William F. Buckley Jr.

William F. Buckley Jr. | |

|---|---|

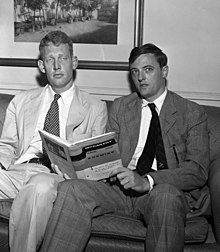

Buckley in an undated handout photograph | |

| Born | William Francis Buckley November 24, 1925 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | February 27, 2008 (aged 82) Stamford, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation |

|

| Education | Yale University (BA) |

| Subject | |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Christopher Buckley |

| Parent | William F. Buckley Sr. |

| Relatives |

|

| Military career | |

| Service/ | United States Army |

| Years of service | 1944–1946 |

| Rank | First lieutenant |

| Battles/wars | World War II |

William Frank Buckley Jr. (born William Francis Buckley;[a] November 24, 1925 – February 27, 2008) was an American conservative writer, public intellectual, and political commentator.[1]

Born in New York City, Buckley spoke Spanish as his first language before learning French and then English as a child.[2] He served stateside in the United States Army during World War II. After the war, he attended Yale University, where he engaged in debate and conservative political commentary. Afterward, he worked for two years in the Central Intelligence Agency.

In 1955, he founded National Review, a magazine that stimulated the conservative movement in the United States. In addition to editorials in National Review, Buckley wrote God and Man at Yale (1951) and more than 50 other books on diverse topics, including writing, speaking, history, politics, and sailing. His works include a series of novels featuring fictitious CIA officer Blackford Oakes and a nationally syndicated newspaper column.[3][4]

From 1966 to 1999, Buckley hosted 1,429 episodes of the public affairs television show Firing Line, the longest-running public affairs show with a single host in American television history, where he became known for his distinctive Transatlantic accent and wide vocabulary.[5]

Buckley's views varied, and are considered less categorically conservative than those of most conservative intellectuals today.[6] His public views on race rapidly changed from the 1950s to the 1960s, from endorsing Southern racism to eagerly anticipating the election of an African American to the presidency.[7]

Buckley called himself both a conservative and a libertarian.[8][9] He is widely considered one of the most influential figures in the conservative movement.[10][11][12]

Early life

[edit]| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in the United States |

|---|

|

Childhood

[edit]William Frank Buckley Jr. was born William Francis Buckley in New York City on November 24, 1925, to Aloise Josephine Antonia (née Steiner) and lawyer and oil developer William Frank Buckley Sr. (1881–1958).[13] His mother hailed from New Orleans and was of German, Irish, and Swiss-German descent, while his father had Irish ancestry and was born in Texas to Canadian parents from Hamilton, Ontario.[14] He had five older siblings and four younger siblings. He moved as a boy with his family to Mexico[15] before moving to Sharon, Connecticut, then began his formal schooling in France, where he attended first grade in Paris. By age seven, the family had moved to England and he received his first formal English-language training at a day school in London; due to the family's movement, his first and second languages were Spanish and French.[16] As a boy, he developed a love for horses, hunting, music, sailing, and skiing, all of which were reflected in his later writings. He was homeschooled through the eighth grade using the Homeschool Curriculum developed by the Calvert School in Baltimore.[17] Just before World War II, around the ages of 12 and 13, he attended the Jesuit preparatory school St John's Beaumont in the English village of Old Windsor.

Buckley's father was an oil developer whose wealth was based in Mexico and became influential in Mexican politics during the military dictatorship of Victoriano Huerta, but was expelled when leftist general Álvaro Obregón became president in 1920. Buckley's nine siblings included eldest sister Aloise Buckley Heath, a writer and conservative activist;[18] sister Maureen Buckley-O'Reilly (1933–1964), who married Richardson-Vicks Drugs CEO Gerald A. O'Reilly; sister Priscilla Buckley, author of Living It Up with National Review: A Memoir, for which Buckley wrote the foreword; sister Patricia Buckley Bozell, who was also an author; brother Reid Buckley, an author and founder of the Buckley School of Public Speaking; and brother James L. Buckley, who became a U.S. senator from New York and a judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.[19]

During the war, Buckley's family took in the English historian-to-be Alistair Horne as a child war evacuee. He and Buckley remained lifelong friends. They both attended the Millbrook School in Millbrook, New York, graduating in 1943. Buckley was a member of the American Boys' Club for the Defense of Errol Flynn (ABCDEF) during Flynn's trial for statutory rape in 1943. At Millbrook, Buckley founded and edited the school's yearbook, The Tamarack; this was his first experience in publishing. When Buckley was a young man, libertarian author Albert Jay Nock was a frequent guest at the Buckley family house in Sharon, Connecticut.[20] William F. Buckley Sr. urged his son to read Nock's works,[21] the best-known of which was Our Enemy, the State, in which Nock maintained that the founding fathers of the United States, at their Constitutional Convention in 1787, had executed a coup d'état of the system of government established under the Articles of Confederation.[22]

Music

[edit]In his youth, Buckley developed many musical talents. He played the harpsichord very well,[23] later calling it "the instrument I love beyond all others",[24] although he admitted he was not "proficient enough to develop [his] own style".[25] He was a close friend of harpsichordist Fernando Valenti, who offered to sell Buckley his sixteen-foot pitch harpsichord.[25] Buckley was also an accomplished pianist and appeared once on Marian McPartland's National Public Radio show Piano Jazz.[26] A great admirer of Johann Sebastian Bach,[24] Buckley wanted Bach's music played at his funeral.[27]

Religion

[edit]Buckley was raised a Catholic and was a member of the Knights of Malta.[28] He described his faith by saying, "I grew up, as reported, in a large family of Catholics without even a decent ration of tentativeness among the lot of us about our religious faith."[29]

The release of his first book, God and Man at Yale, in 1951 was met with some specific criticism pertaining to his Catholicism. McGeorge Bundy, dean of Harvard at the time, wrote in The Atlantic that "it seems strange for any Roman Catholic to undertake to speak for the Yale religious tradition". Henry Sloane Coffin, a Yale trustee, accused Buckley's book of "being distorted by his Roman Catholic point of view" and stated that Buckley "should have attended Fordham or some similar institution".[30]

In his 1997 book Nearer, My God, Buckley condemned what he viewed as "the Supreme Court's war against religion in the public school" and argued that Christian faith was being replaced by "another God [...] multiculturalism".[31] He disapproved of the liturgical reforms following the Second Vatican Council.[32] Buckley also revealed an interest in the writings and revelations of the 20th century Italian writer Maria Valtorta.[33]

Education and military service

[edit]Buckley attended the National Autonomous University of Mexico (or UNAM) until 1943. The next year, upon his graduation from the U.S. Army Officer Candidate School (OCS), he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the United States Army. In his book Miles Gone By, he briefly recounts being a member of Franklin Roosevelt's honor guard upon Roosevelt's death. He served stateside throughout the war at Fort Benning, Georgia; Fort Gordon, Georgia; and Fort Sam Houston, Texas.[34] After the war ended in 1945, Buckley enrolled at Yale University, where he became a member of the secret Skull and Bones society[35][36] and was a masterful debater.[36][37] He was an active member of the Conservative Party of the Yale Political Union,[38] and served as chairman of the Yale Daily News and as an informer for the FBI.[39] At Yale, Buckley studied political science, history, and economics and graduated with honors in 1950.[36] He excelled on the Yale Debate Team; under the tutelage of Yale professor Rollin G. Osterweis, Buckley honed his acerbic style.[40]

Central Intelligence Agency

[edit]Buckley remained at Yale working as a Spanish instructor from 1947 to 1951[41] before being recruited into the CIA like many other Ivy League alumni at that time; he served for two years, including one year in Mexico City working on political action for E. Howard Hunt,[42] who was later imprisoned for his part in the Watergate scandal. The two officers remained lifelong friends.[43] In a November 1, 2005, column for National Review, Buckley recounted that while he worked for the CIA, the only CIA employee he knew was Hunt, his immediate boss. While stationed in Mexico, Buckley edited The Road to Yenan, a book by Peruvian author Eudocio Ravines.[44] After leaving the CIA, he worked as an editor at The American Mercury in 1952, but left after perceiving newly emerging anti-Semitic tendencies in the magazine.[45]

Personal life

[edit]In 1950, Buckley married Patricia Buckley, née Taylor, daughter of Canadian industrialist Austin C. Taylor. He met Taylor, a Protestant from Vancouver, British Columbia, while she was a student at Vassar College. She later became a prominent fundraiser for such charitable organizations as the Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, the Institute of Reconstructive Plastic Surgery at New York University Medical Center, and the Hospital for Special Surgery. She also raised money for Vietnam War veterans. On April 15, 2007, Pat Buckley died at age 80 of an infection after a long illness.[46] After her death, Buckley seemed "dejected and rudderless", according to friend Christopher Little.[47]

William and Patricia Buckley had one son, author Christopher Buckley.[48] They lived at Wallack's Point in Stamford, Connecticut, with a Manhattan duplex apartment at 73 East 73rd Street, a private entrance to 778 Park Avenue in Manhattan.[49]

Beginning in 1970, Buckley and his wife lived and worked in Rougemont, Switzerland, for six to seven weeks per year for more than three decades.[50]

First books

[edit]God and Man at Yale

[edit]

Buckley's first book, God and Man at Yale, was published in 1951. Offering a critique of Yale University, Buckley argued in the book that the school had strayed from its original mission. One critic viewed the work as miscasting the role of academic freedom.[51] The American academic and commentator McGeorge Bundy, a Yale graduate himself, wrote in The Atlantic: "God and Man at Yale, written by William F. Buckley, Jr., is a savage attack on that institution as a hotbed of 'atheism' and 'collectivism.' I find the book is dishonest in its use of facts, false in its theory, and a discredit to its author."[52]

Buckley credited the attention the book received to its "Introduction" by John Chamberlain, saying that it "chang[ed] the course of his life" and that the famous Life magazine editorial writer had acted out of "reckless generosity".[53] Buckley was referred to in Richard Condon's 1959 novel The Manchurian Candidate as "that fascinating younger fellow who had written about men and God at Yale."[54]

McCarthy and His Enemies

[edit]In 1954, Buckley and his brother-in-law L. Brent Bozell Jr. co-authored a book, McCarthy and His Enemies. Bozell worked with Buckley at The American Mercury in the early 1950s when it was edited by William Bradford Huie.[55] The book defended Senator Joseph McCarthy as a patriotic crusader against communism, and asserted that "McCarthyism ... is a movement around which men of good will and stern morality can close ranks."[56] Buckley and Bozell described McCarthy as responding to a communist "ambition to occupy the world". They conceded that he was often "guilty of exaggeration", but believed the cause he pursued was just.[57]

National Review

[edit]Buckley founded National Review in 1955 at a time when there were few publications devoted to conservative commentary. He served as the magazine's editor-in-chief until 1990.[58][59] During that time, National Review became the standard-bearer of American conservatism, promoting the fusionism of traditional conservatives and libertarians. Examining postwar conservative intellectual history, Kim Phillips-Fein writes:[60][61]

The most influential synthesis of the subject remains George H. Nash's The Conservative Intellectual Tradition since 1945 .... He argued that postwar conservatism brought together three powerful and partially contradictory intellectual currents that previously had largely been independent of each other: libertarianism, traditionalism, and anticommunism. Each particular strain of thought had predecessors earlier in the twentieth (and even nineteenth) centuries, but they were joined in their distinctive postwar formulation through the leadership of William F. Buckley Jr. and National Review. The fusion of these different, competing, and not easily reconciled schools of thought led to the creation, Nash argued, of a coherent modern Right.

Buckley sought out intellectuals who were ex-Communists or had once worked on the far Left, including Whittaker Chambers, Willi Schlamm, John Dos Passos, Frank Meyer, and James Burnham,[62] as editors and writers for National Review. When Burnham became a senior editor, he urged the adoption of a more pragmatic editorial position that would extend the influence of the magazine toward the political center. Smant (1991) finds that Burnham overcame sometimes heated opposition from other members of the editorial board (including Meyer, Schlamm, William Rickenbacker, and the magazine's publisher, William A. Rusher), and had a significant impact on both the editorial policy of the magazine and on the thinking of Buckley himself.[63][64]

| Part of a series on |

| Conservatism |

|---|

|

Defining the boundaries of conservatism

[edit]Buckley and his editors used National Review to define the boundaries of conservatism and to exclude people, ideas, or groups they considered unworthy of the conservative title.[65] For example, Buckley denounced Ayn Rand, the John Birch Society, George Wallace, racists, white supremacists, and anti-Semites.

When he first met author Ayn Rand, according to Buckley, she greeted him with the following: "You are much too intelligent to believe in God."[66] In turn, Buckley felt that "Rand's style, as well as her message, clashed with the conservative ethos".[67] He decided that Rand's hostility to religion made her philosophy unacceptable to his understanding of conservatism. After 1957, he attempted to weed her out of the conservative movement by publishing Whittaker Chambers's highly negative review of Rand's Atlas Shrugged.[68][69] In 1964, he wrote of "her desiccated philosophy's conclusive incompatibility with the conservative's emphasis on transcendence, intellectual and moral", as well as "the incongruity of tone, that hard, schematic, implacable, unyielding, dogmatism that is in itself intrinsically objectionable, whether it comes from the mouth of Ehrenburg, Savonarola — or Ayn Rand."[70] Other attacks on Rand were penned by Garry Wills and M. Stanton Evans. Nevertheless, historian Jennifer Burns argues, Rand's popularity and influence on the right forced Buckley and his circle into a reconsideration of how traditional notions of virtue and Christianity could be integrated with all-out support for capitalism.[71]

In 1962, Buckley denounced Robert W. Welch Jr. and the John Birch Society in National Review as "far removed from common sense" and urged the Republican Party to purge itself of Welch's influence.[72] He hedged the statement by insisting that among them were "some of the most morally energetic, self-sacrificing, and dedicated anti-Communists in America."[73]

On Robert Welch and the John Birch Society

[edit]In 1952, their mutual publisher Henry Regnery introduced Buckley to Robert Welch. Both Buckley and Welch became editors of political journals, and both had a knack for communication and organization.[74] Welch launched his publication One Man's Opinion in 1956 (renamed American Opinion in 1958), one year after the founding of The National Review. Welch twice donated $1,000 to Buckley's magazine, and Buckley offered to provide Welch "a little publicity" for his publication.[74] Both believed that the United States suffered from diplomatic and military setbacks during the early years of the Cold War, and both were staunchly anti-communist.[75] But Welch expressed doubts about Eisenhower's loyalties in 1957, and the two disagreed on the reasons for the United States' perceived failure in the Cold War's early years.[76] According to Alvin Felzenberg's assessment, the disagreements between the two blossomed into "a major battle" in 1958.[74] That year, Boris Pasternak won the Nobel Prize in Literature for his novel Doctor Zhivago. Buckley was impressed by the novel's vivid and depressing depictions of life in a communist society, and believed that the CIA's smuggling of the novel into the Soviet Union was an ideological victory.[76] In September 1958, Buckley ran a review of Doctor Zhivago by John Chamberlain. In November 1958, Welch sent Buckley and other associates copies of his unpublished manuscript "The Politician", which accused Eisenhower and several of Eisenhower's appointees of involvement in a communist conspiracy.[76] When Buckley returned the manuscript to Welch, he commented that the allegations were "curiously—almost pathetically optimistic."[75] On December 9, 1958, Welch founded the John Birch Society with a group of business leaders in Indianapolis.[77] By the end of 1958, Welch had both the organizational and the editorial infrastructure to launch his subsequent far-right political advocacy campaigns.

In 1961, reflecting on his correspondences with Welch and Birchers, Buckley told someone who subscribed to both the National Review and the John Birch Society: "I have had more discussions about the John Birch Society in the past year than I have about the existence of God or the financial difficulties of National Review."[75]

Buckley rule

[edit]The Buckley rule states that National Review "will support the rightwardmost viable candidate" for a given office.[78] Buckley first stated the Buckley rule during the 1964 Republican primary election featuring Barry Goldwater and Nelson Rockefeller. The rule is often misquoted and misapplied as proclaiming support for "the rightwardmost electable candidate", or simply the most electable candidate.[79]

According to National Review's Neal B. Freeman, the Buckley rule meant that National Review would support "somebody who saw the world as we did. Somebody who would bring credit to our cause. Somebody who, win or lose, would conservatize the Republican party and the country. It meant somebody like Barry Goldwater."[78]

Starr Broadcasting Group

[edit]Buckley was the chairman of Starr Broadcasting Group, a company in which he owned a 20% stake. Peter Starr was president of the company, and his brother Michael Starr was executive vice president. In February 1979 the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission accused Buckley and 10 other defendants of defrauding shareholders in Starr Broadcasting Group. As part of a settlement, Buckley agreed to return $1.4 million in stock and cash to shareholders in the company. The other defendants were ordered to contribute $360,000.[80] In 1981, there was another agreement with the SEC.[81]

Political commentary and action

[edit]Broadcasts and publications

[edit]

Buckley's column On the Right was syndicated by Universal Press Syndicate beginning in 1962. From the early 1970s, his twice-weekly column was distributed regularly to more than 320 newspapers across the country.[82] He authored 5,600 editions of the column, which totaled to over 4.5 million words.[45]

For many Americans, Buckley's erudition on his weekly PBS show Firing Line (1966–1999) was their primary exposure to him and his manner of speech, often with vocabulary common in academia but unusual on television.[83]

Throughout his career as a media figure, Buckley received much criticism—largely from the American left, but also from certain factions on the right, such as the John Birch Society and its second president, Larry McDonald, as well as from Objectivists.[84]

In 1953–54, long before he founded Firing Line, Buckley was an occasional panelist on the conservative public affairs program Answers for Americans broadcast on ABC and based on material from the H. L. Hunt–supported publication Facts Forum.[85]

Young Americans for Freedom

[edit]In 1960, Buckley helped form Young Americans for Freedom (YAF). The YAF was guided by principles Buckley called "The Sharon Statement". Buckley was proud of the successful campaign of his older brother, Jim Buckley, on the Conservative Party ticket to capture the United States Senate seat from New York State held by incumbent Republican Charles Goodell in 1970, giving very generous credit to the activist support of the New York State chapter of YAF. Buckley served one term in the Senate, then was defeated by Democrat Daniel Patrick Moynihan in 1976.[86]

Edgar Smith murder case

[edit]In 1962, Edgar Smith, who had been sentenced to death for the murder of 15-year-old high-school student Victoria Ann Zielinski in New Jersey, began a correspondence with Buckley from death row. As a result of the correspondence, Buckley began to doubt Smith's guilt. Buckley later said the case against Smith was "inherently implausible".[87] An article by Buckley about the case, published in Esquire in November 1965, drew national media attention:[87]

Smith said he told [friend Don Hommell] during their brief conversation ... on the night of the murder just where he had discarded his pants. The woman who occupies property across the road from which Smith claimed to have thrown the pants ... swore at the trial that she had seen Hommell rummaging there the day after the murder. The pants were later found [by the police] near a well-travelled road .... Did Hommell find them, and leave them in the other location, thinking to discredit Smith's story, and make sure they would turn up?

Buckley's article brought renewed media interest in Hommell, who Smith claimed was the real killer. In 1971, there was a retrial.[87] Smith took a plea deal and was freed from prison that year.[87] Buckley interviewed him on Firing Line soon thereafter.[88]

In 1976, five years after being released from prison, Smith attempted to murder another woman, this time in San Diego, California.[88] After witnesses corroborated the story of Lisa Ozbun, who survived being stabbed by Smith, he was sentenced to life in prison. He admitted at the trial that he had in fact also murdered Zielinski.[88] Buckley subsequently expressed great regret at having believed Smith and supported him.[88] Friends of Buckley said he was devastated and blamed himself for what happened.[89]

Mayoral candidacy

[edit]In 1965, Buckley ran for mayor of New York City as the candidate for the new Conservative Party. He ran to restore momentum to the conservative cause in the wake of Goldwater's defeat.[90] He tried to take votes away from the relatively liberal Republican candidate and fellow Yale alumnus John Lindsay, who later became a Democrat. Buckley did not expect to win; when asked what he would do if he won the race, he responded, "Demand a recount."[91] He used an unusual campaign style. During one televised debate with Lindsay, Buckley declined to use his allotted rebuttal time and instead replied, "I am satisfied to sit back and contemplate my own former eloquence."[92]

During his campaign, Buckley supported many policies that have been perceived as uniquely and unusually progressive. He supported affirmative action, being one of the first American conservatives to endorse a "kind of special treatment [of African Americans] that might make up for centuries of oppression". Buckley also espoused welfare reform to emphasize job training, education and daycare. He criticized the administration of drug laws and in judicial sentencing, and promised to crack down on trade unions that discriminated against minorities. This is considered notable, as his political opponents on the left would have resisted anything that alienated trade union-affiliated voters.[7]

To relieve traffic congestion, Buckley proposed charging drivers a fee to enter the central city and creating a network of bike lanes. He opposed a civilian review board for the New York City Police Department, which Lindsay had recently introduced to control police corruption and install community policing.[93] Buckley finished third with 13.4% of the vote, possibly having inadvertently aided Lindsay's election by instead taking votes from Democratic candidate Abe Beame.[91]

Feud with Gore Vidal

[edit]When asked if there was one person with whom Buckley would not share a stage, Buckley's response was Gore Vidal. Likewise, Vidal's antagonism toward Buckley was well known, even before 1968.[94] Buckley nevertheless appeared in a series of televised debates with Vidal during the 1968 Republican National Convention in Miami and the Democratic National Convention in Chicago.[95]

In their penultimate debate on August 28 of that year, the two disagreed over the actions of the Chicago Police Department and the protesters at the convention. In reference to the response of the police involved in supposedly taking down a Viet Cong flag, moderator Howard K. Smith asked whether raising a Nazi flag during the Second World War would have elicited a similar response. Vidal responded that people were free to state their political views as they saw fit, whereupon Buckley interrupted and noted that people were free to speak their views but others were also free to ostracize them for holding those views, noting that in the US during the Second World War "some people were pro-Nazi and they were well [i.e. correctly] treated by those who ostracized them—and I'm for ostracizing people who egg on other people to shoot American Marines and American soldiers. I know you [Vidal] don't care because you have no sense of identification with—". Vidal then interjected that "the only sort of pro- or crypto-Nazi I can think of is yourself" whereupon Smith interjected, "Now let's not call names". Buckley, visibly angered, rose several inches from his seat and replied, "Now listen, you queer, stop calling me a crypto-Nazi or I'll sock you in your goddamn face, and you'll stay plastered."[95]

Buckley later apologized in print for having called Vidal a "queer" in a burst of anger rather than in a clinical context but also reiterated his distaste for Vidal as an "evangelist for bisexuality": "The man who in his essays proclaims the normalcy of his affliction, and in his art the desirability of it, is not to be confused with the man who bears his sorrow quietly. The addict is to be pitied and even respected, not the pusher."[96] The debates are chronicled in the 2015 documentary Best of Enemies.[95]

This feud continued the next year in Esquire magazine, which commissioned essays from Buckley and Vidal on the incident. Buckley's essay "On Experiencing Gore Vidal" was published in the August 1969 issue. In September, Vidal responded with his own essay, "A Distasteful Encounter with William F. Buckley".[97] In it Vidal strongly implied that, in 1944, Buckley's unnamed siblings and possibly Buckley had vandalized a Protestant church in their Sharon, Connecticut, hometown after the pastor's wife sold a house to a Jewish family. He also implied that Buckley was homosexual and a "racist, antiblack, anti-Semitic and a pro-crypto Nazi."[98][99] Buckley sued Vidal and Esquire for libel; Vidal countersued Buckley for libel, citing Buckley's characterization of Vidal's novel Myra Breckenridge as pornography. After Buckley received an out-of-court settlement from Esquire, he dropped the suit against Vidal. Both cases were dropped,[100] with Buckley settling for court costs paid by Esquire, which had published the piece, while Vidal, who did not sue the magazine, absorbed his own court costs. Neither paid the other compensation. Buckley also received an editorial apology from Esquire as part of the settlement.[100][101]

The feud was reopened in 2003 when Esquire republished the original Vidal essay as part of a collection titled Esquire's Big Book of Great Writing. After further litigation, Esquire agreed to pay $65,000 to Buckley and his attorneys, to destroy every remaining copy of the book that included Vidal's essay, to furnish Buckley's 1969 essay to anyone who asked for it, and to publish an open letter stating that Esquire's current management was "not aware of the history of this litigation and greatly [regretted] the re-publication of the libels" in the 2003 collection.[101]

Buckley maintained a philosophical antipathy toward Vidal's other bête noire, Norman Mailer, calling him "almost unique in his search for notoriety and absolutely unequalled in his co-existence with it."[102] Meanwhile, Mailer called Buckley a "second-rate intellect incapable of entertaining two serious thoughts in a row."[103] After Mailer's 2007 death, Buckley wrote warmly about their personal acquaintance.

Associations with liberal politicians

[edit]Buckley became a close friend of liberal Democratic activist Allard K. Lowenstein. He featured Lowenstein on numerous Firing Line programs, publicly endorsed his candidacies for Congress, and delivered a eulogy at his funeral.[104][105]

Buckley was also a friend of economist John Kenneth Galbraith[106][107] and former senator and presidential candidate George McGovern,[108] both of whom he frequently featured or debated on Firing Line and college campuses. He and Galbraith occasionally appeared on The Today Show, where host Frank McGee would introduce them and then step aside and defer to their verbal thrusts and parries.[109]

Amnesty International

[edit]In the late 1960s, Buckley joined the board of directors of Amnesty International USA.[110] He resigned in January 1978 in protest over the organization's stance against capital punishment as expressed in its Stockholm Declaration of 1977, which he said would lead to the "inevitable sectarianization of the amnesty movement".[111]

Political views

[edit]Political candidates

[edit]In 1963 and 1964, Buckley mobilized support for the candidacy of Senator Barry Goldwater, first for the Republican nomination against New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller and then for the presidency. Buckley used National Review as a forum for mobilizing support for Goldwater.[112]

In July 1971, Buckley assembled a group of conservatives to discuss some of Richard Nixon's domestic and foreign policies that the group opposed. In August 1969, Nixon had proposed and later attempted to enact the Family Assistance Plan (FAP), welfare legislation that would establish a national income floor of $1,600 per year for a family of four.[113]

On the international front Nixon negotiated talks with the Soviet Union and initiated relations with China, which Buckley, as a hawk and anti-communist, opposed. The group, known as the Manhattan Twelve, included National Review's publisher William A. Rusher and editors James Burnham and Frank Meyer. Other organizations represented were the newspaper Human Events, The Conservative Book Club, Young Americans for Freedom, and the American Conservative Union.[114] On July 28, 1971, they published a letter announcing that they would no longer support Nixon.[115] The letter said, "In consideration of his record, the undersigned, who have heretofore generally supported the Nixon Administration, have resolved to suspend our support of the Administration."[116] Nonetheless, in 1973, the Nixon Administration appointed Buckley as a delegate to the United Nations, about which Buckley later wrote a book.[116]

In 1976, Buckley supported Ronald Reagan's presidential campaign against sitting President Gerald Ford and expressed disappointment at Reagan's narrow loss to Ford.[117] In 1981, Buckley informed President-elect Reagan that he would decline any official position offered to him. Reagan jokingly replied that was too bad, because he had wanted to make Buckley ambassador to (then Soviet-occupied) Afghanistan. Buckley later wrote, "When Ronald Reagan offered me the ambassadorship to Afghanistan, I said, 'Yes, but only if you give me fifteen divisions of bodyguards'."[118]

Race and segregation

[edit]"The central question that emerges ... is whether the White community in the South is entitled to take such measures as are necessary to prevail, politically and culturally, in areas where it does not predominate numerically? The sobering answer is Yes—the White community is so entitled because, for the time being, it is the advanced race."

William F. Buckley Jr., National Review, August 1957[119]

In the 1950s and early 1960s, Buckley opposed federal civil rights legislation and expressed support for continued racial segregation in the South. In Freedom Is Not Enough: The Opening of the American Workplace, author Nancy MacLean states that National Review made James J. Kilpatrick—a prominent supporter of segregation in the South—"its voice on the civil rights movement and the Constitution, as Buckley and Kilpatrick united North and South in a shared vision for the nation that included upholding white supremacy".[120] In the August 24, 1957, issue of National Review, Buckley's editorial "Why the South Must Prevail" spoke out explicitly in favor of temporary segregation in the South until "long term equality could be achieved". Buckley opined that temporary segregation in the South was necessary at the time because the black population lacked the education, economic, and cultural development to make racial equality possible.[121][122][123] Buckley claimed that the white South had "the right to impose superior mores for whatever period it takes to effect a genuine cultural equality between the races".[122][124][125][126] Buckley said white Southerners were "entitled" to disenfranchise black voters "because, for the time being, it is the advanced race."[127] Buckley characterized Blacks as distinctly ignorant: "The great majority of the Negroes of the South who do not vote do not care to vote, and would not know for what to vote if they could."[127] Two weeks after that editorial was published, another prominent conservative writer, L. Brent Bozell Jr. (Buckley's brother-in-law), wrote in the National Review: "This magazine has expressed views on the racial question that I consider dead wrong, and capable of doing great hurt to the promotion of conservative causes. There is a law involved, and a Constitution, and the editorial gives White Southerners leave to violate them both in order to keep the Negro politically impotent."[128][129]

Buckley visited South Africa in the 1960s on several paid fact-finding missions in which he distributed publications that supported the South African government's policy of apartheid.[130] On January 15, 1963, the day after George Wallace, the white supremacist governor of Alabama, made his "Segregation Forever" inaugural address, Buckley published a feature essay in National Review on his recent "South African Fortnight", concluding it with these words concerning apartheid: "I know it is a sincere people's effort to fashion the land of peace they want so badly."[131][132] In his report, Buckley tried to define apartheid and came up with four axioms on which the policy stands, the fourth being "The notion that the Bantu could participate in power on equal terms with the whites is the worst kind of ideological and social romance".[133] After publishing this defense of the Hendrik Verwoerd government, Buckley wrote that he was "bursting with pride" over the West German social critic Wilhelm Röpke's praise of the piece.[134]

Politico indicates that during the administration of Lyndon B. Johnson, Buckley's writing grew more accommodating toward the civil rights movement. In his columns, he "ridiculed practices designed to keep African Americans off the voter registration rolls", "condemned proprietors of commercial establishments who declined service to African Americans in violation of the recently enacted 1964 Civil Rights Act", and showed "little patience" for "Southern politicians who incited racial violence and race-baited in their campaigns".[135] According to Politico, the turning point for Buckley was when white supremacists set off a bomb in a Birmingham church on September 15, 1963, which resulted in the deaths of four African American girls.[136] A biographer said that Buckley privately wept about it when he found out about the incident.[136]

Buckley disagreed with the concept of structural racism and placed a large amount of blame for lack of economic growth on the black community itself, most prominently during a highly publicized 1965 debate at the Cambridge Union with African-American writer James Baldwin, in which Baldwin carried the floor vote 544 to 164.[137][138][139] In a 1966 episode of Firing Line with William F. Buckley Jr., "Civil Rights and Foreign Policy", guest Floyd Bixler McKissick was asked whether black power and other concepts could damage black contributions beforehand, McKissick focused in his answer on defining black power: "first of all we mean that black people simply got to determine for themselves the rate of progress, the direction of that progress. And there are six basic ingredients to the accomplishment of black power, and black power is a direction through which you can obtain total equality. And those six points are as follows: One, black people have got to secure for themselves political power. Two, black people have to secure for themselves economic power. Three, black people have got to develop and improve self-image of themselves...Leaving that particular point and going to point four, we'll have to develop militant leadership. And five, we seek enforcement of federal laws, the abolishment of police brutality and the abolishment of police-state tactics, as is in the South. And six, and last, what we mean by black power is the building and acquiring of a black consumer block...if we do not have all basic ingredients that we have talked about we'll never achieve the road to total equality."[140] In response to a question about McKissick's answer, Buckley said: "I endorse all six of those objectives."[140] Buckley also opposed the segregationist 1968 presidential candidate George Wallace, debating against Wallace's platform on a January 1968 episode of Firing Line.[141][142]

Buckley later said he wished National Review had been more supportive of civil rights legislation in the 1960s.[143] He grew to admire Martin Luther King Jr. and supported the creation of Martin Luther King Jr. Day.[144] Buckley anticipated that the U.S. could elect an African-American president within a decade as of the late 1960s and said such an event would be a "welcome tonic for the American soul" that he believed would confer the same social distinction and pride upon African Americans that Catholics had felt upon John F. Kennedy's election.[7] In 2004, Buckley told Time, "I once believed we could evolve our way up from Jim Crow. I was wrong. Federal intervention was necessary."[135] The same year, he endeavored to clarify his earlier comments on race, saying, "[T]he point I made about white cultural supremacy was sociological." Buckley also linked his usage of the word advancement to its usage in the name NAACP, saying that the "call for the 'advancement' of colored people presupposes they are behind. Which they were, in 1958, by any standards of measurement."[145]

Opposition to antisemitism

[edit]During the 1950s, Buckley worked to remove antisemitism from the conservative movement and barred antisemites from working for National Review.[144]

When Norman Podhoretz demanded that the conservative movement banish paleoconservative columnists Patrick Buchanan and Joseph Sobran, who, according to cultural critic Jeffrey Hart, had promulgated a "a neoisolationist nativism tinged with anti-Semitism", Buckley would have none of it, and wrote that Buchanan and Sobran (a colleague of Buckley and formerly a senior editor of National Review) were not antisemitic but anti-Israel.[146]

In 1991, Buckley wrote a 40,000-word article criticizing Buchanan. He wrote, "I find it impossible to defend Pat Buchanan against the charge that what he did and said during the period under examination amounted to anti-Semitism",[147][148] but concluded: "If you ask, do I think Pat Buchanan is an anti-Semite, my answer is he is not one. But I think he's said some anti-Semitic things."[149]

Conservative Roger Scruton wrote: "Buckley used the pages of the National Review to distance conservatism from anti-Semitism and from any other kind of racial stereotyping. The important goal, for him, was to establish a believable stance towards the modern world, in which all Americans, whatever their race or background, could be included, and which would uphold the religious and social traditions of the American people, as well as the institutions of government as the Founders had conceived them."[150]

Buckley's friendship with Ira Glasser, a Jewish American and former executive director of the American Civil Liberties Union, features in the 2020 film Mighty Ira.[151][152]

Foreign policy

[edit]Buckley's opposition to communism extended to support for the overthrow and replacement of leftist governments by nondemocratic forces. Buckley admired Spanish dictator General Francisco Franco, who led the rightist military rebellion in its military defeat of the Spanish Republic, and praised him effusively in his magazine, National Review. In his 1957 "Letter From Spain",[153] Buckley called Franco "an authentic national hero",[153][154] who "above others" had the qualities needed to wrest Spain from "the hands of the visionaries, ideologues, Marxists and nihilists" who had been democratically elected.[155] Buckley also wrote: "however preferable Franco is to Indalecio Prieto, or to anarchy, he is not—at least not all by himself—a legitimate governor of Spain....Franco did not, in virtue of his heroism in the thirties, earn the right to govern absolutely in the fifties."[153] He supported the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet, who led the 1973 coup that overthrew Chilean president Salvador Allende's democratically elected Marxist government; Buckley called Allende "a president who was defiling the Chilean constitution and waving proudly the banner of his friend and idol, Fidel Castro."[156] In 2020, the Columbia Journalism Review uncovered documents that implicated Buckley in a media campaign by the Argentina military junta promoting the regime's image while covering up the Dirty War.[157]

Buckley expressed negative views on Africa and critiqued the nationalist movements against Western colonialism occurring in the 1960s. In 1962 he called African nationalism "self-discrediting" and said "the time is bound to come when" Westerners "realize what is the nature of the beast".[158] In 1961, when asked when Africans would be ready for self-government, he replied, "When they stop eating each other".[159]

Regarding the War in Iraq, Buckley stated, "The reality of the situation is that missions abroad to effect regime change in countries without a bill of rights or democratic tradition are terribly arduous." He added: "This isn't to say that the Iraq war is wrong, or that history will judge it to be wrong. But it is absolutely to say that conservatism implies a certain submission to reality; and this war has an unrealistic frank and is being conscripted by events."[160] In a February 2006 column published at National Review Online and distributed by Universal Press Syndicate, Buckley wrote, "One cannot doubt that the American objective in Iraq has failed" and "it's important that we acknowledge in the inner councils of state that [the war] has failed, so that we should look for opportunities to cope with that failure."[161]

Marijuana

[edit]Бакли поддержал легализацию марихуаны и некоторой другой легализации наркотиков еще в его кандидатуре 1965 года для мэра Нью -Йорка. [162][163] But in 1972, he said that while he supported removing criminal penalties for using marijuana, he also supported cracking down on trafficking marijuana.[164] Бакли написал, что в 2004 году национальный обзор прозамарихуаны для национального обзора в 2004 году он призвал консерваторов изменить свои взгляды на легализацию, написание: «Мы не собираемся найти кого-то, кто баллотируется на пост президента, который выступает за реформирование этих законов. Что такое Требуется подлинная республиканская земля. и сделайте это незаконным только для детей . Это [ 165 ]

Права геев

[ редактировать ]Бакли решительно выступил против однополых браков , но поддержал легализацию гомосексуальных отношений. [ 166 ]

18 марта 1986 года New York Times В сфере СПИД является «особым проклятием гомосексуалиста», он утверждал, что люди, зараженные Бакли обратился к эпидемии СПИДа. Называя это «фактом», что ВИЧ Полем Самое спорно, что он писал: «Все, обнаруженные со СПИДом, должны быть татуированы в верхнем предплечье, чтобы защитить пользователей общего числа и на ягодицах, чтобы предотвратить виктимизацию других гомосексуалистов». [ 167 ] Прочь привела к большой критике; Некоторые гей-активисты выступали за бойкотирование усилий Патрисии Бакли по сбору средств по СПИДу. Бакли позже отступил от произведения, но в 2004 году он сказал журналу New York Times : «Если протокол был принят, многие, кто поймал инфекцию безрассудно, будут живы. Вероятно, более миллиона». [ 168 ]

Шпионский романист

[ редактировать ]В 1975 году Бакли рассказал, что его вдохновили, чтобы написать шпионский роман Фредерика Форсайта « День шакала» : «Если бы я писал книгу художественной литературы, я хотел бы получить что -то в этом роде». [ 169 ] Далее он объяснил, что был полон решимости избежать моральной двусмысленности Грэма Грина и Джона Ле Карре . Бакли написал шпионский роман 1976 года , спасающий королеву , в котором Блэкфорд Оукс в качестве агента ЦРУ, привязанного к правилам, частично основанного на его собственном опыте ЦРУ. В течение следующих 30 лет он писал еще десять романов с участием Oakes. Критик «Нью -Йорк Таймс» Чарли Рубин написал, что сериал «В лучшем случае вызывает Джона О'Хара в его точном смысле места на фоне кипящих классовых иерархий». [ 170 ] Витраж , второй в серии, получил национальную книжную награду 1980 года в категории «Тайна» (в мягкой обложке) 1980 года . [ 171 ] [ B ]

Бакли был особенно обеспокоен тем, что ЦРУ и КГБ делали морально эквивалентны. Он написал в своих мемуарах: «Сказать, что ЦРУ и КГБ участвуют в аналогичных практиках, эквивалентно сказать, что человека, который толкает старушку на путь кружащегося автобуса, не следует отличать от человека, который толкнет Старушка в стороне от дорожного автобуса: на том основании, что, в конце концов, в обоих случаях кто -то толковает старушек ». [ 172 ]

Бакли начал писать на компьютерах в 1982 году, начиная с Zenith Z-89 . [ 173 ] По словам его сына, Бакли развил почти фанатичную верность WordStar , установив его на каждом новом ПК, который он получил, несмотря на растущее устаревание на протяжении многих лет. Бакли использовал его, чтобы написать свой последний роман, и когда его спросили, почему он продолжал использовать что -то настолько устаревшее, он ответил: «Они говорят, что есть лучшее программное обеспечение, но они также говорят, что есть лучшие алфавиты».

Более поздняя карьера

[ редактировать ]

В 1988 году Бакли помог победить либерального республиканского сенатора Лоуэлла Вейкера в Коннектикуте. Бакли организовал комитет для кампании против Вейкера и поддержал своего демократического противника, генерального прокурора Коннектикута Джозеф Либерман . [ 174 ]

В 1991 году Бакли получил президентскую медаль свободы от президента Джорджа Буша . В 1990 году исполнилось 65 лет, он ушел в отставку с повседневной работы Национального обзора . [ 58 ] [ 59 ] В июне 2004 года он отказался от своих контролирующих акций National Review в предварительно выбранную попечительскую комиссию. В следующем месяце он опубликовал мемуары мили, прошедших . Бакли продолжал писать свою колонку с синдицированной газетой, а также статьи для National Review журнала и National Review Online . Он оставался абсолютным источником власти в журнале, а также провел лекции и дал интервью. [ 175 ]

Взгляды на современный консерватизм

[ редактировать ]Бакли раскритиковал определенные аспекты политики в современном консервативном движении. О президентстве Джорджа Буша он сказал: «Если бы у вас был европейский премьер -министр, который испытал то, что мы испытали, ожидается, что он уйдет в отставку или уйдет в отставку». [ 176 ]

По словам Джеффри Харта , написанного в американском консерваторе , у Бакли было «трагическое» представление о войне в Ираке: он «видел это как катастроф Расстояние от администрации Буша .... В конце своей жизни Бакли полагал, что движение, которое он сделал, уничтожило себя, поддерживая войну в Ираке ». [ 177 ] Относительно всплеска войны в Ираке в 2007 году , однако, было отмечено редакторы National Review , что: «Бакли изначально выступил против всплеска, но, увидев его ранний успех, полагал, что он заслужил больше времени для работы». [ 178 ]

В своей колонке от 3 декабря 2007 года, вскоре после смерти своей жены, которую он приписал, по крайней мере частично, ее курению, Бакли, казалось, выступал за запрет употребления табака в Америке. [ 179 ] Бакли написал статьи для Playboy , несмотря на критику журнала и его философию. [ 180 ] Что касается неоконсерваторов , он сказал в 2004 году: «Я думаю, что те, кого я знаю, большинство из них, являются яркими, информированными и идеалистическими, но они просто переоценивают охват власти и влияния США». [ 145 ] [ 181 ] [ 182 ] [ 183 ] [ 184 ]

Смерть и наследие

[ редактировать ]Бакли страдал от эмфиземы и диабета в последующие годы. В колонке в декабре 2007 года он прокомментировал причину своей эмфиземы, сославшись на свою пожизненную привычку курить табак, несмотря на то, что он одобрил его. [ 179 ] 27 февраля 2008 года он умер от сердечного приступа в своем доме в Стэмфорде, штат Коннектикут , в возрасте 82 лет. Первоначально сообщалось, что он был найден мертвым за столом в своем исследовании, обращенном гараже и его сыне, Кристофер Бакли сказал: «Он умер со своими ботинками после жизни, когда она была довольно высокой в седле». [ 47 ] Но в своей книге 2009 года, потеряв мамы и щенка: мемуары , он признал, что этот рассказ был небольшим украшением с его стороны: в то время как его отец умирал в своем учебе, он был найден лежащим на полу. [ 4 ] Бакли был похоронен на кладбище Святого Бернарда в Шароне, штат Коннектикут , рядом со своей женой Патрисией.

Примечательными членами республиканского политического учреждения отдают дань уважения Бакли, включая президента Джорджа Буша, [ 185 ] Бывший спикер палаты представителей Ньют Гингрич и бывшая первая леди Нэнси Рейган . [ 186 ] Буш сказал о Бакли: «Он повлиял на многих людей, включая меня. Он захватил воображение многих людей». [ 187 ] Гингрич добавил: «Билл Бакли стал незаменимым интеллектуальным защитником, чья энергия, интеллект, остроумие и энтузиазм лучший из современного консерватизма вдохновил свое вдохновение и ободрение ... Бакли начал то, что привело к сенатору Барри Голдуотеру и его совестью консерватора , который возглавлял к захвату власти консерваторами из умеренного учреждения в Республиканской партии . [ 188 ] Вдова Рейгана, Нэнси, сказала: «Ронни ценил адвоката Билла на протяжении всей своей политической жизни, и после смерти Ронни Билл и Пэт были для меня во многих отношениях». [ 187 ] Дом меньшинства Кнут Рой Блант заявил, что «Уильям Ф. Бакли был не чем журналистом или комментатором. Он был неоспоримым лидером консервативного движения, которое заложило основу для революции Рейгана. Каждый республиканец должен ему благодарность за его неуправляемые усилия. от имени нашей партии и нации ". [ 189 ]

Различные организации имеют награды и награды, названные в честь Бакли. [ 190 ] [ 191 ] Межвузовский институт исследований присуждает премию Уильяма Ф. Бакли за выдающуюся журналистику кампуса. [ 192 ]

Язык и идиосе

[ редактировать ]Бакли был хорошо известен своим командованием языка. [ 193 ] Он опоздал на официальное обучение на английском языке, не изучая его, пока ему не исполнилось семи лет, и ранее изучив испанский и французский. [ 16 ] Мишель Цай в Слайне говорит, что он говорил по-английски с уникальным акцентом: что-то между старомодным, высшим атлантическим акцентом , и британцы получили произношение , но с южным притяжением . [ 194 ] Социолог Патриция Ливи назвала его «Высшей церковью Бакли, среднеатлантическим акцентом (преподавался актерами в голливудских студиях 1930-х и 1940-х годов), который был сжат восходящей настойкой южного розыгрыша, которая несколько смягчилась над сверхусимой, которая очень вероятала во время его образование в Йельском университете ». [ 195 ]

Профессор политологии Джеральд Л. Хаусман писал, что хваленняя любовь Бакли к языку не обеспечила качество его письма и раскритиковал некоторые работы Бакли для «Неуместных метафоров и неэлегантного синтаксиса» и за его привычку в его привычке в своих цитатах о в скобках. Ссылки на «темперамент или мораль» тех, кто цитируется. [ 196 ]

Риторический стиль

[ редактировать ]На линии стрельбы у Бакли была репутация вежливости для своих гостей. Но он также иногда мягко дразнил своих гостей, если они были друзьями. [ 197 ] Иногда во время горячих дебатов, как и в случае с Gore Vidal , Бакли стал менее вежливым. [ 198 ] [ 199 ]

Эпштейн (1972) говорит, что либералы были особенно очарованы Бакли и часто хотели обсудить его, отчасти потому, что его идеи напоминали их собственные, поскольку Бакли обычно сформулировал его аргументы в ответ на левое мнение, а не основывалось на консервативных принципах которые были чужды либералам. [ 200 ]

Аппель (1992) из риторической теории утверждает, что эссе Бакли часто написаны в «низких» бурлеск в манере Сэмюэля Батлера сатирического стихотворения Худибраса . Считается как драма, такой дискурс включает в себя черно-белое расстройство, логик, занимающийся виной, искаженные противники клоуна, ограниченное отпущение козла и корыстное искупление. [ 201 ]

Ли (2008) утверждает, что Бакли представил новый риторический стиль, который консерваторы часто пытались подражать. «Гладиаторский стиль», как его называет Ли, является ярким и воинственным, наполненным звуковыми укусами и приводит к воспалительной драме. Поскольку консерваторы столкнулись с аргументами Бакли о правительстве, либерализме и рынках, театральной привлекательности гладиаторского стиля Бакли вдохновила консервативных подражателей, став одним из главных шаблонов консервативной риторики. [ 202 ]

Натан Дж. Робинсон , пишущий в текущих делах о роли Бакли в качестве крупного консервативного интеллектуала, говорит: «Бакли создал шаблон консервативного интеллектуализма, который все еще используется сегодня: быть глином, уверенный и некоторые ссылки на классику. [ 203 ]

Прием

[ редактировать ]Джордж Х. Нэш , историк современного американского консервативного движения, заявил в 2008 году, что Бакли был, пожалуй, самым важным общественным интеллектуалом в Соединенных Штатах за последние полвека. Для целого поколения он был выдающимся голосом американского консерватизма и его первая великая экуменическая фигура ". [ 204 ] И наоборот, политический консультант Стюарт Стивенс , который занимал должность лучшего стратега в президентской кампании Митта Ромни в 2012 году. [ 205 ] А позже, как ведущая фигура с проектом Линкольна , пишет, что «несмотря на все его хорошо продуманные предложения и любовь к языку, Бакли часто был более четкой версией того же глубокого уродства и фанатизма, которая является отличительной чертой трупизма ». [ 206 ]

Писатель New York Times Дуглас Мартин писал о нем: «Самым большим достижением мистера Бакли было создание консерватизма не только избирательного республиканизма, но и консерватизма как системы идей, респектабельных в либеральной после Второй мировой войне. Он мобилизовал молодых энтузиастов, которые помогли назначить Барри Голдотер. В 1964 году и увидел, как его мечты исполнились, когда Рейган и кусты захватили овальный кабинет ». [ 207 ]

Консервативный обозреватель Джордж Уилл сказал о Бакли: «Без Билла Бакли, без национального обзора . Без национального обзора , без выдвижения Голдуотер. Без выдвижения Голдуотер нет консервативного поглощения Республиканской партии. Без этого не Рейган. Без Рейгана нет победы в Холодная война. [ 208 ] Джеймс Карден прокомментировал: «Рассуждения Уилла страдают, как мог сказать сам Бакли, из пост -hoc, ergo propter hoc fallacy ». [ 209 ]

В популярной культуре

[ редактировать ]- В фильме 1991 года Хоффман Дастин основал свои вокальные манеры как капитан Хук на Бакли. [ 210 ]

- В фильме 1992 года «Аладдин» ( Джинн озвученный Робин Уильямс ) выдал себя за Бакли. [ 211 ] [ 212 ]

- Фильм 2016 года X-Men: Apocalypse кратко показывает кадры Buckley в телевизионном новостном клипе. [ 213 ] [ 214 ]

- Бакли появляется в Джеймса Грэма игре в 2021 году «Лучшая от врагов» . Пьеса представляет собой выдуманную пересказ дебатов Бакли-Видала 1968 года.

- В 2023 году МИНИСЕРИЯ МАКСИОНАЯ МИНИСЕРИЯ МИНИСЕРИЯ БАКЛИ изображает Питер Серафинович , как друг семьи Э. Ховарда Ханта.

Работа

[ редактировать ]Пояснительные заметки

[ редактировать ]- ^ «Уильям Фрэнсис» в редакционном некрологе «от либерализма», The Wall Street Journal , 28 февраля 2008 г., с. A16; Мартин, Дуглас, «Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший, 82 года, умирает; Sesquipedalian Spark of Right», Некролог, The New York Times , 28 февраля 2008 года, которая сообщила, что его родители предпочли «Фрэнк», что сделало бы его ». Младший ", но в его крещении священник" настаивал на имя святого, так что Фрэнсис был выбран. Он стал Уильямом Ф. Бакли -младшим. "

- ^ С 1980 по 1983 год. В «Истории национальной книжной премии» были представлены двойные награды за книги в твердом переплете и книги в мягкой обложке во многих категориях. Большинство победителей в мягкой обложке были перепечатки, в том числе эта.

Ссылки

[ редактировать ]Цитаты

[ редактировать ]- ^ Италию, Хиллель (27 февраля 2008 г.). «Автор, консервативный комментатор Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший умирает в 82» . KVIA.com. Ассошиэйтед Пресс. Архивировано из оригинала 18 апреля 2021 года . Получено 21 ноября 2020 года .

- ^ «Испанский говорящий Уильям Ф. Бакли» . Инакомыслительный журнал . Получено 14 апреля 2023 года .

- ^ "Cumulus.hillsdale.edu" . Архивировано из оригинала 25 мая 2010 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Мартин, Дуглас (27 февраля 2008 г.). «Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший мертв в 82» . New York Times . Архивировано из оригинала 28 февраля 2008 года . Получено 27 февраля 2008 года .

- ^ The Wall Street Journal , 28 февраля 2008 г., с. A16

- ^ Перлштейн, Рик , Неправдоподобный мистер Бакли: новый документальный фильм PBS, побеждающий консервативного основателя National Review , Адского треугольника , американский проспект , 17 апреля 2024 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Фельценберг, Элвин (13 мая 2017 г.). «Как Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший передумал на гражданские права» . Журнал Politico . Получено 11 апреля 2023 года .

- ^ C-Span BookNotes 23 октября 1993 г.

- ^ Бакли, Уильям Ф. младший. Счастливые дни были здесь снова: размышления либертарианского журналиста , Рэндом Хаус, ISBN 0-679-40398-1 , 1993.

- ^ «Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший и консервативное движение» . Институт Билля о правах . Получено 25 марта 2023 года .

- ^ «Человек, стоящий за современным консервативным движением, с Сэмом Таненхаусом» . Нисканен Центр. 17 марта 2021 года . Получено 25 марта 2023 года .

- ^ Боаз, Дэвид (28 февраля 2008 г.). «Билл Бакли мертв. Сан консерватизм умер с ним?» Полем Сан -Франциско Хроника . Получено 25 марта 2023 года .

- ^ «Происхождение Уильяма Ф. Бакли» . www.wargs.com . Архивировано из оригинала 21 июня 2018 года . Получено 18 февраля 2014 года .

- ^ "Национальная циклопедия американской биографии: быть историей Соединенных Штатов, как показано в жизни основателей, строителей и защитников республики, а также мужчин и женщин, которые делают работу и формируют мысль о настоящем Время" . Университетские микрофильмы. 1 января 1967 года - через Google Books.

- ^ Judis 2001 , p. 29

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Бакли, Уильям Ф. младший (2004). Майлз прошел мимо: литературная автобиография . Регнери издательство. Ранние главы рассказывают о его раннем образовании и мастерстве языков.

- ^ «Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший - Calvert Homeschooler» . Calvert Blog Network - выпускники . Calvert Education. 28 января 2014 года. Архивировано с оригинала 2 апреля 2015 года . Получено 18 марта 2015 года .

- ^ «Алоаз Бакли Хит» . Новости и курьер . 21 января 1967 года . Получено 11 марта 2013 года . [ Постоянная мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ Judis 2001 , стр. 103, 312-316.

- ^ Бакли, Уильям Ф. младший (2008). Давайте поговорим о многих вещах: собранные речи . Основные книги. п. 466. ISBN 978-0-7867-2689-9 Полем Архивировано из оригинала 19 января 2023 года . Получено 3 июня 2022 года .

- ^ Эдвардс 2014 , с. 16

- ^ Нок, Альберт Джей (1937). Наш враг, государство . Людвиг фон Мизес Институт. С. 165–168. ISBN 978-1-61016-372-9 .

- ^ «Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший и Симфония Феникса» . Линия стрельбы . Архивировано из оригинала 17 декабря 2021 года . Получено 8 января 2019 года - через YouTube.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Еще раз, Бакли берет на Баха», а архивировал 5 марта 2016 года на машине Wayback ; New York Times ; 25 октября 1992 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Уильям Ф. Бакли, младший» . Безумно о музыке . WNYC . Получено 18 сентября 2020 года - через американский архив общественного вещания .

- ^ «Джазовый фестиваль Танглвуда, 1–3 сентября 2006 года в Ленокс, штат Массачусетс» . Allaboutjazz.com. 2 августа 2006 г. Архивировано с оригинала 6 июля 2012 года . Получено 6 мая 2015 года .

- ^ «Час с редактором Уильямом Ф. Бакли -младшим». Полем Чарли Роуз . 24 марта 2006 г. 50:43 минуты. Pbs. Архивировано из оригинала 16 декабря 2014 года.

- ^ Фелан, Мэтью (28 февраля 2011 г.) Сеймур Херш и люди, которые хотят, чтобы он совершил архив 2 марта 2011 года, на машине Wayback , Salon.com

- ^ Buckley 1997 , p. 241.

- ^ Buckley 1997 , p. 30

- ^ Buckley 1997 , p. 37

- ^ «Уильям Ф. Бакли на новой мессе» . Архивировано из оригинала 17 июня 2008 года . Получено 11 июля 2008 года .

- ^ «Увлечение Уильяма Ф. Бакли итальянской мистикой Марии Вальтта» . Архивировано из оригинала 27 декабря 2010 года . Получено 25 декабря 2010 года .

- ^ Judis 2001 , p. 49-50.

- ^ Роббинс, Александра (2002). Секреты гробницы: череп и кости, Лига плюща и скрытые пути власти . Бостон: Маленький, Браун . п. 41. ISBN 0-316-72091-7 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в «Бакли, Уильям Ф. (Ранг) младший (1925–2008) Биография» . Получено 27 февраля 2008 года . [ мертвая ссылка ]

- ^ «База данных о рукописях и архивах цифровых изображений (Мадид)» . Архивировано с оригинала 3 марта 2016 года . Получено 27 мая 2010 года .

- ^ «Ричард Шапиро выигрывает дебаты в PU о помощи в Китае» . Йельский ежедневный новости . 22 января 1948 года . Получено 28 апреля 2018 года - Via Yale Daily News Исторический архив, библиотека Йельского университета.

- ^ Diamond, Sigmund (1992). Скомпрометированный кампус: сотрудничество университетов с разведывательным сообществом, 1945–1955 . Нью -Йорк: издательство Оксфордского университета . ISBN 978-0-19-505382-1 Полем Глава 7 посвящена Бакли.

- ^ «История» . Остервейс дебатный турнир . Йельская дискуссионная ассоциация | Остервейс Турнир. Архивировано с оригинала 12 сентября 2019 года . Получено 14 марта 2020 года .

- ^ Воган, Сэм (1996). «Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший, искусство художественной литературы № 146» . Парижский обзор . Тол. Лето 1996, нет. 139 Получено 6 апреля 2021 года .

- ^ Бакли, Уильям Ф. младший (4 марта 2007 г.). "Мой друг, Э. Говард Хант" . Los Angeles Times . ISSN 0458-3035 . Архивировано из оригинала 18 мая 2015 года . Получено 6 мая 2015 года .

- ^ TAD SZULC, Compulsive Spy: Странная карьера Э. Говарда Ханта (Нью -Йорк: Викинг, 1974)

- ^ «Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший» . Салон . 3 сентября 1999 года. Архивировано с оригинала 27 сентября 2020 года . Получено 2 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Мартин, Дуглас (27 февраля 2008 г.). «Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший мертв в 82» . International Herald Tribune . Архивировано из оригинала 25 мая 2010 года . Получено 27 февраля 2008 года .

- ^ CNN 27 февраля 2008 г. Архивировано 5 июня 2008 г. на The Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Бак, Ринкер (28 февраля 2007 г.). «Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший 1925–2008 гг . Хартфорд Курант . Архивировано из оригинала 3 марта 2008 года . Получено 1 марта 2008 года .

- ^ «Боб Колацелло на Пэт и Билл Бакли» . Тщеслаковая ярмарка . Декабрь 2008 года. Архивировано с оригинала 28 июля 2017 года . Получено 22 октября 2019 года .

- ^ Игрушка, Вивиан С. (18 марта 2010 г.). «Либеральное снижение цен» . New York Times . Архивировано с оригинала 6 марта 2019 года . Получено 5 марта 2019 года .

- ^ Почему все работает в Швейцарии, а не в США? » Архивировано 17 декабря 2021 года на линии стрельбы по машине Wayback с Уильямом Ф. Бакли -младшим , EP. 850, 22 февраля 1990 года. Гости: Эван Дж. Гэлбрейт и Жак Фреймонд . Полная стенограмма доступна в учреждении Гувера .

- ^ Countryman, Верн (1952). Обзор «Уильяма Ф. Бакли, Бога и Человека в Йельском университете ». Йельский юридический журнал архивировал 9 октября 2016 года в The Wayback Machine , 61.2: 272–283 («Однажды был маленький мальчик по имени Уильям Бакли. Хотя он был очень маленьким мальчиком, он был слишком большим для своего Сваи. »).

- ^ Банди, Макджордж (1 ноября 1951 г.). «Атака на Йельский университет» . Атлантика .

- ^ Чемберлен, Джон , Жизнь с печатным словом , Чикаго: Регнери , 1982, с. 147

- ^ Макканн, Дэвид Р.; Штраус, Барри С. (2015). Война и демократия: сравнительное исследование корейской войны и пелопоннеса . Routledge.

- ^ Judis 2001 , p. 103

- ^ Бакли (младший), Уильям Ф.; Бозелл, Л. Брент (1954). Маккарти и его враги: запись и ее значение . Х. Регнери Компания. п. 335. ISBN 978-0-89526-472-5 .

- ^ Буккола, Николас (2020). Огонь на нас: Джеймс Болдуин, Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший и дебаты о гонке в Америке . ПРИЗНАЯ УНИВЕРСИТЕТА ПРИСЕТА. С. 62–63. ISBN 978-0-691-21077-3 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Encyclopedia.com 10 июня 1990 г. Архивировано 12 января 2009 г. на The Wayback Machine

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Воспоминание» . Национальный обзор онлайн . Архивировано с оригинала 9 января 2009 года.

- ^ Филлипс-Фейн, Ким; «Консерватизм: состояние поля», журнал американской истории , (декабрь 2011 г.) Vol. 98, № 3, с. 729.

- ^ Нэш, Джордж Х.; Консервативная интеллектуальная традиция с 1945 года (1976)

- ^ Diggins, John P.; «Товарищи Бакли: бывший коммунист как консерватор», инакомыслие , июль 1975 г., вып. 22 № 4, с. 370–386

- ^ Смант, Кевин; «Куда консерватизм? Джеймс Бернхэм и National Review , 1955–1964», «Непрерывность» , № 15 (1991), с. 83–97.

- ^ Смант, Кевин; Принципы и ереси: Фрэнк С. Мейер и формирование американского консервативного движения (2002) с. 33–66.

- ^ Роджер Чепмен, Культурные войны: энциклопедия проблем, точек зрения и голосов (2009) Vol. 1 р. 58

- ^ «Айн Рэнд, Rip», National Review , 2 апреля 1982 года.

- ^ Бернс, Дженнифер; Богиня рынка: Айн Рэнд и американское право, 1930–1980 (2010) с. 162.

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (28 декабря 1957 г.). «Большая сестра смотрит на тебя» . Национальный обзор . Архивировано из оригинала 13 октября 2007 года . Получено 13 октября 2007 года . (Онлайн переиздание, 12 октября 2007 г.)

- ^ Chambers, Whittaker (28 декабря 1957 г.). «Большая сестра смотрит на тебя» . Национальный обзор . Архивировано с оригинала 30 июня 2013 года . Получено 18 марта 2012 года - через WhittakerChambers.org. (Онлайн переиздание.)

- ^ Buckley, William F., Jr.; «Примечания к эмпирическому определению консерватизма»; В Мейере, Фрэнк С. (ред.): Что такое консерватизм? (1964), с. 214

- ^ Бернс, Дженнифер; «Безбожный капитализм: Айн Рэнд и консервативное движение», «Современная интеллектуальная история » , (2004), 1 (3), с. 359–385

- ^ Бакли, Уильям Ф., младший. «Голдуотер, Общество Джона Берча и меня», архивные 30 ноября 2012 года, на машине Wayback . Комментарий (март 2008 г.).

- ^ Хеммер, Николь (2016). Посланники права: консервативные СМИ и трансформация американской политики . Университет Пенсильвании Пресс. п. 189. ISBN 978-0-8122-9307-4 .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Фельценберг, Элвин (19 июня 2017 г.). «Как Уильям Ф. Бакли стал привратником консервативного движения» . Национальный обзор . Получено 18 декабря 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Элвин, Фелценберг (20 июня 2017 г.). «Внутренняя история о крестовом походе Уильяма Ф. Бакли -младшего против общества Джона Берча» . Национальный обзор . Получено 18 декабря 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Фельценберг, Элвин. Человек и его президенты: политическая одиссея Уильяма Ф. Бакли -младшего .

- ^ «Сроки и история» . Общество Джон Берч . Архивировано из оригинала 3 декабря 2020 года . Получено 19 декабря 2020 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Фриман, Нил Б. «Правило Бакли - по словам Билла, а не Карла» . Национальный обзор онлайн . Архивировано из оригинала 16 декабря 2014 года . Получено 20 февраля 2014 года .

- ^ Мердок, Дерок (8 ноября 2016 г.). «Следуйте по стандарту Бакли: проголосуйте за Трампа» . Национальный обзор онлайн . Архивировано с оригинала 14 ноября 2020 года . Получено 14 марта 2020 года .

- ^ Берри, Джон Ф. (8 февраля 1979 г.). «Бакли соглашается погасить 1,4 миллиона долларов в случае мошенничества» . The Washington Post . ISSN 0190-8286 . Получено 14 марта 2022 года .

- ^ Магнусон, изд (16 ноября 1981 г.). «Свободное предприятие, стиль Бакли» . Время . ISSN 0040-781X . Архивировано из оригинала 14 марта 2022 года . Получено 14 марта 2022 года .

- ^ Корлз, Филипп. «Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший, кандидат в мэры, по политической риторике и театре, 1965» . Wnyc.org . Нью -Йорк Общественное радио . Архивировано из оригинала 27 мая 2020 года . Получено 14 марта 2020 года .

- ^ Кеслер, Чарльз Р.; Kienker, John B. (2012). Жизнь, свобода и стремление к счастью: десять лет обзора Клермонт книг . Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. п. 86. ISBN 978-1-4422-1335-7 .

- ^ «Уильям Ф. Бакли-младший: ведьма-ведьма мертва» . Capmag.com. 10 марта 2008 года. Архивировано с оригинала 14 января 2010 года . Получено 6 мая 2015 года .

- ^ «Macdonald & Associates: Facts Forum Press Replesительство» . jfredmacdonald.com. Архивировано с оригинала 12 января 2011 года . Получено 13 июня 2011 года .

- ^ Judis 2001 , p. 185-198, 311.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Мэннинг, Лона (9 октября 2009 г.). «Эдгар Смит: великий предушник» . Криминальный журнал . Архивировано из оригинала 3 января 2010 года . Получено 10 марта 2007 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в дюймовый Стаут, Дэвид (24 сентября 2017 г.). «Эдгар Смит, убийца, который обманул Уильяма Ф. Бакли, умирает в 83 года» . New York Times . Архивировано с оригинала 25 сентября 2017 года . Получено 25 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ «Как убийца обманул Уильяма Ф. Бакли -младшего, чтобы бороться за его освобождение» . New York Post . 19 февраля 2022 года. Архивировано из оригинала 19 февраля 2022 года . Получено 30 мая 2022 года .

- ^ Джонатан Шенвальд, время для выбора: рост современного американского консерватизма (2002), стр. 162–189

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Таненхаус, Сэм (2 октября 2005 г.). «Эффект Бакли» . New York Times . Архивировано из оригинала 24 сентября 2008 года . Получено 12 ноября 2007 года .

- ^ «Перево пива с Уильямом Ф. Бакли -младшим» . Los Angeles Daily News . 28 февраля 2008 г.

- ^ Перлштейн, Рик (2008). Никсонленд: рост президента и разрушение Америки . Саймон и Шустер. С. 144–146. ISBN 978-0-7432-4302-5 .

- ^ Розен, Джеймс (7 сентября 2015 г.). «Длинное, жаркое лето 68» . Национальный обзор . 67 (16): 37–42. Архивировано с оригинала 19 января 2017 года . Получено 28 сентября 2015 года .

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный в Гринбаум, Майкл М. (24 июля 2015 г.). «Бакли против Видала: когда дебаты стали кровью» . The New York Times (Нью -Йорк, ред.). п. 12. EISSN 1553-8095 . ISSN 0362-4331 . OCLC 1645522 . Архивировано из оригинала 5 сентября 2021 года . Получено 14 декабря 2021 года .

В ночь беспорядков на демократической конвенции в Чикаго у Бакли и Видала было свое климатическое столкновение в эфире. Видал назвал Бакли «крипто-нацистом», вызвав реакцию, которая все еще оглушает. «А теперь послушай, ты странный,-ответил Бакли,-перестань называть меня крипто-нацистом, или я буду носку на тебя на чертовье, и ты останешься намазанным».

- ^ Esquire (август 1969), с. 132

- ^ Видал, Гор (сентябрь 1969 г.). «Неприятная встреча с Уильямом Ф. Бакли -младшим» . Esquire . С. 140–145, 150. Архивировано из оригинала 16 февраля 2005 года . Получено 28 февраля 2008 года .

- ^ Колацелло, Боб (январь 2009 г.). "Мистер и миссис справа" . Тщеслаковая ярмарка . Архивировано из оригинала 28 июля 2017 года . Получено 22 июня 2016 года .

В последующих произведениях в Эсквайре Бакли сосредоточился на гомосексуальных темах в работе Видала, и Видал ответил, подразумевая, что Бакли был гомосексуалистом и антисемитом, после чего Бакли подал в суд и Видал противостоял.

- ^ «Бакли бросает видал костюм, соглашается с Esquire» . New York Times . 26 сентября 1972 года. Архивировано с оригинала 24 января 2016 года . Получено 22 июня 2016 года .

Г-н Гингрих подтвердил, что Esquire опубликует заявление в своем ноябрьском выпуске, дезавуавшем «самые яркие заявления» статьи Vidal, называя г-на Бакли «расистским, антиблаком, антисемитским и прокрипто-нацистом».

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный «Национальный обзор» . Национальный обзор . Архивировано из оригинала 26 августа 2009 года.

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Мерфи, Джаррет (20 декабря 2004 г.). «Бакли и Видал: еще один раунд» . Архивировано из оригинала 21 октября 2019 года . Получено 21 октября 2019 года .

- ^ Национальный обзор архив 9 января 2009 г., на машине Wayback

- ^ Мартин, Дуглас (27 февраля 2008 г.). «Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший мертв в 82» . New York Times . Архивировано из оригинала 1 июля 2017 года . Получено 23 февраля 2017 года .

- ^ Линия стрельбы , эпизод 415, «Аллард Лоуэнштейн: ретроспектива» (18 мая 1980 г.) Архивировано 4 ноября 2013 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Бакли, Уильям Ф., младший, на линии стрельбы: общественная жизнь наших общественных деятелей , 1988, с. 423–434

- ^ Sydney Morning Herald , «Мордант остроумие, расположенное на вершине Манхэттенского общества (Пэт Бакли, 1926-2007)», архивировано 24 сентября 2015 года на машине Wayback ; МакГиннесс, Марк; 28 апреля 2007 г.

- ^ The Daily Beast , «Бакли выдыхается из National Review », архивировав 21 июля 2012 года в The Wayback Machine , Кристофер Бакли, 14 октября 2008 г.

- ^ C-Span, "Conservative v. Либеральная идеология" Архивирована 3 ноября 2013 года, на The Wayback Machine (дебаты: Уильям Ф. Бакли против Джорджа С. Макговерн), Университет штата Юго-Восточный Миссури, 10 апреля 1997 года.

- ^ Институт Гувера, Стэнфордский университет, библиотека и архив, Архив линии стрельбы архив 23 апреля 2015 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Бакли, Уильям Ф. (13 апреля 1970 года). "Amnesty International". Ньюарк Адвокат . п. 4

- ^ Монтгомери, Брюс П. (весна 1995). «Архивирование прав человека: записи Amnesty International USA» . Архивария (39): 108–131. Архивировано из оригинала 1 августа 2008 года . Получено 11 апреля 2008 года .

- ^ Judis 2001 , Ch. 10

- ^ Small, Melvin (1999). Президентство Ричарда Никсона. Университетская пресса Канзаса. ISBN 0-7006-0973-3 .

- ^ Лоуренс Юрдем. 25 октября 2016 года. Когда National Review наконец-то имело достаточно Ричарда Никсона: хор неодобрения: http://laurencejurdem.com/2016/10/when-national-review-finally-had-onouth-frichard-nixon- a-chorus-of-opploval/ Archived 12 марта 2018 года на The Wayback Machine

- ^ TAD SZULC. 29 июля 1971 года. 11 Консерваторы критикуют Никсон Нью -Йорк Таймс. стр. 7. https://www.nytimes.com/1971/07/29/archives/11-conservatives-criticize-nixon-gal-by-william-buckley-they.html Архивировано 12 марта 2018 года на машине Wayback

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Редман, Эрик. «Уильям Бакли сообщает о службе» . New York Times . Получено 14 марта 2020 года .

- ^ «Бакли и Рейган, сражаясь с хорошим боем» . Национальный обзор . 27 апреля 2010 года. Архивировано с оригинала 24 ноября 2022 года . Получено 24 ноября 2022 года .

- ^ Фелнер, Эдвин Дж. (1998). Марш свободы: современная классика в консервативной мысли . Spence Publishing Company. п. 9. ISBN 978-0-9653208-8-7 .

- ^ «Вспоминая уродливое время» . New York Times . 24 февраля 2003 года. Архивировано с оригинала 25 января 2021 года . Получено 2 сентября 2020 года .

- ^ Маклин, Нэнси; Свободы недостаточно: открытия американского рабочего места (2008) с. 46

- ^ Виленц, Шон; Эпоха Рейгана: история, 1974–2008 гг. (HarperCollins, 2009) с. 471

- ^ Jump up to: а беременный Judis 2001 , p. 138.

- ^ Бакли, Уильям Ф. (24 августа 1957 г.). «Почему Юг должен преобладать» (PDF) . Национальный обзор . Тол. 4. С. 148–149. Архивировано (PDF) из оригинала 27 марта 2019 года . Получено 16 сентября 2017 года .

- ^ Уитфилд, Стивен Дж.; Смерть в Дельте: история Эмметт Тилль (издательство Джона Хопкинса Университета), с. 11

- ^ Лотт, Джереми; Уильям Ф. Бакли -младший (2010) с. 136

- ^ Креспинон, Джозеф; В поисках другой страны: Миссисипи и консервативная контрреволюция (Princeton University Press, 2007) с. 81–82