Бангладеш

Народная Республика Бангладеш | |

|---|---|

| Гимн: Моя золотая бангла ( бенгальский ) Амар Сонар Бангла ("Моя золотая бенгалия") | |

| Государственная печать | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | Dhaka 23°45′50″N 90°23′20″E / 23.76389°N 90.38889°E |

| Official language and national language | Bengali[1][2] |

| Recognised foreign language | English[3] |

| Ethnic groups (2022 census)[4] | 99% Bengali

1% others |

| Religion | |

| Demonym(s) | Bangladeshi |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary republic under an interim government |

| Mohammed Shahabuddin | |

| Muhammad Yunus | |

| Syed Refaat Ahmed | |

| Legislature | Jatiya Sangsad |

| Independence from Pakistan | |

| 14 August 1947 | |

| 1948–1952 | |

| 5 February 1966 | |

| January–March 1969 | |

| 1–25 March 1971 | |

| 26 March 1971 | |

| 10 April 1971 | |

• Victory | 16 December 1971 |

| 16 December 1972 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 148,460[8] km2 (57,320 sq mi) (92nd) |

• Water (%) | 6.4 |

• Land area | 130,170 km2[8] |

• Water area | 18,290 km2[8] |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | 169,828,911[9][10] (8th) |

• Density | 1,165/km2 (3,017.3/sq mi) (13th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | high inequality |

| HDI (2022) | medium (129th) |

| Currency | Taka (৳) (BDT) |

| Time zone | UTC+6 (BST) |

| Drives on | left |

| Calling code | +880 |

| ISO 3166 code | BD |

| Internet TLD | .bd .বাংলা |

Бангладеш , [ А ] официально Народная Республика Бангладеш , [ B ] это страна в Южной Азии . Это восьмая самая густонаселенная страна в мире, и среди наиболее густонаселенной населения 170 миллионов в районе 148 460 квадратных километров (57 320 кв. Миль). Бангладеш делится земельными границами с Индией на севере, западе и востоке, а Мьянма на юго -восток. На юге у него есть береговая линия вдоль Бенгальского залива . Он отделен от Бутана и Непала коридором Силигури и от Китая от горного индийского штата Сикким . Дакка , столица и крупнейший город , является политическим, финансовым и культурным центром страны. Читтагонг -второй по величине город и самый загруженный порт. Официальный язык - бенгальский , с бангладешским английским языком также использовался в правительстве.

Bangladesh is part of the historic and ethnolinguistic region of Bengal, which was divided during the Partition of British India in 1947 as the eastern enclave of the Dominion of Pakistan, from which it gained independence in 1971 after a bloody war.[17] The country has a Bengali Muslim majority. Ancient Bengal was known as Gangaridai and was a stronghold of pre-Islamic kingdoms. The Muslim conquest after 1204 led to the sultanate and Mughal periods, during which an independent Bengal Sultanate and wealthy Mughal Bengal transformed the region into an important centre of regional affairs, trade, and diplomacy. The Battle of Plassey in 1757 marked the beginning of British rule. The creation of Eastern Bengal and Assam in 1905 set a precedent for the emergence of Bangladesh. The All-India Muslim League was founded in Dhaka in 1906.[18] Резолюция Лахора в 1940 году была поддержана А.К. Фазлулом Хуком , первым премьер -министром Бенгалии . Современная территориальная граница была создана с объявлением линии Рэдклиффа .

In 1947, East Bengal became the most populous province in the Dominion of Pakistan and was renamed East Pakistan, with Dhaka as the legislative capital. The Bengali Language Movement in 1952, the 1958 Pakistani coup d'état, and the 1970 Pakistani general election spurred Bengali nationalism and pro-democracy movements. The refusal of the Pakistani military junta to transfer power to the Awami League, led by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, triggered the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971. The Mukti Bahini, aided by India, waged a successful armed revolution; the conflict saw the Bangladeshi genocide. The new state of Bangladesh became a constitutionally secular state in 1972, although Islam was declared the state religion in 1988.[19] In 2010, the Bangladesh Supreme Court reaffirmed secular principles in the constitution.[20] The Constitution of Bangladesh officially declares it a socialist state.[21]

A middle power in the Indo-Pacific,[22] Bangladesh is home to the fifth-most spoken native language, the third-largest Muslim-majority population, and the second-largest economy in South Asia. It maintains the third-largest military in the region and is the largest contributor to UN peacekeeping operations.[23] Bangladesh is a unitary parliamentary republic based on the Westminster system. Bengalis make up almost 99% of the population.[24] The country consists of eight divisions, 64 districts, and 495 subdistricts, and includes the world's largest mangrove forest. Bangladesh hosts one of the largest refugee populations due to the Rohingya genocide.[25] Bangladesh faces challenges like corruption, political instability, overpopulation, and effects of climate change. Bangladesh has twice chaired the Climate Vulnerable Forum and hosts the Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC) headquarters. It is a founding member of the South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation (SAARC) and a member of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation and the Commonwealth of Nations.

Etymology

The etymology of Bangladesh ("Bengali country") can be traced to the early 20th century, when Bengali patriotic songs, such as Aaji Bangladesher Hridoy by Rabindranath Tagore and Namo Namo Namo Bangladesh Momo by Kazi Nazrul Islam, used the term in 1905 and 1932 respectively.[26] Starting in the 1950s, Bengali nationalists used the term in political rallies in East Pakistan. The term Bangla is a major name for both the Bengal region and the Bengali language. The origins of the term Bangla are unclear, with theories pointing to a Bronze Age proto-Dravidian tribe,[27] and the Iron Age Vanga Kingdom.[28] The earliest known usage of the term is the Nesari plate in 805 AD. The term Vangala Desa is found in 11th-century South Indian records.[29][30] The term gained official status during the Sultanate of Bengal in the 14th century.[31][32] Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah proclaimed himself as the first "Shah of Bangala" in 1342.[31] The word Bangāl became the most common name for the region during the Islamic period.[33] 16th-century historian Abu'l-Fazl ibn Mubarak mentions in his Ain-i-Akbari that the addition of the suffix "al" came from the fact that the ancient rajahs of the land raised mounds of earth in lowlands at the foot of the hills which were called "al".[34] This is also mentioned in Ghulam Husain Salim's Riyaz-us-Salatin.[35] The Indo-Aryan suffix Desh is derived from the Sanskrit word deśha, which means "land" or "country". Hence, the name Bangladesh means "Land of Bengal" or "Country of Bengal".[30]

History

| History of Bangladesh |

|---|

|

|

|

The history of Bangladesh dates back over four millennia to the Chalcolithic period. The region's early history was characterized by a succession of Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms and empires that fought for control over the Bengal region. Islam arrived in the 8th century and gradually became dominant from the early 13th century with the conquests led by Bakhtiyar Khalji and the activities of Sunni missionaries like Shah Jalal. Muslim rulers promoted the spread of Islam by building mosques across the region. From the 14th century onward, Bengal was ruled by the Bengal Sultanate, founded by Fakhruddin Mubarak Shah, who established an individual currency. The Bengal Sultanate expanded under rulers like Shamsuddin Ilyas Shah, leading to economic prosperity and military dominance, with Bengal being referred to by Europeans as the richest country to trade with. The region later became a part of the Mughal Empire, and according to historian C. A. Bayly, it was probably the empire's wealthiest province.

Following the decline of the Mughal Empire in the early 1700s, Bengal became a semi-independent state under the Nawabs of Bengal, ultimately led by Siraj-ud-Daulah. It was later conquered by the British East India Company after the Battle of Plassey in 1757. Bengal played a crucial role in the Industrial Revolution in Britain, but also faced significant deindustrialization. The Bengal Presidency was established during British rule.

The borders of modern Bangladesh were established with the partition of Bengal between India and Pakistan during the Partition of India in August 1947, when the region became East Pakistan as part of the newly formed State of Pakistan following the end of the British rule in the region. The Proclamation of Bangladeshi Independence in March 1971 led to the nine-month-long Bangladesh Liberation War, which culminated in the emergence of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. Independence was declared by Sheikh Mujibur Rahman in 1971.

Since gaining independence, Bangladesh has faced political instability, economic reconstruction, and social transformation. The country experienced military coups and authoritarian rule, notably under General Ziaur Rahman and General Hussain Muhammad Ershad. The restoration of parliamentary democracy in the 1990s saw power alternate between the Awami League, and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party. In recent decades, Bangladesh has achieved significant economic growth, emerging as one of the world's fastest-growing economies, driven by its garment industry, remittances, and infrastructure development. However, it continues to grapple with political instability, human rights issues, and the impact of climate change. The return of the Awami League to power in 2009 under Sheikh Hasina's leadership saw economic progress but criticisms of authoritarianism. Bangladesh has played a critical role in addressing regional issues, including the Rohingya refugee crisis, which has strained its resources and highlighted its humanitarian commitments.

The poverty rate went down from 80% in 1971 to 44% in 1991 to 13% in 2021.[36][37][38] Bangladesh emerged as the second-largest economy in South Asia,[39][40] surpassing the per capita income levels of both India and Pakistan.[41][40] As part of the green transition, Bangladesh's industrial sector emerged as a leader in building green factories, with the country having the largest number of certified green factories in the world in 2023.[42] In January 2024, Awami League led by Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina secured a fourth straight term in Bangladesh's general election. Following nationwide protests against the Awami League government, on 5 August 2024, Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina was forced to resign and flee to India.[43][44][45][46][47] An interim government was formed on 8 August, with Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus as the Chief Advisor.[48]

Geography

Bangladesh is in South Asia on the Bay of Bengal. It is surrounded almost entirely by neighbouring India, and shares a small border with Myanmar to its southeast, though it lies very close to Nepal, Bhutan, and China. The country is divided into three regions. Most of the country is dominated by the fertile Ganges Delta, the largest river delta in the world.[49] The northwest and central parts of the country are formed by the Madhupur and the Barind plateaus. The northeast and southeast are home to evergreen hill ranges.

The Ganges delta is formed by the confluence of the Ganges (local name Padma or Pôdda), Brahmaputra (Jamuna or Jomuna), and Meghna rivers and their tributaries. The Ganges unites with the Jamuna (main channel of the Brahmaputra) and later joins the Meghna, finally flowing into the Bay of Bengal. Bangladesh is called the "Land of Rivers",[50] as it is home to over 57 trans-boundary rivers, the most of any nation-state. Water issues are politically complicated since Bangladesh is downstream of India.[51]

Bangladesh is predominantly rich fertile flat land. Most of it is less than 12 m (39 ft) above sea level, and it is estimated that about 10% of its land would be flooded if the sea level were to rise by 1 m (3.3 ft).[52] 12% of the country is covered by hill systems. The country's haor wetlands are of significance to global environmental science. The highest point in Bangladesh is the Saka Haphong, located near the border with Myanmar, with an elevation of 1,064 m (3,491 ft).[53] Previously, either Keokradong or Tazing Dong were considered the highest.

In Bangladesh forest cover is around 14% of the total land area, equivalent to 1,883,400 hectares (ha) of forest in 2020, down from 1,920,330 hectares (ha) in 1990. In 2020, naturally regenerating forest covered 1,725,330 hectares (ha) and planted forest covered 158,070 hectares (ha). Of the naturally regenerating forest 0% was reported to be primary forest (consisting of native tree species with no clearly visible indications of human activity) and around 33% of the forest area was found within protected areas. For the year 2015, 100% of the forest area was reported to be under public ownership.[54][55]

Climate

Straddling the Tropic of Cancer, Bangladesh's climate is tropical, with a mild winter from October to March and a hot, humid summer from March to June. The country has never recorded an air temperature below 0 °C (32 °F), with a record low of 1.1 °C (34.0 °F) in the northwest city of Dinajpur on 3 February 1905.[56] A warm and humid monsoon season lasts from June to October and supplies most of the country's rainfall. Natural calamities, such as floods, tropical cyclones, tornadoes, and tidal bores occur almost every year,[57] combined with the effects of deforestation, soil degradation and erosion. The cyclones of 1970 and 1991 were particularly devastating, the latter killing approximately 140,000 people.[58]

In September 1998, Bangladesh saw the most severe flooding in modern history, after which two-thirds of the country went underwater, along with a death toll of 1,000.[59] As a result of various international and national level initiatives in disaster risk reduction, the human toll and economic damage from floods and cyclones have come down over the years.[60] The 2007 South Asian floods ravaged areas across the country, leaving five million people displaced, with a death toll around 500.[61]

Climate change

Bangladesh is recognised to be one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change.[62][63] Over the course of a century, 508 cyclones have affected the Bay of Bengal region, 17 percent of which are believed to have made landfall in Bangladesh.[64] Natural hazards that come from increased rainfall, rising sea levels, and tropical cyclones are expected to increase as the climate changes, each seriously affecting agriculture, water and food security, human health, and shelter.[65] It is estimated that by 2050, a three-foot rise in sea levels will inundate some 20 percent of the land and displace more than 30 million people.[66] To address the sea level rise threat in Bangladesh, the Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 has been launched.[67][68]

Biodiversity

Bangladesh is located in the Indomalayan realm, and lies within four terrestrial ecoregions: Lower Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests, Mizoram–Manipur–Kachin rain forests, Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests, and Sundarbans mangroves.[69] Its ecology includes a long sea coastline, numerous rivers and tributaries, lakes, wetlands, evergreen forests, semi evergreen forests, hill forests, moist deciduous forests, freshwater swamp forests and flat land with tall grass. The Bangladesh Plain is famous for its fertile alluvial soil which supports extensive cultivation. The country is dominated by lush vegetation, with villages often buried in groves of mango, jackfruit, bamboo, betel nut, coconut, and date palm.[70] The country has up to 6000 species of plant life, including 5000 flowering plants.[71] Water bodies and wetland systems provide a habitat for many aquatic plants. Water lilies and lotuses grow vividly during the monsoon season. The country has 50 wildlife sanctuaries.

Bangladesh is home to most of the Sundarbans, the world's largest mangrove forest, covering an area of 6,000 square kilometres (2,300 sq mi) in the southwest littoral region. It is divided into three protected sanctuaries–the South, East, and West zones. The forest is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The northeastern Sylhet region is home to haor wetlands, a unique ecosystem. It also includes tropical and subtropical coniferous forests, a freshwater swamp forest, and mixed deciduous forests. The southeastern Chittagong region covers evergreen and semi-evergreen hilly jungles. Central Bangladesh includes the plainland Sal forest running along with the districts of Gazipur, Tangail, and Mymensingh. St. Martin's Island is the only coral reef in the country.

Bangladesh has an abundance of wildlife in its forests, marshes, woodlands, and hills.[70] The vast majority of animals dwell within a habitat of 150,000 square kilometres (58,000 sq mi).[72] The Bengal tiger, clouded leopard, saltwater crocodile, black panther and fishing cat are among the chief predators in the Sundarbans.[73] Northern and eastern Bangladesh is home to the Asian elephant, hoolock gibbon, Asian black bear and oriental pied hornbill.[74] The chital deer are widely seen in southwestern woodlands. Other animals include the black giant squirrel, capped langur, Bengal fox, sambar deer, jungle cat, king cobra, wild boar, mongooses, pangolins, pythons and water monitors. Bangladesh has one of the largest populations of Irrawaddy and Ganges dolphins.[75] The country has numerous species of amphibians (53), reptiles (139), marine reptiles (19) and marine mammals (5). It also has 628 species of birds.[76]

Several animals became extinct in Bangladesh during the last century, including the one-horned and two-horned rhinoceros and common peafowl. The human population is concentrated in urban areas, limiting deforestation to a certain extent. Rapid urban growth has threatened natural habitats. The country has widespread environmental issues; pollution of the Dhaleshwari River by the textile industry and shrimp cultivation in Chakaria Sundarbans have both been described by academics as ecocides.[77][78] Although many areas are protected under law, some Bangladeshi wildlife is threatened by this growth. The Bangladesh Environment Conservation Act was enacted in 1995. The government has designated several regions as Ecologically Critical Areas, including wetlands, forests, and rivers. The Sundarbans tiger project and the Bangladesh Bear Project are among the key initiatives to strengthen conservation.[74] It ratified the Rio Convention on Biological Diversity on 3 May 1994.[79] As of 2014[update], the country was set to revise its National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan.[79]

Government and politics

Bangladesh is a de jure representative democracy under its constitution, with a Westminster-style parliamentary republic that has universal suffrage. The head of government is the Prime Minister, who forms a government every five years. The President invites the leader of the largest party in parliament to become prime minister.[80]

The Government of Bangladesh is overseen by a cabinet headed by the Prime Minister of Bangladesh. The tenure of a parliamentary government is five years. The Bangladesh Civil Service assists the cabinet in running the government. Recruitment for the civil service is based on a public examination. In theory, the civil service should be a meritocracy. But a disputed quota system coupled with politicisation and preference for seniority have allegedly affected the civil service's meritocracy.[81] The President of Bangladesh is the ceremonial head of state[82] whose powers include signing bills passed by parliament into law. The President is the Supreme Commander of the Bangladesh Armed Forces and the chancellor of all universities. The Supreme Court of Bangladesh is the highest court of the land, followed by the High Court and Appellate Divisions. The head of the judiciary is the Chief Justice of Bangladesh, who sits on the Supreme Court. The courts have wide latitude in judicial review, and judicial precedent is supported by Article 111 of the constitution. The judiciary includes district and metropolitan courts divided into civil and criminal courts. Due to a shortage of judges, the judiciary has a large backlog.

The Jatiya Sangshad (National Parliament) is the unicameral parliament. It has 350 members of parliament (MPs), including 300 MPs elected on the first past the post system and 50 MPs appointed to reserved seats for women's empowerment. Article 70 of the Constitution of Bangladesh forbids MPs from voting against their party. However, several laws proposed independently by MPs have been transformed into legislation, including the anti-torture law.[83] The parliament is presided over by the Speaker of the Jatiya Sangsad, who is second in line to the president as per the constitution.[84]

Administrative divisions

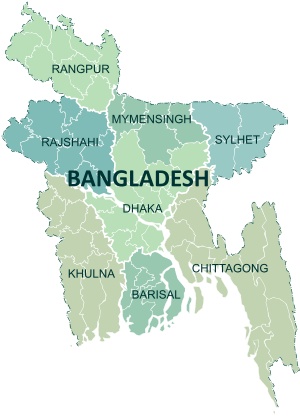

Bangladesh is divided into eight administrative divisions,[85][53][86] each named after their respective divisional headquarters: Barisal (officially Barishal[87]), Chittagong (officially Chattogram[87]), Dhaka, Khulna, Mymensingh, Rajshahi, Rangpur, and Sylhet.

Divisions are subdivided into districts (zila). There are 64 districts in Bangladesh, each further subdivided into upazila (subdistricts) or thana. The area within each police station, except for those in metropolitan areas, is divided into several unions, with each union consisting of multiple villages. In the metropolitan areas, police stations are divided into wards, further divided into mahallas.

There are no elected officials at the divisional or district levels, and the administration is composed only of government officials. Direct elections are held in each union (or ward) for a chairperson and several members. In 1997, a parliamentary act was passed to reserve three seats (out of 12) in every union for female candidates.[88]

| Division | Capital | Established | Area (km2) [89] |

2021 Population (projected)[90] |

Density 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Barisal Division | Barisal | 1 January 1993 | 13,225 | 9,713,000 | 734 |

| Chittagong Division | Chittagong | 1 January 1829 | 33,909 | 34,747,000 | 1,025 |

| Dhaka Division | Dhaka | 1 January 1829 | 20,594 | 42,607,000 | 2,069 |

| Khulna Division | Khulna | 1 October 1960 | 22,284 | 18,217,000 | 817 |

| Mymensingh Division | Mymensingh | 14 September 2015 | 10,584 | 13,457,000 | 1,271 |

| Rajshahi Division | Rajshahi | 1 January 1829 | 18,153 | 21,607,000 | 1,190 |

| Rangpur Division | Rangpur | 25 January 2010 | 16,185 | 18,868,000 | 1,166 |

| Sylhet Division | Sylhet | 1 August 1995 | 12,635 | 12,463,000 | 986 |

Foreign relations

Bangladesh is considered a middle power in global politics.[91] It plays an important role in the geopolitical affairs of the Indo-Pacific,[92] due to its strategic location between South and Southeast Asia.[93] Bangladesh joined the Commonwealth of Nations in 1972 and the United Nations in 1974.[94][95] It relies on multilateral diplomacy on issues like climate change, nuclear nonproliferation, trade policy and non-traditional security issues.[96] Bangladesh pioneered the creation of SAARC, which has been the preeminent forum for regional diplomacy among the countries of the Indian subcontinent.[97] It joined the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation in 1974,[98] and is a founding member of the Developing 8 Countries.[99] In recent years, Bangladesh has focused on promoting regional trade and transport links with support from the World Bank.[100] Dhaka hosts the headquarters of BIMSTEC, an organisation that brings together countries dependent on the Bay of Bengal.

Relations with neighbouring Myanmar have been severely strained since 2016–2017, after over 700,000 Rohingya refugees illegally entered Bangladesh.[101] The parliament, government, and civil society of Bangladesh have been at the forefront of international criticism against Myanmar for military operations against the Rohingya, and have demanded their right of return to Arakan.[102][103]

Bangladesh shares an important bilateral and economic relationship with its largest neighbour India,[104] which is often strained by water politics of the Ganges and the Teesta,[105][106][107] and the border killings of Bangladeshi civilians.[108][109] Post-independent Bangladesh has continued to have a problematic relationship with Pakistan, mainly due to its denial of the 1971 Bangladesh genocide.[110] It maintains a warm relationship with China, which is its largest trading partner, and the largest arms supplier.[111] Japan is Bangladesh's largest economic aid provider, and the two maintain a strategic and economic partnership.[112] Political relations with Middle Eastern countries are robust.[113] Bangladesh receives 59% of its remittances from the Middle East,[114] despite poor working conditions affecting over four million Bangladeshi workers.[115] Bangladesh plays a major role in global climate diplomacy as a leader of the Climate Vulnerable Forum.[116]

Military

The Bangladesh Armed Forces have inherited the institutional framework of the British military and the British Indian Army.[117] In 2022, the active personnel strength of the Bangladesh Army was around 250,000,[118] excluding the Air Force and the Navy (24,000).[119] In addition to traditional defence roles, the military has supported civil authorities in disaster relief and provided internal security during periods of political unrest. For many years, Bangladesh has been the world's largest contributor to UN peacekeeping forces. The military budget of Bangladesh accounts for 1.3% of GDP, amounting to US$4.3 billion in 2021.[120][121]

The Bangladesh Navy, one of the largest in the Bay of Bengal, includes a fleet of frigates, submarines, corvettes, and other vessels. The Bangladesh Air Force has a small fleet of multi-role combat aircraft. Most of Bangladesh's military equipment comes from China.[122] In recent years, Bangladesh and India have increased joint military exercises, high-level visits of military leaders, counter-terrorism cooperation and intelligence sharing. Bangladesh is vital to ensuring stability and security in northeast India.[123][124]

Bangladesh's strategic importance in the eastern subcontinent hinges on its proximity to China, its frontier with Burma, the separation of mainland and northeast India, and its maritime territory in the Bay of Bengal.[125] In 2002, Bangladesh and China signed a Defence Cooperation Agreement.[126] The United States has pursued negotiations with Bangladesh on a Status of Forces Agreement, an Acquisition and Cross-Servicing Agreement and a General Security of Military Information Agreement.[127][128][129] In 2019, Bangladesh ratified the UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[130]

Civil society

Since the colonial period, Bangladesh has had a prominent civil society. There are various special interest groups, including non-governmental organisations, human rights organisations, professional associations, chambers of commerce, employers' associations, and trade unions.[131] The National Human Rights Commission of Bangladesh was set up in 2007. Notable human rights organisations and initiatives include the Centre for Law and Mediation, Odhikar, the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety, the Bangladesh Environmental Lawyers Association, the Bangladesh Hindu Buddhist Christian Unity Council and the War Crimes Fact Finding Committee. The world's largest international NGO BRAC is based in Bangladesh. There have been concerns regarding the shrinking space for independent civil society in recent years.[132][133][134]

Human rights

Torture is banned by the Constitution of Bangladesh,[135] but is rampantly used by Bangladesh's security forces. Bangladesh joined the Convention against Torture in 1998 and it enacted its first anti-torture law, the Torture and Custodial Death (Prevention) Act, in 2013. The first conviction under this law was announced in 2020.[136] Amnesty International Prisoners of Conscience from Bangladesh have included Saber Hossain Chowdhury and Shahidul Alam.[137][138] The widely criticized Digital Security Act was repealed and replaced by the Cyber Security Act in 2023.[139] The repeal was welcomed by the International Press Institute.[140]

On International Human Rights Day in December 2021, the United States Department of Treasury announced sanctions on commanders of the Rapid Action Battalion for extrajudicial killings, torture, and other human rights abuses.[141] Freedom House has criticised the government for human rights abuses, the crackdown on the opposition, mass media, and civil society through politicized enforcement.[142] Bangladesh is ranked "partly free" in Freedom House's Freedom in the World report,[143] but its press freedom has deteriorated from "free" to "not free" in recent years due to increasing pressure from the government.[144] According to the British Economist Intelligence Unit, the country has a hybrid regime: the third of four rankings in its Democracy Index.[145] Bangladesh was ranked 96th among 163 countries in the 2022 Global Peace Index.[146] According to National Human Rights Commission, 70% of alleged human-rights violations are committed by law-enforcement agencies.[147]

LGBT rights are frowned upon among social conservatives.[148] Homosexuality is affected by Section 377 of the Penal Code of Bangladesh, which was originally enacted by the British colonial government.[149][150] An underground LGBT scene is flourishing across the country. However, Bangladesh only recognises the local transgender and intersex community known as the Hijra, which is the most widely accepted LGBT group among poorer sections of society.[151][152] Organized crime by the Hijra is growing, with blackmailing and extortion rackets operating on Grindr and resulting in theft, murder and kidnapping.[153][154] According to the 2016 Global Slavery Index, an estimated 1,531,300 people are enslaved in Bangladesh, or roughly 1% of the population.[155][156][157][158]

Corruption

Like many developing countries, institutional corruption is an issue of concern for Bangladesh. Bangladesh was ranked 146th among 180 countries on Transparency International's 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index.[159] Land administration was the sector with the most bribery in 2015,[160] followed by education,[161] police[162] and water supply.[163] The Anti Corruption Commission was formed in 2004, and it was active during the 2006–08 Bangladeshi political crisis, indicting many leading politicians, bureaucrats and businessmen for graft.[164][165][166]

Economy

Bangladesh is the second largest economy in South Asia after India.[39][40] The country has outpaced India and Pakistan in terms of per capita income.[41][40] According to the World Bank, "when the newly independent country of Bangladesh was born on December 16, 1971, it was the second poorest country in the world—making the country's transformation over the next 50 years one of the great development stories. Since then, poverty has been cut in half at record speed. Enrollment in primary school is now nearly universal. Hundreds of thousands of women have entered the workforce. Steady progress has been made on maternal and child health. And the country is better buttressed against the destructive forces posed by climate change and natural disasters. Bangladesh's success comprises many moving parts—from investing in human capital to establishing macroeconomic stability. Building on this success, the country is now setting the stage for further economic growth and job creation by ramping up investments in energy, inland connectivity, urban projects, and transport infrastructure, as well as focusing on climate change adaptation and disaster preparedness on its path toward sustainable growth."[167] Bangladesh has made one of the greatest leaps on the Human Development Index among Asian countries. According to UNDP, "Asia and the Pacific has observed the fastest Human Development Index (HDI) progress in the world—with Bangladesh being one of the best performers, moving from an HDI of 0.397 in 1990, the fourth lowest in the region, to a HDI of 0.661 in 2021. Only China had greater improvements in the region over this period".[168]

In 2022, Bangladesh had the second largest foreign-exchange reserves in South Asia. The reserves have boosted the government's spending capacity despite tax revenues forming only 7.7% of government revenue.[169] A big chunk of investments have gone into the power sector. In 2009, Bangladesh was experiencing daily blackouts several times a day. In 2022, the country achieved 100% electrification.[170][171][172] One of the major anti-poverty schemes of the Bangladeshi government is the Ashrayan Project which aims to eradicate homelessness by providing free housing.[173] The poverty rate has gone down from 80% in 1971,[174] to 44.2% in 1991,[175] to 12.9% in 2021.[36] The literacy rate was 74.66% in 2022.[176] Bangladesh has a labor force of roughly 70 million,[177] which is the world's seventh-largest; with an unemployment rate of 5.2% as of 2021[update].[178] The government is setting up 100 special economic zones to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) and generate 10 million jobs.[179] The Bangladesh Investment Development Authority (BIDA) and the Bangladesh Economic Zones Authority (BEZA) have been established to help investors in setting up factories; and to complement the longstanding Bangladesh Export Processing Zone Authority (BEPZA).

The Bangladeshi taka is the national currency. The service sector accounts for about 51.3% of total GDP and employs 39% of the workforce. The industrial sector accounts for 35.1% of GDP and employs 20.4% of the workforce. The agriculture sector makes up 13.6% of the economy but is the biggest employment sector, with 40.6% of the workforce.[169] In agriculture, the country is a major producer of rice, fish, tea, fruits, vegetables, flowers,[180] and jute. Lobsters and shrimps are some of Bangladesh's well-known exports.[181]

Private sector

The private sector accounts for 80% of GDP compared to the dwindling role of state-owned companies.[182] Bangladesh's economy is dominated by family-owned conglomerates and small and medium-sized businesses. Some of the largest publicly traded companies in Bangladesh include Beximco, BRAC Bank, BSRM, GPH Ispat, Grameenphone, Summit Group, and Square Pharmaceuticals.[183] Capital markets include the Dhaka Stock Exchange and the Chittagong Stock Exchange. Its telecommunications industry is one of the world's fastest-growing, with 171.854 million cellphone subscribers in January 2021.[184] Over 80% of Bangladesh's export earnings come from the garments industry.[8] Other major industries include shipbuilding, pharmaceuticals, steel, ceramics, electronics, and leather goods.[185] Muhammad Aziz Khan became the first person from Bangladesh to be listed as a billionaire by Forbes.[186]

Infrastructure

Since 2009, Bangladesh has embarked on a series of megaprojects. For instance, the 6.15 km long Padma Bridge was built for US$3.86 billion.[188] The bridge was the first self-financed megaproject in the country's history.[189] Other megaprojects include the Dhaka Metro, a mass rapid-transit system in the capital; Karnaphuli Tunnel, an underwater expressway in Chittagong; Dhaka Elevated Expressway; Chittagong Elevated Expressway; and the Bangladesh Delta Plan, designed to mitigate the impact of climate change.

Tourism

The tourism industry is expanding, contributing some 3.02% of total GDP.[190] Bangladesh's international tourism receipts in 2019 amounted to $391 million.[191] The country has three UNESCO World Heritage Sites (the Mosque City, the Paharpur Buddhist Ruins and the Sundarbans) and five tentative-list sites.[192] Activities for tourists include angling, water skiing, river cruising, hiking, rowing, yachting, and beachgoing.[193][194] The World Travel and Tourism Council (WTTC) reported in 2019 that the travel and tourism industry in Bangladesh directly generated 1,180,500 jobs in 2018 or 1.9% of the country's total employment.[195] According to the same report, Bangladesh experiences around 125,000 international tourist arrivals per year.[195] Domestic spending generated 97.7 percent of direct travel and tourism gross domestic product (GDP) in 2012.[196]

Energy

Bangladesh is gradually transitioning to a green economy. It has the largest off-grid solar power programme in the world, benefiting 20 million people.[197] An electric car called the Palki is being developed for production in the country.[198] Biogas is being used to produce organic fertilizer.[199]

Bangladesh continues to have huge untapped reserves of natural gas, particularly in its maritime territory.[200][201] A lack of exploration and decreasing proven reserves have forced Bangladesh to import LNG from abroad.[202][203][204] Gas shortages were further exasperated by the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[205]

While government-owned companies in Bangladesh generate nearly half of Bangladesh's electricity, privately owned companies like the Summit Group and Orion Group are playing an increasingly important role in both generating electricity, and supplying machinery, reactors, and equipment.[206] Bangladesh increased electricity production from 5 gigawatts in 2009 to 25.5 gigawatts in 2022. It plans to produce 50 gigawatts by 2041. U.S. companies like Chevron and General Electric supply around 55% of Bangladesh's domestic natural gas production and are among the largest investors in power projects. 80% of Bangladesh's installed gas-fired power generation capacity comes from turbines manufactured in the United States.[207]

The government stopped buying spot price LNG in June 2022. The country's forex reserves declined due to surging fuel imports. Bangladesh imported 30% of its LNG on the spot price market in 2022, down from 40% in 2021. Bangladesh continues to trade in LNG on the futures exchange markets.[208]

The Rooppur Nuclear Power Plant, Bangladesh's first operational nuclear plant, is nearing completion as of the end of 2023.[209]

Demographics

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 67,800,000 | — |

| 1980 | 80,600,000 | +1.94% |

| 1990 | 105,300,001 | +2.71% |

| 2000 | 129,600,000 | +2.10% |

| 2010 | 148,700,000 | +1.38% |

| 2012 | 161,100,200 | +4.09% |

| 2022 | 165,160,000 | +0.25% |

| Source: OECD/World Bank[210][211] | ||

According to the 2022 Census, Bangladesh has a population of 165.1 million,[9] and is the eighth-most-populous country in the world, the fifth-most populous country in Asia, and the most densely populated large country in the world, with a headline population density of 1,265 people/km2 as of 2020[update].[212] Its total fertility rate (TFR), once among the highest in the world, has experienced a dramatic decline, from 5.5 in 1985 to 3.7 in 1995, down to 2.0 in 2020,[213] which is below the sub-replacement fertility of 2.1.[214] The majority of Bangladeshis live in rural areas, with only 39% of the population living in urban areas as of 2021[update].[215] It has a median age of roughly 28 years, with 26% of the total population aged 14 or younger,[216] and merely 5% aged 65 and above.[217]

Bangladesh is an ethnically and culturally homogeneous society, as Bengalis form 99% of the population.[211] The Adivasi population includes the Chakmas, Marmas, Santhals, Mros, Tanchangyas, Bawms, Tripuris, Khasis, Khumis, Kukis, Garos, and Bisnupriya Manipuris. The Chittagong Hill Tracts region experienced unrest and an insurgency from 1975 to 1997 in an autonomy movement by its indigenous people. Although a peace accord was signed in 1997, the region remains militarised.[218] Urdu-speaking stranded Pakistanis were given citizenship by the Supreme Court in 2008.[219] Bangladesh also hosts over 700,000 Rohingya refugees since 2017, giving it one of the largest refugee populations in the world.[101]

Urban centres

Bangladesh's capital Dhaka and the largest city and is overseen by two city corporations that manage between them the northern and southern parts of the city. There are 12 city corporations which hold mayoral elections: Dhaka South, Dhaka North, Chittagong, Comilla, Khulna, Mymensingh, Sylhet, Rajshahi, Barisal, Rangpur, Gazipur and Narayanganj. But there are 8 district's in total. There being 8 districts in total. They are- Dhaka, Chittagong, Sylhet, Rangpur, Rajshahi, Khulna, Mymensingh, Barishal. Mayors are elected for five-year terms. Altogether there are 506 urban centres in Bangladesh which 43 cities have a population of more than 100,000.

| Rank | Name | Pop. | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Dhaka |

1 | Dhaka | 10,278,882 |  Gazipur  Narayanganj | |||||

| 2 | Chittagong | 3,227,246 | |||||||

| 3 | Gazipur | 2,674,697 | |||||||

| 4 | Narayanganj | 967,724 | |||||||

| 5 | Khulna | 718,735 | |||||||

| 6 | Rangpur | 708,384 | |||||||

| 7 | Mymensingh | 576,722 | |||||||

| 8 | Rajshahi | 552,791 | |||||||

| 9 | Sylhet | 532,426 | |||||||

| 10 | Cumilla | 439,414 | |||||||

Language

The official and predominant language of Bangladesh is Bengali, which is spoken by more than 99% of the population as their native language.[220][221] Bengali is described as a dialect continuum where there are various dialects spoken throughout the country. There is a diglossia in which much of the population can understand or speak Standard Colloquial Bengali, and their regional dialects.[222] These include Chittagonian and Sylheti,[221] though some linguists consider them as separate languages.

English plays an important role in Bangladesh's judicial and educational affairs, due to the country's history as part of the British Empire. It is widely spoken and commonly understood, and is taught as a compulsory subject in all schools, colleges and universities, while the English-medium educational system is widely attended.[223]

Tribal languages, although increasingly endangered, include the Chakma language, another native Eastern Indo-Aryan language, spoken by the Chakma people. Others are Garo, Meitei, Kokborok and Rakhine. Among the Austroasiatic languages, the most spoken is the Santali language, native to the Santal people.[224]

The stranded Pakistanis and some sections of the Old Dhakaites often use Urdu as their native tongue. Still, the usage of the latter remains highly reproached.[225]

Religion

Religions in Bangladesh (2022)[226]

Bangladesh was constitutionally proclaimed as a secular state in 1972. Secularism is one of its four founding constitutional principles. The constitution also grants freedom of religion, while establishing Islam as the state religion.[227][228][229][230] The constitution bans religion-based politics and discrimination, and proclaims equal recognition of people adhering to all faiths.[231] Islam is the largest religion across the country, being followed by about 91.1% of the population.[211][232][233] The vast majority of Bangladeshi citizens are Bengali Muslims, adhering to Sunni Islam. The country is the third-most populous Muslim-majority state in the world and has the fourth-largest overall Muslim population.[234]

Before the partition of India in 1941, Hindus formed 28% of the population. Mass exodus of Hindu-refugees from the then East Pakistan to India took place during the 1971 Bangladesh War of Independence, due to Pakistan Army's genocidal onslaught. After the formation of Bangladesh, the Hindus constituted 13.50% in 1974. In 2022, Hinduism is followed by 7.9% of the population,[211][232][233] mainly by the Bengali Hindus, who form the country's second-largest religious group and the third-largest Hindu community globally, after India and Nepal. Buddhism is the third-largest religion, at 0.6% of the population. Bangladeshi Buddhists are concentrated among the tribal ethnic groups in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. At the same time, coastal Chittagong is home to many Bengali Buddhists. Christianity is the fourth-largest religion at 0.3%, followed mainly by a small Bengali Christian minority. 0.1% of the population practices other religions like Animism or is irreligious.[211][235]

Education

The constitution states that all children shall receive free and compulsory education.[236] Education in Bangladesh is overseen by the Ministry of Education. The Ministry of Primary and Mass Education is responsible for implementing policy for primary education and state-funded schools at a local level. Primary and secondary education is compulsory, and is financed by the state and free of charge in public schools. Bangladesh has a literacy rate of 74.7% per cent as of 2019: 77.4% for males and 71.9% for females.[237][238] The country's educational system is three-tiered and heavily subsidised, with the government operating many schools at the primary, secondary and higher secondary levels and subsidising many private schools. In the tertiary education sector, the Bangladeshi government funds over 45 state universities[239] through the University Grants Commission (UGC), created by Presidential Order 10 in 1973.[240]

The education system is divided into five levels: primary (first to fifth grade), junior secondary (sixth to eighth grade), secondary (ninth and tenth grade), higher secondary (11th and 12th grade), and tertiary which is university level.[241] According to Hossain 2016, the formal schooling of secondary education in Bangladesh is seven years. The first three years are called junior secondary and include grades six to eight. The next two years are called secondary and include grades nine and ten. The final two years are called higher secondary and include grade eleven and twelve. Based on the information from Hossain 2016 and Daily Star 2010, to pass the fifth grade the Bangladesh Education Ministry requires a public exam called Primary School Certificate (PSC). During the eighth grade students have to pass the Junior School Certificate (JSC) exam to get enrolled in ninth grade, while tenth-grade students have to pass the Secondary School Certificate (SSC) exam to proceed to eleventh grade. Lastly, students have to pass the Higher Secondary Certificate (HSC) exam at grade twelve to apply for university.[242][243]

Universities in Bangladesh are of three general types: public (government-owned and subsidised), private (privately owned universities) and international (operated and funded by international organisations). The country has 47 public,[239] 105 private[244] and two international universities; Bangladesh National University has the largest enrolment, and the University of Dhaka (established in 1921) is the oldest. Bangladesh University of Engineering and Technology (BUET) is a premiere university for engineering education. University of Chittagong, established in 1966, has the largest campus.[245] Dhaka College, established in 1841, is the oldest educational institution for higher education in Bangladesh.[246] Medical education is provided by 29 government and private medical colleges. All medical colleges are affiliated with the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

Bangladesh was ranked 105th in the Global Innovation Index in 2023.[247]

Health

Bangladesh, by the constitution, guarantees healthcare services as a fundamental right to all of its citizens.[249] The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare is the largest institutional healthcare provider in Bangladesh,[250] and contains two divisions: Health Service Division and Medical Education And Family Welfare Division.[251] However, healthcare facilities in Bangladesh are considered less than adequate, although they have improved as the economy has grown and poverty levels have decreased significantly.[250] Bangladesh faces a severe health workforce crisis, as formally trained providers make up a small percentage of the total health workforce.[252] Significant deficiencies in the treatment practices of village doctors persist, with widespread harmful and inappropriate drug prescribing.[253]

Bangladesh's poor healthcare system suffers from severe underfunding from the government.[250] As of 2019[update], some 2.48% of total GDP was attributed to healthcare,[254] and domestic general government spending on healthcare was 18.63% of the total budget,[255] while out-of-pocket expenditures made up the vast majority of the total budget, totalling 72.68%.[256] Domestic private health expenditure was about 75% of the total healthcare expenditure.[257] As of 2020[update], there are only 5.3 doctors per 10,000 people, and about six physicians[258] and three nurses per 10,000 people, while the number of hospital beds is 8 per 10,000.[259][260] The overall life expectancy in Bangladesh at birth was 73 years (71 years for males and 75 years for females) as of 2020[update],[261] and it has a comparably high infant mortality rate (24 per 1,000 live births) and child mortality rate (29 per 1,000 live births).[262][263] Maternal mortality remains high, clocking at 173 per 100,000 live births.[264] Bangladesh is a key source market for medical tourism for various countries, mainly India,[265] due to its citizens dissatisfaction and distrust over their own healthcare system.[266]

The main causes of death are coronary artery disease, stroke, and chronic respiratory disease; comprising 62% and 60% of all adult male and female deaths, respectively.[267] Malnutrition is a major and persistent problem in Bangladesh, mainly affecting the rural regions, more than half of the population suffers from it. Severe acute malnutrition affects 450,000 children, while nearly 2 million children have moderate acute malnutrition. For children under the age of five, 52% are affected by anaemia, 41% are stunted, 16% are wasted, and 36% are underweight. A quarter of women are underweight and around 15% have short stature, while over half also suffer from anaemia.[268]

Culture

Architecture

The architectural traditions of Bangladesh have a 2,500-year-old heritage.[269] Terracotta architecture is a distinct feature of Bengal. Pre-Islamic Bengali architecture reached its pinnacle in the Pala Empire when the Pala School of Sculptural Art established grand structures such as the Somapura Mahavihara. Islamic architecture began developing under the Bengal Sultanate, when local terracotta styles influenced medieval mosque construction.

The Sixty Dome Mosque was the largest medieval mosque built in Bangladesh and is a fine example of Turkic-Bengali architecture.[270] The Mughal style replaced indigenous architecture when Bengal became a province of the Mughal Empire and influenced urban housing development. The Kantajew Temple and Dhakeshwari Temple are excellent examples of late medieval Hindu temple architecture. Indo-Saracenic Revival architecture, based on Indo-Islamic styles, flourished during the British period. The zamindar gentry in Bangladesh built numerous Indo-Saracenic palaces and country mansions, such as the Ahsan Manzil, Tajhat Palace, Dighapatia Palace, Puthia Rajbari and Natore Rajbari.

Bengali vernacular architecture is noted for pioneering the bungalow. Bangladeshi villages consist of thatched roofed houses made of natural materials like mud, straw, wood, and bamboo. In modern times, village bungalows are increasingly made of tin.[citation needed]

Muzharul Islam was the pioneer of Bangladeshi modern architecture. His varied works set the course of modern architectural practice in the country. Islam brought leading global architects, including Louis Kahn, Richard Neutra, Stanley Tigerman, Paul Rudolph, Robert Boughey and Konstantinos Doxiadis, to work in erstwhile East Pakistan. Louis Kahn was chosen to design the National Parliament Complex in Sher-e-Bangla Nagar. Kahn's monumental designs, combining regional red brick aesthetics, his concrete and marble brutalism and the use of lakes to represent Bengali geography, are regarded as one of the masterpieces of the 20th century. In recent times, award-winning architects like Rafiq Azam have set the course of contemporary architecture by adopting influences from the works of Islam and Kahn.[citation needed]

Visual arts and crafts

The recorded history of art in Bangladesh can be traced to the 3rd century BCE, when terracotta sculptures were made in the region. In classical antiquity, notable sculptural Hindu, Jain, and Buddhist art developed in the Pala Empire and the Sena dynasty. Islamic art has evolved since the 14th century. The architecture of the Bengal Sultanate saw a distinct style of domed mosques with complex niche pillars that had no minarets. Mughal Bengal's most celebrated artistic tradition was the weaving of Jamdani motifs on fine muslin, which is now classified by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage. Jamdani motifs were similar to Iranian textile art (buta motifs) and Western textile art (paisley). The Jamdani weavers in Dhaka received imperial patronage.[271] Ivory and brass were also widely used in Mughal art. Pottery is thoroughly used in Bengali culture.

The modern art movement in Bangladesh took shape during the 1950s, particularly with the pioneering works of Zainul Abedin. East Bengal developed its own modernist painting and sculpture traditions, which were distinct from the art movements in West Bengal. The Art Institute Dhaka has been a significant centre for visual art in the region. Its annual Bengali New Year parade was enlisted as an intangible cultural heritage by UNESCO in 2016.

Modern Bangladesh has produced many of South Asia's leading painters, including SM Sultan, Mohammad Kibria, Shahabuddin Ahmed, Kanak Chanpa Chakma, Kafil Ahmed, Saifuddin Ahmed, Qayyum Chowdhury, Rashid Choudhury, Quamrul Hassan, Rafiqun Nabi and Syed Jahangir, among others. Novera Ahmed and Nitun Kundu were the country's pioneers of modernist sculpture.

In recent times, photography as a medium of art has become popular. Biennial Chobi Mela is considered the largest photography festival in Asia.[272]

Literature

Bengali literature is a millennium-old tradition; the Charyapadas are the earliest examples of Bengali poetry. Sufi spiritualism inspired many Bengali Muslim writers. During the Bengal Sultanate, medieval Bengali writers were influenced by Arabic and Persian works. Sultans of Bengal patronized Bengali literature. Examples include the writings of Maladhar Basu, Bipradas Pipilai, Vijay Gupta, and Yasoraj Khan. The Chandidas are notable lyric poets from the early Medieval Age. Syed Alaol was the bard of Middle Bengali literature. The Bengal Renaissance shaped modern Bengali literature, including novels, short stories, and science fiction. Rabindranath Tagore was the first non-European laureate of the Nobel Prize in Literature and is described as the Bengali Shakespeare.[273] Kazi Nazrul Islam was a revolutionary poet who espoused political rebellion against colonialism and fascism. Begum Rokeya is regarded as the pioneer feminist writer of Bangladesh.[274] Other renaissance icons included Michael Madhusudan Dutt and Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay. The writer Syed Mujtaba Ali is noted for his cosmopolitan Bengali worldview.[275] Jasimuddin was a renowned pastoral poet. Shamsur Rahman and Al Mahmud are considered two of the greatest Bengali poets to have emerged in the 20th century. Farrukh Ahmad, Sufia Kamal, Syed Ali Ahsan, Ahsan Habib, Abul Hussain, Shahid Qadri, Fazal Shahabuddin, Abu Zafar Obaidullah, Omar Ali, Al Mujahidi, Syed Shamsul Huq, Nirmalendu Goon, Abid Azad, Hasan Hafizur Rahman and Abdul Hye Sikder are important figures of modern Bangladeshi poetry. Ahmed Sofa is regarded as the most important Bangladeshi intellectual in the post-independence era. Humayun Ahmed was a popular writer of modern Bangladeshi magical realism and science fiction. Notable writers of Bangladeshi fictions include Mir Mosharraf Hossain, Akhteruzzaman Elias, Alauddin Al Azad, Shahidul Zahir, Rashid Karim, Mahmudul Haque, Syed Waliullah, Shahidullah Kaiser, Shawkat Osman, Selina Hossain, Shahed Ali, Razia Khan, Anisul Hoque, and Abdul Mannan Syed.

The annual Ekushey Book Fair and Dhaka Literature Festival, organised by the Bangla Academy, are among the enormous literary festivals in South Asia.

Museums and libraries

Established in 1910, the Varendra Research Museum is the oldest museum in Bangladesh.[276][277] It houses important collections from both the pre-Islamic and Islamic periods, including the sculptures of the Pala-Sena School of Art and the Indus Valley civilisation, and Sanskrit, Arabic, and Persian manuscripts and inscriptions.[278][279]

The Ahsan Manzil, the former residence of the Nawab of Dhaka, is a national museum housing collections from the British Raj.[279][280]

The Tajhat Palace Museum preserves artifacts of the rich cultural heritage of North Bengal, including Hindu-Buddhist sculptures and Islamic manuscripts. The Mymensingh Museum houses the personal antique collections of Bengali aristocrats in central Bengal. The Ethnological Museum of Chittagong showcases the lifestyle of various tribes in Bangladesh. The Bangladesh National Museum is located in Shahbagh, Dhaka, and has a rich collection of antiquities. The Liberation War Museum documents the Bangladeshi struggle for independence and the 1971 genocide.[citation needed]

The Hussain Shahi dynasty established royal libraries during the Bengal Sultanate. Libraries were established in each district of Bengal by the Zamindar gentry during the Bengal Renaissance in the 19th century. The trend of establishing libraries continued until the beginning of World War II. In 1854, four major public libraries were opened, including the Bogra Woodburn Library, the Rangpur Public Library, the Jessore Institute Public Library, and the Barisal Public Library.

The Northbrook Hall Public Library was established in Dhaka in 1882 in honour of Lord Northbrook, the Governor-General. Other libraries inaugurated in the British period included the Victoria Public Library, Natore (1901), the Sirajganj Public Library (1882), the Rajshahi Public Library (1884), the Comilla Birchandra Library (1885), the Shah Makhdum Institute Public Library, Rajshahi (1891), the Noakhali Town Hall Public Library (1896), the Prize Memorial Library, Sylhet (1897), the Chittagong Municipality Public Library (1904) and the Varendra Research Library (1910). The Great Bengal Library Association was formed in 1925.[281] The Central Public Library of Dhaka was established in 1959. The National Library of Bangladesh was established in 1972. The World Literature Centre, founded by Ramon Magsaysay Award winner Abdullah Abu Sayeed, is noted for operating numerous mobile libraries across Bangladesh and was awarded the UNESCO Jon, Amos Comenius Medal.[citation needed]

Women

Although as of 2015[update], several women occupied a key political office in Bangladesh, its women continue to live under a patriarchal social regime where violence is common.[282] Whereas in India and Pakistan, women participate less in the workforce as their education increases, the reverse is the case in Bangladesh.[282]

Bengal has a long history of feminist activism dating back to the 19th century. Begum Rokeya and Faizunnessa Chowdhurani played an important role in emancipating Bengali Muslim women from purdah, before the country's division, as well as promoting girls' education. Several women were elected to the Bengal Legislative Assembly in the British Raj. The first women's magazine, Begum, was published in 1948.

In 2008, Bangladeshi female workforce participation stood at 26%.[282] According to a report published by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics in March 2023, the female labour force participation rate has reached to 42.68%.[283] in 2022 Women dominate blue collar jobs in the Bangladeshi garment industry. Agriculture, social services, healthcare, and education are chosen occupations for Bangladeshi women, while their employment in white collar positions has steadily increased.

Performing arts

Theatre in Bangladesh includes various forms with a history dating back to the 4th century CE.[284] It includes narrative forms, song and dance forms, supra-personae forms, performances with scroll paintings, puppet theatre and processional forms.[284] The Jatra is the most popular form of Bengali folk theatre. The dance traditions of Bangladesh include indigenous tribal and Bengali dance forms, as well as classical Indian dances, including the Kathak, Odissi and Manipuri dances.

The music of Bangladesh features the Baul mystical tradition, listed by UNESCO as a Masterpiece of Intangible Cultural Heritage.[285] Fakir Lalon Shah popularised Baul music in the country in the 18th century and it has since been one of the most popular music genres in the country since then. Most modern Bauls are devoted to Lalon Shah.[286] Numerous lyric-based musical traditions, varying from one region to the next, exist, including Gombhira, Bhatiali and Bhawaiya. Folk music is accompanied by a one-stringed instrument known as the ektara. Other instruments include the dotara, dhol, flute, and tabla. Bengali classical music includes Tagore songs and Nazrul Sangeet. Bangladesh has a rich tradition of Indian classical music, which uses instruments like the sitar, tabla, sarod, and santoor.[287] Sabina Yasmin and Runa Laila were considered the leading playback singers in the 1990s, while musicians such as Ayub Bachchu and James are credited with popularising rock music in Bangladesh.[288][289]

Media and cinema

The Bangladeshi press is diverse and privately owned. Over 200 newspapers are published in the country. Bangladesh Betar is a state-run radio service.[290] The British Broadcasting Corporation operates the popular BBC Bangla news and current affairs service. Bengali broadcasts from Voice of America are also very popular. Bangladesh Television (BTV) is the state-owned television network, operating two main television stations broadcast from Dhaka and Chittagong, alongside a satellite service known as BTV World. Around forty privately owned television networks, including several news channels, are also broadcast in the country.[291] Freedom of the media remains a major concern due to government attempts at censorship and the harassment of journalists.[citation needed]

The cinema of Bangladesh dates back to 1898 when films began screening at the Crown Theatre in Dhaka. The Dhaka Nawab Family patronised the production of several silent films in the 1920s and 30s. In 1931, the East Bengal Cinematograph Society released the first full-length feature film in Bangladesh, titled Last Kiss. The first feature film in East Pakistan, Mukh O Mukhosh, was released in 1956. During the 1960s, 25–30 films were produced annually in Dhaka. By the 2000s, Bangladesh produced 80–100 films a year. While the Bangladeshi film industry has achieved limited commercial success, the country has produced notable independent filmmakers. Zahir Raihan was a prominent documentary maker assassinated in 1971. Tareque Masud is regarded as one of Bangladesh's outstanding directors.[292][293] Masud was honoured by FIPRESCI at the 2002 Cannes Film Festival for his film The Clay Bird. Tanvir Mokammel, Mostofa Sarwar Farooki, Humayun Ahmed, Alamgir Kabir, Chashi Nazrul Islam and Sohanur Rahman Sohan, who was best known in Dhallywood for directing romantic films.[294] His film Ananta Bhalobasha released in 1999 marked a turning point in Bangladeshi cinema by introducing Shakib Khan, who is now one of the biggest superstars in the industry,[295] are some of the prominent directors of Bangladeshi cinema. Bangladesh has a very active film society culture. It started in 1963 in Dhaka. Now around 40 Film Societies are active all over Bangladesh. Federation of Film Societies of Bangladesh is the parent organisation of the film society movement of Bangladesh. Active film societies include the Rainbow Film Society, Children's Film Society, Moviyana Film Society, and Dhaka University Film Society.[citation needed]

Textiles

The Nakshi Kantha is a centuries-old embroidery tradition for quilts, said to be indigenous to eastern Bengal (Bangladesh). The sari is the national dress for Bangladeshi women. Mughal Dhaka was renowned for producing the finest muslin saris, as well as the famed Dhakai and Jamdani, the weaving of which is listed by UNESCO as one of the masterpieces of humanity's intangible cultural heritage.[296] Bangladesh also produces the Rajshahi silk. The shalwar kameez is also widely worn by Bangladeshi women. In urban areas, some women can be seen in Western clothing. The kurta and sherwani are the national dress of Bangladeshi men; the lungi and dhoti are worn in informal settings. Aside from ethnic wear, domestically tailored suits and neckties are customarily worn by the country's men in offices, in schools, and at social events.

The handloom industry supplies 60–65% of the country's clothing demand.[297] The Bengali ethnic fashion industry has flourished. The retailer Aarong is one of South Asia's most successful ethnic wear brands. The development of the Bangladesh textile industry, which supplies leading international brands, has promoted the local production and retail of modern Western attire. The country now has several expanding local brands like Westecs and Yellow. Bangladesh is the world's second-largest garment exporter. Among Bangladesh's fashion designers, Bibi Russell has received international acclaim for her "Fashion for Development" shows.[298]

Cuisine

Bangladeshi cuisine, formed by its geographic location and climate, is rich and diverse; sharing its culinary heritage with the neighbouring Indian state of West Bengal.[299]: 14 The staple dish is white rice, which along with fish, forms the culinary base. Varieties of leaf vegetables, potatoes, gourds and lentils (dal) also play an important role. Curries of beef, mutton, chicken and duck are commonly consumed,[300] along with multiple types of bhortas (mashed vegetables),[301] bhajis (stir fried vegetables) and tarkaris (curried vegetables).[299]: 8 Mughal-influenced dishes include kormas, kalias, biryanis, pulaos, teharis and khichuris.[300]

Among the various used spices, turmeric, fenugreek, nigella, coriander, anise, cardamom and chili powder are widely used; a famous spice mix is the panch phoron. Condiments and herbs used include red onions, green chillies, garlic, ginger, cilantro, and mint.[299]: 12 Coconut milk, mustard paste, mustard seeds, mustard oil, ghee, achars[300] and chutneys are also widely used in the cuisine.[299]: 13–14

Fish is the main source of protein, owing to the country's riverine geography, and it is often enjoyed with its roe. The hilsa is the national fish and is immensely popular; a famous dish is shorshe ilish. Other highly consumed fishes include rohu, pangas, and tilapia.[302] Lobsters, shrimps and dried fish (shutki) also play an important role, with the chingri malai curry being a famous shrimp dish.[299]: 8 In Chittagong, famous dishes include kala bhuna and mezban, the latter being a traditionally popular feast, featuring the serving of mezbani gosht, a hot and spicy beef curry.[299]: 10 [300][303] In Sylhet, the shatkora lemons are used to marinate dishes, a notable one is beef hatkora.[303] Among the tribal communities in the Chittagong Hill Tracts, cooking with bamboo shoots is popular.[304] Khulna is renowned for using chui jhal (piper chaba) in its meat-based dishes.[303][300]

Bangladesh has a vast spread of desserts, including distinctive sweets such as the rôshogolla, roshmalai, chomchom, sondesh, mishti doi and kalojaam, and jilapi.[305] Pithas are traditional boiled desserts made with rice or fruits.[306] Halwa and shemai, the latter being a variation of vermicelli; are popular desserts during religious festivities.[307][308] Ruti, naan, paratha, luchi and bakarkhani are the main local breads.[309][300] Hot milk tea is the most commonly consumed beverage in the country, being the centre of addas.[310] Borhani, mattha and lassi are popular traditionally consumed beverages.[311][312] Kebabs are widely popular, particularly seekh kebab, chapli kebab, shami kebab, chicken tikka and shashlik, along with various types of chaaps.[300] Popular street foods include chotpoti, jhal muri, shingara,[313] samosa and fuchka.[314]

Holidays and festivals

Pahela Baishakh, the Bengali new year, is the major festival of Bengali culture and sees widespread festivities. Of the major holidays celebrated in Bangladesh, only Pahela Baishakh comes without any pre-existing expectations (specific religious identity, a culture of gift-giving, etc.) and has become an occasion for celebrating the simpler, rural roots of Bengal. Other cultural festivals include Nabonno and Poush Parbon, Bengali harvest festivals.[315]

The Muslim festivals of Eid al-Fitr, Eid al-Adha, Mawlid, Muharram, Chand Raat, Shab-e-Barat; the Hindu festivals of Durga Puja, Janmashtami and Rath Yatra; the Buddhist festival of Buddha Purnima, which marks the birth of Gautama Buddha, and the Christian festival of Christmas are national holidays in Bangladesh and see the most widespread celebrations in the country. The two Eids are celebrated with a long streak of public holidays and allow celebrating the festivals with their families outside the city.[315]

Alongside national days like the remembrance of 21 February 1952 Language Movement Day (declared as International Mother Language Day by UNESCO in 1999),[316] Independence Day and Victory Day. On Language Movement Day, people congregate at the Shaheed Minar in Dhaka to remember the national heroes of the Bengali Language Movement. Similar gatherings are observed at the National Martyrs' Memorial on Independence Day and Victory Day to remember the national heroes of the Bangladesh Liberation War.[317]

Sports

In rural Bangladesh, several traditional indigenous sports such as Kabaddi, Boli Khela, Lathi Khela and Nouka Baich remain fairly popular. While Kabaddi is the national sport,[318] Cricket is the most popular sport in the country. The national cricket team participated in their first Cricket World Cup in 1999 and the following year was granted Test cricket status. Bangladesh reached the quarter-final of the 2015 Cricket World Cup, the semi-final of the 2017 ICC Champions Trophy and they reached the final of the Asia Cup 3 times – in 2012, 2016, and 2018. Shakib Al Hasan is widely regarded as one of the greatest All-rounders in the history of Cricket and as one of the greatest Bangladeshi sportsman ever.[319][320][321][322][323][324] On 9 February 2020, the Bangladesh youth national cricket team won the men's Under-19 Cricket World Cup, held in South Africa. This was Bangladesh's first World Cup victory.[325][326] In 2018, the Bangladesh women's national cricket team won the 2018 Women's Twenty20 Asia Cup defeating India women's national cricket team in the final.[327]

Football is also a leading sport in Bangladesh.[328] Although football was seen as the most popular sport in the country before the 21st century, success in cricket has overshadowed its previous popularity. The first instance of a national football team was the emergence of the Shadhin Bangla Team, which played friendly matches throughout India to raise international awareness about the Bangladesh Liberation War in 1971.[329] On 25 July 1971, the team's captain, Zakaria Pintoo, became the first person to hoist the Bangladesh flag on foreign land before their match in Nadia district of West Bengal.[330] Following independence, the national football team participated in the AFC Asian Cup (1980), becoming only the second South Asian team to do so.[331] Bangladesh's most notable achievements in football include the 2003 SAFF Gold Cup and 1999 South Asian Games. In 2022, the Bangladesh women's national football team won the 2022 SAFF Women's Championship.[332][333]

Bangladesh archers Ety Khatun and Roman Sana won several gold medals winning all the 10 archery events (both individual and team events) in the 2019 South Asian Games.[334] The National Sports Council regulates 42 sporting federations.[335] Chess is very popular in Bangladesh. Bangladesh has five grandmasters in chess. Among them, Niaz Murshed was the first grandmaster in South Asia.[336] In 2010, mountain climber Musa Ibrahim became the first Bangladeshi climber to conquer Mount Everest.[337] Wasfia Nazreen is the first Bangladeshi climber to climb the Seven Summits.[338]

Bangladesh hosts several international tournaments. Bangabandhu Cup is an international football tournament hosted in the country. Bangladesh hosted the South Asian Games several times. Bangladesh co-hosted the ICC Cricket World Cup 2011 with India and Sri Lanka in 2011. Bangladesh solely hosted the 2014 ICC World Twenty20 championship. Bangladesh hosted the Cricket Asia Cup in 2000, 2012, 2014 and 2016. Bangladesh has also hosted the 1985 Men's Hockey Asia Cup.[339]

See also

Notes

- ^ /ˌbæŋɡləˈdɛʃ, ˌbɑːŋ-/; Bengali: বাংলাদেশ, romanized: Bāṅlādēś, pronounced [ˈbaŋlaˌdeʃ]

- ^ Bengali: গণপ্রজাতন্ত্রী বাংলাদেশ, romanized: Gôṇôprôjātôntrī Bāṅlādēś, pronounced [ɡɔnopɾodʒat̪ɔnt̪ɾi‿baŋlad̪eʃ]

References

- ^ "The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh". Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. Archived from the original on 10 November 2019. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ^ বাংলা ভাষা প্রচলন আইন, ১৯৮৭ [Bengali Language Implementation Act, 1987]. bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd (in Bengali). Ministry of Law, Justice and Parliamentary Affairs. Archived from the original on 7 January 2024. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ Historical Evolution of English in Bangladesh (PDF). Mohammad Nurul Islam. 1 March 2019. pp. 9–. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 10 November 2023.

- ^ "Ethnic population in 2022 census" (PDF).

- ^ "Census data confirm decline of Bangladesh's religious minorities". asianews.it. Archived from the original on 7 February 2024. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- ^ The Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh ( ACT NO. OF 1972 ). (n.d.). In Bangladesh. Retrieved 13 June 2023, from http://bdlaws.minlaw.gov.bd/act-367/section-24549.html Archived 17 January 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Population of minority religions decrease further in Bangladesh". The Business Standard. 27 July 2022. Archived from the original on 5 May 2023. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d "Bangladesh". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 13 November 2021. (Archived 2021 edition.)

- ^ Jump up to: a b "Population and Housing Census 2022: Post Enumeration Check (PEC) Adjusted Population" (PDF). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. 18 April 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2023. Retrieved 30 May 2023.

- ^ "Report: 68% Bangladeshis live in villages". Dhaka Tribune. 28 November 2023. Archived from the original on 6 February 2024. Retrieved 6 February 2024.

- ^ "Download World Economic Outlook database: April 2023". International Monetary Fund – IMF. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Download World Economic Outlook database: April 2023". International Monetary Fund – IMF. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Download World Economic Outlook database: April 2023". IMF. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "Download World Economic Outlook database: April 2023". IMF. Archived from the original on 4 December 2023. Retrieved 4 December 2023.

- ^ "KEY FINDINGS HIES 2022" (PDF) (Press release). Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. p. 15. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 May 2023. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ Nations, United (13 March 2024). "Human Development Report 2023-24". Archived from the original on 18 March 2024. Retrieved 18 March 2024 – via hdr.undp.org.

- ^ Frank E. Eyetsemitan; James T. Gire (2003). Aging and Adult Development in the Developing World: Applying Western Theories and Concepts. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 91. ISBN 978-0-89789-925-3. Archived from the original on 2 September 2024. Retrieved 25 July 2023.

- ^ "Muslim League – Banglapedia". Archived from the original on 20 March 2024. Retrieved 20 March 2024.

- ^ "Bangladesh profile – Timeline". BBC News. 26 February 2019. Archived from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Bangladesh" (PDF). U.S. State Department. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2016.

- ^ "Article Preamble, Section Preamble" (PDF). Constitution of the People's Republic of Bangladesh. 4 November 1972.

- ^ "A rising Bangladesh starts to exert its regional power". The Interpreter. Lowyinstitute.org. 21 February 2019. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Contribution of Uniformed Personnel to UN by Country and Personnel Type" (PDF). United Nations. 4 April 2023. Archived (PDF) from the original on 12 May 2023. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ Roy, Pinaki; Deshwara, Mintu (9 August 2022). "Ethnic population in 2022 census: Real picture not reflected". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 9 August 2022. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Mahmud, Faisal. "Four years on, Rohingya stuck in Bangladesh camps yearn for home". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 5 June 2022. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ^ "Notation of song aaji bangladesher hridoy". Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 10 September 2015.

- ^ "Bangladesh: early history, 1000 B.C.–A.D. 1202". Bangladesh: A country study. Library of Congress. September 1988. Archived from the original on 7 December 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2014.

Historians believe that Bengal, the area comprising present-day Bangladesh and the Indian state of West Bengal, was settled in about 1000 B.C. by Dravidian-speaking peoples who were later known as the Bang. Their homeland bore various titles that reflected earlier tribal names, such as Vanga, Banga, Bangala, Bangal, and Bengal.

- ^ "Vanga | ancient kingdom, India". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 30 July 2016. Retrieved 24 April 2023.

- ^ Keay, John (2000). India: A History. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 220. ISBN 978-0-87113-800-2.