Демократическая партия (США)

Демократическая партия | |

|---|---|

| |

| Председатель | Джейми Харрисон |

| Руководящий орган | Демократический национальный комитет [1] [2] |

| Президент США | Джо Байден |

| вице-президент США | Камала Харрис |

| Лидер большинства в Сенате | Чак Шумер |

| House Minority Leader | Hakeem Jeffries |

| Founders | |

| Founded | January 8, 1828[3] Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Preceded by | Democratic-Republican Party |

| Headquarters | 430 South Capitol St. SE, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Student wing | |

| Youth wing | Young Democrats of America |

| Women's wing | National Federation of Democratic Women |

| Overseas wing | Democrats Abroad |

| Ideology | |

| Political position | Center-left[b] |

| Caucuses | Problem Solvers Caucus Blue Dog Coalition New Democrat Coalition Congressional Progressive Caucus |

| Colors | Blue |

| Senate | 47 / 100[c] |

| House of Representatives | 212 / 435 |

| State Governors | 23 / 50 |

| State upper chambers | 857 / 1,973 |

| State lower chambers | 2,425 / 5,413 |

| Territorial Governors | 4 / 5 |

| Seats in Territorial upper chambers | 31 / 97 |

| Seats in Territorial lower chambers | 9 / 91 |

| Election symbol | |

| |

| Website | |

| democrats | |

Демократическая партия — одна из двух крупнейших современных политических партий в США . С конца 1850-х годов ее главным политическим соперником была Республиканская партия ; с тех пор эти две партии доминировали в американской политике.

Демократическая партия была основана в 1828 году. Мартин Ван Бюрен из Нью-Йорка сыграл центральную роль в создании коалиции государственных организаций, которая сформировала новую партию как средство избрания Эндрю Джексона из Теннесси. Демократическая партия — старейшая действующая политическая партия в мире. [14] [15] [16] Первоначально оно поддерживало расширение президентской власти . [17] интересы рабовладельческих государств , [18] аграризм , [19] и географический экспансионизм , [19] выступая против национального банка и высоких тарифов . [19] Она раскололась в 1860 году из-за рабства и только дважды выиграла президентские выборы. [д] между 1860 и 1912 годами, хотя за этот период он выигрывал всенародное голосование еще два раза. В конце 19 века оно продолжало выступать против высоких тарифов и вело ожесточенные внутренние дебаты по поводу золотого стандарта . В начале 20-го века оно поддерживало прогрессивные реформы и выступало против империализма , а Вудро Вильсон выиграл Белый дом в 1912 и 1916 годах .

Since Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president in 1932, the Democratic Party has promoted a liberal platform that includes support for Social Security and unemployment insurance.[4][20][21] The New Deal attracted strong support for the party from recent European immigrants but diminished the party's pro-business wing.[22][23][24] From late in Roosevelt's administration through the 1950s, a minority in the party's Southern wing joined with conservative Republicans to slow and stop progressive domestic reforms.[25] Following the Great Society era of progressive legislation under Lyndon B. Johnson, who was often able to overcome the conservative coalition in the 1960s, the core bases of the parties shifted, with the Southern states becoming more reliably Republican and the Northeastern states becoming more reliably Democratic.[26][27] The party's labor union element has become smaller since the 1970s,[28][29] and as the American electorate shifted in a more conservative direction following the Presidency of Ronald Reagan, the election of Bill Clinton marked a move for the party toward the Third Way, moving the party's economic stance towards market-based economic policy.[30][31][32] Barack Obama oversaw the party's passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010. During Joe Biden's presidency, the party has adopted an increasingly progressive economic agenda.[33][34]

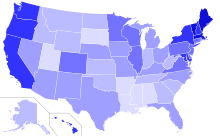

In the 21st century, the party is strongest among urban voters,[35][36] union workers, college graduates,[13][37][38] women, African Americans,[39][40][41] sexual minorities,[42][43] and the unmarried. On social issues, it advocates for abortion rights,[44] voting rights,[45] LGBT rights,[46] action on climate change,[47] and the legalization of marijuana.[48] On economic issues, the party favors healthcare reform, universal child care, paid sick leave and supporting unions.[49][50][51][52] In foreign policy, the party supports liberal internationalism as well as tough stances against China and Russia.[53][54][55]

History

Democratic Party officials often trace its origins to the Democratic-Republican Party, founded by Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and other influential opponents of the conservative Federalists in 1792.[56][57] That party died out before the modern Democratic Party was organized;[58] the Jeffersonian party also inspired the Whigs and modern Republicans.[59] Historians argue that the modern Democratic Party was first organized in the late 1820s with the election of war hero Andrew Jackson[16] of Tennessee, making it the world's oldest active political party.[15] It was predominately built by Martin Van Buren, who assembled a wide cadre of politicians in every state behind Jackson.[14][16]

Since the nomination of William Jennings Bryan in 1896, the party has generally positioned itself to the left of the Republican Party on economic issues. Democrats have been more liberal on civil rights since 1948, although conservative factions within the Democratic Party that opposed them persisted in the South until the 1960s. On foreign policy, both parties have changed positions several times.[60]

Background

The Democratic Party evolved from the Jeffersonian Republican or Democratic-Republican Party organized by Jefferson and Madison in opposition to the Federalist Party.[61] The Democratic-Republican Party favored republicanism; a weak federal government; states' rights; agrarian interests (especially Southern planters); and strict adherence to the Constitution. The party opposed a national bank and Great Britain.[62] After the War of 1812, the Federalists virtually disappeared and the only national political party left was the Democratic-Republicans, which was prone to splinter along regional lines.[63] The era of one-party rule in the United States, known as the Era of Good Feelings, lasted from 1816 until 1828, when Andrew Jackson became president. Jackson and Martin Van Buren worked with allies in each state to form a new Democratic Party on a national basis. In the 1830s, the Whig Party coalesced into the main rival to the Democrats.

Before 1860, the Democratic Party supported expansive presidential power,[17] the interests of slave states,[18] agrarianism,[19] and expansionism,[19] while opposing a national bank and high tariffs.[19]

19th century

The Democratic-Republican Party split over the choice of a successor to President James Monroe.[64] The faction that supported many of the old Jeffersonian principles, led by Andrew Jackson and Martin Van Buren, became the modern Democratic Party.[65] Historian Mary Beth Norton explains the transformation in 1828:

Jacksonians believed the people's will had finally prevailed. Through a lavishly financed coalition of state parties, political leaders, and newspaper editors, a popular movement had elected the president. The Democrats became the nation's first well-organized national party ... and tight party organization became the hallmark of nineteenth-century American politics.[66]

Behind the platforms issued by state and national parties stood a widely shared political outlook that characterized the Democrats:

The Democrats represented a wide range of views but shared a fundamental commitment to the Jeffersonian concept of an agrarian society. They viewed the central government as the enemy of individual liberty. The 1824 "corrupt bargain" had strengthened their suspicion of Washington politics. ... Jacksonians feared the concentration of economic and political power. They believed that government intervention in the economy benefited special-interest groups and created corporate monopolies that favored the rich. They sought to restore the independence of the individual—the artisan and the ordinary farmer—by ending federal support of banks and corporations and restricting the use of paper currency, which they distrusted. Their definition of the proper role of government tended to be negative, and Jackson's political power was largely expressed in negative acts. He exercised the veto more than all previous presidents combined. ... Nor did Jackson share reformers' humanitarian concerns. He had no sympathy for American Indians, initiating the removal of the Cherokees along the Trail of Tears.[67]

Opposing factions led by Henry Clay helped form the Whig Party. The Democratic Party had a small yet decisive advantage over the Whigs until the 1850s when the Whigs fell apart over the issue of slavery. In 1854, angry with the Kansas–Nebraska Act, anti-slavery Democrats left the party and joined Northern Whigs to form the Republican Party.[68][69] Martin van Buren also helped found the Free Soil Party to oppose the spread of slavery, running as its candidate in the 1848 presidential election, before returning to the Democratic Party and staying loyal to the Union.[70]

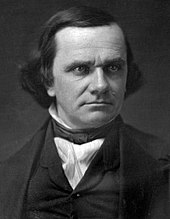

The Democrats split over slavery, with Northern and Southern tickets in the election of 1860, in which the Republican Party gained ascendancy.[71] The radical pro-slavery Fire-Eaters led walkouts at the two conventions when the delegates would not adopt a resolution supporting the extension of slavery into territories even if the voters of those territories did not want it. These Southern Democrats nominated the pro-slavery incumbent vice president, John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky, for president and General Joseph Lane, of Oregon, for vice president. The Northern Democrats nominated Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois for president and former Georgia Governor Herschel V. Johnson for vice president. This fracturing of the Democrats led to a Republican victory and Abraham Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States.[72]

As the American Civil War broke out, Northern Democrats were divided into War Democrats and Peace Democrats. The Confederate States of America deliberately avoided organized political parties. Most War Democrats rallied to Republican President Abraham Lincoln and the Republicans' National Union Party in the election of 1864, which featured Andrew Johnson on the Union ticket to attract fellow Democrats. Johnson replaced Lincoln in 1865, but he stayed independent of both parties.[73]

The Democrats benefited from white Southerners' resentment of Reconstruction after the war and consequent hostility to the Republican Party. After Redeemers ended Reconstruction in the 1870s and following the often extremely violent disenfranchisement of African Americans led by such white supremacist Democratic politicians as Benjamin Tillman of South Carolina in the 1880s and 1890s, the South, voting Democratic, became known as the "Solid South". Although Republicans won all but two presidential elections, the Democrats remained competitive. The party was dominated by pro-business Bourbon Democrats led by Samuel J. Tilden and Grover Cleveland, who represented mercantile, banking, and railroad interests; opposed imperialism and overseas expansion; fought for the gold standard; opposed bimetallism; and crusaded against corruption, high taxes and tariffs. Cleveland was elected to non-consecutive presidential terms in 1884 and 1892.[74]

20th century

Early 20th century

Agrarian Democrats demanding free silver, drawing on Populist ideas, overthrew the Bourbon Democrats in 1896 and nominated William Jennings Bryan for the presidency (a nomination repeated by Democrats in 1900 and 1908). Bryan waged a vigorous campaign attacking Eastern moneyed interests, but he lost to Republican William McKinley.[75]

The Democrats took control of the House in 1910, and Woodrow Wilson won election as president in 1912 (when the Republicans split) and 1916. Wilson effectively led Congress to put to rest the issues of tariffs, money, and antitrust, which had dominated politics for 40 years, with new progressive laws. He failed to secure Senate passage of the Versailles Treaty (ending the war with Germany and joining the League of Nations).[76] The weakened party was deeply divided by issues such as the KKK and prohibition in the 1920s. However, it did organize new ethnic voters in Northern cities.[77]

After World War I ended and continuing through the Great Depression, the Democratic and Republican Parties both largely believed in American exceptionalism over European monarchies and state socialism that existed elsewhere in the world.[78]

1930s–1960s and the rise of the New Deal coalition

The Great Depression in 1929 that began under Republican President Herbert Hoover and the Republican Congress set the stage for a more liberal government as the Democrats controlled the House of Representatives nearly uninterrupted from 1930 until 1994, the Senate for 44 of 48 years from 1930, and won most presidential elections until 1968. Franklin D. Roosevelt, elected to the presidency in 1932, came forth with federal government programs called the New Deal. New Deal liberalism meant the regulation of business (especially finance and banking) and the promotion of labor unions as well as federal spending to aid the unemployed, help distressed farmers and undertake large-scale public works projects. It marked the start of the American welfare state.[79] The opponents, who stressed opposition to unions, support for business and low taxes, started calling themselves "conservatives".[80]

Until the 1980s, the Democratic Party was a coalition of two parties divided by the Mason–Dixon line: liberal Democrats in the North and culturally conservative voters in the South, who though benefitting from many of the New Deal public works projects, opposed increasing civil rights initiatives advocated by northeastern liberals. The polarization grew stronger after Roosevelt died. Southern Democrats formed a key part of the bipartisan conservative coalition in an alliance with most of the Midwestern Republicans. The economically activist philosophy of Franklin D. Roosevelt, which has strongly influenced American liberalism, shaped much of the party's economic agenda after 1932.[81] From the 1930s to the mid-1960s, the liberal New Deal coalition usually controlled the presidency while the conservative coalition usually controlled Congress.[82]

1960s–1980s and the collapse of the New Deal coalition

Issues facing parties and the United States after World War II included the Cold War and the civil rights movement. Republicans attracted conservatives and, after the 1960s, white Southerners from the Democratic coalition with their use of the Southern strategy and resistance to New Deal and Great Society liberalism. Until the 1950s, African Americans had traditionally supported the Republican Party because of its anti-slavery civil rights policies. Following the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965, the Southern states became more reliably Republican in presidential politics, while Northeastern states became more reliably Democratic.[83][84][85][42] Studies show that Southern whites, which were a core constituency in the Democratic Party, shifted to the Republican Party due to racial backlash and social conservatism.[86][87][88]

The election of President John F. Kennedy from Massachusetts in 1960 partially reflected this shift. In the campaign, Kennedy attracted a new generation of younger voters. In his agenda dubbed the New Frontier, Kennedy introduced a host of social programs and public works projects, along with enhanced support of the space program, proposing a crewed spacecraft trip to the moon by the end of the decade. He pushed for civil rights initiatives and proposed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but with his assassination in November 1963, he was not able to see its passage.[89]

Kennedy's successor Lyndon B. Johnson was able to persuade the largely conservative Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and with a more progressive Congress in 1965 passed much of the Great Society, including Medicare, which consisted of an array of social programs designed to help the poor, sick, and elderly. Kennedy and Johnson's advocacy of civil rights further solidified black support for the Democrats but had the effect of alienating Southern whites who would eventually gravitate toward the Republican Party, particularly after the election of Ronald Reagan to the presidency in 1980. Many conservative Southern Democrats defected to the Republican Party, beginning with the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the general leftward shift of the party.[90][91][42][92]

The United States' involvement in the Vietnam War in the 1960s was another divisive issue that further fractured the fault lines of the Democrats' coalition. After the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in 1964, President Johnson committed a large contingency of combat troops to Vietnam, but the escalation failed to drive the Viet Cong from South Vietnam, resulting in an increasing quagmire, which by 1968 had become the subject of widespread anti-war protests in the United States and elsewhere. With increasing casualties and nightly news reports bringing home troubling images from Vietnam, the costly military engagement became increasingly unpopular, alienating many of the kinds of young voters that the Democrats had attracted in the early 1960s. The protests that year along with assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Democratic presidential candidate Senator Robert F. Kennedy (younger brother of John F. Kennedy) climaxed in turbulence at the hotly-contested Democratic National Convention that summer in Chicago (which amongst the ensuing turmoil inside and outside of the convention hall nominated Vice President Hubert Humphrey) in a series of events that proved to mark a significant turning point in the decline of the Democratic Party's broad coalition.[93]

Republican presidential nominee Richard Nixon was able to capitalize on the confusion of the Democrats that year, and won the 1968 election to become the 37th president. He won re-election in a landslide in 1972 against Democratic nominee George McGovern, who like Robert F. Kennedy, reached out to the younger anti-war and counterculture voters, but unlike Kennedy, was not able to appeal to the party's more traditional white working-class constituencies. During Nixon's second term, his presidency was rocked by the Watergate scandal, which forced him to resign in 1974. He was succeeded by vice president Gerald Ford, who served a brief tenure.

Watergate offered the Democrats an opportunity to recoup, and their nominee Jimmy Carter won the 1976 presidential election. With the initial support of evangelical Christian voters in the South, Carter was temporarily able to reunite the disparate factions within the party, but inflation and the Iran Hostage Crisis of 1979–1980 took their toll, resulting in a landslide victory for Republican presidential nominee Ronald Reagan in 1980, which shifted the political landscape in favor of the Republicans for years to come. The influx of conservative Democrats into the Republican Party is often cited as a reason for the Republican Party's shift further to the right during the late 20th century as well as the shift of its base from the Northeast and Midwest to the South.[94][95]

1990s and Third Way centrism

With the ascendancy of the Republicans under Ronald Reagan, the Democrats searched for ways to respond yet were unable to succeed by running traditional candidates, such as former vice president and Democratic presidential nominee Walter Mondale and Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis, who lost to Reagan and George H.W. Bush in the 1984 and 1988 presidential elections, respectively. Many Democrats attached their hopes to the future star of Gary Hart, who had challenged Mondale in the 1984 primaries running on a theme of "New Ideas"; and in the subsequent 1988 primaries became the de facto front-runner and virtual "shoo-in" for the Democratic presidential nomination before a sex scandal ended his campaign. The party nevertheless began to seek out a younger generation of leaders, who like Hart had been inspired by the pragmatic idealism of John F. Kennedy.[96]

Arkansas governor Bill Clinton was one such figure, who was elected president in 1992 as the Democratic nominee. The Democratic Leadership Council was a campaign organization connected to Clinton that advocated a realignment and triangulation under the re-branded "New Democrat" label.[97][30][31] The party adopted a synthesis of neoliberal economic policies with cultural liberalism, with the voter base after Reagan having shifted considerably to the right.[97] In an effort to appeal both to liberals and to fiscal conservatives, Democrats began to advocate for a balanced budget and market economy tempered by government intervention (mixed economy), along with a continued emphasis on social justice and affirmative action. The economic policy adopted by the Democratic Party, including the former Clinton administration, has been referred to as "Third Way".

The Democrats lost control of Congress in the election of 1994 to the Republican Party. Re-elected in 1996, Clinton was the first Democratic president since Franklin D. Roosevelt to be elected to two terms.[98] Al Gore won the popular vote, but after a controversial election dispute over a Florida recount settled by the U.S. Supreme Court (which ruled 5–4 in favor of Bush) he lost the 2000 United States Presidential Election to Republican opponent George W. Bush in the Electoral College.[99]

21st century

2000s

In the wake of the 2001 terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and the Pentagon as well as the growing concern over global warming, some of the party's key issues in the early 21st century have included combating terrorism while preserving human rights, expanding access to health care, labor rights, and environmental protection. Democrats regained majority control of both the House and the Senate in the 2006 elections. Barack Obama won the Democratic Party's nomination and was elected as the first African American president in 2008. Under the Obama presidency, the party moved forward reforms including an economic stimulus package, the Dodd–Frank financial reform act, and the Affordable Care Act.[100]

2010s

In the 2010 midterm elections, the Democratic Party lost control of the House and lost its majority in state legislatures and state governorships. In the 2012 elections, President Obama was re-elected, but the party remained in the minority in the House of Representatives and lost control of the Senate in the 2014 midterm elections. After the 2016 election of Donald Trump, who lost the popular vote, the Democratic Party transitioned into the role of an opposition party and held neither the presidency nor Congress for two years. However, the Democratic Party won back a majority in the House in the 2018 midterm elections under the leadership of Nancy Pelosi.

Democrats were extremely critical of President Trump, particularly his policies on immigration, healthcare, and abortion, as well as his response to the COVID-19 pandemic.[101][102][103] In December 2019, Democrats in the House of Representatives impeached Trump for the first time, although Trump was acquitted in the Republican-controlled Senate.[104]

2020s

In November 2020, Democrat Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election.[105] He began his term with extremely narrow Democratic majorities in the U.S. House and Senate.[106][107] In 2022, Biden appointed Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first Black woman on the Supreme Court. However, she was replacing liberal justice Stephen Breyer, so she did not alter the court's 6–3 split between conservatives (the majority) and liberals.[108][109][110][111] After Dobbs v. Jackson (decided June 24, 2022), which led to abortion bans in much of the country, the Democratic Party rallied behind abortion rights.[44]

In the 2022 midterm elections, Democrats dramatically outperformed historical trends, and a widely anticipated red wave did not materialize.[112][113] The party only narrowly lost its majority in the U.S. House and expanded its majority in the U.S. Senate,[114][115][116] along with several gains at the state level, including acquiring "trifectas" (control of both legislative houses and governor's seat) in several states.[117][118][119][120][121]

During Joe Biden's presidency in the 2020s, the party has adopted an increasingly left-wing cultural and economic agenda.[33] In 2024, Biden was the first incumbent president since Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968 to withdraw from a reelection race, the first since the 19th century to withdraw after serving only one term,[e] and the only one ever to withdraw after already winning the primaries.[122][124]

As of 2024, Democrats hold the presidency and a majority in the U.S. Senate, as well as 23 state governorships, 19 state legislatures, 17 state government trifectas, and the mayorships in the majority of the country's major cities.[125] Three of the nine current U.S. Supreme Court justices were appointed by Democratic presidents. By registered members, the Democratic Party is the largest party in the U.S. and the fourth largest in the world. Including the incumbent Biden, 16 Democrats have served as president of the United States.[4]

Name and symbols

The Democratic-Republican Party splintered in 1824 into the short-lived National Republican Party and the Jacksonian movement which in 1828 became the Democratic Party. Under the Jacksonian era, the term "The Democracy" was in use by the party, but the name "Democratic Party" was eventually settled upon[126] and became the official name in 1844.[127] Members of the party are called "Democrats" or "Dems".

The most common mascot symbol for the party has been the donkey, or jackass.[128] Andrew Jackson's enemies twisted his name to "jackass" as a term of ridicule regarding a stupid and stubborn animal. However, the Democrats liked the common-man implications and picked it up too, therefore the image persisted and evolved.[129] Its most lasting impression came from the cartoons of Thomas Nast from 1870 in Harper's Weekly. Cartoonists followed Nast and used the donkey to represent the Democrats and the elephant to represent the Republicans.

In the early 20th century, the traditional symbol of the Democratic Party in Indiana, Kentucky, Oklahoma and Ohio was the rooster, as opposed to the Republican eagle.[132] The rooster was also adopted as an official symbol of the national Democratic Party.[133] In 1904, the Alabama Democratic Party chose, as the logo to put on its ballots, a rooster with the motto "White supremacy – For the right."[134] The words "White supremacy" were replaced with "Democrats" in 1966.[135][130] In 1996, the Alabama Democratic Party dropped the rooster, citing racist and white supremacist connotations linked with the symbol.[131] The rooster symbol still appears on Oklahoma, Kentucky, Indiana, and West Virginia ballots.[132] In New York, the Democratic ballot symbol is a five-pointed star.[136]

Although both major political parties (and many minor ones) use the traditional American colors of red, white, and blue in their marketing and representations, since election night 2000 blue has become the identifying color for the Democratic Party while red has become the identifying color for the Republican Party. That night, for the first time all major broadcast television networks used the same color scheme for the electoral map: blue states for Al Gore (Democratic nominee) and red states for George W. Bush (Republican nominee). Since then, the color blue has been widely used by the media to represent the party. This is contrary to common practice outside of the United States where blue is the traditional color of the right and red the color of the left.[137]

Jefferson-Jackson Day is the annual fundraising event (dinner) held by Democratic Party organizations across the United States.[138] It is named after Presidents Thomas Jefferson and Andrew Jackson, whom the party regards as its distinguished early leaders.

The song "Happy Days Are Here Again" is the unofficial song of the Democratic Party. It was used prominently when Franklin D. Roosevelt was nominated for president at the 1932 Democratic National Convention and remains a sentimental favorite for Democrats. For example, Paul Shaffer played the theme on the Late Show with David Letterman after the Democrats won Congress in 2006. "Don't Stop" by Fleetwood Mac was adopted by Bill Clinton's presidential campaign in 1992 and has endured as a popular Democratic song. The emotionally similar song "Beautiful Day" by the band U2 has also become a favorite theme song for Democratic candidates. John Kerry used the song during his 2004 presidential campaign and several Democratic Congressional candidates used it as a celebratory tune in 2006.[139][140]

As a traditional anthem for its presidential nominating convention, Aaron Copland's "Fanfare for the Common Man" is traditionally performed at the beginning of the Democratic National Convention.

Structure

National committee

The Democratic National Committee (DNC) is responsible for promoting Democratic campaign activities. While the DNC is responsible for overseeing the process of writing the Democratic Platform, the DNC is more focused on campaign and organizational strategy than public policy. In presidential elections, it supervises the Democratic National Convention. The national convention is subject to the charter of the party and the ultimate authority within the Democratic Party when it is in session, with the DNC running the party's organization at other times. Since 2021, the DNC has been chaired by Jaime Harrison.[141]

State parties

Each state also has a state committee, made up of elected committee members as well as ex officio committee members (usually elected officials and representatives of major constituencies), which in turn elects a chair. County, town, city, and ward committees generally are composed of individuals elected at the local level. State and local committees often coordinate campaign activities within their jurisdiction, oversee local conventions, and in some cases primaries or caucuses, and may have a role in nominating candidates for elected office under state law. Rarely do they have much direct funding, but in 2005 DNC Chairman Dean began a program (called the "50 State Strategy") of using DNC national funds to assist all state parties and pay for full-time professional staffers.[142]

Major party committees and groups

The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC) assists party candidates in House races and is chaired by Representative Suzan DelBene of Washington. Similarly, the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee (DSCC), chaired by Senator Gary Peters of Michigan, raises funds for Senate races. The Democratic Legislative Campaign Committee (DLCC), chaired by Majority Leader of the New York State Senate Andrea Stewart-Cousins, is a smaller organization that focuses on state legislative races. The Democratic Governors Association (DGA) is an organization supporting the candidacies of Democratic gubernatorial nominees and incumbents. Likewise, the mayors of the largest cities and urban centers convene as the National Conference of Democratic Mayors.[143]

The DNC sponsors the College Democrats of America (CDA), a student-outreach organization with the goal of training and engaging a new generation of Democratic activists. Democrats Abroad is the organization for Americans living outside the United States. They work to advance the party's goals and encourage Americans living abroad to support the Democrats. The Young Democrats of America (YDA) and the High School Democrats of America (HSDA) are young adult and youth-led organizations respectively that attempt to draw in and mobilize young people for Democratic candidates but operates outside of the DNC.

Political positions

The party's platform blends civil liberty and social equality with support for a mixed capitalist economy.[144] On social issues, it advocates for the continued legality of abortion,[44] the legalization of marijuana,[48] and LGBT rights.[46]

On economic issues, it favors universal healthcare coverage, universal child care, paid sick leave, corporate governance reform, and supporting unions.[49][50][51][52]

- Economic policy

- Expand Social Security and safety-net programs.[145]

- Increase the capital gains tax rate to 39.6% for taxpayers with annual income above $1 million.[146]

- Cut taxes for the working and middle classes as well as small businesses.[147]

- Change tax rules to discourage shipping jobs overseas.[147]

- Increase federal and state minimum wages.[148]

- Modernize and expand access to public education and provide universal preschool education.[149]

- Support the goal of universal health care through a public health insurance option or expanding Medicare/Medicaid.[150]

- Increase investments in infrastructure development[151] as well as scientific and technological research.[152]

- Offer tax credits to make clean energy more accessible for consumers and increase domestic production of clean energy.[153]

- Uphold labor protections and the right to unionize.[154][155]

- Reform the student loan system and allow for refinancing student loans.[156]

- Make college more affordable.[148][157]

- Mandate equal pay for equal work regardless of gender, race, or ethnicity.[158]

- Social policy

- Decriminalize or legalize marijuana.[148]

- Uphold network neutrality.[159]

- Implement campaign finance reform.[160]

- Uphold voting rights and easy access to voting.[161][162]

- Support same-sex marriage and ban conversion therapy.[148]

- Allow legal access to abortions and women's reproductive health care.[151]

- Reform the immigration system and allow for a pathway to citizenship.[151]

- Expand background checks and reduce access to assault weapons to address gun violence.[151]

- Improve privacy laws and curtail government surveillance.[151]

- Oppose torture.[163][164]

- Abolish capital punishment.[165]

- Recognize and defend Internet freedom worldwide.[147]

Economic issues

The social safety net and strong labor unions have been at the heart of Democratic economic policy since the New Deal in the 1930s.[144] The Democratic Party's economic policy positions, as measured by votes in Congress, tend to align with those of the middle class.[166][167][168][169][170] Democrats support a progressive tax system, higher minimum wages, equal opportunity employment, Social Security, universal health care, public education, and subsidized housing.[144] They also support infrastructure development and clean energy investments to achieve economic development and job creation.[171]

Since the 1990s, the party has at times supported centrist economic reforms that cut the size of government and reduced market regulations.[172] The party has generally rejected both laissez-faire economics and market socialism, instead favoring Keynesian economics within a capitalist market-based system.[173]

Fiscal policy

Democrats support a more progressive tax structure to provide more services and reduce economic inequality by making sure that the wealthiest Americans pay more in taxes.[174]Democrats and Republicans traditionally take differing stances on eradicating poverty. Brady said "Our poverty level is the direct consequence of our weak social policies, which are a direct consequence of weak political actors".[175]They oppose the cutting of social services, such as Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid,[176] believing it to be harmful to efficiency and social justice. Democrats believe the benefits of social services in monetary and non-monetary terms are a more productive labor force and cultured population and believe that the benefits of this are greater than any benefits that could be derived from lower taxes, especially on top earners, or cuts to social services. Furthermore, Democrats see social services as essential toward providing positive freedom, freedom derived from economic opportunity. The Democratic-led House of Representatives reinstated the PAYGO (pay-as-you-go) budget rule at the start of the 110th Congress.[177]

Minimum wage

The Democratic Party favors raising the minimum wage. The Fair Minimum Wage Act of 2007 was an early component of the Democrats' agenda during the 110th Congress. In 2006, the Democrats supported six state-ballot initiatives to increase the minimum wage and all six initiatives passed.[178]

In 2017, Senate Democrats introduced the Raise the Wage Act which would raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour by 2024.[179] In 2021, Democratic president Joe Biden proposed increasing the minimum wage to $15 by 2025.[180] In many states controlled by Democrats, the state minimum wage has been increased to a rate above the federal minimum wage.[181]

Health care

Democrats call for "affordable and quality health care" and favor moving toward universal health care in a variety of forms to address rising healthcare costs. Progressive Democrats politicians favor a single-payer program or Medicare for All, while liberals prefer creating a public health insurance option.[182]

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, signed into law by President Barack Obama on March 23, 2010, has been one of the most significant pushes for universal health care. As of December 2019, more than 20 million Americans have gained health insurance under the Affordable Care Act.[183]

Education

Democrats favor improving public education by raising school standards and reforming the Head Start program. They also support universal preschool, expanding access to primary education, including through charter schools, and are generally opposed to school voucher programs. They call for addressing student loan debt and reforms to reduce college tuition.[184] Other proposals have included tuition-free public universities and reform of standardized testing. Democrats have the long-term aim of having publicly funded college education with low tuition fees (like in much of Europe and Canada), which would be available to every eligible American student. Alternatively, they encourage expanding access to post-secondary education by increasing state funding for student financial aid such as Pell Grants and college tuition tax deductions.[185]

Environment

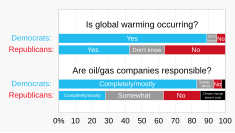

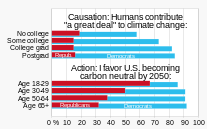

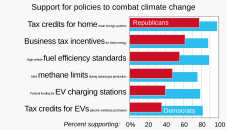

Democrats believe that the government should protect the environment and have a history of environmentalism. In more recent years, this stance has emphasized renewable energy generation as the basis for an improved economy, greater national security, and general environmental benefits.[191] The Democratic Party is substantially more likely than the Republican Party to support environmental regulation and policies that are supportive of renewable energy.[192][193]

The Democratic Party also favors expansion of conservation lands and encourages open space and rail travel to relieve highway and airport congestion and improve air quality and the economy as it "believe[s] that communities, environmental interests, and the government should work together to protect resources while ensuring the vitality of local economies. Once Americans were led to believe they had to make a choice between the economy and the environment. They now know this is a false choice".[194]

The foremost environmental concern of the Democratic Party is climate change. Democrats, most notably former Vice President Al Gore, have pressed for stern regulation of greenhouse gases. On October 15, 2007, Gore won the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to build greater knowledge about man-made climate change and laying the foundations for the measures needed to counteract it.[195]

Renewable energy and fossil fuels

Democrats have supported increased domestic renewable energy development, including wind and solar power farms, in an effort to reduce carbon pollution. The party's platform calls for an "all of the above" energy policy including clean energy, natural gas and domestic oil, with the desire of becoming energy independent.[178] The party has supported higher taxes on oil companies and increased regulations on coal power plants, favoring a policy of reducing long-term reliance on fossil fuels.[196][197] Additionally, the party supports stricter fuel emissions standards to prevent air pollution.

During his presidency, Joe Biden enacted the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022, which is the largest allocation of funds for addressing climate change in the history of the United States to date.[198][199]

Trade

Like the Republican Party, the Democratic Party has taken widely varying views on international trade throughout its history. The Democratic Party has usually been more supportive of free trade than the Republican Party.

The Democrats dominated the Second Party System and set low tariffs designed to pay for the government but not protect industry. Their opponents the Whigs wanted high protective tariffs but usually were outvoted in Congress. Tariffs soon became a major political issue as the Whigs (1832–1852) and (after 1854) the Republicans wanted to protect their mostly northern industries and constituents by voting for higher tariffs and the Southern Democrats, which had very little industry but imported many goods voted for lower tariffs. After the Second Party System ended in 1854 the Democrats lost control and the new Republican Party had its opportunity to raise rates.[200]

During the Third Party System, Democratic president Grover Cleveland made low tariffs the centerpiece of Democratic Party policies, arguing that high tariffs were an unnecessary and unfair tax on consumers. The South and West generally supported low tariffs, while the industrial North high tariffs.[201] During the Fourth Party System, Democratic president Woodrow Wilson made a drastic lowering of tariff rates a major priority for his presidency. The 1913 Underwood Tariff cut rates, and the new revenues generated by the federal income tax made tariffs much less important in terms of economic impact and political rhetoric.[202]

During the Fifth Party System, the Reciprocal Tariff Act of 1934 was enacted during FDR's administration, marking a sharp departure from the era of protectionism in the United States. American duties on foreign products declined from an average of 46% in 1934 to 12% by 1962.[203] After World War II, the U.S. promoted the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) established in 1947 during the Truman administration, to minimize tariffs liberalize trade among all capitalist countries.[204][205]

In the 1990s, the Clinton administration and a number of prominent Democrats pushed through a number of agreements such as the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Since then, the party's shift away from free trade became evident in the Central American Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA) vote, with 15 House Democrats voting for the agreement and 187 voting against.[206][207][208][209]

Social issues

The modern Democratic Party emphasizes social equality and equal opportunity. Democrats support voting rights and minority rights, including LGBT rights. Democratic president Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which outlawed racial segregation. Carmines and Stimson wrote "the Democratic Party appropriated racial liberalism and assumed federal responsibility for ending racial discrimination."[210][211][212]

Ideological social elements in the party include cultural liberalism, civil libertarianism, and feminism. Some Democratic social policies are immigration reform, electoral reform, and women's reproductive rights.

Equal opportunity

The Democratic Party supports equal opportunity for all Americans regardless of sex, age, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, creed, or national origin. The Democratic Party has broad appeal across most socioeconomic and ethnic demographics, as seen in recent exit polls.[213] Democrats also strongly support the Americans with Disabilities Act to prohibit discrimination against people based on physical or mental disability. As such, the Democrats pushed as well the ADA Amendments Act of 2008, a disability rights expansion that became law.[214]

Most Democrats support affirmative action to further equal opportunity. However, in 2020 57% voters in California voted to keep their state constitution's ban on affirmative action, despite Biden winning 63% of the vote in California in the same election.[215]

Voting rights

The party is very supportive of improving voting rights as well as election accuracy and accessibility.[216] They support extensions of voting time, including making election day a holiday. They support reforming the electoral system to eliminate gerrymandering, abolishing the electoral college, as well as passing comprehensive campaign finance reform.[160]

Abortion and reproductive rights

The Democratic position on abortion has changed significantly over time.[217][218] During the late 1960s and early 1970s, Republicans generally favored legalized abortion more than Democrats,[219] although significant heterogeneity could be found within both parties.[220] During this time, opposition to abortion tended to be concentrated within the political left in the United States. Liberal Protestants and Catholics (many of whom were Democratic voters) opposed abortion, while most conservative Protestants supported legal access to abortion services.[217][clarification needed]

In its national platforms from 1992 to 2004, the Democratic Party has called for abortion to be "safe, legal and rare"—namely, keeping it legal by rejecting laws that allow governmental interference in abortion decisions and reducing the number of abortions by promoting both knowledge of reproduction and contraception and incentives for adoption. When Congress voted on the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act in 2003, Congressional Democrats were split, with a minority (including former Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid) supporting the ban and the majority of Democrats opposing the legislation.[221]

According to the 2020 Democratic Party platform, "Democrats believe every woman should be able to access high-quality reproductive health care services, including safe and legal abortion."[222]

Immigration

Like the Republican Party, the Democratic Party has taken widely varying views on immigration throughout its history. Since the 1990s, the Democratic Party has been more supportive overall of immigration than the Republican Party.[223] Many Democratic politicians have called for systematic reform of the immigration system such that residents that have come into the United States illegally have a pathway to legal citizenship. President Obama remarked in November 2013 that he felt it was "long past time to fix our broken immigration system," particularly to allow "incredibly bright young people" that came over as students to become full citizens.[224] In 2013, Democrats in the Senate passed S. 744, which would reform immigration policy to allow citizenship for illegal immigrants in the United States. The law failed to pass in the House and was never re-introduced after the 113th Congress.[225]

As of 2024, no major immigration reform legislation has been enacted into law in the 21st century, mainly due to opposition by the Republican Party.[226][227] Opposition to immigration has increased in the 2020s, with a majority of Democrats supporting increasing border security.[228]

LGBT rights

The Democratic position on LGBT rights has changed significantly over time.[229][230] Before the 2000s, like the Republicans, the Democratic Party often took positions hostile to LGBT rights. As of the 2020s, both voters and elected representatives within the Democratic Party are overwhelmingly supportive of LGBT rights.[229]

Support for same-sex marriage has steadily increased among the general public, including voters in both major parties, since the start of the 21st century. An April 2009 ABC News/Washington Post public opinion poll put support among Democrats at 62%.[231] A 2006 Pew Research Center poll of Democrats found that 55% supported gays adopting children with 40% opposed while 70% support gays in the military, with only 23% opposed.[232] Gallup polling from May 2009 stated that 82% of Democrats support open enlistment.[233] A 2023 Gallup public opinion poll found 84% of Democrats support same-sex marriage, compared to 71% support by the general public and 49% support by Republicans.[234]

The 2004 Democratic National Platform stated that marriage should be defined at the state level and it repudiated the Federal Marriage Amendment.[235] John Kerry, the Democratic presidential nominee in 2004, did not support same-sex marriage in his campaign. While not stating support of same-sex marriage, the 2008 platform called for repeal of the Defense of Marriage Act, which banned federal recognition of same-sex marriage and removed the need for interstate recognition, supported antidiscrimination laws and the extension of hate crime laws to LGBT people and opposed "don't ask, don't tell".[236] The 2012 platform included support for same-sex marriage and for the repeal of DOMA.[237]

On May 9, 2012, Barack Obama became the first sitting president to say he supports same-sex marriage.[238][239] Previously, he had opposed restrictions on same-sex marriage such as the Defense of Marriage Act, which he promised to repeal,[240] California's Prop 8,[241] and a constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage (which he opposed saying that "decisions about marriage should be left to the states as they always have been"),[242] but also stated that he personally believed marriage to be between a man and a woman and that he favored civil unions that would "give same-sex couples equal legal rights and privileges as married couples".[240] Earlier, when running for the Illinois Senate in 1996 he said, "I favor legalizing same-sex marriages, and would fight efforts to prohibit such marriages".[243] Former presidents Bill Clinton[244] and Jimmy Carter[245] along with former Democratic presidential nominees Al Gore[246] and Michael Dukakis[247] support same-sex marriage. President Joe Biden has supported same-sex marriage since 2012, when he became the highest-ranking government official to support it. In 2022, Biden signed the Respect for Marriage Act; the law repealed the Defense of Marriage Act, which Biden had voted for during his Senate tenure.[248]

Status of Puerto Rico and D.C.

The 2016 Democratic Party platform declares, regarding the status of Puerto Rico: "We are committed to addressing the extraordinary challenges faced by our fellow citizens in Puerto Rico. Many stem from the fundamental question of Puerto Rico's political status. Democrats believe that the people of Puerto Rico should determine their ultimate political status from permanent options that do not conflict with the Constitution, laws, and policies of the United States. Democrats are committed to promoting economic opportunity and good-paying jobs for the hardworking people of Puerto Rico. We also believe that Puerto Ricans must be treated equally by Medicare, Medicaid, and other programs that benefit families. Puerto Ricans should be able to vote for the people who make their laws, just as they should be treated equally. All American citizens, no matter where they reside, should have the right to vote for the president of the United States. Finally, we believe that federal officials must respect Puerto Rico's local self-government as laws are implemented and Puerto Rico's budget and debt are restructured so that it can get on a path towards stability and prosperity".[151]

Also, it declares that regarding the status of the District of Columbia: "Restoring our democracy also means finally passing statehood for the District of Columbia, so that the American citizens who reside in the nation's capital have full and equal congressional rights as well as the right to have the laws and budget of their local government respected without Congressional interference."[151]

Legal issues

Gun control

With a stated goal of reducing crime and homicide, the Democratic Party has introduced various gun control measures, most notably the Gun Control Act of 1968, the Brady Bill of 1993 and Crime Control Act of 1994. In its national platform for 2008, the only statement explicitly favoring gun control was a plan calling for renewal of the 1994 Assault Weapons Ban.[250] In 2022, Democratic president Joe Biden signed the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act, which among other things expanded background checks and provided incentives for states to pass red flag laws.[251] According to a 2023 Pew Research Center poll, 20% of Democrats owned firearms, compared to 32% of the general public and 45% of Republicans.[252]

Death penalty

The Democratic Party's 2020 platform states its opposition to the death penalty.[165] Although most Democrats in Congress have never seriously moved to overturn the rarely used federal death penalty, both Russ Feingold and Dennis Kucinich have introduced such bills with little success. Democrats have led efforts to overturn state death penalty laws, particularly in New Jersey and in New Mexico. They have also sought to prevent the reinstatement of the death penalty in those states which prohibit it, including Massachusetts, New York, and Delaware. During the Clinton administration, Democrats led the expansion of the federal death penalty. These efforts resulted in the passage of the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act of 1996, signed into law by President Clinton, which heavily limited appeals in death penalty cases.In 1972, the Democratic Party platform called for the abolition of capital punishment.[253]In 1992, 1993 and 1995, Democratic Texas Congressman Henry González unsuccessfully introduced the Death Penalty Abolition Amendment which prohibited the use of capital punishment in the United States. Democratic Missouri Congressman William Lacy Clay Sr. cosponsored the amendment in 1993.

During his Illinois Senate career, former President Barack Obama successfully introduced legislation intended to reduce the likelihood of wrongful convictions in capital cases, requiring videotaping of confessions. When campaigning for the presidency, Obama stated that he supports the limited use of the death penalty, including for people who have been convicted of raping a minor under the age of 12, having opposed the Supreme Court's ruling in Kennedy v. Louisiana that the death penalty was unconstitutional in which the victim of a crime was not killed.[254] Obama has stated that he thinks the "death penalty does little to deter crime" and that it is used too frequently and too inconsistently.[255]

In June 2016, the Democratic Platform Drafting Committee unanimously adopted an amendment to abolish the death penalty.[256]

Torture

Many Democrats are opposed to the use of torture against individuals apprehended and held prisoner by the United States military, and hold that categorizing such prisoners as unlawful combatants does not release the United States from its obligations under the Geneva Conventions. Democrats contend that torture is inhumane, damages the United States' moral standing in the world, and produces questionable results. Democrats are largely against waterboarding.[257]

Torture became a divisive issue in the party after Barack Obama was elected president.[258]

Privacy

The Democratic Party believes that individuals should have a right to privacy. For example, many Democrats have opposed the NSA warrantless surveillance of American citizens.[259][260]

Some Democratic officeholders have championed consumer protection laws that limit the sharing of consumer data between corporations. Democrats have opposed sodomy laws since the 1972 platform which stated that "Americans should be free to make their own choice of life-styles and private habits without being subject to discrimination or prosecution",[261] and believe that government should not regulate consensual noncommercial sexual conduct among adults as a matter of personal privacy.[262]

Foreign policy issues

The foreign policy of the voters of the two major parties has largely overlapped since the 1990s. A Gallup poll in early 2013 showed broad agreement on the top issues, albeit with some divergence regarding human rights and international cooperation through agencies such as the United Nations.[263]

In June 2014, the Quinnipiac Poll asked Americans which foreign policy they preferred:

A) The United States is doing too much in other countries around the world, and it is time to do less around the world and focus more on our own problems here at home.B) The United States must continue to push forward to promote democracy and freedom in other countries worldwide because these efforts make our own country more secure.

Democrats chose A over B by 65% to 32%; Republicans chose A over B by 56% to 39%; and independents chose A over B by 67% to 29%.[264]

Iran sanctions

The Democratic Party has been critical of Iran's nuclear weapon program and supported economic sanctions against the Iranian government. In 2013, the Democratic-led administration worked to reach a diplomatic agreement with the government of Iran to halt the Iranian nuclear weapon program in exchange for international economic sanction relief.[265] As of 2014[update], negotiations had been successful and the party called for more cooperation with Iran in the future.[266] In 2015, the Obama administration agreed to the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, which provides sanction relief in exchange for international oversight of the Iranian nuclear program. In February 2019, the Democratic National Committee passed a resolution calling on the United States to re-enter the JCPOA, which President Trump withdrew from in 2018.[267]

Invasion of Afghanistan

Democrats in the House of Representatives and in the Senate near-unanimously voted for the Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists against "those responsible for the recent attacks launched against the United States" in Afghanistan in 2001, supporting the NATO coalition invasion of the nation. Most elected Democrats continued to support the Afghanistan conflict for its duration, with some, such as a Democratic National Committee spokesperson, voicing concerns that the Iraq War shifted too many resources away from the presence in Afghanistan.[268][269] During the 2008 Presidential Election, then-candidate Barack Obama called for a "surge" of troops into Afghanistan.[269] After winning the presidency, Obama followed through, sending a "surge" force of additional troops to Afghanistan. Troop levels were 94,000 in December 2011 and kept falling, with a target of 68,000 by fall 2012.[270]

Support for the war among the American people diminished over time. Many Democrats changed their opinion over the course of the war, coming to oppose continuation of the conflict.[271][272] In July 2008, Gallup found that 41% of Democrats called the invasion a "mistake" while a 55% majority disagreed.[272] A CNN survey in August 2009 stated that a majority of Democrats opposed the war. CNN polling director Keating Holland said: "Nearly two thirds of Republicans support the war in Afghanistan. Three quarters of Democrats oppose the war".[271]

During the 2020 Presidential Election, then-candidate Joe Biden promised to "end the forever wars in Afghanistan and the Middle East."[273] Biden went on to win the election, and in April 2021, he announced he would withdraw all US troops from Afghanistan by September 11 of that year.[274] The last troops left in August, bringing America's 20-year-long military campaign in the country to a close.[275] According to a 2023 AP-NORC poll, a majority of Democrats believed that the War in Afghanistan was not worth it.[276]

Israel

Democrats have historically been a stronger supporter of Israel than Republicans.[277] During the 1940s, the party advocated for the cause of an independent Jewish state over the objections of many conservatives in the Old Right, who strongly opposed it.[277] In 1948, Democratic President Harry Truman became the first world leader to recognize an independent state of Israel.[278]

The 2020 Democratic Party platform acknowledges a "commitment to Israel's security, its qualitative military edge, its right to defend itself, and the 2016 Memorandum of Understanding is ironclad" and that "we oppose any effort to unfairly single out and delegitimize Israel, including at the United Nations or through the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions Movement".[279] During the 2023 Israel-Hamas War, the party requested a large-scale military aid package to Israel.[280] Biden also announced military support for Israel, condemned the actions of Hamas and other Palestinian militants as terrorism,[281] and ordered the US military to build a port to facilitate the arrival of humanitarian aid to Palestinian civilians in Gaza.[282] However, parts of the Democratic base also became more skeptical of the Israel government.[283]

Europe, Russia, and Ukraine

The 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine was politically and economically opposed by the Biden Administration, who promptly began an increased arming of Ukraine.[284][285] In October 2023, the Biden administration requested an additional $61.4 billion in aid for Ukraine for the year ahead,[286] but delays in the passage of further aid by the Republican-controlled House of Representatives inhibited progress, with the additional $61 billion in aid to Ukraine added in April 2024.[287][288][289]

Demographics

Since the 2010s, the Democratic Party is strongest among urban residents, union workers, college graduates,[37][38] most ethnic minorities,[41] the unmarried, and sexual minorities.[35][42] In the 2020 presidential election, Democrats won the majority of votes from African American, Hispanic, and Asian voters; young voters; women; urban voters; voters with college degrees; and voters with no religious affiliation.[290] According to exit polling, LGBT Americans typically vote Democratic in national elections.[291]

The victory of Republican Donald Trump in 2016 brought about a realignment in which many voters without college degrees, also referred to as "working class" voters, voted Republican.[292][293][294] Many Democrats without college degrees differ from liberals in their more socially moderate views, and are more likely to belong to an ethnic minority.[295][296][297]

Support for the civil rights movement in the 1960s by Democratic presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson helped increase the Democrats' support within the African American community. African Americans have consistently voted between 85% and 95% Democratic since the 1960s, making African Americans one of the largest of the party's constituencies.[39][40]

According to the Pew Research Center, 78.4% of Democrats in the 116th United States Congress were Christian.[298] However, the vast majority of white evangelical and Latter-day Saint Christians favor the Republican Party.[299] The party also receives strong support from non-religious voters.[300][301]

A major component of the party's coalition has been organized labor. Labor unions supply money, grass roots political organization, and voters for the party. Democrats are more likely to be represented by unions than Republican voters are.[28] Younger Americans have tended to vote mainly for Democratic candidates in recent years.[302]

Since 1980, a "gender gap" has seen stronger support for the Democratic Party among women than among men. Unmarried and divorced women are more likely to vote for Democrats.[303][304] Although women supported Obama over Mitt Romney by a margin of 55–44% in 2012, Romney prevailed amongst married women, 53–46%.[305] Obama won unmarried women 67–31%.[306] According to a December 2019 study, "White women are the only group of female voters who support Republican Party candidates for president. They have done so by a majority in all but 2 of the last 18 elections".[307][308]

Geographically, the party is strongest in the Northeastern United States, the Great Lakes region, most of the Southwestern United States, and the West Coast. The party is also very strong in major cities, regardless of region.[36][309][310]

Factions

Upon foundation, the Democratic Party supported agrarianism and the Jacksonian democracy movement of President Andrew Jackson, representing farmers and rural interests and traditional Jeffersonian democrats.[312] Since the 1890s, especially in northern states, the party began to favor more liberal positions (the term "liberal" in this sense describes modern liberalism, rather than classical liberalism or economic liberalism). Historically, the party has represented farmers, laborers, and religious and ethnic minorities as it has opposed unregulated business and finance and favored progressive income taxes.

In the 1930s, the party began advocating social programs targeted at the poor. Before the New Deal, the party had a fiscally conservative, pro-business wing, typified by Grover Cleveland and Al Smith.[313] The party was dominant in the Southern United States until President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In foreign policy, internationalism (including interventionism) was a dominant theme from 1913 to the mid-1960s. The major influences for liberalism were labor unions (which peaked in the 1936–1952 era) and African Americans. Environmentalism has been a major component since the 1970s.

Even after the New Deal, until the 2010s, the party still had a fiscally conservative faction,[314] such as John Nance Garner and Howard W. Smith.[315] The party's Southern conservative wing began shrinking after President Lyndon B. Johnson supported the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and largely died out in the 2010s, as the Republican Party built up its Southern base.[309][316] The party still receives support from African Americans and urban areas in the Southern United States.[317]

The 21st century Democratic Party is predominantly a coalition of centrists, liberals, and progressives, with significant overlap between the three groups. In 2019, the Pew Research Center found that among Democratic and Democratic-leaning registered voters, 47% identify as liberal or very liberal, 38% identify as moderate, and 14% identify as conservative or very conservative.[318][319] In recent exit polls, the Democratic Party has had broad appeal across most socioeconomic and ethnic demographics.[320][321][322] Political scientists characterize the Democratic Party as less ideologically cohesive than the Republican Party due to the broader diversity of coalitions that compose the Democratic Party.[323][324][325]

Liberals

Modern liberals are a large portion of the Democratic base. According to 2018 exit polls, liberals constituted 27% of the electorate, and 91% of American liberals favored the candidate of the Democratic Party.[326] White-collar college-educated professionals were mostly Republican until the 1950s, but they had become a vital component of the Democratic Party by the early 2000s.[327]

A large majority of liberals favor moving toward universal health care, with many supporting an eventual gradual transition to a single-payer system in particular. A majority also favor diplomacy over military action; stem cell research, same-sex marriage, stricter gun control, environmental protection laws, as well as the preservation of abortion rights. Immigration and cultural diversity are deemed positive as liberals favor cultural pluralism, a system in which immigrants retain their native culture in addition to adopting their new culture. Most liberals oppose increased military spending and the mixing of church and state.[328] They tend to be divided on free trade agreements such as the USMCA and PNTR with China, with some seeing them as more favorable to corporations than workers.[329] As of 2020, the three most significant labor groupings in the Democratic coalition were the AFL–CIO and Change to Win labor federations as well as the National Education Association, a large, unaffiliated teachers' union. Important issues for labor unions include supporting unionized manufacturing jobs, raising the minimum wage, and promoting broad social programs such as Social Security and Medicare.[330]

This ideological group differs from the traditional organized labor base. According to the Pew Research Center, a plurality of 41% resided in mass affluent households and 49% were college graduates, the highest figure of any typographical group.[13] It was also the fastest growing typological group since the late 1990s to the present.[328] Liberals include most of academia[331] and large portions of the professional class.[332]

Moderates

Moderate Democrats, or New Democrats, are an ideologically centrist faction within the Democratic Party that emerged after the victory of Republican George H. W. Bush in the 1988 presidential election.[333] Running as a New Democrat, Bill Clinton won the 1992 and 1996 presidential elections.[334] They are an economically liberal and "Third Way" faction that dominated the party for around 20 years, until the beginning of Obama's presidency.[314][335] They are represented by organizations such as the New Democrat Network and the New Democrat Coalition.

The Blue Dog Coalition was formed during the 104th Congress to give members from the Democratic Party representing conservative-leaning districts a unified voice after the Democrats' loss of Congress in the 1994 Republican Revolution.[336][337][338] However, in the late 2010s and early 2020s, the Coalition's focus shifted towards ideological centrism. One of the most influential centrist groups was the Democratic Leadership Council (DLC), a nonprofit organization that advocated centrist positions for the party. The DLC disbanded in 2011.[339]

Some Democratic elected officials have self-declared as being centrists, including former President Bill Clinton, former Vice President Al Gore, Senator Mark Warner, Kansas governor Laura Kelly, former Senator Jim Webb, President Joe Biden, and former congresswoman Ann Kirkpatrick.[340][341]

The New Democrat Network supports socially liberal and fiscally moderate Democratic politicians and is associated with the congressional New Democrat Coalition in the House.[342] Annie Kuster is the chair of the coalition,[340] and former senator and President Barack Obama was self-described as a New Democrat.[343]

Progressives

Progressives are the most left-leaning faction in the party and support strong business regulations, social programs, and workers' rights.[344][345] Many progressive Democrats are descendants of the New Left of Democratic presidential candidate Senator George McGovern of South Dakota whereas others were involved in the 2016 presidential candidacy of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders. Progressives are often considered to have ideas similar to social democracy due to heavy inspiration from the Nordic Model, believing in federal top marginal income taxes ranging from 52% to 70%,[346] rent control,[347] increased collective bargaining power, a $15-an-hour minimum wage, as well as free tuition and Universal Healthcare (typically Medicare for All).[348]

In 2014, progressive Senator Elizabeth Warren set out "Eleven Commandments of Progressivism": tougher regulation on corporations; affordable education; scientific investment and environmentalism; net neutrality; increased wages; equal pay for women; collective bargaining rights; defending social programs; same-sex marriage; immigration reform; and unabridged access to reproductive healthcare.[349]

Recently, many progressives have made combating economic inequality their top priority.[34] The Congressional Progressive Caucus (CPC) is a caucus of progressive Democrats chaired by Pramila Jayapal of Washington.[350] Its members have included Representatives Dennis Kucinich of Ohio, John Conyers of Michigan, Jim McDermott of Washington, Barbara Lee of California, and Senator Paul Wellstone of Minnesota. Senators Sherrod Brown of Ohio, Tammy Baldwin of Wisconsin, Mazie Hirono of Hawaii, and Ed Markey of Massachusetts were members of the caucus when in the House of Representatives. As of March 2023, no Democratic senators belonged to the CPC, but independent Senator Bernie Sanders was a member.[351]

Democratic presidents

As of 2021[update], there have been a total of 16 Democratic presidents.

Recent electoral history

In congressional elections: 1950–present

| House of Representatives | President | Senate | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election year | No. of seats won | +/– | No. of seats won | +/– | Election year | |||

| 1950 | 235 / 435 | Harry S. Truman | 49 / 96 | 1950 | ||||

| 1952 | 213 / 435 | Dwight D. Eisenhower | 47 / 96 | 1952 | ||||

| 1954 | 232 / 435 | 49 / 96 | 1954 | |||||

| 1956 | 234 / 435 | 49 / 96 | 1956 | |||||

| 1958 | 283 / 437 | 64 / 98 | 1958 | |||||

| 1960 | 262 / 437 | John F. Kennedy | 64 / 100 | 1960 | ||||

| 1962 | 258 / 435 | 66 / 100 | 1962 | |||||

| 1964 | 295 / 435 | Lyndon B. Johnson | 68 / 100 | 1964 | ||||

| 1966 | 248 / 435 | 64 / 100 | 1966 | |||||

| 1968 | 243 / 435 | Richard Nixon | 57 / 100 | 1968 | ||||

| 1970 | 255 / 435 | 54 / 100 | 1970 | |||||

| 1972 | 242 / 435 | 56 / 100 | 1972 | |||||

| 1974 | 291 / 435 | Gerald Ford | 60 / 100 | 1974 | ||||

| 1976 | 292 / 435 | Jimmy Carter | 61 / 100 | 1976 | ||||

| 1978 | 277 / 435 | 58 / 100 | 1978 | |||||

| 1980 | 243 / 435 | Ronald Reagan | 46 / 100 | 1980 | ||||

| 1982 | 269 / 435 | 46 / 100 | 1982 | |||||

| 1984 | 253 / 435 | 47 / 100 | 1984 | |||||

| 1986 | 258 / 435 | 55 / 100 | 1986 | |||||

| 1988 | 260 / 435 | George H. W. Bush | 55 / 100 | 1988 | ||||

| 1990 | 267 / 435 | 56 / 100 | 1990 | |||||

| 1992 | 258 / 435 | Bill Clinton | 57 / 100 | 1992 | ||||

| 1994 | 204 / 435 | 47 / 100 | 1994 | |||||

| 1996 | 206 / 435 | 45 / 100 | 1996 | |||||

| 1998 | 211 / 435 | 45 / 100 | 1998 | |||||

| 2000 | 212 / 435 | George W. Bush | 50 / 100 | 2000[h] | ||||

| 2002 | 204 / 435 | 49 / 100 | 2002 | |||||

| 2004 | 202 / 435 | 45 / 100 | 2004 | |||||

| 2006 | 233 / 435 | 51 / 100 | 2006 | |||||

| 2008 | 257 / 435 | Barack Obama | 59 / 100 | 2008 | ||||

| 2010 | 193 / 435 | 53 / 100 | 2010 | |||||

| 2012 | 201 / 435 | 55 / 100 | 2012 | |||||

| 2014 | 188 / 435 | 46 / 100 | 2014 | |||||

| 2016 | 194 / 435 | Donald Trump | 48 / 100 | 2016 | ||||

| 2018 | 235 / 435 | 47 / 100 | 2018 | |||||

| 2020 | 222 / 435 | Joe Biden | 50 / 100 | 2020[j] | ||||

| 2022 | 213 / 435 | 51 / 100 | 2022 | |||||

In presidential elections: 1828–present

See also

- Democratic Party (United States) organizations

- List of political parties in the United States

- List of United States Democratic Party presidential candidates

- List of United States Democratic Party presidential tickets

- Political party strength in U.S. states

- Politics of the United States

Notes

- ^ According to the Manifesto Project Database MARPOR dataset for 2020, the Democratic Party has a RILE score of -24.662, putting it within the range of being a center to center-left party. Historically, it has classified the party as centrist or center-right, but the database has noted a relatively recent shift to the left in the party's politics.

- ^ [7][8][9][10][11][12][13][a]

- ^ There are 47 senators who are members of the party; however, four independent senators, Angus King, Bernie Sanders, Joe Manchin III, and Kyrsten Sinema caucus with the Democrats, effectively giving the Democrats a 51–49 majority.

- ^ Grover Cleveland in 1884 and 1892

- ^ All three incumbents in the 20th century to withdraw or not seek reelection—Calvin Coolidge, Harry S. Truman, and Lyndon B. Johnson—had succeeded to the presidency when their predecessor died, then won a second term in their own right.[122] Three presidents in the 1800s made and kept pledges to serve only one term, most recently Rutherford B. Hayes.[123]

- ^ Elected as Vice President with the National Union Party ticket in the 1864 presidential election. Ascended to the presidency after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln in 1865. Rejoined the Democratic Party in 1868.

- ^ Jump up to: a b Died in office.

- ^ Republican Vice President Dick Cheney provided a tie-breaking vote, giving Republicans a majority until June 6, 2001, when Jim Jeffords left Republicans to join the Democratic Caucus.

- ^ Jump up to: a b c d e f g h i Includes Independents caucusing with the Democrats.

- ^ Democratic Vice President Kamala Harris provided a tie-breaking vote, giving Democrats a majority throughout the 117th Congress.

- ^ While there was no official Democratic nominee, the majority of the Democratic electors still cast their electoral votes for incumbent Vice President Richard Mentor Johnson.

- ^ Although Tilden won a majority of the popular vote, Republican Rutherford B. Hayes won a majority of votes in the Electoral College.

- ^ Although Cleveland won a plurality of the popular vote, Republican Benjamin Harrison won a majority of votes in the Electoral College.

- ^ Although Gore won a plurality of the popular vote, Republican George W. Bush won a majority of votes in the Electoral College.

- ^ Although Clinton won a plurality of the popular vote, Republican Donald Trump won a majority of votes in the Electoral College.

References

- ^ "About the Democratic Party". Democratic Party. Archived from the original on April 6, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2022.

For 171 years, [the Democratic National Committee] has been responsible for governing the Democratic Party

- ^ Democratic Party (March 12, 2022). "The Charter & The Bylaws of the Democratic Party of the United States" (PDF). p. 3. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 27, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2022.