and carfentanil. However, since opioid antagonists also block the beneficial effects of opioid analgesics, they are generally useful only for treating overdose, with use of opioid antagonists alongside opioid analgesics to reduce side effects, requiring careful dose titration and often being poorly effective at doses low enough to allow analgesia to be maintained.

Naltrexone does not appear to increase risk of serious adverse events, which confirms the safety of oral naltrexone.[152] Mortality or serious adverse events due to rebound toxicity in patients with naloxone were rare.[153]

Pharmacology

[edit]| Drug | Relative Potency [154] | Nonionized Fraction | Protein Binding | Lipid Solubility [155][156][157] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morphine | 1 | ++ | ++ | ++ |

| Pethidine (meperidine) | 0.1 | + | +++ | +++ |

| Hydromorphone | 10 | + | +++ | |

| Alfentanil | 10–25 | ++++ | ++++ | +++ |

| Fentanyl | 50–100[158][159][160] | + | +++ | ++++ |

| Remifentanil | 250[citation needed] | +++ | +++ | ++ |

| Sufentanil | 500–1000 | ++ | ++++ | ++++ |

| Etorphine | 1000–3000 | |||

| Carfentanil | 10000 |

Opioids bind to specific opioid receptors in the nervous system and other tissues. There are three principal classes of opioid receptors, μ, κ, δ (mu, kappa, and delta), although up to seventeen have been reported, and include the ε, ι, λ, and ζ (Epsilon, Iota, Lambda and Zeta) receptors. Conversely, σ (Sigma) receptors are no longer considered to be opioid receptors because their activation is not reversed by the opioid inverse-agonist naloxone, they do not exhibit high-affinity binding for classical opioids, and they are stereoselective for dextro-rotatory isomers while the other opioid receptors are stereo-selective for levo-rotatory isomers. In addition, there are three subtypes of μ-receptor: μ1 and μ2, and the newly discovered μ3. Another receptor of clinical importance is the opioid-receptor-like receptor 1 (ORL1), which is involved in pain responses as well as having a major role in the development of tolerance to μ-opioid agonists used as analgesics. These are all G-protein coupled receptors acting on GABAergic neurotransmission.

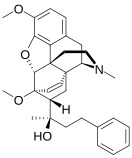

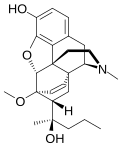

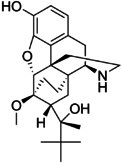

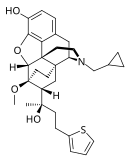

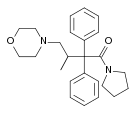

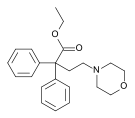

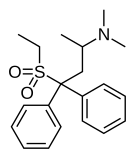

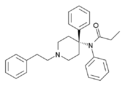

The pharmacodynamic response to an opioid depends upon the receptor to which it binds, its affinity for that receptor, and whether the opioid is an agonist or an antagonist. For example, the supraspinal analgesic properties of the opioid agonist morphine are mediated by activation of the μ1 receptor; respiratory depression and physical dependence by the μ2 receptor; and sedation and spinal analgesia by the κ receptor[citation needed]. Each group of opioid receptors elicits a distinct set of neurological responses, with the receptor subtypes (such as μ1 and μ2 for example) providing even more [measurably] specific responses. Unique to each opioid is its distinct binding affinity to the various classes of opioid receptors (e.g. the μ, κ, and δ opioid receptors are activated at different magnitudes according to the specific receptor binding affinities of the opioid). For example, the opiate alkaloid morphine exhibits high-affinity binding to the μ-opioid receptor, while ketazocine exhibits high affinity to ĸ receptors. It is this combinatorial mechanism that allows for such a wide class of opioids and molecular designs to exist, each with its own unique effect profile. Their individual molecular structure is also responsible for their different duration of action, whereby metabolic breakdown (such as N-dealkylation) is responsible for opioid metabolism.

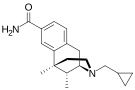

Functional selectivity

[edit]A new strategy of drug development takes receptor signal transduction into consideration. This strategy strives to increase the activation of desirable signalling pathways while reducing the impact on undesirable pathways. This differential strategy has been given several names, including functional selectivity and biased agonism. The first opioid that was intentionally designed as a biased agonist and placed into clinical evaluation is the drug oliceridine. It displays analgesic activity and reduced adverse effects.[162]

Opioid comparison

[edit]Extensive research has been conducted to determine equivalence ratios comparing the relative potency of opioids. Given a dose of an opioid, an equianalgesic table is used to find the equivalent dosage of another. Such tables are used in opioid rotation practices, and to describe an opioid by comparison to morphine, the reference opioid. Equianalgesic tables typically list drug half-lives, and sometimes equianalgesic doses of the same drug by means of administration, such as morphine: oral and intravenous.

Binding profiles

[edit]Usage

[edit]| Substance | Best estimate | Low estimate | High estimate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amphetamine- type stimulants | 34.16 | 13.42 | 55.24 |

| Cannabis | 192.15 | 165.76 | 234.06 |

| Cocaine | 18.20 | 13.87 | 22.85 |

| Ecstasy | 20.57 | 8.99 | 32.34 |

| Opiates | 19.38 | 13.80 | 26.15 |

| Opioids | 34.26 | 27.01 | 44.54 |

Opioid prescriptions in the US increased from 76 million in 1991 to 207 million in 2013.[185]

In the 1990s, opioid prescribing increased significantly. Once used almost exclusively for the treatment of acute pain or pain due to cancer, opioids are now prescribed liberally for people experiencing chronic pain. This has been accompanied by rising rates of accidental addiction and accidental overdoses leading to death. According to the International Narcotics Control Board, the United States and Canada lead the per capita consumption of prescription opioids.[186] The number of opioid prescriptions per capita in the United States and Canada is double the consumption in the European Union, Australia, and New Zealand.[187] Certain populations have been affected by the opioid addiction crisis more than others, including First World communities[188] and low-income populations.[189] Public health specialists say that this may result from the unavailability or high cost of alternative methods for addressing chronic pain.[190] Opioids have been described as a cost-effective treatment for chronic pain, but the impact of the opioid epidemic and deaths caused by opioid overdoses should be considered in assessing their cost-effectiveness.[191] Data from 2017 suggest that in the U.S. about 3.4 percent of the U.S. population are prescribed opioids for daily pain management.[192] Calls for opioid deprescribing have led to broad scale opioid tapering practices with little scientific evidence to support the safety or benefit for patients with chronic pain.

History

[edit]Naturally occurring opioids

[edit]

Opioids are among the world's oldest known drugs.[193] The earliest known evidence of Papaver somniferum in a human archaeological site dates to the Neolithic period around 5,700–5,500 BCE. Its seeds have been found at Cueva de los Murciélagos in the Iberian Peninsula and La Marmotta in the Italian Peninsula.[194][195][196]

Use of the opium poppy for medical, recreational, and religious purposes can be traced to the fourth century BC, when ideograms on Sumerians clay tablets mention the use of "Hul Gil", a "plant of joy".[197][198][199]Opium was known to the Egyptians, and is mentioned in the Ebers Papyrus as an ingredient in a mixture for the soothing of children,[200][199] and for the treatment of breast abscesses.[201]

Opium was also known to the Greeks.[200] It was valued by Hippocrates (c. 460 – c. 370 BC) and his students for its sleep-inducing properties, and used for the treatment of pain.[202] The Latin saying "Sedare dolorem opus divinum est", trans. "Alleviating pain is the work of the divine", has been variously ascribed to Hippocrates and to Galen of Pergamum.[203] The medical use of opium is later discussed by Pedanius Dioscorides (c. 40 – 90 AD), a Greek physician serving in the Roman army, in his five-volume work, De Materia Medica.[204]

During the Islamic Golden Age, the use of opium was discussed in detail by Avicenna (c. 980 – June 1037 AD) in The Canon of Medicine. The book's five volumes include information on opium's preparation, an array of physical effects, its use to treat a variety of illness, contraindications for its use, its potential danger as a poison and its potential for addiction. Avicenna discouraged opium's use except as a last resort, preferring to address the causes of pain rather than trying to minimize it with analgesics. Many of Avicenna's observations have been supported by modern medical research.[205][200]

Exactly when the world became aware of opium in India and China is uncertain, but opium was mentioned in the Chinese medical work K'ai-pao-pen-tsdo (973 AD)[199] By 1590 AD, opium poppies were a staple spring crop in the Subahs of Agra region.[206]

The physician Paracelsus (c. 1493–1541) is often credited with reintroducing opium into medical use in Western Europe, during the German Renaissance. He extolled opium's benefits for medical use. He also claimed to have an "arcanum", a pill which he called laudanum, that was superior to all others, particularly when death was to be cheated. ("Ich hab' ein Arcanum – heiss' ich Laudanum, ist über das Alles, wo es zum Tode reichen will.")[207] Later writers have asserted that Paracelsus' recipe for laudanum contained opium, but its composition remains unknown.[207]

Laudanum

[edit]The term laudanum was used generically for a useful medicine until the 17th century. After Thomas Sydenham introduced the first liquid tincture of opium, "laudanum" came to mean a mixture of both opium and alcohol.[207] Sydenham's 1669 recipe for laudanum mixed opium with wine, saffron, clove and cinnamon.[208] Sydenham's laudanum was used widely in both Europe and the Americas until the 20th century.[200][208] Other popular medicines, based on opium, included Paregoric, a much milder liquid preparation for children; Black-drop, a stronger preparation; and Dover's powder.[208]

The opium trade

[edit]Opium became a major colonial commodity, moving legally and illegally through trade networks involving India, the Portuguese, the Dutch, the British and China, among others.[209]The British East India Company saw the opium trade as an investment opportunity in 1683 AD.[206] In 1773 the Governor of Bengal established a monopoly on the production of Bengal opium, on behalf of the East India Company. The cultivation and manufacture of Indian opium was further centralized and controlled through a series of acts, between 1797 and 1949.[206][210] The British balanced an economic deficit from the importation of Chinese tea by selling Indian opium which was smuggled into China in defiance of Chinese government bans. This led to the First (1839–1842) and Second Opium Wars (1856–1860) between China and Britain.[211][210][209][212]

Morphine

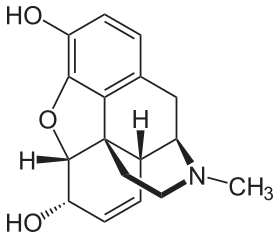

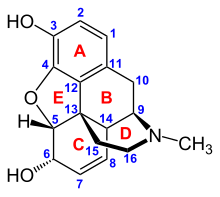

[edit]In the 19th century, two major scientific advances were made that had far-reaching effects. Around 1804, German pharmacist Friedrich Sertürner isolated morphine from opium. He described its crystallization, structure, and pharmacological properties in a well-received paper in 1817.[211][213][208][214] Morphine was the first alkaloid to be isolated from any medicinal plant, the beginning of modern scientific drug discovery.[211][215]

The second advance, nearly fifty years later, was the refinement of the hypodermic needle by Alexander Wood and others. Development of a glass syringe with a subcutaneous needle made it possible to easily administer controlled measurable doses of a primary active compound.[216][208][199][217][218]

Morphine was initially hailed as a wonder drug for its ability to ease pain.[219] It could help people sleep,[211] and had other useful side effects, including control of coughing and diarrhea.[220] It was widely prescribed by doctors, and dispensed without restriction by pharmacists. During the American Civil War, opium and laudanum were used extensively to treat soldiers.[221][219] It was also prescribed frequently for women, for menstrual pain and diseases of a "nervous character".[222]: 85 At first it was assumed (wrongly) that this new method of application would not be addictive.[211][222]

Codeine

[edit]Codeine was discovered in 1832 by Pierre Jean Robiquet. Robiquet was reviewing a method for morphine extraction, described by Scottish chemist William Gregory (1803–1858). Processing the residue left from Gregory's procedure, Robiquet isolated a crystalline substance from the other active components of opium. He wrote of his discovery: "Here is a new substance found in opium ... We know that morphine, which so far has been thought to be the only active principle of opium, does not account for all the effects and for a long time the physiologists are claiming that there is a gap that has to be filled."[223] His discovery of the alkaloid led to the development of a generation of antitussive and antidiarrheal medicines based on codeine.[224]

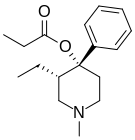

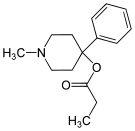

Semisynthetic and synthetic opioids

[edit]Synthetic opioids were invented, and biological mechanisms for their actions discovered, in the 20th century.[199] Scientists have searched for non-addictive forms of opioids, but have created stronger ones instead. In England Charles Romley Alder Wright developed hundreds of opiate compounds in his search for a nonaddictive opium derivative. In 1874 he became the first person to synthesize diamorphine (heroin), using a process called acetylation which involved boiling morphine with acetic anhydride for several hours.[211]

Heroin received little attention until it was independently synthesized by Felix Hoffmann (1868–1946), working for Heinrich Dreser (1860–1924) at Bayer Laboratories.[225] Dreser brought the new drug to market as an analgesic and a cough treatment for tuberculosis, bronchitis, and asthma in 1898. Bayer ceased production in 1913, after heroin's addictive potential was recognized.[211][226][227]

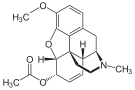

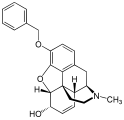

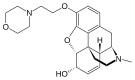

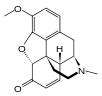

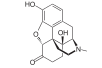

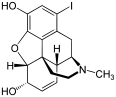

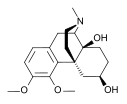

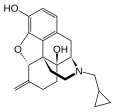

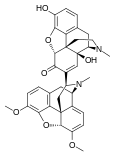

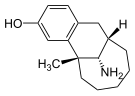

Several semi-synthetic opioids were developed in Germany in the 1910s. The first, oxymorphone, was synthesized from thebaine, an opioid alkaloid in opium poppies, in 1914.[228]Next, Martin Freund and Edmund Speyer developed oxycodone, also from thebaine, at the University of Frankfurt in 1916.[229]In 1920, hydrocodone was prepared by Carl Mannich and Helene Löwenheim, deriving it from codeine. In 1924, hydromorphone was synthesized by adding hydrogen to morphine. Etorphine was synthesized in 1960, from the oripavine in opium poppy straw. Buprenorphine was discovered in 1972.[228]

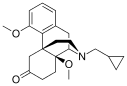

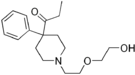

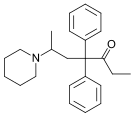

The first fully synthetic opioid was meperidine (later demerol), found serendipitously by German chemist Otto Eisleb (or Eislib) at IG Farben in 1932.[228] Meperidine was the first opiate to have a structure unrelated to morphine, but with opiate-like properties.[199] Its analgesic effects were discovered by Otto Schaumann in 1939.[228]Gustav Ehrhart and Max Bockmühl, also at IG Farben, built on the work of Eisleb and Schaumann. They developed "Hoechst 10820" (later methadone) around 1937.[230]In 1959 the Belgian physician Paul Janssen developed fentanyl, a synthetic drug with 30 to 50 times the potency of heroin.[211][231]Nearly 150 synthetic opioids are now known.[228]

Criminalization and medical use

[edit]Non-clinical use of opium was criminalized in the United States by the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914, and by many other laws.[232][233] The use of opioids was stigmatized, and it was seen as a dangerous substance, to be prescribed only as a last resort for dying patients.[211] The Controlled Substances Act of 1970 eventually relaxed the harshness of the Harrison Act.[citation needed]

In the United Kingdom the 1926 report of the Departmental Committee on Morphine and Heroin Addiction under the Chairmanship of the President of the Royal College of Physicians reasserted medical control and established the "British system" of control—which lasted until the 1960s.[234]

In the 1980s the World Health Organization published guidelines for prescribing drugs, including opioids, for different levels of pain. In the U.S., Kathleen Foley and Russell Portenoy became leading advocates for the liberal use of opioids as painkillers for cases of "intractable non-malignant pain".[235][236]With little or no scientific evidence to support their claims, industry scientists and advocates suggested that people with chronic pain would be resistant to addiction.[211][237][235]

The release of OxyContin in 1996 was accompanied by an aggressive marketing campaign promoting the use of opioids for pain relief. Increasing prescription of opioids fueled a growing black market for heroin. Between 2000 and 2014 there was an "alarming increase in heroin use across the country and an epidemic of drug overdose deaths".[237][211][238]

As a result, health care organizations and public health groups, such as Physicians for Responsible Opioid Prescribing, have called for decreases in the prescription of opioids.[237] In 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued a new set of guidelines for the prescription of opioids "for chronic pain outside of active cancer treatment, palliative care, and end-of-life care" and the increase of opioid tapering.[239]

"Remove the Risk"

[edit]In April 2019 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration announced the launch of a new education campaign to help Americans understand the important role they play in removing and properly disposing of unused prescription opioids from their homes. This new initiative is part of the FDA's continued efforts to address the nationwide opioid crisis (see below) and aims to help decrease unnecessary exposure to opioids and prevent new addiction. The "Remove the Risk" campaign is targeting women ages 35–64, who are most likely to oversee household health care decisions and often serve as the gatekeepers to opioids and other prescription medications in the home.[240]

Society and culture

[edit]Definition

[edit]The term "opioid" originated in the 1950s.[241] It combines "opium" + "-oid" meaning "opiate-like" ("opiates" being morphine and similar drugs derived from opium). The first scientific publication to use it, in 1963, included a footnote stating, "In this paper, the term, 'opioid', is used in the sense originally proposed by George H. Acheson (personal communication) to refer to any chemical compound with morphine-like activities".[242] By the late 1960s, research found that opiate effects are mediated by activation of specific molecular receptors in the nervous system, which were termed "opioid receptors".[243] The definition of "opioid" was later refined to refer to substances that have morphine-like activities that are mediated by the activation of opioid receptors. One modern pharmacology textbook states: "the term opioid applies to all agonists and antagonists with morphine-like activity, and also the naturally occurring and synthetic opioid peptides".[244] Another pharmacology reference eliminates the morphine-like requirement: "Opioid, a more modern term, is used to designate all substances, both natural and synthetic, that bind to opioid receptors (including antagonists)".[2] Some sources define the term opioid to exclude opiates, and others use opiate comprehensively instead of opioid, but opioid used inclusively is considered modern, preferred and is in wide use.[19]

Efforts to reduce recreational use in the US

[edit]In 2011, the Obama administration released a white paper describing the administration's plan to deal with the opioid crisis. The administration's concerns about addiction and accidental overdosing have been echoed by numerous other medical and government advisory groups around the world.[190][245][246][247]

As of 2015, prescription drug monitoring programs exist in every state, except for Missouri.[248] These programs allow pharmacists and prescribers to access patients' prescription histories in order to identify suspicious use. However, a survey of US physicians published in 2015 found that only 53% of doctors used these programs, while 22% were not aware that the programs were available to them.[249] The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention was tasked with establishing and publishing a new guideline, and was heavily lobbied.[250] In 2016, the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published its Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain, recommending that opioids only be used when benefits for pain and function are expected to outweigh risks, and then used at the lowest effective dosage, with avoidance of concurrent opioid and benzodiazepine use whenever possible.[34] Research suggests that the prescription of high doses of opioids related to chronic opioid therapy (COT) can at times be prevented through state legislative guidelines and efforts by health plans that devote resources and establish shared expectations for reducing higher doses.[251]

On 10 August 2017, Donald Trump declared the opioid crisis a (non-FEMA) national public health emergency.[252]

Global shortages

[edit]Morphine and other poppy-based medicines have been identified by the World Health Organization as essential in the treatment of severe pain. As of 2002, seven countries (USA, UK, Italy, Australia, France, Spain and Japan) use 77% of the world's morphine supplies, leaving many emerging countries lacking in pain relief medication.[253] The current system of supply of raw poppy materials to make poppy-based medicines is regulated by the International Narcotics Control Board under the provision of the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs. The amount of raw poppy materials that each country can demand annually based on these provisions must correspond to an estimate of the country's needs taken from the national consumption within the preceding two years. In many countries, underprescription of morphine is rampant because of the high prices and the lack of training in the prescription of poppy-based drugs. The World Health Organization is now working with administrations from various countries to train healthworkers and to develop national regulations regarding drug prescription to facilitate a greater prescription of poppy-based medicines.[254]

Another idea to increase morphine availability is proposed by the Senlis Council, who suggest, through their proposal for Afghan Morphine, that Afghanistan could provide cheap pain relief solutions to emerging countries as part of a second-tier system of supply that would complement the current INCB regulated system by maintaining the balance and closed system that it establishes while providing finished product morphine to those in severe pain and unable to access poppy-based drugs under the current system.

Recreational use

[edit]

Opioids can produce strong feelings of euphoria[255] and are frequently used recreationally. Traditionally associated with illicit opioids such as heroin, prescription opioids are misused recreationally.

Drug misuse and non-medical use include the use of drugs for reasons or at doses other than prescribed. Opioid misuse can also include providing medications to persons for whom it was not prescribed. Such diversion may be treated as crimes, punishable by imprisonment in many countries.[256][257] In 2014, almost 2 million Americans abused or were dependent on prescription opioids.[258][259]

Classification

[edit]There are a number of broad classes of opioids:[260]

- Natural opiates: alkaloids contained in the resin of the opium poppy, primarily morphine, codeine, and thebaine, but not papaverine and noscapine which have a different mechanism of action

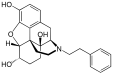

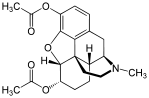

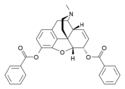

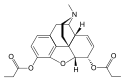

- Esters of morphine opiates: slightly chemically altered but more natural than the semi-synthetics, as most are morphine prodrugs, diacetylmorphine (morphine diacetate; heroin), nicomorphine (morphine dinicotinate), dipropanoylmorphine (morphine dipropionate), desomorphine, acetylpropionylmorphine, dibenzoylmorphine, diacetyldihydromorphine;[261][262]

- Semi-synthetic opioids: created from either the natural opiates or morphine esters, such as hydromorphone, hydrocodone, oxycodone, oxymorphone, ethylmorphine and buprenorphine;

- Fully synthetic opioids: such as fentanyl, pethidine, levorphanol, methadone, tramadol, tapentadol, and dextropropoxyphene;

- Endogenous opioid peptides, produced naturally in the body, such as endorphins, enkephalins, dynorphins, and endomorphins.

- Endogenous opioids, non-peptide: Morphine, and some other opioids, which are produced in small amounts in the body, are included in this category.

- Natural opioids, non-animal, non-opiate: the leaves from Mitragyna speciosa (kratom) contain a few naturally-occurring opioids, active via Mu- and Delta receptors. Salvinorin A, found naturally in the Salvia divinorum plant, is a kappa-opioid receptor agonist.[263]

Tramadol and tapentadol, which act as monoamine uptake inhibitors also act as mild and potent agonists (respectively) of the μ-opioid receptor.[264] Both drugs produce analgesia even when naloxone, an opioid antagonist, is administered.[265]

Some minor opium alkaloids and various substances with opioid action are also found elsewhere, including molecules present in kratom, Corydalis, and Salvia divinorum plants and some species of poppy aside from Papaver somniferum. There are also strains which produce copious amounts of thebaine, an important raw material for making many semi-synthetic and synthetic opioids. Of all of the more than 120 poppy species, only two produce morphine.

Amongst analgesics there are a small number of agents which act on the central nervous system but not on the opioid receptor system and therefore have none of the other (narcotic) qualities of opioids although they may produce euphoria by relieving pain—a euphoria that, because of the way it is produced, does not form the basis of habituation, physical dependence, or addiction. Foremost amongst these are nefopam, orphenadrine, and perhaps phenyltoloxamine or some other antihistamines. Tricyclic antidepressants have painkilling effect as well, but they're thought to do so by indirectly activating the endogenous opioid system. Paracetamol is predominantly a centrally acting analgesic (non-narcotic) which mediates its effect by action on descending serotoninergic (5-hydroxy triptaminergic) pathways, to increase 5-HT release (which inhibits release of pain mediators). It also decreases cyclo-oxygenase activity. It has recently been discovered that most or all of the therapeutic efficacy of paracetamol is due to a metabolite, AM404, which enhances the release of serotonin and inhibits the uptake of anandamide.[citation needed]

Other analgesics work peripherally (i.e., not on the brain or spinal cord). Research is starting to show that morphine and related drugs may indeed have peripheral effects as well, such as morphine gel working on burns. Recent investigations discovered opioid receptors on peripheral sensory neurons.[266] A significant fraction (up to 60%) of opioid analgesia can be mediated by such peripheral opioid receptors, particularly in inflammatory conditions such as arthritis, traumatic or surgical pain.[267] Inflammatory pain is also blunted by endogenous opioid peptides activating peripheral opioid receptors.[268]

It was discovered in 1953,[citation needed] that humans and some animals naturally produce minute amounts of morphine, codeine, and possibly some of their simpler derivatives like heroin and dihydromorphine, in addition to endogenous opioid peptides. Some bacteria are capable of producing some semi-synthetic opioids such as hydromorphone and hydrocodone when living in a solution containing morphine or codeine respectively.

Many of the alkaloids and other derivatives of the opium poppy are not opioids or narcotics; the best example is the smooth-muscle relaxant papaverine. Noscapine is a marginal case as it does have CNS effects but not necessarily similar to morphine, and it is probably in a category all its own.

Dextromethorphan (the stereoisomer of levomethorphan, a semi-synthetic opioid agonist) and its metabolite dextrorphan have no opioid analgesic effect at all despite their structural similarity to other opioids; instead they are potent NMDA antagonists and sigma 1 and 2-receptor agonists and are used in many over-the-counter cough suppressants.

Salvinorin A is a unique selective, powerful ĸ-opioid receptor agonist. It is not properly considered an opioid nevertheless, because:

- chemically, it is not an alkaloid; and

- it has no typical opioid properties: absolutely no anxiolytic or cough-suppressant effects. It is instead a powerful hallucinogen.

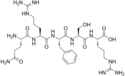

| Opioid peptides | Skeletal molecular images |

|---|---|

| Adrenorphin |  |

| Amidorphin |  |

| Casomorphin | |

| DADLE | |

| DAMGO |  |

| Dermorphin | |

| Endomorphin |  |

| Morphiceptin |  |

| Nociceptin |  |

| Octreotide |  |

| Opiorphin |  |

| TRIMU 5 |  |

Endogenous opioids

[edit]Opioid-peptides that are produced in the body include:

β-endorphin is expressed in Pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) cells in the arcuate nucleus, in the brainstem and in immune cells, and acts through μ-opioid receptors. β-endorphin has many effects, including on sexual behavior and appetite. β-endorphin is also secreted into the circulation from pituitary corticotropes and melanotropes. α-neoendorphin is also expressed in POMC cells in the arcuate nucleus.

Met-enkephalin is widely distributed in the CNS and in immune cells; [met]-enkephalin is a product of the proenkephalin gene, and acts through μ and δ-opioid receptors. leu-enkephalin, also a product of the proenkephalin gene, acts through δ-opioid receptors.

Dynorphin acts through κ-opioid receptors, and is widely distributed in the CNS, including in the spinal cord and hypothalamus, including in particular the arcuate nucleus and in both oxytocin and vasopressin neurons in the supraoptic nucleus.

Endomorphin acts through μ-opioid receptors, and is more potent than other endogenous opioids at these receptors.

Opium alkaloids and derivatives

[edit]Opium alkaloids

[edit]Phenanthrenes naturally occurring in (opium):

Preparations of mixed opium alkaloids, including papaveretum, are still occasionally used.

Esters of morphine

[edit]- Diacetylmorphine (morphine diacetate; heroin)

- Nicomorphine (morphine dinicotinate)

- Dipropanoylmorphine (morphine dipropionate)

- Diacetyldihydromorphine

- Acetylpropionylmorphine

- Desomorphine

- Methyldesorphine

- Dibenzoylmorphine

Ethers of morphine

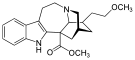

[edit]Semi-synthetic alkaloid derivatives

[edit]- Buprenorphine

- Etorphine

- Hydrocodone

- Hydromorphone

- Oxycodone (sold as OxyContin)

- Oxymorphone

Synthetic opioids

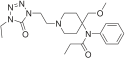

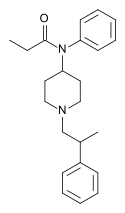

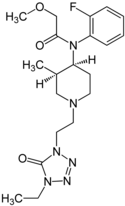

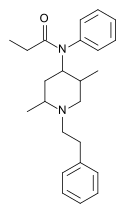

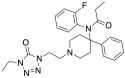

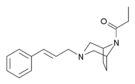

[edit]Anilidopiperidines

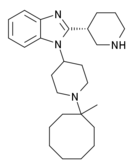

[edit]Benzimidazoles

[edit]Benzimidazoles opioids are also known as nitazenes.

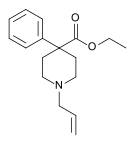

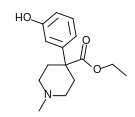

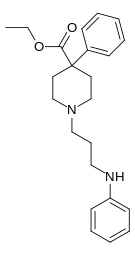

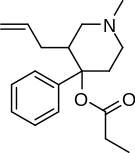

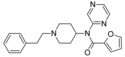

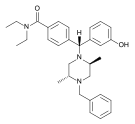

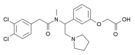

Phenylpiperidines

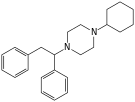

[edit]Diphenylpropylamine derivatives

[edit]- Propoxyphene

- Dextropropoxyphene

- Dextromoramide

- Bezitramide

- Piritramide

- Methadone

- Dipipanone

- Levomethadyl acetate (LAAM)

- Difenoxin

- Diphenoxylate

- Loperamide (does cross the blood–brain barrier but is quickly pumped into the non-central nervous system by P-Glycoprotein. Mild opiate withdrawal in animal models exhibits this action after sustained and prolonged use including rhesus monkeys, mice, and rats.)

Benzomorphan derivatives

[edit]- Dezocine—agonist/antagonist

- Pentazocine—agonist/antagonist

- Phenazocine

Oripavine derivatives

[edit]- Buprenorphine—partial agonist

- Dihydroetorphine

- Etorphine

Morphinan derivatives

[edit]- Butorphanol—agonist/antagonist

- Nalbuphine—agonist/antagonist

- Levorphanol

- Levomethorphan

- Racemethorphan

Others

[edit]Allosteric modulators

[edit]Plain allosteric modulators do not belong to the opioids, instead they are classified as opioidergics.

- Nalmefene

- Naloxone

- Naltrexone

- Methylnaltrexone (Methylnaltrexone is only peripherally active as it does not cross the blood–brain barrier in sufficient quantities to be centrally active. As such, it can be considered the antithesis of loperamide.)

- Naloxegol (Naloxegol is only peripherally active as it does not cross the blood–brain barrier in sufficient quantities to be centrally active. As such, it can be considered the antitheses of loperamide.)

Tables of opioids

[edit]Table of morphinan opioids

[edit]| Table of morphinan opioids: click to |

|---|

Table of non-morphinan opioids

[edit]| Table of non-morphinan opioids: click to |

|---|

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Ogura T, Egan TD (2013). "Chapter 15 – Opioid Agonists and Antagonists". Pharmacology and physiology for anesthesia : foundations and clinical application. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4377-1679-5. Archived from the original on 26 March 2019. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Hemmings HC, Egan TD (2013). Pharmacology and Physiology for Anesthesia: Foundations and Clinical Application: Expert Consult – Online and Print. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 253. ISBN 978-1-4377-1679-5.

Opiate is the older term classically used in pharmacology to mean a drug derived from opium. Opioid, a more modern term, is used to designate all substances, both natural and synthetic, that bind to opioid receptors (including antagonists).

- ^ "Opioids". www.hopkinsmedicine.org. 11 May 2023. Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ "Alcohol and Drug Policy Commission : Opiates or Opioids — What's the difference? : State of Oregon". www.oregon.gov. Archived from the original on 2 November 2023. Retrieved 2 November 2023.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Stromgaard K, Krogsgaard-Larsen P, Madsen U (2009). Textbook of Drug Design and Discovery, Fourth Edition. CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-4398-8240-5.

- ^ Walzer C (2014). "52 Nondomestic Equids". In West G, Heard D, Caulkett N (eds.). Zoo Animal and Wildlife Immobilization and Anesthesia. Vol. 51 (2nd ed.). Ames, USA: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 723, 727. doi:10.1002/9781118792919. ISBN 978-1-118-79291-9. PMC 2871358. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "Carfentanil". www.drugbank.ca. Archived from the original on 6 August 2020. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Sterken J, Troubleyn J, Gasthuys F, Maes V, Diltoer M, Verborgh C (October 2004). "Intentional overdose of Large Animal Immobilon". European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 11 (5): 298–301. doi:10.1097/00063110-200410000-00013. PMID 15359207.

- ^ Lembke A (2016). Drug Dealer, MD: How Doctors Were Duped, Patients Got Hooked, and Why It's So Hard to Stop. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-1-4214-2140-7.

- ^ "Drug Facts: Prescription Opioids". NIDA. June 2019. Archived from the original on 12 June 2019. Retrieved 5 July 2019.

- ^ "FDA requires strong warnings for opioid analgesics, prescription opioid cough products, and benzodiazepine labeling related to serious risks and death from combined use". FDA. 31 August 2016. Archived from the original on 23 April 2019. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ "Status and Trend Analysis of Illict [sic] Drug Markets" (PDF). World Drug Report 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 27 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Report III: FDA Approved Medications for the Treatment of Opiate Dependence: Literature Reviews on Effectiveness & Cost- Effectiveness, Treatment Research Institute". Advancing Access to Addiction Medications: Implications for Opioid Addiction Treatment. p. 41. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ^ Tetrault JM, Butner JL (September 2015). "Non-Medical Prescription Opioid Use and Prescription Opioid Use Disorder: A Review". The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine. 88 (3): 227–33. PMC 4553642. PMID 26339205.

- ^ Tarabar AF, Nelson LS (April 2003). "The resurgence and abuse of heroin by children in the United States". Current Opinion in Pediatrics. 15 (2): 210–5. doi:10.1097/00008480-200304000-00013. PMID 12640281. S2CID 21900231.

- ^ Gray E (4 February 2014). "Heroin Gains Popularity as Cheap Doses Flood the U.S". TIME.com. Archived from the original on 2 December 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Maltoni M (January 2008). "Opioids, pain, and fear". Annals of Oncology. 19 (1): 5–7. doi:10.1093/annonc/mdm555. PMID 18073220. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

[A] number of studies, however, have also reported inadequate pain control in 40%–70% of patients, resulting in the emergence of a new type of epidemiology, that of 'failed pain control', caused by a series of obstacles preventing adequate cancer pain management.... The cancer patient runs the risk of becoming an innocent victim of a war waged against opioid abuse and addiction if the norms regarding the two kinds of use (therapeutic or nontherapeutic) are not clearly distinct. Furthermore, health professionals may be worried about regulatory scrutiny and may opt not to use opioid therapy for this reason.

- ^ McCarberg BH (March 2011). "Pain management in primary care: strategies to mitigate opioid misuse, abuse, and diversion". Postgraduate Medicine. 123 (2): 119–30. doi:10.3810/pgm.2011.03.2270. PMID 21474900. S2CID 25935364.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c Offermanns S (2008). Encyclopedia of Molecular Pharmacology. Vol. 1 (2 ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. p. 903. ISBN 978-3-540-38916-3.

In the strict sense, opiates are drugs derived from opium and include the natural products morphine, codeine, thebaine and many semi-synthetic congeners derived from them. In the wider sense, opiates are morphine-like drugs with non-peptidic structures. The older term opiates is now more and more replaced by the term opioids which applies to any substance, whether endogenous or synthetic, peptidic or non-peptidic, that produces morphine-like effects through action on opioid receptors.

- ^ Freye E (2008). "Part II. Mechanism of action of opioids and clinical effects". Opioids in Medicine: A Comprehensive Review on the Mode of Action and the Use of Analgesics in Different Clinical Pain States. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4020-5947-6.

Opiate is a specific term that is used to describe drugs (natural and semi-synthetic) derived from the juice of the opium poppy. For example morphine is an opiate but methadone (a completely synthetic drug) is not. Opioid is a general term that includes naturally occurring, semi-synthetic, and synthetic drugs, which produce their effects by combining with opioid receptors and are competitively antagonized by nalaxone. In this context the term opioid refers to opioid agonists, opioid antagonists, opioid peptides, and opioid receptors.

- ^ Davies PS, D'Arcy YM (26 September 2012). Compact Clinical Guide to Cancer Pain Management: An Evidence-Based Approach for Nurses. Springer Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8261-0974-3.

- ^ "21 U.S. Code § 802 – Definitions". LII / Legal Information Institute. Archived from the original on 25 January 2021. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ "Definition of NARCOTIC". www.merriam-webster.com. Archived from the original on 14 November 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2016.

- ^ Сатоскар Р.С., Реге Н., Бхандаркар С.Д. (2015). Фармакология и фармакотерапия . Elsevier Науки о здоровье. ISBN 978-81-312-4371-8 .

- ^ Эберт М.Х., Кернс Р.Д. (2010). Поведенческое и психофармакологическое лечение боли . Издательство Кембриджского университета. ISBN 978-1-139-49354-3 .

- ^ Мур Р.А., Виффен П.Дж., Дерри С., Магуайр Т., Рой Ю.М., Тиррелл Л. (ноябрь 2015 г.). «Безрецептурные (безрецептурные) пероральные анальгетики при острой боли – обзор Кокрейновских обзоров» . Кокрановская база данных систематических обзоров . 11 (11): CD010794. дои : 10.1002/14651858.CD010794.pub2 . ПМК 6485506 . ПМИД 26544675 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Флейшер Г.Р., Людвиг С. (2010). Учебник детской неотложной медицины . Липпинкотт Уильямс и Уилкинс. п. 61. ИСБН 978-1-60547-159-4 .

- ^ «Кодеин» . Наркотики.com. 15 мая 2022 года. Архивировано из оригинала 16 июля 2017 года . Проверено 31 января 2023 г.

- ^ Александр Г.К., Крушевский С.П., Вебстер Д.В. (ноябрь 2012 г.). «Переосмысление назначения опиоидов для защиты безопасности пациентов и общественного здоровья». ДЖАМА . 308 (18): 1865–6. дои : 10.1001/jama.2012.14282 . ПМИД 23150006 .

- ^ Мохамади А., Чан Дж. Дж., Лиан Дж., Райт К. Л., Марин А. М., Родригес Е. К. и др. (август 2018 г.). «Факторы риска и совокупная частота длительного употребления опиоидов после травмы или операции: систематический обзор и мета-(регрессионный) анализ». Журнал костной и суставной хирургии. Американский том . 100 (15): 1332–1340. дои : 10.2106/JBJS.17.01239 . ПМИД 30063596 . S2CID 51891341 .

- ^ Дэвис К.С., Либерман А.Дж., Эрнандес-Дельгадо Х., Суба С. (1 января 2019 г.). «Законы, ограничивающие назначение или отпуск опиоидов при острой боли в Соединенных Штатах: национальный систематический юридический обзор». Наркотическая и алкогольная зависимость . 194 : 166–172. doi : 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.022 . ISSN 1879-0046 . ПМИД 30445274 . S2CID 53567522 .

- ^ Франклин Г.М. (сентябрь 2014 г.). «Опиоиды при хронической нераковой боли: документ с изложением позиции Американской академии неврологии» . Неврология . 83 (14): 1277–84. дои : 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000839 . ПМИД 25267983 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Оки С. (ноябрь 2010 г.). «Поток опиоидов, растущая волна смертей» . Медицинский журнал Новой Англии . 363 (21): 1981–5. дои : 10.1056/NEJMp1011512 . ПМИД 21083382 . S2CID 7092234 .

Ответы на точку зрения Оки: Рич Дж.Д., Грин Т.К., Маккензи М.С. (февраль 2011 г.). «Опиоиды и смерть» . Медицинский журнал Новой Англии . 364 (7): 686–687. дои : 10.1056/NEJMc1014490 . ПМЦ 10347760 . ПМИД 21323559 . - ^ Jump up to: а б Доуэлл Д., Хэгерих Т.М., Чоу Р. (апрель 2016 г.). «Руководство CDC по назначению опиоидов при хронической боли – США, 2016 г.» . ДЖАМА . 315 (15): 1624–45. дои : 10.1001/jama.2016.1464 . ПМК 6390846 . ПМИД 26977696 .

- ^ Ян Дж., Бауэр Б.А., Ванер-Рёдлер Д.Л., Чон Т.Ю., Сяо Л. (17 февраля 2020 г.). «Модифицированная анальгетическая лестница ВОЗ: подходит ли она при хронической нераковой боли?» . Журнал исследований боли . 13 : 411–417. дои : 10.2147/JPR.S244173 . ПМК 7038776 . ПМИД 32110089 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б Информацию об использовании и чрезмерном употреблении опиоидов для лечения мигрени см. Американская академия неврологии (февраль 2013 г.), «Пять вопросов, которые должны задать врачи и пациенты» , «Выбирая мудро »: инициатива Фонда ABIM , Американская академия неврологии, заархивировано из оригинала 1 сентября 2013 г. , получено 1 августа 2013 г. , в котором цитируются

- Зильберштейн С.Д. (сентябрь 2000 г.). «Практический параметр: научно обоснованные рекомендации по лечению мигрени (обзор фактических данных): отчет Подкомитета по стандартам качества Американской академии неврологии» . Неврология . 55 (6): 754–62. дои : 10.1212/WNL.55.6.754 . ПМИД 10993991 .

- Эверс С., Афра Дж., Фрезе А., Гоудсби П.Дж., Линде М., Мэй А. и др. (сентябрь 2009 г.). «Руководство EFNS по медикаментозному лечению мигрени — пересмотренный отчет целевой группы EFNS» . Европейский журнал неврологии . 16 (9): 968–81. дои : 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02748.x . ПМИД 19708964 . S2CID 9204782 .

- Институт улучшения клинических систем (2011 г.), Головная боль, диагностика и лечение , Институт улучшения клинических систем, заархивировано из оригинала 29 октября 2013 г. , получено 18 декабря 2013 г.

- ^ Художник Дж.Т., Кроффорд Л.Дж. (март 2013 г.). «Хроническое употребление опиоидов при синдроме фибромиалгии: клинический обзор». Журнал клинической ревматологии . 19 (2): 72–7. дои : 10.1097/RHU.0b013e3182863447 . ПМИД 23364665 .

- ^ Макникол Э.Д., Мидбари А., Айзенберг Э. (август 2013 г.). «Опиоиды при нейропатической боли» . Кокрановская база данных систематических обзоров . 8 (8): CD006146. дои : 10.1002/14651858.CD006146.pub2 . ПМК 6353125 . ПМИД 23986501 .

- ^ Jump up to: а б с Американское общество головной боли (сентябрь 2013 г.), «Пять вопросов, которые должны задать врачи и пациенты» , «Выбирая мудро : инициатива Фонда ABIM» , Американское общество головной боли , заархивировано из оригинала 3 декабря 2013 г. , получено 10 декабря 2013 г. , в котором цитируются

- Бигал М.Э., Липтон Р.Б. (апрель 2009 г.). «Чрезмерное употребление опиоидов и развитие хронической мигрени». Боль . 142 (3): 179–82. дои : 10.1016/j.pain.2009.01.013 . ПМИД 19232469 . S2CID 27949021 .

- Бигал М.Э., Серрано Д., Бусе Д., Шер А., Стюарт В.Ф., Липтон Р.Б. (сентябрь 2008 г.). «Лекарства от острой мигрени и эволюция от эпизодической мигрени к хронической: продольное популяционное исследование» . Головная боль . 48 (8): 1157–68. дои : 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2008.01217.x . ПМИД 18808500 .

- Шер А.И., Стюарт В.Ф., Риччи Дж.А., Липтон Р.Б. (ноябрь 2003 г.). «Факторы, связанные с возникновением и ремиссией хронической ежедневной головной боли в популяционном исследовании» . Боль . 106 (1–2): 81–9. дои : 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00293-8 . ПМИД 14581114 . S2CID 29000302 .

- Кацарава З., Шневайс С., Курт Т., Кронер У., Фриче Г., Эйкерманн А. и др. (март 2004 г.). «Заболеваемость и предикторы хронической головной боли у пациентов с эпизодической мигренью». Неврология . 62 (5): 788–90. дои : 10.1212/01.WNL.0000113747.18760.D2 . ПМИД 15007133 . S2CID 20759425 .