Federal Reserve

Seal of the Federal Reserve System | |

Flag of the Federal Reserve System | |

The Eccles Building in Washington, D.C., which serves as the Federal Reserve System's headquarters | |

| Headquarters | Eccles Building, Washington, D.C., U.S. |

|---|---|

| Established | December 23, 1913 |

| Governing body | Board of Governors |

| Key people | |

| Central bank of | United States |

| Currency | United States dollar USD (ISO 4217) |

| Reserve requirements | None[1] |

| Bank rate | 5.5%[2] |

| Interest rate target | 5.25–5.50%[3] |

| Interest on reserves | 5.40%[4] |

| Interest paid on excess reserves? | Yes |

| Website | www |

| Federal Reserve | |

| Agency overview | |

| Jurisdiction | Federal government of the United States |

| Child agency | |

| Key document | |

| This article is part of a series on |

| Banking in the United States |

|---|

The Federal Reserve System (often shortened to the Federal Reserve, or simply the Fed) is the central banking system of the United States. It was created on December 23, 1913, with the enactment of the Federal Reserve Act, after a series of financial panics (particularly the panic of 1907) led to the desire for central control of the monetary system in order to alleviate financial crises.[list 1] Over the years, events such as the Great Depression in the 1930s and the Great Recession during the 2000s have led to the expansion of the roles and responsibilities of the Federal Reserve System.[6][11]

Congress established three key objectives for monetary policy in the Federal Reserve Act: maximizing employment, stabilizing prices, and moderating long-term interest rates.[12] The first two objectives are sometimes referred to as the Federal Reserve's dual mandate.[13] Its duties have expanded over the years, and currently also include supervising and regulating banks, maintaining the stability of the financial system, and providing financial services to depository institutions, the U.S. government, and foreign official institutions.[14] The Fed also conducts research into the economy and provides numerous publications, such as the Beige Book and the FRED database.

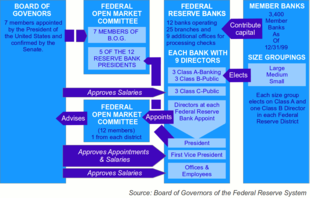

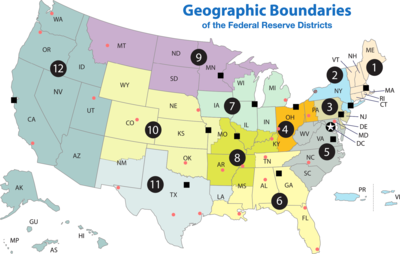

The Federal Reserve System is composed of several layers. It is governed by the presidentially-appointed board of governors or Federal Reserve Board (FRB). Twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, located in cities throughout the nation, regulate and oversee privately-owned commercial banks.[15] Nationally chartered commercial banks are required to hold stock in, and can elect some board members of, the Federal Reserve Bank of their region.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) sets monetary policy by adjusting the target for the federal funds rate, which influences market interest rates generally and via the monetary transmission mechanism in turn US economic activity. The FOMC consists of all seven members of the board of governors and the twelve regional Federal Reserve Bank presidents, though only five bank presidents vote at a time—the president of the New York Fed and four others who rotate through one-year voting terms. There are also various advisory councils.[list 2] It has a structure unique among central banks, and is also unusual in that the United States Department of the Treasury, an entity outside of the central bank, prints the currency used.[21]

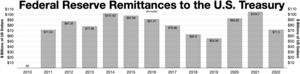

The federal government sets the salaries of the board's seven governors, and it receives all the system's annual profits, after dividends on member banks' capital investments are paid, and an account surplus is maintained. In 2015, the Federal Reserve earned a net income of $100.2 billion and transferred $97.7 billion to the U.S. Treasury,[22] and 2020 earnings were approximately $88.6 billion with remittances to the U.S. Treasury of $86.9 billion.[23] Although an instrument of the U.S. government, the Federal Reserve System considers itself "an independent central bank because its monetary policy decisions do not have to be approved by the president or by anyone else in the executive or legislative branches of government, it does not receive funding appropriated by Congress, and the terms of the members of the board of governors span multiple presidential and congressional terms."[24]

Purpose

[edit]The primary declared motivation for creating the Federal Reserve System was to address banking panics.[6] Other purposes are stated in the Federal Reserve Act, such as "to furnish an elastic currency, to afford means of rediscounting commercial paper, to establish a more effective supervision of banking in the United States, and for other purposes".[25] Before the founding of the Federal Reserve System, the United States underwent several financial crises. A particularly severe crisis in 1907 led Congress to enact the Federal Reserve Act in 1913. Today the Federal Reserve System has responsibilities in addition to stabilizing the financial system.[26]

Current functions of the Federal Reserve System include:[14][26]

- To address the problem of banking panics

- To serve as the central bank for the United States

- To strike a balance between private interests of banks and the centralized responsibility of government

- To supervise and regulate banking institutions

- To protect the credit rights of consumers

- To conduct monetary policy by influencing market interest rates to achieve the sometimes-conflicting goals of

- To maintain the stability of the financial system and contain systemic risk in financial markets

- To provide financial services to depository institutions, the U.S. government, and foreign official institutions, including playing a major role in operating the nation's payments system

- To facilitate the exchange of payments among regions

- To respond to local liquidity needs

- To strengthen U.S. standing in the world economy

Addressing the problem of bank panics

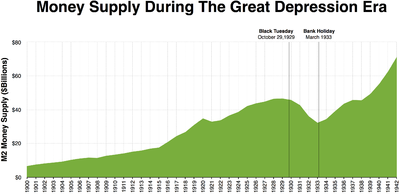

[edit]Banking institutions in the United States are required to hold reserves—amounts of currency and deposits in other banks—equal to only a fraction of the amount of the bank's deposit liabilities owed to customers. This practice is called fractional-reserve banking. As a result, banks usually invest the majority of the funds received from depositors. On rare occasions, too many of the bank's customers will withdraw their savings and the bank will need help from another institution to continue operating; this is called a bank run. Bank runs can lead to a multitude of social and economic problems. The Federal Reserve System was designed as an attempt to prevent or minimize the occurrence of bank runs, and possibly act as a lender of last resort when a bank run does occur. Many economists, following Nobel laureate Milton Friedman, believe that the Federal Reserve inappropriately refused to lend money to small banks during the bank runs of 1929; Friedman argued that this contributed to the Great Depression.[28]

Check clearing system

[edit]Because some banks refused to clear checks from certain other banks during times of economic uncertainty, a check-clearing system was created in the Federal Reserve System. It is briefly described in The Federal Reserve System—Purposes and Functions as follows:[29]

By creating the Federal Reserve System, Congress intended to eliminate the severe financial crises that had periodically swept the nation, especially the sort of financial panic that occurred in 1907. During that episode, payments were disrupted throughout the country because many banks and clearinghouses refused to clear checks drawn on certain other banks, a practice that contributed to the failure of otherwise solvent banks. To address these problems, Congress gave the Federal Reserve System the authority to establish a nationwide check-clearing system. The System, then, was to provide not only an elastic currency—that is, a currency that would expand or shrink in amount as economic conditions warranted—but also an efficient and equitable check-collection system.

Lender of last resort

[edit]In the United States, the Federal Reserve serves as the lender of last resort to those institutions that cannot obtain credit elsewhere and the collapse of which would have serious implications for the economy. It took over this role from the private sector "clearing houses" which operated during the Free Banking Era; whether public or private, the availability of liquidity was intended to prevent bank runs.[30]

Fluctuations

[edit]Through its discount window and credit operations, Reserve Banks provide liquidity to banks to meet short-term needs stemming from seasonal fluctuations in deposits or unexpected withdrawals. Longer-term liquidity may also be provided in exceptional circumstances. The rate the Fed charges banks for these loans is called the discount rate (officially the primary credit rate).

By making these loans, the Fed serves as a buffer against unexpected day-to-day fluctuations in reserve demand and supply. This contributes to the effective functioning of the banking system, alleviates pressure in the reserves market and reduces the extent of unexpected movements in the interest rates.[31] For example, on September 16, 2008, the Federal Reserve Board authorized an $85 billion loan to stave off the bankruptcy of international insurance giant American International Group (AIG).[32]

Central bank

[edit]

In its role as the central bank of the United States, the Fed serves as a banker's bank and as the government's bank. As the banker's bank, it helps to assure the safety and efficiency of the payments system. As the government's bank or fiscal agent, the Fed processes a variety of financial transactions involving trillions of dollars. Just as an individual might keep an account at a bank, the U.S. Treasury keeps a checking account with the Federal Reserve, through which incoming federal tax deposits and outgoing government payments are handled. As part of this service relationship, the Fed sells and redeems U.S. government securities such as savings bonds and Treasury bills, notes and bonds. It also issues the nation's coin and paper currency. The U.S. Treasury, through its Bureau of the Mint and Bureau of Engraving and Printing, actually produces the nation's cash supply and, in effect, sells the paper currency to the Federal Reserve Banks at manufacturing cost, and the coins at face value. The Federal Reserve Banks then distribute it to other financial institutions in various ways.[33] During the Fiscal Year 2020, the Bureau of Engraving and Printing delivered 57.95 billion notes at an average cost of 7.4 cents per note.[34][35]

Federal funds

[edit]Federal funds are the reserve balances (also called Federal Reserve Deposits) that private banks keep at their local Federal Reserve Bank.[36] These balances are the namesake reserves of the Federal Reserve System. The purpose of keeping funds at a Federal Reserve Bank is to have a mechanism for private banks to lend funds to one another. This market for funds plays an important role in the Federal Reserve System as it is the basis for its monetary policy work. Monetary policy is put into effect partly by influencing how much interest the private banks charge each other for the lending of these funds.

Federal reserve accounts contain federal reserve credit, which can be converted into federal reserve notes. Private banks maintain their bank reserves in federal reserve accounts.

Bank regulation

[edit]The Federal Reserve regulates private banks. The system was designed out of a compromise between the competing philosophies of privatization and government regulation. In 2006 Donald L. Kohn, vice chairman of the board of governors, summarized the history of this compromise:[37]

Agrarian and progressive interests, led by William Jennings Bryan, favored a central bank under public, rather than banker, control. But the vast majority of the nation's bankers, concerned about government intervention in the banking business, opposed a central bank structure directed by political appointees.The legislation that Congress ultimately adopted in 1913 reflected a hard-fought battle to balance these two competing views and created the hybrid public-private, centralized-decentralized structure that we have today.

The balance between private interests and government can also be seen in the structure of the system. Private banks elect members of the board of directors at their regional Federal Reserve Bank while the members of the board of governors are selected by the president of the United States and confirmed by the Senate.

Government regulation and supervision

[edit]

The Federal Banking Agency Audit Act, enacted in 1978 as Public Law 95-320 and 31 U.S.C. section 714 establish that the board of governors of the Federal Reserve System and the Federal Reserve banks may be audited by the Government Accountability Office (GAO).[38]

The GAO has authority to audit check-processing, currency storage and shipments, and some regulatory and bank examination functions, however, there are restrictions to what the GAO may audit. Under the Federal Banking Agency Audit Act, 31 U.S.C. section 714(b), audits of the Federal Reserve Board and Federal Reserve banks do not include (1) transactions for or with a foreign central bank or government or non-private international financing organization; (2) deliberations, decisions, or actions on monetary policy matters; (3) transactions made under the direction of the Federal Open Market Committee; or (4) a part of a discussion or communication among or between members of the board of governors and officers and employees of the Federal Reserve System related to items (1), (2), or (3). See Federal Reserve System Audits: Restrictions on GAO's Access (GAO/T-GGD-94-44), statement of Charles A. Bowsher.[39]

The board of governors in the Federal Reserve System has a number of supervisory and regulatory responsibilities in the U.S. banking system, but not complete responsibility. A general description of the types of regulation and supervision involved in the U.S. banking system is given by the Federal Reserve:[40]

The Board also plays a major role in the supervision and regulation of the U.S. banking system. It has supervisory responsibilities for state-chartered banks[41] that are members of the Federal Reserve System, bank holding companies (companies that control banks), the foreign activities of member banks, the U.S. activities of foreign banks, and Edge Act and "agreement corporations" (limited-purpose institutions that engage in a foreign banking business). The Board and, under delegated authority, the Federal Reserve Banks, supervise approximately 900 state member banks and 5,000 bank holding companies. Other federal agencies also serve as the primary federal supervisors of commercial banks; the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency supervises national banks, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation supervises state banks that are not members of the Federal Reserve System.

Some regulations issued by the Board apply to the entire banking industry, whereas others apply only to member banks, that is, state banks that have chosen to join the Federal Reserve System and national banks, which by law must be members of the System. The Board also issues regulations to carry out major federal laws governing consumer credit protection, such as the Truth in Lending, Equal Credit Opportunity, and Home Mortgage Disclosure Acts. Many of these consumer protection regulations apply to various lenders outside the banking industry as well as to banks.

Members of the Board of Governors are in continual contact with other policy makers in government. They frequently testify before congressional committees on the economy, monetary policy, banking supervision and regulation, consumer credit protection, financial markets, and other matters.

The Board has regular contact with members of the President's Council of Economic Advisers and other key economic officials. The Chair also meets from time to time with the President of the United States and has regular meetings with the Secretary of the Treasury. The Chair has formal responsibilities in the international arena as well.

Regulatory and oversight responsibilities

[edit]The board of directors of each Federal Reserve Bank District also has regulatory and supervisory responsibilities. If the board of directors of a district bank has judged that a member bank is performing or behaving poorly, it will report this to the board of governors. This policy is described in law:

Each Federal reserve bank shall keep itself informed of the general character and amount of the loans and investments of its member banks with a view to ascertaining whether undue use is being made of bank credit for the speculative carrying of or trading in securities, real estate, or commodities, or for any other purpose inconsistent with the maintenance of sound credit conditions; and, in determining whether to grant or refuse advances, rediscounts, or other credit accommodations, the Federal reserve bank shall give consideration to such information. The chairman of the Federal reserve bank shall report to the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System any such undue use of bank credit by any member bank, together with his recommendation. Whenever, in the judgment of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, any member bank is making such undue use of bank credit, the Board may, in its discretion, after reasonable notice and an opportunity for a hearing, suspend such bank from the use of the credit facilities of the Federal Reserve System and may terminate such suspension or may renew it from time to time.[42]

National payments system

[edit]The Federal Reserve plays a role in the U.S. payments system. The twelve Federal Reserve Banks provide banking services to depository institutions and to the federal government. For depository institutions, they maintain accounts and provide various payment services, including collecting checks, electronically transferring funds, and distributing and receiving currency and coin. For the federal government, the Reserve Banks act as fiscal agents, paying Treasury checks; processing electronic payments; and issuing, transferring, and redeeming U.S. government securities.[43]

In the Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980, Congress reaffirmed that the Federal Reserve should promote an efficient nationwide payments system. The act subjects all depository institutions, not just member commercial banks, to reserve requirements and grants them equal access to Reserve Bank payment services.The Federal Reserve plays a role in the nation's retail and wholesale payments systems by providing financial services to depository institutions. Retail payments are generally for relatively small-dollar amounts and often involve a depository institution's retail clients—individuals and smaller businesses. The Reserve Banks' retail services include distributing currency and coin, collecting checks, electronically transferring funds through FedACH (the Federal Reserve's automated clearing house system), and beginning in 2023, facilitating instant payments using the FedNow service. By contrast, wholesale payments are generally for large-dollar amounts and often involve a depository institution's large corporate customers or counterparties, including other financial institutions. The Reserve Banks' wholesale services include electronically transferring funds through the Fedwire Funds Service and transferring securities issued by the U.S. government, its agencies, and certain other entities through the Fedwire Securities Service.

Structure

[edit]

The Federal Reserve System has a "unique structure that is both public and private"[44] and is described as "independent within the government" rather than "independent of government".[24] The System does not require public funding, and derives its authority and purpose from the Federal Reserve Act, which was passed by Congress in 1913 and is subject to Congressional modification or repeal.[45] The four main components of the Federal Reserve System are (1) the board of governors, (2) the Federal Open Market Committee, (3) the twelve regional Federal Reserve Banks, and (4) the member banks throughout the country.

Board of governors

[edit]The seven-member board of governors is a large federal agency that functions in business oversight by examining national banks.[46]: 12, 15 It is charged with the overseeing of the 12 District Reserve Banks and setting national monetary policy. It also supervises and regulates the U.S. banking system in general.[47]Governors are appointed by the president of the United States and confirmed by the Senate for staggered 14-year terms.[31][48] One term begins every two years, on February 1 of even-numbered years, and members serving a full term cannot be renominated for a second term.[49] "[U]pon the expiration of their terms of office, members of the Board shall continue to serve until their successors are appointed and have qualified." The law provides for the removal of a member of the board by the president "for cause".[50] The board is required to make an annual report of operations to the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives.

The chair and vice chair of the board of governors are appointed by the president from among the sitting governors. They both serve a four-year term and they can be renominated as many times as the president chooses, until their terms on the board of governors expire.[51]

List of members of the board of governors

[edit]

The current members of the board of governors are:[49]

| Portrait | Current governor | Party | Term start | Term expires |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jerome Powell (Chair) | Republican | February 5, 2018 (as Chair) May 23, 2022 (reappointment) | May 15, 2026 (as Chair) |

| May 25, 2012 (as Governor) June 16, 2014 (reappointment) | January 31, 2028 (as Governor) | |||

| Philip Jefferson (Vice Chair) | Democratic | September 13, 2023 (as Vice Chair) | September 7, 2027 (as Vice Chair) |

| May 23, 2022 (as Governor) | January 31, 2036 (as Governor) | |||

| Michael Barr (Vice Chair for Supervision) | Democratic | July 19, 2022 (as Vice Chair for Supervision) | July 13, 2026 (as Vice Chair for Supervision) |

| July 19, 2022 (as Governor) | January 31, 2032 (as Governor) | |||

| Michelle Bowman | Republican | November 26, 2018 February 1, 2020 (reappointment) | January 31, 2034 |

| Christopher Waller | Republican | December 18, 2020 | January 31, 2030 |

| Lisa Cook | Democratic | May 23, 2022 February 1, 2024 (reappointment) | January 31, 2038 |

| Adriana Kugler | Democratic | September 13, 2023 | January 31, 2026 |

Nominations, confirmations and resignations

[edit]In late December 2011, President Barack Obama nominated Jeremy C. Stein, a Harvard University finance professor and a Democrat, and Jerome Powell, formerly of Dillon Read, Bankers Trust[52] and The Carlyle Group[53] and a Republican. Both candidates also have Treasury Department experience in the Obama and George H. W. Bush administrations respectively.[52]

"Obama administration officials [had] regrouped to identify Fed candidates after Peter Diamond, a Nobel Prize-winning economist, withdrew his nomination to the board in June [2011] in the face of Republican opposition. Richard Clarida, a potential nominee who was a Treasury official under George W. Bush, pulled out of consideration in August [2011]", one account of the December nominations noted.[54] The two other Obama nominees in 2011, Janet Yellen and Sarah Bloom Raskin,[55] were confirmed in September.[56] One of the vacancies was created in 2011 with the resignation of Kevin Warsh, who took office in 2006 to fill the unexpired term ending January 31, 2018, and resigned his position effective March 31, 2011.[57][58] In March 2012, U.S. Senator David Vitter (R, LA) said he would oppose Obama's Stein and Powell nominations, dampening near-term hopes for approval.[59] However, Senate leaders reached a deal, paving the way for affirmative votes on the two nominees in May 2012 and bringing the board to full strength for the first time since 2006[60] with Duke's service after term end. Later, on January 6, 2014, the United States Senate confirmed Yellen's nomination to be chair of the Federal Reserve Board of Governors; she was the first woman to hold the position.[61] Subsequently, President Obama nominated Stanley Fischer to replace Yellen as the vice-chair.[62]

In April 2014, Stein announced he was leaving to return to Harvard May 28 with four years remaining on his term. At the time of the announcement, the FOMC "already is down three members as it awaits the Senate confirmation of ... Fischer and Lael Brainard, and as [President] Obama has yet to name a replacement for ... Duke. ... Powell is still serving as he awaits his confirmation for a second term."[63]

Allan R. Landon, former president and CEO of the Bank of Hawaii, was nominated in early 2015 by President Obama to the board.[64]

In July 2015, President Obama nominated University of Michigan economist Kathryn M. Dominguez to fill the second vacancy on the board. The Senate had not yet acted on Landon's confirmation by the time of the second nomination.[65]

Daniel Tarullo submitted his resignation from the board on February 10, 2017, effective on or around April 5, 2017.[66]

Federal Open Market Committee

[edit]The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) consists of 12 members, seven from the board of governors and 5 of the regional Federal Reserve Bank presidents. The FOMC oversees and sets policy on open market operations, the principal tool of national monetary policy. These operations affect the amount of Federal Reserve balances available to depository institutions, thereby influencing overall monetary and credit conditions. The FOMC also directs operations undertaken by the Federal Reserve in foreign exchange markets. The FOMC must reach consensus on all decisions. The president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York is a permanent member of the FOMC; the presidents of the other banks rotate membership at two- and three-year intervals. All Regional Reserve Bank presidents contribute to the committee's assessment of the economy and of policy options, but only the five presidents who are then members of the FOMC vote on policy decisions. The FOMC determines its own internal organization and, by tradition, elects the chair of the board of governors as its chair and the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York as its vice chair. Formal meetings typically are held eight times each year in Washington, D.C. Nonvoting Reserve Bank presidents also participate in Committee deliberations and discussion. The FOMC generally meets eight times a year in telephone consultations and other meetings are held when needed.[67]

There is very strong consensus among economists against politicising the FOMC.[68]

Federal Advisory Council

[edit]The Federal Advisory Council, composed of twelve representatives of the banking industry, advises the board on all matters within its jurisdiction.

Federal Reserve Banks

[edit]

There are 12 Federal Reserve Banks, each of which is responsible for member banks located in its district. They are located in Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, Richmond, Atlanta, Chicago, St. Louis, Minneapolis, Kansas City, Dallas, and San Francisco. The size of each district was set based upon the population distribution of the United States when the Federal Reserve Act was passed.

The charter and organization of each Federal Reserve Bank is established by law and cannot be altered by the member banks. Member banks do, however, elect six of the nine members of the Federal Reserve Banks' boards of directors.[31][69]

Each regional Bank has a president, who is the chief executive officer of their Bank. Each regional Reserve Bank's president is nominated by their Bank's board of directors, but the nomination is contingent upon approval by the board of governors. Presidents serve five-year terms and may be reappointed.[70]

Each regional Bank's board consists of nine members. Members are broken down into three classes: A, B, and C. There are three board members in each class. Class A members are chosen by the regional Bank's shareholders, and are intended to represent member banks' interests. Member banks are divided into three categories: large, medium, and small. Each category elects one of the three class A board members. Class B board members are also nominated by the region's member banks, but class B board members are supposed to represent the interests of the public. Lastly, class C board members are appointed by the board of governors, and are also intended to represent the interests of the public.[71]

Legal status of regional Federal Reserve Banks

[edit]The Federal Reserve Banks have an intermediate legal status, with some features of private corporations and some features of public federal agencies. The United States has an interest in the Federal Reserve Banks as tax-exempt federally created instrumentalities whose profits belong to the federal government, but this interest is not proprietary.[72] In Lewis v. United States,[73] the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit stated that: "The Reserve Banks are not federal instrumentalities for purposes of the FTCA [the Federal Tort Claims Act], but are independent, privately owned and locally controlled corporations." The opinion went on to say, however, that: "The Reserve Banks have properly been held to be federal instrumentalities for some purposes." Another relevant decision is Scott v. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City,[72] in which the distinction is made between Federal Reserve Banks, which are federally created instrumentalities, and the board of governors, which is a federal agency.

Regarding the structural relationship between the twelve Federal Reserve banks and the various commercial (member) banks, political science professor Michael D. Reagan has written:[74]

... the "ownership" of the Reserve Banks by the commercial banks is symbolic; they do not exercise the proprietary control associated with the concept of ownership nor share, beyond the statutory dividend, in Reserve Bank "profits." ... Bank ownership and election at the base are therefore devoid of substantive significance, despite the superficial appearance of private bank control that the formal arrangement creates.

Member banks

[edit]A member bank is a private institution and owns stock in its regional Federal Reserve Bank. All nationally chartered banks hold stock in one of the Federal Reserve Banks. State chartered banks may choose to be members (and hold stock in their regional Federal Reserve bank) upon meeting certain standards.

The amount of stock a member bank must own is equal to 3% of its combined capital and surplus.[75] However, holding stock in a Federal Reserve bank is not like owning stock in a publicly traded company. These stocks cannot be sold or traded, and member banks do not control the Federal Reserve Bank as a result of owning this stock. From their Regional Bank, member banks with $10 billion or less in assets receive a dividend of 6%, while member banks with more than $10 billion in assets receive the lesser of 6% or the current 10-year Treasury auction rate.[76] The remainder of the regional Federal Reserve Banks' profits is given over to the United States Treasury Department. In 2015, the Federal Reserve Banks made a profit of $100.2 billion and distributed $2.5 billion in dividends to member banks as well as returning $97.7 billion to the U.S. Treasury.[22]

About 38% of U.S. banks are members of their regional Federal Reserve Bank.[24][77]

Accountability

[edit]An external auditor selected by the audit committee of the Federal Reserve System regularly audits the Board of Governors and the Federal Reserve Banks. The GAO will audit some activities of the Board of Governors. These audits do not cover "most of the Fed's monetary policy actions or decisions, including discount window lending (direct loans to financial institutions), open-market operations and any other transactions made under the direction of the Federal Open Market Committee" ...[nor may the GAO audit] "dealings with foreign governments and other central banks."[78]

The annual and quarterly financial statements prepared by the Federal Reserve System conform to a basis of accounting that is set by the Federal Reserve Board and does not conform to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) or government Cost Accounting Standards (CAS). The financial reporting standards are defined in the Financial Accounting Manual for the Federal Reserve Banks.[79] The cost accounting standards are defined in the Planning and Control System Manual.[79] As of 27 August 2012[update], the Federal Reserve Board has been publishing unaudited financial reports for the Federal Reserve banks every quarter.[80]

On November 7, 2008, Bloomberg L.P. brought a lawsuit against the board of governors of the Federal Reserve System to force the board to reveal the identities of firms for which it provided guarantees during the financial crisis of 2007–2008.[81] Bloomberg, L.P. won at the trial court[82] and the Fed's appeals were rejected at both the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court. The data was released on March 31, 2011.[83]

Monetary policy

[edit]The term "monetary policy" refers to the actions undertaken by a central bank, such as the Federal Reserve, to influence economic activity (the overall demand for goods and services) to help promote national economic goals. The Federal Reserve Act of 1913 gave the Federal Reserve authority to set monetary policy in the United States. The Fed's mandate for monetary policy is commonly known as the dual mandate of promoting maximum employment and stable prices, the latter being interpreted as a stable inflation rate of 2 percent per year on average. The Fed's monetary policy influences economic activity by influencing the general level of interest rates in the economy, which again via the monetary transmission mechanism affects households' and firms' demand for goods and services and in turn employment and inflation.[27]

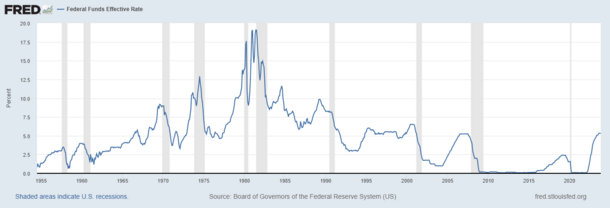

Interbank lending

[edit]The Federal Reserve sets monetary policy by influencing the federal funds rate, which is the rate of interbank lending of reserve balances. The rate that banks charge each other for these loans is determined in the interbank market, and the Federal Reserve influences this rate through the "tools" of monetary policy described in the Tools section below. The federal funds rate is a short-term interest rate that the FOMC focuses on, which affects the longer-term interest rates throughout the economy. The Federal Reserve explained the implementation of its monetary policy in 2021:

The FOMC has the ability to influence the federal funds rate–and thus the cost of short-term interbank credit–by changing the rate of interest the Fed pays on reserve balances that banks hold at the Fed. A bank is unlikely to lend to another bank (or to any of its customers) at an interest rate lower than the rate that the bank can earn on reserve balances held at the Fed. And because overall reserve balances are currently abundant, if a bank wants to borrow reserve balances, it likely will be able to do so without having to pay a rate much above the rate of interest paid by the Fed.[27]

Changes in the target for the federal funds rate affect overall financial conditions through various channels, including subsequent changes in the market interest rates that commercial banks and other lenders charge on short-term and longer-term loans, and changes in asset prices and in currency exchange rates, which again affects private consumption, investment and net export. By easening or tightening the stance of monetary policy, i.e. lowering or raising its target for the federal funds rate, the Fed can either spur or restrain growth in the overall US demand for goods and services.[27]

Tools

[edit]There are four main tools of monetary policy that the Federal Reserve uses to implement its monetary policy:[84][85]

| Tool | Description |

|---|---|

| Interest on reserve balances (IORB) | Interest paid on funds that banks hold in their reserve balance accounts at their Federal Reserve Bank.[86] IORB is the primary tool for moving the federal funds rate within the target range.[84] |

| Overnight reverse repurchase agreement (ON RRP) facility | The Fed’s standing offer to many large nonbank financial institutions to deposit funds at the Fed and earn interest. Acts as a supplementary tool for moving the FFR within the target range.[84] |

| Open market operations | Purchases and sales of U.S. Treasury and federal agency securities. Used to maintain an ample supply of reserves.[84] |

| Discount window | The Fed's lending to banks at the discount rate.[87] Helps put a ceiling on the FFR.[84] |

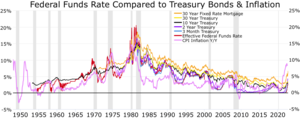

Federal funds rate

[edit]

The Federal Reserve System implements monetary policy largely by targeting the federal funds rate. This is the interest rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans of federal funds, which are the reserves held by banks at the Fed. This rate is actually determined by the market and is not explicitly mandated by the Fed. The Fed therefore tries to align the effective federal funds rate with the targeted rate, mainly by adjusting its IORB rate.[88] The Federal Reserve System usually adjusts the federal funds rate target by 0.25% or 0.50% at a time.

Interest on reserve balances

[edit]The interest on reserve balances (IORB) is the interest that the Fed pays on funds held by commercial banks in their reserve balance accounts at the individual Federal Reserve System banks. It is an administrated interest rate (i.e. set directly by the Fed as opposed to a market interest rate which is determined by the forces of supply and demand).[88] As banks are unlikely to lend their reserves in the FFR market for less than they get paid by the Fed, the IORB guides the effective FFR and is used as the primary tool of the Fed's monetary policy.[89][88]

Open market operations

[edit]Open market operations are done through the sale and purchase of United States Treasury securities, or "Treasurys". The Federal Reserve buys Treasurys both directly and via primary dealers, which have accounts at depository institutions.[90]

The Federal Reserve's objective for open market operations has varied over the years. During the 1980s, the focus gradually shifted toward attaining a specified level of the federal funds rate (the rate that banks charge each other for overnight loans of federal funds, which are the reserves held by banks at the Fed), a process that was largely complete by the end of the decade.[91]

Until the 2007–2008 financial crisis, the Fed used open market operations as its primary tool to adjust the supply of reserve balances in order to keep the federal funds rate around the Fed's target.[92] This regime is also known as a limited reserves regime.[89] After the financial crisis, the Federal Reserve has adopted a so-called ample reserves regime where open market operations leading to modest changes in the supply of reserves are no longer effective in influencing the FFR. Instead the Fed uses its administered rates, in particular the IORB rate, to influence the FFR.[89][88] However, open market operations are still an important maintenance tool in the overall framework of the conduct of monetary policy as they are used for ensuring that reserves remain ample.[89]

Repurchase agreements

[edit]To smooth temporary or cyclical changes in the money supply, the desk engages in repurchase agreements (repos) with its primary dealers. Repos are essentially secured, short-term lending by the Fed. On the day of the transaction, the Fed deposits money in a primary dealer's reserve account, and receives the promised securities as collateral. When the transaction matures, the process unwinds: the Fed returns the collateral and charges the primary dealer's reserve account for the principal and accrued interest. The term of the repo (the time between settlement and maturity) can vary from 1 day (called an overnight repo) to 65 days.[93]

Discount window and discount rate

[edit]The Federal Reserve System also directly sets the discount rate, which is the interest rate for "discount window lending", overnight loans that member banks borrow directly from the Fed. This rate is generally set at a rate close to 100 basis points above the target federal funds rate. The idea is to encourage banks to seek alternative funding before using the "discount rate" option.[94] The equivalent operation by the European Central Bank is referred to as the "marginal lending facility".[95]

Both the discount rate and the federal funds rate influence the prime rate, which is usually about 3 percentage points higher than the federal funds rate.

Term Deposit facility

[edit]The Term Deposit facility is a program through which the Federal Reserve Banks offer interest-bearing term deposits to eligible institutions.[96] It is intended to facilitate the implementation of monetary policy by providing a tool by which the Federal Reserve can manage the aggregate quantity of reserve balances held by depository institutions. Funds placed in term deposits are removed from the accounts of participating institutions for the life of the term deposit and thus drain reserve balances from the banking system. The program was announced December 9, 2009, and approved April 30, 2010, with an effective date of June 4, 2010.[97] Fed Chair Ben S. Bernanke, testifying before the House Committee on Financial Services, stated that the Term Deposit Facility would be used to reverse the expansion of credit during the Great Recession, by drawing funds out of the money markets into the Federal Reserve Banks.[98] It would therefore result in increased market interest rates, acting as a brake on economic activity and inflation.[99] The Federal Reserve authorized up to five "small-value offerings" in 2010 as a pilot program.[100] After three of the offering auctions were successfully completed, it was announced that small-value auctions would continue on an ongoing basis.[101]

Quantitative Easing (QE) policy

[edit]A little-used tool of the Federal Reserve is the quantitative easing policy.[102] Under that policy, the Federal Reserve buys back corporate bonds and mortgage backed securities held by banks or other financial institutions. This in effect puts money back into the financial institutions and allows them to make loans and conduct normal business.The bursting of the United States housing bubble prompted the Fed to buy mortgage-backed securities for the first time in November 2008. Over six weeks, a total of $1.25 trillion were purchased in order to stabilize the housing market, about one-fifth of all U.S. government-backed mortgages.[103]

Expired policy tools

[edit]Reserve requirements

[edit]An instrument of monetary policy adjustment historically employed by the Federal Reserve System was the fractional reserve requirement, also known as the required reserve ratio.[104] The required reserve ratio set the balance that the Federal Reserve System required a depository institution to hold in the Federal Reserve Banks.[105] The required reserve ratio was set by the board of governors of the Federal Reserve System.[106] The reserve requirements have changed over time and some history of these changes is published by the Federal Reserve.[107]

As a response to the financial crisis of 2008, the Federal Reserve started making interest payments on depository institutions' required and excess reserve balances. The payment of interest on excess reserves gave the central bank greater opportunity to address credit market conditions while maintaining the federal funds rate close to the target rate set by the FOMC.[108] The reserve requirement did not play a significant role in the post-2008 interest-on-excess-reserves regime,[109] and in March 2020, the reserve ratio was set to zero for all banks, which meant that no bank was required to hold any reserves, and hence the reserve requirement effectively ceased to exist.[1]

Temporary policy tools during the financial crisis

[edit]In order to address problems related to the subprime mortgage crisis and United States housing bubble, several new tools were created. The first new tool, called the Term auction facility, was added on December 12, 2007. It was announced as a temporary tool,[110] but remained in place for a prolonged period of time.[111] Creation of the second new tool, called the Term Securities Lending Facility, was announced on March 11, 2008.[112] The main difference between these two facilities was that the Term auction Facility was used to inject cash into the banking system whereas the Term securities Lending Facility was used to inject treasury securities into the banking system.[113] Creation of the third tool, called the Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF), was announced on March 16, 2008.[114] The PDCF was a fundamental change in Federal Reserve policy because it enabled the Fed to lend directly to primary dealers, which was previously against Fed policy.[115] The differences between these three facilities was described by the Federal Reserve:[116]

The Term auction Facility program offers term funding to depository institutions via a bi-weekly auction, for fixed amounts of credit. The Term securities Lending Facility will be an auction for a fixed amount of lending of Treasury general collateral in exchange for OMO-eligible and AAA/Aaa rated private-label residential mortgage-backed securities. The Primary Dealer Credit Facility now allows eligible primary dealers to borrow at the existing Discount Rate for up to 120 days.

Some measures taken by the Federal Reserve to address the financial crisis had not been used since the Great Depression.[117]

Term auction facility

[edit]The Term auction Facility was a program in which the Federal Reserve auctioned term funds to depository institutions.[110] The creation of this facility was announced by the Federal Reserve on December 12, 2007, and was done in conjunction with the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Swiss National Bank to address elevated pressures in short-term funding markets.[118] The reason it was created was that banks were not lending funds to one another and banks in need of funds were refusing to go to the discount window. Banks were not lending money to each other because there was a fear that the loans would not be paid back. Banks refused to go to the discount window because it was usually associated with the stigma of bank failure.[119][120][121][122] Under the Term auction Facility, the identity of the banks in need of funds was protected in order to avoid the stigma of bank failure.[123] Foreign exchange swap lines with the European Central Bank and Swiss National Bank were opened so the banks in Europe could have access to U.S. dollars.[123] The final Term Auction Facility auction was carried out on March 8, 2010.[124]

Term securities lending facility

[edit]The Term securities Lending Facility was a 28-day facility that offered Treasury general collateral to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York's primary dealers in exchange for other program-eligible collateral. It was intended to promote liquidity in the financing markets for Treasury and other collateral and thus to foster the functioning of financial markets more generally.[125] Like the Term auction Facility, the TSLF was done in conjunction with the Bank of Canada, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, and the Swiss National Bank. The resource allowed dealers to switch debt that was less liquid for U.S. government securities that were easily tradable. The currency swap lines with the European Central Bank and Swiss National Bank were increased. The TSLF was closed on February 1, 2010.[126]

Primary dealer credit facility

[edit]The Primary Dealer Credit Facility (PDCF) was an overnight loan facility that provided funding to primary dealers in exchange for a specified range of eligible collateral and was intended to foster the functioning of financial markets more generally.[116] It ceased extending credit on March 31, 2021.[127]

Asset Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility

[edit]The Asset Backed Commercial Paper Money Market Mutual Fund Liquidity Facility (ABCPMMMFLF) was also called the AMLF. The Facility began operations on September 22, 2008, and was closed on February 1, 2010.[128]

All U.S. depository institutions, bank holding companies (parent companies or U.S. broker-dealer affiliates), or U.S. branches and agencies of foreign banks were eligible to borrow under this facility pursuant to the discretion of the FRBB.

Collateral eligible for pledge under the Facility was required to meet the following criteria:

- was purchased by Borrower on or after September 19, 2008, from a registered investment company that held itself out as a money market mutual fund;

- was purchased by Borrower at the Fund's acquisition cost as adjusted for amortization of premium or accretion of discount on the ABCP through the date of its purchase by Borrower;

- was rated at the time pledged to FRBB, not lower than A1, F1, or P1 by at least two major rating agencies or, if rated by only one major rating agency, the ABCP must have been rated within the top rating category by that agency;

- was issued by an entity organized under the laws of the United States or a political subdivision thereof under a program that was in existence on September 18, 2008; and

- had stated maturity that did not exceed 120 days if the Borrower was a bank or 270 days for non-bank Borrowers.

Commercial Paper Funding Facility

[edit]On October 7, 2008, the Federal Reserve further expanded the collateral it would loan against to include commercial paper using the Commercial Paper Funding Facility (CPFF). The action made the Fed a crucial source of credit for non-financial businesses in addition to commercial banks and investment firms. Fed officials said they would buy as much of the debt as necessary to get the market functioning again. They refused to say how much that might be, but they noted that around $1.3 trillion worth of commercial paper would qualify. There was $1.61 trillion in outstanding commercial paper, seasonally adjusted, on the market as of 1 October 2008[update], according to the most recent data from the Fed. That was down from $1.70 trillion in the previous week. Since the summer of 2007, the market had shrunk from more than $2.2 trillion.[129][130] This program lent out a total $738 billion before it was closed. Forty-five out of 81 of the companies participating in this program were foreign firms. Research shows that Troubled Asset Relief Program (TARP) recipients were twice as likely to participate in the program than other commercial paper issuers who did not take advantage of the TARP bailout. The Fed incurred no losses from the CPFF.[131]

History

[edit]| Timeline of central banking in the United States | |

|---|---|

| Dates | System |

| 1782–1791 | Bank of North America (de facto, under the Confederation Congress) |

| 1791–1811 | First Bank of the United States |

| 1811–1816 | No central bank |

| 1816–1836 | Second Bank of the United States |

| 1837–1862 | Free Banking Era |

| 1846–1921 | Independent Treasury System |

| 1863–1913 | National Banks |

| 1913–present | Federal Reserve System |

| Sources:[132] | |

Central banking in the United States, 1791–1913

[edit]The first attempt at a national currency was during the American Revolutionary War. In 1775, the Continental Congress, as well as the states, began issuing paper currency, calling the bills "Continentals".[133] The Continentals were backed only by future tax revenue, and were used to help finance the Revolutionary War. Overprinting, as well as British counterfeiting, caused the value of the Continental to diminish quickly. This experience with paper money led the United States to strip the power to issue Bills of Credit (paper money) from a draft of the new Constitution on August 16, 1787,[134] as well as banning such issuance by the various states, and limiting the states' ability to make anything but gold or silver coin legal tender on August 28.[135]

In 1791, the government granted the First Bank of the United States a charter to operate as the U.S. central bank until 1811.[136] The First Bank of the United States came to an end under President Madison when Congress refused to renew its charter. The Second Bank of the United States was established in 1816, and lost its authority to be the central bank of the U.S. twenty years later under President Jackson when its charter expired. Both banks were based upon the Bank of England.[137] Ultimately, a third national bank, known as the Federal Reserve, was established in 1913 and still exists to this day.

First Central Bank, 1791 and Second Central Bank, 1816

[edit]The first U.S. institution with central banking responsibilities was the First Bank of the United States, chartered by Congress and signed into law by President George Washington on February 25, 1791, at the urging of Alexander Hamilton. This was done despite strong opposition from Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, among numerous others. The charter was for twenty years and expired in 1811 under President Madison, when Congress refused to renew it.[138]

In 1816, however, Madison revived it in the form of the Second Bank of the United States. Years later, early renewal of the bank's charter became the primary issue in the reelection of President Andrew Jackson. After Jackson, who was opposed to the central bank, was reelected, he pulled the government's funds out of the bank. Jackson was the only President to completely pay off the national debt[139] but his efforts to close the bank contributed to the Panic of 1837. The bank's charter was not renewed in 1836, and it would fully dissolve after several years as a private corporation.From 1837 to 1862, in the Free Banking Era there was no formal central bank.From 1846 to 1921, an Independent Treasury System ruled.From 1863 to 1913, a system of national banks was instituted by the 1863 National Banking Act during which series of bank panics, in 1873, 1893, and 1907 occurred.[8][9][10]

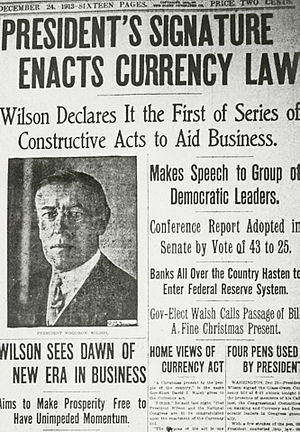

Creation of Third Central Bank, 1907–1913

[edit]The main motivation for the third central banking system came from the Panic of 1907, which caused a renewed desire among legislators, economists, and bankers for an overhaul of the monetary system.[8][9][10][140] During the last quarter of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, the United States economy went through a series of financial panics.[141] According to many economists, the previous national banking system had two main weaknesses: an inelastic currency and a lack of liquidity.[141] In 1908, Congress enacted the Aldrich–Vreeland Act, which provided for an emergency currency and established the National Monetary Commission to study banking and currency reform.[142] The National Monetary Commission returned with recommendations which were repeatedly rejected by Congress. A revision crafted during a secret meeting on Jekyll Island by Senator Aldrich and representatives of the nation's top finance and industrial groups later became the basis of the Federal Reserve Act.[143] The House voted on December 22, 1913, with 298 voting yes to 60 voting no. The Senate voted 43–25 on December 23, 1913.[144] President Woodrow Wilson signed the bill later that day.[145]

Federal Reserve Act, 1913

[edit]

The head of the bipartisan National Monetary Commission was financial expert and Senate Republican leader Nelson Aldrich. Aldrich set up two commissions – one to study the American monetary system in depth and the other, headed by Aldrich himself, to study the European central banking systems and report on them.[142]

In early November 1910, Aldrich met with five well known members of the New York banking community to devise a central banking bill. Paul Warburg, an attendee of the meeting and longtime advocate of central banking in the U.S., later wrote that Aldrich was "bewildered at all that he had absorbed abroad and he was faced with the difficult task of writing a highly technical bill while being harassed by the daily grind of his parliamentary duties".[146] After ten days of deliberation, the bill, which would later be referred to as the "Aldrich Plan", was agreed upon. It had several key components, including a central bank with a Washington-based headquarters and fifteen branches located throughout the U.S. in geographically strategic locations, and a uniform elastic currency based on gold and commercial paper. Aldrich believed a central banking system with no political involvement was best, but was convinced by Warburg that a plan with no public control was not politically feasible.[146] The compromise involved representation of the public sector on the board of directors.[147]

Aldrich's bill met much opposition from politicians. Critics charged Aldrich of being biased due to his close ties to wealthy bankers such as J. P. Morgan and John D. Rockefeller Jr., Aldrich's son-in-law. Most Republicans favored the Aldrich Plan,[147] but it lacked enough support in Congress to pass because rural and western states viewed it as favoring the "eastern establishment".[5][148] In contrast, progressive Democrats favored a reserve system owned and operated by the government; they believed that public ownership of the central bank would end Wall Street's control of the American currency supply.[147] Conservative Democrats fought for a privately owned, yet decentralized, reserve system, which would still be free of Wall Street's control.[147]

The original Aldrich Plan was dealt a fatal blow in 1912, when Democrats won the White House and Congress.[146] Nonetheless, President Woodrow Wilson believed that the Aldrich plan would suffice with a few modifications. The plan became the basis for the Federal Reserve Act, which was proposed by Senator Robert Owen in May 1913. The primary difference between the two bills was the transfer of control of the board of directors (called the Federal Open Market Committee in the Federal Reserve Act) to the government.[5][138] The bill passed Congress on December 23, 1913,[149] on a mostly partisan basis, with most Democrats voting "yea" and most Republicans voting "nay".[138]

Federal Reserve era, 1913–present

[edit]Key laws affecting the Federal Reserve have been:[150]

- Federal Reserve Act, 1913

- Glass–Steagall Act, 1933

- Banking Act of 1935

- Employment Act of 1946

- Federal Reserve-Treasury Department Accord of 1951

- Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 and the amendments of 1970

- Federal Reserve Reform Act of 1977

- International Banking Act of 1978

- Full Employment and Balanced Growth Act (1978)

- Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act (1980)

- Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery and Enforcement Act of 1989

- Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Improvement Act of 1991

- Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act (1999)

- Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act (2006)

- Emergency Economic Stabilization Act (2008)

- Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (2010)

Measurement of economic variables

[edit]The Federal Reserve records and publishes large amounts of data. A few websites where data is published are at the board of governors' Economic Data and Research page,[151] the board of governors' statistical releases and historical data page,[152] and at the St. Louis Fed's FRED (Federal Reserve Economic Data) page.[153] The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) examines many economic indicators prior to determining monetary policy.[154]

Some criticism involves economic data compiled by the Fed. The Fed sponsors much of the monetary economics research in the U.S., and Lawrence H. White objects that this makes it less likely for researchers to publish findings challenging the status quo.[155]

Net worth of households and nonprofit organizations

[edit]

The net worth of households and nonprofit organizations in the United States is published by the Federal Reserve in a report titled Flow of Funds.[156] At the end of the third quarter of fiscal year 2012, this value was $64.8 trillion. At the end of the first quarter of fiscal year 2014, this value was $95.5 trillion.[157]

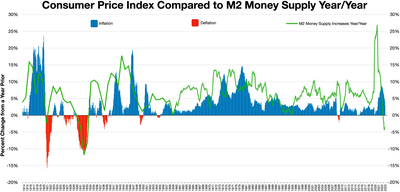

Money supply

[edit]The most common measures are named M0 (narrowest), M1, M2, and M3. In the United States they are defined by the Federal Reserve as follows:

| Measure | Definition |

|---|---|

| M0 | The total of all physical currency, plus accounts at the central bank that can be exchanged for physical currency. |

| M1 | M0 + those portions of M0 held as reserves or vault cash + the amount in demand accounts ("checking" or "current" accounts). |

| M2 | M1 + most savings accounts, money market accounts, and small denomination time deposits (certificates of deposit of under $100,000). |

| M3 | M2 + all other CDs, deposits of eurodollars and repurchase agreements. |

The Federal Reserve stopped publishing M3 statistics in March 2006, saying that the data cost a lot to collect but did not provide significantly useful information.[158] The other three money supply measures continue to be provided in detail.

Personal consumption expenditures price index

[edit]The Personal consumption expenditures price index, also referred to as simply the PCE price index, is used as one measure of the value of money. It is a United States-wide indicator of the average increase in prices for all domestic personal consumption. Using a variety of data including United States Consumer Price Index and U.S. Producer Price Index prices, it is derived from the largest component of the gross domestic product in the BEA's National Income and Product Accounts, personal consumption expenditures.

One of the Fed's main roles is to maintain price stability, which means that the Fed's ability to keep a low inflation rate is a long-term measure of their success.[159] Although the Fed is not required to maintain inflation within a specific range, their long run target for the growth of the PCE price index is between 1.5 and 2 percent.[160] There has been debate among policy makers as to whether the Federal Reserve should have a specific inflation targeting policy.[161]

Inflation and the economy

[edit]Most mainstream economists favor a low, steady rate of inflation.[162] Chief economist, and advisor to the Federal Reserve, the Congressional Budget Office and the Council of Economic Advisers,[163][164] Diane C. Swonk observed, in 2022, that "From the Fed's perspective, you have to remember inflation is kind of like cancer. If you don't deal with it now with something that may be painful, you could have something that metastasized and becomes much more chronic later on."[165]

Low (as opposed to zero or negative) inflation may reduce the severity of economic recessions by enabling the labor market to adjust more quickly in a downturn, and reduce the risk that a liquidity trap prevents monetary policy from stabilizing the economy.[166] The task of keeping the rate of inflation low and stable is usually given to monetary authorities.

Unemployment rate

[edit]

One of the stated goals of monetary policy is maximum employment. The unemployment rate statistics are collected by the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and like the PCE price index are used as a barometer of the nation's economic health.

Budget

[edit]Федеральная резервная система является самофинансируемой. Более 90 процентов доходов ФРС поступает от операций на открытом рынке, в частности от процентов по портфелю казначейских ценных бумаг, а также от «прироста/убытка капитала», который может возникнуть в результате покупки/продажи ценных бумаг и их производных в рамках операций на открытом рынке. . Остальная часть доходов поступает от продажи финансовых услуг (обработка чеков и электронных платежей) и дисконтных кредитов. [167] Совет управляющих (Совет Федеральной резервной системы) раз в год составляет бюджетный отчет для Конгресса. Есть два отчета с бюджетной информацией. Тот, в котором перечислены полные балансовые отчеты с доходами и расходами, а также чистой прибылью или убытком, представляет собой большой отчет, озаглавленный просто «Годовой отчет». Он также включает данные о занятости во всей системе. Другой отчет, в котором более подробно объясняются расходы по различным аспектам всей системы, называется «Годовой отчет: обзор бюджета». Эти подробные и всеобъемлющие отчеты можно найти на веб-сайте Совета управляющих в разделе «Отчеты Конгрессу». [168]

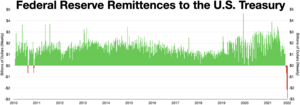

Денежные переводы в казначейство

[ редактировать ]

Федеральная резервная система переводила полученные проценты обратно в Казначейство США . Большую часть активов, которыми владеет ФРС, составляют казначейские облигации США и ценные бумаги, обеспеченные ипотекой , которые ФРС покупала в рамках количественного смягчения после финансового кризиса 2007–2008 годов . В 2022 году ФРС начала количественное ужесточение (QT) и продажу этих активов и получение убытков от них на вторичном рынке облигаций . В результате ожидается, что почти $100 миллиардов, которые он ежегодно переводил в Казначейство, будут прекращены во время QT. [169] [170]

В 2023 году Федеральная резервная система сообщила о чистом отрицательном доходе в размере 114,3 миллиарда долларов. [171] Это привело к созданию отложенного актива-обязательства на балансе Федеральной резервной системы, отраженного как «Проценты по векселям Федеральной резервной системы, причитающимся Казначейству США», на общую сумму 133,3 миллиарда долларов. [172] Отложенный актив — это сумма чистых сверхдоходов, которую Федеральная резервная система должна реализовать, прежде чем денежные переводы смогут продолжиться. Это не оказывает никакого влияния на способность Федеральной резервной системы проводить денежно-кредитную политику или выполнять свои обязательства. [173] По оценкам Федеральной резервной системы, отложенного актива хватит до середины 2027 года. [174]

Баланс

[ редактировать ]

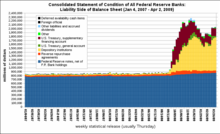

Одним из ключей к пониманию Федеральной резервной системы является ее балансовый отчет (или балансовый отчет ). В соответствии с разделом 11 Закона о Федеральной резервной системе совет управляющих Федеральной резервной системы публикует один раз в неделю «Консолидированный отчет о состоянии всех федеральных резервных банков», показывающий состояние каждого Федерального резервного банка, а также консолидированный отчет по всем федеральным резервным банкам. Федеральные резервные банки. Совет управляющих требует, чтобы избыточные доходы резервных банков переводились в Казначейство в качестве процентов по банкнотам Федеральной резервной системы. [175]

Федеральная резервная система публикует свой баланс каждый четверг. [176] Ниже представлен баланс по состоянию на 8 апреля 2021 года. [update] (в миллиардах долларов):

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Кроме того, в балансе также указывается, какие активы используются в качестве залога под банкноты Федеральной резервной системы .

| Банкноты и обеспечение Федеральной резервной системы | ||

|---|---|---|

| Банкноты Федеральной резервной системы в обращении | 2255.55 | |

| Минус: облигации, принадлежащие банкам FR. | 154.35 | |

| Банкноты Федеральной резервной системы будут обеспечены залогом | 2101.19 | |

| Обеспечение, удерживаемое под банкноты Федеральной резервной системы | 2101.19 | |

| Счет золотого сертификата | 11.04 | |

| Счет сертификата специальных прав заимствования | 5.20 | |

| Казначейство США, долг агентства и ценные бумаги, обеспеченные ипотекой, заложены | 2084.96 | |

| Прочее имущество, переданное в залог | 0 | |

Критика

[ редактировать ]

Федеральная резервная система подвергалась различной критике с момента ее создания в 1913 году. Критика включает отсутствие прозрачности и утверждения о ее неэффективности. [177]

См. также

[ редактировать ]- Коэффициент потребительского кредита

- Базовая инфляция

- Система фермерского кредита

- Модель ФРС

- Федеральные банки жилищного кредитования

- Федеральная резервная полиция

- Статистический релиз Федеральной резервной системы

- Управление финансовыми рисками

- Бесплатное банковское обслуживание

- Золотой стандарт

- Государственный долг

- Гринспен положил

- История действий Федерального комитета по открытому рынку

- История центрального банка в США

- Независимое казначейство

- Закон о снижении инфляции

- Законные тендерные дела

- Список экономических отчетов правительственных агентств США

- Управление рисками

- Участники рынка ценных бумаг (США)

- Раздел 12 Кодекса федеральных правил

- Индекс потребительских цен США

- Хранилище слитков США —известное как Форт-Нокс

- Список центральных банков

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Резервные требования» . Федеральная резервная система . Проверено 10 мая 2020 г.

- ^ «Веб-сайт дисконтного окна и рисков платежной системы Федерального резервного банка» . Федеральная резервная система . Проверено 26 июля 2023 г.

- ^ «Архив операций на открытом рынке» . Федеральная резервная система . Проверено 26 июля 2023 г.

- ^ «Проценты по обязательным резервным остаткам и избыточным остаткам» . Федеральная резервная система . Проверено 26 июля 2023 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Рожденный паникой: Формирование Федеральной резервной системы» . Федеральный резервный банк Миннеаполиса. Август 1988 г. Архивировано из оригинала 16 мая 2008 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с BoG 2006 , стр. 1 «Незадолго до основания Федеральной резервной системы страну охватили финансовые кризисы. Иногда эти кризисы приводили к «панике», когда люди бросались в свои банки, чтобы забрать свои вклады. Паника 1907 года привела к массовому изъятию банковских вкладов, что нанесло ущерб хрупкой банковской системе и в конечном итоге привело Конгресс в 1913 году к написанию Закона о Федеральной резервной системе. Первоначально созданный для борьбы с этой банковской паникой, на Федеральную резервную систему теперь возложен ряд более широких обязанностей, в том числе. содействие созданию здоровой банковской системы и здоровой экономики».

- ^ BoG 2005 , стр. 1–2.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Паника 1907 года: JP Morgan спасает положение» . США-история.com . Проверено 6 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Рожденный паникой: формирование системы ФРС» . Федеральный резервный банк Миннеаполиса . Проверено 6 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с Эбигейл Такер (29 октября 2008 г.). «Финансовая паника 1907 года: бегство от истории» . Смитсоновский журнал . Проверено 6 декабря 2014 г.

- ^ BoG 2005 , стр. 1 «Он был основан Конгрессом в 1913 году, чтобы предоставить стране более безопасную, более гибкую и более стабильную денежно-кредитную и финансовую систему. С годами его роль в банковском деле и экономике расширилась»; Патрик, Сью К. (1993). Реформа Федеральной резервной системы в начале 1930-х годов: политика денег и банковского дела . Гирлянда. ISBN 978-0-8153-0970-3 .

- ^ 12 USC § 225a

- ^ «Каков мандат Федеральной резервной системы в установлении денежно-кредитной политики?» . Federalreserve.gov . 25 января 2012. Архивировано из оригинала 26 января 2012 года . Проверено 30 апреля 2012 г.

Конгресс установил две ключевые цели денежно-кредитной политики — максимальную занятость и стабильные цены — в Законе о Федеральной резервной системе. Эти цели иногда называют двойным мандатом Федеральной резервной системы.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «ФРБ: Миссия» . Federalreserve.gov. 6 ноября 2009 года . Проверено 29 октября 2011 г.

- ^ BoG 2005 , стр. v (см. структуру ); «Округи Федеральной резервной системы» . Федеральная резервная система онлайн. nd Архивировано из оригинала 8 февраля 2012 года . Проверено 29 августа 2011 г. ; «Совет Федеральной резервной системы – Консультативные советы» . Совет управляющих Федеральной резервной системы . Архивировано из оригинала 13 апреля 2015 года.

- ^ «Часто задаваемые вопросы: кому принадлежит Федеральная резервная система?» . Сайт Федеральной резервной системы . Проверено 1 декабря 2015 г.

- ^ Лапидос, Джульетта (19 сентября 2008 г.). «Является ли ФРС частной или государственной?» . Сланец . Проверено 29 августа 2011 г.

- ^ Тома, Марк (1 февраля 2010 г.). «Федеральная резервная система» . ЭХ. Сетевая энциклопедия . Ассоциация экономической истории. Архивировано из оригинала 13 мая 2011 года . Проверено 27 февраля 2011 г.

- ^ «Федеральная резервная система» . эх.нет .

- ^ «Кому принадлежит Федеральный резервный банк?» . Фактчек . 31 марта 2008 года . Проверено 26 февраля 2014 г.

- ^ «Монеты и валюта» . Сайт Министерства финансов США . 24 августа 2011. Архивировано из оригинала 3 декабря 2010 года . Проверено 29 августа 2011 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б «Пресс-релиз – Совет Федеральной резервной системы объявляет данные о доходах и расходах Резервного банка и трансфертах Казначейству за 2015 год» . Совет управляющих Федеральной резервной системы . 11 января 2016 года . Проверено 12 марта 2016 г.

- ^ «Пресс-релиз – Федеральная резервная система публикует годовую финансовую отчетность» . www.federalreserve.gov . Совет управляющих Федеральной резервной системы. 22 марта 2021 г. . Проверено 4 января 2022 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с "ЧАСТО ЗАДАВАЕМЫЕ ВОПРОСЫ" . Кому принадлежит Федеральная резервная система? . Совет управляющих Федеральной резервной системы . Проверено 1 декабря 2015 г.

- ^ «Закон о Федеральной резервной системе» . Совет управляющих Федеральной резервной системы. 14 мая 2003 г. Архивировано из оригинала 17 мая 2008 г.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б BoG 2006 , стр. 1.

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с д «Совет Федеральной резервной системы – денежно-кредитная политика: каковы ее цели? Как она работает?» . Совет управляющих Федеральной резервной системы . 29 июля 2021 г. . Проверено 10 августа 2023 г.

- ^ Бернанке, Бен (24 октября 2003 г.). «Выступление губернатора Бена С. Бернанке: на конференции Федерального резервного банка Далласа, посвященной наследию свободы выбора Милтона и Роуз Фридман , Даллас, Техас» (текст) . ; Выступление ФРБ: FederalReserve.gov: Выступление губернатора Бена С. Бернанке, Конференция в честь Милтона Фридмана, Чикагский университет, 8 ноября 2002 г .; Милтон Фридман; Анна Джейкобсон Шварц (2008). «Речь Б. Бернанке перед М. Фридманом». Великое сокращение, 1929–1933 (новое изд.). Издательство Принстонского университета . п. 247. ИСБН 978-0-691-13794-0 .

- ^ BoG 2005 , стр. 83.

- ^ «Кредитор последней инстанции» . Федеральный резервный банк Миннеаполиса . Архивировано из оригинала 25 января 2010 года . Проверено 21 мая 2010 г. ; Хамфри, Томас М. (1 января 1989 г.). «Кредитор последней инстанции: концепция в истории». ССНН 2125371 .

- ^ Перейти обратно: а б с «Федеральная резервная система, денежно-кредитная политика и экономика – повседневная экономика» . Далласфед.орг. Архивировано из оригинала 22 декабря 2007 года . Проверено 29 августа 2011 г.

- ^ «Пресс-релиз: Совет Федеральной резервной системы при полной поддержке Министерства финансов разрешает Федеральному резервному банку Нью-Йорка предоставить кредит Американской международной группе (AIG) на сумму до 85 миллиардов долларов» . Совет управляющих Федеральной резервной системы. 16 сентября 2008 года . Проверено 29 августа 2011 г. ; Эндрюс, Эдмунд Л.; де ла Мерсед, Майкл Дж.; Уолш, Мэри Уильямс (16 сентября 2008 г.). «Страховая компания, спасающая кредит ФРС на сумму 85 миллиардов долларов» . Нью-Йорк Таймс . Проверено 17 сентября 2008 г.

- ^ «Как валюта попадает в обращение» . Федеральный резервный банк Нью-Йорка. Июнь 2008 года . Проверено 29 августа 2011 г.

- ^ «Годовые производственные отчеты | Гравировка и печать» . www.bep.gov . Проверено 6 января 2023 г.

- ^ Совет управляющих Федеральной резервной системы (2021 г.). «Валютный бюджет на 2021 год» (PDF) . Federalreserve.gov.

- ^ «Федеральные фонды» . Федеральный резервный банк Нью-Йорка. Август 2007 года . Проверено 29 августа 2011 г. ; Кук, Тимоти К.; Ларош, Роберт К., ред. (1993). «Инструменты денежного рынка» (PDF) . Федеральный резервный банк Ричмонда. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 25 марта 2009 г. Проверено 29 августа 2011 г.

- ^ «Выступление – Кон, Развивающаяся роль федеральных резервных банков» . Federalreserve.gov. 3 ноября 2006 г. Проверено 29 августа 2011 г.

- ^ «Часто задаваемые вопросы Федеральной резервной системы» . Архивировано из оригинала 17 февраля 2010 года . Проверено 19 февраля 2010 г.

Совет управляющих, Федеральные резервные банки и Федеральная резервная система в целом подлежат аудиту и проверке на нескольких уровнях. В соответствии с Законом об аудите Федерального банковского агентства Счетная палата правительства (GAO) провела многочисленные проверки деятельности Федеральной резервной системы.

- ^ «Текущие и будущие проблемы Федеральной резервной системы требуют общесистемного внимания: заявление Чарльза А. Баушера» (PDF) . Главное бухгалтерское управление США. 26 июля 1996 года. Архивировано из оригинала (PDF) 9 июля 2011 года . Проверено 29 августа 2011 г.

- ^ BoG 2005 , стр. 4–5.

- ^ См. пример: «Преимущества быть / стать государственным дипломированным банком» . Департамент государственного банка Арканзаса. 31 марта 2009 года . Проверено 29 августа 2011 г.

- ^ «Раздел 12 Кодекса США, Глава 3, Подраздел 7, Раздел 301. Полномочия и обязанности совета директоров; приостановление деятельности банка-участника за неправомерное использование банковского кредита» . Law.cornell.edu. 22 июня 2010 года . Проверено 29 августа 2011 г.

- ^ BoG 2005 , стр. 83–85.